Университет Шеффилда

| ||||||||||||||

| Девиз | Латынь : знать причины вещей. | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Девиз на английском языке | Чтобы обнаружить причины вещей | |||||||||||||

| Тип | Государственный исследовательский университет | |||||||||||||

| Учредил | 1905 — Шеффилдский университет. Предшественники: 1828 – Медицинская школа Шеффилда. 1879 – Firth College 1884 – Sheffield Technical School[1] 1897 – University College of Sheffield[2] | |||||||||||||

| Endowment | £47.1 million (2023)[3] | |||||||||||||

| Budget | £880.2 million (2022/23)[3] | |||||||||||||

| Chancellor | Lady Justice Rafferty | |||||||||||||

| Vice-Chancellor | Koen Lamberts[4] | |||||||||||||

Academic staff | 3,610 (2021/22)[5] | |||||||||||||

Administrative staff | 4,225 (2021/22)[5] | |||||||||||||

| Students | 30,860 (2021/22)[6] | |||||||||||||

| Undergraduates | 20,040 (2021/22)[6] | |||||||||||||

| Postgraduates | 10,820 (2021/22)[6] | |||||||||||||

| Location | , , England 53°22′51″N 1°29′20″W / 53.3807°N 1.4888°W | |||||||||||||

| Campus | Urban | |||||||||||||

| Colours | Black & gold | |||||||||||||

| Affiliations | ||||||||||||||

| Website | sheffield | |||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

Университет Шеффилда (неофициально Шеффилдский университет) [7] [8] или ТУОС ) [9] [10] — государственный исследовательский университет в Шеффилде , Южный Йоркшир , Англия. Его история восходит к основанию Шеффилдской медицинской школы в 1828 году, Ферт-колледжа в 1879 году и Шеффилдской технической школы в 1884 году. [1] Университетский колледж Шеффилда впоследствии был образован путем слияния трех учреждений в 1897 году и получил королевскую хартию как Университет Шеффилда в 1905 году от короля Эдуарда VII .

Шеффилд состоит из 50 академических факультетов, которые разделены на пять факультетов и международный факультет. Годовой доход учреждения на 2022–2023 годы составил 880,2 миллиона фунтов стерлингов, из которых 198,6 миллиона фунтов стерлингов были получены от исследовательских грантов и контрактов, а расходы составили 790,5 миллиона фунтов стерлингов. [3] Известный ведущими в мире инженерными исследованиями, университет сотрудничает с Гарвардом и Массачусетским технологическим институтом. [11] и партнерские отношения с более чем 125 компаниями, включая BAE Systems , Siemens , Boeing , Rolls-Royce и Airbus площадью 150 акров , в Парке передовых производств . [12] Шеффилд входит в десятку лучших университетов Великобритании по финансированию исследовательских грантов. [13] and it has become number one in the UK for income and investment in engineering research according to new data published by the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA).[14]

The university is one of the original red brick universities and a founding member of the Russell Group. It is also part of the Worldwide Universities Network, the N8 Group of the eight most research intensive universities in Northern England and the White Rose University Consortium. Sheffield has been ranked in between 66th and 104th best university in the world by QS for the last fifteen years.[15] ARWU ranked Sheffield 9th overall in the UK[16] and THE ranked the university 22nd in Europe for teaching excellence.[17][18] According to the latest Research Excellence Framework 2021, Sheffield is ranked 11th in the UK for research power calculated by multiplying the institution's GPA by the total number of full-time equivalent staff submitted.[19]

There are eight Nobel laureates affiliated with Sheffield and six of them are the alumni or former long-term staff of the university.[20] They are contributors to the development of penicillin, the discovery of the citric acid cycle, the investigation of high-speed chemical reactions, the discovery of introns in eukaryotic DNA, the discovery of fullerene, and the development of molecular machines. Alumni also include several heads of state, Home Secretaries, Court of Appeal judges, Booker Prize winners, astronauts and Olympic gold medallists.

History[edit]

Origins[edit]

The University of Sheffield was originally formed by the merger of three local institutions: the Sheffield School of Medicine, Firth College, and the Sheffield Technical School. With a history dating back to as early as the 1810s, the Sheffield School of Medicine is the university's oldest predecessor institution, which is also the oldest higher education establishment in Sheffield. In 1795, the General Infirmary was opened, becoming the first hospital in the city. Because of the apprenticeship-type training, the medical education at that time was largely unstructured. Regarded as the father of Sheffield's medical education, surgeon apothecary Hall Overend began to train medical students in 1811.[21] His school of anatomy and medicine was externally recognised in 1828,[22] and he conducted and taught human dissection in an anatomy museum at his home in Church Street. Overend, however, was not officially registered as a lecturer with the Society of Apothecaries, a recognised body for medical education.[23] Physicians and surgeons of the General Infirmary suggested that a school associated with the hospital would be highly eligible for recognition by the society. As a result, in 1828, a public meeting was called by physician Sir Arnold Knight, and supported by Overend, to establish a new medical school. The Sheffield Medical Institution was formally opened a year later in 1829 on Surrey Street, with the Latin motto Ars longa vita brevis (Art is long, life is short), which refers to the difficulty to acquire and practice the art of Medicine.[24] Knight laid the foundation stone and delivered the opening lecture.[25][23]

The University Extension Movement emerged in the 1870s with the aim of providing education in the city which lacked any tertiary institutions.[26] During the period, the steel industry in Sheffield was prospering and the city's population was doubled to around 240,000 from the 1840s.[1] In 1871, the university extension scheme arrived in Sheffield, and a group of lecturers from the universities of Oxford and Cambridge travelled to the city giving lectures and educating people about the benefits of tertiary education. Steel manufacturer and former mayor of Sheffield Mark Firth and clergyman Samuel Earnshaw therefore organised courses in English literature and political economy. The courses became popular so Firth decided to donate £20,000 and purchase a site in the city centre (now Leopold Street and West Street) in 1877 to build a new institution for the classes.[1] Firth College was founded during Firth's late year in 1879 and developed out of the Extension Movement scheme to teach arts and pure science subjects.[27] The college saved the medical school, which had an insecure early history, from collapse and took over the teaching of all background subjects to medical students.[28] In 1888 the medical school was relocated, opposite Firth College, to a new building on Leopold Street.[25]

Firth College also helped to fund the opening of the Sheffield Technical School in 1884 to teach applied science, the only major faculty the existing colleges did not cover. The Sheffield Technical School was created by collecting funds within Firth College because of local concern about the need for technical training, particularly steelmaking in Sheffield. Former mayor of Sheffield Sir Frederick Mappin started to fundraise for the school and £10,240 was raised.[29] A grant was secured in 1883 to fund a professor of Metallurgy and Mechanical Engineering.[1] Many of the steel-making firms in Sheffield contributed to funding the Technical School, and research from the school in turn helped develop new processes and products for the companies.[30] The Technical School was originally founded as a new technical department in Firth College, and in 1886, the school moved to St George's Square (later renamed Charlotte Street and now Mappin Street) on the site of the old Grammar School.[28] William Ripper was appointed as Head of Mechanical Engineering at Firth College from 1889, then Principal of Sheffield Technical School.

Foundation[edit]

Sheffield was at that time the only large city in England without a university. William Mitchinson Hicks, who was Principal of Firth College from 1892 to 1897, had an ambition to establish a university in the city.[31] As a first stage of his ideal, Hicks was devoted to the union of the three higher education institutions in Sheffield and to transform Firth College into a university college. He also extended the college by creating new departments and adding new buildings.[31] In 1897, Firth College merged with the Medical School and the Technical School to form the University College of Sheffield, and Hicks served as its first principal.[1][28] Six years since the foundation of the university college, on 18 May 1903, the resolution to apply for a royal charter was passed.[32] The university college started to develop its estate soon after: Western House by Weston Park on Western Bank was bought and demolished in 1903 for building a new university property.[32] A building with a traditional collegiate quadrangle (later known as Western Bank building and now Firth Court) was planned on the site.[32] Sir Frederick Mappin later successfully sought financial support from the Sheffield City Council and appealed for public donations.[32] In 1904, steelworkers, coal miners, factory workers and the people of Sheffield donated over £50,000 via penny donations to help found the University of Sheffield.[33]

It was originally envisaged that the university college would join Manchester, Liverpool and Leeds as the fourth member of the federal Victoria University. The new university was proposed to be named "Victoria University of Yorkshire" by Leeds[34] but was rejected by the Privy Council.[35] The Victoria University, however, began to split up as independent universities before this could happen, when Liverpool gained a charter of its own in 1903. Rather than joining a Yorkshire university with Leeds, the University College of Sheffield was driven by civic pride to pursue independent university status,[32] to bring higher education, give support to industries and serve as a centre for disease study. Hicks also advocated the independent degree awarding power would attract talented staff.[1] The University College of Sheffield's charter was sealed on 31 May 1905 and became the University of Sheffield.[32] On 12 July 1905, Firth Court on Western Bank was opened by King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra. St George's Square remained the centre of departments of Applied Science, and the departments of Arts, Medicine and Science moved to Western Bank.[28] Sheffield is one of the six pre-World War One red brick universities, the civic universities founded in the major industrial cities of England.

20th century[edit]

In 1905, when the university first opened, there were 363 students[36] and 114 of them were enrolled full-time.[28] Sheffield at the time had 71 members of staff.[36] By then, the first Hall of Residence (Stephenson Hall) and library (Edgar Allen library) had been established. The number of students increased to a short-lived peak of 1,000 in 1919 when returning ex-servicemen were admitted to the university. During the First World War, some of the academic subjects and courses were replaced by teaching of munitions making and medical appliances production.[28] The university has expanded since the 1920s from two ends on Western Bank and on the St George's site.[37] The number of full-time students was stabilized at about 750 between the two world wars.[28] In 1943, the University Grants Committee announced that universities in the UK should look forward to expansion in the years after the Second World War.[38] Sheffield predicted a 50% increase in student population but the university was unprepared for such growth. There was pressure on the university to expand since the student numbers had increased from around 1,000 to 3,000 by 1946.[38] The university announced proposals for development in 1947, which emphasised the need for new departments, medical school, library, administration building, halls of residence, as well as the completion of the Western Bank quadrangle and the extension of the Students' Union.[38]

The university then grew slowly until the 1950s and 1960s when it began to expand rapidly. Many new buildings (including the Main Library and the Arts Tower) were built and older houses were brought into academic use. Student numbers increased to their present levels of just under 26,000. At the same time in the 1950s, the university was expanding at other sites, including the St Georges area.[37] From the 1960s, many more buildings have been constructed or extended, including the Union of Students and St George's Library. The campus master plan proposed in the 1940s was completed by the 1970s, and the university required a new development plan.[39]

The 1980s saw the opening of many new buildings and centres, such as the multi-purpose Octagon Centre and the Sir Henry Stephenson Building. The university's teaching hospital, Northern General Hospital, was also extended.[38] In 1987 the university began to collaborate with its once would-be partners of the Victoria University by co-founding the Northern Consortium; a coalition for the education and recruitment of international students.[28] The university continued to expand in the 1990s. New premises were opened for School of the Clinical Dentistry, the Division of Education, and the Management School.[38] In 1995, the university took over the Sheffield and North Trent College of Nursing and Midwifery, forming a new School of Nursing and Midwifery. The St George's Hospital was extended and a new building at the Northern General Hospital has been constructed, which greatly increased the size of the medical faculty.

Hans Adolf Krebs was appointed as lecturer in pharmacology in 1935. At Sheffield Krebs and his postgraduate student discovered the citric acid cycle (also known as the Krebs cycle) in 1937,[40][41] which earned him a Nobel Prize for Medicine and Physiology for 1953. In 1938, the university opened the Department of Biochemistry (renamed since the 1990s as the Department of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology) and Krebs became its first Head. Krebs Institute, a research centre for mechanistic biology, was founded in 1988 within the Department of Biochemistry. George Porter joined the university as Professor of Physical Chemistry in 1955 and he further developed his later Nobel Prize-winning work flash photolysis at Sheffield. Porter was appointed Firth Professor of Chemistry and became Head of the Department of Chemistry in 1963.[42]

21st century[edit]

In the 21st century, the university opened many more major buildings in the area immediately to the east and west of Upper Hanover Street, such as the Jessop Building, the Soundhouse, Jessop West and the Information Commons. The Arts Tower building, the Students' Union and University House buildings, the Sheffield Bioincubator and University Health Centre were also refurbished. A new campus, North Campus, was opened.[28] In 2003, a development framework was produced by Turnberry Consulting, with proposals aimed to densify the campus.[43][44] In 2005, the South Yorkshire Strategic Health Authority announced that it would split the training between Sheffield and Sheffield Hallam University – however, the university decided to pull out of providing preregistration nursing and midwifery training due to "costs and operational difficulties".[45] On 28 September 2015, a new six-storey building, the Diamond, was opened.[46]

In February 2016, the university started to work with Sheffield City Council to transform public spaces around the campus.[47] The £8 million project includes building and improving pedestrianisation, crossings, cycle routes, as well as greening the campus.[47][48] The university intended to expand the Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre and provision for apprenticeships; however, while the Sheffield City Region Local Enterprise Partnership recommended that the £10 million funding bid should be approved, the university withdrew the bid in November 2018.[49] The University Concourse was refurbished in 2019 to replace the 50-year-old paving and walls.[50] Major development projects in the 2020s include constructions of a new Information School building (Northumberland Road Building), Social Sciences Building, Royce Discovery Centre, energy centre (the Transformer), Translational Energy Research Centre, and redevelopment of the original Henderson's factory.[51]

Campus and locations[edit]

The University of Sheffield is not a campus university, though most of its 430 buildings are located in fairly close proximity to each other.[51] It is divided geographically by the Sheffield Inner Ring Road.[52] The Upper Hanover Street section of the ring road splits university buildings into the Western Bank and the St George's campus areas.[a] Instead of growing from a single centre, since receiving its royal charter, the university has expanded from two academic foci about 1 km apart: Firth Court on Western Bank and Sir Frederick Mappin Building on St George's. The two foci started to fuse in the 1960s, as more buildings have been constructed or acquired by the university. The completion of the Information Commons and Jessop West buildings, in the late 2000s, bridges both west (Western Bank) and east (St George's) campus,[52] and in 2017, a new pedestrian crossing was installed on the Upper Hanover Street, physically connecting the two campus.[52]

The university campus is composed of an eclectic range of buildings from Victorian style to modernism to contemporary. Sir Frederick Mappin Building and Central Block are two Victorian university buildings, now linked by a contemporary curved glass roof constructed in 2020. Opened as the Western Bank Building, Firth Court is a red brick Edwardian building in Perpendicular Revival style,[59] and is connected to the 1971 modernist Alfred Denny Building. The nearby Arts Tower is also an example of postwar modernist building in the International Style.[60] The Diamond, a contemporary architecture designed by Twelve Architects, is situated next to the Victorian Jessop Building on the former site of Jessop's Edwardian wing.[61]

A total of 36 university estate are listed.[52] Of these, the Arts Tower and Western Bank Library are Grade II* listed buildings. Firth Court, Mappin Building, St George's Church, Jessop Building and the Drama Studio are listed Grade II.

Main (Western Bank) Campus[edit]

The centre of the university's presence lies one mile to the west of Sheffield city centre, where there is a mile-long collection of buildings belonging almost entirely to the university. This main campus area[43] is bounded by Upper Hanover Street to the east, Glossop Road to the south, Clarkson Street to the west, and Bolsover Street to the north. Western Bank (A57) runs through the campus.[52] The area to the north of Western Bank includes Firth Court, Alfred Denny Building, Western Bank Library and Arts Tower, Geography and Planning building, Bartolomé House, and Dainton and Richard Roberts Buildings. Within the southern area of the campus are the Sheffield Students' Union, the Octagon Centre, Graves Building and Hicks Building.[62] A concourse under the A57 flyover connects Alfred Denny Building on the north side and Students' Union on the south. Until the completion of three pedestrian crossings on Western Bank in 2017, the concourse underpass was the only link that allowed students to easily move between buildings in this cluster.[63] The Information Commons, a library and computing centre opened in 2007, is also located at the Western Bank Campus on Leavygreave Road. In addition, throughout 2010 the Western Bank Library received a £3.3 million restoration and refurbishment, the University of Sheffield Union of Students underwent a £5 million rebuild, and work commenced on a multimillion-pound refurbishment of the Grade II* listed Arts Tower to extend its lifespan by 30 years.[64]

St George's Campus[edit]

To the east of the main campus lies St George's campus, named after St George's Church (now a lecture theatre and postgraduate residence). The campus is the historical location of the Sheffield Technical School. It is bounded by Upper Hanover Street to the west, Broad Lane to the north, Rockingham Street to the east, and West Street to the south,[52] and is part of St George's Quarter, one of the seven official Sheffield city centre quarters.[65] Also known as the Engineering campus,[66] St George's campus is centred on Mappin Street, the location of the Faculty of Engineering (partly housed in the Grade II-listed Mappin Building) and the Department of Journalism Studies, Department of Economics and Department of Computer Science. The university also maintains the Turner Museum of Glass in this area. As part of the 2000s development plan, the university has converted the listed Victorian Jessop Hospital for Women into the new home of the Department of Music in 2009. The formerly Grade II-listed Edwardian wing of the Jessop Hospital was demolished after Sheffield City Council's planning committee voted for approval.[67] The building was replaced by a new £81 million building for the Faculty of Engineering which opened in September 2015, named the Diamond. It is a purpose-built multi-disciplinary building that houses lecture theatres, laboratories, workrooms and other facilities for the teaching of engineering.[68][69] Amongst the more recent additions to the university's estate located on this campus are the Soundhouse (2008; a music practice and studio facility) and the Jessop West building (2009; the first UK project by Berlin architects Sauerbruch Hutton).[70]

The Sir Frederick Mappin Building is a Grade II-listed building in an area known as the St George's Complex. The building houses much of the Faculty of Engineering and St George's IT centre.[71] Completed in 1885, the oldest part of the building, the former Sheffield Technical School, now the Central Wing, lies in the centre of the building. The extensive Mappin Street frontage includes the main entrance, the John Carr Library and Mappin Hall, and is connected to the Central Wing by a bridge. In early 2020, the Mappin Building and the Central Wing were refurbished. As a result of the refurbishments, the two buildings are joined by a quadruple-height atrium with curved glass roof.[72] The atrium, called the Engineering Heartspace, houses laboratories, offices and social spaces.[66]

Given its name to the campus, St George's Church was the first of three commissioners' churches to be built in Sheffield under the Church Building Act 1818. It was built in the Perpendicular style. The church closed in 1981 and was acquired by the university. It was converted for use as a lecture theatre in 1994,[73] while the upstairs has been converted for use as student accommodation.

Other sites[edit]

Further west lies Weston Park, the Weston Park Museum, the Harold Cantor Gallery, university's sports facilities Goodwin Sports Centre in the Crookesmoor area, and the Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health around the Royal Hallamshire Hospital (although these subjects are taught in the city's extensive teaching hospitals under the Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, and throughout South Yorkshire and North East Lincolnshire). It is in this area that the new £12 million Sheffield Institute for Translational Neuroscience (SITraN), opened by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II in November 2010, is located.[74] There is a cluster of buildings located to the north of Broad Lane, opposite St George's campus, collectively called the north campus. Kroto Research Institute, Kroto Innovation Centre, Nanoscience and Technology Building, Graduate Research Centre, George Porter Building and the International College are based on this campus area.[75] To the south of the city on Warminster Road are where the sports pitches at Norton Sports Park located.[76] The university also operates Advanced Manufacturing Research Centres (AMRCs) on the border of Sheffield, in Rotherham and Lancashire.[77] The Conference Centre and Teaching Hall at Philadelphia Campus of St. Thomas' Church are used as exam venues by the university.[78]

Former locations[edit]

The old Firth College building was built in 1879 at the corner of Leopold Street and West Street. It was designed by Thomas James Flockton and Edward Robert Robson with the front facing West Street. Firth College moved out of the building following the establishment of the university. The building later housed the Sheffield Central Technical School and is currently home to Education Committee offices of Sheffield City Council.[79] Situated on 7 Leopold Street opposite Firth College, the old Medical School building was designed by John Dodsley Webster and completed in 1888. The school moved to Firth Court in 1905 and the building is now used as offices.[80]

The Manvers campus, at Wath-on-Dearne between Rotherham and Barnsley, was where the majority of nursing was taught. A three-storey building, Humphry Davy House (named after chemist Humphry Davy), was built in 1998 on Golden Smithies Lane opposite to Dearne Valley College.[81] The building was home to the School of Nursing and Midwifery, which was established in 1995 after the merger of the university with Sheffield and North Trent College of Nursing and Midwifery.[82] In 2004, the university disagreed with the South Yorkshire Strategic Health Authority's decision to take away part of its nursing and midwifery training contract, and declined the offer due to financial and operational constraints.[45] The last intake of midwifery studies students was in July 2006, and the campus was closed one year later.[81] The building was sold in 2018 and to be converted for residential lettings.[83]

From 2022 to 2023, students protested against the University working with and accepting payment for various activities from companies including Rolls Royce, BAE Systems, and Boeing who are involved in the arms manufacturing industry.[7]

Organisation[edit]

Faculties and departments[edit]

Sheffield had four faculties in 1905, which were Arts, Pure Science, Medicine and Applied Science. The Faculty of Applied Science later split into Engineering and Metallurgy in 1919.[28] As well as educating full-time students, in the early 20th century, the university taught non-degree courses that covered non-conventional, occupation-focused subjects such as cow-keeping, railway economics, mining and razor-grinding.[28]

The university has currently five faculties comprising 50 departments and 82 research centres and institutes,[84] plus an international faculty.[85] The current faculty structure is:

- Faculty of Arts and Humanities

- Archaeology

- School of English

- East Asian Studies

- School of Languages and Cultures

- History

- Modern Languages Teaching Centre

- Music

- Philosophy

- Sheffield Institute for Interdisciplinary Biblical Studies

- Digital Humanities Institute

- Faculty of Engineering

- Aerospace Engineering

- Automatic Control and Systems Engineering

- Bioengineering

- Chemical and Biological Engineering

- Civil and Structural Engineering

- Computer Science

- Electronic and Electrical Engineering

- Material Science and Engineering

- Mechanical Engineering

- Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health

- Infection, Immunity and Cardiovascular Medicine

- School of Dentistry

- Medical School

- Neuroscience

- Health Sciences School

- Oncology and Metabolism

- School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR)

- Faculty of Science

- Animal and Plant Science

- School of Mathematics and Statistics

- Biomedical Science

- Chemistry

- Molecular Biology and Biotechnology

- Physics and Astronomy

- Psychology

- Faculty of Social Sciences

- Architecture

- Economics

- Education

- Geography

- The Information School

- Journalism

- Landscape Architecture

- Law

- Management School

- Politics and International Relations

- Sheffield Methods Institute

- Sociology

- Urban Studies and Planning

- International Faculty – CITY College

- Business Administration & Economics

- Computer Science

- Psychology

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Executive MBA

Faculty of Arts and Humanities[edit]

The Faculty of Arts and Humanities is made up of eight schools and departments. It is also home to three institutes (Humanities Research Institute, Sheffield Institute for Interdisciplinary Biblical Studies, and Digital Humanities Institute) and 16 research centres. The Centre for Research into Freemasonry and Fraternalism of the faculty was the first centre devoted to scholarly research into Freemasonry in a UK university.[86] The centre was closed in 2010, ten years after its establishment, due to its failure to capture substantial grants to support the centre's activities.[87] In May 2021, archaeology staff at the university have been told their jobs could be at risk after a review. A petition to save the department has gathered more than 35,000 signatures but the university said no decisions had yet been taken, but later changed to announcing they intended to dissolve the department, which was met with international outcry.[88][89]

Faculty of Engineering[edit]

The precursor to the Faculty of Engineering is the Sheffield Technical School established in the 1880s, which offered part-time and evening class programme to adults working in the steel industry.[90] During 1917, departments of Electronic and Electrical Engineering, Civil and Structural Engineering and Mechanical Engineering were founded in response to the needs of the First World War. The departments provided training courses for injured and incapacitated soldiers, and manufactured inspection gauges and munition shells.[90] The Faculty of Engineering has now over 6,700 students and 1,000 staff.[91] Over 90% of the research from the department was rated as 4* (world-leading) or 3* (internationally excellent).[92]

Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health[edit]

The Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health is made up of four schools, including the Medical School, Health Sciences School, School of Clinical Dentistry and School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR). The Medical School is the oldest school of the university. It operated independently as the Sheffield School of Medicine until its mergers with Firth College and with Sheffield Technical School.[93] The Medical School is located next to the Royal Hallamshire Hospital, one of the Sheffield's teaching hospitals, and the school is associated with Sheffield Children's Hospital, Northern General Hospital, Weston Park Hospital and Charles Clifford Dental Hospital. It is one of 32 bodies entitled to award medical degrees in the United Kingdom by the General Medical Council (GMC), the body responsible for registering doctors to practise medicine as well as regulating medical education and training in the United Kingdom.[94]

Faculty of Science[edit]

The Faculty of Science comprises seven classical science departments: Animal and Plant Sciences, Biomedical Science, Chemistry, Mathematics and Statistics, Molecular Biology and Biotechnology, Physics and Astronomy, and Psychology. All of the university's six Nobel Laureates have been affiliated with this faculty.[95]

The Department of Animal and Plant Sciences is one of the largest departments dedicated for whole-organism biology studies in the UK.[96] Biology has been taught in Sheffield since 1884 in Firth College. Appointed the first Professor of Biology in 1888, Alfred Denny was the only biologist in the Department of Biology at the college who taught zoology and botany to science and medical students. In 1896, a second biologist, botanist Bertram H. Bentley, joined the college.[97] Soon after the university was founded, in 1908, two separate departments were established: Zoology (head by Denny) and Botany (head by Bentley).[98] The departments were not merged until the establishment of the Department of Animal and Plant Sciences in 1988, as part of a major rationalisation at the university. David H. Lewis, who was Head of Botany, was the first Head of Animal and Plant Sciences.[98] The department was awarded a maximum score of 24 points in the QAA Teaching Quality Assessment in 1999, and top five for biological sciences research in the REF 2014.[99][100]

Faculty of Social Sciences[edit]

The Sheffield School of Architecture is consistently ranked among the top 10 in Europe and the UK for "Architecture and the Built-Environment" and is one of the longest established architecture schools in the UK, opening in 1908. It was first located in the tower of Firth Court but soon moved to the Sunday School in Shearwood Road and is located on the top 6 floors of the Arts Tower since 1965.[101] The school has courses accredited by the Architects Registration Board (ARB) and the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), and has an active student society (SUAS). In the Research Excellence Framework (REF) 2014, Sheffield School of Architecture ranked 4th in the UK.[102]

Established in 1986, the Management School is a triple-accredited (AMBA, AACSB and EQUIS) business school.[103] In 2013 the school moved into newly refurbished facilities close to the University of Sheffield campus and Broomhill. It now has dedicated learning and teaching space, a courtyard, dedicated café and Employability Hub.[104]

The Information School (iSchool) is a constituent school of the Faculty of Social Sciences. It was founded as Postgraduate School of Librarianship in 1963 and became the Department of Information Studies in 1981. In 2010, the Information School devoting to the study of the information field was established. The current head of school is Professor Peter Bath. The school is ranked second in the world and first in Europe for Library and Information Studies in the QS World University Rankings 2020.[105]

The Department of Urban Studies and Planning (USP) was founded as the Department of Town and Regional Planning (TRP) in 1965 and is located in the Geography Building in the Western Bank Campus. It was ranked as the top RTPI accredited planning school in the UK by the 2014 Research Excellence Framework (REF) and second for "Building and town and country planning" by the Guardian University Rankings 2021.

International faculty[edit]

The university has an international faculty called CITY College in Thessaloniki, the second largest city of Greece, which is the only faculty operating outside the UK. The faculty was established in 1989[106] in order to bridge the UK with the Southeast and Eastern Europe. It is a private legal entity operating as CITY College according to the local law in Greece.[107] The International Faculty consists of four departments, namely Business Administration and Economics, Psychology, Computer Science and English Studies. These departments are housed in the L. Sofou Building and the Strategakis Building, two buildings in close proximity in Thessaloniki city centre.[107] The faculty also operates the South East European Research Centre (SEERC), a multidisciplinary research centre established in 2003.[108]

Governance[edit]

There are several bodies which govern the university, including the council, the Senate and the faculties.[109] The council is the governing body of the university, which is responsible for the strategic development, legal and regulatory affairs, and performance of university business (finance and property).[110] Council membership comprises a majority of non-executive lay members appointed under the statutes of the university.[111] The chair and pro-chancellor of the council is currently Tony Pedder.[112] The Senate manages the academic side of the university. It is the highest academic authority of the university, and is also responsible for the regulation of research work and students' discipline.[110] The Senate is chaired by the vice-chancellor, with its membership drawn mainly from the university's academic staff.[113] The five faculties regulates departmental teaching, research, examination, and also admission. They are responsible for making recommendations to the Senate on the award of degrees, fellowships, and academic staff appointments and promotions.[110]

The university central committees also include the University Executive Board, whose members are: president and vice-chancellor (or simply vice-chancellor), provost and deputy vice chancellor, chief financial officer, executive director of corporate services, executive director of academic services, five faculty vice-presidents, three cross-cutting vice-presidents (education, innovation and research), and university secretary.[114] The board provides leadership and management, as well as advises the vice-chancellor on operational matters. the vice-chancellor is the chief executive and accountable officer of the university. The current vice-chancellor is Koen Lamberts, and the provost and deputy vice chancellor is Gill Valentine.[115]

The Court of the university is no longer a university committee.[116] The Court was a large body which fosters relations between the university and the community, and included lay members, many of whom are university alumni. Ex-officio members of the Court included all the members of Parliament (MPs) of Sheffield, the Bishops of Sheffield and Hallam, and the chief constable of South Yorkshire Police.[110] It also included representatives of professional bodies such as the Arts Council, Royal Society and the General Medical Council.[117] The Court met annually to receive reports from the council, the Senate and the Students' Union. It served many official functions including chancellor election.

Vice-chancellors[edit]

- 1905: William Mitchinson Hicks[118]

- 1905: Charles Eliot

- 1912: Herbert Fisher

- 1917: William Ripper (acting)

- 1919: William Henry Hadow

- 1930: Sir Arthur Pickard-Cambridge

- 1938: Irvine Masson

- 1953: John Macnaghten Whittaker

- 1965: Arthur Roy Clapham (acting)

- 1966: Hugh Robson

- 1974: Geoffrey Sims

- 1991: Gareth Roberts

- 2001: Bob Boucher

- 2007: Sir Keith Burnett

- 2018: Koen Lamberts

Finances[edit]

The university's annual income for 2019–20 was £737.5 million, of which £171 million was from research grants and contracts, with an expenditure of £609.2 million resulting in a surplus of £127.1 million. Its endowment was £45.5 million.[119]

Coat of arms[edit]

The arms of the university was granted by the College of Arms on 28 June 1905. It is on an azure shield with a gold-edged book inscribed with the Latin Disce Doce (Learn and Teach) at its centre, a sheaf of eight silver arrows on either side (from the arms of the city), the Crown of Success and the White Rose of York. Below is a scroll carrying the motto Rerum cognoscere causas (To Discover the Causes of Things; from the Georgics[b] by Latin poet Virgil), which was also the motto of Firth College since 1879.[120] In heraldic terminology, the official coat of arms is blazoned as follows:

Azure, an open book proper, edged gold, inscribed with the words Disce Doce between in fess two sheaves of eight arrows interlaced saltireways and banded argent, in chief an open crown or, and in base a rose also argent barbed and seeded proper.[121]

The current university's logo, consists of a redrawn version of the coat of arms and the name of the institution, is introduced in 2005, the centenary year of the university. However, the logo should not supersede and be confused with the coat of arms, which remains the official heraldic symbol of the university.[120]

University Fonts[edit]

The university's fonts are TUOS Stephenson (serif) and TUOS Blake (sans-serif). Both TUOS Stephenson and TUOS Blake are modified versions of a typeface designed by Sheffield company Stephenson & Blake Co. The two fonts are the copyright property of the University of Sheffield and are restricted only to university users.[122][123] The university brand (encompassing the visual identity) is led by its motto Rerum cognoscere causas and centred on the theme of "discovery". The theme has been applied across print, screen and other areas such as signage, vehicle livery and merchandising.[124]

Ceremony[edit]

Academic dress[edit]

As at most universities, Sheffield graduands wear academic dress appropriate to the degree they are to be received when graduating. Bachelors wear a black Oxford BA [b1] gown (see Groves classification system). The hood is in green, half-lined with white fur, and edged with two inches of silk of the colour distinctive of the degree or the faculty.[125] Masters wear a black Oxford MA [m1] gown with a hood of green silk which is lined throughout with the faculty colour. The PhD and the MPhil hoods are lined in green.[125] Research doctors have a fine scarlet cloth gown with green silk facings, with bell-shaped sleeves [d2]; higher doctorates wear the robe with full sleeves that are lined scarlet silk and the lining held up at the elbow level with a scarlet cord and button [d1]. The hood is of the Cambridge shape [f1] and is made of red ottoman silk.[125][126] In 1993, the postgraduate diplomate hood is entered in the Calendar of the University of Sheffield.[127] It is a blend of Bachelors' and Masters' hoods,[126] with a hood of green silk and a neckband of the faculty colour.[125]

The faculty and degree colours are: Arts and Humanities—crushed strawberry; Music (only for BMus, MMus, and DMus degrees)—cream brocade; Engineering—purple; Medicine and Surgery—red; Dental Surgery—pale rose pink; Health—cerise; Science—apricot; Social Sciences—lemon yellow; International Faculty—Saxon blue; Board of Extra Faculty Provision—pale blue.[125] Some schools at Sheffield had previously their own colours but are no longer used.[126][128] They were: Metallurgy—steel grey; Education—pearl; Architecture—old gold; Law—olive green.[128][129] The old colour of the Faculty of Social Sciences was pale green.[129]

University mace[edit]

The university mace is an ornament of governance of the University of Sheffield. It is silver-gilt and carries the coats of arms of both the university and the city of Sheffield, and the White Rose of York. A figure of Minerva holding a wreath and palm branch on a heraldic crown adorns the top of the mace. Used for the first time in 1909, the mace is carried in academic procession as the symbol of authority, which precedes the presiding officer.[129]

Academics[edit]

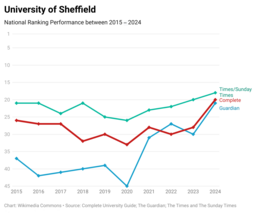

Reputation and rankings[edit]

| National rankings | |

|---|---|

| Complete (2025)[130] | 18= |

| Guardian (2024)[131] | 21 |

| Times / Sunday Times (2024)[132] | 18 |

| Global rankings | |

| ARWU (2023)[133] | 151–200 |

| QS (2025)[134] | 105= |

| THE (2024)[135] | 105 |

The university has been described by The Times as one of the powerhouses of British higher education.[136] The university is a member of the Russell Group, the European University Association, the Worldwide Universities Network and the White Rose University Consortium.[137][138][139] Meanwhile, it was among the top 10 of the Russell Group for research output and top 12 for research strength in Research Excellence Framework 2014.[140] In terms of research citations, Sheffield was ranked 93rd worldwide and 9th in the UK by the CWUR 2018–19.[141] It was also ranked 20th overall in Europe and 10th in the UK for number of signed EU grant agreements according to the data since 2007.[142][143]

Sheffield has received the Queen's Anniversary Prize five times in 1998, 2000, 2002, 2007 and 2019.[144] In 2011 it was named 'University of the Year' in the Times Higher Education awards.[145] The latest Times Higher Education Student Experience Survey 2014 ranked the University of Sheffield 1st for student experience, social life, university facilities and accommodation, among other categories. It was also named as one of the top 50 most international universities in 2018 around the world[146] and its reputation of outstanding teaching has been underlined in the most recent league table which put Sheffield joint 9th in the UK and 11th across Europe.[147]

In the 2021 Research Excellence Framework (REF) Sheffield was ranked 11th for research power in the UK, moving up from 13th in REF2014,[19] with 92% of the research submitted by the academic staff having been rigorously judged as world leading (4*) or internationally excellent (3*).[148] The university was one of only ten in the country to include more than 1500 staffs for the submissions in a wide range of subject areas. A number of areas of research at the University of Sheffield are in the top 10 nationally in terms of the assessment of their research and impact as world-leading or internationally excellent. Some highlights include: Physics and Astronomy – which achieved 100 per cent and came top for research and impact; Biological Sciences – which came in the top five with 98 per cent; Architecture, Built Environment and Planning – which came in the top three with 95 per cent and Engineering – which achieved 96 per cent and came in the top 10.[148]

The University of Sheffield achieved global recognition for its academic strengths in specific fields. In 2023, it secured the top position for Library and Information Management and ranked 32nd for Architecture and Built Environment, along with a 42nd rank for Archaeology, according to QS.[149] In the ARWU rankings of 2022, the university achieved 8th place in Geography and Urban Planning, 38th in Civil Engineering, and 46th in Ecology.[150]

Admissions[edit]

|

The University of Sheffield has a total of 30,195 students in the 2018–19 academic year, including 19,610 undergraduates and 10,585 postgraduates.[158] In terms of average UCAS points of entrants, Sheffield ranked 29th in Britain in 2014.[159] The university gives offers of admission to 85.6% of its applicants, the 4th highest amongst the Russell Group.[160]

According to the 2017 Times and Sunday Times Good University Guide, approximately 13% of Sheffield's undergraduates come from independent schools.[161] In the 2016–17 academic year, the university had a domicile breakdown of 71:5:24 of UK:EU:non-EU students respectively with a female to male ratio of 51:49.[162] 57.8% of international students enrolled at the institution are from China, the second highest proportion out of all mainstream universities in the UK.[163]

Libraries[edit]

The University of Sheffield has currently four libraries: Western Bank Library, the Information Commons, Health Sciences Library (Royal Hallamshire Hospital and Northern General Hospital), and The Diamond,[164] holding a total of 1.5 million printed books.[165] Western Bank Library was the university's main library until the opening of the Information Commons in 2007. The Grade II* listed library has 730 study spaces and contains 1.2 million texts for most subjects, as well as archives and special collections.[166][167] The Information Commons (IC) is a 24/7 learning centre combining both library and IT services, which was the first of its kind in the UK.[166] The IC houses 120,000 core textbooks for all undergraduate and postgraduate subjects, and has approximately 1,300 study spaces and 550 PCs.[167] The university has two medical libraries collectively called the Health Sciences Library.[168] It was opened at the Royal Hallamshire Hospital in 1978, and a year later a branch at the Northern General Hospital was opened.[169] The Royal Hallamshire Hospital library has collections cover medicine, dentistry, nursing and midwifery, and the Northern General Hospital library contains material for medicine and nursing.[167] Opened its door in 2018, the Diamond provides 24-hour library services (and other teaching facilities), with in-demand textbooks, a non-loanable reference collection and over 1,000 study spaces.[167][170] It replaces the 1992 St George's Library on St George's Campus as the main engineering library and study space. The University of Sheffield Library is a member of Research Libraries UK.[171]

Former libraries include Edgar Allen Library closed by the late 1950s and St George's Library closed on 14 June 2015. Edgar Allen Library was the first university library. In 1905 when the university was established, the library was housed in a lecture room due to lack of funds to construct a purpose-built library. William Edgar Allen, a member of the University Council, provided £10,000 to build a proper library named Edgar Allen Library, locating beside the main university building (Firth Court). Edgar Allen Library had 100 seats in its reading room, shelves for 20,000 books, and a stack space for 60,000 more books. Sir Charles Harding Firth, the first lecturer in Modern History in Firth College, donated part of his personal collection to the library. Sheffield Town Trustee also helped the university to transform the General Lecture Theatre into a reading room housing the Firth Collection (rare book collection of approximately 20,000 volumes) in 1931.[172] As the university rapidly expanded in the 1950s, it became necessary to replace Edgar Allen Library with a modern post-war era library. The library, later known as the Western Bank Library, was opened on 12 May 1959.[172] Edgar Allen Library (now the Rotunda in Firth Court)[173] became the Registrar and Secretary's Office. St George's Library (now 38 Mappin Street) was refurbished as an exam venue.[174]

Museums and collections[edit]

The Alfred Denny Museum is a zoology museum operated by the university.[175] Established in 1905, the museum was located in Firth Court, spanning three floors,[176] and was named after the first professor of biology at Sheffield in 1950. It has specimens from all major phyla, and two letters written from Charles Darwin to Henry Denny, father of Alfred Denny. Many of the specimens have been collected since the 1900s, but much of the information about the collection was lost during the Second World War. The museum, now reduced in size, has been moved to Alfred Denny Building after the war.[177] The museum is not open to the public at all time but usually on the first Saturday of each month.

The Turner Museum of Glass houses the university's collections of 19th and 20th century glass.[178] It contains items mainly from major European and American glassworkers and examples from ancient Egypt and Rome. It is in the Hadfield Building. It was founded by W. E. S. Turner of the university in 1943.[178][179] One of the exhibits is the wedding dress of Helen Nairn (Turner's wife) which is made of glass fibre. This has been selected as one of the items in the BBC's A History of the World in 100 Objects.[180]

The Traditional Heritage Museum (THM) was opened to the public in 1985 as part of the National Centre for English Cultural Tradition.[181] It was created (and curated) by Prof John Widdowson in 1964 and was entirely run by volunteers and students.[182] The THM housed collections including a replica kitchen from the 1920s, reconstructed workshops and retail shops, such as Pollard's tea and coffee.[181][183] The university decided to close the Museum in 2011 because the building could not afford continued public access.[181][184] In 2013, the collections from the Traditional Heritage Museum were relocated and are accessible again to the public. The majority of the items was transferred to not-for-profit organisation Green Estate (operators of the Sheffield Manor Lodge). Other major recipients include Sheffield Galleries and Museums Trust, Sheffield Industrial Museums Trust and Ken Hawley Trust.[185]

The Western Bank Library has an Exhibition Gallery.[186] It is located on the mezzanine level of the library, enabling special collections from the university library and the National Fairground Archive to be displayed in controlled conditions.[187] In 2010, the gallery was restored and refurbished by a grant from the Wolfson Foundation. The library usually schedules three temporary exhibitions per year, and most of the exhibitions are free to visit during library opening hours.[188]

The Henry Clifton Sorby Collection contains glass lantern slides of marine organisms prepared and donated by Henry Clifton Sorby in the 1900s. Sorby was president of Firth College after the death of Mark Firth, vice-president of the University College of Sheffield, and a member of the Council of the University of Sheffield. His broad interests included marine biology, and he had developed a technique for preparing and mounting invertebrate marine animals onto slides. The specimens were cleared and stained so that enabling projection onto a screen for viewing. The glass lantern slides are now held in the Department Animal and Plant Sciences.[189] The Sheffield Herbarium is also operated by the Department Animal and Plant Sciences, with a collection of preserved plant specimens collected in the late 19th century and early to mid 20th century. The collection is mainly from the British Isles and Europe focusing on tracheophytes, bryophytes, charophytes and fungi. Many of the micro-fungi specimens are from the collection of mycologist and Sheffield alumnus John Webster.[190]

The National Fairground and Circus Archive (NFCA) is a living archive that collects material from the fairground, circus and the allied entertainment industries.[191] NFCA was in 1994 developed out of the PhD research by Vanessa Toulmin, who was later director of the archive from its inception until 2016.[192] With its own Reading Room situated in Western Bank Library, the archive holds 150,000 photographs, 4,000 books and journals, together with over 20,000 items of printed and video ephemera. Major collections include the Shufflebottom Family Collection, the John Bramwell Taylor Collection, the Malcolm Airey Collection and the John Turner Collection.[191]

Flagship institutes[edit]

Sheffield has four research institutes.[193] Launched in 2019, the institutes focus on clean energy generation, sustainable food, health improvement and quality of life.[194] The Energy Institute is one of the largest energy research centres in Europe.[194] It has over 300 researchers working on energy-related problems, including improving energy efficiency and developing ways to achieve clean growth.[195] The Neuroscience Institute works on the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of neurological disorders. This includes the exploration of artificial intelligence applications in healthcare for diagnosing Alzheimer's disease and improving prognosis.[196] The Healthy Lifespan Institute researches multimorbidity and slowing down the ageing process.[197] The Institute for Sustainable Food studies food security and environmental sustainability.[198][194]

Academic and industrial partners[edit]

The University of Sheffield's major research partners and clients include Boeing, Rolls-Royce, Siemens, Unilever, Boots, AstraZeneca, GSK, ICI, and Slazenger, as well as UK and overseas government agencies and charitable foundations.[199] Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre is a network of centres and a partnership between the university and over a hundred industrial companies on the Advanced Manufacturing Park.[12] The university also works with local small and medium enterprises through the dedicated physical spaces at the Sheffield Bioincubator and Kroto Innovation Centre.[200][201] For many years the university has been engaged in theological publishing through Sheffield Academic Press and JSOT Press. The university is also a partner organisation in Higher Futures, a collaborative association of institutions set up under the government's Lifelong Learning Networks initiative, to co-ordinate vocational and work-based education.[202]

As well as the research carried out in departments, the university has over 180 specialised research centres or institutes.[203] The last Teaching Quality Assessment awarded Sheffield University grades of "excellent" in 29 subject areas, a record equalled by only a few other UK universities.[204]

The University of Sheffield has around 250 student exchange partners in nearly 40 countries world-wide including exchange programs with Georgia Institute of Technology, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, University of Texas at Austin, National University of Singapore, University of Munich and University of Melbourne.[205][206]

Controversies[edit]

Proposed closure of the Department of Archaeology[edit]

On 25 May 2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic, the University of Sheffield Executive Board (UEB) including Vice Chancellor Koen Lamberts and Deputy Vice Chancellor Gill Valentine voted to close the Department of Archaeology and move two areas into other departments; a world leading institution since its formation in 1976.[207] The decision had been made through a commissioned Institutional Review process chaired by Valentine and was met with national and international outcry including a petition signed by over 40,000 people.[208] The decision was announced first on 19 May. [citation needed] The review process had begun in February 2022 led by Valentine.[citation needed]

Involvement with the arms trade[edit]

Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre conducts a wide range of research projects including some funded by arms manufacturers such as BAE Systems.[12] In 2008, the university partnered with BAE Systems to launch a new Centre for Research in Active Control which aimed to improve the stealth of BAE Systems' submarines.[209] In 2012 the Students Union voted in favour of the university ending all links with the arms trade.[210]

In October 2022, students occupied 'The Diamond' over the university's alleged links with Rolls-Royce, and their involvement in arms manufacture.[211] This resulted in the closure of the building, with the occupiers refusing to leave until negotiations with the Vice-Chancellor commenced. Over the past eight years, the university has received some £47 million from Rolls-Royce.[212] The following month, the university hired a private investigator to investigate two students for "alleged misconduct" in relation to the protests.[213][214] In November 2023, students interrupted the opening ceremony of the university's newest building, in support of Palestine and in protest over the university's financial contracts with arms manufacturers, including BAE Systems, GKN and Boeing.[215]

Student life[edit]

Students' Union[edit]

The University of Sheffield Students' Union was founded in 1906 and has nearly 300 student societies and nearly 50 sports teams. The Students' Union has been voted best in the UK for ten consecutive years, from 2009 to 2018, by The Times Higher Education Student Experience Survey.[216]

Sheffield University Football Club has been established for many decades and has previously competed in the FA Amateur Cup and FA Vase. The Union building contains society and union workplaces and coffee shops, restaurants, shops, and the student run cinema Film Unit. Facilities include two bars (Bar One – which has a book-able function room with its own bar, The Raynor Lounge – and The Interval); a three-room club venue (Foundry); There is also a student radio station called Forge Radio, a TV station called Forge TV, and a newspaper called Forge Press, which are run under the umbrella of Forge Media since 2008.[217]

In November 2009 a development project began to redevelop the Students' Union building, funded by £5 million by the HEFCE, which was completed and re-opened in September 2010. Works centred on improving circulation around the building by aligning previously disjointed floors, improving internal access between the Union building and neighbouring University House, and constructing a new entrance and lobby that incorporates the university's traditional colours of black and gold.[218] During 2012–13 the Students' Union went under a further redevelopment costing £20 million which led to the refurbishment of the University House. University House, completed in 1963, has been integrated with the university's Students' Union in one single building.[219]

Student accommodation[edit]

Университетские общежития состоят из двух отдельных объектов: Ранмур/Эндклифф и Сити. [220] Ранмур/Эндклифф расположен в западном пригороде Шеффилда, недалеко от Брумхилла и Экклсолл-роуд . Деревня Эндклифф была открыта в 2008 году, а деревня Ранмур - в 2009 году. [221] Дом Ранмура, открытый осенью 1968 года, когда-то был самым большим общежитием в университете, в котором проживало около 800 студентов. В рамках стратегии университета по созданию студенческих общежитий Ranmoor House был снесен в марте 2008 года, за год до того, как планировалось открыть новую деревню Ranmoor Village. [222] Деревни Эндклифф и Ранмур с 2016 года вместе называются Ранмур/Эндклифф. Деревня Эндклифф была переименована в «Южное жилье (недалеко от Эндклиффа)», а деревня Ранмур — в «Северное жилье (недалеко от Ранмура)». [220] Городские объекты размещения, в том числе Allen Court, Broad Lane Court, St. George's Flats, Mappin Court и Studio 300, расположены в главном кампусе, на территории кампуса Сент-Джордж или рядом с Северным кампусом. [220]

За пределами кампуса находится студенческий жилищный кооператив Шеффилда , студенческий жилищный кооператив, предоставляющий своим членам некоммерческое жилье, управляемое студентами. В настоящее время они управляют недвижимостью на Нортфилд-роуд в Круксе, Шеффилд.

Шеффилдский университет [ править ]

Ежегодный Университет Шеффилда — это ежегодный университетский матч , который проводится между спортивными командами университета и его соперником из Университета Шеффилд Халлам, начиная с 1996 года. [223] Университет разделен на зимние и летние соревнования. Более 1000 студентов обоих университетов соревнуются в более чем 30 университетских видах спорта на более чем 70 соревнованиях. [223] Спортивные цвета университета — черный и золотой. Шеффилд выиграл университетское соревнование в 2013 году, победив Халлама впервые за десять лет. [224] Это продлило вновь обретенную победную серию до семи лет подряд; снова выигрывал с 2014 по 2019 год. [225] [226] [227]

Люди, связанные с университетом [ править ]

выпускники Известные

Многие известные люди в различных дисциплинах посещали Шеффилд. Ряд политиков являются выпускниками университета, в том числе президент Доминики Николас Ливерпуль , заместитель премьер-министра Турции Нуреттин Джаникли , [228] министр внутренних дел Дэвид Бланкетт , министр иностранных дел Сейшельских островов Жан-Поль Адам , [229] Глава администрации Даунинг-стрит Ник Тимоти . [230] По крайней мере десять членов парламента Великобритании и два члена Европейского парламента учились в Шеффилде. Среди известных государственных служащих, обучавшихся в университете, - генеральный секретарь Высшей комиссии по промышленной безопасности Саудовской Аравии Халид С. Аль-Агил , [231] Главный экономист Банка Англии Энди Холдейн [232] глава столичной полиции Лондона Бернард Хоган-Хау , [233] Начальник штаба обороны Стюарт Пич [234] [235] и комиссар по делам детей Англии Мэгги Аткинсон . [236]

Шеффилд воспитал ряд судей и юристов. Университет имеет наибольшее количество выпускников, назначенных в состав Апелляционного суда, после Оксфорда и Кембриджа. [237] В ноябре 2013 года в суде была коллегия судей, состоящая из судей, получивших высшее образование в Шеффилде; действующими судьями были Лорд и Леди-судьи апелляционной инстанции Морис Кей , Энн Рафферти и Джулия Макур . [238] [239] [240] Юридическая школа Шеффилда также выпускает юристов по всему миру. В их число входят заместитель министра юстиции Афганистана Мохаммад Касим Хашимзай , [241] Главный судья Бангладеш Музаммель Хоссейн , [242] Судья Верховного суда Сьерра-Леоне Генри М. Джоко-Смарт , [243] и главный судья Малайзии Арифин Закария . [244]

Среди писателей, посещавших университет, — двукратная обладательница Букеровской премии Хилари Мэнтел , [238] Ли Чайлд , [238] Эндрю Грант , [238] Брук Маньянти (Бель де Жур), Линдси Эшфорд и Кэти Б. Эдвардс . актеры и актрисы Брайан Гловер , Йен Халлард , Рэйчел Шелли и Эдди Иззард Студентами университета были . Среди известных выпускников Шеффилда в области религии - декан Вестминстерского аббатства Уэсли Карр , [245] Декан Церкви Христа в Оксфорде Мартин Перси , [246] Генеральный секретарь организации «Совместные действия церквей Шотландии» Стивен Смит и архиепископ Сиднея Гленн Дэвис . Многие пионеры были студентами университета, в том числе первая британская астронавтка Хелен Шарман , [247] Полярный исследователь Рой Кернер и первая женщина-пилот, совершившая в одиночку перелет из Лондона в Австралию Эми Джонсон . [238] Студенты Шеффилда также преуспели в спорте. Джессика Эннис-Хилл и Холли Уэбб — олимпийские золотые медалисты. [248] [249] Бриони Пейдж и Ник Бейтон завоевали медали на Олимпийских и Паралимпийских играх соответственно. Среди известных выпускников в области спорта также Герберт Чепмен , Зара Дэмпни , Кэтрин Фо , Тим Робинсон и Дэвид Уэтерилл .

Ученый, получивший медаль Варбурга, Ганс Корнберг, изучался в Шеффилде вместе с Олив Скотт и Дональдом Бейли , изобретателем моста Бейли. Химический факультет Шеффилда также воспитал двух лауреатов Нобелевской премии по химии. [95]

- Лорд Дэвид Бланкетт

Нобелевские премии [ править ]

Факультет естественных наук университета связан с шестью нобелевскими лауреатами, двое из которых - с кафедры молекулярной биологии и биотехнологии: [95]

- 1945 года Нобелевская премия по физиологии и медицине (совместная награда) Говард Флори за работу по пенициллину. [250]

- Нобелевская премия по физиологии и медицине 1953 года — Ганс Адольф Кребс «за открытие цикла лимонной кислоты в клеточном дыхании ». [251]

И четыре на его химический факультет:

- Нобелевская премия по химии 1967 года (совместная награда), Джордж Портер , «за работу над чрезвычайно быстрыми химическими реакциями» (см. Флэш-фотолиз ). [252]

- Нобелевская премия 1993 года по физиологии и медицине (совместная награда) Ричард Дж. Робертс «за открытие того, что гены у эукариот не представляют собой непрерывные цепочки, а содержат интроны, и что сращивание информационной РНК с целью удаления этих интронов может происходить по-разному». получение разных белков из одной и той же последовательности ДНК». [253]

- Нобелевская премия по химии 1996 г. (совместная награда), сэр Гарри Крото , «за открытие фуллеренов». [254]

- Нобелевская премия по химии 2016 г. (совместная награда) сэру Джеймсу Фрейзеру Стоддарту «за разработку и синтез молекулярных машин». [255]

Двое нобелевских лауреатов, связанных с университетом, официально не учитываются. Это: сэр Джон Вейн (исследователь) [256] и Воле Сойинка (приглашенный профессор). [257]

В популярной культуре [ править ]

Вымышленная версия Университета Шеффилда является местом действия отмеченной наградами серии комиксов « Дни гиганта» . Действие комедии « Любовь во времена брит-попа» происходит в университете в эпоху «Крутой Британии» 1990-х годов . [258] Библиотека Западного банка университета фигурирует в романе Барри Либина « Тайна рукописи Милтона» .

См. также [ править ]

- Гербовник университетов Великобритании

- Хьюз, профессор испанского языка

- Список современных университетов Европы (1801–1945 гг.)

- Список университетов Великобритании

- Шеффилдская школа

- Университет Шеффилда Халлама

Ссылки [ править ]

Информационные примечания

- ^ Названия «Кампус Западного берега» и «Кампус Святого Георгия» появляются на веб-страницах университета. [53] [54] и документы, [55] [56] [57] хотя они не указаны на карте университета [58]

- ↑ Из книги 2, строка 490.

- ^ Включает тех, кто указывает, что они идентифицируют себя как азиаты , чернокожие , смешанного происхождения , арабы или представители любой другой этнической принадлежности, кроме белых.

- ^ Рассчитано на основе измерения Polar4 с использованием Quintile1 в Англии и Уэльсе. Рассчитано на основе Шотландского индекса множественной депривации (SIMD) с использованием SIMD20 в Шотландии.

Цитаты

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г Мазерс, Хелен (2005). Ученые Стального города, Столетняя история Шеффилдского университета . Джеймс и Джеймс. п. 191. ИСБН 1-904022-01-4 .

- ^ «Королевская хартия» (PDF) . Устав корпорации. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 3 марта 2021 года . Проверено 29 августа 2020 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с «Годовой отчет и финансовая отчетность за 2022–2023 годы» . Университет Шеффилда . Проверено 8 декабря 2023 г.

- ^ Блэкледж, Ричард (26 июня 2018 г.). «Шеффилдский университет назначает нового вице-канцлера» . Звезда . Архивировано из оригинала 6 декабря 2018 года . Проверено 6 декабря 2018 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б «Кто работает в HE?» . www.hesa.ac.uk.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с «Где учатся студенты ВО? | HESA» . www.hesa.ac.uk.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б «Иностранные студенты принесут Шеффилду 120 миллионов фунтов стерлингов » . Новости Би-би-си . Би-би-си. Архивировано из оригинала 8 марта 2021 года . Проверено 22 августа 2020 г.

- ^ «10 лучших университетов для изучения политики» . Телеграф . Телеграф Медиа Группа. Архивировано из оригинала 12 января 2022 года . Проверено 22 августа 2020 г.

- ^ «Подход Шеффилдского университета (TUOS) к управлению и реализации льгот (резюме)» (PDF) . Офис стратегических изменений . Университет Шеффилда. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 21 мая 2022 года . Проверено 28 августа 2020 г.

- ^ «Ссылка на стандарты TUOS» . Учебные пособия по информационной и цифровой грамотности . Университет Шеффилда. 8 декабря 2021 года. Архивировано из оригинала 29 июля 2020 года . Проверено 28 августа 2020 г.

- ^ «Университет возглавляет сотрудничество по разработке микродисплеев нового поколения и средств связи в видимом свете» . Центр материалов и устройств GaN | Университет Шеффилда. 4 января 2022 г. Проверено 4 мая 2023 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с «О АМРК» . amrc.co.uk. AMRC Шеффилд. Архивировано из оригинала 11 мая 2020 года . Проверено 22 августа 2020 г.

- ^ «Оксфорд третий год возглавляет таблицу исследовательских грантов» . 16 ноября 2017 года. Архивировано из оригинала 1 декабря 2017 года . Проверено 23 ноября 2017 г.

- ^ «Университет Шеффилда номер один в Великобритании по доходам и инвестициям в области инженерных исследований – Последние новости – Университет Шеффилда» . www.sheffield.ac.uk . Университет Шеффилда. 23 мая 2019 года. Архивировано из оригинала 1 марта 2021 года . Проверено 7 сентября 2020 г.

- ^ «Университет Шеффилда» . Лучшие университеты . Архивировано из оригинала 28 августа 2020 года . Проверено 12 сентября 2020 г.

- ^ «Академический рейтинг университетов мира по версии ShanghaiRanking» .

- ^ «Университет Шеффилда отмечен за выдающиеся достижения в преподавании» . Где работают женщины . Архивировано из оригинала 27 сентября 2020 года . Проверено 7 сентября 2020 г.

- ^ «Рейтинг преподавания Европы 2019» . Высшее образование Times (THE) . 27 июня 2019 года. Архивировано из оригинала 20 апреля 2021 года . Проверено 29 сентября 2021 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б «REF 2021: Рейтинги качества достигли нового максимума в расширенной оценке» . 12 мая 2022 года. Архивировано из оригинала 14 июня 2022 года . Проверено 7 июня 2022 г.

- ^ «Лауреаты Нобелевской премии, связанные с университетом» . Университет Шеффилда. Архивировано из оригинала 13 октября 2016 года . Проверено 23 февраля 2016 г.

- ^ «Оверенд, Холл» . Оксфордский национальный биографический словарь (онлайн-изд.). Издательство Оксфордского университета. 2004. doi : 10.1093/ref:odnb/68312 . Проверено 16 августа 2020 г. . (Требуется подписка или членство в публичной библиотеке Великобритании .)

- ^ Свон, HT (23 сентября 2004 г.). «Оверенд, Холл» . Оксфордский национальный биографический словарь (онлайн-изд.). Издательство Оксфордского университета. doi : 10.1093/ref:odnb/68312 . Проверено 3 сентября 2020 г. (Требуется подписка или членство в публичной библиотеке Великобритании .)

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б «Медицинское образование в Шеффилде: первые годы» (PDF) . Университет Шеффилда. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 3 марта 2016 года . Проверено 18 августа 2020 г.

- ^ «Медицинский факультет Шеффилда» . Архивировано из оригинала 5 декабря 1998 года . Проверено 16 августа 2020 г. .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Свон, Гарольд Т. (1 февраля 1994 г.). «Медицинская школа Шеффилда: истоки и влияния». Журнал медицинской биографии . 2 (1): 22–32. дои : 10.1177/096777209400200105 . ПМИД 11615265 . S2CID 30810638 .

- ^ Лори, Александра (2014). Движение за расширение университетов. В: Начало университетского английского языка . Пэлгрейв Макмиллан. п. 56. ИСБН 9781349456307 .

- ^ «Наследие совершенства» (PDF) . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 24 сентября 2015 г. Проверено 22 ноября 2013 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к «Историческая справка» . Университет Шеффилда. Архивировано из оригинала 17 ноября 2015 года . Проверено 8 сентября 2015 г.

- ^ Университет Шеффилда. «Наследие Шеффилда» (PDF) . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 13 июля 2021 года . Проверено 17 августа 2020 г. .

- ^ Подъем современного бизнеса: Великобритания, США, Германия, Япония и Китай (3-е изд. и обновленное изд.). Чапел-Хилл: Издательство Университета Северной Каролины. 2008. с. 68. ИСБН 9780807858868 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Милнер, SR (1935). «Уильям Митчинсон Хикс. 1850–1934» . Некрологи членов Королевского общества . 1 (4): 393–399. дои : 10.1098/rsbm.1935.0004 . ISSN 1479-571X . JSTOR 768971 . Архивировано из оригинала 20 октября 2021 года . Проверено 4 сентября 2020 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж «Наш университет, наш день рождения, наша история» . Университет Шеффилда. Архивировано из оригинала 21 октября 2019 года . Проверено 1 сентября 2020 г.

- ^ «Выпускной 2013» (PDF) . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 24 сентября 2015 г. Проверено 12 марта 2015 г.

- ^ «История Общества» . Йоркширское философское общество. Архивировано из оригинала 27 августа 2006 года . Проверено 18 октября 2006 г.

- ^ «Столетние воспоминания» (PDF) . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 18 января 2017 года . Проверено 16 августа 2020 г. .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б «Самостоятельная экскурсия» (PDF) . Университет Шеффилда. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 22 сентября 2013 года . Проверено 1 сентября 2020 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б «Кампус в контексте» (PDF) . Университет Шеффилда. п. 34. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 5 февраля 2016 г. Проверено 3 февраля 2016 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д и «Кампус в контексте» (PDF) . Университет Шеффилда. п. 20. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 5 февраля 2016 года . Проверено 3 февраля 2016 г.

- ^ «Кампус в контексте» (PDF) . Университет Шеффилда. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 5 февраля 2016 года . Проверено 3 февраля 2016 г.

- ^ Кребс, HA; Джонсон, Вашингтон (1937). «Метаболизм кетоновых кислот в тканях животных» . Биохимический журнал . 31 (4): 645–60. дои : 10.1042/bj0310645 . ПМК 1266984 . ПМИД 16746382 .

- ^ Кребс, HA; Джонсон, Вашингтон (1937). «Ацетопировиноградная кислота (альфагамма-дикетовалериановая кислота) как промежуточный метаболит в тканях животных» . Биохимический журнал . 31 (5): 772–9. дои : 10.1042/bj0310772 . ПМК 1267003 . ПМИД 16746397 .

- ^ Коул, Руперт (20 июня 2015 г.). «Важность выбора Портера: Королевский институт, Джордж Портер и две культуры, 1959–64» . Примечания Rec R Soc Lond . 69 (2): 191–216. дои : 10.1098/rsnr.2014.0041 . ПМЦ 4424602 . ПМИД 31390385 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б «Местоположение октагон-центра» . Университет Шеффилда. Архивировано из оригинала 18 апреля 2021 года . Проверено 20 августа 2020 г.

- ^ «Структура развития» . mcwarchitects.com . Архитекторы MCW. Архивировано из оригинала 20 октября 2021 года . Проверено 28 августа 2020 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Маклауд, Дональд (20 июля 2005 г.). «Шеффилд отказывается от контракта на обучение медсестер» . Хранитель . Лондон. Архивировано из оригинала 19 сентября 2014 года . Проверено 4 апреля 2008 г.

- ^ «Наше новое здание Diamond стоимостью 81 миллион фунтов стерлингов открывает свои двери для студентов» . Управление недвижимостью и объектами . Университет Шеффилда. Архивировано из оригинала 16 февраля 2020 года . Проверено 4 февраля 2016 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б «Преобразование наших общественных пространств» . Генеральный план кампуса . Университет Шеффилда. Архивировано из оригинала 5 февраля 2016 года . Проверено 4 февраля 2016 г.

- ^ «Улучшение наших ключевых пространств» . Генеральный план кампуса . Университет Шеффилда. Архивировано из оригинала 5 февраля 2016 года . Проверено 4 февраля 2016 г.

- ^ «Шеффилд отказался от 10 миллионов фунтов стерлингов за стажировку» . Высшее образование Times (THE) . 6 июля 2021 года. Архивировано из оригинала 21 июля 2021 года . Проверено 21 июля 2021 г.

- ^ «Завершено публичное собрание Университета Шеффилда» . Генри Бут. Архивировано из оригинала 25 февраля 2021 года . Проверено 28 августа 2020 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б «Текущие проекты» . Развитие недвижимости . Университет Шеффилда. Архивировано из оригинала 24 апреля 2017 года . Проверено 28 августа 2020 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж «Генеральный план Университета Шеффилда на 2014 год» (PDF) . Университет Шеффилда. 2014. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 21 марта 2019 года . Проверено 20 августа 2020 г.

- ^ «Канцлер» . Управление и менеджмент . Университет Шеффилда. Архивировано из оригинала 24 сентября 2020 года . Проверено 31 августа 2020 г.

- ^ «Строим светлое будущее» . Университет Шеффилда. 22 августа 2012 года. Архивировано из оригинала 5 марта 2021 года . Проверено 2 сентября 2020 г.

- ^ Кампус в контексте (PDF) , Университет Шеффилда, с. 34, заархивировано (PDF) из оригинала 5 февраля 2016 г. , получено 3 февраля 2016 г.

- ^ Добро пожаловать в Университет Шеффилда: Международный 2011–2012 гг. (PDF) , Университет Шеффилда, с. 7, заархивировано (PDF) из оригинала 5 марта 2021 г. , получено 2 сентября 2020 г.