Черные британцы

Распределение по местным органам власти по переписи 2011 года. | |

| Общая численность населения | |

|---|---|

Северная Ирландия : 11 032 – 0,6% (2021 г.) [4] | |

| Регионы со значительной численностью населения | |

| Языки | |

| Английский ( британский английский , черный британский английский , карибский английский , африканский английский ), креольские языки , французский , ямайский патуа , нигерийский пиджин и другие языки. | |

| Религия | |

| Преимущественно христианство (66,9%); меньшинство исповедует ислам (17,3%), другие конфессии (0,8%) [б] или нерелигиозны (8,6%) Перепись 2021 года, только Нью-Йорк, Англия и Уэльс. [5] [6] |

| Часть серии о |

| Культура Соединенного Королевства |

|---|

|

Чернокожие британцы — это многоэтническая группа британцев африканского или афро -карибского происхождения. [7] Термин «черные британцы» появился в 1950-х годах и относится к чернокожим британцам из Вест-Индии из бывших карибских британских колоний в Вест-Индии (т. е. Новому Содружеству ), иногда называемым поколением Виндраш , и чернокожим британцам, происходящим из Африки .

Термин «черный» исторически имел ряд применений в качестве расового и политического ярлыка и может использоваться в более широком социально-политическом контексте, чтобы охватить более широкий круг неевропейских этнических меньшинств в Великобритании. Это определение стало спорным. [8] Чернокожие британцы — одна из различных записей самоназвания, используемых в официальных классификациях этнической принадлежности Великобритании .

Около 3,7 процента населения Соединенного Королевства в 2021 году были чернокожими. Цифры выросли по сравнению с переписью 1991 года, когда 1,63 процента населения были зарегистрированы как чернокожие или чернокожие британцы, до 1,15 миллиона жителей в 2001 году, или 2 процента населения, а в 2011 году эта цифра увеличилась до чуть более 1,9 миллиона, что составляет 3 процент. Почти 96 процентов чернокожих британцев живут в Англии, особенно в крупных городских районах Англии, причем около 1,2 миллиона человек проживают в Большом Лондоне .

Терминология [ править ]

Термин «черные британцы» чаще всего использовался для обозначения чернокожих людей происхождения из Нового Содружества , как западноафриканского, так и южноазиатского происхождения. Например, компания Southall Black Sisters была основана в 1979 году «для удовлетворения потребностей чернокожих (азиатских и афро-карибских) женщин». [9] Обратите внимание, что «азиат» в британском контексте обычно относится к людям южноазиатского происхождения. [10] [11] Черный цвет использовался в этом инклюзивном политическом смысле для обозначения «небелых британцев ». [12]

В 1970-е годы, во время растущей активности против расовой дискриминации, основные общины, описанные таким образом, были выходцами из Британской Вест-Индии и Индийского субконтинента . Солидарность против расизма и дискриминации иногда распространяла этот термин в то время на ирландское население Великобритании . и [13] [14]

Некоторые организации продолжают использовать этот термин включительно, например, Black Arts Alliance , [15] [16] которые распространяют использование этого термина на латиноамериканцев и всех беженцев, [17] и Национальная ассоциация черной полиции . [18] В официальной переписи населения Великобритании есть отдельные записи для самоназвания, в которых респонденты могут идентифицировать себя как «британцы азиатского происхождения», «черные британцы» и «другая этническая группа». [2] Из-за индийской диаспоры и, в частности, изгнания Иди Амином азиатов из Уганды в 1972 году, многие британские азиаты происходят из семей, которые ранее в течение нескольких поколений жили в Британской Вест-Индии или на Коморских островах . [19] Ряд британских азиатов, в том числе такие знаменитости, как Риз Ахмед и Зейн Малик, до сих пор используют термины «черный» и «азиат» как синонимы. [20]

Классификация населения переписи

Перепись 1991 года в Великобритании была первой переписью населения, в которой был включен вопрос об этнической принадлежности . По данным переписи населения Великобритании 2011 года , Управление национальной статистики (ONS) и Агентство статистики и исследований Северной Ирландии (NISRA) разрешают людям в Англии, Уэльсе и Северной Ирландии, которые идентифицируют себя как «черные», выбирать «черных африканцев». Установите флажки «Черный карибский» или «Любой другой черный/африканский/карибский фон». [2] Для шотландской переписи 2011 года Главное регистрационное управление Шотландии (GOS) также установило новые отдельные флажки «Африканские, африканские шотландцы или африканские британцы» и «Карибские, карибские шотландцы или карибские британцы» для лиц в Шотландии из Африки и Карибского бассейна. соответственно, которые не идентифицируют себя как «черные, черные шотландцы или черные британцы». [21] В переписи 2021 года в Англии и Уэльсе были сохранены варианты происхождения карибских, африканцев и любых других чернокожих, чернокожих британцев или карибцев, добавив ответ для группы «черных африканцев». В Северной Ирландии в переписи 2021 года были отмечены галочки «Черные африканцы» и «Другие черные». В Шотландии вариантами были «африканцы», «шотландцы-африканцы» или «британцы-африканцы», «карибцы» или «черные», каждый из которых сопровождался полем для ответа. [22]

Во всех переписях Великобритании лица с несколькими семейными предками могут указывать свою этническую принадлежность в разделе «Смешанные или несколько этнических групп», который включает дополнительные флажки «Белые и черные карибцы» или «Белые и черные африканцы» в Англии. Уэльс и Северная Ирландия. [2]

Историческое использование [ править ]

Черные британцы или черные англичане также были термином для тех чернокожих и людей смешанной расы в Сьерра-Леоне (известных как креолы или крио (а) ), которые были потомками мигрантов из Англии и Канады и идентифицировались как британцы. [23] Как правило, они являются потомками чернокожих людей, которые жили в Англии в 18 веке и освободили чернокожих американских рабов, сражавшихся за корону в американской войне за независимость (см. также Черные лоялисты ). Лондона В 1787 году сотни чернокожих бедняков (категория, в которую входили моряки из Восточной Индии, известные как ласкары ) согласились переехать в эту западноафриканскую колонию при условии, что они сохранят статус британских подданных , будут жить свободно под защитой Британская корона и будет защищена Королевским флотом . Это новое начало вместе с ними начали некоторые белые люди (см. также Комитет помощи чернокожим беднякам ), в том числе любовницы, жены и вдовы чернокожих мужчин. [24] Кроме того, около 1200 черных лоялистов, бывших американских рабов, которые были освобождены и переселены в Новую Шотландию , и 550 ямайских маронов также решили присоединиться к новой колонии. [25] [26]

История [ править ]

Античность [ править ]

Согласно « Истории Августа» , североафриканский римский император Септимус Север предположительно посетил Стену Адриана в 210 году нашей эры. Сообщается, что, возвращаясь с осмотра стены, над ним издевался эфиопский солдат, державший гирлянду из ветвей кипариса. Северус приказал ему уйти, как сообщается, «испугавшись». [27] по его темному цвету кожи [27] [28] [29] и рассматривая его поступок и внешний вид как предзнаменование. Пишут, что эфиоплянин сказал: «Ты был всем, ты победил все, теперь, о победитель, будь богом». [30] [31]

Англосаксонская Англия [ править ]

Было обнаружено, что у девушки , похороненной в Апдауне , недалеко от Истри в Кенте в начале VII века, 33% ее ДНК принадлежало западноафриканскому типу, наиболее близко напоминавшему Эсан или Йоруба . группы [32]

В 2013 году [33] [34] был обнаружен скелет, В Фэрфорде , Глостершир , который, как показала судебно-медицинская антропология , принадлежал африканской женщине из стран Африки к югу от Сахары. Ее останки датируются периодом между 896 и 1025 годами. [34] Местные историки полагают, что она, скорее всего, была либо рабыней , либо подневольной служанкой . [35]

16 век [ править ]

Чернокожий музыкант входит в число шести трубачей, изображенных в королевской свите Генриха VIII в Вестминстерском турнирном списке, иллюминированной рукописи, датируемой 1511 годом. Он носит королевскую ливрею и ездит верхом на лошади. Этого человека обычно называют « Джоном Бланком , черным трубачом», который указан в платежных счетах как Генриха VIII, так и его отца, Генриха VII . [36] [37] В группу африканцев при дворе короля шотландского Якова IV входили Эллен Мор и барабанщик, которого называли « Мор таубронар ». И ему, и Джону Бланку платили зарплату за свои услуги. [38] Небольшое количество чернокожих африканцев работало независимыми владельцами бизнеса в Лондоне в конце 1500-х годов, в том числе ткач шелка Разумный Блэкман . [39] [40] [41]

Когда начали открываться торговые линии между Лондоном и Западной Африкой, люди из этого региона начали прибывать в Великобританию на борту торговых и рабовладельческих судов. Например, купец Джон Лок привез в Лондон в 1555 году из Гвинеи нескольких пленников. В отчете о путешествии в Хаклюйте сообщается, что они «были высокими и сильными людьми и вполне могли согласиться с нашей едой и напитками. Холодный и влажный воздух несколько оскорблял их». [42]

В конце 16 века, а также в первые два десятилетия 17 века 25 человек, названных в записях небольшого прихода Св. Ботольфа в Олдгейте, были идентифицированы как «черные мауры». [43] В период войны с Испанией, между 1588 и 1604 годами, произошло увеличение числа людей, достигших Англии из испанских колониальных экспедиций в части Африки. Англичане освободили многих из этих пленников из рабства на испанских кораблях. Они прибыли в Англию в основном как побочный продукт работорговли; некоторые были представителями смешанной африканской и испанской расы и стали переводчиками или моряками. [44] Американский историк Айра Берлин классифицировал таких людей как атлантических креолов или чартерное поколение рабов и многорасовых рабочих в Северной Америке. [45] Работорговец Джон Хокинс прибыл в Лондон с 300 пленниками из Западной Африки. [44] Однако работорговля укоренилась только в 17 веке, и Хокинс предпринял всего три экспедиции.

Жак Франсис , которого некоторые историки называют рабом, [46] [47] [48] но описал себя на латыни как « famulus », что означает слуга, раб или слуга. [49] [50] Фрэнсис родился на острове у побережья Гвинеи, вероятно, острове Аргуин , у побережья Мавритании . [51] [52] [53] Он работал водолазом у Пьетро Пауло Корси в его спасательных операциях на затонувших кораблях «Сент-Мэри» и «Сент-Эдвард Саутгемптонский » , а также на других кораблях, таких как « Мэри Роуз », затонувшей в гавани Портсмута . Когда Корси был обвинен в краже, Фрэнсис поддержал его в английском суде. С помощью переводчика он подтвердил заявления своего хозяина о невиновности. Некоторые показания по делу отражают негативное отношение к рабам или чернокожим людям в качестве свидетелей. [54] В марте 2019 года было обнаружено, что два скелета, найденные на « Мэри Роуз», имеют южноевропейское или североафриканское происхождение; На одном из них был обнаружен кожаный браслет с гербом Екатерины Арагонской и королевским гербом Англии, возможно, испанский или североафриканский, другой, известный как «Генрих», также имел схожий генетический состав. Митохондриальная ДНК Генри показала, что его предки могли происходить из Южной Европы, Ближнего Востока или Северной Африки, хотя доктор Сэм Робсон из Портсмутского университета «исключил», что Генри был чернокожим или что он был из Африки к югу от Сахары выходцем . Доктор Оньека Нубия предупредил, что число тех, кто находился на борту « Мэри Роуз» , имевших наследие за пределами Британии, не обязательно было репрезентативным для всей Англии того времени, хотя оно определенно не было «единичным». [55] Предполагается, что они, вероятно, путешествовали через Испанию или Португалию, прежде чем прибыли в Великобританию. [55]

Слуги Блэкамура воспринимались как модная новинка и работали в домах нескольких выдающихся елизаветинцев, в том числе королевы Елизаветы I, Уильяма Поула , Фрэнсиса Дрейка , [56] [57] [44] и Анна Датская в Шотландии . [58] Среди этих слуг был «Джон Поскорее, черномор», слуга капитана Томаса Лава. [44] Среди других, включенных в приходские метрические книги, - Доминго, «черный негр, слуга сэра Уильяма Винтера », похороненный в xviii день августа [1587 г.], и «Фраунсис, слуга Блэкамора Томаса Паркера», похороненный в январе 1591 г. [59] Некоторые из них были свободными работниками, хотя большинство из них работали домашней прислугой и артистами. Некоторые работали в портах, но их неизменно называли рабочей силой. [60]

В елизаветинский период население Африки могло насчитывать несколько сотен человек, однако не все были выходцами из Африки к югу от Сахары. [55] Историк Майкл Вуд отметил, что африканцы в Англии были «в основном свободными… [и] как мужчины, так и женщины, женились на коренных англичанах». [61] Архивные данные показывают записи о жизни более 360 африканцев между 1500 и 1640 годами в Англии и Шотландии. [62] [63] [64] Реагируя на более темный цвет лица людей двухрасового происхождения, Джордж Бест в 1578 году утверждал, что черная кожа не связана с солнечным теплом (в Африке ), а вызвана библейским проклятием. Реджинальд Скот отмечал, что суеверные люди связывали черную кожу с демонами и призраками, написав (в своей скептической книге « Открытие колдовства »): «Но в нашем детстве наши матери-служанки так напугали нас уродливым чуваком с рогами на голове и хвостом на голове. его задница, глаза как у басона, клыки как у собаки, когти как у медведя, кожа как у нигера и голос, рычащий как у льва»; историк Ян Мортимер заявил, что такие взгляды «следуют учитывать на всех уровнях общества». [65] [66] На взгляды на чернокожих «повлияли предвзятые представления об Эдемском саду и грехопадении ». [64] Кроме того, в тот период в Англии не существовало концепции натурализации как средства включения иммигрантов в общество. Под английскими подданными он понимал людей, родившихся на острове. Некоторые считали, что те, кто не был таковыми, неспособны стать подданными или гражданами. [67]

В 1596 году королева Елизавета I направила письма лордам-мэрам крупных городов, в которых утверждалось, что «в последнее время в это королевство пришли различные ныряльщики-черные болота, которых уже здесь много...». Во время посещения английского двора Каспер Ван Сенден , немецкий купец из Любека , запросил разрешение на переправку «блэкамуров», живших в Англии, в Португалию или Испанию, предположительно для продажи их там. Впоследствии Элизабет выдала Ван Сендену королевский ордер , предоставив ему на это право. [68] Однако Ван Сендену и Шерли это не удалось, как они признали в переписке с сэром Робертом Сесилом. [69] В 1601 году Елизавета издала еще одну прокламацию, в которой заявила, что она «крайне недовольна тем, что большое количество негров и чернокожих (как ей сообщили) завезено в это царство». [70] и снова разрешил ван Сендену их депортировать. В ее прокламации 1601 года говорилось, что чернокожие «здесь воспитывались и питались, к большому раздражению сюзеренов [королевы], которые жаждут облегчения, которое эти люди потребляют». Далее в нем говорилось, что «большинство из них - неверующие, не понимающие ни Христа, ни Его Евангелия». [71] [72]

Исследования африканцев в Британии раннего Нового времени указывают на их продолжающееся незначительное присутствие. Имтиаза Хабиба К таким исследованиям относятся «Жизни черных в английских архивах, 1500–1677: отпечатки невидимого» (Ashgate, 2008), [73] Блэкамуры Ониеки : африканцы в Англии эпохи Тюдоров, их присутствие, статус и происхождение (Narrative Eye, 2013), [74] Миранды Кауфман Оксфордская докторская диссертация «Африканцы в Британии, 1500–1640 гг.» , [75] и ее Черные Тюдоры: Нерассказанная история ( Oneworld Publications , 2017). [76]

17 и 18 века [ править ]

Рабство и работорговля [ править ]

Великобритания была вовлечена в трехконтинентальную работорговлю между Европой, Африкой и Америкой. Многие из тех, кто участвовал в британской колониальной деятельности, такие как капитаны кораблей , колониальные чиновники , торговцы, работорговцы и владельцы плантаций, привозили с собой в Великобританию чернокожих рабов в качестве слуг. Это привело к увеличению присутствия чернокожих в северных, восточных и южных районах Лондона. Один из самых известных рабов, сопровождавших капитана дальнего плавания, был известен как Самбо. Он заболел вскоре после прибытия в Англию и был похоронен в Ланкашире. Его мемориальная доска и надгробие стоят и по сей день. Было также небольшое количество свободных рабов и моряков из Западной Африки и Южной Азии. Многие из этих людей были вынуждены нищенствовать из-за отсутствия работы и расовой дискриминации. [78] [79] В 1687 году «мавру» была предоставлена свобода города Йорка . он значится В списках свободных граждан как «Джон Мур – Блэк». Он единственный чернокожий человек, которого на сегодняшний день нашли в йоркских списках. [80]

Участие торговцев из Великобритании [81] Трансатлантическая работорговля была важнейшим фактором развития чернокожего британского сообщества. Эти общины процветали в портовых городах, активно вовлеченных в работорговлю, таких как Ливерпуль. [81] и Бристоль . Некоторые ливерпульцы могут проследить свое чернокожее наследие в городе на протяжении десяти поколений. [81] Среди первых чернокожих поселенцев в городе были моряки, дети торговцев смешанной расы, отправленные учиться в Англию, слуги и освобожденные рабы. Ошибочные ссылки на рабов, въехавших в страну после 1722 года и считающихся свободными людьми, взяты из источника, в котором 1722 год является опечаткой 1772 года, что, в свою очередь, основано на неправильном понимании результатов дела Сомерсета, упомянутого ниже. [82] [83] В результате в Ливерпуле проживает старейшая чернокожая община Великобритании, основанная как минимум в 1730-х годах. К 1795 году на Ливерпуль приходилось 62,5 процента европейской работорговли. [81]

В то время лорд Мэнсфилд заявил, что раба, сбежавшего от своего хозяина, нельзя ни силой ни схватить в Англии, ни продать за границу. Однако Мэнсфилд постарался указать, что его решение не комментирует законность самого рабства. [84] Этот приговор увеличил число чернокожих, сбежавших из рабства, и помог привести рабство в упадок. В тот же период многие бывшие американские солдаты-рабы, сражавшиеся на стороне британцев в войне за независимость США , были переселены в качестве свободных людей в Лондон. Им никогда не выплачивали пенсии, и многие из них впали в нищету и вынуждены были попрошайничать на улице. В сообщениях того времени говорилось, что у них «не было никакой перспективы выжить в этой стране, кроме как за счет грабежей среди населения или общей благотворительности». Сочувствующий наблюдатель написал, что «большое количество чернокожих и цветных людей, многие из которых были беженцами из Америки и другими людьми, которые по суше или по морю находились на службе Его Величества, были… в большом бедствии». Даже по отношению к белым лоялистам к новоприбывшим из Америки было мало доброй воли. [85]

Официально рабство в Англии не было законным. [86] Решение Картрайта 1569 года постановило, что в Англии «слишком чистый воздух, чтобы раб мог дышать». Однако чернокожих африканских рабов продолжали покупать и продавать в Англии в восемнадцатом веке. [87] Вопрос о рабстве не оспаривался юридически до тех пор, пока в 1772 году не состоялось дело Сомерсета , которое касалось Джеймса Сомерсетта, беглого черного раба из Вирджинии . Лорд-главный судья Уильям Мюррей, 1-й граф Мэнсфилд, пришел к выводу, что Сомерсета нельзя заставить покинуть Англию против его воли. Позже он повторил: «Решения не идут дальше того, что хозяин не может силой заставить его выйти из королевства». [88] Несмотря на предыдущие постановления, такие как декларация 1706 года (которая была разъяснена годом позже) лорда-главного судьи Холта . [89] Поскольку рабство не является законным в Великобритании, его часто игнорировали, а рабовладельцы утверждали, что рабы были собственностью и поэтому не могли считаться людьми. [90] Рабовладелец Томас Папийон был одним из многих, кто взял своего черного слугу «по характеру и качеству моих товаров и движимого имущества». [91] [92]

Рост населения [ править ]

Чернокожие люди жили среди белых в Лондоне в районах Майл-Энд , Степни , Паддингтон и Сент-Джайлс . После правления Мэнсфилда многие бывшие рабы продолжали работать на своих старых хозяев в качестве оплачиваемых сотрудников. В Англии было немедленно освобождено от 14 000 до 15 000 (по тогдашним оценкам) рабов. [93] Многих из этих эмансипированных людей стали называть «черными бедняками», чернокожие бедняки определялись как бывшие рабы-солдаты после эмансипации, моряки, такие как южноазиатские ласкары, [94] бывшие наемные слуги и бывшие наемные работники плантаций. [95] Примерно в 1750-х годах Лондон стал домом для многих чернокожих, а также евреев, ирландцев, немцев и гугенотов . По словам Гретхен Герзины в ее «Черном Лондоне» , к середине 18 века чернокожие составляли где-то от 1% до 3% населения Лондона. [96] [97] Доказательства количества чернокожих жителей города были обнаружены в зарегистрированных захоронениях. Некоторые чернокожие жители Лондона сопротивлялись рабству, спасаясь бегством. [96] Среди ведущих чернокожих активистов той эпохи были Олауда Эквиано , Игнатиус Санчо и Куобна Оттоба Кугоано . Смешанная раса Дайдо Элизабет Белль , родившаяся рабыней на Карибах, переехала в Великобританию со своим белым отцом в 1760-х годах. В 1764 году журнал The Gentleman's Magazine сообщил, что «предполагалось, что здесь будет около 20 000 слуг-негров». [98]

Джон Истумлин (ок. 1738–1786) был первым хорошо известным чернокожим жителем Северного Уэльса . Возможно, он стал жертвой работорговли в Атлантике и был родом либо из Западной Африки , либо из Вест-Индии . Семья Винн отвезла его в поместье Истумлин в Криксиете и окрестила валлийским именем Джон Истумлин. Местные жители научили его английскому и валлийскому языкам , он стал садовником в поместье и «вырос в красивого и энергичного молодого человека». Его портрет был написан в 1750-х годах. Он женился на местной женщине Маргарет Граффид в 1768 году, и их потомки до сих пор живут в этом районе. [99]

В газете Morning Gazette сообщалось, что в целом по стране их насчитывается 30 000, хотя эти цифры были сочтены «паникерскими» преувеличениями. В том же году вечеринка чернокожих мужчин и женщин в пабе на Флит-стрит была настолько необычной, что о ней написали в газетах. Их присутствие в стране было настолько поразительным, что вызвало горячую вспышку отвращения к колониям готтентотов . [100] По оценкам современных историков, основываясь на приходских списках, регистрах крещения и бракосочетания, а также уголовных контрактах и договорах купли-продажи, в Великобритании в 18 веке проживало около 10 000 чернокожих людей. [101] [102] [91] [103] По другим оценкам, это число составляет 15 000 человек. [104] [105] [106]

В 1772 году лорд Мэнсфилд оценил число чернокожих в стране в 15 000 человек, хотя большинство современных историков считают наиболее вероятной цифру в 10 000 человек. [91] [109] Чернокожее население Лондона оценивается примерно в 10 000 человек, что составляет примерно 1% от общей численности населения Лондона. Черное население составляло около 0,1% от общей численности населения Великобритании в 1780 году. [110] [111] По оценкам, чернокожее женское население едва достигает 20% от общей численности афро-карибского населения страны. [111] В 1780-х годах, после окончания Войны за независимость в США, сотни чернокожих лоялистов из Америки были переселены в Великобританию. [112] Считается, что Маркус Томас был привезен в то время с Ямайки еще мальчиком семьей Стэнхоуп, работал слугой в их доме, крестился в 19 лет, а затем присоединился к Вестминстерской милиции в качестве барабанщика. [107] [108] Позже некоторые эмигрировали в Сьерра-Леоне с помощью Комитета помощи чернокожим беднякам после нищеты, чтобы сформировать этническую идентичность креолов Сьерра-Леоне . [113][114][115]

Discrimination[edit]

In 1731 the Lord Mayor of London ruled that "no Negroes shall be bound apprentices to any Tradesman or Artificer of this City". Due to this ruling, most were forced into working as domestic servants and other menial professions.[116][91] Those black Londoners who were unpaid servants were in effect slaves in anything but name.[117] In 1787, Thomas Clarkson, an English abolitionist, noted at a speech in Manchester: "I was surprised also to find a great crowd of black people standing round the pulpit. There might be forty or fifty of them."[118] There is evidence that black men and women were occasionally discriminated against when dealing with the law because of their skin colour. In 1737, George Scipio was accused of stealing Anne Godfrey's washing, the case rested entirely on whether or not Scipio was the only black man in Hackney at the time.[119] Ignatius Sancho, black writer, composer, shopkeeper and voter in Westminster wrote, that despite being in Britain since the age of two he felt he was "only a lodger, and hardly that."[120] Sancho complained of "the national antipathy and prejudice" of native white Britons "towards their wooly headed brethren."[121] Sancho was frustrated that many resorted to stereotyping their black neighbours.[122] A financially independent householder, he became the first black person of African origin to vote in parliamentary elections in Britain, in a time when only 3% of the British population were allowed to vote.[123]

Sailors of African descent experienced far less prejudice compared to blacks in the cities such as London. Black sailors would have shared the same quarters, duties and pay as their white shipmates. There are some disputes in the estimation of black sailors, conservative estimates put it between 6% and 8% of navy sailors of the time, this proportion is considerably larger than the population as a whole. Notable examples are Olaudah Equiano and Francis Barber.[124]

Abolitionism[edit]

With the support of other Britons, these activists demanded that Blacks be freed from slavery. Supporters involved in these movements included workers and other nationalities of the urban poor. Black people in London who were supporters of the abolitionist movement include Cugoano and Equiano. At this time, slavery in Britain itself had no support from common law, but its definitive legal status was not clearly defined until the 19th century.[citation needed]

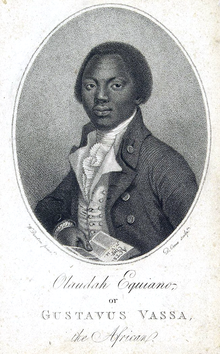

Olaudah Equiano[edit]

During the late 18th century, numerous publications and memoirs were written about the "black poor". One example is the writings of Olaudah Equiano, a former slave who wrote a memoir titled The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano.

In 1786, Equiano became the first black person to be employed by the British government, when he was made Commissary of Provisions and Stores for the 350 black people suffering from poverty who had decided to accept the government's offer of an assisted passage to Sierra Leone.[125] The following year, in 1787, encouraged by the Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor, about 400[126] black Londoners were aided in emigrating to Sierra Leone in West Africa, founding the first British colony on the continent.[127] They asked that their status as British subjects be recognized, along with requests that they be given military protection by the Royal Navy.[128] However, even though the committee signed up about 700 members of the Black Poor, only 441 boarded the three ships that set sail from London to Portsmouth.[129] Many black Londoners were no longer interested in the scheme, and the coercion employed by the committee and the government to recruit them only reinforced their opposition. Equiano, who was originally involved in the scheme, became one of its most vocal critics. Another prominent black Londoner, Ottobah Cugoano, also criticised the scheme.[130][131][132]

Ancestry[edit]

In 2007, scientists found the rare paternal haplogroup A1 in a few living British men with Yorkshire surnames. This clade is today almost exclusively found among males in West Africa, where it is also rare. The haplogroup is thought to have been brought to Britain either through enlisted soldiers during Roman Britain, or much later via the modern slave trade. Turi King, a co-author on the study, noted the most probable "guess" was the West African slave trade. Some of the known individuals who arrived through the slave route, such as Ignatius Sancho and Olaudah Equiano, attained a very high social rank. Some married into the general population.[133]

19th century[edit]

In the late 18th century, the British slave trade declined in response to changing popular opinion. Both Great Britain and the United States abolished the Atlantic slave trade in 1808, and cooperated in liberating slaves from illegal trading ships off the coast of West Africa. Many of these freed slaves were taken to Sierra Leone for settlement. Slavery was abolished completely in the British Empire by 1834, although it had been profitable on Caribbean plantations. Fewer blacks were brought into London from the West Indies and West Africa.[95] The resident British black population, primarily male, was no longer growing from the trickle of slaves and servants from the West Indies and America.[134] Abolition meant a virtual halt to the arrival of black people to Britain, just as immigration from Europe was increasing.[135] The black population of Victorian Britain was so small that those living outside of larger trading ports were isolated from the black population.[136][137] The mentioning of black people and descendants in parish registers declined markedly in the early 19th century. It is possible that researchers simply did not collect the data or that the mostly black male population of the late 18th century had married white women.[138][136] Evidence of such marriages may still be found today with descendants of black servants such as Francis Barber, a Jamaican-born servant who lived in Britain during the 18th century. His descendants still live in England today and are white.[116] Abolition of slavery in 1833, effectively ended the period of small-scale black immigration to London and Britain. Though, there were some exceptions, black and Chinese seamen began putting down the roots of small communities in British ports, not least because they were abandoned there by their employers.[135]

By the late 19th century, race discrimination was furthered by theories of scientific racism, which held that whites were the superior race and that blacks were less intelligent than whites. Attempts to support these theories cited "scientific evidence", such as brain size. James Hunt, President of the London Anthropological Society, in 1863 in his paper "On the Negro's place in nature" wrote that "the Negro is inferior intellectually to the European...[and] can only be humanised and civilised by Europeans."[139] In the 1880s, there was a build-up of small groups of black dockside communities in towns such as Canning Town,[140] Liverpool and Cardiff.

Despite social prejudice and discrimination in Victorian England, some 19th-century black Britons achieved exceptional success. Pablo Fanque, born poor as William Darby in Norwich, rose to become the proprietor of one of Britain's most successful Victorian circuses. He is immortalised in the lyrics of The Beatles song "Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!" Thirty years after his 1871 death, the chaplain of the Showman's Guild said:

"In the great brotherhood of the equestrian world there is no colour line [bar], for, although Pablo Fanque was of African extraction, he speedily made his way to the top of his profession. The camaraderie of the ring has but one test – ability."[141]

Another great circus performer was equestrian Joseph Hillier, who took over and ran Andrew Ducrow's circus company after Ducrow died.[142]

From the early part of the century, students of African descent were admitted to British Universities. One such student, for example, was the African American James McCune Smith, who travelled from New York City to Glasgow University to study medicine. In 1837 he was awarded a medical doctorate and published two scientific articles in the London Medical Gazette. These articles are the first known to be published by an African-American medical doctor in a scientific journal.[143]

An Indian Briton, Dadabhai Naoroji, stood for election to parliament for the Liberal Party in 1886. He was defeated, leading the leader of the Conservative Party, Lord Salisbury to remark that "however great the progress of mankind has been, and however far we have advanced in overcoming prejudices, I doubt if we have yet got to the point of view where a British constituency would elect a Blackman".[144] Naoroji was elected to parliament in 1892, becoming the second Member of Parliament (MP) of Indian descent after David Ochterlony Dyce Sombre.

20th century[edit]

Early 20th century[edit]

According to the Sierra Leone Creole barrister and writer, Augustus Merriman-Labor, in his 1909 book Britons Through Negro Spectacles, London's Black population at the time did "not much exceed one hundred" people and "To every one [Black person in London], there are over sixty thousand whites".[145]

World War I saw a small growth in the size of London's Black communities with the arrival of merchant seamen and soldiers. At that time, there were also small groups of students from Africa and the Caribbean migrating into London. These communities are now among the oldest black communities of London.[146] The largest Black communities were to be found in the United Kingdom's great port cities: London's East End, Liverpool, Bristol and Cardiff's Tiger Bay, with other communities in South Shields in Tyne & Wear and Glasgow. In 1914, the black population was estimated at 10,000 and centred largely in London.[147][148] By 1918 there may have been as many as 20,000[149] or 30,000[147] black people living in Britain. However, the black population was much smaller relative to the total British population of 45 million and official documents were not adapted to record ethnicity.[150] Black residents had for the most part emigrated from parts of the British Empire. The number of black soldiers serving in the British army, (rather than colonial regiments,) prior to World War I is unknown but was likely to have been negligibly low.[148] One of the Black British soldiers during World War I was Walter Tull, an English professional footballer, born to a Barbadian carpenter Daniel Tull and Kent-born Alice Elizabeth Palmer. His grandfather was a slave in Barbados.[151] Tull became the first British-born mixed-heritage infantry officer in a regular British Army regiment, despite the 1914 Manual of Military Law specifically excluding soldiers that were not "of pure European descent" from becoming commissioned officers.[152][153][154]

Colonial soldiers and sailors of Afro-Caribbean descent served in the United Kingdom during the First World War and some settled in British cities. The South Shields community—which also included other "coloured" seamen known as lascars, who were from South Asia and the Arab world—were victims of the UK's first race riot in 1919.[155] Soon eight other cities with significant non-white communities were also hit by race riots.[156] Due to these disturbances, many of the residents from the Arab world as well as some other immigrants were evacuated to their homelands.[157] In that first postwar summer, other racial riots of whites against "coloured" peoples also took place in numerous United States cities, towns in the Caribbean, and South Africa.[156] They were part of the social dislocation after the war as societies struggled to integrate veterans into the work forces again, and groups competed for jobs and housing. At Australian insistence, the British refused to accept the Racial Equality Proposal put forward by the Japanese at the Paris Peace Conference, 1919.

World War II[edit]

World War II marked another period of growth for the Black communities in London, Liverpool and elsewhere in Britain. Many Blacks from the Caribbean and West Africa arrived in small groups as wartime workers, merchant seamen, and servicemen from the army, navy, and air forces.[158] For example, in February 1941, 345 West Indians came to work in factories in and around Liverpool, making munitions.[159] Among those from the Caribbean who joined the Royal Air Force (RAF) and gave distinguished service are Ulric Cross[160] from Trinidad, Cy Grant[161] from Guyana and Billy Strachan[162] from Jamaica. The African and Caribbean War Memorial was installed in Brixton, London, in 2017 by the Nubian Jak Community Trust to honour servicemen from Africa and the Caribbean who served alongside British and Commonwealth Forces in both the First World War and Second World War.[163]

By the end of 1943, there were 3,312 African-American GIs based at Maghull and Huyton, near Liverpool.[164] The Black population in the summer of 1944 was estimated at 150,000, mostly Black GIs from the United States. However, by 1948 the Black population was estimated to have been less than 20,000 and did not reach the previous peak of 1944 until 1958.[165]

June 1943

Learie Constantine, a West Indian cricketer, was a welfare officer with the Ministry of Labour when he was refused service at a London hotel. He sued for breach of contract and was awarded damages. This particular example is used by some to illustrate the slow change from racism towards acceptance and equality of all citizens in London.[166]

Post-war[edit]

In 1950, there were probably fewer than 20,000 non-White residents in Britain, almost all born overseas.[167] After World War II, the largest influx of Black people occurred, mostly from the British West Indies. Over a quarter of a million West Indians, the overwhelming majority of them from Jamaica, settled in Britain in less than a decade. In 1951, the population of Caribbean and African-born people in Britain was estimated at 20,900.[168] In the mid-1960s, Britain had become the centre of the largest overseas population of West Indians.[169] This migration event is often labelled "Windrush", a reference to the HMT Empire Windrush, the ship that carried the first major group of Caribbean migrants to the United Kingdom in 1948.[170]

"Caribbean" is itself not one ethnic or political identity; for example, some of this wave of immigrants were Indo-Caribbean. The most widely used term used at that time was West Indian (or sometimes coloured). Black British did not come into widespread use until the second generation were born to these post-war migrants to the UK. Although British by nationality, due to friction between them and the White majority they were often born into communities that were relatively closed, creating the roots of what would become a distinct Black British identity. By the 1950s, there was a consciousness of Black people as a separate group that had not been there during 1932–1938.[169] The increasing consciousness of Black British peoples was deeply informed by the influx of Black American culture imported by Black servicemen during and after World War II, music being a central example of what Jacqueline Nassy-Brown calls "diasporic resources". These close interactions between Americans and Black British were not only material but also inspired the expatriation of some Black British women to America after marrying servicemen (some of whom later repatriated to the UK).[171]

Late 20th century[edit]

In 1961, the population of people born in Africa or the Caribbean was estimated at 191,600, just under 0.4% of the total UK population.[168] The 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act was passed in Britain along with a succession of other laws in 1968, 1971 and 1981, which severely restricted the entry of Black immigrants into Britain. During this period it is widely argued that emergent blacks and Asians struggled in Britain against racism and prejudice. During the 1970s—and partly in response to both the rise in racial intolerance and the rise of the Black Power movement abroad—black became detached from its negative connotations, and was reclaimed as a marker of pride: black is beautiful.[169] In 1975, David Pitt was appointed to the House of Lords. He spoke against racism and for equality in regards to all residents of Britain. In the years that followed, several Black members were elected into the British Parliament. By 1981, the black population in the United Kingdom was estimated at 1.2% of all countries of birth, being 0.8% Black-Caribbean, 0.3% Black-Other, and 0.1% Black-African residents.[172]

Since the 1980s, the majority of black immigrants into the country have come directly from Africa, in particular, Nigeria and Ghana in West Africa, Uganda and Kenya in East Africa, Zimbabwe, and South Africa in Southern Africa.[citation needed] Nigerians and Ghanaians have been especially quick to accustom themselves to British life, with young Nigerians and Ghanaians achieving some of the best results at GCSE and A-Level, often on a par or above the performance of white pupils.[173] The rate of inter-racial marriage between British citizens born in Africa and native Britons is still fairly low, compared to those from the Caribbean.

By the end of the 20th century the number of black Londoners numbered half a million, according to the 1991 census. The 1991 census was the first to include a question on ethnicity, and the black population of Great Britain (i.e. the United Kingdom excluding Northern Ireland, where the question was not asked) was recorded as 890,727, or 1.6% of the total population. This figure included 499,964 people in the Black-Caribbean category (0.9%), 212,362 in the Black-African category (0.4%) and 178,401 in the Black-Other category (0.3%).[174][175] An increasing number of black Londoners were London- or British-born. Even with this growing population and the first blacks elected to Parliament, many argue that there was still discrimination and a socio-economic imbalance in London among the blacks. In 1992, the number of blacks in Parliament increased to six, and in 1997, they increased their numbers to nine. There are still many problems that black Londoners face; the new global and high-tech information revolution is changing the urban economy and some argue that it is driving up unemployment rates among blacks relative to non-blacks,[95] something, it is argued, that threatens to erode the progress made thus far.[95] By 2001, the Black British population was recorded at 1,148,738 (2.0%) in the 2001 census.[176]

Street conflicts and policing[edit]

The late 1950s through to the late 1980s saw a number of mass street conflicts involving young Afro-Caribbean men and British police officers in English cities, mostly as a result of tensions between members of local black communities and whites.

The first major incident occurred in 1958 in Notting Hill, when roaming gangs of between 300 and 400 white youths attacked Afro-Caribbeans and their houses across the neighbourhood, leading to a number of Afro-Caribbean men being left unconscious in the streets.[177] The following year, Antigua-born Kelso Cochrane died after being set upon and stabbed by a gang of white youths while walking home to Notting Hill.

During the 1970s, police forces across England increasingly began to use the Sus law, provoking a sense that young black men were being discriminated against by the police[178] The next newsworthy outbreak of street fighting occurred in 1976 at the Notting Hill Carnival when several hundred police officers and youths became involved in televised fights and scuffles, with stones thrown at police, baton charges and a number of minor injuries and arrests.[179]

The 1980 St. Pauls riot in Bristol saw fighting between local youths and police officers, resulting in numerous minor injuries, damage to property and arrests. In London, 1981 brought further conflict, with a perceived racist police force after the death of 13 black youngsters who were attending a birthday party that ended in the devastating New Cross Fire. The fire was viewed by many as a racist massacre[177] and a major political demonstration, known as the Black People's Day of Action was held to protest against the attacks themselves, a perceived rise in racism, and perceived hostility and indifference from the police, politicians and media.[177] Tensions were further inflamed when, in nearby Brixton, police launched operation Swamp 81, a series of mass stop-and-searches of young black men.[177] Anger erupted when up to 500 people were involved in street fighting between the Metropolitan Police and local Afro-Caribbean community, leading to a number of cars and shops being set on fire, stones thrown at police and hundreds of arrests and minor injuries. A similar pattern occurred further north in England that year, in Toxteth, Liverpool, and Chapeltown, Leeds.[180]

Despite the recommendations of the Scarman Report (published in November 1981),[177] relations between black youths and police did not significantly improve and a further wave of nationwide conflicts occurred in Handsworth, Birmingham, in 1985, when the local South Asian community also became involved. Photographer and artist Pogus Caesar extensively documented the riots.[178] Following the police shooting of a black grandmother Cherry Groce in Brixton, and the death of Cynthia Jarrett during a raid on her home in Tottenham, in north London, protests held at the local police stations did not end peacefully and further street battles with the police erupted,[177] the disturbances later spreading to Manchester's Moss Side.[177] The street battles themselves (involving more stone-throwing, the discharge of one firearm, and several fires) led to two fatalities (in the Broadwater Farm riot) and Brixton.

In 1999, following the Macpherson Inquiry into the 1993 killing of Stephen Lawrence, Sir Paul Condon, commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, accepted that his organisation was institutionally racist. Some members of the Black British community were involved in the 2001 Harehills race riot and 2005 Birmingham race riots.

Surveillance of black populations[edit]

In the 1950s the British government became concerned about radicalisation within black immigrant communities, and began measures to surveil them at large. For example, in Sheffield, police constables were authorised to "Observe, visit, and report" on the city's black community, with authorisation for the creation of a card index of details such as address and place of employment of the city's then 534 residents.

Documents from the National Archives show that practices continued into the 1960s, with Manchester police creating reports on immigrant communities' "intermixing, miscegenation and illegitimacy", listing numbers of children by race.[181]

Early 21st century[edit]

In 2011, following the shooting of a mixed-race man, Mark Duggan, by police in Tottenham, a protest was held at the local police station. The protest ended with an outbreak of fighting between local youths and police officers leading to widespread disturbances across English cities.

Some analysts claimed that black people were disproportionally represented in the 2011 England riots.[182] Research suggests that race relations in Britain deteriorated in the period following the riots and that prejudice towards ethnic minorities increased.[183] Groups such as the EDL and the BNP were said to be exploiting the situation.[184] Racial tensions between blacks and Asians in Birmingham increased after the deaths of three Asian men at the hands of a black youth.[185]

In a Newsnight discussion on 12 August 2011, historian David Starkey blamed black gangster and rap culture, saying that it had influenced youths of all races.[186] Figures showed that 46 per cent of people brought before a courtroom for arrests related to the 2011 riots were black.[187]

During the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom the first ten healthcare workers to die from the virus came from Black and Minority Ethnic (BAME) backgrounds, prompting the head of the British Medical Association to call on the government to begin investigating if and why minorities are being disproportionally affected.[188] Early statistics found that black and Asian people were being affected worse than white people, with figures showing 35% of COVID-19 patients were non-white,[189] and similar studies in the US had shown a clear racial disparity.[190] The government announced that they will be launching an official inquiry into the disproportionate impact of coronavirus on Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic communities with Communities Minister Robert Jenrick acknowledging that "There does appear to be a disproportionate impact of the virus on BAME communities in the UK."[191] A social media campaign in response to the Clap for our Carers campaign, highlighted the role Black & minority health and key workers and asking the public to continue their support after the pandemic gained over 12 million views online.[192][193][194] 72 per cent of NHS Staff that died from Covid-19 were reported as being from Black & Minority Ethnic groups, far higher than the number of staff from BAME backgrounds working in the NHS, which stood at 44%.[195] Statistics did show that black people were significantly over-represented, but that as the pandemic progressed the disparity in these figures was reducing.[196] Reports discussed a number of complex contributing factors including health and income inequality, social and environmental factors were exacerbating and contributing to the spread of the disease unequally.[197] In April 2020, after his sister's partner died from the virus, Patrick Vernon set up a fundraising initiative called "The Majonzi Fund" which will provide families with access to small financial grants that can be used to access bereavement counselling and organise memorial events and tributes after the social lockdown has been lifted.[198]

Demographics[edit]

Population[edit]

| Region / Country | 2021[200] | 2011[204] | 2001[208] | 1991[211] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| 2,381,724 | 4.22% | 1,846,614 | 3.48% | 1,132,508 | 2.30% | 874,882 | 1.86% | |

| —Greater London | 1,188,370 | 13.50% | 1,088,640 | 13.32% | 782,849 | 10.92% | 535,216 | 8.01% |

| —West Midlands | 269,019 | 4.52% | 182,125 | 3.25% | 104,032 | 1.98% | 102,206 | 1.98% |

| —South East | 221,584 | 2.39% | 136,013 | 1.58% | 56,914 | 0.71% | 46,636 | 0.62% |

| —East of England | 184,949 | 2.92% | 117,442 | 2.01% | 48,464 | 0.90% | 42,310 | 0.84% |

| —North West | 173,918 | 2.34% | 97,869 | 1.39% | 41,637 | 0.62% | 47,478 | 0.71% |

| —East Midlands | 129,986 | 2.66% | 81,484 | 1.80% | 39,477 | 0.95% | 38,566 | 0.98% |

| —Yorkshire and the Humber | 117,643 | 2.15% | 80,345 | 1.52% | 34,262 | 0.69% | 36,634 | 0.76% |

| —South West | 69,614 | 1.22% | 49,476 | 0.94% | 20,920 | 0.42% | 21,779 | 0.47% |

| —North East | 26,635 | 1.01% | 13,220 | 0.51% | 3,953 | 0.16% | 4,057 | 0.16% |

| 65,414[α] | 1.20% | 36,178 | 0.68% | 6,247 | 0.12% | 6,353 | 0.13% | |

| 27,554 | 0.89% | 18,276 | 0.60% | 7,069 | 0.24% | 9,492 | 0.33% | |

| Northern Ireland | 11,032 | 0.58% | 3,616 | 0.20% | 1,136 | 0.07% | — | — |

| 2,485,724 | 3.71% | 1,905,506 | 3.02% | 1,148,738 | 1.95% | 890,727[β] | 1.62% | |

2021 census[edit]

In the 2021 Census, 2,409,278 people in England and Wales were recorded as having Black, Black British, Black Welsh, Caribbean or African ethnicity, accounting for 4.0% of the population.[213] In Northern Ireland, 11,032, or 0.6% of the population, identified as Black African or Black Other.[4] The census in Scotland was delayed for a year and took place in 2022, the equivalent figure was 212,022, representing 1.3% of the population.[3] The ten local authorities with the largest proportion of people who identified as Black were all located in London: Lewisham (26.77%), Southwark (25.13%), Lambeth (23.97%), Croydon (22.64%), Barking and Dagenham (21.39%), Hackney (21.09%), Greenwich (20.96%), Enfield (18.34%), Haringey (17.58%) and Brent (17.51%). Outside of London, Manchester had the largest proportion at 11.94%. In Scotland, the highest proportion was in Aberdeen at 4.20%; in Wales, the highest concentration was in Cardiff at 3.84%; and in Northern Ireland, the highest concentration was in Belfast at 1.34%.[214]

2011 census[edit]

The 2011 UK Census recorded 1,904,684 residents who identified as "Black/African/Caribbean/Black British", accounting for 3 per cent of the total UK population.[215] This was the first UK census where the number of self-reported Black African residents exceeded that of Black Caribbeans.[216]

Within England and Wales, 989,628 individuals specified their ethnicity as "Black African", 594,825 as "Black Caribbean", and 280,437 as "Other Black".[217] In Northern Ireland, 2,345 individuals self-reported as "Black African", 372 as "Black Caribbean", and 899 as "Other Black", totaling 3,616 "Black" residents.[218] In Scotland, 29,638 persons identified themselves as "African", choosing either the "African, African Scottish or African British" tick box or the "Other African" tick box and write-in area. 6,540 individuals also self-reported as "Caribbean or Black", selecting either the "Caribbean, Caribbean Scottish or Caribbean British" tick box, the "Black, Black Scottish or Black British" tick box, or the "Other Caribbean or Black" tick box and write-in area.[219] In order to compare UK-wide results, the Office for National Statistics combined the "African" and "Caribbean or Black" entries at the top-level,[2] and reported a total of 36,178 "Black" residents in Scotland.[215] According to the ONS, individuals in Scotland with "Other African", "White" and "Asian" ethnicities as well as "Black" identities could thus all potentially be captured within this combined output.[2] The General Register Office for Scotland, which devised the categories and administers the Scotland census, does not combine the "African" and "Caribbean or Black" entries, maintaining them as separate for individuals who do not self-identify as "Black" (see census classification).[21]

2001 census[edit]

In the 2001 Census, 575,876 people in the United Kingdom had reported their ethnicity as "Black Caribbean", 485,277 as "Black African", and 97,585 as "Black Other", making a total of 1,148,738 "Black or Black British" residents. This was equivalent to 2 per cent of the UK population at the time.[176]

Population distribution[edit]

Most Black Britons can be found in the large cities and metropolitan areas of the country. The 2011 census found that 1.85 million of a total Black population of 1.9 million lived in England, with 1.09 million of those in London, where they made up 13.3 per cent of the population, compared to 3.5 per cent of England's population and 3 per cent of the UK's population. The ten local authorities with the highest proportion of their populations describing themselves as Black in the census were all in London: Lewisham (27.2 per cent), Southwark (26.9 per cent), Lambeth (25.9 per cent), Hackney (23.1 per cent), Croydon (20.2 per cent), Barking and Dagenham (20.0 per cent), Newham (19.6 per cent), Greenwich (19.1 per cent), Haringey (18.8 per cent) and Brent (18.8 per cent).[215] More specifically, for Black Africans the highest local authority was Southwark (16.4 per cent) followed by Barking and Dagenham (15.4 per cent) and Greenwich (13.8 per cent), whereas for Black Caribbeans the highest was Lewisham (11.2 per cent) followed by Lambeth (9.5 per cent) and Croydon (8.6 per cent).[215]

Outside of London, the next largest populations are in Birmingham (125,760, 11%) / Coventry (30,723, 9%) / Sandwell (29,779, 8.7%) / Wolverhampton (24,636, 9.3%), Manchester (65,893, 12%), Nottingham (32,215, 10%), Leicester (28,766, 8%), Bristol (27,890, 6%), Leeds (25,893, 5.6%), Sheffield (25,512, 4.6%) and Luton (22,735, 10%).[1]

Religion[edit]

| Religion | England and Wales | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011[220] | 2021[221] | |||

| Number | % | Number | % | |

| 1,288,371 | 69.1% | 1,613,753 | 67.0% | |

| 272,015 | 14.6% | 416,327 | 17.3% | |

| No religion | 137,467 | 7.4% | 205,375 | 8.5% |

| 2,809 | 0.2% | 2,336 | 0.1% | |

| 5,474 | 0.3% | 1,919 | 0.08% | |

| 1,611 | 0.09% | 1,632 | 0.07% | |

| 1,431 | 0.08% | 306 | 0.01% | |

| Other religions | 7,099 | 0.4% | 13,413 | 0.6% |

| Not Stated | 148,613 | 8.0% | 154,219 | 6.4% |

| Total | 1,864,890 | 100% | 2,409,280 | 100% |

Mixed marriages[edit]

An academic journal article published in 2005, citing sources from 1997 and 2001, estimated that nearly half of British-born African-Caribbean men, a third of British-born African-Caribbean women, and a fifth of African men, have white partners.[222] In 2014, The Economist reported that, according to the Labour Force Survey, 48 per cent of black Caribbean men and 34 per cent of black Caribbean women in couples have partners from a different ethnic group. Moreover, mixed-race children under the age of ten with black Caribbean and white parents outnumber black Caribbean children by two-to-one.[223]

Culture and community[edit]

Dialect[edit]

Multicultural London English is a variety of the English language spoken by a large number of the Black British population of Afro-Caribbean ancestry.[224] British Black dialect has been influenced by Jamaican Patois owing to the large number of immigrants from Jamaica, but it is also spoken or imitated by those of different ancestry.

British Black speech is also heavily influenced by social class and regional dialect (Cockney, Mancunian, Brummie, Scouse, etc.).

African-born immigrants speak African languages and French as well as English.

Music[edit]

Black British music is a long-established and influential part of British music. Its presence in the United Kingdom stretches back to the 18th century, encompassing concert performers such as George Bridgetower and street musicians the likes of Billy Waters. Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875–1912) achieved great success as a composer at the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries. The Jazz Age also had taken an effect on the generation.[225]

In the late 1970s and 1980s, 2 Tone became popular with the British youth; especially in the West Midlands. A blend of punk, ska and pop made it a favourite among both white and black audiences. Famous bands in the genre include the Selecter, the Specials, the Beat and the Bodysnatchers.

Jungle, dubstep, drum and bass, UK garage and grime music originated in London.

The MOBO Awards recognise performers of "Music of Black Origin".

Black Lives in Music (BLiM) was formed after its founders noticed institutionalised racism in the British entertainment industry. BLiM works for equal opportunities for Black, Asian and ethnically diverse people in the jazz and classical music industry, opportunities that include the chance to learn a musical instrument, attend a music school, pursue a career in music and reach senior levels within the sector without facing discrimination.[226][227][228][229]

Media[edit]

The Black community in Britain has a number of significant publications. The leading key publication is The Voice newspaper, founded by Val McCalla in 1982, and Britain's only national Black weekly newspaper. The Voice primarily targets the Caribbean diaspora and has been printed for more than 35 years.[230] Secondly, the Black History Month magazine is a central point of focus which leads the nationwide celebration of Black History, Arts and Culture throughout the UK.[231] Pride Magazine, published since 1991, is the largest monthly magazine that targets black British, mixed-race, African and African-Caribbean women in the United Kingdom. In 2007, The Guardian reported that the magazine had dominated the black women's magazine market for over 15 years.[232] Keep The Faith magazine is a multi-award winning Black and minority ethnic community magazine produced quarterly since 2005.[233] Keep The Faith's editorial contributors are some of the most powerful and influential movers and shakers, and successful entrepreneurs within BME communities.

Many major Black British publications are handled through Diverse Media Group,[234] which specialises in helping organisations reach Britain's Black and minority ethnic community through the main media they consume. The senior leadership team is a composite of many CEO and owners from the publications listed above.

Publishing[edit]

Among Black-led publishing companies established in the UK are New Beacon Books (co-founded 1966 by John La Rose), Allison and Busby (co-founded 1967 by Margaret Busby), Bogle-L'Ouverture Publications (co-founded 1969 by Jessica Huntley and Eric Huntley), Hansib (founded 1970), Karnak House (founded 1975 by Amon Saba Saakana), Black Ink Collective (founded in 1978), Black Womantalk (founded in 1983), Karnak House (founded by Buzz Johnson), Tamarind Books (founded 1987 by Verna Wilkins), and others.[235][236][237][238] The International Book Fair of Radical Black and Third World Books (1982–1995) was an initiative launched by New Beacon Books, Bogle-L'Ouverture Publications and the Race Today Collective.[239]

Social issues[edit]

This section may have misleading content. (November 2023) |

Racism[edit]

The wave of black immigrants who arrived in Britain from the Caribbean in the 1950s faced significant amounts of racism. For many Caribbean immigrants, their first experience of discrimination came when trying to find private accommodation. They were generally ineligible for council housing because only people who had been resident in the UK for a minimum of five years qualified for it. At the time, there was no anti-discrimination legislation to prevent landlords from refusing to accept black tenants. A survey undertaken in Birmingham in 1956 found that only 15 of a total of 1,000 white people surveyed would let a room to a black tenant. As a result, many black immigrants were forced to live in slum areas of cities, where the housing was of poor quality and there were problems of crime, violence and prostitution.[240][241] One of the most notorious slum landlords was Peter Rachman, who owned around 100 properties in the Notting Hill area of London. Black tenants typically paid twice the rent of white tenants, and lived in conditions of extreme overcrowding.[240]

Historian Winston James argues that the experience of racism in Britain was a major factor in the development of a shared Caribbean identity amongst black immigrants from a range of different island and class backgrounds.[242]

In the 1970s and 1980s, black people in Britain were the victims of racist violence perpetrated by far-right groups such as the National Front.[243] During this period, it was also common for Black footballers to be subjected to racist chanting from crowd members.[244][245]

Racism in Britain in general, including against black people, is considered to have declined over time. Academic Robert Ford demonstrates that social distance, measured using questions from the British Social Attitudes survey about whether people would mind having an ethnic minority boss or have a close relative marry an ethnic minority spouse, declined over the period 1983–1996. These declines were observed for attitudes towards Black and Asian ethnic minorities. Much of this change in attitudes happened in the 1990s. In the 1980s, opposition to interracial marriage were significant.[246][247] Nonetheless, Ford argues that "Racism and racial discrimination remain a part of everyday life for Britain's ethnic minorities. Black and Asian Britons...are less likely to be employed and are more likely to work in worse jobs, live in worse houses and suffer worse health than White Britons".[246] The University of Maryland's Minorities at Risk (MAR) project noted in 2006 that while African-Caribbeans in the United Kingdom no longer face formal discrimination, they continue to be under-represented in politics, and to face discriminatory barriers in access to housing and in employment practices. The project also notes that the British school system "has been indicted on numerous occasions for racism, and for undermining the self-confidence of black children and maligning the culture of their parents". The MAR profile on African-Caribbeans in the United Kingdom notes "growing 'black on black' violence between people from the Caribbean and immigrants from Africa".[248]

There is concern that murders using knives are given insufficient attention because most victims are black. Martin Hewitt of the Metropolitan Police said, "I do fear sometimes that because the majority of those that are injured or killed are coming from certain communities and very often the black communities in London, it doesn't get the sense of collective outrage that it ought to do and really get everyone to a place where we are all doing everything we can to prevent this from happening. It's an enormous effort on our part. We are putting enormous resources in to try and stem the flow of the violence and having some success at doing that. But collectively we all ought to be looking at this and seeing how we can prevent it."[249][250]

A 2023 University of Cambridge survey which featured the largest sample of Black people in Britain found that 88% had reported racial discrimination at work, 79% believed the police unfairly targeted black people with stop and search powers and 80% definitely or somewhat agreed that racial discrimination was the biggest barrier to academic attainment for young Black students.[251]

Education[edit]

Young Nigerians and Ghanaians achieved some of the best results at GCSE and A-Level according to a government report published in 2006, often on a par or above the performance of white pupils.[173] According to Department for Education statistics for the 2021–22 academic year, Black British pupils attained below the national average for academic performance at both A-Level and GCSE level. 12.3% of Black British pupils achieved at least 3 As at A Level[252] and an average score of 48.6 was achieved in Attainment 8 scoring at GCSE level.[253] A disparity exists in academic performance between Black African pupils and Black Caribbean pupils at GCSE level. Black African pupils achieved better results than both white pupils and the national average, with an average score of 50.9 and 54.5% of pupils achieving grade 5 or above in both English and Maths GCSE. Meanwhile, Black Caribbean pupils attained an average score of 41.7 with only 34.6% of pupils attaining grade 5 or above in both English and Maths GCSE.[254]

A 2019 report by Universities UK found that student’s race and ethnicity significantly affect their degree outcomes. According to this report from 2017–18, there was a 13% gap between the likelihood of white students and Black and Minority Ethnic (BAME) students graduating with a first or 2:1 degree classification at British universities.[255][256]

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Employment[edit]

According to the 2005 TUC report Black workers, jobs and poverty, Black and minority ethnic people (BMEs) were more likely to be unemployed than the White population. The rate of unemployment among the White population was 5%, but among ethnic minority groups it was Bangladeshi 17%, Pakistani 15%, Mixed 15%, Black Britons 13%, Other ethnic 12% and Indian 7%. Of the different ethnic groups studied, Asians had the highest poverty rate of 45% (after housing costs), Black Britons 38% and Chinese/other 32% (compared to a poverty rate of 20% for the White population). However, the report did concede that things were slowly improving.[257]

According to 2012 data compiled by the Office for National Statistics, 50% of young black men from 16-24 demographics were unemployed between Q4 2011 and Q1 2012.[258]

A 2014 study by the Black Training and Enterprise Group (BTEG), funded by Trust for London, explored the views of young Black males in London on why their demographic have a higher unemployment rate than any other group of young people, finding that many young Black men in London believe that racism and negative stereotyping are the main reasons for their high unemployment rate.[259]

In 2021, 67% of Black 16 to 64-year-olds were employed, compared to 76% of White British and 69% of British Asians. The employment rate for Black 16 to 24-year-olds was 31%, compared to 56% of White British and 37% of British Asians.[260] The median hourly pay for Black Britons in 2021 was amongst the lowest out of all ethnicity groups at £12.55, ahead of only British Pakistanis and Bangladeshis.[261] In 2023, the Office for National Statistics published more granular analysis and found that UK-born black employees (£15.18) earned more than UK-born white employees (£14.26) in 2022, while non-UK born black employees earned less (£12.95). Overall, black employees had a median hourly pay of £13.53 in 2022.[262] According to Department for Work and Pensions data for between 2018–2021, 24% of black families were in receipt of income-related benefits, compared to 16% of White British families and 8% of British Chinese and Indian families. Black families were also the most likely ethnicity to be in receipt of housing benefit, council tax reduction, and reside in social housing.[263][264] However, White British families (54%) were the most likely out of all ethnic groups to receive state support with 27% of White British families in receipt of the state pension.[263]

Crime[edit]

Both racist crime and gang-related crime continues to affect black communities, so much so that the Metropolitan Police launched Operation Trident to tackle black-on-black crimes. Numerous deaths in police custody of black men has generated a general distrust of police among urban blacks in the UK.[265][266] According to the Metropolitan Police Authority in 2002–03 of the 17 deaths in police custody, 10 were black or Asian – black convicts have a disproportionately higher rate of incarceration than other ethnicities. The government reports[267] The overall number of racist incidents recorded by the police rose by 7 per cent from 49,078 in 2002/03 to 52,694 in 2003/04.

Media representation of young black British people has focused particularly on "gangs" with black members and violent crimes involving black victims and perpetrators.[268] According to a Home Office report,[267] 10 per cent of all murder victims between 2000 and 2004 were black. Of these, 56 per cent were murdered by other black people (with 44 per cent of black people murdered by whites and Asians – making black people disproportionately higher victims of killing by people from other ethnicities). In addition, a Freedom of Information request made by The Daily Telegraph shows internal police data that provides a breakdown of the ethnicity of the 18,091 men and boys who police took action against for a range of offences in London in October 2009. Among those proceeded against for street crimes, 54 per cent were black; for robbery, 59 per cent; and for gun crimes, 67 per cent.[269] According to the Office for National Statistics, 18.4% of homicide suspects in England and Wales over March 2019 - March 2021 were Black.[270]

Black people, who according to government statistics[271] make up 2 per cent of the population, are the principal suspects in 11.7 per cent of murders, i.e. in 252 out of 2163 murders committed 2001/2, 2002/3, and 2003/4.[272] Judging on the basis of prison population, a substantial minority (about 35%) of black criminals in the United Kingdom are not British citizens but foreign nationals.[273] In November 2009, the Home Office published a study that showed that, once other variables had been accounted for, ethnicity was not a significant predictor of offending, anti-social behaviour or drug abuse among young people.[274]

After several high-profile investigations such as that of the murder of Stephen Lawrence, the police have been accused of racism, from both within and outside the service. Cressida Dick, head of the Metropolitan Police's anti-racism unit in 2003, remarked that it was "difficult to imagine a situation where we will say we are no longer institutionally racist".[275] Black people were seven times more likely to be stopped and searched by police compared to white people, according to the Home Office. A separate study said black people were more than nine times more likely to be searched.[276]

In 2010, black Britons accounted for around 2.2% of the general UK population, but made up 15% of the British prison population, which experts say is "a result of decades of racial prejudice in the criminal justice system and an overly punitive approach to penal affairs."[277] This proportion decreased to 12.4% by the end of 2022 even though black Britons now made up around 3–4% of the British population.[278] In the prison environment, Black prisoners are the most likely to be involved in violent incidents. In 2020, Black prisoners were most likely out of all ethnic groups to be assailants (319 incidents for every 1,000 prisoners) or involved in violent incidents with no clear victim or assailant (185 incidents for every 1,000 prisoners).[279] In the same year, 32% of children in prison were Black in contrast to 47% of prisoners aged under 18 being White.[280] The Lammy Review, led by David Lammy MP, provided potential reasons on the disproportionate number of black children in prisons including austerity in public services, lack of diversity in the judiciary, and the school system inadequately serving the black community by failing to identify learning difficulties.[281][282]

Health[edit]

For some key health measures, including life expectancy, general mortality and many of the leading causes of death in the UK, black Britons have better outcomes than their white British counterparts. As an example, compared to the white population in England, cancer rates are 4% lower in black people, who are also less likely to die of the disease than whites.[283][284][285] Generally, black people in England and Wales have a significantly lower mortality rate from all-causes than whites.[286][287][288] Black people in England and Wales also have a higher life expectancy at birth than their white counterparts.[289][285] One contributing factor put forward is that white Britons are more likely to smoke and to drink harmful levels of alcohol.[290] In England, 3.6% of white Britons have harmful or dependant drinking behaviours compared to 2.3% of black people.[291] In 2019, 14.4% of whites in England smoked cigarettes, compared to 9.7% of black people.[292]

Black Britons face worse outcomes in some health measurements compared to the rest of the population. Out of all ethnicity groups, black people were the most likely to be overweight or obese, the most likely to be dependant on drugs, as well as the most likely to have common mental disorders. 72% of black people in Britain are overweight or obese compared to 64.5% of White British people[293] and 7.5% of black people are dependant on drugs compared to 3.0% of White British people.[294] 22.5% of black people experienced a common mental disorder (including depression, OCD and life anxiety) in the past week compared to 17.3% of White British people, with this figure rising to 29.3% for black women.[295] Black women are also 3.7 times more likely to die from childbirth than white women in the UK, equating to 34 women per 100,000 giving birth.[296] Racist attitudes towards the pain tolerances of black women have been cited as one reason why this disparity exists.[297] In 2021, black Britons had the highest rate of STIs with a new STI rate of 1702.6 per 100,000 population compared to 373.9 per 100,000 population in the White British population.[298] This is consistent with data since at least 1994, and potential reasons to explain the difference include poor healthy literacy, underlying socioeconomic factors, and racism in healthcare settings.[299] In 2022, the British Medical Journal reported findings from a survey revealing 65% of black people have said that they had experienced prejudice from doctors and other staff in healthcare settings, rising to 75% among black 18-34 year olds.[300] Another survey found that 64% of black people in the UK believe that the NHS provides better care to white people.[301]

During the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom, the black population faced severe disparity in outcomes compared to the white population, with early data between March to April 2020 revealing that black people were four times more likely to die with Covid-19 than white people.[302][303] An inquiry commissioned for the government found that racism contributed to the disproportionate death of black people.[304] As the Covid-19 vaccine began to be distributed, the UK Household Longitudinal Study found that 72% of black people were unlikely or very unlikely to get vaccinated compared to 82% of all people saying they were likely or very likely to get the jab.[305] In March 2021, uptake was 30% lower for the black population aged 50–60 compared to the same age group in the white population. Vaccine hesitancy was driven by unethical health treatments towards black people in the past, with many surveyed citing the Tuskegee Syphilis Study in the United States as an example. Another reason given was the lack of trust in the authorities and the perceived perception that black people were being targeted as guinea pigs for the vaccine which was spurred by misinformation online and some religious organisations.[306] Analysis from the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities found that the increased risk of dying from COVID-19 was mainly due to the increased risk of exposure. Black people were more likely to live in urban areas with higher population densities and levels of deprivation; work in higher risk occupations such as healthcare or transport; and to live with older relatives who themselves are at higher risk due to their age or having other comorbidities such as diabetes and obesity.[307]

Notable black Britons[edit]

This section may contain unverified or indiscriminate information in embedded lists. (December 2022) |

Pre-20th century[edit]