Шистосома

Эта статья требует дополнительных цитат для проверки . ( июль 2016 г. ) |

Шистосома - это род трематодов , обычно известный как кровяные текущие . Это паразитические плоские черви, ответственные за весьма значительную группу инфекций у людей , называемых шистосомозом , который, как считается Всемирной организацией здравоохранения, считается вторым по социально-экономически разрушительным паразитическим заболеваниям (после малярии ), причем сотни миллионов инфицированы во всем мире. [ 1 ] [ 2 ]

Взрослые плоские черви паразитируют капилляры крови из брыжеечных средств или сплетения мочевого пузыря, в зависимости от заражающих видов. Они уникальны среди трематодов и любых других плоских червей в том смысле, что они диологично с отчетливым сексуальным диморфизмом между мужчинами и женщинами . Тысячи яиц высвобождаются и достигают либо мочевого пузыря, либо кишечника (в соответствии с инфицирующими видами), и затем они выделяются в моче или кале с пресной водой . Затем личинки должны пройти через промежуточный хозяин улитки до появления следующей личиночной стадии паразита, которая может заразить нового хозяина млекопитающих, непосредственно проникнув в кожу.

Evolution

[edit]

The origins of this genus remain unclear. For many years it was believed that this genus had an African origin, but DNA sequencing suggests that the species (S. edwardiense and S. hippopotami) that infect the hippo (Hippopotamus amphibius) could be basal. Since hippos were present in both Africa and Asia during the Cenozoic era, the genus might have originated as parasites of hippos.[3] The original hosts for the South East Asian species were probably rodents.[4]

Based on the phylogenetics of the host snails it seems likely that the genus evolved in Gondwana between 70 million years ago and 120 million years ago.[5]

The sister group to Schistosoma is a genus of elephant-infecting schistosomes — Bivitellobilharzia.

The cattle, sheep, goat and cashmere goat parasite Orientobilharzia turkestanicum appears to be related to the African schistosomes.[6][7] This latter species has since been transferred to the genus Schistosoma.[8]

Within the haematobium group S. bovis and S. curassoni appear to be closely related as do S. leiperi and S. mattheei.[citation needed]

S. mansoni appears to have evolved in East Africa 0.43–0.30 million years ago.[citation needed]

S. mansoni and S. rodhaini appear to have shared a common ancestor between 107.5 and 147.6 thousand years ago.[9] This period overlaps with the earliest archaeological evidence for fishing in Africa. It appears that S. mansoni originated in East Africa and experienced a decline in effective population size 20-90 thousand years ago before dispersing across the continent during the Holocene. This species was later transmitted to the Americas by the slave trade.

S. incognitum and S. nasale are more closely related to the African species rather than the japonicum group.[citation needed]

S. sinensium appears to have radiated during the Pliocene.[10][11]

S. mekongi appears to have invaded South East Asia in the mid-Pleistocene.[4]

Estimated speciation dates for the japonicum group: ~3.8 million years ago for S. japonicum/South East Asian schistosoma and ~2.5 million years ago for S. malayensis/S. mekongi.[4]

Schistosoma turkestanicum is found infecting red deer in Hungary. These strains appear to have diverged from those found in China and Iran.[12] The date of divergence appears to be 270,000 years before present.

Taxonomy

[edit]The genus Schistosoma as currently[when?] defined is paraphyletic,[citation needed] so revisions are likely. Over twenty species are recognised within this genus.

The genus has been divided [citation needed] into four groups: indicum, japonicum, haematobium and mansoni. The affinities of the remaining species are still being clarified.

Thirteen species are found in Africa. Twelve of these are divided into two groups—those with a lateral spine on the egg (mansoni group) and those with a terminal spine (haematobium group).

Mansoni group

[edit]The four mansoni group species are: S. edwardiense, S. hippotami, S. mansoni and S. rodhaini.

Haematobium group

[edit]The nine haematobium group species are: S. bovis, S. curassoni, S. guineensis, S. haematobium, S. intercalatum, S. kisumuensis, S. leiperi, S. margrebowiei and S. mattheei.

S. leiperi and S. matthei appear to be related.[13] S. margrebowiei is basal in this group.[14] S. guineensis is the sister species to the S. bovis and S. curassoni grouping. S. intercalatum may actually be a species complex of at least two species.[15][16]

Indicum group

[edit]The indicum group has three species: S. indicum, S. nasale and S. spindale. This group appears to have evolved during the Pleistocene. All use pulmonate snails as hosts.[17] S. spindale is widely distributed in Asia, but is also found in Africa.[citation needed] They occur in Asia and India.[18]

S. indicum is found in India and Thailand.[citation needed]

The indicum group appears to be the sister clade to the African species.[19]

Japonicum group

[edit]The japonicum group has five species: S. japonicum, S. malayensis and S. mekongi, S. ovuncatum and S. sinensium and these species are found in China and Southeast Asia.[20]

S. ovuncatum forms a clade with S. sinensium and is found in northern Thailand. The definitive host is unknown and the intermediate host is the snail Tricula bollingi. This species is known to use snails of the family Pomatiopsidae as hosts.[20]

S. incognitum appears to be basal in this genus. It may be more closely related to the African-Indian species than to the Southeast Asian group. This species uses pulmonate snails as hosts.[citation needed] Examination of the mitochondria suggests that Schistosoma incognitum may be a species complex.[21]

New species

[edit]As of 2012, four additional species have been transferred to this genus.,[8] previously classified as species in the genus Orientobilharzia. Orientobilharzia differs from Schistosoma morphologically only on the basis of the number of testes. A review of the morphological and molecular data has shown that the differences between these genera are too small to justify their separation. The four species are

- Schistosoma bomfordi

- Schistosoma datta

- Schistosoma harinasutai

- Schistosoma turkestanicum

Hybrids

[edit]The hybrid S. haematobium-S.guineenis was observed in Cameroon in 1996. S. haematobium could establish itself only after deforestation of the tropical rainforest in Loum next to the endemic S. guineensis; hybridization led to competitive exclusion of S. guineensis.[22]

In 2003, a S. mansoni-S. rodhaini hybrid was found in snails in western Kenya,[23] As of 2009, it had not been found in humans.[24]

In 2009, S. haematobium–S. bovis hybrids were described in northern Senegalese children. The Senegal River Basin had changed very much since the 1980s after the Diama Dam in Senegal and the Manantali Dam in Mali had been built. The Diama dam prevented ocean water to enter and allowed new forms of agriculture. Human migration, increasing number of livestock and sites where human and cattle both contaminate the water facilitated mixing between the different schistosomes in N'Der, for example.[24] The same hybrid was identified during the 2015 investigation of a schistosomiasis outbreak on Corsica, traced to the Cavu river.[25]

In 2019, a S. haematobium–S. mansoni hybrid was described in a 14-year-old patient with hematuria from Côte d'Ivoire.[26]

Cladogram

[edit]A cladogram based on 18S ribosomal RNA, 28S ribosomal RNA, and partial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) genes shows phylogenic relations of species in the genus Schistosoma:[27]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

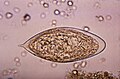

Comparison of eggs

[edit]Geographical distribution

[edit]Geographical areas associated with schistosomiasis by the World Health Organization as of January 2017 include in alphabetical order: Africa, Brazil, Cambodia, the Caribbean, China, Corsica, Indonesia, Laos, the Middle East, the Philippines, Suriname, and Venezuela.[28] There had been no cases in Europe since 1965, until an outbreak occurred on Corsica.[25]

Schistosomiasis

[edit]The parasitic flatworms of Schistosoma cause a group of chronic infections called schistosomiasis known also as bilharziasis.[29] An anti-schistosome drug is a schistosomicide.

Species infecting humans

[edit]Parasitism of humans by Schistosoma appears to have evolved at least three occasions in both Asia and Africa.

- S. guineensis, a recently described species, is found in West Africa. Known snail intermediate hosts include Bulinus forskalii.

- S. haematobium, commonly referred to as the bladder fluke, originally found in Africa, the Near East, and the Mediterranean basin, was introduced into India during World War II. Freshwater snails of the genus Bulinus are an important intermediate host for this parasite. Among final hosts humans are most important. Other final hosts are rarely baboons and monkeys.[30]

- S. intercalatum. The usual final hosts are humans. Other animals can be infected experimentally.[30]

- S. japonicum, whose common name is simply blood fluke, is widespread in East Asia and the southwestern Pacific region. Freshwater snails of the genus Oncomelania are an important intermediate host for S. japonicum. Final hosts are humans and other mammals including cats, dogs, goats, horses, pigs, rats and water buffalo.[30]

- S. malayensis This species appears to be a rare infection in humans and is considered to be a zoonosis [citation needed]. The natural vertebrate host is Müller's giant Sunda rat (Sundamys muelleri). The snail hosts are Robertsiella species (R. gismanni, R. kaporensis and R. silvicola (see Attwood et al. 2005 Journal of Molluscan Studies Volume 71, Issue 4 pp. 379–391).

- S. mansoni, found in Africa, Brazil, Venezuela, Suriname, the lesser Antilles, Puerto Rico, and the Dominican Republic. It is also known as Manson's blood fluke or swamp fever. Freshwater snails of the genus Biomphalaria are an important intermediate host for this trematode. Among final hosts humans are most important. Other final hosts are baboons, rodents and raccoons.[30]

- S. mekongi is related to S. japonicum and affects both the superior and inferior mesenteric veins. S. mekongi differs in that it has smaller eggs, a different intermediate host (Neotricula aperta) and longer prepatent period in the mammalian host. Final hosts are humans and dogs.[30] The snail Tricula aperta can also be experimentally infected with this species.[citation needed]

| Scientific Name | First Intermediate Host | Endemic Area |

|---|---|---|

| Schistosoma guineensis | Bulinus forskalii | West Africa |

| Schistosoma intercalatum | Bulinus spp | Africa |

| Schistosoma haematobium | Bulinus spp. | Africa, Middle East |

| Schistosoma japonicum | Oncomelania spp. | China, East Asia, Philippines |

| Schistosoma malayensis | Robertsiella spp. | Southeast Asia |

| Schistosoma mansoni | Biomphalaria spp. | Africa, South America, Caribbean, Middle East |

| Schistosoma mekongi | Neotricula aperta | Southeast Asia |

Species infecting other animals

[edit]Schistosoma indicum, Schistosoma nasale, Schistosoma spindale, Schistosoma leiperi are all parasites of ruminants.[citation needed]

Schistosoma edwardiense and Schistosoma hippopotami are parasites of the hippo.[citation needed]

Schistosoma ovuncatum and Schistosoma sinensium are parasites of rodents.[citation needed]

Morphology

[edit]Adult schistosomes share all the fundamental features of the digenea. They have a basic bilateral symmetry, oral and ventral suckers, a body covering of a syncytial tegument, a blind-ending digestive system consisting of mouth, esophagus and bifurcated caeca; the area between the tegument and alimentary canal filled with a loose network of mesoderm cells, and an excretory or osmoregulatory system based on flame cells. Adult worms tend to be 10–20 mm (0.39–0.79 in) long and use globins from their hosts' hemoglobin for their own circulatory system.

Reproduction

[edit]

Unlike other trematodes and basically all other flatworms, the schistosomes are dioecious, i.e., the sexes are separate. The two sexes display a strong degree of sexual dimorphism, and the male is considerably larger than the female. The male surrounds the female and encloses her within his gynacophoric canal for the entire adult lives of the worms. As the male feeds on the host's blood, he passes some of it to the female. The male also passes on chemicals which complete the female's development, whereupon they will reproduce sexually. Although rare, sometimes mated schistosomes will "divorce", wherein the female will leave the male for another male. The exact reason is not understood, although it is thought that females will leave their partners to mate with more genetically distant males. Such a biological mechanism would serve to decrease inbreeding, and may be a factor behind the unusually high genetic diversity of schistosomes.[31]

Genome

[edit]The genomes of Schistosoma haematobium, S. japonicum and S. mansoni have been reported.[32][33][34][35]

History

[edit]The eggs of these parasites were first seen by Theodor Maximilian Bilharz, a German pathologist working in Egypt in 1851 who found the eggs of Schistosoma haematobium during the course of a post mortem. He wrote two letters to his former teacher von Siebold in May and August 1851 describing his findings. Von Siebold published a paper in 1852 summarizing Bilharz's findings and naming the worms Distoma haematobium.[36] Bilharz wrote a paper in 1856 describing the worms more fully.[37] Their unusual morphology meant that they could not be comfortably included in Distoma. So in 1856 Meckel von Helmsback (de) created the genus Bilharzia for them.[38] In 1858 David Friedrich Weinland proposed the name Schistosoma (Greek: "split body") because the worms were not hermaphroditic but had separate sexes.[39] Despite Bilharzia having precedence, the genus name Schistosoma was officially adopted by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature. The term Bilharzia to describe infection with these parasites is still in use in medical circles.[citation needed]

Bilharz also described Schistosoma mansoni, but this species was redescribed by Louis Westenra Sambon in 1907 at the London School of Tropical Medicine who named it after his teacher Patrick Manson.[40]

In 1898, all then known species were placed in a subfamily by Stiles and Hassel. This was elevated to family status by Looss in 1899. Poche in 1907 corrected a grammatical error in the family name. The life cycle of Schistosoma mansoni was determined by the Brazilian parasitologist Pirajá da Silva (1873-1961) in 1908.[41]

In 2009, the genomes of Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma japonicum were decoded [32][33] opening the way for new targeted treatments. In particular, the study discovered that the genome of S. mansoni contained 11,809 genes, including many that produce enzymes for breaking down proteins, enabling the parasite to bore through tissue. Also, S. mansoni does not have an enzyme to make certain fats, so it must rely on its host to produce these.[42]

Treatment

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Schistosomiasis Fact Sheet". World Health Organization. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ "Schistosomiasis". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ Morgan JA, DeJong RJ, Kazibwe F, Mkoji GM, Loker ES (August 2003). "A newly-identified lineage of Schistosoma". International Journal for Parasitology. 33 (9): 977–85. doi:10.1016/S0020-7519(03)00132-2. PMID 12906881.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Attwood SW, Fatih FA, Upatham ES (March 2008). "DNA-sequence variation among Schistosoma mekongi populations and related taxa; phylogeography and the current distribution of Asian schistosomiasis". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2 (3): e200. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000200. PMC 2265426. PMID 18350111.

- ^ Beer SA, Voronin MV, Zazornova OP, Khrisanfova GG, Semenova SK (2010). "[Phylogenetic relationships among schistosomatidae]". Meditsinskaia Parazitologiia I Parazitarnye Bolezni (in Russian) (2): 53–9. PMID 20608188.

- ^ Wang CR, Li L, Ni HB, Zhai YQ, Chen AH, Chen J, Zhu XQ (February 2009). "Orientobilharzia turkestanicum is a member of Schistosoma genus based on phylogenetic analysis using ribosomal DNA sequences". Experimental Parasitology. 121 (2): 193–7. doi:10.1016/j.exppara.2008.10.012. PMID 19014940.

- ^ Wang Y, Wang CR, Zhao GH, Gao JF, Li MW, Zhu XQ (December 2011). "The complete mitochondrial genome of Orientobilharzia turkestanicum supports its affinity with African Schistosoma spp". Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 11 (8): 1964–70. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2011.08.030. PMID 21930247.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Aldhoun JA, Littlewood DT (June 2012). "Orientobilharzia Dutt & Srivastava, 1955 (Trematoda: Schistosomatidae), a junior synonym of Schistosoma Weinland, 1858". Systematic Parasitology. 82 (2): 81–8. doi:10.1007/s11230-012-9349-8. PMID 22581244. S2CID 18890027.

- ^ Crellen T, Allan F, David S, Durrant C, Huckvale T, Holroyd N, Emery AM, Rollinson D, Aanensen DM, Berriman M, Webster JP, Cotton JA (February 2016). "Whole genome resequencing of the human parasite Schistosoma mansoni reveals population history and effects of selection". Scientific Reports. 6: 20954. Bibcode:2016NatSR...620954C. doi:10.1038/srep20954. PMC 4754680. PMID 26879532.

- ^ Attwood SW, Upatham ES, Meng XH, Qiu DC, Southgate VR (August 2002). "The phylogeography of Asian Schistosoma (Trematoda: Schistosomatidae)". Parasitology. 125 (Pt 2): 99–112. doi:10.1017/s0031182002001981. PMID 12211613. S2CID 40281441.

- ^ Attwood SW, Ibaraki M, Saitoh Y, Nihei N, Janies DA (2015). "Comparative Phylogenetic Studies on Schistosoma japonicum and Its Snail Intermediate Host Oncomelania hupensis: Origins, Dispersal and Coevolution". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 9 (7): e0003935. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0003935. PMC 4521948. PMID 26230619.

- ^ Lawton SP, Majoros G (March 2013). "A foreign invader or a reclusive native? DNA bar coding reveals a distinct European lineage of the zoonotic parasite Schistosoma turkestanicum (syn. Orientobilharzia turkestanicum ())". Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 14: 186–93. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2012.11.013. PMID 23220360.

- ^ Kaukas A, Dias Neto E, Simpson AJ, Southgate VR, Rollinson D (April 1994). "A phylogenetic analysis of Schistosoma haematobium group species based on randomly amplified polymorphic DNA". International Journal for Parasitology. 24 (2): 285–90. doi:10.1016/0020-7519(94)90040-x. PMID 8026909.

- ^ Webster BL, Southgate VR, Littlewood DT (июль 2006 г.). «Пересмотр взаимосвязи шистосомы, включая недавно описанную шистосому guineensis». Международный журнал по паразитологии . 36 (8): 947–55. doi : 10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.03.005 . PMID 16730013 .

- ^ Кейн Р.А., Саутгейт В.Р., Роллинсон Д., Литтлвуд Д.Т., Локьер А.Е., Пагес -младший, Чуэм Чиентер Л.А., Журдан Дж (август 2003 г.). «Филогения, основанная на трех митохондриальных генах, подтверждает разделение шистосомы интеркалатум на два отдельных вида». Паразитология . 127 (Pt 2): 131–7. doi : 10.1017/s0031182003003421 . PMID 12954014 . S2CID 23973239 .

- ^ Pagès JR, Durand P, Southgate VR, Tchuem Tchuenté LA, Jourdane J (январь 2001 г.). «Молекулярные аргументы для расщепления шистосомы интеркалатум на два разных вида». Паразитологические исследования . 87 (1): 57–62. doi : 10.1007/s00436000000301 . PMID 11199850 . S2CID 11121161 .

- ^ Liu L, Mondal MM, Idirs MA, Lokman HS, Rajapakkse PJ, Strija F, Diaz JL, Upatham ES, Atwood Swed (июль 2010 г.). «Филогиография индоплабиса Exustus (Gastropoda: Planbidae) в Азии » Паразиты и веторы 3 : 57. DOI : 10.1186/ 1756-3305-3-5 PMC 2914737 PMID 20602771

- ^ Attwood SW, Fatih FA, Mondal MM, Alim MA, Fadjar S, Rajapakse RP, Rollinson D (декабрь 2007 г.). «Исследование, основанное на последовательности ДНК, группы Schistosoma Indicum (Trematoda: Digenea): филогения популяции, таксономия и историческая биогеография». Паразитология . 134 (Pt.14): 2009–20. doi : 10.1017/s0031182007003411 . PMID 17822572 . S2CID 22737354 .

- ^ Agatsuma T, Iwagami M, Liu CX, Rajapakse RP, Mondal MM, Kitikoon V, Ambu S, Agatsuma Y, Blair D, Higuchi T (март 2002 г.). «Сродство между азиатскими нечеловеческими видами шистосомы, группой S. Indicum и африканскими человеческими шистомами» Журнал гельминтологии 76 (1): 7–1 Doi : 10.1079/ Joh2 HDL : 10126/3484 12018199PMID 25582541S2CID

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Attwood SW, Panasoponkul C, Upatham ES, Meng XH, Southgate VR (январь 2002 г.). «Schistosoma ovuncatum n. Sp. (Digenea: Schistosomatidae) из северо -западного Таиланда и историческая биогеография Юго -Восточной Азии Шистосомы Вайнленда, 1858». Систематическая паразитология . 51 (1): 1–19. doi : 10.1023/a: 1012988516995 . PMID 11721191 . S2CID 21696073 .

- ^ Webster BL, Littlewood DT (2012) Изменение порядка гена митохондриального гена ( Platyhelminthes: Digenea: Schistosomatidae). Int J Parasitol 42 (3): 313-321

- ^ Tchuem Tchuenté LA, Southgate VR, Njiokou F, Njiné T, Kouemeni Le, Jourdane J (1997). «Эволюция шистосомоза в Луме, Камерун: замена шистосомы интеркалатум S. haematobium посредством интрогрессивной гибридизации». Сделки Королевского общества тропической медицины и гигиены . 91 (6): 664–5. doi : 10.1016/s0035-9203 (97) 90513-7 . PMID 9509173 .

- ^ Morgan JA, Dejong RJ, Lwambo NJ, Mungai BN, Mkoji GM, Loker ES (апрель 2003 г.). «Первый отчет о естественном гибриде между Шистосомой Мансони и С. Родхайни». Журнал паразитологии . 89 (2): 416–8. doi : 10.1645/0022-3395 (2003) 089 [0416: froanh] 2.0.co; 2 . PMID 12760671 . S2CID 948644 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Huyse T, Webster BL, Geldof S, Stothard JR, Diaw OT, Polman K, Rollinson D (сентябрь 2009 г.). «Двунаправленная интрогрессивная гибридизация между крупным рогатым и человеческим видом шистосом» . PLO -патогены . 5 (9): E1000571. doi : 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000571 . PMC 2731855 . PMID 19730700 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Boissier J, Grech-Angelini S, Webster BL, Allienne JF, Huyse T, Mas-Coma S, et al. (Август 2016 г.). «Вспышка урогенитального шистосомоза в Корсике (Франция): эпидемиологическое исследование» (PDF) . Lancet. Заразительные заболевания . 16 (8): 971–9. doi : 10.1016/s1473-3099 (16) 00175-4 . PMID 27197551 . S2CID 3725312 .

- ^ Depaquit J, Akhoundi M, Haouchine D, Mantelet S, Izri A (2019). «Нет ограничения в межвидовой гибридизации в шистосомах: наблюдение из отчета о случае» . Паразит . 26 : 10. doi : 10.1051/parasite/2019010 . PMC 6396650 . PMID 30821247 .

- ^ Брант С.В., Морган Дж.А., Мкоджи Г.М., Снайдер С.Д., Раджапаксе Р.П., Локер Э.С. (февраль 2006 г.). «Подход к выявлению жизненных циклов крови, таксономии и разнообразия: предоставление ключевых эталонных данных, включая последовательность ДНК с стадий одиночных жизненного цикла» . Журнал паразитологии . 92 (1): 77–88. doi : 10.1645/ge-3515.1 . PMC 2519025 . PMID 16629320 .

- ^ Кто на информационный бюллетень

- ^ Британская Краткая Энциклопедия 2007

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый и Manson-Bahr PE, Bell Dr, Eds. (1987). Тропические заболевания Мэнсона . Лондон: Bailliere Tindall. ISBN 978-0-7020-1187-0 .

- ^ «Даже кровопролития разводятся - ткацкий станок» . Закринг . 2008-10-08 . Получено 2016-05-24 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный CHISTOSOMA Japonicum Genome Sequencing Consortium; и др. (Июль 2009 г.). «Геном Schistosoma japonicum выявляет особенности взаимодействия с хост-паразитом» . Природа . 460 (7253): 345–51. Bibcode : 2009natur.460..345Z . doi : 10.1038/nature08140 . PMC 3747554 . PMID 19606140 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Berriman M, Haas BJ, Loverde PT, Wilson RA, Dillon GP, Cerqueira GC, et al. (Июль 2009 г.). «Геном кровообразной флуки Шистосома Мансони» . Природа . 460 (7253): 352–8. Bibcode : 2009natur.460..352b . doi : 10.1038/nature08160 . PMC 2756445 . PMID 19606141 .

- ^ Young ND, Jex AR, Li B, Liu S, Yang L, Xiong Z, et al. (Январь 2012 г.). «Последовательность всего генома гемотобиума шистосомы» . Природа генетика . 44 (2): 221–5. doi : 10.1038/ng.1065 . HDL : 10072/45821 . PMID 22246508 . S2CID 13309839 .

- ^ Протазио А.В., Цай И.Дж., Бэббидж А., Никол С., Хант М., Аслетт М.А. и др. (Январь 2012 г.). Хоффманн К.Ф. (ред.). «Систематически улучшенный высокий качественный геном и транскриптом человеческой кровопролитированной шистосомы Mansoni» . ПЛО не пренебрегали тропическими заболеваниями . 6 (1): E1455. doi : 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001455 . PMC 3254664 . PMID 22253936 .

- ^ Bilharz T, Siebold CT (1852). «Вклад в Гельминтофграфию гуману ...» [Вклад в литературу по гельминтам [страдает] людей ...]. Журнал научной зоологии (на немецком языке). 4 : 53–76. Озеро: «2 -й декомум Haematobium bilh », стр.

- ^ Бильхарц Т (1856). «Defomum haematobium и его связь с определенными патологическими изменениями в органах мочи человека» [Defomum Haematobium и его связь с определенными патологическими изменениями органа мочи человека]. Венский медицинский недель (на немецком языке). 6 : 49–52, 65–68.

- ^ Хемсбах Дж.Х., Биллрот Т (1856). Микрогеология: о конкретном организме Тиери [ Микрогеология: о конкретах в организме животных ] (на немецком языке). Берлин, (Германия): Георг Реймер. п. 114. ISBN 9783112028636 Полем От р. 114: «Билхарц впервые описан в v. Siebold U. Kölliker's Journal F. Zoology 1852. Новый ворота людей, очень похожий на этитомы и, следовательно, называемый Deseomum Haematobium . Название искусства очень важно, общее название не должно остаться Thistoma должна быть заменена Bilharzia. (Билхарц впервые в исполнении Сьиболда и журнала Кёллика для [научной] зоологии 1852 года Новый кишечный червь людей, который очень похож на таковую и, следовательно, был назван его Dedomum Haematobium . Название рода не может быть оправданно оставаться дикомой;

- ^ Вайнланд Д.Ф. (1858). Человеческие цестоиды: эссе о ленточных червях человека ... Кембридж, Массачусетс, США: Меткалф и Компания. п. 87. См. Сноска †.

- ^ См.:

- Sambon LW (1 апреля 1907 г.). "Новый или Питтл из известных африканских энтозо " Гигиена 10 : 117.

- Sambon LW (16 сентября 1907 г.). «Замечания о Шистосоме Мансони» . Журнал тропической медицины и гигиены . 10 : 303–304.

- ^ См.:

- Да Силва П (август 1908 г.). «Вклад в изучение шистосомоза» [вклад в изучение шистосомоза в Баии]. Бразилия-Мадико (на португальском языке). 22 : 281–282.

- Да Сильва П (декабрь 1908 г.). «Вклад в изучение шистосомоза в Баии. Шестнадцать наблюдений» [Вклад в изучение шистосомоза в Баии. Шестнадцать наблюдений.]. Бразилия-Мадико (на португальском языке). 22 : 441–444.

- Да Силва П (1908). «Вклад в изучение шистосомоза. Двадцать наблюдений» [Вклад в изучение шистосомоза в Баии. Двадцать наблюдений.]. Бразилия-Мадико (на португальском языке). 22 : 451–454.

- Да Силва П (1908). «Шистосомоз в Баии» [шистосомоз в Баии]. Архив паразитологии (по -французски). 13 : 283–302.

- Да Силва П (1909). «Вклад в изучение шистосомоза в Баии, Бразилия» . Журнал тропической медицины и гигиены . 12 : 159–164.

- ^ «Гены убийц паразитов декодированы» . BBC News . 16 июля 2009 г. Получено 2009-07-16 .

- ^ «Паразиты - шистосомоз» . Центры для контроля и профилактики заболеваний . Министерство здравоохранения и социальных служб США. 28 октября 2020 года.

Дальнейшее чтение

[ редактировать ]- Ross AG, Sleigh AC, Li Y, Davis GM, Williams GM, Jiang Z, et al. (Апрель 2001 г.). «Шистосомоз в Китайской Народной Республике: перспективы и проблемы для 21 -го века» . Клинические обзоры микробиологии . 14 (2): 270–95. doi : 10.1128/cmr.14.2.270-295.2001 . PMC 88974 . PMID 11292639 .