2011 Tōhoku Earth Quake and Tsunami

| Tohoku Pacific Earthquake Землетрясение Великого Восточной Японии | |

Вертолет пролетает над портом Сендай , чтобы доставить еду пережившим землетрясения и цунами. | |

| |

| UTC time | 2011-03-11 05:46:24 |

|---|---|

| ISC event | 16461282 |

| USGS-ANSS | ComCat |

| Local date | 11 March 2011 |

| Local time | 14:46:24 JST |

| Duration | 6 minutes |

| Magnitude | 9.0–9.1 Mw |

| Depth | 29 km (18 mi) |

| Epicenter | 38°19′19″N 142°22′08″E / 38.322°N 142.369°E |

| Fault | Convergent boundary between Pacific Plate and Okhotsk microplate[1] |

| Type | Megathrust |

| Areas affected |

|

| Total damage | $360 billion USD |

| Max. intensity | JMA 7 (MMI XI)[2][3] |

| Peak acceleration | 2.99 g [4] |

| Peak velocity | 117.41 cm/s |

| Tsunami | Up to 40.5 m (133 ft) in Miyako, Iwate, Tōhoku |

| Landslides | Yes |

| Foreshocks | List of foreshocks and aftershocks of the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake |

| Aftershocks | 13,386 (as of 6 March 2018[update])[5] |

| Casualties | |

| Citations | [9][10][11][12][13][14] |

11 марта 2011 года, в 14:46 JST (05:46 UTC ), M W 9.0–9.1 Землетрясение под подводным мегатром произошло в Тихом океане, 72 км (45 миль) к востоку от полуострова Ошика в регионе Тхоку . Это длилось около шести минут и вызвало цунами . Иногда в Японии он известен как « Землетрясение Великого Восточной Японии » ( 東日本大震災 , Хигаши Нихон Дайшинсай ) , среди других имен. [ в 1 ] Стихивание часто упоминается по численной дате, 3.11 (прочитайте San Ten Ichi-ichi на японском языке). [ 31 ] [ 32 ] [ 33 ]

Это было самое мощное землетрясение, когда -либо записанное в Японии , и четвертое самое мощное землетрясение, записанное в мире с момента начала современной сейсмографии в 1900 году. [ 34 ] [ 35 ] [ 36 ] Землетрясение вызвало мощные волны цунами , которые, возможно, достигли высоты до 40,5 метров (133 фута) в Мияко Tōhoku в префектуре Iwate , [ 37 ] [ 38 ] и который в районе Сендай прошел со скоростью 700 км/ч (435 миль в час) [ 39 ] и до 10 км (6 миль) внутри страны. [40] Residents of Sendai had only eight to ten minutes of warning, and more than a hundred evacuation sites were washed away.[39] The snowfall which accompanied the tsunami[41] and the freezing temperature hindered rescue works greatly;[42] for instance, Ishinomaki, the city with the most deaths,[43] was 0 °C (32 °F) as the tsunami hit.[44] The official figures released in 2021 reported 19,759 deaths,[45] 6,242 injured,[46] and 2,553 people missing,[47] and a report from 2015 indicated 228,863 people were still living away from their home in either temporary housing or due to permanent relocation.[48]

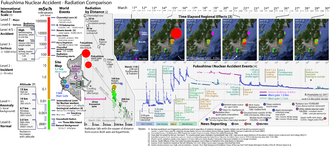

The tsunami caused the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, primarily the meltdowns of three of its reactors, the discharge of radioactive water in Fukushima and the associated evacuation zones affecting hundreds of thousands of residents.[49][50] Many electrical generators ran out of fuel. The loss of electrical power halted cooling systems, causing heat to build up. The heat build-up caused the generation of hydrogen gas. Without ventilation, gas accumulated within the upper refueling hall and eventually exploded causing the refueling hall's blast panels to be forcefully ejected from the structure. Residents within a 20 km (12 mi) radius of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant and a 10 km (6.2 mi) radius of the Fukushima Daini Nuclear Power Plant were evacuated.

Early estimates placed insured losses from the earthquake alone at US$14.5 to $34.6 billion.[51] The Bank of Japan offered ¥15 trillion (US$183 billion) to the banking system on 14 March 2011 in an effort to normalize market conditions.[52] The estimated economic damages amounted to over $300 billion, making it the costliest natural disaster in history.[53][54] According to a 2020 study, "the earthquake and its aftermaths resulted in a 0.47 percentage point decline in Japan's real GDP growth in the year following the disaster."[55]

Earthquake

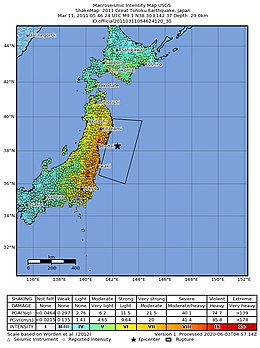

The magnitude 9.1 (Mw) undersea megathrust earthquake occurred on 11 March 2011 at 14:46 JST (05:46 UTC) in the north-western Pacific Ocean at a relatively shallow depth of 32 km (20 mi),[9][56] with its epicenter approximately 72 km (45 mi) east of the Oshika Peninsula of Tōhoku, Japan, lasting approximately six minutes.[9][10] The earthquake was initially reported as 7.9 Mw by the USGS before it was quickly upgraded to 8.8 Mw, then to 8.9 Mw,[57] and then finally to 9.0 Mw.[58][59] On 11 July 2016, the USGS further upgraded the earthquake to 9.1. Sendai was the nearest major city to the earthquake, 130 km (81 mi) from the epicenter; the earthquake occurred 373 km (232 mi) northeast of Tokyo.[9]

The main earthquake was preceded by a number of large foreshocks, with hundreds of aftershocks reported. One of the first major foreshocks was a 7.2 Mw event on 9 March, approximately 40 km (25 mi) from the epicenter of the 11 March earthquake, with another three on the same day in excess of 6.0 Mw.[9][60] Following the main earthquake on 11 March, a 7.4 Mw aftershock was reported at 15:08 JST (6:06 UTC), succeeded by a 7.9 Mw at 15:15 JST (6:16 UTC) and a 7.7 Mw at 15:26 JST (6:26 UTC).[61] Over 800 aftershocks of magnitude 4.5 Mw or greater have occurred since the initial quake,[62] including one on 26 October 2013 (local time) of magnitude 7.1 Mw.[63] Aftershocks follow Omori's law, which states that the rate of aftershocks declines with the reciprocal of the time since the main quake. The aftershocks will thus taper off in time, but could continue for years.[64]

The earthquake moved Honshu 2.4 m (8 ft) east, shifted the Earth on its axis by estimates of between 10 and 25 cm (4 and 10 in),[65][66][67] increased Earth's rotational speed by 1.8 μs per day,[68] and generated infrasound waves detected in perturbations of the low-orbiting Gravity Field and Steady-State Ocean Circulation Explorer satellite.[69] Initially, the earthquake caused sinking of part of Honshu's Pacific coast by up to roughly a metre, but after about three years, the coast rose back and then kept on rising to exceed its original height.[70][71][72][73]

Geology

This megathrust earthquake was a recurrence of the mechanism of the earlier 869 Sanriku earthquake, which has been estimated as having a magnitude of at least 8.4 Mw, which also created a large tsunami that inundated the Sendai plain.[39][74][75] Three tsunami deposits have been identified within the Holocene sequence of the plain, all formed within the last 3,000 years, suggesting an 800 to 1,100 year recurrence interval for large tsunamigenic earthquakes. In 2001 it was reckoned that there was a high likelihood of a large tsunami hitting the Sendai plain as more than 1,100 years had then elapsed.[76] In 2007, the probability of an earthquake with a magnitude of Mw 8.1–8.3 was estimated as 99% within the following 30 years.[77]

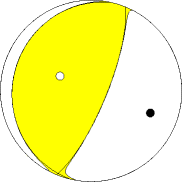

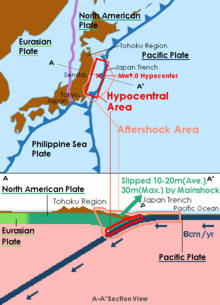

This earthquake occurred where the Pacific Plate is subducting under the plate beneath northern Honshu.[66][78] The Pacific Plate, which moves at a rate of 8 to 9 cm (3.1 to 3.5 in) per year, dips under Honshu's underlying plate, building large amounts of elastic energy. This motion pushes the upper plate down until the accumulated stress causes a seismic slip-rupture event. The break caused the sea floor to rise by several metres.[78] The magnitude of this earthquake was a surprise to some seismologists.[79] A quake of this magnitude usually has a rupture length of at least 500 km (310 mi) and generally requires a long, relatively straight fault surface. Because the plate boundary and subduction zone in the area of the Honshu rupture is not very straight, it is unusual for the magnitude of its earthquake to exceed 8.5 Mw.[79] The hypocentral region of this earthquake extended from offshore Iwate Prefecture to offshore Ibaraki Prefecture.[80] The Japanese Meteorological Agency said that the earthquake may have ruptured the fault zone from Iwate to Ibaraki with a length of 500 km (310 mi) and a width of 200 km (120 mi).[81][82] Analysis showed that this earthquake consisted of a set of three events.[83] Other major earthquakes with tsunamis struck the Sanriku Coast region in 1896 and in 1933.

The source area of this earthquake has a relatively high coupling coefficient surrounded by areas of relatively low coupling coefficients in the west, north, and south. From the averaged coupling coefficient of 0.5–0.8 in the source area and the seismic moment, it was estimated that the slip deficit of this earthquake was accumulated over a period of 260–880 years, which is consistent with the recurrence interval of such great earthquakes estimated from the tsunami deposit data. The seismic moment of this earthquake accounts for about 93% of the estimated cumulative moment from 1926 to March 2011. Hence, earthquakes in this area with magnitudes of about 7 since 1926 had only released part of the accumulated energy. In the area near the trench, the coupling coefficient is high, which could act as the source of the large tsunami.[84]

Most of the foreshocks are interplate earthquakes with thrust-type focal mechanisms. Both interplate and intraplate earthquakes appeared in the aftershocks offshore Sanriku coast with considerable proportions.[85]

Energy

The surface energy of the seismic waves from the earthquake was calculated to be 1.9×1017 joules,[86] which is nearly double that of the 9.1 Mw 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami that killed 230,000 people. If harnessed, the seismic energy from this earthquake would power a city the size of Los Angeles for an entire year.[64] The seismic moment (M0), which represents a physical size for the event, was calculated by the USGS at 3.9×1022 joules,[87] slightly less than the 2004 Indian Ocean quake.

Japan's National Research Institute for Earth Science and Disaster Prevention (NIED) calculated a peak ground acceleration of 2.99 g (29.33 m/s2).[88][en 2] The largest individual recording in Japan was 2.7 g, in Miyagi Prefecture, 75 km from the epicentre; the highest reading in the Tokyo metropolitan area was 0.16 g.[91]

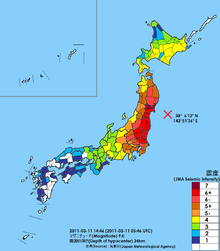

Intensity

The strong ground motion registered at the maximum of 7 on the Japan Meteorological Agency seismic intensity scale in Kurihara, Miyagi Prefecture.[92] Three other prefectures—Fukushima, Ibaraki and Tochigi—recorded a 6 upper on the JMA scale. Seismic stations in Iwate, Gunma, Saitama and Chiba Prefecture measured a 6 lower, recording a 5 upper in Tokyo.

| Intensity | Prefecture[93] |

|---|---|

| JMA 7 | Miyagi |

| JMA 6+ | Fukushima, Ibaraki, Tochigi |

| JMA 6− | Iwate, Gunma, Saitama, Chiba |

| JMA 5+ | Aomori, Akita, Yamagata, Tokyo, Kanagawa, Yamanashi |

| JMA 5− | Niigata, Nagano, Shizuoka |

| JMA 4 | Hokkaido, Gifu, Aichi |

| JMA 3 | Toyama, Ishikawa, Fukui, Mie, Shiga, Kyoto, Osaka, Hyogo, Nara |

| JMA 2 | Wakayama, Tottori, Shimane, Okayama, Tokushima, Kochi, Saga, Kumamoto |

| JMA 1 | Hiroshima, Kagawa, Ehime, Yamaguchi, Fukuoka, Nagasaki, Oita, Kagoshima |

Geophysical effects

Portions of northeastern Japan shifted by as much as 2.4 metres (7 ft 10 in) closer to North America,[65][66] making some sections of Japan's landmass wider than before.[66] Those areas of Japan closest to the epicenter experienced the largest shifts.[66] A 400-kilometre (250 mi) stretch of coastline dropped vertically by 0.6 metres (2 ft 0 in), allowing the tsunami to travel farther and faster onto land.[66] One early estimate suggested that the Pacific plate may have moved westward by up to 20 metres (66 ft),[94] and another early estimate put the amount of slippage at as much as 40 m (130 ft).[95] On 6 April the Japanese coast guard said that the quake shifted the seabed near the epicenter 24 metres (79 ft) and elevated the seabed off the coast of Miyagi Prefecture by 3 metres (9.8 ft).[96] A report by the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology, published in Science on 2 December 2011, concluded that the seabed in the area between the epicenter and the Japan Trench moved 50 metres (160 ft) east-southeast and rose about 7 metres (23 ft) as a result of the quake. The report also stated that the quake had caused several major landslides on the seabed in the affected area.[97]

The Earth's axis shifted by estimates of between 10 and 25 cm (4 and 10 in).[65][66][67] This deviation led to a number of small planetary changes, including the length of a day, the tilt of the Earth, and the Chandler wobble.[67] The speed of the Earth's rotation increased, shortening the day by 1.8 microseconds due to the redistribution of Earth's mass.[98] The axial shift was caused by the redistribution of mass on the Earth's surface, which changed the planet's moment of inertia. Because of conservation of angular momentum, such changes of inertia result in small changes to the Earth's rate of rotation.[99] These are expected changes[67] for an earthquake of this magnitude.[65][98] The earthquake also generated infrasound waves detected by perturbations in the orbit of the GOCE satellite, which thus serendipitously became the first seismograph in orbit.[69]

Following the earthquake, cracks were observed to have formed in the roof of Mount Fuji's magma chamber.[100]

Seiches observed in Sognefjorden, Norway were attributed to distant S waves and Love waves generated by the earthquake. These seiches began to occur roughly half an hour after the main shock hit Japan, and continued to occur for 3 hours, during which waves of up to 1.5 meters high were observed.[101]

Soil liquefaction was evident in areas of reclaimed land around Tokyo, particularly in Urayasu,[102][103] Chiba City, Funabashi, Narashino (all in Chiba Prefecture) and in the Koto, Edogawa, Minato, Chūō, and Ōta Wards of Tokyo. Approximately 30 homes or buildings were destroyed and 1,046 other buildings were damaged to varying degrees.[104] Nearby Haneda Airport, built mostly on reclaimed land, was not damaged. Odaiba also experienced liquefaction, but damage was minimal.[105]

Shinmoedake, a volcano in Kyushu, erupted three days after the earthquake. The volcano had previously erupted in January 2011; it is not known if the later eruption was linked to the earthquake.[106] In Antarctica, the seismic waves from the earthquake were reported to have caused the Whillans Ice Stream to slip by about 0.5 metres (1 ft 8 in).[107]

The first sign international researchers had that the earthquake caused such a dramatic change in the Earth's rotation came from the United States Geological Survey which monitors Global Positioning Satellite (GPS) stations across the world. The Survey team had several GPS monitors located near the scene of the earthquake. The GPS station located nearest the epicenter moved almost 4 m (13 ft). This motivated government researchers to look into other ways the earthquake may have had large scale effects on the planet. Calculations at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory determined that the Earth's rotation was changed by the earthquake to the point where the days are now 1.8 microseconds shorter.[108]

Aftershocks

Japan experienced over 1,000 aftershocks since the earthquake, with 80 registering over magnitude 6.0 Mw and several of which have been over magnitude 7.0 Mw.

A magnitude 7.4 Mw at 15:08 (JST), 7.9 Mw at 15:15 and a 7.7 Mw quake at 15:26 all occurred on 11 March.[109]

A month later, a major aftershock struck offshore on 7 April with a magnitude of 7.1 Mw. Its epicenter was underwater, 66 km (41 mi) off the coast of Sendai. The Japan Meteorological Agency assigned a magnitude of 7.4 MJMA, while the U.S. Geological Survey lowered it to 7.1 Mw.[110] At least four people were killed, and electricity was cut off across much of northern Japan including the loss of external power to Higashidōri Nuclear Power Plant and Rokkasho Reprocessing Plant.[111][112][113]

Four days later on 11 April, another magnitude 7.1 Mw aftershock struck Fukushima, causing additional damage and killing a total of three people.[114][115]

On 7 December 2012 a large aftershock of magnitude 7.3 Mw caused a minor tsunami, and again on 26 October 2013 a small tsunami was recorded after a 7.1 Mw aftershock.[116]

As of 16 March 2012 aftershocks continued, totaling 1887 events over magnitude 4.0; a regularly updated map showing all shocks of magnitude 4.5 and above near or off the east coast of Honshu in the last seven days[117] showed over 20 events.[118]

As of 11 March 2016[update] there had been 869 aftershocks of 5.0 Mw or greater, 118 of 6.0 Mw or greater, and 9 over 7.0 Mw as reported by the Japanese Meteorological Agency.[119]

The number of aftershocks was associated with decreased health across Japan.[120]

On 13 February 2021, a magnitude 7.1–7.3 earthquake struck off the coast of Sendai. It caused some damage in Miyagi and Fukushima prefectures. One person was killed, and 185 were injured.[121][122]

Land subsidence

The Geospatial Information Authority of Japan reported land subsidence based on the height of triangulation stations in the area measured by GPS as compared to their previous values from 14 April 2011.[123]

- Miyako, Iwate – 0.50 metres (1 ft 8 in)

- Yamada, Iwate – 0.53 metres (1 ft 9 in)

- Ōtsuchi, Iwate – 0.35 metres (1 ft 2 in)[124]

- Kamaishi, Iwate – 0.66 metres (2 ft 2 in)

- Ōfunato, Iwate – 0.73 metres (2 ft 5 in)

- Rikuzentakata, Iwate – 0.84 metres (2 ft 9 in)

- Kesennuma, Miyagi – 0.74 metres (2 ft 5 in)

- Minamisanriku, Miyagi – 0.69 metres (2 ft 3 in)

- Oshika Peninsula, Miyagi – 1.2 metres (3 ft 11 in)[124]

- Ishinomaki, Miyagi – 0.78 metres (2 ft 7 in)

- Higashimatsushima, Miyagi – 0.43 metres (1 ft 5 in)

- Iwanuma, Miyagi – 0.47 metres (1 ft 7 in)

- Sōma, Fukushima – 0.29 metres (11 in)

Scientists say that the subsidence is permanent. As a result, the communities in question are now more susceptible to flooding during high tides.[125]

Earthquake Warning System

One minute before the earthquake was felt in Tokyo, the Earthquake Early Warning system, which includes more than 1,000 seismometers in Japan, sent out warnings of impending strong shaking to millions. It is believed that the early warning by the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) saved many lives.[126][127] The warning for the general public was delivered about eight seconds after the first P wave was detected, or about 31 seconds after the earthquake occurred. However, the estimated intensities were smaller than the actual ones in some places, especially in Kanto, Koshinetsu, and Northern Tōhoku regions where the populace warning did not trigger. According to the Japan Meteorological Agency, reasons for the underestimation include a saturated magnitude scale when using maximum amplitude as input, failure to fully take into account the area of the hypocenter, and the initial amplitude of the earthquake being less than that which would be predicted by an empirical relationship.[128][129][130][131]

There were also cases where large differences between estimated intensities by the Earthquake Early Warning system and the actual intensities occurred in the aftershocks and triggered earthquakes. Such discrepancies in the warning were attributed by the JMA to the system's inability to distinguish between two different earthquakes that happened at around same time, as well as to the reduced number of reporting seismometers due to power outages and connection failures.[132] The system's software was subsequently modified to handle this kind of situation.[133]

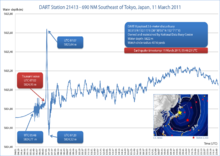

Tsunami

An upthrust of 6 to 8 metres (20 to 26 ft) along a 180 kilometres (110 mi) wide seabed at 60 kilometres (37 mi) offshore from the east coast of Tōhoku[134] resulted in a major tsunami that brought destruction along the Pacific coastline of Japan's northern islands. Thousands of people died and entire towns were devastated. The tsunami propagated throughout the Pacific Ocean region reaching the entire Pacific coast of North and South America from Alaska to Chile. Warnings were issued and evacuations were carried out in many countries bordering the Pacific. Although the tsunami affected many of these places, the heights of the waves were minor.[135][136][137] Chile's Pacific coast, one of the farthest from Japan at about 17,000 kilometres (11,000 mi) away, was struck by waves 2 metres (6.6 ft) high,[138][139][140] compared with an estimated wave height of 38.9 metres (128 ft) at Omoe peninsula, Miyako city, Japan.[38]

Japan

The tsunami warning issued by the Japan Meteorological Agency was the most serious on its warning scale; it was rated as a "major tsunami", being at least 3 metres (9.8 ft) high.[141] The actual height prediction varied, the greatest being for Miyagi at 6 metres (20 ft) high.[142] The tsunami inundated a total area of approximately 561 square kilometres (217 sq mi) in Japan.[143]

The earthquake took place at 14:46 JST (UTC 05:46) around 67 kilometres (42 mi) from the nearest point on Japan's coastline, and initial estimates indicated the tsunami would have taken 10 to 30 minutes to reach the areas first affected, and then areas farther north and south based on the geography of the coastline.[144][145] At 15:55 JST, a tsunami was observed flooding Sendai Airport, which is located near the coast of Miyagi Prefecture,[146][147] with waves sweeping away cars and planes and flooding various buildings as they traveled inland.[148][149] The impact of the tsunami in and around Sendai Airport was filmed by an NHK News helicopter, showing a number of vehicles on local roads trying to escape the approaching wave and being engulfed by it.[150] A 4-metre-high (13 ft) tsunami hit Iwate Prefecture.[citation needed] Wakabayashi Ward in Sendai was also particularly hard hit.[151] At least 101 designated tsunami evacuation sites were hit by the wave.[39][152]

Like the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami, the damage by surging water, though much more localized, was far more deadly and destructive than the actual quake. Entire towns were destroyed in tsunami-hit areas in Japan, including 9,500 missing in Minamisanriku;[153] one thousand bodies had been recovered in the town by 14 March 2011.[154]

Among the factors in the high death toll was the unexpectedly large water surge. The sea walls in several cities had been built to protect against tsunamis of much lower heights. Also, many people caught in the tsunami thought they were on high enough ground to be safe.[156] According to a special committee on disaster prevention designated by the Japanese government, the tsunami protection policy had been intended to deal with only tsunamis that had been scientifically proved to occur repeatedly. The committee advised that future policy should be to protect against the highest possible tsunami. Because tsunami walls had been overtopped, the committee also suggested, besides building taller tsunami walls, also teaching citizens how to evacuate if a large-scale tsunami should strike.[157][158]

Large parts of Kuji and the southern section of Ōfunato including the port area were almost entirely destroyed.[159][160] Also largely destroyed was Rikuzentakata, where the tsunami was three stories high.[161][162] Other cities destroyed or heavily damaged by the tsunami include Kamaishi, Miyako, Ōtsuchi, and Yamada (in Iwate Prefecture), Namie, Sōma, and Minamisōma (in Fukushima Prefecture) and Shichigahama, Higashimatsushima, Onagawa, Natori, Ishinomaki, and Kesennuma (in Miyagi Prefecture).[163][164][165][166][167][168][169] The most severe effects of the tsunami were felt along a 670-kilometre-long (420 mi) stretch of coastline from Erimo, Hokkaido, in the north to Ōarai, Ibaraki, in the south, with most of the destruction in that area occurring in the hour following the earthquake.[170] Near Ōarai, people captured images of a huge whirlpool that had been generated by the tsunami.[171] The tsunami washed away the sole bridge to Miyatojima, Miyagi, isolating the island's 900 residents.[172] A 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) high tsunami hit Chiba Prefecture about 2+1⁄2 hours after the quake, causing heavy damage to cities such as Asahi.[173]

On 13 March 2011, the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) published details of tsunami observations recorded around the coastline of Japan following the earthquake. These observations included tsunami maximum readings of over 3 metres (9.8 ft) at the following locations and times on 11 March 2011, following the earthquake at 14:46 JST:[174]

- 15:12 JST – off Kamaishi – 6.8 metres (22 ft)

- 15:15 JST – Ōfunato – 3.2 metres (10 ft) or higher

- 15:20 JST – Ishinomaki-shi Ayukawa – 3.3 metres (11 ft) or higher

- 15:21 JST – Miyako – 4 metres (13 ft) or higher

- 15:21 JST – Kamaishi – 4.1 metres (13 ft) or higher

- 15:44 JST – Erimo-cho Shoya – 3.5 metres (11 ft)

- 15:50 JST – Sōma – 7.3 metres (24 ft) or higher

- 16:52 JST – Ōarai – 4.2 metres (14 ft)

Many areas were also affected by waves of 1 to 3 metres (3 ft 3 in to 9 ft 10 in) in height, and the JMA bulletin also included the caveat that "At some parts of the coasts, tsunamis may be higher than those observed at the observation sites." The timing of the earliest recorded tsunami maximum readings ranged from 15:12 to 15:21, between 26 and 35 minutes after the earthquake had struck. The bulletin also included initial tsunami observation details, as well as more detailed maps for the coastlines affected by the tsunami waves.[175][176]

JMA also reported offshore tsunami height recorded by telemetry from moored GPS wave-height meter buoys as follows:[177]

- offshore of central Iwate (Miyako) – 6.3 metres (21 ft)

- offshore of northern Iwate (Kuji) – 6 metres (20 ft)

- offshore of northern Miyagi (Kesennuma) – 6 metres (20 ft)

On 25 March 2011, Port and Airport Research Institute (PARI) reported tsunami height by visiting the port sites as follows:[178]

- Port of Hachinohe – 5–6 metres (16–20 ft)

- Port of Hachinohe area – 8–9 metres (26–30 ft)

- Port of Kuji – 8–9 metres (26–30 ft)

- Port of Kamaishi – 7–9 metres (23–30 ft)

- Port of Ōfunato – 9.5 metres (31 ft)

- Run up height, port of Ōfunato area – 24 metres (79 ft)

- Fishery port of Onagawa – 15 metres (49 ft)

- Port of Ishinomaki – 5 metres (16 ft)

- Shiogama section of Shiogama-Sendai port – 4 metres (13 ft)

- Sendai section of Shiogama-Sendai port – 8 metres (26 ft)

- Sendai Airport area – 12 metres (39 ft)

The tsunami at Ryōri Bay (綾里湾), Ōfunato reached a height of 40.1 metres (132 ft) (run-up elevation). Fishing equipment was scattered on the high cliff above the bay.[179][180] At Tarō, Iwate, the tsunami reached a height of 37.9 metres (124 ft) up the slope of a mountain some 200 metres (660 ft) away from the coastline.[181] Also, at the slope of a nearby mountain from 400 metres (1,300 ft) away at Aneyoshi fishery port (姉吉漁港) of Omoe peninsula (重茂半島) in Miyako, Iwate, Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology found estimated tsunami run up height of 38.9 metres (128 ft).[38] This height is deemed the record in Japan historically, as of reporting date, that exceeds 38.2 metres (125 ft) from the 1896 Meiji-Sanriku earthquake.[182] It was also estimated that the tsunami reached heights of up to 40.5 metres (133 ft) in Miyako in Tōhoku's Iwate Prefecture. The inundated areas closely matched those of the 869 Sanriku tsunami.[183]

Inundation heights were observed along 2,000 kilometres (1,200 mi) of the coast from Hokkaido to Kyushu in a 2012 study. Maximum run-up heights greater than 10 metres (33 ft) were distributed along 530 kilometres (330 mi) of coast, and maximum run-up heights greater than 20 metres (66 ft) were distributed along 200 kilometres (120 mi) of the coast, measured directly.[184] The tsunami resulted in significant erosion of the Rikuzen-Takata coastline, mainly caused by backwash. A 2016 study indicated that the coast has not naturally recovered at a desirable rate since the tsunami.[185]

A Japanese government study found that 58% of people in coastal areas in Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima prefectures heeded tsunami warnings immediately after the quake and headed for higher ground. Of those who attempted to evacuate after hearing the warning, only five percent were caught in the tsunami. Of those who did not heed the warning, 49% were hit by the water.[186]

Delayed evacuations in response to the warnings had a number of causes. The tsunami height that had been initially predicted by the tsunami warning system was lower than the actual tsunami height; this error contributed to the delayed escape of some residents. The discrepancy arose as follows: in order to produce a quick prediction of a tsunami's height and thus to provide a timely warning, the initial earthquake and tsunami warning that was issued for the event was based on a calculation that requires only about three minutes. This calculation is, in turn, based on the maximum amplitude of the seismic wave. The amplitude of the seismic wave is measured using the JMA magnitude scale, which is similar to Richter magnitude scale. However, these scales "saturate" for earthquakes that are above a certain magnitude (magnitude 8 on the JMA scale); that is, in the case of very large earthquakes, the scales' values change little despite large differences in the earthquakes' energy. This resulted in an underestimation of the tsunami's height in initial reports. Problems in issuing updates also contributed to delays in evacuations. The warning system was supposed to be updated about 15 minutes after the earthquake occurred, by which time the calculation for the moment magnitude scale would normally be completed. However, the strong quake had exceeded the measurement limit of all of the teleseismometers within Japan, and thus it was impossible to calculate the moment magnitude based on data from those seismometers. Another cause of delayed evacuations was the release of the second update on the tsunami warning long after the earthquake (28 minutes, according to observations); by that time, power failures and similar circumstances reportedly prevented the update from reaching some residents. Also, observed data from tidal meters that were located off the coast were not fully reflected in the second warning. Furthermore, shortly after the earthquake, some wave meters reported a fluctuation of "20 centimetres (7.9 in)", and this value was broadcast throughout the mass media and the warning system, which caused some residents to underestimate the danger of their situation and even delayed or suspended their evacuation.[187][188]

In response to the aforementioned shortcomings in the tsunami warning system, JMA began an investigation in 2011 and updated their system in 2013. In the updated system, for a powerful earthquake that is capable of causing the JMA magnitude scale to saturate, no quantitative prediction will be released in the initial warning; instead, there will be words that describe the situation's emergency. There are plans to install new teleseismometers with the ability to measure larger earthquakes, which would allow the calculation of a quake's moment magnitude scale in a timely manner. JMA also implemented a simpler empirical method to integrate, into a tsunami warning, data from GPS tidal meters as well as from undersea water pressure meters, and there are plans to install more of these meters and to develop further technology to utilize data observed by them. To prevent under-reporting of tsunami heights, early quantitative observation data that are smaller than the expected amplitude will be overridden and the public will instead be told that the situation is under observation. About 90 seconds after an earthquake, an additional report on the possibility of a tsunami will also be included in observation reports, in order to warn people before the JMA magnitude can be calculated.[187][188]

Elsewhere across the Pacific

The Pacific Tsunami Warning Center (PTWC) in Hawaii issued tsunami watches and announcements for locations in the Pacific. At 07:30 UTC, PTWC issued a widespread tsunami warning covering the entire Pacific Ocean.[189][190] Russia evacuated 11,000 residents from coastal areas of the Kuril Islands.[191] The United States National Tsunami Warning Center issued a tsunami warning for the coastal areas in most of California, all of Oregon, and the western part of Alaska, and a tsunami advisory covering the Pacific coastlines of most of Alaska, and all of Washington and British Columbia, Canada.[192][193] In California and Oregon, up to 2.4 m-high (7.9 ft) tsunami waves hit some areas, damaging docks and harbors and causing over US$10 million in damage.[194] In Curry County, Oregon, US$7 million in damage occurred including the destruction of 1,100 m (3,600 ft) of docks at the Brookings harbor; the county received over US$1 million in FEMA emergency grants from the US Federal Government.[195] Surges of up to 1 m (3 ft 3 in) hit Vancouver Island in Canada[193][failed verification] prompting some evacuations, and causing boats to be banned from the waters surrounding the island for 12 hours following the wave strike, leaving many island residents in the area without means of getting to work.[196][197]

In the Philippines, waves up to 0.5 m (1 ft 8 in) high hit the eastern seaboard of the country. Some houses along the coast in Jayapura, Indonesia were destroyed.[198] Authorities in Wewak, East Sepik, Papua New Guinea evacuated 100 patients from the city's Boram Hospital before it was hit by waves, causing an estimated US$4 million in damage.[199] Hawaii estimated damage to public infrastructure alone at US$3 million, with damage to private properties, including resort hotels such as Four Seasons Resort Hualalai, estimated at tens of millions of dollars.[200] It was reported that a 1.5 m-high (4.9 ft) wave completely submerged Midway Atoll's reef inlets and Spit Island, killing more than 110,000 nesting seabirds at the Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge.[201] Some other South Pacific countries, including Tonga and New Zealand, and US territories American Samoa and Guam, experienced larger-than-normal waves, but did not report any major damage.[202] However, in Guam some roads were closed off and people were evacuated from low-lying areas.[203]

Along the Pacific Coast of Mexico and South America, tsunami surges were reported, but in most places caused little or no damage.[204] Peru reported a wave of 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) and more than 300 homes damaged.[204] The surge in Chile was large enough to damage more than 200 houses,[205] with waves of up to 3 m (9.8 ft).[206][207] In the Galápagos Islands, 260 families received assistance following a 3 m (9.8 ft) surge which arrived 20 hours after the earthquake, after the tsunami warning had been lifted.[208][209] There was a great deal of damage to buildings on the islands and one man was injured but there were no reported fatalities.[208][210]

After a 2 m (6 ft 7 in) high surge hit Chile, it was reported that the reflection from those surges traveled back across the Pacific, causing a 30–60 cm (12–24 in) surge in Japan, 47–48 hours after the earthquake, according to observation from multiple tide gauges, including in Onahama, Owase, and Kushimoto.[211][212]

The tsunami broke icebergs off the Sulzberger Ice Shelf in Antarctica, 13,000 km (8,100 mi) away. The main iceberg measured 9.5 km × 6.5 km (5.9 mi × 4.0 mi) (approximately the area of Manhattan Island) and about 80 m (260 ft) thick. A total of 125 km2 (48 sq mi; 31,000 acres) of ice broke away.[213][214]

As of April 2012, wreckage from the tsunami spread around the world, including a soccer ball which was found in Alaska's Middleton Island and a Japanese motorcycle found in British Columbia, Canada.[215][216]

Norway

On the day of the earthquake, the waters of several fjords across Norway appeared to seethe as if boiling, and formed waves that rolled onto shores, most prominently in Sognefjorden, where the phenomenon was caught on film. After two years of research, scientists concluded that the massive earthquake also triggered these surprise seiche waves thousands of miles away.[217][218]

Casualties

Japan

Key statistics

| Age | Among all deaths [219] |

| <9 | 3.0% |

| 10–19 | 2.7% |

| 20–29 | 3.4% |

| 30–39 | 5.5% |

| 40–49 | 7.3% |

| 50–59 | 12.3% |

| 60–69 | 19.2% |

| 70–79 | 24.5% |

| >80 | 22.1% |

| Prefecture | Municipality | Deaths | Missing |

| Miyagi | Ishinomaki City | 3,553 | 418 |

| Iwate | Rikuzentakata City | 1,606 | 202 |

| Miyagi | Kesennuma City | 1,218 | 214 |

| Miyagi | Higashimatsushima City | 1,132 | 23 |

| Fukushima | Minamisoma City | 1,050 | 111 |

| Iwate | Kamaishi City | 994 | 152 |

| Miyagi | Natori City | 954 | 38 |

| Miyagi | Sendai City | 923 | 27 |

| Iwate | Ōtsuchi Town | 856 | 416 |

| Miyagi | Yamamoto Town | 701 | 17 |

| Iwate | Yamada Town | 687 | 145 |

| Miyagi | Minamisanriku Town | 620 | 211 |

| Miyagi | Onagawa Town | 615 | 257 |

The official figures released in 2021 reported 19,759 deaths,[220] 6,242 injured,[221] and 2,553 people missing.[222] There were 10,567 deaths in Miyagi, 5,145 in Iwate, 3,920 in Fukushima, 66 in Ibaraki, 22 in Chiba, eight in Tokyo, six in Kanagawa, four in Tochigi, three each in Aomori and Yamagata, and one each in Gunma, Saitama and Hokkaido.[43] The leading causes of death were drowning (90.64% or 14,308 bodies), burning (0.9% or 145 bodies) and others (4.2% or 667 bodies, mostly crushed by heavy objects).[219] Injuries related to nuclear exposure or the discharge of radioactive water in Fukushima are difficult to trace as 60% of the 20,000 workers on-site declined to participate in state-sponsored free health checks.[223]

Elderly aged over 60 account for 65.8% of all deaths, as shown on the table to the right.[219] In particular, in the Okawa Elementary School tragedy in which 84 drowned, it was discovered that in the wake of the tsunami, young housewives who wanted to pick up their children to high ground found their voices drowned out by retired, elderly, male villagers, who preferred to stay put at the school, which was a sea-level evacuation site meant for earthquakes but not tsunamis. Richard Lloyd Parry concluded the tragedy to be "the ancient dialogue [...] between the entreating voices of women, and the oblivious, overbearing dismissiveness of old men".[224]

For the purpose of relief fund, an "earthquake-related death" was defined to include "Physical and mental fatigue caused by life in temporary shelter", "Physical and mental fatigue caused by evacuation", "Delayed treatment due to an inoperative hospital", "Physical and mental fatigue caused by stress from the earthquake and tsunami". A few cases of suicide are also included. Most of these deaths occurred during the first six months after the earthquake and the number dropped thereafter, but as time has passed, the number has continued to increase. Most of these deaths occurred in Fukushima Prefecture, where the prefectural government has suggested that they could be due to evacuations caused by the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster.[225] Within Fukushima Prefecture, these indirect casualties have already resulted in more deaths than the number of people killed directly by earthquake and tsunami.[226][227][228]

Others

Save the Children reports that as many as 100,000 children were uprooted from their homes, some of whom were separated from their families because the earthquake occurred during the school day.[229] 236 children were orphaned in the prefectures of Iwate, Miyagi and Fukushima by the disaster;[230][231] 1,580 children lost either one or both parents,[232] 846 in Miyagi, 572 in Iwate, and 162 in Fukushima.[233] The quake and tsunami killed 378 elementary, middle-school, and high school students and left 158 others missing.[234] One elementary school in Ishinomaki, Miyagi, Okawa Elementary School, lost 74 of 108 students and 10 of 13 teachers in the tsunami due to poor decision making in evacuation.[41][235][236][237]

The Japanese Foreign Ministry confirmed the deaths of nineteen foreigners.[238] Among them were two English teachers from the United States affiliated with the Japan Exchange and Teaching Program;[239] a Canadian missionary in Shiogama;[240] and citizens of China, North and South Korea, Taiwan, Pakistan and the Philippines.

By 9:30 UTC on 11 March 2011, Google Person Finder, which was previously used in the Haitian, Chilean, and Christchurch, New Zealand earthquakes, was collecting information about survivors and their locations.[241][242]

Japanese funerals are normally elaborate Buddhist ceremonies that entail cremation. The thousands of bodies, however, exceeded the capacity of available crematoriums and morgues, many of them damaged,[243][244] and there were shortages of both kerosene—each cremation requires 50 litres—and dry ice for preservation.[245] The single crematorium in Higashimatsushima, for example, could only handle four bodies a day, although hundreds were found there.[246] Governments and the military were forced to bury many bodies in hastily dug mass graves with rudimentary or no rites, although relatives of the deceased were promised that they would be cremated later.[247]

As of 27 May 2011, three Japan Ground Self-Defense Force members had died while conducting relief operations in Tōhoku.[248] As of March 2012, the Japanese government had recognized 1,331 deaths as indirectly related to the earthquake, such as caused by harsh living conditions after the disaster.[249] As of 30 April 2012, 18 people had died and 420 had been injured while participating in disaster recovery or clean-up efforts.[250]

Overseas

The tsunami was reported to have caused several deaths outside Japan. One man was killed in Jayapura, Papua, Indonesia after being swept out to sea.[13] A man who is said to have been attempting to photograph the oncoming tsunami at the mouth of the Klamath River, south of Crescent City, California, was swept out to sea.[251] His body was found on 2 April 2011 along Ocean Beach in Fort Stevens State Park, Oregon, 530 km (330 mi) to the north.[14]

Damage and effects

The degree and extent of damage caused by the earthquake and resulting tsunami were enormous, with most of the damage being caused by the tsunami. Video footage of the towns that were worst affected shows little more than piles of rubble, with almost no parts of any structures left standing.[252] Estimates of the cost of the damage range well into the tens of billions of US dollars; before-and-after satellite photographs of devastated regions show immense damage to many regions.[253][254] Although Japan has invested the equivalent of billions of dollars on anti-tsunami seawalls which line at least 40% of its 34,751 km (21,593 mi) coastline and stand up to 12 m (39 ft) high, the tsunami simply washed over the top of some seawalls, collapsing some in the process.[255]

Japan's National Police Agency said on 3 April 2011, that 45,700 buildings were destroyed and 144,300 were damaged by the quake and tsunami. The damaged buildings included 29,500 structures in Miyagi Prefecture, 12,500 in Iwate Prefecture and 2,400 in Fukushima Prefecture.[256] Three hundred hospitals with 20 beds or more in Tōhoku were damaged by the disaster, with 11 being completely destroyed.[257] The earthquake and tsunami created an estimated 24–25 million tons of rubble and debris in Japan.[258][259]

A report by the National Police Agency of Japan on 10 September 2018 listed 121,778 buildings as "total collapsed", with a further 280,926 buildings "half collapsed", and another 699,180 buildings "partially damaged".[260] The earthquake and tsunami also caused extensive and severe structural damage in north-eastern Japan, including heavy damage to roads and railways as well as fires in many areas, and a dam collapse.[40][261] Japanese Prime Minister Naoto Kan said, "In the 65 years after the end of World War II, this is the toughest and the most difficult crisis for Japan."[262] Around 4.4 million households in northeastern Japan were left without electricity and 1.5 million without water.[263]

An estimated 230,000 automobiles and trucks were damaged or destroyed in the disaster. As of the end of May 2011, residents of Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima prefectures had requested the deregistration of 15,000 vehicles, meaning that the owners of those vehicles were writing them off as unrepairable or unsalvageable.[264]

Weather conditions

Low temperature and snowfall were major concerns after the earthquake.[265] Snow arrived minutes before or after the tsunami, depending on locations.[41] In Ishinomaki, the city which suffered the most deaths,[43] a temperature of 0 °C (32 °F) was measured, and it began to snow within a couple of hours of the earthquake.[44][41] Major snow fell again on 16 March,[42][266] and intermittently in the coming weeks.[267] 18 March was the coldest of that month, recording −4 to 6 °C (25 to 43 °F) in Sendai.[267][42] Photos of city ruins covered with snow were featured in various photo albums in international media, including NASA.[268][269][270]

Waste

The tsunami produced huge amounts of debris: estimates of 5 million tonnes of waste were reported by the Japanese Ministry of the Environment. Some of this waste, mostly plastic and styrofoam washed up on the coasts of Canada and the United States in late 2011. Along the west coast of the United States, this increased the amount of litter by a factor of ten and may have transported alien species.[271]

Ports

All of Japan's ports were briefly shut down after the earthquake, though the ones in Tokyo and southwards soon re-opened. Fifteen ports were located in the disaster zone. The north eastern ports of Hachinohe, Sendai, Ishinomaki and Onahama were destroyed, while the Port of Chiba (which serves the hydrocarbon industry) and Japan's ninth-largest container port at Kashima were also affected, though less severely. The ports at Hitachinaka, Hitachi, Soma, Shiogama, Kesennuma, Ofunato, Kamashi and Miyako were also damaged and closed to ships.[272] All 15 ports reopened to limited ship traffic by 29 March 2011.[273] A total of 319 fishing ports, about 10% of Japan's fishing ports, were damaged in the disaster.[274] Most were restored to operating condition by 18 April 2012.[275]

The Port of Tokyo suffered slight damage; the effects of the quake included visible smoke rising from a building in the port with parts of the port areas being flooded, including soil liquefaction in Tokyo Disneyland's parking lot.[276][277]

Dams and water problems

The Fujinuma irrigation dam in Sukagawa ruptured,[278] causing flooding and the washing away of five homes.[279] Eight people were missing and four bodies were discovered by the morning.[280][281][282] Reportedly, some locals had attempted to repair leaks in the dam before it completely failed.[283] On 12 March 252 dams were inspected and it was discovered that six embankment dams had shallow cracks on their crests. The reservoir at one concrete gravity dam suffered a small non-serious slope failure. All damaged dams are functioning with no problems. Four dams within the quake area were unreachable.[284]

In the immediate aftermath of the calamity, at least 1.5 million households were reported to have lost access to water supplies.[263][285] By 21 March 2011, this number fell to 1.04 million.[286]

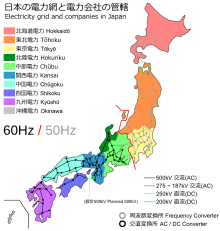

Electricity

According to the Japanese trade ministry, around 4.4 million households served by Tōhoku Electric Power (TEP) in northeastern Japan were left without electricity.[287] Several nuclear and conventional power plants went offline, reducing the Tokyo Electric Power Company's (TEPCO) total capacity by 21 GW.[288] Rolling blackouts began on 14 March due to power shortages caused by the earthquake.[289] TEPCO, which normally provides approximately 40 GW of electricity, announced that it could only provide about 30 GW, because 40% of the electricity used in the greater Tokyo area was supplied by reactors in the Niigata and Fukushima prefectures.[290] The reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi and Fukushima Dai-ni plants were automatically taken offline when the first earthquake occurred and sustained major damage from the earthquake and subsequent tsunami. Rolling blackouts of approximately three hours were experienced throughout April and May while TEPCO scrambled to find a temporary power solution. The blackouts affected Tokyo, Kanagawa, Eastern Shizuoka, Yamanashi, Chiba, Ibaraki, Saitama, Tochigi, and Gunma prefectures.[291] Voluntary reductions in electricity use by consumers in the Kanto area helped reduce the predicted frequency and duration of the blackouts.[292] By 21 March 2011, the number of households in the north without electricity fell to 242,927.[286]

Tōhoku Electric Power was not able to provide the Kanto region with additional power because TEP's power plants were also damaged in the earthquake. Kansai Electric Power Company (Kepco) could not share electricity, because its system operated at 60 hertz, whereas TEPCO and TEP operate their systems at 50 hertz; the disparity is due to early industrial and infrastructure development in the 1880s that left Japan without a unified national power grid.[293] Two substations, one in Shizuoka Prefecture and one in Nagano Prefecture, were able to convert between frequencies and transfer electricity from Kansai to Kanto and Tōhoku, but their capacity was limited to 1 GW. With damage to so many power plants, it was feared it might be years before a long-term solution could be found.[294]

To help alleviate the shortage, three steel manufacturers in the Kanto region contributed electricity produced by their in-house conventional power stations to TEPCO for distribution to the general public. Sumitomo Metal Industries could produce up to 500 MW, JFE Steel 400 MW, and Nippon Steel 500 MW of electric power.[295] Auto and auto parts makers in Kanto and Tōhoku agreed in May 2011 to operate their factories on Saturdays and Sundays and close on Thursdays and Fridays to help alleviate electricity shortages during the summer of 2011.[296] The public and other companies were also encouraged to conserve electricity in the 2011 summer months (Setsuden).[297]

The expected electricity crisis in 2011 summer was successfully prevented thanks to all the setsuden measures. Peak electricity consumption recorded by TEPCO during the period was 49.22GW, which is 10.77GW (18%) lower than the peak consumption in the previous year. Overall electricity consumption during July and August was also 14% less than in the previous year.[298] The peak electricity consumption within TEP's area was 12.46GW during the 2011 summer, 3.11GW (20%) less than the peak consumption in the previous year, and the overall consumption have been reduced by 11% in July with 17% in August compared to previous year.[299][300][301] The Japanese government continued to ask the public to conserve electricity until 2016, when it is predicted that the supply will be sufficient to meet demand, thanks to the deepening of the mindset to conserve electricity among corporate and general public, addition of new electricity providers due to the electricity liberalization policy, increased output from renewable energy as well as fossil fuel power stations, as well as sharing of electricity between different electricity companies.[302][303][304]

Oil, gas and coal

A 220,000-barrel (35,000 m3)-per-day[305] oil refinery of Cosmo Oil Company was set on fire by the quake at Ichihara, Chiba Prefecture, to the east of Tokyo.[306][307] It was extinguished after ten days, injuring six people, and destroying storage tanks.[308] Other refineries halted production due to safety checks and power loss.[309][310] In Sendai, a 145,000-barrel (23,100 m3)-per-day refinery owned by the largest refiner in Japan, JX Nippon Oil & Energy, was also set ablaze by the quake.[305] Workers were evacuated,[311] but tsunami warnings hindered efforts to extinguish the fire until 14 March, when officials planned to do so.[305]

An analyst estimates that consumption of various types of oil may increase by as much as 300,000 barrels (48,000 m3) per day (as well as LNG), as back-up power plants burning fossil fuels try to compensate for the loss of 11 GW of Japan's nuclear power capacity.[312][313]

The city-owned plant for importing liquefied natural gas in Sendai was severely damaged, and supplies were halted for at least a month.[314]

In addition to refining and storage, several power plants were damaged. These include Sendai #4, New-Sendai #1 and #2, Haranomachi #1 and #2, Hirono #2 and #4 and Hitachinaka #1.[315]

Nuclear power plants

The Fukushima Daiichi, Fukushima Daini, Onagawa Nuclear Power Plant and Tōkai nuclear power stations, consisting of a total eleven reactors, were automatically shut down following the earthquake.[316] Higashidōri, also on the northeast coast, was already shut down for a periodic inspection. Cooling is needed to remove decay heat after a Generation II reactor has been shut down, and to maintain spent fuel pools. The backup cooling process is powered by emergency diesel generators at the plants and at Rokkasho nuclear reprocessing plant.[317] At Fukushima Daiichi and Daini, tsunami waves overtopped seawalls and destroyed diesel backup power systems, leading to severe problems at Fukushima Daiichi, including three large explosions and radioactive leakage. Subsequent analysis found that many Japanese nuclear plants, including Fukushima Daiichi, were not adequately protected against tsunamis.[318] Over 200,000 people were evacuated.[319]

The discharge of radioactive water in Fukushima was confirmed in later analysis at the three reactors at Fukushima I (Units 1, 2, and 3), which suffered meltdowns and continued to leak coolant water.[49]

The aftershock on 7 April caused the loss of external power to Rokkasho Reprocessing Plant and Higashidori Nuclear Power Plant but backup generators were functional. Onagawa Nuclear Power Plant lost three of its four external power lines and temporarily lost cooling function in its spent fuel pools for "20 to 80 minutes". A spill of "up to 3.8 litres" of radioactive water also occurred at Onagawa following the aftershock.[320] A report by the IAEA in 2012 found that the Onagawa Nuclear Power Plant had remained largely undamaged.[321]

In 2013, only two nuclear reactors in Japan had been restarted since the 2011 shutdowns.[citation needed] In February 2019, there were 42 operable reactors in Japan. Of these, only nine reactors in five power plants were operating after having been restarted post-2011.[322]

Fukushima meltdowns

Japan declared a state of emergency following the failure of the cooling system at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, resulting in the evacuation of nearby residents.[323][324][325] Officials from the Japanese Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency reported that radiation levels inside the plant were up to 1,000 times normal levels,[326] and that radiation levels outside the plant were up to eight times normal levels.[327] Later, a state of emergency was also declared at the Fukushima Daini nuclear power plant about 11 km (6.8 mi) south.[328] Experts described the Fukushima disaster was not as bad as the Chernobyl disaster, but worse than the Three Mile Island accident.[329]

The discharge of radioactive water of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant was later detected in tap water. Radioactive iodine was detected in the tap water in Fukushima, Tochigi, Gunma, Tokyo, Chiba, Saitama, and Niigata, and radioactive caesium in the tap water in Fukushima, Tochigi and Gunma.[330][331][332] Radioactive caesium, iodine, and strontium[333] were also detected in the soil in some places in Fukushima. There may be a need to replace the contaminated soil.[334] Many radioactive hotspots were found outside the evacuation zone, including Tokyo.[335] Radioactive contamination of food products were detected in several places in Japan.[336] In 2021, the Japanese cabinet finally approved the dumping of radioactive water in Fukushima into the Pacific Ocean over a course of 30 years, with full support of IAEA.[337]

Incidents elsewhere

A fire occurred in the turbine section of the Onagawa Nuclear Power Plant following the earthquake.[317][338] The blaze was in a building housing the turbine, which is sited separately from the plant's reactor,[323] and was soon extinguished.[339] The plant was shut down as a precaution.[340]

On 13 March the lowest-level state of emergency was declared regarding the Onagawa plant as radioactivity readings temporarily[341] exceeded allowed levels in the area of the plant.[342][343] Tōhoku Electric Power Co. stated this may have been due to radiation from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accidents but was not from the Onagawa plant itself.[344]

As a result of the 7 April aftershock, Onagawa Nuclear Power Plant lost three of four external power lines and lost cooling function for as much as 80 minutes. A spill of a couple of litres of radioactive water occurred at Onagawa.[320]

The number 2 reactor at Tōkai Nuclear Power Plant was shut down automatically.[316] On 14 March it was reported that a cooling system pump for this reactor had stopped working;[345] however, the Japan Atomic Power Company stated that there was a second operational pump sustaining the cooling systems, but that two of three diesel generators used to power the cooling system were out of order.[346]

Transport

Japan's transport network suffered severe disruptions. Many sections of Tōhoku Expressway serving northern Japan were damaged. The expressway did not reopen to general public use until 24 March 2011.[347][348] All railway services were suspended in Tokyo, with an estimated 20,000 people stranded at major stations across the city.[349] In the hours after the earthquake, some train services were resumed.[350] Most Tokyo area train lines resumed full service by the next day—12 March.[351] Twenty thousand stranded visitors spent the night of 11–12 March inside Tokyo Disneyland.[352]

A tsunami flooded Sendai Airport at 15:55 JST,[146] about one hour after the initial quake, causing severe damage. Narita and Haneda Airport both briefly suspended operations after the quake, but suffered little damage and reopened within 24 hours.[277] Eleven airliners bound for Narita were diverted to nearby Yokota Air Base.[353][354]

Various train services around Japan were also canceled, with JR East suspending all services for the rest of the day.[355] Four trains on coastal lines were reported as being out of contact with operators; one, a four-car train on the Senseki Line, was found to have derailed, and its occupants were rescued shortly after 8 am the next morning.[356] Minami-Kesennuma Station on the Kesennuma Line was obliterated save for its platform;[357] 62 of 70 (31 of 35) JR East train lines suffered damage to some degree;[273] in the worst-hit areas, 23 stations on 7 lines were washed away, with damage or loss of track in 680 locations and the 30-km radius around the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant unable to be assessed.[358]

There were no derailments of Shinkansen bullet train services in and out of Tokyo, but their services were also suspended.[277] The Tokaido Shinkansen resumed limited service late in the day and was back to its normal schedule by the next day, while the Jōetsu and Nagano Shinkansen resumed services late on 12 March. Services on Yamagata Shinkansen resumed with limited numbers of trains on 31 March.[359]

Derailments were minimized because of an early warning system that detected the earthquake before it struck. The system automatically stopped all high-speed trains, which minimized the damage.[360]

The Tōhoku Shinkansen line was worst hit, with JR East estimating that 1,100 sections of the line, varying from collapsed station roofs to bent power pylons, would need repairs. Services on the Tōhoku Shinkansen partially resumed only in Kantō area on 15 March, with one round-trip service per hour between Tokyo and Nasu-Shiobara,[361] and Tōhoku area service partially resumed on 22 March between Morioka and Shin-Aomori.[362] Services on Akita Shinkansen resumed with limited numbers of trains on 18 March.[363] Service between Tokyo and Shin-Aomori was restored by May, but at lower speeds due to ongoing restoration work; the pre-earthquake timetable was not reinstated until late September.[364]

The rolling blackouts brought on by the crises at the nuclear power plants in Fukushima had a profound effect on the rail networks around Tokyo starting on 14 March. Major railways began running trains at 10–20 minute intervals, rather than the usual 3–5 minute intervals, operating some lines only at rush hour and completely shutting down others; notably, the Tōkaidō Main Line, Yokosuka Line, Sōbu Main Line and Chūō-Sōbu Line were all stopped for the day.[365] This led to near-paralysis within the capital, with long lines at train stations and many people unable to come to work or get home. Railway operators gradually increased capacity over the next few days, until running at approximately 80% capacity by 17 March and relieving the worst of the passenger congestion.

Telecommunications

Cellular and landline phone service suffered major disruptions in the affected area.[366] Immediately after the earthquake cellular communication was jammed across much of Japan due to a surge of network activity. On the day of the quake itself American broadcaster NPR was unable to reach anyone in Sendai with a working phone or access to the Internet.[367] Internet services were largely unaffected in areas where basic infrastructure remained, despite the earthquake having damaged portions of several undersea cable systems landing in the affected regions; these systems were able to reroute around affected segments onto redundant links.[368][369] Within Japan, only a few websites were initially unreachable.[370] Several Wi-Fi hotspot providers reacted to the quake by providing free access to their networks,[370] and some American telecommunications and VoIP companies such as AT&T, Sprint, Verizon,[371] T-Mobile[372] and VoIP companies such as netTALK[373] and Vonage[374] have offered free calls to (and in some cases, from) Japan for a limited time, as did Germany's Deutsche Telekom.[375]

Defense

Matsushima Air Field of the Japan Self-Defense Force in Miyagi Prefecture received a tsunami warning, and the airbase public address 'Tanoy' was used to give the warning: 'A tsunami is coming evacuate to the third floor.' Shortly after the warning the airbase was struck by the tsunami, flooding the base. There was no loss of life, although the tsunami resulted in damage to all 18 Mitsubishi F-2 fighter jets of the 21st Fighter Training Squadron.[376][377][378] Twelve of the aircraft were scrapped, while the remaining six were slated for repair at a cost of 80 billion yen ($1 billion), exceeding the original cost of the aircraft.[379] After the tsunami, elements of the Japanese Maritime Self-Defence Force put to sea without orders and started rescuing those who had been washed out to sea. Tsunami plans were for the Japanese Self-Defence Force assets to be led, directed, and coordinated by local civic governments. However, the earthquake destroyed town halls (the seat of local municipal government), police, and fire services in many places, so the military not only had to respond to but also command rescues.

Cultural properties

754 cultural properties were damaged across nineteen prefectures, including five National Treasures (at Zuigan-ji, Ōsaki Hachiman-gū, Shiramizu Amidadō, and Seihaku-ji); 160 Important Cultural Properties (including at Sendai Tōshō-gū, the Kōdōkan, and Entsū-in, with its Western decorative motifs); 144 Monuments of Japan (including Matsushima, Takata-matsubara, Yūbikan, and the Site of Tagajō); six Groups of Traditional Buildings; and four Important Tangible Folk Cultural Properties. Stone monuments at the UNESCO World Heritage Site: Shrines and Temples of Nikkō were toppled.[380][381][382] In Tokyo, there was damage to Koishikawa Kōrakuen, Rikugien, Hamarikyū Onshi Teien, and the walls of Edo Castle.[383] Information on the condition of collections held by museums, libraries and archives is still incomplete.[384] There was no damage to the Historic Monuments and Sites of Hiraizumi in Iwate Prefecture, and the recommendation for their inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List in June was seized upon as a symbol of international recognition and recovery.[385]

Aftermath

The aftermath of the earthquake and tsunami included a humanitarian crisis and a major economic impact. The tsunami resulted in over 340,000 displaced people in the Tōhoku region, and shortages of food, water, shelter, medicine, and fuel for survivors. In response, the Japanese government mobilized the Self-Defence Forces (under Joint Task Force – Tōhoku, led by Lieutenant General Eiji Kimizuka), while many countries sent search and rescue teams to help search for survivors. Aid organizations in Japan and worldwide responded, with the Japanese Red Cross reporting $1 billion in donations. The economic impact included immediate problems, with industrial production suspended in many factories, and the longer term issue of the cost of rebuilding, which has been estimated at ¥10 trillion ($122 billion). In comparison to the 1995 Great Hanshin earthquake, the East Japan earthquake brought serious damage to an extremely wide range.[386]

The aftermath of the twin disasters left Japan's coastal cities and towns with nearly 25 million tons of debris. In Ishinomaki alone, there were 17 trash collection sites 180 metres (590 ft) long and at least 4.5 metres (15 ft) high. An official in the city's government trash disposal department estimated that it would take three years to empty these sites.[387]

In April 2015, authorities off the coast of Oregon discovered debris that was thought to be from a boat destroyed during the tsunami. The cargo contained yellowtail amberjack, a species of fish that lives off the coast of Japan, still alive. KGW estimates that more than 1 million tons of debris still remain in the Pacific Ocean.[388]

In February 2016, a memorial was inaugurated by two architects for the victims of the disaster, consisting of a 6.5-square-metre structure on a hillside between a temple and a cherry tree in Ishinomaki.[389]

-

Emergency vehicles staging in the ruins of Otsuchi following the tsunami

-

Anti-nuclear protest following the disaster

Scientific and research response

Seismologists anticipated a very large quake would strike in the same place as the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake—in the Sagami Trough, southwest of Tokyo.[390][391] The Japanese government had tracked plate movements since 1976 in preparation for the so-called Tokai earthquake, predicted to take place in that region.[392] However, occurring as it did 373 km (232 mi) north east of Tokyo, the Tōhoku earthquake came as a surprise to seismologists. While the Japan Trench was known for creating large quakes, it had not been expected to generate quakes above an 8.0 magnitude.[391][392] The Headquarters for Earthquake Research Promotion set up by the Japanese government then reassessed the long-term risk of trench-type earthquakes around Japan, and it was announced in November 2011 that research on the 869 Sanriku earthquake indicated that a similar earthquake with a magnitude of Mw 8.4–9.0 would take place off the Pacific coast of northeastern Japan, on average, every 600 years. Also, a tsunami-earthquake with a tsunami magnitude scales (Mt) between 8.6 and 9.0 (Similar to the 1896 Sanriku earthquake, the Mt for the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake was 9.1–9.4) had a 30% chance to occur within 30 years.[393][394]

The quake gave scientists the opportunity to collect a large amount of data to model the seismic events that took place in great detail.[65] This data is expected to be used in a variety of ways, providing unprecedented information about how buildings respond to shaking, and other effects.[395] Gravimetric data from the quake have been used to create a model for increased warning time compared to seismic models, as gravity fields travel faster than seismic waves.[396]

Researchers have also analysed the economic effects of this earthquake and have developed models of the nationwide propagation via interfirm supply networks of the shock that originated in the Tōhoku region.[397][398]

After the full extent of the disaster was known, researchers soon launched a project to gather all digital material relating to the disaster into an online searchable archive to form the basis of future research into the events during and after the disaster. The Japan Digital Archive is presented in English and Japanese and is hosted at the Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Some of the first research to come from the archive was a 2014 paper from the Digital Methods Initiative in Amsterdam about patterns of Twitter usage around the time of the disaster.

After the 2011 disaster, the United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction held its World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction in Tohoku in March 2015, which produced the Sendai Framework document to guide efforts by international development agencies to act before disasters instead of reacting to them after the fact. At this time Japan's Disaster Management Office (Naikakufu Bosai Keikaku) published a bi-lingual guide in Japanese and English, Disaster Management in Japan, to outline the several varieties of natural disaster and the preparations being made for the eventuality of each. In the fall of 2016, Japan's National Research Institute for Earth Science and Disaster Resilience (NIED; Japanese abbreviation, Bosai Kaken; full name Bousai Kagaku Gijutsu Kenkyusho) launched the online interactive "Disaster Chronology Map for Japan, 416–2013" (map labels in Japanese) to display in visual form the location, disaster time, and date across the islands.

The Japan Trench Fast Drilling Project, a scientific expedition conducted in 2012–2013, drilled ocean-floor boreholes through the fault zone of the earthquake and gathered important data about the rupture mechanism and physical properties of the fault that caused the 2011 earthquake and tsunami.[399][400]

Ecological research

The 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami had a great environmental impact on Japan's eastern coast. The rarity and magnitude of the earthquake-tsunami prompted researchers Jotaro Urabe, Takao Suzuki, Tatsuki Nishita, and Wataru Makino to study their immediate ecological impacts on intertidal flat communities at Sendai Bay and the Sanriku Ria coast. Pre- and post-event surveys show a reduction in animal taxon richness and change in taxon composition mainly attributed to the tsunami and its physical impacts. In particular, sessile epibenthic animals and endobenthic animals both decreased in taxon richness. Mobile epibenthic animals, such as hermit crabs, were not as affected. Post-surveys also recorded taxa that were not previously recorded before, suggesting that tsunamis have the potential to introduce species and change taxon composition and local community structure. The long term ecological impacts at Sendai Bay and the greater east coast of Japan require further study.[401]

See also

3.11 and aftermath

Lists of earthquakes and tsunamis

Documentaries and commemoration events

Explanatory notes

- ^ lit. 'Great earthquake disaster of East Japan'. The Japan Meteorological Agency announced the English name as 'The 2011 off the Pacific coast of Tōhoku Earthquake'.[15][16][17] NHK[18][19] used Tōhoku Kantō Great Earthquake disaster (東北関東大震災, Tōhoku Kantō Daishinsai); Tōhoku-Kantō Great earthquake (東北・関東大地震, Tōhoku-Kantō Daijishin) was used by Kyodo News,[20] the Tokyo Shimbun[21] and the Chunichi Shimbun;[22] East Japan Giant earthquake (東日本巨大地震, Higashi Nihon Kyodaijishin) was used by the Yomiuri Shimbun,[23] Nihon Keizai Shimbun[24] and TV Asahi,[25] and East Japan Great earthquake (東日本大地震, Higashi Nihon Daijishin) was used by Nippon Television,[26] Tokyo FM[27] and TV Asahi.[28] Also known as the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake,[29] the Great Sendai earthquake,[30] the Great Tōhoku earthquake,[30] and the great earthquake of 11 March.

- ^ The 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami has been assigned GLIDE identifier EQ-2011-000028-JPN by the Asian Disaster Reduction Center.[89][90]

References

- ^ Plate Tectonic Stories: Tohoku Earthquake, Japan

- ^ Japan Meteorological Agency. "Information on the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake". Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ^ Panjamani Anbazhagan; Sushma Srinivas; Deepu Chandran (2011). "Classification of road damage due to earthquakes". Nat Hazards. 60 (2). Springer Science: 425–460. doi:10.1007/s11069-011-0025-0. ISSN 0921-030X. Retrieved 16 June 2024.

- ^ "平成23年(2011年)東北地方太平洋沖地震による強震動" [About strong ground motion caused by the 2011 off the Pacific coast of Tohoku Earthquake]. Kyoshin Bosai. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ^ Japan Meteorological Agency (ed.). "「平成23年(2011年)東北地方太平洋沖地震」について〜7年間の地震活動〜" [About 2011 Tōhoku earthquake – Seismic activities for 7 years] (PDF). Retrieved 18 June 2018. on 6 March 2018.

- ^ "平成23年(2011年)東北地方太平洋沖地震(東日本大震災)について(第162報)(令和4年3月8日)" [Press release no. 162 of the 2011 Tohuku earthquake] (PDF). 総務省消防庁災害対策本部 [Fire and Disaster Management Agency]. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 23 September 2022. Page 31 of the PDF file.

- ^ "平成23年(2011年)東北地方太平洋沖地震(東日本大震災)について(第162報)(令和4年3月8日)" [Press release no. 162 of the 2011 Tohuku earthquake] (PDF). 総務省消防庁災害対策本部 [Fire and Disaster Management Agency]. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 23 September 2022. Page 31 of the PDF file.

- ^ "平成23年(2011年)東北地方太平洋沖地震(東日本大震災)について(第162報)(令和4年3月8日)" [Press release no. 162 of the 2011 Tohuku earthquake] (PDF). 総務省消防庁災害対策本部 [Fire and Disaster Management Agency]. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 23 September 2022. Page 31 of the PDF file.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "M 9.1 – near the east coast of Honshu, Japan". United States Geological Survey (USGS). Archived from the original on 7 April 2011. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "震災の揺れは6分間 キラーパルス少なく 東大地震研". Asahi Shimbun. Japan. 17 March 2011. Archived from the original on 7 April 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Suzuki, W.; Aoi, S.; Sekiguchi, H.; Kunugi, T. (2012). Source rupture process of the 2011 Tohoku-Oki earthquake derived from strong-motion records (PDF). Proceedings of the fifteenth world conference on earthquake engineering. Lisbon, Portugal. p. 1.

- ^ Amadeo, Kimberly. "How the 2011 Earthquake in Japan Affected the Global Economy". The Balance. Archived from the original on 13 May 2019. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Japan Tsunami Strikes Indonesia, One Confirmed Dead". Jakarta Globe. 12 March 2011. Archived from the original on 15 March 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b

- "Body found in Oregon identified as missing tsunami victim". BNO News. Archived from the original on 14 April 2011. Retrieved 12 April 2011.

- Tsunami victim remains wash ashore near Fort Stevens. Koinlocal6.com (12 March 2011). Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- "Body of Calif. man killed by tsunami washes up". CBS News. Associated Press. 12 April 2011. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ^ Michael Winter (14 March 2011). "Quake shifted Japan coast about 13 feet, knocked Earth 6.5 inches off axis". USA Today. Archived from the original on 7 April 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ^ "The 2011 off the Pacific coast of Tōhoku Earthquake – first report". Japan Meteorological Agency. March 2011. Archived from the original on 16 March 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ^ Abstract of the 191th [sic!] meeting of CCEP – website of the Japanese Coordinating Committee for Earthquake Prediction

- ^ "NHKニュース 東北関東大震災(動画)". .nhk.or.jp. Archived from the original on 14 March 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ^ "仙台放送局 東北関東大震災". .nhk.or.jp. Archived from the original on 14 March 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ^ "東日本大震災 – 一般社団法人 共同通信社 ニュース特集". Kyodo News. Archived from the original on 7 April 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ 【東京】. "東京新聞:収まらぬ余震 ...不安 東北・関東大地震:東京(TOKYO Web)". Tokyo-np.co.jp. Archived from the original on 17 March 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ 【中日新聞からのお知らせ】. "中日新聞:災害義援金受け付け 東日本大震災:中日新聞からのお知らせ(CHUNICHI Web)". Chunichi.co.jp. Archived from the original on 7 April 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ "東日本巨大地震 震災掲示板 : 特集 : YOMIURI ONLINE(読売新聞)". Yomiuri Shimbun. Japan. Archived from the original on 7 April 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ 東日本巨大地震 : 特集 : 日本経済新聞 (in Japanese). Nikkei.com. 1 January 2000. Archived from the original on 7 April 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ "【地震】東日本巨大地震を激甚災害指定 政府". News.tv-asahi.co.jp. Archived from the original on 17 March 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ "東日本大地震 緊急募金受け付け中". Cr.ntv.co.jp. Archived from the original on 31 March 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ "番組表 – Tokyo FM 80.0 MHz – 80.Love FM Radio Station". Tfm.co.jp. Archived from the original on 7 April 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ "「報道特番 〜東日本大地震〜」 2011年3月14日(月)放送内容". Kakaku.com. Archived from the original on 17 March 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ USGS Updates Magnitude of Japan's 2011 Tōhoku Earthquake to 9.03 – website of the United States Geological Survey

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pletcher, Kenneth; Rafferty, John P. (4 March 2019). "Japan earthquake and tsunami of 2011: Facts & Death Toll". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ^ "3.11の映像|Nhk災害アーカイブス" [3.11 footage|Nhk Disaster Archives]. Archived from the original on 25 November 2022. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- ^ "3.11復興特集〜復興の今、そしてこれから〜". kantei.go.jp (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 10 March 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ^ "3.11". 18 August 2023.

- ^ "New USGS number puts Japan quake at fourth largest". CBS News. Associated Press. 14 March 2011. Archived from the original on 7 April 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ^ Branigan, Tania (13 March 2011). "Tsunami, earthquake, nuclear crisis – now Japan faces power cuts". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 11 June 2022. Retrieved 15 March 2011.