Австралийская золотая лихорадка

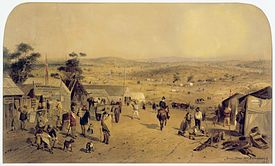

Золотые раскопки, Арарат, Виктория , автор Эдвард Ропер, 1854 год. | |

| Дата | Май 1851 г. - ок. 1914 год |

|---|---|

| Расположение | Австралия |

| Тип | Золотая лихорадка |

| Тема | Значительное количество рабочих (как из других районов Австралии, так и из-за границы) переехало в районы, где было обнаружено золото. |

| Причина | старатель Эдвард Харгрейвс заявил, что обнаружил подлежащее оплате золото возле Оринджа. |

| Outcome | Changed the convict colonies into more progressive cities with the influx of free immigrants; Western Australia joined Federation |

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Eureka Rebellion |

|---|

|

Во время австралийской золотой лихорадки , начавшейся в 1851 году, значительное количество рабочих переехало из других мест Австралии и из-за границы туда, где золото было обнаружено . Золото находили и раньше несколько раз, но колониальное правительство Нового Южного Уэльса ( Виктория стала отдельной колонией только 1 июля 1851 года) скрывало эту новость из опасений, что это приведет к сокращению рабочей силы и дестабилизации экономики. [1]

Австралийская золотая лихорадка превратила колонии каторжников в более прогрессивные города с притоком свободных иммигрантов .

После того, как в 1848 году началась Калифорнийская золотая лихорадка , многие люди приехали туда из Австралии, поэтому правительство Нового Южного Уэльса запросило у Британского колониального управления разрешение на эксплуатацию минеральных ресурсов и предложило вознаграждение за поиск золота. [2]

История открытия

Первая золотая лихорадка в Австралии началась в мае 1851 года после того, как старатель Эдвард Харгрейвс и другие [3] claimed to have discovered payable gold near Orange, at a site called Ophir.[4][5] Hargraves had been to the Californian goldfields and had learned new gold prospecting techniques such as panning and cradling. Hargraves was offered rewards by the Colony of New South Wales and the Colony of Victoria. Before the end of the year, the gold rush had spread to many other parts of the state where gold had been found, not just to the west but also to the south and north of Sydney.[6]

The Australian gold rushes changed the convict colonies into more progressive cities with the influx of free immigrants. These hopefuls, termed diggers, brought new skills and professions, contributing to a burgeoning economy. The mateship that evolved between these diggers and their collective resistance to authority led to the emergence of a unique national identity. Although not all diggers found riches on the goldfields, many decided to stay and integrate into these communities.[7]

In July 1851, Victoria's first gold rush began on the Clunes goldfield.[8] In August, the gold rush had spread to include the goldfield at Buninyong (today a suburb of Ballarat) 45 km (28 mi) away and, by early September 1851, to the nearby goldfield at Ballarat (then also known as Yuille's Diggings),[9][10][11][12] followed in early September to the goldfield at Castlemaine (then known as Forest Creek and the Mount Alexander Goldfield)[13] and the goldfield at Bendigo (then known as Bendigo Creek) in November 1851.[14] Gold, just as in New South Wales, was also found in many other parts of the state. The Victorian Gold Discovery Committee wrote in 1854:

The discovery of the Victorian Goldfields has converted a remote dependency into a country of world wide fame; it has attracted a population, extraordinary in number, with unprecedented rapidity; it has enhanced the value of property to an enormous extent; it has made this the richest country in the world; and, in less than three years, it has done for this colony the work of an age, and made its impulses felt in the most distant regions of the earth.[13]

When the rush began at Ballarat, diggers discovered it was a prosperous goldfield. Lieutenant-Governor Charles La Trobe visited the site and watched five men uncover 136 ounces of gold in one day. Mount Alexander was even richer than Ballarat. With gold sitting just under the surface, the shallowness allowed diggers to easily unearth gold nuggets. In 7 months, 2.4 million pounds of gold was transported from Mount Alexander to nearby capital cities.[15]

The gold rushes caused a huge influx of people from overseas. Australia's total population increased nearly four-fold from 430,000 in 1851 to 1.7 million in 1871.[5] Australia first became a multicultural society during the gold rush period. Between 1852 and 1860, 290,000 people migrated to Victoria from the British Isles, 15,000 came from other European countries, and 18,000 emigrated from the United States.[16] Non-European immigrants, however, were unwelcome, especially the Chinese:

The Chinese were particularly industrious, with techniques that differed widely from the Europeans. This and their physical appearance and fear of the unknown led to them to being persecuted in a racist way that would be regarded as untenable today.[17]

In 1855, 11,493 Chinese arrived in Melbourne.[18] Chinese travelling outside of New South Wales had to obtain special re-entry certificates. In 1855, Victoria enacted the Chinese Immigration Act 1855, severely limiting the number of Chinese passengers permitted on an arriving vessel. To evade the new law, many Chinese were landed in the south-east of South Australia and travelled more than 400 km across country to the Victorian goldfields, along tracks which are still evident today.[19][20]

In 1885, following a call by the Western Australian government for a reward for the first find of payable gold, a discovery was made at Halls Creek, sparking a gold rush in that state.

Pre-rush gold finds

1788: A hoax

In August 1788, convict James Daley reported to several people that he had found gold, "an inexhaustible source of wealth", "some distance down the harbour (Port Jackson, Sydney)".[21] On the pretence of showing an officer the position of his gold find, Daley absconded into the bush for a day. For this escapade, Daley was to receive 50 lashes. Still insisting that he had found gold, Daley next produced a specimen of gold ore. Governor Arthur Phillip then ordered Daley to again be taken down the harbour to point out where he had found the gold.[21]

Before being taken down the harbour, after being warned by an officer that he would be put to death if he attempted to deceive him, Daley confessed that his story about finding gold was "a falsehood". He had manufactured the specimen of gold ore that he had exhibited from a gold guinea and a brass buckle and he produced the remains of the same as proof. For this deception, Daley received 100 lashes. Many convicts continued to believe that Daley had found gold, and that he had only changed his story to keep the place of the gold find to himself. James Daley was hanged in December 1788 for breaking and entering and theft.[21]

Some convicts who were employed cutting a road over the Blue Mountains were rumoured to have found small pieces of gold in 1815.[22]

1820: Blue Mountains, New South Wales

F. Stein was a Russian naturalist with the 1819–1821 Bellingshausen expedition to explore the Southern Ocean. Stein claimed to have sighted gold-bearing ore while he was on a 12-day trip to the Blue Mountains in March 1820. Many people were sceptical of his claim.[22]

1823: Bathurst region, New South Wales

The first officially recognised gold find in Australia was on 15 February 1823,[note 1] by assistant surveyor James McBrien, at Fish River, between Rydal and Bathurst, New South Wales. McBrien noted the date in his field survey book along with, "At E. [End of the survey line] 1 chain 50 links to river and marked a gum tree. At this place I found numerous particles of gold convenient to river."[24]

1834: Monaro district, New South Wales

In 1834, with government help, John Lhotsky travelled to the Monaro district of New South Wales and explored its southern mountains. On returning to Sydney in that same year, he exhibited specimens that he had collected that contained gold.[25][26]

1837: Segenhoe, New South Wales

In 1837, gold and silver ore was found about 30 miles (48 km) from Segenhoe near Aberdeen. The find was described in the newspapers as the discovery of a gold and silver mine about 30 miles from Thomas Potter Macqueen's Segenhoe Estate,[27] by a Russian stockman employed in the neighbourhood of the discovery, which was located on Crown land.[28]

1839: Bathurst region, New South Wales

Paweł Strzelecki, geologist and explorer, found small amounts of gold in silicate in 1839 at the Vale of Clwyd near Hartley, a location on the road to Bathurst.[29]

1840: Lefroy, Tasmania

Gold is believed to have been found in Northern Tasmania at The Den (formerly known as Lefroy or Nine Mile Springs) near George Town in 1840 by a convict. In the 1880s, this became known as the Lefroy goldfields.[30]

1841–1842: Bathurst and Goulburn regions, New South Wales

The Reverend William Branwhite Clarke found gold on the Coxs River, a location on the road to Bathurst, in 1841.[31][29] In 1842, he found gold on the Wollondilly River.[32] In 1843, Clarke spoke to many people of the abundance of gold likely to be found in the colony of New South Wales. On 9 April 1844, Clarke exhibited a sample of gold in quartz to Governor Sir George Gipps. In that same year, Clarke showed the sample and spoke of the probable abundance of gold to some members of the New South Wales Legislative Council including Justice Roger Therry, the member for Camden and Joseph Phelps Robinson,[33] then member for the Town of Melbourne.

In evidence that Clarke gave before a Select Committee of the NSW Legislative Council in September 1852, he stated that the subject was not followed up as "the matter was regarded as one of curiosity only, and considerations of the penal character of the colony kept the subject quiet, as much as the general ignorance of the value of such an indication."[13][34] Towards the end of 1853, Clarke was given a grant of £1,000 (equivalent to A$77,000 in 2022) by the New South Wales government for his services in connection with the discovery of gold. The same amount (£1,000) was voted by the Victorian Gold Discovery Committee in 1854.[13][35]

1841: Pyrenees Ranges and Plenty Ranges, Victoria

Gold was found in the Pyrenees Ranges near Clunes, and in the Plenty Ranges near Melbourne in 1841; the gold was sent to Hobart, where it was sold.[36]

From 1843: Victoria

Beginning in 1843, gold samples were brought several times into the watchmaker's shop of T. J. Thomas in Melbourne by "bushmen". The specimens were looked upon as curiosities.[37]

1844: Bundalong, Victoria

A shepherd named Smith thought that he had found gold near the Ovens River in 1844, and reported the matter to Charles La Trobe, who advised him to say nothing about it.[8]

1845: Middle Districts, New South Wales

On 12 December 1845, a shepherd walked into the George Street, Sydney, shop of goldsmith E. D. Cohen carrying a specimen of gold embedded in quartz for sale, with the gold weighing about four ounces (113 g),[clarification needed] with the shepherd saying he had been robbed of double as much on his way to town. The shepherd did not disclose where he had found the gold; instead, he intimated that, if men were to take engagements with squatters, they, in addition to receiving their wages, may also discover a gold mine.[38]

1846: Castambul, South Australia

Gold was found in South Australia and Australia's first gold mine was established. From the earliest days of the Colony of South Australia men, including Johannes Menge the geologist with the South Australian Company, had been seeking gold. "Armed with miner's pick, numberless explorers are to be found prying into the depths of the valleys or climbing the mountain tops. No place is too remote".[39]

Gold was found in January 1846 by Captain Thomas Terrell at the Victoria Mine near Castambul, in the Adelaide Hills, South Australia, about 10 miles (16 km) east of Adelaide. Some of the gold was made into a brooch sent to Queen Victoria. Samples were displayed at the Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace in 1851. Share prices rose from £2 to £30, but soon fell back to £3 when no further gold was found.[when?] Unfortunately for the investors, and everyone else concerned, the mine's total gold production never amounted to more than 24 ounces (680 g).[40]

1847: Victoria

Gold was found at Port Phillip (Victoria) by a shepherd. About April 1847, a shepherd took a sample of ore about the size of an apple, that he believed to be copper, into the jewellery store of Charles Brentani in Collins Street, Melbourne, where the sample was purchased by an employee, Joseph Forrester, a gold and silver smith. The shepherd refused to disclose to Forrester where he had obtained the nugget, but stated that "there was plenty more of it where it came from" on the station where he worked about 60 miles (97 km) from Melbourne. The sample was tested by Forrester and found to be 65 percent virgin gold. A sample of this ore was given to Captain Clinch who took it to Hobart.[41][42][43][44]

1847: Beaconsfield, Tasmania

It is said that John Gardner found gold-bearing quartz in 1847 on Blythe Creek, near Beaconsfield, on the other side of the Tamar River from George Town.[45]

1848: Wellington, New South Wales

Gold was found by a shepherd named McGregor at Mitchells Creek near Wellington, New South Wales, in 1848 on the Montefiore's squatting run, "Nanima". The Bathurst Free Press noted, on 25 May 1850, that "Neither is there any doubt in the fact that Mr M'Gregor found a considerable quantity of the precious metal some years ago, near Mitchell's Creek, and it is surmised he still gets more in the same locality."[46]

1848: Bathurst, New South Wales

William Tipple Smith found gold near Bathurst in 1848.[47] Smith, a mineralogist and manager of the Fitzroy Ironworks in New South Wales, had been inspired to look for gold near Bathurst by the ideas of Roderick Murchison, president of the Royal Geographical Society, who in 1844 in his first presidential address, had predicted the existence of gold in Australia's Great Dividing Range,[26] ideas which were published again in "The Sydney Morning Herald" on 28 September 1847 suggesting that gold "will be found on the western flanks of the dividing ranges".[48] Smith sent samples of the gold he found to Murchison.[26] Governor FitzRoy visited the Fitzroy Ironworks, in late January 1849, and he was presented with "an elegant knife, containing twelve different instruments, of colonial workmanship, (mounted in colonial gold) the steel of which was smelted from the ore taken from the Fitz Roy mine".[49]

1848–1884: Pre–gold rush finds in Western Australia

Gold was first detected in Western Australia in 1848 in specimens sent for assay to Adelaide from copper and lead deposits found in the bed of the Murchison River, near Northampton, by explorer James Perry Walcott, a member of A. C. Gregory's party:[32][50]

In 1852–53 rich specimens of gold-bearing stone were found by shepherds and others in the eastern districts, but they were unable afterwards to locate the places where the stone was discovered. The late Hon A. C. Gregory found traces of gold in quartz in the Bowes River in 1854. In 1861 Mr Panton found near Northam, while shortly afterwards a shepherd brought in rich specimens of auriferous quartz which he had found to the eastward of Northam, but he failed to locate the spot again.[32]

Various small finds were made up to 1882, when Alexander McRae found gold between Cossack and Roebourne, with one nugget weighing upwards of 9 dwt (14 g).[51]

Edward Hardman, Government Geologist, found traces of gold in the East Kimberley in 1884. His report about his finds subsequently led to the discovery of payable gold and the first Western Australian gold rush.[52][53]

1848–1850: Pyrenees Ranges, Victoria

Gold was found in the Pyrenees Ranges in 1848 by a shepherd, Thomas Chapman.[54] In December 1848, Chapman came into the jewellery store of Charles Brentani, in Collins Street, Melbourne, with a stone that he had "held for several months". Chapman said that he had found the gold where he worked on Charles Browning Hall (later Gold Commissioner) and Edmund McNeill's station[55] at Daisy Hill (near Amherst) in the Pyrenees Ranges. Alexandre Duchene and Joseph Forrester, both working for Charles Brentani, confirmed the stone contained a total of 38 ounces (1,077 grams) of 90 percent pure gold, and Brentani's wife Ann purchased the stone on behalf of her husband.[54]

A sample of this ore was given to Captain Clinch, who took it to Hobart; Captain White, who took it to England; and Charles La Trobe. As a consequence of the gold find by Chapman, official printed notices were posted on a number of prominent places in the town (Melbourne) proclaiming the fact that gold had been found in Port Phillip (Victoria). The Bertini's shop was thronged by persons wanting to see the nugget and asking where it had been found. This find sparked a mini gold rush with about a hundred men rushing to the site. This could perhaps be categorised as the first, though unofficial, gold rush in Victoria,[54] or perhaps the gold rush that was stamped out.

Charles La Trobe quickly put an end to the search for gold in February 1849 by ordering 10 mounted police, William Dana and Richard McLelland in charge of 8 native troopers, to 'take possession of the Gold-mine', 'prevent any unauthorised occupation of Crown Lands in the neighbourhood' (Hall and McNeill's station was leased from the Crown), dismiss the gold-seekers and prevent any further digging at Daisy Hill.[56] The story was then dismissed by some of the press as a hoax.[13][44][57] This did not stop people finding gold. In 1850, according to Brentani's wife Ann, the "gold came down from the country in all directions". She and her husband purchased as much as they could but had difficulty in supplying the money.[58]

1849: Lefroy, Tasmania

The first substantiated find of gold in Tasmania was reported to have been made by a Mr Riva of Launceston, who is stated to have traced gold in slate rocks in the vicinity of The Den (formerly known as Lefroy or Nine Mile Springs) near George Town in 1849.[32]

1849: Woady Yaloak River, Victoria

The following news item from the Geelong Advertiser of 10 July 1849 shows the attitude of scepticism towards gold finds that were being brought into towns like Geelong during the pre–gold rush period:

GOLD. – A specimen of this valuable mineral was brought into town yesterday, having been picked up in a locality near the Wardy-yallock River. Of the identity of the metal there can be no mistake; but whether it was really taken from the spot indicated, or intended merely as a hoax or perhaps a swindle, it is quite impossible, at the present moment, to say. The piece exhibited, is of very small size; but, of course, as in all such instances, the lucky finder can obtain tons from the same spot by the simple mode of stooping down and picking it up.[59]

The attitude was completely different just a couple of years later in 1853 after the Victorian gold rushes had begun:

Smythe's Creek, a branch of the Wardy Yallock river, is also attracting its share of the mining population, who are doing tolerably well. One very fine sample of gold has also been received in town during the week from the Wardy Yallock itself, found in the locality where the exploring party of last winter ended their labours. The parcel is small,- only 22 dwts. [34 g], but was obtained by one man in a week from very shallow surfacing.[60]

1850: Clunes, Victoria

In March 1850, pastoralist William Campbell found several minute pieces of native gold in quartz on the station of Donald Cameron at Clunes. William Campbell is notable as having been the first member of the electoral district of Loddon of the Victorian Legislative Council from November 1851 to May 1854. In 1854, Campbell received a £1,000 reward (equivalent to A$91,000 in 2022) from the Victorian Gold Discovery Committee as the original discoverer of gold at Clunes.[13] At the time of the find in March 1850, Campbell was in the company of Donald Cameron, Cameron's superintendent, and a friend.

This find was concealed at the time because of the fear it would bring undesirable strangers to the run. Observing the migration of the population of New South Wales and the panic created throughout the whole colony, and especially in Melbourne, and further motivated by a £200 reward (equivalent to A$32,000 in 2022) that had been offered the day previous to anyone who could find payable gold within 200 miles (320 km) of Melbourne,[61] on 10 June 1851, Campbell addressed a letter to merchant James Graham (member of Victorian Legislative Council 1853–1854 and 1867–1886[62][63]) stating that within a radius of 15 miles of Burn Bank, on another party's station, he had procured specimens of gold.

Campbell divulged the precise spot where the gold had been found in a letter to Graham dated 5 July 1851. Prior to this date, however, James Esmond and his party were already at work there mining for gold.[13] This was because Cameron had earlier shown specimens of the gold to George Hermann Bruhn, a German doctor and geologist whose services as an analyst were in great demand.[8][64] Communication of this knowledge by Hermann to James Esmond was to result in the discovery by Esmond on 1 July 1851 of payable quantities of alluvial gold at Clunes and lead to the first Victorian gold rush.

Notable gold finds that started rushes

February 1851: Orange, New South Wales

Edward Hargraves, accompanied by John Lister, found five specks of alluvial gold at Ophir near Orange in February 1851. In April 1851, John Lister and William Tom, trained by Edward Hargraves, found 120 grams of gold. This discovery, instigated by Hargraves, led directly to the beginning of the gold rush in New South Wales. This was the first gold rush in Australia. It was in full operation by May 1851,[65] even before it was officially proclaimed on 14 May 1851.[47]

There were an estimated 300 diggers in place by 15 May 1851.[66] Before 14 May 1851, gold was already flowing from Bathurst to Sydney,[67] an example being when Edward Austin[68] brought to Sydney a nugget of gold worth £35 (equivalent to A$6,000 in 2022), which had been found in the Bathurst District.[69]

In 1872, a large gold and quartz "Holtermann Nugget" was discovered by the night shift, in a mine part owned by Bernhardt Holtermann at Hill End, near Bathurst, New South Wales. It was the largest specimen of reef gold ever found: 1.5 meters (59 inches) long, weighing 286 kg (631 lb), in Hill End, near Bathurst,[70] and with an estimated gold content of 5,000 ounces (140 kg).[71]

April 1851: Castlemaine district and Clunes, Victoria

In January 1851, before Hargraves' find of gold in February 1851 at Ophir, George Hermann Bruhn left Melbourne to explore the mineral resources of the countryside of Victoria. On his trek, Bruhn found, on a date unknown, indications of gold in quartz about 2 miles (3.2 km) from Edward Stone Parker's station at Franklinford, between Castlemaine and Daylesford.[72] After leaving Parker's station, Bruhn arrived at Donald Cameron's station at Clunes in April 1851.

Cameron showed Bruhn samples of the gold that had been found on his station at Clunes in March 1850. Bruhn explored the countryside and found quartz reefs in the vicinity. "This information he promulgated through the country in the course of his journey."[13] One of the people to whom Bruhn communicated this information was James Esmond, who was at that time engaged in erecting a building on James Hodgkinson's station "Woodstock" at Lexton about 16 miles (26 km) to the west of Clunes. This then indirectly led to the first gold rush in Victoria from Esmond's discovery of payable gold at Clunes in July 1851.[13]

Bruhn forwarded specimens of gold to Melbourne, which were received by the Gold Discovery Committee on 30 June 1851. In 1854, Bruhn received a £500 reward (equivalent to A$46,000 in 2022) from the Victorian Gold Discovery Committee "in acknowledgment of his services in exploring the country for five or six months, and for diffusing the information of the discovery of gold".[13]

June 1851: Sofala, New South Wales

Gold was found at the Turon Goldfields at Sofala in June 1851.[73]

June 1851: Warrandyte, Victoria

On 9 June 1851 a reward of £200 (equivalent to A$34,000 in 2022) was offered to the first person to discover payable gold within 200 miles (320 km) of Melbourne. Henry Frencham, then a reporter for The Times,[which?] and shortly afterwards for The Argus, was determined to be one of the persons to claim this reward. On 11 June 1851, he formed one of a party of 8 to search for gold north and north-east of Melbourne. Only 2 days later, the party had dwindled to two men, Frencham and W. H. Walsh, who found what they thought to be gold at Warrandyte. At 5pm on 13 June 1851, Frencham deposited with the Town Clerk at Melbourne, William Kerr, specimens of gold. The next day, the headline in The Times newspaper was "Gold Discovery".[74]

On 24 June 1851, Frencham and Walsh lodged a claim for the reward offered by the Gold Committee for the discovery of a payable goldfield in the Plenty Ranges about 25 miles (40 km) from Melbourne. The claim was not allowed. The specimens were tested by chemists Hood and Sydney Gibbons who could not find a trace of gold, but this may have been because they had little expertise in the area. Even if they had determined that the samples contained gold, however, it was not payable gold. Frencham always claimed to have been the first to find gold in the Plenty Ranges.[75]

On 30 June 1851, gold was definitely found about 36 km (22 mi) north-east of Melbourne in the quartz rocks of the Yarra Ranges at Anderson's Creek, Warrandyte, Victoria by Louis John Michel, William Haberlin, James Furnival, James Melville, James Headon and B.Gruening. This gold was shown at the precise spot where it had been found to Webb Richmond, on behalf of the Gold Discovery Committee, on 5 July, the full particulars of the locality were communicated to the Lieutenant-Governor on 8 July and a sample was brought to Melbourne and exhibited to the Gold Discovery Committee on 16 July. As a result, the Gold Discovery Committee were of the opinion that this find was the first publisher of the location of the discovery of a goldfield in the Colony of Victoria.[13]

This site was later named as Victoria's first official gold discovery.[76] Michel and his party were in 1854 to receive a £1,000 reward (equivalent to A$91,000 in 2022) from the Victorian Gold Discovery Committee "as having, at considerable expense, succeeded in discovering and publishing an available goldfield".[13] On 1 September 1851, the first gold licences in Victoria were issued to dig for gold in this locality, "which was previous to their issue on any other Goldfield". About 300 people were at work on this goldfield prior to the discovery of Ballarat.[13]

July 1851: Clunes, Victoria

On 1 July 1851, Victoria became a separate colony, and, on the same day, James Esmond—in company with Pugh, Burns and Kelly—found alluvial gold in payable quantities near Donald Cameron's station on Creswick's Creek, a tributary of the Loddon, at Clunes, 34 km (21 mi) north of Ballarat. Esmond and his party found the gold after Esmond had been told by George Hermann Bruhn of the gold that had been found in March 1850 on Cameron's property at Clunes and that in the vicinity were quartz reefs which were likely to bear gold.[64] Esmond rode into Geelong with a sample of their discovery on 5 July. News of the discovery was published first in the Geelong Advertiser on 7 July[13] and then in Melbourne on 8 July:

Gold in the Pyrenees. The long sought treasure is at length found! Victoria is a gold country, and from Geelong goes forth the first glad tidings of the discovery. Esmonds arrived in Geelong on Saturday with some beautiful specimens of gold, in quartz, and gold-dust in a "debris" of the same species of rock. The specimens have been subjected to the most rigid test by Mr Patterson, in the presence of other competent parties, and he pronounced them to be beyond any possibility of doubt pure gold...[77]

The particulars of the precise location, with Esmond's consent, was published in the Geelong Advertiser on 22 July 1851. Publication of Esmond's find started the first official gold rush in Victoria in that same month. By 1 August between 300 and 400 diggers were encamped on the Clunes Goldfield, but soon moved to other fields as news of other gold discoveries spread. Esmond was in 1854 to receive a £1,000 reward (equivalent to A$91,000 in 2022) as "the first actual producer of alluvial gold for the market".[8][13]

July 1851: Bungonia and other finds, New South Wales

The following goldfields were discovered in New South Wales during July 1851:

- Bungonia (aka Shoalhaven),[78]

- Hill End,[79]

- Louisa Creek (now Hargraves) near Mudgee[80][81]

- Moruya[6][82]

July 1851: Castlemaine, Victoria

On 20 July 1851, gold was found near present-day Castlemaine, Victoria (Mt Alexander Goldfields), at Specimen Gully in today's Castlemaine suburb of Barkers Creek. The gold was first found by Christopher Thomas Peters, a shepherd and hut-keeper on the Barker's Creek, in the service of William Barker. When the gold was shown in the men's quarters Peters was ridiculed for finding fool's gold, and the gold was thrown away. Barker did not want his workmen to abandon his sheep, but in August they did just that.[83]

John Worley, George Robinson and Robert Keen, also in the employ of Barker as shepherds and a bullock driver, immediately teamed with Peters in working the deposits by panning in Specimen Gully, which they did in relative privacy during the next month. When Barker sacked them and ran them off for trespass, Worley, on behalf of the party "to prevent them getting in trouble", mailed a letter to The Argus dated 1 September 1851 announcing this new goldfield with the precise location of their workings. This letter was published on 8 September 1851.[84]

"With this obscure notice, rendered still more so by the journalist as 'Western Port', were ushered to the world the inexhaustible treasures of Mount Alexander",[13] also to become known as the Forest Creek diggings. Within a month there were about 8,000 diggers working the alluvial beds of the creeks near the present day town of Castlemaine, and particularly Forest Creek which runs through the suburb today known as Chewton where the first small township was established. By the end of the year there were about 25,000 on the field.[85][86]

August 1851: Buninyong, Victoria

On 8 August 1851, an auriferous deposit of gold was found 3 kilometres west of Buninyong, Victoria, near Ballarat. The gold was discovered in a gully in the Buninyong ranges, by a resident of Buninyong, Thomas Hiscock.[87] Hiscock communicated the find, with its precise locality, to the editor of the Geelong Advertiser on 10 August. In that same month prospectors began moving from the Clunes to the Buninyong diggings. Hiscock was in 1854 to receive £1,000 (equivalent to A$91,000 in 2022) reward from the Victorian Gold Discovery Committee as the substantial discoverer of the gold deposits of "superior value" in the Ballarat area.[8][13]

August 1851: Ballarat, Victoria

On 21 August 1851, gold was found at Ballarat, Victoria, in Poverty Point by John Dunlop and James Regan.[88] Ballarat is about 10 km (6.2 mi) from Buninyong and upon the same range.[13] John Dunlop and James Regan found their first few ounces of gold while panning in the Canadian Creek[89] after leaving the Buninyong diggings to extend their search for gold.[13] However, Henry Frencham, a newspaperman who in June had claimed, unsuccessfully, the £200 (equivalent to A$17,000 in 2022) reward for finding payable gold within 200 miles (320 km) of Melbourne, had followed them and noticed their work. As a result, they only had the rich Ballarat goldfield to themselves for a week.[88]

By early September 1851, what became known as the Ballarat gold rush had begun,[9][11][12] as reported from the field by Henry Frencham, then a reporter for The Argus.[10] (Henry Frencham claimed in his article of 19 September 1851 to have been the first to discover gold at Ballarat [then also known as Yuille's Diggings] "and make it known to the public",[10] a claim he was later to also make about Bendigo, and which resulted in the sitting of a Select Committee of the Victorian Legislative Assembly in 1890.)[90]

In the report of the Committee on the Claims to Original Discovery of the Goldfields of Victoria published in The Argus newspaper of 28 March 1854, however, a different picture of the discovery of gold at Golden Point at Ballarat is presented. They stated that Regan and Dunlop were one of two parties working at the same time on opposite sides of the ranges forming Golden Point, the other contenders for the first finders of gold at Ballarat being described as "Mr Brown and his party".[13]

The committee stated that "where so many rich deposits were discovered almost simultaneously, within a radius of little more than half a mile, it is difficult to decide to whom is due the actual commencement of the Ballarat diggings." They also agreed that the prospectors "had been attracted there (Ballarat) by the discoveries in the neighbourhood of Messrs. Esmonds (Clunes) and Hiscock (Buninyong)" and "by attracting great numbers of diggers to the neighbourhood" that "the discovery of Ballarat was but a natural consequence of the discovery of Buninyong".[13]

In 1858, the "Welcome Nugget" weighing 2,217 troy ounces 16 pennyweight (68.98 kg) was found at Bakery Hill at Ballarat by a group of 22 Cornish miners working at the mine of the Red Hill Mining Company.[91]

September 1851: Bendigo, Victoria

It has been claimed that Gold was first found at Bendigo, Victoria, in September 1851.

The four sets of serious contenders for the first finders of gold on what became the Bendigo goldfield are, in no particular order:

- Stewart Gibson and Frederick Fenton. Stewart Gibson was one of the two brothers who owned/leased the Mount Alexander North Run in 1851, and Frederick Fenton was the then manager/overseer and later owner. Fenton claimed that he and (his brother-in-law) Stewart Gibson had been together when in they found gold in a water-hole near the junction of Bendigo Creek with what later became known as Golden Gully in September 1851, just before shearing commenced, but they decided at the time to keep it quiet;

- one or more of the shepherds living in the hut, named the Bendigo hut, on the Mount Alexander North Run near the junction of Bendigo Creek with what later became known as Golden Gully, a hut that was within yards of "The Rocks". These were James Graham (alias Ben Hall), Benjamin Bannister, and hut-keeper Christian Asquith, and/or a Sydney-born cook/shepherd who visited them at the hut named William Johnson. These men were mentioned in the evidence of many witnesses at the 1890 Select Committee;

- one or more of Mrs Margaret Kennedy, Mrs Julia Farrell, and/or Margaret Kennedy's 9-year-old son from her first marriage, John Drane; and

- one or both of the husbands of the two women named above. John "Happy Jack" Kennedy, was shepherd/overseer of the Mount Alexander Run who had a hut named after him on the Bullock Creek at what is today known as Lockwood South, and Patrick Peter Farrell was a self-employed cooper working on the Mount Alexander Run during the shearing season. Farrell gave evidence to the 1890 Select Committee that he had been the first to find gold, and Kennedy made similar claims during his lifetime which were published in his obituary in 1883.[92][93][94]

According to the Bendigo Historical Society, it has today, contrary to the findings of the Select Committee of 1890, become "generally agreed"[95] or "acknowledged"[96] that gold was found at Bendigo Creek by two married women from the Mount Alexander North Run (later renamed the Ravenswood Run), Margaret Kennedy and Julia Farrell. A monument to this effect was erected by the City of Greater Bendigo in front of the Senior Citizens Centre at High Street, Golden Square on 28 September 2001.

This acknowledgement is not shared by contemporaneous historians such as Robert Coupe who wrote in his book Australia's Gold Rushes, first published in 2000, that "there are several accounts of the first finds in the Bendigo area".[97] Also, as stated by local Bendigo historian Rita Hull: "For decades many historians[note 2] have made the bold statement that Margaret Kennedy and her friend Julia Farrell were the first to find gold at Bendigo Creek, but on what grounds do they make this statement?".[98][note 3]

On September 1890, a Select Committee of the Victorian Legislative Assembly began sitting to decide who was the first to discover gold at Bendigo. They stated that there were 12 claimants who had made submissions to being the first to find gold at Bendigo (this included Mrs Margaret Kennedy but not Mrs Julia Farrell, who was deceased), plus the journalist Henry Frencham[99] who claimed to have discovered gold at Bendigo Creek in November 1851. (Frencham had previously also claimed to have been the first to have discovered gold at Warrandyte in June 1851 when he, unsuccessfully, claimed the £200 (equivalent to A$17,000 in 2022) reward for finding payable gold within 200 miles (320 km) of Melbourne;[74][75] and then he also claimed to be the first to have discovered gold at Ballarat [then also known as Yuille's Diggings] "and make it known to the public" in September 1851.)[10]

According to a Select Committee of the Victorian Parliament, the name of the first discoverer of gold on the Bendigo goldfield is unknown. The Select Committee inquiring into this matter in September and October 1890 examined many witnesses but was unable to decide between the various claimants. They were, however, able to decide that the first gold on the Bendigo goldfields was found in 1851 at "The Rocks" area of Bendigo Creek at Golden Square, which is near where today's Maple Street crosses the Bendigo Creek. As the date of September 1851, or soon after, and place, at or near "The Rocks" on Bendigo Creek, were also mentioned in relation to three other sets of serious contenders for the first finders of gold on what became the Bendigo goldfields, all associated with the Mount Alexander North Run (later renamed the Ravenswood Run).[100]

They reasoned that:

- Many others have also claimed to have been the first to have found gold at Bendigo Creek.

- Julia Farrell, deceased before the 1890 Select Committee, is never documented to have made this claim.

- Margaret Kennedy also claimed to have found gold without the help of Julia Farrell whilst accompanied by her 9-year-old son John Drane.

- Both their husbands, John "Happy Jack" Kennedy and Patrick Peter Farrell are also documented to have claimed to have been the first to have found gold, and were also seen at various times with their wives at the Bendigo Creek by witnesses.[100][92]

When Margaret Kennedy gave evidence before the Select Committee in September 1890 she claimed to alone have found gold near "The Rocks" in early September 1851. She claimed that she had taken her (9-year-old) son, John Drane[note 4] with her to search for gold near "The Rocks" after her husband had told her that he had seen gravel there that might bear gold, and that she was joined by her husband in the evenings. She also gave evidence that after finding gold she "engaged"[101] Julia Farrell and went back with her to pan for more gold at the same spot, and it was while there that they were seen by a Mr Frencham, he said in November. She confirmed that they had been panning for gold (also called washing) with a milk dish, and had been using a quart-pot and a stocking as storage vessels.[100][93]

In the evidence that Margaret Kennedy gave before the Select Committee in September 1890, Margaret Kennedy claimed that she and Julia Farrell had been secretly panning for gold before Henry Frencham arrived, evidence that was substantiated by others. The Select Committee found "that Henry Frencham's claim to be the discoverer of gold at Bendigo has not been sustained", but could not make a decision as to whom of the other at least 12 claimants had been first as "it would be most difficult, if not impossible, to decide that question now"..."at this distance of time from the eventful discovery of gold at Bendigo".[102]

They concluded that there was "no doubt that Mrs Kennedy and Mrs Farrell had obtained gold before Henry Frencham arrived on the Bendigo Creek", but that Frencham "was the first to report the discovery of payable gold at Bendigo to the Commissioner at Forest Creek (Castlemaine)". An event Frencham dated to 28 November 1851,[100] a date which was, according to Frencham's own contemporaneous writings, after a number of diggers had already begun prospecting on the Bendigo goldfield.[14]

28 November 1851 was the date on which Frencham had a letter delivered to Chief Commissioner Wright at Forest Creek (Castlemaine) asking for police protection at Bendigo Creek, a request that officially disclosed the new gold-field. Protection was granted and the Assistant Commissioner of Crown Lands for the Gold Districts of Buninyong and Mt Alexander, Captain Robert Wintle Home, arrived with three black troopers (native police) to set up camp at Bendigo Creek on 8 December.[103]

In the end, the Select Committee also decided "that the first place at which gold was discovered on Bendigo was at what is now known as Golden Square, called by the station hands in 1851 "The Rocks", a point about 200 yards to the west of the junction of Golden Gully with the Bendigo Creek."[90][93][104][105] (The straight-line distance is nearer to 650 yards [590 metres].) In October 1893, Alfred Shrapnell Bailes (1849–1928),[106] the man who had proposed the Select Committee, who was one of the men who had sat on the Select Committee, and who was chairman of the Select Committee for 6 of the 7 days that it sat, gave an address in Bendigo where he gave his opinion on the matter of who had first found gold at Bendigo. Alfred Shrapnell Bailes, Mayor of Bendigo 1883–84, and member of the Legislative Council of Victoria 1886–1894 & 1897–1907, stated that:

...upon the whole, from evidence which, read with the stations books, can be fairly easily pieced together, it would seem that Asquith, Graham, Johnson and Bannister [the three shepherds residing at the hut on Bendigo Creek and their shepherd visitor Johnson], were the first to discover gold[107]

The first group of people digging for gold at the Bendigo Creek in 1851 were people associated with the Mount Alexander North (Ravenswood) Run. They included, in no particular order:

- The shepherd/overseer John "Happy Jack" Kennedy (c. 1816–1883), his wife Margaret Kennedy nee Mcphee (1822–1905), and her son 9-year-old John Drane (1841–1914). They also had with them Margaret's 3 younger daughters,[100][note 5] Mary Ann Drane (1844–1919), 7; Mary Jane Kennedy (1849–1948), 2; and baby Lucy Kennedy (1851–1926);[108][109]

- The cooper Patrick Peter Farrell (c. 1830–1905) and his wife Julia Farrell (c. 1830–before 1870); and,

- The shepherds employed at the Bendigo Creek, Christian Asquith (c. 1799–1857),[110] James Graham (alias Ben Hall) and Bannister. They were to be joined by others who had been employed elsewhere on the Mount Alexander North (Ravenswood) Run than at Bendigo Creek, including cook/shepherd William Johnson (c. 1827–?),[111] and shepherds James Lister, William Ross, Paddy O'Donnell, William Sandbach (c. 1820–1895)[112] and his brother, Walter Roberts Sandbach (c. 1822–1905),[113][114] who arrived at the Bendigo Creek to prospect in late November 1851.[93][94][115]

They were soon joined by miners from the Forest Creek (Castlemaine) diggings including the journalist Henry Frencham (1816–1897).

There is no doubt that Henry Frencham, under the pen-name of "Bendigo",[90] was the first to publicly write anything about gold-mining at Bendigo Creek, with a report about a meeting of miners at Bendigo Creek on 8 and 9 December 1851, published respectively in the Daily News, Melbourne, date unknown[116] and 13 December 1851 editions of the Geelong Advertiser[117] and The Argus.[14] It was Frencham's words, published in The Argus of 13 December 1851, that were to begin the Bendigo gold rush: "As regards the success of the diggers, it is tolerably certain the majority are doing well, and few making less than half an ounce per man per day."

In late November 1851, some of the miners at Castlemaine (Forest Creek), having heard of the new discovery of gold, began to move to Bendigo Creek joining those from the Mount Alexander North (Ravenswood) Run who were already prospecting there.[95] The beginnings of this gold-mining was reported from the field by Henry Frencham, under the pen-name of "Bendigo",[14][90][118] who stated that the new field at Bendigo Creek, which was at first treated as if it were an extension of the Mount Alexander or Forest Creek (Castlemaine) rush,[119][120] was already about two weeks old on 8 December 1851. Frencham reported then about 250 miners on the field (not counting hut-keepers). On 13 December Henry Frencham's article in The Argus was published announcing to the world that gold was abundant in Bendigo. Just days later, in mid-December 1851 the rush to Bendigo had begun, with a correspondent from Castlemaine for the Geelong Advertiser reported on 16 December 1851 that "hundreds are on the wing thither (to Bendigo Creek)".[121]

Henry Frencham may not have been the first person to find gold at Bendigo, but he was the first person to announce to the authorities (28 November 1851) and then the world (via The Argus, 13 December 1851) the existence of the Bendigo goldfield. He was also the first person to deliver a quantity of payable gold from the Bendigo goldfield to the authorities when, on 28 December 1851—3 days after the 603 men, women, and children then working the Bendigo goldfield had pooled their food resources for a combined Christmas dinner[120]—Frencham and his partner Robert Atkinson, with Trooper Synott as an escort, delivered 30 pounds (14 kg) of gold that they had mined to Assistant Commissioner Charles J. P. Lydiard at Forest Creek (Castlemaine), the first gold received from Bendigo.[122]

Sep–Dec 1851: Other finds in New South Wales

1851 (undated): Other finds in New South Wales

1851 (undated): Other finds in Victoria

Gold was found at Omeo in late 1851 and gold mining continued in the area for many years. Due to the inaccessibility of the area there was only a small Omeo gold rush.[126]

1851–1886: Managa and other finds in Tasmania

Woods Almanac, 1857, states that gold was possibly found at Fingal (near Mangana) in 1851 by the "Old Major" who steadily worked at a gully for two to three years while guarding his secret. This gold find was probably at Mangana and that there is a gully there known as Major's Gully.[127] The first payable alluvial gold deposits were reported in Tasmania in 1852 by James Grant at Managa (then known as The Nook)[45] and Tower Hill Creek which began the Tasmanian gold rushes. The first registered gold strike was made by Charles Gould at Tullochgoram near Fingal and Managa and weighed 2 lb 6 oz (1,077 g). Further small finds were reported during the same year in the vicinity of Nine Mile Springs (Lefroy). In 1854, gold was found at Mt. Mary.[128]

During 1859, the first quartz mine started operations at Fingal. In the same year James Smith found gold at the River Forth, and Mr. Peter Leete at the Calder, a tributary of the Inglis. Gold was discovered in 1869 at Nine Mile Springs (Lefroy) by Samuel Richards. The news of this brought the first big rush to Nine Mile Springs. A township quickly developed beside the present main road from Bell Bay to Bridport, and dozens of miners pegged out claims there and at nearby Back Creek. The first recorded returns from the Mangana goldfields date from 1870; Waterhouse, 1871; Hellyer, Denison, and Brandy Creek, 1872; Lisle, 1878 Gladstone and Cam, 1881; Minnow and River Forth, 1882; Brauxholme and Mount Victoria, 1883; and Mount Lyell, 1886.[32][129]

1852 and 1868: Echunga, South Australia

Payable gold was found in May 1852 at Echunga in the Adelaide Hills in South Australia by William Chapman and his mates Thomas Hardiman and Henry Hampton. After returning to his father's farm from the Victorian goldfields, William Chapman had searched the area around Echunga for gold motivated by his mining experience and the £1,000 reward (equivalent to A$174,000 in 2022) being offered by the South Australian government for the first discoverer of payable gold. Chapman, Hardiman and Hampton were later to receive £500 of this reward, as the required £10,000 (equivalent to $1.75 million in 2022) of gold had not been raised in two months.[130]

Within a few days of the announcement of finding gold, 80 gold licenses had been issued. Within seven weeks, there were about 600 people, including women and children, camped in tents and wattle-and-daub huts in "Chapman's Gully". A township sprang up in the area as the population grew. Soon there were blacksmiths, butchers and bakers to provide the gold diggers' needs. Within 6 months, 684 licences had been issued. Three police constables were appointed to maintain order and to assist the Gold Commissioner.[131]

By August 1852, there were less than 100 gold diggers and the police presence was reduced to two troopers. The gold rush was at its peak for nine months. It was estimated in May 1853 that about £18,000 (equivalent to $2.78 million in 2022) worth of gold, more than 113 kg (4,000 oz, 250 lb), had been sold in Adelaide between September 1852 and January 1853, with an additional unknown value sent overseas to England.[132]

Despite the sales of gold from Echunga, this goldfield could not compete with the richer fields in Victoria and by 1853 the South Australian goldfields were described as being 'pretty deserted'. There were further discoveries of gold in the Echunga area made in 1853, 1854, 1855, and 1858 causing minor rushes. There was a major revival of the Echunga fields in 1868 when Thomas Plane and Henry Saunders found gold at Jupiter Creek. Plane and Saunders were to receive rewards of £300 (equivalent to A$46,000 in 2022) and £200 (equivalent to A$31,000 in 2022), respectively.[39][133]

By September 1868, there were about 1,200 people living at the new diggings and tents and huts were scattered throughout the scrub. A township was established with general stores, butchers and refreshment booths. By the end of 1868 though, the alluvial deposits at Echunga were almost exhausted and the population dwindled to several hundred. During 1869 reef mining was introduced and some small mining companies were established but all had gone into liquidation by 1871.[39][133]

The Echunga goldfields were South Australia's most productive. By 1900, the estimated gold production was 6,000 kg (13,000 lb), compared with 680 g (24 oz), 1½lb) from the Victoria Mine at Castambul. After the revival of the Echunga goldfields in 1868, prospectors searched the Adelaide Hills for new goldfields. News of a new discovery would set off another rush. Gold was found at many locations, including Balhannah, Forest Range, Birdwood, Para Wirra, Mount Pleasant and Woodside.[39][133]

1852–1869: Other finds in Victoria

- Amherst/Daisy Hill/Talbot, 1852 (after initial finds in 1848 and 1851)[54]

- Beechworth, 1852[134]

- Tarnagulla, 1852[134]

- Wedderburn, 1852[135]

- Steiglitz, 1853[136]

- Maldon, 1853[134]

- Homebush near Avoca, 1853[134]

- Bright, 1853[134]

- Stawell, 1853[137]

- Maryborough, 1854[134]

- St Arnaud, 1854[135]

- Caldonia (St Andrews), 1855[138]

- Ararat,1856[134]

- Mansfield, 1855[139]

- Chiltern, 1858[134]

- Inglewood, 1859[135]

- Rutherglen, 1860[140]

- Stuart Mill, 1861[141]

- Walhalla, 1863[134]

- Foster, 1869[134]

1852–1896: Other finds in New South Wales

- Adelong, 1852[142][143]

- Sunny Corner, 1854[144]

- Rocky River near Uralla, 1856[32]

- Broulee, 1857, on the Araluen Field[145]

- Mogo, 1858, on the Araluen Field[145]

- Kiandra, 1859[146]

- Young, 1860, known at that time as Lambing Flat[147]

- Nerrigundah 1861[148]

- Forbes, 1861[149][150]

- Parkes, 1862[150]

- Lucknow near Orange, 1862[151]

- Grenfell 1866[152]

- In beach sands at Northern Rivers, 1870[32]

- Gulgong, 1870[153]

- Hillgrove, 1877[154]

- Mount McDonald near Wyangala, 1880[155]

- Wrightville, near Cobar, 1887 [156]

- Mount Drysdale near Cobar, 1892[32]

- Wyalong, 1893[32]

- Canbelego, near Cobar, 1896

1857/8: Canoona near Rockhampton, Queensland

Gold was found in Queensland near Warwick as early as 1851,[157] beginning small-scale alluvial gold mining in that state.[158]

The first Queensland gold rush did not occur until late 1858, however, after the discovery of what was rumoured to be payable gold for a large number of men at Canoona near what was to become the town of Rockhampton. According to legend,[159] this gold was found at Canoona near Rockhampton by a man named Chappie (or Chapel) in July or August 1858.[160]

The gold in the area had first been found north of the Fitzroy River on 17 November 1857 by Captain (later Sir) Maurice Charles O'Connell, a grandson of William Bligh, a former governor of New South Wales, who was Government Resident at Gladstone. Initially worried that his find would be exaggerated, O'Connell wrote to the Chief Commissioner of Crown Lands on 25 November 1857 to inform him that he had found "very promising prospects of gold" after having some pans of earth washed.[161]

Chapel was a flamboyant and extroverted character who, in 1858 at the height of the gold rush, claimed to have first found the gold. Instead, Chapel had been employed by O'Connell as part of a prospecting party to follow up on O'Connell's initial gold find, a prospecting party which, according to contemporary local pastoralist Colin Archer, "after pottering about for some six months or more, did discover a gold-field near Canoona, yielding gold in paying quantities for a limited number of men".[162] O'Connell was in Sydney in July 1858 when he reported to the Government the success of the measures he had initiated for the development of the goldfield which he had discovered.

This first Queensland gold rush resulted in about 15,000 people flocking to this sparsely populated area in the last months of 1858. This was, however, a small goldfield with only shallow gold deposits and with nowhere near enough gold to sustain the large number of prospectors. This gold rush was given the name of the 'duffer rush' as destitute prospectors "had, in the end, to be rescued by their colonial governments or given charitable treatment by shipping companies" to return home when they did not strike it rich and had used up all their capital.[163]

The authorities had expected violence to break out and had supplied contingents of mounted and foot police as well as warships. The New South Wales government (Queensland was then part of New South Wales) sent up the "Iris" which remained in Keppel Bay during November to preserve the peace. The Victorian government sent up the "Victoria" with orders to the captain to bring back all Victorian diggers unable to pay their fares; they were to work out their passage money on return to Melbourne.[164]

O'Connell had reported that "we have had some trying moments when it seemed as if the weight of a feather would have turned the balance between comparative order and scenes of great violence".[165] According to legend, both O'Connel and Chapel were threatened with lynching.[166][167]

1861–1866: Cape River and other finds in Queensland

In late 1861,[168] the Clermont goldfield was discovered in Central Queensland near Peak Downs, triggering what has (incorrectly) been described as one of Queensland's major gold rushes. Mining extended over a large area,[169] but only a small number of miners was involved. Newspapers of the day, which also warned against a repeat of the Canoona experience of 1858,[168] at the same time as describing lucrative gold-finds reveal that this was only a small gold rush. The Rockhampton Bulletin and Central Queensland Advertiser of 3 May 1862 reported that "a few men have managed to earn a subsistence for some months...others have gone there and returned unsuccessful".[170]

The Courier (Brisbane) of 5 January 1863 describes "40 miners on the diggings at present ... and in the course of a few months there will probably be several hundred miners at work".[171] The Courier reported 200 diggers at Peak Downs in July 1863.[172] The goldfield covering an area of over 1,600 square miles (4,100 km2) was officially declared in August 1863.[173] The Cornwall Chronicle (Launceston, Tasmania), citing the Ballarat Star, reported about 300 men at work, many of them new chums, in October 1863.[174]

In 1862,[175][176][177] gold was found at Calliope near Gladstone,[32] with the goldfield being officially proclaimed in the next year.[178] The small rush attracted around 800 people by 1864 and after that the population declined as by 1870 the gold deposits were worked out.[179]

In 1863, gold was also found at Canal Creek (Leyburn)[32] and some gold-mining began there at that time, but the short-lived gold rush there did not occur until 1871–72.[180]

In 1865, Richard Daintree discovered 100 km (62 mi) south-west of Charters Towers the Cape River goldfield near Pentland[181] in North Queensland.[182] The Cape River Goldfield which covered an area of over 300 square miles (780 km2) was not, however, proclaimed until 4 September 1867, and by the next year the best of the alluvial gold had petered out. This gold rush attracted Chinese diggers to Queensland for the first time.[173][183] The Chinese miners at Cape River moved to Richard Daintree's newly discovered Oaks Goldfield on the Gilbert River in 1869.[173]

The Crocodile Creek (Bouldercombe Gorge) field near Rockhampton was also discovered in 1865.[32] By August 1866 it was reported that there were between 800 and 1,000 men on the field.[184] A new rush took place in March 1867.[185] By 1868 the best of the alluvial gold had petered out. The enterprising Chinese diggers who arrived in the area, however, were still able to make a success of their gold-mining endeavours.[186]

Gold was also found at Morinish near Rockhampton in 1866 with miners working in the area by December 1866,[187] and a "new rush" being described in the newspapers in February 1867[188] with the population being estimated on the field as 600.[189]

1867–1870: Gympie and other finds in Queensland

Queensland had plunged into an economic crisis after the separation of Queensland from New South Wales in 1859. This had led to severe unemployment with a peak in 1866. Gold was being mined in the state but the number of men involved was only small. On 8 January 1867, the Queensland Government offered a £3,000 (equivalent to A$476,000 in 2022) reward for the discovery of more payable goldfields in the state. As a direct result, 1867 saw new gold rushes.[173]

More goldfields were discovered near Rockhampton in early 1867 being Ridgelands and Rosewood.[32][190][191] The rush to Rosewood was described in May 1867 as having "over three hundred miners".[192] Ridgelands with its few hundred miners was described as "the most populous gold-field in the colony" on 5 October 1867,[193] but it was very soon overtaken and far surpassed by Gympie.

The most important discovery in 1867 was later in the year when James Nash discovered gold at Gympie,[194][195] with the rush under way by November 1867.[196]

J. A. Lewis, Inspector of Police arrived on the Gympie goldfield on 3 November 1867 and wrote on 11 November 1867:

On reaching the diggings I found a population numbering about five hundred, the majority of whom were doing little or nothing in the way of digging for the precious metal. Claims, however, were marked out in all directions, and the ground leading from the gullies where the richest finds have been got was taken up for a considerable distance. I have very little hesitation in stating that two-thirds of the people congregated there had never been on a diggings before, and seemed to be quite at a loss what to do. Very few of them had tents to live in or tools to work with; and I am afraid that the majority of those had not sufficient money to keep them in food for one week...From all that I could glean from miners and others, with whom I had an opportunity of speaking, respecting the diggings, I think it very probable that a permanent gold-field will be established at, or in the vicinity of, Gympie Creek; and if reports-which were in circulation when I left the diggings-to the effect that several prospecting parties had found gold at different points, varying from one to five miles from the township, be correct, there is little doubt but it will be an extensive gold-field, and will absorb a large population within a very short period.[196]

The very rich and productive area, which covered only an area of 120 square miles (310 km2), was officially declared the Gympie Goldfield in 1868.[173] In 1868 the mining shanty town which had quickly grown with tents, many small stores and liquor outlets, and was known as "Nashville", was also renamed Gympie after the Gympie Creek named from the aboriginal name for a local stinging tree. Within months there were 25,000 people on the goldfield. This was the first large gold rush after Canoona in 1858, and Gympie became 'The Town That Saved Queensland' from bankruptcy.[197]

The Kilkivan Goldfield (N.W of Gympie) was also discovered in 1867 with the rush to that area beginning in that same year, and, as was commonly the case, before the goldfield was officially declared in July 1868.[173]

Townsville was opened up in 1868, the Gilbert River goldfield (110 km from Georgetown) in 1869,[32] and Etheridge (Georgetown) in 1870.[198]

1868: Gawler region, South Australia

Gold found about 10 km south-east of Gawler in South Australia in 1868. Gold was found by Job Harris and his partners in Spike Valley near the South Para River. This was unsold Crown Land and was proclaimed an official goldfield with a warden appointed. On the second day there were 40 gold seekers, 1,000 within a week and, within a month, 4,000 licensed and 1,000 unlicensed diggers. Three towns were established nearby with about 6,000 people at their peak.[39]

Alluvial gold was easily recovered when the gold was in high concentration. As the alluvial was worked out, companies were formed to extract the gold from the ore with crushers and a mercury process. By 1870 only 50 people remained, although one of the three towns, Barossa, lasted until the 1950s. South of the Barossa goldfield, the Lady Alice Mine in Hamlin Gully, discovered in 1871 by James Goddard, was the first South Australian gold mine to pay a dividend.[39]

1870–1893: Teetulpa and other finds in South Australia

As settlers took up land north of Adelaide, so more goldfields were discovered in South Australia: Ulooloo in 1870, Waukaringa in 1873, Teetulpa in 1886, Wadnaminga in 1888 and Tarcoola in 1893.[39]

Teetulpa, 11 km (6.8 mi) north of Yunta, was a rich goldfield where more gold was found than anywhere else in South Australia at that time. Teetulpa had the largest number of diggers of any field at any time in the history of South Australian gold discoveries. By the end of 1886, two months into the rush, there were more than five thousand men on the field. A reporter noted: "All sorts of people are going – from lawyers to larrikins ... Yesterday's train from Adelaide brought a contingent of over 150 ... Many arrived in open trucks ... Local ironmongers and drapers were busy fitting out intending diggers with tents, picks, shovels, rugs, moleskins, etc." Good mining at Teetulpa lasted about ten years. For a time, it had a bank, shops, hotel, hospital, church and a newspaper. The largest nugget found weighed 30 oz (850 g).[39][199]

1871–1904: Charters Towers, Palmer River, and other finds in Queensland

A significant Queensland goldfield was discovered at Charters Towers on 24 December 1871 by a young 12-year-old Aboriginal stockman, Jupiter Mosman, and soon moved attention to this area.[200][201][202] The gold rush which followed has been argued to be the most important in Queensland's gold-mining history.[203] This was a reef-mining area with only a small amount of alluvial gold.,[204] and as a result received negative reviews from miners who wanted easier pickings.[205] Nevertheless thousands of men rushed to the field, and a public battery was set up to crush the quartz ore in 1872. The town of Charters Towers grew to become the second largest town in Queensland during the late 1880s with a population of about 30,000.[200][206]

In 1872[32] gold was discovered by James Mulligan on the Palmer River inland from Cooktown.[207] This turned out to contain Queensland's richest alluvial deposits.[203] After the rush began in 1873 over 20,000 people made their way to the remote goldfield. This was one of the largest rushes experienced in Queensland. The rush lasted approximately 3 years and attracted a large number of Chinese. In 1877 over 18,000 of the residents were Chinese miners.[208]

Port Douglas dates from 1873, and the Hodgkinson river (west of Cairns) from 1875.[32]

The celebrated Mount Morgan was first worked in 1882, Croydon in 1886, the Starcke river goldfield near the coast 70 km (43 mi) north of Cooktown in 1890, Coen in 1900, and Alice River in 1904.[32]

1871–1909: Pine Creek and other finds in the Northern Territory

Darwin felt the effects of a gold rush at Pine Creek after employees of the Australian Overland Telegraph Line found gold while digging holes for telegraph poles in 1871:[209]

There are numerous deposits of the precious metal at various localities in the Northern Territory, the total yield in 1908 being 8,575 ounces (243.1 kg), valued at £27,512 (equivalent to A$4,200,000 in 2022), of which 1,021 ounces (28.9 kg) were obtained at the Driffield. In June 1909, a rich find of gold was reported from Tanami... Steps are being taken to open up this field by sinking wells to provide permanent water, of which there is a great scarcity in the district. A large number of Chinese are engaged in mining in the Territory. In 1908, out of a total of 824 miners employed, the Chinese numbered 674.[32]

1880: Mt McDonald, New South Wales

Donald McDonald and his party discovered two gold-rich quartz reefs at Mount McDonald, as they were prospecting the mountain ranges around Wyangala. This find resulted in the establishment of the township of Mt McDonald. By the early 1900s, mining declined, and the town slowly faded away.[155][210]

1885: Halls Creek in the Kimberley, Western Australia

In 1872, the Western Australian Government offered a reward of £5,000 (equivalent to A$860,000 in 2022) for the discovery of the colony's first payable goldfield.[52][53]

Ten years later, in 1882, small finds of gold were being made in the Kimberley region of Western Australia, prompting in 1883 the appointment of a Government Geologist. In 1884, Edward Hardman, Government Geologist, published a report that he had found traces of gold throughout the east Kimberley, especially in the area around the present-day town of Halls Creek.[52][53]

On 14 July 1885, having been prompted by Hardman's report, Charles Hall and Jack Slattery[211] found payable gold at what they called Halls Creek, in the Kimberleys, Western Australia. After working for a few weeks Hall returned to Derby with 200 ounces of gold and reported his find.[211] Once this discovery became known it prompted the Kimberley Rush, the first gold rush in Western Australia.[212][213] It is estimated that as many as 10,000 men joined the rush. On 19 May 1886, the Kimberley Goldfield was officially declared:

Thousands of men made their way to the Kimberley from other parts of WA, the eastern colonies, and New Zealand. Most arrived by ship in Derby or Wyndham, and then walked to Halls Creek. Others came overland from the Northern Territory. Most had no previous experience in gold prospecting or of life in the bush. Illness and disease were rife, and when the first warden, C. D. Price, arrived on 3 September 1886, he found that "great numbers were stricken down, in a dying condition, helpless, destitute of money, food, or covering, and without mates or friends simply lying down to die". A few were lucky enough to locate rich alluvial or reef gold, but most had little or no success.[53]

In the early days of the gold rush no records or statistics were recorded for either the arrivals or deaths. Also, no-one knows how many died trying to get to Halls Creek across the waterless desert, or how many simply turned back. When men actually arrived at Halls Creek, dysentery, scurvy, sunstroke and thirst continued to take its toll. The Government applied a gold tax of two shillings and sixpence an ounce. It was a very unpopular levy as gold proved so hard to get. The diggers avoided registering and the Government had a great deal of trouble collecting the tax or statistics of any kind.[211]

Когда К. Д. Прайс прибыл в сентябре 1886 года, он сообщил, что на раскопках осталось около 2000 человек. К концу 1886 года ажиотаж прекратился. Когда в мае 1888 года правительство рассматривало требования о вознаграждении за открытие первого подлежащего выплате месторождения золота, было решено, что месторождение Кимберли, которое оказалось разочаровывающим, недостаточно для выполнения оговоренных условий добычи по крайней мере 10 000 унций (280 кг). ) золота в течение двухлетнего периода, прошедшего через таможню или отправленного в Англию, поэтому вознаграждение не было выплачено. [214] (По оценкам, с месторождений вокруг Холлс-Крик было добыто около 23 000 унций [650 кг] золота, но значительная часть ушла с месторождения через Северную территорию.) [211] Однако вклад Хардмана был отмечен подарком в размере 500 фунтов стерлингов (что эквивалентно 40 000 австралийских долларов в 2022 году) его вдове Луизе Хардман. Еще 500 фунтов были переданы Чарльзу Холлу и его группе. [52] [53]

1887–1891: Южный Крест, Пилбара и другие находки в Западной Австралии.

1887 г. Йилгарн и 1888 г. Южный Крест

В 1887 году было обнаружено первое золото в огромном регионе Восточных золотых приисков. Золотосодержащий кварц был найден возле озера Дебора на холмах Йилгарн к северу от того, что должно было стать городом Южный Крест в октябре 1887 года партией Гарри Фрэнсиса Ансти . [215] Ансти и его группа проводили разведку в этом районе после того, как услышали, что фермер нашел золотой самородок в Йилгарне, проходя бурение. Другими членами его группы были Дик Гривз и Тед Пейн, причем Тед Пейн был первым, кто увидел золото. В результате этого Ансти и один из его сторонников Джордж Лик , тогдашний генеральный солиситор и будущий премьер-министр Западной Австралии, [216] в ноябре 1887 года им была предоставлена концессия на добычу полезных ископаемых площадью 60 000 акров (24 000 га) для поисковых целей. [217] [218]

30 декабря 1887 года, узнав непосредственно от Ансти об успехе своей партии, Бернард Норберт Колриви также обнаружил золотоносный кварцевый риф в Золотой долине на холмах Йилгарн, а 12 января 1888 года коллега Колриви по партии Х. Хаггинс , открыл еще один золотоносный кварцевый риф. Вскоре они нашли и закрепили еще семь золотоносных кварцевых рифов. [219] [220] [221]

В мае 1888 года Майкл Туми и Сэмюэл Фолкнер первыми обнаружили золотосодержащий кварц на месте того, что впоследствии стало городом Саутерн-Кросс на золотом месторождении Йилгарн, примерно в 50 км (31 миле) к юго-востоку от Золотой долины. Лидер партии Томас Райзли впоследствии раздавил и пролил взятые образцы, подтвердившие, что они нашли золото, а затем Райсли и Туми приступили к обоснованию своего заявления от имени Phoenix Prospecting Company. [222] [223] [224]

Известие о находке Ансти привело к тому, что в конце 1887 года началась Йилгарнская гонка. [217] Ажиотаж вокруг золотой лихорадки усилился в начале 1888 года с известием об открытии Колриви и Хаггинсом Золотой долины (названной в честь растущего там Золотого плетня), а всего несколько месяцев спустя еще больше усилился с известием об открытии Райзли. , Туми и Фолкнер, но официально о месторождении не было объявлено до 1 октября 1888 года. В 1892 году правительство наградило Ансти 500 фунтов стерлингов (что эквивалентно 81 000 австралийских долларов в 2022 году), а Колриви и Хаггинсу - по 250 фунтов стерлингов (что эквивалентно 41 000 австралийских долларов в 2022 году) каждый. за открытие золотых приисков Йилгарн. [225] Йилгарнская лихорадка утихла, когда в сентябре 1892 года пришло известие о богатом открытии золота на востоке, в Кулгарди.

1888: Пилбара

было Месторождение Пилбара официально объявлено в тот же день, что и месторождение Йилгарн, 1 октября 1888 года. Правительство предложило награду в размере 1000 фунтов стерлингов (что эквивалентно 160 000 австралийских долларов в 2022 году) первому человеку, который найдет подлежащее оплате золото в Пилбаре. Его разделили трое мужчин: исследователи Фрэнсис Грегори и Н.В. Кук, а также скотовод Джон Уитнелл. Грегори также обнаружил золото в регионе, известном как Собственно Нуллагин, в июне 1888 года, а Гарри Уэллс нашел золото в Мраморном Баре . В результате золотое месторождение Пилбара, занимавшее площадь 34 880 квадратных миль (90 300 км²), 2 ), был разделен на два района: Нулладжин и Мраморный Бар. Чтобы поддержать Пилбарскую лихорадку, правительство в 1891 году построило железнодорожную линию между Марбл-Бар и Порт-Хедлендом. Производство россыпного золота начало снижаться в 1895 году, после чего горнодобывающие компании начали глубокую добычу золота. [226]

1891: Кий

Золото было найдено в Кью в 1891 году Майклом Фицджеральдом, Эдвардом Хеффернаном и Томом Кью. [32] Это стало известно как Мерчисонская лихорадка. [227]

1892–1899: Кулгарди, Калгурли и другие находки в Западной Австралии.

1892: Кулгарди

В сентябре 1892 года золото было найдено во Флай-Флэт ( Кулгарди ) Артуром Уэсли Бэйли и Уильямом Фордом, которые рядом с кварцевым рифом добыли 554 унции (15,7 кг) золота за один день с помощью томагавка. 17 сентября 1892 года Уэсли проехал 185 км (115 миль) с этим золотом до Южного Креста, чтобы зарегистрировать свое требование о вознаграждении за новую находку золота. Через несколько часов началось то, что сначала назвали «Натиском Корявой Байны». Ночью горняки, собравшиеся на раскопках Южного Креста, перебрались на более прибыльное месторождение Кулгарди-Голдфилд. [32] [228] В качестве вознаграждения группе Бэйли за открытие нового золотого прииска должна была быть предоставлена претензия на глубину 100 футов (30,5 метра) вдоль линии рифа. [229] [230] Сообщается, что это требование охватывает площадь в пять акров (2,0 га). [231] 24 августа 1893 года, менее чем через год после открытия Артуром Бэйли и Уильямом Фордом золота в Флай-Флэт, Кулгарди был объявлен городом с предполагаемым населением в 4000 человек (и многие другие добывали месторождения). [232]

Золотая лихорадка Кулгарди стала началом того, что было описано как «величайшая золотая лихорадка в истории Западной Австралии». [233] Его также называют «величайшим движением людей в истории Австралии». [234] но это преувеличение. Наибольшее перемещение людей в истории Австралии произошло в период с 1851 по 1861 год во время золотой лихорадки в восточных штатах, когда зарегистрированное население Австралии выросло на 730 484 человека с 437 665 в 1851 году до 1 168 149 в 1861 году. [32] по сравнению с увеличением этой суммы на 20% в Западной Австралии в период с 1891 по 1901 год, зарегистрированное население Западной Австралии увеличилось на 137 834 человека с 46 290 в 1891 году до 184 124 в 1901 году. [232]

1893: Калгурли

17 июня 1893 года россыпное золото было найдено возле горы Шарлотта, менее чем в 25 милях (40 км) от Кулгарди, на месте, которое впоследствии стало городом Ханнан (Калгурли). Объявление Пэдди Ханнана об этой находке только усилило волнение золотой лихорадки в Кулгарди и привело к созданию в Восточных золотых приисках Западной Австралии городов-побратимов Калгурли-Боулдер . [235] [236] До переезда в Западную Австралию в 1889 году для поиска золота Ханнан вел разведку в Балларате в Виктории в 1860-х годах, в Отаго в Новой Зеландии в 1870-х годах и в Титулпе (к северу от Юнты ) в Южной Австралии в 1886 году. [39] Первыми золото в Калгурли нашли Пэдди Ханнан и его соотечественники-ирландцы Томас Флэнаган и Дэниел Ши:

Утром Фланаган гнал лошадей, когда заметил на земле золото. Пока другие разбивали лагерь неподалеку, он перекинул через куст куст, внимательно запомнил свое положение и поспешил обратно, чтобы сообщить об этом Ханнану и Дэну Ши, еще одному ирландцу, который присоединился к ним. Они оставались там, пока остальные не ушли, а затем вернули золото Фланагана и нашли гораздо больше! Было решено вернуться с золотом в Южный Крест , ближайший административный центр, и потребовать у Смотрителя награду. Тесс Томсон в своей книге «Пэдди Ханнан: Претензия на славу » [237] показывает, что это сделал Ханнан. Таким образом, Фланаган был «искателем», а Ханнан, обнародовавший находку, был «первооткрывателем», поскольку «открыть» означает то, что оно говорит – «снять покров», другими словами, «обнаружить; опубликовать», что не обязательно делает искатель. [238]

После того, как Ханнан зарегистрировал свое требование о вознаграждении за новую находку золота с более чем 100 унциями (2,8 кг) россыпного золота, около 700 человек вели разведку в этом районе в течение трех дней. [235] Наградой для группы Ханнана за обнаружение лучшей аллювиальной находки, когда-либо сделанной в колонии, и, даже не подозревая об этом, одного из лучших рифовых полей в мире, должна была быть предоставлена аренда на добычу полезных ископаемых на шесть акров (2,4 га). [239]

1893: Река Гриноф

Золото было найдено в бассейне Нундамурра на реке Гриноф , между Юной и Муллевой, в августе 1893 года, что вызвало небольшой наплыв в этот район. [32] [240]