История Австралии

Эта статья может оказаться слишком длинной для удобного чтения и навигации . Когда этот тег был добавлен, его читаемый размер составлял 35 000 слов. ( июнь 2023 г. ) |

| Эта статья является частью серии, посвященной |

| История Австралия |

|---|

|

| Эта статья является частью серии, посвященной |

| Культура Австралия |

|---|

|

| Общество |

| Искусство и литература |

| Другой |

| Символы |

Портал Австралии |

История Австралии — это история страны и народов, которые сейчас составляют Австралийское Содружество . Современная нация возникла 1 января 1901 года как федерация бывших британских колоний. Однако человеческая история Австралии начинается с прибытия первых предков австралийских аборигенов по морю из Приморской Юго-Восточной Азии между 50 000 и 65 000 лет назад и продолжается до наших дней с мультикультурной демократией.

Австралийские аборигены расселились по всей континентальной Австралии и на многих близлежащих островах. Созданные ими художественные музыкальные , . и духовные традиции являются одними из старейших сохранившихся в истории человечества [1] Предки сегодняшних этнически и культурно отличающихся жителей островов Торресова пролива прибыли с территории нынешней Папуа-Новой Гвинеи около 2500 лет назад и заселили острова на северной оконечности австралийской суши.

Голландские мореплаватели исследовали западное и южное побережья в 17 веке и назвали континент Новой Голландией . Макассанские трепангеры посещали северное побережье Австралии примерно с 1720 года, а возможно, и раньше. В 1770 году лейтенант Джеймс Кук нанес на карту восточное побережье Австралии и заявил, что оно принадлежит Великобритании . Он вернулся в Лондон с отчетами в пользу колонизации Ботани-Бэй (ныне в Сиднее ). Первый флот британских кораблей прибыл в залив Ботани в январе 1788 года, чтобы основать там исправительную колонию . В последующее столетие британцы основали на континенте другие колонии, а европейские исследователи рискнули проникнуть в его внутренние районы. В этот период наблюдалось сокращение численности аборигенов и разрушение их культуры из-за завезенных болезней, жестоких конфликтов и лишения их традиционных земель. С 1871 года жители островов Торресова пролива приветствовали христианских миссионеров , а позже острова были аннексированы Квинслендом, решив остаться в составе Австралии, когда Папуа-Новая Гвинея столетие спустя получила независимость от Австралии.

Золотая лихорадка и сельскохозяйственная промышленность принесли процветание. Транспортировка британских заключенных в Австралию была прекращена с 1840 по 1868 год. С середины 19 века в шести британских колониях начали создаваться автономные парламентские демократии. Колонии проголосовали на референдуме за объединение в федерацию в 1901 году, и возникла современная Австралия. Австралия воевала в составе Британской империи , а затем и Содружества в двух мировых войнах и должна была стать давним союзником Соединенных Штатов во время холодной войны до настоящего времени. Торговля с Азией увеличилась, и послевоенная иммиграционная программа приняла более 7 миллионов мигрантов со всех континентов. Благодаря иммиграции людей практически из всех стран мира после окончания Второй мировой войны, к 2021 году население страны увеличилось до более чем 25,5 миллионов человек , причем 30 процентов населения родились за границей.

Коренная предыстория

Предки австралийских аборигенов переселились на территорию нынешнего австралийского континента примерно 50 000–65 000 лет назад. [2] [3] [4] [5] во время последнего ледникового периода , прибывая по сухопутным мостам и коротким морским переходам из территории нынешней Юго-Восточной Азии. [6]

в Скальное убежище Маджедбебе Арнемленде , на севере континента, является, пожалуй, старейшим местом проживания человека в Австралии. [2] [7] С севера население распространилось по самым разным средам обитания. Логово Дьявола на крайнем юго-западе континента было заселено около 47 000 лет назад, а Тасмания — 39 000 лет назад. [8] Самые старые человеческие останки, найденные на озере Мунго в Новом Южном Уэльсе, датируются примерно 41 000 лет назад. Это место предполагает одну из старейших известных кремаций в мире, что указывает на ранние свидетельства религиозных ритуалов среди людей. [9]

Распространение населения также изменило окружающую среду. Еще 46 000 лет назад во многих частях Австралии выращивание огненных палочек использовалось для расчистки растительности, облегчения путешествий и создания открытых лугов, богатых животными и растительными источниками пищи. [10]

Коренное население столкнулось со значительными изменениями климата и окружающей среды. Около 30 000 лет назад уровень моря начал падать, температура на юго-востоке континента упала на целых 9 градусов по Цельсию, а внутренние районы Австралии стали более засушливыми. Около 20 000 лет назад Новая Гвинея и Тасмания были соединены с Австралийским континентом, который был более чем на четверть больше современного. [11]

Около 19 000 лет назад температура и уровень моря начали повышаться. Тасмания отделилась от материка около 14 000 лет назад, а между 8 000 и 6 000 лет назад образовались тысячи островов в Торресовом проливе и вокруг побережья Австралии. [11]

Потепление климата было связано с новыми технологиями. Небольшие каменные орудия с задним лезвием появились 15–19 тысяч лет назад. Деревянные дротики и бумеранги были найдены 10 000 лет назад. Найдены каменные наконечники для копий, датированные 5–7 тысячами лет назад. Метатели копья, вероятно, были изобретены совсем недавно, более 6500 лет назад. [12]

Аборигены Тасмании были изолированы от материка примерно 14 000 лет назад. В результате они располагали лишь четвертью инструментов и оборудования прилегающего материка. Прибрежные жители Тасмании перешли с рыбы на морское ушко и раков, и все больше жителей Тасмании переселились во внутренние районы. [13]

Около 4000 лет назад начался первый этап оккупации островов Торресова пролива. К 2500 годам назад большая часть островов была оккупирована, и возникла самобытная морская культура жителей островов Торресова пролива . На некоторых островах также развивалось сельское хозяйство, и 700 лет назад появились деревни. [14]

Общество аборигенов состояло из семейных групп, организованных в группы и кланы численностью в среднем около 25 человек, каждый из которых имел определенную территорию для добывания пищи. Кланы были прикреплены к племенам или народам, связанным с определенными языками и страной. Во время контактов с европейцами существовало около 600 племен или наций и 250 различных языков с различными диалектами. [15] [16] По оценкам, численность аборигенов в то время колеблется от 300 000 до одного миллиона. [17] [18] [19]

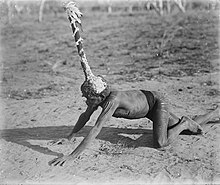

Общество аборигенов было эгалитарным, без формального правительства или вождей. Власть принадлежала старейшинам, и групповые решения обычно принимались путем консенсуса старейшин. Традиционная экономика была кооперативной: мужчины обычно охотились на крупную дичь, а женщины собирали местные продукты питания, такие как мелкие животные, моллюски, овощи, фрукты, семена и орехи. Еду делили внутри групп и обменивали между группами. [20] Некоторые группы аборигенов занимались выращиванием огненных палок . [21] рыбоводство , [22] и построили полупостоянные убежища . [23] [24] Степень участия некоторых групп в сельском хозяйстве вызывает споры. [25] [26] [27] Некоторые антропологи описывают традиционное общество аборигенов Австралии как «сложное общество охотников-собирателей». [24] [28]

Группы аборигенов вели полукочевой образ жизни, обычно обитая на определенной территории, определяемой природными особенностями. Члены группы входили на территорию другой группы на основании прав, установленных браком и родством, или по приглашению для определенных целей, таких как церемонии и обмен обильной сезонной пищей. Поскольку все природные особенности земли были созданы предками, конкретная страна обеспечивала группе физическое и духовное питание. [29] [16]

Австралийские аборигены развили уникальную художественную и духовную культуру. Самое раннее наскальное искусство аборигенов состоит из отпечатков ладоней, ручных трафаретов и гравюр в виде кругов, дорожек, линий и купул и датируется 35 000 лет назад. Около 20 000 лет назад художники-аборигены изображали людей и животных. [30] Согласно мифологии австралийских аборигенов и анимистическим представлениям, Сновидение — это священная эпоха, в которой предковые тотемные духовные существа сформировали Творение . Греза установила законы и структуры общества, а также церемонии, проводимые для обеспечения непрерывности жизни и земли. [31]

Ранние европейские исследования

Голландские открытия и исследования

голландской Ост-Индской компании « Корабль Дюйфкен » под командованием Виллема Янсзона совершил первую задокументированную высадку европейцев в Австралии в 1606 году. [32] Позже в том же году Луис Вас де Торрес отплыл на север Австралии через Торресов пролив вдоль южного побережья Новой Гвинеи. [33]

В 1616 году Дирк Хартог , отклонившись от курса, направляясь от мыса Доброй Надежды в Батавию , высадился на острове у залива Шарк в Западной Австралии. [34] В 1622–1623 годах корабль «Леувин» совершил первый зарегистрированный обход юго-западного угла континента. [35]

В 1627 году южное побережье Австралии было открыто Франсуа Тейссеном и названо в честь Питера Нюйтса . [36] В 1628 году эскадра голландских кораблей исследовала северное побережье, особенно в заливе Карпентария . [35]

Путешествие Абеля Тасмана 1642 года было первой известной европейской экспедицией, достигшей Земли Ван Димена (позже Тасмании) и Новой Зеландии и увидев Фиджи . Во время своего второго путешествия 1644 года он также внес значительный вклад в картографирование материковой части Австралии (которую он назвал Новой Голландией ), проводя наблюдения за сушей и населением северного побережья ниже Новой Гвинеи. [37]

После путешествий Тасмана голландцы смогли составить почти полные карты северного и западного побережий Австралии, а также большей части ее южного и юго-восточного побережья Тасмании . [38]

Британские и французские исследования

Уильям Дампьер , английский пират и исследователь, высадился на северо-западном побережье Новой Голландии в 1688 году и снова в 1699 году и опубликовал влиятельные описания аборигенов. [39]

В 1769 году лейтенант Джеймс Кук, командующий HMS Endeavour , отправился на Таити, чтобы наблюдать и записывать прохождение Венеры . Кук также нес секретные инструкции Адмиралтейства по местонахождению предполагаемого Южного континента . [40] Не сумев найти этот континент, Кук решил обследовать восточное побережье Новой Голландии, единственную крупную часть этого континента, не нанесенную на карту голландскими мореплавателями. [41]

19 апреля 1770 года « Индевор» достиг восточного побережья Новой Голландии и через десять дней бросил якорь в заливе Ботани . Кук нанес на карту побережье до его северной протяженности и официально овладел восточным побережьем Новой Голландии 21/22 августа 1770 года, когда находился на острове Посессион у западного побережья полуострова Кейп-Йорк . [42]

В своем дневнике он отметил, что он «больше не сможет высадиться на этом восточном побережье Новой Голландии, а на западной стороне я не могу сделать никакого нового открытия, честь которого принадлежит голландским мореплавателям , и поэтому они могут претендовать на него как на их собственность [слова, выделенные курсивом, зачеркнуты в оригинале], но восточное побережье от 38° южной широты до этого места, я уверен, никогда не видел и не посещал ни один европеец до нас, и поэтому по тому же правилу принадлежит великой Британии » [ слова, выделенные курсивом, в оригинале зачеркнуты]. [43] [44]

В марте 1772 года Марк-Жозеф Марион дю Френ под командованием двух французских кораблей достиг земли Ван-Димена по пути на Таити и в Южные моря. Его группа стала первыми зарегистрированными европейцами, которые столкнулись с коренными жителями Тасмании и убили одного из них. [45]

В том же году французская экспедиция под руководством Луи Алено де Сен-Алуарна стала первыми европейцами, официально заявившими о суверенитете над западным побережьем Австралии, но никаких попыток последовать за этим с колонизацией предпринято не было. [46]

Колонизация

Планы колонизации до 1788 г.

Хотя до 1788 года выдвигались различные предложения по колонизации Австралии, ни одна из них не была предпринята. В 1717 году Жан-Пьер Перри направил Голландской Ост-Индской компании план колонизации территории в современной Южной Австралии. Компания отклонила этот план, заявив, что «в нем нет никакой перспективы использования или выгоды для Компании, а скорее очень определенные и большие затраты». [47]

Напротив, Эмануэль Боуэн в 1747 году пропагандировал преимущества исследования и колонизации страны, написав: [48]

Невозможно представить страну, которая обещает более справедливое положение, чем TERRA AUSTRALIS , уже не инкогнита, как показывает эта карта, а открытый Южный континент. Он расположен именно в самом богатом климате мира... и поэтому тот, кто в совершенстве откроет и заселит его, станет безошибочно обладателем территорий, столь же богатых, столь же плодородных и столь же способных к улучшению, как и любые, которые до сих пор были обнаружены, либо в Ост-Индия или Запад.

Джон Харрис в своей книге Navigantium atque Itinerantium Bibliotheca, или «Путешествия и путешествия» (1744–1748, 1764), рекомендовал исследовать восточное побережье Новой Голландии с целью британской колонизации. [49] Джон Калландер в 1766 году выдвинул Британии предложение основать колонию для изгнанных каторжников в Южном море или на Terra Australis . [50] Шведский король Густав III имел амбиции основать колонию для своей страны на реке Лебедь в 1786 году, но этот план оказался мертворожденным. [51]

Война за независимость США (1775–1783) привела к тому, что Великобритания потеряла большую часть своих североамериканских колоний и рассмотрела возможность создания новых территорий. Британия перевезла около 50 000 заключенных в Новый Свет с 1718 по 1775 год и теперь искала альтернативу. Временное решение в виде плавучих тюремных корпусов исчерпало свою вместимость и представляло угрозу для здоровья населения, а вариант строительства большего количества тюрем и работных домов считался слишком дорогим. [52] [53]

В 1779 году сэр Джозеф Бэнкс , выдающийся ученый, сопровождавший Джеймса Кука в его путешествии 1770 года, рекомендовал залив Ботани как подходящее место для каторжного поселения. План Бэнкса заключался в том, чтобы отправить от 200 до 300 осужденных в Ботани-Бэй, где они могли быть предоставлены сами себе и не были обузой для британских налогоплательщиков. [54]

Под руководством Бэнкса американский лоялист Джеймс Матра , который также путешествовал с Куком, разработал новый план колонизации Нового Южного Уэльса в 1783 году. [55] Матра утверждал, что страна подходит для плантаций сахара, хлопка и табака; Новозеландская древесина, конопля или лен могут оказаться ценными товарами; он мог бы стать базой для тихоокеанской торговли; и это могло бы стать подходящей компенсацией для перемещенных американских лоялистов. [56] После интервью с госсекретарем лордом Сиднеем в 1784 году Матра внес поправки в свое предложение включить осужденных в число поселенцев, посчитав, что это принесет пользу как «экономике для общества, так и человечности для человека». [57]

Основной альтернативой Ботани-Бэй была отправка осужденных в Африку. С 1775 года осужденных отправляли в гарнизонные британские форты в Западной Африке, но эксперимент оказался безуспешным. В 1783 году правительство Питта рассматривало возможность сосылки осужденных на небольшой речной остров в Гамбии, где они могли бы создать самоуправляющуюся общину, «воровскую колонию», без каких-либо затрат со стороны правительства. [58]

В 1785 году специальный парламентский комитет под председательством лорда Бошана рекомендовал против плана Гамбии, но не смог одобрить альтернативу Ботани-Бей. Во втором отчете Бошан рекомендовал создать исправительное поселение в заливе Дас-Вольтас в современной Намибии. Однако от этого плана отказались, когда исследование этого места в 1786 году показало, что оно непригодно. Две недели спустя, в августе 1786 года, правительство Питта объявило о своем намерении отправить осужденных в Ботани-Бэй. [59] Правительство включило в свой план заселение острова Норфолк с его достопримечательностями древесины и льна, предложенное коллегами Бэнкса из Королевского общества, сэром Джоном Коллом и сэром Джорджем Янгом. [60]

Уже давно ведутся споры о том, была ли ключевым фактором при принятии решения о создании исправительной колонии в Ботани-Бэй насущная необходимость найти решение проблемы управления тюрьмами или же более широкие имперские цели, такие как торговля, обеспечение новых поставок древесина и лен для военно-морского флота, а также желательность стратегических портов в регионе — были первостепенными. [61] Кристофер и Максвелл-Стюарт утверждают, что какими бы ни были первоначальные мотивы правительства при создании колонии, к 1790-м годам оно, по крайней мере, достигло имперской цели - создать гавань, где можно было бы заходить судам и пополнять запасы. [62]

Колония Нового Южного Уэльса

Основание колонии: 1788–1792 гг.

Территория Нового Южного Уэльса, на которую претендует Великобритания, включала всю Австралию к востоку от меридиана 135° восточной долготы. Это включало более половины материковой Австралии. [63] Претензия также включала «все острова, прилегающие к Тихому океану» между широтами мыса Йорк и южной оконечностью Земли Ван-Димена (Тасмания). [64] В 1817 году британское правительство отозвало обширные территориальные претензии на южную часть Тихого океана, приняв закон, в котором указывалось, что Таити, Новая Зеландия и другие острова южной части Тихого океана не входят в пределы владений Его Величества. [63] Однако неясно, распространялось ли когда-либо требование на нынешние острова Новой Зеландии. [65]

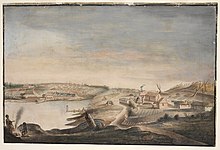

Колония Новый Южный Уэльс была основана с прибытием в январе 1788 года Первого флота из 11 судов под командованием капитана Артура Филлипа . В ее состав входило более тысячи поселенцев, в том числе 778 осужденных (192 женщины и 586 мужчин). [66] Через несколько дней после прибытия в Ботани-Бэй флот двинулся в более подходящий Порт-Джексон, было основано поселение в Сиднейской бухте . где 26 января 1788 года [67] Эта дата позже стала национальным днем Австралии, Днем Австралии . Колония была официально провозглашена губернатором Филиппом 7 февраля 1788 года в Сиднее. Сиднейская бухта предлагала запасы пресной воды и безопасную гавань, которую Филип описал как «без исключения лучшую гавань в мире [...] Здесь тысяча линейных парусов может плавать в самой совершенной безопасности». [68]

Губернатор Филипп был наделен полной властью над жителями колонии. Его намерением было установить гармоничные отношения с местными аборигенами и попытаться реформировать, а также дисциплинировать заключенных колонии. Первые усилия в сельском хозяйстве были трудными, а поставки из-за границы были недостаточными. Между 1788 и 1792 годами в Сиднее было высажено около 3546 мужчин и 766 женщин. Многие вновь прибывшие были больны или нетрудоспособны, а состояние здоровых осужденных также ухудшалось из-за каторжного труда и плохого питания. Продовольственная ситуация достигла критической точки в 1790 году, и Второй флот , который наконец прибыл в июне 1790 года, потерял четверть своих пассажиров из-за болезней, а состояние заключенных Третьего флота ужаснуло Филлипа. Однако с 1791 года более регулярное прибытие кораблей и начало торговли уменьшили чувство изоляции и улучшили снабжение. [69]

В 1788 году Филипп основал дополнительное поселение на острове Норфолк в южной части Тихого океана, где он надеялся получать древесину и лен для военно-морского флота. Однако на острове не было безопасной гавани, из-за чего поселение было заброшено, а поселенцы были эвакуированы на Тасманию в 1807 году. [70] Впоследствии в 1825 году остров был восстановлен как место второстепенного транспорта. [71]

Филипп отправил исследовательские миссии в поисках лучших почв, определил регион Парраматта как перспективный район для расширения и с конца 1788 года переселил многих заключенных, чтобы основать небольшой поселок, который стал главным центром экономической жизни колонии. В результате Сидней-Коув остался лишь важным портом и центром общественной жизни. Плохое оборудование, незнакомые почвы и климат продолжали препятствовать расширению сельского хозяйства от Фарм-Коув до Парраматты и Тунгабби , но программа строительства, при поддержке труда заключенных, неуклонно продвигалась. Между 1788 и 1792 годами каторжники и их тюремщики составляли большинство населения; однако вскоре стало расти свободное население, состоящее из освобожденных каторжников, местных детей, солдат, у которых истек срок военной службы, и, наконец, свободных поселенцев из Британии. Губернатор Филипп покинул колонию и отправился в Англию 11 декабря 1792 года, при этом новое поселение в течение четырех лет переживало голод и огромную изоляцию. [69]

Объединение: 1793–1821 гг.

После отъезда Филиппа военные колонии начали приобретать землю и ввозить товары народного потребления, полученные с заходивших кораблей. Бывшие каторжники также обрабатывали предоставленную им землю и занимались торговлей. Фермы распространились на более плодородные земли, окружающие Параматту , Виндзор , Ричмонд и Камден , и к 1803 году колония стала самодостаточной в зерне. Судостроение развивалось для облегчения путешествий и использования морских ресурсов прибрежных поселений. Тюленебойный и китобойный промысел стали важными отраслями промышленности. [72]

Корпус Нового Южного Уэльса был сформирован в Англии в 1789 году как постоянный полк британской армии для смены морской пехоты, сопровождавшей Первый флот. Офицеры корпуса вскоре стали участвовать в коррумпированной и прибыльной торговле ромом в колонии. Губернатор Уильям Блай (1806–1808) пытался подавить торговлю ромом и незаконное использование земель Короны, что привело к Ромовому восстанию 1808 года. Корпус, тесно сотрудничая с недавно основанным торговцем шерстью Джоном Макартуром , организовал единственный успешный вооруженный переворот. правительства в истории Австралии, свергнув Блая и спровоцировав короткий период военного правления до прибытия из Британии губернатора Лахлана Маккуори в 1810 году. [73] [74]

Маккуори был последним автократическим губернатором Нового Южного Уэльса с 1810 по 1821 год и играл ведущую роль в социальном и экономическом развитии Нового Южного Уэльса, в результате которого он превратился из исправительной колонии в зарождающееся гражданское общество. Он основал банк, валюту и больницу. Он нанял планировщика для проектирования улиц Сиднея и заказал строительство дорог, пристаней, церквей и общественных зданий. Он отправил исследователей из Сиднея, и в 1815 году дорога через Голубые горы была завершена, открыв путь для крупномасштабного земледелия и выпаса скота на слегка лесистых пастбищах к западу от Большого Водораздельного хребта . [75] [76]

Центральным элементом политики Маккуори было его обращение с эмансипистами , которых, по его мнению, следует рассматривать как социальных равных свободным поселенцам в колонии. Он назначил эмансипистов на ключевые государственные должности, в том числе Фрэнсиса Гринуэя колониальным архитектором и Уильяма Редферна мировым судьей. Его политике в отношении эмансипистов противостояли многие влиятельные свободные поселенцы, офицеры и чиновники, и Лондон был обеспокоен ценой его общественных работ. В 1819 году Лондон поручил Дж. Т. Бигге провести расследование в колонии, и Маккуори подал в отставку незадолго до публикации отчета о расследовании. [77] [78]

Расширение: с 1821 по 1850 год.

В 1820 году британское поселение в основном ограничивалось радиусом 100 километров вокруг Сиднея и центральной равниной земли Ван Димена. Население поселенцев составляло 26 000 на материке и 6 000 на Земле Ван Димена. После окончания наполеоновских войн в 1815 году перевозка каторжников быстро увеличилась, а число свободных поселенцев неуклонно росло. [79] С 1821 по 1840 год 55 000 каторжников прибыли в Новый Южный Уэльс и 60 000 на Землю Ван Димена. Однако к 1830 году количество свободных поселенцев и местных жителей превысило численность заключенных Нового Южного Уэльса. [80]

С 1820-х годов скваттеры все чаще устраивали несанкционированные выгоны скота и овец за пределы официальных границ оседлой колонии. была введена система ежегодных лицензий, разрешающих выпас скота на Землях Короны В 1836 году в попытке контролировать скотоводческую промышленность , но растущие цены на шерсть и высокая стоимость земли в населенных пунктах способствовали дальнейшему сквоттингу. К 1844 году шерсть составляла половину экспорта колонии, а к 1850 году большая часть восточной трети Нового Южного Уэльса контролировалась менее чем 2000 скотоводами. [81] [82]

В 1825 году западная граница Нового Южного Уэльса была продлена до 129° восточной долготы, которая является нынешней границей Западной Австралии. В результате территория Нового Южного Уэльса достигла наибольшего размера, охватив территорию современного штата, а также современные Квинсленд, Викторию, Тасманию, Южную Австралию и Северную территорию. [83] [65]

К 1850 году поселенческое население Нового Южного Уэльса выросло до 180 000, не считая 70–75 тысяч, проживавших в этом районе, который в 1851 году стал отдельной колонией Виктория. [84]

Создание дальнейших колоний

После принятия французской военно-морской экспедиции Николаса Бодена в Сиднее в 1802 году губернатор Филип Гидли Кинг решил основать поселение на Земле Ван-Димена (современная Тасмания ) в 1803 году, отчасти для того, чтобы предотвратить возможное французское поселение. Британское поселение на острове вскоре сосредоточилось в Лонсестоне на севере и Хобарте на юге. [85] [86] С 1820-х годов свободных поселенцев поощряло предложение земельных грантов пропорционально капиталу, который они привезут. [87] [88] Земля Ван Димена стала отдельной колонией от Нового Южного Уэльса в декабре 1825 года и продолжала расширяться в течение 1830-х годов, поддерживаемая сельским хозяйством, выпасом овец и китобойным промыслом. После приостановки перевозки осужденных в Новый Южный Уэльс в 1840 году земля Ван Димена стала основным пунктом назначения для осужденных. Перевозка на Землю Ван-Димена завершилась в 1853 году, а в 1856 году колония официально сменила название на Тасманию. [89]

Скотоводы с земель Ван Димена начали селиться на корточках во внутренних районах Порт-Филлип на материке в 1834 году, привлеченные его богатыми лугами. В 1835 году Джон Бэтмен и другие вели переговоры о передаче 100 000 акров земли от народа Кулин. Однако договор был аннулирован в том же году, когда Британское управление по делам колоний издало Прокламацию губернатора Бурка . Прокламация означала, что с этого момента все люди, занимающие землю без разрешения правительства, будут считаться незаконными нарушителями границ. [90] В 1836 году Порт-Филлип был официально признан округом Нового Южного Уэльса и открыт для заселения. Главное поселение Мельбурна было основано в 1837 году как запланированный город по указанию губернатора Бурка. Вскоре в больших количествах прибыли сквоттеры и поселенцы с Земли Ван-Димена и Нового Южного Уэльса. В 1851 году район Порт-Филлип отделился от Нового Южного Уэльса и стал колонией Виктория. [91] [92]

В 1826 году губернатор Нового Южного Уэльса Ральф Дарлинг направил военный гарнизон в пролив Кинг-Джордж, чтобы удержать французов от создания поселения в Западной Австралии. В 1827 году руководитель экспедиции майор Эдмунд Локьер официально аннексировал западную треть континента как британскую колонию. [93] В 1829 году на месте современных Фримантла и Перта была основана колония Суон-Ривер , став первой приватизированной колонией без осужденных в Австралии. Однако к 1850 году здесь проживало чуть более 5000 поселенцев. В колонию принимали осужденных этого года из-за острой нехватки рабочей силы. [94] [95]

Провинция Южная Австралия была основана в 1836 году как поселение, финансируемое из частных источников, на основе теории «систематической колонизации», разработанной Эдвардом Гиббоном Уэйкфилдом . Труд осужденных был запрещен в надежде сделать колонию более привлекательной для «респектабельных» семей и способствовать равному балансу между поселенцами-мужчинами и женщинами. Город Аделаида должен был быть спланирован с щедрым обеспечением церквей, парков и школ. Земля должна была продаваться по единой цене, а вырученные средства использовать для обеспечения достаточного предложения рабочей силы посредством выборочной помощи в миграции. [96] [97] [98] Гарантировались различные религиозные, личные и коммерческие свободы, а Патент на письма, положивший начало Закону о Южной Австралии 1834 года, включал гарантию земельных прав аборигенов. [99] Однако колония сильно пострадала от депрессии 1841–1844 годов. Конфликт с традиционными землевладельцами из числа коренных народов также ослабил обещанную им защиту. В 1842 году поселение стало колонией Короны, управляемой губернатором и назначенным Законодательным советом. Экономика восстановилась, и к 1850 году население поселенцев выросло до 60 000 человек. В 1851 году колония получила ограниченное самоуправление с частично избранным Законодательным советом. [96] [97] [100]

В 1824 году было основано исправительное поселение Мортон-Бей на месте современного Брисбена . В 1842 году исправительную колонию закрыли и территорию открыли для свободного поселения. К 1850 году население Брисбена достигло 8000 человек, и все большее число скотоводов пасли крупный рогатый скот и овец в Дарлинг-Даунс к западу от города. Пограничное насилие между поселенцами и коренным населением стало жестоким, поскольку скотоводство распространилось к северу от реки Твид . Серия споров между северными скотоводами и правительством Сиднея привела к увеличению требований со стороны северных поселенцев об отделении от Нового Южного Уэльса. В 1857 году британское правительство согласилось на отделение, и в 1859 году была провозглашена колония Квинсленд. [101] [102] [103]

Осужденные и колониальное общество

Осужденные и эмансиписты

Между 1788 и 1868 годами около 161 700 осужденных были перевезены в австралийские колонии Нового Южного Уэльса, Земли Ван Димена и Западной Австралии. [104] Уровень грамотности осужденных был выше среднего, и они принесли в новую колонию ряд полезных навыков, включая строительство, сельское хозяйство, парусный спорт, рыбалку и охоту. [105] Небольшое количество свободных поселенцев означало, что первым губернаторам также приходилось полагаться на осужденных и эмансипистов в таких профессиях, как юристы, архитекторы, геодезисты и учителя. [106]

Первоначально осужденные работали на государственных фермах и выполняли общественные работы, такие как расчистка земель и строительство. После 1792 года большинство из них было направлено на работу к частным работодателям, включая эмансипистов . Эмансипистам были пожалованы небольшие участки земли для ведения сельского хозяйства и годовой казенный паек. Позже им поручили работать заключенным, чтобы они помогали им работать на фермах. [107] Некоторые осужденные были прикомандированы к военным для ведения своего бизнеса. Эти осужденные приобрели коммерческие навыки, которые могли помочь им работать на себя, когда срок их наказания истечет или им будет предоставлен «отпуск» (форма условно-досрочного освобождения). [108]

Осужденные вскоре установили систему сдельной работы, которая позволяла им работать за заработную плату после выполнения порученных им задач. [109] К 1821 году каторжники, эмансиписты и их дети владели двумя третями обрабатываемой земли, половиной крупного рогатого скота и одной третью овец. [110] Они также работали в торговле и малом бизнесе. Эмансиписты трудоустроили около половины осужденных, приписанных к частным мастерам. [111]

Ряд реформ, рекомендованных Дж. Т. Бигге в 1822 и 1823 годах, ухудшили условия содержания заключенных. Продовольственный паек был урезан, а их возможности работать за зарплату ограничены. [112] Больше осужденных было направлено в сельские трудовые бригады, бюрократический контроль и надзор за осужденными стали более систематическими, были созданы изолированные поселки как места вторичного наказания, ужесточены правила выдачи отпусков, а предоставление земельных участков было смещено в пользу вольных поселенцев с большой капитал. [113] В результате у каторжников, прибывших после 1820 года, было гораздо меньше шансов стать собственниками, вступить в брак и создать семью. [114]

Свободные поселенцы

Реформы Бигге также были направлены на поощрение свободных поселенцев, предлагая им земельные гранты пропорционально их капиталу. С 1831 года колонии заменили земельные гранты продажей земли на аукционе по фиксированной минимальной цене за акр, а доходы использовались для финансирования помощи в миграции рабочих. С 1821 по 1850 год Австралия привлекла 200 000 иммигрантов из Соединенного Королевства. Однако система земледелия привела к концентрации земли в руках небольшого числа зажиточных поселенцев. [115]

Две трети мигрантов, прибывших в Австралию в этот период, получили помощь от британского или колониального правительства. [116] Семьям осужденных также был предложен бесплатный проезд, и около 3500 мигрантов были отобраны в соответствии с английскими законами о бедных . Различные специальные и благотворительные программы, такие как проекты Кэролайн Чизхолм и Джона Данмора Лэнга , также оказывали помощь в миграции. [117]

Женщины

Женщины составляли лишь около 15% перевозимых осужденных. Из-за нехватки женщин в колонии они чаще вступали в брак, чем мужчины, и, как правило, выбирали в мужья пожилых, квалифицированных мужчин с имуществом. Первые колониальные суды обеспечивали соблюдение имущественных прав женщин независимо от их мужей, а система нормирования также давала женщинам и их детям некоторую защиту от оставления. Женщины активно занимались бизнесом и сельским хозяйством с первых лет существования колонии, среди наиболее успешных были бывшая заключенная, ставшая предпринимателем Мэри Рейби , и земледельец Элизабет Макартур . [118] Треть акционеров первого колониального банка (основанного в 1817 году) составляли женщины. [119]

Одной из целей программ помощи в миграции 1830-х годов было содействие миграции женщин и семей, чтобы обеспечить более равномерный гендерный баланс в колониях. Кэролайн Чисхолм основала приют и биржу труда для женщин-мигрантов в Новом Южном Уэльсе в 1840-х годах и способствовала расселению одиноких и замужних женщин в сельских районах. [120] [121]

Между 1830 и 1850 годами доля женщин среди населения австралийских поселенцев увеличилась с 24 процентов до 41 процента. [122]

Религия

была Англиканская церковь единственной признанной церковью до 1820 года, и ее духовенство тесно сотрудничало с губернаторами. Ричард Джонсон (главный капеллан 1788–1802) был обвинен губернатором Артуром Филлипом в улучшении «общественной морали» в колонии, а также активно участвовал в здравоохранении и образовании. [123] Сэмюэл Марсден (различные министерства, 1795–1838 гг.) Стал известен своей миссионерской деятельностью, суровостью наказаний в качестве магистрата и резкостью публичных обвинений католицизма и ирландских осужденных. [124]

Около четверти осужденных были католиками. Отсутствие официального признания католицизма сочеталось с подозрениями в отношении ирландских заключенных, которые только усилились после восстания в Касл-Хилле под руководством ирландцев в 1804 году. [125] [126] Только два католических священника временно действовали в колонии до того, как губернатор Маккуори назначил официальных католических капелланов в Новом Южном Уэльсе и на Земле Ван-Димена в 1820 году. [127]

В отчетах Бигге рекомендовалось повысить статус Англиканской церкви. Англиканский архидьякон был назначен в 1824 году и получил место в первом консультативном Законодательном совете. Англиканское духовенство и школы также получили государственную поддержку. Эта политика была изменена при губернаторе Берке Церковными актами 1836 и 1837 годов. Теперь правительство оказывало государственную поддержку духовенству и церковным зданиям четырех крупнейших конфессий: англиканской, католической, пресвитерианской и, позже, методистской. [127]

Многие англиканцы считали государственную поддержку католической церкви угрозой. Видный пресвитерианский священник Джон Данмор Лэнг также способствовал сектантским разногласиям в 1840-х годах. [128] [129] Однако государственная поддержка привела к росту церковной деятельности. Благотворительные ассоциации, такие как «Католические сестры милосердия» , основанные в 1838 году, предоставляли больницы, детские приюты и приюты для пожилых людей и инвалидов. Религиозные организации также были основными поставщиками школьного образования в первой половине девятнадцатого века, ярким примером является Австралийский колледж Ланга, открывшийся в 1831 году. Многие религиозные ассоциации, такие как « Сестры Святого Иосифа» , соучредителем которых была Мэри МакКиллоп в 1866 г., продолжили свою образовательную деятельность после того, как с 1850-х гг. [130] [131]

Исследование континента

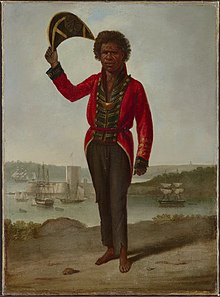

В 1798–1799 годах Джордж Басс и Мэтью Флиндерс отправились из Сиднея на шлюпе и обогнули Тасманию , доказав тем самым, что это остров. [132] В 1801–02 годах Мэтью Флиндерс на корабле HMS Investigator возглавил первое кругосветное плавание над Австралией. На борту корабля находился исследователь-абориген Бунгари , который стал первым человеком, родившимся на австралийском континенте, совершившим кругосветное плавание вокруг него. [132]

В 1798 году бывший каторжник Джон Уилсон и двое его товарищей пересекли Голубые горы к западу от Сиднея в экспедиции по приказу губернатора Хантера. Хантер скрыл новости об этом подвиге, опасаясь, что это побудит заключенных сбежать из поселения. В 1813 году Грегори Блэксленд , Уильям Лоусон и Уильям Вентворт пересекли горы другим маршрутом, и вскоре была построена дорога к Центральному плато . [133]

В 1824 году Гамильтон Хьюм и Уильям Ховелл возглавили экспедицию с целью найти новые пастбища на юге колонии, а также выяснить, где протекают западные реки Нового Южного Уэльса. За 16 недель в 1824–1825 годах они путешествовали в Порт-Филлип и обратно. Они открыли реку Мюррей (которую они назвали Хьюм) и многие ее притоки, а также хорошие сельскохозяйственные и пастбищные угодья. [134]

Чарльз Стёрт возглавил экспедицию вдоль реки Маккуори в 1828 году и открыл реку Дарлинг . Возглавляя вторую экспедицию в 1829 году, Стёрт проследовал по реке Маррамбиджи в реку Мюррей. Затем его группа проследовала по этой реке до ее слияния с рекой Дарлинг . Стёрт продолжил путь вниз по реке к озеру Александрина , где Мюррей встречается с морем в Южной Австралии. [135]

Surveyor General Sir Thomas Mitchell conducted a series of expeditions from the 1830s to follow up these previous expeditions. Mitchell employed three Aboriginal guides and recorded many Aboriginal place names. He also recorded a violent encounter with traditional owners on the Murray in 1836 in which his men pursued them, "shooting as many as they could."[136][137]

The Polish scientist and explorer Count Paul Edmund Strzelecki conducted surveying work in the Australian Alps in 1839 and, led by two Aboriginal guides, became the first European to ascend Australia's highest peak, which he named Mount Kosciuszko in honour of the Polish patriot Tadeusz Kościuszko.[138][139]

The German scientist Ludwig Leichhardt led three expeditions in northern Australia in the 1840s, sometimes with the help of Aboriginal guides. He and his party disappeared in 1848 while attempting to cross the continent from east to west.[140] Edmund Kennedy led an expedition into what is now far-western Queensland in 1847 before being speared by Aborigines in the Cape York Peninsula in 1848.[141]

In 1860, Burke and Wills led the first south–north crossing of the continent from Melbourne to the Gulf of Carpentaria. Lacking bushcraft and unwilling to learn from the local Aboriginal people, Burke and Wills died in 1861, having returned from the Gulf to their rendezvous point at Coopers Creek only to discover the rest of their party had departed the location only a matter of hours previously. They became tragic heroes to the European settlers, their funeral attracting a crowd of more than 50,000 and their story inspiring numerous books, artworks, films and representations in popular culture.[142][143]

In 1862, John McDouall Stuart succeeded in traversing central Australia from south to north. His expedition mapped out the route which was later followed by the Australian Overland Telegraph Line.[144]

The completion of this telegraph line in 1872 was associated with further exploration of the Gibson Desert and the Nullarbor Plain. While exploring central Australia in 1872, Ernest Giles sighted Kata Tjuta from a location near Kings Canyon and called it Mount Olga.[145] The following year Willian Gosse observed Uluru and named it Ayers Rock, in honour of the Chief Secretary of South Australia, Sir Henry Ayers.[146]

In 1879, Alexander Forrest trekked from the north coast of Western Australia to the overland telegraph, discovering land suitable for grazing in the Kimberley region.[144]

Impact of British settlement on Indigenous population

When the First Fleet arrived in Sydney Cove with some 1,300 colonists in January 1788 the Aboriginal population of the Sydney region is estimated to have been about 3,000 people.[147] The first governor of New South Wales, Arthur Phillip, arrived with instructions to: "endeavour by every possible means to open an Intercourse with the Natives and to conciliate their affections, enjoining all Our Subjects to live in amity and kindness with them."[148]

Disease

The relative isolation of the Indigenous population for some 60,000 years meant that they had little resistance to many introduced diseases. An outbreak of smallpox in April 1789 killed about half the Aboriginal population of the Sydney region. The source of the outbreak is controversial; some researchers contend that it originated from contact with Indonesian fisherman in the far north while others argue that it is more likely to have been inadvertently or deliberately spread by settlers.[149][150][151]

There were further smallpox outbreaks devastating Aboriginal populations from the late 1820s (affecting south-eastern Australia), in the early 1860s (travelling inland from the Coburg Peninsula in the north to the Great Australian Bight in the south), and in the late 1860s (from the Kimberley to Geraldton). According to Josphine Flood, the estimated Aboriginal mortality rate from smallpox was 60 per cent on first exposure, 50 per cent in the tropics, and 25 per cent in the arid interior.[152]

Other introduced diseases such as measles, influenza, typhoid and tuberculosis also resulted in high death rates in Aboriginal communities. Butlin estimates that the Aboriginal population in the area of modern Victoria was around 50,000 in 1788 before two smallpox outbreaks reduced it to about 12,500 in 1830. Between 1835 and 1853, the Aboriginal population of Victoria fell from 10,000 to around 2,000. It is estimated that about 60 per cent of these deaths were from introduced diseases, 18 per cent from natural causes and 15 per cent from settler violence.[153]

Venereal diseases were also a factor in Indigenous depopulation, reducing Aboriginal fertility rates in south-eastern Australia by an estimated 40 per cent by 1855. By 1890 up to 50 per cent of the Aboriginal population in some regions of Queensland were affected.[154]

Conflict and dispossession

The British settlement was initially planned to be a self-sufficient penal colony based on agriculture. Karskens argues that conflict broke out between the settlers and the traditional owners of the land because of the settlers' assumptions about the superiority of British civilisation and their entitlement to land which they had "improved" through building and cultivation.[155]

Conflict also arose from cross-cultural misunderstandings and from reprisals for previous actions such as the kidnapping of Aboriginal men, women and children. Reprisal attacks and collective punishments were perpetrated by colonists and Aboriginal groups alike.[157] Sustained Aboriginal attacks on settlers, the burning of crops and the mass killing of livestock were more obviously acts of resistance to the loss of traditional land and food resources.[158]

There were intense conflicts between settlers and the Darug people from 1794 to 1800 in which 26 settlers and up to 200 Darug were killed.[159][160] Conflict also erupted in Dharawal country from 1814 to 1816, culminating in the Appin massacre (April 1816) in which at least 14 Aboriginal people were killed.[161][162]

In the 1820s, the colony spread over the Great Dividing Range, opening the way for large scale farming and grazing in Wiradjuri country.[75] From 1822 to 1824 Windradyne led a group of 50-100 Aboriginal men in raids which resulted in the death of 15-20 colonists. Estimates of Aboriginal deaths in the conflict range from 15 to 100.[163][164]

In Van Diemen's land, the Black War broke out in 1824, following a rapid expansion of settler numbers and sheep grazing in the island's interior. Martial law was declared in November 1828 and in October 1830 a "Black Line" of around 2,200 troops and settlers swept the island with the intention of driving the Aboriginal population from the settled districts. From 1830 to 1834, George Augustus Robinson and Aboriginal ambassadors including Truganini led a series of "Friendly Missions" to the Aboriginal tribes which effectively ended the war.[165] Around 200 settlers and 600 to 900 Aboriginal Tasmanians were killed in the conflict and the Aboriginal survivors were eventually relocated to Flinders Island.[166][167]

The spread of settlers and pastoralists into the region of modern Victoria in the 1830s also sparked conflict with traditional landowners. Broome estimates that 80 settlers and 1,000–1,500 Aboriginal people died in frontier conflict in Victoria from 1835 to 1853.[168]

The growth of the Swan River Colony in the 1830s led to conflict with Aboriginal people, culminating in the Pinjarra massacre in which some 15 to 30 Aboriginal people were killed.[169][170] According to Neville Green, 30 settlers and 121 Aboriginal people died in violent conflict in Western Australia between 1826 and 1852.[171]

The spread of sheep and cattle grazing after 1850 brought further conflict with Aboriginal tribes more distant from the closely settled areas. Aboriginal casualty rates in conflicts increased as the colonists made greater use of mounted police, Native Police units, and newly developed revolvers and breech-loaded guns. Conflict was particularly intense in NSW in the 1840s and in Queensland from 1860 to 1880. In central Australia, it is estimated that 650 to 850 Aboriginal people, out of a population of 4,500, were killed by colonists from 1860 to 1895. In the Gulf Country of northern Australia five settlers and 300 Aboriginal people were killed before 1886.[172] The last recorded massacre of Aboriginal people by settlers was at Coniston in the Northern Territory in 1928 where at least 31 Aboriginal people were killed.[173]

The spread of British settlement also led to an increase in inter-tribal Aboriginal conflict as more people were forced off their traditional lands into the territory of other, often hostile, tribes. Butlin estimated that of the 8,000 Aboriginal deaths in Victoria from 1835 to 1855, 200 were from inter-tribal violence.[174]

Broome estimates the total death toll from settler-Aboriginal conflict between 1788 and 1928 as 1,700 settlers and 17–20,000 Aboriginal people. Reynolds has suggested a higher "guesstimate" of 3,000 settlers and up to 30,000 Aboriginals killed.[175] A project team at the University of Newcastle, Australia, has reached a preliminary estimate of 8,270 Aboriginal deaths in frontier massacres from 1788 to 1930.[176]

Accommodation and protection

In the first two years of settlement the Aboriginal people of Sydney mostly avoided the newcomers. In November 1790, Bennelong led the survivors of several clans into Sydney, 18 months after the smallpox epidemic that had devastated the Aboriginal population.[177] Bungaree, a Kuringgai man, joined Matthew Flinders in his circumnavigation of Australia from 1801 to 1803, playing an important role as emissary to the various Indigenous peoples they encountered.[178]

Governor Macquarie attempted to assimilate Aboriginal people, providing land grants, establishing Aboriginal farms, and founding a Native Institution to provide education to Aboriginal children.[179] However, by the 1820s the Native Institution and Aboriginal farms had failed. Aboriginal people continued to live on vacant waterfront land and on the fringes of the Sydney settlement, adapting traditional practices to the new semi-urban environment.[180][181]

Following escalating frontier conflict, Protectors of Aborigines were appointed in South Australia and the Port Phillip District in 1839, and in Western Australia in 1840. The aim was to extend the protection of British law to Aboriginal people, to distribute rations, and to provide education, instruction in Christianity, and occupational training. However, by 1857 the protection offices had been closed due to their cost and failure to meets their goals.[182][183]

In 1825, the NSW governor granted 10,000 acres for an Aboriginal Christian mission at Lake Macquarie.[184] In the 1830s and early 1840s there were also missions in the Wellington Valley, Port Phillip and Moreton Bay. The settlement for Aboriginal Tasmanians on Flinders Island operated effectively as a mission under George Robinson from 1835 to 1838.[185]

In New South Wales, 116 Aboriginal reserves were established between 1860 and 1894. Most reserves allowed Aboriginal people a degree of autonomy and freedom to enter and leave. In contrast, the Victorian Board for the Protection of Aborigines (created in 1869) had extensive power to regulate the employment, education and place of residence of Aboriginal Victorians, and closely managed the five reserves and missions established since self government in 1858. In 1886, the protection board gained the power to exclude "half caste" Aboriginal people from missions and stations. The Victorian legislation was the forerunner of the racial segregation policies of other Australian governments from the 1890s.[186]

In more densely settled areas, most Aboriginal people who had lost control of their land lived on reserves and missions, or on the fringes of cities and towns. In pastoral districts the British Waste Land Act of 1848 gave traditional landowners limited rights to live, hunt and gather food on Crown land under pastoral leases. Many Aboriginal groups camped on pastoral stations where Aboriginal men were often employed as shepherds and stockmen. These groups were able to retain a connection with their lands and maintain aspects of their traditional culture.[187]

Foreign pearlers moved into the Torres Strait Islands from 1868 bringing exotic diseases which halved the Indigenous population. In 1871, the London Missionary Society began operating in the islands and most Torres Strait Islanders converted to Christianity which they considered compatible with their beliefs. Queensland annexed the islands in 1879.[188]

From autonomy to federation

Colonial self-government and the gold rushes

Towards representative government

Imperial legislation in 1823 had provided for a Legislative Council nominated by the governor of New South Wales, and a new Supreme Court, providing additional limits to the power of governors. A number of prominent colonial figures, including William Wentworth. campaigned for a greater degree of self-government, although there were divisions about the extent to which a future legislative body should be popularly elected. Other issues included traditional British political rights, land policy, transportation and whether a large population of convicts and former convicts could be trusted with self-government. The Australian Patriotic Association was formed in 1835 by Wentworth and William Bland to promote representative government for New South Wales.[189][190][191]

Transportation to New South Wales was suspended in 1840. In 1842 Britain granted limited representative government to the colony by reforming the Legislative Council so that two-thirds of its members would be elected by male voters. However, a property qualification meant that only 20 per cent of males were eligible to vote in the first Legislative Council elections in 1843.[192]

The increasing number of free settlers and people born in the colonies led to further agitation for liberal and democratic reforms.[193] In the Port Phillip District there was agitation for representative government and independence from New South Wales.[194] In 1850, Britain granted Van Diemen's Land, South Australia and the newly created colony of Victoria semi-elected Legislative Councils on the New South Wales model. [195]

The gold rushes of the 1850s

In February 1851, Edward Hargraves discovered gold near Bathurst, New South Wales. Further discoveries were made later that year in Victoria, where the richest gold fields were found. New South Wales and Victoria introduced a gold mining licence with a monthly fee, the revenue being used to offset the cost of providing infrastructure, administration and policing of the goldfields.[196]

The gold rush initially caused inflation and labour shortages as male workers moved to the goldfields. Immigrants als poured in from Britain, Europe, the United States and China. The Australian population increased from 430,000 in 1851 to 1,170,000 in 1861. Victoria became the most populous colony and Melbourne the largest city.[197][198]

Chinese migration was a particular concern for colonial officials due to the widespread belief that it represented a danger to white Australian living standards and morality. Colonial governments responded by imposing taxes and restrictions on Chinese migrants and residents. Anti-Chinese riots erupted on the Victorian goldfields in 1856 and in New South Wales in 1860.[199]

The Eureka stockade

Faced with increasing competition, Victorian miners increasingly complaint about the licence fee, corrupt and heavy-handed officials, and the lack of voting rights for itinerant miners. Protests intensified in October 1854 when three miners were arrested following a riot at Ballarat. Protesters formed the Ballarat Reform League to support the arrested men and demanded manhood suffrage, reform of the mining licence and administration, and land reform to promote small farms. Further protests followed and protesters built a stockade on the Eureka Field at Ballarat. On 3 December troops overran the stockade, killing about 20 protesters. Five troops were killed and 12 seriously wounded.[200]

Following a Royal Commission, the monthly licence was replaced with a cheaper annual miner's right which gave holders the right to vote and build a dwelling on the goldfields. The administration of the Victorian goldfields was also reformed. The Eureka rebellion soon became a part of Australian nationalist mythology.[201][202]

Self-government and democracy

Elections for the semi-representative Legislative Councils, held in New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and Van Diemen's Land in 1851, produced a greater number of liberal members who agitated for full self-government. In 1852, the British Government announced that convict transportation to Van Diemen's Land would cease and invited the eastern colonies to draft constitutions enabling self-government.[203]

The constitutions for New South Wales, Victoria and Van Diemen's Land (renamed Tasmania in 1856) gained Royal Assent in 1855, that for South Australia in 1856. The constitutions varied, but each created a lower house elected on a broad male franchise and an upper house which was either appointed for life (New South Wales) or elected on a more restricted property franchise. When Queensland became a separate colony in 1859 it immediately became self-governing. Western Australia was granted self-government in 1890.[204]

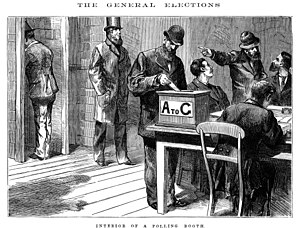

The secret ballot was adopted in Tasmania, Victoria and South Australia in 1856, followed by New South Wales (1858), Queensland (1859) and Western Australia (1877). South Australia introduced universal male suffrage for its lower house in 1856, followed by Victoria in 1857, New South Wales (1858), Queensland (1872), Western Australia (1893) and Tasmania (1900). Queensland excluded Aboriginal males from voting in 1885.[205] In Western Australia a property qualification for voting existed for male Aboriginals, Asians, Africans and people of mixed descent.[204]

Societies to promote women's suffrage were formed in Victoria in 1884, South Australia in 1888 and New South Wales in 1891. The Women's Christian Temperance Union also established branches in most Australian colonies in the 1880s, promoting votes for women and a range of social causes.[206] Female suffrage, and the right to stand for office, was first won in South Australia in 1895.[207] Women won the vote in Western Australia in 1899, with racial restrictions. Women in the rest of Australia only won full rights to vote and to stand for elected office in the decade after Federation, although there were some racial restrictions.[208][209]

The long boom (1860 to 1890)

From the 1850s to 1871 gold was Australia's largest export and allowed the colony to import a range of consumer and capital goods. The increase in population in the decades following the gold rush stimulated demand for housing, consumer goods, services and urban infrastructure.[210]

In the 1860s, New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland and South Australia introduced Selection Acts intended to promote family farms and mixed farming and grazing.[211] Improvements in farming technology and the introduction of crops adapted to Australian conditions eventually led to the diversification of rural land use. The expansion of the railways from the 1860s allowed wheat to be cheaply transported in bulk, stimulating the development of a wheat belt from South Australia to Queensland.[212][213]

The period 1850 to 1880 saw a revival in bushranging. The resurgence of bushranging from the 1850s drew on the grievances of the rural poor (several members of the Kelly gang, the most famous bushrangers, were the sons of impoverished small farmers). The exploits of Ned Kelly and his gang garnered considerable local community support and extensive national press coverage at the time. After Kelly's capture and execution for murder in 1880 his story inspired numerous works of art, literature and popular culture and continuing debate about the extent to which he was a rebel fighting social injustice and oppressive police, or a murderous criminal.[214]

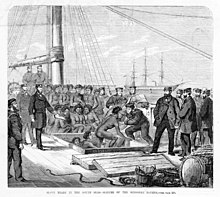

The Pacific Slave trade operated between 1863 to 1904 saw tens of thousands of South Sea Islanders brought to the sugarcane plantations of Queensland either as indentured workers or slaves

By the 1880s half the Australian population lived in towns, making Australia more urbanised than the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada.[215] Between 1870 and 1890 average income per person in Australia was more than 50 per cent higher than that of the United States, giving Australia one of the highest living standards in the world.[216]

The size of the government sector almost doubled from 10 per cent of national expenditure in 1850 to 19 per cent in 1890. Colonial governments spent heavily on infrastructure such as railways, ports, telegraph, schools and urban services. Much of the money for this infrastructure was borrowed on the London financial markets, but land-rich governments also sold land to finance expenditure and keep taxes low.[217][218]

In 1856, building workers in Sydney and Melbourne were the first in the world to win the eight hour working day. The 1880s saw trade unions grow and spread to lower skilled workers and also across colonial boundaries. By 1890 about 20 per cent of male workers belonged to a union, one of the highest rates in the world.[219][220]

Economic growth was accompanied by expansion into northern Australia. Gold was discovered in northern Queensland in the 1860s and 1870s, and in the Kimberley and Pilbara regions of Western Australia in the 1880s. Sheep and cattle runs spread to northern Queensland and on to the Gulf Country of the Northern Territory and the Kimberley region of Western Australia in the 1870s and 1880s. Sugar plantations also expanded in northern Queensland during the same period.[221][222]

From the late 1870s trade unions, Anti-Chinese Leagues and other community groups campaigned against Chinese immigration and low-wage Chinese labour. Following intercolonial conferences on the issue in 1880–81 and 1888, colonial governments responded with a series of laws which progressively restricted Chinese immigration and citizenship rights.[223]

1890s depression

Falling wool prices and the collapse of a speculative property bubble in Melbourne heralded the end of the long boom. A number of major banks suspended business and the economy contracted by 20 per cent from 1891 to 1895. Unemployment rose to almost a third of the workforce. The depression was followed by the "Federation Drought" from 1895 to 1903.[224]

In 1890, a strike in the shipping industry spread to wharves, railways, mines and shearing sheds. Employers responded by locking out workers and employing non-union labour, and colonial governments intervened with police and troops. The strike failed, as did subsequent strikes of shearers in 1891 and 1894, and miners in 1892 and 1896.[225]

The defeat of the 1890 Maritime Strike led trade unions to form political parties. In New South Wales, the Labor Electoral League won a quarter of seats in the elections of 1891 and held the balance of power between the Free Trade Party and the Protectionist Party. Labor parties also won seats in the South Australian and Queensland elections of 1893. The world's first Labor government was formed in Queensland in 1899, but it lasted only a week.[226]

At an Intercolonial Conference in 1896, the colonies agreed to extend restrictions on Chinese immigration to "all coloured races". Labor supported the Reid government of New South Wales in passing the Coloured Races Restriction and Regulation Act, a forerunner of the White Australia Policy. However, after Britain and Japan voiced objections to the legislation, New South Wales, Tasmania and Western Australia instead introduced European language tests to restrict "undesirable" immigrants.[227]

Growth of nationalism

By the late 1880s, a majority of people living in the Australian colonies were native born, although more than 90 per cent were of British and Irish heritage.[228] The Australian Natives Association, campaigned for an Australian federation within the British Empire, promoted Australian literature and history, and successfully lobbied for the 26 January to be Australia's national day.[229]

Many nationalists spoke of Australians sharing common blood as members of the British "race".[230] Henry Parkes stated in 1890, "The crimson thread of kinship runs through us all...we must unite as one great Australian people."[231]

A minority of nationalists saw a distinctive Australian identity rather than shared "Britishness" as the basis for a unified Australia. Some, such as the radical magazine The Bulletin and the Tasmanian Attorney-General Andrew Inglis Clark, were republicans, while others were prepared to accept a fully independent country of Australia with only a ceremonial role for the British monarch.[232]

A unified Australia was usually associated with a white Australia. In 1887, The Bulletin declared that all white men who left the religious and class divisions of the old world behind were Australians.[233] A white Australia also meant the exclusion of cheap Asian labour, an idea strongly promoted by the labour movement.[234]

The growing nationalist sentiment in the 1880s and 1890s was associated with the development of a distinctively Australian art and literature. Artists of the Heidelberg School such as Arthur Streeton, Frederick McCubbin and Tom Roberts followed the example of the European Impressionists by painting in the open air. They applied themselves to capturing the light and colour of the Australian landscape and exploring the distinctive and the universal in the "mixed life of the city and the characteristic life of the station and the bush".[235]

In the 1890s Henry Lawson, Banjo Paterson and other writers associated with The Bulletin produced poetry and prose exploring the nature of bush life and themes of independence, stoicism, masculine labour, egalitarianism, anti-authoritarianism and mateship. Protagonists were often shearers, boundary riders and itinerant bush workers. In the following decade Lawson, Paterson and other writers such as Steele Rudd, Miles Franklin, and Joseph Furphy helped forge a distinctive national literature. Paterson's ballad "The Man from Snowy River" (1890) achieved popularity, and his lyrics to the song "Waltzing Matilda" (c. 1895) helped make it the unofficial national anthem for many Australians.[236]

Federation movement

Growing nationalist sentiment coincided with business concerns about the economic inefficiency of customs barriers between the colonies, the duplication of services by colonial governments and the lack of a single national market for goods and services.[237] Colonial concerns about German and French ambitions in the region also led to British pressure for a federated Australian defence force and a unified, single-gauge railway network for defence purposes.[238]

A Federal Council of Australasia was formed in 1885 but it had few powers and New South Wales and South Australia declined to join.[239]

An obstacle to federation was the fear of the smaller colonies that they would be dominated by New South Wales and Victoria. Queensland, in particular, although generally favouring a white Australia policy, wished to maintain an exception for South Sea Islander workers in the sugar cane industry.[240]

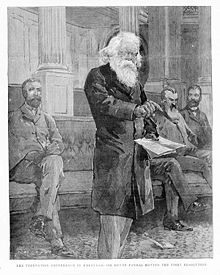

Another major barrier was the free trade policies of New South Wales which conflicted with the protectionist policies dominant in Victoria and most of the other colonies. Nevertheless, the NSW premier Henry Parkes was a strong advocate of federation and his Tenterfield Oration in 1889 was pivotal in gathering support for the cause.[241]

In 1891, a National Australasian Convention was held in Sydney, with all the colonies and New Zealand represented. A draft constitutional Bill was adopted, but the worsening economic depression and opposition in colonial parliaments delayed progress.[242]

Citizen Federation Leagues were formed, and at a conference in Corowa in July 1893 they developed a new plan for federation involving a constitutional convention with directly elected delegates and a referendum in each colony to endorse the proposed constitution. The new NSW premier, George Reid, endorsed the "Corowa plan" and in 1895 convinced the majority of other premiers to adopt it.[243]

All of the colonies except Queensland sent representatives to a constitutional convention which held sessions in 1897 and 1898. The convention drafted a proposed constitution for a Commonwealth of federated states under the British Crown.[244]

Referendums held in 1898 resulted in solid majorities for the constitution in Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania. However, the referendum failed to gain the required majority in New South Wales.[245] The premiers of the other colonies agreed to a number of concessions to New South Wales (particularly that the future Commonwealth capital would be located in that state), and in 1899 further referendums were held in all the colonies except Western Australia. All resulted in yes votes.[246]

In March 1900, delegates were dispatched to London, including leading federation advocates Edmund Barton and Alfred Deakin. Following negotiations with the British government, the federation Bill was passed by the imperial parliament on 5 July 1900 and gained Royal Assent on 9 July. Western Australia subsequently voted to join the new federation.[247]

From federation to war (1901—1914)

The Commonwealth of Australia was proclaimed by the Governor-General, Lord Hopetoun on 1 January 1901, and Barton was sworn in as Australia's first prime minister.[247] The first Federal elections were held in March 1901 and resulted in a narrow plurality for the Protectionist Party over the Free Trade Party with the Australian Labor Party (ALP) polling third. Labor declared it would support the party which offered concessions to its program, and Barton's Protectionists formed a government, with Deakin as Attorney-General.[248]

The Immigration Restriction Act 1901 was one of the first laws passed by the new Australian parliament. This centrepiece of the White Australia policy, the act used a dictation test in a European language to exclude Asian migrants, who were considered a threat to Australia's living standards and majority British culture.[249][250]

With federation, the Commonwealth inherited the small defence forces of the six former Australian colonies. By 1901, units of soldiers from all six Australian colonies had been active as part of British forces in the Boer War. When the British government asked for more troops from Australia in early 1902, the Australian government obliged with a national contingent. Some 16,500 men had volunteered for service by the war's end in June 1902.[251][252]

In 1902, the government introduced female suffrage in the Commonwealth jurisdiction, but at the same time excluded Aboriginal people from the franchise unless they already had the vote in a state jurisdiction.[253]

The government also introduced a tariff on imports, designed to raise revenue and protect Australian industry.[254] However, disagreements over industrial relations legislation led to the fall of Deakin's Protectionist government in April 1904 and the appointment of the first national Labor government under prime minister Chris Watson. The Watson government itself fell in April and a Free Trade government under prime minister Reid successfully introduced legislation for a Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Court to settle interstate industrial disputes.[255]

In July 1905, Deakin formed a Protectionist government with the support of Labor. The new government embarked on a series of social reforms and a program dubbed "new protection" under which tariff protection for Australian industries would be linked to their provision of "fair and reasonable" wages. In the Harvester case of 1907, H. B. Higgins of the Conciliation and Arbitration Court set a basic wage based on the needs of a male breadwinner supporting a wife and three children. By 1914 the Commonwealth and all the states had introduced systems to settle industrial disputes and fix wages and conditions.[256][257]

The base of the Labor Party was the Australian Trade Union movement which grew from under 100,000 members in 1901 to more than half a million in 1914.[258] The party also drew considerable support from clerical workers, Catholics and small farmers.[259] In 1905, the Labor party adopted objectives at the federal level which included the "cultivation of an Australian sentiment based upon the maintenance of racial purity" and "the collective ownership of monopolies". In the same year, the Queensland branch of the party adopted an overtly socialist objective.[260]

After the December 1906 elections Deakin's Protectionist government remained in power, but following the passage of legislation for old age pensions and a new protective tariff in 1908, Labor withdrew its support for the government. In November, Andrew Fisher became the second Labor prime minister. In response, opposition parties formed an anti-Labor coalition and Deakin became prime minister in June 1909.[261]

In the elections of May 1910, Labor won a majority in both houses of parliament and Fisher again became prime minister. The Labor government introduced a series of reforms including a progressive land tax (1910), invalid pensions (1910) and a maternity allowance (1912). The government established the Commonwealth Bank (1911) but referendums to nationalise monopolies and extend Commonwealth trade and commerce powers were defeated in 1911 and 1913. The Commonwealth took over responsibility for the Northern Territory from South Australia in 1911.[262][263] The government increased defence spending, expanding the system of compulsory military training which had been introduced by the previous government and establishing the Royal Australian Navy.[264][265][266]

The new Commonwealth Liberal Party won the May 1913 elections and former Labor leader Joseph Cook became prime minister. The Cook government's attempt to pass legislation abolishing preferential treatment for union members in the Commonwealth Public Service triggered a double dissolution of parliament. Labor comfortably won the September 1914 elections and Fisher resumed office.[267]

The prewar period saw strong growth in the population and economy. The economy grew by 75 per cent, with rural industries, construction, manufacturing and government services leading the way.[268] The population increased from four million in 1901 to five million in 1914. From 1910 to 1914 just under 300,000 migrants arrived, all white, and almost all from Britain.[269]

First World War

Australia at war 1914–18

When the United Kingdom declared war on Germany on 4 August 1914, the declaration automatically involved all of Britain's colonies and dominions.[270] Both major parties offered Britain 20,000 Australian troops. As the Defence Act 1903 precluded sending conscripts overseas, a new volunteer force, the Australian Imperial Force (AIF), was raised to meet this commitment.[271][272]

Public enthusiasm for the war was high, and the initial quota for the AIF was quickly filled. The troops left for Egypt on 1 November 1914, one of the escort ships, HMAS Sydney, sinking the German cruiser Emden along the way. Meanwhile, in September, a separate Australian expeditionary force had captured German New Guinea.[273]

After arriving in Egypt, the AIF was incorporated into an Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC). The Anzacs formed part of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force with the task of opening the Dardanelles to allied battleships, threatening Constantinople, the capital of the Ottoman Empire which had entered the war on the side of the Central Powers. The Anzacs, along with French, British and Indian troops, landed on the Gallipoli peninsula on 25 April 1915. The Australian and New Zealand position at Anzac Cove was vulnerable to attack and the troops suffered heavy losses in establishing a narrow beachhead. After it had become clear that the expeditionary force would be unable to achieve its objectives, the Anzacs were evacuated in December, followed by the British and French in early January.[274][275]

The Australians suffered about 8,000 deaths in the campaign.[276] Australian war correspondents variously emphasised the bravery and fighting qualities of the Australians and the errors of their British commanders. The 25 April soon became an Australian national holiday known as Anzac Day, centring on themes of "nationhood, brotherhood and sacrifice".[277][278]

In 1916, five infantry divisions of the AIF were sent to the Western Front. In July 1916, at Fromelles, the AIF suffered 5,533 casualties in 24 hours, the most costly single encounter in Australian military history.[279] Elsewhere on the Somme, 23,000 Australians were killed or wounded in seven weeks of attacks on German positions. In Spring 1917, Australian troops suffered 10,000 casualties at the First Battle of Bullecourt and the Second Battle of Bullecourt. In the summer and autumn of 1917, Australian troops also sustained heavy losses during the British offensive around Ypres. Overall, almost 22,000 Australian troops were killed in 1917.[280]

In November 1917 the five Australian divisions were united in the Australian Corps, and in May 1918 the Australian general John Monash took over command. The Australian Corps was heavily involved in halting the German Spring Offensive of 1918 and in the allied counter-offensive of August that year.[281]

In the Middle East, the Australian Light Horse brigades were prominent at the Battle of Romani in August 1916. In 1917, they participated in the allied advance through the Sinai Peninsula and into Palestine. In 1918, they pressed on through Palestine and into Syria in an advance that led to the Ottoman surrender on 31 October.[282]

By the time the war ended on 11 November 1918, 324,000 Australians had served overseas. Casualties included 60,000 dead and 150,000 wounded—the highest casualty rate of any allied force. Australian troops also had higher rates of unauthorised absence, crime and imprisonment than other allied forces.[283]

The home front

In October 1914, the Fisher Labor government introduced the War Precautions Act which gave it the power to make regulations "for securing the public safety and defence of the Commonwealth".[284] After Billy Hughes replaced Fisher as prime minister in October 1915, regulations under the act were increasingly used to censor publications, penalise public speech and suppress organisations that the government considered detrimental to the war effort.[285][286] Anti-German leagues were formed and 7,000 Germans and other "enemy aliens" were sent to internment camps during the war.[287][285]

The economy contracted by 10 per cent during the course of hostilities. Inflation rose in the first two years of war and real wages fell.[288][289] Lower wages and perceptions of profiteering by some businesses led, in 1916, to a wave of strikes by miners, waterside workers and shearers.[290]

Enlistments in the military also declined, falling from 35,000 a month at its peak in 1915 to 6,000 a month in 1916.[291] In response, Hughes decided to hold a referendum on conscription for overseas service. Following the narrow defeat of the October 1916 conscription referendum, Hughes and 23 of his supporters left the parliamentary Labor party and formed a new Nationalist government with the former opposition. The Nationalists comfortably won the May 1917 elections and Hughes continued as prime minister.[292]