Отель Пенсильвания

| Отель Пенсильвания | |

|---|---|

Отель Пенсильвания в апреле 2019 года | |

| |

| General information | |

| Address | 401 Seventh Avenue, New York, NY |

| Coordinates | 40°44′59″N 73°59′26″W / 40.74972°N 73.99056°W |

| Opening | January 25, 1919 |

| Closed | April 1, 2020 |

| Owner | Vornado Realty Trust |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 22 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | McKim, Mead & White |

| Developer | Pennsylvania Railroad |

| Other information | |

| Number of rooms | 2,200 at opening, 1,704 at closing |

| Website | |

| hotelpenn | |

Отель «Пенсильвания» — отель на Седьмой авеню, 401 (Пенн Плаза, 15) на Манхэттене , напротив вокзала Пенсильвания и Мэдисон-Сквер-Гарден в Нью-Йорке . Открытый в 1919 году, когда-то это был самый большой отель в мире. Он оставался четвертым по величине в Нью-Йорке до тех пор, пока не закрылся навсегда 1 апреля 2020 года. После нескольких лет безуспешных боев за сохранение он был снесен в 2023 году. На месте отеля появится Penn Plaza, 15 68-этажная башня .

Пенсильванская железная дорога объявила о строительстве отеля на Седьмой авеню в 1916 году, через шесть лет после завершения строительства первоначального нью-йоркского Пенсильванского вокзала . Отель Pennsylvania был официально открыт 25 января 1919 года, и первоначально им управлял Эллсуорт М. Статлер из сети Statler Hotels . Statler Hotels согласилась купить недвижимость в 1948 году, и отель Pennsylvania был переименован в Hotel Statler . Отель стал The Statler Hilton в 1958 году, через четыре года после того, как его приобрела Hilton Hotels & Resorts .

Девелопер Уильям Зекендорф-младший купил Statler Hilton в 1979 году, после чего отелем управляла компания Dunfey Hotels и он был переименован в New York Statler . В 1983 году отель был снова продан совместному предприятию, переименованному в New York Penta , и подвергся капитальному ремонту. В 1990-х годах хостел несколько раз переименовывался и в конечном итоге стал отелем «Пенсильвания». Vornado Realty Trust и Онг Бенг Сенг купили отель в 1997 году, хотя позже Vornado выкупила долю Онга. Vornado несколько раз рассматривал возможность закрытия и сноса отеля «Пенсильвания», прежде чем окончательно закрыть его в 2020 году.

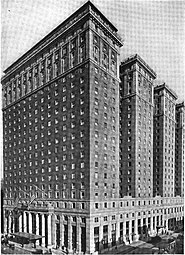

The Hotel Pennsylvania was designed by McKim, Mead & White. It was 22 stories high, including the street level and the rooftop; there was also a three-story penthouse. The first four stories occupied nearly the entire site and had an Indiana Limestone facade. Above the fourth story, the facade was made of buff-colored and gray brick, and the hotel building was divided into four wings that faced south toward 32nd Street. The public rooms were largely on the lower floors and included a ground-level lobby, a restaurant called the Cafe Rouge, and a ballroom level. The hotel originally had 2,200 guestrooms, which started at the fifth story. The Hotel Pennsylvania used the prominent and memorable telephone number, PEnnsylvania 6-5000 (736–5000), which inspired the lyrics and title of the song "Pennsylvania 6-5000".

History

[edit]In the late 19th century, the site around the Hotel Pennsylvania was mostly residential, with three- and four-story row houses and four- and five-story tenements.[1] The Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) had completed the original Pennsylvania Station in Midtown Manhattan, New York City, in 1910.[2] In conjunction with the railroad station's opening, the PRR had acquired all lots on the eastern side of Seventh Avenue between 31st and 33rd Streets, directly east of the station, though the railroad did not initially develop the sites.[3] The northern site, which became the Hotel Pennsylvania, measured 400 feet (120 m) long on 32nd and 33rd Streets and 197.5 feet (60.2 m) long on Seventh Avenue.[4][5] The southern site was sold in 1921 to Equitable Holdings, which developed 11 Penn Plaza there.[3]

Development

[edit]In January 1916, the PRR announced that it would build a 1,000-room hotel on the Seventh Avenue site for about $9 million; the hotel itself would cost $5 million, while the furnishings and land would cost $4 million.[6][7] The hotel was to be designed by McKim, Mead & White,[6][7][4] which had also designed the original Pennsylvania Station.[8] The planned hotel was cited as being either ten[6] or twelve stories.[7][4] The PRR hoped that the hotel's construction would spur development in the surrounding area, particularly after the Interborough Rapid Transit Company's 34th Street–Penn Station subway station opened in two years.[4] In addition, the site was near several major attractions, including multiple Broadway theaters, department stores, and hotels.[9] The PRR wished to compete with the New York Central Railroad, which was concurrently constructing the Commodore Hotel near Grand Central Terminal, as well as attract business travelers and professional conventions.[10]

The PRR hired the George A. Fuller Company as the hotel's general contractor in March 1916;[5][11] the Fuller Company constructed the Pennsylvania and the Commodore simultaneously.[12] The PRR also hired Post & McCord as the steel contractor.[13] The hotel's cost had increased to $11 million by that April; this cost included $7.5 million for the actual hotel, $2.5 million for the land, and $1 million for furnishings.[14] The PRR filed plans for a 20-story hotel in May 1916, to be designed by McKim, Mead & White.[15][16] Initially, the PRR leased the hotel to Franklin J. Matchette for 21 years.[14] In December 1916, Ellsworth M. Statler of the Statler Hotels chain purchased a controlling interest in Matchette's lease.[17][18] Matchette and Statler formed the New York Hotel Statler Company, which issued stock to finance the hotel's construction. Both men initially had a 50 percent stake in the company, but Matchette turned over a 25 percent stake to Statler shortly after the company was established.[19]

The PRR announced in December 1916 that the hotel would be named the Hotel Pennsylvania and that construction of the hotel's foundations would commence the next month.[20] Matchette's firm, the Servidor Company, also provided the hotel's original equipment and furnishings including the doors for each guestroom.[21] The hotel's construction required over 18,000 short tons (16,000 long tons; 16,000 t) of steel and nine million bricks,[22] although some of these materials were difficult to obtain because of World War I restrictions.[12] During construction, in July 1917, one worker was killed by a falling steel girder.[23] In addition, the hotel's dynamo room caught fire and then exploded in April 1918,[24][25] damaging the facade and a sidewalk shed around the hotel.[26] That June, Statler Hotels issued $3 million in bonds to finance the hotel's construction.[27][28] Roy Carruthers was hired as the hotel's first general manager in late 1918.[29] Statler planned to rent rooms within a relatively narrow price range, saying: "I am working on the assumption that New York wants a first-class hotel where the ratio between the minimum and maximum rates will be nearer together than is usually the case."[30]

Statler operation

[edit]The Hotel Pennsylvania was formally dedicated on January 25, 1919.[31][32] On that day, 3,000 spectators viewed the hotel, and 2,000 people ate in the main dining room.[31] The Pennsylvania's 2,200 guest rooms and baths made it the largest hotel in the world at the time; it was slightly larger than the Commodore, which opened a few days later on January 28.[33][34] However, only 1,200 rooms were available when the hotel opened,[34] and some of the public rooms were still incomplete.[33] Thirty days after the hotel opened, Statler Hotels started paying $200,000 in annual rent for the site; this amounted to five percent of the hotel building's assessed value of $4 million.[35][36] In addition, Statler would pay six percent of the construction cost each year.[37] One architectural critic wrote that the hotel's completion "marked a great step forward in hotel efficiency", as it had an efficient design that was not overly ornate.[38]

1920s and 1930s

[edit]In the hotel's early years, it hosted such events as a charity event for the Jewish Federations of North America,[39] a meeting for veterans,[40] and a showcase of radio equipment.[41] Employees established a newspaper called The Pennsylvania Register in 1921, which according to The Christian Science Monitor was "said to be the only daily newspaper published in a hotel".[42] In 1922, the Pennsylvania became the first hotel on the East Coast of the United States to receive radio telegraph service.[43] The Pennsylvania remained the world's largest hotel until the late 1920s,[44] when the New Yorker Hotel was constructed.[45]

E. M. Statler managed the hotel until January 1928, when Frank A. Duggan took over as the hotel's manager.[46] After Duggan left for the Hotel McAlpin that April, Statler again became the hotel's manager,[47] although Statler died two weeks later.[48] Following Statler's death, Leo Molony was appointed as the hotel's manager.[49] In 1929, Matchette filed two lawsuits in the New York Surrogate's Court, seeking a combined $10 million in damages from the New York Hotel Statler Company Inc. and Ellsworth Statler's estate. Matchette claimed that Statler had given excessive salaries to himself and his family members and that Statler had mismanaged the hotel's construction.[19] Matchette filed four lawsuits in the New York Supreme Court in 1930, seeking $17.5 million in damages from Statler's estate, the Hotel Statler Company, and the directors of the hotel company.[50][51]

PRR received a $5 million mortgage loan from Prudential Insurance in 1933, replacing two loans that the hotel had received in 1917 and 1923.[52] The Automobile Club of New York moved its headquarters to the hotel in 1933,[53] and the hotel's Madhattan Room, decorated with cartoons depicting life in New York City, opened the same year.[54] The hotel continued to host large events in the 1930s, including ping-pong matches,[55] home equipment exhibitions,[56] National Board of Review conferences,[57] and architects' conventions.[58] Molony managed the hotel until January 1937, when Duggan replaced him.[59] James H. McCabe became the hotel's manager that June after Duggan was promoted to a vice president within Statler Hotels.[60]

1940s and 1950s

[edit]Statler Hotels agreed to buy the property outright from the Pennsylvania Railroad on June 30, 1948.[61][62] Statler Hotels president Arthur F. Douglas officially took over the hotel that August,[63] paying approximately $13 million.[64] The Statler chain renovated the hotel's main dining room, the Cafe Rouge, that year.[65] The Pennsylvania was renamed the Hotel Statler on January 1, 1949.[66][67] The hotel's managers had supported the name change because the Pennsylvania had hosted Statler Hotels' main offices for many years.[64] Statler Hotels spent $200,000 on replacing items with the hotel's old name or initial, including nearly 800,000 pieces of linen, 127,000 pieces of china, and 134,000 pieces of silver.[64][68] The hotel also replaced signs in subway stations and sent notices to 300,000 people who held Statler-branded credit cards. The hotel was branded as the "Hotel Statler, formerly the Hotel Pennsylvania" for two years after the name change.[68]

Mid-to-late 20th century

[edit]Hilton operation

[edit]In August 1954, Conrad Hilton acquired a controlling interest in all 17 of Statler Hotels' properties, including the Hotel Statler.[69][70] Hilton paid an estimated $76 million for the controlling stake.[70] At the time, Hilton already owned multiple large hotels in New York City.[71] Hilton was installing air conditioners in all of the hotel's guestrooms by early 1956.[72] The hotel became The Statler Hilton in 1958.[73] Over the years, the hotel was reduced to 1,592 rooms. Many of the smaller rooms had been combined to create larger suites with alcoves for businessmen.[74] In 1960, Hilton renovated the hotel at a cost of $1 million. The work included the reduction of the original two-story lobby to one story, to add more meeting space.[75]

Zeckendorf and Abelco/Penta operation

[edit]In January 1979, Hilton Hotels agreed to sell the New York Statler Hilton to developer William Zeckendorf Jr. for $24 million.[74][76][77] At the time, the hotel had 1,756 rooms.[77] Hilton completed its sale in May 1979,[78] recording an estimated after-tax profit of $8.8 million.[79] The hotel was renamed the New York Statler and was operated by Dunfey Hotels, a division of Aer Lingus.[77][80] Dunfey Hotels sought to market the hotel to business travelers and conventions.[80] During April 1981, the hotel was affected by two fires in as many weeks; the second fire caused damage to the grand ballroom.[81]

The hotel was sold again in August 1983 for $46 million. A half-interest in the hotel was acquired by Abelco, an investment group consisting of developers Elie Hirschfeld, Abraham Hirschfeld, and Arthur G. Cohen, and the other half was bought by the Penta Hotels chain, a joint venture of British Airways, Lufthansa, and Swissair.[82][83] The new owners renamed the hotel the New York Penta.[83][84][85] Anna Quindlen of The New York Times Magazine wrote: "Real New Yorkers, who will be damned if they will call Sixth Avenue Avenue of the Americas, still call it the Statler."[86] The owners renovated the facade and the public spaces,[82] creating two restaurant spaces within the hotel. They also refurbished its 1,705 guestrooms, combining some of the rooms to create larger suites.[84] The project was expected to cost $23 million and was timed to coincide with the completion of Javits Center on the west side of Manhattan.[87] Despite the cost of the renovation, the Abelco/Penta partnership planned to retain the hotel's $100 nightly room rates.[85]

A grand reopening celebration for the Penta was held from December 7 to 10, 1985.[88] It was one of two major structures to open on the west side of Midtown Manhattan that month, the other being the Axa Equitable Center.[89] The Penta's owners hired James Parry Inc. as the hotel's marketing agency. When James Parry Inc. shuttered in 1988, the hotel's partners hired Kirshenbaum & Bond as the Penta Hotel's new agency.[90]

Ramada and Best Western operation

[edit]In 1991, the Hirschfelds acquired the Penta Hotels chain's stake in the hotel.[91][92] The hostelry was renamed the Ramada Pennsylvania Hotel in April 1991, two weeks after the Penta chain exited the venture.[92] Hampton Hotels Co. took over the hotel's operation in 1993.[91][93] The hotel remained the third-largest in New York City, after the New York Hilton Midtown and the Sheraton New York Times Square Hotel. Hampton Hotels spent $15 million on renovations over the next two years.[91] In advance of the 1992 Democratic National Convention, the hotel's owners spent $4 million to $6 million on renovations, including a refurbishment of the lobby.[94] By the early 1990s, celebrities no longer frequented the Ramada Pennsylvania, which tried to attract guests by offering discounts for guests' pets.[95] A Sports Authority store at the hotel's base was announced in 1993,[96] and it opened the following year, within the hotel's former bar and mezzanine.[97]

The board of directors of the Best Western hotel chain voted in November 1993 to rename the hotel New York's Hotel Pennsylvania, pending an inspection of the hotel's quality.[93] The Image Group leased the hotel's ballrooms in February 1995 for twenty years, converting the seldom-used ballrooms into television studios.[98][99] Best Western also added a business center to the hotel the same year, equipped with fax machines, computers, and televisions.[100] At that point, the Pennsylvania no longer had any restaurants, and guest-service directories instead listed restaurants near the hotel.[101] Hirschfeld rebranded the hotel as the Hotel Pennsylvania in 1995,[91] and he placed the hotel for sale in April 1996 for $150 million.[102] Hirschfeld had installed Lover's Bench, a bronze sculpture depicting a nude couple and a partly clothed woman, outside the Pennsylvania's entrance. The sculpture was ultimately removed in 1997.[103]

Vornado acquisition

[edit]Planet Hollywood plans

[edit]In June 1997, Vornado Realty Trust and Singaporean developer Ong Beng Seng agreed to buy the hotel for $159 million.[104] Vornado and Ong sought to convert the Pennsylvania to a sports-themed hotel operated by Planet Hollywood (in which Ong held a large stake),[105] citing the hotel's proximity to Madison Square Garden.[106] The plans were complicated by the fact that the Riese family held a long-term lease on commercial space at the Pennsylvania.[105][107] At the end of June 1997, Vornado paid $75 million to terminate the Rieses' lease and acquire several buildings that the family owned nearby.[105] Vornado and Ong finalized their acquisition on September 25, 1997, with plans to convert the Pennsylvania into Planet Hollywood's first Official All Star Hotel.[108][109] Vornado and Ong would each own a 40 percent stake in the hotel, while Planet Hollywood would own 20 percent.[109][110] The Official All Star Hotel plan was announced amid a revival in tourism in New York City,[111] as well as demand for office space in Penn Plaza.[112] The hotel's renovation was expected to cost about $200 million.[113] Vornado would operate about 400,000 square feet (37,000 m2) of commercial and office space at the hotel.[109]

The planned conversion did not happen, as Planet Hollywood suffered major financial losses in the late 1990s.[114][115] Vornado bought out Ong's 40 percent stake in the hotel in early 1998 for $70 million,[116][117] paying $22 million in cash and taking on $48 million in debt.[117] When Ong decided to sell his stake, many Asian companies were selling off real estate in New York City.[118] Vornado Realty Trust transferred the hotel's management to a subsidiary, Vornado Operating Company, in October 1998 because of regulations concerning non-real-estate holdings of real estate investment trusts.[119] Vornado then acquired the remaining 20 percent stake from Planet Hollywood in August 1999 for $42 million, paying $18 million in cash and assuming $24 million in debt.[114][115] Vornado thus obtained full ownership of the hotel.[104][114] The Planet Hollywood transaction valued the hotel at $216 million.[104] By late 1999, to attract business travelers, the Hotel Pennsylvania was advertising rooms at $150 to $300 per night.[120]

2000s

[edit]As early as 2001, a Lehman Brothers analyst said that Vornado officials were considering replacing the hotel with a 50- to 60-story tower.[121] Through the 2000s, the hotel remained popular enough that its managers trademarked the slogan "World's Most Popular Hotel" in 2002.[122] However, the hotel had become noticeably rundown, and guests reported bedbug infestations, darkened windows, and dirty carpets, among other things. By the mid-2000s, Vornado officials said the hotel was merely "a placeholder, sort of like a parking lot".[122][123] Observer described the hotel as having "devolved into a cheap, decrepit tourist trap more commonly associated with reported bedbug attacks than big-band nostalgia".[124] The hotel was divided into two sections by then: the main hotel and the more upscale Penn 5000 Club.[125] Vornado also rented out some of the hotel's space to small businesses during the 2000s,[126] and the T. R. Engle Group gradually renovated the hotel's lobby and rooms during this decade.[127] As part of the planning process for the 7 Subway Extension, in 2003, city and state officials determined that the Hotel Pennsylvania was eligible for official landmark protections on the city, state, and national levels.[10]

With the redevelopment of west Midtown in the mid-2000s, the Hotel Pennsylvania was again being considered as a prime site for redevelopment.[128] In early 2007, Vornado announced plans to demolish the hotel and develop the 15 Penn Plaza skyscraper there,[44][129] as part of a redevelopment of the area around Penn Station.[130] Vornado intended to complete the 2,500,000-square-foot (230,000 m2) building by 2011,[131][132] marketing the tower to financial tenants.[129] At the time, there was little interest in protecting the hotel as a landmark.[124] Investment firm Merrill Lynch & Co. announced plans to relocate from lower Manhattan to the skyscraper that October.[133][134] Had the hotel been demolished at that time, Vornado would have been required to maintain a "museum-quality" exhibit of the Hotel Pennsylvania's history in the new building's lobby.[135] Ultimately, Merrill Lynch opted to move to the World Financial Center in January 2008,[136][137] in part because of the firm's financial troubles.[138] At a conference call in June 2008, Vornado chairman Steven Roth said he was considering downsizing his planned development or renovating the Hotel Pennsylvania.[139]

The redevelopment plans prompted the staff of 2600: The Hacker Quarterly, a magazine that sponsored biennial HOPE hacker conventions at the hotel, began investigating possible ways to save the hotel from demolition.[140] They were joined by the new Save the Hotel Pennsylvania Foundation (later the Hotel Pennsylvania Preservation Society),[141] whose members included a number of city organizations and politicians to aid in designating the hotel as a landmark, including the Historic Districts Council, Manhattan Community Board 5, and Assemblyman Richard Gottfried.[142] In November 2007, Manhattan Community Board 5 voted 21–8 in support of a landmark designation.[143] Three months later, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) rejected the landmark request.[144] Emmanuel Goldstein of 2600 noted that while people overseas expressed concern over the fate of the hotel:

New Yorkers might not care enough to get involved. The hotel was old; the rooms weren't as big and luxurious as other more modern facilities; and New Yorkers simply weren't in a position to grasp the importance of such a place since they normally don't need cheap and easily accessible hotels if they already live here.[145]

2010s

[edit]In May 2010, the hotel was again in danger of demolition.[146] Manhattan borough president Scott Stringer gave a conditional approval[147][148] overruling Manhattan Community Board 5.[149] The LPC reviewed the hotel's Cafe Rouge for landmark status[150] based on a request by the Hotel Pennsylvania Preservation Society,[141] but on October 22, 2010, the LPC declined to designate the cafe as a landmark.[151] On July 14, 2010, the New York City Department of City Planning voted unanimously in favor of the construction of the tower.[152] On August 23, 2010, the NYC Council voted to approve the proposed Uniform Land Use Review Procedure submitted by the building owners.[153][3] In December 2011, Vornado announced a delay in the demolition of the hotel because it was financially infeasible to do so at the moment.[154] Steven Roth said in March 2013 that he wanted to renovate the hotel instead of demolishing it.[155][156]

By 2014, Vornado was again looking to develop a skyscraper on the Hotel Pennsylvania's site.[157][158] Due to uncertainty over the site's future, Roth opted not to renovate the hotel during the mid-2010s.[158] In the hotel's final years, the mezzanine levels above the lobby were operated as a separate business, the Penn Plaza Pavilion, a series of raw spaces used as function facilities. They were the site of numerous trade shows and conventions, including the annual Big Apple Comic Con.[159] The guestrooms were frequented by students and shoppers who sought discounted room rates.[160]

In March 2018, Vornado renewed special permits from the City Planning Commission to develop 15 Penn Plaza on the Hotel Pennsylvania's site. In an April 2018 letter to investors, Roth mentioned the demolition and 15 Penn skyscraper plan as a continued option, but also described Vornado as being at "a tipping point" with regard to redeveloping the Pennsylvania into a "giant convention/entertainment hotel".[161] In June 2019, Vornado unsuccessfully tried to lure Facebook to rent space in the proposed office building, with a new design done by Rafael Viñoly.[162][163][164]

Closure and demolition

[edit]The hotel was forced to close in April 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City.[165][166] Seeing an opportunity to redevelop the site, Steven Roth again contemplated closing the hotel permanently.[165] Roth announced plans in April 2021 to replace the hotel with a skyscraper,[167][168] now known as Penn15.[169] According to Roth, "the hotel math has deteriorated significantly over the last five years", and the benefits of continuing to operate the hotel were outweighed by the drawbacks of maintenance, taxes, and lack of demand.[170] Several groups, such as the Hotel Trades Council, supported the plans for redeveloping the Pennsylvania's site.[171] By then, the hotel had been neglected for several years. Christopher Bonanos of Curbed wrote: "Architecturally, it is like a lot of early-20th-century midsize hotels and office buildings around the city, only larger; it is surely a better-quality example from its period [...] Even if you're a hardcore preservationist, your energies might be better spent elsewhere."[160] The author and former landmarks commission member Roberta Gratz said, "If anyone thinks that another office tower is more useful than a creatively repurposed hotel as big and beautiful as the Pennsylvania, I don't know what to say."[172]

In late 2021, International Content Liquidations finished selling the hotel's contents in preparation for demolition.[173] Items for sale included chandeliers and lighting, ornate staircase railings, guest room furniture, unused mattresses and linens, televisions, the entirety of the hotel's fitness center and commercial kitchens, banquet tables and chairs, and the original guest room doors.[174] Some artifacts were salvaged by the Hotel Pennsylvania Preservation Society during this time. The hotel's demolition began in January 2022, and the main entrance was converted to a turnstile for demolition workers.[175] The Pennsylvania caught fire on February 7, 2022, while it was being demolished.[166][176] By the middle of that year, demolition of the hotel had resumed;[177] the hotel had been deconstructed to the 12th floor by March 2023.[172] The hotel was supposed to have been completely demolished by July 2023,[178] but was still partially standing by that August.[179] In July 2023, Steven Lepore of the Hotel Pennsylvania Preservation Society successfully negotiated with the owners to salvage an 8-foot (2.4 m) section of original staircase railing from the rear entrance lobby.[173] This side lobby had a three story staircase leading to the former grand ballroom. By October 2023, the entire above ground structure was gone. The site remains a vacant lot.[173][180]

Architecture

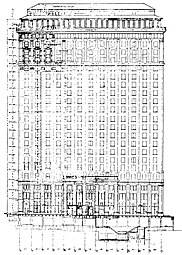

[edit]The Hotel Pennsylvania was designed by William Symmes Richardson of McKim, Mead & White.[181] The hotel measured 22 stories high, including the street level and the rooftop; there was also a three-story penthouse.[182][183] The hotel's design was intended not only to complement that of the original Penn Station, which was demolished in 1963, but also that of the General Post Office one block west, which still exists.[10]

Form and facade

[edit]The first four stories occupied nearly the entire site.[182][184] The hotel was set back 15 feet (4.6 m) from the property line on Seventh Avenue, creating a plaza in front of the hotel's entrance.[185][186][187] The plaza had been intended as a forecourt for the original Penn Station, though the hotel's height blunted this effect. When the PRR had leased the site to the hotel's original operators, the lease agreement included a clause that prevented the hotel's operators from constructing any structure, except for an entrance portico, on the westernmost 15 feet of the site for twenty-one years.[3] Three light courts on the southern facade, each measuring 40 feet (12 m) wide, divided the hotel into four wings that faced south.[186][187][188] Each wing measured 54 feet (16 m) wide. There was another light court facing eastward toward the former Gimbels department store (now Manhattan Mall), which measured 50 feet (15 m) wide.[188] The two western wings collectively contained 1,000 rooms, while the two eastern wings collectively contained 1,200 rooms.[186][187]

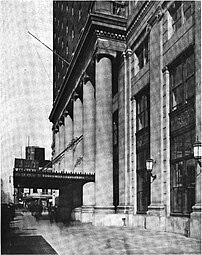

The Indiana Limestone facade of the lower stories was intentionally designed to closely mirror the architecture of the station. A colonnade of Ionic-style pilasters divided the lowest three stories vertically into bays, with lightly rusticated walls between each set of pilasters.[184][189] Over the years, the first three stories were modified significantly, and storefronts with various signs and awnings were installed.[10] In the center of the Seventh Avenue facade was a portico of six Ionic columns marking the main entrance.[3][189] This portico protruded 6 feet (1.8 m) from the facade, although it remained well within the property line.[3] When the entrance was widened in the hotel's later years, four of the columns were truncated to make way for a marquee.[10] The fourth story was faced in plain ashlar.[184][189]

Above the fourth story, the facade was made of buff-colored and gray brick.[190] Over the years, the windows on the upper stories were replaced in a piecemeal fashion, and numerous signs were installed on the facade. Near the end of the hotel's existence, the upper stories contained aluminum windows of various designs.[191] The top three stories contained a colonnade of pilasters, above which was a cornice made of terracotta.[190] Sometime during the hotel's existence, a half-story penthouse was installed above part of the cornice.[192]

Above the westernmost wing was a roof garden with a restaurant, which was topped by the elevator penthouse.[190] The roof restaurant had a simple design, with a plaster vaulted ceiling supported by a colonnade, which formed a central hall with aisles. The walls were of plaster above a tile wainscoting, and the restaurant had simple details, which allowed the decorations to be changed between different seasons.[193] The second-westernmost wing contained an outdoor lounge, connected to the restaurant by a wide bridge. When the hotel opened, the roofs of the two eastern wings were left undeveloped.[190]

Mechanical features

[edit]The hotel received electricity from three sources: a power generator in the building and two power stations outside of it.[194][195] The hotel received steam from a nearby plant on 32nd Street, and the subbasement also contained a 500-kilowatt (670 hp) steam-driven generator. The hotel also received alternating current from a PRR substation in the Long Island City neighborhood of Queens.[195][196] Cables carried power from the substation to a room in the hotel's basement, which contained five banks of transformers. Two of the banks of transformers supplied the hotel's lighting system, while the other three banks supplied a set of rotary converters.[197] The lights were operated from three sets of circuits, allowing some parts of the hotel to remain illuminated even if a blackout affected the entire hotel.[194]

The ventilation system contained 27 motors, which powered fans that ventilated the air from all of the hotel's bathrooms. In addition, a pair of 20-horsepower (15 kW) motors powered a vacuum system that collected dust from 487 openings throughout the hotel.[194] The hotel received water from the city's water supply system, which supplied ice machines, faucets, and mechanical equipment. The water-drainage system included sewers to the city's sewage system, as well as sump pumps that drained water from the basements.[198]

As built, there were two banks of six passenger elevators, which all ran from the basement to the roof.[199][200] The elevators could be configured so that one bank only served the upper floors and the lobby, while the other bank only served the lower floors. The southeast corner of the hotel contained two elevators which connected the lobby to the subway and railroad stations. Closer to 33rd Street, two elevators ran from ground level to the ballrooms 25 feet (7.6 m) above. Three elevators, at the eastern end of the hotel, ran from the basement to the kitchen on the first mezzanine level, stopping at the driveway.[199] There were also eight service elevators and six dumbwaiters. One of the service elevators operated at a slightly slower speed than the remaining service elevators and all of the passenger elevators.[199][200]

Interior

[edit]The public rooms were largely on the lower floors.[183][185] The ground level was largely designed in an Italian style.[201] The hotel also had 24,000 square feet (2,200 m2) for exhibitions and 58,000 square feet (5,400 m2) of ballrooms.[82] Large portions of the interiors were clad in Mycenaean marble, including corridors, stairways, and elevator lobbies.[202] Prior to the hotel's demolition, most of the interior spaces were substantially altered.[192]

Basements

[edit]There were three floor levels below the street. The first basement contained main and auxiliary kitchens, grill room, lunch room, barber shop, and bathroom.[203] The grill room was designed to resemble an Italian garden with bright colors; its columns and walls contained sgraffito decorations.[193] The sub-basement mezzanine only covered part of the site and contained the hotel's workshops, service dining rooms, and locker rooms. The sub-basement contained laundry rooms for staff and guests; refrigerating, pumping, and filtering plants; and machine rooms.[203]

The first basement level also contained a direct entrance to the 34th Street–Penn Station on the New York City Subway's IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line (later serving the 1, 2, and 3 trains). In addition, there were underpasses leading to the railroad station at 32nd and 33rd Streets;[203][204] these underpasses were outside of the subway station's fare control area.[204] Under 33rd Street was a connection to the Gimbels passageway,[203] which opened in 1920[205][206] and was shuttered in 1986.[207] The Gimbels passageway led east to the 34th Street–Herald Square station and to the Hudson & Manhattan Railroad (later PATH)'s 33rd Street station.[9][14] Further connections to Madison Square Garden and the current Pennsylvania Station were built in the late 20th century.[82] The hotel also contained direct subway entrances from the street to the platform, though these entrances had deteriorated significantly by the early 1990s.[208]

Ground level

[edit]At ground level were the main lobby, office, dining room, tea room, men's cafe, bar, and main serving pantry.[185][209] There were various shops that could be accessed both from the street and from inside the hotel, as well as a florist shop, telegraph office, public telephones, and check rooms at ground level.[185]

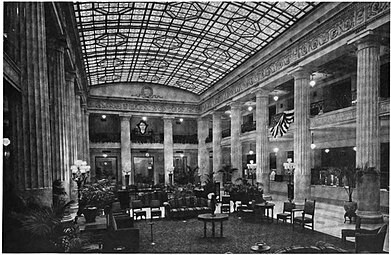

Lobby

[edit]The two-story main lobby was accessible from the main entrance on Seventh Avenue and from one entrance each on 32nd and 33rd Streets.[184][210] The lobby, measuring 70 by 133 feet (21 by 41 m),[184] was described by the New-York Tribune as the largest in the city.[183] It was surrounded by 16 fluted columns,[183][184] designed in the Doric order.[210] Both the columns and the lobby's walls were made of Botticino marble. In addition, the lobby originally contained multicolored carpets and walnut furniture, including a walnut registration desk near 32nd Street.[184] The lobby's ceiling measured 35 feet (11 m) high[184][210] and had a two-color steel-and-glass skylight,[195][196] designed by G. Rae & Co.[10][184] Above the skylight were reflectors,[195][196] which provided gold-tinted illumination;[209][210] workers replaced the reflectors using a set of trolley tracks.[200] The lobby was flanked by a promenade to the north and south.[211] By the early 21st century, the skylight had been removed and the columns had been reclad multiple times, but the floor was extant.[192]

At the mezzanine level was a gallery that surrounded the lobby.[183] The mezzanine also contained the lounging and writing rooms, a library, a large exhibition space, a hairdresser's shop, and the maitre d'hotel's office.[183][185] The writing room, opening off the southern side of the mezzanine, was designed in a Jacobean style and was paneled in oak.[209][212][213] The writing room's bookshelves extended nearly to the top of the plaster ceiling,[212] which contained molded centerpieces that represented 16th-century printers' marks.[213] From the mezzanine's gallery, a short flight of steps led to the ballroom floor.[193]

The upper level of the two-story lobby was severed from the room by Hilton in 1960, during major renovations, which reduced the lobby to one story.[75] The mezzanine level floor was extended over the lobby, creating 30,000 sq ft of new exhibition space for conventions, giving the hotel the largest such facilities in the country at the time.[214] In the mid-1990s, part of the mezzanine became a Sports Authority store.[97][215]

Other ground-level spaces

[edit]The Men's Cafe was just south of the main entrance and could also be accessed directly from the street. It contained a chestnut-paneled ceiling, tiled floors, Georgian and Flemish-inspired light fixtures,[184][216] as well as a fireplace and grill on one wall.[217] Just north of the main entrance was a Tuscan-style bar, which had wood paneling, stone walls and ceiling and a mosaic tile floor.[211][212] Later known as the Penn Bar, the space had become a storefront by the mid-1990s.[97] East of the main lobby was the Tea Room, designed in the Adam style with arches and murals on the wall,[209][211] as well as mirrored panels, Chinese-style carpets, and a decorative plaster ceiling.[212] The Tea Room was surrounded by an extension of the lobby's promenade,[211] which contained Caen stone walls and Italian furniture.[212]

The main restaurant, most famously known later on as the Cafe Rouge,[44] was a double-height space to the south of the tea room.[209][211] The Cafe Rouge measured approximately 60 by 140 feet (18 by 43 m), with a ceiling height of approximately 20 feet (6.1 m).[209][211][218] It consisted of a central space flanked on either side by a terrace measuring 18 inches (46 cm) high.[218] At the end of each terrace was a colonnade of four columns.[209][211] Both the wall base and door trim were made of terracotta, while the walls were artificial limestone. The beamed ceiling had various carvings in the Italian and French Renaissance styles, and the ceiling itself was painted to increase the perceived height of the room.[209][211][218] The east end of the cafe had a large floor-to-ceiling fountain. A bandstand was located on the central floor of the room on the exterior wall.[218]

The easternmost 50 feet (15 m) of the first floor, under the eastern light court, contained two parallel driveways, as well as a service driveway with loading platforms. Elevators led to workshops on the upper floors and the storage rooms and kitchen in the basement, and a conveyor belt connected with a baggage storage area on the mezzanine. At the extreme east end was a driveway for the adjacent Gimbels store, which contained elevators and a loading platform.[203] Between the Gimbels store and the Pennsylvania Hotel was a shopping arcade, which was built in 1919. Originally known as the Pennsylvania Arcade, it was known as Gallery 34 by the 1990s.[219]

Ballroom floor

[edit]The ballroom floor, above the lobby's mezzanine, contained a flexible entertainment area with a grand foyer and ballroom, two large parlors, banquet room and foyer, and three smaller dining rooms.[185][212] The ballrooms had their own stair and elevator from 33rd Street,[184][210] which led to a grand foyer flanked by parlors.[209][193] The ballroom facilities covered 40,000 square feet (3,700 m2) and were 30 feet (9.1 m) high.[98][99] Each of the ballrooms was a large, open space without columns.[98]

The main ballroom alone covered 10,366 square feet (963.0 m2) and was one of the largest hotel ballrooms in New York City,[220] having been planned with a capacity of 1,200 people.[30] The main ballroom was on the south side of the building, directly over the main dining room,[193] and measured 72 by 114 feet (22 by 35 m).[212] It had a vaulted ceiling with Italian arabesques and was surrounded on three sides by a gallery with boxes.[193][209][212] Two silk-and-crystal chandeliers illuminated the space.[193] The banquet room, on the north side of the same floor, had white-oak floors and a foyer with artificial stone walls. The private dining rooms were designed in the Georgian style.[193][209] The ballroom floor was served by a large banquet kitchen, and the ballrooms could host one large event or multiple smaller events simultaneously.[185]

In 1995, the main ballroom was converted into a television studio measuring 75 by 145 feet (23 by 44 m) across. The areas around the main ballroom were converted into offices, conference rooms, telecommunications facilities, and audience rooms.[99] The studio was used to tape television shows including The People's Court,[221] Idiot Savants,[222] Maury, Sally Jessy Raphael, 2 Minute Drill, and The Opposition with Jordan Klepper.[223] In 2009, the studios in the hotel were rebuilt and consolidated into a new 10,000-square-foot (930 m2) studio for the sitcom Sherri.[224] The television studios continued to operate through the 2010s.[192]

Other public spaces

[edit]Half a story above the ground floor were hotel executives' offices, baggage and parcel rooms, a print shop, and staff dining rooms. A conveyor belt connected the baggage room to a service driveway on the eastern end of the building.[185]

The second mezzanine and the entire second floor contained service bedrooms, storerooms, sewing and linen rooms, and a telephone exchange. When the hotel opened, American Architect said the telephone exchange was "the largest of its kind ever built".[185] The eastern end of the fifth floor contained two Turkish baths, one for men and one for women.[183][190] The women's bath was accessed by a stair from the sixth floor.[190] The hotel also originally contained a swimming pool with filtered water.[202]

Guest rooms

[edit]Guest rooms started at the fifth story, above the roofline of the original Penn Station.[9] There were 17 stories of guest rooms, each of which contained a central corridor flanked by bedrooms. Each story contained an average of 125 rooms, and the larger rooms were generally concentrated in the western part of the hotel. Each room contained its own bathroom; some of the larger guest rooms had bathrooms that faced outward toward the street, while other guest rooms had bathrooms that faced inward toward the corridor.[183][190] Two of the guest room floors contained living and reception rooms, dining rooms, pantries and bedrooms, which could arranged into different suites with three to ten rooms.[183][190] In the two eastern wings, three of the upper floors contained large guest rooms with large closets.[190] Each guest room floor contained its own "floor clerk", stationed outside the elevators, which acted as concierges for their respective stories. There was also a pantry,[199] as well as a fire lookout station and an electrical clock system, on each story.[196][199]

Each guest room contained a Servidor, a valet guest room door with exterior and compartments used for various services. These allowed guests to give the valet their clothes to be pressed and shoes to be polished without fully opening the door,[21][183][225] as well enabling servants to deliver newspapers, room service, and other deliveres. The items could be delivered to the guest without disturbing them by placing the items within the hall side of the compartment.[34] The Servidor doors, a marvel at the time of their construction, were still in place when the hotel was demolished. A few have been saved from destruction to be preserved.[160] The guest rooms also contained Chippendale furniture; each room typically contained a bed, two chairs, a writing desk, and a dresser. Curtains were hung from cornices or rods, and there were radiators on the ceilings and walls.[212] The bathrooms in each guestroom contained a shower.[225] To reduce the complexity of the electrical equipment, each guest room was originally equipped with a telephone that could only be used for room service.[199] To send messages, guests had to contact their floor clerks,[200] who then sent the messages using telautograph machines or pneumatic tubes.[199][200]

Notable guests and events

[edit]The hotel hosted multiple notable guests in its early years. On May 6 and 8, 1924, Harry Houdini debunked Joaquin María Argamasilla, a 19-year-old Spaniard who claimed he had X-ray vision.[226] In December 1925, William Faulkner stayed at the Pennsylvania while writing one of his many novels; he subsequently received the Nobel Prize in Literature.[227] Galveston crime boss Johnny Jack Nounes threw a $40,000 party at the Pennsylvania in the 1920s, inviting silent film stars Clara Bow and Nancy Carroll, who were said to have bathed in tubs of champagne.[228] Herbert Hoover spoke before the Ohio Society of New York at the Hotel Pennsylvania in November 1935.[229] The American Russian Institute presented its first annual award to the late President Franklin D. Roosevelt at the Hotel Pennsylvania in 1946,[230] and Edwin H. Land demonstrated his invention of an instant camera at the hotel in 1947.[231]

U.S. Army bacteriologist Frank Olson died after he crashed through a window on the 10th floor in 1953;[232] the U.S. government first described his death as a suicide, and then as misadventure, while others alleged that he was murdered.[233] Fidel Castro stayed at the Statler Hilton in 1959, shortly after he became the leader of Cuba.[234][235] Gameel al-Batouti (who was first officer of EgyptAir Flight 990 when it crashed in 1999, killing all 217 people aboard) was reportedly sexually promiscuous with female staff[236] and was nearly banned from the hotel.[237]

The Statler also hosted delegates during several Democratic National Convention meetings at Madison Square Garden.[82] During the 1976 convention,[238] the Statler allocated 80 percent of its rooms to delegates;[239] In advance of the 1980 convention, the Statler spent $5 million just on preparations, which included a "fast food" delicatessen as well as a kitchen in an elevator.[240] Other events at the hotel included Esto 92, an Estonian heritage festival that had booked the entire hotel at the beginning of the 1992 DNC convention,[94][241] as well as the 1994 edition of the Gay Games.[242] By the 2000s, the hotel hosted hundreds of dogs every year during the Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show.[243][244] The hotel's other events in the 2000s included auditions for reality TV show America's Next Top Model.[245]

Cafe Rouge

[edit]Big band era

[edit]The hotel's main dining room, later named the Cafe Rouge, was known for several decades as a major venue for big bands.[74][246] Numerous acclaimed musicians performed at the Cafe Rouge, including Count Basie, the Dorsey Brothers, Duke Ellington, Glenn Miller, Artie Shaw, and Fred Waring.[246] In the late 1930s and early 1940s, the Cafe Rouge had a big band remote connection to the NBC Red Network (after 1942, the NBC Radio Network) and became known for the performances held inside.

One evening in November 1939, while in the midst of a steady long-term engagement at the Cafe Rouge, bandleader Artie Shaw left the bandstand between sets and decided to quit his own band on the spot.[247] Shaw's principal orchestrator from 1937 to 1939, Jerry Gray, was immediately hired by Miller as a staff arranger when Shaw deserted his band.[248] The Glenn Miller Orchestra also had repeated long-term bookings in the Cafe Rouge from 1940 to 1942, when the band was broken up.[249] Miller's orchestra broadcast from the cafe; some were recorded by RCA Victor.[250][251] Les Brown's band, with its vocalist Doris Day, introduced their song "Sentimental Journey" at the Cafe Rouge in 1944.[252] The cafe was closed for renovation during mid-1948.[65]

Other spaces in the hotel were also used for musical performances. Before air-conditioning became popular, major bands performed in the hotel's roof garden ballroom during the summer.[247] In addition, Benny Goodman's band frequented the hotel's Madhattan Room[44][253] and started performing there in late 1936.[254][255]

Use as event venue

[edit]In later years, the former Cafe Rouge space within the structure operated separately from the hotel business, with a separate address and entrance at 145 West 32nd Street. In 2007, for the Garden in Transit project, adhesive weatherproof paintings of flowers attached to taxicabs in New York City were painted inside the cafe.[256] Numerous events from the 2013 New York Fashion Week were held in the Cafe Rouge.[257] In 2014, the Cafe Rouge space was converted to an indoor basketball court known as Terminal 23, celebrating the launch of the Melo M10 by the Jordan Brand division of Nike.[258][259] In its final years, the room operated as Station 32, a rental function/event space.[260]

Impact

[edit]In media

[edit]- The Muppet character Statler of Statler and Waldorf was named after the hotel, when it was the Statler Hilton.[261]

- The New York Penta Hotel appeared in the 1986 film The Manhattan Project as the setting of a science fair. Rather than construct a set and populate it with actors, the filmmakers hosted an actual science fair in the hotel and filmed as it was going on.

Phone number

[edit]В начале своего существования отелю был присвоен номер телефона (212) 736-5000. Номер телефона был более широко известен как PEnsylvania 6-5000 , записанный в формате 2L + 5N (две буквы, пять цифр), который был распространен в середине 20 века; две буквы обозначали телефонную станцию . [262] [263] Номер мог быть присвоен после того, как в 1930 году был введен формат 2L+5N. [264] С внедрением Североамериканского плана нумерации код города 212 . к номеру был добавлен [263] Первоначально этот номер использовался на всех стационарных телефонах отеля. [265] Во время помолвки Гленна Миллера в отеле в 1940 году Джерри Грей написал мелодию « Пенсильвания 6-5000 » (текст позже добавил Карл Сигман) . [266] ), который воспользовался номером телефона отеля. [267]

Хотя владельцы отеля утверждали, что (212) 736-5000 был «самым старым постоянно действующим телефонным номером в Нью-Йорке», [268] достоверность этого утверждения оспаривается. [269] [270] Телефонные номера в Нью-Йорке существовали еще в 1880-х годах. [269] и номер телефона мог быть изменен где-то до 1992 года. [270] Отель все еще носил этот номер, когда в 1983 году стал называться Penta. [271] [246] В 1993 году автор газеты Toronto Star сообщил, что, когда он набрал номер (212) 736-5000, оператор в прямом эфире отеля Ramada Pennsylvania разговаривал с ним, пока на заднем плане играла песня «Pennsylvania 6-5000». [272] В 1996 году корреспондент Chicago Tribune сообщил, что автоматический голос предлагал звонящим нажать кнопку, чтобы получить доступ к одному из отделов отеля. [270] Стивен Рот заявил в 2022 году, что Penn15 сохранит номер телефона (212) 736-5000, хотя и не уточнил, как будет переназначен номер телефона. [268]

Галерея

[ редактировать ]- Внешний вид отеля Пенсильвания

- Общий вид снаружи отеля Pennsylvania

- Фойе

- Главный вестибюль

- Детали вестибюльной колоннады

- Коридор вестибюля

- Деталь главного вестибюля

- Главный ресторан отеля «Пенсильвания» — The Cafe Rouge.

- Вид на террасу кафе Rouge

- Вид на восточную стену Cafe Rouge.

- Вид на западную стену Cafe Rouge.

- Фонтан Кафе Руж

- Деталь Кафе Руж

- Пальмовый номер

- Деталь Пальмовой комнаты

- Большой бальный зал

- Деталь внешней колоннады

- Деталь экстерьера отеля Pennsylvania

- Столовая при открытии отеля, прежде чем стать Cafe Rouge.

- Деталь стены бывшего кафе Rouge в 2012 году.

- Фонтан в Cafe Rouge в 2012 году.

См. также

[ редактировать ]Ссылки

[ редактировать ]Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Департамент городского планирования 2010 , с. 2.

- ^ «Открыт новый вокзал Пенсильвании; движение поездов начнется 8 сентября в самом большом здании в мире, когда-либо построенном» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 29 августа 1910 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 27 мая 2018 года . Проверено 26 мая 2018 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж Грей, Кристофер (15 мая 2011 г.). «Роскошный отель: больше комнат на тротуаре» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . п. РЕ7. ISSN 0362-4331 . ПроКвест 2217036420 . Архивировано из оригинала 23 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 22 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д «Планы строительства отеля в терминале Пенсильвании реализуются» . Христианский научный монитор . 1 февраля 1916 г. с. 5. ПроКвест 509590359 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Новый 18-этажный отель на 7-м авеню: Пенсильванская железная дорога дает контракт на строительство компании George A. Fuller Co. Стоимость строительства всего квартала между 32-й и 33-й улицами и 1000 номеров составит 9 000 000 долларов» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 18 марта 1916 г. с. 8. ISSN 0362-4331 . ПроКвест 97993459 . Архивировано из оригинала 22 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 22 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с «Отель стоимостью 9 000 000 долларов на Седьмой авеню: структура Пенсильванской железной дороги станет началом великих улучшений» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 29 января 1916 г. с. 1. ISSN 0362-4331 . ПроКвест 98032560 . Архивировано из оригинала 22 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 22 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с «Отель на 1000 номеров на Седьмой авеню». Нью-Йорк Трибьюн . 29 января 1916 г. с. 13. ПроКвест 575498541 .

- ^ Джоннес, Джилл (2007). Покорение Готэма: эпопея позолоченного века: строительство Пенсильванского вокзала и его туннелей . Викинг. стр. 167 –. ISBN 978-0-670-03158-0 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с «Отель Penn RR — город сам по себе» . Бруклинский гражданин . 30 апреля 1916 г. с. 3. Архивировано из оригинала 22 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 22 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж Департамент городского планирования 2010 , с. 5.

- ^ «Компания Geo. A. Fuller построит отель» . Отчет о недвижимости: отчет о недвижимости и руководство для строителей . Том. 97, нет. 2505. 18 марта 1916. с. 450. Архивировано из оригинала 19 января 2023 года . Проверено 22 ноября 2022 г. - через columbia.edu .

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Строительное достижение: два гигантских отеля успешно построены в условиях войны» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 26 января 1919 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 23 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 23 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Отели» . Отчет о недвижимости: отчет о недвижимости и руководство для строителей . Том. 97, нет. 2508. 8 апреля 1916. с. 568. Архивировано из оригинала 22 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 22 ноября 2022 г. - через columbia.edu .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с «PRR построит отель стоимостью 11 500 000 долларов: через десять дней начнутся работы на Седьмой авеню, напротив станции». Нью-Йорк Трибьюн . 30 апреля 1916 г. с. 10. ПроКвест 575552098 .

- ^ «Центральный Нью-Йорк построит здесь отель стоимостью 6 000 000 долларов: новое 26-этажное здание будет содержать 2 000 номеров» . Нью-Йорк Трибьюн . 12 мая 1916 г. с. 3. ПроКвест 575573804 .

- ^ «Большой строительный бум возле Таймс-сквер: самая большая активность за последние годы в бизнес-центре на Сорок второй улице. Два гигантских отеля на сумму более 20 000 000 долларов будут инвестированы в список новых построек». Нью-Йорк Таймс . 14 мая 1916 г. с. С4. ISSN 0362-4331 . ПроКвест 97949612 .

- ^ «Стэтлер получает аренду гостиницы» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 17 декабря 1916 г. с. 89. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 22 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 22 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Стэтлер берет в аренду отель «Пенсильвания»» . Нью-Йорк Трибьюн . 17 декабря 1916 г. с. 15. ПроКвест 575646167 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Требует Statler Estate 10 000 000 долларов США: FK Machette подает иск в отношении строительства и эксплуатации отеля Pennsylvania. Говорит, что доход был перенаправлен. Статлер получил бонусы и нарушил соглашение на основании аренды, которой он владел, и сборов акционеров. Дело, представленное Machette. Изложены претензии и обвинения " . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 30 апреля 1929 г. с. Б60. ISSN 0362-4331 . ПроКвест 105008792 . Архивировано из оригинала 23 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 22 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Роуд Пенсильвании построит отель: обещан самый большой в мире - напротив вокзала в Нью-Йорке». Хартфорд Курант . 21 декабря 1916 г. с. 22. ПроКвест 556413097 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Мебель, продаваемая специальной службой в отеле «Пенсильвания»: может расширить полуавтоматическую продажу воротников, галстуков, заколок, сеток для волос и т. д.». Женская одежда . Том. 17, нет. 143. 19 декабря 1918. с. 26. ПроКвест 1666113021 .

- ^ «Возобновление работы крупнейших отелей — признак нового отношения правительства к строительству» . Нью-Йорк Геральд . 18 августа 1918 г. с. 14. Архивировано из оригинала 19 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 23 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Слесарь убит упавшей балкой» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 1 июля 1917 г. с. 15. ISSN 0362-4331 . ПроКвест 99904534 . Архивировано из оригинала 23 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 22 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Взрывы потрясли новый отель: пламя вырвалось из Пенсильвании и разрушило шесть зданий» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 9 апреля 1918 г. с. 24. ISSN 0362-4331 . ПроКвест 100251309 . Архивировано из оригинала 23 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 22 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Взрыв последовал за пожаром в новом отеле на Седьмой авеню». Нью-Йорк Трибьюн . 9 апреля 1918 г. с. 16. ПроКвест 575858053 .

- ^ «Архитектурно-строительный отдел: Противопожарная безопасность при строительстве». Американский архитектор . Том. 114, нет. 2224. 7 августа 1918. с. 178. ПроКвест 124689343 .

- ^ «Выпуск облигаций Statler Co.: найти 3 000 000 долларов на погашение долгов и оборудовать отель «Пенсильвания»» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 24 июня 1918 г. с. 15. ISSN 0362-4331 . ПроКвест 100132677 . Архивировано из оригинала 23 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 22 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Договоренности по выводу на рынок крупного выпуска облигаций недвижимости: известный инвестиционный дом выводит ценные бумаги Hotel Statler Co. на сумму 3 000 000 долларов». Хроники Сан-Франциско . 26 июня 1918 г. с. 17. ПроКвест 576740671 .

- ^ «Управлять отелем Пенсильвания» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 27 сентября 1918 г. с. 15. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 22 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 22 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Новые идеи в управлении крупнейшим отелем города: Э. М. Статлер излагает свои планы относительно Новой Пенсильвании - когда-то посыльный, он формулирует правила обслуживания, цен и чаевых» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 3 июня 1917 г. с. 59. ISSN 0362-4331 . ПроКвест 99886533 . Архивировано из оригинала 23 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 22 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Отель «Пенсильвания» открыт; 3000 посетителей осматривают здание и 2000 из них обедают там» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 26 января 1919 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 23 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 23 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Открылся самый большой отель в мире» . Вечернее Солнце . 25 января 1919 г. с. 2. Архивировано из оригинала 23 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 23 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Сегодня открывается самый большой отель в мире» (PDF) . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 25 января 1919 г. с. 9. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 29 января 2022 г. Проверено 23 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с «Отель «Пенсильвания», крупнейший в мире, откроется в субботу: 27-этажное здание имеет 2200 номеров и ванных комнат; обслуживание будет предлагать множество инноваций». Нью-Йорк Трибьюн . 22 января 1919 г. с. 14. ПроКвест 575960932 .

- ^ «Аренда отелей в Пенсильвании» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 26 января 1919 г. с. 91. ISSN 0362-4331 . ПроКвест 100374729 . Архивировано из оригинала 23 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 23 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Арендная плата отеля в Пенсильвании высока: руководство будет платить 200 000 долларов в год за землю; 6 процентов на строительство». Нью-Йорк Трибьюн . 25 января 1919 г. с. 16. ПроКвест 576009263 .

- ^ «Текущие новости: Отели Пенсильвании и арендная плата Commodore устанавливают новую отметку» . Американский архитектор . Том. 115, нет. 2253. 26 февраля 1919. с. 314. ПроКвест 124689768 .

- ^ Моисей, Лайонел (24 мая 1922 г.). «МакКим, Мид и Уайт - история: Муниципальное здание Здание почтового отделения США Отель Пенсильвания Мемориал МакКинли Мемориал МакКима, Мид и Уайт Теннесси». Американский архитектор и архитектурное обозрение . Том. 121, нет. 2394. с. 420. ПроКвест 124696411 .

- ^ «Открытие благотворительной выставки; работа Еврейской федерации продемонстрирована в отеле «Пенсильвания»» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 15 декабря 1920 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 24 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 23 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «78-я церемония «собирается вместе»; более 500 ветеранов посетили мероприятие в отеле «Пенсильвания»» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 18 апреля 1920 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 24 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 23 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Открывается радиоконвенция; на выставке в отеле Pennsylvania Show представлены новые наборы и устройства» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 4 марта 1924 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 24 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 23 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Гостиничная газета со штатом 2250 человек: все сотрудники отеля «Пенсильвания» являются репортерами четырехстраничного ежедневного журнала, издаваемого для гостей. Газета «Помощь сотрудникам». Ни одна из сторон не принята». Христианский научный монитор . 28 сентября 1921 г. с. 5. ПроКвест 510505825 .

- ^ «Отель Бонд будет иметь собственную станцию беспроводной связи: оборудование для радиотелеграфной службы будет установлено сразу - отель Пенсильвания, Нью-Йорк, первый отель со станцией». Хартфорд Курант . 9 августа 1922 г. с. 1. ПроКвест 557092106 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Колфорд, Пол Д. (5 января 2007 г.). «Отель Office Tower Dooms в Пенсильвании. Принимал Гленн Миллер, герцог Эллингтон». Нью-Йорк Дейли Ньюс . п. 38. ПроКвест 306093962 .

- ^ «Здесь будет построен 60-этажный офис и 38-этажный отель: Рейнольдс построит 700-футовый небоскреб на 42-й улице и Лексингтон-авеню; общежитие на 34-й и 8-й авеню». Нью-Йорк Геральд Трибьюн . 16 февраля 1928 г. с. 1. ISSN 1941-0646 . ПроКвест 1133907817 .

- ^ «Ф.А. Дагган назначен менеджером отеля» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 1 января 1928 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 24 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 24 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Стэтлер снова менеджер отеля «Пенсильвания»». Женская одежда на каждый день . Том. 36, нет. 79. 4 апреля 1928. с. 12. ПроКвест 1653267443 .

- ^ «Э.М. Статлер умер в возрасте 64 лет от пневмонии; основатель и владелец сети отелей, который вырос из посыльного, заболел две недели» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 17 апреля 1928 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 24 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 24 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Многие ужинают в ресторане White Sulphur; генерал и миссис У. В. Эттербери среди хозяев выходного дня в Greenbrier» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 30 апреля 1928 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 19 января 2023 года . Проверено 24 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «FJ Matchette требует 17 500 000 долларов: Statler Corporation и Statler Estate предъявили иск по обвинению в нарушении контракта с отелем Pennsylvania». Ежедневная газета Boston Globe . 11 апреля 1930 г. с. 15. ПроКвест 758265751 .

- ^ «Hotels Statler Inc. предъявили иск на 20 000 000 долларов: миноритарный владелец нью-йоркской компании Fj Matchette обвиняет в нарушении контракта» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 11 апреля 1930 г. с. 25. ISSN 0362-4331 . ПроКвест 98940409 . Архивировано из оригинала 23 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 22 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Продлевает ссуду на сумму 5 000 000 долларов на отель «Пенсильвания»» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 11 августа 1933 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 19 января 2023 года . Проверено 24 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Автомобильный клуб займет этаж в отеле «Пенсильвания»» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 18 января 1933 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 19 января 2023 года . Проверено 23 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Отель открывает номер в Мадхэттене» . Нью-Йорк Геральд Трибьюн . 24 ноября 1933 г. с. 17. ISSN 1941-0646 . ПроКвест 1114806395 .

- ^ «Поле 369 открывает матчи по пинг-понгу; в отеле «Пенсильвания» начинается первый национальный чемпионат» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 26 марта 1931 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 24 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 24 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Выставлены новые товары для дома; 700 покупателей посетили торговую выставку в отеле Pennsylvania» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 31 июля 1934 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 24 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 24 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Сегодня состоится заседание совета по кинематографии; национальная группа рецензентов откроет заседание в отеле «Пенсильвания»» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 7 марта 1935 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 24 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 24 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Встреча государственных архитекторов; сегодня в отеле «Пенсильвания» начинается трехдневный съезд» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 27 октября 1938 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 24 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 24 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Управление отелем Пенсильвания» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 30 января 1937 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 24 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 24 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Чтобы управлять отелем здесь; Джеймс Х. Маккейб назначен на должность в Пенсильвании» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 20 июля 1937 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 24 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 24 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Группа отелей покупает Пенсильванию; организация Statler, которая управляет номером на 2200 номеров, берет на себя управление железной дорогой» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 1 июля 1948 г. с. 40. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 21 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 21 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Отель «Пенсильвания» приобретен за наличные сетью Statler». Нью-Йорк Геральд Трибьюн . 1 июля 1948 г. с. 38. ISSN 1941-0646 . ПроКвест 1327390602 .

- ^ «Отель Пенсильвания сдан» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 12 августа 1948 г. с. 36. ISSN 0362-4331 . ПроКвест 108398410 . Архивировано из оригинала 21 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 21 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с «Отель Пенсильвания меняет название на Statler; стоимость: 200 000 долларов: означает «новый облик» для 798 000 кусков белья, 127 000 китайских предметов, 134 000 серебряных монет». Уолл Стрит Джорнал . 19 ноября 1948 г. с. 1. ISSN 0099-9660 . ПроКвест 131771165 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Музыка: Кафе Руж в Нью-Йорке, чтобы сделать подтяжку лица» . Рекламный щит . Том. 60, нет. 31. 31 июля 1948. с. 20. ПроКвест 1039904609 .

- ^ «Отель Пенсильвания становится Statler 1 января; владельцы заняты распространением информации среди таксистов» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 19 ноября 1948 г. с. 29. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 21 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 21 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Курорты: отель «Пенсильвания» переименован в «Стэтлер». Женская одежда на каждый день . Том. 77, нет. 99. 19 ноября 1948. с. 41. ПроКвест 1565274622 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Проблемы изменения названия гостиницы» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 26 декабря 1948 г. с. Х15. ISSN 0362-4331 . ПроКвест 108353667 . Архивировано из оригинала 21 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 21 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ Морахан, Джон М. (4 августа 1954 г.). «Hilton покупает 49% акций сети отелей Statler». Нью-Йорк Геральд Трибьюн . п. 1. ISSN 1941-0646 . ПроКвест 1322542655 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Сеть отелей Statler куплена Hilton: рекордная сделка может включать общий объем инвестиций в размере 76 000 000 долларов» . Лос-Анджелес Таймс . 4 августа 1954 г. с. А1. ПроКвест 166667836 .

- ^ «Хилтон, подчиняясь указу, продает отель New Yorker» . Нью-Йорк Геральд Трибьюн . 15 мая 1956 г. с. 18. ISSN 1941-0646 . ПроКвест 1325258852 .

- ^ Брэдли, Джон А. (12 февраля 1956 г.). «Отели рассматривают возможность установки кондиционеров: приняты меры по обеспечению климат-контроля во всех номерах» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . п. Р1. ISSN 0362-4331 . ПроКвест 113906724 . Архивировано из оригинала 22 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 22 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Отели Hilton, годовой отчет за 1957 год» . digitalcollections.lib.uh.edu . Архивировано из оригинала 14 августа 2021 года . Проверено 14 августа 2021 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с «Личные выступления: Зекендорф-младший в сделке на 24 миллиона долларов о покупке отеля Statler-Hilton» . Разнообразие . Том. 293, нет. 12. 24 января 1979. с. 88. ПроКвест 1401344213 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Отели Hilton, годовой отчет за 1960 год» . Архивировано из оригинала 20 декабря 2022 года . Проверено 20 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ «Отели Hilton собираются продать нью-йоркский Statler Hilton» . Уолл Стрит Джорнал . 19 января 1979 г. с. 4. ISSN 0099-9660 . ПроКвест 134323252 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с «Стэтлер Хилтон в Нью-Йорке продается» . Вашингтон Пост . 3 февраля 1979 г. с. Е32. ISSN 0190-8286 . ПроКвест 147159963 .

- ^ «Hilton завершает продажу отеля». Уолл Стрит Джорнал . 18 мая 1979 г. с. 20. ISSN 0099-9660 . ПроКвест 134372479 .

- ^ «Hilton оценивает прибыль от продажи недвижимости». Уолл Стрит Джорнал . 7 июня 1979 г. с. 16. ISSN 0099-9660 . ПроКвест 134428208 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Отели Данфи управляются как семейное дело» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 15 июня 1979 г. с. Д2. ISSN 0362-4331 . ПроКвест 120819908 . Архивировано из оригинала 22 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 22 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Пожар в отеле «Стэтлер» под названием «Определенно поджог» » . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 19 апреля 1981 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 2 декабря 2022 года . Проверено 2 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Кеннеди, Шон Г. (17 августа 1983 г.). «Недвижимость: начало нового этапа для Statler» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . п. Д21. ISSN 0362-4331 . ПроКвест 424750851 . Архивировано из оригинала 22 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 22 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Стэтлер продан». Нью-Йорк Дейли Ньюс . 12 августа 1983 г. с. 150. ПроКвест 2304145334 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Гудман, Джордж У. (23 сентября 1984 г.). «Для городских отелей настало время привести себя в порядок» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 10 октября 2022 года . Проверено 22 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б «6 августа 1983 года». Журнал-Новости . 6 августа 1983 г. с. 11. ПроКвест 2038870319 .

- ^ Квиндлен, Анна (28 апреля 1985 г.). «Большой квест для гостей отеля» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . п. 6.28. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 2 ноября 2021 года . Проверено 22 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ Депальма, Энтони (16 ноября 1983 г.). «О недвижимости; Уэст-Мидтаун видит выгоды от конференц-центра» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 2 декабря 2022 года . Проверено 2 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ «Домашняя страница RootsWeb.com» . Freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com . Архивировано из оригинала 25 сентября 2015 года . Проверено 1 января 2018 г.

- ^ Шепард, Джоан (6 декабря 1985 г.). «Возвышающийся прилив поворачивает на запад» . Ежедневные новости . п. 158. Архивировано из оригинала 22 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 22 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ Догерти, Филип Х. (9 мая 1988 г.). «Медиа-бизнес: Реклама; Агентство отеля Пента» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . п. Д9. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 22 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 22 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Осер, Алан С. (3 декабря 1995 г.). «Перспективы; название восстановлено, отель на волне туризма» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . п. 9.7. ISSN 0362-4331 . ПроКвест 430436019 . Архивировано из оригинала 14 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 14 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Отель «Пенсильвания» снова получил свое название». Орландо Сентинел . 4 апреля 1991 г. с. А12. ПроКвест 277838541 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Феннер, Остин Эванс (3 ноября 1993 г.). «Новое имя, новая безопасность для отеля». Нью-Йорк Дейли Ньюс . п. 31. ПроКвест 390836038 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Дойч, Клаудия Х. (2 февраля 1992 г.). «Коммерческая недвижимость: высокий уровень конвенции; отели Манхэттена не боятся июльского упадка» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . п. А10. ISSN 0362-4331 . ПроКвест 428375304 . Архивировано из оригинала 22 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 22 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ Капуццо, Майк (14 февраля 1993 г.). «Старая Пенсильвания 6-5000 добилась успеха во время Вестминстерской выставки с 450 гостями-собаками» . Чикаго Трибьюн . стр. 325, 326 . Архивировано из оригинала 24 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 24 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ Брезник, Алан (26 июля 1993 г.). «Спортивный ритейлер K mart борется со всеми желающими в Нью-Йорке» . Нью-йоркский бизнес Крэйна . Том. 9, нет. 30. с. 4. ПроКвест 219118938 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с «Объявления: Напротив Мэдисон-Сквер-Гарден; спортивный магазин в центре города» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 13 ноября 1994 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 2 декабря 2022 года . Проверено 2 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Слатин, Питер (8 февраля 1995 г.). "Недвижимость" . Нью-Йорк Таймс . ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 19 января 2023 года . Проверено 2 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Верник, Илана (17 февраля 1995 г.). «В фокусе: от отеля Pennsylvania до студии House TV». Задняя сцена . Том. 36, нет. 7. С. 2, 19. ПроКвест 963018921 .

- ^ Камен, Робин (7 августа 1995 г.). «Туристические гостиницы ведут первоклассный бизнес». Нью-йоркский бизнес Крэйна . Том. 11, нет. 32. с. 1. ПроКвест 219180426 .

- ^ Дойч, Клаудия Х. (12 мая 1996 г.). «Коммерческая недвижимость; отели меняют рецепт общественного питания» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 2 декабря 2022 года . Проверено 2 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ «Цена отеля в Нью-Йорке в размере 150 миллионов долларов США» . Южно-Китайская Морнинг Пост . 17 апреля 1996 г. с. 59. ПроКвест 1658165657 .

- ^ Шнайдер, Дэниел Б. (2 ноября 1997 г.). «К вашему сведению» « Нью-Йорк Таймс» . ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 2 декабря 2022 года . Проверено 2 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Bloomberg News (10 августа 1999 г.). «Метро Бизнес; Ворнадо покупает отель» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 22 ноября 2021 года . Проверено 30 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Хальбфингер, Дэвид М. (28 июня 1997 г.). «Застройщик покупает участок в центре города с видом на сад» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 2 декабря 2022 года . Проверено 2 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ Фельдман, Эми (28 июля 1997 г.). «Тематические отели в стиле Лас-Вегаса направляются в Нью-Йорк». Нью-йоркский бизнес Крэйна . Том. 13, нет. 30. с. 1. ПроКвест 219137879 .

- ^ Превитт, Милфорд (21 июля 1997 г.). «Ризе распродает первоклассную недвижимость Нью-Йорка в рамках рефинансирования долга». Новости ресторана страны . Том. 31, нет. 29. С. 3, 91. ПроКвест 229293926 .

- ^ Ясуда, Джин (26 сентября 1997 г.). «Отель — новое предприятие для планеты Голливуд» . Орландо Сентинел . Архивировано из оригинала 23 июня 2018 года . Проверено 22 июня 2018 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с «Сделка с отелем Planet Hollywood завершена» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 26 сентября 1997 г. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 30 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 30 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ Гибсон, Ричард (26 сентября 1997 г.). «Планета Голливуд купит 20% акций гостиничного предприятия» . Уолл Стрит Джорнал . п. Б, 19:3. ISSN 0099-9660 . ПроКвест 398798684 .

- ^ Холуша, Джон (2 ноября 1997 г.). «Коммерческая недвижимость/жилье в Нью-Йорке; заполняемость отелей и стоимость номеров выросли» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 30 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 30 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ Брукман, Фэй (11 августа 1997 г.). «Низкая арендная плата привлекает малый бизнес, пострадавший от бума на рынке недвижимости». Нью-йоркский бизнес Крэйна . Том. 13, нет. 32. с. 26. ПроКвест 219136118 .

- ^ Пандья, Мукул (6 октября 1997 г.). «Сделки Ворнадо имеют эффект торнадо» . Деловые новости Нью-Джерси . Том. 10, нет. 34. с. 34. ПроКвест 228502649 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с «Маркетинговый обзор - Planet Hollywood International Inc.: Vornado Realty Trust покупает остальную часть отеля в Пенсильвании». Уолл Стрит Джорнал . 9 августа 1999 г. с. Б9. ISSN 0099-9660 . ПроКвест 398663321 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Джексон, Джерри (7 августа 1999 г.). «Планета Голливуд сбрасывает долю в отеле. Проблемная сеть ресторанов отказалась от планов превратить отель на Манхэттене в официальный отель всех звезд» . Орландо Сентинел . п. С1. ПроКвест 279332777 .

- ^ Bloomberg News (31 марта 1998 г.). «Metro Business; Vornado покупает долю в отеле» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 30 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 30 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Vornado приобретает долю в отеле» . Уолл Стрит Джорнал . 5 мая 1998 г. с. А8. ISSN 0099-9660 . ПроКвест 398777306 .

- ^ Багли, Чарльз В. (24 января 1999 г.). «Больные азиатские компании разгружают свои отели» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 2 декабря 2022 года . Проверено 2 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ Bloomberg News (19 сентября 1998 г.). «Новости компании; Vornado Realty выделит подразделение стоимостью 100 миллионов долларов» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 2 декабря 2022 года . Проверено 2 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ Кантер, Ларри (29 ноября 1999 г.). «Отель New Yorker прибегает к франшизе» . Нью-йоркский бизнес Крэйна . Том. 15, нет. 48. с. 3. ПроКвест 219156846 .

- ^ «Пенсильвания, 6-5000, ваш номер исчерпан! Знаменитый отель могут снести». Национальная почта . 17 февраля 2001 г. с. Д08. ПроКвест 329933388 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Шотт, Крис (14 августа 2006 г.). «Отель Landmark Pennsylvania нуждается в большой дозе лизола» . Наблюдатель . Архивировано из оригинала 22 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 22 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Что даст вам номер в отеле стоимостью менее 200 долларов на Манхэттене» . Обузданный Нью-Йорк . 9 августа 2006 г. Архивировано из оригинала 22 ноября 2022 г. . Проверено 22 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Шотт, Крис (9 октября 2007 г.). «Одинокая битва за отель «Пенсильвания»» . Наблюдатель . Архивировано из оригинала 22 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 22 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Нью-Йоркский отель Пенсильвания». Нью-Йорк Таймс . 1 июня 2003 г. с. СМ58. ISSN 0362-4331 . ПроКвест 92502262 .