Мел-палеогеновое вымирание

- Artist's rendering of an asteroid a few kilometers across colliding with the Earth. Such an impact can release the equivalent energy of several million nuclear weapons detonating simultaneously;

- Badlands near Drumheller, Alberta, where erosion has exposed the K–Pg boundary;

- Complex Cretaceous–Paleogene clay layer (gray) in the Geulhemmergroeve tunnels near Geulhem, The Netherlands (finger is just below the actual Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary);

- Wyoming rock with an intermediate claystone layer that contains 1,000 times more iridium than the upper and lower layers. Picture taken at the San Diego Natural History Museum;

- Rajgad Fort's Citadel, an eroded hill from the Deccan Traps, which are another hypothesized cause of the K–Pg extinction event.

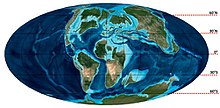

Мел -палеогеновое ( K-Pg ) вымирание , [ а ] также известное как мел-третичное ( K-T ) вымирание , [ б ] произошло массовое вымирание трех четвертей растений и животных видов на Земле. [ 2 ] [ 3 ] примерно 66 миллионов лет назад. Это событие привело к исчезновению всех нептичьих динозавров . Большинство других четвероногих весом более 25 килограммов (55 фунтов) также вымерло, за исключением некоторых экзотермных видов, таких как морские черепахи и крокодилы . [ 4 ] Оно ознаменовало конец мелового периода, а вместе с ним и мезозойской эры, одновременно возвещая начало нынешней эры – кайнозойской . В геологических записях событие K-Pg отмечено тонким слоем отложений , называемым границей K-Pg или границей K-T , который можно найти по всему миру в морских и наземных породах. Пограничная глина демонстрирует необычно высокий уровень металлического иридия . [ 5 ] [ 6 ] [ 7 ] что чаще встречается на астероидах, чем в земной коре . [ 8 ]

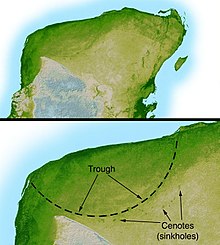

Первоначально предложенный в 1980 г. [ 9 ] группой ученых во главе с Луисом Альваресом и его сыном Уолтером , сейчас принято считать, что вымирание K – Pg было вызвано ударом массивного астероида шириной от 10 до 15 км (от 6 до 9 миль), [10][11] 66 million years ago, which devastated the global environment, mainly through a lingering impact winter which halted photosynthesis in plants and plankton.[12][13] The impact hypothesis, also known as the Alvarez hypothesis, was bolstered by the discovery of the 180 km (112 mi) Chicxulub crater in the Gulf of Mexico's Yucatán Peninsula in the early 1990s,[14] which provided conclusive evidence that the K–Pg boundary clay represented debris from an asteroid impact.[8] The fact that the extinctions occurred simultaneously provides strong evidence that they were caused by the asteroid.[8] A 2016 drilling project into the Chicxulub peak ring confirmed that the peak ring comprised granite ejected within minutes from deep in the earth, but contained hardly any gypsum, the usual sulfate-containing sea floor rock in the region: the gypsum would have vaporized and dispersed as an aerosol into the atmosphere, causing longer-term effects on the climate and food chain. In October 2019, researchers asserted that the event rapidly acidified the oceans and produced long-lasting effects on the climate, detailing the mechanisms of the mass extinction.[15][16]

Other causal or contributing factors to the extinction may have been the Deccan Traps and other volcanic eruptions,[17][18] climate change, and sea level change. However, in January 2020, scientists reported that climate-modeling of the extinction event favored the asteroid impact and not volcanism.[19][20][21]

A wide range of terrestrial species perished in the K–Pg extinction, the best-known being the non-avian dinosaurs, along with many mammals, birds,[22] lizards,[23] insects,[24][25] plants, and all the pterosaurs.[26] In the oceans, the K–Pg extinction killed off plesiosaurs and mosasaurs and devastated teleost fish,[27] sharks, mollusks (especially ammonites, which became extinct), and many species of plankton. It is estimated that 75% or more of all species on Earth vanished.[28] However, the extinction also provided evolutionary opportunities: in its wake, many groups underwent remarkable adaptive radiation—sudden and prolific divergence into new forms and species within the disrupted and emptied ecological niches. Mammals in particular diversified in the Paleogene,[29] evolving new forms such as horses, whales, bats, and primates. The surviving group of dinosaurs were avians, a few species of ground and water fowl, which radiated into all modern species of birds.[30] Among other groups, teleost fish[31] and perhaps lizards[23] also radiated.

Extinction patterns

[edit]The K–Pg extinction event was severe, global, rapid, and selective, eliminating a vast number of species. Based on marine fossils, it is estimated that 75% or more of all species became extinct.[28]

The event appears to have affected all continents at the same time. Non-avian dinosaurs, for example, are known from the Maastrichtian of North America, Europe, Asia, Africa, South America, and Antarctica, but are unknown from the Cenozoic anywhere in the world.[32] Similarly, fossil pollen shows devastation of the plant communities in areas as far apart as New Mexico, Alaska, China, and New Zealand.[26]

Despite the event's severity, there was significant variability in the rate of extinction between and within different clades. Species that depended on photosynthesis declined or became extinct as atmospheric particles blocked sunlight and reduced the solar energy reaching the ground. This plant extinction caused a major reshuffling of the dominant plant groups.[33] Omnivores, insectivores, and carrion-eaters survived the extinction event, perhaps because of the increased availability of their food sources. Neither strictly herbivorous nor strictly carnivorous mammals seem to have survived. Rather, the surviving mammals and birds fed on insects, worms, and snails, which in turn fed on detritus (dead plant and animal matter).[34][35][36]

In stream communities and lake ecosystems, few animal groups became extinct, including large forms like crocodyliforms and champsosaurs, because such communities rely less directly on food from living plants, and more on detritus washed in from the land, protecting them from extinction.[37][38] Modern crocodilians can live as scavengers and survive for months without food, and their young are small, grow slowly, and feed largely on invertebrates and dead organisms for their first few years. These characteristics have been linked to crocodilian survival at the end of the Cretaceous. Similar, but more complex patterns have been found in the oceans. Extinction was more severe among animals living in the water column than among animals living on or in the sea floor. Animals in the water column are almost entirely dependent on primary production from living phytoplankton, while animals on the ocean floor always or sometimes feed on detritus.[34] Coccolithophorids and mollusks (including ammonites, rudists, freshwater snails, and mussels), and those organisms whose food chain included these shell builders, became extinct or suffered heavy losses. For example, it is thought that ammonites were the principal food of mosasaurs, a group of giant marine reptiles that became extinct at the boundary.[39]

The K–Pg extinction had a profound effect on the evolution of life on Earth. The elimination of dominant Cretaceous groups allowed other organisms to take their place, causing a remarkable amount of species diversification during the Paleogene Period.[29] After the K–Pg extinction event, biodiversity required substantial time to recover, despite the existence of abundant vacant ecological niches.[34] Evidence from the Salamanca Formation suggests that biotic recovery was more rapid in the Southern Hemisphere than in the Northern Hemisphere.[40]

Microbiota

[edit]The mass extinction of marine plankton appears to have been abrupt and right at the K–Pg boundary.[41]

The K–Pg boundary represents one of the most dramatic turnovers in the fossil record for various calcareous nanoplankton that formed the calcium deposits for which the Cretaceous is named. The turnover in this group is clearly marked at the species level.[42][43] Statistical analysis of marine losses at this time suggests that the decrease in diversity was caused more by a sharp increase in extinctions than by a decrease in speciation.[44] The K–Pg boundary record of dinoflagellates is not so well understood, mainly because only microbial cysts provide a fossil record, and not all dinoflagellate species have cyst-forming stages, which likely causes diversity to be underestimated.[34] Recent studies indicate that there were no major shifts in dinoflagellates through the boundary layer.[45]

Radiolaria have left a geological record since at least the Ordovician times, and their mineral fossil skeletons can be tracked across the K–Pg boundary. There is no evidence of mass extinction of these organisms, and there is support for high productivity of these species in southern high latitudes as a result of cooling temperatures in the early Paleocene.[34] Approximately 46% of diatom species survived the transition from the Cretaceous to the Upper Paleocene, a significant turnover in species but not a catastrophic extinction.[34][46]

The occurrence of planktonic foraminifera across the K–Pg boundary has been studied since the 1930s.[47] Research spurred by the possibility of an impact event at the K–Pg boundary resulted in numerous publications detailing planktonic foraminiferal extinction at the boundary;[34] there is ongoing debate between groups which think the evidence indicates substantial extinction of these species at the K–Pg boundary,[48] and those who think the evidence supports multiple extinctions and expansions through the boundary.[49][50]

Numerous species of benthic foraminifera became extinct during the event, presumably because they depend on organic debris for nutrients, while biomass in the ocean is thought to have decreased. As the marine microbiota recovered, it is thought that increased speciation of benthic foraminifera resulted from the increase in food sources.[34] Phytoplankton recovery in the early Paleocene provided the food source to support large benthic foraminiferal assemblages, which are mainly detritus-feeding. Ultimate recovery of the benthic populations occurred over several stages lasting several hundred thousand years into the early Paleocene.[51][52]

Marine invertebrates

[edit]

There is significant variation in the fossil record as to the extinction rate of marine invertebrates across the K–Pg boundary. The apparent rate is influenced by a lack of fossil records, rather than extinctions.[34]

Ostracods, a class of small crustaceans that were prevalent in the upper Maastrichtian, left fossil deposits in a variety of locations. A review of these fossils shows that ostracod diversity was lower in the Paleocene than any other time in the Cenozoic. Current research cannot ascertain whether the extinctions occurred prior to, or during, the boundary interval.[53][54]

Among decapods, extinction patterns were highly heterogeneous and cannot be neatly attributed to any particular factor. Decapods that inhabited the Western Interior Seaway were especially hard-hit, while other regions of the world's oceans were refugia that increased chances of survival into the Palaeocene.[55]

Approximately 60% of late-Cretaceous Scleractinia coral genera failed to cross the K–Pg boundary into the Paleocene. Further analysis of the coral extinctions shows that approximately 98% of colonial species, ones that inhabit warm, shallow tropical waters, became extinct. The solitary corals, which generally do not form reefs and inhabit colder and deeper (below the photic zone) areas of the ocean were less impacted by the K–Pg boundary. Colonial coral species rely upon symbiosis with photosynthetic algae, which collapsed due to the events surrounding the K–Pg boundary,[56][57] but the use of data from coral fossils to support K–Pg extinction and subsequent Paleocene recovery, must be weighed against the changes that occurred in coral ecosystems through the K–Pg boundary.[34]

The numbers of cephalopod, echinoderm, and bivalve genera exhibited significant diminution after the K–Pg boundary. Entire groups of bivalves, including rudists (reef-building clams) and inoceramids (giant relatives of modern scallops), became extinct at the K–Pg boundary,[58][59] with the gradual extinction of most inoceramid bivalves beginning well before the K–Pg boundary.[60]

Most species of brachiopods, a small phylum of marine invertebrates, survived the K–Pg extinction event and diversified during the early Paleocene.[34]

Except for nautiloids (represented by the modern order Nautilida) and coleoids (which had already diverged into modern octopodes, squids, and cuttlefish) all other species of the molluscan class Cephalopoda became extinct at the K–Pg boundary. These included the ecologically significant belemnoids, as well as the ammonoids, a group of highly diverse, numerous, and widely distributed shelled cephalopods.[61][62] The extinction of belemnites enabled surviving cephalopod clades to fill their niches.[63] Ammonite genera became extinct at or near the K–Pg boundary; there was a smaller and slower extinction of ammonite genera prior to the boundary associated with a late Cretaceous marine regression, and a small, gradual reduction in ammonite diversity occurred throughout the very late Cretaceous.[60] Researchers have pointed out that the reproductive strategy of the surviving nautiloids, which rely upon few and larger eggs, played a role in outsurviving their ammonoid counterparts through the extinction event. The ammonoids utilized a planktonic strategy of reproduction (numerous eggs and planktonic larvae), which would have been devastated by the K–Pg extinction event. Additional research has shown that subsequent to this elimination of ammonoids from the global biota, nautiloids began an evolutionary radiation into shell shapes and complexities theretofore known only from ammonoids.[61][62]

Approximately 35% of echinoderm genera became extinct at the K–Pg boundary, although taxa that thrived in low-latitude, shallow-water environments during the late Cretaceous had the highest extinction rate. Mid-latitude, deep-water echinoderms were much less affected at the K–Pg boundary. The pattern of extinction points to habitat loss, specifically the drowning of carbonate platforms, the shallow-water reefs in existence at that time, by the extinction event.[64]

Fish

[edit]There are fossil records of jawed fishes across the K–Pg boundary, which provide good evidence of extinction patterns of these classes of marine vertebrates. While the deep-sea realm was able to remain seemingly unaffected, there was an equal loss between the open marine apex predators and the durophagous demersal feeders on the continental shelf. Within cartilaginous fish, approximately 7 out of the 41 families of neoselachians (modern sharks, skates, and rays) disappeared after this event and batoids (skates and rays) lost nearly all the identifiable species, while more than 90% of teleost fish (bony fish) families survived.[65][66]

In the Maastrichtian age, 28 shark families and 13 batoid families thrived, of which 25 and 9, respectively, survived the K–T boundary event. Forty-seven of all neoselachian genera cross the K–T boundary, with 85% being sharks. Batoids display with 15%, a comparably low survival rate.[65][67] Among elasmobranchs, those species that inhabited higher latitudes and lived pelagic lifestyles were more likely to survive, whereas epibenthic lifestyles and durophagy were strongly associated with the likelihood of perishing during the extinction event.[68]

There is evidence of a mass extinction of bony fishes at a fossil site immediately above the K–Pg boundary layer on Seymour Island near Antarctica, apparently precipitated by the K–Pg extinction event;[69] the marine and freshwater environments of fishes mitigated the environmental effects of the extinction event.[70]

Teleost fish diversified explosively after the mass extinction, filling the niches left vacant by the extinction. Groups appearing in the Paleocene and Eocene epochs include billfish, tunas, eels, and flatfish.[31]

Terrestrial invertebrates

[edit]Insect damage to the fossilized leaves of flowering plants from fourteen sites in North America was used as a proxy for insect diversity across the K–Pg boundary and analyzed to determine the rate of extinction. Researchers found that Cretaceous sites, prior to the extinction event, had rich plant and insect-feeding diversity. During the early Paleocene, flora were relatively diverse with little predation from insects, even 1.7 million years after the extinction event.[71][72] Studies of the size of the ichnotaxon Naktodemasis bowni, produced by either cicada nymphs or beetle larvae, over the course of the K-Pg transition show that the Lilliput effect occurred in terrestrial invertebrates thanks to the extinction event.[73]

The extinction event produced major changes in Paleogene insect communities. Many groups of ants were present in the Cretaceous, but in the Eocene ants became dominant and diverse, with larger colonies. Butterflies diversified as well, perhaps to take the place of leaf-eating insects wiped out by the extinction. The advanced mound-building termites, Termitidae, also appear to have risen in importance.[74]

Terrestrial plants

[edit]Plant fossils illustrate the reduction in plant species across the K–Pg boundary. There is overwhelming evidence of global disruption of plant communities at the K–Pg boundary.[75][33] Extinctions are seen both in studies of fossil pollen, and fossil leaves.[26] In North America, the data suggests massive devastation and mass extinction of plants at the K–Pg boundary sections, although there were substantial megafloral changes before the boundary.[76] In North America, approximately 57% of plant species became extinct. In high southern hemisphere latitudes, such as New Zealand and Antarctica, the mass die-off of flora caused no significant turnover in species, but dramatic and short-term changes in the relative abundance of plant groups.[71][77] European flora was also less affected, most likely due to its distance from the site of the Chicxulub impact.[78] Another line of evidence of a major floral extinction is that the divergence rate of subviral pathogens of angiosperms sharply decreased, which indicates an enormous reduction in the number of flowering plants.[79] However, phylogenetic evidence shows no mass angiosperm extinction.[80]

Due to the wholesale destruction of plants at the K–Pg boundary, there was a proliferation of saprotrophic organisms, such as fungi, that do not require photosynthesis and use nutrients from decaying vegetation. The dominance of fungal species lasted only a few years while the atmosphere cleared and plenty of organic matter to feed on was present. Once the atmosphere cleared photosynthetic organisms returned – initially ferns and other ground-level plants.[81]

In some regions, the Paleocene recovery of plants began with recolonizations by fern species, represented as a fern spike in the geologic record; this same pattern of fern recolonization was observed after the 1980 Mount St. Helens eruption.[82] Just two species of fern appear to have dominated the landscape for centuries after the event.[83] In the sediments below the K–Pg boundary the dominant plant remains are angiosperm pollen grains, but the boundary layer contains little pollen and is dominated by fern spores.[84] More usual pollen levels gradually resume above the boundary layer. This is reminiscent of areas blighted by modern volcanic eruptions, where the recovery is led by ferns, which are later replaced by larger angiosperm plants.[85] In North American terrestrial sequences, the extinction event is best represented by the marked discrepancy between the rich and relatively abundant late-Maastrichtian pollen record and the post-boundary fern spike.[75]

Polyploidy appears to have enhanced the ability of flowering plants to survive the extinction, probably because the additional copies of the genome such plants possessed allowed them to more readily adapt to the rapidly changing environmental conditions that followed the impact.[86]

Beyond extinction impacts, the event also caused more general changes of flora such as giving rise to neotropical rainforest biomes like the Amazonia, replacing species composition and structure of local forests during ~6 million years of recovery to former levels of plant diversity.[87][88]

Fungi

[edit]While it appears that many fungi were wiped out at the K-Pg boundary, there is some evidence that some fungal species thrived in the years after the extinction event. Microfossils from that period indicate a great increase in fungal spores, long before the resumption of plentiful fern spores in the recovery after the impact. Monoporisporites and hypha are almost exclusive microfossils for a short span during and after the iridium boundary. These saprophytes would not need sunlight, allowing them to survive during a period when the atmosphere was likely clogged with dust and sulfur aerosols.[81]

The proliferation of fungi has occurred after several extinction events, including the Permian–Triassic extinction event, the largest known mass extinction in Earth's history, with up to 96% of all species suffering extinction.[89]

Amphibians

[edit]There is limited evidence for extinction of amphibians at the K–Pg boundary. A study of fossil vertebrates across the K–Pg boundary in Montana concluded that no species of amphibian became extinct.[90] Yet there are several species of Maastrichtian amphibian, not included as part of this study, which are unknown from the Paleocene. These include the frog Theatonius lancensis[91] and the albanerpetontid Albanerpeton galaktion;[92] therefore, some amphibians do seem to have become extinct at the boundary. The relatively low levels of extinction seen among amphibians probably reflect the low extinction rates seen in freshwater animals.[37]

Reptiles

[edit]Choristoderes

[edit]The choristoderes (a group of semi-aquatic diapsids of uncertain position) survived across the K–Pg boundary[34] subsequently becoming extinct in the Miocene.[93] The gharial-like choristodere genus Champsosaurus' palatal teeth suggest that there were dietary changes among the various species across the K–Pg event.[94]

Turtles

[edit]More than 80% of Cretaceous turtle species passed through the K–Pg boundary. All six turtle families in existence at the end of the Cretaceous survived into the Paleogene and are represented by living species.[95]

Lepidosauria

[edit]The rhynchocephalians which were a globally distributed and diverse group of lepidosaurians during the early Mesozoic, had begun to decline by the mid-Cretaceous, although they remained successful in the Late Cretaceous of southern South America.[96] They are represented today by a single species, the tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus) found in New Zealand.[97] Outside of New Zealand, one rhynchocephalian is known to have crossed the K-Pg boundary, Kawasphenodon peligrensis, known from the earliest Paleocene (Danian) of Patagonia.[98]

The order Squamata comprising lizards and snakes first diversified during the Jurassic and continued to diversify throughout the Cretaceous.[99] They are currently the most successful and diverse group of living reptiles, with more than 10,000 extant species. The only major group of terrestrial lizards to go extinct at the end of the Creteaceous were the polyglyphanodontians, a diverse group of mainly herbivorous lizards known predominantly from the Northern Hemisphere[100] The mosasaurs, a diverse group of large predatory marine reptiles, also became extinct. Fossil evidence indicates that squamates generally suffered very heavy losses in the K–Pg event, only recovering 10 million years after it. The extinction of Cretaceous lizards and snakes may have led to the evolution of modern groups such as iguanas, monitor lizards, and boas.[23] The diversification of crown group snakes has been linked to the biotic recovery in the aftermath of the K-Pg extinction event.[101]

Marine reptiles

[edit]∆44/42Ca values indicate that prior to the mass extinction, marine reptiles at the top of food webs were feeding on only one source of calcium, suggesting their populations exhibited heightened vulnerability to extinctions at the terminus of the Cretaceous.[102] Along with the aforementioned mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, represented by the families Elasmosauridae and Polycotylidae, became extinct during the event.[103][104][105][106] The ichthyosaurs had disappeared from fossil record tens of millions of years prior to the K-Pg extinction event.[107]

Crocodyliforms

[edit]Ten families of crocodilians or their close relatives are represented in the Maastrichtian fossil records, of which five died out prior to the K–Pg boundary.[108] Five families have both Maastrichtian and Paleocene fossil representatives. All of the surviving families of crocodyliforms inhabited freshwater and terrestrial environments—except for the Dyrosauridae, which lived in freshwater and marine locations. Approximately 50% of crocodyliform representatives survived across the K–Pg boundary, the only apparent trend being that no large crocodiles survived.[34] Crocodyliform survivability across the boundary may have resulted from their aquatic niche and ability to burrow, which reduced susceptibility to negative environmental effects at the boundary.[70] Jouve and colleagues suggested in 2008 that juvenile marine crocodyliforms lived in freshwater environments as do modern marine crocodile juveniles, which would have helped them survive where other marine reptiles became extinct; freshwater environments were not so strongly affected by the K–Pg extinction event as marine environments were.[109] Among the terrestrial clade Notosuchia, only the family Sebecidae survived; the exact reasons for this pattern are not known.[110] Sebecids were large terrestrial predators, are known from the Eocene of Europe, and would survive in South America into the Miocene.[111]

Pterosaurs

[edit]Two families of pterosaurs, Azhdarchidae and Nyctosauridae, were definitely present in the Maastrichtian, and they likely became extinct at the K–Pg boundary. Several other pterosaur lineages may have been present during the Maastrichtian, such as the ornithocheirids, pteranodontids, a possible tapejarid, a possible thalassodromid and a basal toothed taxon of uncertain affinities, though they are represented by fragmentary remains that are difficult to assign to any given group.[112][113] While this was occurring, modern birds were undergoing diversification; traditionally it was thought that they replaced archaic birds and pterosaur groups, possibly due to direct competition, or they simply filled empty niches,[70][114][115] but there is no correlation between pterosaur and avian diversities that are conclusive to a competition hypothesis,[116] and small pterosaurs were present in the Late Cretaceous.[117] At least some niches previously held by birds were reclaimed by pterosaurs prior to the K–Pg event.[118]

Non-avian dinosaurs

[edit]

Scientists agree that all non-avian dinosaurs became extinct at the K–Pg boundary. The dinosaur fossil record has been interpreted to show both a decline in diversity and no decline in diversity during the last few million years of the Cretaceous, and it may be that the quality of the dinosaur fossil record is simply not good enough to permit researchers to distinguish between the options.[119] There is no evidence that late Maastrichtian non-avian dinosaurs could burrow, swim, or dive, which suggests they were unable to shelter themselves from the worst parts of any environmental stress that occurred at the K–Pg boundary. It is possible that small dinosaurs (other than birds) did survive, but they would have been deprived of food, as herbivorous dinosaurs would have found plant material scarce and carnivores would have quickly found prey in short supply.[70]

The growing consensus about the endothermy of dinosaurs (see dinosaur physiology) helps to understand their full extinction in contrast with their close relatives, the crocodilians. Ectothermic ("cold-blooded") crocodiles have very limited needs for food (they can survive several months without eating), while endothermic ("warm-blooded") animals of similar size need much more food to sustain their faster metabolism. Thus, under the circumstances of food chain disruption previously mentioned, non-avian dinosaurs died out,[33] while some crocodiles survived. In this context, the survival of other endothermic animals, such as some birds and mammals, could be due, among other reasons, to their smaller needs for food, related to their small size at the extinction epoch.[120]

Whether the extinction occurred gradually or suddenly has been debated, as both views have support from the fossil record. A highly informative sequence of dinosaur-bearing rocks from the K–Pg boundary is found in western North America, particularly the late Maastrichtian-age Hell Creek Formation of Montana.[121] Comparison with the older Judith River Formation (Montana) and Dinosaur Park Formation (Alberta), which both date from approximately 75 Ma, provides information on the changes in dinosaur populations over the last 10 million years of the Cretaceous. These fossil beds are geographically limited, covering only part of one continent.[119] The middle–late Campanian formations show a greater diversity of dinosaurs than any other single group of rocks. The late Maastrichtian rocks contain the largest members of several major clades: Tyrannosaurus, Ankylosaurus, Pachycephalosaurus, Triceratops, and Torosaurus, which suggests food was plentiful immediately prior to the extinction.[122] A study of 29 fossil sites in Catalan Pyrenees of Europe in 2010 supports the view that dinosaurs there had great diversity until the asteroid impact, with more than 100 living species.[123] More recent research indicates that this figure is obscured by taphonomic biases and the sparsity of the continental fossil record. The results of this study, which were based on estimated real global biodiversity, showed that between 628 and 1,078 non-avian dinosaur species were alive at the end of the Cretaceous and underwent sudden extinction after the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event.[124] Alternatively, interpretation based on the fossil-bearing rocks along the Red Deer River in Alberta, Canada, supports the gradual extinction of non-avian dinosaurs; during the last 10 million years of the Cretaceous layers there, the number of dinosaur species seems to have decreased from about 45 to approximately 12. Other scientists have made the same assessment following their research.[125]

Several researchers support the existence of Paleocene non-avian dinosaurs. Evidence of this existence is based on the discovery of dinosaur remains in the Hell Creek Formation up to 1.3 m (4 ft 3.2 in) above and 40,000 years later than the K–Pg boundary.[126] Pollen samples recovered near a fossilized hadrosaur femur recovered in the Ojo Alamo Sandstone at the San Juan River in Colorado, indicate that the animal lived during the Cenozoic, approximately 64.5 Ma (about 1 million years after the K–Pg extinction event). If their existence past the K–Pg boundary can be confirmed, these hadrosaurids would be considered a dead clade walking.[127] The scientific consensus is that these fossils were eroded from their original locations and then re-buried in much later sediments (also known as reworked fossils).[128]

Birds

[edit]Most paleontologists regard birds as the only surviving dinosaurs (see Origin of birds). It is thought that all non-avian theropods became extinct, including then-flourishing groups such as enantiornithines and hesperornithiforms.[129] Several analyses of bird fossils show divergence of species prior to the K–Pg boundary, and that duck, chicken, and ratite bird relatives coexisted with non-avian dinosaurs.[130] Large collections of bird fossils representing a range of different species provide definitive evidence for the persistence of archaic birds to within 300,000 years of the K–Pg boundary. The absence of these birds in the Paleogene is evidence that a mass extinction of archaic birds took place there.[22]

The most successful and dominant group of avialans, enantiornithes, were wiped out. Only a small fraction of ground and water-dwelling Cretaceous bird species survived the impact, giving rise to today's birds.[22][131] The only bird group known for certain to have survived the K–Pg boundary is the Aves.[22] Avians may have been able to survive the extinction as a result of their abilities to dive, swim, or seek shelter in water and marshlands. Many species of avians can build burrows, or nest in tree holes, or termite nests, all of which provided shelter from the environmental effects at the K–Pg boundary. Long-term survival past the boundary was assured as a result of filling ecological niches left empty by extinction of non-avian dinosaurs.[70] Based on molecular sequencing and fossil dating, many species of birds (the Neoaves group in particular) appeared to radiate after the K–Pg boundary.[30][132] The open niche space and relative scarcity of predators following the K-Pg extinction allowed for adaptive radiation of various avian groups. Ratites, for example, rapidly diversified in the early Paleogene and are believed to have convergently developed flightlessness at least three to six times, often fulfilling the niche space for large herbivores once occupied by non-avian dinosaurs.[30][133][134]

Mammals

[edit]Mammalian species began diversifying approximately 30 million years prior to the K–Pg boundary. Diversification of mammals stalled across the boundary.[135] All major Late Cretaceous mammalian lineages, including monotremes (egg-laying mammals), multituberculates, metatherians (which includes modern marsupials), eutherians (which includes modern placentals), meridiolestidans,[136] and gondwanatheres[137] survived the K–Pg extinction event, although they suffered losses. In particular, metatherians largely disappeared from North America, and the Asian deltatheroidans became extinct (aside from the lineage leading to Gurbanodelta).[138] In the Hell Creek beds of North America, at least half of the ten known multituberculate species and all eleven metatherians species are not found above the boundary.[119] Multituberculates in Europe and North America survived relatively unscathed and quickly bounced back in the Paleocene, but Asian forms were devastated, never again to represent a significant component of mammalian fauna.[139] A recent study indicates that metatherians suffered the heaviest losses at the K–Pg event, followed by multituberculates, while eutherians recovered the quickest.[140] K–Pg boundary mammalian species were generally small, comparable in size to rats; this small size would have helped them find shelter in protected environments. It is postulated that some early monotremes, marsupials, and placentals were semiaquatic or burrowing, as there are multiple mammalian lineages with such habits today. Any burrowing or semiaquatic mammal would have had additional protection from K–Pg boundary environmental stresses.[70]

After the K–Pg extinction, mammals evolved to fill the niches left vacant by the dinosaurs.[141] Some research indicates that mammals did not explosively diversify across the K–Pg boundary, despite the ecological niches made available by the extinction of dinosaurs.[142] Several mammalian orders have been interpreted as diversifying immediately after the K–Pg boundary, including Chiroptera (bats) and Cetartiodactyla (a diverse group that today includes whales and dolphins and even-toed ungulates),[142] although recent research concludes that only marsupial orders diversified soon after the K–Pg boundary.[135] However, morphological diversification rates among eutherians after the extinction event were thrice those of before it.[143] Also significant, within the mammalian genera, new species were approximately 9.1% larger after the K–Pg boundary.[144] After about 700,000 years, some mammals had reached 50 kilos (110 pounds), a 100-fold increase over the weight of those which survived the extinction.[145] It is thought that body sizes of placental mammalian survivors evolutionarily increased first, allowing them to fill niches after the extinctions, with brain sizes increasing later in the Eocene.[146][147]

Dating

[edit]A 1991 study of fossil leaves dated the extinction-associated freezing to early June.[148] A later study shifted the dating to spring season, based on the osteological evidence and stable isotope records of well-preserved bones of acipenseriform fishes. The study noted that "the palaeobotanical identities, taphonomic inferences and stratigraphic assumptions" for the June dating have since all been refuted.[149] Another modern study opted for the spring–summer range.[150] A study of fossilized fish bones found at Tanis in North Dakota suggests that the Cretaceous-Paleogene mass extinction happened during the Northern Hemisphere spring.[151][152][153][154]

Duration

[edit]The rapidity of the extinction is a controversial issue,[needs update] because some theories about its causes imply a rapid extinction over a relatively short period (from a few years to a few thousand years), while others imply longer periods. The issue is difficult to resolve because of the Signor–Lipps effect, where the fossil record is so incomplete that most extinct species probably died out long after the most recent fossil that has been found.[155] Scientists have also found very few continuous beds of fossil-bearing rock that cover a time range from several million years before the K–Pg extinction to several million years after it.[34]

The sedimentation rate and thickness of K–Pg clay from three sites suggest rapid extinction, perhaps over a period of less than 10,000 years.[156] At one site in the Denver Basin of Colorado, after the K–Pg boundary layer was deposited, the fern spike lasted approximately 1,000 years, and no more than 71,000 years; at the same location, the earliest appearance of Cenozoic mammals occurred after approximately 185,000 years, and no more than 570,000 years, "indicating rapid rates of biotic extinction and initial recovery in the Denver Basin during this event."[157] Models presented at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union demonstrated that the period of global darkness following the Chicxulub impact would have persisted in the Hell Creek Formation nearly 2 years.[158]

Causes

[edit]Chicxulub impact

[edit]Evidence for impact

[edit]

In 1980, a team of researchers consisting of Nobel Prize-winning physicist Luis Alvarez, his son, geologist Walter Alvarez, and chemists Frank Asaro and Helen Michel discovered that sedimentary layers found all over the world at the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary contain a concentration of iridium many times greater than normal (30, 160, and 20 times in three sections originally studied). Iridium is extremely rare in Earth's crust because it is a siderophile element which mostly sank along with iron into Earth's core during planetary differentiation.[12] Instead, iridium is more common in comets and asteroids.[8] Because of this, the Alvarez team suggested that an asteroid struck the Earth at the time of the K–Pg boundary.[12] There were earlier speculations on the possibility of an impact event,[159] but this was the first hard evidence,[12] and since then, studies have continued to demonstrate elevated iridium levels in association with the K-Pg boundary.[7][6][5] This hypothesis was viewed as radical when first proposed, but additional evidence soon emerged. The boundary clay was found to be full of minute spherules of rock, crystallized from droplets of molten rock formed by the impact.[160] Shocked quartz[c] and other minerals were also identified in the K–Pg boundary.[161][162] The identification of giant tsunami beds along the Gulf Coast and the Caribbean provided more evidence,[163] and suggested that the impact might have occurred nearby, as did the discovery that the K–Pg boundary became thicker in the southern United States, with meter-thick beds of debris occurring in northern New Mexico.[26] Further research identified the giant Chicxulub crater, buried under Chicxulub on the coast of Yucatán, as the source of the K–Pg boundary clay. Identified in 1990[14] based on work by geophysicist Glen Penfield in 1978, the crater is oval, with an average diameter of roughly 180 km (110 mi), about the size calculated by the Alvarez team.[164] In March 2010, an international panel of 41 scientists reviewed 20 years of scientific literature and endorsed the asteroid hypothesis, specifically the Chicxulub impact, as the cause of the extinction, ruling out other theories such as massive volcanism. They had determined that a 10-to-15-kilometer (6 to 9 mi) asteroid hurtled into Earth at Chicxulub on Mexico's Yucatán Peninsula.[8] Additional evidence for the impact event is found at the Tanis site in southwestern North Dakota, United States.[165] Tanis is part of the heavily studied Hell Creek Formation, a group of rocks spanning four states in North America renowned for many significant fossil discoveries from the Upper Cretaceous and lower Paleocene.[166] Tanis is an extraordinary and unique site because it appears to record the events from the first minutes until a few hours after the impact of the giant Chicxulub asteroid in extreme detail.[167][168] Amber from the site has been reported to contain microtektites matching those of the Chicxulub impact event.[169] Some researchers question the interpretation of the findings at the site or are skeptical of the team leader, Robert DePalma, who had not yet received his Ph.D. in geology at the time of the discovery and whose commercial activities have been regarded with suspicion.[170] Furthermore, indirect evidence of an asteroid impact as the cause of the mass extinction comes from patterns of turnover in marine plankton.[171]

In a 2013 paper, Paul Renne of the Berkeley Geochronology Center dated the impact at 66.043±0.011 million years ago, based on argon–argon dating. He further posits that the mass extinction occurred within 32,000 years of this date.[172]

In 2007, it was proposed that the impactor belonged to the Baptistina family of asteroids.[173] This link has been doubted, though not disproved, in part because of a lack of observations of the asteroid and its family.[174] It was reported in 2009 that 298 Baptistina does not share the chemical signature of the K–Pg impactor.[175] Further, a 2011 Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) study of reflected light from the asteroids of the family estimated their break-up at 80 Ma, giving them insufficient time to shift orbits and impact Earth by 66 Ma.[176]

Effects of impact

[edit]

The collision would have released the same energy as 100 teratonnes of TNT (4.2×1023 joules)—more than a billion times the energy of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[8] The Chicxulub impact caused a global catastrophe. Some of the phenomena were brief occurrences immediately following the impact, but there were also long-term geochemical and climatic disruptions that devastated the ecology.[178][41][179]

The scientific consensus is that the asteroid impact at the K–Pg boundary left megatsunami deposits and sediments around the area of the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico, from the colossal waves created by the impact.[180] These deposits have been identified in the La Popa basin in northeastern Mexico,[181] platform carbonates in northeastern Brazil,[182] in Atlantic deep-sea sediments,[183] and in the form of the thickest-known layer of graded sand deposits, around 100 m (330 ft), in the Chicxulub crater itself, directly above the shocked granite ejecta. The megatsunami has been estimated at more than 100 m (330 ft) tall, as the asteroid fell into relatively shallow seas; in deep seas it would have been 4.6 km (2.9 mi) tall.[184] Fossiliferous sedimentary rocks deposited during the K–Pg impact have been found in the Gulf of Mexico area, including tsunami wash deposits carrying remains of a mangrove-type ecosystem, indicating that water in the Gulf of Mexico sloshed back and forth repeatedly after the impact; dead fish left in these shallow waters were not disturbed by scavengers.[185][186][187][188][189]

The re-entry of ejecta into Earth's atmosphere included a brief (hours-long) but intense pulse of infrared radiation, cooking exposed organisms.[70] This is debated, with opponents arguing that local ferocious fires, probably limited to North America, fall short of global firestorms. This is the "Cretaceous–Paleogene firestorm debate". A paper in 2013 by a prominent modeler of nuclear winter suggested that, based on the amount of soot in the global debris layer, the entire terrestrial biosphere might have burned, implying a global soot-cloud blocking out the sun and creating an impact winter effect.[178] If widespread fires occurred this would have exterminated the most vulnerable organisms that survived the period immediately after the impact.[190]

Aside from the hypothesized fire effects on reduction of insolation, the impact would have created a humongous dust cloud that blocked sunlight for up to a year, inhibiting photosynthesis.[13][41] The asteroid hit an area of gypsum and anhydrite rock containing a large amount of combustible hydrocarbons and sulfur,[191] much of which was vaporized, thereby injecting sulfuric acid aerosols into the stratosphere, which might have reduced sunlight reaching the Earth's surface by more than 50%.[192] Fine silicate dust also contributed to the intense impact winter.[193] The climatic forcing of this impact winter was about 100 times more potent than that of the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo.[194] According to models of the Hell Creek Formation, the onset of global darkness would have reached its maximum in only a few weeks and likely lasted upwards of 2 years.[158] Freezing temperatures probably lasted for at least three years.[179] At Brazos section, the sea surface temperature dropped as much as 7 °C (13 °F) for decades after the impact.[195] It would take at least ten years for such aerosols to dissipate, and would account for the extinction of plants and phytoplankton, and subsequently herbivores and their predators. Creatures whose food chains were based on detritus would have a reasonable chance of survival.[120][41] In 2016, a scientific drilling project obtained deep rock-core samples from the peak ring around the Chicxulub impact crater. The discoveries confirmed that the rock comprising the peak ring had been shocked by immense pressure and melted in just minutes from its usual state into its present form. Unlike sea-floor deposits, the peak ring was made of granite originating much deeper in the earth, which had been ejected to the surface by the impact. Gypsum is a sulfate-containing rock usually present in the shallow seabed of the region; it had been almost entirely removed, vaporized into the atmosphere. The impactor was large enough to create a 190-kilometer-wide (120 mi) peak ring, to melt, shock, and eject deep granite, to create colossal water movements, and to eject an immense quantity of vaporized rock and sulfates into the atmosphere, where they would have persisted for several years. This worldwide dispersal of dust and sulfates would have affected climate catastrophically, led to large temperature drops, and devastated the food chain.[196][197]

The release of large quantities of sulphur aerosols into the atmosphere as a consequence of the impact would also have caused acid rain.[198][192] Oceans acidified as a result.[15][16] This decrease in ocean pH would kill many organisms that grow shells of calcium carbonate.[192] The heating of the atmosphere during the impact itself may have also generated nitric acid rain through the production of nitrogen oxides and their subsequent reaction with water vapour.[199][198]

After the impact winter, the Earth entered a period of global warming as a result of the vapourisation of carbonates into carbon dioxide, whose long residence time in the atmosphere ensured significant warming would occur after more short-lived cooling gases dissipated.[200] Carbon monoxide concentrations also increased and caused particularly devastating global warming because of the consequent increases in tropospheric ozone and methane concentrations.[201] The impact's injection of water vapour into the atmosphere also produced major climatic perturbations.[202]

The end-Cretaceous event is the only mass extinction definitively known to be associated with an impact, and other large extraterrestrial impacts, such as the Manicouagan Reservoir impact, do not coincide with any noticeable extinction events.[203]

Multiple impact event

[edit]Other crater-like topographic features have also been proposed as impact craters formed in connection with Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction. This suggests the possibility of near-simultaneous multiple impacts, perhaps from a fragmented asteroidal object similar to the Shoemaker–Levy 9 impact with Jupiter. In addition to the 180 km (110 mi) Chicxulub crater, there is the 24 km (15 mi) Boltysh crater in Ukraine (65.17±0.64 Ma), the 20 km (12 mi) Silverpit crater in the North Sea (59.5±14.5 Ma) possibly formed by bolide impact, and the controversial and much larger 600 km (370 mi) Shiva crater. Any other craters that might have formed in the Tethys Ocean would since have been obscured by the northward tectonic drift of Africa and India.[204][205][206][207]

Deccan Traps

[edit]The Deccan Traps, which erupted close to the boundary between the Mesozoic and Cenozoic,[208][209][210] have been cited as an alternate explanation for the mass extinction.[211][212] Before 2000, arguments that the Deccan Traps flood basalts caused the extinction were usually linked to the view that the extinction was gradual, as the flood basalt events were thought to have started around 68 Mya and lasted more than 2 million years. The most recent evidence shows that the traps erupted over a period of only 800,000 years spanning the K–Pg boundary, and therefore may be responsible for the extinction and the delayed biotic recovery thereafter.[213]

The Deccan Traps could have caused extinction through several mechanisms, including the release of dust and sulfuric aerosols into the air, which might have blocked sunlight and thereby reduced photosynthesis in plants.[214] In addition, the latest Cretaceous saw a rise in global temperatures;[215][216] Deccan Traps volcanism might have resulted in carbon dioxide emissions that increased the greenhouse effect when the dust and aerosols cleared from the atmosphere.[217][209] The increased carbon dioxide emissions also caused acid rain, evidenced by increased mercury deposition due to increased solubility of mercury compounds in more acidic water.[218]

Evidence for extinctions caused by the Deccan Traps includes the reduction in diversity of marine life when the climate near the K–Pg boundary increased in temperature. The temperature increased about three to four degrees very rapidly between 65.4 and 65.2 million years ago, which is very near the time of the extinction event. Not only did the climate temperature increase, but the water temperature decreased, causing a drastic decrease in marine diversity.[219] Evidence from Tunisia indicates that marine life was deleteriously affected by a major period of increased warmth and humidity linked to a pulse of intense Deccan Traps activity.[220] Charophyte declines in the Songliao Basin, China before the asteroid impact have been concluded to be connected to climate changes caused by Deccan Traps activity.[221]

In the years when the Deccan Traps hypothesis was linked to a slower extinction, Luis Alvarez (d. 1988) replied that paleontologists were being misled by sparse data. While his assertion was not initially well-received, later intensive field studies of fossil beds lent weight to his claim. Eventually, most paleontologists began to accept the idea that the mass extinctions at the end of the Cretaceous were largely or at least partly due to a massive Earth impact. Even Walter Alvarez acknowledged that other major changes might have contributed to the extinctions.[222] More recent arguments against the Deccan Traps as an extinction cause include that the timeline of Deccan Traps activity and pulses of climate change has been found by some studies to be asynchronous,[223] that palynological changes do not coincide with intervals of volcanism,[224] and that many sites show climatic stability during the latest Maastrichtian and no sign of major disruptions caused by volcanism.[225] Multiple modelling studies conclude that an impact event, not volcanism, fits best with available evidence of extinction patterns.[21][20][19]

Combining these theories, some geophysical models suggest that the impact contributed to the Deccan Traps. These models, combined with high-precision radiometric dating, suggest that the Chicxulub impact could have triggered some of the largest Deccan eruptions, as well as eruptions at active volcano sites anywhere on Earth.[226][227]

Maastrichtian sea-level regression

[edit]There is clear evidence that sea levels fell in the final stage of the Cretaceous by more than at any other time in the Mesozoic era. In some Maastrichtian stage rock layers from various parts of the world, the later layers are terrestrial; earlier layers represent shorelines and the earliest layers represent seabeds. These layers do not show the tilting and distortion associated with mountain building, therefore the likeliest explanation is a regression, a drop in sea level. There is no direct evidence for the cause of the regression, but the currently accepted explanation is that the mid-ocean ridges became less active and sank under their own weight.[34][228]

A severe regression would have greatly reduced the continental shelf area, the most species-rich part of the sea, and therefore could have been enough to cause a marine mass extinction, but this change would not have caused the extinction of the ammonites. The regression would also have caused climate changes, partly by disrupting winds and ocean currents and partly by reducing the Earth's albedo and increasing global temperatures.[60] Marine regression also resulted in the loss of epeiric seas, such as the Western Interior Seaway of North America. The loss of these seas greatly altered habitats, removing coastal plains that ten million years before had been host to diverse communities such as are found in rocks of the Dinosaur Park Formation. Another consequence was an expansion of freshwater environments, since continental runoff now had longer distances to travel before reaching oceans. While this change was favorable to freshwater vertebrates, those that prefer marine environments, such as sharks, suffered.[119]

Multiple causes

[edit]Proponents of multiple causation view the suggested single causes as either too small to produce the vast scale of the extinction, or not likely to produce its observed taxonomic pattern. In a review article, J. David Archibald and David E. Fastovsky discussed a scenario combining three major postulated causes: volcanism, marine regression, and extraterrestrial impact. In this scenario, terrestrial and marine communities were stressed by the changes in, and loss of, habitats. Dinosaurs, as the largest vertebrates, were the first affected by environmental changes, and their diversity declined. At the same time, particulate materials from volcanism cooled and dried areas of the globe. Then an impact event occurred, causing collapses in photosynthesis-based food chains, both in the already-stressed terrestrial food chains and in the marine food chains.[119]

Based on studies at Seymour Island in Antarctica, Sierra Petersen and colleagues argue that there were two separate extinction events near the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary, with one correlating to Deccan Trap volcanism and one correlated with the Chicxulub impact. The team analyzed combined extinction patterns using a new clumped isotope temperature record from a hiatus-free, expanded K–Pg boundary section. They documented a 7.8±3.3 °C warming synchronous with the onset of Deccan Traps volcanism and a second, smaller warming at the time of meteorite impact. They suggested that local warming had been amplified due to the simultaneous disappearance of continental or sea ice. Intra-shell variability indicates a possible reduction in seasonality after Deccan eruptions began, continuing through the meteorite event. Species extinction at Seymour Island occurred in two pulses that coincide with the two observed warming events, directly linking the end-Cretaceous extinction at this site to both volcanic and meteorite events via climate change.[229]

See also

[edit]- Climate across Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary

- Late Devonian extinction – One of the five most severe extinction events in the history of the Earth's biota

- List of possible impact structures on Earth

- Late Ordovician mass extinction – Extinction event around 444 million years ago

- Permian–Triassic extinction event – Earth's most severe extinction event

- Timeline of Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event research – Research timeline

- Triassic–Jurassic extinction event – Mass extinction ending the Triassic period

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ The abbreviation is derived from the juxtaposition of K, the common abbreviation for the Cretaceous, which in turn originates from the correspondent German term Kreide, and Pg, which is the abbreviation for the Paleogene.

- ^ The former designation includes the term 'Tertiary' (abbreviated as T), which is now discouraged as a formal geochronological unit by the International Commission on Stratigraphy.[1]

- ^ Shocked minerals have their internal structure deformed, and are created by intense pressures as in nuclear blasts and meteorite impacts.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Ogg, James G.; Gradstein, F. M.; Gradstein, Felix M. (2004). A geologic time scale 2004. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78142-8.

- ^ "International Chronostratigraphic Chart". International Commission on Stratigraphy. 2015. Archived from the original on 30 May 2014. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ^ Fortey, Richard (1999). Life: A natural history of the first four billion years of life on Earth. Vintage. pp. 238–260. ISBN 978-0-375-70261-7.

- ^ Muench, David; Muench, Marc; Gilders, Michelle A. (2000). Primal Forces. Portland, Oregon: Graphic Arts Center Publishing. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-55868-522-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jones, Heather L.; Westerhold, Thomas; Birch, Heather; Hull, Pincelli; Negra, M. Hédi; Röhl, Ursula; Sepúlveda, Julio; Vellekoop, Johan; Whiteside, Jessica H.; Alegret, Laia; Henehan, Michael; Robinson, Libby; Van Dijk, Joep; Bralower, Timothy (18 January 2023). "Stratigraphy of the Cretaceous/Paleogene (K/Pg) boundary at the Global Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) in El Kef, Tunisia: New insights from the El Kef Coring Project". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 135 (9–10): 2451. Bibcode:2023GSAB..135.2451J. doi:10.1130/B36487.1. S2CID 256021543. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Irizarry, Kayla M.; Witts, James T.; Garb, Matthew P.; Rashkova, Anastasia; Landman, Neil H.; Patzkowsky, Mark E. (15 January 2023). "Faunal and stratigraphic analysis of the basal Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) boundary event deposits, Brazos River, Texas, USA". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 610: 111334. Bibcode:2023PPP...61011334I. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2022.111334. S2CID 254345541. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ferreira da Silva, Luiza Carine; Santos, Alessandra; Fauth, Gerson; Manríquez, Leslie Marcela Elizabeth; Kochhann, Karlos Guilherme Diemer; Do Monte Guerra, Rodrigo; Horodyski, Rodrigo Scalise; Villegas-Martín, Jorge; Ribeiro da Silva, Rafael (April 2023). "High-latitude Cretaceous–Paleogene transition: New paleoenvironmental and paleoclimatic insights from Seymour Island, Antarctica". Marine Micropaleontology. 180: 102214. Bibcode:2023MarMP.180j2214F. doi:10.1016/j.marmicro.2023.102214. S2CID 256834649. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Schulte, Peter; et al. (5 March 2010). "The Chicxulub Asteroid Impact and Mass Extinction at the Cretaceous-Paleogene Boundary" (PDF). Science. 327 (5970): 1214–1218. Bibcode:2010Sci...327.1214S. doi:10.1126/science.1177265. PMID 20203042. S2CID 2659741.

- ^ Alvarez, Luis (10 March 1981). "The Asteroid and the Dinosaur (Nova S08E08, 1981)". IMDB. PBS-WGBH/Nova. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ Sleep, Norman H.; Lowe, Donald R. (9 April 2014). "Scientists reconstruct ancient impact that dwarfs dinosaur-extinction blast". American Geophysical Union. Archived from the original on 1 January 2017. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (15 May 2017). "Dinosaur asteroid hit 'worst possible place'". BBC News Online. Archived from the original on 18 March 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Alvarez, Luis W.; Alvarez, Walter; Asaro, F.; Michel, H. V. (1980). "Extraterrestrial cause for the Cretaceous–Tertiary extinction" (PDF). Science. 208 (4448): 1095–1108. Bibcode:1980Sci...208.1095A. doi:10.1126/science.208.4448.1095. PMID 17783054. S2CID 16017767. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 August 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Vellekoop, J.; Sluijs, A.; Smit, J.; et al. (May 2014). "Rapid short-term cooling following the Chicxulub impact at the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (21): 7537–41. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.7537V. doi:10.1073/pnas.1319253111. PMC 4040585. PMID 24821785.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Хильдебранд, Арканзас; Пенфилд, GT; и др. (1991). «Кратер Чиксулуб: возможный ударный кратер на границе мелового и третичного периодов на полуострове Юкатан, Мексика». Геология . 19 (9): 867–871. Бибкод : 1991Geo....19..867H . doi : 10.1130/0091-7613(1991)019<0867:ccapct>2.3.co;2 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Джоэл, Лукас (21 октября 2019 г.). «Астероид, убивший динозавров, мгновенно окислил океан: событие Чиксулуб нанесло такой же ущерб жизни в океанах, как и существам на суше, как показывает исследование» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 24 октября 2019 года . Проверено 24 октября 2019 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хенехан, Майкл Дж. (21 октября 2019 г.). «Быстрое закисление океана и длительное восстановление системы Земли последовали за ударом Чиксулуб в конце мелового периода» . Труды Национальной академии наук Соединенных Штатов Америки . 116 (45): 22500–22504. Бибкод : 2019PNAS..11622500H . дои : 10.1073/pnas.1905989116 . ПМК 6842625 . ПМИД 31636204 .

- ^ Келлер, Герта (2012). «Мел-третичное массовое вымирание, воздействие Чиксулуб и деканский вулканизм. Земля и жизнь». В Таланте, Джон (ред.). Земля и жизнь: глобальное биоразнообразие, интервалы вымирания и биогеографические возмущения во времени . Спрингер . стр. 759–793 . ISBN 978-90-481-3427-4 .

- ^ Боскер, Бьянка (сентябрь 2018 г.). «Самая отвратительная вражда в науке: геолог из Принстона десятилетиями терпела насмешки за утверждение, что пятое вымирание было вызвано не астероидом, а серией колоссальных извержений вулканов. Но она возобновила эту дискуссию» . Атлантический Ежемесячник . Архивировано из оригинала 21 февраля 2019 года . Проверено 30 января 2019 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Джоэл, Лукас (16 января 2020 г.). «Астероид или вулкан? Новые разгадки гибели динозавров» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Проверено 17 января 2020 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Халл, Пинчелли М.; Борнеманн, Андре; Пенман, Дональд Э. (17 января 2020 г.). «Об ударе и вулканизме на рубеже мела и палеогена» . Наука . 367 (6475): 266–272. Бибкод : 2020Sci...367..266H . дои : 10.1126/science.aay5055 . hdl : 20.500.11820/483a2e77-318f-476a-8fec-33a45fbdc90b . ПМИД 31949074 . S2CID 210698721 . Проверено 17 января 2020 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кьяренца, Альфио Алессандро; Фарнсворт, Александр; Мэннион, Филип Д.; Лант, Дэниел Дж.; Вальдес, Пол Дж.; Морган, Джоанна В .; Эллисон, Питер А. (21 июля 2020 г.). «Вымирание динозавров в конце мелового периода было вызвано ударом астероида, а не вулканизмом» . Труды Национальной академии наук Соединенных Штатов Америки . 117 (29): 17084–17093. Бибкод : 2020PNAS..11717084C . дои : 10.1073/pnas.2006087117 . ISSN 0027-8424 . ПМЦ 7382232 . ПМИД 32601204 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Лонгрич, Николас Р.; Токарик, Тим; Филд, Дэниел Дж. (2011). «Массовое вымирание птиц на рубеже мела и палеогена (K – Pg)» . Труды Национальной академии наук Соединенных Штатов Америки . 108 (37): 15253–15257. Бибкод : 2011PNAS..10815253L . дои : 10.1073/pnas.1110395108 . ПМК 3174646 . ПМИД 21914849 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Лонгрич, Северная Каролина; Бхуллар, Б.-А.С.; Готье, Ж.А. (декабрь 2012 г.). «Массовое вымирание ящериц и змей на рубеже мела и палеогена» . Труды Национальной академии наук Соединенных Штатов Америки . 109 (52): 21396–401. Бибкод : 2012PNAS..10921396L . дои : 10.1073/pnas.1211526110 . ПМЦ 3535637 . ПМИД 23236177 .

- ^ Лабандейра, CC; Джонсон, КР; и др. (2002). «Предварительная оценка травоядных насекомых на границе мелового и третичного периодов: значительное вымирание и минимальное восстановление». В Хартмане, Дж. Х.; Джонсон, КР; Николс, диджей (ред.). Формирование Хелл-Крик и граница мелового и третичного периодов на севере Великих равнин: комплексная континентальная запись конца мелового периода . Геологическое общество Америки. стр. 297–327. ISBN 978-0-8137-2361-7 .

- ^ Рехан, Сандра М.; Лейс, Ремко; Шварц, Майкл П. (2013). «Первое свидетельство массового вымирания пчел вблизи границы КТ» . ПЛОС ОДИН . 8 (10): е76683. Бибкод : 2013PLoSO...876683R . дои : 10.1371/journal.pone.0076683 . ПМК 3806776 . ПМИД 24194843 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Николс, диджей; Джонсон, КР (2008). Растения и граница К – Т. Кембридж, Англия: Издательство Кембриджского университета .

- ^ Фридман, М. (2009). «Экоморфологическая избирательность среди морских костистых рыб во время вымирания в конце мелового периода» . Труды Национальной академии наук . 106 (13). Вашингтон, округ Колумбия: 5218–5223. Бибкод : 2009PNAS..106.5218F . дои : 10.1073/pnas.0808468106 . ПМК 2664034 . ПМИД 19276106 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Яблонски, Д.; Чалонер, WG (1994). «Вымирания в летописи окаменелостей (и обсуждение)». Философские труды Лондонского королевского общества Б. 344 (1307): 11–17. дои : 10.1098/rstb.1994.0045 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Элрой, Джон (1999). «Летопись окаменелостей североамериканских млекопитающих: свидетельства эволюционной радиации палеоцена» . Систематическая биология . 48 (1): 107–118. дои : 10.1080/106351599260472 . ПМИД 12078635 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Федучча, Алан (1995). «Взрывная эволюция третичных птиц и млекопитающих». Наука . 267 (5198): 637–638. Бибкод : 1995Sci...267..637F . дои : 10.1126/science.267.5198.637 . ПМИД 17745839 . S2CID 42829066 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Фридман, М. (2010). «Взрывное морфологическое разнообразие колючих костистых рыб после вымирания в конце мелового периода» . Труды Королевского общества Б. 277 (1688): 1675–1683. дои : 10.1098/rspb.2009.2177 . ПМЦ 2871855 . ПМИД 20133356 .

- ^ Вейшампель, Д.Б.; Барретт, премьер-министр (2004). «Распространение динозавров». В Вейшампеле, Дэвид Б.; Додсон, Питер; Осмольска, Гальшка (ред.). Динозаврия (2-е изд.). Беркли, Калифорния: Издательство Калифорнийского университета. стр. 517 –606. ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8 . OCLC 441742117 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Уилф, П.; Джонсон, КР (2004). «Вымирание наземных растений в конце мелового периода: количественный анализ мегафлоры Северной Дакоты». Палеобиология . 30 (3): 347–368. doi : 10.1666/0094-8373(2004)030<0347:LPEATE>2.0.CO;2 . S2CID 33880578 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м н тот Маклауд, Н.; Роусон, ПФ; Фори, Польша; Баннер, FT; Будагер-Фадель, депутат Кнессета; Баун, PR; Бернетт, Дж.А.; Чемберс, П.; Калвер, С.; Эванс, SE; Джеффри, К.; Камински, Массачусетс; Лорд, Арканзас; Милнер, AC; Милнер, Арканзас; Моррис, Н.; Оуэн, Э.; Розен, БР; Смит, AB; Тейлор, PD; Уркарт, Э.; Янг, младший (1997). «Мел-третичный биотический переход». Журнал Геологического общества . 154 (2): 265–292. Бибкод : 1997JGSoc.154..265M . дои : 10.1144/gsjgs.154.2.0265 . S2CID 129654916 .

- ^ Шиэн, Питер М.; Хансен, Тор А. (1986). «Детрит, питающийся как буфер на пути вымирания в конце мелового периода» (PDF) . Геология . 14 (10): 868–870. Бибкод : 1986Geo....14..868S . doi : 10.1130/0091-7613(1986)14<868:DFAABT>2.0.CO;2 . S2CID 54860261 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 27 февраля 2019 года.

- ^ Аберхан, М.; Вайдемейер, С.; Кислинг, В.; Скассо, РА; Медина, ФА (2007). «Фаунистические свидетельства снижения продуктивности и нескоординированного восстановления в пограничных участках мела и палеогена Южного полушария». Геология . 35 (3): 227–230. Бибкод : 2007Geo....35..227A . дои : 10.1130/G23197A.1 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Шиэн, Питер М.; Фастовский, Д.Э. (1992). «Крупное вымирание наземных позвоночных на границе мелового и третичного периодов, восточная Монтана». Геология . 20 (6): 556–560. Бибкод : 1992Geo....20..556S . doi : 10.1130/0091-7613(1992)020<0556:MEOLDV>2.3.CO;2 .

- ^ Гарсиа-Хирон, Хорхе; Кьяренца, Альфио Алессандро; Алахухта, Янне; ДеМар, Дэвид Г.; Хейно, Яни; Мэннион, Филип Д.; Уильямсон, Томас Э.; Уилсон Мантилья, Грегори П.; Брусатте, Стивен Л. (9 декабря 2022 г.). «Изменения в пищевых цепях и стабильность ниш сформировали выживание и вымирание в конце мелового периода» . Достижения науки . 8 (49): eadd5040. дои : 10.1126/sciadv.add5040 . ПМЦ 9728968 . ПМИД 36475805 .

- ^ Кауфман, Э. (2004). «Хищничество мозазавров на наутилоидах и аммонитах верхнего мела с Тихоокеанского побережья США» (PDF) . ПАЛЕОС . 19 (1): 96–100. Бибкод : 2004Палай..19...96К . doi : 10.1669/0883-1351(2004)019<0096:MPOUCN>2.0.CO;2 . S2CID 130690035 .

- ^ Клайд, Уильям К.; Уилф, Питер; Иглесиас, Ари; Слингерленд, Руди Л.; Барнум, Тимоти; Бийл, Питер К.; Бралоуэр, Тимоти Дж.; Бринкхейс, Хенк; Комер, Эмили Э.; Хубер, Брайан Т.; Ибаньес-Мехия, Маурисио; Джича, Брайан Р.; Краузе, Дж. Марсело; Шуэт, Джонатан Д.; Певец Брэдли С.; Райгемборн, Мария Соль; Шмитц, Марк Д.; Слейс, Аппи; Замалоа, Мария дель Кармен (1 марта 2014 г.). «Новые возрастные ограничения для формации Саламанка и нижней части группы Рио-Чико в западной части бассейна Сан-Хорхе, Патагония, Аргентина: последствия для восстановления мел-палеогенового вымирания и корреляции возраста наземных млекопитающих» . Бюллетень Геологического общества Америки . 126 (3–4): 289–306. Бибкод : 2014GSAB..126..289C . дои : 10.1130/B30915.1 . hdl : 11336/80135 . S2CID 129962470 . Проверено 21 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Поуп, КО; д'Ондт, SL; Маршалл. ЧР (1998). «Удар метеорита и массовое вымирание видов на границе мелового и третичного периодов» . Труды Национальной академии наук Соединенных Штатов Америки . 95 (19): 11028–11029. Бибкод : 1998PNAS...9511028P . дои : 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11028 . ПМК 33889 . ПМИД 9736679 .

- ^ Поспичаль, Джей Джей (1996). «Известковые наннофоссилии и обломочные отложения на границе мелового и третичного периодов, северо-восток Мексики». Геология . 24 (3): 255–258. Бибкод : 1996Geo....24..255P . doi : 10.1130/0091-7613(1996)024<0255:CNACSA>2.3.CO;2 .

- ^ Баун, П. (2005). «Селективное выживание известкового наннопланктона на границе мелового и третичного периодов». Геология . 33 (8): 653–656. Бибкод : 2005Geo....33..653B . дои : 10.1130/G21566.1 .

- ^ Бамбах, РК; Нолл, АХ; Ван, Южная Каролина (2004). «Происхождение, исчезновение и массовое истощение морского разнообразия» (PDF) . Палеобиология . 30 (4): 522–542. doi : 10.1666/0094-8373(2004)030<0522:OEAMDO>2.0.CO;2 . S2CID 17279135 .

- ^ Гедль, П. (2004). «Запись цист динофлагеллят на глубоководной границе мелового и третичного периодов в Узгру, Карпаты, Чехия». Специальные публикации Лондонского геологического общества . 230 (1): 257–273. Бибкод : 2004GSLSP.230..257G . дои : 10.1144/ГСЛ.СП.2004.230.01.13 . S2CID 128771186 .

- ^ Маклауд, Н. (1998). «Воздействия и вымирание морских беспозвоночных». Специальные публикации Лондонского геологического общества . 140 (1): 217–246. Бибкод : 1998ГСЛСП.140..217М . дои : 10.1144/ГСЛ.СП.1998.140.01.16 . S2CID 129875020 .

- ^ Куртильо, В. (1999). Эволюционные катастрофы: наука о массовом вымирании . Кембридж, Великобритания: Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 2. ISBN 978-0-521-58392-3 .

- ^ Аренильяс, И.; Арз, Дж.А.; Молина, Э.; Дюпюи, К. (2000). «Независимое испытание круговорота планктических фораминифер на границе мелового и палеогенового периода (K/P) в Эль-Кефе, Тунис: катастрофическое массовое вымирание и возможное выживание». Микропалеонтология . 46 (1): 31–49. JSTOR 1486024 .

- ^ Маклауд, Н. (1996). «Природа мел-третичных (K – T) записей планктонных фораминифер: стратиграфические доверительные интервалы, эффект Синьора-Липпса и закономерности выживаемости». В МакЛауде, Н.; Келлер, Г. (ред.). Мел-третичные массовые вымирания: биотические и экологические изменения . WW Нортон. стр. 85–138. ISBN 978-0-393-96657-2 .

- ^ Келлер, Г.; Адатте, Т.; Стиннесбек, В.; Реболледо-Виейра, _; Фукугаучи, Ю.; Крамар, У.; Штюбен, Д. (2004). «Удар Чиксулуб предшествовал массовому вымиранию на границе K – T» . Труды Национальной академии наук Соединенных Штатов Америки . 101 (11). Вашингтон, округ Колумбия: 3753–3758. Бибкод : 2004PNAS..101.3753K . дои : 10.1073/pnas.0400396101 . ПМЦ 374316 . ПМИД 15004276 .

- ^ Галеотти, С.; Беллагамба, М.; Камински, Массачусетс; Монтанари, А. (2002). «Реколонизация глубоководных донных фораминифер после вулканокластического события в нижнем кампане формации Скалья Росса (бассейн Умбрия-Марке, центральная Италия)». Морская микропалеонтология . 44 (1–2): 57–76. Бибкод : 2002МарМП..44...57Г . дои : 10.1016/s0377-8398(01)00037-8 .

- ^ Кунт, В.; Коллинз, ЕС (1996). «8. Бентосные фораминиферы от мела до палеогена с абиссальной равнины Иберии». Труды программы океанского бурения, научные результаты . Материалы программы океанского бурения. 149 : 203–216. doi : 10.2973/odp.proc.sr.149.254.1996 .

- ^ Коулз, врач общей практики; Айресс, Массачусетс; Уотли, Р.К. (1990). «Сравнение североатлантических и 20 тихоокеанских глубоководных остракод». В Уотли, Колорадо; Мэйбери, К. (ред.). Остракода и глобальные события . Чепмен и Холл. стр. 287–305. ISBN 978-0-442-31167-4 .

- ^ Брауэрс, Э.М.; де Деккер, П. (1993). «Позднемаастрихтская и датская остракодовая фауна Северной Аляски: реконструкция окружающей среды и палеогеография». ПАЛЕОС . 8 (2): 140–154. Бибкод : 1993Палай...8..140B . дои : 10.2307/3515168 . JSTOR 3515168 .

- ^ Швейцер, Кэрри Э; Фельдманн, Родни М. (1 июня 2023 г.). «Избирательное вымирание в конце мела и появление современных десятиногих» . Журнал биологии ракообразных . 43 (2). doi : 10.1093/jcbiol/ruad018 . ISSN 0278-0372 . Проверено 18 ноября 2023 г.

- ^ Весчей, А.; Муссавян, Э. (1997). «Палеоценовые рифы на окраине платформы Майелла, Италия: пример воздействия пограничных событий мелового и третичного периода на рифы и карбонатные платформы». Фации . 36 (1): 123–139. Бибкод : 1997Faci...36..123V . дои : 10.1007/BF02536880 . S2CID 129296658 .

- ^ Розен, БР; Турншек, Д. (1989). Желе А; Пикетт Дж.В. (ред.). «Схемы вымирания и биогеография склерактиновых кораллов на границе мелового и третичного периодов». Мемуары Ассоциации австралийской палеонтологии . Материалы Пятого Международного симпозиума по ископаемым книдариям, включая археоциатов и спонгиоморф (8). Брисбен, Квинсленд: 355–370.

- ^ Рауп, Д.М.; Яблонски, Д. (1993). «География вымирания морских двустворчатых моллюсков в конце мела». Наука . 260 (5110): 971–973. Бибкод : 1993Sci...260..971R . дои : 10.1126/science.11537491 . ПМИД 11537491 .

- ^ Маклауд, КГ (1994). «Вымирание двустворчатых моллюсков иноцерамидов в маастрихтских слоях региона Бискайского залива во Франции и Испании». Журнал палеонтологии . 68 (5): 1048–1066. Бибкод : 1994JPal...68.1048M . дои : 10.1017/S0022336000026652 . S2CID 132641572 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Маршалл, ЧР; Уорд, PD (1996). «Внезапное и постепенное вымирание моллюсков в последнем меловом периоде западноевропейского Тетиса». Наука . 274 (5291): 1360–1363. Бибкод : 1996Sci...274.1360M . дои : 10.1126/science.274.5291.1360 . ПМИД 8910273 . S2CID 1837900 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Уорд, ПД; Кеннеди, WJ; Маклауд, КГ; Маунт, Дж. Ф. (1991). «Модели вымирания двустворчатых моллюсков аммонитов и иноцерамидов в меловых и третичных пограничных участках региона Бискайя (юго-запад Франции, север Испании)». Геология . 19 (12): 1181–1184. Бибкод : 1991Geo....19.1181W . doi : 10.1130/0091-7613(1991)019<1181:AAIBEP>2.3.CO;2 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Харрис, Пи Джей; Джонсон, КР; Коббан, Вашингтон; Николс, диджей (2002). «Участок морской границы мелового и третичного периодов на юго-западе Южной Дакоты: комментарий и ответ». Геология . 30 (10): 954–955. Бибкод : 2002Geo....30..954H . doi : 10.1130/0091-7613(2002)030<0955:MCTBSI>2.0.CO;2 .

- ^ Иба, Ясухиро; Муттерлоуз, Джордж; Танабэ, Казусигэ; Здоров, Синъити; Мисаки, Акихиро; Терабе, Казунобу (1 мая 2011 г.). «Вымирание белемнитов и происхождение современных головоногих моллюсков за 35 млн. лет до мел-палеогенового события» . Геология . 39 (5): 483–486. Бибкод : 2011Geo....39..483I . дои : 10.1130/G31724.1 . ISSN 1943-2682 . Получено 18 ноября.

- ^ Неродо, Дидье; Тьерри, Жак; Моро, Пьер (1 января 1997 г.). «Изменение биоразнообразия морских ежей во время трансгрессивного эпизода сеномана-раннего турона в Шаранте (Франция)» . Бюллетень Французского геологического общества . 168 (1): 51–61.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кривет, Юрген; Бентон, Майкл Дж. (2004). «Неоселахское (Chondrichthyes, Elasmobranchii) разнообразие на меловой и третичной границе». Палеогеография, Палеоклиматология, Палеоэкология . 214 (3): 181–194. Бибкод : 2004PPP...214..181K . дои : 10.1016/j.palaeo.2004.02.049 .

- ^ Паттерсон, К. (1993). «Остейхтис: Телеостей». В Бентоне, MJ (ред.). Ископаемая запись . Том. 2. Спрингер. стр. 621–656. ISBN 978-0-412-39380-8 .

- ^ Нубхани, Абдельмаджид (2010). «Фауна селахов марокканских фосфатных месторождений и массовое вымирание КТ». Историческая биология . 22 (1–3): 71–77. Бибкод : 2010HBio...22...71N . дои : 10.1080/08912961003707349 . S2CID 129579498 .