Crocodilia

| Crocodilia Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

| Clockwise from top-left: saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus), American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis), and gharial (Gavialis gangeticus) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Archosauria |

| Clade: | Pseudosuchia |

| Clade: | Crocodylomorpha |

| Clade: | Crocodyliformes |

| Clade: | Eusuchia |

| Order: | Crocodilia Owen, 1842 |

| Subgroups | |

| |

| Crocodylia distribution on land (green) and at sea (blue) | |

Crocodilia (or Crocodylia, both /krɒkəˈdɪliə/) is an order of semiaquatic, predatory reptiles known as crocodilians. They first appeared during the Late Cretaceous and are the closest living relatives of birds. Crocodilians are a type of crocodylomorph pseudosuchian, a subset of archosaurs that appeared about 235 million years ago and were the only survivors of the Triassic–Jurassic extinction event. The order includes the true crocodiles (family Crocodylidae), the alligators and caimans (family Alligatoridae), and the gharial and false gharial (family Gavialidae). Although the term "crocodiles" is sometimes used to refer to all of these, it is less ambiguous to use "crocodilians".

Extant crocodilians have long flattened snouts and laterally compressed tails, with their eyes, ears, and nostrils at the top of the head. They are good swimmers and can move on land in a "high walk" position, traveling with their legs erect rather than sprawling. Crocodilians have thick skin covered in non-overlapping scales. They have conical, peg-like teeth and a powerful bite. Like birds, crocodilians possess a four-chambered heart and lungs with unidirectional airflow. Like most other reptiles, they are ectotherms.

Crocodilians are found mainly in lowlands in the tropics, but alligators also live in the southeastern United States and the Yangtze River in China. They have a largely carnivorous diet. Some species like the gharial are specialized feeders, while others like the saltwater crocodile have generalized diets. Crocodilians are generally solitary and territorial, though they sometimes hunt in groups. During the breeding season, dominant males try to monopolize available females. Females lay their eggs in holes or mounds, and similar to many birds, care for their hatched young.

Some species of crocodilians (particularly the Nile crocodile) are known to have attacked humans. Humans are the greatest threat to crocodilian populations through activities that include hunting, poaching, and habitat destruction, but farming of crocodilians has greatly reduced unlawful trading in wild skins. Artistic and literary representations of crocodilians have appeared in human cultures around the world since Ancient Egypt.

Spelling and etymology

[edit]"Crocodilia" and "Crocodylia" have been used interchangeably for decades starting with Schmidt's redescription of the group from the formerly defunct term Loricata.[1] Schmidt used the older term "Crocodilia", based on Owen's original name for the group.[2] Wermuth opted for "Crocodylia" as the proper name,[3] basing it on the type genus Crocodylus (Laurenti, 1768).[4] Dundee—in a revision of many reptilian and amphibian names—argued strongly for "Crocodylia".[5] However, it was not until the advent of cladistics and phylogenetic nomenclature that a more solid justification for one spelling over the other was proposed.[6]

Prior to 1988, Crocodilia was a group that encompassed the modern-day animals, as well as their more distant relatives now in the larger groups called Crocodylomorpha and Pseudosuchia.[6] Under its current definition as a crown group (as opposed to a stem-based group), Crocodylia is now restricted to only the last common ancestor of today's modern-day crocodilians (alligators, crocodiles, and gharials) and all of its descendants (living or extinct).[6]

Crocodilia[2] appears to be a Latinizing of the Greek κροκόδειλος (crocodeilos), which means both lizard and Nile crocodile.[7] Crocodylia, as coined by Wermuth,[3] in regards to the genus Crocodylus appears to be derived from the ancient Greek[8] κρόκη (kroke)—meaning shingle or pebble—and δρîλος or δρεîλος (dr(e)ilos) for "worm". The name may refer to the animal's habit of basking on the pebbled shores of the Nile.[9]

Phylogeny and evolution

[edit]Origins from pseudosuchians

[edit]

Crocodilians are a type of archosaur, a clade containing the most recent common ancestor of crocodilians, birds, and all their descendants. Archosaurs are distinguished from other reptiles particularly by two sets of extra openings in the skull: the antorbital fenestra located in front of the animal's eye socket and the mandibular fenestra in the middle of the jaw. Archosaurs comprise two main groups: the Pseudosuchia (crocodilians and their relatives), and the Avemetatarsalia (dinosaurs, pterosaurs, and their relatives).[10] The split between these two is assumed to have happened close to the Permian–Triassic extinction event (informally known as the Great Dying).[11]

During the Early Triassic, pseudosuchians flourished and diversified. One form, the crocodylomorphs, would later give rise to modern crocodilians. While the most basal crocodylomorphs were large, the ones that gave rise to crocodilians were small, gracile, and leggy.[12] This evolutionary grade, the so-called "sphenosuchians" first appeared around Carnian of the Late Triassic.[13] They ate small, fast prey and survived into the Late Jurassic.[14][15] As the Triassic ended, crocodylomorphs became the only surviving pseudosuchians.[16]

Early crocodyliform diversity

[edit]

During the early Jurassic period, the dinosaurs became dominant on land, and the crocodylomorphs underwent major adaptive diversifications to fill ecological niches vacated by recently extinguished groups. Mesozoic crocodylomorphs had a much greater diversity of forms than modern crocodilians. Some became small fast-moving insectivores, others specialist fish-eaters, still others marine and terrestrial carnivores, and a few became herbivores.[17] The earliest stage of crocodilian evolution was the protosuchians in the late Triassic and early Jurassic. They were followed by the mesosuchians, which diversified widely during the Jurassic and the Tertiary. The eusuchians first appeared during the Early Cretaceous, and includes modern crocodilians.[18]

Protosuchians were small, mostly terrestrial animals with short snouts and long limbs. They had bony armor in the form of two rows of plates extending from head to tail; this armor is retained by most modern crocodilians. Their vertebrae were convex on the two main articulating surfaces, and their bony palates were little developed. The mesosuchians saw a fusion of the palatine bones to form a secondary bony palate and a great extension of the nasal passages to near the pterygoid bones. This allowed the animal to breathe through its nostrils while its mouth was open underwater. The eusuchians continued this process with the interior nostrils now opening through an aperture in the pterygoid bones. The vertebrae of eusuchians had one convex and one concave articulating surface, allowing for a ball and socket type joint between the vertebrae, bringing greater flexibility and strength.[19] The oldest known eusuchian is Hylaeochampsa vectiana from the Early Cretaceous of the Isle of Wight in the United Kingdom.[18] It was followed by crocodilians such as the Planocraniidae, the so-called 'hoofed crocodiles', in the Palaeogene.[20] Spanning the Cretaceous and Palaeogene periods is the genus Borealosuchus of North America, with six species, though its phylogenetic position is not settled.[21]

Diversification of modern crocodilians

[edit]The three primary branches of Crocodilia had diverged by the Late Cretaceous. The possible earliest-known members of the group may be Portugalosuchus and Zholsuchus from the Cenomanian-Turonian stages.[22][23] The classification of Portugalosuchus has been disputed by some researchers who claimed that it may be outside the crown group crocodilians.[24][25] The morphology-based phylogenetic analyses based on the new neuroanatomical data obtained from its skull using micro-CT scans suggested that this taxon is a crown group crocodilian and a member of the 'thoracosaurs', recovered as a sister taxon of Thoracosaurus within Gavialoidea,[26] though it is uncertain whether 'thoracosaurs' were true gavialoids.[27]

Definitive alligatoroids first appeared during the Santonian-Campanian stages,[28] while definitive longirostres first appeared during the Maastrichtian stage.[29][30] The earliest known alligatoroids and gavialoids include highly derived forms, which indicates that the time of the actual divergence between the three lineages must have been a pre-Campanian event.[31] Additionally, scientists conclude that environmental factors played a major role in the evolution of crocodilians and their ancestors, with warmer climate being associated with high evolutionary rates and large body sizes.[32]

Relationships

[edit]Crocodylia is cladistically defined as the last common ancestor of Gavialis gangeticus (the gharial), Alligator mississippiensis (American alligator), and Crocodylus rhombifer (the Cuban crocodile) and all of its descendants.[6][33] The phylogenetic relationships of crocodilians has been the subject of debate and conflicting results. Many studies and their resulting cladograms, or "family trees" of crocodilians, have found the "short-snouted" families of Crocodylidae and Alligatoridae to be close relatives, with the long-snouted Gavialidae as a divergent branch of the tree. The resulting group of short-snouted species, named Brevirostres, was supported mainly by morphological studies which analyzed skeletal features alone.[34]

However, recent molecular studies using DNA sequencing of living crocodilians have rejected this distinct group Brevirostres, with the long-snouted gavialids more closely related to crocodiles than to alligators, with the new grouping of gavialids and crocodiles named Longirostres.[35][36][37][38][39]

Below is a cladogram from 2021 showing the relationships of the major extant crocodilian groups. This analysis was based off mitochondrial DNA, including that of the recently extinct Voay robustus:[39]

| Crocodilia | |

Anatomy and physiology

[edit]

Crocodilians range in size from the Paleosuchus and Osteolaemus species, which reach 1–1.5 m (3 ft 3 in – 4 ft 11 in), to the saltwater crocodile, which reaches 7 m (23 ft) and weighs up to 2,000 kg (4,400 lb), though some prehistoric species such as the late Cretaceous Deinosuchus were even larger at up to about 11 m (36 ft)[40] and 3,450 kg (7,610 lb).[37] They tend to be sexually dimorphic, with males much larger than females.[41] Though there is diversity in snout and tooth shape, all crocodilian species have essentially the same body morphology.[37] They have solidly built, lizard-like bodies with elongated, flattened snouts and laterally compressed tails.[41] Their limbs are reduced in size; the front feet have five digits with the phalangeal formula 2-3-4-4-3 and little or no webbing, and the hind feet four webbed digits with the phalangeal formula 2-3-4-4 and the fifth digit reduced to a vestigial metatarsal bone with no phalanges.[42][43] Both the front and hind feet have claws on the three inner digits only.[44]

The skeleton is somewhat typical of tetrapods, although the skull, pelvis and ribs are specialised;[41] in particular, the cartilaginous processes of the ribs allow the thorax to collapse during diving and the structure of the pelvis can accommodate large masses of food,[45] or more air in the lungs.[46] Both sexes have a cloaca, a single chamber and outlet at the base of the tail into which the intestinal, urinary and genital tracts open.[41] It houses the penis in males and the clitoris in females.[47] The crocodilian penis is permanently erect and relies on cloacal muscles for eversion and elastic ligaments and a tendon for recoil.[48] The gonads are located near the kidneys.[49]

Locomotion

[edit]

Crocodilians are excellent swimmers. During aquatic locomotion, the muscular tail undulates from side to side to drive the animal through the water while the limbs are held close to the body to reduce drag.[50][51] When the animal needs to stop or steer in a different direction, the limbs are splayed out.[50] Crocodilians generally cruise slowly on the surface or underwater with gentle sinuous movements of the tail, but when pursued or chasing prey they can move rapidly.[52] Crocodilians are less well-adapted for moving on land, and are unusual among vertebrates in having two different means of terrestrial locomotion: the "high walk" and the "low walk".[42] Their ankle joints flex in a different way from those of other reptiles, a feature they share with some early archosaurs. One of the upper row of ankle bones, the astragalus, moves with the tibia and fibula. The other, the calcaneum, is functionally part of the foot, and has a socket into which a peg from the astragalus fits. The result is that the legs can be held almost vertically beneath the body when on land, and the foot can swivel during locomotion with a twisting movement at the ankle.[53]

The high walk of crocodilians, with the belly and most of the tail held off the ground, is unique among living reptiles. It somewhat resembles the walk of a mammal, with the same sequence of limb movements: left fore, right hind, right fore, left hind.[52] The low walk is similar to the high walk, but without the body being raised, and is quite different from the sprawling walk of salamanders and lizards. The animal can change from one walk to the other instantaneously, but the high walk is the usual means of locomotion on land. The animal may push its body up and use this form immediately, or may take one or two strides of low walk before raising the body higher. Unlike most other land vertebrates, when crocodilians increase their pace of travel they increase the speed at which the lower half of each limb (rather than the whole leg) swings forward, so stride length increases while stride duration decreases.[54]

Though typically slow on land, crocodilians can produce brief bursts of speed, and some can run at 12 to 14 km/h (7.5 to 8.7 mph) for short distances.[55] A fast entry into water from a muddy bank can be effected by plunging to the ground, twisting the body from side to side and splaying out the limbs.[52] In some small species such as the freshwater crocodile, a running gait can progress to a bounding gallop. This involves the hind limbs launching the body forward and the fore limbs subsequently taking the weight. Next, the hind limbs swing forward as the spine flexes dorso-ventrally, and this sequence of movements is repeated.[56] During terrestrial locomotion, a crocodilian can keep its back and tail straight, since the scales are attached to the vertebrae by muscles.[45] Whether on land or in water, crocodilians can jump or leap by pressing their tails and hind limbs against the substrate and launching themselves into the air.[50][57]

Jaws and teeth

[edit]The snout shape of crocodilians varies between species. Crocodiles may have either broad or slender snouts, while alligators and caimans have mostly broad ones. Gharials have snouts that are extremely elongated. The muscles that close the jaws are much more massive and powerful than the ones that open them,[41] and a crocodilian's jaws can be held shut by a person fairly easily. Conversely, the jaws are extremely difficult to pry open.[58] The powerful closing muscles attach at the median portion of the lower jaw and the jaw hinge attaches to the atlanto-occipital joint, allowing the animal to open its mouth fairly wide. The tongue cannot move freely but is held in place by a folded membrane.[45]

Crocodilians have some of the strongest bite forces in the animal kingdom. In a study published in 2003, an American alligator's bite force was measured at up to 2,125 lbf (9.45 kN).[59] In a 2012 study, a saltwater crocodile's bite force was measured even higher, at 3,700 lbf (16 kN). This study also found no correlation between bite force and snout shape. Nevertheless, the gharial's extremely slender jaws are relatively weak and built more for quick jaw closure. The bite force of Deinosuchus may have measured 23,000 lbf (100 kN),[37] even greater than that of theropod dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus.[59] Studies have shown that when adjusted for body size, the bite force is identical in all species except for the gharials, which have a weaker bite compared to the other species due to their specialized jaws.[60]

Crocodilian teeth vary from blunt and dull to sharp and needle-like.[37] Broad-snouted species have teeth that vary in size, while those of slender-snouted species are more uniform. The teeth of crocodiles and gharials tend to be more visible than those of alligators and caimans when the jaws are closed.[61] The easiest way to distinguish crocodiles from alligators is by looking at their jaw line. The teeth on the lower jaw of an alligator fit into sockets in the upper jaw, so only the upper teeth are visible when the mouth is closed. The teeth on the lower jaw of a crocodile fit into grooves on the outside of the top jaw making both the upper and lower teeth visible when the mouth is closed.[62]

Crocodilians are homodonts, meaning each of their teeth are all of the same type (they do not possess different tooth types, such as canines and molars) and polyphyodonts are able to replace each of their approximately 80 teeth up to 50 times in their 35- to 75-year lifespan.[63] They are the only non-mammalian vertebrates with tooth sockets.[64] Next to each full-grown tooth there is a small replacement tooth and an odontogenic stem cell in the dental lamina, which can be activated when required.[65] Tooth replacement slows significantly and eventually stops as the animal ages.[61]

Sense organs

[edit]

The eyes, ears and nostrils of crocodilians are at the top of the head. This allows them to stalk their prey with most of their bodies underwater.[50] The eyes possess a tapetum lucidum which enhances vision in low light.[42] Crocodilians appear to have gone through a nocturnal bottleneck early in their history where they became dichromatic (red-green colorblindness) and their eyes lost features like sclerotic rings, an annular pad of the lens and colored cone oil droplets. Since them, some crocodilians appears to have re-evolved a trichromatic color vision.[66][67][68] While eyesight is fairly good in air, it is significantly weakened underwater.[69] The fovea in other vertebrates is usually circular, but in crocodiles it is a horizontal bar of tightly packed receptors across the middle of the retina. When the animal completely submerges, the nictitating membranes cover its eyes. In addition, glands on the nictitating membrane secrete a salty lubricant that keeps the eye clean. When a crocodilian leaves the water and dries off, this substance is visible as "tears".[42]

The ears are adapted for hearing both in air and underwater, and the eardrums are protected by flaps that can be opened or closed by muscles.[70] Crocodilians have a wide hearing range, with sensitivity comparable to most birds and many mammals.[71] The well-developed trigeminal nerve allows them to detect vibrations in the water (such as those made by potential prey).[72] Crocodilians have only one olfactory chamber and the vomeronasal organ is absent in the adults[73] indicating all olfactory perception is limited to the olfactory system. Behavioural and olfactometer experiments indicate that crocodiles detect both air-borne and water-soluble chemicals and use their olfactory system for hunting. When above water, crocodiles enhance their ability to detect volatile odorants by gular pumping, a rhythmic movement of the floor of the pharynx.[74][75] They appear to have lost their pineal organ, but still show signs of melatonin rhythms.[76]

Skin and scales

[edit]

The skin of crocodilians is thick and cornified, and is clad in non-overlapping scales known as scutes, arranged in regular rows and patterns. These scales are continually being produced by cell division in the underlying layer of the epidermis, the stratum germinativum, and the surface of individual scutes sloughs off periodically. The outer surface of the scutes consists of the relatively rigid beta-keratin while the hinge region between the scutes contains only the more pliable alpha-keratin.[77]

Many of the scutes are strengthened by bony plates known as osteoderms, which are the same size and shape as the superficial scales but grow beneath them. They are most numerous on the back and neck of the animal and may form a protective armour. They often have prominent, lumpy ridges and are covered in hard-wearing beta-keratin.[41] The osteoderms fuse with the dorsal skull elements on the head.[78] Both the head and jaws lack actual scales and are instead covered in tight keratinised skin that is fused directory to the bones of the skull,[79] and which over time develop a pattern of cracks as the skull develops.[80][81] The skin on the neck and flanks is loose, while that on the abdomen and underside of the tail is sheathed in large, flat square scutes arranged in neat rows.[41][82] The scutes contain blood vessels and may act to absorb or radiate heat during thermoregulation.[41] Research also suggests that alkaline ions released into the blood from the calcium and magnesium in these dermal bones act as a buffer during prolonged submersion when increasing levels of carbon dioxide would otherwise cause acidosis.[83]

Some scutes contain a single pore known as an integumentary sense organ. Crocodiles and gharials have these on large parts of their bodies, while alligators and caimans only have them on the head. Their exact function is not fully understood, but it has been suggested that they may be mechanosensory organs.[84] Another possibility is that they may produce an oily secretion that prevents mud from adhering to the skin. There are prominent paired integumentary glands in skin folds on the throat, and others in the side walls of the cloaca. Various functions for these have been suggested. They may play a part in communication, as indirect evidence suggest that they secrete pheromones used in courtship or nesting.[41] The skin of crocodilians is tough and can withstand damage from conspecifics, and the immune system is effective enough to heal wounds within a few days.[85]

In the genus Crocodylus the skin contains chromatophores, allowing them to change color from dark to light and vice versa.[86]

Circulation

[edit]

The crocodilian has perhaps the most complex vertebrate circulatory system. It has a four-chambered heart and two ventricles, an unusual trait among extant reptiles,[87] and both a left and right aorta which are connected by a hole called the Foramen of Panizza. Like birds and mammals, crocodilians have heart valves that direct blood flow in a single direction through the heart chambers. They also have unique cog-teeth-like valves that, when interlocked, direct blood to the left aorta and away from the lungs, and then back around the body.[88] This system may allow the animals to remain submerged for a longer period,[89] but this explanation has been questioned.[90] Other possible reasons for the peculiar circulatory system include assistance with thermoregulatory needs, prevention of pulmonary oedema, or faster recovery from metabolic acidosis. Retaining carbon dioxide within the body permits an increase in the rate of gastric acid secretion and thus the efficiency of digestion, and other gastrointestinal organs such as the pancreas, spleen, small intestine, and liver also function more efficiently.[91]

When submerged, a crocodilian's heart rate slows to one or two beats a minute, and blood flow to the muscles is reduced. When it rises and takes a breath, its heart rate speeds up in seconds, and the muscles receive newly oxygenated blood.[92] Unlike many marine mammals, crocodilians have little myoglobin to store oxygen in their muscles. During diving, an increasing concentration of bicarbonate ions causes haemoglobin in the blood to release oxygen for the muscles.[93]

Respiration

[edit]Crocodilians were traditionally thought to breathe like mammals, with airflow moving in and out tidally, but studies published in 2010 and 2013 conclude that crocodilians breathe more like birds, with airflow moving in a unidirectional loop within the lungs. When a crocodilian inhales, air flows through the trachea and into two primary bronchi, or airways, which branch off into narrower secondary passageways. The air continues to move through these, then into even narrower tertiary airways, and then into other secondary airways which were bypassed the first time. The air then flows back into the primary airways and is exhaled. These aerodynamic valves within the bronchial tree have been hypothesised to explain how crocodilians can have unidirectional airflow without the aid of avian-like air sacs.[94][95]

The lungs of crocodilians are attached to the liver and the pelvis by the diaphragmaticus muscle (analogous of the diaphragm in mammals). During inhalation, the external intercostal muscles expand the ribs, allowing the animal to take in more air, while the ischiopubis muscle causes the hips to swing downwards and push the belly outward, and the diaphragmaticus pulls the liver back. When exhaling, the internal intercostal muscles push the ribs inward, while the rectus abdominis pulls the hips and liver forwards and the belly inward.[46][87][96][97] Because the lungs expand into the space formerly occupied by the liver and are compressed when it moves back into position, this motion is sometimes referred to as a "hepatic piston". Crocodilians can also use these muscles to adjust the position of their lungs, controlling their buoyancy in the water. An animal sinks when the lungs are pulled towards the tail and floats when they move back towards the head. This allows them to move through the water without creating disturbances that could alert potential prey. They can also spin and twist by moving their lungs laterally.[96]

Swimming and diving crocodilians appear to rely on lung volume more for buoyancy than oxygen storage.[87] Just before diving, the animal exhales to reduce its lung volume and achieve negative buoyancy.[98] When submerging, the nostrils of a crocodilian shut tight.[42] All species have a palatal valve, a membranous flap of skin at the back of the oral cavity that prevents water from flowing into the oesophagus and trachea.[41][42] This enables them to open their mouths underwater without drowning.[42] Crocodilians typically remain underwater for fifteen minutes or less at a time, but some can hold their breath for up to two hours under ideal conditions.[99] The maximum diving depth is unknown, but crocodiles can dive to at least 20 m (66 ft).[100]

Vocalizing is produced by vibrating vocal folds in the larynx.[101][102] The folds of the American alligator have a complex morphology consisting of epithelium, lamina propria and muscle, and according to Riede et al. (2015), "it is reasonable to expect species-specific morphologies in vocal folds/analogues as far back as basal reptiles".[103] Crocodilian vocal folds lack the elasticity of mammalian ones; but the larynx is still capable of complex motor control similar to birds and mammals and can adequately control its fundamental frequency.[103][104]

Digestion

[edit]Crocodilian teeth are adapted for seizing and holding prey, and food is swallowed unchewed. The digestive tract is relatively short, as meat is fairly simple to digest. The stomach is divided into two parts: a muscular gizzard that grinds food, and a digestive chamber where enzymes work on it.[105] Indigestible items are regurgitated as pellets.[106]The stomach is more acidic than that of any other vertebrate and contains ridges for gastroliths, which play a role in the mechanical breakdown of food. Digestion takes place more quickly at higher temperatures.[50] When digesting a meal, CO2-rich blood towards the lungs is redirected to the stomach where glands make use of the CO2 to form bicarbonate and gastric acid secretions approximately 10 times the highest rates measured in mammals.[107][108] Alligators have a higher ability to digest carbohydrates relative to protein compared to crocodiles.[109] Crocodilians have a very low metabolic rate and consequently, low energy requirements. This allows them to survive for many months on a single large meal, digesting the food slowly. They can withstand extended fasting, living on stored fat between meals. Even recently hatched crocodiles are able to survive 58 days without food, losing 23% of their bodyweight during this time.[110] An adult crocodile needs between a tenth and a fifth of the amount of food necessary for a lion of the same weight, and can live for half a year without eating.[110]

Thermoregulation

[edit]

Crocodilians are ectotherms, producing relatively little heat internally and relying on external sources to raise their body temperatures. The sun's heat is the main means of warming for any crocodilian, while immersion in water may either raise its temperature by conduction, or cool the animal in hot weather. The main method for regulating its temperature is behavioural. For example, an alligator in temperate regions may start the day by basking in the sun on land. A bulky animal, it warms up slowly, but later in the day it moves into the water, still exposing its dorsal surface to the sun. At night it remains submerged, and its temperature slowly falls. The basking period is extended in winter and reduced in summer. For crocodiles in the tropics, avoiding overheating is generally the main problem. They may bask briefly in the morning but then move into the shade, remaining there for the rest of the day, or submerge themselves in water to keep cool. Gaping with the mouth can provide cooling by evaporation from the mouth lining.[111] By these means, the temperature range of crocodilians is usually maintained between 25 and 35 °C (77 and 95 °F), and mainly stays in the range 30 to 33 °C (86 to 91 °F).[112]

The ranges of the American and Chinese alligator extend into regions that sometimes experience periods of frost in winter. Being ectothermic, the internal body temperature of crocodilians falls as the temperature drops, and they become sluggish. They may become more active on warm days, but do not usually feed at all during the winter. In cold weather, they remain submerged with their tails in deeper, less cold water and their nostrils just projecting through the surface. If ice forms on the water, they maintain ice-free breathing holes, and there have been occasions when their snouts have become frozen into the ice. Temperature sensing probes implanted in wild American alligators have found that their core body temperatures can descend to around 5 °C (41 °F), but as long as they remain able to breathe they show no ill effects when the weather warms up.[111]

Osmoregulation

[edit]

No living species of crocodilian can be considered truly marine; although the saltwater crocodile and the American crocodile are able to swim out to sea, their normal habitats are river mouths, estuaries, mangrove swamps, and hypersaline lakes, though several extinct species have had marine habitats, including the recently extinct Ikanogavialis papuensis, which occurred in a fully marine habitat in the Solomon Islands coastlines.[113] All crocodilians need to maintain a suitable concentration of salt in body fluids. Osmoregulation is related to the quantity of salts and water exchanged with the environment. Intake of water and salts takes place across the lining of the mouth, when water is drunk, incidentally while feeding, and when present in foods.[114] Water is lost during breathing, and both salts and water are lost in the urine and faeces, through the skin, and via salt-excreting glands on the tongue, though these are only present in crocodiles and gharials.[115][116] The skin is a largely effective barrier to both water and ions. Gaping causes water loss by evaporation from the lining of the mouth, and on land, water is also lost through the skin.[115] Large animals are better able to maintain homeostasis at times of osmotic stress than smaller ones.[117] Newly hatched crocodilians are much less tolerant of exposure to salt water than are older juveniles, presumably because they have a higher surface-area-to-volume ratio.[115]

The kidneys and excretory system are much the same as in other reptiles, but crocodilians do not have a bladder.[118] In fresh water, the osmolality (the concentration of solutes that contribute to a solution's osmotic pressure) in the plasma is much higher than it is in the surrounding water. The animals are well-hydrated, and the urine in the cloaca is abundant and dilute, nitrogen being excreted as ammonium bicarbonate.[117] Sodium loss is low and mainly takes place through the skin in freshwater conditions. In seawater, the opposite is true. The osmolality in the plasma is lower than the surrounding water, which is dehydrating for the animal. The cloacal urine is much more concentrated, white, and opaque, with the nitrogenous waste being mostly excreted as insoluble uric acid.[115][117]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]

Crocodilians are amphibious reptiles, spending part of their time in water and part on land. The last surviving fully terrestrial genus, Mekosuchus, became extinct about 3000 years ago after humans had arrived on its Pacific islands, making the extinction possibly anthropogenic.[119] Typically they are creatures of the tropics; the main exceptions are the American and Chinese alligators, whose ranges consist of the southeastern United States and the Yangtze River, respectively. Florida, in the United States, is the only place that crocodiles and alligators live side by side.[120] Most crocodilians live in the lowlands, and few are found above 1,000 metres (3,300 ft), where the temperatures are typically about 5 °C (9 °F) lower than at the coast. None of them permanently reside in the sea, though some can venture into it, and several species can tolerate the brackish water of estuaries, mangrove swamps, and the extreme salinity of hypersaline lakes.[121] The saltwater crocodile has the widest distribution of any crocodilian, with a range extending from eastern India to New Guinea and northern Australia. Much of its success is due to its ability to swim out to sea and colonise new locations, but it is not restricted to the marine environment and spends much time in estuaries, rivers, and large lakes.[122]

Various types of aquatic habitats are used by different crocodilians. Some species are relatively more terrestrial and prefer swamps, ponds, and the edges of lakes, where they can bask in the sun and there is plenty of plant life supporting a diverse fauna. Others spend more time in the water and inhabit the lower stretches of rivers, mangrove swamps, and estuaries. These habitats also have a rich flora and provide plenty of food. The Asian gharials find the fish on which they feed in the pools and backwaters of swift rivers. South American dwarf caimans inhabit cool, fast-flowing streams, often near waterfalls, and other caimans live in warmer, turbid lakes and slow-moving rivers. The crocodiles are mainly river dwellers, and the Chinese alligator is found in slow-moving, turbid rivers flowing across China's floodplains. The American alligator is an adaptable species and inhabits swamps, rivers, or lakes with clear or turbid water.[121] Climatic factors also affect crocodilians' distribution locally. During the dry season, caimans can be restricted to deep pools in rivers for several months; in the rainy season, much of the savanna in the Orinoco Llanos is flooded, and they disperse widely across the plain.[123] Desert crocodiles in Mauritania have adapted to their arid environment by staying in caves or burrows in a state of aestivation during the driest periods. When it rains, the reptiles gather at gueltas.[124]

Dry land is also important as it provides opportunities for basking, nesting, and escaping from temperature extremes. Gaping allows evaporation of moisture from the mouth lining and has a cooling effect, and several species make use of shallow burrows on land to keep cool. Wallowing in mud can also help prevent them from overheating.[125] Four species of crocodilians climb trees to bask in areas lacking a shoreline.[126] The type of vegetation bordering the rivers and lakes inhabited by crocodilians is mostly humid tropical forest, with mangrove swamps in estuarine areas. These forests are of great importance to the crocodilians, creating suitable microhabitats where they can flourish. The roots of the trees absorb water when it rains, releasing it back slowly into the environment. When the forests are cleared to make way for agriculture, rivers tend to silt up, the water runs off rapidly, the water courses can dry up in the dry season and flooding can occur in the wet season. Destruction of forest habitat is probably a greater threat to crocodilians than hunting.[127]

Ecological roles

[edit]

Being highly efficient predators, crocodilians tend to be top of the food chain in their watery environments.[128] The nest mounds built by some species of crocodilian are used by other animals for their own purposes. American alligator mounds are used by turtles and snakes, both for basking and for laying their own eggs. The Florida red-bellied turtle specialises in this, and alligator mounds may have several clutches of turtle eggs developing alongside the owner's eggs.[129] Alligators modify some wetland habitats in flat areas such as the Everglades by constructing small ponds known as "alligator holes". These create wetter or drier habitats for other organisms, such as plants, fish, invertebrates, amphibians, reptiles, and mammals. In the limestone depressions of cypress swamps, alligator holes tend to be large and deep. Those in marl prairies and rocky glades are usually small and shallow, while those in peat depressions of ridge and slough wetlands are more variable. Man-made holes do not appear to have as large an effect.[130]

In the Amazon basin, when caimans became scarce as a result of overhunting in the mid-20th century, the number of local fish, such as the important arapaima (Arapaima gigas), also decreased. These are nutrient-poor waters, and the urine and faeces of the caimans may have increased primary production by contributing plant nutrients. Thus the presence of the reptiles could have benefited the fish stock;[131] the number of crocodilians in a stretch of water appears to be correlated with the fish population.[132]

Behavior and life history

[edit]Cognition

[edit]Crocodilians are among the most cognitively complex nonavian reptiles, though their behavioral repertoire is less well understood than other vertebrates due to the difficulty of monitoring solitary and often nocturnal predators in aquatic habitats.

Embryological studies of developing amniotes have shown similar brain structures in the telencephalon between crocodilians, mammals, and birds.[133] Accordingly, several behaviors once thought unique to mammals and birds have been recently discovered in crocodilians. Some crocodilian species have been observed to use sticks and branches to lure nest-building birds, though other authors have argued the purpose of stick-displaying is ambiguous at best.[134][135] Several species have been observed to hunt cooperatively, herding and chasing prey.[136] Play, or the free, intrinsically motivated activity by young individuals, has been observed on numerous occasions in crocodilians in both captive and wild settings, with young alligators and crocodiles regularly engaging in object play and social play.[137] As with their mammalian and avian counterparts, play likely performs a significant role in helping these predators to hone their hunting skills and develop their understanding of behavioral tradeoffs. It is important to note that not all higher social behaviors are endemic across these clades. A 2023 study of tinamou, a paleognath avian, and American alligator test subjects found that while the paleognaths were able to engage in visual perspective taking – a cornerstone of advanced social cognition – the alligators did not appear to do so.[138] Some researchers have proposed to increase the use of crocodilians as test animals in comparative cognition studies.[139]

Spacing

[edit]Adult crocodilians are typically territorial and solitary. Individuals may defend basking spots, nesting sites, feeding areas, nurseries, and overwintering sites. Male saltwater crocodiles establish year-round territories that encompass several female nesting sites. Some species are occasionally gregarious, particularly during droughts, when several individuals gather at remaining water sites. Individuals of some species may share basking sites at certain times of the day.[50]

Feeding

[edit]

Crocodilians are largely carnivorous, and the diets of different species can vary with snout shape and tooth sharpness. Species with sharp teeth and long slender snouts, like the Indian gharial and Australian freshwater crocodile, are specialised for feeding on fish, insects, and crustaceans, while extremely broad-snouted species with blunt teeth, like the Chinese alligator and broad-snouted caiman, specialise in eating hard-shelled molluscs. Species whose snouts and teeth are intermediate between these two forms, such as the saltwater crocodile and American alligator, have generalised diets and opportunistically feed on invertebrates, fish, amphibians, other reptiles, birds, and mammals.[37][128] Though mostly carnivorous, several species of crocodilian have been observed to consume fruit, and this may play a role in seed dispersal.[140]

In general, crocodilians are stalk-and-ambush predators,[37] though hunting strategies vary depending on the individual species and the prey being hunted.[50] Terrestrial prey is stalked from the water's edge and then grabbed and drowned.[50][141] Gharials and other fish-eating species sweep their jaws sideways to snap up prey, and these animals can leap out of the water to catch birds, bats, and leaping fish.[128] A small animal can be killed by whiplash as the predator shakes its head.[141] Caimans use their tails and bodies to herd fish into shallow water.[50] They may also dig for bottom-dwelling invertebrates,[42] and the smooth-fronted caiman will even hunt on land.[37] Most species will eat anything suitable that comes within reach and are also opportunistic scavengers.[42]

Crocodilians are unable to chew and need to swallow food whole, so prey that is too large to swallow is torn into pieces. They may be unable to deal with a large animal with a thick hide, and may wait until it becomes putrid and comes apart more easily.[128] To tear a chunk of tissue from a large carcass, a crocodilian spins its body continuously while holding on with its jaws, a maneuver known as the "death roll".[142] During cooperative feeding, some individuals may hold on to the prey, while others perform the roll. The animals do not fight, and each retires with a piece of flesh and awaits its next feeding turn.[143] After feeding together, individuals may go their separate ways.[136] Food is typically consumed by crocodilians with their heads above water. The food is held with the tips of the jaws, tossed towards the back of the mouth by an upward jerk of the head and then gulped down.[141] Nile crocodiles may store carcasses underwater for later consumption.[42]

Reproduction and parenting

[edit]

Crocodilians are generally polygynous, and individual males try to mate with as many females as they can.[144] Monogamous pairings have been recorded in American alligators,[145] and parthenogenesis has been observed in the American crocodile.[146] Dominant male crocodilians patrol and defend territories which contain several females. Males of some species, like the American alligator, try to attract females with elaborate courtship displays. During courtship, crocodilian males and females may rub against each other, circle around, and perform swimming displays. Copulation typically occurs in the water. When a female is ready to mate, she arches her back while her head and tail submerge. The male rubs across the female's neck and then grasps her with his hindlimbs, placing his tail underneath hers so their cloacas align and his penis can be inserted. Mating can last up to 15 minutes, during which time the pair continuously submerge and surface.[144] While dominant males usually monopolise reproductive females, multiple paternity is known to exist in American alligators, where as many as three different males may sire offspring in a single clutch. Within a month of mating, the female crocodilian begins to make a nest.[50]

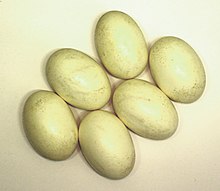

Depending on the species, female crocodilians may construct either holes or mounds as nests,[50] the latter made from vegetation, litter, sand, or soil.[117] Nests are typically found near dens or caves. Those made by different females are sometimes close to each other, particularly in hole-nesting species. The number of eggs laid in a single clutch ranges from ten to fifty. Crocodilian eggs are protected by hard shells made of calcium carbonate. The incubation period is two to three months.[50] The temperature at which the eggs incubate determines the sex of the hatchlings. Constant nest temperatures above 32 °C (90 °F) produce more males, while those below 31 °C (88 °F) produce more females. However, sex in crocodilians may be determined in a short interval, and nests are subject to changes in temperature. Most natural nests produce hatchlings of both sexes, though single-sex clutches do occur.[117]

The young may all hatch in a single night.[148] Crocodilians are unusual among reptiles in the amount of parental care provided after the young hatch.[147][50] The mother helps excavate hatchlings from the nest and carries them to water in her mouth. Newly hatched crocodilians gather together and stay close to their mother.[149] Both male and female adult crocodilians will respond to vocalizations by hatchlings.[147] For spectacled caimans in the Venezuelan llanos, individual mothers are known to leave their young in the same nurseries, or crèches, and one of the mothers guards them.[150] Hatchlings of many species tend to bask in a group during the day and disperse at nightfall to feed.[148] The time it takes young crocodilians to reach independence can vary. For American alligators, groups of young associate with adults for one to two years, while juvenile saltwater and Nile crocodiles become independent in a few months.[50]

Communication

[edit]Crocodilians can communicate with various sounds, including bellows, roars, growls, grunts, barks, coughs, hisses, toots, moos, whines, and chirps.[101] Young start communicating with each other before they are hatched. It has been shown that a light tapping noise near the nest will be repeated by the young, one after another. Such early communication may help them to hatch simultaneously. Once it has broken out of the egg, a juvenile produces yelps and grunts either spontaneously or as a result of external stimuli and even unrelated adults respond quickly to juvenile distress calls.[148]

Вокализации часты, когда молодые особи расходятся, и снова, когда они собираются утром. Соседние взрослые особи, предположительно родители, также подают сигналы, предупреждающие о хищниках или предупреждающие молодняк о наличии пищи. Диапазон и количество вокализаций различаются у разных видов. Аллигаторы самые шумные, а некоторые виды крокодилов почти полностью бесшумны. Взрослые самки крокодилов Новой Гвинеи и сиамских крокодилов ревут, когда к ним приближается другая взрослая особь, в то время как нильские крокодилы ворчат или ревут в аналогичной ситуации. Американский аллигатор исключительно шумный; он издает серию из семи хрипловатых мычаний, каждый продолжительностью в пару секунд, с десятисекундными интервалами. Он также издает различные хрюканья и шипения. [148] Males create vibrations in the water to send out infrasonic signals that serve to attract females and intimidate rivals.[151] Когда люди кричат на поверхности воды, инфразвук возмущает воду неслучайными, но визуально привлекательными узорами, что заставляет некоторых экотуристов описывать это как «танец воды». Увеличенный выступ самца гавиала может служить звуковым резонатором . [152]

Другая форма акустической коммуникации — удар по голове. Обычно это начинается с того, что животное в воде поднимает морду и остается неподвижным. Через некоторое время челюсти резко открываются, а затем смыкаются кусающим движением, издающим громкий хлопающий звук, за которым сразу же следует громкий всплеск, после чего голова может погружаться в воду и образовываться обильные пузыри. Некоторые виды тогда ревут, а другие шлепают хвостом по воде. По группе распространились эпизоды пощечин. Цель варьируется, но, по-видимому, она связана с поддержанием социальных отношений, а также используется при ухаживании. [148] Доминирующие особи могут также демонстрировать размер своего тела, плавая на поверхности воды, а подчиненный подчиняется, держа голову под острым углом с открытой пастью, прежде чем уйти под воду. [50]

Рост и смертность

[ редактировать ]

Смертность яиц и птенцов высока, а гнездам угрожают наводнения, перегрев и хищники. [50] Наводнение является основной причиной неудачного размножения крокодилов: гнезда затопляются, развивающиеся эмбрионы лишаются кислорода, а молодь смывается водой. [127] Многочисленные хищники, как млекопитающие, так и рептилии, могут совершать набеги на гнезда и поедать яйца крокодилов. [153] [154] Несмотря на материнскую заботу, которую они получают, детеныши обычно становятся жертвами хищников. [155] Пока самка переносит одних в зону выгула, других отбирают хищники, скрывающиеся возле гнезда. Помимо наземных хищников, только что вылупившиеся птенцы также подвергаются нападениям рыб в воде. Птицы берут свое, и в любой кладке могут оказаться уродливые особи, которые вряд ли выживут. [153] В северной Австралии выживаемость детенышей морских крокодилов составляет всего двадцать пять процентов, но с каждым последующим годом жизни этот показатель увеличивается, достигая шестидесяти процентов к пятому году. [155]

Уровень смертности среди подростков и взрослых довольно низок, хотя иногда на них охотятся крупные кошки и змеи. [155] Ягуар [156] и гигантская выдра [157] могут охотиться на кайманов в Южной Америке. В других частях мира слоны и бегемоты могут убивать крокодилов в целях защиты. [50] Авторитетные мнения расходятся во мнениях относительно того, каннибализм распространен ли среди крокодилов . Взрослые особи обычно не едят свое потомство, но есть некоторые свидетельства того, что полувзрослые особи питаются молодью, а взрослые особи нападают на полувзрослых особей. Соперничающие самцы нильских крокодилов иногда убивают друг друга во время сезона размножения. [153]

Рост птенцов и молодых крокодилов зависит от запасов пищи, а половая зрелость связана с длиной, а не с возрастом. Самки морских крокодилов достигают зрелости на высоте 2,2–2,5 м (7–8 футов), а самцы – на высоте 3 м (10 футов). Австралийским пресноводным крокодилам требуется десять лет, чтобы достичь зрелости на высоте 1,4 м (4 фута 7 дюймов). Очковый кайман взрослеет раньше, достигая взрослой длины 1,2 м (4 фута) за четыре-семь лет. [144] Крокодилы продолжают расти на протяжении всей своей жизни. Мужчины, в частности, продолжают прибавлять в весе с возрастом, но в основном это происходит за счет увеличения обхвата, а не длины. [158] Крокодилы могут жить 35–75 лет. [63] а их возраст можно определить по годичным кольцам в костях. [144] [158] Самый старый известный крокодил, который также является самой крупной известной особью, — это австралийский крокодил, который живет в неволе с 1984 года, его возраст оценивается в 120 лет. [159]

Взаимодействие с людьми

[ редактировать ]Сельское хозяйство и скотоводство

[ редактировать ]

Аллигаторов и крокодилов впервые стали выращивать в начале 20-го века, но их объекты напоминали зоопарки , а их основным источником дохода был туризм . К началу 1960-х годов возможность выращивания этих рептилий в коммерческих масштабах была исследована в ответ на сокращение численности многих видов крокодилов во всем мире. Сельское хозяйство предполагает разведение и выращивание поголовья в неволе на автономной основе, тогда как скотоводство означает использование яиц, молоди или взрослых особей, ежегодно добываемых из дикой природы. Коммерческие организации должны соответствовать критериям Конвенции о международной торговле видами, находящимися под угрозой исчезновения (СИТЕС), доказав, что в соответствующей зоне они не оказывают негативного воздействия на дикую популяцию. [160]

Разведение аллигаторов и крокодилов началось из-за спроса на их шкуры, но сейчас используются почти все части животных. Из кожи боков и брюха делают лучшую кожу, мясо едят, желчные пузыри ценятся в Восточной Азии, а из голов иногда делают украшения. [161] В традиционной китайской медицине считается, что мясо аллигатора излечивает простуду и предотвращает рак, а различные внутренние органы обладают лечебными свойствами. [162]

Атаки

[ редактировать ]Крокодилы — оппортунистические хищники, которые наиболее опасны в воде и у кромки воды. Известно, что некоторые виды нападают на людей и могут делать это, чтобы защитить свою территорию, гнезда или молодняк; по ошибке, нападая на домашних животных, например собак; или в пищу, поскольку более крупные крокодилы могут ловить добычу размером с человека или даже больше. Виды, по которым имеется больше всего данных, — это морской крокодил , нильский крокодил и американский аллигатор . Другими видами, которые иногда нападали на людей, являются черный кайман , крокодил Морелета , крокодил-грабитель , американский крокодил , гавиал и пресноводный крокодил . [163]

Нильский крокодил имеет репутацию крупнейшего убийцы крупных животных, включая человека, на африканском континенте. Он широко распространен, встречается во многих местах обитания и имеет загадочную окраску. Из положения ожидания, когда над водой находятся только глаза и ноздри, он может броситься на пьющих животных, рыбаков, купающихся или людей, набирающих воду или стирающих одежду. Если жертву схватить и затащить в воду, у жертвы мало шансов спастись. Анализ нападений показывает, что большинство из них происходит во время сезона размножения или когда крокодилы охраняют гнезда или только что вылупившихся детенышей. [164] Хотя о многих нападениях не сообщается, по оценкам, их происходит более 300 в год, 63% из которых заканчиваются смертельным исходом. [163] В период с 1971 по 2004 год дикие морские крокодилы в Австралии совершили 62 подтвержденных и неспровоцированных нападения, повлекших за собой ранения или смерть. Эти животные также стали причиной гибели людей в Малайзии, Новой Гвинее и других странах. Они очень территориальны и возмущаются вторжением на их территорию других крокодилов, людей или лодок, таких как каноэ. Нападения могут исходить от животных разного размера, но в смертельных случаях обычно виноваты более крупные самцы. По мере увеличения их размера растет и их потребность в более крупной добыче среди млекопитающих; свиньи, крупный рогатый скот, лошади и люди — все они находятся в том диапазоне размеров, который им нужен. Большинство атакованных людей либо плавали, либо шли вброд, но в двух случаях они спали в палатках. [165]

Зарегистрировано, что в период с 1948 по середину 2004 года американские аллигаторы совершили 242 неспровоцированных нападения, в результате которых погибло шестнадцать людей. Десять из них находились в воде и двое на суше; обстоятельства остальных четырех неизвестны. Большинство нападений произошло в теплые месяцы, хотя во Флориде, с ее более теплым климатом, нападения могут произойти в любое время года. [163] Аллигаторы считаются менее агрессивными, чем нильский или морской крокодил. [166] но увеличение плотности населения в Эверглейдс привело к сближению людей и аллигаторов и увеличило риск нападений аллигаторов. [163] [166] И наоборот, в Мавритании , где рост крокодилов сильно замедлен из-за засушливых условий, местные жители плавают с ними, не подвергаясь нападению. [124]

Как домашние животные

[ редактировать ]Некоторые виды крокодилов продаются как экзотические домашние животные . В молодости они привлекательны, но из крокодилов не получаются хорошие домашние животные; они вырастают большими, и их содержание опасно и дорого. По мере взросления домашних крокодилов хозяева часто бросают, а дикие популяции очковых кайманов существуют в Соединенных Штатах и на Кубе. В большинстве стран действуют строгие правила содержания этих рептилий. [167]

В медицине

[ редактировать ]Кровь аллигаторов и крокодилов содержит пептиды с антибиотическими свойствами, которые могут способствовать созданию будущих антибактериальных препаратов. [168] Хрящ крокодилов, выращенных на крокодиловых фермах, также используется в исследованиях по 3D-печати новых хрящей для людей путем смешивания стволовых клеток человека с разжиженным крокодиловым хрящом после удаления белков, которые могут активировать иммунную систему человека. [169]

Сохранение

[ редактировать ]

Главной угрозой для крокодилов во всем мире является деятельность человека, включая охоту и разрушение среды обитания. В начале 1970-х годов было продано более 2 миллионов шкур диких крокодилов, что привело к сокращению большинства популяций крокодилов, а в некоторых случаях почти к исчезновению. Начиная с 1973 года СИТЕС пыталась предотвратить торговлю частями тел находящихся под угрозой исчезновения животных, такими как крокодиловые шкуры. В 1980-х годах это оказалось проблематичным, поскольку в некоторых частях Африки крокодилы были многочисленны и опасны для людей, а охота на них была законной. На Конференции сторон в Ботсване в 1983 году от имени недовольных местных жителей утверждалось, что продавать шкуры, добытые на законных основаниях, было разумно. В конце 1970-х годов крокодилов начали разводить в разных странах, начиная с яиц, добытых в дикой природе. К 1980-м годам выращенные крокодиловые шкуры были произведены в достаточном количестве, чтобы положить конец незаконной торговле дикими крокодилами. К 2000 году шкуры двенадцати видов крокодилов, законно добытых в дикой природе или выращенных на фермах, продавались в тридцати странах, и незаконная торговля практически исчезла. [170]

Гавиал претерпел хроническое долгосрочное сокращение численности в сочетании с быстрым краткосрочным сокращением, что привело к тому, что МСОП включил этот вид в список находящихся под угрозой исчезновения . В 1946 году популяция гавиалов была широко распространена и насчитывала от 5 000 до 10 000 человек; однако к 2006 году оно сократилось на 96–98%, превратившись в небольшое количество широко расположенных субпопуляций, насчитывающих менее 235 особей. Это долгосрочное снижение имело ряд причин, включая сбор яиц и охоту, например, в целях местной медицины . Быстрое снижение примерно на 58% в период с 1997 по 2006 год было вызвано увеличением использования жаберных сетей и утратой речной среды обитания. [171] Популяции гавиалов по-прежнему угрожают такие экологические опасности, как тяжелые металлы и простейшие паразиты. [172] но по состоянию на 2013 год их численность растет из-за защиты гнезд от яичных хищников. [173] Китайский аллигатор исторически был широко распространен по всей восточной системе реки Янцзы, но в настоящее время его распространение ограничено некоторыми районами юго-восточной провинции Аньхой из-за фрагментации и деградации среды обитания. Считается, что дикая популяция существует только в небольших фрагментированных прудах. В 1972 году правительство Китая объявило этот вид видом, находящимся под угрозой исчезновения класса I, и получило максимальную правовую защиту. С 1979 года программы разведения в неволе были созданы в Китае и Северной Америке, что позволило создать здоровую популяцию в неволе. [174] В 2008 году аллигаторы, выращенные в зоопарке Бронкса, были успешно реинтродуцированы на остров Чонгминг . [175] Филиппинский крокодил, пожалуй, является крокодилом, находящимся под наибольшей угрозой исчезновения, и МСОП считает его находящимся под угрозой исчезновения. В результате охоты и разрушительного рыболовства к 2009 году его популяция сократилась примерно до 100 особей. В том же году 50 выращенных в неволе крокодилов были выпущены в дикую природу, чтобы помочь увеличить популяцию. Поддержка местного населения имеет решающее значение для выживания вида. [176]

Американский аллигатор также серьезно пострадал от охоты и утраты среды обитания по всему ареалу, что угрожает ему исчезновением. В 1967 году он был внесен в список исчезающих видов, но Служба рыболовства и дикой природы США и государственные агентства по охране дикой природы на юге США вмешались и начали работать над его восстановлением. Охрана позволила виду восстановиться, и в 1987 году его исключили из списка исчезающих видов. [177] Много исследований по разведению аллигаторов было проведено в заповеднике Рокфеллера , большой болотистой местности в штате Луизиана . Доходы от аллигаторов, содержащихся в заповеднике Рокфеллера, способствуют сохранению болот. [178] Исследование, посвященное фермам аллигаторов в Соединенных Штатах, показало, что они добились значительных успехов в сохранении природы, а браконьерство в отношении диких аллигаторов значительно сократилось. [179]

Культурные изображения

[ редактировать ]В мифологии

[ редактировать ]

Крокодилы сыграли выдающуюся роль в повествованиях различных культур по всему миру и, возможно, даже вдохновили истории о драконах . [180] В древнеегипетской религии , Аммит пожиратель недостойных душ, и Себек , бог силы, защиты и плодородия, оба изображаются с крокодильими головами. Это отражает взгляд египтян на крокодила как на ужасающего хищника и как на важную часть экосистемы Нила. Крокодил был одним из нескольких животных, мумифицировавшихся египтянами . [181] Крокодилы также ассоциировались с различными водными божествами . у народов Западной Африки [182] Во времена Бенинской империи крокодилы считались «водными полицейскими» и символизировали власть короля или Оба по наказанию правонарушителей. [183] Левиафан , описанный в Книге Иова, возможно, был основан на крокодиле. [184] В Мезоамерике был у ацтеков крокодиловый бог плодородия по имени Чипактли, который защищал посевы. В мифологии ацтеков земное божество Тлалтекутли иногда изображается в виде монстра, похожего на крокодила. [185] Майя также ассоциировали крокодилов с плодородием и смертью. [186] Австралийская история Dreamtime рассказывает о предке-крокодиле, у которого был весь огонь, пока «радужная птица» не украла у человека огненные палки; следовательно, крокодил живет в воде. [187]

В литературе и фольклоре

[ редактировать ]

Древние историки описывали крокодилов по самым ранним письменным источникам, хотя часто их описания содержат столько же предположений, сколько и наблюдений. Древнегреческий историк Геродот (ок. 440 г. до н. э.) подробно описал крокодила, хотя большая часть его описаний является причудливой; он утверждал , что он лежал с открытой пастью, чтобы позволить птице «трохилус» (возможно, египетской ржанке ) удалить пиявок . [188] конца XIII века Крокодил был описан в Рочестерском Бестиарии на основе классических источников, в том числе ( Плиния «Historia naturalis» ок. 79 г. н.э.). [189] и » Исидора Севильского «Этимологии . [190] [191] Исидор утверждает, что крокодил назван в честь своего шафранового цвета (лат. croceus, «шафран») и может быть убит рыбой с зазубренными гребнями, врезающейся в его мягкое подбрюшье. [192]

Считается, что крокодилы плачут 9-го века о своих жертвах со времен Библиотеки Фотия I Константинопольского . [193] История стала широко известна в 1400 году, когда английский путешественник Джон Мандевиль написал свое описание «кокодриллов»: [194]

- «В этой стране [ пресвитера Иоанна ] и по всей Индии [Индии] обитает великое множество кокодрилов, это разновидность длинной змеи, как я уже говорил ранее. А ночью они обитают в воде и на день на земле, в скалах и пещерах. И они не едят мяса всю зиму, но лежат, как во сне, как змеи эти убивают людей, и они едят их, плача, и когда они едят, они. сдвинь верхнюю челюсть, а не нижнюю, и не будет у них языка». [194]

Крокодилы, особенно крокодилы, были постоянными персонажами детских сказок. Льюиса Кэрролла В книге «Приключения Алисы в стране чудес» (1865) есть стихотворение « Как поживает маленький крокодил» : [195] пародия на морализаторское стихотворение Уоттса Исаака «Против праздности и озорства» . [196] В Дж. М. Барри « романе Питер и Венди» (1911) капитан Крюк потерял руку из-за крокодила. [197] В » Редьярда Киплинга ( «Такие истории 1902) слоненок завладел своим хоботом, когда крокодил очень сильно потянул его за нос. [198] В книге Роальда Даля « Огромный крокодил» (1978) рассказывается, как крокодил бродит по джунглям в поисках детей, чтобы поесть. [199]

Гавиал фигурирует в народных сказках Индии. В одной истории гавиал и обезьяна становятся друзьями, когда обезьяна дает гавиалу плод, но дружба заканчивается после того, как гавиал признается, что пытался заманить его в этот дом, чтобы съесть. [200] Подобные истории существуют в легендах коренных американцев и в афроамериканских сказках об аллигаторе и кролике Братце . [201] В популярной малайской народной сказке мышь-олень обманом заставляет группу крокодилов стать мостом, по которому он может пересечь реку. [202] Легенда из Восточного Тимора рассказывает, как мальчик спасает гигантского крокодила, который застрял на мели. Взамен крокодил защищает его до конца своей жизни, а когда он умирает, его чешуйчатая спина становится холмами Тимора. [203]

В СМИ

[ редактировать ]Крокодилов часто представляют как опасные препятствия. [204] в приключенческих фильмах, таких как «Живи и дай умереть » (1973) и «Индиана Джонс и Храм Судьбы» (1984), или в роли чудовищных людоедов в фильмах ужасов, таких как «Съеденные заживо» (1977), «Аллигатор» (1980), «Лейк-Плэсид» (1999). , Крокодил (2000), Разбойник (2007), Первобытный (2007), Черная вода (2007) и Ползти (2019). [205] В фильме «Крокодил Данди » прозвище главного героя происходит от животного, откусившего ему ногу. [206] Некоторые средства массовой информации пытались изобразить этих рептилий в более позитивном или познавательном свете, например, Стива Ирвина о в документальном сериале дикой природе «Охотник на крокодилов» . [204]

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Шмидт, КП, 1953. Контрольный список североамериканских амфибий и рептилий. Шестое издание. амер. Соц. Ихти. Герп. Чикаго, Издательство Чикагского университета.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Оуэн, Р. 1842. Отчет о британских ископаемых рептилиях. Часть II. Отчет Британской ассоциации Adv. наук. Плимутская встреча. 1841: 60–240.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Вермут, Х. 1953. Систематика современных крокодилов. Середина Муз. Берлин. Том 29 (2): 275–514.

- ^ Лауренти, JN 1768. Медицинский образец, демонстрирующий краткий обзор рептилий, улучшенных с помощью экспериментов, касающихся ядов и противоядий австрийских рептилий. Джоан. Том. Мы Траттерн, Вена.

- ^ Данди, штат Калифорния, 1989. Использование названий более высокой категории для амфибий и рептилий. Сист. Зоол. Том. 38(4):398–406, DOI 10.2307/2992405.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Брошу, Калифорния (2003). «Филогенетические подходы к истории крокодилов». Ежегодный обзор наук о Земле и планетах . 31 (31): 357–397. Бибкод : 2003AREPS..31..357B . doi : 10.1146/annurev.earth.31.100901.141308 . S2CID 86624124 .

- ^ Лидделл, Генри Джордж; Скотт, Роберт (1901). «Промежуточный греко-английский лексикон» . Университет Тафтса . Проверено 22 октября 2013 г.

- ^ Гоув, Филип Б., изд. (1986). "Крокодил". Третий новый международный словарь Вебстера . Британская энциклопедия.

- ^ Келли, 2006. с. xiii.

- ^ Хатчинсон, Джон Р.; Спир, Брайан Р.; Ведель, Мэтт (2007). «Архозаврия» . Музей палеонтологии Калифорнийского университета . Проверено 24 октября 2013 г.

- ^ Сен-Флер, Николас (16 февраля 2017 г.). «После худшего массового вымирания на Земле жизнь быстро восстановилась, как свидетельствуют окаменелости» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Проверено 6 июля 2024 г.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: статус URL ( ссылка ) - ^ Ирмис, Рэндалл Б.; Несбитт, Стерлинг Дж.; Сьюс, Ханс-Дитер (январь 2013 г.). «Ранние крокодиломорфы» . Геологическое общество, Лондон, специальные публикации . 379 (1): 275–302. Бибкод : 2013GSLSP.379..275I . дои : 10.1144/SP379.24 . ISSN 0305-8719 .

- ^ Кольбер, Эдвин Харрис; Барнум; Прайс (1952). «Псевдозуховая рептилия из Аризоны» . Архив.орг . Бюллетень Американского музея естественной истории . Проверено 7 июля 2024 г.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: статус URL ( ссылка ) - ^ Ирмис, РБ; Несбитт, С.Дж.; Сьюс, Х.-Д. (2013). «Ранние крокодиломорфы». Геологическое общество, Лондон, специальные публикации . 379 (1): 275–302. Бибкод : 2013GSLSP.379..275I . дои : 10.1144/SP379.24 . S2CID 219190410 .

- ^ Леарди, Хуан Мартин; Пол, Диего; Кларк, Джеймс Мэтью (2020). «Анатомия черепной коробки Almadasuchus figarii (Archosauria, Crocodylomorpha) и обзор краниальной пневматическости в происхождении Crocodylomorpha» . Журнал анатомии . 237 (1): 48–73. дои : 10.1111/joa.13171 . ISSN 0021-8782 . ПМК 7309285 . ПМИД 32227598 .

- ^ Рубеншталь, Александр А.; Кляйн, Майкл Д.; Йи, Хунъюй; Сюй, Син; Кларк, Джеймс М. (14 июня 2022 г.). «Анатомия и взаимоотношения ранних дивергентных крокодиломорфов Junggarsurusus sloani и Dibothrosuchus elaphros» . Анатомическая запись . 305 (10): 2463–2556. дои : 10.1002/ar.24949 . ISSN 1932-8486 . ПМК 9541040 . ПМИД 35699105 .

- ^ Стаббс, Томас Л.; Пирс, Стефани Э.; Рэйфилд, Эмили Дж.; Андерсон, Филип С.Л. (2013). «Морфологическое и биомеханическое несоответствие архозавров крокодиловой линии после вымирания в конце триаса» (PDF) . Труды Королевского общества Б. 280 (20131940): 20131940. doi : 10.1098/rspb.2013.1940 . ПМЦ 3779340 . ПМИД 24026826 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Мартин, Джереми Э.; Бентон, Майкл Дж. (2008). «Коронные клады в номенклатуре позвоночных: исправление определения крокодилов» . Систематическая биология . 57 (1): 173–181. дои : 10.1080/10635150801910469 . ПМИД 18300130 .

- ^ Бюффо, стр. 26–37.

- ^ Брочу, Калифорния (2007). «Систематика и филогенетические взаимоотношения копытных крокодилов (Pristichampsinae)». Журнал палеонтологии позвоночных . 27 (3, доп.): 53А. дои : 10.1080/02724634.2007.10010458 . S2CID 220411226 .

- ^ Брочу, Калифорния; Пэррис, округ Колумбия; Грандстафф, бакалавр наук; Дентон, Р.К. младший; Галлахер, ВБ (2012). «Новый вид Borealosurus (Crocodyliformes, Eusuria) из позднего мела – раннего палеогена Нью-Джерси». Журнал палеонтологии позвоночных . 32 (1): 105–116. Бибкод : 2012JVPal..32..105B . дои : 10.1080/02724634.2012.633585 . S2CID 83931184 .

- ^ Матеус, Октавио; Пуэртолас-Паскуаль, Эдуардо; Каллапез, Педро М. (2018). «Новый евзуховый крокодиломорф из сеномана (позднего мела) Португалии раскрывает новые последствия для происхождения Crocodylia». Зоологический журнал Линнеевского общества . 186 (2): 501–528. doi : 10.1093/zoolnnean/zly064 . hdl : 10362/67793 .

- ^ Кузьмин И.Т. (2022). «Останки крокодилиформ из верхнего мела Центральной Азии – свидетельство существования одного из древнейших крокодилов?» . Меловые исследования . 138 : Статья 105266. doi : 10.1016/j.cretres.2022.105266 . S2CID 249355618 .

- ^ Рио, Джонатан П.; Маннион, Филип Д. (6 сентября 2021 г.). «Филогенетический анализ нового набора морфологических данных проясняет эволюционную историю крокодилов и решает давнюю проблему гавиалов» . ПерДж . 9 : е12094. дои : 10.7717/peerj.12094 . ПМЦ 8428266 . ПМИД 34567843 .

- ^ Дарлим, Г.; Ли, MSY; Уолтер, Дж.; Раби, М. (2022). «Влияние молекулярных данных на филогенетическое положение предполагаемого старейшего крокодила и возраст клады» . Письма по биологии . 18 (2): 20210603. doi : 10.1098/rsbl.2021.0603 . ПМЦ 8825999 . ПМИД 35135314 .

- ^ Пуэртолас-Паскуаль, Эдуардо; Кузьмин Иван Т.; Серрано-Мартинес, Алехандро; Матеус, Октавио (2 февраля 2023 г.). «Нейроанатомия крокодиломорфа Portugalosuchus azenhae из позднего мела Португалии» . Журнал анатомии : joa.13836. дои : 10.1111/joa.13836 . ISSN 0021-8782 .

- ^ Хеккала, Э.; Гейтси, Дж.; Наречания, А.; Мередит, Р.; Расселло, М.; Аардема, ML; Дженсен, Э.; Монтанари, С.; Брошу, К.; Норелл, М.; Амато, Г. (27 апреля 2021 г.). «Палеогеномика освещает эволюционную историю вымершего голоценового «рогатого» крокодила Мадагаскара Voayrobustus» . Коммуникационная биология . 4 (1): 505. дои : 10.1038/s42003-021-02017-0 . ISSN 2399-3642 . ПМК 8079395 . ПМИД 33907305 .

- ^ Молер, Б.Ф.; Макдональд, AT; Вулф, генеральный директор (2021). «Первые останки огромного аллигатороида дейнозуха из верхнемеловой формации Менефи, Нью-Мексико» . ПерДж . 9 : е11302. дои : 10.7717/peerj.11302 . ПМЦ 8080887 . ПМИД 33981505 .

- ^ Иидзима М, Цяо Ю, Линь В, Пэн Ю, Йонеда М, Лю Дж (2022). «Промежуточный крокодил, связывающий двух современных гавиалов бронзового века Китая и его исчезновения, вызванного деятельностью человека» . Труды Королевского общества B: Биологические науки . 289 (1970): Идентификатор статьи 20220085. doi : 10.1098/rspb.2022.0085 . ПМЦ 8905159 .

- ^ Жув, Стефан; Барде, Натали; Джалиль, Нур-Эддин; Субербиола, Хавьер Переда; Буя; Баада; Амагзаз, Мбарек (2008). «Самый старый африканский крокодил: филогения, палеобиогеография и дифференциальная выживаемость морских рептилий на границе мелового и третичного периодов» (PDF) . Журнал палеонтологии позвоночных . 28 (2): 409–421. doi : 10.1671/0272-4634(2008)28[409:TOACPP]2.0.CO;2 .

- ^ Брошу, Калифорния (2003). «Филогенетические подходы к истории крокодилов». Ежегодный обзор наук о Земле и планетах . 31 (31): 357–397. Бибкод : 2003AREPS..31..357B . doi : 10.1146/annurev.earth.31.100901.141308 . S2CID 86624124 .

- ^ Стокдейл, Максимилиан Т.; Бентон, Майкл Дж. (7 января 2021 г.). «Экологические факторы эволюции размеров тела архозавров крокодиловой линии» . Коммуникационная биология . 4 (1): 38. дои : 10.1038/s42003-020-01561-5 . ISSN 2399-3642 . ПМЦ 7790829 . ПМИД 33414557 .

- ^ Гейтси, Хорхе; Амато, Г.; Норелл, М.; ДеСалле, Р.; Хаяши, К. (2003). «Комбинированная поддержка массового таксического атавизма у гавиалиновых крокодилов» (PDF) . Систематическая биология . 52 (3): 403–422. дои : 10.1080/10635150309329 . ПМИД 12775528 .

- ^ Холлидей, Кейси М.; Гарднер, Николас М. (2012). Фарке, Эндрю А. (ред.). «Новая евзухиевая крокодилиформная форма с новым черепным покровом и ее значение для происхождения и эволюции Crocodylia» . ПЛОС ОДИН . 7 (1): e30471. Бибкод : 2012PLoSO...730471H . дои : 10.1371/journal.pone.0030471 . ПМЦ 3269432 . ПМИД 22303441 .

- ^ Харшман, Дж.; Хаддлстон, CJ; Болбак, Япония; Парсонс, Ти Джей; Браун, MJ (2003). «Истинные и ложные гавиалы: филогения ядерных генов крокодилов» . Систематическая биология . 52 (3): 386–402. дои : 10.1080/10635150309323 . ПМИД 12775527 .

- ^ Гейтси, Дж.; Амато, Г. (2008). «Быстрое накопление последовательной молекулярной поддержки межродовых крокодиловых отношений». Молекулярная филогенетика и эволюция . 48 (3): 1232–1237. Бибкод : 2008МОЛПЭ..48.1232Г . дои : 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.02.009 . ПМИД 18372192 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час Эриксон, генеральный директор; Жиньяк, премьер-министр; Степпан, С.Дж.; Лаппин, АК; Влит, штат Калифорния; Брюгген, Дж.А.; Иноуе, Б.Д.; Кледзик, Д.; Уэбб, GJW (2012). Классенс, Леон (ред.). «Понимание экологии и эволюционного успеха крокодилов, выявленное посредством экспериментов по силе укуса и давлению зубов» . ПЛОС ОДИН . 7 (3): e31781. Бибкод : 2012PLoSO...731781E . дои : 10.1371/journal.pone.0031781 . ПМЦ 3303775 . ПМИД 22431965 .

- ^ Майкл С.И. Ли; Адам М. Йейтс (27 июня 2018 г.). «Тип-датировка и гомоплазия: примирение неглубоких молекулярных расхождений современных гавиалов с их длинными ископаемыми» . Труды Королевского общества Б. 285 (1881). дои : 10.1098/rspb.2018.1071 . ПМК 6030529 . ПМИД 30051855 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хеккала, Э.; Гейтси, Дж.; Наречания, А.; Мередит, Р.; Расселло, М.; Аардема, ML; Дженсен, Э.; Монтанари, С.; Брошу, К.; Норелл, М.; Амато, Г. (27 апреля 2021 г.). «Палеогеномика освещает эволюционную историю вымершего голоценового «рогатого» крокодила Мадагаскара Voayrobustus» . Коммуникационная биология . 4 (1): 505. дои : 10.1038/s42003-021-02017-0 . ISSN 2399-3642 . ПМК 8079395 . ПМИД 33907305 .

- ^ Швиммер, Дэвид Р. (2002). «Размер дейнозуха ». Король крокодилов: Палеобиология дейнозуха . Издательство Университета Индианы. стр. 42–63. ISBN 978-0-253-34087-0 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж Григг и Ганс, стр. 326–327.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж Келли, стр. 70–75.

- ^ Земноводные и рептилии Коста-Рики: герпетофауна между двумя континентами, между двумя морями

- ^ Медицина и хирургия рептилий

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Хухцермейер, стр. 7–10.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Фермер, CG; Перевозчик ДР (2000). «Тазовая аспирация у американского аллигатора ( Alligator Mississippiensis )». Журнал экспериментальной биологии . 203 (11): 1679–1687. дои : 10.1242/jeb.203.11.1679 . ПМИД 10804158 .

- ^ Григг и Ганс, с. 336.

- ^ Келли, окружной прокурор (2013). «Анатомия полового члена и гипотезы эректильной функции американского аллигатора ( Alligator Mississippiensis ): мышечная выворотность и эластическое втягивание». Анатомическая запись . 296 (3): 488–494. дои : 10.1002/ar.22644 . ПМИД 23408539 . S2CID 33816502 .

- ^ Хухцермейер, с. 19.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м н тот п д Ланг, JW (2002). «Крокодилы». В Холлидее, Т.; Адлер, К. (ред.). Энциклопедия рептилий и амфибий Firefly . Книги Светлячка. стр. 212–221 . ISBN 978-1-55297-613-5 .

- ^ Фиш, FE (1984). «Кинематика волнообразного плавания американского аллигатора» (PDF) . Копейя . 1984 (4): 839–843. дои : 10.2307/1445326 . JSTOR 1445326 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 21 октября 2013 года.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Маццотти, стр. 43–46.

- ^ Сьюс, с. 21.

- ^ Рейли, С.М.; Элиас, Дж. А. (1998). «Передвижение аллигатора Mississippiensis : кинематические эффекты скорости и позы и их отношение к парадигме от растягивания до вертикального положения» (PDF) . Журнал экспериментальной биологии . 201 (18): 2559–2574. дои : 10.1242/jeb.201.18.2559 . ПМИД 9716509 .

- ^ Келли, стр. 81–82.