Джерард Креффт

Джерард Креффт | |

|---|---|

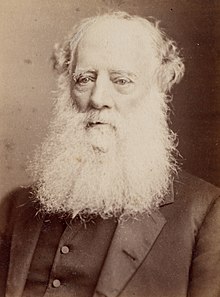

Krefft (c.1857) | |

| Рожденный | 17 февраля 1830 г. |

| Умер | 18 февраля 1881 года (в возрасте 51 года) Woolloomooloo , Новый Южный Уэльс |

| Место отдыха | Церковь Святого Иуды, Рэндвик |

| Национальность | Натурализованный британский предмет в Новом Южном Уэльсе (1864) [ 2 ] |

| Образование | Колледж Святого Мартина, Брауншвейг |

| Известен для | Обнаружение, идентификация и название Квинслендский легкий рыба |

| Супруг | Энни Макфейл (умер в 1926 году) (М.1869) |

| Дети | 4 |

| Родители |

|

| Родственники | Ихтиолог и Герпетолог Герхард Креффт (1912–1993) (Великий племянник) [ 3 ] |

| Награды | Рыцарь , [ 1 ] Порядок Короны Италии , Парень , Линневое общество Соответствующий член , зоологическое общество Лондона |

| Научная карьера | |

| Поля | Естественная история , зоология , палеонтология , ихтиология , энтомология , герпетология |

| Учреждения | Национальный музей Виктории Австралийский музей |

| Автор Аббрево. (Зоология) | рак |

Иоганн Людвиг (Луи) Джерард Креффт (17 февраля 1830 - 18 февраля 1881 года) был австралийским художником, рисунком, ученым и естественным историком , который служил куратором Австралийского музея в течение 13 лет (1861–1874). [ 4 ] Он был одним из Австралии первых и влиятельных зоологов и палеонтологов .

Он также отмечен в качестве ихтиолога своим научным описанием легкого в Квинсленде (теперь признан классическим примером «Живых окаменелостей» Дарвина ); [ 7 ] И, в дополнение к его многочисленным научным документам и его обширной серии еженедельных газетных статей по естественной истории, его публикации включают в себя змеи Австралии (1869), гид по австралийскому ископаемому остается в Австралийском музее (1870F), млекопитающих Австралии. (1871f), на австралийском Entozoa (1872a) и каталог минералов и скал в Австралийском музее (1873a). [ 8 ]

Креффт был одним из немногих австралийских ученых в 1860 -х и 1870 -х годах, чтобы поддержать позицию Дарвина в отношении происхождения видов с помощью естественного отбора. Согласно MacDonald, et al. (2007), он был одним из первых, кто предупреждал о разрушительных эффектах инвазивных видов (овец, кошек и т. Д.) На местных видов. [ 9 ] [ 10 ] Кроме того, наряду с несколькими значимыми другими, такими как Чарльз Дарвин , во время его визита в 1836 году в Голубые горы , [ 11 ] Эдвард Уилсон , владелец Мельбурна Аргус , [ 12 ] и Джордж Беннетт , один из попечителей Австралийского музея [ 13 ] - Креффт выразил значительную обеспокоенность в отношении последствий расширяющегося европейского поселения на коренное население. [ 14 ] [ 15 ]

- Джерард Креффт является важной фигурой в истории австралийской науки XIX века. Он празднуется не только за его зоологическую работу, но и как человек, который был готов бросить вызов людям на точках научных фактов, независимо от их позиции в Сиднейском обществе или в столичной науке. Его также помнят как тот, кто мог бы быть абразивным и недвожденным в деликатных политических ситуациях и человеке, чья карьера и жизнь в конечном итоге закончились трагедией. Драматический окончание карьеры Креффта в 1874 году, где он был лишен своего должности куратора австралийского музея, физически удаленного из музея, и его персонаж убил, - часто затмевает его раннюю карьеру и его развитие как ученый. - Стэфены (2013), P Полем 187.

Семья

[ редактировать ]

Креффт родился 17 февраля 1830 года в герцогстве Брансуика (ныне часть Германии), сын Уильяма Креффта, кондитерского изделия , и его жены Йоханны ( урожденная Бишхофф). [ 17 ]

Образование

[ редактировать ]Он получил образование в колледже Святого Мартина в Брауншвейге (то есть Мартино-Катаринеум ) с 1834 по 1845 год. [ 17 ] В молодости он интересовался искусством, особенно рисованием животных, и хотел пойти на официальное изучение живописи; Однако после его обучения его семья нашла трудоустройство для него в торговой фирме в Хальберстадте . [ 18 ]

Свадьба

[ редактировать ]Он женился на Энни Макфейл (1847–1926), [ 19 ] Позже (1893) миссис Роберт Макинтош, [ 20 ] 6 февраля 1869 года. [ 17 ] Согласно Nancarrow (2007, стр. 5), Энни МакФайл была дочерью австралийской дочери шотландских боевых иммигрантов , которые прибыли в Австралию в 1837 году, чтобы работать на Джорджа Боумана , и она была на пять месяцев беременности на момент ее брака. Креффт. [ 21 ]

У них было четверо детей, [ 22 ] Только два из которых пережили их младенчество: Рудольф Джерард Креффт (1869–1951), [ 23 ] [ 24 ] [ 25 ] и Герман Джерард Креффт (1879–1911). [ 26 ] Пятый ребенок, неназванная мертворожденная дочь, была доставлена 2 июля 1874 года. [ 27 ]

Немецкое наследие

[ редактировать ]Будучи немецким спикером, Креффт принадлежал к крупнейшей неанглийской группе в Австралии в 1800-х годах ; [ 28 ] [ 29 ] И, как таковой, Креффт был одним из многих влиятельных немецкоязычных ученых [ 30 ] Кто, по словам Барретта и др. (2018, стр. 2) принесли свои «эпистемические традиции» в Австралию и не только «глубоко запутались в австралийском колониальном проекте», но и «невыразительно вовлечены в воображение, знание и формирование колониальной Австралии». [ 31 ]

Более того, и в отношении Креффта (ученых) и его более широкой дисциплинарной верности и его ограниченного уважения к предполагаемой власти устоявшейся британской научной элиты, в отличие от англо-австралийских попечителей Австралийского музея и «как многие [из немецких] Ученые, работающие в Австралии, Англия никогда не была «домом» для Креффта, как это было для большинства колонистов », и, как правило, Англия не« обеспечила [e] единственное интеллектуальное Влияние на расследования [Креффта] ». [ 32 ]

"Естественная история"

[ редактировать ]Учитывая трехстороннее подразделение Vallances (1978) девятнадцатого века Австралийская наука [ 33 ] -т.е. прото-научный период (1788–1839), [ 34 ] пионер -научный период (1840–1874), [ 35 ] и классический научный период (1875-) [ 36 ] -Влиятельная австралийская карьера Креффта была твердо сосредоточена в научном периоде пионера. Следовательно, и чтобы избежать прохронистической ошибки, просматривая прошлое глазами настоящего и дано,

- То, что Австралийский музей (основанный в 1827 году) является пятым старейшим музеем естественной истории в мире, [ 37 ] [ 38 ]

- необходимость определить ориентацию австралийского музея во время пребывания Креффта,

- Необходимость определения конкретных доменов, представляющих интерес (и влияния) Креффта как ученого, [ 39 ]

- продолжающееся значение статей Креффта (более 180) «естественная история», опубликованные в Сиднейской почте с марта 1871 года по июнь 1875 года, и

- это 19 -е. Кентерикальная естественная история была связана с изучением природы; и из этого он был непосредственно связан с доказательствами, полученными в результате прямого наблюдения природы (как бы ни было описано «природа») [ 41 ]

- что в 1822 году (стр. III-IV) Фридрих Мохс обратил внимание на неуместность естественной истории ярлыка на том основании, что она «не выражает основные свойства науки, к которой она применяется», [ 42 ] и

- Это, в 1837 году, вызвано замечаниями Моха, Уильямом Уэвеллом , минералогом, ученым, а затем, Мастером Тринити -колледжа, Кембридж (с 1841 по 1866 год), который в свое время было «признано ведущей властью на новом [терминологические] чеканки " [ 43 ] -как часть его новаторской работы в отношении вопросов терминологии и классификации в науках, [ 44 ] и расширение значения (недавно введенного) английского термина палеонтология [ 45 ] - предложил альтернативное представление о «палетиологических науках» [ 46 ] Обозначать «те исследования, в которых объект поднимается от нынешнего состояния до более древнего состояния, из которого настоящее получено по понятным причинам» (Wheell, 1837, p. 481). [ 47 ]

Важно отметить, что широко используемые «зонтичные» термины естественной истории и естественного историка (или натуралиста ), как правило, были поняты (и по-разному применялись) в середине 1800-х годов, чтобы определить коллективные усилия чрезвычайно широкого диапазона различных предприятий, которые теперь, отдельно идентифицированы как, по крайней мере, дисциплины антропологии , астрономии , биологии , ботаники , экологии , этнологии , этнологии , геологии , герпетологии , Ихтиология , млекопитающие , минералогия , микология , орнитология , палеонтология и зоология . [ 48 ]

«Дарвиновская доктрина» и последующее «дарвиновское противоречие»

[ редактировать ]- В 1859 году английский натуралист Чарльз Дарвин… опубликовал свои противоречивые взгляды на происхождение видов. В ориентирной книге, озаглавленной о происхождении видов с помощью естественного отбора , [ 49 ] Он выступил против общепринятого представления о том, что Бог сверхъестественно создал первоначальные типы растений и животных [а именно: «Необвишаемость видов » и в пользу идеи, что они развивались естественным образом в течение длительных периодов времени, хотя и не исключительно. , посредством случайных вариаций и естественного отбора. - Numbers & Stenhouse (1999), p. 1

Профессиональная карьера Креффта, его музейное кураторство, его взаимодействие с англо-австралийскими попечителями австралийского музея и его профессиональные усилия распространять последнее научное понимание для людей Нового Южного Уэльса в середине 1800-х Мир, полученный из обилия текущих научных достижений, технологических инноваций, геологических открытий и колониальных исследований, а также Новый рациональный скептицизм в отношении объективной достоверности конкретных христианских писаний наряду с сопутствующими проблемами в до сих пор принял богословие, принципы веры и установил религиозные практики.

Епископ Натала (1875).

Программы Просвещения для библейской власти

[ редактировать ]Задача Дарвина с точки зрения религиозных консерваторов о том, что виды были неизменными, сосуществовали с совершенно другим (и незаслуженным) набором противоречий, связанных с вызовами библейских властей , которые приходили со многих направлений; [ 51 ] Не только в отношении богословских / доктринальных Библии вопросов непогрешимости , непогрешимости и литерализма (а не аллегоризма ), а не только в отношении его все более и более глубоких научных, исторических , географических и хронологических неточностей и последствий Эпоха земли , [ 52 ] Но также, в отношении точной точности переводов, представленных в конкретных версиях , [ 53 ] а также отдельный вопрос о том, как развивалась сама Библия - и какие части (когда написаны и кем) из каких конкретных текстов (и в каком порядке) должны быть включены в саму Библию .

из наиболее важных и провокационных проблем для преобладающего статус -кво ) публикации первого (и наиболее спорного) рассмотрения - Пятью возникла с (октябрь 1862 г. Одна , Трактат Джона Коленсо из семи частей, Пятикнижие и Книга Джошуа критически изучили (1862–1879). Коленсо из его исследований и его текстовых исследований «убедили себя в том, что в Ветхи -Завете писания содержали много в их заявлениях о людях, времени и расстоянии, которые были мифическими и легендарными» (Mozley, 1967, p. 427); [ 54 ] и, обращая внимание на широкий спектр статистических и практических аномалий в тексте (например, Ковчег Ноя , Потоп , пересечение Красного моря , Исход и т. Д.), Продажи Коленсо были «огромными» (Vance, 2013,, 2013,, 2013,, 2013,, 2013,, 2013 г. P. [ 55 ] [ 56 ] [ 57 ]

(В конце 1862 года) редакционная статья в английской церкви , которая была широко переиздана в Австралии, сравнила влияние противоречивых проблем Коленсо на власть Библии с теми, которые уже сделаны Чарльзом Дарвином и Джоном Кроуфурдом , [ 58 ] и обширная редакционная статья в Сиднее Утреннем Геральде защитила библейские отчеты и напрямую атаковала как Коленсо, так и его публикацию, [ 59 ] решительно утверждая, что «мозаичная запись остается одной из самых благородных книг, когда -либо составленных смертным агентством. Это книга, которая содержит единственный рациональный отчет о происхождении и нынешних обстоятельствах человечества ...». [ 60 ]

Спор о проблемах Коленсо в библейской власти, принятой авторстве и исторической точности продолжалась в Австралии. Десять лет спустя, 7 июля 1873 года, иезуит из Мельбурна Джозеф О'Мэлли, [ 61 ] Автор Ноя Арк -Арк оправдал и объяснил: ответ на трудности доктора Коленсо (1871) (в который включал «воображаемый план О'Мэлли [1080 киосков в Арк»), посещал Сидней и проказывал лекции по «Ковчегу Ноя», [ 62 ] предоставление стандартной римско -католической позиции на Ковчете Ноя и потопе и попытка объяснить многие из проблем Коленсо. Лекция под председательством набожного ирландского католического непрофессионала судья Питер Фаусетт , [ 63 ] Судья Пуйна из Верховного суда Нового Южного Уэльса , который впоследствии (в 1875 году) выразил судебное мнение, что увольнение Креффта из его музейного куратора было оправдано. [ 64 ] [ 65 ]

Эволюция

[ редактировать ]

Дарвин был не первым, кто говорил об «эволюции»; и сам Дарвин не использовал термин «эволюция» до шестого (1872) издания своего происхождения (в первых пяти изданиях Дарвин говорил о « спуск через модификацию »).

Роберт Чемберс в своих популярных работах, остатках естественной истории творения (1844/1884) и объяснений (1845), уже сделал представление об «эволюции», что общедоступное обсуждение. [ 66 ] Кроме того, были два ранее (анонимные) статьи, недавно приписанные (см.: Tanghe & Kestemont, 2018) Роберту Джеймсону , Regius профессору естественной истории в Университете Эдинбурга и также редактором журнала - «Наблюдения за Природа и важность геологии »(Anon, 1826; особенно с. 297–299) и« Изменений, которые пережила жизнь на мире »(Anon, 1827), который был опубликован в новом философском журнале в Эдинбурге в то время, когда Дарвин изучал медицину в Эдинбургском университете.

Статьи Джеймсона были еще более влиятельными в случае с Дарвином, учитывая тот факт, что в течение 1826/1827 учебного года Дарвин, в качестве внеклассного исследования, «усердно» посещал популярные лекции по естественной истории Джеймсона в Эдинбургском университете, в которых участвовали пять лекций Джеймсона в Эдинбургском университете. Дни в неделю в течение пяти месяцев »(Secord, 1991, с. 134–135), по крайней мере, один из которых был назван « Происхождение видов животных »(Tanghe & Kestemont, 2018, с. 586).

Естественный отбор

[ редактировать ]- Оплодотворяется его Beagle журналом из его четырех лет в качестве путешествующего натуралиста и его последующих экспериментов и исследований, происхождение было снабжена новыми биологическими данными, взятыми из источников по всему миру, его широкий компас предлагал подробное предложение для прогрессивного развития Виды и позитивистская биологическая структура для понимания человека природы мира. - Moyal & Marks, 2019, p. 5

В статье, прочитанном Лондонскому обществу Лоннского Линниса 1 июля 1858 года, написанного отдельно от, но представленное совместно с Альфредом Расселом Уоллесом (т.е. Darwin & Wallace, 1858), который был прочно основан на основе обширных и разнообразные доказательства, предоставленные его всесторонними наблюдениями в поле, за два десятилетия, [ 67 ] Дарвин был первым, кто предложил «естественный отбор» (в отличие от «искусственного отбора» животноводства или растений) [ 68 ] - тем самым «[заменить] естественный для сверхъестественного объяснения материальной органической вселенной» (Abbott, 1912, p. 18) - как процесс , ответственный за разнообразие жизни на Земле. [ 69 ] [ 70 ]

Вместе с ботанистом Сиднея Робертом Д. Фицджеральдом и Мельбурнским экономистом профессором Уильямом Эдвардом Хирном , [ 71 ] [ 72 ] Креффт был одним из немногих австралийских ученых в 1860 -х и 1870 -х годах, которые поддерживали позицию Дарвина в отношении происхождения видов с помощью естественного отбора. [ 73 ] [ 74 ] [ 75 ]

- Сила] до- и антиэволюционных тенденций [кураторов] кураторов и музейных директоров [и] ученых, основанных на музеях в Австралии ... [означала] большая часть первоначального направления, сделанного дарвинизмом в Австралии, поступила из международных сетей- Как и в институтах механики , связанных с трудовым движением, предоставляя его сильные социалистические и светские ассоциации, которые нашли небольшую пользу среди колониальных администраторов и членов « СКАТТОКАРИИ », которые доминировали в музейных советах Попечители. - Беннетт (2004), с. 139

Пять «позиций» Эллегарда, занимаемые учеными в дарвиновском споре

[ редактировать ]

- То, что кажется настолько примечательным для [тех, кто в более позднем возрасте, так это то, что в середине девятнадцатого века ученые могли рассматривать сверхъестественное объяснение как действительную альтернативу научной. 15 [ 76 ] [ 77 ] [ 78 ]

- Дарвинизм приехал рано в Австралию. Чарльза Дарвина Происхождение видов появилось в продаже в Сиднее всего через четыре месяца после публикации в Британии. [ 79 ] —Butcher (1999), p. 39 [ 80 ]

Обширный обзор Альвара Эльлегарда (1958) о освещении «дарвинистской доктрины» в британской прессе в период с 1859 по 1872 год. [ 81 ] Различили три аспекта - «Во -первых, идея эволюции в своем общем применении ко всему органическому миру; во -вторых, теория естественного отбора; и, в -третьих, [] теория происхождения человека от нижних животных» (Ellegård, 1990, p .. [ 82 ] которые были определены в значительной степени, не только по уровням образования, но [ 83 ] но также по их конкретному политико-социальному, [ 84 ] философский, [ 85 ] и/или религиозная ориентация. [ 86 ]

Эти пять позиций (в совокупности) отражали простую серию, которая «указывает на [D] растущую степень любитности в отношении теории Дарвина от полного отклонения до полного принятия» (стр. 30); и, когда один перемещался от нижнего ( а ) к более высокого ( е ) вдоль серии Эллегард, «все меньше и меньше процессов, идущих в образование видов, были признаны [теми, кто занимает эту позицию] как сверхъестественное или вне диапазона обычных Научное объяснение ... [и, следовательно,] любой, кто принимает должность с более высоким [уровнем] принятым IPSO FACTO Все научные объяснения, уже предоставленные теми, кто занимает более низкую позицию »(стр. 31):

- ( А ): абсолютное творение (стр. 30): «Фундаменталистское религиозное положение, согласно которой каждый вид возник как отдельное и мгновенное творение, в буквальном и наивном смысле слова»; [ 87 ]

- ( Б ): прогрессивное создание (стр. 30): «где виды загадочно развивались из самой простой органической формы»; [ 88 ] [ 89 ]

- ( C ): вывод (стр. 30): «который признал принцип спуска в прогрессивной эволюции, но позволил, чтобы этот механизм был только одним из вторичных процессов, которые использовал создатель»; [ 88 ]

- ( D ): направленный отбор (стр. 31): «который признал эффективность естественного отбора для значительного числа конкретных дифференциаций, но полагалось на телеологическое объяснение как незаменимую часть объяснения органического мира»; [ 88 ] [ 90 ] и

- ( E ): естественный отбор (стр. 31): «Научное, нетелеологическое, не супернатурное объяснение эволюции всего органического мира». [ 88 ]

Согласно опросу Эллегард (стр. 32), до 1863 года, большинство британских ученых принадлежали либо, либо ( а ) или ( б ); Но к 1873 году большинство переехало в ( c ) или ( d ), причем небольшое количество из них продолжалось на положение ( E ). [ 91 ]

Тем не менее, в Австралии все отличалось. Отметить дисциплинарные « выбросы », такие как Фицджеральд, Хирн и Креффт (каждый из которых занимал должность ( е )) - и игнорирование (периферийного) факта, что Чарльз Дарвин был избран почетным членом Королевского общества Нового Южного Уэльса в 1879, [ 92 ] и что про-дарвиницы, естественный историк, Томас Хаксли и ботаник, сэр Джозеф Далтон Хукер , были награждены престижной медалью Общества Кларк в 1880 году. [ 93 ] и 1885 [ 94 ] соответственно - это было не в конце 1890 -х годов, из -за влияния академических назначений Уильяма Эйчесона Хасвелла в Университет Сиднея, Болдуин Спенсер в Мельбурнский университет, Ральф Тейт в Университет Аделаиды и Джеймс Томас Уилсон Университет Сиднея и т. д., [ 95 ] и административные/кураторские назначения Роберта Этериджа в Австралийский музей в Сиднее, Болдуин Спенсер в Национальный музей Виктории в Мельбурне и Герберт Скотт в музей королевы Виктории в Лонсестоне и т. Д. вдали от ( а ) или ( б ), и что «вклад Дарвина и его преемников [может] начать серьезно повлиять на мышление австралийского в мейнстрим научной мысли »(Mozley, p. 430).

Художник

[ редактировать ]

Джерард Креффт (1857). [ 96 ]

Чтобы избежать военного проекта, Креффт переехал в Нью -Йорк в 1850 году, [ 97 ] [ 98 ] где он работал клерком и рисователем, и был в основном обеспокоен созданием изображений видов моря и доставки. [ 99 ]

В то время как в Нью -Йорке он столкнулся с работой Джона Джеймса Одюбона в нью -йоркской торговой библиотеке . Получив разрешение на это, Креффт сделал копии некоторых плитов Одюбона, которые он затем продал, чтобы поднять свой тариф в Австралию. [ 98 ] [ 100 ] Креффт прибыл в Мельбурн из Нью -Йорка 15 октября 1852 года по доходам , [ 101 ] [ 102 ] и работал в викторианском золото -сайте «с большим успехом» в течение пяти лет. [ 99 ] Креффт внес примеры своих рисунков на выставку Викторианского промышленного общества в Мельбурне, в феврале 1858 года. [ 103 ] [ 104 ]

Виктория (1852 - 1858)

[ редактировать ]Мельбурн

[ редактировать ]

Джерард Креффт (1857).

Встречав Уильяма Бландовски, когда он (Креффт) делал копии иллюстраций Гулда местных животных в млекопитающих Австралии в публичной библиотеке Виктории , [ 105 ] [ 106 ] Талантливый художник и чертежник был нанят Бландовски, «на основе способности Креффта создавать подробные рисунки образцов естественной истории», [ 107 ] Чтобы помочь нарисовать и собирать образцы для Национального музея Виктории [ 108 ] На исследовании Уильяма Бландовского о относительно плохо известной и полузасушливой стране вокруг слияния реки Мюррей и Река Дарлинг в 1856–1857 годах. [ 109 ] [ 97 ] [ 110 ] [ 111 ]

- Во время экспедиции Креффт отвечал за надзор за подготовкой образцов, а также регистрацию и ведение записей для всего биологического материала. Креффт, очевидно, также провел большую часть повседневной работы вокруг лагеря, включая приготовление пищи и уход за лошадьми и тельцами. Blandowski Он также должен был выступить в роли Amanuensis , принимая диктовку от Blandowski за при свечах после обеда. Креффт оказался увлеченным и проницательным наблюдателем дикой природы и прекрасным иллюстратором естественной истории. На протяжении всей экспедиции он держал многочисленные виды млекопитающих в неволе, чтобы узнать больше об их привычках, документируя диету и информацию о размножении, включая сезонность и размер мусора. - Менхорст (2009), с. 65

- Во время экспедиции 1856/1857 гг. 163.

Бландовски, когда в начале августа 1857 года в Мельбурне было отозвано в Мельбурн, вернул с собой весь свой собственный материал в Мельбурн. Креффт взял на себя командование экспедицией, пока она не вернулась в конце ноября 1857 года. [ 112 ] В 1858 году Креффт был назначен в Национальный музей Виктории , [ 113 ] Чтобы каталогизировать коллекцию образцов, которые он (т. Е. Креффт) привез с собой в Мельбурн, [ 114 ] который он перечислил под 3389 номеров каталога. [ 115 ]

Бландовски, Музей естественной истории и профессор Маккой

[ редактировать ]Поздние отчеты Креффта о открытиях экспедиции (а именно, 1865a и 1865b) не только сами по себе значительны, но и имеют дополнительное значение из-за споров, связанных с внезапным уходом Бландовски из Австралии вместе с его коллекцией иллюстраций, документов, в поле Примечания и образцы. Помимо противоречивого австралийского австралийского (1862) в 142 Photographischen Abbildungen Nach Zehnjährigen Erfahrungen («Австралия в 142 фотографических иллюстрациях после десятилетия опыта»), [ 116 ] Бландовски никогда не публиковал ничего дальше по отношению к этой экспедиции.

Бландовски, один из первых членов Совета Философского общества Виктории , [ 117 ] был назначен правительственным зоологом в 1854 году Эндрю Кларком , генеральным геодезистом Виктории . Он также служил ( Ex Officio ) в качестве куратора Музея естественной истории , который открылся 9 марта 1854 года, был открыт для публики в течение шести часов в день и находился в офисе анализа на улице Ла Троб, Мельбурн. [ 118 ] [ 119 ] [ 120 ]

Оппозиция Бландовски противоречивому (1856) решению (постоянно, а не временно) [ 121 ] Переместить коллекцию музея естественной истории в (тогда отдаленное) [ 122 ] Кампус Фледелинг Университета Мельбурна и доставил его под стражу профессора естественных наук университета Фредерика Маккой , [ 123 ] [ 124 ] который утверждал (1857), что музеи должны существовать, чтобы служить интересам реальной науки, а не их, «в лучшем случае, чтобы быть просто местом просто для [невинного развлечения школьников и бездельников», а не, то есть следовать примеру Британский музей и найдите коллекцию в помещениях (центральной) публичной библиотеки Мельбурна , «которая была первой бесплатной публичной библиотекой в Виктории и центром государственного образования и улучшения в колонии» [ 125 ] - привел ко многим столкновениям с Маккоем («после его возвращения в Мельбурн [Бландовски] никогда не сообщал на службу в музее»). [ 126 ]

Были также обоснованные обвинения в том, что «[прибыв] в Аделаиде в августе 1857 года с двадцать восемь коробок, содержащих 17 400 образцов», [ 126 ] Бландовски не смог доставить материал, собранной во время его экспедиции после его возвращения в Мельбурн, несмотря на то, что правительство виктории «три раза» приказано вернуть свои образцы и рукописи » [ 126 ] - Факт, который объясняет, в отсутствие какого -либо согласованного счета на английском языке из собранного материала Бландовского, стоимость более поздних счетов Креффта (1865a и 1865b) открытий экспедиции.

Когда ему угрожает судебный иск, Бландовски поспешно покинул Мельбурн, 17 марта 1859 года (на прусской матильде капитана А.А. Балласиерса , никогда не возвращаясь. [ 127 ]

Германия

[ редактировать ]В 1858 году, после смерти своего отца, Креффт был вынужден вернуться в Германию, где он путешествовал по Англии - где он посетил главные музеи, встретился с Джоном Гулдом , Джоном Эдвардом Греем , Альбертом Гюнтером и Ричардом Оуэном . [ 98 ] и представил статью (Krefft, 1858b) Зоологическому обществу Лондона .

Креффт взял с собой много иллюстраций и образцов; [ 112 ] Однако, как отмечает Аллен (2006, стр. 33): «После его возвращения в Германию Креффт попытался опубликовать свои наблюдения и рисунки, но Бландовски ... [с] Бландовски ] что произведение искусства из экспедиции принадлежало ему, как лидер экспедиции ». [ 128 ]

Естественный историк, музейный куратор и администратор

[ редактировать ]| Внешние носители | |

|---|---|

| Изображения | |

| Аудио | |

| Видео | |

Креффт вернулся в Австралию из своего пребывания в Германии, с кратким пребыванием в пути на мысе Гуд Хоуп и Аделаиду , прибыв в Сидней 6 мая 1860 года. [ 129 ]

В июне 1860 года по рекомендации губернатора сэра Уильяма Денисона , [ 17 ] [ 130 ] [ 131 ] Он был назначен помощником куратора Саймона Руда Питтарда (1821–1861) [ 132 ] [ 133 ] [ 134 ] в австралийском музее , [ 135 ] «К большому раздражению попечителей музея, которые предпочли бы кого -то с официальной степенью». [ 136 ] Питтард, управляемый его англо-католическими , видами и после практики Чарльза Уилсона Пила в музее Пила , в Филадельфии [ 137 ] - Украшены стены музея надписями библейских текстов. [ 138 ] [ 139 ] Менее чем через три недели после смерти Питтарда (в августе 1861 года) попечители решили, что эти надписи были «[чтобы] быть удалены, и что в будущем« не будут вписаны слова на стенах зала заседаний без согласия попечителей ». " [ 140 ]

Выполнив все обязанности этой должности после смерти Питтарда в августе 1861 года, Креффт был в конечном итоге назначен куратором музея в мае 1864 года. [ 141 ] [ 142 ] [ 143 ] [ 144 ] Во время своего пребывания в австралийском музее Креффт сохранил отношения с Мельбурнским музеем , соответствующим и обменялся образцами с Фредериком Маккой , его директором. [ 97 ] Он также переписывался с широким спектром выдающихся зарубежных натуралистов, включая Чарльза Дарвина , Аклга Гюнтера и сэра Ричарда Оуэна в Великобритании; LJR Agassiz в США; «И многие изученные немецкие ученые». [ 17 ] Важно, что взаимодействие Креффта было «неформальным общением с частными лицами, а не официальными сделками через государственные учреждения, причем последовавшие связи приводят к дальнейшему взаимодействию с Савантами и музеями в других центрах знаний и власти, включая Германию, Австрию, Италию, Францию, Францию, Швеция, Аргентина, Канада, Индия и Соединенные Штаты, а также Великобритания »(Davidson, 2017, p. 8).

- Как ученый, Креффт занимал позицию, далекую, удаленную от типичного коллекционера на периферии. Он был теоретически сложным натуралистом, чей вклад в зоологическую литературу Австралии был существенным и имеющим длительную ценность. Его письма в Дарвин были письмами коллеги и коллеги -ученого, а не просто информатора, [ 145 ] И он воспользовался существующими сети переписки в продвижении как своей карьеры, так и причины науки в австралийских колониях в целом. Несмотря на шансы, он оставался вокальным, отстаивая новые идеи. В результате он выиграл международную репутацию за пределами Австралии, но в конечном итоге был разрушен укоренившимися интересами тех, кого он был привержен против. - Batcher (1992), p. 57

Он также отвечал за организацию и каталогизацию музейной коллекции пожертвованных окаменелостей, а также тех, которые он обнаружил в своих собственных исследовательских усилиях в этой области, таких как две важные раскопки ископаемых останков млекопитающих, птиц и рептилий, которые он провели в 1866 и 1869 годах в пещерах Веллингтона . [ 146 ] [ 147 ] [ 148 ] [ 149 ]

дарвинизм

[ редактировать ]

- [] Попечители ... [из] Австралийского музея ... большинство из которых были англиканцами или нонконформистами, отвергли теорию эволюционного происхождения видов ... как [Креффт] позже заявил, когда писал Дарвину, его эволюционизм Была ли главной причиной его отношений с попечителями, становящимися все более отмеченными неразрешимыми, лично изнурительными спорами, которые в конечном итоге закончились его увольнением в 1874 году. (2017), с. 220.

Научная карьера Креффта [ 150 ] - и, в частности, всю свою профессиональную жизнь в австралийском музее [ 151 ] - был одновременно и сильно влиял на «дарвиновские противоречия» и его широко распространенные последствия; [ 152 ] Не в последнюю очередь был центральный вопрос, какие отдельные образцы должны быть выставлены (или нет) в музее, и, если так, в каком порядке и в каком способе. [ 153 ]

"Новая музейная идея"

[ редактировать ]Креффт, который вернулся в Австралию в 1860 году «с полным знанием новых подходов, принятых в Европе для роли и цели музеев», [ 154 ] был «динамичной фигурой, которая энергично исследовала, писал и продвигал и продвигал коллекции [австралийского] музея». [ 155 ] [ 156 ]

Он служил куратором во время значительных изменений культуры , как с точки зрения науки, так и научных стандартов в сообществе, [ 157 ] и с точки зрения встроенных предположений, принципов фонда и экспериментальных стратегий самой науки. С Креффтом в качестве куратора, и, несмотря на сопротивление его попечителям, музей медленно менялся »от [быть] колониальным ответвлением британского научного учреждения, управляемого группой джентльменских натуралистов, к [становлению] учреждением, обслуживающим потребности из все более независимой и профессиональной группы ученых ». [ 158 ] [ 159 ] [ 160 ]

Шкафы куриьеров

[ редактировать ]

Domenico Remps (1689s).

- Который является наиболее важным объектом: - что собирать шкаф с естественными любопытствами, чтобы стать восхищением детей и их медсестер, или до передачи знаний и истины невежественным, тем, в чьи лицах проживают та власть, которая решит Будущее этой большой и важной ? страны [ 161 ]

По крайней мере два столетия британских (и колониальных) музеев, четко отражающих их наследие в Wunderkämmer/шкафы о наследии , сделали чуть больше, чем присутствовавшие «бесцельные коллекции курьеров и BRIC-BRAC , собравшиеся без метода или системы коллекции "; Где, например, одна из самых известных коллекций в «ушедших днях», коллекции семнадцатого века Musæum Tradescancantianum (впоследствии предоставила ядро для музея Ашмолевского университета Оксфордского университета ), «была ошибкой без дидактической ценности», «его Договоренность была ненаучной, и общественность мало или вообще не получила преимущества от своего существования »(Lindsay, 1911, p. 60). [ 162 ]

В августе 1846 года в рамках Закона о создании Смитсоновского института , [ 163 ] Было ли положение, передаваемое опекой официального национального кабинета курьеров Соединенных Штатов , [ 164 ] Это было ранее депонировано в здании патентного офиса США в Смитсоновский институт.

Общественные музеи

[ редактировать ]

Признавая различия между исследованиями музея и функциями публичной педагогики и выражением надежды на то, что его коллеги «от всей души согласуются с тем, что все, что есть в наших силах, чтобы сделать [Британский музей] и другие учреждения, способствующие увеличению знаний, знаний, знаниям, знания счастье и комфорт людей », [ 165 ] Джон Эдвард Грей , к концу своей длительной карьеры в качестве куратора Британского музея, [ 166 ] отметил, что, по его мнению, «общественные музеи» должны были служить двойным целям «распространения обучения и рационального развлечения среди массы людей и ... чтобы позволить себе научно Образцы, из которых состоит музей ». [ 165 ] [ 167 ]

В 1860-х годах, когда «колониальные музеи, как правило, демонстрировали образцы в ряду, и по большей части пренебрегали для включения современных методов, таких как объяснительные этикетки и случаи среды обитания» (Sheets-Pyenson, 1988, p. 123 ), Научная позиция Грея, его кураторское обоснование и его административный подход был решительно поддержан Креффтом. Креффт, который был «посвящен интересам музея», а не интересам попечителей, [ 17 ] уже начал отделять собственные исследовательские коллекции музея от своих коллекций выставок и уже принял многие из мер Грея к началу 1860 -х годов.

Только что получил брошюру Грея (1868) по почте, он подчеркнул - в презентации («Улучшения, достигнутые в современных музеях в Европе и Австралии»), который он дал Королевскому обществу Нового Южного Уэльса 5 августа 1868 года - что его (Креффт ) продолжающиеся усилия в австралийском музее были предприняты в надежде изменить его с того, что он «один из старых любопытства пятидесяти лет назад» в «полезный музей» (Креффт, 1868b, p. Эти кураторские устремления не были уникальными для Креффта; Они полностью соответствовали лучшей практике в мире , как описано Грей, в связи с демонстрацией экспонатов и монтированных образцов в Британском музее «с наилучшим преимуществом, как для студента, так и для общего посетителя» (Krefft, 1868b, p. 21). [ 168 ]

«Новый музей»

[ редактировать ]

В 1893 году сэр Уильям Генри Флауэр , помеченный Грей (1864), « Новая идея музея »; [ 170 ] и охарактеризовал его как «ключ почти всей музейной реформы недавней даты» (Flower, 1893, pp. 29–30). Хотя эти взгляды не были уникальными для серого, [ 171 ] Похоже, что аксиома Грея (1864) имел самую широкую распространенность в течение последующих лет, была наиболее широко цитируемой и, следовательно, можно сказать, что оказал наибольшее влияние-влияя на многие во всем мире, включая Креффт и в Великобритании , например, цветок, в Британском музее (см.: Flower, 1898), [ 172 ] а в США, например, Г. Браун Гуд в Смитсоновском институте (см.: Гуд, 1895), [ 173 ] и Генри Фэрфилд Осборн , в Американском музее естественной истории (см. Osborn, 1912), [ 174 ] и т. д.

В 1917 году директор американского музея Джон Коттон Дана посетовал на то, что все еще было много места для улучшения, отметив, что лучшие музейные демонстрации можно было найти в универмагах , а не в музеях дня.

Кураторское обоснование Креффта

[ редактировать ]- В августе 1861 года куратор музея, мистер С.Р. Питтард умер. Обязанности с этой даты до 30 июня 1864 года были выполнены г-ном Джерардом Креффтом в качестве субцентора. Затем он был назначен куратором, с большим преимуществом учреждения. Под наблюдением этого джентльмена различные образцы были настолько организованы, что стали гораздо более ценными для общественности и для научных людей, чем под их старой несколько запутанной классификацией. - Империя , 16 мая 1868 года. [ 175 ]

Креффт активно продвигал концепцию музея как популярного учреждения, привлекающегося к более широкой аудитории: то есть учреждение, предназначенное для предоставления опыта, который привлекать, развлекать и обучать всех возрастов, экономических групп, уровней образования и социальных классов, [ 176 ] а также место для сбора, сохранения и отображения образцов, а также производства и распространения научных знаний. [ 177 ] [ 178 ]

Кураторская пропаганда Креффта о полном разделении музейного музейного времени запутанной и неупорядоченной коллекции в: [ 179 ]

- (а) Выставочные пространства и упорядоченные, всеобъемлющие, демонстрации для общественности (известные сегодня как синоптические коллекции ), [ 180 ] и

- (b) (систематически размещенные в других местах на помещениях), каталоги и другие исследовательские материалы, в основном предназначенные для исследований, а не отображение, [ 181 ]

Произведено продолжающееся культурное бешеное с (преимущественно экспатриантом ) « джентльменными любителями » среди попечителей, включая доктора Джеймса Чарльза Кокса , Эдварда Смита Хилла , [ 182 ] Сэр Уильям Джон МакЛей , капитан Артур Онслоу и Александр Уокер Скотт , [ 17 ] которые были самими коллекционерами, и были «создавали [свои собственные] частные коллекции иногда за счет музея» [ 17 ] [ 183 ] - Это в конечном итоге привело к увольнению Креффта (1874).

Отсутствие финансирования

[ редактировать ]- Мы считаем, что это ведет правительство, которое объявляет себя таким напряженным другом образования, чтобы обратиться к [Австралийскому музею] с небольшим соображением, чем оно до сих пор выставлялось на него. Ибо здесь есть национальный школьный учитель, преподающий в созерцании самых чудесных творений, насколько велика и насколько неловкости такая сила, от которой эти творения возникают; Более того, школьный учитель, который вызывает мысли и размышления, призывает к тому, чтобы играть на способности сравнения и анализа, и вносит активные действия те функции ума, которые, изгнанием, возвышают душу. - Империя , 16 мая 1868 года. [ 175 ]

В то же время, когда Креффт испытывал трудности со своими (антидарвинистскими) попечителями в отношении вопросов демонстрации образцов, классификации и презентации, попечители, которые действовали в соответствии с положениями Австралийского музея, г. 1853 Из отсутствия соответствующего государственного финансирования, независимо от того, какой материал они могут содержать, строительство необходимого количества таблиц отображения, витрины и отображения шкафов. [ 184 ]

Многие из этих годовых отчетов также содержат конкретные, срочные обращения для дополнительного финансирования, чтобы разрешить публикацию различных предметов, созданных Krefft, которые в то время были полными и готовыми к принтеру. Расширенный, критический отчет о прессе в Империи в 1868 году отметил («это удивительно и сожалеть»), что, хотя у Креффта был «объемный каталог образцов, содержащийся в библиотеке, организованный для принтера», казалось, что », что, что» Не существует средств, позволяющих попечителям выполнить это необходимое значение ». [ 175 ]

Фотография

[ редактировать ]Среди экспонатов в секции изобразительных искусств сельскохозяйственного

Выставка общества, посетители заметят несколько красивых

Цветные фотографии, показанные мистером Креффтом.

Эти картинки окрашены процессом, изобретенным мистером Креффтом,

который, по -видимому, полностью отличается от любого метода в обычном

Использовать, создавать эффект, замечательный для его деликатности тона, хотя

строго придерживаться верности к природе и сохранение нетронутой наибольшей

Миловые детали оригинальной фотографии.

Это особенно относится к архитектурным взглядам;

которые выявляются этим процессом с большой ясностью, и

Похоже, стоит вперед с почти стереоскопической прочностью.

Некоторые виды листвы и лесных пейзажей также появляются

Преимущество, как окрашено под умелым манипуляциями с мистером Креффтом.

Sydney Morning Herald , 16 апреля 1875 года.

- Фотографическое заведение является одной из самых важных частей современного музея. - Герард Креффт, 5 августа 1868 года. [ 186 ]

Одним из наиболее важных кураторских инноваций Креффта было его введение фотографии, первоначально используя свою личную камеру, фотографическое оборудование, химические вещества и фотографические материалы - среда, с которой он впервые столкнулся во время своего времени с экспедицией Бландовски в 1856–1857 гг. [ 187 ] - в практику Австралийского музея. [ 188 ]

Фотография не только предоставила ценные средства, с помощью которых объекты и коллекции музея могут быть задокументированы, но и послужили для обоснования правдивости колониальных наблюдений Креффта и улучшить его (и музейное) международное признание в целом из -за того, что в отличие от одиночных Физические образцы, фотографии также могут быть «бесконечно дублироваться» [ 189 ] и, следовательно, отправили одновременно в широкий спектр экспертов и центров европейской и американской стипендии, кроме только только Лондона.

Более того, со временем фотографии значительно сократили необходимость отправки драгоценных образцов и образцов за рубежом в ущерб собственным коллекциям музея: [ 190 ] См., Например, (1870) фотография первого в истории образец Квинслендского легкого (в Финни, 2022, стр. 6) и четырех (1870) фотографиях образца на различных этапах его рассечения (в Финни) , 2022, с. 6–7).

Тысячи тщательно расположенных визуальных изображений на стеклянных пластинах, которые Креффт и его помощник Генри Барнс произвели (более 15 лет) в процессе влажной пластины коллодиона , оба на месте (в музее) [ 191 ] и на поле, записывающие ландшафты и люди (в экспедициях), продемонстрировали и подтвердили опыт Креффта для всех и Рашни.

Согласно Davidson (2017, с. 16, 57, 68), учитывая широко распространенную лондонскую элиту. [ 192 ] Изображения Креффта не только предоставили «неопровержимые фотографии фотографических» его претензий на конкретный предмет интереса, но и, учитывая чрезвычайно широкий спектр дисциплинарных мышлений, преобладающих в то время, служил (включительно) « граничные объекты »: а именно, сущности. Это «облегчает [D] экологический подход к созданию и обмену знаниями» путем «обеспечения] связей между разными людьми и группами, которые, тем не менее, могут их смотреть, интерпретировать их и использовать их различными способами или для разных целей »(стр. 10). [ 193 ]

Квинслендская легкая рыба ( Neoceratodus forsteri )

[ редактировать ]- Странно, что такое любопытное существо, которое было хорошо известно ранним поселенцам в широком заливе и других районах Квинсленда, должно так долго избежать глаз тех, кто интересуется естественной историей. - Герард Креффт, 28 апреля 1870 года. [ 194 ]

- Для Креффта, Ceratodus был не просто новым видом, он также создал уникальное устройство и уникальную возможность создать и построить собственную научную власть Креффта и его репутацию как человека, а также поставить Австралию в центре научной мысли. - Ванесса Финни (2023). [ 195 ]

Луи Агассиз и Чимара

[ редактировать ]In 1835, having examined teeth that had been extracted from the Rhaetian (latest stage of the Triassic) fossil beds of the Aust Cliff region of Gloucestershire in South West England, the Swiss natural historian Louis Agassiz had identified and described ten different species of a holotype (or "type specimen"), which he named ceratodus latissimus ('horned tooth' + 'broadest'),[196] and had supposed — based upon the structure of their teeth plates resembling that of a Port Jackson shark[197][198] - То, что они были своего рода акулой или лучей , и от этого он постулировал, принадлежал к Ордену класса хрящевых рыб ( хондрихти ), известных как Чимара .

Gerard Krefft, William Forster, and the cartilaginous Burnett Salmon or barramunda

[edit]

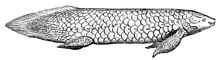

(Neoceratodus forsteri).

Over the 1860s, Krefft's regular dinner companion, the pastoralist squatter and former Premier of New South Wales, William Forster, had often spoken of the Queensland fresh-water salmon with a cartilaginous backbone,[199] well known to the Queensland squatters as Burnett Salmon — called "salmon" because of its pink, salmon-coloured flesh and its good eating — or "barramunda" (N.B. not barramundi). On each occasion, Krefft expressed his view that Forster's claim of the existence of such a salmon was entirely mistaken.[200]

January 1870

[edit]

In January 1870, Forster presented Krefft with an approx. 3 ft (92 cm) specimen[201] of the Burnett Salmon that had been sent to him [Forster] by his cousin, William Forster M'Cord.[202][203]

It was the first complete specimen that Krefft had ever seen. From his detailed (and, perhaps, unique to Australia) familiarity with the relevant scientific literature, and from the specimen's unusual teeth, Krefft immediately "understood its enormous significance",[204] and recognized it as being something that "was halfway between dead (fossilised, like its nearest relatives) and alive (known to science)[205] — and, thus, "a living example of [Agassiz's] Ceratodus, a creature, thought to have been like a shark, which had hitherto been known only from fossil teeth":[206] a parallel to the (1994) recognition of the true identity of the Wollemi pine as a "living fossil".[207]

- The lungfish is a member of an extraordinary group of fishes, the Dipnoi, which have lungs as well as gills, allowing them to breathe air as well as water. Of the once widespread Dipnoan fish, only three survive today: Neoceratodus in Queensland, Protopterus in Africa, and Lepidosiren in South America. Neoceratodus appears to be more primitive than its overseas cousins. It is the closest surviving relative of the fish from which the first land vertebrates, the Labyrinthodonts, arose about three hundred and twenty-five million years ago.—Grigg (1973), p. 14.

The lungfish is now widely recognized as a classic example of Darwin's "living fossils"[208] — Huxley (1880, p. 660) noted that, "this wonderful creature [sc. Ceratodus] seems contrived for the illustration of the doctrine of Evolution" — and its recognition as such, by the sagacious Krefft, represents a classic example of one of Walpole's serendipitous discoveries: i.e., those made by "accident and sagacity",[209] in that:

(a) they were accidental: in that the discoverer was 'not in quest of' the thing discovered;

(b) they were made by one who was sufficiently sagacious to apprehend the connection between items that, to others, were completely random;[210] and

(c) they were not hidden: they were clearly visible to the sufficiently sagacious — i.e., 'hidden in plain sight'— and, once their location was indicated, could be seen by all.[211]

founder and Editor of Nature.

Krefft immediately announced his discovery in a letter to the Editor of the Sydney Morning Herald, published on 18 January 1870 (1870a); and, in doing so, he also named the specimen:

- In honour of the gentleman who presented this valuable specimen to the Museum, and in justice to him (whose observations I questioned when the subject was mentioned years ago, and to whom I now apologise), I have named this strange animal Ceratodus Forsteri.—Gerard Krefft, 18 January 1870.[212][213]

It is significant that, by announcing his discovery in the pages of a Sydney daily newspaper,[214] rather than in some "learned British journal ... Krefft was not only claiming the lungfish, [but] was also staking a claim for Australian scientific independence".[215][216] At the same time Krefft also made a request for regional settlers to provide observations and specimens of the Ceratodus for the Australian Museum.[217]

Krefft's discovery was specifically mentioned within the comments of Australian Museum trustee Rev. William Branwhite Clarke on the mineralogical and geological exhibits at the 1870 Intercolonial Exhibition, held in Sydney;[218] and, moreover, it was of such significance that the Exhibition's report also included a poem, highlighting Krefft's discovery, written by Clarke himself.[219]

In November 1889, Norman Lockyer, the founding Editor of Nature, noted that Krefft's discovery of "the Dipnoous [viz., 'having both gills and lungs'] fish-like creature Ceratodus of the Queensland rivers" was "[one] of the more striking zoological discoveries which come within our [first] twenty years [of publication]".[220]

Krefft's "Natural History" articles in The Sydney Mail

[edit]- For Krefft, scientific credibility was tied not to the mere amassing of collections, but to scientific reputation built on fieldwork and field observations, experiment, knowledge sharing, and publication. In this way, Krefft's museum practice created a public power base outside the control of the trustees. It was bolstered by increasing local museum visitation, large local networks of small-scale donors and collectors, and frequent local publicity in Sydney's newspapers to teach the interested public more about Australia's environments and animals.—Finney (2023), p. 35 (emphasis added to original).

In relation to Kreff't considerable contributions to "natural history" whilst serving as the Museum's curator, it is important to recognize that, over that time, rather than being disinterested in (or not entirely convinced by) Darwin's views on the progressive development of species, a wide range of influential individuals in Australia were implacably opposed to Darwin, Darwin's theories, and "Darwinism" in general.[221]

George B. Mason and The Australian Home Companion and Band of Hope Journal

[edit]The Australian Home Companion and Band of Hope Journal was a fortnightly temperance-oriented journal with a limited circulation (specifically aimed at young people) that only lasted for three years (1859–1861).

Over the entire three years of the journal's existence, the wood engraver, George Birkbeck Mason, supplied a regular series of 49 wood-engravings (as "G. B. Mason"), along with brief companion articles (as "G.B.M."), under the title "Australian Natural History", which introduced various Australian animals and birds to its young readers. Mason's first article (on 2 July 1859) was on "The Ornithorhynchus; or Water Mole of Australia" (i.e., the Platypus), and his last (on 18 May 1861) was on the recently-introduced-to-Australia animal, the Llama.

Krefft and The Sydney Mail

[edit]One of Krefft's main objectives, as its curator, was to re-position the Australian Museum as a "forum of people's science" (Moyal, 1986, p. 99). Krefft recognized the economic, social, and educational value of a wider dissemination of an accurate, up-to-date knowledge and understanding of scientific matters (especially Australian natural history) to the emerging colony and its developing community.

In the absence of funding for potential museum publications, and in pursuit of a wider dissemination of these scientific matters, it is significant that from March 1871 until June 1874 Krefft published more than one hundred and fifty, lengthy, once-a-week "Natural History" articles in The Sydney Mail — a widely-read weekly magazine published every Saturday by The Sydney Morning Herald — on an extremely wide range of relevant subjects (see: [4]), specifically directed at an educated Australian lay audience; rather than, that is, engaging with his well-informed fellow scientists.[222]

Krefft's Enterprise

[edit]

In his first article (Krefft, 1871a) — reflecting a view that had been expressed a decade earlier[223] by the botanist Joseph Dalton Hooker[224][225] — Krefft noted that, although "few countries offer such a wide field to the student of nature as Australia", there were very few "handy books for the beginner" available in Sydney, "which has caused, in some measure, the apathy of the people to study our natural products". Moreover, he wrote, because "the most useful books" were little known, and given that many of those were "so expensive that they cannot be purchased, except by the wealthy", he proposed to present a series of articles on Australian natural history, with the hope that their aggregate would eventually be published as a complete work.

Charles Darwin (naturalist)

[edit]As part of Krefft's determination to disseminate up-to-date scientific knowledge, as reflected in the professional literature, a number of his Natural History articles[226] mention Darwin's matter-of-fact observations and opinions as an in-the-field naturalist:[227] including, for instance, comments such as:

- Mr. Darwin has been quoted [in this article] at great length, because his experience ... [of] animals under domestication ... will interest all breeders. (1873c)

[In relation to the ruminants, and in] speaking about ten different varieties of oxen, I call attention to a curious breed of South America, of which Mr. Darwin, who first noticed it, remarks ... (1873b)

According to Mr. Darwin, [earthworms] give a kind of under tillage to the land, performing the same below ground that the spade does above for the garden, and the plough for arable soil.(1871d), etc.

- Mr. Darwin has been quoted [in this article] at great length, because his experience ... [of] animals under domestication ... will interest all breeders. (1873c)

Support of Darwin, Darwinism, and Natural Selection

[edit]By July 1873, according to his (c.12 July 1873) letter to Charles Darwin,[228] Krefft had become exasperated by the widespread resistance to Darwin's theories and observations (and, indirectly, also to those of Bishop Colenso); an unwillingness which, Krefft observed, was not only driven by the persistent outright misrepresentations of Darwin's works by certain prominent critics (such as Professor McCoy and Bishop Perry), but was also explained by the fact that the preponderance of those in Australia who were opposed to Darwin's "theories" had never read any of Darwin's works and (with no other sources of information to go by) were basing their steadfast adversarial positions entirely upon the supposed authority of others:[228] "if ever there was a season when people flock round those who interpret the faith in which they were brought up, it is the present time, in Australia at least" (Krefft, 12 July 1873).[229][230]

Krefft wrote of the "dreadful [overall] ... ignorance of even well educated people", and the constant criticisms of Darwin's "theories" that were still being voiced in Melbourne, 13 years after the publication of Origins, by the devout Irish Roman Catholic Professor Frederick McCoy, Professor of Natural Science at the University of Melbourne, and the director of the National Museum of Victoria, and the Evangelical Anglican Bishop of Melbourne Charles Perry, as well as the recent (7 July 1873) well-attended "Noah’s Ark" lectures,[64] that had been delivered in Sydney by the Melbourne-based Irish Jesuit, Joseph O'Malley, and chaired by the devout Irish Roman Catholic layman, Justice Peter Faucett of the Supreme Court of New South Wales.[228]

In his letter to Darwin, noting that he "never meddles with religion", Krefft states that he deliberately avoided any reference to questions relating to the existence (or not) of the Abrahamic deity in his articles: "Of course I shall not deny the existence of a supreme superintendent or whatever people choose to call the power of nature as yet unknown to us otherwise rather [to his "astonishment"] religious papers will not like to print my remarks".[228]

July 1873

[edit]

Sydney Mail, 5 July 1873.[231]

In his quest to encourage people to read Darwin's works, and to present a summary of the relevant scientific advances in the field (as represented in the professional literature), Krefft published two important "Natural History" articles in July 1873[232] — and, as was his habit,[233] Krefft took the position of presenting the latest views and opinions of others (for the edification of his readers), rather than expressing his own:

- "Remarks on New Creations" on 5 July 1873.[231]

- "Remarks on New Hypotheses" on 12 July 1873.[229]

"Remarks on New Creations"

[edit]The first article, centred upon an objective discussion of the current developments in the scientific understanding of artificial selection and human evolution (contrasted with the supposed 'immutability of species'), only expressing Krefft's personal views towards the end of the article, when speaking of the "poor, ignorant, and superstitious" people, whose artistic representations of angels were "decidedly against the laws of nature".[231]

"Remarks on New Hypotheses"

[edit]According to Krefft's postscript to his letter to Darwin,[228] the second article was only published after significant censorship by the editor of the Sydney Mail, George Eld (1829–1895),[234] at the express (and extraordinary) instruction of John Fairfax, proprietor of the Sydney Mail, to remove Krefft's favourable references to Darwin and his works — according to Krefft, despite being "rather a thorough believer in revealed Religion", Fairfax generally "allow[ed] me to give an opinion now and then as long as [I] do not come it too strong":[235]

At the last moment the Editor [viz., Eld] sent word that the owner of the paper [viz., Fairfax] objected to my remarks regarding your works which I advised people to read & test before they judged you ... [the result was that] about a Column [viz., approx 1,200 words] of my own observations were cut out — Still there is hope that people will learn something from what is left.[228]

Consequently, rather than expressing his own views, opinions, and explanations of Darwin's work, as he had intended, three-quarters of Krefft's second article directly refers to the opinions expressed in a recent address, "The Progress of Natural Science During the Last Twenty-Five Years",[236] given at Breslau (now Wrocław, Poland), by the University of Breslau's Professor Ferdinand Cohn in late 1872.[237] Krefft's direct quotations included:

There are three discoveries which, during the last quarter of a century, have entirely changed the position of natural science — the mechanical equivalent of heat, spectrum analysis, and the Darwinian theories.[238]

No book of recent times, Dr. Cohen thinks, has influenced to such an extent the aspects of modern natural science as Charles Darwin's work On the Origin of Species, the first edition of which appeared in 1859 (the last or sixth edition in January, 1872);[239] for even so late a period was the immutability of species believed in; so long was it accepted as indubitable that all characteristics which belong to any species of plants and animals were transmitted unaltered through all generations, and were under no circumstances changeable; so long did the appearance of a new fauna and flora remain one of the impenetrable mysteries of science.[240]

Post-dismissal

[edit]Due to the distractions connected with the last stages of his disputes with the trustees of the Australian Museum, the last item he published whilst still Museum curator was on 27 June 1874.[241] Sixteen weeks later, following his separation from the Museum, he resumed his weekly articles,[242] and went on to publish another thirty-three "Natural History" articles over the next nine months.[243]

Although Krefft produced more than 250,000 words in the more than 180 "Natural History" articles published over that four-year period, his hope of eventually producing an aggregated single work was never realized; no doubt mainly due to his dismissal from office having greatly limited his resources and significantly restricted his capacity to continue his dissemination enterprise.[244]

Dismissal from office

[edit]- Krefft's self-assured propriety infuriated William Sharp McLeay [sic], chairman of trustees, who assumed that the Museum's resources should be directed towards the enhancement of [Macleay's own] private collection. After living under siege ... for three months, Krefft and his ... wife Annie were evicted from the Museum in 1874 under McLeay's [sic] instructions. Still clinging to his directorial chair, Krefft was thrown down the stars at the entrance to the Museum. Krefft's removal resulted in the impoverishment of the Natural sciences in New South Wales until the rise of inter-colonial science in the 1890s.—John Kean (2013), emphasis added to original.[245][246]

The Trustees controversially dismissed Krefft from his position of Curator in 1874.[247][248]

Krefft's assistant curator for the preceding decade, George Masters, had resigned in February 1874 in order "to become curator of the growing collection of Sir William Macleay" (Strahan, 1979, p. 135)[249][250][251] — a collection which Masters continued to curate, once it was transferred to the Macleay Museum at the University of Sydney, until his death in 1912.[252]

The Museum trustees, at a special meeting held the day after Krefft's removal from the Museum's premises, appointed the Macleay protégé, Edward Pierson Ramsay, to the position of Curator (Strahan, 1979, p. 38), an office that Ramsay held until 1895, when he was succeeded by Robert Etheridge.

Gold theft and its aftermath

[edit]

23 December 1873 robbery.[253]

23 December 1873 robbery.[254]

23 December 1873 robbery.[255]

Following his report to the trustees that, upon his return to the Museum on Christmas Eve 1873, Krefft had discovered a robbery (which was never solved) of "specimens of gold to the value of £70",[256][257][258][259][260][261] the trustees (although eager to do so) were unable to find any evidence of Krefft's complicity.[262]

By this stage, with his accusations that the trustees were using the Museum's resources to augment their own private collections,[263][264] the "cosmopolitan" Krefft had fallen foul of most of the Trustees — especially William John Macleay, whose own extensive private collection, which included the comprehensive collections he had inherited from his uncle, Alexander Macleay (1767–1848), and his cousin, William Sharp Macleay (1792–1865), went on to become the foundation of the collections of the Macleay Museum at the University of Sydney in the 1890s.[265][266]

Museum closure

[edit]In the process of the escalating dispute between the trustees and Krefft,[267] the Museum was closed to the public, by order of the trustees, for eleven weeks (from 4 July to 23 September 1874),[268][269] At the same time, a police guard was stationed at the Museum, and Krefft was denied access to all parts of the Museum (including the cellar within which the fuel for his much-needed-in-the-winter fires was stored), except his private residence.[270][271][272][273]

Krefft had been suspended following an investigation by a subcommittee of trustees — Christopher Rolleston, Auditor-General of New South Wales, was appointed chairman, and Archibald Liversidge, Professor of Geology and Mineralogy at the University of Sydney, Edward Smith Hill, wine and spirit merchant, and Haynes Gibbes Alleyne, of the New South Wales Medical Board — who, having examined a number of witnesses, found some of the charges against Krefft sustained, and also claim to have discovered "a number of [other] grave irregularities".[274]

Krefft had been unable to meet the trustees' request to appear before them on the Thursday (2 July 1874) because he was unwell (he had supplied a medical certificate to that effect),[275] and that his wife, whose difficult confinement had been attended by George Bennett, had just delivered a stillborn child (on 2 July 1874), a daughter, after two days of intense labour (with Krefft by her side the whole time) in their residence over the Museum.[276][277]

Eviction from his residential quarters

[edit]On 1 September 1874, three weeks before Krefft's forceful eviction, long-term trustees George Bennett (who, at the time, was attending Mrs Krefft's confinement) and William Branwhite Clarke both resigned "as a consequence of the steps recently taken by the trustees of the Museum with respect to the Curator".[278]

On 21 September 1874, Krefft and his family were physically removed from his Museum apartment within which he had barricaded himself,[279] by the "diminutive bailiff" Charles H. Peart — i.e., at least "diminutive" when compared with Krefft, "a man of herculean stature"[280][281][282] — in the company of one of the trustees, Edward Smith Hill, and assisted by two known prizefighters (identified as Kelly and Williams) who had been expressly hired (from Kiss's Horse Bazaar) to effect the eviction,[283][280][284] because the Police refused to act, on the grounds that Krefft had not been dismissed by the Government, only by the trustees (and, therefore, it was a civil (and not a police) matter).

At the time of his eviction, Krefft was forcibly carried out of his apartment, refusing to move from his chair, and was unceremoniously thrown out into Macquarie street by the prizefighters.[285][286] The press report of Krefft's subsequent (November 1874) damages action noted that, "throughout the affair [Krefft] had denied the trustees' power to dismiss him; and, on the trustees appealing to the Government, the Colonial Secretary [viz., Henry Parkes] had cautiously told the trustees that, as they thought it expedient to expel [Krefft] without first seeking the advice of the Government, no assistance could be afforded".[280]

At the time of Krefft's forcible eviction, all of his possessions were seized; and, almost two years after the eviction Krefft was still complaining that "my own and my wife's personal property, my books, specimens, scientific instruments, medals and testimonials", all of which had been "illegally taken possession of by the trustees", were still to be returned to him.[287][288]

Krefft's position

[edit]Krefft's position was that the trustees, acting independently of the New South Wales government, had no right to dismiss him.

Trustee's allegations

[edit]

- The Trustees have to express their deep regret that circumstances have occurred during the past year which disclosed an utter want of care and attention in the discharge of his duties on the part of Mr. Krefft, their curator and secretary, and which resulted, after repeated acts of disobedience to the lawful orders of the trustees, in the removal of that officer from his position, and in the closing of the institution to the public for a short period.—Trustees' justification for Krefft's dismissal in their Report to the NSW Parliament for the year 1874.[290]

The trustees — two members of which, William Macleay and Captain Arthur Onslow (although both were Members of the Legislative Assembly they were not trustees, ex officio, but had been elected to their trustee position), "manifested great animus towards Mr. Krefft, and used their utmost exertions to cast obloquy upon that gentleman"[291][292] — responded by accusing Krefft of drunkenness, falsifying attendance records, and wilfully destroying a fossil sent to the Museum by one of its trustees, George Bennett, for its preparation to be sent on the Richard Owen at the British Museum. This entirely false allegation was completely (and independently) refuted by a letter from Owen, that Bennett had received in late June 1874, in which Owen "acknowledged receiving [the fossil specimen] in good order".[293][294][295]

Krefft was even accused of condoning the sale of pornographic postcards.[98] The (fifty to sixty) postcards in question, of which the trustees claimed in their justification of Krefft's dismissal, "some of which were of the most indecent character" (and had been "seen" by one of the trustees "in the workshop of the Museum")[296] — which, rather than being salacious items were, in fact, standard ethnographic photographs taken in the field — had been copied, entirely without Krefft's knowledge or consent, by taxidermist/photographer Robert Barnes and his brother Henry Barnes, who were museum employees and Krefft's subordinates.

Legal actions

[edit]

- Apart from promoting Darwin's controversial ideas, Krefft was also critical of the Australian Museum's trustees — he believed they were using the institution's resources for personal gain. Krefft ended up being dismissed from his post based on false allegations. There have been suggestions that Krefft was the first Australian scientist to suffer discrimination after promoting Darwin's work.—Frame (2009), pp. 93–94.

- [In these matters] I am only one against many and you know that law is expensive and only made for the rich. Had I been an Englishman by birth, had I humbugged people, attended at Church, and spread knowledge on the principle that the God of Moses and of the Prophets made "little apples",[297] I would have gained the day, but [as] a true believer in [your] theory of developement [sic] I am hounded down in this [Paradise] of Bushrangers' of rogues, Cheats, and Vagabonds".—Krefft to Charles Darwin (22 October 1874), seeking Darwin's support.[298]

In November 1874 Krefft brought an action to recover £2,000 damages for trespass and assault against the trustee, Edward Smith Hill, who was physically present at, and had directed his eviction.[299][300][280]

The trial lasted four days, and Justice Alfred Cheeke, the presiding judge "ruled that [Hill] and his co-trustees had acted illegally", and that, "as the trustees had no power to appoint a Curator, they clearly had no power to remove him from office, or expel him from the Museum premises", and, finally, that "[because] the Curator was an officer receiving his salary from the Government, ... he could not be removed from the premises without the sanction of the Government".[301] "The jury [of four], after a short deliberation, found a verdict for the plaintiff, with £250 for damages".[280][302]

In September 1875, Hill applied to the NSW Supreme Court for a retrial, and his motion for a new trial was heard by Justices John Fletcher Hargrave and Peter (Noah's Ark) Faucett over three days (7 to 9 September).[303] Justice Hargrave, noting that the trustees' behaviour was "altogether illegal, harsh, and unjust", and that they had acted "without affording [Krefft] the slightest means of vindicating himself personally, or his scientific or official character as Curator of our Museum"[304] was of the opinion that a new trial should be refused. In contrast, Justice Faucett, noting that Krefft "[had] taken an altogether erroneous view of his position and of the powers of the trustees; and [he, Faucett was] clearly of [the] opinion that his conduct justified his dismissal",[305] was of the opinion that a new trial should be granted. Given these conflicting opinions, the court decided that Hill's action could not be heard.[306]

Hill's counsel, Sir William Manning, immediately applied for a rehearing of the action before the full court of three judges.[308] The application was unanimously refused by Justices Martin, Faucett, and Hargrave, on the grounds that, because the Chief Justice, Sir James Martin, was a Museum trustee ex officio and, therefore, could not sit on the Bench, the opinions of the remaining two members, Faucett and Hargrave, had already been clearly expressed.[309]

"When the courts awarded Krefft damages [in 1874], the trustees refused to pay up, though they had plundered the museum's coffers to recoup their own legal costs" (Macinnes, 2012, p. 114). In November 1877 Krefft sued the trustees for damages, and for the value of his medals and property detained by them, and was awarded £925.[310] They offered to return his belongings with only £200.[311]

Legislative proceedings

[edit]In 1876, with John Robertson (rather than Henry Parkes) as Premier, the New South Wales parliament passed a vote of £1,000[312] to be applied in satisfaction of Krefft's claims.[313] The Government refused to pay unless Krefft renounced all other claims,[314] which Krefft refused to do. In December 1876 Krefft failed in his attempt to have the Supreme Court In Banco force the Colonial Treasurer to make the legislated-for payment.[315]

Insolvency

[edit]

He was declared insolvent in 1880.[317][318]

Death

[edit]- The museum affair demoralized Krefft and destroyed his livelihood. Many of his research papers remained unpublished and his collections were damaged and muddled.—Rutledge & Whitley (1974).

Krefft failed to find new employment after his dismissal, and his financial difficulties meant that he could not leave Australia.

He died, at the age of 51, from congestion of the lungs, "after suffering for some months past from dropsy and Bright's disease",[319] in Sydney, on 18 February 1881,[320][321] and was buried in the churchyard of St Jude's Church of England, Randwick.[17][322]

Obituaries

[edit]- "The Lounger", The (Melbourne) Herald, 21 February 1881.[323]

- The Sydney Daily Telegraph, 21 February 1881.[324]

- The (Sydney) Evening News, 22 February 1881.[325]

- Sydney Morning Herald, 24 February 1881.[326]

- Australian Town and Country Journal, Sydney, 26 February 1881.[327]

- The Sydney Mail, 26 February 1881.[328]

- Nature, 21 April 1881.[6]

Research

[edit]- 1864: Published a Catalogue of Mammalia in the Collection of the Australian Museum.

- 1865: Published the pamphlet, Two Papers on the Vertebrata of the Lower Murray and Darling and on the Snakes of Sydney (1865a) — the two papers had been read before the Philosophical Society of New South Wales.

The pamphlet also included a third paper on the Aborigines of the Lower Murray and Darling (i.e., Krefft, 1865b). - 1869: The Snakes of Australia was published, which was the first definitive work on this group of Australian animals.[97]

In the absence of funds for its publication, Krefft eventually financed the publication himself, and it was published by the Government Printer.[329] Krefft and his publication were praised at the Sydney Intercolonial Exhibition of 1870 and the Scott sisters, Helena Scott (a.k.a. Helena Forde) and Harriet Scott (a.k.a. Harriet Morgan), received a Very High Commendation for the striking artwork that accompanied Krefft's text.[329][330] - 1870: Published the first scientific description of the Queensland lungfish (Krefft, 1870a, 1870b, 1870c, 1870d, 1870e).

- 1871: Published The Mammals of Australia, which also included plates by the Scott sisters.

- 1872: Krefft was one of the few scientists supporting Darwinism in Australia during 1870s;[331][332] and, as of May 1872, became a correspondent of Charles Darwin[333] — see, for instance, Darwin's acknowledgement, in The Formation of Vegetable Mould Through the Action of Worms (Darwin, 1881, p. 122) of Krefft's contribution to his investigations.[334]

- 1872: On 30 December 1872, Krefft wrote to Charles Darwin (1872c); and, based upon Krefft's direct, in-the-field experience as an anthropological linguist, informed Darwin that "Australian natives" could, indeed, count far beyond the number four — thus correcting Darwin's erroneous assertion that they could not (in Descent (1871a, p. 62), with Darwin apparently following Ludwig Büchner.[335]

- 1873: Catalogue of the Minerals and Rocks in the Collection of the Australian Museum was published.[8]

- 1877: Began publishing Krefft's Nature in Australia — see: item in the collection of the State Library of New South Wales — a popular journal for the discussion of questions of natural history, but it soon ceased publication.[17]

-

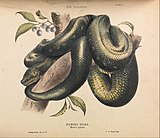

The Black-Headed Snake,

Aspidiotes melanocephalus,

illustration by Harriet Morgan,

from Krefft's The Snakes of Australia (1869). -

The Diamond Snake,

Morelia spilotes,

illustration by Helena Forde,

from Krefft's The Snakes of Australia (1869). -

The Koala, or Native Bear,

Phascolarctos cinereus,

illustration by Harriet Morgan,

from Krefft's The Mammals of Australia (1871f). -

The Kangaroo,

Macropus major,

illustration by Helena Forde,

from Krefft's The Mammals of Australia (1871f).

Learned Society affiliations; awards, etc.

[edit]Affiliations

[edit]Krefft was:

- A Fellow of the Linnean Society in London.[99]

- A Master and Honorary Member of the Freies Deutsches Hochstift (Free German Foundation) at Frankfurt am Main.[99]

- A Member of the Société Humanitaire et Scientifique du Sud-Ouest de la France (Humanitarian and Scientific Society of the Southwest of France), the Imperial and Royal Geological Society of Austro-Hungary in Vienna, the Royal Geographical Society of Dresden; Royal Society of New South Wales, and the Royal Society of Tasmania.[99]

- A Corresponding Member of the Zoological Society of London,[99] the Société Humanitaire et Scientifique de Sud-Ouest de France of Bordeaux,[336] the Senckenberg Nature Research Society of Frankfurt am Main,[99] and the "Society of Scientific Naturalists in Hamburg".[337]

Awards

[edit]- In 1869, the Cross of the Order of the Crown of Italy was conferred upon Krefft by Victor Emmanuel II, "in token of his Majesty's appreciation of Mr. Krefft's services in the cause of science".[338]

- He received a gold medal from the Government of New South Wales "for services rendered".[99]

- He held "a silver medal for exhibits from the Emperor of the French, and ... various other silver and bronze medals awarded in the colony".[99]

- He was awarded "the honorary degree of Doctor of Philosophy".[339]

Legacy

[edit]

by Gerard Krefft (1857).

His natural science expertise was often sought on unusual matters. In May 1870, for instance, he appeared as an expert witness in a case of infanticide (prosecution, J.E. Salomons; defence, W.B. Dalley) wherein Krefft testified that a set of exhumed bones were from "a human skeleton".[340][341] Apart from his scientific contributions, Krefft is remembered for the demonstration he provided at the Australian Museum, on 14 February 1868, for Prince Alfred — at the time, the Duke of Edinburg and, later, the Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha — involving Henry Parkes' pet mongoose killing several snakes. The mongoose was subsequently presented to the Prince who took it with him when he left Australia on the HMS Galatea in May 1868.[342][343][344]