Альфред Рассел Уоллес

Альфред Рассел Уоллес | |

|---|---|

Уоллес в 1895 году | |

| Рожденный | 8 января 1823 г. Лланбадок , Монмутшир, Уэльс |

| Died | 7 November 1913 (aged 90) Broadstone, Dorset, England |

| Known for |

|

| Spouse | Annie Mitten (m. 1866) |

| Children | Herbert, Violet, William |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Author abbrev. (botany) | Wallace |

Альфред Рассел Уоллес OM FRS (8 января 1823 - 7 ноября 1913) был англичанином. [1] натуралист , исследователь, географ , антрополог , биолог и иллюстратор. [2] Он независимо разработал теорию эволюции посредством естественного отбора ; его статья 1858 года по этому вопросу была опубликована в том же году вместе с выдержками из Чарльза Дарвина по этой теме. более ранних работ [3] [4] Это побудило Дарвина отложить «большую книгу о видах», которую он писал, и быстро написать реферат ее , который был опубликован в 1859 году под названием «Происхождение видов» .

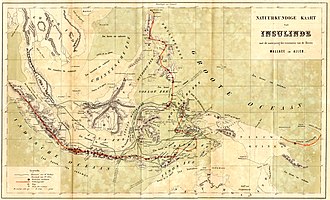

Wallace did extensive fieldwork, starting in the Amazon River basin. He then did fieldwork in the Malay Archipelago, where he identified the faunal divide now termed the Wallace Line, which separates the Indonesian archipelago into two distinct parts: a western portion in which the animals are largely of Asian origin, and an eastern portion where the fauna reflect Australasia. He was considered the 19th century's leading expert on the geographical distribution of animal species, and is sometimes called the "father of biogeography", or more specifically of zoogeography.[5]

Wallace was one of the leading evolutionary thinkers of the 19th century, working on warning coloration in animals and reinforcement (sometimes known as the Wallace effect), a way that natural selection could contribute to speciation by encouraging the development of barriers against hybridisation. Wallace's 1904 book Man's Place in the Universe was the first serious attempt by a biologist to evaluate the likelihood of life on other planets. He was one of the first scientists to write a serious exploration of whether there was life on Mars.[6]

Aside from scientific work, he was a social activist, critical of what he considered to be an unjust social and economic system in 19th-century Britain. His advocacy of spiritualism and his belief in a non-material origin for the higher mental faculties of humans strained his relationship with other scientists. He was one of the first prominent scientists to raise concerns over the environmental impact of human activity. He wrote prolifically on both scientific and social issues; his account of his adventures and observations during his explorations in Southeast Asia, The Malay Archipelago, was first published in 1869. It continues to be both popular and highly regarded.

Biography[edit]

Early life[edit]

Alfred Russel Wallace was born on 8 January 1823 in Llanbadoc, Monmouthshire.[a][7] He was the eighth of nine children born to Mary Anne Wallace (née Greenell) and Thomas Vere Wallace. His mother was English, while his father was of Scottish ancestry. His family claimed a connection to William Wallace, a leader of Scottish forces during the Wars of Scottish Independence in the 13th century.[8]

Wallace's father graduated in law but never practised it. He owned some income-generating property, but bad investments and failed business ventures resulted in a steady deterioration of the family's financial position. Wallace's mother was from a middle-class family of Hertford,[8] to which place his family moved when Wallace was five years old. He attended Hertford Grammar School until 1837, when he reached the age of 14, the normal leaving age for a pupil not going on to university.[9][10]

Wallace then moved to London to board with his older brother John, a 19-year-old apprentice builder. This was a stopgap measure until William, his oldest brother, was ready to take him on as an apprentice surveyor. While in London, Alfred attended lectures and read books at the London Mechanics Institute. Here he was exposed to the radical political ideas of the Welsh social reformer Robert Owen and of the English-born political theorist Thomas Paine. He left London in 1837 to live with William and work as his apprentice for six years. They moved repeatedly to different places in Mid-Wales. Then at the end of 1839, they moved to Kington, Herefordshire, near the Welsh border, before eventually settling at Neath in Wales. Between 1840 and 1843, Wallace worked as a land surveyor in the countryside of the west of England and Wales.[11][12] The natural history of his surroundings aroused his interest; from 1841 he collected flowers and plants as an amateur botanist.[9]

One result of Wallace's early travels is a modern controversy about his nationality. Since he was born in Monmouthshire, some sources have considered him to be Welsh.[13] Other historians have questioned this because neither of his parents were Welsh, his family only briefly lived in Monmouthshire, the Welsh people Wallace knew in his childhood considered him to be English, and because he consistently referred to himself as English rather than Welsh. One Wallace scholar has stated that the most reasonable interpretation is therefore that he was an Englishman born in Wales.[2]

In 1843 Wallace's father died, and a decline in demand for surveying meant William's business no longer had work available.[9] For a short time Wallace was unemployed, then early in 1844 he was engaged by the Collegiate School in Leicester to teach drawing, mapmaking, and surveying.[14][15] He had already read George Combe's The Constitution of Man, and after Spencer Hall lectured on mesmerism, Wallace as well as some of the older pupils tried it out. Wallace spent many hours at the town library in Leicester; he read An Essay on the Principle of Population by Thomas Robert Malthus, Alexander von Humboldt's Personal Narrative, Darwin's Journal (The Voyage of the Beagle), and Charles Lyell's Principles of Geology.[9][16] One evening Wallace met the entomologist Henry Bates, who was 19 years old, and had published an 1843 paper on beetles in the journal Zoologist. He befriended Wallace and started him collecting insects.[14][15]

When Wallace's brother William died in March 1845, Wallace left his teaching position to assume control of his brother's firm in Neath, but his brother John and he were unable to make the business work. After a few months, he found work as a civil engineer for a nearby firm that was working on a survey for a proposed railway in the Vale of Neath. Wallace's work on the survey was largely outdoors in the countryside, allowing him to indulge his new passion for collecting insects. Wallace persuaded his brother John to join him in starting another architecture and civil engineering firm. It carried out projects including the design of a building for the Neath Mechanics' Institute, founded in 1843.[17] During this period, he exchanged letters with Bates about books. By the end of 1845, Wallace was convinced by Robert Chambers's anonymously published treatise on progressive development, Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, but he found Bates was more critical.[18][19] Wallace re-read Darwin's Journal, and on 11 April 1846 wrote "As the Journal of a scientific traveller, it is second only to Humboldt's 'Personal Narrative'—as a work of general interest, perhaps superior to it."[20]

William Jevons, the founder of the Neath institute, was impressed by Wallace and persuaded him to give lectures there on science and engineering. In the autumn of 1846, Wallace and his brother John purchased a cottage near Neath, where they lived with their mother and sister Fanny.[21][22]

Exploration and study of the natural world[edit]

Inspired by the chronicles of earlier and contemporary travelling naturalists, Wallace decided to travel abroad.[23] He later wrote that Darwin's Journal and Humboldt's Personal Narrative were "the two works to whose inspiration I owe my determination to visit the tropics as a collector."[24] After reading A voyage up the river Amazon, by William Henry Edwards, Wallace and Bates estimated that by collecting and selling natural history specimens such as birds and insects they could meet their costs, with the prospect of good profits.[9] They therefore engaged as their agent Samuel Stevens who would advertise and arrange sales to institutions and private collectors, for a commission of 20% on sales plus 5% on despatching freight and remittances of money.[25]

In 1848, Wallace and Bates left for Brazil aboard the Mischief. They intended to collect insects and other animal specimens in the Amazon Rainforest for their private collections, selling the duplicates to museums and collectors back in Britain to fund the trip. Wallace hoped to gather evidence of the transmutation of species. Bates and he spent most of their first year collecting near Belém, then explored inland separately, occasionally meeting to discuss their findings. In 1849, they were briefly joined by another young explorer, the botanist Richard Spruce, along with Wallace's younger brother Herbert. Herbert soon left (dying two years later from yellow fever), but Spruce, like Bates, would spend over ten years collecting in South America.[26][27] Wallace spent four years charting the Rio Negro, collecting specimens and making notes on the peoples and languages he encountered as well as the geography, flora, and fauna.[28]

On 12 July 1852, Wallace embarked for the UK on the brig Helen. After 25 days at sea, the ship's cargo caught fire, and the crew was forced to abandon ship. All the specimens Wallace had on the ship, mostly collected during the last, and most interesting, two years of his trip, were lost. He managed to save a few notes and pencil sketches, but little else. Wallace and the crew spent ten days in an open boat before being picked up by the brig Jordeson, which was sailing from Cuba to London. The Jordeson's provisions were strained by the unexpected passengers, but after a difficult passage on short rations, the ship reached its destination on 1 October 1852.[29][30]

The lost collection had been insured for £200 by Stevens.[31] After his return to Britain, Wallace spent 18 months in London living on the insurance payment, and selling a few specimens that had been shipped home. During this period, despite having lost almost all the notes from his South American expedition, he wrote six academic papers (including "On the Monkeys of the Amazon") and two books, Palm Trees of the Amazon and Their Uses and Travels on the Amazon.[32] At the same time, he made connections with several other British naturalists.[30][33][34]

Bates and others were collecting in the Amazon area, Wallace was more interested in new opportunities in the Malay Archipelago as demonstrated by the travel writings of Ida Laura Pfeiffer, and valuable insect specimens she collected which Stevens sold as her agent. In March 1853 Wallace wrote to Sir James Brooke, Rajah of Sarawak, who was then in London, and who arranged assistance in Sarawak for Wallace.[35][36] In June Wallace wrote to Murchison at the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) for support, proposing to again fund his exploring entirely from sale of duplicate collections.[37] He later recalled that, while researching in the insect-room of the British Museum, he was introduced to Darwin and they "had a few minutes' conversation." After presenting a paper and a large map of the Rio Negro to the RGS, Wallace was elected a Fellow of the society on 27 February 1854.[38][39] Free passage arranged on Royal Navy ships was stalled by the Crimean War, but eventually the RGS funded first class travel by P&O steamships. Wallace and a young assistant, Charles Allen, embarked at Southampton on 4 March 1854. After the overland journey to Suez and another change of ship at Ceylon they disembarked at Singapore on 19 April 1854.[40]

From 1854 to 1862, Wallace travelled around the islands of the Malay Archipelago or East Indies (now Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia).[41] His main objective "was to obtain specimens of natural history, both for my private collection and to supply duplicates to museums and amateurs". In addition to Allen, he "generally employed one or two, and sometimes three Malay servants" as assistants, and paid large numbers of local people at various places to bring specimens. His total was 125,660 specimens, most of which were insects including more than 83,000 beetles,[42][43] Several thousand of the specimens represented species new to science,[44] Overall, more than thirty men worked for him at some stage as full-time paid collectors. He also hired guides, porters, cooks and boat crews, so well over 100 individuals worked for him.[45]

After collecting expeditions to Bukit Timah Hill in Singapore, and to Malacca, Wallace and Allen reached Sarawak in October 1854, and were welcomed at Kuching by Sir James Brooke's (then) heir Captain John Brooke. Wallace hired a Malay named Ali as a general servant and cook, and spent the early 1855 wet season in a small Dyak house at the foot of Mount Santubong, overlooking a branch outlet of the Sarawak River. He read about species distribution, notes on Pictets's Palaeontology, and wrote his "Sarawak Paper".[46] In March he moved to the Simunjon coal-works, operated by the Borneo Company under Ludvig Verner Helms, and supplemented collecting by paying workers a cent for each insect. A specimen of the previously unknown gliding tree frog Rhacophorus nigropalmatus (now called Wallace's flying frog) came from a Chinese workman who told Wallace that it glided down. Local people also assisted with shooting orangutans.[47][43] They spent time with Sir James, then in February 1856 Allen chose to stay on with the missionaries at Kuching.[48][49]

On reaching Singapore in May 1856, Wallace hired a bird-skinner. With Ali as cook, they collected for two days on Bali, then from 17 June to 30 August on Lombok.[50] In December 1856, Darwin had written to contacts worldwide to get specimens for his continuing research into variation under domestication.[51][52] At Lombok's port city, Ampanam, Wallace wrote telling his agent, Stevens, about specimens shipped, including a domestic duck variety "for Mr. Darwin & he would perhaps also like the jungle cock, which is often domesticated here & is doubtless one of the originals of the domestic breed of poultry."[53]In the same letter, Wallace said birds from Bali and Lombok, divided by a narrow strait, "belong to two quite distinct zoological provinces, of which they form the extreme limits", Java, Borneo, Sumatra and Malacca, and Australia and the Moluccas. Stevens arranged publication of relevant paragraphs in the January 1857 issue of The Zoologist. After further investigation, the zoogeographical boundary eventually became known as the Wallace Line.[54][55]

Ali became Wallace's most trusted assistant, a skilled collector and researcher. Wallace collected and preserved the delicate insect specimens, while most of the birds were collected and prepared by his assistants; of those, Ali collected and prepared around 5000.[45]While exploring the archipelago, Wallace refined his thoughts about evolution, and had his famous insight on natural selection. In 1858 he sent an article outlining his theory to Darwin; it was published, along with a description of Darwin's theory, that same year.[56]

Accounts of Wallace's studies and adventures were eventually published in 1869 as The Malay Archipelago. This became one of the most popular books of scientific exploration of the 19th century, and has never been out of print. It was praised by scientists such as Darwin (to whom the book was dedicated), by Lyell, and by non-scientists such as the novelist Joseph Conrad. Conrad called the book his "favorite bedside companion" and used information from it for several of his novels, especially Lord Jim.[57]A set of 80 bird skeletons Wallace collected in Indonesia are held in the Cambridge University Museum of Zoology, and described as of exceptional historical significance.[58]

|

Return to Britain, marriage and children[edit]

In 1862, Wallace returned to Britain, where he moved in with his sister Fanny Sims and her husband Thomas. While recovering from his travels, Wallace organised his collections and gave numerous lectures about his adventures and discoveries to scientific societies such as the Zoological Society of London. Later that year, he visited Darwin at Down House, and became friendly with both Lyell and the philosopher Herbert Spencer.[59] During the 1860s, Wallace wrote papers and gave lectures defending natural selection. He corresponded with Darwin about topics including sexual selection, warning coloration, and the possible effect of natural selection on hybridisation and the divergence of species.[60] In 1865, he began investigating spiritualism.[61]

After a year of courtship, Wallace became engaged in 1864 to a young woman whom, in his autobiography, he would only identify as Miss L. Miss L. was the daughter of Lewis Leslie who played chess with Wallace,[62] but to Wallace's great dismay, she broke off the engagement.[63] In 1866, Wallace married Annie Mitten. Wallace had been introduced to Mitten through the botanist Richard Spruce, who had befriended Wallace in Brazil and who was a friend of Annie Mitten's father, William Mitten, an expert on mosses. In 1872, Wallace built the Dell, a house of concrete, on land he leased in Grays in Essex, where he lived until 1876. The Wallaces had three children: Herbert (1867–1874), Violet (1869–1945), and William (1871–1951).[64]

Financial struggles[edit]

In the late 1860s and 1870s, Wallace was very concerned about the financial security of his family. While he was in the Malay Archipelago, the sale of specimens had brought in a considerable amount of money, which had been carefully invested by the agent who sold the specimens for Wallace. On his return to the UK, Wallace made a series of bad investments in railways and mines that squandered most of the money, and he found himself badly in need of the proceeds from the publication of The Malay Archipelago.[65]

Despite assistance from his friends, he was never able to secure a permanent salaried position such as a curatorship in a museum. To remain financially solvent, Wallace worked grading government examinations, wrote 25 papers for publication between 1872 and 1876 for various modest sums, and was paid by Lyell and Darwin to help edit some of their works.[66]

In 1876, Wallace needed a £500 advance from the publisher of The Geographical Distribution of Animals to avoid having to sell some of his personal property.[67] Darwin was very aware of Wallace's financial difficulties and lobbied long and hard to get Wallace awarded a government pension for his lifetime contributions to science. When the £200 annual pension was awarded in 1881, it helped to stabilise Wallace's financial position by supplementing the income from his writings.[68]

Social activism[edit]

In 1881, Wallace was elected as the first president of the newly formed Land Nationalisation Society. In the next year, he published a book, Land Nationalisation; Its Necessity and Its Aims,[69] on the subject. He criticised the UK's free trade policies for the negative impact they had on working-class people.[34][70] In 1889, Wallace read Looking Backward by Edward Bellamy and declared himself a socialist, despite his earlier foray as a speculative investor.[71] After reading Progress and Poverty, the bestselling book by the progressive land reformist Henry George, Wallace described it as "Undoubtedly the most remarkable and important book of the present century."[72]

Wallace opposed eugenics, an idea supported by other prominent 19th-century evolutionary thinkers, on the grounds that contemporary society was too corrupt and unjust to allow any reasonable determination of who was fit or unfit.[73] In his 1890 article "Human Selection" he wrote, "Those who succeed in the race for wealth are by no means the best or the most intelligent ..."[74] He said, "The world does not want the eugenicist to set it straight," "Give the people good conditions, improve their environment, and all will tend towards the highest type. Eugenics is simply the meddlesome interference of an arrogant, scientific priestcraft."[75]

In 1898, Wallace wrote a paper advocating a pure paper money system, not backed by silver or gold, which impressed the economist Irving Fisher so much that he dedicated his 1920 book Stabilizing the Dollar to Wallace.[76]

Wallace wrote on other social and political topics, including in support of women's suffrage and repeatedly on the dangers and wastefulness of militarism.[77][78] In an 1899 essay, he called for popular opinion to be rallied against warfare by showing people "that all modern wars are dynastic; that they are caused by the ambition, the interests, the jealousies, and the insatiable greed of power of their rulers, or of the great mercantile and financial classes which have power and influence over their rulers; and that the results of war are never good for the people, who yet bear all its burthens (burdens)".[79] In a letter published by the Daily Mail in 1909, with aviation in its infancy, he advocated an international treaty to ban the military use of aircraft, arguing against the idea "that this new horror is 'inevitable', and that all we can do is to be sure and be in the front rank of the aerial assassins—for surely no other term can so fitly describe the dropping of, say, ten thousand bombs at midnight into an enemy's capital from an invisible flight of airships."[80]

In 1898, Wallace published The Wonderful Century: Its Successes and Its Failures, about developments in the 19th century. The first part of the book covered the major scientific and technical advances of the century; the second part covered what Wallace considered to be its social failures including the destruction and waste of wars and arms races, the rise of the urban poor and the dangerous conditions in which they lived and worked, a harsh criminal justice system that failed to reform criminals, abuses in a mental health system based on privately owned sanatoriums, the environmental damage caused by capitalism, and the evils of European colonialism.[81][82] Wallace continued his social activism for the rest of his life, publishing the book The Revolt of Democracy just weeks before his death.[83]

Further scientific work[edit]

In 1880, he published Island Life as a sequel to The Geographic Distribution of Animals. In November 1886, Wallace began a ten-month trip to the United States to give a series of popular lectures. Most of the lectures were on Darwinism (evolution through natural selection), but he also gave speeches on biogeography, spiritualism, and socio-economic reform. During the trip, he was reunited with his brother John who had emigrated to California years before. He spent a week in Colorado, with the American botanist Alice Eastwood as his guide, exploring the flora of the Rocky Mountains and gathering evidence that would lead him to a theory on how glaciation might explain certain commonalities between the mountain flora of Europe, Asia and North America, which he published in 1891 in the paper "English and American Flowers". He met many other prominent American naturalists and viewed their collections. His 1889 book Darwinism used information he collected on his American trip and information he had compiled for the lectures.[84][85]

Death[edit]

On 7 November 1913, Wallace died at home, aged 90, in the country house he called Old Orchard, which he had built a decade earlier.[86] His death was widely reported in the press. The New York Times called him "the last of the giants [belonging] to that wonderful group of intellectuals composed of Darwin, Huxley, Spencer, Lyell, Owen, and other scientists, whose daring investigations revolutionized and evolutionized the thought of the century".[87] Another commentator in the same edition said: "No apology need be made for the few literary or scientific follies of the author of that great book on the 'Malay Archipelago'."[88]

Some of Wallace's friends suggested that he be buried in Westminster Abbey, but his wife followed his wishes and had him buried in the small cemetery at Broadstone, Dorset.[86] Several prominent British scientists formed a committee to have a medallion of Wallace placed in Westminster Abbey near where Darwin had been buried. The medallion was unveiled on 1 November 1915.[89]

Theory of evolution[edit]

Early evolutionary thinking[edit]

Wallace began his career as a travelling naturalist who already believed in the transmutation of species. The concept had been advocated by Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, Erasmus Darwin, and Robert Grant, among others. It was widely discussed, but not generally accepted by leading naturalists, and was considered to have radical, even revolutionary connotations.[90][91] Prominent anatomists and geologists such as Georges Cuvier, Richard Owen, Adam Sedgwick, and Lyell attacked transmutation vigorously.[92][93] It has been suggested that Wallace accepted the idea of the transmutation of species in part because he was always inclined to favour radical ideas in politics, religion and science,[90] and because he was unusually open to marginal, even fringe, ideas in science.[94]

Wallace was profoundly influenced by Robert Chambers's Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, a controversial work of popular science published anonymously in 1844. It advocated an evolutionary origin for the solar system, the earth, and living things.[95] Wallace wrote to Henry Bates in 1845 describing it as "an ingenious hypothesis strongly supported by some striking facts and analogies, but which remains to be proven by ... more research".[94] In 1847, he wrote to Bates that he would "like to take some one family [of beetles] to study thoroughly, ... with a view to the theory of the origin of species."[96]

Wallace planned fieldwork to test the evolutionary hypothesis that closely related species should inhabit neighbouring territories.[90] During his work in the Amazon basin, he came to realise that geographical barriers—such as the Amazon and its major tributaries—often separated the ranges of closely allied species. He included these observations in his 1853 paper "On the Monkeys of the Amazon". Near the end of the paper he asked the question, "Are very closely allied species ever separated by a wide interval of country?"[97]

In February 1855, while working in Sarawak on the island of Borneo, Wallace wrote "On the Law which has Regulated the Introduction of New Species". The paper was published in the Annals and Magazine of Natural History in September 1855.[98] In this paper, he discussed observations of the geographic and geologic distribution of both living and fossil species, a field that became biogeography. His conclusion that "Every species has come into existence coincident both in space and time with a closely allied species" has come to be known as the "Sarawak Law", answering his own question in his paper on the monkeys of the Amazon basin. Although it does not mention possible mechanisms for evolution, this paper foreshadowed the momentous paper he would write three years later.[99]

The paper challenged Lyell's belief that species were immutable. Although Darwin had written to him in 1842 expressing support for transmutation, Lyell had continued to be strongly opposed to the idea. Around the start of 1856, he told Darwin about Wallace's paper, as did Edward Blyth who thought it "Good! Upon the whole! ... Wallace has, I think put the matter well; and according to his theory the various domestic races of animals have been fairly developed into species." Despite this hint, Darwin mistook Wallace's conclusion for the progressive creationism of the time, writing that it was "nothing very new ... Uses my simile of tree [but] it seems all creation with him." Lyell was more impressed, and opened a notebook on species in which he grappled with the consequences, particularly for human ancestry. Darwin had already shown his theory to their mutual friend Joseph Hooker and now, for the first time spelt out the full details of natural selection to Lyell. Although Lyell could not agree, he urged Darwin to publish to establish priority. Darwin demurred at first, but began writing up a species sketch of his continuing work in May 1856.[100][101]

Natural selection and Darwin[edit]

By February 1858, Wallace had been convinced by his biogeographical research in the Malay Archipelago that evolution was real. He later wrote in his autobiography that the problem was of how species change from one well-marked form to another.[102] He stated that it was while he was in bed with a fever that he thought about Malthus's idea of positive checks on human population, and had the idea of natural selection. His autobiography says that he was on the island of Ternate at the time; but the evidence of his journal suggests that he was in fact on the island of Gilolo.[103] From 1858 to 1861, he rented a house on Ternate from the Dutchman Maarten Dirk van Renesse van Duivenbode, which he used as a base for expeditions to other islands such as Gilolo.[104]

Wallace describes how he discovered natural selection as follows:

It then occurred to me that these causes or their equivalents are continually acting in the case of animals also; and as animals usually breed much more quickly than does mankind, the destruction every year from these causes must be enormous to keep down the numbers of each species, since evidently they do not increase regularly from year to year, as otherwise the world would long ago have been crowded with those that breed most quickly. Vaguely thinking over the enormous and constant destruction which this implied, it occurred to me to ask the question, why do some die and some live? And the answer was clearly, on the whole the best fitted live ... and considering the amount of individual variation that my experience as a collector had shown me to exist, then it followed that all the changes necessary for the adaptation of the species to the changing conditions would be brought about ... In this way every part of an animals organization could be modified exactly as required, and in the very process of this modification the unmodified would die out, and thus the definite characters and the clear isolation of each new species would be explained.[105]

Wallace had once briefly met Darwin, and was one of the correspondents whose observations Darwin used to support his own theories. Although Wallace's first letter to Darwin has been lost, Wallace carefully kept the letters he received.[107] In the first letter, dated 1 May 1857, Darwin commented that Wallace's letter of 10 October which he had recently received, as well as Wallace's paper "On the Law which has regulated the Introduction of New Species" of 1855, showed that they thought alike, with similar conclusions, and said that he was preparing his own work for publication in about two years time.[108] The second letter, dated 22 December 1857, said how glad he was that Wallace was theorising about distribution, adding that "without speculation there is no good and original observation" but commented that "I believe I go much further than you".[109] Wallace believed this and sent Darwin his February 1858 essay, "On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart Indefinitely From the Original Type", asking Darwin to review it and pass it to Charles Lyell if he thought it worthwhile.[3] Although Wallace had sent several articles for journal publication during his travels through the Malay archipelago, the Ternate essay was in a private letter. Darwin received the essay on 18 June 1858. Although the essay did not use Darwin's term "natural selection", it did outline the mechanics of an evolutionary divergence of species from similar ones due to environmental pressures. In this sense, it was very similar to the theory that Darwin had worked on for 20 years, but had yet to publish. Darwin sent the manuscript to Charles Lyell with a letter saying "he could not have made a better short abstract! Even his terms now stand as heads of my chapters ... he does not say he wishes me to publish, but I shall, of course, at once write and offer to send to any journal."[110][111] Distraught about the illness of his baby son, Darwin put the problem to Charles Lyell and Joseph Hooker, who decided to publish the essay in a joint presentation together with unpublished writings which highlighted Darwin's priority. Wallace's essay was presented to the Linnean Society of London on 1 July 1858, along with excerpts from an essay which Darwin had disclosed privately to Hooker in 1847 and a letter Darwin had written to Asa Gray in 1857.[112]

Communication with Wallace in the far-off Malay Archipelago involved months of delay, so he was not part of this rapid publication. Wallace accepted the arrangement after the fact, happy that he had been included at all, and never expressed bitterness in public or in private. Darwin's social and scientific status was far greater than Wallace's, and it was unlikely that, without Darwin, Wallace's views on evolution would have been taken seriously. Lyell and Hooker's arrangement relegated Wallace to the position of co-discoverer, and he was not the social equal of Darwin or the other prominent British natural scientists. All the same, the joint reading of their papers on natural selection associated Wallace with the more famous Darwin. This, combined with Darwin's (as well as Hooker's and Lyell's) advocacy on his behalf, would give Wallace greater access to the highest levels of the scientific community.[113] The reaction to the reading was muted, with the president of the Linnean Society remarking in May 1859 that the year had not been marked by any striking discoveries;[114] but, with Darwin's publication of On the Origin of Species later in 1859, its significance became apparent. When Wallace returned to the UK, he met Darwin. Although some of Wallace's opinions in the ensuing years would test Darwin's patience, they remained on friendly terms for the rest of Darwin's life.[115]

Over the years, a few people have questioned this version of events. In the early 1980s, two books, one by Arnold Brackman and another by John Langdon Brooks, suggested not only that there had been a conspiracy to rob Wallace of his proper credit, but that Darwin had actually stolen a key idea from Wallace to finish his own theory. These claims have been examined and found unconvincing by a number of scholars.[116][117][118] Shipping schedules show that, contrary to these accusations, Wallace's letter could not have been delivered earlier than the date shown in Darwin's letter to Lyell.[119][120]

Defence of Darwin and his ideas[edit]

After Wallace returned to England in 1862, he became one of the staunchest defenders of Darwin's On the Origin of Species. In an incident in 1863 that particularly pleased Darwin, Wallace published the short paper "Remarks on the Rev. S. Haughton's Paper on the Bee's Cell, And on the Origin of Species". This rebutted a paper by a professor of geology at the University of Dublin that had sharply criticised Darwin's comments in the Origin on how hexagonal honey bee cells could have evolved through natural selection.[121]An even longer defence was a 1867 article in the Quarterly Journal of Science called "Creation by Law". It reviewed George Campbell, the 8th Duke of Argyll's book, The Reign of Law, which aimed to refute natural selection.[122]After an 1870 meeting of the British Science Association, Wallace wrote to Darwin complaining that there were "no opponents left who know anything of natural history, so that there are none of the good discussions we used to have".[123]

Differences between Darwin and Wallace[edit]

Historians of science have noted that, while Darwin considered the ideas in Wallace's paper to be essentially the same as his own, there were differences.[124] Darwin emphasised competition between individuals of the same species to survive and reproduce, whereas Wallace emphasised environmental pressures on varieties and species forcing them to become adapted to their local conditions, leading populations in different locations to diverge.[125][126] The historian of science Peter J. Bowler has suggested that in the paper he mailed to Darwin, Wallace might have been discussing group selection.[127] Against this, Malcolm Kottler showed that Wallace was indeed discussing individual variation and selection.[128]

Others have noted that Wallace appeared to have envisioned natural selection as a kind of feedback mechanism that kept species and varieties adapted to their environment (now called 'stabilizing", as opposed to 'directional' selection).[129] They point to a largely overlooked passage of Wallace's famous 1858 paper, in which he likened "this principle ... [to] the centrifugal governor of the steam engine, which checks and corrects any irregularities".[3] The cybernetician and anthropologist Gregory Bateson observed in the 1970s that, although writing it only as an example, Wallace had "probably said the most powerful thing that'd been said in the 19th Century".[130] Bateson revisited the topic in his 1979 book Mind and Nature: A Necessary Unity, and other scholars have continued to explore the connection between natural selection and systems theory.[129]

Warning coloration and sexual selection[edit]

Warning coloration was one of Wallace's contributions to the evolutionary biology of animal coloration.[131] In 1867, Darwin wrote to Wallace about a problem in explaining how some caterpillars could have evolved conspicuous colour schemes. Darwin had come to believe that many conspicuous animal colour schemes were due to sexual selection, but he saw that this could not apply to caterpillars. Wallace responded that he and Bates had observed that many of the most spectacular butterflies had a peculiar odour and taste, and that he had been told by John Jenner Weir that birds would not eat a certain kind of common white moth because they found it unpalatable. Since the moth was as conspicuous at dusk as a coloured caterpillar in daylight, it seemed likely that the conspicuous colours served as a warning to predators and thus could have evolved through natural selection. Darwin was impressed by the idea. At a later meeting of the Entomological Society, Wallace asked for any evidence anyone might have on the topic.[132] In 1869, Weir published data from experiments and observations involving brightly coloured caterpillars that supported Wallace's idea.[133] Wallace attributed less importance than Darwin to sexual selection. In his 1878 book Tropical Nature and Other Essays, he wrote extensively about the coloration of animals and plants, and proposed alternative explanations for a number of cases Darwin had attributed to sexual selection.[134] He revisited the topic at length in his 1889 book Darwinism. In 1890, he wrote a critical review in Nature of his friend Edward Bagnall Poulton's The Colours of Animals which supported Darwin on sexual selection, attacking especially Poulton's claims on the "aesthetic preferences of the insect world".[135][136]

Wallace effect[edit]

In 1889, Wallace wrote the book Darwinism, which explained and defended natural selection. In it, he proposed the hypothesis that natural selection could drive the reproductive isolation of two varieties by encouraging the development of barriers against hybridisation. Thus it might contribute to the development of new species. He suggested the following scenario: When two populations of a species had diverged beyond a certain point, each adapted to particular conditions, hybrid offspring would be less adapted than either parent form and so natural selection would tend to eliminate the hybrids. Furthermore, under such conditions, natural selection would favour the development of barriers to hybridisation, as individuals that avoided hybrid matings would tend to have more fit offspring, and thus contribute to the reproductive isolation of the two incipient species. This idea came to be known as the Wallace effect,[137][138] later called reinforcement.[139] Wallace had suggested to Darwin that natural selection could play a role in preventing hybridisation in private correspondence as early as 1868, but had not worked it out to this level of detail.[140] It continues to be a topic of research in evolutionary biology today, with both computer simulation and empirical results supporting its validity.[141]

Application of theory to humans, and role of teleology in evolution[edit]

In 1864, Wallace published a paper, "The Origin of Human Races and the Antiquity of Man Deduced from the Theory of 'Natural Selection'", applying the theory to humankind. Darwin had not yet publicly addressed the subject, although Thomas Huxley had in Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature. Wallace explained the apparent stability of the human stock by pointing to the vast gap in cranial capacities between humans and the great apes. Unlike some other Darwinists, including Darwin himself, he did not "regard modern primitives as almost filling the gap between man and ape".[142] He saw the evolution of humans in two stages: achieving a bipedal posture that freed the hands to carry out the dictates of the brain, and the "recognition of the human brain as a totally new factor in the history of life".[142] Wallace seems to have been the first evolutionist to see that the human brain effectively made further specialisation of the body unnecessary.[142] Wallace wrote the paper for the Anthropological Society of London to address the debate between the supporters of monogenism, the belief that all human races shared a common ancestor and were one species, and the supporters of polygenism, who held that different races had separate origins and were different species. Wallace's anthropological observations of Native Americans in the Amazon, and especially his time living among the Dayak people of Borneo, had convinced him that human beings were a single species with a common ancestor. He still felt that natural selection might have continued to act on mental faculties after the development of the different races; and he did not dispute the nearly universal view among European anthropologists of the time that Europeans were intellectually superior to other races.[143][144] According to political scientist Adam Jones, "Wallace found little difficulty in reconciling the extermination of native peoples with his progressive political views".[145] In 1864, in the aforementioned paper, he stated "It is the same great law of the preservation of favored races in the struggle for life, which leads to the inevitable extinction of all those low and mentally undeveloped populations with which Europeans come in contact."[146] He argued that the natives die out due to an unequal struggle.[147]

Вскоре после этого Уоллес стал спиритуалистом . Примерно в то же время он начал утверждать, что естественный отбор не может объяснить математический, художественный или музыкальный гений, метафизические размышления, остроумие и юмор. Он заявил, что что-то в «невидимой вселенной Духа» вмешивалось в историю по крайней мере трижды: создание жизни из неорганической материи; введение сознания у высших животных; и формирование высших умственных способностей человечества. Он считал, что смыслом существования Вселенной является развитие человеческого духа. [148]

Хотя некоторые историки пришли к выводу, что вера Уоллеса в то, что естественный отбор недостаточен для объяснения развития сознания и высших функций человеческого разума, была напрямую вызвана его принятием спиритуализма, другие ученые не согласились с этим, а некоторые утверждают, что Уоллес никогда не верил в естественный отбор. применяется к этим областям. [149] [150] Реакция на идеи Уоллеса по этой теме среди ведущих натуралистов того времени была разной. Лайель поддерживал взгляды Уоллеса на эволюцию человека, а не Дарвина. [151] [152] Веру Уоллеса в то, что человеческое сознание не может быть полностью продуктом чисто материальных причин, разделяли ряд выдающихся интеллектуалов конца 19 - начала 20 веков. [153] Тем не менее, многие, в том числе Хаксли, Хукер и сам Дарвин, критически относились к взглядам Уоллеса. [154]

Как заявил историк науки и скептик Майкл Шермер , взгляды Уоллеса в этой области противоречили двум основным принципам зарождающейся дарвиновской философии. Они заключались в том, что эволюция не была телеологической (целенаправленной) и не была антропоцентрической (ориентированной на человека). [155] Намного позже в своей жизни Уоллес вернулся к этим темам: эволюция предполагает, что у Вселенной может быть цель и что некоторые аспекты живых организмов не могут быть объяснены с точки зрения чисто материалистических процессов. Он изложил свои идеи в журнальной статье 1909 года под названием « Мир жизни» , позже расширенной в одноименную книгу. [156] Шермер отметил, что это предвосхитило идеи о замысле в природе и направило эволюцию, которая возникла из религиозных традиций на протяжении всего 20 века. [153]

Оценка роли Уоллеса в эволюционной истории теории

Во многих отчетах о развитии эволюционной теории Уоллес упоминается лишь вскользь как просто стимул к публикации собственной теории Дарвина. [157] На самом деле Уоллес разработал свои собственные взгляды на теорию эволюции, которые расходились с взглядами Дарвина, и многие (особенно Дарвин) считали его ведущим мыслителем эволюции своего времени, чьи идеи нельзя было игнорировать. Один историк науки отметил, что посредством частной переписки и опубликованных работ Дарвин и Уоллес обменивались знаниями и стимулировали идеи и теории друг друга в течение длительного периода. [158] Уоллес — наиболее цитируемый натуралист в книге Дарвина «Происхождение человека» , с которым иногда резко расходятся во мнениях. [159] Дарвин и Уоллес согласились с важностью естественного отбора и некоторых факторов, ответственных за него: конкуренции между видами и географической изоляции. Но Уоллес считал, что цель эволюции («телеология») заключалась в поддержании приспособленности видов к окружающей среде, тогда как Дарвин не решался приписать какую-либо цель случайному естественному процессу. Научные открытия XIX века подтверждают точку зрения Дарвина, определяя дополнительные механизмы и триггеры, такие как мутации, вызванные радиацией окружающей среды или мутагенными химическими веществами. [160] Уоллес оставался ярым защитником естественного отбора до конца своей жизни. К 1880-м годам теория эволюции была широко признана в научных кругах, а вот естественный отбор — меньше. Уоллеса 1889 года Дарвинизм был ответом научной критике естественного отбора. [161] Из всех книг Уоллеса она наиболее цитируется научными изданиями. [162]

научные вклады Другие

Биогеография и экология [ править ]

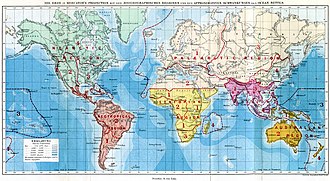

В 1872 году по настоянию многих своих друзей, в том числе Дарвина, Филипа Склейтера и Альфреда Ньютона , Уоллес начал исследования по общему обзору географического распространения животных. Первоначально прогресс был медленным, отчасти потому, что системы классификации многих типов животных постоянно менялись. [163] Он серьезно возобновил работу в 1874 году после публикации ряда новых работ по классификации. [164] Расширив систему, разработанную Склетером для птиц, которая разделила Землю на шесть отдельных географических регионов для описания распространения видов, чтобы охватить также млекопитающих, рептилий и насекомых, Уоллес создал основу для зоогеографических регионов, используемых сегодня. Он обсудил факторы, которые, как тогда было известно, влияли на нынешнее и прошлое географическое распределение животных в каждом географическом регионе. [165]

Эти факторы включали последствия появления и исчезновения сухопутных мостов (таких как тот, который в настоящее время соединяет Северную Америку и Южную Америку ) и последствия периодов усиления оледенения. Он предоставил карты, показывающие такие факторы, как высота гор, глубина океанов и характер региональной растительности, влияющие на распределение животных. Он суммировал все известные семейства и роды высших животных и перечислил их известное географическое распространение. Текст был организован так, чтобы путешественнику было легко узнать, каких животных можно встретить в том или ином месте. Получившийся в результате двухтомный труд « Географическое распространение животных » был опубликован в 1876 году и служил окончательным текстом по зоогеографии на следующие 80 лет. [166]

В книгу вошли данные из летописи окаменелостей, обсуждающие процессы эволюции и миграции, которые привели к географическому распространению современных видов. Например, он обсуждал, как ископаемые свидетельства показали, что тапиры возникли в Северном полушарии , мигрировали между Северной Америкой и Евразией, а затем, гораздо позже, в Южную Америку, после чего северные виды вымерли, оставив современное распространение двух изолированных групп. видов тапиров в Южной Америке и Юго-Восточной Азии. [167] Уоллес был очень осведомлен и интересовался массовым вымиранием мегафауны в позднем плейстоцене . В «Географическом распространении животных » (1876 г.) он писал: «Мы живем в зоологически обедненном мире, из которого недавно исчезли все самые огромные, самые свирепые и самые странные формы». [168] Он добавил, что, по его мнению, наиболее вероятной причиной быстрого вымирания было оледенение, но к тому времени, когда он написал « Мир жизни» (1911), он пришел к выводу, что эти вымирания произошли «по вине человека». [169]

В 1880 году Уоллес опубликовал книгу « Островная жизнь» как продолжение книги «Географическое распространение животных» . Он исследовал распространение видов животных и растений на островах. Уоллес классифицировал острова на океанические и два типа континентальных островов. Океанические острова, по его мнению, такие как Галапагосские и Гавайские острова (тогда называвшиеся Сандвичевыми островами), образовались посреди океана и никогда не были частью какого-либо большого континента. Такие острова характеризовались полным отсутствием наземных млекопитающих и земноводных, а их обитатели (за исключением перелетных птиц и видов, завезенных человеком), как правило, были результатом случайной колонизации и последующей эволюции. Континентальные острова, в его схеме, были разделены на те, которые недавно отделились от континента (например, Британия) и те, которые значительно позже (например, Мадагаскар ). Уоллес рассказал, как эта разница повлияла на флору и фауну. Он обсуждал, как изоляция повлияла на эволюцию и как это может привести к сохранению таких классов животных, как лемуры Мадагаскара, которые были остатками некогда широко распространенной континентальной фауны. Он подробно обсуждал, как изменения климата, особенно периоды усиления оледенения, могли повлиять на распределение флоры и фауны на некоторых островах, а в первой части книги обсуждаются возможные причины этих великих ледниковых периодов . Островная жизнь» На момент публикации « считалась очень важной работой. Оно широко обсуждалось в научных кругах как в опубликованных обзорах, так и в частной переписке. [170]

Энвайронментализм [ править ]

Обширная работа Уоллеса в области биогеографии позволила ему осознать влияние человеческой деятельности на мир природы. В «Тропической природе и других очерках» (1878 г.) он предупреждал об опасности вырубки лесов и эрозии почвы, особенно в тропическом климате, склонном к сильным дождям. Отметив сложную взаимосвязь между растительностью и климатом, он предупредил, что обширная вырубка тропических лесов для выращивания кофе на Цейлоне (ныне Шри-Ланка ) и Индии отрицательно повлияет на климат в этих странах и приведет к их обеднению из-за эрозии почвы. [171] В «Жизни на острове » Уоллес снова упомянул вырубку лесов и инвазивные виды . О влиянии европейской колонизации на остров Святой Елены он писал, что остров «теперь настолько бесплоден и неприступен, что некоторым людям трудно поверить, что когда-то он был весь зеленый и плодородный». [172] Он объяснил, что почва защищена растительностью острова; как только он был разрушен, почва с крутых склонов была смыта сильным тропическим дождем, оставив «голые камни или стерильную глину». [172] Он приписал «непоправимое разрушение» [172] диким козам, завезенным в 1513 году. Леса острова еще больше пострадали от «безрассудного расточительства». [172] Ост-Индской компании с 1651 года, которая использовала для дубления кору ценных красных и эбеновых деревьев, оставляя древесину гнить неиспользованной. [172] Комментарии Уоллеса по поводу окружающей среды стали более актуальными в дальнейшем в его карьере. В «Мире жизни » (1911) он писал, что люди должны рассматривать природу «как наделенную определенной святостью, которую мы можем использовать, но не злоупотреблять, и никогда не подвергать безрассудному уничтожению или порче». [173]

Астробиология [ править ]

Книга Уоллеса 1904 года « Место человека во Вселенной» стала первой серьёзной попыткой биолога оценить вероятность существования жизни на других планетах . Он пришел к выводу, что Земля — единственная планета в Солнечной системе , на которой возможно существование жизни, главным образом потому, что это единственная планета, на которой вода может существовать в жидкой фазе . [174] Его описание Марса в этой книге было кратким, и в 1907 году Уоллес вернулся к этой теме с книгой « Обитаем ли Марс?» критиковать утверждения американского астронома Персиваля Лоуэлла о том, что марсианские каналы разумные существа построили . Уоллес провел месяцы исследований, консультировался с различными экспертами и провел собственный научный анализ марсианского климата и атмосферных условий. [175] Он указал, что спектроскопический анализ не выявил никаких признаков водяного пара в марсианской атмосфере , что анализ климата Марса, проведенный Лоуэллом, сильно переоценил температуру поверхности и что низкое атмосферное давление сделало бы невозможным создание жидкой воды, не говоря уже о опоясывающей планету ирригационной системе. . [176] Ричард Милнер комментирует, что Уоллес «фактически развенчал иллюзорную сеть марсианских каналов Лоуэлла». [177] Уоллес заинтересовался этой темой, потому что его антропоцентрическая философия склоняла его к убеждению, что человек будет уникальным во Вселенной. [178]

Другая деятельность [ править ]

Спиритизм [ править ]

Уоллес был энтузиастом френологии . [179] В начале своей карьеры он экспериментировал с гипнозом , известным тогда как месмеризм , сумев загипнотизировать некоторых своих учеников в Лестере. [180] Когда он начал эти эксперименты, тема была очень спорной: первые экспериментаторы, такие как Джон Эллиотсон , подверглись резкой критике со стороны медицинского и научного истеблишмента. [181] Уоллес установил связь между своим опытом месмеризма и спиритизмом, утверждая, что не следует отрицать наблюдения на «априорных основаниях абсурдности или невозможности». [182]

Уоллес начал исследовать спиритизм летом 1865 года, возможно, по настоянию своей старшей сестры Фанни Симс. [183] Изучив литературу и попытавшись проверить то, чему он стал свидетелем на сеансах , он поверил в это. Всю оставшуюся жизнь он оставался убежденным, что по крайней мере некоторые сеансы были подлинными, несмотря на обвинения в мошенничестве и доказательства обмана. Один биограф предположил, что эмоциональное потрясение, когда его первая невеста разорвала помолвку, способствовало его восприимчивости к спиритизму. [184] Другие ученые подчеркивали его стремление найти научное объяснение всем явлениям. [181] [185] В 1874 году Уоллес посетил дух-фотографа Фредерика Хадсона . Он заявил, что фотография, на которой он изображен с умершей матерью, подлинная. [186] Другие пришли к другому выводу: фотографии Хадсона ранее были разоблачены как поддельные в 1872 году. [187]

Публичная защита Уоллесом спиритизма и его неоднократная защита медиумов-спиритов от обвинений в мошенничестве в 1870-х годах повредили его научную репутацию. В 1875 году он опубликовал доказательства, которые, по его мнению, подтверждали его позицию, в книге « О чудесах и современном спиритуализме» . [188] Его отношение постоянно обостряло его отношения с ранее дружественными учёными, такими как Генри Бейтс , Томас Хаксли и даже Дарвин. [189] [190] Другие, такие как физиолог Уильям Бенджамин Карпентер и зоолог Э. Рэй Ланкестер, стали публично враждебно относиться к Уоллесу по этому поводу. Уоллес подвергся резкой критике со стороны прессы; «Ланцет» был особенно резким. [190] Когда в 1879 году Дарвин впервые попытался заручиться поддержкой среди натуралистов, чтобы добиться назначения Уоллесу гражданской пенсии, Джозеф Хукер ответил, что «Уоллес значительно утратил кастовую принадлежность не только из-за своей приверженности спиритуализму, но и из-за того, что он сознательно и вопреки всему голосу комитета своей секции Британской ассоциации, спровоцировал дискуссию о спиритуализме на одном из ее секционных заседаний... Говорят, что он сделал это закулисно, и я хорошо помню возмущение, которое это вызвало. подняться в Совет БА». [191] [192] В конце концов Хукер уступил и согласился поддержать просьбу о пенсии. [193]

Ставка на плоскую Землю [ править ]

В 1870 году сторонник теории плоской Земли по имени Джон Хэмпден предложил ставку в 500 фунтов стерлингов (что примерно эквивалентно 60 000 фунтов стерлингов в 2023 году). [194] ) в журнальной рекламе для всех, кто может продемонстрировать выпуклую кривизну водоема, такого как река, канал или озеро. Уоллес, заинтригованный этой задачей и в то время ощущавший недостаток денег, разработал эксперимент, в ходе которого он установил два объекта на шестимильном (10-километровом) участке канала. Оба объекта находились на одинаковой высоте над водой, и на такой же высоте над водой он установил телескоп на мосту. При взгляде в телескоп один объект казался выше другого, показывая кривизну Земли . Судья по ставкам, редактор журнала Field , объявил Уоллеса победителем, но Хэмпден отказался признать результат. Он подал в суд на Уоллеса и начал продолжавшуюся несколько лет кампанию по написанию писем в различные издания и организации, членом которых был Уоллес, объявляя его мошенником и вором. Уоллес выиграл несколько исков о клевете против Хэмпдена, но последующий судебный процесс стоил Уоллесу больше, чем сумма ставки, и споры расстраивали его на долгие годы. [195]

Кампания против вакцинации [ править ]

В начале 1880-х годов Уоллес присоединился к дебатам по поводу обязательной вакцинации от оспы . [196] Первоначально Уоллес рассматривал эту проблему как вопрос личной свободы; но после изучения статистики, предоставленной активистами против вакцинации, он начал сомневаться в эффективности вакцинации. В то время микробная теория болезней была новой и далеко не общепринятой. Более того, никто не знал достаточно об иммунной системе человека , чтобы понять, почему вакцинация эффективна. Уоллес обнаружил случаи, когда сторонники вакцинации использовали сомнительные, а в некоторых случаях совершенно ложные статистические данные в поддержку своих аргументов. Всегда с подозрением относившийся к властям, Уоллес подозревал, что врачи были лично заинтересованы в пропаганде вакцинации, и пришел к убеждению, что снижение заболеваемости оспой, связанное с вакцинацией, произошло благодаря улучшению гигиены и улучшению общественной санитарии. [197]

Еще одним фактором в размышлениях Уоллеса была его вера в то, что благодаря действию естественного отбора организмы находятся в состоянии баланса с окружающей средой и что все в природе служит полезной цели. [198] Уоллес отметил, что вакцинация, которая в то время часто была антисанитарной, могла быть опасной. [198]

В 1890 году Уоллес дал показания Королевской комиссии, расследующей спор. В его показаниях были обнаружены ошибки, в том числе некоторые сомнительные статистические данные. The Lancet утверждает, что Уоллес и другие активисты были избирательны в выборе статистических данных. Комиссия пришла к выводу, что вакцинация против оспы эффективна и должна оставаться обязательной, хотя она рекомендовала внести некоторые изменения в процедуры для повышения безопасности и сделать менее суровыми наказания для людей, отказывающихся подчиняться. Спустя годы, в 1898 году, Уоллес написал брошюру « Вакцинация — заблуждение»; Его уголовное правоприменение является преступлением , критикуя выводы комиссии. Он, в свою очередь, подвергся нападкам со стороны The Lancet , заявившего, что он повторил многие из тех же ошибок, что и его показания, данные комиссии. [197]

и восприятие историческое Наследие

Почести [ править ]

Благодаря своим произведениям Уоллес стал известной фигурой как учёный, так и общественный деятель, и его взгляды часто разыскивались. [199] Он стал президентом секции антропологии Британской ассоциации в 1866 году. [200] и Лондонского энтомологического общества в 1870 году. [201] Он был избран членом Американского философского общества в 1873 году. [202] Британская ассоциация избрала его главой своей секции биологии в 1876 году. [203] Он был избран членом Королевского общества в 1893 году. [203] Его попросили возглавить Международный конгресс спиритуалистов, собравшийся в Лондоне в 1898 году. [204] Он получил почетные докторские степени и профессиональные награды, такие как Королевского общества в Королевская медаль 1868 году и медаль Дарвина в 1890 году. [201] и орден «За заслуги» в 1908 году. [205]

и реабилитация Безвестность

Слава Уоллеса быстро угасла после его смерти. Долгое время к нему относились как к относительно малоизвестной фигуре в истории науки. [157] Причинами такого отсутствия внимания могли быть его скромность, его готовность отстаивать непопулярные идеи, не обращая внимания на собственную репутацию, а также дискомфорт большей части научного сообщества некоторыми из его нетрадиционных идей. [206] Причина, по которой теорию эволюции широко приписывают Дарвину, вероятно, связана с влиянием книги Дарвина « Происхождение видов» . [206]

В последнее время Уоллес стал более известен благодаря публикации как минимум пяти книжных биографий и двух антологий его сочинений, опубликованных с 2000 года. [207] ведется веб-страница, посвященная стипендии Уоллеса В Университете Западного Кентукки . [208] В книге 2010 года защитник окружающей среды Тим Флэннери утверждал, что Уоллес был «первым современным ученым, который понял, насколько важно сотрудничество для нашего выживания», и предположил, что понимание Уоллесом естественного отбора и его более поздние работы по атмосфере следует рассматривать как предшественника. современному экологическому мышлению. [209] Коллекция его медалей, включая Орден «За заслуги», была продана на аукционе за 273 000 фунтов стерлингов в 2022 году. [210]

Празднование столетия [ править ]

Музей естественной истории в Лондоне координировал памятные мероприятия по случаю столетия Уоллеса во всем мире в рамках проекта «Wallace100» в 2013 году. [211] [212] 24 января его портрет был открыт в главном зале музея Биллом Бейли , ярым поклонником. [213] Бейли также поддержал Уоллеса в своем сериале BBC Two 2013 года «Герой джунглей Билла Бейли». [214] 7 ноября 2013 года, в 100-летие со дня смерти Уоллеса, сэр Дэвид Аттенборо открыл в музее статую Уоллеса. [215] Статуя, созданная Энтони Смитом , была подарена Мемориальному фонду А. Р. Уоллеса. [216] На нем Уоллес изображен молодым человеком, собирающим деньги в джунглях. В ноябре 2013 года состоялся дебют «Анимированной жизни А. Р. Уоллеса» — анимационного фильма с бумажными марионетками, посвященного столетнему юбилею Уоллеса. [217] Кроме того, в ноябре 2021 года Бейли представил бюст Уоллеса работы Фелисити Кроули на Твин-сквер в Аске , Монмутшир. [218]

Празднование двухсотлетия [ править ]

Празднования 200-летия со дня рождения Уоллеса, отмечаемые в течение 2023 года, варьируются от прогулок натуралистов. [219] на научные конгрессы и презентации. [220] Мероприятие в Гарвардском музее естественной истории в апреле 2023 года также будет включать в себя специальный коктейль, разработанный миксологом в честь наследия Уоллеса. [221]

Мемориалы [ править ]

Гора Уоллес в горном массиве Сьерра-Невада в Калифорнии была названа в его честь в 1895 году. [222] В 1928 году в честь Уоллеса был назван дом в школе Ричарда Хейла (тогда называвшейся Хертфордской гимназией, где он учился). [223] [224] Здание Альфреда Рассела Уоллеса является выдающейся особенностью кампуса Глинтафа в Университете Южного Уэльса , построенного Понтиприддом , с несколькими учебными помещениями и лабораториями для научных курсов. университета . В его честь названы Здание естественных наук в Университете Суонси и лекционный зал Кардиффского [224] как и ударные кратеры на Марсе и Луне . [223] В 1986 году Королевское энтомологическое общество организовало годовую экспедицию в национальный парк Думога-Боун в Северном Сулавеси под названием «Проект Уоллес». [224] Группа индонезийских островов известна как биогеографический регион Уоллеса в его честь, а операция «Уолласеа», названная в честь региона, присуждает «Гранты Альфреда Рассела Уоллеса» студентам-экологам. [225] В честь Уоллеса названо несколько сотен видов растений и животных, как живых, так и ископаемых. [226] например, геккон Cyrtodactylus wallacei . [227] и пресноводный скат Potamotrygon wallacei . [228] Совсем недавно в год двухсотлетия со дня рождения Уоллеса было названо несколько новых видов, в том числе большой паук из Перу , Linothele wallacei Sherwood et al ., 2023. [229] и южноафриканский долгоносик Meregalli Nama wallacei & Borovec, 2023 г. [230]

Сочинения [ править ]

Уоллес был плодовитым писателем. В 2002 году историк науки Майкл Шермер опубликовал количественный анализ публикаций Уоллеса. Он обнаружил, что Уоллес опубликовал 22 полноформатные книги и по меньшей мере 747 более коротких статей, 508 из которых были научными статьями (191 из них опубликованы в журнале Nature ). Далее он разбил 747 коротких статей по основным темам: 29% были по биогеографии и естествознанию, 27% по эволюционной теории, 25% по социальным комментариям, 12% по антропологии и 7% по спиритизму и френологии. [231] Интернет-библиография произведений Уоллеса насчитывает более 750 статей. [34]

Стандартное авторское сокращение Уоллес используется для указания этого человека как автора при цитировании названия ботанического . [232]

Ссылки [ править ]

Примечания [ править ]

- ↑ Хотя сегодня в статус Монмутшира Уэльсе был неоднозначным , некоторые даже считали, что он находится в Англии, с которой он граничит.

Цитаты [ править ]

- ^ Уоллес, Альфред Рассел (1905). Моя жизнь: запись событий и мнений . Добро пожаловать в библиотеку. Лондон: Chapman & Hall, Ld. п. 34.

Я был единственным англичанином, который несколько месяцев прожил один в этой стране....

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Смит, Чарльз Х. «Ответы на часто задаваемые вопросы об Альфреде Расселе Уоллесе» . Пейдж Альфреда Рассела Уоллеса . Проверено 25 мая 2022 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Уоллес, Альфред. «О склонности разновидностей к бесконечному отклонению от исходного типа» . Альфред Рассел Уоллес Пейдж, организованный Университетом Западного Кентукки . Архивировано из оригинала 29 апреля 2007 года . Проверено 22 апреля 2007 г.

- ^ Дарвин и Уоллес 1858 .

- ^ Смит, Чарльз Х. «Альфред Рассел Уоллес: эволюция эволюционного введения» . Пейдж Альфреда Рассела Уоллеса . Проверено 25 мая 2022 г.

- ^ Смит, Чарльз Х. «Обитаем ли Марс?» Альфреда Рассела Уоллеса . Пейдж Альфреда Рассела Уоллеса . Проверено 25 мая 2022 г.

- ^ Уилсон 2000 , с. 1.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Смит, Чарльз Х. «Альфред Рассел Уоллес: капсульная биография» . Пейдж Альфреда Рассела Уоллеса . Проверено 25 мая 2022 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д и Ван Уай, Джон . «Альфред Рассел Уоллес. Биографический очерк» . Уоллес онлайн . Проверено 22 сентября 2022 г.

- ^ Уилсон 2000 , стр. 6–10.

- ^ Raby 2002 , pp. 77–78.

- ^ Слоттен 2004 , стр. 11–14.

- ^ «28. Альфред Рассел Уоллес» . 100 валлийских героев. Архивировано из оригинала 24 января 2010 года . Проверено 23 сентября 2008 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Шермер 2002 , с. 53.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Слоттен 2004 , стр. 22–26.

- ^ Уоллес 1905a , стр. 232–235 , 256 .

- ^ «Нитский механический институт» . Университет Суонси . Архивировано из оригинала 10 ноября 2013 года . Проверено 21 апреля 2013 г.

- ^ Уоллес 1905a , с. 254 .

- ^ Шермер 2002 , с. 65.

- ^ Уоллес 1905a , с. 256 .

- ^ Слоттен 2004 , стр. 26–29.

- ^ Уилсон 2000 , стр. 19–20.

- ^ Слоттен 2004 , стр. 34–37.

- ^ Уоллес 1905a , с. 256 .

- ^ ван Вайе, 2013 , стр. 34–36.

- ^ Уилсон 2000 , с. 36.

- ^ Raby 2002 , pp. 89, 98–99, 120–121.

- ^ Raby 2002 , pp. 89–95.

- ^ Шермер 2002 , стр. 72–73.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Слоттен 2004 , стр. 84–88.

- ^ ван Вайе 2013 , с. 36.

- ^ Уилсон 2000 , с. 45.

- ^ Raby 2002 , p. 148.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Смит, Чарльз Х. «Библиография произведений Альфреда Рассела Уоллеса» . Пейдж Альфреда Рассела Уоллеса . Проверено 25 мая 2022 г.

- ^ ван Вайе, 2013 , стр. 37–40.

- ^ «Письмо WCP3072 - Джеймс Брук Альфреду Расселу Уоллесу, 1 апреля (1853 г.), из Ranger's Lodge, Гайд-парк, Лондон» . Беккалони, GW (редактор), Ɛpsilon: Коллекция Альфреда Рассела Уоллеса . Проверено 13 октября 2022 г.

- ^ «Письмо WCP4308 — Альфреда Рассела Уоллеса Родерику Импи Мерчисону, Королевское географическое общество, июнь 1853 года» . Беккалони, GW (редактор), Ɛpsilon: Коллекция Альфреда Рассела Уоллеса . Проверено 14 октября 2022 г.

- ^ ван Вайе 2013 , с. 41.

- ^ «Альфред Рассел Уоллес, Рассвет великого открытия: «Мои отношения с Дарвином в отношении теории естественного отбора» » . Черное и белое . 17 января 1903 года . Проверено 14 октября 2022 г.

- ^ ван Вайе, 2013 , стр. 41, 46, 54–59.

- ^ «Хронология путешествий Уоллеса по Малайскому архипелагу» . Веб-сайт Альфреда Рассела Уоллеса . 4 апреля 2018 года . Проверено 20 октября 2022 г.

- ^ Уоллес 1869 , с. xiii–xiv .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б ван Вай, Джон (2018). «Помощь Уоллеса: многие люди, которые помогали А. Р. Уоллесу на Малайском архипелаге». Журнал малазийского отделения Королевского азиатского общества . 91 (1). Проект Муза: 41–68. дои : 10.1353/рас.2018.0003 . ISSN 2180-4338 . S2CID 201769115 . pdf в Darwin Online. Архивировано 31 октября 2022 г. в Wayback Machine.

- ^ Шермер 2002 , с. 14.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б ван Вай, Джон; Дрохорн, Геррелл М. (2015). « Я Али Уоллес»: малайский помощник Альфреда Рассела Уоллеса». Журнал малазийского отделения Королевского азиатского общества . 88 : 3–31. дои : 10.1353/ras.2015.0012 . S2CID 159453047 . pdf в Darwin Online. Архивировано 31 октября 2022 г. в Wayback Machine.

- ^ ван Вайе, 2013 , стр. 97, 99–101, 103–105.

- ^ «Летающая лягушка Уоллеса ( Rhacophorus nigropalmatus )» . Веб-сайт Альфреда Рассела Уоллеса . Проверено 20 октября 2022 г.

- ^ Рукмакер, Кес; Уай, Джон ван (2012). «В тени Альфреда Рассела Уоллеса: его забытый помощник Чарльз Аллен (1839–1892)» . Журнал малазийского отделения Королевского азиатского общества . 85 (2 303): 17–54. ISSN 0126-7353 . JSTOR 24894190 . Проверено 24 октября 2022 г. pdf в Darwin Online. Архивировано 31 октября 2022 г. в Wayback Machine.

- ^ ван Вайе 2013 , стр. 133–137.

- ^ ван Вайе, 2013 , стр. 137, 145–147.

- ^ ван Вайе, 2013 , стр. 133–134.

- ^ «Письмо № 1812, меморандум на компакт-диске» . Дарвиновский заочный проект . Декабрь 1855 года . Проверено 30 октября 2022 г.

- ^ «Письмо WCP1703 — Альфред Рассел Уоллес Сэмюэлю Стивенсу из Ампанама, остров Ломбок, 21 августа 1856 года» . Беккалони, GW (редактор), Ɛpsilon: Коллекция Альфреда Рассела Уоллеса . Проверено 30 октября 2022 г.

- ^ ван Вайе, 2013 , стр. 149–151.

- ^ «S31. Уоллес, AR 1857. [Письмо от 21 августа 1856 года, Ломбок]. Зоолог 15 (171–172): 5414–5416» . Уоллес онлайн . Проверено 8 ноября 2022 г. , также «Записки собирателей естественной истории в зарубежных странах», Альфред Рассел Уоллес.

- ^ Браун 2002 , стр. 35–42.

- ^ Слоттен 2004 , стр. 267.

- ^ «Историческое значение» . Зоологический музей Кембриджского университета . 18 апреля 2009 года. Архивировано из оригинала 19 ноября 2010 года . Проверено 13 марта 2013 г.

- ^ Шермер 2002 , стр. 151–152.

- ^ Слоттен 2004 , стр. 249–258.

- ^ Слоттен 2004 , стр. 235.

- ^ ван Вайе 2013 , с. 210.

- ^ Шермер 2002 , с. 156.

- ^ Слоттен 2004 , стр. 239–240.

- ^ Слоттен 2004 , стр. 265–267.

- ^ Слоттен 2004 , стр. 299–300.

- ^ Слоттен 2004 , стр. 325.

- ^ Слоттен 2004 , стр. 361–364.

- ^ Уоллес, Альфред Рассел (1906). Национализация земли; Его необходимость и его цели . Лебединый Зонненшайн.

- ^ Слоттен 2004 , стр. 365–372.

- ^ Слоттен 2004 , стр. 436.

- ^ Стэнли, Будер (1990). Провидцы и планировщики: движение «Город-сад» и современное сообщество . Издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 20. ISBN 978-0195362886 .

- ^ Слоттен 2004 , стр. 436–438.

- ^ Уоллес, Альфред Рассел. «Человеческий отбор (S427:1890)» . Пейдж Альфреда Рассела Уоллеса . Проверено 25 мая 2022 г.

- ^ Сайни, Анжела (2019). Превосходство: возвращение расовой науки . Бостон. п. 66. ИСБН 978-0-8070-7691-0 . OCLC 1091260230 .

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: отсутствует местоположение издателя ( ссылка ) - ^ Уоллес, Альфред Рассел. «Бумажные деньги как стандарт стоимости (S557: 1898)» . Пейдж Альфреда Рассела Уоллеса . Проверено 25 мая 2022 г.

- ^ Слоттен 2004 , стр. 366, 453, 487–488.

- ^ Шермер 2002 , стр. 23, 279.

- ^ Уоллес, Альфред Рассел. «Причины войны и средства правовой защиты (S567: 1899)» . Пейдж Альфреда Рассела Уоллеса . Проверено 25 мая 2022 г.

- ^ Уоллес, Альфред Рассел. «Летающие машины на войне. (С670:1909)» . Пейдж Альфреда Рассела Уоллеса . Проверено 25 мая 2022 г.

- ^ Слоттен 2004 , стр. 453–455.

- ^ Уоллес, Альфред Рассел (1903) [1898]. Чудесный век: его успехи и неудачи . Лебединый Зонненшайн. OCLC 935283134 .

- ^ Уоллес, Альфред Рассел. «Восстание демократии (S734: 1913)» . Пейдж Альфреда Рассела Уоллеса . Проверено 25 мая 2022 г.

- ^ Шермер 2002 , стр. 274–278.

- ^ Слоттен 2004 , стр. 379–400.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Слоттен 2004 , стр. 490.

- ^ Анон (8 октября 1911 г.). «Нас охраняют духи, — заявляет доктор А. Р. Уоллес» . Нью-Йорк Таймс .

- ^ Слоттен 2004 , стр. 491.

- ^ Холл, Арканзас (1966). Ученые аббатства . Роджер и Роберт Николсон. п. 52. ОСЛК 2553524 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Ларсон 2004 , с. 73.

- ^ Боулер и Морус 2005 , с. 141.

- ^ Макгоуэн 2001 , стр. 101, 154–155.

- ^ Ларсон 2004 , стр. 23–24, 37–38.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Шермер 2002 , с. 54.

- ^ Слоттен 2004 , стр. 31.

- ↑ Семейный архив Уоллеса, 11 октября 1847 г., цитируется в Raby 2002 , стр. 1.

- ^ Слоттен 2004 , стр. 94.

- ^ «Коллекция Уоллеса - документ Уоллеса о законе Саравака» . Музей естественной истории . 2012 . Проверено 14 февраля 2012 г.

- ^ Уоллес, Альфред Рассел (1855). «О законе, регулирующем интродукцию видов» . Университет Западного Кентукки . Архивировано из оригинала 28 апреля 2007 года . Проверено 8 мая 2007 г.

- ^ Десмонд и Мур 1991 , с. 438.

- ^ Браун 1995 , стр. 537–546.

- ^ Уоллес 1905a , с. 361.

- ^ Слоттен 2004 , стр. 144–145.

- ^ Хейдж, CJ (2011). Биографические заметки Антони Августа Брюйна (1842–1890) . Богор: IBP Press. ISBN 978-979-493-294-0 .

- ^ Уоллес 1905a , стр. 361–362.

- ^ «Медаль Дарвина-Уоллеса» . Веб-сайт Уоллеса .

- ^ Маршан 1916 , с. 105 .

- ^ Дарвин 2009 , с. 95 .

- ^ Дарвин 2009 , с. 108 .

- ^ Слоттен 2004 , стр. 153–154.

- ^ Дарвин 2009 , с. 116 .

- ^ Браун 2002 , стр. 33–42.

- ^ Шермер 2002 , стр. 148–150.

- ^ Браун 2002 , стр. 40–42.

- ^ Браун, Джанет (2013). «Уоллес и Дарвин» (PDF) . Современная биология . 23 (24): Р1071–Р1072. дои : 10.1016/j.cub.2013.10.045 . ПМИД 24501768 . S2CID 4281426 .

- ^ Слоттен 2004 , стр. 157–162.

- ^ Шермер 2002 , Глава 5: «Джентльменское соглашение: Альфред Рассел Уоллес, Чарльз Дарвин и спор о научном приоритете» .

- ^ Смит, Чарльз Х. «Ответы на часто задаваемые вопросы об Уоллесе: действительно ли Дарвин украл материал у Уоллеса, чтобы завершить свою теорию естественного отбора?» . Альфред Рассел Уоллес Пейдж, организованный Университетом Западного Кентукки . Архивировано из оригинала 9 мая 2008 года . Проверено 29 апреля 2008 г.

- ^ ван Уай, Джон ; Рукмакер, Кес (2012). «Новая теория, объясняющая получение Дарвином тройного эссе Уоллеса в 1858 году». Биологический журнал Линнеевского общества . 105 : 249–252. дои : 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2011.01808.x .

- ^ Болл, Филип (12 декабря 2011 г.). «Расписания поставок опровергают обвинения Дарвина в плагиате» . Природа . дои : 10.1038/nature.2011.9613 . S2CID 178946874 .

- ^ Слоттен 2004 , стр. 197–199.

- ^ Уоллес, Альфред. «Творение по закону (S140:1867)» . Альфред Рассел Уоллес Пейдж, организованный Университетом Западного Кентукки . Архивировано из оригинала 2 июня 2007 года . Проверено 23 мая 2007 г.

- ^ Слоттен 2004 , стр. 261.

- ^ Кучера, Ульрих (19 декабря 2003 г.). «Сравнительный анализ статей Дарвина-Уоллеса и развитие концепции естественного отбора». Теория в биологических науках . 122 (4): 343–59. дои : 10.1007/s12064-003-0063-6 . S2CID 24297627 .

- ^ Ларсон 2004 , с. 75.

- ^ Боулер и Морус 2005 , с. 149.

- ^ Боулер 2013 , стр. 61–63.

- ^ Коттлер, Малькольм (1985). «Чарльз Дарвин и Альфред Рассел Уоллес: Два десятилетия дебатов о естественном отборе». В Коне, Дэвид Кон (ред.). Дарвиновское наследие . Издательство Принстонского университета . стр. 367–432. ISBN 978-0691083568 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Смит, Чарльз Х. (2004). «Неоконченное дело Уоллеса» . Сложность . 10 (2). дои : 10.1002/cplx.20062 .

- ^ Брэнд, Стюарт. «Ради бога, Маргарет» . CoEvolutionary Quarterly, июнь 1976 г. Архивировано из оригинала 15 апреля 2007 г. Проверено 4 апреля 2007 г.

- ^ Слоттен 2004 , стр. 251–254.

- ^ Смит, Фредерик (1867). «4 марта 1867 года». Труды Лондонского королевского энтомологического общества . 15 (7): 509–566. дои : 10.1111/j.1365-2311.1967.tb01466.x .

- ^ Слоттен 2004 , стр. 253–254.

- ^ Слоттен 2004 , стр. 353–356.

- ^ Уоллес, Альфред Рассел (24 июля 1890 г.). «[Обзор] Цвета животных» . Природа . 42 (1082): 289–291. Бибкод : 1890Natur..42..289W . дои : 10.1038/042289a0 . S2CID 27117910 .

- ^ Уоллес, Альфред Рассел. «Цвета животных» . Пейдж Альфреда Рассела Уоллеса . Проверено 25 мая 2022 г.