Odaenathus

| Odaenathus 𐡠𐡣𐡩𐡮𐡶 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| King of Palmyra King of Kings of the East (Western Aramaic: Mlk Mlk dy Mdnh) | |||||

| |||||

| King of Kings of the East | |||||

| Reign | 263–267 | ||||

| Predecessor | Title created | ||||

| Successor | Vaballathus | ||||

| Co-ruler | Hairan I | ||||

| King of Palmyra | |||||

| Reign | 260–267 | ||||

| Predecessor | Himself as Ras of Palmyra | ||||

| Successor | Vaballathus | ||||

| Ras (lord) of Palmyra | |||||

| Reign | 240s–260 | ||||

| Predecessor | Office established | ||||

| Successor | Himself as King of Palmyra | ||||

| Born | c. 220 Palmyra, Roman Syria | ||||

| Died | 267 (aged 46–47) Heraclea Pontica (modern-day Karadeniz Ereğli, Turkey), or Emesa (modern-day Homs, Syria) | ||||

| Spouse | Zenobia | ||||

| Issue | Hairan I (Herodianus) Vaballathus Hairan II | ||||

| |||||

| House | House of Odaenathus | ||||

| Father | Hairan | ||||

Septimius Odaenathus (Palmyrene Aramaic: 𐡠𐡣𐡩𐡮𐡶, ʾŌdainaṯ; Arabic: أذينة, romanized: Uḏaina; c. 220 – 267) was the founder king (Mlk) of the Palmyrene Kingdom who ruled from Palmyra, Syria. He elevated the status of his kingdom from a regional center subordinate to Rome into a formidable state in the Near East. Odaenathus was born into an aristocratic Palmyrene family that had received Roman citizenship in the 190s under the Severan dynasty. He was the son of Hairan, the descendant of Nasor. The circumstances surrounding his rise are ambiguous; he became the lord (ras) of the city, a position created for him, as early as the 240s and by 258, he was styled a consularis, indicating a high status in the Roman Empire.

The defeat and captivity of Emperor Valerian at the hands of the Sassanian emperor Shapur I in 260 left the eastern Roman provinces largely at the mercy of the Persians. Odaenathus remained on the side of Rome; assuming the title of king, he led the Palmyrene army, fell upon the Persians before they could cross the Euphrates to the eastern bank, and inflicted upon them a considerable defeat.[1] He took the side of Emperor Gallienus, the son and successor of Valerian, who was facing the attempted usurpation of Fulvius Macrianus. The rebel declared his sons emperors, leaving one in Syria and taking the other with him to Europe. Odaenathus attacked the remaining usurper and quelled the rebellion. He was rewarded with many exceptional titles by the Emperor, who formalized his self-established position in the East. In reality, the Emperor may have done little but accept the declared nominal loyalty of Odaenathus.

In a series of rapid and successful campaigns starting in 262, Odaenathus crossed the Euphrates and recovered Carrhae and Nisibis. He then took the offensive into the heartland of Persia, and arrived at the walls of its capital, Ctesiphon.[1] The city withstood the short siege but Odaenathus reclaimed the entirety of the Roman lands occupied by the Persians since the beginning of their invasions in 252. Odaenathus celebrated his victories and declared himself "King of Kings", crowning his son Herodianus as co-king. By 263, Odaenathus was in effective control of the Levant, Roman Mesopotamia and Anatolia's eastern region.

Odaenathus observed all due formalities towards the Emperor, but in practice ruled as an independent monarch. In 266, he launched a second invasion of Persia but had to abandon the campaign and head north to Bithynia to repel the attacks of Germanic raiders besieging the city of Heraclea Pontica. He was assassinated in 267 during or immediately after the Anatolian campaign, together with Herodianus. The identities of the perpetrator or the instigator are unknown and many stories, accusations and speculations exist in ancient sources. He was succeeded by his son Vaballathus under the regency of his widow Zenobia, who used the power established by Odaenathus to forge the Palmyrene Empire in 270.

Name, family and appearance

[edit]"Odaenathus" is the Latin transliteration of the king's name;[note 1][2] he was born Septimius Odainat in c. 220.[note 2][4] His name is written in transliterated Palmyrene as Sptmyws ʾDynt.[5][6] "Sptmyws" (Septimius), which means "born in September",[7] was Odaenathus' family gentilicium (Roman surname), adopted as an expression of loyalty to the Roman Severan dynasty and the emperor Septimius Severus who had granted the family Roman citizenship in the late second century.[8][9] ʾDynt (Odainat) is the Palmyrene diminutive for ear, related to Uḏaina in Arabic and 'Ôden in Aramaic.[10][6] Odaenathus' genealogy is known from a stone block in Palmyra with a sepulchral inscription that mentions the building of a tomb and records the genealogy of the builder: Odaenathus, son of Hairan, son of Wahb Allat, son of Nasor.[11][12] In Rabbinic sources, Odaenathus is named "Papa ben Nasor" (Papa son of Nasor);[note 3][15] the meaning of the name "Papa" and how Odaenathus earned it is unclear.[note 4][15]

The King appears to be of mixed Arab and Aramean descent:[17] his name, the name of his father, Hairan, and that of his grandfather, Wahb-Allat, are Arabic;[18][19] while Nasor, his great-grandfather, has an Aramaic name.[20] Nasor might not have been the great-grandfather of Odaenathus, but a more distant ancestor;[21] the archaeologist Frank Edward Brown considered Nasor to be Odaenathus' great-great or great-great-great grandfather.[22] This has led some scholars, such as Lisbeth Soss Fried and Javier Teixidor, to consider the origin of the family to be Aramean.[23][20] In practice, the citizenry of Palmyra were the result of Arab and Aramaean tribes merging into a unity with a corresponding consciousness; they thought and acted as Palmyrenes.[19][24]

The fifth-century historian Zosimus asserted that Odaenathus descended from "illustrious forebears",[note 5][20] but the position of the family in Palmyra is debated; it was probably part of the wealthy mercantile class.[29] Alternatively, the family may have belonged to the tribal leadership which amassed a fortune as landowners and patrons of the Palmyrene caravans.[note 6][17] The historians Franz Altheim and Ruth Stiehl suggested that Odaenathus was part of a new elite of Bedouins driven from their home east of the Euphrates by the aggressive Sassanian dynasty after 220.[31][32] However, it is certain that Odaenathus came from a family which had belonged to the upper class of the city for several generations;[33] in Dura-Europos, a relief dated to 159/158 (470 of the Seleucid era, SE) was commissioned by Hairan son of Maliko son of Nasor.[note 7][16] This Hairan might have been the head of the Palmyrene trade colony in Dura-Europos and probably belonged to the same family as Odaenathus.[35][36] According to Brown, it is plausible, based on the occurrence of the name Nasor in both Dura-Europos and Palmyra (where it was a rare name), that Odaenathus and Hairan son of Maliko belonged to the same family.[22]

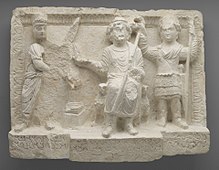

No definite images of Odaenathus have been discovered, hence, there is no information about his appearance; all sculptures identified as Odaenathus lack any inscriptions to confirm whom they represent.[37] Two sculpted heads from Palmyra, one preserved in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek museum and the other in the Archaeological Museum in Istanbul, were identified by the archaeologist Harald Ingholt as representing Odaenathus based on their monumentality and regal style.[38] The academic consensus does not support Ingholt's view,[39][40] and the heads he ascribed to the king can be dated to the end of the second century.[41] More likely, two marble heads, one depicting a man wearing a royal tiara, the crown of Palmyra, and the other depicting a man in a royal Hellenistic diadem, are depictions of the king.[42] In addition, a Palmyrene clay tessera, depicting a bearded man wearing a diadem, could be a portrait of the king.[43]

Odaenathus I

[edit]Traditional scholarship, based on the sepulchral inscription from Odaenathus' tomb, believed the builder to be an ancestor of the king and he was given the designation "Odaenathus I".[note 8][46] The name of King Odaenathus' father is Hairan as attested in many inscriptions.[47] In an inscription dated to 251, the name of the ras ("lord") of Palmyra, Hairan, son of Odaenathus, is written,[48] and he was thought to be the son of Odaenathus I.[46] Prior to the 1980s, the earliest known inscription attesting King Odaenathus was dated to 257, leading traditional scholarship to believe that Hairan, ras of Palmyra, was the father of the king and that Odaenathus I was his grandfather.[note 9][46][50] However, an inscription published in 1985 by the archaeologist Michael Gawlikowski and dated to 252 mentions King Odaenathus as a ras and records the same genealogy found in the sepulchral inscription, confirming the name of King Odaenathus' grandfather as Wahb Allat;[46] thus, he cannot be a son of Hairan son of Odaenathus (I).[21][51] Therefore, it is certain that King Odaenathus was the builder of the tomb, ruling out the existence of "Odaenathus I".[note 10][45][46] The ras Hairan mentioned in the 251 inscription is identical with Odaenathus' elder son and co-ruler, Prince Hairan I.[46][53]

Rise

[edit]Palmyra was an autonomous city within the Roman Empire, subordinate to Rome and part of the province of Syria Phoenice.[54] Odaenathus descended from an aristocratic family, albeit not a royal one as the city was ruled by a council and had no tradition of hereditary monarchy.[55][56][57] For most of its existence, the Palmyrene army was decentralized under the command of several generals,[58] but the rise of the Sassanian Empire in 224, and its incursions, which affected Palmyrene trade,[59] combined with the weakness of the Roman Empire, probably prompted the Palmyrene council to elect a lord for the city in order for him to lead a strengthened army:[29][58][60]

Ras of Palmyra

[edit]The Roman emperor, Gordian III, died in 244 during a campaign against Persia and this might have been the event which led to the election of a lord for Palmyra to defend it: Odaenathus,[61] whose elevation, according to the historian Udo Hartmann, can be explained by Odaenathus probably being a successful military or caravan commander, and his descent from one of the most influential families in the city.[62] Odaenathus' title as lord was ras in Palmyrene and exarchos in Greek as revealed by bilingual inscriptions from Palmyra.[note 11][65] The ras title enabled the bearer to effectively deal with the Sassanid threat, in that it probably vested in him supreme civil and military authority;[note 12][58] an undated inscription refers to Odaenathus as a ras and records the gift of a throne to him by a Palmyrene citizen named "Ogeilu son of Maqqai Haddudan Hadda", which confirms the supreme character of Odaenathus' title.[61] The office was created for Odaenathus,[58] and was not a usual title in the Roman Empire, and not a part of Palmyrene government traditions.[61][68]

Hairan I was apparently elevated to co-lordship by his father, as an inscription from 251 testifies.[64] As early as the 240s, Odaenathus bolstered the Palmyrene army, recruiting desert nomads and increasing the number of the Palmyrene heavy cavalry (clibanarii).[58][70] In 252, the Persian emperor, Shapur I, started a full-scale invasion of the Roman provinces in the east.[71][72] During the second campaign of the invasion, Shapur I conquered Antioch on the Orontes, the traditional capital of Syria,[73] and headed south, where his advance was checked in 253 by a noble from Emesa, Uranius Antoninus.[74] The events of 253 were mentioned in the works of the sixth-century historian John Malalas who also mentioned a leader by the name "Enathus" inflicting a defeat upon the retreating Shapur I near the Euphrates.[74] "Enathus" is probably identical with Odaenathus,[75] and while Malalas' account indicates that Odaenathus defeated the Persians in 253,[76] there is no proof that the Palmyrene leader engaged Shapur I before 260 and Malalas' account seems to be confusing Odaenathus' future actions during 260 with the events of 253.[77]

Shapur I destroyed the Palmyrene trade colonies along the Euphrates, including the colonies at Anah in 253 and at Dura-Europos in 256.[78] The sixth-century historian Peter the Patrician wrote that Odaenathus approached Shapur I to negotiate Palmyrene interests but was rebuffed and the gifts sent to the Persians were thrown into the river.[74][75][79] The date for the attempted negotiations is debated: some scholars, including John F. Drinkwater, set the event in 253; while others, such as Alaric Watson, set it in 256, following the destruction of Dura-Europos.[63][75]

Governor of Syria Phoenice

[edit]Several inscriptions dating to the end of 257 or early 258 show Odaenathus bearing the Greek title ὁ λαμπρότατος ὑπατικός (ho lamprótatos hupatikós; Latin: clarissimus consularis).[49][76][80] This title was usually bestowed on Roman senators who held the consulship.[80] The title was also mentioned in Odaenathus' undated tomb inscription and Hairan I was mentioned with the same title in the 251 inscription.[81] Scholarly opinions vary on the exact date of Odaenathus' elevation to this position.[61] Gawlikowski and the linguist Jean Starcky maintained that the senatorial rank predates the ras elevation.[81] Hartmann concluded that Odaenathus first became a ras in the 240s, then a senator in 250.[81] Another possibility is that the senatorial rank and lordship occurred simultaneously; Odaenathus was chosen as a ras following Gordian's death, then, after Emperor Philip the Arab concluded a peace treaty with the Persians, the Emperor ratified Odaenathus' lordship and admitted him to the senate to guarantee Palmyra's continued subordination.[61]

The clarissimus consularis title could be a mere honorific or a sign that Odaenathus was appointed as the legatus of Phoenice.[66][82] However, the title (ὁ λαμπρότατος ὑπατικός) was sometimes used in Syria to denote the provincial governor and the archaeologist William Waddington proposed that Odaenathus was indeed the governor of Phoenice.[note 14][49][20] Five of the inscriptions mentioning Odaenathus as consul are dated to 569 SE (258) during which no governor for Phoenice is attested, which might indicate that this was Odaenathus' year of governorship.[83] In Phoenice's capital city Tyre, the lines "To Septimius Odaenathus, the most illustrious. The Septimian colony of Tyre" were found inscribed on a marble base;[83][84] the inscription is not dated and if it was made after 257 then it indicates that Odaenathus was appointed as the governor of the province.[83] These speculations cannot be proven, but as a governor Odaenathus would have been the highest authority in the province, above legionary commanders and provincial officials; this would make him commander of the Roman forces in the province.[83] Whatever the case may be, starting from 258 Odaenathus strengthened his position and extended his political influence in the region.[66] By 260, Odaenathus held the rank, credibility and power to pacify the Roman East following the Battle of Edessa.[83]

Reign

[edit]

Faced with Shapur I's third campaign,[85] the Roman emperor Valerian marched against the Persian monarch but was defeated near Edessa in late spring 260 and taken prisoner.[86] The Persian emperor then ravaged Cappadocia and Cilicia, and claimed to have captured Antioch on the Orontes.[note 15][87] Taking advantage of the situation, Fulvius Macrianus, the commander of the imperial treasury, declared his sons Quietus and Macrianus Minor as joint emperors in August 260, in opposition to Valerian's son Gallienus.[note 16][88] Fulvius Macrianus took Antioch on the Orontes as his center and organized the resistance against Shapur I; he dispatched Balista, his praetorian prefect, to Anatolia.[88] Shapur I was defeated in the region of Sebaste at Pompeiopolis, prompting the Persians to evacuate Cilicia while Balista returned to Antioch on the Orontes.[50][88][89] Balista's victory was only partial: Shapur I withdrew east of Cilicia, which Persian units continued to occupy.[90] A Persian force took advantage of Balista's return to Syria and headed further west into Anatolia.[88] According to the Augustan History, Odaenathus was declared king of Palmyra as soon as the news of the Roman defeat at Edessa reached the city.[91] It is not known if Odaenathus contacted Fulvius Macrianus and there is no evidence that he took orders from him.[92]

Persian war of 260 and pacifying Syria

[edit]Odaenathus assembled the Palmyrene army and Syrian peasants, then marched north to meet the Persian emperor, who was returning to Persia.[note 17][78][92] The Palmyrene monarch fell upon the retreating Persian army between Samosata and Zeugma, west of the Euphrates, in late summer 260.[note 18][92][97] He defeated the Persians, expelling Shapur I from the province of Syria.[92] In early 261, Fulvius Macrianus headed to Europe accompanied by Macrianus Minor, leaving Quietus and Balista in Emesa.[92] Odaenathus' whereabouts during this episode are not clear; he could have distributed the army in garrisons along the frontier or might have brought it back to his capital.[79] The Palmyrene monarch seems to have waited until the situation clarified, declaring loyalty to neither Fulvius Macrianus nor Gallienus.[79] In the spring of 261, Fulvius Macrianus arrived in the Balkans but was defeated and killed along with Macrianus Minor; Odaenathus, when it became clear that Gallienus would eventually win, sided with the Emperor and marched on Emesa, where Quietus and Balista were staying. The Emesans killed Quietus as Odaenathus approached the city,[79] while Balista was captured and executed by the King in autumn 261.[84][98]

Ruler of the East

[edit]The elimination of the usurpers left Odaenathus as the most powerful leader in the Roman East.[79] He was granted many titles by the Emperor but those honors are debated among scholars:[99]

- Dux Romanorum (commander of the Romans) was probably given to Odaenathus to recognize his position as the commander in chief of the forces in the east against the Persians; it was inherited by Odaenathus' son and successor Vaballathus.[100]

- Corrector totius orientis (righter of the entire East): it is generally accepted by modern scholars that he bore this title.[101] A corrector had overall command of Roman armies and authority over provincial governors in his designated region.[102][103] There are no known attestations of the title during Odaenathus' lifetime.[101] Evidence for the King bearing the title consists of two inscriptions in Palmyrene: one posthumous dedication describing him as MTQNNʿ of the East (derived from the Semitic root TQN, meaning to set in order);[note 19] and the other describing his heir Vaballathus with the same title, albeit using the word PNRTTʿ instead of MTQNNʿ.[102][105]

- However, the sort of authority accorded by this position is widely debated.[102] The problem arises from the word MTQNNʿ; its exact meaning is unclear.[105] The word is translated into Latin as corrector, but "restitutor" is another possible translation; the latter title was an honorary one meant to praise the bearer for driving enemies out of Roman territories.[105] However, the inscription of Vaballathus is clearer, as the word PNRTTʿ is not a Palmyrene word but a direct Palmyrene translation of the Greek term Epanorthotes, which is usually an equivalent to a corrector.[105]

- According to the historian David Potter, Vaballathus inherited his father's exact titles.[102] Hartmann points out that there have been cases where a Greek word was translated directly to Palmyrene and a Palmyrene equivalent was also used to mean the same thing.[105] The dedication to Odaenathus would be the use of a Palmyrene equivalent, while the inscription of Vaballathus would be the direct translation.[102] It cannot be certain that Odaenathus was a corrector.[105]

- Imperator totius orientis (commander-in-chief of the entire East): only the Augustan History claims that Odaenathus was given this title; the same source also claims that he was made an Augustus, or co-emperor, following his defeat of the Persians.[99] Both claims are dismissed by scholars.[99] Odaenathus seems to have been acclaimed as imperator by his troops, which was a salutation usually reserved for the Roman emperor; this acclamation might explain the erroneous reports of the Augustan History.[106]

Regardless of his titles, Odaenathus controlled the Roman East with the approval of Gallienus, who could do little but formalize Odaenathus' self-achieved status and settle for his formal loyalty.[note 20][108][109] Odaenathus' authority extended from the Pontic coast in the north to Palestine in the south.[110] This area included the Roman provinces of Syria, Phoenice, Palaestina, Arabia, Anatolia's eastern regions and, following the campaign of 262, Osroene and Mesopotamia.[110][111][112]

First Persian campaign 262

[edit]Perhaps driven by a desire to take revenge for the destruction of Palmyrene trade centers and to discourage Shapur I from initiating future attacks, Odaenathus launched an offensive against the Persians.[113] The suppression of Fulvius Macrianus' rebellion probably prompted Gallienus to entrust the Palmyrene monarch with the war in Persia and Roman soldiers were in the ranks of Odaenathus' army for this campaign.[91] In the spring of 262, the King marched north into the occupied Roman province of Mesopotamia, driving out the Persian garrisons and recapturing Edessa and Carrhae.[114][115] The first onslaught was aimed at Nisibis, which Odaenathus regained but sacked, since the inhabitants had been sympathetic towards the Persian occupation.[115] A little later he destroyed the Jewish city of Nehardea, 45 kilometres (28 mi) west of the Persian capital Ctesiphon,[note 21][118] as he considered the Jews of Mesopotamia to be loyal to Shapur I.[119] By late 262 or early 263, Odaenathus stood outside the walls of the Persian capital.[120]

The exact route taken by Odaenathus from Palmyra to Ctesiphon remains uncertain; it was probably similar to the route Emperor Julian took in 363 during his campaign against Persia.[121] If he did use this route, Odaenathus would have crossed the Euphrates at Zeugma then moved east to Edessa followed by Carrhae then Nisibis. Here, he would have descended south along the Khabur River to the Euphrates valley and then marched along the river's left bank to Nehardea.[121] He then penetrated the Sassanian province of Asōristān and marched along the royal canal Naarmalcha towards the Tigris, where the Persian capital stood.[121]

Once at Ctesiphon, Odaenathus immediately began a siege of the well-fortified winter residence of the Persian kings; severe damage was inflicted upon the surrounding areas during several battles with Persian troops.[120] The city held out and the logistical problems of fighting in enemy territory probably prompted the Palmyrenes to lift the siege.[120] Odaenathus headed north along the Euphrates carrying with him numerous prisoners and much booty.[120] The invasion resulted in the full restoration of the Roman lands which had been occupied by Shapur I since the beginning of his invasions in 252: Osroene and Mesopotamia.[note 22][111][123] However, Dura-Europus and other Palmyrene posts south of Circesium, such as Anah, were not rebuilt.[114] Odaenathus sent the captives to Rome, and by the end of 263 Gallienus assumed the title Persicus maximus ("the great victor in Persia") and held a triumph in Rome.[124]

King of Kings of the East

[edit]In 263, after his return, Odaenathus assumed the title of King of Kings of the East (Mlk Mlk dy Mdnh),[note 23] and crowned his son Herodianus (Hairan I) as co-King of Kings.[126][127] A statue was erected and dedicated for Herodianus to celebrate his coronation by Septimius Worod, the duumviri (magistrate) of Palmyra, and Julius Aurelius, the Queen's procurator (treasurer). The dedication, in Greek, is undated,[128] but Septimius Worod was a duumviri between 263 and 264. Hence, the coronation took place c. 263.[note 24][130] Contemporary evidence for Odaenathus bearing the title of King of Kings is lacking; all firmly dated inscriptions attesting Odaenathus with the title were commissioned after his death, including one that is dated to 271.[51][78] However, Herodianus died with his father,[131] and since he is directly attested as "King of Kings" during his father's lifetime, it is unimaginable that Odaenathus was simply a king while his son was the King of Kings.[132][133] An undated inscription, written in Greek and difficult to decipher, found on a stone reused in the Palmyrene Camp of Diocletian, addresses Odaenathus as King of Kings (Rex regum) and was probably set during his reign.[134]

According to the dedication, Herodianus was crowned near the Orontes, which indicates a ceremony taking place in Antioch on the Orontes, the metropolis of Syria.[note 25][128] The title was a symbol of legitimacy in the East, dating back to the Assyrians, then the Achaemenids, who used it to symbolize their supremacy over all other rulers; it was later adopted by the Parthian monarchs to legitimize their conquests.[135] The first Sassanian monarch, Ardashir I, adopted the title following his victory over the Parthians.[136] Odaenathus' son was crowned with a diadem and a tiara; the choice of Antioch on the Orontes was probably meant to demonstrate that the Palmyrene monarchs were now the successors of the Seleucid and Iranian rulers who had controlled Syria and Mesopotamia in the past.[127]

Relation with Rome

[edit]

In analyzing the rise of Odaenathus and his complicated relationship with Rome, the historian Gary K. Young concluded that "to search for any kind of regularity or normality in such a situation is clearly pointless".[137] In practice, Palmyra became an allied kingdom of Rome, but legally, it remained part of the empire. The "King of Kings" title was probably not aimed at the position of the Roman emperor but at Shapur I; Odaenathus was declaring that he, not the Persian monarch, was the legitimate King of Kings of the East.[138] Odaenathus' intentions are questioned by some historians, such as Drinkwater, who attributed the attempted negotiations with Shapur I to Odaenathus' quest for power.[75] However, in contrast to the norm of this period when powerful generals frequently proclaimed themselves emperors, Odaenathus chose not to attempt to usurp Gallienus' throne.[139]

The relationship between Odaenathus and the Emperor should be understood from two different perspectives: Roman and Syrian. In Rome, broad power delegation by the Emperor to an individual from outside the imperial family was not considered a problem;[140] such authority had been granted several times since the days of Augustus in the first century.[141] The Syrian perspective was different:[140] according to Potter, the dedication celebrating Herodianus' coronation on the Orontes should be interpreted to mean a "Palmyrene claim to kingship in Syria" and control over it during the reign of Odaenathus.[142] What the central government thought of such claims is unclear, but it is doubtful that Gallienus recognized the situation as the Palmyrenes understood it.[141] In the Roman Empire's hierarchical system, a vassal king using the title of King of Kings did not indicate that he was a peer of the Emperor or that the ties of vassalage were cut.[143] Such different understandings eventually led to the conflict between Rome and Palmyra during the reign of Zenobia, who considered her husband's Roman offices hereditary and an expression of independent authority.[note 26][144]

The King had effective control over the Roman East where his military authority was absolute.[108][145] Odaenathus respected Gallienus' authority to appoint provincial governors,[145] but dealt swiftly with opposition: the Anonymus post Dionem, usually associated with the sixth-century historian Eustathius of Epiphania or Peter the Patrician,[44] mentions the story of Kyrinus, or Quirinus, a Roman official, who showed dissatisfaction with Odaenathus' authority over the Persian frontier, and was immediately executed by the King.[note 27][146][96][147] In general, Odaenathus' actions were connected to his and Palmyra's interests only. His support of Gallienus and his Roman titles did not hide the Palmyrene base of his power and the local origin of his armies, as with his decision not to wait for the Emperor to help in 260.[82][106] Odaenathus' status seems to have been, as Watson puts it, "something between powerful subject, independent vassal king and rival emperor".[106]

Administration and royal image

[edit]

Odaenathus behaved as a sovereign monarch;[148] outside his kingdom of Palmyra, he had overall administrative and military authority over the provincial governors of the Roman eastern provinces.[149] Inside Palmyra, no Roman provincial official had any authority; the King filled the government with Palmyrenes.[150] In parallel to the Iranian practice of making the government a family enterprise, Odaenathus bestowed his own gentilicium (Septimius) upon his leading generals and officials such as Zabdas, Zabbai and Worod.[note 28][150] Most Palmyrene constitutional institutions continued to function normally during Odaenathus' reign;[102] he maintained many civic establishments,[66][152] but the last magistrates were elected in 264,[59] and the Palmyrene council was not attested after that year. After this year, a governor, Septimius Worod, was appointed by the King for the city of Palmyra,[153] who also functioned as a viceroy when Odaenathus was on campaign.[154]

A lead token depicting Herodianus shows him wearing a tiara crown shaped like that of the Parthian monarchs, so it must have been Odaenathus' crown;[155] this combination of imagery, together with the "King of Kings" title, indicates that Odaenathus considered himself the rival of the Sassanians and the protector of the region against them.[156] Many intellectuals relocated to Palmyra and enjoyed the King's patronage;[157] most prominently Cassius Longinus, who probably arrived in the 260s.[158] It is possible that Odaenathus influenced local writers to promote his rule;[159] a prophecy in the thirteenth Sibylline Oracle, written after the events it "prophesied",[160] reads: "Then shall come one who was sent by the sun [i.e., Odaenathus], a mighty and fearful lion, breathing much flame. Then he with much shameless daring will destroy ... the greatest beast – venomous, fearful and emitting a great deal of hisses [i.e., Shapur I]".[161] The authority of Odaenathus did not appease all factions in Syria and the glorification of the King in the oracle could be a politically sponsored propaganda aimed at expanding Odaenathus' support.[note 29][159] Another writer in the Palmyrene court, Nicostratus of Trebizond, probably accompanied the King on his campaigns and wrote a history of the period, starting with Philip the Arab and ending shortly before Odaenathus' death.[162] According to Potter, Nicostratus' account was meant to glorify Odaenathus and demonstrate his superiority over the Roman Emperor.[163]

Coinage

[edit]

Odaenathus minted coinage only in the name of Gallienus,[164] and produced no coins bearing his own image.[102] The engraver Hubertus Goltzius forged coins of Odaenathus in the sixteenth century;[165] according to the eighteenth-century numismatist Joseph Hilarius Eckhel "The coins of Odenathus are known only to Goltzius; and if anyone will put faith in their existence, let him go to the fountain head (i.e. Goltzius)". According to the Augustan History, Gallienus minted a coin in honour of Odaenathus where he was depicted taking the Persians captive;[166] a coin of Gallienus minted in Antioch and dated to c. 264–265 depicts two seated captives on its reverse and was associated with the victories of Odaenathus by the historian Michael Geiger.[167] Other coins of Gallienus depict lions on their reverses; the animal was portrayed in several fashions: bare headed with a bull's head between its paws; radiate head; radiate head with a bull's head between its paws; or an eagle standing on its back. The historian Erika Manders considered it possible that those coins were issued for Odaenathus, as the depiction of a lion is reminiscent of the thirteenth Sibylline Oracle's description of Odaenathus as a "mighty and fearful lion, breathing much flame".[note 30][169]

Second Persian campaign 266 and war in Anatolia

[edit]The primary sources are silent regarding events following the first Persian campaign, but this is an indication of the peace that prevailed and that the Persians had ceased being a threat to the Roman East.[170] The evidence for the second campaign is meager; Zosimus is the only one to mention it specifically.[171] A passage in the thirteenth Sibylline Oracle is interpreted by Hartmann as an indication of a second offensive.[172] With the rise of the Sassanid dynasty, Palmyrene trade caravans to the East diminished with only three recorded after 224. The last caravan returned to Palmyra in 266, and this was probably facilitated by the campaign, which probably took place in 266.[173] The King marched directly to Ctesiphon, but he had to break off the siege and march north to face an influx of Germanic raiders attacking Anatolia.[171][174]

The Romans used the designation "Scythian" to denote many tribes, regardless of their ethnic origin, and sometimes the term would be interchangeable with Goths. The tribes attacking Anatolia were probably the Heruli who built ships to cross the Black Sea in 267 and ravaged the coasts of Bithynia and Pontus, besieging Heraclea Pontica.[171] According to the eighth-century historian George Syncellus, Odaenathus arrived at Anatolia with Herodianus and headed to Heraclea but the riders were already gone, having loaded their ships with booty.[171] Many perished, perhaps in a sea battle with Odaenathus' forces, or possibly they were shipwrecked.[171]

Assassination

[edit]Odaenathus was assassinated, together with Herodianus, in late 267. The date is debated and some scholars propose 266 or 268, but Vaballathus dated the first year of his reign between August 267 and August 268, making late 267 the most probable date.[175] The assassination took place in either Anatolia or Syria.[176][177] There is no consensus on the manner, perpetrator or the motive behind the act.[176]

- According to Syncellus, Odaenathus was assassinated near Heraclea Pontica by an assassin also named Odaenathus who was killed by the King's bodyguard.[178]

- Zosimus states that Odaenathus was killed by conspirators near Emesa at a friend's birthday party without naming the killer.[178][179] The twelfth-century historian Zonaras attributed the crime to a nephew of Odaenathus but did not give a name.[180] The Anonymus post Dionem also does not name the assassin.[178]

- The Augustan History claims that a cousin of the King named Maeonius killed him.[181]

Theories of instigators and motives

[edit]- Roman conspiracy: the seventh-century historian John of Antioch accused Gallienus of being behind the assassination.[178] A passage in the work of the Anonymus post Dionem speaks of a certain "Rufinus" who orchestrated the assassination on his own initiative, then explained his actions to the Emperor who condoned them.[176] This account has Rufinus ordering the murder of an older Odaenathus out of fear that he would rebel, and has the younger Odaenathus complaining to the Emperor.[note 31][178] Since the older Odaenathus (Odaenathus I) has proven to be a fictional character, the story is ignored by most scholars.[183] However, the younger Odaenathus could be an oblique reference to Vaballathus and Rufinus could be identified with Cocceius Rufinus, the Roman governor of Arabia in 261–262. The evidence for such a Roman conspiracy is weak.[183]

- Family feud: according to Zonaras, Odaenathus' nephew misbehaved during a lion hunt.[184] He made the first attack and killed the animal to the dismay of the King.[185] Odaenathus warned his nephew, who ignored the warning and repeated the act twice more, causing the King to deprive him of his horse, a great insult in the East.[185][186] The nephew threatened Odaenathus and was put in chains as a result. Herodianus asked his father to forgive his cousin and his request was granted. However, as the King was drinking, the nephew approached him with a sword and killed him along with Herodianus.[185] The bodyguard immediately executed the nephew.[185]

- Zenobia: the wife of Odaenathus was accused by the Augustan History of having formerly conspired with Maeonius, as Herodianus was her stepson and she could not accept that he was the heir to her husband instead of her own children.[178] However, there is no suggestion in the Augustan History that Zenobia was directly involved in her husband's murder;[186] the act is attributed to Maeonius' degeneracy and jealousy.[178] Those accounts by the Augustan History can be dismissed as fiction.[187] The hints in modern scholarship that Zenobia had a hand in the assassination out of her desire to rule the empire and her dismay at her husband's pro-Roman policy can be dismissed as there was no reversal of that policy during the first years following Odaenathus' death.[176]

- Persian agents: the possibility of a Persian involvement exists, but the outcome of the assassination would not have served Shapur I unless a pro-Persian monarch was established on the Palmyrene throne.[188]

- Palmyrene traitors: another possibility would be Palmyrenes dissatisfied with Odaenathus' reign and the changes of their city's governmental system.[186]

The historian Nathanael Andrade, noting that since the Augustan History, Zosimus, Zonaras, and Syncellus all refer to a family feud or a domestic conspiracy in their writings, they must have been recounting an early tradition regarding the assassination. Also, the story of Rufinus is a clue to tensions between Odaenathus and the Roman court.[189] The mint of Antioch on the Orontes ceased the production of Gallienus' coins in early 268, and while this could be related to fiscal troubles, it could also have been ordered by Zenobia in retaliation for the murder of her husband.[190] Andrade proposed that the assassination was the result of a coup conducted by Palmyrene notables in collaboration with the imperial court whose officials were dissatisfied with Odaenathus' autonomy.[191] On the other hand, Hartmann concluded that it is more probable that Odaenathus was killed in Pontus.[176]

Marriages and descendants

[edit]

Odaenathus was married twice. Nothing is known about his first wife's name or fate.[192] Zenobia was the King's second wife, whom he married in the late 250s when she was 17 or 18.[193]

How many children Odaenathus had with his first wife is unknown and only one is attested:

- Hairan I – Herodianus: the name Hairan appears on a 251 inscription from Palmyra describing him as ras, implying that he was already an adult by then.[192] In the Augustan History, Odaenathus' eldest son is named Herod; the dedication at Palmyra from 263 which celebrates Hairan I's coronation mentions him with the name Herodianus.[192] It is possible that the Hairan of the 251 inscription is not the same as the Herodianus of the dedication from 263,[192] but this is contested by Hartmann, who concludes that the reason for the difference in the spelling is the language used in the inscription (Herodianus being the Greek version),[187] meaning that Odaenathus' eldest son and co-king was Hairan Herodianus.[194] Hartmann's view is in line with the academic consensus.[195]

The children of Odaenathus and Zenobia were:

- Vaballathus: he is attested on several coins, inscriptions, and in the ancient literature.[196]

- Hairan II: his image appears on a seal impression along with his older brother Vaballathus; his identity is much debated.[196] Potter suggested that he is the same as Herodianus, who was crowned in 263, and that the Hairan I mentioned in 251 died before the birth of Hairan II.[197] Andrade suggested the opposite, maintaining that Hairan I, Herodianus and Hairan II are the same.[198]

- Herennianus and Timolaus: the two were mentioned in the Augustan History and are not attested in any other source;[196] Herennianus might be a conflation of Hairan and Herodianus while Timolaus is most probably a fabrication,[187] although the historian Dietmar Kienast suggests that he might be Vaballathus.[199]

Possible descendants of Odaenathus living in later centuries are reported: Lucia Septimia Patabiniana Balbilla Tyria Nepotilla Odaenathiana is known through a dedication dating to the late third or early fourth century inscribed on a tombstone erected by a wet nurse to her "sweetest and most loving mistress".[note 32][201] The tombstone was found in Rome at the San Callisto in Trastevere.[202] Another possible relative is Eusebius who is mentioned by the fourth century rhetorician Libanius in 391 as a son of one Odaenathus, who was in turn a descendant of the King;[203] the father of Eusebius is mentioned as fighting against the Persians (most probably in the ranks of Emperor Julian's army).[204] In 393, Libanius mentioned that Eusebius promised him a speech written by Longinus for the King.[203] In the fifth century, the philosopher "Syrian Odaenathus" lived in Athens and was a student of Plutarch of Athens;[205] he might have been a distant descendant of the King.[206]

Burial and succession

[edit]

Mummification was practiced in Palmyra alongside inhumation and it is a possibility that Zenobia had her husband mummified.[207] The stone block bearing Odaenathus' sepulchral inscription was in the Temple of Bel in the nineteenth century,[11] and it was originally the architrave of the tomb.[47] It had been moved to the temple at some point and so the location of the tomb to which the block belonged is not known.[11] The tomb was probably built early in Odaenathus' career and before his marriage to Zenobia and it is plausible that another, more elaborate, tomb was built after Odaenathus became King of Kings.[208]

Roman law forbade the burial of individuals within a city.[209] This rule was strictly observed in the west, but it was applied more leniently in the eastern parts of the empire.[210] A burial within a city was one of the highest honors an individual other than the Emperor and his family could receive in the Roman Empire.[211] A notable person may be buried in this manner for different reasons, such as his leadership or monetary donations.[210] It meant that the deceased was not sent beyond the walls for fear of miasma (pollution), and that he would be part of the city's future civic life.[note 33][211] At the western end of the Great Colonnade at Palmyra, a shrine designated "Funerary Temple no. 86" (also known as the House Tomb) is located.[212][213] Inside its chamber, steps lead down to a vault crypt which is now lost.[213][214] This mausoleum might have belonged to the royal family, being the only tomb inside the city's walls. Odaenathus' royal power in itself was sufficient to earn him a burial within the city walls.[215][216]

The Augustan History claims that Maeonius was proclaimed emperor for a brief period before being killed by soldiers.[176][183][186] However, no inscriptions or other evidence exist for Maeonius' reign,[217] the very existence of which is doubtful.[218] The disappearance of Septimius Worod in 267 could be related to the internal coup; he could have been executed by Zenobia if he was involved; or killed by the conspirators if he was loyal to the King.[189] Odaenathus was succeeded by his son, the ten-year-old Vaballathus, under the regency of Zenobia;[219] Hairan II probably died soon after his father,[220] as only Vaballathus succeeded to the throne.[221]

Legacy and reception

[edit]

Оденат был основателем королевской династии Пальмирен. [222] He left Palmyra the premier power in the East,[223] and his actions laid the foundation of Palmyrene strength which culminated in the establishment of the Palmyrene Empire in 270.[76] Hero cults were not common in Palmyra, but the unprecedented position and achievements of Odaenathus might have given rise to such a practice:[224] a mosaic excavated in Palmyra depicts the Greek myth of Bellerophon defeating the Chimera on the back of Pegasus in one panel,[225] and a man in Palmyrene military outfit riding a horse and shooting at two tigers, with an eagle flying above in the other. According to Gianluca Serra, the conservation zoologist based in Palmyra at the time of the panel's discovery, the tigers are Panthera tigris virgata, once common in the region of Hyrcania in Iran.[226] Gawlikowski proposed that Odaenathus is heroized as Bellerophon, and that the archer is also a depiction of Odaenathus fighting the Persians depicted as tigers. This is supported by the title of mrn (lord) which appear on the archer panel, an honor carried only by Odaenathus and Hairan I.[227] Мозаика с двумя панелями указывает на то, что Оденат, вероятно, считался божественной фигурой и ему, возможно, поклонялись в Пальмире. [224]

Память Одената как способного царя и верного римлянина использовалась императорами Клавдием II и Аврелианом , чтобы запятнать репутацию Зенобии, изображая себя мстителями Одената против его жены, узурпатора, завоевавшего трон посредством заговора. [228] Царя похвалил Либаний, [229] и автор « Истории Августа» четвертого века , поместивший Одената в число Тридцати тиранов (вероятно, потому, что он принял титул короля, по мнению историка восемнадцатого века Эдварда Гиббона ), [230] высоко отзывается о его роли в Персидской войне и приписывает ему спасение империи: «Если бы Оденат, принц Пальмирены, не захватил имперскую власть после пленения Валериана, когда силы римского государства были исчерпаны, все было бы потерянный на Востоке». [231] С другой стороны, в раввинистических источниках Оденат рассматривается негативно. Его мешок Нехардеи унизил евреев, [232] и он был проклят как вавилонскими евреями, так и евреями Палестины . [111] В христианской версии Апокалипсиса Илии , написанной, вероятно, в Египте после пленения Валериана, [233] Оденат назван царем, который восстанет из «города солнца» и в конце концов будет убит персами; [234] это пророчество является ответом на преследование евреев Оденатом и разрушение им Нахардеи. [235] Еврейский Апокалипсис Илии идентифицирует Одената как Антихриста . [примечание 34] [239]

Современный скептицизм

[ редактировать ]Оденат, одно только упоминание имени которого заставляло сердца персов дрогнуть. Повсюду победоносно он освобождал принадлежащие каждому из них города и территории и заставлял врагов полагать свое спасение в молитвах, а не в силе оружия.

- Либаний о подвигах Одената. [203]

К успехам Одената ряд современных ученых относится скептически. [240] Согласно « Истории Августа» , Оденат «захватил царские сокровища, а также то, что парфянским монархам дороже сокровищ, а именно, своих наложниц. По этой причине Шапур [I] теперь больше боялся римских полководцев, и опасаясь Баллисты и Одената, он поскорее удалился в свое королевство». [241] Ученые-скептики, такие как Мартин Шпренглинг, считали такие отчеты древнеримских историков «бедными, скудными и запутанными». [242] Однако коронационное посвящение статуи Иродиана, стоявшей на Монументальной арке Пальмиры , [132] записывает свое поражение персов, за что он был коронован, [130] [128] тем самым предоставив Пальмирене доказательства, в которых прямо упоминается война против Персии; засвидетельствованная победа, вероятно, связана с первой персидской кампанией, а не с битвой 260 г. [243]

Историк Андреас Альфельди пришел к выводу, что Оденат начал свои войны с Персией, напав на отступающую персидскую армию в Эдессе в 260 году. Скептически настроенные ученые отвергают такое нападение; Спренглинг отметил, что никаких доказательств такого взаимодействия не существует. [242] Иранолог Уолтер Бруно Хеннинг считал сообщения о нападении Одената в 260 году сильно преувеличенными. Шапур I упоминает, что он заставил римских пленников построить ему Банде -Кайсар возле Сузианы и построил для этих пленников город, который превратился в нынешний Гундешапур ; Хеннинг привел эти аргументы как свидетельство успеха Шапура I в возвращении своей армии и пленных домой, а также как преувеличение римлян относительно успехов Одената. [244] Спренглинг предположил, что у Шапура I не было достаточно войск для размещения гарнизонов в оккупированных им римских городах, а он был стар и сосредоточен на религии и строительстве; следовательно, Оденат просто вернул себе заброшенные города и двинулся на Ктесифон, чтобы исцелить гордость Рима, стараясь при этом не беспокоить персов и их императора. [245] Другие ученые, такие как Якоб Нойснер , отмечали, что, хотя отчеты о сражении 260 г. могут быть преувеличением, Оденат действительно стал реальной угрозой для Персии, когда он вернул себе города, ранее захваченные Шапуром I, и осадил Ктесифон. [246] Историк Луи Фельдман отверг предложения Хеннинга; [247] и историк Тревор Брайс пришел к выводу, что каким бы ни был характер кампаний Одената, они привели к восстановлению всех римских территорий, оккупированных Шапуром I - Рим был свободен от персидских угроз в течение нескольких лет после войн Одената. [240]

Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ Греческие транслитерации ( древнегреческий : Ὀδαίναθος Odaínathos или Ὠδέναθος Ōdénathos ) и латинские транслитерации ( латынь : Odaenathus , Odenathus , Odinatus или Ordinatus ) представляют собой более или менее искаженные транслитерации пальмиренского и арабского языков соответственно. [2]

- ↑ Дату 220 предложил археолог Михаил Гавликовский , руководитель польской археологической экспедиции в Пальмире; археолог Эрнест Уилл , однако, утверждал, что король родился ок. 200. [3]

- ↑ По мнению авторов « Бытия Раба» (76,6), стих из Книги Даниила (7.8) относится к некоему бен Насору, которого несколько современных историков и талмудистов , включая Генриха Греца , Маркуса, идентифицировали как Оденфа. Ястроу и Саул Либерман . [13] Раввин Соломон Функ считал бен Насора родственником Одената, а историк Якоб Нойснер считал возможным, что бен Насор был либо Оденатом, либо членом его семьи. По мнению историка Лукаса де Блуа , Оденат — самый сильный кандидат; в Кетуботе (51B) бен Насор упоминается как царь, а единственный известный царь с именем «Насор», упомянутым в его генеалогии, - это Оденат. [14]

- ↑ По мнению историка Луиса Фельдмана , «Папа», скорее всего, является латинским переводом семитского имени Абба (отец). [13] Папа — имя собственное, использовавшееся в Хатре , а некоторые еврейские амораимы носили имена «Паппа» ( Ppʿ ) или «Паппус» ( Ppws ), от корня ppy или pph , что означает «говорить гордо»; По мнению историка Удо Хартмана , возможно, раввины прозвали Одената Папой за его высокомерие. Также возможно, что, поскольку дедушка Одената был сыном Насора, Папа — греческий заимствованный человек, родственный πάππος ( páppos ), что означает дедушка. [15]

- ↑ Оденат упоминается как «низший из царей» в Книге Илии. [25] который представляет собой собрание текстов, относящихся к разным периодам, таких как фрагменты из Первой книги Царств , апокалиптическое изображение сражений Сасанидов против Рима и авраамический апокалипсис, изображающий возвышение Израиля и унижение языческого мира. [26] Византийский историк шестого века Агафий упоминает Одената как человека низкого происхождения. Заявление Зосимы противоречит этим сообщениям о низком рождении. По мнению историка Аверила Кэмерона , фраза, использованная Агафием, ἀφανὴς μὲν τὰ πρῶτα ( наш aphanḗs ta prṓta ), является противоположностью ἀράμενος δόξαν ( meg, они арамейцы доксаны ), и Агафий использовал ту же самую фразу для описания первый Сасанидский царь Ардашир I , [27] который проследил свое происхождение от авестийских и ахеменидских царей. [28]

- ^ Покровители караванов Пальмирены владели землей, на которой выращивались караванные животные, предоставляя животных и охрану торговцам, возглавлявшим караваны. [30]

- ^ Каждый год Селевкидов начинался поздней осенью григорианского года ; таким образом, год Селевкидов перекрывает два года по григорианскому календарю. [34]

- ↑ Этому предположению способствовал отрывок в работе Anonymus post Dionem , обычно связываемый с историками шестого века Евстафием Епифанийским или Петром Патрицием , [44] в котором говорится о младшем Оденате, который просит римского императора наказать своего чиновника Руфина за роль последнего в убийстве старшего Одената. [45] Для получения информации см. «Убийство Одената: римский заговор» .

- ↑ Археолог Уильям Уоддингтон считал короля Одената сыном Рас Хайрана, а историк Теодор Моммзен считал последнего старшим братом короля. [49]

- ↑ Хотя выводы Гавликовского стали академическим консенсусом, археолог Жан-Шарль Балти утверждал, что Оденат, построивший гробницу, не был тем же, что король Оденат, заявив, что новая надпись может изменить все, что ранее было известно о семье. [52]

- ↑ Датированные надписи, в которых упоминается название, относятся к 251 октября и 252 апреля: надпись 251 относится к старшему сыну Одената Хайрану I как ras , а надпись 252 относится к Оденату. [63] [64] Хотя первая известная надпись, подтверждающая титул Одената, датируется 252 годом, подтверждено, что он поднялся на эту должность как минимум на год раньше, на основании свидетельства Хайрана I как раса в 251 году, и вполне вероятно, что он получил этот титул впоследствии. о смерти Гордиана III. [61]

- ^ ли титул раса на военную или священническую должность. Неизвестно, указывает [66] но военная роль более вероятна. [67]

- ^ В Дура-Европосе есть два храма Бела; первый был основан Пальмиренами в начале первого века за городской стеной в некрополе, а второй (изображенный на этой картине, также называемый «храмом Пальмирских богов») находился под управлением Пальмиренов только в третьем веке. [69]

- ↑ Педагог Герман Шиллер отверг утверждение, что Оденат был губернатором Финикии; титул ( ὁ λαμπρότατος ὑπατικός ) также был засвидетельствован в Пальмире для разных знатных людей и мог быть почетным титулом высокой степени. [49]

- ^ Нет никаких доказательств того, что Шапур I вошел в центральные районы северной Сирии; кажется, он двинулся прямо на запад, в Киликию. [85]

- ↑ Сначала Фульвий Макриан проявил лояльность к Галлиену. [88]

- ↑ Зосим писал, что армия Одената, с которой он сражался с Шапуром I в 260 году, включала его собственные пальмиренские войска и остатки римских легионов Валериана. [93] Никаких свидетельств присутствия в его рядах римских частей не существует, но это возможно, учитывая, что он сражался вблизи баз римских легионеров. Базировавшиеся там войска могли быть лояльны Галлиену и поэтому решили присоединиться к Оденату. [79] Сражались ли римские солдаты под началом Одената или нет, остается только предполагать. [79]

Крестьянский элемент в армии упоминался в трудах более поздних историков, таких как писатели четвертого века Фест и Орозий ; [94] последний назвал войско Одената рукой сирийцев , [93] побудив историка Эдварда Гиббона изобразить войска Одената как «царапинную армию крестьян». Историк Ричард Стоунман отверг вывод Гиббона, утверждая, что успех Пальмирены против Шапура I и победы, достигнутые Зенобией после смерти ее мужа, в результате которых Сирия, Египет и Анатолия оказались под властью Пальмирены, вряд ли можно приписать плохо подготовленному, необученная крестьянская армия. [94] Более логично интерпретировать agrestis как обозначение войск, находящихся за пределами городских центров, и, таким образом, можно сделать вывод, что Оденат набирал своих кавалеристов из регионов, окружающих Пальмиру, где обычно разводили и содержали лошадей. [95] - ^ Рассказ о нападении Одената на отступающих персов принадлежит историку VIII века Синцеллу . [96]

- ^ Корень TQN существует в нескольких языках: арамейском (что означает «подготовить», «исправить», «привести в порядок»), аккадском (где слово taqan означает «урегулироваться», «в порядке»), арабском (что означает «улучшить», «исправить», «навести порядок»). [104]

- ^ Римский Восток традиционно включал все римские земли в Азии к востоку и югу от Босфора . [107]

- ↑ десятого века Геоним Шерира Гаон в своей работе «Иггерет Рав Шерира Гаон» заявил, что Папа бен Насор разрушил город в 570 году Ю.В., что соответствует 259 году. [5] де Блуа предположил, что разрушение Нехардеи Оденатом в 259 году было в поддержку Валериана. [116] Однако Нойснер предположил, что правильная дата — 262 или 263 год. [117] и считал дату, указанную Шерирой Гаоном, невозможной, поскольку для разрушения города потребовалась бы большая армия, а единственную крупную силу, вторгшуюся в регион в тот период, возглавлял Оденат во время его первой кампании. Фельдман отметил, что Пальмира рассчитывала на маневренность своих солдат, а не на численность своих армий, тем самым усомнившись в выводах Нойснера. [13]

- ^ Вопреки отчету « Истории Августа» , нет никаких доказательств того, что Оденат оккупировал Армению . [122]

- ↑ Титул Одената, как он появляется в надписях Пальмирены, был «Царь царей и Корректор Востока». [125]

- ↑ Гавликовский предложил установить статую и провести коронацию после победы в 260 году. [129] Гавликовский также предположил, что Оденат принял титул «Царь царей» перед своей первой персидской кампанией в рамках подготовки к войне и замене династии Сасанидов, но эта цель не была достигнута. [43]

- ↑ Археолог Даниэль Шлюмберже Эмеса (современный Хомс предположил , что местом коронации является ), но древний город находился примерно в миле от реки. Следовательно, академический консенсус отдает предпочтение Антиохии Оронту; [130] В городе был найден свинцовый жетон с изображением Иродиана, отчеканенный, вероятно, в честь коронации. [127]

- ↑ Как королева-консорт Зенобия оставалась на заднем плане и не упоминалась в исторических записях. [133]

- ^ Никакой информации о личности Киринуса не существует; [146] возможно, что это тот же человек, что и Аврелий Квириний, который записан как глава финансового управления Египта в 262 году. [147]

- ↑ Этот гентилиций принадлежал исключительно семье Одената до 260-х годов. [151]

- ↑ «Тринадцатый Сивиллинский оракул» был составлен несколькими писателями, которые, вероятно, были сирийцами и пытались продвигать сирийских правителей, изображая их спасителями Рима от Персии. Первоначальный текст был завершен во времена Урания и отредактирован во время правления Одената с добавлением 19 строк, содержащих пророчество о победах Одената. [159]

- ↑ Историк Дэвид Вудс отверг различные интерпретации лучистого льва, считая его признаком краткости Императора; этот мотив можно проследить до легенд о рождении Александра Македонского в Македонии . [168]

- ↑ Эта история способствовала появлению теперь уже не принятого во внимание предположения о существовании Одената I. [182]

- ^ Спорится о том, следует ли понимать надпись как свидетельство потомков Одената в Риме. [200]

- ^ Как правило, инициатива о предоставлении человеку интрастенального захоронения исходила от демоса и должна была быть подтверждена аккламацией ; из-за этого требования эта честь была редкостью. [211]

- ^ Апокалипсис Илии — апокрифическое произведение, существующее в двух версиях: одна — еврейская, написанная на иврите , а другая — христианская и написанная на коптском языке . [236] Христианская версия, похоже, основана на еврейском пророчестве, написанном в Египте во время беспорядков после пленения Валериана; евреи, вероятно, ожидали, что персы победят и позволят им вернуться в Иерусалим, уничтожив Одената, которого они считали врагом. [233] Согласно пророчеству: «В те дни восстанет царь в городе, который называется «городом солнца», и вся земля будет потрясена. [Он] побежит в Мемфис (с персами). в шестой год персидские цари устроят засаду в Мемфисе. Они убьют ассирийского царя». [237] Коптолог Оскар Лемм что под персидскими и ассирийскими царями пророчество подразумевало царей Персии Кира Великого , живших в шестом веке до нашей эры , и халдейского Навуходоносора II Вавилонского считал , . Лемм также считал убийство ассирийского царя в Мемфисе намеком на поражение вавилонян от Персии. [237] Богослов Вильгельм Буссе считал пророчество бессмысленным, если оно на самом деле означало, что персидские и ассирийские цари воевали в Египте, поскольку такого конфликта никогда не было. Отмечая путаницу между Сирией и Ассирией во многих римских источниках, включая пророчества Сивиллы , Буссе отождествлял ассирийского царя с Оденатом; Пальмира была известна как город Солнца во многих апокалиптических традициях. [238]

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Jump up to: а б Кук 1911 год .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Лето 2018 , стр. 167.

- ^ Хартманн 2008 , с. 348 .

- ^ Лето 2018 г. , стр. 146 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Доджон и Лью 2002 , с. 61 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б аль-Асад, Йон и Фурне 2001 , с. 18.

- ^ Петерсен 1962 , стр. 347, 348, 351.

- ^ Шахид 1995 , с. 296 .

- ^ Матышак и Берри 2008 , с. 244.

- ^ Старк 1971 , с. 65.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Аддисон 1838 , с. 166 .

- ^ Доджон и Лью 2002 , с. 59 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Фельдман 1996 , с. 431 .

- ^ де Блуа 1975 , с. 13.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Хартманн 2001 , с. 42 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Тело 2013 , с. 225 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Пауэрс 2010 , с. 130 .

- ^ Старк 1971 , стр. 65, xx, 85.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Хартманн 2001 , с. 88 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Тейксидор 2005 , с. 195 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Гавликовский 1985 , стр. 260.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Браун 1939 , с. 257 .

- ^ Фрид 2014 , с. 95 .

- ^ Лето 2018 г. , стр. 146.

- ^ Рисслер 1928 , стр. 235 , 1279 .

- ^ Рисслер 1928 , с. 1279 .

- ^ Кэмерон 1969–1970 , с. 141.

- ^ Кэмерон 1969–1970 , с. 108.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Болл 2002 , с. 77 .

- ^ Ховард 2012 , с. 159 .

- ^ Альтхайм и др. 1965 , с. 256.

- ^ Стоунман 1994 , с. 77 .

- ^ Хартманн 2001 , с. 89 .

- ^ Бирс 1992 , стр. 13.

- ^ Смит II 2013 , с. 154 .

- ^ Дрейверс 1980 , с. 67 .

- ^ Уэйдсон 2014 , стр. 49, 54.

- ^ Уэйдсон 2014 , с. 54.

- ^ Хартманн 2001 , с. 87 .

- ^ Балти 2002 , стр. 731, 732.

- ^ Эквини Шнайдер 1992 , с. 128.

- ^ Кропп и Раджа 2016 , стр. 13.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Гавликовский 2016 , стр. 131.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Катауделла 2003 , с. 440 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Доджон и Лью 2002 , с. 314.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж Сартр 2005а , с. 512 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Гавликовский 1985 , стр. 253.

- ^ Доджон и Лью 2002 , с. 60 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Харрер 2006 , с. 59 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Уотсон 2004 , с. 29 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Стоунман 1994 , с. 78 .

- ^ Кайзер 2008 , с. 660.

- ^ Сартр 2005b , с. 352 .

- ^ Эдвелл 2007 , с. 27 .

- ^ Болл 2002 , с. 76 .

- ^ Эдвелл 2007 , с. 34 .

- ^ Голдсуорси 2009 , с. 125 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Южный 2008 , с. 45 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Южный 2008 , с. 43 .

- ^ Поттер 2010 , с. 160 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж Южный 2008 , с. 44 .

- ^ Хартманн 2001 , с. 90 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Уотсон 2004 , с. 30 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Янг 2003 , с. 210 .

- ^ Янг 2003 , с. 209 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Смит II 2013 , с. 131 .

- ^ Ведущий 2011 , с. 224 .

- ^ Маккей 2004 , с. 272 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Дирвен 1999 , с. 42 .

- ^ Хартманн 2001 , с. 99 .

- ^ Миллар 1993 , с. 159 .

- ^ Эдвелл 2007 , с. 185 .

- ^ Дауни 2015 , с. 97 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Клин 1999 , с. 98 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Южный 2008 , с. 182 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Dignas & Winter 2007 , с. 158 .

- ^ Хартманн 2001 , с. 100 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Смит II 2013 , с. 177 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г Южный 2008 , с. 60 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Южный 2008 , с. 47 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Южный 2008 , с. 179 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Янг 2003 , с. 159 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Южный 2008 , с. 48 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Доджон и Лью 2002 , с. 77 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Миллар 1993 , с. 166 .

- ^ Андо 2012 , с. 167 .

- ^ Dignas & Winter 2007 , с. 23 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Дринкуотер 2005 , с. 44 .

- ^ Доджон и Лью 2002 , с. 57 .

- ^ Южный 2008 , с. 58 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Dignas & Winter 2007 , с. 159 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Южный 2008 , с. 59 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б де Блуа 2014 , с. 191 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Стоунман 1994 , с. 107 .

- ^ Накамура 1993 , с. 138.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Доджон и Лью 2002 , с. 66 .

- ^ Хартманн 2001 , стр. 139 , 144 .

- ^ Хартманн 2001 , стр. 144 , 145.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Брайс 2014 , с. 290 .

- ^ Брайс 2014 , с. 291 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Южный 2008 , с. 67 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г Янг 2003 , с. 215 .

- ^ Голдсуорси 2009 , с. 124 .

- ^ Муртонен 1989 , стр. 446 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж Южный 2008 , с. 68 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Уотсон 2004 , с. 32 .

- ^ Болл 2002 , с. 6 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Янг 2003 , с. 214 .

- ^ Вервает 2007 , с. 137 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Dignas & Winter 2007 , с. 160 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Фальк 1996 , с. 333 .

- ^ де Блуа 1976 , с. 35 .

- ^ Южный 2008 , с. 70 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Хартманн 2001 , с. 173 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Хартманн 2001 , с. 168 .

- ^ де Блуа 1976 , с. 2 .

- ^ Доджон и Лью 2002 , с. 370 .

- ^ Хартманн 2001 , с. 169 .

- ^ Дубнов 1968 , с. 151 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Хартманн 2001 , с. 172 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Хартманн 2001 , с. 171 .

- ^ Хартманн 2001 , с. 174 .

- ^ де Блуа 1976 , с. 3 .

- ^ Южный 2008 , с. 71 .

- ^ Мясник 2003 , с. 60 .

- ^ Хартманн 2001 , стр. 149 , 176 , 178 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Андраде 2013 , с. 333 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Доджон и Лью 2002 , с. 67 .

- ^ Гавликовский 2005b , стр. 1301.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Хартманн 2001 , с. 178 .

- ^ Тейксидор 2005 , с. 198 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Кайзер 2008 , с. 659.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Южный 2008 , с. 72 .

- ^ Хартманн 2001 , с. 176 .

- ^ Хартманн 2001 , с. 180 .

- ^ Хартманн 2001 , с. 181 .

- ^ Янг 2003 , с. 216 .

- ^ Янг 2003 , стр. 214 , 215.

- ^ Моммзен 2005 , с. 298 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Поттер 1996 , с. 271.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Поттер 1996 , с. 274.

- ^ Поттер 1996 , стр. 273, 274.

- ^ Хартманн 2001 , с. 182 .

- ^ Поттер 1996 , с. 281.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Андо 2012 , с. 171 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Хартманн 2001 , с. 156 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Альфельди 1939 , с. 176 .

- ^ Сартр 2005a , с. 514 .

- ^ Южный 2008 , с. 75 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Поттер 2014 , с. 257 .

- ^ Миллар 1971 , с. 9 .

- ^ Сиверцев 2002 , с. 72 .

- ^ Хартманн 2016 , с. 64.

- ^ Кук 1903 , с. 286 .

- ^ Поттер 2014 , с. 256 .

- ^ Поттер 2010 , с. 162 .

- ^ Поттер 1990 , с. 154.

- ^ Хит 1999 , с. 4.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Мясник 1996 , с. 525.

- ^ Андраде 2018 , с. 137 .

- ^ Кайзер 2009 , с. 185 .

- ^ Тейксидор 2005 , с. 205 .

- ^ Тейксидор 2005 , с. 206 .

- ^ Фаулкс-Чилдс и Сеймур 2019 , с. 256 .

- ^ Клинтон 2010 , с. 63 .

- ^ Стивенсон 1889 , с. 583 .

- ^ Гейгер 2015 , с. 224.

- ^ Вудс 2018 , с. 193.

- ^ Мандерс 2012 , стр. 297–298.

- ^ Южный 2008 , с. 73 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Южный 2008 , с. 76 .

- ^ Южный 2008 , с. 183 .

- ^ Смит II 2013 , с. 176, 177 .

- ^ Хартманн 2001 , с. 216 .

- ^ Южный 2008 , с. 77 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж Южный 2008 , с. 78 .

- ^ Андо 2012 , с. 172 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г Доджон и Лью 2002 , с. 71 .

- ^ Хартманн 2001 , с. 220 .

- ^ Поттер 2014 , стр. 259 , 629 .

- ^ Доджон и Лью 2002 , с. 70 .

- ^ Доджон и Лью 2002 , стр. 314, 315.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Стоунман 1994 , с. 108 .

- ^ Поттер 2014 , с. 259 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Доджон и Лью 2002 , с. 72 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Брайс 2014 , с. 292 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Уотсон 2004 , с. 58 .

- ^ Южный 2008 , с. 79 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Андраде 2018 , с. 146 .

- ^ Андраде 2018 , с. 151 .

- ^ Андраде 2018 , стр. 146 , 152 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Южный 2008 , с. 8 .

- ^ Южный 2008 , с. 4 .

- ^ Южный 2008 , с. 9 .

- ^ Кайзер 2008 , с. 661.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Южный 2008 , с. 10 .

- ^ Поттер 2014 , с. 628 .

- ^ Андраде 2018 , с. 121 .

- ^ Южный 2008 , с. 174 .

- ^ Бальдини 1978 , с. 148.

- ^ Стоунман 1994 , с. 187 .

- ^ Ланчиани 1909 , с. 169 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Доджон и Лью 2002 , с. 110 .

- ^ Хартманн 2001 , с. 415 .

- ^ Курноу 2011 , с. 199 .

- ^ Трейна 2011 , с. 47 .

- ^ Андраде 2018 , стр. 154 , 155 .

- ^ Андраде 2018 , с. 154 .

- ^ Николай 2014 , с. 18 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Кормак 2004 , с. 38.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Кун 2017 , с. 200 .

- ^ Гавликовский 2005а , стр. 55 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Казуле 2008 , с. 103 .

- ^ Дарк 2006 , с. 238 .

- ^ Стоунман 1994 , с. 67 .

- ^ Андраде 2018 , с. 158 .

- ^ Брауэр 1975 , с. 163.

- ^ Хартманн 2001 , с. 223 .

- ^ Брайс 2014 , с. 299 .

- ^ Стоунман 1994 , с. 115 .

- ^ Южный 2015 , с. 150 .

- ^ Санер 2014 , с. 133 .

- ^ Янг 2003 , с. 163 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Андраде 2018 , с. 139 .

- ^ Гавликовский 2010 , стр. 11-12.

- ^ Гавликовский 2005b , стр. 1300, 1302.

- ^ Гавликовский 2005c , стр. 29–31.

- ^ Андраде 2018 , с. 152 .

- ^ Хартманн 2001 , с. 200 .

- ^ Гиббон 1906 , с. 352.

- ^ Доджон и Лью 2002 , с. 64 .

- ^ Тейксидор 2005 , с. 209 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Буссе 1900 , с. 108 .

- ^ Буссе 1900 , стр. 105 , 106 .

- ^ Буссе 1900 , стр. 106, 107 .

- ^ Wintermute 2011 , стр. 729, 730 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Зимнее Безмолвие 2011 , с. 743 .

- ^ Буссе 1900 , с. 106 .

- ^ Буссе 1908 , с. 580 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Брайс 2014 , с. 289 .

- ^ Доджон и Лью 2002 , с. 63 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Спрендлинг 1953 , с. 108 .

- ^ Лето 2018 г. , стр. 152, 153 .

- ^ Хеннинг 1939 , с. 843.

- ^ Спрендлинг 1953 , с. 109 .

- ^ Нойснер 1966 , с. 10 .

- ^ Фельдман 1996 , с. 432 .

Источники

[ редактировать ]- Аддисон, Чарльз Гринстрит (1838). Дамаск и Пальмира: путешествие на Восток . Том. 2. Ричард Бентли. OCLC 833460514 .

- аль-Асад, Халед; Йон, Жан-Батист; Фурне, Тибо (2001). Надписи Пальмиры: эпиграфические прогулки по древнему городу Пальмире . Археологические справочники Французского института археологии Ближнего Востока. Полет. 3. Главное управление древностей и музеев Сирийской Арабской Республики и Французский институт археологии Ближнего Востока. ISBN 978-2-912-73812-7 .

- Альфельди, Андреас (1939). «Кризис империи». В Куке, Стэнли Артур; Адкок, Фрэнк Эзра; Чарльзуорт, Мартин Персиваль; Бэйнс, Норман Хепберн (ред.). Имперский кризис и восстановление 193–324 гг . Кембриджская древняя история (первая серия). Том. 12. Издательство Кембриджского университета. OCLC 654926028 .

- Альтхайм, Франц; Штиль, Рут; Кнаповски, Рох; Кеберт, Раймунд; Лозован, Евгений; Мачух, Рудольф; Траутманн-Неринг, Эрика (1965). Арабы в Старом Свете (на немецком языке). Том 2: До разделения империи. Вальтер де Грюйтер. OCLC 645381310 .

- Андо, Клиффорд (2012). Имперский Рим, 193–284 годы нашей эры: критический век . Издательство Эдинбургского университета. ISBN 978-0-7486-5534-2 .

- Андраде, Натанаэль Дж. (2013). Сирийская идентичность в греко-римском мире . Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 978-1-107-01205-9 .

- Андраде, Натанаэль Дж. (2018). Зенобия: Падающая звезда Пальмиры . Издательство Оксфордского университета. ISBN 978-0-190-63881-8 .

- Бальдини, Антонио (1978). «Discendenti a Roma da Zenobia?». Журнал папирологии и эпиграфики (на итальянском языке). 30 . Доктор Рудольф Хабельт ГмбХ. ISSN 0084-5388 .

- Болл, Уорик (2002). Рим на Востоке: трансформация империи . Рутледж . ISBN 978-1-134-82387-1 .

- Балти, Жан-Шарль (2002). «Одейнат. «Король королей» ». Отчеты сессий Академии надписей и изящной словесности (на французском языке). 146 (2). Академия надписей и изящной словесности: 729–741. дои : 10.3406/crai.2002.22470 . ISSN 0065-0536 .

- Бирс, Уильям Р. (1992). Искусство, артефакты и хронология в классической археологии . Приближение к Древнему миру. Том. 2. Рутледж. ISBN 978-0-415-06319-7 .

- Буссе, Вильгельм (1900). Бригер, Иоганн Фридрих Теодор; Бесс, Бернхард (ред.). «Вклады в историю эсхатологии». Журнал церковной истории (на немецком языке). ХХ (2). Фридрих Андреас Пертес. ISSN 0044-2925 . OCLC 797692163 .

- Буссе, Вильгельм (1908). «Антихрист». В Гастингсе, Джеймс; Селби, Джон А. (ред.). Энциклопедия религии и этики . Том. Я, А-Ст. Т. и Т. Кларк. OCLC 705902930 .

- Брауэр, Джордж К. (1975). Эпоха императоров-солдат: Имперский Рим, 244–284 гг. н.э. Нойес Пресс. ISBN 978-0-8155-5036-5 .

- Браун, Фрэнк Эдвард (1939). «Раздел H, Блок 1. Храм Гадде». Ростовцев Михаил Иванович; Браун, Фрэнк Эдвард; Уэллс, Чарльз Брэдфорд (ред.). Раскопки в Дура-Европос. Проведено Йельским университетом и Французской академией надписей и литературы: предварительный отчет о седьмом и восьмом сезонах работы, 1933–1934 и 1934–1935 гг . Издательство Йельского университета. стр. 218–277. OCLC 491287768 .

- Брайс, Тревор (2014). Древняя Сирия: трехтысячелетняя история . Издательство Оксфордского университета. ISBN 978-0-19-100292-2 .

- Мясник, Кевин (1996). «Воображаемые императоры: личности и неудачи в третьем веке. Д.С. Поттер, Пророчество и история в период кризиса Римской империи: исторический комментарий к Тринадцатому Сивиллинскому оракулу (Оксфорд, 1990). Стр. 443 + XIX, 2 карты, 27 половин. -Тональные иллюстрации ISBN 0-19-814483-0 ». Журнал римской археологии . 9 . Издательство Мичиганского университета: 515–527. дои : 10.1017/S1047759400017013 . ISSN 1047-7594 .

- Мясник, Кевин (2003). Римская Сирия и Ближний Восток . Публикации Гетти. ISBN 978-0-89236-715-3 .

- Кэмерон, Аверил (1969–1970). «Агафий о Сасанидах». Документы Думбартон-Окса . 23/24. Думбартон-Оукс, попечители Гарвардского университета: 67–183. дои : 10.2307/1291291 . ISSN 0070-7546 . JSTOR 1291291 .

- Казуле, Франческа (2008). Искусство и история: Сирия . Перевод Бумслитера, Паулы Элиз; Данбар, Ричард. Дом Эдитрис Бонечи. ISBN 978-88-476-0119-2 .

- Катауделла, Мишель Р. (2003). «Историография на Востоке». В Мараско, Габриэле (ред.). Греческая и римская историография в поздней античности: с четвертого по шестой век нашей эры . Брилл. стр. 391–448 . ISBN 978-9-047-40018-9 .

- В эту статью включен текст из публикации, которая сейчас находится в свободном доступе : Кук, Джордж Альберт (1911). « Оденат ». В Чисхолме, Хью (ред.). Британская энциклопедия . Том. 19 (11-е изд.). Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 995.

- Клинтон, Генри Файнс (2010) [1850]. Фасти Романи: От смерти Августа до смерти Ираклия . Том. 2. Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 978-1-108-01248-5 .

- Кук, Джордж Альберт (1903). Учебник северо-семитских надписей: моавитянских, еврейских, финикийских, арамейских, набатейских, пальмиренских, еврейских . Кларендон Пресс. OCLC 632346580 .

- Кормак, Сара (2004). Пространство смерти в римской Малой Азии . Венские исследования по археологии. Том 6. Фойб. ISBN 978-3-901-23237-4 .

- Курноу, Тревор (2011) [2006]. Философы древнего мира: Путеводитель от А до Я. Бристоль Классик Пресс. ISBN 978-1-84966-769-2 .

- Дарк, Диана (2006). Сирия . Брэдт Путеводители. ISBN 978-1-84162-162-3 .

- де Блуа, Лукас (1975). «Оденат и римско-персидская война 252–264 годов нашей эры». Таланта – Труды Голландского археологического и исторического общества . VI . Брилл. ISSN 0165-2486 . OCLC 715781891 .

- де Блуа, Лукас (1976). Политика императора Галлиена . Голландское археологическое и историческое общество: исследования Голландского археологического и исторического общества. Том. 7. Брилл. ISBN 978-90-04-04508-8 .

- де Блуа, Лукас (2014). «Интеграция или дезинтеграция? Римская армия в третьем веке нашей эры». Ин де Клейн, Герда; Бенуа, Стефан (ред.). Интеграция в Риме и в римском мире: материалы десятого семинара по международному сетевому влиянию империи (Лилль, 23–25 июня 2011 г.) . Том. 17. Брилл. стр. 187–196. ISBN 978-9-004-25667-5 . ISSN 1572-0500 .

- Дигнас, Беате; Винтер, Энгельберт (2007) [2001]. Рим и Персия в поздней античности: соседи и соперники . Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 978-0-521-84925-8 .

- Дирвен, Люсинда (1999). Пальмирены Дура-Европоса: исследование религиозного взаимодействия в римской Сирии . Религии в греко-римском мире. Том. 138. Брилл. ISBN 978-90-04-11589-7 . ISSN 0927-7633 .

- Доджон, Майкл Х; Лью, Сэмюэл Н.К. (2002). Римская восточная граница и персидские войны 226–363 гг. Н. Э.: Документальная история . Рутледж. ISBN 978-1-134-96113-9 .

- Дауни, Гланвилл (2015) [1963]. Древняя Антиохия . Библиотека наследия Принстона. Том. 2111. Издательство Принстонского университета. ISBN 978-1-400-87671-6 .

- Дрейверс, Хендрик Ян Виллем (1980). Культы и верования в Эдессе . Предварительные исследования восточных религий в Римской империи. Полет. 82. Брилл. ISBN 978-90-04-06050-0 .

- Дринкуотер, Джон (2005). «Максимин Диоклетиану и «кризису» ». В Боумене, Алан К.; Гарнси, Питер; Кэмерон, Аверил (ред.). Кризис империи, 193-337 гг. н.э. Кембриджская древняя история (вторая исправленная серия). Том. 12. Издательство Кембриджского университета. стр. 28–66. ISBN 978-0-521-30199-2 .

- Дубнов, Симон (1968) [1916]. История евреев от Римской империи до периода раннего средневековья . Том. 2. Перевод Шпигеля Моше. Томас Йоселофф. OCLC 900833618 .

- Эдвелл, Питер (2007). Между Римом и Персией: Средний Евфрат, Месопотамия и Пальмира под контролем Рима . Рутледж. ISBN 978-1-134-09573-5 .

- Эквини Шнайдер, Евгения (1992). «Почетная скульптура и портретная живопись в Пальмире: некоторые гипотезы». Классическая археология (на итальянском языке). 44 . Герм Бретшнейдера. ISSN 0391-8165 .

- Фальк, Авнер (1996). Психоаналитическая история евреев . Ассошиэйтед Юниверсити Пресс. ISBN 978-0-8386-3660-2 .