Чернобыльская катастрофа

Эта статья может оказаться слишком длинной для удобного чтения и навигации . Когда этот тег был добавлен, его читаемый размер составлял 15 500 слов. ( сентябрь 2023 г. ) |

Reactor 4 several months after the disaster. Reactor 3 can be seen behind the ventilation stack. | |

| |

| Date | 26 April 1986 |

|---|---|

| Time | 01:23 MSD (UTC+04:00) |

| Location | Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, Pripyat, Chernobyl Raion, Kiev Oblast, Ukrainian SSR, Soviet Union(now Vyshhorod Raion, Kyiv Oblast, Ukraine) |

| Type | Nuclear and Radiation accident |

| Cause | Reactor design and operator error |

| Outcome | INES Level 7 (major accident) |

| Deaths | 2 killed by debris (including 1 missing) and 28 killed by acute radiation sickness. 15 terminal cases of thyroid cancer, with varying estimates of increased cancer mortality over subsequent decades (for more details, see Deaths due to the disaster) |

| Chernobyl disaster |

|---|

|

Чернобыльская катастрофа [ а ] Началось 26 апреля 1986 года со взрыва реактора № 4 Чернобыльской АЭС вблизи города Припять на севере Украинской ССР , недалеко от границы с Белорусской ССР , на территории Советского Союза . [ 1 ] Это одна из двух аварий на атомной энергетике, которым присвоен семь баллов (максимальная тяжесть) по Международной шкале ядерных событий (второй является ядерная авария на Фукусиме в 2011 году) . В первоначальном реагировании на чрезвычайную ситуацию и последующих усилиях по смягчению последствий приняли участие более 500 000 человек , а стоимость оценивается в 18 миллиардов рублей — примерно миллиардов долларов США 68 в 2019 году с поправкой на инфляцию. [ 2 ] Это была самая страшная ядерная катастрофа в истории. [ 3 ] [ 4 ] [ 5 ] и самая дорогостоящая катастрофа в истории человечества , стоимость которой оценивается примерно в 700 миллиардов долларов США. [ 6 ]

The accident occurred during a test of the steam turbine's ability to power the emergency feedwater pumps in the event of a simultaneous loss of external power and coolant pipe rupture. Following an accidental drop in reactor power to near-zero, the operators restarted the reactor in preparation for the turbine test with a prohibited control rod configuration. Upon successful completion of the test, the reactor was then shut down for maintenance. Due to a variety of factors, this action resulted in a power surge at the base of the reactor which brought about the rupture of reactor components and the loss of coolant. This process led to steam explosions and a meltdown, which destroyed the containment building. This was followed by a reactor core fire which lasted until 4 May 1986, during which airborne radioactive contaminants were spread throughout the USSR and Europe.[7][8] In response to the initial accident, a 10-kilometre (6.2 mi) radius exclusion zone was created 36 hours after the accident, from which approximately 49,000 people were evacuated, primarily from Pripyat. The exclusion zone was later increased to a radius of 30 kilometres (19 mi), from which an additional ~68,000 people were evacuated.[9]

Following the reactor explosion, which killed two engineers and severely burned two more, an emergency operation to put out the fires and stabilize the surviving reactor began, during which 237 workers were hospitalized, of whom 134 exhibited symptoms of acute radiation syndrome (ARS). Among those hospitalized, 28 died within the following three months. In the following 10 years, 14 more workers (9 of whom had been hospitalized with ARS) died of various causes mostly unrelated to radiation exposure.[10] It remains the only time in the history of commercial nuclear power that radiation-related fatalities occurred.[11][12] 15 childhood thyroid cancer deaths were attributed to the disaster as of 2011[update].[13] A United Nations committee found that to date fewer than 100 deaths have resulted from the fallout.[14] Model predictions of the eventual total death toll in the coming decades vary. The most widely cited study conducted by the World Health Organization in 2006, predicted 9,000 cancer-related fatalities in Ukraine, Belarus and Russia.[15]

Following the disaster, Pripyat was abandoned and eventually replaced by the new purpose-built city of Slavutych. The Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant sarcophagus was built by December 1986. It reduced the spread of radioactive contamination from the wreckage and protected the site from weathering. The confinement shelter also provided radiological protection for the crews of the undamaged reactors at the site, which were restarted in late 1986 and 1987. However, the containment structure was only intended to last for 30 years, and required sizeable reinforcement in the early 2000s. The shelter was largely supplemented in 2017 by the Chernobyl New Safe Confinement, which was constructed around the old sarcophagus structure. The new enclosure aims to enable the removal of the sarcophagus and the reactor debris while containing the radioactive materials inside, with clean-up scheduled for completion by 2065.[16]

Background

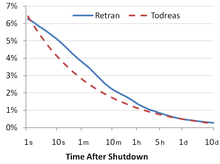

Reactor cooling after shutdown

In nuclear reactor operation, most heat is generated by nuclear fission, but over 6% comes from radioactive decay heat, which continues after the reactor shuts down. Continued coolant circulation is essential to prevent core overheating or a core meltdown.[17] RBMK reactors, like those at Chernobyl, use water as a coolant, circulated by electrically driven pumps.[18][19] Reactor No. 4 had 1,661 individual fuel channels, each requiring a coolant flow of 28 m³/h, totaling over 12 million US gallons per hour for the entire reactor.

In case of a total power loss, each of Chernobyl's reactors had three backup diesel generators, but they took 60–75 seconds to reach full load and generate the 5.5 MW needed to run one main pump.[20]: 15 Special counterweights on each pump provided coolant via inertia to bridge the gap to generator startup.[21][22] However, a potential safety risk existed in the event that a station blackout occurred simultaneously with the rupture of a 600-millimetre (24 in) coolant pipe (the so-called Design Basis Accident). In this scenario the emergency core cooling system (ECCS) is needed to pump additional water into the core, replacing coolant lost to evaporation.[23]

It had been theorized that the rotational momentum of the reactor's steam turbine could be used to generate the required electrical power to operate the ECCS via the feedwater pumps. The turbine's speed would run down as energy was taken from it, but analysis indicated that there might be sufficient energy to provide electrical power to run the coolant pumps for 45 seconds.[20]: 16 This would not quite bridge the gap between an external power failure and the full availability of the emergency generators, but would alleviate the situation.[24]

Safety test

The turbine run-down energy capability still needed to be confirmed experimentally, and previous tests had ended unsuccessfully. An initial test carried out in 1982 indicated that the excitation voltage of the turbine-generator was insufficient; it did not maintain the desired magnetic field after the turbine trip. The electrical system was modified, and the test was repeated in 1984 but again proved unsuccessful. In 1985, the test was conducted a third time but also yielded no results due to a problem with the recording equipment. The test procedure was to be run again in 1986 and was scheduled to take place during a controlled power-down of reactor No. 4, which was preparatory to a planned maintenance outage.[24][23]: 51

A test procedure had been written, but the authors were not aware of the unusual RBMK-1000 reactor behaviour under the planned operating conditions.[23]: 52 It was regarded as purely an electrical test of the generator, not a complex unit test, even though it involved critical unit systems. According to the regulations in place at the time, such a test did not require approval by either the chief design authority for the reactor (NIKIET) or the Soviet nuclear safety regulator.[23]: 51–52 The test program called for disabling the emergency core cooling system, a passive/active system of core cooling intended to provide water to the core in a loss-of-coolant accident, and approval from the Chernobyl site chief engineer had been obtained according to regulations.[23]: 18

The test procedure was intended to run as follows:

Test preparation

- The test would take place prior to a scheduled reactor shutdown

- The reactor thermal power was to be reduced to between 700 MW and 1,000 MW (to allow for adequate cooling, as the turbine would be spun at operating speed while disconnected from the power grid)

- The steam-turbine generator was to be run at normal operating speed

- Four out of eight main circulating pumps were to be supplied with off-site power, while the other four would be powered by the turbine

Electrical test

- When the correct conditions were achieved, the steam supply to the turbine generator would be closed, and the reactor would be shut down

- The voltage provided by the coasting turbine would be measured, along with the voltage and revolutions per minute (RPMs) of the four main circulating pumps being powered by the turbine

- When the emergency generators supplied full electrical power, the turbine generator would be allowed to continue free-wheeling down

Test delay and shift change

The test was to be conducted during the day-shift of 25 April 1986 as part of a scheduled reactor shut down. The day shift crew had been instructed in advance on the reactor operating conditions to run the test, and, in addition, a special team of electrical engineers was present to conduct the one-minute test of the new voltage regulating system once the correct conditions had been reached.[25][non-primary source needed] As planned, a gradual reduction in the output of the power unit began at 01:06 on 25 April, and the power level had reached 50% of its nominal 3,200 MW thermal level by the beginning of the day shift.[23]: 53

The day shift performed many unrelated maintenance tasks, and was scheduled to perform the test at 14:15.[26]: 3 Preparations for the test were carried out, including the disabling of the emergency core cooling system.[23]: 53 Meanwhile, another regional power station unexpectedly went offline. At 14:00,[23]: 53 the Kiev electrical grid controller requested that the further reduction of Chernobyl's output be postponed, as power was needed to satisfy the peak evening demand, so the test was postponed.

Soon, the day shift was replaced by the evening shift.[26]: 3 Despite the delay, the emergency core cooling system was left disabled. This system had to be disconnected via a manual isolating slide valve,[23]: 51 which in practice meant that two or three people spent the whole shift manually turning sailboat-helm-sized valve wheels.[26]: 4 The system would have no influence on the events that unfolded next, but allowing the reactor to run for 11 hours outside of the test without emergency protection was indicative of a general lack of safety culture.[23]: 10, 18

At 23:04, the Kiev grid controller allowed the reactor shutdown to resume. This delay had some serious consequences: the day shift had long since departed, the evening shift was also preparing to leave, and the night shift would not take over until midnight, well into the job. According to plan, the test should have been finished during the day shift, and the night shift would only have had to maintain decay heat cooling systems in an otherwise shut-down plant.[20]: 36–38

The night shift had very limited time to prepare for and carry out the experiment. Anatoly Dyatlov, deputy chief-engineer of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant (ChNPP), was present to supervise and direct the test. He was one of the test's chief authors and he was the highest-ranking individual present. Unit Shift Supervisor Aleksandr Akimov was in charge of the Unit 4 night shift, and Leonid Toptunov was the Senior Reactor Control Engineer responsible for the reactor's operational regimen, including the movement of the control rods. 25-year-old Toptunov had worked independently as a senior engineer for approximately three months.[20]: 36–38

Unexpected drop of the reactor power

The test plan called for a gradual decrease in reactor power to a thermal level of 700–1000 MW,[27] and an output of 720 MW was reached at 00:05 on 26 April.[23]: 53 However, due to the reactor's production of a fission byproduct, xenon-135, which is a reaction-inhibiting neutron absorber, power continued to decrease in the absence of further operator action, a process known as reactor poisoning. In steady-state operation, this is avoided because xenon-135 is "burned off" as quickly as it is created from decaying iodine-135 by the absorption of neutrons from the ongoing chain reaction, becoming highly stable xenon-136. With the reactor power reduced, high quantities of previously produced iodine-135 were decaying into the neutron-absorbing xenon-135 faster than the reduced neutron flux could "burn it off".[28] Xenon poisoning in this context made reactor control more difficult, but was a predictable and well-understood phenomenon during such a power reduction.

When the reactor power had decreased to approximately 500 MW, the reactor power control was switched from LAR (local automatic regulator) to the automatic regulators, to manually maintain the required power level.[23]: 11 AR-1 then activated, removing all four of AR-1's control rods automatically, but AR-2 failed to activate due to an imbalance in its ionization chambers. In response, Toptunov reduced power to stabilize the automatic regulators' ionization sensors. The result was a sudden power drop to an unintended near-shutdown state, with a power output of 30 MW thermal or less. The exact circumstances that caused the power drop are unknown. Most reports attribute the power drop to Toptunov's error, but Dyatlov reported that it was due to a fault in the AR-2 system.[23]: 11

The reactor was now producing only 5% of the minimum initial power level prescribed for the test.[23]: 73 This low reactivity inhibited the burn-off of xenon-135[23]: 6 within the reactor core and hindered the rise of reactor power. To increase power, control-room personnel removed numerous control rods from the reactor.[29][non-primary source needed] Several minutes elapsed before the reactor was restored to 160 MW at 00:39, at which point most control rods were at their upper limits, but the rod configuration was still within its normal operating limit, with Operational Reactivity Margin (ORM) equivalent to having more than 15 rods inserted. Over the next twenty minutes, reactor power would be increased further to 200 MW.[23]: 73

The operation of the reactor at the low power level (and high poisoning level) was accompanied by unstable core temperatures and coolant flow, and, possibly, by instability of neutron flux. The control room received repeated emergency signals regarding the low levels in one half of the steam/water separator drums, with accompanying drum separator pressure warnings. In response, personnel triggered several rapid influxes of feedwater. Relief valves opened to relieve excess steam into a turbine condenser.[citation needed]

Reactor conditions priming the accident

When a power level of 200 MW was reattained, preparation for the experiment continued, although the power level was much lower than the prescribed 700 MW. As part of the test program, two additional main circulating (coolant) pumps were activated at 01:05. The increased coolant flow lowered the overall core temperature and reduced the existing steam voids in the core. Because water absorbs neutrons better than steam, the neutron flux and reactivity decreased. The operators responded by removing more manual control rods to maintain power.[30][31] It was around this time that the number of control rods inserted in the reactor fell below the required value of 15. This was not apparent to the operators, because the RBMK did not have any instruments capable of calculating the inserted rod worth in real time.

The combined effect of these various actions was an extremely unstable reactor configuration. Nearly all of the 211 control rods had been extracted, and excessively high coolant flow rates meant that the water had less time to cool between trips through the core, therefore entering the reactor very close to the boiling point. Unlike other light-water reactor designs, the RBMK design at that time had a positive void coefficient of reactivity at typical fuel burnup levels. This meant that the formation of steam bubbles (voids) from boiling cooling water intensified the nuclear chain reaction owing to voids having lower neutron absorption than water. Unknown to the operators, the void coefficient was not counterbalanced by other reactivity effects in the given operating regime, meaning that any increase in boiling would produce more steam voids which further intensified the chain reaction, leading to a positive feedback loop. Given this characteristic, reactor No. 4 was now at risk of a runaway increase in its core power with nothing to restrain it. The reactor was now very sensitive to the regenerative effect of steam voids on reactor power.[23]: 3, 14

Accident

Test execution

neutron detectors (12)

control rods (167)

short control rods from below reactor (32)

automatic control rods (12)

pressure tubes with fuel rods (1661)

At 01:23:04, the test began.[32] Four of the eight main circulating pumps (MCP) were to be powered by voltage from the coasting turbine, while the remaining four pumps received electrical power from the grid as normal. The steam to the turbines was shut off, beginning a run-down of the turbine generator. The diesel generators started and sequentially picked up loads; the generators were to have completely picked up the MCPs' power needs by 01:23:43. As the momentum of the turbine generator decreased, so did the power it produced for the pumps. The water flow rate decreased, leading to increased formation of steam voids in the coolant flowing up through the fuel pressure tubes.[23]: 8

Reactor shutdown and power excursion

At 01:23:40, as recorded by the SKALA centralized control system, a scram (emergency shutdown) of the reactor was initiated[33] as the experiment was wrapping up.[34][non-primary source needed] The scram was started when the AZ-5 button (also known as the EPS-5 button) of the reactor emergency protection system was pressed: this engaged the drive mechanism on all control rods to fully insert them, including the manual control rods that had been withdrawn earlier.

The personnel had already intended to shut down using the AZ-5 button in preparation for scheduled maintenance[35][non-primary source needed] and the scram preceded the sharp increase in power.[23]: 13 However, the precise reason why the button was pressed when it was is not certain, as only the deceased Akimov and Toptunov partook in that decision, though the atmosphere in the control room was calm at that moment, according to several eyewitnesses.[36][37]: 85 Meanwhile, the RBMK designers claim that the button had to have been pressed only after the reactor already began to self-destruct.[38]: 578

When the AZ-5 button was pressed, the insertion of control rods into the reactor core began. The control rod insertion mechanism moved the rods at 0.4 metres per second (1.3 ft/s), so that the rods took 18 to 20 seconds to travel the full height of the core, about 7 metres (23 ft). A bigger problem was the design of the RBMK control rods, each of which had a graphite neutron moderator section attached to its end to boost reactor output by displacing water when the control rod section had been fully withdrawn from the reactor. That is, when a control rod was at maximum extraction, a neutron-moderating graphite extension was centered in the core with 1.25 metres (4.1 ft) columns of water above and below it.[23]

Consequently, injecting a control rod downward into the reactor in a scram initially displaced neutron-absorbing water in the lower portion of the reactor with neutron-moderating graphite. Thus, an emergency scram could initially increase the reaction rate in the lower part of the core.[23]: 4 This behaviour was discovered when the initial insertion of control rods in another RBMK reactor at Ignalina Nuclear Power Plant in 1983 induced a power spike. Procedural countermeasures were not implemented in response to Ignalina. The IAEA investigative report INSAG-7 later stated, "Apparently, there was a widespread view that the conditions under which the positive scram effect would be important would never occur. However, they did appear in almost every detail in the course of the actions leading to the Chernobyl accident."[23]: 13

A few seconds into the scram, a power spike occurred, and the core overheated, causing some of the fuel rods to fracture. Some have speculated that this also blocked the control rod columns, jamming them at one-third insertion. Within three seconds the reactor output rose above 530 MW.[20]: 31

Instruments did not register the subsequent course of events; it was reconstructed through mathematical simulation. Per the simulation, the power spike would have caused an increase in fuel temperature and steam buildup, leading to a rapid increase in steam pressure. This caused the fuel cladding to fail, releasing the fuel elements into the coolant and rupturing the channels in which these elements were located.[40]

Steam explosions

As the scram continued, the reactor output jumped to around 30,000 MW thermal, 10 times its normal operational output, the indicated last reading on the power meter on the control panel. Some estimate the power spike may have gone 10 times higher than that. It was not possible to reconstruct the precise sequence of the processes that led to the destruction of the reactor and the power unit building, but a steam explosion—like the explosion of a steam boiler from excess vapour pressure—appears to have been the next event. There is a general understanding that it was explosive steam pressure from the damaged fuel channels escaping into the reactor's exterior cooling structure that caused the explosion that destroyed the reactor casing, tearing off and blasting the upper plate called the upper biological shield,[41] to which the entire reactor assembly is fastened, through the roof of the reactor building. This is believed to be the first explosion that many heard.[42]: 366

This explosion ruptured further fuel channels, as well as severing most of the coolant lines feeding the reactor chamber, and as a result, the remaining coolant flashed to steam and escaped the reactor core. The total water loss combined with a high positive void coefficient further increased the reactor's thermal power.[23]

A second, more powerful explosion occurred about two or three seconds after the first; this explosion dispersed the damaged core and effectively terminated the nuclear chain reaction. This explosion also compromised more of the reactor containment vessel and ejected hot lumps of graphite moderator. The ejected graphite and the demolished channels still in the remains of the reactor vessel caught fire on exposure to air, significantly contributing to the spread of radioactive fallout and the contamination of outlying areas.[30][b] The explosion is estimated to have had the power equivalent of 225 tons of TNT.[45]

According to observers outside Unit 4, burning lumps of material and sparks shot into the air above the reactor. Some of them fell onto the roof of the machine hall and started a fire. About 25% of the red-hot graphite blocks and overheated material from the fuel channels was ejected. Parts of the graphite blocks and fuel channels were out of the reactor building. As a result of the damage to the building, an airflow through the core was established by the core's high temperature. The air ignited the hot graphite and started a graphite fire.[20]: 32

After the larger explosion, several employees at the power station went outside to get a clearer view of the extent of the damage. One such survivor, Alexander Yuvchenko, said that once he stepped out and looked up towards the reactor hall, he saw a "very beautiful" laser-like beam of blue light caused by the ionized-air glow that appeared to be "flooding up into infinity".[46][47]

There were initially several hypotheses about the nature of the second explosion. One view was that the second explosion was caused by the combustion of hydrogen, which had been produced either by the overheated steam-zirconium reaction or by the reaction of red-hot graphite with steam that produced hydrogen and carbon monoxide. Another hypothesis, by Konstantin Checherov, published in 1998, was that the second explosion was a thermal explosion of the reactor due to the uncontrollable escape of fast neutrons caused by the complete water loss in the reactor core.[48]

Crisis management

Fire containment

Contrary to safety regulations, bitumen, a combustible material, had been used in the construction of the roof of the reactor building and the turbine hall. Ejected material ignited at least five fires on the roof of the adjacent reactor No. 3, which was still operating. It was imperative to put out those fires and protect the cooling systems of reactor No. 3.[20]: 42 Inside reactor No. 3, the chief of the night shift, Yuri Bagdasarov, wanted to shut down the reactor immediately, but chief engineer Nikolai Fomin would not allow this. The operators were given respirators and potassium iodide tablets and told to continue working. At 05:00, Bagdasarov made his own decision to shut down the reactor,[20]: 44 which was confirmed in writing by Dyatlov and Station Shift Supervisor Rogozhkin.

Shortly after the accident, firefighters arrived to try to extinguish the fires.[32] First on the scene was a Chernobyl Power Station firefighter brigade under the command of Lieutenant Volodymyr Pravyk, who died on 11 May 1986 of acute radiation sickness. They were not told how dangerously radioactive the smoke and the debris were, and may not even have known that the accident was anything more than a regular electrical fire: "We didn't know it was the reactor. No one had told us."[49] Grigorii Khmel, the driver of one of the fire engines, later described what happened:

We arrived there at 10 or 15 minutes to two in the morning ... We saw graphite scattered about. Misha asked: "Is that graphite?" I kicked it away. But one of the fighters on the other truck picked it up. "It's hot," he said. The pieces of graphite were of different sizes, some big, some small enough to pick them up [...] We didn't know much about radiation. Even those who worked there had no idea. There was no water left in the trucks. Misha filled a cistern and we aimed the water at the top. Then those boys who died went up to the roof—Vashchik, Kolya and others, and Volodya Pravik ... They went up the ladder ... and I never saw them again.[50]

Anatoli Zakharov, a fireman stationed in Chernobyl since 1980, offered a different description in 2008: "I remember joking to the others, 'There must be an incredible amount of radiation here. We'll be lucky if we're all still alive in the morning.'"[51] He also stated, "Of course we knew! If we'd followed regulations, we would never have gone near the reactor. But it was a moral obligation—our duty. We were like kamikaze."[51]

The immediate priority was to extinguish fires on the roof of the station and the area around the building containing Reactor No. 4 to protect No. 3 and keep its core cooling systems intact. The fires were extinguished by 5:00, but many firefighters received high doses of radiation. The fire inside reactor No. 4 continued to burn until 10 May 1986; it is possible that well over half of the graphite burned out.[20]: 73

It was thought by some that the core fire was extinguished by a combined effort of helicopters dropping more than 5,000 tonnes (11 million pounds) of sand, lead, clay, and neutron-absorbing boron onto the burning reactor. It is now known that virtually none of these materials reached the core.[52] Historians estimate that about 600 Soviet pilots risked dangerous levels of radiation to fly the thousands of flights needed to cover reactor No. 4 in this attempt to seal off radiation.[53]

From eyewitness accounts of the firefighters involved before they died (as reported on the CBC television series Witness), one described his experience of the radiation as "tasting like metal", and feeling a sensation similar to that of pins and needles all over his face. This is consistent with the description given by Louis Slotin, a Manhattan Project physicist who died days after a fatal radiation overdose from a criticality accident.[54]

The explosion and fire threw hot particles of the nuclear fuel and also far more dangerous fission products (radioactive isotopes such as caesium-137, iodine-131, strontium-90, and other radionuclides) into the air. The residents of the surrounding area observed the radioactive cloud on the night of the explosion.[citation needed]

Radiation levels

The ionizing radiation levels in the worst-hit areas of the reactor building have been estimated to be 5.6 roentgens per second (R/s), equivalent to more than 20,000 roentgens per hour. A lethal dose is around 500 roentgens (~5 Gray (Gy) in modern radiation units) over five hours, so in some areas, unprotected workers received fatal doses in less than a minute. Unfortunately, a dosimeter capable of measuring up to 1,000 R/s was buried in the rubble of a collapsed part of the building, and another one failed when turned on. Most remaining dosimeters had limits of 0.001 R/s and therefore read "off scale". Thus, the reactor crew could ascertain only that the radiation levels were somewhere above 0.001 R/s (3.6 R/h), while the true levels were vastly higher in some areas.[20]: 42–50

Because of the inaccurate low readings, the reactor crew chief Aleksandr Akimov assumed that the reactor was intact. The evidence of pieces of graphite and reactor fuel lying around the building was ignored, and the readings of another dosimeter brought in by 04:30 were dismissed under the assumption that the new dosimeter must have been defective.[20]: 42–50 Akimov stayed with his crew in the reactor building until morning, sending members of his crew to try to pump water into the reactor. None of them wore any protective gear. Most, including Akimov, died from radiation exposure within three weeks.[55][56]: 247–248

Evacuation

The nearby city of Pripyat was not immediately evacuated. The townspeople, in the early hours of the morning, at 01:23 local time, went about their usual business, completely oblivious to what had just happened. However, within a few hours of the explosion, dozens of people fell ill. Later, they reported severe headaches and metallic tastes in their mouths, along with uncontrollable fits of coughing and vomiting.[57][better source needed] As the plant was run by authorities in Moscow, the government of Ukraine did not receive prompt information on the accident.[58]

Valentyna Shevchenko, then Chairwoman of the Presidium of Verkhovna Rada of the Ukrainian SSR, said that Ukraine's acting Minister of Internal Affairs Vasyl Durdynets phoned her at work at 09:00 to report current affairs; only at the end of the conversation did he add that there had been a fire at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, but it was extinguished and everything was fine. When Shevchenko asked "How are the people?", he replied that there was nothing to be concerned about: "Some are celebrating a wedding, others are gardening, and others are fishing in the Pripyat River".[58]

Shevchenko then spoke by telephone to Volodymyr Shcherbytsky, General Secretary of the Communist Party of Ukraine and de facto head of state, who said he anticipated a delegation of the state commission headed by Boris Shcherbina, the deputy chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR.[58]

A commission was established later in the day to investigate the accident. It was headed by Valery Legasov, First Deputy Director of the Kurchatov Institute of Atomic Energy, and included leading nuclear specialist Evgeny Velikhov, hydro-meteorologist Yuri Izrael, radiologist Leonid Ilyin, and others. They flew to Boryspil International Airport and arrived at the power plant in the evening of 26 April.[58] By that time two people had already died and 52 were hospitalized. The delegation soon had ample evidence that the reactor was destroyed and extremely high levels of radiation had caused a number of cases of radiation exposure. In the early daylight hours of 27 April, they ordered the evacuation of Pripyat. Initially it was decided to evacuate the population for three days; later this was made permanent.[58]

By 11:00 on 27 April, buses had arrived in Pripyat to start the evacuation.[58] The evacuation began at 14:00. A translated excerpt of the evacuation announcement follows:

For the attention of the residents of Pripyat! The City Council informs you that due to the accident at Chernobyl Power Station in the city of Pripyat the radioactive conditions in the vicinity are deteriorating. The Communist Party, its officials and the armed forces are taking necessary steps to combat this. Nevertheless, with the view to keep people as safe and healthy as possible, the children being top priority, we need to temporarily evacuate the citizens in the nearest towns of Kiev region. For these reasons, starting from 27 April 1986, 14:00 each apartment block will be able to have a bus at its disposal, supervised by the police and the city officials. It is highly advisable to take your documents, some vital personal belongings and a certain amount of food, just in case, with you. The senior executives of public and industrial facilities of the city has decided on the list of employees needed to stay in Pripyat to maintain these facilities in a good working order. All the houses will be guarded by the police during the evacuation period. Comrades, leaving your residences temporarily please make sure you have turned off the lights, electrical equipment and water and shut the windows. Please keep calm and orderly in the process of this short-term evacuation.[59]

To expedite the evacuation, residents were told to bring only what was necessary, and that they would remain evacuated for approximately three days. As a result, most personal belongings were left behind, and residents were only allowed to recover certain items after months had passed. By 15:00, 53,000 people were evacuated to various villages of the Kiev region.[58] The next day, talks began for evacuating people from the 10-kilometre (6.2 mi) zone.[58] Ten days after the accident, the evacuation area was expanded to 30 kilometres (19 mi).[60]: 115, 120–121 The Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant Exclusion Zone has remained ever since, although its shape has changed and its size has been expanded.

The surveying and detection of isolated fallout hotspots outside this zone over the following year eventually resulted in 135,000 long-term evacuees in total agreeing to be moved.[9] The years between 1986 and 2000 saw the near tripling in the total number of permanently resettled persons from the most severely contaminated areas to approximately 350,000.[61][62]

Official announcement

Evacuation began one and a half days before the accident was publicly acknowledged by the Soviet Union. In the morning of 28 April, radiation levels set off alarms at the Forsmark Nuclear Power Plant in Sweden,[63][64] over 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) from the Chernobyl Plant. Workers at Forsmark reported the case to the Swedish Radiation Safety Authority, which determined that the radiation had originated elsewhere. That day, the Swedish government contacted the Soviet government to inquire about whether there had been a nuclear accident in the Soviet Union. The Soviets initially denied it, and it was only after the Swedish government suggested they were about to file an official alert with the International Atomic Energy Agency, that the Soviet government admitted that an accident had taken place at Chernobyl.[64][65]

At first, the Soviets only conceded that a minor accident had occurred, but once they began evacuating more than 100,000 people, the full scale of the situation was realized by the global community.[66] At 21:02 the evening of 28 April, a 20-second announcement was read in the TV news programme Vremya: "There has been an accident at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. One of the nuclear reactors was damaged. The effects of the accident are being remedied. Assistance has been provided for any affected people. An investigative commission has been set up."[67][68]

This was the entire announcement, and the first time the Soviet Union officially announced a nuclear accident. The Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union (TASS) then discussed the Three Mile Island accident and other American nuclear accidents, which Serge Schmemann of The New York Times wrote was an example of the common Soviet tactic of whataboutism. The mention of a commission also indicated to observers the seriousness of the incident,[65] and subsequent state radio broadcasts were replaced with classical music, which was a common method of preparing the public for an announcement of a tragedy in the USSR.[67]

Around the same time, ABC News released its report about the disaster.[69] Shevchenko was the first of the Ukrainian state top officials to arrive at the disaster site early on 28 April. There she spoke with members of medical staff and people, who were calm and hopeful that they could soon return to their homes. Shevchenko returned home near midnight, stopping at a radiological checkpoint in Vilcha, one of the first that were set up soon after the accident.[58]

There was a notification from Moscow that there was no reason to postpone the 1 May International Workers' Day celebrations in Kiev (including the annual parade), but on 30 April a meeting of the Political bureau of the Central Committee of the CPSU took place to discuss the plan for the upcoming celebration. Scientists were reporting that the radiological background level in Kiev was normal. At the meeting, which was finished at 18:00, it was decided to shorten celebrations from the regular three and a half to four hours to under two hours.[58]

Several buildings in Pripyat were officially kept open after the disaster to be used by workers still involved with the plant. These included the Jupiter factory (which closed in 1996) and the Azure Swimming Pool, used by the Chernobyl liquidators for recreation during the clean-up (which closed in 1998).

Core meltdown risk mitigation

Bubbler pools

Two floors of bubbler pools beneath the reactor served as a large water reservoir for the emergency cooling pumps and as a pressure suppression system capable of condensing steam in case of a small broken steam pipe; the third floor above them, below the reactor, served as a steam tunnel. The steam released by a broken pipe was supposed to enter the steam tunnel and be led into the pools to bubble through a layer of water. After the disaster, the pools and the basement were flooded because of ruptured cooling water pipes and accumulated firefighting water.

The smoldering graphite, fuel and other material, at more than 1,200 °C (2,190 °F),[71] started to burn through the reactor floor and mixed with molten concrete from the reactor lining, creating corium, a radioactive semi-liquid material comparable to lava.[70][72] It was feared that if this mixture melted through the floor into the pool of water, the resulting steam production would further contaminate the area or even cause a steam explosion, ejecting more radioactive material from the reactor. It became necessary to drain the pool.[73] These fears ultimately proved unfounded, since corium began dripping harmlessly into the flooded bubbler pools before the water could be removed.[74] The molten fuel hit the water and cooled into a light-brown ceramic pumice, whose low density allowed the substance to float on the water's surface.[74]

Unaware of this fact, the government commission directed that the bubbler pools be drained by opening its sluice gates. The valves controlling it, however, were located in a flooded corridor in a subterranean annex adjacent to the reactor building. Volunteers in diving suits and respirators (for protection against radioactive aerosols), and equipped with dosimeters, entered the knee-deep radioactive water and managed to open the valves.[75][76] These were the engineers Oleksiy Ananenko and Valeri Bezpalov (who knew where the valves were), accompanied by the shift supervisor Boris Baranov.[77][78][79] The three men were awarded the Order For Courage by Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko in May 2018.[80]

Numerous media reports falsely suggested that all three men died just days after the incident. In fact, all three survived and continued to work in the nuclear energy industry.[81] Ananenko and Bezpalov were still alive as of 2021, while Baranov had died of heart failure in 2005 at age 65.[82] Once the bubbler pool gates were opened by the three volunteers, fire brigade pumps were then used to drain the basement. The operation was not completed until 8 May, after 20,000 tonnes (20,000 long tons; 22,000 short tons) of water were pumped out.[83]

Foundation protection measures

The government commission was concerned that the molten core would burn into the earth and contaminate groundwater below the reactor. To reduce the likelihood of this, it was decided to freeze the earth beneath the reactor, which would also stabilize the foundations. Using oil well drilling equipment, the injection of liquid nitrogen began on 4 May. It was estimated that 25 tonnes (55 thousand pounds) of liquid nitrogen per day would be required to keep the soil frozen at −100 °C (−148 °F).[20]: 59 This idea was quickly scrapped.[84]

As an alternative, subway builders and coal miners were deployed to excavate a tunnel below the reactor to make room for a cooling system. The final makeshift design for the cooling system was to incorporate a coiled formation of pipes cooled with water and covered on top with a thin thermally conductive graphite layer. The graphite layer as a natural refractory material would prevent the concrete above from melting. This graphite cooling plate layer was to be encapsulated between two concrete layers, each 1 metre (3 ft 3 in) thick for stabilisation. This system was designed by Leonid Bolshov, the director of the Institute for Nuclear Safety and Development formed in 1988. Bolshov's graphite-concrete "sandwich" would be similar in concept to later core catchers that are now part of many nuclear reactor designs.[85]

Bolshov's graphite cooling plate, alongside the prior nitrogen injection proposal, were not used following the drop in aerial temperatures and indicative reports that the fuel melt had stopped. It was later determined that the fuel had flowed three floors, with a few cubic meters coming to rest at ground level. The precautionary underground channel with its active cooling was therefore deemed redundant, as the fuel was self-cooling. The excavation was then simply filled with concrete to strengthen the foundation below the reactor.[86]

Immediate site and area remediation

Debris removal

In the months after the explosion, attention turned to removing the radioactive debris from the roof.[87] While the worst of the radioactive debris had remained inside what was left of the reactor, it was estimated that there was approximately 100 tons of debris on that roof which had to be removed to enable the safe construction of the "sarcophagus"—a concrete structure that would entomb the reactor and reduce radioactive dust being released into the atmosphere.[87] The initial plan was to use robots to clear the debris off the roof. The Soviets used approximately 60 remote-controlled robots, most of them built in the Soviet Union itself. Many failed due to the difficult terrain, combined with the effect of high radiation fields on their batteries and electronic controls.[87] In 1987, Valery Legasov, first deputy director of the Kurchatov Institute of Atomic Energy in Moscow, said: "We learned that robots are not the great remedy for everything. Where there was very high radiation, the robot ceased to be a robot—the electronics quit working."[88]

Consequently, the most highly radioactive materials were shoveled by Chernobyl liquidators from the military wearing heavy protective gear (dubbed "bio-robots"). These soldiers could only spend a maximum of 40–90 seconds working on the rooftops of the surrounding buildings because of the extremely high doses of radiation given off by the blocks of graphite and other debris. Only 10% of the debris cleared from the roof was performed by robots; the other 90% was removed by 3,828 men who absorbed, on average, an estimated dose of 25 rem (250 mSv) of radiation each.[87]

Construction of the sarcophagus

With the extinguishing of the open air reactor fire, the next step was to prevent the spread of contamination. This could be due to wind action which could carry away loose contamination, and by birds which could land within the wreckage and then carry contamination elsewhere. In addition, rainwater could wash contamination away from the reactor area and into the sub-surface water table, where it could migrate outside the site area. Rainwater falling on the wreckage could also weaken the remaining reactor structure by accelerating corrosion of steelwork. A further challenge was to reduce the large amount of emitted gamma radiation, which was a hazard to the workforce operating the adjacent reactor No. 3.[citation needed]

The solution chosen was to enclose the wrecked reactor by the construction of a huge composite steel and concrete shelter, which became known as the "Sarcophagus". It had to be erected quickly and within the constraints of high levels of ambient gamma radiation. The design started on 20 May 1986, 24 days after the disaster, and construction was from June to late November.[89] This major construction project was carried out under the very difficult circumstances of high levels of radiation both from the core remnants and the deposited radioactive contamination around it.

The construction workers had to be protected from radiation, and techniques such as crane drivers working from lead-lined control cabins were employed. The construction work included erecting walls around the perimeter, clearing and surface concreting the surrounding ground to remove sources of radiation and to allow access for large construction machinery, constructing a thick radiation shielding wall to protect the workers in reactor No. 3, fabricating a high-rise buttress to strengthen weak parts of the old structure, constructing an overall roof, and provisioning a ventilation extract system to capture any airborne contamination arising within the shelter.[citation needed]

Investigations of the reactor condition

During the construction of the sarcophagus, a scientific team, as part of an investigation dubbed "Complex Expedition", re-entered the reactor to locate and contain nuclear fuel to prevent another explosion. These scientists manually collected cold fuel rods, but great heat was still emanating from the core. Rates of radiation in different parts of the building were monitored by drilling holes into the reactor and inserting long metal detector tubes. The scientists were exposed to high levels of radiation and radioactive dust.[52]

In December 1986, after six months of investigation, the team discovered with the help of a remote camera that an intensely radioactive mass more than 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) wide had formed in the basement of Unit Four. The mass was called "the elephant's foot" for its wrinkled appearance.[90] It was composed of melted sand, concrete, and a large amount of nuclear fuel that had escaped from the reactor. The concrete beneath the reactor was steaming hot, and was breached by now-solidified lava and spectacular unknown crystalline forms termed chernobylite. It was concluded that there was no further risk of explosion.[52]

Area cleanup

The official contaminated zones saw a massive clean-up effort lasting seven months.[60]: 177–183 The official reason for such early (and dangerous) decontamination efforts, rather than allowing time for natural decay, was that the land must be repopulated and brought back into cultivation. Within fifteen months 75% of the land was under cultivation, even though only a third of the evacuated villages were resettled. Defence forces must have done much of the work. Yet this land was of marginal agricultural value. According to historian David Marples, the administration had a psychological purpose for the clean-up: they wished to forestall panic regarding nuclear energy, and even to restart the Chernobyl power station.[60]: 78–79, 87, 192–193

Helicopters regularly sprayed large areas of contaminated land with "Barda", a sticky polymerizing fluid, designed to entrap radioactive dust.[91]

Although a number of radioactive emergency vehicles were buried in trenches, many of the vehicles used by the liquidators, including the helicopters, still remained, as of 2018, parked in a field in the Chernobyl area. Scavengers have since removed many functioning, but highly radioactive, parts.[92] Liquidators worked under deplorable conditions, poorly informed and with poor protection. Many, if not most of them, exceeded radiation safety limits.[60]: 177–183 [93]

A unique "clean up" medal was given to the clean-up workers, known as "liquidators".[94]

Investigations and the evolution of identified causes

To investigate the causes of the accident the IAEA used the International Nuclear Safety Advisory Group (INSAG), which had been created by the IAEA in 1985.[95] It produced two significant reports on Chernobyl; INSAG-1 in 1986, and a revised report, INSAG-7 in 1992. In summary, according to INSAG-1, the main cause of the accident was the operators' actions, but according to INSAG-7, the main cause was the reactor's design.[23]: 24 [96] Both IAEA reports identified an inadequate "safety culture" (INSAG-1 coined the term) at all managerial and operational levels as a major underlying factor of different aspects of the accident. This was stated to be inherent not only in operations but also during design, engineering, construction, manufacture and regulation.[23]: 21, 24

Fizzled nuclear explosion hypothesis

The force of the second explosion and the ratio of xenon radioisotopes released after the accident led Sergei A. Pakhomov and Yuri V. Dubasov in 2009 to theorize that the second explosion could have been an extremely fast nuclear power transient resulting from core material melting in the absence of its water coolant and moderator. Pakhomov and Dubasov argued that there was no delayed supercritical increase in power but a runaway prompt criticality which would have developed much faster. He felt the physics of this would be more similar to the explosion of a fizzled nuclear weapon, and it produced the second explosion.[97]

Their evidence came from Cherepovets, a city 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) northeast of Chernobyl, where physicists from the V.G. Khlopin Radium Institute measured anomalous high levels of xenon-135—a short half-life isotope—four days after the explosion. This meant that a nuclear event in the reactor may have ejected xenon to higher altitudes in the atmosphere than the later fire did, allowing widespread movement of xenon to remote locations.[98] This was an alternative to the more accepted explanation of a positive-feedback power excursion where the reactor disassembled itself by steam explosion.[23][97]

The energy released by the second explosion, which produced the majority of the damage, was estimated by Pakhomov and Dubasov to be at 40 billion joules, the equivalent of about 10 tons of TNT.[97]

Pakhomov and Dubasov's nuclear fizzle hypothesis was examined in 2017 by Lars-Erik De Geer, Christer Persson and Henning Rodhe, who put the hypothesized fizzle event as the more probable cause of the first explosion.[45]: 11 [99][100] Both analyses argue that the nuclear fizzle event, whether producing the second or first explosion, consisted of a prompt chain reaction that was limited to a small portion of the reactor core, since self-disassembly occurs rapidly in fizzle events.[97][45]

De Geer, Persson and Rodhe commented:

We believe that thermal neutron mediated nuclear explosions at the bottom of a number of fuel channels in the reactor caused a jet of debris to shoot upwards through the refuelling tubes. This jet then rammed the tubes' 350kg plugs, continued through the roof and travelled into the atmosphere to altitudes of 2.5–3km where the weather conditions provided a route to Cherepovets. The steam explosion which ruptured the reactor vessel occurred some 2.7 seconds later.[98]

This second explosion was estimated by the authors to have had the power equivalent of 225 tons of TNT.[45]

Release and spread of radioactive materials

Although it is difficult to compare releases between the Chernobyl accident and a deliberate air burst nuclear detonation, it has nevertheless been estimated that about four hundred times more radioactive material was released from Chernobyl than by the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki together. However, the Chernobyl accident only released about one hundredth to one thousandth of the total amount of radioactivity released during nuclear weapons testing at the height of the Cold War; the wide estimate being due to the different abundances of isotopes released.[101]

At Chernobyl, approximately 100,000 square kilometres (39,000 sq mi) of land was significantly contaminated with fallout, with the worst hit regions being in Belarus, Ukraine and Russia.[102] Lower levels of contamination were detected over all of Europe except for the Iberian Peninsula.[103][104][105] Most of the fallout with radioactive dust particles was released during the first ten days after the accident. By around 2 May, a radioactive cloud had reached the Netherlands and Belgium.

The initial evidence that a major release of radioactive material was affecting other countries came not from Soviet sources, but from Sweden. On the morning of 28 April,[106] workers at the Forsmark Nuclear Power Plant in central Sweden (approximately 1,100 km (680 mi) from the Chernobyl site) were found to have radioactive particles on their clothes, except they had this whenever they came to work rather than when exiting.[107]

It was Sweden's elevated radioactivity level, detected at noon on 28 April that, having been determined as not caused by a leak at the Swedish plant, first suggested a serious nuclear problem originating from the western Soviet Union. The evacuation of Pripyat on 27 April had been silently completed without the disaster being declared outside the Soviet Union. A rise in radiation levels in the subsequent days had also been measured in Finland, but a civil service strike delayed the response and publication.[108]

| Country | 37–185 kBq/m2 | 185–555 kBq/m2 | 555–1,480 kBq/m2 | > 1,480 kBq/m2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| km2 | % of country | km2 | % of country | km2 | % of country | km2 | % of country | |

| Belarus | 29,900 | 14.4 | 10,200 | 4.9 | 4,200 | 2.0 | 2,200 | 1.1 |

| Ukraine | 37,200 | 6.2 | 3,200 | 0.53 | 900 | 0.15 | 600 | 0.1 |

| Russia | 49,800 | 0.3 | 5,700 | 0.03 | 2,100 | 0.01 | 300 | 0.002 |

| Sweden | 12,000 | 2.7 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Finland | 11,500 | 3.4 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Austria | 8,600 | 10.3 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Norway | 5,200 | 1.3 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Bulgaria | 4,800 | 4.3 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Switzerland | 1,300 | 3.1 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Greece | 1,200 | 0.9 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Slovenia | 300 | 1.5 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Italy | 300 | 0.1 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Moldova | 60 | 0.2 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Totals | 162,160 km2 | 19,100 km2 | 7,200 km2 | 3,100 km2 | ||||

Contamination from the Chernobyl accident was scattered irregularly depending on weather conditions, much of it deposited on mountainous regions such as the Alps, the Welsh mountains and the Scottish Highlands, where adiabatic cooling caused radioactive rainfall. The resulting patches of contamination were often highly localized, and localized water-flows contributed to large variations in radioactivity over small areas. Sweden and Norway also received heavy fallout when the contaminated air collided with a cold front, bringing rain.[110]: 43–44, 78 There was also groundwater contamination.

Rain was deliberately seeded over 10,000 square kilometres (3,900 sq mi) of Belarus by the Soviet Air Force to remove radioactive particles from clouds heading toward highly populated areas. Heavy, black-coloured rain fell on the city of Gomel.[111] Reports from Soviet and Western scientists indicate that the Belarusian SSR received about 60% of the contamination that fell on the former Soviet Union. However, the 2006 TORCH report stated that up to half of the volatile particles had actually landed outside the former USSR area currently making up Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia. An unconnected large area in Russian SFSR south of Bryansk was also contaminated, as were parts of northwestern Ukrainian SSR. Studies in surrounding countries indicate that more than one million people could have been affected by radiation.[112]

2016 data from a long-term monitoring program (The Korma Report II)[113] showed a decrease in internal radiation exposure of the inhabitants of a region in Belarus close to Gomel. Resettlement may now be possible in prohibited areas provided that people comply with appropriate dietary rules.

In Western Europe, precautionary measures taken in response to the radiation included banning the importation of certain foods.[citation needed] A 2006 study by the French society for nuclear energy found that contamination was "relatively limited, diminishing from west to east", such that a hunter consuming 40 kilograms of contaminated wild boar in 1997 would be exposed to about one millisievert.[114]

Relative isotopic abundances

The Chernobyl release was characterized by the physical and chemical properties of the radio-isotopes in the core. Particularly dangerous were the highly radioactive fission products, those with high nuclear decay rates that accumulate in the food chain, such as some of the isotopes of iodine, caesium and strontium. Iodine-131 was and caesium-137 remains the two most responsible for the radiation exposure received by the general population.[2]

Detailed reports on the release of radioisotopes from the site were published in 1989[115] and 1995,[116] with the latter report updated in 2002.[2]

At different times after the accident, different isotopes were responsible for the majority of the external dose. The remaining quantity of any radioisotope, and therefore the activity of that isotope, after 7 decay half-lives have passed, is less than 1% of its initial magnitude,[117] and it continues to reduce beyond 0.78% after 7 half-lives to 0.10% remaining after 10 half-lives have passed and so on.[118][119] Some radionuclides have decay products that are likewise radioactive, which is not accounted for here. The release of radioisotopes from the nuclear fuel was largely controlled by their boiling points, and the majority of the radioactivity present in the core was retained in the reactor.

- All of the noble gases, including krypton and xenon, contained within the reactor were released immediately into the atmosphere by the first steam explosion.[2] The atmospheric release of xenon-133, with a half-life of 5 days, is estimated at 5200 PBq.[2]

- 50 to 60% of all core radioiodine in the reactor, about 1760 PBq (1760×1015 becquerels), or about 0.4 kilograms (0.88 lb), was released, as a mixture of sublimed vapour, solid particles, and organic iodine compounds. Iodine-131 has a half-life of 8 days.[2]

- 20 to 40% of all core caesium-137 was released, 85 PBq in all.[2][120] Caesium was released in aerosol form; caesium-137, along with isotopes of strontium, are the two primary elements preventing the Chernobyl exclusion zone being re-inhabited.[121] 8.5×1016 Bq equals 24 kilograms of caesium-137.[121] Cs-137 has a half-life of 30 years.[2]

- Tellurium-132, half-life 78 hours, an estimated 1150 PBq was released.[2]

- An early estimate for total nuclear fuel material released to the environment was 3±1.5%; this was later revised to 3.5±0.5%. This corresponds to the atmospheric emission of 6 tonnes (5.9 long tons; 6.6 short tons) of fragmented fuel.[116]

Two sizes of particles were released: small particles of 0.3 to 1.5 micrometres, each an individually unrecognizable small dust or smog sized particulate matter and larger settling dust sized particles that therefore were quicker to fall-out of the air, of 10 micrometres in diameter. These larger particles contained about 80% to 90% of the released high boiling point or non-volatile radioisotopes; zirconium-95, niobium-95, lanthanum-140, cerium-144 and the transuranic elements, including neptunium, plutonium and the minor actinides, embedded in a uranium oxide matrix.

The dose that was calculated is the relative external gamma dose rate for a person standing in the open. The exact dose to a person in the real world who would spend most of their time sleeping indoors in a shelter and then venturing out to consume an internal dose from the inhalation or ingestion of a radioisotope, requires a personnel specific radiation dose reconstruction analysis and whole body count exams, of which 16,000 were conducted in Ukraine by Soviet medical personnel in 1987.[122]

Environmental impact

Water bodies

The Chernobyl nuclear power plant is located next to the Pripyat River, which feeds into the Dnieper reservoir system, one of the largest surface water systems in Europe, which at the time supplied water to Kiev's 2.4 million residents, and was still in spring flood when the accident occurred.[60]: 60 The radioactive contamination of aquatic systems therefore became a major problem in the immediate aftermath of the accident.[123]

In the most affected areas of Ukraine, levels of radioactivity (particularly from radionuclides 131I, 137Cs and 90Sr) in drinking water caused concern during the weeks and months after the accident.[123] Guidelines for levels of radioiodine in drinking water were temporarily raised to 3,700 Bq/L, allowing most water to be reported as safe.[123] Officially it was stated that all contaminants had settled to the bottom "in an insoluble phase" and would not dissolve for 800–1000 years.[60]: 64 [better source needed] A year after the accident it was announced that even the water of the Chernobyl plant's cooling pond was within acceptable norms. Despite this, two months after the disaster the Kiev water supply was switched from the Dnieper to the Desna River.[60]: 64–65 [better source needed] Meanwhile, massive silt traps were constructed, along with an enormous 30-metre (98 ft) deep underground barrier to prevent groundwater from the destroyed reactor entering the Pripyat River.[60]: 65–67 [better source needed]

Groundwater was not badly affected by the Chernobyl accident since radionuclides with short half-lives decayed away long before they could affect groundwater supplies, and longer-lived radionuclides such as radiocaesium and radiostrontium were adsorbed to surface soils before they could transfer to groundwater.[124] However, significant transfers of radionuclides to groundwater have occurred from waste disposal sites in the 30 km (19 mi) exclusion zone around Chernobyl. Although there is a potential for transfer of radionuclides from these disposal sites off-site (i.e. out of the 30 km (19 mi) exclusion zone), the IAEA Chernobyl Report[124] argues that this is not significant in comparison to current levels of washout of surface-deposited radioactivity.

Bio-accumulation of radioactivity in fish[125] resulted in concentrations (both in western Europe and in the former Soviet Union) that in many cases were significantly above guideline maximum levels for consumption.[123] Guideline maximum levels for radiocaesium in fish vary from country to country but are approximately 1000 Bq/kg in the European Union.[126] In the Kiev Reservoir in Ukraine, concentrations in fish were in the range of 3000 Bq/kg during the first few years after the accident.[125]

In small "closed" lakes in Belarus and the Bryansk region of Russia, concentrations in a number of fish species varied from 100 to 60,000 Bq/kg during the period 1990–1992.[127] The contamination of fish caused short-term concern in parts of the UK and Germany and in the long term (years rather than months) in the affected areas of Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia as well as in parts of Scandinavia.[123]

Chernobyl's radiocaesium deposits were used to calibrate sedimentation samples from Lake Qattinah in Syria. The 137

55Cs

provides a sharp, maximal, data point in radioactivity of the core sample at the 1986 depth, and acts as a date check on the depth of the 210

82Pb

in the core sample.[128]

Flora, fauna, and funga

After the disaster, four square kilometres (1.5 sq mi) of pine forest directly downwind of the reactor turned reddish-brown and died, earning the name of the "Red Forest".[129] Some animals in the worst-hit areas also died or stopped reproducing. Most domestic animals were removed from the exclusion zone, but horses left on an island in the Pripyat River 6 km (4 mi) from the power plant died when their thyroid glands were destroyed by radiation doses of 150–200 Sv.[130] Some cattle on the same island died and those that survived were stunted because of thyroid damage. The next generation appeared to be normal.[130] The mutation rates for plants and animals have increased by a factor of 20 because of the release of radionuclides from Chernobyl. There is evidence for elevated mortality rates and increased rates of reproductive failure in contaminated areas, consistent with the expected frequency of deaths due to mutations.[131]

On farms in Narodychi Raion of Ukraine it is claimed that from 1986 to 1990 nearly 350 animals were born with gross deformities such as missing or extra limbs, missing eyes, heads or ribs, or deformed skulls; in comparison, only three abnormal births had been registered in the five years prior.[132][better source needed]

Subsequent research on microorganisms, while limited, suggests that in the aftermath of the disaster, bacterial and viral specimens exposed to the radiation (including Mycobacterium tuberculosis, herpesvirus, cytomegalovirus, hepatitis-causing viruses, and tobacco mosaic virus) underwent rapid changes.[133] Activations of soil micromycetes have been reported.[133] It is currently unclear how these changes in species with rapid reproductive turnover (which were not destroyed by the radiation but instead survived) will manifest in terms of virulence, drug resistance, immune evasion, and so on. A paper in 1998 reported the discovery of an Escherichia coli mutant that was hyper-resistant to a variety of DNA-damaging elements, including x-ray radiation, UV-C, and 4-nitroquinoline 1-oxide (4NQO).[134] Cladosporium sphaerospermum, a species of fungus that has thrived in the Chernobyl contaminated area, has been investigated for the purpose of using the fungus' particular melanin to protect against high-radiation environments, such as space travel.[135] The disaster has been described by lawyers, academics and journalists as an example of ecocide.[136][137][138][139]

Human food chain

With radiocaesium binding less with humic acid, peaty soils than the known binding "fixation" that occurs on kaolinite rich clay soils, many marshy areas of Ukraine had the highest soil to dairy-milk transfer coefficients, of soil activity in ~ 200 kBq/m2 to dairy milk activity in Bq/L, that had ever been reported, with the transfer, from initial land activity into milk activity, ranging from 0.3−2 to 20−2 times that which was on the soil, a variance depending on the natural acidity-conditioning of the pasture.[122]

In 1987, Soviet medical teams conducted some 16,000 whole-body count examinations on inhabitants in otherwise comparatively lightly contaminated regions with good prospects for recovery. This was to determine the effect of banning local food and using only food imports on the internal body burden of radionuclides in inhabitants. Concurrent agricultural countermeasures were used when cultivation did occur, to further reduce the soil to human transfer as much as possible. The expected highest body activity was in the first few years, where the unabated ingestion of local food (primarily milk) resulted in the transfer of activity from soil to body. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the now reduced scale initiative to monitor human body activity in these regions of Ukraine recorded a small and gradual half-decade-long rise in internal committed dose before returning to the previous trend of observing ever lower body counts each year.[This paragraph needs citation(s)]

This momentary rise is hypothesized to be due to the cessation of the Soviet food imports together with many villagers returning to older dairy food cultivation practices and large increases in wild berry and mushroom foraging, the latter of which have similar peaty soil to fruiting body, radiocaesium transfer coefficients.[122]

In a 2007 paper, a robot sent into the No. 4 reactor returned with samples of black, melanin-rich radiotrophic fungi that grow on the reactor's walls.[142]

Of the 440,350 wild boar killed in the 2010 hunting season in Germany, approximately one thousand were contaminated with levels of radiation above the permitted limit of 600 becquerels of caesium per kilogram, of dry weight, due to residual radioactivity from Chernobyl.[143] While all animal meat contains a natural level of potassium-40 at a similar level of activity, with both wild and farm animals in Italy containing "415 ± 56 becquerels kg−1 dw" of that naturally occurring gamma emitter.[144]

Because Elaphomyces fungal species bioaccumulate radiocaesium, boars of the Bavarian Forest that consume these "deer truffles" are contaminated at higher levels than their environment's soil.[145] Given that nuclear weapons release a higher 135C/137C ratio than nuclear reactors, the high 135C content in these boars suggests that their radiological contamination can be largely attributed to the Soviet Union's nuclear weapons testing in Ukraine, which peaked during the late 1950s and early 1960s.[146]

In 2015, long-term empirical data showed no evidence of a negative influence of radiation on mammal abundance.[147]

Precipitation on distant high ground

On high ground, such as mountain ranges, there is increased precipitation due to adiabatic cooling. This resulted in localized concentrations of contaminants on distant areas; higher in Bq/m2 values to many lowland areas much closer to the source of the plume. This effect occurred on high ground in Norway and the UK.

Norway

The Norwegian Agricultural Authority reported that in 2009, a total of 18,000 livestock in Norway required uncontaminated feed for a period before slaughter, to ensure that their meat had an activity below the government permitted value of caesium per kilogram deemed suitable for human consumption. This contamination was due to residual radioactivity from Chernobyl in the mountain plants they graze on in the wild during the summer. 1,914 sheep required uncontaminated feed for a time before slaughter during 2012, with these sheep located in only 18 of Norway's municipalities, a decrease from the 35 municipalities in 2011 and the 117 municipalities affected during 1986.[148] The after-effects of Chernobyl on the mountain lamb industry in Norway were expected to be seen for a further 100 years, although the severity of the effects would decline over that period.[149] Scientists report this is due to radioactive caesium-137 isotopes being taken up by fungi such as Cortinarius caperatus which is in turn eaten by sheep while grazing.[148]

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom restricted the movement of sheep from upland areas when radioactive caesium-137 fell across parts of Northern Ireland, Wales, Scotland, and northern England. In the immediate aftermath of the disaster in 1986, the movement of a total of 4,225,000 sheep was restricted across a total of 9,700 farms, to prevent contaminated meat entering the human food chain.[150] The number of sheep and the number of farms affected has decreased since 1986. Northern Ireland was released from all restrictions in 2000, and by 2009, 369 farms containing around 190,000 sheep remained under the restrictions in Wales, Cumbria, and northern Scotland.[150] The restrictions applying in Scotland were lifted in 2010, while those applying to Wales and Cumbria were lifted during 2012, meaning no farms in the UK remain restricted because of Chernobyl fallout.[151][152]

The legislation used to control sheep movement and compensate farmers (farmers were latterly compensated per animal to cover additional costs in holding animals prior to radiation monitoring) was revoked during October and November 2012, by the relevant authorities in the UK.[153] Had restrictions in the UK not occurred, a heavy consumer of lamb meat would likely have received a dose of 4.1 mSv over a lifetime.[154]

Human impact

Acute radiation effects and immediate aftermath

The only known causal deaths from the accident involved plant workers and firefighters. The reactor explosion killed two engineers, and 28 others died within three months from acute radiation syndrome (ARS), with most of the fatalities among those hospitalized for grade 3 or 4 ARS.[10] Some sources report a total initial fatality of 31,[155][156] including one additional off-site death due to coronary thrombosis attributed to stress.[10]

Most serious ARS cases were treated with the assistance of American specialist Robert Peter Gale, who supervised bone marrow transplant procedures, although these were unsuccessful.[157][158] In 2019, Gale corrected the portrayal of his patients as dangerous to visitors.[159] The fatalities were largely due to wearing dusty, soaked uniforms causing beta burns over large areas of skin.[160] Bacterial infection was a leading cause of death in ARS patients.

Long-term impact

In the 10 years following the accident, 14 more people who had been initially hospitalized died, mostly from causes unrelated to radiation exposure, with only two deaths resulting from myelodysplastic syndrome.[10] Scientific consensus, supported by the Chernobyl Forum, suggests no statistically significant increase in solid cancer incidence among rescue workers.[161] However, childhood thyroid cancer increased, with about 4,000 new cases reported by 2002 in contaminated areas of Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine, largely due to high levels of radioactive iodine. The recovery rate is ~99%, with 15 terminal cases reported.[161] No increase in mutation rates was found among children of liquidators or those living in contaminated areas.[162]

Psychosomatic illness and post-traumatic stress, driven by widespread fear of radiological disease, have had a significant impact, often exacerbating health issues by fostering fatalistic attitudes and harmful behaviors. Misunderstanding of radiation effects plays a role in these psychological issues.[163][161]

By 2000, the number of Ukrainians claiming radiation-related "sufferer" status reached 3.5 million, or 5% of the population, many of whom were resettled from contaminated zones or former Chernobyl workers.[93]: 4–5 Increased medical surveillance after the accident led to higher recorded rates of benign conditions and cancers.[102]

Effects of main harmful radionuclides

The four most harmful radionuclides spread from Chernobyl were iodine-131, caesium-134, caesium-137 and strontium-90, with half-lives of 8 days, 2.07 years, 30.2 years and 28.8 years respectively.[164]: 8 The iodine was initially viewed with less alarm than the other isotopes, because of its short half-life, but it is highly volatile and appears to have travelled furthest and caused the most severe health problems.[102]: 24 Strontium is the least volatile and of main concern in the areas near Chernobyl.[164]: 8

Iodine tends to become concentrated in thyroid and milk glands, leading, among other things, to increased incidence of thyroid cancers. The total ingested dose was largely from iodine and, unlike the other fission products, rapidly found its way from dairy farms to human ingestion.[165] Similarly in dose reconstruction, for those evacuated at different times and from various towns, the inhalation dose was dominated by iodine (40%), along with airborne tellurium (20%) and oxides of rubidium (20%) both as equally secondary, appreciable contributors.[166]

Long term hazards such as caesium tends to accumulate in vital organs such as the heart,[167] while strontium accumulates in bones and may be a risk to bone-marrow and lymphocytes.[164]: 8 Radiation is most damaging to cells that are actively dividing. In adult mammals cell division is slow, except in hair follicles, skin, bone marrow and the gastrointestinal tract, which is why vomiting and hair loss are common symptoms of acute radiation sickness.[168]: 42

Disputed investigation

The mutation rates among animals in the Chernobyl zone have been a topic of ongoing scientific debate. Notably, the research conducted by Anders Moller and Timothy Mousseau has attracted attention.[169][170] Their research, which suggests higher mutation rates among wildlife in the Chernobyl zone, has been met with criticism. Some critics have raised concerns over the reproducibility of their findings and questioned the methodologies used.[171][172]

Moller and Mousseau have faced scrutiny for some of their publications. For instance, Moller was reprimanded over concerns related to scientific integrity, while Mousseau’s association with advocacy groups has been noted in critiques of his objectivity.[173] The pair has published several meta-analyses, but some critics argue these analyses overly rely on their own studies and other disputed sources.[174]

Withdrawn investigation