Они были там

Туран ( мнение : Турийиананананайн -мм ; Средний : Туран ; Персидский : , romanized: تر𝑉 Персидский произносится [tʰuːˈɾɒːn] , горит. « Земля Тур » ) является историческим регионом в Центральной Азии . Термин имеет иранское происхождение [ 1 ] [ 2 ] и может относиться к конкретному доисторическому человеческому поселению, историческому географическому региону или культуре. Первоначальные туранцы были иранским [ 3 ] [ 4 ] [ 5 ] Племя эпохи Авентана .

Обзор

[ редактировать ]

В древней иранской мифологии, Тур или Турадж ( Тужа на среднем персидском языке ) [ 6 ] [ Лучший источник необходим ] это сын императора Фереидун . Согласно отчету в Шахнаме , кочевые племена, которые населяли эти земли, управляли Тор. В этом смысле турановцы могут быть членами двух иранских народов, спускающихся от Фереидуна, но с разными географическими областями и часто во время войны друг с другом. [ 7 ] [ 8 ] Таким образом, Туран состоял из пяти областей: регион Копет Даг , долина атрек , части Бактрии , Согдии и Маргиана . [ 9 ]

Более поздняя ассоциация первоначальных турановцев с тюркскими народами основана главным образом на последующей туркификации Центральной Азии, включая вышеупомянутые области. [ 10 ] [ 11 ] Однако, согласно C.E. Bosworth , не было никаких культурных отношений между древними тюркскими культурами и туранами Шахнаме . [ 12 ]

История

[ редактировать ]Древняя литература

[ редактировать ]Авеста

[ редактировать ]Самое старое существующее упоминание о Туране - в Фарвардина Яштс , которые находятся на языке молодого авеняна и были датированы лингвистами до 2500 лет назад. [ 13 ] Согласно Герардо Гноли , в «Авесте» содержится имена различных племен, которые жили в непосредственной близости от друг друга: « Айня [арийцы], Турияс [тураны], Сайримы [сарматские], Санус [Сакэ] и Дахис [Дахэ]». [ 14 ] В гимнах Авесты прилагательное Туя прикреплена к различным врагам зороастризма , таких как фрасин (Шахнаме: Афрасиб ). Слово происходит только один раз в Гатх , но в 20 раз в более поздних частях Авесты . Турии, как их называли в авесте, играют более важную роль в «Авесте» , чем Сайримы, Санус и Дахис. Сам Зороастр приветствовал народа Эйрья, но он также проповедовал свое послание другим соседним племенам. [ 14 ] [ 15 ]

По словам Мэри Бойс , в Фарвардина Яшт, «в нем (стихи 143–144) восхваляют фраваши праведных мужчин и женщин не только среди арий (как назывался« авестан »), но и среди туриев, Саиримас, Санус и Дахис; [ 16 ] Враждебность между Турией и Айрья также указывается в Фарвардтне Яст (ст. 37-8), где, как говорят, Фраваши, которые справедливы, оказывали поддержку в борьбе против Дануса, которые, по-видимому, являются кланом народа Тура. [ 17 ] Таким образом, в «Авесте» некоторые из Турий верили в послание Зороастра, в то время как другие отвергли религию.

Подобно древней родине Зороастра, точная география и расположение Турана неизвестны. [ 18 ] В традициях пост-Эстанда они считали, что обитают в регионе к северу от Оксуса , река отделяет их от иранцев. Их присутствие сопровождается непрекращающимися войнами с иранцами, помогло определить последнюю как отдельную нацию, гордящую их землей и готовы пролить свою кровь в защиту. [ 19 ] Обычные имена даньанцев в Авесте и Шахнаме включают Фрарасин, [ 20 ] Аграфи, [ 21 ] Bideafsh, [ 22 ] Arjaspa [ 23 ] Намкхпаст. [ 22 ] Имена иранских племен, в том числе имена турановцев, которые появляются в Авесте, были изучены Манфредом Мэйрхофером в его всесторонней книге об этимологиях Avesta личного имени. [ 24 ]

Сассан отчет

[ редактировать ]С 5 -го века н.э. Сасанианская империя определила «Туран» в противодействии «Ирану», как землю, где возложены враги на северо -восток. [ 25 ]

Продолжение кочевых вторжений на северо-восточных границах в исторические времена сохранила память о тураранцах. [ 19 ] После 6 -го века турки, которые были подтолкнули другие племена на запад, стали соседями Ирана и были отождествлены с туранами. [ 19 ] [ 26 ] Идентификация турановцев с турками была поздним развитием, возможно, сделанным в начале 7 -го века; Теркс впервые вступил в контакт с иранцами только в 6 веке. [ 20 ]

Средняя литература

[ редактировать ]Ранняя исламская эра

[ редактировать ]По словам Клиффорда Э. Босворта: [ 27 ]

В ранние исламские времена персы склонялись к выявлению всех земель к северо -востоку от Хорасана и лежали за оксом с регионом Туран, который в Шахнаме Фердоуси считается землей, выделенной сыну Фереидун Тур. Обитатели Тура, которые были включены в включение турок, в первые четыре столетия ислама, по сути, те, кто кочевые за пределами Jaxartes, и позади них китайцы (см. Kowalski; Minorsky, «Туран»). Таким образом, Туран стал как этническим, так и географическим термином, но всегда содержал неясности и противоречия, возникающие в результате того, что на протяжении всего исламского времени земли непосредственно за оксом и вдоль его нижних границ были не турки, а из иранских народов, таких как согдийцы и кхверианцы.

Термины «турок» и «туран» стали использовались взаимозаменяемо в исламскую эпоху. Шахнаме или Книга царей, сборник иранского мифического наследия, использует два термина эквивалентно. Другие авторы, в том числе Табари, Хаким Ираншах и многие другие тексты, как. Примечательным исключением является арабский историк, арабский историк, арабский историк, который пишет: «Рождение Афрасияба было в стране турок, и ошибка, которую историки и неисторцы совершали в том, что он был турком, связана с этой причиной, связана с этой причиной, связана с этой причиной, связана ". [ 28 ] К 10 веку миф о Афрасиябе был принят династией Караханида. [ 20 ] В эпоху Сафевида , после общей географической конвенции Шахнамех , термин Туран использовался для обозначения домена Узбекской империи в конфликте с Safavids. [ Цитация необходима ]

Some linguists derive the word from the Indo-Iranian root *tura- "strong, quick, sword(Pashto)", Pashto turan (thuran) "swordsman". Others link it to old Iranian *tor "dark, black", related to the New Persian tār(ik), Pashto tor (thor), and possibly English dark. In this case, it is a reference to the "dark civilization" of Central Asian nomads in contrast to the "illuminated" Zoroastrian civilization of the settled Ārya.[citation needed]

Shahnameh

[edit]In the Persian epic Shahnameh, the term Tūrān ("land of the Tūrya" like Ērān, Īrān = "land of the Ārya") refers to the inhabitants of the eastern-Iranian border and beyond the Oxus. According to the foundation myth given in the Shahnameh, King Firēdūn (= Avestan Θraētaona) had three sons, Salm, Tūr and Iraj, among whom he divided the world: Asia Minor was given to Salm, Turan to Tur and Iran to Īraj. The older brothers killed the younger, but he was avenged by his grandson, and the Iranians became the rulers of the world. However, the war continued for generations. In the Shahnameh, the word Turan appears nearly 150 times and that of Iran nearly 750 times.

Some examples from the Shahnameh:

نه خاکست پیدا نه دریا نه کوه

ز بس تیغداران توران گروه

No earth is visible, no sea, no mountain,

From the many blade-wielders of the Turan horde

تهمتن به توران سپه شد به جنگ

بدانسان که نخجیر بیند پلنگ

Tahamtan (Powerful-Bodied) Rostam took the fight to the Turan army

Just as a leopard sights its prey.

Modern literature

[edit]Geography

[edit]

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Western languages borrowed the word Turan as a general designation for modern Central Asia, although this expression has now fallen into disuse. Turan appears next to Iran on numerous maps of the 19th century[29] to designate a region encompassing modern Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and northern parts of Afghanistan and Pakistan. This area roughly corresponds to what is called Central Asia today.

The phrase Turan Plain or Turan Depression became a geographical term referring to a part of Central Asia.

Linguistics

[edit]The term Turanian, now obsolete, formerly[when?] occurred in the classifications used by European (especially German, Hungarian, and Slovak) ethnologists, linguists, and Romantics to designate populations speaking non-Indo-European, non-Semitic, and non-Hamitic languages[30] and specially speakers of Altaic, Dravidian, Uralic, Japanese, Korean and other languages.[31]

Max Müller (1823–1900) identified different sub-branches within the Turanian language family:

- the Middle Altaic division branch, comprising Tungusic, Mongolic, Turkic.

- The Northern Ural Samoyedic, Ugriche and Finnic.

- the Southern branch consisted of Dravidian languages such as Tamil, Kannada, Telugu, Malayalam, and other Dravidian languages.

- the languages of the Caucasus which Müller classified as the scattered languages of the Turanian family.

Müller also began to muse whether Chinese belonged to the Northern branch or Southern branch.[32]

The main relationships between Dravidian, Uralic, and Altaic languages were considered typological. According to Crystal & Robins, "Language families, as conceived in the historical study of languages, should not be confused with the quite separate classifications of languages by reference to their sharing certain predominant features of grammatical structure."[33] As of 2013[update] linguists classify languages according to the method of comparative linguistics rather than using their typological features. According to Encyclopædia Britannica, Max's Müller's "efforts were most successful in the case of the Semites, whose affinities are easy to demonstrate, and probably least successful in the case of the Turanian peoples, whose early origins are hypothetical".[34] As of 2014[update] the scholarly community no longer uses the word Turanian to denote a classification of language families. The relationship between Uralic and Altaic, whose speakers were also designated as Turanian people in 19th-century European literature, remains uncertain.[35]

Ideology

[edit]In European discourse, the words Turan and Turanian can designate a certain mentality, i.e. the nomadic in contrast to the urbanized agricultural civilizations. This usage probably[original research?] matches the Zoroastrian concept of the Tūrya, which is not primarily a linguistic or ethnic designation, but rather a name of the infidels that opposed the civilization based on the preaching of Zoroaster.

Combined with physical anthropology, the concept of the Turanian mentality has a clear potential for cultural polemic. Thus in 1838 the scholar J.W. Jackson described the Turanid or Turanian race in the following words:[36]

The Turanian is the impersonation of material power. He is the merely muscular man at his maximum of collective development. He is not inherently a savage, but he is radically a barbarian. He does not live from hand to mouth, like a beast, but neither has he in full measure the moral and intellectual endowments of the true man. He can labour and he can accumulate, but he cannot think and aspire like a Caucasian. Of the two grand elements of superior human life, he is more deficient in the sentiments than in the faculties. And of the latter, he is better provided with those that conduce to the acquisition of knowledge than the origination of ideas.

Polish philosopher Feliks Koneczny claimed the existence of a distinctive Turanian civilization, encompassing both Turkic and some Slavs, such as Russians. This alleged civilization's hallmark would be militarism, anti-intellectualism and an absolute obedience to the ruler. Koneczny saw this civilization as inherently inferior to Latin (Western European) civilization.[citation needed]

Politics

[edit]In the declining days of the Ottoman Empire, some Turkish nationalists adopted the word Turanian to express a pan-Turkic ideology, also called Turanism. As of 2013[update] Turanism forms an important aspect of the ideology of the Turkish Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), whose members are also known as Grey Wolves.

In recent times[when?], the word Turanian has sometimes expressed a pan-Altaic nationalism (theoretically including Manchus and Mongols in addition to Turks), though no political organization seems to have adopted such an ambitious platform.

Names

[edit]

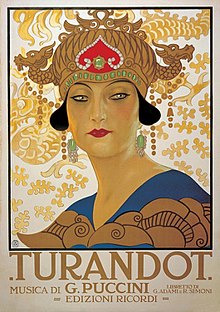

Turandot – or Turandokht – is a female name in Iran and it means "Turan's Daughter" in Persian (it is best known in the West through Puccini's famous opera Turandot (1921–24)).

Turan is also a common name in the Middle East, and as family surnames in some countries including Bahrain, Iran, Bosnia and Turkey.

The Ayyubid ruler Saladin had an older brother with the name Turan-Shah.

Turaj, whom ancient Iranian myths depict as the ancestor of the Turanians, is also a popular name and means Son of Darkness. The name Turan according to Iranian myths derives from the homeland of Turaj. The Pahlavi pronunciation of Turaj is Tuzh, according to the Dehkhoda dictionary. Similarly, Iraj, which is also a popular name, is the brother of Turaj in the Shahnameh. An altered version of Turaj is Zaraj, which means son of gold.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Houtsma, M. Th.; Arnold, T.W.; Basset, R.; Hartmann, R., eds. (1913–1936). "Tūrān". Encyclopaedia of Islam (First ed.). doi:10.1163/2214-871X_ei1_COM_0206.

an Iranian term applied to the country to the north-east of Iran.

- ^ van Donzel, Emeri (1994). Islamic Reference Desk. Brill Academic. p. 461. ISBN 9789004097384.

Iranian term applied to region lying to the northeast of Iran and ultimately indicating very vaguely the country of the Turkic peoples.

- ^ Allworth, Edward A. (1994). Central Asia: A Historical Overview. Duke University Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-8223-1521-6.

- ^ Diakonoff, I. M. (1999). The Paths of History. Cambridge University Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-521-64348-1.

Turan was one of the nomadic Iranian tribes mentioned in the Avesta. However, in Firdousi's poem, and in the later Iranian tradition generally, the term Turan is perceived as denoting 'lands inhabited by Turkic speaking tribes.'

- ^ Gnoli, Gherardo (1980). Zoroaster's Time and Homeland. Naples: Instituto Univ. Orientale. OCLC 07307436.

Iranian tribes that also keep on recurring in the Yasht, Airyas, Tuiryas, Sairimas, Sainus and Dahis

- ^ Dehkhoda dictionary: Turaj

- ^ Yarshater, Ehsan (2004). "Iran iii. Traditional History of Persia". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- ^ Menges, Karl Heinrich (1989). "Altaic". Encyclopædia Iranica.

In a series of relatively minor movements, Turkic groups began to occupy territories in western Central Asia and eastern Europe which had previously been held by Iranians (i.e. Turan). The Volga Bulgars, following the Avars, proceeded to the Volga and Ukraine in the 6th–7th centuries.

- ^ Possehl, Raymond (2002). The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective. Rowman Altamira Press. p. 276.

- ^ Firdawsi (2004). The Epic of Kings. Translated by Zimmern, Helen. Archived from the original on 13 June 2007 – via eBooks@Adelaide.

- ^ Inlow, Edgar Burke (1979). Shahanshah: A Study of the Monarchy of Iran. Motilal Banarsidass Pub. p. 17.

Faridun divided his vast empire between his three sons, Iraj, the youngest receiving Iran. After his murder by his brothers and the avenging Manuchihr, one would have thought the matter was ended. But, the fraternal strife went on between the descendants of Tur and Selim (Salm) and those of Iraj. The former – the Turanians – were the Turks or Tatars of Central Asia, seeking access to Iran. The descendants of Iraj were the resisting Iranians.

- ^ Bosworth, C. Edmund (1973). "Barbarian Incursions: The Coming of the Turks into the Islamic World". In Richards, D.S. (ed.). Islamic Civilization. Oxford. p. 2.

Hence as Kowalski has pointed out, a Turkologist seeking for information in the Shahnama on the primitive culture of the Turks would definitely be disappointed.

- ^ Prods Oktor Skjærvø, "Avestan Quotations in Old Persian?" in S. Shaked and A. Netzer, eds., Irano-Judaica IV, Jerusalem, 1999, pp. 1–64

- ^ Jump up to: a b G. Gnoli, Zoroaster's time and homeland, Naples 1980

- ^ M. Boyce, History of Zoroastrianism. 3V. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1991. (Handbuch Der Orientalistik/B. Spuler)

- ^ M. Boyce, History of Zoroastrianism. 3V. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1991. (Handbuch Der Orientalistik/B. Spuler)., pg 250

- ^ G. Gnoli, Zoroaster's time and homeland, Naples 1980, pg 107

- ^ G. Gnoli, Zoroaster's time and homeland, Naples 1980, pg 99–130

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Ehsan Yarshater, "Iranian National History," in The Cambridge History of Iran 3(1)(1983), 408–409

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Yarshater, Ehsan (1984). "Afrāsīāb". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ^ Khaleghi-Motlagh, Djalal (1984). "Aḡrēraṯ". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tafażżolī, Aḥmad (1989). "Bīderafš". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- ^ Tafażżolī, Aḥmad (1986). "Arjasp". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- ^ Mayrhofer, Manfred (1977). Iranisches Personennamenbuch (in German). Vol. I/1 – Die altiranischen Namen/Die Avestischen Namen. Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press. pp. 74f. Reviewed in Dresden, Mark J. (1981). "Iranisches Personennamenbuch". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 101 (4): 466. doi:10.2307/601282. JSTOR 601282.

- ^ Maas, Michael (2014). The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Attila. Cambridge University Press. p. 284. ISBN 9781316060858.

- ^ Frye, R. (1963). The Heritage of Persia: The pre-Islamic History of One of the World's Great Civilizations. New York: World Publishing Company. p. 41.

- ^ Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (1990). "Central Asia iv. In the Islamic Period up to the Mongols". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- ^ Abi al-Ḥasan Ali ibn al-Ḥusayn ibn Ali al-Masudi (2005). Muruj al-dhahab wa-maadin al-jawhar. Beirut, Lebanon: Dar al-Marifah.

- ^ File:Iran Turan map 1843.jpg

- ^ Abel Hovelacque, The Science of Language: Linguistics, Philology, Etymology, pg 144, [1]

- ^ Chevallier, Elisabeth; Lenormant, François (1871). A Manual of the Ancient History of the East. J. B. Lippincott & co. p. 68.

- ^ van Driem, George (2001). Handbuch Der Orientalistik [Handbook of Oriental Studies] (in German). Brill Academic Publishers. pp. 335–336. ISBN 9004120629.

- ^ Crystal, David; Robins, Robert Henry. "Language". Encyclopædia Britannica. 5 – Linguistic change / Language typology.

- ^ "religions, classification of." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^ "Ural–Altaic languages." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007

- ^ "The Iran and Turan", Anthropological Review 6:22 (1868), p. 286

Further reading

[edit]- Biscione, R. (1981). "Centre and Periphery in Late Protohistoric Turan: the Settlement Pattern". In Härtel, H. (ed.). South Asian Archaeology 1979 : Papers from the fifth International Conference of the Association of South Asian Archaeologists. Berlin: D. Reimer. ISBN 3-496-00158-5.

- Archäologie in Iran und Turan, Verlag Philipp von Zabern GmbH. Publisher – Verlag Marie Leidorf GmbH (Volume 1–3) ISSN 1433-8734