Хуавей

Логотип с 2018 года | |

Штаб-квартира в Шэньчжэне, Гуандун, Китай. | |

Родное имя | Компания Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd. |

|---|---|

Romanized name | Huáwéi jìshù yǒuxiàn gōngsī |

| Company type | Private |

| ISIN | HK0000HWEI11 |

| Industry | |

| Founded | 15 September 1987 |

| Founder | Ren Zhengfei |

| Headquarters | , |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people | Ren Zhengfei (CEO) Liang Hua (chairman) Meng Wanzhou (deputy chairwoman & CFO) He Tingbo (Director) |

| Products | |

| Brands | Huawei |

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

Number of employees | 207,272 (2023)[3] |

| Parent | Huawei Investment & Holding[4] |

| Subsidiaries | Caliopa Chinasoft International FutureWei Technologies HexaTier HiSilicon iSoftStone |

| Website | www |

| Huawei | |||

|---|---|---|---|

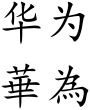

"Huawei" in Simplified (top) and Traditional (bottom) Chinese characters | |||

| Simplified Chinese | 华为 | ||

| Traditional Chinese | 華為 | ||

| Literal meaning | "Splendid Achievement" or "Chinese Achievement" | ||

| |||

| Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd. | |||

| Simplified Chinese | 华为技术有限公司 | ||

| Traditional Chinese | 華為技術有限公司 | ||

| |||

Компания Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd. ( / ˈ hw ɑː w eɪ / HWAH -way , / ˈ w ɑː w eɪ / WAH -way ; китайский : 华为 ; пиньинь : ) — китайская многонациональная цифровых коммуникационных технологий корпорация- конгломерат со штаб-квартирой в Бантьяне, район Лунган, Шэньчжэнь, провинция Гуандун . Компания проектирует, разрабатывает, производит и продает телекоммуникационное оборудование , бытовую электронику , интеллектуальные устройства и различные солнечные продукты на крышах. Корпорацию основал в 1987 году Жэнь Чжэнфэй , бывший офицер Народно -освободительной армии (НОАК). [5]

Первоначально сосредоточившись на производстве телефонных коммутаторов , компания Huawei расширила свою деятельность на более чем 170 стран, включая строительство телекоммуникационных сетей, предоставление операционных и консультационных услуг и оборудования, а также производство коммуникационных устройств для потребительского рынка. [6] В 2012 году она обогнала Ericsson как крупнейшего производителя телекоммуникационного оборудования в мире. [7] Huawei обогнала Apple и Samsung в 2018 и 2020 годах соответственно и стала крупнейшим производителем смартфонов в мире. [8] [9] Amidst its rise, Huawei has been accused of intellectual property infringement, for which it has settled with companies like Cisco.[10]

Questions regarding the extent of state influence on Huawei have revolved around its national champions role in China, subsidies and financing support from state entities,[11] and reactions of the Chinese government in light of oppositions in certain countries to Huawei's participation in 5G.[12] Its software and equipment have been linked to the mass surveillance of Uyghurs and Xinjiang internment camps, drawing sanctions from the US.[13][14][15]

The company has faced difficulties in some countries arising from concerns that its equipment may enable surveillance by the Chinese government due to perceived connections with the country's military and intelligence agencies.[11][16] Huawei has argued that critics such as the US government have not shown evidence of espionage.[17] Experts say that China's 2014 Counter-Espionage Law and 2017 National Intelligence Law can compel Huawei and other companies to cooperate with state intelligence.[18] In 2012, Australian and US intelligence agencies concluded that a hack on Australia's telecom networks was conducted by or through Huawei, although the two network operators have disputed that information.[19][20]

In the midst of a trade war between China and the United States, the US government alleged that Huawei had violated sanctions against Iran and restricted it from doing business with American companies. In June 2019, Huawei cut jobs at its Santa Clara research center, and in December Ren Zhengfei said it was moving to Canada.[21][22] In 2020, Huawei agreed to sell the Honor brand to a state-owned enterprise of the Shenzhen government to "ensure its survival" under US sanctions.[23] In November 2022, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) banned sales or import of equipment made by Huawei out of national security concerns.[24] Other countries such as Quad members India and Japan, members of the Five Eyes, and ten European Union states have also banned or restricted Huawei products.[25][26][27][28][29]

Name

[edit]According to the company founder Ren Zhengfei, the name Huawei comes from a slogan he saw on a wall, Zhonghua youwei meaning "China has promise" (中华有为; Zhōng huá yǒu wéi), when he was starting up the company and needed a name.[30] Zhonghua or Hua means China,[31] while youwei means "promising/to show promise".[32][33] Huawei has also been translated as "splendid achievement" or "China is able", which are possible readings of the name.[34]

In Chinese pinyin, the name is Huáwéi,[35] and pronounced [xwǎwěɪ] in Mandarin Chinese; in Cantonese, the name is transliterated with Jyutping as Waa4-wai4 and pronounced [wa˩wɐj˩]. However, the pronunciation of Huawei by non-Chinese varies in other countries, for example "Hoe-ah-wei" in Belgium and the Netherlands.[36]

The company had considered changing the name in English out of concern that non-Chinese people may find it hard to pronounce,[37] but decided to keep the name, and launched a name recognition campaign instead to encourage a pronunciation closer to "Wah-Way" using the words "Wow Way".[38][39] Ren states, "We will not change the name of our brand and will teach foreigners how to pronounce it. We have to make sure they do not pronounce it like 'Hawaii.'"[5]: 85

History

[edit]Early years

[edit]In the 1980s, the Chinese government endeavored to overhaul the nation's underdeveloped telecommunications infrastructure. A core component of the telecommunications network was telephone exchange switches, and in the late 1980s, several Chinese research groups endeavored to acquire and develop the technology, usually through joint ventures with foreign companies.

Ren Zhengfei, a former deputy director of the People's Liberation Army engineering corps, founded Huawei in 1987 in Shenzhen. The company reports that it had RMB 21,000 (about $5,000 at the time) in registered capital from Ren Zhengfei and five other investors at the time of its founding where each contributed RMB 3,500.[40] These five initial investors gradually withdrew their investments in Huawei. The Wall Street Journal has suggested, however, that Huawei received approximately "$46 billion in loans and other support, coupled with $25 billion in tax cuts" since the Chinese government had a vested interest in fostering a company to compete against Apple and Samsung.[11][41]

Ren sought to reverse engineer foreign technologies with local researchers. China borrowed liberally from Qualcomm and other industry leaders (PBX as an example) in order to enter the market. At a time when all of China's telecommunications technology was imported from abroad, Ren hoped to build a domestic Chinese telecommunications company that could compete with, and ultimately replace, foreign competitors.[42]

During its first several years the company's business model consisted mainly of reselling private branch exchange (PBX) switches imported from Hong Kong.[43][44] Meanwhile, it was reverse-engineering imported switches and investing heavily in research and development to manufacture its own technologies.[43] By 1990 the company had approximately 600 R&D staff and began its own independent commercialization of PBX switches targeting hotels and small enterprises.[45]

In order to grow despite difficult competition from Alcatel, Lucent, and Nortel Networks, in 1992 Huawei focused on low-income and difficult to access market niches.[5]: 12 Huawei's sales force traveled from village to village in underdeveloped regions, gradually moving into more developed areas.[5]: 12

The company's first major breakthrough came in 1993 when it launched its C&C08 program controlled telephone switch. It was by far the most powerful switch available in China at the time. By initially deploying in small cities and rural areas and placing emphasis on service and customizability, the company gained market share and made its way into the mainstream market.[46]

Huawei also won a key contract to build the first national telecommunications network for the People's Liberation Army, a deal one employee described as "small in terms of our overall business, but large in terms of our relationships".[47] In 1994, founder Ren Zhengfei had a meeting with General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party Jiang Zemin, telling him that "switching equipment technology was related to national security, and that a nation that did not have its own switching equipment was like one that lacked its own military." Jiang reportedly agreed with this assessment.[43]

In the 1990s, Canadian telecom giant Nortel outsourced production of their entire product line to Huawei.[48] They subsequently outsourced much of their product engineering to Huawei as well.[49]

Another major turning point for the company came in 1996 when the government in Beijing adopted an explicit policy of supporting domestic telecommunications manufacturers and restricting access to foreign competitors. Huawei was promoted by both the government and the military as a national champion, and established new research and development offices.[43]

Foreign expansion

[edit]Beginning in the late 1990s, Huawei built communications networks throughout sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East.[50] It has become the most important Chinese telecommunications company operating in these regions.[50]

In 1997, Huawei won a contract to provide fixed-line network products to Hong Kong company Hutchison Whampoa.[46] Later that year, Huawei launched wireless GSM-based products and eventually expanded to offer CDMA and UMTS. In 1999, the company opened a research and development (R&D) centre in Bengaluru, India to develop a wide range of telecom software.[45]

In May 2003, Huawei partnered with 3Com on a joint venture known as H3C, which was focused on enterprise networking equipment. It marked 3Com's re-entrance into the high-end core routers and switch market, after having abandoned it in 2000 to focus on other businesses. 3Com bought out Huawei's share of the venture in 2006 for US$882 million.[51][52]

In 2004, Huawei signed a $10 billion credit line with China Development Bank to provide low-cost financing to customers buying its telecommunications equipment to support its sales outside of China. This line of credit was tripled to $30 billion in 2009.[53]

In 2005, Huawei's foreign contract orders exceeded its domestic sales for the first time. Huawei signed a global framework agreement with Vodafone. This agreement marked the first time a telecommunications equipment supplier from China had received Approved Supplier status from Vodafone Global Supply Chain.[54][non-primary source needed]

In 2007, Huawei began a joint venture with US security software vendor Symantec Corporation, known as Huawei Symantec, which aimed to provide end-to-end solutions for network data storage and security. Huawei bought out Symantec's share in the venture in 2012, with The New York Times noting that Symantec had fears that the partnership "would prevent it from obtaining United States government classified information about cyber threats".[55]

In May 2008, Australian carrier Optus announced that it would establish a technology research facility with Huawei in Sydney.[56] In October 2008, Huawei reached an agreement to contribute to a new GSM-based HSPA+ network being deployed jointly by Canadian carriers Bell Mobility and Telus Mobility, joined by Nokia Siemens Networks.[57] Huawei delivered one of the world's first LTE/EPC commercial networks for TeliaSonera in Oslo, Norway in 2009.[45] Norway-based telecommunications Telenor instead selected Ericsson due to security concerns with Huawei.[58]

In July 2010, Huawei was included in the Global Fortune 500 2010 list published by the US magazine Fortune for the first time, on the strength of annual sales of US$21.8 billion and net profit of US$2.67 billion.[59][60]

In October 2012, it was announced that Huawei would move its UK headquarters to Green Park, Reading, Berkshire.[61]

Huawei also has expanding operations in Ireland since 2016. As well as a headquarters in Dublin, it has facilities in Cork and Westmeath.[62]

In September 2017, Huawei created a Narrowband IoT city-aware network using a "one network, one platform, N applications" construction model utilizing Internet of things (IoT), cloud computing, big data, and other next-generation information and communications technology, it also aims to be one of the world's five largest cloud players in the near future.[63][64]

In 2017, Huawei and the government of Malaysia began cooperating to develop public security programs and Malaysian Smart City programs, as well as a related lab in Kuala Lumpur.[65]: 82 In April 2019, Huawei established the Huawei Malaysia Global Training Centre (MGTC) at Cyberjaya, Malaysia.[66]

Huawei has had a major role in building, by 2019, approximately 70% of Africa's 4G networks.[65]: 76

In November 2020, Telus Mobility dropped Huawei in favor of Samsung, Ericsson, and Nokia for their 5G/Radio Access Network[67]

Recent performance

[edit]

By 2018, Huawei had sold 200 million smartphones.[68] In 2019, Huawei reported revenue of US$122 billion.[69] By the second quarter of 2020, Huawei had become the world's top smartphone seller, overtaking Samsung for the first time.[9] In 2021, Huawei was ranked the second-largest R&D investor in the world by the EU Joint Research Centre (JRC) in its EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard[70] and ranked fifth in the world in US patents according to a report by Fairview Research's IFI Claims Patent Services.[71][5]: 10

However, heavy international sanctions saw Huawei's revenues drop by 32% in the 2021 third quarter.[72] Linghao Bao, an analyst at policy research firm Trivium China said the "communications giant went from being the second-largest smartphone maker in the world, after Samsung, to essentially dead."[73] By the end of third quarter in 2022, Huawei revenue had dropped a further 19.7% since the beginning of the year.[74]

By mid-2024, the company had recovered after a brief decline in turnover and profit and continued its expansion. Most foreign parts in the supply chain were successfully replaced by domestic products in a relatively short period of time. In the first quarter of 2024, the company's profits increased nearly six-fold compared to the previous year to just under US$2.7 billion.[75] On 21 June 2024, Huawei announced that HarmonyOS is now installed on over 900 million devices and has become the second most popular mobile OS in China.[76]

Corporate affairs

[edit]Huawei classifies itself as a "collective" entity and prior to 2019 did not refer to itself as a private company. Richard McGregor, author of The Party: The Secret World of China's Communist Rulers, said that this is "a definitional distinction that has been essential to the company's receipt of state support at crucial points in its development".[77] McGregor argued that "Huawei's status as a genuine collective is doubtful."[77] Huawei's position has shifted in 2019 when, Dr. Song Liuping, Huawei's chief legal officer, commented on the US government ban, said: "Politicians in the US are using the strength of an entire nation to come after a private company." (emphasis added).[78]

Leadership

[edit]Ren Zhengfei is the founder and CEO of Huawei and has the power to veto any decisions made by the board of directors.[79][80] Huawei also has rotating co-CEOs.[5]: 11

Huawei disclosed its list of board of directors for the first time in 2010.[81] Liang Hua is the current chair of the board. As of 2019[update], the members of the board are Liang Hua, Guo Ping, Xu Zhijun, Hu Houkun, Meng Wanzhou (CFO and deputy chairwoman), Ding Yun, Yu Chengdong, Wang Tao, Xu Wenwei, Shen-Han Chiu, Chen Lifang, Peng Zhongyang, He Tingbo, Li Yingtao, Ren Zhengfei, Yao Fuhai, Tao Jingwen, and Yan Lida.[82]

Guo Ping is the Chairman of Huawei Device, Huawei's mobile phone division.[83] Huawei's Chief Ethics & Compliance Officer is Zhou Daiqi[84] who is also Huawei's Chinese Communist Party Committee Secretary.[85] Their chief legal officer is Song Liuping.[78]

Ownership

[edit]At its founding in 1987, Huawei was established as a collectively-owned enterprise.[5]: 213 Collectively-owned enterprises were an intermediary corporate ownership status between state-owned enterprises and private businesses.[86][5]: 213 The Chinese government began issuing licenses for private businesses starting in 1992.[5]: 213

Huawei states it is an employee-owned company, but this remains a point of dispute.[79][87] Ren Zhengfei retains approximately 1 percent of the shares of Huawei's holding company, Huawei Investment & Holding,[87] with the remainder of the shares held by a trade union committee (not a trade union per se, and the internal governance procedures of this committee, its members, its leaders or how they are selected all remain undisclosed to the public) that is claimed to be representative of Huawei's employee shareholders.[79][88] The company's trade union committee is registered with and pays dues to the Shenzhen federation of the All-China Federation of Trade Unions, which is controlled by the Chinese Communist Party.[89] About half of Huawei staff participate in this structure (foreign employees are not eligible), and hold what the company calls "virtual restricted shares". These shares are non-tradable and are allocated to reward performance.[90] When employees leave Huawei, their shares revert to the company, which compensates them for their holding.[91] Although employee shareholders receive dividends,[88] their shares do not entitle them to any direct influence in management decisions, but enables them to vote for members of the 115-person Representatives' Commission from a pre-selected list of candidates.[88] The Representatives' Commission selects Huawei Holding's board of directors and Board of Supervisors.[92]

Academics Christopher Balding of Fulbright University and Donald C. Clarke of George Washington University have described Huawei's virtual stock program as "purely a profit-sharing incentive scheme" that "has nothing to do with financing or control".[93] They found that, after a few stages of historical morphing, employees do not own a part of Huawei through their shares. Instead, the "virtual stock is a contract right, not a property right; it gives the holder no voting power in either Huawei Tech or Huawei Holding, cannot be transferred, and is cancelled when the employee leaves the firm, subject to a redemption payment from Huawei Holding TUC at a low fixed price".[94][79] Balding and Clarke add, "given the public nature of trade unions in China, if the ownership stake of the trade union committee is genuine, and if the trade union and its committee function as trade unions generally function in China, then Huawei may be deemed effectively state-owned."[79] Tim Rühlig, a Research Fellow at the Swedish Institute of International Affairs, asked Huawei for a response to the Balding and Clarke paper; the "information provided by Huawei gives an indication of how difficult it is to run an independent company in such a crucial sector in China".[95] After the publication of Balding and Clarke's paper, Huawei has "engaged in a PR blitz to manufacture an image of a transparent company".[96]

Academic Toshio Goto of the Japan University of Economics has disagreed with Balding and Clarke's assessment of Huawei employee shareholders’ ownership.[97]: 13 Goto writes that the Huawei's ownership structure is a function of its formation amid the Chinese reforms, with the only mechanism for concentrating employee ownership under Shenzen's 1997 Provisions on State-owned Company Employee Stock Option Plans being to do so via Huawei's trade union.[97]: 25 In contrast to Balding and Clarke, Goto writes that the Huawei's virtual shares are substantially equivalent to voting stock, and that nominal ownership through the trade union does not change the legal and financial independence of employee ownership from the union itself.[97]: 25 Goto concludes that the firm is effectively owned by employees and therefore it is not effectively state-owned.[97]: 25 In analyzing Huawei's corporate governance and ownership structure, Academic Wang Jun of the Chinese University of Politics and Law also rejects the argument that Huawei is a state-owned enterprise controlled by a labor union, writing that normative practices and legal requirements distinguish between the shareholding vehicle of union-held employee assets and assets belonging to the union itself.[98] Academics Kunyuan Qiao of Cornell University and Christopher Marquis of the University of Cambridge likewise conclude that Huawei is a private company owned collectively by its employees and is neither owned nor controlled directly by the Chinese government.[5]: 11

Academics Steve Tsang and Olivia Cheung write that Huawei is a private company.[99]: 131 Likewise, academics Simon Curtis and Ian Klaus write that Huawei is not state-owned, but is a private company which the Chinese government views as a national champion.[100]: 156–157

In 2021, Huawei did not report its ultimate beneficial ownership in Europe as required by European anti-money laundering laws.[101]

Lobbying and public relations

[edit]In July 2021, Huawei hired Tony Podesta as a consultant and lobbyist, with a goal of nurturing the company's relationship with the Biden administration.[102][103]

Huawei has also hired public relations firms Ruder Finn, Wavemaker, Racepoint Global, and Burson Cohn & Wolfe for various campaigns.[104]

In January 2024, Bloomberg News reported that Huawei ended its in-house lobbying operations in Washington, D.C.[105]

Corporate culture

[edit]According to its CEO and founder Ren Zhengfei, Huawei's corporate culture is the same as the culture of the CCP, "and to serve the people wholeheartedly means to be customer-centric and responsible to society."[5]: 9 Ren frequently states that Huawei's management philosophy and strategy are commercial applications of Maoism.[5]: 11

Ren states that in the event of a conflict between Huawei's business interests and the CCP's interests, he would "choose the CCP whose interest is to serve the people and all human beings".[5]: 11 Qiao and Marquis observe that company founder Ren is a dedicated communist who seeks to ingrain communist values at Huawei.[5]: 9

Finances

[edit]| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total revenue (CNY¥ bn) | 721 | 858 | 891 | 636 | 642 | 704 |

| Operating profit (CNY¥ bn) | 73.2 | 77.8 | 72.5 | 121 | 42.2 | 104 |

| Net profit (CNY¥ bn) | 59.3 | 62.6 | 64.6 | 113 | 35.5 | 86.9 |

| Total assets (CNY¥ bn) | 665 | 858 | 876 | 982 | 1,063 | 1,263 |

| References | [106] | [106] | [106] | [106] | [106] | [107] |

Partners

[edit]

As of the beginning of 2010[update], approximately 80% of the world's top 50 telecoms companies had worked with Huawei.[108]

In 2016, German camera company Leica has established a partnership with Huawei, and Leica cameras will be co-engineered into Huawei smartphones, including the P and Mate Series. The first smartphone to be co-engineered with a Leica camera was the Huawei P9.[109] As of May 2022, Huawei partnership with Leica had ended.[110][111] As of 2023, smartphone makers Honor and Xiaomi have partnerships with Leica.[112]

In August 2019, Huawei collaborated with eyewear company Gentle Monster and released smartglasses.[113] In November 2019, Huawei partners with Devialet and unveiled a new specifically designed speaker, the Sound X.[114] In October 2020, Huawei released its own mapping service, Petal Maps, which was developed in partnership with Dutch navigation device manufacturer TomTom.[115]

Products and services

[edit]Telecommunication networks

[edit]Huawei offers mobile and fixed softswitches, plus next-generation home location register and Internet Protocol Multimedia Subsystems (IMS). Huawei sells xDSL, passive optical network (PON) and next-generation PON (NG PON) on a single platform. The company also offers mobile infrastructure, broadband access and service provider routers and switches (SPRS). Huawei's software products include service delivery platforms (SDPs), base station subsystems, and more.[116]

Fiber-optic cable projects

[edit]Huawei Marine Networks delivered the HANNIBAL submarine communications cable system for Tunisie Telecom across the Mediterranean Sea to Italy in 2009.[117]: 310

Huawei Marine is involved in many fiber-optic cable projects connected with the Belt and Road Initiative.[65]: 78 Huawei Marine completed the China-Pakistan Fiber Optic Project which runs along the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor.[65]: 78 In 2018, Huawei Marine completed the South Atlantic Interlink (SAIL) Cable System which runs from Kribi, Cameroon to Fortaleza, Brazil.[65]: 78 It also built the Kumul Domestic Fiber Cable from Indonesia to Papua New Guinea.[65]: 78

As part of the Smart Africa project, Huawei Marine built the 2,800 mile fiber-optic network Guinea Backbone Network.[65]: 78

Global services

[edit]Huawei Global Services provides telecommunications operators with equipment to build and operate networks as well as consulting and engineering services to improve operational efficiencies.[118] These include network integration services such as those for mobile and fixed networks; assurance services such as network safety; and learning services, such as competency consulting.[116]

Devices

[edit]

Huawei's Devices division provides white-label products to content-service providers, including USB modems, wireless modems and wireless routers for mobile Wi-Fi,[119] embedded modules, fixed wireless terminals, wireless gateways, set-top boxes, mobile handsets and video products.[120] Huawei also produces and sells a variety of devices under its own name, such as the smartphones, tablet PCs, earbuds and Huawei Smartwatch.[121][122]

Phones

[edit]Huawei is the second-biggest smartphone maker in the world, after Samsung, as of the first quarter of 2019. Their portfolio of phones includes both high-end smartphones, its Huawei Mate series and Huawei Pura series, and cheaper handsets that fall under its Honor brand.[123]

Cheaper handsets fall under its Honor brand.[124] Honor was created in order to elevate Huawei-branded phones as premium offerings. In 2020, Huawei agreed to sell the Honor brand to a state-owned enterprise of the Shenzhen municipal government. Consequently, Honor was initially reported to be cut off from access to Huawei's IPs, which consists of more than 100,000 active patents by the end of 2020, and additionally cannot tap into Huawei's large R&D resources where $20 billion had been committed for 2021. However, Wired magazine noted in 2021 that Honor devices still had not differentiated their software much from Huawei phones and that core apps and certain engineering features, like the Honor-engineered camera features looked "virtually identical' across both phones.[23][124]

History of Huawei phones

[edit]

In July 2003, Huawei established their handset department and by 2004, Huawei shipped their first phone, the C300. The U626 was Huawei's first 3G phone in June 2005 and in 2006, Huawei launched the first Vodafone-branded 3G handset, the V710. The U8220 was Huawei's first Android smartphone and was unveiled in MWC 2009. At CES 2012, Huawei introduced the Ascend range starting with the Ascend P1 S. At MWC 2012, Huawei launched the Ascend D1. In September 2012, Huawei launched their first 4G ready phone, the Ascend P1 LTE. At CES 2013, Huawei launched the Ascend D2 and the Ascend Mate. At MWC 2013, the Ascend P2 was launched as the world's first LTE Cat4 smartphone. In June 2013, Huawei launched the Ascend P6 and in December 2013, Huawei introduced Honor as a subsidiary independent brand in China. At CES 2014, Huawei launched the Ascend Mate2 4G in 2014 and at MWC 2014, Huawei launched the MediaPad X1 tablet and Ascend G6 4G smartphone. Other launched in 2014 included the Ascend P7 in May 2014, the Ascend Mate7, the Ascend G7 and the Ascend P7 Sapphire Edition as China's first 4G smartphone with a sapphire screen.[125]

In January 2015, Huawei discontinued the "Ascend" brand for its flagship phones, and launched the new P series with the Huawei P8.[126][127] Huawei also partnered with Google to build the Nexus 6P which was released in September 2015.[128]

In May 2018, Huawei stated that they will no longer allow unlocking the bootloader of their phones to allow installing third party system software or security updates after Huawei stops them.[129]

Huawei is currently the most well-known international corporation in China and a pioneer of the 5G mobile phone standard, which has come to be used globally in the last few years.[130]

Laptops

[edit]

In 2016, Huawei entered the laptop markets with the release of its Huawei MateBook series of laptops.[131] They have continued to release laptop models in this series into 2020 with their most recent models being the MateBook X Pro and Matebook 13 2020.[132]

Tablets

[edit]The Huawei MatePad Pro, launched in November 2019, after that, subsequent releases of their MatePad tablet line.[133] Huawei is number one in the Chinese tablet market and number two globally as of 4Q 2019.[134]

PCs

[edit]The MateStation S and X was released in September 2021 among successor releases of variants, marking Huawei entrance into the workstation, desktop PC space with All-in-one and Thin client PCs.[135][136]

Wearables

[edit]The Huawei Watch is an Android Wear-based smartwatch developed by Huawei. It was released at Internationale Funkausstellung Berlin on 2 September 2015. Since 2020, Huawei released subsequent models using in-house operating systems from LiteOS powered models to the latest HarmonyOS powered watches.[137] It is the first smartwatch produced by Huawei.[137] Their latest watch, Huawei Watch Ultimate Design announced on September 25, 2023, and released 4, October 2023 worldwide.[138]

Software

[edit]EMUI (Emotion User Interface)

[edit]Emotion UI (EMUI) was a ROM/OS developed by Huawei Technologies Co. Ltd. and based on Google's Android Open Source Project (AOSP). EMUI is pre-installed on most Huawei Smartphone devices and its subsidiaries the Honor series.[139]

Harmony OS

[edit]

Huawei Mobile Services (HMS)

[edit]Huawei Mobile Services (HMS) is Huawei's solution to GMS (Google Mobile services) for Android - providing many of the same features for app developers. It also serves as the umbrella brand for Huawei's core set of mobile applications, including Huawei AppGallery, which was created as a competitor to Google's Play Store. In December 2019, Huawei unveiled HMS version 4.0, and as of 16 January 2020, the company reported that it had signed up 55,000 apps using its HMS Core software.[143]

Automobile

[edit]Huawei has secured collaboration with a few automakers including Seres, Chery, BAIC Motor, Changan Automobile and GAC Group.[144]

AITO

[edit]The Aito brand (问界 Wenjie) is Huawei's premium EV brand in cooperation with Seres. In December 2021, the AITO M5 was unveiled as the first vehicle to be developed in cooperation with Huawei. The model was developed mainly by Seres and is essentially a restyled Seres SF5 crossover.[145] The model was sold under a new brand called AITO, which stands for "Adding Intelligence to Auto" and uses Huawei DriveONE and HarmonyOS, while the Seres SF5 used Huawei DriveONE and HiCar.[146]

- AITO M5 front quarter view

- AITO M5 rear quarter view

- AITO M5 interior

AVATR

[edit]The Avatr (阿维塔 Aweita) brand is Huawei's premium EV brand in cooperation with Changan Automobile and CATL.

Luxeed

[edit]The Luxeed (智界 Zhijie) brand is Huawei's premium EV brand in cooperation with Chery, with the first vehicle being the Luxeed S7, previously called the Chery EH3,[147] an upcoming premium electric executive sedan due to be unveiled in Q3 2023, and would be the first car to have the Harmony OS 4 system on board.[148]

Huawei Solar

[edit]Huawei entered the photovoltaic (PV) market in 2011, and opened an Energy Center of Competence in Nuremberg, Germany the same year.[149] In September 2016, Huawei integrated new manufacturing capabilities into its Eindhoven hub in the Netherlands, where it can produce 7,000 inverter units per month.[149] In October that same year, Huawei entered the North American market and formed a strategic partnership with Strata Solar.[149] In April 2017, Huawei enters the residential solar market with the launch of its string solar inverters and DC power optimizers.[149]

As of 2022, Huawei is the largest producer of solar inverters in the world with a 29% market share, which saw a significant shipment increase of 83% compared to 2021.[150]

Competitive position

[edit]Huawei's global growth has largely been driven by its offering of competitive telecommunications equipment at a lesser price than rival firms.[151]: 95

Huawei Technologies Co. Ltd. was the world's largest telecom equipment maker in 2012[7] and China's largest telephone-network equipment maker.[152] With 3,442 patents, Huawei became the world's No. 1 applicant for international patents in 2014.[153] In 2019, Huawei had the second most patents granted by the European Patent Office.[154] In 2021, the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO)'s annual World Intellectual Property Indicators report ranked Huawei's number of patent applications published under the PCT System as 1st in the world, with 5464 patent applications being published during 2020.[155]

As of 2023[update], Huawei is the leading 5G equipment manufacturer and has the greatest market share of 5G equipment and has built approximately 70% of worldwide 5G base stations.[156]: 182

Research and development

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (March 2024) |

As of 2021[update], more than half of Huawei's employees are involved in research.[157]: 119 In the same year, Huawei spent $22.1 billion on R&D, around 22.4% of its net sales, being one of the six companies in the world to spend more than $20 billion on R&D spending.[158]

The company has numerous R&D institutes in countries including China, the United States,[159] Canada,[160] the United Kingdom,[161] Pakistan, Finland, France, Belgium, Germany, Colombia, Sweden, Ireland, India,[162] Russia, and Turkey.[163][164] It opened in July 2024 its biggest R&D center to date near Shanghai to accommodate nearly 35,000 members of its personnel.[165]

Huawei also funds research partnerships with universities such as the University of British Columbia, the University of Waterloo, the University of Western Ontario, the University of Guelph, and Université Laval.[166][167]

Controversies

[edit]Huawei has faced allegations that its products contain backdoors for Chinese government espionage and domestic laws require Chinese citizens and companies to cooperate with state intelligence when warranted. Huawei executives denied these claims, saying that the company has not received requests by the Chinese government to introduce backdoors in its equipment, would refuse to do so, and that Chinese law does not compel them to do so. As of 2019, the United States had not produced evidence of coordinated hacking by Huawei.[168][169][170][171]

Early business practices

[edit]Huawei employed a complex system of agreements with local state-owned telephone companies that seemed to include illicit payments to the local telecommunications bureau employees. During the late 1990s, the company created several joint ventures with their state-owned telecommunications company customers. By 1998, Huawei had signed agreements with municipal and provincial telephone bureaus to create Shanghai Huawei, Chengdu Huawei, Shenyang Huawei, Anhui Huawei, Sichuan Huawei, and other companies. The joint ventures were actually shell companies, and were a way to funnel money to local telecommunications employees so that Huawei could get deals to sell them equipment. In the case of Sichuan Huawei, for example, local partners could get 60–70 percent of their investment returned in the form of annual 'dividends'.[172]

Allegations of state support

[edit]Martin Thorley of the University of Nottingham noted that a "company of Huawei’s size, working in what is considered a sensitive sector, simply cannot succeed in China without extensive links to the Party".[18] Klon Kitchen has suggested that 5G dominance is essential to China in order to achieve its vision where "the prosperity of state-run capitalism is combined with the stability and security of technologically enabled authoritarianism".[173] Nigel Inkster of the International Institute for Strategic Studies suggested that "Huawei involvement in the core backbone 5G infrastructure of developed western liberal democracies is a strategic game-changer because 5G is a game-changer”, with “national telecoms champions” playing a key role, which in turn is part of China's "ambitious strategy to reshape the planet in line with its interests” through the Belt and Road Initiative.[18] On 7 October 2020, the U.K. Parliament's Defence Committee released a report concluding that there was evidence of collusion between Huawei and Chinese state and the Chinese Communist Party, based upon ownership model and government subsidies it has received.[174]

Huawei has a strong rapport with, and support from, the Chinese government.[99]: 131 The Chinese government has granted Huawei much more comprehensive support than other domestic companies facing troubles abroad, such as ByteDance, since Huawei is considered a national champion along with Alibaba Group and Tencent.[12][175] For instance after Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou was detained in Canada pending extradition to the United States for fraud charges, China immediately arrested Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor in what was widely viewed as "hostage diplomacy".[12][176] China has also imposed tariffs on Australian imports in 2020, in apparent retaliation for Huawei and ZTE being excluded from Australia's 5G network in 2018.[12] In June 2020, when the UK mulled reversing an earlier decision to permit Huawei's participation in 5G, China threatened retaliation in other sectors by withholding investments in power generation and high-speed rail. A House of Commons defence committee found that "Beijing had exerted pressure through "covert and overt threats" to keep Huawei in the UK's 5G network".[174] US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo reassured the UK saying "the US stands with our allies and partners against the Chinese Communist Party's coercive bullying tactics," and "the US stands ready to assist our friends in the UK with any needs they have, from building secure and reliable nuclear power plants to developing trusted 5G solutions that protect their citizens' privacy".[177]

The "optics of Beijing's diplomats coming to [Huawei]'s defense" in the European Union has also contradicted Huawei's claims that it is "fully independent from the Chinese government".[178] In November 2019, the Chinese ambassador to Denmark, in meetings with high-ranking Faroese politicians, directly linked Huawei's 5G expansion with Chinese trade, according to a sound recording obtained by Kringvarp Føroya. According to Berlingske, the ambassador threatened with dropping a planned trade deal with the Faroe Islands, if the Faroese telecom company Føroya Tele did not let Huawei build the national 5G network. Huawei said they did not knоw about the meetings.[179] China's ambassador to Germany, Wu Ken, warned that ‘there will be consequences’ if Huawei was excluded, and floated the "possibility of German cars being banned on safety grounds".[180][181]

The Wall Street Journal has suggested that Huawei received approximately "$46 billion in loans and other support, coupled with $25 billion in tax cuts" since the Chinese government had a vested interest in fostering a company to compete against Apple and Samsung.[11] In particular, China's state-owned banks such as the China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China make loans to Huawei customers which substantially undercut competitors' financing with lower interest and cash in advance, with China Development Bank providing a credit line totaling US$30 billion between 2004 and 2009. In 2010, the European Commission launched an investigation into China's subsidies that distorted global markets and harmed European vendors, and Huawei offered the initial complainant US$56 million to withdraw the complaint in an attempt to shut down the investigation. Then-European Trade Commissioner Karel De Gucht found that Huawei leveraged state support to underbid competitors by up to 70 percent.[182]

Allegations of military and intelligence ties

[edit]This section may be too long and excessively detailed. |

In 2011, a report by the Open Source Enterprise detailed its "suspicions over potential close links between Huawei and the Chinese Government," such as former chairwoman Sun Yafang's prior employment by the Ministry of State Security (MSS)'s Communications Department.[183][184][185]

In 2019, Ren Zhengfei stated "we never participate in espionage and we do not allow any of our employees to do any act like that. And we absolutely never install backdoors. Even if we were required by Chinese law, we would firmly reject that".[186][187] Chinese Premier Li Keqiang was quoted saying "the Chinese government did not and will not ask Chinese companies to spy on other countries, such kind of action is not consistent with the Chinese law and is not how China behaves." Huawei has cited the opinion of Zhong Lun Law Firm, co-signed by a CCP member,[188] whose lawyers testified to the FCC that the National Intelligence Law doesn't apply to Huawei. The opinion of Zhong Lun lawyers, reviewed by British law firm Clifford Chance, has been distributed widely by Huawei as an "independent legal opinion", although Clifford Chance added a disclaimer stated that "the material should not be construed as constituting a legal opinion on the application of PRC law".[188][189] Follow up reporting from Wired cast doubt on the findings of Zhong Lun, particularly because the Chinese "government doesn't limit itself to what the law explicitly allows" when it comes to national security.[190] "All Chinese citizens and organisations are obliged to cooperate upon request with PRC intelligence operations—and also maintain the secrecy of such operations", as explicitly stipulated in Article 7 of the 2017 PRC national intelligence-gathering activities law.[188] Tim Rühlig, a Research Fellow at the Swedish Institute of International Affairs, observed that "Not least in the light of the lack of the rule of law in China, but also given the clarity of the Intelligence Law, this legal opinion [by Clifford Chance] does not provide any substantial reassurance that Huawei could decline to cooperate with Chinese intelligence, even if the company wanted to do so".[191]

Experts have pointed out that under Xi Jinping's "intensifying authoritarianism [since] Beijing promulgated a new national intelligence law" in 2017, as well as the 2014 Counter-Espionage Law, both of which are vaguely defined and far-reaching. The two laws "[compel] Chinese businesses to work with Chinese intelligence and security agencies whenever they are requested to do so", suggesting that Huawei or other domestic major technology companies could not refuse to cooperate with Chinese intelligence. Jerome Cohen, a New York University law professor and Council on Foreign Relations adjunct senior fellow stated "Not only is this mandated by existing legislation but, more important, also by political reality and the organizational structure and operation of the Party-State’s economy. The Party is embedded in Huawei and controls it".[18] One former Huawei employee said "The state wants to use Huawei, and it can use it if it wants. Everyone has to listen to the state. Every person. Every company and every individual, and you can't talk about it. You can't say you don't like it. That's just China." The new cybersecurity law also requires domestic companies, and eventually foreign subsidiaries, to use state-certified network equipment and software so that their data and communications are fully visible to China's Cybersecurity Bureau.[12][192][188][189] University of Nottingham's Martin Thorley has suggested that Huawei would have no recourse to oppose the CCP's request in court, since the party controls the police, the media, the judiciary and the government.[18] Klon Kitchen has suggested that 5G dominance is essential to China in order to achieve its vision where "the prosperity of state-run capitalism is combined with the stability and security of technologically enabled authoritarianism".[173]

In 2019, Henry Jackson Society researchers conducted an analysis of 25,000 Huawei employee CVs and found that some had worked or trained with China's Ministry of State Security, the People's Liberation Army (PLA), its academies, and a military unit accused of hacking US corporations, including 11 alumni from a PLA information engineering school.[193] One of the study researchers says this shows "a strong relationship between Huawei and all levels of the Chinese state, Chinese military and Chinese intelligence. This to me appears to be a systemized, structural relationship."[194] In a report by academics Christopher Balding of Fulbright University and Donald C. Clarke of George Washington University, a person "simultaneously held a position at Huawei and a teaching and research role at a military university through which they were employed by the Chinese People’s Liberation Army...a section in the PLA that is responsible for the Chinese military’s space, cyber, and electronic warfare capabilities".[195] Charles Parton, a British diplomat, said this "give the lie to Huawei's claim that there is no evidence that they help the Chinese intelligence services. This gun is smoking."[193] Huawei said that while it does not work on Chinese military or intelligence projects, it is no secret that some employees have a previous government background. It criticized the report's speculative language such as ‘believes’, ‘infers’, and ‘cannot rule out’.[195] In 2014, the National Security Agency penetrated Huawei's corporate networks in China to search for links between the company and the People's Liberation Army. It was able to monitor accounts belonging to Huawei employees and its founder Ren Zhengfei.[19]

U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission member Michael Wessel said: “If there’s a locksmith who’s installing more and more locks on the doors in a community and suddenly there’s a rash of silent robberies, at some point the locksmith becomes a person of interest. Huawei around that time became a significant entity of interest".[19] A Bloomberg News report stated that Australian intelligence in 2012 detected a backdoor in the country's telecom network and shared its findings with the United States, who reported similar hacks. It was reportedly caused by a software update from Huawei carrying malicious code that transmitted data to China before deleting itself. Investigators managed to reconstruct the exploit and determined that Huawei technicians must have pushed the update through the network on behalf of China's spy agencies. Huawei said updates would have required authorization from the customer and that no tangible evidence was presented. China's Ministry of Foreign Affairs called the accusation a "slander". Australian telecom operators Optus and Vodafone disputed that they were compromised.[19][20] Senior security officials in Uganda and Zambia told The Wall Street Journal that Huawei played key roles enabling their governments to spy on political opponents.[12] Several IT sources told Le Monde that inside the African Union headquarters, whose computer systems were supplied by Huawei,[12] data transfers on its servers peaked after hours from January 2012 to January 2017, with the AU's internal data sent to unknown servers hosted in Shanghai.[196] In May 2019, a Huawei Mediapad M5 belonging to a Canadian IT engineer living in Taiwan was found to be sending data to servers in China despite never being authorized to do so, as the apps could not be disabled and continued to send sensitive data even after appearing to be deleted.[197] At the end of 2019, United States officials disclosed to the United Kingdom and Germany that Huawei has had the ability to covertly exploit backdoors intended for law enforcement officials since 2009, as these backdoors are found on carrier equipment like antennas and routers, and Huawei's equipment is widely used around the world due to its low cost.[198][199] The United Kingdom established a lab that it ran, but which was paid for by Huawei, to evaluate Huawei equipment.[117]: 322 After eight years of study, the lab did not identify any Huawei backdoor, but concluded that Huawei's equipment had bugs that could be exploited by hackers.[117]: 322

Timeline

[edit]Yale University economist Stephen Roach stated in 2022 that there was no hard evidence to support the allegations of Huawei having a backdoor for industrial espionage other than one arguable instance,[157]: 118 which was when UK telecom Vodafone disclosed in 2011 that its Italian fixed line network contained a security vulnerability in its Huawei-installed software.[157]: 118–119 Huawei fixed the vulnerability at Vodafone's request.[157]: 118 There was no report of any suspicious data capture or systems control activity.[200][157] Vodafone was satisfied with the outcome and thereafter increased its reliance on Huawei as an equipment-supplier.[157]: 118

A 2012 White House-ordered security review found no evidence that Huawei spied for China and said instead that security vulnerabilities on its products posed a greater threat to its users. The details of the leaked review came a week after a US House Intelligence Committee report which warned against letting Huawei supply critical telecommunications infrastructure in the United States.[201]

Huawei has been at the center of concerns over Chinese involvement in 5G wireless networks. In 2018, the United States passed a defense funding bill that contained a passage barring the federal government from doing business with Huawei, ZTE, and several Chinese vendors of surveillance products, due to security concerns.[202][203][204] The Chinese government has threatened economic retaliation against countries that block Huawei's market access.[177]

Similarly in November 2018, New Zealand blocked Huawei from supplying mobile equipment to national telecommunications company Spark New Zealand's 5G network, citing a "significant network security risk" and concerns about China's National Intelligence Law.[205][206]

Huawei was involved in developing the United Kingdom's 5G network, which initially led to serious policy and diplomatic disagreements between the UK and the United States, which opposed Huawei's involvement.[65]: 77 Between December 2018 and January 2019, German and British intelligence agencies initially pushed back against the US' allegations, stating that after examining Huawei's 5G hardware and accompanying source code, they have found no evidence of malevolence and that a ban would therefore be unwarranted.[207][208] Additionally, the head of Britain's National Cyber Security Centre (the information security arm of GCHQ) stated that the US has not managed to provide the UK with any proof of its allegations against Huawei and also their agency had concluded that any risks involving Huawei in UK's telecom networks are "manageable".[209][208] The Huawei Cyber Security Evaluation Centre (HCSEC), set up in 2010 to assuage security fears as it examined Huawei hardware and software for the UK market, was staffed largely by employees from Huawei but with regular oversight from GCHQ, which led to questions of operating independence from Huawei.[210] On 1 October 2020, an official report released by National Cyber Security Centre noted that "Huawei has failed to adequately tackle security flaws in equipment used in the UK's telecoms networks despite previous complaints", and flagged one vulnerability of "national significance" related to broadband in 2019. The report concluded that Huawei was not confident of implementing the five-year plan of improving its software engineering processes, so there was "limited assurance that all risks to UK national security" could be mitigated in the long-term.[211] On 14 July 2020, the United Kingdom Government announced a ban on the use of company's 5G network equipment, citing security concerns.[212] In October 2020, the British Defence Select Committee announced that it had found evidence of Huawei's collusion with the Chinese state and that it supported accelerated purging of Huawei equipment from Britain's telecom infrastructure by 2025, since they concluded that Huawei had "engaged in a variety of intelligence, security, and intellectual property activities" despite its repeated denials.[174][213] In November 2020, Huawei challenged the UK government's decision, citing an Oxford Economics report that it had contributed £3.3 billion to the UK's GDP.[214]

In March 2019, Huawei filed three defamation claims over comments suggesting ties to the Chinese government made on television by a French researcher, a broadcast journalist and a telecommunications sector expert.[215] In June 2020 ANSSI informed French telecommunications companies that they would not be allowed to renew licenses for 5G equipment made from Huawei after 2028.[216] On 28 August 2020, French President Emmanuel Macron assured the Chinese government that it did not ban Huawei products from participating in its fifth-generation mobile roll-out, but favored European providers for security reasons. The head of the France's cybersecurity agency also stated that it has granted time-limited waivers on 5G for wireless operators that use Huawei products, a decision that likely started a "phasing out" of the company's products.[217]

In February 2020, US government officials claimed that Huawei has had the ability to covertly exploit backdoors intended for law enforcement officials in carrier equipment like antennas and routers since 2009.[198][199]

In mid July 2020, Andrew Little, the Minister in charge of New Zealand's signals intelligence agency the Government Communications Security Bureau (GCSB), announced that New Zealand would not join the United Kingdom and United States in banning Huawei from the country's 5G network.[218][219]

In May 2022, Canada's industry minister Francois-Philippe Champagne announced that Canada will ban Huawei from the country's 5G network, in an effort to protect the safety and security of Canadians, as well as to protect Canada's infrastructure.[220] The Canadian federal government cited national security concerns for the move, saying that the suppliers could be forced to company with "extrajudicial directions from foreign governments" in ways that could "conflict with Canadian laws or would be detrimental to Canadian interests". Telcos will be prevented from procuring new 4G or 5G equipment from Huawei and ZTE and must remove all ZTE- and Huawei-branded 5G equipment from their networks by 28 June 2024.[221]

Meng Wanzhou case

[edit]

On December 1, 2018, Meng Wanzhou, the board deputy chairperson and daughter of the founder of the Chinese multinational technology corporation Huawei, was detained upon arrival at Vancouver International Airport by Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) officers for questioning, which lasted three hours.[222][223] The Royal Canadian Mounted Police subsequently arrested her on a provisional U.S. extradition request for fraud and conspiracy to commit fraud in order to circumvent U.S. sanctions against Iran.[222][224] On January 28, 2019, the United States Department of Justice formally announced financial fraud charges against Meng.[225][226] The first stage of the extradition hearing for Meng began Monday, January 20, 2020, and concluded on May 27, 2020, when the Supreme Court of British Columbia ordered the extradition to proceed.[227][228]

During the extradition courtroom proceedings, Meng's lawyers made several allegations against the prosecution, including allegations of unlawful detention of Meng,[229] unlawful search and seizure,[230] extradition law violations,[231] misrepresentation,[232][233][234] international law violation,[235] and fabricated testimonies by the CBSA,[236] each of which were responded to by the prosecution.[237][238][239][240] In August 2021, the extradition judge questioned the regularity of the case and expressed great difficulty in understanding how the Record of Case (ROC) presented by the US supported their allegation of criminality.[241][242][243]

On September 24, 2021, the Department of Justice announced it had reached a deal with Meng to resolve the case through a deferred prosecution agreement. As part of the deal, Meng agreed to a statement of facts that said she had made untrue statements to HSBC to enable transactions in the United States, at least some of which supported Huawei's work in Iran in violation of U.S. sanctions, but did not have to pay a fine nor plead guilty to her key charges.[244][245][246] The Department of Justice said it would move to dismiss all charges against Meng when the deferral period ends on 21 December 2022, on the condition that Meng is not charged with a crime before then.[247] Meng was released from house arrest and left Canada for China on September 24, 2021; hours after news of the deal, Michael Spavor and Michael Kovrig, two Canadian citizens whose arrest in mainland China were widely seen as retaliation for Meng's arrest in Canada, were released from detention in China and flown back to Canada.[248] On December 2, 2022, the presiding judge dismissed the charges against Meng following the United States government's request.[249]Intellectual property infringement

[edit]Huawei has settled with Cisco Systems, Motorola, and PanOptis in patent infringement lawsuits.[10][250][251] In 2018, a German court ruled against Huawei and ZTE in favor of MPEG LA, which holds patents related to Advanced Video Coding.[252]

Huawei has been accused of intellectual property theft.[253][254] In February 2003, Cisco Systems sued Huawei Technologies for allegedly infringing on its patents and illegally copying source code used in its routers and switches.[255][non-primary source needed] By July 2004, Huawei removed the contested code, manuals and command-line interfaces and the case was subsequently settled out of court.[256] As part of the settlement Huawei admitted that it had copied some of Cisco's router software.[257]

At the 2004 Supercomm tech conference in Chicago, a Huawei employee allegedly opened up the networking equipment of other companies to photograph the circuit boards.[257][258]

Brian Shields, former chief security officer at Nortel, said that his company was compromised in 2004 by Chinese hackers; executive credentials were accessed remotely, and entire computers were taken over. Shields does not believe Huawei was directly involved but thinks that Huawei was a beneficiary of the hack. Documents taken included product roadmaps, sales proposals, and technical papers.[258] Nortel sought for but failed to receive help from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. The Canadian Security Intelligence Service said it approached the company but was rebuffed.[259][48]

Cybersecurity experts have some doubts about a hack of such magnitude as described by Shields, calling it "unlikely".[259] An extensive analysis by University of Ottawa professor Jonathan Calof and recollections of former Nortel executive Tim Dempsey place the blame mostly on strategic mistakes and poor management at Nortel. On the other hand, some employees recall when Huawei or a front company returned a fibre card to Nortel disassembled, around a time when knock-offs products emerged in Asia. There remains a suspicion that industrial espionage brought down or at least accelerated Nortel's demise.[258]

In 2017, a jury found that Huawei had misappropriated trade secrets of T-Mobile US but awarded damages only for a breach of supplier contract; it did not compensate T-Mobile for claims of espionage.[260]

In February 2020, the United States Department of Justice charged Huawei with racketeering and conspiring to steal trade secrets from six US firms.[261] Huawei said those allegations, some going back almost 20 years, had never been found as a basis for any significant monetary judgment.[262][261]

North Korea

[edit]Leaked documents obtained by The Washington Post in 2019 raised questions about whether Huawei conducted business secretly with North Korea, which was under numerous US sanctions.[263]

Xinjiang internment camps

[edit]Huawei has been accused of providing technology used in the mass surveillance and detention of Uyghurs in Xinjiang internment camps, resulting in sanctions by the United States Department of State.[13][264][14][265] Documents show that it has developed facial recognition software that recognizes ethnicity-specific features for surveillance[15][266] and filed a patent in China for a technology that could identify Han and Uyghur pedestrians.[267] The company and its suppliers have also been accused of using forced labor.[268][269] Huawei denied operating such technology.[270]

Alleged use by Hamas

[edit]On 8 October 2023, former MI6 spy Aimen Dean posted on X that Israel's failure to detect the Hamas-led attack on Israel was due partly to its militants use of Huawei phones, tablets and laptops, elaborating that US tech companies barring of Huawei had forced it to develop its own systems that were not easy to hack except by China.[271][272]

Lawsuit

[edit]In January 2024, Netgear, a computer networking company based in San Jose, California, filed a lawsuit with a California federal court against Huawei, claiming the company broke the United States antitrust law by withholding patent licenses, in addition to allegations of fraud and racketeering.[273][274]

NSA infiltration

[edit]In 2014, Der Spiegel and The New York Times reported that, according to global surveillance disclosures, the National Security Agency (NSA) infiltrated Huawei's computer network in 2009. The White House intelligence coordinator and the FBI were also involved. The operation obtained Huawei's customer list and internal training documents. In addition, the company's central email archive was accessed, including messages from founder Ren Zhengfei and chairwoman Sun Yafang. So much data was gathered that "we don't know what to do with it", according to one document. The NSA was concerned that Huawei's infrastructure could provide China with signals intelligence capabilities. It also wanted to find ways to exploit the company's products because they are used by targets of interest to the NSA.[275]

Sanctions, bans, and restrictions

[edit]United States

[edit]Before the 2020 semiconductor ban

[edit]In August 2018, the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019 (NDAA 2019) was signed into law, containing a provision that banned Huawei and ZTE equipment from being used by the US federal government, citing security concerns.[276] Huawei filed a lawsuit over the act in March 2019,[277] alleging it to be unconstitutional because it specifically targeted Huawei without granting it a chance to provide a rebuttal or due process.[278]

Additionally, on 15 May 2019, the Department of Commerce added Huawei and 70 foreign subsidiaries and "affiliates" to its Entity List under the Export Administration Regulations, citing the company having been indicted for "knowingly and willfully causing the export, re-export, sale and supply, directly and indirectly, of goods, technology and services (banking and other financial services) from the United States to Iran and the government of Iran without obtaining a license from the Department of Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC)".[279] This restricts US companies from doing business with Huawei without a government license.[280][281][282] Various US-based companies immediately froze their business with Huawei to comply with the regulation.[283]

The May 2019 ban on Huawei was partial: it did not affect most non-American produced chips, and the Trump administration granted a series of extensions on the ban in any case,[284] with another 90-day reprieve issued in May 2020.[285] In May 2020, the US extended the ban to cover semiconductors customized for Huawei and made with US technology.[286] In August 2020, the US again extended the ban to a blanket ban on all semiconductor sales to Huawei.[286] The blanket ban took effect in September 2020.[287] Samsung and LG Display were banned from supplying displays to Huawei.[288]

After 2020

[edit]The sanctions regime established in September 2020 negatively affected Huawei production, sales and financial projections.[289][290][291] However, on 29 June 2019 at the G20 summit, the US President made statements implicating plans to ease the restrictions on US companies doing business with Huawei.[292][293][294] Despite this statement, on 15 May 2020, the U.S. Department of Commerce extended its export restrictions to bar Huawei from producing semiconductors derived from technology or software of US origin, even if the manufacturing is performed overseas.[295][296][297] In June 2020, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) designated Huawei a national security threat, thereby barring it from any US subsidies.[298] In July 2020, the Federal Acquisition Regulation Council published a Federal Register notice prohibiting all federal government contractors from selling Huawei hardware to the federal government and preventing federal contractors from using Huawei hardware.[299]

In November 2020, Donald Trump issued an executive order prohibiting any American company or individual from owning shares in companies that the United States Department of Defense has listed as having links to the People's Liberation Army, which included Huawei.[300][301][302] In January 2021, the Trump administration revoked licenses from US companies such as Intel from supplying products and technologies to Huawei.[303] In June 2021, the FCC voted unanimously to prohibit approvals of Huawei gear in US telecommunication networks on national security grounds.[304]

In June 2021, the administration of Joe Biden began to persuade the United Arab Emirates to remove the Huawei Technologies Co. equipment from its telecommunications network, while ensuring to further distance itself from China. It came as an added threat to the $23 billion arms deal of F-35 fighter jets and Reaper drones between the US and the UAE. The Emirates got a deadline of four years from Washington to replace the Chinese network.[305] A report in September 2021 analyzed how the UAE was struggling between maintaining its relations with both the United States and China. While Washington had a hawkish stance towards Beijing, the increasing Emirati relations with China have strained those with America. In that light, the Western nation has raised concerns for the UAE to beware of the security threat that the Chinese technologies like Huawei 5G telecommunications network possessed. However, the Gulf nations like the Emirates and Saudi Arabia defended their decision of picking Chinese technology over the American, saying that it is much cheaper and had no political conditions.[306]

On 25 November 2022, the FCC issued a ban on Huawei for national security reasons, citing the national security risk posed by the technology owned by China.[307] In May 2024, the U.S. Department of Commerce revoked some export licenses that allow Intel and Qualcomm to supply Huawei with semiconductors.[308][309]

Huawei's reaction

[edit]Stockpiling of processors

[edit]Before the 15 September 2020 deadline, Huawei was in "survival mode" and stockpiled "5G mobile processors, Wifi, radio frequency and display driver chips and other components" from key chip suppliers and manufacturers, including Samsung, SK Hynix, TSMC, MediaTek, Realtek, Novatek, and RichWave.[287] Even in 2019, Huawei spent $23.45 billion on the stockpiling of chips and other supplies in 2019, up 73% from 2018.[287] In May 2020, SMIC manufactured 14nm chips for Huawei, which was the first time Huawei used a foundry other than TSMC.[310] In July 2020, TSMC confirmed it would halt the shipment of silicon wafers to Chinese telecommunications equipment manufacturer Huawei and its subsidiary HiSilicon by 14 September.[311][312]

On its most crucial business, namely, its telecoms business (including 5G) and server business, Huawei has stockpiled 1.5 to 2 years' worth of chips and components.[313] It began massively stockpiling from 2018, when Meng Wanzhou, the daughter of Huawei's founder, was arrested in Canada upon US request.[313] Key Huawei suppliers included Xilinx, Intel, AMD, Samsung, SK Hynix, Micron and Kioxia.[313] On the other hand, analysts predicted that Huawei could ship 195 million units of smartphones from its existing stockpile in 2021, but shipments may drop to 50 million in 2021 if rules are not relaxed.[287]

Development of processors

[edit]In late 2020, it was reported that Huawei had planned to build a semiconductor manufacturing facility in Shanghai that did not involve US technology.[314] The plan may have helped Huawei obtain necessary chips after its existing stockpile became depleted, which would have helped the company chart a sustainable path for its telecoms business.[314] Huawei had also planned to collaborate with the government-run Shanghai IC R&D Center, which is partially owned by the state-owned enterprise Hua Hong Semiconductor.[314] Huawei may have been purchasing equipment from Chinese firms such as AMEC and NAURA Technology Group, as well as using foreign tools which it could still find on the market.[314]

In August 2023, the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA), a US trade association, alleged that Huawei was building a collection of secret semiconductor-fabrication facilities across China, a shadow manufacturing network that would let the company skirt US sanctions.[315][316][317] Huawei was receiving an estimated $30 billion in state funding from the government at the time and had acquired at least two existing plants, with plans to construct at least three others.[315][317] The United States Department of Commerce had put Huawei on its entity list in 2019,[317] eventually "prohibiting it from working with American companies in almost all circumstances." However, if Huawei were to function under the names of other companies without disclosing its own involvement, it might have been able to circumvent those restrictions to "indirectly purchase American chipmaking equipment and other supplies that would otherwise be prohibited."[315]

On 6 September 2023, Huawei launched its new Mate 60 smartphone.[318] The phone is powered by a new Kirin 9000s chip, made in China by Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp (SMIC).[319] This processor was the first to use the new 7 nanometre SMIC technology. TechInsights had stated in 2022 that it believed SMIC had managed to produce 7 nm chips, even though faced by a harsh sanctions regime, by adapting simpler machines that it could still purchase from ASML.[319] Holger Mueller of Constellation Research Inc. said that this showed that the US sanctions might have had the effect of sending China's chip-making industry into overdrive: "If SMIC really has perfected its 7nm process, this would be a major advance that can help Huawei remain at the forefront of the smartphone industry."[320] TechInsights found evidence that the processor had been manufactured using SMIC's N+2 7 nm node.[321] One of its analysts, Dan Hutcheson, who had led the breakdown of the new device, stated that it demonstrates "impressive technical progress China's semiconductor industry has made" despite not having EUVL tools, and that "the difficulty of this achievement also shows the resilience of the country's chip technological ability". However other analysts have said that such an achievement may lead to harsher sanctions against it.[322]

Replacement operating systems

[edit]After the US sanctions regime started in summer 2018, Huawei started working on its own in-house operating system codenamed "HongMeng OS": in an interview with Die Welt, executive Richard Yu stated in 2019 that an in-house OS could be used as a "plan B" if it were prevented from using Android or Windows as the result of US action.[323][324][325] Huawei filed trademarks for the names "Ark", "Ark OS", and "Harmony" in Europe, which were speculated to be connected to this OS.[326][327] On 9 August 2019, Huawei officially unveiled Harmony OS at its inaugural HDC developers' conference in Dongguan with the ARK compiler which can be used to port Android APK packages to the OS.[328][329]

In September 2019, Huawei began offering the Linux distribution Deepin as a pre-loaded operating system on selected Matebook models in China.[330]

Whereas at first the official Huawei line was that Harmony OS was not intended for smartphones, in June 2021 Huawei began shipping its smartphones[331] with Harmony OS by default in China (in Europe it kept Android, in its own version EMUI, as the default). The operating system proved a success in China, rising from no market share at all to 10 per cent of the Chinese market for smartphones within two years (from mid-2021 to mid-2023), at the expense of Android.[332]

Other countries

[edit]In 2013, Taiwan blocked mobile network operators and government departments from using Huawei equipment.[333]

In 2018, Japan banned Huawei from receiving government contracts.[25][29][334]

In 2019, Vietnam left Huawei out of bids to build the country's 5G network out of national security concerns.[335][336]

Following the initial 2020–2021 China–India skirmishes, India announced that Huawei telecommunication gear would be removed from the country and that the company would be blocked from participating in India's 5G network out of national security concerns.[337][26]

Ten out of the 27 European Union member states have regulatory frameworks curbing Huawei products. They range from bans, higher barriers to approval, refusal to renew licenses, and unimplemented proposals.[28][338]

Having previously banned Huawei from participating in its 5G auction, Brazil reversed its position in early 2021 and allowed Huawei to participate.[99]: 131

In May 2022, Canada's government banned Huawei and ZTE equipment from the country's 5G network, with network operators having until 28 June 2024 to remove what they had already installed. The ban followed years of lobbying from the US, part of the Five Eyes intelligence alliance that also includes Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the UK.[339][340] Australia and New Zealand have also banned or restricted Huawei products.[341]

In October 2022, the UK extended the deadline by a year to the end of 2023 for removing core Huawei equipment from network functions. The ban, originally announced in 2020 following US pressure, calls for the phasing out of all Huawei gear from UK's 5G network by the end of 2027, which remains unchanged.[342]

Per an August 2023 decree on 5G network development, Costa Rica barred firms from all countries that have not signed the Budapest Convention on cybercrime.[343][344] The decree affects Chinese firms like Huawei, as well as firms from South Korea, Russia and Brazil, among others.[343]

In July 2024, the German government announced a deal with telecommunication companies in the country to remove Chinese 5G equipment, including from Huawei, by 2029.[345]

Chinese view

[edit]Western distrust and targeting of Huawei is generally viewed by the Chinese public as unjustified.[151]: 66 This has led to a perspective in the Chinese public and among city governments that patronizing Huawei helps support China in geopolitical and technological competition with the United States.[151]: 66 Huawei has thus received high levels of support in terms of public sentiment which its rival firms do not benefit from to the same extent.[151]: 66 Huawei's top position in China's smart cities technology market has in particular been boosted by these sentiments.[151]: 66

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "https://www.huawei.com/en/news/2024/3/huawei-annual-report-2023". Huawei. 29 March 2024. Archived from the original on 29 March 2024. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ "Huawei Investment & Holding Co., Ltd". Archived from the original on 29 March 2024. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ^ "Huawei Annual Report 2023". Huawei. Archived from the original on 29 March 2024. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ^ Zhong, Raymond (25 April 2019). "Who Owns Huawei? The Company Tried to Explain. It Got Complicated". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 May 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Marquis, Christopher; Qiao, Kunyuan (2022). Mao and Markets: The Communist Roots of Chinese Enterprise. Kunyuan Qiao. New Haven: Yale University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv3006z6k. ISBN 978-0-300-26883-6. JSTOR j.ctv3006z6k. OCLC 1348572572. S2CID 253067190.

- ^ Feng, Emily; Cheng, Amy (24 October 2019). "China's Tech Giant Huawei Spans Much Of The Globe Despite U.S. Efforts To Ban It". NPR. Archived from the original on 24 October 2023. Retrieved 20 October 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Who's afraid of Huawei?". The Economist. 3 August 2012. Archived from the original on 3 August 2012. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

Huawei has just overtaken Sweden's Ericsson to become the world's largest telecoms-equipment-maker.

- ^ Gibbs, Samuel (1 August 2018). "Huawei beats Apple to become second-largest smartphone maker". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 1 August 2018.