Пало (религия)

Пало , также известный как Лас Реглас -де -Конго , является африканской диаспорической религией , которая развивалась на Кубе в конце 19 или начале 20 -го века. Это в значительной степени опирается на традиционную религию Конго в Центральной Африке, с дополнительными влияниями, взятыми из -католической ветви христианства римско и от спиритизма . Посвященная религия, практикуемая Палеросом (мужчина) и Палеры (женщина), Пало организована с помощью небольших автономных групп под названием Мунансо Конго , каждый из которых возглавлял тата (отец) или Яйи (мать).

Несмотря на обучение существованию божественности Создателя, обычно называемой Нсамби , Пало считает эту сущность как не вовлеченную в человеческие дела и вместо этого сосредотачивает свое внимание на духах мертвых. Центральным в Пало является Нганга , сосуд, обычно изготовленный из железного котла. Многие нганга считаются материальными проявлениями наследственных или природы, известных как Мпунгу . Нганга , как правило, будет содержать широкий спектр объектов, одни из наиболее важных из которых являются палки и человеческие останки, последняя называется Nfumbe . В Пало присутствие Nfumbe означает , что дух этого мертвого человека населяет Нгангу и служит палеро или палере , которые его обладают. Практикующий PALO приказывает Nganga выполнять свои приказы, как правило, исцелять, но также нанести вред. Те, кто в основном предназначен для доброжелательных действий, крещены; Те, кто в значительной степени разработана для злобных действий, остаются неспольбоченными. Нганга «питается » кровью жертвованных животных и других предложений, в то время как ее воля и советы интерпретируются через гадания . Групповые ритуалы часто включают пение, барабан и танцы, чтобы облегчить владение духами мертвых.

Palo developed among Afro-Cuban communities following the Atlantic slave trade of the 16th to 19th centuries. It emerged largely from the traditional religions brought to Cuba by enslaved Bakongo people from Central Africa, but also incorporated ideas from Roman Catholicism, the only religion legally permitted on the island by the Spanish colonial government. The minkisi, spirit-vessels that were key to various Bakongo healing societies, provided the basis for the nganga of Palo. The religion took its distinct form around the late 19th or early 20th century, about the same time that Yoruba religious traditions merged with Roman Catholic and Spiritist ideas in Cuba to produce Santería. After the Cuban War of Independence resulted in an independent republic in 1898, the country's new constitution enshrined freedom of religion. Palo nevertheless remained marginalized by Cuba's Roman Catholic, Euro-Cuban establishment, which typically viewed it as brujería (witchcraft), an identity that many Palo practitioners have since embraced. In the 1960s, growing emigration following the Cuban Revolution spread Palo abroad.

Palo is divided into multiple traditions or ramas, including Mayombe, Monte, Briyumba, and Kimbisa, each with their own approaches to the religion. Many practitioners also identify as Roman Catholics and practice additional Afro-Cuban traditions such as Santería or Abakuá. Palo is most heavily practiced in eastern Cuba although it is found throughout the island and abroad, including in other parts of the Americas such as Venezuela, Mexico, and the United States. In many of these countries, Palo practitioners have faced problems with law enforcement for engaging in grave robbery to procure human bones for their nganga.

Definitions

[edit]Palo is an Afro-Cuban religion,[1] and more broadly an Afro-American religion.[2] Its name derives from palo, a Spanish term for sticks, referencing the important role that these items play in the religion's practices.[3] Another term for the religion is La Regla de Congo ("Kongo Rule" or "Law of Kongo") or Regla Congo, a reference to its origins among the traditional Kongo religion of Central Africa's Bakongo people.[4] Palo is also sometimes referred to as brujería (witchcraft), both by outsiders and by some practitioners themselves.[5]

Although its beliefs and practices come principally from the Kongo religion, Palo also draws upon the traditional religions of other African peoples who were brought to Cuba, such as the West African Yoruba. These African elements combined with influences from Roman Catholicism and also from Spiritism, a French variant of Spiritualism.[6] Palo's African heritage is important to practitioners, who often refer to their religious homeland as Ngola;[7] this indicates a belief in the historical Kingdom of Kongo as Palo's place of origin, a place where the spirits are more powerful.[8]

There is no central authority in control of Palo,[9] but separate groups of practitioners who operate autonomously.[10] It is largely transmitted orally,[11] and has no sacred text,[12] nor any systematized doctrine.[11] There is thus no overarching orthodoxy,[13] and no strict ritual protocol,[12] giving its practitioners scope for innovation and change.[10] Different practitioners often interpret the religion differently,[14] resulting in highly variable practices.[12] Several distinct traditions or denominations of Palo exist, called ramas ("branches"), with the main ramas being Mayombe, Briyumba, Monte, and Kimbisa.[15]

Practitioners are usually termed paleros if male,[16] paleras if female,[17] terms which can be translated as "one who handles tree branches".[18] An alternative term for adherents is mayomberos.[19] Another term applied to Palo practitioners in Cuba is ngangulero and ngangulera, meaning "a person who works a nganga", the latter being the spirit-vessel central to the religion.[20] The term carries pejorative connotations in Cuban society although some practitioners adopt it as a term of pride.[21] A similarly pejorative term embraced by some adherents is brujo (witch),[22] with Palo being one of several African-derived religions in the Americas whose practitioners adopt the identity of the witch as a form of reappropriation.[23]

Relationship to Afro-Cuban religions

[edit]Palo is one of three major Afro-Cuban religions present on Cuba, the other two being Santería, which derives largely from the Yoruba religion of West Africa, and Abakuá, which has its origins in the Ekpe society of West Africa's Efik-Ibibio peoples.[24] Many Palo initiates are also involved in Santería,[25] Abakuá,[26] Spiritism,[27] or Roman Catholicism;[28] some Palo practitioners believe that only baptised Roman Catholics should be initiated into the tradition.[29] Practitioners often see these various religions as offering complementary skills and mechanisms to solve people's issues,[30] or alternatively as each being best suited to resolving different problems.[31]

"Cruzar palo con cha" ("cross Palo with Ocha") is a phrase used to indicate that an individual practises both Palo and Santería,[32] ocha being one of the terms used for Santería's deities.[33] Those following both will usually keep the rituals of the two traditions separate,[34] with some Palo initiates objecting to the introduction of elements from Santería into their religion.[35] If someone is to be initiated into both, generally they will be initiated into Palo first;[36] some claim that this is because moving from Santería to Palo represents a spiritual regression, while others maintain that the oricha spirit placed within the adherent's body during Santería initiation would not tolerate the flesh-cutting process required for initiation into Palo.[37]

Comparisons have also been drawn between Palo and other African-derived traditions in the Americas. Certain similarities in practice have for instance been identified between Palo and Haitian Vodou.[38] Palo also has commonalities with Obeah, a practice found in Jamaica, and it is possible that Palo and Obeah cross-fertilised via Jamaican migration to Cuba from 1925 onward.[39]

Beliefs

[edit]Deities and spirits

[edit]Although Palo lacks a full mythology,[10] its worldview includes a supreme creator divinity, Nsambi or Sambia.[40] In the religion's mythology, Nsambi is believed responsible for creating the world and the first man and woman.[41] This entity is regarded as being remote and inaccessible from humanity, and thus no prayers or sacrifices are directed towards it.[41] The anthropologist Todd Ramón Ochoa, an initiate of Palo Briyumba, describes Nsambi as "the power in matter that pushes back against human manipulation and imposes itself against a person's will".[42] In the context of Afro-Cuban religion, Nsambi has been compared to Olofi in Santería and Abasí in Abakuá.[43]

In Palo, veneration is directed towards ancestors and spirits of the natural world,[44] both of which are called mpungus.[45] According to the anthropologist Katerina Kerestetzi, a mpungu represents "a sort of minor divinity".[46] Each mpungu commonly has its own names and epithets,[47] and may display multiple aspects or manifestations, each with their own specific names.[7] Among the most prominent of these mpungu, at least in Havana, are Lucero, Sarabanda, Siete Rayos, Ma' Kalunga, Mama Chola, Centella Ndoki, and Tiembla Tierra.[48] Others include Nsasi, Madre de Agua, Brazo Fuerte, Lufo Kuyo, Mama canata, Bután, and Baluandé.[49] Each mpungu may have its own particular associations; Lucero for instance opens and closes paths while Sarabanda is seen as being strong and wild.[47] The mpungus of nature are deemed to live in rivers and the sea,[44] as well as in trees,[50] with uncultivated areas of forest regarded as being especially potent locations of spiritual power.[51] Practitioners are expected to make agreements with these nature spirits.[52]

Particular mpungus are often equated with specific oricha spirits from Santería, as well as with saints from Roman Catholicism.[53] Sarabanda, for example, is associated with the oricha Oggun and with Saint Peter,[47] while Lufo Kuyo is connected to the oricha Ochosi and to Saint Norbert.[54] However, mpungus play a less important role in Palo than the oricha do in Santería.[55] There is also a difference in how the relationship between these entities is established; in Santería it is believed that the oricha call people to their worship, pressuring them to do so by inflicting sickness or misfortune, whereas in Palo it is the human practitioner who desires and instigates the relationship with the spirit.[56] In Cuba, Palo is often regarded as being cruder, wilder, and more violent than Santería,[37] with its spirits being fierce and unruly.[57] Those initiates who work with both the oricha and the Palo spirits are akin to those practitioners of Haitian Vodou who conduct rituals for both the Rada and Petwo branches of the lwa spirits; the oricha, like the Rada, are even-tempered, while the Palo spirits, like the Petwo, are more chaotic and unpredictable.[57]

Spirits of the dead

[edit]The spirits of the dead play a prominent role in Palo,[58] with Kerestetzi observing that one of Palo's central features is its belief that "the spirits of the dead mediate and organize human action and rituals."[12] In Palo, the spirit of a dead person is referred to as a nfumbe (or nfumbi),[59] a term deriving from the Kikongo word for a deceased individual, mvumbi.[60] Alternative terms used for the dead in Palo include the Yoruba term eggun,[61] or Spanish words like el muerto ("the dead")[62] or, more rarely, espíritu ("spirit").[63] Practitioners will sometimes refer to themselves, as living persons, as the "walking dead".[10] In Palo, the dead are often viewed as what Ochoa called "a dense and indistinguishable mass" rather than as discrete individuals,[64] and in this collective sense they are often termed Kalunga.[65]

Palo teaches that the individual comprises both a physical body and a spirit termed the sombra ("shade"), which are connected via a cordón de plata ("silver cord").[66] This conception reflects a combination of the Bakongo notion of the spirit "shadow" with the Spiritist notion of the perisperm, a spirit-vapor surrounding the human body.[66] Once a person dies they are thought to gain additional powers and knowledge such as prescience.[12] They can contact and assist the living,[57] but also cause them problems such as anxiety and sleeplessness.[67]

Paleros/paleras venerate the souls of their ancestors;[66] when a group feast is held, the ancestors of the house will typically be invoked and their approval to proceed requested.[68] To ascertain the consent of the dead, Palo's practitioners will often employ divination or forms of spirit mediumship from Spiritism.[68] Some practitioners claim an innate capacity to sense the presence of spirits of the dead,[69] and initiates are often expected to interact with these spirits and to try and influence them for their own personal benefit.[10] In communicating with the dead, paleros and paleras are sometimes termed muerteros ("mediums of the dead").[70]

The dead are also believed capable of existing within physical matter.[65] They can for instance be represented by small assemblages of material, often discarded or everyday household objects, which are placed together, typically in the corner of the patio or an outhouse. They are often called a rinconcito ("little corner").[71] Offerings of food and drink are often placed at the rinconcito and allowed to decay.[72] This is a practice also maintained by many followers of Santería,[73] although this emphasis placed on the material presence of the dead differs from the Spiritist views of deceased spirits.[74]

The Nganga

[edit]

A key role in Palo is played by a spirit-vessel called the nganga,[19] a term which in Central Africa referred not to an object but to a man who oversaw religious rituals.[75] This spirit-vessel is also commonly known as the prenda, a Spanish term meaning "treasure" or "jewel".[76] Alternative terms that are sometimes used for it are el brujo (the sorcerer),[55] the caldero (cauldron),[77] or the cazuela (pot),[75] while a small, portable version is termed the nkuto.[78] On rare occasions, a practitioner may also refer to the nganga as a nkisi (plural minkisi).[77] The minkisi are Bakongo ritual objects believed to possess an indwelling spirit and are the basis of the Palo nganga tradition,[79] the latter being a "uniquely Cuban" development.[80]

The nganga comprises either a clay pot,[81] gourd,[7] or an iron pot or cauldron.[82] This is often wrapped tightly in heavy chains.[83] Every nganga is physically unique,[84] bearing its own individual name;[85] some are deemed male, others female.[86] It is custom that the nganga should not stand directly on either a wooden or tile base, and for that reason the area beneath it is often packed with bricks and earth.[87] The nganga is kept in a domestic sanctum, the munanso,[88] or cuarto de fundamento.[89] This may be a cupboard,[90] a room in a practitioner's house,[91] or a structure in their backyard.[92] This may be decorated in a way that alludes to the forest, for instance with the remains of animal species that live in forest areas, as the latter are deemed abodes of the spirits.[93] When an individual practices both Palo and Santería, they typically keep the spirit-vessels of the respective traditions separate, in different rooms.[94]

Terms like nganga and prenda designate not only the physical vessel but also the spirit believed to inhabit it.[95] For many practitioners, the nganga is regarded as a material manifestation of a mpungu deity.[96] Different mpungu will lend different traits to the nganga; Sarabanda for instance imbues it with his warrior skills.[97] The mpungu involved may dictate the choice of vessel used for the nganga,[52] as well as the stone placed in it and the symbol, the firma, which is drawn onto it.[46] The name of the nganga may refer to the indwelling mpungu; an example would be a nganga called the "Sarabanda Noche Oscura" because it contains the mpungu Sarabanda.[46] The nganga is deemed to be alive;[98] Ochoa commented that, in the view of Palo's followers, the ngangas are not static objects, but "agents, entities, or actors" with an active role in society.[99] They are believed to express their will to Palo's practitioners both through divination and through spirit possession.[100]

Palo revolves around service and submission to the nganga.[101] Kerestetzi observed that in Palo, "the nganga is not an intermediary of the divine, it is the divine itself [...] It is a god in its own right."[46] Those who keep ngangas are termed the perros (dogs) or criados (servants) of the spirit-vessel,[102] which in turn is deemed to protect them.[13] The relationship that a Palo practitioner develops with their nganga is supposed to be lifelong,[103] and a common notion is that the keeper becomes like their nganga.[104] A practitioner may receive their own nganga only once they have reached a certain level of seniority in the tradition,[105] and the highest-ranking members may have multiple ngangas, some of which they have inherited from their own teachers.[91] Some practitioners will consult a nganga to help them make decisions in life, deeming it omniscient.[106] The nganga desires its keeper's attention;[107] initiates believe that they often become jealous and possessive of their keepers.[108] Ochoa characterised the relationship between the palero/palera and their nganga as a "struggle of wills",[109] with the Palo practitioner looking upon the nganga with "respect based on fear".[110]

The nganga is regarded as the source of a palero or palera's supernatural power.[111] Within the religion's beliefs, it can both heal and harm,[112] and in the latter capacity is thought capable of causing misfortune, illness, and death.[113] Practitioners believe that the better a nganga is cared for, the stronger it is and the better it can protect its keeper,[103] but at the same time the more it is thought capable of dominating its keeper,[109] potentially even killing them.[114] Various stories circulating the Palo community tell of practitioners driven to disastrous accidents, madness, or destitution.[115] Tales of a particular nganga's rebelliousness and stubbornness contribute to the prestige of its keeper, as it indicates that their nganga is powerful.[107]

Fundamentos

[edit]The contents of the nganga are termed the fundamentos,[116] and are believed to contribute to its power.[117] Sticks, called palos, are key ingredients; palos are selected from certain species of tree.[118] The choice of tree selected indicates the branch of Palo involved,[119] with the sticks believed to embody the properties and powers of the trees from which they came.[18] Soil may be added from various locations, for instance from a graveyard, hospital, prison, and a market,[120] as may water taken from a river, a well, and the sea.[121] A matari stone, representing the specific mpungu linked to that nganga, may be incorporated.[122] Other material added can include animal remains, feathers, shells, plants, gemstones, coins, razorblades, knives, padlocks, horseshoes, railway spikes, blood, wax, aguardiente liquor, wine, quicksilver, and spices.[123] Objects that are precious to the owner, or which have been obtained from far away, may be added,[124] and the harder that these objects are to obtain, the more significant they are often considered to be.[125] This varied selection of material can result in the nganga being characterised as a microcosm of the world.[126]

The precise form of the nganga, such as its size, can reflect the customs of the different Palo traditions.[127] Ngangas in the Briyumba tradition are for instance characterised by a ring of sticks extending beyond their rim.[128] Objects may also be selected for their connection with the indwelling mpungu. A nganga of Sarabanda for instance may feature many metal objects, reflecting his association with metals and war.[129] As more objects are added over time, typically as offerings, the quantity of material will often spill out from the vessel itself and be arranged around it, sometimes taking up a whole room.[130] The mix of items produces a strong, putrid odour and attracts insects,[131] with Ochoa describing the ngangas as being "viscerally intimidating to confront".[91]

The Nfumbe

[edit]

Human bones are also typically included in the nganga.[132] Some traditions, like Briyumba, consider this an essential component of the spirit-vessel;[133] other initiates feel that soil or a piece of clothing from a grave may suffice.[134] Practitioners will often claim that their nganga contains human remains even if it does not.[135] The most important body part for this purpose is the skull, called the kiyumba.[136] The human bones are termed the nfumbe, a Palo Kikongo word meaning "dead one"; it characterises both the bones themselves and the dead person they belonged to.[133]

Bones are selected judiciously; the sex of the nfumbe is typically chosen to match the gender of the nganga it is being incorporated into.[137] According to Palo tradition, an initiate should exhume the bones from a graveyard themselves, although in urban areas this is often impractical and practitioners instead obtain them through black market agreements with the groundskeepers and administrators responsible for maintaining cemeteries.[138] Elsewhere, they may purchase humans remains through botánicas or obtain anatomical teaching specimens.[139]

By tradition, a Palo practitioner travels to a graveyard at night. There, they focus on a specific grave and seek to communicate with the spirit of the person buried there, typically through divination.[140] Following negotiations, they create a trata (pact) with the spirit, whereby the latter agrees to serve the practitioner in exchange for promises of offerings. Once they believe that they have the spirit's consent, the palero/palera will dig up their bones, or at least collect soil from their grave, and take it home.[141] After being removed from their grave, the bones of the nfumbe may undergo attempts to "cool" and settle them,[142] being aspirated with white wine and aguardiente and fumigated with cigar smoke.[143] Placing the bones in the spirit-vessel is perceived as sealing the pact between the practitioner and the nfumbe.[144] A paper note on which the nfumbe's name is written may also be added.[97]

Palo teaches that the nfumbe spirit then resides in the nganga.[55] This becomes the owner's slave,[145] making the relationship between the palero/palera and their nfumbe quite different from the reciprocal relationship that the santero/santera has with their oricha in Santería.[57] The keeper of the nganga promises to feed the nfumbe, for instance with animal blood, rum, and cigars.[146] In turn, the nfumbe offers services called trabajos,[147] protects its keeper,[119] and carries out their commands.[148] Practitioners will sometimes talk of their nfumbe having a distinct personality, displaying traits such as stubbornness or jealousy.[144] The nfumbe will rule over other spirits in the nganga, including those of plants and animals.[119] Specific animal parts added are believed to enhance the skills of the nfumbe in the nganga;[149] a bat's skeleton for instance might give the nfumbe the ability to fly at night,[131] a turtle would give it a ferocious bite,[97] and a dog's head would give it a powerful sense of smell.[150]

Ngangas cristiana and judía

[edit]The nganga generally divide into two categories, the cristiana (Christian) and the judía (Jewish).[151] The terms cristiana and judía in this context reflect the influence of 19th-century Spanish Catholic ideas about good and evil,[152] with the word judía connoting something being non-Christian rather than being specifically associated with Judaism.[153] Nganga cristianas are deemed "baptised" because holy water from a Roman Catholic church is included as one of their ingredients;[154] they may also include a crucifix.[155] The human remains included in them are also expected to be that of a Christian.[154] While nganga cristianas can be used to counter-strike against attackers, they are prohibited from killing.[154] Conversely, nganga judías are used for trabajos malignos, or harmful work,[156] and are capable of murder.[157] Human remains included in nganga judías are typically those of a non-Christian, although not necessarily of a Jew.[158] Sometimes, the bones of a criminal or mad person are deliberately sought.[35] Those observing Palo during the 1990s, including Ochoa and the medical anthropologist Johann Wedel, noted that judía ngangas were then rare.[159]

Many practitioners maintain that the two types of nganga should be kept separate to stop them fighting.[160] Unlike ngangas cristianas, which only receive their keeper's blood at the latter's initiation, ngangas judías are fed their keeper's blood more often;[161] they are feared capable of betraying their keeper to drain more of their blood.[162] Palo teaches that although nganga judías are more powerful, they are less effective.[163] This is because nganga judías are scared of the nganga cristianas and thus vulnerable to them on every day of the year except Good Friday. In Christianity, Good Friday marks the day on which Jesus Christ was crucified, and thus paleros and paleras believe that the powers of nganga cristianas are temporarily nullified, allowing the nganga judías to be used.[164] On Good Friday, a white sheet will often be placed over nganga cristianas to keep them "cool" and protect them during this vulnerable period.[163]

Creating a nganga

[edit]The nganga does not merely transcend different ontological categories, it also blurs common oppositions, for example between living and dead, material and immaterial, sacred and profane. It is a living being but its main component is a dead man; it overflows with materiality but its body represents an invisible being; its word is infallible but its personality is drawn from the history of an ordinary person.

— Anthropologist Katerina Kerestetzi[165]

The making of a nganga is a complex procedure.[119] It can take several days,[166] with its components occurring at specific times during the day and month.[119] The process of creating a new nganga is often kept secret, amid concerns that if a rival Palo practitioner learns the exact ingredients of the particular nganga, it will leave the latter vulnerable to supernatural attacks.[167]

When a new nganga is created for a practitioner, it is said to nacer ("spring forth" or "be born") from the "mother" nganga which rules the house.[168] Elements may be removed from this parent nganga for incorporation into the new creation.[13] The first nganga of a tradition, from which all others ultimately stem, is called the tronco ("trunk").[8] The senior practitioner creating the nganga may ask a high-ranking initiate to assist them, something considered a great privilege.[169]

The new cauldron or vessel will be washed in agua ngongoro, a mix of water and various herbs; the purpose of this is to "cool" the vessel, for the dead are considered "hot".[170] After this, markings known as firmas may be drawn onto the new vessel.[171] During the process of constructing the nganga, an experienced Palo practitioner will divine to ensure that everything is going well.[172] Corn husk packets called masangó may be added to establish the capacities of that nganga.[173] The creator may also add some of their own blood, providing the new nganga with an infusion of vital force.[174] Within a day of its creation, Palo custom holds that it must be fed with animal blood.[175] Some practitioners will then bury the nganga, either in a cemetery or natural area, before recovering it for use in their rituals.[119]

Maintaining a nganga

[edit][The nganga] mediates and concretizes a mystical relationship between the spirit and its human counterpart, a relationship often described as a pact or bargain entered into (pacto, trata) and surrounded not by images of domestic nurturance, reciprocal exchange, and beneficial dependence, but by symbols of wage labor and payment, dominance and subalternity, enslavement and revolt.

— Historian Stefan Palmié[56]

The nganga is "fed" with blood from sacrificed male animals, including dogs, pigs, goats, and cockerels.[55] This blood is poured into the nganga,[131] over time blackening it.[46] Practitioners believe that the blood maintains the nganga's power and vitality and ensures ongoing reciprocity with its keeper.[88]

Human blood is typically only given to the nganga when the latter is created, so as to animate it, and later when a neophyte is being initiated, to help seal the pact between them.[176] It is feared that a nganga that develops a taste for human blood will continually demand it, ultimately killing its keeper.[177] As well as blood, the nganga will be offered food and tobacco,[131] fumigated with cigar smoke and aspirated with cane liquor,[178] often sprayed onto it by mouth.[179]

Initiates follow a specific etiquette when engaging with the nganga. They typically wear white,[180] go barefoot,[181] and draw marks on their body to keep them "cool" and protect from the tumult of the dead.[182] Practitioners kneel before the ngangas in greeting;[183] they may greet them with the Arabic-derived phrase "Salaam alaakem, malkem salaam."[184] The nganga likes to be addressed in song and each nganga has particular songs that "belong" to it.[185] Candles will often be burned while the keeper seeks to work with the vessel.[186] A glass of water may be placed nearby, intended to "cool" the presence of the dead,[187] and to assist their crossing to the human world.[184] Objects like necklaces, small packages, and dolls may be placed around the nganga so as to be vitalized with power, allowing them to be used in other rites.[188] To ensure that a nganga does its keeper's bidding, the latter sometimes threatens it,[189] sometimes insulting it or hitting it with a broom or whip.[190]

When a practitioner dies, their nganga may be disassembled if it is believed that the inhabiting nfumbi refuses to serve anyone else and wishes to be set free.[191] The nganga may then be buried beneath a tree,[192] placed into a river or the sea,[192] or buried with the deceased initiate.[13] Alternatively, Palo teaches that the nganga may desire a new keeper,[192] thus being inherited by another practitioner.[13]

Morality, ethics, and gender roles

[edit]Palo teaches deference to teachers, elders, and the dead.[68] According to Ochoa, the religion maintains that "speed, strength, and clever decisiveness" are positive traits for practitioners,[193] while also exulting the values of "revolt, risk and change".[194] The religion has not adopted the Christian notion of sin,[195] and does not present a particular model of ethical perfection for its practitioners to strive towards.[196] The focus of the practice is thus not perfection, but power.[11] It has been characterised as a world-embracing religion, rather than a world-renouncing one.[197]

Both men and women are allowed to practice Palo.[198] While women can hold the religion's most senior positions,[199] most praise houses in Havana are run by men,[200] and an attitude of machismo is common among Palo groups.[201] Ochoa thought that Palo could be described as patriarchal,[202] and the scholar of religion Mary Ann Clark encountered many women who deemed the community of practitioners to be too masculinist.[203] Many Palo initiates maintain that women should not be given a nganga while they are still capable of menstruating;[200] the religion teaches that a menstruating woman's presence would weaken the nganga and that the nganga's thirst for blood would cause the woman to bleed excessively, potentially killing her.[204] For this reason, many female practitioners only receive a nganga once they are passed the age of menopause, decades after their male contemporaries.[200] Gay men are often excluded from Palo,[203] and observers have reported high levels of homophobia within the tradition, in contrast to the large numbers of gay men involved in Santería.[205]

Practices

[edit]Palo is an initiatory religion.[12] Rather than being practised openly, its practices are typically secretive,[206] but revolve around the nganga, which is central to its ceremonies, trabajos ("works"), and divination.[100] The language used in Palo ceremonies, as in its songs, is often called Palo Kikongo;[207] a "Creole speech" based on both Kikingo and Spanish,[208] it Hispanicizes the spelling of many Kikongo words and gives them new meanings.[209] Practitioners greet one another with the phrase nsala malekum.[78] They also acknowledge each other with a special handshake in which their right thumbs are locked together and the palms meet.[78]

Praise houses

[edit]

Palo is organized around autonomous initiatory groups.[210] Each of these groups is called a munanso congo ("Kongo House"),[211] or sometimes a casa templo ("temple house").[212] Ochoa rendered this as "praise house".[211] Their gatherings for ceremonies are supposed to be kept secret.[213] Practitioners sometimes seek to protect the praise house by placing small packets, termed makutos (sing. nkuto), at each corner of the block around the building; these packets contain dirt from four corners and material from the nganga.[78]

Munanso congo form familias de religión ("religious families").[12] Each is led by a man or woman regarded as a symbolic parent of their initiates;[12] this senior palero is called a tata nganga ("father nganga"), while the senior palera is a yayi nganga ("mother nganga").[214] This person must have their own nganga and the requisite knowledge of ritual to lead others.[215] This figure is referred to as the padrino ("godfather") or madrina ("godmother") of their initiates;[216] their pupil is the ahijado ("godchild").[217]

A person's rank within the house depends on the length of their involvement and the depth of their knowledge about Palo.[13] Below the tata and yayi are initiates of long-standing, referred to as a padre nganga if male and a madre nganga if female.[113] The initiation of people to this level are rare.[218] At their initiation ceremony to the level of padre or madre, a palero/palera will often be given their own nganga.[105] The tata or yayi may choose not to tell the padre/madre the contents of the new nganga or instructions regarding how to use it, thus ensuring that the teacher maintains control in their relationship with the student.[113]

A tata or yayi may be reluctant to teach their padres and madres too much about Palo, fearing that if they do so the student will break from their praise house to establish their own.[113] A padre or madre will not have initiates of their own.[169] A particular padre (but not a madre) might be selected as a special assistant of the tata or yayi; if they serve the former then they are called a bakofula, if they serve the latter they are a mayordomo ("butler", "steward").[169] The madrinas and padrinas are often considered possessive of their student initiates.[216] Experienced practitioners who run their own praise houses often vie with one another for prospective initiates and will sometimes try to steal members from each other.[219]

An individual seeking initiation into a praise house is usually someone who has previously consulted a palero or palera to request their aid, for instance in the area of health, love, property, or money, or in the fear that they have been bewitched.[220] The Palo practitioner may suggest that the client's misfortunes result from their bad relationship with the spirits of the dead, and that this can be improved by receiving initiation into Palo.[221] New initiates are called ngueyos,[169] a term meaning "child" in the Palo Kikongo language.[222] In the Briyumba and Monte traditions, new initiates are also known as pinos nuevos ("saplings").[222] Ngueyos may attend feasts for the praise house's nganga, to which they are expected to contribute, and may seek advice from it, but they will not receive their own personal nganga nor attend initiation ceremonies for the higher grades.[223] Many practitioners are content to remain at this level and do not pursue further initiation to reach the status of padre or madre.[221]

When the tata or yayi of a house is close to death, they are expected to announce a successor, who will then be ritually accepted as the new tata or yayi by the house members.[224] The new leader may adopt the nganga of their predecessor, resulting in them having multiple nganga to care for.[91] Alternatively, at a leader's death, the senior initiates of the house may leave to join another or establish their own. This results in some Palo practitioners being members of multiple familias de religion.[224]

Firmas

[edit]

Drawings called firmas, their name taken from the Spanish for "signature", play an important role in Palo ritual.[225] They are alternatively referred to as tratados ("pacts" or "deals").[226] The firmas often incorporate lines, arrows, circles, and crosses,[227] as well as skulls, suns, and moons.[228] They allow the mpungu to enter the ceremonial space,[78] with a sign corresponding to the mpungu that is being invoked drawn at any given ceremony.[229]

As they facilitate contact between the worlds,[230] the firmas are deemed to be caminos ("roads").[231] They also help to establish the will of the living over the dead,[226] directing the action of both the human and spirit participants in a ritual.[232] The firmas are akin to the vèvè employed in Haitian Vodou and the anaforuana used by Abakuá members.[233]

Firmas may derive from the sigils employed in European ceremonial magic traditions.[229] However, some of the designs commonly found in firmas, such as that of the sun circling the Earth and of a horizon line dividing the worlds, are probably borrowed from traditional Kongo cosmology.[234] There are many different designs; some are specific to the mpungu it invokes, others to a particular munanso congo or to an individual practitioner.[78] As they are deemed very powerful, knowledge of the firmas' meanings are often kept secret, even from new initiates.[235] Some practitioners have a notebook in which they have drawn the firmas that they use, and from which they may teach others.[236]

Before a ceremony, the firmas are drawn around the room, including on the floor, on the walls, and on ritual objects.[237] They are often placed at locations suggesting a direction of movement, such as a window or a door.[238] They may also be drawn on handkerchiefs worn by participants on their head or chest.[228] The creation of these drawings is accompanied by chants called mambos.[230] Gunpowder piles at specific points of the firma may then be lit, with the explosion deemed to attract the mpungu.[239] Firmas are also cut into the bodies of new initiates,[235] and drawn onto the nganga as it is being created.[226]

Offerings and animal sacrifice

[edit]While offerings to the nganga are often given privately,[240] it is also expected that the nganga receives sacrifices on its cumplimiento ("birthday"), the anniversary of its creation.[241] Sacrifices will similarly often be given on the feast day of the Roman Catholic saint thought to have most in common with the mpungu manifested in the nganga in question.[103] The mpungu spirit Sarabanda is for instance feasted on June 29, the feast day of Saint Peter (San Pedro), who in Cuban tradition is associated with Sarabanda.[103]

Among the offerings given to the nganga are food, aguardiente, cigars, candles, flowers, money,[169] but especially blood, which the nganga feeds on to grow and gain power.[103] Animal sacrifice is thus a key part of Palo ritual,[242] where it is known by the Spanish language term matanza ("slaughter").[243] The choice of animal to be sacrificed depends on the reason for the offerings. Typically a rooster or two will be killed, but for more important issues a four-legged animal will usually be chosen.[103] The head of the munanso congo is typically responsible for determining what sacrifice is appropriate for the situation.[244] Animal blood is deemed very "hot",[245] although the levels of heat depend on the species in question; human blood is thought "hottest", followed by that of turtles, sheep, ducks, and goats, while the blood of other birds, such as chickens and pigeons, is "cooler". Animals deemed to have "hotter" blood are usually killed first.[246]

Where the killing is to take place, a firma will be drawn on the floor.[244] There will often be singing, chanting, and sometimes drumming while the sacrificial animal is brought before the nganga;[247] the victim's feet may be washed and it is given water to drink.[169] The animal's throat will then typically be cut,[244] usually by a senior figure in the munanso congo.[169] The blood may be spilled over the ngangas and onto the floor.[187] The animal will be butchered, its severed head often placed upon the nganga.[245] Several organs will be removed, sautéed, and placed before the nganga, where they will often be left to decompose, producing a strong odor and attracting maggots.[248] Other body parts will be prepared for the consumption of the attendees;[249] attempts are often made to ensure that everyone attending the ritual consumes some of the sacrificed flesh.[250] The sacrifice will often be followed by more generalized celebration involving singing, drumming, and dancing.[244]

Music, dancing, and possession

[edit]Music is an important part of Palo ceremonies,[13] with practitioners putting on performances for the nganga that involve singing, drumming and dancing.[101] These will be performed at initiations, feast days, or on occasions when the nganga is being asked to do something.[251] The songs employed are typically simpler than those found in Santería, consisting of repeating short melodies.[252] The lyrics often invoke supernatural entities or are focused on making a talisman work.[252] The songs are also antiphonal, with the soloist and chorus alternating, as is common in various African diasporic traditions.[253]

The main style of drum used in Palo is the three-headed tumbadoras; this is distinct from the batá drum used in Santería.[101] These drums are often played in groups of three.[254] As tumbadoras are not always available, Palo's adherents sometimes use plywood boxes as drums.[101] Various styles of drumming have been transmitted within Palo, including the ritmas congos ("Congo rhythms") and influencias bantu ("Bantu influences").[255] Each rama or Palo tradition also has its own ritual drumming style; the drumming rhythms favored in Mayombe and Briyumba are faster than those in Monte or Kimbisa.[185] While performing, the drummers may vie against one another to display their skills.[256]

The anthropologist Miguel Barnet observed a "striking element of pantomime" in Palo dances,[251] during which dancers will often work themselves into an "absolute frenzy".[257] A typical dance style used in Palo involves the dancer being slightly bent at the waist, swinging their arms and kicking their legs back at the knee.[256] Another Palo dance style is the garabato, in which dancers wield sticks, usually taken from a guava tree, and bang them against each other.[252] Unlike in Santería, dancers at Palo ceremonies do not proceed in a fixed line during the dance.[256]

In Palo, it is believed that during the dancing, one of the dancers may be possessed by the dead.[258] This individual will be known as the perro de prenda (possessed dog);[257] they may drop to the floor at the start of the possession, reflecting a belief that the possessing spirit has come up from the ground.[259] Practitioners believe that the spirit will control the body of the host for a time, during which the possessed person will adopt the traits of this entity.[257] The possessed individual will often give advice, reveal secrets, predict the future, and cleanse attendees of negative influences.[260]

Initiation and rites of passage

[edit]Церемония посвящения в пало -хаус похвален известен как Rayamiento («резка»). [ 261 ] Церемония, как правило, предназначена для того, чтобы происходить в ночь на восковой луны, выполняемой, когда луна достигает своего полного света из -за убеждения, что потенциал луны растет в тандеме с потенциалом мертвых. [ 262 ] Это будет проходить в Эль Куарто -де -религион («Комната религии»), иногда просто известная как Эль Куарто («Комната»). [ 263 ] Церемония Rayamiento включает в себя жертву животного; Требуются две петушины, хотя иногда будут убиты дополнительные животные, чтобы накормить Нгангу . [ 264 ]

Перед инициационным ритуалом инициат будет промыть в Агуа Нгонгоро , вода, смешанная с различными травами, в процедуре, называемой лимпизой ; Это сделано, чтобы «охладить» их. [ 265 ] Затем инициат будет привезен в ритуальное пространство с завязанными глазами и носить белое; [ 266 ] Брюки могут быть свернуты на колени, полотенце над плечами и бандану на голове. Туловины и ноги остаются некадравлированными. [ 267 ] Они могут быть направлены на то, чтобы стоять на вершине фирмы, нарисованной на полу. [ 268 ] Они дают обещания посвятить себя Нганге из Дома похвалы, принося его предложения на его праздники на день рождения в обмен на его защиту. [ 269 ]

Затем инициат будет вырезан; Используемые инструменты включали лезвие бритвы, петух или Юа Торн. Ренки могут быть сделаны на груди, плечах, спине, руках, ногах или языке. [ 270 ] Некоторые из сокращений будут прямыми линиями, другие могут быть скрещиваниями или более сложными дизайнами, образующими отток . [ 271 ] Считается, что сокращения открывают инициируют духи мертвых, что позволяет владеть. [ 135 ] Распространенным убеждением в Пало является то, что мертвые могут обладать инициативом в момент резки, и, следовательно, не считается необычным, если они в обморок. [ 272 ] Затем полученная кровь собирается и отдается Нганге , что, по мнению практиков, усиливает силу котла, чтобы либо исцелить, либо навредить инициативе. [ 273 ] Низки волос инициата также могут быть помещены в Нганга . [ 274 ] Части содержимого нганги могут быть втиснуты в раны посвященного, [ 275 ] Иногда, включая костную пыль, соскобнувшую от NFUMBE . [ 276 ] Эти раны будут заполнены свечой и Чамбой , [ 277 ] Последнее смесь порошкообразной человеческой кости, рома, чили и чеснока. [ 278 ] Разрешки иногда оставляют шрамы. [ 279 ]

Как только резка будет сделана, повязка на глаза будет удалена. [ 280 ] Затем новый инициат выйдет на улицу, чтобы поприветствовать Луну, прежде чем посетить соседнее кладбище. [ 281 ] Страдания, переживаемые во время обряда инициации, рассматриваются как тест, чтобы определить, имеет ли неофит те качества, требуемые от палеро или палеры . [ 278 ] Затем новые инициативы должны научиться правильному способу, чтобы приблизиться к нганге и как принести жертву. [ 222 ] Студенты проинструктированы в Пало через рассказы, песни и воспоминания старейшин; Они также будут следить за своими старейшинами и стремятся расшифровать свои загадки. [ 282 ]

Практикующий может позже испытать второй Rayamiento , позволяющий им стать полным инициатом похвалы, падре или мадрей , и, таким образом, создать свою собственную нгангу . [ 283 ] На похоронах инициата можно пожертвовать петухом, и его кровь вылилась на гроб, содержащий умершего, что завершило идентификацию мертвого практикующего врача с духами мертвых. [ 284 ] Как и на посвящении, фирма часто будет нарисована на тело. [ 278 ]

Гадание

[ редактировать ]Практикующие Пало общаются со своим духом с помощью гадания. [ 102 ] Стиль используемого гадания определяется характером вопроса, на который палеро или Палера хочет ответить. [ 234 ] Два используемых стиля -гадании - это Ndungui , которые влекут за собой повторение с кусочками кокосовой оболочки, и Chamalongos , которые используют раковины моллюсков. Оба эти гаданисты также используются, хотя и с разными именами, последователями Сантерии. [ 102 ]

Фула - это форма гадания с использованием пороха. Это влечет за собой небольшие груды пороха, размещенные на доске или на полу. Задается вопрос, а затем одна из свай подходит. Если все свай взорвутся одновременно, это воспринимается как позитивный ответ на вопрос. [ 285 ] Другая форма гадания, используемая в Пало, - это Vititi Mensu . Это включает в себя небольшое зеркало, расположенное на открытии животного рога, украшенного бисером, Mpaka . Затем зеркало покрыта дымовой сажей, а палеро или палера интерпретирует значения из форм, образованных сажи. [ 286 ] Мупака и иногда называют «глазами Нганга » часто держат на вершине самой Нганга . [ 278 ] И Fula , и Vititi Mensu - это формы гадания, которыми Пало не разделяет с Santería. [ 102 ]

Исцеление и прописывание

[ редактировать ]Практики Пало часто утверждают, что их ритуалы немедленно решат проблему, [ 169 ] и, таким образом, клиенты регулярно подходят к палеро или палере , когда они хотят быстрого решения проблемы. [ 112 ] Природа проблемы варьируется; он может включать в себя решение государственной бюрократии или эмиграционных вопросов, [ 287 ] Проблемы в отношениях, [ 288 ] Или потому, что они боятся, что они страдают от вредного духа. [ 289 ] Иногда клиент может попросить, чтобы Пало инициировал кого -то убить кого -то за них, используя свою нгангу . [ 164 ] Плата, выплачиваемая практикующему PALO за их услуги, называется Derecho . [ 166 ] Очоа отметил, что «общая мудрость» на Кубе постановил, что сборы, взимаемые с инициативами Пало, были меньше, чем предъявленные практикующие Сантерии. [ 166 ] Действительно, во многих случаях клиенты обращаются к практикующим специалистам PALO за помощью после того, как уже не обращались за помощью, безуспешно, от инициации Santería. [ 290 ]

Практикующие участвуют в исцелении благодаря использованию чар, формул и заклинания, [ 19 ] Часто опираясь на усовершенствованные знания о растениях и травах Кубы. [ 291 ] Первыми шагами, которые палеро или палера предпримет , чтобы помочь кому -то, могут быть лимпизой или десподжо («очистка»), в которых вредные мертвые отчитываются от страдающего человека. [ 292 ] Лимпиза будет включать в себя комбинацию трав , объединенных вместе, вытерясь над телом, а затем сжигаются или похоронены. Практикующие считают, что эффект этих трав состоит в том, чтобы «охладить» человека, чтобы противостоять турбулентному «жару» мертвых, которые вокруг них. [ 293 ] Уборка также используется в Сантерии. [ 293 ]

Другая процедура исцеления включает в себя создание спасения , чары, которые могут включать крошечные кусочки Nfumbe , стружку из палочек Пало , Земля из могилы и муравьев, травы кимбанса и части тела животных. Обычно они будут привязаны к маленьким пучкам и вставляются в кукурузную шелуху, прежде чем их сшивают в тканевые пакеты, которые могут носить страдающий человек. [ 294 ] Песни часто будут петь при создании Resguardo , в то время как кровь будет предлагаться, чтобы отнести его. [ 294 ] Взаимодействие . может быть размещено Нгангой на время, чтобы поглотить его влияние [ 295 ] Практикующий PALO может также обратиться к Камбио-де-Виде или переключению жизни, в результате чего болезнь терминала пациента передается другому, обычно нечеловеческому животному, но иногда кукла или человеку, тем самым спасая клиента. [ 296 ]

Смести или пакет, созданный для клиента, можно назвать тратадо («договор») и содержать многие из тех же элементов, которые попадают в нгангу . [ 297 ] Эти пакеты считаются получением своей силы как от материала, включенного в них, так и от молитвы, так и песен, которые были исполнены во время их создания. [ 298 ] Это может быть помещено на Нганга, чтобы передать свое послание духовному сосуду. [ 299 ] Части нганги также могут быть выбраны и использованы для создания Guardiero («Guardian»), сосуда, предназначенного для определенной цели; Как только эта цель будет завершена, Guardiero может быть разобрана, а его части возвращаются в Нгангу . [ 300 ] Если проблема клиента сохраняется, Палеро / Палера часто рекомендует первым перенести посвящение в Пало для обеспечения защиты и помощи Нганги . [ 169 ]

Билонгос

[ редактировать ]На Кубе широко распространено мнение, что болезнь может быть вызвана злобным духом, посланным против больного Палеро или Палеры . [ 301 ] Некоторые практикующие PALO будут идентифицировать Muertos Oscuros («Dark Dead»), сущности, которые были отправлены против страдающего человека, враги, касающиеся таких сущностей, которые скрываются в растениях, материализованные в одежде или мебели, скрытые в стенах или принимают животное Полем [ 302 ] Если такие методы, как Limpieza или Reguardos, не справляются с проблемами клиента, практикующий PALO часто применяет более агрессивные методы, чтобы помочь страдающему человеку. [ 294 ] Они будут использовать гадание, чтобы определить, кто именно, проклял их клиента; [ 303 ] Затем они могут получить следы кровь, пот или почву предполагаемого преступника, которые они прошли, чтобы ритуально манипулировать ими. [ 304 ]

Пало-контратаки называются билонго . [ 305 ] Часто размещается в банке или бутылке, [ 306 ] Эти смеси содержат почвы и порошки, [ 307 ] а также сушеные жабы, ящерицы, насекомые, пауки, человеческие волосы или рыбные кости. [ 308 ] Полагают, что Билонго будет эффективным, считают, что он должен быть связан в крови с определенной нгангой . [ 154 ] Большинство Билонго будут похоронены рядом с домом своей жертвы, в идеале на заднем дворе или рядом с их входной дверью. [ 309 ] По убеждению Пало, Билонго затем вытягивает дух Nfumbe из Нганги, чтобы пойти и напасть на предполагаемую жертву. [ 309 ] Дух, посланник для атаки, может быть связан с темными мертвыми или оборотными . [ 310 ] Это может рассматриваться не как дух мертвого человека, а сущность, специально созданную для этой цели, своего рода «оживленного или живого автомата». [ 310 ] Атака такой природы называется Киндиамбазо (« Хит Пренда ») или казуэлазо («удар котла»). [ 22 ] Это, в свою очередь, может привести к ряду ударов и контр-ударов различными палеросами или палеры, действующими для разных клиентов. [ 154 ] Принимая агрессивные контратаки против воспринимаемых злоумышленников, Пало отличается от Сантерии. [ 290 ]

История

[ редактировать ]Фон

[ редактировать ]Я знаю о двух африканских религиях в Барракуне: Лукуми и Конголезские ... Конголезцы использовали мертвых и змей для своих религиозных обрядов. Они назвали мертвые нкисе и змеи Эмбобы . Они подготовили большие горшки под названием Нганга , которые ходили и все, и именно здесь был секрет их заклинаний. У всех конголезцев были эти горшки для Майомба .

- Эстебан Монтехо, раб в конце 19 -го века [ 311 ]

острова После того, как испанская империя завоевала Кубу, популяции Аравака и Сибони резко сократились. [ 312 ] Затем испанцы обратились к рабам, продаваемым в западноафриканских портах в качестве источника труда для сахара, табака и кофейных плантаций Кубы. [ 313 ] Рабство было широко распространено в Западной Африке , где военнопленные и некоторые преступники были порабощены. [ 314 ] От 702 000 до 1 миллиона порабощенных африканцев были привезены на Кубу, [ 315 ] самый ранний в 1511 году, [ 316 ] Хотя большинство пришло в 19 веке. [ 317 ] На Кубе рабы были разделены на группы, называемые Naciones (нации), часто основанные на их порте посадки, а не на их собственном этнокультурном фоне. [ 318 ]

Между 1760 и 1790 годами крупнейшим Нациком на Кубе был Баконго, который затем включал более 30 процентов порабощенных африканцев на острове: [ 319 ] В то время их обычно называли конго . [ 320 ] Хотя все в основном часть одной и той же лингвистической семьи, эти рабы Баконго говорили на разных языках и не были единообразными людьми. [ 321 ] Они приехали в основном из Королевства Конго и вокруг него, которое охватывало область, охватывающую то, что сейчас является северной Анголой, Кабиндой , Республикой Конго, и некоторыми частями Габона и Демократической Республики Конго. [ 12 ] Многие из порабощенных людей Баконго, которые прибыли на Кубу, принесли бы с собой свои традиционные религии. [ 322 ]

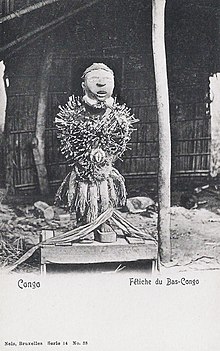

Ключом ко многим традициям Баконго были объекты, содержащие духовную силу, minkisi , [ 323 ] из которого происходит Пало Нганга . [ 324 ] Минкиси мог принимать различные формы, но часто были корзинами или мешками, причем некоторые из самых ранних зарегистрированных кубинских нгангов также были мешками. [ 77 ] Самое раннее однозначное доказательство такого духовного сосуда на Кубе состоит из 1875 года, когда испанский периодически описывал антропоморфную деревянную статую с полостью, в которой были размещены лекарства. [ 325 ] Другой отчет заключался в том, что в автобиографии раба Эстебана Монтехо , который жил в конце 19 и начала 20 веков. [ 326 ]

Когда Нганга появилась в своей нынешней форме среди баконго, давно погашенных народами на Кубе, не известна. [ 327 ] Социолог Julynne E. Dodson предложил возможную связь между железными котлами, используемыми для нганги, и теми, которые используются для обработки сахарного тростника на острове. [ 327 ] В период рабства Нганга , вероятно, была бы одним из очень немногих оружия, которое порабощенные могли бы использовать против своих владельцев. [ 112 ] Также возможно, что ритуальные роли, сосредоточенные на сосудах Minkisi или Nganga , создавали формы социальной власти »и, следовательно, некоторую форму власти среди порабощенных афро-кубинских популяций. [ 328 ]

На испанской Кубе римско -католицизм был единственной религией, которая могла бы быть юридической практикой. [ 329 ] Римско -католическая церковь Кубы приложила усилия по обращению порабощенных африканцев, но инструкция по римскому католицизму, предоставленную последнему [ 318 ] Традиционные африканские ритуалы могли бы продолжаться среди некоторых порабощенных людей, которые сбежали от плантаций, образуя независимые колонии или палленки . [ 330 ] Другие присоединились к африканским обществам взаимной помощи, называемыми кабильдос или кофрадиами , некоторые из которых были под руководством Баконго и в которых традиционные обряды также можно было тайно провести. [ 331 ] Со временем афро-кубины происхождения Баконго потеряли бы способность свободно говорить по-киконго и вместо этого разработали гибридную лексику, сочетающую испанский с избранными словами Киконго, последние часто сохраняют чувство загадки для своих пользователей. [ 332 ]

Формирование и ранняя история

[ редактировать ]Хронологическое развитие Пало менее ясное, чем у Сантерии. [ 333 ] Принимая более ранние влияния и объединяя их в новую форму, Пало развивался как отдельная религия в конце 19 или начале 20 -го века. [ 334 ] Это могло возникнуть в Гаване, [ 335 ] Ибо к началу 20 -го века он передавался из районы Матансаса на западе острова до Восточной провинции Востока. [ 322 ]

Очоа описал формирование Пало как происходит «в сочетании с или, возможно, в ответ на», формирование сантерии, [ 28 ] традиция, основанная на йоруба, которая появилась в городских частях Западной Кубы в конце 19-го века. [ 336 ] Историк Стефан Палми прокомментировал, что Пало показал «значительное влияние» от религий, полученных из йоруба, и утверждал, что, поскольку Сантерия распространилась по всей Кубе в конце 19-го и начале 20-го веков, это повлияло на существующие традиции, полученные в Конго на острове. [ 34 ] Очоа утверждал, что Сантерия, тем не менее, смог стать доминирующей над Пало, потому что понимание богословия йоруба было ближе к пониманию католицизма и мог бы легче адаптироваться к нему. [ 335 ] Пало также будет влиять на спиритизм, [ 337 ] Религия, основанная на идеях французского писателя Аллана Кардека , которая представляла растущий интерес среди белого крестьянства, класса креольского и небольшого городского среднего класса на Кубе конца 19-го века. [ 338 ]

После Кубинской войны за независимость остров стал независимой республикой в 1898 году. В Республике афро-кубины оставались в значительной степени исключенными из экономической и политической власти, [ 339 ] И негативные стереотипы о них оставались распространенными по всей евро-кубинской популяции. [ 340 ] Хотя новая конституция Республики закрепила свободу религии, кампании все еще были начаты против афро-кубинских традиций. [ 341 ] С конца 19 -го века и дома Пало и Сантерия столкнулись с неоднократными полицейскими рейдами, [ 342 ] с этим преследованием, продолжающимся в середине 20 -го века. [ 78 ] На повороте 20-го века неоднократные случаи афро-кубин обвиняли в жертвах белых христианских детей в своих нгангах . [ 162 ] В 1904 году было проведено судебное разбирательство по афро-кубанским, обвиняемым в ритуальном убийстве малыша, Зойлы Диас, чтобы вылечить одного из своих членов бесплодия; Двое обвиняемых были признаны виновными и казнены. [ 343 ] Ссылки на дело, переданное в песнях Пало в последующих поколениях, [ 344 ] С более поздними научными оценками предполагают, что обвинения опирались на «превзошли обвинения, слухи, маскируясь под доказательство, расизм и публичная истерия». [ 345 ]

В 1920-х годах были предприняты усилия по включению афро-кубинских элементов в более широкое понимание кубинской культуры, как в Afrocubanismo литературном и художественном движении . Они часто опираются на афро-кубинскую музыку, танцы и мифологию, но обычно отвергали ритуал африканского происхождения. [ 346 ] В 1940 -х годах кубинский антрополог Лидия Кабрера изучала Пало; [ 163 ] Писания ее и других ученых позже будут заинтересоваться различными инициациями, которые надеялись, что изучение их может обогатить традицию. [ 46 ]

После кубинской революции

[ редактировать ]Кубинская революция 1959 года привела к тому, что остров стал марксистско -лининистским государством, управляемым Кастро Коммунистической партией Фиделя на Кубе . [ 347 ] Приверженное утверждению атеизма , правительство Кастро негативно взглянуло на афро-кубинские религии. [ 348 ] Однако после краха Советского Союза в 1990 -х годах администрация Кастро заявила, что Куба вступает в « специальный период », в котором будут необходимы новые экономические меры. В рамках этого священники Сантерии, Ифа и Пало приняли участие в спонсируемых правительством тура для иностранцев, желающих посвящения в такие традиции. [ 349 ] Очоа отметил, что Пало «расцвел» на фоне этих либерализирующих реформ середины 1990-х годов. [ 350 ]

Через десятилетия после Кубинской революции эмигрировали сотни тысяч кубинцев, в том числе практикующие Пало. [ 352 ] В 1960 -х годах кубинские эмигранты прибыли в Венесуэлу, вероятно, принесли с собой Пало, что -то поддерживаемое дальнейшими прибывающими кубинцами в начале 21 -го века. В 2000 -х годах жители сообщили, что многие могилы в генерале Cementerio в Каракасе были открыты, чтобы удалить их содержимое для церемоний Пало. [ 353 ] Пало также появился в Мексике: в 1989 году кубинско-американский наркоман Адольфо Констанцо и его банда убили по меньшей мере 14 человек на своем ранчо за пределами Матаморос, Тамаулипас, прежде чем поместить кости своих жертв в Пало Коулдронах. [ 354 ] статуя мексиканского народного святого Санта -Муерта . Группа Констанца объединила Пало с элементами из мексиканских религий, и в собственности была найдена [ 355 ] Много освещения в СМИ неправильно помечало эти практики « сатанизм ». [ 356 ]

Пало также установил присутствие в Соединенных Штатах. В 1995 году Служба рыбы и дикой природы США арестовала инициацию Пало в Майами, штат Флорида , у которой были человеческие черепа и экзотические животные. [ 357 ] В Ньюарке, штат Нью -Джерси , в 2002 году был найден практикующий PALO с останками как минимум двух человек в его Нганга . [ 358 ] Последователь Пало был арестован в 2015 году за то, что якобы крала кости у мавзолей в Вустере, штат Массачусетс , [ 359 ] В то время как в 2021 году два практикующих во Флориде были арестованы за то, что они ограбили могилы военных ветеранов. [ 360 ] В нескольких частях США археологи и криминалистические антропологи часто сталкиваются с остатками Нганга , часто называют их «черепами сантерии», термин, который ошибочно принимает сантерию за Пало; [ 361 ] Один пример был восстановлен во время дренирования канала Массачусетса в 2012 году. [ 362 ] Американская рэппер Азеалия Бэнкс также была публичной в своей практике Пало -Майомбе, обсуждая это и другие африканские диаспорические религии в социальных сетях, по крайней мере, с 2016 года. [ 351 ]

Деноминации

[ редактировать ]Пало делится на различные конфессии или традиции, называемые Рамасом , [ 334 ] Каждый образует ритуальную линию. [ 192 ] Основными четыре являются Blag, Bundle, Tips и Monture; [ 334 ] Другие Рамас КЛЮД Мусунде, Квиримпа и Вриллумлум. [ 19 ] Некоторые практикующие утверждают, что Mayombe и Monte являются той же традицией, тогда как в других местах они считались отдельными. [ 363 ] Потому что Пало Монте - название которого означает «палочки леса» [ 364 ] -был одним из доминирующих рамы в Гаване конца 20-го века, многие академические и популярные источники ошибочно приняли термин «Пало Монте» для всей религии. [ 28 ] [ А ]

Многие инициативы считают, что имена Рамаса происходят из разных этнических групп из и вокруг Королевства Конго и вокруг него. [ 368 ] И наоборот, Барнет отметил, что эти имена не могут быть идентифицированы с известными этническими группами в Центральной Африке и что «они могут быть просто случайно выбраны именами этимологии Bantu, которые стали фальсифицированными на Кубе». [ 369 ] Последователи Пало часто критикуют соперника Рамаса , полагая, что их собственная традиция сохраняет правильную процедуру, унаследованную от прошлого. [ 370 ]

Особенно синчевым в своем подходе к Пало является Кимбиса, Рама, основанная в 19 веке Андресом Факундо Кристо де Лос Долорес Пети . [ 371 ] Пети объединился с элементами из Сантерии, спиритизма и римско -католицизма, [ 372 ] с традицией, действующей на принципах христианской благотворительности. [ 373 ] В kimbisa rhise Houses обычно можно найти образы Девы Марии, святых, распятия и алтаря Сан -Луис Белтран , покровителя традиции. [ 373 ] В отличие от других Рамаса , у Кимбиса есть высший лидер и письменная конституция. [ 374 ] Некоторые члены других традиций Пало критически смотрят на Кимбиса, полагая, что она отклоняется слишком далеко от традиционных практик Баконго. [ 375 ] Пало Джас также была включена в кубинский вариант Spiritissm, El Espiritism Cruzao , [ 376 ] В другом месте называется Пало Крузадо, [ 375 ] или смерть. [ 377 ]

Демография

[ редактировать ]Пало найден по всей Кубе, [ 378 ] Хотя это особенно сильнее в восточных провинциях острова. [ 379 ] Описывая ситуацию в 2000 -х годах, Очоа отметил, что были «сотни, если не больше», как домов, активные на Кубе, [ 68 ] А в 2015 году Керестецзи прокомментировал, что религия «широко распространена» на острове. [ 12 ] Несмотря на то, что Афро-кубины из традиций Баконго, выходя из традиций Баконго, также практиковались афро-кубиками других этнических наследий, а также евро-кубанскими, криоллосом и людьми за пределами Кубы. [ 380 ] Например, в Соединенных Штатах Пало приобрел популярность среди молодежи в различных городских районах. [ 39 ]

На Кубе люди иногда готовы путешествовать по значительным расстояниям, чтобы проконсультироваться с конкретным Палеро или Палерой по поводу их проблем. [ 381 ] Люди сначала подходят к религии, потому что они стремятся практической помощи в решении своих проблем, а не потому, что хотят поклоняться его божествам. [ 382 ] В таких случаях Пало часто пользуется предпочтением других религий, потому что он утверждает, что дает более быстрые результаты, при этом Пало иногда считается более мощным, хотя и менее этичным в своем подходе, чем Сантерия. [ 383 ]

Прием

[ редактировать ]В кубинском обществе Пало ценится и боятся. [ 112 ] Очоа описал «значительный воздух страха», окружающий его в кубинском обществе, [ 384 ] В то время как Керестецзи отметил, что кубинцы обычно считают Палероса и Палеры «опасными и недобросовестными ведьмами». [ 122 ] Это часто связано со стереотипом, который Палерос и Палеры могут убить детей за включение в их Нганга ; Очоа отметил, что в 1990 -х годах он услышал, как кубинские родители предупреждают своих детей, что «черный человек с мешком» уведет их, чтобы накормить его котел. [ 162 ]

Пало также стал ассоциироваться с уголовной практикой, отчасти из -за незаконного характера получения похороненных человеческих останков; [ 385 ] На Кубе осуждение за серьезное осквернение может привести к тюремному заключению срока до 30 лет. [ 386 ] Существование Пало повлияло на погребение различных людей на Кубе. Ремиджио Эррера , последний выживший африканский бабалаво , или священник Ифа , был, например, был похоронен в неопознанной могиле, чтобы не допустить, чтобы Палерос / Палеры копают его труп для включения в их Нганга . [ 387 ]

Пало также был включен в популярную культуру, как в Фуэнтес года романе Леонардо [ 119 ] К началу 21 -го века различные кубинские художники включали в свою работу образы Пало; [ 52 ] Одним из примеров был Хосе Бедия Вальдес , который получает Мунгу Сарибанду при его посвящении в Пало. [ 388 ] В других случаях художники и художники -графики использовали в своей работе FILO FIRMAS, не будучи посвященными религией.

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]Примечания

[ редактировать ]Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Фернандес Олмос и Парависи-Геберт 2011 , с. 215; Kerestzi 2015 , с. 145–146; Святой Дух 2018 , с. 68

- ^ Святой Дух 2018 , с. 83; 2018 Keteretesi , p. xii.

- ^ Betteelheim 2001 , p. 36; Ayorinde 2004 , p. 15; Palmié 2013 , p. 120; Pakines 2015 , p. 2

- ^ Ведель 2004 , с. 53; Ochoa 2010 , с. 9; Olmos and Paravisini-Gebert 2011 , с. 88

- ^ Velez 2000 , p. 31; Ayorinde 2004 , p. 18; Wedel 2004 , p. 53; Ochoa 2010 , с. 1

- ^ Барнет 2001 , стр. 86, 88; Olmos and Paravisini-Gebert 2011 , с. 89, 95.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Bettelheim 2001 , p. 36

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Страх 2015 , с. 172.

- ^ Vélez 2000 , p. 16; Espírito Santo, Kerestzi & Panagiopulolos 2013 , p. 200; Espírito Santo 2018 , p. 69

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и Espírito Santo, Kerestzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013 , p. 200

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Espírito Santo 2018 , p. 69

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час я Дж Страх 2015 , с. 146

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин Kélez 2000 , p. 16

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Ребенок 2001 , с. Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Додсон 2008 , с. 94; Olmos and Paravisini-Gebert 2011 , с. 89; Santo Home, сертификат, и Paniatoptopous 2013 , p. 195.

- ^ Espírito Santo 2018 , с. 81.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Страх 2015 , с. 163.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Фернандес Олмос и Парависи-Геберт 2011 , с. 89

- ^ Додсон 2008 , с. 95; Ochoa 2010 , с. 274

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Дойл Белый 2024 , с. 37–38.

- ^ Мейсон 2002 , П. 88; Фернандес Олмос и Парависи-Геберт 2011 , с. 33.

- ^ Weedel 2004 , P. 54; Flores-Peo 2005 , p. 117; Ochoa 2010 , с. 10, 23; Фернандес Олмос и Парависи-Геберт 2011 , с. 89

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с. 106; Espírito Santo, Kerestzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013 , p. 196

- ^ Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011 , с. 216; Espírito Santo, Kerestzi & Panagiopulolos 2013 , p. 196

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Espírito Santo, Kerestzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013 , p. 196

- ^ Palmié 2002 , p. 165.

- ^ Kélez 2000 , p. 34

- ^ Хагедорн 2001 , с. 14

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Palmié 2002 , p. 163.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Palmié 2002 , p. 164; Фернандес Олмос и Парависи-Геберт 2011 , с. 96

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Palmié 2002 , p. 164.

- ^ McAlister 2002 , с. 100–102.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Flores-Peña 2005 , p. 117

- ^ Beast 2001 , p. 36; Додсон 2008 , с. 92; Olmos and Paravisini-Gebert 2011 , с. 95; 2015 2015 , с. 160.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Barnet 1997 , p. 159; Olmos and Paravisini-Gebert 2011 , с. 95

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Ребенок 1997 , с.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Ребенок 1997 , с. 159–160.

- ^ Betteelheim 2001 , p. 36; Ayorinde 2004 , p. 16; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011 , с. 94

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон Страх 2015 , с. 151.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Ребенок 1997 , с.

- ^ Ochola 2010 , с. 200; Winburn, Schoff & Warren 2016 , с. 5

- ^ Ребенок 1997 , с. Bettelheim 2001 , p.

- ^ Барнет 1997 , с. 160; Страх 2015 , с. 163; Страх 2018 , с. х

- ^ Додсон 2008 , с. 93.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Bettelheim 2001 , p. 37

- ^ Vielez 2000 , p. 12; Protect 2004 , p. 16

- ^ Ребенок 1997 , с.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Wedel 2004 , p.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Palmié 2002 , p. 167

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Фернандес Олмос и Парависи-Геберт 2011 , с. 96

- ^ Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011 , с. 216; Espírito Santo, Kerestzi & Panagiopulolos 2013 , p. 199.

- ^ Palmié 2013 , p. 121; Страх 2015 , с. 146

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , стр. 24, 35; Фернандес Олмос и Парависи-Геберт 2011 , с. 216

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с. 21; Palmié 2013 , p. 121; Страх 2015 , с. 146

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Ochoa 2010 , с. 21, 24, 35.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Фернандес Олмос и Парависи-Геберт 2011 , с. 95

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Espírito Santo, Kerestzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013 , p. 205.

- ^ Espírito Santo, Kerestzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013 , p. 199; Espírito Santo 2018 , p. 81.

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , стр. 40–41.

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Espírito Santo, Kerestzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013 , стр. 203–204, 205.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Bettelheim 2001 , p. 36; Страх 2015 , с. 150

- ^ Ведель 2004 , с. 54; Ochoa 2010 , с. 1; Olmos and Paravisini-Gebert 2011 , с. 94; Palmé 2013 , p. 21; 2015 2015 , с. 150

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Страх 2015 , с. 150

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин Bettelheim 2001 , p. 38

- ^ Palmié 2002 , p. 168; Ochoa 2010 , с. 131; Страх 2015 , с. 150

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Bettelheim 2001 , p. 36; Ochoa 2010 , с. 140.

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с. 140; Фернандес Олмос и Парависи-Геберт 2011 , с. 89; Palmé 2013 , P. 121.

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , стр. 87, 176; Palmié 2013 , P. 121; Kerestzi 2015 , стр. 166-167.

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с. 221; 2015 2015 , с. 156

- ^ Velez 2000 , p. 16; Ochoa 2010 , с. 88; 2015 2015 , с. 156

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Palmié 2013 , p. 121.

- ^ Espírito Santo, Kerestzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013 , p. 203; Kerestzi 2015 , p. 155

- ^ Vélez 2000 , p. 33; Palmié 2002 , p. 163; Ochoa 2010 , с. 88

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Beast 2001 , p. 36; Ochoa 2010 , с. 88–89; Olmos and Paravisini-Gebert 2011 , с. 96; 2015 2015 , с. 154

- ^ Додсон 2008 , с. 93, 99.

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с. 221; Фернандес Олмос и Парависи-Геберт 2011 , с. 96

- ^ Velez 2000 , стр. 15–16; Бетталлинг 2001 , с. 37; Olmos and Paravisini-Gebert 2011 , с. 89

- ^ 2015 , с. 151; Winburn, Shop & Warren 2016 , с. 5

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Страх 2015 , с. 160.

- ^ Ведель 2004 , с. 54; Kererestzi 2015 , p. 171; Espírito Santo 2018 , p. 69

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , стр. 11-12.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Страх 2015 , с. 152

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Velez 2000 , p. 15; Olmos and Paravisini-Gebert 2011 , с. 94

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Ochoa 2010 , с. 73, 133.

- ^ Kerestzi 2015 , p. 153

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011 , с. 9; Espírito Santo, Kerestzi & Panagiopulolos 2013 , p. 198.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Wedel 2004 , p.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с. 91; 2015 2015 , с. 154

- ^ Espírito Santo, Kerestzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013 , стр. 212–213.

- ^ Fernandez Olmos & Paravisii-Gebert 2011 , стр. 89–9

- ^ Espírito Santo, Kerestzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013 , p. 200; Kerestzi 2015 , p. 164.

- ^ Ochoes 2010 , стр. 173–174; Olmos and Paravisini-Gebert 2011 , с. 90; 2015 2015 , с. 163.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин Фернандес Олмос и Парависи-Геберт 2011 , с. 90

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , стр. 135, 172; Palmié 2013 , P. 122

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с. 135; Palmié 2013 , p. 122; Страх 2015 , с. 161.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Страх 2015 , с. 162.

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , стр. 135–136; Фернандес Олмос и Парависи-Геберт 2011 , с. 90; Palmé 2013 , P. 122

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Kerestzi 2015 , p. 166

- ^ Ayorinde 2004 , p. 16; Espírito Santo, Kerestzi & Panagiopulolos 2013 , p. 198; Kerestzi 2015 , стр. 150–151.

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Kerestzi 2015 , стр. 166-167.

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с. 89; Palmié 2013 , p. 123; Страх 2015 , с. 169

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Palmié 2013 , p. 122

- ^ Weedel 2004 , P. 54; Фернандес Олмос и Парависи-Геберт 2011 , с. 90

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Espírito Santo, Kerestzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013 , стр. 201–202; Palmié 2013 , p. 121.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Espírito Santo, Kerestzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013 , p. 202

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с. 167; Фернандес Олмос и Парависи-Геберт 2011 , с. 90; Palmé 2013 , P. 121.

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Pokines 2015 , p. 6.

- ^ Palmies 2013 , стр. 120-121.

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с. 164; Palmié 2013 , p. 121.

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Espírito Santo, Kerestzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013 , p. 207

- ^ Olmos and Paravisini-Gebert 2011 , с. 96; Winburn, Shop & Warren 2016 , с. 5; Hope Hon 2018 , с. 70

- ^ Espírito Santo, Kerestzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013 , p. 197

- ^ Palmié 2013 , p. 121; Espírito Santo, Kerestzi & Panagiopulolos 2013 , p. 207

- ^ Ведель 2004 , с. 55; Palmié 2013 , p. 123.

- ^ Palmié 2013 , p. 122; Страх 2015 , с. 164.

- ^ Espírito Santo, Kerestzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013 , p. 198; Kerestzi 2015 , стр. 164, 200.

- ^ Wedel 2004 , стр. 55–56; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011 , с. 90; Pokines 2015 , p. 2

- ^ Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Bettelheim 2001 , p. 43

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и Ochoa 2010 , с.

- ^ Bettelheim 2001 , p. 43; Pokines 2015 , p. 2; Kerestetzi 2015 , p. 167.

- ^ Bettelheim 2001 , p. 43; Wedel 2004 , p. 56