ИСРО

| Бхаратия Амтарикша Анусамадхана Самгатхана | |

| |

Штаб-квартира в Бангалоре , Индия. | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 15 August 1969 |

| Preceding agency |

|

| Type | Space agency |

| Jurisdiction | Department of Space |

| Headquarters | Bengaluru, Karnataka 13°2′7″N 77°34′16″E / 13.03528°N 77.57111°E |

| Sreedhara Somanath | |

| Primary spaceports | |

| Owner | Government of India |

| Employees | 19,247 (as on 1 March 2022)[1] |

| Annual budget | |

| Website | www |

Индийская организация космических исследований ( ISRO) [3] / ˈ ɪ s r oʊ / ) [а] Индии — национальное космическое агентство . Он действует как основное подразделение исследований и разработок Министерства космоса (DoS), которое непосредственно контролируется премьер-министром Индии , а председатель ISRO также является исполнительным директором DoS. ISRO располагает крупнейшей в мире группировкой спутников дистанционного зондирования Земли и управляет GAGAN и IRNSS (NavIC) системами спутниковой навигации . Он отправил три миссии на Луну и одну на Марс . ISRO в первую очередь отвечает за космические операции, исследование космоса , международное космическое сотрудничество и разработку соответствующих технологий. [4]

ISRO — одно из шести правительственных космических агентств в мире, которые обладают полными возможностями запуска, способностью развертывать криогенные двигатели , способностью запускать внеземные миссии и способностью управлять большим парком искусственных спутников . [5] [6] [б] ISRO также является одним из четырех государственных космических агентств в мире, обладающих посадки . возможностями мягкой (беспилотной) [7] [с]

ISRO was formerly known as the Indian National Committee for Space Research (INCOSPAR). It was set up at the behest of the then-Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru at the recommendation of Dr. Vikram Sarabhai in 1962, a prescient scientist. INCOSPAR was renamed ISRO in 1969 and was subsumed into the Department of Atomic Energy (DAE).[8] In 1972, the Government of India set up a Space Commission and the DoS, bringing ISRO under its purview.

The establishment of ISRO had institutionalised space research activities in India.[9][10] It has since then been managed by the DoS, which also governs various other institutions in India in the domain of astronomy and space technology.[11]

ISRO built India's first satellite, Aryabhata, which was launched by the Soviet space agency Interkosmos in 1975.[12] In 1980, ISRO launched satellite RS-1 onboard SLV-3, making India only the seventh country on the planet to undertake orbital launches.

SLV-3 was followed by ASLV, which was subsequently succeeded by the development of many medium-lift launch vehicles, rocket engines, satellite systems and networks enabling the agency to launch hundreds of domestic and foreign satellites and various deep space missions.

ISRO's programmes have played a significant role in the socio-economic development of India and have supported both civilian and military domains in various aspects including disaster management, telemedicine, navigation and reconnaissance missions. ISRO's spin-off technologies have also undergirded many ground-breaking innovations in India's engineering and medical landscapes.[13]

History

[edit]Formative years

[edit]Modern space research in India can be traced to the 1920s, when scientist S. K. Mitra conducted a series of experiments sounding the ionosphere through ground-based radio in Kolkata.[14] Later, Indian scientists like C.V. Raman and Meghnad Saha contributed to scientific principles applicable in space sciences.[14] After 1945, important developments were made in coordinated space research in India[14] by two scientists: Vikram Sarabhai, founder of the Physical Research Laboratory at Ahmedabad, and Homi Bhabha, who established the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research in 1945.[14] Initial experiments in space sciences included the study of cosmic radiation, high-altitude and airborne testing, deep underground experimentation at the Kolar mines—one of the deepest mining sites in the world—and studies of the upper atmosphere.[15] These studies were done at research laboratories, universities, and independent locations.[15][16]

In 1950, the Department of Atomic Energy (DAE) was founded with Bhabha as its secretary.[16] It provided funding for space research throughout India.[17] During this time, tests continued on aspects of meteorology and the Earth's magnetic field, a topic that had been studied in India since the establishment of the Colaba Observatory in 1823. In 1954, the Aryabhatta Research Institute of Observational Sciences (ARIES) was established in the foothills of the Himalayas.[16] The Rangpur Observatory was set up in 1957 at Osmania University, Hyderabad. Space research was further encouraged by the government of India.[17] In 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1 and opened up possibilities for the rest of the world to conduct a space launch.[17]

The Indian National Committee for Space Research (INCOSPAR) was set up in 1962 by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru on the suggestion of Dr. Vikram Sarabhai.[10] Initially there was no dedicated ministry for the space programme and all activities of INCOSPAR relating to space technology continued to function within the DAE.[18][9] IOFS officers were drawn from the Indian Ordnance Factories to harness their knowledge of propellants and advanced light materials used to build rockets.[19] H.G.S. Murthy, an IOFS officer, was appointed the first director of the Thumba Equatorial Rocket Launching Station,[20] where sounding rockets were fired, marking the start of upper atmospheric research in India.[21] An indigenous series of sounding rockets named Rohini was subsequently developed and started undergoing launches from 1967 onwards.[22] Waman Dattatreya Patwardhan, another IOFS officer, developed the propellant for the rockets.

1970s and 1980s

[edit]Under the government of Indira Gandhi, INCOSPAR was superseded by ISRO. Later in 1972, a space commission and Department of Space (DoS) were set up to oversee space technology development in India specifically. ISRO was brought under DoS, institutionalising space research in India and forging the Indian space programme into its existing form.[9][11] India joined the Soviet Interkosmos programme for space cooperation[23] and got its first satellite Aryabhatta in orbit through a Soviet rocket.[12]

Efforts to develop an orbital launch vehicle began after mastering sounding rocket technology. The concept was to develop a launcher capable of providing sufficient velocity for a mass of 35 kg (77 lb) to enter low Earth orbit. It took 7 years for ISRO to develop Satellite Launch Vehicle capable of putting 40 kg (88 lb) into a 400-kilometre (250 mi) orbit. An SLV Launch Pad, ground stations, tracking networks, radars and other communications were set up for a launch campaign. The SLV's first launch in 1979 carried a Rohini technology payload but could not inject the satellite into its desired orbit. It was followed by a successful launch in 1980 carrying a Rohini Series-I satellite, making India the seventh country to reach Earth's orbit after the USSR, the US, France, the UK, China and Japan. RS-1 was the third Indian satellite to reach orbit as Bhaskara had been launched from the USSR in 1979. Efforts to develop a medium-lift launch vehicle capable of putting 600-kilogram (1,300 lb) class spacecrafts into 1,000-kilometre (620 mi) Sun-synchronous orbit had already begun in 1978.[24] They would later lead to the development of PSLV.[25] The SLV-3 later had two more launches before discontinuation in 1983.[26] ISRO's Liquid Propulsion Systems Centre (LPSC) was set up in 1985 and started working on a more powerful engine, Vikas, based upon the French Viking.[27] Two years later, facilities to test liquid-fuelled rocket engines were established and development and testing of various rocket engines thrusters began.[28]

At the same time, another solid-fuelled rocket Augmented Satellite Launch Vehicle based upon SLV-3 was being developed, and technologies to launch satellites into geostationary orbit (GTO). ASLV had limited success and multiple launch failures; it was soon discontinued.[29] Alongside, technologies for the Indian National Satellite System of communication satellites[30] and the Indian Remote Sensing Programme for earth observation satellites[31] were developed and launches from overseas initiated. The number of satellites eventually grew and the systems were established as among the largest satellite constellations in the world, with multi-band communication, radar imaging, optical imaging and meteorological satellites.[32]

1990s

[edit]The arrival of PSLV in 1990s became a major boost for the Indian space programme. With the exception of its first flight in 1994 and two partial failures later, PSLV had a streak of more than 50 successful flights. PSLV enabled India to launch all of its low Earth orbit satellites, small payloads to GTO and hundreds of foreign satellites.[33] Along with the PSLV flights, development of a new rocket, a Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle (GSLV) was going on. India tried to obtain upper-stage cryogenic engines from Russia's Glavkosmos but was blocked by the US from doing so. As a result, KVD-1 engines were imported from Russia under a new agreement which had limited success[34] and a project to develop indigenous cryogenic technology was launched in 1994, taking two decades to reach fulfillment.[35] A new agreement was signed with Russia for seven KVD-1 cryogenic stages and a ground mock-up stage with no technology transfer, instead of five cryogenic stages along with the technology and design in the earlier agreement.[36] These engines were used for the initial flights and were named GSLV Mk.1.[37] ISRO was under US government sanctions between 6 May 1992 to 6 May 1994.[38] After the United States refused to help India with Global Positioning System (GPS) technology during the Kargil war, ISRO was prompted to develop its own satellite navigation system IRNSS (now NaVIC i.e. Navigation with Indian Constellation) which it is now expanding further.[39]

21st century

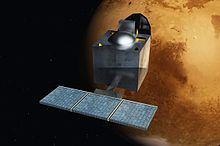

[edit]In 2003, when China sent humans into space, Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee urged scientists to develop technologies to land humans on the Moon[40] and programmes for lunar, planetary and crewed missions were started. ISRO launched Chandrayaan-1 in 2008, purportedly the first probe to verify the presence of water on the Moon,[41] and the Mars Orbiter Mission in 2013, the first Asian spacecraft to enter Martian orbit, making India the first country to succeed at this on its first attempt.[42] Subsequently, the cryogenic upper stage for GSLV rocket became operational, making India the sixth country to have full launch capabilities.[43] A new heavier-lift launcher LVM3 was introduced in 2014 for heavier satellites and future human space missions.[44]

On 23 August 2023, India achieved its first soft landing on an extraterrestrial body and became the first nation to successfully land a spacecraft near the lunar south pole with ISRO's Chandrayaan-3, the third Moon mission.[45] Indian moon mission, Chandrayaan-3 (translated as "mooncraft" in English), saw the successful soft landing of its Vikram lander at 6.04pm IST (1234 GMT) near the little-explored region of the Moon in a world's first for any space programme.[46] India then successfully launched its first sun probe, the Aditya-L1, aboard a PSLV on September 2.[47][48]

Agency logo

[edit]ISRO did not have an official logo until 2002. The one adopted consists of an orange arrow shooting upwards attached with two blue coloured satellite panels with the name of ISRO written in two sets of text, orange-coloured Devanagari on the left and blue-coloured English in the Prakrta typeface on the right.[49][50]

Goals and objectives

[edit]

As the national space agency of India, ISRO's purpose is the pursuit of all space-based applications such as research, reconnaissance, and communications. It undertakes the design and development of space rockets and satellites, and undertakes explores upper atmosphere and deep space exploration missions. ISRO has also incubated technologies in India's private space sector, boosting its growth.[51][52]

On the topic of the importance of a space programme to India as a developing nation, Vikram Sarabhai as INSCOPAR chair said in 1969:[53][54][55]

To us, there is no ambiguity of purpose. We do not have the fantasy of competing with the economically advanced nations in the exploration of the Moon or the planets or manned space-flight. But we are convinced that if we are to play a meaningful role nationally, and in the community of nations, we must be second to none in the application of advanced technologies to the real problems of man and society, which we find in our country. And we should note that the application of sophisticated technologies and methods of analysis to our problems is not to be confused with embarking on grandiose schemes, whose primary impact is for show rather than for progress measured in hard economic and social terms.

The former president of India and chairman of DRDO, A. P. J. Abdul Kalam, said:[56]

Very many individuals with myopic vision questioned the relevance of space activities in a newly independent nation which was finding it difficult to feed its population. But neither Prime Minister Nehru nor Prof. Sarabhai had any ambiguity of purpose. Their vision was very clear: if Indians were to play a meaningful role in the community of nations, they must be second to none in the application of advanced technologies to their real-life problems. They had no intention of using it merely as a means of displaying our might.

India's economic progress has made its space programme more visible and active as the country aims for greater self-reliance in space technology.[57] In 2008, India launched as many as 11 satellites, including nine from other countries, and went on to become the first nation to launch 10 satellites on one rocket.[57] ISRO has put into operation two major satellite systems: the Indian National Satellite System (INSAT) for communication services, and the Indian Remote Sensing Programme (IRS) satellites for management of natural resources.[30][32]

Organisation structure and facilities

[edit]

ISRO is managed by the DOS, which itself falls under the authority of the Space Commission and manages the following agencies and institutes:[58][59][60]

- Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO)

- Antrix Corporation – The marketing arm of ISRO, Bengaluru

- Physical Research Laboratory (PRL), Ahmedabad

- National Atmospheric Research Laboratory (NARL), Gadanki, Andhra Pradesh

- NewSpace India Limited – Commercial wing, Bengaluru

- North-Eastern Space Applications Centre[61] (NE-SAC), Umiam

- Indian Institute of Space Science and Technology (IIST), Thiruvananthapuram – India's space university

Research facilities

[edit]| Facility | Location | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre | Thiruvananthapuram | The largest ISRO base is also the main technical centre and the venue for development of the SLV-3, ASLV, and PSLV series.[62] The base supports TERLS and the Rohini Sounding Rocket programme.[62] It is also developing the GSLV series.[62] |

| Liquid Propulsion Systems Centre | Thiruvananthapuram and Bengaluru | The LPSC handles design, development, testing and implementation of liquid propulsion control packages, liquid stages and liquid engines for launch vehicles and satellites.[62] The testing of these systems is largely conducted at IPRC at Mahendragiri.[62] The LPSC, Bengaluru also produces precision transducers.[63] |

| Physical Research Laboratory | Ahmedabad | Solar planetary physics, infrared astronomy, geo-cosmo physics, plasma physics, astrophysics, archaeology, and hydrology are some of the branches of study at this institute.;[62] it also operates the observatory at Udaipur.[62] |

| National Atmospheric Research Laboratory | Tirupati | The NARL carries out fundamental and applied research in atmospheric and space sciences.[64] |

| Space Applications Centre | Ahmedabad | The SAC deals with the various aspects of the practical use of space technology.[62] Among the fields of research at the SAC are geodesy, satellite based telecommunications, surveying, remote sensing, meteorology, environment monitoring etc.[62] The SAC also operates the Delhi Earth Station, which is located in Delhi and is used for demonstration of various SATCOM experiments in addition to normal SATCOM operations.[65] |

| North-Eastern Space Applications Centre | Shillong | Providing developmental support to North East by undertaking specific application projects using remote sensing, GIS, satellite communication and conducting space science research.[66] |

Test facilities

[edit]| Facility | Location | Description |

|---|---|---|

| ISRO Propulsion Complex | Mahendragiri | Formerly called LPSC-Mahendragiri, was declared a separate centre. It handles testing and assembly of liquid propulsion control packages, liquid engines, and stages for launch vehicles and satellites.[62] |

Construction and launch facilities

[edit]| Facility | Location | Description |

|---|---|---|

| U R Rao Satellite Centre | Bengaluru | The venue of eight successful spacecraft projects is also one of the main satellite technology bases of ISRO. The facility serves as a venue for implementing indigenous spacecraft in India.[62] The satellites Aaryabhata, Bhaskara, APPLE, and IRS-1A were built at this site, and the IRS and INSAT satellite series are presently under development here. This centre was formerly known as ISRO Satellite Centre.[63] |

| Laboratory for Electro-Optics Systems | Bengaluru | The Unit of ISRO responsible for the development of altitude sensors for all satellites. The high precision optics for all cameras and payloads in all ISRO satellites are developed at this laboratory, located at Peenya Industrial Estate, Bengaluru. |

| Satish Dhawan Space Centre | Sriharikota | With multiple sub-sites the Sriharikota island facility acts as a launching site for India's satellites.[62] The Sriharikota facility is also the main launch base for India's sounding rockets.[63] The centre is also home to India's largest Solid Propellant Space Booster Plant (SPROB) and houses the Static Test and Evaluation Complex (STEX).[63] The Second Vehicle Assembly Building (SVAB) at Sriharikota is being realised as an additional integration facility, with suitable interfacing to a second launch pad.[67][68] |

| Thumba Equatorial Rocket Launching Station | Thiruvananthapuram | TERLS is used to launch sounding rockets.[69] |

Tracking and control facilities

[edit]| Facility | Location | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Indian Deep Space Network (IDSN) | Bengaluru | This network receives, processes, archives and distributes the spacecraft health data and payload data in real-time. It can track and monitor satellites up to very large distances, even beyond the Moon.[70] |

| National Remote Sensing Centre | Hyderabad | The NRSC applies remote sensing to manage natural resources and study aerial surveying.[62] With centres at Balanagar and Shadnagar it also has training facilities at Dehradun acting as the Indian Institute of Remote Sensing.[62] |

| ISRO Telemetry, Tracking and Command Network | Bengaluru (headquarters) and a number of ground stations throughout India and the world.[65] | Software development, ground operations, Tracking Telemetry and Command (TTC), and support is provided by this institution.[62] ISTRAC has Tracking stations throughout the country and all over the world in Port Louis (Mauritius), Bearslake (Russia), Biak (Indonesia) and Brunei.[71] |

| Master Control Facility | Bhopal; Hassan | Geostationary satellite orbit raising, payload testing, and in-orbit operations are performed at this facility.[72] The MCF has Earth stations and the Satellite Control Centre (SCC) for controlling satellites.[72] A second MCF-like facility named 'MCF-B' is being constructed at Bhopal.[72] |

| Space Situational Awareness Control Centre | Peenya, Bengaluru | A network of telescopes and radars are being set up under the Directorate of Space Situational Awareness and Management to monitor space debris and to safeguard space-based assets. The new facility will end ISRO's dependence on NORAD. The sophisticated multi-object tracking radar installed in Nellore, a radar in Northeast India and telescopes in Thiruvananthapuram, Mount Abu and North India will be part of this network.[73][74] |

Human resource development

[edit]| Facility | Location | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Indian Institute of Remote Sensing (IIRS) | Dehradun | The Indian Institute of Remote Sensing (IIRS) is a premier training and educational institute set up for developing trained professionals (P.G. and PhD level) in the field of remote sensing, geoinformatics and GPS technology for natural resources, environmental and disaster management. IIRS is also executing many R&D projects on remote sensing and GIS for societal applications. IIRS also runs various outreach programmes (Live & Interactive and e-learning) to build trained skilled human resources in the field of remote sensing and geospatial technologies.[75] |

| Indian Institute of Space Science and Technology (IIST) | Thiruvananthapuram | The institute offers undergraduate and graduate courses in Aerospace Engineering, Electronics and Communication Engineering (Avionics), and Engineering Physics. The students of the first three batches of IIST were inducted into different ISRO centres.[76] |

| Development and Educational Communication Unit | Ahmedabad | The centre works for education, research, and training, mainly in conjunction with the INSAT programme.[62] The main activities carried out at DECU include GRAMSAT and EDUSAT projects.[63] The Training and Development Communication Channel (TDCC) also falls under the operational control of the DECU.[65] |

| Space Technology Incubation Centres (S-TICs) at: | Jalandhar, Bhopal, Agartala, Rourkela, Nagpur | The S-TICs opened at premier technical universities in India to promote startups to build applications and products in tandem with the industry and would be used for future space missions. The S-TIC will bring the industry, academia and ISRO under one umbrella to contribute towards research and development (R&D) initiatives relevant to the Indian Space Programme.[79] |

| Space Innovation Centre at: | Burla, Sambalpur | In line with its ongoing effort to promote R&D in space technology through industry as well as academia, ISRO in collaboration with Veer Surendra Sai University of Technology (VSSUT), Burla, Sambalpur, Odisha, has set up Veer Surendra Sai Space Innovation Centre (VSSSIC) within its campus at Sambalpur. The objective of its Space Innovation Research Lab is to promote and encourage the students in research and development in the area of space science and technology at VSSUT and other institutes within this region.[80][81] |

| Regional Academy Centre for Space (RAC-S) at: | Varanasi, Guwahati, Kurukshetra, Jaipur, Mangaluru, Patna | All these centres are set up in tier-2 cities to create awareness, strengthen academic collaboration and act as incubators for space technology, space science and space applications. The activities of RAC-S will maximise the use of research potential, infrastructure, expertise, experience and facilitate capacity building. |

Antrix Corporation Limited (Commercial Wing)

[edit]Set up as the marketing arm of ISRO, Antrix's job is to promote products, services and technology developed by ISRO.[83][84]

NewSpace India Limited (Commercial Wing)

[edit]Set up for marketing spin-off technologies, tech transfers through industry interface and scale up industry participation in the space programmes.[85]

Space Technology Incubation Centre

[edit]ISRO has opened Space Technology Incubation Centres (S-TIC) at premier technical universities in India which will incubate startups to build applications and products in tandem with the industry and for use in future space missions. The S-TIC will bring the industry, academia and ISRO under one umbrella to contribute towards research and development (R&D) initiatives relevant to the Indian Space Programme. S-TICs are at the National Institute of Technology, Agartala serving for east region, National Institute of Technology, Jalandhar for the north region, and the National Institute of Technology, Tiruchirappalli for the south region of India.[79]

Advanced Space Research Group

[edit]Similar to NASA's CalTech-operated Jet Propulsion Laboratory, ISRO and the Indian Institute of Space Science and Technology (IIST) implemented a joint working framework in 2021, wherein ISRO will approve all short-, medium- and long-term space research projects of common interest between the two. In return, an Advanced Space Research Group (ASRG) formed at IIST under the guidance of the EOC will have full access to ISRO facilities. This was done with the aim of "transforming" the IIST into a premier space research and engineering institute with the capability of leading future space exploration missions for ISRO.[86][87]

Directorate of Space Situational Awareness and Management

[edit]To reduce dependency on North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) for space situational awareness and protect the civilian and military assets, ISRO is setting up telescopes and radars in four locations to cover each direction. Leh, Mount Abu and Ponmudi were selected to station the telescopes and radars that will cover North, West and South of Indian territory. The last one will be in Northeast India to cover the entire eastern region. Satish Dhawan Space Centre at Sriharikota already supports Multi-Object Tracking Radar (MOTR).[88] All the telescopes and radars will come under Directorate of Space Situational Awareness and Management (DSSAM) in Bengaluru. It will collect tracking data on inactive satellites and will also perform research on active debris removal, space debris modelling and mitigation.[89]

For early warning, ISRO began a ₹400 crore (4 billion; US$53 million) project called Network for Space Object Tracking and Analysis (NETRA). It will help the country track atmospheric entry, intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), anti-satellite weapon and other space-based attacks. All the radars and telescopes will be connected through NETRA. The system will support remote and scheduled operations. NETRA will follow the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IASDCC) and United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOSA) guidelines. The objective of NETRA is to track objects at a distance of 36,000 kilometres (22,000 mi) in GTO.[73][90]

India signed a memorandum of understanding on the Space Situational Awareness Data Sharing Pact with the US in April 2022.[91][92] It will enable Department of Space to collaborate with the Combined Space Operation Center (CSpOC) to protect the space-based assets of both nations from natural and man-made threats.[93] On 11 July 2022, ISRO System for Safe and Sustainable Space Operations Management (IS4OM) at Space Situational Awareness Control Centre, in Peenya was inaugurated by Jitender Singh. It will help provide information on on-orbit collision, fragmentation, atmospheric re-entry risk, space-based strategic information, hazardous asteroids, and space weather forecast. IS4OM will safeguard all the operational space assets, identify and monitor other operational spacecraft with close approaches which have overpasses over Indian subcontinent and those which conduct intentional manoeuvres with suspicious motives or seek re-entry within South Asia.[94]

ISRO System for Safe and Sustainable Space Operations Management

[edit]On 7 March 2023, ISRO System for Safe and Sustainable Space Operations Management (IS4OM) conducted successful controlled re-entry of decommissioned satellite Megha-Tropiques after firing four on-board 11 Newton thrusters for 20 minutes each. A series of 20 manoeuvres were performed since August 2022 by spending 120 kg fuel. The final telemetry data confirmed disintegtration over Pacific Ocean. It was part of a compliance effort following international guidelines on space debris mitigation.[95]

Speaking at the 42nd annual meeting of the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC) in Bengaluru, S. Somanath stated that the long-term goal is for all Indian space actors—both governmental and non-governmental—to accomplish debris-free space missions by 2030.[96]

Other facilities

[edit]- Balasore Rocket Launching Station (BRLS) – Balasore

- Bhaskaracharya Institute For Space Applications and Geo-Informatics (BISAG), Gandhinagar

- Human Space Flight Centre (HSFC), Bengaluru

- Indian Regional Navigation Satellite System (IRNSS)

- Indian Space Science Data Centre (ISSDC)

- Integrated Space Cell

- Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics (IUCAA)

- ISRO Inertial Systems Unit (IISU) – Thiruvananthapuram

- Master Control Facility

- National Deep Space Observation Centre (NDSPO)

- Regional Remote Sensing Service Centres (RRSSC)

General satellite programmes

[edit]

Since the launch of Aryabhata in 1975,[12] a number of satellite series and constellations have been deployed by Indian and foreign launchers. At present, ISRO operates one of the largest constellations of active communication and earth imaging satellites for military and civilian uses.[32]

The IRS series

[edit]The Indian Remote Sensing satellites (IRS) are India's earth observation satellites. They are the largest collection of remote sensing satellites for civilian use in operation today, providing remote sensing services.[32] All the satellites are placed in polar Sun-synchronous orbit (except GISATs) and provide data in a variety of spatial, spectral and temporal resolutions to enable several programs to be undertaken relevant to national development. The initial versions are composed of the 1 (A, B, C, D) nomenclature while the later versions were divided into sub-classes named based on their functioning and uses including Oceansat, Cartosat, HySIS, EMISAT and ResourceSat etc. Their names were unified under the prefix "EOS" regardless of functioning in 2020.[97] They support a wide range of applications including optical, radar and electronic reconnaissance for Indian agencies, city planning, oceanography and environmental studies.[32]

The INSAT series

[edit]

The Indian National Satellite System (INSAT) is the country's telecommunication system. It is a series of multipurpose geostationary satellites built and launched by ISRO to satisfy the telecommunications, broadcasting, meteorology and search-and-rescue needs. Since the introduction of the first one in 1983, INSAT has become the largest domestic communication system in the Asia-Pacific Region. It is a joint venture of DOS, the Department of Telecommunications, India Meteorological Department, All India Radio and Doordarshan. The overall coordination and management of INSAT system rests with the Secretary-level INSAT Coordination Committee.[30] The nomenclature of the series was changed to "GSAT" from "INSAT", then further changed to "CMS" from 2020 onwards.[98] These satellites have been used by the Indian Armed Forces as well.[99][100] GSAT-9 or "SAARC Satellite" provides communication services for India's smaller neighbors.[101]

Gagan Satellite Navigation System

[edit]The Ministry of Civil Aviation has decided to implement an indigenous Satellite-Based Regional GPS Augmentation System also known as Space-Based Augmentation System (SBAS) as part of the Satellite-Based Communications, Navigation, Surveillance and Air Traffic Management plan for civil aviation. The Indian SBAS system has been given the acronym GAGAN – GPS Aided GEO Augmented Navigation. A national plan for satellite navigation including implementation of a Technology Demonstration System (TDS) over Indian airspace as a proof of concept has been prepared jointly by Airports Authority of India and ISRO. The TDS was completed during 2007 with the installation of eight Indian Reference Stations at different airports linked to the Master Control Centre located near Bengaluru.[102]

Navigation with Indian Constellation (NavIC)

[edit]IRNSS with an operational name NavIC is an independent regional navigation satellite system developed by India. It is designed to provide accurate position information service to users in India as well as the region extending up to 1,500 km (930 mi) from its borders, which is its primary service area. IRNSS provides two types of services, namely, Standard Positioning Service (SPS) and Restricted Service (RS), providing a position accuracy of better than 20 m (66 ft) in the primary service area.[103]

Other satellites

[edit]Kalpana-1 (MetSat-1) was ISRO's first dedicated meteorological satellite.[104][105] Indo-French satellite SARAL on 25 February 2013. SARAL (or "Satellite with ARgos and AltiKa") is a cooperative altimetry technology mission, used for monitoring the oceans' surface and sea levels. AltiKa measures ocean surface topography with an accuracy of 8 mm (0.31 in), compared to 2.5 cm (0.98 in) on average using altimeters, and with a spatial resolution of 2 km (1.2 mi).[106][107]

Launch vehicles

[edit]

During the 1960s and 1970s, India initiated its own launch vehicles owing to geopolitical and economic considerations. In the 1960s–1970s, the country developed a sounding rocket, and by the 1980s, research had yielded the Satellite Launch Vehicle-3 and the more advanced Augmented Satellite Launch Vehicle (ASLV), complete with operational supporting infrastructure.[108]

Satellite Launch Vehicle

[edit]

The Satellite Launch Vehicle (known as SLV-3) was the first space rocket to be developed by India. The initial launch in 1979 was a failure followed by a successful launch in 1980 making India the sixth country in world with orbital launch capability. The development of bigger rockets began afterwards.[25]

Augmented Satellite Launch Vehicle

[edit]Augmented or Advanced Satellite Launch Vehicle (ASLV) was another small launch vehicle released in 1980s to develop technologies required to place satellites into geostationary orbit. ISRO did not have adequate funds to develop ASLV and PSLV at once. Since ASLV suffered repeated failures, it was dropped in favour of a new project.[109][29]

Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle

[edit]

Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle or PSLV is the first medium-lift launch vehicle from India which enabled India to launch all its remote-sensing satellites into Sun-synchronous orbit. PSLV had a failure in its maiden launch in 1993. Besides two other partial failures, PSLV has become the primary workhorse for ISRO with more than 50 launches placing hundreds of Indian and foreign satellites into orbit.[33]

Decade-wise summary of PSLV launches:

| Decade | Successful | Partial success | Failure | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990s | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| 2000s | 11 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| 2010s | 33 | 0 | 1 | 34 |

| 2020s | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Total | 57 | 1 | 2 | 60 |

Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle

[edit]

Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle was envisaged in 1990s to transfer significant payloads to geostationary orbit. ISRO initially had a great problem realising GSLV as the development of CE-7.5 in India took a decade. The US had blocked India from obtaining cryogenic technology from Russia, leading India to develop its own cryogenic engines.[34]

Decade-wise summary of GSLV Launches:

| Decade | Successful | Partial success | Failure | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000s | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| 2010s | 6 | 0 | 2 | 8 |

| 2020s | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Total | 10 | 2 | 4 | 16 |

Launch Vehicle Mark-3

[edit]

Launch Vehicle Mark-3 (LVM3), previously known as GSLV Mk III, is the heaviest rocket in operational service with ISRO. Equipped with a more powerful cryogenic engine and boosters than GSLV, it has significantly higher payload capacity and allows India to launch all its communication satellites.[110] LVM3 is expected to carry India's first crewed mission to space[111] and will be the testbed for SCE-200 engine which will power India's heavy-lift rockets in the future.[112]

Decade-wise summary of LVM3 launches:

| Decade | Successful | Partial success | Failure | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010s | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4[113] |

| 2020s | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3[114] |

| Total | 7 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

Small Satellite Launch Vehicle

[edit]

The Small Satellite Launch Vehicle (SSLV) is a small-lift launch vehicle developed by the ISRO with payload capacity to deliver 500 kg (1,100 lb) to low Earth orbit (500 km (310 mi)) or 300 kg (660 lb) to Sun-synchronous orbit (500 km (310 mi))[115] for launching small satellites, with the capability to support multiple orbital drop-offs.[116][117][118]

Decade-wise summary of SSLV launches:

| Decade | Successful | Partial success | Failure | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020s | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

Human Spaceflight Programme

[edit]The first proposal to send humans into space was discussed by ISRO in 2006, leading to work on the required infrastructure and spacecraft.[119][120] The trials for crewed space missions began in 2007 with the 600-kilogram (1,300 lb) Space Capsule Recovery Experiment (SRE), launched using the Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV) rocket, and safely returned to earth 12 days later.[121]

In 2009, the Indian Space Research Organisation proposed a budget of ₹124 billion (equivalent to ₹310 billion or US$3.7 billion in 2023) for its human spaceflight programme. An unmanned demonstration flight was expected after seven years from the final approval and a crewed mission was to be launched after seven years of funding.[122] A crewed mission initially was not a priority and left on the backburner for several years.[123] A space capsule recovery experiment in 2014[124][125] and a pad abort test in 2018[126] were followed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi's announcement in his 2018 Independence Day address that India will send astronauts into space by 2022 on the new Gaganyaan spacecraft.[127] To date, ISRO has developed most of the technologies needed, such as the crew module and crew escape system, space food, and life support systems. The project would cost less than ₹100 billion (US$1.3 billion) and would include sending two or three Indians to space, at an altitude of 300–400 km (190–250 mi), for at least seven days, using a GSLV Mk-III launch vehicle.[128][129]

Astronaut training and other facilities

[edit]The newly established Human Space Flight Centre (HSFC) will coordinate the IHSF campaign.[130][60] ISRO will set up an astronaut training centre in Bengaluru to prepare personnel for flights in the crewed vehicle. It will use simulation facilities to train the selected astronauts in rescue and recovery operations and survival in microgravity, and will undertake studies of the radiation environment of space. ISRO had to build centrifuges to prepare astronauts for the acceleration phase of the launch. Existing launch facilities at Satish Dhawan Space Centre will have to be upgraded for the Indian human spaceflight campaign.[131] Human Space Flight Centre and Glavcosmos signed an agreement on 1 July 2019 for the selection, support, medical examination and space training of Indian astronauts.[132] An ISRO Technical Liaison Unit (ITLU) was to be set up in Moscow to facilitate the development of some key technologies and establishment of special facilities which are essential to support life in space.[133] Four Indian Air Force personnel finished training at Yuri Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center in March 2021.[134]

Crewed spacecraft

[edit]ISRO is working towards an orbital crewed spacecraft that can operate for seven days in low Earth orbit. The spacecraft, called Gaganyaan, will be the basis of the Indian Human Spaceflight Programme. The spacecraft is being developed to carry up to three people, and a planned upgraded version will be equipped with a rendezvous and docking capability. In its first crewed mission, ISRO's largely autonomous 3-tonne (3.3-short-ton; 3.0-long-ton) spacecraft will orbit the Earth at 400 km (250 mi) altitude for up to seven days with a two-person crew on board. A source in April 2023 suggested that ISRO was aiming for a 2025 launch.[135]

Space station

[edit]India plans to build a space station as a follow-up programme to Gaganyaan. ISRO chairman K. Sivan has said that India will not join the International Space Station programme and will instead build a 20-tonne (22-short-ton; 20-long-ton) space station on its own.[136][137] It is expected to be placed in a low Earth orbit at 400 kilometres (250 mi) altitude and be capable of harbouring three humans for 15–20 days. The rough time-frame is five to seven years after completion of the Gaganyaan project.[138][139] "Giving out broad contours of the planned space station, Dr. Sivan said it has been envisaged to weigh 20 tonnes and will be placed in an orbit of 400 km above earth where astronauts can stay for 15-20 days. The time frame is 5-7 years after Gaganyaan," he stated.[140]

As per S. Somanath, the Phase1 will be ready by 2028 and the entire space station will be completed by 2035. The space station will be an international platform for collaborative research on future interplanetary missions, microgravity studies, space biology, medicine and research.[141]

Planetary sciences and astronomy

[edit]ISRO and Tata Institute of Fundamental Research have operated a balloon launch base at Hyderabad since 1967.[142] Its proximity to the geo-magnetic equator,[143] where both primary and secondary cosmic ray fluxes are low, makes it an ideal location to study diffuse cosmic X-ray background.[142]

ISRO played a role in the discovery of three species of bacteria in the upper stratosphere at an altitude between 20–40 km (12–25 mi). The bacteria, highly resistant to ultra-violet radiation, are not found elsewhere on Earth, leading to speculation on whether they are extraterrestrial in origin.[144] They are considered extremophiles, and named as Bacillus isronensis in recognition of ISRO's contribution in the balloon experiments, which led to its discovery, Bacillus aryabhata after India's celebrated ancient astronomer Aryabhata and Janibacter hoylei after the distinguished astrophysicist Fred Hoyle.[145]

Astrosat

[edit]

Launched in 2015, Astrosat is India's first dedicated multi-wavelength space observatory. Its observation study includes active galactic nuclei, hot white dwarfs, pulsations of pulsars, binary star systems, and supermassive black holes located at the centre of the galaxy.[146]

XPoSat

[edit]

The X-ray Polarimeter Satellite (XPoSat) is a satellite for studying polarisation.[147][148] The spacecraft carries the Polarimeter Instrument in X-rays (POLIX) payload which will study the degree and angle of polarisation of bright astronomical X-ray sources in the energy range 5–30 keV.[149] It launched on 1 January 2024 on a PSLV-DL rocket,[150] and it has an expected operational lifespan of at least five years.[148][151]

Extraterrestrial exploration

[edit]Lunar exploration

[edit]Chandryaan (lit. 'Mooncraft') are India's series of lunar exploration spacecraft. The initial mission included an orbiter and controlled impact probe while later missions include landers, rovers and sampling missions.[112][152]

- Chandrayaan-1

Chandrayaan-1 was India's first mission to the Moon. The robotic lunar exploration mission included a lunar orbiter and an impactor called the Moon Impact Probe. ISRO launched it using a modified version of the PSLV on 22 October 2008 from Satish Dhawan Space Centre. It entered lunar orbit on 8 November 2008, carrying high-resolution remote sensing equipment for visible, near infrared, and soft and hard X-ray frequencies. During its 312-day operational period (two years were planned), it surveyed the lunar surface to produce a complete map of its chemical characteristics and three-dimensional topography. The polar regions were of special interest, as they had possible ice deposits. Chandrayaan-1 carried 11 instruments: five Indian and six from foreign institutes and space agencies (including NASA, ESA, the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Brown University and other European and North American institutions and companies), which were carried for free. The mission team was awarded the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics SPACE 2009 award,[153] the International Lunar Exploration Working Group's International Co-operation award in 2008,[154] and the National Space Society's 2009 Space Pioneer Award in the science and engineering category.[155][156]

- Chandrayaan-2

Chandrayaan-2, the second mission to the Moon, which included an orbiter, a lander and a rover. It was launched on a Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle Mark III (GSLV Mk III) on 22 July 2019, consisting of a lunar orbiter, the Vikram lander, and the Pragyan lunar rover, all developed in India.[157][158] It was the first mission meant to explore the little-explored lunar south pole region.[159] The objective of the Chandrayaan-2 mission was to land a robotic rover to conduct various studies on the lunar surface.[160]

The Vikram lander, carrying the Pragyan rover, was scheduled to land on the near side of the Moon, in the south polar region at a latitude of about 70° S at approximately 1:50 am(IST) on 7 September 2019. However, the lander deviated from its intended trajectory starting from an altitude of 2.1 km (1.3 mi), and telemetry was lost seconds before touchdown was expected.[161] A review board concluded that the crash-landing was caused by a software glitch.[162] The lunar orbiter was efficiently positioned in an optimal lunar orbit, extending its expected service time from one year to seven.[163] It was planned that there will be another attempt to soft-land on the Moon in 2023, without an orbiter.[164]

- Chandrayaan-3

Chandryaan-3 is India's second attempt to soft-land on the Moon after the partial failure of Chandrayaan-2. The mission will only include a lander-rover set and will communicate with the orbiter from the previous mission.

On 23 August 2023, ISRO became the first space agency to successfully land a spacecraft on the lunar south pole region, and only the fourth space agency ever to land on the Moon.[165]

Mars exploration

[edit]- Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM) or (Mangalyaan-1)

The Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM), informally known as Mangalyaan (eng: ''MarsCraft'' ) was launched into Earth orbit on 5 November 2013 by the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) and has entered Mars orbit on 24 September 2014.[166] India thus became the first country to have a space probe enter Mars orbit on its first attempt. It was completed at a record low cost of $74 million.[167]

MOM was placed into Mars orbit on 24 September 2014. The spacecraft had a launch mass of 1,337 kg (2,948 lb), with 15 kg (33 lb) of five scientific instruments as payload.[168][169]

The National Space Society awarded the Mars Orbiter Mission team the 2015 Space Pioneer Award in the science and engineering category.[170][171]

Solar probes

[edit]- Aditya-L1

On 2 September 2023, ISRO launched the 400 kg (880 lb) Aditya-L1 mission to study the solar corona.[172][173][174] It is the first Indian space-based solar coronagraph to study the corona in visible and near-infrared bands. The main objective of the mission is to study coronal mass ejections (CMEs), their properties (the structure and evolution of their magnetic fields for example), and consequently constrain parameters that affect space weather.[175] On 6 January 2024, Aditya-L1 spacecraft, India's first solar mission, has successfully entered its final orbit around the first Sun-Earth Lagrangian point (L1), approximately 1.5 million kilometers from Earth.[176]

Future projects

[edit]ISRO is developing and operationalising more powerful and less pollutive rocket engines so it can eventually develop much heavier rockets. It also plans km above earth where astronauts can stay for 15–20 days. The time frame is 5–7 years after Gaganyaan, he stated.[140] to develop electric and nuclear propulsion for satellites and spacecraft to reduce their weight and extend their service lives.[177] Long-term plans may include crewed landings on Moon and other planets as well.[178]

Engines and launch vehicles

[edit]- Semi-cryogenic engine

SCE-200 is a rocket-grade kerosene (dubbed "ISROsene") and liquid oxygen (LOX)-based semi-cryogenic rocket engine inspired by RD-120. The engine will be less polluting and far more powerful. When combined with the LVM3, it will boost its payload capacity; it will be clustered in future to power India's heavy rockets.[179]

- Methalox engine

Reusable methane and LOX-based engines are under development. Methane is less pollutive, leaves no residue and hence the engine needs very little refurbishment.[179] The LPSC began cold flow tests of engine prototypes in 2020.[28]

- Modular heavy rockets

ISRO is studying heavy (HLV) and super-heavy lift launch vehicles (SHLV). Modular launchers are being designed, with interchangeable parts, to reduce production time. A 10-tonne (11-short-ton; 9.8-long-ton) capacity HLV and an SHLV capable of delivering 50–100 tonnes (55–110 short tons; 49–98 long tons) into orbit have been mentioned in statements and presentations from ISRO officials.[180][181]

The agency intends to develop a launcher in the 2020s which can carry nearly 16 t (18 short tons; 16 long tons) to geostationary transfer orbit, nearly four times the capacity of the existing LVM3.[179] A rocket family of five medium to heavy-lift class modular rockets described as "Next Generation Launch Vehicle or NGLV"[182] (initially planned as Unified Modular Launch Vehicle or Unified Launch Vehicle) are being planned which will share parts and will replace ISRO's existing PSLV, GSLV and LVM3 rockets completely. The rocket family will be powered by SCE-200 cryogenic engine and will have a capacity of lifting from 4.9 t (5.4 short tons; 4.8 long tons) to 16 t (18 short tons; 16 long tons) to geostationary transfer orbit.[183]

- Reusable launch vehicles

There have been two reusable launcher projects ongoing at ISRO. One is the ADMIRE test vehicle, conceived as a VTVL system and another is RLV-TD programme, being run to develop an autonomous spacecraft which will be launched vertically but land like a plane.[184]

To realise a fully re-usable two-stage-to-orbit (TSTO) launch vehicle, a series of technology demonstration missions have been conceived. For this purpose, the winged Reusable Launch Vehicle Technology Demonstrator (RLV-TD) has been configured. The RLV-TD acts as a flying testbed to evaluate various technologies such as hypersonic flight, autonomous landing, powered cruise flight, and hypersonic flight using air-breathing propulsion. First in the series of demonstration trials was the Hypersonic Flight Experiment (HEX). ISRO launched the prototype's test flight, RLV-TD, from the Sriharikota spaceport in February 2016. It weighs around 1.5 t (1.7 short tons; 1.5 long tons) and flew up to a height of 70 km (43 mi).[185] HEX was completed five months later. A scaled-up version of it could serve as fly-back booster stage for the winged TSTO concept.[186] HEX will be followed by a landing experiment (LEX) and return flight experiment (REX).[187]

Spacecraft propulsion and power

[edit]- Electric thrusters

India has been working on replacing conventional chemical propulsion with Hall-effect and plasma thrusters which would make spacecraft lighter.[179] GSAT-4 was the first Indian spacecraft to carry electric thrusters, but it failed to reach orbit.[188] GSAT-9 launched later in 2017, had xenon-based electric propulsion system for in-orbit functions of the spacecraft. GSAT-20 is expected to be the first fully electric satellite from India.[189][190]

- Alpha source thermoelectric propulsion technology

Radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG), also called alpha source thermoelectric technology by ISRO, is a type of atomic battery which uses nuclear decay heat from radioactive material to power the spacecraft.[191] In January 2021, the U R Rao Satellite Centre issued an Expression of Interest (EoI) for design and development of a 100-watt RTG. RTGs ensure much longer spacecraft life and have less mass than solar panels on satellites. Development of RTGs will allow ISRO to undertake long-duration deep space missions to the outer planets.[192][193]

Radioisotope heater unit

ISRO included two radioisotope heater units developed by the Department of Atomic Energy (DAE) in the propulsion module of Chandrayaan-3 on a trial basis which worked flawlessly.[141]

Nuclear propulsion

ISRO has plans for collaboration with Department of Atomic Energy to power future space missions using nuclear propulsion technology.[141]

Quantum technology

[edit]Satellite-based quantum communication

At the Indian Mobile Congress (IMC) 2023, ISRO presented its satellite-based quantum communication technology. It's called quantum key distribution (QKD) technology. According to ISRO, it is creating technologies to thwart quantum computers, which have the ability to readily breach the current generation of encrypted secure communication. A significant milestone for unconditionally secured satellite data communication was reached in September 2023 when ISRO demonstrated free-space quantum communication across a 300-meter distance, including live video conferencing using quantum-key encrypted signals.[194]

Extraterrestrial probes

[edit]| Destination | Craft name | Launch vehicle | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moon | LUPEX | H3 | 2026[195] |

| Moon | Chandrayaan-4 | PSLV,LVM3 | 2028 |

| Venus | Venus Orbiter Mission | GSLV | 2028-31[196] |

| Mars | Mars Orbiter Mission 2 (Mangalyaan-2) | LVM3 | 2024 |

- Lunar exploration

The Lunar Polar Exploration mission (LUPEX) is a planned robotic lunar mission concept by Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) and Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) that would send a lunar rover and lander to explore the south pole region of the Moon no earlier than 2026. JAXA is likely to provide the under-development H3 launch vehicle and the rover, while ISRO would be responsible for the lander.[197][198]

Crewed Lunar Landing

ISRO aims to put an astronaut on the lunar surface by 2040.[199]

- Mars exploration

The next Mars mission, Mars Orbiter Mission 2 or Mangalyaan 2, has been proposed for launch in 2024.[200] The newer spacecraft will be significantly heavier and better equipped than its predecessor;[112] it will only have an orbiter.[201]

- Venus exploration

ISRO is considering an orbiter mission to Venus called Venus Orbiter Mission, that could launch as early as 2023 to study the planet's atmosphere.[202] Some funds for preliminary studies were allocated in the 2017–18 Indian budget under Space Sciences;[203][204][205] solicitations for potential instruments were requested in 2017[206] and 2018. A mission to Venus is scheduled for 2025 that will include a payload instrument called Venus Infrared Atmospheric Gases Linker (VIRAL) which has been co-developed with the Laboratoire atmosphères, milieux, observations spatiales (LATMOS) under French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) and Roscosmos.[207]

- Asteroids and outer solar system

Conceptual studies are underway for spacecraft destined for the asteroids and Jupiter, as well, in the long term. The ideal launch window to send a spacecraft to Jupiter occurs every 33 months. If the mission to Jupiter is launched, a flyby of Venus would be required.[208] Development of RTEG power might allow the agency to further undertake deeper space missions to the other outer planets.[192]

Space telescopes and observatories

[edit]- AstroSat-2

AstroSat-2 is the successor to the AstroSat mission.[209]

- Exoworlds

Exoworlds is a joint proposal by ISRO, IIST and the University of Cambridge for a space telescope dedicated for atmospheric studies of exoplanets, planned for 2025.[210][211]

Forthcoming satellites

[edit]| Satellite name | Launch vehicle | Year | Purpose | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSAT-20 | Falcon 9 | 2024 | Communications | |

| GISAT 2 | GSLV | 2024 | Earth observation | Geospatial imagery to facilitate continuous observation of Indian sub-continent, quick monitoring of natural hazards and disaster.[212] |

| IDRSS | GSLV | 2024 | Data relay and satellite tracking constellation | Facilitates continuous real-time communication between Low Earth orbit bound spacecraft to the ground station as well as inter-satellite communication. Such a satellite in geostationary orbit can track a low altitude spacecraft up to almost half of its orbit.[213] |

| DISHA | PSLV | 2024–25[214] | Aeronomy | Disturbed and quite-type Ionosphere System at High Altitude (DISHA) satellite constellation with two satellites in 450 km (280 mi) LEO.[200] |

| AHySIS-2 | PSLV | 2024 | Earth observation | Follow-up to HySIS hyperspectral Earth imaging satellite.[215] |

| NISAR | GSLV | 2025[216] | Earth observation | NASA-ISRO Synthetic Aperture Radar (NISAR) is a joint project between NASA and ISRO to co-develop and launch a dual frequency synthetic aperture radar satellite to be used for remote sensing. It is notable for being the first dual band radar imaging satellite.[217] |

Geospatial intelligence satellites

A family of 50 artificial intelligence based satellites will be launched by ISRO between 2024 and 2028 to collect geospatial intelligence (GEOINT) in different orbits to track military movements and photograph areas of interest. For the sake of national security, the satellites will monitor the neighboring areas and the international border. It will use thermal, optical, synthetic aperture radar (SAR), among other technologies, for GEOINT application. Each satellite using artificial intelligence will have the ability to communicate and collaborate with the remaining satellites in space at different orbits to monitor the environment for intelligence gathering operations.[218][219]

Upcoming launch facilities

[edit]- Kulasekharapatnam Spaceport

Kulasekharapatnam Spaceport is an under-development spaceport in Thoothukudi district of Tamil Nadu. After completion, it would serve as the second launch facility of ISRO. This spaceport will mainly be used by ISRO for launching small payloads.[220]

Applications

[edit]Telecommunication

[edit]India uses its satellite communication network – one of the largest in the world – for applications such as land management, water resources management, natural disaster forecasting, radio networking, weather forecasting, meteorological imaging and computer communication.[221] Business, administrative services, and schemes such as the National Informatics Centre (NIC) are direct beneficiaries of applied satellite technology.[222]

Military

[edit]The Integrated Space Cell, under the Integrated Defence Staff headquarters of the Ministry of Defence,[223] has been set up to utilise more effectively the country's space-based assets for military purposes and to look into threats to these assets.[224][225] This command will leverage space technology including satellites. Unlike an aerospace command, where the Air Force controls most of its activities, the Integrated Space Cell envisages cooperation and coordination between the three services as well as civilian agencies dealing with space.[223]

With 14 satellites, including GSAT-7A for exclusive military use and the rest as dual-use satellites, India has the fourth largest number of satellites active in the sky which includes satellites for the exclusive use of its air force (IAF) and navy.[226] GSAT-7A, an advanced military communications satellite built exclusively for the Air Force,[197] is similar to the Navy's GSAT-7, and GSAT-7A will enhance the IAF's network-centric warfare capabilities by interlinking different ground radar stations, ground airbases and airborne early warning and control (AWACS) aircraft such as the Beriev A-50 Phalcon and DRDO AEW&CS.[197][227]

GSAT-7A will also be used by the Army's Aviation Corps for its helicopters and unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) operations.[197][227] In 2013, ISRO launched GSAT-7 for the exclusive use of the Navy to monitor the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) with the satellite's 2,000-nautical-mile (3,700 km; 2,300 mi) 'footprint' and real-time input capabilities to Indian warships, submarines and maritime aircraft.[226] To boost the network-centric operations of the IAF, ISRO launched GSAT-7A in December 2018.[228][226] The RISAT series of radar-imaging earth observation satellites is also meant for Military use.[229] ISRO launched EMISAT on 1 April 2019. EMISAT is a 436-kilogram (961 lb) electronic intelligence (ELINT) satellite. It will improve the situational awareness of the Indian Armed Forces by providing information and the location of hostile radars.[230]

India's satellites and satellite launch vehicles have had military spin-offs. While India's 150–200-kilometre (93–124 mi) range Prithvi missile is not derived from the Indian space programme, the intermediate range Agni missile is derived from the Indian space programme's SLV-3. In its early years, under Sarabhai and Dhawan, ISRO opposed military applications for its dual-use projects such as the SLV-3. Eventually, the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO)-based missile programme borrowed staff and technology from ISRO. Missile scientist A.P.J. Abdul Kalam (later elected president), who had headed the SLV-3 project at ISRO, took over as missile programme at DRDO. About a dozen scientists accompanied him, helping to design the Agni missile using the SLV-3's solid fuel first stage and a liquid-fuel (Prithvi-missile-derived) second stage. The IRS and INSAT satellites were primarily intended, and used, for civilian-economic applications, but they also offered military spin-offs. In 1996 the Ministry of Defence temporarily blocked the use of IRS-1C by India's environmental and agricultural ministries in order to monitor ballistic missiles near India's borders. In 1997, the Air Force's "Airpower Doctrine" aspired to use space assets for surveillance and battle management.[231]

Academic

[edit]Institutions like the Indira Gandhi National Open University and the Indian Institutes of Technology use satellites for educational applications.[232] Between 1975 and 1976, India conducted its largest sociological programme using space technology, reaching 2,400 villages through video programming in local languages aimed at educational development via ATS-6 technology developed by NASA.[233] This experiment—named Satellite Instructional Television Experiment (SITE)—conducted large-scale video broadcasts resulting in significant improvement in rural education.[233]

Telemedicine

[edit]ISRO has applied its technology for telemedicine, directly connecting patients in rural areas to medical professionals in urban locations via satellite.[232] Since high-quality healthcare is not universally available in some of the remote areas of India, patients in those areas are diagnosed and analysed by doctors in urban centers in real time via video conferencing.[232] The patient is then advised on medicine and treatment,[232] and treated by the staff at one of the 'super-specialty hospitals' per instructions from those doctors.[232] Mobile telemedicine vans are also deployed to visit locations in far-flung areas and provide diagnosis and support to patients.[232]

Biodiversity Information System

[edit]ISRO has also helped implement India's Biodiversity Information System, completed in October 2002.[234] Nirupa Sen details the programme: "Based on intensive field sampling and mapping using satellite remote sensing and geospatial modeling tools, maps have been made of vegetation cover on a 1: 250,000 scale. This has been put together in a web-enabled database that links gene-level information of plant species with spatial information in a BIOSPEC database of the ecological hot spot regions, namely northeastern India, Western Ghats, Western Himalayas and Andaman and Nicobar Islands. This has been made possible with collaboration between the Department of Biotechnology and ISRO."[234]

Cartography

[edit]The Indian IRS-P5 (CARTOSAT-1) was equipped with high-resolution panchromatic equipment to enable it for cartographic purposes.[53] IRS-P5 (CARTOSAT-1) was followed by a more advanced model named IRS-P6 developed also for agricultural applications.[53] The CARTOSAT-2 project, equipped with single panchromatic camera that supported scene-specific on-spot images, succeeded the CARTOSAT-1 project.[235]

Spin-offs

[edit]ISRO's research has been diverted into spin-offs to develop various technologies for other sectors. Examples include bionic limbs for people without limbs, silica aerogel to keep Indian soldiers serving in extremely cold areas warm, distress alert transmitters for accidents, Doppler weather radar and various sensors and machines for inspection work in engineering industries.[236][237]

International cooperations

[edit]ISRO has signed various formal cooperative arrangements in the form of either Agreements or Memoranda of Understanding (MoU) or Framework Agreements with Afghanistan, Algeria, Argentina, Armenia, Australia, Bahrain, Bangladesh, Bolivia, Brazil, Brunei, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, China, Egypt, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Japan, Kazakhstan, Kuwait, Maldives, Mauritius, Mexico, Mongolia, Morocco, Myanmar, Norway, Peru, Portugal, South Korea, Russia, São Tomé and Príncipe, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, Oman, Sweden, Syria, Tajikistan, Thailand, Netherlands, Tunisia, Ukraine, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, United States, Uzbekistan, Venezuela and Vietnam. Formal cooperative instruments have been signed with international multilateral bodies including European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), European Commission, European Organisation for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites (EUMETSAT), European Space Agency (ESA) and South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC).[238]

Notable collaborative projects

[edit]- Chandrayaan-1 also carried scientific payloads to the Moon from NASA, ESA, Bulgarian Space Agency, and other institutions/companies in North America and Europe.[239]

- Indo-French satellite missions

ISRO has two collaborative satellite missions with France's CNES, namely the now retired Megha-Tropiques to study water cycle in the tropical atmosphere[240] and the presently avtive SARAL for altimetry.[107] A third mission consisting of an Earth observation satellite with a thermal infrared imager, TRISHNA (Thermal infraRed Imaging Satellite for High resolution Natural resource Assessment) is being planned by the two countries.[241]

- LUPEX

The Lunar Polar Exploration Mission (LUPEX) is a joint Indo-Japanese mission to study the polar surface of the Moon where India is tasked with providing soft landing technologies.[242]

- NISAR

NASA-ISRO Synthetic Aperture Radar (NISAR) is a joint Indo-US radar project carrying an L Band and an S Band radar. It will be world's first radar imaging satellite to use dual frequencies.[243]

Some other notable collaborations include:

- ISRO operates LUT/MCC under the international COSPAS/SARSAT Programme for Search and Rescue.[244]

- India has established a Centre for Space Science and Technology Education in Asia and the Pacific (CSSTE-AP) that is sponsored by the United Nations.[245]

- India is a member of the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space, Cospas-Sarsat, International Astronautical Federation, Committee on Space Research (COSPAR), Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC), International Space University, and the Committee on Earth Observation Satellite (CEOS).[240]

- Contributing to planned BRICS virtual constellation for remote sensing.[246][247]

Statistics

[edit]Last updated: 26 March 2023

- Total number of foreign satellites launched by ISRO: 417 (34 countries)[248]

- Spacecraft missions: 116[249]

- Launch missions: 86

- Student satellites: 13 [250]

- Re-entry missions: 2

Budget for the Department of Space

[edit]| Calendar Year | GDP (2011–12 base year) in crores(₹)[251] | Total Expenditure in crores (₹) | Budget of Department of Space[252] | Notes and references | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal INR (crore) | % of GDP | % of Total Expenditure | 2020 Constant INR (crore) | ||||

| 1972–73 | 55245 | 18.2325000 | 0.03% | 696.489 | Revised Estimate as Actuals are not available [253][254] | ||

| 1973–74 | 67241 | 19.0922000 | 0.03% | 624.381 | Revised Estimate as Actuals are not available [254]: 13 [255] | ||

| 1974–75 | 79378 | 30.7287000 | 0.04% | 781.901 | [256] | ||

| 1975–76 | 85212 | 36.8379000 | 0.04% | 879.281 | [257] | ||

| 1976–77 | 91812 | 41.1400000 | 0.04% | 1,062.174 | Revised Estimate as Actuals are not available [257] | ||

| 1977–78 | 104024 | 37.3670000 | 0.04% | 890.726 | [258] | ||

| 1978–79 | 112671 | 51.4518000 | 0.05% | 1,196.291 | [259] | ||

| 1979–80 | 123562 | 57.0062000 | 0.05% | 1,247.563 | [260] | ||

| 1980–81 | 147063 | 82.1087000 | 0.06% | 1,613.259 | [261]: 39 | ||

| 1981–82 | 172776 | 109.132100 | 0.06% | 1,896.051 | Revised Estimate as Actuals are not available[261]: 38 [262] | ||

| 1982–83 | 193255 | 94.8898000 | 0.05% | 1,527.408 | [263] | ||

| 1983–84 | 225074 | 163.365600 | 0.07% | 2,351.37 | [264] | ||

| 1984–85 | 252188 | 181.601000 | 0.07% | 2,410.543 | [265] | ||

| 1985–86 | 284534 | 229.102300 | 0.08% | 2,881.303 | [266] | ||

| 1986–87 | 318366 | 309.990900 | 0.1% | 3,585.645 | [267] | ||

| 1987–88 | 361865 | 347.084600 | 0.1% | 3,690.41 | [268] | ||

| 1988–89 | 429363 | 422.367000 | 0.1% | 4,105.274 | [269] | ||

| 1989–90 | 493278 | 398.559500 | 0.08% | 3,616.972 | [270] | ||

| 1990–91 | 576109 | 105298 | 386.221800 | 0.07% | 0.37% | 3,217.774 | [271][272] |

| 1991–92 | 662260 | 111414 | 460.101000 | 0.07% | 0.41% | 3,366.237 | [273][272] |

| 1992–93 | 761196 | 122618 | 490.920400 | 0.06% | 0.4% | 3,210.258 | [274][272] |

| 1993–94 | 875992 | 141853 | 695.335000 | 0.08% | 0.49% | 4,277.163 | [275][272] |

| 1994–95 | 1027570 | 160739 | 759.079300 | 0.07% | 0.47% | 4,237.768 | [276][272][277] |

| 1995–96 | 1205583 | 178275 | 755.778596 | 0.06% | 0.42% | 3,826.031 | [278][272][277] |

| 1996–97 | 1394816 | 201007 | 1062.44660 | 0.08% | 0.53% | 4,935.415 | [279][272][277] |

| 1997–98 | 1545294 | 232053 | 1050.50250 | 0.07% | 0.45% | 4,550.066 | [280][277] |

| 1998–99 | 1772297 | 279340 | 1401.70260 | 0.08% | 0.5% | 5,364.608 | [281][277][282] |

| 1999–00 | 1988262 | 298053 | 1677.38580 | 0.08% | 0.56% | 6,123.403 | [283][277][282] |

| 2000–01 | 2139886 | 325592 | 1905.39970 | 0.09% | 0.59% | 6,686.851 | [284][277][282] |

| 2001–02 | 2315243 | 362310 | 1900.97370 | 0.08% | 0.52% | 6,429.035 | [285][282][286] |

| 2002–03 | 2492614 | 413248 | 2162.22480 | 0.09% | 0.52% | 7,010.441 | [287][282][286] |

| 2003–04 | 2792530 | 471203 | 2268.80470 | 0.08% | 0.48% | 7,085.999 | [288][282][286] |

| 2004–05 | 3186332 | 498252 | 2534.34860 | 0.08% | 0.51% | 7,627.942 | [289][282][286] |

| 2005–06 | 3632125 | 505738 | 2667.60440 | 0.07% | 0.53% | 7,701.599 | [290][282][286] |

| 2006–07 | 4254629 | 583387 | 2988.66550 | 0.07% | 0.51% | 8,156.366 | [291][286][292] |

| 2007–08 | 4898662 | 712671 | 3278.00440 | 0.07% | 0.46% | 8,408.668 | [293][286][292] |

| 2008–09 | 5514152 | 883956 | 3493.57150 | 0.06% | 0.4% | 8,273.225 | [294][286][292] |

| 2009–10 | 6366407 | 1024487 | 4162.95990 | 0.07% | 0.41% | 8,894.965 | [295][292] |

| 2010–11 | 7634472 | 1197328 | 4482.23150 | 0.06% | 0.37% | 8,542.8 | [296][292] |

| 2011–12 | 8736329 | 1304365 | 3790.78880 | 0.04% | 0.29% | 6,636.301 | [297][292] |

| 2012–13 | 9944013 | 1410372 | 4856.28390 | 0.05% | 0.34% | 7,778.216 | [298][292] |

| 2013–14 | 11233522 | 1559447 | 5168.95140 | 0.05% | 0.33% | 7,464 | [299][292] |

| 2014–15 | 12467960 | 1663673 | 5821.36630 | 0.05% | 0.35% | 7,902.702 | [300][301] |

| 2015–16 | 13771874 | 1790783 | 6920.00520 | 0.05% | 0.39% | 8,872.483 | [302][303] |

| 2016–17 | 15391669 | 1975194 | 8039.99680 | 0.05% | 0.41% | 9,820.512 | [304][305] |

| 2017–18 | 17090042 | 2141975 | 9130.56640 | 0.05% | 0.43% | 10,881.647 | [306][307] |

| 2018–19 | 18899668 | 2315113 | 11192.6566 | 0.06% | 0.48% | 12,722.226 | [308][309] |

| 2019–20 | 20074856 | 2686330 | 13033.2917 | 0.06% | 0.49% | 13,760.472 | [310][311] |

| 2020–21 | 19800914 | 3509836 | 9490.05390 | 0.05% | 0.27% | 9,490.054 | [312][313] |

| 2021–22 | 23664637 | 3793801 | 12473.84 | 0.05% | 0.33% | 12,473.84 | [314][313][315] |

Corporate affairs

[edit]S-band spectrum scam

[edit]In India, electromagnetic spectrum, a scarce resource for wireless communication, is auctioned by the Government of India to telecom companies for use. As an example of its value, in 2010, 20 MHz of 3G spectrum was auctioned for ₹677 billion (US$8.1 billion). This part of the spectrum is allocated for terrestrial communication (cell phones). However, in January 2005, Antrix Corporation (commercial arm of ISRO) signed an agreement with Devas Multimedia (a private company formed by former ISRO employees and venture capitalists from the US) for lease of S band transponders (amounting to 70 MHz of spectrum) on two ISRO satellites (GSAT 6 and GSAT 6A) for a price of ₹14 billion (US$170 million), to be paid over a period of 12 years. The spectrum used in these satellites (2500 MHz and above) is allocated by the International Telecommunication Union specifically for satellite-based communication in India. Hypothetically, if the spectrum allocation is changed for utilisation for terrestrial transmission and if this 70 MHz of spectrum were sold at the 2010 auction price of the 3G spectrum, its value would have been over ₹2,000 billion (US$24 billion). This was a hypothetical situation. However, the Comptroller and Auditor-General considered this hypothetical situation and estimated the difference between the prices as a loss to the Indian Government.[316][317]

There were lapses on implementing official procedures. Antrix/ISRO had allocated the capacity of the above two satellites exclusively to Devas Multimedia, while the rules said it should always be non-exclusive. The Cabinet was misinformed in November 2005 that several service providers were interested in using satellite capacity, while the Devas deal was already signed. Also, the Space Commission was not informed when approving the second satellite (its cost was diluted so that Cabinet approval was not needed). ISRO committed to spending ₹7.66 billion (US$92 million) of public money on building, launching, and operating two satellites that were leased out for Devas.[318]In late 2009, some ISRO insiders exposed information about the Devas-Antrix deal,[317][319] and the ensuing investigations led to the deal's annulment. G. Madhavan Nair (ISRO Chairperson when the agreement was signed) was barred from holding any post under the Department of Space. Some former scientists were found guilty of "acts of commission" or "acts of omission". Devas and Deutsche Telekom demanded US$2 billion and US$1 billion, respectively, in damages.[320] The Department of Revenue and Ministry of Corporate Affairs began an inquiry into Devas shareholding.[318]

The Central Bureau of Investigation registered a case against the accused in the Antrix-Devas deal under Section 120-B, besides Section 420 of IPC and Section 13(2) read with 13(1)(d) of PC Act, 1988 in March 2015 against the then executive director of Antrix Corporation, two officials of a USA-based company, a Bengaluru-based private multimedia company, and other unknown officials of the Antrix Corporation or the Department of Space.[321][322]

Devas Multimedia started arbitration proceedings against Antrix in June 2011. In September 2015, the International Court of Arbitration of the International Chamber of Commerce ruled in favour of Devas, and directed Antrix to pay US$672 million (Rs 44.35 billion) in damages to Devas.[323] Antrix opposed the Devas plea for tribunal award in the Delhi High Court.[324]

Heads of ISRO

[edit]List of Chairmen (since 1963) of ISRO.

- Vikram Sarabhai (1963–1971)

- M. G. K. Menon (1972)

- Satish Dhawan (1973–1984)

- U. R. Rao (1984–1994)

- K. Kasturirangan (1994–2003)

- G. Madhavan Nair (2003–2009)

- K. Radhakrishnan (2009–2014)

- Shailesh Nayak (2015)

- A. S. Kiran Kumar (2015–2018)

- K. Sivan (2018–2022)

- S. Somanath (2022–present)

See also

[edit]- Deep Ocean mission

- Defence Space Agency

- Indian Institute of Space Science and Technology

- List of government space agencies

- List of ISRO missions

- NewSpace India Limited

- IN–SPACe

- Indian Space Association

- Science and technology in India

- Space industry of India

- Swami Vivekananda Planetarium

- Telecommunications in India

- Timeline of Solar System exploration

- National Space Science Symposium

Notes

[edit]- ^ ISO 15919: Bhāratīya Antarikṣa Anusandhāna Saṅgaṭhana

- ^ CNSA (China), ESA (most of Europe), ISRO, (India), JAXA (Japan), NASA (United States) and Roscosmos (Russia) are space agencies with full launch capabilities.

- ^ The Soviet Union (Interkosmos), The United States (NASA), China (CNSA) and India (ISRO) are the only four nations to have successfully achieved soft landing.

References