Юпитер

Юпитер запечатлен космическим зондом New Horizons . Небольшое пятно на вершине Юпитера — это тень его спутника Ганимеда . | |||||||||||||

| Designations | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈdʒuːpɪtər/ [1] | ||||||||||||

Named after | Jupiter | ||||||||||||

| Adjectives | Jovian /ˈdʒoʊviən/ | ||||||||||||

| Symbol | |||||||||||||

| Orbital characteristics[2] | |||||||||||||

| Epoch J2000 | |||||||||||||

| Aphelion | 5.4570 AU (816.363 million km) | ||||||||||||

| Perihelion | 4.9506 AU (740.595 million km) | ||||||||||||

| 5.2038 AU (778.479 million km) | |||||||||||||

| Eccentricity | 0.0489 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| 398.88 d | |||||||||||||

Average orbital speed | 13.07 km/s[citation needed] | ||||||||||||

| 20.020°[4] | |||||||||||||

| Inclination | |||||||||||||

| 100.464° | |||||||||||||

| 21 January 2023[6] | |||||||||||||

| 273.867°[4] | |||||||||||||

| Known satellites | 95 (as of 2023[update])[7] | ||||||||||||

| Physical characteristics[2][8][9] | |||||||||||||

| 69911 km[a] 10.973 of Earth's | |||||||||||||

Equatorial radius | 71492 km[a] 11.209 R🜨 (of Earth's) 0.10045 R☉ (of Sun's) | ||||||||||||

Polar radius | 66854 km[a] 10.517 of Earth's | ||||||||||||

| Flattening | 0.06487 | ||||||||||||

| 6.1469×1010 km2 120.4 of Earth's | |||||||||||||

| Volume | 1.4313×1015 km3[a] 1,321 of Earth's | ||||||||||||

| Mass | 1.8982×1027 kg

| ||||||||||||

Mean density | 1.326 g/cm3[b] | ||||||||||||

Equatorial surface gravity | 24.79 m/s2 2.528 g0[a][citation needed] | ||||||||||||

| 0.2756±0.0006[11] | |||||||||||||

Equatorial escape velocity | 59.5 km/s[a] | ||||||||||||

| 9.9258 h (9 h 55 m 33 s)[3] | |||||||||||||

| 9.9250 hours (9 h 55 m 30 s) | |||||||||||||

Equatorial rotation velocity | 12.6 km/s | ||||||||||||

| 3.13° (to orbit) | |||||||||||||

North pole right ascension | 268.057°; 17h 52m 14s | ||||||||||||

North pole declination | 64.495° | ||||||||||||

| 0.503 (Bond)[12] 0.538 (geometric)[13] | |||||||||||||

| Temperature | 88 K (−185 °C) (blackbody temperature) | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| −2.94[14] to −1.66[14] | |||||||||||||

| −9.4[15] | |||||||||||||

| 29.8" to 50.1" | |||||||||||||

| Atmosphere[2] | |||||||||||||

Surface pressure | 200–600 kPa (30–90 psi) (opaque cloud deck)[16] | ||||||||||||

| 27 km (17 mi) | |||||||||||||

| Composition by volume | |||||||||||||

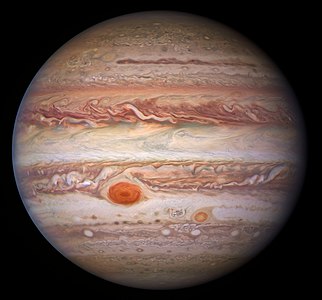

Юпитер — пятая планета от Солнца и самая большая в Солнечной системе . Газовый гигант , масса Юпитера более чем в два с половиной раза превышает массу всех остальных планет Солнечной системы вместе взятых и чуть меньше одной тысячной массы Солнца. Юпитер вращается вокруг Солнца на расстоянии 5,20 а.е. (778,5 Гм ) с периодом орбитальным 11,86 лет . Это третий по яркости природный объект на Земли ночном небе после Луны и Венеры , который наблюдался с доисторических времен . Его название происходит от Юпитера , главного божества древнеримской религии .

Юпитер был первой сформировавшейся планетой, и его миграция внутрь во время древней Солнечной системы повлияла на большую часть истории формирования других планет. Водород составляет 90% объема Юпитера, за ним следует гелий , который составляет 25% его массы и 10% его объема. Продолжающееся сжатие недр Юпитера генерирует больше тепла, чем планета получает от Солнца. Считается, что его внутренняя структура состоит из внешней мантии из жидкого металлического водорода и диффузного внутреннего ядра из более плотного материала. Из-за высокой скорости вращения (один оборот за десять часов) форма Юпитера представляет собой сплюснутый сфероид ; у него есть небольшая, но заметная выпуклость вокруг экватора. Внешняя атмосфера разделена на ряд широтных полос, вдоль взаимодействующих границ которых наблюдаются турбулентность и штормы. Наиболее очевидным результатом этого является Большое Красное Пятно , гигантский шторм, который регистрируется как минимум с 1831 года.

Jupiter is surrounded by a faint planetary ring system and has a powerful magnetosphere, the second largest contiguous structure in the Solar System (after the heliosphere). Jupiter forms a system of 95 known moons and probably many more, including the four large moons discovered by Galileo Galilei in 1610: Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. Ganymede, the largest of the four, is larger than the planet Mercury. Callisto is the second largest; Io and Europa are approximately the size of Earth's Moon.

Since 1973, Jupiter has been visited by nine robotic probes: seven flybys and two dedicated orbiters, with one more en route and one awaiting launch.

Name and symbol

In both the ancient Greek and Roman civilizations, Jupiter was named after the chief god of the divine pantheon: Zeus to the Greeks and Jupiter to the Romans.[17] The International Astronomical Union formally adopted the name Jupiter for the planet in 1976, and has since named its newly discovered satellites for the god's lovers, favourites, and descendants.[18] The planetary symbol for Jupiter, ![]() , descends from a Greek zeta with a horizontal stroke, ⟨Ƶ⟩, as an abbreviation for Zeus.[19][20]

, descends from a Greek zeta with a horizontal stroke, ⟨Ƶ⟩, as an abbreviation for Zeus.[19][20]

In Latin, Iovis is the genitive case of Iuppiter, i.e. Jupiter. It is associated with the etymology of Zeus ('sky father'). The English equivalent, Jove, is only known to have come into use as a poetic name for the planet around the 14th century.[21]

Jovian is the adjectival form of Jupiter. The older adjectival form jovial, employed by astrologers in the Middle Ages, has come to mean 'happy' or 'merry', moods ascribed to Jupiter's influence in astrology.[22]

The original Greek deity Zeus supplies the root zeno-, which is used to form some Jupiter-related words, such as zenographic.[c]

Formation and migration

Jupiter is believed to be the oldest planet in the Solar System, having formed just one million years after the Sun and roughly 50 million years before Earth.[23] Current models of Solar System formation suggest that Jupiter formed at or beyond the snow line: a distance from the early Sun where the temperature was sufficiently cold for volatiles such as water to condense into solids.[24] The planet began as a solid core, which then accumulated its gaseous atmosphere. As a consequence, the planet must have formed before the solar nebula was fully dispersed.[25] During its formation, Jupiter's mass gradually increased until it had 20 times the mass of the Earth, approximately half of which was made up of silicates, ices and other heavy-element constituents.[23] When the proto-Jupiter grew larger than 50 Earth masses it created a gap in the solar nebula.[23] Thereafter, the growing planet reached its final mass in 3–4 million years.[23] Since Jupiter is made of the same elements as the Sun (hydrogen and helium) it has been suggested that the Solar System might have been early in its formation a system of multiple protostars, which are quite common, with Jupiter being the second but failed protostar. But the Solar System never developed into a system of multiple stars and Jupiter today does not qualify as a protostar or brown dwarf since it does not have enough mass to fuse hydrogen.[26][27][28]

According to the "grand tack hypothesis", Jupiter began to form at a distance of roughly 3.5 AU (520 million km; 330 million mi) from the Sun. As the young planet accreted mass, interaction with the gas disk orbiting the Sun and orbital resonances with Saturn caused it to migrate inward.[24][29] This upset the orbits of several super-Earths orbiting closer to the Sun, causing them to collide destructively.[30] Saturn would later have begun to migrate inwards at a faster rate than Jupiter, until the two planets became captured in a 3:2 mean motion resonance at approximately 1.5 AU (220 million km; 140 million mi) from the Sun.[31] This changed the direction of migration, causing them to migrate away from the Sun and out of the inner system to their current locations.[30] All of this happened over a period of 3–6 million years, with the final migration of Jupiter occurring over several hundred thousand years.[29][32] Jupiter's migration from the inner solar system eventually allowed the inner planets—including Earth—to form from the rubble.[33]

There are several unresolved issues with the grand tack hypothesis. The resulting formation timescales of terrestrial planets appear to be inconsistent with the measured elemental composition.[34] It is likely that Jupiter would have settled into an orbit much closer to the Sun if it had migrated through the solar nebula.[35] Some competing models of Solar System formation predict the formation of Jupiter with orbital properties that are close to those of the present day planet.[25] Other models predict Jupiter forming at distances much farther out, such as 18 AU (2.7 billion km; 1.7 billion mi).[36][37]

According to the Nice model, infall of proto-Kuiper belt objects over the first 600 million years of Solar System history caused Jupiter and Saturn to migrate from their initial positions into a 1:2 resonance, which caused Saturn to shift into a higher orbit, disrupting the orbits of Uranus and Neptune, depleting the Kuiper belt, and triggering the Late Heavy Bombardment.[38]

Based on Jupiter's composition, researchers have made the case for an initial formation outside the molecular nitrogen (N2) snow line, which is estimated at 20–30 AU (3.0–4.5 billion km; 1.9–2.8 billion mi) from the Sun, and possibly even outside the argon snow line, which may be as far as 40 AU (6.0 billion km; 3.7 billion mi).[39][40] Having formed at one of these extreme distances, Jupiter would then have, over a roughly 700,000-year period, migrated inwards to its current location,[36][37] during an epoch approximately 2–3 million years after the planet began to form. In this model, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune would have formed even further out than Jupiter, and Saturn would also have migrated inwards.[36]

Physical characteristics

Jupiter is a gas giant, meaning its chemical composition is primarily hydrogen and helium. These materials are classified as gasses in planetary geology, a term that does not denote the state of matter. It is the largest planet in the Solar System, with a diameter of 142,984 km (88,846 mi) at its equator, giving it a volume 1,321 times that of the Earth.[2][41] Its average density, 1.326 g/cm3,[d] is lower than those of the four terrestrial planets.[43][44]

Composition

By mass, Jupiter's atmosphere is approximately 76% hydrogen and 24% helium, though, because helium atoms are more massive than hydrogen molecules, Jupiter's upper atmosphere is about 90% hydrogen and 10% helium by volume.[45] The atmosphere also contains trace amounts of methane, water vapour, ammonia, and silicon-based compounds, as well as fractional amounts of carbon, ethane, hydrogen sulfide, neon, oxygen, phosphine, and sulfur.[46] The outermost layer of the atmosphere contains crystals of frozen ammonia.[47] Through infrared and ultraviolet measurements, trace amounts of benzene and other hydrocarbons have also been found.[48] The interior of Jupiter contains denser materials—by mass it is roughly 71% hydrogen, 24% helium, and 5% other elements.[49][50]

The atmospheric proportions of hydrogen and helium are close to the theoretical composition of the primordial solar nebula.[51] Neon in the upper atmosphere only consists of 20 parts per million by mass, which is about a tenth as abundant as in the Sun.[52] Jupiter's helium abundance is about 80% that of the Sun due to precipitation of these elements as helium-rich droplets, a process that happens deep in the planet's interior.[53][54]

Based on spectroscopy, Saturn is thought to be similar in composition to Jupiter, but the other giant planets Uranus and Neptune have relatively less hydrogen and helium and relatively more of the next most common elements, including oxygen, carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur.[55] These planets are known as ice giants because during their formation these elements are thought to have been incorporated into them as ices; however, they probably contain little ice today.[56]

Size and mass

Jupiter's mass is 318 times that of Earth;[2] 2.5 times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined. It is so massive that its barycentre with the Sun lies above the Sun's surface at 1.068 solar radii from the Sun's centre.[57][58]: 6 Jupiter's radius is about one tenth the radius of the Sun,[59] and its mass is one thousandth the mass of the Sun, as the densities of the two bodies are similar.[60] A "Jupiter mass" (MJ or MJup) is often used as a unit to describe masses of other objects, particularly extrasolar planets and brown dwarfs. For example, the extrasolar planet HD 209458 b has a mass of 0.69 MJ, while the brown dwarf Gliese 229 b has a mass of 60.4 MJ.[61][62]

Theoretical models indicate that if Jupiter had over 40% more mass, the interior would be so compressed that its volume would decrease despite the increasing amount of matter. For smaller changes in its mass, the radius would not change appreciably.[63] As a result, Jupiter is thought to have about as large a diameter as a planet of its composition and evolutionary history can achieve.[64] The process of further shrinkage with increasing mass would continue until appreciable stellar ignition was achieved.[65] Although Jupiter would need to be about 75 times more massive to fuse hydrogen and become a star,[66] its diameter is sufficient as the smallest red dwarf may be only slightly larger in radius than Saturn.[67]

Jupiter radiates more heat than it receives through solar radiation, due to the Kelvin–Helmholtz mechanism within its contracting interior.[68]: 30 [69] This process causes Jupiter to shrink by about 1 mm (0.039 in) per year.[70][71] At the time of its formation, Jupiter was hotter and was about twice its current diameter.[72]

Internal structure

Before the early 21st century, most scientists proposed one of two scenarios for the formation of Jupiter. If the planet accreted first as a solid body, it would consist of a dense core, a surrounding layer of fluid metallic hydrogen (with some helium) extending outward to about 80% of the radius of the planet,[73] and an outer atmosphere consisting primarily of molecular hydrogen.[71] Alternatively, if the planet collapsed directly from the gaseous protoplanetary disk, it was expected to completely lack a core, consisting instead of a denser and denser fluid (predominantly molecular and metallic hydrogen) all the way to the centre. Data from the Juno mission showed that Jupiter has a diffuse core that mixes into its mantle, extending for 30–50% of the planet's radius, and comprising heavy elements with a combined mass 7–25 times the Earth.[74][75][76][77][78] This mixing process could have arisen during formation, while the planet accreted solids and gases from the surrounding nebula.[79] Alternatively, it could have been caused by an impact from a planet of about ten Earth masses a few million years after Jupiter's formation, which would have disrupted an originally compact Jovian core.[80][81]

Outside the layer of metallic hydrogen lies a transparent interior atmosphere of hydrogen. At this depth, the pressure and temperature are above molecular hydrogen's critical pressure of 1.3 MPa and critical temperature of 33 K (−240.2 °C; −400.3 °F).[82] In this state, there are no distinct liquid and gas phases—hydrogen is said to be in a supercritical fluid state. The hydrogen and helium gas extending downward from the cloud layer gradually transitions to a liquid in deeper layers, possibly resembling something akin to an ocean of liquid hydrogen and other supercritical fluids.[68]: 22 [83][84][85] Physically, the gas gradually becomes hotter and denser as depth increases.[86][87]

Rain-like droplets of helium and neon precipitate downward through the lower atmosphere, depleting the abundance of these elements in the upper atmosphere.[53][88] Calculations suggest that helium drops separate from metallic hydrogen at a radius of 60,000 km (37,000 mi) (11,000 km (6,800 mi) below the cloud tops) and merge again at 50,000 km (31,000 mi) (22,000 km (14,000 mi) beneath the clouds).[89] Rainfalls of diamonds have been suggested to occur, as well as on Saturn[90] and the ice giants Uranus and Neptune.[91]

The temperature and pressure inside Jupiter increase steadily inward as the heat of planetary formation can only escape by convection.[54] At a surface depth where the atmospheric pressure level is 1 bar (0.10 MPa), the temperature is around 165 K (−108 °C; −163 °F). The region where supercritical hydrogen changes gradually from a molecular fluid to a metallic fluid spans pressure ranges of 50–400 GPa with temperatures of 5,000–8,400 K (4,730–8,130 °C; 8,540–14,660 °F), respectively. The temperature of Jupiter's diluted core is estimated to be 20,000 K (19,700 °C; 35,500 °F) with a pressure of around 4,000 GPa.[92]

Atmosphere

The atmosphere of Jupiter is primarily composed of molecular hydrogen and helium, with a smaller amount of other compounds such as water, methane, hydrogen sulfide, and ammonia.[93] Jupiter's atmosphere extends to a depth of approximately 3,000 km (2,000 mi) below the cloud layers.[92]

Cloud layers

Jupiter is perpetually covered with clouds of ammonia crystals, which may contain ammonium hydrosulfide as well.[94] The clouds are located in the tropopause layer of the atmosphere, forming bands at different latitudes, known as tropical regions. These are subdivided into lighter-hued zones and darker belts. The interactions of these conflicting circulation patterns cause storms and turbulence. Wind speeds of 100 metres per second (360 km/h; 220 mph) are common in zonal jet streams.[95] The zones have been observed to vary in width, colour and intensity from year to year, but they have remained stable enough for scientists to name them.[58]: 6

The cloud layer is about 50 km (31 mi) deep and consists of at least two decks of ammonia clouds: a thin, clearer region on top and a thicker, lower deck. There may be a thin layer of water clouds underlying the ammonia clouds, as suggested by flashes of lightning detected in the atmosphere of Jupiter.[96] These electrical discharges can be up to a thousand times as powerful as lightning on Earth.[97] The water clouds are assumed to generate thunderstorms in the same way as terrestrial thunderstorms, driven by the heat rising from the interior.[98] The Juno mission revealed the presence of "shallow lightning" which originates from ammonia-water clouds relatively high in the atmosphere.[99] These discharges carry "mushballs" of water-ammonia slushes covered in ice, which fall deep into the atmosphere.[100] Upper-atmospheric lightning has been observed in Jupiter's upper atmosphere, bright flashes of light that last around 1.4 milliseconds. These are known as "elves" or "sprites" and appear blue or pink due to the hydrogen.[101][102]

The orange and brown colours in the clouds of Jupiter are caused by upwelling compounds that change colour when they are exposed to ultraviolet light from the Sun. The exact makeup remains uncertain, but the substances are thought to be made up of phosphorus, sulfur or possibly hydrocarbons.[68]: 39 [103] These colourful compounds, known as chromophores, mix with the warmer clouds of the lower deck. The light-coloured zones are formed when rising convection cells form crystallising ammonia that hides the chromophores from view.[104]

Jupiter has a low axial tilt, thus ensuring that the poles always receive less solar radiation than the planet's equatorial region. Convection within the interior of the planet transports energy to the poles, balancing out temperatures at the cloud layer.[58]: 54

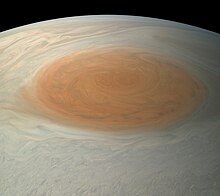

Great Red Spot and other vortices

A well-known feature of Jupiter is the Great Red Spot,[105] a persistent anticyclonic storm located 22° south of the equator. It was first observed in 1831,[106] and possibly as early as 1665.[107][108] Images by the Hubble Space Telescope have shown two more "red spots" adjacent to the Great Red Spot.[109][110] The storm is visible through Earth-based telescopes with an aperture of 12 cm or larger.[111] The oval object rotates counterclockwise, with a period of about six days.[112] The maximum altitude of this storm is about 8 km (5 mi) above the surrounding cloud tops.[113] The Spot's composition and the source of its red colour remain uncertain, although photodissociated ammonia reacting with acetylene is a likely explanation.[114]

The Great Red Spot is larger than the Earth.[115] Mathematical models suggest that the storm is stable and will be a permanent feature of the planet.[116] However, it has significantly decreased in size since its discovery. Initial observations in the late 1800s showed it to be approximately 41,000 km (25,500 mi) across. By the time of the Voyager flybys in 1979, the storm had a length of 23,300 km (14,500 mi) and a width of approximately 13,000 km (8,000 mi).[117] Hubble observations in 1995 showed it had decreased in size to 20,950 km (13,020 mi), and observations in 2009 showed the size to be 17,910 km (11,130 mi). As of 2015[update], the storm was measured at approximately 16,500 by 10,940 km (10,250 by 6,800 mi),[117] and was decreasing in length by about 930 km (580 mi) per year.[115][118] In October 2021, a Juno flyby mission measured the depth of the Great Red Spot, putting it at around 300–500 kilometres (190–310 mi).[119]

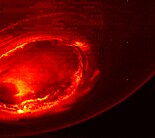

Juno missions show that there are several polar cyclone groups at Jupiter's poles. The northern group contains nine cyclones, with a large one in the centre and eight others around it, while its southern counterpart also consists of a centre vortex but is surrounded by five large storms and a single smaller one for a total of 7 storms.[120][121]

In 2000, an atmospheric feature formed in the southern hemisphere that is similar in appearance to the Great Red Spot, but smaller. This was created when smaller, white oval-shaped storms merged to form a single feature—these three smaller white ovals were formed in 1939–1940. The merged feature was named Oval BA. It has since increased in intensity and changed from white to red, earning it the nickname "Little Red Spot".[122][123]

In April 2017, a "Great Cold Spot" was discovered in Jupiter's thermosphere at its north pole. This feature is 24,000 km (15,000 mi) across, 12,000 km (7,500 mi) wide, and 200 °C (360 °F) cooler than surrounding material. While this spot changes form and intensity over the short term, it has maintained its general position in the atmosphere for more than 15 years. It may be a giant vortex similar to the Great Red Spot, and appears to be quasi-stable like the vortices in Earth's thermosphere. This feature may be formed by interactions between charged particles generated from Io and the strong magnetic field of Jupiter, resulting in a redistribution of heat flow.[124]

Magnetosphere

(Hubble). False colour image composite.

Jupiter's magnetic field is the strongest of any planet in the Solar System,[104] with a dipole moment of 4.170 gauss (0.4170 mT) that is tilted at an angle of 10.31° to the pole of rotation. The surface magnetic field strength varies from 2 gauss (0.20 mT) up to 20 gauss (2.0 mT).[125] This field is thought to be generated by eddy currents—swirling movements of conducting materials—within the fluid, metallic hydrogen core. At about 75 Jupiter radii from the planet, the interaction of the magnetosphere with the solar wind generates a bow shock. Surrounding Jupiter's magnetosphere is a magnetopause, located at the inner edge of a magnetosheath—a region between it and the bow shock. The solar wind interacts with these regions, elongating the magnetosphere on Jupiter's lee side and extending it outward until it nearly reaches the orbit of Saturn. The four largest moons of Jupiter all orbit within the magnetosphere, which protects them from solar wind.[68]: 69

The volcanoes on the moon Io emit large amounts of sulfur dioxide, forming a gas torus along its orbit. The gas is ionized in Jupiter's magnetosphere, producing sulfur and oxygen ions. They, together with hydrogen ions originating from the atmosphere of Jupiter, form a plasma sheet in Jupiter's equatorial plane. The plasma in the sheet co-rotates with the planet, causing deformation of the dipole magnetic field into that of a magnetodisk. Electrons within the plasma sheet generate a strong radio signature, with short, superimposed bursts in the range of 0.6–30 MHz that are detectable from Earth with consumer-grade shortwave radio receivers.[126][127] As Io moves through this torus, the interaction generates Alfvén waves that carry ionized matter into the polar regions of Jupiter. As a result, radio waves are generated through a cyclotron maser mechanism, and the energy is transmitted out along a cone-shaped surface. When Earth intersects this cone, the radio emissions from Jupiter can exceed the radio output of the Sun.[128]

| Moon | rem/day |

|---|---|

| Io | 3600[129] |

| Europa | 540[129] |

| Ganymede | 8[129] |

| Callisto | 0.01[129] |

| Earth (Max) | 0.07 |

| Earth (Avg) | 0.0007 |

Planetary rings

Jupiter has a faint planetary ring system composed of three main segments: an inner torus of particles known as the halo, a relatively bright main ring, and an outer gossamer ring.[130] These rings appear to be made of dust, whereas Saturn's rings are made of ice.[68]: 65 The main ring is most likely made out of material ejected from the satellites Adrastea and Metis, which is drawn into Jupiter because of the planet's strong gravitational influence. New material is added by additional impacts.[131] In a similar way, the moons Thebe and Amalthea are believed to produce the two distinct components of the dusty gossamer ring.[131] There is evidence of a fourth ring that may consist of collisional debris from Amalthea that is strung along the same moon's orbit.[132]

Orbit and rotation

Jupiter is the only planet whose barycentre with the Sun lies outside the volume of the Sun, though by only 7% of the Sun's radius.[133][134] The average distance between Jupiter and the Sun is 778 million km (5.2 AU) and it completes an orbit every 11.86 years. This is approximately two-fifths the orbital period of Saturn, forming a near orbital resonance.[135] The orbital plane of Jupiter is inclined 1.30° compared to Earth. Because the eccentricity of its orbit is 0.049, Jupiter is slightly over 75 million km nearer the Sun at perihelion than aphelion,[2] which means that its orbit is nearly circular. This low eccentricity is at odds with exoplanet discoveries, which have revealed Jupiter-sized planets with very high eccentricities. Models suggest this may be due to there being only two giant planets in our Solar System, as the presence of a third or more giant planets tends to induce larger eccentricities.[136]

The axial tilt of Jupiter is relatively small, only 3.13°, so its seasons are insignificant compared to those of Earth and Mars.[137]

Jupiter's rotation is the fastest of all the Solar System's planets, completing a rotation on its axis in slightly less than ten hours; this creates an equatorial bulge easily seen through an amateur telescope. Because Jupiter is not a solid body, its upper atmosphere undergoes differential rotation. The rotation of Jupiter's polar atmosphere is about 5 minutes longer than that of the equatorial atmosphere.[138] The planet is an oblate spheroid, meaning that the diameter across its equator is longer than the diameter measured between its poles.[87] On Jupiter, the equatorial diameter is 9,276 km (5,764 mi) longer than the polar diameter.[2]

Three systems are used as frames of reference for tracking planetary rotation, particularly when graphing the motion of atmospheric features. System I applies to latitudes from 7° N to 7° S; its period is the planet's shortest, at 9h 50 m 30.0s. System II applies at latitudes north and south of these; its period is 9h 55 m 40.6s.[139] System III was defined by radio astronomers and corresponds to the rotation of the planet's magnetosphere; its period is Jupiter's official rotation.[140]

Observation

Jupiter is usually the fourth brightest object in the sky (after the Sun, the Moon, and Venus),[104] although at opposition Mars can appear brighter than Jupiter. Depending on Jupiter's position with respect to the Earth, it can vary in visual magnitude from as bright as −2.94 at opposition down to −1.66 during conjunction with the Sun.[14] The mean apparent magnitude is −2.20 with a standard deviation of 0.33.[14] The angular diameter of Jupiter likewise varies from 50.1 to 30.5 arc seconds.[2] Favourable oppositions occur when Jupiter is passing through the perihelion of its orbit, bringing it closer to Earth.[141] Near opposition, Jupiter will appear to go into retrograde motion for a period of about 121 days, moving backward through an angle of 9.9° before returning to prograde movement.[142]

Because the orbit of Jupiter is outside that of Earth, the phase angle of Jupiter as viewed from Earth is always less than 11.5°; thus, Jupiter always appears nearly fully illuminated when viewed through Earth-based telescopes. It was only during spacecraft missions to Jupiter that crescent views of the planet were obtained.[143] A small telescope will usually show Jupiter's four Galilean moons and the prominent cloud belts across Jupiter's atmosphere. A larger telescope with an aperture of 4–6 inches (10–15 cm) will show Jupiter's Great Red Spot when it faces Earth.[144][145]

History

Pre-telescopic research

Observation of Jupiter dates back to at least the Babylonian astronomers of the 7th or 8th century BC.[146] The ancient Chinese knew Jupiter as the "Suì Star" (Suìxīng 歲星) and established their cycle of 12 earthly branches based on the approximate number of years it takes Jupiter to rotate around the Sun; the Chinese language still uses its name (simplified as 歲) when referring to years of age. By the 4th century BC, these observations had developed into the Chinese zodiac,[147] and each year became associated with a Tai Sui star and god controlling the region of the heavens opposite Jupiter's position in the night sky. These beliefs survive in some Taoist religious practices and in the East Asian zodiac's twelve animals. The Chinese historian Xi Zezong has claimed that Gan De, an ancient Chinese astronomer,[148] reported a small star "in alliance" with the planet,[149] which may indicate a sighting of one of Jupiter's moons with the unaided eye. If true, this would predate Galileo's discovery by nearly two millennia.[150][151]

A 2016 paper reports that trapezoidal rule was used by Babylonians before 50 BC for integrating the velocity of Jupiter along the ecliptic.[152] In his 2nd century work the Almagest, the Hellenistic astronomer Claudius Ptolemaeus constructed a geocentric planetary model based on deferents and epicycles to explain Jupiter's motion relative to Earth, giving its orbital period around Earth as 4332.38 days, or 11.86 years.[153]

Ground-based telescope research

In 1610, Italian polymath Galileo Galilei discovered the four largest moons of Jupiter (now known as the Galilean moons) using a telescope. This is thought to be the first telescopic observation of moons other than Earth's. Just one day after Galileo, Simon Marius independently discovered moons around Jupiter, though he did not publish his discovery in a book until 1614.[154] It was Marius's names for the major moons, however, that stuck: Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. The discovery was a major point in favour of Copernicus' heliocentric theory of the motions of the planets; Galileo's outspoken support of the Copernican theory led to him being tried and condemned by the Inquisition.[155]

In the autumn of 1639, the Neapolitan optician Francesco Fontana tested a 22-palm telescope of his own making and discovered the characteristic bands of the planet's atmosphere.[156]

During the 1660s, Giovanni Cassini used a new telescope to discover spots in Jupiter's atmosphere, observe that the planet appeared oblate, and estimate its rotation period.[157] In 1692, Cassini noticed that the atmosphere undergoes a differential rotation.[158]

The Great Red Spot may have been observed as early as 1664 by Robert Hooke and in 1665 by Cassini, although this is disputed. The pharmacist Heinrich Schwabe produced the earliest known drawing to show details of the Great Red Spot in 1831.[159] The Red Spot was reportedly lost from sight on several occasions between 1665 and 1708 before becoming quite conspicuous in 1878.[160] It was recorded as fading again in 1883 and at the start of the 20th century.[161]

Both Giovanni Borelli and Cassini made careful tables of the motions of Jupiter's moons, which allowed predictions of when the moons would pass before or behind the planet. By the 1670s, Cassini observed that when Jupiter was on the opposite side of the Sun from Earth, these events would occur about 17 minutes later than expected. Ole Rømer deduced that light does not travel instantaneously (a conclusion that Cassini had earlier rejected),[50] and this timing discrepancy was used to estimate the speed of light.[162][163]

In 1892, E. E. Barnard observed a fifth satellite of Jupiter with the 36-inch (910 mm) refractor at Lick Observatory in California. This moon was later named Amalthea.[164] It was the last planetary moon to be discovered directly by a visual observer through a telescope.[165] An additional eight satellites were discovered before the flyby of the Voyager 1 probe in 1979.[e]

In 1932, Rupert Wildt identified absorption bands of ammonia and methane in the spectra of Jupiter.[166] Three long-lived anticyclonic features called "white ovals" were observed in 1938. For several decades, they remained as separate features in the atmosphere, sometimes approaching each other but never merging. Finally, two of the ovals merged in 1998, then absorbed the third in 2000, becoming Oval BA.[167]

Radiotelescope research

In 1955, Bernard Burke and Kenneth Franklin discovered that Jupiter emits bursts of radio waves at a frequency of 22.2 MHz.[68]: 36 The period of these bursts matched the rotation of the planet, and they used this information to determine a more precise value for Jupiter's rotation rate. Radio bursts from Jupiter were found to come in two forms: long bursts (or L-bursts) lasting up to several seconds, and short bursts (or S-bursts) lasting less than a hundredth of a second.[168]

Scientists have discovered three forms of radio signals transmitted from Jupiter:

- Decametric radio bursts (with a wavelength of tens of metres) vary with the rotation of Jupiter, and are influenced by the interaction of Io with Jupiter's magnetic field.[169]

- Decimetric radio emission (with wavelengths measured in centimetres) was first observed by Frank Drake and Hein Hvatum in 1959.[68]: 36 The origin of this signal is a torus-shaped belt around Jupiter's equator, which generates cyclotron radiation from electrons that are accelerated in Jupiter's magnetic field.[170]

- Thermal radiation is produced by heat in the atmosphere of Jupiter.[68]: 43

Exploration

Jupiter has been visited by automated spacecraft since 1973, when the space probe Pioneer 10 passed close enough to Jupiter to send back revelations about its properties and phenomena.[171][172] Missions to Jupiter are accomplished at a cost in energy, which is described by the net change in velocity of the spacecraft, or delta-v. Entering a Hohmann transfer orbit from Earth to Jupiter from low Earth orbit requires a delta-v of 6.3 km/s,[173] which is comparable to the 9.7 km/s delta-v needed to reach low Earth orbit.[174] Gravity assists through planetary flybys can be used to reduce the energy required to reach Jupiter.[175]

Flyby missions

| Spacecraft | Closest approach | Distance (km) |

|---|---|---|

| Pioneer 10 | December 3, 1973 | 130,000 |

| Pioneer 11 | December 4, 1974 | 34,000 |

| Voyager 1 | March 5, 1979 | 349,000 |

| Voyager 2 | July 9, 1979 | 570,000 |

| Ulysses | February 8, 1992[176] | 408,894 |

| February 4, 2004[176] | 120,000,000 | |

| Cassini | December 30, 2000 | 10,000,000 |

| New Horizons | February 28, 2007 | 2,304,535 |

Beginning in 1973, several spacecraft performed planetary flyby manoeuvres that brought them within the observation range of Jupiter. The Pioneer missions obtained the first close-up images of Jupiter's atmosphere and several of its moons. They discovered that the radiation fields near the planet were much stronger than expected, but both spacecraft managed to survive in that environment. The trajectories of these spacecraft were used to refine the mass estimates of the Jovian system. Radio occultations by the planet resulted in better measurements of Jupiter's diameter and the amount of polar flattening.[58]: 47 [177]

Six years later, the Voyager missions vastly improved the understanding of the Galilean moons and discovered Jupiter's rings. They also confirmed that the Great Red Spot was anticyclonic. Comparison of images showed that the Spot had changed hues since the Pioneer missions, turning from orange to dark brown. A torus of ionized atoms was discovered along Io's orbital path, which were found to come from erupting volcanoes on the moon's surface. As the spacecraft passed behind the planet, it observed flashes of lightning in the night side atmosphere.[58]: 87 [178]

The next mission to encounter Jupiter was the Ulysses solar probe. In February 1992, it performed a flyby manoeuvre to attain a polar orbit around the Sun. During this pass, the spacecraft studied Jupiter's magnetosphere, although it had no cameras to photograph the planet. The spacecraft passed by Jupiter six years later, this time at a much greater distance.[176]

In 2000, the Cassini probe flew by Jupiter on its way to Saturn, and provided higher-resolution images.[179]

The New Horizons probe flew by Jupiter in 2007 for a gravity assist en route to Pluto.[180] The probe's cameras measured plasma output from volcanoes on Io and studied all four Galilean moons in detail.[181]

Galileo mission

The first spacecraft to orbit Jupiter was the Galileo mission, which reached the planet on December 7, 1995.[64] It remained in orbit for over seven years, conducting multiple flybys of all the Galilean moons and Amalthea. The spacecraft also witnessed the impact of Comet Shoemaker–Levy 9 when it collided with Jupiter in 1994. Some of the goals for the mission were thwarted due to a malfunction in Galileo's high-gain antenna.[182]

A 340-kilogram titanium atmospheric probe was released from the spacecraft in July 1995, entering Jupiter's atmosphere on December 7.[64] It parachuted through 150 km (93 mi) of the atmosphere at a speed of about 2,575 km/h (1,600 mph)[64] and collected data for 57.6 minutes until the spacecraft was destroyed.[183] The Galileo orbiter itself experienced a more rapid version of the same fate when it was deliberately steered into the planet on September 21, 2003. NASA destroyed the spacecraft to avoid any possibility of the spacecraft crashing into and possibly contaminating the moon Europa, which may harbour life.[182]

Data from this mission revealed that hydrogen composes up to 90% of Jupiter's atmosphere.[64] The recorded temperature was more than 300 °C (570 °F), and the wind speed measured more than 644 km/h (>400 mph) before the probes vaporized.[64]

Juno mission

NASA's Juno mission arrived at Jupiter on July 4, 2016, with the goal of studying the planet in detail from a polar orbit. The spacecraft was originally intended to orbit Jupiter thirty-seven times over a period of twenty months.[184][76][185] During the mission, the spacecraft will be exposed to high levels of radiation from Jupiter's magnetosphere, which may cause the failure of certain instruments.[186] On August 27, 2016, the spacecraft completed its first flyby of Jupiter and sent back the first-ever images of Jupiter's north pole.[187]

Juno completed 12 orbits before the end of its budgeted mission plan, ending in July 2018.[188] In June of that year, NASA extended the mission operations plan to July 2021, and in January of that year the mission was extended to September 2025 with four lunar flybys: one of Ganymede, one of Europa, and two of Io.[189][190] When Juno reaches the end of the mission, it will perform a controlled deorbit and disintegrate into Jupiter's atmosphere. This will avoid the risk of collision with Jupiter's moons.[191][192]

Cancelled missions and future plans

There is great interest in missions to study Jupiter's larger icy moons, which may have subsurface liquid oceans.[193] Funding difficulties have delayed progress, causing NASA's JIMO (Jupiter Icy Moons Orbiter) to be cancelled in 2005.[194] A subsequent proposal was developed for a joint NASA/ESA mission called EJSM/Laplace, with a provisional launch date around 2020. EJSM/Laplace would have consisted of the NASA-led Jupiter Europa Orbiter and the ESA-led Jupiter Ganymede Orbiter.[195] However, the ESA formally ended the partnership in April 2011, citing budget issues at NASA and the consequences on the mission timetable. Instead, ESA planned to go ahead with a European-only mission to compete in its L1 Cosmic Vision selection.[196] These plans have been realized as the European Space Agency's Jupiter Icy Moon Explorer (JUICE), launched on April 14, 2023,[197] followed by NASA's Europa Clipper mission, scheduled for launch in 2024.[198]

Other proposed missions include the Chinese National Space Administration's Tianwen-4 mission which aims to launch an orbiter to the Jovian system and possibly Callisto around 2035,[199] and CNSA's Interstellar Express[200] and NASA's Interstellar Probe,[201] which would both use Jupiter's gravity to help them reach the edges of the heliosphere.

Moons

Jupiter has 95 known natural satellites,[7] and it is likely that this number would go up in the future due to improved instrumentation.[202] Of these, 79 are less than 10 km in diameter.[7] The four largest moons are Ganymede, Callisto, Io, and Europa (in order of decreasing size), collectively known as the "Galilean moons", and are visible from Earth with binoculars on a clear night.[203]

Galilean moons

The moons discovered by Galileo—Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto—are among the largest in the Solar System. The orbits of Io, Europa, and Ganymede form a pattern known as a Laplace resonance; for every four orbits that Io makes around Jupiter, Europa makes exactly two orbits and Ganymede makes exactly one. This resonance causes the gravitational effects of the three large moons to distort their orbits into elliptical shapes, because each moon receives an extra tug from its neighbours at the same point in every orbit it makes. The tidal force from Jupiter, on the other hand, works to circularize their orbits.[204]

The eccentricity of their orbits causes regular flexing of the three moons' shapes, with Jupiter's gravity stretching them out as they approach it and allowing them to spring back to more spherical shapes as they swing away. The friction created by this tidal flexing generates heat in the interior of the moons.[205] This is seen most dramatically in the volcanic activity of Io (which is subject to the strongest tidal forces),[205] and to a lesser degree in the geological youth of Europa's surface, which indicates recent resurfacing of the moon's exterior.[206]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Galilean satellites Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto (in order of increasing distance from Jupiter) in false colour | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Classification

Jupiter's moons were traditionally classified into four groups of four, based on their similar orbital elements.[207] This picture has been complicated by the discovery of numerous small outer moons since 1999. Jupiter's moons are currently divided into several different groups, although there are several moons which are not part of any group.[208]

The eight innermost regular moons, which have nearly circular orbits near the plane of Jupiter's equator, are thought to have formed alongside Jupiter, whilst the remainder are irregular moons and are thought to be captured asteroids or fragments of captured asteroids. The irregular moons within each group may have a common origin, perhaps as a larger moon or captured body that broke up.[209][210]

| Regular moons | |

|---|---|

| Inner group | The inner group of four small moons all have diameters of less than 200 km, orbit at radii less than 200,000 km, and have orbital inclinations of less than half a degree.[211] |

| Galilean moons[212] | These four moons, discovered by Galileo Galilei and by Simon Marius in parallel, orbit between 400,000 and 2,000,000 km, and are some of the largest moons in the Solar System. |

| Irregular moons | |

| Himalia group | A tightly clustered group of prograde-orbiting moons with orbits around 11,000,000–12,000,000 km from Jupiter.[213] |

| Carpo group | A sparsely populated group of small moons with highly inclined prograde orbits around 16,000,000–17,000,000 km from Jupiter.[7] |

| Ananke group | This group of retrograde-orbiting moons has rather indistinct borders, averaging 21,276,000 km from Jupiter with an average inclination of 149 degrees.[210] |

| Carme group | A tightly clustered group of retrograde-orbiting moons that averages 23,404,000 km from Jupiter with an average inclination of 165 degrees.[210] |

| Pasiphae group | A dispersed and only vaguely distinct retrograde group that covers all the outermost moons.[214] |

Interaction with the Solar System

As the most massive of the eight planets, the gravitational influence of Jupiter has helped shape the Solar System. With the exception of Mercury, the orbits of the system's planets lie closer to Jupiter's orbital plane than the Sun's equatorial plane. The Kirkwood gaps in the asteroid belt are mostly caused by Jupiter,[215] and the planet may have been responsible for the purported Late Heavy Bombardment in the inner Solar System's history.[216]

In addition to its moons, Jupiter's gravitational field controls numerous asteroids that have settled around the Lagrangian points that precede and follow the planet in its orbit around the Sun. These are known as the Trojan asteroids, and are divided into Greek and Trojan "camps" to honour the Iliad. The first of these, 588 Achilles, was discovered by Max Wolf in 1906; since then more than two thousand have been discovered.[217] The largest is 624 Hektor.[218]

The Jupiter family is defined as comets that have a semi-major axis smaller than Jupiter's; most short-period comets belong to this group. Members of the Jupiter family are thought to form in the Kuiper belt outside the orbit of Neptune. During close encounters with Jupiter, they are perturbed into orbits with a smaller period, which then becomes circularized by regular gravitational interactions with the Sun and Jupiter.[219]

Impacts

Jupiter has been called the Solar System's vacuum cleaner[220] because of its immense gravity well and location near the inner Solar System. There are more impacts on Jupiter, such as comets, than on any other planet in the Solar System.[221] For example, Jupiter experiences about 200 times more asteroid and comet impacts than Earth.[64] In the past, scientists believed that Jupiter partially shielded the inner system from cometary bombardment.[64] However, computer simulations in 2008 suggest that Jupiter does not cause a net decrease in the number of comets that pass through the inner Solar System, as its gravity perturbs their orbits inward roughly as often as it accretes or ejects them.[222] This topic remains controversial among scientists, as some think it draws comets towards Earth from the Kuiper belt, while others believe that Jupiter protects Earth from the Oort cloud.[223]

In July 1994, the Comet Shoemaker–Levy 9 comet collided with Jupiter.[224][225] The impacts were closely observed by observatories around the world, including the Hubble Space Telescope and Galileo spacecraft.[226][227][228][229] The event was widely covered by the media.[230]

Surveys of early astronomical records and drawings produced eight examples of potential impact observations between 1664 and 1839. However, a 1997 review determined that these observations had little or no possibility of being the results of impacts. Further investigation by this team revealed a dark surface feature discovered by astronomer Giovanni Cassini in 1690 may have been an impact scar.[231]

In culture

The existence of the planet Jupiter has been known since ancient times. It is visible to the naked eye in the night sky and can occasionally be seen in the daytime when the Sun is low.[232] To the Babylonians, this planet represented their god Marduk,[233] chief of their pantheon from the Hammurabi period.[234] They used Jupiter's roughly 12-year orbit along the ecliptic to define the constellations of their zodiac.[233]

The mythical Greek name for this planet is Zeus (Ζεύς), also referred to as Dias (Δίας), the planetary name of which is retained in modern Greek.[235] The ancient Greeks knew the planet as Phaethon (Φαέθων), meaning "shining one" or "blazing star".[236][237] The Greek myths of Zeus from the Homeric period showed particular similarities to certain Near-Eastern gods, including the Semitic El and Baal, the Sumerian Enlil, and the Babylonian god Marduk.[238] The association between the planet and the Greek deity Zeus was drawn from Near Eastern influences and was fully established by the fourth century BC, as documented in the Epinomis of Plato and his contemporaries.[239]

The god Jupiter is the Roman counterpart of Zeus, and he is the principal god of Roman mythology. The Romans originally called Jupiter the "star of Jupiter" (Iuppiter Stella), as they believed it to be sacred to its namesake god. This name comes from the Proto-Indo-European vocative compound *Dyēu-pəter (nominative: *Dyēus-pətēr, meaning "Father Sky-God", or "Father Day-God").[240] As the supreme god of the Roman pantheon, Jupiter was the god of thunder, lightning, and storms, and was called the god of light and sky.[241]

In Vedic astrology, Hindu astrologers named the planet after Brihaspati, the religious teacher of the gods, and often called it "Guru", which means the "Teacher".[242][243] In Central Asian Turkic myths, Jupiter is called Erendiz or Erentüz, from eren (of uncertain meaning) and yultuz ("star"). The Turks calculated the period of the orbit of Jupiter as 11 years and 300 days. They believed that some social and natural events connected to Erentüz's movements in the sky.[244] The Chinese, Vietnamese, Koreans, and Japanese called it the "wood star" (Chinese: 木星; pinyin: mùxīng), based on the Chinese Five Elements.[245][246][247] In China, it became known as the "Year-star" (Sui-sing), as Chinese astronomers noted that it jumped one zodiac constellation each year (with corrections). In some ancient Chinese writings, the years were, in principle, named in correlation with the Jovian zodiac signs.[248]

Gallery

- Infrared view of Jupiter, imaged by the Gemini North telescope in Hawaii, January 11, 2017. False colour added.

- Jupiter imaged in visible light by the Hubble Space Telescope, January 11, 2017. Colours and contrasts are enhanced.

- Ultraviolet view of Jupiter by Hubble, January 11, 2017.[249] False coloured image.

- Jupiter and Europa, taken by Hubble on August 25, 2020, when the planet was 653 million kilometres from Earth. False colour image.[250]

See also

- Outline of Jupiter – Overview of and topical guide to Jupiter

- Eccentric Jupiter – Jovian planet that orbits its star in an eccentric orbit

- Hot Jupiter – Class of high mass planets orbiting close to a star

- Super-Jupiter – Class of planets with more mass than Jupiter

- Jovian–Plutonian gravitational effect – Astronomical hoax

- List of gravitationally rounded objects of the Solar System

Notes

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Refers to the level of 1 bar atmospheric pressure

- ^ Based on the volume within the level of 1 bar atmospheric pressure

- ^ See for example: "IAUC 2844: Jupiter; 1975h". International Astronomical Union. October 1, 1975. Retrieved October 24, 2010. That particular word has been in use since at least 1966. See: "Query Results from the Astronomy Database". Smithsonian/NASA. Retrieved July 29, 2007.

- ^ About the same as sugar syrup (syrup USP),[42]

- ^ See Moons of Jupiter for details and cites

References

- ^ Simpson, J. A.; Weiner, E. S. C. (1989). "Jupiter". Oxford English Dictionary. Vol. 8 (2nd ed.). Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-861220-9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Williams, David R. (December 23, 2021). "Jupiter Fact Sheet". NASA. Archived from the original on December 29, 2019. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Seligman, Courtney. "Rotation Period and Day Length". Archived from the original on September 29, 2018. Retrieved August 13, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Simon, J. L.; Bretagnon, P.; Chapront, J.; Chapront-Touzé, M.; Francou, G.; Laskar, J. (February 1994). "Numerical expressions for precession formulae and mean elements for the Moon and planets". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 282 (2): 663–683. Bibcode:1994A&A...282..663S.

- ^ Суами, Д.; Сучай, Дж. (июль 2012 г.). «Неизменная плоскость Солнечной системы» . Астрономия и астрофизика . 543 : 11. Бибкод : 2012A&A...543A.133S . дои : 10.1051/0004-6361/201219011 . А133.

- ^ «ГОРИЗОНТЫ Планетно-центровый пакетный вызов перигелия в январе 2023 года» . ssd.jpl.nasa.gov (Перигелий центра планеты Юпитера (599) происходит 21 января 2023 г. на высоте 4,9510113 а.е. во время перехода rdot с отрицательного на положительное значение). НАСА/Лаборатория реактивного движения. Архивировано из оригинала 7 сентября 2021 года . Проверено 7 сентября 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Шеппард, Скотт С. «Спутники Юпитера» . Лаборатория Земли и планет . Научный институт Карнеги. Архивировано из оригинала 24 апреля 2019 года . Проверено 20 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ Зайдельманн, П. Кеннет; Аринал, Брент А.; А'Хирн, Майкл Ф.; Конрад, Альберт Р.; Консольманьо, Гай Дж.; Хестроффер, Дэниел; Хилтон, Джеймс Л.; Красинский, Георгий А.; Нойманн, Грегори А.; Оберст, Юрген; Стук, Филип Дж.; Тедеско, Эдвард Ф.; Толен, Дэвид Дж.; Томас, Питер С.; Уильямс, Иван П. (2007). «Отчет рабочей группы IAU/IAG по картографическим координатам и элементам вращения: 2006» . Небесная механика и динамическая астрономия . 98 (3): 155–180. Бибкод : 2007CeMDA..98..155S . дои : 10.1007/s10569-007-9072-y . ISSN 0923-2958 .

- ^ де Патер, Имке; Лиссауэр, Джек Дж. (2015). Планетарные науки (2-е обновленное изд.). Нью-Йорк: Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 250. ИСБН 978-0-521-85371-2 . Архивировано из оригинала 17 июля 2023 года . Проверено 17 августа 2016 г.

- ^ «Астродинамические константы» . JPL Динамика Солнечной системы. 27 февраля 2009 года. Архивировано из оригинала 21 марта 2019 года . Проверено 8 августа 2007 г.

- ^ Ни, Д. (2018). «Эмпирические модели внутренней части Юпитера по данным Юноны» . Астрономия и астрофизика . 613 : А32. Бибкод : 2018A&A...613A..32N . дои : 10.1051/0004-6361/201732183 .

- ^ Ли, Известняк; Цзян, X.; Вест, РА; Гираш, П.Дж.; Перес-Ойос, С.; Санчес-Лавега, А.; Флетчер, Л.Н.; Фортни, Джей-Джей; Ноулз, Б.; Порко, CC; Бейнс, К.Х.; Фрай, премьер-министр; Маллама, А.; Ахтерберг, РК; Саймон, А.А.; Никсон, Калифорния; Ортон, Г.С.; Дюдина, ЮА; Эвальд, СП; Шмуде, RW (2018). «Меньше поглощаемой солнечной энергии и больше внутреннего тепла Юпитера» . Природные коммуникации . 9 (1): 3709. Бибкод : 2018NatCo...9.3709L . дои : 10.1038/s41467-018-06107-2 . ПМК 6137063 . ПМИД 30213944 .

- ^ Маллама, Энтони; Кробусек, Брюс; Павлов, Христо (2017). «Комплексные широкополосные данные о звездных величинах и альбедо планет с применением к экзопланетам и Девятой планете». Икар . 282 : 19–33. arXiv : 1609.05048 . Бибкод : 2017Icar..282...19M . дои : 10.1016/j.icarus.2016.09.023 . S2CID 119307693 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Маллама, А.; Хилтон, JL (2018). «Вычисление видимых звездных величин планет для астрономического альманаха». Астрономия и вычислительная техника . 25 : 10–24. arXiv : 1808.01973 . Бибкод : 2018A&C....25...10M . дои : 10.1016/j.ascom.2018.08.002 . S2CID 69912809 .

- ^ "Энциклопедия - самые яркие тела" . ИМЦСЕ . Архивировано из оригинала 24 июля 2023 года . Проверено 29 мая 2023 г.

- ^ Бьоракер, Г.Л.; Вонг, Миннесота; де Патер, И.; Адамкович, М. (сентябрь 2015 г.). «Структура глубоких облаков Юпитера обнаружена с помощью наблюдений Кека за формами линий со спектральным разрешением». Астрофизический журнал . 810 (2): 10. arXiv : 1508.04795 . Бибкод : 2015ApJ...810..122B . дои : 10.1088/0004-637X/810/2/122 . S2CID 55592285 . 122.

- ^ Рэйчел Александр (2015). Мифы, символы и легенды тел Солнечной системы . Серия Патрика Мура по практической астрономии. Том. 177. Нью-Йорк, штат Нью-Йорк: Спрингер. стр. 141–159. Бибкод : 2015msls.book.....A . дои : 10.1007/978-1-4614-7067-0 . ISBN 978-1-4614-7066-3 .

- ^ «Наименование астрономических объектов» . Международный астрономический союз. Архивировано из оригинала 31 октября 2013 года . Проверено 23 марта 2022 г.

- ^ Джонс, Александр (1999). Астрономические папирусы из Оксиринха . Американское философское общество. стр. 62–63. ISBN 978-0-87169-233-7 .

Теперь можно проследить средневековые символы по крайней мере четырех из пяти планет до форм, встречающихся в некоторых новейших папирусных гороскопах ([ P.Oxy. ] 4272, 4274, 4275 [...]). Что касается Юпитера, это очевидная монограмма, происходящая от начальной буквы греческого имени.

- ^ Маундер, ASD (август 1934 г.). «Происхождение символов планет». Обсерватория . 57 : 238–247. Бибкод : 1934Obs....57..238M .

- ^ Харпер, Дуглас. «Юпитер» . Интернет-словарь этимологии . Архивировано из оригинала 23 марта 2022 года . Проверено 22 марта 2022 г.

- ^ «Весёлый» . Словарь.com . Архивировано из оригинала 16 февраля 2012 года . Проверено 29 июля 2007 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Крюйер, Томас С.; Буркхардт, Кристоф; Бадд, Геррит; Кляйне, Торстен (июнь 2017 г.). «Возраст Юпитера выведен на основе различных генетики и времени образования метеоритов» . Труды Национальной академии наук . 114 (26): 6712–6716. Бибкод : 2017PNAS..114.6712K . дои : 10.1073/pnas.1704461114 . ПМЦ 5495263 . ПМИД 28607079 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Босман, AD; Кридленд, Эй Джей; Мигель, Ю. (декабрь 2019 г.). «Юпитер образовался в виде груды гальки вокруг линии льда N2». Астрономия и астрофизика . 632 : 5.arXiv : 1911.11154 . Бибкод : 2019A&A...632L..11B . дои : 10.1051/0004-6361/201936827 . S2CID 208291392 . Л11.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Д'Анджело, Дж.; Вайденшиллинг, С.Дж.; Лиссауэр, Джей Джей; Боденхаймер, П. (2021). «Рост Юпитера: образование в дисках газа и твердого тела и эволюция до современной эпохи». Икар . 355 : 114087. arXiv : 2009.05575 . Бибкод : 2021Icar..35514087D . дои : 10.1016/j.icarus.2020.114087 . S2CID 221654962 .

- ^ «Я слышал, как люди называют Юпитер «неудавшейся звездой», которая просто не стала достаточно большой, чтобы сиять. Делает ли это наше Солнце своего рода двойной звездой? И почему Юпитер не стал настоящей звездой?» . Научный американец . 21 октября 1999 года . Проверено 5 декабря 2023 г.

- ^ ДРОБЫШЕВСКИЙ, Э.М. (1974). «Был ли Юпитер ядром протосолнца?». Природа . 250 (5461). ООО «Спрингер Сайенс энд Бизнес Медиа»: 35–36. Бибкод : 1974Natur.250...35D . дои : 10.1038/250035a0 . ISSN 0028-0836 . S2CID 4290185 .

- ^ «Почему Юпитер не звезда и не коричневый карлик?» . Астрономический журнал . 7 августа 2023 года. Архивировано из оригинала 5 декабря 2023 года . Проверено 5 декабря 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Уолш, К.Дж.; Морбиделли, А.; Раймонд, С.Н.; О'Брайен, ДП; Манделл, AM (2011). «Низкая масса Марса из-за ранней газовой миграции Юпитера». Природа . 475 (7355): 206–209. arXiv : 1201.5177 . Бибкод : 2011Natur.475..206W . дои : 10.1038/nature10201 . ПМИД 21642961 . S2CID 4431823 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Батыгин, Константин (2015). «Решающая роль Юпитера в ранней эволюции внутренней Солнечной системы» . Труды Национальной академии наук . 112 (14): 4214–4217. arXiv : 1503.06945 . Бибкод : 2015PNAS..112.4214B . дои : 10.1073/pnas.1423252112 . ПМЦ 4394287 . ПМИД 25831540 .

- ^ Рауль О Чаметла; Дженнаро Д'Анджело; Маурисио Рейес-Руис; F Хавьер Санчес-Сальседо (март 2020 г.). «Захват и миграция Юпитера и Сатурна в резонансе среднего движения в газовом протопланетном диске» . Ежемесячные уведомления Королевского астрономического общества . 492 (4): 6007–6018. arXiv : 2001.09235 . дои : 10.1093/mnras/staa260 .

- ^ Хайш-младший, Кентукки; Лада, Е.А.; Лада, CJ (2001). «Частота дисков и время жизни в молодых кластерах» . Астрофизический журнал . 553 (2): 153–156. arXiv : astro-ph/0104347 . Бибкод : 2001ApJ...553L.153H . дои : 10.1086/320685 . S2CID 16480998 .

- ^ Фазекас, Эндрю (24 марта 2015 г.). «Наблюдайте: Юпитер, разрушительный шар ранней Солнечной системы» . Нэшнл Географик . Архивировано из оригинала 14 марта 2017 года . Проверено 18 апреля 2021 г.

- ^ Зубе, Н.; Ниммо, Ф.; Фишер, Р.; Джейкобсон, С. (2019). «Ограничения на сроки формирования планет земной группы и процессы уравновешивания в сценарии Гранд-Так, обусловленные эволюцией изотопов Hf-W» . Письма о Земле и планетологии . 522 (1): 210–218. arXiv : 1910.00645 . Бибкод : 2019E&PSL.522..210Z . дои : 10.1016/j.epsl.2019.07.001 . ПМЦ 7339907 . ПМИД 32636530 . S2CID 199100280 .

- ^ Д'Анджело, Дж.; Марзари, Ф. (2012). «Внешняя миграция Юпитера и Сатурна в эволюционировавших газовых дисках». Астрофизический журнал . 757 (1): 50 (23 стр.). arXiv : 1207.2737 . Бибкод : 2012ApJ...757...50D . дои : 10.1088/0004-637X/757/1/50 . S2CID 118587166 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Пирани, С.; Йохансен, А.; Битч, Б.; Мастилл, Эй Джей; Туррини, Д. (март 2019 г.). «Последствия планетарной миграции на малых телах ранней Солнечной системы» . Астрономия и астрофизика . 623 : А169. arXiv : 1902.04591 . Бибкод : 2019A&A...623A.169P . дои : 10.1051/0004-6361/201833713 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Раскрыто неизвестное путешествие Юпитера» . ScienceDaily . Лундский университет. 22 марта 2019 года. Архивировано из оригинала 22 марта 2019 года . Проверено 25 марта 2019 г.

- ^ Левисон, Гарольд Ф.; Морбиделли, Алессандро; Ван Лаэрховен, Криста; Гомес, Р. (2008). «Происхождение структуры пояса Койпера при динамической нестабильности орбит Урана и Нептуна». Икар . 196 (1): 258–273. arXiv : 0712.0553 . Бибкод : 2008Icar..196..258L . дои : 10.1016/j.icarus.2007.11.035 . S2CID 7035885 .

- ^ Оберг, К.И.; Вордсворт, Р. (2019). «Композиция Юпитера предполагает внешний вид его ядра в виде снежной линии N_{2}» . Астрономический журнал . 158 (5). arXiv : 1909.11246 . дои : 10.3847/1538-3881/ab46a8 . S2CID 202749962 .

- ^ Оберг, К.И.; Вордсворт, Р. (2020). «Ошибка: «Композиция Юпитера предполагает внешний вид его ядра в сборе со снежной линией N2» » . Астрономический журнал . 159 (2): 78. дои : 10.3847/1538-3881/ab6172 . S2CID 214576608 .

- ^ Денеке, Эдвард Дж. (7 января 2020 г.). Экзамены Риджентс и ответы: Науки о Земле — физические условия 2020 . Образовательная серия Бэрронса. п. 419. ИСБН 978-1-5062-5399-2 .

- ^ Сворбрик, Джеймс (2013). Энциклопедия фармацевтических технологий . Том. 6. ЦРК Пресс. п. 3601. ИСБН 978-1-4398-0823-8 . Архивировано из оригинала 26 марта 2023 года . Проверено 19 марта 2023 г.

Сироп USP (1,31 г/см 3 )

- ^ Аллен, Клэбон Уолтер ; Кокс, Артур Н. (2000). Астрофизические величины Аллена . Спрингер. стр. 295–296. ISBN 978-0-387-98746-0 . Архивировано из оригинала 21 февраля 2023 года . Проверено 18 марта 2022 г.

- ^ Полянин Андрей Дмитриевич; Черноуцан, Алексей (18 октября 2010 г.). Краткий справочник по математике, физике и инженерным наукам . ЦРК Пресс. п. 1041. ИСБН 978-1-4398-0640-1 .

- ^ Гийо, Тристан; Готье, Даниэль; Хаббард, Уильям Б. (декабрь 1997 г.). «ПРИМЕЧАНИЕ: Новые ограничения на состав Юпитера на основе измерений Галилея и моделей внутреннего пространства». Икар . 130 (2): 534–539. arXiv : astro-ph/9707210 . Бибкод : 1997Icar..130..534G . дои : 10.1006/icar.1997.5812 . S2CID 5466469 .

- ^ Фрэн Багеналь; Тимоти Э. Даулинг; Уильям Б. Маккиннон, ред. (2006). Юпитер: Планета, спутники и магнитосфера . Издательство Кембриджского университета. стр. 59–75. ISBN 0521035457 .

- ^ Вдовиченко В.Д.; Каримов А.М.; Кириенко Г.А.; Лысенко, П.Г.; Тейфель, В.Г.; Филиппов В.А.; Харитонова Г.А.; Хоженец, АП (2021). «Зональные особенности поведения полос слабого молекулярного поглощения на Юпитере». Исследования Солнечной системы . 55 (1): 35–46. Бибкод : 2021SoSyR..55...35В . дои : 10.1134/S003809462101010X . S2CID 255069821 .

- ^ Ким, С.Дж.; Колдуэлл, Дж.; Риволо, Арканзас; Вагнер, Р. (1985). «Инфракрасное полярное просветление на Юпитере III. Спектрометрия в ходе эксперимента Voyager 1 IRIS». Икар . 64 (2): 233–248. Бибкод : 1985Icar...64..233K . дои : 10.1016/0019-1035(85)90201-5 .

- ^ Готье, Д.; Конрат, Б.; Фласар, М.; Ханель, Р.; Кунде, В.; Чедин, А.; Скотт, Н. (1981). «Изобилие гелия на Юпитере с «Вояджера». Журнал геофизических исследований . 86 (А10): 8713–8720. Бибкод : 1981JGR....86.8713G . дои : 10.1029/JA086iA10p08713 . hdl : 2060/19810016480 . S2CID 122314894 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кунде, В.Г.; Флазар, FM; Дженнингс, Делавэр; Безар, Б.; Штробель, Д.Ф.; и др. (10 сентября 2004 г.). «Состав атмосферы Юпитера по данным эксперимента по тепловой инфракрасной спектроскопии Кассини» . Наука . 305 (5690): 1582–1586. Бибкод : 2004Sci...305.1582K . дои : 10.1126/science.1100240 . ПМИД 15319491 . S2CID 45296656 .

- ^ «Супермаркет Солнечной туманности» (PDF) . НАСА.gov. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 17 июля 2023 г. Проверено 10 июля 2023 г.

- ^ Ниманн, HB; Атрея, СК; Кариньян, Греция; Донахью, ТМ; Хаберман, Дж.А.; и др. (1996). «Масс-спектрометр зонда Галилео: состав атмосферы Юпитера». Наука . 272 (5263): 846–849. Бибкод : 1996Sci...272..846N . дои : 10.1126/science.272.5263.846 . ПМИД 8629016 . S2CID 3242002 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б фон Зан, У.; Хантен, DM; Лемахер, Г. (1998). «Гелий в атмосфере Юпитера: результаты эксперимента с гелиевым интерферометром зонда Галилео» . Журнал геофизических исследований . 103 (Е10): 22815–22829. Бибкод : 1998JGR...10322815V . дои : 10.1029/98JE00695 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Стивенсон, Дэвид Дж. (май 2020 г.). «Внутреннее пространство Юпитера, раскрытое Юноной» . Ежегодный обзор наук о Земле и планетах . 48 : 465–489. Бибкод : 2020AREPS..48..465S . doi : 10.1146/annurev-earth-081619-052855 . S2CID 212832169 .

- ^ Ингерсолл, AP; Хаммель, HB; Спилкер, Т.Р.; Янг, RE (1 июня 2005 г.). «Внешние планеты: Ледяные гиганты» (PDF) . Лунно-планетарный институт. Архивировано (PDF) оригинала 9 октября 2022 г. Проверено 1 февраля 2007 г.

- ^ Хофштадтер, Марк (2011), «Атмосферы ледяных гигантов, Урана и Нептуна» (PDF) , Белая книга Десятилетнего исследования планетарной науки , Национальный исследовательский совет США , стр. 1–2, в архиве (PDF) из оригинала 17 июля 2023 г. , получено 18 января 2015 г.

- ^ Макдугал, Дуглас В. (2012). «Двойная система, близкая к дому: как Луна и Земля вращаются вокруг друг друга». Гравитация Ньютона . Конспект лекций бакалавриата по физике. Спрингер Нью-Йорк. стр. 193–211 . дои : 10.1007/978-1-4614-5444-1_10 . ISBN 978-1-4614-5443-4 .

барицентр находится на расстоянии 743 000 км от центра Солнца. Радиус Солнца составляет 696 000 км, то есть оно находится на высоте 47 000 км над поверхностью.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Берджесс, Эрик (1982). Юпитер: Одиссея гиганта . Нью-Йорк: Издательство Колумбийского университета. ISBN 978-0-231-05176-7 .

- ^ Шу, Фрэнк Х. (1982). Физическая вселенная: введение в астрономию . Серия книг по астрономии (12-е изд.). Университетские научные книги. п. 426 . ISBN 978-0-935702-05-7 .

- ^ Дэвис, Эндрю М.; Турекян, Карл К. (2005). Метеориты, кометы и планеты . Трактат по геохимии. Том. 1. Эльзевир. п. 624. ИСБН 978-0-08-044720-9 .

- ^ Шнайдер, Жан (2009). «Энциклопедия внесолнечных планет: интерактивный каталог» . Энциклопедия внесолнечных планет . Архивировано из оригинала 28 октября 2023 года . Проверено 9 августа 2014 г.

- ^ Фэн, Фабо; Батлер, Р. Пол; и др. (август 2022 г.). «3D-выбор 167 субзвездных спутников близлежащих звезд» . Серия дополнений к астрофизическому журналу . 262 (21): 21. arXiv : 2208.12720 . Бибкод : 2022ApJS..262...21F . дои : 10.3847/1538-4365/ac7e57 . S2CID 251864022 .

- ^ Сигер, С.; Кушнер, М.; Иер-Маджумдер, Калифорния; Милицер, Б. (2007). «Отношения массы и радиуса твердых экзопланет». Астрофизический журнал . 669 (2): 1279–1297. arXiv : 0707.2895 . Бибкод : 2007ApJ...669.1279S . дои : 10.1086/521346 . S2CID 8369390 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час Как устроена Вселенная 3 . Том. Юпитер: разрушитель или спаситель? Канал Дискавери. 2014.

- ^ Гийо, Тристан (1999). «Внутренности планет-гигантов внутри и за пределами Солнечной системы» (PDF) . Наука . 286 (5437): 72–77. Бибкод : 1999Sci...286...72G . дои : 10.1126/science.286.5437.72 . ПМИД 10506563 . Архивировано (PDF) оригинала 9 октября 2022 г. Проверено 24 апреля 2022 г.

- ^ Берроуз, Адам; Хаббард, Всемирный банк; Лунин, Дж.И.; Либерт, Джеймс (июль 2001 г.). «Теория коричневых карликов и внесолнечных планет-гигантов». Обзоры современной физики . 73 (3): 719–765. arXiv : astro-ph/0103383 . Бибкод : 2001РвМП...73..719Б . дои : 10.1103/RevModPhys.73.719 . S2CID 204927572 .

Следовательно, HBMM при солнечной металличности и Y α = 50,25 составляет 0,07 – 0,074 M ☉ , ... тогда как HBMM при нулевой металличности составляет 0,092 M ☉

- ^ фон Беттичер, Александр; Трио, Амори HMJ; Кело, Дидье; Гилл, Сэм; Лендл, Моника; Дельрес, Летиция; Андерсон, Дэвид Р.; Коллиер Кэмерон, Эндрю; Фаеди, Франческа; Гиллон, Майкл; Гомес Макео Чу, Илен; Хебб, Лесли; Хеллиер, Коэл; Жехин, Эммануэль; Макстед, Пьер Флорида; Мартин, Дэвид В.; Пепе, Франческо; Поллакко, Дон; Сегрансан, Дэмиен; Смолли, Барри; Удри, Стефан; Уэст, Ричард (август 2017 г.). «Проект EBLM. III. Маломассивная звезда размером с Сатурн на пределе горения водорода». Астрономия и астрофизика . 604 : 6.arXiv : 1706.08781 . Бибкод : 2017A&A...604L...6V . дои : 10.1051/0004-6361/201731107 . S2CID 54610182 . Л6.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час Элкинс-Тантон, Линда Т. (2011). Юпитер и Сатурн (переработанная ред.). Нью-Йорк: Дом Челси. ISBN 978-0-8160-7698-7 .

- ^ Ирвин, Патрик (2003). Планеты-гиганты нашей Солнечной системы: атмосфера, состав и структура . Springer Science & Business Media. п. 62. ИСБН 978-3-540-00681-7 . Архивировано из оригинала 19 июня 2024 года . Проверено 23 апреля 2022 г.

- ^ Ирвин, Патрик Дж.Дж. (2009) [2003]. Гигантские планеты нашей Солнечной системы: атмосфера, состав и структура (второе изд.). Спрингер. п. 4. ISBN 978-3-642-09888-8 . Архивировано из оригинала 19 июня 2024 года . Проверено 6 марта 2021 г.

По оценкам, радиус Юпитера в настоящее время сокращается примерно на 1 мм/год

. - ^ Перейти обратно: а б Гийо, Тристан; Стивенсон, Дэвид Дж.; Хаббард, Уильям Б.; Сомон, Дидье (2004). «Глава 3: Внутренняя часть Юпитера». В Багенале, Фрэн; Даулинг, Тимоти Э.; Маккиннон, Уильям Б. (ред.). Юпитер: Планета, спутники и магнитосфера . Издательство Кембриджского университета . ISBN 978-0-521-81808-7 .

- ^ Боденхаймер, П. (1974). «Расчеты ранней эволюции Юпитера». Икар . 23. 23 (3): 319–325. Бибкод : 1974Icar...23..319B . дои : 10.1016/0019-1035(74)90050-5 .

- ^ Смолуховский, Р. (1971). «Металлические недра и магнитные поля Юпитера и Сатурна» . Астрофизический журнал . 166 : 435. Бибкод : 1971ApJ...166..435S . дои : 10.1086/150971 .

- ^ Валь, С.М.; Хаббард, Уильям Б.; Милитцер, Б.; Гийо, Тристан; Мигель, Ю.; Мовшовиц, Н.; Каспи, Ю.; Хеллед, Р.; Риз, Д.; Галанти, Э.; Левин, С.; Коннерни, Дж. Э.; Болтон, SJ (2017). «Сравнение моделей внутренней структуры Юпитера с гравитационными измерениями Юноны и ролью разреженного ядра» . Письма о геофизических исследованиях . 44 (10): 4649–4659. arXiv : 1707.01997 . Бибкод : 2017GeoRL..44.4649W . дои : 10.1002/2017GL073160 .

- ^ Шан-Фей Лю; и др. (15 августа 2019 г.). «Формирование разбавленного ядра Юпитера в результате гигантского удара». Природа . 572 (7769): 355–357. arXiv : 2007.08338 . Бибкод : 2019Natur.572..355L . дои : 10.1038/s41586-019-1470-2 . ПМИД 31413376 . S2CID 199576704 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Чанг, Кеннет (5 июля 2016 г.). «Космический корабль НАСА «Юнона» вышел на орбиту Юпитера» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 2 мая 2019 года . Проверено 5 июля 2016 г.

- ^ Уолл, Майк (26 мая 2017 г.). «Еще странности Юпитера: планета-гигант может иметь огромное «нечеткое» ядро» . space.com . Архивировано из оригинала 20 апреля 2021 года . Проверено 20 апреля 2021 г.

- ^ Вейтеринг, Ханнеке (10 января 2018 г.). « Совершенно неправильно» на Юпитере: что ученые почерпнули из миссии НАСА «Юнона» . space.com . Архивировано из оригинала 9 ноября 2020 года . Проверено 26 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Стивенсон, диджей; Боденхаймер, П.; Лиссауэр, Джей Джей; Д'Анджело, Дж. (2022). «Смешение конденсируемых компонентов с H-He во время формирования и эволюции Юпитера» . Планетарный научный журнал . 3 (4): там же 74. arXiv : 2202.09476 . Бибкод : 2022PSJ.....3...74S . дои : 10.3847/PSJ/ac5c44 . S2CID 247011195 .

- ^ Лю, Сан-Франциско; Хори, Ю.; Мюллер, С.; Чжэн, X.; Хеллед, Р.; Лин, Д.; Изелла, А. (2019). «Формирование разреженного ядра Юпитера в результате гигантского удара». Природа . 572 (7769): 355–357. arXiv : 2007.08338 . Бибкод : 2019Natur.572..355L . дои : 10.1038/s41586-019-1470-2 . ПМИД 31413376 . S2CID 199576704 .

- ^ Гийо, Т. (2019). «Признаки того, что Юпитер был перемешан гигантским ударом» . Природа . 572 (7769): 315–317. Бибкод : 2019Natur.572..315G . дои : 10.1038/d41586-019-02401-1 . ПМИД 31413374 .

- ^ Траченко К.; Бражкин В.В.; Болматов, Д. (март 2014 г.). «Динамический переход сверхкритического водорода: определение границы между недром и атмосферой газовых гигантов». Физический обзор E . 89 (3): 032126. arXiv : 1309.6500 . Бибкод : 2014PhRvE..89c2126T . дои : 10.1103/PhysRevE.89.032126 . ПМИД 24730809 . S2CID 42559818 . 032126.

- ^ Коултер, Дауна. «Причудливая жидкость внутри Юпитера?» . НАСА . Архивировано из оригинала 9 декабря 2021 года . Проверено 8 декабря 2021 г.

- ^ Буолдуин, Эмили. «На Уране и Нептуне возможны океаны алмазов» . Астрономия сейчас . Архивировано из оригинала 8 апреля 2022 года . Проверено 8 декабря 2021 г.

- ^ «Исследование системы НАСА Юпитер» . НАСА . Архивировано из оригинала 4 ноября 2021 года . Проверено 8 декабря 2021 г.

- ^ Гийо, Т. (1999). «Сравнение недр Юпитера и Сатурна» . Планетарная и космическая наука . 47 (10–11): 1183–1200. arXiv : astro-ph/9907402 . Бибкод : 1999P&SS...47.1183G . дои : 10.1016/S0032-0633(99)00043-4 . S2CID 19024073 . Архивировано из оригинала 19 мая 2021 года . Проверено 21 июня 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Ланг, Кеннет Р. (2003). «Юпитер: гигантская примитивная планета» . НАСА. Архивировано из оригинала 14 мая 2011 года . Проверено 10 января 2007 г.

- ^ Лоддерс, Катарина (2004). «Юпитер состоит из большего количества смолы, чем льда» (PDF) . Астрофизический журнал . 611 (1): 587–597. Бибкод : 2004ApJ...611..587L . дои : 10.1086/421970 . S2CID 59361587 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 12 апреля 2020 г.

- ^ Бригоо, С.; Лубейр, П.; Милло, М.; Ригг, младший; Сельерс, премьер-министр; Эггерт, Дж. Х.; Жанлоз, Р.; Коллинз, GW (2021). «Доказательства несмешиваемости водорода с гелием во внутренних условиях Юпитера». Природа . 593 (7860): 517–521. Бибкод : 2021Natur.593..517B . дои : 10.1038/s41586-021-03516-0 . ОСТИ 1820549 . ПМИД 34040210 . S2CID 235217898 .

- ^ Крамер, Мириам (9 октября 2013 г.). «Алмазный дождь может заполнить небо Юпитера и Сатурна» . Space.com . Архивировано из оригинала 27 августа 2017 года . Проверено 27 августа 2017 г.

- ^ Каплан, Сара (25 августа 2017 г.). «На Уран и Нептун идет дождь из сплошных алмазов» . Вашингтон Пост . Архивировано из оригинала 27 августа 2017 года . Проверено 27 августа 2017 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Гийо, Тристан; Стивенсон, Дэвид Дж.; Хаббард, Уильям Б.; Сомон, Дидье (2004). «Внутренности Юпитера» . В Багенале, Фрэн; Даулинг, Тимоти Э.; Маккиннон, Уильям Б. (ред.). Юпитер. Планета, спутники и магнитосфера . Кембриджская планетология. Том. 1. Кембридж, Великобритания: Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 45. Бибкод : 2004jpsm.book...35G . ISBN 0-521-81808-7 . Архивировано из оригинала 26 марта 2023 года . Проверено 19 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Атрея, Сушил К.; Махаффи, PR; Ниманн, HB; Вонг, Миннесота; Оуэн, TC (февраль 2003 г.). «Состав и происхождение атмосферы Юпитера - обновленная информация и последствия для внесолнечных планет-гигантов». Планетарная и космическая наука . 51 (2): 105–112. Бибкод : 2003P&SS...51..105A . дои : 10.1016/S0032-0633(02)00144-7 .

- ^ Леффлер, Марк Дж.; Хадсон, Реджи Л. (март 2018 г.). «Окрашивание облаков Юпитера: Радиолиз гидросульфида аммония (NH4SH)» (PDF) . Икар . 302 : 418–425. Бибкод : 2018Icar..302..418L . дои : 10.1016/j.icarus.2017.10.041 . Архивировано (PDF) оригинала 9 октября 2022 г. Проверено 25 апреля 2022 г.

- ^ Ингерсолл, Эндрю П .; Даулинг, Тимоти Э.; Гираш, Питер Дж.; Ортон, Гленн С.; Прочтите, Питер Л.; Санчес-Лавега, Агустин; Шоумен, Адам П.; Саймон-Миллер, Эми А.; Васавада, Ашвин Р. (2004). Багеналь, Фрэн; Даулинг, Тимоти Э.; Маккиннон, Уильям Б. (ред.). «Динамика атмосферы Юпитера» (PDF) . Юпитер. Планета, спутники и магнитосфера . Кембриджская планетология. 1 . Кембридж, Великобритания: Издательство Кембриджского университета: 105–128. ISBN 0-521-81808-7 . Архивировано (PDF) оригинала 9 октября 2022 г. Проверено 8 марта 2022 г.