Gun violence in the United States

Gun violence is a term of political, economic and sociological interest referring to the tens of thousands of annual firearms-related deaths and injuries occurring in the United States.[2]

A U.S. male aged 15–24 is 70 times more likely to be killed with a gun than a French male or British male[3]

In 2022, up to 100 daily fatalities and hundreds of daily injuries were attributable to gun violence in the United States.[4] In 2018, the most recent year for which data are available, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC) National Center for Health Statistics reported 38,390 deaths by firearm, of which 24,432 were suicides.[5][6] The national rate of firearm deaths rose from 10.3 people for every 100,000 in 1999 to 11.9 people per 100,000 in 2018, equating to over 109 daily deaths (or about 14,542 annual homicides).[7][8][9][10] In 2010, there were 19,392 firearm-related suicides, and 11,078 firearm-related homicides in the U.S.[11] In 2010, 358 murders were reported involving a rifle while 6,009 were reported involving a handgun; another 1,939 were reported with an unspecified type of firearm.[12] In 2011, a total of 478,400 fatal and nonfatal violent crimes were committed with a firearm.[13]

According to a Pew Research Center report, gun deaths among America's children rose 50% from 2019 to 2021.[14]

Firearms are overwhelmingly used in more defensive scenarios (self-defense and home protection) than offensive scenarios in the United States.[15][16] In 2021, The National Firearms Survey, currently the nation's largest and most comprehensive study into American firearm ownership, found that privately owned firearms are used in roughly 1.7 million defensive usage cases (self-defense from an attacker/attackers inside and outside the home) per year across the nation, compared to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (C.D.C.) report of 20,958 homicides in that same year.[17][18][19]

Legislation at the federal, state, and local levels has attempted to address gun violence through methods including restricting firearms purchases by youths and other "at-risk" populations, setting waiting periods for firearm purchases, establishing gun buyback programs, law enforcement and policing strategies, stiff sentencing of gun law violators, education programs for parents and children, and community outreach programs.

Some medical professionals express concern regarding the prevalence and growth of gun violence in America, even comparing gun violence in the United States to a disease or epidemic.[20] Relatedly, recent polling suggests up to 26% of Americans believe guns are the number one national public health threat.[21]

Gun ownership

[edit]

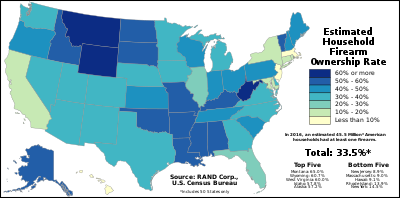

The Congressional Research Service in 2009 estimated that among US population of 306 million people, there were 310 million firearms in the U.S., not including military armaments, and of these, 114 million were handguns, 110 million were rifles, and 86 million were shotguns.[24][25] Accurate figures for civilian gun ownership are difficult to determine.[26] The percentage of Americans and American households who claim to own guns has been in long-term decline, according to the General Social Survey poll. It found that gun ownership by households may have declined from about half, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, down to 32% in 2015. The percentage of individual owners may have declined from 31% in 1985 to 22% in 2014.[27]

Gun ownership figures are generally estimated via polling, by such organizations as the General Social Survey (GSS), Harris Interactive, and Gallup. There are significant disparities in the results across polls by different organizations, calling into question their reliability.[28] In Gallup's 1972 survey, 43% reported having a gun in their home, while GSS's 1973 survey resulted in 49% reporting a gun in the home; in 1993, Gallup's poll results were 51%, while GSS's 1994 poll showed 43%.[29] In 2012, Gallup's survey showed 47% of Americans reporting having a gun in their home,[30] while the GSS in 2012 reports 34%.[29] In 2018 it was estimated that U.S. civilians own 393 million firearms,[31] and that 40% to 42% of the households in the country have at least one gun. However, record gun sales followed in the subsequent years.[32][33][34]

In 1997, estimates were about 44 million gun owners in the United States. These owners possessed around 192 million firearms, of which an estimated 65 million were handguns.[35] A National Survey on Private Ownership and Use of Firearms (NSPOF), conducted in 1994, estimated that Americans owned 192 million guns: 36% rifles, 34% handguns, 26% shotguns, and 4% other types of long guns.[35] Most firearm owners owned multiple firearms, with the NSPOF survey indicating 25% of adults owned firearms.[35] Throughout the 1970s and much of the 1980s, the estimated rate of gun ownership in the home ranged from 45 to 50%.[29] After highly publicized mass murders, it is consistently observed that there are rapid increases in gun purchases and large crowds at gun vendors and gun shows, due to fears of increased gun control .[36][37][38][39][40]

Gun ownership rates also vary across geographic regions, ranging from estimates of 25% in the Northeastern United States to 60% in the East South Central States.[41] A Gallup poll (2004) estimated that 49% of men reported gun ownership, compared to 33% of women, while 44% of whites owned a gun, compared to only 24% of nonwhites.[42] An estimated 56% of those living in rural areas owned a gun, compared to 40% of suburbanites and 29% of those in urban areas.[42] Approximately 53% of Republicans owned guns, compared to 36% of political independents and 31% of Democrats.[42] One criticism of the GSS survey and other proxy measures of gun ownership, is that they do not provide adequate macro-level detail to allow conclusions on the relationship between overall firearm ownership and gun violence.[43] Gary Kleck compared various survey and proxy measures and found no correlation between overall firearm ownership and gun violence.[44][45] Studies by David Hemenway and his colleagues, which used GSS data and the fraction of suicides committed with a gun as a proxy for gun ownership rates, found a strong positive correlation between gun ownership and homicide in the United States.[46][47] A 2006 study by Philip J. Cook and Jens Ludwig, also using the percentage of suicides committed with a gun as a proxy, found that gun prevalence correlated with increased homicide rates.[48]

Defensive gun violence

[edit]The effectiveness and safety of guns used for personal defense is debated. Studies place the instances of guns used in personal defense as low as 65,000 times per year, and as high as 2.5 million times per year. Under President Bill Clinton, the Department of Justice conducted a survey in 1994 that placed the usage rate of guns used in personal defense at 1.5 million times per year, based on an extrapolation from 45 survey respondents reporting using a firearm for self-defense, but noted this was likely to be an overestimate due to the low sample size.[45] A May 2014 Harvard Injury Control Research Center (HICRC) survey of 150 firearms researchers found that only 8% of them agreed that 'In the United States, guns are used in self-defense far more often than they are used in crime'.[49]

HICRC random-respondent national surveys were also conducted in 1996 and 1999 to investigate the use of guns in self-defense. Survey participants were asked open-ended questions about defensive gun use incidents and detailed questions about both gun victimization and self-defense gun use; self-reported defensive gun use incidents were then examined by five criminal court judges, who were asked to determine whether these self-defense gun uses were likely to be legal. The surveys found that far more respondents reported having been threatened or intimidated with a gun, than having used a gun to protect themselves, even after having excluded many of these responses; and, a majority of the reported self-defense gun uses were rated by a majority of judges as probably illegal. This was true even when it was assumed that the respondent had a permit to own and carry the gun, and that the event was described honestly. The conclusion being from this report that most self-described 'defensive' gun uses, are gun uses in escalating arguments, and are both socially undesirable and illegal.[50][51] Further studies by HICRC also found the following: firearms in the home are used more often to intimidate intimates than to thwart crime;[52] gun use in self-defense is rare and not more effective at preventing injury than other protective actions;[53] and a study of hospital gun-shot appearances does not back up the claim of millions of defensive gun use, as virtually all criminals with a gunshot wound go to hospital;[54][55] with virtually all having been shot whilst the victim of crime and not shot whilst offending.[56][50]

Between 1987 and 1990, David McDowall et al. found that guns were used in defense during a crime incident 64,615 times annually (258,460 times total over the whole period).[57] This equated to two times out of 1,000 criminal incidents (0.2%) that occurred in this period, including criminal incidents where no guns were involved at all.[57] For violent crimes, assault, robbery, and rape, guns were used 0.8% of the time in self-defense.[57] Of the times that guns were used in self-defense, 71% of the crimes were committed by strangers, with the rest of the incidents evenly divided between offenders that were acquaintances or persons well known to the victim.[57] In 28% of incidents where a gun was used for self-defense, victims fired the gun at the offender.[57] In 20% of the self-defense incidents, the guns were used by police officers.[57] During this same period, 1987 to 1990, there were 11,580 gun homicides per year (46,319 total),[58] and the National Crime Victimization Survey estimated that 2,628,532 nonfatal crimes involving guns occurred.[57]

McDowall's study for the American Journal of Public Health contrasted with a 1995 study by Gary Kleck and Marc Gertz, which found that 2.45 million crimes were thwarted each year in the U.S. using guns, and in most cases, the potential victim never fired a shot.[59] The results of the Kleck studies have been cited many times in scholarly and popular media.[60][61][62][63][64][65][66] The methodology of the Kleck and Gertz study has been criticized by some researchers[67][68] but also defended by gun-control advocate Marvin Wolfgang.[69]

Using cross-sectional time-series data for U.S. counties from 1977 to 1992, Lott and Mustard of the Law School at the University of Chicago found that allowing citizens to carry concealed weapons deters violent crimes and appears to produce no increase in accidental deaths. They claimed that if those states which did not have right-to-carry concealed gun provisions had adopted them in 1992, approximately 1,570 murders, 4,177 rapes, and over 60,000 aggravated assaults would have been avoided yearly.[70] On the other hand, regarding the efficacy of laws allowing use of firearms for self-defense like stand your ground laws, a 2018 RAND Corporation review of existing research concluded that "there is moderate evidence that stand-your-ground laws may increase homicide rates and limited evidence that the laws increase firearm homicides in particular."[71] In 2019, RAND authors published an update, writing "Since publication of RAND's report, at least four additional studies meeting RAND's standards of rigor have reinforced the finding that "stand your ground" laws increase homicides. None of them found that "stand your ground" laws deter violent crime. No rigorous study has yet determined whether "stand your ground" laws promote legitimate acts of self-defense.[72]

Suicides

[edit]

In the U.S., most people who die of suicide use a gun, and most deaths by gun are suicides.

In 2010, there were 19,392 firearm-related suicides in the U.S.[11] In 2017, over half of the nation's 47,173 suicides involved a firearm.[77][78] In 2010, the U.S. Department of Justice reported that about 60% of all adult firearm deaths were by suicide, 61% more than deaths by homicide.[79] One study found that military veterans used firearms in about 67% of suicides in 2014.[80] Firearms are the most lethal method of suicide, with a lethality rate 2.6 times higher than suffocation (the second-most lethal method).[81]

In the United States, access to firearms is associated with an increased risk of suicide.[82] A 1992 case-control study in the New England Journal of Medicine showed an association between estimated household firearm ownership and suicide rates, finding that individuals living in a home where firearms are present are more likely to successfully commit suicide than those individuals who do not own firearms, by a factor of 3 or 4.[2][83] A 2006 study by researchers from the Harvard School of Public Health found a significant association between changes in estimated household gun ownership rates and suicide rates in the United States among men, women, and children.[84]

A 2007 study by the same research team found that in the United States, estimated household gun ownership rates were strongly associated with overall suicide rates and gun suicide rates, but not with non-gun suicide rates.[85] A 2013 study reproduced this finding, even after controlling for different underlying rates of suicidal behavior by states.[86] A 2015 study also found a strong association between estimated gun ownership rates in American cities and rates of both overall and gun suicide, but not with non-gun suicide.[87] Correlation studies comparing different countries do not always find a statistically significant effect.[88]: 30

A 2016 cross-sectional study showed a strong association between estimated household gun ownership rates and gun-related suicide rates among men and women in the United States. The same study found a strong association between estimated gun ownership rates and overall suicide rates, but only in men.[89] During the 1980s and early 1990s, there was a strong upward trend in adolescent suicides with guns[90] as well as a sharp overall increase in suicides among those age 75 and over.[91] A 2018 study found that temporary gun seizure laws were associated with a 13.7% reduction in firearm suicides in Connecticut and a 7.5% reduction in firearm suicides in Indiana.[92]

David Hemenway, professor of health policy at Harvard University's School of Public Health, and director of the Harvard Injury Control Research Center and the Harvard Youth Violence Prevention Center, stated

Differences in overall suicide rates across cities, states and regions in the United States are best explained not by differences in mental health, suicide ideation, or even suicide attempts, but by availability of firearms. Many suicides are impulsive, and the urge to die fades away. Firearms are a swift, lethal method of suicide with a high case-fatality rate.[93]

There are over twice as many gun-related suicides as gun-related homicides in the United States.[94] Firearms are the most popular method of suicide due to the lethality of the weapon. 90% of all suicides attempted using a firearm result in a fatality, as opposed to less than 3% of suicide attempts involving cutting or drug-use.[86] The risk of someone attempting suicide is also 4.8 times greater if they are exposed to a firearm on a regular basis; for example, in the home.[95]

Homicides

[edit]

Statistics

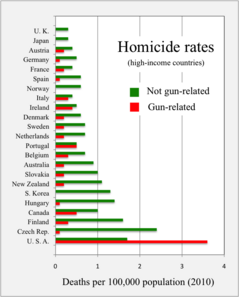

[edit]Unlike other high-income OECD countries, most homicides in the U.S. are gun homicides.[76] In the U.S. in 2011, 67 percent of homicide victims were killed using a firearm: 66 percent of single-victim homicides and 79 percent of multiple-victim homicides.[97] Between 1968 and 2011, about 1.4 million people died from firearms in the U.S. This number includes all deaths resulting from a firearm, including suicides, homicides, and accidents.[98] Compared to 22 other high-income nations, the U.S. gun-related homicide rate is 25 times higher.[93] Although it has half the population of the other 22 nations combined, among those 22 nations studied, the U.S. had 82 percent of gun deaths, 90 percent of all women killed with guns, 91 percent of children under 14 and 92 percent of young people between ages 15 and 24 killed with guns, with guns being the leading cause of death for children.[93] The ownership and regulation of guns are among the most widely debated issues in the country.

In 1993, there were seven gun homicides for every 100,000 people; by 2013, that figure had fallen to 3.6, according to Pew Research.[99]

The Centers for Disease Control reports that there were 11,078 gun homicides in the U.S. in 2010.[11] This is higher than the FBI's count.[12] The CDC also stated there were 14,414 (or 4.4 per 100,000 population) homicides by firearm in 2018, and stated that there were a total of 19,141 homicides (5.8 per 100,000 population) in 2019.[100] Gun-related deaths among children in the U.S. in 2021 was 4,752, surpassing the record total seen during the first year of the pandemic, a new analysis of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data found.[101]

The police chief of Washington, DC attributes the 203 homicides in 2022 to an influx of guns from out-of-town, marking the first time in nearly 20 years that the nation's capital exceeded the 200 homicide threshold in consecutive years. According to information from the Metropolitan Police Department, the city last experienced such violence in 2002 and 2003, when it recorded 262 and 246 homicides, respectively. Property crime has decreased by 3% and violent crime decreased by 7% overall since 2021.[102][103]

2021

[edit]A little above 80% of all murders (20,958 out of 26,031) in the United States in 2021 involved a firearm— the highest percentage since at least 1968, the earliest year for which the CDC has online records. Moreover, a little under 55% of all suicides (26,328 out of 48,183) that year likewise involved a gun, the highest percentage since 2001.[104]

History

[edit]In the 19th century, gun violence played a role in civil disorder such as the Haymarket riot.[105] Homicide rates in cities such as Philadelphia were significantly lower in the 19th century than in modern times.[106] During the 1980s and early 1990s, homicide rates surged in cities across the United States (see applicable graphs).[107] Handgun homicides accounted for nearly all of the overall increase in the homicide rate, from 1985 to 1993, while homicide rates involving other weapons declined during that time frame.[43] The rising trend in homicide rates during the 1980s and early 1990s was most pronounced among lower income and especially unemployed males. Youths and Hispanic and African American males in the U.S. were the most represented, with the injury and death rates tripling for black males aged 13 through 17 and doubling for black males aged 18 through 24.[108][109] The rise in crack cocaine use in cities across the U.S. has been cited as a factor for increased gun violence among youths during this time period.[110][111][112] After 1993, however, gun violence in the United States began a period of dramatic decline.[113][114]

Demographics of risk

[edit]Prevalence of homicide and violent crime is higher in statistical metropolitan areas of the U.S. than it is in non-metropolitan counties;[115] the vast majority of the U.S. population lives in statistical metropolitan areas.[116] In metropolitan areas, the homicide rate in 2013 was 4.7 per 100,000 compared with 3.4 in non-metropolitan counties.[117] More narrowly, the rates of murder and non-negligent manslaughter are identical in metropolitan counties and non-metropolitan counties.[118] In U.S. cities with populations greater than 250,000, the mean homicide rate was 12.1 per 100,000.[119] According to FBI statistics, the highest per capita rates of gun-related homicides in 2005 were in Washington, D.C. (35.4/100,000), Puerto Rico (19.6/100,000), Louisiana (9.9/100,000), and Maryland (9.9/100,000).[120] In 2017, according to the Associated Press, Baltimore broke a record for homicides.[121] [citation needed]

In 2005, the 17-24 age group was significantly over-represented in violent crime statistics, particularly homicides involving firearms.[122] In 2005, 17- to 19-year-olds were 4.3% of the overall population of the U.S.[123] but 11.2% of those killed in firearm homicides.[124] This age group also accounted for 10.6% of all homicide offenses.[125] The 20-24-year-old age group accounted for 7.1% of the population,[123] but 22.5% of those killed in firearm homicides.[124] The 20-24 age group also accounted for 17.7% of all homicide offenses.[125]

African American populations in the United States disproportionately represent the majority of firearms injury and homicide compared to other racial groupings.[126][8] Although mass shootings are covered extensively in the media, mass shootings in the United States account for only a small fraction of gun-related deaths.[127] Regardless, mass shootings occur on a larger scale and much more frequently than in other developed countries. School shootings are described as a "uniquely American crisis", according to The Washington Post in 2018.[128] Children at U.S. schools have active shooter drills.[129] According to USA Today in 2019, "About 95% of public schools now have students and teachers practice huddling in silence, hiding from an imaginary gunman."[129] Those under 17 are not over-represented in homicide statistics. In 2005, 13-16-year-olds accounted for 6% of the overall population of the U.S., but only 3.6% of firearm homicide victims,[124] and 2.7% of overall homicide offenses.[125]

People with a criminal record are more likely to die as homicide victims.[108] Between 1990 and 1994, 75% of all homicide victims age 21 and younger in the city of Boston had a prior criminal record.[130] In Philadelphia, the percentage of those killed in gun homicides that had prior criminal records increased from 73% in 1985 to 93% in 1996.[108][131] In Richmond, Virginia, the risk of gunshot injury is 22 times higher for those males involved with crime.[132]

It is significantly more likely that a death will result when either the victim or the attacker has a firearm.[133][134] The mortality rate for gunshot wounds to the heart is 84%, compared to 30% for people who suffer stab wounds to the heart.[135]

In the United States, states with higher gun ownership rates have higher rates of gun homicides and homicides overall, but not higher rates of non-gun homicides.[136][137][138] Higher gun availability is positively associated with homicide rates.[139][140][141]

Some studies suggest that the concept of guns can prime aggressive thoughts and aggressive reactions. An experiment by Berkowitz and LePage in 1967 examined this "weapons effect." Ultimately, when study participants were provoked, their reaction was substantially more aggressive when a gun (in contrast with a more benign object like a tennis racket) was visibly present in the room.[142] Other similar experiments like those conducted by Carson, Marcus-Newhall and Miller yield similar results.[143] Such results imply that the presence of a gun in an altercation could elicit an aggressive reaction which may result in homicide.[144][145]

Comparison to other countries

[edit]

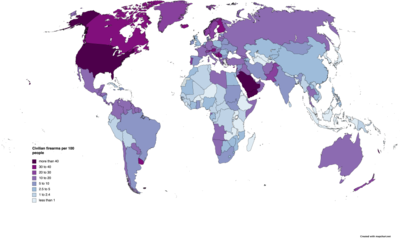

The U.S. is ranked 4th out of 34 developed nations for the highest incidence rate of homicides committed with a firearm, according to Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) data. Mexico, Turkey, and Estonia are ranked ahead of the U.S. in incidence of homicides. However, according to comprehensive research by the University of Sydney, the firearm-related homicide rates in Estonia and Turkey are both below the US (0.78 in Turkey and 0 in Estonia, while 5.9 in the US), with Estonia registering zero in 2015.[147] A U.S. male aged 15–24 is 70 times more likely to be killed with a gun than their counterpart in the eight (G-8) largest industrialized nations in the world (United Kingdom, France, Germany, Japan, Canada, Italy, Russia).[3] In a broader comparison of 218 countries the U.S. is ranked 111.[148] In 2010, the U.S.' homicide rate is 7 times higher than the average for populous developed countries in the OECD, and its firearm-related homicide rate was 25.2 times higher.[149] In 2013, the United States' firearm-related death rate was 10.64 deaths for every 100,000 inhabitants, a figure very close to Mexico's 11.17, although in Mexico firearm deaths are predominantly homicides whereas in the United States they are predominantly suicides.[150] (Although Mexico has strict gun laws, the laws restricting carry are often unenforced, and the laws restricting manufacture and sale are often circumvented by trafficking from the United States and other countries.)[151] Canada and Switzerland each have much looser gun control regulation than the majority of developed nations, although significantly more than in the United States, and have firearm death rates of 2.22 and 2.91 per 100,000 citizens, respectively. By comparison Australia, which imposed sweeping gun control laws in response to the Port Arthur massacre in 1996, has a firearm death rate of 0.86 per 100,000, and in the United Kingdom the rate is 0.26. In the year of 2014, there were a total of 8,124 gun homicides in the U.S.[152] In 2015, there were 33,636 deaths due to firearms in the U.S, with homicides accounting for 13,286 of those, while guns were used to kill about 50 people in the U.K., a country with population one-fifth of the size of the U.S. population.[3] More people are typically killed with guns in the U.S. in a day (about 85) than in the U.K. in a year, if suicides are included.[3] With deaths by firearm reaching almost 40,000 in the U.S. in 2017, their highest level since 1968, almost 109 people died per day.[9] A study conducted by the Journal of the American Medical Association determined that worldwide yearly gun deaths had reached 250,000 by 2018 and that the United States was one of only six countries that collectively accounted for roughly half of those fatalities.[153][154] According to the Small Arms Survey, there are about 120 guns for every 100 Americans; in other words, there are more civilian guns in the United States than there are people. The rate of deaths from gun violence in the United States is eight times greater than in Canada, which has the seventh-highest rate of gun ownership in the world.[155]

Mass shootings

[edit]

The definition of a mass shooting remains under debate. The precise inclusion criteria are disputed, and there no broadly accepted definition exists.[158][159] Mother Jones, using their standard of a mass shooting where a lone gunman kills at least four people in a public place for motivations excluding gang violence or robbery,[160] concluded that between 1982 and 2006 there were 40 mass shootings (an average of 1.6 per year). More recently, from 2007 through May 2018, there have been 61 mass shootings (an average of 5.4 per year).[161] More broadly, the frequency of mass shootings steadily declined throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, then increased dramatically.[162][163]

Studies indicate that the rate at which public mass shootings occur has tripled since 2011. Between 1982 and 2011, a mass shooting occurred roughly once every 200 days. However, between 2011 and 2014 that rate accelerated greatly with at least one mass shooting occurring every 64 days in the United States.[164] In "Behind the Bloodshed", a report by USA Today, said that there were mass killings every two weeks and that public mass killings account for 1 in 6 of all mass killings (26 killings annually would thus be equivalent to 26/6, 4 to 5, public killings per year).[165] Mother Jones listed seven mass shootings in the U.S. for 2015.[160] The average for the period 2011–2015 was about 5 a year.[166] An analysis by Michael Bloomberg's gun violence prevention group, Everytown for Gun Safety, identified 110 mass shootings, defined as shootings in which at least four people were murdered with a firearm, between January 2009 and July 2014; at least 57% were related to domestic or family violence.[167]

Other media outlets have reported that hundreds of mass shootings take place in the United States in a single calendar year, citing a crowd-funded website known as Shooting Tracker which defines a mass shooting as having four or more people injured.[168] In December 2015, The Washington Post reported that there had been 355 mass shootings in the United States so far that year.[169] In August 2015, The Washington Post reported that the United States was averaging one mass shooting per day.[170] An earlier report had indicated that in 2015 alone, there had been 294 mass shootings that killed or injured 1,464 people.[171] Shooting Tracker and Mass Shooting Tracker, the two sites that the media have been citing, have been criticized for using a criterion much more inclusive than that used by the government—they count four victims injured as a mass shooting—thus producing much higher figures.[172][173]

Handguns figured in the Virginia Tech shooting, the Binghamton shooting, the 2009 Fort Hood shooting, the 2012 Oikos University shooting, and the 2011 Tucson shooting, but both a handgun and a rifle were used in the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting.[174] The Aurora theater shooting and the Columbine High School massacre were committed by assailants armed with multiple weapons. AR-15 style rifles have been used in a number of the deadliest mass shooting incidents, and have come to be widely characterized as the weapon of choice for perpetrators of mass shootings,[175][176][177][178][179][180][181][182] despite statistics which show that handguns are the most commonly used weapon type in mass shootings.[183]

The number of public mass shootings has increased substantially over several decades, with a steady increase in gun-related deaths.[184][185] Although mass shootings are covered extensively in the media, they account for a small fraction of gun-related deaths[127] (only 1 percent of all gun deaths between 1980 and 2008).[186] Between January 1 and May 18, 2018, 31 students and teachers were killed inside U.S. schools exceeding the number of U.S. military service members who died in combat and noncombat roles during the same period.[187]

Accidental and negligent injuries

[edit]The perpetrators and victims of accidental and negligent gun discharges may be of any age. Accidental injuries are most common in homes where guns are kept for self-defense.[188] The injuries are self-inflicted in half of the cases.[188] On January 16, 2013, President Barack Obama issued 23 Executive Orders on Gun Safety,[189] one of which was for the Center for Disease Control (CDC) to research causes and possible prevention of gun violence. The five main areas of focus were gun violence, risk factors, prevention/intervention, gun safety and how media and violent video games influence the public. They also researched the area of accidental firearm deaths. According to this study not only have the number of accidental firearm deaths been on the decline over the past century but they now account for less than 1% of all unintentional deaths, half of which are self-inflicted.[190]

Violent crime

[edit]In the United States, states with higher levels of gun ownership were associated with higher rates of gun assault and gun robbery.[136] However it is unclear if higher crime rates are a result of increased gun ownership or if gun ownership rates increase as a result of increased crime.[191]

Costs

[edit]

In 2000, the costs of gun violence in the United States were estimated to be on the order of $100 billion per year, plus the costs associated with the gun violence avoidance and prevention behaviors.[194]

In 2010, gun violence cost U.S. taxpayers about $516 million in direct hospital costs.[195]

U.S. presidential assassinations and attempts

[edit]

At least eleven assassination attempts with firearms have been made on U.S. presidents (over one-fifth of all presidents); four sitting presidents have been killed, three with handguns and one with a rifle.

Abraham Lincoln survived an earlier attack,[196] but was killed using a .44-caliber Derringer pistol fired by John Wilkes Booth.[197] James A. Garfield was shot two times and mortally wounded by Charles J. Guiteau using a .44-caliber revolver on July 2, 1881. He would die of pneumonia the same year on September 19. On September 6, 1901, William McKinley was fatally wounded by Leon Czolgosz when he fired twice at point-blank range using a .32-caliber revolver. Struck by one of the bullets and receiving immediate surgical treatment, McKinley died 8 days later of gangrene infection.[197] John F. Kennedy was killed by Lee Harvey Oswald with a bolt-action rifle on November 22, 1963.[198]

Andrew Jackson, Harry S. Truman, and Gerald Ford (the latter twice) survived unharmed from assassination attempts involving firearms.[199][200][201]

Ronald Reagan was critically wounded in the March 30, 1981 assassination attempt by John Hinckley, Jr. with a .22-caliber revolver. He is the only U.S. president to survive being shot while in office.[202] Former president Theodore Roosevelt was shot and wounded right before delivering a speech during his 1912 presidential campaign. Despite bleeding from his chest, Roosevelt refused to go to a hospital until he delivered the speech.[203] On February 15, 1933, Giuseppe Zangara attempted to assassinate president-elect Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who was giving a speech from his car in Miami, Florida, with a .32-caliber pistol.[204] Roosevelt was unharmed, but Chicago mayor Anton Cermak died in the attempt, and several other bystanders received non-fatal injuries.[205]

Response to these events has resulted in federal legislation to regulate the public possession of firearms. For example, the attempted assassination of Franklin Roosevelt contributed to passage of the National Firearms Act of 1934,[205] and the Kennedy assassination (along with others) resulted in the Gun Control Act of 1968. The GCA is a federal law signed by President Lyndon Johnson that broadly regulates the firearms industry and firearms owners. It primarily focuses on regulating interstate commerce in firearms by largely prohibiting interstate firearms transfers except among licensed manufacturers, dealers, and importers.[206]

Other violent crime

[edit]A quarter of robberies of commercial premises in the U.S. are committed with guns.[207] Fatalities are three times as likely in robberies committed with guns than where other, or no, weapons are used,[207][208][209] with similar patterns in cases of family violence.[210] Criminologist Philip J. Cook hypothesized that if guns were less available, criminals might commit the same crime, but with less-lethal weapons.[211] He finds that the level of gun ownership in the 50 largest U.S. cities correlates with the rate of robberies committed with guns, but not with overall robbery rates.[212][213] He also finds that robberies in which the assailant uses a gun are more likely to result in the death of the victim, but less likely to result in injury to the victim.[214] Overall robbery and assault rates in the U.S. are comparable to those in other developed countries, such as Australia and Finland, with much lower levels of gun ownership.[211][215] A 2000 study showed a strong association between the availability of illegal guns and violent crime rates, but not between legal gun availability and violent crime rates.[216]

Victims

[edit]

Firearms are the leading cause of death for ages 16–19 in United States since 2020; with the US accounting for 97% of gun-related deaths of late-teens among similarly large and wealthy countries.[218][219] According to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, from 1980 to 2008, 84% of white homicide victims were killed by white offenders and 93% of black homicide victims were killed by black offenders.[220]

African-Americans, who were only 13% of the U.S. population in 2010, were 55% of the victims of gun homicide. In 2017 African-American males aged 15 to 34 years were the most frequent victims of firearm homicide in the United States with a 81 deaths per 100,000 population.[221][8] Non-Hispanic whites were 65% of the U.S. population in 2010, but only 25% of the victims. Hispanics were 16% of the population in 2010 and 17% of victims.[222]

According to a 2021 CDC study, the male gun homicide rate was over five times the female gun homicide rate. The highest gun homicide rate was among those age 25-44. Non-Hispanic blacks had the highest gun homicide rate in every age group, with a rate 13 times higher than whites in the 25-44 age group.[223] According to ABC News, so far, more than 11,500 Americans killed by firearms in 2023.[224]

Public opinion

[edit]With a rise in gun violence and mass shootings in the United States, many surveys have been conducted throughout the recent years to examine the public opinion on certain gun policies and prevention methods in an effort to gain an understanding on the major trends in public opinion. Americans have found to have a range of opinions regarding this issue.

Across different studies conducted, it has been found that US public opinion varies based on gender, age, gun ownership status, occupation, education, political affiliation among many other demographics. However, most Americans support some form of restrictions and limitations with firearms, whether they are gun owners or not.

A study conducted by Berry College's Department of Political Science utilized data from surveys that were administered from 1999–2001, 2011, 2012, 2015, 2017 and 2018. They compared the attitude of the massacre generation which refers to people born after the Columbine high school shooting in 1999 to the older generation. An age effect was only seen in studies conducted after 2012.[225] Results from these surveys indicated that the younger generation are more likely to believe that the government can effectively prevent future mass shootings with more gun prevention laws.[225] The data also suggested that the younger generation are more likely to attribute mass shootings to lack of government regulation.[225]

Another study was conducted in April 2015 which measured public opinion of carrying firearms in public places. Results from the study showed that overall, less than one third of the adults in the US supported carrying firearms in public spaces.[226] Support was greater in gun owners compared to non- gun owners.[226] Support for carrying firearms in public was lowest for schools, bars, and sport stadiums.[226] According to the data, 18.2 percent of the respondents supported carrying guns in bars, 17.1 percent supported carrying guns in sport stadiums and 18.8 percent supported carrying guns in schools.[226] Support for carrying firearms was greatest in restaurants and retail stores. 32.9 percent of the respondents support carrying guns in restaurants and 30.8 percent support carrying guns in retail stores.[226] From this study it was concluded that most people in the United States, even most gun owners, are in support of limiting the places gun owners are allowed to carry their weapons.

Another study that was conducted in 2015 by Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health revealed that the majority of Americans supported various gun laws and there was minimal difference between gun owners and non-gun owners for a majority of the policies.[227] Support for "prohibiting a person subject to a temporary domestic violence restraining order from having a gun" was around 77.5 percent among gun owners and around 79.6 percent among non-gun owners.[227] Overall, support for a policy that authorizes law enforcement to remove firearms from a person temporarily who may be a threat to themselves or others was 70.9 percent, non- gun owner support was 71.8 percent and gun owner support was 67 percent.[227] The study examined a comparison between public opinion on gun policy immediately after the 2013 school shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary school in Newton, Connecticut and 2 years after the shooting. In most cases there was only a slight change in opinion. For example, overall support for prohibiting a person under the age of 21 from having a gun only decreased 4 percent.[227]

A national study of gun policy was conducted in 2019 examining the trends in data from surveys that were administered by the Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Policy and Research in 2012, 2015, 2017 and 2019. This study analyzed how the attitude towards certain gun policies changed overtime based on political party affiliation and gun ownership status. The study has found that the majority of the people supported a range of gun policies whether they were gun owners or not. From 2015 to 2019, there was an overall increase in support among American adults for 18- gun policies.[228] For instance, support for requiring purchaser licensing and safe gun storage laws increased 5 percent. There was a 4 percent increase in support for universal background checks.[228] Moreover, data showed that a majority of Republicans and Independents supported all except one of the 18 policies.[228] The data reveal high support for safety training among gun owners and non-gun owners. The results of the study indicated that overall 81 percent of the respondents supported the requirement of a safety test for those who have applied for a license to carry firearms in public, in which the support was 73 percent from gun owners and 83 percent from non-gun owners.[228] Additionally, 36 percent of the participants in the study supported permitting a person to carry a concealed gun on a college campus and only 31 percent supported permitting someone to carry guns in elementary school.[228] Overall support for prohibiting a person convicted of a violent crime from carrying a gun in public for 10 years was around 78 percent, where gun owner support was around 71 percent and non-gun owner support was around 80%.[228] Data from this study suggests that both gun owners and non- gunowners support a range of gun policies.

A study conducted in 2021 examines American public opinion on several gun violence prevention funding policies among different racial and ethnic groups.[229] Support for funding community-based prevention programs that provide social support was 71 percent among blacks, 68 percent among whites and 69 percent among Hispanics.[229] Moreover, support for funding hospital- based gun violence prevention programs that provide counseling to people to reduce an individual's risk of future violence was 57 percent among whites, 66 percent among blacks and 57 percent among Hispanics.[229] Support for redirecting government funding from police to social programs was 35% among whites, 60% among blacks and 43% among Hispanics.[229] Overall, data revealed that black support for most of the policies examined was greater than white support, however the differences were minimal.[229] Public opinion polls show Americans are about evenly split on banning guns like the AR-15, with recent polls showing support for the ban has dipped slightly.[230]

Poll (2023)

[edit]In the midst of a recent surge in mass shootings, including a record 46 school shootings in 2022, an April 2023 Fox News poll found registered voters overwhelmingly supported a wide variety of gun restrictions:

- 87% said they support requiring criminal background checks for all gun buyers;

- 81% support raising the age requirement to buy guns to 21;

- 80% said police should be allowed take guns away from people considered a danger to themselves or others;

- 80% support requiring mental health checks for all gun purchasers;

- 61% supported banning assault rifles and semi-automatic weapons.[231][232]

Public policy

[edit]

Public policy as related to preventing gun violence is an ongoing political and social debate regarding both the restriction and availability of firearms within the United States. Policy at the Federal level is/has been governed by the Second Amendment, National Firearms Act, Gun Control Act of 1968, Firearm Owners Protection Act, Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act, Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, and the Domestic Violence Offender Act. Gun policy in the U.S. has been revised many times with acts such as the Firearm Owners Protection Act, which loosened provisions for gun sales while banning civilian ownership of machine guns made after 1986.[234]

At the federal, state and local level, gun laws such as handgun bans have been overturned by the Supreme Court in cases such as District of Columbia v. Heller and McDonald v. Chicago. These cases hold that the Second Amendment protects an individual right to possess a firearm. D.C. v. Heller only addressed the issue on Federal enclaves, while McDonald v. Chicago addressed the issue as relating to the individual states.[235]

Gun control proponents often cite the relatively high number of homicides committed with firearms as reason to support stricter gun control laws.[236] Policies and laws that reduce homicides committed with firearms prevent homicides overall; a decrease in firearm-related homicides is not balanced by an increase in non-firearm homicides.[237] Firearm laws are a subject of debate in the U.S., with firearms used for recreational purposes as well as for personal protection.[2] Gun rights advocates cite the use of firearms for self-protection, and to deter violent crime, as reasons why more guns can reduce crime.[238] Gun rights advocates also say criminals are the least likely to obey firearms laws, and so limiting access to guns by law-abiding people makes them more vulnerable to armed criminals.[57]

In a survey of 41 studies, half of the studies found a connection between gun ownership and homicide but these were usually the least rigorous studies. Only six studies controlled at least six statistically significant confounding variables, and none of them showed a significant positive effect. Eleven macro-level studies showed that crime rates increase gun levels (not vice versa). The reason that there is no opposite effect may be that most owners are noncriminals and that they may use guns to prevent violence.[239]

Access to firearms

[edit]

The United States Constitution enshrines the right to gun ownership in the Second Amendment of the United States Bill of Rights to ensure the security of a free state through a well regulated Militia. It states: "A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms shall not be infringed." The Constitution makes no distinction between the type of firearm in question or state of residency.[241]

Age limits, background checks

[edit]

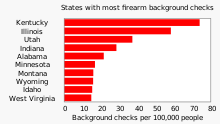

Gun dealers in the U.S. are prohibited from selling handguns to those under the age of 21, and long guns to those under the age of 18.[211] In 2017, the National Safety Council released a state ranking on firearms access indicators such as background checks, waiting periods, safe storage, training, and sharing of mental health records with the NICS database to restrict firearm access.[243]

Guns favored by criminals

[edit]

Assuming access to guns, the top ten guns involved in crime in the United States show a definite tendency to favor handguns over long guns. The top ten guns used in crime, as reported by the ATF in 1993, were the Smith & Wesson .38 Special and .357 revolvers; Raven Arms .25 caliber, Davis P-380 .380 caliber, Ruger .22 caliber, Lorcin L-380 .380 caliber, and Smith & Wesson semi-automatic handguns; Mossberg and Remington 12 gauge shotguns; and the Tec DC-9 9 mm handgun.[244] An earlier 1985 study of 1,800 incarcerated felons showed that criminals preferred revolvers and other non-semi-automatic firearms over semi-automatic firearms.[245] In Pittsburgh a change in preferences towards pistols occurred in the early 1990s, coinciding with the arrival of crack cocaine and the rise of violent youth gangs.[246] Background checks in California from 1998 to 2000 resulted in 1% of sales being initially denied.[247] The types of guns most often denied included semiautomatic pistols with short barrels and of medium caliber.[247] A 2018 study determined that California's implementation of comprehensive background checks and misdemeanor violation policies was not associated with a net change in the firearm homicide rate over the ensuing 10 years.[248] A 2018 study found no evidence of an association between the repeal of comprehensive background check policies and firearm homicide and suicide rates in Indiana and Tennessee.[249]

Gun possession by juvenile offenders

[edit]Among juveniles (minors under the age of 16, 17, or 18, depending on legal jurisdiction) serving in correctional facilities, 86% had owned a gun, with 66% acquiring their first gun by age 14.[250] There was also a tendency for juvenile offenders to have owned several firearms, with 65% owning three or more.[250] Juveniles most often acquired guns illegally from family, friends, drug dealers, and street contacts.[250] Inner city youths cited "self-protection from enemies" as the top reason for carrying a gun.[250] In Rochester, New York, 22% of young males have carried a firearm illegally, most for only a short time.[251] There is little overlap between legal gun ownership and illegal gun carrying among youths.[251]

Effect of laws on mortality

[edit]A 2011 study indicated that in states where local background checks for gun purchases are completed, the suicide rate was lower than states without.[252]

Firearms market

[edit]

Gun rights advocates argue that policy aimed at the supply side of the firearms market is based on limited research.[2] One consideration is that 60–70% of firearms sales in the U.S. are transacted through federally licensed firearm dealers, with the remainder taking place in the "secondary market", in which previously owned firearms are transferred by non-dealers.[35][254][255][256] Access to secondary markets is generally less convenient to purchasers, and involves such risks as the possibility of the gun having been used previously in a crime.[257] Unlicensed private sellers were permitted by law to sell privately owned guns at gun shows or at private locations in 24 states as of 1998.[258] Regulations that limit the number of handgun sales in the primary, regulated market to one handgun a month per customer have been shown to be effective at reducing illegal gun trafficking by reducing the supply into the secondary market.[259] Taxes on firearm purchases are another means for government to influence the primary market.[260]

Criminals tend to obtain guns through multiple illegal pathways, including large-scale gun traffickers, who tend to provide criminals with relatively few guns.[261] Federally licensed firearm dealers in the primary (new and used gun) market are regulated by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF). Firearm manufacturers are required to mark all firearms manufactured with serial numbers. This allows the ATF to trace guns involved in crimes back to their last Federal Firearms License (FFL) reported change of ownership transaction, although not past the first private sale involving any particular gun. A report by the ATF released in 1999 found that 0.4% of federally licensed dealers sold half of the guns used criminally in 1996 and 1997.[262][263] This is sometimes done through "straw purchases."[262] State laws, such as those in California, that restrict the number of gun purchases in a month may help stem such "straw purchases."[262] States with gun registration and licensing laws are generally less likely to have guns initially sold there used in crimes.[264] Similarly, crime guns tend to travel from states with weak gun laws to states with strict gun laws.[265][266][267] An estimated 500,000 guns are stolen each year, becoming available to prohibited users.[254][260] During the ATF's Youth Crime Gun Interdiction Initiative (YCGII), which involved expanded tracing of firearms recovered by law enforcement agencies,[268] only 18% of guns used criminally that were recovered in 1998 were in possession of the original owner.[269] Guns recovered by police during criminal investigations were often sold by legitimate retail sales outlets to legal owners, and then diverted to criminal use over relatively short times ranging from a few months to a few years,[130][269][270] which makes them relatively new compared with firearms in general circulation.[260][271]

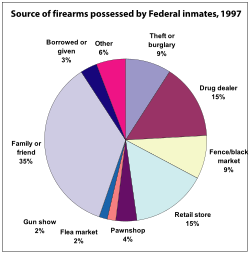

A 2016 survey of prison inmates by the Bureau of Justice Statistics found that 43% of guns used in crimes were obtained from the black market, 25% from an individual, 10% from a retail source (including 0.8% from a gun show), and 6% from theft.[272]

Legislation

[edit]

The first Federal legislation related to firearms was the Second Amendment to the United States Constitution ratified in 1791. For 143 years, this was the only major Federal legislation regarding firearms. The next Federal firearm legislation was the National Firearms Act of 1934, which created regulations for the sale of firearms, established taxes on their sale, and required registration of some types of firearms such as machine guns.[274]

Following the Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. assassinations, the Gun Control Act of 1968 was enacted. This Act regulated gun commerce, restricting mail order sales, and allowing shipments only to licensed firearm dealers. The Act also prohibited sale of firearms to felons, those under indictment, fugitives, illegal aliens, drug users, those dishonorably discharged from the military, and those in mental institutions.[211] The law also restricted importation of so-called Saturday night specials and other types of guns, and limited the sale of automatic weapons and semi-automatic weapon conversion kits.[262]

The Firearm Owners Protection Act, also known as the McClure-Volkmer Act, was passed in 1986. It changed some restrictions in the 1968 Act, allowing federally licensed gun dealers and individual unlicensed private sellers to sell at gun shows, while continuing to require licensed gun dealers to require background checks.[262] The 1986 Act also restricted the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms from conducting punitively repetitive inspections, reduced the amount of record-keeping required of gun dealers, raised the burden of proof for convicting gun law violators, and changed restrictions on convicted felons from owning firearms.[262] In addition it also banned new machine guns for sale to the public, but grandfathered in any that were already registered.

In the years following the passage of the Gun Control Act of 1968, people buying guns were required to show identification and sign a statement affirming that they were not in any of the prohibited categories.[211] Many states enacted background check laws that went beyond the federal requirements.[276] The Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act passed by Congress in 1993 imposed a waiting period before the purchase of a handgun, giving time for, but not requiring, a background check to be made.[277] The Brady Act also required the establishment of a national system to provide instant criminal background checks, with checks to be done by firearms dealers.[278] The Brady Act only applied to people who bought guns from licensed dealers, whereas felons buy some percentage of their guns from black market sources.[270] Restrictions, such as waiting periods, impose costs and inconveniences on legitimate gun purchasers, such as hunters.[260] A 2000 study found that the implementation of the Brady Act was associated with "reductions in the firearm suicide rate for persons aged 55 years or older but not with reductions in homicide rates or overall suicide rates."[279]

Federal Assault Weapons Ban

[edit]

The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, enacted in 1994, included the Federal Assault Weapons Ban, and was a response to public fears over mass shootings.[282] This provision prohibited the manufacture and importation of some firearms with certain features such as a folding stock, pistol grip, flash suppressor, and magazines holding more than ten rounds.[282] A grandfather clause was included that allowed firearms manufactured before 1994 to remain legal. A short-term evaluation by University of Pennsylvania criminologists Christopher S. Koper and Jeffrey A. Roth did not find any clear impact of this legislation on gun violence.[283] Given the short study time period of the evaluation, the National Academy of Sciences advised caution in drawing any conclusions.[260] In September 2004, the assault weapon ban expired, with its sunset clause.[284]

Domestic Violence Offender Gun Ban

[edit]The Domestic Violence Offender Gun Ban, the Lautenberg Amendment, prohibited anyone previously convicted of a misdemeanor or felony crime of domestic violence from shipment, transport, ownership and use of guns or ammunition. This was ex post facto, in the opinion of Representative Bob Barr.[285] This law also prohibited the sale or gift of a firearm or ammunition to such a person. It was passed in 1996, and became effective in 1997. The law does not exempt people who use firearms as part of their duties, such as police officers or military personnel with applicable criminal convictions; they may not carry firearms.

Disaster Recovery Personal Protection Act of 2006

[edit]In the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, police and National Guard units in New Orleans confiscated firearms from private citizens in an attempt to prevent violence. In reaction, Congress passed the Disaster Recovery Personal Protection Act of 2006 in the form of an amendment to Department of Homeland Security Appropriations Act, 2007. Section 706 of the Act prohibits federal employees and those receiving federal funds from confiscating legally possessed firearms during a disaster.[286]

2016 White House background check initiative

[edit]On January 5, 2016, President Obama unveiled his new strategy to curb gun violence in America. His proposals focus on new background check requirements that are intended to enhance the effectiveness of the National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS), and greater education and enforcement efforts of existing laws at the state level.[287][288] In an interview with Bill Simmons of HBO, President Obama also confirmed that gun control will be the "dominant" issue on his agenda in his last year of presidency.[289][290]

State legislation

[edit]Right-to-carry

[edit]

All 50 U.S. states allow for the right to carry firearms. A majority of states either require a shall-issue permit or allow carrying without a permit and a minority require a may-issue permit. Right-to-carry laws expanded in the 1990s as homicide rates from gun violence in the U.S. increased, largely in response to incidents such as the Luby's shooting of 1991 in Texas which directly resulted in the passage of a carrying concealed weapon, or CCW, law in Texas in 1995.[291] As Rorie Sherman, staff reporter for the National Law Journal wrote in an article published on April 18, 1994, "It is a time of unparalleled desperation about crime. But the mood is decidedly 'I'll do it myself' and 'Don't get in my way.'"[292]

The result was laws, or the lack thereof, that permitted persons to carry firearms openly, known as open carry, often without any permit required, in 22 states by 1998.[293] Laws that permitted persons to carry concealed handguns, sometimes termed a concealed handgun license, CHL, or concealed pistol license, CPL in some jurisdictions instead of CCW, existed in 34 states in the U.S. by 2004.[2] Since then, the number of states with CCW laws has increased; as of 2014[update], all 50 states have some form of CCW laws on the books.[294]

Economist John Lott has argued that right-to-carry laws create a perception that more potential crime victims might be carrying firearms, and thus serve as a deterrent against crime.[295] Lott's study has been criticized for not adequately controlling for other factors, including other state laws also enacted, such as Florida's laws requiring background checks and waiting period for handgun buyers.[296] When Lott's data was re-analyzed by some researchers, the only statistically significant effect of concealed-carry laws found was an increase in assaults,[296] with similar findings by Jens Ludwig.[297] Lott and Mustard's 1997 study has also been criticized by Paul Rubin and Hashem Dezhbakhsh for inappropriately using a dummy variable; Rubin and Dezhbakhsh reported in a 2003 study that right-to-carry laws have much smaller and more inconsistent effects than those reported by Lott and Mustard, and that these effects are usually not crime-reducing.[298] Since concealed-carry permits are only given to adults, Philip J. Cook suggested that analysis should focus on the relationship with adult and not juvenile gun incident rates.[211] He found no statistically significant effect.[211] A 2004 National Academy of Sciences survey of existing literature found that the data available "are too weak to support unambiguous conclusions" about the impact of right-to-carry laws on rates of violent crime.[2] NAS suggested that new analytical approaches and datasets at the county or local level are needed to adequately evaluate the impact of right-to-carry laws.[299] A 2014 study found that Arizona's SB 1108, which allowed adults in the state to concealed carry without a permit and without passing a training course, was associated with an increase in gun-related fatalities.[300] A 2018 study by Charles Manski and John V. Pepper found that the apparent effects of RTC laws on crime rates depend significantly on the assumptions made in the analysis.[301] A 2019 study found no statistically significant association between the liberalization of state level firearm carry legislation over the last 30 years and the rates of homicides or other violent crime.[302]

Child Access Prevention (CAP)

[edit]

Child Access Prevention (CAP) laws, enacted by many states, require parents to store firearms safely, to minimize access by children to guns, while maintaining ease of access by adults.[303] CAP laws hold gun owners liable should a child gain access to a loaded gun that is not properly stored.[303] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) said that, on average, one child died every three days in accidental incidents in the U.S. from 2000 to 2005.[304] In most states, CAP law violations are considered misdemeanors.[303] Florida's CAP law, enacted in 1989, permits felony prosecution of violators.[303] Research indicates that CAP laws are correlated with a reduction in unintentional gun deaths by 23%,[305] and gun suicides among those aged 14 through 17 by 11%.[306] A study by Lott did not detect a relationship between CAP laws and accidental gun deaths or suicides among those age 19 and under between 1979 and 1996.[307] However, two studies disputed Lott's findings.[306][308] A 2013 study found that CAP laws are correlated with a reduction of non-fatal gun injuries among both children and adults by 30–40%.[303] In 2016 the American Academy of Pediatrics found that safe gun storage laws were associated with lower overall adolescent suicide rates.[309] Research also indicated that CAP laws were most highly correlated with reductions of non-fatal gun injuries in states where violations were considered felonies, whereas in states that considered violations as misdemeanors, the potential impact of CAP laws was not statistically significant.[310]

Local restrictions

[edit]Some local jurisdictions in the U.S. have more restrictive laws, such as Washington, D.C.'s Firearms Control Regulations Act of 1975, which banned residents from owning handguns, and required permitted firearms be disassembled and locked with a trigger lock. On March 9, 2007, a U.S. Appeals Court ruled the Washington, D.C., handgun ban unconstitutional.[311] The appeal of that case later led to the Supreme Court's ruling in District of Columbia v. Heller that D.C.'s ban was unconstitutional under the Second Amendment.

Despite New York City's strict gun control laws, guns are often trafficked in from other parts of the U.S., particularly the southern states.[263][312] Results from the ATF's Youth Crime Gun Interdiction Initiative indicate that the percentage of imported guns involved in crimes is tied to the stringency of local firearm laws.[268]

Prevention programs

[edit]Violence prevention and educational programs have been established in many schools and communities across the United States. These programs aim to change personal behavior of both children and their parents, encouraging children to stay away from guns, ensure parents store guns safely, and encourage children to solve disputes without resorting to violence.[313] Programs aimed at altering behavior range from passive (requiring no effort on the part of the individual) to active (supervising children, or placing a trigger lock on a gun).[313] The more effort required of people, the more difficult it is to implement a prevention strategy.[314][315] Prevention strategies focused on modifying the situational environment and the firearm itself may be more effective.[313] Empirical evaluation of gun violence prevention programs has been limited.[2] Of the evaluations that have been done, results indicate such programs have minimal effectiveness.[313]

Hotline

[edit]SPEAK UP is a national youth violence prevention initiative created by The Center to Prevent Youth Violence,[316] which provides young people with tools to improve the safety of their schools and communities. The SPEAK UP program is an anonymous, national hot-line for young people to report threats of violence in their communities or at school. The hot-line is operated in accordance with a protocol developed in collaboration with national education and law enforcement authorities, including the FBI. Trained counselors, with access to translators for 140 languages, collect information from callers and then report the threat to appropriate school and law enforcement officials.[317][318][non-primary source needed]

Gun safety parent counseling

[edit]One of the most widely used parent counseling programs is Steps to Prevent Firearm Injury program (STOP), which was developed in 1994 by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Brady Center to Prevent Gun Violence (the latter of which was then known as the Center to Prevent Handgun Violence).[313][319] STOP was superseded by STOP 2 in 1998, which has a broader focus including more communities and health care providers.[313] STOP has been evaluated and found not to have a significant effect on gun ownership or firearm storage practices by inner-city parents.[319] Marjorie S. Hardy suggests further evaluation of STOP is needed, as this evaluation had a limited sample size and lacked a control group.[313] A 1999 study found no statistically significant effect of STOP on rates of gun ownership or better gun storage.[319]

Children

[edit]Prevention programs geared towards children have also not been greatly successful.[313] Many inherent challenges arise when working with children, including their tendency to perceive themselves as invulnerable to injury,[320] limited ability to apply lessons learned,[321][322] their innate curiosity,[321] and peer pressure.

The goal of gun safety programs, usually administered by local firearms dealers and shooting clubs, is to teach older children and adolescents how to handle firearms safely.[313] There has been no systematic evaluation of the effect of these programs on children.[313] For adults, no positive effect on gun storage practices has been found as a result of these programs.[35][323] Also, researchers have found that gun safety programs for children may likely increase a child's interest in obtaining and using guns, which they cannot be expected to use safely all the time, even with training.[324]

One approach taken is gun avoidance, such as when encountering a firearm at a neighbor's home. The Eddie Eagle Gun Safety Program, administered by the National Rifle Association (NRA), is geared towards younger children from pre-kindergarten to sixth grade, and teaches kids that real guns are not toys by emphasizing a "just say no" approach.[313] The Eddie Eagle program is based on training children in a four-step action to take when they see a firearm: (1) Stop! (2) Don't touch! (3) Leave the area. (4) Go tell an adult. Materials, such as coloring books and posters, back the lessons up and provide the repetition necessary in any child-education program. ABC News challenged the effectiveness of the "just say no" approach promoted by the NRA's Eddie the Eagle program in an investigative piece by Diane Sawyer in 1999.[325] Sawyer's piece was based on an academic study conducted by Dr. Marjorie Hardy.[326] Dr. Hardy's study tracked the behavior of elementary age schoolchildren who spent a day learning the Eddie the Eagle four-step action plan from a uniformed police officer. The children were then placed into a playroom which contained a hidden gun. When the children found the gun, they did not run away from the gun, but rather, they inevitably played with it, pulled the trigger while looking into the barrel, or aimed the gun at a playmate and pulled the trigger. The study concluded that children's natural curiosity was far more powerful than the parental admonition to "Just say no".[327]

Community programs

[edit]Programs targeted at entire communities, such as community revitalization, after-school programs, and media campaigns, may be more effective in reducing the general level of violence that children are exposed to.[328][329] Community-based programs that have specifically targeted gun violence include Safe Kids/Healthy Neighborhoods Injury Prevention Program in New York City,[330][331] and Safe Homes and Havens in Chicago.[313] Evaluation of such community-based programs is difficult, due to many confounding factors and the multifaceted nature of such programs.[313] A Chicago-based program, "BAM" (Becoming a Man) has produced positive results, according to the University of Chicago Crime Lab, and is expanding to Boston in 2017.[332]

March for Our Lives

[edit]The March for Our Lives was a student-led demonstration in support of legislation to prevent gun violence in the United States. It took place in Washington, D.C., on March 24, 2018, with over 880 sibling events throughout the U.S.[333][334][335][336][337] It was planned by Never Again MSD in collaboration with the nonprofit organization.[338] The demonstration followed the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Parkland, Florida on February 14, 2018, which was described by several media outlets as a possible tipping point for gun control legislation.[339][340][341]

Intervention programs

[edit]Sociologist James D. Wright suggests that to convince inner-city youths not to carry guns "requires convincing them that they can survive in their neighborhood without being armed, that they can come and go in peace, that being unarmed will not cause them to be victimized, intimidated, or slain."[250] Intervention programs, such as CeaseFire Chicago, Operation Ceasefire in Boston and Project Exile in Richmond, Virginia during the 1990s, have been shown to be effective.[2][342] Other intervention strategies, such as gun "buy-back" programs have been demonstrated to be ineffective.[343]

Gun buyback programs

[edit]Gun "buyback" programs are a strategy aimed at influencing the firearms market by taking guns "off the streets".[343] Gun "buyback" programs have been shown to be effective to prevent suicides, but ineffective to prevent homicides[344][345] with the National Academy of Sciences citing theory underlying these programs as "badly flawed."[343] Guns surrendered tend to be those least likely to be involved in crime, such as old, malfunctioning guns with little resale value, muzzleloading or other black-powder guns, antiques chambered for obsolete cartridges that are no longer commercially manufactured or sold, or guns that individuals inherit but have little value in possessing.[345] Other limitations of gun buyback programs include the fact that it is relatively easy to obtain gun replacements, often of better guns than were relinquished in the buyback.[343] Also, the number of handguns used in crime (about 7,500 per year) is very small compared to about 70 million handguns in the U.S.. (i.e., 0.011%).[343]

"Gun bounty" programs launched in several Florida cities have shown more promise. These programs involve cash rewards for anonymous tips about illegal weapons that lead to an arrest and a weapons charge. Since its inception in May 2007, the Miami program has led to 264 arrests and the confiscation of 432 guns owned illegally and $2.2 million in drugs, and has solved several murder and burglary cases.[346]

Operation Ceasefire

[edit]In 1995, Operation Ceasefire was established as a strategy for addressing youth gun violence in Boston. Violence was particularly concentrated in poor, inner-city neighborhoods including Roxbury, Dorchester, and Mattapan.[347] There were 22 youths (under the age of 24) killed in Boston in 1987, with that figure rising to 73 in 1990.[347] Operation Ceasefire entailed a problem-oriented policing approach, and focused on specific places that were crime hot spots—two strategies that when combined have been shown to be quite effective.[348][349][350] Particular focus was placed on two elements of the gun violence problem, including illicit gun trafficking[351] and gang violence.[347] Within two years of implementing Operation Ceasefire in Boston, the number of youth homicides dropped to ten, with only one handgun-related youth homicide occurring in 1999 and 2000.[262] The Operation Ceasefire strategy has since been replicated in other cities, including Los Angeles.[352] Erica Bridgeford, spearheaded a "72-hour ceasefire" in August 2017, but the ceasefire was broken with a homicide. Councilman Brandon Scott, Mayor Catherine Pugh and others talked of community policing models that might work for Baltimore.[353][121]

Project Exile

[edit]

Project Exile, conducted in Richmond, Virginia during the 1990s, was a coordinated effort involving federal, state, and local officials that targeted gun violence. The strategy entailed prosecution of gun violations in Federal courts, where sentencing guidelines were tougher. Project Exile also involved outreach and education efforts through media campaigns, getting the message out about the crackdown.[354] Research analysts offered different opinions as to the program's success in reducing gun crime. Authors of a 2003 analysis of the program argued that the decline in gun homicide was part of a "general regression to the mean" across U.S. cities with high homicide rates.[355] Authors of a 2005 study disagreed, concluding that Richmond's gun homicide rate fell more rapidly than the rates in other large U.S. cities with other influences controlled.[354][356]

Project Safe Neighborhoods

[edit]Project Safe Neighborhoods (PSN) is a national strategy for reducing gun violence that builds on the strategies implemented in Operation Ceasefire and Project Exile.[357] PSN was established in 2001, with support from the Bush administration, channelled through the United States Attorney's Offices in the United States Department of Justice. The Federal government has spent over US$1.5 billion since the program's inception on the hiring of prosecutors, and providing assistance to state and local jurisdictions in support of training and community outreach efforts.[358][359]

READI Chicago

[edit]In 2016, Chicago saw a 58% increase in homicides.[360] In response to the spike in gun violence, a group of foundations and social service agencies created the Rapid Employment and Development Initiative (READI) Chicago.[361] A Heartland Alliance program,[362] READI Chicago targets those most at risk of being involved in gun violence – either as perpetrator or a victim.[363] Individuals are provided with 18 months of transitional jobs, cognitive behavioral therapy and legal and social services.[363] Individuals are also provided with 6 months of support as they transition to full-time employment at the end of the 18 months.[363] The University of Chicago Crime Lab is evaluating READI Chicago's impact on gun violence reduction.[364] The evaluation, expected to be completed in Spring 2021, is showing early signs of success.[365] Eddie Bocanegra, senior director of READI Chicago, hopes that the early success of READI Chicago will result in funding from the City of Chicago.[364]

Reporting of crime

[edit]The National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS) is used by law enforcement agencies in the United States for collecting and reporting data on crimes.[366] The NIBRS is one of four subsets of the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) program.

- Traditional Summary Reporting System (SRS) and the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS) – Offense and arrest data

- Law Enforcement Officers Killed and Assaulted (LEOKA) Program

- Hate Crime Statistics Program – hate crimes

- Cargo Theft Reporting Program – cargo theft

The FBI states the UCR Program is retiring the SRS and will transition to a NIBRS-only data collection by January 1, 2021.[366] Additionally, the FBI states NIBRS will collect more detailed information, including incident date and time, whether reported offenses were attempted or completed, expanded victim types, relationships of victims to offenders and offenses, demographic details, location data, property descriptions, drug types and quantities, the offender's suspected use of drugs or alcohol, the involvement of gang activity, and whether a computer was used in the commission of the crime.[366]

Though NIBRS will be collecting more data the reporting if the firearm used was legally or illegally obtained by the suspect will not be identified. Nor will the system have the capability to identify if a legally obtained firearm used in the crime was used by the owner or registered owner, if required to be registered. Additionally, the information of how an illegally obtained firearm was acquired will be left to speculation. The absence of collecting this information into NIBRS the reported "gun violence" data will remain a gross misinterpretation lending anyone information that can be skewed to their liking/needs and not pinpoint where actual efforts need to be directed to curb the use of firearms in crime.

Research limitations