Харьков

Харьков

Харьков | |

|---|---|

| Украинская транскрипция(и) | |

| • Национальный , ALA-LC , BGN/PCGN | Харьков |

| • Научно | Харьков |

Сверху по часовой стрелке: Успенский собор , Харьковский вокзал , Харьковский национальный университет , Харьковский городской совет. | |

| Прозвище: Умный город | |

Интерактивная карта Харькова. | |

| Координаты: 49 ° 59'33 "N 36 ° 13'52" E / 49,99250 ° N 36,23111 ° E | |

| Страна | |

| Область | |

| Округ | Харкив Район |

| Куча | Kharkiv urban hromadа |

| Основан | 1654 [ 1 ] |

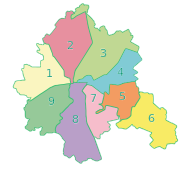

| Районы | Список из 9 [ 2 ] |

| Правительство | |

| • Мэр | Игорь Терехов [ 3 ] ( Блок Кернес — Успешный Харьков [ 4 ] ) |

| Область | |

| • Город | 350 км 2 (140 квадратных миль) |

| • Метро | 3223 км 2 (1244 квадратных миль) |

| Высота | 152 м (499 футов) |

| Население (2022) | |

| • Город | 1,421,125 |

| • Rank | 2nd in Ukraine |

| • Density | 4,500/km2 (12,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,729,049[5] |

| Demonym | Kharkivite[6] |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal code | 61001–61499 |

| Licence plate | AX, KX, ХА (old), 21 (old) |

| Sister cities | Albuquerque, Bologna, Cincinnati, Kaunas, Lille, Nuremberg, Poznań, Tianjin, Jinan, Kutaisi, Varna, Rishon LeZion, Brno, Daugavpils |

| Website | www |

Харьков ( Russian : Харьков , МФА: [ˈxɑrkiu̯] , HAR -kiv ), also known as Kharkov ( Russian : Харькoв , ВЛИЯНИЕ: [ˈxarʲkəf] , второй по величине город Украины ) . [ 7 ] Расположен на северо-востоке страны, это крупнейший город исторической области Слободской Украины . Харьков — административный центр Харьковской области и Харьковского района . Население составляет 1 421 125 человек (оценка на 2022 год). [ 8 ]

Харьков был основан в 1654 году как крепость и превратился в крупный центр промышленности, торговли и украинской культуры Слободской Украины в многонациональной Российской империи . В начале 20-го века в городе проживало преимущественно украинское и русское население, но по мере того, как промышленная экспансия привлекла дополнительную рабочую силу из бедной сельской местности, а Советский Союз смягчил предыдущие ограничения на украинское культурное самовыражение, украинцы стали крупнейшей этнической группой. в городе накануне Второй мировой войны . С декабря 1919 по январь 1934 года Харьков был столицей Украинской Советской Социалистической Республики .

Харьков — крупный культурный, научный, образовательный, транспортный и промышленный центр Украины с многочисленными музеями, театрами и библиотеками, в том числе Благовещенским и Успенским соборами, зданием Госпрома на площади Свободы и Харьковским национальным университетом . Промышленность играет значительную роль в экономике Харькова, специализируясь в первую очередь на машиностроении и электронике . По всему городу расположены сотни промышленных объектов, в том числе ОКБ Морозова , завод Малышева , Хартрон , Турбоатом и Антонов .

В марте и апреле 2014 года силы безопасности и контрдемонстранты отразили попытки поддерживаемых Россией сепаратистов захватить контроль над городской и областной администрацией. Харьков был главной целью российских войск в кампании на востоке Украины во время российского вторжения в Украину в 2022 году, прежде чем они были отброшены к российско-украинской границе . Город по-прежнему находится под периодическим российским огнем , и сообщается, что к апрелю 2024 года почти четверть города была разрушена. [ 9 ] [ 10 ] [ 11 ]

История

[ редактировать ]Снимите ругательства:

РТ / РИ 1654–1789 гг.

Де-факто:Kharkiv Regiment 1654–1789

Российская империя 1789–1917 гг.

Начало революции 1917-1921 гг.Временное правительство России, март – ноябрь 1917 г.

УНР ноябрь-декабрь 1917 г.

УПРС, декабрь 1917 г. - апрель 1918 г.

Украинская Народная Республика / Украинское государство , апрель 1918 г. - январь 1919 г.

ПВПГУ /

УССР 1919 г., январь – июнь.

АРСР 1919 г., июнь – декабрь.

УССР декабрь 1919 г. - декабрь 1922 г.

Конец революции 1917-1921 гг.СССР 1922–1941 гг.

Третий Рейх 1941–1943 гг.

СССР февраль – март 1943 г.

Третий рейх, март – сентябрь 1943 г.

СССР 1943–1991 гг.

Украина 1991 – настоящее время

Ранняя история

[ редактировать ]

Самые ранние исторические упоминания об этом регионе относятся к поселениям скифов и сарматов во II веке до нашей эры. Между 2-м и 6-м веками нашей эры имеются свидетельства черняховской культуры , полиэтнической смеси гето - дакского , сарматского и готского населения . [ 12 ] В VIII-X веках хазарская крепость Верхнее Салтово стояла примерно в 25 милях (40 км) к востоку от современного города, недалеко от Старого Салтова . [ 13 ] В течение 12 века эта территория входила в состав территории половцев , а затем с середины 13 века монголо - татарской Золотой Орды .

By the early 17th century, the area was a contested frontier region with renegade populations that had begun to organise in Cossack formations and communities defined by a common determination to resist both Tatar slavery, and Polish-Lithuanian and Russian serfdom. Mid-century, the Khmelnytsky Uprising against the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth saw the brief establishment of an independent Cossack Hetmanate.[14]

Kharkiv Fortress

[edit]In 1654, in the midst of this period of turmoil for Right-bank Ukraine, groups of people came onto the banks of Lopan and Kharkiv rivers where they resurrected and fortified an abandoned settlement.[15] There is a folk etymology that connects the name of both the settlement and the river to a legendary Cossack founder named Kharko[16] (a diminutive form of the Greek name Chariton, Ukrainian: Харитон, romanized: Kharyton,[1] or Zechariah, Ukrainian: Захарій, romanized: Zakharii).[17] But the river's name is attested earlier than the foundation of the fortress.[18]

The settlement reluctantly accepted the protection and authority of a Russian voivode from Chuhuiv 40 kilometres (25 mi) to the east. The first appointed voivode from Moscow was Voyin Selifontov in 1656, who began to build a local ostrog (fort). In 1658, a new voivode, Ivan Ofrosimov, commanded the locals to kiss the cross in a demonstration of loyalty to Tsar Alexis. Led by their otaman Ivan Kryvoshlyk, they refused. However, with the election of a new otaman, Tymish Lavrynov, relations appear to have been repaired, the Tsar in Moscow granting the community's request (signed by the deans of the new Assumption Cathedral and parish churches of Annunciation and Trinity) to establish a local market.[15]

At that time the population of Kharkiv was just over 1000, half of whom were local Cossacks. Selifontov had brought with him a Moscow garrison of only 70 soldiers.[15] Defence rested with a local Sloboda Cossack regiment under the jurisdiction of the Razryad Prikaz, a military agency commanded from Belgorod.[15]

The original walls of Kharkiv enclosed today's streets: vulytsia Kvitky-Osnovianenko, Constitution Square, Rose Luxemburg Square, Proletarian Square, and Cathedral Descent.[15] There were 10 towers of which the tallest, Vestovska, was some 16 metres (52 ft) high. In 1689 the fortress was expanded to include the Intercession Cathedral and Monastery, which became a seat of a local church hierarch, the Protopope.[15]

Russian Empire

[edit]

Administrative reforms led to Kharkiv being governed from 1708 from Kyiv,[19] and from 1727 from Belgorod. In 1765 Kharkiv was established as the seat of a separate Sloboda Ukraine Governorate.[20]

Kharkiv University was established in 1805 in the Palace of Governorate-General.[15] Alexander Mikolajewicz Mickiewicz, brother of the Polish national poet Adam Mickiewicz, was a professor of law in the university, while another celebrity, Goethe, searched for instructors for the school.[15] One of its later graduates was In Ivan Franko, to whom it awarded a doctorate in Russian linguistics in 1906.[15][21]

The streets were first cobbled in the city centre in 1830.[22] In 1844 the 90 metres (300 ft) tall Alexander Bell Tower, commemorating the victory over Napoleon I in 1812, was built next to the first Assumption Cathedral (later to be transformed by the Soviet authorities into a radio tower). A system of running water was established in 1870.[15]

In the course of the 19th century, although predominantly Russian speaking, Kharkiv became a centre of Ukrainian culture.[23] The first Ukrainian newspaper was published in the city in 1812. Soon after the Crimean War, in 1860–61, a hromada was established in the city, one of a network of secret societies that laid the groundwork for the appearance of a Ukrainian national movement. Its most prominent member was the philosopher, linguist and pan-slavist activist Oleksandr Potebnia. Members of a student hromada in the city included the future national leaders Borys Martos and Dmytro Antonovych,[23] and reputedly were the first to employ the slogan "Glory to Ukraine!" and its response "Glory on all of earth!".[24]

In 1900, the student hromada founded the Revolutionary Ukrainian Party (RUP), which sought to unite all Ukrainian national elements, including the growing number of socialists.[25] Following the revolutionary events 1905 in which Kharkiv distinguished itself by avoiding a reactionary pogrom against its Jewish population,[26] the RUP in Kharkiv, Poltava, Kyiv, Nizhyn, Lubny, and Yekaterinodar repudiated the more extreme elements of Ukrainian nationalism. Adopting the Erfurt Program of German Social Democracy, they restyled themselves the Ukrainian Social Democratic Labour Party (USDLP). This was to remain independent of, and opposed by, the Bolshevik faction of the Russian SDLP.[27][28]

After the February Revolution of 1917, the USDLP was the main party in the first Ukrainian government, the General Secretariat of Ukraine. The Tsentralna Rada (central council) of Ukrainian parties in Kyiv authorised the Secretariat to negotiate national autonomy with the Russian Provisional Government. In the succeeding months, as wartime conditions deteriorated, the USDLP lost support in Kharkiv and elsewhere to the Ukrainian Socialist Revolutionary Party (SR) which organised both in peasant communities and in disaffected military units.[28]

Soviet era

[edit]Capital of Soviet Ukraine

[edit]

In the Russian Constituent Assembly election held in November 1917, the Bolsheviks who had seized power in Petrograd and Moscow received just 10.5 percent of the vote in the Governorate, compared to 73 percent for a bloc of Russian and Ukrainian Socialist Revolutionaries. Commanding worker, rather than peasant, votes, within the city itself the Bolsheviks won a plurality.[29]

When in Petrograd Lenin's Council of People's Commissars disbanded the Constituent Assembly after its first sitting, the Tsentralna Rada in Kyiv proclaimed the independence of the Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR).[1] Bolsheviks withdrew from Tsentralna Rada and formed their own Rada (national council) in Kharkiv.[30][31] By February 1918 their forces had captured much of Ukraine.[32]

They made Kharkiv the capital of the Donetsk-Krivoy Rog Soviet Republic.[33] Six weeks later, under the treaty terms agreed with the Central Powers at Brest-Litovsk, they abandoned the city and ceded the territory to the German-occupied Ukrainian State.[34]

After the German withdrawal, the Red Army returned but, in June 1919, withdrew again before the advancing forces of Anton Denikin's White movement Volunteer.[35] By December 1919 Soviet authority was restored.[36] The Bolsheviks established Kharkiv as the capital of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic and, in 1922, this was formally incorporated as a constituent republic of the Soviet Union.[37]

A number of prestige construction projects in new officially-approved Constructivist style were completed,[38] among them Derzhprom (Palace of Industry) then the tallest building in the Soviet Union (and the second tallest in Europe),[39] the Red Army Building, the Ukrainian Polytechnic Institute of Distance Learning (UZPI), the City Council building, with its massive asymmetric tower, and the central department store that was opened on the 15th Anniversary of the October Revolution.[15] As new buildings were going up, many of city's historic architectural monuments were being torn down. These included most of the baroque churches: Saint Nicholas's Cathedral of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox church, the Church of the Myrrhophores, Saint Demetrius's Church, and the Cossack fortified Church of the Nativity.[40]

Under Stalin's First Five Year Plan, the city underwent intensified industrialisation, led by a number of national projects. Chief among these were the Kharkiv Tractor Factory (HTZ), described by Stalin as "a steel bastion of the collectivisation of agriculture in the Ukraine",[41] and the Malyshev Factory, an enlargement of the old Kharkiv Locomotive Factory, which at its height employed 60,000 workers in the production of heavy equipment.[42] By 1937 the output of Kharkiv's industries was reported as being 35 times greater than in 1913.[40]

Since the turn of the century, the influx of new workers from the countryside changed the ethnic composition of Kharkiv. According to census returns, by 1939 the Russian share of the population had fallen from almost two thirds to one third, while the Ukrainian share rose from a quarter to almost half. The Jewish population rose from under 6 percent of the total, to over 15 percent[43][44] (sustaining a Hebrew secondary school, a popular Jewish university and extensive publication in Yiddish and Hebrew).[45]

In the 1920s, the Ukrainian SSR promoted the use of the Ukrainian language, mandating it for all schools. In practice the share of secondary schools teaching in the Ukrainian language remained lower than the ethnic Ukrainian share of the Kharkiv Oblast's population.[46] The Ukrainization policy was reversed, with the prosecution in Kharkiv in 1930 of the Union for the Freedom of Ukraine. Hundreds of Ukrainian intellectuals were arrested and deported.[47]

In 1932 and 1933, the combination of grain seizures and the forced collectivisation of peasant holdings created famine conditions, the Holodomor, driving people off the land and into Kharkiv, and other cities, in search of food.[48][49] Eye-witness accounts by westerners—among them those of American Communist Fred Beal employed in the Kharkiv Tractor Factory[50] —were cited in the international press but, until the era of Glasnost were consistently denounced in the Soviet Union as fabrications.[51][52][53]

In 1934 hundreds of Ukrainian writers, intellectuals and cultural workers were arrested and executed in the attempt to eradicate all vestiges of Ukrainian nationalism. The purges continued into 1938. Blind Ukrainian street musicians Kobzars were also rounded up in Kharkiv and murdered by the NKVD.[54] Confident in his control over Ukraine, in January 1934 Stalin had the capital of the Ukrainian SSR moved from Kharkiv to Kyiv.[55]

During April and May 1940 about 3,900 Polish prisoners of Starobilsk camp were executed in the Kharkiv NKVD building, later secretly buried on the grounds of an NKVD pansionat in Piatykhatky forest (part of the Katyn massacre) on the outskirts of Kharkiv.[56][57] The site also contains the numerous bodies of Ukrainian cultural workers who were arrested and shot in the 1937–38 Stalinist purges.

German occupation

[edit]During World War II, Kharkiv was the focus of major battles. The city was captured by Nazi Germany on 24 October 1941.[58][59] A disastrous Red Army offensive failed to recover the city in May 1942.[60][61] It was retaken (Operation Star) on 16 February 1943, but lost again to the Germans on 15 March 1943. 23 August 1943 saw a final liberation.[62]

On the eve of the occupation, Kharkiv's prewar population of 700,000 had been doubled by the influx of refugees.[63] What remained of the pre-war Jewish population of 130,000, were slated by the Germans for "special treatment": between December 1941 and January 1942, they massacred and buried an estimated 15,000 Jews in a ravine outside of town named Drobytsky Yar.[64] Over their 22 months occupation they executed a further 30,000 residents, among them suspected Soviet partisans and, after a brief period of toleration, Ukrainian nationalists. 80,000 people died of hunger, cold and disease. 60,000 were forcibly transported to Germany as slave workers (Ostarbeiter).[65][40] Among these was Boris Romanchenko. The 96-year old survivor of forced labor at the Buchenwald, Peenemünde, Dora and Bergen Belsen concentration camps was killed when Russian fire hit his apartment bloc on 18 March 2022.[66][67]

By the time of Kharkiv's liberation in August 1943, the surviving population had been reduced to under 200,000.[63] Seventy percent of the city had been destroyed.[62] According to a New York Time's piece, "The city was more battered than perhaps any other in the Soviet Union save Stalingrad."[68]

Post-World War II

[edit]Before the occupation, Kharkiv's tank industries had been evacuated to the Urals with all their equipment, and became the heart of Red Army's tank programs (particularly, producing the T-34 tank earlier designed in Kharkiv). These enterprises returned to Kharkiv after the war, and became central elements of the post-war Soviet military industrial complex.[65] Houses and factories were rebuilt, and much of the city's center was reconstructed in the style of Stalinist Classicism.[15] Kharkiv's Jewish community revived after World War II: by 1959 there were 84,000 Jews living in the city. However, Soviet anti-Zionism restricted expressions of Jewish religion and culture, and was sustained until the final Gorbachev years (the confiscated Kharkiv Choral Synagogue reopened as a synagogue in 1990).[45]

In the Brezhnev-era, Kharkiv was promoted as a "model Soviet city". Propaganda made much of its “youthfulness”, a designation broadly used to suggest the relative absence in the city of "material and spiritual relics" from the pre-revolutionary era, and its commitment to the new frontiers of Soviet industry and science. The city's machine-and-weapons building prowess was attributed to a forward-looking collaboration between its large-scale industrial enterprises and new research institutes and laboratories.[69]

The last Communist Party chief of Ukraine, Vladimir Ivashko, appointed in 1989, trained as a mining engineer and served as a party functionary in Kharkiv.[70] He led the Communists to victory in Kharkiv and across the country in the parliamentary election held in the Ukrainian SSR in March 1990.[71] The election was relatively free, but occurred well before organised political parties had time to form, and did not arrest the decline in the CPSU's legitimacy.[72] This was accelerated by the intra-party coup attempt against President Mikhail Gorbachev and his reforms on August 18, 1991, during which Ivashko temporarily replaced Gorbachev as CPSU General Secretary.[73]

The National University of Kharkiv was at the forefront of democratic agitation. In October 1991, a call from Kyiv for an all-Ukrainian university strike to protest Gorbachev's new Union Treaty and to call for new multi-party elections was met with a rally at the entrance to the university attended not only by students and university teachers, but also by a range of public and cultural figures.[74] The protests—the so-called Revolution on Granite[75]—ended on October 17 with a resolution of the Verkhovna Rada of the Ukrainian SSR promising further democratic reform. In the event, the only demand fulfilled was the removal of the Communist Prime Minister.[76]

Independent Ukraine

[edit]In the 1 December 1991 Referendum on the Act of Declaration of Independence, on a turnout of 76 percent 86 percent of the Kharkiv Oblast approved separate Ukrainian statehood.[77]

During the 1990s post-Soviet aliyah, many Jews from Kharkiv emigrated to Israel or to Western countries.[78] The city's Jewish population, 62,800 in 1970,[45] dropped to 50,000 by the end of the century.[79]

The collapse of the Soviet Union disrupted, but did not sever, the ties that bound Kharkiv heavy's industries to the integrated Soviet market and supply chains, and did not diminish dependency on Russian oil, minerals, and gas.[80] In Kharkiv and elsewhere in eastern Ukraine, the limited prospects for securing new economic partners in the West, and concern for the rights of Russian-speakers in the new national state, combined to promote the interests of political parties and candidates emphasising understanding and cooperation with the Russian Federation. In the new century, these were represented by the Party of Regions and by the presidential ambitions of Victor Yanukovych,[81] which in Kharkiv triumphed in the city council elections of 2006, in the parliamentary elections of 2007 and in the presidential elections of 2010.[82]

Although never attaining the level of protest witnessed in Kyiv and in communities further west, following the disputed 2012 Parliamentary elections public opposition to President Yanukovych and his party surfaced in Kharkiv amid accusations of systematic corruption and of sabotaging prospects for new ties to the European Union.[83]

2014 pro-Russian unrest

[edit]The Euromaidan protests in the winter of 2013–2014 against then president Viktor Yanukovych consisted of daily gatherings of about 200 protestors near the statue of Taras Shevchenko and were predominantly peaceful.[84] Disappointed at the turnout, an activist at Kharkiv University suggested that his fellow students "proved to be as much of an inert, grey and cowed mass as Kharkiv’s ‘biudzhetniki’ " (those whose income derives from the state budget, mostly public servants).[85] But Pro-Yanukovych demonstrations, held near the statue of Lenin in Freedom (previously Dzerzhinsky) Square, were similarly small.[84]

In the wake Yanukovych's ouster in February, there were attempts in Kharkiv to follow the example of separatists in neighbouring Donbas.[86] On 2 March 2014, a Russian "tourist" from Moscow replaced the Ukrainian flag with a Russian flag on the Kharkiv Regional State Administration Building.[87] On 6 April 2014 pro-Russian protestors occupied the building and unilaterally declared independence from Ukraine as the "Kharkiv People's Republic".[84][88] Doubts arose about their local origin as they had initially targeted the city's Opera and Ballet Theatre before recognising their mistake.[89]

Kharkiv's mayor, Hennadiy "Gepa" Kernes, elected in 2010 as the nominee of the Party of Regions, was placed under house arrest. Claiming to have been "prisoner of Yanukovych's system",[90] he now declared his loyalty to acting President Oleksandr Turchynov.[84] In a televised address on April 7, Turchynov had announced that "a second wave of the Russian Federation's special operation against Ukraine [has] started" with the "goal of destabilising the situation in the country, toppling Ukrainian authorities, disrupting the elections, and tearing our country apart".[91] Kernes persuaded the police to storm the regional administration building and push out the separatists. He was allowed to return to his mayoral duties.[92]

Police action against the separatists was reinforced by a special forces unit from Vinnytsia directed by Ukrainian Interior Minister Arsen Avakov and Stepan Poltorak the acting commander of the Ukrainian Internal Forces.[84][93] On 13 April, some pro-Russian protesters again made it inside the Kharkiv regional state administration building, but were quickly evicted.[93][94][95] Violent clashes resulted in the severe beating of at least 50 pro-Ukrainian protesters in attacks by pro-Russian protesters.[94][95] On 28 April, Kernes was shot by a sniper,[96] a victim, commentators suggested, of his former pro-Russian allies.[92]

Relatively peaceful demonstrations continued to be held, with "pro-Russian" rallies gradually diminishing and "pro-Ukrainian unity" demonstrations growing in numbers.[97][98][99] On 28 September, activists dismantled Ukraine's largest monument to Lenin at a pro-Ukrainian rally in the central square.[100] Polls conducted from September to December 2014 found little support in Kharkiv for joining Russia.[101][102]

From early November until mid-December, Kharkiv was struck by seven non-lethal bomb blasts. Targets of these attacks included a rock pub known for raising money for Ukrainian forces, a hospital for Ukrainian forces, a military recruiting centre, and a National Guard base.[103] According to SBU investigator Vasyliy Vovk, Russian covert forces were behind the attacks, and had intended to destabilise the otherwise calm city of Kharkiv.[104] On 8 January 2015 five men wearing balaclavas broke into an office of Station Kharkiv, a volunteer group aiding refugees from Donbas.[105] On 22 February an improvised explosive device killed four people and wounded nine during a march commemorating the Euromaidan victims.[84] The authorities launched an 'anti-terrorist operation'.[106] Further bombings targeted army fuel tanks, an unoccupied passenger train and a Ukrainian flag in the city centre.[107]

On 23 September 2015, 200 people in balaclavas and camouflage picketed the house of former governor Mykhailo Dobkin, and then went to Kharkiv town hall, where they tried to force their way through the police cordon. At least one tear gas grenade was used. The rioters asked the mayor, Hennadiy Kernes, a supporter of the president, to come out.[108][109] Following recovery from his wounds, Kernes had been re-elected mayor, and was so again in 2020. He died of COVID-19 related complication in December 2020.[110][111] He was succeeded by Ihor Terekhov of the "Kernes Bloc — Successful Kharkiv".[3][4]

After the Euromaidan events and Russian actions in the Crimea and Donbas ruptured relations with Moscow, the Kharkiv region experienced a sharp fall in output and employment. Once a hub of cross border trade, Kharkiv was turned into a border fortress. A reorientation to new international markets, increased defense contracts (after Kyiv, the region contains the second-largest number of military-related enterprises) and export growth in the economy's services sector helped fuel a recovery, but people's incomes did not return to pre-2014 levels.[112]

By 2018 Kharkiv officially has the lowest unemployment rate in Ukraine, 6 percent. But in part this reflected labor shortages caused by the steady outflow of young and skilled workers to Poland and other European countries.[112]

Until 18 July 2020, Kharkiv was incorporated as a city of oblast significance and served as the administrative center of Kharkiv Raion though it did not belong to the raion. In July 2020, as part of the administrative reform of Ukraine, which reduced the number of raions of Kharkiv Oblast to seven, the city of Kharkiv was merged into Kharkiv Raion.[113][114]

2022 Russian invasion

[edit]During the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Kharkiv was the site of heavy fighting between the Ukrainian and Russian forces.[115] On 27 February, the governor of Kharkiv Oblast Oleh Synyehubov claimed that Russian troops were repelled from Kharkiv.[116]

According to a 28 February 2022, report from Agroportal 24h, the Kharkiv Tractor Plant (KhTZ), in the south east of the city, was destroyed and “engulfed in fire” by “massive shelling” from Russian forces.[117] Video purported to record explosions and fire at the plant on 25 and 27 February 2022.[118][119] UNESCO has confirmed that in the first three weeks of bombardment the city experienced the loss or damage of at least 27 major historical buildings.[120]

On 4 March 2022, Human Rights Watch reported that on the fourth day of the invasion of Ukraine by the Russian Federation, 28 February 2022, Federation forces used cluster munitions in the KhTZ, the Saltivskyi and Shevchenkivskyi districts of the city. The rights group—which noted the "inherently indiscriminate nature of cluster munitions and their foreseeable effects on civilians"—based its assessment on interviews and an analysis of 40 videos and photographs.[121] In March 2022, during the Battle of Kharkiv, the city was designated as a Hero City of Ukraine.[122]

In May 2022, Ukrainian forces began a counter-offensive to drive Russian forces away from the city and towards the international border. By 12 May, the United Kingdom Ministry of Defence reported that Russia had withdrawn units from the Kharkiv area.[123] Russian artillery and rockets remain within range of the city, and it continues to suffer shelling[124] and missile strikes.[125][126]

In May 2024, after two weeks intensive fighting, and the loss of a number of border villages, Ukrainian forces halted a renewed Russian advance toward Kharkiv. The Ukrainian defence was assisted by American-supplied Himar missiles, and by US permission to fire these across the border at military targets within Russian territory.[127]

Geography

[edit]

Kharkiv is located at the banks of the Kharkiv, Lopan, and Udy rivers, where they flow into the Siverskyi Donets watershed in the north-eastern region of Ukraine.

Historically, Kharkiv lies in the Sloboda Ukraine region (Slobozhanshchyna also known as Slobidshchyna) in Ukraine, in which it is considered to be the main city.

The approximate dimensions of city of Kharkiv are: from the North to the South — 24.3 km; from the West to the East — 25.2 km.

Based on Kharkiv's topography, the city can be conditionally divided into four lower districts and four higher districts.

The highest point above sea level, in Piatykhatky, is 202m, and the lowest is Novoselivka in Kharkiv is 94m.[citation needed]

Kharkiv lies in the large valley of rivers of Kharkiv, Lopan, Udy, and Nemyshlia. This valley lies from the North West to the South East between the Mid Russian highland and Donets lowland. All the rivers interconnect in Kharkiv and flow into the river of Northern Donets. A special system of concrete and metal dams was designed and built by engineers to regulate the water level in the rivers in Kharkiv.[citation needed]

Kharkiv has a large number of green city parks with a long history of more than 100 years with very old oak trees and many flowers.[citation needed] Central Park is Kharkiv's largest public garden. The park has nine areas: children, extreme sports, family entertainment, a medieval area, entertainment center, French park, cable car, sports grounds, retro park. This park was previously named after Maxim Gorky until June 2023 when it was renamed Central Park for Culture and Recreation.[128]

Climate

[edit]Kharkiv's climate is humid continental (Köppen climate classification Dfa/Dfb) with long, cold, snowy winters and warm to hot summers.

The average rainfall totals 519 mm (20 in) per year, with the most in June and July.

| Climate data for Kharkiv, Ukraine (1991−2020, extremes 1841–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 11.1 (52.0) |

14.6 (58.3) |

23.7 (74.7) |

30.5 (86.9) |

34.5 (94.1) |

39.8 (103.6) |

38.4 (101.1) |

39.8 (103.6) |

34.5 (94.1) |

29.3 (84.7) |

20.3 (68.5) |

13.4 (56.1) |

39.8 (103.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −2.1 (28.2) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

5.2 (41.4) |

14.7 (58.5) |

21.4 (70.5) |

25.2 (77.4) |

27.4 (81.3) |

26.8 (80.2) |

20.5 (68.9) |

12.6 (54.7) |

4.3 (39.7) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

12.9 (55.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −4.5 (23.9) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

1.4 (34.5) |

9.7 (49.5) |

16.1 (61.0) |

20.0 (68.0) |

22.0 (71.6) |

21.1 (70.0) |

15.1 (59.2) |

8.2 (46.8) |

1.6 (34.9) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

8.7 (47.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −6.8 (19.8) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

4.8 (40.6) |

10.7 (51.3) |

14.7 (58.5) |

16.6 (61.9) |

15.4 (59.7) |

10.2 (50.4) |

4.4 (39.9) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

−5.1 (22.8) |

4.6 (40.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −35.6 (−32.1) |

−29.8 (−21.6) |

−32.2 (−26.0) |

−11.4 (11.5) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

2.2 (36.0) |

5.7 (42.3) |

2.2 (36.0) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

−9.1 (15.6) |

−20.9 (−5.6) |

−30.8 (−23.4) |

−35.6 (−32.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 37 (1.5) |

33 (1.3) |

36 (1.4) |

32 (1.3) |

54 (2.1) |

58 (2.3) |

63 (2.5) |

39 (1.5) |

44 (1.7) |

44 (1.7) |

39 (1.5) |

40 (1.6) |

519 (20.4) |

| Average extreme snow depth cm (inches) | 8 (3.1) |

11 (4.3) |

8 (3.1) |

1 (0.4) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.4) |

4 (1.6) |

11 (4.3) |

| Average rainy days | 10 | 8 | 10 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 13 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 143 |

| Average snowy days | 19 | 18 | 12 | 2 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.03 | 2 | 9 | 18 | 80 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 85.6 | 83.0 | 77.3 | 65.7 | 60.9 | 65.2 | 65.3 | 62.9 | 70.2 | 77.6 | 85.7 | 86.5 | 73.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 44 | 68 | 131 | 187 | 267 | 289 | 308 | 286 | 205 | 123 | 55 | 36 | 1,999 |

| Source 1: Pogoda.ru.net[129] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NCEI (humidity 1981–2010, sun 1991-2020)[130] [131] | |||||||||||||

Governance

[edit]Legal status and local government

[edit]The mayor of Kharkiv and the city council govern all the business and administrative affairs in the City of Kharkiv.

The mayor of Kharkiv has the executive powers; the city council has the administrative powers as far as the government issues are concerned.

The mayor of Kharkiv is elected by direct public election in Kharkiv every four years.

The city council is composed of elected representatives, who approve or reject the initiatives on the budget allocation, tasks priorities and other issues in Kharkiv. The representatives to the city council are elected every four years.

The mayor and city council hold their regular meetings in the City Hall in Kharkiv.

Administrative divisions

[edit]While Kharkiv is the administrative centre of the Kharkiv Oblast (province), the city affairs are managed by the Kharkiv Municipality. Kharkiv is a city of oblast subordinance.

|

The territory of Kharkiv is divided into 9 administrative raions (districts), until February 2016 they were named for people, places, events, and organizations associated with early years of the Soviet Union but many were renamed in February 2016 to comply with decommunization laws.[2] Also, owing to this law, over 200 streets have been renamed in Kharkiv since 20 November 2015.[132]

- Kholodnohirskyi (Ukrainian: Холодногірський район, Cold Mountain; namesake: the historic name of the neighbourhood[134]) (formerly Leninskyi; namesake: Vladimir Lenin)

- Shevchenkivskyi (Ukrainian: Шевченківський район); namesake: Taras Shevchenko (formerly Dzerzhynskyi; namesake Felix Dzerzhinsky)

- Kyivskyi (Ukrainian: Київський район); namesake: Kyiv (formerly Kahanovychskyi; namesake: Lazar Kaganovich)

- Saltivskyi (Ukrainian: Салтівський район); namesake: Saltivka residential area (formerly Moskovskyi; namesake: Moscow)

- Nemyshlianskyi (Ukrainian: Немишлянський район) (formerly Frunzenskyi: namesake: Mikhail Frunze[133]);

- Industrialnyi (Ukrainian: Індустріальний район) (formerly Ordzhonikidzevskyi; namesake: Sergo Ordzhonikidze)

- Slobidskyi (Ukrainian: Слобідський район) (formerly Kominternіvskyi[133]); namesake: Sloboda Ukraine

- Osnovianskyi (Ukrainian: Основ'янський район) (formerly Chervonozavodskyi[133]); namesake: Osnova, a city neighborhood

- Novobavarskyi (Ukrainian: Новобаварський район) (formerly Zhovtnevyi[133]); namesake: Nova Bavaria, a city neighborhood

Demographics

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (February 2023) |

| Year | Pop. |

|---|---|

| 1660[135] | 1,000 |

| 1788[136] | 10,742 |

| 1850[137] | 41,861 |

| 1861[137] | 50,301 |

| 1901[137] | 198,273 |

| 1916[138] | 352,300 |

| 1917[139] | 382,000 |

| 1920[138] | 285,000 |

| 1926[138] | 417,000 |

| 1939[140] | 833,000 |

| 1941[138] | 902,312 |

| 1941[141] | 1,400,000 |

| 1941[138][142] | 456,639 |

| 1943[143] | 170,000 |

| 1959[137] | 930,000 |

| 1962[137] | 1,000,000 |

| 1976[137] | 1,384,000 |

| 1982[136] | 1,500,000 |

| 1989 | 1,593,970 |

| 1999 | 1,510,200 |

| 2001[144] | 1,470,900 |

| 2014[145] | 1,430,885 |

According to the 1989 Soviet Union Census, the population of the city was 1,593,970. In 1991, it decreased to 1,510,200, including 1,494,200 permanent residents.[146] The population in 2023 was 1,430,885.[147] Kharkiv is the second-largest city in Ukraine after the capital, Kyiv.[148] The first independent all-Ukrainian population census was conducted in December 2001, and the next all-Ukrainian population census is decreed to be conducted after the end of the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian war. As of 2001, the population of Kharkiv Oblast is as follows: 78.5% living in urban areas, and 21.5% living in rural areas.[149]

Ethnicity

[edit]| Ethnic group | 1897[43] | 1926 | 1939 | 1959[44] | 1989[146] | 2001[150][151][dubious – discuss] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ukrainians | 25.9% | 38.6% | 48.5% | 48.4% | 50.4% | 62.8% |

| Russians | 63.2% | 37.2% | 32.9% | 40.4% | 43.6% | 33.2% |

| Jews | 5.7% | 19.5% | 15.6% | 8.7% | 3.0% | 0.7% |

Notes

[edit]- 1660 year – approximated estimation

- 1788 year – without the account of children

- 1920 year – times of the Russian Civil War

- 1941 year – estimation on 1 May, right before German-Soviet War

- 1941 year – next estimation in September varies between 1,400,000 and 1,450,000

- 1941 year – another estimation in December during the occupation without the account of children

- 1943 year – 23 August, liberation of the city; estimation varied 170,000 and 220,000

- 1976 year – estimation on 1 June

- 1982 year – estimation in March

Kharkiv has a sizeable Vietnamese community who dominate the local Barabashovo market (one of the largest markets in Europe).[152] At the market most of these (Vietnamese) traders use a Ukrainianised version of their names.[152]

Language

[edit]Distribution of the population of the city of Kharkiv by native language according to the 2001 census:[153]

| Language | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Ukrainian | 460 607 | 31.77% |

| Russian | 954 901 | 65.86% |

| Other or undecided | 34 363 | 2.37% |

| Total | 1 449 871 | 100.00% |

According to a survey conducted by the International Republican Institute in April-May 2023, 16% of the city's population spoke Ukrainian at home, and 78% spoke Russian.[154]

Religion

[edit]

Kharkiv is an important religious centre in Eastern Ukraine.

There are many old and new religious buildings, associated with various denominations in Kharkiv. Assumption Orthodox Cathedral was built in Kharkiv in the 1680s and rebuilt in the 1820s and 1830s.[155] Holy Trinity Orthodox Church was built in Kharkiv in 1758–1764 and rebuilt in 1857–1861.[156] Annunciation Orthodox Cathedral, one of the tallest Orthodox churches in the world, was completed in Kharkiv on 2 October 1888.[157]

Recently built churches include St. Valentine's Orthodox Church and St. Tamara's Orthodox Church.[158][159]

Kharkiv's Jewish population is estimated to be around 8,000 people.[160] It is served by the old Kharkiv Choral Synagogue, which was fully renovated in Kharkiv in 1991–2016.

There are two mosques including the Kharkiv Cathedral Mosque and one Islamic center in Kharkiv.[citation needed]

Economy

[edit]

The 2016–2020 economic development strategy: "Kharkiv Success Strategy", is created in Kharkiv.[161][162][163] Kharkiv has a diversified service economy, with employment spread across a wide range of professional services, including financial services, manufacturing, tourism, and high technology.

International Economic Forum

[edit]The International Economic Forum: Innovations. Investments. Kharkiv Innitiatives! is being conducted in Kharkiv every year.[164]

In 2015, the International Economic Forum: Innovations. Investments. Kharkiv Innitiatives! was attended by the diplomatic corps representatives from 17 world countries, working in Ukraine together with top-management of trans-national corporations and investment funds; plus Ukrainian People's Deputies; plus Ukrainian Central government officials, who determine the national economic development strategy; plus local government managers, who perform practical steps in implementing that strategy; plus managers of technical assistance to Ukraine; plus business and NGO's representatives; plus media people.[164][165][166][167][168]

The key topics of the plenary sessions and panel discussions of the International Economic Forum: Innovations. Investments. Kharkiv Innitiatives! are the implementation of Strategy for Sustainable Development "Ukraine – 2020", the results achieved and plan of further actions to reform the local government and territorial organization of power in Ukraine, export promotion and attraction of investments in Ukraine, new opportunities for public-private partnerships, practical steps to create "electronic government", issues of energy conservation and development of oil and gas industry in the Kharkiv Region, creating an effective system of production and processing of agricultural products, investment projects that will receive funding from the State Fund for Regional Development, development of international integration, preparation for privatization of state enterprises.[164][165][166][167][168]

International Industrial Exhibitions

[edit]The international industrial exhibitions are usually conducted at the Radmir Expohall exhibition center in Kharkiv.[169]

Industrial corporations

[edit]

During the Soviet era, Kharkiv was the capital of industrial production in Ukraine and a large centre of industry and commerce in the USSR. After the collapse of the Soviet Union the largely defence-systems-oriented industrial production of the city decreased significantly. In the early 2000s, the industry started to recover and adapt to market economy needs. The enterprises form machine-building, electro-technology, instrument-making, and energy conglomerates.

State-owned industrial giants, such as Turboatom and Elektrovazhmash[170] occupy 17% of the heavy power equipment construction (e.g., turbines) market worldwide. Multipurpose aircraft are produced by the Antonov aircraft manufacturing plant. The Malyshev factory produces not only armoured fighting vehicles, but also harvesters. Khartron[171] is the leading designer of space and commercial control systems in Ukraine and the former CIS.

IT industry

[edit]As of April 2018, there were 25,000 specialists in IT industry of the Kharkiv region, 76% of them were related to computer programming. Thus, Kharkiv accounts for 14% of all IT specialists in Ukraine and makes the second largest IT location in the country, right after the capital Kyiv.[172]

Also, the number of active IT companies in the region to be 445, five of them employing more than 601 people. Besides, there are 22 large companies with the workers' number ranging from 201 to 600. More than half of IT-companies located in the Kharkiv region fall into "extra small" category with less than 20 persons engaged. The list is compiled with 43 medium (81-200 employers) and 105 small companies (21-80).[citation needed]

Due to the comparably narrow market for IT services in Ukraine, the majority of Kharkiv companies are export-oriented with more than 95% of total sales generated overseas in 2017. Overall, the estimated revenue of Kharkiv IT companies will more than double from $800 million in 2018 to $1.85 billion by 2025. The major markets are North America (65%) and Europe (25%).[173]

Finance industry

[edit]Kharkiv is also the headquarters of one of the largest Ukrainian banks, UkrSibbank, which has been part of the BNP Paribas group since December 2005.

Trade industry

[edit]There are many large modern shopping malls in Kharkiv.

There is a large number of markets:

- Barabashovo market, the largest market in Ukraine[citation needed] and one of the largest markets in Europe[152]

- Tsentralnyi market (Blahovishchenskyi market)

- Kinnyi (Horse) market

- Sumskyi market[174]

- Raiskyi book market

Science and education

[edit]Higher education

[edit]The Vasyl N. Karazin Kharkiv National University is the most prestigious reputable classic university, which was founded due to the efforts by Vasily Karazin in Kharkiv in 1804–1805.[175][176] On 29 January [O.S. 17 January] 1805, the Decree on the Opening of the Imperial University in Kharkiv came into force.

The Roentgen Institute opened in 1931. It was a specialist cancer treatment facility with 87 research workers, 20 professors, and specialist medical staff. The facilities included chemical, physiology, and bacteriology experimental treatment laboratories. It produced x-ray apparatus for the whole country.[177]

The city has 13 national universities and numerous professional, technical and private higher education institutions, offering its students a wide range of disciplines. These universities include Kharkiv National University (12,000 students), National Technical University "KhPI" (20,000 students), Kharkiv National University of Radioelectronics (12,000 students), Yaroslav Mudryi National Law University, Kharkiv National Aerospace University "KhAI", Kharkiv National University of Economics, Kharkiv National University of Pharmacy, and Kharkiv National Medical University.

More than 17,000 faculty and research staff are employed in the institutions of higher education in Kharkiv.

Scientific research

[edit]The city has a high concentration of research institutions, which are independent or loosely connected with the universities. Among them are three national science centres: Kharkiv Institute of Physics and Technology, Institute of Meteorology, Institute for Experimental and Clinical Veterinary Medicine and 20 national research institutions of the National Academy of Science of Ukraine, such as the B Verkin Institute for Low Temperature Physics and Engineering, Institute for Problems of Cryobiology and Cryomedicine, State Scientific Institution "Institute for Single Crystals", Usikov Institute of Radiophysics and Electronics (IRE), Institute of Radio Astronomy (IRA), and others. A total number of 26,000 scientists are working in research and development.

A number of world-renowned scientific schools appeared in Kharkiv, such as the theoretical physics school and the mathematical school.

There is the Kharkiv Scientists House in the city, which was built by A. N. Beketov, architect in Kharkiv in 1900. All the scientists like to meet and discuss various scientific topics at the Kharkiv Scientists House in Kharkiv.[178]

Public libraries

[edit]

In addition to the libraries affiliated with the various universities and research institutions, the Kharkiv State Scientific V. Korolenko-library is a major research library.

Secondary schools

[edit]Kharkiv has 212 (secondary education) schools, including 10 lyceums and 20 gymnasiums.[citation needed] In May 2024 the first of a scatter of underground schools in Kharkiv was opened in Industrialnyi District, so children could continue their education amidst the missile strikes in Kharkiv by the Russian Armed Forces during the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[179]

Education centers

[edit]There is the educational "Landau Center", which is named after L.D. Landau, Nobel laureate in Kharkiv.[180]

Culture

[edit]Kharkiv is one of the main cultural centres in Ukraine. It is home to 20 museums, over 10 theatres [citation needed] and a number of art galleries. Large music and cinema festivals are hosted in Kharkiv almost every year.

Theatres

[edit]

The Kharkiv National Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre named after N. V. Lysenko is the biggest theatre in Kharkiv.[181][182]

In 2017 the Kharkiv Ukrainian Drama Theatre named after T. G. Shevchenko was especially popular among theater audiences more prone to speak Ukrainian in daily life.[183]

The Kharkiv Academic Drama Theatre was recently renovated, and it is quite popular among locals.[184] Until October 2023 this theater was named after Russian poet Alexander Pushkin; the derussification of Ukraine campaign of that area led to its renaming that also meant the removal of (the word) "Russian" from the name.[185]

The Kharkiv Theatre of the Young Spectator (now the Theatre for Children and Youth) is one of the oldest theatres for children.[186]

The Kharkiv Puppet Theatre (The Kharkiv State Academic Puppet Theatre named after VA Afanasyev) is the first puppet theatre in the territory of Kharkiv. It was created in 1935.

The Kharkiv Academic Theatre of Musical Comedy is a theatre founded on 1 November 1929 in Kharkiv.

Literature

[edit]

In the 1930s Kharkiv was referred to as a Literary Klondike.[citation needed] It was the centre for the work of literary figures such as: Les Kurbas, Mykola Kulish, Mykola Khvylovy, Mykola Zerov, Valerian Pidmohylny, Pavlo Filipovych, Marko Voronny, Oleksa Slisarenko. Over 100 of these writers were repressed during the Stalinist purges of the 1930s. This tragic event in Ukrainian history is called the "Executed Renaissance" (Rozstrilene vidrodzhennia). Today, a literary museum located on Frunze Street marks their work and achievements.

Today, Kharkiv is often referred to as the "capital city" of Ukrainian science fiction and fantasy.[187][188] It is home to a number of popular writers, such as H. L. Oldie, Alexander Zorich, Andrey Dashkov, Yuri Nikitin and Andrey Valentinov; most of them write in Russian and are popular in both Russia and Ukraine. The annual science fiction convention "Star Bridge" (Звёздный мост) has been held in Kharkiv since 1999.[189]

Music

[edit]

There is the Kharkiv Philharmonic Society in the city. The leading group active in the Philharmonic is the Academic Symphony Orchestra. It has 100 musicians of a high professional level, many of whom are prize-winners in international and national competitions.

There is the Organ Music Hall in the city.[190] The Organ Music Hall is situated at the Assumption Cathedral presently. The Rieger–Kloss organ was installed in the building of the Organ Music Hall back in 1986. The new Organ Music Hall will be opened at the extensively renovated building of Kharkiv Philharmonic Society in Kharkiv in November 2016.

The Kharkiv Conservatory is in the city.

The Kharkiv National University of Arts named after I.P. Kotlyarevsky is situated in the city.[191]

Kharkiv sponsors the prestigious Hnat Khotkevych International Music Competition of Performers of Ukrainian Folk Instruments, which takes place every three years. Since 1997 four tri-annual competitions have taken place. The 2010 competition was cancelled by the Ukrainian Ministry of Culture two days before its opening.[192]

The music festival: "Kharkiv - City of Kind Hopes" is conducted in Kharkiv.[193]

From Kharkiv comes also black metal band Drudkh.

Films

[edit]From 1907 to 2008, at least 86 feature films were shot in the city's territory and its region. The most famous is Fragment of an Empire (1929). Arriving in Leningrad, the main character, in addition to the usual pre-revolutionary buildings, sees the Derzhprom - a symbol of a new era.

Film festivals

[edit]The Kharkiv Lilacs international film festival is very popular among movie stars, makers and producers in Ukraine, Eastern Europe, Western Europe and North America.[194][195]

The annual festival is usually conducted in May.[194][195]

There is a special alley with metal hand prints by popular movies actors at Shevchenko park in Kharkiv. [195][196]

Visual arts

[edit]Kharkiv has been a home for many famous painters, including Ilya Repin, Zinaida Serebryakova, Henryk Siemiradzki, and Vasyl Yermilov. There are many modern arts galleries in the city: the Yermilov Centre, Lilacs Gallery, the Kharkiv Art Museum, the Kharkiv Municipal Gallery, the AC Gallery, Palladium Gallery, the Semiradsky Gallery, AVEK Gallery, and Arts of Slobozhanshyna Gallery among others.

Museums

[edit]

There are around 147 museums in the Kharkiv's region.[197] Museums in the city include:

- The M. F. Sumtsov Kharkiv Historical Museum[198]

- The Kharkiv Art Museum[199]

- The Natural History Museum at V. N. Karazin Kharkiv National University was founded in Kharkiv on 2 April 1807. The museum is visited by 40000 visitors every year.[200][201]

- The V. N. Karazin Kharkiv National University History Museum was established in Kharkiv in 1972.[202][203][204]

- The V. N. Karazin Kharkiv National University Archeology Museum was founded in Kharkiv on 20 March 1998.[205][206]

- The National Technical University "Kharkiv Polytechnical Institute" Museum was created in Kharkiv on 29 December 1972.[207][208][209][210][211]

- The National Aerospace University "Kharkiv Aviation Institute" Museum was founded on 29 May 1992.[212]

- The "National University of Pharmacy" Museum was founded in Kharkiv on 15 September 2010.[213][214][215]

- The Kharkiv Maritime Museum - a museum dedicated to the history of shipbuilding and navigation.[216]

- The Kharkiv Puppet Museum is the oldest museum of dolls in Ukraine.[citation needed]

- Memorial museum-apartment of the family Grizodubov.[citation needed]

- Club-Museum of Claudia Shulzhenko.[217]

- The Museum of "First Aid".[citation needed]

- The Museum of Urban Transport.[citation needed]

- The Museum of Sexual Cultures.[218]

Landmarks

[edit]

The city is famous for its churches as well as Art Nouveau and constructivist architecture:

- Dormition Cathedral, built in 17th century in Baroque style and rebuilt in 18th and 19th centuries

- Pokrovskyi Monastery, built in 18th century in Baroque style

- Annunciation Cathedral, built in 1887-1901 in Neo-Byzantine style

- Kharkiv Ukrainian Drama Theatre, built in 1841

- Kharkiv Puppet Theatre, former Volga-Kama Commercial Bank, built in 1907 in Art Nouveau style

- Kharkiv State Academy of Design and Arts, built in 1912 in Art Nouveau style

- Choral Synagogue, built in 1909-1913

- Central Market Hall, built 1912-1914

- Derzhprom building, built in 1925-1928 in constructivist style

- Freedom Square

- Railway Pochtamt (post office), built 1927-29 in constructivist style

- Palace of Culture of Railway Workers, built 1928-31 in constructivist style

- Kharkiv railway station, rebuilt in socialist-realist style in 1952

- Kharkiv Opera, built in 1970-1990 in brutalist style

Other attractions include: Taras Shevchenko Monument, Mirror Stream, Historical Museum, T. Shevchenko Gardens, Zoo, Children's narrow-gauge railroad, World War I Tank Mk V, Memorial Complex, and many more.

After the 2014 Russian annexation of Crimea the monument to Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny in Sevastopol was removed and handed over to Kharkiv.[219]

-

Kharkiv Puppet Theatre (former Volga-Kama Bank)

-

Kharkiv Central Market Hall

-

Railway Pochtamt (post office)

-

Palace of Culture of Railway Workers

Parks

[edit]

Kharkiv contains numerous parks and gardens such as the Central Park, Shevchenko park, Hydro park, Strelka park, Sarzhyn Yar and Feldman ecopark. The Central Park is a common place for recreation activities among visitors and local people.[citation needed] The Shevchenko park is situated in close proximity to the V.N. Karazin National University. It is also a common place for recreation activities among the students, professors, locals and foreigners.

The Ecopark is situated at circle highway around Kharkiv. It attracts kids, parents, students, professors, locals and foreigners to undertake recreation activities. Sarzhyn Yar is a natural ravine three minutes walk from "Botanichniy Sad" station. It is an old girder that now - is a modern park zone more than 12 km length. There is also a mineral water source with cupel and a sporting court.[220]

Language

[edit]The majority spoken language in Kharkiv (especially until 2022) was Russian, despite the ukrainization policies enforced during the times of the Soviet Union. Even after Ukraine gained its independence, Russian was still used predominantly by ethnic Russians and Ukrainians alike, although after the onset of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, many of the city’s residents are attempting to transition to Ukrainian.[221][222]

Media

[edit]There are a large number of broadcast and internet TV channels, AM/FM/PM/internet radio-stations, and paper/internet newspapers in Kharkiv. Some are listed below.

Newspapers

[edit]- Slobidskyi Krai

- Vremya

- Vecherniy Kharkov

- Segodnya

- Vesti

- Kharkovskie Izvestiya

Magazines

[edit]- Guberniya [223]

TV stations

[edit]- "7 kanal" channel

- "А/ТВК" channel

- "Simon" channel

- "ATN Kharkiv" channel

- "UA: Kharkiv" channel

Radio stations

[edit]- Promin

- Ukrainske Radio

- Radio Kharkiv

- Kharkiv Oblastne Radio

- Russkoe Radio Ukraina

- Shanson

- Retro FM

Online news in English

[edit]- The Kharkiv Times

- Kharkiv Observer

Transport

[edit]The city of Kharkiv is one of the largest transportation centres in Ukraine, which is connected to numerous other cities of the world by air, rail and road traffic. There are about 250 thousand cars in the city.[224] Kharkiv is one out of four Ukrainian cities with a subway system.[225]

Local transport

[edit]Being an important transportation centre of Ukraine, many different means of transportation are available in Kharkiv. Kharkiv's Metro is the city's rapid transit system operating since 1975. It includes three different lines with 30 stations in total.[226][227] The Kharkiv buses carry about 12 million passengers annually. [citation needed] Trolleybuses, trams (which celebrated its 100-year anniversary of service in 2006), and marshrutkas (private minibuses) are also important means of transportation in the city.

Railways

[edit]The first railway connection of Kharkiv was opened in 1869. The first train to arrive in Kharkiv came from the north on 22 May 1869, and on 6 June 1869, traffic was opened on the Kursk–Kharkiv–Azov line. Kharkiv's passenger railway station was reconstructed and expanded in 1901, to be later destroyed in the Second World War. A new Kharkiv railway station was built in 1952.[228]

Kharkiv is connected with all main cities in Ukraine and abroad by regular railway services. Regional trains known as elektrychkas connect Kharkiv with nearby towns and villages.

Air

[edit]Kharkiv is served by Kharkiv International Airport. Charter flights are also available. The former largest carrier of the Kharkiv Airport — Aeromost-Kharkiv — is not serving any regular destinations as of 2007[update]. The Kharkiv North Airport is a factory airfield and was a major production facility for Antonov aircraft company.

Sport

[edit]Kharkiv International Marathon

[edit]The Kharkiv International Marathon is considered as a prime international sportive event, attracting many thousands of professional sportsmen, young people, students, professors, locals and tourists to travel to Kharkiv and to participate in the international event.[229][230][231][232]

Football (soccer)

[edit]

The most popular sport is football. The city has several football clubs playing in the Ukrainian national competitions. The most successful is FC Dynamo Kharkiv that won eight national titles back in the 1920s–1930s.

- FC Metalist Kharkiv, which plays at the Metalist Stadium

- FC Metalist 1925 Kharkiv, which plays at the Metalist Stadium

- FC Helios Kharkiv, a defunct club, which played at the Helios Arena

- FC Kharkiv, a defunct club, which played at the Dynamo Stadium

- FC Arsenal Kharkiv, which played at the Arsenal-Spartak Stadium (participates in regional competitions)

- FC Shakhtar Donetsk also play at the Metalist Stadium since 2017, due to the war in Donbas

There is also a female football club WFC Zhytlobud-1 Kharkiv, which represented Ukraine in the European competitions and constantly is the main contender for the national title.

Metalist Stadium hosted three group matches at UEFA Euro 2012.

Other sports

[edit]

Kharkiv also had some ice hockey clubs, MHC Dynamo Kharkiv, Vityaz Kharkiv, Yunost Kharkiv, HC Kharkiv, who competed in the Ukrainian Hockey Championship.

Avangard Budy is a bandy club from Kharkiv, which won the Ukrainian championship in 2013.

There are a men's volleyball teams, Lokomotyv Kharkiv and Yurydychna Akademiya Kharkiv, which performed in Ukraine and in European competitions.

RC Olymp is the city's rugby union club. They provide many players for the national team.

Tennis is also a popular sport in Kharkiv. There are many professional tennis courts in the city. Elina Svitolina is a tennis player from Kharkiv.

There is a golf club in Kharkiv.[233]

Horseriding as a sport is also popular among locals.[234][235][236][237] There are large stables and horse riding facilities at Feldman Ecopark in Kharkiv.[238]

There is a growing interest in cycling among locals.[239][240] There is a large bicycles producer, Kharkiv Bicycle Plant within the city.[241] Presently, the modern bicycle highway is under construction at the "Leso park" (Лісопарк) district in Kharkiv.

Notable people

[edit]

- Anastasia Afanasieva (born 1982) – psychiatrist, poet, writer, translator

- Serhii Babkin (born 1978) – singer and actor

- Snizhana Babkina (born 1985) – actress and music manager

- Nikolai P. Barabashov (1894–1971) – astronomer, co-author of the first pictures of the far side of the Moon

- Pavel Batitsky (1910–1984) – Soviet military leader

- Vladimir Bobri (1898–1986) – illustrator, author, composer, educator and guitar historian

- Inna Bohoslovska (born 1960) – lawyer, politician and leader of the Ukrainian public organization Viche

- Sergei Bortkiewicz (1877–1952) – Russian Romantic composer and pianist

- Maria Burmaka (born 1970) – Ukrainian singer, musician and songwriter

- Leonid Bykov (1928–1979) – Soviet actor, film director, and script writer

- Cassandre (1901–1968) – Ukrainian-French painter, commercial poster artist, and typeface designer

- Juliya Chernetsky (born 1982) – TV host, actress, model, and music promoter in the US. (Mistress Juliya)

- Andrey Denisov (born 1952) - Russian diplomat in China

- Vladimir Drinfeld (born 1954) – mathematician, awarded Fields Medal in 1990

- Isaak Dunayevsky (1900–1955) – Soviet composer and conductor

- Konstanty Gorski (1859–1924) – Polish composer, violist, organist and music teacher

- Valentina Grizodubova (1909–1993) – one of the first female pilots in the Soviet Union

- Lyudmila Gurchenko (1935–2011) – Soviet and Russian actress, singer and entertainer

- Mikhail Gurevich (1892–1976) – Soviet aircraft designer, a partner (with Artem Mikoyan) of the MiG military aviation bureau

- Diana Harkusha (born 1994) – Miss Ukraine Universe 2014 and Miss Universe 2014's 2nd Runner-up

- Leonid Haydamaka (1898–1991) – bandurist and conductor

- Vasily Karazin (1773–1842) – founder of National University of Kharkiv, which bears his name

- Hnat Khotkevych (1877–1938) – writer, ethnographer, composer, bandurist

- Mikhail Koshkin (1898–1940)– chief designer of the T-34 Soviet tank

- Olga Krasko (born 1981) – Russian actress

- Mykola Kulish (1892–1937) – Ukrainian prose writer, playwright and pedagogue

- Les Kurbas (1887–1937) - movie and theatre director and dramatist

- Simon Kuznets (1901–1985) – Russian-American economist

- Евгений Лифшиц (1915–1985) – советский физик.

- Эдуард Лимонов (1943–2020) – писатель, поэт и скандальный политик; вырос в Харькове и учился в Харьковском национальном педагогическом университете имени Г.С. Сковороды.

- Gleb Lozino-Lozinskiy (1909–2001) – lead developer of Soviet Shuttle Buran program

- Александр Ляпунов (1857–1918) – русский математик и физик, изобрел теорию устойчивости движения.

- Борис Михайлов (род.1938) – фотограф и художник.

- Николай Михновский (1873–1924) – украинский политический деятель и деятель.

- T-DJ Milana (1989 г.р.) – диджей, композитор, танцовщица и модель, живет в Харькове.

- Юрий Никитин (род. 1939) – российский писатель-фантаст и фэнтези.

- Фам Нхот Вынг - вьетнамский предприниматель и первый миллиардер, начал свою бизнес-карьеру в Харькове в 1990-е годы. [ 152 ]

- Х.Л. Олди (Дмитрий Громов и Олег Ладыженский) (оба 1963 г.р.) – писатели

- Жюстин Пасек (1979 г.р.) - Мисс Вселенная 2002.

- Валериан Пидмогильный (1901–1937) – поэт, прозаик и литературный критик.

- Ольга Рапай-Маркиш (1929–2012) – керамист.

- Элизабетта ди Сассо Руффо (1886–1940) – русская принцесса.

- Серафина Щахова – врач-нефролог

- Ойген Шауман (1875–1904) – финский националист, убил русского генерала Н. А. Бобрикова.

- Александр Щетинский (род. 1960) – автор сольных, оркестровых и хоровых произведений.

- Георгий Шевелов (1908–2002) – лингвист, публицист, историк литературы и литературный критик.

- Елена Шейнина (1965 г.р.) - детский писатель.

- Лев Шубников (1901–1937) – советский физик- экспериментатор , работал в Нидерландах и СССР.

- Klavdiya Shulzhenko (1906–1984) – Soviet and Russian popular female singer and actress.

- Henryk Siemiradzki (1843-1902) – учился в харьковской школе

- Александр Силоти (1863–1945) – русский пианист, дирижер и композитор.

- Hryhorii Skovoroda (1722–1794) – поэт, philosopher and composer

- Карина Смирнофф (1978 г.р.) - чемпионка мира по танцам, снялась в сериале « Танцы со звездами».

- Katya Soldak (Ukrainian: Катя Солдак; born 1977 in Kharkiv) journalist, filmmaker, and author

- Юра Сойфер (1912–1939) – австрийский политический журналист и кабаре . писатель

- Отто Струве (1897–1963) – русско-американский астроном.

- Сергей Святченко (род.1952) датско-украинский художник, фотограф и архитектор.

- Марк Тайманов (1926–2016) – концертирующий пианист и шахматист.

- Николай Тихонов (1905–1997) — советский российско-украинский государственный деятель времен Холодной войны.

- Yevgeniy Timoshenko (born 1988) – poker player in the US

- Андрей Цаплиенко (род. 1968) — журналист, ведущий, кинорежиссер и писатель.

- Анна Цыбулева (1990 г.р.) – классическая пианистка, победительница Международного конкурса пианистов в Лидсе.

- Анна Ушенина (1985 г.р.) - чемпионка мира по шахматам среди женщин.

- Владимир Васютин (1952–2002) – советский космонавт украинского происхождения.

- Виталий Виталиев (1954 г.р.) - журналист и писатель.

- Александр Воеводин (1949 г.р.) – ученый-биомедик и педагог.

- Евгения Иосифовна Яхина (1918–1983) – композитор.

- Василий Ермилов (1894–1968) – украинский и советский живописец, художник-авангардист и дизайнер.

- Serhiy Zhadan (born 1974) – украинский поэт, novelist, essayist and translator.

- Валентина Яновна Жубинская (1926–2013) украинский композитор, концертмейстер и пианистка.

- Ирина Журина (род.1946) русское оперное колоратурное сопрано .

- Александр Зорич (Дмитрий Гордевский и Яна Боцман) (оба 1973 г.р.) - писатели

- Oksana Cherkashyna (born 1988) – actress

Спорт

[ редактировать ]- Леонид Буряк (1953 г.р.) - футбольный тренер и бывший футболист.

- Валентина Чепига (1962 г.р.) - культуристка , Мисс Олимпия 2000 года. чемпионка

- Olga Danilov (born 1973) – Israeli Olympic speed skater

- Alexander Davidovich (born 1967) – Israeli Olympic wrestler

- Михаил Гуревич – (род.1959) бельгийский шахматист.

- Oleksandr Gvozdyk (born 1987) – boxer

- Pavlo Ishchenko (born 1992) – Olympic Ukrainian-Israeli boxer

- Александр Качоренко (1980 г.р.) – профессиональный футболист.

- Максим Калиниченко (born 1979) – footballer

- Игорь Ольшанецкий (1986 г.р.) – израильский олимпийский тяжелоатлет.

- Геннадий Орлов (1945 г.р.) - российский спортивный журналист и бывший футболист.

- Иван Правилов (1963–2012) - тренер по хоккею, изнасиловал студента-подростка, покончил жизнь самоубийством, повесившись в тюрьме.

- Ирина Пресс (1939–2004) – спортсменка, завоевавшая две олимпийские золотые медали.

- Тамара Пресс (1937–2021) – советская толкательница ядра и метательница диска.

- Птачик (1981 г.р.) – футболист на пенсии.

- Сергей Рихтер (1989 г.р.) – израильский олимпийский спортивный стрелок.

- Игорь Рыбак (1934–2005) – олимпийский чемпион тяжелоатлет в легком весе.

- Элина Свитолина (1994 г.р.) - теннисистка.

- Катерина Табашник (1994 г.р.) - прыгунья в высоту.

- Евгения Тетельбаум (1991 г.р.) - израильская олимпийская синхронистка.

- Артем Цоглин (1997 г.р.) – израильский фигурист-парник.

- Юрий Венгеровский (1938–1998) - волейболист, олимпийский чемпион.

- Игорь Вовчанчин (born 1973) – mixed martial artist

- Oleksandr Zhdanov (born 1984) – Ukrainian-Israeli footballer

- Oleksandr Zakolodny (1987-2023) - mountaineer

Лауреаты Нобелевской премии и премии Филдса

[ редактировать ]- Эли Мечников (1845–1916) – русский/французский зоолог; исследованная иммунология; совместно удостоены Нобелевской премии 1908 года по физиологии и медицине.

- Саймон Кузнец (1901–1985) – американский экономист и статистик; получил Нобелевскую премию по экономике 1971 года.

- Лев Ландау (1908–1968) – советский физик, внес фундаментальный вклад в теоретическую физику; Нобелевская премия по физике 1962 г.

- Владимир Дринфельд (род. 1954) – математик, сейчас находится в США; награжден медалью Филдса в 1990 году.

Города-побратимы – города-побратимы

[ редактировать ]Харьков является побратимом : [ 242 ]

Альбукерке , США (2023 г.) [ 243 ]

Альбукерке , США (2023 г.) [ 243 ]  Болонья , Италия (1966)

Болонья , Италия (1966)  Брно , Чехия (2005)

Брно , Чехия (2005)  Цетинье , Черногория (2011)

Цетинье , Черногория (2011)  Цинциннати , США (1989)

Цинциннати , США (1989)  Тэджон , Южная Корея (2013)

Тэджон , Южная Корея (2013)  Даугавпилс , Латвия (2006)

Даугавпилс , Латвия (2006)  Дебрецен , Венгрия (2016)

Дебрецен , Венгрия (2016)  Газиантеп , Турция (2011)

Газиантеп , Турция (2011)  Героскипу , Кипр (2018)

Героскипу , Кипр (2018)  Цзинань , Китай (2004 г.)

Цзинань , Китай (2004 г.)  Каунас , Литва (2001)

Каунас , Литва (2001)  Кутаиси , Грузия (2005)

Кутаиси , Грузия (2005)  Лилль , Франция (1978)

Лилль , Франция (1978)  Марибор , Словения (2012)

Марибор , Словения (2012)  Нюрнберг , Германия (1990)

Нюрнберг , Германия (1990)  Полис , Кипр (2018)

Полис , Кипр (2018)  Познань , Польша (1998)

Познань , Польша (1998)  Ришон-ле-Цион , Израиль (2008 г.)

Ришон-ле-Цион , Израиль (2008 г.)  Тбилиси , Грузия (2012)

Тбилиси , Грузия (2012)  Тяньцзинь , Китай (1993)

Тяньцзинь , Китай (1993)  Тирана , Албания (2017)

Тирана , Албания (2017)  Трнава , Словакия (2013)

Трнава , Словакия (2013)  Турку , Финляндия (2022)

Турку , Финляндия (2022)  Варна, Болгария (1995)

Варна, Болгария (1995)

См. также

[ редактировать ]

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Что делает Харьков украинским. Архивировано 8 декабря 2014 г. на Wayback Machine , The Украинская неделя (23 ноября 2014 г.).

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с В Харькове "декоммунизировали" еще 48 улиц и 5 районов [Еще 48 улиц и 5 районов "декоммунизировали" в Харькове]. Украинская правда (на украинском языке). Архивировано из оригинала 1 июля 2023 года . Проверено 1 июля 2023 г.

Переименование районов [Три района переименованы в Харьков]. Статус-кво (на русском языке). 30 июня 2023 года. Архивировано из оригинала 1 июля 2023 года . Проверено 1 июля 2023 г.

(на украинском языке) Октябрьский и Фрунзенский районы Харькова решено не переименовывать. Архивировано 4 февраля 2016 года на Wayback Machine , Корреспондент.net (3 февраля 2015 г.). - ^ Перейти обратно: а б "Терехов офіційно став мером Харкова" [Terekhov officially became the mayor of Kharkiv]. Ukrainska Pravda (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 25 January 2022 . Retrieved 1 July 2023 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б "Блок Кернеса висунув Терехова кандидатом у мери" [Kernes' bloc nominated Terekhov as a candidate for mayor]. Ukrainska Pravda (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 11 November 2021 . Retrieved 1 July 2023 .

- ^ Численность доступного населения Украины по состоянию на 1 января 2022 г. (PDF) , заархивировано (PDF) из оригинала 10 августа 2022 г. , получено 26 марта 2023 г.

- ↑ Вторые зимние Олимпийские игры в Украине: одна медаль, несколько хороших выступлений. Архивировано 3 октября 2020 г. в Wayback Machine , The Украинский еженедельник (1 марта 1998 г.).

- ↑ В Харькове «никогда не было конфликтов между Востоком и Западом». Архивировано 20 марта 2022 г. в Wayback Machine , Euronews (23 октября 2014 г.).

- ^ Численность населения Украины на 1 января 2022 года [ Численность нынешнего населения Украины на 1 января 2022 года ] (PDF) (на украинском и английском языках). Киев: Государственная служба статистики Украины . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 4 июля 2022 года.

- ^ Балмфорт, Том. «Из-за нехватки средств противовоздушной обороны в Украине Харьков становится более уязвимым для российских бомб» . Рейтер . (12 апреля 2024 г.)

- ^ Охрана, Элли Кук; Репортер Министерства обороны (11 апреля 2024 г.). «Зеленский выступил с грозным предупреждением Харькову» . Newsweek . Проверено 11 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ «Брифинг по войне в Украине: жители Харькова страдают, поскольку Россия усиливает атаки | Украина | The Guardian» . amp.theguardian.com . Проверено 1 мая 2024 г.

- ^ Эйддон, Йорверт; Эдвардс, Стивен; Хизер, Питер (1998). «Готы и гунны». Поздняя Империя . Кембриджская древняя история. Том. 13. Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 488. ИСБН 0-521-30200-5 .

- ^ Кевин Алан Брук, Евреи Хазарии (2006), с. 34. Архивировано 5 апреля 2023 года в Wayback Machine .

- ^ Роман Солчаник (январь 2001 г.). Украина и Россия: постсоветский переход . Роуман и Литтлфилд. п. 6. ISBN 978-0-7425-1018-0 . Архивировано из оригинала 2 октября 2023 года . Проверено 31 марта 2015 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л Живой Харьков. Ночная экскурсия по городу-хозяину [Живой Харьков. Ночная экскурсия по городу-хозяину. Украинская правда . Архивировано из оригинала 7 мая 2021 года . Проверено 1 июля 2023 г.

- ^ Иван Качановский и др. (ред.), Исторический словарь Украины (2013), с. 253. Архивировано 5 апреля 2023 года в Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Страница:Котляревский. Энеида на малороссийский языкъ перелицирована. 1798.pdf/175 — Викиисточники" . ru.wikisource.org. Archived из original на 19 октября 2017 . Retrieved 18 июня 2017 .

- ^ Славяне в Канаде, том. 2, Межуниверситетский комитет по канадским славянам (1968), с. 255.

- ^ Указ об учреждении губерний и о росписании к ним городов, 1708 г., декабря 18 [Указ об учреждении губерний и закрепленных за ними городов, 18 декабря 1708 г.]. Constitution.garant.ru (на русском языке). Архивировано из оригинала 28 июля 2017 года . Проверено 31 марта 2015 г.

- ^ История административно-территориального деления воронежского края. 2. Воронежская губерния [История административно-территориального деления Воронежской области. 2. Воронежская губерния.] (на русском языке). Архивная служба Воронежской области. Архивировано из оригинала 25 мая 2013 года . Проверено 10 июня 2012 г.

- ^ В Харькове открыли мемориальную доску Ивану Франко [В Харькове открыта мемориальная доска Ивану Франко] (на украинском языке). Istpravda.com.ua. 23 августа 2011 года. Архивировано из оригинала 10 ноября 2012 года . Проверено 21 июля 2012 г.

- ^ Харьков и харьковчане XIX века [Харьковчане и харьковчане на фотографиях XIX века] (на украинском языке). Istpravda.com.ua. 24 января 2011 года. Архивировано из оригинала 22 июня 2012 года . Проверено 21 июля 2012 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Громадас» . Энциклопедия Украины . Архивировано из оригинала 27 декабря 2015 года . Проверено 14 января 2016 г.

- ^ « Слава Украине!»: кем и когда был создан лозунг?» . www.istpravda.com.ua . Архивировано из оригинала 25 февраля 2022 года . Проверено 14 августа 2022 г.

- ^ «Революционная украинская партия» . www.энциклопедияofukraine.com . Архивировано из оригинала 15 августа 2022 года . Проверено 14 августа 2022 г.

- ^ ХАММ, МАЙКЛ Ф. (2013), Хейвуд, Энтони Дж; Смеле, Джонатан Д. (ред.), «Евреи и революция в Харькове: как один украинский город избежал погрома в 1905 году» , Русская революция 1905 года , doi : 10.4324/9780203002087 , ISBN 9780203002087 , заархивировано из оригинала 14 августа 2022 года , получено 14 августа 2022 года.

- ^ "УКРАИНСКАЯ СОЦИАЛ-ДЕМОКРАТИЧЕСКАЯ РАБОЧАЯ ПАРТИЯ, Ukrainian Soviet Encyclopedia" . leksika.com.ua . Archived из original на 25 января 2021 . Retrieved 14 августа 2022 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Сенькус, Роман; Жуковский, Аркадий (1993). «Украинская социал-демократическая рабочая партия» . www.энциклопедияofukraine.com . Архивировано из оригинала 22 сентября 2022 года . Проверено 14 августа 2022 г.

- ^ Оливер Генри Рэдки (1989). Россия идет на выборы: выборы во Всероссийское Учредительное собрание, 1917 год . Издательство Корнельского университета. стр. 115, 117. ISBN. 978-0-8014-2360-4 . Архивировано из оригинала 2 октября 2023 года . Проверено 11 августа 2022 г.