Тысяча Ми-24

| Ми-24/Ми-25/Ми-35 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ми-24W Сухопутных войск Польши. | |

| Роль | Ударный вертолет с транспортными возможностями, боевой вертолет |

| Национальное происхождение | Советский Союз / Россия |

| Производитель | Тысяча |

| Первый полет | 19 сентября 1969 г. |

| Введение | 1972 |

| Статус | В эксплуатации |

| Основные пользователи | Воздушно-космические силы России 58 других пользователей (см. раздел «Операторы» ниже) |

| Произведено | 1969 – настоящее время [ нужна ссылка ] |

| Количество построенных | 2,648 |

| Разработано на основе | Миль Ми-8 |

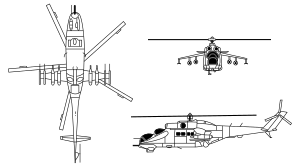

Ми -24 ( русский : Миль Ми-24 ; кодовое название НАТО : Hind ) — это большой боевой вертолет , ударный вертолет и малотоннажный военный транспорт , вмещающий восемь пассажиров. [ 1 ] Он производится Московским вертолетным заводом имени Миля и был принят на вооружение ВВС СССР в 1972 году. В настоящее время вертолет используется в 58 странах мира.

В кругах НАТО экспортные версии Ми-25 и Ми-35 обозначаются буквенным суффиксом как «Hind D» и «Hind E». Советские летчики называли Ми-24 «летающим танком» (русский: летающий танк , латинизированный: летающий танк ), термин, который исторически использовался в отношении знаменитого советского Ил-2 времен бронированного штурмовика Второй мировой войны. Другими распространенными неофициальными прозвищами были «Галина» (или «Галя»), «Крокодил» (русский: Крокодил , латинизированный: Крокодил ), из-за схемы камуфляжа вертолета, и « Стакан для питья » (русский: Стакан , латинизированный: Стакан ), из-за плоских стекол, окружающих кабины более ранних вариантов Ми-24 . [ 2 ]

Разработка

[ редактировать ]стало очевидно, В начале 1960-х годов советскому конструктору Михаилу Милю что тенденция к постоянному увеличению мобильности на поле боя приведет к созданию летающих боевых машин пехоты , которые можно будет использовать как для огневой поддержки, так и для транспортировки пехоты. Первым выражением этой концепции стал макет, представленный в 1966 году в экспериментальном отделе завода № 329 Минавиации, где Миль был главным конструктором. Макет, получивший обозначение V-24, был основан на другом проекте многоцелевого вертолета V-22 , который так и не летал. Фау-24 имел центральное пехотное отделение, в котором могли разместиться восемь военнослужащих, сидящих спиной к спине, и набор небольших крыльев, расположенных в верхней части задней части пассажирской кабины, способных вместить до шести ракет или ракет, а также двухствольный пулемет ГШ. Пушка -23Л закреплена на посадочной полозке.

Миль предложил проект руководству советских вооруженных сил. Хотя он пользовался поддержкой ряда стратегов, ему противостояли несколько более высокопоставленных военнослужащих, которые считали, что обычное оружие позволяет лучше использовать ресурсы. Несмотря на сопротивление, Милю удалось убедить первого заместителя министра обороны маршала Андрея Гречко созвать экспертную комиссию для рассмотрения этого вопроса. Хотя мнения комиссии были неоднозначными, сторонники проекта в конечном итоге взяли верх, и был отправлен запрос на проектные предложения для вертолета боевой поддержки. Разработка и использование боевых вертолетов и ударных вертолетов армией США во время войны во Вьетнаме убедили Советы в преимуществах наземной поддержки вооруженных вертолетов и способствовали поддержке разработки Ми-24. [ 3 ]

Инженеры Миля подготовили два базовых проекта: одномоторный 7-тонный и двухмоторный 10,5-тонный, оба на базе турбовального двигателя Изотова ТВ3-177А мощностью 1700 л.с. Позже были изготовлены три полных макета, а также пять макетов кабины, чтобы можно было отрегулировать позиции пилота и оператора боевой станции.

ОКБ Камова предложило Ка-25 в качестве бюджетного варианта армейский вариант своего противолодочного вертолета . Этот вариант рассматривался, но позже от него отказались в пользу новой двухмоторной конструкции Миля. По настоянию военных был внесен ряд изменений, в том числе замена 23-мм пушки на скорострельный крупнокалиберный пулемет, установленный в подбородочной башне, а также использование противотанкового комплекса 9К114 «Штурм» (АТ-6 «Спираль»). танковая ракета.

A directive was issued on 6 May 1968 to proceed with the development of the twin-engine design. Work proceeded under Mil until his death in 1970. Detailed design work began in August 1968 under the codename Yellow 24. A full-scale mock-up of the design was reviewed and approved in February 1969. Flight tests with a prototype began on 15 September 1969 with a tethered hover, and four days later the first free flight was conducted. A second prototype was built, followed by a test batch of ten helicopters.

Acceptance testing for the design began in June 1970, continuing for 18 months. Changes made in the design addressed structural strength, fatigue problems and vibration levels. Also, a 12-degree anhedral was introduced to the wings to address the aircraft's tendency to Dutch roll at speeds in excess of 200 km/h (124 mph), and the Falanga missile pylons were moved from the fuselage to the wingtips. The tail rotor was moved from the right to the left side of the tail, and the rotation direction reversed. The tail rotor now rotated up on the side towards the front of the aircraft, into the downwash of the rotor, which increased its efficiency. A number of other design changes were made until the production version Mi-24A (izdeliye 245) entered production in 1970, obtaining its initial operating capability in 1971 and was officially accepted into the state arsenal in 1972.[4]

In 1972, following completion of the Mi-24, development began on a unique attack helicopter with transport capability. The new design had a reduced transport capability (three troops instead of eight) and was called the Mi-28, and that of the Ka-50 attack helicopter, which is smaller and more maneuverable and does not have the large cabin for carrying troops. In October 2007, the Russian Air Force announced it would replace its Mi-24 fleet with Mi-28Ns and Ka-52s by 2015.[5][6] However, after the successful operation of the type in Syria it was decided to keep it in service and upgrade it with new electronics, sights, arms and night vision goggles.[7]

Design

[edit]Overview

[edit]

The core of the aircraft was derived from the Mil Mi-8 (NATO reporting name "Hip") with two top-mounted turboshaft engines driving a mid-mounted 17.3 m five-blade main rotor and a three-blade tail rotor. The engine configuration gave the aircraft its distinctive double air intake. Original versions have an angular greenhouse-style cockpit; Model D and later have a characteristic tandem cockpit with a "double bubble" canopy. Other airframe components came from the Mi-14 "Haze". Two mid-mounted stub wings provide weapon hardpoints, each offering three stations, in addition to providing lift. The loadout mix is mission dependent; Mi-24s can be tasked with close air support, anti-tank operations, or aerial combat.

The Mi-24's titanium rotor blades are resistant to 12.7 mm rounds.[citation needed] The cockpit is protected by ballistic-resistant windscreens and a titanium-armored tub.[8] The cockpit and crew compartment are overpressurized to protect the crew in NBC conditions.[9]

Flight characteristics

[edit]

Considerable attention was given to making the Mi-24 fast. The airframe was streamlined, and fitted with retractable tricycle undercarriage landing gear to reduce drag. At high speed, the wings provide considerable lift (up to a quarter of total lift). The main rotor was tilted 2.5° to the right from the fuselage to compensate for translating tendency at a hover. The landing gear was also tilted to the left so that the rotor would still be level when the aircraft was on the ground, making the rest of the airframe tilt to the left. The tail was also asymmetrical to give a side force at speed, thus unloading the tail rotor.[10]

A modified Mi-24B, named A-10, was used in several speed and time-to-climb world record attempts. The helicopter had been modified to reduce weight as much as possible—one measure was the removal of the stub wings.[4] The previous official speed record was set on 13 August 1975 over a closed 1000 km course of 332.65 km/h (206.7 mph); many of the female-specific records were set by the all-female crew of Galina Rastorguyeva and Lyudmila Polyanskaya.[11] On 21 September 1978, the A-10 set the absolute speed record for helicopters with 368.4 km/h (228.9 mph) over a 15/25 km course. The record stood until 1986, when it was broken by the current official record holder, a modified British Westland Lynx.[12]

Comparison to Western helicopters

[edit]

As a combination of armoured gunship and troop transport, the Mi-24 has no direct NATO counterpart. While the UH-1 ("Huey") helicopters were used by the US in the Vietnam War either to ferry troops, or as gunships, they were not able to do both at the same time. Converting a UH-1 into a gunship meant stripping the entire passenger area to accommodate extra fuel and ammunition, and removing its troop transport capability. The Mi-24 was designed to do both, and this was greatly exploited by airborne units of the Soviet Army during the 1980–89 Soviet–Afghan War. The closest Western equivalent was the American Sikorsky S-67 Blackhawk, which used many of the same design principles and was also built as a high-speed, high-agility attack helicopter with limited troop transport capability using many components from the existing Sikorsky S-61. The S-67, however, was never adopted for service.[1] Other Western equivalents are the Romanian Army's IAR 330, which is a licence-built armed version of the Aérospatiale SA 330 Puma, and the MH-60 Direct Action Penetrator, a special purpose armed variant of the Sikorsky UH-60 Black Hawk.

Operational history

[edit]Ogaden War (1977–1978)

[edit]The first combat use of the Mi-24 was with the Ethiopian forces during the Ogaden War against Somalia. The helicopters formed part of a massive airlift of military equipment from the Soviet Union, after the Soviets switched sides towards the end of 1977. The helicopters were instrumental in the combined air and ground assault that allowed the Ethiopians to retake the Ogaden by the beginning of 1978.[13]

Chadian–Libyan conflict (1978–1987)

[edit]The Libyan air force used Mi-24A and Mi-25 units during their numerous interventions in Chad's civil war.[10] The Mi-24s were first used in October 1980 in the battle of N'Djamena, where they helped the People's Armed Forces seize the capital.

In March 1987, the Armed Forces of the North, which were backed by the US and France, captured a Libyan air force base at Ouadi-Doum in Northern Chad. Among the aircraft captured during this raid were three Mi-25s. These were supplied to France, which in turn sent one to the United Kingdom and one to the US.[4]

Soviet war in Afghanistan (1979–1989)

[edit]

The aircraft was operated extensively during the Soviet–Afghan War, mainly for bombing Mujahideen fighters. When the U.S. supplied heat-seeking Stinger missiles to the Mujahideen, the Soviet Mi-8 and Mi-24 helicopters proved to be favorite targets of the rebels.

It is difficult to find the total number of Mi-24s used in Afghanistan.[14] At the end of 1990, the whole Soviet Army had 1,420 Mi-24s.[15] During the Afghan war, sources estimated the helicopter strength to be as much as 600 units, with up to 250 being Mi-24s,[16] whereas a (formerly secret) 1987 Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) report says that the number of Mi-24s in theatre increased from 85 in 1980 to 120 in 1985.[17]

First deployment and combat

[edit]In April 1979, Mi-24s were supplied to the Afghan government to deal with Mujahideen guerrillas.[18] The Afghan pilots were well-trained and made effective use of their machines, but the Mujahideen were not easy targets. The first Mi-24 to be lost in action was shot down by guerrillas on 18 July 1979.[19][20]

Despite facing strong resistance from Afghan rebels, the Mi-24 proved to be very destructive. The rebels called the Mi-24 "Shaitan-Arba (Satan's Chariot)".[18] In one case, an Mi-24 pilot who was out of ammunition managed to rescue a company of infantry by maneuvering aggressively towards Mujahideen guerrillas and scaring them off. The Mi-24 was popular with ground troops, since it could stay on the battlefield and provide fire as needed, while "fast mover" strike jets could only stay for a short time before heading back to base to refuel.

The Mi-24's favoured munition was the 80-millimetre (3.1 in) S-8 rocket, the 57 mm (2.2 in) S-5 having proven too light to be effective. The 23 mm (0.91 in) gun pod was also popular. Extra rounds of rocket ammunition were often carried internally so that the crew could land and self-reload in the field. The Mi-24 could carry ten 100-kilogram (220 lb) iron bombs for attacks on camps or strongpoints, while harder targets could be dealt with a load of four 250-kilogram (550 lb) or two 500-kilogram (1,100 lb) iron bombs.[21] Some Mi-24 crews became experts at dropping bombs precisely on targets. Fuel-air explosive bombs were also used in a few instances, though crews initially underestimated the sheer blast force of such weapons and were caught by the shock waves. The 9K114 Shturm was used infrequently, largely due to a lack of targets early in the war that required the precision and range the missile offered and a need to keep to stocks of anti tank missiles in Europe. After the Mujahideen got access to more advanced anti aircraft weapons later in the war the Shturm was used more often by Mi-24 units.[22]

Combat experience quickly demonstrated the disadvantages of having an Mi-24 carrying troops. Gunship crews found the soldiers a concern and a distraction while being shot at, and preferred to fly lightly loaded anyway, especially given their operations from high ground altitudes in Afghanistan. Mi-24 troop compartment armour was often removed to reduce weight. Troops would be carried in Mi-8 helicopters while the Mi-24s provided fire support.

It proved useful to carry a technician in the Mi-24's crew compartment to handle a light machine gun in a window port. This gave the Mi-24 some ability to "watch its back" while leaving a target area. In some cases, a light machine gun was fitted on both sides to allow the technician to move from one side to the other without having to take the machine gun with him.

This weapon configuration still left the gunship blind to the direct rear, and Mil experimented with fitting a machine gun in the back of the fuselage, accessible to the gunner through a narrow crawl-way. The experiment was highly unsuccessful, as the space was cramped, full of engine exhaust fumes, and otherwise unbearable. During a demonstration, an overweight Soviet Air Force general got stuck in the crawl-way.[4] Operational Mi-24s were retrofitted with rear-view mirrors to help the pilot spot threats and take evasive action.

Besides protecting helicopter troop assaults and supporting ground actions, the Mi-24 also protected convoys, using rockets with flechette warheads to drive off ambushes; performed strikes on predesignated targets; and engaged in "hunter-killer" sweeps. Hunter-killer Mi-24s operated at a minimum in pairs, but were more often in groups of four or eight, to provide mutual fire support. The Mujahideen learned to move mostly at night to avoid the gunships, and in response the Soviets trained their Mi-24 crews in night-fighting, dropping parachute flares to illuminate potential targets for attack. The Mujahideen quickly caught on and scattered as quickly as possible when Soviet target designation flares were lit nearby.

Attrition in Afghanistan

[edit]The war in Afghanistan brought with it losses by attrition.[18] The environment itself, dusty and often hot, was rough on the machines; dusty conditions led to the development of the twin PZU ('PyleZashchitnoe Ustroystvo') air intake filters. The rebels' primary air-defence weapons early in the war were heavy machine guns and anti-aircraft cannons, though anything smaller than a 23 millimetre shell generally did not do much damage to an Mi-24. The cockpit glass panels were resistant to 12.7 mm (.50 in calibre) rounds.[citation needed]

The rebels also quickly began to use Soviet-made and US shoulder-launched, man-portable air-defense system (MANPADS) missiles such as the Strela and Redeye which had either been captured from the Soviets or their Afghan allies or were supplied from Western sources. Many of them came from stocks that the Israelis had captured during wars with Soviet backed states in the Middle East. Owing to a combination of the limited capabilities of these early types of missiles, poor training and poor material condition of the missiles, they were not particularly effective. Instead, the RPG-7, originally developed as an antitank weapon, was the first effective countermeasure to the Hind. The RPG-7, not designed for air defence, had inherent shortcomings in this role. When fired at the angles needed to hit aerial targets, the back-blast could easily wound the shooter, and the inevitable cloud of smoke and dust made it easy for gunners to spot the shooter's position.[citation needed]

From 1986,[21] the CIA began supplying the Afghan rebels with newer Stinger shoulder-launched, heat-seeking SAMs.[23] These were a marked improvement over earlier weapons. Unlike the Redeye and SA-7, which locked on to only infrared emissions, the Stinger could lock onto both infrared and ultraviolet emissions. This enabled the operator to engage an aircraft from all angles rather than just the tail and made it significantly more resistant to countermeasures like flares. In addition the Mil helicopters, particularly the Mi-24, suffered from a design flaw in the configuration of their engines that made them highly vulnerable to the Stinger. The Mi-24, along with the related Mi-8 and Mi-17 helicopters, had its engines placed in an inline configuration in an attempt to streamline the helicopter to increase speed and minimize the aircraft's overall frontal profile to incoming fire in a head on attack. However this had the opposite effect of leaking all the exhaust gasses from the Mi-24's engines directly out the side of the aircraft and away from the helicopter's rotor wash, creating two massive sources of heat and ultraviolet radiation for the Stinger to lock onto.[24] The inline placement of the engines was seen as so problematic in this regard that Mil designers abandoned the configuration on the planned successor to the Mi-24, the Mil Mi-28, in favour of an engine placement more akin to Western attack helicopters which vents the exhaust gasses into the helicopter's main rotor wash to dissipate heat.[citation needed]

Initially, the attack doctrine of the Mi-24 was to approach its target from high altitude and dive downwards. After the introduction of the Stinger, doctrine changed to "nap of the earth" flying, where they approached very low to the ground and engaged more laterally, popping up to only about 200 ft (61 m) in order to aim rockets or cannons.[25] Countermeasure flares and missile warning systems would be installed in all Soviet Mil Mi-2, Mi-8, and Mi-24 helicopters, giving pilots a chance to evade missiles fired at them. Heat dissipation devices were also fitted to exhausts to decrease the Mi-24's heat signature. Tactical and doctrinal changes were introduced to make it harder for the enemy to deploy these weapons effectively. These reduced the Stinger threat, but did not eliminate it.

Mi-24s were also used to shield jet transports flying in and out of Kabul from Stingers. The gunships carried flares to blind the heat-seeking missiles. The crews called themselves "Mandatory Matrosovs", after a Soviet hero of World War II who threw himself across a German machine gun to let his comrades break through.[citation needed]

According to Russian sources, 74 helicopters were lost, including 27 shot down by Stinger and two by Redeye.[21] In many cases, the helicopters with their armour and durable construction could withstand significant damage and able to return to base.[citation needed]

Mi-24 crews and end of Soviet involvement

[edit]Mi-24 crews carried AK-74 assault rifles and other hand-held weapons to give them a better chance of survival if forced down.[18] Early in the war, Marat Tischenko, head of the Mil design bureau visited Afghanistan to see what the troops thought of his helicopters, and gunship crews put on several displays for him. They even demonstrated manoeuvres, such as barrel rolls, which design engineers considered impossible. An astounded Tischenko commented, "I thought I knew what my helicopters could do, now I'm not so sure!"[18]

The last Soviet Mi-24 shot down was during the night of 2 February 1989, with both crewmen killed. It was also the last Soviet helicopter lost during nearly 10 years of warfare.[21]

Mi-24s in Afghanistan after Soviet withdrawal

[edit]

Mi-24s passed on to Soviet-backed Afghan forces during the war remained in dwindling service in the grinding civil war that continued after the Soviet withdrawal.[18]

Afghan Air Force Mi-24s in the hands of the ascendant Taliban gradually became inoperable, but a few flown by the Northern Alliance, which had Russian assistance and access to spares, remained operational up to the US invasion of Afghanistan in late 2001. In 2008, the Afghan Air Force took delivery of six refurbished Mi-35 helicopters, purchased from the Czech Republic. The Afghan pilots were trained by India and began live firing exercises in May 2009 in order to escort Mi-17 transport helicopters on operations in restive parts of the country.

Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988)

[edit]The Mi-25 saw considerable use by the Iraqi Army during the long war against Iran.[26] Its heavy armament caused severe losses to Iranian ground forces during the war. However, the Mi-25 lacked an effective anti-tank capability, as it was only armed with obsolete 9M17 Skorpion missiles.[27] This led the Iraqis to develop new gunship tactics, with help from East German advisors. The Mi-25s would form "hunter-killer" teams with French-built Aérospatiale Gazelles, with the Mi-25s leading the attack and using their massive firepower to suppress Iranian air defences, and the Gazelles using their HOT missiles to engage armoured fighting vehicles. These tactics proved effective in halting Iranian offensives, such as Operation Ramadan in July 1982.[27]

This war also saw the only confirmed air-to-air helicopter battles in history with the Iraqi Mi-25s flying against Iranian AH-1J SeaCobras (supplied by the United States before the Iranian Revolution) on several separate occasions. In November 1980, not long after Iraq's initial invasion of Iran, two Iranian SeaCobras engaged two Mi-25s with TOW wire-guided antitank missiles. One Mi-25 went down immediately, the other was badly damaged and crashed before reaching base.[21][28] The Iranians repeated this accomplishment on 24 April 1981, destroying two Mi-25s without incurring losses to themselves.[21] One Mi-25 was also downed by an IRIAF F-14A.[29]

The Iraqis hit back, claiming the destruction of a SeaCobra on 14 September 1983 (with YaKB machine gun), then three SeaCobras on 5 February 1984[28] and three more on 25 February 1984 (two with Falanga missiles, one with S-5 rockets).[21] A 1982 news article published on the Iraqi Observer claimed an Iraqi Mi-24D shot down an Iranian F-4 Phantom II using its armaments, either antitank missiles, guns or S-5 unguided rockets.[30]

After a lull in helicopter losses, each side lost a gunship on 13 February 1986.[21] Later, a Mi-25 claimed a SeaCobra shot down with YaKB gun on 16 February, and a SeaCobra claimed a Mi-25 shot down with rockets on 18 February.[21] The last engagement between the two types was on 22 May 1986, when Mi-25s shot down a SeaCobra. The final claim tally was 10 SeaCobras and 6 Mi-25s destroyed. The relatively small numbers and the inevitable disputes over actual kill numbers makes it unclear if one gunship had a real technical superiority over the other. Iraqi Mi-25s also claimed 43 kills against other Iranian helicopters, such as Agusta-Bell UH-1 Hueys.[28]

In general, the Iraqi pilots liked the Mi-25, in particular for its high speed, long range, high versatility and large weapon load, but disliked the relatively ineffectual anti-tank guided weapons and lack of agility.[27]

Nicaraguan civil war (1980–1988)

[edit]Mi-25s were also used by the Nicaraguan Army during the civil war of the 1980s.[31][32] Nicaragua received 12 Mi-25s (some sources claim 18) in the mid-1980s to deal with "Contra" insurgents.[28] The Mi-25s performed ground attacks on the Contras and were also fast enough to intercept light aircraft being used by the insurgents. The U.S. Reagan Administration regarded introduction of the Mi-25s as a major escalation of tensions in Central America.

Two Mi-25s were shot down by Stingers fired by the Contras. A third Mi-25 was damaged while pursuing Contras near the Honduran border, when it was intercepted by Honduran F-86 Sabres and A-37 Dragonflies. A fourth was flown to Honduras by a defecting Sandinista pilot in December 1988.

Sri Lankan Civil War (1987–2009)

[edit]The Indian Peace Keeping Force (1987–90) in Sri Lanka used Mi-24s when an Indian Air Force detachment was deployed there in support of the Indian and Sri Lankan armed forces in their fight against various Tamil militant groups such as the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). It is believed that Indian losses were considerably reduced by the heavy fire support from their Mi-24s. The Indians lost no Mi-24s in the operation, as the Tigers had no weapons capable of downing the gunship at the time.[28][33]

Since 14 November 1995, the Mi-24 has been used by the Sri Lanka Air Force in the war against the LTTE liberation group and has proved highly effective at providing close air support for ground forces. The Sri Lanka Air Force operates a mix of Mi-24/-35P and Mi-24V/-35 versions attached to its No. 9 Attack Helicopter Squadron. They have recently been upgraded with modern Israeli FLIR and electronic warfare systems. Five were upgraded to intercept aircraft by adding radar, fully functional helmet mounted target tracking systems, and AAMs. More than five Mi-24s have been lost to LTTE MANPADS, and another two lost in attacks on air bases, with one heavily damaged but later returned to service.[33]

Peruvian operations (1989–present)

[edit]The Peruvian Air Force received 12 Mi-25Ds and 2 Mi-25DU from the Soviets in 1983, 1984, and 1985 after ordering them in the aftermath of 1981 Paquisha conflict with Ecuador. Seven more second hand units (4 Mi-24D and 3 Mi-25D) were obtained from Nicaragua in 1992. These have been permanently based at the Vitor airbase near La Joya ever since, operated by the 2nd Air Group of the 211th Air Squadron. Their first deployment occurred in June 1989 during the war against Communist guerrillas in the Peruvian highlands, mainly against Shining Path. Despite the conflict continuing, it has decreased in scale and is now limited to the jungle areas of Valley of Rivers Apurímac, Ene and Mantaro (VRAEM).[34][35][36][37]

Persian Gulf War (1991)

[edit]

The Mi-24 was also heavily employed by the Iraqi Army during their invasion of Kuwait, although most were withdrawn by Saddam Hussein when it became apparent that they would be needed to help retain his grip on power in the aftermath of the war. In the ensuing 1991 uprisings in Iraq, these helicopters were used against dissidents as well as fleeing civilian refugees.[38][39]

Sierra Leone Civil War (1991–2002)

[edit]Three Mi-24Vs owned by Sierra Leone and flown by South African military contractors, including Neall Ellis, were used against RUF rebels.[40] In 1995, they helped drive the RUF from the capital, Freetown.[41] Neall Ellis also piloted a Mi-24 during the British-led Operation Barras against West Side Boys.[42] Guinea also used its Mi-24s against the RUF on both sides of the border and was alleged to have provided air support to the LURD insurgency in northern Liberia in 2001–03.

Croatian War of Independence (1990s)

[edit]Twelve Mi-24s were delivered to Croatia in 1993, and were used effectively in 1995 by the Croatian Army in Operation Storm against the Army of Krajina. The Mi-24 was used to strike deep into enemy territory and disrupt Krajina army communications. One Croatian Mi-24 crashed near the city of Drvar, Bosnia and Herzegovina due to strong winds. Both the pilot and the operator survived. The Mi-24s used by Croatia were obtained from Ukraine. One Mi-24 was modified to carry Mark 46 torpedoes. The helicopters were withdrawn from service in 2004.[43]

First and Second Wars in Chechnya (1990s–2000s)

[edit]During the First and Second Chechen Wars, beginning in 1994 and 1999 respectively, Mi-24s were employed by the Russian armed forces.

In the first year of the Second Chechen War, 11 Mi-24s were lost by Russian forces, about half of which were lost as a result of enemy action.[44]

Cenepa War (1995)

[edit]Peru employed Mi-25s against Ecuadorian forces during the short Cenepa conflict in early 1995. The only loss occurred on 7 February, when a FAP Mi-25 was downed after being hit in quick succession by at least two, probably three, 9K38 Igla shoulder-fired missiles during a low-altitude mission over the Cenepa valley. The three crewmen were killed.[45]

By 2011 two Mi-35P were purchased from Russia to reinforce the 211th Air Squadron.[46]

Sudanese Civil War (1995–2005)

[edit]In 1995, the Sudanese Air Force acquired six Mi-24s for use in Southern Sudan and the Nuba mountains to engage the SPLA. At least two aircraft were lost in non-combat situations within the first year of operation. A further twelve were bought in 2001,[47] and used extensively in the oil fields of Southern Sudan. Mi-24s were also deployed to Darfur in 2004–5.

First and Second Congo Wars (1996–2003)

[edit]Three Mi-24s were used by Mobutu's army and were later acquired by the new Air Force of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[48] These were supplied to Zaire in 1997 as part of a French-Serbian contract. At least one was flown by Serbian mercenaries. One hit a power line and crashed on 27 March 1997, killing the three crew and four passengers.[49] Zimbabwean Mi-24s were also operated in coordination with the Congolese Army.

The United Nations peacekeeping mission employed Indian Air Force Mi-24/-35 helicopters to provide support during the Second Congo War. The IAF has been operating in the region since 2003.[50]

Kosovo War (1998–1999)

[edit]Two second-hand Mi-24Vs procured from Ukraine earlier in the 1990s were used by the Yugoslav Special Operation Unit (JSO) against Kosovo Albanian rebels during the Kosovo War.[51]

Insurgency in Macedonia (2001)

[edit]

The Macedonian military acquired used Ukrainian Mi-24Vs, which were then used frequently against Albanian insurgents during the 2001 insurgency in Macedonia (now North Macedonia). The main areas of action were in Tetovo, Radusha and Aracinovo.[52]

Ivorian Civil War (2002–2004)

[edit]During the Ivorian Civil War, five Mil Mi-24s piloted by mercenaries were used in support of government forces. They were later destroyed by the French Army in retaliation for an air attack on a French base that killed nine soldiers.[53]

War in Afghanistan (2001–2021)

[edit]

In 2008 and 2009, the Czech Republic donated six Mi-24s under the ANA Equipment Donation Programme. As a result, the Afghan National Army Air Corps (ANAAC) gained the ability to escort its own helicopters with heavily armed attack helicopters. ANAAC operates nine Mi-35s. Major Caleb Nimmo, a United States Air Force Pilot, was the first American to fly the Mi-35 Hind, or any Russian helicopter, in combat.[54][55] On 13 September 2011, a Mi-35 of the Afghan Air Force was used to hold back an attack on ISAF and police buildings.[56]

The Polish Helicopter Detachment contributed Mi-24s to the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF). The Polish pilots trained in Germany before deploying to Afghanistan and train with U.S. service personnel. On 26 January 2011, one Mi-24 caught on fire during take-off from its base in Ghazni. One American and four Polish soldiers evacuated unharmed.[57]

India has also donated Mi-35s to Afghanistan. Four helicopters were to be supplied, with three already transferred in January 2016.[58] The three Mi-35s made a big difference in the offensive against militants, according to General John Campbell, commander of US forces in Afghanistan.[59]

Iraq War (2003–2011)

[edit]The Polish contingent in Iraq used six Mi-24Ds after December 2004. One of them crashed on 18 July 2006 in an air base in Al Diwaniyah.[60] Polish Mi-24Ds used in Iraq were not returned to Poland due to their age, condition, low combat value of the Mi-24D variant, and high shipping costs; depending on their condition, they were transferred to the new Iraqi Army or scrapped.

War in Somalia (2006–2009)

[edit]The Ethiopian Air Force operated about three Mil Mi-35 and ten Mil Mi-24D helicopter gunships in the Somali theatre. One was shot down near Mogadishu International Airport on 30 March 2007 by Somali insurgents.[61]

2008 Russo-Georgian War

[edit]Mil Mi-24s were used by both sides during the fighting in South Ossetia.[62] During the war Georgian Air Force Mi-24s attacked their first targets on an early morning hour of 8 August, targeting the Ossetian presidential palace. The second target was a cement factory near Tskhinvali, where major enemy forces and ammunition were located.[62] The last combat mission of the GAF Mi-24s was on 11 August, when a large Russian convoy, consisting of light trucks and BMP IFVs which were heading to the Georgian village of Avnevi was targeted by Mi-24s, completely destroying the convoy.[62] The Georgian Air Force lost 2 Mi-24s on Senaki air base. They were destroyed by Russian troops on the ground. Both helicopters were in-operational.[63] The Russian army heavily used Mi-24s in the conflict. Russian upgraded Mi-24PNs were credited for destroying 2 Georgian T-72SIM1 tanks, using guided missiles at night time, though some sources attribute those kills to Mil Mi-28.[62] The Russian army did not lose any Mi-24s throughout the conflict, mainly because those helicopters were deployed to areas where Georgian air defence was not active,[62] though some were damaged by small arms fire and at least one Mi-24 was lost due to technical reasons.

War in Chad (2008)

[edit]On returning to Abeche, one of the Chadian Mi-35s made a forced landing at the airport. It was claimed that it was shot down by rebels.[64][65]

Libyan civil war (2011)

[edit]The Libyan Air Force Mi-24s were used by both sides to attack enemy positions during the 2011 Libyan civil war.[66] A number were captured by the rebels, who formed the Free Libyan Air Force together with other captured air assets. During the battle for Benina airport, one Mi-35 (serial number 853), was destroyed on the ground on 23 February 2011. In the same action, serial number 854 was captured by the rebels together with an Mi-14 (serial number 1406).[citation needed] Two Mi-35s operating for the pro-Gaddafi Libyan Air Force were destroyed on the ground on 26 March 2011 by French aircraft enforcing the no-fly zone.[67] One Free Libyan Air Force Mi-25D (serial number 854, captured at the beginning of the revolt) violated the no-fly-zone on 9 April 2011 to strike loyalist positions in Ajdabiya. It was shot down by Libyan ground forces during the action. The pilot, Captain Hussein Al-Warfali, died in the crash.[citation needed] The rebels claimed that a number of other Mi-25s were shot down.

2010–2011 Ivorian crisis

[edit]Ukrainian army Mi-24P helicopters as part of the United Nations peacekeeping force fired four missiles at a pro-Gbagbo military camp in Ivory Coast's main city of Abidjan.[68]

Syrian Civil War (2011–present)

[edit]The Syrian Air Force has used Mi-24s during the ongoing Syrian Civil War, including in many of the country's major cities.[69] Controversy has surrounded an alleged delivery of Mi-25s[by whom?] to the Syrian military, due to Turkey and other NATO members disallowing such arms shipments through their territory.[vague][70]

On 3 November 2016, a Russian Mi-35 made an emergency landing near Syria's Palmyra city, and was hit and destroyed, most likely by an unguided recoilless weapon after it touched down. The crew returned safely to the Khmeimim air base.[71]

Second Kachin conflict (2011–present)

[edit]The Myanmar Air Force used the Mi-24 in the Kachin conflict against the Kachin Independence Army.[72] Two Mi-35 helicopters were shot down by the Kachin Independence Army during the heavy fighting in the mountains of northern Burma in 2012 and early 2013.[73] On 3 May 2021, in the morning, a Myanmar Air Force Mi-35 was shot down by the Kachin Independence Army, hit by a MANPADS during air raids involving attack helicopters and fighter jets. A video emerged showing the helicopter being hit while flying over a village.[74][75]

Post-U.S. Iraqi insurgency

[edit]Iraq ordered a total of 34 Mi-35Ms in 2013, as part of an arms deal with Russia that also included Mi-28 attack helicopters.[76] The delivery of the first four was announced by then-Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki in November 2013.[77][78]

Their first deployment began in late December against camps of the al-Qaeda linked Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) and several Islamist militants in the al-Anbar province that had taken control of several areas of Fallujah and Ramadi.[79] FLIR footage of the strikes has been released by the military.[80]

On 3 October 2014, ISIL militants reportedly used a FN-6 shoulder-launched missile in Baiji to shoot down an Iraqi Army Mi-35M attack helicopter.[81] Video footage released by ISIL militants shows at least another two Iraqi Mi-35s brought down by light anti-aircraft artillery.[82]

Balochistan Insurgency (2012-present)

[edit]In 2018, Pakistan received 4 Mi-35M Hind-E Gunships from Russia under the $153 million deal.[83][84] They are now stationed at the Army Aviation Corps base at Quetta Cantonment. The gunships have since been used in several counter insurgency operations against various militant groups in the Balochistan province of Pakistan. In early 2022, a base in Nushki and a check-post in Panjgur belonging to the Frontier Corps Balochistan Paramilitary were attacked by BLA terrorists. The attack in Nushki was swiftly repulsed but the situation in Panjgaur was not good to which Mi-35 Hind and AH-1F Cobra gunships were called in for support. It provided much needed ground support and reconnaissance in the counter offensive which led to success.[85][86]

Crimean crisis (2014)

[edit]During the annexation of the Crimean Peninsula, Russia deployed 13 Mi-24s to support their infantry as they advanced through the region. However these aircraft saw no combat during their deployment.[87]

War in Donbas (2014)

[edit]During the Siege of Sloviansk, on 2 May 2014, two Ukrainian Mi-24s were shot down by pro-Russian insurgents. The Ukrainian armed forces claim that they were downed by MANPADS while on patrol close to Slavyansk.[88] The Ukrainian government confirmed that both aircraft were shot down, along with an Mi-8 damaged by small arms fire. Initial reports mentioned two dead and others wounded; later, five crew members were confirmed dead and one taken prisoner until being released on 5 May.[89][90][91]

On 5 May 2014, another Ukrainian Mi-24 was forced to make an emergency landing after being hit by machine gun fire while on patrol close to Slavyansk. The Ukrainian forces recovered the two pilots and destroyed the helicopter with a rocket strike by an Su-25 aircraft to prevent its capture by pro-Russian insurgents.[92]

Ukrainian Su-25s, with MiG-29 fighters providing top cover, supported Mi-24s during the battle for Donetsk Airport.[93]

сбил «Орлан-10» БПЛА 13 октября 2018 года украинский Ми-24 артиллерийским огнем недалеко от Лисичанска . [ 94 ]

Наступление Чада против Боко Харам (2015 г.)

[ редактировать ]Чадские Ми-24 использовались во время западноафриканского наступления против Боко Харам в 2015 году . [ 95 ]

Азербайджан-Карабах (2014–2016, 2020 гг.)

[ редактировать ]12 ноября 2014 года азербайджанские силы сбили Ми-24 армянских сил из группы из двух человек, которые летели вдоль спорной границы, недалеко от линии фронта между азербайджанскими и армянскими войсками на спорной территории Карабаха. Вертолет был сбит переносной ракетой «Игла-С», выпущенной азербайджанскими солдатами во время полета на малой высоте, и разбился, в результате чего погибли все трое находившихся на борту. [ 96 ] [ 97 ] [ 98 ]

2 апреля 2016 года в ходе столкновения азербайджанских и армянских сил силами «Нагорного Карабаха» был сбит азербайджанский вертолет Ми-24. Сбитие подтвердили в министерстве обороны Азербайджана. [ 99 ] [ 100 ] [ 101 ] [ 102 ]

9 ноября 2020 года во время войны в Нагорном Карабахе российский Ми-24 был сбит азербайджанскими войсками из ПЗРК. [ 103 ] В МИД Азербайджана заявили, что сбитие произошло случайно. Два члена экипажа погибли, один получил травмы средней степени тяжести. В тот же день министерство обороны России подтвердило факт сбития в пресс-релизе. [ 104 ]

Российское вторжение в Украину (2022-настоящее время)

[ редактировать ]Во время российского вторжения в Украину в 2022 году и Украина, и Россия использовали вертолеты Ми-24. 1 марта 2022 года украинские войска сбили российский вертолет Ми-35М с помощью ПЗРК на Киевском водохранилище (см. также « Битва за Киев »). 5 мая 2022 года вертолет был поднят украинскими инженерами в Вышгороде . [ 105 ] [ нужен лучший источник ] Два российских Ми-35 были сбиты ПЗРК 5 марта 2022 года. [ 106 ] [ 107 ] 6 марта один Ми-24П с регистрационным номером RF-94966 был сбит украинскими ПЗРК в Киевской области. [ 108 ] [ 109 ] 8 марта 2022 года один украинский Ми-24 из 16-й армейской авиационной бригады Украины был потерян над Броварами в Киеве. Пилоты полковник Александр Мариняк и капитан. Иван Беззуб был убит. [ 110 ] [ 111 ] 17 марта сообщалось, что российский Ми-35М был уничтожен Министерством обороны Украины , местонахождение неизвестно. [ 112 ] [ нужен лучший источник ] Сообщается, что 1 апреля 2022 года два украинских Ми-24 вторглись в Россию и атаковали нефтехранилище в Белгороде . [ 113 ]

В мае 2022 года Чехия подарила Украине вертолеты Ми-24. [ 114 ] В июле 2023 года сообщалось, что Польша тайно передала Украине не менее десятка Ми-24. [ 115 ]

Варианты

[ редактировать ]Операторы

[ редактировать ]

- ВВС Египта , 549-е авиакрыло/43-я эскадрилья - Борг-аль-Араб [ 117 ]

- Воздушно-космические силы России [ 116 ]

- Пограничная служба России [ 120 ]

- Внутренние Войска России [ 121 ]

Бывшие операторы

[ редактировать ]- Кипрская национальная гвардия - продана Сербии в ноябре 2023 г. [ 128 ]

- Чешские ВВС - выведены в отставку и переведены в Украину в августе 2023 года. [ 116 ] [ 129 ]

Чехословацкие ВВС [ 130 ] [ 131 ]

- ВВС Восточной Германии - переданы Германии после воссоединения. [ 132 ] [ 133 ]

- Немецкая армия - унаследована от Восточной Германии в 1990 году, в отставке в 1993 году. [ 134 ] [ 135 ]

- Советские ВВС - переданы государствам-преемникам [ 140 ] [ 141 ]

Самолет на выставке

[ редактировать ]Вертолеты Ми-24 можно увидеть в следующих музеях:

| Россия | Центральный музей ВВС , Монино – Ми-24А, Ми-25. |

| Бельгия | Королевский музей вооруженных сил и военной истории , Брюссель – Ми-24 |

| Бразилия | Аэрокосмический музей , Рио-де-Жанейро - Ми-35М |

| Болгария | Аэропорт Пловдив , Музей авиации - Ми-24 [ 145 ]

Национальный музей военной истории, Болгария - Ми-24 д/б |

| Чешская Республика | Пражский музей авиации, Кбелы – Ми-24Д, тактический номер 0220. |

| Китай | Музей китайской авиации , Пекин – Ми-24 |

| Дания | Panzermuseum East , Слагельсе — восточногерманский Ми-24П Hind-F 1989 г. (строительный номер: 340339). Присвоен серийный номер NVA 464, позже немецкой армии 96+49. серийный номер [ 146 ] |

| Эфиопия | Мемориальный памятник мученикам , Бахр-Дар - Ми 24А [ 147 ] |

| Германия |

|

| Венгрия |

|

| Иран | Музей Саад Абада в Тегеране |

| Латвия | Рижский музей авиации , Рига – Ми-24А, тактический номер 20. |

| Никарагуа | База ВВС , международный аэропорт Август К. Сандино , Манагуа , Ми-25, тактический номер 361 |

| Польша |

|

| ЮАР | Музей ВВС ЮАР , база ВВС Сварткопс - на выставке представлен один Ми-24А ВВС Алжира . |

| Словакия | Военно-исторический музей, Пиештяны – Ми-24Д, тактический номер 0100. [ 148 ] |

| Шри-Ланка | |

| Украина |

|

| Великобритания |

|

| Соединенные Штаты |

|

| Вьетнам |

|

Технические характеристики (Ми-24)

[ редактировать ]

Данные Indian-Military.org. [ 154 ] [ ненадежный источник? ]

Общие характеристики

- Экипаж: 2-3 пилота, офицер систем вооружения и техник (по желанию).

- Вместимость: 8 военнослужащих / 4 носилки / 2400 кг (5291 фунт) груза на внешней подвеске.

- Длина: только фюзеляж 17,5 м (57 футов 5 дюймов)

- 19,79 м (65 футов), включая роторы

- Размах крыльев: короткие крылья 6,5 м (21 фут 4 дюйма).

- Высота: 6,5 м (21 фут 4 дюйма)

- Вес пустого: 8500 кг (18739 фунтов)

- Максимальный взлетный вес: 12 000 кг (26 455 фунтов)

- Силовая установка: 2 двигателя «Исотов ТВ3-117» турбовальных мощностью 1600 кВт (2200 л.с.) каждый.

- Диаметр несущего винта: 17,3 м (56 футов 9 дюймов)

- Площадь несущего винта: 235,1 м 2 (2531 кв. фут) NACA 23012 [ 155 ]

Производительность

- Максимальная скорость: 335 км/ч (208 миль в час, 181 узел)

- Дальность: 450 км (280 миль, 240 миль)

- Практический потолок: 4900 м (16 100 футов)

Вооружение

- Внутренние пушки

-

- Гибкая 12,7-мм пушка Якушева-Борзова Як-Б Гатлинга на большинстве вариантов. Максимальный боезапас 1470 патронов.

- исправлена двухствольная автоматическая пушка ГШ-30К на Ми-24П. Боекомплект 250 патронов.

- гибкая двухствольная автоматическая пушка ГШ-23Л на Ми-24ВП, Ми-24ВМ и Ми-35М. Боекомплект 450 патронов.

- гибкая 20-мм автоматическая пушка GIAT с двойной подачей (M693) на Ми-24 SuperHind Mk.II/III/IV/V. Боекомплект 320 патронов.

- Пулеметы ПКБ пассажирского салона, установленные на окнах

- Внешние магазины

-

- Общая полезная нагрузка внешних магазинов составляет 1500 кг.

- Внутренние точки подвески выдерживают не менее 500 кг.

- Внешние точки подвески выдерживают до 250 кг.

- Пилоны законцовок крыла могут нести только 9М17 «Фаланга» (на Ми-24А-Д) или комплекс 9К114 «Штурм» (на Ми-24В-Ф).

- Бомбовая нагрузка

-

- Бомбы в весовом диапазоне (предположительно ЗАБ, ФАБ, РБК, ОДАБ и т.д.) до 500 кг.

- Многоэжекторные стойки МБД (предположительно МБД-4 с 4 × ФАБ-100)

- Контейнеры-раздатчики суббоеприпасов/мин КГМУ2В

- Вооружение первого поколения (штатный Ми-24Д)

-

- Пушечная установка ГУВ-8700 (с комбинацией 12,7-мм Як-Б + 2 × 7,62-мм ГШГ-7,62-мм или одной 30-мм АГС-17 )

- УБ-16 С-5 Реактивные установки

- УБ-32 С-5 Реактивные установки

- С-24 240-мм ракета

- 9М17 Флейта (по паре на каждом пилоне законцовок крыла)

- Вооружение второго поколения (Ми-24В, Ми-24П и наиболее модернизированный Ми-24Д).

-

- Пулеметная установка УПК-23-250 с ГШ-23Л

- Б-8В20 - легкий длиннотрубный вертолетный вариант С-8. ракетной установки

- 9К114 Штурмы попарно на крайних и законцовках крыла.

- Зенитные ракеты

-

- Р-60 Инфракрасные ракеты

- Инфракрасные ракеты Р-60М

- Оба можно переносить по одному или по два на пилон.

Популярная культура

[ редактировать ]Ми-24 появлялся в нескольких фильмах и часто использовался во многих видеоиграх.

См. также

[ редактировать ]Связанные разработки

Самолеты сопоставимой роли, конфигурации и эпохи

- 330 ирландских фунтов в шоке

- Атлас XTP-1 Бета

- Мах Маринеон

- Sikorsky AH-60L/S-70 Battlehawk

- Сикорский S-67 Блэкхок

- Хэл Рудра

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Jump up to: а б «Защита воздух-воздух для ударных вертолетов» (PDF) . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 4 декабря 2011 года . Проверено 22 ноября 2012 г.

- ^ Дэй, Дуэйн А. «Ми-24 Хинд «Крокодил» » . Комиссия по столетию полетов США. Архивировано из оригинала 18 октября 2015 года . Проверено 1 июля 2011 г.

- ^ Калхейн, Кевин В. (1977). «Отчет о студенческом исследовании: Советский ударный вертолет» (PDF) . ДТИК . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 29 июня 2011 года . Проверено 1 июля 2011 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Yefim Gordon & Dmitry Komissarov (2001). Mil Mi-24, Attack Helicopter . Airlife.

- ^ «Ми-28 на замену Ми-24» . Страница стратегии . 1 октября 2007 г. Архивировано из оригинала 3 декабря 2007 г. Проверено 19 ноября 2007 г.

- ^ «ВВС России заменят боевые вертолеты к 2015 году» . Коммерсант . 24 октября 2007 г. Архивировано из оригинала 26 октября 2007 г.

- ^ «Россия обновляет парк вертолетов Ми-24» . www.airrecognition.com .

- ^ Хальберштадт, Ганс (1994). «Истребители Красной Звезды и штурмовики» . Уиндроу и Грин. стр. 85, 88. Архивировано из оригинала 19 октября 2013 года . Проверено 2 декабря 2011 г.

- ^ «Вертолет Ми-24 – Военные Силы» . Военные силы . Архивировано из оригинала 2 сентября 2017 года . Проверено 4 июля 2017 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Gordon, Yefim; Komissarov, Dmitry (2001). Mil Mi-24 Hind, Attack Helicopter . Airlife. ISBN 9781840372380 .

- ^ «Мировые рекорды винтокрылых машин: Список рекордов, установленных «А-10» » . Международная авиационная федерация . Архивировано из оригинала 23 июля 2003 года . Проверено 17 сентября 2009 г.

- ^ «Мировые рекорды винтокрылых машин: История мировых рекордов винтокрылых машин» . Международная авиационная федерация . Архивировано из оригинала 11 января 2009 года . Проверено 17 сентября 2009 г.

- ^ Купер, Том. «Огаденская война, 1977–1978» . Информационная группа воздушного боя. Архивировано из оригинала 7 января 2007 года . Проверено 18 марта 2007 г.

- ^ Грау, Лестер В. Медведь перешел через гору: советская боевая тактика в Афганистане. Архивировано 1 декабря 2012 года в Wayback Machine . Издательство Национального университета обороны, 1996.

- ^ Международный институт стратегических исследований (1989). Военный баланс, 1989-1990 гг . Лондон: Брасси. п. 34. ISBN 978-0080375694 .

- ^ «Советская авиация» . Airpower.au.af.mil. Архивировано из оригинала 24 февраля 2013 года . Проверено 22 ноября 2012 г.

- ^ «Цена советского участия в Афганистане». Архивировано 29 ноября 2011 года в Wayback Machine . Управление советского анализа

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж Гебель, Грег (1 апреля 2009 г.). «Сзади варианты/Советская служба» . Архивировано из оригинала 20 января 2008 года . Проверено 17 января 2008 г.

- ^ Харро Рантер. «АСН Авиационная катастрофа 18 июля 1979 г. Ми-24А» . Aviation-safety.net . Архивировано из оригинала 13 ноября 2014 года . Проверено 13 ноября 2014 г.

- ^ «Афганистан – ВВС в локальных войнах» . Skywar.ru . Архивировано из оригинала 13 мая 2015 года . Проверено 13 ноября 2014 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г час я Yakubovich, Nikolay. Boevye vertolety Rossii. Ot "Omegi" do "Alligatora" (Russia's combat helicopters. From Omega to Alligator). Moscow, Yuza & Eksmo, 2010, ISBN 978-5-699-41797-1 , стр. 164–173.

- ^ Оружие, Системы. «9К114 Штурм» . Weapon Systems.net .

- ^ Кордовес, Диего; Харрисон, Селиг С. (29 июня 1995 г.). Уход из Афганистана: внутренняя история вывода советских войск . Издательство Оксфордского университета. стр. 194−198. ISBN 978-0-19-536268-8 . Проверено 7 августа 2023 г.

- ^ Канал, Дискавери (3 сентября 2011 г.). «Крылья: Ми-24 Хинд «Медвежий капкан» 4/5» . Ютуб . Канал Дискавери. Архивировано из оригинала 21 декабря 2021 года . Проверено 28 июля 2021 г.

- ↑ В Сирии намеки на тактику советских вертолетов из Афганистана. Архивировано 29 октября 2015 г. на Wayback Machine - Washingtonpost.com, 8 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Купер, Том; Епископ Фарзад (9 сентября 2003 г.). «Первая война в Персидском заливе: иракское вторжение в Иран, сентябрь 1980 года» . Информационная группа воздушного боя. Архивировано из оригинала 21 февраля 2014 года . Проверено 12 ноября 2006 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Купер, Том; Епископ Фарзад (9 сентября 2003 г.). «Огонь на холмах: иранские и иракские сражения осени 1982 года» . Информационная группа воздушного боя. Архивировано из оригинала 22 августа 2014 года . Проверено 17 января 2008 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Гебель, Грег (16 сентября 2012 г.). «Hind на дипломатической службе / Модернизация Hind / Ми-28 Havoc» . Ми-24 Hind и Ми-28 Havoc . Архивировано из оригинала 13 ноября 2013 года . Проверено 16 сентября 2012 г.

- ^ «Архивная копия» . Архивировано из оригинала 8 августа 2016 года . Проверено 18 июня 2016 г.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: архивная копия в заголовке ( ссылка ) - ^ "Как Ми-24В уничтожил израильский истребитель: уникальные рекорды российских вертолетов" . TV Zvezda . 17 October 2015 . Retrieved 3 November 2019 .

- ^ «Ми-24» . Палитра «Крылья» . Архивировано из оригинала 23 июля 2011 года . Проверено 1 июля 2011 г.

- ^ «Миль Ми-24» . Aerospaceweb.org . Архивировано из оригинала 7 июня 2011 года . Проверено 1 июля 2011 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Купер, Том (29 октября 2003 г.). «Шри-Ланка, с 1971 года» . Информационная группа воздушного боя. Архивировано из оригинала 3 октября 2008 года . Проверено 26 июня 2006 г.

- ^ «Лос Ми-25 де ла ФАП» . Geocities.ws . Архивировано из оригинала 26 апреля 2014 года . Проверено 13 ноября 2014 г.

- ^ «Арекипа: Вертолеты МИ-25 представлены для боя во ВРАЭМ» . Перу.com . 19 октября 2012 года. Архивировано из оригинала 13 ноября 2014 года . Проверено 13 ноября 2014 г.

- ^ «Ofensiva Mayor en el VRAE» . Ютуб . 8 мая 2012 года. Архивировано из оригинала 18 мая 2015 года . Проверено 13 ноября 2014 г.

- ^ «PeruDefensa.com – Фотографии с PeruDefensa.com – Facebook» . Facebook.com . Архивировано из оригинала 18 октября 2015 года . Проверено 13 ноября 2014 .

- ^ Джонс, Дэйв. «Подавление восстания 1991 года» . Преступления Саддама Хусейна . ПБС . Архивировано из оригинала 30 ноября 2011 года . Проверено 1 июля 2011 г.

- ^ Брю, Найджел (16 июня 2003 г.). «За спиной моджахедов-и-Хальк (МеК)» . Парламент Австралии . Архивировано из оригинала 28 сентября 2009 года.

- ^ Коркоран, Марк (28 сентября 2000 г.). «Наемный боевой корабль» . Иностранный корреспондент . ABC News (Австралия). Архивировано из оригинала 26 декабря 2007 года . Проверено 20 октября 2006 г.

- ^ Купер, Том; Чик, Корт «Скайлер» (5 августа 2004 г.). «Сьерра-Леоне, 1990–2002» . Информационная группа воздушного боя. Архивировано из оригинала 14 апреля 2012 года . Проверено 20 октября 2006 г.

- ^ Фаулер, Уилл (10 апреля 2010 г.). Эллис Верная смерть в Сьерра-Леоне: SAS и операция «Баррас», 2000 г. Рейд 10. Издательство Osprey . п. 46. ИСБН 9781846038501 .

{{cite book}}: Проверять|url=ценность ( помощь ) - ^ Бергер, Хайнц (июль 2011 г.). «Хорватским ВВС в 20 лет». Боевой самолет . 12 (7): 83. ISSN 2041-7470 .

- ^ Пашин, Александр. «Действия и вооружение Российской армии в ходе второй военной кампании в Чечне» . Обзор обороны Москвы. Архивировано из оригинала 1 мая 2014 года . Проверено 6 марта 2014 г.

- ^ Купер, Том. «Перу против Эквадора; Война Альто-Сенепа, 1995 г.» . ACIG.org . Архивировано из оригинала 4 октября 2013 года . Проверено 18 февраля 2013 г.

- ^ «Перу получает два российских боевых вертолета Ми-35» . 5 апреля 2011 г.

- ^ «Государственные доходы от нефти и расходы на вооружение» . Судан, нефть и права человека . Хьюман Райтс Вотч . Сентябрь 2003 г. ISBN. 978-1-56432-291-3 . Проверено 1 июля 2011 г.

- ^ Купер, Том (26 ноября 2004 г.). «Вертолеты Миля на службе по всему миру, Часть 1» . Информационная группа воздушного боя. Архивировано из оригинала 13 мая 2007 года . Проверено 25 мая 2007 г.

- ^ Купер, Том; Вайнерт, Пит (2 сентября 2003 г.). «Заир/ДР Конго с 1980 года» . Информационная группа воздушного боя. Архивировано из оригинала 30 июля 2007 года . Проверено 26 августа 2009 г.

- ^ Датт, Гаутам (27 июля 2005 г.). «В Конго может быть отправлено больше войск» . ОборонаИндия . Архивировано из оригинала 27 сентября 2007 года.

- ^ «Ми-24 до сих пор служат в Восточной Европе» . 20 августа 2020 г.

- ^ Купер, Том (30 ноября 2003 г.). «Северная Македония, 2001» . Информационная группа воздушного боя. Архивировано из оригинала 8 февраля 2012 года . Проверено 27 октября 2006 г.

- ^ Бриджланд, Фред (8 ноября 2004 г.). «Берег Слоновой Кости погружается в хаос и войну» . Шотландец . Великобритания. Архивировано из оригинала 7 января 2008 года.

- ^ «Первый американец пилотирует Ми-35 HIND в бою» . Аф.мил . 17 мая 2010 г. Архивировано из оригинала 18 июля 2018 г. . Проверено 17 июля 2018 г.

- ^ Радин, CJ (июль 2009 г.). «Боевой порядок Сил национальной безопасности Афганистана, Воздушный корпус Афганской национальной армии (ANAAC)» (PDF) . Длинный военный журнал . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 2 сентября 2009 г. Проверено 2 октября 2009 г.

- ^ «Талибан атаковал посольство США и другие здания в Кабуле» . Ассошиэйтед Пресс. 13 сентября 2011 г. [ мертвая ссылка ]

- ^ «Ми-24 Газни, Афганистан» . Helihub – источник данных о вертолетной отрасли. 26 января 2011 года. Архивировано из оригинала 22 июля 2011 года . Проверено 22 ноября 2012 г.

- ^ «Почему Индия перебросила ударные вертолеты в Афганистан» . Дипломат . 1 февраля 2016 года. Архивировано из оригинала 1 апреля 2016 года . Проверено 12 апреля 2016 г.

- ^ «Индийские многоцелевые вертолеты Ми-35 изменили ситуацию в Афганистане: генерал США Джон Кэмпбелл» . Новости ДНК. 3 февраля 2016 года. Архивировано из оригинала 8 марта 2016 года . Проверено 12 апреля 2016 г.

- ^ «Вертолеты Ми-24 в составе Польского военного контингента в Ираке» (на польском языке). Министерство национальной обороны . 24 января 2005 г. Архивировано из оригинала 2 марта 2008 г.

- ^ «Вертолет сбит в Сомали» . Би-би-си. 30 марта 2007 г. Архивировано из оригинала 2 июня 2007 г. Проверено 30 марта 2007 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и «Танки августа» (PDF) . Каст.ру. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 10 сентября 2018 года . Проверено 12 сентября 2018 г.

- ^ Ираклий Аладашвили. Потери ВВС Грузии были минимальными. //Авиация и время. — 2008. — No. 6. — С.19.

- ^ Акс, Дэвид (4 августа 2008 г.). «Сбит вертолет в Чаде» . Демотикс . Архивировано из оригинала 29 июля 2012 года.

- ^ «Вертолет Чада совершил жесткую посадку после воздушной атаки на повстанцев» . АФП. 12 июня 2008 г. Архивировано из оригинала 3 октября 2012 г.

- ^ «Варианты в Ливии после голосования в ООН», Стратегические комментарии , том. 17, IISS, 2011, заархивировано из оригинала 31 мая 2011 г. , получено 4 июня 2011 г.

- ^ «Ливия: обновленная ситуация, операция Харматтан», News , Operations (на французском языке), FR: Defense, заархивировано из оригинала 15 июня 2012 г. , получено 27 марта 2011 г.

- ^ «Вертолеты ООН обстреляли армейский лагерь Гбагбо – свидетели» . Рейтер . 4 апреля 2011 г. Архивировано из оригинала 20 июня 2017 г. Проверено 1 июля 2017 года .

- ^ «Сирийские силы атакуют Алеппо» . Ютуб. 25 июля 2012 года. Архивировано из оригинала 18 октября 2015 года . Проверено 14 августа 2012 г.

- ^ «Чтобы вернуть боевые вертолеты из России, Сирия обращается за помощью к Ираку, свидетельствуют документы» . ПроПублика . 29 ноября 2012 года. Архивировано из оригинала 19 октября 2017 года . Проверено 1 декабря 2012 г.

- ^ «В Сирии сбит российский вертолет – агентство со ссылкой на Минобороны России» . Reuters.com . 3 ноября 2016 г. Проверено 4 июня 2017 г.

- ^ «Мьянма продолжает наступление на повстанцев Качина» . Аль Джазира. 8 января 2013 г. Архивировано из оригинала 10 января 2013 г. . Проверено 8 января 2013 г.

- ^ «Армия потеряла 2 вертолета и понесла тяжелые потери личного состава в ходе прошлого наступления на Качин: отчет» . 24 марта 2014 г.

- ^ «Вертолет армии Мьянмы сбит Армией независимости Качина» . 4 мая 2021 г.

- ^ «Повстанцы Качина сбили военный вертолет, а бомба в посылке убила 5 человек в центральной Мьянме» . CNN . 4 мая 2021 г.

- ^ Делаланд 2016 , с. 38

- ^ «Ирак начинает принимать российские вертолеты Ми-35» . IHS Jane's. Архивировано 28 января 2014 г. в Wayback Machine.

- ^ «Командование армейской авиации получает Ирак получает вертолеты Ми-35 — YouTube » . Ютуб . Архивировано из оригинала 30 ноября 2014 года . Проверено 13 ноября 2014 г.

- ^ «Использование Аль-Каидой старых лагерей порождает напряженность и насилие в Ираке» . Аль Баваба . Архивировано из оригинала 15 ноября 2014 года . Проверено 13 ноября 2014 г.

- ^ «Иракские военные уничтожают лагеря ИГИЛ в Анбаре» . Ютуб . Архивировано из оригинала 18 октября 2015 года . Проверено 13 ноября 2014 г.

- ^ Кирк Семпл и Эрик Шмитт (26 октября 2014 г.). «Ракеты ИГИЛ могут представлять опасность для экипажей в Ираке» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 2 ноября 2014 года . Проверено 2 ноября 2014 г.

- ^ Джереми Бинни. «Выявлены потери иракских «Абрамсов»» . Еженедельник защиты Джейн IHS . Архивировано из оригинала 2 мая 2015 года . Проверено 20 июня 2014 г.

- ^ Али Осман (29 сентября 2015 г.). «Орудие войны Пакистана: почему Ми-35 Hind-E — отличный выбор» . Рассвет .

- ^ Камран Юсуф (19 августа 2015 г.). «Россия согласна продать Пакистану четыре ударных вертолета Ми-35» . «Экспресс Трибьюн» .

- ^ Нихад, Галиб (2 февраля 2022 г.). «ISPR сообщает, что нападения в Наушках и Панджгуре Белуджистана отражены; 4 террориста убиты» . РАССВЕТ.КОМ .

- ^ @TBPEnglish (4 февраля 2022 г.). «The Balochistan Post» ( Твит ) – через Twitter .

- ^ «The Aviationist «Новое видео показывает 12 российских вертолетов Ми-24 и Ми-8 в Крыму» . The Aviationist . 28 февраля 2014. Архивировано из оригинала 13 октября 2014. Проверено 13 ноября 2014 .

- ^ Харро Рантер. «АСН Авиационная катастрофа 02 мая 2014 г. Ми-24П 02 ЖЕЛТЫЙ» . Aviation-safety.net . Архивировано из оригинала 30 октября 2014 года . Проверено 13 ноября 2014 г.

- ^ «Два украинских Ми-24 сбиты ПЗРК» . Архивировано из оригинала 13 ноября 2014 года . Проверено 13 ноября 2014 г.

- ^ «Новости» . Архивировано из оригинала 6 мая 2014 года . Проверено 8 мая 2014 г.

- ^ «Новости» . Архивировано из оригинала 8 мая 2014 года . Проверено 8 мая 2014 г.

- ^ Харро Рантер. «Авиакатастрофа АСН 05 мая 2014 г. Ми-24П Хинд 29 RED» . Aviation-safety.net . Архивировано из оригинала 30 октября 2014 года . Проверено 13 ноября 2014 г.

- ^ «The Aviationist «Впечатляющие видео украинских авиаударов по Донецку» . The Aviationist . 27 мая 2014. Архивировано из оригинала 19 ноября 2014. Проверено 13 ноября 2014 .

- ^ «Украинский Ми-24 сбил из пушек российский дрон» . funker530.com . 15 октября 2018 года. Архивировано из оригинала 9 декабря 2018 года . Проверено 1 января 2019 г.

- ^ Форестье, Патрик (17 апреля 2015 г.). «Наступление против Боко Харам» . Парижский матч . Архивировано из оригинала 29 августа 2018 года . Проверено 28 августа 2018 г.

- ^ «Азербайджан сбил армянский вертолет» . Новости Би-би-си . 12 ноября 2014 года. Архивировано из оригинала 14 ноября 2014 года . Проверено 13 ноября 2014 г.

- ^ Харро Рантер. «АСН Авиационная катастрофа 12 ноября 2014 г. Ми-24» . Aviation-safety.net . Архивировано из оригинала 12 ноября 2014 года . Проверено 13 ноября 2014 г.

- ^ «Момент сбития вертолёта в Агдаме (реальные кадры)» . Ютуб . Архивировано из оригинала 13 ноября 2014 года . Проверено 13 ноября 2014 г.

- ^ "Азербайджанские вооруженные силы уничтожили 10 армянских танков и военнослужащих - Обновление" . AzerNews.az . 3 апреля 2016 г. Архивировано из оригинала 10 декабря 2018 г. . Проверено 1 января 2019 г.

- ^ "Армия обороны НКР обнародовала свежие данные о сбитом азербайджанском вертолете" . Арменпресс.am . 23 апреля 2016 г. Архивировано из оригинала 10 декабря 2018 г. . Проверено 1 января 2019 г.

- ^ Ходж, Натан (2 апреля 2016 г.). «Сообщено о дюжине погибших в тяжелых боях в Нагорном Карабахе» . Уолл Стрит Джорнал . Архивировано из оригинала 2 апреля 2016 года . Проверено 2 апреля 2016 г.

- ^ Аида Султанова, Associate Press. «Азербайджан заявляет, что в боях погибли 12 его солдат – ABC News» . Abcnews.go.com . Архивировано из оригинала 2 апреля 2016 года . Проверено 3 апреля 2016 г.

- ^ «В Армении сбит задний боевой корабль российского Ми-24, два члена экипажа погибли» . 9 ноября 2020 г.

- ^ «Азербайджан признает, что случайно сбил российский вертолет, приносит извинения» . Вион . 9 ноября 2020 г.

- ^ «Российский вертолет подняли со дна Киевского моря» . Mil.in.ua. 5 мая 2022 г.

- ^ "Глава Николаевщины заявил о 3 сбитых вертолетах врага. ВМС плюсуют еще один" . Pravda ua (в Украину). 5 марта 2022.

- ^ «Видео, как украинские ПЗРК сбивают поверхность российского боевого вертолета» . Авиационист . 5 марта 2022 г. Проверено 7 марта 2022 г.

- ^ Купер, Том (7 марта 2022 г.). «Против Украины Россия развертывает свои штурмовики Су-34, вооруженные «тупыми бомбами», потому что у нее нет PGM (а Польша не пожертвует свои МиГ-29 Киеву)» . Клуб любителей авиации .

(возвышенная) местность и растительность на заднем плане. На этом фото, вероятно, запечатлены обломки Ми-24, сбитого 5 марта в районе Баштанки.

- ^ «Происшествие в Викибазе ASN № 276264» . Сеть авиационной безопасности . 6 марта 2022 г.

- ^ "Во Львовской области простились с экипажем Ми-24, сбившего оккупанты в бою на Киевщине" (in Ukrainian). 11 марта 2022.

- ^ "В бою за Киев погиб военный летчик Александр Мариняк. ФОТО Источник" . Censor Net (in Russian). 13 марта 2022.

- ^ "Найдены обломки российского вертолета Мы-35" . mil.in.ua (in Russian). 17 марта 2022.

- ^ «Россия обвиняет Украину в взрыве на складе ГСМ; Киев отрицает свою причастность» . ВТНХ . 1 апреля 2022 г. Проверено 1 апреля 2022 г.

- ^ Хиншоу, Дрю (23 мая 2022 г.). «Чехия подарила Украине ударные вертолеты» . Уолл Стрит Джорнал .

- ^ "Польша тайно передала Украине Ми-24 - Военный" . mil.in.ua. Проверено 9 июля 2023 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м н тот п д р с т в v В х и С аа аб и объявление но из в ах есть также и аль являюсь а к ап ак с как в В из хорошо топор является тот нет бб до нашей эры др. быть парень «ВВС мира 2019» . Flightglobal Insight. 2019 . Проверено 14 октября 2019 г.

- ^ «Египет подтверждает, что он эксплуатирует ударные вертолеты Ми-24В в составе 43-й эскадрильи/549-го авиакрыла с авиабазы Борг-эль-Араб» . 14 января 2020 г.

- ^ «Россия поставляет в Казахстан четыре вертолета Ми-35М» .

- ^ "В этом году Россия поставит боевые самолеты, ракетные комплексы в Казахстан и Узбекистан" .

- ^ Mladenov Air International , май 2011 г., с. 112.

- ^ Mladenov Air International , май 2011 г., с. 114.

- ^ «Вертолеты Ми-35М прибыли в Сербию» . rts.rs. Проверено 2 декабря 2019 г.

- ^ «Военно-воздушные силы тренировались с российскими боевыми вертолетами в Аризоне» . Бизнес-инсайдер . Проверено 9 июня 2021 г.

- ^ «ВВС мира 2021» . FlightGlobal. 4 декабря 2020 г. Проверено 10 августа 2021 г.

- ^ «Азербайджан прекращает боевые действия в спорном регионе, поскольку армяне уступают» . Bloomberg.com . 20 сентября 2023 г. Проверено 20 сентября 2023 г.

- ^ «ФАБ выводит из эксплуатации два последних Ми-35» . 3 августа 2022 г.

- ^ «ВВС Хорватии» . aeroflight.co.uk. Архивировано из оригинала 4 марта 2016 года . Проверено 10 февраля 2015 г.

- ^ «Президент Вучич осмотрел вновь приобретенное вооружение и военную технику для сербских вооруженных сил» . defence-aerospace.com . Оборонно-космическая промышленность. 24 ноября 2023 г. Проверено 26 ноября 2023 г.

- ^ Финнерти, Райан (17 августа 2023 г.). «Чешские AH-1Z взлетают, а Прага списывает Ми-24, направляющиеся в Украину» . Полет Глобал . Архивировано из оригинала 20 августа 2023 года . Проверено 5 октября 2023 г.

- ^ «ВВС мира, 1987 г., стр. 49» . Flightglobal.com. Архивировано из оригинала 1 ноября 2013 года . Проверено 7 марта 2013 г.

- ^ «ВВС Чехословацкой армии» . Архивировано из оригинала 2 ноября 2013 года . Проверено 7 марта 2013 г.

- ^ «ВВС мира, 1987 г., стр. 50» . Flightglobal.com. Архивировано из оригинала 17 мая 2013 года . Проверено 7 марта 2013 г.

- ^ «Ландстрайткрафт Ми-24» . Архивировано из оригинала 2 ноября 2013 года . Проверено 7 марта 2013 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Кто еще этим пользовался?» . Nationalcoldwareexhibition.org. Архивировано из оригинала 14 февраля 2015 года . Проверено 7 марта 2013 г.

- ^ «96+50 Ми-24 ВВС Восточной Германии – Planespotters.net Just Aviation» . Planespotters.net. 25 апреля 2010 г. Архивировано из оригинала 2 ноября 2013 г. . Проверено 6 июля 2012 г.

- ^ «Торговые реестры» . Armstrade.sipri.org. Архивировано из оригинала 14 апреля 2010 года . Проверено 20 ноября 2014 г.

- ^ «Словакия Ми-24 снята с вооружения» (PDF) . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 5 марта 2016 года . Проверено 3 апреля 2016 г.

- ^ SME – Petit Press, так как «Вертолеты Ми-24 в последний раз взлетели в Прешове» . presov.korzar.sme.sk . Архивировано из оригинала 13 ноября 2014 года . Проверено 13 ноября 2014 г.

- ^ Купер, Том (2017). Жаркое небо над Йеменом, Том 1: Воздушная война над южной частью Аравийского полуострова, 1962–1994 гг . Солихалл, Великобритания: Издательство Helion & Company. п. 43. ИСБН 978-1-912174-23-2 .

- ^ «ВВС мира, 1987 г., стр. 86» . Flightglobal.com. Архивировано из оригинала 17 мая 2013 года . Проверено 7 марта 2013 г.

- ^ "Советский Союз" . Nationalcoldwareexhibition.org. Архивировано из оригинала 6 ноября 2013 года . Проверено 7 марта 2013 г.

- ^ «Военизированная полиция Сербии» . Aeroflight.co.uk . Архивировано из оригинала 4 марта 2016 года . Проверено 13 ноября 2014 г.

- ^ «Авиабаза Тирасполь – Приднестровье, Молдова» . eurodemobbed.org.uk . Проверено 22 октября 2023 г.

- ^ «Какие войска и вооружение есть в Приднестровье: 5 тысяч внутренних солдат и 1500 нелегально, у россиян» . revista22.ro (на румынском языке). 27 апреля 2022 г.

- ^ «Вертолеты» .

- ^ Хеннигер, Майк (28 апреля 2024 г.). «Досье по планеру» . Досье планера . Проверено 28 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ «Вклад Субхабраты Самала» . Вклад Субхабраты Самала . Проверено 12 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Военно-исторический музей, Пьештяны». Архивировано на Wayback Machine. 26 июня 2013 г., фотография номер 7

- ^ «Почтение наследия вертолета Ми-24 «Хинд» в истории ВВС» . ВВС Шри-Ланки . 2 марта 2024 года. Архивировано из оригинала 3 марта 2024 года . Проверено 3 марта 2024 г.

- ^ "Вертолеты Восточной Европы". Архивировано 9 мая 2015 года в Wayback Machine Музее вертолетов . Проверено: 10 августа 2014 г.

- ^ «Музей авиации Мидленда — ознакомьтесь с нашими экспонатами — список самолетов» . Midlandairmuseum.co.uk . Архивировано из оригинала 18 июня 2007 года . Проверено 17 июля 2018 г.

- ^ «Самолет» . Cwam.org . Архивировано из оригинала 14 декабря 2014 года . Проверено 13 ноября 2014 г.

- ^ «Военный музей Рассела» . Архивировано из оригинала 15 марта 2019 года . Проверено 17 мая 2019 г.

- ^ «Миль Ми-24, Ми-25, Ми-35 (Хинд) Акбар» . Indian-Military.org . 5 октября 2009 г. Архивировано из оригинала 5 сентября 2012 г.

- ^ Леднисер, Дэвид. «Неполное руководство по использованию аэродинамического профиля» . m-selig.ae.illinois.edu . Проверено 16 апреля 2019 г.

- Делаланд, Арно (2016). Иракская авиация возрождается. Иракская авиация с 2004 года . Хьюстон: Издательство Harpia. ISBN 978-0-9854554-7-7 .

- Хойл, Крейг (11–17 декабря 2012 г.). «Справочник ВВС мира». Рейс Интернешнл . Том. 182, нет. 5370. стр. 40–64. ISSN 0015-3710 .

- Хойл, Крейг (5–11 декабря 2017 г.). «Справочник ВВС мира». Рейс Интернешнл . Том. 192, нет. 5615. стр. 26–57. ISSN 0015-3710 .

- Младенов, Александр (май 2011 г.). «Борьба с терроризмом и обеспечение соблюдения закона в России». Эйр Интернешнл . Том. 80, нет. 5. С. 108–114. ISSN 0306-5634 .

Дальнейшее чтение

[ редактировать ]- Иден, Пол, изд. (июль 2006 г.). Энциклопедия современных военных самолетов . Лондон, Великобритания: Amber Books, 2004. ISBN. 978-1-904687-84-9 .