Пакистанская армия

Пакистанская Urdu: پاکستان فوج, romanized: Pākistān Fãujармия произносится [ˈpaːkɪstaːn faːɔːdʒ] ), широко известная как Пак Армия ( урду : پاک فوج , латинизированная : Pāk Fãuj ), является подразделением сухопутной службы и крупнейшим компонентом Вооружённых сил Пакистана . Президент Пакистана является верховным главнокомандующим армии. начальник штаба армии (COAS) , четырехзвездный генерал Командует армией . Армия была создана в августе 1947 года после того, как Пакистан получил независимость от Соединенного Королевства . [3] : 1–2 Согласно статистическим данным, предоставленным Международным институтом стратегических исследований (IISS) в 2024 году, пакистанская армия насчитывает около 560 000 военнослужащих, находящихся на действительной военной службе , при поддержке резерва пакистанской армии , Национальной гвардии и Гражданских вооруженных сил . [4] Пакистанская армия является шестой по величине армией мира и самой крупной армией мусульманского мира . [5]

Граждане Пакистана могут поступить на добровольную военную службу по достижении 16-летнего возраста, но не могут быть призваны в боевые действия до достижения 18-летнего возраста в соответствии с Конституцией Пакистана .

The primary objective and constitutional mission of the Pakistan Army is to ensure the national security and national unity of Pakistan by defending it against any form of external aggression or the threat of war. It can also be requisitioned by the Pakistani federal government to respond to internal threats within its borders.[6] During events of national and international calamities and emergencies, it conducts humanitarian rescue operations at home and is an active participant in peacekeeping missions mandated by the United Nations (UN)—most notably playing a major role in rescuing trapped American soldiers who had requested for a quick reaction force during Operation Gothic Serpent in Somalia. Troops from the Pakistan Army also had a relatively strong presence as part of a larger UN and NATO coalition during the Bosnian War and larger Yugoslav Wars.: 70 [7]

The Pakistan Army, a major component of the Pakistani military alongside the Pakistan Navy and Pakistan Air Force, is a volunteer force that has seen extensive combat during three major wars with India, several border skirmishes with Afghanistan at the Durand Line as well as a long-running insurgency in the Balochistan region which it has been combatting alongside Iranian security forces since 1948.[8][9]: 31 Since the 1960s, elements of the army have been repeatedly deployed to act in an advisory capacity in the Arab states during the events of the Arab–Israeli wars as well as to aid the United States-led coalition against Iraq during the First Gulf War. Other notable military operations during the global war on terrorism in the 21st century included: Zarb-e-Azb, Black Thunderstorm, and Rah-e-Nijat.[10]

In violation of its constitutional mandate, it has repeatedly overthrown elected civilian governments, overreaching its protected constitutional mandate to "act in the aid of civilian federal governments when called upon to do so".[11] The army has been involved in enforcing martial law against the federal government with the claim of restoring law and order in the country by dismissing the legislative branch and parliament on multiple occasions in past decades—while maintaining a wider commercial, foreign and political interest in the country. This has led it facing allegations of acting as a state within a state.[12][13][14][15]

The Pakistan Army is operationally and geographically divided into various corps.[16] The Pakistani constitution mandates the role of the president of Pakistan as the civilian commander-in-chief of the Pakistani military.[17] The Pakistan Army is commanded by the Chief of Army Staff, who is by statute a four star general and a senior member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee appointed by the prime minister and subsequently affirmed by the president.[18] As of December 2022[update], the current Chief of Army Staff is General Asim Munir, who was appointed to the position on 29 November 2022.[19][20]

Mission

Its existence and constitutional role are protected by the Constitution of Pakistan, where its role is to serve as the land-based uniform service branch of the Pakistan Armed Forces. The Constitution of Pakistan establishes the principal land warfare uniform branch in the Pakistan Armed Forces as its states:

The Armed Forces shall, under the directions of the Federal Government, defend Pakistan against external aggression or threat of war, and, subject to law, act in aid of civil power when called upon to do so.

— Constitution of Pakistan[21]

History

Division of British Indian Army and the first war with India (1947–52)

The Pakistan Army came into its modern birth from the division of the British Indian Army that ceased to exist as a result of the partition of India that resulted in the creation of Pakistan on 14 August 1947.: 1–2 [3] Before even the partition took place, there were plans ahead of dividing the British Indian Army into different parts based on the religious and ethnic influence on the areas of India.: 1–2 [3]

On 30 June 1947, the War Department of the British administration in India began planning the dividing of the ~400,000 men strong British Indian Army, but that only began few weeks before the partition of India that resulted in violent religious violence in India.: 1–2 [3] The Armed Forces Reconstitution Committee (AFRC) under the chairmanship of British Field Marshal Sir Claude Auchinleck had devised the formula to divide the military assets between India and Pakistan with ratio of 2:1, respectively.: conts. [22]

A major division of the army was overseen by Sir Chandulal Madhavlal Trivedi, an Indian civil servant who was influential in making sure that ~260,000 men would be transferred into forming the Indian Army whilst the remaining balance going to Pakistan after the independence act was enacted by the United Kingdom on the night of 14/15 August 1947.: 2–3 [3]

Command and control at all levels of the new army was extremely difficult, as Pakistan had received six armoured, eight artillery and eight infantry regiments compared to the twelve armoured, forty artillery and twenty-one infantry regiments that went to India.: 155–156 [23] In total, the size of the new army was about ~150,000 men strong.: 155–156 [23] To fill the vacancy in the command positions of the new army, around 13,500: 2 [3] military officers from the British Army had to be employed in the Pakistan Army, which was quite a large number, under the command of Lieutenant-General Frank Messervy, the first commander-in-chief of the Pakistan Army.: 70 [24]

Eminent fears of India's seizing the control over the state of Kashmir, the armed tribes and the irregular militia entered in the Muslim-majority valley of Kashmir to oppose the rule of Hari Singh, a Hindu and the ruling Maharaja of Kashmir, in October 1947.: conts. [25] Attempting to maintain his control over the princely state, Hari Singh deployed his troops to check on the tribal advances but his troops failed to halt the advancing tribes towards the valley.: 40 [26] Eventually, Hari Singh appealed to Louis Mountbatten, the Governor-General of India, requesting for the deployment of the Indian Armed Forces but Indian government maintained that the troops could be committed if Hari Singh acceded to India.: 40 [26] Hari Singh eventually agreed to concede to the Indian government terms which eventually led to the deployment of the Indian Army in Kashmir– this agreement, however, was contested by Pakistan since the agreement did not include the consent of the Kashmiri people.: 40 [26] Sporadic fighting between militia and Indian Army broke out, and units of the Pakistan Army under Maj-Gen. Akbar Khan, eventually joined the militia in their fight against the Indian Army.: 40 [26]

Although, it was Lieutenant-General Sir Frank Messervy who opposed the tribal invasion in a cabinet meeting with Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan in 1947, later leaving the command of the army in 1947,: 447 [27] in a view of that British officers in the Indian and Pakistan Army would be fighting with each other in the war front.: 417 [28] It was Lt-Gen. Douglas Gracey who reportedly disobeyed the direct orders from Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the Governor-General of Pakistan, for the deployment of the army units and ultimately issued standing orders that refrained the units of Pakistan Army to further participate in the conflict.: 59 [29]

By 1948, when it became imperative in Pakistan that India was about to mount a large-scale operation against Pakistan, Gen. Gracey did not object to the deployment of the army units in the conflict against the Indian Army.: 59 [29]

This earlier insubordination of Gen. Gracey eventually forced India and Pakistan to reach a compromise through the United Nations' intervention, with Pakistan controlling the Western Kashmir and India controlling the Eastern Kashmir.: 417 [28]

20th Century: Cold war and conflict performances

Reorganization under the United States Army (1952–58)

At the time of the partition of British India, British Field Marshal (United Kingdom) Sir Claude Auchinleck favored the transfer of the infantry divisions to the Pakistan Army including the 7th, 8th and 9th.: 55 [30] In 1948, the British army officers in the Pakistan Army established and raised the 10th, 12th, and the 14th infantry divisions— with the 14th being established in East Bengal.: 55 [30] In 1950, the 15th Infantry Division was raised with the help from the United States Army, followed by the establishment of the 15th Lancers in Sialkot.: 36 [31] Dependence on the United States grew furthermore by the Pakistan Army despite it had worrisome concerns to the country's politicians.: 36 [31] Between 1950 and 1954, Pakistan Army raised six more armoured regiments under the U.S. Army's guidance: including, 4th Cavalry, 12th Cavalry, 15th Lancers, and 20th Lancers.: 36 [31]

After the incident involving Gracey's disobedience, there was a strong belief that a native commander of the Pakistan army should be appointed, which resulted in the Government of Pakistan rejecting the British Army Board's replacement of Gen. Gracey upon his replacement, in 1951.: 34 [32] Eventually, Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan approved the promotion paper of Maj-Gen. Iftikhar Khan as the first native commander-in-chief, a graduate of the Imperial Defence College in England, but died in an aviation accident en route to Pakistan from the United Kingdom.[33]

After the death of Maj-Gen. Iftikhar, there were four senior major-generals in the army in the race of promotion but the most junior, Maj-Gen. Ayub Khan, whose name was not included in the promotion list was elevated to the promotion that resulted in a lobbying provided by Iskandar Mirza, the Defense Secretary in Ali Khan administration.[34] A tradition of appointment based on favoritism and qualification that is still in practice by the civilian Prime Ministers in Pakistan.[34] Ayub was promoted to the acting rank of full general to command the army as his predecessors Frank Messervy and Douglas Gracey were performing the duty of commander-in-chief of the Pakistan Army in the acting rank of general, the neighboring country India's first commanders-in-chief were same in this context.

The department of the army under General Ayub Khan steered the army's needs towards heavy focus and dependence towards the imported hardware acquired from the United States, in spite of acquiring it from the domestic industry, under the Military Assistance Advisory Group attached to Pakistan in 1954–56.: 36 [31] In 1953, the 6th Infantry Division was raised and disbanded the 6th Division in 1956 followed by the disbandment of the 9th Infantry Division as the American assistance was available only for one armored and six infantry divisions.: 36 [31] During this time, an army combat brigade team was readily made available by Gen. Ayub Khan to deploy to support the American Army's fighting troops in the Korean war.: 270 [35]

Working as cabinet minister in Bogra administration, Gen. Ayub's impartiality was greatly questioned by country's politicians and drove Pakistan's defence policy towards the dependence on the United States when the country becoming the party of the CENTO and the SEATO, the U.S. active measures against the expansion of the global communism.: 60 [36][37]

In 1956, the 1st Armored Division in Multan was established, followed by the Special Forces in Cherat under the supervision of the U.S Army's Special Forces.: 55 [30]: 133 [38] Under Gen. Ayub's control, the army had eradicated the British influence but invited the American expansion and had reorganized the East Bengal Regiment in East Bengal, the Frontier Force Regiment in Northern Pakistan, Kashmir Regiment in Kashmir, and Frontier Corps in the Western Pakistan.[3] The order of precedence change from Navy–Army–Air Force to Army–Navy-Air Force, with army being the most senior service branch in the structure of the Pakistani military.: 98 [36]

In 1957, the I Corps was established and headquarter was located in Punjab.: 55 [30] Between 1956 and 1958, the schools of infantry and tactics,[39] artillery,[40] ordnance,[41] armoured,[42] medical, engineering, services, aviation,[43] and several other schools and training centers were established with or without U.S. participation.: 60 [36]

Military takeovers in Pakistan and second war with India (1958–1969)

As early as 1953, the Pakistan Army became involved in national politics in a view of restoring the law and order situation when Governor-General Malik Ghulam, with approval from Prime Minister Khawaja Nazimuddin, dismissed the popularly-mandated state government of Chief Minister Mumtaz Daultana in Punjab in Pakistan, and declared martial law under Lt-Gen. Azam Khan and Col. Rahimuddin Khan who successfully quelled the religious agitation in Lahore.: 17–18 [44]: 158 In 1954, the Pakistan Army's Military Intelligence Corps reportedly sent the intelligence report indicating the rise of communism in East Pakistan during the legislative election held in East-Bengal.: 75 [45] Within two months of the elections, Prime Minister Mohammad Ali Bogra, with approval from Governor-General Malik Ghulam, dismissed another popularly-mandated state government of Chief Minister Fazlul Huq in East Bengal in Pakistan, and declared governor's rule under Iskandar Mirza who relied in the Pakistan Army to manage the control and security of the East Bengal at all levels of command.: 75 [45] With General Ayub Khan becoming the Defense Minister under Ministry of Talents led by Prime Minister Bogra, the involvement of the army in the national politics grew further with the implementation of the controversial One Unit program, abolishing the status of Four Provinces, despite the strong protests by the public and the West Pakistan's politicians.: 80 [45] Major defense funding and spending was solely focused towards Ayub's army department and the air force department led by Air Marshal Asghar Khan, giving less priority to the national needs for the Navy.[46]

From 1954 to 1958, Ayub Khan was made subjected with receiving multiple service extensions by the civilian Prime Ministers first receiving in 1954 that extended his service to last till 1958.: contents [47]: 232 [48]

The Pakistan Army under Ayub Khan had been less supportive towards the implementation of the first set of Constitution of Pakistan that had established the civilian control of the military, and the army went on to completely endorse and support the first martial law in the country imposed by President Iskander Mirza– the army later took control of the power from President Mirza in mere two weeks and installed Ayub Khan as the second President.: 81 [45] The subsequent change of command resulted in Gen. Musa Khan becoming the army commander with Ayub Khan promoting himself as controversial rank of field marshal.: 22 [49][self-published source?] In 1969, the Supreme Court reversed its decision and overturned its convictions that called for validation of martial law in 1958.: 60 [50]

The army held the referendum and tightly control the political situation through the intelligence agencies, and banned the political activities in the country.[51]

From 1961 to 1962, military aid continued to Pakistan from the United States and they established the 25th Cavalry, followed by the 24th Cavalry, 22nd, and 23rd Cavalry.: 36 [31] In 1960–61, the Army Special Forces was reportedly involved in taking over the control of the administration of Dir from the Nawab of Dir in Chitral in North-West Frontier Province over the concerns of Afghan meddling in the region.[52] In 1964–65, the border fighting and tensions flared with the Indian Army with a serious incident taking place near the Rann of Kutch, followed by the failed covert action to take control of the Indian-side of Kashmir resulted in a massive retaliation by the Indian Army on 5 August 1965.[53] On the night of 6 September 1965, India opened the front against Pakistan when the Indian Army's mechanized corps charged forwards taking over the control of the Pakistan-side of Punjab, almost reaching Lahore.: 294 [54] At the time of the conflict in 1965, Pakistan's armory and mechanized units' hardware was imported from the United States including the M4 Sherman, M24 Chaffee, M36 Jackson, and the M47 and M48 Patton tanks, equipped with 90 mm guns.[55] In contrast, the Indian Army's armor had outdated in technology with Korean war-usage American M4 Sherman and World War II manufactured British Centurion Tank, fitted with the French-made CN-75 guns.[56]

In spite of Pakistan enjoying the numerical advantage in tanks and artillery, as well as better equipment overall,: 69 [57][58] the Indian Army successfully penetrated the defences of Pakistan's borderline and successfully conquered around 360 to 500 square kilometres (140 to 190 square miles)[54][59] of Pakistani Punjab territory on the outskirts of Lahore.[60] A major tank battle took place in Chawinda, at which the newly established 1st Armoured Division was able to halt the Indian invasion.: 35 [61] Eventually, the Indian invasion of Pakistan came to halt when the Indian Army concluded the battle near Burki.[60][62][page needed][63][64] With diplomatic efforts and involvement by the Soviet Union to bring two nation to end the war, the Ayub administration reached a compromise with Shastri ministry in India when both governments signed and ratified the Tashkent Declaration.[63][64] According to the Library of Congress Country Studies conducted by the Federal Research Division of the United States:

The war was militarily inconclusive; each side held prisoners and some territory belonging to the other. Losses were relatively heavy—on the Pakistani side, twenty aircraft, 200 tanks, and 3,800 troops. Pakistan's army had been able to withstand Indian pressure, but a continuation of the fighting would only have led to further losses and ultimate defeat for Pakistan. Most Pakistanis, schooled in the belief of their own martial prowess, refused to accept the possibility of their country's military defeat by "Hindu India" and were, instead, quick to blame their failure to attain their military aims on what they considered to be the ineptitude of Ayub Khan and his government.[65]

At the time of ceasefire declared, per neutral sources, Indian casualties stood at 3,000 whilst the Pakistani casualties were 3800.[66][67][68] Pakistan lost between 200 and 300 tanks during the conflict and India lost approximately 150-190 tanks.[69][70][better source needed]

However, most neutral assessments agree that India had the upper hand over Pakistan when ceasefire was declared,[71][72][73][74][75] but the propaganda in Pakistan about the war continued in favor of Pakistan Army.[76] The war was not rationally analysed in Pakistan with most of the blame being heaped on the leadership and little importance given to intelligence failures that persisted until the debacle of the third war with India in 1971.[77] The Indian Army's action was restricted to Punjab region of both sides with Indian Army mainly in fertile Sialkot, Lahore and Kashmir sectors,[78][79] while Pakistani land gains were primarily in southern deserts opposite Sindh and in the Chumb sector near Kashmir in the north.[78]

With the United States' arms embargo on Pakistan over the issue of the war, the army instead turned to the Soviet Union and China for hardware acquisition, and correctly assessed that a lack of infantry played a major role in the failure of Pakistani armour to translate its convincing material and technical superiority into a major operational or strategic success against the Indian Army.[80] Ultimately, the army's high command established the 9th, 16th, and 17th infantry divisions in 1966–68.[80] In 1966, the IV Corps was formed and its headquarter was established, and permanently stationed in Lahore, Punjab in Pakistan.[81]

The army remained involved in the nation's civic affairs, and ultimately imposed the second martial law in 1969 when the writ of the constitution was abrogated by then-army commander, Gen. Yahya Khan, who took control of the nation's civic affairs after the resignation of President Ayub Khan, resulted in a massive labor strikes instigated by the Pakistan Peoples Party in West and Awami League in East Pakistan.[82]

In a lawsuit settled by the Supreme Court of Pakistan, the legality of the martial law was deemed questionable as the Supreme Court settled the suit by retroactively invalidated the martial law that suspended the Constitution and notably ruled that Yahya Khan's assumption of power was "illegal usurpation".: 59–60 [50] In light of the Supreme Court's judgement, the army held the publicly televised conference when President Yahya Khan announced to hold the nationwide general elections in 1969–70.: 59–60 [50]

Suppression, civil conflict in East Pakistan and Indian invasion (1969–1971)

In 1969, President Yahya Khan decided to make administrative changes in the army by appointing the Gen. Abdul Hamid Khan as the Army Chief of Staff (ACOS) of the Pakistan Army, who centralized the chain of command in Rawalpindi in a headquarters known as "High Command".: 32 [83] From 1967 to 1969, a series of major military exercises was conducted by infantry units on East Pakistan's border with India.: 114–119 [84] In 1970, the Pakistan army's military mission in Jordan was reportedly involved in tackling and curbing down the Palestinian infiltration in Jordan.[85] In June 1971, the enlistment in the army had allowed the Army GHQ in Rawalpindi to raise and established the 18th infantry division, stationed in Hyderabad, Sindh, for the defence of 900 kilometres (560 mi) from Rahimyar Khan to Rann of Kutch, and restationed the 23rd infantry division for defending the Chhamb-Dewa Sector.[80]

In 1971, the II Corps was established and headquartered in Multan, driven towards defending the mass incursion from the Indian Army.[81] In December 1971, the 33rd infantry division was established from the army reserves of the II Corps, followed by raising the 37th Infantry Division.[80] Pakistan Army reportedly helped the Pakistan Navy towards establishing its amphibious branch, the Pakistan Marines, whose battalions was airlifted to East Pakistan along with the 9th Infantry Division.[80]

The intervention in East Pakistan further grew when the Operation Searchlight resulted in the overtaking of the government buildings, communication centers, and restricting the politicians opposed to military rule.: 263 [86] Within a month, Pakistani national security strategists realized their failure of implementing the plan which had not anticipated civil resistance in East, and the real nature of Indian strategy behind their support of the resistance.: 2–3 [87]

The Yahya administration is widely accused of permitting the army to commit the war crimes against the civilians in East and curbing civil liberties and human rights in Pakistan. The Eastern Command under Lt-Gen. A. A. K. Niazi, who had area responsibility of the defending the Eastern Front and had the responsibility to protect, was leveled with accusations of escalating the political violence in the East by the serving military officers, politicians, and journalists in Pakistan.[88][89] Since the general elections in 1970, the army had detained several key politicians, journalists, peace activists, student unionists, and other members of civil society while curbing the freedoms of movement and speech in Pakistan.: 112 [90] In East Pakistan, the unified Eastern Military Command under Lt-Gen. A.A.K. Niazi, began its engagement with the armed militia that had support from India in April 1971, and eventually fought against the Indian Army in December 1971.: 596 [91]: 596 The army, together with marines, launched ground offensives on both fronts but the Indian Army successfully held its ground and initiated well-coordinated ground operations on both fronts, initially capturing 15,010 square kilometres (5,795 sq mi): 239 [38] of Pakistan's territory; this land gained by India in Azad Kashmir, Punjab and Sindh sectors.: 239 [38]

Responding to the ultimatum issued on 16 December 1971 by the Indian Army in East, Lt-Gen. Niazi agreed to concede defeat and move towards signing the documented surrender with the Indian Army which effectively and unilaterally ended the armed resistance and led the creation of Bangladesh, only after India's official engagement that lasted 13 days.[92] It was reported that the Eastern Command had surrendered ~93,000–97,000 uniform personnel to Indian Army– the largest surrender in a war by any country after the World War II.[93] Casualties inflicted to army's I Corps, II Corps, and Marines did not sit well with President Yahya Khan who turned over control of the civic government to Zulfikar Ali Bhutto through an executive decree.[94]

Commenting on the defeat, the military observer in the Pakistan Army, Major A.H. Amin, reported that the war strategists in the army had not seriously considered a full-fledged invasion from India until December 1971, because it was presumed that the Indian military would not risk intervention by China or the United States, and the high command failed to realize that the Chinese would be unable to intervene during the winter months of November to December, due to snowbound Himalayan passes, and the Americans had not made any real effort to persuade India against attacking East Pakistan.[95]

Restructuring of armed forces, stability and restoration (1971–1977)

In January 1972, the Bhutto administration formed the POW Commission to investigate the numbers of war prisoners held by the Indian Army while requesting the Supreme Court of Pakistan to investigate the causes of the war failure with India in 1971.: 7–10 [97] The Supreme Court formed the famed War Enquiry Commission (WEC) that identified many failures, fractures, and faults within the institution of the department of the army and submitted recommendations to strengthen the armed forces overall.[3] Under the Yahya administration, the army was highly demoralized and there were unconfirmed reports of mutiny by soldiers against the senior army generals at the Corps garrisons and the Army GHQ in Rawalpindi.: 5 [97]

Upon returning from the quick visit in the United States in 1971, President Bhutto forcefully dishonourably discharge seven senior army generals, which he called the "army waderas" (lit. Warlords).: 71 [98] In 1972, the army leadership under Lt-Gen. Gul Hassan refrained from acting under Bhutto administration's order to tackle the labor strikes in Karachi and to detained the labor union leaders in Karachi, instead advising the federal government to use the Police Department to take the actions.: 7 [97]

On 2 March 1972, President Bhutto dismissed Lt-Gen. Gul Hassan as the army commander, replacing with Lt-Gen. Tikka Khan who was later promoted to four-star rank and appointed as the first Chief of Army Staff (COAS).: 8 [97] The army under Bhutto administration was reconstructed in its structure, improving its fighting ability, and reorganized with the establishment of the X Corps in Punjab in 1974, followed by the V Corps in Sindh and XI Corps in the Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa in Pakistan in 1975.[99] The trilateral agreement in India, the Bhutto administration transferred all the war prisoners back to the country but the military struggle to fill in the vacancies and employments due to some suffering from the PTSD and other mental health complications, while others simply did not wanted to serve in the military any longer.: 19–20 [97] During Bhutto's administration, Pakistan's military pursued a policy of greater self-reliance in arms production. This involved efforts to develop domestic capabilities for manufacturing weapons and military equipment. To address material shortages, Pakistan also turned to China for cooperation in establishing essential metal and material industries.[100]

In 1973, the Bhutto administration dismissed the state government in Balochistan that resulting in another separatist movement, culminating the series of army actions in largest province of the country that ended in 1977.: 319 [101] With the military aid receiving from Iran including the transfer of the Bell AH-1 Cobra to Aviation Corps,: 319 [101] the conflict came to end with the Pakistani government offering the general amnesties to separatists in the 1980s.: 151 [102]: 319 : 319 [101] Over the issue of Baloch conflict, the Pakistani military remained engage in Omani civil war in favor of Omani government until the rebels were defeated in 1979.[103] The War Enquiry Commission noted the lack of joint grand strategy between the four-branches of the military during the first, the second, and the third wars with India, recommending the establishment of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee to maintain strategic military communication between the inter-services and the federal government, that is to be chaired by the appointed Chairman joint chiefs as the government's principal military adviser.: 145 [104] In 1976, the first Chairman joint chiefs was appointed from the army with Gen. Muhammad Shariff taking over the chairmanship, but resigned a year later.: 145 [104] In 1975, Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto controversially superseded at least seven senior army generals to promote Lt-Gen. Zia-ul-Haq to the four-star rank, appointing him the Chief of Army Staff (COAS) in spite of army recommendations forwarded to the federal government.: 24 [97]

In the 1970s, the army's engineering formations, notable the Corps of Engineers, played a crucial role in supporting the clandestine atomic bomb program to reach its parity and feasibility, including the constructions of iron-steel tunnels in the secretive nuclear weapons-testing sites in 1977–78.: 144–145 [96]

PAF and Navy fighter pilots voluntarily served in Arab nations' militaries against Israel in the Yom Kippur War (1973). According to modern Pakistani sources, in 1974 one of the PAF pilots, Flt. Lt. Sattar Alvi flying a MiG-21 shot down an Israeli Air Force Mirage flown by Captain M. Lutz, and was honoured by the Syrian government.[105][106][107] The Israeli pilot later succumbed to wounds he sustained during ejection. However, no major sources from the time reported on such an incident,[108][109][110] and there is no mention of "Captain Lutz" in Israel's Ministry of Defense's record of Israel's casualties of war.[111]

Middle East operations, peacekeeping missions, and covert actions (1977–1999)

The political instability increased in the country when the conservative alliance refused to accept the voting turnout in favor of Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) after the general elections held in 1977.: 25–26 [97] The army, under Gen. Zia-ul-Haq–the army chief, began planning the military takeover of the federal government under Prime Minister Zulfikar Bhutto, eventually leading the coup d'état that suspended the writ of the Constitution amid responding to the call from one of the opposition leader of threatening to call for another civil war.: 27 [97] The military interference in civic matters grew further when the martial law was extended for an infinite period despite maintaining that the elections to be held in 90-days prior.: 30–31 [97] At the request from the Saudi monarchy, the Zia administration deployed the company of the special forces to end seizure of the Grand Mosque in Mecca from Islamists.: 265–280 [112]

The army under President Zia weakened due to the army officers were needed in running the affairs of civic government and the controversial military courts that held trials of the communists, dissidents, and the oppositions of Zia's administration.: 31–32 [97] In 1984–85, Pakistan lost the control of her northern glaciers due to the successful expedition and penetration by the Indian Army, and army had to engage in years long difficult battles with Indian Army to regain their areas from the Indian Army.: 45 [97] Concerns over the military officers and army personnel needed to counter the further advances by the Indian Army in Northern fronts in 1984, the martial law was lifted following the referendum that approved Zia's presidency and provided a way of holding the general elections in 1985.: 45 [97] The military control the under army administration had successfully stabilized the law and order in Balochistan despite the massive illegal immigration from Afghanistan, and issued the general amnesties to separatists and rebels.[113] To address the Afghan containment and security, the army established the XII Corps in 1985 that is permanently headquartered in Quetta, that is designed to provide defence against the infiltration by the Afghan National Army from Afghanistan.[citation needed]

In 1985, the United States approved the military aid package, worth $4.02 billion, to Pakistan when the mujaheddin fighting with the Soviet Union in Afghanistan increased and intensified, with Soviet Army began violating and attacking the insurgents in the tribal areas in Pakistan.: 45–46 [97] In 1986, the tensions with India increased when the Indian Army's standing troops mobilized in combat position in Pakistan's southern frontier with India failing to give notification of exercise to Pakistan prior.: 46 [97] In 1987–88, the XXX Corps, headquartered in North of Punjab, and the XXXI Corps, headquartered in South of Punjab, was raised and established to provide defence against the Indian army's mass infiltration.[81]

After the aviation accident that resulted in passing of President Zia in 1988, the army organized the massive military exercise with the Pakistan Air Force to evaluate the technological assessment of the weapon systems and operational readiness.: 57 [97][115] In the 1980s, Pakistan Army remained engage in the affairs of Middle East, first being deployed in Saudi Arabia during the Iran–Iraq War in 1980–1988, and later overseeing operational support measures and combat actions during the Gulf War in 1990–91.[3]

The period from 1991 to 1998 saw the army engaged in professionalism and proved its fighting skills in the Somalian theater (1991–94), Bosnian-Serb War (on Bosnian side from 1994 to 1998[116]), and the other theaters of the Yugoslav Wars, as part of the United Nation's deployment.: 69–73 [117][118] In 1998, the army's Corps of Engineers played a crucial role in providing the military administration of preparing the atomic weapon-testing in Balochistan when the air force's bombers flown and airlifted the atomic devices.[119] The controversial relief of Gen. Jehangir Karamat by the Sharif administration reportedly disturbed the balance of the civil-military relations with the junior most Lt-Gen. Pervez Musharraf replacing it as chairman joint chiefs and the army chief in 1999.[120]

In May 1999, the Northern Light Infantry, a paramilitary unit based in Gilgit, slipped into Kargil that resulted in heavy border fighting with the Indian Army, inflicted with heavy casualties on both sides.[121] The ill-devised plan without meaningful consideration of the outcomes of the border war with India, the army under Chairman joint chiefs Gen. Pervez Musharraf (also army chief at that time) failed to its combat performance and suffered with similar outcomes as the previous plan in 1965, with the American military observers in the Pakistan military famously commenting to news channels in Pakistan: Kargil was yet another example of Pakistan's (lack of) grand strategy, repeating the follies of the previous wars with India.": 200 [122][123][124]

After its commendable performance, the President of Pakistan made the Northern Light Infantry as a regular army regiment. Its personnel eventually became officers and enlisted personnel in the army in 1999.[125]

21st Century: War performances

Religious insurgency and War on terror (2001 – present)

Responding to the terror attacks in New York in the United States, the army joined the combat actions in Afghanistan with the United States and simultaneously engage in military standoff with Indian Army in 2001–02. In 2004–06, the military observers from the army were deployed to guide the Sri Lankan army to end the civil war with the Tamil fighters.[126]

To overcome the governance crises in 2004–07, the Musharraf administration appointed several army officers in the civilian institutions with some receiving extensions while others were deployed from their combat service– thus affecting the fighting capabilities and weakening the army.: 37 [127] Under Gen. Musharraf's leadership, the army's capabilities fighting the fanatic Talibans and Afghan Arab fighters in Pakistan further weakened and suffered serious setbacks in gaining control of the tribal belt that fell under the control of the Afghan Arabs and Uzbek fighters.: 37 [127] From 2006 to 2009, the army fought the series of bloody battles with the fanatic Afghan Arabs and other foreign fighters including the army action in a Red Mosque in Islamabad to control the religious fanaticism.: 37 [127] With the controversial assassination of Baloch politician in 2006, the army had to engage in battles with the Baloch separatists fighting for the Balochistan's autonomy.: 37 [127]

In April 2007, the major reorganization of the commands of the army was taken place under Gen. Ahsan S. Hyatt, the vice army chief under Gen. Musharraf, established the Southern, Central, and the Northern Commands.[citation needed] With Gen. Musharraf's resignation and Gen. Ashfaq Parvez Kayani becoming the army chief, the army realigned itself to review its combat policies and withdrew officers in civilian institutions to focus on its primary constitutional mission to protect and responsible in 2009–14.: 37 [127][128] In 2012, there was a serious accident involving the entire battalion from the Northern Light Infantry when the avalanche struck the battalion base in Siachen, entrapping 135 soldiers and including several army officers.[129]

In 2013–16, the homegrown far-right guerrilla war with the Taliban, Afghan Arabs, and the Central Asian fighters took the decisive turn in favor of the army under Sharif administration, eventually gaining the control of the entire country and established the writ of the constitution in the affected lawless regions.[130] As of its current deployment as of 2019, the army remained engage in border fighting with the Indian Army while deploying its combat strike brigade teams in Saudi Arabia in a response of Saudi intervention in Yemen.[131]

Organization

Command and control structure

| Pakistan Army |

|---|

|

| Leadership |

| Organisation and components |

| Installations |

| Personnel |

| Equipment |

| History and traditions |

| Awards, decorations and badges |

Leadership in the army is provided by the Minister of Defense, usually leading and controlling the direction of the department of the army from the Army Secretariat-I at the Ministry of Defense, with the Defense Secretary who is responsible for the bureaucratic affairs of the army's department.[132] The Constitution empowers the President of Pakistan, an elected civilian official, to act as the Commander-in-Chief while the Prime Minister, an elected civilian, to act as the Chief Executive.[133] The Chief of Army Staff, an appointed four-star rank army general, is the highest general officer, under Chairman Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee and Secretary Defense, who acts as the principal military adviser on the expeditionary and land/ground warfare affairs, and a senior member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee– a military body that advises and briefs the elected Prime Minister and its executive cabinet on national security affairs and operational military matters under the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee.[134]

The single combat headquarter, the Army GHQ, is located in Rawalpindi Cantonment in Punjab in Pakistan, in the vicinity of the Joint Staff Headquarters.[134] The Chief of Army Staff controls and commands the army at all levels of operational command, and is assisted the number of Principal Staff Officers (PSOs) who are three-star rank generals.[134]The military administration under the army chief operating at the Army GHQ including the appointed Principal Staff Officers:

- Chief of General Staff, under whom the Military Operations and Intelligence Directorates function.[134]

- Chief of Logistics Staff.[134]

- Quartermaster General (QMG).[134]

- Master General of Ordnance (MGO).[134]

- Engineer-in-Chief, the chief army engineer and topographer.[134]

- Judge Advocate General.[134]

- Military Secretary.[134]

- Comptroller of Civilian Personnel.[134]

In 2008, a major introduction was made in the military bureaucracy at the Army GHQ under Gen. Ashfaq Parvez Kayani, when two new PSO positions were introduced: the Inspector-General of Arms and the Inspector-General Communications and IT.[135]

The Army's corps are divided into three regional-level commands which are assigned for defending the territories of Pakistan.

Personnel

Commissioned officers

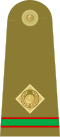

The commissioned army ranks and insignia authorized in the Pakistan Army are modified and patterned on the British Army's officer ranks and insignia system.[136] There are several paths of becoming the commissioned officer in the army including the admission and required graduation from the Pakistan Military Academy in Kakul. [citation needed] To become an officer in the army, the academic four-year college degree is required for the candidates to become officers in the army, and therefore they are designated by insignia unique to their staff community.[citation needed]

Selection to the officer candidates is highly competitive with ~320–700 individuals are allowed to enter in the Pakistan Military Academy annually, with a small number of already graduated physicians, specialists, veterinaries and the engineers from the civilian universities are directly recruited in the administrative staff corps such as Medical Corps, Veterinary Corps, Engineering Corps, Dental Corps and these graduated individuals are the heart of the administrative corps.: 293 [137] The product of a highly competitive selection process, members of the staff corps have completed twelve years of education in their respected fields (such as attending the schools and universities), and has to spend two years at the Pakistan Military Academy, with their time divided about equally between military training and academic work to bring them up to a baccalaureate education level, which includes English-language skills.: 293 [137] The Department of Army also offers employment to civilians in financial management, accountancy, engineering, construction, and administration, and has currently employed 6,500 civilians.[138]

The military officers in the Pakistani military seek retirement between the ages of forty-two and sixty, depending on their ranks, and often seeks employment in the federal government or the private sector where the pay scales are higher as well as the opportunity for gain considerably greater.: 294 [137]

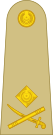

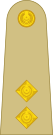

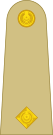

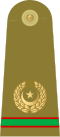

| Rank | O-10 | O-9 | O-8 | O-7 | O-6 | O-5 | O-4 | O-3 | O-2 | O-1 | O-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insignia |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Title | Field Marshal | General | Lieutenant-General | Major-General | Brigadier | Colonel | Lieutenant-Colonel | Major | Captain | Lieutenant | Second Lieutenant |

| Abbreviation | FM | Gen. | Lt-Gen. | Maj-Gen. | Brig. | Col. | Lt-Col. | Maj. | Capt. | Lt. | 2nd-Lt. |

| NATO Code | OF-10 | OF-9 | OF-8 | OF-7 | OF-6 | OF-5 | OF-4 | OF-3 | OF-2 | OF-1 | OF-1 |

| Rank Hierarchy | Five-star | Four-star | Three-star | Two-star | One-star |

Warrant officers

The Pakistan Army uniquely uses the junior commissioned officer (JCO) ranks, equivalent of the Warrant officers or the Limited duty officers in the United States military, inherited from the former British Indian Army introduced by the British Army in India between the enlisted and officer ranks.[citation needed] The JCOs are single-track specialists with their subject of expertise in their particular part of the job and initially appointed (NS1) after risen from their enlisted ranks, receiving the promotion (SM3) from the commanding officer.[citation needed]

The usage of the junior commissioned officer is the continuation of the former Viceroy's commissioned officer rank, and the JCO ranking system benefited the army since there was a large gap existed between the officers and the enlisted personnel at the time of the establishment of the new army in 1947.[citation needed] Over the several years, the JCOs rank system has outlived its usefulness because the educational level of the enlisted personnel has risen and the army has more comfortably adopted the U.S. Army's ranking platform than the British.[37] Promotion to the JCO ranks remains a powerful and influential incentive for that enlisted personnel desire not to attend the accredited four-year college.[citation needed]

| Insignia |  |  |  |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infantry/other title | Subedar-Major | Subedar | Naib Subedar |

| Cavalry/armor title | Risaldar Major | Risaldar | Naib Risaldar |

Enlisted personnel

The recruiting and enlistment in the army is nationwide but the army's recruiting command maintains an ethnic balance, with those who turned away are encourage to join the either the Marines or the Air Force.: 292 [137] Most enlisted personnel had come from the poor and rural families with many had only rudimentary literacy skills in the past, but with the increase in the affordable education have risen to the matriculation level (12th Grade).: 292 [137] In the past, the army recruits had to re-educate the illiterate personnel while processing them gradually through a paternalistically run regimental training center, teaching the official language, Urdu, if necessary, and given a period of elementary education before their military training actually starts.: 292 [137]

In the thirty-six-week training period, they develop an attachment to the regiment they will remain with through much of their careers and begin to develop a sense of being a Pakistani rather than primarily a member of a tribe or a village.: 292 [137] Enlisted personnel usually serve for eighteen to twenty years, before retiring or gaining a commission, during which they participate in regular military training cycles and have the opportunity to take academic courses to help them advance.: 292 [137]

The noncommissioned officers (or enlists) wear respective regimental color chevrons on the right sleeve.: 292 [137] Center point of the uppermost chevron must remain 10 cm from the point of the shoulder.: 292 [137] The Company/battalion appointments wear the appointments badges on the right wrist.: 292 [137] Pay scales and incentives are greater and attractive upon enlistment including the allocation of land, free housing, and financial aid to attend the colleges and universities.: 294 [137] Retirement age for the enlisted personnel varies and depends on the enlisted ranks that they have attained during their services.: 294 [137]

| Pay grade | E-9 | E-8 | E-7 | E-6 | E-5 | E-4 | E-3 | E-2 | E-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insignia |  |  |  |  |  |  | No insignia | No insignia | |

| Title | Battalion Havildar Major/Regimental Daffadar Major | Battalion Quartermaster Havildar/Regimental Quartermaster Daffadar | Company Havildar Major/Squadron Daffadar Major | Company Quartermaster Havildar/Squadron Quartermaster Daffadar | Havildar/Daffadar | Naik/Lance Daffadar | Lance Naik/Acting Lance Daffadar | Sepoy/Sowar | No Equivalent |

| Abbreviation | BHM/RDM | BQMH/RQD | CHM/SDM | CQMH/SQD | Hav/Dfdr | Nk/L Dfdr | L/Nk/Actg L/Dfdr | Sep/Swr | NE |

| NATO Code | OR-9 | OR-8 | OR-7 | OR-6 | OR-5 | OR-4 | OR-3 | OR-2 | OR-1 |

| U.S. Code | SGM | MSG | SFC | SSG | SGT | CPL | PFC | PVT | – |

Recruitment and training

Prior to August 1947, the British Army's recruiting administration had recruited the enlists from the districts of the Jhelum, Rawalpindi, and Campbellpur that dominated the recruitment flows.[3] From 1947 to 1971, the Pakistan Army was predominantly favored to recruit from Punjab and was popular in the country as the "Punjabi Army" because of heavy recruiting interests coming from the rural and poor families of villages in Punjab as well as being the most populous province of Pakistan.: 149 [140][141]

Even as of today, the Pakistan Army's recruiters struggle to enlist citizens and their selfless commitment to the military from the urban areas (i.e. Karachi and Peshawar) where the preference of the college education is quite popular (especially attending post-graduate schools in the United States and the English-speaking countries) as well as working in the settled private industry for lucrative salaries and benefits, while the military enlistment still comes from the most rural and remote areas of Pakistan, where commitment to the military is much greater than in the metropolitan cities.: 31 [8]

After 1971, the Bhutto administration introduced the Quota system and drastically reduced the officers and enlists from Punjab and gave strong preference to residents in Sindh, Balochistan, and Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, and such policy continue to exists to maintain an ethnic balance in the army.: 163 [142] Those who are turned away are strongly encourage to join the Marines Corps or the Air Force.[3]

In 1991, the department of the army drastically reduced the size of personnel from Punjab, downsizing the army personnel to 63%, and issues acceptable medical waivers interested enlists while encouraging citizens of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and Sindh. This decision has given a fair chance to every citizen of Pakistan to be part of the Pakistan Army as each district possesses a fixed percentage of seats in all branches of the Army, as per census records.[citation needed] By 2003–05, the department of army continued its policy by drastically downsizing the personnel from Punjab to 43–70%.[143]

The Department of Army has relaxed its recruitment and medical standards in Sindh and Balochistan where the height requirement of 5 feet 4 inches is considered acceptable even with the enlists educational level at eighth grade is acceptable for the waiver; since the army recruiters take responsibility of providing education to 12th grade to the interested enlists from Balochistan and Sindh.: 31 [8] In Punjab and Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa where the recruitment is popular, the height requirement remains to be at 5 feet 6 inches with minimum education of 10th grade.[8]

The army cadets undergo training in Kakul at the Pakistan Military Academy where basic training takes place. Such training usually lasts for two years until the cadets are able to meet their graduation requirements from the academy.[139] All the cadets have to attend and be trained at the PMA regardless of attending the military schools and colleges in other parts of the country.[139]

Duration wise, it is one of the longest military training period in the country, and the training continues for two years until the cadet is being able pass out from the academy, before selecting the college to start the career of their choice in the military.[139]

Women and religion in the Pakistan Army

Women have been part of the Pakistan Army since 1947, and currently there are approximately 4,000 women serving in the military.[144] In the years of 1947, '48 and '49, women were inducted into the Women's Guard Section of the National Guard and trained in medical work, welfare, and clerical positions (this was later disbanded).[145] Pakistan Army has a separate cadet course for women which is known as 'Lady Cadet Course', female cadets are trained in Pakistan Military Academy.[146] After induction, women army officers go through a six-month military training at the Pakistan Military Academy like their male counterparts. The comprehensive training includes military education and development of physical efficiency skills.[147]

Pakistan is the only Muslim-majority nation which appoints women to general officer ranks, such as Major-General Shahida Malik, the first woman army officer and military physician by profession who was promoted to a two-star rank.[148] In July 2013, the Army trained female paratrooper officers for the first time.[149][150][151] In 2020, Nigar Johar became the first female Lieutenant General in the army, she was from the Pakistan Army Medical Corps.[152]

The Army recruits from all religions in Pakistan including Hindus, Sikhs, Zoroastrians, Christians who have held command-level positions.[153] Religious services are provided by the Chaplain Corps for Muslims, Hindus, Christians, Sikhs, and Zoroastrians.[81]

In 1993, Major-General Julian Peter was the first Christian to be appointed at the command position while Hercharn Singh became the first Sikh to be commissioned in the army. Between 1947 and 2000, a policy of restricting Hindus prior enlisting in the Pakistan Army was in practice until the policy was reversed by the federal government.[154] In 2006, army recruiters began recruiting Hindus into the army and people of all faith or no faith can be promoted to any rank or commanding position in the army.[155][156]

Equipment

The equipment and weapon system of Pakistan Army is developed and manufactured by the local weapons industry and modern arms have been imported from China, Turkey, United Kingdom, United States, France and other countries in the European Union.[3]

The Heavy Industries Taxila (HIT), Pakistan Ordnance Factories (POF), National Radio and Telecommunication Corporation (NRTC) and the Pakistan Aeronautical Complex (PAC) are the major defense contractors for the Army.[157]

The Heavy Industries Taxila designs and manufactured main battle tanks (MBT) in cooperation with the China and the Ukraine, while the fire arms and standard rifles for the army are licensed manufactured by the Pakistan Ordnance Factories (POF).[157] The Chinese cooperation and further assistance with the Pakistan Army is vital in designing, vehicular construction, and material manufacturing of the main battle tanks.: xxxv [158] The standard rifle for the army is the German designed and POF manufactured Koch G3P4.[157]

The defense funding for the army was preferential, which was described as the "lion's share", however, in light of CPEC's security demanding to secure the seaborne borders, the army financial planners significantly lowered its share in a view of strengthening the under-funded Pakistan navy.[159]

Uniforms

From 1947 to 1971, the army service uniform of the Pakistan Army closely resembled to the army uniform of the British Army, but the uniform changed in preference of Sherwani.[citation needed] The army service uniform in the Pakistan Army consists of the Sherwani with two front pockets, cap of a synthetic material, trousers with two pockets, with Golden Khaki colors.: 222 [160]

In the 1970s, the Ministry of Defense introduced the first camouflage pattern in the army combat uniform, resembling the British-styled DPM but this was changed in 1990 in favor of adopting the U.S. Woodland which continued until 2010.[161] In winter front such as in the Siachen and near the Wakhan Corridor, the Pakistan Army personnel wears the heavy winter all white military gear.[162]

As of 2011, the camouflage pattern of the brown and black BDU was issued and is worn by the officers and the army troops in their times of deployments.[citation needed] The Pakistan Army has introduced arid camouflage patterns in uniform and resized qualification badges which are now service ribbons and no longer worn along with the ranks are now embroidered and are on the chest.[citation needed] The name is badged on the right pocket and the left pocket displays achievement badges by Pakistan Army.[citation needed]

Unlike other countries in South Asia, Pakistan army officer uniforms don't include a aiguillette, rather it is used mostly by aid-de-camps.

Flag of Pakistan is placed over the black embroidered formation sign on the left arm and class course insignias are put up for the Goldish uniform,[citation needed] decorations and awards[citation needed] and the ranks.[citation needed]

- A Pak Army officer wearing the standard Sherwani-based ceremonial uniform of the Pakistan Army

- The standard army service uniform of the Pakistan Army, worn by officers and enlisted personnel

- The army service uniform of the Pakistan Army closely resembled to the army uniform of the British Army as seen and active from 1947–1970s

Components and structure

Army components and branches

Since its organization that commenced in 1947, the army's functionality is broadly maintained in two main branches: Combat Arms and Administrative Services.: 46 [36]: 570 [163] From 1947 to 1971, the Pakistan Army had responsibility of maintaining the British-built Forts, till the new and modern garrisons were built in post 1971, and performs the non-combat duties such as engineering and construction.[3]

Currently, the Army's combat services are kept in active-duty personnel and reservists that operate as members of either Reserves, the National Guard and the paramilitary Civil Armed Forces.[134] The latter includes the Frontier Corps and the Pakistan Rangers, which often perform military police duties for the provincial governments in Pakistan to help control and manage the law and control situation.[134]

The two main branches of the army, Combat Arms and Administrative Services, also consist of several branches and functional areas that include the army officers, junior commissioned (or warrant officers), and the enlisted personnel who are classified from their branches in their uniforms and berets.[134] In Pakistan Army, the careers are not restricted to military officials but are extended to civilian personnel and contractors who can progress in administrative branches of the army.[164]

| Combined Arms | Insignia | Administrative Services | Insignia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armoured Corps (AC) | Service Corps (ASC) | |||

| Air Defence (AD) | Military Police (MP) | |||

| Aviation Corps (AVN) | Electrical and Mechanical Engineering (EME) | |||

| Artillery Corps (ARTY) | Medical (AMC) | |||

| Signals Corps (SIGS) | Education (AEC) | |||

| Engineers Corps (ENG) | Remount Veterinary and Farms (RVFC) | |||

| Infantry Regiments (INF) | Ordnance (ORD) | |||

| Special Forces (SSG) | Military Intelligence (MI) |

Command structure

The reorganization of the position standing army in 2008, the Pakistan Army now operates six tactical commands, each commanded by the GOC-in-C, with a holding three-star rank: Lieutenant-General.[99][failed verification] Each of the six tactical commands directly reports to the office of Chief of Army Staff, operating directly at the Army GHQ.[99][failed verification] Each command consists of two or more Corps– an army field formation responsible for zone within a command theater.[134][failed verification]

There are nine active Corps in the Pakistan Army, composing of mixed infantry, mechanized, armored, artillery divisions, while the Air Defense, Aviation, and the Aviation and Special Forces are organized and maintained in the separate level of their commands.[134][failed verification]

Established and organized in March 2000, the Army Strategic Forces Command is exercise its authority for responsible training in safety, weapons deployments, and activation of the atomic missile systems.[165]

Combat maneuvering organizations

In events involving the large and massive foreign invasion by the Indian Army charging towards the Pakistan-side Punjab sector, the Pakistan Army maintains the "Pakistan Army Reserves" as a strategic reserve component for conducting the offense and defense measures against the advancing enemy.[166]

Infantry branch

Since its establishment in 1947, the Pakistan Army has traditionally followed the British regimental system and culture, and currently there are six organized infantry regiments.[167]

In the infantry branch, there are originally six regiments are in fact the administrative military organization that are not combat field formation, and the size of the regiments are vary as their rotation and deployments including assisting the federal government in civic administration.[168]

In each of original six regiments, there are multiple battalions that are associated together to form an infantry regiment and such battalions do not fight together as one formation as they are all deployed over various formations in shape of being part of the brigade combat team (under a Brigadier), division, or a being part of much larger corps.[169]

After the independence from the Great Britain in 1947, the Pakistan Army begin to follow the U.S. Army's standing formation of their Infantry Branch, having the infantry battalion serving for a time period under a different command zone before being deployed to another command zone, usually in another sector or terrain when its tenure is over.[169]

| The Infantry Regiments by seniority | Insignia | Activation Date | Commanding Regimental Center | Motto | War Cry |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Punjab Regiment | 1759 | Mardan, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa | Urdu: نارا-یا-حیدری یا علی (English lit. Ali the Great) | ||

| Baloch Regiment | 1798 | Abbottabad, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa | غازی یا شہید (English lit. Honoured or Martyr) | کی کی بلوچ (English lit. Of the Baloch) | |

| Frontier Force Regiment | 1843 | Abbottabad, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa | لبّیک (English lit. Lucky) | ||

| Northern Light Infantry Regiment | 1913 | Gilgit, Gilgit Baltistan | سبط قدم (English lit. Consistent) | ||

| Azad Kashmir Regiment | 1947 | Mansar, Punjab | |||

| Sind Regiment | 1980 | Hyderabad, Sindh |

Special operations forces

The Pakistan Army has a division dedicated towards conducting the unconventional and asymmetric warfare operations, established with the guidance provided by the United States Army in 1956.[171] This competitive special operation force is known as the Special Services Group (Army SSG, distinguishing the Navy SSG), and is assembled in eight battalions, commanded by the Lieutenant-Colonel, with addition of three companies commanded by the Major or a Captain, depending on the availability.[172]

The special operation forces training school is located in Cherat in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa in Pakistan where the training and education on the philosophy of military arts and tactics take place by the army instructors.[172]

Each battalion in the Pakistan Army Special Forces is specifically trained for a specific type of operation, and each battalion is a specialist in their nature of conducting the operation.[172] Due to their distinctive service headgear, the Army SSG is colloquially known as the Maroon Berets.[172]

In addition to the Army Special Service Group (SSG), the Pakistan Army has trained specialized Ranger units in counter-terrorism tactics. These Rangers are equipped to handle complex counter-terrorism operations involving civilian hostages and assist the Sindh and Punjab governments in maintaining law and order.[173]

Military philosophy

Combat doctrine (1947–2007)

In 1947, the Pakistan Army's war strategists developed a combat doctrine which was called "The Riposte", which featured a strategy of "offensive-defense".: 310 [174][175] In 1989, the first and official implementation of this strategy was refined and featured in the major military exercise, Exercise Zab-e-Momin, organized under Lt-Gen. Hamid Gul[176]– this combat doctrine was fully focused in engaging towards its primary adversary, Indian Army.: 310 [174]

In 1989–99, the JS HQ, working with the Army GHQ to identify several key factors considering the large conventional attacks from the better equipped and numerically advantage adversary, the Indian Army, derived the combat doctrine to assess the vulnerability of Pakistan where its vast majority of population centers as well as political and military targets lies closer to the international border with India.[177]

The national security strategists explored the controversial idea of strategic depth in form of fomenting friendly foreign relations with Afghanistan and Iran while India substantially enhancing its offensive capabilities designed in its doctrine, the Cold Start Doctrine.[177] Due to the numerical advantage of Indian Army over its smaller adversary, the Pakistan Army, the Pakistani national security analysts noted that any counterattack on advancing Indian Army would be very tricky and miscalculated – the ideal response of countering the attacks from the Indian ground forces would be operationalizing the battle-ranged Hatf-IA/Hatf-IB missiles.[177] In times of national emergency, the Pakistan Army Reserves, supported by the National Guard and Civil Armed Forces, would likely be deployed to reinforce defensive positions and fortifications.[178] However, after the orders are authorized the Corps in both nation's will take between 24 and 72 hours to completely mobilize their combat assets. Therefore, both nation's armies will be evenly matched in the first 24 hours since the Pakistani units have to travel a shorter distance to their forward positions.[178]

Pakistan's military doctrine emphasizes a proactive defense, also referred to as "offensive-defense". This strategy prioritizes seizing the initiative in a conflict and launching limited counteroffensives to preempt potential enemy advances.[178] Proponents of Pakistan's "offensive-defense" doctrine argue that it offers several advantages. One key benefit is the potential to disrupt an enemy's offensive plans, forcing them to shift focus from their initial attack to defending their own territory. This could place Pakistan in a more favorable position by dictating the terms of engagement on the battlefield.[178] The strategic calculations by Pakistan Army's war strategists hope that the Pakistan Army's soldiers would keep the Indian Army engaged in fighting on the Indian territory, therefore the collateral damage being suffered by the Indian Army will be higher.[178] Pakistani planners also estimate that since Indian forces will not be able to reach their maximum strength near the border for another 48–72 hours, Pakistan might have parity or numerical superiority against India.[178] An important aspect in "offensive-defense" doctrine was to seize sizable Indian territory which gives Pakistan an issue to negotiate with India in the aftermath of a possible ceasefire brought about by the international pressure after 3–4 weeks of fighting.[178]

Due to fortification of LoC in Kashmir and difficult terrains in Northern Punjab, the Army created the Pakistan Army Reserves in the 1990s that is concentrated in the desert terrain of Sindh-Rajasthan sector, The Army Reserve South of the Pakistan Army Reserves is grouped in several powerful field-level corps and designed to provide defensive maneuvers in case of war with the Indian Army.[178]

Threat Matrix (2010 – present)

After the failure of the "Offensive-defense" in 1999, the national security institutions engaged in critical thinking to evaluate new doctrine that would provide a comprehensive grand strategy against the infiltrating enemy forces, and development began 2010–11 for the new combat doctrine.[179] In 2013, the new combat doctrine, the Threat Matrix, was unveiled by the ISPR, that was the first time in its history that the army's national security analysts realized that Pakistan faces a real threat from within, a threat that is concentrated in areas along western borders.[179] The Threat Matrix doctrine analyze the military's comprehensive operational priorities and goes beyond in comprehensively describing both existential and non-existential threats to the country.[179]

Based on that strategy in 2013, the Pakistani military organized a four-tier joint military exercise, code-named: Exercise Azm-e-Nau, in which the aim was to update the military's "readiness strategy for dealing with the complex security threat environment."[180] The objective of such exercises is to assess tactics, procedures, and techniques, and explore joint operations strategies involving all three branches of the military: the Army, Air Force, and Navy.[180] In successive years, the Pakistani military combined all the branch-level exercises into joint warfare exercises, in which all four branches now participate, regardless of the terrain, platforms, and control of command.[180]

Education and training

Schooling, teachings, and institutions

The Pakistan Army offers wide range of extensive and lucrative careers in the military to young high school graduates and the college degree holders upon enlistment, and Pakistan Army operates the large number of training schools in all over the country.[181] The overall directions and management of the army training schools are supervised and controlled by the policies devised by the Education Corps, and philosophy on instructions in army schools involves in modern education with combat training.[182]

At the time of its establishment of the Pakistan Army in 1947, the Command and Staff College in Quetta was inherited to Pakistan, and is the oldest college established during the colonial period in India in 1905.[183] The British officers in the Pakistan Army had to established the wide range of schools to provide education and to train the army personnel in order to raise the dedicated and professional army.[184] The wide range of military officers in the Pakistani military were sent to attend the staff colleges in the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada who were trained and excelled in courses in armory, infantry, artillery, and ordnance in 1950–1961.: 293 [137]

The United States eventually took over the overall training programs in the Pakistan Army under the International Military Education and Training (IMET) but the U.S. coordination with Pakistan varied along with the vicissitudes of the military relations between two countries.: 12 [185] In the 1980s, the army had sent ~200 army officers abroad annually, two-thirds actually decided to attend schooling in the United States but the cessation of the United States' aid to Pakistan led the suspension of the IMET, leading Pakistani military officers to choose the schooling in the United Kingdom.: 294 [137]

After the terrorist attacks in the United States in 2001, the IMET cooperation was again activated with army officers begin attending the schooling in the United States but the training program was again suspended in 2018 by the Trump administration, leveling accusations on supporting armed Jihadi groups in Afghanistan.[186]

During the reconstruction and reorganization of the armed forces in the 1970s, the army established more training schools as below:

| Army schools and colleges | Year of establishment | School and college principal locations | Website |

|---|---|---|---|

| School of Armour and Mechanized Warfare | 1947 | Nowshera in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa | "School of Armour and Mechanized Warfare". Archived from the original on 3 January 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2019. |

| School of Artillery | 1948 | Kakul in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa | "School of Artillery". Archived from the original on 3 January 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2019. |

| School of Army Air Defense | 1941 | Karachi in Sindh | "School of Army Air Defence". Archived from the original on 21 January 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2019. |

| Military College of Engineering | 1947 | Risalpur in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa | "Military College of Engineering". Archived from the original on 21 January 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2019. |

| Military College of Signals | 1947 | Rawalpindi in Punjab | "Military College of Signals". Archived from the original on 21 January 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2019. |

| School of Infantry and Tactics | 1947 | Quetta in Balochistan | "School of Infantry and Tactics". Archived from the original on 3 January 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2019. |

| Aviation School | 1964 | Gujranwala in Punjab | "Army Aviation School". Archived from the original on 3 January 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2019. |

| Service Corps School | 1947 | Nowshera in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa | "Army Service Corps School". Archived from the original on 20 January 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2019. |

| Army Desert Warfare School | 1977 | Rawalpindi in Punjab | "Army Medical College". Archived from the original on 21 January 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2019. |

| Ordnance College | 1980 | Karachi in Sindh | "Ordnance College". Archived from the original on 3 January 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2019. |

| College of Electrical and Mechanical Engineering | 1957 | Rawalpindi in Punjab | "College of Electrical and Mechanical Engineering". Archived from the original on 21 January 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2019. |

| Special warfare and skills schools | Year of establishment | School and college principal locations | Website |

| Special Operations School | 1956 | Cherat in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa | "Special Operations School".[permanent dead link] |

| Parachute Training School | 1964 | Kakul in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa | "Parachute Training School". Archived from the original on 20 January 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2019. |

| Corps of Military Police School | 1949 | D.I. Khan in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa | "Corps of Military Police School". Archived from the original on 21 January 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2019. |

| School of Logistics | 1974 | Murree in Punjab | "Army School of Logistics". Archived from the original on 2 August 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2019. |

| School of Mountain Warfare and Physical Training | 1978 | Kakul in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa | "Army School of Mountain Warfare and Physical Training". Archived from the original on 21 January 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2019. |

| High Altitude School | 1987 | Rattu in Gilgit-Baltistan | "Army High Altitude School". Archived from the original on 21 January 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2019. |

| Army Desert Warfare School | 1987 | Chor in Sindh | "Army Desert Warfare School".[permanent dead link] |

| School of Music | 1970 | Abbottabad in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa | "Army School of Music". Archived from the original on 21 January 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2019. |

| Dog Breeding Training Center and School | 1952 | Rawalpindi in Punjab | "Army Dog Breeding Training Centre and School". Archived from the original on 21 January 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2019. |

| Veterinary School | 1947 | Sargodha in Punjab | "Army Veterinary School" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 January 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2019. |

| Higher education institutions | Year of establishment | Locations | Website |

| Command and Staff College | 1905 | Quetta in Balochistan | "Command and Staff College". Archived from the original on 21 January 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2019. |

| National Defense University | 1971 | Islamabad | "National Defense University". Archived from the original on 21 January 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2019. |

| National University of Sciences and Technology | 1991 | Multiple campuses | "National University of Sciences and Technology". Archived from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 20 January 2019. |

Sources: Army Schools Archived 3 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine and Skills Schools Archived 21 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine of Pakistan Army

The Pakistan Army's training schools are not restricted to the department of the army only but inter-services officers and personnel have been trained and educated as part of the interdepartmental cooperation.[181] The Pakistan Army takes responsibility of providing the military training and education to Pakistan Marines at their School of Infantry and Tactics, and military officers in other branches have attended and qualified psc from the Command and Staff College in Quetta.[181] Officers holding the ranks of captains, majors, lieutenants and lieutenant-commanders in marines are usually invited to attend the courses at the Command and Staff College in Quetta to be qualified as psc.: 9 [45]

Established in 1971, the National Defense University (NDU) in Islamabad is the senior and higher education learning institution that provides the advance critical thinking level and research-based strategy level education to the senior military officers in the Pakistani military.[187] The NDU in Islamabad is a significant institution of higher learning in understanding the institutional norms of military tutelage in Pakistan because it constitutes the "highest learning platform where the military leadership comes together for common instruction", according to thesis written by Pakistani author Aqil Shah.: 8 [45] Without securing their graduation from their master's program, no officer in the Pakistani military can be promoted as general in the army or air force, or admiral in the navy as it is a prerequisite for their promotion to become a senior member at the Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee.: 8–9 [45]