Эдвард I Англии

| Эдвард I | |

|---|---|

Портрет в Вестминстерском аббатстве, вероятно, изображающий Эдварда I, установленный где-то во время его правления. | |

| Король Англии | |

| Царствование | 20 ноября 1272 г. - 7 июля 1307 г. |

| Coronation | 19 August 1274 |

| Predecessor | Henry III |

| Successor | Edward II |

| Born | 17/18 June 1239 Palace of Westminster, London, England |

| Died | 7 July 1307 (aged 68) Burgh by Sands, Cumberland, England |

| Burial | 27 October 1307 Westminster Abbey, London |

| Spouses | |

| Issue Detail | |

| House | Plantagenet |

| Father | Henry III of England |

| Mother | Eleanor of Provence |

Эдвард I [а] (17/18 июня 1239 — 7 июля 1307), также известный как Эдвард Длинноногий и Молот Шотландии , был королем Англии с 1272 по 1307 год. Одновременно он был лордом Ирландии , а с 1254 по 1306 год правил Гасконью как Герцог Аквитании в качестве вассала французского короля . До восшествия на престол его обычно называли лордом Эдвардом . Старший сын Генриха III , Эдвард с раннего возраста был вовлечен в политические интриги правления своего отца. В 1259 году он ненадолго встал на сторону баронского реформаторского движения, поддержав Оксфордские положения . После примирения со своим отцом он оставался верным на протяжении всего последующего вооруженного конфликта, известного как Вторая баронская война . После битвы при Льюисе Эдвард был заложником мятежных баронов, но через несколько месяцев сбежал и победил вождя баронов Симона де Монфора в битве при Ившеме в 1265 году. В течение двух лет восстание было подавлено, а Англия умиротворена. , Эдвард ушел, чтобы присоединиться к Девятый крестовый поход на Святую Землю в 1270 году. Он возвращался домой в 1272 году, когда ему сообщили о смерти отца. Медленно возвращаясь, он достиг Англии в 1274 году и был коронован в Вестминстерском аббатстве .

Edward spent much of his reign reforming royal administration and common law. Through an extensive legal inquiry, he investigated the tenure of several feudal liberties. The law was reformed through a series of statutes regulating criminal and property law, but the King's attention was increasingly drawn towards military affairs. After suppressing a minor conflict in Wales in 1276–77, Edward responded to a second one in 1282–83 by conquering Wales. He then established English rule, built castles and towns in the countryside and settled them with English people. After the death of the heir to the Scottish throne, Edward was invited to arbitrate a succession dispute. He claimed feudal suzerainty over Scotland and invaded the country, and the ensuing First Scottish War of Independence continued after his death. Simultaneously, Edward found himself at war with France (a Scottish ally) after King Philip IV confiscated the Duchy of Gascony. The duchy was eventually recovered but the conflict relieved English military pressure against Scotland. By the mid-1290s, extensive military campaigns required high levels of taxation and this met with both lay and ecclesiastical opposition in England. In Ireland, he had extracted soldiers, supplies and money, leaving decay, lawlessness and a revival of the fortunes of his enemies in Gaelic territories. When the King died in 1307, he left to his son Edward II a war with Scotland and other financial and political burdens.

Edward's temperamental nature and height (6'2", 188 cm) made him an intimidating figure. He often instilled fear in his contemporaries, although he held the respect of his subjects for the way he embodied the medieval ideal of kingship as a soldier, an administrator, and a man of faith. Modern historians are divided in their assessment of Edward; some have praised him for his contribution to the law and administration, but others have criticised his uncompromising attitude towards his nobility. Edward is credited with many accomplishments, including restoring royal authority after the reign of Henry III and establishing Parliament as a permanent institution, which allowed for a functional system for raising taxes and reforming the law through statutes. At the same time, he is also often condemned for vindictiveness, opportunism and untrustworthiness in his dealings with Wales and Scotland, coupled with a colonialist approach to their governance and to Ireland, and for antisemitic policies leading to the expulsion of the Jews from England in 1290.

Early years, 1239–1263

[edit]Childhood and marriage

[edit]

Edward was born at the Palace of Westminster on the night of 17–18 June 1239, to King Henry III and Eleanor of Provence.[4][5] Edward, an Anglo-Saxon name, was not commonly given among the aristocracy of England after the Norman conquest, but Henry was devoted to the veneration of Edward the Confessor and decided to name his firstborn son after the saint.[6] Edward's birth was widely celebrated at the royal court and throughout England, and he was baptised three days later at Westminster Abbey.[5][7] He was commonly referred to as the Lord Edward until his accession to the throne in 1272.[8] Among his childhood friends was his cousin Henry of Almain, son of King Henry's brother Richard of Cornwall.[9] Henry of Almain remained a close companion of the prince for the rest of his life.[10] Edward was placed in the care of Hugh Giffard – father of the future Chancellor Godfrey Giffard – until Bartholomew Pecche took over at Giffard's death in 1246.[5][11] Edward received an education typical of an aristocratic boy his age, including in military studies,[5] although the details of his upbringing are unknown.[12]

There were concerns about Edward's health as a child, and he fell ill in 1246, 1247, and 1251.[9] Nonetheless, he grew up to become a strong, athletic, and imposing man.[5] At 6 ft 2 in (188 cm) he towered over most of his contemporaries,[13][14] hence his epithet "Longshanks", meaning "long legs" or "long shins". The historian Michael Prestwich states that his "long arms gave him an advantage as a swordsman, long thighs one as a horseman. In youth, his curly hair was blond; in maturity it darkened, and in old age it turned white. The regularity of his features was marred by a drooping left eyelid ... His speech, despite a lisp, was said to be persuasive."[15]

In 1254, English fears of a Castilian invasion of the English-held province of Gascony induced King Henry to arrange a politically expedient marriage between fifteen-year-old Edward and thirteen-year-old Eleanor, the half-sister of King Alfonso X of Castile.[16] They were married on 1 November 1254 in the Abbey of Santa María la Real de Las Huelgas in Castile.[17] As part of the marriage agreement, Alfonso X gave up his claims to Gascony, and Edward received grants of land worth 15,000 marks a year.[18][b] The marriage eventually led to the English acquisition of Ponthieu in 1279 upon Eleanor's inheritance of the county.[20] Henry made sizeable endowments to Edward in 1254, including Gascony;[5] most of Ireland, which was granted to Edward, while making the claim for the first time that dominion of Ireland would never be separated from the English crown;[21] and much land in Wales and England,[22] including the Earldom of Chester. They offered Edward little independence for Henry retained much control over the land in question, particularly in Ireland, and benefited from most of the income from those lands.[23] Split control caused problems. Between 1254 and 1272, eleven different Justiciars were appointed to head the Irish government, encouraging further conflict and instability; corruption rose to very high levels.[24] In Gascony, Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, had been appointed as royal lieutenant in 1253 and drew its income, so in practice Edward derived neither authority nor revenue from this province.[25] Around the end of November 1254, Edward and Eleanor left Castile and entered Gascony, where they were warmly received by the populace. Here, Edward styled himself as "ruling Gascony as prince and lord", a move that the historian J. S. Hamilton states was a show of his blooming political independence.[26]

From 1254 to 1257, Edward was under the influence of his mother's relatives, known as the Savoyards,[26][27] the most notable of whom was Peter II of Savoy, the Queen's uncle.[28] After 1257, Edward became increasingly close to the Lusignan faction – the half-brothers of his father Henry III – led by such men as William de Valence.[29][c] This association was significant because the two groups of privileged foreigners were resented by the established English aristocracy, who would be at the centre of the ensuing years' baronial reform movement.[31] Edward's ties to his Lusignan kinsmen were viewed unfavourably by contemporaries,[26] including the chronicler Matthew Paris, who circulated tales of unruly and violent conduct by Edward's inner circle, which raised questions about his personal qualities.[32]

Early ambitions

[edit]Edward showed independence in political matters as early as 1255, when he sided with the Soler family in Gascony in their conflict with the Colomb family.[26] This ran contrary to his father's policy of mediation between the local factions.[33] In May 1258, a group of magnates drew up a document for reform of the King's government – the so-called Provisions of Oxford – largely directed against the Lusignans. Edward stood by his political allies and strongly opposed the Provisions.[34] The reform movement succeeded in limiting the Lusignan influence, and Edward's attitude gradually changed. In March 1259, he entered into a formal alliance with one of the main reformers, Richard de Clare, 6th Earl of Gloucester, and on 15 October announced that he supported the barons' goals and their leader, the Earl of Leicester.[35]

The motive behind Edward's change of heart could have been purely pragmatic: the Earl of Leicester was in a good position to support his cause in Gascony.[36] When the King left for France in November, Edward's behaviour turned into pure insubordination. He made several appointments to advance the cause of the reformers, and his father believed that Edward was considering a coup d'état.[37] When Henry returned from France, he initially refused to see his son, but through the mediation of Richard of Cornwall and Boniface, Archbishop of Canterbury, the two were eventually reconciled.[38] Edward was sent abroad to France, and in November 1260 he again united with the Lusignans, who had been exiled there.[39]

Back in England, early in 1262, Edward fell out with some of his former Lusignan allies over financial matters. The next year, King Henry sent him on a campaign in Wales against the Welsh prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, but Edward's forces were besieged in northern Wales and achieved only limited results.[40] Around the same time, Leicester, who had been out of the country since 1261, returned to England and reignited the baronial reform movement.[41] As the King seemed ready to give in to the barons' demands, Edward began to take control of the situation. From his previously unpredictable and equivocating attitude, he changed to one of firm devotion to protection of his father's royal rights.[42] He reunited with some of the men he had alienated the year before – including Henry of Almain and John de Warenne, 6th Earl of Surrey – and retook Windsor Castle from the rebels.[43] Through the arbitration of King Louis IX of France an agreement was made between the two parties. This Mise of Amiens was largely favourable to the royalist side and would cause further conflict.[44]

Civil war and crusades, 1264–1273

[edit]Second Barons' War

[edit]The years 1264–1267 saw the conflict known as the Second Barons' War, in which baronial forces led by the Earl of Leicester fought against those who remained loyal to the King. Edward initiated the armed conflict by capturing the rebel-held city of Gloucester. When Robert de Ferrers, 6th Earl of Derby, came to the assistance of the baronial forces, Edward negotiated a truce with the Earl. Edward later broke the terms of the agreement.[45] He then captured Northampton from Simon de Montfort the Younger before embarking on a retaliatory campaign against Derby's lands.[46] The baronial and royalist forces met at the Battle of Lewes, on 14 May 1264. Edward, commanding the right wing, performed well, and soon defeated the London contingent of the Earl of Leicester's forces. Unwisely, he pursued the scattered enemy, and on his return found the rest of the royal army defeated.[47] By the Mise of Lewes, Edward and his cousin Henry of Almain were given up as hostages to Leicester.[48]

Edward remained in captivity until March 1265, and even after his release he was kept under strict surveillance.[49] In Hereford, he escaped on 28 May while out riding and joined up with Gilbert de Clare, 7th Earl of Gloucester, who had recently defected to the King's side.[50] The Earl of Leicester's support was now dwindling, and Edward retook Worcester and Gloucester with little effort.[51] Meanwhile, Leicester had made an alliance with Llywelyn and started moving east to join forces with his son Simon. Edward made a surprise attack at Kenilworth Castle, where the younger Montfort was quartered, before moving on to cut off the Earl of Leicester.[52] The two forces then met at the Battle of Evesham, on 4 August 1265.[53] The Earl of Leicester stood little chance against the superior royal forces, and after his defeat he was killed and mutilated on the field.[54]

Through such episodes as the deception of Derby at Gloucester, Edward acquired a reputation as untrustworthy. During the summer campaign he began to learn from his mistakes and gained the respect and admiration of contemporaries through actions such as showing clemency towards his enemies.[55] The war did not end with the Earl of Leicester's death, and Edward participated in the continued campaigning. At Christmas, he came to terms with Simon the Younger and his associates at the Isle of Axholme in Lincolnshire, and in March he led a successful assault on the Cinque Ports.[56] A contingent of rebels held out in the virtually impregnable Kenilworth Castle and did not surrender until the drafting of the conciliatory Dictum of Kenilworth in October 1266.[57][d] In April it seemed as if the Earl of Gloucester would take up the cause of the reform movement, and civil war would resume, but after a renegotiation of the terms of the Dictum of Kenilworth, the parties came to an agreement.[58][e] Around this time, Edward was made steward of England and began to exercise influence in the government.[59] He was also appointed Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports in 1265.[60] Despite this, he was little involved in the settlement negotiations following the wars. His main focus was on planning his forthcoming crusade.[61]

Crusade and accession

[edit]

Edward pledged himself to undertake a crusade in an elaborate ceremony on 24 June 1268, with his brother Edmund Crouchback and cousin Henry of Almain. Some of Edward's former adversaries, such as John de Vescy and the 7th Earl of Gloucester, similarly committed themselves, although some, like Gloucester, did not ultimately participate.[62] With the country pacified, the greatest impediment to the project was acquiring sufficient finances.[63] King Louis IX of France, who was the leader of the crusade, provided a loan of about £17,500.[64] This was not enough, and the rest had to be raised through a direct tax on the laity, which had not been levied since 1237.[64] In May 1270, Parliament granted a tax of one-twentieth of all movable property; in exchange the King agreed to reconfirm Magna Carta, and to impose restrictions on Jewish money lending.[65][f] On 20 August Edward sailed from Dover for France.[67] Historians have not determined the size of his accompanying force with any certainty, but it was probably fewer than 1000 men, including around 225 knights.[63]

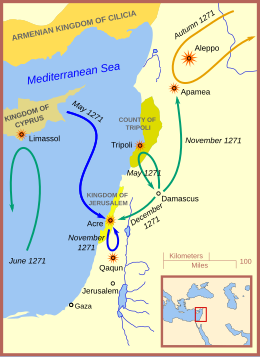

Originally, the Crusaders intended to relieve the beleaguered Christian stronghold of Acre in Palestine, but King Louis and his brother Charles of Anjou, the king of Sicily, decided to attack the emirate of Tunis to establish a stronghold in North Africa.[68] The plans failed when the French forces were struck by an epidemic which, on 25 August, killed Louis himself.[g] By the time Edward arrived at Tunis, Charles had already signed a treaty with the Emir, and there was little to do but return to Sicily.[70] Further military action was postponed until the following spring, but a devastating storm off the coast of Sicily dissuaded both Charles and Philip III, Louis's successor, from any further campaigning.[71] Edward decided to continue alone, and on 9 May 1271 he finally landed at Acre.[72]

The Christian situation in the Holy Land was precarious. Jerusalem had been reconquered by the Muslims in 1244, and Acre was now the centre of the Kingdom of Jerusalem.[73] The Muslim states were on the offensive under the Mamluk leadership of Baibars, and were threatening Acre. Though Edward's men were an important addition to the garrison, they stood little chance against Baibars's superior forces, and an initial raid at nearby St Georges-de-Lebeyne in June was largely futile.[74] An embassy to the Ilkhan Abaqa of the Mongols helped bring about an attack on Aleppo in the north, which distracted Baibars's forces.[75] The Mongol invasion ultimately failed. In November, Edward led a raid on Qaqun, which could have served as a bridgehead to Jerusalem, but this was unsuccessful. The situation in Acre grew desperate, and in May 1272 Hugh III of Cyprus, who was the nominal king of Jerusalem, signed a ten-year truce with Baibars.[76] Edward was initially defiant, but in June 1272 he was the victim of an assassination attempt by a member of the Syrian Order of Assassins, supposedly ordered by Baibars. Although he managed to kill the assassin, he was struck in the arm by a dagger feared to be poisoned, and was severely weakened over the following months. This finally persuaded Edward to abandon the campaign.[70][77][h]

It was not until 24 September 1272 that Edward left Acre. Shortly after arriving in Sicily, he was met with the news that his father had died on 16 November.[79] Edward was deeply saddened by this news,[80] but rather than hurrying home at once, he made a leisurely journey northwards.[81] This was due partly to his still-poor health, but also to a lack of urgency.[82] The political situation in England was stable after the mid-century upheavals, and Edward was proclaimed king after his father's death, rather than at his own coronation, as had until then been customary.[83][i] In Edward's absence, the country was governed by a royal council, led by Robert Burnell.[84] Edward passed through Italy and France, visiting Pope Gregory X and paying homage to Philip III in Paris for his French domains.[85][81] Edward travelled by way of Savoy to receive homage from his great-uncle Count Philip I for castles in the Alps held by a treaty of 1246.[81]

Edward then journeyed to Gascony to order its affairs and put down a revolt headed by Gaston de Béarn.[84][86] While there, he launched an investigation into his feudal possessions, which, as Hamilton puts it, reflects "Edward's keen interest in administrative efficiency ... [and] reinforced Edward's position as lord in Aquitaine and strengthened the bonds of loyalty between the king-duke and his subjects".[86] Around the same time, the King organised political alliances with the kingdoms in Iberia. His four-year-old daughter Eleanor was promised in marriage to Alfonso, the heir to the Crown of Aragon, and Edward's heir Henry was betrothed to Joan, heiress to the Kingdom of Navarre.[87] Neither union would come to fruition. Only on 2 August 1274 did Edward return to England, landing at Dover.[87][88] The thirty-five-year-old king held his coronation on 19 August at Westminster Abbey, alongside Queen Eleanor.[13][89] Immediately after being anointed and crowned by Robert Kilwardby, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Edward removed his crown, saying that he did not intend to wear it again until he had recovered all the crown lands that his father had surrendered during his reign.[90]

Early reign, 1274–1296

[edit]Conquest of Wales

[edit]

Llywelyn ap Gruffudd enjoyed an advantageous situation in the aftermath of the Barons' War. The 1267 Treaty of Montgomery recognised his ownership of land he had conquered in the Four Cantrefs of Perfeddwlad and his title of Prince of Wales.[91] Armed conflicts nevertheless continued, in particular with certain dissatisfied Marcher Lords, such as the Earl of Gloucester, Roger Mortimer and Humphrey de Bohun, 3rd Earl of Hereford.[92] Problems were exacerbated when Llywelyn's younger brother Dafydd and Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn of Powys, after failing in an assassination attempt against Llywelyn, defected to the English in 1274.[93] Citing ongoing hostilities and Edward's harbouring of his enemies, Llywelyn refused to do homage to the King.[94] For Edward, a further provocation came from Llywelyn's planned marriage to Eleanor, daughter of Simon de Montfort the Elder.[95]

In November 1276, Edward declared war.[96][97] Initial operations were launched under the captaincy of Mortimer, Edward's brother Edmund, Earl of Lancaster, and William de Beauchamp, 9th Earl of Warwick.[96][j] Support for Llywelyn was weak among his own countrymen.[98] In July 1277 Edward invaded with a force of 15,500, of whom 9,000 were Welshmen.[99] The campaign never came to a major battle, and Llywelyn soon realised he had no choice but to surrender.[99] By the Treaty of Aberconwy in November 1277, he was left only with the land of Gwynedd, though he was allowed to retain the title of Prince of Wales.[100]

When war broke out again in 1282, it was an entirely different undertaking. For the Welsh, this war was over national identity and the right to traditional Welsh law, enjoying wide support, provoked by attempts to abuse the English legal system to dispossess prominent Welsh landowners, many of whom were Edward's former opponents.[101] For Edward, it became a war of conquest aimed to "put an end finally to … the malice of the Welsh".[102] The war started with a rebellion by Dafydd, who was discontented with the reward he had received from Edward in 1277.[103] Llywelyn and other Welsh chieftains soon joined in, and initially the Welsh experienced military success. In June, Gloucester was defeated at the Battle of Llandeilo Fawr.[104] On 6 November, while John Peckham, Archbishop of Canterbury, was conducting peace negotiations, Edward's commander of Anglesey, Luke de Tany, decided to carry out a surprise attack. A pontoon bridge had been built to the mainland, but shortly after Tany and his men crossed over, they were ambushed by the Welsh and suffered heavy losses at the Battle of Moel-y-don.[105] The Welsh advances ended on 11 December, when Llywelyn was lured into a trap and killed at the Battle of Orewin Bridge.[106] The conquest of Gwynedd was complete with the capture in June 1283 of Dafydd, who was taken to Shrewsbury and executed as a traitor the following autumn;[107] Edward ordered Dafydd's head to be publicly exhibited on London Bridge.[108]

Edward I

By the 1284 Statute of Rhuddlan, the principality of Wales was incorporated into England and was given an administrative system like the English, with counties policed by sheriffs.[109] English law was introduced in criminal cases, though the Welsh were allowed to maintain their own customary laws in some cases of property disputes.[110] After 1277, and increasingly after 1283, Edward embarked on a project of English settlement of Wales, creating new towns like Flint, Aberystwyth and Rhuddlan.[111] Their new residents were English migrants, the local Welsh being banned from living inside them, and many were protected by extensive walls.[112][k]

An extensive project of castle-building was also initiated, under the direction of James of Saint George,[114] a prestigious architect whom Edward had met in Savoy on his return from the crusade.[115] These included the Beaumaris, Caernarfon, Conwy and Harlech castles, intended to act as fortresses, royal palaces and as the new centres of civilian and judicial administration.[116] His programme of castle building in Wales heralded the introduction of the widespread use of arrowslits in castle walls across Europe, drawing on Eastern architectural influences.[117] Also a product of the Crusades was the introduction of the concentric castle, and four of the eight castles Edward founded in Wales followed this design.[118] The castles drew on imagery associated with the Byzantine Empire and King Arthur in an attempt to build legitimacy for his new regime, and they made a clear statement about Edward's intention to rule Wales permanently.[119] The Welsh aristocracy were nearly wholly dispossessed of their lands.[120] Edward was the greatest beneficiary of this process.[121] Further rebellions occurred in 1287–88 and, more seriously, in 1294, under the leadership of Madog ap Llywelyn, a distant relative of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd.[122] The causes included deep resentment at the occupation, poor, colonial-style governance, and very heavy taxation.[123] This last conflict demanded the King's own attention, but in both cases the rebellions were put down.[124] The revolt was followed by immediate punitive measures including taking 200 hostages.[125] Measures to stop the Welsh from bearing arms or residing in the new boroughs probably date from this time, and the Welsh administration continued to be nearly wholly imported.[126]

In 1284, King Edward had his son Edward (later Edward II) born at Caernarfon Castle, probably to make a deliberate statement about the new political order in Wales.[127] [l] In 1301 at Lincoln, the young Edward became the first English prince to be invested with the title of Prince of Wales, when the King granted him the Earldom of Chester and lands across North Wales, hoping to give his son more financial independence.[129][m] Edward began a more concilatory policy to rebuild systems of patronage and service, particularly through his son as Prince of Wales, but Wales remained politically volatile, and a deep divide and distrust remained between the English settlers and the Welsh.[131]

Diplomacy and war on the Continent

[edit]

Edward never again went on crusade after his return to England in 1274, but he maintained an intention to do so, and in 1287 took a vow to go on another Crusade.[70][132] This intention guided much of his foreign policy, until at least 1291. To stage a European-wide crusade, it was essential to prevent conflict between the sovereigns on the Continent.[133] A major obstacle to this was represented by the conflict between the French Capetian House of Anjou ruling southern Italy and the Crown of Aragon in Spain.[133] In 1282, the citizens of Palermo rose up against Charles of Anjou and turned for help to Peter III of Aragon, in what has become known as the Sicilian Vespers.[134] In the war that followed, Charles of Anjou's son, Charles of Salerno, was taken prisoner by the Aragonese.[135] The French began planning an attack on Aragon, raising the prospect of a large-scale European war. To Edward, it was imperative that such a war be avoided, and in Paris in 1286 he brokered a truce between France and Aragon that helped secure Charles's release.[136] As far as the crusades were concerned, Edward's efforts proved ineffective. A devastating blow to his plans came in 1291, when the Mamluks captured Acre, the last Christian stronghold in the Holy Land.[137]

Edward had long been deeply involved in the affairs of his own Duchy of Gascony.[138] In 1278 he assigned an investigating commission to his trusted associates Otto de Grandson and the chancellor Robert Burnell, which caused the replacement of the seneschal Luke de Tany.[139] In 1286, Edward visited the region himself and stayed for almost three years.[140] On Easter Sunday 1287, Edward was standing in a tower when the floor collapsed. He fell 80 feet, broke his collarbone, and was confined to bed for several months. Several others died.[141] Soon after he regained his health, he ordered the local Jews expelled from Gascony,[142] seemingly as a "thank-offering" for his recovery.[143][n]

The perennial problem was the status of Gascony within the Kingdom of France, and Edward's role as the French king's vassal. On his diplomatic mission in 1286, Edward had paid homage to the new king, Philip IV, and—following an outbreak of piracy and informal war between English, Gascon, Norman, and French sailors in 1293—his brother Edmund Crouchback even went so far as to allow Philip IV's occupation of Gascony's chief fortresses as a show of good faith that Edward had not intended the seizure of several French ships or the sacking of the French port of La Rochelle. Philip, however, refused to release the fortresses and declared Gascony forfeit when Edward refused to appear before him again in Paris.[145]

Correspondence between Edward and the Mongol court of the east continued during this time.[146] Diplomatic channels between the two had begun during Edward's time on crusade, regarding a possible alliance to retake the Holy Land for Europe. Edward received Mongol envoys at his court in Gascony while there in 1287, and one of their leaders, Rabban Bar Sauma, recorded an extant account of the interaction.[146] Other embassies arrived in Europe in 1289 and 1290, the former relaying Ilkhan Abaqa's offer to join forces with the crusaders and supply them with horses.[147] Edward responded favourably, declaring his intent to embark on a journey to the east once he obtained papal approval. Although this would not materialise, the King's decision to send Geoffrey of Langley as his ambassador to the Mongols revealed that he was seriously considering the prospective Mongol alliance.[148]

Eleanor of Castile died on 28 November 1290.[149] The couple loved each other, and like his father, Edward was very devoted to his wife and was faithful to her throughout their marriage.[150] He was deeply affected by her death,[151] and displayed his grief by erecting twelve so-called Eleanor crosses,[152] one at each place where her funeral cortège stopped for the night.[153] As part of the peace accord between England and France in 1294, it was agreed that Edward should marry Philip IV's half-sister Margaret, but the marriage was delayed by the outbreak of war.[154] Edward made expensive alliances with the German king, the counts of Flanders and Guelders, and the Burgundians, who would attack France from the north.[155] The alliances proved volatile and Edward was facing trouble at home at the time, both in Wales and Scotland. His admiral Barrau de Sescas kept remaining English forces in Gascony supplied, but it was not until August 1297 that he was finally able to sail for Flanders, at which time his allies there had already suffered defeat.[156] The support from Germany never materialised, and Edward was forced to seek peace. In 1299, the Treaties of Montreuil and Chartres, along with Edward's marriage to Margaret, produced a prolonged armistice, but the whole affair had proven both costly and fruitless for the English.[157][158][o] French occupation of most of Gascony would not end until the 1303 Treaty of Paris, at which point it was partially returned to the English crown, again as a French fief.[159]

Great Cause

[edit]

The relationship between England and Scotland by the 1280s was one of relatively harmonious coexistence.[161] The issue of homage did not reach the same level of controversy as it did in Wales; in 1278 King Alexander III of Scotland paid homage to Edward, who was his brother-in-law, but apparently only for the lands he held in England.[162] Problems arose only with the Scottish succession crisis of the early 1290s. When Alexander died in 1286, he left as heir to the Scottish throne Margaret, his three-year-old granddaughter and sole surviving descendant.[163] By the Treaty of Birgham, it was agreed that Margaret should marry King Edward's six-year-old son Edward of Caernarfon, though Scotland would remain free of English overlordship.[164][165] Margaret, by now seven years of age, sailed from Norway for Scotland in the autumn of 1290, but fell ill on the way and died in Orkney.[166][167] This left the country without an obvious heir, and led to the succession dispute known to history as the Great Cause.[168][p]

Even though as many as fourteen claimants put forward their claims to the title, the foremost competitors were John Balliol and Robert de Brus, 5th Lord of Annandale.[169] The Scottish magnates made a request to Edward to conduct the proceedings and administer the outcome, but not to arbitrate in the dispute. The actual decision would be made by 104 auditors – 40 appointed by Balliol, 40 by Brus and the remaining 24 selected by Edward from senior members of the Scottish political community.[170] At Birgham, with the prospect of a personal union between the two realms, the question of suzerainty had not been of great importance to Edward. Now he insisted that, if he were to settle the contest, he had to be fully recognised as Scotland's feudal overlord.[171] The Scots were reluctant to make such a concession, and replied that since the country had no king, no one had the authority to make this decision.[172] This problem was circumvented when the competitors agreed that the realm would be handed over to Edward until a rightful heir had been found.[173] After a lengthy hearing, a decision was made in favour of John Balliol on 17 November 1292.[174][q]

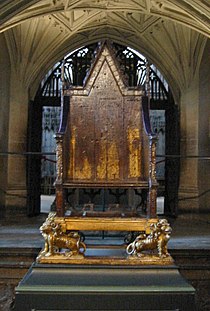

Even after Balliol's accession, Edward still continued to assert his authority over Scotland. Against the objections of the Scots, he agreed to hear appeals on cases ruled on by the court of guardians that had governed Scotland during the interregnum.[175] A further provocation came in a case brought by Macduff, son of Malcolm II, Earl of Fife, in which Edward demanded that Balliol appear in person before the English Parliament to answer the charges.[176] This the Scottish King did, but the final straw was Edward's demand that the Scottish magnates provide military service in the war against France.[177] This was unacceptable; the Scots instead formed an alliance with France and launched an unsuccessful attack on Carlisle.[178] Edward responded by invading Scotland in 1296 and taking the town of Berwick-upon-Tweed which included the massacre of civilians.[179] At the Battle of Dunbar, Scottish resistance was effectively crushed.[180] Edward confiscated the Stone of Destiny – the Scottish coronation stone – and brought it to Westminster, placing it in what became known as King Edward's Chair; he deposed Balliol and placed him in the Tower of London, and installed Englishmen to govern the country.[181] The campaign had been very successful, but the English triumph would be only temporary.[182]

Government and law

[edit]Character as king

[edit]

Edward had a reputation for a fierce and sometimes unpredictable temper,[183] and he could be intimidating; one story tells of how the Dean of St Paul's, wishing to confront Edward over the high level of taxation in 1295, fell down and died once he was in the King's presence,[184] and one 14th-century chronicler attributed the death of Archbishop Thomas of York to the King's harsh conduct towards him.[185] When Edward of Caernarfon demanded an earldom for his favourite Piers Gaveston, the King erupted in anger and supposedly tore out handfuls of his son's hair.[186] Some of his contemporaries considered Edward frightening, particularly in his early days. The Song of Lewes in 1264 described him as a leopard, an animal regarded as particularly powerful and unpredictable.[187] At times, Edward exhibited a gentler disposition, and was known to be devoted to his large family. He was close to his daughters, and frequently lavished expensive gifts on them whenever they visited court.[150]

Despite his harsh disposition, Edward's English contemporaries considered him an able, even an ideal, king.[188] Though not loved by his subjects, he was feared and respected, as reflected in the fact that there were no armed rebellions in England during his reign.[189] Edward is often noted as exhibiting vindictiveness towards his defeated enemies, and triumphalism in his actions.[190] Historian R. R. Davies considered Edward's repeated and "gratuitous belittling of his opponents", to have been "one of the most consistent and unattractive features of his character as king".[191] Examples include the seizure of fragments of the Holy Cross from Wales after its defeat in 1283, and subsequently the Stone of Scoon and regalia from Scotland after defeats in 1296.[192] Some historians question Edward's good faith and trustworthiness in relation to his dealing with Wales and Scotland, believing him to have been capable of going back on his word or behaving duplicitously.[193]

Historian Michael Prestwich believes Edward met contemporary expectations of kingship in his role as an able, determined soldier and in his embodiment of shared chivalric ideals.[194] In religious observance he also fulfilled the expectations of his age: he attended chapel regularly, gave alms generously and showed a fervent devotion to the Virgin Mary and Saint Thomas Becket.[195] Like his father, Edward was a keen participant in the tradition of the royal touch, which had the supposed effect of curing those who were touched from scrofula. Contemporary records suggest that the King touched upwards of a thousand people each year.[185] Despite his personal piety, Edward was frequently in conflict with the Archbishops of Canterbury who served during his reign. Relations with the Papacy were at times no better, Edward coming into conflict with Rome over the issue of ecclesiastical taxation.[185] Edward's use of the church extended to war mobilisation including disseminating official justifications for war, usually through the issue of writs to England's archbishops, who distributed his requests for services and prayers.[196] Edward's architectural programme similarly had an element of propaganda, sometimes combining this with religious messages of piety, as with the Eleanor Crosses.[197]

Edward took a keen interest in the stories of King Arthur, which were highly popular in Europe during his reign.[198] In 1278 he visited Glastonbury Abbey to open what was then believed to be the tomb of Arthur and Guinevere, recovering "Arthur's crown" from Llywelyn after the conquest of North Wales;[199] his castle-building campaign in Wales drew upon the Arthurian myths in their design and location.[200] He held "Round Table" events in 1284 and 1302, involving tournaments and feasting, and chroniclers compared him and the events at his court to Arthur.[201] In some cases Edward appears to have used his interest in the Arthurian myths to serve his own political interests, including legitimising his rule in Wales and discrediting the Welsh belief that Arthur might return as their political saviour.[202]

Administration and the law

[edit]

Soon after assuming the throne, Edward set about restoring order and re-establishing royal authority after the troubled reign of his father.[203] To accomplish this, he immediately ordered an extensive change of administrative personnel. The most important of these was the designation of Robert Burnell as chancellor in 1274, a man who would remain in the post until 1292 as one of the King's closest associates.[204] The same year as Burnell's appointment, Edward replaced most local officials, such as the escheators and sheriffs.[205] This last measure was taken in preparation for an extensive inquest covering all of England, that would hear complaints about abuse of power by royal officers. The second purpose of the inquest was to establish what land and rights the Crown had lost during the reign of Henry III.[206]

The inquest produced a set of census documents called the Hundred Rolls.[207] These have been likened to the 11th-century Domesday Book,[208] and they formed the basis for the later legal inquiries called the Quo warranto proceedings.[209] The purpose of these inquiries was to establish by what warrant (Latin: Quo warranto) liberties were held.[210][r] If the defendant could not produce a royal licence to prove the grant of the liberty, then it was the Crown's opinion – based on the writings of the influential thirteenth-century legal scholar Henry de Bracton – that the liberty should revert to the King. Both the Statute of Westminster 1275 and Statute of Westminster 1285 codified the existing law in England.[211] By enacting the Statute of Gloucester in 1278 the King challenged baronial rights through a revival of the system of general eyres (royal justices to go on tour throughout the land) and through a significant increase in the number of pleas of quo warranto to be heard by such eyres.[212]

This caused great consternation among the aristocracy,[213] who insisted that long use in itself constituted licence.[214] A compromise was eventually reached in 1290, whereby a liberty was considered legitimate as long as it could be shown to have been exercised since the coronation of Richard the Lionheart in 1189.[215] Royal gains from the Quo warranto proceedings were insignificant as few liberties were returned to the King,[216] but he had nevertheless won a significant victory by establishing the principle that all liberties emanated from the Crown.[217]

The 1290 statute of Quo warranto was only one part of a wider legislative reform, which was one of the most important contributions of Edward's reign.[218] This era of legislative action had started already at the time of the baronial reform movement; the Statute of Marlborough (1267) contained elements both of the Provisions of Oxford and the Dictum of Kenilworth.[219] The compilation of the Hundred Rolls was followed shortly after by the issue of Westminster I (1275), which asserted the royal prerogative and outlined restrictions on liberties.[220] The Statutes of Mortmain (1279) addressed the issue of land grants to the Church.[221] The first clause of Westminster II (1285), known as De donis conditionalibus, dealt with family settlement of land, and entails.[222] The Statute of Merchants (1285) established firm rules for the recovery of debts,[223] and the Statute of Winchester (1285) dealt with security and peacekeeping on a local level by bolstering the existing police system.[224] Quia emptores (1290) – issued along with Quo warranto – set out to remedy land ownership disputes resulting from alienation of land by subinfeudation.[225] The age of the great statutes largely ended with the death of Robert Burnell in 1292.[226]

Finances and Parliament

[edit]

Edward's reign saw an overhaul of the coinage system, which was in a poor state by 1279.[227] Compared to the coinage already circulating at the time of Edward's accession, the new coins issued proved to be of superior quality. In addition to minting pennies, halfpences and farthings, a new denomination called the groat (which proved to be unsuccessful) was introduced.[228] The coinmaking process itself was also improved. The moneyer William Turnemire introduced a novel method of minting coins that involved cutting blank coins from a silver rod, in contrast with the old practice of stamping them out from sheets; this technique proved to be efficient.[228] The practice of minting coins with the moneyer's name on them became obsolete under Edward's rule because England's mint administration became far more centralised under the Crown's authority. During this time, English coins were frequently counterfeited on the Continent, especially the Low Countries, and despite a ban in 1283, English coinage was secretly exported to the European continent.[229] In August 1280, Edward forbade the usage of the old long cross coinage, which forced the populace to switch to the newly minted versions.[227] Records indicate that the coinage overhaul successfully provided England with a stable currency.[230]

Edward's frequent military campaigns put a great financial strain on the nation.[232] There were several ways through which the King could raise money for war, including customs duties, loans and lay subsidies, which were taxes collected at a certain fraction of the moveable property of all laymen who held such assets. In 1275, Edward negotiated an agreement with the domestic merchant community that secured a permanent duty on wool, England's primary export.[233] In 1303, a similar agreement was reached with foreign merchants, in return for certain rights and privileges.[234] The revenues from the customs duty were handled by the Riccardi, a group of bankers from Lucca in Italy.[235] This was in return for their service as moneylenders to the crown, which helped finance the Welsh Wars. When the war with France broke out, the French king confiscated the Riccardi's assets, and the bank went bankrupt.[236] After this, the Frescobaldi of Florence took over the role as money lenders to the English crown.[237] Edward also sought to reduce pressure on his finances by helping his wife Eleanor to build an independent income.[238]

Edward held Parliament on a regular basis throughout his reign.[239] In 1295, a significant change occurred. For this Parliament, as well as the secular and ecclesiastical lords, two knights from each county and two representatives from each borough were summoned.[240][241] The representation of commons in Parliament was nothing new; what was new was the authority under which these representatives were summoned. Whereas previously the commons had been expected simply to assent to decisions already made by the magnates, it was now proclaimed that they should meet with the full authority (plena potestas) of their communities, to give assent to decisions made in Parliament.[242] The King now had full backing for collecting lay subsidies from the entire population.[243] Whereas Henry III had only collected four of these in his reign, Edward collected nine.[244] This format eventually became the standard for later Parliaments, and historians have named the assembly the "Model Parliament",[245] a term first introduced by the English historian William Stubbs.[246]

Parliament and the expulsion of the Jews

[edit]

Another source of political conflict was Edward's policy towards the English Jews, which dominated his financial relations with Parliament until 1290.[247] Jews, unlike Christians, were allowed to charge interest on loans, known as usury. Edward faced pressure from the church, who were increasingly intolerant of Judaism and usury.[248] The Jews were the King's personal property, and he was free to tax them at will.[249] Over-taxation of the Jews forced them to sell their debt bonds at cut prices, which was exploited by the crown to transfer vast land wealth from indebted landholders to courtiers and particularly his wife, Eleanor of Provence, causing widespread resentment.[250] In 1275, facing the resulting discontent in Parliament, Edward issued the Statute of the Jewry, which outlawed loans with interest and encouraged the Jews to take up other professions.[251] In 1279, in the context of a supposed crack-down on coin-clippers, he organised the arrest of all the heads of Jewish households in England. Approximately a tenth of the Jewish population, around 300 people, were executed. Others were allowed to pay fines. At least £16,000 was raised through fines and the seizure of property from the dead.[252][s] In 1280, he ordered all Jews to attend special sermons, preached by Dominican friars, with the hope of persuading them to convert, but unsurprisingly these exhortations were not followed.[254] By 1280, the Jews had been exploited to a level at which they were no longer of much financial use to the crown,[255] but they could still be used in political bargaining.[256]

The final attack on the Jews in England came in the Edict of Expulsion in 1290, whereby Edward formally expelled all Jews from England.[t] As they crossed the channel to France, some became victims to piracy, but many more were disposessed or died in the storms of October.[258] The Crown disposed of their property, through sales and 85 grants made to courtiers and family.[259][u] The Edict appears to have been issued as part of a deal to secure a lay subsidy of £110,000 from Parliament, the largest granted in the medieval period.[261] Although expulsions had taken place on a local, temporary basis,[v] the English expulsion was regarded as unprecedented because it was permanent.[262] It was eventually reversed in the 1650s.[263] Edward claimed the Expulsion was done "in honour of the Crucified" and blamed the Jews for their treachery and criminality.[264] He helped pay for the renovation of the tomb of Little Saint Hugh, a child falsely claimed to have been ritually crucified by Jews, in the same style as the Eleanor crosses, to take political credit for his actions. As historian Richard Stacey notes, "a more explicit identification of the crown with the ritual crucifixion charge can hardly be imagined."[265][w]

Administration in Ireland

[edit]

Edward's primary interest in Ireland was as a source of resources, soldiers and funds for his wars, in Gascony, Wales, Scotland and Flanders. Royal interventions aimed at maximising economic extraction.[267] Corruption among Edward's officials was at a concerningly high level, and despite Edward's efforts after 1272 to reform the Irish administration, record keeping was poor.[268]

Disturbances in Ireland increased during the period. The weakness and lack of direction given to the Lordship's rule allowed factional fighting to grow, reinforced by the introduction of indentured military service by Irish magnates from around 1290.[269] The funnelling of revenue to Edward's wars left Irish castles, bridges and roads in a state of disrepair, and alongside the withdrawal of troops to be used against Wales and Scotland and elsewhere, helped induce lawless behaviour. Resistance to 'purveyances', or forced purchase of supplies such as grain, added to lawlessness, and caused speculation and inflation in the price of basic goods.[270] Pardons were granted to lawbreakers for service for the King in England.[271] Revenues and removal of troops for Edward's wars left the country unable to address its basic needs, while the administration was wholly focused on providing for Edward's war demands;[272] troops looted and fought with townspeople when on the move.[273] Gaelic Ireland enjoyed a revival, due to the absence of English magnates and the weakness of the Lordship, assimilating some of the settlers.[274] Edward's government was hostile to the use of Gaelic law, which it condemned in 1277 as "displeasing to God and to reason".[275] Conflict was firmly entrenched by the time of the 1297 Irish Parliament, which attempted to create measures to counter disorder and the spread of Gaelic customs and law, while the results of the distress included many abandoned lands and villages.[276]

Later reign, 1297–1307

[edit]Constitutional crisis

[edit]The incessant warfare of the 1290s put a great financial demand on Edward's subjects. Whereas the King had levied only three lay subsidies until 1294, four such taxes were granted in the years 1294–1297, raising over £200,000.[277] Along with this came the burden of prises, seizure of wool and hides, and the unpopular additional duty on wool, dubbed the maltolt ("unjustly taken").[278] The fiscal demands on the King's subjects caused resentment, which eventually led to serious political opposition. The initial resistance was caused not by the lay taxes, but by clerical subsidies. In 1294, Edward made a demand of a grant of one-half of all clerical revenues. There was some resistance, but the King responded by threatening opponents with outlawry, and the grant was eventually made.[279] At the time, Robert Winchelsey, the designated Archbishop of Canterbury, was in Italy to receive consecration.[280][x] Winchelsey returned in January 1295 and had to consent to another grant in November of that year. In 1296, his position changed when he received the papal bull Clericis laicos. This bull prohibited the clergy from paying taxes to lay authorities without explicit consent from the Pope.[281] When the clergy, with reference to the bull, refused to pay, Edward responded with outlawry.[282] Winchelsey was presented with a dilemma between loyalty to the King and upholding the papal bull, and he responded by leaving it to every individual clergyman to pay as he saw fit.[283] By the end of the year, a solution was offered by the new papal bull Etsi de statu, which allowed clerical taxation in cases of pressing urgency.[284] This allowed Edward to collect considerable sums by taxing the English clergy.[285]

Edward

By God, Sir Earl, either go or hang

Roger Bigod

By that same oath, O king, I shall neither go nor hang

Chronicle of Walter of Guisborough[286]

Opposition from the laity took longer to surface. This resistance focused on two things: the King's right to demand military service and his right to levy taxes. At the Salisbury Parliament of February 1297, the Earl Marshal Roger Bigod, 5th Earl of Norfolk, objected to a royal summons of military service. Bigod argued that the military obligation only extended to service alongside the King; if the King intended to sail to Flanders, he could not send his subjects to Gascony.[287] In July, Bigod and Humphrey de Bohun, 3rd Earl of Hereford and Constable of England, drew up a series of complaints known as the Remonstrances, in which objections to the extortionate level of taxation were voiced.[288] Undeterred, Edward requested another lay subsidy. This one was particularly provocative, because the King had sought consent from only a small group of magnates, rather than from representatives of the communities in Parliament.[289] While Edward was in Winchelsea, preparing for the campaign in Flanders, Bigod and de Bohun arrived at the Exchequer to prevent the collection of the tax.[290] As the King left the country with a greatly reduced force, the kingdom seemed to be on the verge of civil war.[291][292] The English defeat by the Scots at the Battle of Stirling Bridge resolved the situation. The renewed threat to the homeland gave king and magnates common cause.[293] Edward signed the Confirmatio cartarum – a confirmation of Magna Carta and its accompanying Charter of the Forest – and the nobility agreed to serve with the King on a campaign in Scotland.[294][295]

Edward's problems with the opposition did not end with the Scottish campaign. Over the following years he would be held to the promises he had made, in particular that of upholding the Charter of the Forest.[y] In the Parliament of 1301, the King was forced to order an assessment of the royal forests, but in 1305 he obtained a papal bull that freed him from this concession.[296] Ultimately, it was a change in personnel that spelt the end of the opposition against Edward. De Bohun died late in 1298, after returning from the Scottish campaign.[297] In 1302 Bigod arrived at an agreement with the King that was beneficial for both: Bigod, who had no children, made Edward his heir, in return for a generous annual grant.[298] Edward finally got his revenge on Winchelsey, who had been opposed to the King's policy of clerical taxation,[299] in 1305, when Clement V was elected pope. Clement was a Gascon sympathetic to the King, and on Edward's instigation had Winchelsey suspended from office.[300]

Return to Scotland

[edit]

Edward believed that he had completed the conquest of Scotland when he left the country in 1296, but resistance soon emerged under the leadership of Andrew de Moray in the north and William Wallace in the south. On 11 September 1297, a large English force under the leadership of John de Warenne, 6th Earl of Surrey, and Hugh de Cressingham was routed by a much smaller Scottish army led by Wallace and Moray at the Battle of Stirling Bridge.[301] The defeat sent shockwaves into England, and preparations for a retaliatory campaign started immediately. Soon after Edward returned from Flanders, he headed north.[302] On 22 July 1298, in the only major battle he had fought since Evesham in 1265, Edward defeated Wallace's forces at the Battle of Falkirk.[303] Edward underestimated the gravity of the ever-changing military condition in the north and was not able to take advantage of the momentum;[304] the next year the Scots managed to recapture Stirling Castle.[305] Even though Edward campaigned in Scotland both in 1300, when he successfully besieged Caerlaverock Castle and in 1301, the Scots refused to engage in open battle again, preferring instead to raid the English countryside in smaller groups.[306]

The Scots appealed to Pope Boniface VIII to assert a papal claim of overlordship to Scotland in place of the English. His papal bull addressed to King Edward in these terms was firmly rejected on Edward's behalf by the Barons' Letter of 1301. The English managed to subdue the country by other means: in 1303, a peace agreement was reached between England and France, effectively breaking up the Franco-Scottish alliance.[307] Robert the Bruce, the grandson of the claimant to the crown in 1291, had sided with the English in the winter of 1301–02.[308] In 1304, most of the other nobles of the country had also pledged their allegiance to Edward, and the English also managed to re-take Stirling Castle.[309] A great propaganda victory was achieved in 1305 when Wallace was betrayed by Sir John de Menteith and turned over to the English, who had him taken to London where he was publicly executed.[310] With Scotland largely under English control, Edward installed Englishmen and collaborating Scots to govern the country.[311]

The situation changed again on 10 February 1306, when Robert the Bruce murdered his rival John Comyn,[312] and a few weeks later, on 25 March, was crowned King of Scotland.[313] Bruce now embarked on a campaign to restore Scottish independence, and this campaign took the English by surprise.[314] Edward was suffering ill health by this time, and instead of leading an expedition himself, he gave different military commands to Aymer de Valence, 2nd Earl of Pembroke, and Henry Percy, 1st Baron Percy, while the main royal army was led by the Prince of Wales.[315] The English initially met with success; on 19 June, Aymer de Valence routed Bruce at the Battle of Methven.[316] Bruce was forced into hiding, and the English forces recaptured their lost territory and castles.[317]

Edward acted with unusual brutality against Bruce's family, allies, and supporters. His sister, Mary, was imprisoned in a cage at Roxburgh Castle for four years. Isabella MacDuff, Countess of Buchan, who had crowned Bruce, was held in a cage at Berwick Castle.[318] His younger brother Neil was executed by being hanged, drawn, and quartered; he had been captured after he and his garrison held off Edward's forces who had been seeking his wife, daughter and sisters.[319] Edward now regarded the struggle not as a war between two nations, but as the suppression of a rebellion of disloyal subjects.[320] This brutality, though, rather than helping to subdue the Scots, had the opposite effect, and rallied growing support for Bruce.[321]

Death and burial

[edit]

В феврале 1307 года Брюс возобновил свои усилия и начал собирать людей, а в мае он победил Валанса в битве при Лаудоун-Хилл . [322] Эдвард, который несколько сплотился, теперь сам двинулся на север. у него развилась дизентерия По дороге , и его состояние ухудшилось. 6 июля он расположился лагерем в Бурге у Сэндса , к югу от шотландской границы. Когда на следующее утро его слуги пришли, чтобы поднять его, чтобы он мог поесть, король умер у них на руках. [323] [324]

Появилось несколько историй о желаниях Эдварда на смертном одре; согласно одной традиции, он попросил, чтобы его сердце перенесли в Святую Землю вместе с армией для борьбы с неверными. [325] Более сомнительная история рассказывает о том, как он хотел, чтобы его кости возили с собой в будущие экспедиции против шотландцев. [324] Другой рассказ о сцене его смерти более правдоподобен; согласно одной из хроник, Эдуард собрал вокруг себя Генри де Лейси, 3-го графа Линкольна ; Ги де Бошан, 10-й граф Уорик ; Эймер де Валенс; и Роберт де Клиффорд, 1-й барон де Клиффорд , и поручил им присматривать за его сыном Эдвардом. В частности, им следует убедиться, что Пирс Гавестон, которого он изгнал ранее в том же году, [326] не разрешили вернуться в страну. [327] Новый король Эдуард II проигнорировал желание своего отца и почти сразу же отозвал своего фаворита из ссылки. [328] Эдуард II оставался на севере до августа, но затем отказался от кампании и направился на юг, частично из-за финансовых ограничений. [329] Он был коронован 25 февраля 1308 года. [330]

Тело Эдуарда I было перевезено на юг, где оно лежало в Уолтемском аббатстве , а затем было похоронено в Вестминстерском аббатстве 27 октября. [331] [332] Есть несколько записей о похоронах, стоимость которых составила 473 фунта стерлингов. [331] Могила Эдварда представляла собой необычно простой саркофаг из мрамора Пурбек без обычного королевского изображения , возможно, из-за нехватки королевских средств. [333] открыло Лондонское общество антикваров гробницу в 1774 году, обнаружив, что тело хорошо сохранилось за предыдущие 467 лет, и воспользовалось возможностью определить первоначальный рост короля. [334] [С] Следы латинской надписи Edwardus Primus Hammer of the Scotts находятся здесь, 1308 год. Pactum Serva («Вот Эдвард I, молот шотландцев, 1308 год. Держите Трот») [335] до сих пор можно увидеть рисунок на стене гробницы, намекающий на его клятву отомстить за восстание Роберта Брюса. [336] В результате историки дали Эдварду прозвище «Молот шотландцев», но оно не современно по происхождению, а было добавлено аббатом Джоном Фекенхэмом в 16 веке. [337]

Наследие

[ редактировать ]

Первые истории Эдуарда в 16 и 17 веках основывались в основном на трудах летописцев и мало использовали официальные записи того периода. [338] Они ограничились общими комментариями о значении Эдуарда как монарха и повторили похвалы летописцев его достижениям. [338] [339] В 17 веке адвокат Эдвард Кок много писал о законодательстве Эдварда, называя короля «английским Юстинианом» в честь известного византийского законодателя Юстиниана I. [340] Позже в том же столетии историки использовали доступные записи в качестве доказательства, чтобы прояснить роль парламента и королевской власти при Эдуарде, проводя сравнения между его правлением и политическими раздорами своего века. [341] Историки восемнадцатого века создали образ Эдварда как способного, хотя и безжалостного монарха, обусловленного обстоятельствами своего времени. [342]

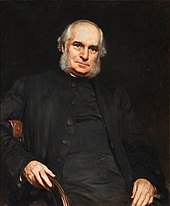

Вместо этого влиятельный викторианский историк Уильям Стаббс предположил, что Эдвард активно формировал национальную историю, формируя английские законы и институты и помогая Англии развивать парламентскую и конституционную монархию . [343] Его сильные и слабые стороны как правителя считались символом английского народа в целом. [344] Ученик Стаббса, Томас Таут , первоначально придерживался той же точки зрения, но после обширного исследования королевского двора Эдварда и при поддержке исследований его современников о первых парламентах того периода он изменил свое мнение. [345] Таут стал рассматривать Эдварда как корыстного, консервативного лидера, использующего парламентскую систему как «хитрый прием автократа, стремящегося использовать массы людей в качестве сдерживания своих потомственных врагов среди высшего баронаства». [346]

Историки 20-го и 21-го веков провели обширные исследования Эдварда и его правления. [347] Большинство пришли к выводу, что это был весьма значительный период в английской средневековой истории, а некоторые пошли еще дальше и описали Эдварда как одного из величайших средневековых королей. [240] хотя большинство также согласны с тем, что его последние годы были менее успешными, чем первые десятилетия его правления. [348] Дж. Темплман в своем историографическом очерке 1950 года утверждал, что «общепризнанно, что Эдуард I заслуживает высокого места в истории средневековой Англии». [349] За этот период были созданы три основных академических повествования об Эдварде. [350] Тома Ф.М. Повике , опубликованные в 1947 и 1953 годах и составившие стандартные труды об Эдварде на несколько десятилетий, в основном позитивно восхваляли достижения его правления и, в частности, его внимание к справедливости и закону. [351] В 1988 году Майкл Прествич подготовил авторитетную биографию короля, сосредоточив внимание на его политической карьере, по-прежнему изображая его сочувственно, но подчеркивая некоторые последствия его неудачной политики. [352] В 2008 году последовала биография Марка Морриса , в которой больше подробностей о личности Эдварда и в целом более резко рассматривается его слабости и менее приятные характеристики, указывая, что современные аналитики правления Эдварда осуждают короля за его политику против евреев. сообщество в Англии. [353] Значительные академические дебаты развернулись вокруг характера королевской власти Эдварда, его политических навыков и, в частности, его управления графами, а также степени, в которой это носило коллаборационистский или репрессивный характер. [354]

Историки спорят о том, как следует оценивать правление Эдуарда I: Майкл Прествич в 1988 году попытался судить о нем по стандартам своего времени. [355] Фред Кэзел согласен с таким подходом, особенно в отношении отсутствия у него политической «чувствительности» и бескомпромиссности, утверждая, что «гнев» был его политическим оружием. [356] Прествич заключает, что «Эдвард был грозным королем; его правление, с его успехами и разочарованиями, было великим», и он был «без сомнения, одним из величайших правителей своего времени». [357] Однако GWS Барроу возражает, что современники Эдварда знали «значение сострадания, великодушия, справедливости и щедрости», что он редко поднимался выше минимальных моральных стандартов своего времени, а скорее демонстрировал крайне мстительную жилку и является одним из «самых смелых оппортунистов эпохи». Английская политическая история». [358] Джон Джиллингем утверждает, что Эдвард был «эффективным хулиганом», но «ни один король Англии не оказал большего влияния на народы Британии, чем Эдуард I» и что «современные историки английского государства… всегда признавали правление Эдуарда I ключевым. " [359] Совсем недавно Эндрю Спенсер и Кэролайн Берт дали новую оценку правлению Эдварда с точки зрения английской конституции, заявив, что он сыграл личную роль в реформах и моральную цель своего руководства. [360] Спенсер заключает, что правление Эдварда «действительно было… великим», а Берт утверждает, что «убеждения и способности Эдварда сделали его одним из самых новаторских, концептуально творческих, целеустремленных и успешных правителей Англии. Он не только играл роль хорошего короля». ну, он сыграл это с апломбом». [361] Колин Вич спрашивает, согласились ли бы «валлийцы, шотландцы, ирландцы и евреи». [362]

Существует большая разница между английской и шотландской историографией короля Эдуарда. [363] GWS Барроу считал, что Эдвард безжалостно эксплуатировал безлидерное государство Шотландия, чтобы получить феодальное превосходство над королевством и превратить его в владение Англии. [364] По его мнению, настойчивость Эдварда в отношении войны и неправильное понимание способности Шотландии к сопротивлению создали «горький антагонизм… который длился веками». Майкл Браун предупреждает, что независимость Шотландии не следует рассматривать как неизбежную; Эдвард мог бы достичь своих целей. [365] Валлийские историки рассматривают правление и завоевания Эдварда как катастрофу для национальной уверенности и культуры Уэльса. Р. Р. Дэвис рассматривает свои методы в Уэльсе как по существу колониальные. [366] создавая глубокое негодование и социальную структуру, подобную апартеиду. [367] Джон Дэвис отметил «антиваллийский фанатизм» английских колонистов, вызванный завоеванием Эдварда. [368] Они признают возможные попытки Эдварда восстановить какое-то сотрудничество с коренным валлийским обществом, но заявляют, что этого было недостаточно, чтобы залечить травму завоевания. [369] Ирландский историк Джеймс Лайдон считал тринадцатый век и правление Эдварда поворотным моментом для Ирландии, поскольку светлость извлекала ирландские ресурсы для своих войн, не смогла сохранить мир и допустила возрождение судьбы гэльской Ирландии, что привело к продолжительному конфликту. [370] Ряд историков, в том числе Саймон Шама , Норман Дэвис , а также историки из Шотландии, Уэльса и Ирландии, пытались оценить правление Эдварда в контексте развития Британии и Ирландии. [371] Они подчеркивают растущую силу закона, централизованного государства и короны по всей Европе и считают, что Эдвард отстаивает свои права в Англии и в отношении других стран Британии и Ирландии. [372] Браун добавляет, что от этого пострадал сам Эдуард, будучи подданным французского короля в Гаскони. [373] Централизация имела тенденцию подразумевать единообразие и усиление дискриминации периферийных идентичностей и враждебность к законам Ирландии и Уэльса. [374] Хотя эта группа историков не считает, что Эдвард проводил спланированную политику экспансионизма, [375] они часто считают, что тактика и результаты его политики часто вызывают ненужные разногласия и конфликты. [376]

Точно так же в исследованиях англо-еврейской истории встречается гораздо более негативная оценка Эдварда. Барри Добсон говорит, что действия Эдварда I по отношению к еврейскому меньшинству часто кажутся современной аудитории наиболее значимой частью его правления. [377] в то время как в 1992 году Колин Ричмонд выразил тревогу по поводу того, что Эдвард не получил более широкой переоценки. [378] Пол Хайамс считает, что его «искренний религиозный фанатизм» играет центральную роль в его действиях против евреев. [379] Ричмонд считает его «новаторским антисемитом», а Роберт Стейси определяет его как первого английского монарха, проводящего государственную политику антисемитизма. [380] [аа] Роберт Мур подчеркивает, что антисемитизм был разработан церковными лидерами и поддержан такими фигурами, как Эдвард, а не был частью народных предрассудков. [382] Исследования средневекового антисемитизма показывают, что правление Генриха III и Эдварда, а также изгнание, как развитие стойкого английского антисемитизма, основанного на идее о вытеснении англичанами евреев как избранного Богом народа, а также на уникальности Англии как страны, свободной от евреев. [383]

Семья

[ редактировать ]Первый брак

[ редактировать ]

От первой жены Элеоноры Кастильской у Эдварда было как минимум четырнадцать детей, а возможно, и шестнадцать. Из них пять дочерей дожили до взрослого возраста, но только один сын пережил отца, став королем Эдуардом II ( годы правления 1307–1327 ). [150] Детьми Эдварда и Элеоноры были: [384]

- Кэтрин (1261 или 1263–1264) [385]

- Жанна (1265–1265) [385]

- Джон (1266–1271) [385]

- Генри (1268–1274) [385]

- Элеонора (1269–1298) [385]

- Безымянная дочь (1271–1271 или 1272) [385]

- Жанна (1272–1307) [385]

- Альфонсо (1273–1284) [385]

- Маргарет (1275–1333) [385]

- Беренгария (1276–1277 или 1278) [385]

- Безымянный ребенок (1278–1278) [385]

- Мария (1278–1332) [385]

- Елизавета (1282–1316) [385]

- Эдуард II (1284–1327) [385]

Второй брак

[ редактировать ]От Маргариты Французской у Эдварда было два сына, оба дожили до совершеннолетия, и дочь, умершая в детстве. Его потомками от Маргарет были: [386]

Генеалогия в хрониках аббатства Хейлс указывает на то, что Джон Ботетур мог быть внебрачным сыном Эдварда, но это утверждение необоснованно. [386] [390]

Генеалогическая таблица

[ редактировать ]| Отношения Эдварда I с современными лидерами Великобритании [391] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

См. также

[ редактировать ]Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ Номера Царствования во времена Эдварда обычно не использовались; его называли просто «королем Эдвардом» или «королем Эдвардом, сыном короля Генриха». [1] Только после преемственности сначала его сына, а затем его внука, оба из которых носили одно и то же имя, «Эдуард I» вошло в обиход. [2]

- ^ Средневековая английская марка была расчетной единицей, эквивалентной двум третям фунта стерлингов . [19]

- ↑ Мать Генриха III Изабелла Ангулемская вышла замуж за Хью X Лузиньяна после смерти короля Англии Иоанна . [30]

- ^ Изречение вернуло землю обездоленным повстанцам в обмен на штраф, зависящий от уровня их участия в войнах. [57]

- ^ Существенной уступкой было то, что обездоленным теперь будет разрешено вступить во владение своими землями до уплаты штрафов. [58]

- ↑ Парламент в мае 1270 года подтвердил постановление, разработанное парламентом Хилари в январе 1269 года, запрещающее еврейским ростовщикам взимать арендную плату за земли должников, что часто приводило к тому, что должники теряли саму землю. [66]

- ^ Заболевание было то ли дизентерией , то ли тифом . [69]

- ↑ Анекдот о том, как королева Элеонора спасла жизнь Эдварду, высасывая яд из его раны, почти наверняка является более поздней выдумкой. [78] уводит плачущую Элеонору В других рассказах об этой сцене Джон де Весси , и предполагают, что это был другой близкий друг Эдварда, Отто де Грансон , который пытался высосать яд из раны. [77]

- ↑ Хотя письменных доказательств не существует, предполагается, что эта договоренность была согласована до отъезда Эдварда. [83]

- ↑ До апреля пост Ланкастера занимал Пейн де Чаворт. [96]

- ↑ В городские уставы также были включены положения, гласящие, что «евреи не должны проживать в этом месте в любое время», как до, так и после изгнания евреев в 1290 году. [113]

- ↑ Дэвид Пауэл , священнослужитель 16-го века, предположил, что ребенок был предложен валлийцам как принц, «который родился в Уэльсе и никогда не говорил ни слова по-английски», но нет никаких доказательств, подтверждающих эту широко распространенную версию. [128]

- ↑ Этот титул стал традиционным титулом наследника английского престола. Принц Эдвард не родился наследником, но стал таковым, когда в 1284 году умер его старший брат Альфонсо, граф Честер . [130]

- ↑ Обычно предполагалось, что изгнание было попыткой собрать капитал для обеспечения освобождения Чарльза. Однако Эдвард пожертвовал доходы, полученные от конфискации имущества, на нужды нищенствующих орденов. [144]

- ↑ Прествич оценивает общую стоимость примерно в 400 000 фунтов стерлингов. [157]

- ^ Этот термин является изобретением 18 века. [168]

- ↑ Несмотря на то, что принцип первородства не обязательно распространялся на происхождение от наследников женского пола, нет никаких сомнений в том, что утверждение Баллиола было самым сильным. [174]

- ↑ Среди тех, кого особенно выделили королевские судьи, был Жильбер де Клэр, 6-й граф Хартфорд , который, как было замечено, безжалостно посягал на королевские права в предыдущие годы. [210]

- ↑ Цифры Рокеа ясно показывают, что подавляющее большинство этой неожиданной прибыли поступило от евреев, но быть точными невозможно. Христиан также арестовывали и штрафовали, особенно в течение длительного периода, но казнили гораздо меньше. [253]

- ^ Jump up to: а б Датой Указа об изгнании, 18 июля 1290 года, был пост девятого Аба , посвященный падению Храма в Иерусалиме и другим бедствиям, пережитым еврейским народом; вряд ли это совпадение. Датой, к которой евреи должны были покинуть страну, было назначено 1 ноября, День всех святых . [257]

- ↑ Например, Элеонора Кастильская отдала Кентерберийскую синагогу своему портному. [260]

- ↑ Например, Филипп II Французский , Иоанн I, герцог Бретани и Людовик IX Французский временно изгнали евреев.

- ^ На гробнице был изображен Королевский герб. Ассоциация с крестами Элеоноры, вероятно, была попыткой Эдварда связать ее память с противодействием предполагаемой преступности евреев, учитывая ее непопулярные сделки с недвижимостью, которые включали приобретение земель путем покупки еврейских облигаций. [266]