Замок

Замок военными - это тип укрепленной структуры, построенной в средневековье , преимущественно из -за дворянства или королевской семьи и приказами . Ученые обычно считают, что замок является частной укрепленной резиденцией Господа или благородного. Это отличается от особняка , дворца и виллы , главная цель которого была исключительно для удовольствия и не является в основном крепостями, но может быть укреплена. [ А ] Использование этого термина варьировалось со временем, а иногда также применяется к таким структурам, как Хилл-Форты и дома 19-го и 20-го века, созданные для напоминания замков. В течение средневековья, когда были построены подлинные замки, они приняли очень много форм с множеством различных особенностей, хотя некоторые, такие как шрифтные стены , стрелковые и портколизы , были обычным явлением.

Замки в европейском стиле возникли в 9-м и 10-м веках, после того, как падение Каролинговой империи привело к тому, что ее территория была разделена между отдельными лордами и князьями. Эти дворяне построили замки, чтобы контролировать область, непосредственно окружающую их, и замки были как оскорбительными, так и защитными сооружениями: они предоставили базу, с которой могут быть запущены рейды, а также предлагают защиту от врагов. Хотя их военное происхождение часто подчеркивается в исследованиях замков, структуры также служили центрами администрирования и символов власти. Городские замки использовались для контроля местного населения и важных маршрутов путешествий, и сельские замки часто находились вблизи функций, которые были неотъемлемой частью жизни в обществе, таких как мельницы, плодородные земли или источник воды.

Many northern European castles were originally built from earth and timber but had their defences replaced later by stone. Early castles often exploited natural defences, lacking features such as towers and arrowslits and relying on a central keep. In the late 12th and early 13th centuries, a scientific approach to castle defence emerged. This led to the proliferation of towers, with an emphasis on flanking fire. Many new castles were polygonal or relied on concentric defence – several stages of defence within each other that could all function at the same time to maximise the castle's firepower. These changes in defence have been attributed to a mixture of castle technology from the Crusades, such as concentric fortification, and inspiration from earlier defences, such as Roman forts. Not all the elements of castle architecture were military in nature, so that devices such as moats evolved from their original purpose of defence into symbols of power. Some grand castles had long winding approaches intended to impress and dominate their landscape.

Although gunpowder was introduced to Europe in the 14th century, it did not significantly affect castle building until the 15th century, when artillery became powerful enough to break through stone walls. While castles continued to be built well into the 16th century, new techniques to deal with improved cannon fire made them uncomfortable and undesirable places to live. As a result, true castles went into decline and were replaced by artillery star forts with no role in civil administration, and château or country houses that were indefensible. From the 18th century onwards, there was a renewed interest in castles with the construction of mock castles, part of a Romantic revival of Gothic architecture, but they had no military purpose.

Definition

[edit]Etymology

[edit]

The word castle is derived from the Latin word castellum, which is a diminutive of the word castrum, meaning "fortified place". The Old English castel, Occitan castel or chastel, French château, Spanish castillo, Portuguese castelo, Italian castello, and a number of words in other languages also derive from castellum.[2] The word castle was introduced into English shortly before the Norman Conquest to denote this type of building, which was then new to England.[3]

Defining characteristics

[edit]In its simplest terms, the definition of a castle accepted amongst academics is "a private fortified residence".[4] This contrasts with earlier fortifications, such as Anglo-Saxon burhs and walled cities such as Constantinople and Antioch in the Middle East; castles were not communal defences but were built and owned by the local feudal lords, either for themselves or for their monarch.[5] Feudalism was the link between a lord and his vassal where, in return for military service and the expectation of loyalty, the lord would grant the vassal land.[6] In the late 20th century, there was a trend to refine the definition of a castle by including the criterion of feudal ownership, thus tying castles to the medieval period; however, this does not necessarily reflect the terminology used in the medieval period. During the First Crusade (1096–1099), the Frankish armies encountered walled settlements and forts that they indiscriminately referred to as castles, but which would not be considered as such under the modern definition.[4]

Castles served a range of purposes, the most important of which were military, administrative, and domestic. As well as defensive structures, castles were also offensive tools which could be used as a base of operations in enemy territory. Castles were established by Norman invaders of England for both defensive purposes and to pacify the country's inhabitants.[7] As William the Conqueror advanced through England, he fortified key positions to secure the land he had taken. Between 1066 and 1087, he established 36 castles such as Warwick Castle, which he used to guard against rebellion in the English Midlands.[8][9]

Towards the end of the Middle Ages, castles tended to lose their military significance due to the advent of powerful cannons and permanent artillery fortifications;[10] as a result, castles became more important as residences and statements of power.[11] A castle could act as a stronghold and prison but was also a place where a knight or lord could entertain his peers.[12] Over time the aesthetics of the design became more important, as the castle's appearance and size began to reflect the prestige and power of its occupant. Comfortable homes were often fashioned within their fortified walls. Although castles still provided protection from low levels of violence in later periods, eventually they were succeeded by country houses as high-status residences.[13]

Terminology

[edit]Castle is sometimes used as a catch-all term for all kinds of fortifications, and as a result has been misapplied in the technical sense. An example of this is Maiden Castle which, despite the name, is an Iron Age hill fort which had a very different origin and purpose.[14]

Although castle has not become a generic term for a manor house (like château in French and Schloss in German), many manor houses contain castle in their name while having few if any of the architectural characteristics, usually as their owners liked to maintain a link to the past and felt the term castle was a masculine expression of their power.[15] In scholarship the castle, as defined above, is generally accepted as a coherent concept, originating in Europe and later spreading to parts of the Middle East, where they were introduced by European Crusaders. This coherent group shared a common origin, dealt with a particular mode of warfare, and exchanged influences.[16]

In different areas of the world, analogous structures shared features of fortification and other defining characteristics associated with the concept of a castle, though they originated in different periods and circumstances and experienced differing evolutions and influences. For example, shiro in Japan, described as castles by historian Stephen Turnbull, underwent "a completely different developmental history, were built in a completely different way and were designed to withstand attacks of a completely different nature".[17] While European castles built from the late 12th and early 13th century onwards were generally stone, shiro were predominantly timber buildings into the 16th century.[18]

By the 16th century, when Japanese and European cultures met, fortification in Europe had moved beyond castles and relied on innovations such as the Italian trace italienne and star forts.[17]

Common features

[edit]Motte

[edit]

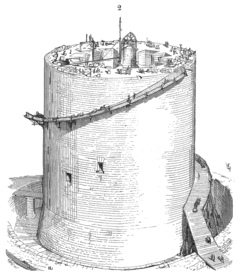

A motte was an earthen mound with a flat top. It was often artificial, although sometimes it incorporated a pre-existing feature of the landscape. The excavation of earth to make the mound left a ditch around the motte, called a moat (which could be either wet or dry). Although the motte is commonly associated with the bailey to form a motte-and-bailey castle, this was not always the case and there are instances where a motte existed on its own.[19]

"Motte" refers to the mound alone, but it was often surmounted by a fortified structure, such as a keep, and the flat top would be surrounded by a palisade.[19] It was common for the motte to be reached over a flying bridge (a bridge over the ditch from the counterscarp of the ditch to the edge of the top of the mound), as shown in the Bayeux Tapestry's depiction of Château de Dinan.[20] Sometimes a motte covered an older castle or hall, whose rooms became underground storage areas and prisons beneath a new keep.[21]

Bailey and enceinte

[edit]

A bailey, also called a ward, was a fortified enclosure. It was a common feature of castles, and most had at least one.[22] The keep on top of the motte was the domicile of the lord in charge of the castle and a bastion of last defence, while the bailey was the home of the rest of the lord's household and gave them protection. The barracks for the garrison, stables, workshops, and storage facilities were often found in the bailey. Water was supplied by a well or cistern. Over time the focus of high status accommodation shifted from the keep to the bailey; this resulted in the creation of another bailey that separated the high status buildings – such as the lord's chambers and the chapel – from the everyday structures such as the workshops and barracks.[22]

From the late 12th century there was a trend for knights to move out of the small houses they had previously occupied within the bailey to live in fortified houses in the countryside.[23] Although often associated with the motte-and-bailey type of castle, baileys could also be found as independent defensive structures. These simple fortifications were called ringworks.[24] The enceinte was the castle's main defensive enclosure, and the terms "bailey" and "enceinte" are linked. A castle could have several baileys but only one enceinte. Castles with no keep, which relied on their outer defences for protection, are sometimes called enceinte castles;[25] these were the earliest form of castles, before the keep was introduced in the 10th century.[26]

Keep

[edit]

A keep was a great tower or other building that served as the main living quarters of the castle and usually the most strongly defended point of a castle before the introduction of concentric defence. "Keep" was not a term used in the medieval period – the term was applied from the 16th century onwards – instead "donjon" was used to refer to great towers,[27] or turris in Latin. In motte-and-bailey castles, the keep was on top of the motte.[19] "Dungeon" is a corrupted form of "donjon" and means a dark, unwelcoming prison.[28] Although often the strongest part of a castle and a last place of refuge if the outer defences fell, the keep was not left empty in case of attack but was used as a residence by the lord who owned the castle, or his guests or representatives.[29]

At first, this was usual only in England, when after the Norman Conquest of 1066 the "conquerors lived for a long time in a constant state of alert";[30] elsewhere the lord's wife presided over a separate residence (domus, aula or mansio in Latin) close to the keep, and the donjon was a barracks and headquarters. Gradually, the two functions merged into the same building, and the highest residential storeys had large windows; as a result for many structures, it is difficult to find an appropriate term.[31] The massive internal spaces seen in many surviving donjons can be misleading; they would have been divided into several rooms by light partitions, as in a modern office building. Even in some large castles the great hall was separated only by a partition from the lord's chamber, his bedroom and to some extent his office.[32]

Curtain wall

[edit]

Curtain walls were defensive walls enclosing a bailey. They had to be high enough to make scaling the walls with ladders difficult and thick enough to withstand bombardment from siege engines which, from the 15th century onwards, included gunpowder artillery. A typical wall could be 3 m (10 ft) thick and 12 m (39 ft) tall, although sizes varied greatly between castles. To protect them from undermining, curtain walls were sometimes given a stone skirt around their bases. Walkways along the tops of the curtain walls allowed defenders to rain missiles on enemies below, and battlements gave them further protection. Curtain walls were studded with towers to allow enfilading fire along the wall.[33] Arrowslits in the walls did not become common in Europe until the 13th century, for fear that they might compromise the wall's strength.[34]

Gatehouse

[edit]

The entrance was often the weakest part in a circuit of defences. To overcome this, the gatehouse was developed, allowing those inside the castle to control the flow of traffic. In earth and timber castles, the gateway was usually the first feature to be rebuilt in stone. The front of the gateway was a blind spot and to overcome this, projecting towers were added on each side of the gate in a style similar to that developed by the Romans.[35] The gatehouse contained a series of defences to make a direct assault more difficult than battering down a simple gate. Typically, there were one or more portcullises – a wooden grille reinforced with metal to block a passage – and arrowslits to allow defenders to harry the enemy. The passage through the gatehouse was lengthened to increase the amount of time an assailant had to spend under fire in a confined space and unable to retaliate.[36]

It is a popular myth that murder holes – openings in the ceiling of the gateway passage – were used to pour boiling oil or molten lead on attackers; the price of oil and lead and the distance of the gatehouse from fires meant that this was impractical.[37] This method was, however, a common practice in Middle Eastern and Mediterranean castles and fortifications, where such resources were abundant.[38][39] They were most likely used to drop objects on attackers, or to allow water to be poured on fires to extinguish them.[37] Provision was made in the upper storey of the gatehouse for accommodation so the gate was never left undefended, although this arrangement later evolved to become more comfortable at the expense of defence.[40]

During the 13th and 14th centuries the barbican was developed.[41] This consisted of a rampart, ditch, and possibly a tower, in front of the gatehouse[42] which could be used to further protect the entrance. The purpose of a barbican was not just to provide another line of defence but also to dictate the only approach to the gate.[43]

Moat

[edit]

A moat was a ditch surrounding a castle – or dividing one part of a castle from another – and could be either dry or filled with water. Its purpose often had a defensive purpose, preventing siege towers from reaching walls making mining harder, but could also be ornamental.[44][45][46] Water moats were found in low-lying areas and were usually crossed by a drawbridge, although these were often replaced by stone bridges.[44] The site of the 13th-century Caerphilly Castle in Wales covers over 30 acres (12 ha) and the water defences, created by flooding the valley to the south of the castle, are some of the largest in Western Europe.[47]

Battlements

[edit]Battlements were most often found surmounting curtain walls and the tops of gatehouses, and comprised several elements: crenellations, hoardings, machicolations, and loopholes. Crenellation is the collective name for alternating crenels and merlons: gaps and solid blocks on top of a wall. Hoardings were wooden constructs that projected beyond the wall, allowing defenders to shoot at, or drop objects on, attackers at the base of the wall without having to lean perilously over the crenellations, thereby exposing themselves to retaliatory fire. Machicolations were stone projections on top of a wall with openings that allowed objects to be dropped on an enemy at the base of the wall in a similar fashion to hoardings.[48]

Arrowslits

[edit]Arrowslits, also commonly called loopholes, were narrow vertical openings in defensive walls which allowed arrows or crossbow bolts to be fired on attackers. The narrow slits were intended to protect the defender by providing a very small target, but the size of the opening could also impede the defender if it was too small. A smaller horizontal opening could be added to give an archer a better view for aiming.[49] Sometimes a sally port was included; this could allow the garrison to leave the castle and engage besieging forces.[50] It was usual for the latrines to empty down the external walls of a castle and into the surrounding ditch.[51]

Postern

[edit]A postern is a secondary door or gate in a concealed location, usually in a fortification such as a city wall.[52]

Great hall

[edit]The great hall was a large, decorated room where a lord received his guests. The hall represented the prestige, authority, and richness of the lord. Events such as feasts, banquets, social or ceremonial gatherings, meetings of the military council, and judicial trials were held in the great hall. Sometimes the great hall existed as a separate building, in that case, it was called a hall-house.[53]

History

[edit]

Antecedents

[edit]

Historian Charles Coulson states that the accumulation of wealth and resources, such as food, led to the need for defensive structures. The earliest fortifications originated in the Fertile Crescent, the Indus Valley, Europe, Egypt, and China where settlements were protected by large walls. In Northern Europe, hill forts were first developed in the Bronze Age, which then proliferated across Europe in the Iron Age. Hillforts in Britain typically used earthworks rather than stone as a building material.[57]

Many earthworks survive today, along with evidence of palisades to accompany the ditches. In central and western Europe, oppida emerged in the 2nd century BC; these were densely inhabited fortified settlements, such as the oppidum of Manching.[58] Some oppida walls were built on a massive scale, utilising stone, wood, iron and earth in their construction.[59][60] The Romans encountered fortified settlements such as hill forts and oppida when expanding their territory into northern Europe.[58] Their defences were often effective, and were only overcome by the extensive use of siege engines and other siege warfare techniques, such as at the Battle of Alesia. The Romans' own fortifications (castra) varied from simple temporary earthworks thrown up by armies on the move, to elaborate permanent stone constructions, notably the milecastles of Hadrian's Wall. Roman forts were generally rectangular with rounded corners – a "playing-card shape".[61]

In the medieval period, castles were influenced by earlier forms of elite architecture, contributing to regional variations. Importantly, while castles had military aspects, they contained a recognisable household structure within their walls, reflecting the multi-functional use of these buildings.[62]

Origins (9th and 10th centuries)

[edit]The subject of the emergence of castles in Europe is a complex matter which has led to considerable debate. Discussions have typically attributed the rise of the castle to a reaction to attacks by Magyars, Muslims, and Vikings and a need for private defence.[63] The breakdown of the Carolingian Empire led to the privatisation of government, and local lords assumed responsibility for the economy and justice.[64] However, while castles proliferated in the 9th and 10th centuries the link between periods of insecurity and building fortifications is not always straightforward. Some high concentrations of castles occur in secure places, while some border regions had relatively few castles.[65]

It is likely that the castle evolved from the practice of fortifying a lordly home. The greatest threat to a lord's home or hall was fire as it was usually a wooden structure. To protect against this, and keep other threats at bay, there were several courses of action available: create encircling earthworks to keep an enemy at a distance; build the hall in stone; or raise it up on an artificial mound, known as a motte, to present an obstacle to attackers.[66] While the concept of ditches, ramparts, and stone walls as defensive measures is ancient, raising a motte is a medieval innovation.[67]

A bank and ditch enclosure was a simple form of defence, and when found without an associated motte is called a ringwork; when the site was in use for a prolonged period, it was sometimes replaced by a more complex structure or enhanced by the addition of a stone curtain wall.[68] Building the hall in stone did not necessarily make it immune to fire as it still had windows and a wooden door. This led to the elevation of windows to the second storey – to make it harder to throw objects in – and to move the entrance from ground level to the second storey. These features are seen in many surviving castle keeps, which were the more sophisticated version of halls.[69] Castles were not just defensive sites but also enhanced a lord's control over his lands. They allowed the garrison to control the surrounding area,[70] and formed a centre of administration, providing the lord with a place to hold court.[71]

Building a castle sometimes required the permission of the king or other high authority. In 864 the King of West Francia, Charles the Bald, prohibited the construction of castella without his permission and ordered them all to be destroyed. This is perhaps the earliest reference to castles, though military historian R. Allen Brown points out that the word castella may have applied to any fortification at the time.[72]

In some countries the monarch had little control over lords, or required the construction of new castles to aid in securing the land so was unconcerned about granting permission – as was the case in England in the aftermath of the Norman Conquest and the Holy Land during the Crusades. Switzerland is an extreme case of there being no state control over who built castles, and as a result there were 4,000 in the country.[73] There are very few castles dated with certainty from the mid-9th century. Converted into a donjon around 950, Château de Doué-la-Fontaine in France is the oldest standing castle in Europe.[74]

11th century

[edit]From 1000 onwards, references to castles in texts such as charters increased greatly. Historians have interpreted this as evidence of a sudden increase in the number of castles in Europe around this time; this has been supported by archaeological investigation which has dated the construction of castle sites through the examination of ceramics.[75] The increase in Italy began in the 950s, with numbers of castles increasing by a factor of three to five every 50 years, whereas in other parts of Europe such as France and Spain the growth was slower. In 950, Provence was home to 12 castles; by 1000, this figure had risen to 30, and by 1030 it was over 100.[76] Although the increase was slower in Spain, the 1020s saw a particular growth in the number of castles in the region, particularly in contested border areas between Christian and Muslim lands.[77]

Despite the common period in which castles rose to prominence in Europe, their form and design varied from region to region. In the early 11th century, the motte and keep – an artificial mound with a palisade and tower on top – was the most common form of castle in Europe, everywhere except Scandinavia.[76] While Britain, France, and Italy shared a tradition of timber construction that was continued in castle architecture, Spain more commonly used stone or mud-brick as the main building material.[78]

The Muslim invasion of the Iberian Peninsula in the 8th century introduced a style of building developed in North Africa reliant on tapial, pebbles in cement, where timber was in short supply.[79] Although stone construction would later become common elsewhere, from the 11th century onwards it was the primary building material for Christian castles in Spain,[80] while at the same time timber was still the dominant building material in north-west Europe.[77]

Historians have interpreted the widespread presence of castles across Europe in the 11th and 12th centuries as evidence that warfare was common, and usually between local lords.[82] Castles were introduced into England shortly before the Norman Conquest in 1066.[83] Before the 12th century castles were as uncommon in Denmark as they had been in England before the Norman Conquest. The introduction of castles to Denmark was a reaction to attacks from Wendish pirates, and they were usually intended as coastal defences.[73] The motte and bailey remained the dominant form of castle in England, Wales, and Ireland well into the 12th century.[84] At the same time, castle architecture in mainland Europe became more sophisticated.[85]

The donjon[86] was at the centre of this change in castle architecture in the 12th century. Central towers proliferated, and typically had a square plan, with walls 3 to 4 m (9.8 to 13.1 ft) thick. Their decoration emulated Romanesque architecture, and sometimes incorporated double windows similar to those found in church bell towers. Donjons, which were the residence of the lord of the castle, evolved to become more spacious. The design emphasis of donjons changed to reflect a shift from functional to decorative requirements, imposing a symbol of lordly power upon the landscape. This sometimes led to compromising defence for the sake of display.[85]

Innovation and scientific design (12th century)

[edit]- See also maison forte, French article here

Until the 12th century, stone-built and earth and timber castles were contemporary,[87] but by the late 12th century the number of castles being built went into decline. This has been partly attributed to the higher cost of stone-built fortifications, and the obsolescence of timber and earthwork sites, which meant it was preferable to build in more durable stone.[88] Although superseded by their stone successors, timber and earthwork castles were by no means useless.[89] This is evidenced by the continual maintenance of timber castles over long periods, sometimes several centuries; Owain Glyndŵr's 11th-century timber castle at Sycharth was still in use by the start of the 15th century, its structure having been maintained for four centuries.[90][91]

At the same time there was a change in castle architecture. Until the late 12th century castles generally had few towers; a gateway with few defensive features such as arrowslits or a portcullis; a great keep or donjon, usually square and without arrowslits; and the shape would have been dictated by the lay of the land (the result was often irregular or curvilinear structures). The design of castles was not uniform, but these were features that could be found in a typical castle in the mid-12th century.[92] By the end of the 12th century or the early 13th century, a newly constructed castle could be expected to be polygonal in shape, with towers at the corners to provide enfilading fire for the walls. The towers would have protruded from the walls and featured arrowslits on each level to allow archers to target anyone nearing or at the curtain wall.[93]

These later castles did not always have a keep, but this may have been because the more complex design of the castle as a whole drove up costs and the keep was sacrificed to save money. The larger towers provided space for habitation to make up for the loss of the donjon. Where keeps did exist, they were no longer square but polygonal or cylindrical. Gateways were more strongly defended, with the entrance to the castle usually between two half-round towers which were connected by a passage above the gateway – although there was great variety in the styles of gateway and entrances – and one or more portcullis.[93]

A peculiar feature of Muslim castles in the Iberian Peninsula was the use of detached towers, called Albarrana towers, around the perimeter as can be seen at the Alcazaba of Badajoz. Probably developed in the 12th century, the towers provided flanking fire. They were connected to the castle by removable wooden bridges, so if the towers were captured the rest of the castle was not accessible.[94]

When seeking to explain this change in the complexity and style of castles, antiquarians found their answer in the Crusades. It seemed that the Crusaders had learned much about fortification from their conflicts with the Saracens and exposure to Byzantine architecture. There were legends such as that of Lalys – an architect from Palestine who reputedly went to Wales after the Crusades and greatly enhanced the castles in the south of the country – and it was assumed that great architects such as James of Saint George originated in the East. In the mid-20th century this view was cast into doubt. Legends were discredited, and in the case of James of Saint George it was proven that he came from Saint-Georges-d'Espéranche, in France. If the innovations in fortification had derived from the East, it would have been expected for their influence to be seen from 1100 onwards, immediately after the Christians were victorious in the First Crusade (1096–1099), rather than nearly 100 years later.[96] Remains of Roman structures in Western Europe were still standing in many places, some of which had flanking round-towers and entrances between two flanking towers.

The castle builders of Western Europe were aware of and influenced by Roman design; late Roman coastal forts on the English "Saxon Shore" were reused and in Spain the wall around the city of Ávila imitated Roman architecture when it was built in 1091.[96] Historian Smail in Crusading warfare argued that the case for the influence of Eastern fortification on the West has been overstated, and that Crusaders of the 12th century in fact learned very little about scientific design from Byzantine and Saracen defences.[97] A well-sited castle that made use of natural defences and had strong ditches and walls had no need for a scientific design. An example of this approach is Kerak. Although there were no scientific elements to its design, it was almost impregnable, and in 1187 Saladin chose to lay siege to the castle and starve out its garrison rather than risk an assault.[97]

During the late 11th and 12th centuries in what is now south-central Turkey the Hospitallers, Teutonic Knights and Templars established themselves in the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, where they discovered an extensive network of sophisticated fortifications which had a profound impact on the architecture of Crusader castles. Most of the Armenian military sites in Cilicia are characterized by: multiple bailey walls laid with irregular plans to follow the sinuosities of the outcrops; rounded and especially horseshoe-shaped towers; finely-cut often rusticated ashlar facing stones with intricate poured cores; concealed postern gates and complex bent entrances with slot machicolations; embrasured loopholes for archers; barrel, pointed or groined vaults over undercrofts, gates and chapels; and cisterns with elaborate scarped drains.[98] Civilian settlement are often found in the immediate proximity of these fortifications.[99] After the First Crusade, Crusaders who did not return to their homes in Europe helped found the Crusader states of the Principality of Antioch, the County of Edessa, the Kingdom of Jerusalem, and the County of Tripoli. The castles they founded to secure their acquisitions were designed mostly by Syrian master-masons. Their design was very similar to that of a Roman fort or Byzantine tetrapyrgia which were square in plan and had square towers at each corner that did not project much beyond the curtain wall. The keep of these Crusader castles would have had a square plan and generally be undecorated.[100]

While castles were used to hold a site and control movement of armies, in the Holy Land some key strategic positions were left unfortified.[101] Castle architecture in the East became more complex around the late 12th and early 13th centuries after the stalemate of the Third Crusade (1189–1192). Both Christians and Muslims created fortifications, and the character of each was different. Saphadin, the 13th-century ruler of the Saracens, created structures with large rectangular towers that influenced Muslim architecture and were copied again and again, however they had little influence on Crusader castles.[102]

13th to 15th centuries

[edit]

In the early 13th century, Crusader castles were mostly built by Military Orders including the Knights Hospitaller, Knights Templar, and Teutonic Knights. The orders were responsible for the foundation of sites such as Krak des Chevaliers, Margat, and Belvoir. Design varied not just between orders, but between individual castles, though it was common for those founded in this period to have concentric defences.[104]

The concept, which originated in castles such as Krak des Chevaliers, was to remove the reliance on a central strongpoint and to emphasise the defence of the curtain walls. There would be multiple rings of defensive walls, one inside the other, with the inner ring rising above the outer so that its field of fire was not completely obscured. If assailants made it past the first line of defence they would be caught in the killing ground between the inner and outer walls and have to assault the second wall.[105]

Concentric castles were widely copied across Europe, for instance when Edward I of England – who had himself been on Crusade – built castles in Wales in the late 13th century, four of the eight he founded had a concentric design.[104][105] Not all the features of the Crusader castles from the 13th century were emulated in Europe. For instance, it was common in Crusader castles to have the main gate in the side of a tower and for there to be two turns in the passageway, lengthening the time it took for someone to reach the outer enclosure. It is rare for this bent entrance to be found in Europe.[104]

One of the effects of the Livonian Crusade in the Baltic was the introduction of stone and brick fortifications. Although there were hundreds of wooden castles in Prussia and Livonia, the use of bricks and mortar was unknown in the region before the Crusaders. Until the 13th century and start of the 14th centuries, their design was heterogeneous, however this period saw the emergence of a standard plan in the region: a square plan, with four wings around a central courtyard.[106] It was common for castles in the East to have arrowslits in the curtain wall at multiple levels; contemporary builders in Europe were wary of this as they believed it weakened the wall. Arrowslits did not compromise the wall's strength, but it was not until Edward I's programme of castle building that they were widely adopted in Europe.[34]

The Crusades also led to the introduction of machicolations into Western architecture. Until the 13th century, the tops of towers had been surrounded by wooden galleries, allowing defenders to drop objects on assailants below. Although machicolations performed the same purpose as the wooden galleries, they were probably an Eastern invention rather than an evolution of the wooden form. Machicolations were used in the East long before the arrival of the Crusaders, and perhaps as early as the first half of the 8th century in Syria.[107]

The greatest period of castle building in Spain was in the 11th to 13th centuries, and they were most commonly found in the disputed borders between Christian and Muslim lands. Conflict and interaction between the two groups led to an exchange of architectural ideas, and Spanish Christians adopted the use of detached towers. The Spanish Reconquista, driving the Muslims out of the Iberian Peninsula, was complete in 1492.[94]

Although France has been described as "the heartland of medieval architecture", the English were at the forefront of castle architecture in the 12th century. French historian François Gebelin wrote: "The great revival in military architecture was led, as one would naturally expect, by the powerful kings and princes of the time; by the sons of William the Conqueror and their descendants, the Plantagenets, when they became dukes of Normandy. These were the men who built all the most typical twelfth-century fortified castles remaining today".[109] Despite this, by the beginning of the 15th century, the rate of castle construction in England and Wales went into decline. The new castles were generally of a lighter build than earlier structures and presented few innovations, although strong sites were still created such as that of Raglan in Wales. At the same time, French castle architecture came to the fore and led the way in the field of medieval fortifications. Across Europe – particularly the Baltic, Germany, and Scotland – castles were built well into the 16th century.[110]

Advent of gunpowder

[edit]

Artillery powered by gunpowder was introduced to Europe in the 1320s and spread quickly. Handguns, which were initially unpredictable and inaccurate weapons, were not recorded until the 1380s.[111] Castles were adapted to allow small artillery pieces – averaging between 19.6 and 22 kg (43 and 49 lb) – to fire from towers. These guns were too heavy for a man to carry and fire, but if he supported the butt end and rested the muzzle on the edge of the gun port he could fire the weapon. The gun ports developed in this period show a unique feature, that of a horizontal timber across the opening. A hook on the end of the gun could be latched over the timber so the gunner did not have to take the full recoil of the weapon. This adaptation is found across Europe, and although the timber rarely survives, there is an intact example at Castle Doornenburg in the Netherlands. Gunports were keyhole shaped, with a circular hole at the bottom for the weapon and a narrow slit on top to allow the gunner to aim.[112]

This form is very common in castles adapted for guns, found in Egypt, Italy, Scotland, and Spain, and elsewhere in between. Other types of port, though less common, were horizontal slits – allowing only lateral movement – and large square openings, which allowed greater movement.[112] The use of guns for defence gave rise to artillery castles, such as that of Château de Ham in France. Defences against guns were not developed until a later stage.[113] Ham is an example of the trend for new castles to dispense with earlier features such as machicolations, tall towers, and crenellations.[114]

Bigger guns were developed, and in the 15th century became an alternative to siege engines such as the trebuchet. The benefits of large guns over trebuchets – the most effective siege engine of the Middle Ages before the advent of gunpowder – were those of a greater range and power. In an effort to make them more effective, guns were made ever bigger, although this hampered their ability to reach remote castles. By the 1450s guns were the preferred siege weapon, and their effectiveness was demonstrated by Mehmed II at the Fall of Constantinople.[115]

The response towards more effective cannons was to build thicker walls and to prefer round towers, as the curving sides were more likely to deflect a shot than a flat surface. While this sufficed for new castles, pre-existing structures had to find a way to cope with being battered by cannon. An earthen bank could be piled behind a castle's curtain wall to absorb some of the shock of impact.[116]

Часто замки, построенные до эпохи пороха, были неспособны использовать оружие, поскольку их стены были слишком узкими. Решением этого было потянуть верхнюю часть башни и заполнить нижнюю часть обломками, чтобы обеспечить поверхность для стрельбы из оружия. Снижение защиты таким образом привело к тому, что они облегчали их масштабировать с лестницами. Более популярной альтернативной защитой, которая избегала повреждения замка, состояла в том, чтобы установить булочки за пределами защиты замка. Они могут быть построены с земли или камня и использовались для укрепления оружия. [ 117 ]

Бастионы и звездные форты (16 век)

[ редактировать ]

инновация углового бастиона . Около 1500 года в Италии было разработано [ 118 ] С такими событиями, как эти, Италия впервые стала постоянными артиллерийскими укреплениями, которые захватили оборонительную роль замков. Из этих развитых звездных фортов , также известных как Trace Italienne . [ 10 ] Элита, ответственная за строительство замка, должна была выбирать между новым типом, который мог выдерживать Cannon Fire и более ранний, более сложный стиль. Первый был уродливым и неудобным, а последний был менее безопасным, хотя он предлагал большую эстетическую привлекательность и ценность в качестве символа статуса. Второй выбор оказался более популярным, так как стало очевидно, что было мало смысла в попытке сделать сайт по -настоящему защищенным перед лицом Кэннона. [ 119 ] По разным причинам, не в последнюю очередь из -за того, что во многих замках нет зарегистрированной истории, в средневековом периоде нет твердого количества замков. Тем не менее, было подсчитано, что в Западной Европе были построены от 75 000 до 100 000; [ 120 ] из них около 1700 были в Англии и Уэльсе [ 121 ] и около 14 000 в немецкоязычных районах. [ 122 ]

настоящие замки были построены в Америке испанскими Некоторые и французскими колониями . Первый этап испанского строительства форта был назван «Период замка», который длился с 1492 года до конца 16 -го века. [ 123 ] Начиная с Форталезы Озамы , «эти замки были по сути европейские средневековые замки, перенесенные в Америку». [ 124 ] Среди других оборонительных сооружений (включая форты и цитадели), замки также были построены в Новой Франции к концу 17 -го века. [ 125 ] В Монреале артиллерия была не такой развитой, как на боевых полях Европы, некоторые отдаленные форты региона были построены как укрепленные усадьбы Франции. Форт Лонгюил , построенный с 1695 по 1698 год барониальной семьей , был описан как «самый средневековый форт, построенный в Канаде». [ 126 ] Усадьба и конюшни находились в пределах укрепленного Бейли с высокой круглой башней в каждом углу. «Самый существенный форт, похожий на замок» возле Монреала, был Форт Сенневилл , построенный в 1692 году с квадратными башнями, соединенными толстыми каменными стенами, а также укрепленной ветряной мельницы. [ 127 ] Каменные форты, подобные этим, служили оборонительными резиденциями, а также навязывая структуры для предотвращения вторжений в ирокезов . [ 128 ]

Хотя строительство замка исчезла к концу 16 -го века, замки не обязательно выпали из использования. Некоторые сохранили роль в местной администрации и стали судебными судами, в то время как другие все еще передаются в аристократических семьях в качестве наследственных мест. Особенно известным примером этого является Виндзорский замок в Англии, который был основан в 11 веке и является домом для монарха Соединенного Королевства. [ 129 ] В других случаях они все еще играли роль в защите. Башенные дома , которые тесно связаны с замками и включают башни Пеле , были защищенными башнями, которые были постоянными резиденциями, построенными в 14 -м по 17 веках. Особенно распространено в Ирландии и Шотландии, они могут быть до пяти этажей высотой и сменили общие замки в корпусе и были построены большим социальным диапазоном людей. Несмотря на то, что они вряд ли обеспечат такую же защиту, как более сложный замок, они предложили безопасность от рейдеров и других небольших угроз. [ 130 ] [ 131 ]

Позднее использовать и возродить замки

[ редактировать ]

По словам археологов Оливера Крейтона и Роберта Хайэма, «великие загородные дома семнадцатого -двадцатого веков были в социальном смысле, замки их дня». [ 132 ] Несмотря на то, что элита была тенденция переехать из замков в загородные дома в 17 веке, замки не были полностью бесполезными. В более поздних конфликтах, таких как Английская гражданская война (1641–1651), многие замки были восстановлены, хотя впоследствии обозначали, чтобы предотвратить их использование. [ 133 ] Некоторые загородные резиденции, которые не должны были быть укреплены, получили внешний вид замка, чтобы отпугнуть потенциальных захватчиков, таких как добавление турелей и использование небольших окон. Примером этого является замок Бубакры 16 -го века в Бубакре , Мальта, который был изменен в 18 -м веке. [ 134 ]

Возрождение или фиктивные замки стали популярными как проявление романтического интереса к средневековье и рыцарству , и как часть более широкого готического возрождения в архитектуре. Примеры этих замков включают Chapultepec в Мексике, [ 135 ] Neuschwanstein в Германии, [ 136 ] и Edwin Lutyens ( Castle Drogo 1911–1930) - последний мерцание этого движения на Британских островах. [ 137 ] В то время как церкви и соборы в готическом стиле могли верно подражать средневековым примерам, новые загородные дома, построенные в «стиле замка», отличались внутренне от их средневековых предшественников. Это было потому, что быть верным средневековому дизайну, оставило бы дома холодными и темными по современным стандартам. [ 138 ]

Искусственные руины , построенные для напоминания остатков исторических зданий, также были отличительной чертой периода. Они обычно строились в качестве центральных кусочков в аристократических запланированных пейзажах. Фолли были похожи, хотя они отличались от искусственных руин тем, что они не были частью запланированного ландшафта, а скорее, казалось, не имели причин для построения. Оба опирались на элементы архитектуры замка, такие как замка и башни, но не служили военной цели и были исключительно для демонстрации. [ 139 ] Игрушечный замок используется в качестве общей привлекательности детей в игровых площадках и забавных парках, таких как замок Flaymobil Funpark в «ħal Far , Malta». [ 140 ] [ 141 ]

Строительство

[ редактировать ]

После того, как место замка было выбрано - будь то стратегическая позиция или предназначенная для доминирования ландшафта как знак власти - необходимо выбрать строительный материал. Земля и деревянный замок был дешевле и легче установить, чем из камня. Затраты, связанные с строительством, не записаны, и большинство сохранившихся записей связаны с королевскими замками. [ 142 ] Замок с глиняными валами, мотт, древесная защита и здания могли быть построены неквалифицированной рабочей силой. Источник человеческой силы, вероятно, был из местного светлости, и арендаторы уже имели бы необходимые навыки вырубки деревьев, копания и работы древесины, необходимой для замок Земли и Трумбер. Возможно, принуждая работать на своего лорда, строительство замок Земли и Тумбер не было бы истощением средств клиента. С точки зрения времени, было подсчитано, что средний размер Motte - 5 м (16 футов) высотой и шириной 15 м (49 футов) на саммите - 50 человек занял бы 50 человек около 40 рабочих дней. Исключительно дорогим Motte и Bailey были клоны в Ирландии, построенные в 1211 году за 20 фунтов стерлингов. Высокая стоимость по сравнению с другими замками его типа была связана с тем, что работники должны были быть импортированы. [ 142 ]

Стоимость строительства замка варьировалась в зависимости от таких факторов, как их сложность и транспортные затраты на материал. Несомненно, что каменные замки стоят намного больше, чем те, которые построены из земли и древесины. Даже очень маленькая башня, такая как замок Певерил , стоила бы около 200 фунтов стерлингов . В середине были такие замки, как Орфорд , который был построен в конце 12 -го века для Великобритании 1400 фунтов стерлингов, а в верхнем конце были такие, как Дувр , который стоит около 7000 фунтов стерлингов в период с 1181 и 1191. [ 143 ] Расходы на масштаб обширных замков, таких как Château Gaillard (по оценкам, Великобритании в размере 15 000 фунтов стерлингов в 20 000 фунтов стерлингов по 1198 г. в период с 1196 в Полем Каменному замку было обычно, чтобы занять лучшую часть десятилетия, чтобы закончить. Стоимость крупного замка, построенного за это время (где -то от 1000 фунтов стерлингов до 10 000 фунтов стерлингов ) получит доход от нескольких поместье , что сильно повлияет на финансы лорда. [ 144 ] Затраты в конце 13 -го века были аналогичным образом, причем такие замки, как Боумарис и Рудлан, стоили британские £ 14 500 и Великобританию в 9 000 фунтов стерлингов соответственно. 80 Кампания по строительству замков в Уэльсе в Уэльсе стоила 000 фунтов стерлингов в период с 1277 по 1304, а Великобритания- 95 000 фунтов стерлингов в период с 1277 и 1329. [ 145 ] Известный дизайнер Мастер Джеймс Сент -Джордж , ответственный за строительство Боумариса, объяснил стоимость:

Если вы должны задаться вопросом, куда может пойти так много денег через неделю, мы бы знали, что нам нужно-и по-прежнему понадобится 400 масонов, оба кареты и слои, а также 2000 менее квалифицированных рабочих, 100 тележек, 60 вагоны и 30 лодок, которые приносят каменный и морской уголь; 200 карьеры; 30 Смитов; и плотники за внедрение балок и досок для пола и другие необходимые работы. Все это не учитывает гарнизон ... ни о покупке материала. Из которых должно быть огромное количество ... мужская зарплата была и до сих пор находится в задолженности, и мы испытываем наибольшую трудность в сохранении их, потому что им просто нечего жить.

— [ 146 ]

Мало того, что каменные замки были дороги в первую очередь, но их обслуживание было постоянным канализацией. Они содержали много древесины, которая часто была не приглашена, и в результате необходимо было осторожно осторожно. Например, задокументировано, что в конце 12 -го века ремонт в замках, таких как Эксетер и Глостер, стоимость между британскими £ 20 и Великобританией в 50 фунтов стерлингов в год. [ 147 ]

Средневековые машины и изобретения, такие как трюк -кран , стали незаменимыми во время строительства, а методы строительства деревянных каркасов были улучшены с древности . [ 148 ] Когда строительство в камне была заметной озабоченности средневековых строителей, было закрыто карьеры. Есть примеры некоторых замков, где на месте был добыт Стоун, такие как Chinon , Château de Coucy и Château Gaillard. [ 149 ] Когда он был построен в 992 году во Франции, каменная башня в Шато -де -Лангеи составляла 16 метров (52 фута) высотой, 17,5 метра (57 футов) шириной и 10 метров (33 фута), с стенами в среднем 1,5 метра (4 фута 11 дюймов. ) Стены содержат 1200 кубических метров (42 000 куб. Футов) камня и имеют общую поверхность (как внутри, так и снаружи) 1600 квадратных метров (17 000 кв. Футов). По оценкам, башня потребовалась 83 000 средних рабочих дней, большая часть которых была неквалифицированной рабочей силой. [ 150 ]

Во многих странах были деревянные и каменные замки, [ 151 ] Однако в Дании было мало карьеров, и в результате большинство его замков - это земля и лесоматериалы, или позже, построенные из кирпича. [ 152 ] Кирпичные сооружения не обязательно были слабее, чем их каменные аналоги. Кирпичные замки встречаются реже в Англии, чем конструкции из камня или земля и древесины, и часто они были выбраны за его эстетическую привлекательность или потому, что они были модными, поощряются кирпичной архитектурой низких стран . Например, когда замок Таттершалл поблизости было построено в Англии, поблизости было много камня, но владелец, лорд Кромвель, решил использовать кирпич. Около 700 000 кирпичей были использованы для построения замка, который был описан как «лучший кусок средневековой кирпичной работы в Англии». [ 153 ] Большинство испанских замков были построены из камня, тогда как замки в Восточной Европе обычно были из деревянной строительства. [ 154 ]

На строительстве замка , написанного в начале 1260 -х годов, описывает строительство нового замка в Safed . Это «один из самых полных» средневековых сообщений о строительстве замка. [ 155 ]

Социальный центр

[ редактировать ]

Из -за присутствия Господа в замке это был центр администрации, откуда он контролировал свои земли. Он полагался на поддержку тех, кто находится под ним, так как без поддержки своих более могущественных арендаторов, Господь мог ожидать, что его сила будет подорвана. Успешные лорды регулярно держали суд с теми, кто непосредственно под ними в социальном масштабе, но заочные могли ожидать, что их влияние ослаблена. Большие светлости могут быть обширными, и для Господа было бы нецелесообразно посещать все свои свойства регулярно, поэтому депутаты были назначены. Это особенно применимо к королевской семье, которая иногда владела землей в разных странах. [ 158 ]

Чтобы позволить Господу сконцентрироваться на своих обязанностях в отношении администрации, у него было домашнее хозяйство слуг, чтобы позаботиться о таких обязанностях, как обеспечение пищи. Домохозяйством управляли камерсен , а казначей позаботился о письменных записях поместья. Королевские домохозяйства принимали по сути ту же форму, что и барониальные домохозяйства, хотя в гораздо большем масштабе, и позиции были более престижными. [ 159 ] Важной ролью домашних слуг была приготовление пищи ; Кухни замков были бы занятым местом, когда был занят замок, призванные обеспечить большие блюда. [ 160 ] Без присутствия семьи Господа, как правило, потому, что он остался в другом месте, замок был бы тихим местом с несколькими жителями, сосредоточенным на поддержании замка. [ 161 ]

Как социальные центры были важными местами для демонстрации. Строители воспользовались возможностью, чтобы опираться на символику, используя мотивы, чтобы вызвать чувство рыцарства, к которому стремились в средние века среди элиты. Более поздние структуры романтического возрождения будут опираться на элементы архитектуры замка, такие как битвы для той же цели. Замки сравнивались с соборами как объекты архитектурной гордости, а некоторые замки включали в себя сады в качестве декоративных черт. [ 162 ] Право на Crenellate, когда монарх предоставляется - хотя это не всегда было необходимым - было важно не только так, как это позволило лорду защищать его имущество, но и потому, что Crenellations и другие сопровождения, связанные с замками, были престижными благодаря их использованию элитой. [ 163 ] Лицензии на Crenellate также были доказательством отношений с монархом или предпочтительнее, которое отвечало за разрешение. [ 164 ]

«Замок, как большая и внушительная архитектурная структура в ландшафте, вызывает эмоции и привязанности и создал бы наследие для тех, кто его построил, работал в нем и жил в нем и вокруг него, а также для тех, кто просто прошел его ежедневно ".

Торстад 2019 , с

Судебная любовь была эротизацией любви между дворянством. Акцент был сделан на сдержанность между любовниками. Несмотря на то, что иногда выражаются через рыцарские мероприятия, такие как турниры , где рыцари сражались в знаком от своей леди, это также может быть частным и провести в тайне. Легенда о Тристане и Иселту является одним из примеров историй о придворной любви, рассказанных в средневековье. [ 165 ] Это был идеал любви между двумя людьми, не женатыми друг с другом, хотя мужчина может быть женат на кого -то другого. Для лорда было нередко или невнимательно быть прелюбодеяющим - у Генриха I из Англии было более 20 ублюдков - но для того, чтобы быть беспорядочной, была рассматривалась как бесчестная. например, [ 166 ]

Цель брака между средневековыми элитами состояла в том, чтобы обеспечить землю. Девочки были женаты в подростковом возрасте, но мальчики не женились, пока они не достигли совершеннолетия. [ 167 ] Существует популярная концепция, что женщины сыграли периферическую роль в домашнем хозяйстве средневекового замка, и что в ней доминировал сам Господь. Это происходит от изображения замка как боевого учреждения, но большинство замков в Англии, Франции, Ирландии и Шотландии никогда не участвовали в конфликтах или осадках, поэтому внутренняя жизнь является заброшенным аспектом. [ 168 ] Леди дала усадьбу поместья ее мужа - обычно около трети - которая была ее на всю жизнь, и ее муж унаследовал ее смерть. Это была ее обязанность управлять им напрямую, так как Господь управлял своей собственной землей. [ 169 ] Несмотря на то, что в целом исключается из военной службы, женщина может отвечать за замок, либо от имени своего мужа, либо, если она овдовела. Из -за их влияния в средневековом домохозяйстве женщины повлияли на строительство и дизайн, иногда посредством прямого покровительства; Историк Чарльз Коулсон подчеркивает роль женщин в применении «утонченного аристократического вкуса» к замкам из -за их долгосрочного проживания. [ 170 ]

Места и ландшафты

[ редактировать ]

На расположение замков повлияла доступная местность. Принимая во внимание, что в Германии были распространены холмские замки, такие как Марксбург , где 66 процентов всех известных средневековых были на высоком уровне, в то время как 34 процента находились на низменных землях , [ 172 ] Они сформировали меньшинство мест в Англии. [ 171 ] Из -за диапазона функций, которые они должны были выполнять, замки были построены в различных местах. При выборе сайта было рассмотрено многочисленные факторы, уравновешивая потребность в защитной позиции с другими соображениями, такими как близость к ресурсам. Например, многие замки расположены рядом с римскими дорогами, которые оставались важными транспортными маршрутами в средние века или могут привести к изменению или созданию новых дорожных систем в этом районе. Там, где было доступно, было обычным целым, чтобы использовать ранее существовавшую защиту, такую как строительство с римским фортом или валы железного века Hillfort. Выдающийся сайт, на котором выходили из виду окружающую область и предложили некоторые естественные защиты, также может быть выбрана, потому что его видимость сделала его символом власти. [ 173 ] Городские замки были особенно важны в контрольных центрах населения и производства, особенно с силой вторжения, например, после нормандского завоевания Англии в 11 -м веке большинство королевских замков были построены в городах или рядом с ним. [ 174 ]

Поскольку замки были не просто военными зданиями, а центры администрации и символов власти, они оказали значительное влияние на окружающий ландшафт. Расположенный по часто используемой дороге или реке, замок Toll гарантировал, что лорд получит свои платные деньги от торговцев. Сельские замки часто ассоциировались с мельницами и полевыми системами из -за их роли в управлении имуществом Господа, [ 175 ] что дало им большее влияние на ресурсы. [ 176 ] Другие были рядом с королевскими лесами или в парках или оленях и были важны в их содержании. Рыбные пруды были роскошью бордотной элиты, и многие были найдены рядом с замками. Мало того, что они были практичными в том смысле, что они обеспечивали водоснабжение и свежую рыбу, но и были символом статуса, поскольку они были дорогими для строительства и обслуживания. [ 177 ]

Хотя иногда строительство замка приводило к разрушению деревни, например, в Итоне Соконе в Англии, поблизости было более распространено, что поблизости выросли в результате присутствия замка. Иногда запланированные города или деревни были созданы вокруг замка. [ 175 ] Преимущества строительства замков на поселениях не ограничивались Европой. 13-го века замок Сафад в Галилейке был основан Когда в Галилее , 260 деревень получили выгоду от обретенной способности жителей свободно двигаться. [ 178 ] При построении замок может привести к реструктуризации местного ландшафта, а дороги двинулись для удобства Господа. [ 179 ] Поселения могут также расти естественным путем вокруг замка, а не планировать, из -за преимуществ близости к экономическому центру в сельском ландшафте и безопасности, предоставленной защитой. Не все такие поселения выжили, так как когда -то замок потерял свое значение - возможно, сменил усадьбу в качестве центра администрации - преимущества жизни рядом с замком исчезли, и поселение обнаружено. [ 180 ]

Во время и вскоре после нормандского завоевания Англии замки были вставлены в важные ранее существовавшие города, чтобы контролировать и подчинить население. Они обычно располагались рядом с любой существующей городской защитой, такие как римские стены, хотя это иногда приводило к сносу сооружений, занимающих желаемый участок. В Линкольне 166 домов были разрушены, чтобы очистить пространство для замка, а в сельскохозяйственных землях Йорка было затоплено, чтобы создать ров для замка. Поскольку военная важность городских замков исчезла от их раннего происхождения, они стали более важными в качестве центров администрации, а также их финансовые и судебные роли. [ 181 ] Когда норманны вторглись в Ирландию, Шотландию и Уэльс в 11-м и 12-м веках, поселение в этих странах было преимущественно нерадосленным, а основание городов часто связана с созданием замка. [ 182 ]

Расположение замков по отношению к высокому статусу, таким как рыбные пруды, было утверждением власти и контроля ресурсов. Также часто встречались при приходской церкви . [ 185 ] Это означало тесную связь между феодальными лордами и церковью, одним из самых важных институтов средневекового общества. [ 186 ] Даже элементы архитектуры замка, которые обычно интерпретируются как военные, могут быть использованы для демонстрации. Водные особенности замка Кенилворта в Англии, включающие рва и несколько спутниковых прудов, - заставили кого -то приблизиться к входу на водный замок , чтобы пойти по очень косвенному маршруту, ходя по обороне перед окончательным подходом к воротам. [ 187 ] Другим примером является пример 14-го века замка Бодиам , также в Англии; Хотя это, по -видимому, это состояние искусства, Advanced Castle, он находится в месте, имеющем мало стратегического значения, а ров был мелким и, скорее всего, намеревался сделать сайт впечатляющим, чем защита от добычи. Подход был длинным и взял зрителя вокруг замка, гарантируя, что они хорошо смотрели, прежде чем войти. Более того, Gunports были непрактичными и вряд ли были эффективными. [ 188 ]

Война

[ редактировать ]

Как статическая структура, часто можно избежать замков. Их непосредственная область влияния составляла около 400 метров (1300 футов), и их оружие имело на короткие сроки даже в начале артиллерии. Тем не менее, оставление врага позади позволило бы им вмешиваться в связь и совершать рейды. Гарризоны были дорогими, и в результате часто маленькие, если замок не был важен. [ 190 ] Стоимость также означала, что в геррисонах мирного времени были меньше, а небольшие замки были укомплектованы, возможно, пара сторожевых и ворот. Даже на войне гарнизоны не обязательно были большими, так как слишком много людей в защитной силе напрягают поставки и ухудшают способность замка выдерживать долгую осаду. В 1403 году сила из 37 лучников успешно защитила замок Кернарфон от двух нападений союзников Оуина Глиндра во время длинной осады, демонстрируя, что небольшая сила может быть эффективной. [ 191 ]

В начале, укомплектование замка было феодальной обязанностью вассалов перед их магнатами и магнатами их царей, однако впоследствии это было заменено платными силами. [ 191 ] [ 192 ] Гарнизон обычно командовал констеблем, чья роль в мирном времени была бы заботой о замке в отсутствие владельца. Под ним были бы рыцари, которые благодаря своей военной подготовке действовали как тип офицерского класса. Под ними были лучники и боумены, роль которого заключалась в том, чтобы не допустить, чтобы враг достиг стен, как видно из позиционирования Arrowlits. [ 193 ]

Если бы необходимо было захватить контроль над замком, армия может либо запустить нападение, либо осаду. Было более эффективно пропустить гарнизон, чем напасть на его, особенно на наиболее сильно защищенные сайты. Без облегчения от внешнего источника защитники в конечном итоге подадут. Осады могли длиться недели, месяцы и в редких случаях годы, если бы поставки пищи и воды были в изобилии. Длинная осада может замедлить армию, позволяя прийти помощи или для врага подготовить большую силу на потом. [ 194 ] Такой подход не был ограничен замками, но также был применен в укрепленных городах дня. [ 195 ] В некоторых случаях осадные замки будут построены, чтобы защитить осаждающих от внезапного Салли и были бы заброшены после того, как осада закончилась так или иначе. [ 196 ]

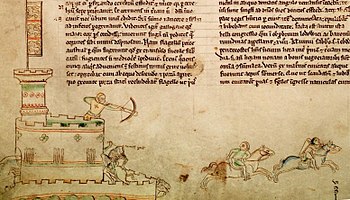

Если вынуждены напасть на замок, для злоумышленников было много вариантов. Для деревянных сооружений, таких как ранние мотте и заглушки, пожар был реальной угрозой, и были бы предприняты попытки поджечь их, как это видно в гобелене Bayeux. [ 197 ] Оружие снаряда использовалось с тех пор, как древность и мангонель и Петрария - от восточного и римского происхождения соответственно - были основными двумя, которые использовались в средние века. Требуше , который , вероятно, развивался из Петрарии в 13 -м веке, был самым эффективным осадным оружием перед развитием пушек. Это оружие было уязвимы для стрельбы из замка, так как у них был короткий диапазон и были большими машинами. И наоборот, оружие, такое как Trebuchets, может быть выпущено из замка из -за высокой траектории его снаряда, и будет защищено от прямых огней от занавесных стен. [ 198 ]

Ballistas или Springalds были осадными двигателями, которые работали над теми же принципами, что и в арбалетах. С их происхождением в древней Греции напряжение использовалось для проецирования болта или копья. Ракеты, выпущенные из этих двигателей, имели более низкую траекторию, чем трюхеты или мангонели, и были более точными. Они чаще использовались против гарнизона, а не зданий замка. [ 199 ] В конечном итоге пушки развивались до такой степени, что они были более мощными и имели больший диапазон, чем Требуше, и стали главным оружием в осадной войне. [ 115 ]

Стены могут быть подорваны соком . Шахта, ведущая к стене, будет вырыт, и как только цель была достигнута, деревянные опоры, предотвращая сгорание туннеля, будет сожжена. Это будет сбросить и снизить структуру выше. [ 200 ] Строительство замка на обнажении камня или окружение его широким, глубоким рвом помогло предотвратить это. Контрактная рука может быть выкопана в направлении туннеля осаждающих; Предполагая, что два сходились, это приведет к подземному бою с рукой. Добыча была настолько эффективна, что во время осады Маргата в 1285 году, когда гарнизон был проинформирован о том, что сок вырыл, сдавшись. [ 201 ] Также использовались избиение баранов , обычно в виде ствола дерева, полученного железной крышкой. Они использовались, чтобы заставить открыть замки, хотя они иногда использовались против стен с меньшим эффектом. [ 202 ]

В качестве альтернативы трудоемкой задаче-создать нарушение, можно попытаться захватить стены сражаться вдоль дорожек за битвами. [ 203 ] В этом случае злоумышленники были бы уязвимы для огня стрелы. [ 204 ] Более безопасным вариантом для тех, кто напал на замок, было использовать осаду , иногда называемую колокольней. После того, как катан вокруг замка были частично заполнены, эти деревянные, подвижные башни можно было толкнуть к шторной стене. Помимо предложения некоторой защиты для тех, кто внутри, осадная башня могла пропустить внутреннюю часть замка, давая Боумена выгодную позицию, из которой можно было развязать ракеты. [ 203 ]

Смотрите также

[ редактировать ]- Альказар

- Бургсталл

- Пещерный замок

- Концентрический замок

- Укрепленный дом

- Хилл замок

- Замок склона холма

- Островный замок

- Низменная замок

- Орденсбург

- Ридж замок

- Споховая замок

- ТОЛЬКО

- Водный замок

Особенности замка:

- Эрроуслит

- Битва

- Drawbar (защита)

- Подтяжка моста

- Подземелье

- Накопление

- Держать

- Средневековое укрепление

- Дыра убийства

Подобные структуры:

Сноски

[ редактировать ]- ^ «Плезас»-это стиль королевской или благородной резиденции, используемой каким-то благородством в конце средневековья . В частности, у «приятного» обязательно было обширные, сложные сады; Иногда их называют современной описательной фразой «величественные сады удовольствия». Они были построены в Северной Европе после того, как порох и пушка установила ранние средневековые военные замки. В общем, «удовольствие» было преднамеренно создано для того, чтобы напоминать по военную деятельность, так что он мог служить тем, что можно назвать « ландшафтной пропагандой »-напоминание о тех, кто рассматривает его из-за пределов превосходной силы и статуса жительница дворянства, которая была отправлена из замок за замками в предыдущем поколении. И «удовольствие» было построено, чтобы напоминать эти запоминающиеся замки, хотя для сокращения расходов стены не были адекватны, как укрепления, как построенные; [ 1 ] За возможным исключением из тех (если таковые имеются), сделанные путем реконструкции устаревшей, ранее функциональные замки.

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Tregruk (записанная телевизионная программа). Время команда. Поселение Трегрук, деревня Ллангиби, город Понтипул, Монмут Шир, Великобритания: 4 -й канал . 2013-03-11 [2010-10-10]. Сезон 17, Эпизод 8. Архивировано с оригинала 2021-10-30 . Получено 2021-08-14 -через YouTube.

- ^ Creighton & Higham 2003 , p. 6, ХПП 1

- ^ Cathcart King 1988 , p. 32

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Coulson 2003 , p. 16

- ^ Лиддиард 2005 , с. 15–17

- ^ Herish 1970 , p. xvii - xvii

- ^ Friar 2003 , p. 47

- ^ Лиддиард 2005 , с. 18

- ^ Стивенс, 1969 , с. 452–475

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Даффи, 1979 , с. 23–25

- ^ Лиддиард 2005 , с. 2, 6–7

- ^ Cathcart King 1983 , с. XVI - XVII

- ^ Лиддиард 2005 , с. 2

- ^ Creighton & Higham 2003 , с. 6–7

- ^ Томпсон, 1987 , с. 1–2, 158–159

- ^ Аллен Браун, 1976 , с. 2–6

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Turnbull 2003 , p. 5

- ^ Turnbull 2003 , p. 4

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Friar 2003 , p. 214

- ^ Cathcart King 1988 , с. 55–56

- ^ Barthélemy 1988 , p. 397

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Friar 2003 , p. 22

- ^ Barthélemy 1988 , стр. 408–410, 412–4

- ^ Friar 2003 , с. 214, 216

- ^ Friar 2003 , p. 105

- ^ Barthélemy 1988 , p. 399

- ^ Friar 2003 , p. 163

- ^ Cathcart King 1988 , p. 188

- ^ Cathcart King 1988 , p. 190

- ^ Barthélemy 1988 , p. 402

- ^ Barthélemy 1988 , стр. 402–406

- ^ Barthélemy 1988 , стр. 416–422

- ^ Friar 2003 , p. 86

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Cathcart King 1988 , p. 84

- ^ Friar 2003 , с. 124–125

- ^ Friar 2003 , с. 126, 232

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный McNeill 1992 , с. 98–99

- ^ Jaccarini, CJ (2002). «Притяжение, наследие ислама на мальтийских островах» (PDF) . Мнара (на мальтийских). 7 (1). Журнал Ассоциации фольклора Мальты: 19. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 18 апреля 2016 года.

- ^ Azzopardi, Joe (апрель 2012 г.). «Обзор мальтийских мадев» (PDF) . Вигило (41). Валлетта: Эта сладкая земля : 26–33. ISSN 1026-132X . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 15 ноября 2015 года.

- ^ Аллен Браун 1976 , с. 64

- ^ Friar 2003 , p. 25

- ^ McNeill 1992 , p. 101

- ^ Аллен Браун 1976 , с. 68

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Friar 2003 , p. 208

- ^ Лиддиард 2005 , с. 10

- ^ Тейлор 2000 , с. 40–41.

- ^ Friar 2003 , с. 210–211

- ^ Friar 2003 , p. 32

- ^ Friar 2003 , с. 180–182

- ^ Friar 2003 , p. 254

- ^ Джонсон 2002 , с. 20

- ^ Средневековый замок . St. Cloud, Minn: North Star Press of St. Cloud. 1991. с. 17. ISBN 9780816620036 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 25 ноября 2021 года . Получено 9 февраля 2021 года .

- ^ Lepage 2002 , p. 123.

- ^ Brkljača, Seka (1996). Урбан-Босния и Герцеговина (на сербо-хорватском). Сараево: Международный центр мира, Институт истории. п. 27. Архивировано из оригинала 25 ноября 2021 года . Получено 28 октября 2021 года .

- ^ «Естественный и архитектурный ансамбль столака» . Центр Всемирного наследия ЮНЕСКО . Архивировано с оригинала 15 ноября 2017 года . Получено 28 октября 2021 года .

- ^ Zammit, Винсент (1984). «Мальтийские укрепления». Цивилизация . 1 Ħamrun : Peg Ltd: 22–25. См. Также укрепления Мальты#Древние и средневековые укрепления (до 1530 года)

- ^ Coulson 2003 , p. 15

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Cunliffe 1998 , p. 420.

- ^ Fernánndz G Ore, Мануэль (декабрь 2019 г.). «Мир или 200 OPDA: до-римский Urbanm в умеренной Европе Opda». В низком, Люк; Бинтлифф, Джон (ред.). Региональные городские системы в римском мире, 150 г. до н.э. - 250 г. н.э. Брилль стр. 35–66. ISBN 978-90-04-41436-5 .

- ^ Ралстон, Ян (1995). «Укрепления и защита». В зеленом, Миранда (ред.). Кельтский мир . Routledge. п. 75. ISBN 9781135632434 .

- ^ Ward 2009 , p. 7

- ^ Creighton 2012 , с. 27–29, 45–48

- ^ Аллен Браун, 1976 , с. 6–8

- ^ Coulson 2003 , с. 18, 24

- ^ Creighton 2012 , с. 44–45

- ^ Cathcart King 1988 , p. 35

- ^ Аллен Браун 1976 , с. 12

- ^ Friar 2003 , p. 246

- ^ Cathcart King 1988 , с. 35–36

- ^ Аллен Браун 1976 , с. 9

- ^ Cathcart King 1983 , с. XVI - XX

- ^ Аллен Браун 1984 , с. 13

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Cathcart King 1988 , с. 24–25

- ^ Аллен Браун, 1976 , с. 8–9

- ^ Aurell 2006 , стр. 32-33

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Нефть 2006 , с. 33

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Higham & Barker 1992 , p. 79

- ^ Higham & Barker 1992 , с. 78–79

- ^ Burton 2007–2008 , с. 229–230

- ^ Вода 2006 , с

- ^ Friar 2003 , p. 95

- ^ Ear 2006 , p. 34

- ^ Cathcart King 1988 , с. 32–34

- ^ Cathcart King 1988 , p. 26

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Aurelnx 2006 , стр. 33-34.

- ^ Friar 2003 , с. 95–96

- ^ Аллен Браун 1976 , с. 13

- ^ Аллен Браун, 1976 , с. 108–109

- ^ Cathcart King 1988 , с. 29–30

- ^ Friar 2003 , p. 215

- ^ Norris 2004 , с. 122–123

- ^ Cathcart King 1988 , p. 77

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Cathcart King 1988 , с. 77–78

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Бертон 2007–2008 , с. 241–243

- ^ Аллен Браун, 1976 , с. 64, 67

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Cathcart King 1988 , с. 78–79

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Cathcart King 1988 , p. 29

- ^ Эдвардс, Роберт В. (1987). Укрепления армянской Киликии: Дамбартон Оукс Исследования XXIII . Вашингтон, округ Колумбия: Дамбартон Оукс, попечители Гарвардского университета. С. 3–282. ISBN 0-88402-163-7 .

- ^ Эдвардс, Роберт В., «Поселения и топонимия в армянской цилисии», Revue des études Armeniennes 24, 1993, с.181-204.

- ^ Cathcart King 1988 , p. 80

- ^ Cathcart King 1983 , с. XX - XXII

- ^ Cathcart King 1988 , с. 81–82

- ^ Crac des Chevaliers и Qal'at Salah El-Din , ЮНЕСКО , архивированы из оригинала 2019-12-02 , извлечены 2009-10-20

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Cathcart King 1988 , p. 83

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Friar 2003 , p. 77

- ^ Ekdahl 2006 , p

- ^ Cathcart King 1988 , с. 84–87

- ^ Кассар, Джордж (2014). «Защита средиземноморского острова наставления испанской империи - случай Мальты» . Сакра милиция (13): 59–68. Архивировано из оригинала 2021-08-31 . Получено 2019-06-30 .

- ^ Gebelin 1964 , с. 43, 47, цитируется в Cathcart King 1988 , p. 91

- ^ Cathcart King 1988 , с. 159–160

- ^ Cathcart King 1988 , с. 164–165

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Cathcart King 1988 , с. 165–167

- ^ Cathcart King 1988 , p. 168

- ^ Томпсон, 1987 , с. 40–41

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Cathcart King 1988 , p. 169

- ^ Томпсон 1987 , с. 38

- ^ Томпсон, 1987 , с. 38–39

- ^ Томпсон, 1987 , с. 41–42

- ^ Томпсон 1987 , с. 42

- ^ Томпсон 1987 , с. 4

- ^ Cathcart King 1983

- ^ Тиллман 1958 , с. VIII, цитируется в Thompson 1987 , с. 4

- ^ Chartrand & Spedaliere 2006 , с. 4–5

- ^ Chartrand & Spedaliere 2006 , p. 4

- ^ Chartrand 2005

- ^ Chartrand 2005 , p. 39

- ^ Chartrand 2005 , p. 38

- ^ Chartrand 2005 , p. 37

- ^ Creighton & Higham 2003 , p. 64

- ^ Томпсон 1987 , с. 22

- ^ Friar 2003 , с. 286–287

- ^ Creighton & Higham 2003 , p. 63

- ^ Friar 2003 , p. 59

- ^ Guillaumier, Alfie (2005). Мальтийские города и деревни . Тол. 2. Мальтийский клуб книг. п. 1028. ISBN 99932-39-40-2 .

- ^ Исторический опыт (на испанском языке), Национальный исторический музей, архивированный из оригинала на 2009-11-14 , извлечен 2009-11-24

- ^ Buse 2005 , p. 32

- ^ Томпсон 1987 , с. 166

- ^ Томпсон 1987 , с. 164

- ^ Friar 2003 , p. 17

- ^ Коллеве, Джулия (30 мая 2011 г.). «Тематический парк Playmobil на Мальте запечатлел детское воображение» . Хранитель . Архивировано с оригинала 24 октября 2016 года.

- ^ Галере, Мэри-Ан (1 марта 2007 г.). Топ 10 Мальта и Гозо . ООО п. 53. ISBN 978-1-4053-1784-9 Полем Архивировано с оригинала 22 декабря 2016 года . Получено 3 июля 2017 года - через Google Books.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный McNeill 1992 , с. 39–40

- ^ McNeill 1992 , с. 41–42

- ^ McNeill 1992 , p. 42

- ^ McNeill 1992 , с. 42–43

- ^ McNeill 1992 , p. 43

- ^ McNeill 1992 , с. 40–41

- ^ Рейбл-Бранденбург 1995 , стр

- ^ Арлинг-Бранденбург 1995 , с

- ^ Bachrach 1991 , с. 47–52

- ^ Higham & Barker 1992 , p. 78

- ^ Cathcart King 1988 , p. 25

- ^ Friar 2003 , с. 38–40

- ^ Higham & Barker 1992 , с. 79, 84–88

- ^ Кеннеди 1994 , с. 190.

- ^ «Замок тевтонского ордена в Мальборе» . ЮНЕСКО . Архивировано из оригинала 2020-11-01 . Получено 2009-10-16 .

- ^ Эмери 2007 , с. 139

- ^ McNeill 1992 , с. 16–18

- ^ McNeill 1992 , с. 22–24

- ^ Friar 2003 , p. 172

- ^ McNeill 1992 , с. 28–29

- ^ Coulson 1979 , с. 74–76

- ^ Coulson 1979 , с. 84–85

- ^ Лиддиард 2005 , с. 9

- ^ Schultz 2006 , стр. XV-XXI

- ^ Gies & Gies 1974 , с. 87–90

- ^ McNeill 1992 , с. 19–21

- ^ Coulson 2003 , p. 382

- ^ McNeill 1992 , p. 19

- ^ Coulson 2003 , с. 297–299, 382

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Creighton 2002 , p. 64

- ^ Krahe 2002 , стр. 21–23

- ^ Creighton 2002 , с. 35–41

- ^ Creighton 2002 , p. 36

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Creighton & Higham 2003 , с. 55–56

- ^ Creighton 2002 , с. 181–182

- ^ Creighton 2002 , с. 184–185

- ^ Смаил 1973 , с. 90

- ^ Creighton 2002 , p. 198

- ^ Creighton 2002 , с. 180–181, 217

- ^ Creighton & Higham 2003 , с. 58–59

- ^ Creighton & Higham 2003 , с. 59–63