Мария Терезия

Мария Терезия (Мария Терезия Вальбурга Амалия Кристина; 13 мая 1717 - 29 ноября 1780) была правительницей владений Габсбургов с 1740 года до своей смерти в 1780 году и единственной женщиной, занимавшей эту должность suo jure (самостоятельно). Она была правительницей Австрии , Венгрии , Хорватии , Богемии , Трансильвании , Мантуи , Милана , Галиции и Лодомерии , Австрийских Нидерландов и Пармы . По браку она была герцогиней Лотарингской , великой герцогиней Тосканской и императрицей Священной Римской империи .

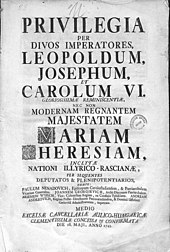

Maria Theresa started her 40-year reign when her father, Emperor Charles VI, died on 20 October 1740. Charles VI paved the way for her accession with the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713 and spent his entire reign securing it. He neglected the advice of Prince Eugene of Savoy, who believed that a strong military and a rich treasury were more important than mere signatures. Eventually, Charles VI left behind a weakened and impoverished state, particularly due to the War of the Polish Succession and the Russo-Turkish War (1735–1739). Moreover, upon his death, Saxony, Prussia, Bavaria, and France all repudiated the sanction they had recognised during his lifetime. Frederick II of Prussia (who became Maria Theresa's greatest rival for most of her reign) promptly invaded and took the affluent Habsburg province of Silesia in the eight-year conflict known as the War of the Austrian Succession. In defiance of the grave situation, she managed to secure the vital support of the Hungarians for the war effort. During the course of the war, Maria Theresa successfully defended her rule over most of the Habsburg monarchy, apart from the loss of Silesia and a few minor territories in Italy. Maria Theresa later unsuccessfully tried to recover Silesia during the Семилетняя война .

Although she was expected to cede power to her husband, Emperor Francis I, and her eldest son, Emperor Joseph II, who were officially her co-rulers in Austria and Bohemia, Maria Theresa ruled as an autocratic sovereign with the counsel of her advisers. She promulgated institutional, financial, medical, and educational reforms, with the assistance of Wenzel Anton of Kaunitz-Rietberg, Friedrich Wilhelm von Haugwitz, and Gerard van Swieten. She also promoted commerce and the development of agriculture, and reorganised Austria's ramshackle military, all of which strengthened Austria's international standing. A pious Catholic, she despised Jews and Protestants, and on certain occasions she ordered their expulsion to remote parts of the realm. She also advocated for the state church.

Birth and early life

[edit]

The second and eldest surviving child of Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI and Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, Archduchess Maria Theresa was born on 13 May 1717 in Vienna, a year after the death of her elder brother, Archduke Leopold Johann,[1] and was baptised on that same evening. The dowager empresses, her aunt Wilhelmine Amalia of Brunswick-Lüneburg and grandmother Eleonore Magdalene of Neuburg, were her godmothers.[2] Most descriptions of her baptism stress that the infant was carried ahead of her cousins, Maria Josepha and Maria Amalia, the daughters of Charles VI's elder brother and predecessor, Joseph I, before the eyes of their mother, Wilhelmine Amalia.[3] It was clear that Maria Theresa would outrank them,[3] even though their grandfather, Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I, had his sons sign the Mutual Pact of Succession, which gave precedence to the daughters of the elder brother.[4] Her father was the only surviving male member of the House of Habsburg and hoped for a son who would prevent the extinction of his dynasty and succeed him. Thus, the birth of Maria Theresa was a great disappointment to him and the people of Vienna; Charles never managed to overcome this feeling.[4]

Maria Theresa replaced Maria Josepha as heir presumptive to the Habsburg realms the moment she was born; Charles VI had issued the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713 which had placed his nieces behind his own daughters in the line of succession.[5] Charles sought the other European powers' approval for disinheriting his nieces. They exacted harsh terms: in the Treaty of Vienna, Great Britain demanded that Austria abolish the Ostend Company in return for its recognition of the Pragmatic Sanction.[6] In total, Great Britain, France, Saxony, United Provinces, Spain, Prussia, Russia, Denmark, Sardinia, Bavaria, and the Diet of the Holy Roman Empire recognised the sanction.[7] France, Spain, Saxony, Bavaria, and Prussia later reneged.

Little more than a year after her birth, Maria Theresa was joined by a sister, Maria Anna, and another one, named Maria Amalia, was born in 1724.[8] The portraits of the imperial family show that Maria Theresa resembled Elisabeth Christine and Maria Anna.[9] The Prussian ambassador noted that she had large blue eyes, fair hair with a slight tinge of red, a wide mouth and a notably strong body.[10] Unlike many other members of the House of Habsburg, neither Maria Theresa's parents nor her grandparents were closely related to each other.[a]

Maria Theresa was a serious and reserved child who enjoyed singing and archery. She was barred from horse riding by her father, but she would later learn the basics for the sake of her Hungarian coronation ceremony. The imperial family staged opera productions, often conducted by Charles VI, in which she relished participating. Her education was overseen by Jesuits. Contemporaries thought her Latin to be quite good, but in all else, the Jesuits did not educate her well.[11] Her spelling and punctuation were unconventional and she lacked the formal manner and speech which had characterised her Habsburg predecessors.[b] Maria Theresa developed a close relationship with Countess Marie Karoline von Fuchs-Mollard, who taught her etiquette. She was educated in drawing, painting, music and dancing – the disciplines which would have prepared her for the role of queen consort.[12] Her father allowed her to attend meetings of the council from the age of 14 but never discussed the affairs of state with her.[13] Even though he had spent the last decades of his life securing Maria Theresa's inheritance, Charles never prepared his daughter for her future role as sovereign.[14]

Marriage

[edit]The question of Maria Theresa's marriage was raised early in her childhood. Leopold Clement of Lorraine was first considered to be the appropriate suitor, and he was supposed to visit Vienna and meet the Archduchess in 1723. These plans were forestalled by his death from smallpox that year.[15]

Leopold Clement's younger brother, Francis Stephen, was invited to Vienna. Even though Francis Stephen was his favourite candidate for Maria Theresa's hand,[16] the Emperor considered other possibilities. Religious differences prevented him from arranging his daughter's marriage to the Protestant prince Frederick of Prussia.[17] In 1725, he betrothed her to Charles of Spain and her sister, Maria Anna, to Philip of Spain. However, other European powers compelled him to renounce the pact he had made with the Queen of Spain, Elisabeth Farnese, and the betrothal to Charles was broken off. Maria Theresa, who had become close to Francis Stephen, was relieved.[18][19]

Francis Stephen remained at the imperial court until 1729, when he ascended the throne of Lorraine,[17] but was not formally promised Maria Theresa's hand until 31 January 1736, during the War of the Polish Succession.[20] Louis XV of France demanded that Maria Theresa's fiancé surrender his ancestral Duchy of Lorraine to accommodate his father-in-law, Stanisław I, who had been deposed as King of Poland.[c] Francis Stephen was to receive the Grand Duchy of Tuscany upon the death of childless Grand Duke Gian Gastone de' Medici.[21] The couple were married on 12 February 1736 at the Augustinian Church in Vienna.[22]

The Duchess of Lorraine's love for her husband was strong and possessive.[23] The letters she sent to him shortly before their marriage expressed her eagerness to see him; his letters, on the other hand, were stereotyped and formal.[24][25] She was very jealous of her husband and his infidelity was the greatest problem of their marriage,[26] with Maria Wilhelmina, Princess of Auersperg, as his best-known mistress.[27]

Upon Gian Gastone's death on 9 July 1737, Francis Stephen ceded Lorraine and became Grand Duke of Tuscany. In 1738, Charles VI sent the young couple to make their formal entry into Tuscany. The Triumphal Arch of the Lorraine was erected at the Porta Galla in celebration, where it remains today. Their stay in Florence was brief. Charles VI soon recalled them, as he feared he might die while his heiress was miles away in Tuscany.[28] In the summer of 1738, Austria suffered defeats during the ongoing Russo-Turkish War. The Turks reversed Austrian gains in Serbia, Wallachia and Bosnia. The Viennese rioted at the cost of the war. Francis Stephen was popularly despised, as he was thought to be a cowardly French spy.[29] The war was concluded the next year with the Treaty of Belgrade.[30][page needed]

Accession

[edit]

Charles VI died on 20 October 1740, probably of mushroom poisoning. He had ignored the advice of Prince Eugene of Savoy who had urged him to concentrate on filling the treasury and equipping the army rather than on acquiring signatures of fellow monarchs.[5] The Emperor, who spent his entire reign securing the Pragmatic Sanction, left Austria in an impoverished state, bankrupted by the recent Turkish war and the War of the Polish Succession;[32] the treasury contained only 100,000 florins, which were claimed by his widow.[33] The army had also been weakened due to these wars; instead of the full number of 160,000, the army had been reduced to about 108,000, and they were scattered in small areas from the Austrian Netherlands to Transylvania, and from Silesia to Tuscany. They were also poorly trained and discipline was lacking. Later Maria Theresa even made a remark: "as for the state in which I found the army, I cannot begin to describe it."[34]

Maria Theresa found herself in a difficult situation. She did not know enough about matters of state and she was unaware of the weakness of her father's ministers. She decided to rely on her father's advice to retain his counselors and to defer to her husband, whom she considered to be more experienced, on other matters. Both decisions later gave cause for regret. Ten years later, Maria Theresa recalled in her Political Testament the circumstances under which she had ascended: "I found myself without money, without credit, without army, without experience and knowledge of my own and finally, also without any counsel because each one of them at first wanted to wait and see how things would develop."[14]

She dismissed the possibility that other countries might try to seize her territories and immediately started ensuring the imperial dignity for herself;[14] since a woman could not be elected Holy Roman Empress, Maria Theresa wanted to secure the imperial office for her husband, but Francis Stephen did not possess enough land or rank within the Holy Roman Empire.[d] In order to make him eligible for the imperial throne and to enable him to vote in the imperial elections as King of Bohemia (which she could not do because of her sex), Maria Theresa made Francis Stephen co-ruler of the Austrian and Bohemian lands on 21 November 1740.[35] It took more than a year for the Diet of Hungary to accept Francis Stephen as co-ruler, since they asserted that the sovereignty of Hungary could not be shared.[36] Despite her love for him and his position as co-ruler, Maria Theresa never allowed her husband to decide matters of state and often dismissed him from council meetings when they disagreed.[37]

The first display of the new queen's authority was the formal act of homage of the Lower Austrian Estates to her on 22 November 1740. It was an elaborate public event which served as a formal recognition and legitimation of her accession. The oath of fealty to Maria Theresa was taken on the same day in the Ritterstube of the Hofburg.[31]

War of the Austrian Succession

[edit]

Immediately after her accession, a number of European sovereigns who had recognised Maria Theresa as heir broke their promises. Queen Elisabeth of Spain and Elector Charles Albert of Bavaria, married to Maria Theresa's deprived cousin Maria Amalia and supported by Empress Wilhelmine Amalia, coveted portions of her inheritance.[33] Maria Theresa did secure recognition from King Charles Emmanuel III of Sardinia, who had not accepted the Pragmatic Sanction during her father's lifetime, in November 1740.[38]

In December, Frederick II of Prussia invaded the Duchy of Silesia and requested that Maria Theresa cede it, threatening to join her enemies if she refused. Maria Theresa decided to fight for the mineral-rich province.[39] Frederick even offered a compromise: he would defend Maria Theresa's rights if she agreed to cede to him at least a part of Silesia. Francis Stephen was inclined to consider such an arrangement, but the Queen and her advisers were not, fearing that any violation of the Pragmatic Sanction would invalidate the entire document.[40] Maria Theresa's firmness soon assured Francis Stephen that they should fight for Silesia,[e] and she was confident that she would retain "the jewel of the House of Austria".[41] The resulting war with Prussia is known as the First Silesian War. The invasion of Silesia by Frederick was the start of a lifelong enmity; she referred to him as "that evil man".[42]

As Austria was short of experienced military commanders, Maria Theresa released Marshall Neipperg, who had been imprisoned by her father for his poor performance in the Turkish War.[43] Neipperg took command of the Austrian troops in March. The Austrians suffered a crushing defeat at the Battle of Mollwitz in April 1741.[44] France drew up a plan to partition Austria between Prussia, Bavaria, Saxony and Spain: Bohemia and Upper Austria would be ceded to Bavaria, whose Elector would become emperor, whereas Moravia and Upper Silesia would be granted to the Electorate of Saxony, Lower Silesia and Glatz to Prussia, and the entire Austrian Lombardy to Spain.[45] Marshall Belle-Isle joined Frederick at Olmütz. Vienna was in a panic, as none of Maria Theresa's advisors had expected France to betray them. Francis Stephen urged Maria Theresa to reach a rapprochement with Prussia, as did Great Britain.[46] Maria Theresa reluctantly agreed to negotiations.[47]

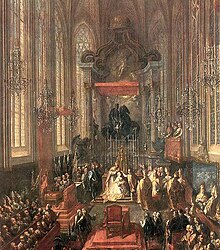

Contrary to all expectations, the young Queen gained significant support from Hungary.[48] Her coronation as Queen of Hungary suo jure took place in St. Martin's Cathedral, Pressburg (today's Bratislava), on 25 June 1741. She had spent months honing the equestrian skills necessary for the ceremony and negotiating with the Hungarian Diet. To appease those who considered her gender to be a serious obstacle, Maria Theresa assumed masculine titles. Thus, in nomenclature, Maria Theresa was archduke and king; normally, however, she was styled as queen.[49][50]

By July, attempts at conciliation had completely collapsed. Maria Theresa's ally, Augustus III of Poland, now became her enemy,[51] and George II declared the Electorate of Hanover to be neutral.[52] Therefore, she needed troops from Hungary in order to support the war effort. Although she had already won the admiration of the Hungarians, the number of volunteers was only in the hundreds. Since she required them in thousands or even tens of thousands, she decided to appear before the Hungarian Diet on 11 September 1741 while wearing the Holy Crown of Hungary. She began addressing the Diet in Latin, and she asserted that "the very existence of the Kingdom of Hungary, of our own person and children, and our crown, are at stake. Forsaken by all, we place our sole reliance in the fidelity and long-tried valor of the Hungarians."[53] The response was rather boorish, with the queen being questioned and even heckled by members of the Diet; someone cried that she "better apply to Satan than the Hungarians for help."[54] However, she managed to show her gift for theatrical displays by holding her son and heir, Joseph, while weeping, and she dramatically consigned the future king to the defense of the "brave Hungarians".[54] This act managed to win the sympathy of the members, and they declared that they would die for Maria Theresa.[54][55]

In 1741, the Austrian authorities informed Maria Theresa that the Bohemian populace would prefer Charles Albert, Elector of Bavaria, to her as sovereign. Maria Theresa, desperate and burdened by pregnancy, wrote plaintively to her sister: "I don't know if a town will remain to me for my delivery."[56] She bitterly vowed to spare nothing and no one to defend her kingdom when she wrote to the Bohemian chancellor, Count Philip Kinsky: "My mind is made up. We must put everything at stake to save Bohemia."[57][f] On 26 October, the Elector of Bavaria captured Prague and declared himself King of Bohemia. Maria Theresa, then in Hungary, wept on learning of the loss of Bohemia.[58] Charles Albert was unanimously elected Holy Roman Emperor as Charles VII on 24 January 1742, which made him the only non-Habsburg to be in that position since 1440.[59] The Queen, who regarded the election as a catastrophe,[60] caught her enemies unprepared by insisting on a winter campaign;[61] the same day he was elected emperor, Austrian troops under Ludwig Andreas von Khevenhüller captured Munich, Charles Albert's capital.[62]

She has, as you well know, a terrible hatred for France, with which nation it is most difficult for her to keep on good terms, but she controls this passion except when she thinks to her advantage to display it. She detests Your Majesty, but acknowledges your ability. She cannot forget the loss of Silesia, nor her grief over the soldiers she lost in wars with you.

Prussian ambassador's letter to Frederick the Great[g]

The Treaty of Breslau of June 1742 ended hostilities between Austria and Prussia. With the First Silesian War at an end, the Queen soon made the recovery of Bohemia her priority.[63] French troops fled Bohemia in the winter of the same year. On 12 May 1743, Maria Theresa was crowned Queen of Bohemia in St. Vitus Cathedral suo jure.[64]

Prussia became anxious at Austrian advances on the Rhine frontier, and Frederick again invaded Bohemia, beginning a Second Silesian War; Prussian troops sacked Prague in August 1744. The French plans fell apart when Charles VII died in January 1745. The French overran the Austrian Netherlands in May.[65]

Francis Stephen was elected Holy Roman Emperor on 13 September 1745. Prussia recognised Francis as emperor, and Maria Theresa once again recognised the loss of Silesia (with the exception of Austrian Silesia by the Treaty of Dresden in December 1745, ending the Second Silesian War).[66] The wider war dragged on for another three years, with fighting in northern Italy and the Austrian Netherlands; however, the core Habsburg domains of Austria, Hungary and Bohemia remained in Maria Theresa's possession. The Treaty of Aix-la-Chappelle, which concluded the eight-year conflict, recognised Prussia's possession of Silesia, and Maria Theresa ceded the Duchy of Parma to Philip of Spain.[67] France had successfully conquered the Austrian Netherlands, but Louis XV, wishing to prevent potential future wars with Austria, returned them to Maria Theresa.[68]

Seven Years' War

[edit]

Frederick of Prussia's invasion of Saxony in August 1756 began a Third Silesian War and sparked the wider Seven Years' War. Maria Theresa and Prince Kaunitz wished to exit the war with possession of Silesia.[69] Before the war started, Kaunitz had been sent as an ambassador to Versailles from 1750 to 1753 to win over the French. Meanwhile, the British rebuffed requests from Maria Theresa to aid her in reclaiming Silesia, and Frederick II himself managed to secure the Treaty of Westminster (1756) with them. Subsequently, Maria Theresa sent Georg Adam, Prince of Starhemberg, to negotiate an agreement with France, and the result was the First Treaty of Versailles of 1 May 1756. Thus, the efforts of Kaunitz and Starhemberg managed to pave a way for a Diplomatic Revolution; previously, France was one of Austria's archenemies together with Russia and the Ottoman Empire, but after the agreement, they were united by a common cause against Prussia.[70] However, historians have blamed this treaty for France's devastating defeats in the war, since Louis XV was required to deploy troops in Germany and to provide subsidies of 25–30 million pounds a year to Maria Theresa that were vital for the Austrian war effort in Bohemia and Silesia.[71]

On 1 May 1757, the Second Treaty of Versailles was signed, whereby Louis XV promised to provide Austria with 130,000 men in addition to 12 million florins yearly. They would also continue the war in Continental Europe until Prussia could be compelled to abandon Silesia and Glatz. In return, Austria would cede several towns in the Austrian Netherlands to the son-in-law of Louis XV, Philip of Parma, who in turn would grant his Italian duchies to Maria Theresa.[71]

Maximilian von Browne commanded the Austrian troops. Following the indecisive Battle of Lobositz in 1756, he was replaced by Prince Charles Alexander of Lorraine, Maria Theresa's brother-in-law.[72] However, he was appointed only because of his familial relations; he turned out to be an incompetent military leader, and he was replaced by Leopold Joseph von Daun, Franz Moritz von Lacy and Ernst Gideon von Laudon.[73] Frederick himself was startled by Lobositz; he eventually re-grouped for another attack in June 1757. The Battle of Kolín that followed was a decisive victory for Austria. Frederick lost one third of his troops, and before the battle was over, he had left the scene.[74] Subsequently, Prussia was defeated at Hochkirch in Saxony on 14 October 1758, at Kunersdorf in Brandenburg on 12 August 1759, and at Landeshut near Glatz in June 1760. Hungarian and Croat light hussars led by Count Hadik raided Berlin in 1757. Austrian and Russian troops even occupied Berlin for several days in August 1760. However, these victories did not enable the Habsburgs to win the war, as the French and Habsburg armies were destroyed by Frederick at Rossbach in 1757.[73] After the defeat in Torgau on 3 November 1760, Maria Theresa realised that she could no longer reclaim Silesia without Russian support, which vanished after the death of Empress Elizabeth in early 1762. In the meantime, France was losing badly in America and India, and thus they had reduced their subsidies by 50%. Since 1761, Kaunitz had tried to organise a diplomatic congress to take advantage of the accession of George III of Great Britain, as he did not really care about Germany. Finally, the war was concluded by the Treaty of Hubertusburg and Paris in 1763. Austria had to leave the Prussian territories that were occupied.[73] Although Silesia remained under the control of Prussia, a new balance of power was created in Europe, and Austrian position was strengthened by it thanks to its alliance with the Bourbons in Madrid, Parma and Naples. Maria Theresa herself decided to focus on domestic reforms and refrain from undertaking any further military operations.[75]

Family life

[edit]

Childbearing

[edit]Maria Theresa gave birth to sixteen children in nineteen years from 1737 to 1756. Thirteen survived infancy, but only ten survived into adulthood. The first child, Maria Elisabeth (1737–1740), was born a little less than a year after the wedding. The child's sex caused great disappointment and so would the births of Maria Anna, the eldest surviving child, and Maria Carolina (1740–1741). While fighting to preserve her inheritance, Maria Theresa gave birth to a son, Joseph, named after Saint Joseph, to whom she had repeatedly prayed for a male child during the pregnancy. Maria Theresa's favourite child, Maria Christina, was born on her 25th birthday, four days before the defeat of the Austrian army at Chotusitz. Five more children were born during the war: (the second) Maria Elisabeth, Charles, Maria Amalia, Leopold and (the second) Maria Carolina (b. & d. 1748). During this period, there was no rest for Maria Theresa during pregnancies or around the births; the war and child-bearing were carried on simultaneously. Five children were born during the peace between the War of the Austrian Succession and the Seven Years' War: Maria Johanna, Maria Josepha, (the third) Maria Carolina, Ferdinand and Maria Antonia. She delivered her last child, Maximilian Francis, during the Seven Years' War, aged 39.[76][77] Maria Theresa asserted that, had she not been almost always pregnant, she would have gone into battle herself.[42]

Illnesses and deaths

[edit]

Four of Maria Theresa's children died before reaching adolescence. Her eldest daughter Maria Elisabeth died from stomach cramps at the age of three. Her third child, the first of three daughters named Maria Carolina, died shortly after her first birthday. The second Maria Carolina was born feet first in 1748. As it became evident that she would not survive, preparations were hastily made to baptize her while still living; according to traditional Catholic belief, unbaptized infants would be condemned to eternity in limbo. Maria Theresa's physician Gerard van Swieten assured her that the infant was still living when baptized, but many at court doubted this.[78]

Maria Theresa's mother, Empress Elisabeth Christine, died in 1750. Four years later, Maria Theresa's governess, Marie Karoline von Fuchs-Mollard, died. She showed her gratitude to Countess Fuchs by having her buried in the Imperial Crypt along with the members of the imperial family.[79]

Smallpox was a constant threat to members of the royal family. In July 1749, Maria Christina survived a bout of the disease, followed in January 1757 by Maria Theresa's eldest son Joseph.[80] In January 1761, the disease killed her second son Charles at the age of fifteen.[81] In December 1762, her twelve-year-old daughter Johanna likewise died in agony from the disease.[80] In November 1763, Joseph's first wife Isabella died from the disease.[82] Joseph's second wife Empress Maria Josepha likewise caught the disease in May 1767 and died a week later. Maria Theresa ignored the risk of infection and embraced her daughter-in-law before the sick chamber was sealed to outsiders.[83][84]

Maria Theresa in fact contracted smallpox from her daughter-in-law. Throughout the city prayers were made for her recovery, and the sacrament was displayed in all churches. Joseph slept in one of his mother's antechambers and hardly left her bedside. On 1 June, Maria Theresa was given the last rites. When the news came in early June that she had survived the crisis, there was huge rejoicing at the court and amongst the populace of Vienna.[85]

In October 1767, Maria Theresa's sixteen-year-old daughter Josepha also showed signs of the disease. It was assumed that she had caught the infection when she went with her mother to pray in the Imperial Crypt next to the unsealed tomb of Empress Maria Josepha (Joseph's wife). Archduchess Josepha started showing smallpox rash two days after visiting the crypt and soon died. Maria Carolina was to replace her as the pre-determined bride of King Ferdinand IV of Naples. Maria Theresa blamed herself for her daughter's death for the rest of her life because, at the time, the concept of an extended incubation period was largely unknown and it was believed that Josepha had caught smallpox from the body of the late empress.[h][86] The last in the family to be infected with the illness was the twenty-four year old Elisabeth. Although she recovered, she was badly scarred with pock marks from the illness.[86] Maria Theresa's losses to smallpox, especially in the epidemic of 1767, were decisive in her sponsoring trials to prevent the illness through inoculation, and subsequently insisting on members of the imperial family receiving inoculation.[87]

Dynastic marriage policy

[edit]Shortly after giving birth to the younger children, Maria Theresa was confronted with the task of marrying off the elder ones. She led the marriage negotiations along with the campaigns of her wars and the duties of state. She used them as pawns in dynastic games and sacrificed their happiness for the benefit of the state.[88] A devoted but self-conscious mother, she wrote to all of her children at least once a week and believed herself entitled to exercise authority over her children regardless of their age and rank.[89]

In April 1770, Maria Theresa's youngest daughter, Maria Antonia, married Louis, Dauphin of France, by proxy in Vienna. Maria Antonia's education was neglected, and when the French showed an interest in her, her mother went about educating her as best she could about the court of Versailles and the French. Maria Theresa kept up a fortnightly correspondence with Maria Antonia, now called Marie Antoinette, in which she often reproached her for laziness and frivolity and scolded her for failing to conceive a child.[89]

Maria Theresa was not just critical of Marie Antoinette. She disliked Leopold's reserve and often blamed him for being cold. She criticized Maria Carolina for her political activities, Ferdinand for his lack of organization, and Maria Amalia for her poor French and haughtiness. The only child she did not constantly scold was Maria Christina, who enjoyed her mother's complete confidence, though she failed to please her mother in one aspect – she did not produce any surviving children.[89]

One of Maria Theresa's greatest wishes was to have as many grandchildren as possible, but she had only about two dozen at the time of her death, of which all the eldest surviving daughters were named after her, with the exception of Princess Carolina of Parma, her eldest granddaughter by Maria Amalia.[89][i]

Religious views and policies

[edit]

Like all members of the House of Habsburg, Maria Theresa was a Catholic, and a devout one. She believed that religious unity was necessary for a peaceful public life and explicitly rejected the idea of religious toleration. She even advocated for a state church[j] and contemporary travelers criticized her regime as bigoted, intolerant and superstitious.[90] However, she never allowed the church to interfere with what she considered to be prerogatives of a monarch and kept Rome at arm's length. She controlled the selection of archbishops, bishops and abbots.[91] Overall, the ecclesiastical policies of Maria Theresa were enacted to ensure the primacy of state control in church-state relations.[92] She was also influenced by Jansenist ideas. One of the most important aspects of Jansenism was the advocacy of maximum freedom of national churches from Rome. Although Austria had always stressed the rights of the state in relation to the church, Jansenism provided new theoretical justification for this.[93]

Maria Theresa promoted the Greek Catholics and emphasized their equal status with Latin Church Catholics.[94] Although Maria Theresa was a very pious person, she also enacted policies that suppressed exaggerated display of piety, such as the prohibition of public flagellantism. Furthermore, she significantly reduced the number of religious holidays and monastic orders.[95]

Jesuits

[edit]Her relationship with the Jesuits was complex. Members of this order educated her, served as her confessors, and supervised the religious education of her eldest son. The Jesuits were powerful and influential in the early years of Maria Theresa's reign. However, the queen's ministers convinced her that the order posed a danger to her monarchical authority. Not without much hesitation and regret, she issued a decree that removed them from all the institutions of the monarchy, and carried it out thoroughly. She forbade the publication of Pope Clement XIII's Apostolicum pascendi bull, which was in favour of the Jesuits, and promptly confiscated their property when Pope Clement XIV suppressed the order.[96]

Jews

[edit]

Maria Theresa regarded both the Jews and Protestants as dangerous to the state and actively tried to suppress them.[97][98] She was probably the most anti-Jewish monarch of her time, having inherited the traditional prejudices of her ancestors and acquired new ones. This was a product of commonplace antisemitism and was not kept secret in her time. In 1777, she wrote of the Jews: "I know of no greater plague than this race, which on account of its deceit, usury and avarice is driving my subjects into beggary. Therefore as far as possible, the Jews are to be kept away and avoided."[99] Her animosity was such that she was willing to tolerate Protestant businessmen and financiers in Vienna, such as the Swiss-born Johann von Fries, since she wanted to break free from the Jewish financiers.[100]

In December 1744, she proposed to her ministers the expulsion of around 10,000 Jews from Prague amid accusations that they were disloyal at the time of the Bavarian-French occupation during the War of the Austrian Succession. The order was then expanded to all Jews of Bohemia and major cities of Moravia. Her first intention was to deport all Jews by 1 January, but having accepted the advice of her ministers, had the deadline postponed.[101] The expulsion was executed only for Prague and only retracted in 1748 due to economic considerations and pressures from other countries, including Great Britain.[100][102]

In the third decade of her reign, Maria Theresa issued edicts that offered some state protection to her Jewish subjects. She forbade the forcible conversion of Jewish children to Christianity in 1762, and in 1763 she forbade Catholic clergy from extracting surplice fees from her Jewish subjects. In 1764, she ordered the release of those Jews who had been jailed for a blood libel in the village of Orkuta.[103] Notwithstanding her continuing strong dislike of Jews, Maria Theresa supported Jewish commercial and industrial activity in Austria.[104] There were also parts of the realm where the Jews were treated better, such as Trieste, Gorizia and Vorarlberg.[105]

Protestants

[edit]In contrast to Maria Theresa's efforts to expel the Jews, she aimed to convert the Protestants (whom she regarded as heretics) to Catholicism.[106] Commissions were formed to seek out secret Protestants and intern them in workhouses, where they would be given the chance to subscribe to approved statements of Catholic faith. If they accepted, they were to be allowed to return to their homes. However, any sign of a return to Protestant practice was treated harshly, often by exile.[107] Maria Theresa exiled Protestants from Austria to Transylvania, including 2,600 from Upper Austria in the 1750s.[100] Her son and co-ruler Joseph regarded his mother's religious policies as "unjust, impious, impossible, harmful and ridiculous".[97] Despite her policies, practical, demographic and economic considerations prevented her from expelling the Protestants en masse. In 1777, she abandoned the idea of expelling Moravian Protestants after Joseph, who was opposed to her intentions, threatened to abdicate as emperor and co-ruler.[105] In February 1780, after a number of Moravians publicly declared their faith, Joseph demanded a general freedom to worship. However, Maria Theresa refused to grant this for as long as she lived. In May 1780, a group of Moravians who had assembled for a worship service on the occasion of her birthday were arrested and deported to Hungary.[108] Freedom of religion was granted only in the Declaration of Tolerance issued by Joseph immediately after Maria Theresa's death.[109]

Eastern Orthodox Christians

[edit]

The policies of Maria Theresa's government toward their Eastern Orthodox subjects were marked by special interests, relating not only to complex religious situations in various southern and eastern regions of the Habsburg monarchy, inhabited by Eastern Orthodox Christians, mainly Serbs and Romanians, but also regarding the political aspirations of the Habsburg court toward several neighbouring lands and regions in Southeastern Europe still held by the declining Ottoman Empire and inhabited by an Eastern Orthodox population.[110]

Maria Theresa's government confirmed (1743) and continued to uphold old privileges granted to their Eastern Orthodox subjects by previous Habsburg monarchs (emperors Leopold I, Joseph I and Charles VI), but at the same time, new reforms were enforced, establishing much firmer state control over the Serbian Orthodox Metropolitanate of Karlovci. Those reforms were initiated by royal patents, known as Regulamentum privilegiorum (1770) and Regulamentum Illyricae Nationis (1777), and finalized in 1779 by the Declaratory Rescript of the Illyrian Nation, a comprehensive document that regulated all major issues relating to the religious life of their Eastern Orthodox subjects and the administration of the Serbian Metropolitanate of Karlovci. Maria Theresa's rescript of 1779 was kept in force until 1868.[111][112]

Reforms

[edit]

Institutional

[edit]Maria Theresa was as conservative in matters of state as in those of religion, but she implemented significant reforms to strengthen Austria's military and bureaucratic efficiency.[113] She employed Friedrich Wilhelm von Haugwitz, who modernised the empire by creating a standing army of 108,000 men, paid for with 14 million florins extracted from crown lands. The central government was responsible for funding the army, although Haugwitz instituted taxation of the nobility, who had never before had to pay taxes.[114] Moreover, after Haugwitz was appointed the head of the new central administrative agency, dubbed the Directory, (Directorium in publicis et cameralibus) in 1749, he initiated a radical centralization of state institutions down to the level of the District Office (Kreisamt).[115] Thanks to this effort, by 1760 there was a class of government officials numbering around 10,000. However, Lombardy, the Austrian Netherlands and Hungary were almost completely untouched by this reform.[115] In the case of Hungary, Maria Theresa was particularly mindful of her promise that she would respect the privileges in the kingdom, including the immunity of nobles from taxation.[116]

In light of the failure to reclaim Silesia during the Seven Years' War, the governing system was once again reformed to strengthen the state.[117] The Directory was transformed into the United Austrian and Bohemian Chancellery in 1761, which was equipped with a separate, independent judiciary and separate financial bodies.[117] She also refounded the Hofkammer in 1762, which was a ministry of finances that controlled all revenues from the monarchy. In addition to this, the Hofrechenskammer, or exchequer, was tasked with the handling of all financial accounts.[118] Meanwhile, in 1760, Maria Theresa created the Council of State (Staatsrat), composed of the state chancellor, three members of the high nobility and three knights, which served as a committee of experienced people who advised her. The council of state lacked executive or legislative authority; nevertheless, it showed the difference between the form of government employed by Maria Theresa and that of Frederick II of Prussia. Unlike the latter, Maria Theresa was not an autocrat who acted as her own minister. Prussia would adopt this form of government only after 1807.[119]

Maria Theresa doubled the state revenue from 20 to 40 million florins between 1754 and 1764, though her attempt to tax clergy and nobility was only partially successful.[113][120] These financial reforms greatly improved the economy.[121] After Kaunitz became the head of the new Staatsrat, he pursued a policy of "aristocratic enlightenment" that relied on persuasion to interact with the estates, and he was also willing to retract some of Haugwitz's centralization to curry favour with them. Nonetheless, the governing system remained centralised, and a strong institution made it possible for Kaunitz to increase state revenues substantially. In 1775, the Habsburg monarchy achieved its first balanced budget, and by 1780, the Habsburg state revenue had reached 50 million florins.[122]

Medicine

[edit]After Maria Theresa recruited Gerard van Swieten from the Netherlands, he also employed a fellow Dutchman named Anton de Haen, who founded the Viennese Medicine School (Wiener Medizinische Schule).[123] Maria Theresa also banned the creation of new burial grounds without prior government permission, thus countering wasteful and unhygienic burial customs.[124]

After the smallpox epidemic of 1767, she promoted inoculation, which she had learned of through her correspondence with Maria Antonia, Electress of Saxony (who in turn probably knew of it through her own correspondence with Frederick the Great). After unsuccessfully inviting the Sutton brothers from England to introduce their technique in Austria, Maria Theresa obtained information on current practices of smallpox inoculation in England. She overrode the objections of Gerard van Swieten (who doubted the effectiveness of the technique), and ordered that it be tried on thirty-four newborn orphans and sixty-seven orphans between the ages of five and fourteen years. The trial was successful, establishing that inoculation was effective in protecting against smallpox, and safe (in the case of the test subjects). The empress therefore ordered the construction of an inoculation centre, and had herself and two of her children inoculated. She promoted inoculation in Austria by hosting a dinner for the first sixty-five inoculated children in Schönbrunn Palace, waiting on the children herself. Maria Theresa was responsible for changing Austrian physicians' negative view of inoculation.[125][87]

In 1770, she enacted a strict regulation of the sale of poisons, and apothecaries were obliged to keep a poison register recording the quantity and circumstances of every sale. If someone unknown tried to purchase a poison, that person had to provide two character witnesses before a sale could be effectuated. Three years later, she prohibited the use of lead in any eating or drinking vessels; the only permitted material for this purpose was pure tin.[126]

Law

[edit]She is most unusually ambitious and hopes to make the House of Austria more renowned than it has ever been.

Prussian ambassador's letter to Frederick II of Prussia[127]

The centralization of the Habsburg government necessitated the creation of a unified legal system. Previously, various lands in the Habsburg realm had their own laws. These laws were compiled and the resulting Codex Theresianus could be used as a basis for legal unification.[128] In 1769, the Constitutio Criminalis Theresiana was published, and this was a codification of the traditional criminal justice system since the Middle Ages. This criminal code allowed the possibility of establishing the truth through torture, and it also criminalised witchcraft and various religious offenses. Although this law came into force in Austria and Bohemia, it was not valid in Hungary.[129]

Maria Theresa is credited, however, in ending the witch hunts in Zagreb, opposing the methods used against Magda Logomer (also called Herrucina), who was the last prosecuted witch in Zagreb following her intervention.[130][131]

She was particularly concerned with the sexual morality of her subjects. Thus, she established a Chastity Commission (Keuschheitskommission) in 1752[132] to clamp down on prostitution, homosexuality, adultery and even sex between members of different religions.[133] This Commission cooperated closely with the police, and the Commission even employed secret agents to investigate private lives of men and women with bad reputation.[134] They were authorised to raid banquets, clubs, and private gatherings, and to arrest those suspected of violating social norms.[135] The punishments included whipping, deportation, or even the death penalty.[133]

In 1776, Austria outlawed torture, at the particular behest of Joseph II. Much unlike Joseph, but with the support of religious authorities, Maria Theresa was opposed to the abolition of torture. Born and raised between Baroque and Rococo eras, she found it difficult to fit into the intellectual sphere of the Enlightenment, which is why she only slowly followed humanitarian reforms on the continent.[136]

From an institutional perspective, in 1749, she founded the Supreme Judiciary as a court of final appeal for all hereditary lands.[118]

Education

[edit]Throughout her reign, Maria Theresa made the promotion of education a priority. Initially this was focused on the wealthier classes. She permitted non-Catholics to attend university and allowed the introduction of secular subjects (such as law), which influenced the decline of theology as the main foundation of university education.[113] Furthermore, educational institutions were created to prepare officials for work in the state bureaucracy: the Theresianum was established in Vienna in 1746 to educate nobles' sons, a military school named the Theresian Military Academy was founded in Wiener Neustadt in 1751, and an Oriental Academy for future diplomats was created in 1754.[137]

In the 1770s, reform of the schooling system for all levels of society became a major policy. Stollberg-Rilinger notes that the reform of the primary schools in particular was the most long-lasting success of Maria Theresa's later reign, and one of the few policy agendas in which she was not in open conflict with her son and nominal co-ruler Joseph II.[138] The need for the reform became evident after the census of 1770–1771, which revealed the widespread illiteracy of the populace. Maria Theresa thereupon wrote to her rival Frederick II of Prussia to request him to allow the Silesian school reformer Johann Ignaz von Felbiger to move to Austria. Felbiger's first proposals were made law by December 1774.[139] Austrian historian Karl Vocelka observed that the educational reforms enacted by Maria Theresa were "really founded on Enlightenment ideas," although the ulterior motive was still to "meet the needs of an absolutist state, as an increasingly sophisticated and complicated society and economy required new administrators, officers, diplomats and specialists in virtually every area."[140]

Maria Theresa's reform established secular primary schools, which children of both sexes from the ages of six to twelve were required to attend.[141][140] The curriculum focused on social responsibility, social discipline, work ethic and the use of reason rather than mere rote learning.[142] Education was to be multilingual; children were to be instructed first in their mother tongue and then in later years in German.[143] Prizes were given to the most able students to encourage ability. Attention was also given to raising the status and pay of teachers, who were forbidden to take on outside employment. Teacher training colleges were established to train teachers in the latest techniques.[144]

The education reform was met with considerable opposition. Predictably, some of this came from peasants who wanted the children to work in the fields instead.[142] Maria Theresa crushed the dissent by ordering the arrest of all those opposed.[141] Однако большая часть оппозиции исходила от императорского двора, особенно среди аристократов, которые видели угрозу своей власти со стороны реформаторов, или тех, кто боялся, что повышение грамотности приведет к тому, что население станет знакомо с протестантскими идеями или идеями Просвещения. Реформы Фельбигера, тем не менее, были реализованы благодаря последовательной поддержке Марии Терезии и ее министра Франца Салеса Грейнера. [145] Реформа начальных школ в значительной степени соответствовала цели Марии Терезии по повышению уровня грамотности, о чем свидетельствует более высокая доля детей, посещающих школу; особенно это касалось Венской архиепархии, где посещаемость школ выросла с 40% в 1780 году до сенсационных 94% к 1807 году. [138] Тем не менее, в некоторых частях Австрии сохранялся высокий уровень неграмотности: половина населения была неграмотной даже в XIX веке. [140] Педагогические колледжи (в частности, Венская педагогическая школа) подготовили сотни новых учителей, которые распространили новую систему в последующие десятилетия. Однако количество средних школ уменьшилось, поскольку количество основанных новых школ не смогло компенсировать количество упраздненных иезуитских школ. В результате среднее образование стало более эксклюзивным. [146]

Цензура

[ редактировать ]Ее режим также был известен введением цензуры публикаций и обучения. Английский писатель сэр Натаниэль Рэксалл однажды написал из Вены: «[Т] неразумный фанатизм императрицы можно объяснить главным образом недостатком [образованности]. Едва ли можно поверить, сколько книг и произведений каждого вида и на каждом языке написано. запрещены ею. Не только Вольтер и Руссо включены в этот список из-за аморальной тенденции или распущенного характера их сочинений, но многие авторы, которых мы считаем безупречными или безобидными, подвергаются подобному обращению». [147] Цензура особенно затронула произведения, которые считались противоречащими католической религии. По иронии судьбы, в этом ей помог Жерар ван Свитен, считавшийся «просвещенным» человеком. [147]

Экономика

[ редактировать ]Мария Терезия стремилась повысить уровень и качество жизни народа, поскольку видела причинно-следственную связь между уровнем жизни крестьян, производительностью и государственными доходами. [148] Правительство Габсбургов под ее правлением также пыталось укрепить свою промышленность посредством государственного вмешательства. После потери Силезии они ввели субсидии и торговые барьеры, чтобы стимулировать перемещение силезской текстильной промышленности в северную Богемию. Кроме того, были урезаны цеховые привилегии, а внутренние пошлины на торговлю были либо реформированы, либо отменены (как это произошло с австро-чешскими землями в 1775 г.). [142]

В конце своего правления Мария Терезия провела реформу системы крепостного права , которая была основой сельского хозяйства в восточных частях ее земель (особенно в Богемии, Моравии, Венгрии и Галиции). Хотя Мария Терезия изначально не хотела вмешиваться в подобные дела, вмешательство правительства стало возможным благодаря осознанной потребности в экономической мощи и появлению функционирующей бюрократии. [149] Перепись 1770–1771 гг. дала крестьянам возможность выразить свое недовольство непосредственно королевским комиссарам и продемонстрировала Марии Терезии, в какой степени их бедность была результатом крайних требований принудительного труда (называемого « робота по-чешски ») со стороны помещики. В некоторых поместьях помещики требовали, чтобы крестьяне работали до семи дней в неделю на обработке дворянской земли, так что крестьяне могли обрабатывать свою землю только ночью. [150]

Дополнительным стимулом к реформам стал голод, поразивший империю в начале 1770-х годов. Особенно сильно пострадала Богемия. Мария Терезия находилась под все большим влиянием реформаторов Франца Антона фон Блана и Тобиаса Филиппа фон Геблера, которые призывали к радикальным изменениям в крепостной системе, чтобы позволить крестьянам зарабатывать на жизнь. [151] В 1771–1778 годах Мария Терезия издала серию « Патентов на роботов » (т.е. правил, касающихся принудительного труда), которые регулировали и ограничивали крестьянский труд только в немецкой и чешской частях королевства. Цель заключалась в том, чтобы крестьяне не только могли прокормить себя и членов своих семей, но и помогли покрыть национальные расходы в мирное или военное время. [152]

К концу 1772 года Мария Терезия решила провести более радикальную реформу. В 1773 году она поручила своему министру Францу Антону фон Раабу типовой проект коронных земель в Богемии: ему было поручено разделить крупные имения на мелкие фермы, превратить принудительные трудовые договоры в аренду и дать возможность фермерам пройти арендуют своих детей. Рааб настолько успешно реализовал проект, что его имя было отождествлено с программой, которая стала известна как Раабизация . После успеха программы на землях короны Мария Терезия реализовала ее также на бывших землях иезуитов, а также на землях короны в других частях своей империи. [153]

Однако попытки Марии Терезии распространить систему Рааба на крупные поместья, принадлежавшие чешской знати, встретили яростное сопротивление со стороны дворян. Они утверждали, что корона не имела права вмешиваться в крепостную систему, поскольку дворяне были первоначальными владельцами земли и позволяли крестьянам обрабатывать ее на оговоренных условиях. Дворяне также утверждали, что система принудительного труда не имеет никакой связи с крестьянской бедностью, которая была результатом собственной расточительности крестьян и повышенных царских налогов. Несколько удивительно, но дворян поддержал сын и соправитель Марии Терезии Иосиф II, ранее призывавший к отмене крепостного права. [154] В письме своему брату Леопольду от 1775 года Иосиф жаловался, что его мать намеревалась «полностью отменить крепостное право и самовольно разрушить многовековые отношения собственности». Он жаловался, что «не было принято во внимание помещиков, которым грозила потеря более половины доходов. Для многих из них, у которых есть долги, это означало бы финансовый крах». [155] К 1776 году двор был поляризован: на одной стороне была небольшая партия реформ (включая Марию Терезию, Рааба, Бланка, Геблера и Грейнера); на консервативной стороне были Джозеф и остальные члены двора. [155] Иосиф утверждал, что трудно найти золотую середину между интересами крестьян и дворян; вместо этого он предложил крестьянам вести переговоры со своими помещиками для достижения результата. [156] Биограф Джозефа Дерек Билс называет это изменение курса «загадочным». [157] В завязавшейся борьбе Жозеф вынудил Блана покинуть площадку. Из-за противодействия Мария Терезия не смогла провести запланированную реформу и была вынуждена пойти на компромисс. [158] Система крепостного права была отменена только после смерти Марии Терезии Патентом на крепостное право (1781 г.), выданным (разумеется, с другим изменением курса) Иосифом II как единоличным правителем. [152]

Позднее правление

[ редактировать ]

Император Франциск умер 18 августа 1765 года, когда он и двор находились в Инсбруке, празднуя свадьбу своего второго выжившего сына Леопольда. Мария Терезия была опустошена. Их старший сын Иосиф стал императором Священной Римской империи. Мария Терезия отказалась от всех украшений, коротко постриглась, покрасила комнаты в черный цвет и всю оставшуюся жизнь носила траур. Она полностью отстранилась от придворной жизни, общественных мероприятий и театра. На протяжении всего своего вдовства она проводила весь август и восемнадцатое число каждого месяца одна в своей комнате, что отрицательно сказывалось на ее психическом здоровье. [160] Она описала свое душевное состояние вскоре после смерти Фрэнсиса: «Теперь я почти не знаю себя, потому что я стала похожа на животное, лишенное истинной жизни и способности рассуждать». [161]

После своего восшествия на императорский престол Йозеф правил меньшим количеством земель, чем его отец в 1740 году, поскольку он уступил свои права на Тоскану Леопольду и, таким образом, контролировал только Фалькенштейна и Тешена . Полагая, что император должен обладать достаточным количеством земли, чтобы поддерживать свой статус императора, [162] Мария Терезия, привыкшая к помощи в управлении ее обширными владениями, 17 сентября 1765 года объявила Иосифа своим новым соправителем. [163] С тех пор у матери и сына часто возникали идеологические разногласия. 22 миллиона флоринов, унаследованных Джозефом от отца, были вложены в казну. Мария Терезия понесла еще одну потерю в феврале 1766 года, когда умер Хаугвиц. Она дала своему сыну абсолютный контроль над армией после смерти Леопольда Йозефа фон Дауна . [164]

По мнению австрийского историка Роберта А. Канна, Мария Терезия была монархом квалификации выше среднего, но интеллектуально уступала Иосифу и Леопольду. Канн утверждает, что она все же обладала качествами, ценимыми в монархе: горячее сердце, практичный ум, твердая решимость и здравое восприятие. Самое главное, она была готова признать умственное превосходство некоторых своих советников и уступить место более высокому уму, пользуясь при этом поддержкой своих министров, даже если их идеи отличались от ее собственных. Джозефу, однако, так и не удалось установить контакт с одними и теми же советниками, хотя их философия управления была ближе к философии Иосифа, чем к философии Марии Терезии. [165]

Отношения между Марией Терезией и Иосифом не были лишены тепла, но были сложными, и их личности противоречили. Несмотря на свой интеллект, сила личности Марии Терезии часто заставляла Джозефа съеживаться. [166] Иногда она открыто восхищалась его талантами и достижениями, но и не стеснялась его упрекать. Она даже написала: «Мы никогда не видимся, кроме как за ужином… Его характер ухудшается с каждым днем… Пожалуйста, сожгите это письмо… Я просто стараюсь избежать публичного скандала». [167] В другом письме, также адресованном спутнику Иосифа, она жаловалась: «Он избегает меня... Я единственный человек на его пути, и потому я препятствие и бремя... Только отречение может исправить положение». [167] После долгих размышлений она решила не отречься от престола. Сам Иосиф часто угрожал уйти с поста соправителя и императора, но его тоже заставили не делать этого. Ее угрозы отречения редко воспринимались всерьез; Мария Терезия считала, что ее выздоровление от оспы в 1767 году было знаком того, что Бог желает, чтобы она царствовала до самой смерти. В интересах Иосифа было, чтобы она оставалась суверенной, поскольку он часто обвинял ее в своих неудачах и таким образом избегал брать на себя обязанности монарха. [168]

Йозеф и принц Кауниц устроили первый раздел Польши, несмотря на протесты Марии Терезии. Ее чувство справедливости подтолкнуло ее отказаться от идеи раздела, который нанес бы вред польскому народу . [169] Однажды она даже заявила: «Какое право мы имеем грабить невинную нацию, которую до сих пор мы гордились защитой и поддержкой?» [170] Дуэт утверждал, что сейчас уже слишком поздно прерывать отношения. Кроме того, сама Мария Терезия согласилась с разделом, когда поняла, что Фридрих II Прусский и Екатерина II Российская сделают это с участием Австрии или без него. Мария Терезия заявила права и в конечном итоге взяла Галисию и Лодомерию ; по словам Фредерика, «чем больше она плакала, тем больше она брала». [171]

Через несколько лет после раздела Россия разгромила Османскую империю в русско-турецкой войне (1768–1774) . После подписания Кучук-Кайнарджийского договора в 1774 году, завершившего войну, Австрия вступила в переговоры с Блистательной Портой . Так, в 1775 году Османская империя уступила северо-западную часть Молдавии (впоследствии известную как Буковина ). Австрии [172] Впоследствии, 30 декабря 1777 года, Максимилиан III Иосиф, курфюрст Баварии, умер, не оставив детей. [171] В результате на его территории жаждали амбициозные люди, в том числе Йозеф, который пытался обменять Баварию на Австрийские Нидерланды. [173] Это встревожило Фридриха II Прусского, и поэтому в 1778 году разразилась война за баварское наследство. Мария Терезия очень неохотно согласилась на оккупацию Баварии, а год спустя она сделала Фридриху II мирные предложения, несмотря на возражения Иосифа. [174] Хотя Австрии удалось получить территорию Иннфиртеля , эта «Картофельная война» подорвала финансовое улучшение, которого добилась императрица. [173] Годовой доход 500 000 флоринов от 100 000 жителей Иннфиртеля не мог сравниться со 100 000 000 флоринов, потраченных во время войны. [174]

Маловероятно, что Мария Терезия когда-либо полностью оправилась от приступа оспы в 1767 году, как утверждали писатели XVIII века. Она страдала от одышки , усталости , кашля , дистресса, некрофобии и бессонницы . Позже у нее развился отек . [175]

Мария Терезия заболела 24 ноября 1780 года. Ее врач доктор Стерк счел ее состояние серьезным, хотя ее сын Йозеф был уверен, что она выздоровеет в кратчайшие сроки. К 26 ноября она попросила о последнем обряде , а 28 ноября врач сказал ей, что время пришло. 29 ноября она умерла в окружении оставшихся детей. [176] [177] Ее тело похоронено в Императорском склепе в Вене рядом с мужем в гробу, который она надписала при жизни. [178]

Ее давний соперник Фридрих Великий , узнав о ее смерти, заявил, что она почтила свой трон и свой пол, и хотя он сражался против нее в трех войнах, он никогда не считал ее своим врагом. [179] С ее смертью Дом Габсбургов вымер и был заменен Домом Габсбургов-Лотарингий . Иосиф II, уже соправитель владений Габсбургов, сменил ее и провел радикальные реформы в империи; Иосиф издавал около 700 указов в год (или почти два в день), тогда как Мария Терезия издавала лишь около 100 указов ежегодно. [180]

Наследие

[ редактировать ]Мария Терезия понимала важность своей публичной персоны и умела одновременно вызывать у своих подданных и уважение, и привязанность; Ярким примером было то, как она демонстрировала достоинство и простоту, вызывая трепет у людей в Прессбурге, прежде чем она была коронована как королева (регентша) Венгрии. [181] Ее 40-летнее правление считалось очень успешным по сравнению с другими правителями Габсбургов. Ее реформы превратили империю в современное государство со значительным международным авторитетом. [182] Она централизовала и модернизировала ее институты, а ее правление считалось началом эпохи « просвещенного абсолютизма » в Австрии, с совершенно новым подходом к управлению: меры, предпринимаемые правителями, стали более современными и рациональными, а мысли были отданы благосостояние государства и народа. [183] Многие из ее политики не соответствовали идеалам Просвещения ( например, ее поддержка пыток ), и она все еще находилась под сильным влиянием католицизма предыдущей эпохи. [184] Воцелка даже заявил, что «в целом реформы Марии Терезии кажутся скорее абсолютистскими и централистскими, чем просвещенными, даже если признать, что влияние просвещенных идей в известной степени заметно». [185] Несмотря на то, что Мария Терезия была одной из самых успешных монархов Габсбургов и выдающихся лидеров 18-го века, она не привлекла внимания современных историков или средств массовой информации, возможно, из-за ее закаленного характера. [186]

Мемориалы и почести

[ редактировать ]

В ее честь по всей империи было названо множество улиц и площадей, а также построены статуи и памятники. был установлен большой бронзовый памятник. в ее честь на Марии-Терезиен-Плац В Вене в 1888 году Садовый сквер Марии Терезии (Ужгород) Совсем недавно, в 2013 году, в ее память был построен .

Город Суботица был переименован в ее честь в 1779 году в Марию-Терезиаполис, иногда называемую Марией-Терезиопель или Терезиопель. [187]

Ряд ее потомков были названы в ее честь. К ним относятся:

- Эрцгерцогиня Мария Терезия Австрийская (1762–1770) ,

- Мария Терезия Австрийская (1767–1827) ,

- Мария Терезия Неаполитанская и Сицилийская ,

- Мария Терезия Австрийская-Эсте, королева Сардинии .

- Мария Тереза из Франции ,

- Мария Терезия Австрийская (1801–1855) ,

- Мария Терезия Савойская (1803–1879) ,

- Мария Терезия Австрийская (1816–1867) ,

- Эрцгерцогиня Мария Терезия Австрийская-Эсте (1817–1886) ,

- Мария Терезия Австрийская-Эсте (1849–1919) ,

- Принцесса Мария Тереза Бурбон-Обеих Сицилий (1867–1909) и

- Эрцгерцогиня Мария Терезия Австрийская (1862–1933) . Ее внучка Мария Терезия Неаполитанская и Сицилийская также стала императрицей Священной Римской империи в 1792 году.

- Корабль Императорского и Королевского флота «СМС Кайзерин и королева Мария Терезия» был заложен в 1891 году.

- Военный орден Марии Терезии был основан ею в 1757 году и просуществовал до окончания Первой мировой войны.

- Терезианум был основан ею в 1746 году и является одной из лучших школ Австрии.

- Талер Марии Терезии был выпущен во время ее правления, но чеканку продолжали и впоследствии, и он стал законным платежным средством в регионе Персидского залива и Юго-Восточной Азии . Австрийский монетный двор продолжает их выпускать. [188]

- астероид 295 Терезия . В 1890 году в ее честь был назван

- Гарнизонный город Терезин ( Терезинштадт ) в Богемии был построен в 1780 году и назван в ее честь.

- В ее честь была названа хрустальная люстра из богемского хрусталя, известная как люстра Марии Терезы . [189] [190] [191] [192] [193]

- Зал Марии Терезии ( Мария-Терезиен-Циммер ) в Леопольдинском крыле дворца Хофбург назван в ее честь, а в зале висит ее большой государственный портрет работы школы Мартина ван Мейтенса 1741 года, изображающий ее в венгерском коронационном платье. центр. Все церемонии присяги новоизбранному правительству Австрии проводятся в этой комнате, а подписание происходит под ее портретом. [194]

- 22-я добровольческая кавалерийская дивизия «Мария Терезия» (1943–1945).

- Зал Марии Терезии — самый элегантный зал дворца Шандор в Будапеште , официальной резиденции президента Венгрии . На нем есть портрет королевы, одетой для ее коронации, а на другой стороне - портрет ее мужа императора Франциска I. Помещение было специально создано в память о примирении монарха и правительства и используется для официальных государственных приемов.

В СМИ

[ редактировать ]Она появилась в качестве главной фигуры в ряде фильмов и сериалов, таких как « Мария Терезия» и «Мария Терезия» 1951 года , австрийско-чешский телевизионный мини-сериал 2017 года. В фильме 2006 года « Мария-Антуанетта» Марианна Фейтфулл изобразила Марию Терезию вместе с Кирстен Данст в заглавная роль.

За несколько лет до этого она появилась в роли второстепенного персонажа в фильме 1938 года « Мария-Антуанетта» в главной роли с Нормой Ширер , в котором ее сыграла Альма Крюгер .

Титулы, стили, почести и оружие

[ редактировать ]Названия и стили

[ редактировать ]Ее титул после смерти мужа был:

Мария Терезия, милостью Божией , вдовствующая императрица римлян, королева Венгрии, Богемии, Далмации, Хорватии, Славонии, Галиции, Лодомерии и т. д.; Эрцгерцогиня Австрии; герцогиня Бургундская, Штирийская, Каринтийская и Карниолская; Великая принцесса Трансильвании; маркграфина Моравская; Герцогиня Брабанта, Лимбурга, Люксембурга, Гельдерса, Вюртемберга, Верхней и Нижней Силезии, Милана, Мантуи, Пармы, Пьяченцы, Гуасталлы, Освенцима и Затора; Принцесса Швабии; Княжеская графиня Габсбургская, Фландрская, Тироля, Эно, Кибурга, Гориции и Градиски; маркграфина Бургау, Верхней и Нижней Лужицкой; Графиня Намюр; Леди Вендиш-Марки и Мехлина; Вдовствующая герцогиня Лотарингии и Бара, вдовствующая великая герцогиня Тосканы. [195] [к]

Оружие

[ редактировать ] |  |

| Герб Марии Терезии | Герб Марии Терезии, найден на корабле Марии Терезии Талер |

Проблема

[ редактировать ]| Нет. | Имя | Рождение | Смерть | Примечания |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Эрцгерцогиня Мария Элизабет Австрийская | 5 февраля 1737 г. | 7 июня 1740 г. | умер в детстве, не беда |

| 2 | Эрцгерцогиня Мария Анна | 6 октября 1738 г. | 19 ноября 1789 г. | умер незамужним, не проблема |

| 3 | Эрцгерцогиня Мария Каролина Австрийская | 12 января 1740 г. | 25 января 1741 г. | умер в детстве, вероятно, от оспы, никаких проблем |

| 4 | Император Священной Римской империи Иосиф II | 13 марта 1741 г. | 20 февраля 1790 г. | женат 1) на принцессе Изабелле Марии Пармской (1741–1763), женат 2) на принцессе Марии Жозефе Баварской (1739–1767) – троюродной сестре, имел проблемы от первого брака (две дочери умерли молодыми) |

| 5 | Эрцгерцогиня Мария Кристина Австрийская | 13 мая 1742 г. | 24 июня 1798 г. | вышла замуж за принца Альберта Саксонского, герцога Тешенского (1738–1822), ее троюродного брата, имела проблему (одна мертворожденная дочь) |

| 6 | Эрцгерцогиня Мария Элизабет Австрийская | 13 августа 1743 г. | 22 сентября 1808 г. | умер незамужним, не проблема |

| 7 | Эрцгерцог Австрии Карл Иосиф | 1 февраля 1745 г. | 18 января 1761 г. | умер от оспы , ничего страшного |

| 8 | Эрцгерцогиня Мария Амалия Австрийская | 26 февраля 1746 г. | 18 июня 1806 г. | вышла замуж за Фердинанда, герцога Пармского (1751–1802), имела проблемы. |

| 9 | Император Священной Римской империи Леопольд II | 5 мая 1747 г. | 1 марта 1792 г. | женился на инфанте Марии Луизе Испанской (1745–1792), имел проблемы. Великий герцог Тосканы с 1765 г. (отрекся от престола в 1790 г.), император Священной Римской империи с 1790 г., эрцгерцог Австрийский , король Венгрии и король Богемии с 1790 г. |

| 10 | Эрцгерцогиня Мария Каролина Австрийская | 17 сентября 1748 г. | 17 сентября 1748 г. | умер во время родов. |

| 11 | Эрцгерцогиня Мария Йоханна Габриэла Австрийская | 4 февраля 1750 г. | 23 декабря 1762 г. | умер от оспы, ничего страшного |

| 12 | Эрцгерцогиня Мария Жозефа Австрийская | 19 марта 1751 г. | 15 октября 1767 г. | умер от оспы, ничего страшного |

| 13 | Эрцгерцогиня Мария Каролина Австрийская | 13 августа 1752 г. | 7 сентября 1814 г. | вышла замуж за короля Неаполя и Сицилии Фердинанда IV (1751–1825); была проблема |

| 14 | Эрцгерцог Фердинанд Австрии | 1 июня 1754 г. | 24 декабря 1806 г. | женился на Марии Беатрис д'Эсте, герцогине Массе , наследнице Брайсгау и Модены , имел проблему ( Австрия-Эсте ). Герцог Брейсгау с 1803 года. |

| 15 | Эрцгерцогиня Мария Антония Австрийская | 2 ноября 1755 г. | 16 октября 1793 г. | вышла замуж за Людовика XVI Французского и Наваррского (1754–1793) и стала Марией-Антуанеттой, королевой Франции и Наварры. Были дети, но не было внуков. Казнен на гильотине . |

| 16 | Эрцгерцог Максимилиан Франц Австрийский | 8 декабря 1756 г. | 27 июля 1801 г. | Архиепископ-курфюрст Кельна , 1784 г. |

Родословная

[ редактировать ]| Предки Марии Терезии [196] |

|---|

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Генеалогическое древо королей Богемии

- Генеалогическое древо королей Венгрии

- Список людей с наибольшим количеством детей

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]Сноски

[ редактировать ]- ^ Члены династии Габсбургов часто женились на своих близких родственниках; примерами такого инбридинга были пары дядя-племянница (дедушка Марии Терезии Леопольд и Маргарет Тереза Испанская , Филипп II Испанский и Анна Австрийская , Филипп IV Испанский и Мариана Австрийская и т. д.). Однако Мария Терезия происходила от третьей жены Леопольда I, которая не была с ним тесной родственницей, а ее родители были лишь отдаленными родственниками. Билз 1987 , стр. 20–21.

- ↑ Вместо того, чтобы использовать формальную манеру и речь, Мария Терезия говорила (а иногда и писала) на венском немецком языке , который она переняла от своих слуг и фрейлин. Спилман 1993 , с. 206.

- ↑ Отец Марии Терезии вынудил Фрэнсиса Стефана отказаться от своих прав на Лотарингию и сказал ему: « Нет отречения, нет эрцгерцогини». Билз 1987 , с. 23.

- ^ Франциск Стефан был в то время великим герцогом Тосканы, но Тоскана не была частью Священной Римской империи со времен Вестфальского мира . Его единственными владениями в пределах Империи были герцогство Тешен и графство Фалькенштейн. Билз 2005 , с. 190.

- ↑ На следующий день после вступления Пруссии в Силезию Франциск Стефан воскликнул прусскому посланнику генерал-майору Борке : «Лучше турки перед Веной, лучше капитуляция Нидерландов Франции, лучше каждая уступка Баварии и Саксонии, чем отказ Силезии!" Браунинг 1994 , с. 43.

- ^ Кроме того, она объяснила графу свое решение: «Я прикажу перебить все мои армии, всех моих венгров, прежде чем я уступлю хотя бы дюйм земли». Браунинг 1994 , с. 76.

- ↑ В конце войны за австрийское наследство граф Подевильс был отправлен послом при австрийском дворе королем Пруссии Фридрихом II. Подевильс написал подробные описания внешности Марии Терезии и того, как она проводила свои дни. Махан 1932 , с. 230.

- ^ После заражения человека требуется не менее недели, чтобы сыпь от оспы появилась. Поскольку сыпь появилась через два дня после того, как Мария Жозефа посетила хранилище, эрцгерцогиня, должно быть, заразилась задолго до посещения хранилища. Хопкинс 2002 , с. 64.

- ^ Старшими выжившими дочерьми детей Марии Терезии были Мария Терезия Австрийская (от Иосифа), Мария Терезия Тосканская (от Леопольда), Мария Терезия Неаполитанская и Сицилийская (от Марии Каролины), Мария Терезия Австрийская-Эсте (от Фердинанда). и Мария Тереза из Франции (Мария-Антуанетта).

- ↑ В письме к Джозефу она писала: «Что, без господствующей религии? Терпимость, индифферентизм — совершенно правильные средства, чтобы подорвать всё… Какие еще существуют ограничения? Никаких. Ни виселицы, ни колеса … Я говорите теперь политически, а не по-христиански. Нет ничего столь необходимого и полезного, как религия. Разрешили бы вы каждому действовать по своей фантазии, если бы не было твердого культа, никакого подчинения Церкви, где бы мы были? мог бы принять командование». Крэнкшоу 1970 , с. 302

- ^ На немецком языке: Мария Терезия по милости Божией, вдовствующая императрица Священной Римской империи, королева Венгрии, Богемии, Далмации, Хорватии, Славонии, Галиции, Лодомерии и т. д., эрцгерцогиня Австрии, герцогиня Бургундская, Штайер, Каринтия и Крейн, Великая княгиня Трансильвании, маркграфина Моравская, герцогиня Брабандская, Лимбурга, Люксембурга и Гельдерна, Вюртемберга, Верхней и Нижней Силезии, Милана, Мантуи, Пармы, Пьяченцы, Гуасталы, Освенцима и Затора, принцессы Швабии, принца графини Габсбургской, Фландрии , Тироль, Эно, Кибург, Гориция и Градиска, маркграфина Священной Римской империи, Бургау, Верхняя и Нижняя Лужица, графиня Намюр, госпожа Виндишенского марша и в Мехелене, вдовствующая герцогиня Лотарингии и Баара, великая вдовствующая герцогиня Тосканы

Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Голдсмит 1936 , с. 17.

- ^ Моррис 1937 , с. 21.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Махан 1932 , с. 6.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Махан 1932 , с. 12.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Инграо 2000 , с. 129.

- ^ Крэнкшоу 1970 , с. 24.

- ^ «Прагматическая санкция императора Карла VI» . Британская энциклопедия . Проверено 29 ноября 2018 г.

- ^ Инграо 2000 , с. 128.

- ^ Махан 1932 , с. 23.

- ^ Махан 1932 , с. 228.

- ^ Crankshaw 1970 , стр. 19–21.

- ^ Махан 1932 , стр. 21–22.

- ^ Моррис 1937 , с. 28.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Браунинг 1994 , с. 37.

- ^ Махан 1932 , стр. 24–25.

- ^ Крэнкшоу 1970 , с. 22.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Махан 1932 , с. 27.

- ^ Махан 1932 , с. 26.

- ^ Моррис 1937 , стр. 25–26.

- ^ Махан 1932 , с. 37.

- ^ Крэнкшоу 1970 , с. 25.

- ^ Махан 1932 , с. 38.

- ^ Махан 1932 , с. 261.

- ^ Голдсмит 1936 , с. 55.

- ^ Махан 1932 , с. 39.

- ^ Махан 1932 , стр. 261–262.

- ^ Махан 1932 , стр. 262–263.

- ^ Крэнкшоу 1970 , с. 26.

- ^ Crankshaw 1970 , стр. 25–26.

- ^ Ройдер 1972 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Спилман 1993 , с. 207.

- ^ Крэнкшоу 1970 , с. 3.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Моррис 1937 , с. 47.

- ^ Даффи 1977 , стр. 145–146.

- ^ Билз 2005 , стр. 182–183.

- ^ Билз 2005 , с. 189.

- ^ Ройдер 1973 , с. 8.

- ^ Браунинг 1994 , с. 38.

- ^ Крэнкшоу 1970 , с. 43.

- ^ Браунинг 1994 , с. 43.

- ^ Браунинг 1994 , стр. 42, 44.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Холборн 1982 , с. 218.

- ^ Браунинг 1994 , с. 44.

- ^ Браунинг 1994 , стр. 52–53.

- ^ Крэнкшоу 1970 , с. 56.

- ^ Крэнкшоу 1970 , с. 57.

- ^ Крэнкшоу 1970 , с. 58.

- ^ Браунинг 1994 , с. 66.

- ^ Йонан 2003 , с. 118.

- ^ Варга, Бенедек М. (2020). «Сделать Марию Терезию королем Венгрии» . Исторический журнал . 64 (2): 233–254. дои : 10.1017/S0018246X20000151 . ISSN 0018-246X .

- ^ Крэнкшоу 1970 , с. 75.

- ^ Крэнкшоу 1970 , с. 77.

- ^ Махан 1932 , с. 121.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Махан 1932 , с. 122.

- ^ Моррис 1937 , с. 74.

- ^ Браунинг 1994 , с. 65.

- ^ Даффи 1977 , с. 151.

- ^ Браунинг 1994 , с. 79.

- ^ Беллер 2006 , с. 86.

- ^ Браунинг 1994 , с. 88.

- ^ Браунинг 1994 , с. 92.

- ^ Крэнкшоу 1970 , с. 93.

- ^ Браунинг 1994 , с. 114.

- ^ Crankshaw 1970 , стр. 96–97.

- ^ Крэнкшоу 1970 , с. 97.

- ^ Крэнкшоу 1970 , с. 99.

- ^ Crankshaw 1970 , стр. 99–100.

- ^ Митфорд 1970 , с. 158.

- ^ Крэнкшоу 1970 , с. 238.

- ^ Беренджер 2014 , стр. 80–82.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Беренгер 2014 , стр. 82.

- ^ Крэнкшоу 1970 , с. 240.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Беренгер 2014 , стр. 83.

- ^ Крэнкшоу 1970 , с. 242.

- ^ Беренджер 2014 , стр. 84.

- ^ Махан 1932 , стр. 266–271, 313.

- ^ Столлберг-Рилингер 2017 , стр. 291f.

- ^ Столлберг-Рилингер 2017 , стр. 306–310.

- ^ Махан 1932 , с. 22.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Столльберг-Рилингер 2017 , с. 507.

- ^ Столлберг-Рилингер 2017 , стр. 507, 935, №193.

- ^ Столлберг-Рилингер 2017 , стр. 497, 508.

- ^ Крэнкшоу 1970 , с. 273.

- ^ Столлберг-Рилингер 2017 , с. 508.

- ^ Столлберг-Рилингер 2017 , стр. 508f.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Столльберг-Рилингер 2017 , с. 511.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Столлберг-Рилингер 2017 , стр. 504–515.

- ^ Махан 1932 , с. 271.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Билз 1987 , с. 194.

- ^ Билз 2005 , с. 69.

- ^ Махан 1932 , с. 251.

- ^ Май 1980 г. , с. 187.

- ^ Холборн 1982 , с. 223.

- ^ Химка 1999 , с. 5.

- ^ Холборн 1982 , с. 222.

- ^ Махан 1932 , с. 253.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Билз 2005 , с. 14.

- ^ Столлберг-Рилингер 2017 , с. 644.

- ^ Крэнкшоу 1970 , с. 313.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Беллер 2006 , с. 87.

- ^ Махан 1932 , с. 254.

- ^ Май 1980 г. , стр. 189–190.

- ^ Вопрос 1996 г. , с. 203.

- ^ Кисти 2001 , стр. 32–33.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Воцелка 2000 , с. 201.

- ^ Столлберг-Рилингер 2017 , стр. 644–647.

- ^ Столлберг-Рилингер 2017 , стр. 647–666.

- ^ Столлберг-Рилингер 2017 , с. 665.

- ^ Столлберг-Рилингер 2017 , с. 666.

- ^ Бронза 2010 , стр. 51–62.

- ^ Циркович 2004 , стр. 166–167, 196–197.

- ^ Боксан 2015 , стр. 243–258.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Бирн 1997 , с. 38.

- ^ Крэнкшоу 1970 , с. 192.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Беллер 2006 , с. 88.

- ^ Беренджер 2014 , стр. 86.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Беллер 2006 , с. 89.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Беренгер 2014 , стр. 85.

- ^ Холборн 1982 , стр. 221–222.

- ^ Крэнкшоу 1970 , с. 195.

- ^ Крэнкшоу 1970 , с. 196.

- ^ Беллер 2006 , с. 90.

- ^ Воцелка 2009 , с. 160.

- ^ Крэнкшоу 1970 , с. 310.

- ^ Хопкинс 2002 , стр. 64–65.

- ^ Крэнкшоу 1970 , с. 309.

- ^ Махан 1932 , с. 230.

- ^ Воцелка 2009 , стр. 157–158.