Сребеника Резня

| Сребеника Резня Сребеника Геноцид | |

|---|---|

| Часть боснийской войны и боснийский геноцид | |

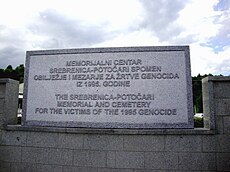

Некоторые из надгробиев для почти 7000 человек идентифицировали жертв, похороненные на Мемориале и кладбище Сребеники-Поточари для жертв геноцида 1995 года . [ 1 ] | |

| Родное имя | Геноцид в Srebrenica / геноцид в Srebrenica |

| Расположение | Сребрена , Босния и Герцеговина |

| Координаты | 44 ° 06′N 19 ° 18′E / 44,100 ° N 19 300 ° E |

| Дата | 11 июля 1995 г. -31 июля 1995 г |

| Цель | Босняк мужчины и мальчики |

Тип атаки | Геноцид , массовое убийство , этническая очистка , геноцидное изнасилование |

| Летальные исходы | 8,372 [ 2 ] |

| Преступники | |

| Мотив | Антино Босняк настроения, сербский Ирредентизм , Исламофобия , Сербианизация |

Резня в Сребенике , [ А ] также известен как геноцид Srebrenica , [ B ] [ 8 ] было геноцида в июле 1995 года убийством [ 9 ] более 8000 [ 10 ] Босняк -мусульманские мужчины и мальчики в городе Сребреница и его окрестностях во время боснийской войны . [ 11 ] В основном это было совершено подразделениями боснийской сербской армии Республики Српска при Ratko Mladić Serb , хотя участвовали также участвовали в скорпионах . [ 6 ] [ 12 ] Резня была первым юридически признанным геноцидом в Европе с конца Второй мировой войны . [ 13 ]

Перед резней Организация Объединенных Наций (ООН) объявила осажденного анклава Сребеницы « безопасной зоной » под ее защитой. Защита ООН, контингент 370 [ 14 ] Слегка вооруженные голландские солдаты не смогли сдержать захват города и последующую резню. [ 15 ] [ 16 ] [ 17 ] [ 18 ] Список людей, пропавших без вести или убитых во время резни, содержит 8 372 имени. [ 2 ] По состоянию на июль 2012 года [update], 6838 жертв геноцида были идентифицированы с помощью ДНК -анализа частей тела, извлеченных из массовых могил; [ 19 ] По состоянию на июль 2021 г. [update]6671 тело было похоронены в Мемориальном центре Поточари , а еще 236 были похоронены в другом месте. [ 20 ]

Некоторые сербы утверждают, что резня была возмездием по жертвам гражданского населения, нанесенным сербам солдатами Босняка из Сребеницы под командованием Назер Орич . [ 21 ] [ 22 ] Эти претензии «Месть» были отвергнуты и осуждены Международным преступным трибуналом бывшей Югославии (ICTY) и ООН как недобросовестных попыток оправдать геноцид.

В 2004 году, в единогласном решении по делу прокурора против Крстича , апелляционная палата ИКти управляла резней жителей мужского пола анклава, представляла собой геноцид, преступление в соответствии с международным правом. [ 23 ] Постановление также было поддержано Международным судом в 2007 году. [ 24 ] Было обнаружено, что насильственный перевод и злоупотребление от 25 000 до 30 000 мусульманских женщин, детей и пожилых людей Босняка, которые сопровождались убийствами и разделением мужчин. [ 25 ] [ 26 ] В 2002 году, после отчета о резне, правительство Нидерландов подало в отставку, сославшись на его неспособность предотвратить резню. В 2013, 2014 и 2019 годах голландский штат был признан ответственным его Верховным судом и окружным судом Гаага, за то, что они не предотвратили более 300 смертей. [ 27 ] [ 28 ] [ 29 ] [ 30 ] В 2013 году президент Сербия Томислав Николич извинился за «преступление» Сребеницы, но отказался называть его геноцидом. [ 31 ]

В 2005 году тогда генеральный секретарь ООН Кофи Аннан назвал резню «ужасным преступлением-худшим на европейской земле со времен Второй мировой войны», [ 32 ] а в мае 2024 года ООН назначил 11 июля ежегодным Международным днем размышлений и поминовения геноцида 1995 года в Сребенике . [ 33 ] [ 34 ]

Фон

[ редактировать ]Конфликт в Восточной Боснии и Герцеговине

[ редактировать ]Мультитническая социалистическая Республика Босния и Герцеговина была в основном населенной мусульманскими босняками (44%), православными сербами (31%) и католическими хорватами (17%). Поскольку бывшая Югославия начала распадаться, регион объявил национальный суверенитет в 1991 году и провел референдум о независимости в феврале 1992 года. Результат, который предпочитал независимость, противостоял политическим представителям боснийцев, которые бойкотировали референдум. Республика Босния и Герцеговина были официально признаны Европейским сообществом в апреле 1992 года и ООН в мае 1992 года. [ 35 ] [ 36 ]

После заявления о независимости боснийские сербские силы, поддерживаемые сербским правительством и Слободана Милошевича Югославской народной армии (JNA), атаковали Боснию и Герцеговину, чтобы обеспечить и объединить территорию под контролем серб и создавать этническую гомогену Республика Српска . [ 37 ] В борьбе за территориальный контроль нежирб-популяции из районов под сербским контролем, особенно популяция Босняка в Восточной Боснии, недалеко от сербских границ, подвергались этническому очищению. [ 38 ]

Этническая чистка

[ редактировать ]Srebrenica и окружающий центральный регион Подринье имели огромное стратегическое значение для руководства боснийского серба. Это был мост, чтобы отключить части предполагаемого этнического состояния Республики Српска . [ 39 ] Захват Сребеницы и устранение ее мусульманского населения также подорвало бы жизнеспособность боснийского мусульманского государства. [ 39 ]

В 1991 году 73% населения в Сребенике были боснийскими мусульманами и 25% боснийских сербов. [ 40 ] Напряженность между мусульманами и сербами усилилась в начале 1990 -х годов, поскольку местному населению серб было предоставлено оружие и военная техника, распределенная военизированными группами серб, югославской армией («JNA») и Сербской Демократической партией («SDS») Полем [ 40 ] : 35

К апреле 1992 года Сребеника стала изолированной сербскими силами. 17 апреля боснийскому мусульманскому населению было дано 24-часовое ультиматум, чтобы сдать все оружие и покинуть город. Сребрена была кратко захвачена боснийскими сербами и приняла боснийские мусульмане 8 мая 1992 года. Тем не менее боснийские мусульмане остались в окружении сербских сил и отрезали из отдаленных районов. Судебное решение NASER ORIć описало ситуацию: [ 40 ] : 47

В период с апреля 1992 года по март 1993 года ... Сребрена и деревни в этом районе, принадлежащих Боснейке, постоянно подвергались военным нападениям серб, включая артиллерийские атаки, снайперский огонь ... случайные бомбардировки с самолетов. Каждый натиск последовал за аналогичной схемой. Сербские солдаты и военизированные формирования окружали боснийскую мусульманскую деревню ... призвали население сдать свое оружие, а затем начались с неизбирательного обстрела и стрельбы ... затем они вошли в деревню ... изгнали или убили население, которое не предложило значительного Сопротивление и уничтожило их дома ... Сребрена была подвергнута неизбирательному обстрелу из всех направлений ежедневно. Поточари, в частности, был ежедневной целью ... потому что это была чувствительная точка в линии обороны вокруг Сребеницы. Другие боснийские мусульманские поселения были также обычно атакованы. Все это привело к большому количеству беженцев и жертв.

В период с апреля по июнь 1992 года боснийские сербские силы, при поддержке JNA, уничтожили 296 преимущественно Боснейских деревень вокруг Сребеницы, насильственно искореные 70 000 босников из своих домов и систематически убили по меньшей мере 3166 босниаков, включая женщин, детей и пожилых людей. [ 41 ] В соседнем Братунаке босняки были либо убиты, либо вынуждены бежать в Сребенику, что привело к 1156 смертельным случаям. [ 42 ] Thousnds of Bosniaks были убиты в FOCA , Zvornik , Cerka и Snovo . [ 43 ]

1992-3: борьба за Сребенику

[ редактировать ]В течение оставшейся части 1992 года наступления боснианскими правительственными силами из Сребеницы увеличили этот район под их контролем, и к янвату 1993 года они связались с Босниак-Хельдом Жепа на юге и Серской на западе. Анклав Сребеницы достиг своего пикового размера 900 квадратных километров (350 квадратных миль), хотя он никогда не был связан с основной областью боснийской управляемой земли на западе и оставался, «уязвимый остров среди территории, контролируемой серб». [ 44 ] Армия Республики Босния и Герцеговина (Арбих) под руководством Назера Орич использовала Сребрена в качестве постановки, чтобы напасть на соседние сербские деревни, нанесенные на многие жертвы. [ 45 ] [ 46 ] военизированной сербской деревней Кравика В 1993 году Арбих был атакован , что привело к жертвам гражданского населения. Сопротивление Сербской осаде Сребеницы Арбихом, под Оричем, рассматривалось как катализатор резни.

Сербы начали преследовать боснийков в 1992 году. Сербская пропаганда считала сопротивление Боснийак атакам сербами как земля для мести. По словам французского генерала Филиппа Морильона , командующего Силами защиты ООН (непрофор), в показаниях в ICTY в 2004 году:

Судья Робинсон: Тогда вы говорите, что то, что произошло в 1995 году, было прямой реакцией на то, что Naser Oric сделал с сербами два года назад?

Свидетель: [интерпретация] Да. Да, ваша честь. Я убежден в этом. Это не означает просить или уменьшить ответственность людей, совершивших это преступление, но я убежден в этом, да. [ 47 ]

В течение следующих нескольких месяцев сербские военные захватили деревни Конжевича Поля и Серски, разорвав связь между Сребеникой и Жепой, и уменьшив анклав Сребеники до 150 квадратных километров. Жители отдаленных районов Босняка сходились на Сребенице, и ее население растет до 50 000 до 60 000, примерно в десять раз превышало довоенное население. [ 48 ] Генерал Морильон посетил Сребренику в марте 1993 года. Город был переполнен, а условия осады преобладали. Там почти не было водопроводной воды, так как продвигающиеся сербские силы разрушили водоснабжения; Люди полагались на самодельные генераторы для электричества. Еда, лекарства и другие предметы первой необходимости были скудными. Условия сделали Сребенику медленным лагерем смерти. [ 48 ] Морильон сказал паническим жителям на общественном собрании, что город находится под защитой ООН, и он никогда не отказался от них. В течение марта и апреля 1993 года было эвакуировано несколько тысяч боснийков под эгидой Верховного комиссара ООН по беженцам (УВКБ ООН). Эвакуации были против боснийского правительства в Сараево , что способствовало этническому очищению территории Босняка.

Власти серба оставались намерением захватить анклав. 13 апреля 1993 года сербы сообщили представителям УВКБ ООН, что они нападут на город в течение 2 дней, если только босняки не сдались и не согласятся эвакуироваться. [ 49 ]

Голод

[ редактировать ]Благодаря неспособности демилитаризации и нехваткой входа в поставки, Орич консолидировал свою силу и контролировал черный рынок. Люди Орича начали накопить еду, топливо, сигареты и растрату денег, отправленные агентствами по оказанию помощи для поддержки мусульманских сирот. [ 50 ] Основные потребности были недоступны для многих в Сребенице из -за действий Орича. Чиновники ООН начали терять терпение с Арбихом в Сребенице и считали их «лидерами преступных бандов, сутенерных и чернокожими». [ 51 ]

Бывший серб -солдат подразделения « Красные береты » описал тактику, используемую для голода и убийства осажденного населения:

Это было почти как игра, охота на кошку и мыши. Но, конечно, мы значительно превосходили численности мусульман, поэтому во всех случаях мы были охотниками, и они были добычей. Нам нужно было сдаться, но как заставить кого -то сдаться в такой войне? Вы голодаете их до смерти. Так что очень быстро мы поняли, что на самом деле не было оружие, которое ввещается в Сребенику, о котором мы должны беспокоиться, но еда. Они действительно голодали там, поэтому они посылали людей, чтобы украсть крупный рогатый скот или собирать урожай, и наша работа заключалась в том, чтобы найти и убить их ... никаких заключенных. Ну, да, если мы думали, что у них есть полезная информация, мы могли бы сохранить их в живых, пока мы не вытащим ее из них, но в конце Передай им [чтобы убить], чтобы они были счастливы. [ 52 ]

Когда в марте 1993 года британский журналист Тони Биртли посетил Сребренику, он снял кадры гражданских лиц, голодающих. [ 53 ] Гаагский трибунал в случае Орича пришел к выводу:

Боснийские сербские силы, контролирующие дороги доступа, не позволяли международной гуманитарной помощи, что самое главное, еда и медицина - добраться до Сребеницы. Как следствие, существовала постоянная и серьезная нехватка пищи, вызывающая голод до пика зимой 1992/1993 года. Многочисленные люди погибли или находились в чрезвычайно истощенном состоянии из -за недоедания. Однако боснийскому мусульманским бойцам и их семьям были предоставлены продовольственные рационы из существующих хранилищ. Наиболее обездоленной группой среди боснийских мусульман была группа беженцев, которые обычно жили на улицах и без укрытия, при температуре замерзания. Только в ноябре и декабре 1992 года два конвоя ООН с гуманитарной помощью достигли анклава, и это, несмотря на обструкцию боснского серба ». [ 54 ]

1993-95: Srebrenica "безопасная зона"

[ редактировать ]Совет Безопасности ООН объявляет Сребенику «безопасной зоной»

[ редактировать ]

16 апреля 1993 года Совет Безопасности Организации Объединенных Наций принял резолюцию 819 , которая требовала «всех сторон ... относиться к Сребенике и ее окрестностям как безопасную область , которая должна быть свободна от любого вооруженного атаки или ... враждебного акта». [ 55 ] 18 апреля в Сребеница прибыла первая группа непрофильных войск. Непрофильные развернули канадские войска, чтобы защитить его как один из пяти недавно установленных «безопасных зон» ООН. [ 48 ] Присутствие Неумпорита предотвратило тотальное нападение, хотя стычки и растворы продолжались. [ 48 ]

8 мая 1993 года было достигнуто соглашение о демилитаризации Сребеницы. Согласно сообщению ООН, «Генерал [Сефер] Халилович и генерал Младич согласились на меры, охватывающие весь анклав Сребеники и ... Жепа. ... Боснякские силы ... передадут свое оружие, боеприпасы и шахты , после чего серб «тяжелое оружие и подразделения, которые представляют угрозу для демилитаризованных зон ... будут отозваны». В отличие от более раннего соглашения, в нем конкретно указано, что Srebrenica должна считаться «демилитаризованной зоной», как упоминалось в ... Женевских конвенциях ». [ 56 ] Обе стороны нарушили соглашение, хотя два года относительной стабильности последовали за установлением анклава. [ 57 ] Подполковник Том Карреманс ( командир из голландского коса ) показал, что его персонал не смог вернуться в анклав сербскими силами, и что оборудование и боеприпасы были предотвращены. [ 58 ] Босняки в Сребенике жаловались на атаки со стороны сербских солдат, в то время как сербам, по-видимому, боснийские силы использовали «безопасную зону», в качестве удобной базы для запуска противодействий, и непревзойденное не было, чтобы предотвратить ее. [ 58 ] : 24 Генерал Сефер Халилович признал, что вертолеты Арбих летали в нарушение зоны без лета, и он отправил 8 вертолетов с боеприпасами для 28-й дивизии. [ 58 ] : 24

корпусов VRS Drina От 1000 до 2000 солдат из бригад были развернуты вокруг анклава, оснащенные танками, бронированными транспортными средствами, артиллерией и минометами . 28 -я горная дивизия армии Республики Босния и Герцеговина (Арбих) в анклаве не была ни хорошо организована, ни оборудована, и не имела твердой командной структуры и системы связи. Некоторые из его солдат несли старые охотничьи винтовки или не было оружием, немногие имели надлежащую форму.

ООН неспособность демилитаризировать

[ редактировать ]Миссия Совета Безопасности, возглавляемая Диего Аррией, прибыла 25 апреля 1993 года, и в своем отчете ООН осудила сербов за совершение «процесса медленного движения геноцида». [ 59 ] Миссия заявила, что «силы серб должны выйти на точки, из которых они не могут атаковать, преследовать или терроризировать город. Непрофильный должен быть в состоянии определить связанные параметры. Миссия верит, как и не достоверно, что фактическое 4,5 км (3 мили. ) на 0,5 км (530 ярдов) определяется, поскольку безопасная область должна быть значительно расширена ». Конкретные инструкции штаб -квартиры ООН в Нью -Йорке заявили, что не должен быть слишком усердным в поиске оружия Босняка, и сербы должны снять свое тяжелое оружие, прежде чем босняки разоружались, что сербы никогда не делали. [ 59 ]

Попытки демилитаризации арбиха и отмены силы VRS оказались бесполезными. Арбих спрятал большую часть своего тяжелого оружия, современного оборудования и боеприпасов в окружающем лесу и только передал заброшенное и старое оружие. [ 60 ] VRS отказалась выйти из линии фронта из -за интеллекта, которую они получили в отношении скрытого оружия Арбиха. [ 60 ]

В марте 1994 года дока не послал 600 голландских солдат («голландский»), чтобы заменить канадцев. К марту 1995 года сербские силы контролировали всю территорию, окружающую Сребренику, предотвращая даже доступ к дороге по снабжению. Гуманитарная помощь уменьшилась, и условия жизни быстро ухудшились. [ 48 ] Неудовлетворительное присутствие предотвращало всеобъемлющее нападение на безопасную область, хотя стычки и растворы продолжались. [ 48 ] Голландский дюйм предупредил достоверное командование о страшных условиях, но донфор отказался посылать гуманитарную помощь или военную поддержку. [ 48 ]

Организация допророчных и UNPF

[ редактировать ]В апреле 1995 года «Неудовлетворительный» стал именем, используемым для регионального командования Боснии и Герцеговины, давших давних сил Соединенных Наций (UNPF). [ 61 ] Отчет Srebrenica 2002 года: «Безопасные» участки »12 июня 1995 года. Новая команда была создана в соответствии с UNPF», [ 61 ] с «12 500 британскими, французскими и голландскими войсками, оснащенными танками и артиллерией высокого калибра, чтобы повысить эффективность и доверие к миротворческой операции». [ 61 ] В отчете говорится:

В цепочке командования допрофки голландский балл занимал четвертый уровень, а командиры сектора занимали третий уровень. Четвертый уровень в первую очередь имел оперативную задачу ... Ожидалось, что Dutchbat будет работать в качестве независимой единицы со своими собственными логистическими соглашениями. Голландскийбат в некоторой степени зависел от непрофильной организации для таких важных поставок, как топливо. В остальном он должен был получить свои припасы из Нидерландов. С организационной точки зрения, в батальоне было две линии жизни: допрофра и Королевская Армия Нидерландов. Голландец была назначена ответственность за безопасную зону Сребеники. Однако ни допрофор, ни Босния-Херцеговина уделяли особое внимание Сребенике. Сребрена была расположена в Восточной Боснии и Герцеговине, которая географически и психически удалена от Сараево и Загреба. Остальной мир была сосредоточена на борьбе за Сараево ... как безопасная область, Сребеница лишь иногда сумела привлечь внимание мировой прессы или Совета Безопасности ООН. Вот почему голландские войска там оставались второстепенными, в оперативных и логистических терминах так долго; и почему важность анклава в битве за доминирование между боснийскими сербами и боснийскими мусульманами не смогла быть признанными так долго. [ 62 ]

Ситуация ухудшается

[ редактировать ]К началу 1995 года меньше и меньше конвоя снабжения добрались до анклава. Ситуация в Сребенике и других анклавах ухудшилась в беззаконии как проституция среди молодых мусульманских девушек, кражи и чернокожих рынка, распространенных. [ 63 ] Уже скудные ресурсы сократились дальше, и даже силы ООН начали опасно набрать пищу, медицину, боеприпасы и топливо, в конечном итоге были вынуждены начать патрулирование пешком. Голландские солдаты, которые ушли в отпуске, не разрешалось вернуться, [ 59 ] И их номер упал с 600 до 400 человек. В марте и апреле голландские солдаты заметили создание сербских сил.

В марте 1995 года Радан Караджич , президент Республики Српска (RS), несмотря на давление со стороны международного сообщества, чтобы положить конец войне и усилия по переговорам о мире, выпустил директиву VRS, касающуюся долгосрочной стратегии в анклаве. Директива, известная как «Директива 7», указала, что VRS была:

Завершите физическое отделение Srebrenica от žepa как можно скорее, предотвращая даже общение между людьми в двух анклавах. Попланированными и продуманными боевыми операциями, создайте невыносимую ситуацию полной незащищенности без надежды на дальнейшее выживание или жизнь для жителей Сребреницы. [ 64 ]

К середине 1995 года гуманитарная ситуация в анклаве была катастрофической. В мае, по приказу, Орич и его сотрудники покинули анклав, оставив старших офицеров в команде 28 -го дивизиона. В конце июня и начале июля 28 -й дивизион опубликовал отчеты, в том числе срочные просьбы о том, чтобы гуманитарный коридор был вновь открыт. Когда это потерпело неудачу, гражданские жители Босняка начали умирать от голода. 7 июля мэр сообщил, что 8 жителей умерли. [ 65 ] 4 июня, командир -докарнар Бернард Янвье , француз, тайно встретился с Младичем, чтобы получить освобождение заложников, многие из которых были французскими. Младич потребовал от Янвьера, что не будет больше авиаударов. [ 66 ]

В течение недель, предшествовавших нападению на Сребенику в результате VRS, силам Арбиха было приказано провести атаки в отвлечение и разрушение на VRS High Command. [ 67 ] Однажды 25 июня силы Арбих атаковали подразделения VRS на Сараево -Зворник дороге , нанеся высокие жертвы и грабежи запасы VRS. [ 67 ]

6–11 июля 1995 г.: поглощение серба

[ редактировать ]Наступление Серба против Сребеницы началось всерьез 6 июля. VRS, с 2000 солдатами, были превзойдены защитниками и не ожидали, что нападение будет легкой победой. [ 67 ] 5 непревзойденных наблюдений на юге Анклава упали перед лицом боснийского сербского аванса. Некоторые голландские солдаты отступили в анклав после нападения на их посты, экипажи других наблюдений сдались под стражей в серб. Защищающиеся боснийские силы, насчитывающие 6000, попали под огонь и были отодвинуты обратно к городу. Как только южный периметр начал рушиться, около 4000 жителей Босняка, которые жили в шведском жилищном комплексе для беженцев поблизости, бежали на север в Сребренику. Голландские солдаты сообщили, что продвинутые сербы были «очищают» дома на юге анклава. [ 68 ]

8 июля голландская бронетанковая машина YPR-765 подожгла с сербов и ушел. Группа боснийков потребовала, чтобы автомобиль оставался для их защиты, и создала импровизированную баррикаду, чтобы предотвратить его отступление. Когда автомобиль вышел, боснийский фермер, управляющий баррикадой, бросил на нее гранату и убил голландского солдата Равив Ван Ренсен. [ 69 ] 9 июля, воодушевленный успехом, небольшое сопротивление от демилитаризованных боснийков и отсутствие реакции международного сообщества, президент Караджич издал новый приказ, разрешающий 1500 человек. [ 70 ] VRS Drina Corps для захвата Srebrenica. [ 68 ]

На следующее утро, 10 июля, подполковник Карреман сделал неотложные просьбы о поддержке воздуха со стороны НАТО защитить Сребенику, когда толпы заполняли улицы, некоторые из которых носили оружие. Приближались танки VRS, и авиаудары НАТО на них начались 11 июля. Бомбардировщики НАТО пытались атаковать артиллерийские места VRS за пределами города, но плохая видимость заставила НАТО отменить это. Дальнейшие воздушные атаки были отменены после угроз VRS бомбить комплекс Поточари ООН, убийства голландских и французских военных заложников и нападения вокруг мест, где находились от 20 000 до 30 000 гражданских беженцев. [ 68 ] 30 голландских заложников были заложны войсками Младика. [ 48 ]

В конце дня 11 июля генерал Младич в сопровождении генерала Живановича (командующего корпусом Дрины), генералом Крстичем (заместитель командира Корпуса Дрины) и других офицеров VRS, прошел триумфальную прогулку по пустынным улицам Сребренки. [ 68 ] Вечером, [ 71 ] Подполковник Карреманс был снят, выпивая тост с Младичем во время охваченных переговоров о судьбе гражданского населения, сгруппированного в Поточари. [ 14 ] [ 72 ]

Резня

[ редактировать ]Два высокопоставленных сербских политиков из Боснии и Герцеговины, Караджич и Момхило Краджишника , оба обвиненных в геноциде, были предупреждены командиром VRS Mladić (признан виновным в геноциде в 2017 году) о том, что их планы не могли реализоваться без совершения геноцида. Младич сказал на парламентской сессии от 12 мая 1992 года:

Люди - это не маленькие камни или ключи в чьем -то кармане, которые могут быть перемещены из одного места в другое, так же, как это ... поэтому мы не можем точно устроить только сербы, чтобы остаться в одной части страны, при этом безболезненно снимая других. Я не знаю, как г -н Краджишник и мистер Караджич объяснит это миру. Это геноцид. [ 73 ]

Увеличение концентрации беженцев в Поточари

[ редактировать ]

К вечеру 11 июля в Поточари были собраны примерно 20 000-25 000 беженцев Босняка из Сребеницы, в результате чего в штаб-квартире голландского коса . Несколько тысяч давили внутри соединения, в то время как остальные были распространены на соседних заводах и полях. Хотя большинство из них были женщины, дети, пожилые люди или инвалиды, 63 свидетелей, по оценкам, в толпе находились не менее 300 мужчин, и от 600 до 900 на улице. [ 74 ]

Условия включали «маленькую пищу или воду» и душное жар. Офицер -офицер в голландском языке описал эту сцену:

Они были в панике, они были напуганы, и они прижимали друг к другу против солдат, моих солдат, солдат ООН, которые пытались их успокоить. Люди, которые упали, были растоптаны. Это была хаотическая ситуация. [ 74 ]

12 июля Совет Безопасности ООН в резолюции 1004 выразил обеспокоенность по поводу гуманитарной ситуации в Поточари, осудил наступление боснийскими сербскими силами и потребовал немедленного вывода. 13 июля голландские войска изгнали 5 беженцев Босняка из комплекса, несмотря на то, что знали, что мужчины снаружи были убиты. [ 75 ]

Преступления, совершенные в Потокари

[ редактировать ]12 июля беженцы в комплексе могли видеть, как члены VRS поджигают дома и стоки сена. В течение дня сербские солдаты смешались с толпой, и произошли краткие казни людей. [ 74 ] Утром 12 июля свидетель увидел кучу из 20-30 тел, собравшихся за транспортным зданием, вдоль тракторной машины. Другой показал, что он увидел, как солдат убил ребенка с ножом, посреди толпы отчитанных. Он сказал, что видел, как солдаты Сербов казнили более ста босняк -мусульманских мужчин за фабрикой цинка, а затем загружают свои тела на грузовик, хотя число и природа убийств в отличие от других доказательств в судебном процессе, которые указывали на убийства в Поточари, были спорадический характер. Солдаты выбирали людей из толпы и убирали их. Свидетель рассказал, как три брата - один просто ребенок, остальные в подростковом возрасте - были вывезены ночью. Когда мать мальчиков пошла искать их, она обнаружила, что они резко обнажены, а с надбил горло. [ 74 ] [ 76 ]

Той ночью медицинский медицинский голландский бассейн упорядочил, что два солдата Серба изнасиловали женщину. [ 76 ] Оставшийся в живых, Зарфа Туркович, описал ужасы: «Двое [солдат -серб] взяли ее ноги и подняли их в воздухе, в то время как третье начало насиловать ее. Четверо из них по очереди. Люди молчали, и никто не двигался I. [ 77 ] [ 78 ]

Убийство мужчин и мальчиков Босняка и Поточари

[ редактировать ]С утра 12 июля войска сербов начали собирать мужчин и мальчиков из населения беженцев в Поточари и удерживая их в отдельных местах, и когда беженцы начали садиться на автобусы, направлявшиеся на север в сторону территории, удерживаемой Боснейаком, сербские солдаты отделяли мужчины военного возраста. которые пытались карабкаться на борту. Иногда молодые и пожилые мужчины также останавливались (некоторые из них в возрасте 14 лет). [ 79 ] [ 80 ] [ 81 ] Эти люди были доставлены в здание, называемое «Белым домом». К вечеру 12 июля майор Франкен из голландского, услышав, что ни один мужчина не прибывает с женщинами и детьми, в их пункт назначения в Кладандже . [ 74 ] Директор по операциям УВКБ ООН, Питер Уолш, был отправлен в Сребенику руководителем миссии Дамасо Фечи, чтобы оценить, какая чрезвычайная помощь может быть быстро предоставлена. Уолш и его команда прибыли в Гостилдж, недалеко от Сребеницы, во второй половине дня, чтобы быть отвергнутыми силами VRS. Несмотря на то, что команде УВКБ ООН не разрешалось продолжить свободу движения, команде УВКБ ООН не разрешили отправиться в Биджелину. Повсюду Уолш ретранзировал отчеты в УВКБ ООН в Загребе о разворачивающейся ситуации, в том числе свидетельствует о насильственном движении и злоупотреблении мусульманскими мужчинами и мальчиками, а также о звучании казней. [ Цитация необходима ]

13 июля войска Голландии стали свидетелями определенных признаков, которые солдаты, которые были убиты босняками, которые были разделены. Капрал Васен увидел, как два солдата взяли человека за «Белым домом», услышал выстрел и увидел, как два солдата появились в одиночестве. Другой офицер из голландского коса увидел, как Сербские солдаты убивали безоружного человека с огнестрельным выстрелом в голову и услышал выстрелы 20–40 раз в час в течение дня. Когда солдаты из голландея рассказали полковнику Джозефу Кингори, военному наблюдателю Организации Объединенных Наций (ЮМП) в районе Сребеницы, что мужчин брали за «Белым домом» и не вернулись, Кингори отправился на расследование. Он услышал выстрелы, когда подошел, но был остановлен солдатами серб, прежде чем он смог выяснить, что происходит. [ 74 ]

Некоторые казни проводились ночью под дуговыми огнями, а бульдозеры затем толкнули тела в массовые могилы. [ 82 ] Согласно доказательствам, собранным у Босняков французским полицейским Жан-Рен Руэсом, некоторые были похоронены заживо; Он услышал показания, описывающие, что сербские силы убивают и мучали беженцев, улицы завалены трупами, люди, совершающие самоубийство, чтобы избежать их носов, губ и ушей, а взрослые заставляют наблюдать, как солдаты убивают своих детей. [ 82 ]

Изнасилование и злоупотребление гражданскими лицами

[ редактировать ]Тысячи женщин и девочек перенесли изнасилование, сексуальное насилие и другие формы пыток. Согласно показаниям Zumra ushomerovic:

Сербы начались в определенный момент, чтобы вывести девушек и молодых женщин из группы беженцев. Они были изнасилованы. Изнасилования часто происходили под глазами других, а иногда даже под глазами детей матери. Голландский солдат стоял рядом, и он просто оглянулся с пешеходом на голове. Он вообще не отреагировал на то, что происходило. Это произошло не как раз перед моими глазами, потому что я видел это лично, но и перед глазами всех нас. Голландские солдаты ходили повсюду. Невозможно, чтобы они этого не видели.

Была женщина с маленьким ребенком несколько месяцев. Четник сказал матери , что ребенок должен перестать плакать. Когда ребенок не перестал плакать, он вырвал ребенка и вырезал горло. Затем он засмеялся. Там был голландский солдат, который смотрел. Он вообще не отреагировал.

Я видел еще более страшные вещи. Например, была девушка, которой, должно быть, было около девяти лет. В определенный момент некоторые Четники рекомендовали ее брату, чтобы он изнасиловал девушку. Он не сделал этого, и я также думаю, что он не мог сделать это, потому что он все еще был просто ребенком. Затем они убили этого молодого мальчика. Я лично видел все это. Я действительно хочу подчеркнуть, что все это произошло в непосредственной близости от базы. Точно так же я видел других людей, которые были убиты. Некоторые из них вырезали горло. Другие были обезглавлены . [ 83 ]

Свидетельство Рамизы Гурдич:

Я видел, как молодой мальчик из десяти был убит сербами в голландской форме. Это произошло на моих собственных глазах. Мать сидела на земле, и ее маленький сын сидел рядом с ней. Молодой мальчик был помещен на колени его матери. Молодой мальчик был убит. Его голова была отрезана. Тело осталось на коленях матери. Сербский солдат положил голову молодому мальчику на нож и показал его всем. ... Я видел, как была забита беременной женщиной. Были сербы, которые зарезали ее в живот, вырезали ее и вытащили двух маленьких детей из живота, а затем избили их до смерти на земле. Я видел это своими глазами. [ 84 ]

Свидетельство о том, когда хит:

На пути к автобусу была молодая женщина с ребенком. Ребенок плакал, и сербский солдат сказал ей, что она должна убедиться, что ребенок тихо. Затем солдат взял ребенка из матери и перерезал ему горло. Я не знаю, видели ли голландские солдаты это. ... На левой стороне дороги был своего рода забор. Я услышал, как молодая женщина кричала очень близко (4 или 5 метров). Затем я услышал, как другая женщина просила: «Оставь ее, ей всего девять лет». Крик внезапно остановился. Я был так в шоке, что едва ли мог двигаться. ... Позднее слухи быстро распространились, что девятилетняя девочка была изнасилована. [ 85 ]

Той ночью медицинский медицинский голландский бассейн наткнулся на двух сербских солдат, насиловающих молодую женщину:

[Мы увидели двух сербских солдат, один из них стоял на страже, а другой лежал на девушке, с его штанами. И мы увидели девушку, лежащую на земле, на каком -то матрасе. На матрасе была кровь, даже она была покрыта кровью. У нее были синяки на ногах. Спускалась даже кровь. Она была в полном шоке. Она сошла с ума.

Боснийские мусульманские беженцы поблизости могли видеть изнасилование, но ничего не могли с этим поделать из -за, стоящих поблизости сербских солдат. Другие люди слышали, как женщины кричали или видели, как женщины вытащили. Несколько человек были настолько напуганы, что покончили жизнь самоубийством, повесившись. В течение ночи и рано следующее утро истории об изнасилованиях и убийствах распространились по толпе, и террор в лагере обострился.

Крики, выстрелы и другие пугающие звуки были слышен в течение ночи, и никто не мог спать. Солдаты выбирали людей из толпы и убирали их: некоторые вернулись; другие не сделали .... [ 86 ]

Депортация женщин

[ редактировать ]В результате исчерпывающих переговоров ООН с сербскими войсками около 25 000 женщин Сребреницы были насильственно переведены на территорию, контролируемую Боснийак. Некоторые автобусы, очевидно, никогда не достигли безопасности. Согласно свидетельству Кадира Хабибовича, который спрятался на одном из первых автобусов с базы в Поточари в Кладандж, он увидел по крайней мере один автомобиль, полный боснийских женщин, изгнанных от территории, удостоенной Боснианской правительства. [ 87 ]

Колонка босняк

[ редактировать ]

Вечером 11 июля распространилось, что трудоспособные люди должны взять в лес, сформировать колонну с 28-м дивизией Арбиха и попытаться прорывать в направлении боснийской территории правительства на севере. [ 88 ] Они верили, что у них больше шансов выжить, пытаясь сбежать, чем если бы они попали в серб. [ 89 ] Около 10 часов вечера 11 июля командование подразделения, с муниципальными властями, приняло решение сформировать колонку и попытаться достичь правительственной территории вокруг Тузлы. [ 90 ] Обезвоживание, наряду с отсутствием сна и истощения были дальнейшими проблемами; Было мало сплоченности или общей цели. [ 91 ] Попутно колонна была обстреляна и засада. В тяжелом психическом расстройстве некоторые беженцы погибли. Другие были вызваны сдачей. Оставшиеся в живых утверждали, что на них напали химический агент, который вызвал галлюцинации, дезориентацию и странное поведение. [ 92 ] [ 93 ] [ 94 ] [ 95 ] Протекатели в гражданской одежде смущены, напали и убивали беженцев. [ 92 ] [ 96 ] Многие взятые в плен были убиты на месте. [ 92 ] Другие были собраны и отправлены в отдаленные местоположения, для исполнения.

Атаки разбили колонку на меньшие сегменты. Только около одной трети удалось пересечь асфальтовую дорогу между Конжевичем Польже и Новой Касабой . Эта группа достигла территории правительства Боснина на и после 16 июля. Вторая меньшая группа (700-800) попыталась сбежать в Сербию через гору Кварак , Братунак или через реку Дрину и через Баджину Башту . Неизвестно, сколько было перехвачено и убито. Третья группа направилась к žepa, оценки того, сколько варьируется от 300 до 850 лет. Карманы сопротивления, по -видимому, оставались позади и задействовали сербские силы. [ Цитация необходима ]

Колонна Tuzla выходит

[ редактировать ]Почти все 28 -й дивизион, от 5500 до 6000 солдат, не все вооруженные, собрались в Шушнджари , на холмах к северу от Сребеницы, а также около 7000 гражданских лиц. Они включали несколько женщин. [ 90 ] Другие собрались в соседней деревне Джагличи. [ 97 ]

Около полуночи колонна начала двигаться вдоль оси между Конжевичем Польже и Братунаком. Ему предшествовали четыре скаута, на 5 км впереди. [ 98 ] Участники ходили один позади другой, следуя бумажной тропе, проложенной упущенным подразделением. [ 99 ]

Колонна была возглавляна 50–100 лучших солдат из каждой бригады с лучшим оборудованием. За элементами 284 -й бригады последовали 280 -я бригада. Последовали гражданские лица, сопровождаемые другими солдатами, и сзади был независимый батальон. [ 90 ] Команда и вооруженные люди были на передней части, после подразделения полумарина. [ 99 ] Другие включали политических лидеров анклава, медицинского персонала и семей выдающихся шребренеров. Несколько женщин, детей и пожилых людей путешествовали с колонкой в лесу. [ 88 ] [ 100 ] Колонна была длиной 12-15 км, два с половиной часа отделяя голову от хвоста. [ 90 ]

Попытка добраться до Тузлы удивила VRS и вызвала путаницу, поскольку VR ожидали, что люди отправятся в Поточари. Генерал Серб Милан Гверо на брифинге назвал колонку «закаленными и насильственными преступниками, которые не останутся ни перед чем, чтобы не допустить в плен». [ 101 ] Дрина, основной персонал VRS, приказал всем доступным рабочей силе найти любые наблюдаемые мусульманские группы, не допустить их перехода на мусульманскую территорию, взять их в плену и держать их в зданиях, которые могут быть закреплены небольшими силами. [ 102 ]

Засад и Каменика Хилл

[ редактировать ]Ночью плохая видимость, страх перед шахтами и паника, вызванная артиллерийским огнем, разделили колонну на две части. [ 103 ] Во второй половине дня 12 июля передняя часть появилась из леса и переселала асфальтовую дорогу от Коньевича Поля и Нова Касабы. Около 6 вечера армия VRS обнаружила основную часть колонны вокруг Каменицы. Около 8 вечера эта часть, возглавляемая муниципальными властями и ранеными, начала спускаться с холмом Каменики к дороге. После того, как примерно 40 человек пересекли, солдаты VRS прибыли со стороны Kravica в грузовиках и бронетехниках, в том числе белый автомобиль с непроформированными символами, призывая к сдачу громкоговорителя. [ 103 ]

Наблюдался желтый дым, за которым последовало странное поведение, включая самоубийства, галлюцинации и члены колонны, атаковывающие друг друга. [ 92 ] Оставшиеся в живых утверждали, что на них напали химический агент, который вызвал галлюцинации и дезориентацию. [ 93 ] [ 94 ] Генерал Толимир был сторонником использования химического оружия против Арбиха. [ 95 ] [ 104 ] Стрельба и обстрел начались, которые продолжались до ночи. Вооруженные члены колонны вернули огонь и все разбросаны. Оставшиеся в живых не менее 1000 человек на близком расстоянии задействованы с помощью стрелкового оружия. Похоже, что сотни были убиты, когда они бежали на открытую площадку, а некоторые убили себя, чтобы избежать захвата. [ Цитация необходима ]

VRS и Министерство внутренних сотрудников убедили членов колонны сдаться, обещая им безопасную транспортировку в сторону Тузлы под присмотром и Красного Креста. Присвоенное оборудование ООН и Красного Креста использовалось для их обмана. Вещи были конфискованы, а некоторые казнены на месте. [ 103 ]

Задняя часть колонны потеряла контакт, а паника вспыхнула. Многие оставались в районе холма Каменица в течение нескольких дней, а маршрут побега заблокирована сербскими силами. Тысячи боснийцев сдались или были захвачены. Некоторым было приказано вызвать друзей и семью из леса. Были сообщения о том, что сербские силы, использующие мегафоны, чтобы призвать марша сдаться, сообщив им, что их обменены на солдаты серб. Именно в Каменице сообщалось, что сотрудники VRS в гражданской одежде проникли в колонку. Мужчины, которые выжили, описали это как охоту. [ 88 ]

Резня в Сандиси

[ редактировать ]

Рядом с Сандичи, на главной дороге от Братунака до Конжевича Поля, свидетель описал сербов, заставляющих босняка, чтобы вызвать других босняков вниз с гор. 200-300 человек, включая брата-свидетеля, спустились, чтобы встретить VRS, предположительно ожидая обмена заключенными. Свидетель спрятался за деревом и наблюдал за тем, как мужчины выстроились в семь рядов, каждый 40 метров, с руками за головой; Затем они были сшиты пулеметами. [ 92 ]

Некоторым женщинам, детям и пожилым людям, которые были частью колонны, было разрешено присоединиться к автобусам, эвакуационным женщинам и детям из Поточари. [ 105 ]

Поездка на гору Удру

[ редактировать ]Центральная часть колонны удалось избежать стрельбы, достигла Каменицы около 11 часов утра и ждала раненых. Капитан Голич и независимый батальон повернулись к Хадждучко Гроббле, чтобы помочь потери. Оставшиеся в живых с задней части пересекали асфальтовые дороги на севере или на западе и присоединились к центральной части. Передняя треть колонны, которая покинула Каменици -Хилл к тому времени, когда произошла засада, направилась на гору Удру ( 44 ° 16′59 ″ с.ш. 19 ° 3′6 ″ E / 44,28306 ° N 19,05167 ° E ); пересечение главной асфальтовой дороги. Они достигли основания горы в четверг 13 июля и перегруппировались. Сначала было решено отправить 300 солдат Арбих обратно, чтобы прорваться через блокады. Когда появились сообщения о том, что центральная часть переселала дорогу в Коньевичах Полже, этот план был заброшен. Приблизительно 1000 дополнительных мужчин удалось добраться до Удрчу в ту ночь. [ 106 ]

Снагово засаду

[ редактировать ]От Удрча марша переехал к реке Дринджача и горы Вельджа Глава. В пятницу, 14 июля, в пятницу, 14 июля, нахождение сербов в горе Вельджа и ждала на его склонах, прежде чем двигаться к Липле и Марчичи. Прибыв в Марчичи вечером 14 июля, они снова попали в засаду недалеко от Снагово силами, оснащенными зенитными орудиями, артиллерией и танками. [ 107 ] Колонна прорвалась и захватила офицера VRS, предоставив им счетчик переговоров. Это вызвало попытку договориться о прекращении огня, но это не удалось. [ 91 ]

Приближаясь к фронта

[ редактировать ]Вечер 15 июля увидел первый радиосвязь между 2 -м корпусом и 28 -й дивизией. Братья Шабич смогли идентифицировать друг друга, когда они стояли по обе стороны от линий VRS. Рано утром колонна пересекла дорогу, связывающую Зворник с Капардом, и направилась к Планинчи, оставив 100-200 вооруженных маршам позади, чтобы ждать отставших. [ Цитация необходима ] Колонна достигла Крижевичи позже в тот же день и осталась, когда была предпринята попытка договориться с сербскими силами для безопасного прохода. Им посоветовали остаться там, где они были, и позволили сербским силам организовать безопасный проход. Стало очевидным, что небольшая сербская сила только пыталась получить время, чтобы организовать еще одну атаку. В районе Марчичи - Crni vrh вооруженные силы VRS развернули 500 солдат и полицейских, чтобы остановить разделенную часть колонны, около 2500 человек, которые двигались из Глоди в сторону Марчичи. [ Цитация необходима ] Лидеры колонки решили сформировать небольшие группы из 100-200 и отправить их в разведку вперед. 2 -й корпус и 28 -й дивизион Арбих встретились друг с другом в Поточани.

Прорыв в Baljkovica

[ редактировать ]Склон холма в Baljkovica ( 44 ° 27′N 18 ° 58′E / 44,450 ° N 18,967 ° E ) сформировала последнюю линию VRS, отделяющую колонку от боснийской территории. Кордон VRS состоял из двух линий, первая из которых представил фронт на стороне Тузла, против 2 -го корпуса, а другой - фронт против приближающегося 28 -го дивизиона. [ Цитация необходима ]

Вечером 15 июля град заставил сербских сил укрыться. Предварительная группа колонны воспользовалась преимуществом, чтобы атаковать сербные задние линии в Baljkovica. Основное тело того, что осталось от колонны, начало двигаться от Кризвичи. Он достиг области борьбы около 3 часов утра в воскресенье, 16 июля. [ Цитация необходима ] Примерно в 5 часов утра 2 -й корпус предпринял свою первую попытку прорваться через кордон VRS. Цель состояла в том, чтобы прорываться рядом с деревнями Парлога и Реника. К ним присоединились Орич и некоторые из его людей. [ Цитация необходима ] Около 8 часов утра, части 28 -й дивизии, с 2 -м корпусом армии RBIH от Тузла, обеспечивающего артиллерийскую поддержку, атаковали и нарушали линии VRS. Был ожесточенные борьбы по всему Бальджковике. [ 108 ] Колонна, наконец, удалось пробиться на боснийскую территорию, контролируемую правительством, с 1 до 22 часов. [ Цитация необходима ]

BALJKOVICA CORIDOR

[ редактировать ]После переговоров по радио между 2 -м корпусом и бригадой Zvornik командование бригады согласилась открыть коридор, чтобы разрешить «эвакуацию» колонны в обмен на выпуск захваченных полицейских и солдат. Коридор был открыт 2-5 вечера. [ 109 ] После того, как коридор был закрыт с 5 до 6 часов вечера, бригада Zvornik Command сообщила, что около 5000 гражданских лиц, вероятно, с ними было пропустило «определенное количество солдат», но «все, кто прошел, были безоружны». [ 110 ]

Примерно к 4 августа Арбих определил, что 3175 членам 28 -й дивизии удалось добраться до Тузлы. 2628 членов Отдела, солдаты и офицеры, считались уверенными. Убитые члены колонки были от 8300 до 9,722. [ 111 ]

После закрытия коридора

[ редактировать ]После того, как коридор закрылся, силы сербов возобновили охоту по частям колонны. Сообщалось, что около 2000 беженцев скрывались в лесу в районе Побустре. [ 110 ] 17 июля четверо детей в возрасте от 8 до 14 лет, захваченных бригадой Братунак, были доставлены в военные казармы в Братуне. [ 110 ] [ 112 ] Командир бригады Благоевич предложил записи пресс -блока корпуса Дрины это показания на видео. [ 112 ]

18 июля, после того, как солдат был убит, «пытаясь запечатлеть некоторых людей во время поисковой операции», командование бригады Zvornik издало приказ о казнях заключенных, чтобы избежать каких -либо рисков, связанных с их захватом. Предполагалось, что приказ оставался в силе до тех пор, пока 21 июля не будет выполнено. [ 110 ]

Влияние на выживших

[ редактировать ]Согласно качественному исследованию в 1998 году с участием выживших, многие члены колонки в различной степени проявляли симптомы галлюцинаций. [ 113 ] Несколько раз мужчины Босняк атаковали друг друга, в страхе, что другой был солдатом серба. Оставшиеся в живых сообщили, что люди бессвязно говорят, что в ярости бегут в ярости и совершают самоубийство, используя огнестрельное оружие и ручные гранаты. Хотя не было никаких доказательств того, что именно вызвало поведение, исследование показало, что усталость и стресс, возможно, вызвали это. [ 113 ]

План выполнения мужчин

[ редактировать ]Хотя войска сербов долгое время обвиняли в убийстве, только в 2004 году - последовало за отчетом Комиссии Сребреники - чиновники серба признали, что их силы совершили массовые убийства. Их доклад признал, что было запланировано массовое убийство мужчин и мальчиков, и более 7800 были убиты. [ 114 ] [ 115 ] [ 116 ]

Были предприняты согласованные усилия, чтобы запечатлеть всех боснийских людей военного века. [ 117 ] Фактически, захваченные включали много мальчиков, намного ниже этого возраста, и мужчины выше этого возраста, которые остались в анклаве после взлета Сребеники. Эти мужчины и мальчики были нацелены, независимо от того, решили ли они бежать в Поточари или присоединиться к колонке. Операция по захвату и задержанию мужчин была хорошо организована и всеобъемлющей. Автобусы, которые транспортировали женщин и детей, систематически искали мужчин. [ 117 ]

Массовые казни

[ редактировать ]Сумма планирования и координации высокого уровня, инвестированных в убийство тысяч за несколько дней, очевидно из шкалы и методического характера, в котором были выполнены казни. [ Цитация необходима ]

Армия Республики Српска взяла самое большое количество заключенных 13 июля вдоль дороги Братунак-Конжевича Полже. Свидетели описывают пункты собрания, такие как поле в Сандичи, сельскохозяйственные склады в Кравике, школа в Коньевиче Поле, футбольное поле в Новой Касабе, Лоличи и Луки. Несколько тысяч человек были загнаны в поле возле Сандичи и на поле Новой Касабы, где их обыскивали и помещали в более мелкие группы. В видео журналиста Зорана Петровича солдат серба заявляет, что по меньшей мере 3000-4000 человек отдали себя на дороге. К концу дня 13 июля общая сумма выросла до 6000 в соответствии с перехваченным радиосвязи; На следующий день майор Франкен из голландского, дал такую же фигуру полковник Радислав Янкович из сербской армии. Многие заключенные были замечены в описанных местах, передавая конвои, доставляющие женщин и детей в Кладандж на автобусе, в то время как аэрофотоснимки предоставили доказательства для подтверждения этого. [ 100 ] [ 117 ]

Через час после того, как эвакуация женщин из Поточари была завершена, сотрудники корпуса Drina отвезли автобусы в районы, в которых содержались мужчины. Полковник Крсманович, который 12 июля организовал автобусы для эвакуации, приказал собрать 700 человек в Сандичи, а солдаты охраняли их, заставил их бросить свои имущества на кучу и руку на ценности. Во второй половине дня группа в Сандичи посетила Младич, который сказал им, что они не причинят вреда, будут рассматриваться как военнопленные, обмены на другие заключенные, и их семьи сопровождались в Тузлу в безопасности. Некоторые мужчины были помещены на транспорт в Братунак и другие места, в то время как некоторые были отправлены на склады в Кравике. Мужчины, собравшиеся на поле в Новой Касабе, были вынуждены передавать вещи. Они тоже получили визит Младича в течение дня 13 июля; По этому случаю он объявил, что боснийские власти в Тузле не хотели их, и поэтому их должны были быть взяты в другом месте. Мужчины в Новой Касабе были загружены на автобусы и грузовики и доставлены в Братунак, или в другие места. [ 117 ]

The Bosnian men who had been separated from the women, children and elderly in Potočari, numbering approximately 1,000, were transported to Bratunac and joined by Bosnian men captured from the column.[118] Almost without exception, the thousands of prisoners captured after the take-over were executed. Some were killed individually, or in small groups, by the soldiers who captured them. Most were killed in carefully orchestrated mass executions, commencing on 13 July, just north of Srebrenica.

The mass executions followed a well-established pattern. The men were taken to empty schools or warehouses. After being detained for hours, they were loaded onto buses or trucks and taken to another site, usually in an isolated location. They were unarmed and often steps were taken to minimise resistance, such as blindfolding, binding their wrists behind their backs with ligatures, or removing their shoes. Once at the killing fields, the men were taken off the trucks in small groups, lined up and shot. Those who survived the initial shooting were shot with an extra round, though sometimes only after they had been left to suffer.[117]

Morning of 13 July: Jadar River

[edit]Prior to midday on 13 July, seventeen men were transported by bus a short distance to a spot on the banks of the Jadar River where they were lined up and shot. One man, after being hit in the hip by a bullet, jumped into the river and managed to escape.[119]

Early afternoon of 13 July: Cerska Valley

[edit]

The first mass executions began on 13 July in the valley of the River Cerska, to the west of Konjević Polje. One witness, hidden among trees, saw 2 or 3 trucks, followed by an armoured vehicle and earthmoving machine proceeding towards Cerska. He heard gunshots for half an hour and then saw the armoured vehicle going in the opposite direction, but not the earthmoving machine. Other witnesses report seeing a pool of blood alongside the road to Cerska. Muhamed Duraković, a UN translator, probably passed this execution site later that day. He reports seeing bodies tossed into a ditch alongside the road, with some men still alive.[120][121]

Aerial photos, and excavations, confirmed the presence of a mass grave near this location. Bullet cartridges, found at the scene, showed that the victims were first lined up on one side of the road, whereupon their executioners shot from the other. The 150 bodies were covered with earth where they lay. It was later established they had been killed by gunfire. All were men, aged 14-50, and all but three was wearing civilian clothes. Many had their hands tied behind their backs. 9 were later identified who were on the list of Srebrenica missing persons list.[120]

Late afternoon of 13 July: Kravica

[edit]Later on 13 July executions were conducted in the largest of four farm sheds, owned by the Agricultural Cooperative in Kravica. Between 1,000 and 1,500 men had been captured in fields near Sandići and detained in Sandići Meadow. They were brought to Kravica, either by bus or on foot, the distance being approximately 1km. A witness recalls seeing around 200 men, stripped to the waist and with their hands in the air, being forced to run in the direction of Kravica. An aerial photo taken at 2pm shows 2 buses standing in front of the sheds.[122]

At around 6pm, when the men were all held in the warehouse, VRS soldiers threw in hand grenades and fired with weapons, including rocket propelled grenades. This mass murder seemed "well organised and involved a substantial amount of planning, requiring the participation of the Drina Corps Command."[122]

Supposedly, there was more killing in and around Kravica and Sandići. Even before the murders in the warehouse, some 200 or 300 men were formed up in ranks near Sandići, then executed en masse with concentrated machine gun fire. At Kravica, it was claimed some local men assisted the killings. Some victims were mutilated and killed with knives. The bodies were taken to Bratunac, or simply dumped in the river that runs alongside the road. One witness stated this all took place on 14 July. There were 3 survivors of the mass murder in the farm sheds at Kravica.[122]

Armed guards shot at the men who tried to climb out the windows to escape the massacre. When the shooting stopped, the shed was full of bodies. Another survivor, who was only slightly wounded, reports:

I was not even able to touch the floor, the concrete floor of the warehouse... After the shooting, I felt a strange kind of heat, warmth, which was coming from the blood that covered the concrete floor and I was stepping on the dead people who were lying around. But there were even men (just men) who were still alive, who were only wounded and as soon as I would step on him, I would hear him cry, moan, because I was trying to move as fast as I could. I could tell that people had been completely disembodied and I could feel bones of the people that had been hit by those bursts of bullets or shells, I could feel their ribs crushing. Then I would get up again and continue....[74]

When this witness climbed out of a window, he was seen by a guard who shot at him. He pretended to be dead and managed to escape the following morning. The other witness quoted above spent the night under a heap of bodies; the next morning, he watched as the soldiers examined the corpses for signs of life. The few survivors were forced to sing Serbian songs and were then shot. Once the final victim had been killed, an excavator was driven in to shunt the bodies out of the shed; the asphalt outside was then hosed down with water. In September 1996, however, it was still possible to find the evidence.[122]

Analyses of hair, blood and explosives residue collected at the Kravica Warehouse provide strong evidence of the killings. Experts determined the presence of bullet strikes, explosives residue, bullets and shell cases, as well as human blood, bones and tissue adhering to the walls and floors of the building. Forensic evidence presented by the ICTY Prosecutor established a link between the executions in Kravica and the 'primary' mass grave known as Glogova 2, in which the remains of 139 people were found. In the 'secondary' grave known as Zeleni Jadar 5, there were 145 bodies, several were charred. Pieces of brick and window frame found in the Glogova 1 grave that was opened later, also established a link with Kravica. Here, the remains of 191 victims were found.[122]

13–14 July: Tišća

[edit]As the buses crowded with Bosnian women, children and elderly made their way from Potočari to Kladanj, they were stopped at Tišća village, searched, and the Bosnian men and boys found on board were removed. The evidence reveals a well-organised operation in Tišća.[123]

From the checkpoint, an officer directed the soldier escorting the witness towards a nearby school where many other prisoners were being held. At the school, a soldier on a field telephone appeared to be transmitting and receiving orders. Around midnight, the witness was loaded onto a truck with 22 other men with their hands tied behind their backs. At one point the truck stopped and a soldier said: "Not here. Take them up there, where they took people before." The truck reached another stopping point and the soldiers came to the back of the truck and started shooting the prisoners. The survivor escaped by running away from the truck and hiding in a forest.[123]

14 July: Grbavci and Orahovac

[edit]A large group of prisoners held overnight in Bratunac were bussed in a convoy of 30 vehicles to the Grbavci school in Orahovica, early on 14 July. When they arrived, the gym was already half-full with prisoners and within a few hours, the building was full. Survivors estimated there were about 2,000 men, some very young, others elderly, although the ICTY Prosecution suggested this maybe an overestimation, with the number closer to 1,000. Some prisoners were taken outside and killed. At some point, a witness recalled, General Mladić arrived and told the men: "Well, your government does not want you and I have to take care of you."[124]

After being held in the gym for hours, the men were led out in small groups to the execution fields that afternoon. Each prisoner was blindfolded and given water as he left. The prisoners were taken in trucks to the fields less than 1km away. The men were lined up and shot in the back; those who survived were killed with an extra shot. Two adjacent meadows were used; once one was full of bodies, the executioners moved to the other. While the executions were in progress, the survivors said earth-moving equipment dug the graves. A witness who survived by pretending to be dead, reported that Mladić drove up in a red car and watched some of the executions.[124]

The forensic evidence supports crucial aspects of the testimony. Aerial photos show the ground in Orahovac was disturbed between 5-27 July and between 7-27 September. Two primary mass graves were uncovered in the area and named Lazete 1 and Lazete 2 by investigators.[124] Lazete 1 was exhumed by the ICTY in 2000. All of the 130 individuals uncovered, for whom sex could be determined, were male; 138 blindfolds were found. Identification material for 23 persons, listed as missing following the fall of Srebrenica, was located during the exhumations. Lazete 2 was partly exhumed by a joint team, from the Office of the Prosecutor and Physicians for Human Rights, in 1996 and completed in 2000. All of the 243 victims associated with Lazete 2 were male, and experts determined most died of gunshot injuries. 147 blindfolds were located.[124] Forensic analysis of soil/pollen samples, blindfolds, ligatures, shell cases and aerial images of creation/disturbance dates, further revealed that bodies, from Lazete 1 and 2, were reburied at secondary graves named Hodžići Road 3, 4 and 5. Aerial images show these secondary gravesites were begun in early September 1995 and all were exhumed in 1998.[124]

14–15 July: Petkovići

[edit]

On 14 and 15 July 1995, another group of prisoners numbering 1,500 to 2,000 were taken from Bratunac to the school in Petkovići. The conditions at the Petkovići school were even worse than Grbavci. It was hot, and overcrowded and there was no food or water. In the absence of anything else, some prisoners chose to drink their urine. Now and then, soldiers would enter the room and physically abuse prisoners or call them outside. A few contemplated an escape attempt, but others said it would be better to stay since the International Red Cross would be sure to monitor the situation and they could not all be killed.[125]

The men were called outside in small groups. They were ordered to strip to the waist and remove their shoes, whereupon their hands were tied behind their backs. During the night of 14 July, the men were taken by truck to the dam at Petkovići. Those who arrived later could see immediately what was happening. Bodies were strewn on the ground, hands tied behind their backs. Small groups of five to ten men were taken out of the trucks, lined up and shot. Some begged for water but their pleas were ignored.[125] A survivor described his feelings of fear combined with thirst:

I was really sorry that I would die thirsty, and I was trying to hide amongst the people as long as I could, like everybody else. I just wanted to live for another second or two. And when it was my turn, I jumped out with what I believe were four other people. I could feel the gravel beneath my feet. It hurt... I was walking with my head bent down and I wasn't feeling anything.... And then I thought that I would die very fast, that I would not suffer. And I just thought that my mother would never know where I had ended up. This is what I was thinking as I was getting out of the truck. [As the soldiers walked around to kill the survivors of the first round of shooting] I was still very thirsty. But I was sort of between life and death. I didn't know whether I wanted to live or die anymore. I decided not to call out for them to shoot and kill me, but I was sort of praying to God that they'd come and kill me.[74]

After the soldiers had left, 2 survivors helped each other to untie their hands and crawled over the bodies towards the woods, where they intended to hide. As dawn arrived, they could see the execution site where bulldozers were collecting the bodies. On the way to the execution site, one survivor peeked out from under his blindfold and saw Mladić on his way to the scene.[74]

Aerial photos confirmed the earth near the Petkovići dam had been disturbed and it was disturbed again in late September 1995. When the grave was opened in April 1998, there seemed to be many bodies missing. Their removal had been accomplished with mechanical apparatus, causing considerable disturbance. The grave contained the remains of no more than 43 persons. Other bodies had been removed to a secondary grave, Liplje 2, before 2 October. Here, the remains of at least 191 individuals were discovered.[74]

14–16 July: Branjevo

[edit]On 14 July, more prisoners from Bratunac were bussed northward to a school in Pilica. As at other detention facilities, there was no food or water and several died from heat and dehydration. The men were held at the school for two nights. On 16 July, following a now familiar pattern, the men were called out and loaded onto buses with their hands tied behind their backs, driven to the Branjevo Military Farm, where groups of 10 were lined up and shot.[126]

Dražen Erdemović—who confessed to killing at least 70 Bosniaks—was a member of the VRS 10th Sabotage Detachment. Erdemović appeared as a prosecution witness and testified: "The men in front of us were ordered to turn their backs...we shot at them. We were given orders to shoot."[127] On this point, a survivors recalls:

When they shot, I threw myself on the ground... one man fell on my head. I think that he was killed on the spot. I could feel the hot blood pouring over me... I could hear one man crying for help. He was begging them to kill him. And they simply said "Let him suffer. We'll kill him later."

— Witness Q[128]

Erdemović said nearly all the victims wore civilian clothes and, except for one person who tried to escape, offered no resistance. Sometimes the executioners were particularly cruel. When some soldiers recognised acquaintances, they beat and humiliated them, before killing them. Erdemović had to persuade fellow soldiers to stop using machine guns; while it mortally wounded the prisoners, it did not cause death immediately and prolonged their suffering.[127] Between 1,000 and 1,200 men were killed in that day at this execution site.[129]

Aerial photos, taken on 17 July of an area around the Branjevo Military Farm, show many bodies lying in a field, as well as traces of the excavator that collected the bodies.[130] Erdemović testified that, at around 3pm on 16 July, after he and fellow soldiers from the 10th Sabotage Detachment had finished executing prisoners at the Farm, they were told there was a group of 500 Bosnian prisoners from Srebrenica, trying to break out of a Dom Kultura club. Erdemović and other members of his unit refused to carry out more killings. They were told to meet with a Lieutenant Colonel at a café in Pilica. Erdemović and his fellow soldiers travelled to the café and, as they waited, could hear shots and grenades being detonated. The sounds lasted 15–20 minutes after which a soldier entered the café to inform them "everything was over".[131]

There were no survivors to explain exactly what happened in the Dom Kultura.[131] The executions there were remarkable as this was not remote, but a town centre on the main road from Zvornik to Bijeljina.[132] Over a year later, it was still possible to find physical evidence of this crime. As in Kravica, many traces of blood, hair and body tissue were found in the building, with cartridges and shells littered throughout the two storeys.[133] It could be established that explosives and machine guns had been used. Human remains and personal possessions were found under the stage, where blood had dripped down through the floorboards.

Two of the three survivors of the executions at the Branjevo Military Farm, were arrested by Bosnian Serb police on 25 July and sent to the prisoner of war compound at Batkovici. One had been a member of the group separated from the women in Potočari on 13 July. The prisoners who were taken to Batkovici survived[134] and testified before the Tribunal.[135]

Čančari Road 12 was the site of the reinterment of at least 174 bodies, moved from the mass grave at the Branjevo Military Farm.[136] Only 43 were complete sets of remains, most of which established that death was due to rifle fire. Of the 313 body parts found, 145 displayed gunshot wounds of a severity likely to prove fatal.[137]

14–17 July: Kozluk

[edit]

The exact date of the executions at Kozluk is unknown, though most probably 15-16 July, partly due to its location, between Petkovići Dam and the Branjevo Military Farm. It falls within the pattern of ever more northerly execution sites: Orahovac on 14 July, Petkovići Dam on 15 July, the Branjevo Military Farm and Pilica Dom Kultura on 16 July.[138] Another indication is that a Zvornik Brigade excavator spent 8 hours in Kozluk on 16 July and a truck belonging to the same brigade made two journeys between Orahovac and Kozluk that day. A bulldozer is known to have been active in Kozluk on 18 and 19 July.[139]

Among Bosnian refugees in Germany, there were rumours of executions in Kozluk, during which 500 or so prisoners were forced to sing Serbian songs as they were being transported to the execution site. Though no survivors have come forward, investigations in 1999 led to the discovery of a mass grave near Kozluk.[140] This proved to be the location of execution as well, and lay alongside the Drina accessible only by driving through the barracks occupied by the Drina Wolves, a police unit of Republika Srpska. The grave was not dug specifically for the purpose: it had previously been a quarry and landfill site. Investigators found many shards of glass which the nearby 'Vitinka' bottling plant had dumped there. This facilitated the process of establishing links with the secondary graves along Čančari Road.[141] The grave at Kozluk had been partly cleared before 27 September 1995, but no fewer than 340 bodies were found there.[142] In 237 cases, it was clear they had died as the result of rifle fire: 83 by a single shot to the head, 76 by one shot through the torso region, 72 by multiple bullet wounds, five by wounds to the legs and one by bullet wounds to the arm. Their ages were between 8 and 85. Some had been physically disabled, occasionally as the result of amputation. Many had been tied and bound using strips of clothing or nylon thread.[141]

Along the Čančari Road are twelve known mass graves, of which only two—Čančari Road 3 and 12—have been investigated in detail (as of 2000[update]).[143] Čančari Road 3 is known to have been a secondary grave linked to Kozluk, as shown by the glass fragments and labels from the Vitinka factory.[144] The remains of 158 victims were found here, of which 35 bodies were more or less intact and indicated most had been killed by gunfire.[145]

13–18 July: Bratunac-Konjević Polje road

[edit]On 13 July, near Konjević Polje, Serb soldiers summarily executed hundreds of Bosniaks, including women and children.[146] The men found attempting to escape by the Bratunac-Konjević Polje road were told the Geneva Convention would be observed if they gave themselves up.[147] In Bratunac, men were told there were Serbian personnel standing by to escort them to Zagreb for a prisoner exchange. The visible presence of UN uniforms and vehicles, stolen from Dutchbat, were intended to contribute to the feeling of reassurance. On 17 to 18 July, Serb soldiers captured about 150–200 Bosnians in the vicinity of Konjevic Polje and summarily executed about one-half.[146]

18–19 July: Nezuk–Baljkovica frontline

[edit]After the closure of the corridor at Baljkovica, groups of stragglers nevertheless attempted to escape into Bosnian territory. Most were captured by VRS troops in the Nezuk–Baljkovica area and killed on the spot. In the vicinity of Nezuk, about 20 small groups surrendered to Bosnian Serb military forces. After the men surrendered, soldiers ordered them to line up and summarily executed them.[92]

On 19 July, for example, a group of approximately 11 men was killed at Nezuk itself by units of the 16th Krajina Brigade, then operating under the direct command of the Zvornik Brigade. Reports reveal a further 13 men, all ARBiH soldiers, were killed at Nezuk on 19 July.[148] The report of the march to Tuzla includes the account of an ARBiH soldier who witnessed executions carried out by police. He survived because 30 ARBiH soldiers were needed for an exchange of prisoners following the ARBiH's capture of a VRS officer at Baljkovica. The soldier was exchanged in late 1995; at that time, there were still 229 men from Srebrenica in the Batkovici prisoner of war camp, including two who had been taken prisoner in 1994.[citation needed]

RS Ministry of the Interior forces searching the terrain from Kamenica as far as Snagovo killed eight Bosniaks.[149] Around 200 Muslims armed with automatic and hunting rifles were reported to be hiding near the old road near Snagovo.[149] During the morning, about 50 Bosniaks attacked the Zvornik Brigade line in the area of Pandurica, attempting to break through to Bosnian government territory.[149] The Zvornik Public Security Centre planned to surround and destroy these two groups the following day using all available forces.[150]

20–22 July: Meces area

[edit]According to ICTY indictments of Karadžić and Mladić, on 20 to 21 July near Meces, VRS personnel, using megaphones, urged Bosniak men who had fled Srebrenica to surrender and assured them they would be safe. Approximately 350 men responded to these entreaties and surrendered. The soldiers then took approximately 150, instructed them to dig their graves and executed them.[151]

After the massacre

[edit]

During the days following the massacre, US spy planes overflew Srebrenica and took photos showing the ground in vast areas around the town had been removed, a sign of mass burials.

On 22 July, the commanding officer of the Zvornik Brigade, Lieutenant Colonel Vinko Pandurević, requested the Drina Corps set up a committee to oversee the exchange of prisoners. He asked for instructions on where the prisoners of war his unit had already captured should be taken and to whom they should be handed over. Approximately 50 wounded captives were taken to the Bratunac hospital. Another group was taken to the Batkovići camp, and these were mostly exchanged later.[152] On 25 July, the Zvornik Brigade captured 25 more ARBiH soldiers who were taken directly to the camp at Batkovići, as were 34 ARBiH men captured the following day. Zvornik Brigade reports up until 31 July continue to describe the search for refugees and the capture of small groups of Bosniaks.[153]

Several Bosniaks managed to cross over the River Drina into Serbia at Ljubovija and Bajina Bašta. 38 were returned to RS. Some were taken to the Batkovići camp, where they were exchanged. The fate of the majority has not been established.[152] Some attempting to cross the Drina drowned.[152]

By 17 July, 201 Bosniak soldiers had arrived in Žepa, exhausted and many with light wounds.[152] By 28 July another 500 had arrived in Žepa from Srebrenica.[152][154] After 19 July, small Bosniak groups were hiding in the woods for days and months, trying to reach Tuzla.[152] Numerous refugees found themselves cut off in the area around Mount Udrc.[155][156] They did not know what to do next or where to go; they managed to stay alive by eating vegetables and snails.[155][156] The MT Udrc had become a place for ambushing marchers, and the Bosnian Serbs swept through and, according to one survivor, killed many people there.[155][156]

Meanwhile, the VRS had commenced the process of clearing the bodies from around Srebrenica, Žepa, Kamenica and Snagovo. Work parties and municipal services were deployed to help.[156][157] In Srebrenica, the refuse that had littered the streets since the departure of the people was collected and burnt, the town disinfected and deloused.[156][157]

Wanderers

[edit]Many people in the part of the column which had not succeeded in passing Kamenica, did not wish to give themselves up and decided to turn back towards Žepa.[158] Others remained where they were, splitting up into smaller groups of no more than ten.[159] Some wandered around for months, either alone or groups of two, four or six men.[159] Once Žepa had succumbed to the Serb pressure, they had to move on once more, either trying to reach Tuzla or crossing the River Drina into Serbia.[160]

Zvornik 7

The most famous group of seven men wandered about in occupied territory for the entire winter. On 10 May 1996, after 9 months on the run and over six months after the end of the war, they were discovered in a quarry by American IFOR soldiers. They immediately turned over to the patrol; they were searched and their weapons were confiscated. The men said they had been in hiding near Srebrenica since its fall. They did not look like soldiers and the Americans decided this was a matter for the police.[161] The operations officer of the American unit ordered that a Serb patrol should be escorted into the quarry whereupon the men would be handed over to the Serbs.

The prisoners said they were initially tortured after the transfer, but later treated relatively well. In April 1997 the local court in Republika Srpska convicted the group, known as the Zvornik 7, for illegal possession of firearms and three of them for the murder of four Serbian woodsmen. When announcing the verdict the presenter of the TV of Republika Srpska described them as the group of Muslim terrorists from Srebrenica who last year massacred Serb civilians.[162] The trial was condemned by the international community as "a flagrant miscarriage of justice",[163][164] and the conviction quashed for 'procedural reasons' following international pressure. In 1999, the three remaining defendants in the Zvornik 7 case were swapped for three Serbs serving 15 years each in a Bosnian prison.

Reburials in the secondary mass graves

[edit]

From August to October 1995, there was organised effort to remove the bodies from primary gravesites and transport them to secondary and tertiary gravesites.[165] In the ICTY court case "Prosecutor v. Blagojević and Jokić", the trial chamber found that this reburial effort was an attempt to conceal evidence of the mass murders.[166] The trial chamber found that the cover-up operation was ordered by the VRS Main Staff and carried out by members of the Bratunac and Zvornik Brigades.[166]

The cover-up had a direct impact on the recovery and identification of the remains. The removal and reburial of the bodies caused them to become dismembered and co-mingled, making it difficult for forensic investigators to positively identify the remains.[167] In one case, the remains of a single person were found in two locations, 30 km apart.[168] In addition to the ligatures and blindfolds found, the effort to hide the bodies has been seen as evidence of the organised nature of the massacres and the non-combatant status of the victims.[167][169]

Greek Volunteers controversy

[edit]10 Greek volunteers fought alongside the Serbs in the fall of Srebrenica.[170][171] They were members of the Greek Volunteer Guard, a contingent of paramilitaries requested by Mladić, as an integral part of the Drina Corps. The volunteers were motivated to support their "Orthodox brothers" in battle.[172] They raised the Greek flag at Srebrenica, at Mladić's request, to honour "the brave Greeks fighting on our side"[173] and Karadžić decorated four.[174][175][176][177] In 2005, Greek deputy Andrianopoulos called for an investigation,[178] Justice Minister Papaligouras commissioned an inquiry[179] and in 2011, a judge said there was insufficient evidence to proceed.[171] In 2009, Stavros Vitalis announced the volunteers were suing Takis Michas for libel over allegations in his book Unholy Alliance, which described Greece's support for the Serbs during the war. Insisting the volunteers had simply taken part in the "re-occupation" of Srebrenica, Vitalis was present with Serb officers in "all military operations".[180][181][182]

Post-war developments

[edit]1995-2000: Indictments and UN Secretary-General's report