Темная сторона Луны

| Темная сторона Луны | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Студийный альбом | ||||

| Выпущенный | 1 марта 1973 г. | |||

| Записано | 31 мая 1972 г. - 9 февраля 1973 г. [1] | |||

| Студия | ЭМИ , Лондон | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 42:50 | |||

| Label | ||||

| Producer | Pink Floyd | |||

| Pink Floyd chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from The Dark Side of the Moon | ||||

| ||||

The Dark Side of the Moon — восьмой студийный альбом английской рок-группы Pink Floyd , выпущенный 1 марта 1973 года на лейблах Harvest Records в Великобритании и Capitol Records в США. Разработанный во время живых выступлений до начала записи, он был задуман как концептуальный альбом , в котором основное внимание будет уделено трудностям, с которыми группа сталкивалась во время их тяжелого образа жизни, а также проблемам психического здоровья бывшего участника группы Сида Барретта , покинувшего группу. группа в 1968 году. Новый материал был записан за две сессии в 1972 и 1973 годах в EMI Studios (ныне Abbey Road Studios ) в Лондоне.

Пластинка основана на идеях, изложенных в более ранних записях и выступлениях Pink Floyd, но без расширенных инструментальных партий, которые характеризовали ранние работы группы. Группа использовала многодорожечную запись , лупы и аналоговые синтезаторы включая эксперименты с EMS VCS 3 и Synthi A. , Инженер Алан Парсонс отвечал за многие звуковые аспекты записи, а также за набор сессионной певицы Клэр Торри , которая появляется на " The Great Gig in the Sky ".

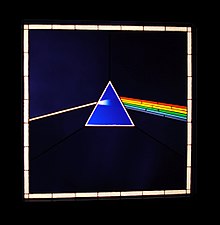

The Dark Side of the Moon explores themes such as conflict, greed, time, death, and mental illness. Snippets from interviews with the band's road crew and others are featured alongside philosophical quotations. The sleeve, which depicts a prismatic spectrum, was designed by Storm Thorgerson in response to the keyboardist Richard Wright's request for a "simple and bold" design which would represent the band's lighting and the album's themes. The album was promoted with two singles: "Money" and "Us and Them".

The Dark Side of the Moon is among the most critically acclaimed albums and often features in professional listings of the greatest of all time. It brought Pink Floyd international fame, wealth and plaudits to all four band members. A blockbuster release of the album era, it also propelled record sales throughout the music industry during the 1970s. The Dark Side of the Moon is certified 14x platinum in the United Kingdom, and topped the US Billboard Top LPs & Tape chart, where it has charted for 990 weeks. By 2013, The Dark Side of the Moon had sold over 45 million copies worldwide, making it the band's best-selling release, the best-selling album of the 1970s, and the fourth-best-selling album in history.[3] In 2012, the album was selected for preservation in the United States National Recording Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant". It was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1999.[4]

Background

[edit]Following Meddle in 1971, Pink Floyd assembled for a tour of Britain, Japan and the United States in December of that year. In a band meeting at the drummer Nick Mason's home in north London, the bassist Roger Waters proposed that a new album could form part of the tour. Waters conceived an album that dealt with things that "make people mad", focusing on the pressures associated with the band's arduous lifestyle, and dealing with the mental health problems suffered by the former band member Syd Barrett.[5][6] The band had explored a similar idea with the 1969 concert suite The Man and The Journey.[7] In an interview for Rolling Stone, the guitarist David Gilmour said: "I think we all thought – and Roger definitely thought – that a lot of the lyrics that we had been using were a little too indirect. There was definitely a feeling that the words were going to be very clear and specific."[8]

The band approved of Waters' concept for an album unified by a single theme,[8] and Waters, Gilmour, Mason and the keyboardist Richard Wright all participated in writing and producing new material. Waters created the early demo tracks in a small studio in a garden shed at his home in Islington.[9] Parts of the album were taken from previously unused material; the opening line of "Breathe" came from an earlier work by Waters and Ron Geesin, written for the soundtrack of The Body,[10] and the basic structure of "Us and Them" was borrowed from an original composition, "The Violent Sequence" by Wright for Zabriskie Point.[11] The band rehearsed at a warehouse in London owned by the Rolling Stones and at the Rainbow Theatre in Finsbury Park, London. They also purchased extra equipment, which included new speakers, a PA system, a 28-track mixing desk with a four channel quadraphonic output, and a custom-built lighting rig. Nine tonnes of kit was transported in three lorries. This would be the first time the band had taken an entire album on tour.[12][13] The album had been given the provisional title of Dark Side of the Moon (an allusion to lunacy, rather than astronomy).[14] After discovering that title had already been used by another band, Medicine Head, it was temporarily changed to Eclipse. The new material was premiered at The Dome in Brighton, on 20 January 1972,[15] and after the commercial failure of Medicine Head's album the title was changed back to the band's original preference.[16][17][nb 1]

Dark Side of the Moon: A Piece for Assorted Lunatics, as it was then known,[7] was performed for an assembled press on 17 February 1972 at the Rainbow Theatre, more than a year before its release, and was critically acclaimed.[18] Michael Wale of The Times described the piece as "bringing tears to the eyes. It was so completely understanding and musically questioning."[19] Derek Jewell of The Sunday Times wrote "The ambition of the Floyd's artistic intention is now vast."[16] Melody Maker was less enthusiastic: "Musically, there were some great ideas, but the sound effects often left me wondering if I was in a bird-cage at London Zoo."[20] The following tour was praised by the public. The new material was performed in the same order in which it was eventually sequenced on the album. Differences included the lack of synthesisers in tracks such as "On the Run", and Clare Torry's vocals on "The Great Gig in the Sky" replaced by readings from the Bible.[18]

Pink Floyd's lengthy tour through Europe and North America gave them the opportunity to make improvements to the scale and quality of their performances.[21] Work on the album was interrupted in late February when the band travelled to France and recorded music for the French director Barbet Schroeder's film La Vallée.[22][nb 2] They performed in Japan, returned to France in March to complete work on the film, played more shows in North America, then flew to London and resumed recording in May and June. After more concerts in Europe and North America, the band returned to London on 9 January 1973 to complete the album.[23][24][25]

Concept

[edit]The Dark Side of the Moon was built upon experiments Pink Floyd had attempted in their previous live shows and recordings, although it lacked the extended instrumental excursions which, according to the critic David Fricke, had become characteristic of the band following the departure of the founding member Syd Barrett in 1968. Gilmour, Barrett's replacement, later referred to those instrumentals as "that psychedelic noodling stuff". He and Waters cited 1971's Meddle as a turning point towards what would later be realised on the album. The Dark Side of the Moon's lyrical themes include conflict, greed, the passage of time, death and insanity, the last inspired in part by Barrett's deteriorating mental state.[11] The album contains musique concrète on several tracks.[7]

Each side of the vinyl album is a continuous piece of music. The five tracks on each side reflect various stages of human life, beginning and ending with a heartbeat, exploring the nature of the human experience and, according to Waters, "empathy".[11] "Speak to Me" and "Breathe" together highlight the mundane and futile elements of life that accompany the ever-present threat of madness, and the importance of living one's own life – "Don't be afraid to care".[26] By shifting the scene to an airport, the synthesiser-driven instrumental "On the Run" evokes the stress and anxiety of modern travel, in particular Wright's fear of flying.[27] "Time" examines the manner in which its passage can control one's life and offers a stark warning to those who remain focused on mundane pursuits; it is followed by a retreat into solitude and withdrawal in "Breathe (Reprise)". The first side of the album ends with Wright and Clare Torry's soulful metaphor for death, "The Great Gig in the Sky".[7]

"Money", the first track on side two, opens with the sound of cash registers and rhythmically jingling coins. The song mocks greed and consumerism with sarcastic lyrics and cash-related sound effects. "Money" became the band's most commercially successful track and was covered by other artists.[28] "Us and Them" addresses the isolation of the depressed with the symbolism of conflict and the use of simple dichotomies to describe personal relationships. "Any Colour You Like" tackles the illusion of choice one has in society. "Brain Damage" looks at mental illness resulting from the elevation of fame and success above the needs of the self; in particular, the line "and if the band you're in starts playing different tunes" reflects the mental breakdown of Syd Barrett. The album ends with "Eclipse", which espouses the concepts of otherness and unity, while encouraging the listener to recognise the common traits shared by humanity.[29][30]

Recording

[edit]

The Dark Side of the Moon was recorded at EMI Studios (now Abbey Road Studios) in approximately 60 days[31] between 31 May 1972 and 9 February 1973. Pink Floyd were assigned the staff engineer Alan Parsons, who had worked as the assistant tape operator on their fifth album, Atom Heart Mother (1970), and had gained experience as a recording engineer on the Beatles albums Abbey Road and Let It Be.[32][33] The Dark Side of the Moon sessions made use of advanced studio techniques, as the studio was capable of 16-track mixes which offered greater flexibility than the eight- or four-track mixes Pink Floyd had previously worked with, although the band often used so many tracks that second-generation copies were still needed to make more space available on the tape.[34] The mix supervisor Chris Thomas recalled later, "There were only two or three tracks of drums when we came to mixing it. Depending on the song, there would be one or two tracks of guitar, and these would include the solo and the rhythm guitar parts. One track for keyboard, one track for bass, and one or two sound effects tracks. They had been very, very efficient in the way they'd worked."[35]

The first track recorded was "Us and Them" on 31 May, followed seven days later by "Money".[1] For "Money", Waters had created effects loops in an unusual 7

4 time signature[36] from recordings of money-related objects, including coins thrown into a mixing bowl in his wife's pottery studio. These were re-recorded to take advantage of the band's decision to create a quadraphonic mix of the album, although Parsons later expressed dissatisfaction with the result of this mix, which he attributed to a lack of time and a shortage of multitrack tape recorders.[33]

"Time" and "The Great Gig in the Sky" were recorded next, followed by a two-month break, during which the band spent time with their families and prepared for a tour of the United States.[37] The recording sessions were frequently interrupted: Waters, a supporter of Arsenal F.C., would break to see his team compete, and the band would occasionally stop to watch Monty Python's Flying Circus on television while Parsons worked on the tracks.[34] Gilmour recalled, "...but when we were on a roll, we would get on."[38][39]

After returning from the US in January 1973, they recorded "Brain Damage", "Eclipse", "Any Colour You Like" and "On the Run", and fine-tuned work from previous sessions. Four female vocalists were assembled to sing on "Brain Damage", "Eclipse" and "Time", and the saxophonist Dick Parry was booked to play on "Us and Them" and "Money". With the director Adrian Maben, the band also filmed studio footage for Pink Floyd: Live at Pompeii.[40] The album was completed and signed off at Abbey Road on 9 February 1973.[41]

Instrumentation

[edit]The album features metronomic sound effects during "Speak to Me" and tape loops for the opening of "Money". Mason created a rough version of "Speak to Me" at his home before completing it in the studio. The track serves as an overture and contains cross-fades of elements from other pieces on the album. A piano chord, replayed backwards, serves to augment the build-up of effects, which are immediately followed by the opening of "Breathe". Mason received a rare solo composing credit for "Speak to Me".[nb 3][42][43]

The sound effects on "Money" were created by splicing together Waters' recordings of clinking coins, tearing paper, a ringing cash register, and a clicking adding machine, which were used to create a 7-beat effects loop. This was later adapted to four tracks to create a "walk around the room" effect in quadraphonic presentations of the album.[44] At times, the degree of sonic experimentation on the album required the studio engineers and all four band members to operate the mixing console's faders simultaneously, in order to mix down the intricately assembled multitrack recordings of several of the songs, particularly "On the Run".[11]

Along with conventional rock band instrumentation, Pink Floyd introduced prominent synthesisers to their sound. The band experimented with an EMS VCS 3 on "Brain Damage" and "Any Colour You Like", and a Synthi A on "Time" and "On the Run". They also devised and recorded unconventional sounds, such as assistant engineer Peter James[45] running around the studio's echo chamber during "On the Run",[46] and a specially treated bass drum made to simulate a human heartbeat during "Speak to Me", "On the Run", "Time" and "Eclipse". This heartbeat is most prominent in the intro and the outro to the album, but it can also be heard sporadically on "Time" and "On the Run".[11] "Time" features assorted clocks ticking, then chiming simultaneously at the start of the song, accompanied by a series of Rototoms. The recordings were initially created as a quadraphonic test by Parsons, who recorded each timepiece at an antique clock shop.[42] Although these recordings had not been created specifically for the album, elements of this material were eventually used in the track.[47]

Voices

[edit]Several tracks, including "Us and Them" and "Time", demonstrated Wright's and Gilmour's ability to harmonise their similar-sounding voices, and the engineer Alan Parsons used techniques such as double tracking vocals and guitars, which allowed Gilmour to harmonise with himself. Prominent use was also made of flanging and phase-shifting on vocals and instruments, odd trickery with reverb,[11] and the panning of sounds between channels, most notably in the quadraphonic mix of "On the Run", where the sound of the Hammond B3 organ played through a Leslie speaker swirls around the listener.[48]

Wright's "The Great Gig in the Sky" features Clare Torry, a session singer and songwriter and a regular at Abbey Road. Parsons liked her voice, and when the band decided to use a female vocalist he suggested that she could sing on the track. The band explained the album concept to her, but they were unable to tell her exactly what she should do, and Gilmour, who was in charge of the session, asked her to try to express emotions rather than sing words.[49] In a few takes on a Sunday night, Torry improvised a wordless melody to accompany Wright's emotive piano solo. She was initially embarrassed by her exuberance in the recording booth and wanted to apologise to the band, who were impressed with her performance but did not tell her so.[50][51] Her takes were edited to produce the version used on the track.[8] She left the studio under the impression that her vocals would not make the final cut,[52] and she only became aware that she had been included in the final mix when she picked up the album at a local record store and saw her name in the credits.[52] For her contribution she was paid her standard session fee[48] of £30,[53] equivalent to about £500 in 2024.[50][54]

In 2004, Torry sued EMI and Pink Floyd for 50% of the songwriting royalties, arguing that her contribution to "The Great Gig in the Sky" was substantial enough to be considered co-authorship. The case was settled out of court for an undisclosed sum, with all post-2005 pressings crediting Wright and Torry jointly.[55][56]

In the final week of recording,[57] Waters asked staff and others at Abbey Road to respond to questions printed on flashcards and some of their replies were edited into the final mix. The interviewees were placed in front of a microphone in a darkened Studio 3[58] and shown such questions as "What's your favourite colour?" and "What's your favourite food?", before moving on to themes central to the album, including those of madness, violence, and death. Questions such as "When was the last time you were violent?", followed immediately by "Were you in the right?", were answered in the order they were presented.[11]

Roadie Roger "The Hat" Manifold was recorded in a conventional sit-down interview. Waters asked him about a violent encounter he had had with a motorist, and Manifold replied "... give 'em a quick, short, sharp shock ..." Asked about death, he responded, "Live for today, gone tomorrow, that's me ..."[59] Another roadie, Chris Adamson, recorded the words that open the album: "I've been mad for fucking years. Absolutely years. Over the edge... It's working with bands that does it."[60]

The band's road manager Peter Watts (father of the actress Naomi Watts)[61] contributed the repeated laughter during "Brain Damage" and "Speak to Me", as well as the line "I can't think of anything to say". His second wife, Patricia "Puddie" Watts (now Patricia Gleason), was responsible for the line about the "geezer" who was "cruisin' for a bruisin'", used in the segue between "Money" and "Us and Them", and the words "I never said I was frightened of dying" halfway through "The Great Gig in the Sky".[62]

Several of the responses – "I am not frightened of dying. Any time will do, I don't mind. Why should I be frightened of dying? There's no reason for it ... you've got to go sometime"; "I know I've been mad, I've always been mad, like most of us have"; and the closing "There is no dark side in the moon really. Matter of fact, it's all dark" – came from the studios' Irish doorman, Gerry O'Driscoll.[63][64] "The bit you don't hear," said Parsons, "is that, after that, he said, 'The only thing that makes it look alight is the sun.' The band were too overjoyed with his first line, and it would have been an anticlimax to continue."[65]

Paul and Linda McCartney were interviewed, but their answers – judged to be "trying too hard to be funny" – were not used.[66] The McCartneys' Wings bandmate Henry McCullough contributed the line, "I don't know, I was really drunk at the time."[67]

Completion

[edit]When the flashcard sessions were finished, producer Chris Thomas was hired to provide "a fresh pair of ears" for the final mix. Thomas's background was in music rather than engineering; he had worked with Beatles producer George Martin and was an acquaintance of Pink Floyd's manager, Steve O'Rourke.[68] The members of the band were said to have disagreed over the mix, with Waters and Mason preferring a "dry" and "clean" mix that made more use of the non-musical elements and Gilmour and Wright preferring a subtler and more "echoey" mix.[69] Thomas said later, "There was no difference in opinion between them, I don't remember Roger once saying that he wanted less echo. In fact, there were never any hints that they were later going to fall out. It was a very creative atmosphere. A lot of fun."[70]

Thomas's intervention resulted in a compromise between Waters and Gilmour, who were both satisfied with the result. Thomas was responsible for significant changes, including the perfect timing of the echo used on "Us and Them". He was also present for the recording of "The Great Gig in the Sky".[71] Waters said in an interview in 2006, when asked if he felt his goals had been accomplished in the studio:

When the record was finished I took a reel-to-reel copy home with me and I remember playing it for my wife then, and I remember her bursting into tears when it was finished. And I thought, "This has obviously struck a chord somewhere", and I was kinda pleased by that. You know when you've done something, certainly if you create a piece of music, you then hear it with fresh ears when you play it for somebody else. And at that point I thought to myself, "Wow, this is a pretty complete piece of work", and I had every confidence that people would respond to it.[72]

Packaging

[edit]

It felt like the whole band were working together. It was a creative time. We were all very open.

– Richard Wright[73]

The album was originally released in a gatefold LP sleeve designed by Hipgnosis and George Hardie. Hipgnosis had designed several of the band's previous albums, with controversial results; EMI had reacted with confusion when faced with the cover designs for Atom Heart Mother and Obscured by Clouds, as they had expected to see traditional designs which included lettering and words. Designers Storm Thorgerson and Aubrey Powell were able to ignore such criticism, as they were employed by the band. For The Dark Side of the Moon, Wright suggested something "smarter, neater – more classy",[74] and simple, "like the artwork of a Black Magic chocolate box".[49]

The design was inspired by a photograph of a prism with a beam of white light projected through it and emerging in the colours of the visible spectrum that Thorgerson had found in a 1963 physics textbook,[49] as well as by an illustration by Alex Steinweiss, the inventor of album cover art, for the New York Philharmonic's 1942 performance of Ludwig van Beethoven's Emperor Concerto.[75] The artwork was created by an associate of Hipgnosis, George Hardie.[49] Hipgnosis offered a choice of seven designs for the sleeve, but all four members of the band agreed that the prism was the best. "There were no arguments," said Roger Waters. "We all pointed to the prism and said 'That's the one'."[49]

The design depicts a glass prism dispersing white light into colours and represents three elements: the band's stage lighting, the album lyrics, and Wright's request for a "simple and bold" design.[11] At Waters' suggestion, the spectrum of light continues through to the gatefold.[76] Added shortly afterwards, the gatefold design also includes a visual representation of the heartbeat sound used throughout the album, and the back of the album cover contains Thorgerson's suggestion of another prism recombining the spectrum of light, to make possible interesting layouts of the sleeve in record shops.[77] The light band emanating from the prism on the album cover has six colours, missing indigo, compared with the usual division of the visible spectrum into red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet. Inside the sleeve were two posters and two pyramid-themed stickers. One poster bore pictures of the band in concert, overlaid with scattered letters to form PINK FLOYD, and the other an infrared photograph of the Great Pyramids of Giza, created by Powell and Thorgerson.[77]

The band were so confident of the quality of Waters' lyrics that, for the first time, they printed them on the album's sleeve.[12]

Release

[edit]| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Billboard | |

| Christgau's Record Guide | B[79] |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| MusicHound Rock | 5/5[81] |

| NME | 8/10[82] |

| Pitchfork | 9.3/10[83] |

| Q | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Uncut | |

(left to right) David Gilmour, Nick Mason, Dick Parry, Roger Waters

As the quadraphonic mix of the album was not then complete, the band (with the exception of Wright) boycotted the press reception held at the London Planetarium on 27 February.[86] The guests were, instead, presented with a quartet of life-sized cardboard cut-outs of the band, and the stereo mix of the album was played over a poor-quality public address system.[87][88] Generally, however, the press were enthusiastic; Melody Maker's Roy Hollingworth described Side One as "so utterly confused with itself it was difficult to follow", but praised Side Two, writing: "The songs, the sounds, the rhythms were solid and sound, Saxophone hit the air, the band rocked and rolled, and then gushed and tripped away into the night."[89] Steve Peacock of Sounds wrote: "I don't care if you've never heard a note of the Pink Floyd's music in your life, I'd unreservedly recommend everyone to The Dark Side of the Moon".[87] In his 1973 review for Rolling Stone magazine, Loyd Grossman declared Dark Side "a fine album with a textural and conceptual richness that not only invites, but demands involvement".[90] In Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies (1981), Robert Christgau found its lyrical ideas clichéd and its music pretentious, but called it a "kitsch masterpiece" that can be charming with highlights such as taped speech fragments, Parry's saxophone, and studio effects which enhance Gilmour's guitar solos.[79]

The Dark Side of the Moon was released first in the US on 1 March 1973,[91][92] and then in the UK on 16 March.[93] It became an instant chart success in Britain and throughout Western Europe;[87] by the following month, it had gained a gold certification in the US.[94] Throughout March 1973 the band played the album as part of their US tour, including a midnight performance at Radio City Music Hall in New York City on 17 March before an audience of 6,000. The album reached the Billboard Top LPs & Tape chart's number one spot on 28 April 1973,[95] and was so successful that the band returned two months later for another tour.[96]

Label

[edit]Much of the album's early American success is attributed to the efforts of Pink Floyd's US record company, Capitol Records. Newly appointed chairman Bhaskar Menon set about trying to reverse the relatively poor sales of the band's 1971 studio album Meddle. Meanwhile, disenchanted with Capitol, the band and manager O'Rourke had been quietly negotiating a new contract with CBS president Clive Davis, on Columbia Records. The Dark Side of the Moon was the last album that Pink Floyd were obliged to release before formally signing a new contract. Menon's enthusiasm for the new album was such that he began a huge promotional advertising campaign, which included radio-friendly truncated versions of "Us and Them" and "Time".[97]

In some countries – notably the UK – Pink Floyd had not released a single since 1968's "Point Me at the Sky", and unusually "Money" was released as a single on 7 May, with "Any Colour You Like" on the B-side.[86][nb 4] It reached number 13 on the Billboard Hot 100 in July 1973.[98][nb 5] A two-sided white label promotional version of the single, with mono and stereo mixes, was sent to radio stations. The mono side had the word "bullshit" removed from the song – leaving "bull" in its place – however, the stereo side retained the uncensored version. This was subsequently withdrawn; the replacement was sent to radio stations with a note advising disc jockeys to dispose of the first uncensored copy.[100] On 4 February 1974, a double A-side single was released with "Time" on one side, and "Us and Them" on the opposite side.[nb 6][101] Menon's efforts to secure a contract renewal with Pink Floyd were in vain however; at the beginning of 1974, the band signed for Columbia with a reported advance fee of $1M (in Britain and Europe they continued to be represented by Harvest Records).[102]

Sales

[edit]The Dark Side of the Moon became one of the best-selling albums of all time[103] and is in the top 25 of a list of best-selling albums in the United States.[56][104] Although it held the number one spot in the US for only a week, it remained in the Billboard 200 albums chart for 736 nonconsecutive weeks (from 17 March 1973 to 16 July 1988).[105][106] Of those first 736 charted weeks, the album had two notable consecutive runs in the Billboard 200 chart: 84 weeks (from 17 March 1973 to 19 October 1974) and 593 weeks (from 18 December 1976 to 23 April 1988).[107] It made its final appearance in the Billboard 200 albums chart during its initial run on the week ending 8 October 1988, in its 741st charted week.[108] It re-appeared on the Billboard charts with the introduction of the Top Pop Catalog Albums chart in the issue dated 25 May 1991, and was still a perennial feature ten years later.[109] It reached number one on the Pop Catalog chart when the 2003 hybrid CD/SACD edition was released and sold 800,000 copies in the US.[56] On the week of 5 May 2006 The Dark Side of the Moon achieved a combined total of 1,716 weeks on the Billboard 200 and Pop Catalog charts.[72]

After a change in chart methodology in 2009 which allowed catalogue titles to be included in the Billboard 200,[110] The Dark Side of the Moon returned to the chart at number 189 on 12 December of that year for its 742nd charting week.[111] It has continued to sporadically appear on the Billboard 200 since then, with the total at 990 weeks on the chart as of May 2024.[112] "On a slow week" between 8,000 and 9,000 copies are sold.[103] As of April 2013, the album had sold 9,502,000 copies in the US since 1991 when Nielsen SoundScan began tracking sales for Billboard.[113] One in every fourteen people in the US under the age of 50 is estimated to own, or to have owned, a copy.[56]

The Dark Side of the Moon was released before the introduction of platinum certification in 1976 by Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), and therefore held only a gold certification until 16 February 1990, when it was certified 11 times platinum. On 4 June 1998, the RIAA certified the album 15× platinum,[56] denoting sales of fifteen million in the United States. This makes it Pink Floyd's biggest-selling work there; The Wall is 23 times platinum, but as a double album this signifies sales of 11.5 million.[114] "Money" has sold well as a single, and as with "Time", remains a radio favourite; in the US, for the year ending 20 April 2005, "Time" was played on 13,723 occasions, and "Money" on 13,731 occasions.[nb 7] In 2017, The Dark Side of the Moon was the seventh-bestselling album of all time in the UK and the highest-selling album never to reach number one.[115] As one of the blockbuster LPs of the album era (1960s–2000s), The Dark Side of the Moon also led to an increase in record sales overall into the late 1970s.[116] In 2013, industry sources suggested that worldwide sales of The Dark Side of the Moon totalled about 45 million.[3][117]

In 1993, Gilmour attributed the album's success to the combination of music, lyrics and cover art: "All the music before had not had any great lyrical point to it. And this one was clear and concise."[118] Mason said that, when they finished the album, Pink Floyd felt confident it was their best work to date, but were surprised by its commercial success. He said it was "not only about being a good album but also about being in the right place at the right time".[88]

Reissues and remasters

[edit]

In 1979, The Dark Side of the Moon was released as a remastered LP by Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab,[119] and in April 1988 on their "Ultradisc" gold CD format.[120] It was released by EMI and Harvest on CD in Japan in June 1983 and[nb 8] in the US and Europe in August 1984.[nb 9] In 1992, it was rereleased as a remastered CD in the box set Shine On.[121] This version was re-released as a 20th-anniversary box set edition with postcards the following year, with a cover design by Thorgerson.[122] On some pressings, an orchestral version of the Beatles' "Ticket to Ride" is faintly audible after "Eclipse" over the closing heartbeats.[56]

30th-anniversary 5.1 surround sound mix

[edit]

A quadraphonic mix,[nb 10] created by Alan Parsons,[123] was commissioned by EMI but never endorsed by Pink Floyd, as Parsons was disappointed with his mix.[33][123] For the album's 30th anniversary, an updated surround version was released in 2003. The band elected not to use Parsons' quadraphonic mix, and instead had the engineer James Guthrie create a new 5.1 channel surround sound mix on the SACD format.[33][124] Guthrie had worked with Pink Floyd since their eleventh album, The Wall, and had previously worked on surround versions of The Wall for DVD-Video and Waters' In the Flesh for SACD. In 2003, Parsons expressed disappointment with Guthrie's SACD mix, suggesting he was "possibly a little too true to the original mix", but was generally complimentary.[33] The 30th-anniversary edition won four Surround Music Awards in 2003,[125] and sold more than 800,000 copies.[126]

The cover image of the 30th-anniversary edition was created by a team of designers including Thorgerson.[122] The image is a photograph of a custom-made stained glass window, built to match the dimensions and proportions of the original prism design. Transparent glass, held in place by strips of lead, was used in place of the opaque colours of the original. The idea is derived from the "sense of purity in the sound quality, being 5.1 surround sound ..." The image was created out of a desire to be "the same but different, such that the design was clearly DSotM, still the recognisable prism design, but was different and hence new".[127]

Later reissues

[edit]The Dark Side of the Moon was rereleased in 2003 on 180-gram virgin vinyl and mastered by Kevin Gray at AcousTech Mastering. It included slightly different versions of the posters and stickers that came with the original vinyl release, along with a new 30th-anniversary poster.[128]

In 2007, the album was included in Oh, by the Way, a box set celebrating the 40th anniversary of Pink Floyd,[129] and a DRM-free version was released on the iTunes Store.[126] In 2011, it was reissued featuring a remastered version with various other material.[130]

In 2023, Pink Floyd released the Dark Side of the Moon 50th Anniversary box set, including a newly remastered edition of the album, surround sound mixes (including the 5.1 mix and a new Dolby Atmos mix), a photo book, and The Dark Side of the Moon Live at Wembley 1974, on vinyl.[131]

In 2024, the 50th Anniversary LP edition was rereleased as The Dark Side Of The Moon 50th Anniversary 2 LP UV Printed Clear Vinyl Collector's Edition. The new edition uses 2 clear LP instead of one, just one side is playable so the UV artwork can be printed on the non-groove side.[132]

Legacy

[edit]It's changed me in many ways, because it's brought in a lot of money, and one feels very secure when you can sell an album for two years. But it hasn't changed my attitude to music. Even though it was so successful, it was made in the same way as all our other albums, and the only criterion we have about releasing music is whether we like it or not. It was not a deliberate attempt to make a commercial album. It just happened that way. We knew it had a lot more melody than previous Floyd albums, and there was a concept that ran all through it. The music was easier to absorb and having girls singing away added a commercial touch that none of our records had.

– Richard Wright[133]

The success of the album brought wealth to all four members of the band; Richard Wright and Roger Waters bought large country houses, and Nick Mason became a collector of upmarket cars.[134] The group were fans of the British comedy troupe Monty Python, and as such, some of the profits were invested in the production of Monty Python and the Holy Grail.[135] Engineer Alan Parsons received a Grammy Award nomination for Best Engineered Recording, Non-Classical for The Dark Side of the Moon,[136] and he went on to have a successful career as a recording artist with the Alan Parsons Project. Although Waters and Gilmour have on occasion downplayed his contribution to the success of the album, Mason has praised his role.[137] In 2003, Parsons reflected: "I think they all felt that I managed to hang the rest of my career on Dark Side of the Moon, which has an element of truth to it. But I still wake up occasionally, frustrated about the fact that they made untold millions and a lot of the people involved in the record didn't."[39][nb 11]

Part of the legacy of The Dark Side of the Moon is its influence on modern music and on the musicians who have performed cover versions of its songs. It is often seen as a pivotal point in the history of rock music, and comparisons are sometimes made with Radiohead's 1997 album OK Computer,[139][140] including a premise explored by Ben Schleifer in 'Speak to Me': The Legacy of Pink Floyd's The Dark Side of the Moon (2006) that the two albums share a theme that "the creative individual loses the ability to function in the [modern] world".[141]

In a 2018 book about classic rock, Steven Hyden recalls concluding, in his teens, that The Dark Side of the Moon and Led Zeppelin IV were the two greatest albums of the genre, vision quests "encompass[ing] the twin poles of teenage desire". They had similarities, in that both albums' cover and internal artwork eschew pictures of the bands in favour of "inscrutable iconography without any tangible meaning (which always seemed to give the music packaged inside more meaning)". But whereas Led Zeppelin had looked outward, toward "conquering the world" and were known at the time for their outrageous sexual antics on tour, Pink Floyd looked inward, toward "overcoming your own hang-ups".[142] In 2013, The Dark Side of the Moon was selected for preservation in the United States National Recording Registry by the Library of Congress as "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[143]

Rankings

[edit]The Dark Side of the Moon frequently appears on professional rankings of the greatest albums. In 1987, Rolling Stone ranked it the 35th best album of the preceding 20 years.[144] Rolling Stone ranked it number 43 on its 2003 and 2012 lists of the "500 Greatest Albums of All Time"[145] and number 55 in its 2020 list, Pink Floyd's highest placement.[146] Both Rolling Stone and Q have listed The Dark Side of the Moon as the best progressive rock album.[147][148]

In 2006, Australian Broadcasting Corporation viewers voted The Dark Side of the Moon their favourite album.[149] NME readers voted it the eighth-best album in a 2006 poll,[150] and in 2009, Planet Rock listeners voted it the greatest of all time.[151] The album is also number two on the "Definitive 200" list of albums, made by the National Association of Recording Merchandisers "in celebration of the art form of the record album".[152] It ranked 29th in The Observer's 2006 list of "The 50 Albums That Changed Music",[153] and 37th in The Guardian's 1997 list of the "100 Best Albums Ever", as voted for by a panel of artists and music critics.[154] In 2014, readers of Rhythm voted it the seventh most influential progressive drumming album.[155] It was voted number 9 in Colin Larkin's All Time Top 1000 Albums 3rd Edition (2000).[156]

The album's cover has also been praised by critics and listeners, with VH1 proclaiming it to be the fourth greatest in history.[157]

Covers, tributes and samples

[edit]Return to the Dark Side of the Moon: A Tribute to Pink Floyd, released in 2006, is a cover album of The Dark Side of the Moon featuring artists such as Adrian Belew, Tommy Shaw, Dweezil Zappa, and Rick Wakeman.[158] In 2000, The Squirrels released The Not So Bright Side of the Moon, which features a cover of the entire album.[159][160] The New York dub collective Easy Star All-Stars released Dub Side of the Moon in 2003[161] and Dubber Side of the Moon in 2010.[162] The group Voices on the Dark Side released the album Dark Side of the Moon a Cappella, a complete a cappella version of the album.[163] The bluegrass band Poor Man's Whiskey frequently play the album in bluegrass style, calling the suite Dark Side of the Moonshine.[164] A string quartet version of the album was released in 2003.[165] In 2009, the Flaming Lips released a track-by-track remake of the album in collaboration with Stardeath and White Dwarfs, and featuring Henry Rollins and Peaches as guest musicians.[166]

Several notable acts have covered the album live in its entirety, and a range of performers have used samples from The Dark Side of the Moon in their own material. Jam-rock band Phish performed a semi-improvised version of the entire album as part of their show on 2 November 1998 in West Valley City, Utah.[167] Progressive metal band Dream Theater have twice covered the album in their live shows,[168] and in May 2011 Mary Fahl released From the Dark Side of the Moon, a song-by-song "re-imagining" of the album.[169] Milli Vanilli used the tape loops from Pink Floyd's "Money" to open their track "Money", followed by Marky Mark and the Funky Bunch on Music for the People.[170]

The Wizard of Oz

[edit]In the 1990s, it was discovered that playing The Dark Side of the Moon alongside the 1939 film The Wizard of Oz produced moments of apparent synchronicity, and it was suggested that this was intentional.[171][172] Such moments include Dorothy beginning to jog at the lyric "no one told you when to run" during "Time", balancing on a fence, tightrope-style, during the line "balanced on the biggest wave" in "Breathe",[173][174] and putting her ear to the Tin Man's chest as the album's closing heartbeats are heard.[175] Parsons and members of Pink Floyd denied any connection, with Parsons calling it "a complete load of eyewash ... If you play any record with the sound turned down on the TV, you will find things that work."[172][176]

The Dark Side of the Moon Redux

[edit]For the 50th anniversary of The Dark Side of the Moon, Waters recorded a new version, The Dark Side of the Moon Redux, set for release on 6 October 2023.[177] It was recorded with no other members of Pink Floyd,[177] and features spoken word sections and more downbeat arrangements, with no guitar solos. Waters said he wanted to "bring out the heart and soul of the album musically and spiritually".[178][179] He also said it is intended to be taken from the perspective of an older man, as "not enough people recognised what it's about, what it was I was saying then".[177]

Track listing

[edit]All lyrics are written by Roger Waters.

| No. | Title | Music | Lead vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Speak to Me" | Nick Mason | instrumental | 1:07 |

| 2. | "Breathe (In the Air)" | Gilmour | 2:49 | |

| 3. | "On the Run" |

| instrumental | 3:45 |

| 4. | "Time" |

|

| 6:53 |

| 5. | "The Great Gig in the Sky" |

| Torry | 4:44 |

| Total length: | 19:18 | |||

| No. | Title | Music | Lead vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6. | "Money" | Waters | Gilmour | 6:23 |

| 7. | "Us and Them" |

| Gilmour | 7:49 |

| 8. | "Any Colour You Like" |

| instrumental | 3:26 |

| 9. | "Brain Damage" | Waters | Waters | 3:46 |

| 10. | "Eclipse" | Waters | Waters | 2:12 |

| Total length: | 23:36 (43:09) | |||

Note

- Since the 2011 remasters, and the Discovery box set, "Speak to Me" and "Breathe (In the Air)" are indexed as individual tracks.

Personnel

[edit]Pink Floyd

- David Gilmour - guitars, vocals, Synthi AKS

- Nick Mason – drums, percussion, tape effects

- Roger Waters – bass guitar, vocals, VCS 3, tape effects

- Richard Wright – organs (Hammond and Farfisa), piano, electric pianos (Wurlitzer and Rhodes), EMS VCS 3, Synthi AKS, vocals

Additional musicians

| Production

Design

|

Charts

[edit]Weekly charts[edit]

| Year-end charts[edit]

|

Сертификация и продажи

[ редактировать ]| Область | Сертификация | Сертифицированные подразделения /продажи |

|---|---|---|

| Аргентина ( CAPIF ) [310] сертифицирован в 1991 году | 2× Платина | 120,000 ^ |

| Аргентина ( CAPIF ) [310] сертифицирован в 1994 году | 2× Платина | 120,000 ^ |

| Австралия ( ВОЗДУХ ) [311] видео | 4× Платина | 60,000 ^ |

| Австралия ( ВОЗДУХ ) [313] | 14× Платина | 1,020,000 [312] |

| Австрия ( IFPI Австрия ) [314] | 2× Платина | 100,000 * |

| Бельгия ( BEA ) [315] | Золото | 25,000 * |

| Канада ( Музыка Канады ) [316] видео | 5× Платина | 50,000 ^ |

| Канада ( Музыка Канады ) [317] | 2× Алмаз | 2,000,000 ^ |

| Канада ( Музыка Канады ) [318] Бокс-сет для погружения | Золото | 50,000 ^ |

| Чешская Республика [319] | Золото | 50,000 [319] |

| Дания ( IFPI Дания ) [320] | 5× Платина | 100,000 ‡ |

| Франция ( СНЭП ) [322] | Платина | 2,500,000 [321] |

| Германия ( BVMI ) [323] | 3× Платина | 1,500,000 ‡ |

| Германия ( BVMI ) [324] видео | Золото | 25,000 ^ |

| Греция | — | 45,000 [325] |

| Италия продажи 1973–1989 гг. | — | 1,000,000 [326] |

| Италия ( ФИМИ ) [327] продажи с 2009 года | 7× Платина | 350,000 ‡ |

| Новая Зеландия ( RMNZ ) [328] | 16× Платина | 240,000 ^ |

| Польша ( ЗПАВ ) [329] Warner Music PL издание | 2× Платина | 40,000 ‡ |

| Польша ( ЗПАВ ) [330] Поматом издание EMI | Платина | 70,000 * |

| Португалия ( AFP ) [331] переиздание | 2× Платина | 14,000 ‡ |

| Россия ( НФФФ ) [332] Обновленный | Платина | 20,000 * |

| Испания | — | 50,000 [333] |

| Великобритания ( BPI ) [334] Видео "Создание" | Платина | 50,000 ^ |

| Великобритания ( BPI ) [335] | 15× Платина | 4,500,000 ‡ |

| США ( RIAA ) [336] видео | 3× Платина | 300,000 ^ |

| США ( RIAA ) [337] сертифицированные продажи 1973–1998 гг. | 15× Платина | 15,000,000 ^ |

| Соединенные Штаты Продажи Нильсена, 1991–2008 гг. | — | 8,360,000 [338] |

| Резюме | ||

| По всему миру | — | 45,000,000 [3] |

* Данные о продажах основаны только на сертификации. | ||

История выпусков

[ редактировать ]| Страна | Дата | Этикетка | Формат | Каталожный номер. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Канада | 10 марта 1973 г. | Урожайные отчеты | Винил , Кассета , 8 дорожек | СМАС-11163 (ЛП) 4XW-11163 (СС) 8XW-11163 (8-гусеничный) |

| Соединенные Штаты | Кэпитол Рекордс | |||

| Великобритания | 16 марта 1973 г. | Урожайные отчеты | SHVL 804 (LP) TC-SHVL 804 (CC) Q8-SHVL 804 (8-гусеничный) | |

| Австралия | 1973 | Винил | Q4 SHVLA.804 |

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Список самых продаваемых альбомов

- Список самых продаваемых альбомов в Австралии

- Список самых продаваемых альбомов в Канаде

- Список самых продаваемых альбомов во Франции

- Список самых продаваемых альбомов в Германии

- Список самых продаваемых альбомов в Италии

- Список самых продаваемых альбомов в Новой Зеландии

- Список самых продаваемых альбомов в Великобритании

- Список самых продаваемых альбомов в США

- Список альбомов Канады, имеющих бриллиантовую сертификацию

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]Информационные примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ «Одно время он назывался Eclipse , потому что Medicine Head записали альбом под названием Dark Side of the Moon . Но он плохо продавался, так что, черт возьми. Я был против Eclipse , и мы были немного раздражены, потому что уже подумали об этом названии еще до выхода Medicine Head. Не злились на них, а потому, что хотели использовать это название». — Дэвид Гилмор [17]

- ↑ Этот материал позже был выпущен под названием Obscured by Clouds . [18]

- ↑ Мейсон отвечает за большую часть звуковых эффектов, использованных в дискографии Pink Floyd.

- ^ Жатва / Капитолий 3609

- ↑ По словам Пола Маккартни в интервью 1975 года, исполнительный директор Capitol Эл Кури предложил группе выпустить сингл. Маккартни вспоминал: «Эл Коури, первоклассный плаггер Capitol, позвонил нам и сказал: «Я убедил Pink Floyd взять «Money» с Dark Side of the Moon , и вы хотите знать, сколько копий мы продали?» сингл [99]

- ^ Жатва / Капитолий 3832

- ^ По данным Nielsen Broadcast Data Systems [103]

- ^ EMI/Harvest CP35-3017

- ^ Урожай CDP 7 46001 2

- ^ Урожай Q4SHVL-804

- ↑ Алану Парсонсу во время работы над оригинальным альбомом платили еженедельную зарплату в размере 35 фунтов стерлингов (что эквивалентно 600 фунтам стерлингов в 2023 году). [54] ). [138]

- ↑ Во всех тиражах после 2005 года, включая "The Great Gig in the Sky", авторы песни упоминаются как Райтом, так и Торри, что подтверждает ее успешный судебный иск. [48]

Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Гедон, Жан-Мишель (2017). Все песни Pink Floyd . Беговой пресс. ISBN 9780316439237 .

- ^ Смирк, Ричард. «Pink Floyd, «Темная сторона луны» в 40 лет: классический обзор треков» . Рекламный щит . Проверено 25 февраля 2022 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Смирк, Ричард (16 марта 2013 г.). «Pink Floyd, «Темная сторона луны» в 40 лет: классический обзор треков» . Рекламный щит . Проверено 25 ноября 2014 г.

- ^ «Премия Зала славы Грэмми» . Премия «Грэмми» Академии звукозаписи . Проверено 9 августа 2023 г.

- ^ Мейсон 2005 , с. 165

- ^ Харрис, Джон (12 марта 2003 г.). « Тёмная сторона» в 30 лет: Роджер Уотерс» . Роллинг Стоун . Архивировано из оригинала 26 марта 2009 года . Проверено 8 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Маббетт 1995 , с. н/д

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Харрис, Джон (12 марта 2003 г.). « Темная сторона» в 30 лет: Дэвид Гилмор» . Роллинг Стоун . Архивировано из оригинала 19 сентября 2007 года . Проверено 31 мая 2010 г.

- ^ Мейсон 2005 , с. 166

- ^ Харрис 2006 , стр. 73–74.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час Классические альбомы: The Making of The Dark Side of the Moon (DVD), Eagle Rock Entertainment, 26 августа 2003 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Мейсон 2005 , с. 167

- ^ Харрис 2006 , стр. 85–86.

- ^ Шаффнер 1991 , с. 159

- ^ Путешествие 2005 , стр. 28.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Шаффнер 1991 , с. 162

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Повей 2007 , с. 154

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Повей 2007 , стр. 154–155.

- ^ Уэйл, Майкл (18 февраля 1972 г.), Pink Floyd — The Rainbow, выпуск 58405; столбец F , infotrac.galegroup.com, стр. 10 , получено 21 марта 2009 г.

- ^ Харрис 2006 , стр. 91–93.

- ^ Пови 2007 , с. 159

- ^ Мейсон 2005 , с. 168

- ^ Шаффнер 1991 , с. 157

- ^ Povey 2007 , стр. 164–173.

- ^ Путешествие 2005 , стр. 60.

- ^ Уайтли 1992 , стр. 105–106.

- ^ Харрис 2006 , стр. 78–79.

- ^ Уайтли 1992 , с. 111

- ^ Путешествие 2005 , стр. 181–184.

- ^ Уайтли 1992 , с. 116

- ^ Алан Парсонс (февраль 2023 г.). «Все звезды высокой точности». Моджо .

- ^ Мейсон 2005 , с. 171

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Ричардсон, Кен (май 2003 г.). «Другая фаза Луны» . Звук и видение . п. 1. Архивировано из оригинала 14 марта 2012 года . Проверено 20 марта 2012 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Харрис 2006 , стр. 101–102.

- ^ Каннингем, Марк (январь 1995 г.). «Обратная сторона луны». Создание музыки . п. 18.

- ^ Мир гитары , февраль 1993 г. Получено с Pink Floyd Online 3 ноября 2008 г.

- ^ Харрис 2006 , стр. 103–108.

- ^ Уолдон, Стив (24 июня 2003 г.). «Темной стороны Луны на самом деле не существует…» Эпоха . Проверено 19 марта 2009 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Харрис, Джон (12 марта 2003 г.). « Темная сторона» в 30 лет: Алан Парсонс» . Роллинг Стоун . Архивировано из оригинала 24 июня 2008 года . Проверено 31 мая 2010 г.

- ^ Шаффнер 1991 , с. 158

- ^ «Документы студии «Тёмная сторона Луны»» . Проверено 12 сентября 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Шаффнер 1991 , с. 164

- ^ Мейсон 2005 , с. 172

- ^ Харрис 2006 , стр. 104–105.

- ^ Алан Парсонс (февраль 2023 г.). «Все звезды высокой точности». Моджо .

- ^ Харрис 2006 , стр. 118–120.

- ^ Мейсон 2005 , с. 173

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Повей 2007 , с. 161

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Марк Блейк (февраль 2023 г.). «Искусство шума». Моджо .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Блейк 2008 , стр. 198–199.

- ^ Мейсон 2005 , с. 174

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Джон Харрис (октябрь 2005 г.). «Клэр Торри – Повреждение головного мозга – Интервью» . Brain-damage.co.uk .

- ^ Симпсон, Дэйв (21 октября 2014 г.). «Малоизвестные музыканты, стоящие за некоторыми из самых известных моментов в музыке» . Хранитель . Проверено 3 июня 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Великобритании Данные по инфляции в индексе розничных цен основаны на данных Кларк, Грегори (2017). «Годовой ИРЦ и средний заработок в Великобритании с 1209 года по настоящее время (новая серия)» . Измерительная ценность . Проверено 7 мая 2024 г.

- ^ Энн Харрисон (3 июля 2014 г.). Музыка: Бизнес (6-е изд.). Случайный дом. п. 350. ИСБН 9780753550717 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Повей 2007 , с. 345

- ^ Алан Парсонс (февраль 2023 г.). «Все звезды высокой точности». Моджо .

- ^ Мейсон 2005 , с. 175

- ^ Шаффнер 1991 , с. 165

- ^ Харрис 2006 , с. 133

- ^ Сэмс, Кристина (23 февраля 2004 г.). «Как Наоми рассказала маме об Оскаре» . Сидней Морнинг Геральд . Проверено 17 марта 2009 г.

- ^ Сатклифф, Фил; Хендерсон, Питер (март 1998 г.). «Правдивая история Темной стороны Луны». Моджо . № 52.

- ^ Харрис 2006 , стр. 127–134.

- ^ Алан Парсонс (февраль 2023 г.). «Все звезды высокой точности». Моджо .

- ^ Каннингем, Марк (январь 1995 г.). «Обратная сторона луны». Создание музыки . п. 19.

- ^ Марк Блейк (28 октября 2008 г.). «10 вещей, которые вы, вероятно, не знали о Pink Floyd» . Таймс . Проверено 17 марта 2009 г.

- ^ Прайс, Стивен (27 августа 2006 г.). «Рок: Генри Маккалоу» . Таймс . Проверено 16 марта 2009 г.

- ^ Мейсон 2005 , с. 177

- ^ Мейсон 2005 , с. 178

- ^ Харрис 2006 , с. 135

- ^ Харрис 2006 , стр. 134–140.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Уодделл, Рэй (5 мая 2006 г.). «Роджер Уотерс возвращается к «Темной стороне» » . Рекламный щит . Проверено 2 августа 2009 г.

- ^ Харрис 2006 , с. 3

- ^ Харрис 2006 , с. 143

- ^ Хебблтуэйт, Фил (23 апреля 2018 г.). «Кто дизайнеры некоторых из самых ярких обложек музыкальных альбомов?» . Би-би-си . Проверено 6 марта 2022 г.

- ^ Шаффнер 1991 , стр. 165–166.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Харрис 2006 , стр. 141–147.

- ^ Эрлевайн, Стивен Томас . «Рецензия: Темная сторона Луны » . Вся музыка . Проверено 27 сентября 2018 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кристгау 1981 , с. 303.

- ^ Ларкин, Колин (2011). «Пинк Флойд» . Энциклопедия популярной музыки (5-е изд.). Омнибус Пресс. п. 1985. ISBN 978-0-85712-595-8 . Проверено 13 августа 2020 г.

- ^ Графф и Дурххольц 1999 , с. 874.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Обзор Темной стороны Луны» . Тауэр Рекордс . 20 марта 1993 г. с. 33. Архивировано из оригинала 18 августа 2009 года . Проверено 13 августа 2020 г.

- ^ Харви, Эрик (6 августа 2023 г.). «Pink Floyd: The Dark Side of the Moon обзор альбома » . Вилы . Проверено 6 августа 2023 г.

- ^ Дэвис, Джонни (октябрь 1994 г.). «Обзор темной стороны Луны». Вопрос . п. 137.

- ^ Коулман 1992 , с. 545.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Повей 2007 , с. 175

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Шаффнер 1991 , с. 166

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Повей 2007 , с. 160

- ^ Холлингворт, Рой (1973). «Историческая справка – обзор 1973 года, Melody Maker» . сайт Pinkfloyd.com. Архивировано из оригинала 28 февраля 2009 года . Проверено 30 марта 2009 г.

- ^ Гроссман, Ллойд (24 мая 1973 г.). «Обзор Темной стороны Луны» . Роллинг Стоун . Архивировано из оригинала 18 июня 2008 года . Проверено 31 мая 2010 г.

- ^ "[Реклама]" . Рекламный щит . Том. 85, нет. 8. 24 февраля 1973 г. с. 1 . Проверено 13 августа 2020 г.

Альбом доступен 1 марта. Тур начнется 5 марта.

- ^ «Студия Abbey Road представляет эксклюзивную коллекцию товаров Pink Floyd» . Студия Эбби Роуд . 28 февраля 2023 г. Проверено 1 марта 2023 г.

- ^ «EMI предлагает дилерам специальные предложения» . Рекламный щит . Том. 85, нет. 12. Лондон. 24 марта 1973 г. с. 54 . Проверено 13 августа 2020 г.

EMI предложит акции по принципу продажи или возврата избранным дилерам, принявшим участие в кампании стоимостью 50 000 долларов за четыре альбома, выпущенных 16 марта. ... Эти четыре альбома: "Dark Side of the Moon" группы Pink Floyd...

- ^ Мейсон 2005 , с. 187

- ^ Рекламный щит . Nielsen Business Media, Inc., 28 апреля 1973 г.

- ^ Шаффнер 1991 , стр. 166–167.

- ^ Харрис 2006 , стр. 158–161.

- ^ ДеГань, Майк. "Деньги" . Вся музыка . Проверено 2 августа 2009 г.

- ^ Гамбаччини, Пол (1996). Интервью Маккартни: после распада . Омнибус. ISBN 978-0-7119-5494-6 .

- ^ Нили, Тим (1999), Путеводитель по ценам Goldmine для пластинок со скоростью 45 об / мин (2-е изд.)

- ^ Пови 2007 , с. 346

- ^ Шаффнер 1991 , с. 173

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Верде, Билл (13 мая 2006 г.). «Теория Флойдиана» . Рекламный щит . Том. 118, нет. 19. с. 12 . Проверено 13 августа 2020 г.

- ^ «100 лучших альбомов» . РИАА . Архивировано из оригинала 1 июля 2007 года . Проверено 17 марта 2009 г.

- ^ Унтербергер, Ричи. «Биография Пинк Флойд» . Вся музыка . Проверено 2 августа 2009 г.

- ^ Галлуччи, Майкл (14 июля 2013 г.). «День, когда «Темная сторона Луны» завершила свой рекордный пробег» . Абсолютный классический рок . Проверено 27 апреля 2018 г.

- ^ Графф, Гэри (1 марта 2023 г.). «50 фактов о Pink Floyd «Темная сторона Луны», которые вам нужно знать» . Абсолютный классический рок . Проверено 26 мая 2023 г.

- ^ «Лучшие поп-альбомы Billboard» (PDF) . Рекламный щит . Том. 100, нет. 41. 1988. с. 81. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 9 октября 2022 года . Проверено 26 июля 2021 г.

- ^ Бэшам, Дэвид (15 ноября 2001 г.). «Есть чарты? Бритни и Linkin Park дают своим коллегам возможность побороться за показатели продаж» . МТВ . Архивировано из оригинала 17 ноября 2001 года . Проверено 30 марта 2009 г.

- ^ «Похоже на старые времена: каталог возвращается к 200». Рекламный щит . 5 декабря 2009 г.

- ^ «Горячий ящик» . Рекламный щит . Том. 121, нет. 49. 12 декабря 2009 г. с. 33 . Проверено 13 августа 2020 г.

- ^ «История чарта Pink Floyd (Billboard 200)» . Рекламный щит . Проверено 30 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Грейн, Пол (1 мая 2013 г.), неделя, закончившаяся 28 апреля 2013 г. Альбомы: Snoop Lamb Is More Like It , music.yahoo.com, заархивировано из оригинала 4 ноября 2013 г. , получено 9 июля 2013 г.

- ^ Рульманн 2004 , с. 175

- ^ «Обнародованы 60 официальных самых продаваемых альбомов Великобритании за все время» . Проверено 9 июня 2017 г.

- ^ Хоган, Марк (20 марта 2017 г.). «Exit Music: Как компьютер Radiohead уничтожил арт-поп-альбом, чтобы спасти его» . Вилы . Проверено 11 марта 2010 г.

- ^ Бут, Роберт (11 марта 2010 г.), «Pink Floyd одержали победу над концептуальным альбомом в судебном разбирательстве по поводу рингтонов» , The Guardian , Лондон , получено 22 июня 2016 г.

- ^ Гвитер, Мэтью (7 марта 1993 г.). «Темная сторона успеха». Журнал «Обозреватель» . п. 37.

- ^ "Архив MFSL распродан - оригинальная пластинка с основной записью" . МОФИ . Архивировано из оригинала 30 мая 2014 года . Проверено 20 марта 2012 г.

- ^ «Архив MFSL распродан – Золотой компакт-диск Ultradisc II» . МОФИ . Архивировано из оригинала 5 ноября 2011 года . Проверено 20 марта 2012 г.

- ^ Пови 2007 , с. 353

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Темная сторона луны – переиздание SACD» . Pinkfloyd.co.uk. Архивировано из оригинала 18 марта 2009 года . Проверено 12 августа 2009 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Томпсон, Дэйв (9 августа 2008 г.). «Множество сторон «Тёмной стороны Луны» ». Золотая жила . Том. 34, нет. 18. Иола, Висконсин: Публикации Краузе . стр. 38–41. ISSN 1055-2685 . ПроКвест 1506040 .

- ^ Ричардсон, Кен (19 мая 2003 г.). «Сказки с темной стороны» . Звук и видение . Архивировано из оригинала 22 июля 2012 года . Проверено 19 марта 2009 г.

- ^ «Премия Surround Music Awards 2003» . Surroundpro.com . 11 декабря 2003 года. Архивировано из оригинала 5 мая 2008 года . Проверено 19 марта 2009 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Музил, Стивен (1 июля 2007 г.), «Темная сторона луны» сияет на iTunes , news.cnet.com, заархивировано из оригинала 16 июня 2011 г. , получено 12 августа 2009 г.

- ^ Торгерсон, Шторм. «Эволюция обложки альбома – объясняет Сторм Торгерсон» . Официальный сайт Pink Floyd . Проверено 18 августа 2015 г. - из-за повреждения головного мозга.

- ^ Pink Floyd - Dark Side of the Moon - 180-граммовая виниловая пластинка , store.acousticsounds.com , получено 29 марта 2009 г.

- ^ Крепс, Дэниел (25 октября 2007 г.). « Да, кстати»: Pink Floyd отмечают запоздалое 40-летие мегабокс-сетом» . Роллинг Стоун . Архивировано из оригинала 28 июня 2011 года . Проверено 22 августа 2009 г.

- ^ ДеКертис, Энтони (11 мая 2011 г.). «Pink Floyd объявляют о масштабном переиздании» . Роллинг Стоун . Проверено 26 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ Монро, Джаз (19 января 2023 г.). «Pink Floyd анонсируют бокс-сет «Темной стороны Луны» к 50-летию» . Вилы . Проверено 21 января 2023 г.

- ^ «Pink Floyd выпустят обновленный ремастер «The Dark Side Of The Moon» на виниле Collector’s Edition с УФ-обложкой» . Полка искусств . 31 января 2024 г. Проверено 3 марта 2024 г.

- ^ Даллас 1987 , стр. 107–108.

- ^ Харрис 2006 , стр. 164–166.

- ^ Паркер и О'Ши, 2006 , стр. 50–51.

- ^ Шаффнер 1991 , с. 163

- ^ Харрис 2006 , стр. 173–174.

- ^ «Инкрустация к проекту Алана Парсонса», «Сказки о тайнах и воображении».

- ^ Гриффитс 2004 , с. 109

- ^ Бакли 2003 , с. 843

- ^ Путешествие 2005 , стр. 210.

- ^ Хайден, Стивен (2018). Сумерки богов: Путешествие к концу классического рока . Дейская улица. стр. 25–27. ISBN 9780062657121 .

- ^ "Chubby Checker Pink Floyd And Ramones внесены в Национальный реестр звукозаписывающих компаний" , VNN music , 22 марта 2013 г. , получено 22 марта 2013 г.

- ^ Путешествие 2005 , стр. 7.

- ^ «RS 500 величайших альбомов всех времен» . Роллинг Стоун . 18 ноября 2003 г. Архивировано из оригинала 16 мая 2013 г. . Проверено 31 мая 2010 г.

- ^ «500 величайших альбомов всех времён: Pink Floyd, «Тёмная сторона луны» » . Роллинг Стоун . 31 мая 2012 года. Архивировано из оригинала 16 мая 2013 года . Проверено 12 июня 2012 г.

- ^ Фишер, Рид (17 июня 2015 г.). «50 величайших альбомов в стиле прог-рок всех времен» . Роллинг Стоун . Архивировано из оригинала 22 декабря 2017 года . Проверено 26 января 2020 г. .

- ^ Браун, Джонатан (27 июля 2010 г.). «АЗ прогрессивного рока» . Белфастский телеграф . Проверено 26 января 2020 г. .

- ^ «Мой любимый альбом» . abc.net.au. Архивировано из оригинала 5 декабря 2006 года . Проверено 22 марта 2009 г.

- ^ «Объявлен лучший альбом всех времен» . НМЕ . 2 июня 2006 г. Проверено 22 ноября 2009 г.

- ^ «Топ-40 лучших альбомов по опросу» . Планета Рок . 2009. Архивировано из оригинала 4 октября 2011 года . Проверено 20 марта 2012 г.

- ^ «Окончательные 200» . рокхолл.com . Архивировано из оригинала 1 августа 2008 года . Проверено 21 июня 2010 г.

- ^ «50 альбомов, которые изменили музыку» . Guardian.co.uk. 16 июля 2006 г. Проверено 22 ноября 2009 г.

- ^ Свитинг, Адам (19 сентября 1997 г.). «Тонна радости» (требуется регистрация) . Хранитель . п. 28.

- ^ Маккиннон, Эрик (3 октября 2014 г.). «Пирт назван самым влиятельным прогрессивным барабанщиком» . Громче . Проверено 21 августа 2015 г.

- ^ Колин Ларкин , изд. (2000). 1000 лучших альбомов всех времен (3-е изд.). Девственные книги . п. 37. ИСБН 0-7535-0493-6 .

- ^ «Величайшие: 50 величайших обложек альбомов» . vh1.com. Архивировано из оригинала 12 ноября 2007 года . Проверено 17 марта 2009 г.

- ^ Прато, Грег. «Возвращение на темную сторону Луны: дань уважения Pink Floyd» . allmusic.com . Проверено 22 августа 2009 г.

- ^ Путешествие 2005 , стр. 198–199.

- ^ «Не очень светлая сторона Луны» . thesquirrels.com. Архивировано из оригинала 3 июля 2008 года . Проверено 27 марта 2009 г.

- ^ «Дуб Сторона Луны» . easystar.com. Архивировано из оригинала 6 февраля 2009 года . Проверено 27 марта 2009 г.

- ^ Джеффрис, Дэвид (25 октября 2010 г.). « Дубберская сторона луны – Easy Star All-Stars» . Вся музыка . Проверено 11 декабря 2012 г.

- ^ «Темная сторона Луны – а капелла» . darksidevoices.com . Проверено 27 марта 2009 г.

- ^ «Темная сторона самогона» . poormanswhiskey.com. 8 мая 2007 г. Архивировано из оригинала 5 июля 2008 г. Проверено 28 марта 2009 г.

- ^ Трибьют струнного квартета к песне Pink Floyd "Темная сторона луны" , billboard.com, 2004 г. , получено 2 августа 2009 г.

- ^ Линч, Джозеф Брэнниган (31 декабря 2009 г.). «Flaming Lips перепели альбом Pink Floyd «Dark Side of the Moon»; результаты на удивление ужасны» . music-mix.ew.com . Проверено 14 января 2010 г.

- ^ Ивасаки, Скотт (3 ноября 1998 г.). « Джем 'Phish Phans' на мелодии Pink 'Phloyd' » . deseretnews.com . Проверено 20 марта 2012 г.

- ^ Компакт-диск "Темная сторона Луны" . ytsejamrecords.com. Архивировано из оригинала 27 января 2011 года . Проверено 28 марта 2009 г.

- ^ Интервью: Мэри Фаль , nippertown.com, 22 сентября 2010 г. , дата обращения 11 мая 2011 г.

- ^ Путешествие 2005 , стр. 189–190.

- ^ Сэвидж, Чарльз (1 августа 1995 г.). «Темная сторона радуги» . Газета журнала Fort Wayne Journal . Архивировано из оригинала 13 октября 2007 г. – через rbsavage.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Связь Pink Floyd и Волшебника страны Оз» . Новости МТВ . Архивировано из оригинала 12 июня 2018 года . Проверено 9 июня 2018 г.

- ^ Путешествие 2005 , стр. 59.

- ^ Путешествие 2005 , стр. 57.

- ^ Марк Блейк (февраль 2023 г.). «Искусство шума». Моджо .

- ^ Килти, Мартин (9 октября 2022 г.). «Роджер Уотерс делится своим любимым слухом о «Темной стороне радуги»» . Абсолютный классический рок . Проверено 15 октября 2022 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Землер, Эмили (21 июля 2023 г.). «Роджер Уотерс выпустит сольный альбом «The Dark Side of the Moon Redux» в октябре» . Роллинг Стоун . Проверено 21 июля 2023 г.

РОДЖЕР УОТЕРС перезаписал плодотворный альбом Pink Floyd The Dark Side of the Moon и выпустит его как сольный альбом The Dark Side of the Moon Redux 6 октября на лейбле SGB Music.

- ^ «Роджера Уотерса подробно расспросили об Украине, России, Израиле и США» Pressenza . 4 февраля 2023 года. Архивировано из оригинала 6 февраля 2023 года . Проверено 6 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ Сондерс, Тристрам Фейн (8 февраля 2023 г.). «Роджер Уотерс: Я написал «Тёмную сторону Луны» — давайте избавимся от всей этой чуши «мы»» . «Дейли телеграф» . ISSN 0307-1235 . Архивировано из оригинала 8 февраля 2023 года . Проверено 9 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ Темная сторона Луны (буклет). Пинк Флойд. Кэпитол Рекордс (CDP 7 46001 2). 1993.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: другие цитируют AV Media (примечания) ( ссылка ) - ^ Темная сторона Луны (буклет). Пинк Флойд. ЭМИ (50999 028955 2 9). 2011.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: другие цитируют AV Media (примечания) ( ссылка ) - ^ Кент, Дэвид (1993), Австралийский картографический справочник 1970–1992 (иллюстрированное издание), Сент-Айвс, Новый Южный Уэльс: Австралийский картографический справочник, стр. 233, ISBN 0-646-11917-6

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Austriancharts.at – Pink Floyd – Темная сторона луны» (на немецком языке). Хунг Медиен. Проверено 9 июня 2016 г.

- ^ «Лучшие альбомы RPM: выпуск 4816» . Об/мин . Библиотека и архивы Канады . Проверено 9 июня 2016 г.

- ^ Найман, Джейк (2005). Suomi soi 4: Suuri suomalainen listkirja (на финском языке) (1-е изд.). Хельсинки: Дуб. стр. 130. ISBN 951-31-2503-3 .

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl - Pink Floyd - Темная сторона луны" (на голландском языке). Хунг Медиен. Проверено 9 июня 2016 г.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de - Pink Floyd - Темная сторона луны" (на немецком языке). Чарты GfK Entertainment . Проверено 9 июня 2016 г.

- ^ «Классификаш» . Musica e Dischi (на итальянском языке) . Проверено 30 мая 2022 г. Установите «Типо» на «Альбом». Затем в поле «Титоло» найдите «Темная сторона луны».

- ^ «Портал норвежских карт (17/1973)» . norwegiancharts.com . Проверено 9 июня 2016 г.

- ^ Салаверри, Фернандо (сентябрь 2005 г.). Только успехи: год за годом, 1959–2002 (1-е изд.). Испания: Fundación Autor-SGAE. ISBN 84-8048-639-2 .

- ^ "Pink Floyd | Артист | Официальные чарты" . Чарт альбомов Великобритании . Проверено 9 июня 2016 г.

- ^ "История чарта Pink Floyd ( Billboard 200)" . Рекламный щит . Проверено 9 июня 2016 г.

- ^ «Лучшие альбомы RPM: выпуск 4008a» . Об/мин . Библиотека и архивы Канады . Проверено 10 апреля 2022 г.

- ^ "Charts.nz - Pink Floyd - Темная сторона Луны" . Хунг Медиен. Проверено 9 июня 2016 г.

- ^ "Pink Floyd | Артист | Официальные чарты" . Чарт альбомов Великобритании . Проверено 9 июня 2016 г.

- ^ "История чарта Pink Floyd ( Billboard 200)" . Рекламный щит . Проверено 9 июня 2016 г.

- ^ «Портал австралийских карт (05.09.1993)» . australiancharts.com . Проверено 9 июня 2016 г.

- ^ «Лучшие альбомы RPM: выпуск 1775» . Об/мин . Библиотека и архивы Канады . Проверено 17 июня 2016 г.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl - Pink Floyd - Темная сторона луны" (на голландском языке). Хунг Медиен. Проверено 17 июня 2016 г.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de - Pink Floyd - Темная сторона луны" (на немецком языке). Чарты GfK Entertainment . Проверено 17 июня 2016 г.

- ^ "Norwegiancharts.com - Pink Floyd - Темная сторона Луны" . Хунг Медиен. Проверено 17 июня 2016 г.

- ^ «Портал новозеландских чартов (18.04.1993)» . .charts.nz . Проверено 11 июня 2016 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Swedishcharts.com – Pink Floyd – Темная сторона Луны» . Хунг Медиен. Проверено 17 июня 2016 г.

- ^ "Ultratop.be - Pink Floyd - Темная сторона луны" (на голландском языке). Хунг Медиен. Проверено 17 июня 2016 г.

- ^ "Ultratop.be - Pink Floyd - Темная сторона луны" (на французском языке). Хунг Медиен. Проверено 17 июня 2016 г.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl - Pink Floyd - Темная сторона луны" (на голландском языке). Хунг Медиен. Проверено 17 июня 2016 г.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de - Pink Floyd - Темная сторона луны" (на немецком языке). Чарты GfK Entertainment . Проверено 17 июня 2016 г.

- ^ «Альбомы чартов GFK: 15-я неделя, 2003 г.» . Чарт-трек . ИРМА . Проверено 17 июня 2016 г.

- ^ «Портал итальянских чартов (17.04.2003)» . italiancharts.com . Проверено 9 июня 2016 г.

- ^ "Charts.nz - Pink Floyd - Темная сторона Луны" . Хунг Медиен. Проверено 11 июня 2016 г.

- ^ "Norwegiancharts.com - Pink Floyd - Темная сторона Луны" . Хунг Медиен. Проверено 17 июня 2016 г.

- ^ "Официальный список обновлений :: OLiS - Официальный график розничных продаж" . ОЛиС . Польское общество фонографической индустрии . Проверено 17 июня 2016 г.

- ^ "Portuguesecharts.com - Pink Floyd - Темная сторона Луны" . Хунг Медиен. Проверено 9 июня 2016 г.

- ^ "Australiancharts.com - Pink Floyd - Темная сторона Луны" . Хунг Медиен. Проверено 17 июня 2016 г.

- ^ "Ultratop.be - Pink Floyd - Темная сторона луны" (на голландском языке). Хунг Медиен. Проверено 17 июня 2016 г.

- ^ "Ultratop.be - Pink Floyd - Темная сторона луны" (на французском языке). Хунг Медиен. Проверено 17 июня 2016 г.

- ^ "Danishcharts.dk - Pink Floyd - Темная сторона Луны" . Хунг Медиен. Проверено 17 июня 2016 г.

- ^ « Pink Floyd: Темная сторона луны» (на финском языке). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Финляндия . Проверено 17 июня 2016 г.

- ^ «Альбомы чартов GFK: 33-я неделя, 2006 г.» . Чарт-трек . ИРМА . Проверено 17 июня 2016 г.

- ^ "Italiancharts.com - Pink Floyd - Темная сторона Луны" . Хунг Медиен. Проверено 17 июня 2016 г.

- ^ "Norwegiancharts.com - Pink Floyd - Темная сторона Луны" . Хунг Медиен. Проверено 17 июня 2016 г.

- ^ "Официальный список обновлений :: OLiS - Официальный график розничных продаж" . ОЛиС . Польское общество фонографической индустрии . Проверено 17 июня 2016 г.

- ^ "Spanishcharts.com - Pink Floyd - Темная сторона Луны" . Хунг Медиен. Проверено 17 июня 2016 г.

- ^ "Swisscharts.com - Pink Floyd - Темная сторона Луны" . Хунг Медиен. Проверено 17 июня 2016 г.

- ^ «Австралийский чартерный портал (10.09.2011)» . australiancharts.com . Проверено 9 июня 2016 г.

- ^ "Ultratop.be - Pink Floyd - Темная сторона луны" (на голландском языке). Хунг Медиен. Проверено 2 апреля 2023 г.

- ^ "Ultratop.be - Pink Floyd - Темная сторона луны - Experience Edition" (на французском языке). Хунг Медиен. Проверено 28 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ «Чешские альбомы – 100 лучших» . ЧНС ИФПИ . Примечание . На странице диаграммы выберите 39.Týden 2011 в поле рядом со словами « CZ – АЛЬБОМЫ – TOP 100 », чтобы получить правильную диаграмму. Проверено 17 июня 2016 г.

- ^ «Портал датских чартов (10.07.2011)» . Danishcharts.dk . Проверено 9 июня 2016 г.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl - Pink Floyd - Темная сторона луны" (на голландском языке). Хунг Медиен. Проверено 9 июня 2016 г.

- ^ «Портал финского чарта (40/2011)» . finnishcharts.com . Проверено 9 июня 2016 г.

- ^ "Lescharts.com - Pink Floyd - Темная сторона Луны - Издание Experience" . Хунг Медиен. Проверено 28 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de - Pink Floyd - Темная сторона луны" (на немецком языке). Чарты GfK Entertainment . Проверено 9 июня 2016 г.

- ^ «Хит-лист альбома Top 40 – 42 неделя 2023 года» (на венгерском языке). МАШИНЫ . Проверено 26 октября 2023 г.

- ^ «Альбомы чартов GFK: 39-я неделя, 2011 г.» . Чарт-трек . ИРМА . Проверено 17 июня 2016 г.

- ^ «Портал итальянских чартов (10.06.2011)» . italiancharts.com . Проверено 9 июня 2016 г.

- ^ «Портал новозеландских чартов (10.03.2011)» . .charts.nz . Проверено 9 июня 2016 г.

- ^ "Norwegiancharts.com - Pink Floyd - Темная сторона Луны - Опытное издание" . Хунг Медиен. Проверено 28 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ «OLiS - официальный список продаж - альбомы» (на польском языке). ОЛиС . Польское общество фонографической индустрии . Примечание. Измените дату на 13 октября 2023 г.–19 октября 2023 г. в разделе «диапазон изменения от–до:» . Проверено 26 октября 2023 г.

- ^ «Портал португальских карт» . www.portuguesecharts.com . Проверено 6 июня 2022 г.

- ^ «Портал испанских чартов (11.02.2011)» . сайт испанских чартов . Проверено 9 июня 2016 г.

- ^ "Таблица альбомов круга Южной Кореи" . На странице выберите «2011.09.25», чтобы получить соответствующий график. Круговая диаграмма , получено 12 октября 2020 г.

- ^ "Международный чарт альбомов South Korea Circle" . На странице выберите «2011.09.25», чтобы получить соответствующий график. Круговая диаграмма , получено 12 октября 2020 г.

- ^ «Шведский портал чартов (10.07.2011)» . swedishcharts.com . Проверено 9 июня 2016 г.

- ^ "Swisscharts.com - Pink Floyd - Темная сторона Луны" . Хунг Медиен. Проверено 2 апреля 2023 г.

- ^ "Pink Floyd | Артист | Официальные чарты" . Чарт альбомов Великобритании . Проверено 11 июня 2016 г.

- ^ «Рейтинги (февраль 2022 г.)» (на испанском языке). Камара Уругвая дель Дискотека . Архивировано из оригинала 29 марта 2022 года . Проверено 6 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ "История чарта Pink Floyd ( Billboard 200)" . Рекламный щит . Проверено 11 июня 2016 г.

- ^ "История чарта Pink Floyd (лучшие рок-альбомы)" . Рекламный щит . Проверено 26 октября 2020 г.

- ^ «Ежегодный хит-парад альбомов 1973 года» . austriancharts.at . Проверено 25 октября 2020 г.

- ^ «Годовые обзоры - Альбом 1973 г.» . Dutchcharts.nl . Проверено 9 апреля 2021 г.

- ^ «100 лучших альбомов-Jahrescharts» (на немецком языке). ГфК Развлечения . Проверено 23 мая 2021 г.

- ^ «Лучшие альбомы Billboard 200 – конец 1973 года» . Рекламный щит . 2 января 2013 года . Проверено 25 октября 2020 г.

- ^ «Лучшие альбомы Billboard 200 – конец 1974 года» . Рекламный щит . 2 января 2013 года . Проверено 25 октября 2020 г.

- ^ «Самые продаваемые альбомы 1975 года — официальный музыкальный чарт Новой Зеландии» . Записанная музыка Новая Зеландия . Проверено 3 ноября 2021 г.

- ^ «Самые продаваемые альбомы 1975 года» (PDF) . Музыкальная неделя . 27 декабря 1975 г. с. 10. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 9 марта 2021 года . Проверено 30 ноября 2021 г. - через worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ «Лучшие альбомы Billboard 200 – конец 1975 года» . Рекламный щит . 2 января 2013 года . Проверено 11 марта 2021 г.

- ^ «Самые продаваемые альбомы 1976 года — официальный музыкальный чарт Новой Зеландии» . Записанная музыка Новая Зеландия . Проверено 26 января 2022 г.

- ^ «50 лучших альбомов 1976 года» (PDF) . Музыкальная неделя . 25 декабря 1976 г. с. 14. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 9 марта 2021 года . Проверено 30 ноября 2021 г. - через worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ «Самые продаваемые альбомы 1977 года — официальный музыкальный чарт Новой Зеландии» . Записанная музыка Новая Зеландия . Проверено 26 января 2022 г.

- ^ «Лучшие альбомы 1977 года» (PDF) . Музыкальная неделя . 24 декабря 1977 г. с. 14. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 9 марта 2021 года . Получено 1 декабря 2021 г. - через worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ «Самые продаваемые альбомы 1978 года — официальный музыкальный чарт Новой Зеландии» . Записанная музыка Новая Зеландия . Проверено 26 января 2022 г.

- ^ «Самые продаваемые альбомы 1980 года — официальный музыкальный чарт Новой Зеландии» . Записанная музыка Новая Зеландия . Проверено 28 января 2022 г.

- ^ «Лучшие альбомы Billboard 200 – конец 1980 года» . Рекламный щит . 2 января 2013 года . Проверено 23 апреля 2021 г.

- ^ «Самые продаваемые альбомы 1981 года — официальный музыкальный чарт Новой Зеландии» . Записанная музыка Новая Зеландия . Проверено 1 февраля 2022 г.

- ^ «Лучшие альбомы Billboard 200 – конец 1982 года» . Рекламный щит . Проверено 28 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ «Лучшие альбомы Billboard 200 – конец 1983 года» . Рекламный щит . Проверено 1 марта 2021 г.

- ^ «100 лучших альбомов 1993 года» (PDF) . Музыкальная неделя . 15 января 1994 г. с. 25. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 9 октября 2022 года . Проверено 20 апреля 2022 г.

- ^ «Официальный чарт альбомов Великобритании 2003» (PDF) . UKChartsPlus . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 9 октября 2022 года . Проверено 2 апреля 2021 г.