Курт Воннегут

Курт Воннегут | |

|---|---|

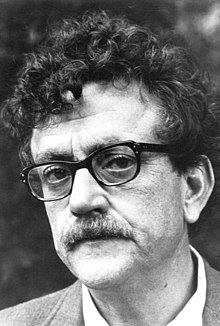

Воннегут в 1965 году | |

| Рожденный | Kurt Vonnegut Jr. November 11, 1922 Индианаполис , Индиана, США |

| Died | April 11, 2007 (aged 84) New York City, U.S. |

| Occupation | Author |

| Education | |

| Genre | |

| Literary movement | Postmodernism |

| Years active | 1951–2007 |

| Notable works | |

| Spouse |

|

| Children |

|

| Signature | |

| |

Kurt Vonnegut ( / ˈ V ɒ n ə ɡ ə t / von -Chish -gət ; 11 ноября 1922 года -11 апреля 2007 г.) был американским автором, известным своими сатирическими и мрачными юмористическими романами. [ 1 ] Его опубликованная работа включает в себя четырнадцать романов, три коротких коллекция, пять пьес и пять научных работ более пятидесяти с лишним лет; Дальнейшие работы были опубликованы с момента его смерти.

Воннегут родился и вырос в Индианаполисе , учился в Корнелльском университете , но вышел в январе 1943 года и поступил в армию США . В рамках своего обучения он изучал машиностроение в Технологическом институте Карнеги и Университете Теннесси . Затем он был развернут в Европе, чтобы сражаться во Второй мировой войне и был захвачен немцами во время битвы при выпуклости . Он был интернирован в Дрездене , где он пережил бомбардировку союзников города в шкафчике мяса от бойни, где он был заключен в тюрьму. После войны он женился на Джейн Мари Кокс. Он и его жена оба учились в Чикагском университете , когда он работал ночным репортером в городском бюро новостей . [ 2 ]

Vonnegut published his first novel, Player Piano, in 1952. It received positive reviews yet sold poorly. In the nearly 20 years that followed, several well regarded novels were published, including The Sirens of Titan (1959) and Cat's Cradle (1963), both of which were nominated for the Hugo Award for best science fiction or fantasy novel of the year. His short-story collection, Welcome to the Monkey House, was published in 1968.

Vonnegut's breakthrough was his commercially and critically successful sixth novel, Slaughterhouse-Five (1969). Its anti-war sentiment resonated with its readers amid the Vietnam War, and its reviews were generally positive. It rose to the top of The New York Times Best Seller list and made Vonnegut famous. Later in his career, Vonnegut published autobiographical essays and short-story collections such as Fates Worse Than Death (1991) and A Man Without a Country (2005). He has been hailed for his darkly humorous commentary on American society. His son Mark published a compilation of his work, Armageddon in Retrospect, in 2008. In 2017, Seven Stories Press published Complete Stories, a collection of Vonnegut's short fiction.

Biography

[edit]Family and early life

[edit]Vonnegut was born in Indianapolis, on November 11, 1922, the youngest of three children of Kurt Vonnegut Sr. (1884–1956) and his wife Edith (1888–1944; née Lieber). His older siblings were Bernard (1914–1997) and Alice (1917–1958). He descended from a long line of German Americans whose immigrant ancestors settled in the United States in the mid-19th century; his paternal great-grandfather, Clemens Vonnegut, settled in Indianapolis and founded the Vonnegut Hardware Company. His father and grandfather Bernard were architects; the architecture firm under Kurt Sr. designed such buildings as Das Deutsche Haus (now called "The Athenæum"), the Indiana headquarters of the Bell Telephone Company, and the Fletcher Trust Building.[3] Vonnegut's mother was born into Indianapolis's Gilded Age high society, as her family, the Liebers, were among the wealthiest in the city based on a fortune deriving from a successful brewery.[4]

Both of Vonnegut's parents were fluent speakers of the German language, but pervasive anti-German sentiment during and after World War I caused them to abandon German culture, which many German Americans were told at the time was a precondition for American patriotism. Thus, they did not teach Vonnegut to speak German or introduce him to German literature, cuisine, or traditions, leaving him feeling "ignorant and rootless".[5][6] Vonnegut later credited Ida Young, his family's African-American cook and housekeeper during the first decade of his life, for raising him and giving him values; he said, "she gave me decent moral instruction and was exceedingly nice to me", and "was as great an influence on me as anybody". He described her as "humane and wise" and added that "the compassionate, forgiving aspects of [his] beliefs" came from her.[7]

The financial security and social prosperity that the Vonneguts had once enjoyed were destroyed in a matter of years. The Liebers' brewery closed down in 1921 after the advent of prohibition. When the Great Depression hit, few people could afford to build, causing clients at Kurt Sr.'s architectural firm to become scarce.[8] Vonnegut's brother and sister had finished their primary and secondary educations in private schools, but Vonnegut was placed in a public school called Public School No. 43 (now the James Whitcomb Riley School).[9] He was bothered by the Great Depression,[a] and both his parents were affected deeply by their economic misfortune. His father withdrew from normal life and became what Vonnegut called a "dreamy artist".[11] His mother became depressed, withdrawn, bitter, and abusive. She labored to regain the family's wealth and status, and Vonnegut said that she expressed hatred for her husband that was "as corrosive as hydrochloric acid".[12] She often tried in vain to sell short stories she had written to Collier's, The Saturday Evening Post, and other magazines.[5]

High school and Cornell University

[edit]

Vonnegut enrolled at Shortridge High School in Indianapolis in 1936. While there, he played clarinet in the school band and became a co-editor (along with Madelyn Pugh) for the Tuesday edition of the school newspaper, The Shortridge Echo. Vonnegut said that his tenure with the Echo allowed him to write for a large audience—his fellow students—rather than for a teacher, an experience, he said, was "fun and easy".[3] "It just turned out that I could write better than a lot of other people", Vonnegut observed. "Each person has something he can do easily and can't imagine why everybody else has so much trouble doing it."[9]

After graduating from Shortridge in 1940, Vonnegut enrolled at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. He wanted to study the humanities and had aspirations of becoming an architect like his father, but his father[b] and brother Bernard, an atmospheric scientist, urged him to study a "useful" discipline.[3] As a result, Vonnegut majored in biochemistry, but he had little proficiency in the area and was indifferent towards his studies.[14] As his father had been a member at MIT,[15] Vonnegut was entitled to join the Delta Upsilon fraternity, and did.[16] He overcame stiff competition for a place at the university's independent newspaper, The Cornell Daily Sun, first serving as a staff writer, then as an editor.[17][18] By the end of his first year, he was writing a column titled "Innocents Abroad", which reused jokes from other publications. He later penned a piece "Well All Right" focusing on pacifism, a cause he strongly supported,[9] arguing against US intervention in World War II.[19]

World War II

[edit]

The attack on Pearl Harbor brought the United States into WWII. Vonnegut was a member of Reserve Officers' Training Corps, but poor grades and a satirical article in Cornell's newspaper cost him his place there. He was placed on academic probation in May 1942 and dropped out the following January. No longer eligible for a deferment as a member of ROTC, he faced likely conscription into the U.S. Army. Instead of waiting to be drafted, he enlisted in the Army and in March 1943 reported to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, for basic training.[20] Vonnegut was trained to fire and maintain howitzers and later received instruction in mechanical engineering at the Carnegie Institute of Technology and the University of Tennessee as part of the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP).[13]

In early 1944, the ASTP was canceled due to the Army's need for soldiers to support the D-Day invasion, and Vonnegut was ordered to an infantry battalion at Camp Atterbury, south of Indianapolis in Edinburgh, Indiana, where he trained as a scout.[21] He lived so close to his home that he was "able to sleep in [his] own bedroom and use the family car on weekends".[22]

On May 14, 1944, Vonnegut returned home on leave for Mother's Day weekend to discover that his mother had committed suicide the previous night by overdosing on sleeping pills.[23] Possible factors that contributed to Edith Vonnegut's suicide include the family's loss of wealth and status, Vonnegut's forthcoming deployment overseas, and her own lack of success as a writer. She was inebriated at the time and under the influence of prescription drugs.[23]

Three months after his mother's suicide, Vonnegut was sent to Europe as an intelligence scout with the 106th Infantry Division. In December 1944, he fought in the Battle of the Bulge, one of the last German offensives of the war.[23] On December 22, Vonnegut was captured with about 50 other American soldiers.[24] Vonnegut was taken by boxcar to a prison camp south of Dresden, in the German province of Saxony. During the journey, the Royal Air Force mistakenly attacked the trains carrying Vonnegut and his fellow prisoners of war, killing about 150 of them.[25] Vonnegut was sent to Dresden, the "first fancy city [he had] ever seen". He lived in a slaughterhouse when he got to the city, and worked in a factory that made malt syrup for pregnant women. Vonnegut recalled the sirens going off whenever another city was bombed. The Germans did not expect Dresden to be bombed, Vonnegut said. "There were very few air-raid shelters in town and no war industries, just cigarette factories, hospitals, clarinet factories."[26]

On February 13, 1945, Dresden became the target of Allied forces. In the hours and days that followed, the Allies engaged in a firebombing of the city.[23] The offensive subsided on February 15, with about 25,000 civilians killed in the bombing. Vonnegut marveled at the level of both the destruction in Dresden and the secrecy that attended it. He had survived by taking refuge in a meat locker three stories underground.[9] "It was cool there, with cadavers hanging all around", Vonnegut said. "When we came up the city was gone ... They burnt the whole damn town down."[26] Vonnegut and other American prisoners were put to work immediately after the bombing, excavating bodies from the rubble.[27] He described the activity as a "terribly elaborate Easter-egg hunt".[26]

The American POWs were evacuated on foot to the border of Saxony and Czechoslovakia after U.S. General George S. Patton's 3rd Army captured Leipzig. With the captives abandoned by their guards, Vonnegut reached a prisoner-of-war repatriation camp in Le Havre, France, in May 1945, with the aid of the Soviets.[25] Sent back to the United States, he was stationed at Fort Riley, Kansas, typing discharge papers for other soldiers.[28] Soon after he was awarded a Purple Heart, about which he remarked: "I myself was awarded my country's second-lowest decoration, a Purple Heart for frost-bite."[29] He was discharged from the U.S. Army and returned to Indianapolis.[30]

Marriage, University of Chicago, and early employment

[edit]After he returned to the United States, 22-year-old Vonnegut married Jane Marie Cox, his high-school girlfriend and classmate since kindergarten, on September 1, 1945. The pair moved to Chicago; there, Vonnegut enrolled in the University of Chicago on the G.I. Bill, as an anthropology student in an unusual five-year joint undergraduate/graduate program that conferred a master's degree. There, he studied under anthropologist Robert Redfield, his "most famous professor".[31] He also worked as a reporter for the City News Bureau of Chicago.[32][33]

Jane, who had graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Swarthmore,[34] accepted a scholarship from the university to study Russian literature as a graduate student. Jane dropped out of the program after becoming pregnant with the couple's first child, Mark (born May 1947), while Kurt also left the university without any degree (despite having completed his undergraduate education). Vonnegut failed to write a dissertation, as his ideas had all been rejected.[26] One abandoned topic was about the Ghost Dance and Cubist movements.[35][36][37] A later topic, rejected "unanimously", had to do with the shapes of stories.[38][39][40] Vonnegut received his graduate degree in anthropology 25 years after he left, when the university accepted his novel Cat's Cradle in lieu of his master's thesis.[41]

Shortly thereafter, General Electric (GE) hired Vonnegut as a technical writer, then publicist,[42] for the company's Schenectady, New York, News Bureau, a publicity department that operated like a newsroom.[43] His brother Bernard had worked at GE since 1945, focusing mainly on a silver-iodide-based cloud seeding project that quickly became a joint GE-U.S. Army Signal Corps program, Project Cirrus. In The Brothers Vonnegut, Ginger Strand draws connections between many real events at General Electric, including Bernard's work, and Vonnegut's early stories, which were regularly being rejected everywhere he sent them.[44] Throughout this period, Jane Vonnegut encouraged him, editing his stories, strategizing about submissions and buoying his spirits.[45]

In 1949, Kurt and Jane had a daughter named Edith. Still working for GE, Vonnegut had his first piece, titled "Report on the Barnhouse Effect", published in the February 11, 1950, issue of Collier's, for which he received $750.[46] The story concerned a scientist who fears that his invention will be used as a weapon, much as Bernard was fearing at the time about his cloudseeding work.[47] Vonnegut wrote another story, after being coached by the fiction editor at Collier's, Knox Burger, and again sold it to the magazine, this time for $950. While Burger supported Vonnegut's writing, he was shocked when Vonnegut quit GE as of January 1, 1951, later stating: "I never said he should give up his job and devote himself to fiction. I don't trust the freelancer's life, it's tough."[48] Nevertheless, in early 1951 Vonnegut moved with his family to Cape Cod, Massachusetts, to write full time, leaving GE behind.[49] He initially moved to Osterville, but he ended up purchasing a home in Barnstable.[50]

First novel

[edit]In 1952, Vonnegut's first novel, Player Piano, was published by Scribner's. The novel has a post-Third World War setting, in which factory workers have been replaced by machines.[51] Player Piano draws upon Vonnegut's experience as an employee at GE. The novel is set at a General Electric-like company and includes many scenes based on things Vonnegut saw there.[52] He satirizes the drive to climb the corporate ladder, one that in Player Piano is rapidly disappearing as automation increases, putting even executives out of work. His central character, Paul Proteus, has an ambitious wife, a backstabbing assistant, and a feeling of empathy for the poor. Sent by his boss, Kroner, as a double agent among the poor (who have all the material goods they want, but little sense of purpose), he leads them in a machine-smashing, museum-burning revolution.[53] Player Piano expresses Vonnegut's opposition to McCarthyism, something made clear when the Ghost Shirts, the revolutionary organization Paul penetrates and eventually leads, is referred to by one character as "fellow travelers".[54]

In Player Piano, Vonnegut originates many of the techniques he would use in his later works. The comic, heavy-drinking Shah of Bratpuhr, an outsider to this dystopian corporate United States, is able to ask many questions that an insider would not think to ask, or would cause offense by doing so. For example, when taken to see the artificially intelligent supercomputer EPICAC, the Shah asks it "what are people for?" and receives no answer. Speaking for Vonnegut, he dismisses it as a "false god". This type of alien visitor would recur throughout Vonnegut's literature.[53]

The New York Times writer and critic Granville Hicks gave Player Piano a positive review, favorably comparing it to Aldous Huxley's Brave New World. Hicks called Vonnegut a "sharp-eyed satirist". None of the reviewers considered the novel particularly important. Several editions were printed—one by Bantam with the title Utopia 14, and another by the Doubleday Science Fiction Book Club—whereby Vonnegut gained the repute of a science fiction writer, a genre held in disdain by writers at that time. He defended the genre and deplored a perceived sentiment that "no one can simultaneously be a respectable writer and understand how a refrigerator works".[51]

Struggling writer

[edit]

After Player Piano, Vonnegut continued to sell short stories to various magazines. Contracted to produce a second novel (which eventually became Cat's Cradle), he struggled to complete it, and the work languished for years. In 1954, the couple had a third child, Nanette. With a growing family and no financially successful novels yet, Vonnegut's short stories helped to sustain the family, though he frequently needed to find additional sources of income as well. In 1957, he and a partner opened a Saab automobile dealership on Cape Cod, but it went bankrupt by the end of the year.[55]

In 1958, his sister, Alice, died of cancer two days after her husband, James Carmalt Adams, was killed in a train accident. The Vonneguts took in three of the Adams' young sons—James, Steven, and Kurt, aged 14, 11, and 9, respectively.[56] A fourth Adams son, Peter (2), also stayed with the Vonneguts for about a year before being given to the care of a paternal relative in Georgia.[57]

Grappling with family challenges, Vonnegut continued to write, publishing novels vastly dissimilar in terms of plot. The Sirens of Titan (1959) features a Martian invasion of Earth, as experienced by a bored billionaire Malachi Constant. He meets Winston Niles Rumfoord, an aristocratic space traveler, who is virtually omniscient but stuck in a time warp that causes him to appear on Earth every 59 days. The billionaire learns that his actions and the events of all of history are determined by a race of robotic aliens from the planet Tralfamadore, who need a replacement part that can only be produced by an advanced civilization in order to repair their spaceship and return home—human history has been manipulated to produce it. Some human structures, such as the Kremlin, are coded signals from the aliens to their ship as to how long it may expect to wait for the repair to take place. Reviewers were uncertain what to think of the book, with one comparing it to Offenbach's opera The Tales of Hoffmann.[58]

Rumfoord, who is based on Franklin D. Roosevelt, also physically resembles the former president. Rumfoord is described this way: he "put a cigarette in a long, bone cigarette holder, lighted it. He thrust out his jaw. The cigarette holder pointed straight up."[59] William Rodney Allen, in his guide to Vonnegut's works, stated that Rumfoord foreshadowed the fictional political figures who would play major roles in God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater and Jailbird.[60]

Mother Night, published in 1961, received little attention at the time of its publication. Howard W. Campbell Jr., Vonnegut's protagonist, is an American who is raised in Germany from age 11 and joins the Nazi party during the war as a double agent for the US Office of Strategic Services, rising to the regime's highest ranks as a radio propagandist. After the war, the spy agency refuses to clear his name, and he is eventually imprisoned by the Israelis in the same cell block as Adolf Eichmann. Vonnegut wrote in a foreword to a later edition: "we are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful about what we pretend to be".[61] Literary critic Lawrence Berkove considered the novel, like Mark Twain's Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, to illustrate the tendency for "impersonators to get carried away by their impersonations, to become what they impersonate and therefore to live in a world of illusion".[62]

Also published in 1961 was Vonnegut's short story "Harrison Bergeron", set in a dystopic future where all are equal, even if that means disfiguring beautiful people and forcing the strong or intelligent to wear devices that negate their advantages. Fourteen-year-old Harrison is a genius and athlete forced to wear record-level "handicaps" and imprisoned for attempting to overthrow the government. He escapes to a television studio, tears away his handicaps, and frees a ballerina from her lead weights. As they dance, they are killed by the Handicapper General, Diana Moon Glampers.[63] Vonnegut, in a later letter, suggested that "Harrison Bergeron" might have sprung from his envy and self-pity as a high-school misfit. In his 1976 biography of Vonnegut, Stanley Schatt suggested that the short story shows "in any leveling process, what really is lost, according to Vonnegut, is beauty, grace, and wisdom".[64] Darryl Hattenhauer, in his 1998 journal article on "Harrison Bergeron", theorized that the story was a satire on American Cold War understandings of communism and socialism.[64]

With Cat's Cradle (1963), Allen wrote, "Vonnegut hit full stride for the first time".[65] The narrator, John, intends to write of Dr. Felix Hoenikker, one of the fictional fathers of the atomic bomb, seeking to cover the scientist's human side. Hoenikker, in addition to the bomb, has developed another threat to mankind, "ice-nine", solid water stable at room temperature, but more dense than liquid water. If a particle of ice-nine is dropped in water, all of the surrounding water becomes ice-nine. Felix Hoenikker is based on Bernard Vonnegut's boss at the GE Research Lab, Irving Langmuir, and the way ice-nine is described in the novel is reminiscent of how Bernard Vonnegut explained his own invention, silver-iodide cloudseeding, to Kurt.[66] Much of the second half of the book is spent on the fictional Caribbean island of San Lorenzo, where John explores a religion called Bokononism, whose holy books (excerpts from which are quoted) give the novel the moral core science does not supply. After the oceans are converted to ice-nine, wiping out most of humankind, John wanders the frozen surface, seeking to save himself and to make sure that his story survives.[67][68]

Vonnegut based the title character of God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater (1964), on an accountant he knew on Cape Cod, who specialized in clients in trouble and often had to comfort them. Eliot Rosewater, the wealthy son of a Republican senator, seeks to atone for his wartime killing of noncombatant firefighters by serving in a volunteer fire department and by giving away money to those in trouble or need. Stress from a battle for control of his charitable foundation pushes him over the edge, and he is placed in a mental hospital. He recovers and ends the financial battle by declaring the children of his county to be his heirs.[69] Allen deemed God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater more "a cry from the heart than a novel under its author's full intellectual control", that reflected family and emotional stresses Vonnegut was going through at the time.[70]

In the mid-1960s, Vonnegut contemplated abandoning his writing career. In 1999, he wrote in The New York Times: "I had gone broke, was out of print and had a lot of kids..." But then, on the recommendation of an admirer, he received a surprise offer of a teaching job at the Iowa Writers' Workshop, employment that he likened to the rescue of a drowning man.[71]

Slaughterhouse-Five

[edit]

After spending almost two years at the writer's workshop at the University of Iowa, teaching one course each term, Vonnegut was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship for research in Germany. By the time he won it, in March 1967, he was becoming a well-known writer. He used the funds to travel in Eastern Europe, including to Dresden, where he found many prominent buildings still in ruins.[72]

Vonnegut had been writing about his war experiences at Dresden ever since he returned from the war, but had never been able to write anything acceptable to himself or his publishers—chapter 1 of Slaughterhouse-Five tells of his difficulties.[73][74] Released in 1969, the novel rocketed Vonnegut to fame.[75] It tells of the life of Billy Pilgrim, who like Vonnegut was born in 1922 and survives the bombing of Dresden. The story is told in a non-linear fashion, with many of the story's climaxes—Billy's death in 1976, his kidnapping by aliens from the planet Tralfamadore nine years earlier, and the execution of Billy's friend Edgar Derby in the ashes of Dresden for stealing a teapot—disclosed in the story's first pages.[73] In 1970, Vonnegut was also a correspondent in Biafra during the Nigerian Civil War.[76][77]

Slaughterhouse-Five received generally positive reviews, with Michael Crichton writing in The New Republic:

he writes about the most excruciatingly painful things. His novels have attacked our deepest fears of automation and the bomb, our deepest political guilts, our fiercest hatreds and loves. No one else writes books on these subjects; they are inaccessible to normal novelists.[78]

The book went immediately to the top of The New York Times Best Seller list. Vonnegut's earlier works had appealed strongly to many college students, and the antiwar message of Slaughterhouse-Five resonated with a generation marked by the Vietnam War. He later stated that the loss of confidence in government that Vietnam caused finally allowed an honest conversation regarding events like Dresden.[75]

Later life

[edit]

After Slaughterhouse-Five was published, Vonnegut embraced the fame and financial security that attended its release. He was hailed as a hero of the burgeoning anti-war movement in the United States, was invited to speak at numerous rallies, and gave college commencement addresses around the country.[79] In addition to briefly teaching at Harvard University as a lecturer in creative writing in 1970, Vonnegut taught at the City College of New York as a distinguished professor during the 1973–1974 academic year.[80] He was later elected vice president of the National Institute of Arts and Letters and given honorary degrees by, among others, Indiana University and Bennington College. Vonnegut also wrote a play called Happy Birthday, Wanda June, which opened on October 7, 1970, at New York's Theatre de Lys. Receiving mixed reviews, it closed on March 14, 1971. In 1972, Universal Pictures adapted Slaughterhouse-Five into a film, which the author said was "flawless".[81]

When the last living thing

has died on account of us,

how poetical it would be

if Earth could say,

in a voice floating up

perhaps

from the floor

of the Grand Canyon,

"It is done."

People did not like it here.

Kurt Vonnegut,

A Man Without a Country, 2005[32]

Vonnegut's personal difficulties thereafter materialized in numerous ways, including the painfully slow progress made on his next novel, the darkly comical Breakfast of Champions. In 1971, he stopped writing the novel altogether.[81] When it was finally released in 1973, it was panned critically. In Thomas S. Hischak's book American Literature on Stage and Screen, Breakfast of Champions was called "funny and outlandish", but reviewers noted that it "lacks substance and seems to be an exercise in literary playfulness".[82] Vonnegut's 1976 novel Slapstick, which meditates on the relationship between him and his sister (Alice), met a similar fate. In The New York Times's review of Slapstick, Christopher Lehmann-Haupt said that Vonnegut "seems to be putting less effort into [storytelling] than ever before" and that "it still seems as if he has given up storytelling after all".[83] At times, Vonnegut was disgruntled by the personal nature of his detractors' complaints.[81]

In subsequent years, his popularity resurged as he published several satirical books, including Jailbird (1979), Deadeye Dick (1982), Galápagos (1985), Bluebeard (1987), and Hocus Pocus (1990).[84] Although he remained a prolific writer in the 1980s, Vonnegut struggled with depression and attempted suicide in 1984.[85] Two years later, Vonnegut was seen by a younger generation when he played himself in Rodney Dangerfield's film Back to School.[86] The last of Vonnegut's fourteen novels, Timequake (1997), was, as University of Detroit history professor and Vonnegut biographer Gregory Sumner said, "a reflection of an aging man facing mortality and testimony to an embattled faith in the resilience of human awareness and agency".[84] Vonnegut's final book, a collection of essays entitled A Man Without a Country (2005), became a bestseller.[32]

Personal life

[edit]Vonnegut married his first wife, Jane Marie Cox, in 1945. She later embraced Christianity, which was contrary to Vonnegut's atheistic beliefs, and after five of their six children having left home, Vonnegut said that the two were forced to find "other sorts of seemingly important work to do". The couple battled over their differing beliefs until Vonnegut moved from their Cape Cod home to New York in 1971. Vonnegut called the disagreements "painful" and said that the resulting split was a "terrible, unavoidable accident that we were ill-equipped to understand".[79] The couple divorced but remained friends until Jane's death in late 1986.[87][79]

Beyond his failed marriage, Vonnegut was deeply affected when his son Mark suffered a mental breakdown in 1972, which exacerbated Vonnegut's chronic depression and led him to take Ritalin. When he stopped taking the drug in the mid-1970s, he began to see a psychologist weekly.[81]

In 1979, Vonnegut married Jill Krementz, a photographer whom he met while she was working on a series about writers in the early 1970s. With Jill, he adopted a daughter, Lily, when the baby was three days old.[88] They remained married until his death.

Death and legacy

[edit]Vonnegut's sincerity, his willingness to scoff at received wisdom, is such that reading his work for the first time gives one the sense that everything else is rank hypocrisy. His opinion of human nature was low, and that low opinion applied to his heroes and his villains alike—he was endlessly disappointed in humanity and in himself, and he expressed that disappointment in a mixture of tar-black humor and deep despair. He could easily have become a crank, but he was too smart; he could have become a cynic, but there was something tender in his nature that he could never quite suppress; he could have become a bore, but even at his most despairing he had an endless willingness to entertain his readers: with drawings, jokes, sex, bizarre plot twists, science fiction, whatever it took.

Lev Grossman, Time, 2007[89]

In a 2006 Rolling Stone interview, Vonnegut sardonically stated that he would sue the Brown & Williamson tobacco company, the maker of the Pall Mall-branded cigarettes he had been smoking since he was around 12 or 14 years old, for false advertising: "And do you know why? Because I'm 83 years old. The lying bastards! On the package Brown & Williamson promised to kill me."[89]

Vonnegut died in Manhattan on the night of April 11, 2007, as a result of brain injuries incurred several weeks prior, from a fall at his brownstone home.[32][90] His death was reported by his wife Jill. He was 84 years old.[32] At the time of his death, he had written fourteen novels, three short-story collections, five plays, and five nonfiction books.[89] A book composed of his unpublished pieces, Armageddon in Retrospect, was compiled and posthumously published by his son Mark in 2008.[91]

When asked about the impact Vonnegut had on his work, author Josip Novakovich stated that he has "much to learn from Vonnegut—how to compress things and yet not compromise them, how to digress into history, quote from various historical accounts, and not stifle the narrative. The ease with which he writes is sheerly masterly, Mozartian."[92] Los Angeles Times columnist Gregory Rodriguez said that the author will "rightly be remembered as a darkly humorous social critic and the premier novelist of the counterculture",[93] and Dinitia Smith of The New York Times dubbed Vonnegut the "counterculture's novelist".[32]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Vonnegut has inspired numerous posthumous tributes and works. In 2008, the Kurt Vonnegut Society[94] was established, and in November 2010, the Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library was opened in Vonnegut's hometown of Indianapolis. The Library of America published a compendium of Vonnegut's compositions between 1963 and 1973 the following April, and another compendium of his earlier works in 2012. Late 2011 saw the release of two Vonnegut biographies: Gregory Sumner's Unstuck in Time and Charles J. Shields's And So It Goes.[95] Shields's biography of Vonnegut created some controversy. According to The Guardian, the book portrays Vonnegut as distant, cruel and nasty. "Cruel, nasty and scary are the adjectives commonly used to describe him by the friends, colleagues, and relatives Shields quotes", said The Daily Beast's Wendy Smith. "Towards the end he was very feeble, very depressed and almost morose", said Jerome Klinkowitz of the University of Northern Iowa, who has examined Vonnegut in depth.[96]

Like Mark Twain, Mr. Vonnegut used humor to tackle the basic questions of human existence: Why are we in this world? Is there a presiding figure to make sense of all this, a god who in the end, despite making people suffer, wishes them well?

Dinitia Smith, The New York Times, 2007[32]

Vonnegut's works have evoked ire on several occasions. His most prominent novel, Slaughterhouse-Five, has been objected to or removed at various institutions in at least 18 instances.[97] In the case of Island Trees School District v. Pico, the United States Supreme Court ruled that a school district's ban on Slaughterhouse-Five—which the board had called "anti-American, anti-Christian, anti-Semitic, and just plain filthy"—and eight other novels was unconstitutional. When a school board in Republic, Missouri, decided to withdraw Vonnegut's novel from its libraries, the Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library offered a free copy to all the students of the district.[97]

Tally, writing in 2013, suggests that Vonnegut has only recently become the subject of serious study rather than fan adulation, and much is yet to be written about him. "The time for scholars to say 'Here's why Vonnegut is worth reading' has definitively ended, thank goodness. We know he's worth reading. Now tell us things we don't know."[98] Todd F. Davis notes that Vonnegut's work is kept alive by his loyal readers, who have "significant influence as they continue to purchase Vonnegut's work, passing it on to subsequent generations and keeping his entire canon in print—an impressive list of more than twenty books that [Dell Publishing] has continued to refurbish and hawk with new cover designs."[99] Donald E. Morse notes that Vonnegut "is now firmly, if somewhat controversially, ensconced in the American and world literary canon as well as in high school, college and graduate curricula".[100] Tally writes of Vonnegut's work:[101]

Vonnegut's 14 novels, while each does its own thing, together are nevertheless experiments in the same overall project. Experimenting with the form of the American novel itself, Vonnegut engages in a broadly modernist attempt to apprehend and depict the fragmented, unstable, and distressing bizarreries of postmodern American experience ... That he does not actually succeed in representing the shifting multiplicities of that social experience is beside the point. What matters is the attempt, and the recognition that ... we must try to map this unstable and perilous terrain, even if we know in advance that our efforts are doomed.

The Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame inducted Vonnegut posthumously in 2015.[102][103] The asteroid 25399 Vonnegut is named in his honor.[104] A crater on the planet Mercury has also been named in his honor.[105] In 2021, the Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library in Indianapolis was designated a Literary Landmark by the Literary Landmarks Association.[106] In 1986, the University of Evansville library located in Evansville, Indiana, was named after Vonnegut, where he spoke during the dedication ceremony.[107]

Views

[edit]The beliefs I have to defend are so soft and complicated, actually, and, when vivisected, turn into bowls of undifferentiated mush. I am a pacifist, I am an anarchist, I am a planetary citizen, and so on.[108]

— Kurt Vonnegut

War

[edit]In the introduction to Slaughterhouse-Five, Vonnegut recounts meeting the film producer Harrison Starr at a party, who asked him whether his forthcoming book was an anti-war novel—"Yes, I guess", replied Vonnegut. Starr responded: "Why don't you write an anti-glacier novel?" In the novel, Vonnegut's character continues: "What he meant, of course, is that there would always be wars, that they were as easy to stop as glaciers. I believe that, too. And even if wars didn't keep coming like glaciers, there would still be plain old death". Vonnegut was a pacifist.[108]

In 2011, NPR wrote: "Kurt Vonnegut's blend of anti-war sentiment and satire made him one of the most popular writers of the 1960s." Vonnegut stated in a 1987 interview: "my own feeling is that civilization ended in World War I, and we're still trying to recover from that", and that he wanted to write war-focused works without glamorizing war itself.[109] Vonnegut had not intended to publish again, but his anger against the George W. Bush administration led him to write A Man Without a Country.[110]

Slaughterhouse-Five is the Vonnegut novel best known for its antiwar themes, but the author expressed his beliefs in ways beyond the depiction of the destruction of Dresden. One character, Mary O'Hare, opines that "wars were partly encouraged by books and movies", starring "Frank Sinatra or John Wayne or some of those other glamorous, war-loving, dirty old men".[111] Vonnegut made a number of comparisons between Dresden and the bombing of Hiroshima in Slaughterhouse-Five[112] and wrote in Palm Sunday (1991): "I learned how vile that religion of mine could be when the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima".[113]

Nuclear war, or at least deployed nuclear arms, is mentioned in almost all of Vonnegut's novels. In Player Piano, the computer EPICAC is given control of the nuclear arsenal and is charged with deciding whether to use high-explosive or nuclear arms. In Cat's Cradle, John's original purpose in setting pen to paper was to write an account of what prominent Americans had been doing as Hiroshima was bombed.[114]

Religion

[edit]Some of you may know that I am neither Christian nor Jewish nor Buddhist, nor a conventionally religious person of any sort. I am a humanist, which means, in part, that I have tried to behave decently without any expectation of rewards or punishments after I'm dead. ... I myself have written, "If it weren't for the message of mercy and pity in Jesus' Sermon on the Mount, I wouldn't want to be a human being. I would just as soon be a rattlesnake."

Kurt Vonnegut, God Bless You, Dr. Kevorkian, 1999[115]

Vonnegut was an atheist, a humanist and a freethinker, serving as the honorary president of the American Humanist Association.[116][117] In an interview for Playboy, he stated that his forebears who came to the United States did not believe in God, and he learned his atheism from his parents.[118] Vonnegut did not, however, disdain those who seek the comfort of religion, hailing church associations as a type of extended family.[119] He occasionally attended a Unitarian church, but with little consistency. In his autobiographical work Palm Sunday, Vonnegut says that he is a "Christ-worshipping agnostic".[120] During a speech to the Unitarian Universalist Association, he called himself a "Christ-loving atheist". However, he was keen to stress that he was not a Christian.[121]

Vonnegut was an admirer of Jesus' Sermon on the Mount, particularly the Beatitudes, and incorporated it into his own doctrines.[122] He also referred to it in many of his works.[123] In his 1991 book Fates Worse than Death, Vonnegut suggests that during the Reagan administration, "anything that sounded like the Sermon on the Mount was socialistic or communistic, and therefore anti-American".[124] In Palm Sunday, he wrote that "the Sermon on the Mount suggests a mercifulness that can never waver or fade".[124] However, Vonnegut had a deep dislike for certain aspects of Christianity, often reminding his readers of the bloody history of the Crusades and other religion-inspired violence. He despised the televangelists of the late 20th century, feeling that their thinking was narrow-minded.[125]

Religion features frequently in Vonnegut's work, both in his novels and elsewhere. He laced a number of his speeches with religion-focused rhetoric[115][116] and was prone to using such expressions as "God forbid" and "thank God".[117][126] He once wrote his own version of the Requiem Mass, which he then had translated into Latin and set to music.[121] In God Bless You, Dr. Kevorkian, Vonnegut goes to heaven after he is euthanized by Dr. Jack Kevorkian. Once in heaven, he interviews 21 deceased celebrities, including Isaac Asimov, William Shakespeare, and Kilgore Trout—the last a fictional character from several of his novels.[127] Vonnegut's works are filled with characters founding new faiths,[125] and religion often serves as a major plot device, for example, in Player Piano, The Sirens of Titan and Cat's Cradle. In The Sirens of Titan, Rumfoord proclaims The Church of God the Utterly Indifferent. Slaughterhouse-Five sees Billy Pilgrim, lacking religion himself, nevertheless become a chaplain's assistant in the military and display a large crucifix on his bedroom wall.[128] In Cat's Cradle, Vonnegut invented the religion of Bokononism.[129]

Politics

[edit]Vonnegut's thoughts on politics were shaped in large part by Robert Redfield, an anthropologist at the University of Chicago, co-founder of the Committee on Social Thought, and one of Vonnegut's professors during his time at the university. In a commencement address, Vonnegut remarked that "Dr. Redfield's theory of the Folk Society ... has been the starting point for my politics, such as they are".[130] Vonnegut did not particularly sympathize with liberalism or conservatism and mused on the specious simplicity of American politics, saying facetiously: "If you want to take my guns away from me, and you're all for murdering fetuses, and love it when homosexuals marry each other ... you're a liberal. If you are against those perversions and for the rich, you're a conservative. What could be simpler?"[131] Regarding political parties, Vonnegut said: "The two real political parties in America are the Winners and the Losers. The people don't acknowledge this. They claim membership in two imaginary parties, the Republicans and the Democrats, instead."[132]

Vonnegut disregarded more mainstream American political ideologies in favor of socialism, which he thought could provide a valuable substitute for what he saw as social Darwinism and a spirit of "survival of the fittest" in American society,[133] believing that "socialism would be a good for the common man".[134] Vonnegut would often return to a quote by socialist and five-time presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs: "As long as there is a lower class, I am in it. As long as there is a criminal element, I'm of it. As long as there is a soul in prison, I am not free."[135][136] Vonnegut expressed disappointment that communism and socialism seemed to be unsavory topics to the average American and believed that they offered beneficial substitutes to contemporary social and economic systems.[137]

Technology

[edit]In A Man Without a Country, Vonnegut quipped "I have been called a Luddite. I welcome it. Do you know what a Luddite is? A person who hates newfangled contraptions."[138] The negative effects of the progress of technology is a constant theme throughout Vonnegut's works, from Player Piano to his final essay collection A Man Without a Country. Political theorist Patrick Deneen has identified this skepticism of technological progress as a theme of Vonnegut novels and stories, including Player Piano , "Harrison Bergeron", and "Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow".[139] Scholars who position Vonnegut as a critic of liberalism reference his pessimism toward technological progress.[140][141][142] Vonnegut described Player Piano some years after its publication as "a novel about people and machines, and machines frequently got the best of it, as machines will."[143] Loss of jobs due to machine innovation, and thus loss of meaning or purpose in life, is a key plot point in the novel. The "newfangled contraptions" Vonnegut hated included the television, which he critiqued often throughout his non-fiction and fiction. In Timequake, for example, Vonnegut tells the story of "Booboolings", human analogs who develop morally through their imaginative formation. However, one evil sister on the planet of the Booboolings learns to build televisions from lunatics. He writes:

When the bad sister was a young woman, she and the nuts worked up designs for television cameras and transmitters and receivers. Then she got money from her very rich mom to manufacture these satanic devices, which made imaginations redundant. They were instantly popular because the shows were so attractive and no thinking was involved... Generations of Booboolings grew up without imaginations. . . . Without imaginations, though, they couldn't do what their ancestors had done, which was read interesting, heartwarming stories in the faces of one another. So . . . Booboolings became among the most merciless creatures in the local family of galaxies.[144]

Against imagination-killing devices like televisions, and against electronic substitutes for embodied community, Vonnegut argued that "Electronic communities build nothing. You wind up with nothing. We are dancing animals. How beautiful it is to get up and go out and do something."[145]

Writing

[edit]Influences

[edit]Письмо Воннегута было вдохновлено эклектичным сочетанием источников. Когда он был моложе, Воннегут заявил, что читал произведения Криминальной литературы , научной фантастики, фантазии и приключения действий. Он также читал классику , такую как пьесы Аристофана - например, работы Воннегута, юмористическая критика современного общества. [146] Жизнь и работа Воннегута также разделяют сходство с приключениями Геклберри Финн писателя Марка Твена . Оба общих пессимистических взглядов на человечество и скептическое представление о религии и, как сказал Воннегут, были «связаны с врагом в крупной войне», как Твена кратко зарегистрировался в делу Юга во время гражданской американском гражданском войны в и происхождение связало его с врагом Соединенных Штатов в обеих мировых войнах. [ 147 ] Он также назвал Амброуза Бирса влиянием, назвав « появление на мосту Ова Крик « величайшим американским рассказом и считая любого, кто не согласен или не читал историю «Тверпс». [ 148 ]

Воннегут назвал Джорджа Оруэлла своим любимым писателем и признал, что пытался подражать Оруэллу. «Мне нравится его забота о бедных, мне нравится его социализм, мне нравится его простота», - сказал Воннегут. [ 149 ] Воннегут также сказал, что девятнадцать восьмидесяти четырехдесят четыре и смелый новый мир Олдоус Хаксли сильно повлиял на его дебютный роман « Пианино животное » в 1952 году. Роман также включал идеи из «Кибернетика» математика Норберта Винера книги : или контроль и общение в животном, а и и Машина . [ 150 ] Воннегут прокомментировал, что истории Роберта Луи Стивенсона были эмблемами вдумчиво собранных работ, которые он пытался имитировать в своих собственных композициях. [ 119 ] Воннегут также приветствовал драматурга и социалистического Джорджа Бернарда Шоу «героем [его]» и «огромным влиянием». [ 151 ] В его собственной семье Воннегут заявил, что его мать, Эдит, оказала на него наибольшее влияние. «[Моя] мать подумала, что она может сделать новое состояние, написав для гладких журналов. Она прошла короткие курсы ночью. Она изучала писателей, как игроки изучают лошадей». [ 152 ]

В начале своей карьеры Воннегут решил смоделировать свой стиль после Генри Дэвида Торо , который написал так, как будто с точки зрения ребенка, позволяя произведениям Торо более широко понятны. [ 147 ] Использование молодого повествовательного голоса позволило Воннегуту доставить концепции скромным и простым способом. [ 153 ] Другие влияния на Воннегут включают в себя «Война мирового автора» Х. Г. Уэллса и сатириста Джонатана Свифта . Воннегут приписывал американского журналиста и критика Х. Л. Менкена за то, что он вдохновил его стать журналистом. [ 119 ]

Стиль и техника

[ редактировать ]Книга жалет читателя: о написании стиля Курта Воннегута и его давнего друга и бывшей ученики Сюзанны Макконнелл, опубликованной посмертно Rosetta Books и Seven Stories Press в 2019 году, углубляется в стиль, юмор и методологии. Этот должен «писать как человек. Пишите как писатель». [ 154 ] [ 155 ]

Я слышал, как голос Воннегут описан как «маниакальный депрессив», и в этом, конечно, есть что -то. У него невероятное количество энергии женат на очень глубоком и мрачном чувстве отчаяния. Это часто чрезмерно и скудно сатирически, но никогда не остается слишком далеко от пафоса-от огромного симпатии к уязвимой, угнетенной и бессильной обществу. Но тогда он также содержит огромное выделение тепла. Большую часть времени чтение Курта Воннегута больше похоже на то, чтобы быть очень близким другом. В его письме есть инклюзивность, которая привлекает вас, и его повествовательный голос редко отсутствует в истории в течение любого времени. Обычно это прямо на переднем плане - разыгрывая, вовлекая и чрезвычайно уникально.

Gavin Entense , The Huffington Post , 2013 [ 156 ]

В своей книге «Популярные современные писатели » Майкл Д. Шарп описывает лингвистический стиль Воннегута как прост, его предложения краткие, его язык просты, его абзацы и его обычный тон. [ 135 ] Воннегут использует этот стиль, чтобы передать обычно сложную тематическую ситуацию таким образом, чтобы это понятно для большой аудитории. Он приписывал свое время журналисту за свои способности и указал на свою работу в Бюро новостей Чикаго Сити, что требовало от него передавать истории в телефонных разговорах. [ 156 ] [ 135 ] Композиции Воннегута включают в себя отдельные ссылки на его собственную жизнь, особенно в Slaughterhouse Five и Slapstick . [ 157 ]

Воннегут полагал, что идеи и убедительное общение с этими идеями с читателем были жизненно важны для литературного искусства. Он не всегда приукрашивал свои очки: большая часть фортепиано приводит к моменту, когда Пол, на суде и подключился к детектору лжи, просят рассказать о лжи. Павел заявляет: «Каждая новая часть научных знаний - это хорошая вещь для человечества». [ 158 ] Роберт Т. Талли-младший, в своем томе на романах Воннегута, написал: «Вместо того, чтобы разорвать и разрушать иконы американской жизни среднего класса двадцатого века, Воннегут мягко раскрывает свою основную хламоз». [ 159 ] Воннегут не просто предложил утопические решения для болезней американского общества, но и показал, как такие схемы не позволят обычным людям жить свободными от желания и беспокойства. Большие, искусственные американские семьи в фарсе вскоре служат оправданием для племени. Люди не оказывают никакой помощи тем, кто не является частью их группы; Место расширенной семьи в социальной иерархии становится жизненно важным. [ 160 ]

Во введении в их эссе «Курт Воннегут и Юмор», Талли и Питер К. Кунзе предполагают, что Воннегут был не « черным юмористом », а «разочарованный идеалист», который использовал «комические притчи», чтобы научить читателя абсурда, горького или горького или горького или горького или горького Безнадежные истины, с его мрачным остроумием, служащим, чтобы читатель смеялся, а не плакать. «Vonnegut имеет смысл через юмор, который, по мнению автора, является действительным средством отображения этого сумасшедшего мира как любых других стратегий». [ 161 ] Воннегут возмущался тем, что его называют черным юмористом, чувствуя, что, как и во многих литературных лейблах, это позволяет читателям игнорировать аспекты работы писателя, которые не соответствуют лейблу. [ 162 ]

Работы Воннегута были названы научной фантастикой, сатирой и постмодерн . [ 163 ] Он сопротивлялся таким ярлыкам, но его работы содержат общие тропы в этих жанрах. В своих книгах Воннегут представляет инопланетные общества и цивилизации, как это распространено в научной фантастике. Воннегут подчеркивает или преувеличивает абсурды и идиосинкразии. [ 164 ] Кроме того, Воннегут высмеивает проблемы, как это делает сатира. Тем не менее, литературный теоретик Роберт Скоулз отметил в Fabulation и Metefiction , что Воннегут «отвергает веру традиционного сатирика в эффективность сатиры как инструмента по реформированию. [У него] более тонкая вера в гуманизирующую ценность смеха». [ 165 ]

Постмодернизм влечет за собой ответ на теорию о том, что наука будет раскрывать истины. [ 162 ] Постмодернисты утверждают, что истина субъективна, а не объективна. Истина включает в себя предвзятость к индивидуальным убеждениям и взглядам на мир. используют ненадежные Авторы постмодернистов повествования от первого лица и повествовательную фрагментацию . Один критик утверждал, что самый известный роман Vonnegut, -Five , показывает метафициальный прогноз Janus Slaughterhouse , и стремится представлять исторические события, сомневаясь в способности представлять историю. Сомнение очевидно в первых линиях романа: «Все это произошло, более или менее. Во всяком случае, части войны в значительной степени верны». Напыщенное открытие - «все это произошло» - гласит как заявление о полном мимесисе », которое радикально ставит под сомнение в остальной части цитаты, и« [t] создает интегрированную перспективу, которая ищет экстратекстуальные темы [как война и травма] в то время как тематизируя текстуальность романа и неотъемлемая конструктивность в одно и то же время ». [ 166 ] Хотя Воннегут использует фрагментацию и метафизию в некоторых своих работах, он более отчетливо сосредотачивается на опасности людей, которые находят субъективные истины, принимают их за объективные истины и продолжают навязывать эти истины другим людям. [ 167 ]

Темы

[ редактировать ]Воннегут был вокальным критиком американского общества, и это было отражено в его работах. Несколько ключевых социальных тем в работах Воннегута, таких как богатство, его отсутствие и его неравное распределение между обществами. В сиренах Титана главный герой романа, Константа Малахи, изгнан в Сатурна Лунный Титан в результате его огромного богатства, что сделало его высокомерным и смешным. [ 168 ] В Боге, благослови вас, г -н Роузотер , читателям может быть трудно определить, находятся ли богатые или бедные в худших обстоятельствах, поскольку жизнь членов обеих групп управляется их богатством или их бедностью. [ 149 ] Кроме того, в Hocus Pocus главный герой называется Юджином Дебсом Хартке, дань уважения знаменитую социалистическую Юджину В. Дебс и социалистические взгляды Воннегута. [ 135 ]

В Курте Воннегуте: критический компаньон , Томас Ф. Марвин заявляет: «Воннегут указывает, что, оставив без контроля, капитализм разрушит демократические основы Соединенных Штатов». Марвин предполагает, что работы Воннегута демонстрируют, что происходит, когда развивается «наследственная аристократия», где богатство наследуется по семейным линиям: способность бедных американцев преодолевать свои ситуации значительно или полностью уменьшена. [ 149 ] Воннегут также часто сетует на социальное дарвинизм и «выживание самого приспособленного» взгляда на общество. Он отмечает, что социальное дарвинизм приводит к обществу, которое осуждает его бедных за их собственное несчастье и не помогает им из -за их бедности, потому что «они заслуживают своей судьбы». [ 133 ]

Наука и этические обязательства ученых также являются общей темой в работах Воннегута. Его первая опубликованная история «Отчет о эффекте Барнхауса», как и многие его ранние истории, была сосредоточена на ученом, обеспокоенном использованием его собственного изобретения. [ 169 ] Игрок пианино и кошачья колыбель исследуют влияние на людей научных достижений. В 1969 году Воннегут произнес речь перед Американской ассоциацией учителей физики под названием «Добродетельный физик». Впоследствии спросил, что такое добродетельный ученый, Воннегут ответил: «Тот, кто отказывается работать над оружием». [ 170 ]

Воннегут также сталкивается с идеей свободной воли в ряде своих произведений. В Flaughterhouse Five и Timequake у персонажей нет выбора в том, что они делают; В завтраке чемпионов персонажи очень явно лишены своей бесплатной воли и даже получают ее в качестве подарка; и в колыбели колы , бокононизм рассматривает свободную волю как еретическую . [ 119 ]

Большинство персонажей Воннегута отчуждены от их реальных семей и стремятся построить замену или расширенные семьи. Например, инженеры игрока на пианино назвали супругу своего менеджера «мама». В колыбели кошки Воннегут разрабатывает два отдельных метода борьбы с одиночеством: «карасс», которая является группой людей, назначенных Богом, для выполнения Его воли, и « гранаулуд », определяемый Марвином как «бессмысленная ассоциация людей , например, братская группа или нация ». [ 171 ] Точно так же, в Slapstick , правительство США кодифицирует, что все американцы являются частью крупных расширенных семей. [ 137 ]

Страх перед потерей своей цели в жизни - тема в работах Воннегута. Великая депрессия заставила Воннегута стать свидетелями опустошения, которые многие люди испытывали, когда потеряли свою работу, и в то время как в General Electric Vonnegut были созданы машины, которые были созданы, чтобы занять место человеческого труда. Он противостоит этим вещам в своих работах посредством ссылок на растущее использование автоматизации и ее влияние на человеческое общество. Это наиболее резко представлено в его первом романе «Player Piano» , где многие американцы остаются бессмысленными и не могут найти работу, поскольку машины заменяют человеческих работников. Потеря цели также изображена в Галапагосе , где флорист бушут у ее супруга за создание робота, способного выполнять свою работу, и в Timequake , где архитектор убивает себя, когда его заменяет компьютерное программное обеспечение. [ 172 ]

Самоубийство за огнем - еще одна распространенная тема в работах Воннегута; Автор часто возвращается к теории, что «многие люди не любят жизнь». Он использует это в качестве объяснения того, почему люди так сильно повредили их окружающую среду и создали такие устройства, как ядерное оружие , которые могут вымирать их создателей. [ 137 ] В Deadeye Dick Vonnegut имеет нейтронную бомбу , которая предназначена для убийства людей, но оставляет здания и сооружения нетронутыми. Он также использует эту тему, чтобы продемонстрировать безрассудство тех, кто вкладывает мощные, вызывающие апокалипсис, в распоряжение политиков. [ 173 ]

"Какой смысл жизни?" это вопрос, который часто размышлял в своих работах. Когда один из персонажей Воннегута, Форель Килгора, находит вопрос: «Какова цель жизни?» Написано в ванной, его ответ: «Быть глазами, ушами и совестью создателя вселенной, ты дурак». Марвин находит теорию Траута любопытной, учитывая, что Воннегут был атеистом, и, следовательно, для него нет никакого создателя, чтобы сообщить, и комментирует, что »[как] форель хронирует одну бессмысленную жизнь за другой, читателям остается задуматься о том, как Сострадательный создатель мог бы стоять и ничего не делать, пока входят такие отчеты ». В « Эпиграфе» в Голубое Борость Воннегут цитирует своего сына Марка и дает ответ на то, что, по его мнению, является смыслом жизни: «Мы здесь, чтобы помочь друг другу пройти через эту вещь, что бы это ни было». [ 171 ]

Награды и номинации

[ редактировать ]| Премия | Год | Категория | Книга | Результат | Рефери | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Международная фантастическая награда | 1953 | - | Игрок пианино | Номинирован | - | |

| Награда Гильдии писателей Америки | 1960 | Телевизионный сценарий | "До свидания" | Выиграл | - | |

| Награда Хьюго | 1960 | Лучший роман | Сирены Титана | Номинирован | [ 174 ] | |

| Награда Хьюго | 1964 | Лучший роман | Кошачья колыбель | Номинирован | [ 175 ] | |

| Премия туманности | 1970 | Лучший роман | Бойня пять | Номинирован | [ 176 ] | |

| Награда Хьюго | 1970 | Лучший роман | Бойня пять | Номинирован | [ 177 ] | |

| Drama Desk Award | 1971 | Выдающаяся новая игра | С Днем Рождения, Ванда Джун | Выиграл | - | |

| Награда Seiun | 1973 | Иностранный роман | Сирены Титана | Выиграл | - | |

| Награда Хьюго за лучшую драматическую презентацию | 1973 | Лучшая драматическая презентация | Бойня пять | Выиграл | - | |

| Награда Джона У. Кэмпбелла | 1986 | Лучший научно -фантастический роман | Галапагос | Номинирован | [ 178 ] | |

| Audie Award | 2009 | Короткие рассказы/коллекции | Армагеддон в ретроспективе | Выиграл | - | |

| Зал славы научной фантастики и фэнтезий | 2015 | - | - | Введен | - | |

| Премия Зала славы Прометея Либертарианского общества футуриста | 2019 | - | Харрисон Бержерон | Введен | - |

Работа

[ редактировать ]Если не указано иное, пункты в этом списке взяты из книги Томаса Ф. Марвина 2002 года Курта Воннегута: критический компаньон , а дата в скобках - дата, когда работа была опубликована: [ 179 ]

Романы

[ редактировать ]- Player Piano (1952)

- Сирены Титана (1959)

- Мать ночь (1962)

- Кошачья колыбель (1963)

- Да благословит вас Бог, мистер Роузотер (1965)

- Сбой-пять (1969)

- Завтрак чемпионов (1973)

- Шлеп (1976)

- Jailbird (1979)

- Deadeye Dick (1982)

- Галапагос (1985)

- BlueBeard (1987)

- Hocus pocus (1990)

- Timequake (1997)

Короткие художественные коллекции

[ редактировать ]- Канарейка в кошачьем доме (1961)

- Добро пожаловать в дом обезьян (1968)

- Bagombo Snuff Box (1997)

- Да благословит вас Бог, доктор Кеворкиан (1999)

- Армагеддон в ретроспективе (2008) - рассказы и эссе

- Посмотрите на птичку (2009)

- Пока смертные спят (2011)

- Мы то, кем мы притворяемся (2012)

- Портфолио Sucker (2013)

- Полные истории (2017)

Пьесы

[ редактировать ]- Первое рождественское утро (1962)

- Стойкость (1968)

- С Днем Рождения, Ванда Джун (1970)

- Между временем и Тимбукту (1972)

- Камни, время и элементы (гуманистическая реквием) (1987)

- Примите мнение (1993)

- История солдата (1997)

Научная литература

[ редактировать ]- Wampeters, Foma and Granfalloons (1974)

- Вербное воскресенье (1981)

- Ничего не потеряно, Save Honor: два эссе (1984)

- Судьбы хуже смерти (1991)

- Человек без страны (2005) [ 32 ]

- Курт Воннегут: Годы Корнелла Сан 1941–1943 (2012)

- Если это не хорошо, что?: Совет молодым (2013)

- Воннегут по дюжине (2013)

- Курт Воннегут: Письма (2014)

- Жаль читатель: на написании со стилем (2019) с Сюзанной Макконнелл

- Любовь, Курт: Любовные письма Воннегут, 1941–1945 (2020) Редактор Эдит Воннегут

Интервью

[ редактировать ]- Беседы с Куртом Воннегутом (1988) с Уильямом Родни Алленом

- Как пожимая руку Богу: разговор о письме (1999) с Ли Стрингером

- Курт Воннегут: Последнее интервью: и другие разговоры (2011)

Детские книги

[ редактировать ]- Звезда Sun Moon (1980)

Искусство

[ редактировать ]- Курт Воннегут Рисунки (2014)

Смотрите также

[ редактировать ]Пояснительные заметки

[ редактировать ]- ^ На самом деле, Воннегут часто называл себя «ребенком Великой депрессии». Он также заявил о депрессии и ее последствиях, подстрекавших пессимизм по поводу обоснованности американской мечты . [ 10 ]

- ^ Курт -старший был озлоблен его собственной недостаткой работы в качестве архитектора во время Великой депрессии и боялся подобной судьбы для его сына. Он отклонил желаемые участки своего сына как «мусорные украшения» и убедил своего сына против посторонних по его стопам. [ 13 ]

Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ "Курт Воннегут" . Британская . Архивировано из оригинала 26 апреля 2022 года . Получено 26 апреля 2022 года .

- ^ «Городское бюро новостей» . www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org . Получено 15 июня 2024 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в Boomhower 1999 ; Farrell 2009 , с. 4–5.

- ^ Марвин 2002 , с. 2

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Sharp 2006 , p. 1360.

- ^ Марвин 2002 , с. 2; Фаррелл 2009 , с. 3–4.

- ^ Марвин 2002 , с. 4

- ^ Sharp 2006 , с. 1360.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый Boomhower 1999 .

- ^ Самнер 2014 .

- ^ Sharp 2006 , с. 1360; Marvin 2002 , с. 2–3.

- ^ Marvin 2002 , с. 2–3.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Фаррелл 2009 , с. 5; Boomhower 1999 .

- ^ Самнер 2014 ; Фаррелл 2009 , с. 5

- ^ Шилдс 2011 , с. 41

- ^ Лоури 2007 .

- ^ Фаррелл 2009 , с. 5

- ^ Шилдс 2011 , с. 41–42.

- ^ Шилдс 2011 , с. 44–45.

- ^ Шилдс 2011 , с. 45–49.

- ^ Shields 2011 , с. 50–51.

- ^ Фаррелл 2009 , с. 6

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый Фаррелл 2009 , с. 6; Marvin 2002 , p. 3

- ^ Sharp 2006 , с. 1363; Фаррелл 2009 , с. 6

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Воннегут 2008 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый Hayman et al. 1977 .

- ^ Boomhower 1999 ; Фаррелл 2009 , с. 6–7.

- ^ Воннегут, Курт (6 апреля 2006 г.). "Курт Воннегут" . Книжный червь (интервью). Интервью Майкл Сильверблатт . Санта -Моника, Калифорния: KCRW. Архивировано из оригинала 5 апреля 2023 года . Получено 6 октября 2015 года .

- ^ Далтон 2011 .

- ^ Томас 2006 , с. 7; Shields 2011 , с. 80–82.

- ^ Воннегут, Курт (1991). Судьбы хуже смерти: автобиографический коллаж 1980 -х годов . Нью -Йорк: Сыновья Г.П. Путнэма. п. 122. ISBN 978-0-399-13633-7 Полем OCLC 23253474 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час Смит 2007 .

- ^ «Курт Воннегут, чтобы посетить кампус в роли парня Ковлера» . Chronicle.uchicago.edu . 3 февраля 1994 года.

- ^ Strand 2015 , с. 26

- ^ «Выдержка из Курта Воннегута» . Пингвин Рэндом Хаус Канада . Архивировано из оригинала 24 марта 2023 года . Получено 24 марта 2023 года .

- ^ Электрическаялитература (7 апреля 2015 г.). «Выпускная речь Курта Воннегута: что« танец призрака »коренных американцев и французский ...» Электрическая литература . Архивировано из оригинала 25 марта 2023 года . Получено 24 марта 2023 года .

- ^ «Призрачных рубашек и шарниров» . 18 мая 2017 года. Архивировано из оригинала 18 мая 2017 года . Получено 24 марта 2023 года .

- ^ Клинковиц, Джером (5 июня 2012 г.). Эффект Воннегута . Univ of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-61117-114-3 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 24 марта 2023 года . Получено 24 марта 2023 года .

- ^ «Курт Воннегут, писатель контркультуры, умирает» . archive.nytimes.com . Архивировано из оригинала 24 марта 2023 года . Получено 24 марта 2023 года .

- ^ Vonnegut 2009 , p. 285

- ^ Марвин 2002 , с. 7

- ^ Нобл 2017 , с. 166: «В начале 1950 -х годов писатель Курт Воннегут был техническим писателем и публицистом в штаб -квартире GE в Скенектади».

- ^ Strand 2015 , с. 81

- ^ Strand 2015 , с. 87

- ^ Strand 2015 , с. 89

- ^ Boomhower 1999 ; Самнер 2014 ; Farrell 2009 , с. 7–8.

- ^ Strand 2015 , с. 117

- ^ Шилдс 2011 , с. 115.

- ^ Boomhower 1999 ; Hayman et al. 1977 ; Фаррелл 2009 , с. 8

- ^ Сидман, Дэн. «Кейп связывается с писателем Куртом Воннегутом» . Кейп -Код времена . Получено 4 апреля 2023 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Boomhower 1999 ; Farrell 2009 , с. 8–9; Marvin 2002 , p. 25

- ^ Strand 2015 , с. 202–212

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Аллен 1991 , с. 20–30.

- ^ Аллен 1991 , с. 32

- ^ Шилдс 2011 , с. 142

- ^ Фаррелл 2009 , с. 9

- ^ Шилдс 2011 , с. 164.

- ^ Шилдс 2011 , с. 159–161.

- ^ Аллен 1991 , с. 39

- ^ Аллен 1991 , с. 40

- ^ Шилдс 2011 , с. 171–173.

- ^ Морс 2003 , с. 19

- ^ Лидс 1995 , с. 46

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Хаттенхауэр 1998 , с. 387.

- ^ Аллен 1991 , с. 53

- ^ Strand 2015 , с. 236–237

- ^ Аллен 1991 , с. 54–65.

- ^ Умер 2003 , с. 62-63.

- ^ Шилдс 2011 , с. 182–183.

- ^ Аллен 1991 , с. 75

- ^ Воннегут, Курт (24 мая 1999 г.). «Писатели по написанию: несмотря на жесткие парни, жизнь - не единственная школа для настоящих романистов» . New York Times . Архивировано из оригинала 19 декабря 2019 года . Получено 2 января 2020 года .

- ^ Shields 2011 , с. 219–228.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Аллен , с. 82–85.

- ^ Strand 2015 , с. 49–50.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Shields 2011 , с. 248–249.

- ^ Блум, Гарольд (2007). Курт Воннегут бойня пять . Гиды Блума. Infobase Publishing. п. 12. ISBN 978-1-4381-2709-5 .

- ^ Клинковиц, Джером (2009). Курт Воннегут Америка . Университет Южной Каролины Пресс. п. 55. ISBN 978-1-57003-826-6 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 12 марта 2024 года . Получено 2 сентября 2017 года .

- ^ Шилдс 2011 , с. 254

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в Marvin 2002 , p. 10

- ^ «Маркизовые биографии онлайн» . Биографии маркиза онлайн . Архивировано из оригинала 12 марта 2024 года . Получено 2 декабря 2017 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый Marvin 2002 , p. 11

- ^ Hischak 2012 , p. 31

- ^ Lehmann-Haupt 1976 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Самнер 2014 .

- ^ "Курт Воннегут" . Энциклопедия Британская . Архивировано из оригинала 24 мая 2018 года . Получено 24 мая 2018 года .

- ^ Марвин 2002 , с. 12

- ^ Вольф 1987 .

- ^ Фаррелл 2009 , с. 451.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в Гроссман 2007 .

- ^ Аллен .

- ^ Blount 2008 .

- ^ Banach 2013 .

- ^ Родригес 2007 .

- ^ «Общество Курт Воннегут, способствующее научному изучению Курта Воннегута, его жизни и произведений» . Blogs.cofc.edu . Архивировано с оригинала 25 октября 2017 года . Получено 2 декабря 2017 года .

- ^ Out & Tally 2012 , с. 7

- ^ Harris 2011 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Morais 2011 .

- ^ Tally 2013 , с. 14–15.

- ^ Дэвис 2006 , с. 2

- ^ Морс 2013 , с. 56

- ^ Tally 2011 , с. 158

- ^ "2015 SF & F Зал Славы Индуцированные и Джеймс Гунн Архивируется 15 июля 2017 года на The Wayback Machine . 12 июня 2015 года . Publications . Получено 17 июля 2015 года.

- ^ «Курт Воннегут: американский автор, который объединил сатирический социальный комментарий с сюрреалистическими и научными вымышленными элементами» ( архивировано 10 сентября 2015 года, на машине Wayback ). Научная фантастика и зал славы фэнтези . МУЗЕЙ ЭМС (EMPMUSEUM.ORG). Получено 10 сентября 2015 года.

- ^ Хейли, Гай (2014). Научно-фантастические хроники: визуальная история величайшей научной фантастики Галактики . Лондон: Aurum Press (Quarto Group). п. 135. ISBN 978-1-78131-359-6 Полем

Астероид 25399 Воннегут назван в его честь.

- ^ "Курт Воннегут" . Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclaturation . Программа исследований астрогеологии USGS.

- ^ «Музей Курта Воннегута Индианаполиса назвал литературную достопримечательность» . AP News . 26 сентября 2021 года. Архивировано с оригинала 26 сентября 2021 года . Получено 26 сентября 2021 года .

- ^ LINC 1987 Ежегодник . Университет Эвансвилля. 1987. с. 34

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Бейкер, Фил (13 апреля 2007 г.). "Курт Воннегут" . Хранитель . Лондон Архивировано из оригинала 21 июня 2023 года . Получено 21 июня 2023 года .

- ^ NPR 2011 .

- ^ Daily Telegraph 2007 .

- ^ Фриз 2013 , с. 101.

- ^ Лидс 1995 , с. 2

- ^ Лидс 1995 , с. 68

- ^ Лидс 1995 , с. 1–2.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Vonnegut 1999 , введение.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Vonnegut 2009 , с. 177, 185, 191.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Niose 2007 .

- ^ Лидс 1995 , с. 480.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый Sharp 2006 , p. 1366.

- ^ Vonnegut 1982 , p. 327.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Уэйкфилд, Дэн (2014). «Курт Воннегут, любящий Христос атеист» . Изображение (82): 67–75. Архивировано из оригинала 13 октября 2017 года . Получено 13 октября 2017 года .

- ^ Дэвис 2006 , с. 142

- ^ Vonnegut 2006b .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Лидс 1995 , с. 525.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Фаррелл 2009 , с. 141.

- ^ Vonnegut 2009 , p. 191.

- ^ Kohn 2001 .

- ^ Leeds 1995 , с. 477–479.

- ^ Марвин 2002 , с. 78

- ^ Воннегут, Курт (2014). Если это не хорошо, что? Полем Семь историй прессы. п. 97. ISBN 978-1-60980-591-3 .

- ^ Zinn & Arnove 2009 , p. 620.

- ^ Vonnegut 2006a , «таким образом, который должен позорить сам Бога».

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Sharp 2006 , с. 1364–1365.

- ^ Gannon & Taylor 2013 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый Sharp 2006 , p. 1364.

- ^ Zinn & Arnove 2009 , p. 618.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в Sharp 2006 , p. 1365.

- ^ Воннегут, Курт (2007). Человек без страны . Семь историй прессы. п. 55

- ^ «Народные сказки» . Claremont Review книг . Архивировано из оригинала 30 сентября 2023 года . Получено 12 марта 2024 года .

- ^ Hamlin, DA (2005). «Искусство гражданства в выпускных выступлениях Курта Воннегута». В Денине, Патрик (ред.). Литература демократии: политика и художественная литература в Америке . Ланхэм, доктор медицины: Роуман и Литтлфилд. п. 294

- ^ МакГрат, Майкл Дж. Гаргас (1982). «Кесет и Воннегут: критика либеральной демократии в современной литературе». В парикмахере, Бенджамин (ред.). Художник и политическое видение . Нью -Брансуик, Нью -Джерси: издатели транзакций.

- ^ Банн, Филипп Д. (сентябрь 2019 г.). «Сообщества-все это существенное: постлиберальная мысль Курт Воннегута» . Американская политическая мысль . 8 (4): 504–527. doi : 10.1086/705602 . ISSN 2161-1580 . S2CID 211321082 . Архивировано из оригинала 12 марта 2024 года . Получено 12 марта 2024 года .

- ^ Воннегут, Курт (1974). Wampeters, Foma и Granfalloons (мнения) . Делл п. 1

- ^ Воннегут, Курт (1999b). Timequake . Путнэм. п. 501

- ^ Воннегут, Курт (2007). Человек без страны . Семь историй прессы. С. 61–62.

- ^ Marvin 2002 , с. 17–18.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Marvin 2002 , p. 18

- ^ «Цитата Курта Воннегута» . www.goodreads.com . Архивировано из оригинала 8 марта 2021 года . Получено 8 декабря 2019 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в Marvin 2002 , p. 19

- ^ Strand 2015 , с. 155–156.

- ^ I Bulkian 2004 , p. 15

- ^ Hayman et al. 1977 .

- ^ Marvin 2002 , с. 18–19.

- ^ Курт Воннегут; Сюзанна Макконнелл (2019). Жаль читатель: при написании стиля . Семь историй прессы. ISBN 978-1-60980-962-1 .

- ^ «Курт Воннегут о письме и таланте» . Поэты и писатели . 12 октября 2019 года. Архивировано с оригинала 1 июля 2022 года . Получено 1 июля 2022 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Расширение 2013 .

- ^ Sharp 2006 , с. 1363–1364.

- ^ Дэвис 2006 , стр. 45-46.

- ^ Tally 2011 , с. 157

- ^ Tally 2011 , с. 103–105.

- ^ Kunze & Tally 2012 , Введение.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Marvin 2002 , p. 16

- ^ Марвин 2002 , с. 13

- ^ Marvin 2002 , с. 14–15.

- ^ Марвин 2002 , с. 15

- ^ Jensen 2016 , с. 8–11.

- ^ Marvin 2002 , с. 16–17.

- ^ Marvin 2002 , с. 19, 44–45.

- ^ Strand 2015 , с. 147–157.

- ^ Strand 2015 , с. 245

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Marvin 2002 , p. 20

- ^ Sharp 2006 , с. 1365–1366.

- ^ Марвин 2002 , с. 21

- ^ https://www.worldwithoutend.com/books_year_index.asp?year=1960

- ^ https://www.worldwithoutend.com/novel.asp?id=315

- ^ https://www.worldwithoutend.com/books_year_index.asp?year=1969

- ^ https://www.worldwithoutend.com/books_year_index.asp?year=1970

- ^ https://www.worldwithoutend.com/books_year_index.asp?year=1986

- ^ Marvin 2002 , с. 157–158.

Общие и цитируемые источники

[ редактировать ]- Аллен, Уильям Р. «Краткая биография Курта Воннегута» . Мемориальная библиотека Курта Воннегута . Архивировано с оригинала 18 января 2015 года . Получено 14 августа 2015 года .

- Аллен, Уильям Р. (1991). Понимание Курта Воннегута . Университет Южной Каролины Пресс. ISBN 978-0-87249-722-1 .

- Банах, JE (11 апреля 2013 г.). «Смех перед лицом смерти: круглый стол vonnegut» . Парижский обзор . Получено 13 августа 2015 года .

- Барсамиан, Дэвид (2004). Громче, чем бомбы: интервью из прогрессивного журнала . South End Press. ISBN 978-0-89608-725-5 .

- Блаунт, Рой -младший (4 мая 2008 г.). "Так идет" . Sunday Book Review. New York Times . Получено 14 августа 2015 года .

- Boomhower, Ray E. (1999). «Сламтя-пять: Курт Воннегут-младший». Следы истории Индианы и Среднего Запада . 11 (2): 42–47. ISSN 1040-788X .

- «Некролог Курта Воннегута: Гуру контркультуры, чей научный фантастический роман « Слогар-пять » , вдохновленный его выживанием взрывов Дрезден, стал антивоенной классикой». Ежедневный телеграф . 13 мая 2007 г. с. 25

- Далтон, Кори М. (24 октября 2011 г.). «Сокровища Мемориальной библиотеки Курта Воннегута» . Субботний вечерний пост . Архивировано с оригинала 9 декабря 2014 года . Получено 14 августа 2015 года .

- Дэвис, Тодд Ф. (2006). Крестовый поход Курта Воннегута . Государственный университет Нью -Йорк Пресс. ISBN 978-0-7914-6675-9 .

- Расширение, Гэвин (25 июня 2013 г.). «Большая часть того, что я знаю о письме, я узнал от Курта Воннегута» . Huffington Post . Получено 14 августа 2015 года .

- Фаррелл, Сьюзен Э. (2009). Критический компаньон для Курта Воннегута: литературная ссылка на его жизнь и работу . Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-0023-4 .

- Фриз, Питер (2013). « Инструкции по использованию»: вступительная глава «Слога-пяти» и читатель историографических метафикций ». В подсчете Роберт Т. младший (ред.). Курт Воннегут . Критические идеи. Салем Пресс. С. 95–117. ISBN 978-1-4298-3848-1 .

- Гэннон, Мэтью; Тейлор, Уилсон (4 сентября 2013 г.). «Рабочий класс нуждается в следующем Курте Воннегут» . Якобин . Salon.com . Получено 14 августа 2015 года .

- Гроссман, Лев (12 апреля 2007 г.). «Курт Воннегут, 1922–2007» . Время .