Президентство Джорджа Буша-младшего

| |

| Президентство Джорджа Буша-младшего 20 января 2001 г. - 20 января 2009 г. | |

| Кабинет | Посмотреть список |

|---|---|

| Вечеринка | республиканец |

| Election | |

| Seat | White House |

| Archived website Library website | |

| ||

|---|---|---|

46th Governor of Texas 43rd President of the United States

Policies Appointments First term Second term Presidential campaigns Post-presidency  | ||

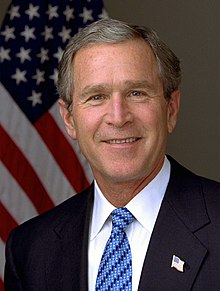

Джорджа Буша Срок полномочий на посту 43-го президента Соединенных Штатов начался с его первой инаугурации 20 января 2001 года и закончился 20 января 2009 года. Буш, республиканец из Техаса , вступил в должность после своей незначительной в Коллегии выборщиков победы от Демократической партии над Действующий вице-президент Эл Гор на президентских выборах 2000 года , на которых он проиграл Гору всенародное голосование с перевесом в 543 895 голосов. Четыре года спустя, на президентских выборах 2004 года , он с небольшим перевесом победил кандидата от демократов Джона Керри и выиграл переизбрание. Буш пробыл два срока, и его сменил демократ Барак Обама , победивший на президентских выборах 2008 года . Буш — старший сын 41-го президента Джорджа Буша-старшего .

A decisive event reshaping Bush's administration was the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001. In its aftermath, Congress created the United States Department of Homeland Security and Bush declared a global war on terrorism. He ordered an invasion of Afghanistan in an effort to overthrow the Taliban, destroy al-Qaeda, and capture Osama bin Laden. He also signed the controversial Patriot Act in order to authorize surveillance of suspected terrorists. In 2003, Bush ordered an invasion of Iraq, alleging that the Saddam Hussein regime possessed weapons of mass destruction. Intense criticism came when neither WMD stockpiles nor evidence of an operational relationship with al-Qaeda were found. Before 9/11, Bush had pushed through a $1.3 trillion tax cut program and the No Child Left Behind Act, a major education bill. He also pushed for socially conservative efforts, such as the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act and faith-based welfare initiatives. Also in 2003, he signed the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act, который создал Medicare Part D.

During his second term, Bush reached multiple free trade agreements and successfully nominated John Roberts and Samuel Alito to the Supreme Court. He sought major changes to Social Security and immigration laws, but both efforts failed. The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq continued, and in 2007 he launched a surge of troops in Iraq. The Bush administration's response to Hurricane Katrina and the dismissal of U.S. attorneys controversy came under attack, with a drop in his approval ratings. A global meltdown in financial markets dominated his last days in office as policymakers looked to avert a major economic disaster, and he established the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) to buy toxic assets from financial institutions.

At various points in his presidency, Bush was among both the most popular and unpopular presidents in U.S. history. He received the highest recorded approval ratings in the wake of the September 11 attacks, but also one of the lowest such ratings during the Iraq War and 2007–2008 financial crisis. Although public sentiment of Bush has improved since he left office, his presidency has generally been rated as below-average by scholars.[1]

2000 election[edit]

The oldest son of George H. W. Bush, the 41st president of the United States, George W. Bush emerged as a presidential contender in his own right with his victory in the 1994 Texas gubernatorial election. After winning re-election by a decisive margin in the 1998 Texas gubernatorial election, Bush became the widely acknowledged front-runner in the race for the Republican nomination in the 2000 presidential election. In the years preceding the 2000 election, Bush established a stable of advisers, including supply-side economics advocate Lawrence B. Lindsey and foreign policy expert Condoleezza Rice.[2] With a financial team led by Karl Rove and Ken Mehlman, Bush built up a commanding financial advantage over other prospective Republican candidates.[3] Though several prominent Republicans declined to challenge Bush, Arizona senator John McCain launched a spirited challenge that was supported by many moderates and foreign policy hawks. McCain's loss in the South Carolina primary effectively ended the 2000 Republican primaries, and Bush was officially nominated for president at the 2000 Republican National Convention. Bush selected former secretary of defense Dick Cheney as his running mate; though Cheney offered little electoral appeal and had health problems, Bush believed that Cheney's extensive experience would make him a valuable governing partner.[2]

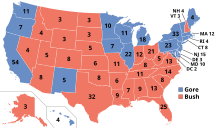

With President Bill Clinton term-limited, the Democrats nominated Vice President Al Gore for president. Bush's campaign emphasized their own candidate's character in contrast with that of Clinton, who had been embroiled in the Lewinsky scandal. Bush held a substantial lead in several polls taken after the final debate in October, but the unearthing of Bush's 1976 DUI arrest appeared to sap his campaign's momentum. By the end of election night, Florida emerged as the key state in the election, as whichever candidate won the state would win the presidency. Bush held an extremely narrow lead in the vote by the end of election night, triggering an automatic recount. The Florida Supreme Court ordered a partial manual recount, but the Supreme Court of the United States effectively ordered an end to this process, on equal protection grounds, in the case of Bush v. Gore, leaving Bush with a victory in both the state and the election. Though Gore narrowly won a plurality of the nationwide popular vote, Bush won the presidential election with 271 electoral votes compared to Gore's 266. In the concurrent congressional elections, Republicans retained a narrow majority in the House, but lost five seats in the Senate, leaving the partisan balance in the Senate at fifty Republicans and fifty Democrats.[4]

Administration[edit]

Rejecting the idea of a powerful White House chief of staff, Bush had high-level officials report directly to him rather than Chief of Staff Andrew Card. Vice President Cheney emerged as the most powerful individual in the White House aside from Bush himself. Bush brought to the White House several individuals who had worked under him in Texas, including Senior Counselor Karen Hughes, Senior Adviser Karl Rove, legal counsel Alberto Gonzales, and Staff Secretary Harriet Miers.[5] Other important White House staff appointees included Margaret Spellings as a domestic policy adviser, Michael Gerson as chief speechwriter, and Joshua Bolten and Joe Hagin as White House deputy chiefs of staff.[6] Paul H. O'Neill, who had served as deputy director of the OMB under Gerald Ford, was appointed secretary of the treasury, while former Missouri senator John Ashcroft was appointed attorney general.[7]

As Bush had little foreign policy experience, his appointments would serve an important role in shaping U.S. foreign policy during his tenure. Several of his initial top foreign policy appointees had served in his father's administration; Vice President Cheney had been secretary of defense, National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice had served on the National Security Council, and deputy secretaries Paul Wolfowitz and Richard Armitage had also served in important roles. Secretary of State Colin Powell had served as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff under the first president Bush.[8] Bush had long admired Powell, and the former general was Bush's first choice for the position. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, who had served in the same position during the Ford administration, rounded out the key figures in the national security team.[9] Rumsfeld and Cheney, who had served together in the Ford administration, emerged as the leading foreign policy figures during Bush's first term.[10]

O'Neill, who opposed the Iraq War and feared that the Bush tax cuts would lead to deficits, was replaced by John W. Snow in February 2003.[11] Frustrated by the decisions of the Bush administration, particularly the launching of the Iraq War, Powell resigned following the 2004 elections.[12] He was replaced by Rice, while then-deputy national security adviser Stephen Hadley took Rice's former position.[13] Most of Bush's top staffers stayed on after the 2004 election, although Spellings joined the Cabinet as secretary of education and Gonzales replaced Ashcroft as attorney general.[14] In early 2006, Card left the White House in the wake of the Dubai Ports World controversy and several botched White House initiatives, and he was replaced by Joshua Bolten.[15] Bolten stripped Rove of some of his responsibilities and convinced Henry Paulson, the head of Goldman Sachs, to replace Snow as secretary of the treasury.[16]

After the 2006 elections, Rumsfeld was replaced by former CIA director Robert Gates.[17] The personnel shake-ups left Rice as one of the most prominent individuals in the administration, and she played a strong role in directing Bush's second term foreign policy.[18] Gonzales and Rove both left in 2007 after controversy regarding the dismissal of U.S. attorneys, and Gonzales was replaced by Michael Mukasey, a former federal judge.[19]

Senior non-cabinet officials and advisers[edit]

- Senior Advisor to the President – Karl Rove (2001–2007), Barry Steven Jackson (2007–2009)

- Counselor to the President – Karen Hughes (2001–2002), Dan Bartlett (2002–2007), Ed Gillespie (2007–2009)

- National Security Advisor – Condoleezza Rice (2001–2005), Stephen Hadley (2005–2009)

- White House Deputy Chief of Staff – Joe Hagin (2001–2008), Joshua Bolten (2001–2003), Harriet Miers (2003–2004), Karl Rove (2005–2007), Joel Kaplan (2006–2009), Blake Gottesman (2008–2009)

- White House Communications Director – Karen Hughes (2001), Dan Bartlett (2001–2005), Nicolle Wallace (2005–2006), Kevin Sullivan (2006–2009)

- White House Counsel – Alberto Gonzales (2001–2005), Harriet Miers (2005–2007), Fred Fielding (2007–2009)

- White House Press Secretary – Ari Fleischer (2001–2003), Scott McClellan (2003–2006), Tony Snow (2006–2007), Dana Perino (2007–2009)

- Chair of the Council of Economic Advisers – Glenn Hubbard (2001–2003), Greg Mankiw (2003–2005), Harvey S. Rosen (2005), Ben Bernanke (2005–2006), Edward Lazear (2006–2009)

- Ambassador to the United Nations – John Negroponte (2001–2004), John Danforth (2004–2005), John Bolton (2005–2006), Zalmay Khalilzad (2007–2009)

- Director of National Intelligence – John Negroponte (2005–2007), Mike McConnell (2007–2009)

- CIA Director – George Tenet (2001–2004), John E. McLaughlin (acting, 2004), Porter Goss (2004–2006), Michael Hayden (2006–2009)

- FBI Director – Louis Freeh (2001), Thomas J. Pickard (acting, 2001), Robert Mueller (2001–2009)

- FCC Chairman – Michael Powell (2001–2005), Kevin Martin (2005–2009)

Judicial appointments[edit]

Supreme Court[edit]

After the 2004 election, many expected that the aging Chief Justice William Rehnquist would step down from the United States Supreme Court. Cheney and White House Counsel Harriet Miers selected two widely respected conservatives, D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals judge John Roberts and Fourth Circuit judge Michael Luttig, as the two finalists. In June 2005, Justice Sandra Day O'Connor unexpectedly announced that she would retire from the court, and Bush nominated Roberts for her position the following month. After Rehnquist died in September, Bush briefly considered elevating Associate Justice Antonin Scalia to the position of chief justice, but instead chose to nominate Roberts for the position. Roberts won confirmation from the Senate in a 78–22 vote, with all Republicans and a narrow majority of Democrats voting to confirm Roberts.[20]

To replace O'Connor, the Bush administration wanted to find a female nominee, but was unsatisfied with the conventional options available.[20] Bush settled on Miers, who had never served as a judge, but who had worked as a corporate lawyer and White House staffer.[21] Her nomination immediately faced opposition from conservatives (and liberals) who were wary of her unproven ideology and lack of judicial experience. After Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist informed Bush that Miers did not have the votes necessary to win confirmation, Miers withdrew from consideration. Bush then nominated Samuel Alito, who received strong support from conservatives but faced opposition from Democrats. Alito won confirmation in a 58–42 vote in January 2006.[20][22] In the years immediately after Roberts and Alito took office, the Roberts Court was generally more conservative than the preceding Rehnquist Court, largely because Alito tended to be more conservative than O'Connor had been.[23]

Other courts[edit]

Bush also appointed 62 judges to the United States Courts of Appeals, 261 judges to the United States district courts, and 2 judges to the United States Court of International Trade. Among them were two future Supreme Court associate justices: Neil Gorsuch to a seat on the Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit in 2006, and Brett Kavanaugh to the Court of Appeals District of Columbia Circuit in 2006.

Domestic affairs[edit]

Bush tax cuts[edit]

| Fiscal Year | Receipts | Outlays | Surplus/ Deficit | GDP | Debt as a % of GDP[25] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 1,991.1 | 1,862.8 | 128.2 | 10,526.5 | 31.5 |

| 2002 | 1,853.1 | 2,010.9 | −157.8 | 10,833.7 | 32.7 |

| 2003 | 1,782.3 | 2,159.9 | −377.6 | 11,283.8 | 34.7 |

| 2004 | 1,880.1 | 2,292.8 | −412.7 | 12,025.5 | 35.7 |

| 2005 | 2,153.6 | 2,472.0 | −318.3 | 12,834.2 | 35.8 |

| 2006 | 2,406.9 | 2,655.1 | −248.2 | 13,638.4 | 35.4 |

| 2007 | 2,568.0 | 2,728.7 | −160.7 | 14,290.8 | 35.2 |

| 2008 | 2,524.0 | 2,982.5 | −458.6 | 14,743.3 | 39.4 |

| Ref. | [26] | [27] | [28] | ||

Bush's promise to cut taxes was the centerpiece of his 2000 presidential campaign, and upon taking office, he made tax cuts his first major legislative priority. A budget surplus had developed during the Bill Clinton administration, and with the Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan's support, Bush argued that the best use of the surplus was to lower taxes.[29] By the time Bush took office, reduced economic growth had led to less robust federal budgetary projections, but Bush maintained that tax cuts were necessary to boost economic growth.[30] After Treasury secretary Paul O'Neill expressed concerns over the tax cut's size and the possibility of future deficits, Vice President Cheney took charge of writing the bill, which the administration proposed to Congress in March 2001.[29]

Bush initially sought a $1.6 trillion tax cut over a ten-year period, but ultimately settled for a $1.35 trillion tax cut.[31] The administration rejected the idea of "triggers" that would phase out the tax reductions should the government again run deficits. The Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 won the support of congressional Republicans and a minority of congressional Democrats, and Bush signed it into law in June 2001. The act lowered the top income tax rate from 39 percent to 35 percent, and it also reduced the estate tax. The narrow Republican majority in the Senate necessitated the use of the reconciliation, which in turn necessitated that the tax cuts would phase out in 2011 barring further legislative action.[32]

After the tax bill was passed, Senator Jim Jeffords left the Republican Party and began caucusing with the Democrats, giving them control of the Senate. After Republicans re-took control of the Senate during the 2002 mid-term elections, Bush proposed further tax cuts. With little support among Democrats, Congress passed the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003, which cut taxes by another $350 billion over 10 years. That law also lowered the capital gains tax and taxes on dividends. Collectively, the Bush tax cuts reduced federal individual tax rates to their lowest level since World War II, and government revenue as a share of gross domestic product declined from 20.9% in 2000 to 16.3% in 2004.[32] Most of the Bush tax cuts were later made permanent by the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012, though that act rolled back the tax cuts on top earners.[33]

Contrary to the rhetoric of the Bush administration and Republicans, the budget deficit increased, leaving many to believe the tax cuts were at fault. Statements by President Bush, Vice President Dick Cheney, and Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist that these tax cuts effectively "paid for themselves" were disputed by the CBPP,[34] the U.S. Treasury Department and the CBO.[35][36][37][38]

Education[edit]

Aside from tax cuts, Bush's other major policy initiative upon taking office was education reform. Bush had a strong personal interest in reforming education, especially regarding the education of low-income and minority groups. He often derided the "soft bigotry of low expectations" for allowing low-income and minority groups to fall behind.[39] Although many conservatives were reluctant to increase federal involvement in education, Bush's success in campaigning on education reform in the 2000 election convinced many Republicans, including Congressman John Boehner of Ohio, to accept an education reform bill that increased federal funding.[40] Seeking to craft a bipartisan bill, Bush courted Democratic senator Ted Kennedy, a leading liberal senator who served as the ranking member on the Senate Committee on Health, Education, and Pensions.[41]

Bush favored extensive testing to ensure that schools met uniform standards for skills such as reading and math. Bush hoped that testing would make schools more accountable for their performances and provide parents with more information in choosing which schools to send their children. Kennedy shared Bush's concern for the education of impoverished children, but he strongly opposed the president's proposed school vouchers, which would allow parents to use federal funding to pay for private schools. Both men cooperated to pass the No Child Left Behind Act, which dropped the concept of school vouchers but included Bush's idea of nationwide testing. Both houses of Congress registered overwhelming approval for the bill's final version, which Bush signed into law in January 2002.[41] However, Kennedy would later criticize the implementation of the act, arguing that Bush had promised greater federal funding for education.[42]

Surveillance and homeland security[edit]

Shortly after the September 11 attacks, Bush announced the creation of the Office of Homeland Security and appointed former governor of Pennsylvania Tom Ridge its director.[43] After Congress passed the Homeland Security Act to create the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Ridge became the first director of the newly created department. The department was charged with overseeing immigration, border control, customs, and the newly established Transportation Security Administration (TSA), which focused on airport security.[44] Though the FBI and CIA remained independent agencies, the DHS was assigned jurisdiction over the Coast Guard, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (which was divided into three agencies), the United States Customs Service (which was also divided into separate agencies), and the Federal Emergency Management Agency. The Homeland Security Act represented the most significant departmental reorganization since the National Security Act of 1947.[45]

On October 26, 2001, Bush signed into law the Patriot Act. Passed on the president's request, the act permitted increased sharing of intelligence among the U.S. Intelligence Community and expanded the government's domestic authority to conduct surveillance of suspected terrorists.[44] The Patriot Act also authorized the use of roving wiretaps on suspected terrorists and expanded the government's authority to conduct surveillance of suspected "lone wolf" terrorists.[46] Bush also secretly authorized the National Security Agency to conduct warrantless surveillance of communications in and out of the United States.[44]

Campaign finance reform[edit]

McCain's 2000 presidential campaign brought the issue of campaign finance reform to the fore of public consciousness in 2001.[47] McCain and Russ Feingold pushed a bipartisan campaign finance bill in the Senate, while Chris Shays (R-CT) and Marty Meehan (D-MA) led the effort of passing it in the House.[47] In just the second successful use of the discharge petition since the 1980s, a mixture of Democrats and Republicans defied Speaker Dennis Hastert and passed a campaign finance reform bill.[48] The House approved the bill with a 240–189 vote,[49] while the bill passed the Senate in a 60–40 vote, the bare minimum required to overcome the filibuster.[50] Throughout the congressional battle on the bill, Bush declined to take a strong position.[49] However, in March 2002, Bush signed into law the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act, stating that he thought the law would improve the financing system for elections but was "far from perfect."[51] The law placed several limits on political donations and expenditures, and closed loopholes on contribution limits on donations to political candidates by banning the use of so-called "soft money."[47] Portions of the law restricting independent expenditures would later be struck down by the Supreme Court in the 2010 case of Citizens United v. FEC.[52]

Healthcare[edit]

After the passage of the Bush tax cuts and the No Child Left Behind Act, Bush turned his domestic focus to healthcare. He sought to expand Medicare so it would also cover the cost of prescription drugs, a program that became known as Medicare Part D. Many congressional Democrats opposed the bill because it did not allow Medicare to negotiate the prices of drugs, while many conservative Republicans opposed the expansion of the government's involvement in healthcare. Assisted by Speaker of the House Dennis Hastert and Senate majority leader Bill Frist, Bush overcame strong opposition and won passage of his Medicare bill.[53] In December 2003, Bush signed the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act, the largest expansion of Medicare since the program's creation in 1965.[54]

Attempted Social Security reform[edit]

After winning re-election in 2004, Bush made the partial privatization of Social Security his top domestic priority.[55] He proposed restructuring the program so that citizens could invest some of the money they paid in payroll taxes, which fund the Social Security program.[56] The president argued that Social Security faced an imminent funding crisis and that reform was necessary to ensure its continuing solvency.[57] Bush expected a difficult congressional battle over his proposal, but, as he put it, "I've got political capital, and I intend to spend it."[58] Groups like the AARP strongly opposed the plan, as did moderate Democrats like Max Baucus, who had supported the Bush tax cuts. Ultimately, Bush failed to win the backing of a single congressional Democrat for his plan, and even moderate Republicans like Olympia Snowe and Lincoln Chafee refused to back privatization. In the face of unified opposition, Republicans abandoned Bush's Social Security proposal in mid-2005.[59]

Response to Hurricane Katrina[edit]

Hurricane Katrina, one of the largest and most powerful hurricanes ever to strike the United States, ravaged several states along the Gulf of Mexico in August 2005. On a working vacation at his ranch in Texas, Bush initially allowed state and local authorities to respond to the natural disaster. The hurricane made landfall on August 29, devastating the city of New Orleans after the failure of that city's levees. Over eighteen hundred people died in the hurricane, and Bush was widely criticized for his slow response to the disaster.[60] Stung by the public response, Bush removed Federal Emergency Management Agency director Michael D. Brown from office and stated publicly that "Katrina exposed serious problems in our response capability at all levels of government."[61] After Hurricane Katrina, Bush's approval rating fell below 40 percent, where it would remain for the rest of his tenure in office.[60]

Proposed immigration reform[edit]

Although he concentrated on other domestic policies during his first term, Bush supported immigration reform throughout his administration. In May 2006, he proposed a five-point plan that would increase border security, establish a guest worker program, and create a path to citizenship for the twelve million illegal immigrants living in the United States. The Senate passed the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act of 2006, which included many of the president's proposals, but the bill did not pass the House of Representatives. After Democrats took control of Congress in the 2006 mid-term elections, Bush worked with Ted Kennedy to re-introduce the bill as the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act of 2007. The bill received intense criticism from many conservatives, who had become more skeptical of immigration reform, and it failed to pass the Senate.[62]

Great Recession[edit]

After years of financial deregulation accelerating under the Bush administration, banks lent subprime mortgages to more and more home buyers, causing a housing bubble. Many of these banks also invested in credit default swaps and derivatives that were essentially bets on the soundness of these loans. In response to declining housing prices and fears of an impending recession, the Bush administration arranged passage of the Economic Stimulus Act of 2008. Falling home prices started threatening the financial viability of many institutions, leaving Bear Stearns, a prominent U.S.-based investment bank, on the brink of failure in March 2008. Recognizing the growing threat of a financial crisis, Bush allowed Treasury secretary Paulson to arrange for another bank, JPMorgan Chase, to take over most Bear Stearn's assets. Out of concern that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac might also fail, the Bush administration put both institutions into conservatorship. Shortly afterwards, the administration learned that Lehman Brothers was on the verge of bankruptcy, but the administration ultimately declined to intervene on behalf of Lehman Brothers.[63]

Paulson hoped that the financial industry had shored itself up after the failure of Bear Stearns and that the failure of Lehman Brothers would not strongly impact the economy, but news of the failure caused stock prices to tumble and froze credit. Fearing a total financial collapse, Paulson and the Federal Reserve took control of American International Group (AIG), another major financial institution that teetered on the brink of failure. Hoping to shore up the other banks, Bush and Paulson proposed the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008, which would create the $700 billion Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) to buy toxic assets. The House rejected TARP in a 228–205 vote; although support and opposition crossed party lines, only about one-third of the Republican caucus supported the bill. After the Dow Jones Industrial Average dropped 778 points on the day of the House vote, the House and Senate both passed TARP. Bush later extended TARP loans to U.S. automobile companies, which faced their own crisis due to the weak economy. Though TARP helped end the financial crisis, it did not prevent the onset of the Great Recession, which would continue after Bush left office.[64][65]

Social issues[edit]

On his first day in office, President Bush reinstated the Mexico City policy, thereby blocking federal aid to foreign groups that offered assistance to women in obtaining abortions. Days later, he announced his commitment to channeling more federal aid to faith-based service organizations, despite the fears of critics that this would dissolve the traditional separation of church and state in the United States.[66][67] To further this commitment, he created the White House Office of Faith-Based and Community Initiatives to assist faith-based service organizations.[68] In 2003, Bush signed the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act, which banned intact dilation and extraction, an abortion procedure.[69]

Early in his administration, President Bush became personally interested in the issue of stem cell research.[70] The Clinton administration had issued guidelines allowing the federal funding of research utilizing stem cells, and Bush decided to study the situation's ethics before issuing his own executive order on the issue. Evangelical religious groups argued that the research was immoral as it destroyed human embryos, while various advocacy groups touted the potential scientific advances afforded by stem cell research.[71] In August 2001, Bush issued an executive order banning federal funding for research on new stem cell lines; the order allowed research on existing stem cell lines to continue.[72] In July 2006, Bush used his first presidential veto on the Stem Cell Research Enhancement Act, which would have expanded federal funding of embryonic stem cell research. A similar bill was passed in both the House of Representatives and the Senate early in mid-2007 as part of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi's 100-Hour Plan, but was vetoed by Bush.[73]

After the Supreme Court struck down a state sodomy law in the 2003 case of Lawrence v. Texas, conservatives began pushing for the Federal Marriage Amendment, which would define marriage as a union between a man and a woman. Bush endorsed this proposal and made it part of his campaign during the 2004 and 2006 election cycles.[74][75] However, President Bush did break from his party in his tolerance of civil unions for homosexual couples.[76][77][78]

Bush was staunchly opposed to euthanasia and supported Attorney General John Ashcroft's ultimately unsuccessful suit against the Oregon Death with Dignity Act.[79] However, while he was governor of Texas, Bush had signed a law giving hospitals the authority to remove life support from terminally ill patients against the wishes of spouses or parents, if the doctors deemed it as medically appropriate.[80] This perceived inconsistency in policy became an issue in 2005, when Bush signed controversial legislation to initiate federal intervention in the court battle of Terri Schiavo, a comatose Florida woman who ultimately died.[81]

Environmental policies[edit]

In March 2001, the Bush administration announced that it would not implement the Kyoto Protocol, an international treaty signed in 1997 that required nations to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. The administration argued that ratifying the treaty would unduly restrict U.S. growth while failing to adequately limit emissions from developing nations.[82] The administration questioned the scientific consensus on climate change.[83] Bush stated that he believed global warming is real[84] and a serious problem, although he asserted that there existed a "debate over whether it's man-made or naturally caused".[85] The Bush administration's stance on global warming remained controversial in the scientific and environmental communities. Critics alleged that the administration[86] misinformed the public and did not do enough to reduce carbon emissions and deter global warming.[87]

On January 6, 2009, President Bush designated the world's largest protected marine area. The Pacific Ocean habitat includes the Mariana Trench and the waters and corals surrounding three uninhabited islands in the Northern Mariana Islands, Rose Atoll in American Samoa, and seven islands along the equator.[88]

Other legislation[edit]

In July 2002, following several accounting scandals such as the Enron scandal, Bush signed the Sarbanes–Oxley Act into law. The act expanded reporting requirements for public companies[89] Shortly after the start of his second term, Bush signed the Class Action Fairness Act of 2005, which had been a priority of his administration and part of his broader goal of instituting tort reform. The act was designed to remove most class action lawsuits from state courts to federal courts, which were regarded as less sympathetic to plaintiffs in class action suits.[90]

Minorities, civil rights and affirmative action[edit]

Bush endorsed civil rights and appointed blacks, women and gays to high positions. The premier cabinet position, Secretary of State, went to Colin Powell (2001–2005), the first Black appointee at that high a level. He was followed by Condoleezza Rice (2005–2009), the first Black woman. Attorney General Alberto Gonzales (2005–2007) was and remains in 2024 the highest appointed Hispanic in the history of American government. In addition Bush appointed the first senior officials who were publicly gay. However he campaigned against quotas, and warned that affirmative action that involved quotas were unacceptable. He deliberately selected minorities known as opponents of affirmative action for key civil rights positions. Thus in 2001 Bush nominated Linda Chavez to be the first Latina in the cabinet as Secretary of Labor. She had to withdraw when it was reported that a decade earlier she had hired an illegal immigrant.[91][92][93][94]

Foreign affairs[edit]

Taking office[edit]

Upon taking office, Bush had little experience with foreign policy, and his decisions were guided by his advisers. Bush embraced the views of Cheney and other neoconservatives, who de-emphasized the importance of multilateralism; neoconservatives believed that because the United States was the world's lone superpower, it could act unilaterally if necessary.[96] At the same time, Bush sought to enact the less interventionist foreign policy he had promised during the 2000 campaign.[97] Though the first several months of his presidency focused on domestic issues, the Bush administration pulled the U.S. out of several existing or proposed multilateral agreements, including the Kyoto Protocol, the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, and the International Criminal Court.[96]

September 11 attacks[edit]

Terrorism had emerged as an important national security issue in the Clinton administration, and it became one of the dominant issues of the Bush administration.[98] In the late 1980s, Osama bin Laden had established al-Qaeda, a militant Sunni Islamist multi-national organization that sought to overthrow Western-backed governments in Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Egypt, and Pakistan. In response to Saudi Arabia's decision to begin hosting U.S. soldiers in 1991, al-Qaeda had begun a terrorist campaign against U.S. targets, orchestrating attacks such as the 1998 United States embassy bombings and the 2000 USS Cole bombing. During Bush's first months in office, U.S. intelligence organizations intercepted communications indicating that al-Qaeda was planning another attack on the United States, but foreign policy officials were unprepared for a major attack on the United States.[99] Bush was briefed on al-Qaeda's activities, but focused on other foreign policy issues during his first months in office.[100]

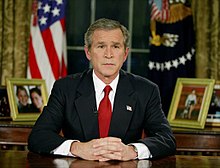

On September 11, 2001, al-Qaeda terrorists hijacked four airliners and flew two of them into the twin towers of the World Trade Center in New York City, destroying both 110-story skyscrapers. Another plane crashed into Pentagon, and a fourth plane was brought down in Pennsylvania following a struggle between the terrorists and the aircraft's passengers.[101] The attacks had a profound effect on many Americans, who felt vulnerable to international attacks for the first time since the end of the Cold War.[102] Appearing on national television on the night of the attacks, Bush promised to punish those who had aided the attacks, stating, "we will make no distinction between the terrorists who committed these acts and those who harbor them." In the following days, Bush urged the public to renounce hate crimes and discrimination against Muslim-Americans and Arab-Americans.[101] He also declared a "War on Terror", instituting new domestic and foreign policies in an effort to prevent future terrorist attacks.[103]

War in Afghanistan[edit]

As Bush's top foreign policy advisers were in agreement that merely launching strikes against al-Qaeda bases would not stop future attacks, the administration decided to overthrow Afghanistan's conservative Taliban government, which harbored the leaders of al-Qaeda.[104] Powell took the lead in assembling allied nations in a coalition that would launch attacks on multiple fronts.[105] The Bush administration focused especially on courting Pakistani leader Pervez Musharraf, who agreed to join the coalition.[106] On September 14, Congress passed a resolution called the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Terrorists, authorizing the president to use the military against those responsible for the attacks. On October 7, 2001, Bush ordered the invasion of Afghanistan.[104]

General Tommy Franks, the commander of the United States Central Command (CENTCOM), drew up a four-phase invasion plan. In the first phase, the U.S. built up forces in the surrounding area and inserted CIA and special forces operatives who linked up with the Northern Alliance, an Afghan resistance group opposed to the Taliban. The second phase consisted of a major air campaign against Taliban and al-Qaeda targets, while the third phase involved the defeat of the remaining Taliban and al-Qaeda forces. The fourth and final phase consisted of the stabilization of Afghanistan, which Franks projected would take three to five years. The war in Afghanistan began on October 7 with several air and missile strikes, and the Northern Alliance began its offensive on October 19. The capital of Kabul was captured on November 13, and Hamid Karzai was inaugurated as the new president of Afghanistan. However, the senior leadership of the Taliban and al-Qaeda, including bin Laden, avoided capture. Karzai would remain in power for the duration of Bush's presidency, but his effective control was limited to the area around Kabul, as various warlords took control of much of the rest of the country.[107] While the Karzai's government struggled to control the countryside, the Taliban regrouped in neighboring Pakistan. As Bush left office, he considered sending additional troops to bolster Afghanistan against the Taliban, but decided to leave the issue for the next administration.[108]

Bush Doctrine[edit]

After the September 11 attacks, Bush's approval ratings increased tremendously. Inspired in part by the Truman administration, Bush decided to use his newfound political capital to fundamentally change U.S. foreign policy. He became increasingly focused on the possibility of a hostile country providing weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) to terrorist organizations.[109] During his early 2002 State of the Union Address, Bush set forth what has become known as the Bush Doctrine, which held that the United States would implement a policy of preemptive military strikes against nations known to be harboring or aiding a terrorist organization hostile to the United States.[110] Bush outlined what he called the "Axis of Evil," consisting of three nations that, he argued, posed the greatest threat to world peace due to their pursuit of weapons of mass destruction and potential to aid terrorists. The axis consisted of Iraq, North Korea and Iran.[111] Bush also began emphasizing the importance of spreading democracy worldwide, stating in 2005 that "the survival of liberty in our land depends on the success of liberty in other land." Pursuant to this newly-interventionist policy, the Bush administration boosted foreign aid and increased defense expenditures.[112] Defense spending rose from $304 billion in fiscal year 2001 to $616 billion in fiscal year 2008.[113]

Iraq[edit]

Prelude to the war[edit]

During the presidency of his father, the United States had launched the Gulf War against Iraq after the latter invaded Kuwait. Though the U.S. forced Iraq's withdrawal from Kuwait, it left Saddam Hussein's administration in place, partly to serve as a counterweight to Iran. After the war, the Project for the New American Century, consisting of influential neoconservatives like Paul Wolfowitz and Cheney, advocated for the overthrow of Hussein.[114] Iraq had developed biological and chemical weapons prior to the Gulf War; after the war, it had submitted to WMD inspections conducted by the United Nations Special Commission until 1998, when Hussein demanded that all UN inspectors leave Iraq.[115] The administration believed that, by 2001, Iraq was developing weapons of mass destruction, and could possibly provide those weapons to terrorists.[116] Some within the administration also believed that Iraq shared some responsibility for the September 11 attacks,[116] and hoped that the fall of Hussein's regime would help spread democracy in the Middle East, deter the recruitment of terrorists, and increase the security of Israel.[10]

In the days following the September 11 attacks, hawks in the Bush administration such as Wolfowitz argued for immediate military action against Iraq, but the issue was temporarily set aside in favor of planning the invasion of Afghanistan.[117] Beginning in September 2002, the Bush administration mounted a campaign designed to win popular and congressional support for the invasion of Iraq.[118] In October 2002, Congress approved the Iraq Resolution, authorizing the use of force against Iraq. While congressional Republicans almost unanimously supported the measure, congressional Democrats were split in roughly equal numbers between support and opposition to the resolution.[119] Bowing to domestic and foreign pressure, Bush sought to win the approval of the United Nations before launching an attack on Iraq.[120] Led by Powell, the administration won the November 2002 passage of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1441, which called on Iraq to dismantle its WMD program.[121] Meanwhile, senior administration officials became increasingly convinced that Iraq did indeed possess WMDs and was likely to furnish those WMDs to al-Qaeda; CIA Director George Tenet assured Bush that it was a "slam dunk" that Iraq possessed a stockpile of WMDs.[122]

After a U.N. weapons inspections team led by Hans Blix, as well as another team led by Mohamed ElBaradei, failed to find evidence of an ongoing Iraqi WMD program, Bush's proposed regime change in Iraq faced mounting international opposition. Germany, China, France, and Russia all expressed skepticism about the need for regime change, and the latter three countries each possessed veto power on the United Nations Security Council.[123] At the behest of British prime minister Tony Blair, who supported Bush but hoped for more international cooperation, Bush dispatched Powell to the U.N. to make the case to the Security Council that Iraq maintained an active WMD program.[124] Though Powell's presentation preceded a shift in U.S. public opinion towards support of the war, it failed to convince the French, Russians, or Germans.[124] Contrary to the findings of Blix and ElBaradei, Bush asserted in a March 17 public address that there was "no doubt" that the Iraqi regime possessed weapons of mass destruction. Two days later, Bush authorized Operation Iraqi Freedom, and the Iraq War began on March 20, 2003.[125]

Invasion of Iraq[edit]

U.S.-led coalition forces, led by General Franks, launched a simultaneous air and land attack on Iraq on March 20, 2003, in what the American media called "shock and awe." With 145,000 soldiers, the ground force quickly overcame most Iraqi resistance, and thousands of Iraqi soldiers deserted. The U.S. captured the Iraqi capital of Baghdad on April 9, but Hussein escaped and went into hiding. While the U.S. and its allies quickly achieved military success, the invasion was strongly criticized by many countries; UN secretary-general Kofi Annan argued that the invasion was a violation of international law and the U.N. Charter.[126]

On May 1, 2003, Bush delivered the "Mission Accomplished speech," in which he declared the end of "major combat operations" in Iraq.[127] Despite the failure to find evidence of an ongoing WMD program[a] or an operational relationship between Hussein and al-Qaeda, Bush declared that the toppling of Hussein "removed an ally of al-Qaeda" and ended the threat that Iraq would supply weapons of mass destruction to terrorist organizations. Believing that only a minimal residual American force would be required after the success of the invasion, Bush and Franks planned for a drawdown to 30,000 U.S. troops in Iraq by August 2003. Meanwhile, Iraqis began looting their own capital, presenting one of the first of many challenges the U.S. would face in keeping the peace in Iraq.[131]

Bush appointed Paul Bremer to lead the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA), which was charged with overseeing the transition to self-government in Iraq. In his first major order, Bremer announced a policy of de-Ba'athification, which denied government and military jobs to members of Hussein's Ba'ath Party. This policy angered many of Iraq's Sunnis, many of whom had joined the Ba'ath Party merely as a career move. Bremer's second major order disbanded the Iraqi military and police services, leaving over 600,000 Iraqi soldiers and government employees without jobs. Bremer also insisted that the CPA remain in control of Iraq until the country held elections, reversing an earlier plan to set up a transition government led by Iraqis. These decisions contributed to the beginning of the Iraqi insurgency opposed to the continuing U.S. presence. Fearing the further deterioration of Iraq's security situation, General John Abizaid ordered the end of the planned drawdown of soldiers, leaving over 130,000 U.S. soldiers in Iraq. The U.S. captured Hussein on December 13, 2003, but the occupation force continued to suffer casualties. Between the start of the invasion and the end of 2003, 580 U.S. soldiers died, with two thirds of those casualties occurring after Bush's "Mission Accomplished" speech.[132]

Continuing occupation[edit]

| Year | Iraq | Afghanistan |

|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 0 | 0 |

| 2002 | 0 | 4,067 |

| 2003 | 0 | 9,600 |

| 2004 | 108,900 | 13,600 |

| 2005 | 159,000 | 17,200 |

| 2006 | 137,000 | 19,700 |

| 2007 | 137,000 | 26,000 |

| 2008 | 154,000 | 27,500 |

| 2009 | 139,500 | 34,400 |

After 2003, more and more Iraqis began to see the U.S. as an occupying force. The fierce fighting of the First Battle of Fallujah alienated many in Iraq, while cleric Muqtada al-Sadr encouraged Shia Muslims to oppose the CPA.[134] Sunni and Shia insurgents engaged in a campaign of guerrilla warfare against the United States, blunting the technological and organizational advantages of the U.S. military.[135] While fighting in Iraq continued, Americans increasingly came to disapprove of Bush's handling of the Iraq War, contributing to a decline in Bush's approval ratings.[136]

Bremer left Iraq in June 2004, transferring power to the Iraqi Interim Government, which was led by Ayad Allawi.[135] In January 2005, the Iraqi people voted on representatives for the Iraqi National Assembly, and the Shia United Iraqi Alliance formed a governing coalition led by Ibrahim al-Jaafari. In October 2005, the Iraqis ratified a new constitution that created a decentralized governmental structure dividing Iraq into communities of Sunni Arabs, Shia Arabs, and Kurds. After a December 2005 election, Jafari was succeeded as prime minister by another Shia, Nouri al-Maliki. The elections failed to quell the insurgency, and hundreds of U.S. soldiers stationed in Iraq died during 2005 and 2006. Sectarian violence between Sunnis and Shias also intensified following the 2006 al-Askari mosque bombing.[137] In a December 2006 report, the bipartisan Iraq Study Group described the situation in Iraq as "grave and deteriorating," and the report called for the U.S. to gradually withdraw soldiers from Iraq.[138]

As the violence mounted in 2006, Rumsfeld and military leaders such as Abizaid and George Casey, the commander of the coalition forces in Iraq, called for a drawdown of forces in Iraq, but many within the administration argued that the U.S. should maintain its troop levels.[139] Still intent on establishing a democratic government in Iraq, the Bush administration rejected a drawdown and began planning for a change in strategy and leadership following the 2006 elections.[140] After the elections, Bush replaced Rumsfeld with Gates, while David Petraeus replaced Casey and William J. Fallon replaced Abizaid.[141] Bush and his National Security Council formed a plan to "double down" in Iraq, increasing the number of U.S. soldiers in hopes of establishing a stable democracy.[142] After Maliki indicated his support for an increase of U.S. soldiers, Bush announced in January 2007 that the U.S. would send an additional 20,000 soldiers to Iraq as part of a "surge" of forces.[143] Though Senator McCain and a few other hawks supported Bush's new strategy, many other members of Congress from both parties expressed doubt or outright opposition to it.[144]

In April 2007, Congress, now controlled by Democrats, passed a bill that called for a total withdrawal of all U.S. troops by April 2008, but Bush vetoed the bill.[145] Without the votes to override the veto, Congress passed a bill that continued to fund the war but also included the Fair Minimum Wage Act of 2007, which increased the federal minimum wage.[146] U.S. and Iraqi casualties continuously declined after May 2007, and Bush declared that the surge had been a success in September 2007.[147] He subsequently ordered a drawdown of troops, and the number of U.S. soldiers in Iraq declined from 168,000 in September 2007 to 145,000 when Bush left office.[147] The decline in casualties following the surge coincided with several other favorable trends, including the Anbar Awakening and Muqtada al-Sadr's decision to order his followers to cooperate with the Iraqi government.[148] In 2008, at the insistence of Maliki, Bush signed the U.S.–Iraq Status of Forces Agreement, which promised complete withdrawal of U.S. troops by the end of 2011.[149] The U.S. would withdraw its forces from Iraq in December 2011,[150] though it later re-deployed soldiers to Iraq to assist government forces in the Iraqi Civil War.[151]

Guantanamo Bay and enemy combatants[edit]

During and after the invasion of Afghanistan, the U.S. captured numerous members of al-Qaeda and the Taliban. Rather than bringing the prisoners before domestic or international courts, Bush decided to set up a new system of military tribunals to try the prisoners. In order to avoid the restrictions of the United States Constitution, Bush held the prisoners at secret CIA prisons in various countries as well as at the Guantanamo Bay detention camp. Because the Guantanamo Bay camp is on territory that the U.S. technically leases from Cuba, individuals within the camp are not accorded the same constitutional protections that they would have on U.S. territory. Bush also decided that these "enemy combatants" were not entitled to all of the protections of the Geneva Conventions as they were not affiliated with sovereign states. In hopes of obtaining information from the prisoners, Bush allowed the use of "enhanced interrogation techniques" such as waterboarding.[152] The treatment of prisoners at Abu Ghraib, a U.S. prison in Iraq, elicited widespread outrage after photos of prisoner abuse were made public.[153]

In 2005, Congress passed the Detainee Treatment Act, which purported to ban torture, but in his signing statement Bush asserted that his executive power gave him the authority to waive the restrictions put in place by the bill.[154] Bush's policies suffered a major rebuke from the Supreme Court in the 2006 case of Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, in which the court rejected Bush's use of military commissions without congressional approval and held that all detainees were protected by the Geneva Conventions.[155] Following the ruling, Congress passed the Military Commissions Act of 2006, which effectively overturned Hamdan.[156] The Supreme Court overturned a portion of that act in the 2008 case of Boumediene v. Bush, but the Guantanamo detention camp remained open at the end of Bush's presidency.[157]

Israel[edit]

The Israeli–Palestinian conflict, ongoing since the middle of the 20th century, continued under Bush. After President Clinton's 2000 Camp David Summit had ended without an agreement, the Second Intifada had begun in September 2000.[158] While previous administrations had tried to act as a neutral authority between the Israelis and Palestinians, the Bush administration placed the blame for the violence on the Palestinians, angering Arab states such as Saudi Arabia.[158][159] However, Bush's support for a two-state solution helped smooth over a potential diplomatic split with the Saudis.[160] In hopes of establishing peace between the Israelis and Palestinians, the Bush administration proposed the road map for peace, but his plan was not implemented and tensions were heightened following the victory of Hamas in the 2006 Palestinian elections.[161]

Free trade agreements[edit]

Believing that protectionism hampered economic growth, Bush concluded free trade agreements with numerous countries. When Bush took office, the United States had free trade agreements with just three countries: Israel, Canada, and Mexico. Bush signed the Chile–United States Free Trade Agreement and the Singapore–United States Free Trade Agreement in 2003, and he concluded the Morocco-United States Free Trade Agreementand the Australia–United States Free Trade Agreement the following year. He also concluded the Bahrain–United States Free Trade Agreement, the Oman–United States Free Trade Agreement, the Peru–United States Trade Promotion Agreement, and the Dominican Republic–Central America Free Trade Agreement. Additionally, Bush reached free trade agreements with South Korea, Colombia, and Panama, though agreements with these countries were not ratified until 2011.[162]

NATO and arms control treaties[edit]

In 2002 the US withdrew from the U.S.-Russian Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty.[163] This marked the first time in post-WW2 history that the United States has withdrawn from a major international arms treaty.[164] China expressed displeasure at America's withdrawal.[165] Then newly elected Russian President Vladimir Putin stated that American withdrawal from the ABM Treaty was a mistake,[165] and subsequently in a 1 March 2018 Presidential Address to the Federal Assembly announced the development of a series of technologically new missile systems in response to the Bush withdrawal.[166][167][168] In Oliver Stone's 2017 The Putin Interviews, Putin said that in trying to persuade Russia to accept US withdrawal from the treaty, both Clinton and Bush had tried to convince him of an emerging nuclear threat from Iran.[169]

On 14 July 2007, Russia announced that it would suspend implementation of its Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe obligations, effective after 150 days. This failure can be said to mark the start of the Putinian Revanchism.[170]

Russia[edit]

Bush emphasized creating a better personal relationship with Russian president Vladimir Putin in order to ensure harmonious relations between the U.S. and Russia. After meeting with Putin in June 2001, both presidents expressed optimistic views regarding cooperation between the two former Cold War rivals.[171] After the 9/11 attacks, Putin allowed the U.S. to use Russian airspace, and Putin encouraged Central Asian states to grant basing rights to the U.S.[172] In May 2002, the U.S. and Russia signed the Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty, which sought to dramatically reduce the nuclear stockpiles of both countries.[173] Relations between Bush and Putin cooled during Bush's second term, as Bush became increasingly critical of Putin's suppression of political opponents in Russia, and they fell to new lows after the outbreak of the Russo-Georgian War in 2008.[174]

Iran[edit]

In his 2002 State of the Union Address, Bush grouped Iran with Iraq and North Korea as a member of the "Axis of Evil", accusing Iran of aiding terrorist organizations.[175] In 2006, Iran re-opened three of its nuclear facilities, potentially allowing it to begin the process of building a nuclear bomb.[176] After the resumption of the Iranian nuclear program, many within the U.S. military and foreign policy community speculated that Bush might attempt to impose regime change on Iran.[177] In December 2006, the United Nations Security Council unanimously passed Resolution 1737, which imposed sanctions on Iran in order to curb its nuclear program.[178]

North Korea[edit]

North Korea had developed weapons of mass destruction for several years prior to Bush's inauguration, and the Clinton administration had sought to trade economic assistance for an end to the North Korean WMD program. Though Secretary of State Powell urged the continuation of the rapprochement, other administration officials, including Vice President Cheney, were more skeptical of the good faith of the North Koreans. Bush instead sought to isolate North Korea in the hope that the regime would eventually collapse.[179]

North Korea launched missile tests on July 5, 2006, leading to United Nations Security Council Resolution 1695. The country said on October 3, "The U.S. extreme threat of a nuclear war and sanctions and pressure compel the DPRK to conduct a nuclear test", which the Bush administration denied and denounced.[180] Days later, North Korea followed through on its promise to test nuclear weapons.[181] On October 14, the Security Council unanimously passed United Nations Security Council Resolution 1718, sanctioning North Korea for the test.[182] In the waning days of his presidency, Bush attempted to re-open negotiations with North Korea, but North Korea continued to develop its nuclear programs.[183]

AIDS relief[edit]

Вскоре после вступления в должность Буш пообещал выделить 200 миллионов долларов Глобальному фонду для борьбы со СПИДом, туберкулезом и малярией . [184] Finding this effort insufficient, Bush assembled a team of experts to find the best way for the U.S. reduce the worldwide damage caused by the AIDS epidemic.[184] Эксперты во главе с Энтони С. Фаучи рекомендовали США сосредоточиться на предоставлении антиретровирусных препаратов развивающимся странам Африки и Карибского бассейна. [184] В своем послании о положении страны в январе 2003 года президент Буш изложил пятилетнюю стратегию глобальной чрезвычайной в связи со СПИДом помощи – Чрезвычайный план президента по борьбе со СПИДом . С одобрения Конгресса Буш выделил на эти усилия 15 миллиардов долларов, что представляло собой огромное увеличение по сравнению с финансированием при предыдущих администрациях. Ближе к концу своего президентства Буш подписал повторное разрешение на программу, которое удвоило ее финансирование. К 2012 году программа ПЕПФАР обеспечила антиретровирусными препаратами более 4,5 миллионов человек. [185]

Споры [ править ]

Скандал с утечкой из информации ЦРУ

Буша и вице-президента Дика Чейни В июле 2005 года главные политические советники , Карл Роув и Льюис «Скутер» Либби личность тайного Центрального разведывательного управления (ЦРУ) агента Валери Плейм , подверглись критике за то, что раскрыли журналистам в связи с утечкой информации ЦРУ. скандал . [186] Муж Плейма, Джозеф К. Уилсон , оспорил утверждение Буша о том, что Хусейн пытался получить уран из Африки, и специальному прокурору было поручено определить, раскрыли ли представители администрации личность Плейма в отместку Уилсону. [187] Либби подал в отставку 28 октября, через несколько часов после того, как большое жюри предъявило ему многочисленным обвинение по пунктам обвинения в даче ложных показаний , ложных заявлениях и препятствовании этому делу. В марте 2007 года Либби была признана виновной по четырем пунктам обвинения, и Чейни потребовал от Буша помиловать Либби. Вместо того, чтобы помиловать Либби или позволить ему попасть в тюрьму, Буш смягчил приговор Либби, создав раскол с Чейни, который обвинил Буша в том, что он оставил «солдата на поле боя». [186]

США Увольнение адвокатов

В декабре 2006 года Буш уволил восемь прокуроров США . Хотя эти адвокаты служат по усмотрению президента, крупномасштабное увольнение в середине срока не имело прецедента, и Бушу предъявили обвинения в том, что он уволил адвокатов по чисто политическим причинам. Во время выборов 2006 года несколько республиканских чиновников жаловались, что прокуроры США недостаточно расследовали фальсификации результатов голосования . При поддержке Гарриет Майерс и Карла Роува генеральный прокурор Гонсалес уволил восемь американских прокуроров, которые были сочтены недостаточно поддерживающими политику администрации. Хотя Гонсалес утверждал, что адвокаты были уволены по соображениям производительности, опубликованные документы показали, что адвокаты были уволены по политическим мотивам. В результате увольнений и последующего расследования Конгресса Роув и Гонсалес подали в отставку. В отчете генерального инспектора Министерства юстиции за 2008 год было установлено, что увольнения были политически мотивированными, но никто так и не был привлечен к ответственности в связи с увольнениями. [188]

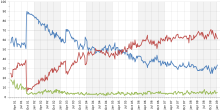

Рейтинги одобрения [ править ]

Буша Рейтинг одобрения варьировался от высокого до рекордно низкого за всю историю. Буш начал свое президентство с рейтингом около пятидесяти процентов. [189] Во время национального кризиса, последовавшего за терактами 11 сентября , опросы показали, что рейтинг одобрения превышает 85%, достигнув пика в одном опросе в октябре 2001 года и составив 92%. [189] и стабильное одобрение 80–90% в течение примерно четырех месяцев после атак. [190] Впоследствии его рейтинги неуклонно падали, поскольку экономика пострадала, а война в Ираке , инициированная его администрацией, продолжалась. К началу 2006 года его средний рейтинг был ниже 40%, а в июле 2008 года опрос показал почти исторический минимум в 22%. После ухода с поста последний опрос показал, что его рейтинг одобрения составил 19%, что является рекордно низким показателем для любого президента США. [189] [191] [192]

президентства Буша во время Выборы

| Конгресс | Сенат | Дом |

|---|---|---|

| 107-е место [с] | 50 [д] | 221 |

| 108-е место | 51 | 229 |

| 109-е место | 55 | 231 |

| 110-е место | 49 | 202 |

| 111-е место [с] | 41 | 178 |

Промежуточные выборы 2002 г.

На промежуточных выборах 2002 года Буш стал первым президентом с 1930-х годов, добившимся того, чтобы его собственная партия получила места в обеих палатах Конгресса. Республиканцы получили два места на выборах в Сенат , что позволило им вновь взять под свой контроль палату. [194] Буш выступил на нескольких площадках с речами в поддержку своей партии, агитируя за свое желание свергнуть администрацию Саддама Хусейна. Буш рассматривал результаты выборов как подтверждение своей внутренней и внешней политики. [195]

по переизбранию Кампания 2004 г.

Буш и его предвыборная команда ухватились за идею Буша как о «сильном лидере военного времени», хотя эта идея была подорвана все более непопулярной войной в Ираке. [54] Его консервативная политика по снижению налогов и ряду других вопросов нравилась многим правым, но Буш мог также претендовать на некоторые центристские достижения, в том числе на «Ни одного ребенка не останется позади», Сарбейнса-Оксли и Medicare Part D. [196] Опасаясь, что он может подорвать шансы Буша на переизбрание, Чейни предложил уйти из списка кандидатов, но Буш отказался от этого предложения, и эти двое были повторно выдвинуты без сопротивления на Национальном съезде Республиканской партии 2004 года . [197] По совету социолога Мэтью Дауда , который заметил устойчивое снижение числа колеблющихся избирателей , в кампании Буша 2004 года упор делался на мобилизацию консервативных избирателей, а не на убеждение умеренных. [198]

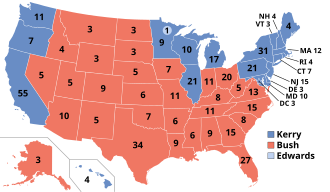

На праймериз Демократической партии 2004 года сенатор от Массачусетса Джон Керри победил нескольких других кандидатов, фактически добившись выдвижения своей кандидатуры 2 марта. Ветеран войны во Вьетнаме Керри проголосовал за санкционирование войны в Ираке, но выступил против нее. [199] Кампания Буша стремилась назвать Керри «шлепателем» из-за его голосования по законопроекту о финансировании войн в Афганистане и Ираке. [200] Керри пытался убедить сенатора-республиканца Джона Маккейна стать его кандидатом на пост вице-президента , но выбрал сенатора Джона Эдвардса от Северной Каролины после того, как Маккейн отклонил это предложение. на эту должность [201] На выборах произошел резкий скачок явки; в то время как в 2000 году проголосовали 105 миллионов человек, в 2004 году проголосовали 123 миллиона человек. Буш получил 50,7% голосов избирателей, что сделало его первым человеком, получившим большинство голосов избирателей после президентских выборов 1988 года .в то время как Керри получил 48,3% голосов избирателей. Буш набрал 286 голосов выборщиков, одержав победу в Айове, Нью-Мексико и во всех штатах, в которых он победил в 2000 году, за исключением Нью-Гэмпшира. [202]

Промежуточные г. 2006 выборы

| Лидеры Сената | Лидеры палат | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Конгресс | Год | Большинство | Меньшинство | Спикер | Меньшинство |

| 107-е место | 2001 | Лотт [д] | Дэшл | Хастер | Гепхардт |

| 2001–2002 | Дэшл | Лотт | Хастер | Гепхардт | |

| 108-е место | 2003–2004 | крайний срок | Дэшл | Хастер | Пелоси |

| 109-е место | 2005–2006 | крайний срок | Рид | Хастер | Пелоси |

| 110-е место | 2007–2008 | Рид | МакКоннелл | Пелоси | Бёнер |

| 111-е место [с] | 2009 | Рид | МакКоннелл | Пелоси | Бёнер |

Пострадавшие от непопулярности войны в Ираке и президента Буша, республиканцы потеряли контроль над обеими палатами Конгресса на выборах 2006 года. Республиканцы также пострадали от различных скандалов, в том числе от индийского лоббистского скандала с Джеком Абрамоффом и скандала с Марком Фоули . Выборы подтвердили падение популярности Буша, поскольку многие кандидаты, за которых он лично агитировал, потерпели поражение. После выборов Буш объявил об отставке Рамсфелда и пообещал работать с новым демократическим большинством. [203]

года и период переходный Выборы 2008

Согласно условиям двадцать второй поправки , Буш не имел права баллотироваться на третий срок в 2008 году. Сенатор Джон Маккейн выиграл республиканские президентские праймериз 2008 года , а сенатор-демократ Барак Обама от Иллинойса победил сенатора Хиллари Клинтон от Нью-Йорка и выиграл президентские выборы 2008 года от Демократической партии. президентские праймериз . [204] Победа Обамы на президентских праймериз Демократической партии во многом объяснялась его решительным сопротивлением войне в Ираке, поскольку Клинтон проголосовала за санкционирование войны в Ираке в 2002 году. [205] Маккейн стремился дистанцироваться от непопулярной политики Буша, а Буш появился на Национальном съезде Республиканской партии в 2008 году только через спутник , что сделало его первым действующим президентом со времен Линдона Б. Джонсона , который не появился на съезде своей партии в 1968 году . [204]

Маккейн ненадолго лидировал в опросах предвыборной гонки, проведенных после съезда республиканцев, но Обама быстро снова стал лидером опросов. [206] Кампании Маккейна был нанесен серьезный ущерб из-за непопулярности администрации Буша и войны в Ираке, а реакция Маккейна на начало полномасштабного финансового кризиса в сентябре 2008 года широко рассматривалась как беспорядочная. [207] Обама получил 365 голосов выборщиков и 52,9% голосов избирателей. Выборы предоставили демократам единый контроль над законодательной и исполнительной ветвями власти впервые после выборов 1994 года . После выборов Буш поздравил Обаму и пригласил его в Белый дом. С помощью администрации Буша смена президента Барака Обамы была широко расценена как успешная, особенно в отношении смены президентов разных партий. [208] Во время своей инаугурации 20 января 2009 года Обама поблагодарил Буша за его службу на посту президента и поддержку перехода Обамы. [209]

и наследие Оценка

в 2009 году, C-SPAN Опрос историков, проведенный поставил Буша на 36-е место среди 42 бывших президентов. [210] 2017 года поставил Буша на 33-е место среди величайших президентов. C-SPAN Опрос историков [211] По результатам опроса, проведенного в 2018 году секцией президентов и исполнительной политики Американской ассоциации политических наук, Буш занял 30-е место среди величайших президентов. [212] Историк Мелвин Леффлер пишет, что достижения администрации Буша во внешней политике «были перевешены неспособностью администрации достичь многих из своих наиболее важных целей». [213]

Подводя итог оценкам президентства Буша, Гэри Л. Грегг II пишет:

Президентство Буша изменило американскую политику, ее экономику и ее место в мире, но не так, как можно было предсказать, когда губернатор Техаса выдвинул свою кандидатуру на высший пост Америки. Став президентом, Буш стал громоотводом противоречий. Его противоречивые выборы и политика, особенно война в Ираке, глубоко разделили американский народ. Возможно, его величайшим моментом на посту президента стал его первый и искренний ответ на трагедию терактов 11 сентября. Однако вскоре его администрацию омрачили войны в Афганистане и Ираке. Место президента Буша в истории США будет обсуждаться и пересматриваться еще многие годы. [214]

Эндрю Рудалевиге составил список из 14 наиболее важных достижений администрации Буша: [215]

- Серьезные изменения в налоговом кодексе с дополнительными сокращениями в каждый из первых шести лет его пребывания у власти.

- Основные изменения в образовательной политике и повторное принятие основных федеральных законов об образовании.

- Расширение Medicare за счет покрытия лекарств.

- Назовите двух судей Верховного суда и 350 судей федеральных судов низшей инстанции.

- Продвигал запрет на частичный аборт при рождении.

- Крупномасштабные программы по борьбе со СПИДом и малярией, особенно для Африки.

- Увеличение в четыре раза числа стран с соглашениями о свободной торговле.

- Огромная помощь банковской системе после почти краха финансовой системы.

- Создано Министерство внутренней безопасности.

- Контроль Белого дома над федеральной бюрократией.

- Патриотические законы, расширяющие полномочия федеральных правоохранительных органов.

- Усилить полномочия президента по наблюдению за подозреваемыми в терроризме.

- Закон о военных комиссиях, особенно применимый к тюрьме Гуантанамо.

- Свержение двух враждебных режимов – Талибана в Афганистане и Саддама Хусейна в Ираке.

См. также [ править ]

- Президентство Джорджа Буша-старшего , его отца

- Президентский центр Джорджа Буша-младшего

- Попытки объявить импичмент Джорджу Бушу

- Список людей, помилованных Джорджем Бушем

- Политические последствия урагана Катрина

- Протесты против Джорджа Буша-младшего

- Общественный имидж Джорджа Буша-младшего

- Список федеральных политических скандалов в США (21 век)

Примечания [ править ]

- ^ Никакой действующей программы создания оружия массового уничтожения в Ираке так и не было обнаружено. [128] [129] хотя США действительно обнаружили некоторое химическое оружие, которое было произведено до 1991 года. [130]

- ^ В таблице указана численность американских войск в Ираке и Афганистане на начало каждого года.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с 17 дней 107-го Конгресса (3 января 2001 г. - 19 января 2001 г.) прошли при президенте Клинтоне, а 17 дней 111-го Конгресса (3 января 2009 г. - 19 января 2009 г.) прошли во время второго срока Буша.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Поскольку вице-президент-республиканец Дик Чейни обеспечивает решающее голосование, республиканцы также имеют большинство в Сенате с 20 января 2001 года. В июне 2001 года Джим Джеффордс покинул Республиканскую партию и начал консультироваться с демократами, что дало демократам большинство. .

Ссылки [ править ]

- ^ «Все рейтинги и таблицы» (PDF) . 2022.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Манн (2015), стр. 31–37.

- ^ Дрейпер (2007), стр. 5–6.

- ^ Манн (2015), стр. 35–42.

- ^ Смит (2016), стр. 152–156.

- ^ Дрейпер (2007), стр. 94–95.

- ^ Смит (2016), стр. 134–135.

- ^ Манн (2015), стр. 53–54, 76–77.

- ^ Смит (2016), стр. 129–134.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Сельдь (2008), стр. 938–939.

- ^ Смит (2016), стр. 389–390.

- ^ Смит (2016), стр. 382–383.

- ^ Смит (2016), стр. 417–418.

- ^ Дрейпер (2007), стр. 278–280, 283.

- ^ Дрейпер (2007), стр. 363–367.

- ^ Дрейпер (2007), стр. 369–371.

- ^ Смит (2016), стр. 515–517.

- ^ Сельдь (2008), с. 959

- ^ Смит (2016), стр. 572–575.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Смит (2016), стр. 427–428, 445–452.

- ^ Дрейпер (2007), стр. 343–345.

- ^ Джеймс Л. Гибсон и Грегори А. Калдейра, «Политика подтверждения и легитимность Верховного суда США: институциональная лояльность, предвзятость позитива и номинация Алито». Американский журнал политической науки 53.1 (2009): 139–155. онлайн. Архивировано 24 октября 2020 г. на Wayback Machine.

- ^ Липтак, Адам (24 июля 2010 г.). «Суд при Робертсе является самым консервативным за последние десятилетия» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 23 февраля 2019 года . Проверено 21 февраля 2019 г.

- ^ Все цифры, кроме процента долга, представлены в миллиардах долларов. Показатели поступлений, расходов, дефицита, ВВП и долга рассчитываются для финансового года , который заканчивается 30 сентября. Например, 2020 финансовый год закончился 30 сентября 2020 года.

- ^ Представляет собой государственный долг населения в процентах от ВВП.

- ^ «Исторические таблицы» . Белый дом . Управление управления и бюджета. Таблица 1.1 . Проверено 4 марта 2021 г.

- ^ «Исторические таблицы» . Белый дом . Управление управления и бюджета. Таблица 1.2 . Проверено 4 марта 2021 г.

- ^ «Исторические таблицы» . Белый дом . Управление управления и бюджета. Таблица 7.1 . Проверено 4 марта 2021 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Смит (2016), стр. 160–161.

- ^ Дрейпер (2007), стр. 119–120.

- ^ Дрейпер (2007), с. 120

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Манн (2015), стр. 43–48, Смит, стр. 161–162.

- ^ Штайнхауэр, Дженнифер (1 января 2013 г.). «Разделенный дом принял налоговое соглашение в конце последнего финансового противостояния» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 17 октября 2015 года . Проверено 13 ноября 2015 г.

- ^ Коган, Ричард; Арон-Дайн, Авива (27 июля 2006 г.). «Утверждение о том, что снижение налогов «окупается» слишком хорошо, чтобы быть правдой» . Центр бюджетных и политических приоритетов . Проверено 19 июля 2007 г.

- ^ «Анализ экономических и бюджетных последствий 10-процентного снижения ставок подоходного налога» (PDF) . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 12 января 2012 года . Проверено 31 марта 2011 г.

- ^ «Динамическая оценка: краткое руководство» (PDF) . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 16 мая 2008 г. Проверено 30 марта 2008 г.

- ^ «Заявление Хекувы» . Washingtonpost.com . 6 января 2007 года . Проверено 31 марта 2011 г.

- ^ Маллаби, Себастьян (15 мая 2006 г.). «Возвращение экономики вуду» . Washingtonpost.com . Проверено 31 марта 2011 г.

- ^ Дрейпер (2007), стр. 113–114.

- ^ Смит (2016), стр. 163–164.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Смит (2016), стр. 166–167.

- ^ Манн (2015), стр. 50–52.

- ^ Дрейпер (2007), с. 157

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Манн (2015), стр. 63–65.

- ^ Гласс, Эндрю (26 ноября 2018 г.). «Буш создает Министерство внутренней безопасности, 26 ноября 2002 года» . Политик . Архивировано из оригинала 25 февраля 2019 года . Проверено 24 февраля 2019 г.

- ^ Даймонд, Джереми (23 мая 2015 г.). «Все, что вам нужно знать о дебатах по поводу Патриотического акта» . Си-Эн-Эн. Архивировано из оригинала 25 февраля 2019 года . Проверено 24 февраля 2019 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Гителл, Сет (август 2003 г.). «Осмысление реформы Маккейна-Фейнгольда и финансирования избирательных кампаний» . Атлантика . Архивировано из оригинала 16 июня 2017 года . Проверено 17 ноября 2017 г.

- ^ Эренфройнд, Макс (29 июня 2013 г.). «Объяснена роль петиции об увольнении в дебатах по иммиграционной реформе» . Вашингтон Пост . Архивировано из оригинала 5 октября 2015 года . Проверено 16 октября 2015 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Барретт, Тед (15 февраля 2002 г.). «Битва за финансирование избирательной кампании переходит в Сенат» . Си-Эн-Эн. Архивировано из оригинала 20 марта 2017 года . Проверено 16 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Уэлч, Уильям (20 марта 2002 г.). «Проход завершает долгую борьбу за Маккейна, Файнголд» . США сегодня . Архивировано из оригинала 19 ноября 2015 года . Проверено 16 октября 2015 г.

- ^ «Буш подписывает закон о реформе финансирования избирательной кампании» . Фокс Ньюс. 27 марта 2002 г. Архивировано из оригинала 23 февраля 2017 г. Проверено 23 февраля 2017 г.

- ^ Бай, Мэтт (17 июля 2012 г.). «Насколько организация Citizens United изменила политическую игру?» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 17 ноября 2017 года . Проверено 17 ноября 2017 г.

- ^ Смит (2016), стр. 390–391.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Манн (2015), стр. 88–89.

- ^ Дрейпер (2007), стр. 295–296.

- ^ Смит (2016), стр. 425–426.

- ^ Прокоп, Андрей (9 января 2017 г.). «В 2005 году Вашингтон контролировали республиканцы. Их программа провалилась. И вот почему» . Вокс. Архивировано из оригинала 9 апреля 2017 года . Проверено 8 апреля 2017 г.

- ^ Дрейпер (2007), стр. 294–295.

- ^ Дрейпер (2007), стр. 293, 300–304.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Смит (2016), стр. 430–443.

- ^ Дрейпер (2007), стр. 335–336.

- ^ Смит (2016), стр. 582–584.

- ^ Манн (2015), стр. 126–132.

- ^ Манн (2015), стр. 132–137.

- ^ Смит (2016), стр. 631–632, 659–660.

- ^ Бакли, Томас Э. (11 ноября 2002 г.). «Церковь, государство и религиозная инициатива» . Америка, Национальный католический еженедельник. Архивировано из оригинала 29 мая 2006 г. Проверено 30 июня 2006 г.

- ^ Бранкаччо, Дэвид (26 сентября 2003 г.). «Религиозные инициативы» . Бог и правительство . СЕЙЧАС , PBS . Архивировано из оригинала 8 сентября 2006 г. Проверено 30 июня 2006 г.