Джеймс Бьюкенен

Джеймс Бьюкенен | |

|---|---|

Портрет ок. 1850–1868 гг. | |

| 15-й президент Соединенных Штатов | |

| В офисе 4 марта 1857 г. - 4 марта 1861 г. | |

| Vice President | John C. Breckinridge |

| Preceded by | Franklin Pierce |

| Succeeded by | Abraham Lincoln |

| United States Minister to the United Kingdom | |

| In office August 23, 1853 – March 15, 1856 | |

| President | Franklin Pierce |

| Preceded by | Joseph Reed Ingersoll |

| Succeeded by | George M. Dallas |

| 17th United States Secretary of State | |

| In office March 10, 1845 – March 7, 1849 | |

| President | |

| Preceded by | John C. Calhoun |

| Succeeded by | John M. Clayton |

| United States Senator from Pennsylvania | |

| In office December 6, 1834 – March 5, 1845 | |

| Preceded by | William Wilkins |

| Succeeded by | Simon Cameron |

| United States Minister to Russia | |

| In office June 11, 1832 – August 5, 1833 | |

| President | Andrew Jackson |

| Preceded by | John Randolph |

| Succeeded by | William Wilkins |

| Chairman of the House Judiciary Committee | |

| In office March 5, 1829 – March 3, 1831 | |

| Preceded by | Philip P. Barbour |

| Succeeded by | Warren R. Davis |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Pennsylvania | |

| In office March 4, 1821 – March 3, 1831 | |

| Preceded by |

|

| Succeeded by |

|

| Constituency |

|

| Member of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives Lancaster County | |

| In office 1814–1816 | |

| Preceded by | Emanuel Reigart, Joel Lightner, Jacob Grosh, John Graff, Henry Hambright, Robert Maxwell |

| Succeeded by | Joel Lightner, Hugh Martin, John Forrey, Henry Hambright, Jasper Slaymaker, Jacob Grosh[1] |

| Personal details | |

| Born | April 23, 1791 Cove Gap, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | June 1, 1868 (aged 77) Lancaster, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Resting place | Woodward Hill Cemetery |

| Political party |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Education | Dickinson College (BA) |

| Occupation |

|

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | Pennsylvania Militia |

| Years of service | 1814[2] |

| Rank | Private |

| Unit | Shippen's Cavalry, 1st Brigade, 4th Division |

| Battles/wars | |

| Official name | James Buchanan |

| Type | Roadside |

| Designated | January 1955 |

Джеймс Бьюкенен мл. ( / b j uː ˈ k æ n n ə / bew- KAN -ən ; [3] 23 апреля 1791 — 1 июня 1868) — американский юрист , дипломат и политик, занимавший пост 15-го президента Соединённых Штатов с 1857 по 1861 год. Бьюкенен также занимал должность государственного секретаря с 1845 по 1849 год и представлял Пенсильванию в обе палаты Конгресса США . Он был защитником прав штатов , особенно в отношении рабства , и минимизировал роль федерального правительства до Гражданской войны .

штата Бьюкенен был юристом в Пенсильвании и выиграл свои первые выборы в Палату представителей как федералист . Он был избран в Палату представителей США в 1820 году и сохранял этот пост в течение пяти сроков, присоединившись к Эндрю Джексона Демократической партии . Бьюкенен служил министром Джексона в России в 1832 году. Он выиграл выборы в 1834 году в качестве сенатора США от Пенсильвании и оставался на этой должности в течение 11 лет. В 1845 году он был назначен государственным секретарем президента Джеймса К. Полка , а восемь лет спустя был назначен министром президента Пирса Франклина в Соединенном Королевстве .

Beginning in 1844, Buchanan became a regular contender for the Democratic Party's presidential nomination. He was nominated and won the 1856 presidential election. As President, Buchanan intervened to assure the Supreme Court's majority ruling in the pro-slavery decision in the Dred Scott case. He acceded to Southern attempts to engineer Kansas' entry into the Union as a slave state under the Lecompton Constitution, and angered not only Republicans but also Northern Democrats. Buchanan honored his pledge to serve only one term and supported Breckinridge's unsuccessful candidacy in the 1860 presidential election. He failed to reconcile the fractured Democratic Party amid the grudge against Stephen Douglas, leading to the election of Republican and former Congressman Abraham Lincoln.

Buchanan's leadership during his lame duck period, before the American Civil War, has been widely criticized. He simultaneously angered the North by not stopping secession and the South by not yielding to their demands. He supported the Corwin Amendment in an effort to reconcile the country. He made an unsuccessful attempt to reinforce Fort Sumter, but otherwise refrained from preparing the military. In his personal life, Buchanan never married and was the only U.S. president to remain a lifelong bachelor, leading some historians and authors to question his sexual orientation. His failure to forestall the Civil War has been described as incompetence, and he spent his last years defending his reputation. Historians and scholars rank Buchanan as among the worst presidents in American history.

Early life

[edit]

Childhood and education

[edit]James Buchanan Jr. was born into a Scottish-Irish family on April 23, 1791, in a log cabin on a farm called Stony Batter, near Cove Gap, Peters Township, in the Allegheny Mountains of southern Pennsylvania. He was the last president born in the 18th century.[4] Buchanan was the second of eleven children with six sisters and four brothers, and the eldest son of James Buchanan Sr. (1761–1821) and his wife Elizabeth Speer (1767–1833).[5] James Buchanan Sr., was an Ulster-Scot from just outside Ramelton, a small town in the north-east of County Donegal in the north-west of Ulster, the northern province in Ireland, who emigrated to the newly formed United States in 1783, having sailed from Derry.[6][7] He belonged to the Clan Buchanan, whose members had emigrated in large numbers from the Scottish Highlands to Ulster in the north of Ireland during the Plantation of Ulster in the seventeenth century and, later, largely because of poverty and persecution by the Crown due to their Presbyterian faith, had further emigrated in large numbers from Ulster to America from the early eighteenth century onwards. Shortly after Buchanan's birth, the family relocated to a farm near Mercersburg, Pennsylvania, and later settled in the town in 1794. His father became the area's wealthiest resident, working as a merchant, farmer, and real estate investor. Buchanan attributed his early education primarily to his mother, whereas his father had a greater influence on his character. His mother had discussed politics with him as a child and had an interest in poetry, quoting John Milton and William Shakespeare to Buchanan.[5]

Buchanan attended the Old Stone Academy in Mercersburg and then Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.[8] In 1808, he was nearly expelled for disorderly conduct; he and his fellow students had attracted negative attention for drinking in local taverns, disturbing the peace at night and committing acts of vandalism,[9] but he pleaded for a second chance and ultimately graduated with honors in 1809.[10] Later that year, he moved to the state capital at Lancaster, to train as a lawyer for two and a half years with the well-known James Hopkins. Following the fashion of the time, Buchanan studied the United States Code and the Constitution of the United States as well as legal authorities such as William Blackstone during his education.[9]

Early law practice and Pennsylvania House of Representatives

[edit]In 1812, Buchanan passed the bar exam and after being admitted to the bar, he remained in Lancaster, even when Harrisburg became the new capital of Pennsylvania. Buchanan quickly established himself as a prominent legal representative in the city. His income rapidly rose after he established his practice, and by 1821 he was earning over $11,000 per year (equivalent to $250,000 in 2023).[9] At this time, Buchanan became a Freemason, and served as the Worshipful Master of Masonic Lodge No. 43 in Lancaster and as a District Deputy Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania.[11]

Buchanan also served as chairman of the Lancaster chapter of the Federalist Party. Like his father, he supported their political program, which provided federal funds for building projects and import duties as well as the re-establishment of a central bank after the First Bank of the United States' license expired in 1811. He became a strong critic of Democratic-Republican President James Madison during the War of 1812.[12] Although he did not himself serve in a militia during the War of 1812, during the British occupation he joined a group of young men who stole horses for the United States Army in the Baltimore area.[13] He is the last president involved in the War of 1812.[14]

In 1814, he was elected for the Federalists to the Pennsylvania House of Representatives,[15] where he was the youngest member, and held this seat until 1816. Since the sessions in the Pennsylvania General Assembly lasted only three months, Buchanan continued practicing law at a profit by charging higher fees, and his service helped him acquire more clients.[16] In 1815, Buchanan defended District Judge Walter Franklin in an impeachment trial before the Pennsylvania Senate, over alleged judicial misconduct. Impeachments were more common at the time because the line between abuse of office and a wrong legal decision was determined by the ruling parties' preferences and the popularity of the judge's decision. Buchanan persuaded the senators that only judicial crimes and clear violations of the law justified impeachment.[12]

Congressional career

[edit]U.S. House of Representatives

[edit]In the congressional elections of 1820, Buchanan ran for a seat in the House of Representatives. Shortly after his election victory, his father died in a carriage accident.[17] As a young Representative, Buchanan was one of the most prominent leaders of the "Amalgamator party" faction of Pennsylvanian politics, named that because it was made up of both Democratic-Republicans and former Federalists, which transitioned from the First Party System to the Era of Good Feelings. During this era, the Democratic-Republicans became the most influential party. Buchanan's Federalist convictions were weak, and he switched parties after opposing a nativist Federalist bill.[18] During the 1824 presidential election, Buchanan initially supported Henry Clay, but switched to Andrew Jackson (with Clay as a second choice) when it became clear that the Pennsylvanian public overwhelmingly preferred Jackson.[19] After Jackson lost the 1824 election, he joined his faction, but Jackson had contempt for Buchanan due to his misinterpretation of his efforts to mediate between the Clay and Jackson camps.[18]

In Washington, Buchanan became an avid defender of states' rights, and was close with many southern Congressmen, viewing some New England Congressmen as dangerous radicals. Buchanan's close proximity to his constituency allowed him to establish a Democratic coalition in Pennsylvania, consisting of former Federalist farmers, Philadelphia artisans, and Ulster-Scots-Americans. In the 1828 presidential election, he secured Pennsylvania, while the "Jacksonian Democrats", an independent party after splitting from the National Republican Party, won an easy victory in the parallel congressional election.[20]

Buchanan gained most attention during an impeachment trial where he acted as prosecutor for federal district judge James H. Peck, however, the Senate rejected Buchanan's plea and acquitted Peck by a majority vote. He was appointed to the Agriculture Committee in his first year, and he eventually became Chairman of the Judiciary Committee. In 1831, Buchanan declined a nomination for the 22nd United States Congress from his constituency consisting of Dauphin, Lebanon, and Lancaster counties. He still had political ambitions and some Pennsylvania Democrats put him forward as a candidate for the vice presidency in the 1832 election.[21]

Minister to Russia

[edit]After Jackson was re-elected in 1832, he offered Buchanan the position of United States Ambassador to Russia. Buchanan was reluctant to leave the country, as the distant St. Petersburg was a kind of political exile, which was the intention of Jackson, who considered Buchanan to be an "incompetent busybody" and untrustworthy, but he ultimately agreed.[18] His work focused on concluding a trade and shipping treaty with Russia. While Buchanan was successful with the former, negotiating an agreement on free merchant shipping with Foreign Minister Karl Nesselrode proved difficult.[22] He had denounced Tsar Nicholas I as a despot merely a year prior during his tenure in Congress; many Americans had reacted negatively to Russia's reaction to the 1830 Polish uprising.[23]

U.S. Senator

[edit]Buchanan returned home and lost the election in the State Legislature for a full six-year term in the 23rd Congress, but was appointed by the Pennsylvania state legislature to succeed William Wilkins in the U.S. Senate. Wilkins, in turn, replaced Buchanan as the ambassador to Russia. The Jacksonian Buchanan, who was re-elected in 1836 and 1842, opposed the re-chartering of the Second Bank of the United States and sought to expunge a congressional censure of Jackson stemming from the Bank War.[24] Buchanan served in the Senate until March 1845 and was twice confirmed in office.[25] To unite Pennsylvania Democrats at the State Convention, he was chosen as their candidate for the National Convention. Buchanan maintained a strict adherence to the Pennsylvania State Legislature's guidelines and sometimes voted against positions in Congress which he promoted in his own speeches, despite open ambitions for the White House.[26]

Buchanan was known for his commitment to states' rights and the Manifest Destiny ideology.[27] He rejected President Martin Van Buren's offer to become United States Attorney General and chaired prestigious Senate committees such as the Committee on the Judiciary and the Committee on Foreign Relations.[28] Buchanan was one of only a few senators to vote against the Webster–Ashburton Treaty for its "surrender" of lands to the United Kingdom, as he demanded the entire Aroostook River Valley for the United States. In the Oregon Boundary Dispute, Buchanan adopted the maximum demand of 54°40′ as the northern border and spoke out in favor of annexing the Republic of Texas.[26] During the contentious 1838 Pennsylvania gubernatorial election, Buchanan chose to support the Democratic challenger, David Rittenhouse Porter,[29] who was elected by fewer than 5,500 votes as Pennsylvania's first governor under the state's revised Constitution of 1838.[30][31]

Buchanan also opposed a gag rule sponsored by John C. Calhoun that would have suppressed anti-slavery petitions. He joined the majority in blocking the rule, with most senators of the belief that it would have the reverse effect of strengthening the abolitionists.[32] He said, "We have just as little right to interfere with slavery in the South, as we have to touch the right of petition."[25] Buchanan thought that the issue of slavery was the domain of the states, and he faulted abolitionists for exciting passions over the issue. In the lead-up to the 1844 Democratic National Convention, Buchanan positioned himself as a potential alternative to former President Martin Van Buren, but the nomination went to James K. Polk, who won the election.[26]

Diplomatic career

[edit]Secretary of State

[edit]

Buchanan was offered the position of Secretary of State in the Polk administration or, as the alternative, a seat on the Supreme Court, to compensate him for his support in the election campaign but also in order to eliminate him as an internal party rival. He accepted the State Department post and served for the duration of Polk's single term in office. During his tenure, the United States recorded its largest territorial gain in history through the Oregon Treaty and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which included territory that is now Texas, California, Nevada, New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, and Colorado.[33] In negotiations with Britain over Oregon, Buchanan initially favored the 49th parallel as the boundary of Oregon Territory, while Polk called for a more northerly boundary line. When Northern Democrats rallied around the popular slogan Fifty-Four Forty or Fight ("54°40′ or war") in the 1844 election campaign, Buchanan adopted this position, but later followed Polk's direction, leading to the Oregon Compromise of 1846, which established the 49th parallel as the boundary in the Pacific Northwest.[34]

In regards to Mexico, Buchanan maintained a dubious view that its attack on American troops on the other side of the Rio Grande in April 1846 constituted a border violation and a legitimate reason for war. During the Mexican-American War, Buchanan initially advised against claiming territory south of the Rio Grande, fearing war with Britain and France. However, as the war came to an end, Buchanan changed his mind and argued for the annexation of further territory, arguing that Mexico was to blame for the war and that the compensation negotiated for the American losses was too low. Buchanan sought the nomination at the 1848 Democratic National Convention, as Polk had promised to serve only one term, but he only won the support of the Pennsylvania and Virginia delegations, so Senator Lewis Cass of Michigan was nominated.[35]

Civilian life and 1852 presidential election

[edit]

With the 1848 election of Whig Zachary Taylor, Buchanan returned to private life. Buchanan was getting on in years and still dressed in the old-fashioned style of his adolescence, earning him the nickname "Old Public Functionary" from the press. Slavery opponents in the North mocked him as a relic of prehistoric man because of his moral values.[36] He bought the house of Wheatland on the outskirts of Lancaster and entertained various visitors while monitoring political events.[37] During this period, Buchanan became the center of a family network consisting of 22 nieces, nephews and their descendants, seven of whom were orphans. He found public service jobs for some through patronage, and for those in his favor, he took on the role of surrogate father. He formed the strongest emotional bond with his niece Harriet Lane, who later became First Lady for Buchanan in the White House.[36]

In 1852, he was named president of the Board of Trustees of Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, and he served in this capacity until 1866.[38] Buchanan did not completely leave politics. He intended to publish a collection of speeches and an autobiography, but his political comeback was thwarted by the 1852 presidential election. Buchanan traveled to Washington to discuss Pennsylvania Democratic Party politics, which were divided into two camps led by Simon Cameron and George Dallas.[39] He quietly campaigned for the 1852 Democratic presidential nomination. In light of the Compromise of 1850, which had led to the admission of California into the Union as a free state and a stricter Fugitive Slave Act, Buchanan now rejected the Missouri Compromise and welcomed Congress's rejection of the Wilmot Proviso, which prohibited slavery in all territories gained in the Mexican-American War. Buchanan criticized abolitionism as a fanatical attitude and believed that slavery should be decided by state legislatures, not Congress. He disliked abolitionist Northerners due to his party affiliation, and became known as a "doughface" due to his sympathy toward the South. Buchanan emerged as a promising candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination, alongside Lewis Cass, Stephen Douglas, and William L. Marcy; however, the Pennsylvania convention did not vote unanimously in his favor, with over 30 delegates protesting against him.[40] At the 1852 Democratic National Convention, he won the support of many southern delegates but failed to win the two-thirds support needed for the presidential nomination, which went to Franklin Pierce. Buchanan declined to serve as the vice presidential nominee, and the convention instead nominated his close friend, William R. King.[41]

Minister to the United Kingdom

[edit]Pierce won the election in 1852, and six months later, Buchanan accepted the position of United States Minister to the United Kingdom, a position that represented a step backward in his career and that he had twice previously rejected.[41] Buchanan sailed for England in the summer of 1853, and he remained abroad for the next three years. In 1850, the United States and Great Britain signed the Clayton–Bulwer Treaty, which committed both countries to joint control of any future canal that would connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans through Central America. Buchanan met repeatedly with Lord Clarendon, the British foreign minister, in hopes of pressuring the British to withdraw from Central America. He was able to reduce British influence in Honduras and Nicaragua while also raising the kingdom's awareness of American interests in the region.[42] He also focused on the potential annexation of Cuba, which had long interested him.[43]

At Pierce's prompting, Buchanan met in Ostend, Belgium, with U.S. Ambassador to Spain Pierre Soulé and U.S. Ambassador to France John Mason, to work out a plan for the acquisition of Cuba. A memorandum draft resulted, called the Ostend Manifesto, which proposed the purchase of Cuba from Spain, then in the midst of revolution and near bankruptcy. The document declared the island "as necessary to the North American republic as any of its present ... family of states". Against Buchanan's recommendation, the final draft of the manifesto suggested that "wresting it from Spain", if Spain refused to sell, would be justified "by every law, human and Divine".[44] The manifesto was met with a divided response and was never acted upon. It weakened the Pierce administration and reduced support for Manifest Destiny.[44][45] In 1855, as Buchanan's desire to return home grew, Pierce asked him to hold the fort in London in light of the relocation of a British fleet to the Caribbean.[42]

Election of 1856

[edit]

Buchanan's service abroad allowed him to conveniently avoid the debate over the Kansas–Nebraska Act then roiling the country in the slavery dispute.[46] While he did not overtly seek the presidency, he assented to the movement on his behalf.[47] While still in England, he campaigned by praising John Joseph Hughes, who was Archbishop of New York, to a Catholic archbishop. The latter campaigned for Buchanan among high-ranking Catholics as soon as he heard about it.[46] When Buchanan arrived home at the end of April 1856, he led on the first ballot, supported by powerful Senators John Slidell, Jesse Bright, and Thomas F. Bayard, who presented Buchanan as an experienced leader appealing to the North and South. The 1856 Democratic National Convention met in June 1856, producing a platform that reflected Buchanan's views, including support for the Fugitive Slave Law, which required the return of escaped slaves. The platform also called for an end to anti-slavery agitation and U.S. "ascendancy in the Gulf of Mexico".[48] President Pierce hoped for re-nomination, while Senator Stephen A. Douglas also loomed as a strong candidate. He won the nomination after seventeen ballots after Douglas' resignation. He was joined on the ticket by John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky in order to maintain regional proportional representation, placating supporters of Pierce and Douglas, also allies of Breckinridge.[49]

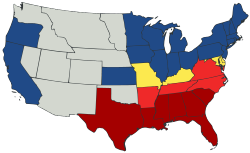

Buchanan faced two candidates in the general election: former Whig President Millard Fillmore ran as the candidate for the anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant American Party (or "Know-Nothing"), while John C. Frémont ran as the Republican nominee. The contrast between Buchanan and Frémont was particularly stark, with opposing caricaturists drawing the Democratic candidate as a fussy old man in drag.[50] Buchanan did not actively campaign, but he wrote letters and pledged to uphold the Democratic platform. In the election, he carried every slave state except for Maryland, as well as five slavery-free states, including his home state of Pennsylvania.[49] He won 45 percent of the popular vote and decisively won the electoral vote, taking 174 of 296 votes. His election made him the first president from Pennsylvania. In a combative victory speech, Buchanan denounced Republicans, calling them a "dangerous" and "geographical" party that had unfairly attacked the South.[50] He also declared, "the object of my administration will be to destroy sectional party, North or South, and to restore harmony to the Union under a national and conservative government."[51] He set about this initially by feigning a sectional balance in his cabinet appointments.[52]

Presidency (1857–1861)

[edit]Inauguration

[edit]Buchanan was inaugurated on March 4, 1857, taking the oath of office from Chief Justice Roger B. Taney. In his lengthy inaugural address, Buchanan committed himself to serving only one term, as his predecessor had done. He abhorred the growing divisions over slavery and its status in the territories, saying that Congress should play no role in determining the status of slavery in the states or territories.[53] He proposed a solution based on the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which stated that the principle of popular sovereignty was decisive, and Congress had no say in the matter. Buchanan recommended that a federal slave code be enacted to protect the rights of slaveowners in federal territories. He alluded to a then-pending Supreme Court case, Dred Scott v. Sandford, which he said would permanently settle the issue of slavery. Dred Scott was a slave who was temporarily taken from a slave state to a free territory by his owner, John Sanford. After Scott returned to the slave state, he filed a petition for his freedom based on his time in the free territory.[53]

Associate Justice Robert C. Grier leaked the decision in the "Dred Scott" case early to Buchanan. In his inaugural address, Buchanan declared that the issue of slavery in the territories would be "speedily and finally settled" by the Supreme Court.[54] According to historian Paul Finkelman:

Buchanan already knew what the Court was going to decide. In a major breach of Court etiquette, Justice Grier, who, like Buchanan, was from Pennsylvania, had kept the President-elect fully informed about the progress of the case and the internal debates within the Court. When Buchanan urged the nation to support the decision, he already knew what Taney would say. Republican suspicions of impropriety turned out to be fully justified.[55]

Historians agree that the Court decision was a major disaster because it dramatically inflamed tensions, leading to the Civil War.[56][57][58] In 2022, historian David W. Blight argued that the year 1857 was, "the great pivot on the road to disunion...largely because of the Dred Scott case, which stoked the fear, distrust and conspiratorial hatred already common in both the North and the South to new levels of intensity."[59]

Personnel

[edit]Cabinet and administration

[edit]| The Buchanan cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | James Buchanan | 1857–1861 |

| Vice President | John C. Breckinridge | 1857–1861 |

| Secretary of State | Lewis Cass | 1857–1860 |

| Jeremiah S. Black | 1860–1861 | |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Howell Cobb | 1857–1860 |

| Philip Francis Thomas | 1860–1861 | |

| John Adams Dix | 1861 | |

| Secretary of War | John B. Floyd | 1857–1860 |

| Joseph Holt | 1861 | |

| Attorney General | Jeremiah S. Black | 1857–1860 |

| Edwin Stanton | 1860–1861 | |

| Postmaster General | Aaron V. Brown | 1857–1859 |

| Joseph Holt | 1859–1860 | |

| Horatio King | 1861 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | Isaac Toucey | 1857–1861 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Jacob Thompson | 1857–1861 |

From left to right: Jacob Thompson, Lewis Cass, John B. Floyd, James Buchanan, Howell Cobb, Isaac Toucey, Joseph Holt and Jeremiah S. Black

As his inauguration approached, Buchanan sought to establish an obedient, harmonious cabinet to avoid the in-fighting that had plagued Andrew Jackson's administration.[60] The cabinet's composition had to do justice to the proportional representation within the party and between the regions of the country. Buchanan first worked on this task in Wheatland until he traveled to the capital in January 1857. There, like many other guests at the National Hotel, he contracted severe dysentery, from which he did not fully recover until several months later. Dozens of those who fell ill died, including Buchanan's nephew and private secretary Eskridge Lane.[52]

The cabinet selection was disastrous, with four Southern ministers being large-scale slaveholders who later became loyal to the Confederate States of America.[61] Secretary of the Treasury Howell Cobb was considered the greatest political talent in the Cabinet,[62] while the three department heads from the northern states were all considered to be doughfaces.[63] His objective was to dominate the cabinet, and he chose men who would agree with his views.[64] Buchanan had a troubled relationship with his vice president from the beginning, when he did not receive him during his inaugural visit but referred him to his niece and First Lady, which Breckinridge never forgave him for and saw as disrespectful.[65] He left out the influential Stephen A. Douglas, who had made Buchanan's nomination possible by resigning at the National Convention the previous year, when filling the post.[66] Concentrating on foreign policy, he appointed the aging Lewis Cass as Secretary of State. Buchanan's appointment of Southerners and their allies alienated many in the North, and his failure to appoint any followers of Douglas divided the party.[52] Outside of the cabinet, he left in place many of Pierce's appointments but removed a disproportionate number of Northerners who had ties to Democratic opponents Pierce or Douglas.[65]

Judicial appointments

[edit]Buchanan appointed one Justice, Nathan Clifford, to the Supreme Court of the United States.[67] He appointed seven other federal judges to United States district courts. He also appointed two judges to the United States Court of Claims.[68]

Intervention in the Dred Scott case

[edit]The case of Dred Scott v. Sandford, to which Buchanan referred to in his inaugural address, dated back to 1846. Scott sued for his release in Missouri, claiming he lived in service to the proprietor in Illinois and Wisconsin Territory. The case reached the Supreme Court and gained national attention by 1856. Buchanan consulted with Judge John Catron in January 1857, inquiring about the outcome of the case and suggesting that a broader decision, beyond the specifics of the case, would be more prudent.[69] Buchanan hoped that a broad decision protecting slavery in the territories could lay the issue to rest, allowing him to focus on other issues.[70]

Catron replied on February 10, saying that the Supreme Court's Southern majority would decide against Scott, but would likely have to publish the decision on narrow grounds unless Buchanan could convince his fellow Pennsylvanian, Justice Robert Cooper Grier, to join the majority of the court.[71] Buchanan then wrote to Grier and prevailed upon him, providing the majority leverage to issue a broad-ranging decision sufficient to render the Missouri Compromise of 1820 unconstitutional.[72][73]

Two days after Buchanan was sworn in as president, Chief Justice Taney delivered the Dred Scott decision, which denied the petitioner's request to be set free from slavery. The ruling broadly asserted that Congress had no constitutional power to exclude slavery in the territories.[74] According to this decision, slaves were forever the property of their owners without rights and no African American could ever be a full citizen of the United States, even if they had full civil rights in a state.[75] Buchanan's letters were not made public at the time, but he was seen conversing quietly with the Chief Justice during his inauguration. When the decision was issued, Republicans began spreading the word that Taney had informed Buchanan of the impending outcome. Rather than destroying the Republican platform as Buchanan had hoped, the decision infuriated Northerners, who condemned it.[76]

Panic of 1857

[edit]The Panic of 1857 began in the summer of that year, when the New York branch of Ohio Life Insurance and Trust Company announced its insolvency.[77] The crisis spread rapidly, and by the fall, 1,400 state banks and 5,000 businesses had gone bankrupt. Unemployment and hunger became common in northern cities, but the agricultural south was more resilient. Buchanan agreed with the southerners who attributed the economic collapse to over-speculation.[78]

Buchanan acted in accordance with Jacksonian Democracy principles, which restricted paper money issuance, and froze federal funds for public works projects, causing resentment among some of the population due to his refusal to implement an economic stimulus program.[79] While the government was "without the power to extend relief",[78] it would continue to pay its debts in specie, and while it would not curtail public works, none would be added. In hopes of reducing paper money supplies and inflation, he urged the states to restrict the banks to a credit level of $3 to $1 of specie and discouraged the use of federal or state bonds as security for bank note issues. The economy recovered in several years, though many Americans suffered as a result of the panic.[80] Buchanan had hoped to reduce the deficit, but by the time he left office the federal budget grew by 15%.[78]

Utah War

[edit]In the spring of 1857, the Latter-day Saints and their leader Brigham Young had been challenging federal representatives in Utah Territory, causing harassment and violence against non-Mormons. Young harassed federal officers and discouraged outsiders from settling in the Salt Lake City area. In September 1857, the Utah Territorial Militia, associated with the Latter-day Saints, perpetrated the Mountain Meadows massacre, in which Young's militia attacked a wagon train and killed 125 settlers. Buchanan was offended by the militarism and polygamous behavior of Young.[81] With reports of violence against non-Mormons, Buchanan authorized a military expedition into Utah Territory in late March 1857 to replace Young as governor. The force consisted of 2,500 men, including Alfred Cumming and his staff, and was commanded by General William S. Harney. Complicating matters, Young's notice of his replacement was not delivered because the Pierce administration had annulled the Utah mail contract, and Young portrayed the approaching forces as an unauthorized overthrow.[82][74]

Buchanan's personnel decision incited resistance from the Mormons around Young, as Harney was known for his volatility and brutality. In August 1857, Albert S. Johnston replaced him for organizational reasons.[83] Young reacted to the military action by mustering a two-week expedition, destroying wagon trains, oxen, and other Army property. Buchanan then dispatched Thomas L. Kane as a private agent to negotiate peace. The mission was successful, a peaceful agreement to replace Governor Young with Cumming was reached, and the Utah War ended. The President granted amnesty to inhabitants affirming loyalty to the government, and placed the federal troops at a peaceable distance for the balance of his administration.[84]

Buchanan did not comment on the conflict again until his State of the Union Address in December 1857, leaving open the question of whether it was a rebellion in Utah. One of Buchanan's last official acts in March 1861 was to reduce the size of Utah Territory in favor of Nevada, Colorado, and Nebraska.[85] While the Latter-day Saints had frequently defied federal authority, some historians consider Buchanan's action was an inappropriate response to uncorroborated reports.[74]

Transatlantic telegraph cable

[edit]Buchanan was the first recipient of an official telegram transmitted across the Atlantic. Following the dispatch of test and configuration telegrams, on August 16, 1858 Queen Victoria sent a 98-word message to Buchanan at his summer residence in the Bedford Springs Hotel in Pennsylvania, expressing hope that the newly laid cable would prove "an additional link between the nations whose friendship is founded on their common interest and reciprocal esteem". Queen Victoria's message took 16 hours to send.[86][87]

Buchanan responded: "It is a triumph more glorious, because far more useful to mankind, than was ever won by conqueror on the field of battle. May the Atlantic telegraph, under the blessing of Heaven, prove to be a bond of perpetual peace and friendship between the kindred nations, and an instrument destined by Divine Providence to diffuse religion, civilization, liberty, and law throughout the world."[88]

Bleeding Kansas and constitutional dispute

[edit]

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 created the Kansas Territory and allowed the settlers there to decide whether to allow slavery. This resulted in violence between "Free-Soil" (antislavery) and pro-slavery settlers, which developed into the "Bleeding Kansas" period. The antislavery settlers, with the help of Northern abolitionists, organized their own territorial government in Topeka. The more numerous proslavery settlers, many from the neighboring slave state Missouri, established a government in Lecompton, giving the Territory two different governments for a time, with two distinct constitutions, each claiming legitimacy. The admission of Kansas as a state required a constitution be submitted to Congress with the approval of a majority of its residents. Under President Pierce, a series of violent confrontations escalated over who had the right to vote in Kansas. The situation drew national attention, and some in Georgia and Mississippi advocated secession should Kansas be admitted as a free state. Buchanan chose to endorse the pro-slavery Lecompton government.[89]

Buchanan appointed Robert J. Walker to replace John W. Geary as Territorial Governor, and there ensued conflicting referendums from Topeka and Lecompton, where election fraud occurred. In October 1857, the Lecompton government framed the pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution that agreed to a referendum limited solely to the slavery question. However, the vote against slavery, as provided by the Lecompton Convention, would still permit existing slaves, and all their issue, to be enslaved, so there was no referendum that permitted the majority anti-slavery residents to prohibit slavery in Kansas. As a result, anti-slavery residents boycotted the referendum since it did not provide a meaningful choice.[90]

Despite the protests of Walker and two former Kansas governors, Buchanan decided to accept the Lecompton Constitution. In a December 1857 meeting with Stephen A. Douglas, the chairman of the Senate Committee on Territories, Buchanan demanded that all Democrats support the administration's position of admitting Kansas under the Lecompton Constitution. On February 2, he transmitted the Lecompton Constitution to Congress. He also transmitted a message that attacked the "revolutionary government" in Topeka, conflating them with the Mormons in Utah. Buchanan made every effort to secure congressional approval, offering favors, patronage appointments, and even cash for votes. The Lecompton Constitution won the approval of the Senate in March, but a combination of Know-Nothings, Republicans, and Northern Democrats defeated the bill in the House.[91]

Buchanan never forgave Douglas, as the Northern Democrats' rejection was the deciding factor in the House's decision, and he removed all Douglas supporters from his patronage in Illinois and Washington, D.C, installing pro-administration Democrats, including postmasters.[92][93] Rather than accepting defeat, Buchanan backed the 1858 English Bill, which offered Kansas immediate statehood and vast public lands in exchange for accepting the Lecompton Constitution. In August 1858, Kansans by referendum strongly rejected the Lecompton Constitution.[91] The territory received an abolitionist constitution, which was bitterly opposed in Congress by representatives and senators from the southern states until Kansas was admitted to the Union in January 1861.[92]

The dispute over Kansas became the battlefront for control of the Democratic Party. On one side were Buchanan, the majority of Southern Democrats, and the "doughfaces". On the other side were Douglas and the majority of northern Democrats, as well as a few Southerners. Douglas's faction continued to support the doctrine of popular sovereignty, while Buchanan insisted that Democrats respect the Dred Scott decision and its repudiation of federal interference with slavery in the territories.[94]

1858 mid-term elections

[edit]Douglas's Senate term was coming to an end in 1859, with the Illinois legislature, elected in 1858, determining whether Douglas would win re-election. The Senate seat was the primary issue of the legislative election, marked by the famous debates between Douglas and his Republican opponent for the seat, Abraham Lincoln. Buchanan, working through federal patronage appointees in Illinois, ran candidates for the legislature in competition with both the Republicans and the Douglas Democrats. This could easily have thrown the election to the Republicans, and showed the depth of Buchanan's animosity toward Douglas.[95] In the end, Douglas Democrats won the legislative election and Douglas was re-elected to the Senate. In that year's elections, Douglas forces took control throughout the North, except in Buchanan's home state of Pennsylvania. Buchanan's support was otherwise reduced to a narrow base of southerners.[96][97]

The division between northern and southern Democrats allowed the Republicans to win a plurality of the House in the 1858 elections, and allowed them to block most of Buchanan's agenda. Buchanan, in turn, added to the hostility with his veto of six substantial pieces of Republican legislation.[98] Among these measures were the Homestead Act, which would have given 160 acres of public land to settlers who remained on the land for five years, and the Morrill Act, which would have granted public lands to establish land-grant colleges. Buchanan argued that these acts were unconstitutional. In the western and northwestern United States, where the Homestead Act was very popular, even many Democrats condemned the president's policies, while many Americans who considered education an important asset resented Buchanan's veto of agricultural colleges.[99]

Foreign policy

[edit]Buchanan took office with an ambitious foreign policy, designed to establish U.S. hegemony over Central America at the expense of Great Britain.[100] Buchanan sought to revitalize Manifest Destiny and to enforce the Monroe Doctrine, which had been under attack from the Spanish, French, and especially the British in the 1850s.[101] He hoped to re-negotiate the Clayton–Bulwer Treaty to counter European imperialism in the Western Hemisphere, which he thought limited U.S. influence in the region. He also sought to establish American protectorates over the Mexican states of Chihuahua and Sonora to secure American citizens and investments, and most importantly, he hoped to achieve his long-term goal of acquiring Cuba. However, Buchanan's ambitions in Cuba and Mexico were largely blocked by the House of Representatives. After long negotiations with the British, he convinced them to cede the Bay Islands to Honduras and the Mosquito Coast to Nicaragua.[102]

In 1858, Buchanan ordered the Paraguay expedition to punish Paraguay for firing on the USS Water Witch, ordering 2,500 marines and 19 warships there. This costly expedition took months to reach Asunción, which successfully resulted in a Paraguayan apology and payment of an indemnity.[102] The chiefs of Raiatea and Tahaa in the South Pacific, refusing to accept the rule of King Tamatoa V, unsuccessfully petitioned the United States to accept the islands under a protectorate in June 1858.[103] Buchanan also considered buying Alaska from the Russian Empire, as whaling in the waters there had become of great economic importance to the United States. Buchanan fueled this by spreading the rumor to the Russian ambassador Eduard de Stoeckl in December 1857 that a large amount of Mormons intended to emigrate to Russian Alaska. In the winter of 1859, an initial purchase offer of $5,000,000 (equivalent to $169,560,000 in 2023) was made. Although the project ultimately failed due to the reservations of Foreign Minister Alexander Gorchakov, the talks formed the basis for the later negotiations to purchase Alaska.[104]

Buchanan sought trade agreements with the Qing Dynasty and Japan. In China, his envoy William Bradford Reed succeeded in having the United States included as a party to the Treaty of Tianjin. In May 1860, Buchanan received a Japanese delegation consisting of several princes who carried the Harris Treaty negotiated by Townsend Harris for mutual ratification.[105] Buchanan was offered a herd of elephants by King Rama IV of Siam, though the letter arrived after Buchanan's departure from office and Buchanan's successor Abraham Lincoln declined the offer stating that the U.S. had an unsuitable climate.[106] Other presidential pets included a pair of bald eagles and a Newfoundland dog.[107]

Covode Committee

[edit]In March 1860, the House impaneled the Covode Committee to investigate the Buchanan administration's patronage system for alleged impeachable offenses, such as bribery and extortion of representatives. Buchanan supporters accused the committee, consisting of three Republicans and two Democrats, of being blatantly partisan, and claimed its chairman, Republican Rep. John Covode, was acting on a personal grudge stemming from a disputed land grant designed to benefit Covode's railroad company.[108] The Democratic committee members, as well as Democratic witnesses, were enthusiastic in their condemnation of Buchanan.[109][110]

The committee was unable to establish grounds for impeaching Buchanan; however, the majority report issued on June 17 alleged corruption and abuse of power among members of his cabinet. The committee gathered evidence that Buchanan had tried to bribe members of Congress in his favor through intermediaries in the spring of 1858 in connection with the pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution of Kansas, and threatened their relatives with losing their posts if they did not vote in favor of the Lecompton Constitution.[110] Witnesses also testified that the federal government used public funds to strengthen the intra-party faction of Douglas's opponents in Illinois.[111] The Democrats pointed out that evidence was scarce, but did not refute the allegations; one of the Democratic members, Rep. James Robinson, stated that he agreed with the Republicans, though he did not sign it.[110]

The public was shocked by the extent of the bribery, which affected all levels and agencies of government.[112] Buchanan claimed to have "passed triumphantly through this ordeal" with complete vindication. Republican operatives distributed thousands of copies of the Covode Committee report throughout the nation as campaign material in that year's presidential election.[113][114]

Election of 1860

[edit]

As he had promised in his inaugural address, Buchanan did not seek re-election. He went so far as to tell his ultimate successor, "If you are as happy in entering the White House as I shall feel on returning to Wheatland, you are a happy man."[115]

На Национальном съезде Демократической партии 1860 года в Чарльстоне партия раскололась по вопросу рабства на территориях, что нанесло ущерб репутации Бьюкенена как главного человека, ответственного за этот вопрос. Хотя Дуглас лидировал после каждого голосования, он не смог набрать необходимое большинство в две трети. Съезд был прерван после 53 голосований и вновь собрался в Балтиморе в июне. После того, как Дуглас, наконец, выиграл номинацию, несколько южан отказались принять результат и выдвинули вице-президента Брекинриджа своим кандидатом. Дуглас и Брекинридж согласились по большинству вопросов, за исключением защиты рабства. Бьюкенен, затаив обиду на Дугласа, не смог примирить партию и прохладно поддержал Брекинриджа. После раскола Демократической партии кандидат от республиканской партии Авраам Линкольн победил на четырехсторонних выборах, в которых также участвовал Джон Белл от Партии Конституционного союза . Поддержки Линкольна на Севере было достаточно, чтобы дать ему большинство в Коллегии выборщиков. Бьюкенен стал последним демократом, победившим на президентских выборах. Гровер Кливленд в 1884 году. [116]

армией Еще в октябре командующий , Уинфилд Скотт оппонент Бьюкенена, предупредил его, что избрание Линкольна, вероятно, приведет к выходу из союза как минимум семи штатов. Он рекомендовал направить в эти штаты огромное количество федеральных войск и артиллерии для защиты федеральной собственности, хотя он также предупредил, что подкреплений в наличии мало. С 1857 года Конгресс не прислушался к призывам об усилении ополчения и допустил, что армия пришла в плачевное состояние. [117] Бьюкенен не доверял Скотту и игнорировал его рекомендации. [118] После избрания Линкольна Бьюкенен поручил военному министру Джону Б. Флойду укрепить южные форты провиантом, оружием и людьми, которые были в наличии; однако Флойд убедил его отозвать приказ. [117]

Сецессия

[ редактировать ]После победы Линкольна разговоры об отделении и разъединении достигли точки кипения, что возложило на Бьюкенена бремя обращения к этому вопросу в его заключительной речи перед Конгрессом 10 декабря. В своем послании, которого ожидали обе фракции, Бьюкенен отрицал право штатов на отделиться, но утверждал, что федеральное правительство не имеет полномочий предотвратить их. Он возложил вину за кризис исключительно на «неумеренное вмешательство северных народов в вопрос рабства в южных штатах» и предположил, что, если они не «отменят свои неконституционные и оскорбительные постановления… пострадавшие штаты, после первым использовал все мирные и конституционные средства для получения возмещения, было бы оправдано революционным сопротивлением Правительству Союза». [119] [120] Единственным предложением Бьюкенена по разрешению кризиса была «пояснительная поправка», подтверждающая конституционность рабства в штатах, законов о беглых рабах и народный суверенитет на территориях. [119] Его выступление подверглось резкой критике как со стороны Севера за отказ остановить отделение, так и со стороны Юга за отрицание его права на отделение. [121] Через пять дней после произнесения обращения министр финансов Хауэлл Кобб подал в отставку, поскольку его взгляды стали несовместимы со взглядами президента. [122] Даже когда зимой 1860 года образование Конфедерации сепаратистскими штатами становилось все более очевидным, президент продолжал окружать себя южанами и игнорировать республиканцев. [123]

Южная Каролина, долгое время являвшаяся самым радикальным южным штатом, вышла из Союза 20 декабря 1860 года. Однако юнионистские настроения оставались сильными среди многих жителей Юга, и Бьюкенен стремился обратиться к умеренным южанам, которые могли бы предотвратить отделение в других штатах. Он встретился с комиссарами Южной Каролины, пытаясь разрешить ситуацию в форте Самтер , который федеральные силы продолжали контролировать, несмотря на его расположение в Чарльстоне, Южная Каролина. [124] Бьюкенен считал Конгресс, а не себя ответственным за поиск решения кризиса отделения. В качестве компромисса для южных штатов Бьюкенен предполагал принятие поправок к Конституции США, которые гарантировали бы право на рабство в южных штатах и территориях и усилили бы право рабовладельцев вернуть себе беглых рабов в качестве собственности в северных штатах. [123]

Он отказался уволить министра внутренних дел Джейкоба Томпсона после того, как последний был выбран агентом Миссисипи для обсуждения отделения, и отказался уволить военного министра Джона Б. Флойда, несмотря на скандал с хищениями. В конце концов Флойд ушел в отставку, но не раньше, чем отправил большое количество огнестрельного оружия в южные штаты, где оно в конечном итоге попало в руки Конфедерации. Несмотря на отставку Флойда, Бьюкенен продолжал обращаться за советом к советникам с Глубокого Юга, включая Джефферсона Дэвиса и Уильяма Генри Трескота . [124] Подруга Бьюкенена Роуз О'Нил Гринхоу воспользовалась близостью к президенту и шпионила в пользу Конфедерации, которая еще до своего формирования уже создала сложную сеть для сбора информации от своего возможного противника. [123]

предприняли тщетные попытки Сенатор Джон Дж. Криттенден , член палаты представителей Томас Корвин и бывший президент Джон Тайлер договориться о компромиссе, чтобы остановить отделение при поддержке Бьюкенена. Неудачные попытки были также предприняты группой губернаторов, собравшихся в Нью-Йорке. Бьюкенен тайно попросил избранного президента Линкольна объявить национальный референдум по вопросу рабства, но Линкольн отказался. [125] В декабре 1860 года, когда была созвана вторая сессия 36-го Конгресса , Палата представителей учредила Комитет тридцати трех, чтобы предотвратить отделение новых штатов. Они предложили поправку Корвина , которая запретила бы Конгрессу вмешиваться в проблему рабства в штатах. Несмотря на сопротивление республиканцев, он был принят обеими палатами Конгресса и предложен штатам для ратификации, но так и не был ратифицирован необходимым количеством штатов. [126]

Несмотря на усилия Бьюкенена и других, еще шесть рабовладельческих штатов. к концу января 1861 года откололись Бьюкенен заменил ушедших членов южного кабинета министров Джоном Адамсом Диксом , Эдвином М. Стэнтоном и Джозефом Холтом , все из которых были привержены сохранению Союза. . Когда Бьюкенен рассматривал возможность сдачи форта Самтер , новые члены кабинета пригрозили уйти в отставку, и Бьюкенен уступил. 5 января Бьюкенен решил усилить форт Самтер, отправив « Звезду Запада» с 250 людьми и припасами. Однако ему не удалось попросить майора Роберта Андерсона обеспечить прикрытие корабля огнем, и он был вынужден вернуться на север, не доставив войска и припасы. Бьюкенен решил не реагировать на этот акт войны и вместо этого стремился найти компромисс, чтобы избежать отделения. 3 марта он получил сообщение от Андерсона о том, что запасы на исходе, но ответ должен был дать Линкольн, поскольку на следующий день последний стал президентом. [127]

Государства, принятые в Союз

[ редактировать ]были приняты три новых штата в Союз Пока Бьюкенен был у власти, :

Последние годы и смерть (1861–1868)

[ редактировать ]

Покинув свой пост, Бьюкенен ушел в частную жизнь в Уитленд, где проводил большую часть времени в своем кабинете. Гражданская война разразилась через два месяца после выхода Бьюкенена на пенсию. Он поддержал Союз и военные усилия, написав бывшим коллегам, что «нападение на Самтер стало началом войны со стороны штатов Конфедерации, и не осталось никакой альтернативы, кроме как энергично продолжать ее с нашей стороны». [130] Бьюкенен поддержал введение Линкольном всеобщей воинской повинности в северных штатах, но был противником его Прокламации об освобождении рабов . Хотя он признал нарушения Конституции в некоторых указах президента, он никогда не критиковал их публично. [131] Он также написал письмо своим коллегам-демократам из Пенсильвании в Гаррисбурге, призывая их вступить в армию Союза и «присоединиться к многим тысячам храбрых и патриотичных добровольцев, которые уже находятся в боевых действиях». [130]

Бьюкенен посвятил себя защите своих действий до гражданской войны, которую некоторые называли «войной Бьюкенена». [130] Он ежедневно получал письма с ненавистью и письма с угрозами, а в магазинах Ланкастера было изображено изображение Бьюкенена с накрашенными красными глазами, петлей на шее и надписью «Предатель» на лбу. Сенат предложил резолюцию с осуждением, которая в конечном итоге провалилась, а газеты обвинили его в сговоре с Конфедерацией. Его бывшие члены кабинета министров, пятеро из которых получили работу в администрации Линкольна, отказались публично защищать Бьюкенена. [132]

Бьюкенен обезумел от язвительных нападок на него, заболел и впал в депрессию. В октябре 1862 года он защищался в обмене письмами с Уинфилдом Скоттом , опубликованными в National Intelligencer . [133] Вскоре он начал писать свою самую полную публичную защиту в форме своих мемуаров « Администрация г-на Бьюкенена накануне восстания », которые были опубликованы в 1866 году. Бьюкенен объяснил отделение «пагубным влиянием» республиканцев и аболиционистского движения . Он обсудил свои внешнеполитические успехи и выразил удовлетворение своими решениями даже во время кризиса отделения. Он обвинил Роберта Андерсона, Уинфилда Скотта и Конгресс в нерешенности проблемы. [131] Вскоре после публикации мемуаров Бьюкенен в мае 1868 года простудился , ситуация быстро ухудшилась из-за его преклонного возраста. Он умер 1 июня 1868 года от дыхательной недостаточности в возрасте 77 лет в своем доме в Уитленде . Он был похоронен на кладбище Вудворд-Хилл в Ланкастере. [131]

Политические взгляды

[ редактировать ]

Северяне, выступающие против рабства, часто считали Бьюкенена « болваном », северянином с проюжными принципами. [134] Симпатии Бьюкенена к южным штатам выходили за рамки политической целесообразности на его пути в Белый дом. Он отождествлял себя с культурными и социальными ценностями, которые, по его мнению, нашли отражение в кодексе чести и образе жизни плантаторов и с которыми он все чаще соприкасался в своем пенсионном сообществе, начиная с 1834 года. [135] Вскоре после своего избрания он заявил, что «величайшей целью» его администрации было «остановить, если возможно, агитацию по вопросу рабства на Севере и уничтожить секционные партии». [134] Хотя Бьюкенен лично был против рабства, [24] он считал, что аболиционисты мешают решению проблемы рабства. Он заявил: «До того, как [аболиционисты] начали эту агитацию, в нескольких рабовладельческих штатах существовала очень большая и растущая партия, выступавшая за постепенную отмену рабства; и теперь там не слышно ни голоса в поддержку такой меры. Аболиционисты отложили освобождение рабов в трех или четырех штатах как минимум на полвека». [136] Из уважения к намерениям типичного рабовладельца он был готов предоставить презумпцию невиновности. В своем третьем ежегодном послании Конгрессу президент заявил, что с рабами «относились с добротой и человечностью… И филантропия, и личный интерес хозяина объединились, чтобы дать этот гуманный результат». [137]

Бьюкенен считал, что сдержанность — это суть хорошего самоуправления. Он считал, что конституция включает в себя «... ограничения, налагаемые не произвольной властью, а людьми на самих себя и своих представителей. предубеждений, они всегда кажутся противоречивыми... и зависть, которая будет постоянно возникать, может быть подавлена только взаимной терпимостью, которая пронизывает конституцию». [138] Что касается рабства и Конституции, он заявил: «Хотя в Пенсильвании мы все абстрактно выступаем против рабства, мы никогда не сможем нарушить конституционный договор, который мы заключили с нашими братскими штатами. Их права будут считаться для нас священными. это их собственный вопрос; и пусть он останется». [136]

Одним из важных вопросов дня были тарифы . [139] Бьюкенен был в противоречии со свободной торговлей, а также с запретительными тарифами , поскольку любой из них принес бы пользу одной части страны в ущерб другой. Будучи сенатором от Пенсильвании, он сказал: «В других штатах меня считают самым решительным сторонником защиты, в то время как в Пенсильвании меня осуждают как ее врага». [140]

Бьюкенен также разрывался между своим желанием расширить страну ради общего благосостояния нации и гарантировать права людей, населяющих определенные территории. Что касается территориальной экспансии, он сказал: «Что, сэр? Помешать людям пересечь Скалистые горы ? С таким же успехом вы могли бы приказать Ниагаре не течь. Мы должны исполнить свое предназначение». [141] О последующем распространении рабства посредством безоговорочного расширения он заявил: «Я чувствую сильное отвращение к любому моему действию, направленному на расширение нынешних границ Союза на новую рабовладельческую территорию». Например, он надеялся, что приобретение Техаса «станет средством ограничения, а не расширения господства рабства». [141]

Личная жизнь

[ редактировать ]Бьюкенен страдал эзотропией . Кроме того, один глаз был близорук , а другой дальнозорок . Чтобы скрыть это, он наклонял голову вперед и наклонял ее в сторону во время социальных взаимодействий. [142] Это привело к насмешкам, которые Генри Клей , среди прочих, безжалостно использовал во время дебатов в Конгрессе. [143]

В 1818 году Бьюкенен встретил Энн Кэролайн Коулман на большом балу в Ланкастере , и они начали встречаться. Энн была дочерью богатого производителя железа Роберта Коулмана ; Роберт, как и отец Бьюкенена, был родом из графства Донегол в Ольстере . Энн также была невесткой судьи из Филадельфии Джозефа Хемфилла , одного из коллег Бьюкенена. К 1819 году они были помолвлены, но мало времени проводили вместе. Бьюкенен был занят своей юридической фирмой и политическими проектами во время паники 1819 года , которая отлучала его от Коулмана на несколько недель. Ходили слухи, некоторые предполагали, что он был связан с другими (неопознанными) женщинами. [144] Письма Коулмана показали, что ей было известно о нескольких слухах, и она обвинила его в том, что он интересуется только ее деньгами. Она разорвала помолвку и вскоре после этого, 9 декабря 1819 года, необъяснимым образом умерла от «истерических судорог», возникших в результате передозировки лауданума , в возрасте 23 лет. Так и не было установлено, был ли препарат принят по инструкции или случайно. , или намеренно. [131] [145] Бьюкенен написала отцу с просьбой разрешить присутствовать на похоронах, но ему было отказано. [146] Во время ее похорон он сказал: «Я чувствую, что счастье ушло от меня навсегда». [147] Впоследствии Бьюкенен утверждал, что остался холостым из-за преданности своей единственной любви, которая умерла молодой. [131]

В 1833 и 1840-х годах он говорил о планах жениться, но это ни к чему не привело и, возможно, было просто связано с его амбициями получить место в федеральном Сенате или Белом доме. В последнем случае претенденткой была 19-летняя Анна Пейн, племянница бывшей первой леди Долли Мэдисон . [131] Во время его президентства осиротевшая племянница Гарриет Лейн , которую он усыновил, была официальной хозяйкой Белого дома. [148] Ходили необоснованные слухи, что у него был роман с вдовой президента Полка Сарой Чилдресс Полк . [149]

У Бьюкенена были близкие отношения с Уильямом Руфусом Кингом , который стал популярной целью сплетен. Кинг был политиком из Алабамы, который некоторое время занимал пост вице-президента при Франклине Пирсе . Бьюкенен и Кинг жили вместе в вашингтонском пансионе и вместе посещали общественные мероприятия с 1834 по 1844 год. Такой образ жизни в то время был обычным явлением, хотя Кинг однажды назвал эти отношения «общением». [149] Эндрю Джексон насмешливо называл их «мисс Нэнси» и «тетя Фэнси», причем первое слово в XIX веке было эвфемизмом для женоподобного мужчины. [150] [151] Генеральный почтмейстер Бьюкенена Аарон В. Браун также называл Кинга «тетей Фэнси», а также «лучшей половиной» и «женой» Бьюкенена. [152] [153] [154] Кинг умер от туберкулеза вскоре после инаугурации Пирса, за четыре года до того, как Бьюкенен стал президентом. Бьюкенен охарактеризовал его как «одного из лучших, самых чистых и последовательных общественных деятелей, которых я знал». [149] Биограф Бейкер полагает, что племянницы обоих мужчин, возможно, уничтожили переписку между ними. Однако она считает, что их сохранившиеся письма иллюстрируют лишь «привязанность особой дружбы». [155]

Холостяцкая жизнь Бьюкенена после смерти Энн Коулман вызвала интерес и спекуляции. [155] Некоторые предполагают, что смерть Анны просто отвлекла вопросы о сексуальности и холостяцкой жизни Бьюкенена. [147] Один из его биографов, Джин Бейкер, предполагает, что Бьюкенен был целомудренным , если не асексуальным . [156] Некоторые писатели предполагают, что он был гомосексуалистом , в том числе Джеймс У. Лоуэн . [157] Роберт П. Уотсон и Шелли Росс . [158] [159] Лоуэн указал, что Бьюкенен в конце жизни написал письмо, в котором признал, что может жениться на женщине, которая сможет смириться с его «отсутствием пылкой или романтической привязанности». [160] [161]

Наследие

[ редактировать ]Историческая репутация

[ редактировать ]Хотя Бьюкенен предсказал, что «история оправдает мою память», [162] историки критиковали Бьюкенена за его нежелание или неспособность действовать перед лицом отделения. Исторические рейтинги всех без исключения президентов Соединенных Штатов ставят Бьюкенена в число наименее успешных президентов. [163] При опросе ученых он занимает последнее место или около него с точки зрения видения/постановки повестки дня. [164] внутреннее руководство, внешнеполитическое руководство, [165] моральный авторитет, [166] и положительное историческое значение их наследия. [167] [ нужен лучший источник ] Согласно опросам, проведенным американскими учеными и политологами в период с 1948 по 1982 год, Бьюкенен всякий раз входит в число худших президентов США, наряду с Грантом , Хардингом , Филлмором и Никсоном . [168]

Биограф Бьюкенена Филип С. Кляйн в 1962 году, во время движения за гражданские права , сосредоточил внимание на проблемах, с которыми столкнулся Бьюкенен:

Бьюкенен взял на себя руководство... когда беспрецедентная волна гневных страстей захлестнула нацию. То, что он держал под контролем враждебные слои в эти революционные времена, само по себе было выдающимся достижением. Его слабости в бурные годы его президентства были усилены разъяренными сторонниками Севера и Юга. Его многочисленные таланты, которые в более спокойную эпоху могли бы принести ему место среди великих президентов, были быстро омрачены катастрофическими событиями гражданской войны и величественным Авраамом Линкольном. [169]

Биограф Джин Бейкер менее снисходительна к Бьюкенену, заявив в 2004 году:

Американцы удобно ввели себя в заблуждение относительно президентства Джеймса Бьюкенена, предпочитая классифицировать его как нерешительного и бездействующего... На самом деле неудача Бьюкенена во время кризиса вокруг Союза была не бездействием, а скорее его пристрастием к Югу, фаворитизмом, граничащим нелояльность офицера, поклявшегося защищать все Соединенные Штаты. Он был самым опасным из руководителей, упрямым, ошибочным идеологом , чьи принципы не допускали компромиссов. Его опыт работы в правительстве только сделал его слишком самоуверенным, чтобы принимать во внимание другие точки зрения. В своем предательстве национального доверия Бьюкенен был ближе к измене, чем любой другой президент в американской истории. [170]

Другие историки, такие как Роберт Мэй, утверждали, что его политика была «чем угодно, только не защитой рабства». [171] [172] [173] о Бьюкенене можно найти весьма негативный взгляд . Майкла Биркнера тем не менее, в работах [174] [175] По мнению Лори Кокс Хан , он входит в число ученых «либо как худший президент в [американской] истории, либо как представитель категории неудачников с самым низким рейтингом». [176]

Мемориалы

[ редактировать ]из бронзы и гранита Мемориал в Вашингтоне, округ Колумбия, недалеко от юго-восточного угла парка Меридиан-Хилл был спроектирован архитектором Уильямом Горденом Бичером и создан художником из Мэриленда Гансом Шулером . Он был сдан в эксплуатацию в 1916 году, но не одобрен Конгрессом США до 1918 года, а завершен и открыт только 26 июня 1930 года. Мемориал представляет собой статую Бьюкенена, забронированную классическими деятелями мужского и женского пола, представляющими закон и дипломатию, с выгравированным текстом. : «Неподкупный государственный деятель, ступавший по горным хребтам закона», — цитата члена кабинета Бьюкенена Иеремии С. Блэка . [177]

Более ранний памятник был построен в 1907–1908 годах и освящен в 1911 году на месте рождения Бьюкенена в Стоуни-Баттер, штат Пенсильвания . Часть первоначального участка площадью 18,5 акров (75 000 м²). 2 ) Мемориальный комплекс представляет собой 250-тонную пирамидальную конструкцию, стоящую на месте первоначальной хижины, где родился Бьюкенен. Памятник был спроектирован так, чтобы показать первоначальную выветрившуюся поверхность местных щебня и раствора. [178]

В его честь названы три округа: в Айове , Миссури и Вирджинии . Другой в Техасе был крещен в 1858 году, но переименован в округ Стивенс в честь вновь избранного вице-президента Конфедеративных Штатов Америки Александра Стивенса в 1861 году. [179] Город Бьюкенен, штат Мичиган , также был назван в его честь. [180] В его честь названы несколько других сообществ: некорпоративное сообщество Бьюкенен, штат Индиана , город Бьюкенен, штат Джорджия , город Бьюкенен, штат Висконсин , и поселки Бьюкенен-Тауншип, штат Мичиган , и Бьюкенен, штат Миссури .

Средняя школа Джеймса Бьюкенена — небольшая сельская средняя школа, расположенная на окраине родного города его детства, Мерсерсбурга, штат Пенсильвания .

Изображения популярной культуры

[ редактировать ]Бьюкенен и его наследие занимают центральное место в фильме «Воспитывая Бьюкенена» (2019). Его играет Рене Обержонуа . [181]

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Исторические рейтинги президентов США

- Список президентов США

- Список президентов США по предыдущему опыту

- Президенты США на почтовых марках США

- Список федеральных политических сексуальных скандалов в США

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Эллис, Франклин; Эванс, Сэмюэл (1883). История округа Ланкастер, штат Пенсильвания . Том. 1. Филадельфия: Эвертс и Пек. п. 214.

- ^ Кертис, Джордж Тикнор (1883). Жизнь Джеймса Бьюкенена, пятнадцатого президента США . Том. 1. Нью-Йорк: Харпер и братья. п. 10. ISBN 978-1-62376-821-8 .

- ^ Олауссон, Лена; Сангстер, Кэтрин (2006). Оксфордское руководство BBC по произношению . Издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 56. ИСБН 0-19-280710-2 .

- ^ «Хронология президентов» .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бейкер 2004 , стр. 9–12.

- ^ Откройте для себя Ольстер-Шотландцы: эмиграция и влияние - Ольстер и Белый дом. https://discoverulsterscots.com/emigration-influence/america/1718-migration-east-donegal/ulster-and-white-house

- ^ Агентство Ольстер-Шотландия : Новости - «Собрание клана Бьюкенен» в графстве Донегол (30 июня 2010 г.). https://www.ulsterscotsagency.com/news/article/39/the-buchanan-clan-gathering-in-co-donegal/

- ^ Бейкер 2004 , стр. 12.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Бейкер 2004 , стр. 13–16.

- ^ Кляйн 1962 , стр. 9–12.

- ^ Кляйн 1962 , с. 27.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бейкер 2004 , стр. 17–18.

- ^ Кляйн 1962 , с. 17-18.

- ^ Муди, Уэсли (2016). Битва при форте Самтер: первые выстрелы гражданской войны в США . Нью-Йорк, штат Нью-Йорк: Рутледж. п. 23. ISBN 978-1-3176-6718-6 – через Google Книги .

- ^ Кертис 1883 , с. 22.

- ^ Бейкер 2004 , с. 18.

- ^ Бейкер 2004 , с. 22.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Николь Этчесон, «Генерал Джексон мертв: Джеймс Бьюкенен, Стивен А. Дуглас и политика Канзаса», в книге « Джеймс Бьюкенен и наступление гражданской войны» , изд. Джон В. Квист и Майкл Дж. Биркнер, (2013), стр. 88–90.

- ^ Кляйн, Филип Шрайвер; Хугенбум, Ари (1980). История Пенсильвании . Пенсильвания: Издательство Пенсильванского государственного университета. стр. 135–136. ISBN 978-0-271-01934-5 .

- ^ Бейкер 2004 , с. 24–27.

- ^ Бейкер 2004 , стр. 28–30.

- ^ Бейкер 2004 , стр. 30–31.

- ^ О'Лири, Дерек Кейн (6 марта 2023 г.). «Миссия Джеймса Бьюкенена к царю 1832 года, тяжелое положение Польши и пределы революционного наследия Америки в джексоновской внешней политике» . Эпоха революций . Проверено 11 июня 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бейкер 2004 , с. 30.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бейкер 2004 , с. 32.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Бейкер 2004 , стр. 35–38.

- ^ Биндер, Фредерик Мур (1992). «Джеймс Бьюкенен: джексоновский экспансионист» . Историк . 55 (1): 69–84. дои : 10.1111/j.1540-6563.1992.tb00886.x . ISSN 0018-2370 . JSTOR 24448261 .

- ^ Бейкер 2004 , с. 33–34.

- ^ « Письмо Джеймса Бьюкенена Руэлу Уильяму » (сенатор США Бьюкенен обсуждает Дэвида Портера и выборы губернатора 1838 года в Пенсильвании). Карлайл, Пенсильвания: Колледж Дикинсон, архивы и специальные коллекции, получено в Интернете 30 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ «Губернатор Дэвид Риттенхаус Портер | PHMC > Губернаторы Пенсильвании» . www.phmc.state.pa.us . Проверено 3 февраля 2024 г.

- ^ «Губернатор Джозеф Ритнер | PHMC > Губернаторы Пенсильвании» . www.phmc.state.pa.us . Проверено 3 февраля 2024 г.

- ^ Секретарь Сената США. «Правило кляпа» . Сенат США . Проверено 9 января 2022 г.

- ^ Бейкер 2004 , стр. 38–40.

- ^ Бейкер 2004 , с. 40–41.

- ^ Бейкер 2004 , стр. 41–43.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бейкер 2004 , с. 46–48.

- ^ Бейкер 2004 , стр. 43–46.

- ^ Кляйн 1962 , с. 210, 415.

- ^ Бейкер 2004 , стр. 49–51.

- ^ Бейкер 2004 , стр. 52–56.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бейкер 2004 , с. 57–59.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бейкер 2004 , с. 65–67.

- ^ Бейкер 2004 , стр. 58–64.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Макферсон 1988 , с. 110.

- ^ Такер 2009 , стр. 456–57.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бейкер 2004 , стр. 67–68.

- ^ Кляйн 1962 , стр. 248–252.

- ^ Бейкер 2004 , с. 69.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бейкер 2004 , стр. 69–70.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бейкер 2004 , стр. 70–73.

- ^ Кляйн 1962 , стр. 261–262.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Бейкер 2004 , стр. 77–80.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бейкер 2004 , стр. 80–83, 85.

- ↑ Джеймс Бьюкенен, «Инаугурационная речь», Вашингтон, округ Колумбия, 4 марта 1857 г.

- ^ Финкельман, Пол (2007). «Скотт против Сэндфорда: самое ужасное дело Суда и как оно изменило историю» . Обзор права Чикаго-Кент . 82 : 3–48.

- ^ Каррафьелло, Майкл Л. (весна 2010 г.). «Дипломатическая неудача: инаугурационная речь Джеймса Бьюкенена». История Пенсильвании . 77 (2): 145–165. дои : 10.5325/pennhistory.77.2.0145 . JSTOR 10.5325/pennhistory.77.2.0145 .

- ^ Уолланс, Грегори Дж. (2006). «Иск, положивший начало гражданской войне». Иллюстрированные времена гражданской войны . Том. 45, нет. 2. С. 47–50.

- ^ Александр, Роберта (2007). «Дред Скотт: Решение, которое спровоцировало гражданскую войну» . Обзор законодательства Северного Кентукки . 34 (4): 643–662.

- ^ Блайт, Дэвид В. (21 декабря 2022 г.). «Была ли гражданская война неизбежной?» . Нью-Йорк Таймс .

- ^ Бейкер 2004 , с. 77.

- ^ Уильям Г. Шейд, «В разгар великой революции»: Северный ответ на кризис отделения, в книге « Джеймс Бьюкенен и начало гражданской войны », под редакцией Джона В. Квиста и Майкла Дж. Биркнера, (2013 г.) ) стр. 186–188.

- ^ Дэниел В. Крофтс, «Джозеф Холт, Джеймс Бьюкенен и кризис отделения» в книге « Джеймс Бьюкенен и наступление гражданской войны» , изд. Джон В. Квист и Майкл Дж. Биркнер, (2013), стр. 211.

- ^ Бейкер 2004 , с. 78.

- ^ Бейкер 2004 , с. 79.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бейкер 2004 , стр. 86–88.

- ^ Бейкер 2004 , с. 80.

- ^ «Натан Клиффорд, 1858–1881» . Историческое общество Верховного суда . Проверено 21 августа 2019 г.

- ^ «Судьи судов США» . Биографический справочник федеральных судей . Федеральный судебный центр . Проверено 30 мая 2020 г.

- ^ Кляйн 1962 , стр. 271–272.

- ^ Бейкер 2004 , стр. 83–84.

- ^ Холл 2001 , с. 566.

- ^ Поттер 1976 , с. 287.

- ^ Бейкер 2004 , с. 85.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Кляйн 1962 , с. 316.

- ^ Пол Финкельман, «Джеймс Бьюкенен, Дред Скотт и шепот заговора» в книге « Джеймс Бьюкенен и наступление гражданской войны» , изд. Джон В. Квист и Майкл Дж. Биркнер, (2013), стр. 28–32.

- ^ Бейкер 2004 , стр. 85–86.

- ^ Собел, Роберт (1999). Паника на Уолл-стрит: история финансовых катастроф Америки . Книги о бороде. ISBN 978-1-893122-46-8 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Бейкер 2004 , с. 90.

- ^ Майкл А. Моррисон, «Президент Джеймс Бьюкенен, исполнительное руководство и кризис демократии» в книге « Джеймс Бьюкенен и наступление гражданской войны» , изд. Джон В. Квист и Майкл Дж. Биркнер, (2013), стр. 151.

- ^ Кляйн 1962 , стр. 314–315.

- ^ Бейкер 2004 , стр. 90–92.

- ^ Уильям П. Маккиннон, «Прелюдия к Армагеддону: Джеймс Бьюкенен, Бригам Янг и начало кровопролития президента», в книге « Джеймс Бьюкенен и наступление гражданской войны» , изд. Джон В. Квист и Майкл Дж. Биркнер, (2013), стр. 52–59.

- ^ Уильям П. Маккиннон, «Прелюдия к Армагеддону: Джеймс Бьюкенен, Бригам Янг и начало кровопролития президента», в книге « Джеймс Бьюкенен и наступление гражданской войны» , изд. Джон В. Квист и Майкл Дж. Биркнер, (2013), стр. 59–62.

- ^ Кляйн 1962 , с. 317.

- ^ Уильям П. Маккиннон, «Прелюдия к Армагеддону: Джеймс Бьюкенен, Бригам Янг и начало кровопролития президента», в книге « Джеймс Бьюкенен и наступление гражданской войны» , изд. Джон В. Квист и Майкл Дж. Биркнер, (2013), стр. 75–78.

- ^ «Манипулирование Атлантической телеграфной линией. С 10 августа по 1 сентября включительно» . Отчет Объединенного комитета, назначенного лордами Комитета Тайного совета по торговле и Атлантической телеграфной компании для расследования строительства подводных телеграфных кабелей: вместе с протоколами доказательств и приложением . Эйр и Споттисвуд: Эйр. 1861. С. 230–232 . Проверено 1 марта 2018 г.

- ^ Джим Аль-Халили. Шок и трепет: История электричества , Эп. 2 « Эпоха изобретений ». 13 октября 2011 г., BBC TV, Использование оригинального блокнота главного инженера Брайта. Проверено 12 июня 2014 г.

- ^ Джесси Эймс Спенсер (1866). «Глава IX. 1857–1858. Открытие администрации Бьюкенена» (оцифрованная электронная книга) . «ПОСЛАНИЕ КОРОЛЕВЫ» и «ОТВЕТ ПРЕЗИДЕНТА» (полный текст) . Том. 3. Джонсон, Фрай. п. 542 . Проверено 10 сентября 2023 г.

История США: от самого раннего периода до администрации президента Джонсона

- ^ Бейкер 2004 , стр. 93–98.

- ^ Бейкер 2004 , стр. 97–100.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бейкер 2004 , стр. 100–105.