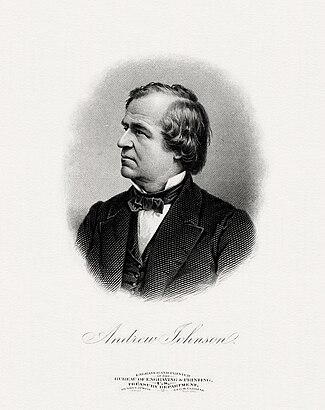

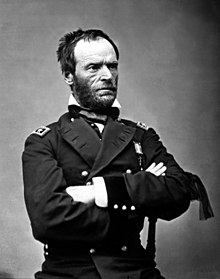

Эдвин Стэнтон

Эдвин Стэнтон | |

|---|---|

Фотография с. 1866-1869 гг. | |

| Помощник судьи Верховного суда США - назначенный | |

| В офисе Умер до вступления в должность | |

| Номинирован | Улисс С. Грант |

| Preceded by | Robert Cooper Grier |

| Succeeded by | William Strong |

| 27th United States Secretary of War | |

| In office January 20, 1862 – May 28, 1868[Note 1] | |

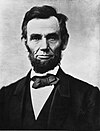

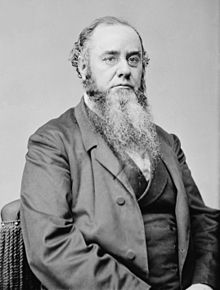

| President | Abraham Lincoln Andrew Johnson |

| Preceded by | Simon Cameron |

| Succeeded by | John Schofield |

| 25th United States Attorney General | |

| In office December 20, 1860 – March 4, 1861 | |

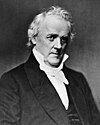

| President | James Buchanan |

| Preceded by | Jeremiah Black |

| Succeeded by | Edward Bates |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Edwin McMasters Stanton December 19, 1814 Steubenville, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | December 24, 1869 (aged 55) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Oak Hill Cemetery, Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic (before 1862) Republican (1862–1869) |

| Spouses | Mary Lamson (m. 1836–1844)Ellen Hutchison (m. 1856) |

| Parents |

|

| Education | Kenyon College |

| Signature | |

Эдвин Макмастерс Стэнтон (19 декабря 1814 — 24 декабря 1869) — американский юрист и политик, который занимал пост военного министра США при администрации Линкольна на протяжении большей части Гражданской войны в США . Руководство Стэнтона помогло организовать огромные военные ресурсы Севера и привести Союз к победе. Однако он подвергся критике со стороны многих генералов Союза, которые считали его чрезмерно осторожным и микроуправленческим. [1] Он также организовал розыск Авраама Линкольна убийцы Джона Уилкса Бута .

После убийства Линкольна Стэнтон оставался военным министром при новом президенте США Эндрю Джонсоне в течение первых лет Реконструкции . Он выступал против снисходительной политики Джонсона по отношению к бывшим Конфедеративным Штатам . Попытка Джонсона уволить Стэнтона в конечном итоге привела к импичменту Джонсона радикальными республиканцами в Палате представителей. Стэнтон вернулся к юриспруденции после того, как ушел с поста военного министра. В 1869 году он был назначен помощником судьи Верховного суда преемником Джонсона Улиссом С. Грантом , но Стэнтон умер через четыре дня после того, как его кандидатура была подтверждена Сенатом. Он остается единственным подтвержденным кандидатом, который согласился, но умер до вступления в должность в Суде.

Family and early life

[edit]Ancestry

[edit]Before the American Revolution, Stanton's paternal ancestors, the Stantons and the Macys, both of whom were Quakers, moved from Massachusetts to North Carolina. In 1774, Stanton's grandfather, Benjamin Stanton, married Abigail Macy. Benjamin died in 1800. That year, Abigail moved to the Northwest Territory, accompanied by much of her family. Soon, Ohio was admitted to the Union,[2] and Macy proved to be one of the early developers of the new state. She bought a tract of land at Mount Pleasant, Ohio, from the government and settled there.[3] One of her sons, David, became a physician in Steubenville, and married Lucy Norman, the daughter of a Virginia planter. Their marriage was met with the ire of Ohio's Quaker community, as Lucy was a Methodist,[4] and not a Quaker. This forced David Stanton to abandon the Quaker sect.[5]

Early life and education

[edit]

Edwin McMasters was born to David and Lucy Stanton on December 19, 1814, in Steubenville, Ohio, the first of their four children.[6] Edwin's early formal education consisted of a private school and a seminary behind the Stantons' residence, called "Old Academy".[7] When he was ten, he was transferred to a school taught by a Presbyterian minister.[8][7] It was also at ten that Edwin experienced his first asthma attack, a malady that would haunt him for life, sometimes to the point of convulsion. Because of his asthma he was unable to participate in highly physical activities, so he found interest in books and poetry. Edwin attended Methodist church services and Sunday school regularly. At the age of thirteen, Stanton became a full member of the Methodist church.[9]

David Stanton's medical practice afforded him and his family a decent living. When David Stanton suddenly died in December 1827 at his residence,[9] Edwin and family were left destitute.[10] Edwin's mother opened a store in the front room of their residence, selling the medical supplies her husband left her, along with books, stationery and groceries.[9] The youthful Edwin was removed from school, and worked at the store of a local bookseller.[11]

Stanton began his college studies at the Episcopal Church-affiliated Kenyon College in 1831. At Kenyon, Stanton was involved in the college's Philomathesian Literary Society. Stanton sat on several of the society's committees and often partook in its exercises and debates. Stanton was forced to leave Kenyon just at the end of his third semester for lack of finances. At Kenyon, his support of President Andrew Jackson's actions during the 1832 Nullification Crisis, a hotly debated topic among the Philomathesians, led him into the Democratic Party. Further, Stanton's conversion to Episcopalianism and his revulsion of the practice of slavery were solidified there.[12] After Kenyon, Stanton worked as a bookseller in Columbus. Stanton had hoped to obtain enough money to complete his final year at Kenyon. However, a small salary at the bookstore dashed the notion. He soon returned to Steubenville to pursue studies in law.[13]

Early career and first marriage

[edit]Stanton studied law under the tutelage of Daniel Collier in preparation for the bar. He was admitted to practice in 1835, and began work at a prominent law firm in Cadiz, Ohio, under Chauncey Dewey, a well-known attorney. The firm's trial work often fell to him.[14]

At the age of 18, Stanton met Mary Ann Lamson at Trinity Episcopal Church in Columbus, and they soon were engaged.[15] After buying a home in Cadiz, Stanton went to Columbus where his betrothed was. Stanton and Lamson had wished to be married at Trinity Episcopal, but Stanton's illness rendered this idea moot. Instead, the ceremony was performed at the home of Trinity Episcopal's rector on December 31, 1836. Afterwards, Stanton went to Virginia where his mother and sisters were, and escorted the women back to Cadiz, where they would live with him and his wife.[16]

After his marriage, Stanton partnered with the lawyer and federal judge Benjamin Tappan. Stanton's sister also married Tappan's son. In Cadiz, Stanton was situated prominently in the local community. He worked with the town's anti-slavery society, and with a local newspaper, the Sentinel, writing and editing articles there.[17] In 1837, Stanton was elected the prosecutor of Harrison County, on the Democratic ticket. Further, Stanton's increasing wealth allowed him to purchase a large tract of land in Washington County, and several tracts in Cadiz.[18][17]

Rising attorney (1839–1860)

[edit]Return to Steubenville

[edit]

Stanton's relationship with Benjamin Tappan expanded when Tappan was elected the United States Senator from Ohio in 1838. Tappan asked Stanton to oversee his law operations, which were based in Steubenville. When his time as county prosecutor was finished, Stanton moved back to the town.[17][19] Stanton's work in politics also expanded. He served as a delegate at the Democrats' 1840 national convention in Baltimore, and was featured prominently in Martin Van Buren's campaign in the 1840 presidential election, which Van Buren lost.[20]

He was a member of Steubenville Lodge No. 45 in Steubenville, Ohio, and when he moved to Pittsburgh became a member of Washington Lodge No. 253 on 25 March 1852 as a charter member. He resigned on 29 Nov. 1859. pp. 189-81.“ (Denslow, William R. 10,000 Famous Freemasons. Independence, Missouri: Missouri Lodge of Research, 1957. )[1]

In Steubenville, the Stantons welcomed two children. Their daughter, Lucy Lamson, was born in March 1840. Within months of her birth, Lucy was stricken with an unknown illness. Stanton put aside his work to spend that summer at baby Lucy's bedside. She died in 1841, shortly after her second birthday. Their son, Edwin Lamson, was born in August 1842. The boy's birth refreshed the spirits in the Stanton household after baby Lucy's death.[21] Unlike Lucy's early years, Edwin was healthy and active. Grief, however, would return once again to the Stanton household in 1844, when Mary Stanton was left bedridden by a bilious fever. Never recovering, she died in March 1844. Stanton's sorrow "verged on insanity", say historians Benjamin P. Thomas and Harold M. Hyman.[22] He had Mary's burial attire redone repeatedly, as he demanded she look just as she had when they were wed seven years prior. In the evenings, Stanton would emerge from his room with his eyes filled with tears and search the house frantically with a lamp, all the while asking, "Where is Mary?"[23]

Stanton regrouped and began to focus on his cases by the summer. One such case was defending Caleb J. McNulty, whom Stanton had previously labelled "a glorious fellow". McNulty, a Democrat, was dismissed from his clerkship of the United States House of Representatives by unanimous vote and charged with embezzlement when thousands of the House's money went missing. Democrats, fearing their party's disrepute, made clamorous cries for McNulty to be punished, and his conviction was viewed as a foregone conclusion. Stanton, at Tappan's request, came on as McNulty's defense. Stanton brought a motion to dismiss McNulty's indictment. He employed the use of numerous technicalities and, to the shock and applause of the courtroom, the motion was granted with all charges against McNulty dropped. As every detail of the affair was covered by newspapers around the country, Stanton's name was featured prominently nationwide.[24][25]

After the McNulty scandal, Stanton and Tappan parted ways professionally. Stanton formed a partnership with one of his former students, George Wythe McCook of the "Fighting McCooks". At the beginning of the Mexican–American War, men across the country hastened to enlist in the United States Army, with McCook among them. Stanton might have enlisted as well, if not for his doctor's fears about his asthma. Instead, he focused on law. Stanton's practice was no longer only in Ohio, having expanded to Virginia and Pennsylvania. He concluded that Steubenville would no longer prove adequate as a headquarters, and thought Pittsburgh most appropriate for his new base. He was admitted to the bar there by late 1847.[26]

Attorney in Pittsburgh

[edit]

In Pittsburgh, Stanton formed a partnership with a prominent retired judge, Charles Shaler, while maintaining his collaboration with McCook, who had remained in Steubenville after returning from service in the Mexican–American War. Stanton argued several high-profile suits. One such proceeding was State of Pennsylvania v. Wheeling and Belmont Bridge Company and others in the United States Supreme Court. The case concerned the Wheeling Suspension Bridge, the largest suspension bridge in the world at that time, and an important connector for the National Road. The bridge's center rose some ninety feet (twenty-seven meters) but proved to be a nuisance to passing ships with tall smokestacks. With ships unable to clear the bridge, enormous amounts of traffic, trade and commerce would be redirected to Wheeling, West Virginia, which at the time was still part of Virginia. On August 16, 1849, he urged the Supreme Court to enjoin Wheeling and Belmont, as the bridge was obstructing traffic into Pennsylvania, and hindering trade and commerce. Associate Justice R. C. Grier directed those who were aggrieved by the bridge's operations to go to a lower court, but left an avenue open for Stanton to file for an injunction in the Supreme Court, which he did.[27][Note 2]

Oral arguments for the Pennsylvania v. Wheeling and Belmont began on February 25, 1850, which was also when Stanton was admitted to practice in the Supreme Court.[28] Wheeling and Belmont argued that the court lacked jurisdiction over the matters concerning the case; the justices disagreed.[29] The case proceeded, allowing Stanton to exhibit a dramatic stunt, which was widely reported on and demonstrated how the bridge was a hindrance—he had the steamer Hibernia ram its eighty-five-foot (twenty-six-meter) smokestack into the bridge, which destroyed it and a piece of the ship itself.[30] May 1850 saw the case handed over to Reuben H. Walworth, the former Chancellor of New York, who returned a vivid opinion in February 1851 stating that the Wheeling Bridge was "an unwarranted and unlawful obstruction to navigation, and that it must be either removed or raised so as to permit the free and usual passage of boats." The Supreme Court concurred; in May 1852, the court ordered in a 7–2 ruling that the bridge's height be increased to one hundred eleven feet (thirty-four meters). Wheeling and Belmont were unsatisfied with the ruling and asked Congress to act.[29] To Stanton's horror, a bill declaring the Wheeling bridge permissible became law on August 31, effectively overriding the Supreme Court's ruling and authority. Stanton was disgruntled that the purpose of the court—to peacefully decide and remedy disputes between states—had been diminished by Congress.[31][32]

McCormick v. Manny

[edit]

A by-effect of Stanton's performance in Pennsylvania v. Wheeling and Belmont was that he was sought after for other prominent cases, such as the McCormick Reaper patent case of inventor Cyrus McCormick. In 1831, a young McCormick created a machine to harvest crops. The device was particularly useful in the burgeoning wheat fields of the Western United States. Demand for McCormick's invention grew rapidly, attracting fierce competition, especially from fellow inventor and businessman John Henry Manny. In 1854 McCormick and his two prominent lawyers, Reverdy Johnson and Edward M. Dickinson, filed suit against Manny claiming he had infringed on McCormick's patents. McCormick demanded an injunction on Manny's reaper. Manny was also defended by two esteemed lawyers, George Harding and Peter H. Watson. McCormick v. Manny was initially to be tried in Chicago, and the two lawyers wanted another attorney local to the city to join their team; the recommended choice was Abraham Lincoln. When Watson met Lincoln in Springfield, Illinois, he had a dim first impression of him, but after speaking with Lincoln, Watson saw that he might be a good choice. However, when the venue of the proceedings was transferred to Cincinnati rather than Chicago, and the necessity for Lincoln was negated, Harding and Watson went for their first choice, Edwin Stanton. Lincoln was not made aware that he had been replaced, and still appeared at the proceedings in Cincinnati with his arguments prepared.[33] Stanton's apprehension towards Lincoln was immediate and severe, and he did well to indicate to Lincoln that he wanted him to absent himself from the case. The case proceeded with Harding, Watson and Stanton and Manny's true defenders; Lincoln did not actively participate in the planning or arguing of the case, but stayed in Cincinnati as a spectator.[34]

Stanton's role in Manny's legal trio was as a researcher. Though he admitted that George Harding, an established patent lawyer, was more adept at the scientific aspects of the case, Stanton worked to summarize the relevant jurisprudence and case law.[35] To win McCormick v. Manny for Manny, Stanton, Harding and Watson had to impress upon the court that McCormick had no claim to exclusivity in his reaper's use of a divider, a mechanism on the outer end of the cutter-bar which separated the grain. A harvesting machine would not have worked properly without a divider, and Manny's defense knew this. However, to assure a win, Watson opted to use duplicity—he employed a model maker named William P. Wood to retrieve an older version of McCormick's reaper and alter it to be presented in court. Wood found a reaper in Virginia which was built in 1844, one year prior to McCormick's patent being granted. He had a blacksmith straighten the curved divider, knowing that the curved divider in Manny's reaper would not conflict with a straight one in McCormick's reaper. After using a salt and vinegar solution to add rust to where the blacksmith had worked to ensure the antiquity of the machine was undeniable, Wood sent the reaper to Cincinnati. Stanton was joyed when he examined the altered reaper, and knew the case was theirs. Arguments for the case began in September 1855. In March 1856, Justices John McLean and Thomas Drummond delivered a ruling in favor of John Manny. McCormick appealed the decision to the Supreme Court, and McCormick v. Manny, was, all of a sudden, a political issue, and the matters concerning the case found their way to the floor of Congress.[36][37] Stanton would later appoint Wood to be superintendent of the military prisons of the District of Columbia during the Civil War.[38]

Second marriage

[edit]In February 1856 Stanton became engaged to Ellen Hutchinson, sixteen years Stanton's junior.[39] She came from a prominent family in the city; her father was Lewis Hutchinson, a wealthy merchant and warehouseman and a descendant of Merriweather Lewis.[40] They were married on June 25, 1856, at Hutchinson's father's home. [41][42] Stanton moved to Washington where Stanton expected important work with the Supreme Court. [43]

Emergence in Washington

[edit]

In Pennsylvania, Stanton had become intimately acquainted with Jeremiah S. Black, the chief judge in the state's supreme court. This friendship proved profitable for Stanton when in March 1857, the recently inaugurated fifteenth President, James Buchanan, made Black his Attorney General.[43][44] Black's accession to his new post was soon met with a land claims issue in California. In the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that ended the Mexican–American War and gave California to the United States, the United States agreed to recognize valid land grants by Mexican authorities. This was followed by the California Land Claims Act of 1851, which established a board to review claims to California lands. One such claim was made by Joseph Yves Limantour, a French-born merchant who asserted ownership of an assemblage of lands that included important sections of the state, such as a sizeable part of San Francisco. When his claims were recognized by the land commissioners, the U.S. government appealed. Meanwhile, Black corresponded with a person named Auguste Jouan, who stated that Limantour's claims were invalid, and that he, under Limantour's employ, forged the date listed on one of the approved grants. Black needed an individual loyal to the Democratic Party and to the Buchanan administration, who could faithfully represent the administration's interests in California; he chose Stanton.[45][46]

Ellen Stanton loathed the idea. In California Edwin would be thousands of miles away from her for what was sure to be months, leaving her lonely in Washington, where she had few friends. Moreover, on May 9, 1857, Ellen had a daughter whom the Stantons named Eleanor Adams. After the girl's delivery, Ellen fell ill, which frightened Edwin and delayed his decision to go to California. In October 1857 Stanton finally agreed to represent the Buchanan administration's interests in California. Having agreed to a compensation of $25,000, (~$685,370 in 2023) Stanton set sail from New York on February 19, 1858, aboard the Star of the West, along with his son Eddie, James Buchanan Jr., the President's nephew, and Lieutenant H. N. Harrison, who was assigned to Stanton's detail by the Navy.[47] After a tempestuous voyage, the company docked in Kingston, Jamaica, where slavery was disallowed. On the island, the climate pleased Stanton greatly, and at a church there, Stanton was surprised to see blacks and whites sitting together. Afterwards, Stanton and his entourage landed in Panama, and left there on a ship three times larger than the one on which they came, the Sonora. On March 19 the company finally docked in San Francisco, and bunkered at the International Hotel.[48]

Stanton took to his work with haste. In aid of his case Stanton, along with his entire party and two clerks, went about arranging disordered records from California's time under Mexico. The "Jemino Index" that he uncovered gave information on land grants up to 1844, and with the assistance of a Congressional act, Stanton unearthed records from all over the state pertaining to Mexican grants.[49] Stanton and company worked for months sorting the land archives; meanwhile, Stanton's arrival in California produced gossip and scorn from locals, especially from those whose land claims would be in jeopardy should Stanton's work prove victorious.[50] Further, President Buchanan and Senator Douglas were wrestling for control of California, and Stanton was caught in the crosshairs, resulting in a defamatory campaign against Stanton by Douglas' supporters. The campaign disheartened Stanton, but barely distracted him.[51]

Limantour had built up a speciously substantial case. He had accrued a preponderance of ostensibly sound evidence, such as witness testimony, grants signed by Manuel Micheltorena, the Mexican governor of California prior to cessation, and paper with a special Mexican government stamp. However, Auguste Jouan's information was instrumental in Stanton's case. According to Jouan, Limantour had received dozens of blank documents signed by Governor Micheltorena, which Limantour could fill in as he willed. Further, Jouan had borne a hole in one of the papers to erase something, a hole that was still present in the document. Stanton also acquired letters that explicitly laid out the fraud, and stamps used by customs officials, one authentic and the other fraudulent. The fraudulent one had been used eleven times, all on Limantour's documents. When Stanton sent to the Minister of the Exterior in Mexico City, they could not locate records corroborating Limantour's grants. In late 1858 Limantour's claims were denied by the land commission, and he was arrested on perjury charges. He posted a $35,000 bail and left the country.[52]

As 1858 drew to a close, and Stanton prepared to return home, Eddie became sick. Whenever Stanton made arrangements to leave California, his son's condition grew worse.[53] Edwin had written Ellen as often as he could as her anxiety and loneliness increased in Washington. She criticized him for leaving her in the town alone with young "Ellie".[51] January 3, 1859, saw Stanton and company leave San Francisco.[54] He was home in early February. In the nation's capital Stanton advised President Buchanan on patronage, and helped Attorney General Black extensively, even being mistaken as an Assistant Attorney General. Nonetheless, Stanton's affairs in Washington paled in comparison to the excitement he had experienced on the other side of the country—at least until he found himself defending a man who had become fodder for sensationalists and gossipers around the country.[55]

Daniel Sickles trial

[edit]

Daniel Sickles was a member of the United States House of Representatives from New York. He was married to Teresa Bagioli Sickles, the daughter of composer Antonio Bagioli. Sickles' wife had begun an affair with Philip Barton Key, the United States Attorney for the District of Columbia and the son of Francis Scott Key, writer of The Star-Spangled Banner. On Sunday, February 27, 1859, Sickles confronted Key in Lafayette Square, declaring, "Key, you scoundrel, you have dishonored my home; you must die", then shot Key to death.[54] Sickles then went to the home of Attorney General Black and admitted his crime.[55] The subsequent Thursday he was charged with murder by a grand jury. The Sickles affair gained nationwide media attention for both its scandalous nature and its proximity to the White House. Soon, the press speculated that Daniel Sickles' political esteem was on the account of an affair between his wife and President Buchanan. Prominent criminal lawyer James T. Brady and his partner, John Graham, came to Sickles' defense, and solicited Stanton to join their team.[55]

Arguments for the trial began on April 4. The prosecution wanted to advance the theory that Sickles had also committed adultery and did not pay very much mind to his wife or her activities. When the judge disallowed this, the prosecution opted instead to highlight the heinous nature of Sickles' murder, and not address his reasons for doing the crime. Sickles' defense countered that Sickles had suffered from a temporary bout of insanity, the first successful such instance of an insanity plea in American jurisprudence. The events in the courtroom during the trial were nothing if not dramatic. When Stanton delivered closing arguments, stating that marriage is sacred and that a man should have the right to defend his marriage against those who chose to defile the purity of the sacrament, the courtroom erupted in cheers. A law student described Stanton's argument during the trial, "a typical piece of Victorian rhetoric, an ingenious thesaurus of aphorisms on the sanctity of the family."[56] The jury in the case deliberated for just over an hour before declaring Sickles not guilty. The judge ordered that Sickles be released from his arrest. Outside the courthouse, Sickles, Stanton and company met a throng of individuals in adulation of the victory.[57]

Early work in politics (1860–1862)

[edit]During the 1860 United States presidential election Stanton supported Vice President John C. Breckinridge, due to his work with the Buchanan administration and his belief that only a win by Breckinridge would keep the country together. Privately he predicted that Lincoln would win.[58]

In Buchanan's cabinet

[edit]In late 1860, President Buchanan was formulating his yearly State of the Union address to Congress, and asked Attorney General Black to offer insight into the legality and constitutionality of secession. Black then asked Stanton for advice.[59] Stanton approved a strongly worded draft of Black's response to Buchanan, which denounced secession from the Union as illegal. Buchanan gave his address to Congress on December 3.[60] Meanwhile, Buchanan's cabinet were growing more discontent with his handling of secession, and several members deemed him too weak on the issue. On December 5th, his Secretary of the Treasury, Howell Cobb resigned. On December 9th, Secretary of State Lewis Cass, disgruntled over Buchanan's failure to defend the government's interests in the South, tendered his resignation. Black was nominated to replace Cass on December 12.[61] About a week later, Stanton, at the time in Cincinnati, was told to come to Washington at once, for he had been confirmed by the Senate as Buchanan's new Attorney General. He was sworn in on December 20th.[61][62]

Stanton met a cabinet in disarray over the issue of secession. Buchanan did not want to agitate the South any further, and sympathized with the South's cause.[63] On December 9th, Buchanan had agreed with South Carolinian congressmen that the military installations in the state would not be reinforced unless force against them was perpetrated. However, on the day that Stanton assumed his position, Maj. Robert Anderson moved his unit to Fort Sumter, South Carolina, which the Southerners viewed as Buchanan reneging on his promise. South Carolina issued an ordinance of secession soon after, declaring itself independent of the United States.[64] The South Carolinians demanded that federal forces leave Charleston Harbor altogether; they threatened carnage if they did not get compliance.[65] The following day, Buchanan gave his cabinet a draft of his response to the South Carolinians. Secretaries Thompson and Philip Francis Thomas, of the Treasury Department, thought the President's response too pugnacious; Stanton, Black and Postmaster General Joseph Holt thought it too placatory. Isaac Toucey, Secretary of the Navy, was alone in his support of the response.[66]

Stanton was unnerved by Buchanan's ambivalence towards the South Carolina secession crisis, and wanted to stiffen him against complying to the South's demands.[67] On December 30th, Black came to Stanton's home, and the two agreed to pen their objections to Buchanan ordering a withdrawal from Fort Sumter. If he did such a thing, the two men, along with Postmaster General Holt, agreed that they would resign, delivering a crippling blow to the administration. Buchanan obliged them.[68][Note 3] The South Carolinian delegates got their response from President Buchanan on New Year's Eve 1860; the President would not withdraw forces from Charleston Harbor.[70]

By February 1st, six Southern states had followed South Carolina's lead and passed ordinances of secession, declaring themselves to no longer be a part of the United States.[71] On February 18th, Jefferson Davis was sworn in as the President of the Confederate States.[72] Meanwhile, Washington was astir with talk of coups and conspiracies. Stanton thought that discord would ravage the capital on February 13, when electoral votes were being counted; nothing happened. Again, Stanton thought, when Lincoln was sworn in on March 4th there would be violence; this did not come to pass. Lincoln's inauguration did give Stanton a flickering of hope that his efforts to keep Fort Sumter defended would not be in vain, and that Southern aggression would be met with force in the North. In his inauguration speech, Lincoln did not say he would outlaw slavery throughout the nation, but he did say that he would not support secession in any form, and that any attempt to leave the Union was not lawful. In Stanton, Lincoln's words were met with cautious optimism.[73] The new president submitted his choices for his cabinet on March 5,[74] and by that day's end, Stanton was no longer the attorney general.[75] He lingered in his office for a while to help settle in and guide his replacement, Edward Bates.[74]

Cameron's advisor

[edit]

On July 21st, the North and the South experienced their first major clash at Manassas Junction in Virginia, the First Battle of Bull Run. Northerners thought the battle would end the war, and defeat the Confederacy decisively; however, the bloody encounter ended with the Union Army retreating to Washington. Lincoln wanted to bolster Northern numbers afterwards, with many in the North believing the war would be more arduous than they initially expected, but when more than 250,000 men signed up, the federal government did not have enough supplies for them. The War Department had states buy the supplies, assuring them that they would be reimbursed. This led to states selling the federal government items that were usually damaged or worthless at very high prices. Nonetheless, the government bought them.[76]

Soon, Simon Cameron, Lincoln's Secretary of War, was being accused of incompetently handling his department, and some wanted him to resign. Cameron sought out Stanton to advise him on legal matters concerning the War Department's acquisitions, among other things.[77] Calls for Cameron to resign grew louder when he endorsed a bombastic November 1861 speech given by Col. John Cochrane to his unit. "[W]e should take the slave by the hand, placing a musket in it, and bid him in God's name strike for the liberty of the human race", Cochrane said.[78] Cameron embraced Cochrane's sentiment that slaves should be armed, but it was met with repudiation in Lincoln's cabinet. Caleb B. Smith, the Secretary in the Department of the Interior, scolded Cameron for his support of Cochrane.[79]

Cameron inserted a call to arm the slaves in his report to Congress, which would be sent along with Lincoln's address to the legislature.[79] Cameron gave the report to Stanton, who amended it with a passage that went even further in demanding that slaves be armed,[80] stating that those who rebel against the government lose their claims to any type of property, including slaves, and that it was "clearly the right of the Government to arm slaves when it may become necessary as it is to use gunpowder or guns taken from the enemy".[81] Cameron gave the report to Lincoln, and sent several copies to Congress and the press. Lincoln wanted the portions containing calls to arm the slaves removed, and ordered the transmission of Cameron's report be stopped and replaced with an altered version. Congress received the version without the call to arm slaves, while the press received a version with it. When newspapers published the document in its entirety, Lincoln was excoriated by Republicans, who thought him weak on the issue of slavery, and disliked that he wanted the plea to arm slaves removed.[80]

The President resolved to dismiss Cameron when abolitionists in the North settled over the controversy. Cameron would not resign until he was sure of his successor, and that he could leave the cabinet without damaging his reputation. When a vacancy in the post of Minister to Russia presented itself, Cameron and Lincoln agreed that he would fill the post when he resigned. As for a successor, Lincoln thought Joseph Holt best for the job, but his Secretary of State, William H. Seward, wanted Stanton to succeed Cameron. Salmon Chase, Stanton's friend and Lincoln's Treasury Secretary, agreed.[82] Stanton had been preparing for a partnership with Samuel L. M. Barlow in New York, but abandoned these plans when he heard of his possible nomination.[83] Lincoln nominated Stanton to the post of Secretary of War on January 13. He was confirmed two days following.[84]

Lincoln's Secretary of War (1862–1865)

[edit]Early days in office

[edit]

Under Cameron, the War Department had earned the moniker "the lunatic asylum."[85] The department was barely respected among soldiers or government officials, and its authority was routinely disregarded. The army's generals held the brunt of the operating authority in the military, while the President and the War Department interceded only in exceptional circumstances.[86] The department also had strained relations with Congress, especially Representative John Fox Potter, head of the House's "Committee on Loyalty of Federal employees", which sought to root out Confederate sympathizers in the government. Potter had prodded Cameron to remove about fifty individuals he suspected of Confederate sympathies; Cameron had paid him no mind.[87]

Stanton was sworn in on January 20.[88] Immediately, he set about repairing the fractious relationship between Congress and the War Department. Stanton met with Potter on his first day as secretary, and on the same day, dismissed four persons whom Potter deemed unsavory. This was well short of the fifty people Potter wanted gone from the department, but he was nonetheless pleased. Stanton also met with Senator Benjamin Wade and his Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. The committee was a necessary and fruitful ally; it had subpoena power, thus allowing it to acquire information Stanton could not, and could help Stanton remove War Department staffers. Wade and his committee were happy to find an ally in the executive branch, and met with Stanton often thereafter.[89] Stanton made a number of organizational changes within the department as well. He appointed John Tucker, an executive at the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, and Peter H. Watson, his partner in the reaper case, to be his assistant secretaries,[90] and had the staff at the department expanded by over sixty employees.[85] Further, Stanton appealed to the Senate to cease appointments of military officials until he could review the more than 1,400 individuals up for promotion. Hitherto, military promotions were a spoils system, where individuals favorable to the administration were given promotions, regardless of merit. This ceased under Stanton.[91][Note 4]

On January 29 Stanton ordered that all contracts to manufacturers of military materials and supplies outside the United States be voided and replaced with contracts within the country, and that no such further contracts be made with foreign companies. The order provoked apprehension in Lincoln's cabinet.[94] The United Kingdom and France were searching for cause to recognize and support the Confederates, and Stanton's order may have given it to them.[95] Secretary of State Seward thought the order would "complicate the foreign situation." Stanton persisted, and his January 29 order stood.[96]

Meanwhile, Stanton worked to create an effective transportation and communication network across the North. His efforts focused on the railroad system and the telegraph lines. Stanton worked with Senator Wade to push through Congress a bill that would codify the ability of the President and his administration to forcibly seize railroad and telegraph lines for their purposes. Railroad companies in the North were accommodating to the needs and desires of the federal government for the most part, and the law was rarely used.[97] Stanton also secured the government's use of telegraph. He relocated the military's telegraphing operations from McClellan's army headquarters to his department, a decision the general was none too pleased with. The relocation gave Stanton closer control over the military's communications operations, and he exploited this. Stanton forced all members of the press to work through Assistant Secretary Watson, where unwanted journalists would be disallowed access to official government correspondence. If a member of the press went elsewhere in the department, they would be charged with espionage.[98]

Prior to Stanton's incumbency as War Secretary, President Lincoln apportioned responsibility for the security of government against treachery and other unsavory activities to several members of his cabinet, mostly Secretary Seward, as he did not trust Attorney General Bates or Secretary Cameron. Under Secretary Stanton, the War Department would have consolidated responsibility for internal security. A lynchpin of Seward's strategy to maintain internal security was the use of arbitrary arrests and detentions, and Stanton continued this practice. Democrats harshly criticized the use of arbitrary arrests, but Lincoln contended that it was his primary responsibility to maintain the integrity and security of the government, and that waiting until possible betrayers committed guilty acts would hurt the government.[99] At Stanton's behest, Seward continued the detention of only the most risky inmates, and released all others.[100]

General-in-Chief

[edit]

Lincoln eventually grew tired of McClellan's inaction, especially after his January 27, 1862, order to advance against the Confederates in the Eastern Theatre had provoked little military response from McClellan. On March 11, Lincoln relieved McClellan of his position as general-in-chief of the whole Union army—leaving him in charge of only the Army of the Potomac—and replaced him with Stanton. This created a bitter chasm in the relationship between Stanton and McClellan, and led McClellan's supporters to claim that Stanton "usurped" the role of general-in-chief, and that a Secretary of War should be subordinate to military commanders.[101][102] Lincoln ignored such calls, leaving military power consolidated with himself and Stanton.[103]

Meanwhile, McClellan was preparing for the first major military operation in the Eastern Theatre, the Peninsula Campaign. The Army of the Potomac began its movement to the Virginia Peninsula on March 17.[104] The first action of the campaign was at Yorktown. Lincoln wanted McClellan to attack the town outright, but McClellan's inspection of the Confederate defensive works there compelled him to lay siege to the town instead.[105] Washington politicians were angered at McClellan's choice to delay an attack. McClellan, however, requested reinforcements for his siege—the 11,000 men in Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin's division, of Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell's corps. Stanton wanted Maj. Gen. McDowell's corps to stay together and march on to Richmond, but McClellan persisted, and Stanton eventually capitulated.[106]

McClellan's campaign lasted several months. However, after Gen. Robert E. Lee became the commander of local Confederate forces on June 1, he launched a series of offensives against the Army of the Potomac, which, by late June 1862, was just a few miles from the Confederate capital, Richmond.[107] In addition, Stanton ordered McClellan to transfer one of his corps east to defend Washington.[108] McClellan and the Army of the Potomac were pushed back to Harrison's Landing in Virginia, where they were protected by Union gunboats.[109] In Washington, Stanton was blamed for McClellan's defeat by the press and the public. On April 3 Stanton had suspended military recruiting efforts under the mistaken impression that McClellan's Peninsula Campaign would end the war. With McClellan retreating and the casualties from the campaign piling up, the need for more men rose significantly. Stanton restored recruiting operations on July 6, when McClellan's defeat on the Peninsula was firmly established, but the damage was done. The press, angered by Stanton's strict measures regarding journalistic correspondence, unleashed torrents of scorn on him, furthering the narrative that he was the only encumbrance to McClellan's victory.[110]

The attacks hurt Stanton, and he considered resigning, but he remained in his position, at Lincoln's request.[111] As defeats piled up, Lincoln sought to give some order to the disparate divisions of Union forces in Virginia. He decided to consolidate the commands of Maj. Gens. McDowell, John C. Frémont, and Nathaniel P. Banks into the Army of Virginia, which was to be commanded by Maj. Gen. John Pope who was brought east after success in the West.[112] Lincoln was also convinced that the North's army needed reformation at the highest ranks; he and Stanton being the de facto commanders of Union forces had proved too much to bear, so Lincoln would need a skilled commander. He chose Gen. Henry W. Halleck. Halleck arrived in Washington on July 22, and was confirmed as the general-in-chief of Union forces the following day.[113]

War rages on

[edit]

In the final days of August 1862, Gen. Lee scourged Union forces, routing them at Manassas Junction in the Second Battle of Bull Run, this time, against Maj. Gen. Pope and his Army of Virginia. A number of people, including Maj. Gen. Halleck and Secretary Stanton, thought Lee would turn his attention to Washington. Instead, Lee began the Maryland Campaign. The campaign started with a skirmish at Mile Hill on September 4, followed by a major confrontation at Harpers Ferry. Lincoln, without consulting Stanton, perhaps knowing Stanton would object, merged Pope's Army of Virginia into McClellan's Army of the Potomac. With 90,000 men, McClellan launched his army into the bloody Battle of Antietam, and emerged victorious, pushing the Army of Northern Virginia back into Virginia, and effectively ending Lee's Maryland offensive.[114] McClellan's success at Antietam Creek emboldened him to demand that Lincoln and his government cease obstructing his plans, Halleck and Stanton be removed, and he be made general-in-chief of the Union Army. Meanwhile, he refused to move aggressively against Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia, which was withdrawing towards Richmond. McClellan's unreasonable requests continued, as did his indolence, and Lincoln's patience with him soon grew thin.[115] Lincoln dismissed him from leadership of the Army of the Potomac on November 5. Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside replaced McClellan days later.[116]

Burnside, at Halleck's request, submitted a plan to create a ruse at Culpeper and Gordonsville, while the brunt of his force took Fredericksburg, then moved on to Richmond. Halleck's response was sent on November 14: "The President has just assented to your plan. He thinks that it will succeed, if you move rapidly; otherwise not."[117] The following Battle of Fredericksburg was a disaster, and the Army of the Potomac was handily defeated.[118]

Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker replaced Burnside on January 26, 1863. Stanton did not much care for Hooker, who had loudly denounced Lincoln's administration, and had been insubordinate while serving under Burnside. He would have preferred for Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans to head the army; Lincoln disregarded Stanton's opinion. As Thomas and Hyman tell it, Lincoln "chose Hooker because that general had a reputation as a fighter and stood higher in popular esteem at that moment than any other eastern general."[119] Hooker spent considerable time strengthening the Army of the Potomac, especially regarding morale. Hooker's only major engagement with Lee's Army of Northern Virginia was the Battle of Chancellorsville in early May 1863. Lee had Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson engage Hooker's rearguard in a precipitous flanking maneuver. Stonewall Jackson's maneuver was skilfully employed, resulting a Confederate victory when the fighting ended on May 6, leaving 17,000 Union casualties.[120]

Stanton's attempts to raise Northern spirits after the defeat were hampered by news that, under Hooker, the Army of the Potomac had become grossly undisciplined. Indeed, Hooker's headquarters were described as "combination of barroom and brothel." Stanton petitioned for liquor and women to be forbidden in Hooker's camps.[121] Meanwhile, Lee was again pushing into the North. Lee's movements were wracking nerves in Washington by mid-June, more so when disturbing reports came from Hooker's subordinates, such as that of Brig. Gen. Marsena Patrick: "[Hooker] acts like a man without a plan, & is entirely at a loss what to do, or how to match the enemy, or counteract his movements."[122] Furthermore, like McClellan, Hooker kept overestimating Lee's numbers, and said the Lincoln's administration did not have full confidence in him. Hooker resigned on June 27; Stanton and Lincoln decided that his replacement would be Maj. Gen. George Meade, who was appointed the following day.[123]

Lee and Meade first clashed in the Battle of Gettysburg on July 1. News of a victory at Gettysburg, and a great Confederate retreat, came on July 4. Soon after, word came of Maj. Gen. Grant's victory at Vicksburg. Northerners were exultant. Stanton even gave a rare speech to a huge crowd outside of the War Department's headquarters.[124] The administration's celebrations soon ended, however, when Maj. Gen. Meade refused to launch an attack against Lee while the Army of Northern Virginia was stuck on the banks of the Potomac river. When Lee crossed the river untouched on July 14, Lincoln and Stanton were upset.[125] Stanton affirmed in a letter to a friend that Meade would have his support unreservedly, but that "since the world began no man ever missed so great an opportunity of serving his country as was lost by his neglecting to strike his adversary." Stanton knew, though, that Meade's reluctance came at the advice of his corps commanders, who formerly outranked him.[126]

While action in the Eastern Theater wound down, action in the West heated up. After the two-day Battle of Chickamauga in late September, Maj. Gen. Rosecrans, the commander of the Army of the Cumberland, was left trapped in Chattanooga, Tennessee and beset on all sides by Gen. Braxton Bragg's forces. Rosecrans telegraphed Washington: "We have met a serious disaster, extent not yet ascertained." The situation in Chattanooga was desperate. The North needed the town in its hands. According to journalist Charles Anderson Dana, who had been Stanton's assistant secretary since March 1863,[127] Rosecrans might only be able to fight for another 15–20 more days and that, without at least 20,000 to 25,000 more men, Chattanooga would be lost.[128] Stanton organized the secret transportation of thousands of Union troops west by rail.[108] Lincoln and Stanton agreed to make Maj. Gen. Grant the commander of almost all forces in the West, giving Grant the option to dismiss Rosecrans from command of the Army of the Cumberland and replace him with Maj. Gen. George Henry Thomas.[129] This Grant did. In late November, Grant, with good efforts from Thomas and Hooker, broke Gen. Bragg's siege at Chattanooga, while Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman failed to achieve his stated objective. Confederate Lt. Gen. James Longstreet attempted to besiege Maj. Gen. Burnside's army at Knoxville, but Sherman moved east from Chattanooga, causing the Confederates to retreat.[130]

End of the war

[edit]Grant, having been promoted to the rank of lieutenant general and made the general-in-chief of the Union Army, crossed the Rapidan River on May 4, 1864. The following day, his and Lee's armies clashed in the Battle of the Wilderness. The result was inconclusive, but Grant, unlike previous commanders, was loath to stop his onward push; "there will be no turning back," he told Lincoln.[131] Grant again engaged Lee at Spotsylvania Court House, and again Union losses far exceeded those of the Confederates.[132] Several days later, Grant and Lee battled at Cold Harbor, where Grant launched numerous assaults in an open field, incurring heavy losses. Nevertheless, Grant pushed on, secretly moving his army across the James River in a masterful display of engineering, but failed to take Petersburg, the important rail junction south of Richmond. The Union army was forced to forego further attacks and began entrenching; so began the Siege of Petersburg.[133] "Long lines of parallel entrenchments curled south and east of Richmond as both armies dug in," say Thomas and Hyman. "Grant stabbed at Lee's fortifications, always keeping the pressure on, and at the same time probed westward, feeling for the railroads that brought Lee's supplies."[134]

In the 1864 presidential election, Lincoln and his new Vice President, Andrew Johnson, emerged victorious against their Democratic opponents, George B. McClellan and George H. Pendleton. Republicans also won major congressional and gubernatorial victories in Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky and New York.[135] Stanton played no small part in securing the victory. Several days prior to the election, he ordered soldiers from key states such as Illinois, Lincoln's home state, to be returned home to vote. "The men who were doing the fighting had voted for more of it in order to make their efforts worth while," Thomas and Hyman state. Stanton also used his powers at the War Department to ensure that Republican voters were not harassed or threatened at the polls. Thomas and Hyman credit Stanton's troop furlough and other moves for much of the Republican success in the 1864 elections.[136]

On March 3, 1865, the day before Lincoln's second inauguration, Grant wired to Washington that Lee had sent representatives to him to sue for peace. Lincoln initially told Grant that he should get peace with the South by any means necessary. Stanton declared, however, that it is the president's duty to sue for peace; otherwise, the president is useless and little more than a figure-head. This engendered an immediate change of tone from the president. Stanton, at Lincoln's urging, told Grant that he was to "have no conference with General Lee unless it be for the capitulation of Gen. Lee's army, or on some minor, and purely, military matter". Further, Grant was not to "decide, discuss, or confer upon any political questions. Such matters the President holds in his own hands; and will submit them to no military conferences or conventions". Grant agreed.[137] Days later, Lincoln visited Grant at his siege headquarters (the Siege of Petersburg was still ongoing). Once Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan had rejoined his army from the Shenandoah Valley, Grant prepared to make his final push into Richmond.[138] On April 1, 1865, Sheridan defeated Lee's army in the Battle of Five Forks, forcing a retreat from Petersburg. Stanton, who had stayed close to his telegraph for days, told his wife the following evening: "Petersburg is evacuated and probably Richmond. Put out your flags."[139] Stanton was worried that President Lincoln, who had stayed around to watch Grant's push into Richmond, was in danger of being captured, and warned him. Lincoln disagreed, but was happy for Stanton's concern. The President wrote Stanton: "It is certain now that Richmond is in our hands, and I think I will go there to-morrow."[139]

News of Richmond's fall, which came on April 3,[140] touched off furious excitement throughout the North. "The news spread fast, and people streaming from stores and offices speedily filled the thoroughfares. Cannons began firing, whistles tooted, horns blew, horsecars were forced to a standstill, the crowd yelled and cheered," say Thomas and Hyman.[141] Stanton was overjoyed. At his bidding, candles were put in the windows of each of the Department's properties, while bands played "The Star-Spangled Banner." Furthermore, the department's headquarters were adorned with American flags, along with an image of a bald eagle holding in its talons a scroll with "Richmond" written on it.[141] The night Richmond fell, Stanton tearily gave an impromptu speech to the crowd outside the War Department.[140]

Lee and his army had slipped out of Richmond before its fall, though.[141] Grant marched west to stymie Lee's retreat, while Lincoln remained in Richmond. News of Grant's victories over the withdrawing Confederates lit up Washington's telegraphs. The Union Army was pressing on Lee's tail, and capturing thousands of Confederate prisoners of war. On April 9 Lee finally surrendered, ending the war.[142] On April 13, Stanton suspended conscription and recruiting, as well as the army's acquisition efforts.[143]

Линкольн убит

[ редактировать ]14 апреля Линкольн пригласил Стэнтона, Гранта и их жен присоединиться к нему в театре Форда следующим вечером. Линкольн несколько раз приглашал Стэнтона пойти с ним в театр, но Стэнтон обычно отклонял приглашения. Более того, ни жены Стэнтона, ни жены Гранта не пойдут, если не пойдет другая. В качестве оправдания Гранты использовали поездку к своим детям в Нью-Джерси. Наконец Линкольн решил пойти в театр вместе с майором Генри Рэтбоуном и его невестой. В тот вечер Стэнтон вернулся домой после посещения прикованного к постели секретаря Сьюарда. Он лег спать около 10 часов вечера. Вскоре после этого он услышал крик Эллен снизу: «Мистер Сьюард убит!» [144] Стэнтон бросился вниз. Услышав, что Линкольн тоже может быть мертв, Стэнтон сильно оживился. Он хотел уйти немедленно. Его предупредили: «Выходить нельзя... Подойдя к дому, я увидел за ящиком на дереве человека, но он убежал, и я не последовал за ним». [144] Стэнтон не обращал на этого человека особого внимания; он нашел такси и поехал к дому Сьюарда. [144]

По прибытии Стэнтону сказали, что Линкольн действительно подвергся нападению. Стэнтон приказал поставить под охрану дома всех членов кабинета министров и вице-президента. [145] Стэнтон протолкался сквозь толпу у дома министра и обнаружил Сьюарда без сознания, которого оказывал врач в окровавленной комнате на третьем этаже. Сын Сьюарда, Фредерик , был парализован в результате нападения. Стэнтон и министр военно-морского флота Гидеон Уэллс , которые несколько минут назад пришли в дом Сьюарда, решили пойти в театр Форда, чтобы увидеть президента. Два секретаря поехали в экипаже в сопровождении генерал-квартирмейстера Мейгса и Дэвида К. Картера , судьи окружного суда округа Колумбия . [146]

Стэнтон нашел Линкольна в доме Петерсенов напротив театра. Линкольн лежал на кровати по диагонали из-за своего роста. [146] По некоторым сведениям, когда Стэнтон увидел умирающего президента, он начал плакать. Однако Уильям Марвел в своей книге « Самодержец Линкольна: Жизнь Эдвина Стэнтона» утверждает , что «эмоциональная отстраненность Стэнтона и его властная личность сделали его ценным в ту ночь, когда другие погрязли в тоске». [147] Томас и Хайман также заявляют: «Раньше всегда близкая смерть выводила его из равновесия до точки дисбаланса. Теперь он казался спокойным, мрачным, решительным, полностью внешне контролирующим себя». [148] Эндрю Джонсон, о котором Стэнтон и страна мало что знали, был приведен к присяге в качестве президента в 11 часов утра 15 апреля в отеле «Кирквуд» . [149] Однако Стэнтон, который планировал уйти в отставку в конце войны, «действительно фактически контролировал правительство», говорят Томас и Хайман. «Он руководил армией, Джонсон едва был приведен к присяге и совершенно не уверен в себе, а Конгресс не заседал». [150]

Стэнтон приказал взять показания у тех, кто видел нападение. Свидетели обвинили актера Джона Уилкса Бута . в убийстве [151] Стэнтон поставил всех солдат в Вашингтоне на стражу, [152] и приказал закрыть город. [153] Железнодорожное движение на юг должно было быть остановлено, а рыбацкие лодки на Потомаке не должны были приходить на берег. [152] Стэнтон также перезвонил Гранту в столицу из Нью-Джерси . [147]

15 апреля Вашингтон был, как сказал журналист Джордж А. Таунсенд , «полон детективной полиции». По просьбе Стэнтона полицейское управление Нью-Йорка . к неутомимым поискам Бута и сообщников присоединилось [154] У Стэнтона была нижняя палуба монитора USS Montauk , который располагался недалеко от Вашингтонской военно-морской верфи . [155] принимают у себя нескольких заговорщиков, Льюиса Пауэлла , Майкла О'Лафлена , Эдмунда Спенглера и Джорджа Ацеродта . Остальные заговорщики, кроме Бута и Мэри Сурратт , находились на борту военного корабля США « Саугус» . Заключенные на обеих лодках были связаны шаром и цепью , и наручниками прикрепленными к железному стержню. Стэнтон также приказал надеть на головы пленников мешок с отверстием в нем, чтобы можно было есть и дышать. [156] Сурратт содержалась в тюрьме Старого Капитолия , где она находилась с момента ареста. [157] Бут, оставшийся виновник, был застрелен в сарае в Вирджинии Бостоном Корбеттом и вскоре умер. Тело Бута было помещено на борт « Монтаука» . После того, как было проведено вскрытие и личность Бута была подтверждена вне всякого сомнения, он был похоронен в «секретной, безымянной и неосвящённой могиле» по приказу Стэнтона. Стэнтон знал, что Бута будут прославлять на Юге, и думал, что никому не даст такой возможности. [158] Заговорщиков предстали перед судом и признали виновными. Все, кроме троих, были повешены . [159]

Администрация Джонсона (1865–1868)

[ редактировать ]Перемирие Шермана

[ редактировать ]

Генерал-лейтенант Грант, не найдя Стэнтона в военном министерстве, вечером 21 апреля отправил с курьером записку к себе домой. Дело было срочным. [160] Генерал-майор Шерман, разместивший штаб своей армии в Роли, Северная Каролина , заключил мирное соглашение с командующим Конфедерации генералом Джозефом Э. Джонстоном с милости военного министра Конфедеративных Штатов Джона К. Брекинриджа . Шерману было разрешено вести переговоры с южанами только по военным вопросам, как Грант был уполномочен Ли. Шерман прямо признал, что его переговоры с лидерами Конфедерации должны были оставаться в сфере военной политики, но все равно проигнорировал ограничения. Соглашение Шермана, как и ожидалось, предусматривало прекращение военных действий с Югом, но также оговаривало, что правительства Юга, восставшие против Соединенных Штатов, должны были быть признаны федеральным правительством после того, как они присягнули на верность Соединенным Штатам. Кроме того, условия сделки предусматривали восстановление федеральных судов в мятежных штатах, а также восстановление собственности и избирательных прав южан, а также полное помилование восставших южан. Сделка пошла еще дальше, позволив южным войскам передать свое оружие в руки правительств своих штатов, что фактически перевооружило бы южные штаты. Перемирие Шермана также наделило Верховный суд полномочиями разрешать споры о юрисдикции между органами власти штата и местными властями на Юге, что было политическим вопросом, а не юридическим вопросом, что делало эти полномочия судом не имеющимися по конституции. [161]

Курьер прибыл в дом Стэнтона, запыхавшись, прервав его ужин. Услышав эту новость, Стэнтон «в состоянии сильного волнения» бросился в военное министерство. Он послал за всеми членами кабинета от имени президента. Кабинет Джонсона вместе с Грантом и Престоном Кингом , советником Джонсона, собрался в тот же вечер в 8 часов вечера. Слухи о действиях Шермана были встречены присутствующими единодушным осуждением. Президент Джонсон поручил Стэнтону сообщить Шерману, что его сделка была отклонена и что «военные действия должны быть немедленно возобновлены после направления конфедератам уведомления за сорок восемь часов, необходимого для прекращения перемирия». Грант должен был немедленно отправиться в Роли, чтобы сообщить Шерману об указе Стэнтона, а также принять на себя командование войсками на Юге. [162]

Стэнтон сообщил об этом прессе. Помимо обнародования деталей сделки Шермана, Стэнтон заявил, что Шерман намеренно игнорировал прямые приказы Линкольна и Джонсона, и перечислил девять причин, по которым сделка Шермана была категорически отклонена. Кроме того, Стэнтон обвинил Шермана в том, что он безрассудно открыл путь, по которому Джефферсон Дэвис мог бежать из страны с деньгами, которые Дэвис якобы взял с собой после того, как покинул Ричмонд. [163] Последнее утверждение было основано на выводе Шерманом сил генерал-майора Джорджа Стоунмана с железной дороги Гринсборо - Гринсборо был местом, куда бежали Дэвис и другие официальные лица Конфедерации. [162] Слова Стэнтона были убийственными. «Это было равносильно критике Шермана и фактически обвинению его в нелояльности», - говорят Томас и Хайман. Более того, поскольку Шерман был одним из самых уважаемых генералов в стране, публикация Стэнтона поставила под угрозу его место в администрации. [163]

Не видя послания Стэнтона прессе, Шерман написал Стэнтону примирительное письмо, назвав его соглашение «глупостью» и заявив, что, хотя он все еще считает, что его сделка с Джонстоном и Брекинриджем была прочной, он не имеет права оспаривать решение своего начальника и что он будет выполнять приказы. [164] Тем временем генерал-майор Халлек по просьбе Гранта сообщил нескольким подчиненным Шермана, что они должны перебросить свои войска в Северную Каролину, независимо от того, что скажет Шерман. Халлек разослал генералам Шермана еще одну депешу, в которой просил их вообще не слушать указы Шермана. После приказа Халлека и прочтения послания Стэнтона прессе в газете ярость Шермана достигла головокружительного, взрывного тона. Шерман считал, что Стэнтон неоправданно охарактеризовал его как нелояльного изгоя. «Я уважаю офис [Стэнтона], но не могу его лично, пока он не исправит несправедливость прошлого», - сказал Шерман Гранту. [165] Брат Шермана, сенатор Джон Шерман , хотел, чтобы генерала осудили за его действия, но при этом к нему относились справедливо. Сам Шерман и влиятельная семья его жены , Юинги, хотели, чтобы Стэнтон публично отказался от своих заявлений. Стэнтон, что характерно, отказался. [166]

В конце мая состоится Большой смотр армий , во время которого армия Союза пройдет парадом по улицам Вашингтона. Халлек предложил Шерману гостеприимство в своем доме; генерал наотрез отказался. Он сообщил Гранту о своем отказе, заявив также, что он будет слушать приказы Стэнтона только в том случае, если они также будут явно санкционированы президентом. Шерман далее заявил, что «опровержение или малодушное оправдание» больше не помогут. Единственное, что приемлемо для Шермана, — это объявить Стэнтона себя «обычным клеветником». «Я буду относиться к мистеру Стэнтону с таким же презрением и презрением, если у вас нет иных причин, поскольку я считаю, что моя военная карьера окончена, за исключением случаев, когда это необходимо, чтобы отдать мою армию в ваши руки». [167]

Шерман сдержал свое обещание. На Гранд-ревью Шерман приветствовал президента и Гранта, но пренебрег военным министром, пройдя мимо него без рукопожатия на виду у публики. Стэнтон не дал немедленного ответа. Журналист Ной Брукс написал: «Лицо Стэнтона, никогда не очень выразительное, оставалось неподвижным». [168] Это оскорбление вызвало слухи о том, что Стэнтон собирается уйти в отставку. Стэнтон тоже подумывал покинуть свой пост, но по просьбе президента и многих других, в том числе военных, остался. Чтобы исправить ситуацию, жена Шермана приносила Стэнтонам цветы и проводила время в их доме, но Шерман продолжал питать обиду на Стэнтона. [169]

Реконструкция

[ редактировать ]Война была окончена, и перед Стэнтоном теперь стояла серьезная задача по перестройке американского военного ведомства таким образом, чтобы в мирное время он был таким же боеспособным аппаратом, каким он оказался в военное время. [170] С этой целью на Севере Стэнтон реорганизовал армию на две части; один занимался «обучением и церемониальными обязанностями», а другой - подавлял американских индейцев на западе, которые были взволнованы и буйны в результате войны. [171] На Юге первоочередной задачей было устранение вакуума власти, образовавшегося в южных штатах после восстания. [172] Стэнтон представил президенту свое предложение о военной оккупации, которое было одобрено Линкольном: в Вирджинии и Северной Каролине будут созданы два военных правительства с маршалами-провостами для обеспечения соблюдения законов и установления порядка - задачи, с которыми маршалы оказались наиболее способными в недель после окончания войны. [173]

Президент Джонсон пообещал своему кабинету министров на их первом заседании 15 апреля, что он поддержит планы своего предшественника по Реконструкции , планы, которые покойный президент подробно обсуждал со Стэнтоном. [174] [Примечание 5] 29 мая 1865 г. Джонсон издал две прокламации; один назначил Уильяма Вудса Холдена временным губернатором Северной Каролины, а другой помиловал лиц, участвовавших в восстании, за некоторыми исключениями, если они согласились на лояльность и принятие всех законов и указов, касающихся рабства. [176] Джонсон также признал правительство Фрэнсиса Харрисона Пирпонта в Вирджинии, а также правительства в Арканзасе , Луизиане и Теннесси Линкольна , которые были сформированы в соответствии с десятипроцентным планом . Кроме того, Джонсон предложил десятипроцентный план нескольким другим южным штатам. [177]

В своем послании Конгрессу в 1865 году демократ Джонсон утверждал, что единственным необходимым доказательством лояльности, которое должно было показать государство, является ратификация Тринадцатой поправки . Республиканцы в Конгрессе не согласились; Сенатор Чарльз Самнер и член Палаты представителей Таддеус Стивенс считали, что избирательное право чернокожих жизненно необходимо для безопасности страны и дальнейшего доминирования Республиканской партии. Республиканцы использовали парламентские процедуры, чтобы гарантировать, что ни один из южных делегатов, которые в основном были бывшими лидерами Конфедерации, не заняли места в Конгрессе, и создали преимущественно республиканский объединенный комитет для решения вопросов Реконструкции. [178]

Что касается Реконструкции, президент и Конгресс были глубоко разделены. Джонсон, даже когда его политика амнистии подверглась резкой критике, упорно поддерживал и продолжал ее. Однако республиканцы в Конгрессе отдали предпочтение предложению Стэнтона о военной оккупации. [179] Поддержка президента со стороны умеренных республиканцев уменьшилась после ужасных антинегритянских беспорядков в Мемфисе и Новом Орлеане . [180] Общественность, похоже, тоже была против Джонсона. На выборах в Конгресс 1866 года республиканцы добились огромных успехов над своими соперниками-демократами. На в Палату представителей и выборах Сенат республиканцы получили большинство в две трети мест. [181] В новом году некоторые республиканцы попытались использовать свое большинство, чтобы свергнуть Джонсона. Они представили законопроект о сроках пребывания в должности , написанный с учетом Стэнтона. [182] Президент давно подумывал об увольнении Стэнтона и замене его генерал-майором Шерманом; Законопроект о сроке пребывания в должности сделал бы это незаконным без совета и согласия Конгресса, которое вряд ли было дано Стэнтону, которого твердо поддерживали республиканцы и сотрудничали с ними. Когда законопроект попал на стол президента, он наложил на него вето. В тот же день его вето было преодолено. [183]

Благодаря защите, обеспечиваемой Законом о сроке пребывания в должности, оппозиция Стэнтона Джонсону стала более открытой. [184] В последующие месяцы Джонсон все больше раздражался своим военным министром. [185] Джонсон сказал Гранту, что намерен сместить Стэнтона и передать ему пост военного министра. Грант выступил против этой идеи. Он выступал за сохранение Стэнтона и заявил, что Закон о сроке пребывания в должности защищает Стэнтона. Кроме того, сказал Грант, если закон о землевладении окажется бессильным, общественное мнение еще больше настроится против администрации. Сьюард, который все еще очень уважал Стэнтона, также не согласился с его отстранением. [186] Слова этих двух мужчин заставили Джонсона пошатнуться в неуверенности; однако его воля была усилена поддержкой со стороны секретаря Уэллса и Сэлмона Чейза, ныне главного судьи Верховного суда - первый ранее описывал Стэнтона как «эгоистичного, неискреннего, лицемера и предателя», а второй разорвал свою дружбу со Стэнтоном. в поддержку его политических устремлений. [187] 12 августа 1867 года Джонсон отправил Стэнтону записку, в которой говорилось, что он отстранен от должности военного министра и должен передать файлы и полномочия департамента Гранту. В соответствии с Законом о сроках пребывания в должности он также уведомил Сенат о его рассмотрении. Стэнтон неохотно, но без особого сопротивления, подчинился. [188]

Импичмент

[ редактировать ]

13 января 1868 года Сенат подавляющим большинством голосов проголосовал за восстановление Стэнтона на посту военного министра. Грант, опасаясь предусмотренного Законом наказания в виде штрафа в размере 10 000 долларов и пяти лет тюремного заключения, вдвойне из-за его высокой вероятности стать кандидатом в президенты от республиканской партии на предстоящих выборах, немедленно сдал свой пост. [189] Вскоре после этого Стэнтон вернулся в военное министерство в «необычайно хорошем настроении и непринужденной беседе», как сообщали газеты. [190] Его возвращение вызвало волну поздравительных писем и жестов, в которых выражалась благодарность за его оппозицию крайне нелюбимому Джонсону. Тем временем президент снова начал искать подходящего человека, который возглавил бы военное министерство, но через несколько недель, похоже, принял восстановление Стэнтона в отставке. Однако он действительно пытался уменьшить власть офиса Стэнтона, регулярно игнорируя это. Однако благодаря своей способности подписывать казначейские ордера и поддержке Конгресса Стэнтон по-прежнему обладал значительной властью. [191]

Джонсон сосредоточился исключительно на разыгрывании падения Стэнтона. «Больше не в силах выносить оскорбление Конгресса, нанесенное врагом его официальной семье, — говорит Марвел, — Джонсон начал обдумывать возможность полного отстранения Стэнтона и замены его кем-то достаточно приемлемым, чтобы получить одобрение Сената». [192] Джонсон искал Лоренцо Томаса , генерал-адъютанта армии, вместо Стэнтона, на что тот согласился. 21 февраля Джонсон уведомил Конгресс, что увольняет Стэнтона и назначает Томаса временным секретарем . Стэнтон, по настоянию сенаторов-республиканцев, отказался уступить свой пост. Той ночью республиканцы в Сенате, несмотря на сопротивление демократов, протолкнули резолюцию, объявляющую отстранение Стэнтона незаконным. В Палате представителей было представлено предложение об импичменте Джонсону. 24 февраля предложение было одобрено, и Джонсону был объявлен импичмент, при этом партийная линия составила 126 «за» и 47 «против». [193]

Суд над Джонсоном начался в конце марта. Учитывая, что в Сенате преобладают республиканцы, приговор Джонсону казался многим предрешенным. Однако на протяжении всего процесса некоторые сенаторы начали проявлять нерешительность по поводу отстранения президента от должности. Тем временем Стэнтон несколько недель оставался забаррикадированным в штаб-квартире военного министерства, время от времени ускользая, чтобы навестить свой дом. Когда Стэнтону показалось, что Джонсон не отстранит его принудительно от должности, он стал проводить больше времени дома. Стэнтон внимательно следил за тем, как судебный процесс, который, как он был убежден, закончится вынесением приговора Джонсону, продолжался несколько месяцев. Когда пришло время голосовать, 35 человек проголосовали за осуждение, 19 — за оправдание, что на один балл меньше сверхбольшинства в 36 голосов , необходимого для вынесения обвинительного приговора. Остальные слушания были отложены на несколько дней из-за Национального съезда Республиканской партии . 26 мая, после того как Джонсон был оправдан по всем десяти другим обвинениям, Стэнтон подал президенту прошение об отставке. [194]

Спустя годы и смерть

[ редактировать ]Предвыборная кампания 1868 года

[ редактировать ]После оправдания Джонсона и отставки Стэнтона администрация Джонсона ухватилась за версию о том, что те, кто хотел его импичмента, были жестокосердными, особенно Стэнтон. Однако Стэнтон покинул свой пост при сильной поддержке общественности и республиканцев. Однако в остальном Стэнтон находился в опасности. Его здоровье было в тяжелом состоянии, что стало результатом его неустанных усилий во время и после войны, а его финансов очень не хватало. После отставки Стэнтону остались лишь остатки зарплаты и кредит в 500 долларов. Стэнтон отклонил призывы своих коллег-республиканцев баллотироваться в Сенат, решив вместо этого возобновить свою юридическую практику. [195]

Законодательные усилия Стэнтона застопорились, когда в августе 1868 года его вызвал Роберт К. Шенк , кандидат от республиканской партии на одно из мест от Огайо в Палате представителей. Соперник Шенка, демократ Клемент Валландигэм , был хорошо известен среди республиканцев своей политикой Копперхеда и не нравился Стэнтону. [196] Полагая, что победа демократов на любом уровне поставит под угрозу результаты войны и сведет на нет усилия республиканцев во время войны, Стэнтон отправился в турне по Огайо, чтобы провести кампанию за Шенка, других республиканцев Огайо и Гранта, кандидата в президенты от республиканской партии. [197] Тем временем здоровье Стэнтона продолжало ухудшаться. Его врач предостерег его от длинных речей, поскольку его сильно раздражала астма. Болезнь Стэнтона ускорила его возвращение в Вашингтон в начале ноября. Его слабое состояние сменилось волнением, когда республиканцы одержали победу в гонке Шенка-Валландингема и на президентских выборах. [198]

Болезнь ухудшается

[ редактировать ]После этого Стэнтон приступил к рассмотрению дела в федеральном суде Пенсильвании, касающегося спорных земель Западной Вирджинии, которые оценивались в миллионы долларов из-за находящегося на них угля и древесины. К этому времени болезнь Стэнтона стала болезненно заметной. [Примечание 6] Он настолько заболел, что документы по делу пришлось доставить ему на дом. Суд вынес решение против клиента Стэнтона, но Стэнтон выиграл апелляцию в Верховном суде США о возвращении дела в суд низшей инстанции. На Рождество Стэнтон не мог спуститься по лестнице своего дома, поэтому семья праздновала в его комнате. [200]

В то время многие предполагали, что Грант, который в течение нескольких месяцев по большей части игнорировал Стэнтона, должен был вознаградить его за его предвыборную кампанию. Стэнтон заявил, однако, что, если ему будет предложена должность в администрации Гранта, он отклонит ее. Конгрессмен от Огайо Сэмюэл Шеллабаргер написал: «[Стэнтон] говорит, что жить ему осталось недолго, и он должен посвятить это время своей семье…» [201] В начале нового года Стэнтон готовил провизию на свою смерть. Однако с приходом весны состояние Стэнтона улучшилось. Когда помолодевший Стэнтон появился на расследовании в Конгрессе, переговоры о награждении Гранта Стэнтона возобновились. [202] Некоторые считали, что Стэнтон хорошо подходит на уважаемую роль посла в Англии; вместо этого Грант предложил Стэнтону дипломатическую миссию США в Мексике, но тот отказался. [203]

Номинация в Верховный суд

[ редактировать ]Здоровье Стэнтона менялось на протяжении большей части 1869 года. [204] Во второй половине года, узнав о том, что Конгресс учредил новое место помощника судьи в Верховном суде, Стэнтон решил, что он будет лоббировать у Гранта назначение его на эту должность. Стэнтон использовал близкого друга Гранта, епископа Мэтью Симпсона , в качестве своего доверенного лица, чтобы убедить Гранта в его пригодности для работы в Верховном суде. [205] [206] Однако Грант обошел Стэнтона и 14 декабря 1869 года назначил на это место генерального прокурора Эбенезера Р. Хоара . На следующий день помощник судьи Роберт Купер Гриер объявил о своей отставке с датой вступления в силу 1 февраля 1870 года, создав таким образом еще одну вакансию. для Гранта, чтобы заполнить. Петиции в поддержку назначения Стэнтона для заполнения вакансии в Суде были распространены как в Палате представителей, так и в Сенате. Они были доставлены президенту 18 декабря 1869 года. Грант и вице-президент Колфакс отправились в дом Стэнтона, чтобы лично продлить номинацию 19 декабря, в день 55-летия Стэнтона. [205] [207] Грант официально представил свою кандидатуру в Сенат 20 декабря, и Стэнтон был утвержден в тот же день 46 голосами против 11. [208] На следующий день Стэнтон написал письмо о принятии подтверждения, но умер, не успев вступить в должность помощника судьи. [205] Он остается единственным утвержденным кандидатом в Верховный суд, который согласился, но умер до принятия предписанной присяги.

Смерть и похороны

[ редактировать ]В ночь на 23 декабря Стэнтон пожаловался на боли в голове, шее и позвоночнике. его врача, главного хирурга Джозефа Барнса Вызвали . Как и в предыдущие ночи, астма Стэнтона затрудняла дыхание. Легкие и сердце Стэнтона сжимались, из-за чего жена и дети Стэнтона, а также Барнс оставались у его постели. [209] Состояние Стэнтона начало улучшаться в полночь, но затем он начал, как утверждает Марвин, «[задыхаться] так сильно, что кто-то побежал за пастором церкви Богоявления, и вскоре после его прибытия Стэнтон потерял сознание». [207] Стэнтон умер около 3 часов ночи 24 декабря 1869 года. [207]