Президентство Ричарда Никсона

| |

| Президентство Ричарда Никсона 20 января 1969 г. - 9 августа 1974 г. [1] | |

| Кабинет | Посмотреть список |

|---|---|

| Вечеринка | республиканец |

| Выборы | |

| Seat | White House |

| Library website | |

| ||

|---|---|---|

Pre-vice presidency 36th Vice President of the United States Post-vice presidency 37th President of the United States

Judicial appointments Policies First term

Second term

Post-presidency Presidential campaigns Vice presidential campaigns  | ||

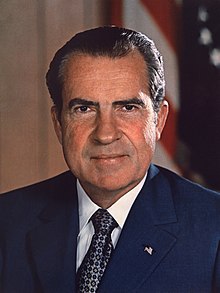

Ричарда Никсона Срок пребывания на посту 37-го президента США начался с его первой инаугурации 20 января 1969 года и закончился, когда он ушел в отставку 9 августа 1974 года, несмотря на почти неизбежный импичмент и отстранение от должности, единственного в США президент когда-либо делал это. Его сменил Джеральд Форд , которого он назначил вице-президентом после того, как Спиро Агнью оказался втянутым в отдельный коррупционный скандал и был вынужден уйти в отставку. Никсон, видный член Республиканской партии из Калифорнии , ранее занимавший пост вице-президента в течение двух сроков при президенте Дуайте Д. Эйзенхауэре , вступил в должность после своей незначительной победы над от Демократической партии действующим вице-президентом Хьюбертом Хамфри и Американской независимой партии кандидатом от Джорджем Уоллесом на выборах 1968 года. президентские выборы . Четыре года спустя, на президентских выборах 1972 года , он победил кандидата от демократов Джорджа Макговерна и с большим перевесом выиграл переизбрание. Хотя он заработал себе репутацию очень активного республиканского борца , Никсон преуменьшил значение своей партийной принадлежности во время своего убедительного переизбрания в 1972 году.

Nixon's primary focus while in office was on foreign affairs. He focused on détente with the People's Republic of China and the Soviet Union, easing Cold War tensions with both countries. As part of this policy, Nixon signed the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty and SALT I, two landmark arms control treaties with the Soviet Union. Nixon promulgated the Nixon Doctrine, which called for indirect assistance by the United States rather than direct U.S. commitments as seen in the ongoing Vietnam War. After extensive negotiations with North Vietnam, Nixon withdrew the last U.S. soldiers from South Vietnam in 1973, ending the military draft that same year. To prevent the possibility of further U.S. intervention in Vietnam, Congress passed the War Powers Resolution over Nixon's veto.

In domestic affairs, Nixon advocated a policy of "New Federalism", in which federal powers and responsibilities would be shifted to state governments. However, he faced a Democratic Congress that did not share his goals and, in some cases, enacted legislation over his veto. Nixon's proposed reform of federal welfare programs did not pass Congress, but Congress did adopt one aspect of his proposal in the form of Supplemental Security Income, which provides aid to low-income individuals who are aged or disabled. The Nixon administration adopted a "low profile" on school desegregation, but the administration enforced court desegregation orders and implemented the first affirmative action plan in the United States. Nixon also presided over the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency and the passage of major environmental laws like the Clean Water Act, although that law was vetoed by Nixon and passed by override. Economically, the Nixon years saw the start of a period of "stagflation" that would continue into the 1970s.

Nixon was far ahead in the polls in the 1972 presidential election, but during the campaign, Nixon operatives conducted several illegal operations designed to undermine the opposition. They were exposed when the break-in of the Democratic National Committee Headquarters ended in the arrest of five burglars and gave rise to a congressional investigation. Nixon denied any involvement in the break in, but, after a tape emerged revealing that Nixon had known about the White House connection to the Watergate burglaries shortly after they occurred, the House of Representatives initiated impeachment proceedings. Facing removal by Congress, Nixon resigned from office. Though some scholars believe that Nixon "has been excessively maligned for his faults and inadequately recognised for his virtues",[2] Nixon is generally ranked as a below average president in surveys of historians and political scientists.[3][4][5]

1968 election[edit]

Republican nomination[edit]

Richard Nixon had served as vice president from 1953 to 1961, and had been defeated in the 1960 presidential election by John F. Kennedy. In the years after his defeat, Nixon established himself as an important party leader who appealed to both moderates and conservatives.[6] Nixon entered the race for the 1968 Republican presidential nomination confident that, with the Democrats torn apart over the war in Vietnam, a Republican had a good chance of winning the presidency in November, although he expected the election to be as close as in 1960.[7] One year prior to the 1968 Republican National Convention the early favorite for the party's presidential nomination was Michigan governor George Romney, but Romney's campaign foundered on the issue of the Vietnam War.[8] Nixon established himself as the clear front-runner after a series of early primary victories. His chief rivals for the nomination were Governor Ronald Reagan of California, who commanded the loyalty of many conservatives, and Governor Nelson Rockefeller of New York, who had a strong following among party moderates.[9]

At the August Republican National Convention in Miami Beach, Florida, Reagan and Rockefeller discussed joining forces in a stop-Nixon movement, but the coalition never materialized and Nixon secured the nomination on the first ballot.[10] He selected Governor Spiro Agnew of Maryland as his running mate, a choice which Nixon believed would unite the party by appealing to both Northern moderates and Southerners disaffected with the Democrats.[11] The choice of Agnew was poorly received by many; a Washington Post editorial described Agnew as "the most eccentric political appointment since the Roman Emperor Caligula named his horse a consul.[12] In his acceptance speech, Nixon articulated a message of hope, stating, "We extend the hand of friendship to all people... And we work toward the goal of an open world, open sky, open cities, open hearts, open minds."[13]

General election[edit]

At the start of 1967, most Democrats expected that President Lyndon B. Johnson would be re-nominated. Those expectations were shattered by Senator Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota, who centered his campaign on opposition to Johnson's policies on the Vietnam War.[14] McCarthy narrowly lost to Johnson in the first Democratic Party primary on March 12 in New Hampshire, and the closeness of the results startled the party establishment and spurred Senator Robert F. Kennedy of New York to enter the race. Two weeks later, Johnson told a stunned nation that he would not seek a second term. In the weeks that followed, much of the momentum that had been moving the McCarthy campaign forward shifted toward Kennedy.[15] Vice President Hubert Humphrey declared his own candidacy, drawing support from many of Johnson's supporters. Kennedy was assassinated by Sirhan Sirhan in June 1968, leaving Humphrey and McCarthy as the two remaining major candidates in the race.[16] Humphrey won the presidential nomination at the August Democratic National Convention in Chicago, and Senator Edmund Muskie of Maine was selected as his running mate. Outside the convention hall, thousands of young antiwar activists who had gathered to protest the Vietnam War clashed violently with police. The mayhem, which had been broadcast to the world in television, crippled the Humphrey campaign. Post-convention Labor Day surveys had Humphrey trailing Nixon by more than 20 percentage points.[17]

In addition to Nixon and Humphrey, the race was joined by former Democratic Governor George Wallace of Alabama, a vocal segregationist who ran on the American Independent Party ticket. Wallace held little hope of winning the election outright, but he hoped to deny either major party candidate a majority of the electoral vote, thus sending the election to the House of Representatives, where segregationist congressmen could extract concessions for their support.[18] The assassinations of Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr., combined with disaffection towards the Vietnam War, the disturbances at the Democratic National Convention, and a series of city riots in various cities, made 1968 the most tumultuous year of the decade.[19] Throughout the year, Nixon portrayed himself as a figure of stability during a period of national unrest and upheaval.[20] He appealed to what he later called the "silent majority" of socially conservative Americans who disliked the 1960s counterculture and the anti-war demonstrators.[21] Nixon waged a prominent television advertising campaign, meeting with supporters in front of cameras.[22] He promised "peace with honor" in the Vietnam War but did not release specifics of how he would accomplish this goal, resulting in media intimations that he must have a "secret plan".[23]

Humphrey's polling position improved in the final weeks of the campaign as he distanced himself from Johnson's Vietnam policies.[24] Johnson sought to conclude a peace agreement with North Vietnam in the week before the election; controversy remains over whether the Nixon campaign interfered with any ongoing negotiations between the Johnson administration and the South Vietnamese by engaging Anna Chennault, a prominent Chinese-American fundraiser for the Republican party.[25] Whether or not Nixon had any involvement, the peace talks collapsed shortly before the election, blunting Humphrey's momentum.[24]

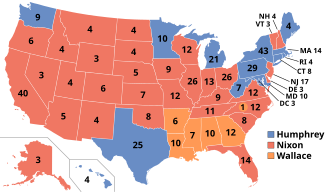

On election day, Nixon defeated Humphrey by about 500,000 votes, 43.4% to 42.7%; Wallace received 13.5% of the vote. Nixon secured 301 electoral votes to Humphrey's 191 and 46 for Wallace.[17][26] Nixon gained the support of many white ethnic and Southern white voters who traditionally had supported the Democratic Party, but he lost ground among African American voters.[27] In his victory speech, Nixon pledged that his administration would try to bring the divided nation together.[28] Despite Nixon's victory, Republicans failed to win control of either the House or the Senate in the concurrent congressional elections.[27]

Administration[edit]

Cabinet[edit]

For the major decisions of his presidency, Nixon relied on the Executive Office of the President rather than his Cabinet. Chief of Staff H. R. Haldeman and adviser John Ehrlichman emerged as his two most influential staffers regarding domestic affairs, and much of Nixon's interaction with other staff members was conducted through Haldeman.[29] Early in Nixon's tenure, conservative economist Arthur F. Burns and liberal former Johnson administration official Daniel Patrick Moynihan served as important advisers, but both had left the White House by the end of 1970.[30] Conservative attorney Charles Colsonalso emerged as an important adviser after he joined the administration in late 1969.[31] Unlike many of his fellow Cabinet members, Attorney General John N. Mitchell held sway within the White House, and Mitchell led the search for Supreme Court nominees.[32] In foreign affairs, Nixon enhanced the importance of the National Security Council, which was led by National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger.[29] Nixon's first Secretary of State, William P. Rogers, was largely sidelined during his tenure, and in 1973, Kissinger succeeded Rogers as Secretary of State while continuing to serve as National Security Advisor. Nixon presided over the reorganization of the Bureau of the Budget into the more powerful Office of Management and Budget, further concentrating executive power in the White House.[29] He also created the Domestic Council, an organization charged with coordinating and formulating domestic policy.[33] Nixon attempted to centralize control over the intelligence agencies, but he was generally unsuccessful, in part due to pushback from FBI director J. Edgar Hoover.[34]

Despite his centralization of power in the White House, Nixon allowed his cabinet officials great leeway in setting domestic policy in subjects he was not strongly interested in, such as environmental policy.[35] In a 1970 memo to top aides, he stated that in domestic areas other than crime, school integration, and economic issues, "I am only interested when we make a major breakthrough or have a major failure. Otherwise don't bother me."[36] Nixon recruited former campaign rival George Romney to serve as the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, but Romney and Secretary of Transportation John Volpe quickly fell out of favor as Nixon attempted to cut the budgets of their respective departments.[37] Nixon did not appoint any female or African American cabinet officials, although Nixon did offer a cabinet position to civil rights leader Whitney Young.[38] Nixon's initial cabinet also contained an unusually small number of Ivy League graduates, with the notable exceptions of George P. Shultz and Elliot Richardson, who each held three different cabinet positions during Nixon's presidency.[39] Nixon attempted to recruit a prominent Democrat like Humphrey or Sargent Shriver into his administration, but was unsuccessful until early 1971, when former Governor John Connally of Texas became Secretary of the Treasury.[38] Connally would become one of the most powerful members of the cabinet and coordinated the administration's economic policies.[40]

In 1973, as the Watergate scandal came to light, Nixon accepted the resignations of Haldeman, Erlichman, and Mitchell's successor as Attorney General, Richard Kleindienst.[41] Haldeman was succeeded by Alexander Haig, who became the dominant figure in the White House during the last months of Nixon's presidency.[42]

Vice presidency[edit]

As the Watergate scandal heated up in mid-1973, Vice President Spiro Agnew became a target in an unrelated investigation of corruption in Baltimore County, Maryland of public officials and architects, engineering, and paving contractors. He was accused of accepting kickbacks in exchange for contracts while serving as Baltimore County Executive, then when he was Governor of Maryland and Vice President.[43]

On October 10, 1973, Agnew pleaded no contest to tax evasion and became the second Vice President after John C. Calhoun to resign from office.[43] Nixon used his authority under the 25th Amendment to nominate Gerald Ford for vice president. The well-respected Ford was confirmed by Congress and took office on December 6, 1973.[44][45] This represented the first time that an intra-term vacancy in the office of vice president was filled. The Speaker of the House, Carl Albert from Oklahoma, was next in line to the presidency during the 57-day vacancy.

Judicial appointments[edit]

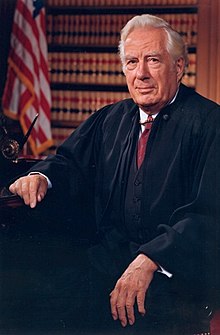

Nixon made four successful appointments to the Supreme Court while in office, shifting the Court in a more conservative direction following the era of the liberal Warren Court.[46] Nixon took office with one pending vacancy, as the Senate had rejected President Johnson's nomination of Associate Justice Abe Fortas to succeed retiring Chief Justice Earl Warren. Months after taking office, Nixon nominated federal appellate judge Warren E. Burger to succeed Warren, and the U.S. Senate quickly confirmed him. Another vacancy arose in 1969 after Fortas resigned from the Court, partially due to pressure from Attorney General Mitchell and other Republicans who criticized him for accepting compensation from financier Louis Wolfson.[47] To replace Fortas, Nixon successively nominated two Southern federal appellate judges, Clement Haynsworth and G. Harrold Carswell, but both were rejected by the Senate. Nixon then nominated federal appellate judge Harry Blackmun, who was confirmed by the Senate in 1970.[48]

The retirements of Hugo Black and John Marshall Harlan II created two Supreme Court vacancies in late 1971. One of Nixon's nominees, corporate attorney Lewis F. Powell Jr., was easily confirmed. Nixon's other 1971 Supreme Court nominee, Assistant Attorney General William Rehnquist, faced significant resistance from liberal Senators, but he was ultimately confirmed.[48] Burger, Powell, and Rehnquist all compiled a conservative voting record on the Court, while Blackmun moved to the left during his tenure. Rehnquist would later succeed Burger as chief justice in 1986.[46] Nixon appointed a total of 231 federal judges, surpassing the previous record of 193 set by Franklin D. Roosevelt. In addition to his four Supreme Court appointments, Nixon appointed 46 judges to the United States Courts of Appeals, and 181 judges to the United States district courts.

Domestic affairs[edit]

Economy[edit]

| Fiscal Year | Receipts | Outlays | Surplus/ Deficit | GDP | Debt as a % of GDP[50] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1969 | 186.9 | 183.6 | 3.2 | 980.3 | 28.4 |

| 1970 | 192.8 | 195.6 | −2.8 | 1,046.7 | 27.1 |

| 1971 | 187.1 | 210.2 | −23.0 | 1,116.6 | 27.1 |

| 1972 | 207.3 | 230.7 | −23.4 | 1,216.3 | 26.5 |

| 1973 | 230.8 | 245.7 | −14.9 | 1,352.7 | 25.2 |

| 1974 | 263.2 | 269.4 | −6.1 | 1,482.9 | 23.2 |

| 1975 | 279.1 | 332.3 | −53.2 | 1,606.9 | 24.6 |

| Ref. | [51] | [52] | [53] | ||

When Nixon took office in January 1969, the inflation rate had reached 4.7%, the highest rate since the Korean War. Johnson's Great Society programs and the Vietnam War effort had resulted in large budget deficits. There was little unemployment,[54] but interest rates were at their highest in a century.[55] Nixon's major economic goal was to reduce inflation; the most obvious means of doing so was to end the war.[55] As the war continued, the administration adopted a policy of restricting the growth of the money supply to address the inflation problem. In February 1970, as a part of the effort to keep federal spending down, Nixon delayed pay raises to federal employees by six months. When the nation's postal workers went on strike, he used the army to keep the postal system going. In the end, the government met the postal workers' wage demands, undoing some of the desired budget-balancing.[56]

In December 1969, Nixon somewhat reluctantly signed the Tax Reform Act of 1969 despite its inflationary provisions; the act established the alternative minimum tax, which applied to wealthy individuals who used deductions to limit their tax liabilities.[57] In 1970, Congress granted the president the power to impose wage and price controls, though the Democratic congressional leadership, knowing Nixon had opposed such controls through his career, did not expect Nixon to actually use the authority.[58] With inflation unresolved by August 1971, and an election year looming, Nixon convened a summit of his economic advisers at Camp David. He then announced temporary wage and price controls, allowed the dollar to float against other currencies, and ended the convertibility of the dollar into gold.[59] Nixon's monetary policies effectively took the United States off the gold standard and brought an end to the Bretton Woods system, a post-war international fixed exchange-rate system. Nixon believed that this system negatively affected the U.S. balance of trade; the U.S. had experienced its first negative balance of trade of the 20th century in 1971.[60] Bowles points out, "by identifying himself with a policy whose purpose was inflation's defeat, Nixon made it difficult for Democratic opponents ... to criticize him. His opponents could offer no alternative policy that was either plausible or believable since the one they favored was one they had designed but which the president had appropriated for himself."[58] Nixon's policies dampened inflation in 1972, but their aftereffects contributed to inflation during his second term and into the Ford administration.[59]

As Nixon began his second term, the economy was plagued by a stock market crash, a surge in inflation, and the 1973 oil crisis.[61] With the legislation authorizing price controls set to expire on April 30, the Senate Democratic Caucus recommended a 90-day freeze on all profits, interest rates, and prices.[62] Nixon re-imposed price controls in June 1973, echoing his 1971 plan, as food prices rose; this time, he focused on agricultural exports and limited the freeze to 60 days.[62] The price controls became unpopular with the public and business people, who saw powerful labor unions as preferable to the price board bureaucracy.[62] Business owners, however, now saw the controls as permanent rather than temporary, and voluntary compliance among small businesses decreased.[62] The controls and the accompanying food shortages—as meat disappeared from grocery stores and farmers drowned chickens rather than sell them at a loss—only fueled more inflation.[62] Despite their failure to rein in inflation, controls were slowly ended, and on April 30, 1974, their statutory authorization lapsed.[62] Between Nixon's accession to office and his resignation in August 1974, unemployment rates had risen from 3.5% to 5.6%, and the rate of inflation had grown from 4.7% to 8.7%.[61] Observers coined a new term for the undesirable combination of unemployment and inflation: "stagflation", a phenomenon that would worsen after Nixon left office.[63]

Social programs[edit]

Welfare[edit]

One of Nixon's major promises in the 1968 campaign was to address what he described as the "welfare mess". The number of individuals enrolled in the Aid to Families with Dependent Children program had risen from 3 million in 1960 to 8.4 million in 1970, contributing to a drop in poverty. However, many Americans, particularly conservatives, believed that welfare programs discouraged individuals from finding employment; conservatives also derided "welfare queens" who they alleged collected excessive amounts of welfare benefits.[64] On taking office, Nixon established the Council of Urban Affairs, under the leadership of Daniel Patrick Moynihan, to develop a welfare reform proposal. Moynihan's proposed plan centered on replacing welfare programs with a negative income tax, which would provide a guaranteed minimum income to all Americans. Nixon became closely involved in the proposal and, despite opposition from Arthur Burns and other conservatives, adopted Moynihan's plan as the central legislative proposal of his first year in office. In an August 1969 televised address, Nixon proposed the Family Assistance Plan (FAP), which would establish a national income floor of $1600 per year for a family of four.[65]

Public response to the FAP was highly favorable, but it faced strong opposition in Congress, partly due to the lack of congressional involvement in the drafting of the proposal. Many conservatives opposed the establishment of the national income floor, while many liberals believed that the floor was too low. Though the FAP passed the House, the bill died in the Senate Finance Committee in May 1970.[66] Though Nixon's overall proposal failed, Congress did adopt one aspect of the FAP, as it voted to establish the Supplemental Security Income program, which provides aid to low-income individuals who are aged or disabled.[67]

Determined to dismantle much of Johnson's Great Society and its accompanying federal bureaucracy, Nixon defunded or abolished several programs, including the Office of Economic Opportunity, the Job Corps, and the Model Cities Program.[68] Nixon advocated a "New Federalism", which would devolve power to state and local elected officials, but Congress was hostile to these ideas and enacted only a few of them.[69] During Nixon's tenure, spending on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid all increased dramatically.[67] Total spending on social insurance programs grew from $27.3 billion in 1969 to $67.4 billion in 1975, while the poverty rate dropped from 12.8 percent in 1968 to 11.1 percent in 1973.[70]

Healthcare[edit]

In August 1970, Democratic Senator Ted Kennedy introduced legislation to establish a single-payer universal health care system financed by taxes and with no cost sharing.[71] In February 1971, Nixon proposed a more limited package of health care reform, consisting of an employee mandate to offer private health insurance if employees volunteered to pay 25 percent of premiums, the federalization of Medicaid for poor families with dependent minor children, and support for health maintenance organizations (HMOs).[72] This market-based system would, Nixon argued, "build on the strengths of the private system."[73] Both the House and Senate held hearings on national health insurance in 1971, but no legislation emerged from either committee.[74] In October 1972, Nixon signed the Social Security Amendments of 1972, extending Medicare to those under 65 who had been severely disabled for over two years or had end stage renal disease and gradually raising the Medicare Part A payroll tax.[75] In December 1973, he signed the Health Maintenance Organization Act of 1973, establishing a trial federal program to promote and encourage the development of HMOs.[76]

There was a renewed push for health insurance reform in 1974. In January, representatives Martha Griffiths and James C. Corman introduced the Health Security Act, a universal national health insurance program providing comprehensive benefits without any cost sharing backed by the AFL–CIO and UAW.[74] The following month Nixon proposed the Comprehensive Health Insurance Act, consisting of an employer mandate to offer private health insurance if employees volunteered to pay 25 percent of premiums, replacement of Medicaid by state-run health insurance plans available to all with income-based premiums and cost sharing, and replacement of Medicare with a new federal program that eliminated the limit on hospital days, added income-based out-of-pocket limits, and added outpatient prescription drug coverage.[74][77] In April, Kennedy and House Ways and Means committee chairman Wilbur Mills introduced the National Health Insurance Act, a bill to provide near-universal national health insurance with benefits identical to the expanded Nixon plan—but with mandatory participation by employers and employees through payroll taxes and with lower cost sharing.[74] Both plans were criticized by labor, consumer, and senior citizens organizations, and neither gained traction.[78] In mid-1974, shortly after Nixon's resignation, Mills tried to advance a compromise based on Nixon's plan, but gave up when unable to get more than a 13–12 majority of his committee to support his compromise.[74][79]

Environmental policy[edit]

Environmentalism had emerged as a major movement during the 1960s, especially after the 1962 publication of Silent Spring.[80] Between 1960 and 1969, membership in the twelve largest environmental groups had grown from 124,000 to 819,000, and polling showed that millions of voters shared many of the goals of environmentalists.[81] Nixon was largely uninterested in environmental policy, but he did not oppose the goals of the environmental movement. In 1970, he signed the National Environmental Policy Act and established the Environmental Protection Agency, which was charged with coordinating and enforcing federal environmental policy. During his presidency, Nixon also signed the Clean Air Act of 1970, and the Clean Water Act. He signed the Endangered Species Act of 1973, the primary law for protecting imperiled species from extinction as a "consequence of economic growth and development untempered by adequate concern and conservation".[81][82]

Nixon also pursued environmental diplomacy,[83] and Nixon administration official Russell E. Train opened a dialog on global environmental issues with Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin.[84][85] Political scientists Byron Daines and Glenn Sussman rate Nixon as the only Republican president since World War II to have a positive impact on the environment, asserting that "Nixon did not have to be personally committed to the environment to become one of the most successful presidents in promoting environmental priorities."[86]

While applauding Nixon's progressive policy agenda, environmentalists found much to criticize in his record.[54] The administration strongly supported continued funding of the "noise-polluting" Supersonic transport (SST), which Congress dropped funding for in 1971. Additionally, he vetoed the Clean Water Act of 1972, and after Congress overrode the veto, Nixon impounded the funds Congress had authorized to implement it. While not opposed to the goals of the legislation, Nixon objected to the amount of money to be spent on reaching them, which he deemed excessive.[87] Faced as he was with a generally liberal Democratic Congress, Nixon used his veto power on multiple occasions during his presidency.[88][89][90] Congress's response came in the form of the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974, which established a new budget process, and included a procedure providing congressional control over the impoundment of funds by the president. Nixon, mired in Watergate, signed the legislation in July 1974.[91]

Desegregation and civil rights[edit]

The Nixon years witnessed the first large-scale efforts to desegregate the nation's public schools.[92] Seeking to avoid alienating Southern whites, whom Nixon hoped would form part of a durable Republican coalition, the president adopted a "low profile" on school desegregation. He pursued this policy by allowing the courts to receive the criticism for desegregation orders, which Nixon's Justice Department would then enforce.[93] By September 1970, less than ten percent of black children were attending segregated schools.[94] After the Supreme Court handed down its decision in the 1971 case of Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, cross-district school busing it emerged as a major issue in both the North and the South. Swann permitted lower federal courts to mandate busing in order to remedy racial imbalance in schools. Though he enforced the court orders, Nixon believed that "forced integration of housing or education" was just as improper as legal segregation, and he took a strong public stance against its continuation. The issue of cross-district busing faded from the fore of national politics after the Supreme Court placed limits on the use of cross-district busing with its decision in the 1974 case of Milliken v. Bradley.[95]

Nixon established the Office of Minority Business Enterprise to promote the establishment of minority-owned businesses.[96] The administration also worked to increase the number of racial minorities hired across the nation in various construction trades, implementing the first affirmative action plan in the United States. The Philadelphia Plan required government contractors in Philadelphia to hire a minimum number of minority workers.[97] In 1970, Nixon extended the Philadelphia Plan to encompass all federal contracts worth more than $50,000, and in 1971 he expanded the plan to encompass women and racial minorities.[98] Nixon and Attorney General Mitchell also helped enact an extension of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that expanded federal supervision of voting rights to all jurisdictions in which less than 50 percent of the minority population was registered to vote.[99]

Dean J. Kotlowski states that:

- recent scholars have concluded that the president was neither a segregationist nor a conservative on the race question. These writers have shown that Nixon desegregated more schools than previous presidents, approved a strengthened Voting Rights Act, developed policies to aid minority businesses, and supported affirmative action.[100]

Protests and crime[edit]

Over the course of the Vietnam War, a large segment of the American population came to be opposed to U.S. involvement in South Vietnam. Public opinion steadily turned against the war following 1967, and by 1970 only a third of Americans believed that the U.S. had not made a mistake by sending troops to fight in Vietnam.[101] Anti-war activists organized massive protests like the Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam, which attracted over 600,000 protesters in various cities.[102] Opinions concerning the war grew more polarized after the Selective Service System instituted a draft lottery in December 1969. Some 30,000 young men fled to Canada to evade the draft between 1970 and 1973.[103] A wave of protests swept the country in reaction to the invasion of Cambodia.[104] In what is known as the Kent State shootings, a protest at Kent State University ended in the deaths of four students after the Ohio Army National Guard opened fire on an unarmed crowd.[105] The shootings increased tensions on other college campuses, and more than 75 colleges and universities were forced to shut down until the start of the next academic year.[104] As the U.S. continually drew down the number of troops in Vietnam, the number of protests declined, especially after 1970.[106]

The Nixon administration vigorously prosecuted anti-war protesters like the "Chicago Seven", and ordered the FBI, CIA, NSA, and other intelligence agencies to monitor radical groups. Nixon also introduced anti-crime measures like the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act and the District of Columbia Crime Control Bill, which included no-knock warrants and other provisions that concerned many civil libertarians.[106] In response to growing drug-related crime, Nixon became the first president to emphasize drug control, and he presided over the establishment of the Drug Enforcement Administration.[107]

Space program[edit]

After a nearly decade-long national effort, the United States won the race to land astronauts on the Moon on July 20, 1969, with the flight of Apollo 11. Nixon spoke with Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin during their moonwalk, calling the conversation "the most historic phone call ever made from the White House".[108] Nixon, however, was unwilling to keep funding for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) at the high level seen through the 1960s, and rejected NASA Administrator Thomas O. Paine's ambitious plans for the establishment of a permanent base on the Moon by the end of the 1970s and the launch of a crewed expedition to Mars in the 1980s.[109] On May 24, 1972, Nixon approved a five-year cooperative program between NASA and the Soviet space program, culminating in the Apollo–Soyuz Test Project, a joint mission of an American Apollo and a Soviet Soyuz spacecraft in 1975.[110]

Other issues[edit]

Medical research initiatives[edit]

Nixon submitted two significant medical research initiatives to Congress in February 1971.[111] The first, popularly referred to as the War on Cancer, resulted in passage that December of the National Cancer Act, which injected nearly $1.6 billion (equivalent to $9 billion in 2016) in federal funding to cancer research over a three-year period. It also provided for establishment of medical centers dedicated to clinical research and cancer treatment, 15 of them initially, whose work is coordinated by the National Cancer Institute.[112][113] The second initiative, focused on Sickle-cell disease (SCD), resulted in passage of the National Sickle Cell Anemia Control Act in May 1972. Long ignored, the lifting of SCD from obscurity to high visibility reflected the changing dynamics of electoral politics and race relations in America during the early 1970s. Under this legislation, the National Institutes of Health established several sickle cell research and treatment centers and the Health Services Administration established sickle cell screening and education clinics around the country.[114][115]

Governmental reorganization[edit]

Nixon proposed reducing the number of government departments to eight. Under his plan, the existing departments of State, Justice, Treasury, and Defense would be retained, while the remaining departments would be folded into the new departments of Economic Affairs, Natural Resources, Human Resources, and Community Development. Although Nixon did not succeed in this major reorganization,[116] he was able to convince Congress to eliminate one cabinet-level department, the United States Post Office Department. In July 1971, after passage of the Postal Reorganization Act, the Post Office Department was transformed into the United States Postal Service, an independent entity within the executive branch of the federal government.[117]

Federal regulations[edit]

Nixon supported passage of the Occupational Safety and Health Act, which established the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).[118] Other significant regulatory legislation enacted during Nixon's presidency included the Noise Control Act and the Consumer Product Safety Act.[54]

Constitutional amendments[edit]

When Congress extended the Voting Rights Act of 1965 in 1970 it included a provision lowering the age qualification to vote in all elections—federal, state, and local—to 18. Later that year, in Oregon v. Mitchell (1970), the Supreme Court held that Congress had the authority to lower the voting age qualification in federal elections, but not the authority to do so in state and local elections.[119] Nixon sent a letter to Congress supporting a constitutional amendment to lower the voting age, and Congress quickly moved forward with a proposed constitutional amendment guaranteeing the 18 year-old vote.[120] Sent to the states for ratification on March 23, 1971, the proposal became the Twenty-sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution on July 1, 1971, after being ratified by the requisite number of states (38).[121]

Nixon also endorsed the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), which passed both houses of Congress in 1972 and was submitted to the state legislatures for ratification.[122] The amendment failed to be ratified by 38 states within the period set by Congress for ratification. Nixon had campaigned as an ERA supporter in 1968, though feminists criticized him for doing little to help the ERA or their cause after his election. Nevertheless, he appointed more women to administration positions than Lyndon Johnson had.[123]

Foreign affairs[edit]

Nixon Doctrine[edit]

Green — Non-self-governing possessions of U.S. allies

Blue — U.S. and U.S. allies

Red — Soviet Union and its communist allies

Orange — Communist countries not aligned with the Soviet Union

Pink — Non Communist allies of Soviet Union

Light Blue — Non-NATO members of EFTA and OECD

Gray — Unknown or non aligned

Upon taking office, Nixon pronounced the "Nixon Doctrine", a general statement of foreign policy under which the United States would not "undertake all the defense of the free nations." While existing commitments would be upheld, potential new commitments would be sharply scrutinized. Rather than becoming directly involved in conflicts, the United States would provide military and economic aid to nations that were subject to insurgency or aggression, or that were otherwise vital to U.S. strategic interests.[124] As part of the Nixon Doctrine, the U.S. greatly increased arms sales to the Middle East, especially Israel, Iran, and Saudi Arabia.[125] Another major beneficiary of aid was Pakistan, which the U.S. backed during the Bangladesh Liberation War.[126]

Vietnam War[edit]

At the time Nixon took office, there were over 500,000 American soldiers in Southeast Asia. Over 30,000 U.S. military personnel serving in the Vietnam War had been killed since 1961, with approximately half of those deaths occurring in 1968.[127] The war was broadly unpopular in the United States with widespread and sometimes violent protests taking place on a regular basis. The Johnson administration agreed to suspend bombing in exchange for negotiations without preconditions, but this agreement never fully took force. According to Walter Isaacson, soon after taking office, Nixon concluded that the Vietnam War could not be won and he was determined to end the war quickly.[128] Conversely, Black argues that Nixon sincerely believed he could intimidate North Vietnam through the Madman theory.[129] Regardless of his opinion of the war, Nixon wanted to end the American role in it without the appearance of an American defeat, which he feared would badly damage his presidency and precipitate a return to isolationism.[130] He sought some arrangement which would permit American forces to withdraw, while leaving South Vietnam secure against attack.[131]

In mid-1969, Nixon began efforts to negotiate peace with the North Vietnamese, but negotiators were unable to reach an agreement.[132] With the failure of the peace talks, Nixon implemented a strategy of "Vietnamization," which consisted of increased U.S. aid and Vietnamese troops taking on a greater combat role in the war. To great public approval, he began phased troop withdrawals by the end of 1969, sapping the strength of the domestic anti-war movement.[133] Despite the failure of Operation Lam Son 719, which was designed to be the first major test of the South Vietnamese Army since the implementation of Vietnamization, the drawdown of American soldiers in Vietnam continued throughout Nixon's tenure.[134]

In early 1970, Nixon sent U.S. and South Vietnamese soldiers into Cambodia to attack North Vietnamese bases, expanding the ground war out of Vietnam for the first time.[133] He had previously approved a secret B-52 carpet bombing campaign of North Vietnamese positions in Cambodia in March 1969 (code-named Operation Menu), without the consent of Cambodian leader Norodom Sihanouk.[135][136] Even within the administration, many disapproved of the incursions into Cambodia, and anti-war protesters were irate.[105] The bombing of Cambodia continued into the 1970s in support of the Cambodian government of Lon Nol, which was then battling a Khmer Rouge insurgency in the Cambodian Civil War, as part of Operation Freedom Deal.[137]

In 1971, Nixon ordered incursions into Laos to attack North Vietnamese bases, provoking further domestic unrest.[138] That same year, excerpts from the "Pentagon Papers" were published by The New York Times and The Washington Post. When news of the leak first appeared, Nixon was inclined to do nothing, but Kissinger persuaded him to try to prevent their publication. The Supreme Court ruled for the newspapers in the 1971 case of New York Times Co. v. United States, thereby allowing for the publication of the excerpts.[139] By mid-1971, disillusionment with the war had reached a new high, as 71 percent of Americans believed that sending soldiers to Vietnam had been a mistake.[140] By the end of 1971, 156,000 U.S. soldiers remained in Vietnam; 276 American soldiers serving in Vietnam were killed in the last six months of that year.[141]

North Vietnam launched the Easter Offensive in March 1972, overwhelming the South Vietnamese army.[142] In reaction to the Easter Offensive, Nixon ordered a massive bombing campaign in North Vietnam known as Operation Linebacker.[143] As U.S. troop withdrawals continued, conscription was reduced and in 1973 ended; the armed forces became all-volunteer.[144] In the aftermath of the Easter Offensive, peace talks between the United States and North Vietnam resumed, and by October 1972 a framework for a settlement had been reached. Objections from South Vietnamese President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu derailed this agreement, and the peace talks broke down. In December 1972, Nixon ordered another massive bombing campaign, Operation Linebacker II; domestic criticism of the operation convinced Nixon of the necessity to quickly reach a final agreement with North Vietnam.[145]

After years of fighting, the Paris Peace Accords were signed at the beginning of 1973. The agreement implemented a cease fire and allowed for the withdrawal of remaining American troops; however, it did not require the 160,000 North Vietnam Army regulars located in the South to withdraw.[146] By March 1973, U.S. military forces had been withdrawn from Vietnam.[147] Once American combat support ended, there was a brief truce, but fighting quickly broke out again, as both South Vietnam and North Vietnam violated the truce.[148][149] Congress effectively ended any possibility of another American military intervention by passing the War Powers Resolution over Nixon's veto.[150]

China and the Soviet Union[edit]

Nixon took office in the midst of the Cold War, a sustained period of geopolitical tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union. The United States and Soviet Union had been the clear leaders of their respective blocs of allies during the 1950s, but the world became increasingly multipolar during the 1960s. U.S. allies in Western Europe and East Asia had recovered economically, and while they remained allied with United States, they set their own foreign policies. The fracture in the so-called "Second World" of Communist states was more serious, as the split between the Soviet Union and China escalated into a border conflict in 1969. The United States and the Soviet Union continued to compete for worldwide influence, but tensions had eased considerably since the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. In this shifting international context, Nixon and Kissinger sought to realign U.S. foreign policy and establish peaceful coexistence with both the Soviet Union and China.[151] Nixon's goal of closer relations with China and the Soviet Union was closely linked to ending the Vietnam War,[152][153][154] since he hoped that rapprochement with the two leading Communist powers would pressure North Vietnam into accepting a favorable settlement.[155]

China[edit]

Since the end of the Chinese Civil War, the United States had refused to formally recognize the People's Republic of China (PRC) as the legitimate government of China, though the PRC controlled Mainland China. The U.S. had instead supported the Republic of China (ROC), which controlled Taiwan.[156] By the time Nixon took office, many leading foreign policy figures in the United States had come to believe the U.S. should end its policy of isolating the PRC.[157] The vast Chinese markets presented an economic opportunity for the increasingly-weak U.S. economy, and the Sino-Soviet split offered an opportunity to play the two Communist powers against each other. Chinese leaders, meanwhile, were receptive to closer relations with the U.S. for several reasons, including hostility to the Soviet Union, a desire for increased trade, and hopes of winning international recognition.[156]

Both sides faced domestic pressures against closer relations. A conservative faction of Republicans led by Barry Goldwater and Ronald Reagan strongly opposed a rapprochement with China, while Lin Biao led a similar faction in the PRC. For the first two years of his presidency, Nixon and China each made subtle moves designed to lower tensions, including the removal of travel restrictions. The expansion of the Vietnam War into Laos and Cambodia hindered, but did not derail, the move towards normalization of relations.[158] Due to a misunderstanding at the 1971 World Table Tennis Championships, the Chinese table tennis team invited the U.S. table tennis team to tour China, creating an opening for further engagement between the U.S. and China.[159] In the aftermath of the visit, Nixon lifted the trade embargo on China. At a July 1971 meeting with Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai, Henry Kissinger promised not to support independence for Taiwan, while Zhou invited Nixon to China for further talks.[158] After the meeting, China and the United States astounded the world by simultaneously announcing that Nixon would visit China in February 1972.[160] In the aftermath of the announcement, the United Nations passed Resolution 2758, which recognized the PRC as the legitimate government of China and expelled representatives from the ROC.[161]

In February 1972, Nixon traveled to China; Kissinger briefed Nixon for over 40 hours in preparation.[162] Upon touching down in the Chinese capital of Beijing, Nixon made a point of shaking Zhou's hand, something which then-Secretary of State John Foster Dulles had refused to do in 1954 when the two met in Geneva.[163] The visit was carefully choreographed by both governments, and major events were broadcast live during prime time to reach the widest possible television audience in the U.S.[164] When not in meetings, Nixon toured architectural wonders such as the Forbidden City, Ming Tombs, and the Great Wall, giving many Americans received their first glimpse into Chinese life.[163]

Nixon and Kissinger discussed a range of issues with Zhou and Mao Zedong, the Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party.[165] China provided assurances that it would not intervene in the Vietnam War, while the United States promised to prevent Japan from acquiring nuclear weapons. Nixon recognized Taiwan as part of China, while the Chinese agreed to pursue a peaceful settlement in the dispute with the Republic of China. The United States and China increased trade relations and established unofficial embassies in each other's respective capitals. Though some conservatives criticized his visit, Nixon's opening of relations with China was widely popular in the United States.[166] The visit also aided Nixon's negotiations with the Soviet Union, which feared the possibility of a Sino-American alliance.[167]

Soviet Union[edit]

Nixon made détente, the easing of tensions with the Soviet Union, one of his top foreign policy priorities. Through détente, he hoped to "minimize confrontation in marginal areas and provide, at least, alternative possibilities in the major ones." West Germany had also pursued closer relations with the Soviet Union in a policy known as "Ostpolitik", and Nixon hoped to re-establish American dominance in NATO by taking the lead in negotiations with the Soviet Union. Nixon also believed that expanding trade with the Soviet Union would help the U.S. economy and could allow both countries to devote fewer resources to defense spending. The Soviets were motivated by a struggling economy and their ongoing split with China.[168]

Upon taking office, Nixon took several steps to signal to the Soviets his desire for negotiation. In his first press conference, he noted that the United States would accept nuclear parity, rather than superiority, with the Soviet Union. Kissinger conducted extensive backchannel talks with Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin over arms control negotiations and potential Soviet assistance in negotiations with North Vietnam. Seeking a bargaining chip in negotiations, Nixon funded development of MIRVs, which were not easily countered by existing anti-ballistic missile (ABM) systems. Arms control negotiations would thus center over ABM systems, MIRVs, and the various components of each respective country's nuclear arsenal. After over a year of negotiations, both sides agreed to the outlines of two treaties; one treaty would focus on ABM systems, while the other would focus on limiting nuclear arsenals.[169]

In May 1972, Nixon met with Leonid Brezhnev and other leading Soviet officials at the 1972 Moscow Summit. The two sides reached the Strategic Arms Limitation Agreement (SALT I), which set upper limits on the number of offensive missiles and ballistic missile submarines that each county could maintain. A separate agreement, the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, stipulated that each country could only field two anti-ballistic missile systems. The United States also agreed to the creation of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe.[170] An October 1972 trade agreement between the United States and the Soviet Union vastly increased trade between the two countries, though Congress did not approve of Nixon's proposal to extend most favored nation status to the Soviet Union.[171]

Nixon would embark on a second trip to the Soviet Union in 1974, meeting with Brezhnev in Yalta. They discussed a proposed mutual defense pact and other issues, but there were no significant breakthroughs in the negotiations.[172] During Nixon's final year in office, Congress undercut Nixon's détente policies by passing the Jackson–Vanik amendment.[173] Senator Henry M. Jackson, an opponent of détente, introduced the Jackson–Vanik amendment in response to a Soviet tax that curbed the flow of Jewish emigrants, many of whom sought to immigrate to Israel. Angered by the amendment, the Soviets canceled the 1972 trade agreement and reduced the number of Jews who were permitted to emigrate.[174] Though détente was unpopular with many on the left due to humanitarian concerns, and with many on the right due to concerns about being overly accommodating to the Soviets, Nixon's policies helped significantly diminish Cold War tensions even after he left office.[175]

India[edit]

Relations with India hit an all-time low under the Nixon administration in the early 1970s. Nixon shifted away from the neutral stance which his predecessors had taken towards India-Pakistan hostilities. He established a very close relationship with Pakistan, aiding it militarily and economically, as India, now under the leadership of Indira Gandhi, was leaning towards Soviet Union. He considered Pakistan as a very important ally to counter Soviet influence in the Indian subcontinent and establish ties with China, with whom Pakistan was very close.[176] The frosty personal relationship between Nixon and Indira further contributed to the poor relationship between the two nations.[177]

During the 1971 Indo-Pakistani War, the U.S. openly supported Pakistan and deployed its aircraft carrier USS Enterprise towards the Bay of Bengal, which was seen as a show of force by the U.S. in support of the West Pakistani forces. Later in 1974, India conducted its first nuclear test, Smiling Buddha, which was opposed by the US, however it also concluded that the test did not violate any agreement and proceeded with a June 1974 shipment of enriched uranium for the Tarapur reactor.[178][179]

Princeton University professor Gary Bass contends that Nixon's actions and the U.S. administration's policy toward South Asia under Nixon was influenced by his hatred of, and sexual repulsion toward, Indians.[180]

Latin America[edit]

Cuba[edit]

Nixon had been a firm supporter of Kennedy in the 1961 Bay of Pigs Invasion and 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis; on taking office he stepped up covert operations against Cuba and Cuban president Fidel Castro. He maintained close relations with the Cuban-American exile community through his friend, Bebe Rebozo, who often suggested ways of irritating Castro. These activities concerned the Soviets and Cubans, who feared Nixon might attack Cuba in violation of the understanding between Kennedy and Khrushchev which had ended the missile crisis. In August 1970, the Soviets asked Nixon to reaffirm the agreement. Despite his hard line against Castro, Nixon agreed. The process, which began in secret but quickly leaked, had not been completed when the U.S. deduced that the Soviets were expanding their base at the Cuban port of Cienfuegos in October 1970. A minor confrontation ensued, which was concluded with an understanding that the Soviets would not use Cienfuegos for submarines bearing ballistic missiles. The final round of diplomatic notes, reaffirming the 1962 accord, were exchanged in November.[181]

Chile[edit]

Like his predecessors, Nixon was determined to prevent the rise of another Soviet-aligned state in Latin America, and his administration was greatly distressed by the victory of Marxist candidate Salvador Allende in the 1970 Chilean presidential election.[130] Nixon pursued a vigorous campaign of covert resistance to Allende, intended to first prevent Allende from taking office, called Track I, and then when that failed, to provide a "military solution", called Track II.[182] As part of Track II, CIA operatives approached senior Chilean military leaders, using false flag operatives, and encouraged a coup d'état, providing both finances and weapons.[183] These efforts failed, and Allende took office in November 1970.[184]

The Nixon administration drastically cut economic aid to Chile and convinced World Bank leaders to block aid to Chile.[185] Extensive covert efforts continued as the U.S. funded black propaganda, organized strikes against Allende, and provided funding for Allende opponents. When the Chilean newspaper El Mercurio requested significant funds for covert support in September 1971, Nixon personally authorized the funds in "a rare example of presidential micromanagement of a covert operation."[186]: 93 In September 1973, General Augusto Pinochet assumed power in a violent coup d'état.[187] During the coup, the deposed president died under disputed circumstances, and there were allegations of American involvement.[188] According to diplomatic historian George Herring, "no evidence has ever been produced to prove conclusively that the United States instigated or actively participated in the coup." Herring also notes, however, that whether or not it took part in the coup, the U.S. created the atmosphere in which the coup took place.[189]

Middle East[edit]

Early in his first term, Nixon pressured Israel over its nuclear program, and his administration developed a peace plan in which Israel would withdraw from the territories it conquered in the Six-Day War. After the Soviet Union upped arms shipments to Egypt in mid-1970, Nixon moved closer to Israel, authorizing the shipment of F-4 fighter aircraft.[190] In October 1973, after Israel declined Egyptian President Anwar Sadat's offer of negotiations over the lands it had won control of in the Six-Day War, Egypt and Syria launched a surprise attack against Israel. After Egypt and Syria experienced early successes in what became known as the Yom Kippur War, the United States began to supply massive amounts of military aid to Israel, as Nixon overrode Kissinger's early reluctance to provide strong support to Israel. After Israel turned the tide in the war and advanced into Egypt and Syria, Kissinger and Brezhnev organized a cease fire. Cutting out the Soviet Union from further involvement, Kissinger helped arrange agreements between Israel and the Arab states.[191]

Though it had been established in 1960, OPEC did not gain effective control over oil prices until 1970, when Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi forced oil companies in Libya to agree to a price increase; other countries followed suit. U.S. leaders did not attempt to block these price increases, as they believed that higher prices would help increase domestic production of oil. This increased production failed to materialize, and by 1973 the U.S. consumed over one and a half times the oil that it produced domestically.[192] In 1973, in response to the U.S. support of Israel in the Yom Kippur War, OPEC countries cut oil production, raised prices, and initiated an embargo targeted against the United States and other countries that had supported Israel.[193] The embargo caused gasoline shortages and rationing in the United States in late 1973, but was eventually ended by the oil-producing nations as the Yom Kippur War peace took hold.[194]

Europe[edit]

Just weeks after his 1969 inauguration, Nixon made an eight-day trip to Europe. He met with British Prime Minister Harold Wilson in London and French President Charles de Gaulle in Paris. He also made groundbreaking trips to several Eastern European nations, including Romania, Yugoslavia, and Poland. However, the NATO allies of the United States generally did not play a large role in Nixon's foreign policy, as he focused on the Vietnam War and détente. In 1971, the United States, Britain, France, and the Soviet Union reached the Four Power Agreement, in which the Soviet Union guaranteed access to West Berlin so long as it was not incorporated into West Germany.[195]

List of international trips[edit]

| Dates | Country | Locations | Details | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | February 23–24, 1969 | Brussels | Attended the 23rd meeting of North Atlantic Council. Met with King Baudouin I. | |

| February 24–26, 1969 | London | Informal visit. Delivered several public addresses. | ||

| February 26–27, 1969 | West Berlin Bonn | Delivered several public addresses. Addressed the Bundestag. | ||

| February 27–28, 1969 | Rome | Met with President Giuseppe Saragat and Prime Minister Mariano Rumor and other officials. | ||

| February 28 – March 2, 1969 | Paris | Met with President Charles de Gaulle. | ||

| March 2, 1969 | Apostolic Palace | Audience with Pope Paul VI. | ||

| 2 | July 26–27, 1969 | Manila | State visit. Met with President Ferdinand Marcos. | |

| July 27–28, 1969 | Jakarta | State visit. Met with President Suharto. | ||

| July 28–30, 1969 | Bangkok | State visit. Met with King Bhumibol Adulyadej. | ||

| July 30, 1969 | Saigon, Di An | Met with President Nguyen Van Thieu. Visited U.S. military personnel. | ||

| July 31 – August 1, 1969 | New Delhi | State visit. Met with Acting President Mohammad Hidayatullah. | ||

| August 1–2, 1969 | Lahore | State visit. Met with President Yahya Khan. | ||

| August 2–3, 1969 | Bucharest | Official visit. Met with President Nicolae Ceaușescu. | ||

| August 3, 1969 | RAF Mildenhall | Informal meeting with Prime Minister Harold Wilson. | ||

| 3 | September 8, 1969 | Ciudad Acuña | Dedication of Amistad Dam with President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz. | |

| 4 | August 20–21, 1970 | Puerto Vallarta | Official visit. Met with President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz. | |

| 5 | September 27–30, 1970 | Rome, Naples | Official visit. Met with President Giuseppe Saragat. Visited NATO Southern Command. | |

| September 28, 1970 | Apostolic Palace | Audience with Pope Paul VI. | ||

| September 30 – October 2, 1970 | Belgrade, Zagreb | State visit. Met with President Josip Broz Tito. | ||

| October 2–3, 1970 | Madrid | State visit. Met with Generalissimo Francisco Franco. | ||

| October 3, 1970 | Chequers | Met informally with Queen Elizabeth II and Prime Minister Edward Heath. | ||

| October 3–5, 1970 | Limerick, Timahoe, Dublin | State visit. Met with Prime Minister Jack Lynch. | ||

| 6 | November 12, 1970 | Paris | Attended the memorial services for former President Charles de Gaulle. | |

| 7 | December 13–14, 1971 | Terceira Island | Discussed international monetary problems with French President Georges Pompidou and Portuguese Prime Minister Marcelo Caetano. | |

| 8 | December 20–21, 1971 | Hamilton | Met with Prime Minister Edward Heath. | |

| 9 | February 21–28, 1972 | Shanghai, Beijing, Hangzhou | State visit. Met with Party Chairman Mao Zedong and Premier Zhou Enlai. | |

| 10 | April 13–15, 1972 | Ottawa | State visit. Met with Governor General Roland Michener and Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. Addressed Parliament. Signed the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement.[197] | |

| 11 | May 20–22, 1972 | Salzburg | Informal visit. Met with Chancellor Bruno Kreisky. | |

| May 22–30, 1972 | Moscow, Leningrad, Kyiv | State visit. Met with Premier Alexei Kosygin and General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev. Signed the SALT I and ABM Treaties. | ||

| May 30–31, 1972 | Tehran | Official visit. Met with Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. | ||

| May 31 – June 1, 1972 | Warsaw | Official visit. Met with First Secretary Edward Gierek. | ||

| 12 | May 31 – June 1, 1973 | Reykjavík | Met with President Kristján Eldjárn and Prime Minister Ólafur Jóhannesson and French President Georges Pompidou. | |

| 13 | April 5–7, 1974 | Paris | Attended the memorial services for former President Georges Pompidou. Met afterward with interim President Alain Poher, Italian President Giovanni Leone, British Prime Minister Harold Wilson, West German Chancellor Willy Brandt, Danish Prime Minister Poul Hartling, Soviet leader Nikolai Podgorny and Japanese Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka. | |

| 14 | June 10–12, 1974 | Salzburg | Met with Chancellor Bruno Kreisky. | |

| June 12–14, 1974 | Cairo, Alexandria | Met with President Anwar Sadat. | ||

| June 14–15, 1974 | Jedda | Met with King Faisal. | ||

| June 15–16, 1974 | Damascus | Met with President Hafez al-Assad. | ||

| June 16–17, 1974 | Tel Aviv, Jerusalem | Met with President Ephraim Katzir and Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin. | ||

| June 17–18, 1974 | Amman | State visit. Met with King Hussein. | ||

| June 18–19, 1974 | Lajes Field | Met with President António de Spínola. | ||

| 15 | June 25–26, 1974 | Brussels | Attended the North Atlantic Council Meeting. Met separately with King Baudouin I and Queen Fabiola, Prime Minister Leo Tindemans, and with German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt, British Prime Minister Harold Wilson and Italian Prime Minister Mariano Rumor. | |

| June 27 – July 3, 1974 | Moscow, Minsk, Oreanda | Official visit. Met with General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev, Chairman Nikolai Podgorny and Premier Alexei Kosygin. Signing of the Threshold Test Ban Treaty. |

1972 presidential election[edit]

Nixon explored the possibility of establishing a new center-right party and running on a ticket with John Connally, but he ultimately chose to seek re-election as a Republican.[198] His success with the People's Republic of China and the Soviet Union bolstered his approval ratings in the lead-up to the 1972 presidential election, and he was the overwhelming favorite to be re-nominated at the start of the 1972 Republican primaries.[199] He was challenged in the primaries by two congressmen: anti-war candidate Pete McCloskey and détente opponent John Ashbrook. Nixon virtually assured his nomination by winning the New Hampshire primary with a comfortable 67.8 percent of the vote. He was re-nominated at the August 1972 Republican National Convention, receiving 1,347 of the 1,348 votes. Delegates also re-nominated Spiro Agnew by acclamation.[200]

Первоначально Никсон ожидал, что его оппонентом-демократом станет сенатор США Тед Кеннеди от Массачусетса, но инцидент с Чаппакиддиком 1969 года фактически исключил Кеннеди из борьбы. [201] Nonetheless, Nixon ordered constant surveillance of Kennedy by E. Howard Hunt.[202] Nixon also feared the effect of another independent candidacy by George Wallace, and worked to defeat Wallace's 1970 gubernatorial campaign by contributing $400,000 to the unsuccessful campaign of Albert Brewer.[203] Уоллес выиграл несколько праймериз Демократической партии во время кампании 1972 года, но любая вероятность того, что он выиграет номинацию от Демократической партии или будет баллотироваться по билету третьей стороны, исчезла после того, как он был серьезно ранен в результате покушения. [204]

После того, как Кеннеди выбыл из гонки, сенатор Эдмунд Маски от штата Мэн и Хьюберт Хамфри стали фаворитами в номинации от Демократической партии 1972 года. [205] Победа сенатора Джорджа Макговерна на июньских праймериз в Калифорнии сделала его подавляющим фаворитом на июльском Национальном съезде Демократической партии . Макговерн был номинирован в первом туре голосования, но на съезде произошел хаотичный процесс выбора вице-президента. [206] В конечном итоге съезд выдвинул кандидатуру сенатора Томаса Иглтона от штата Миссури кандидатом на пост вице-президента Макговерна. После того, как стало известно, что Иглтон прошел курс лечения психических заболеваний , включая электрошоковую терапию , Иглтон отказался от участия в гонке. Макговерн заменил его Сарджентом Шрайвером из Мэриленда , Кеннеди . зятем [207]

Макговерн намеревался резко сократить расходы на оборону [208] и поддержал амнистию для уклонистов от призыва и защитников прав на аборты . Поскольку некоторые из его сторонников считались сторонниками легализации наркотиков, Макговерн считался сторонником «амнистии, абортов и кислоты». [209] Еще больше ему навредило широко распространенное мнение о том, что он плохо справился со своей кампанией, главным образом из-за инцидента с Иглтоном. [210] Макговерн утверждал, что «администрация Никсона — самая коррумпированная администрация в нашей национальной истории», но его нападки не имели большого эффекта. [211] Тем временем Никсон обратился ко многим демократам из рабочего класса, которых оттолкнула позиция Демократической партии по расовым и культурным вопросам. [212] Несмотря на новые ограничения на сбор средств для избирательной кампании, наложенные Законом о федеральной избирательной кампании , Никсон значительно превзошел Макговерна, и его кампания доминировала в рекламе на радио и телевидении. [213]

Никсон, лидировавший по опросам на протяжении всего 1972 года, сосредоточил свое внимание на перспективах мира во Вьетнаме и подъеме экономики. Он был избран на второй срок 7 ноября 1972 года, одержав одну из крупнейших убедительных побед на выборах в американской истории . Он набрал 61% голосов избирателей, получив 47 168 710 голосов против 29 173 222 голосов Макговерна, и одержал еще большую победу Коллегии выборщиков , набрав 520 голосов выборщиков против 17 за Макговерна. [214] Несмотря на убедительную победу Никсона, демократы сохранили контроль над обеими палатами Конгресса на одновременных выборах в Конгресс . [215] После выборов многие консервативные конгрессмены-южные демократы серьезно обсуждали возможность смены партии, чтобы дать республиканцам контроль над Палатой представителей, но эти переговоры были сорваны Уотергейтским скандалом. [216]

Уотергейт отставка и

Комитет по переизбранию президента [ править ]

После того, как Верховный суд отклонил просьбу администрации Никсона предотвратить публикацию документов Пентагона, Никсон и Эрлихман создали Отдел специальных расследований Белого дома, также известный как «Сантехники». Сантехникам было предъявлено обвинение в предотвращении будущих утечек новостей и в ответных мерах против Дэниела Эллсберга , который стоял за утечкой документов Пентагона. Среди тех, кто присоединился к Сантехникам, были Дж. Гордон Лидди , Э. Говард Хант и Чарльз Колсон. Вскоре после создания «Сантехников» организация ворвалась в кабинет психиатра Эллсберга. [217] Вместо того, чтобы полагаться на Республиканский национальный комитет , кампания по переизбранию Никсона в основном велась через Комитет по переизбранию президента (CRP), высшее руководство которого состояло из бывших сотрудников Белого дома. [218] Лидди и Хант стали сотрудничать с CRP, ведя шпионаж против демократов. [219]

Во время праймериз Демократической партии 1972 года Никсон и его союзники полагали, что сенатор Макговерн будет самым слабым вероятным кандидатом от Демократической партии на всеобщих выборах, и CRP работала над укреплением силы Макговерна. Никсон не был проинформирован о деталях каждого мероприятия CRP, но он одобрил всю операцию. [205] CRP особенно преследовал Маски, тайно используя водителя Маски в качестве шпиона. CRP также создала фальшивые организации, которые номинально поддерживали Маски, и использовала эти организации для нападок на других кандидатов от Демократической партии; Сенатора Генри Джексона обвинили в аресте за гомосексуальную деятельность, а Хамфри предположительно был причастен к вождению в нетрезвом виде. [220] В июне 1972 года Хант и Лидди возглавили вторжение в штаб- квартиру Национального комитета Демократической партии в комплексе Уотергейт . Взлом был предотвращен полицией, а администрация Никсона отрицала свою причастность к инциденту. [221] Обвинения виновным во взломе были предъявлены в сентябре 1972 года, но федеральный судья Джон Сирика распорядился закрыть дело до окончания выборов. Хотя Уотергейт оставался в новостях во время кампании 1972 года, он оказал относительно мало влияния на выборы. [222] Мотивация взлома Уотергейта остается предметом споров. [223]

Уотергейт [ править ]

| Уотергейтский скандал |

|---|

|

| События |

| Люди |

Никсон, возможно, не знал заранее о взломе Уотергейта, [219] но он стал участвовать в сокрытии. Никсон и Холдеман оказали давление на ФБР , чтобы оно прекратило расследование дела Уотергейта, а советник Белого дома Джон Дин пообещал грабителям Уотергейта деньги и помилование руководства, если они не обвинят Белый дом во взломе. [224] Грабители Уотергейта были осуждены в январе 1973 года без привлечения Белого дома, но члены Конгресса организовали расследование роли Никсона в Уотергейте. Как заявил конгрессмен Тип О'Нил , в ходе предвыборной кампании 1972 года Никсон и его союзники «сделали слишком много вещей. Слишком много людей знают об этом. Невозможно сохранить это в тайне. Придет время, когда начнется импичмент». этот Конгресс». [225] Хотя Никсон продолжал активно заниматься иностранными делами во время своего второго срока, последствия Уотергейтского скандала фактически исключили любые крупные внутренние инициативы. [226]

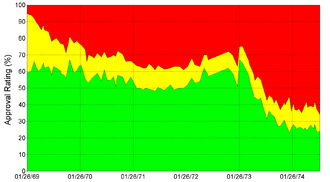

По настоянию лидера большинства в Сенате Майка Мэнсфилда сенатор от Северной Каролины Сэм Эрвин взял на себя инициативу в сенатском расследовании Уотергейта. Под руководством Эрвина Сенат учредил Специальный комитет по деятельности президентской кампании для расследования и проведения слушаний по Уотергейту. [225] «Уотергейтские слушания» транслировались по телевидению и широко смотрелись. Поскольку различные свидетели подробно рассказали не только о взломе в Уотергейте, но и о различных других предполагаемых должностных преступлениях со стороны различных чиновников администрации, рейтинг одобрения Никсона резко упал. [54] Журналисты Боб Вудворд и Карл Бернштейн также помогли сохранить Уотергейтское расследование в числе главных новостей. [227] Никсон попытался дискредитировать слушания как партийную охоту на ведьм, но некоторые сенаторы-республиканцы приняли активное участие в расследованиях. [225] В апреле 1973 года Никсон уволил Холдемана, Эрлихмана и генерального прокурора Ричарда Кляйндиенста в апреле 1973 года, заменив Кляйндиенста Эллиотом Ричардсоном . С разрешения Никсона Ричардсон назначил Арчибальда Кокса независимым специальным прокурором, которому было поручено расследование Уотергейтского дела. [228]

Опасаясь, что Никсон будет использовать его как козла отпущения для сокрытия, Джон Дин начал сотрудничать со следователями Уотергейта. [229] 25 июня Дин обвинил Никсона в том, что он помог спланировать сокрытие ограбления. [230] а в следующем месяце помощник Белого дома Александр Баттерфилд показал, что у Никсона была секретная система записи, которая записывала его разговоры и телефонные звонки в Овальном кабинете. [88] Кокс и Уотергейтский комитет Сената просили Никсона передать записи, но Никсон отказался, сославшись на привилегии исполнительной власти и соображения национальной безопасности. [231] Белый дом и Кокс оставались в ссоре до « Субботней ночной резни » 23 октября 1973 года, когда Никсон потребовал от Министерства юстиции уволить Кокса. Ричардсон и заместитель генерального прокурора Уильям Ракелсхаус подали в отставку вместо того, чтобы выполнить приказ Никсона, но Роберт Борк , следующий в министерстве юстиции, уволил Кокса. [232]

Увольнение возмутило Конгресс и вызвало общественный протест. 30 октября Юридический комитет Палаты представителей начал рассмотрение возможной процедуры импичмента; на следующий день Леон Яворски был назначен на замену Кокса, и вскоре после этого президент согласился передать запрошенные записи. [233] Когда несколько недель спустя записи были переданы, адвокаты Никсона обнаружили, что на одной аудиозаписи разговоров, состоявшихся в Белом доме 20 июня 1972 года, был перерыв в 18,5 минут. [234] Роуз Мэри Вудс , личный секретарь президента, взяла на себя ответственность за пробел, утверждая, что она случайно стерла этот раздел во время расшифровки записи, хотя ее объяснение было широко высмеяно. Этот разрыв, хотя и не является убедительным доказательством правонарушений президента, поставил под сомнение заявление Никсона о том, что он не знал о сокрытии. [235] В том же месяце во время часовой телевизионной сессии вопросов и ответов с прессой [236] Никсон настаивал на том, что он допустил ошибки, но ничего не знал об ограблении, не нарушал никаких законов и не узнал о сокрытии до начала 1973 года. Он заявил: «Я не мошенник. заработал все, что у меня есть. [237]

В конце 1973 - начале 1974 года Никсон продолжал отвергать обвинения в правонарушениях и поклялся, что будет оправдан. [234] Тем временем в судах и Конгрессе события продолжали приближать разворачивающуюся сагу к кульминации. 1 марта 1974 года большое жюри предъявило семи бывшим чиновникам администрации обвинение в сговоре с целью помешать расследованию ограбления в Уотергейте. Большое жюри, как выяснилось позже, также назвало Никсона заговорщиком, которому не предъявлены обвинения . [233] В апреле Юридический комитет Палаты представителей проголосовал за вызов в суд записей 42 президентских разговоров, а специальный прокурор также вызвал в суд еще больше записей и документов. Белый дом отклонил обе повестки, еще раз сославшись на привилегии исполнительной власти. [88] В ответ Юридический комитет Палаты представителей 9 мая открыл слушания по импичменту президенту. [233] Эти слушания, которые транслировались по телевидению, завершились голосованием по статьям импичмента, первое из которых 27 июля 1974 года было 27–11 за воспрепятствование осуществлению правосудия ; шесть республиканцев проголосовали «за» вместе со всеми 21 демократом. [238] 24 июля Верховный суд единогласно постановил , что необходимо опубликовать полные записи, а не только отдельные стенограммы. [239]

Отставка [ править ]

Несмотря на то, что его поддержка уменьшилась из-за продолжающейся серии разоблачений, Никсон надеялся избежать импичмента. Однако одна из недавно выпущенных пленок, «дымящийся пистолет» , записанная всего через несколько дней после взлома, продемонстрировала, что Никсону сообщили о связи Белого дома с Уотергейтскими кражами со взломом вскоре после того, как они произошли, и он утвердил планы по пресечению расследования. В заявлении, сопровождавшем публикацию записей 5 августа 1974 года, Никсон взял на себя вину за то, что ввел страну в заблуждение относительно того, когда ему рассказали правду о взломе в Уотергейте, заявив, что у него провал в памяти. [240]

7 августа Никсон встретился в Овальном кабинете с лидерами республиканского Конгресса, «чтобы обсудить картину импичмента», и ему сказали, что его поддержка в Конгрессе практически исчезла. Они нарисовали президенту мрачную картину: ему грозит неизбежный импичмент, когда статья будет вынесена на голосование при полном составе Палаты представителей, а в Сенате не только достаточно голосов, чтобы осудить его, но и не более 15 или около того сенаторов были готовы голосовать за оправдание. [241] [242] Той ночью, зная, что его президентство фактически закончилось, Никсон окончательно принял решение уйти в отставку. [243]