Комета

| Комета | |

|---|---|

Комета Хейла-Боппа | |

| Характеристики | |

| Тип | Маленькое тело Солнечной системы |

| Найденный | Звездные системы |

| Диапазон размеров | Ширина ~10 км (ядро) [1] |

| Плотность | 0,6 г/см 3 (средний) |

| External links | |

Комета дегазацией — это небольшое ледяное тело Солнечной системы , которое нагревается и начинает выделять газы при прохождении близко к Солнцу (процесс, называемый ) . Это создает протяженную, гравитационно-несвязанную атмосферу или кому, окружающую ядро, а иногда и хвост газа и пылевого газа, выбрасываемый из комы. Эти явления обусловлены воздействием солнечной радиации и выходящей плазмы солнечного ветра, воздействующей на ядро кометы. Ядра комет имеют диаметр от нескольких сотен метров до десятков километров и состоят из рыхлых скоплений льда, пыли и мелких каменистых частиц. Размер комы может достигать 15-кратного диаметра Земли, а хвост может простираться за пределы одной астрономической единицы . Если комету достаточно близко и ярко, ее можно увидеть с Земли без помощи телескопа, и она может огибать небо по дуге до 30 ° (60 лун). Кометы наблюдались и записывались с древних времен представителями многих культур и религий.

Comets usually have highly eccentric elliptical orbits, and they have a wide range of orbital periods, ranging from several years to potentially several millions of years. Short-period comets originate in the Kuiper belt or its associated scattered disc, which lie beyond the orbit of Neptune. Long-period comets are thought to originate in the Oort cloud, a spherical cloud of icy bodies extending from outside the Kuiper belt to halfway to the nearest star.[2] Длиннопериодические кометы движутся к Солнцу под действием гравитационных возмущений от проходящих звезд и галактических приливов . Гиперболические кометы могут один раз пройти через внутреннюю часть Солнечной системы, прежде чем оказаться в межзвездном пространстве. Появление кометы называется призраком.

Extinct comets that have passed close to the Sun many times have lost nearly all of their volatile ices and dust and may come to resemble small asteroids.[3] Asteroids are thought to have a different origin from comets, having formed inside the orbit of Jupiter rather than in the outer Solar System.[4][5] However, the discovery of main-belt comets and active centaur minor planets has blurred the distinction between asteroids and comets. In the early 21st century, the discovery of some minor bodies with long-period comet orbits, but characteristics of inner solar system asteroids, were called Manx comets. They are still classified as comets, such as C/2014 S3 (PANSTARRS).[6] Twenty-seven Manx comets were found from 2013 to 2017.[7]

As of November 2021[update], there are 4,584 known comets.[8] However, this represents a very small fraction of the total potential comet population, as the reservoir of comet-like bodies in the outer Solar System (in the Oort cloud) is about one trillion.[9][10] Roughly one comet per year is visible to the naked eye, though many of those are faint and unspectacular.[11] Particularly bright examples are called "great comets". Comets have been visited by uncrewed probes such as NASA's Deep Impact, which blasted a crater on Comet Tempel 1 to study its interior, and the European Space Agency's Rosetta, which became the first to land a robotic spacecraft on a comet.[12]

Etymology

The word comet derives from the Old English cometa from the Latin comēta or comētēs. That, in turn, is a romanization of the Greek κομήτης 'wearing long hair', and the Oxford English Dictionary notes that the term (ἀστὴρ) κομήτης already meant 'long-haired star, comet' in Greek. Κομήτης was derived from κομᾶν (koman) 'to wear the hair long', which was itself derived from κόμη (komē) 'the hair of the head' and was used to mean 'the tail of a comet'.[13][14]

The astronomical symbol for comets (represented in Unicode) is U+2604 ☄ COMET, consisting of a small disc with three hairlike extensions.[15]

Physical characteristics

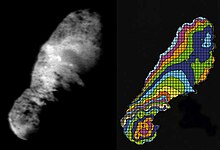

Nucleus

The solid, core structure of a comet is known as the nucleus. Cometary nuclei are composed of an amalgamation of rock, dust, water ice, and frozen carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, methane, and ammonia.[16] As such, they are popularly described as "dirty snowballs" after Fred Whipple's model.[17] Comets with a higher dust content have been called "icy dirtballs".[18] The term "icy dirtballs" arose after observation of Comet 9P/Tempel 1 collision with an "impactor" probe sent by NASA Deep Impact mission in July 2005. Research conducted in 2014 suggests that comets are like "deep fried ice cream", in that their surfaces are formed of dense crystalline ice mixed with organic compounds, while the interior ice is colder and less dense.[19]

The surface of the nucleus is generally dry, dusty or rocky, suggesting that the ices are hidden beneath a surface crust several metres thick. The nuclei contains a variety of organic compounds, which may include methanol, hydrogen cyanide, formaldehyde, ethanol, ethane, and perhaps more complex molecules such as long-chain hydrocarbons and amino acids.[20][21] In 2009, it was confirmed that the amino acid glycine had been found in the comet dust recovered by NASA's Stardust mission.[22] In August 2011, a report, based on NASA studies of meteorites found on Earth, was published suggesting DNA and RNA components (adenine, guanine, and related organic molecules) may have been formed on asteroids and comets.[23][24]

The outer surfaces of cometary nuclei have a very low albedo, making them among the least reflective objects found in the Solar System. The Giotto space probe found that the nucleus of Halley's Comet (1P/Halley) reflects about four percent of the light that falls on it,[25] and Deep Space 1 discovered that Comet Borrelly's surface reflects less than 3.0%;[25] by comparison, asphalt reflects seven percent. The dark surface material of the nucleus may consist of complex organic compounds. Solar heating drives off lighter volatile compounds, leaving behind larger organic compounds that tend to be very dark, like tar or crude oil. The low reflectivity of cometary surfaces causes them to absorb the heat that drives their outgassing processes.[26]

Comet nuclei with radii of up to 30 kilometers (19 mi) have been observed,[27] but ascertaining their exact size is difficult.[28] The nucleus of 322P/SOHO is probably only 100–200 meters (330–660 ft) in diameter.[29] A lack of smaller comets being detected despite the increased sensitivity of instruments has led some to suggest that there is a real lack of comets smaller than 100 meters (330 ft) across.[30] Known comets have been estimated to have an average density of 0.6 g/cm3 (0.35 oz/cu in).[31] Because of their low mass, comet nuclei do not become spherical under their own gravity and therefore have irregular shapes.[32]

Roughly six percent of the near-Earth asteroids are thought to be the extinct nuclei of comets that no longer experience outgassing,[33] including 14827 Hypnos and 3552 Don Quixote.

Results from the Rosetta and Philae spacecraft show that the nucleus of 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko has no magnetic field, which suggests that magnetism may not have played a role in the early formation of planetesimals.[34][35] Further, the ALICE spectrograph on Rosetta determined that electrons (within 1 km (0.62 mi) above the comet nucleus) produced from photoionization of water molecules by solar radiation, and not photons from the Sun as thought earlier, are responsible for the degradation of water and carbon dioxide molecules released from the comet nucleus into its coma.[36][37] Instruments on the Philae lander found at least sixteen organic compounds at the comet's surface, four of which (acetamide, acetone, methyl isocyanate and propionaldehyde) have been detected for the first time on a comet.[38][39][40]

| Name | Dimensions (km) | Density (g/cm3) | Mass (kg)[41] | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Halley's Comet | 15 × 8 × 8 | 0.6 | 3×1014 | [42][43] |

| Tempel 1 | 7.6 × 4.9 | 0.62 | 7.9×1013 | [31][44] |

| 19P/Borrelly | 8 × 4 × 4 | 0.3 | 2.0×1013 | [31] |

| 81P/Wild | 5.5 × 4.0 × 3.3 | 0.6 | 2.3×1013 | [31][45] |

| 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko | 4.1 × 3.3 × 1.8 | 0.47 | 1.0×1013 | [46][47] |

Coma

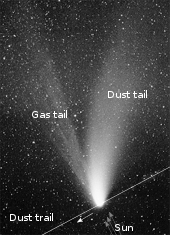

The streams of dust and gas thus released form a huge and extremely thin atmosphere around the comet called the "coma". The force exerted on the coma by the Sun's radiation pressure and solar wind cause an enormous "tail" to form pointing away from the Sun.[49]

The coma is generally made of water and dust, with water making up to 90% of the volatiles that outflow from the nucleus when the comet is within 3 to 4 astronomical units (450,000,000 to 600,000,000 km; 280,000,000 to 370,000,000 mi) of the Sun.[50] The H2O parent molecule is destroyed primarily through photodissociation and to a much smaller extent photoionization, with the solar wind playing a minor role in the destruction of water compared to photochemistry.[50] Larger dust particles are left along the comet's orbital path whereas smaller particles are pushed away from the Sun into the comet's tail by light pressure.[51]

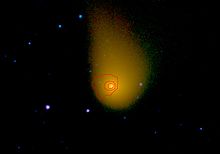

Although the solid nucleus of comets is generally less than 60 kilometers (37 mi) across, the coma may be thousands or millions of kilometers across, sometimes becoming larger than the Sun.[52] For example, about a month after an outburst in October 2007, comet 17P/Holmes briefly had a tenuous dust atmosphere larger than the Sun.[53] The Great Comet of 1811 had a coma roughly the diameter of the Sun.[54] Even though the coma can become quite large, its size can decrease about the time it crosses the orbit of Mars around 1.5 astronomical units (220,000,000 km; 140,000,000 mi) from the Sun.[54] At this distance the solar wind becomes strong enough to blow the gas and dust away from the coma, and in doing so enlarging the tail.[54] Ion tails have been observed to extend one astronomical unit (150 million km) or more.[53]

Both the coma and tail are illuminated by the Sun and may become visible when a comet passes through the inner Solar System, the dust reflects sunlight directly while the gases glow from ionisation.[55] Most comets are too faint to be visible without the aid of a telescope, but a few each decade become bright enough to be visible to the naked eye.[56] Occasionally a comet may experience a huge and sudden outburst of gas and dust, during which the size of the coma greatly increases for a period of time. This happened in 2007 to Comet Holmes.[57]

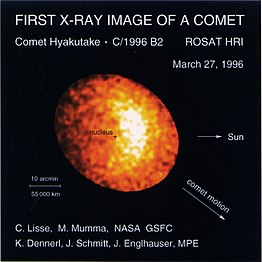

In 1996, comets were found to emit X-rays.[58] This greatly surprised astronomers because X-ray emission is usually associated with very high-temperature bodies. The X-rays are generated by the interaction between comets and the solar wind: when highly charged solar wind ions fly through a cometary atmosphere, they collide with cometary atoms and molecules, "stealing" one or more electrons from the atom in a process called "charge exchange". This exchange or transfer of an electron to the solar wind ion is followed by its de-excitation into the ground state of the ion by the emission of X-rays and far ultraviolet photons.[59]

Bow shock

Bow shocks form as a result of the interaction between the solar wind and the cometary ionosphere, which is created by the ionization of gases in the coma. As the comet approaches the Sun, increasing outgassing rates cause the coma to expand, and the sunlight ionizes gases in the coma. When the solar wind passes through this ion coma, the bow shock appears.

The first observations were made in the 1980s and 1990s as several spacecraft flew by comets 21P/Giacobini–Zinner,[60] 1P/Halley,[61] and 26P/Grigg–Skjellerup.[62] It was then found that the bow shocks at comets are wider and more gradual than the sharp planetary bow shocks seen at, for example, Earth. These observations were all made near perihelion when the bow shocks already were fully developed.

The Rosetta spacecraft observed the bow shock at comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko at an early stage of bow shock development when the outgassing increased during the comet's journey toward the Sun. This young bow shock was called the "infant bow shock". The infant bow shock is asymmetric and, relative to the distance to the nucleus, wider than fully developed bow shocks.[63]

Tails

In the outer Solar System, comets remain frozen and inactive and are extremely difficult or impossible to detect from Earth due to their small size. Statistical detections of inactive comet nuclei in the Kuiper belt have been reported from observations by the Hubble Space Telescope[64][65] but these detections have been questioned.[66][67] As a comet approaches the inner Solar System, solar radiation causes the volatile materials within the comet to vaporize and stream out of the nucleus, carrying dust away with them.

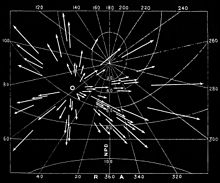

The streams of dust and gas each form their own distinct tail, pointing in slightly different directions. The tail of dust is left behind in the comet's orbit in such a manner that it often forms a curved tail called the type II or dust tail.[55] At the same time, the ion or type I tail, made of gases, always points directly away from the Sun because this gas is more strongly affected by the solar wind than is dust, following magnetic field lines rather than an orbital trajectory.[68] On occasions—such as when Earth passes through a comet's orbital plane, the antitail, pointing in the opposite direction to the ion and dust tails, may be seen.[69]

The observation of antitails contributed significantly to the discovery of solar wind.[70] The ion tail is formed as a result of the ionization by solar ultra-violet radiation of particles in the coma. Once the particles have been ionized, they attain a net positive electrical charge, which in turn gives rise to an "induced magnetosphere" around the comet. The comet and its induced magnetic field form an obstacle to outward flowing solar wind particles. Because the relative orbital speed of the comet and the solar wind is supersonic, a bow shock is formed upstream of the comet in the flow direction of the solar wind. In this bow shock, large concentrations of cometary ions (called "pick-up ions") congregate and act to "load" the solar magnetic field with plasma, such that the field lines "drape" around the comet forming the ion tail.[71]

If the ion tail loading is sufficient, the magnetic field lines are squeezed together to the point where, at some distance along the ion tail, magnetic reconnection occurs. This leads to a "tail disconnection event".[71] This has been observed on a number of occasions, one notable event being recorded on 20 April 2007, when the ion tail of Encke's Comet was completely severed while the comet passed through a coronal mass ejection. This event was observed by the STEREO space probe.[72]

In 2013, ESA scientists reported that the ionosphere of the planet Venus streams outwards in a manner similar to the ion tail seen streaming from a comet under similar conditions."[73][74]

Jets

Uneven heating can cause newly generated gases to break out of a weak spot on the surface of comet's nucleus, like a geyser.[75] These streams of gas and dust can cause the nucleus to spin, and even split apart.[75] In 2010 it was revealed dry ice (frozen carbon dioxide) can power jets of material flowing out of a comet nucleus.[76] Infrared imaging of Hartley 2 shows such jets exiting and carrying with it dust grains into the coma.[77]

Orbital characteristics

Most comets are small Solar System bodies with elongated elliptical orbits that take them close to the Sun for a part of their orbit and then out into the further reaches of the Solar System for the remainder.[78] Comets are often classified according to the length of their orbital periods: The longer the period the more elongated the ellipse.

Short period

Periodic comets or short-period comets are generally defined as those having orbital periods of less than 200 years.[79] They usually orbit more-or-less in the ecliptic plane in the same direction as the planets.[80] Their orbits typically take them out to the region of the outer planets (Jupiter and beyond) at aphelion; for example, the aphelion of Halley's Comet is a little beyond the orbit of Neptune. Comets whose aphelia are near a major planet's orbit are called its "family".[81] Such families are thought to arise from the planet capturing formerly long-period comets into shorter orbits.[82]

At the shorter orbital period extreme, Encke's Comet has an orbit that does not reach the orbit of Jupiter, and is known as an Encke-type comet. Short-period comets with orbital periods less than 20 years and low inclinations (up to 30 degrees) to the ecliptic are called traditional Jupiter-family comets (JFCs).[83][84] Those like Halley, with orbital periods of between 20 and 200 years and inclinations extending from zero to more than 90 degrees, are called Halley-type comets (HTCs).[85][86] As of 2023[update], 70 Encke-type comets, 100 HTCs, and 755 JFCs have been reported.[87]

Recently discovered main-belt comets form a distinct class, orbiting in more circular orbits within the asteroid belt.[88][89]

Because their elliptical orbits frequently take them close to the giant planets, comets are subject to further gravitational perturbations.[90] Short-period comets have a tendency for their aphelia to coincide with a giant planet's semi-major axis, with the JFCs being the largest group.[84] It is clear that comets coming in from the Oort cloud often have their orbits strongly influenced by the gravity of giant planets as a result of a close encounter. Jupiter is the source of the greatest perturbations, being more than twice as massive as all the other planets combined. These perturbations can deflect long-period comets into shorter orbital periods.[91][92]

Based on their orbital characteristics, short-period comets are thought to originate from the centaurs and the Kuiper belt/scattered disc[93] —a disk of objects in the trans-Neptunian region—whereas the source of long-period comets is thought to be the far more distant spherical Oort cloud (after the Dutch astronomer Jan Hendrik Oort who hypothesized its existence).[94] Vast swarms of comet-like bodies are thought to orbit the Sun in these distant regions in roughly circular orbits. Occasionally the gravitational influence of the outer planets (in the case of Kuiper belt objects) or nearby stars (in the case of Oort cloud objects) may throw one of these bodies into an elliptical orbit that takes it inwards toward the Sun to form a visible comet. Unlike the return of periodic comets, whose orbits have been established by previous observations, the appearance of new comets by this mechanism is unpredictable.[95] When flung into the orbit of the sun, and being continuously dragged towards it, tons of matter are stripped from the comets which greatly influence their lifetime; the more stripped, the shorter they live and vice versa.[96]

Long period

Long-period comets have highly eccentric orbits and periods ranging from 200 years to thousands or even millions of years.[97] An eccentricity greater than 1 when near perihelion does not necessarily mean that a comet will leave the Solar System.[98] For example, Comet McNaught had a heliocentric osculating eccentricity of 1.000019 near its perihelion passage epoch in January 2007 but is bound to the Sun with roughly a 92,600-year orbit because the eccentricity drops below 1 as it moves farther from the Sun. The future orbit of a long-period comet is properly obtained when the osculating orbit is computed at an epoch after leaving the planetary region and is calculated with respect to the center of mass of the Solar System. By definition long-period comets remain gravitationally bound to the Sun; those comets that are ejected from the Solar System due to close passes by major planets are no longer properly considered as having "periods". The orbits of long-period comets take them far beyond the outer planets at aphelia, and the plane of their orbits need not lie near the ecliptic. Long-period comets such as C/1999 F1 and C/2017 T2 (PANSTARRS) can have aphelion distances of nearly 70,000 AU (0.34 pc; 1.1 ly) with orbital periods estimated around 6 million years.

Single-apparition or non-periodic comets are similar to long-period comets because they have parabolic or slightly hyperbolic trajectories[97] when near perihelion in the inner Solar System. However, gravitational perturbations from giant planets cause their orbits to change. Single-apparition comets have a hyperbolic or parabolic osculating orbit which allows them to permanently exit the Solar System after a single pass of the Sun.[99] The Sun's Hill sphere has an unstable maximum boundary of 230,000 AU (1.1 pc; 3.6 ly).[100] Only a few hundred comets have been seen to reach a hyperbolic orbit (e > 1) when near perihelion[101] that using a heliocentric unperturbed two-body best-fit suggests they may escape the Solar System.

As of 2022[update], only two objects have been discovered with an eccentricity significantly greater than one: 1I/ʻOumuamua and 2I/Borisov, indicating an origin outside the Solar System. While ʻOumuamua, with an eccentricity of about 1.2, showed no optical signs of cometary activity during its passage through the inner Solar System in October 2017, changes to its trajectory—which suggests outgassing—indicate that it is probably a comet.[102] On the other hand, 2I/Borisov, with an estimated eccentricity of about 3.36, has been observed to have the coma feature of comets, and is considered the first detected interstellar comet.[103][104] Comet C/1980 E1 had an orbital period of roughly 7.1 million years before the 1982 perihelion passage, but a 1980 encounter with Jupiter accelerated the comet giving it the largest eccentricity (1.057) of any known solar comet with a reasonable observation arc.[105] Comets not expected to return to the inner Solar System include C/1980 E1, C/2000 U5, C/2001 Q4 (NEAT), C/2009 R1, C/1956 R1, and C/2007 F1 (LONEOS).

Some authorities use the term "periodic comet" to refer to any comet with a periodic orbit (that is, all short-period comets plus all long-period comets),[106] whereas others use it to mean exclusively short-period comets.[97] Similarly, although the literal meaning of "non-periodic comet" is the same as "single-apparition comet", some use it to mean all comets that are not "periodic" in the second sense (that is, to include all comets with a period greater than 200 years).

Early observations have revealed a few genuinely hyperbolic (i.e. non-periodic) trajectories, but no more than could be accounted for by perturbations from Jupiter. Comets from interstellar space are moving with velocities of the same order as the relative velocities of stars near the Sun (a few tens of km per second). When such objects enter the Solar System, they have a positive specific orbital energy resulting in a positive velocity at infinity () and have notably hyperbolic trajectories. A rough calculation shows that there might be four hyperbolic comets per century within Jupiter's orbit, give or take one and perhaps two orders of magnitude.[107]

| Year | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 12 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 13 | 10 | 16 | 9 | 16 | 5 | 18 | 10 | 15 | 17 |

Oort cloud and Hills cloud

The Oort cloud is thought to occupy a vast space starting from between 2,000 and 5,000 AU (0.03 and 0.08 ly)[109] to as far as 50,000 AU (0.79 ly)[85] from the Sun. This cloud encases the celestial bodies that start at the middle of the Solar System—the Sun, all the way to outer limits of the Kuiper Belt. The Oort cloud consists of viable materials necessary for the creation of celestial bodies. The Solar System's planets exist only because of the planetesimals (chunks of leftover space that assisted in the creation of planets) that were condensed and formed by the gravity of the Sun. The eccentric made from these trapped planetesimals is why the Oort Cloud even exists.[110] Some estimates place the outer edge at between 100,000 and 200,000 AU (1.58 and 3.16 ly).[109] The region can be subdivided into a spherical outer Oort cloud of 20,000–50,000 AU (0.32–0.79 ly), and a doughnut-shaped inner cloud, the Hills cloud, of 2,000–20,000 AU (0.03–0.32 ly).[111] The outer cloud is only weakly bound to the Sun and supplies the long-period (and possibly Halley-type) comets that fall to inside the orbit of Neptune.[85] The inner Oort cloud is also known as the Hills cloud, named after Jack G. Hills, who proposed its existence in 1981.[112] Models predict that the inner cloud should have tens or hundreds of times as many cometary nuclei as the outer halo;[112][113][114] it is seen as a possible source of new comets that resupply the relatively tenuous outer cloud as the latter's numbers are gradually depleted. The Hills cloud explains the continued existence of the Oort cloud after billions of years.[115]

Exocomets

Exocomets beyond the Solar System have been detected and may be common in the Milky Way.[116] The first exocomet system detected was around Beta Pictoris, a very young A-type main-sequence star, in 1987.[117][118] A total of 11 such exocomet systems have been identified as of 2013[update], using the absorption spectrum caused by the large clouds of gas emitted by comets when passing close to their star.[116][117] For ten years the Kepler space telescope was responsible for searching for planets and other forms outside of the solar system. The first transiting exocomets were found in February 2018 by a group consisting of professional astronomers and citizen scientists in light curves recorded by the Kepler Space Telescope.[119][120] After Kepler Space Telescope retired in October 2018, a new telescope called TESS Telescope has taken over Kepler's mission. Since the launch of TESS, astronomers have discovered the transits of comets around the star Beta Pictoris using a light curve from TESS.[121][122] Since TESS has taken over, astronomers have since been able to better distinguish exocomets with the spectroscopic method. New planets are detected by the white light curve method which is viewed as a symmetrical dip in the charts readings when a planet overshadows its parent star. However, after further evaluation of these light curves, it has been discovered that the asymmetrical patterns of the dips presented are caused by the tail of a comet or of hundreds of comets.[123]

Effects of comets

Connection to meteor showers

As a comet is heated during close passes to the Sun, outgassing of its icy components releases solid debris too large to be swept away by radiation pressure and the solar wind.[124] If Earth's orbit sends it through that trail of debris, which is composed mostly of fine grains of rocky material, there is likely to be a meteor shower as Earth passes through. Denser trails of debris produce quick but intense meteor showers and less dense trails create longer but less intense showers. Typically, the density of the debris trail is related to how long ago the parent comet released the material.[125][126] The Perseid meteor shower, for example, occurs every year between 9 and 13 August, when Earth passes through the orbit of Comet Swift–Tuttle. Halley's Comet is the source of the Orionid shower in October.[127][128]

Comets and impact on life

Many comets and asteroids collided with Earth in its early stages. Many scientists think that comets bombarding the young Earth about 4 billion years ago brought the vast quantities of water that now fill Earth's oceans, or at least a significant portion of it. Others have cast doubt on this idea.[129] The detection of organic molecules, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons,[19] in significant quantities in comets has led to speculation that comets or meteorites may have brought the precursors of life—or even life itself—to Earth.[130] In 2013 it was suggested that impacts between rocky and icy surfaces, such as comets, had the potential to create the amino acids that make up proteins through shock synthesis.[131] The speed at which the comets entered the atmosphere, combined with the magnitude of energy created after initial contact, allowed smaller molecules to condense into the larger macro-molecules that served as the foundation for life.[132] In 2015, scientists found significant amounts of molecular oxygen in the outgassings of comet 67P, suggesting that the molecule may occur more often than had been thought, and thus less an indicator of life as has been supposed.[133]

It is suspected that comet impacts have, over long timescales, delivered significant quantities of water to Earth's Moon, some of which may have survived as lunar ice.[134] Comet and meteoroid impacts are thought to be responsible for the existence of tektites and australites.[135]

Fear of comets

Fear of comets as acts of God and signs of impending doom was highest in Europe from AD 1200 to 1650.[136] The year after the Great Comet of 1618, for example, Gotthard Arthusius published a pamphlet stating that it was a sign that the Day of Judgment was near.[137] He listed ten pages of comet-related disasters, including "earthquakes, floods, changes in river courses, hail storms, hot and dry weather, poor harvests, epidemics, war and treason and high prices".[136]

By 1700 most scholars concluded that such events occurred whether a comet was seen or not. Using Edmond Halley's records of comet sightings, however, William Whiston in 1711 wrote that the Great Comet of 1680 had a periodicity of 574 years and was responsible for the worldwide flood in the Book of Genesis, by pouring water on Earth. His announcement revived for another century fear of comets, now as direct threats to the world instead of signs of disasters.[136] Spectroscopic analysis in 1910 found the toxic gas cyanogen in the tail of Halley's Comet,[138] causing panicked buying of gas masks and quack "anti-comet pills" and "anti-comet umbrellas" by the public.[139]

Fate of comets

Departure (ejection) from Solar System

If a comet is traveling fast enough, it may leave the Solar System. Such comets follow the open path of a hyperbola, and as such, they are called hyperbolic comets. Solar comets are only known to be ejected by interacting with another object in the Solar System, such as Jupiter.[140] An example of this is Comet C/1980 E1, which was shifted from an orbit of 7.1 million years around the Sun, to a hyperbolic trajectory, after a 1980 close pass by the planet Jupiter.[141] Interstellar comets such as 1I/ʻOumuamua and 2I/Borisov never orbited the Sun and therefore do not require a 3rd-body interaction to be ejected from the Solar System.

Extinction

Jupiter-family comets and long-period comets appear to follow very different fading laws. The JFCs are active over a lifetime of about 10,000 years or ~1,000 orbits whereas long-period comets fade much faster. Only 10% of the long-period comets survive more than 50 passages to small perihelion and only 1% of them survive more than 2,000 passages.[33] Eventually most of the volatile material contained in a comet nucleus evaporates, and the comet becomes a small, dark, inert lump of rock or rubble that can resemble an asteroid.[142] Some asteroids in elliptical orbits are now identified as extinct comets.[143][144][145][146] Roughly six percent of the near-Earth asteroids are thought to be extinct comet nuclei.[33]

Breakup and collisions

The nucleus of some comets may be fragile, a conclusion supported by the observation of comets splitting apart.[147] A significant cometary disruption was that of Comet Shoemaker–Levy 9, which was discovered in 1993. A close encounter in July 1992 had broken it into pieces, and over a period of six days in July 1994, these pieces fell into Jupiter's atmosphere—the first time astronomers had observed a collision between two objects in the Solar System.[148][149] Other splitting comets include 3D/Biela in 1846 and 73P/Schwassmann–Wachmann from 1995 to 2006.[150] Greek historian Ephorus reported that a comet split apart as far back as the winter of 372–373 BC.[151] Comets are suspected of splitting due to thermal stress, internal gas pressure, or impact.[152]

Comets 42P/Neujmin and 53P/Van Biesbroeck appear to be fragments of a parent comet. Numerical integrations have shown that both comets had a rather close approach to Jupiter in January 1850, and that, before 1850, the two orbits were nearly identical.[153] Another group of comets that is the result of fragmentation episodes is the Liller comet family made of C/1988 A1 (Liller), C/1996 Q1 (Tabur), C/2015 F3 (SWAN), C/2019 Y1 (ATLAS), and C/2023 V5 (Leonard).[154][155]

Some comets have been observed to break up during their perihelion passage, including great comets West and Ikeya–Seki. Biela's Comet was one significant example when it broke into two pieces during its passage through the perihelion in 1846. These two comets were seen separately in 1852, but never again afterward. Instead, spectacular meteor showers were seen in 1872 and 1885 when the comet should have been visible. A minor meteor shower, the Andromedids, occurs annually in November, and it is caused when Earth crosses the orbit of Biela's Comet.[156]

Some comets meet a more spectacular end – either falling into the Sun[157] or smashing into a planet or other body. Collisions between comets and planets or moons were common in the early Solar System: some of the many craters on the Moon, for example, may have been caused by comets. A recent collision of a comet with a planet occurred in July 1994 when Comet Shoemaker–Levy 9 broke up into pieces and collided with Jupiter.[158]

Nomenclature

The names given to comets have followed several different conventions over the past two centuries. Prior to the early 20th century, most comets were referred to by the year when they appeared, sometimes with additional adjectives for particularly bright comets; thus, the "Great Comet of 1680", the "Great Comet of 1882", and the "Great January Comet of 1910".

After Edmond Halley demonstrated that the comets of 1531, 1607, and 1682 were the same body and successfully predicted its return in 1759 by calculating its orbit, that comet became known as Halley's Comet.[160] Similarly, the second and third known periodic comets, Encke's Comet[161] and Biela's Comet,[162] were named after the astronomers who calculated their orbits rather than their original discoverers. Later, periodic comets were usually named after their discoverers, but comets that had appeared only once continued to be referred to by the year of their appearance.[163]

In the early 20th century, the convention of naming comets after their discoverers became common, and this remains so today. A comet can be named after its discoverers or an instrument or program that helped to find it.[163] For example, in 2019, astronomer Gennadiy Borisov observed a comet that appeared to have originated outside of the solar system; the comet was named 2I/Borisov after him.[164]

History of study

Early observations and thought

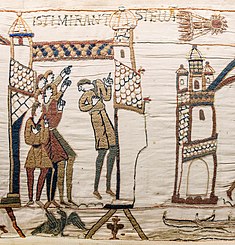

From ancient sources, such as Chinese oracle bones, it is known that comets have been noticed by humans for millennia.[165] Until the sixteenth century, comets were usually considered bad omens of deaths of kings or noble men, or coming catastrophes, or even interpreted as attacks by heavenly beings against terrestrial inhabitants.[166][167]

Aristotle (384–322 BC) was the first known scientist to use various theories and observational facts to employ a consistent, structured cosmological theory of comets. He believed that comets were atmospheric phenomena, due to the fact that they could appear outside of the zodiac and vary in brightness over the course of a few days. Aristotle's cometary theory arose from his observations and cosmological theory that everything in the cosmos is arranged in a distinct configuration.[168] Part of this configuration was a clear separation between the celestial and terrestrial, believing comets to be strictly associated with the latter. According to Aristotle, comets must be within the sphere of the moon and clearly separated from the heavens. Also in the 4th century BC, Apollonius of Myndus supported the idea that comets moved like the planets.[169] Aristotelian theory on comets continued to be widely accepted throughout the Middle Ages, despite several discoveries from various individuals challenging aspects of it.[170]

In the 1st century AD, Seneca the Younger questioned Aristotle's logic concerning comets. Because of their regular movement and imperviousness to wind, they cannot be atmospheric,[171] and are more permanent than suggested by their brief flashes across the sky.[a] He pointed out that only the tails are transparent and thus cloudlike, and argued that there is no reason to confine their orbits to the zodiac.[171] In criticizing Apollonius of Myndus, Seneca argues, "A comet cuts through the upper regions of the universe and then finally becomes visible when it reaches the lowest point of its orbit."[172] While Seneca did not author a substantial theory of his own,[173] his arguments would spark much debate among Aristotle's critics in the 16th and 17th centuries.[170][b]

In the 1st century AD, Pliny the Elder believed that comets were connected with political unrest and death.[175] Pliny observed comets as "human like", often describing their tails with "long hair" or "long beard".[176] His system for classifying comets according to their color and shape was used for centuries.[177]

In India, by the 6th century AD astronomers believed that comets were apparitions that re-appeared periodically. This was the view expressed in the 6th century by the astronomers Varāhamihira and Bhadrabahu, and the 10th-century astronomer Bhaṭṭotpala listed the names and estimated periods of certain comets, but it is not known how these figures were calculated or how accurate they were.[178][179]

There is a claim that an Arab scholar in 1258 noted several recurrent appearances of a comet (or a type of comet), and though it's not clear if he considered it to be a single periodic comet, it might have been a comet with a period of around 63 years.[180]

In 1301, the Italian painter Giotto was the first person to accurately and anatomically portray a comet. In his work Adoration of the Magi, Giotto's depiction of Halley's Comet in the place of the Star of Bethlehem would go unmatched in accuracy until the 19th century and be bested only with the invention of photography.[181]

Astrological interpretations of comets proceeded to take precedence clear into the 15th century, despite the presence of modern scientific astronomy beginning to take root. Comets continued to forewarn of disaster, as seen in the Luzerner Schilling chronicles and in the warnings of Pope Callixtus III.[181] In 1578, German Lutheran bishop Andreas Celichius defined comets as "the thick smoke of human sins ... kindled by the hot and fiery anger of the Supreme Heavenly Judge". The next year, Andreas Dudith stated that "If comets were caused by the sins of mortals, they would never be absent from the sky."[182]

Scientific approach

Crude attempts at a parallax measurement of Halley's Comet were made in 1456, but were erroneous.[183] Regiomontanus was the first to attempt to calculate diurnal parallax by observing the Great Comet of 1472. His predictions were not very accurate, but they were conducted in the hopes of estimating the distance of a comet from Earth.[177]

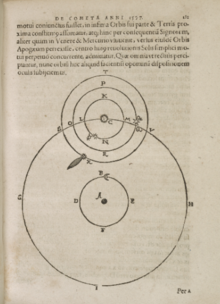

In the 16th century, Tycho Brahe and Michael Maestlin demonstrated that comets must exist outside of Earth's atmosphere by measuring the parallax of the Great Comet of 1577.[184] Within the precision of the measurements, this implied the comet must be at least four times more distant than from Earth to the Moon.[185][186] Based on observations in 1664, Giovanni Borelli recorded the longitudes and latitudes of comets that he observed, and suggested that cometary orbits may be parabolic.[187] Despite being a skilled astronomer, in his 1623 book The Assayer, Galileo Galilei rejected Brahe's theories on the parallax of comets and claimed that they may be a mere optical illusion, despite little personal observation.[177] In 1625, Maestlin's student Johannes Kepler upheld that Brahe's view of cometary parallax was correct.[177] Additionally, mathematician Jacob Bernoulli published a treatise on comets in 1682.

During the early modern period comets were studied for their astrological significance in medical disciplines. Many healers of this time considered medicine and astronomy to be inter-disciplinary and employed their knowledge of comets and other astrological signs for diagnosing and treating patients.[188]

Isaac Newton, in his Principia Mathematica of 1687, proved that an object moving under the influence of gravity by an inverse square law must trace out an orbit shaped like one of the conic sections, and he demonstrated how to fit a comet's path through the sky to a parabolic orbit, using the comet of 1680 as an example.[189]He describes comets as compact and durable solid bodies moving in oblique orbit and their tails as thin streams of vapor emitted by their nuclei, ignited or heated by the Sun. He suspected that comets were the origin of the life-supporting component of air.[190] He pointed out that comets usually appear near the Sun, and therefore most likely orbit it.[171] On their luminosity, he stated, "The comets shine by the Sun's light, which they reflect," with their tails illuminated by "the Sun's light reflected by a smoke arising from [the coma]".[171]

In 1705, Edmond Halley (1656–1742) applied Newton's method to 23 cometary apparitions that had occurred between 1337 and 1698. He noted that three of these, the comets of 1531, 1607, and 1682, had very similar orbital elements, and he was further able to account for the slight differences in their orbits in terms of gravitational perturbation caused by Jupiter and Saturn. Confident that these three apparitions had been three appearances of the same comet, he predicted that it would appear again in 1758–59.[191] Halley's predicted return date was later refined by a team of three French mathematicians: Alexis Clairaut, Joseph Lalande, and Nicole-Reine Lepaute, who predicted the date of the comet's 1759 perihelion to within one month's accuracy.[192][193] When the comet returned as predicted, it became known as Halley's Comet.[194]

From his huge vapouring train perhaps to shake

Reviving moisture on the numerous orbs,

Thro' which his long ellipsis winds; perhaps

To lend new fuel to declining suns,

To light up worlds, and feed th' ethereal fire.

James Thomson The Seasons (1730; 1748)[195]

As early as the 18th century, some scientists had made correct hypotheses as to comets' physical composition. In 1755, Immanuel Kant hypothesized in his Universal Natural History that comets were condensed from "primitive matter" beyond the known planets, which is "feebly moved" by gravity, then orbit at arbitrary inclinations, and are partially vaporized by the Sun's heat as they near perihelion.[196] In 1836, the German mathematician Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel, after observing streams of vapor during the appearance of Halley's Comet in 1835, proposed that the jet forces of evaporating material could be great enough to significantly alter a comet's orbit, and he argued that the non-gravitational movements of Encke's Comet resulted from this phenomenon.[197]

In the 19th century, the Astronomical Observatory of Padova was an epicenter in the observational study of comets. Led by Giovanni Santini (1787–1877) and followed by Giuseppe Lorenzoni (1843–1914), this observatory was devoted to classical astronomy, mainly to the new comets and planets orbit calculation, with the goal of compiling a catalog of almost ten thousand stars. Situated in the Northern portion of Italy, observations from this observatory were key in establishing important geodetic, geographic, and astronomical calculations, such as the difference of longitude between Milan and Padua as well as Padua to Fiume.[198] Correspondence within the observatory, particularly between Santini and another astronomer Giuseppe Toaldo, mentioned the importance of comet and planetary orbital observations.[199]

In 1950, Fred Lawrence Whipple proposed that rather than being rocky objects containing some ice, comets were icy objects containing some dust and rock.[200] This "dirty snowball" model soon became accepted and appeared to be supported by the observations of an armada of spacecraft (including the European Space Agency's Giotto probe and the Soviet Union's Vega 1 and Vega 2) that flew through the coma of Halley's Comet in 1986, photographed the nucleus, and observed jets of evaporating material.[201]

On 22 January 2014, ESA scientists reported the detection, for the first definitive time, of water vapor on the dwarf planet Ceres, the largest object in the asteroid belt.[202] The detection was made by using the far-infrared abilities of the Herschel Space Observatory.[203] The finding is unexpected because comets, not asteroids, are typically considered to "sprout jets and plumes". According to one of the scientists, "The lines are becoming more and more blurred between comets and asteroids."[203] On 11 August 2014, astronomers released studies, using the Atacama Large Millimeter/Submillimeter Array (ALMA) for the first time, that detailed the distribution of HCN, HNC, H2CO, and dust inside the comae of comets C/2012 F6 (Lemmon) and C/2012 S1 (ISON).[204][205]

Spacecraft missions

- The Halley Armada describes the collection of spacecraft missions that visited and/or made observations of Halley's Comet 1980s perihelion. The space shuttle Challenger was intended to do a study of Halley's Comet in 1986, but exploded shortly after being launched.

- Deep Impact. Debate continues about how much ice is in a comet. In 2001, the Deep Space 1 spacecraft obtained high-resolution images of the surface of Comet Borrelly. It was found that the surface of comet Borrelly is hot and dry, with a temperature of between 26 and 71 °C (79 and 160 °F), and extremely dark, suggesting that the ice has been removed by solar heating and maturation, or is hidden by the soot-like material that covers Borrelly.[206] In July 2005, the Deep Impact probe blasted a crater on Comet Tempel 1 to study its interior. The mission yielded results suggesting that the majority of a comet's water ice is below the surface and that these reservoirs feed the jets of vaporized water that form the coma of Tempel 1.[207] Renamed EPOXI, it made a flyby of Comet Hartley 2 on 4 November 2010.

- Ulysses. In 2007, the Ulysses probe unexpectedly passed through the tail of the comet C/2006 P1 (McNaught) which was discovered in 2006. Ulysses was launched in 1990 and the intended mission was for Ulysses to orbit around the Sun for further study at all latitudes.

- Stardust. Data from the Stardust mission show that materials retrieved from the tail of Wild 2 were crystalline and could only have been "born in fire", at extremely high temperatures of over 1,000 °C (1,830 °F).[208][209] Although comets formed in the outer Solar System, radial mixing of material during the early formation of the Solar System is thought to have redistributed material throughout the proto-planetary disk.[210] As a result, comets contain crystalline grains that formed in the early, hot inner Solar System. This is seen in comet spectra as well as in sample return missions. More recent still, the materials retrieved demonstrate that the "comet dust resembles asteroid materials".[211] These new results have forced scientists to rethink the nature of comets and their distinction from asteroids.[212]

- Rosetta. The Rosetta probe orbited Comet Churyumov–Gerasimenko. On 12 November 2014, its lander Philae successfully landed on the comet's surface, the first time a spacecraft has ever landed on such an object in history.[213]

Classification

Great comets

Approximately once a decade, a comet becomes bright enough to be noticed by a casual observer, leading such comets to be designated as great comets.[151] Predicting whether a comet will become a great comet is notoriously difficult, as many factors may cause a comet's brightness to depart drastically from predictions.[214] Broadly speaking, if a comet has a large and active nucleus, will pass close to the Sun, and is not obscured by the Sun as seen from Earth when at its brightest, it has a chance of becoming a great comet. However, Comet Kohoutek in 1973 fulfilled all the criteria and was expected to become spectacular but failed to do so.[215] Comet West, which appeared three years later, had much lower expectations but became an extremely impressive comet.[216]

The Great Comet of 1577 is a well-known example of a great comet. It passed near Earth as a non-periodic comet and was seen by many, including well-known astronomers Tycho Brahe and Taqi ad-Din. Observations of this comet led to several significant findings regarding cometary science, especially for Brahe.

The late 20th century saw a lengthy gap without the appearance of any great comets, followed by the arrival of two in quick succession—Comet Hyakutake in 1996, followed by Hale–Bopp, which reached maximum brightness in 1997 having been discovered two years earlier. The first great comet of the 21st century was C/2006 P1 (McNaught), which became visible to naked eye observers in January 2007. It was the brightest in over 40 years.[217]

Sungrazing comets

A sungrazing comet is a comet that passes extremely close to the Sun at perihelion, generally within a few million kilometers.[218] Although small sungrazers can be completely evaporated during such a close approach to the Sun, larger sungrazers can survive many perihelion passages. However, the strong tidal forces they experience often lead to their fragmentation.[219]

About 90% of the sungrazers observed with SOHO are members of the Kreutz group, which all originate from one giant comet that broke up into many smaller comets during its first passage through the inner Solar System.[220] The remainder contains some sporadic sungrazers, but four other related groups of comets have been identified among them: the Kracht, Kracht 2a, Marsden, and Meyer groups. The Marsden and Kracht groups both appear to be related to Comet 96P/Machholz, which is the parent of two meteor streams, the Quadrantids and the Arietids.[221]

Необычные кометы

Из тысяч известных комет некоторые обладают необычными свойствами. Комета Энке (2P/Энке) движется по орбите за пределами пояса астероидов прямо внутри орбиты планеты Меркурий , тогда как комета 29P/Швассмана-Вахмана в настоящее время движется по почти круговой орбите полностью между орбитами Юпитера и Сатурна. [222] Хирон 2060 года , чья нестабильная орбита находится между Сатурном и Ураном , первоначально классифицировался как астероид, пока не была замечена слабая кома. [223] Точно так же комета Шумейкера-Леви 2 первоначально называлась астероидом 1990 UL 3 . [224]

Самый большой

Самая крупная известная периодическая комета — 95P/Хирон диаметром 200 км, которая каждые 50 лет приходит в перигелий прямо внутри орбиты Сатурна на расстоянии 8 а.е. Предполагается, что самой крупной из известных комет облака Оорта является комета Бернардинелли-Бернштейна на расстоянии ≈150 км, которая не достигнет перигелия до января 2031 года, недалеко от орбиты Сатурна на расстоянии 11 а.е. По оценкам, комета 1729 года имела диаметр ≈100 км и достигла перигелия внутри орбиты Юпитера на расстоянии 4 а.е.

Кентавры

Кентавры обычно ведут себя с характеристиками как астероидов, так и комет. [225] Кентавров можно классифицировать как кометы, такие как 60558 Echeclus и 166P/NEAT . 166P/NEAT была обнаружена в состоянии комы и поэтому классифицируется как комета, несмотря на ее орбиту, а 60558 Эхеклюс был открыт без комы, но позже стал активным. [226] и затем был классифицирован как комета и астероид (174P/Echeclus). Один из планов Кассини заключался в отправке его кентавру, но вместо этого НАСА решило его уничтожить. [227]

Наблюдение

Комету можно обнаружить фотографически с помощью широкоугольного телескопа или визуально в бинокль . все еще может Тем не менее, даже не имея доступа к оптическому оборудованию, астроном-любитель обнаружить комету, пасущуюся на солнце, онлайн, загрузив изображения, накопленные некоторыми спутниковыми обсерваториями, такими как SOHO . [228] 2000-я комета SOHO была открыта польским астрономом-любителем Михалом Кусяком 26 декабря 2010 года. [229] и оба первооткрывателя Хейла-Боппа использовали любительское оборудование (хотя Хейл не был любителем).

Потерянный

Ряд периодических комет, обнаруженных в предыдущие десятилетия или предыдущие столетия, теперь являются потерянными кометами . Их орбиты никогда не были известны достаточно хорошо, чтобы предсказать будущие появления, иначе кометы распались. Однако иногда обнаруживают «новую» комету, и расчет ее орбиты показывает, что это старая «потерянная» комета. Примером может служить комета 11P/Tempel-Swift-LINEAR , открытая в 1869 году, но ненаблюдаемая после 1908 года из-за возмущений Юпитера. Он не был найден снова, пока случайно не был заново открыт LINEAR в 2001 году. [230] К этой категории относятся как минимум 18 комет. [231]

В популярной культуре

Изображение комет в массовой культуре прочно укоренилось в давней западной традиции рассматривать кометы как предвестников гибели и предзнаменования изменяющих мир перемен. [232] Одна только комета Галлея вызывала множество сенсационных публикаций всех видов при каждом своем новом появлении. Особо отмечалось, что рождение и смерть некоторых известных людей совпадали с отдельными появлениями кометы, например, у писателей Марка Твена (который правильно предположил, что он «уйдет с кометой» в 1910 году). [232] и Юдора Уэлти , жизни которой Мэри Чапин Карпентер посвятила песню « Halley Came to Jackson ». [232]

В прошлые времена яркие кометы часто вызывали панику и истерию среди населения, считаясь плохим предзнаменованием. Совсем недавно, во время прохождения кометы Галлея в 1910 году, Земля прошла через хвост кометы, и ошибочные газетные сообщения породили опасения, что цианоген в хвосте может отравить миллионы людей. [233] тогда как появление кометы Хейла-Боппа в 1997 году спровоцировало массовое самоубийство культа Небесных Врат . [234]

В научной фантастике столкновение комет изображалось как угроза, преодолеваемая технологиями и героизмом (как в фильмах 1998 года «Столкновение с глубиной» и «Армагеддон» ), или как триггер глобального апокалипсиса ( «Молот Люцифера» , 1979) или зомби ( «Ночь света»). Комета , 1984). [232] В романе Жюля Верна « На комете» группа людей застряла на комете, вращающейся вокруг Солнца, в то время как большая космическая экспедиция с экипажем посещает комету Галлея в сэра Артура Кларка романе «2061: Одиссея третья» . [235]

В литературе

Длиннопериодическая комета, впервые зарегистрированная Понсом во Флоренции 15 июля 1825 года, вдохновила Лидию Сигурни на написание юмористического стихотворения. ![]() Комета 1825 года . в котором все небесные тела спорят о внешнем виде и предназначении кометы.

Комета 1825 года . в котором все небесные тела спорят о внешнем виде и предназначении кометы.

Галерея

- Комета C/2020 F3 NEOWISE , июль 2020 г.

- Комета C/2006 P1 (Макнота), взятая из Виктории, Австралия, 2007 г.

- Большая комета 1882 года входит в группу Крейца.

- Австрийский астроном Эдмунд Вайс нарисовал Большую комету 1861 года.

- «Активный астероид» 311P/PANSTARRS с несколькими хвостами [236]

- Комета Сайдинг Спринг ( Хаббл ; 11 марта 2014 г.)

- Мозаика из 20 комет, обнаруженная WISE космическим телескопом

- NEOWISE – Кометы отмечены желтым цветом за Neowise (с декабря 2013 г. по декабрь 2017 г.). первые четыре года сбора данных

- Солнечная STEREO обсерватория засняла на видео комету Лавджоя, движущуюся против солнечного ветра при ее приближении к Солнцу в декабре 2011 года.

- Вид с ударного элемента Deep Impact в последние минуты перед столкновением с кометой Темпель 1 , 4 июля 2005 года.

- Видео

- НАСА разрабатывает кометный гарпун для доставки образцов на Землю

- Солнечная обсерватория STEREO засняла, как комета Энке на мгновение теряет хвост, 20 апреля 2007 г.

См. также

- Большой всплеск

- Винтажные кометы

- Список ударных кратеров на Земле

- Список возможных ударных структур на Земле

- Списки комет

Ссылки

Сноски

- ^ «Я не думаю, что комета — это просто внезапный пожар, но что она принадлежит к числу вечных творений природы». ( Саган и Друян 1997 , стр. 26)

- ^ Цитируется высказывание Сенеки: «Почему... мы удивлены тем, что кометы, такое редкое зрелище во Вселенной, еще не подчиняются фиксированным законам и что их начало и конец неизвестны, хотя их возвращение происходит через огромные промежутки времени. ? ... Придет время, когда усердные исследования в течение очень длительных периодов времени выявят вещи, которые сейчас скрыты». [174]

Цитаты

- ^ «Спроси астронома» . Крутой Космос . Проверено 11 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Рэндалл, Лиза (2015). Темная материя и динозавры: поразительная взаимосвязанность Вселенной . Нью-Йорк: Издательство Ecco/HarperCollins. стр. 104–105. ISBN 978-0-06-232847-2 .

- ^ «Чем отличаются астероиды от комет» . Часто задаваемые вопросы Розетты . Европейское космическое агентство . Проверено 30 июля 2013 г.

- ^ «Что такое астероиды и кометы» . Часто задаваемые вопросы по программе «Объекты, сближающиеся с Землей» . НАСА. Архивировано из оригинала 28 июня 2004 года . Проверено 30 июля 2013 г.

- ^ Исии, штат Ха; и др. (2008). «Сравнение пыли кометы 81P/Wild 2 с межпланетной пылью от комет». Наука . 319 (5862): 447–50. Бибкод : 2008Sci...319..447I . дои : 10.1126/science.1150683 . ПМИД 18218892 . S2CID 24339399 .

- ^ «Браузер базы данных малых корпусов JPL C/2014 S3 (PANSTARRS)» .

- ^ Стивенс, Хейнс; и др. (октябрь 2017 г.). «В погоне за Мэнскими островами: долгопериодические кометы без хвостов». Тезисы совещаний AAA/Отдела планетарных наук . 49 (49). 420.02. Бибкод : 2017ДПС....4942002С .

- ^ «Открыты кометы» . Центр малых планет . Проверено 27 апреля 2021 г.

- ^ Эриксон, Джон (2003). Астероиды, кометы и метеориты: космические захватчики Земли . Живая Земля. Нью-Йорк: Информационная база. п. 123. ИСБН 978-0-8160-4873-1 .

- ^ Купер, Хизер; и др. (2014). Планеты: Полный путеводитель по нашей Солнечной системе . Лондон: Дорлинг Киндерсли. п. 222. ИСБН 978-1-4654-3573-6 .

- ^ Лихт, А. (1999). «Скорость появления комет, видимых невооруженным глазом, с 101 г. до н.э. по 1970 г. н.э.». Икар . 137 (2): 355–356. Бибкод : 1999Icar..137..355L . дои : 10.1006/icar.1998.6048 .

- ^ «Приземление! Зонд Филе Розетты приземляется на комете» . Европейское космическое агентство. 12 ноября 2014 года . Проверено 11 декабря 2017 г.

- ^ «комета» . Оксфордский словарь английского языка (онлайн-изд.). Издательство Оксфордского университета . (Требуется подписка или членство участвующей организации .)

- ^ Харпер, Дуглас. «Комета (н.)» . Интернет-словарь этимологии . Проверено 30 июля 2013 г.

- ^ Американская энциклопедия: библиотека универсальных знаний . Том. 26. Американская энциклопедия Corp., 1920. стр. 162–163.

- ^ Гринберг, Дж. Мэйо (1998). «Создание ядра кометы». Астрономия и астрофизика . 330 : 375. Бибкод : 1998A&A...330..375G .

- ^ «Грязные снежки в космосе» . Звездное небо. Архивировано из оригинала 29 января 2013 года . Проверено 15 августа 2013 г.

- ^ «Данные, полученные с космического корабля «Розетта» ЕКА, позволяют предположить, что кометы — это скорее «ледяной грязный ком», чем «грязный снежок » . Высшее образование Таймс . 21 октября 2005 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Клавин, Уитни (10 февраля 2015 г.). «Почему кометы похожи на жареное мороженое» . НАСА . Проверено 10 февраля 2015 г.

- ^ Мич, М. (24 марта 1997 г.). «Появление кометы Хейла-Боппа в 1997 году: чему мы можем научиться у ярких комет» . Открытия планетарных исследований . Проверено 30 апреля 2013 г.

- ^ «Находки по звездной пыли предполагают, что кометы более сложны, чем считалось» . НАСА. 14 декабря 2006 года . Проверено 31 июля 2013 г.

- ^ Элсила, Джейми Э.; и др. (2009). «Кометный глицин обнаружен в образцах, возвращенных Stardust» . Метеоритика и планетология . 44 (9): 1323. Бибкод : 2009M&PS...44.1323E . дои : 10.1111/j.1945-5100.2009.tb01224.x .

- ^ Каллахан, член парламента; и др. (2011). «Углеродистые метеориты содержат широкий спектр внеземных азотистых оснований» . Труды Национальной академии наук . 108 (34): 13995–8. Бибкод : 2011PNAS..10813995C . дои : 10.1073/pnas.1106493108 . ПМК 3161613 . ПМИД 21836052 .

- ^ Штайгервальд, Джон (8 августа 2011 г.). «Исследователи НАСА: строительные блоки ДНК можно создавать в космосе» . НАСА. Архивировано из оригинала 26 апреля 2020 года . Проверено 31 июля 2013 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Уивер, штат Ха; и др. (1997). «Активность и размер ядра кометы Хейла-Боппа (C/1995 O1)». Наука . 275 (5308): 1900–1904. Бибкод : 1997Sci...275.1900W . дои : 10.1126/science.275.5308.1900 . ПМИД 9072959 . S2CID 25489175 .

- ^ Хансльмайер, Арнольд (2008). Обитаемость и космические катастрофы . Спрингер. п. 91. ИСБН 978-3-540-76945-3 .

- ^ Фернандес, Янга Р. (2000). «Ядро кометы Хейла-Боппа (C/1995 O1): размер и активность». Земля, Луна и планеты . 89 (1): 3–25. Бибкод : 2002EM&P...89....3F . дои : 10.1023/А:1021545031431 . S2CID 189899565 .

- ^ Джуитт, Дэвид (апрель 2003 г.). «Ядро кометы» . Департамент наук о Земле и космосе Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе . Проверено 31 июля 2013 г.

- ^ «Новый улов SOHO: первая официально периодическая комета» . Европейское космическое агентство . Проверено 16 августа 2013 г.

- ^ Саган и Друян 1997 , с. 137

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Бритт, DT; и др. (2006). «Плотность и пористость малых тел: новые данные, новые идеи» (PDF) . 37-я ежегодная конференция по наукам о Луне и планетах . 37 : 2214. Бибкод : 2006LPI....37.2214B . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 17 декабря 2008 года . Проверено 25 августа 2013 г.

- ^ Веверка, Дж. (январь 1984 г.). «Геология малых тел» . НАСА . Проверено 15 августа 2013 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Уитмен, К.; и др. (2006). «Размерно-частотное распределение спящих комет семейства Юпитера». Икар . 183 (1): 101–114. arXiv : astro-ph/0603106v2 . Бибкод : 2006Icar..183..101W . дои : 10.1016/j.icarus.2006.02.016 . S2CID 14026673 .

- ^ Бауэр, Маркус (14 апреля 2015 г.). «Розетта и Филы обнаруживают, что комета не намагничена» . Европейское космическое агентство . Проверено 14 апреля 2015 г.

- ^ Ширмайер, Квирин (14 апреля 2015 г.). «Комета Розетты не имеет магнитного поля». Природа . дои : 10.1038/nature.2015.17327 . S2CID 123964604 .

- ^ Эгл, округ Колумбия; и др. (2 июня 2015 г.). «Прибор НАСА на Розетте открывает атмосферу кометы» . НАСА . Проверено 2 июня 2015 г.

- ^ Фельдман, Пол Д.; и др. (2 июня 2015 г.). «Измерения околоядерной комы кометы 67P/Чурюмова-Герасименко спектрографом дальнего ультрафиолета Алисы на Розетте» (PDF) . Астрономия и астрофизика . 583 : А8. arXiv : 1506.01203 . Бибкод : 2015A&A...583A...8F . дои : 10.1051/0004-6361/201525925 . S2CID 119104807 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 8 июня 2015 года . Проверено 3 июня 2015 г.

- ^ Джорданс, Фрэнк (30 июля 2015 г.). «Зонд Philae нашел доказательства того, что кометы могут быть космическими лабораториями» . Вашингтон Пост . Ассошиэйтед Пресс. Архивировано из оригинала 23 декабря 2018 года . Проверено 30 июля 2015 г.

- ^ «Наука на поверхности кометы» . Европейское космическое агентство. 30 июля 2015 года . Проверено 30 июля 2015 г.

- ^ Бибринг, Ж.-П.; и др. (31 июля 2015 г.). «Первые дни Филы на комете - Введение в специальный выпуск» . Наука . 349 (6247): 493. Бибкод : 2015Sci...349..493B . дои : 10.1126/science.aac5116 . ПМИД 26228139 .

- ^ Галлей: Используя объем эллипсоида 15×8×8 км * плотность груды щебня 0,6 г/см. 3 дает массу (m=d*v) 3,02E+14 кг.

Темпель 1: использование сферы диаметром 6,25 км; объем сферы * плотность 0,62 г/см 3 дает массу 7,9E+13 кг.

19P/Боррелли: Используя объем эллипсоида 8x4x4 км * плотность 0,3 г/см. 3 дает массу 2,0E+13 кг.

81P/Wild: Использование объема эллипсоида 5,5x4,0x3,3 км * плотность 0,6 г/см. 3 дает массу 2,28E+13 кг. - ^ «Что мы узнали о комете Галлея?» . Астрономическое общество Тихого океана. 1986 год . Проверено 4 октября 2013 г.

- ^ Сагдеев Р.З.; и др. (1988). «Является ли ядро кометы Галлея телом низкой плотности?». Природа . 331 (6153): 240. Бибкод : 1988Natur.331..240S . дои : 10.1038/331240a0 . ISSN 0028-0836 . S2CID 4335780 .

- ^ «9П/Темпель 1» . Лаборатория реактивного движения . Проверено 16 августа 2013 г.

- ^ «Комета 81P/Вайлд 2» . Планетарное общество. Архивировано из оригинала 6 января 2009 года . Проверено 20 ноября 2007 г.

- ^ «Жизненная статистика кометы» . Европейское космическое агентство. 22 января 2015 года . Проверено 24 января 2015 г.

- ^ Болдуин, Эмили (21 августа 2014 г.). «Определение массы кометы 67P/CG» . Европейское космическое агентство . Проверено 21 августа 2014 г.

- ^ «Последний взгляд Хаббла на комету ISON перед перигелием» . Европейское космическое агентство. 19 ноября 2013 года . Проверено 20 ноября 2013 г.

- ^ Клей Шеррод, П. и Коед, Томас Л. (2003). Полное руководство любительской астрономии: инструменты и методы астрономических наблюдений . Курьерская корпорация. п. 66. ИСБН 978-0-486-15216-5 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Комби, Майкл Р.; и др. (2004). «Газодинамика и кинетика в комете кометы: теория и наблюдения» (PDF) . Кометы II : 523. Бибкод : 2004come.book..523C . дои : 10.2307/j.ctv1v7zdq5.34 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 15 марта 2007 г.

- ^ Моррис, Чарльз С. «Определения комет» . Майкл Галлахер . Проверено 31 августа 2013 г.

- ^ Лаллемент, Розин; и др. (2002). «Тень кометы Хейла-Боппа в Лайман-Альфе». Земля, Луна и планеты . 90 (1): 67–76. Бибкод : 2002EM&P...90...67L . дои : 10.1023/A:1021512317744 . S2CID 118200399 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Джуитт, Дэвид . «Расщепление кометы 17P/Холмса во время мегавспышки» . Гавайский университет . Проверено 30 августа 2013 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Кронк, Гэри В. «Букварь по кометам» . Кометография Гэри В. Кронка . Архивировано из оригинала 17 мая 2011 года . Проверено 30 августа 2013 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бринкворт, Кэролин и Томас, Клэр. «Кометы» . Университет Лестера . Проверено 31 июля 2013 г.

- ^ Пасачофф, Джей М (2000). Путеводитель по звездам и планетам . Хоутон Миффлин. п. 75. ИСБН 978-0-395-93432-6 .

- ^ Джуитт, Дэвид. «Комета Холмса больше Солнца» . Институт астрономии Гавайского университета . Проверено 31 июля 2013 г.

- ^ Лиссе, CM; и др. (1996). «Открытие рентгеновского и крайнего ультрафиолетового излучения кометы C/Hyakutake 1996 B2» . Наука . 274 (5285): 205. Бибкод : 1996Sci...274..205L . дои : 10.1126/science.274.5285.205 . S2CID 122700701 .

- ^ Лиссе, CM; и др. (2001). «Рентгеновское излучение кометы C/1999 S4, вызванное перезарядкой (LINEAR)». Наука . 292 (5520): 1343–8. Бибкод : 2001Sci...292.1343L . дои : 10.1126/science.292.5520.1343 . ПМИД 11359004 .

- ^ Джонс, Делавэр; и др. (март 1986 г.). «Луковая волна кометы Джакобини-Циннера - наблюдения магнитного поля ICE». Письма о геофизических исследованиях . 13 (3): 243–246. Бибкод : 1986GeoRL..13..243J . дои : 10.1029/GL013i003p00243 .

- ^ Грингауз, К.И.; и др. (15 мая 1986 г.). «Первые натурные измерения плазмы и нейтрального газа на комете Галлея». Природа . 321 : 282–285. Бибкод : 1986Natur.321..282G . дои : 10.1038/321282a0 . S2CID 117920356 .

- ^ Нойбауэр, FM; и др. (февраль 1993 г.). «Первые результаты эксперимента с магнитометром Джотто во время встречи П / Григга и Скьеллерупа». Астрономия и астрофизика . 268 (2): L5–L8. Бибкод : 1993A&A...268L...5N .

- ^ Гунелл, Х.; и др. (ноябрь 2018 г.). «Младенческая ударная волна: новый рубеж кометы со слабой активностью» (PDF) . Астрономия и астрофизика . 619 . Л2. Бибкод : 2018A&A...619L...2G . дои : 10.1051/0004-6361/201834225 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 30 апреля 2019 г.

- ^ Кокран, Анита Л.; и др. (1995). «Открытие объектов пояса Койпера размером с Галлея с помощью космического телескопа Хаббл». Астрофизический журнал . 455 : 342. arXiv : astro-ph/9509100 . Бибкод : 1995ApJ...455..342C . дои : 10.1086/176581 . S2CID 118159645 .

- ^ Кокран, Анита Л.; и др. (1998). «Калибровка поиска объектов пояса Койпера космического телескопа Хаббл: установка рекорда». Астрофизический журнал . 503 (1): Л89. arXiv : astro-ph/9806210 . Бибкод : 1998ApJ...503L..89C . дои : 10.1086/311515 . S2CID 18215327 .

- ^ Браун, Майкл Э.; и др. (1997). «Анализ статистики поиска объектов пояса Койпера \ITAL Космическим телескопом Хаббла\/ITAL]» . Астрофизический журнал . 490 (1): Л119–Л122. Бибкод : 1997ApJ...490L.119B . дои : 10.1086/311009 .

- ^ Джуитт, Дэвид; и др. (1996). «Мауна-Кеа-Серро-Тололо (MKCT) Пояс Койпера и Исследование кентавров». Астрономический журнал . 112 : 1225. Бибкод : 1996AJ....112.1225J . дои : 10.1086/118093 .

- ^ Ланг, Кеннет Р. (2011). Кембриджский путеводитель по Солнечной системе . Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 422. ИСБН 978-1-139-49417-5 .

- ^ Немиров Р.; Боннелл, Дж., ред. (29 июня 2013 г.). «PanSTARRS: Антихвостовая комета» . Астрономическая картина дня . НАСА . Проверено 31 июля 2013 г.

- ^ Бирманн, Л. (1963). «Плазменные хвосты комет и межпланетная плазма». Обзоры космической науки . 1 (3): 553. Бибкод : 1963ССРв....1..553Б . дои : 10.1007/BF00225271 . S2CID 120731934 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кэрролл, Б.В. и Остли, Д.А. (1996). Введение в современную астрофизику . Аддисон-Уэсли. стр. 864–874. ISBN 0-201-54730-9 .

- ^ Эйлс, CJ; и др. (2008). «Гелиосферные сканеры на борту миссии STEREO» (PDF) . Солнечная физика . 254 (2): 387. Бибкод : 2009SoPh..254..387E . дои : 10.1007/s11207-008-9299-0 . hdl : 2268/15675 . S2CID 54977854 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 22 июля 2018 года.

- ^ «Когда планета ведет себя как комета» . Европейское космическое агентство. 29 января 2013 года . Проверено 30 августа 2013 г.

- ^ Крамер, Мириам (30 января 2013 г.). «Венера может иметь атмосферу, подобную комете» . Space.com . Проверено 30 августа 2013 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Кометы и джеты» . Сайт Хабблсайт.org . 12 ноября 2013 г.

- ^ Болдуин, Эмили (11 ноября 2010 г.). «Сухой лед питает реактивные кометы» . Астрономия сейчас . Архивировано из оригинала 17 декабря 2013 года.

- ^ Чанг, Кеннет (18 ноября 2010 г.). «Комета Хартли-2 извергает лед, фото НАСА» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 1 января 2022 года.

- ^ «Орбита кометы» . Университет Сент-Эндрюс . Проверено 1 сентября 2013 г.

- ^ Дункан, Мартин; и др. (май 1988 г.). «Происхождение короткопериодических комет» . Письма астрофизического журнала . 328 : L69–L73. Бибкод : 1988ApJ...328L..69D . дои : 10.1086/185162 .

- ^ Дельсем, Арманд Х. (2001). Наше космическое происхождение: от Большого взрыва до возникновения жизни и разума . Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 117. ИСБН 978-0-521-79480-0 .

- ^ Уилсон, ХК (1909). «Семейства комет Сатурна, Урана и Нептуна». Популярная астрономия . 17 : 629–633. Бибкод : 1909PA.....17..629W .

- ^ Датч, Стивен. «Кометы» . Естественные и прикладные науки, Университет Висконсина. Архивировано из оригинала 29 июля 2013 года . Проверено 31 июля 2013 г.

- ^ «Кометы семейства Юпитера» . Отделение земного магнетизма Института Карнеги в Вашингтоне . Проверено 11 августа 2013 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Кометы – где они?» . Британская астрономическая ассоциация. 6 ноября 2012 года. Архивировано из оригинала 5 августа 2013 года . Проверено 11 августа 2013 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Дункан, Мартин Дж. (2008). «Динамическое происхождение комет и их резервуаров». Обзоры космической науки . 138 (1–4): 109–126. Бибкод : 2008ССРв..138..109Д . дои : 10.1007/s11214-008-9405-5 . S2CID 121848873 .

- ^ Джуитт, Дэвид К. (2002). «От объекта пояса Койпера до ядра кометы: недостающая ультракрасная материя» . Астрономический журнал . 123 (2): 1039–1049. Бибкод : 2002AJ....123.1039J . дои : 10.1086/338692 . S2CID 122240711 .

- ^ «Малый запрос к базе данных» . Динамика Солнечной системы - Лаборатория реактивного движения . НАСА – Калифорнийский технологический институт . Проверено 1 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ Эндрюс, Робин Джордж (18 ноября 2022 г.). «Таинственные кометы, скрывающиеся в поясе астероидов. Обычно кометы прилетают из дальних уголков космоса. Однако астрономы обнаружили, что они, по-видимому, неуместны в поясе астероидов. Почему они там?» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Проверено 18 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ Редди, Фрэнсис (3 апреля 2006 г.). «Новый класс комет на задворках Земли» . Астрономия . Архивировано из оригинала 24 мая 2014 года . Проверено 31 июля 2013 г.

- ^ «Кометы» . Государственный университет Пенсильвании . Проверено 8 августа 2013 г.

- ^ Саган и Друян 1997 , стр. 102–104.

- ^ Купелис, Тео (2010). В поисках Солнечной системы . Издательство Джонс и Бартлетт. п. 246. ИСБН 978-0-7637-9477-4 .

- ^ Дэвидссон, Бьёрн-младший (2008). «Кометы – реликвии зарождения Солнечной системы» . Уппсальский университет. Архивировано из оригинала 19 января 2013 года . Проверено 30 июля 2013 г.

- ^ Оорт, Дж. Х. (1950). «Строение кометного облака, окружающего Солнечную систему, и гипотеза его происхождения». Бюллетень астрономических институтов Нидерландов . 11 : 91. Бибкод : 1950BAN....11...91O .

- ^ Хансльмайер, Арнольд (2008). Обитаемость и космические катастрофы . Спрингер. п. 152. ИСБН 978-3-540-76945-3 .

- ^ Рошельо, Джейк (12 сентября 2011 г.). «Что такое короткопериодическая комета – орбитальный цикл менее 200 лет» . Факты о планете . Проверено 1 декабря 2019 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Малые тела: Профиль» . НАСА/Лаборатория реактивного движения. 29 октября 2008 года . Проверено 11 августа 2013 г.

- ^ Еленин Леонид (7 марта 2011 г.). «Влияние планет-гигантов на орбиту кометы C/2010 X1» . Архивировано из оригинала 19 марта 2012 года . Проверено 11 августа 2013 г.

- ^ Жоардар, С.; и др. (2008). Астрономия и астрофизика . Джонс и Бартлетт Обучение. п. 21. ISBN 978-0-7637-7786-9 .

- ^ Чеботарев, Г. А. (1964). «Гравитационные сферы больших планет, Луны и Солнца». Советская астрономия . 7 : 618. Бибкод : 1964СвА.....7..618С .

- ^ «Поисковая система базы данных малых тел JPL: e > 1» . Лаборатория реактивного движения . Проверено 13 августа 2013 г.

- ^ Год, Челси (27 июня 2018 г.). «Межзвездный гость Оумуамуа все-таки комета» . Space.com . Проверено 27 сентября 2018 г.

- ^ Гроссман, Лиза (12 сентября 2019 г.). «Астрономы обнаружили второй межзвездный объект» . Новости науки . Проверено 16 сентября 2019 г.

- ^ Стрикленд, Эшли (27 сентября 2019 г.). «Второй межзвездный гость в нашей Солнечной системе подтвержден и назван» . Си-Эн-Эн.

- ^ «C/1980 E1 (Боуэлл)» . База данных JPL Small Body (последние наблюдения 2 декабря 1986 г.) . Проверено 13 августа 2013 г.

- ^ «Комета» . Британская онлайн-энциклопедия . Проверено 13 августа 2013 г.

- ^ МакГлинн, Томас А. и Чепмен, Роберт Д. (1989). «О необнаружении внесолнечных комет» . Астрофизический журнал . 346 . Л105. Бибкод : 1989ApJ...346L.105M . дои : 10.1086/185590 .

- ^ «Поисковая система базы данных малых тел JPL: e > 1 (отсортировано по имени)» . Лаборатория реактивного движения . Проверено 7 декабря 2020 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Левисон, Гарольд Ф. и Доннес, Люк (2007). «Популяция комет и динамика комет» . В Макфаддене — Люси-Энн Адамс; Джонсон, Торренс В. и Вайсман, Пол Роберт (ред.). Энциклопедия Солнечной системы (2-е изд.). Академическая пресса. стр. 575–588 . ISBN 978-0-12-088589-3 .

- ^ «В глубине | Облако Оорта» . Исследование Солнечной системы НАСА . Проверено 1 декабря 2019 г.

- ^ Рэндалл, Лиза (2015). Темная материя и динозавры: поразительная взаимосвязанность Вселенной . Издательство Харпер Коллинз. п. 115. ИСБН 978-0-06-232847-2 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хиллз, Джек Г. (1981). «Кометные дожди и стационарное падение комет из Облака Оорта» . Астрономический журнал . 86 : 1730–1740. Бибкод : 1981AJ.....86.1730H . дои : 10.1086/113058 .

- ^ Левисон, Гарольд Ф.; и др. (2001). «Происхождение комет типа Галлея: исследование внутреннего облака Оорта» . Астрономический журнал . 121 (4): 2253–2267. Бибкод : 2001AJ....121.2253L . дои : 10.1086/319943 .

- ^ Донахью, Томас М., изд. (1991). Планетарные науки: американские и советские исследования, Материалы американо-советского семинара по планетарным наукам . Триверс, Кэтлин Кирни и Абрамсон, Дэвид М. Издательство Национальной академии. п. 251. дои : 10.17226/1790 . ISBN 0-309-04333-6 . Проверено 18 марта 2008 г.

- ^ Фернендес, Хулио А. (1997). «Формирование облака Оорта и примитивная галактическая среда» (PDF) . Икар . 219 (1): 106–119. Бибкод : 1997Icar..129..106F . дои : 10.1006/icar.1997.5754 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 24 июля 2012 года . Проверено 18 марта 2008 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Сандерс, Роберт (7 января 2013 г.). «Экзокометы могут быть так же распространены, как и экзопланеты» . Калифорнийский университет в Беркли . Проверено 30 июля 2013 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б « Экзокометы, распространенные по всей галактике Млечный Путь» . Space.com. 7 января 2013 года. Архивировано из оригинала 16 сентября 2014 года . Проверено 8 января 2013 г.

- ^ Беуст, Х.; и др. (1990). «Околозвездный диск Beta Pictoris. X – Численное моделирование падения испаряющихся тел». Астрономия и астрофизика . 236 : 202–216. Бибкод : 1990A&A...236..202B . ISSN 0004-6361 .

- ^ Бартельс, Меган (30 октября 2017 г.). «Астрономы впервые обнаружили кометы за пределами нашей Солнечной системы» . Newsweek . Проверено 1 декабря 2019 г.

- ^ Раппапорт, С.; Вандербург, А.; Джейкобс, Т.; ЛаКурс, Д.; Дженкинс, Дж.; Краус, А.; Риццуто, А.; Лэтэм, Д.В.; Берила, А.; Лазаревич, М.; Шмитт, А. (21 февраля 2018 г.). «Вероятно, транзитные экзокометы обнаружены Кеплером» . Ежемесячные уведомления Королевского астрономического общества . 474 (2): 1453–1468. arXiv : 1708.06069 . Бибкод : 2018MNRAS.474.1453R . дои : 10.1093/mnras/stx2735 . ISSN 0035-8711 . ПМЦ 5943639 . ПМИД 29755143 .

- ^ Паркс, Джейк (3 апреля 2019 г.). «TESS обнаружила свою первую экзокомету вокруг одной из самых ярких звезд на небе» . Астрономия.com . Проверено 25 ноября 2019 г.