Charlie Hebdo shooting

| Charlie Hebdo shooting | |

|---|---|

| Part of the January 2015 Île-de-France attacks | |

Police officers, emergency vehicles, and journalists at the scene two hours after the shooting | |

| Location | 10 Rue Nicolas-Appert, 11th arrondissement of Paris, France[1] |

| Coordinates | 48°51′33″N 2°22′13″E / 48.85925°N 2.37025°E |

| Date | 7 January 2015 11:30 CET (UTC+01:00) |

| Target | Charlie Hebdo employees |

Attack type | Mass shooting |

| Weapons |

|

| Deaths | 12 |

| Injured | 11 |

| Perpetrators | Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula[4] |

| Assailants | Chérif and Saïd Kouachi |

| Motive | Islamic terrorism |

On 7 January 2015, at about 11:30 a.m. in Paris, France, the employees of the French satirical weekly magazine Charlie Hebdo were targeted in a terrorist shooting attack by two French-born Algerian Muslim brothers, Saïd Kouachi and Chérif Kouachi. Armed with rifles and other weapons, the duo murdered 12 people and injured 11 others; they identified themselves as members of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, which claimed responsibility for the attack. They fled after the shooting, triggering a manhunt, and were killed by the GIGN on 9 January. The Kouachi brothers' attack was followed by several related Islamist terrorist attacks across the Île-de-France between 7 and 9 January 2015, including the Hypercacher kosher supermarket siege, in which a French-born Malian Muslim took hostages and murdered four people (all Jews) before being killed by French commandos.

In response to the shooting, France raised its Vigipirate terror alert and deployed soldiers in Île-de-France and Picardy. A major manhunt led to the discovery of the suspects, who exchanged fire with police. The brothers took hostages at a signage company in Dammartin-en-Goële on 9 January and were shot dead when they emerged from the building firing.

On 11 January, about two million people, including more than 40 world leaders, met in Paris for a rally of national unity, and 3.7 million people joined demonstrations across France. The phrase Je suis Charlie became a common slogan of support at rallies and on social media. The staff of Charlie Hebdo continued with the publication, and the following issue print ran 7.95 million copies in six languages, compared to its typical print run of 60,000 in French only.

Charlie Hebdo is a publication that has always courted controversy with satirical attacks on political and religious leaders. It published cartoons of the Islamic prophet Muhammad in 2012, forcing France to temporarily close embassies and schools in more than 20 countries amid fears of reprisals. Its offices were firebombed in November 2011 after publishing a previous caricature of Muhammad on its cover.

On 16 December 2020, 14 people who were accomplices to both the Charlie Hebdo and Jewish supermarket attackers were convicted.[5] However, three of these accomplices were still not yet captured and were tried in absentia.[5]

Background

Charlie Hebdo satirical works

Charlie Hebdo (French for Charlie Weekly) is a French satirical weekly newspaper that features cartoons, reports, polemics, and jokes. The publication, irreverent and stridently non-conformist in tone, is strongly secularist, antireligious,[6] and left-wing, publishing articles that mock Catholicism, Judaism, Islam, and various other groups as local and world news unfolds. The magazine was published from 1969 to 1981 and has been again from 1992 on.[7]

Charlie Hebdo has a history of attracting controversy. In 2006, Islamic organisations under French hate speech laws unsuccessfully sued over the newspaper's re-publication of the Jyllands-Posten cartoons of Muhammad.[8][9][10] The cover of a 2011 issue retitled Charia Hebdo (French for Sharia Weekly), featured a cartoon of Muhammad, whose depiction is forbidden in most interpretations of Islam, with some Persian exceptions.[11] The newspaper's office was fire-bombed and its website hacked.[12][13] In 2012, the newspaper published a series of satirical cartoons of Muhammad, including nude caricatures;[14][15] this came days after a series of violent attacks on U.S. embassies in the Middle East, purportedly in response to the anti-Islamic film Innocence of Muslims, prompting the French government to close embassies, consulates, cultural centres, and international schools in about 20 Muslim countries.[16] Riot police surrounded the newspaper's offices to protect it against possible attacks.[15][17]

Cartoonist Stéphane "Charb" Charbonnier had been the director of publication of Charlie Hebdo since 2009.[18] Two years before the attack he stated, "We have to carry on until Islam has been rendered as banal as Catholicism."[19] In 2013, al-Qaeda added him to its most wanted list, along with three Jyllands-Posten staff members: Kurt Westergaard, Carsten Juste, and Flemming Rose.[18][20][21] Being a sport shooter, Charb applied for permit to be able to carry a firearm for self-defence. The application went unanswered.[22][23]

Numerous violent plots related to the Jyllands-Posten cartoons were discovered, primarily targeting cartoonist Westergaard, editor Rose, and the property or employees of Jyllands-Posten and other newspapers that printed the cartoons.[a] Westergaard was the subject of several attacks and planned attacks, and lived under police protection for the rest of his life. On 1 January 2010, police used guns to stop a would-be assassin in his home,[28][29] who was sentenced to nine years in prison.[b][30][31] In 2010, three men based in Norway were arrested on suspicion of planning a terror attack against Jyllands-Posten or Kurt Westergaard; two of them were convicted.[32][33] In the United States, David Headley and Tahawwur Hussain Rana were convicted in 2013 of planning terrorism against Jyllands-Posten.[34][35][36]

Secularism and blasphemy

In France, blasphemy law ceased to exist with progressive emancipation of the Republic from the Catholic Church between 1789 and 1830. In France, the principle of secularism (laïcité – the separation of church and state) was enshrined in the 1905 law on the Separation of the Churches and the State, and in 1945 became part of the constitution. Under its terms, the government and all public administrations and services must be religion-blind and their representatives must refrain from any display of religion, but private citizens and organisations are free to practise and express the religion of their choice where and as they wish (although discrimination based on religion is prohibited).[37]

In recent years, there has been a trend towards a stricter interpretation of laïcité which would also prohibit users of certain public services from expressing their religion (e.g. the 2004 law which bans school pupils from wearing "blatant" religious symbols[38]) or ban citizens from expressing their religion in public even outside the administration and public services (e.g. a 2015 law project prohibiting the wearing of religious symbols by the employees of private crèches). This restrictive interpretation is not supported by the initial law on laïcité and is challenged by the representatives of all the major religions.[39]

Authors, humorists, cartoonists, and individuals have the right to satirise people, public actors, and religions, a right which is balanced by defamation laws. These rights and legal mechanisms were designed to protect freedom of speech from local powers, among which was the then-powerful Catholic Church in France.[40]

Though images of Muhammad are not explicitly banned by the Quran itself, prominent Islamic views have long opposed human images, especially those of prophets. Such views have gained ground among militant Islamic groups.[41][42][43] Accordingly, some Muslims take the view that the satire of Islam, of religious representatives, and above all of Islamic prophets is blasphemy in Islam punishable by death.[44] This sentiment was most famously actualized in the murder of the controversial Dutch filmmaker Theo van Gogh. According to the BBC, France has seen "the apparent desire of some younger, often disaffected children or grandchildren of immigrant families not to conform to western, liberal lifestyles – including traditions of religious tolerance and free speech".[45]

Attack

Charlie Hebdo headquarters

On the morning of 7 January 2015, a Wednesday, Charlie Hebdo staff were gathered at 10 Rue Nicolas-Appert in the 11th arrondissement of Paris for the weekly editorial meeting starting around 10:30. The magazine had moved into an unmarked office at this address following the 2011 firebombing of their previous premises due to the magazine's original satirization of Muhammad.[46]

Around 11:00 a.m., two armed and hooded men first burst into the wrong address at 6 Rue Nicolas-Appert, shouting "Is this Charlie Hebdo?" and threatening people. After realizing their mistake and firing a bullet through a glass door, the two men left for 10 Rue Nicolas-Appert.[47] There, they encountered cartoonist Corinne "Coco" Rey and her young daughter outside and at gunpoint, forced her to enter the passcode into the electronic door.[48]

The men sprayed the lobby with gunfire upon entering. The first victim was maintenance worker Frédéric Boisseau, who was killed as he sat at the reception desk.[49] The gunmen forced Rey at gunpoint to lead them to a second-floor office, where 15 staff members were having an editorial meeting,[50] Charlie Hebdo's first news conference of the year. Reporter Laurent Léger said they were interrupted by what they thought was the sound of a firecracker—the gunfire from the lobby—and recalled, "We still thought it was a joke. The atmosphere was still joyous."[51]

The gunmen burst into the meeting room. The shooting lasted five to ten minutes. The gunmen aimed at the journalists' heads and killed them.[52][53] During the gunfire, Rey survived uninjured by hiding under a desk, from where she witnessed the murders of Wolinski and Cabu.[54] Léger also survived by hiding under a desk as the gunmen entered.[55] Ten of the twelve people murdered were shot on the second floor, past the security door.[56]

Psychoanalyst Elsa Cayat, a French columnist of Tunisian Jewish descent, was killed.[57] Another female columnist present at the time, crime reporter Sigolène Vinson, survived; one of the shooters aimed at her but spared her, saying, "I'm not killing you because you are a woman", and telling her to convert to Islam, read the Quran and wear a veil. She said he left shouting, "Allahu Akbar! Allahu Akbar!"[58][59][60] Other witnesses reported that the gunmen identified themselves as belonging to al-Qaeda in Yemen.[61]

Escape

An authenticated video surfaced on the Internet that shows two gunmen and a police officer, Ahmed Merabet, who is wounded and lying on a sidewalk after an exchange of gunfire. This took place near the corner of Boulevard Richard-Lenoir and Rue Moufle, 180 metres (590 ft) east of the main crime scene. One of the gunmen ran towards the policeman and shouted, "Did you want to kill us?" The policeman answered, "No, it's fine, boss", and raised his hand toward the gunman, who then murdered the policeman with a fatal shot to the head at close range.[62]

Sam Kiley, of Sky News, concluded from the video that the two gunmen were "military professionals" who likely had "combat experience", saying that the gunmen were exercising infantry tactics such as moving in "mutual support" and were firing aimed, single-round shots at the police officer. He also stated that they were using military gestures and were "familiar with their weapons" and fired "carefully aimed shots, with tight groupings".[63]

The gunmen then left the scene, shouting, "We have avenged the Prophet Muhammad. We have killed Charlie Hebdo!"[64][65][60] They escaped in a getaway car, and drove to Porte de Pantin, hijacking another car and forcing its driver out. As they drove away, they ran over a pedestrian and shot at responding police officers.[66]

It was initially believed that there were three suspects. One identified suspect turned himself in at a Charleville-Mézières police station.[67][68] Seven of the Kouachi brothers' friends and family were taken into custody.[69] Jihadist flags and Molotov cocktails were found in an abandoned getaway car, a black Citroën C3.[70]

Motive

Charlie Hebdo had attracted considerable worldwide attention for its controversial depictions of Muhammad. Hatred for Charlie Hebdo's cartoons, which made jokes about Islamic leaders as well as Muhammad, is considered to be the principal motive for the massacre. Michael Morell, former deputy director of the CIA, suggested that the motive of the attackers was "absolutely clear: trying to shut down a media organisation that lampooned the Prophet Muhammad".[71]

In March 2013, al-Qaeda's branch in Yemen, commonly known as al-Qaeda on the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), released a hit list in an edition of their English-language magazine Inspire. The list included Stéphane Charbonnier (known as Charb, the editor of Charlie Hebdo) and others whom AQAP accused of insulting Islam.[72][73] On 9 January, AQAP claimed responsibility for the attack in a speech from AQAP's top Shariah cleric Harith bin Ghazi al-Nadhari, citing the motive as "revenge for the honour" of Muhammad.[74]

Victims

Killed

- Cartoonists and journalists

- Cabu (Jean Cabut), 76, cartoonist.

- Elsa Cayat, 54, psychoanalyst and columnist – [75][76] the only woman killed in the shooting.[77]

- Charb (Stéphane Charbonnier), 47, cartoonist, columnist, and director of publication of Charlie Hebdo.

- Philippe Honoré, 73, cartoonist.

- Bernard Maris, 68, economist, editor, and columnist.[78][79]

- Mustapha Ourrad, 60, copy editor.[80]

- Tignous (Bernard Verlhac), 57, cartoonist.[81]

- Georges Wolinski, 80, cartoonist.[82]

- Others

- Frédéric Boisseau, 42, building maintenance worker for Sodexo, killed in the lobby as he came to the building on a call, the first victim of the shooting.

- Franck Brinsolaro, 49, Protection Service police officer assigned as a bodyguard for Charb.[83]

- Ahmed Merabet, 42, police officer, shot in the head as he lay wounded on the ground outside.[84]

- Michel Renaud, 69, a travel writer and festival organiser visiting Cabu.[85]

Wounded

- Philippe Lançon, journalist—shot in the face and left in a critical condition, but recovered.[86]

- Fabrice Nicolino, 59, journalist—shot in the leg.

- Riss (Laurent Sourisseau), 48, cartoonist and editorial director—shot in the shoulder.[87]

- Unidentified police officers.[50][88][89]

Uninjured and absent

Several people at the meeting were unharmed, including book designer Gérard Gaillard, who was a guest, and staff members, Sigolène Vinson,[90] Laurent Léger, and Éric Portheault.

The cartoonist Coco was coerced into letting the murderers into the building, and was not harmed.[91] Several other staff members were not in the building at the time of the shooting, including medical columnist Patrick Pelloux, cartoonists Rénald "Luz" Luzier and Catherine Meurisse and film critic Jean-Baptiste Thoret, who were late for work, cartoonist Willem, who never attends, editor-in-chief Gérard Biard and journalist Zineb El Rhazoui who were on holiday, journalist Antonio Fischetti, who was at a funeral, and comedian and columnist Mathieu Madénian. Luz arrived in time to see the gunmen escaping.[92]

Assailants

Chérif and Saïd Kouachi

Biography

Chérif and Saïd Kouachi | |

|---|---|

| Born | Chérif: 29 November 1982 Saïd: 7 September 1980 10th Ardt, Paris, France |

| Died | 9 January 2015 (aged 32 and 34) Dammartin-en-Goële, France |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wounds |

| Nationality | French |

| Details | |

| Date | 7–9 January 2015 |

| Location(s) | Charlie Hebdo offices |

| Target(s) | Charlie Hebdo staff |

| Killed | 12 |

| Injured | 11 |

| Weapons |

|

Police quickly identified brothers Saïd Kouachi (French: [sa.id kwaʃi]; 7 September 1980 – 9 January 2015) and Chérif Kouachi (French: [ʃeʁif]; 29 November 1982 – 9 January 2015) as the main suspects.[c] French citizens born in Paris to Algerian immigrants, the brothers were orphaned at a young age after their mother's apparent suicide and placed in a foster home in Rennes.[94] After two years, they were moved to an orphanage in Corrèze in 1994, along with a younger brother and an older sister.[98][99] The brothers moved to Paris around 2000.[100]

Chérif, also known as Abu Issen, was part of an informal gang that met in the Parc des Buttes Chaumont in Paris to perform military-style training exercises and sent would-be jihadists to fight for al-Qaeda in Iraq after the 2003 invasion.[101][102] Chérif was arrested at age 22 in January 2005 when he and another man were about to leave for Syria, at the time a gateway for jihadists wishing to fight US troops in Iraq.[103] He went to Fleury-Mérogis Prison, where he met Amedy Coulibaly.[104] In prison, they found a mentor, Djamel Beghal, who had been sentenced to ten years in prison in 2001 for his part in a plot to bomb the US embassy in Paris.[103] Beghal had once been a regular worshipper at Finsbury Park Mosque in London and a disciple of the radical preachers Abu Hamza al-Masri[105] and Abu Qatada.

Upon leaving prison, Chérif Kouachi married and got a job in a fish market on the outskirts of Paris. He became a student of Farid Benyettou, a radical Muslim preacher at the Addawa Mosque in the 19th arrondissement of Paris. Kouachi wanted to attack Jewish targets in France, but Benyettou told him that France, unlike Iraq, was not "a land of jihad".[106]

On 28 March 2008, Chérif was convicted of terrorism and sentenced to three years in prison, with 18 months suspended, for recruiting fighters for militant Islamist Abu Musab al-Zarqawi's group in Iraq.[94] He said outrage at the torture of inmates by the US Army at Baghdad Central Prison in Abu Ghraib inspired him to help Iraq's insurgency.[107][108]

French judicial documents state Amedy Coulibaly and Chérif Kouachi travelled with their wives in 2010 to central France to visit Djamel Beghal. In a police interview in 2010, Coulibaly identified Chérif as a friend he had met in prison and said they saw each other frequently.[109] In 2010, the Kouachi brothers were named in connection with a plot to break out of jail with another Islamist, Smaïn Aït Ali Belkacem. Belkacem was one of those responsible for the 1995 Paris Métro and RER bombings that killed eight people.[103][110] For lack of evidence, they were not prosecuted.

From 2009 to 2010, Saïd Kouachi visited Yemen on a student visa to study at the San'a Institute for the Arabic Language. There, according to a Yemeni reporter who interviewed Saïd, he met and befriended Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, the perpetrator of the attempted bombing of Northwest Airlines Flight 253 later in 2009. Also according to the reporter, the two shared an apartment for "one or two weeks".[111]

In 2011, Saïd returned to Yemen for a number of months and trained with al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula militants.[112] According to a senior Yemeni intelligence source, he met al Qaeda preacher Anwar al-Awlaki in the southern province of Shabwa.[113] Chérif Kouachi told BFM TV that he had been funded by a network loyal to Anwar al-Awlaki, who was killed by a drone strike in 2011 in Yemen.[114] According to US officials, the US provided France with intelligence in 2011 showing the brothers received training in Yemen. French authorities monitored them until the spring of 2014.[115] During the time leading to the Charlie Hebdo attack, Saïd lived with his wife and children in a block of flats in Reims. Neighbours described him as solitary.

The weapons used in the attack were supplied via the Brussels underworld. According to the Belgian press, a criminal sold Amedy Coulibaly the rocket-propelled grenade launcher and Kalashnikov rifles that the Kouachi brothers used for less than EUR €5,000 (US$5,910).[116]

In an interview between Chérif Kouachi and Igor Sahiri, one of France's BFM TV journalists, Chérif stated that "We are not killers. We are defenders of the prophet, we don't kill women. We kill no one. We defend the prophet. If someone offends the prophet then there is no problem, we can kill him. We don't kill women. We are not like you. You are the ones killing women and children in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan. This isn't us. We have an honour code in Islam."[117]

After the attack: Manhunt (8 and 9 January)

A massive manhunt began immediately after the attack. One suspect left his ID card in an abandoned getaway car.[118][119] Police officers searched apartments in the Île-de-France region, in Strasbourg and in Reims.[120][121]

Police detained several people during the manhunt for the two main suspects. A third suspect voluntarily reported to a police station after hearing he was wanted and was not charged. Police described the assailants as "armed and dangerous". France raised its terror alert to its highest level and deployed soldiers in Île-de-France and Picardy regions.

At 10:30 CET on 8 January, the day following the attack, the two primary suspects were spotted in Aisne, north-east of Paris. Armed security forces, including the National Gendarmerie Intervention Group (GIGN) and the Force d'intervention de la police nationale (FIPN), were deployed to the department to search for the suspects.[122]

Later that day, the police search concentrated on the Picardy, particularly the area around Villers-Cotterêts and the village of Longpont, after the suspects robbed a petrol station near Villers-Cotterêts,[123] then reportedly abandoned their car before hiding in a forest near Longpont.[124] Searches continued into the surrounding Forêt de Retz (130 km2), one of the largest forests in France.[125]

The manhunt continued with the discovery of the two fugitive suspects early on the morning of 9 January. The Kouachis had hijacked a Peugeot 206 near the town of Crépy-en-Valois. They were chased by police cars for approximately 27 kilometres (17 miles) south down the N2 trunk road. At some point they abandoned their vehicle and an exchange of gunfire between pursuing police and the brothers took place near the commune of Dammartin-en-Goële, 35 kilometres (22 miles) northeast of Paris. Several blasts went off as well and Saïd Kouachi sustained a minor neck wound. Several others may have been injured as well but no one was killed in the gunfire. The suspects were not apprehended and escaped on foot.[126]

Dammartin-en-Goële hostage crisis, death of Chérif and Saïd (9 January)

At around 9:30 am on 9 January 2015, the Kouachi brothers fled into the office of Création Tendance Découverte, a signage production company on an industrial estate in Dammartin-en-Goële. Inside the building were owner Michel Catalano and a male employee, 26-year-old graphics designer Lilian Lepère. Catalano told Lepère to go hide in the building and remained in his office by himself.[127] Not long after, a salesman named Didier went to the printworks on business. Catalano came out with Chérif Kouachi who introduced himself as a police officer. They shook hands and Kouachi told Didier, "Leave. We don't kill civilians anyhow." These words were what caused Didier to guess that Kouachi was a terrorist and he alerted the police.[128]

The Kouachi brothers remained inside and a lengthy standoff began. Catalano re-entered the building and closed the door after Didier had left.[129] The brothers were not aggressive towards Catalano, who stated, "I didn't get the impression they were going to harm me." He made coffee for them and helped bandage the neck wound that Saïd Kouachi had sustained during the earlier gunfire. Catalano was allowed to leave after an hour.[130] Before doing so, Catalano swore three different times to the terrorists that he was alone and did not reveal Lepère's presence; ultimately the Kouachi brothers never became aware of him being there. Lepère hid inside a cardboard box and sent the Gendarmerie text messages for around three hours during the siege, providing them with "tactical elements such as [the brothers'] location inside the premises".[131]

Given the proximity (10 km) of the siege to Charles de Gaulle Airport, two of the airport's runways were closed.[126][132] Interior Minister Bernard Cazeneuve called for a Gendarmerie operation to neutralise the perpetrators. An Interior Ministry spokesman announced that the Ministry wished first to "establish a dialogue" with the suspects. Officials tried to establish contact with the suspects to negotiate the safe evacuation of a school 500 metres (1,600 feet) from the siege. The Kouachi brothers did not respond to attempts at communication by the French authorities.[133]

The siege lasted for eight to nine hours, and at around 4:30 p.m. there were at least three explosions near the building. At around 5:00 pm, a GIGN team landed on the roof of the building and a helicopter landed nearby.[134] Before gendarmes could reach them, the pair ran out of the building and opened fire on gendarmes. The brothers had stated a desire to die as martyrs[135] and the siege came to an end when both Kouachi brothers were shot and killed. Lilian Lepère was rescued unharmed.[136][137] A cache of weapons, including Molotov cocktails and a rocket launcher, was found in the area.[131]

During the standoff in Dammartin-en-Goële, another jihadist named Amedy Coulibaly, who had met the brothers in prison,[138] took hostages in a kosher supermarket at Porte de Vincennes in east Paris, killing those of Jewish faith while leaving the others alive. Coulibaly was reportedly in contact with the Kouachi brothers as the sieges progressed, and told police that he would kill hostages if the brothers were harmed.[126][139] Coulibaly and the Kouachi brothers died within minutes of each other.[140]

Suspected Charlie Hebdo attack driver

The police initially identified the 18-year-old brother-in-law of Chérif Kouachi, a French Muslim student of North African descent and unknown nationality, as a third suspect in the shooting, accused of driving the getaway car.[94] He was believed to have been living in Charleville-Mézières, about 200 kilometres (120 mi) northeast of Paris near the border with Belgium.[141] He turned himself in at a Charleville-Mézières police station early in the morning on 8 January 2015.[141] The man said he was in class at the time of the shooting, and that he rarely saw Chérif Kouachi.[citation needed] Many of his classmates said that he was at school in Charleville-Mézières during the attack.[142] After detaining him for nearly 50 hours, police decided not to continue further investigations into the teenager.[143]

Peter Cherif

In December 2018, French authorities arrested Peter Cherif also known as Abu Hamza, for playing an "important role in organizing" the Charlie Hebdo attack.[144] Not only was Cherif a close friend of brothers Chérif Kouachi and Saïd Kouachi,[145] but had been on the run from French authorities since 2011. Cherif fled Paris in 2011 just before a court sentenced him to five years in prison on terrorism charges for fighting as an insurgent in Iraq.[citation needed]

2020 trial

On 2 September 2020, fourteen people went on trial in Paris charged with providing logistical support and procuring weapons for those who carried out both the Charlie Hebdo shooting and the Hypercacher kosher supermarket siege. Of the fourteen on trial Mohamed and Mehdi Belhoucine and Amedy Coulibaly's girlfriend, Hayat Boumeddiene, were tried in absentia, having fled to either Iraq or Syria in the days before the attacks took place.[146][147] In anticipation of the trial getting underway Charlie Hebdo reprinted cartoons of Muhammad with the caption: "Tout ça pour ça" ("All of that for this").[148]

The trial was scheduled to be filmed for France's official archives.[149] On 16 December 2020, the trial concluded with all fourteen defendants being convicted by a French court.[5]

Aftermath

France

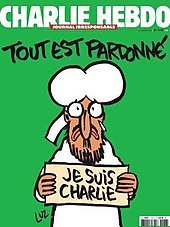

The remaining staff of Charlie Hebdo continued normal weekly publication, and the following issue print run had 7.95 million copies in six languages.[150] In contrast, its normal print run was 60,000, of which it typically sold 30,000 to 35,000 copies.[151] The cover depicts Muhammad holding a "Je suis Charlie" sign ("I am Charlie"), and is captioned "Tout est pardonné" ("All is forgiven").[152] The issue was also sold outside France.[153] The Digital Innovation Press Fund donated €250,000 to support the magazine, matching a donation by the French Press and Pluralism Fund.[154][155] The Guardian Media Group pledged £100,000 to the same cause.[156]

On the night of 8 January, police commissioner Helric Fredou, who had been investigating the attack, committed suicide in his office in Limoges while he was preparing his report shortly after meeting with the family of one of the victims. He was said to have been experiencing depression and burnout.[citation needed]

In the week after the shooting, 54 anti-Muslim incidents were reported in France. These included 21 reports of shootings, grenade throwing at mosques and other Islamic centres, an improvised explosive device attack,[157] and 33 cases of threats and insults.[d] Authorities classified these acts as right-wing terrorism.[157]

On 7 January 2016, the first anniversary of the shooting, an attempted attack occurred at a police station in the Goutte d'Or district of Paris. The assailant, a Tunisian man posing as an asylum-seeker from Iraq or Syria, wearing a fake explosive belt charged police officers with a meat cleaver while shouting "Allahu Akbar!" and was subsequently shot and killed.[164][165][166][167]

Denmark

On 14 February 2015 in Copenhagen, Denmark, a public event called "Art, blasphemy and the freedom of expression", was organised to honour victims of the attack in January against the French satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo. A series of shootings took place that day and the following day in Copenhagen, with two people killed and five police officers wounded. The suspect, Omar Abdel Hamid El-Hussein, a recently released, radicalized prisoner, was later shot dead by police on 15 February.

United States

On 3 May 2015, two men attempted an attack on the Curtis Culwell Center in Garland, Texas. The centre was hosting an exhibit featuring cartoons depicting Muhammad. The event was presented as a response to the attack on Charlie Hebdo, and organised by the group American Freedom Defense Initiative (AFDI).[168] Both gunmen were killed by police.

Security

Following the attack, France raised Vigipirate to its highest level in history: Attack alert, an urgent terror alert which triggered the deployment of soldiers in Paris to the public transport system, media offices, places of worship and the Eiffel Tower.[169] The British Foreign Office warned its citizens about travelling to Paris. The New York City Police Department ordered extra security measures to the offices of the Consulate General of France in New York in Manhattan's Upper East Side as well as the Lycée Français de New York, which was deemed a possible target due to the proliferation of attacks in France as well as the level of hatred of the United States within the extremist community.[53] In Denmark, which was the centre of a controversy over cartoons of Muhammad in 2005, security was increased at all media outlets.[170]

Hours after the shooting, Spanish Interior Minister Jorge Fernández Díaz said that Spain's anti-terrorist security level had been upgraded and that the country was sharing information with France in relation to the attacks. Spain increased security in public places such as railway stations and increased the police presence on streets throughout the country's cities.[171]

The British Transport Police confirmed on 8 January that they would establish new armed patrols in and around St Pancras International railway station in London, following reports that the suspects were moving north towards Eurostar stations. They confirmed that the extra patrols were for the reassurance of the public and to maintain visibility and that there were no credible reports yet of the suspects heading towards St Pancras.[172]

In Belgium, the staff of P-Magazine were given police protection, although there were no specific threats. P-Magazine had previously published a cartoon of Muhammad drawn by the Danish cartoonist Kurt Westergaard.[173]

Demonstrations

7 January

On the evening of the day of the attack, demonstrations against the attack were held at the Place de la République in Paris[174] and in other cities including Toulouse,[175] Nice, Lyon, Marseille and Rennes.

The phrase Je suis Charlie (French for "I am Charlie") came to be a common worldwide sign of solidarity against the attacks.[176] Many demonstrators used the slogan to express solidarity with the magazine. It appeared on printed and hand-made placards, and was displayed on mobile phones at vigils, and on many websites, particularly media sites such as Le Monde. The hashtag #jesuischarlie quickly trended at the top of Twitter hashtags worldwide following the attack.[177]

Not long after the attack, it is estimated that around 35,000 people gathered in Paris holding "Je suis Charlie" signs. 15,000 people also gathered in Lyon and Rennes.[178] 10,000 people gathered in Nice and Toulouse; 7,000 in Marseille; and 5,000 each in Nantes, Grenoble and Bordeaux. Thousands also gathered in Nantes at the Place Royale.[179] More than 100,000 people in total gathered within France to partake in these demonstrations the evening of 7 January.[180]

- Protests in France

-

Demonstrators gather at the Place de la République in Paris on the night of the attack

-

Memorial for Ahmed Merabet

-

Demonstrators in Bordeaux

-

Tribute to Charlie Hebdo in Strasbourg

-

Tributes to the victims in Toulouse

Similar demonstrations and candle vigils spread to other cities outside France as well, including Amsterdam,[181] Brussels, Barcelona,[182] Ljubljana,[183] Berlin, Copenhagen, London and Washington, D.C.[184] Around 2,000 demonstrators gathered in London's Trafalgar Square and sang La Marseillaise, the French national anthem.[185][186] In Brussels, two vigils have been held thus far, one immediately at the city's French consulate and a second one at Place du Luxembourg. Many flags around the city were at half-mast on 8 January.[187] In Luxembourg, a demonstration was held in the Place de la Constitution.[188]

A crowd gathered on the evening of 7 January, at Union Square in Manhattan, New York City. French ambassador to the United Nations François Delattre was present; the crowd lit candles, held signs, and sang the French national anthem.[189] Several hundred people also showed up outside of the French consulate in San Francisco with "Je suis Charlie" signs to show their solidarity.[190] In downtown Seattle, another vigil was held where people gathered around a French flag laid out with candles lit around it. They prayed for the victims and held "Je suis Charlie" signs.[191] In Argentina, a large demonstration was held to denounce the attacks and show support for the victims outside the French embassy in the Buenos Aires.[192]

More vigils and gatherings were held in Canada to show support to France and condemn terrorism. Many cities had notable "Je suis Charlie" gatherings, including Calgary, Montreal, Ottawa and Toronto.[193] In Calgary, there was a strong anti-terrorism sentiment. "We're against terrorism and want to show them that they won't win the battle. It's horrible everything that happened, but they won't win," commented one demonstrator. "It's not only against the French journalists or the French people, it's against freedom – everyone, all over the world, is concerned at what's happening."[194] In Montreal, despite a temperature of −21 °C (−6 °F), over 1,000 people gathered chanting "Liberty!" and "Charlie!" outside of the city's French Consulate. Montreal Mayor Denis Coderre was among the gatherers and proclaimed, "Today, we are all French!" He confirmed the city's full support for the people of France and called for strong support regarding freedom, stating that "We have a duty to protect our freedom of expression. We have the right to say what we have to say."[195][196]

8 January

By 8 January, vigils had spread to Australia, with thousands holding "Je suis Charlie" signs. In Sydney, people gathered at Martin Place – the location of a siege less than a month earlier – and in Hyde Park dressed in white clothing as a form of respect. Flags were at half-mast at the city's French consulate where mourners left bouquets.[197] A vigil was held at Federation Square in Melbourne with an emphasis on togetherness. French consul Patrick Kedemos described the gathering in Perth as "a spontaneous, grassroots event". He added, "We are far away but our hearts today [are] with our families and friends in France. It [was] an attack on the liberty of expression, journalists that were prominent in France, and at the same time it's an attack or a perceived attack on our culture."[198]

On 8 January over 100 demonstrations were held from 18:00 in the Netherlands at the time of the silent march in Paris, after a call to do so from the mayors of Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Utrecht, and other cities. Many Dutch government members joined the demonstrations.[199][200]

- Protests around the world

-

Brisbane, Australia

-

Berlin, Germany

-

Luxembourg, 8 January 2015

-

Bologna, Italy

-

Daley Plaza, Chicago, U.S.

-

French Embassy, Moscow, Russia

-

Brussels, Belgium

-

Istanbul, Turkey

10–11 January

Around 700,000 people walked in protest in France on 10 January. Major marches were held in Toulouse (attended by 180,000), Marseille (45,000), Lille (35–40,000), Nice (23–30,000), Pau (80,000), Nantes (75,000), Orléans (22,000), and Caen (6,000).[201]

On 11 January, up to 2 million people, including President Hollande and more than 40 world leaders, led a rally of national unity in the heart of Paris to honour the 17 victims. The demonstrators marched from Place de la République to Place de la Nation. 3.7 million joined demonstrations nationwide in what officials called the largest public rally in France since World War II.[e]

There were also large marches in many other French towns and cities, and marches and vigils in many other cities worldwide.[f]

- Republican marches on 11 January in France

Arrests of "apologists for terrorism"

This section needs to be updated. (October 2016) |

About 54 people in France, who had publicly supported the attack on Charlie Hebdo, were arrested as "apologists for terrorism" and about 12 people were sentenced to several months in jail.[208][209] Comedian Dieudonné faces the same charges for having written on Facebook "I feel like Charlie Coulibaly".[210]

Planned attacks in Belgium

Following a series of police raids in Belgium, in which two suspected terrorists were killed in a shootout in the city of Verviers, Belgian police stated that documents seized after the raids appear to show that the two were planning to attack sellers of the next edition of Charlie Hebdo released following the attack in Paris.[211] Police named the men killed in the raid as Redouane Hagaoui and Tarik Jadaoun.[211]

Protests following resumed publication

Unrest in Niger following the publication of the post-attack issue of Charlie Hebdo resulted in ten deaths,[212] dozens injured, and at least 45 churches were burned down.[213] The Guardian reported seven churches burned in Niamey alone. Churches were also reported to be on fire in eastern Maradi and Goure. There were violent demonstrations in Karachi in Pakistan, where Asif Hassan, a photographer working for the Agence France-Presse, was seriously injured by a shot to the chest. In Algiers and Jordan, protesters clashed with police, and there were peaceful demonstrations in Khartoum, Sudan, Russia, Mali, Senegal, and Mauritania.[214] In the week after the shooting, 54 anti-Muslim incidents were reported in France. These included 21 reports of shootings and grenade-throwing at mosques and other Islamic centres and 33 cases of threats and insults.[g]

RT reported that a million people attended a demonstration in Grozny, the capital city of the Chechen Republic, protesting the depictions of Muhammad in Charlie Hebdo and proclaiming that Islam is a religion of peace. One of the slogans was "Violence is not the method".[215]

On 8 February 2015 the Muslim Action Forum, an Islamic rights organization, orchestrated a mass demonstration outside Downing Street in London. Placards read, "Stand up for the Prophet" and "Be careful with Muhammad".[216]

2015 Marseille shooting

| 2015 Marseille shooting | |

|---|---|

| Part of aftermath of 2015 Île-de-France attacks | |

La Castellane | |

| Location | La Castellane, Marseille |

| Date | 9 February 2015 |

| Target | Drug gang, police |

Attack type | Shooting |

| Weapons | Kalashnikov rifles |

| Deaths | 0 |

| Injured | 1[citation needed] |

| Perpetrators | Drug gang |

On 9 February 2015, hooded gunmen in the French city of Marseille sparked a lockdown after they fired Kalashnikov rifles at police officers while Manuel Valls, the French Prime Minister, was visiting the city. It is thought that the shooting was gang-related, but due to the recent Charlie Hebdo shooting and the Porte de Vincennes hostage crisis during the 2015 Île-de-France attacks, the entire troubled Marseille suburb of La Castellane was under lockdown for hours.[specify] No one was injured.[citation needed]

Shortly after gunfire occurred near a police car,[217] the National Gendarmerie Intervention Group locked down the area. A number of arrests were made, resulting in the seizure of seven Kalashnikovs, two .357 Magnum revolvers and around 20 kilograms of drugs.[218] However, it soon became clear that the gunmen were not aiming at the police; instead, the gunfire was the result of a turf war between two gangs,[219] selling primarily cannabis and cocaine. Drug-traffickers as a whole in La Castellane are reported to make between 50,000 and 60,000 euros a day as of 2015.

Shortly after the shooting, Manuel Valls called it an example of "apartheid", whereby some French citizens who live in such neighbourhoods feel excluded from society.

Reactions

French government

President François Hollande addressed media outlets at the scene of the shooting and called it "undoubtedly a terrorist attack", adding that "several [other] terrorist attacks were thwarted in recent weeks".[220] He later described the shooting as a "terrorist attack of the most extreme barbarity",[10] called the slain journalists "heroes",[221] and declared a day of national mourning on 8 January.[222]

At a rally in the Place de la République in the wake of the shooting, mayor of Paris Anne Hidalgo said, "What we saw today was an attack on the values of our republic; Paris is a peaceful place. These cartoonists, writers and artists used their pens with a lot of humour to address sometimes awkward subjects and as such performed an essential function." She proposed that Charlie Hebdo "be adopted as a citizen of honour" by Paris.[223]

Prime Minister Manuel Valls said that his country was at war with terrorism, but not at war with Islam or Muslims.[224] French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius said, "The terrorists' religion is not Islam, which they are betraying. It's barbarity."[225]

Other countries

The attack received immediate condemnation from dozens of governments worldwide. International leaders including Barack Obama, Vladimir Putin, Stephen Harper, Narendra Modi, Benjamin Netanyahu, Angela Merkel, Matteo Renzi, David Cameron, Mark Rutte and Tony Abbott offered statements of condolence and outrage.[226]

Media

Some English-language media outlets republished the cartoons on their websites in the hours following the shootings. Prominent examples included Bloomberg News, The Huffington Post, The Daily Beast, Gawker, Vox, and The Washington Free Beacon.[h]

Other news organisations covered the shootings without showing the drawings, such as The New York Times, New York Daily News, CNN,[232] Al Jazeera America,[233] Associated Press, NBC, MSNBC, and The Daily Telegraph.[232] Accusations of self-censorship came from the websites Politico[233] and Slate.[232] The BBC, which previously had guidelines against all depictions of Muhammad, showed a depiction of him on a Charlie Hebdo cover and announced that they were reviewing these guidelines.[234]

Other media publications such as Germany's Berliner Kurier and Poland's Gazeta Wyborcza reprinted cartoons from Charlie Hebdo the day after the attack; the former had a cover of Muhammad reading Charlie Hebdo whilst bathing in blood.[235] At least three Danish newspapers featured Charlie Hebdo cartoons, and the tabloid BT used one on its cover depicting Muhammad lamenting being loved by "idiots".[170] The German newspaper Hamburger Morgenpost re-published the cartoons, and their office was fire-bombed.[236][237] In Russia, LifeNews and Komsomolskaya Pravda suggested that the US had carried out the attack.[238][239] "We are Charlie Hebdo" appeared on the front page of Novaya Gazeta.[239] Russia's media supervision body, Roskomnadzor, stated that publication of the cartoons could lead to criminal charges.[240]

Russian President Vladimir Putin has sought to harness and direct Muslim anger over the Charlie Hebdo cartoons against the West.[241] Putin is believed to have backed protests by Muslims in Russia against Charlie Hebdo and the West.[242]

In China, the state-run Xinhua advocated limiting freedom of speech, while another state-run newspaper, Global Times, said the attack was "payback" for what it characterised as Western colonialism.[243][244]

Media organisations carried out protests against the shootings. Libération, Le Monde, Le Figaro, and other French media outlets used black banners carrying the slogan "Je suis Charlie" across the tops of their websites.[245] The front page of Libération's printed version was a different black banner that stated, "Nous sommes tous Charlie" ("We are all Charlie"), while Paris Normandie renamed itself Charlie Normandie for the day.[170] The French and UK versions of Google displayed a black ribbon of mourning on the day of the attack.[10]

Ian Hislop, editor of the British satirical magazine Private Eye, stated, "I am appalled and shocked by this horrific attack – a murderous attack on free speech in the heart of Europe. ... Very little seems funny today."[246] The editor of Titanic, a German satirical magazine, declared, "[W]e are scared when we hear about such violence. However, as a satirist, we are beholden to the principle that every human being has the right to be parodied. This should not stop just because of some idiots who go around shooting".[247] Many cartoonists from around the world responded to the attack on Charlie Hebdo by posting cartoons relating to the shooting.[248] Among them was Albert Uderzo, who came out of retirement at age 87 to depict his character Astérix supporting Charlie Hebdo.[249] In Australia, what was considered the iconic national cartoonist's reaction[250] was a cartoon by David Pope in the Canberra Times, depicting a masked, black-clad figure with a smoking rifle standing poised over a slumped figure of a cartoonist in a pool of blood, with a speech balloon showing the gunman saying, "He drew first."[251]

In India, Mint ran the photographs of copies of Charlie Hebdo on their cover, but later apologised after receiving complaints from the readers.[252] The Hindu also issued an apology after it printed a photograph of some people holding copies of Charlie Hebdo.[253] The editor of the Urdu newspaper Avadhnama, Shireen Dalvi, which printed the cartoons faced several police complaints. She was arrested and released on bail. She began to wear the burqa for the first time in her life and went into hiding.[254][255]

Egyptian daily Al-Masry Al-Youm featured drawings by young cartoonists signed with "Je suis Charlie" in solidarity with the victims.[256] Al-Masry al-Youm also displayed on their website a slide show of some Charlie Hebdo cartoons, including controversial ones. This was seen by analyst Jonathan Guyer as a "surprising" and maybe "unprecedented" move, due to the pressure Arab artists can be subject to when depicting religious figures.[257]

In Los Angeles, the Jewish Journal weekly changed its masthead that week to Jewish Hebdo and published the offending Muhammad cartoons.[258]

The Guardian reported that many Muslims and Muslim organisations criticised the attack while some Muslims support it and other Muslims stated they would only condemn it if France condemned the killings of Muslims worldwide".[259] Zvi Bar'el argued in Haaretz that believing the attackers represented Muslims was like believing that Ratko Mladić represented Christians.[260] Al Jazeera English editor and executive producer Salah-Aldeen Khadr attacked Charlie Hebdo as the work of solipsists, and sent out a staff-wide e-mail where he argued: "Defending freedom of expression in the face of oppression is one thing; insisting on the right to be obnoxious and offensive just because you can is infantile." The e-mail elicited different responses from within the organisation.[261][clarification needed]

The Shia Islamic journal Ya lasarat Al-Hussein, founded by Ansar-e Hezbollah, praised the shooting, saying, "[the cartoonists] met their legitimate justice, and congratulations to all Muslims" and "according to fiqh of Islam, punishment of insulting of Muhammad is death penalty".[262][263][264][265][266][267]

Activist organisations

Reporters Without Borders criticised the presence of leaders from Egypt, Russia, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates, saying, "On what grounds are representatives of regimes that are predators of press freedom coming to Paris to pay tribute to Charlie Hebdo, a publication that has always defended the most radical concept of freedom of expression?"[268]

Hacktivist group Anonymous released a statement in which they offered condolences to the families of the victims and denounced the attack as an "inhuman assault" on freedom of expression. They addressed the terrorists: "[a] message for al-Qaeda, the Islamic State and other terrorists – we are declaring war against you, the terrorists." As such, Anonymous plans to target jihadist websites and social media accounts linked to supporting Islamic terrorism with the aim of disrupting them and shutting them down.[269]

Muslim reactions

Condemning the attack

Lebanon, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Bahrain, Morocco, Algeria, and Qatar all denounced the incident, as did Egypt's Al-Azhar University, the leading Sunni institution of the Muslim world.[259] Islamic organisations, including the French Council of the Muslim Faith, the Muslim Council of Britain and Islamic Forum of Europe, spoke out against the attack. Sheikh Abdul Qayum and Imam Dalil Boubakeur stated, "[We] are horrified by the brutality and the savagery."[270] The Union of Islamic Organisations of France released a statement condemning the attack, and Imam Hassen Chalghoumi stated that those behind the attack "have sold their soul to hell".[271]

The US-based Muslim civil liberties group, the Council on American–Islamic Relations, condemned the attacks and defended the right to freedom of speech, "even speech that mocks faiths and religious figures".[272] The vice president of the US Ahmadiyya Muslim Community condemned the attack, saying, "The culprits behind this atrocity have violated every Islamic tenet of compassion, justice, and peace."[273] The National Council of Canadian Muslims, a Muslim civil liberties organisation, also condemned the attacks.[274]

The League of Arab States released a collective condemnation of the attack. Al-Azhar University released a statement denouncing the attack, stating that violence was never appropriate regardless of "offence committed against sacred Muslim sentiments".[275] The Organisation of Islamic Cooperation condemned the attack, saying that it went against Islam's principles and values.[276]

Both the Palestinian Liberation Organization and the Hamas government of the Gaza Strip stated that "differences of opinion and thought cannot justify murder".[277] The leader of Hezbollah, Hassan Nasrallah declared that "takfiri terrorist groups" had insulted Islam more than "even those who have attacked the Prophet".[278][279]

Malek Merabet, the brother of Ahmed Merabet, a Muslim police officer killed in the shooting, condemned the terrorists who killed his brother: "My brother was Muslim and he was killed by two terrorists, by two false Muslims".[280] Just hours after the shootings, the mayor of Rotterdam, Ahmed Aboutaleb, a Muslim born in Morocco, condemned Islamist extremists living in the West who "turn against freedom" and told them to "fuck off".[281]

Supporting the attack

Saudi-Australian Islamic preacher Junaid Thorne said: "If you want to enjoy 'freedom of speech' with no limits, expect others to exercise 'freedom of action'."[282] Anjem Choudary, a radical British Islamist, wrote an editorial in USA Today in which he professes justification from the words of Muhammad that those who insult the prophets of Islam should face death, and that Muhammad should be protected to prevent further violence.[283] Hizb ut-Tahrir Australia[284] said that "as a result, it is assumed necessary in all cases to ensure that the pressure does not exceed the red lines, which will then ultimately lead to irreversible problems".[285] Bahujan Samaj Party leader Yaqub Qureishi, a Muslim MLA and former Minister from Uttar Pradesh in India, offered a reward of ₹510 million (US$8 million) to the perpetrators of the Charlie Hebdo shootings.[i] On 14 January, about 1,500 Filipino Muslims held a rally in Muslim-majority Marawi in support of the attacks.[290]

The massacre was praised by various militant and terrorist groups, including al-Qaeda on the Arabian Peninsula,[73] the Taliban in Afghanistan,[291][292] Al-Shabaab,[293] Boko Haram,[294] and Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant.[295][296]

Two Islamist newspapers in Turkey ran headlines that were criticised on social media as justifying the attack. The Yeni Akit ran an article entitled "Attack on the magazine that provoked Muslims", and Türkiye ran an article entitled "Attack on the magazine that insulted our Prophet".[297] Reuters reported a rally in support of the shootings in southern Afghanistan, where the demonstrators called the gunmen "heroes" who meted out punishment for the disrespectful cartoons. The demonstrators also protested Afghan President Ashraf Ghani's swift condemnation of the shootings.[298] Around 40 to 60[299] people gathered in Peshawar, Pakistan, to praise the killers, with a local cleric holding a funeral for the killers, lionizing them as "heroes of Islam."[300][301]

Schools

Le Figaro reported that in a Seine-Saint-Denis primary school, up to 80% of the pupils refused[302] to participate in the minute of silence that the French government decreed for schools.[303] A student told a teacher, "I'll drop you with a Kalashnikov, mate." Other teachers were told Charlie Hebdo "had it coming", and "Me, I'm for the killers". One teacher requested to be transferred.[302] They also reported that students from a vocational school in Senlis tried to attack and beat students from a neighbouring school while saying "we will kill more Charlie Hebdos". The incident is being investigated by authorities who are handling 37 proceedings of "terrorism glorification" and 17 proceedings of threats of violence in schools.[304]

La Provence reported that a fight broke out in the l'Arc à Orange high school during the minute of silence, as a result of a student post on a social network welcoming the atrocities. The student was later penalised for posting the message.[305] Le Point reported on the "provocations" at a grade school in Grenoble, and cited a girl who said "Madame, people won't let the insult of a drawing of the prophet pass by, it is normal to take revenge. This is more than a joke, it's an insult!"[306]

Le Monde reported that the majority of students they met at Saint-Denis condemned the attack. For them, life is sacred, but so is religion. Marie-Hélène, age 17, said "I didn't really want to stand for the one minute silence, I didn't think it was right to pay homage to a man who insulted Islam and other religions too". Abdul, age 14, said "of course everyone stood for the one minute silence, and that includes all Muslims... I did it for those who were killed, but not for Charlie. I have no pity for him, he had no respect for us Muslims". It also reported that for most students at the Paul Eluard high school in Saint-Denis, freedom of expression is perceived as being "incompatible with their faith". For Erica, who describes herself as Catholic, "there are wrongs on both sides". A fake bomb was planted in the faculty lounge at the school.[307]

France Télévisions reported that a fourth-grade student told her teacher, "We will not be insulted by a drawing of the prophet, it is normal that we take revenge." It also reported that the fake bomb contained the message "I Am Not Charlie".[308]

Public figures

The Head of the Chechen Republic, Ramzan Kadyrov, said "we will not allow anyone to insult the prophet, even if it costs us our lives."[309]

Salman Rushdie, who is on the al-Qaeda hit list[18][73] and received death threats over his novel The Satanic Verses, said, "I stand with Charlie Hebdo, as we all must, to defend the art of satire, which has always been a force for liberty and against tyranny, dishonesty and stupidity ... religious totalitarianism has caused a deadly mutation in the heart of Islam and we see the tragic consequences in Paris today."[310]

Swedish artist Lars Vilks, also on the al-Qaeda hit list[73] for publishing his own satirical drawings of Muhammad, condemned the attacks and said that the terrorists "got what they wanted. They've scared people. People were scared before, but with this attack fear will grow even larger"[311] and that the attack "expose[s] the world we live in today".[312]

American journalist David Brooks wrote an article titled "I Am Not Charlie Hebdo" in The New York Times, arguing that the magazine's humor was childish, but necessary as a voice of satire. He also criticised many of those in America who were ostensibly voicing support for free speech, noting that were the cartoons to be published in an American university newspaper, the editors would be accused of "hate speech" and the university would "have cut financing and shut them down." He called on the attacks to be an impetus toward tearing down speech codes.[313]

American linguist and philosopher Noam Chomsky views the popularisation of the Je suis Charlie slogan by politicians and media in the West as hypocritical, comparing the situation to the NATO bombing of the Radio Television of Serbia headquarters in 1999, when 16 employees were killed. "There were no demonstrations or cries of outrage, no chants of 'We are RTV'," he noted. Chomsky also mentioned other incidents where US military forces have caused higher civilian death tolls, without leading to intensive reactions such as those that followed the 2015 Paris attacks.[314]

German politician Sahra Wagenknecht, the deputy leader of the party Die Linke in the German Parliament, has compared the US drone attacks in Afghanistan, Pakistan or Yemen with the terrorist attacks in Paris. ″If a drone controlled by the West extinguishes an innocent Arab or Afghan family, which is just a despicable crime as the attacks in Paris, and it should fill us with the same sadness and the same horror". We should not operate a double standard. Through the drone attacks had been "murdered thousands of innocent people", in the concerned countries, this created helplessness, rage and hatred: "Thereby we prepare the ground for the terror, we officially want to fight." The politician stressed that this war is also waged from German ground. Regarding the Afghanistan war with German participation for years, she said: "Even the Bundeswehr is responsible for the deaths of innocent people in Afghanistan." As the most important consequence of the terrorist attacks in Paris, Wagenknecht demanded the end of all military operations of the West in the Middle East.[315][316]

Cartoonist-journalist Joe Sacco expressed grief for the victims in a comic strip, and wrote

but ... tweaking the noses of Muslims ... has never struck me as anything other than a vapid way to use the pen ... I affirm our right to "take the piss" ... but we can try to think why the world is the way it is ... and [retaliating with violence against Muslims] is going to be far easier than sorting out how we fit in each other's world.[317]

Japanese film director Hayao Miyazaki criticized the magazine's decision to publish the content cited as the trigger for the incident. He said, "I think it's a mistake to caricaturize the figures venerated by another culture. You shouldn't do it." He asserted, "Instead of doing something like that, you should first make caricatures of your own country's politicians." Charlie Hebdo had already published numerous caricatures of European public officials in the years prior to the attack.[318][319]

Political scientist Norman Finkelstein criticized the Western response to the shooting, comparing Charlie Hebdo to Julius Streicher, saying "So two despairing and desperate young men act out their despair and desperation against this political pornography no different than [sic] Der Stürmer, who in the midst of all of this death and destruction decide it's somehow noble to degrade, demean, humiliate and insult the people. I'm sorry, maybe it is very politically incorrect. I have no sympathy for [the staff of Charlie Hebdo]. Should they have been killed? Of course not. But of course, Streicher shouldn't have been hung [sic]. I don't hear that from many people."[320]

Social media

French Minister of the Interior Bernard Cazeneuve declared that by the morning of 9 January 2015, a total of 3,721 messages "condoning the attacks" had already been documented through the French government Pharos system.[321][322]

In an open letter titled "To the Youth in Europe and North America", Iran's Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei urged young people in Europe and North America not to judge Islam by the attacks, but to seek their own understanding of the religion.[323] Holly Dagres of Al-Monitor wrote that Khamenei's followers "actively spammed Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Google+ and even Tumblr with links" to the letter with the aim of garnering the attention of people in the West.[324]

On social media, the hashtag "#JeSuisAhmed" trended, a tribute to the Muslim policeman Ahmed Merabet, along with the quote "I am not Charlie, I am Ahmed the dead cop. Charlie ridiculed my faith and culture and I died defending his right to do so."[325][326][327] The Economist compared this to a quote commonly misattributed to Voltaire, "I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it".[328]

See also

- 2015 TV5Monde cyber-attack

- 2020 Paris stabbing attack

- Brussels ISIL terror cell

- Censorship in Islamic societies

- Charlie Mensuel

- Everybody Draw Mohammed Day

- Freedom of the press

- Hara-Kiri (magazine)

- Islam and violence

- Islam in France

- Список исламских террористических атак

- Список журналистов, убитых в Европе

- Молатер псалмса является частью псалмов.

- Ноябрь 2015 Парижские атаки

- Терроризм в Европейском Союзе

- Jyllands-Posten Muhammad Cartionds Carmons

Примечания

- ^ Источники для «заговоров против ' jyllands-posten

- ^ Для получения подробной информации о различных инцидентах см.: 2006 Германский бомбардировка поезда , 2008 год бомбардировки посольства Дании в Исламабаде , отель Йоргенсен взрыв и террористический заговор 2010 года .

- ^ Информация о Черифе и Саид Куачи.

- ^ Атаки на мечеты

- ^ Источники, подтверждающие крупнейший общественный митинг во Франции со времен Второй мировой войны

- ^ Источники для мировых маршей и бдений

- ^ Атаки на мечеты

- ^ Англоязычные средства массовой информации, которые переиздали мультфильмы

- ^ Источники, подтверждающие вознаграждение в 510 миллионов

Ссылки

- ^ «На фотографиях: в 11:30 вооруженные мужчины открывают огонь на Рю Николас-Апперт» . Мир . 7 января 2015 года.

- ^ Вульф, Кристофер (15 января 2015 г.). "Где нападавшие Парижа взяли свое оружие?" Полем ПРИ мир . Миннеаполис, США: Public Radio International . Получено 16 января 2015 года .

Оружие, видимое на различных изображениях злоумышленников, включают в себя Заставы M70 штурмовую винтовку ; VZ 61 Submachine Gun; Несколько российских пистолетов Tokarev TT и гранат или ракета-вероятно, югослав M80 Zolja.

- ^ С помощью Адама; Личфилд, Джон (7 января 2015 г.). «Стрельба Чарли Хебдо: по крайней мере 12 убитых в виде выстрелов, выстрел в парижский офис« Сатирический журнал » . Независимый . Лондон Получено 9 января 2015 года .

- ^ «Аль -Каида утверждает, что Французская атака высмеивает парижское ралли» . Рейтер . 14 января 2015 года. Архивировано с оригинала 14 января 2015 года . Получено 14 января 2015 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Салаун, Танги (16 декабря 2020 г.). «Французский суд признает соучастников нападающим Чарли Хебдо виновным» . Рейтер . Получено 16 декабря 2020 года .

- ^ Час (20 ноября 2013 г.). «Не», Чарли Хебдо », но и в расисте!» [Нет, Чарли Хебдо не расист!]. Ле Монд (по -французски) . Получено 4 марта 2014 года .

- ^ Кабу, Джин; Вэл, Филипп (5 сентября 2008 г.). «Кабу и Вэл пишут в L'Us» . NOUVER NASERATEUR . Получено 9 января 2015 года .

- ^ Левек, Тьерри (22 марта 2007 г.). «Французский суд еженедельно очищается в мультипликационном отделении Мухаммеда» . Рейтер . Архивировано из оригинала 21 сентября 2013 года . Получено 10 июня 2013 года .

- ^ «Чарли Хебдо: майор -охота на боевиков Парижа» . BBC News . 8 января 2015 года . Получено 8 января 2015 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Саул, Хизер (9 января 2015 г.). «Google отдает дань уважения жертвам атаки Чарли Хебдо с черной лентой на домашней странице» . Независимый . Лондон Получено 9 января 2015 года .

- ^ «BBC News: нападение на французскую сатирическую газету Чарли Хебдо (2 ноября 2011 г.)» . Би -би -си. 2 ноября 2011 г. Получено 21 декабря 2011 года .

- ^ Boxel, Джеймс (2 ноября 2011 г.). «Атака пожарной бомбы на сатирический французский журнал» . Финансовые времена . Получено 19 сентября 2012 года .

- ^ Чарли Хебдо (3 ноября 2011 г.). "Les Sdf du Net" . Получено 9 января 2015 года .

- ^ «Charlie Hebdo Publie des Caricatures de Mahomet» [ Чарли Хебдо публикует некоторые карикатуры Мухаммеда]. BFM TV (по -французски). 18 сентября 2012 года . Получено 19 сентября 2012 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Винокур, Николас (19 сентября 2012 года). «Обнаженные мультфильмы журнала Mohammad побуждают Францию закрыть посольства, школы в 20 странах» . Национальный пост . Рейтер . Получено 19 сентября 2012 года .

- ^ Самуил, Генри (19 сентября 2012 г.). «Франция закрыла школы и посольства, опасаясь мультфильма Мухаммеда» . Телеграф . Лондон Архивировано из оригинала 12 января 2022 года . Получено 20 сентября 2012 года .

- ^ Хазан, Ольга (19 сентября 2012 г.). «Чарли Хебдо мультфильмы высказывают дебаты о свободе слова и исламофобии» . The Washington Post . Получено 19 сентября 2012 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Дашиэлл Беннет (1 марта 2013 г.). «Послушайте, кто находится в самом размном списке Аль-Каиды» . Проволока . Архивировано с оригинала 17 ноября 2015 года . Получено 8 января 2015 года .

- ^ Мюррей, Дон (8 января 2015 г.). «Франция еще более сломана после Rampage Charlie Hebdo» . CBC News . Получено 9 января 2015 года .

- ^ Conal Urquhart (7 января 2015 г.). «Полиция Парижа сообщает 12 погибших после стрельбы в Чарли Хебдо» . Время . Получено 8 января 2015 года .

- ^ Уорд, Виктория (7 января 2015 г.). «Убитый карикатурист Чарли Хебдо был в списке разыскиваемой Аль -Каиды» . Телеграф . Лондон Архивировано из оригинала 12 января 2022 года . Получено 8 января 2015 года .

- ^ Delesalle, Николас (16 Janogy 2015). "Антонио Фишетти:" Биен Сур, на S'engueulait, à 'Charlie' " . Telerama.fr (по -французски) . Получено 2 сентября 2015 года .

- ^ «Жаннетт Буграб:« У Чарб был нож над ее кроватью » - Гала» . Июнь 2015.

- ^ Рейманн, Анна (12 февраля 2008 г.). «Интервью с редактором Jyllands-Posten:« Я не боюсь за свою жизнь » » . Spiegel Online International . Получено 22 сентября 2013 года .

- ^ Гебауэр, Матиас; Мушарбаш, Яссин (5 мая 2006 г.). «Самоубийство после попытки нападения на редактора -в« Мир » » . Зеркало (на немецком языке) . Получено 16 сентября 2013 года .

- ^ Кристофферсен, Джон (8 сентября 2009 г.). «Йельский университет раскритиковал за то, что мусульманские мусульманские карикатуры в книге» . USA сегодня . Доступа Архивировано из оригинала 10 октября 2011 года . Получено 17 сентября 2013 года .

- ^ Брикс, Кнуд (20 октября 2008 г.). «Талибы угрожают Дании» . Дополнительный блэйк (на датском) . Получено 25 октября 2008 года .

- ^ «Стрельба Чарли Хебдо Париж: как критика, сатиры ислама вызвали насилие» . CBC News . 7 января 2015 года . Получено 13 января 2015 года .

- ^ «Датская полиция стреляет в злоумышленника в доме карикатуры» . BBC News . 2 января 2010 г. Получено 1 февраля 2010 года .

- ^ «Судебный процесс в Дании: Курт Вестергаард, напал на тюрьму» . BBC News . 4 февраля 2011 года . Получено 14 июля 2013 года .

- ^ Венберг, Кристиан (29 декабря 2010 г.). «Полиция арестовывает атаку по планированию воинствующих исламистов в Дании» . Блумберг . Получено 23 марта 2013 года .

- ^ «Издевательство и Пророк: история европейских СМИ по поводу возвышенности сатиры» . Глобус и почта . Торонто. 7 января 2015 года . Получено 13 января 2015 года .

- ^ Пока расщепление, Øyvind; Дёвик, Олав (5 мая 2013 г.). «Поражение для планировщиков террора в Верховном суде» (на норвежском языке). NRK . Получено 17 сентября 2013 года .

- ^ Суини, Энни (17 января 2013 г.). «Бывший чикагский бизнесмен получает 14 лет в терроризме» . Чикаго Трибьюн . Получено 2 июня 2013 года .

- ^ «Атака Чарли Хебдо повторяет датский сюжет Дэвида Хедли» . Получено 13 января 2015 года .

- ^ Питер Берген (8 января 2015 г.). «Американцы заговорили, чтобы убить карикатуристов, которые пупили ислам - CNN» . CNN . Получено 13 января 2015 года .

- ^ «Закон от 9 декабря 1905 года относительно разделения церквей и государства. Версия консолидирована 8 апреля 2015 года» . Legifrance.gouv.fr . Получено 8 апреля 2015 года .

- ^ «Официальный бюллетень Министерства национального образования от 27 мая 2004 года. Уважение к секуляризму носить знаки или наряды, демонстрирующие религиозную принадлежность в государственных школах, колледжах и средних школах» . Получено 8 апреля 2015 года .

- ^ «Секуляризм, Франция в полном сомнении» . Крест . 11 марта 2015 года . Получено 8 апреля 2015 года .

- ^ «Секуляризм в Турции, Франции и Соединенных Штатах» . Сентябрь 2011 года. Архивировано с оригинала 30 сентября 2015 года.

- ^ «Коран не запрещает изображения Пророка» , Newsweek , 9 января 2015 г.

- ^ Берк, Даниэль (9 января 2015 г.). «Почему ислам запрещает образы Мухаммеда» . Би -би -си . Получено 16 января 2015 года .

- ^ «Проблема изображения пророка Мухаммеда» . Би -би -си. 14 января 2015 года . Получено 16 января 2015 года .

- ^ «Фокус - молитва за прощение: христианин приговорен к смерти за« богохульство против ислама » . Франция 24. 2 декабря 2010 г. Получено 11 января 2015 года .

- ^ «Парижская атака подчеркивает борьбу Европы с исламизмом» . BBC News . 7 января 2015 года . Получено 11 января 2015 года .

- ^ Джолли, Дэвид (2 ноября 2011 г.). «Чарли Хебдо, французский журнал, пожарно» . New York Times . ISSN 0362-4331 . Получено 6 ноября 2019 года .

- ^ «Атака Чарли Хебдо»: «Вы заплатите, потому что вы оскорбили пророка » . Мир . 8 января 2015 года.

- ^ «Чарли Хебдо: показания кокосового дизайнера» . Человечество (по -французски). 7 января 2015 года.

- ^ « Виньетки: больше о 17 убитых во французских террористических атаках» . CNN . Получено 11 января 2015 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Чарли Хебдо стреляет:« Это бойня, кровавая бата. Все мертвы » . Хранитель . 7 января 2015 года . Получено 7 января 2015 года .

- ^ Александр, Гарриет (9 января 2015 г.). «Внутри атаки Чарли Хебдо:« Мы все думали, что это шутка » . Ежедневный телеграф . Лондон Архивировано из оригинала 12 января 2022 года . Получено 12 января 2015 года .

- ^ «Стрельба из Парижа: охота на боевиков Атаки Атаки Чарли Хебдо, французский сатирический журнал» . CBS News . 7 января 2015 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Атака Атаки Чарли Хебдо выявила» . ABC News . Получено 8 января 2015 года .

- ^ « Я спрятался под столом»: как развернулась атака Чарли Хебдо » . Глобус и почта . Торонто. 9 января 2015 года . Получено 12 января 2015 года .

- ^ «Журналист Сиголен Винсон говорит, что ее избавлены боевики из -за ее пола» . news.com.au. 10 января 2015 года. Архивировано с оригинала 18 сентября 2015 года . Получено 12 января 2015 года .

- ^ «Стрельба Чарли Хебдо | Факты, жертвы и ответ» . 28 апреля 2023 года.

- ^ «Единственная женщина, убитая в Чарли Хебдо, была нацелена, потому что« она была евреем », говорит двоюродный брат» . Algemeiner . Получено 11 января 2015 года .

- ^ «Глобус в Париже: полиция идентифицирует трех подозреваемых» . Глобус и почта . Торонто. Архивировано с оригинала 10 января 2015 года . Получено 9 января 2015 года .

- ^ «Журналист Сиголен Винсон говорит, что ее избавлены боевики из -за ее пола» .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Защитники свободы» (PDF) .

- ^ Ватт, Холли (7 января 2015 г.). «Террористы кричали, что они были из Аль -Каиды в Йемене до нападения Чарли Хебдо» . Ежедневный телеграф . Лондон Архивировано с оригинала 7 января 2015 года . Получено 7 января 2015 года .

- ^ SL (7 января 2015 г.). «Атака Чарли Хебдо: сценарий убийства» . Mytf1news . Архивировано с оригинала 4 марта 2016 года.

- ^ «Какие видео рассказывают нам о Чарли Хебдо Парижском нападении» . YouTube. 7 января 2015 года . Получено 14 января 2015 года .

- ^ «Живи: выстрелы в штаб -квартире Чарли Хебдо» . Ле Монд (по -французски).

Смотрите комментарии в 13:09 и 1:47: «Lemonde.fr: @antoine Все, что мы знаем, это то, что они говорят по -французски без акцента». И «Lemonde.fr: На том же видео мы можем слышать нападавших. Из того, что мы можем воспринимать, мужчины, кажется, говорят по -французски без акцента».

- ^ «Смертельная атака на офис французского журнала Чарли Хебдо» . BBC News . 7 января 2015 года . Получено 7 января 2015 года .

- ^ «12 мертвых в« террористке »нападения в Парижской газете» . Agence France-Presse . Получено 7 января 2015 года .

- ^ Le Courrier Picard (8 января 2015 г.). «Братья Кууачи расположены недалеко от Виллерс-Коттере» . Пикард почта .

- ^ «Атака Чарли Хебдо: двое подозреваемых ограбили бы курорт в Villers-Cotterêts» . 20 минут . 8 января 2015 года.

- ^ « Чарли Хебдо»: минута в минуту, в четверг утром » . Le Point.fr . 8 января 2015 года . Получено 8 января 2015 года .

- ^ «Атака на« Чарли Хебдо »: джихадистские флаги и коктейли Молотова в заброшенной машине ... Двое подозреваемых заметили в Виллерс-Котеретах ...» 20 минут . 8 января 2015 года . Получено 8 января 2015 года .

- ^ Билефский, Дэн (7 января 2015 г.). «Террористы поражают газету Чарли Хебдо в Париже, оставив 12 мертвых» . New York Times . Получено 8 января 2015 года .

- ^ «Аль-Каида ударила? Часть первая» . 8 января 2015 года . Получено 8 января 2015 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Люси Кормак (8 января 2015 г.). «Редактор Charlie Hebdo Стефан Чарбоннер вышел из Hlyling Al-Qaeda Hetlist» . Возраст . Мельбурн.

- ^ «Группа Аль-Каиды претендует на ответственность за террористическую атаку Парижа» . Время . 9 января 2015 года . Получено 14 января 2015 года .

- ^ Par Florence Saugues (8 Janogy 2015). "Caretat Contre" Charlie Hebdo " - Эльза Каят, псих" Чарли "Assassinée" . Парижский матч . Получено 11 Janogy 2015 .

- ^ «Она была определенно убита, потому что она была евреем» . CNN. 9 января 2015 года.

Также на MSN - ^ «Атака Чарли Хебдо: некрологи жертвы» . BBC News . Получено 10 января 2015 года .

- ^ «Живи. Резня в« Чарли Хебдо »: 12 мертвых, включая Чарб и Кабу» . Точка (на французском). 7 января 2015 года.

- ^ «Карикатуристы Чарб и Кабу погибли» . Основное (на французском). 7 января 2015 года . Получено 7 января 2015 года .

- ^ Саул, Хизер (8 января 2015 г.). «Атака Чарли Хебдо: все 12 жертв названы» . Независимый . Лондон Получено 9 января 2015 года .

- ^ «Чарли Хебдо жертв» . Би -би -си. 8 января 2015 года . Получено 8 января 2015 года .

- ^ «Бесстрашные: убитые французские карикатуристы приветствовали противоречие» . Fox News Channel. 7 января 2015 года. Архивировано с оригинала 10 января 2015 года . Получено 10 января 2015 года .

- ^ «Атака Чарли Хебдо, один из полицейских жил в Нормандии» . Trendouest.com (на французском языке). 7 января 2015 года . Получено 11 января 2015 года . Google "переведен"

- ^ Полли Мозенц. «Офицер полиции Ахмед Мерабет застрелил во время резни Чарли Хебдо» . Newsweek .

- ^ Мануэль Арманд (8 января 2015 г.). «Мишель Рено, ненасытный путешественник» . Мир .

- ^ Тонер, Eneida. «Филипп Ланчон, PLAS -Visting [ sic ] для AY15, ранен в парижской террористической атаке», программа в блоге латиноамериканских исследований (8 января 2015 г.).

- ^ «Атака на Чарли Хебдо. Свидетельство о дяде Рисса, директора редакции Чарли Хебдо» . Телеграмма . 8 января 2015 года . Получено 8 января 2015 года . [ мертвая ссылка ]

- ^ « Чарли Хебдо»: La Traque des подозреваемые SE Poursuit » . Le Point (по -французски). 8 января 2015 года . Получено 11 января 2015 года . Переведенный текст

- ^ «Живи . Le Parisien (по -французски). Франция. 7 января 2015 года . Получено 7 января 2015 года .