Тадеуш Кохиуско

Тадеуш Кохиуско | |

|---|---|

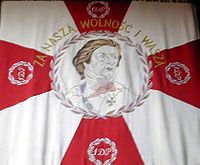

Портрет Карла Готлиба Швейкарта. Kościuszko показан в орете Общества Цинциннати , награжденного ему генералом Вашингтоном .  Coat of arms: Роч II | |

| Birth name | Andrzej Tadeusz Bonawentura Kościuszko |

| Born | 4 February 1746 Mereczowszczyzna, Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth |

| Died | 15 October 1817 (aged 71) Solothurn, Switzerland |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1765–1794 |

| Rank |

|

| Unit |

|

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards | |

| Signature | |

| Part of a series on |

| Agrarianism in Poland |

|---|

|

Andrzej Tadeusz Bonawentura Kościuszko [ Примечание 1 ] (Английский: Эндрю Фаддеус Бонавентура Костюшко ; [ Примечание 2 ] 4 или 12 февраля 1746 - 15 октября 1817 года) был польским военным инженером , государственным деятелем и военным лидером, который затем стал национальным героем в Польше, Соединенных Штатах, Литве и Беларуси. [ 3 ] [ 4 ] [ 5 ] [ 6 ] [ 7 ] Он сражался в борьбе по пользу - литюанскому Содружеству против России и Пруссии , а также со стороны США в американской войне за революцию . Будучи верховным командиром Польских национальных вооруженных сил, он возглавлял восстание Kościuszko 1794 года .

Kościuszko родился в феврале 1746 года в усадьбе в поместье Мереквшцизна в Брест Литск -воевороде , а затем в Великом Герцогстве Литва , часть Содружества из польского - Литуанского Содружество, теперь в районе Ивацевичи в Беларусе. [ 8 ] В возрасте 20 лет он окончил корпус курсантов в Варшаве , Польша. После начала гражданской войны в 1768 году Кошчиуско переехал во Францию в 1769 году, чтобы учиться. Он вернулся в Содружество в 1774 году, через два года после первого перегородка , и был репетитором в Йозефа Силвестера Сосновского семье . В 1776 году Кошчиуско переехал в Северную Америку, где он принял участие в американской войне за революцию в качестве полковника в континентальной армии . Опытный военный архитектор, он спроектировал и наблюдал за строительством современных укреплений, в том числе в Вест-Пойнте , Нью-Йорк. В 1783 году, в знак признания его услуг, Континентальный конгресс продвинул его до бригадного генерала .

Upon returning to Poland in 1784, Kościuszko was commissioned as a major general in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth Army in 1789. After the Polish–Russian War of 1792 resulted in the Commonwealth's Second Partition, he commanded an uprising against the Russian Empire in March 1794 until he was captured at the Battle of Maciejowice in October 1794. The defeat of the Kościuszko Uprising that November led to Poland's Third Partition in 1795, which ended the Commonwealth. In 1796, following the death of Tsaritsa Catherine II, Kościuszko was pardoned by her successor, Tsar Paul I, and he emigrated to the United States. A close friend of Thomas Jefferson, with whom he shared ideals of human rights, Kościuszko wrote a will in 1798, dedicating his U.S. assets to the education and freedom of the U.S. slaves. Kościuszko eventually returned to Europe and lived in Switzerland until his death in 1817. The execution of his testament later proved difficult, and the funds were never used for the purpose he intended.[9]

Early life

[edit]Kościuszko was born in February 1746 in a manor house on the Mereczowszczyzna estate near Kosów in Nowogródek Voivodeship, Grand Duchy of Lithuania, a part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[10][11] His exact birthdate is unknown; commonly cited are 4 February[10] and 12 February.[note 3]

Kościuszko was the youngest son of a member of the Szlachta (untitled Polish nobility), Ludwik Tadeusz Kościuszko, an officer in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth Army, and his wife Tekla Ratomska.[14] The family held the Polish Roch III coat of arms.[15] At the time of Tadeusz Kościuszko's birth, the family possessed modest landholdings in the Grand Duchy worked by 31 peasant families.[16][17]

Tadeusz was baptized in the Catholic church, thereby receiving the names Andrzej, Tadeusz, and Bonawentura.[18][19][20][21] His paternal family was originally Ruthenian[16] and traced their ancestry to Konstanty Fiodorowicz Kostiuszko, a courtier of Polish King and Grand Duke of Lithuania Sigismund I the Old.[22] Kościuszko's maternal family, the Ratomskis, were also Ruthenian.[23]

His family had become Polonized as early as the 16th century.[24] Like most Polish–Lithuanian nobility of the time, the Kościuszkos spoke Polish and identified with Polish culture.[25] Kościuszko also, as was common for Polish nobility in the region,[26] clearly stressed his attachment to the multiethnic Identity of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in later letters.[27] For example, in 1790 Kościuszko wrote "If this does not soften you and you do not raise my case in the Sejm so that I can return, I myself will probably, God sees, do something bad to myself, as I am angry because being from Lithuania I serve the Kingdom [of Poland] when you do not have three generals", while during the Uprising of 1794 Kościuszko wrote "Lithuania! My countrymen and tribesmen! I was born in your land, sincere love for my homeland evokes in me a special favor for those among whom I began my life".[27]

In 1755, Kościuszko began attending school in Lubieszów but never finished due to his family's financial straits after his father's death in 1758. Poland's King Stanisław August Poniatowski established a Corps of Cadets (Korpus Kadetów) in 1765, at what is now Warsaw University, to educate military officers and government officials. Kościuszko enrolled in the Corps on 18 December 1765, likely thanks to the Czartoryski family's patronage. The school emphasized military subjects and the liberal arts,[28] and after graduating on 20 December 1766, Kościuszko was promoted to chorąży, a military rank roughly equivalent to modern lieutenant. He stayed on as a student instructor and, by 1768, had attained the rank of captain.[14]

European travels

[edit]In 1768, civil war broke out in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, when the Bar Confederation sought to depose King Stanisław August Poniatowski. One of Kościuszko's brothers, Józef, fought on the side of the insurgents. Faced with a difficult choice between the rebels and his sponsors—the King and the Czartoryski family, who favored a gradualist approach to shedding Russian domination—Kościuszko chose to leave Poland. In late 1769, he and a colleague, artist Aleksander Orłowski, were granted royal scholarships; on 5 October, they embarked for Paris. They wanted to further their military education. As foreigners they were barred from enrolling in French military academies, and so they enrolled in the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture.[14] There Kościuszko pursued his interest in drawing and painting and took private lessons in architecture from architect Jean-Rodolphe Perronet.[29][note 4]

Kościuszko did not give up on improving his military knowledge. He audited lectures for five years and frequented the libraries of the Paris military academies. His exposure to the French Enlightenment, along with the religious tolerance practiced in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, strongly influenced his later career. The French economic theory of physiocracy made a particularly strong impression on his thinking.[30] He also developed his artistic skills, and while his career took him in a different direction, all his life he continued drawing and painting.[14][31]

In the First Partition of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1772, Russia, Prussia, and Austria annexed large swaths of Commonwealth territory and gained influence over the internal politics. When Kościuszko returned home in 1774, he found that his brother Józef had squandered most of the family fortune, and there was no place for him in the Army, as he could not afford to buy an officer's commission.[32] He took a position as tutor to the family of the magnate, province governor (voivode) and hetman Józef Sylwester Sosnowski and fell in love with the governor's daughter Ludwika.[note 5] Their elopement was thwarted by her father's retainers.[14] Kościuszko received a thrashing at their hands, an event that may have led to his antipathy for class distinctions.[16]

In the autumn of 1775 he emigrated to avoid Sosnowski and his retainers.[14] In late 1775 he attempted to join the Saxon army but was turned down and decided to return to Paris.[14] There he learned of the American Revolutionary War outbreak, in which the British colonies in North America had revolted against the British Crown and begun their struggle for independence. The first American successes were well-publicized in France, and the French people and government openly supported the revolutionaries' cause.[35]

American Revolutionary War

[edit]On learning of the American Revolution, Kościuszko, a man of revolutionary aspirations, sympathetic to the American cause and an advocate of human rights, sailed for the Americas in June 1776 along with other foreign officers, likely with the help of a French supporter of the American revolutionaries, Pierre Beaumarchais.[14][30] After finally arriving in Philadelphia (after a Caribbean shipwreck) he sought out Benjamin Franklin at his print shop; offering to take engineering subject exams (in lieu of any letters of recommendation), he received a high mark on a geometry exam and Franklin's recommendation.[36] On 30 August 1776, Kościuszko submitted an application to the Second Continental Congress at the Pennsylvania State House, and was assigned to the Continental Army the next day.[14]

Northern region

[edit]

Kościuszko's first task was building fortifications at Fort Billingsport in Paulsboro, New Jersey, to protect the banks of the Delaware River and prevent a possible British advance up the river to Philadelphia.[37] He initially served as a volunteer in the private employ of Benjamin Franklin, but on 18 October 1776, Congress commissioned him a colonel of engineers in the Continental Army.[38]

In spring 1777, Kościuszko was attached to the Northern Army under Major General Horatio Gates, arriving at the Canada–U.S. border in May 1777. Subsequently, posted to Fort Ticonderoga, he reviewed the defences of what had been one of the most formidable fortresses in North America.[14][39] His surveys prompted him to strongly recommend the construction of a battery on Sugar Loaf, a high point overlooking the fort.[39] His prudent recommendation, in which his fellow engineers concurred, was turned down by the garrison commander, Brigadier General Arthur St. Clair.[14][39]

This proved a tactical blunder: when a British army under Major General John Burgoyne arrived in July 1777, Burgoyne did exactly what Kościuszko had warned of, and had his engineers place artillery on the hill.[39] With the British in complete control of the high ground, the Americans realized their situation was hopeless and abandoned the fortress with hardly a shot fired in the siege of Ticonderoga.[39] The British advance force nipped hard on the heels of the outnumbered and exhausted Continentals as they fled south. Major General Philip Schuyler, desperate to put distance between his men and their pursuers, ordered Kościuszko to delay the enemy.[40] Kościuszko designed an engineer's solution: his men felled trees, dammed streams, and destroyed bridges and causeways.[40] Encumbered by their huge supply train, the British began to bog down, giving the Americans the time needed to safely withdraw across the Hudson River.[40]

Gates tapped Kościuszko to survey the country between the opposing armies, choose the most defensible position, and fortify it. Finding just such a spot near Saratoga, overlooking the Hudson at Bemis Heights, Kościuszko laid out a robust array of defences, nearly impregnable. His judgment and meticulous attention to detail frustrated the British attacks during the Battle of Saratoga,[14] and Gates accepted the surrender of Burgoyne's force there on 16 October 1777.[41] The dwindling British army had been dealt a sound defeat, turning the tide to American advantage.[42] Kościuszko's work at Saratoga received great praise from Gates, who later told his friend, Dr. Benjamin Rush: "The great tacticians of the campaign were hills and forests, which a young Polish engineer was skillful enough to select for my encampment."[14]

At some point in 1777, Kościuszko composed a polonaise and scored it for the harpsichord. Named for him, and with lyrics by Rajnold Suchodolski, it later became popular with Polish patriots during the November 1830 Uprising.[43] Around that time, Kościuszko was assigned an African American orderly, Agrippa Hull, whom he treated as an equal and a friend.[44]

In March 1778, Kościuszko arrived at West Point, New York, and spent more than two years[45] strengthening the fortifications and improving the stronghold's defences.[46][47] It was these defences that the American General Benedict Arnold subsequently attempted to surrender to the British when he defected.[48] Soon after Kościuszko finished fortifying West Point, in August 1780, General George Washington granted Kościuszko's request to transfer to combat duty with the Southern Army. Kościuszko's West Point fortifications were widely praised as innovative for the time.[49][50]

Southern region

[edit]

After travelling south through rural Virginia in October 1780, Kościuszko proceeded to North Carolina to report to his former commander General Gates.[46] Following Gates's disastrous defeat at Camden on 16 August 1780, the Continental Congress selected Washington's choice, Major General Nathanael Greene, to replace Gates as commander of the Southern Department.[51] When Greene formally assumed command on 3 December 1780, he retained Kościuszko as his chief engineer. By then, he had been praised by both Gates and Greene.[46]

During this campaign, Kościuszko was placed in command of building bateaux, siting the location for camps, scouting river crossings, fortifying positions, and developing intelligence contacts. Many of his contributions were instrumental in preventing the destruction of the Southern Army. This was especially so during the "Race to the Dan", when British General Charles Cornwallis chased Greene across 200 miles (320 km) of rough backcountry in January and February 1781. Thanks largely to a combination of Greene's tactics, Kościuszko's bateaux, and accurate scouting of the rivers ahead of the main body, the Continentals safely crossed each river, including the Yadkin and the Dan.[46] Cornwallis, having no boats, and finding no way to cross the swollen Dan, abandoned the chase and withdrew into North Carolina. The Continentals regrouped south of Halifax, Virginia, where Kościuszko had earlier, at Greene's request, established a fortified depot.[52]

During the Race to the Dan, Kościuszko had helped select the site where Greene eventually returned to fight Cornwallis at Guilford Courthouse. Though tactically defeated, the Americans all but destroyed Cornwallis's army as an effective fighting force and gained a permanent strategic advantage in the South.[53] Thus, when Greene began his reconquest of South Carolina in the spring of 1781, he summoned Kościuszko to rejoin the main body of the Southern Army. The combined forces of the Continentals and Southern militia gradually forced the British from the backcountry into the coastal ports during the latter half of 1781 and, on 25 April, Kościuszko participated in the Second Battle of Camden.[54] At Ninety-Six, Kościuszko besieged the Star Fort from 22 May to 18 June. During the unsuccessful siege, he suffered his only wound in seven years of service, bayonetted in the buttocks during an assault by the fort's defenders on the approach trench that he was constructing.[55]

Kościuszko subsequently helped fortify the American bases in North Carolina,[56] before taking part in several smaller operations in the final year of hostilities, harassing British foraging parties near Charleston, South Carolina. After the death of his friend, Colonel John Laurens, Kościuszko became engaged in these operations, taking over Laurens's intelligence network in the area. He commanded two cavalry squadrons and an infantry unit, and his last known battlefield command of the war occurred at James Island, South Carolina, on 14 November 1782. In what has been described as the Continental Army's final armed action of the war,[57] he was nearly killed as his small force was routed.[58] A month later, he was among the Continental troops that reoccupied Charleston following the city's British evacuation. Kościuszko spent the rest of the war there, conducting a fireworks display on 23 April 1783, to celebrate the signing of the Treaty of Paris earlier that month.[59]

Leaving for home

[edit]Having not been paid in his seven years of service, in late May 1783, Kościuszko decided to collect the salary owed to him.[60] That year, he was asked by Congress to supervise the fireworks during the 4 July celebrations at Princeton, New Jersey.[61] On 13 October 1783, Congress promoted him to brigadier general, but he still had not received his back pay. Many other officers and soldiers were in the same situation.[62] While waiting for his pay, unable to finance a voyage back to Europe, Kościuszko, like several others, lived on money borrowed from the Polish–Jewish banker Haym Solomon. Eventually, he received a certificate for 12,280 dollars, at 6%, to be paid on 1 January 1784 (equivalent to ~$323,000, paid as installments ~$19,400 a month in 2022), and the right to 500 acres (202.34 ha; 0.78 sq mi) of land, but only if he chose to settle in the United States.[63]

For the winter of 1783–84, his former commanding officer, General Greene, invited Kościuszko to stay at his mansion.[64] He was inducted into the Society of the Cincinnati[46][65] and into the American Philosophical Society in 1785.[66] During the Revolution, Kościuszko carried an old Spanish sword at his side, which was inscribed with the words Do not draw me without reason; do not sheathe me without honour.[67]

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

[edit]

On 15 July 1784, Kościuszko set off for Poland, where he arrived on 26 August. Due to a conflict between his patrons, the Czartoryski family, and King Stanisław August Poniatowski, Kościuszko once again failed to get a commission in the Commonwealth Army. He settled in a small town called Siechnowicze.[46] His brother Józef had lost most of the family's lands through bad investments, but with the help of his sister Anna, Kościuszko secured part of the lands for himself.[68] He decided to limit his male peasants' corvée (obligatory service to the lord of the manor) to two days a week and completely exempted the female peasants. His estate soon stopped being profitable, and he began going into debt.[46] The situation was not helped by the failure of the money promised by the American government—interest on late payment for his seven years' military service—to materialize.[69] Kościuszko struck up friendships with liberal activists; Hugo Kołłątaj offered him a position as lecturer at Kraków's Jagiellonian University, which Kościuszko declined.[70]

The Great Sejm of 1788–1792 introduced some reforms, including a planned build-up of the army to defend the Commonwealth's borders. Kościuszko saw a chance to return to military service and spent some time in Warsaw, among those who engaged in the political debates outside the Great Sejm. He wrote a proposal to create a militia force, on the American model.[46][71] As political pressure grew to build up the army, and Kościuszko's political allies gained influence with the King, Kościuszko again applied for a commission, and on 12 October 1789, received a royal commission as a major general, but to Kosciuszko's dismay[72] in the Army of the Kingdom of Poland.[46]

He began receiving a high salary of 12,000 zlotys a year, ending his financial difficulties. On 1 February 1790, he reported for duty in Włocławek, and wrote in a letter after a few days, calling the local inhabitants "lazy" and "careless", in contrast to "good and economical Lithuanians". In the same letter, Kosciuszko begged general Franciszek Ksawery Niesiołowski for a transfer to the Army of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, but his wishes were not granted.[72] Around summer, he commanded some infantry and cavalry units in the region between the Bug and Vistula Rivers. In August 1790 he was posted to Volhynia, stationed near Starokostiantyniv and Międzyborze.[46] Prince Józef Poniatowski, who was the King's nephew, recognized Kościuszko's superior experience and made him his second-in-command, leaving him in command when he was absent.[73]

Meanwhile, Kościuszko became more closely involved with political reformers such as Hugo Kołłątaj, Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz and others.[74] Kościuszko argued that the peasants and Jews should receive full citizenship status, as this would motivate them to help defend Poland in the event of war.[75] The political reformers centered in the Patriotic Party scored a significant victory with adopting the Constitution of 3 May 1791. Kościuszko saw the Constitution as a step in the right direction, but was disappointed that it retained the monarchy and did little to improve the situation of the most underprivileged, the peasants and the Jews.[76] The Commonwealth's neighbors saw the Constitution's reforms as a threat to their influence over Polish internal affairs. A year after the Constitution's adoption, on 14 May 1792, reactionary magnates formed the Targowica Confederation, which asked Russia's Tsaritsa Catherine II for help in overthrowing the Constitution. Four days later, on 18 May 1792, a 100,000-man Russian army crossed the Polish border, headed for Warsaw, beginning the Polish–Russian War of 1792.[77]

Defence of the Constitution

[edit]

The Russians had a 3:1 advantage in strength, with some 98,000 troops against 37,000 Poles;[78] they also had an advantage in combat experience.[79] Before the Russians invaded, Kościuszko had been appointed deputy commander of Prince Józef Poniatowski's infantry division, stationed in West Ukraine. When the Prince became Commander-in-Chief of the entire Polish (Crown) Army on 3 May 1792, Kościuszko was given command of a division near Kiev.[80]

The Russians attacked a wide front with three armies. Kościuszko proposed that the entire Polish army be concentrated and engage one of the Russian armies, to assure numerical parity and boost the morale of the most inexperienced Polish forces with a quick victory; but Poniatowski rejected this plan.[79] On 22 May 1792, the Russian forces crossed the border in Ukraine, where Kościuszko and Poniatowski were stationed. The Crown Army was judged too weak to oppose the four enemy columns advancing into West Ukraine, and began a fighting withdrawal to the western side of the Southern Bug River, with Kościuszko commanding the rear guard.[80][81]

On 18 June, Poniatowski won the Battle of Zieleńce; Kościuszko's division, on detached rear-guard duty, did not take part in the battle and rejoined the main army only at nightfall. His diligent protection of the main army's rear and flanks won him the newly created Virtuti Militari, to this day Poland's highest military decoration. Storożyński states that Kościuszko received the Virtuti Militari for his later, 18 July victory at Dubienka.[80][82] The Polish withdrawal continued, and on 7 July Kościuszko's forces fought a delaying battle against the Russians at Volodymyr-Volynskyi, the Battle of Włodzimierz. On reaching the northern Bug River, the Polish Army was split into three divisions to hold the river defensive line—weakening the Poles' point of numerical superiority, against Kościuszko's counsel of a single strong, concentrated army.[80]

Kościuszko's force was assigned to protect the front's southern flank, touching up to the Austrian border. At the Battle of Dubienka (18 July 1792), Kościuszko repulsed a numerically superior enemy, skilfully using terrain obstacles and field fortifications, and came to be regarded as one of Poland's most brilliant military commanders of the age.[80] With some 5,300 men, he defeated 25,000 Russians led by General Michail Kachovski.[83] Despite the tactical victory, Kościuszko had to retreat from Dubienka, as the Russians crossed the nearby Austrian border and began flanking his positions.[83]

After the battle, King Stanisław August Poniatowski promoted Kościuszko to lieutenant-general and also offered him the Order of the White Eagle, but Kościuszko, a convinced republican would not accept a royal honor.[84][85] News of Kościuszko's victory spread over Europe, and on 26 August he received the honorary citizenship of France from the Legislative Assembly of revolutionary France. While Kościuszko considered the war's outcome to still be unsettled, the King requested a ceasefire.[80][86] On 24 July 1792, before Kościuszko had received his promotion to lieutenant-general, the King shocked the army by announcing his accession to the Targowica Confederation and ordering the Polish–Lithuanian troops to cease hostilities against the Russians. Kościuszko considered abducting the King as the Bar Confederates had done two decades earlier, in 1771, but was dissuaded by Prince Józef Poniatowski. On 30 August, Kościuszko resigned from his army position and briefly returned to Warsaw, where he received his promotion and pay, but refused the King's request to remain in the Army. Around that time, he also fell ill with jaundice.[80]

Émigré

[edit]

The King's capitulation was a hard blow for Kościuszko, who had not lost a single battle in the campaign. By mid-September 1792, he was resigned to leaving the country, and in early October, he departed from Warsaw. First, he went east, to the Czartoryski family manor at Sieniawa, which gathered various malcontents. In mid-November, he spent two weeks in Lwów, where he was welcomed by the populace. Since the war's end, his presence had drawn crowds eager to see the famed commander. Izabela Czartoryska discussed having him marry her daughter Zofia.[80][87] The Russians planned to arrest him if he returned to territory under their control; the Austrians, who held Lwów, offered him a commission in the Austrian Army, which he turned down.[88] Subsequently, they planned to deport him, but he left Lwów before they could do so. At the turn of the month, he stopped in Zamość at the Zamoyskis' estate, met Stanisław Staszic, then went on to Puławy.[80][88]

He did not tarry there for long: on 12–13 December, he was in Kraków; on 17 December, in Wrocław; and shortly after, he settled in Leipzig, where many notable Polish soldiers and politicians formed an émigré community.[80] Soon he and some others began plotting an uprising against Russian rule in Poland.[89] The politicians, grouped around Ignacy Potocki and Hugo Kołłątaj, sought contacts with similar opposition groups in Poland and by spring 1793 had been joined by other politicians and revolutionaries, including Ignacy Działyński. While Kołłątaj and others had begun planning an uprising before Kościuszko joined them, his support was a significant boon to them, as he was among the most famous individuals in Poland.[90]

After two weeks in Leipzig, before the second week of January 1793, Kościuszko set off for Paris, where he tried to gain French support for Poland's planned uprising. He stayed there until summer, but despite the growing revolutionary influence, the French paid only lip service to the Polish cause and refused to commit themselves to anything concrete.[89] Kościuszko concluded that the French authorities were not interested in Poland beyond what use it could have for their cause, and he was increasingly disappointed in the pettiness of the French Revolution—the infighting among different factions, and the growing reign of terror.[91]

On 23 January 1793, Prussia and Russia signed the Second Partition of Poland. The Grodno Sejm, convened under duress in June, ratified the partition and was also forced to rescind the Constitution of 3 May 1791.[92][93] With the second partition, Poland became a small country of roughly 200,000 square kilometers (77,000 sq mi)[94] and a population of some 4 million.[92] This came as a shock to the Targowica Confederates, who had seen themselves as defenders of centuries-old privileges of the magnates but had hardly expected that their appeal for help to the Tsarina of Russia would further reduce and weaken their country.[93][95]

In August 1793, Kościuszko, though worried that an uprising would have little chance against the three partitioning powers, returned to Leipzig, where he was met with demands to start planning one as soon as possible.[96] In September he clandestinely crossed the Polish border to conduct personal observations and meet with sympathetic high-ranking officers in the residual Polish Army, including General Józef Wodzicki. The preparations went slowly, and he left for Italy,[why?] planning to return in February 1794. However, the situation in Poland was changing rapidly. The Russian and Prussian governments forced Poland to again disband most of her army, and the reduced units were to be incorporated into the Russian Army. In March, Tsarist agents discovered the revolutionaries in Warsaw and began arresting notable Polish politicians and military commanders. Kościuszko was forced to execute his plan earlier than he had intended and, on 15 March 1794, set off for Kraków.[89]

Kościuszko Uprising

[edit]

Learning that the Russian garrison had departed Kraków, Kościuszko entered the city on the night of 23 March 1794. The next morning, in the Main Square, he announced an uprising.[89] Kościuszko received the title of Naczelnik (commander-in-chief) of Polish–Lithuanian forces fighting against the Russian occupation.[97]

Kościuszko gathered an army of some 6,000, including 4,000 regular soldiers and 2,000 recruits, and marched on Warsaw.[89] The Russians succeeded in organizing an army to oppose him more quickly than he had expected. Still, he scored a victory at Racławice on 4 April 1794, where he turned the tide by personally leading an infantry charge of peasant volunteers (kosynierzy, scythemen). Nonetheless, this Russian defeat was not strategically significant, and the Russian forces quickly forced Kościuszko to retreat toward Kraków. Near Połaniec he received reinforcements and met with other Uprising leaders (Kołłątaj, Potocki); at Połaniec he issued a major political declaration of the Uprising, the Proclamation of Połaniec. The declaration stated that serfs were entitled to civil rights and reduced their work obligations (corvée).[98] Meanwhile, the Russians set a bounty for Kościuszko's capture, "dead or alive".[99]

К июню пруссасин начал активно помогая русским, а 6 июня 1794 года Косчиузко вступил в оборонительную битву против прусско -роспийских сил в Zczekociny . [98] С конца июня в течение нескольких недель он защищал Варшаву , контролируемую повстанцами. 28 июня толпа повстанцев в Варшаве захватила и повесила епископа Игнаси Массальски и шесть других. Kościuszko выпустил публичный упрек, написав: «То, что произошло в Варшаве вчера, наполнило мое сердце горечью и печалью», убедившись, успешно не лисинологиям в этом районе. [ 100 ]

К утру 6 сентября прусские силы были отозваны, чтобы подавить восстание в Большой Польше , осада Варшава была поднята. 10 октября, во время вылета против новой российской атаки, Кохиуско был ранен и захвачен в Maciejowice . Он был заключен в тюрьму русскими в Санкт -Петербурге в крепости Петра и Пола . [ 101 ] Вскоре после этого восстание закончилось битвой при Праге , где, по словам современного российского свидетеля, российские войска убили 20 000 жителей Варшавы. [ 102 ] Последующее третье разделение Польши прекратило существование суверенного польского и литовского государства в течение следующих 123 лет. [ 103 ]

Позже жизнь

[ редактировать ]

Смерть Царитсы Кэтрин Великая 17 ноября 1796 года привела к изменению политики России в отношении Польши. [ 101 ] 28 ноября Царь Павел I , который ненавидел Кэтрин, помиловал Кохиуско и освободил его после того, как он дал присягу верности . Павел пообещал освободить всех польских политических заключенных, проводимых в российских тюрьмах, и тех, кто был насильственно поселен в Сибири . Царь дал Kościuszko 12 000 рублей , которые полюс позже, в 1798 году, попытался вернуться, когда также отказался от клятвы. [ 104 ]

Kościuszko уехал в Соединенные Штаты через Стокгольм , Швеция и Лондон, отправившись из Бристоля 17 июня 1797 года и прибыв в Филадельфию 18 августа. [ 104 ] Несмотря на то, что он приветствовал население, он с подозрением рассматривал американское правительство, контролируемое федералистами , которые не доверяли Кошчизко за его предыдущую ассоциацию с партией-демократической республикой . [ 104 ]

В марте 1798 года Косчиуско получил пакет писем из Европы. Новости в одном из них стали для него шоком, заставляя его, все еще в его раненых условиях, выходить из его дивана и хромотать до середины комнаты и восклицает генералу Энтони Уолтона Уайта : «Я должен сразу вернуться сразу в Европу! " В рассматриваемом письме было известие о том, что польский генерал Ян Генрик Динбровский и польские солдаты сражались во Франции при Наполеоне, и что сестра Косчиуско отправила его двух племянников во имя Кохчиуско, чтобы служить в рядах Наполеона. [ 105 ] Примерно в это время Косчиуцко также получил новости о том, что Таляйран искал моральное и публичное одобрение Кошчиузко для французской борьбы с одним из разделов Польши, Пруссии. [ 104 ]

Призыв семьи и страны вернул Кохиуско обратно в Европу. [ 105 ] Он немедленно проконсультировался с тогдашним вице -президентом Соединенных Штатов Томаса Джефферсона , который приобрел для него паспорт под ложным именем и организовал его секретный уход во Францию. Kościuszko не оставил ни слова ни для Джулиана Урсина Нимсевича, его бывшего товарища в руках и коллеги из Санкт-Петербурга, или для его слуги, оставив для них только немного денег. [ 106 ] [ 107 ]

Другие факторы способствовали его решению уйти. Его французские связи означали, что он был уязвим в отношении депортации или тюремного заключения в соответствии с условиями инопланетных и мятежных актов . [ 108 ] Джефферсон был обеспокоен тем, что США и Франция были на грани войны после дела XYZ и считали его неформальным посланником. Позже Косчико писал: «Джефферсон считал, что я был бы самым эффективным посредником в заключении соглашения с Францией, поэтому я принял миссию, даже если без какого -либо официального разрешения». [ 109 ]

Расположение американского недвижимости

[ редактировать ]До того, как Косчиузко уехал во Францию, он собрал свою спину, написал завещание и поручил Джефферсону исполнителю. [ 104 ] [ 106 ] Кошчиуско и Джефферсон стали близкими друзьями к 1797 году, а затем переписывались в течение двадцати лет в духе взаимного восхищения. Джефферсон написал, что «он такой же чистый сын Свободы, как я когда -либо знал». [ 110 ] В завещании Коньско покинул свое американское поместье, чтобы быть проданным, чтобы купить свободу чернокожих рабов , включая собственную Джефферсона, и обучать их независимой жизни и работе. [ 111 ] [ 112 ]

Через несколько лет после смерти Косчиузко Джефферсон, 77 лет, признал неспособность действовать в качестве исполнителя из -за возраста [ 113 ] и многочисленные юридические сложности завещания. Это было связано в судах до 1856 года. [ 114 ] Джефферсон порекомендовал своему другу Джону Хартвеллу Кокке , который также выступил против рабства, в качестве исполнителя, но Кок также отказался выполнить завещание. [ 113 ]

Дело о американском имуществе Коньско достигало Верховного суда США . трижды [ Примечание 6 ] Kościuszko сделал четыре завещания, три из которых последовали американскому. [ 116 ]

Ни один из денег, которые Коньско не выделял на манимиссию и образование афроамериканцев в Соединенных Штатах, никогда не использовалось для этой цели. [ 117 ] Хотя американская воля никогда не была выполнена, как определено, его наследие использовалось для того, чтобы основать учебный институт в Ньюарке, штат Нью -Джерси , в 1826 году, для афроамериканцев в Соединенных Штатах. Это было названо в честь Кохиуско. [ 105 ] [ 118 ]

Вернуться в Европу

[ редактировать ]

Кошчиуско прибыл в Байонн , Франция, 28 июня 1798 года. [ 104 ] К тому времени планы Talleyrand изменились и больше не включали его. [ 104 ] Kościuszko оставался политически активным в польских кругах эмигранцев во Франции, и 7 августа 1799 года он присоединился к Обществу польских республиканцев ( Towarzystwo Republickanów Polskich ). [ 104 ] Kościuszko отказался от предложенной команды польских легионов, созданных для обслуживания во Франции. [ 104 ] 17 октября и 6 ноября 1799 года он встретился с Наполеоном Бонапартом . Он не смог достичь соглашения с французским генералом, который рассматривал Кохиуско как «дурак», который «переоценил свое влияние» в Польше. [ Примечание 7 ] [ 119 ] Кошчиуцко не любил Наполеона за его диктаторские устремления и назвал его «Гробовщиком [французской] республики». [ 104 ] В 1807 году Кошчиуско поселился в Шато -де -Бервилле, недалеко от Женевра , дистанцируя себя от политики. [ 104 ]

Кохиуско не верил, что Наполеон восстановит Польшу в любой долговечной форме. [ 120 ] Когда силы Наполеона подошли к границам Польши, Кохиуско написал ему письмо, требующее гарантий парламентской демократии и существенных национальных границ, которые Наполеон проигнорировал. [ 119 ] Кохчиуско пришел к выводу, что Наполеон создал герцогство Варшавского в 1807 году только как целесообразно, а не потому, что он поддерживал польский суверенитет. [ 121 ] Следовательно, Кохиуско не переехал в герцогство Варшавского и не присоединившись к новой армии герцогства , союзникому с Наполеоном. [ 119 ]

После падения Наполеона он встретился с российским царом Александра I , в Париже, а затем в Braunau Am Inn . [ 119 ] Царь надеялся, что Кохиуско может быть убежден вернуться в Польшу, где царь планировал создать новое, Российское союзник польское государство ( Королевство Конгресса ). В обмен на свои проспективные услуги Коньско потребовал социальных реформ и восстановления территории, которые, как он пожелал, достигнет рек Двины и Днипер на востоке. [ 119 ] Однако вскоре после этого в Вене Косчиуско узнал, что царство Польши будет создано царом, будет еще меньше, чем более раннее герцогство Варшав. Кохиуско назвал такую сущность «шуткой». [ 122 ]

2 апреля 1817 года Косчиуско освободил крестьян в оставшихся землях в Польше, [ 119 ] Но царь Александр отказался от этого. [ 123 ] Страдая от плохого здоровья и старых ран, Коньсчко умер в Солотурне в возрасте 71 года после того, как упал с лошади, развив лихорадку и перенес инсульт через несколько дней, 15 октября 1817 года. [ 124 ]

Похороны

[ редактировать ]

Первые похороны Косчиузко состоялись 19 октября 1817 года в бывшей иезуитской церкви в Солотурн. [ 119 ] [ 125 ] В качестве новостей о его смерти распространились, массы и поминальные службы были проведены в разделенной Польше . [ 126 ] Его наклеиваемое тело было отложено в склепе о Солоттерн -Церкви. В 1818 году тело Косчиуско было переведено в Кракоу, прибыв в церковь Святого Флориана 11 апреля 1818 года. 22 июня 1818 года, [ 126 ] или 23 июня 1819 года [ 119 ] (Счета варьируются), к толлингу Sigismund Bell и стрельбе из пушки, он был помещен в склеп в соборе Вавель , пантеон польских королей и национальных героев . [ 119 ] [ 126 ]

Кошчиузко Внутренние органы , которые были удалены во время бальзамирования, были отдельно погребены на кладбище в Зучвиле , недалеко от Солотурна. Органы Кохиуско остаются там и по сей день; Большой мемориальный камень был построен в 1820 году, рядом с польской мемориальной часовней. Тем не менее, его сердце не было похоронен с другими органами, а вместо этого хранилось в урне в Польском музее в Rapperswil , Швейцария . [ 119 ] [ 126 ] Сердце, наряду с остальными активами музея, было репатриировано обратно в Варшаву в 1927 году, где теперь сердце покоится в часовне в Королевском замке . [ 119 ] [ 126 ]

Мемориалы и дань

[ редактировать ]

Он был провозглашен и претендует в качестве национального героя Польши, Соединенных Штатов Америки, Беларуси и Литвы.

Польский историк Станислав Хербст государств в польском биографическом словаре 1967 года , который Кохчиуско может быть Польшей и самым популярным полюсом в мире. [ 119 ] У него есть памятники по всему миру, начиная с кургана Kościuszko в Кракове, построенном в 1820–23 годах мужчинами, женщинами и детьми, которые приносят землю с полей битвы, где он сражался. [ 119 ] [ 127 ] [ 128 ] Мосты, названные в его честь, включают в себя мост Костюшко, построенный в 1939 году в Нью -Йорке [ 129 ] и мост Фаддеуса Костюшко, завершенный в 1959 году через реку Могавк между округами Олбани и Саратога в северной части штата Нью -Йорк [ 130 ] Мост из Нью -Йорка был частично заменен в апреле 2017 года новым одноименным мостом с дополнительным мостом, который открылся в августе 2019 года. [ 131 ] [ 132 ] Памятная табличка, посвященная Тадеуш Костюшко, была поставлена на недавно построенный мост в октябре 2022 года польским фондом "Będziem Polakami" (мы будем поляками) [ 133 ] Вместе с Фондом Добры Польска Школа из Нью -Йорка при финансовой поддержке со стороны польского правительства.

Резиденция Филадельфии в 1796 году в 1796 году является национальным мемориалом Фаддеуса Костюшко , самым маленьким национальным парком Америки или подразделением системы национальных парков. [ 134 ] есть музей Косчико . В его последней резиденции в Солотурне, Швейцария, [ 135 ] Польское американское культурное агентство, Фонд Костюшко со штаб-квартирой в Нью-Йорке, было создано в 1925 году. [ 136 ]

Серия польских подразделений ВВС носила название « Эскадрилья Kościuszko ». Во время Второй мировой войны Польский военно -морской корабль носил свое имя, как и Польский 1 -й Тадеуш Кошчиуско пехотный дивизион . [ 137 ]

Один из первых примеров исторического романа « Фаддеус из Варшавы » был написан в честь Кохчиуско шотландским автором Джейн Портер ; Он оказался очень популярным, особенно в Соединенных Штатах, и прошел более восьмидесяти изданий в 19 веке. [ 138 ] [ 139 ] Опера Фрэнсисека Перекези , Kościuszko nad Seine (Kościuszko в Sene ), написанная в начале 1820 -х годов, показала музыку Дукевича и Либретто Константи Маджрановски . Более поздние работы включали драмы Аполлона Корзениуски , Джастина Хосовски и Владислава Людвика Анцика ; Три романа Йозефа Игнаси Крашевски , они от Валери Прзиборовски , они от Владислава Станислава Реймонта ; И работает Мария Конопникка . Kościuszko также появляется в неполистской литературе, в том числе сонета Сэмюэля Тейлора Клэриджа , еще один Джеймс Генри Ли Хант , стихи Джона Китса и Уолтера Сэвиджа и работа Карла Эдуарда фон Холтея . [ 137 ]

В 1933 году почтовое отделение США выпустило памятную печать с изображением гравюры « бригадного генерала Тэддеуса Костюшко », статуи Кошчиуско, которая стоит в Вашингтоне, округ Колумбия , недалеко от Белого дома. Марка была выпущена в 150 -ю годовщину натурализации Кохчиузко как американского гражданина. Польша также выпустила несколько марок в его честь. [ 140 ] В 2010 году была представлена копия памятника . в Варшаве , Польша, [ 141 ]

В Польше в Польше в Кракове есть статуи Кошчиуско , которая была разрушена немецкими войсками во время оккупации Второй мировой войны и позже была заменена репликой Германией в 1960 году. [ 142 ] и Лодзи ( Мицзислав Любельски ); [ 119 ] в Соединенных Штатах в Бостоне , [ 142 ] Вест -Пойнт , [ 142 ] Филадельфия ( Мариан Конечни ), [ 142 ] Детройт [ 143 ] (копия статуи Кракоу Леонарда Маркони), [ 144 ] Вашингтон, округ Колумбия, [ 119 ] Чикаго , [ 119 ] Милуоки [ 119 ] и Кливленд ; [ 119 ] и в Швейцарии в Солотурн. [ 119 ] Kościuszko был предметом картин Ричарда Косвея , Фрэнсисека Сумглевича , Михала Стачовича , Юлиуса Коссака и Яна Матжко . Монументальная панорама Raclawice была нарисована Ян Стайка и Войчехом Коссаком за столетие в 1794 году битвы при Раковице. [ 119 ] был построен памятный памятник В Минске, Беларусь, . [ 145 ]

В 2023 году памятник в Вест -Пойнте был демонтирован для ремонта, а запечатанная свинцовая коробка составляет около 1 кубического фута (28 л), в базе была обнаружена. Считается, что капсула времени датируется либо с 1828 года, когда она была возведена Корпус -курсантом , либо 1913 год, когда польское духовенство и миряне Соединенных Штатов пожертвовали статую Костюшко, чтобы сидеть на вершине колонки. В июне 2023 года рентгеновские снимки показали, что в ведущем случае была коробка. [ 146 ] Открытие коробки в августе показало, что казалось грязным [ 147 ] но позже было обнаружено, что он содержит медаль и несколько монет. [ 148 ]

Географические особенности, которые носят его имя, включают гору Костюшко , самая высокая гора в Австралии , за исключением внешних территорий. Это в национальном парке Нового Южного Уэльса, также названном в его честь Национальный парк Костюшко . Другие географические организации, названные в честь Кохиушко, включают остров Костюшко на Аляске , округ Костюшко в Индиане , а также многочисленные города, города, улицы и парки, особенно в Соединенных Штатах. [ 119 ]

Kościuszko был предметом многих письменных произведений. Первая его биография была опубликована в 1820 году Джулианом Урсином Нимсевичцем , который служил рядом с Кохиуско в качестве помощника-де-лагерь и также был заключен в Россию после восстания. [ 149 ] БИОГРАФИЯ АНГЛИЙСКОГО ЧЕЛОВЕКА включали Кошчиузко Моники Мэри Гарднер : биография , которая была впервые опубликована в 1920 году, и работа Алекса Сторозинского в 2009 году под названием «Крестьянский принц: Тэддеус Косциуско» и «Эпоха революции» . [ 150 ]

Костюшко памятные бляшки

[ редактировать ]Памятными таблицами Tadeusz Kosciuszko являются семь бронзовых табличек, посвященных Тадеуш Костюшко, на мосту Костюшко через Ньютаун -Крик в Нью -Йорке . Бляшки висели на главной колонне моста в направлении на запад, вдоль пешеходной и велосипедной дорожки. Две бляшки, « Битва за Саратога » и « Академия Вест -Пойнт », посвящены самым важным военным достижениям Костюшко во время американской революции . Костюшко разработал успешную оборонительную стратегию для битвы при Саратоге , которая стала поворотным моментом американской революции. Костюшко составил планы по строительству крепости Вест -Пойнт, предложив Томасу Джефферсону, что она будет использована в качестве военной академии Вест -Пойнт. Основные бляшки содержит самую важную информацию о Tadeusz Kościuszko.

Творческая концепция для бляшек была инициирована Анджеем Сьеркош. Текст для табличек был написан Алексом Сторозинским . Дизайн был создан Анджеем Сьеркош и Грегорцом Годавой и проведен скульптором Грзегорцом Годавой в Польше. Они были брошены в польский бронзовый литейный завод Brązart в Польше.

Проект был спонсируется Фондом Добры Полской Школа из Нью -Йорка и Фондом Бедзием Полаками из Польши. Он получил финансовую поддержку от Andrzej Cierkosz, губернатора Нью -Йорка Кэти Хочул , и получила значительную финансовую поддержку от Управления премьер -министра польского Матеуса Моравицки . 15 октября 2022 года на церемонии были представлены бляшки, 205 -летие смерти Костюшко.

-

Кохчиуско памятник, Монтиньи-Сур-Линг , Франция

-

Kościuszko Mound , 34 м (112 футов) высотой, Краков, Польша

-

Tadeusz Kościuszko памятник в Лодзи

-

Польская почтовая марка (1938): Kościuszko с сабли (слева), Томас Пейн и Джордж Вашингтон .

-

Почтовая марка США (1933): Статуя Коньскоко

-

Белорусская почтовая марка (1994): Kościuszko

-

Маунт Костюшко , самая высокая вершина в Австралии на материковой части.

-

SP-LBG, названный в честь Kościuszko, изображенного в JFK , который впоследствии участвовал в полете Airlines Airlines 5055 .

-

Фонд Kościuszko Bldg. Нью -Йорк

-

Историческая табличка Фонда Кускаушко.

-

КОНСКОНА ФОНДА ФОНДА В НЬЮ -НИК.

-

Текст.

Смотрите также

[ редактировать ]- Казимирц Пуласки (Англизирован как «Казимир Пуласки»), аналогично почитаемый польский командир в американской революционной войне

- Майкл Коватс де Фабрик , венгерский командир в американской революционной войне, известный как «Отец американской кавалерии»

- Генерал -бригадиатор Таддеус Костюшко - Вашингтонский памятник , округ Колумбия

- Список полюсов

- Лагерь Костюшко

Пояснительные заметки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Polish pronunciation: [ˈandʐɛj taˈdɛ.uʐ bɔnavɛnˈtura А , Аппроксимирован на английском языке AS / T ə ˈ D Eɪ ə ʃ K ɒ ʃ ˈ Tʃ ʊ S K Oʊ , - ʃ ʃ K Oʊ / Tə- Day -Chosh- Chuus (h) k -Oh . [ 1 ] Литовский : Андриус Тадас Бонавентура Коскаушка ; Беларус : Андрей Тадеуш Бонавентур Костюшко , Романизированный : Андрей Тадевуш Банавиентуру Кастсишка . [ 2 ]

- ^ Ряд англизированных написаний имени Кохчиуско появляется в записях, включая полную версию, указанную здесь или более короткую Фаддеус Косциуско . Общее англизированное произношение его / фамилии k s ɒ i ˈ s usk k oʊ / Koss -ee- -Oh составляет .

- ^ Алекс Сторозински, в своей биографии Кохчиуско 2009 года, отмечает, что «двенадцатый вообще используется», и что Синдлер (1991: 103) обсуждает теории о дате рождения Кошчиузко. [ 12 ] [ 13 ]

- ^ Эскизы из руки Коньско все еще выживают и охраняются как национальные сокровища в польских музеях.

- ^ После того, как он вернулся в Польшу из Америки и искал комиссию по польской армии, тогдашняя примирация Любомирски-она была вынуждена ее отцом выйти замуж за высшее дворянство-погашение королю, чтобы предложить Кошчиузко комиссию. Когда он отправился в Варшаву летом 1789 года, чтобы заняться этим вопросом, он столкнулся с ней у мяча. Как позже рассказал его друг Джулиан Урсин Нимсевич : «Встреча была настолько эмоциональной [для обоих], что они не смогли говорить друг с другом; каждый из них отодвинулся в другой угол салона и плакал». [ 33 ] В 1791 году он стремился выйти замуж за Текла Цуровеска, но снова встретился с отцовской оппозицией. [ 34 ]

- ^ Ассоциированный судья Джозеф Стори принял решение о приговоре по делу Армстронг против Лира , 25 США, 12 пшениц. 169 169 (1827), основанный на непредоставлении завещания для завещания. Такое же поместье также было предметом Estho v Lear , 32 US 130 (7 Pet. 130, 8 L.Ed. 632) (1832), в котором председатель судьи Джон Маршалл написал краткое мнение, предполагающее, что предварительный предварительный предварительный пример, по -видимому, в Вирджинию. Наконец, решение по делу Ennis v. Smith , 55 US 14 как. 400 400 (1852) упоминает ни одного отдельного автора; Главным судьей был Роджер Тейни , и единственными упомянутыми юрисдикциями были юридические лица Мэриленда , округа Колумбия и Гродно . [ 115 ]

- ^ Письмо Наполеона своему министру полиции Джозефу Фуше , 1807.

Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Президент Коморовский чтит Костюшко в Уэст -Пойнте на YouTube , 3'33 ″.

- ^ Bumblauskas, 1994 , p. 4

- ^ Музей, посвященный польскому военному герою Тадеуш Кохиуско. «Музей Кошчиузко - музей Кохиушко существовал в Солотурн (Швейцария) в Гурзельнгассе 12 с 1936 года. Польский национальный герой Тадеуш Кошчизко жил и умер в этом доме» . www.solothurn-city.ch . Получено 6 июня 2022 года .

Жизнь польского военного героя Тадеуш Кохиуско - который провел последние несколько лет своей жизни в Солотурне с 1814 по 1817 год - через документы, изображения и объекты. Дом, где он умер, был преобразован в музей Кохиуско и представляет собой как его близкие отношения с Солотурн, так и часть мировой истории.

- ^ Долан, Шон (1997). Польские американцы . Челси Хаус. ISBN 978-0-7910-3364-7 .

- ^ Грин, Мег (2002). Kosaus Kos ´icuszko: Яд Джерарал и Патриот . Общественная информация. ISBN 978-1-4381-2513-8 .

- ^ «Программы и мероприятия 2015 года | Минск, Беларусь - Посольство Соединенных Штатов» . 17 ноября 2015 года. Архивировано с оригинала 17 ноября 2015 года.

- ^ Мемориальная выставка Таддеус Косциуско, уважаемый польский и американский герой, его патриотизм, видение и рвение, раскрытые в коллекции автографов, а также в коллекции автографов о нем выдающимися лидерами американской революции и других, а также нефти. Живопись, медали, гравюры, книги, бродяги и другие реликвии - это коллекция, сформированная доктором и миссис. Александр Каханович: Выставка с воскресенья, мая, пятнадцатый по один, одиннадцатый, Андерсон Галереи [...], Нью -Йорк . Андерсон Галереи - Музей Метрополитен. 1927.

- ^ Владимир Арлов "Уладзимер Арло" "Имена свободы") (на беларусии) стр. 26-27

- ^ Пула, Джеймс С. (1977). «Американская воля Фаддеуса Костюшко» . Польские американские исследования . 34 (1): 16–25. ISSN 0032-2806 . JSTOR 20147972 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Осень, 1969 с. 430.

- ^ Институт мировой политики, 2009 , статья.

- ^ Szyndler, 1994 , p. 103

- ^ Storozynski, 2009 , p. 13.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час я Дж k л м Осень, 1969 с. 431.

- ^ Szyndler, 1991 , p. 476.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Cizauskas 1986 , с. 1–10.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , p. 2.

- ^ Szyndler, 1991 , p. 27

- ^ Krol, 2005 , публичный адрес.

- ^ Гарднер, 1920 стр. 317

- ^ Kajencki, 1998 , p.

- ^ Корзон, 1894 , с. 135.

- ^ Новости [ Novosti ], 2009 , p. 317.

- ^ 100 великих аристократов , эссе.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , p. 27.

- ^ «Очевидный необвиженный - одна матрица, многие нации ... - Jaworzno - Социальная сеть - jaw.pl» (на лаке). 15 мая 2021 года . Получено 5 ноября 2023 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Куолис, Дарий. "Тадас Косциушка . " Источники.info (в литовском языке) . Получено 2 октября 2023 года .

«Если это не подло, и вы не будете воспитаны в сеймах сейма, я, вероятно, вижу Бога, я сделаю себя плохо, потому что гнев приведет меня, потому что я из Литвы до Царства Литвы, (...) Литва !

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , p. 28.

- ^ Гарднер, 1942 , с. 17

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Storozynski, 2009 , pp. 17–18.

- ^ NPS, 2009 , эссе.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , p. 32.

- ^ Маковский, 2013 , с.

- ^ Bain 1911 , с. 914.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , pp. 36–38.

- ^ Трики, Эрик (8 марта 2017 г.). «Польский патриот, который помог американцам победить англичан» . Смитсоновский журнал.

- ^ Колимор , новостная статья.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , pp. 41–42.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и Storozynski, 2011 , pp. 47–52.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Storozynski, 2011 , pp. 53–54.

- ^ Afflerbach, 2012 , с. 177–79.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , p. 65.

- ^ Anderton, 2002 , Vol. 5, № 2.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , pp. 111–12.

- ^ Usgovernment Printing Office, 1922 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час я Дж Осень, 1969 , с. 43

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , p. 85.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , pp. 128–30.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , pp. 131–32.

- ^ Палмер, 1976 , с. 171–74.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , pp. 141–42.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , pp. 144–46.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , p. 147.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , p. 148.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , pp. 149–53.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , p. 154.

- ^ Kajencki, 1998 , p.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , pp. 158–60.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , pp. 161–62.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , p. 163.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , p. 164.

- ^ Storozynski, 2009 , p. 114.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , pp. 166–67.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , p. 168.

- ^ Гарднер, 1920 стр. 31

- ^ «История членов APS» . search.amphilsoc.org . Получено 14 декабря 2020 года .

- ^ Ленгель, 2017 , с. 105

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , p. 177.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , p. 178.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , p. 181.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , p. 187.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Чрезвычайно раздражительность была отражена в письме, написанном генералу Низеовски из Влоцлавека 7 февраля 1790 года: Я клянусь на все, что является самым приятным в жизни, - жена и дети. Полем Полем Что вы хотели бы заставить меня вытащить меня из такого неприятного, дорогого и еще ничего. Бог видит: у меня нет ни слова, чтобы говорить - и хорошо, потому что я никогда не разговаривал с волами. Что за гашенов! Но я позволю национальной комнате описать; Я только скажу, что страна прекрасна, и она должна быть для хороших и экономичных литовцев, не для них, не стройных и незначительных. Хочу вернуться в Литву; Думаю, ты отречься и увидишь меня, чтобы служить тебе? Кто я Азали не маленький, ваше великолепие, выбран из вас? Коммуна у меня есть благодарность, чтобы показать (за рекомендацию регионального совета Бреста?), Если не вы? Кого я должен защищать, если не вы и я себя? Если это не смягчает вас, чтобы принести меня в SEJM, я бы вернулся: я думаю, что Бог увидит, что я сделаю! Ну, он злит меня: из Литвы я бы служил в короне, когда у вас нет трех генералов. Когда вы будете на струне, будет насилие, вы проснетесь, и вы позаботитесь о себе » Из «Списка Кохчиузко» Симиньского, нет. 62, с.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , p. 203.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , p. 194.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , p. 195.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , pp. 213–14.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , pp. 218–23.

- ^ Martinth, 1987 , P. 317

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Storozynski, 2011 , p. 223.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час я Дж Осень, 1969 , с. 433.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , p. 224.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , p. 230.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Storozynski, 2011 , pp. 228–29.

- ^ Otrębski, 1994 , p.

- ^ Falkenstein, 1831 , p. 8

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , p. 231.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , p. 237.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Storozynski, 2011 , pp. 239–40.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и Осень, 1969 , с. 434.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , p. 238.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 pp. 244–45.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Lukowski, 2001 , с. 101–3.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Sujiedėlis, 1944 , с. 292-93.

- ^ Дэвис, 2005 , с. 394.

- ^ Stone, 2001 , с. 282–85.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , p. 245.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , p. 252.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Осень, 1969 , с. 435.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , p. 283.

- ^ Storozynski, 2009 , pp. 195–96.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Осень, 1969 , с. 435–36.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , p. 291.

- ^ Ландау и Томашевский, 1985 , с.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час я Дж k Осень, 1969 , с. 437.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Гарднер 1942 , с. 183.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Гарднер, 1943 , с. 124

- ^ Sullin, 1944 , p. 48

- ^ Нэш, Ходжес, Рассел, 2012 , с. 161–62.

- ^ Александр, 1968 , статья.

- ^ Фонд Джефферсона: Т. Костюшко , эссе.

- ^ «Основатели онлайн: воля Тадеуша Косциуско, 5 мая 1798 года» .

- ^ Сулькин. 1944 , с. 48

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Storozynski, 2009 , p. 280.

- ^ Нэш, Ходжес, Рассел, 2012 , с. 218

- ^ Ennis v. Smith , 55 US 400, 14 как. 400, 14 L.Ed. 427 (1852).

- ^ Yiannopoulos, 1958 , p.

- ^ Storozynski, 2009 , p. 282.

- ^ Нэш, Ходжес, Рассел, 2012 , с. 241.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час я Дж k л м не а п Q. ведущий с Т в Осень, 1969 , с. 438.

- ^ Дэвис, 2005 , с. 216–17.

- ^ Дэвис, 2005 , с. 208

- ^ Feliks , on line essay.

- ^ Cizauskas, 1986 , Journal.

- ^ Storozynski, 2011 , pp. 380–81.

- ^ Szyndler, 1991 , p. 366

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и Kościuszko Mound, Essay .

- ^ Нэш, Ходжес, Рассел, 2012 , с. 212.

- ^ «Курган Кохчиузко - европейские романтизм в ассоциации» . 19 июня 2020 года.

- ^ Департамент транспорта штата Нью -Йорк .

- ^ Капитальные автомагистрали .

- ^ Баррелл, Джанель; Адамс, Шон (28 апреля 2017 г.). «Первый промежуток нового моста Костюшко открывается для движения» . CBS Нью -Йорк . Получено 28 апреля 2017 года .

- ^ Данлэп, Дэвид В. (28 апреля 2017 г.). «Как ты произносишь Костюшко? Это зависит от того, откуда ты» . New York Times . ISSN 0362-4331 . Получено 29 апреля 2017 года .

- ^ Я буду полюсами

- ^ Kosciuszko National Memorial (.gov) .

- ^ Herbst, 1969 , с. 438–39.

- ^ Костюшко Фонд, Миссия и История .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Осень, 1969 , с. 439.

- ^ Национальная идентичность в Фаддеус Варшав, эссе .

- ^ Looser, 2010 , с. 166

- ^ Смитсоновский Национальный почтовый музей .

- ^ Редакторы (16 ноября 2010 г.). «TADEUSZ KOśCIUSZKO представил представленный памятник» . Варшав Насз Миасто (на лаке) . Получено 18 янур 2022 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Tadeusz Kościuszko Gallery (Buffalo.edu) .

- ^ «Генерал Костюшко памятник - этнические слои Детройта» . Колледж гуманитарных наук и наук, Уэйнский государственный университет . Получено 20 июля 2020 года .

- ^ Город Детройт Веб -сайт .

- ^ Нэш, Ходжес, Рассел, 2012 , с. 10

- ^ Десять-Машина времени? West Point, чтобы открыть капсулу времени, возможно, оставленная курсантами в 1820-х годах , Майкл Хилл, Associated Press / Anity , 2023-08-27

- ^ Грязное раскрытие для таинственной капсулы Вест-Пойнт времени с 1820-х годов , Холли Хондерих, BBC News, 2023-08-28

- ^ Монеты и медаль, найденные в капсуле Time West Point с 1820-х годов , Max Matza, BBC News, 2023-08-31

- ^ Мартин С. Новак, эссе, 2007 .

- ^ Storozynski, 2009 .

Общая библиография

[ редактировать ]Книги

[ редактировать ]- Аффлербах, Хольгер; Страчан, Хью (2012). Как заканчивается борьба: история сдачи . Великобритания: издательство Оксфордского университета, 473 страницы. ISBN 978-0-19-969362-7 .

- Бардс, Юлиус; Передний, поддельный; Сыр, Мишель (1987). Гисторы полих -государства и закона . VEWS: Государственная научная собственность.

- Бэйн, Роберт Нисбет (1911). " В Чишхушолме, Хью (ред.). Британская Тол. 15 (11 -е изд.). Издательство Кембриджского университета. стр. 914–915.

- Дэвис, Норман (2005). Божья детская площадка: история Польши в двух томах . Нью -Йорк: издательство Колумбийского университета, вып. 1, 616 страниц; Тол. 2, 591 страницы. ISBN 978-0-19-925340-1 .

- Гарднер, Моника Мэри (1942). Kościuszko: биография . G. Allen & Unwin., Ltd, 136 страниц. , Книга ( Google ) , книга ( Гутенберг )

- Хербст, Станислав (1969). "Тадеуш Кохиуско". Польский биографический словарь, 439 страниц (на лаке). Vol. 14. Варшава: Институт истории (Польская академия наук).

- Кайт, Элизабет С. (1918). Бомархайс и война за независимость американской независимости . Бостон: Gorham Press, 614 страниц. E'Book

- Кадженки, Фрэнсис С. (1998). Фаддеус Кошчиуско: военный инженер американской революции . Hedgesville: Southwest Polonia Press, 334 страницы. ISBN 978-0-9627190-4-2 .

- Корзон, Тадеш (1894). Kościuszko: Биография из документов . Накл. Национальный музей в Rapperswel, 819 страниц.

- Ландау, Zbigniew; Tomaszewski, Jerzy (1985). Польская экономика: в двадцатом веке . Польша: Крюм Хелм, 346 страниц. ISBN 978-0-7099-1607-9 . [ Постоянная мертвая ссылка ]

- Ленгель, Эдвард Л. (2017). Вест -Пойнт История американской революции . Военная академия Соединенных Штатов. ISBN 978-1-4767-8276-8 .

- Loaser, Devoney (2010). Женские писатели и старость в Великобритании, 1750–1850 . Балтимор: издательство Университета Джона Хопкинса, 252 страницы. ISBN 978-1-4214-0022-8 .

- Луковски, Джери; Zawadzki, WH (2001). Краткая история Польши . Кембридж, Великобритания: издательство Кембриджского университета, 317 страниц. ISBN 978-0-521-55917-1 .

- Маковски, Марцин Лукаш (2013). Настоящее лицо Тадеуша Кохиуско («Истинное лицо Тадеуша Кохиуско»), Полярная звезда , нет. 10 Общество и СМИ.

- Нэш, Гэри; Ходжес, Грэм Рассел Гао (2012). Друзья Свободы: рассказ о трех патриотах, двух революциях и предательство, которое разделило нацию - Томас Джефферсон, Тадеуш Кохчиуско и Агриппа Халл . Нью -Йорк: Основные книги, 328 страниц. ISBN 978-0-465-03148-1 .

- Под Красным, С. Каун (2006). Большое герцогство Литвы: История обучения . Минск: Medison, 544 страницы. ISBN 985-6530-29-6 .

- Otrębski, Tomasz (1994). «Кохиуско», 1893–1896 . «Партнер» издательство, 304 страницы. ISBN 978-83-900984-0-1 .

- Otrębski, Tomasz (1831). «Tadeusz Kościuszko: Это биография этого героя: умноженная на множество дополнений и комментариев из исторических источников, полученных переводчиком», 1831 .

- Паулаускиен, Аушра (2007). Потерянный и найденный: открытие Литвы в американской художественной литературе Амстердам; Нью -Йорк: Родопи Б.В., 173 страницы. ISBN 978-90-420-2266-9 .

- Палмер, Дейв Р. (1976). «Крепость Вест -Пойнт: концепция 19 -го века в войне 18 -го века». Военный инженер (68).

- Савас, Теодор П.; Dameron, J. David (2010). Новая Американская Революция Справочник: Факты и произведения искусства для читателей всех возрастов, 1775–1783 . Нью -Йорк: Casemate Publishers, 168 страниц. ISBN 978-1-932714-93-7 .

- Саверченко, Иван; Sanko, Dmitry (1999). 150 вопросов и ответов истории Беларуси . ТОНСКОЙ. Архивировано с оригинала 3 марта 2016 года.

- Стоун, Даниэль (2001). Польское - литюанское государство: 1386–1795 . Сиэтл, Вашингтон: Университет Вашингтонской прессы, 374 страницы. ISBN 978-0-295-98093-5 .

- Storozynski, Alex (2009). Крестьянский принц: Фаддеус Косссиуско и эпоха революции Нью -Йорк: Св. Пресса Мартина, 352 страницы. ISBN 978-1-4299-6607-8 Полем , Книга

- —— (2011). Церковный принц крестьян . Ваб ISBN 978-83-7414-930-3 .

- Салкин, Сидни; Салкин, Эдит (1944). Демократическое наследие Польши, «за вашу свободу и нашу»: антология . Польша: Аллен и Анвин.

- Sujiedėlis, Saulius (7 февраля 2011 г.). Исторический словарь Литвы . Ланхэм, Мэриленд: Пресса Чика, 428 страниц. ISBN 978-0-8108-4914-3 .

- Szyndler, Bartłomiej (1994). Кошчиуско восстание 1794 (на лаке). Польша: Анкоре, 455 страниц. ISBN 978-83-85576-10-5 .

- Szyndler, Bartłomiej (1991). Tadeusz Kościuszko, 1746–1817 (на лаке). Польша: издательство Беллона, 487 страниц. ISBN 978-83-11-07728-7 .

Другие источники

[ редактировать ]- «Американское философское общество: о» . Американское философское общество. 2019 . Получено 20 августа 2019 года .

- "100 ВЕЛИКИХ АРИСТОКРАТОВ – Костюшко Тадеуш Андрей Бонавентура – всемирная история" [Kościuszko, Tadeusz Andrzej Bonawentura – 100 Great Aristocrats – World History] (in Belarusian). History.vn.ua . Retrieved 17 November 2012 .

- Александр, Эдвард П. (1968). «Джефферсон и Костюшко: Друзья свободы и человека» . Пеннский государственный университет . Архивировано из оригинала 16 декабря 2013 года . Получено 11 декабря 2013 года .

- Андертон, Маргарет (2002). «Дух Полонеза» . Польский музыкальный журнал . 5 (2). Архивировано из оригинала 18 октября 2012 года . Получено 17 ноября 2012 года .

- Анесси, Томас. Будущее Англии/Польше прошло: история и национальная идентичность в Фаддеусе Варшавы (магистрация). Университет Южной Каролины . Получено 26 сентября 2013 года .

- Bumblauskas, Alfredas . «Тысячелетие в Литве - тысячелетие литовство, или то, что Литва может рассказать миру по этому случаю» (PDF) . Получено 20 января 2010 года .

- Cizauskas, Albert C. (1986). Zdanys, Jonas (ред.). «Необычная история Фаддеуса Костюшко» . Литовский ежеквартальный журнал искусств и наук . 32 (1 - прес). ISSN 0024-5089 .

- Chodakiewicz, Марек Ян . Институт мировой политики . Получено 3 июля 2009 г.

- Колимор, Эдвард (10 декабря 2007 г.). «Борьба, чтобы спасти остатки форта» . Филадельфийский запросчик , страница статьи.

- «Комплексный план - свобода от моего имени» (PDF) . Служба национальных парков , 58 страниц. 4 октября 2007 г. Получено 3 июля 2009 г.

- Феликс, Конечни (ND). «Святые в истории польской нации» (на лаке). Nonpossumus.pl. Архивировано из оригинала 25 июня 2012 года . Получено 17 ноября 2012 года .

- Новости (24 March 2009). "TUTэйшыя ў свеце. Касцюшка – Общество – TUT.BY | НОВОСТИ – 24.03.2009, 13:46" . News.tut.by. Archived from the original on 26 July 2012 . Retrieved 17 November 2012 .

- Охота, Гайярд, изд. (1922). "Тадеуш Кохиуско" . Вашингтон, округ Колумбия: Правительственная типография . Получено 14 октября 2013 года .

- Джордан, Кристофер, изд. (2006). «Мост Фаддеус Костюшко» . Капитальные автомагистрали. Архивировано из оригинала 2 апреля 2003 года . Получено 3 октября 2013 года .

- «Проект моста Костюшко» . Департамент транспорта штата Нью -Йорк . Получено 3 октября 2013 года .

- Крол, Джордж (8 июля 2005 г.). «Замечания посла США Джорджа Крола на церемонии, чтобы представить памятник Tadeusz Kościuszko» . Хартия 97 . Архивировано с оригинала 5 октября 2013 года . Получено 1 октября 2013 года .

- Нэш, Гэри; Ходжес, Грэм Рассел Гао (2008). «Почему мы все должны сожалеть о разбитом обещании Джефферсона Кохчиуско» . Новости истории . Получено 21 апреля 2013 года .

- Новак, Мартин С. (2007). «Джулиан Урсин Нимсевич» . Польский американский журнал, эссе . Получено 3 октября 2013 года .

- "Kościuszko насыпь" . Официальный веб -сайт кургана Kościuszko в Кракове (на лаке). Kopieckościuszki.pl . Получено 17 ноября 2012 года .

- «Статуя генерала Тэддеуса Костюшко - Третья улица на Мичиган -авеню в центре Детройта» . Мичиганский университет . Получено 21 апреля 2013 года .

- «Галерея Тадеуша Кохиуско - памятники» . Info-poland.buffalo.edu. 2000. Архивировано с оригинала 4 марта 2014 года . Получено 12 сентября 2013 года .

- "Тадес Костюшко " Томаса Джефферсона Фонд Получено 7 октября

- «Национальный мемориал Фаддеуса Костюшко - Национальный мемориал Фаддеуса Костюшко» . Nps.gov . Получено 12 сентября 2013 года .

- «Фонд Костюшко: миссия и история» . Фонд Костюшко, Нью -Йорк. Архивировано с оригинала 12 июля 2014 года . Получено 29 сентября 2013 года .

- Троттер, Гордон Т., изд. (2007). «Костюшко выпуск» . Смитсоновский Национальный почтовый музей . Получено 25 сентября 2013 года .

- Яннопулос, Атанассиос Н. (31 мая 1958 г.). «Завещания движений в американском законе о конфликтах: критика правила жилья» . Калифорнийский юридический обзор . Получено 3 октября 2013 года .

Дальнейшее чтение

[ редактировать ]- Honeyman, A. van Doren (1918). Исторический квартал округа Сомерсет, том 7 . Сомерсет, Нью -Джерси: Историческое общество округа Сомерсет, 334 страницы.

- Niestsirchuk, Leanid (2006). Андрей Тадеуш Бонавентур Костюшко: Возвращение Хисма (Андреме Тадеуш Бонавентуру Костюшко: Возвращение героя в свою родину) . Брест, Беларусь: OJSC "Брест Печатный дом". ISBN 985-6665-93-0 .

- Нимсевич, Джулиан Урсин (1965). Будка, Мехи Дж. (Ред.). Под вашей лозой и фиговым деревом . Grassmann Pub. Ко, 398 страниц. ISBN 9780686818083 .

- Нимсевич, Джулиан Урсин (1844). Записки моего плена в России: в 1794, 1795 и 1796 годах . Уильям Тейт, 251 страница.

- Пула, Джеймс С. (1998). Фаддеус Косциуско: самый чистый сын Свободы . Нью -Йорк: Книги Гиппокрены. ISBN 0-7818-0576-7 .

- Белый, Энтони Уолтон (1883). Мемуары Фаддеуса Костюшко: Герой и патриот Польши, офицер американской армии революции и член Общества Цинциннати . GA Thitchener. п. 58

Внешние ссылки

[ редактировать ]- Тадеуш Кохиуско

- 1746 Рождения

- 1817 Смерть

- Рутенанское дворянство польского илитуанского Содружества

- Похороны в соборе Вавель

- Континентальная армия Генералов

- Офицеры континентальной армии из Польши

- Генералы польского - литюанского Содружества

- Кошчиуско повстанцы

- Члены американского философского общества

- Люди из района Ивацевиши

- Люди из брест -лит для вообще

- Люди польской - русско -война 1792 года

- Польские эмигранты в Соединенные Штаты

- Польские инженеры

- Польские генералы

- Польский народ белорусского происхождения

- Польские политики

- Польские римские католики

- Литовские эмигранты в Соединенные Штаты

- Литовские инженеры

- Литовские генералы

- Литовский народ белорусского происхождения

- Литовские политики

- Литовские римские католики

- Беларусские эмигранты в Соединенные Штаты

- Белорусские инженеры

- Беларусские генералы

- Беларусские политики

- Беларусские римские католики

- Получатели властных военных

- Получатели порядка белого орла (Польша)