Галаф -культура

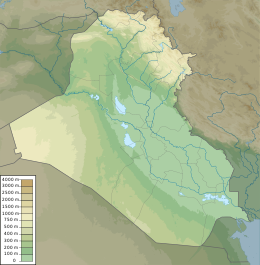

Культура Халаф (в зеленом), рядом с культурами Самарры , Хассуны и Убаида . | |

| Географический диапазон | Месопотамия |

|---|---|

| Период | Неолит 3 - керамика неолита (PN) |

| Даты | в 6 100-5 100 до н.э. |

| Тип сайта | Скажи Халаф |

| Major sites | Tell Brak |

| Preceded by | Pre-Pottery Neolithic B, Yarmukian culture |

| Followed by | Halaf-Ubaid Transitional period, Hassuna culture, Samarra culture |

| The Neolithic |

|---|

| ↑ Mesolithic |

| ↓ Chalcolithic |

Культура Халафа - это доисторический период, который длился от 6100 до н.э. до 5100 до н.э. [ 1 ] Период является непрерывным развитием из более раннего гончарного неолита и расположен в основном в плодородной долине реки Хабур (Нахр аль-Хабур), на юго-востоке Турции , Сирии и северного Ирака , хотя найден материал с влиянием Халафа по всей Большой Месопотамии .

В то время как период назван в честь места «Телл Халаф» в Северной Сирии , выкопанный Максом фон Оппенгеймом в период с 1911 по 1927 год, самый ранний материал из Халаф был раскопан Джоном Гарстаном в 1908 году на месте Саксе Гёзю . [ 2 ] Небольшое количество материала Халафа также было раскопано в 1913 году Леонардом Вулли в Кархимисе, на турецкой/сирийской границе. [ 3 ] Тем не менее, наиболее важным местом для традиции Халаф был место Tell Arpachiyah , в настоящее время расположенное в пригороде Мосула , Ирак . [ 4 ]

Период Халафа был сменен переходным периодом Халаф-Обейд , который включал поздний Халаф (ок. 5400–5000 г. до н.э.), а затем в период UBAID .

Origin

[edit]Previously, the Syrian plains were not considered as the homeland of Halaf culture, and the Halafians were seen either as hill people who descended from the nearby mountains of southeastern Anatolia, or herdsmen from northern Iraq.[5] However, those views changed with the recent archaeology conducted since 1986 by Peter Akkermans, which have produced new insights and perspectives about the rise of Halaf culture.[6] A formerly unknown transitional culture between the pre-Halaf Neolithic's era and Halaf's era was uncovered in the Balikh valley, at Tell Sabi Abyad (the Mound of the White Boy).

Currently, eleven occupational layers have been unearthed in Sabi Abyad. Levels from 11 to 7 are considered pre-Halaf; from 6 to 4, transitional; and from 3 to 1, early Halaf. No hiatus in occupation is observed except between levels 11 and 10.[5] The new archaeology demonstrated that Halaf culture was not sudden and was not the result of foreign people, but rather a continuous process of indigenous cultural changes in northern Syria[7] that spread to the other regions.[1]

Culture

[edit]Architecture

[edit]Halaf pottery

[edit]Halaf pottery has been found in other parts of northern Mesopotamia, such as at Nineveh and Tepe Gawra, Chagar Bazar, Tell Amarna[8] and at many sites in Anatolia (Turkey) suggesting that it was widely used in the region.

-

Fragment of a bowl; 5600–5000 BC; ceramic; 8.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Halafian ware

-

Fertility figurine (maybe a goddess?); 5000–4000 BC; terracotta with traces of pigment; 8.1 × 5 × 5.4 cm; by Halaf culture; Walters Art Museum (Baltimore, US)

Stamp seals

[edit]The Halaf culture saw the earliest known appearance of stamp seals in the Near East.[9] They featured essentially geometric patterns.[9]

-

Loop-handled rectangular seal, Halaf culture.

-

Loop-handled circular seal.

-

Stamp seal and modern impression – geometric pattern. Halaf culture

Halaf's end (Northern Ubaid)

[edit]Halaf culture ended by 5000 BC after entering the so-called Halaf-Ubaid Transitional period.[10] Many Halafian settlements were abandoned, and the remaining ones showed Ubaidian characters.[11] The new period is named Northern Ubaid to distinguish it from the proper Ubaid in southern Mesopotamia,[12] and two explanations were presented for the transformation. The first maintains an invasion and a replacement of the Halafians by the Ubaidians; however, there is no hiatus between the Halaf and northern Ubaid which exclude the invasion theory.[11][13] The most plausible theory is a Halafian adoption of the Ubaid culture,[11] which is supported by most scholars, including Oates, Breniquet, and Akkermans.[12][13][14]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Jump up to: a b Mario Liverani (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. p. 48. ISBN 9781134750849.

- ^ Castro Gessner, G. 2011. "A Brief Overview of the Halaf Tradition" in Steadman, S and McMahon, G (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Ancient anatolia. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 780

- ^ Castro Gessner, G. 2011. "A Brief Overview of the Halaf Tradition" in Steadman, S and McMahon, G (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Ancient anatolia. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 781

- ^ Campbell, S. 2000. "The Burnt House at Arpachiyah: A Reexamination" Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research no. 318. p. 1

- ^ Jump up to: a b Maria Grazia Masetti-Rouault; Olivier Rouault; M. Wafler (2000). La Djéziré et l'Euphrate syriens de la protohistoire à la fin du second millénaire av. J.C, Tendances dans l'interprétation historique des données nouvelles, (Subartu) – Chapter : Old and New Perspectives on the Origins of the Halaf Culture by Peter Akkermans. pp. 43–44.

- ^ Peter M.M.G. Akkermans, Glenn M. Schwartz (2003). The Archaeology of Syria: From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (c. 16,000–300 BC). p. 101. ISBN 9780521796668.

- ^ Peter M.M.G. Akkermans, Glenn M. Schwartz (2003). The Archaeology of Syria: From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (c. 16,000–300 BC). p. 116. ISBN 9780521796668.

- ^ Clop Garcia, X.; Alvarez Perez, A.; Hatert, Frédéric (2004). "Characterization study of Halaf ceramic production at Tell Amarna (Euphrates Valley, Syria)". hdl:2268/102885.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Brown, Brian A.; Feldman, Marian H. (2013). Critical Approaches to Ancient Near Eastern Art. Walter de Gruyter. p. 304. ISBN 978-1614510352.

- ^ John L. Brooke (2014). Climate Change and the Course of Global History: A Rough Journey. p. 204. ISBN 9780521871648.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Georges Roux (1992). Ancient Iraq. p. 101. ISBN 9780141938257.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Susan Pollock; Reinhard Bernbeck (2009). Archaeologies of the Middle East: Critical Perspectives. p. 190. ISBN 9781405137232.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Peter M.M.G. Akkermans, Glenn M. Schwartz (2003). The Archaeology of Syria: From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (c. 16,000–300 BC). p. 157. ISBN 9780521796668.

- ^ Robert J. Speakman; Hector Neff (2005). Laser Ablation ICP-MS in Archaeological Research. p. 128. ISBN 9780826332547.

Bibliography

[edit]- Akkermans, Peter M.M.G.; Schwartz, Glenn M. (2003). The Archaeology of Syria: From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (c. 16,000–300 BC). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52179-666-8.

- Liverani, Mario (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-75091-7.

- Масетти-Руу, Мария Грация; Руу, Оливье; Wafler, Markus (2000). Сирийский Джезире и Евфрат протогистории в конце второго тысячелетия до н.э. JC, тенденции в исторической интерпретации новых данных (Subartu) . Бреполс . ISBN 978-2-50351-063-7 .

Внешние ссылки

[ редактировать ]- Галаф культура Метрополитен -музей искусств

- Галаф чаша из Арпахия - Британский музей