Эдвард II из Англии

| Эдвард II | |

|---|---|

Чучело в Глостерском соборе | |

| Король Англии | |

| Правление | 7 июля 1307 - 13/25 января 1327 |

| Коронация | 25 февраля 1308 |

| Предшественник | Эдвард я |

| Преемник | Эдвард III |

| Рожденный | 25 April 1284 Caernarfon Castle , Gwynedd, Уэльс |

| Died | 21 September 1327 (aged 43) Berkeley Castle, Gloucestershire, England |

| Burial | 20 December 1327 Gloucester Cathedral, Gloucestershire |

| Spouse | |

| Issue Detail | |

| House | Plantagenet |

| Father | Edward I of England |

| Mother | Eleanor of Castile |

Эдвард II (25 апреля 1284 - 21 сентября 1327 г.), также известный как Эдвард Кернарфон или Кернарвон , был королем Англии с 1307 года, пока он не был свергнут в январе 1327 года. Четвертый сын Эдварда I , Эдвард стал наследником престола. Смерть его старшего брата Альфонсо . Начиная с 1300 года, Эдвард сопровождал своего отца в кампаниях в Шотландии , а в 1306 году он был в рыцари на грандиозной церемонии в Вестминстерском аббатстве . Эдвард преуспел на престоле в следующем году после смерти отца. В 1308 году он женился на Изабелле , дочери влиятельного короля Филиппа IV из Франции , в рамках долгосрочных усилий по разрешению напряженности между английскими и французскими коронами.

У Эдварда были близкие и противоречивые отношения с Пирсом Гэвстоном , который присоединился к его семье в 1300 году. Точный характер отношений Эдварда и Гейвстона неопределенна; Возможно, они были друзьями, любовниками или присяжными братьями . Высокомерие и власть Гейвстона как любимое недовольство Эдварда как среди баронов, так и французской королевской семьи, и Эдвард был вынужден изгнать его. По возвращении Гэвстона Бароны заставили Корона согласиться на широкие реформы, называемые постановлениями 1311 года . Недавно уполномоченные бароны изгнали Gaveston, на что Эдвард ответил, отменив реформы и вспомнив его любимую. Во главе с двоюродным братом Эдварда Томасом, 2 -м графом Ланкастером , группа баронов захватила и казня в 1312 году, начиная с нескольких лет вооруженной конфронтации. Английские войска были отодвинуты в Шотландию, где Эдвард был решительно победил Роберт Брюс в битве при Баннокберне в 1314 году. Последовало широко распространенное голод и критика царства царя.

The Despenser family, in particular Hugh Despenser the Younger, became close friends and advisers to Edward, but in 1321 Lancaster and many of the barons seized the Despensers' lands and forced the King to exile them. In response, Edward led a short military campaign, capturing and executing Lancaster. Edward and the Despensers strengthened their grip on power, revoking the 1311 reforms, executing their enemies and confiscating estates. Unable to make progress in Scotland, Edward finally signed a truce with Robert. Opposition to the regime grew, and when Isabella was sent to France to negotiate a peace treaty in 1325, she turned against Edward and refused to return. Isabella allied herself with the exiled Roger Mortimer, and invaded England with a small army in 1326. Edward's regime collapsed and he fled into Wales, where he was captured in November. Edward was forced to relinquish his crown in January 1327 in favour of his son, Edward III, and he died in Berkeley Castle on 21 September, probably murdered on the orders of the new regime.

Edward's relationship with Gaveston inspired Christopher Marlowe's 1592 play Edward II, along with other plays, films, novels and media. Many of these have focused on the possible sexual relationship between the two men. Edward's contemporaries criticised his performance as a king, noting his failures in Scotland and the oppressive regime of his later years, although 19th-century academics have argued that the growth of parliamentary institutions during his reign was a positive development for England over the longer term. Debate has continued into the 21st century as to whether Edward was a lazy and incompetent king, or simply a reluctant and ultimately unsuccessful ruler.

Background

[edit]Edward II was the fourth son[1] of Edward I, King of England, Lord of Ireland, and ruler of Gascony in south-western France (which he held as the feudal vassal of the king of France),[2] and Eleanor, Countess of Ponthieu in northern France. Eleanor was from the Castilian royal family. Edward I proved a successful military leader, leading the suppression of the baronial revolts in the 1260s and joining the Ninth Crusade.[3] During the 1280s he conquered North Wales, removing the native Welsh princes from power and, in the 1290s, he intervened in Scotland's civil war, claiming suzerainty over the country.[4] He was considered an extremely successful ruler by his contemporaries, largely able to control the powerful earls that formed the senior ranks of the English nobility.[5] The historian Michael Prestwich describes Edward I as "a king to inspire fear and respect", while John Gillingham characterises him as an "efficient bully".[6]

Despite Edward I's successes, when he died in 1307 he left a range of challenges for his son to resolve.[7] One of the most critical was the problem of English rule in Scotland, where Edward I's long but ultimately inconclusive military campaign was ongoing when he died.[8] His control of Gascony created tension with the French kings.[9] They insisted that the English kings give homage to them for the lands; the English kings saw this demand as insulting to their honour, and the issue remained unresolved.[9] Edward I also faced increasing opposition from his barons over the taxation and requisitions required to resource his wars, and left his son debts of around £200,000 on his death.[10][a]

Early life (1284–1307)

[edit]Birth

[edit]

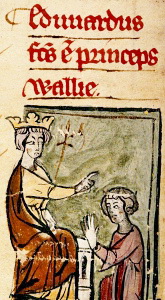

Edward II was born in Caernarfon Castle in north Wales on 25 April 1284, less than a year after Edward I had conquered the region, and as a result is sometimes called Edward of Caernarfon.[12] The King probably chose the castle deliberately as the location for Edward's birth as it was an important symbolic location for the native Welsh, associated with Roman imperial history, and it formed the centre of the new royal administration of North Wales.[13] Edward's birth brought predictions of greatness from contemporary prophets, who believed that the Last Days of the world were imminent, declaring him a new King Arthur, who would lead England to glory.[14] David Powel, a 16th-century clergyman, suggested that the baby was offered to the Welsh as a prince "that was borne in Wales and could speake never a word of English", but there is no evidence to support this account.[15]

Edward's name was English in origin, linking him to the Anglo-Saxon saint Edward the Confessor, and was chosen by his father instead of the more traditional Norman and Castilian names selected for Edward's brothers:[16] John and Henry, who had died before Edward was born, and Alphonso, who died in August 1284, leaving Edward as the heir to the throne.[17] Although Edward was a relatively healthy child, there were enduring concerns throughout his early years that he too might die and leave his father without a male heir.[17] After his birth, Edward was looked after by a wet nurse called Mariota or Mary Maunsel for a few months until she fell ill, when Alice de Leygrave became his foster mother.[18] He would have barely known his natural mother, Eleanor, who was in Gascony with his father during his earliest years.[18] An official household, complete with staff, was created for the new baby, under the direction of a clerk, Giles of Oudenarde.[19]

Childhood, personality and appearance

[edit]

Spending increased on Edward's personal household as he grew older and, in 1293, William of Blyborough took over as its administrator.[20] Edward was probably given a religious education by the Dominican friars, whom his mother invited into his household in 1290.[21] He was assigned one of his grandmother's followers, Guy Ferre, as his magister, who was responsible for his discipline, training him in riding and military skills.[22] It is uncertain how well educated Edward was; there is little evidence for his ability to read and write, although his mother was keen that her other children be well educated, and Ferre was himself a relatively learned man for the period.[23][24][b] Edward likely mainly spoke Anglo-Norman French in his daily life, in addition to some English and possibly Latin.[26][c]

Edward had a normal upbringing for a member of a royal family.[28][d] He was interested in horses and horsebreeding, and became a good rider; he also liked dogs, in particular greyhounds.[30] In his letters, he shows a quirky sense of humour, joking about sending unsatisfactory animals to his friends, such as horses who disliked carrying their riders, or lazy hunting dogs too slow to catch rabbits.[31] He was not particularly interested in hunting or falconry, both popular activities in the 14th century.[32] He enjoyed music, including Welsh music and the newly invented crwth instrument, as well as musical organs.[33] He did not take part in jousting, either because he lacked the aptitude or because he had been banned from participating for his personal safety, but he was certainly enthusiastic in his support of the sport.[34]

Edward grew up to be tall and muscular, and was considered good-looking by the standards of the period.[35] He had a reputation as a competent public speaker and was known for his generosity to household staff.[36] Unusually, he enjoyed rowing, as well as hedging and ditching, and enjoyed associating with labourers and other lower-class workers.[37][38][e] This behaviour was not considered normal for the nobility of the period and attracted criticism from contemporaries.[39][38]

In 1290, Edward's father had confirmed the Treaty of Birgham, in which he promised to marry his six-year-old son to the young Margaret of Norway, who had a potential claim to the crown of Scotland.[40] Margaret died later that year, bringing an end to the plan.[41] Edward's mother, Eleanor, died shortly afterwards, followed by his grandmother, Eleanor of Provence.[42] Edward I was distraught at his wife's death and held a huge funeral for her; his son inherited the County of Ponthieu from Eleanor.[42] Next, a French marriage was considered for the young Edward, to help secure a lasting peace with France, but King Philip IV's refusal to release fortresses in Gascony offered by Edward I provoked the Gascon War in 1294.[43] The idea was replaced with the proposal of a marriage to a daughter of the rebellious Guy, Count of Flanders, but this too failed after King Philip was able to have the proposed bride sent to Paris.[43]

Early campaigns in Scotland

[edit]

Between 1297 and 1298, Edward was left as regent in charge of England while the King campaigned in Flanders against Philip IV, who had occupied part of the English king's lands in Gascony.[44] On his return, Edward I signed a peace treaty, under which he took Philip's sister Margaret as his wife and agreed that Prince Edward would in due course marry Philip's daughter, Isabella, who was then only two years old.[45] In theory, this marriage would mean that the disputed Duchy of Gascony would be inherited by a descendant of both Edward and Philip, providing a possible end to the long-running tensions.[46] The young Edward seems to have got on well with his new stepmother, who gave birth to two sons, Thomas of Brotherton in 1300 and Edmund of Woodstock in 1301.[47] As king, Edward later provided his half-brothers with financial support and titles.[48][f]

Edward I returned to Scotland once again in 1300, and this time took his son with him, making him the commander of the rearguard at the siege of Caerlaverock Castle.[49] In the spring of 1301, the King declared Edward the Prince of Wales, granting him the earldom of Chester and lands across North Wales; he seems to have hoped that this would help pacify the region, and that it would give his son some financial independence.[50] Edward received homage from his Welsh subjects and then joined his father for the 1301 Scottish campaign; he took an army of around 300 soldiers north with him and captured Turnberry Castle.[51] Prince Edward also took part in the 1303 campaign during which he besieged Brechin Castle, deploying his own siege engine in the operation.[52] In the spring of 1304, Edward conducted negotiations with the rebel Scottish leaders on the King's behalf and, when these failed, he joined his father for the siege of Stirling Castle.[53]

In 1305, Edward and his father quarrelled, probably over the issue of money.[54] The prince had an altercation with Bishop Walter Langton, who served as the royal treasurer, apparently over the amount of financial support Edward received from the Crown.[53] The king defended his treasurer, and banished Prince Edward and his companions from his court, cutting off their financial support.[55] After some negotiations involving family members and friends, the two men were reconciled.[56]

The Scottish conflict flared up once again in 1306, when Robert the Bruce killed his rival John Comyn III of Badenoch, and declared himself King of the Scots.[57] Edward I mobilised a fresh army, but decided that, this time, his son would be formally in charge of the expedition.[57] Prince Edward was made the duke of Aquitaine and then, along with many other young men, he was knighted in a lavish ceremony at Westminster Abbey called the Feast of the Swans.[58] Amid a huge feast in the neighbouring hall, reminiscent of Arthurian legends and crusading events, the assembly took a collective oath to defeat Bruce.[59] It is unclear what role Prince Edward's forces played in the campaign that summer, which, under the orders of Edward I, saw a punitive, brutal retaliation against Bruce's faction in Scotland.[60][g] Edward returned to England in September, where diplomatic negotiations to finalise a date for his wedding to Isabella continued.[62]

Piers Gaveston and sexuality

[edit]

During this time, Edward became close to Piers Gaveston.[63] Gaveston was the son of one of the King's household knights whose lands lay adjacent to Gascony, and had himself joined Prince Edward's household in 1300, possibly on Edward I's instruction.[64] The two got on well; Gaveston became a squire and was soon being referred to as a close companion of Edward, before being knighted by the King during the Feast of the Swans in 1306.[65] The King then exiled Gaveston to Gascony in 1307 for reasons that remain unclear.[66] According to one chronicler, Edward had asked his father to allow him to give Gaveston the County of Ponthieu, and the King responded furiously, pulling his son's hair out in great handfuls, before exiling Gaveston.[67] The official court records, however, show Gaveston being only temporarily exiled, supported by a comfortable stipend; no reason is given for the order, suggesting that it may have been an act aimed at punishing the prince.[68]

The possibility that Edward had a sexual relationship with Gaveston or his later favourites has been extensively discussed by historians, complicated by the paucity of surviving evidence to determine for certain the details of their relationships.[69][h] Homosexuality was fiercely condemned by the Church in 14th-century England, which equated it with heresy.[71] Both men had sexual relationships with their wives, who bore them children; Edward also had an illegitimate son, and may have had an affair with his niece, Eleanor de Clare.[72]

The contemporary evidence supporting their homosexual relationship comes primarily from an anonymous chronicler in the 1320s who described how Edward "felt such love" for Gaveston that "he entered into a covenant of constancy, and bound himself with him before all other mortals with a bond of indissoluble love, firmly drawn up and fastened with a knot."[73] The first specific suggestion that Edward engaged in sex with men was recorded in 1334, when Adam Orleton, the Bishop of Winchester, was accused of having stated in 1326 that Edward was a "sodomite", although Orleton defended himself by arguing that he had meant that Edward's adviser, Hugh Despenser the Younger, was a sodomite, rather than the late king.[74] The Meaux Chronicle from the 1390s simply notes that Edward gave himself "too much to the vice of sodomy".[75]

Alternatively, Edward and Gaveston may have simply been friends with a close working relationship.[76] Contemporary chronicler comments are vaguely worded; Orleton's allegations were at least in part politically motivated, and are very similar to the highly politicised sodomy allegations made against Pope Boniface VIII and the Knights Templar in 1303 and 1308, respectively.[77] Later accounts by chroniclers of Edward's activities may trace back to Orleton's original allegations, and were certainly adversely coloured by the events at the end of Edward's reign.[78] Such historians as Michael Prestwich and Seymour Phillips have argued that the public nature of the English royal court would have made it unlikely that any homosexual affairs would have remained discreet; neither the contemporary Church, Edward's father nor his father-in-law appear to have made any adverse comments about Edward's sexual behaviour.[79]

A more recent theory, proposed by the historian Pierre Chaplais, suggests that Edward and Gaveston entered into a bond of adoptive brotherhood.[80] Compacts of adoptive brotherhood, in which the participants pledged to support each other in a form of "brotherhood-in-arms", were not unknown between close male friends in the Middle Ages.[81] Many chroniclers described Edward and Gaveston's relationship as one of brotherhood, and one explicitly noted that Edward had taken Gaveston as his adopted brother.[82] Chaplais argues that the pair may have made a formal compact in either 1300 or 1301, and that they would have seen any later promises they made to separate or to leave each other as having been made under duress, and therefore invalid.[83]

Early reign (1307–1311)

[edit]Coronation and marriage

[edit]

Edward I mobilised another army for the Scottish campaign in 1307, which Prince Edward was due to join that summer, but the elderly king had been increasingly unwell and died on 7 July at Burgh by Sands.[84] Edward travelled from London immediately after the news reached him, and on 20 July he was proclaimed king.[85] He continued north into Scotland and on 4 August received homage from his Scottish supporters at Dumfries, before abandoning the campaign and returning south.[85] Edward promptly recalled Piers Gaveston, who was then in exile, and made him Earl of Cornwall, before arranging his marriage to the wealthy Margaret de Clare.[86][i] Edward also arrested his old adversary Bishop Langton, and dismissed him from his post as treasurer.[88] Edward I's body was kept at Waltham Abbey for several months before being taken for burial to Westminster, where Edward erected a simple marble tomb for his father.[89][j]

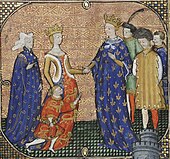

In 1308, Edward's marriage to Isabella of France proceeded.[91] Edward crossed the English Channel to France in January, leaving Gaveston as his custos regni in charge of the kingdom.[92] This arrangement was unusual, and involved unprecedented powers being delegated to Gaveston, backed by a specially engraved Great Seal.[93] Edward probably hoped that the marriage would strengthen his position in Gascony and bring him much needed funds.[9] The final negotiations, however, proved challenging: Edward and Philip IV did not like each other, and the French king drove a hard bargain over the size of Isabella's dower and the details of the administration of Edward's lands in France.[94] As part of the agreement, Edward gave homage to Philip for the Duchy of Aquitaine and agreed to a commission to complete the implementation of the 1303 Treaty of Paris.[95]

The pair were married in Boulogne on 25 January.[96] Edward gave Isabella a psalter as a wedding gift, and her father gave her gifts worth over 21,000 livres and a fragment of the True Cross.[97] The pair returned to England in February, where Edward had ordered Westminster Palace to be lavishly restored in readiness for their coronation and wedding feast, complete with marble tables, forty ovens and a fountain that produced wine and pimento, a spiced medieval drink.[98] After some delays, the ceremony went ahead on 25 February at Westminster Abbey, under the guidance of Henry Woodlock, the Bishop of Winchester.[99] As part of the coronation, Edward swore to uphold "the rightful laws and customs which the community of the realm shall have chosen".[100] It is uncertain what this meant: It might have been intended to force Edward to accept future legislation, it may have been inserted to prevent him from overturning any future vows he might take, or it may have been an attempt by the king to ingratiate himself with the barons.[101][k] The event was marred by the large crowds of eager spectators who surged into the palace, knocking down a wall and forcing Edward to flee by the back door.[102]

Isabella was only twelve at the time of her wedding, young even by the standards of the period, and Edward probably had sexual relations with mistresses during their first few years together.[103][104] During this time he fathered an illegitimate son, Adam, who was born possibly as early as 1307.[103][104] Edward and Isabella's first son, the future Edward III, was born in 1312 amid great celebrations, and three more children followed: John in 1316, Eleanor in 1318 and Joan in 1321.[104][105]

Tensions over Gaveston

[edit]

Gaveston's return from exile in 1307 was initially accepted by the barons, but opposition quickly grew.[106] He appeared to have an excessive influence on royal policy, leading to complaints from one chronicler that there were "two kings reigning in one kingdom, the one in name and the other in deed".[107] Accusations, probably untrue, were levelled at Gaveston that he had stolen royal funds and had purloined Isabella's wedding presents.[108] Gaveston had played a key role at Edward's coronation, provoking fury from both the English and the French contingents about the earl's ceremonial precedence and magnificent clothes, and about Edward's apparent preference for Gaveston's company over that of Isabella at the feast.[109]

Parliament met in February 1308 in a heated atmosphere.[110] Edward was eager to discuss the potential for governmental reform, but the barons were unwilling to begin any such debate until the problem of Gaveston had been resolved.[110] Violence seemed likely, but the situation was resolved through the mediation of the moderate Henry de Lacy, 3rd Earl of Lincoln, who convinced the barons to back down.[111] A fresh parliament was held in April, where the barons once again criticised Gaveston, demanding his exile, this time supported by Isabella and the French monarchy.[112] Edward resisted, but finally acquiesced, agreeing to send Gaveston to Aquitaine, under threat of excommunication by the Archbishop of Canterbury should he return.[113] At the last moment, Edward changed his mind and instead sent Gaveston to Dublin, appointing him as the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland.[114]

Edward called for a fresh military campaign for Scotland, but this idea was quietly abandoned, and instead the king and the barons met in August 1308 to discuss reform.[115] Behind the scenes, Edward started negotiations to convince both Pope Clement V and Philip IV to allow Gaveston to return to England, offering in exchange to suppress the Knights Templar in England, and to release Bishop Langton from prison.[116] Edward called a new meeting of members of the Church and key barons in January 1309, and the leading earls then gathered in March and April, possibly under the leadership of Thomas, 2nd Earl of Lancaster.[117] Another parliament followed, which refused to allow Gaveston to return to England, but offered to grant Edward additional taxes if he agreed to a programme of reform.[118]

Edward sent assurances to the Pope that the conflict surrounding Gaveston's role was at an end.[119] On the basis of these promises, and procedural concerns about how the original decision had been taken, the Pope agreed to annul the Archbishop's threat to excommunicate Gaveston, thus opening the possibility of Gaveston's return.[120] Gaveston arrived back in England in June, where he was met by Edward.[121] At the parliament the next month, Edward made a range of concessions to placate those opposed to Gaveston, including agreeing to limit the powers of the royal steward and the marshal of the royal household, to regulate the Crown's unpopular powers of purveyance, and to abandon recently enacted customs legislation; in return, parliament agreed to fresh taxes for the war in Scotland.[122] Temporarily, at least, Edward and the barons appeared to have come to a successful compromise.[123]

Ordinances of 1311

[edit]Following his return, Gaveston's relationship with the major barons became increasingly difficult.[124] He was considered arrogant, and he took to referring to the earls by offensive names, including calling one of their more powerful members the "dog of Warwick".[125] The Earl of Lancaster and Gaveston's enemies refused to attend parliament in 1310 because Gaveston would be present.[126] Edward was facing increasing financial problems, owing £22,000 to his Frescobaldi Italian bankers, and facing protests about how he was using his right of prises to acquire supplies for the war in Scotland.[127] His attempts to raise an army for Scotland collapsed and the earls suspended the collection of the new taxes.[128]

The king and parliament met again in February 1310, and the proposed discussions of Scottish policy were replaced by debate of domestic problems.[129] Edward was petitioned to abandon Gaveston as his counsellor and instead adopt the advice of 21 elected barons, termed Ordainers, who would carry out a widespread reform of both the government and the royal household.[130] Under huge pressure, he agreed to the proposal and the Ordainers were elected, broadly evenly split between reformers and conservatives.[131] While the Ordainers began their plans for reform, Edward and Gaveston took a new army of around 4,700 men to Scotland, where the military situation had continued to deteriorate.[132] Robert the Bruce declined to give battle and the campaign progressed ineffectually over the winter until supplies and money ran out in 1311, forcing Edward to return south.[133]

By now the Ordainers had drawn up their Ordinances for reform and Edward had little political choice but to give way and accept them in October.[134] The Ordinances of 1311 contained clauses limiting the king's right to go to war or to grant land without parliament's approval, giving parliament control over the royal administration, abolishing the system of prises, excluding the Frescobaldi bankers, and introducing a system to monitor the adherence to the Ordinances.[135] In addition, the Ordinances exiled Gaveston once again, this time with instructions that he should not be allowed to live anywhere within Edward's lands, including Gascony and Ireland, and that he should be stripped of his titles.[136] Edward retreated to his estates at Windsor and Kings Langley; Gaveston left England, possibly for northern France or Flanders.[137]

Mid-reign (1311–1321)

[edit]Death of Gaveston

[edit]Tensions between Edward and the barons remained high, and the earls opposed to the king kept their personal armies mobilised late into 1311.[138] By now Edward had become estranged from his cousin, the Earl of Lancaster, who was also the Earl of Leicester, Lincoln, Salisbury and Derby, with an income of around £11,000 a year from his lands, almost double that of the next wealthiest baron.[139] Backed by the earls of Arundel, Gloucester, Hereford, Pembroke and Warwick, Lancaster led a powerful faction in England, but he was not personally interested in practical administration, nor was he a particularly imaginative or effective politician.[140]

Edward responded to the baronial threat by revoking the Ordinances and recalling Gaveston to England, being reunited with him at York in January 1312.[141] The barons were furious and met in London, where Gaveston was excommunicated by the Archbishop of Canterbury and plans were put in place to capture Gaveston and prevent him from fleeing to Scotland.[142] Edward, Isabella and Gaveston left for Newcastle, pursued by Lancaster and his followers.[143] Abandoning many of their belongings, the royal party fled by ship and landed at Scarborough, where Gaveston stayed while Edward and Isabella returned to York.[144] After a short siege, Gaveston surrendered to the earls of Pembroke and Surrey, on the promise that he would not be harmed.[145] He had with him a huge collection of gold, silver and gems, probably part of the royal treasury, which he was later accused of having stolen from Edward.[146]

On the way back from the north, Pembroke stopped in the village of Deddington in the Midlands, putting Gaveston under guard there while he went to visit his wife.[147] The Earl of Warwick took this opportunity to seize Gaveston, taking him to Warwick Castle, where the Earl of Lancaster and the rest of his faction assembled on 18 June.[148] At a brief trial, Gaveston was declared guilty of being a traitor under the terms of the Ordinances; he was beheaded on Blacklow Hill the following day, under the authority of Lancaster.[149] Gaveston's body was not buried until 1315, when his funeral was held in King's Langley Priory.[150]

Tensions with Lancaster and France

[edit]

Reactions to the death of Gaveston varied considerably.[151] Edward was furious and deeply upset over what he saw as the murder of Gaveston; he made provisions for Gaveston's family, and intended to take revenge on the barons involved.[152] The earls of Pembroke and Surrey were embarrassed and angry about Warwick's actions, and shifted their support to Edward in the aftermath.[153] To Lancaster and his core of supporters, the execution had been both legal and necessary to preserve the stability of the kingdom.[151] Civil war again appeared likely, but in December, the Earl of Pembroke negotiated a potential peace treaty between the two sides, which would pardon the opposition barons for the killing of Gaveston, in exchange for their support for a fresh campaign in Scotland.[154] Lancaster and Warwick, however, did not give the treaty their immediate approval, and further negotiations continued through most of 1313.[155]

Meanwhile, the Earl of Pembroke had been negotiating with France to resolve the long-standing disagreements over the administration of Gascony, and as part of this Edward and Isabella agreed to travel to Paris in June 1313 to meet with Philip IV.[156] Edward probably hoped both to resolve the problems in the south of France and to win Philip's support in the dispute with the barons; for Philip it was an opportunity to impress his son-in-law with his power and wealth.[157] It proved a spectacular visit, including a grand ceremony in which the two kings knighted Philip's sons and two hundred other men in Notre-Dame de Paris, large banquets along the River Seine, and a public declaration that both kings and their queens would join a crusade to the Levant.[158] Philip gave lenient terms for settling the problems in Gascony, and the event was spoiled only by a serious fire in Edward's quarters.[159]

On his return from France, Edward found his political position greatly strengthened.[160] After intense negotiation, the earls, including Lancaster and Warwick, came to a compromise in October 1313, fundamentally very similar to the draft agreement of the previous December.[161] Edward's finances improved, thanks to parliament agreeing to the raising of taxes, a loan of 160,000 florins (£25,000) from the Pope, £33,000 borrowed from Philip, and further loans organised by Edward's new Italian banker, Antonio Pessagno.[162] For the first time in his reign, Edward's government was well funded.[163]

Battle of Bannockburn

[edit]

By 1314, Robert the Bruce had recaptured most of the castles in Scotland once held by Edward, pushing raiding parties into northern England as far as Carlisle.[164] In response, Edward planned a major military campaign with the support of Lancaster and the barons, mustering a large army between 15,000 and 20,000 strong.[165] Meanwhile, Robert had besieged Stirling Castle, a key fortification in Scotland; its English commander had stated that unless Edward arrived by 24 June, he would surrender.[164] News of this reached the king in late May, and he decided to speed up his march north from Berwick-upon-Tweed to relieve the castle.[166] Robert, with between 5,500 and 6,500 troops, predominantly spearmen, prepared to prevent Edward's forces from reaching Stirling.[167]

The battle began on 23 June as the English army attempted to force its way across the high ground of the Bannock Burn, which was surrounded by marshland.[168] Skirmishing between the two sides broke out, resulting in the death of Sir Henry de Bohun, whom Robert killed in personal combat.[168] Edward continued his advance the following day, and encountered the bulk of the Scottish army as they emerged from the woods of New Park.[169] Edward appears not to have expected the Scots to give battle here, and as a result had kept his forces in marching, rather than battle, order, with the archers—who would usually have been used to break up enemy spear formations—at the back of his army, rather than the front.[169] His cavalry found it hard to operate in the cramped terrain and were crushed by Robert's spearmen.[170] The English army was overwhelmed and its leaders were unable to regain control.[170]

Edward stayed behind to fight, but it became obvious to the Earl of Pembroke that the battle was lost and he dragged the king away from the battlefield, hotly pursued by the Scottish forces.[171] Edward only just escaped the heavy fighting, making a vow to found a Carmelite religious house at Oxford if he survived.[171] The historian Roy Haines describes the defeat as a "calamity of stunning proportions" for the English, whose losses in the battle were huge.[172] In the aftermath of the defeat, Edward retreated to Dunbar, then travelled by ship to Berwick, and then back to York; in his absence, Stirling Castle quickly fell.[173]

Famine and criticism

[edit]After the fiasco of Bannockburn, the Earls of Lancaster and Warwick saw their political influence increase, and they pressured Edward to re-implement the Ordinances of 1311.[174] Lancaster became the head of the royal council in 1316, promising to take forward the Ordinances through a new reform commission, but he appears to have abandoned this role soon afterwards, partially because of disagreements with the other barons, and possibly because of ill-health.[175] Lancaster refused to meet with Edward in parliament for the next two years, bringing effective governance to a standstill. This stymied any hopes for a fresh campaign into Scotland and raised fears of civil war.[176] After much negotiation, once again involving the Earl of Pembroke, Edward and Lancaster finally agreed to the Treaty of Leake in August 1318, which pardoned Lancaster and his faction and established a new royal council, temporarily averting conflict.[24][177]

Edward's difficulties were exacerbated by prolonged problems in English agriculture, part of a wider phenomenon in northern Europe known as the Great Famine. It began with torrential rains in late 1314, followed by a very cold winter and heavy rains the following spring that killed many sheep and cattle. The bad weather continued, almost unabated, into 1321, resulting in a string of bad harvests.[178] Revenues from the exports of wool plummeted and the price of food rose, despite attempts by Edward's government to control prices.[179] Edward called for hoarders to release food, and tried to encourage both internal trade and the importation of grain, but with little success.[180] The requisitioning of provisions for the royal court during the famine years only added to tensions.[181]

Meanwhile, Robert the Bruce exploited his victory at Bannockburn to raid northern England, initially attacking Carlisle and Berwick, and then reaching further south into Lancashire and Yorkshire, even threatening York itself.[182] Edward undertook an expensive but unsuccessful campaign to stem the advance in 1319, but the famine made it increasingly difficult to keep his garrisons supplied with food.[183] Meanwhile, a Scottish expedition led by Robert's brother Edward Bruce successfully invaded Ireland in 1315. Edward Bruce declared himself the High King of Ireland.[184] He was finally defeated in 1318 by Edward II's Irish justiciar, Edmund Butler, at the Battle of Faughart, and Edward Bruce's severed head was sent back to Edward II.[185] Revolts also broke out in Lancashire and Bristol in 1315, and in Glamorgan in Wales in 1316, but were suppressed.[186]

The famine and the Scottish policy were felt to be a punishment from God, and complaints about Edward multiplied, one contemporary poem describing the "Evil Times of Edward II".[187] Many criticised Edward's "improper" and ignoble interest in rural pursuits.[188] In 1318, a mentally ill man named John of Powderham appeared in Oxford, claiming that he was the real Edward II, and that Edward was a changeling, swapped at birth.[189] John was duly executed, but his claims resonated with those criticising Edward for his lack of regal behaviour and steady leadership.[189][190] Opposition also grew around Edward's treatment of his royal favourites.[191]

Edward had managed to retain some of his previous advisers, despite attempts by the Ordainers to remove them, and divided the extensive de Clare inheritance among two of his new favourites, the former household knights Hugh Audley and Roger Damory, instantly making them extremely rich.[192][l] Many of the moderates who had helped deliver the peaceful compromise in 1318 now began to turn against Edward, making violence ever more likely.[194]

Later reign (1321–1326)

[edit]The Despenser War

[edit]The long-threatened civil war finally broke out in England in 1321,[195] triggered by the tension between many of the barons and the royal favourites, the Despenser family.[196] Hugh Despenser the Elder had served both Edward and his father, while Hugh Despenser the Younger had married into the wealthy de Clare family, become the King's chamberlain, and acquired Glamorgan in the Welsh Marches in 1317.[197] Hugh the Younger subsequently expanded his holdings and power across Wales, mainly at the expense of the other Marcher Lords.[198] The Earl of Lancaster and the Despensers were fierce enemies, and Lancaster's antipathy was shared by most of the Despensers' neighbours, including the Earl of Hereford, the Mortimer family and the recently elevated Hugh Audley and Roger Damory.[199] Edward, however, increasingly relied on the Despensers for advice and support, and he was particularly close to Hugh the Younger, whom one chronicler noted he "loved ... dearly with all his heart and mind".[200]

In early 1321, Lancaster mobilised a coalition of the Despensers' enemies across the Marcher territories.[201] Edward and Hugh the Younger became aware of these plans in March and headed west, hoping that negotiations led by the moderate Earl of Pembroke would defuse the crisis.[202] This time, Pembroke made his excuses and declined to intervene, and war broke out in May.[203] The Despensers' lands were quickly seized by a coalition of the Marcher Lords and the local gentry, and Lancaster held a high-level gathering of the barons and clergy in June which condemned the Despensers for having broken the Ordinances.[204] Edward attempted reconciliation, but in July the opposition occupied London and called for the permanent removal of the Despensers.[205] Fearing that he might be deposed if he refused, Edward agreed to exile the Despensers and pardoned the Marcher Lords for their actions.[206]

Edward began to plan his revenge.[207] With the help of Pembroke, he formed a small coalition of his half-brothers, a few of the earls and some of the senior clergy, and prepared for war.[208] Edward started with Bartholomew de Badlesmere, 1st Baron Badlesmere, and Isabella was sent to Bartholomew's stronghold, Leeds Castle, to deliberately create a casus belli.[209] Bartholomew's wife, Margaret, took the bait and her men killed several of Isabella's retinue, giving Edward an excuse to intervene.[209] Lancaster refused to help Bartholomew, his personal enemy, and Edward quickly regained control of south-east England.[210] Alarmed, Lancaster now mobilised his own army in the north of England, and Edward mustered his own forces in the south-west.[211] The Despensers returned from exile and were pardoned by the royal council.[212]

In December, Edward led his army across the River Severn and advanced into the Welsh Marches, where the opposition forces had gathered.[213] The coalition of Marcher Lords crumbled and the Mortimers surrendered to Edward,[214] but Damory, Audley, and the Earl of Hereford marched north in January to join Lancaster, who had laid siege the king's castle at Tickhill.[215] Bolstered by fresh reinforcements from the Marcher Lords, Edward pursued them, meeting Lancaster's army on 10 March at Burton-on-Trent. Lancaster, outnumbered, retreated without a fight, fleeing north.[215] Andrew Harclay cornered Lancaster at the Battle of Boroughbridge, and captured the earl.[216] Edward and Hugh the Younger met Lancaster at Pontefract Castle, where, after a summary trial, the earl was found guilty of treason and beheaded.[217]

Edward and the Despensers

[edit]

Edward punished Lancaster's supporters through a system of special courts across the country, with the judges instructed in advance how to sentence the accused, who were not allowed to speak in their own defence.[218] Many of these so-called "Contrariants" were simply executed, and others were imprisoned or fined, with their lands seized and their surviving relatives detained.[219] The Earl of Pembroke, whom Edward now mistrusted, was arrested; he was released only after pledging all his possessions as collateral for his own loyalty.[220] Edward was able to reward his loyal supporters, especially the Despenser family, with the confiscated estates and new titles.[221] The fines and confiscations made Edward rich: almost £15,000 was brought in during the first few months, and by 1326, Edward's treasury contained £62,000.[222] A parliament was held at York on 2 May 1322 at which the Ordinances were formally revoked through the Statute of York, and fresh taxes agreed for a new campaign against the Scots.[223]

The English campaign against Scotland was planned on a massive scale, with a force of about 23,000 men.[224] Edward advanced through Lothian towards Edinburgh, but Robert the Bruce declined to meet him in battle, drawing Edward further into Scotland. Plans to resupply the campaign by sea failed, and the large army rapidly ran out of food.[224] Edward was forced to retreat south of the border, pursued by Scottish raiding parties.[224] Edward's illegitimate son, Adam, died during the campaign, and the raiding parties almost captured Isabella, who was staying at Tynemouth and was forced to flee by sea.[225] Edward planned a fresh campaign, backed by a round of further taxes, but confidence in his Scottish policy was diminishing.[226] Andrew Harclay, instrumental in securing Edward's victories the previous year and recently made the Earl of Carlisle, independently negotiated a peace treaty with Robert the Bruce, proposing that Edward would recognise Robert as the King of Scotland and that, in return, Robert would cease to interfere in England.[227] Edward was furious and immediately executed Harclay, but agreed to a thirteen-year truce with Robert.[228]

Hugh Despenser the Younger lived and ruled in grand style, playing a leading role in Edward's government, and executing policy through a wide network of family retainers.[229] Supported by Chancellor Robert Baldock and Lord Treasurer Walter Stapledon, the Despensers accumulated land and wealth, using their position in government to provide superficial cover for what historian Seymour Phillips describes as "the reality of fraud, threats of violence and abuse of legal procedure".[230] Meanwhile, Edward faced growing opposition. Miracles were reported around the late Earl of Lancaster's tomb, and at the gallows used to execute members of the opposition in Bristol.[231] Law and order began to break down, encouraged by the chaos caused by the seizure of lands.[232] The old opposition consisting of Marcher Lords' associates attempted to free the prisoners Edward held in Wallingford Castle, and Roger Mortimer, one of the most prominent of the imprisoned Marcher Lords, escaped from the Tower of London and fled to France.[233]

War with France

[edit]The disagreements between Edward and the French Crown over the Duchy of Gascony led to the War of Saint-Sardos in 1324.[234] Charles, Edward's brother-in-law, had become King of France in 1322, and was more aggressive than his predecessors.[235] In 1323, he insisted that Edward come to Paris to give homage for Gascony, and demanded that Edward's administrators in Gascony allow French officials there to carry out orders given in Paris.[236] Matters came to a head in October when a group of Edward's soldiers hanged a French sergeant for attempting to build a new fortified town in the Agenais, a contested section of the Gascon border.[237] Edward denied any responsibility for this incident, but relations between Edward and Charles soured.[238] In 1324, Edward dispatched the Earl of Pembroke to Paris to broker a solution, but the earl died suddenly of an illness along the way. Charles mobilised his army and ordered the invasion of Gascony.[239]

Edward's forces in Gascony were around 4,400 strong, but the French army, commanded by Charles of Valois, numbered 7,000.[240] Valois took the Agenais and then advanced further and cut off the main city of Bordeaux.[240] In response, Edward ordered the arrest of any French persons in England and seized Isabella's lands, on the basis that she was of French origin.[241] In November 1324 he met with the earls and the English Church, who recommended that Edward should lead a force of 11,000 men to Gascony.[242] Edward decided not to go personally, sending instead the Earl of Surrey.[243] Meanwhile, Edward opened up fresh negotiations with the French king.[244] Charles advanced various proposals, the most tempting of which was the suggestion that if Isabella and Prince Edward were to travel to Paris, and the prince was to give homage to Charles for Gascony, he would terminate the war and return the Agenais.[245] Edward and his advisers had concerns about sending the prince to France, but agreed to send Isabella on her own as an envoy in March 1325.[246]

Fall from power (1326–1327)

[edit]Rift with Isabella

[edit]

Isabella, with Edward's envoys, carried out negotiations with the French in late March.[247] The negotiations proved difficult, and they arrived at a settlement only after Isabella personally intervened with her brother, Charles.[247] The terms favoured the French Crown: In particular, Edward would give homage in person to Charles for Gascony.[248] Concerned about the consequences of war breaking out once again, Edward agreed to the treaty but decided to give Gascony to his son, Edward, and sent the prince to give homage in Paris.[249] The young Prince Edward crossed the English Channel and completed the bargain in September.[250][m]

Edward now expected Isabella and their son to return to England, but instead she remained in France and showed no intention of making her way back.[252] Until 1322, Edward and Isabella's marriage appears to have been successful, but by the time Isabella left for France in 1325, it had deteriorated.[253] Isabella appears to have disliked Hugh Despenser the Younger intensely, not least because of his abuse of high-status women.[254] Isabella was embarrassed that she had fled from Scottish armies three times during her marriage to Edward, and she blamed Hugh for the final occurrence in 1322.[255] When Edward had negotiated the recent truce with Robert the Bruce, he had severely disadvantaged a range of noble families who owned land in Scotland, including the Beaumonts, close friends of Isabella.[256] She was also angry about the arrest of her household and seizure of her lands in 1324. Finally, Edward had taken away her children and given custody of them to Hugh Despenser's wife.[257]

By February 1326 it was clear that Isabella was involved in a relationship with an exiled Marcher Lord, Roger Mortimer.[258] It is unclear when Isabella first met Mortimer or when their relationship began, but they both wanted to see Edward and the Despensers removed from power.[259][n] Edward appealed for his son to return, and for Charles to intervene on his behalf, but this had no effect.[261]

Edward's opponents began to gather around Isabella and Mortimer in Paris, and Edward became increasingly anxious about the possibility that Mortimer might invade England.[262] Isabella and Mortimer turned to William I, Count of Hainaut, and proposed a marriage between Prince Edward and William's daughter, Philippa.[263] In return for the advantageous alliance with the English heir to the throne, and a sizeable dower for the bride, William offered 132 transport vessels and eight warships to assist in the invasion of England.[264] Prince Edward and Philippa were betrothed on 27 August, and Isabella and Mortimer prepared for their campaign.[265]

Invasion

[edit]

During August and September 1326, Edward mobilised his defences along the coasts of England to protect against the possibility of an invasion either by France or by Roger Mortimer.[267] Fleets were gathered at the ports of Portsmouth in the south and Orwell on the east coast, and a raiding force of 1,600 men was sent across the English Channel into Normandy as a diversionary attack.[268] Edward issued a nationalistic appeal for his subjects to defend the kingdom, but with little impact.[269] The regime's hold on power at the local level was fragile, the Despensers were widely disliked, and many of those Edward entrusted with the defence of the kingdom proved incompetent or promptly turned against the regime.[270] Some 2,000 men were ordered to gather at Orwell to repel any invasion, but only 55 appear to have actually arrived.[271]

Roger Mortimer, Isabella and thirteen-year-old Prince Edward, accompanied by King Edward's half-brother Edmund of Woodstock, landed in Orwell on 24 September with a small force of men and met with no resistance.[272] Instead, enemies of the Despensers moved rapidly to join them, including Edward's other half-brother, Thomas of Brotherton; Henry, 3rd Earl of Lancaster, who had inherited the earldom from his brother Thomas; and a range of senior clergy.[273] Ensconced in the residence halls of the fortified and secure Tower of London, Edward attempted to garner support from within the capital. The city of London rose against his government, and on 2 October he left London, taking the Despensers with him.[274] London descended into anarchy, as mobs attacked Edward's remaining officials and associates, killing his former treasurer Walter Stapledon in St Paul's Cathedral, and taking the Tower and releasing the prisoners inside.[275]

Edward continued west up the Thames Valley, reaching Gloucester between 9 and 12 October; he hoped to reach Wales and from there mobilise an army against the invaders.[276] Mortimer and Isabella were not far behind. Proclamations condemned the Despensers' recent regime. Day by day they gathered new supporters.[277] Edward and the younger Despenser crossed over the border and set sail from Chepstow, probably aiming first for Lundy and then for Ireland, where the king hoped to receive refuge and raise a fresh army.[278] Bad weather drove them back, though, and they landed at Cardiff. Edward retreated to Caerphilly Castle and attempted to rally his remaining forces.[279]

Edward's authority collapsed in England where, in his absence, Isabella's faction took over the administration with the support of the Church.[280] Her forces surrounded Bristol, where Hugh Despenser the Elder had taken shelter; he surrendered and was promptly executed.[281] Edward and Hugh the Younger fled their castle around 2 November, leaving behind jewellery, considerable supplies, and at least £13,000 in cash, possibly once again hoping to reach Ireland, but on 16 November they were betrayed and captured by a search party north of Caerphilly.[282] Edward was escorted first to Monmouth Castle, and from there back into England, where he was held at the Earl of Lancaster's fortress at Kenilworth.[283] Edward's final remaining forces, by now besieged in Caerphilly Castle, surrendered after four months in March 1327.[284]

Abdication

[edit]

Isabella and Mortimer rapidly took revenge on the former regime. Hugh Despenser the Younger was put on trial, declared a traitor and sentenced to be disembowelled, castrated and quartered; he was duly executed on 24 November 1326.[285] Edward's former chancellor, Robert Baldock, died in Fleet Prison; the Earl of Arundel was beheaded.[286] Edward's position, however, was problematic; he was still married to Isabella and, in principle, he remained the king, but most of the new administration had much to lose were he to be released and potentially regain power.[287]

There was no established procedure for removing an English king.[288] Adam Orleton, the bishop of Hereford, made a series of public allegations about Edward's conduct as king, and in January 1327 a parliament convened at Westminster at which the question of Edward's future was raised; Edward refused to attend the gathering.[289] Parliament, initially ambivalent, responded to the London crowds that called for the king's son Edward to take the throne. On 12 January the leading barons and clergy agreed that Edward II should be removed and replaced by his son.[290] The following day it was presented to an assembly of the barons, where it was argued that Edward's weak leadership and personal faults had led the kingdom into disaster, and that he was incompetent to lead the country.[291]

Shortly after this, a representative delegation of barons, clergy and knights was sent to Kenilworth to speak to the king.[292] On 20 January 1327, the Earl of Lancaster and the bishops of Winchester and Lincoln met privately with Edward in the castle.[293] They informed Edward that if he were to resign as monarch, his son Edward would succeed him, but if he failed to do so, his son might be disinherited as well, and the crown given to an alternative candidate.[294] In tears, Edward agreed to abdicate, and on 21 January, Sir William Trussell, representing the kingdom as a whole, withdrew his homage and formally ended Edward's reign.[295] A proclamation was sent to London, announcing that Edward, now known as Edward of Caernarvon, had freely resigned his kingdom and that his son Edward would succeed him. The coronation took place at Westminster Abbey on 1 February 1327.[296]

Death (1327)

[edit]Death and aftermath

[edit]

Those opposed to the new government began to make plans to free Edward, and Roger Mortimer decided to move him to the more secure location of Berkeley Castle in Gloucestershire, where Edward arrived around 5 April 1327.[297] Once at the castle, he was kept in the custody of Mortimer's son-in-law, Thomas de Berkeley, 3rd Baron Berkeley, and John Maltravers, who were given £5 a day for Edward's maintenance.[298] It is unclear how well cared for Edward was; the records show luxury goods being bought on his behalf, but some chroniclers suggest that he was often mistreated.[298] A poem, the "Lament of Edward II", has been attributed to Edward during his imprisonment by some scholars, but this is disputed.[299][o]

Concerns continued to be raised over fresh plots to liberate Edward, some involving the Dominican order and former household knights, and one such attempt got at least as far as breaking into the prison within the castle.[300] As a result of these threats, Edward was moved around to other locations in secret for a period, before returning to permanent custody at the castle in late summer 1327.[301] The political situation remained unstable, and new plots appear to have been formed to free him.[302]

On 23 September Edward III was informed that his father had died at Berkeley Castle during the night of 21 September.[303] Most historians agree that Edward II did die at Berkeley on that date, although there is a minority view that he died much later.[304][p] His death was, as Mark Ormrod notes, "suspiciously timely", as it simplified Mortimer's political problems considerably, and most historians believe that Edward probably was murdered on the orders of the new regime, although it is impossible to be certain.[305] Several of the individuals suspected of involvement in the death, including Sir Thomas Gurney, Maltravers and William Ockley, later fled.[306][q] If Edward died from natural causes, his death may have been hastened by depression following his imprisonment.[308]

The rule of Isabella and Mortimer did not last long after the announcement of Edward's death. They made peace with the Scots in the Treaty of Northampton, but this move was highly unpopular.[309] Isabella and Mortimer both amassed and spent great wealth, and criticism of them mounted.[310] Relations between Mortimer and Edward III became strained and in 1330 the king conducted a coup d'état at Nottingham Castle.[311] He arrested Mortimer and then executed him on fourteen charges of treason, including the murder of Edward II.[312] Edward III's government sought to blame Mortimer for all the recent problems, effectively politically rehabilitating Edward II.[313] Edward III put his mother under arrest but she was released soon after.[314]

Burial and cult

[edit]

Edward's body was embalmed at Berkeley Castle, where it was viewed by local leaders from Bristol and Gloucester.[315] It was then taken to Gloucester Abbey on 21 October, and on 20 December, Edward was buried by the high altar, the funeral having probably been delayed to allow Edward III to attend in person.[316][r] Gloucester was probably chosen because other abbeys had refused or been forbidden to take the king's body, and because it was close to Berkeley.[318][s] The funeral was a grand affair and cost £351 in total, complete with gilt lions, standards painted with gold leaf and oak barriers to manage the anticipated crowds.[320] Edward III's government probably hoped to put a veneer of normality over the recent political events, increasing the legitimacy of the young king's own reign.[321]

A temporary wooden effigy with a copper crown was made for the funeral; this is the first known use of a funeral effigy in England, and was probably necessary because of the condition of the King's body, as he had been dead for three months.[322] Edward's heart was removed, placed in a silver container, and later buried with Isabella at Newgate Church in London.[323] His tomb includes a very early example of an English alabaster effigy, with a tomb chest and a canopy made of oolite and Purbeck stone.[324] Edward was buried in the shirt, coif and gloves from his coronation, and his effigy depicts him as king, holding a sceptre and orb, and wearing a strawberry-leaf crown.[325] The effigy features a pronounced lower lip, and may be a close likeness of Edward.[326][t]

Edward II's tomb rapidly became a popular site for visitors, probably encouraged by the local monks, who lacked an existing pilgrimage attraction.[328] Visitors donated extensively to the abbey, allowing the monks to rebuild much of the surrounding church in the 1330s.[324] Miracles reportedly took place at the tomb, and modifications had to be made to enable visitors to walk around it in larger numbers.[329] The chronicler Geoffrey le Baker depicted Edward as a saintly, tortured martyr, and Richard II gave royal support for an unsuccessful bid to have Edward canonised in 1395.[330] The tomb was opened by officials in 1855, uncovering a wooden coffin, still in good condition, and a sealed lead coffin inside it.[331] The tomb remains in what is now Gloucester Cathedral, and was extensively restored in 2007 and 2008 at a cost of over £100,000.[332]

Controversies

[edit]Controversy rapidly surrounded Edward's death.[333] With Mortimer's execution in 1330, rumours began to circulate that Edward had been murdered at Berkeley Castle. Accounts that he had been killed by the insertion of a red-hot iron or poker into his anus slowly began to spread, possibly as a result of deliberate propaganda; chroniclers in the mid-1330s and 1340s disseminated this account further, supported in later years by Geoffrey le Baker's colourful account of the killing.[334] It became incorporated into most later histories of Edward, typically being linked to his possible homosexuality.[335] Most historians now dismiss this account of Edward's death, querying the logic in his captors murdering him in such an easily detectable fashion.[336][u]

Another set of theories surround the possibility that Edward did not really die in 1327. These theories typically involve the "Fieschi Letter", sent to Edward III by an Italian priest called Manuel Fieschi, who claimed that Edward escaped Berkeley Castle in 1327 with the help of a servant and ultimately retired to become a hermit in the Holy Roman Empire.[338] The body buried at Gloucester Cathedral was said to be that of the porter of Berkeley Castle, killed by the assassins and presented by them to Isabella as Edward's corpse to avoid punishment.[339] The letter is often linked to an account of Edward III meeting with a man called William the Welshman in Antwerp in 1338, who claimed to be Edward II.[340] Some parts of the letter's content are considered broadly accurate by historians, although other aspects of its account have been criticised as implausible.[341] A few historians have supported versions of its narrative. Paul C. Doherty questions the veracity of the letter and the identity of William the Welshman, but nonetheless has suspicions that Edward may have survived his imprisonment.[342] The popular historian Alison Weir believes the events in the letter to be essentially true, using the letter to argue that Isabella was innocent of murdering Edward.[343] and Natalie Fryde has claimed that Edward's survival is "a possibility".[344] The historian Ian Mortimer suggests that the story in Fieschi's letter is broadly accurate, but argues that it was in fact Mortimer and Isabella who had Edward secretly released, and who then faked his death, a fiction later maintained by Edward III when he came to power.[345] Ian Mortimer's account was criticised by most scholars when it was first published, in particular by historian David Carpenter, who argues that there is no "convincing evidence for Edward’s survival, let alone for it being the result of a Mortimer plot”.[346][v]

Edward as king

[edit]Kingship, government and law

[edit]Эдвард в конечном итоге был провалом как королем; Историк Майкл Прествич отмечает, что он «был ленивым и некомпетентным, подвергнулся вспышкам отказа от неважных проблем, но при этом нерешительный, когда дело дошло до серьезных вопросов», поддержанное описанием Роя Хейнса Эдварда как «некомпетентного и порочного» и как », и как« как « Нет человека бизнеса ». [348] Эдвард не только делегировал рутинное правительство своим подчиненным, но и принятие решений на более высоком уровне, но и Пьер Каслайс утверждает, что он «был не столько некомпетентным королем, сколько неохотно», предпочитая править через могущественного депутата, такого как Гвартовой Или Хью Дессенсер Младший. [ 349 ] Готовность Эдварда по продвижению своих любимых имела серьезные политические последствия, хотя он также пытался купить лояльность более широкой группировки дворян через гранты денег и сборов. [ 350 ] Однако он мог бы проявлять большой интерес к мелочам администрации, а иногда и в подробности широкого спектра проблем по всей Англии и его более широких доменах. [ 351 ] [ В ]

Одной из постоянных проблем Эдварда в течение большей части его правления была нехватка денег; Из долгов, которые он унаследовал от своего отца, около 60 000 фунтов стерлингов все еще были в 1320 -х годах. [ 353 ] Эдвард пробирался через многих казначеев и других финансовых чиновников, немногие из которых оставались долгими, увеличивая доходы через часто непопулярные налоги и реквизиция товаров, используя его право на приз. [ 354 ] Он также взял много займов, сначала через семью Фресскобальди, а затем через своего банкира Антонио Пессаньо. [ 354 ] Эдвард проявил большой интерес к финансовым вопросам к концу своего правления, не доверяя своим чиновникам и напрямую сокращая расходы его собственного домохозяйства. [ 355 ]

Эдвард отвечал за реализацию королевского правосудия через свою сеть судей и должностных лиц. [ 356 ] Неясно, в какой степени Эдвард проявил личный интерес к распределению справедливости, но, похоже, он в некоторой степени участвовал в первой части своего правления и все больше вмешался лично после 1322 года. [ 357 ] Эдвард широко использовал римскую гражданское право во время своего правления, когда спорил в защиту своих причин и фаворитов, которые могли привлечь критику со стороны тех, кто воспринимал это как отказ от установленных принципов английского общего права . [ 358 ] Эдвард также подвергся критике со стороны современников за то, что он позволил преподавателям эксплуатировать систему королевской справедливости для своих собственных целей; Дессенсеры, безусловно, злоупотребляли этой системой, хотя, насколько широко они сделали это, неясно. [ 359 ] На фоне политической турбулентности, вооруженных бандов и насилия распространились по всей Англии при правлении Эдварда, дестабилизируя позицию многих местных джентри ; Большая часть Ирландии также распалась в анархию. [ 360 ]

Согласно правлению Эдварда, важность парламента росла как средство принятия политических решений и ответа на петиции, хотя, как отмечает историк Клэр Валенте, собрания были «все еще таким же событием, как и институт». [ 361 ] После 1311 года парламент начал включать, в дополнение к баронам, представителей рыцарей и бурджессов , которые в последующие годы будут составлять « общины ». [ 362 ] Хотя парламент часто выступал против повышения новых налогов, активная оппозиция Эдварду в основном поступила в основном из баронов, а не самого парламента, хотя бароны действительно стремились использовать парламентские собрания как способ придать легитимность их давних политических требованиям. [ 363 ] После многих лет сопротивляясь этому, Эдвард начал вмешиваться в парламент во второй половине своего правления, чтобы достичь своих собственных политических целей. [ 364 ] Остается неясным, был ли он свергнут в 1327 году официальным собранием парламента или просто собранием политических классов наряду с существующим парламентом. [ 365 ]

Суд

[ редактировать ]

Королевский суд Эдварда был странным, путешествуя по всей стране с ним. [ 366 ] В Вестминстерском дворце размещались в Вестминстерском дворце, суд занимал комплекс из двух залов, семь камер и три часовни , а также другие небольшие комнаты, но из -за шотландского конфликта суд провел большую часть своего времени в Йоркшире и Нортумбрии. [ 367 ] В основе суда лежала королевская семья Эдварда, в свою очередь, разделена на «зал» и «Палату»; Размер домохозяйства со временем варьировался, но в 1317 году было около пятисот человек, в том числе домашних рыцарей, сквиров, а также кухонный и транспортный персонал. [ 368 ] Домохозяйство было окружено более широкой группой придворных и, по -видимому, также привлекла круг проституток и уголовных элементов. [ 369 ]

Музыка и менестрели были очень популярны в Корт Эдварда, но охота, по -видимому, была гораздо менее важной деятельностью, и было мало акцента на рыцарские события. [ 370 ] Эдвард интересовался зданиями и картинами, но менее в литературных работах, которые не были широко спонсированы в суде. [ 371 ] Было широкое использование золотых и серебряных тарелок, драгоценностей и эмалирования в суде, которые были бы богато оформлены. [ 372 ] [ x ] Эдвард держал верблюда в качестве домашнего животного и, будучи молодым человеком, взял с собой льва на кампании в Шотландию. [ 373 ] Суд можно было бы развлечь экзотическими способами: итальянским змеистом в 1312 году, а в следующем году-54 обнаженными французскими танцорами. [ 374 ] [ и ]

Религия

[ редактировать ]Подход Эдварда к религии был нормальным в течение периода, и историк Майкл Пресвич описывает его как «человека совершенно обычных религиозных взглядов». [ 376 ] На его дворе были ежедневные службы часовни и милостыню , и Эдвард благословил больных, хотя он делал это реже, чем свои предшественники. [ 376 ] Эдвард оставался близким к доминиканскому приказу, который помог его обучить, и последовал их совету, чтобы попросить папского разрешения быть помазанным со святым маслом Святого Томаса Кентерберийского в 1319 году; В этой просьбе была отклонена, что привело к некоторому смущению короля. [ 377 ] Эдвард поддержал расширение университетов во время его правления, создав Кингс-Холл в Кембридже для содействия обучению религиозному и гражданскому праву, Ориэльскому колледжу в Оксфорде и недолгого университета в Дублине . [ 378 ]

Эдвард наслаждался хорошими отношениями с Папой Климентом V , несмотря на неоднократное вмешательство короля в деятельность английской церкви, в том числе наказание епископов, с которыми он не согласен. [ 379 ] При поддержке Клемента Эдвард попытался получить финансовую поддержку английской церкви для его военных кампаний в Шотландии, включая налогообложение и заимствование денег на средства, собранные на крестовые походы. [ 380 ] Церковь относительно мало, чтобы повлиять или смягчить поведение Эдварда во время его правления, возможно, из-за личных интересов епископов и заботы о их собственной защите. [ 381 ]

Папа Иоанн XXII , избранный в 1316 году, обратился за поддержкой Эдварда нового крестового похода, а также был склонен поддержать его политически. [ 382 ] В 1317 году, в обмен на папскую поддержку в его войне с Шотландией, Эдвард согласился возобновить выплату ежегодной папской дани, которую впервые согласился королем Джоном в 1213 году; Однако Эдвард вскоре прекратил платежи, и никогда не предложил свое уважение, еще одну часть соглашения 1213 года. [ 382 ] В 1325 году Эдвард попросил папу Иоанна поручить ирландской церкви открыто проповедовать в пользу своего права управлять островом и угрожать отлучить любые противоположные голоса. [ 383 ]

Наследие

[ редактировать ]Историография

[ редактировать ]

Ни один хрониклер этого периода не является полностью заслуживающим доверия или непредвзятым, часто потому, что их рассказы были написаны, чтобы поддержать определенную причину, но ясно, что большинство современных летописцев очень критиковали Эдварда. [ 384 ] Полихронон например , , Вита Эдвардс Секнди , Вита и Морс Эдварди Секунди и геста Эдвард, все презервативы, привычки и выбор компаний. [ 385 ] Другие записи из его царствования показывают критику его современников, включая церковь и членов его собственной семьи. [ 386 ] Политические песни были написаны о нем, жалуясь на его неудачу в войне и его репрессивном правительстве. [ 387 ] Позже, в 14 веке, некоторые летописцы, такие как Джеффри Ле Бейкер и Томас Рингстед , реабилитировали Эдварда, представляя его как мученика и потенциального святого, хотя эта традиция вымерла в последующие годы. [ 388 ]

Историки в 16 и 17 веках, сосредоточенные на отношениях Эдварда с Гэзестоном, проводя сравнения между правлением Эдварда и событиями, связанными с отношениями Жана Луи де Ногарет де ла Валета, герцога Эпернона и Генриха Франции , и между Джорджем Вильерс, 1 -е место Герцог Букингемский и Чарльз I из Англии . [ 389 ] В первой половине 19 -го века популярные историки, такие как Чарльз Диккенс и Чарльз Найт, популяризировали жизнь Эдварда с викторианской публикой , сосредоточившись на отношениях короля со своими фаворитами и все чаще, все больше, намекая на его возможную гомосексуализм. [ 390 ] Однако с 1870 -х годов открытая академическая дискуссия о сексуальности Эдварда была ограничена изменением английских ценностей. К началу 20 -го века правительство было рекомендовано английским школам избежать явного обсуждения личных отношений Эдварда в уроках истории. [ 391 ] Взгляды на его сексуальность продолжали развиваться на протяжении многих лет. [ 38 ]

К концу 19 -го века больше административных записей с этого периода стали доступны для таких историков, как Уильям Стаббс , Томас Тут и JC Davies, которые сосредоточились на развитии английской конституционной и правительственной системы во время его правления. [ 392 ] Несмотря на то, что они считали недостатки Эдварда II как короля, они также подчеркнули рост роли парламента и сокращение личной королевской власти в рамках Эдварда, которое они воспринимали как позитивные события. [ 393 ] В течение 1970 -х годов историография правления Эдварда отошла от этой модели, поддерживаемой дальнейшей публикацией записей с периода в последней четверти 20 -го века. [ 392 ] Работа Джеффри Дентона, Джеффри Гамильтона, Джона Мэддикотта и Сеймура Филлипса повторно ориентировано внимание на роль отдельных лидеров в конфликтах. [ 394 ] За исключением работы Хильды Джонстон над первыми годами Эдварда и исследования Натали Фрайде в последние годы Эдварда, в центре внимания основных исторических исследований в течение нескольких лет было опубликовано ведущие магнаты, а не сам Эдвард, до тех пор, пока не были опубликованы существенные биографии короля Рой Хейнс и Сеймур Филлипс в 2003 и 2011 годах. [ 395 ]

Культурные ссылки

[ редактировать ]

Несколько пьес сформировали современный образ Эдварда. [ 396 ] Кристофера Марлоу Пьеса Эдварда II была впервые исполнена около 1592 года и сосредоточена на отношениях Эдварда с Пирс Гэвстон, отражая опасения 16-го века по поводу отношений между монархами и их фаворитами. [ 397 ] Марлоу представляет смерть Эдварда как убийство, проводя параллели между убийством и мученичеством; Хотя Марлоу не описывает фактическую природу убийства Эдварда в сценарии, это обычно проводилось после традиции, что Эдвард был убит раскаленным покером. [ 398 ] Персонаж Эдварда в пьесе, которого сравнивали с современниками Марлоу Джеймса VI из Шотландии и Генриха III из Франции, мог повлиять на изображение Уильяма Шекспира Ричарда II . [ 399 ] В 17 -м веке драматург Бен Джонсон поднял ту же тему для своей незаконченной работы, Мортимер, его падение . [ 400 ]

Режиссер Дерек Джарман адаптировал игру «Марлоу» к фильму в 1991 году, создав постмодернистскую пастическую болью оригинала, изображая Эдварда как сильного, явно гомосексуального лидера, в конечном итоге преодолевшим мощные враги. [ 401 ] В версии Джармана Эдвард, наконец, избегает плена, следуя традиции в письме Фиси. [ 402 ] Нынешнее популярное изображение Эдварда также сформировалось его контрастным появлением в в 1995 году Мела Гибсона фильме «Храброе сердце» , где он изображается как слабый и неявно гомосексуалист, носив шелковую одежду и тяжелую космети Полем [ 403 ] Фильм получил обширную критику, как за его исторические неточности, так и за его негативное изображение гомосексуализма. [ 404 ]

Жизнь Эдварда также использовалась в самых разных средствах массовой информации. В викторианскую эпоху картина Эдвард II и Гэвстон Пирс от Маркуса Стоуна намекала на гомосексуальные отношения между парой, избегая при этом, чтобы сделать этот аспект явным. Первоначально он был показан в Королевской академии в 1872 году, но в последующие десятилетия был маргинализован, поскольку проблема гомосексуализма стала более чувствительной. [ 405 ] Совсем недавно режиссер Дэвид Бинтли использовал игру Марлоу в качестве основы для балета Эдварда II , впервые выступившего в 1995 году; Музыка из балета является частью Композитора Джона МакКейба симфонии Эдварда II , созданной в 2000 году. [ 396 ] Такие романы, как Gascon and Chris Hunt 1992 года 1984 года, сосредоточились на сексуальных аспектах отношений Эдварда и Гейвестона, в то время как Стефани Мерритт в 2002 году Гэвстон транспортирует историю в 20 -й век. [ 396 ]

Проблема

[ редактировать ]

У Эдварда II было четверо детей с Изабеллой: [ 406 ]

- Эдвард III Англии (13 ноября 1312 - 21 июня 1377 г.). Женился на Филиппе из Хайно 24 января 1328 года. У них было восемь сыновей и пять дочерей.

- Джон Элтхам (15 августа 1316 - 13 сентября 1336). Умер в возрасте 20 лет. Никогда не женат. Нет проблем.

- Элеонора Вудстока (18 июня 1318 - 22 апреля 1355 г.). Женился на Rinoud II из Guelders в мае 1332 года и имел двух сыновей.

- Джоан из башни (5 июля 1321 - 7 сентября 1362). Женился на Дэвиде II из Шотландии 17 июля 1328 года и стал королевой шотландцев, но не имел никаких проблем.

Эдвард также родил незаконного Адама Фицрой ( ок. 1307–1322 ), который сопровождал своего отца в шотландских кампаниях 1322 года и вскоре умер. [ 407 ]

Происхождение

[ редактировать ]| Предки Эдварда II из Англии [ 408 ] |

|---|

Смотрите также

[ редактировать ]- История однополых отношений , в частности, примечание об историографических соображениях

- Список графов в правлении Эдварда II Англии

Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ Невозможно точно преобразовать суммы средневековых денег в современные доходы и цены. Для сравнения, отец Эдварда, Эдвард I, около 15 000 фунтов стерлингов, чтобы построить замок и городские стены Конви, в то время как годовой доход дворянина 14-го века, такого как Ричард Ле Скроп, 1-й барон Скроп из Болтона , составил около 600 фунтов стерлингов. год. [ 11 ]

- ^ Более ранние истории Эдварда II считали его плохо образованным, главным образом потому, что он принял свою клятву коронации по -французски, а не на латыни, и из -за его интереса к сельскохозяйственным ремеслам. Его использование француза на его коронации больше не интерпретируется таким образом, но есть и другие доказательства, чтобы показать, в какой степени Эдвард был образован. Связи, проведенные между интересом к ремеслам и низким интеллектом, больше не считаются точными. [ 25 ]

- ^ Историк Сеймур Филлипс считает вероятным, что Эдвард обладал некоторым латинским; Рой Хейнс менее убежден. [ 24 ] [ 27 ]