Zelda Fitzgerald

Zelda Fitzgerald | |

|---|---|

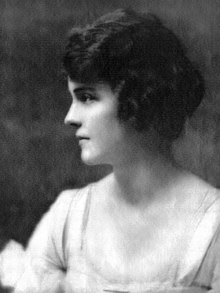

Fitzgerald in February 1920 | |

| Born | Zelda Sayre July 24, 1900 Montgomery, Alabama, U.S. |

| Died | March 10, 1948 (aged 47) Asheville, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Period | 1920–1948 |

| Spouse | |

| Children | Frances Scott Fitzgerald |

| Relatives | Anthony D. Sayre (father) |

| Signature | |

| |

Zelda Fitzgerald (née Sayre; July 24, 1900 – March 10, 1948) was an American novelist, painter, and socialite.[1] Born in Montgomery, Alabama, to a wealthy Southern family, she became locally famous for her beauty and high spirits.[1] In 1920, she married writer F. Scott Fitzgerald after the popular success of his debut novel, This Side of Paradise. The novel catapulted the young couple into the public eye, and she became known in the national press as the first American flapper.[2] Due to their wild antics and incessant partying, she and her husband became regarded in the newspapers as the enfants terribles of the Jazz Age.[3][4] Alleged infidelity and bitter recriminations soon undermined their marriage. After traveling abroad to Europe, Zelda's mental health deteriorated, and she had suicidal and homicidal tendencies which required psychiatric care.[a][6][7] Her doctors diagnosed Zelda with schizophrenia,[8][9] although later posthumous diagnoses posit bipolar disorder.[10]

While institutionalized at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland, she authored the 1932 novel Save Me the Waltz, a semi-autobiographical account of her early life in the American South during the Jim Crow era and her marriage to F. Scott Fitzgerald.[11] Upon its publication by Scribner's, the novel garnered mostly negative reviews and experienced poor sales.[11] The critical and commercial failure of Save Me the Waltz disappointed Zelda and led her to pursue her other interests as a playwright and a painter.[12] In Fall 1932, she completed a stage play titled Scandalabra,[13] but Broadway producers unanimously declined to produce the play.[12] Disheartened, Zelda next attempted to paint watercolors but, when her husband arranged their exhibition in 1934, the critical response proved equally disappointing.[12][14]

While the two lived apart, Scott died of occlusive coronary arteriosclerosis in December 1940.[15] After her husband's death, she attempted to write a second novel Caesar's Things, but her recurrent voluntary institutionalization for mental illness interrupted her writing, and she failed to complete the work.[16] By this time, she had endured over ten years of electroshock therapy and insulin shock treatments,[17][18] and she suffered from severe memory loss.[19] In March 1948, while sedated and locked in a room on the fifth floor of Highland Hospital in Asheville, North Carolina, she died in a fire.[16][20] Her body was identified by her dental records and one of her slippers.[21] A follow-up investigation raised the possibility that the fire had been a work of arson by a disgruntled or mentally disturbed hospital employee.[22][20]

A 1970 biography by Nancy Milford was a finalist for the National Book Award.[23] After the success of Milford's biography, scholars viewed Zelda's artistic output in a new light.[24] Her novel Save Me the Waltz became the focus of literary studies exploring different facets of the work: how her novel contrasted with Scott's depiction of their marriage in Tender Is the Night,[25] and how 1920s consumer culture placed mental stress on modern women.[26] Concurrently, renewed interest began in Zelda's artwork, and her paintings were posthumously exhibited in the United States and Europe.[27] In 1992, she was inducted into the Alabama Women's Hall of Fame.[28]

Early life and family background

[edit]Zelda Sayre was born in Montgomery, Alabama, on July 24, 1900, the youngest of six children.[1] Her parents were Episcopalians.[29] Her mother, Minerva Buckner "Minnie" Machen, named her daughter after the Roma heroine in a novel, presumably Jane Howard's "Zelda: A Tale of the Massachusetts Colony" (1866) or Robert Edward Francillon's "Zelda's Fortune" (1874).[30] Zelda was a spoiled child; her mother doted upon her daughter's every whim, but her father, Alabama politician Anthony Dickinson Sayre, was a strict and remote man whom Zelda described as a "living fortress".[31][30] Sayre was a state legislator in the post-Reconstruction era who authored the landmark 1893 Sayre Act which disenfranchised black Alabamians for seventy years and ushered in the racially segregated Jim Crow period in the state.[32][33] There is scholarly speculation regarding whether Anthony Sayre sexually abused Zelda as a child based on later writings,[34][35] but there is no evidence confirming that Zelda was a victim of incest.[36]

At the time of Zelda's birth, her family was a prominent and influential Southern clan who had been slave-holders before the Civil War.[37][38][39] According to biographer Nancy Milford, "if there was a Confederate establishment in the Deep South, Zelda Sayre came from the heart of it".[40] Zelda's maternal grandfather was Willis Benson Machen, a Confederate Senator and later an U.S. Senator from Kentucky.[40] Her father's uncle was John Tyler Morgan,[41] a Confederate general and the second Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan in Alabama.[42][43] An outspoken advocate of lynching who served six terms in the United States Senate, Morgan played a key role in laying the foundation for the Jim Crow era in the American South.[44] In addition to wielding considerable influence in national politics, Zelda's extended family owned the First White House of the Confederacy.[45][38] According to biographer Sally Cline, "in Zelda's girlhood, ghosts of the late Confederacy drifted through the sleepy oak-lined streets,"[46] and Zelda claimed that she drew her strength from Montgomery's Confederate past.[46]

During her idle youth in Montgomery, Zelda's affluent Southern family employed half a dozen domestic servants, many of whom were African-American.[45] Consequently, Zelda was unaccustomed to domestic labor or responsibilities of any kind.[47][48] As the privileged child of wealthy parents,[1] she danced, took ballet lessons, and enjoyed the outdoors.[49] In her youth, the family spent summers in Saluda, North Carolina, a village that would appear in her artwork decades later.[50] In 1914, Zelda began attending Sidney Lanier High School.[1] She was bright, but uninterested in her lessons. During high school, she continued her interest in ballet. She also drank gin, smoked cigarettes, and spent much of her time flirting with boys.[51] A newspaper article about one of her dance performances quoted her as saying that she cared only about "boys and swimming".[51]

She developed an appetite for attention, actively seeking to flout convention, whether by dancing or by wearing a tight, flesh-colored bathing suit to fuel rumors that she swam nude.[51] Her father's reputation was something of a safety net, preventing her social ruin.[49] Southern women of the time were expected to be delicate and docile, and Zelda's antics shocked the local community. Along with her childhood friend and future Hollywood star Tallulah Bankhead, she became a mainstay of Montgomery gossip.[52] Her ethos was encapsulated beneath her graduation photo at Sidney Lanier High School in Montgomery: "Why should all life be work, when we all can borrow? Let's think only of today, and not worry about tomorrow."[53] In her final year of high school, she was voted "prettiest" and "most attractive" in her graduating class.[1]

Courtship by F. Scott Fitzgerald

[edit]

In July 1918, Zelda Sayre first met aspiring novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald at the Montgomery Country Club.[1] At the time, Fitzgerald had been freshly rejected by his first love, Chicago socialite and heiress Ginevra King, due to his lack of financial prospects.[54] Heartbroken by this rejection, Scott had dropped out of Princeton University and volunteered for the United States Army amid World War I.[55][56] While awaiting deployment to the Western front,[56] he was stationed at Camp Sheridan, outside Montgomery.[57]

While writing to Ginevra King and begging her to resume their relationship,[58] a lonely Fitzgerald began courting Zelda and other young Montgomery women.[58] Scott called Zelda daily, and he visited Montgomery on his free days.[59] He often spoke of his ambition to become a famous novelist, and he sent her a chapter of a book he was writing.[59] At the time, Zelda dismissed Fitzgerald's remarks as mere boastfulness, and she concluded that he would never become a famous writer.[60] Infatuated with Zelda, Scott redrafted the character of Rosalind Connage in his unpublished manuscript The Romantic Egotist to resemble her,[61] and he told Zelda that "the heroine does resemble you in more ways than four."[62]

In addition to inspiring the character of Rosalind Connage, Scott used a quote from Zelda's letters for a soliloquy by the narrator at the conclusion of The Romantic Egotist, later retitled and published as This Side of Paradise.[63] Zelda wrote Scott a letter eulogizing the Confederate dead who perished during the American Civil War. "I've spent today in the graveyard... Isn't it funny how, out of a row of Confederate soldiers, two or three will make you think of dead lovers and dead loves—when they're exactly like the others, even to the yellowish moss," she wrote to Scott.[64] In the final pages of his novel, Fitzgerald altered Zelda's sentiments to refer to Union soldiers instead of Confederates.[65]

During the early months of their courtship, Zelda and Scott strolled through the Confederate Cemetery at Oakwood Cemetery.[60][66] While walking past the headstones, Scott ostensibly failed to show sufficient reverence, and Zelda informed Scott that he would never understand how she felt about the Confederate dead.[67][66] Scott drew upon Zelda's intense feelings about the Confederacy and the Old South in his 1920 short story The Ice Palace about a Southern girl who becomes lost in an ice maze while visiting a northern town.[60]

While dating Zelda and other women in Montgomery, Scott received a letter from Ginevra King informing him of her engagement to polo player William "Bill" Mitchell.[68] Three days after Ginevra King married Bill Mitchell on September 4, 1918, Scott professed his affections for Zelda.[69] In his ledger, Scott wrote that he had fallen in love on September 7, 1918.[1] His love for Zelda increased as time passed, and he wrote to his friend Isabelle Amorous: "I love her and that's the beginning and end of everything. You're still a Catholic, but Zelda's the only God I have left now."[70] Ultimately, Zelda fell in love as well.[59] Her biographer Nancy Milford wrote, "Scott had appealed to something in Zelda which no one before him had perceived: a romantic sense of self-importance which was kindred to his own."[59]

Their courtship was interrupted in October when he was summoned north. He expected to be sent to France, but he was instead assigned to Camp Mills, Long Island. While he was there, the Allied Powers signed an armistice with Imperial Germany. He then returned to the base near Montgomery.[71] Together again, Zelda and Scott now engaged in what he later described as sexual recklessness, and by December 1918, they had consummated their relationship.[72] Although this was the first time they were sexually intimate, both Zelda and Scott had other sexual partners prior to their first meeting and courtship.[73][74] Initially, Fitzgerald did not intend to marry Zelda,[75] but the couple gradually viewed themselves as informally engaged, although Zelda declined to marry him until he proved financially successful.[76][77]

On February 14, 1919, he was discharged from the military and went north to establish himself in New York City.[78] During this time, Zelda mistakenly feared she was pregnant.[79] Scott mailed her pills to induce an abortion, but Zelda refused to take them and replied in a letter: "I simply can't and won't take those awful pills... I'd rather have a whole family than sacrifice my self-respect... I'd feel like a damn whore if I took even one."[80][79] They wrote frequently, and by March 1920, Scott had sent Zelda his mother's ring, and the two had become engaged.[81] However, when Scott's attempts to become a published author faltered during the next four months, Zelda became convinced that he could not support her accustomed lifestyle, and she broke off the engagement during the Red Summer of 1919.[82][83] Having been rejected by both Zelda and Ginevra during the past year due to his lack of financial prospects, Scott suffered from intense despair,[84] and he carried a revolver daily while contemplating suicide.[85]

Soon after, in July 1919, Scott returned to St. Paul.[86] Having returned to his hometown as a failure, Scott became a social recluse and lived on the top floor of his parents' home at 599 Summit Avenue, on Cathedral Hill.[87] He decided to make one last attempt to become a novelist and to stake everything on the success of a book.[86] Abstaining from alcohol and parties,[87] he worked day and night to revise The Romantic Egotist as This Side of Paradise—an autobiographical account of his Princeton years and his romances with Ginevra, Zelda, and others.[88] At the time, Scott's feelings for Zelda were at an all-time low, and he remarked to a friend, "I wouldn't care if she died, but I couldn't stand to have anybody else marry her."[87]

Marriage and celebrity

[edit]

By September 1919, Scott completed his first novel, This Side of Paradise, and editor Maxwell Perkins of Charles Scribner's Sons accepted the manuscript for publication.[89] Scott requested an accelerated release to renew Zelda's faith in him: "I have so many things dependent on its success—including of course a girl."[90] After Scott informed Zelda of his novel's upcoming publication, a shocked Zelda replied apologetically: "I hate to say this, but I don't think I had much confidence in you at first.... It's so nice to know you really can do things do—anything—and I love to feel that maybe I can help just a little."[60]

Zelda agreed to marry Scott once Scribner's published the novel;[79] in turn, Fitzgerald promised to bring her to New York with "all the iridescence of the beginning of the world."[91] Scribner's published This Side of Paradise on March 26, 1920, and Zelda arrived in New York on March 30. A few days later, on April 3, 1920, they married in a small ceremony at St. Patrick's Cathedral.[92]

At the time of their wedding, Fitzgerald later claimed neither he nor Zelda still loved each other,[93][94] and the early years of their marriage in New York City proved to be a disappointment.[95][96][97] According to biographer Andrew Turnbull, "victory was sweet, though not as sweet as it would have been six months earlier before Zelda had rejected him. Fitzgerald couldn't recapture the thrill of their first love".[60] As the affections between Zelda and Scott cooled, her husband continued to obsess over the loss of his first love Ginevra King and, for the remainder of their marriage, Scott could not think of Ginevra "without tears coming to his eyes".[98][99]

Despite the cooling of their affections, Scott and Zelda quickly became celebrities of New York, as much for their wild behavior as for the success of This Side of Paradise. They were ordered to leave both the Biltmore Hotel and the Commodore Hotel for disturbing other guests.[97] Their daily lives consisted of outrageous pranks and drunken escapades.[100] While fully dressed, they jumped into the water fountain in front of the Plaza Hotel in New York.[100] They frequently hired taxicabs and rode on the hood.[100] One evening, while inebriated, they decided to visit the county morgue where they inspected the unidentified corpses and, on another evening, Zelda insisted on sleeping in a dog kennel.[101] Alcohol increasingly fueled their nightly escapades. Publicly, this meant little more than napping when they arrived at parties, but privately it increasingly led to bitter arguments.[102] To their mutual delight, New York newspapers depicted Zelda and Scott as cautionary examples of youth and excess—the enfants terribles of the hedonistic Jazz Age.[3][4]

After a month of hotel evictions,[97] the Fitzgeralds moved to a cottage in Westport, Connecticut, where Scott worked on drafts of his second novel.[103] Due to her privileged upbringing with many African-American servants, Zelda could not perform household responsibilities at Westport.[104] During the early months of their marriage, Scott's unwashed clothes began disappearing.[105] One day, he opened a closet and discovered his dirty clothes piled to the ceiling.[105] Uncertain of what to do with unwashed clothes, Zelda had never sent them out for cleaning: she had simply tossed everything into the closet.[105]

Soon after, Scott employed two maids and a laundress.[106] Zelda's complete dependence upon servants became the comedic focus of magazine articles.[107] When Harper & Brothers asked Zelda to contribute her favorite recipes in an article, she wrote: "See if there is any bacon, and if there is, ask the cook which pan to fry it in. Then ask if there are any eggs, and if so try and persuade the cook to poach two of them. It is better not to attempt toast, as it burns very easily. Also, in the case of bacon, do not turn the fire too high, or you will have to get out of the house for a week. Serve preferably on china plates, though gold or wood will do if handy."[107]

While Scott attempted to write his next novel at their home in Westport, Zelda announced that she was homesick for the Deep South.[108] In particular, she missed eating Southern cuisine such as peaches and biscuits for breakfast.[108] She suggested that they travel to Montgomery, Alabama.[108] On July 15, 1920, the couple traveled in a touring car—which Scott derogatorily nicknamed "the rolling junk"—to her parents' home in Montgomery.[108] After visiting Zelda's family for several weeks, they abandoned the unreliable vehicle and returned via train to Westport, Connecticut.[108] Zelda's parents visited their Westport cottage soon after, but her father Judge Anthony Sayre took a dim view of the couples' constant partying and scandalous lifestyle.[108] Following this visit, the Fitzgeralds relocated to an apartment at 38 West 59th Street in New York City.[108]

Pregnancy and Scottie

[edit]In February 1921, while Scott labored on drafts of his inchoate second novel The Beautiful and Damned, Zelda discovered she was pregnant.[109] She requested that the child be born on Southern soil in Alabama, but Fitzgerald adamantly refused.[110] Zelda wrote despondently to a friend: "Scott's changed... He used... to say he loved the South, but now he wants to get as far away from it as he can."[110] To Zelda's chagrin, her husband insisted upon having the baby at his northern home in Saint Paul, Minnesota.[111] On October 26, 1921, she gave birth to Frances "Scottie" Fitzgerald. As she emerged from the anesthesia, Scott recorded Zelda saying, "Oh, God, goofo I'm drunk. Mark Twain. Isn't she smart—she has the hiccups. I hope it's beautiful and a fool—a beautiful little fool."[112] Many of her words found their way into Scott's novels: in The Great Gatsby, the character Daisy Buchanan expresses a similar hope for her daughter.[113]

While writing The Beautiful and Damned, Scott drew upon "bits and pieces" of Zelda's diary and letters.[b][115] He modeled the characters of Anthony Patch on himself and Gloria Patch on—in his words—the chill-mindedness and selfishness of Zelda.[116] Prior to publication, Zelda proofread the drafts, and she urged her husband to cut the cerebral ending which focused on the main characters' lost idealism.[115] Upon its publication, Burton Rascoe, the newly appointed literary editor of the New York Tribune, approached Zelda for an opportunity to entice readers with a satirical review of Scott's latest work as a publicity stunt.[117]

Although Zelda had carefully proofread drafts of the novel,[115] she pretended in her review to read the novel for the very first time, and she wrote partly in jest that "on one page I recognized a portion of an old diary of mine... and, also, scraps of letters which, though considerably edited, sound to me vaguely familiar. In fact, Mr. Fitzgerald—I believe that is how he spells his name—seems to believe that plagiarism begins at home."[118][119] In the same review, Zelda joked that she hoped her husband's novel would become a commercial success as "there is the cutest cloth of gold dress for only $300 in a store on Forty-second Street".[118]

The satirical review led to Zelda receiving offers from other magazines to write stories and articles. According to their daughter, Scott "spent many hours editing the short stories she sold to College Humor and to Scribner's Magazine".[120] In June 1922, Metropolitan Magazine published an essay by Zelda Fitzgerald titled "Eulogy on the Flapper".[121] At the time flappers were typically young, modern women who bobbed their hair and wore short skirts.[122][123] They also drank alcohol and had premarital sex.[124][125] Though ostensibly a piece about the decline of the flapper lifestyle after its heyday in the early 1920s, Zelda's biographer Nancy Milford wrote that Zelda's essay served as "a defense of her own code of existence."[126] In the article, Zelda described the ephemeral phenomenon of the flapper:

The Flapper awoke from her lethargy of sub-deb-ism, bobbed her hair, put on her choicest pair of earrings and a great deal of audacity and rouge and went into the battle. She flirted because it was fun to flirt and wore a one-piece bathing suit because she had a good figure ... she was conscious that the things she did were the things she had always wanted to do. Mothers disapproved of their sons taking the Flapper to dances, to teas, to swim and most of all to heart.[126]

After the publication of The Beautiful and Damned in March 1922, the Fitzgeralds traveled to either New York or St. Paul in order for Zelda to procure an abortion.[127] Ultimately, Zelda would have three abortions during their marriage, and her sister Rosalind later questioned whether Zelda's later mental deterioration was due to health side-effects of these unsafe procedures.[128] Zelda's thoughts on terminating her second pregnancy are unknown, but in the first draft of The Beautiful and Damned, Scott wrote a scene in which Gloria Gilbert believes she is pregnant and Anthony Patch suggests she "talk to some woman and find out what's best to be done. Most of them fix it some way."[129] Anthony's suggestion was removed from the final version, and this significant alteration shifted the focus from a moral dilemma about the act of abortion to Gloria's superficial concern that a baby would ruin her figure.[129]

Following the financial failure of Scott's play The Vegetable,[130] the Fitzgeralds found themselves mired in debt. Although Scott wrote short stories furiously to pay the bills, he became burned out and depressed.[131] During this period, while Scott wrote short stories at home, the New York Police Department detained Zelda near the Queensboro Bridge on the suspicion of her being the "Bobbed Haired Bandit," an infamous spree-robber later identified as Celia Cooney.[132] Following this incident, the couple departed in April 1924 for Paris, France, in the hope of living a more frugal existence abroad in Europe.[133]

Expatriation to Europe

[edit]

After arriving in Paris, the couple soon relocated to Antibes on the French Riviera.[134] While Scott labored on drafts of The Great Gatsby, Zelda became infatuated with a French naval aviator, Edouard Jozan.[135] The exact details of the supposed romance are unverifiable and contradictory,[136][137] and Jozan himself claimed the Fitzgeralds invented the entire incident.[138] According to conflicting accounts, Zelda spent afternoons swimming at the beach and evenings dancing at the casinos with Jozan. After several weeks, she asked Scott for a divorce.[139] Scott purportedly challenged Jozan to duel and locked Zelda in their villa until he could kill him.[140] Before any fatal confrontation could occur, Jozan—who had no intention of marrying Zelda—fled the Riviera, and the Fitzgeralds never saw him again.[139] Soon after, Zelda possibly overdosed on sleeping pills.[7]

On his part, Jozan dismissed the entire story as pure fabrication and claimed no romance with Zelda had ever occurred: "They both had a need of drama, they made it up and perhaps they were the victims of their own unsettled and a little unhealthy imagination."[138][141] In later retellings, both Zelda and Scott embellished the story, and Zelda later falsely told Ernest Hemingway and his wife Hadley Richardson that the affair ended when Jozan committed suicide.[142] In fact, Jozan had been transferred by the French military to Indochina.[143]

Regardless of whether any extramarital affair with Jozan occurred,[144] the episode led to a breach of trust in their marriage,[145] and Fitzgerald wrote in his notebook, "I knew something had happened that could never be repaired."[136] The incident likely influenced Fitzgerald's writing of The Great Gatsby, and he drew upon many elements of his tempestuous relationship with Zelda, including the loss of certainty in her love.[143] In August, he wrote to his friend Ludlow Fowler: "I feel old too, this summer ... the whole burden of this novel—the loss of those illusions that give such color to the world that you don't care whether things are true or false as long as they partake of the magical glory."[143]

Scott finalized The Great Gatsby in October 1924.[133] The couple attempted to celebrate with travel to Rome and Capri, but both were unhappy and unhealthy. When he received the galleys for his novel, Scott fretted over the best title: Trimalchio in West Egg, just Trimalchio or Gatsby, Gold-hatted Gatsby, or The High-bouncing Lover. Disliking Fitzgerald's chosen title of Trimalchio in West Egg, editor Max Perkins persuaded him that the reference was too obscure and that people would be unable to pronounce it.[146] After both Zelda and Perkins expressed their preference for The Great Gatsby, Fitzgerald agreed.[147] It was also on this trip, while ill with colitis, that Zelda began painting artworks.[148]

Meeting Ernest Hemingway

[edit]

Returning to Paris in April 1925, Zelda met Ernest Hemingway, whose career her husband did much to promote. Through Hemingway, the Fitzgeralds were introduced to Gertrude Stein, Alice B. Toklas, Robert McAlmon, and others.[136] Scott and Hemingway became close friends, but Zelda and Hemingway disliked each other from their first meeting. She openly referred to him with homophobic slurs and denounced him as a "fairy with hair on his chest".[149] She considered Hemingway's domineering macho persona to be merely a posture to conceal his homosexuality; in turn, Hemingway told Scott that Zelda was "insane".[150] In his memoir A Moveable Feast, Hemingway claims he realized that Zelda had a mental illness when she insisted that jazz singer Al Jolson was greater than Jesus Christ.[151] Hemingway alleged that Zelda sought to destroy her husband, and she purportedly taunted Fitzgerald over his penis' size.[152] After examining it in a public restroom, Hemingway confirmed Fitzgerald's penis to be of average size.[152]

Hemingway claimed that Zelda urged her husband to write lucrative short stories as opposed to novels in order to support her accustomed lifestyle.[153][154] To supplement their income, Fitzgerald often wrote stories for magazines such as The Saturday Evening Post, Collier's Weekly, and Esquire.[155] "I always felt a story in The Post was tops", Zelda later recalled, "But Scott couldn't stand to write them. He was completely cerebral, you know. All mind."[156] Scott would write his stories in an 'authentic' manner, then rewrite them to add plot twists which increased their salability as magazine stories.[157] This "whoring" for Zelda—as Hemingway dubbed these sales—emerged as a sore point in their friendship.[157] After reading The Great Gatsby, Hemingway vowed to put any differences with Fitzgerald aside and to aid him in any way he could, although he feared Zelda would derail Fitzgerald's career.[158] In a letter to Fitzgerald, Hemingway warned him that Zelda would derail his career:

Of all people on earth you needed discipline in your work and instead you marry someone who is jealous of your work, wants to compete with you and ruins you. It's not as simple as that and I thought Zelda was crazy the first time I met her and you complicated it even more by being in love with her and, of course, you're a rummy.[159]

A more serious rift in the Fitzgerald's marriage occurred when Zelda suspected that Scott was closeted homosexual,[160] and she alleged that Fitzgerald and Hemingway engaged in homosexual relations.[161][162] In the ensuing months, she frequently belittled Scott with homophobic slurs during their public excursions.[163] Biographer Matthew J. Bruccoli posits that Zelda's inordinate preoccupation with other persons' sexual behavior likely indicated the onset of her paranoid schizophrenia.[164] However, Fitzgerald's sexuality was a popular subject of debate among his friends and acquaintances.[165][166][167] As a youth, Fitzgerald had a close relationship with Father Sigourney Fay,[168] a possibly gay Catholic priest,[169][170] and Fitzgerald later used his last name for the idealized romantic character of Daisy Fay Buchanan.[171] After college, Fitzgerald cross-dressed during outings in Minnesota and flirted with men at social events.[172] While staying in Paris, rumors dogged Fitzgerald among the American expat community that he was gay.[166]

Irritated by Zelda's recurrent homophobic attacks on his sexual identity,[c] Scott decided to have sex with a Parisian prostitute.[164] Zelda found condoms that he had purchased before any sexual encounter occurred, and a bitter quarrel ensued, resulting in ingravescent jealousy.[174] Soon after, a jealous Zelda threw herself down a flight of marble stairs at a party because Fitzgerald, engrossed in talking to American dancer Isadora Duncan, ignored her.[175] In December 1926, after two unpleasant years in Europe which considerably strained their marriage, the Fitzgeralds returned to America, but their marital difficulties continued to fester.[176]

In January 1927, the Fitzgeralds relocated to Los Angeles where Scott wrote Lipstick for United Artists and met Hollywood starlet Lois Moran.[177] Jealous of Moran, Zelda set fire to her clothing in a bathtub as a self-destructive act.[178] She disparaged Moran as "a breakfast food that many men identified with whatever they missed from life."[179] Fitzgerald's relations with Moran exacerbated the Fitzgeralds' marital difficulties and, after merely two months in Hollywood, the unhappy couple relocated to Ellerslie in Wilmington, Delaware, in March 1927.[180][177] Literary critic Edmund Wilson, recalling a party at the Fitzgerald home in Edgemoor, Delaware, in February 1928, described Zelda as follows:

I sat next to Zelda, who was at her iridescent best. Some of Scott's friends were irritated; others were enchanted, by her. I was one of the ones who were charmed. She had the waywardness of a Southern belle and the lack of inhibitions of a child. She talked with so spontaneous a color and wit—almost exactly in the way she wrote—that I very soon ceased to be troubled by the fact that the conversation was in the nature of a 'free association' of ideas and one could never follow up anything. I have rarely known a woman who expressed herself so delightfully and so freshly: she had no ready-made phrases on the one hand and made no straining for effect on the other. It evaporated easily, however, and I remember only one thing she said that night: that the writing of Galsworthy was a shade of blue for which she did not care.[181]

Obsession and illness

[edit]

By 1927, at the Ellersie estate in Wilmington, Delaware, Scott had become severely alcoholic, and Zelda's behavior became increasingly erratic.[182] Much of the conflict between them stemmed from the boredom and isolation Zelda experienced when Scott was writing.[182] She would often interrupt him when he was working, and the two grew increasingly miserable.[182] Stung by Fitzgerald's criticism that all great women use their talents constructively, Zelda had a deep desire to develop a talent that was entirely her own.[115]

At the age of 28, she became obsessed with Russian ballet, and she decided to embark upon a career as a prima ballerina.[101] Her friend Gerald Murphy counseled against their ambition and remarked that "there are limits to what a woman of Zelda's age can do and it was obvious that she had taken up the dance too late."[183] Despite being far too old to achieve such an ambition, Scott Fitzgerald paid for Zelda to begin practicing under the tutelage of Catherine Littlefield, director of the Philadelphia Opera Ballet.[115][184] After the Fitzgeralds returned to Europe in summer 1928, Scott paid for Zelda to study under Russian ballerina Lubov Egorova in Paris.[185]

In September 1929, the San Carlo Opera Ballet Company in Naples invited her to join their ballet school.[185] In preparation, Zelda undertook a grueling daily practice of up to eight hours a day,[186] and she "punished her body in strenuous efforts to improve."[115] According to Zelda's daughter, although Scott "greatly appreciated and encouraged his wife's unusual talents and ebullient imagination,"[120] he became alarmed when her "dancing became a twenty-four-hour preoccupation which was destroying her physical and mental health."[120] Soon after, Zelda collapsed from physical and mental exhaustion.[186] One evening, Scott returned home to find an exhausted Zelda seated on the floor and entranced with a pile of sand.[101] When he asked her what she was doing, she could not speak.[101] He summoned a French physician, who examined Zelda and informed him that "your wife is mad."[101]

Soon after her physical and mental collapse, Zelda's mental health further deteriorated.[187] In October 1929, during an automobile trip to Paris along the mountainous roads of the Grande Corniche, Zelda seized the car's steering wheel and tried to kill herself, her husband, and her nine-year-old daughter Scottie by driving over a cliff.[5] After this homicidal incident, Zelda sought psychiatric treatment. On April 23, 1930, the Malmaison Clinic near Paris admitted her for observation.[188] On May 22, 1930, she moved to Valmont sanatorium in Montreux, Switzerland.[189] The clinic primarily treated gastrointestinal ailments and, due to her profound psychological problems, she was moved again to a psychiatric facility in Prangins on the shores of Lake Geneva on June 5, 1930.[189] At Prangins in June, Dr. Oscar Forel issued a tentative diagnosis of schizophrenia,[8] but he feared her psychological condition might be far worse.[190] Zelda's biographer, Nancy Milford, quotes Dr. Forel's full diagnosis at length:

The more I saw Zelda, the more I thought at the time [that] she is neither [suffering from] a pure neurosis nor a real psychosis—I considered her a constitutional, emotionally unbalanced psychopath—she may improve, [but] never completely recover.[190]

After five months of observation, Doctor Eugen Bleuler—one of Europe's leading psychiatrists—confirmed Dr. Forel's diagnosis of Zelda as a schizophrenic on November 22, 1930.[9] (Following Zelda's death, later psychiatrists speculated that Zelda instead had bipolar disorder.[191]) She was released from Prangins in September 1931.[189] In an attempt to keep his wife out of an asylum, Scott hired nurses and attendants to care for Zelda at all times.[101] Although there were periods where her behavior was merely eccentric, she could frequently become a danger to herself and others.[101] In one instance, she attempted to throw herself in front of a moving train and, in another instance, she attacked a visiting guest at their home without provocation.[192] Despite her precarious mental health, the couple traveled to Montgomery, Alabama, where her father, Judge Anthony Sayre, lay dying. After her father's death, her mental health again deteriorated and she had another breakdown.[189]

Save Me the Waltz

[edit]

In February 1932, after an episode of hysteria, Zelda insisted that she be readmitted to a mental hospital.[193] On February 12, 1932, over her husband's objections,[194] the The Henry Phipps Psychiatric Clinic at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore admitted Fitzgerald, where her treatment was overseen by Dr. Adolf Meyer, an expert on schizophrenia.[193][194] As part of her recovery routine, she spent at least two hours a day writing a manuscript.[195] At the Phipps Clinic, Zelda developed a bond with Dr. Mildred Squires, a female resident.[194] When Dr. Squires asked Scott to speculate why Zelda's mental health had deteriorated, Fitzgerald replied:

Perhaps fifty percent of our friends and relatives would tell you in all honest conviction that my drinking drove Zelda insane—the other half would assure you that her insanity drove me to drink. Neither judgement would mean anything.[189]

Toward the end of February 1932, Zelda shared fragments of her manuscript with Dr. Squires, who wrote to Scott that the unfinished novel was vivid and had charm.[196] Zelda wrote to Scott from the hospital, "I am proud of my novel, but I can hardly restrain myself enough to get it written. You will like it—It is distinctly École Fitzgerald, though more ecstatic than yours—perhaps too much so."[197] Zelda finished the novel on March 9. She sent the unaltered manuscript to Scott's editor, Maxwell Perkins, at Scribner's.[198]

Surprised to receive an unannounced novel in the mail from Zelda, Perkins carefully perused the manuscript.[198] He concluded the work had "a slightly deranged quality which gave him the impression that the author had difficulty in separating fiction from reality."[198] He felt the manuscript contained several good sections, but its overall tone seemed hopelessly "dated" and tonally resembled Fitzgerald's 1922 work The Beautiful and Damned.[198] Perkins hoped that her husband might be able to improve its overall quality with his criticism.[198]

Upon learning that Zelda had submitted her manuscript to Perkins, Scott became angry that she had not shown her manuscript to him beforehand.[199] After reading the manuscript, he objected to her novel's plagiarism of his protagonist in This Side of Paradise.[198] He was further upset to learn that Zelda's novel used the very same plot elements as his upcoming novel, Tender Is the Night.[200] After receiving letters from Scott delineating these objections, Zelda wrote to Scott apologetically that she was "afraid we might have touched the same material."[201]

Despite Scott's initial annoyance, a debt-ridden Fitzgerald realized that Zelda's book might earn a tidy profit.[202] Consequently, his requested revisions were "relatively few", and "the disagreement was quickly resolved, with Scott recommending the novel to Perkins."[200][203] Several weeks later, Scott wrote to Perkins: "Here is Zelda's novel. It is a good novel now, perhaps a very good novel—I am too close to tell. It has the faults and virtues of a first novel.... It should interest the many thousands in dancing. It is about something and absolutely new, and should sell."[204] Although unimpressed,[205] Perkins agreed to publish the work as a way for Fitzgerald to repay his financial debt to Scribner's.[206] Perkins arranged for half of Zelda's royalties to be applied against Scott's debt to Scribner's until at least $5,000 had been repaid.[206]

In March 1932, the Phipps Clinic discharged Zelda, and she joined her husband Scott and her daughter at the La Paix estate in Baltimore, Maryland.[207] Although discharged, she remained mentally unwell.[208] One month later, Fitzgerald took her to lunch with critic H. L. Mencken, the literary editor of The American Mercury.[208] In his diary, Mencken noted Zelda "went insane in Paris a year or so ago, and is still plainly more or less off her base."[208] Throughout the luncheon, she manifested signs of mental distress.[208] A year later, when Mencken met Zelda for the last time, he described her mental illness as immediately evident to any onlooker and her mind as "only half sane."[209] He regretted that F. Scott Fitzgerald could not write novels, as he had to write magazine stories to pay for Zelda's psychiatric treatment.[208]

On October 7, 1932, Scribner's published Save Me the Waltz with a printing of 3,010 copies—not unusually low for a first novel in the middle of the Great Depression—on cheap paper, with a cover of green linen.[210] According to Zelda, the book derived its title from a Victor record catalog,[211] and the title evoked the romantic glitter of the lifestyle which F. Scott Fitzgerald and herself experienced during the riotous Jazz Age. The parallels to the Fitzgeralds were obvious: The protagonist of the novel is Alabama Beggs—like Zelda, the daughter of a Southern judge—who marries David Knight, an aspiring painter who abruptly becomes famous for his work. They live the fast life in Connecticut before departing to live in France. Dissatisfied with her marriage, Alabama throws herself into ballet. Though told she has no chance, she perseveres and after three years becomes the lead dancer in an opera company. Alabama becomes ill from exhaustion, however, and the novel ends when they return to her family in the South, as her father is dying.[212]

A shooting star, an ectoplasmic arrow, sped through the nebulous hypothesis like a wanton hummingbird. From Venus to Mars to Neptune it trailed the ghost of comprehension, illuminating far horizons over the pale battlefields of reality.

—Zelda Fitzgerald, Save Me the Waltz (1932)[213]

Echoing Zelda's frustrations, the novel portrays Alabama's struggle to establish herself independently of her husband and to earn respect for her own accomplishments.[214] In contrast to Scott's unadorned prose, Zelda's writing style in Save Me the Waltz is replete with verbal flourishes and complex metaphors. The novel is also deeply sensual; as literary scholar Jacqueline Tavernier-Courbin observed in 1979, "the sensuality arises from Alabama's awareness of the life surge within her, the consciousness of the body, the natural imagery through which not only emotions but simple facts are expressed, the overwhelming presence of the senses, in particular touch and smell, in every description."[215]

The reviews of Save Me the Waltz by literary critics were overwhelmingly negative.[11] The critics savaged Zelda's florid prose as overwritten, attacked her fictional characters as uninteresting, and mocked her tragic scenes as grotesquely "harlequinade".[216] The New York Times published a particularly harsh review and lambasted her editor Max Perkins: "It is not only that her publishers have not seen fit to curb an almost ludicrous lushness of writing but they have not given the book the elementary services of a literate proofreader."[216] The overwhelmingly negative reviews bewildered and distressed Zelda.[216]

Painting and later years

[edit]From the mid-1930s onward, Zelda would be hospitalized sporadically for the rest of her life at sanatoriums in Baltimore, New York, and in Asheville, North Carolina.[189] When Scott visited Zelda in the sanatoriums, she increasingly exhibited signs of mental instability.[217] During one visit, Scott and friends took Zelda on an outing to a nearby home in Tryon, North Carolina.[217] During the lunch, she became withdrawn and ceased communication.[217] On the return drive to the sanatorium, she wrenched open the car door and threw herself out of the moving vehicle in an attempt to kill herself.[217] In another incident, Zelda's unexpected loss of a tennis match at the Asheville sanatorium resulted in her physically attacking her tennis partner and beating them over the head with her tennis racket.[217]

Despite the deterioration of her mental health, she continued pursuing her artistic ambitions. After the critical and commercial failure of Save Me the Waltz, she attempted to write a farcical stage play titled Scandalabra in Fall 1932.[12][189] However, after submitting the manuscript to agent Harold Ober, Broadway producers rejected her play.[13] Following this rejection, Scott arranged for her play Scandalabra to be staged by a Little Theater group in Baltimore, Maryland, and he sat through long hours of rehearsals of the play.[120] A year later, during a group therapy session with her husband and a psychiatrist, Fitzgerald remarked that she was "a third-rate writer and a third-rate ballet dancer."[218] Following this remark, Zelda attempted to paint watercolors while in and out of sanatoriums.[219]

In March 1934, Scott Fitzgerald arranged the first exhibition of Zelda's artwork—13 paintings and 15 drawings—in New York City.[14][220] As with the tepid reception of her book, New York critics were ill-disposed towards her paintings.[219] The New Yorker described them merely as "paintings by the almost mythical Zelda Fitzgerald; with whatever emotional overtones or associations may remain from the so-called Jazz Age." No actual description of the paintings was provided in the review.[221]

Following the critical failure of her artwork exhibition, Scott awoke one morning to discover Zelda had gone missing.[217] After the arrival of a doctor and several attendants, a manhunt ensued in New York City.[217] Ultimately, they found Zelda in Central Park digging a grave.[217] Soon after, she became even more violent and reclusive. In 1936, Scott placed her in the Highland Hospital in Asheville, North Carolina, writing to friends:[222]

Zelda now claims to be in direct contact with Christ, William the Conqueror, Mary Stuart, Apollo and all the stock paraphernalia of insane-asylum jokes ... For what she has really suffered, there is never a sober night that I do not pay a stark tribute of an hour to in the darkness. In an odd way, perhaps incredible to you, she was always my child (it was not reciprocal as it often is in marriages) ... I was her great reality, often the only liaison agent who could make the world tangible to her.[222]

Zelda remained in the hospital while Scott returned to Hollywood for a $1,000-a-week job with MGM in June 1937.[223] Estranged from Zelda, he attempted to reunite with his first love Ginevra King when she visited California in October 1938, but his uncontrolled alcoholism sabotaged their brief reunion.[224][225] When a disappointed King returned to Chicago, Fitzgerald settled into a clandestine relationship with Hollywood gossip columnist Sheilah Graham.[223] Throughout their relationship, Graham claimed Fitzgerald felt constant guilt over Zelda's mental illness and confinement.[226] He repeatedly attempted sobriety, had depression, had violent outbursts, and attempted suicide.[227]

For the next several years, a depressed Scott continued screenwriting on the West Coast and visiting a hospitalized Zelda on the East Coast. In April 1939, a coterie from Zelda's mental hospital had planned to go to Cuba, but Zelda had missed the trip. The Fitzgeralds decided to go on their own. The trip proved to be a disaster. During this trip, spectators at a cockfight beat F. Scott Fitzgerald when he tried to intervene against animal cruelty.[228] He returned to the United States so exhausted and intoxicated that he required hospitalization.[229] The Fitzgeralds never saw each other again.[230]

I am sorry that there should be nothing to greet you but an empty shell . . . I love you anyway . . . even if there isn't any me or any love or even any life . . . I love you.

—Zelda Fitzgerald, Letter to F. Scott Fitzgerald, December 1940[231]

Скотт вернулся в Голливуд, чтобы оплатить постоянно растущие счета за продолжающуюся госпитализацию Зельды. Она добилась некоторых успехов в Эшвилле, и в марте 1940 года, через четыре года после госпитализации, ее выписали на попечение матери. [232] She was nearly forty now, her friends were long gone, and the Fitzgeralds no longer had much money. They wrote to each other frequently, and they made plans to meet again in December 1940. In a letter Zelda wrote to Fitzgerald shortly before he died of a heart attack, she said: "I am sorry that there should be nothing to greet you but an empty shell . . . I love you anyway . . . even if there isn't any me or any love or even any life . . . I love you."[231] Их запланированное свидание не состоялось из-за смерти Скотта от окклюзионного коронарного атеросклероза в возрасте 44 лет в декабре 1940 года. Из-за своего хрупкого психического здоровья Зельда не смогла присутствовать на его похоронах в Роквилле, штат Мэриленд . [ 233 ]

После смерти Скотта Зельда прочитала его незаконченную рукопись под названием «Любовь последнего магната» . Она написала его другу Эдмунду Уилсону , который согласился отредактировать книгу и восхвалить его наследие. Зельда считала, что в работах Скотта присутствует «американский темперамент, основанный на вере в себя и «воле к выживанию», от которой отказались современники Скотта. ." [ 233 ] Прочитав «Последний магнат» , Зельда приступила к работе над новым романом « Дела Цезаря» . Поскольку она пропустила похороны Скотта из-за своего психического здоровья, она также пропустила свадьбу Скотти. К августу 1943 года она вернулась в Хайлендскую больницу. Она работала над своим романом во время госпитализации и выхода из больницы. Ей не стало лучше, и роман она не закончила. [ 16 ]

Пожар в больнице и смерть

[ редактировать ]

К концу своей жизни Зельда жила в санаториях и за их пределами. Зельда снова легла в больницу в сентябре 1946 года, а затем вернулась, чтобы жить со своей матерью Минни в их доме в Алабаме. [ 156 ] К этому моменту своей жизни она уже более десяти лет подвергалась электрошоковой терапии и лечению инсулиновым шоком . [ 17 ] [ 18 ] Следовательно, теперь она «страдала от тяжелой потери памяти и апатии личности из-за постоянной шоковой терапии». [ 19 ]

Возможно, из-за такого лечения или из-за ухудшения психического здоровья она поддержала фашизм как политическую идеологию. [ 234 ] По словам биографа Нэнси Милфорд, Зельда «увлеклась идеей фашизма как способа объединить все и упорядочить массы». [ 234 ] Когда знакомый Генри Дэн Пайпер посетил Зельду в марте 1947 года, она заявила, что фашизм служит «предотвратить развал вещей и предотвратить потерю или уничтожение самых прекрасных вещей». [ 234 ]

В ноябре 1947 года Зельда в последний раз вернулась в больницу Хайленд в Эшвилле, Северная Каролина . [ 232 ] Благодаря лечению инсулином ее вес увеличился до 130 фунтов. [ 235 ] Знакомая Эдна Гарлингтон Спратт вспоминала мрачный вид Зельды в последние месяцы перед ее смертью: «Когда я ее увидел, она была совсем не красивой. Она вела себя нормально, но выглядела так ужасно. Ее волосы были густыми, и она потеряла всякую гордость за себя. " [ 20 ] В начале марта 1948 года врачи сказали ей, что ей лучше и она может уехать, но она якобы осталась для дальнейшего лечения. [ 20 ]

В ночь на 10 марта 1948 года на больничной кухне вспыхнул пожар. Зельду ввели успокоительное и заперли в комнате на пятом этаже, возможно, ожидая шоковой терапии. [ 236 ] [ 20 ] Огонь прошел через шахту кухонного лифта и распространился на каждый этаж. Пожарные лестницы были деревянными и тоже загорелись. Девять женщин, включая Зельду, погибли. [ 16 ] Ее опознали по стоматологическим картам и, по другим данным, по одной из ее тапочек. [ 237 ] Последующее расследование выявило неподтвержденную возможность того, что пожар был поджогом Уилли Мэй, недовольного или психически неуравновешенного сотрудника больницы, который инициировал пожар на кухне. [ 22 ] [ 20 ]

Зельда и Скотт были похоронены в Роквилле, штат Мэриленд, первоначально на кладбище Роквилл , вдали от его семейного участка. [ 220 ] Известно, что существует только одна фотография оригинального захоронения, сделанная в 1970 году ученым Фицджеральда Ричардом Андерсоном и опубликованная в 2016 году. По просьбе ее дочери Скотти Зельда и Скотт были похоронены вместе с другими Фицджеральдами на католическом кладбище Святой Марии . [ 220 ] На их надгробии высечена последняя фраза из «Великого Гэтсби» : «Итак, мы плывем вперед, лодки против течения, непрерывно несясь назад в прошлое». [ 238 ]

Критическая переоценка

[ редактировать ]

Во время третьего и смертельного сердечного приступа в декабре 1940 года ее муж Скотт Фицджеральд умер, считая себя неудачником как писатель. [ 239 ] Два года спустя, после вступления Соединенных Штатов во Вторую мировую войну , ассоциация руководителей издательств создала Совет по книгам во время войны , который распространил 155 000 экземпляров «Великого Гэтсби» среди американских солдат за рубежом. [ 240 ] и книга оказалась популярной среди осажденных войск. [ 241 ] К 1944 году произошло полномасштабное возрождение Фицджеральда. [ 242 ] Несмотря на возобновление интереса к творчеству Скотта, смерть Зельды в марте 1948 года мало была отмечена в прессе.

В 1950 году знакомый и сценарист Бадд Шульберг написал «Разочарованные » с персонажами, узнаваемо основанными на Фицджеральдах, которые в конечном итоге оказались забытыми бывшими знаменитостями: он напился алкоголя, а она одурманена психическим заболеванием. За ней в 1951 году последовала книга профессора Корнеллского университета Артура Мизенера «Дальняя сторона рая» , биография Ф. Скотта Фицджеральда, которая возродила интерес к этой паре среди ученых. Биография Мизенера была опубликована в The Atlantic Monthly , а рассказ о книге появился в журнале Life . Скотта изображали как потрясающего неудачника; Психическое здоровье Зельды во многом обвиняли в его утраченном потенциале. [ 243 ]

Однако в 1970 году история брака Зельды и Скотта получила наиболее глубокий пересмотр в книге Нэнси Милфорд , аспирантки Колумбийского университета . «Зельда: Биография» , первая книга, посвященная жизни Зельды, стала финалистом Национальной книжной премии и несколько недель фигурировала в The New York Times . списке бестселлеров [ 23 ] Книга превращает Зельду в самостоятельную художницу, чьи таланты были принижены властным мужем. Зельда посмертно стала иконой феминистского движения 1970-х годов — женщиной, чей недооцененный потенциал был подавлен патриархальным обществом. [ 244 ]

После успеха биографии Милфорда 1970 года ученые начали рассматривать работу Зельды в новом свете. [ 24 ] Еще до написания биографии Милфорда ученый Мэтью Дж. Брукколи писал в 1968 году, что роман Зельды « Спаси меня вальс » «стоит прочитать отчасти потому, что все, что освещает карьеру Ф. Скотта Фицджеральда, стоит прочитать, а также потому, что это единственный опубликованный роман Милфорда». смелая и талантливая женщина, которую помнят за ее поражения». [ 245 ] Однако после биографии Милфорда появилась новая точка зрения. [ 26 ] и ученый Жаклин Тавернье-Курбен написала в 1979 году: « Спасите меня, вальс» - трогательный и увлекательный роман, который следует читать сам по себе так же, как и « Ночь нежна ». Ему не требуется никакого другого оправдания, кроме его сравнительного превосходства». [ 245 ] После биографии Милфорд 1970 года «Спаси меня вальс» стала предметом многих литературных исследований, в которых изучались различные аспекты ее творчества: как роман контрастировал с изображением их брака Скоттом в «Ночи нежной» ; [ 25 ] и как потребительская культура , возникшая в 1920-е годы, оказывала давление на современных женщин . [ 26 ]

В 1991 году собрание сочинений Зельды, в том числе « Спаси меня вальс», было отредактировано Мэтью Дж. Брукколи и опубликовано. [ 246 ] Рецензируя сборник, The New York Times литературный критик Мичико Какутани написала: «То, что роман был написан за два месяца, поразительно. То, что, несмотря на все свои недостатки, ему все же удается очаровать, развлечь и взволновать читателя, еще более примечательно. Это удалось Зельде Фицджеральд», в этом романе она выразила свое героическое отчаяние добиться успеха в чем-то своем, а также сумела отличиться как писательница, обладающая, как однажды сказал о ее муже Эдмунд Уилсон, «даром превращать язык во что-то радужное и удивительное». .'" [ 247 ]

В дополнение к критической переоценке ее романа, произведения Зельды также были оценены как интересные сами по себе. Проведя большую часть 1950-х и 1960-х годов на семейных чердаках (мать Зельды даже сожгла большую часть произведений искусства, потому что они ей не нравились), ее работа вызвала новый интерес ученых. [ 27 ] Посмертные выставки ее акварелей гастролировали по Соединенным Штатам и Европе. В обзоре выставки куратора Эверла Адэра отмечено влияние Винсента Ван Гога и Джорджии О'Киф на ее картины, и сделан вывод, что ее сохранившийся корпус произведений искусства «представляет собой работу талантливой, дальновидной женщины, которая преодолела огромные трудности, чтобы создать увлекательная работа, которая вдохновляет нас прославлять жизнь, которая могла бы быть». [ 27 ]

Ученые продолжают обсуждать роль Зельды и Скотта в вдохновении и подавлении творчества друг друга. [ 248 ] Биограф Салли Клайн писала, что эти два лагеря могут быть «столь же диаметрально противоположными, как литературные лагеря Плата и Хьюза» - отсылка к горячим спорам об отношениях поэтов мужа и жены Теда Хьюза и Сильвии Плат . [ 249 ] В частности, сторонники Зельды часто изображают Скотта Фицджеральда властным мужем, который довел свою жену до безумия. [ 250 ]

В ответ на это повествование дочь Зельды Скотти Фицджеральд написала эссе, опровергающее такие «неточные» интерпретации. [ 251 ] Она особенно возражала против ревизионистских изображений своей матери как «классической «униженной» жены, чьи усилия выразить свою артистическую натуру были пресечены типичным мужем-шовинистом-мужчиной». [ 252 ] Напротив, Скотти настаивал, «что мой отец очень ценил и поощрял необычные таланты и бурное воображение своей жены. Он не только организовал первый показ ее картин в Нью-Йорке в 1934 году, но и провел долгие часы репетиций ее единственной пьесы, «Скандалабра» , поставленная группой «Маленький театр» в Балтиморе, он провел много часов, редактируя рассказы, которые она продавала в «Колледж юмора» и в журнал «Скрибнерс »; [ 252 ] Ближе к концу жизни Скотти написала биографу заключительную статью о своих родителях: «Я никогда не могла поверить в то, что пьянство моего отца привело ее в санаторий. Я также не думаю, что она привела его туда. пьянство». [ 250 ]

Наследие и влияние

[ редактировать ]Зельда была вдохновением для « Женщины-ведьмы ». [ 23 ] песня о соблазнительных волшебницах, написанная Доном Хенли и Берни Лидоном для The Eagles после того, как Хенли прочитала биографию Зельды; музы, частичного гения, стоящего за ее мужем Ф. Скоттом Фицджеральдом , дикого, чарующего, завораживающего, типичного « флапера » века джаза . [ 253 ]

Имя Зельды послужило источником вдохновения для создания принцессы Зельды , одноименного персонажа The Legend of Zelda . серии видеоигр [ 254 ] В 2003 году дикая индейка, бродившая по Бэттери-парку в Нью-Йорке, была названа Зельдой из-за известного эпизода, когда во время одного из нервных срывов она пропала и была найдена в Бэттери-парке, очевидно, пройдя несколько миль до центра города. [ 255 ] [ 256 ] В 1989 году в Монтгомери, штат Алабама, открылся музей Ф. Скотта и Зельды Фицджеральд. Музей находится в доме, который они ненадолго арендовали в 1931 и 1932 годах. Это одно из немногих мест, где выставлены некоторые картины Зельды. [ 257 ]

В 1992 году Зельда и ее дочь Скотти были посмертно включены в Зал женской славы Алабамы . [ 258 ]

В 2023 году Hatteras Sky и Lark Hotels запланировали три бутик-отеля в Эшвилле, Северная Каролина, два из которых будут оформлены в стиле Зельды Фицджеральд. Zelda Dearest с 20 комнатами будет обладать «красотой и оптимизмом» ранней жизни Зельды. Салон Zelda, названный в честь дома Гертруды Стайн во Франции, будет иметь 35 комнат, дизайн которых основан на том, где Фицджеральды останавливались в 1920-х годах. [ 259 ]

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ↑ Во время поездки по горным дорогам Лазурного берега во Франции Зельда схватила руль и попыталась покончить с собой, своим мужем и их 9-летней дочерью Скотти , съехав со скалы. [ 5 ]

- ↑ По словам исследователя Фицджеральда Мэтью Дж. Брукколи , «Зельда не говорит, что участвовала в работе над «Прекрасными и проклятыми» : только то, что Фицджеральд поместил часть ее дневника «на одну страницу» и что он исправил «обрывки» ее писем. Ни одно из Сохранившиеся рукописи Фицджеральда показывают ее руку». [ 114 ]

- ^ Фессенден (2005) утверждает, что Фицджеральд боролся со своей сексуальной ориентацией. [ 173 ] Напротив, Брукколи (2002) настаивает на том, что «любого можно назвать скрытым гомосексуалистом, но нет никаких доказательств того, что Фицджеральд когда-либо был вовлечен в гомосексуальную привязанность». [ 164 ]

Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час Тейт 1998 , с. 85.

- ^ Фицджеральд 2004 , с. 46.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Клайн 2002 , с. 87: «Они наполнили свои первые недели выходками, а газеты заполнили свои страницы Фицджеральдами… Будучи enfants ужасными , они действительно провоцировали людей, но они никогда не были вульгарными и часто забавными, поэтому им это сходило с рук».

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кернатт 2004 , стр. 31, 62; Брукколи 2002 , с. 131.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Милфорд 1970 , с. 156.

- ^ Милфорд 1970 , с. 156; Штамберг 2013 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Брукколи 2002 , с. 201: «Однажды ночью Фицджеральд разбудил Мерфи сообщением о том, что Зельда приняла большую дозу снотворного, и они помогли ему не дать ей заснуть. Неясно, был ли ее самоубийственный жест связан с кризисом Джозана».

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Milford 1970 , стр. 161, 387: «Они еще не осознавали ни масштабы нервного расстройства Зельды, ни количество времени, которое потребуется, чтобы «вылечить» ее, и даже то, можно ли ее вылечить. Форель как шизофреник».

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Брукколи 2002 , с. 305: «После того, как осенью 1930 года у Зельды случился рецидив, 22 ноября был вызван доктор Пауль Ойген Блейлер на консультацию. диагноз Фореля и надежду на то, что три из четырех случаев шизофрении излечимы».

- ^ Штамберг 2013 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Брукколи 2002 , стр. 327–328.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Брукколи 2002 , стр. 343, 362.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Брукколи 2002 , с. 343.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Фицджеральд 1991 , с. vi: По словам ее дочери, Скотт Фицджеральд организовал «первый показ ее картин в Нью-Йорке в 1934 году».

- ^ Брукколи 2002 , стр. 486–489.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Милфорд 1970 , стр. 382–383.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Клайн 2002 , с. 359: «Кэрролл был пионером в инъекциях плацентарной крови, меда и гипертонических растворов, а также лошадиной крови в спинномозговую жидкость пациентов. Лошадиная сыворотка вызывала асептический менингит с рвотой, лихорадкой и головными болями, но Кэрролл использовал ее на Зельде, потому что она могла вызвать длительные периоды осознанности. Он также регулярно давал Зельде стандартные теперь методы лечения электрошоком и инсулиновым шоком, не обращая внимания на их известные эффекты потери памяти».

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Клайн 2002 , с. 286: «Зельде провели курс лечения инсулиновым шоком, который продолжался в течение десяти лет».

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Клайн 2002 , с. 351.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Смит 2022 .

- ^ Янг 1979 ; Смит 2022 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Клайн 2002 , с. 402: Уилли Мэй Холл «заявляла, что хотела устроить «небольшую неприятность», чтобы разоблачить ночного сторожа, который отверг ее ухаживания и возложил на себя вину».

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Сандомир 2022 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Дэвис 1995 , с. 327; Тавернье-Курбен 1979 , с. 23.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Тавернье-Курбен 1979 , с. 22.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Дэвис 1995 , с. 327.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Адэр 2005 .

- ^ Зал женской славы Алабамы, 1992 год .

- ^ Милфорд 1970 , с. 43; Брукколи 2002 , с. 91.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Тейт 1998 , с. 85; Клайн 2002 , с. 13.

- ^ Тейт 2007 , с. 373.

- ^ Левицкий и Зиблатт 2018 , с. 111; Куссер 1974 , стр. 134–137.

- ^ Уоррен 2011 ; Ланахан 1996 , с. 444.

- ^ Бэйт 2021 , с. 251.

- ↑ Дэниел 2021 : «... что Фицджеральд включил в сюжет фильма «Ночь нежная» в конце 1931 года инцестуозное изнасилование, потому что Зельду мог изнасиловать ее отец, судья Энтони Сэйр…»

- ^ Тейт 1998 , с. 59.

- ^ Тейт 1998 , с. 85; Милфорд 1970 , с. 3.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Брукколи, Смит и Керр 2003 , с. 38.

- ^ Национальный архив 2016 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Милфорд 1970 , стр. 3–4.

- ^ Милфорд 1970 , с. 5.

- ^ Дэвис 1924 , стр. 45, 56, 59; Бауэрс 1929 , с. 310; Рекламодатель Монтгомери , 1960 , с. 4.

- ^ Сврлуга 2016 ; Хаузер 2022 ; Холтхаус 2008 .

- ^ Апчерч 2004 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Вагнер-Мартин 2004 , с. 24.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Клайн 2002 , с. 13.

- ^ Вагнер-Мартин 2004 , с. 24; Брукколи 2002 , стр. 189, 437.

- ^ Тернбулл 1962 , с. 111: «Зельда не была домохозяйкой. Неохотно заказывая еду, она совершенно игнорировала стирку».

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Милфорд 1970 , стр. 9–13.

- ^ Вагнер-Мартин 2004 , с. 211.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Милфорд 1970 , стр. 16–17.

- ^ Клайн 2002 , стр. 23–25, 37.

- ^ Милфорд 1970 , с. 22.

- ^ Милфорд 1970 , с. 32; Мизенер 1951 , с. 70.

- ^ Мизенер 1951 , с. 70.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Bruccoli 2002 , стр. 80, 82: Фицджеральд хотел умереть в бою и надеялся, что его неопубликованный роман после его смерти станет большим успехом.

- ^ Тейт 1998 , стр. 6, 32; Брукколи 2002 , стр. 79, 82.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Вест 2005 , стр. 65–66.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Милфорд 1970 , стр. 33–34.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Тернбулл 1962 , с. 102.

- ^ Брукколи 2002 , с. 122.

- ^ Милфорд 1970 , с. 32.

- ^ Клайн 2002 , с. 65; Брукколи 2002 , с. 95.

- ^ Фицджеральд и Фицджеральд 2002 , с. 96.

- ^ Фицджеральд 1920 , с. 304.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Фицджеральд 1991 , с. vii: По словам ее дочери Скотти, «надгробия на кладбище Конфедерации в Оквуде» были «ее любимым местом, когда она чувствовала себя совершенно одинокой».

- ^ Тернбулл 1962 , с. 102: «Пока они задерживались среди надгробий мертвых конфедератов, Зельда сказала, что Фицджеральд никогда не поймет, что она чувствует по поводу этих могил».

- ^ Вест 2005 , стр. 67–68; Брукколи 2002 , с. 86.

- ^ Запад 2005 , с. 73.

- ^ Брукколи 2002 , с. 111.

- ^ Запад 2005 , с. 73; Брукколи 2002 , с. 89.

- ^ Милфорд 1970 , стр. 35–36; Брукколи 2002 , с. 89.

- ^ Fitzgerald & Fitzgerald 2002 , стр. 314–315: «По вашему собственному признанию, много лет спустя (и в чем я [никогда] вас не упрекал), вы были соблазнены и стали изгоем из провинции. Я почувствовал это в ту ночь, когда мы впервые переспали вместе ты плохой блеф».

- ^ Тернбулл 1962 , с. 70: «Одним мартовским днем [1916 года] казалось, что я потеряла все, что хотела, — и в ту ночь я впервые выследила призрак женственности, который на какое-то время заставляет все остальное казаться неважным».

- ^ Брукколи 2002 , с. 91: Фицджеральд написал 4 декабря 1918 года: «Я твердо решил, что я не буду, не буду, не смогу, не должен, не должен жениться».

- ^ Брукколи 2002 , с. 91.

- ^ Mizener 1951 , стр. 85, 89, 90: «Зельда сомневалась, сможет ли он когда-нибудь заработать достаточно денег, чтобы они поженились», и Фицджеральд, таким образом, был вынужден доказывать, что «он достаточно богат для нее».

- ^ Милфорд 1970 , стр. 35–36.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Брукколи 2002 , с. 109.

- ^ Клайн 2002 , с. 73.

- ^ Милфорд 1970 , с. 42; Тернбулл 1962 , с. 92.

- ^ Тейт 1998 , с. 82: «Не желая ждать, пока Фицджеральд преуспеет в рекламном бизнесе, и не желая жить на свою небольшую зарплату, Зельда разорвала помолвку».

- ^ Милфорд 1970 , с. 52: «Когда все в Нью-Йорке его рухнуло, его карьера и писательство, он обратился к Зельде с предложением немедленного брака... Это была попытка со стороны Скотта искупить хотя бы часть его мечтаний об успехе и счастье, но Зельда, должно быть, чувствовала, что оно основано на неудаче, и не могла принять брак на этом основании».

- ^ Брукколи 2002 , стр. 95–96; Фицджеральд 1966 , с. 108.

- ^ Тернбулл 1962 , стр. 93–94.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Брукколи 2002 , с. 96.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Брукколи 2002 , с. 97.

- ^ Милфорд 1970 , с. 55; Вест 2005 , стр. 65, 74, 95.

- ^ Фицджеральд 1945 , с. 86.

- ^ Брукколи 2002 , с. 99.

- ^ Милфорд 1970 , с. 57.

- ^ Тернбулл 1962 , с. 105; Брукколи 2002 , с. 128.

- ^ Брукколи 2002 , с. 479: Фицджеральд писал в 1939 году: «Вы [Зельда] подчинились в момент нашей свадьбы, когда ваша страсть ко мне была на таком же упадке, как и моя к вам... Я никогда не хотел Зельду, на которой женился. Я не любил тебя снова, пока ты не забеременеешь».

- ^ Тернбулл 1962 , с. 102: «Победа была сладкой, хотя и не такой сладкой, как шесть месяцев назад, прежде чем Зельда отвергла его. Фицджеральд не смог вернуть себе острые ощущения их первой любви».

- ^ Брукколи 2002 , с. 437: В июле 1938 года Фицджеральд написал своей дочери: «Я все-таки решил жениться на твоей матери, хотя я знал, что она избалована и не значит для меня ничего хорошего. Я сразу же пожалел, что женился на ней, но, проявив терпение в в те дни сделал все возможное».

- ^ Брукколи 2002 , с. 129: Описывая свой брак с Зельдой, Фицджеральд сказал, что — помимо «долгих разговоров» поздно ночью — их отношениям не хватало «близости», которой они никогда «не достигали в повседневном мире брака».

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Тернбулл 1962 , с. 110.

- ^ Мизенер 1972 , с. 28: «Джиневра воплотила в жизнь идеал, за который Фицджеральд цеплялся всю жизнь; до конца его дней мысль о ней могла вызвать слезы на его глазах».

- ^ Стивенс 2003 ; Нужен 2003 год ; Корриган 2014 , с. 58.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Грэм и Фрэнк 1958 , с. 180.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г Грэм и Фрэнк 1958 , с. 242.

- ^ Брукколи 2002 , стр. 131–32.

- ^ Брукколи 2002 , с. XXV.

- ^ Вагнер-Мартин 2004 , с. 24; Брукколи 2002 , стр. 139, 189, 437; Тернбулл 1962 , с. 111.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Грэм и Фрэнк 1958 , с. 241.

- ^ Милфорд 1970 , с. 95.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Фицджеральд и Фицджеральд 2002 , с. xxvii, Введение.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г Брукколи 2002 , с. 143.

- ^ Клайн 2002 , с. 108.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Клайн 2002 , с. 111.

- ^ Кернатт 2004 , с. 32.

- ^ Тейт 1998 , с. 85; Мизенер 1951 , с. 63.

- ^ Милфорд 1970 , с. 84; Мизенер 1951 , с. 63.

- ^ Брукколи 2002 , с. 166.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Тейт 1998 , с. 86.

- ^ Фицджеральд 1966 , стр. 355–356.

- ^ Милфорд 1970 , с. 89.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Фицджеральд и Фицджеральд 2002 , стр. xxvii–viii.

- ^ Тейт 1998 , с. 14: «Обзор был частично шуткой».

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Фицджеральд 1991 , с. ты.

- ^ Брукколи 2002 , с. 162.

- ^ Конор 2004 , с. 209: «Больше, чем любой другой тип современной женщины, именно Флэппер олицетворяла скандал, связанный с новой общественной известностью женщин, от их растущего присутствия на улицах до их механического воспроизведения в качестве очков».

- ^ Конор 2004 , стр. 210, 221.

- ^ Фицджеральд 1945 , с. 16, «Отголоски века джаза»: Флэпперы, «если они вообще что-то делают, в шестнадцать лет узнают вкус джина или кукурузы ».

- ^ Фицджеральд 1945 , стр. 14–15, «Отголоски века джаза»: «Оставленные без присмотра молодые люди из небольших городов обнаружили мобильную конфиденциальность этого автомобиля, подаренного юному Биллу в шестнадцать лет, чтобы сделать его« самостоятельным ». Первые ласки были отчаянным приключением даже при таких благоприятных условиях, но вскоре обменялись признаниями, и старая заповедь была нарушена ».

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Милфорд 1970 , стр. 91–92.

- ^ Брукколи 2002 , с. 158; Кернатт 2004 , с. 31.

- ^ Брукколи 2002 , с. 158.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Милфорд 1970 , с. 88.

- ^ Тернбулл 1962 , с. 140; Мизенер 1951 , стр. 155–156.

- ^ Брукколи 2002 , с. 185.

- ^ Фицджеральд 1945 , с. 21; Поллак 2015 , с. МБ2.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Брукколи 2002 , с. xxvi

- ^ Фицджеральд 1945 , с. 272.

- ^ Тейт 1998 , с. 86; Брукколи 2002 , с. 195; Милфорд 1970 , стр. 108–112.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Брукколи 2002 , с. 195.

- ^ Тейт 1998 , с. 86: «Определить, было ли дело завершено, невозможно».

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Милфорд 1970 , стр. 108–112.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Милфорд 1970 , стр. 108–112; Брукколи, 2002 г. , стр. 195–196; Тейт 1998 , с. 86.

- ^ Брукколи 2002 , с. 195: «...Фицджеральд сказал Шейле Грэм... что он дрался на дуэли с Джозаном».

- ^ Тейт 1998 , с. 86: «У Зельды возник романтический интерес к Эдуарду, французскому военно-морскому летчику. Невозможно определить, был ли этот роман доведен до конца, но, тем не менее, это было разрушительное злоупотребление доверием».

- ^ Брукколи 2002 , стр. 195–196.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Брукколи 2002 , с. 196.

- ^ Милфорд 1970 , стр. 108–112, 114.

- ^ Мизенер 1951 , с. 164; Милфорд 1970 , с. 112.

- ^ Фицджеральд и Перкинс 1971 , с. 87.

- ^ Брукколи 2002 , стр. 206–207.

- ^ Милфорд 1970 , с. 113.

- ^ Милфорд 1970 , с. 122.

- ^ Милфорд 1970 ; Брукколи 2002 , с. 226.

- ^ Хемингуэй 1964 , с. 186.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хемингуэй 1964 , с. 190.

- ^ Хемингуэй 1964 , стр. 180–181.

- ^ Брукколи 2002 , стр. 437, 468–469: «Она хотела, чтобы я слишком много работал для нее и недостаточно для своей мечты».

- ^ Тернбулл 1962 , стр. 116, 280; Мизенер 1951 , с. 270.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Милфорд 1970 , с. 380.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хемингуэй 1964 , с. 155.

- ^ Хемингуэй 1964 , с. 176.

- ^ Ашер 2014 , с. 230.

- ^ Фессенден 2005 , с. 33.

- ^ Фицджеральд и Фицджеральд 2002 , с. 65.

- ^ Брукколи 2002 , с. 275: «Зельда расширила свою атаку на мужественность Фицджеральда, обвинив его в гомосексуальной связи с Хемингуэем».

- ^ Милфорд 1970 , с. 183.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Брукколи 2002 , с. 275.

- ^ Фессенден 2005 , с. 28: «Карьера Фицджеральда свидетельствует о постоянном настойчивом давлении, направленном на то, чтобы отвергнуть обвинения в собственной гомосексуальности».

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Брукколи 2002 , с. 284: По словам Брукколи, писатель Роберт Макалмон и другие современники в Париже публично утверждали, что Фицджеральд был гомосексуалистом, а Хемингуэй позже избегал Фицджеральда из-за этих слухов.

- ^ Милфорд 1970 , с. 154; Керр 1996 , с. 417.

- ^ Фессенден 2005 , с. 28: «Биографы описывают Фэй как весьма привлекательного « эстета конца века », «денди, всегда сильно надушенного», который познакомил подростка Фицджеральда с Оскаром Уайльдом и хорошим вином».

- ^ Фессенден 2005 , с. 28.

- ^ Брукколи 2002 , с. 275: «Если Фэй была гомосексуалисткой, как утверждалось без доказательств, Фицджеральд, по-видимому, не знал об этом».

- ^ Фессенден 2005 , с. 30.

- ^ Мизенер 1951 , с. 57: «В феврале он накрасился своим макияжем Show Girl и отправился на танцы Psi U в Университете Миннесоты со своим старым другом Гасом Шурмайером в качестве сопровождения. Он провел вечер, случайно прося сигареты посреди танцпола. и рассеянно вытаскиваю из-под синего чулка небольшой косметичку».

- ^ Фессенден 2005 , стр. 32–33.

- ^ Брукколи 2002 , стр. 275, 277.

- ^ Милфорд 1970 , с. 117; Фицджеральд и Фицджеральд 2002 , с. 57.

- ^ Тернбулл 1962 , с. 352.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Брукколи 2002 , с. xxvii

- ^ Буллер 2005 , с. 9.

- ^ Брукколи 2002 , с. 256.

- ^ Тернбулл 1962 , с. 352; Буллер 2005 , стр. 6–8.

- ^ Уилсон 2007 , с. 311.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Милфорд 1970 , стр. 135–138.

- ^ Милфорд 1970 , с. 141.

- ^ Фицджеральд 1991 , с. vi: По словам их дочери, Скотт «даже поддерживал ее уроки балета (в конце концов, он платил за них), пока танцы не стали круглосуточным занятием, разрушающим ее физическое и психическое здоровье».

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Тейт 1998 , стр. 86–87, 283.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Милфорд 1970 , стр. 141, 157.

- ^ Брукколи 2002 , стр. 288–289; Милфорд 1970 , с. 156.

- ^ Тейт 1998 , стр. 87–88, 283; Людвиг 1995 , с. 181.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г Тейт 1998 , стр. 87–88, 283.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Милфорд 1970 , с. 179.

- ^ Штамберг 2013 ; Крамер 1996 , с. 106.

- ^ Грэм и Фрэнк 1958 , стр. 242–243.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Брукколи 2002 , с. 320; Тейт 1998 , стр. 87–88, 283.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Брукколи 2002 , с. 320.

- ^ Милфорд 1970 , стр. 209–212.

- ^ Фицджеральд и Фицджеральд 2002 , с. 145; Милфорд 1970 , с. 213.

- ^ Фицджеральд и Фицджеральд 2002 , с. 156.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Берг 1978 , стр. 235–236.

- ^ Фицджеральд и Фицджеральд 2002 , с. 163; Берг 1978 , с. 236.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Фицджеральд и Фицджеральд 2002 , с. 164.

- ^ Фицджеральд и Фицджеральд 2002 , с. 163.

- ^ Берг 1978 , стр. 237, 251.

- ^ Фицджеральд 1991 , с. 9.

- ^ Фицджеральд 1966 , с. 262.

- ^ Берг 1978 , с. 250: «У нее есть несколько очень плохих писательских приемов, но сейчас она преодолевает худшие из них».

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Берг 1978 , стр. 251.

- ^ Брукколи 2002 , с. xxviii.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Менкен 1989 , стр. 44–45.

- ^ Менкен 1989 , с. 56.

- ^ Клайн 2002 , с. 320; Милфорд 1970 , с. 264.

- ^ Фицджеральд и Фицджеральд 2002 , с. 207.

- ^ Тавернье-Курбен 1979 , стр. 31–33.

- ^ Брукколи 2002 , с. 328.

- ^ Тавернье-Курбен 1979 , с. 36.

- ^ Тавернье-Курбен 1979 , с. 40.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Милфорд 1970 , стр. 262–263.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час Грэм и Фрэнк 1958 , стр. 243–244.

- ^ Брукколи 2002 , с. 345.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Брукколи 2002 , с. 362.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Тейт 1998 , с. 88.

- ^ Милфорд 1970 , с. 290.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Милфорд 1970 , с. 308.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Милфорд 1970 , стр. 311–313.

- ^ Корриган 2014 , с. 59; Смит 2003 , с. Е1; Ноден 2003 .