Словарь птичьих терминов

Ниже приводится словарь общеупотребительных англоязычных терминов, используемых при описании птиц — теплокровных позвоночных животных класса Aves и единственных ныне живущих динозавров . [1] характеризуются перьями , способностью летать у всех, кроме примерно 60 существующих видов нелетающих птиц , беззубыми, клювистыми челюстями , откладкой яиц с твердой скорлупой , высокой скоростью обмена веществ , четырехкамерным сердцем и крепким, но легким скелетом .

Среди других деталей, таких как размер, пропорции и форма, были разработаны термины, определяющие особенности птиц, которые используются для описания особенностей, уникальных для этого класса, особенно эволюционных адаптаций, которые развились для облегчения полета . Существует, например, множество терминов, описывающих сложную структурную структуру перьев (например, бородки , рахиды и лопасти ); типы перьев (например, нитевидные , перистые и перистые перья); а также их рост и потеря (например, изменение цвета , брачного оперения и птерилеза ).

Существуют тысячи терминов, уникальных для изучения птиц. Этот глоссарий не пытается охватить их все, а концентрируется на терминах, которые можно встретить в описаниях множества видов птиц, сделанных любителями птиц и орнитологами . Хотя также включены слова, которые не являются уникальными для птиц, например « спина » или « живот », они определяются в связи с другими уникальными особенностями внешней анатомии птиц , иногда называемыми « топографией ». Как правило, этот глоссарий не содержит отдельных записей ни о одном из примерно 11 000 признанных ныне живущих отдельных видов птиц мира. [2] [3] [а]

А [ править ]

- запутанные яйца

- Also, wind eggs; hypanema.[5] Eggs that are not viable and will not hatch.[6] See related: overbrooding.

- afterfeather

- Any structure projecting from the shaft of the feather at the rim of the superior umbilicus (at the base of the vanes), but typically a small area of downy barbs growing in rows or as tufts.[b] Entirely absent in some birds—notably from many members of the Columbidae family (pigeons and doves)—afterfeathers can significantly increase the insulative attributes of a bird's plumage.[8]

- allopreening

- A form of social grooming among birds, in which one bird preens another or a pair does so mutually. At times it may be used to redirect or sublimate aggression, such as one bird assuming a solicitation posture to indicate its non-aggression and invite allopreening by the aggressive individual.[9]

- alternate plumage

- Also, nuptial plumage; breeding plumage. The plumage of birds during the courtship or breeding season. It results from a prealternate moult that many birds undergo just prior to the season. The alternate plumage is commonly brighter than the basic plumage, for the purposes of sexual display, but may also be cryptic, to hide incubating birds that might be vulnerable on the nest.[10]

- altricial

- Also defined: semi-altricial; altricial-precocial spectrum. Young that, at hatching, have their eyes closed; are naked or only sparsely covered in down feathers (psilopaedic); are not fully able to regulate their body temperature (ectothermic);[11] and are unable to walk or leave the nest for an extended period of time to join their parents in foraging activities (nidicolous), whom they rely on for food.[12] The contrasting state is precocial young, which are born more or less with their eyes open, covered in down, homeothermic, able to leave the nest and ambulate and to participate in foraging.[11][13] The young of many bird species do not precisely fit into either the precocial or altricial category, having some aspects of each and thus fall somewhere on an altricial-precocial spectrum.[14] A defined intermediate state is termed semi-altricial, typified by young that, though born covered in down (ptilopaedic), are unable to leave the nest or walk and are reliant on their parents for food.[15][16]

- alula

- Also, bastard wing; alular digit; alular quills.[17] A small, freely-moving projection on the anterior edge of the wing of modern birds (and a few non-avian dinosaurs)—a bird's "thumb"—the word is Latin and means 'winglet'; it is the diminutive of ala, meaning 'wing'. Alula typically bear three to five small flight feathers, with the exact number depending on the species. The bastard wing normally lies flush against the anterior edge of the wing proper, but can be raised to function in similar manner to the slats of airplane wings that aid in lift by allowing a higher than normal angle of attack. By manipulating the alula structure to create a gap between it and the rest of the wing, a bird can avoid stalling when flying at low speeds or when landing. Feathers on the alular digit are not generally considered to be flight feathers in the strict sense; though they are asymmetrical, they lack the length and stiffness of most true flight feathers. Nevertheless, alula feathers are a distinct aid to slow flight.[18]

- anisodactylous

- Descriptive of tetradactyl (four-toed) birds in which the architecture of the foot consists of three toes projecting forward and one toe projecting backward (the hallux), such as in most passerine species.[19][20]

- anting

- Also defined: passive anting. A self-anointing behaviour during which birds rub insects, usually ants and sometimes millipedes, on their feathers and skin. Anting birds may pick up the insects in their bill and rub them on their bodies, or may simply lie in an area with a high density of the insects and perform dust bathing-like movements. Insects used for anting secrete chemical liquids such as formic acid, which can act as insecticides, miticides, fungicides and bactericides. The practice may also act to supplement a bird's own preen oil. A third purpose may be to render the insects more palatable, by causing removal of distasteful compounds. More than 200 species of bird are known to ant.[21] "Passive anting" refers to when birds simply position themselves so as to allow insects to crawl through their plumage.[6]

- apical spot

- A visible spot near the outer tip of a feather.[22]

- apterylae

- Singular: apteryla. Also, apteria. Regions of a bird's skin, between the pterylae (feather tracts), which are free of contour feathers; filoplumes and down may grow in these areas.[23][24] See related: pterylosis.

- aviculture

- The captive breeding and keeping of birds.[6]

- axilla

- Also, axillar region; "underarm"; "armpit". The "armpit" of a bird, often hosting covert feathers called axillaries.[25]

- axillaries

- Also, axillary feathers; lower humeral coverts; hypopteron. Covert feathers found in the axillar region or "armpit" of a bird, which are typically long, stiff and white in colour.[26]

B[edit]

- back

- The exterior region of a bird's upper parts between the mantle and the rump.[27]

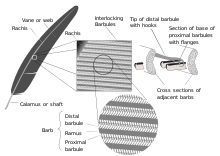

- barb

- Also defined: ramus (plural: rami). The individual structures growing out of the shaft that collectively make up the vanes of the feathers, more or less interconnected by the hooklets of the barbules, extending from each side of the distal part of the feather's shaft known as the rachis. The central axis of a barb is known as the ramus.[8]

- barbules

- Also, radius / radii; tertiary fibres.[28] Also defined: proximal barbules; distal barbules; barbicels; hooklets (hamuli); pennulum; teeth. Just as barbs branch off on parallel sides of the rachis, the barbs in turn have a set of structures called barbules, branching from each side of the ramus. The base cells of the barbule form a plate from which a thinner stalk projects called the pennulum. At one more level of branching, the pennulum hosts small outgrowths from it called barbicels—which when found on pennaceous feathers, vary in structure depending on which side of a barb's ramus they project from. Proximal barbules (on the proximal side of the ramus) have ventral projections near the base called teeth, while growing from the pennulum are cilia—simple pointed structures. At the base of the proximal barbule, the "dorsal edge is recurved into a flange".[29] The distal barbules (on the distal side of the ramus) have a thicker base with more elaborate teeth, and a longer pennulum with hooklets (also called hamuli[30]) at the end, as well as cilia in greater number than on proximal barbules. The hooklets overlap one to four rows of proximal barbules on the next higher barb, locking into their flanges, thereby giving the vane structure, strength, flexibility and stability.[29] See also: friction barbules.

- basic plumage

- Also, winter plumage; non-breeding plumage. Also defined: supplementary plumage. The plumage of birds during the non-breeding season. It results from the prebasic moult that many birds undergo just after the season, and sometimes (rarely) even a second non-breeding season moult (resulting in what's termed "supplementary plumage") prior to the next breeding season.[c] The basic plumage is commonly duller than the alternate or nuptial plumage.[10][31]

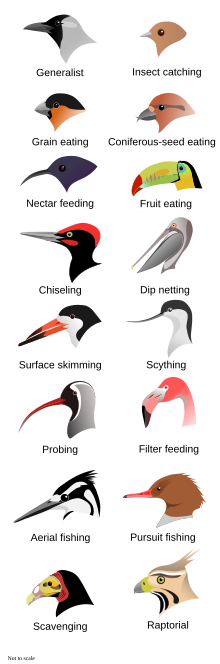

- beak

- Also, bill or rostrum. An external anatomical structure of a bird's head, roughly corresponding with the "nose" of a mammal, that is used for eating, grooming, manipulating objects, killing prey, fighting, probing for food, courtship and feeding young. Although beaks vary significantly in size and shape from species to species, their underlying structures follow a similar pattern. All beaks are composed of two jaws, generally known as the upper mandible (or maxilla) and lower mandible (or mandible),[32] covered with a thin, horny sheath of keratin called the rhamphotheca,[33][34] which can be subdivided into the rhinotheca of the upper mandible and the gnathotheca of the lower mandible.[35] The tomia (singular: tomium) are the cutting edges of the two mandibles.[36] Most species of birds have external nares (nostrils) located somewhere on their beak—two holes—circular, oval or slit-like in shape—which lead to the nasal cavities within the bird's skull, and thus to the rest of the respiratory system.[37] Although the word beak was, in the past, generally restricted to describing the sharpened bills of birds of prey,[38] in modern ornithology, the terms beak and bill are generally used synonymously.[33]

- beak colour

- The colour of a bird's beak results from concentrations of pigments—primarily melanins and carotenoids—in the epidermal layers, including the rhamphotheca.[39] In general, beak colour depends on a combination of the bird's hormonal state and diet. Colours are typically brightest as the breeding season approaches and palest after breeding.[40]

- beak trimming

- Also, debeaking and coping. The partial removal of the beak of poultry, especially layer hens and turkeys, although it may also be performed on quail and ducks. Because the beak is a sensitive organ with many sensory receptors, beak trimming or debeaking is "acutely painful"[41] to the birds it is performed on. It is nonetheless routinely done to intensively farmed bird species, because it helps reduce the damage the flocks inflict on themselves due to a number of stress-induced behaviours, including cannibalism, vent pecking and feather pecking. A cauterizing blade or infrared beam is used to cut off about half of the upper beak and about a third of the lower beak. Pain and sensitivity can persist for weeks or months after the procedure, and neuromas can form along the cut edges. Food intake typically decreases for some period after the beak is trimmed. However, studies show that trimmed poultry's adrenal glands weigh less, and their plasma corticosterone levels are lower than those found in untrimmed poultry, indicating that they are less stressed overall.[41] A less radical, separate practice, usually performed by an avian veterinarian or an experienced birdkeeper, involves clipping, filing or sanding the beaks of captive birds for health purposes—in order to correct or temporarily alleviate overgrowths or deformities and better allow the bird to go about its normal feeding and preening activities.[42] "Coping" is the name for this practice amongst raptor keepers.[43]

- belly

- Also, abdomen. The topographical region of a bird's underparts between the posterior end of the breast and the vent.[44]

- billing

- Also, nebbing (chiefly UK). Describes the tendency of mated pairs of many bird species to touch or clasp each other's bills.[45] This behaviour appears to strengthen pair bonding.[46] The amount of contact involved varies among species. Some gently touch only a part of their partner's beak while others clash their beaks vigorously together.[47]

- bill tip organ

- A region found near the tip of the bill in several types of birds that forage particularly by probing. The region has a high density of nerve endings known as the corpuscles of Herbst. These consist of pits in the bill's surface lined with cells that sense pressure changes. The assumption is that these cells allow a bird to perform "remote touch", meaning that it can detect the movement of animals by pressure variations in water, without directly touching the prey. Bird species known to have bill-tip organs include ibises, shorebirds of the family Scolopacidae and kiwis.[48]

- bird ringing

- Also, bird banding. The attachment of small, individually numbered metal or plastic tags to the legs or wings of wild birds to enable individual identification. The practice helps in keeping track of bird movement and life history. Upon capture for ringing, it is common to take measurements and examine the conditions of feather moult, amount of subcutaneous fat, age indications and sex. The subsequent recapture or recovery of banded birds can provide information on migration, longevity, mortality, population, territoriality, feeding behaviour and other aspects that are studied by ornithologists. Bird ringing is the term used in the UK and in some other parts of Europe, while the term bird banding is more often used in the U.S. and Australia.[49]

- bird strike

- The impact of a bird or birds with an airplane in flight.[50]

- body down

- The layer of small, fluffy down feathers that lie underneath the outer contour feathers on a bird's body.[51] Compare: natal down and powder down.

- breast

- The topographical region of a bird's external anatomy between the throat and the belly.[52]

- breeding plumage

- See alternate plumage.

- brood

- The collective term for the offspring of birds, or the act of brooding the eggs.[53]

- brooding

- See egg incubation.

- broodiness

- Also defined: broody. The action or behavioural tendency of a bird to sit on a clutch of eggs to incubate them, often requiring the non-expression of many other behaviours including feeding and drinking.[54] The adjective "broody" is defined as "[b]eing in a state of readiness to brood eggs that is characterized by cessation of laying and by marked changes in behavior and physiology". Example usage: "a broody hen".[55]

- brood patch

- A bare patch of skin that most female birds gain during the nesting season for thermoregulation purposes, by shedding feathers close to the belly, in an area that will be in contact with the eggs during incubation. The patch of bare skin is well supplied with blood vessels at the surface, facilitating heat transfer to the eggs.[56]

- brood parasite

- Birds, such as the common goldeneye, indigobirds, whydahs, honeyguides, cowbirds and New World cuckoos, that lay their eggs in other birds' nests, in order to have their chicks incubated through fledging by the parents of another bird, often of another species.[57][58][59]

C[edit]

- calamus

- Plural: calami. The basal part of the quill of pennaceous feathers, which embeds at its proximal tip in the skin of a bird. The calamus is hollow and has pith formed from the dry remains of the feather pulp. The calamus stretches between two openings—at its base is the inferior umbilicus and at its distal end is the superior umbilicus; the rachis of the stem, hosting the vanes, continues above it.[60][61] Calamus derives from the Latin for 'reed' or 'arrow'.[62]

- call

- Specific types: alarm; contact; duet; antiphonal duetting; food begging; flight; mobbing. A type of bird vocalization tending to serve such functions as giving alarm or keeping members of a flock in contact—as opposed to a bird's song, which is longer, more complex and is usually associated with courtship and mating.[63] Individual birds may be sensitive enough to identify each other through their calls. Many birds that nest in colonies can locate their chicks using their calls.[64] Alarm calls are used to sound alarm to other individuals. Food-begging calls are made by baby birds to beg for food, such as the "wah" of infant blue jays.[65] Mobbing calls signal other individuals in mobbing species while harassing a predator. They differ from alarm calls, which alert other species members to allow escape from predators. As an example, the great tit, a European songbird, uses such a signal to call on nearby birds to harass a perched bird of prey, such as an owl. This call occurs in the 4.5kHz range,[66] and carries over long distances. However, when such prey species are in flight, they employ an alarm signal in the 7–8 kHz range. This call is less effective at traveling great distances, but is much more difficult for both owls and hawks to hear (and detect the direction from which the call came).[67] Contact calls are used by birds for the purpose of letting others of their species know their location.[68] Relatedly, flight calls are vocalizations made by birds while flying, which often serve to keep flocks together.[69] These calls are also used for when birds want to alert others that they are taking flight.[70] Many birds engage in duet calls—a call made by two birds at or nearly at the same time. In some cases, the duets are so perfectly timed as to appear almost as one call. This kind of calling is termed antiphonal duetting.[71] Such duetting is noted in a wide range of families including quails,[72] bushshrikes,[73] babblers such as scimitar babblers and some owls[74] and parrots.[75]

- canopy feeding

- Also defined: double-wing feeding. Some herons, such as the black heron, adopt an unusual position while hunting for prey. With their head held down in a hunting position, they sweep their wings forward to meet in front of their head, thereby forming an umbrella shaped canopy. To achieve full canopy closure, the primaries and secondaries touch the water, the nape feathers are erected and the tail is drooped. The bird may take several strides in this position. One theory about the function of this behaviour is that it reduces glare from the water surface, allowing the bird to more easily locate and catch prey. Alternatively, the shade provided by the canopy may attract fish making their capture easier. Some herons adopt a similar behaviour called double-wing feeding in which the wings are swept forward to create an area of shade, though a canopy is not formed.[76]

- carpal bar

- A patch seen on the upperwing of some birds that usually appears as a long stripe or line. It is created by the contrast between the greater coverts and the other wing feathers.[77]

- caruncle

- The collective term for the several fleshy protuberances on the heads and throats of gallinaceous birds, i.e., combs, wattles, ear lobes and nodules. They can be present on the head, neck, throat, cheeks or around the eyes of some birds. Caruncles may be featherless, or present with a small array of scattered feathers. In some species, they may form pendulous structures of erectile tissue, such as the "snood" of the domestic turkey.[78][79] While caruncles are ornamental elements used by males to attract females to breed,[80] it has been proposed that these organs are also associated with genes that encode resistance to disease,[81] and for birds living in tropical regions, that caruncles also play a role in thermoregulation by making the blood cool faster when flowing through them.[82]

- casque

- A horny ridge found on the upper mandible of a bird's bill, especially used in relation to hornbills and cassowaries,[83][84] though other birds may have casques such as common moorhens,[85] tufted puffins[86] and (male) friarbirds.[87] The ridge line on the upper maxilla may extend to a prominent crest on the front of the face and on the head, such as in the "flamboyant" crest of the rhinoceros hornbill.[88] Some hornbill casques contain a hollow space that may act as a resonance chamber, amplifying calls.[89] Similar function has been proposed for cassowary casques, as well as for protection of the head while dense vegetation is traversed, as a sexual ornament and for use as a "shovel" for digging food.[90] Compare: frontal shield.

- cere

- From the Latin cera meaning 'wax', a waxy structure which covers the base of the bills of some bird species from a handful of families—including raptors, owls, skuas, parrots, turkeys and curassows. The cere structure typically contains the nares, except in owls, where the nares are distal to the cere. Although it is sometimes feathered in parrots,[91] the cere is typically bare and often brightly coloured.[92] In raptors, the cere is a sexual signal which indicates the "quality" of a bird; the orangeness of a Montague's harrier's cere, for example, correlates to its body mass and physical condition.[93] The colour or appearance of the cere can be used to distinguish between males and females in some species. For example, the male great curassow has a yellow cere, which the female (and young males) lack,[94] and the male budgerigar's cere is blue, while the female's is pinkish or brown.[95]

- cheek

- Also, malar / malar region. The area of the sides of a bird's head, behind and below the eyes.[96]

- chin

- A small feathered area located just below the base of the bill's lower mandible.[97]

- cloaca

- A multi-purpose opening terminating at the vent at the posterior of a bird: birds expel waste from it; most birds mate by joining cloaca (a "cloacal kiss"); and females lay eggs from it. Birds do not have a urinary bladder or external urethral opening and (with exception of the ostrich) uric acid is excreted from the cloaca, along with faeces, as a semisolid waste.[98][99][100] Additionally, in those few bird species in which males possess a penis (Palaeognathae [with the exception of the kiwis], the Anseriformes [with the exception of screamers] and in rudimentary forms in Galliformes[101][102]) it is hidden within the proctodeum compartment within the cloaca, just inside the vent.[103]

- cloacal kiss

- Most male birds lack a phallus and instead have erectile genital papilla at the terminus of their vas deferens. When male and female birds of such species copulate, they each evert and then press together, or "kiss" their respective proctodeum (the lip of the cloaca). Upon the clocal kiss, the male's sperm spurts into the female's urodoeum (a compartment inside the cloaca), which then make their way into the oviduct.[104][105]

- clutch

- All of the eggs produced by birds often at a single time in a nest. Clutch size differs greatly between species, sometimes even within the same genus. It may also differ intraspecies due to many factors including habitat, health, nutrition, predation pressures and time of year.[106] Average clutch size ranges from one (as in northern gannet[107]) to about 17 (as in grey partridge[108]).

- comb

- Also, cockscomb (coxcomb and other sp. variants). A fleshy growth or crest on the top of the head of gallinaceous birds, such as turkeys, pheasants and domestic chickens. Its alternative name, cockscomb (or coxcomb) reflects that combs are generally larger on males than on females (a male gallinaceous bird is called a cock). Comb shape varies considerably depending on the breed or species of bird. The "comb" most often refers to chickens in which the most common shape is the "single comb" of a rooster from breeds such as the leghorn. Other common comb types are the "rose comb" of, e.g., the eponymous rosecomb; the "pea comb" of, e.g., the brahma and araucana; and others.[109]

- colony

- Also defined: seabird colony; breeding colony; communal roost; heronries; rookery. A large congregation of individuals of one or more species of bird that nest or roost in proximity at a particular location. Many kinds of birds are known to congregate in groups of varying size; a congregation of nesting birds is called a breeding colony. A group of birds congregating for rest is called a communal roost. Approximately 13% of all bird species nest colonially.[110] Nesting colonies are very common among seabirds on cliffs and islands. Nearly 95% of seabirds are colonial,[111] leading to the usage, seabird colony, sometimes called a rookery. Many species of terns nest in colonies on the ground. Herons, egrets, storks and other large waterfowl also nest communally in what are called heronries. Colony nesting may be an evolutionary response to a shortage of safe nesting sites and abundance or unpredictable food sources which are far away from the nest sites.[112]

- colour morph

- See morph.

- commissure

- Depending on usage, may refer to the junction of the upper and lower mandibles,[113] or alternately, to the full-length apposition of the closed mandibles, from the corners of the mouth to the tip of the beak.[114]

- contact call

- A type of call used by birds for the purpose of letting others of their species know their location.[68]

- corpuscles of Herbst

- Nerve-endings similar to the Pacinian corpuscle, found in the mucous membrane of the tongue, in pits on the beak and in other parts of the bodies of birds. They differ from Pacinian corpuscles in being smaller and more elongated, in having thinner and more closely placed capsules and in that the axis-cylinder in the central clear space is encircled by a continuous row of nuclei.[115]

- coverts

- Also, covert feathers; tectrices – singular: tectrix. A layer of non-flight feathers overlaying and protecting the quills of flight feathers. At least one layer of covert feathers appear both above and beneath the flight feathers of the wings as well as above and below the rectrices of the tail.[116] These feathers may vary widely in size. For example, the upper tail tectrices of peacocks—the male peafowl—rather than its rectrices, are what constitute its elaborate and colourful "train".[117] There are a number of types and subtypes of covert feathers—primary, secondary, greater, lesser, marginal, median, etc.—see broadly wing coverts and tail coverts.

- cranial kinesis

- Also defined: prokinesis, amphikinesis and distal rhynchokinesis. Movement of the upper mandible in relation to the front of the skull. There is very little of this movement in birds that feed primarily through grazing and thus do not need to open their bills very widely. This is in contrast to parrots, which use their bills to manipulate food and as a support when climbing trees. There are multiple types of cranial kinesis: prokinesis, where the bill moves only at the craniofacial hinge; amphikinesis, where the whole upper jaw is raised; and distal rhynchokinesis, where the bill flexes somewhere along the length of the bill, compared to just at the base.[118]

- crest feather

- Collectively, the/a crest. Long crest feathers are sometimes called quill feathers.[119] Also defined: recumbent crests and recursive crests. A type of semiplume feather with a long rachis with barbs on either side, that often presents as a prominent tuft on the crown and (or through) the neck and upper back.[120][121] Birds with crests include Victoria crowned pigeons, northern lapwings, macaroni penguins and others, but the most recognizable are cockatoos and cockatiels, which can raise or lower their crests at will and use them to communicate with fellow members of their species, or as a form of defence to frighten away other species that approach too closely, making the bird appear larger when the crest is suddenly and unexpectedly raised.[122] In some species the position of the crest is a threat signal that can be used to predict behaviour. In Steller's jays, for example, a raised crest indicates a likelihood of attack, and a lowered crest indicates a likelihood of retreat.[123] Crests can be recumbent or recursive, depending on the species. The recumbent crest, such as in white cockatoos, has feathers that are straight and lie down essentially flat on the head until fanned out.[124] The recursive crest, such as in sulphur-crested cockatoos and Major Mitchell's cockatoos, is noticeable even when its feathers are not fanned out because they curve upward at the tips even when lying flat, and when standing up, often bend slightly forward toward the front of the head. Some birds, like galahs (also known as the rose-breasted cockatoo), have modified crests that have both recumbent and recursive features.[122]

- crissum

- The feathered area between the vent and the tail. Also, the collective name for the undertail coverts.[125] The crissal thrasher derives its name from the term, having distinctive colouring in the region, in contrast with the balance of its plumage. Other birds having distinctive crissum colouration include Le Conte's thrashers and grey catbirds.[126]

- crop

- An expanded, muscular pouch near the gullet or throat found in some but not all birds. It is a part of the digestive tract, essentially an enlarged part of the esophagus, used for the storage of food prior to digestion. As with most other organisms that have a crop, birds use it to temporarily store food. In adult doves and pigeons, the crop can produce crop milk to feed newly-hatched chicks.[127]

- crop milk

- A secretion from the lining of the crop of parent birds that is regurgitated to young birds. It is found among all pigeons and doves where it is referred to as pigeon milk. An analogue to crop milk is also secreted from the esophagus of flamingos and some penguins.[128][129][130] Crop milk bears little physical resemblance to mammalian milk, the former being a semi-solid substance somewhat like pale yellow cottage cheese. It is extremely high in protein and fat, containing higher levels than cow or human milk[131] and has been shown to also contain antioxidants and immune-enhancing factors.[132]

- crown

- Also defined: occiput / hindhead. The portion of a bird's head found between the forehead—demarcated by an imaginary line drawn from the anterior corners of the eyes—and through the "remainder of the upper part of the head", to the superciliary line. The occiput or hindhead, is the posterior part of the crown.[133]

- cryptic plumage

- Also defined: phaneric plumage. Plumage of a bird that is camouflaging. For example, the white winter plumage of ptarmigans is cryptic as it serves to conceal it in snowy environments.[134] The opposite, "advertising" plumage, is termed "phaneric", such as male birds in colourful nuptial plumage for sexual display, making them stand out to a high degree.[135]

- culmen

- The dorsal ridge of the upper mandible.[136] Likened by ornithologist Elliott Coues to the ridge line of a roof, it is the "highest middle lengthwise line of the bill" and runs from the point where the upper mandible emerges from the forehead's feathers to its tip.[137] The bill's length along the culmen is one of the regular measurements made during bird ringing[138] and is particularly useful in feeding studies.[139] The shape or colour of the culmen can also help with the identification of birds in the field. For example, the culmen of the parrot crossbill is strongly decurved, while that of the very similar appearing red crossbill is more moderately curved.[140]

D[edit]

- definitive plumage

- Adult plumage sufficiently developed and fixed following the juvenile years such that it no longer changes significantly in appearance with age.[31]

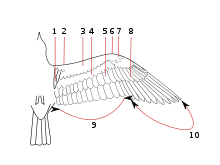

- diastataxis

- The state of lacking a fifth secondary feather on each wing, which occurs in birds in more than 40 non-passerine families. In these birds, the fifth set of secondary covert feathers does not cover any remex. Loons, grebes, pelicans, hawks and eagles, cranes, sandpipers, gulls, parrots and owls are among the families missing this feather.[18]

- dietary classification terms (-vores)

- Birds may be classified by terms related to the types of foods they forage for and eat.[141] The -vore suffix is derived from the Latin vorare, meaning 'to devour'. Equivalent adjectives can be formed through use of the suffix -vorous.[142] For example, granivore (n.) / granivorous (adj.). Generally, classification terms are used based on predominance of food source and/or specialization. There can be much cross-over and mixing between classifications. For example, insectivores and piscivores may at times be described more broadly as types of carnivores, and hummingbirds, though they do eat insects, are often described as nectarivores, rather than insectivores, as nectar is a specialized and predominant food foraging source for that bird family.[143] The feeding strategies of birds is intimately tied to their physiology and evolutionary development. For example, beak shape and structure such as the makeup of the tomia, the presence (or not) of a bill tip organ and myriad other adaptations are tied to a species' feeding strategies.[144] Feeding habits also correlate with aspects of brain development and size. For example, the spatial memory of birds that store food in various locations has been shown to be highly developed and contributes towards success at that feeding tactic.[145]

carnivores (sometimes called faunivores): birds that predominantly forage for the meat of vertebrates—generally hunters as in certain birds of prey—including eagles, owls and shrikes, though piscivores, insectivores and crustacivores may be called specialized types of carnivores.[146] crustacivores: birds that forage for and eat crustaceans, such as crab-plovers and some rails.[146] detritivores: birds that forage for and eat decomposing material, such as vultures. It is usually used as a more general term than "saprovore" (defined below), which often connotes the eating of decaying flesh alone.[147] florivores: birds that forage for and eat plant material in general. Other terms for plant foraging specialization may apply to florivorous species, such as "frugivore" and "granivore".[148] folivores: birds that forage for and eat leaves, such as hoatzin and mousebirds.[141][146] frugivores: birds that forage for and eat fruit, such as turacos, tanagers and birds-of-paradise.[146] granivores: (sometimes called seed-eating): birds that forage for seeds and grains,[149] such as geese, grouse and estrildid finches.[141][146] herbivore: birds that predominantly eat plant material, and mostly do not eat meat; especially of birds that are both granivorous and frugivorous or are grass eaters, such as whistling ducks, ostriches and mute swans.[146][150] insectivores: birds that forage for and eat insects and other arthropods, such as cuckoos, swallows, thrushes, drongos and woodpeckers.[141][146] nectarivores: birds that drink the nectar of flowers, such as hummingbirds, sunbirds and lorikeets.[146] omnivores (sometimes called general feeders): birds that forage for a variety of both plant and meat food sources, such as pheasants, tinamouses and quails. More birds fall under the omnivore classification than any other.[146] piscivores: birds that forage for and eat fish and other sea life, such as darters, loons, pelicans, penguins and storks.[141][146] sanguinivores: birds that forage for and drink blood, such as oxpeckers and sharp-beaked ground finches.[141][148] saprovores: birds that forage for and eat decaying flesh (carrion), such as vultures and crows.[141] However, the term is also used at times synonymously with "detritivore" (defined above), for eaters of any dead matter.[141][147][151] - dimorphism

- See sexual dimorphism.

- diving

- Also defined: surface diving; plunge diving. Some birds dive into the water for food. Two diving strategies are differentiated: surface diving birds dive from the surface of the water and swim actively underwater; and plunge diving birds dive from the air into the water. Plunge diving birds may use the momentum from the plunge to propel themselves underwater, whereas others may swim actively.[152]

- down

- Also, down feathers or plumulaceous feathers. The down of birds—their plumulaceous feathers, as opposed to pennaceous feathers—are a layer of fine, silky feathers found under the tougher exterior feathers, that are often used by humans as a thermal insulator and padding in goods such as jackets, bedding, pillows and sleeping bags. Considered to be the "simplest" of all feather types,[153] down feathers have a short or vestigial rachis (shaft), few barbs and barbules that lack hooks,[154] and (unlike contour feathers) grow from both the pterylae and the apteria.[61] Very young birds are often only clad in down. The loose structure of down feathers traps air, which helps to insulate birds against heat loss[51] and contributes to the buoyancy of waterbirds. Species that experience annual temperature fluctuations typically have more down feathers following their autumn moult.[155] There are three types of down: natal down, body down and powder down.[156]

- drumming

- A form of non-vocal communication engaged in by members of the woodpecker family. It involves the beak striking a hard surface multiple times per second. The drumming pattern, the number of beats per roll and the gap between rolls is specific to each species. Drumming is usually associated with territorial behaviour, with male birds drumming more frequently than females.[157] Drumming may also refer to the sounds produced by the specialised outer tail-feathers of snipe in the course of their courtship display flights.[158]

E[edit]

- ear-coverts

- Small covert feathers located behind a bird's eye, in one to four rows, which cover the ear opening (bird ears have no external features[159]) and may aid in the acuity of bird hearing.[160]

- egg

- Also defined: eggshell; yolk; albumen; chalaza. The organic vessel containing the zygote, in which birds develop until hatching. Eggs are usually oval in shape, and have a base white colour from the predominant calcium carbonate makeup of the outer shell, called the eggshell, though passerine birds especially may have eggs of other colours,[161] such as through deposition of biliverdin and its zinc chelate, which give a green or blue ground colour, and protoporphyrin which produces reds and browns.[162] A viable bird egg (as opposed to a non-viable egg: see addled eggs) consists of a number of structures. The eggshell is 95–97% calcium carbonate crystals, at least in chickens, stabilized by a protein matrix,[163][164][165] without which the crystalline structure would be too brittle to keep its form; the organic matrix is thought to have a role in deposition of calcium during the mineralization process.[166][167][168] The structure and composition of the avian eggshell serves to protect the egg against damage and microbial contamination, prevention of desiccation, regulation of gas and water exchange for the growing embryo and provides calcium for embryogenesis.[164] Inside the eggshell are two shell membranes (inner and outer), and at the center is a yolk—a spherical structure, usually some shade of yellow, to which the fertilized gamete attaches and which the embryonic bird uses as sustenance as it grows. The yolk is suspended in the albumen (also called egg white or glair / glaire) by one or two spiral bands of tissue called the chalazae.[169] The albumen protects the yolk and provides additional nutrition for the embryo's growth,[170] though it is made up of approximately 90% water in most birds.[171] Prior to fertilization, the yolk is a single cell ovum or egg cell; one of the few single cells that can be seen by the naked eye.[172]

- egg binding

- An egg that while traversing the reproductive tract during the process of being laid, becomes stuck near to the opening of the cloaca or further inside the oviduct.[173] The condition may be caused by obesity, nutritional imbalances such as calcium deficiency, environmental stress such as temperature changes, or malformed eggs.[174]

- egg incubation

- Also, brooding. The general care of unhatched eggs by parent birds (more often by females but by birds of both sexes), especially by temperature regulation through sitting on them, crouching or squatting over them, covering them with their wings, providing shade, wetting eggs and related behaviours. The target temperature of most species is 37 °C (99 °F) to 38 °C (100 °F). In monogamous species incubation duties are often shared, whereas in polygamous species one parent is wholly responsible for incubation. Warmth from parents passes to the eggs through brood patches—areas of bare skin on the abdomen or breast of the incubating birds. Incubation can be an energetically demanding process; adult albatrosses, for instance, lose as much as 83 grams (2.9 oz) of body weight per day of incubation.[175][176][177]

- egg tooth

- A small, sharp, calcified projection on the beak that full-term chicks of most bird species have, which they use to chip their way out of their egg.[178] This white spike is located near the tip of the upper mandible in most species (e.g., gulls);[179] near the tip of the lower mandible instead in a minority of others, such as northern lapwings;[179] with a few species, such as Eurasian whimbrels, black-winged stilts and semipalmated sandpipers,[179] having one on each mandible.[180] Despite its name, the projection is not an actual tooth (as the similarly-named projections of some reptiles are); instead, it is part of the integumentary system, as are claws and scales.[181] The hatching chick first uses its egg tooth to break the membrane around an air chamber at the wide end of the egg. Then it pecks at the eggshell while turning slowly within the egg, eventually (over a period of hours or days) creating a series of small circular fractures in the shell.[182] Once it has breached the egg's surface, the chick continues to chip at it until it has made a large hole. The weakened egg eventually shatters under the pressure of the bird's movements.[183] The egg tooth is so critical to a successful escape from the egg that chicks of most species will perish unhatched if they fail to develop one.[180]

- emargination

- A pronounced narrowing at some variable distance along the feather edges at the outermost primaries of large soaring birds, particularly raptors. Whether these narrowings are called notches or emarginations' depends on the degree of their slope.[18] An emargination is a gradual change, and can be found on either side of the feather. A notch is an abrupt change, and is only found on the wider trailing edge of the remige. The presence of notches and emarginations creates gaps at the wingtip; air is forced through these gaps, increasing the generation of lift.[184]

- eye-ring

- Also defined: orbital ring. A visible ring of feathers around a bird's eye; the eye-ring is often paler than the surrounding feathers. By contrast, an orbital ring is bare skin ringing the eye. In some species, such as little ringed plover, the orbital ring may be quite conspicuous.[97]

- eyestripe

- Also, eye line / eyeline. A visible stripe on the feathers of a bird's head, often darker than the surrounding feathers, running through the eye region.[97] Compare supercilium.

- Blue-headed vireo, with a conspicuous eye-ring

- Little ringed plover chick, with a conspicuous orbital ring

- White-eared sibia, with a conspicuous eyestripe

- Whinchat, with a conspicuous supercilium (eyebrow)

F[edit]

- feather

- Epidermal growths that form the distinctive outer covering, or plumage, on birds. They are considered the most complex integumentary structures found in vertebrates,[185][186] and, indeed, a premier example of a complex evolutionary novelty.[187] Feathers are among the characteristics that distinguish the extant birds from other living groups.[188] Although feathers cover most parts of the body of birds, they arise only from certain well-defined tracts on the skin. They aid in flight, thermal insulation and waterproofing, with their colouration helping in communication and protection.[189] Although there are many subdivisions of feathers, at the broadest levels, feathers are either classified as i) vaned feathers, which cover the exterior of the body and include pennaceous feathers, or ii) down feathers, which grow underneath the vaned feathers. A third rarer type of feather, the filoplume, is hairlike and (if present in a bird; they are entirely absent in ratites[190]) grows alongside the contour feathers.[185] A typical vaned feather features a main shaft called the quill with an upper section called the rachis. Fused to the rachis are a series of branches, or barbs; the barbs in turn have barbules branching off them, and they in turn branch yet again with a series of growths called barbicels, some of which have minute hooks called hooklets for cross-attachment. Down feathers are fluffy because they lack barbicels, so the barbules float free of each other, allowing the down to trap air and provide excellent thermal insulation. At the base of the feather, the rachis expands to form the hollow tubular calamus which inserts into a follicle in the skin. The basal part of the calamus is without vanes. This part is embedded within the skin follicle and has an opening at the base (proximal umbilicus) and a small opening on the side (distal umbilicus).[191]

- feather pecking

- A behavioural problem in which one bird repeatedly pecks at the feathers of another, that occurs most frequently amongst domestic hens reared for egg production,[192][193] although it is seen in other poultry such as pheasants,[194] turkeys,[195] ducks[196] and sometimes in farmed ostriches.[197] Two levels of severity are recognised: "gentle" and "severe".[198]

- feather-plucking

- Also feather-picking, feather damaging behaviour or pterotillomania.[199] A maladaptive, behavioural disorder commonly seen in captive birds which chew, bite or pluck their own feathers with their beak, resulting in damage to the feathers and occasionally the skin.[200][201] It is especially common among Psittaciformes, with an estimated 10% of captive parrots exhibiting the disorder.[202] The chief areas of the body that are pecked or plucked are the more accessible regions such as the neck, chest, flank, inner thigh and ventral wing area. Contour and down feathers are generally identified as the main targets, although in some cases, tail and flight feathers are affected. Although feather-plucking shares characteristics with feather pecking, commonly seen in commercial poultry, the two behaviours are currently considered to be distinct, as in the latter, the birds peck at and pull out the feathers of other individuals.

- feather tract

- See: pterylae.

- fecal sac

- Also, faecal sac. A mucous membrane, generally white or clear with a dark end,[203] that surrounds the feces of some species of nestling birds,[204] and allows parent birds to more easily remove fecal material from the nest. The nestling usually produces a fecal sac within seconds of being fed; if not, a waiting adult may prod around the youngster's cloaca to stimulate excretion.[205] Young birds of some species adopt specific postures or engage in specific behaviours to signal that they are producing fecal sacs.[206] For example, nestling curve-billed thrashers raise their posteriors in the air, while young cactus wrens shake their bodies.[207] Other species deposit the sacs on the rim of the nest, where they are likely to be seen (and removed) by parent birds.[206] Not all species generate fecal sacs. They are most prevalent in passerines and their near relatives, which have young that remain in the nest for longer periods.[205]

- filoplume

- Also, filoplume feather; hair feather, thread feather. A hairlike type of feather that, if present in a bird (they are entirely absent in ratites[190]) grows alongside the contour feathers.[185] The typical filoplume is silky in appearance, lacks pith and a superior umbilicous opening, has a very slender, straight shaft lacking differentiation into calamus and rachis, and is naked or has only a few barbs (that lack cross-attachment) at the distal end. They are closely associated with contour feathers and often entirely hidden by them, with one or two filoplumes attached and sprouting from near the same point of the skin as each contour feather, at least on a bird's head, neck and trunk.[208][209] Filoplume feathers host a cluster of sensory corpuscles at their base,[210] that serve to detect air currents that affect contour and flight feathers.[92] Filoplumes are one of the three major classes of feathers, the others being pennaceous and plumulaceous feathers.

- flange

- Also, recurved margin. "The thickened dorsal edge of the bases of pennaceous barbules, generally recurved in proximal barbules, and frequently so in distal barbules also"[211] which anchor the hooklets.[29] (See diagram; refer to figures 3 [in which the flange is referred to as the "folded edge"] and 6 [in which the mechanism of interlocking between a flange and hooklet is shown].)

- flanks

- The topographical region of the underparts[d] sketched "between the posterior half of the abdomen and the rump".[96]

- fledge

- Also, fledging. The stage in a young bird's life when the feathers and wing muscles are sufficiently developed for flight, or describing the act of a chick's parents in raising it to that time threshold.[212]

- fledgling

- A juvenile bird during the period it is venturing from or has left the nest and is learning to run and fly; a young bird during the period immediately after fledging, when it is still dependent upon parental care and feeding.[213]

- flight

- Most birds can fly, which distinguishes them from almost all other vertebrate classes (cf. bats and pterosaurs). Flight is the primary means of locomotion for most bird species and is used for breeding, feeding and predator avoidance and escape. Birds have various adaptations for flight, including a lightweight skeleton, two large flight muscles, the pectoralis (which accounts for 15% of the total mass of the bird) and the supracoracoideus, as well as modified forelimbs (wings) that serve as aerofoils.[214] Wing shape and size generally determine a bird species' type of flight; many birds combine powered, flapping flight with less energy-intensive soaring flight. About 60 extant bird species are flightless, as were many extinct birds.[215] Flightlessness often arises in birds on isolated islands, probably due to limited resources and the absence of land predators.[216] Though flightless, penguins use similar musculature and movements to "fly" through the water, as do auks, shearwaters and dippers.[217]

- flight feather

- Also, Pennae volatus.[218] The long, stiff, asymmetrically shaped, but symmetrically paired pennaceous feathers on the tail or wings of a bird; those on the tail are called rectrices (singular: rectrix), while those on the wings are called remiges (singular: remex). Based on their location, remiges are subdivided into primaries, secondaries and tertiaries.[219]

- foot paddling

- A foraging behaviour of gulls in which individuals stand at a location, often in shallow water, and perform rapid stepping actions that are thought to make subterranean worms or other food rise to the surface.[220]

- forehead

- The portion of a bird's head extending "up and back from the bill to an imaginary line joining the anterior corners of the eyes".[133]

- fovea

- Plural: foveas or foveae. A small cavity in the retina of the eye that hosts a large number of light receptors; more than anywhere else on the retina. About one half of bird species with fovea have a single one, but uniquely in birds,[221] some, such as terns, kingfishers and hummingbirds, have a second fovea,[222] called the temporal fovea, that assists in judging speed and distance and increases visual acuity. Birds that do not have a second fovea will sometimes bob their head to improve their visual field.[223]

- friction barbules

- A specialized type of barbule located on the distal part of the inner vane of primary feathers on the wings of most flighted birds. Friction barbules support lobe-shaped ("lobular") barbicels that are broader than the typical barbicel hosted by other vaned feathers, and which in turn support more hooklets. The theory is that the augmented surface area and other adaptations significantly increases grip through friction when the outer web of barbs of one primary feather come into contact and rub against the inner web of barbs of another primary feather it overlays, thereby preventing slippage during the rigors of flight.[224][225] Friction barbules are found only on those parts of primary feathers that are in "zones of overlap" with neighboring primaries. The theory (and the use of "friction" in the title of the defined phrase) has been criticized. In Avian Flight (2005), the author notes that "most birds open and close their wings during every wing beat cycle", and proposes that the energetic cost to overcome friction during the "wing extension and flexion" of each beat cycle would be prohibitive. Offered instead is the theory that the function of these specialized barbules is to lock the primary feathers together on the wings' downstroke, during which high pressure from below the wings' surface would otherwise tend to cause the feathers to spread.[226]

- frontal shield

- Also facial shield; face shield; frontal plate. A hard or fleshy plate extending from the base of the upper mandible over the forehead of several bird species including some water birds in the rail family, especially the gallinules and moorhens, swamphens and coots, as well as in jacana.[227] While most face shields are made up of fatty tissues, some birds, such as certain turacos, e.g., the red-crested turaco, have face shields that are hard extensions of the mandible.[228] The size, shape and colour may exhibit testosterone-dependent variation in either sex during the year.[229] Functionality appears to relate to protection of the face while feeding in or moving through dense vegetation, as well as to courtship display and territorial defence.[230] Compare: casque.

- furcula

- Also, wishbone; merry-thought. From the Latin for "little fork", the furcula is a forked bone, also found in some dinosaurs, located below the neck and formed by the fusion of the two clavicles. Its primary function is in the strengthening of the thoracic skeleton to withstand the rigors of flight. It works as a strut between a bird's shoulders, and articulates to each of a bird's scapulae. In conjunction with the coracoid and the scapula, it forms a unique structure called the triosseal canal, which houses a strong tendon that connects the supracoracoideus muscles to the humerus. This system is responsible for lifting the wings during a recovery stroke. As the thorax is compressed by the flight muscles during a downstroke, the upper ends of the furcula spread apart, expanding by as much as 50% of its resting width, and then contract. Furcula may also aid in respiration, by helping to pump air through the air sacs.[231][232]

G[edit]

- gape

- The interior of the open mouth of a bird.[233] The width of the gape can be a factor in the choice of food.[234]

- gape flange

- The region where the upper and lower mandibles join together at the base of the beak.[233] When born, the chick's gape flanges are fleshy. As it grows into a fledgling, the gape flanges remain somewhat swollen and can thus be used to recognize that a particular bird is young.[235] Gape flanges can serve as a target for food for parents, and when touched, stimulate the nestling to open its mouth to eat.[236]

- gizzard

- Also, ventriculus; gastric mill; gigerium. A specialized stomach organ found in the digestive tract of some birds constructed of thick muscular walls that is used for grinding up food, often aided by particles of stone or grit. Food, after going through the crop and proventriculus, passes into the gizzard where it can be ground with previously swallowed stones and passed back to the proventriculus, and vice versa. Bird gizzards are lined with a tough layer made of a carbohydrate-protein complex called koilin, that protects the muscles in the gizzard.[237][238]

- gleaning

- Specialized cases: foliage gleaning; hover-gleaning; crevice-gleaning. The strategy of gleaning over surfaces by birds to catch invertebrate prey—chiefly insects and other arthropods—by plucking them from foliage or the ground, from crevices such as of rock faces and under the eaves of houses, or even, as in the case of ticks and lice, from living animals. Gleaning the leaves and branches of trees and shrubs is called "foliage gleaning", which can involve a variety of styles and maneuvers. Some birds, such as the common chiffchaff[239] of Eurasia and the Wilson's warbler of North America, feed actively and appear energetic. Some will even hover in the air near a twig while gleaning from it; this behaviour is called "hover-gleaning". Other birds are more methodical in their approach to gleaning, even seeming lethargic as they perch upon and deliberately pick over foliage. This behaviour is characteristic of the bay-breasted warbler[240] and many vireos. Another tactic is to hang upside-down from the tips of branches to glean the undersides of leaves. Tits such as the familiar black-capped chickadee are often observed feeding in this manner. Some birds, like the ruby-crowned kinglet, use a combination of these tactics. "Crevice-gleaning" is a niche particular to dry and rocky habitats. Gleaning birds are typically small with compact bodies and have small, sharply pointed beaks. Birds often specialize in a particular niche, such as a particular stratum of forest or type of vegetation.[241]

- gnathotheca

- The rhamphotheca (thin horny sheath of keratin) covering the lower mandible.[33][34][35]

- gonys

- The ventral ridge of the lower mandible, created by the junction of the bone's two rami, or lateral plates.[242]

- gonydeal angle

- Also, gonydeal expansion. The proximal end of the junction created by the gonys two rami, or lateral plates—the place where the two plates separate. The size and shape of the gonydeal angle can be useful in identifying between otherwise similar species.[40]

- gonydeal spot

- The spot near the gonydeal expansion, in adults of many bird species but especially in gulls, usually reddish or orangish in colour, that triggers begging behaviour. Gull chicks, for example, peck at the spot on its parent's bill, which in turn stimulates the parent to regurgitate food.[40][243]

- gorget

- A patch of coloured feathers found on the throat or upper breast of some species of birds.[242] It is a feature found on many male hummingbirds, particularly those found in North America, whose gorgets are typically iridescent.[244] Other species having gorgets include the purple-throated fruitcrow[245] and the chukar partridge.[246] The term is derived from the gorget used in military armor to protect the throat.[247]

- grooming

- See entry for preening.

- gular region

- The posterior part of the underside of a bird's head, described as "a continuation of the chin to an imaginary line drawn between the angles of the jaw".[8] See also: gular skin.

- gular skin

- Also defined, gular sac / throat sac; gular pouch; gular flutter. Describes the gular region when it is featherless. In many species, the gular skin forms a flap, or gular pouch, which is generally used to store fish and other prey while hunting. In many others, such as frigatebirds, the gular skin may overlie a sac—the gular sac or throat sac—that may be dramatically inflated by males during courtship display. In some species the gular region is used for thermoregulation, by the fluttering of the hyoid bone and surrounding muscles, vibrating as many as 735 times per minute, which causes an increase in heat dissipation from the gular skin.[248][249][250]

H[edit]

- hallux

- Also, hind toe; first digit. Specialized types: incumbent and elevated. A bird's usually rear-facing toe; its hind toe. When it is attached near the base of the metatarsus it is termed incumbent, and when projecting from a higher portion of the metatarsus (as in rails), it is termed elevated. The hallux is a bird's first digit, in many birds being the sole rear-facing toe (including in most passerine species that have anisodactylous feet) and is homologous to the human big toe.[251][252][253]

- home range

- Also defined: territory. The area of land in which a bird performs most of its activities. When the area is guarded (in whole or in part) from individuals of the same species it is called a territory.[254] These territories may be temporary or permanent, breeding or non-breeding. Breeding territories may be of four types: i) an all-purpose territory where all activities are conducted; ii) a separate breeding and feeding territory (or just a breeding territory, with foraging conducted outside of it); iii) a territory surrounding the nest and a very small area outside of it; iv) a small territory used solely for display within a lek.[255] The size of the home range can be affected by what food a bird eats and how much the bird weighs. Birds that weigh more usually have larger ranges, and carnivores on average have larger ranges than non-carnivores.[256]

- Humphrey–Parkes terminology

- A system of nomenclature for the plumage of birds proposed in 1959 by Philip S. Humphrey and Kenneth C. Parkes[10] to make the terminology for describing bird plumages more uniform.[257] Examples of Humphrey–Parkes terminology versus traditional terminology may be seen in the entries for prealternate moult and prebasic moult.

- hyoid apparatus

- The system of bones to which the tongue is attached. It usually includes the tongue bone, to which the tongue is actually attached,[258] the basihyal, behind the tongue bone, the urohyal, itself behind the basihyal, a pair of ceratobranchial bones, and a pair of epibranchial.[259] The latter two bones form the hyoid horns, which are contained in a pair of fascia vaginalis. This allows the tongue to slide out smoothly. The hyoid apparatus is attached to the larynx.[258]

I[edit]

- inferior umbilicus

- Also, proximal umbilicus. A small opening located at the bottom tip of a feather's shaft, i.e., at the base of the calamus, that is embedded within the skin of a bird. The growth of the feather is fed by the flow through the inferior umbilicus of a nutrient (or nutritive) pulp of highly vascular dermal cells (sometimes called the nutritive dermis; a part of what is termed the Malpighian layer), that in turn produce a nourishing plasma. In mature feathers the opening is sometimes sealed over by a keratinous plate.[189][260][261] Compare: superior umbilicus.

- inner wing

- Also defined: outer wing. The inner wing of a bird is that portion of the wing stretching from its connection to the body and through the "wrist" joint. The outer wing stretches from the wrist to the wingtip.[262]

- iris

- The coloured outer ring that surrounds a bird's pupil. Though brown predominates, the iris may be of or include a variety of colours—red, yellow, grey, blue, etc.—and the colouration may vary according to the age, sex and species.[159]

J[edit]

- jizz

- Also, gestalt,[263] of which the term may be a corruption[264] (or possibly deriving from the air force acronym GISS for "General Impression of Size and Shape (of an aircraft)", associated with World War II lingo; though this derivation may by anachronistic as jizz was first used in birdwatching as early as 1922),[265] it describes the overall impression or appearance of a bird—"the indefinable quality of a particular species, the 'vibe' it gives off"[266]—garnered from such features as shape, posture, flying style or other habitual movements, size and colouration combined with voice, habitat and location.[267][268][269] Example use: "It had the jizz of a thrush, but I couldn't make out what kind."

K[edit]

- keel

- Also, carina. An extension of the sternum (breastbone) which runs axially along the midline of the sternum and extends outward, perpendicular to the plane of the ribs. The keel provides an anchor to which a bird's wing muscles attach, thereby providing adequate leverage for flight. Keels do not exist on all birds; in particular, some flightless birds lack a keel structure. Historically, the presence or absence of a pronounced keel structure was used as a broad classification of birds into two orders: Carinatae (from Latin carina, 'keel'), having a pronounced keel; and ratites (from Latin ratis, 'raft'—referring to the flatness of the sternum), having a subtle keel structure or lacking one entirely. However, this classification has fallen into disuse as evolutionary studies have shown that many flightless birds have evolved from flighted birds.[270][271]

- kleptoparasitism

- A bird's propensity to steal food from other birds, either opportunistically, or on a regular basis.[272]

L[edit]

- lateral throat-stripe

- A usually dark stripe of colour bordering the throat below both the moustachial stripe and the submoustachial stripe, if any.[27]

- lek

- Also defined: lekking; dispersed lek. An aggregation of male birds gathered to engage in competitive displays (known as lekking) that may entice visiting females that are assessing prospective partners for copulation.[273] These males are usually in sight of each other, but when they are only in earshot, it is called a dispersed lek or an exploded lek. Mating usually occurs on the display area.[274]

- lore

- Adj. form: loreal. The topographical region of a bird's head between the eye and the beak on the sides of the head.[96]

- lower mandible

- Also, mandible. The lower part of a bird's bill or beak, roughly corresponding to the lower jaw of mammals, it is supported by a bone known as the inferior maxillary bone—a compound bone composed of two distinct ossified pieces. These ossified plates (or rami), which can be U-shaped or V-shaped,[32] join distally (the exact location of the joint depends on the species) but are separated proximally, attaching on either side of the head to the quadrate bone. The jaw muscles, which allow the bird to close its beak, attach to the proximal end of the lower mandible and to the bird's skull.[34] The muscles that depress the lower mandible are usually weak, except in a few birds such as the starlings (and the extinct Huia), which have well-developed digastric muscles that aid in foraging by prying or gaping actions.[275] In most birds, these muscles are relatively small as compared to the jaw muscles of similarly sized mammals.[276] The outer surface is covered in thin horny sheath of keratin called rhamphotheca,[33][34] specially called gnathotheca in the lower mandible.[35] Compare: upper mandible.

M[edit]

- maintenance behaviour

- Also, comfort behaviour. The name given to any behaviour or activity which a bird uses to maintain its plumage and soft parts: preening, bathing, anting, sunbathing, stretching, scratching, and other such activities.[277][278] Roosting is also often considered to be a comfort behaviour.[279] The phrase is sometimes used more inclusively, to describe all life-sustaining activities, such as feeding, drinking, predator avoidance, and locomotion,[280] and even involuntary biological processes, like moulting.[281]

- mandible

- In birds, the word mandible, alone, usually refers to the lower mandible.

- mantle

- The forward area of a bird's upper side sandwiched between the nape and the start of the back. However, in gulls and terns, the term is often used to refer to much of the upper surface below the nape.[27]

- migration

- Also defined: partial migration. The regular seasonal movement, often north and south, undertaken by many species of birds. Bird movements include those made in response to changes in food availability, habitat, or weather. Sometimes journeys are not termed "true migration" because they are irregular (nomadism, invasions, irruptions) or only in one direction (dispersal, movement of young away from natal areas). Migration is marked by its annual seasonality.[282][283] Non-migratory birds are said to be resident or sedentary. Approximately 1,800 of the world's bird species are long-distance migrants.[284][285] Many bird populations migrate long distances along a flyway. The most common pattern involves flying north in the northern spring to breed in the temperate or Arctic summer, and returning in the autumn to wintering grounds in warmer regions to the south. In the southern hemisphere the directions are reversed, but there is less land area in the far south to support long-distance migration.[286] Not all populations within a species may be migratory; this is known as "partial migration". Partial migration is very common in birds of the southern continents. For example, in Australia, 44% of non-passerine birds and 32% of passerine species are partially migratory.[287] Many, if not most birds migrate in flocks. For larger birds, flying in flocks reduces the energy cost, e.g., geese in a V-formation may conserve 12–20% of the energy they would otherwise need if flying alone.[288][289]

- morph

- Also, colour/color morph. Polymorphic variance in the colouring of the plumage between individuals of the same species, unrelated to age, sex or season. For example, the snow goose has two plumage morphs, white (snow) or grey/blue (blue), thus the common description of individuals as either "snows" or "blues". At one time this colour morph resulted in the "blue goose" being classified as a separate species.[290][291]

- moult

- Also, molt (chiefly U.S.) and moulting / molting. The periodic replacement of feathers by shedding old feathers while producing new ones. Feathers are dead structures at maturity which are gradually abraded and need to be replaced. Adult birds moult at least once a year, although many moult twice and a few three times each year. It is generally a slow process, as birds rarely shed all their feathers at any one time; the bird must retain sufficient feathers to regulate its body temperature and repel moisture. The number and area of feathers that are shed varies. In some moulting periods, a bird may renew only the feathers on the head and body, shedding the wing and tail feathers during a later moulting period. Some species of bird become flightless during an annual "wing moult" and must seek a protected habitat with a reliable food supply during that time. Typically, a bird begins to shed some old feathers, then pin feathers grow in to replace the old feathers. As the pin feathers become full feathers, other feathers are shed. This is a cyclical process that occurs in many phases. It is usually symmetrical, with feather loss equal on each side of the body. Because feathers make up 4–12% of a bird's body weight, it takes a large amount of energy to replace them. For this reason, moults often occur immediately after the breeding season, but while food is still abundant. The plumage produced during this time is called postnuptial plumage.[292]

- moult strategy

- Specialized types defined: simple basic strategy; simple alternate strategy; complex basic strategy; complex alternate strategy. The pattern of moults that occurs regularly based on the season and time. There are four main moulting strategies: i) simple basic strategy, in which there is one moult per year, every year; ii) simple alternate strategy, in which there are two moults per year, every year; iii) complex basic strategy, in which there is one moult per year, except in the first year of life, where there is an additional moult; and iv) complex alternate strategy, in which there are two moults per year, except in the first year of life, where there is an additional moult.[293]

- moustachial stripe

- Also, mustache stripe; whisker stripe; malar stripe. A dark feather colouration line running "obliquely from the gape down and along the lower border of the ear-coverts". Compare: submoustachial stripe and lateral throat-stripe.[27] Birds with moustachial stripes include some of the pipits as well as buntings.[27]

N[edit]

- nail

- A plate of hard horny tissue at the tip of the beak of all birds in the family Anatidae (ducks, geese and swans).[294] This shield-shaped structure, which sometimes spans the entire width of the beak, is often bent at the tip to form a hook.[295] It serves different purposes depending on the bird's primary food source. Most species use their nails to dig seeds out of mud or vegetation,[296] while diving ducks use theirs to pry molluscs from rocks.[297] There is evidence that the nail may help a bird to grasp things; species which use strong grasping motions to secure their food (such as when catching and holding onto a large squirming frog) have very wide nails.[298] Certain types of mechanoreceptors, nerve cells that are sensitive to pressure, vibration or touch, are located under the nail.[299]

- nares

- The two holes—circular, oval or slit-like in shape—which lead to the nasal cavities within the bird's skull, and thus to the rest of the respiratory system.[37] In most bird species, the nares are located in the basal third of the upper mandible. Kiwis are a notable exception; their nares are located at the tip of their bills.[92] A handful of species have no external nares. Cormorants and darters have primitive external nares as nestlings, but these close soon after the birds fledge; adults of these species (and gannets and boobies of all ages, which also lack external nostrils) breathe through their mouths. There is typically a septum made of bone or cartilage that separates the two nares, but in some families (including gulls, cranes and New World vultures), the septum is missing. While the nares are uncovered in most species, they are covered with feathers in a few groups of birds, including grouse and ptarmigans, crows and some woodpeckers.[37]

- nasal canthus

- The area where the eyelids come together at the anterior corner of the eye, on the side of the nares, as opposed to the temporal canthus.[133]

- natal down

- Also, neossoptiles. Also defined: protoptiles; mesoptiles. The layer of down feathers that cover most birds at some point in their early development. Precocial nestlings are already covered with a layer of down when they hatch, while altricial nestlings develop their down layer within days or weeks of hatching. Megapode hatchlings are the sole exception; they are already covered with contour feathers when they hatch.[300] The natal down coat is usually lost within a week or two of hatching.[301] There are two different kinds of natal down feathers; protoptiles and mesoptiles.[302] The former appears first[303] and the latter appears second.[304] Hathchlings born naked or with a diffuse coat of scant natal down feathers are called psilopaedic, while those born covered with a dense fuzz of natal down are termed ptilopaedic.[301] Compare: body down and powder down.

- nest

- Also, bird nest. Specialized types: burrow; cavity; cup (adherent cup; statant cup); dome; dormitory; eyries (or aeries); hanging; ledge; mound; pendant; platform; roost (or winter-nest); scrape; saucer or plate; and sphere. The spot in which a bird lays and incubates its eggs and raises its young. Although the term popularly refers to a specific structure made by the bird itself—such as the grassy cup nest of the American robin or Eurasian blackbird, or the elaborately woven hanging nest of the Montezuma oropendola or the village weaver—for some species, a nest is simply a shallow depression made in sand; for others, it is the knot-hole left by a broken branch, a burrow dug into the ground, a chamber drilled into a tree, an enormous rotting pile of vegetation and earth, a shelf made of dried saliva or a mud dome with an entrance tunnel. The smallest bird nests are those of some hummingbirds, tiny cups which can be a mere 2 cm (0.79 in) across and 2–3 cm (0.79–1.18 in) high.[305] At the other extreme, some nest mounds built by the dusky scrubfowl measure more than 11 m (36 ft) in diameter and stand nearly 5 m (16 ft) tall.[306] Not all bird species build nests. Some species lay their eggs directly on the ground or rocky ledges, while brood parasites lay theirs in the nests of other birds, letting unwitting "foster parents" do all the work of rearing the young. Although nests are primarily used for breeding, they may also be reused in the non-breeding season for roosting and some species build special dormitory nests or roost nests (or winter-nest) that are used only for roosting.[307] Most birds build a new nest each year, though some refurbish their old nests.[308] The large eyries (or aeries) of some eagles are platform nests that have been used and refurbished for several years. In most species, the female does most or all of the nest construction, though the male often helps.[309] The nest may form a part of the courtship display, such as in weaver birds.[274]

- nictitating membrane

- Also, third eyelid. A transparent or translucent third eyelid that is drawn across the eye for protection, to moisten it while maintaining vision.[310] The nictitating membrane also covers the eye and acts as a contact lens in many aquatic birds.[311] With the exception of pigeons and a few other species, most birds blink only with their nictitating membrane, and when not sleeping, use the eyelids chiefly only when the eye is threatened with some foreign matter.[312]

- nidicolous

- Young that remain in their nest after hatching for an extended period of time and thus must be fed by their parents.[16] Contrast: nidifugous.

- nidifugous

- Young that leave the nest soon after hatching, joining their parents in foraging.[16] Contrast: nidicolous.

- non-breeding plumage

- See basic plumage.

- notch