Вирджинии Дело

Кубинские волонтеры и Сантьяго и Сантьяго и Сантьяго и Сантьяго (см.) Графический , | |

| Дата | 8 ноября 1873 г. |

|---|---|

| Расположение | Сантьяго де Куба |

| Участники |

|

| Исход | Мирные переговоры |

| Летальные исходы | 53 |

Дело Вирджиуса было дипломатическим спором , который произошел с октября 1873 года по февраль 1875 года между Соединенными Штатами, Великобританией и Испанией (тогда под контролем Кубы ) в течение десятилетней войны . Вирджиния был быстрым американским кораблем, нанятым кубинскими повреждниками для землевладельцев и боеприпасов на Кубе, чтобы напасть на испанский режим там. Он был захвачен испанским, который хотел попробовать мужчин на борту (многие из которых были американскими и британскими гражданами) в качестве пиратов и казнить их. Испанские казнили 53 человека, но остановились, когда вмешалось британское правительство.

На протяжении всего испытания были свободные разговоры о том, что США могли объявить войну Испании. Во время длительных переговоров правительство Испании претерпело несколько изменений в лидерстве. Американский консул Калеб Кушинг закончил этот эпизод, переговорив 80 000 долларов на репарации, которые будут выплачены семьям казненных американцев. Правительство Испании компенсировало британские семьи за счет переговоров перед американской компенсацией. Инцидент был замечательным для использования международной дипломатии для мирного поселения, осуществляемого государственным секретарем США Гамильтоном Фиш, а не для выбора дорогостоящей войны между Соединенными Штатами и Испанией. Дело Вирджиуса начало возрождение военно -морского флота США в конце 19 -го века. До тех пор его флот уступал военным кораблям Испании.

Десятилетняя война

[ редактировать ]После американской гражданской войны островная страна Куба под испанским правлением была одной из немногих стран Западного полушария, где рабство оставалось законным и широко практиковалось. [ 1 ] 10 октября 1868 года началась революция, известная как Десятилетняя война кубинскими землевладельцами, во главе с Карлосом Мануэлем де Сеспедесом . [ 2 ] Испанцы, возглавляемые изначально Франсиско Лерсунди , использовали военные для подавления восстания. [ 3 ] В 1870 году государственный секретарь Гамильтон -рыба убедил президента Гранта не признавать кубинское воинственность, а Соединенные Штаты сохранили нестабильный мир с Испанией. [ 4 ]

Поскольку кубинская война продолжалась, международное патриотическое мятеж начал возникать в поддержку кубинского восстания; Военные связи были проданы в США, чтобы поддержать кубинское сопротивление. [ 5 ] Одним из кубинских патриотов США был Джон Ф. Паттерсон, который купил бывшего парохода Конфедерации, Вирджин , у Вашингтонского военно -морского двора , переименовавшись в ее Вирджингья . [ 6 ] Легальность покупки Паттерсона Вирджиуса позже привлечет внимание национального и международного и международного внимания. [ 7 ] Кубинское восстание закончилось перемирием в 1878 году после того, как испанский генерал Арсенио Мартинес-Кампов помиловал всех кубинских повстанцев. [ 8 ]

Вирджиния

[ редактировать ]Вирджиния представлял собой небольшой высокоскоростной пароход с боковым колесом, созданный для того, чтобы служить блокадным бегуном между Гаваной и Мобил, штат Алабама, для Конфедерации во время гражданской войны. [ 9 ] [ 10 ] Первоначально построенная как Virgin от Aitken & Mansel of Whiteinch , Глазго , в 1864 году, она стала призом Соединенных Штатов, когда он был захвачен 12 апреля 1865 года. [ 9 ] В августе 1870 года Вирджинг был приобретен американцем, Джоном Ф. Паттерсоном, который действовал тайно в качестве агента кубинского повстанца Мануэля де Кесада и двух граждан США, Маршалла О. Робертса и Дж. К. Робертса. [ 9 ] Корабль был первоначально капитан Фрэнсисом Шеппердом. И Паттерсон, и Шеппхард немедленно зарегистрировали корабль в нью -йоркском пользовательском доме, заплатив 2000 долларов, чтобы быть связанным. Тем не менее, поручителей не было перечислено. [ 11 ] Паттерсон взял на себя обязательную клятву, подтверждая, что он был единственным владельцем Вирджиуса . Секретной целью покупки Вирджиуса было перевозку мужчин, боеприпасов и поставки, чтобы помочь кубинскому восстанию. В течение трех лет корабль помогал кубинскому восстанию; Он был защищен военно -морскими кораблями США, в том числе USS Kansas и USS Canandaigua . [ 10 ] Испанцы сказали, что это был преступник, и он агрессивно стремился запечатлеть его. [ 10 ] [ 11 ]

Захват, испытание и казни

[ редактировать ]

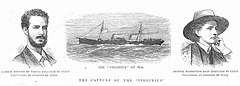

Капитан Джозеф Фрай стал новым капитаном Вирджиния в октябре 1873 года. [ 12 ] Фрай служил в военно -морском флоте США в течение 15 лет, прежде чем присоединиться к Конфедерации во время гражданской войны. Фрай был повышен в Коммодоре в военно -морском флоте Конфедерации . Однако после того, как эта позиция исчезла после победы в США в 1865 году, Фрай был неполный труд. В 1873 году он взял работу в качестве капитана Вирджинии . Вирджиния , пришвартованный в Кингстоне, на Ямайке, к этому времени нуждался в ремонте, и котлы ломались. [ 13 ] Поскольку большая часть предыдущей команды покинула, Фрай завербовал новую команду из 52 американских и британских мужчин. Многие были неопытными и не понимали, что Вирджиния поддерживает кубинское восстание. Три были очень молодыми новобранцами, не старше 13 лет. [ 12 ] Virginius took on 103 native Cuban soldiers that arrived on board a New York steamer. The US Consul at Kingston, Thomas H. Pearne, had warned Fry that he would be shot if captured. However, Fry did not believe the Spanish would shoot a blockade runner.[14] In mid-October, Captain Fry, accompanied by the four principal Cuban patriots, Pedro de Céspedes (brother of Carlos Manuel de Céspedes), Bernabé Varona, Jesús del Sol, and William A.C. Ryan, took Virginius to Haiti and loaded the ship with munitions.[15] On October 30, Virginius sailed to Comito to pick up more weapons and then, on the same day, started toward Cuba. The Spanish had been warned when Virginius left Jamaica and sent out the warship Tornado to capture the vessel.[12]

On October 30, 1873 Tornado spotted Virginius on open water 6 miles (9.7 km) from Cuba and gave chase. Virginius was heavily weighted, and the stress from the boilers caused the ship to take on water, significantly slowing any progress.[16] As the chase continued, Tornado, a fast warship, fired on Virginius several times, damaging the top deck. Captain Fry surrendered Virginius, knowing that his ship's overworked boilers and leaking hull could not outrun Tornado on the open sea. The Spanish quickly boarded and secured the ship, taking the entire crew prisoner and sailing the ship to Santiago de Cuba.[17]

The Spanish immediately ordered the entire crew to be put on trial as pirates.[18] The entire Virginius crew, both American and British citizens, as well as the Cuban patriots, were found guilty by a court martial and were sentenced to death. The Spanish ignored the protest of the US vice-consul, who attempted to give American citizens legal aid. On November 4, 1873, the four principal Cuban patriots who accompanied Fry were executed by a firing squad without trial since he had already been condemned as a pirate. After the executions, the British vice-consul at Santiago, concerned that one of the patriots killed, George Washington Ryan, claimed British citizenship, wired Jamaica to receive aid from the Royal Navy to stop further executions.[19] Hearing news of the ship's capture and the executions, Altamont de Cordova, a Jamaican resident, was able to get British Commodore A.F.R. de Horsey to send the sloop HMS Niobe under Sir Lambton Loraine, 11th Baronet to Santiago to stop further executions.[20] On November 7, an additional 37 crew members, including Captain Fry, were executed by firing squad.[21] The Spanish soldiers decapitated them and trampled their bodies with horses. On November 8, twelve more crew members were executed until finally, both the USS Wyoming, under the command of Civil War Naval hero Will Cushing, and HMS Niobe reached Santiago.[22] The carnage stopped on the same day that Cushing (and possibly the British Captain Lorraine) threatened local commander Juan N. Burriel that he would bombard Santiago if there were any more executions.[22] 53 were executed at Santiago under Burriel's authority. On a lighter note in the midst of the carnage, in an interview that Burriel requested with Sir Lambton Lorraine, he attempted to shake hands with the English captain, who stood straight and exclaimed, "I will not shake hands with a butcher".

US public reaction

[edit]The initial press reaction to the capture of Virginius was conservative, but as news of executions poured into the nation, certain newspapers became more aggressive in promoting Cuban intervention and war.[23] The New York Times stated that if the executions of Americans from Virginius were illegal, war needed to be declared.[24] The New York Tribune asserted that actions of Burriel and the Cuban Volunteers necessitated "the death knell of Spanish power in America."[24] The New York Herald demanded Secretary Hamilton Fish's resignation and the recognition by the US of the Cuban belligerency.[24] The National Republican, believing the threat of war with Spain to be imminent, encouraged the sale of Cuban bonds.[25] The American public considered the executions a national insult and rallied for intervention. Protest rallies took place across the nation in New Orleans, St. Louis, and Georgia, encouraging intervention in Cuba and vengeance on Spain.[26]

The British Minister to the United States, Sir Edward Thornton, believed the American public was ready for war with Spain.[27] A large rally in New York's Steinway Hall on November 17, 1873, led by future Secretary of State William Evarts, took a moderate position, and the meeting adopted a resolution that war would be necessary, yet regrettable, if Spain chose to "consider our defense against savage butchery as a cause of war...."[28]

US diplomatic response

[edit]Hamilton Fish and State Department

[edit]

On Wednesday, November 5, 1873, the first news from the US Consul-General in Havana, Henry C. Hall, informed the US State Department that Virginius had been captured.[29] There was no knowledge that four mercenaries had already been killed; Secretary of State Hamilton Fish believed the Virginius was just another ship captured aiding the Cuban rebellion.[29] On November 7, Cuba headed the agenda of US President Ulysses S. Grant's Cabinet meeting as news came in of the deaths of Ryan and three other mercenaries.[30] The Cabinet agreed that the executions would be "regarded as an inhuman act not in accordance with the spirit of the civilization of the nineteenth century."[31] On November 8, Fish met with Spanish minister Don José Polo de Bernabé and discussed the legality of the capture of Virginius.[32]

On November 11, Grant's Cabinet decided that war with Spain was not desirable, but Cuban intervention was possible.[33] On November 12, five days after the event, Fish received the devastating news that 37 crew members of Virginius had been executed.[34] Fish ordered US Minister to Spain Daniel Sickles to protest the executions and demand reparations for any persons considered US citizens who were killed.[34] On November 13, Fish formally protested to Polo and stated that the US had a free hand on Cuba and the Virginius Affair.[34] On November 14, Grant's cabinet agreed that if US reparation demands were not met, the Spanish legation would be closed. An exaggerated report came into the White House that more crew members had been shot. In reality, twelve crew members had been executed.[35] On November 15, Polo visited Fish and stated that Virginius was a pirate ship and that her crew had been a hostile threat to Cuba.[36] Fish, although doubtful of the legality of the ship's US ownership, was determined to advocate the nation's honor in demanding reparations from Spain.[37]

On the same day, a cable from Fish arrived in Spain for Sickles demanding the return of Virginius to the US, the release of the crew that had escaped execution, a salute from Spain to the US flag, punishment for the perpetrators, and reparations for families.[38]

Negotiations in Spain between Sickles and Minister of State José de Carvajal became heated, and progress towards a settlement became unlikely.[39] The Spanish press openly attacked Sickles, the US, and Britain, intending to promote war between the three countries.[40] As the Sickles-Carvajal negotiations broke down, President Emilio Castelar decided to settle the Virginius matter[41] through Fish and Polo in Washington.[42]

On Thanksgiving Day, November 27, Polo proposed to Fish that Spain would give up the Virginius and the remaining crew if the US would investigate the legal status of its ownership.[43] Both Fish and Grant agreed to Polo's offer and that the Spanish salute to the US flag would be dispensed with if Virginius was found not to have legal US private citizen ownership.[43] On November 28, Polo and Fish met at the State Department and signed a formal agreement that included the return of Virginius and crew and an investigation by both governments of the legal ownership of Virginius and any crimes committed by the Spanish Volunteers.[44]

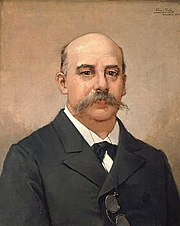

The threat of war between the two countries had been averted through negotiations, but the time and place of the surrender of the Virginius and the remaining crew remained undetermined for several days.[45] On December 5, Fish and Polo signed an agreement that Virginius, with the US flag flying, would be turned over to the US Navy on December 16 at the port of Bahía Honda.[46] Sickles, having lost the confidence of Grant and Fish, resigned on December 20, 1873.[47] On January 6, 1874, after advice from Fish on a replacement for Sickles, Grant appointed eminent attorney and Spanish scholar Caleb Cushing as Minister to Spain.[48]

Virginius and crew returned

[edit]

On December 16, Virginius, now in complete disrepair and taking on water, was towed out to open sea with the US flag flying to be turned over to the US Navy. US Captain W.D. Whiting on board USS Despatch agreed with Spanish Commander Manuel de la Cámara to turn over Virginius the following day.[49] On December 17, at exactly 9:00 a.m., Virginius was formally turned over to the US Navy without incident.[50] The same day, after an investigation, US Attorney General George H. Williams ruled that the US ownership of Virginius had been fraudulent and that she had no right to fly the US flag; however, Spain had no right to capture Virginius and her crew on the open sea.[51]

At 4:17 a.m., on December 26, while under tow by USS Ossipee, Virginius foundered off Cape Fear[52] en route to the United States.[53] Her 91 remaining crewmen, who had been held as prisoners under harsh conditions, were handed over to Captain D.L. Braine of Juanita and were taken safely to New York City.[54]

Reparations awarded

[edit]

On January 3, 1874, Spanish President Emilio Castelar was voted out of office and replaced by Francisco Serrano.[55] Cushing, who had replaced Sickles as US Consul to Spain, stated that the US had been fortunate that Castelar, a university scholar, had been President of Spain, given that his replacement, Serrano, might have been more apt to go to war over the affair.[56] Cushing's primary duty was to get Spanish reparations for Virginius family victims and punishment of Burriel for the 53 Santiago executions.[57] Cushing met Serrano in May on June 26, Augusto Ulloa.[57] On July 5, Cushing, now well respected by Spanish authority, wrote to Fish that Spain was ready to make reparations.[58] In October, Cushing was informed that President Castelar had secretly negotiated reparations between Spain and Britain that totaled £7,700, but black British citizen families were given less money.[59] On November 7, Grant and Fish demanded $2,500 from Spain for each US citizen shot, regardless of race.[59]

On November 28, 1874, Fish instructed Cushing that all Virginius crew members not considered British would be considered American.[60]

Spanish Consul Antonio Mantilla, Polo's replacement, agreed with the reparations. Grant's 1875 State of the Union Address announced that reparations were near, quieting anger over the Virginius affair.[60] Reparations, however, were put on hold as Spain changed governments on December 28, from a republic back to a monarchy. Alfonso XII became King of Spain on January 11, 1875.[60]

On January 16, Cushings met with the new Spanish state minister Castro, urged settlement before the US Congress adjourned, and noted that reparations would be a minor matter compared to an all-out war between Spain and the US.[61]

Under an agreement of February 7, 1875, signed on March 5, the Spanish government paid the US an indemnity of $80,000 for the execution of the Americans.[62] Burriel's Santiago executions were considered illegal by Spain, and President Serrano and King Alfonso condemned him.[63] The case against Burriel was taken up by the Spanish Tribunal of the Navy in June 1876. However, Burriel died on December 24, 1877, before any trial could occur.[64]

In addition to the reparation, a private indemnity in St. Louis was given to Captain Fry's financially troubled family, which had been unable to pay rent and had no permanent place to live.[65]

Aftermath

[edit]When the Virginius affair first broke out, a Spanish ironclad—the Arapiles—happened to be anchored in New York Harbor for repairs, leading to the uncomfortable realization on the part of the US Navy that it had no ship capable of defeating such a vessel. US Secretary of War George M. Robeson believed a US naval resurgence was necessary. Congress hastily issued contracts to construct five new ironclads and accelerated its repair program for several more.[66] USS Puritan and the four Amphitrite-class monitors were subsequently built as a result of the Virginius war scare.[67] All five vessels would later take part in the Spanish–American War of 1898.

References

[edit]- ^ Bradford, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Bradford, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Bradford, p. 8.

- ^ Bradford, pp. 5, 14.

- ^ Bradford, p. 12.

- ^ Bradford, p. 16.

- ^ Bradford, pp. 100–101.

- ^ Bradford, pp. 136–137.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Bancroft, p. 25

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Судалтер, с. 62

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Bancroft, p. 26

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Судалтер, с. 64

- ^ Судальтер, с. 63.

- ^ Hartford Weekly (22 ноября 1873 г.), кубинская резня

- ^ Судальтер, стр. 63–64.

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 38–41.

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 43, 45.

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 45

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 47–48.

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 48–49.

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 52–53.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Брэдфорд, с. 54

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 64–65.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Брэдфорд, с. 65

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 64

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 65–66.

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 66

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 70–71.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Брэдфорд, с. 57

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 57–58.

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 58

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 58–59.

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 59

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Брэдфорд, с. 60

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 61.

- ^ Bradford, p. 62–63.

- ^ Bradford, p. 63.

- ^ Bradford, p. 79.

- ^ Bradford, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Bradford, p. 83

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 470.

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 89

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Брэдфорд, с. 93.

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 94

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 94–95.

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 99–100.

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 117

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 120, 122.

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 109–110.

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 111.

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 102

- ^ «Последний путешествие Вирджиния» . New York Herald : 3. 31 декабря 1873 года.

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 114

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 106–107.

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 119

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 120.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Брэдфорд, с. 123.

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 123–124.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Брэдфорд, с. 124

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Брэдфорд, с. 125

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 125–126.

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 126

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 127

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 128

- ^ Брэдфорд, с. 138.

- ^ Домашняя эскадрилья: военно -морской флот США на северной атлантической станции, Джеймс Блфрю, Аннаполис: военно -морской инст. Пресс, 2014

- ^ Swann, pp. 138, 141–142.

Источники

[ редактировать ]- Брэдфорд, Ричард Х. (1980). Дело Вирджиуса . Боулдер: Колорадо ассоциированное университетское издательство. ISBN 0870810804 .

- Судалтер, Рон (2009). "До грани на Кубе в 1873 году" Военная история 26 (4): 62–67.

- Суонн, Леонард Александр (1965). Джон Роуч, морской предприниматель: годы в качестве военно -морского подрядчика, 1862–1886 . - Военно -морской институт США. (Перепечатано: 1980. Ayer Publishing). ISBN 9780405130786 .

Дальнейшее чтение

[ редактировать ]- Аллин, Лоуренс Кэрролл. «Первая кубинская война: Дело Вирджиуса». Американский Нептун 38 (1978): 233–48.

- КМЕН, Генри А. «Помните Вирджиния: Новый Орлеан и Куба в 1873 году». История Луизианы 11.4 (1970): 313–331. онлайн

- Невинс, Аллан Гамильтон Фиш: Внутренняя история администрации грантов (два тома 1936) 2: 657-694. онлайн

- Оуэн, Джон Маллой. Либеральный мир, Либеральная война: от дела Вирджиния до испано-американской войны (издательство Корнелльского университета, 1997).

Внешние ссылки

[ редактировать ]- . Appletons 'Cyclopædia американской биографии . 1900.

- Отчет об инциденте Вирджиуса на веб -сайте Кубинского генеалогии Центра

- Инцидент Вирджиуса в испанском -американском войне столетии

- Virginius на Ships of the World Вирджинг на веб -сайте

- 1873 в международных отношениях

- 1875 в международных отношениях

- Дипломатические инциденты

- История иностранных отношений Соединенных Штатов

- 1873 в Соединенных Штатах

- Международные морские инциденты

- Военная история 19-го века Соединенных Штатов

- Десятилетняя война

- Президентство Улисса С. Грант

- Испания -United Kingdom Relations

- Испания -UNITED STATES Отношения

- Морская история Кубы

- 1873 на Кубе

- Морские инциденты в декабре 1873 года