Кассини – Гюйгенс

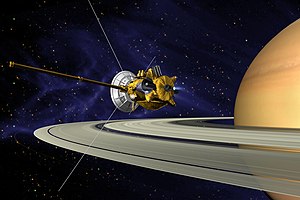

Художественная концепция Кассини . выхода на орбиту вокруг Сатурна | |

| Имена | Орбитальный аппарат Сатурна и зонд Титан (SOTP) |

|---|---|

| Тип миссии | Кассини : Сатурна . орбитальный аппарат Гюйгенс : Титан приземляется |

| Оператор | Кассини : НАСА / Лаборатория реактивного движения. Гюйгенс : ЕКА / АСИ |

| ИДЕНТИФИКАТОР КОСПЭРЭ | 1997-061А |

| SATCAT no. | 25008 |

| Website | |

| Mission duration |

|

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Manufacturer | Cassini: JPL Huygens: Thales Alenia Space (then Aerospatiale)[1] |

| Launch mass | 5,712 kg (12,593 lb)[2][3] |

| Dry mass | 2,523 kg (5,562 lb)[2] |

| Power | ~885 watts (BOL)[2] ~670 watts (2010)[4] ~663 watts (EOM/2017)[2] |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | October 15, 1997, 08:43:00 UTC |

| Rocket | Titan IV(401)B/ Centaur-T B-33 |

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral SLC-40 |

| Contractor | Lockheed Martin |

| End of mission | |

| Disposal | Controlled entry into Saturn[5][6] |

| Last contact | September 15, 2017

|

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Kronocentric |

| Flyby of Venus (Gravity assist) | |

| Closest approach | April 26, 1998 |

| Distance | 283 km (176 mi) |

| Flyby of Venus (Gravity assist) | |

| Closest approach | June 24, 1999 |

| Distance | 623 km (387 mi) |

| Flyby of Earth-Moon system (Gravity assist) | |

| Closest approach | August 18, 1999, 03:28 UTC |

| Distance | 1,171 km (728 mi) |

| Flyby of 2685 Masursky (Incidental) | |

| Closest approach | January 23, 2000 |

| Distance | 1,600,000 km (990,000 mi) |

| Flyby of Jupiter (Gravity assist) | |

| Closest approach | December 30, 2000 |

| Distance | 9,852,924 km (6,122,323 mi) |

| Saturn orbiter | |

| Spacecraft component | Cassini |

| Orbital insertion | July 1, 2004, 02:48 UTC |

| Titan lander | |

| Spacecraft component | Huygens |

| Landing date | January 14, 2005 |

| Landing site | 10°34′23″S 192°20′06″W / 10.573°S 192.335°W[8] |

Large Strategic Science Missions Planetary Science Division | |

Кассини-Гюйгенс ( / k ə ˈ s iː n i ˈ h ɔɪ ɡ ən z / kə- SEE -nee HOY -gənz ), обычно называемый Кассини , был космической исследовательской миссией НАСА , Европейского космического агентства (ЕКА), и Итальянское космическое агентство (ASI) отправить космический зонд для изучения планеты Сатурн и ее системы, включая ее кольца и естественные спутники . класса Флагман» « Роботизированный космический корабль включал в себя космический зонд НАСА «Кассини» ЕКА «Гюйгенс» и спускаемый аппарат , который приземлился на крупнейшем спутнике Сатурна, Титане . [9] Кассини был четвертым космическим зондом, посетившим Сатурн, и первым, вышедшим на его орбиту, где он оставался с 2004 по 2017 год. Оба аппарата получили свои имена в честь астрономов Джованни Кассини и Христиана Гюйгенса .

Запущенный на борту Титана IVB/Кентавра 15 октября 1997 года, Кассини находился в космосе почти 20 лет, из них 13 лет он провел на орбите Сатурна и изучал планету и ее систему после выхода на орбиту 1 июля 2004 года. [10]

The voyage to Saturn included flybys of Venus (April 1998 and July 1999), Earth (August 1999), the asteroid 2685 Masursky, and Jupiter (December 2000). The mission ended on September 15, 2017, when Cassini's trajectory took it into Saturn's upper atmosphere and it burned up[11][12] in order to prevent any risk of contaminating Saturn's moons, which might have offered habitable environments to stowaway terrestrial microbes on the spacecraft.[13][14] The mission was successful beyond expectations – NASA's Planetary Science Division Director, Jim Green, described Cassini-Huygens as a "mission of firsts"[15] that has revolutionized human understanding of the Saturn system, including its moons and rings, and our understanding of where life might be found in the Solar System.[16]

Cassini's planners originally scheduled a mission of four years, from June 2004 to May 2008. The mission was extended for another two years until September 2010, branded the Cassini Equinox Mission. The mission was extended a second and final time with the Cassini Solstice Mission, lasting another seven years until September 15, 2017, on which date Cassini was de-orbited to burn up in Saturn's upper atmosphere.[17]

The Huygens module traveled with Cassini until its separation from the probe on December 25, 2004; Huygens landed by parachute on Titan on January 14, 2005. The separation was facilitated by the SED (Spin/Eject device), which provided a relative separation speed of 0.35 metres per second (1.1 ft/s) and a spin rate of 7.5 rpm.[18] It returned data to Earth for around 90 minutes, using the orbiter as a relay. This was the first landing ever accomplished in the outer Solar System and the first landing on a moon other than Earth's Moon.

At the end of its mission, the Cassini spacecraft executed its "Grand Finale": a number of risky passes through the gaps between Saturn and its inner rings.[5][6]This phase aimed to maximize Cassini's scientific outcome before the spacecraft was intentionally destroyed[19] to prevent potential contamination of Saturn's moons if Cassini were to unintentionally crash into them when maneuvering the probe was no longer possible due to power loss or other communication issues at the end of its operational lifespan. The atmospheric entry of Cassini ended the mission, but analysis of the returned data will continue for many years.[16]

Overview

[edit]Scientists and individuals from 27 countries made up the joint team responsible for designing, building, flying and collecting data from the Cassini orbiter and the Huygens probe.[16]

NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in the United States, where the orbiter was assembled, managed the mission. The European Space Research and Technology Centre developed Huygens. The centre's prime contractor, Aérospatiale of France (part of Thales Alenia Space from 2005), assembled the probe with equipment and instruments supplied by many European countries (including Huygens' batteries and two scientific instruments from the United States). The Italian Space Agency (ASI) provided the Cassini orbiter's high-gain radio antenna, with the incorporation of a low-gain antenna (to ensure telecommunications with the Earth for the entire duration of the mission), a compact and lightweight radar, which also used the high-gain antenna and served as a synthetic-aperture radar, a radar altimeter, a radiometer, the radio science subsystem (RSS), and the visible-channel portion VIMS-V of VIMS spectrometer.[20]

NASA provided the VIMS infrared counterpart, as well as the Main Electronic Assembly, which included electronic sub-assemblies provided by CNES of France.[21][22]

On April 16, 2008, NASA announced a two-year extension of the funding for ground operations of this mission, at which point it was renamed the Cassini Equinox Mission.[23]The round of funding was again extended[by whom?] in February 2010 with the Cassini Solstice Mission.

Naming

[edit]The mission consisted of two main elements: the ASI/NASA Cassini orbiter, named for the Italian astronomer Giovanni Domenico Cassini, discoverer of Saturn's ring divisions and four of its satellites; and the ESA-developed Huygens probe, named for the Dutch astronomer, mathematician and physicist Christiaan Huygens, discoverer of Titan.

The mission was commonly called Saturn Orbiter Titan Probe (SOTP) during gestation, both as a Mariner Mark II mission and generically.[24]

Cassini-Huygens was a Flagship-class mission to the outer planets.[9] The other planetary flagships include Galileo, Voyager, and Viking.[9]

Objectives

[edit]Cassini had several objectives, including:[25]

- Determining the three-dimensional structure and dynamic behavior of the rings of Saturn.

- Determining the composition of the satellite surfaces and the geological history of each object.

- Determining the nature and origin of the dark material on Iapetus's leading hemisphere.

- Measuring the three-dimensional structure and dynamic behavior of the magnetosphere.

- Studying the dynamic behavior of Saturn's atmosphere at cloud level.

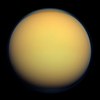

- Studying the time variability of Titan's clouds and hazes.

- Characterizing Titan's surface on a regional scale.

Cassini–Huygens was launched on October 15, 1997, from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station's Space Launch Complex 40 using a U.S. Air Force Titan IVB/Centaur rocket. The complete launcher was made up of a two-stage Titan IV booster rocket, two strap-on solid rocket engines, the Centaur upper stage, and a payload enclosure, or fairing.[26]

The total cost of this scientific exploration mission was about US$3.26 billion, including $1.4 billion for pre-launch development, $704 million for mission operations, $54 million for tracking and $422 million for the launch vehicle. The United States contributed $2.6 billion (80%), the ESA $500 million (15%), and the ASI $160 million (5%).[27] However, these figures are from the press kit which was prepared in October 2000. They do not include inflation over the course of a very long mission, nor do they include the cost of the extended missions.

The primary mission for Cassini was completed on July 30, 2008. The mission was extended to June 2010 (Cassini Equinox Mission).[28] This studied the Saturn system in detail during the planet's equinox, which happened in August 2009.[23]

On February 3, 2010, NASA announced another extension for Cassini, lasting 61⁄2 years until 2017, ending at the time of summer solstice in Saturn's northern hemisphere (Cassini Solstice Mission). The extension enabled another 155 revolutions around the planet, 54 flybys of Titan and 11 flybys of Enceladus.[29]In 2017, an encounter with Titan changed its orbit in such a way that, at closest approach to Saturn, it was only 3,000 km (1,900 mi) above the planet's cloudtops, below the inner edge of the D ring. This sequence of "proximal orbits" ended when its final encounter with Titan sent the probe into Saturn's atmosphere to be destroyed.

Itinerary

[edit]| Selected destinations (ordered largest to smallest but not to scale) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Titan | Earth's Moon | Rhea | Iapetus | Dione | Tethys | Enceladus |

|  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Mimas | Hyperion | Phoebe | Janus | Epimetheus | Prometheus | Pandora |

|  |  |  |  |  | |

| Helene | Atlas | Pan | Telesto | Calypso | Methone | |

History

[edit]

Cassini–Huygens's origins date to 1982, when the European Science Foundation and the American National Academy of Sciences formed a working group to investigate future cooperative missions. Two European scientists suggested a paired Saturn Orbiter and Titan Probe as a possible joint mission. In 1983, NASA's Solar System Exploration Committee recommended the same Orbiter and Probe pair as a core NASA project. NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) performed a joint study of the potential mission from 1984 to 1985. ESA continued with its own study in 1986, while the American astronaut Sally Ride, in her influential 1987 report NASA Leadership and America's Future in Space, also examined and approved of the Cassini mission.[30]

While Ride's report described the Saturn orbiter and probe as a NASA solo mission, in 1988 the Associate Administrator for Space Science and Applications of NASA, Len Fisk, returned to the idea of a joint NASA and ESA mission. He wrote to his counterpart at ESA, Roger Bonnet, strongly suggesting that ESA choose the Cassini mission from the three candidates at hand and promising that NASA would commit to the mission as soon as ESA did.[31]

At the time, NASA was becoming more sensitive to the strain that had developed between the American and European space programs as a result of European perceptions that NASA had not treated it like an equal during previous collaborations. NASA officials and advisers involved in promoting and planning Cassini–Huygens attempted to correct this trend by stressing their desire to evenly share any scientific and technology benefits resulting from the mission. In part, this newfound spirit of cooperation with Europe was driven by a sense of competition with the Soviet Union, which had begun to cooperate more closely with Europe as ESA drew further away from NASA. Late in 1988, ESA chose Cassini–Huygens as its next major mission and the following year the program received major funding in the US.[32][33]

The collaboration not only improved relations between the two space programs but also helped Cassini–Huygens survive congressional budget cuts in the United States. Cassini–Huygens came under fire politically in both 1992 and 1994, but NASA successfully persuaded the United States Congress that it would be unwise to halt the project after ESA had already poured funds into development because frustration on broken space exploration promises might spill over into other areas of foreign relations. The project proceeded politically smoothly after 1994, although citizens' groups concerned about the potential environmental impact a launch failure might have (because of its plutonium power source) attempted to derail it through protests and lawsuits until and past its 1997 launch.[34][35][36][37][38]

Spacecraft design

[edit]The spacecraft was planned to be the second three-axis stabilized, RTG-powered Mariner Mark II, a class of spacecraft developed for missions beyond the orbit of Mars, after the Comet Rendezvous Asteroid Flyby (CRAF) mission, but budget cuts and project rescopings forced NASA to terminate CRAF development to save Cassini. As a result, Cassini became more specialized. The Mariner Mark II series was cancelled.

The combined orbiter and probe is the third-largest uncrewed interplanetary spacecraft ever successfully launched, behind the Phobos 1 and 2 Mars probes, as well as being among the most complex.[39][40] The orbiter had a mass of 2,150 kg (4,740 lb), the probe 350 kg (770 lb) including 30 kg (66 lb) of probe support equipment left on the orbiter. With the launch vehicle adapter and 3,132 kg (6,905 lb) of propellants at launch, the spacecraft had a mass of 5,600 kg (12,300 lb).

The Cassini spacecraft was 6.8 meters (22 ft) high and 4 meters (13 ft) wide. Spacecraft complexity was increased by its trajectory (flight path) to Saturn, and by the ambitious science at its destination. Cassini had 1,630 interconnected electronic components, 22,000 wire connections, and 14 kilometers (8.7 mi) of cabling.[41] The core control computer CPU was a redundant system using the MIL-STD-1750A instruction set architecture. The main propulsion system consisted of one prime and one backup R-4D bipropellant rocket engine. The thrust of each engine was 490 N (110 lbf) and the total spacecraft delta-v was 2,352 m/s (5,260 mph).[42] Smaller monopropellant rockets provided attitude control.

Cassini was powered by 32.7 kg (72 lb) of nuclear fuel, mainly plutonium dioxide (containing 28.3 kg (62 lb) of pure plutonium).[43] The heat from the material's radioactive decay was turned into electricity. Huygens was supported by Cassini during cruise, but used chemical batteries when independent.

The probe contained a DVD with more than 616,400 signatures from citizens in 81 countries, collected in a public campaign.[44][45]

Until September 2017 the Cassini probe continued orbiting Saturn at a distance of between 8.2 and 10.2 astronomical units (1.23×109 and 1.53×109 km; 760,000,000 and 950,000,000 mi) from the Earth. It took 68 to 84 minutes for radio signals to travel from Earth to the spacecraft, and vice versa. Thus ground controllers could not give "real-time" instructions for daily operations or for unexpected events. Even if response were immediate, more than two hours would have passed between the occurrence of a problem and the reception of the engineers' response by the satellite.

Instruments

[edit]

Summary

[edit]Instruments:[47]

- Optical Remote Sensing ("Located on the remote sensing pallet")[47]

- Composite Infrared Spectrometer (CIRS)

- Imaging Science Subsystem (ISS)

- Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrograph (UVIS)

- Visible and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS)

- Fields, Particles and Waves (mostly in situ)

- Cassini Plasma Spectrometer (CAPS)

- Cosmic Dust Analyzer (CDA)

- Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer (INMS)

- Magnetometer (MAG)

- Magnetospheric Imaging Instrument (MIMI)

- Radio and Plasma Wave Science (RPWS)

- Microwave Remote Sensing

- Radar

- Radio Science (RSS)

Description

[edit]Cassini's instrumentation consisted of: a synthetic aperture radar mapper, a charge-coupled device imaging system, a visible/infrared mapping spectrometer, a composite infrared spectrometer, a cosmic dust analyzer, a radio and plasma wave experiment, a plasma spectrometer, an ultraviolet imaging spectrograph, a magnetospheric imaging instrument, a magnetometer and an ion/neutral mass spectrometer. Telemetry from the communications antenna and other special transmitters (an S-band transmitter and a dual-frequency Ka-band system) was also used to make observations of the atmospheres of Titan and Saturn and to measure the gravity fields of the planet and its satellites.

- Cassini Plasma Spectrometer (CAPS)

- CAPS was an in situ instrument that measured the flux of charged particles at the location of the spacecraft, as a function of direction and energy. The ion composition was also measured using a time-of-flight mass spectrometer. CAPS measured particles produced by ionisation of molecules originating from Saturn's and Titan's ionosphere, as well as the plumes of Enceladus. CAPS also investigated plasma in these areas, along with the solar wind and its interaction with Saturn's magnetosphere.[47][48] CAPS was turned off in June 2011, as a precaution due to a "soft" electrical short circuit that occurred in the instrument. It was powered on again in March 2012, but after 78 days another short circuit forced the instrument to be shut down permanently.[49]

- Cosmic Dust Analyzer (CDA)

- The CDA was an in situ instrument that measured the size, speed, and direction of tiny dust grains near Saturn. It could also measure the grains' chemical elements.[50] Some of these particles orbited Saturn, while others came from other star systems. The CDA on the orbiter was designed to learn more about these particles, the materials in other celestial bodies and potentially about the origins of the universe.[47]

- Composite Infrared Spectrometer (CIRS)

- The CIRS was a remote sensing instrument that measured the infrared radiation coming from objects to learn about their temperatures, thermal properties, and compositions. Throughout the Cassini–Huygens mission, the CIRS measured infrared emissions from atmospheres, rings and surfaces in the vast Saturn system. It mapped the atmosphere of Saturn in three dimensions to determine temperature and pressure profiles with altitude, gas composition, and the distribution of aerosols and clouds. It also measured thermal characteristics and the composition of satellite surfaces and rings.[47]

- Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer (INMS)

- The INMS was an in situ instrument that measured the composition of charged particles (protons and heavier ions) and neutral particles (atoms and molecules) near Titan and Saturn to learn more about their atmospheres. The instrument used a quadrupole mass spectrometer. INMS was also intended to measure the positive ion and neutral environments of Saturn's icy satellites and rings.[47][51][52]

- Imaging Science Subsystem (ISS)

- The ISS was a remote sensing instrument that captured most images in visible light, and also some infrared images and ultraviolet images. The ISS took hundreds of thousands of images of Saturn, its rings, and its moons. The ISS had both a wide-angle camera (WAC) and a narrow-angle camera (NAC). Each of these cameras used a sensitive charge-coupled device (CCD) as its electromagnetic wave detector. Each CCD had a 1,024x1,024 square array of pixels, each pixel 12 μm square. Both cameras allowed for many data collection modes, including on-chip data compression, and were fitted with spectral filters that rotated on a wheel to view different bands within the electromagnetic spectrum ranging from 0.2 to 1.1 μm.[47][53]

- Dual Technique Magnetometer (MAG)

- The MAG was an in situ instrument that measured the strength and direction of the magnetic field around Saturn. The magnetic fields are generated partly by the molten core at Saturn's center. Measuring the magnetic field is one of the ways to probe the core. MAG aimed to develop a three-dimensional model of Saturn's magnetosphere, and determine the magnetic state of Titan and its atmosphere, and the icy satellites and their role in the magnetosphere of Saturn.[47][54]

- Magnetospheric Imaging Instrument (MIMI)

- The MIMI was both an in situ and remote sensing instrument that produces images and other data about the particles trapped in Saturn's huge magnetic field, or magnetosphere. The in situ component measured energetic ions and electrons while the remote sensing component (the Ion And Neutral Camera, INCA) was an energetic neutral atom imager.[55] This information was used to study the overall configuration and dynamics of the magnetosphere and its interactions with the solar wind, Saturn's atmosphere, Titan, rings, and icy satellites.[47][56]

- Radar

- The on-board radar was an active and passive sensing instrument that produced maps of Titan's surface. Radar waves were powerful enough to penetrate the thick veil of haze surrounding Titan. By measuring the send and return time of the signals it is possible to determine the height of large surface features, such as mountains and canyons. The passive radar listened for radio waves that Saturn or its moons may emit.[47]

- Radio and Plasma Wave Science instrument (RPWS)

- The RPWS was an in situ instrument and remote sensing instrument that receives and measures radio signals coming from Saturn, including the radio waves given off by the interaction of the solar wind with Saturn and Titan. RPWS measured the electric and magnetic wave fields in the interplanetary medium and planetary magnetospheres. It also determined the electron density and temperature near Titan and in some regions of Saturn's magnetosphere using either plasma waves at characteristic frequencies (e.g. the upper hybrid line) or a Langmuir probe. RPWS studied the configuration of Saturn's magnetic field and its relationship to Saturn Kilometric Radiation (SKR), as well as monitoring and mapping Saturn's ionosphere, plasma, and lightning from Saturn's (and possibly Titan's) atmosphere.[47]

- Radio Science Subsystem (RSS)

- The RSS was a remote-sensing instrument that used radio antennas on Earth to observe the way radio signals from the spacecraft changed as they were sent through objects, such as Titan's atmosphere or Saturn's rings, or even behind the Sun. The RSS also studied the compositions, pressures and temperatures of atmospheres and ionospheres, radial structure and particle size distribution within rings, body and system masses and the gravitational field. The instrument used the spacecraft X-band communication link as well as S-band downlink and Ka-band uplink and downlink.[47]

Cassini UVIS instrument built by the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics at the University of Colorado. - Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrograph (UVIS)

- The UVIS was a remote-sensing instrument that captured images of the ultraviolet light reflected off an object, such as the clouds of Saturn and/or its rings, to learn more about their structure and composition. Designed to measure ultraviolet light over wavelengths from 55.8 to 190 nm, this instrument was also a tool to help determine the composition, distribution, aerosol particle content and temperatures of their atmospheres. Unlike other types of spectrometer, this sensitive instrument could take both spectral and spatial readings. It was particularly adept at determining the composition of gases. Spatial observations took a wide-by-narrow view, only one pixel tall and 64 pixels across. The spectral dimension was 1,024 pixels per spatial pixel. It could also take many images that create movies of the ways in which this material is moved around by other forces.[47]

UVIS consisted of four separate detector channels, the Far Ultraviolet (FUV), Extreme Ultraviolet (EUV), High Speed Photometer (HSP) and the Hydrogen-Deuterium Absorption Cell (HDAC). UVIS collected hyperspectral imagery and discrete spectra of Saturn, its moons and its rings, as well as stellar occultation data.[57]

The HSP channel is designed to observe starlight that passes through Saturn's rings (known as stellar occultations) in order to understand the structure and optical depth of the rings.[58] Stellar occultation data from both the HSP and FUV channels confirmed the existence of water vapor plumes at the south pole of Enceladus, as well as characterized the composition of the plumes.[59]

VIMS spectra taken while looking through Titan's atmosphere towards the Sun helped understand the atmospheres of exoplanets (artist's concept; May 27, 2014). - Visible and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS)

- The VIMS was a remote sensing instrument that captured images using visible and infrared light to learn more about the composition of moon surfaces, the rings, and the atmospheres of Saturn and Titan. It consisted of two cameras - one used to measure visible light, the other infrared. VIMS measured reflected and emitted radiation from atmospheres, rings and surfaces over wavelengths from 350 to 5100 nm, to help determine their compositions, temperatures and structures. It also observed the sunlight and starlight that passes through the rings to learn more about their structure. Scientists used VIMS for long-term studies of cloud movement and morphology in the Saturn system, to determine Saturn's weather patterns.[47]

Plutonium power source

[edit]

Because of Saturn's distance from the Sun, solar arrays were not feasible as power sources for this space probe.[60] To generate enough power, such arrays would have been too large and too heavy.[60] Instead, the Cassini orbiter was powered by three GPHS-RTG radioisotope thermoelectric generators, which use heat from the decay of about 33 kg (73 lb) of plutonium-238 (in the form of plutonium dioxide) to generate direct current electricity via thermoelectrics.[60]The RTGs on the Cassini mission have the same design as those used on the New Horizons, Galileo, and Ulysses space probes, and they were designed to have very long operational lifetimes.[60]At the end of the nominal 11-year Cassini mission, they were still able to produce 600 to 700 watts of electrical power.[60] (Leftover hardware from the Cassini RTG Program was modified and used to power the New Horizons mission to Pluto and the Kuiper belt, which was designed and launched later.[61])

Power distribution was accomplished by 192 solid-state power switches, which also functioned as circuit breakers in the event of an overload condition. The switches used MOSFETs that featured better efficiency and a longer lifetime as compared to conventional switches, while at the same time eliminating transients. However, these solid-state circuit breakers were prone to erroneous tripping (presumably from cosmic rays), requiring them to reset and causing losses in experimental data.[62]

To gain momentum while already in flight, the trajectory of the Cassini mission included several gravitational slingshot maneuvers: two fly-by passes of Venus, one more of the Earth, and then one of the planet Jupiter. The terrestrial flyby was the final instance when the probe posed any conceivable danger to human beings. The maneuver was successful, with Cassini passing by 1,171 km (728 mi) above the Earth on August 18, 1999.[2]Had there been any malfunction causing the probe to collide with the Earth, NASA's complete environmental impact study estimated that, in the worst case (with an acute angle of entry in which Cassini would gradually burn up), a significant fraction of the 33 kg[43] of nuclear fuel inside the RTGs would have been dispersed into the Earth's atmosphere so that up to five billion people (i.e. almost the entire terrestrial population) could have been exposed, causing up to an estimated 5,000 additional cancer deaths over the subsequent decades[63] (0.0005 per cent, i.e. a fraction 0.000005, of a billion cancer deaths expected anyway from other causes; the product is incorrectly calculated elsewhere[64] as 500,000 deaths). However, the chance of this happening were estimated to be less than one in one million, i.e. a chance of one person dying (assuming 5,000 deaths) as less than 1 in 200.[63]

NASA's risk analysis to use plutonium was publicly criticized by Michio Kaku on the grounds that casualties, property damage, and lawsuits resulting from a possible accident, as well as the potential use of other energy sources, such as solar and fuel cells, were underestimated.[65]

Telemetry

[edit]The Cassini spacecraft was capable of transmitting in several different telemetry formats. The telemetry subsystem is perhaps the most important subsystem, because without it there could be no data return.

The telemetry was developed from the ground up, due to the spacecraft using a more modern set of computers than previous missions.[66] Therefore, Cassini was the first spacecraft to adopt mini-packets to reduce the complexity of the Telemetry Dictionary, and the software development process led to the creation of a Telemetry Manager for the mission.

There were around 1088 channels (in 67 mini-packets) assembled in the Cassini Telemetry Dictionary. Out of these 67 lower complexity mini-packets, 6 mini-packets contained the subsystem covariance and Kalman gain elements (161 measurements), not used during normal mission operations. This left 947 measurements in 61 mini-packets.

A total of seven telemetry maps corresponding to 7 AACS telemetry modes were constructed. These modes are: (1) Record; (2) Nominal Cruise; (3) Medium Slow Cruise; (4) Slow Cruise; (5) Orbital Ops; (6) Av; (7) ATE (Attitude Estimator) Calibration. These 7 maps cover all spacecraft telemetry modes.

Huygens probe

[edit]The Huygens probe, supplied by the European Space Agency (ESA) and named after the 17th century Dutch astronomer who first discovered Titan, Christiaan Huygens, scrutinized the clouds, atmosphere, and surface of Saturn's moon Titan in its descent on January 15, 2005. It was designed to enter and brake in Titan's atmosphere and parachute a fully instrumented robotic laboratory down to the surface.[67]

The probe system consisted of the probe itself which descended to Titan, and the probe support equipment (PSE) which remained attached to the orbiting spacecraft. The PSE includes electronics that track the probe, recover the data gathered during its descent, and process and deliver the data to the orbiter that transmits it to Earth. The core control computer CPU was a redundant MIL-STD-1750A control system.

The data were transmitted by a radio link between Huygens and Cassini provided by Probe Data Relay Subsystem (PDRS). As the probe's mission could not be telecommanded from Earth because of the great distance, it was automatically managed by the Command Data Management Subsystem (CDMS). The PDRS and CDMS were provided by the Italian Space Agency (ASI).

After Cassini's launch, it was discovered that data sent from the Huygens probe to Cassini orbiter (and then re-transmitted to Earth) would be largely unreadable. The cause was that the bandwidth of signal processing electronics was too narrow and the anticipated Doppler shift between the lander and the mother craft would put the signals out of the system's range. Thus, Cassini's receiver would be unable to receive the data from Huygens during its descent to Titan.[19]

A work-around was found to recover the mission. The trajectory of Cassini was altered to reduce the line of sight velocity and therefore the doppler shift.[19][68] Cassini's subsequent trajectory was identical to the previously planned one, although the change replaced two orbits prior to the Huygens mission with three, shorter orbits.

Selected events and discoveries

[edit]

Venus and Earth fly-bys and the cruise to Jupiter

[edit]

The Cassini space probe performed two gravitational-assist flybys of Venus on April 26, 1998, and June 24, 1999. These flybys provided the space probe with enough momentum to travel all the way out to the asteroid belt, while the Sun's gravity pulled the space probe back into the inner Solar System.

On August 18, 1999, at 03:28 UTC, the craft made a gravitational-assist flyby of the Earth. One hour and 20 minutes before closest approach, Cassini made its closest approach to the Earth's Moon at 377,000 kilometers, and it took a series of calibration photos.

On January 23, 2000, Cassini performed a flyby of the asteroid 2685 Masursky at around 10:00 UTC. It took photos[69] in the period five to seven hours before the flyby at a distance of 1.6×106 km (0.99×106 mi) and a diameter of 15 to 20 km (9.3 to 12.4 mi) was estimated for the asteroid.

Jupiter flyby

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2018) |

Cassini made its closest approach to Jupiter on December 30, 2000, at 9.7 million kilometers, and made many scientific measurements. About 26,000 images of Jupiter, its faint rings, and its moons were taken during the six-month flyby. It produced the most detailed global color portrait of the planet yet (see image at right), in which the smallest visible features are approximately 60 km (37 mi) across.[70]

A major finding of the flyby, announced on March 6, 2003, was of Jupiter's atmospheric circulation. Dark "belts" alternate with light "zones" in the atmosphere, and scientists had long considered the zones, with their pale clouds, to be areas of upwelling air, partly because many clouds on Earth form where air is rising. But analysis of Cassini imagery showed that individual storm cells of upwelling bright-white clouds, too small to see from Earth, pop up almost without exception in the dark belts. According to Anthony Del Genio of NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies, "the belts must be the areas of net-rising atmospheric motion on Jupiter, [so] the net motion in the zones has to be sinking".

Other atmospheric observations included a swirling dark oval of high atmospheric haze, about the size of the Great Red Spot, near Jupiter's north pole. Infrared imagery revealed aspects of circulation near the poles, with bands of globe-encircling winds, with adjacent bands moving in opposite directions.

The same announcement also discussed the nature of Jupiter's rings. Light scattering by particles in the rings showed the particles were irregularly shaped (rather than spherical) and likely originate as ejecta from micrometeorite impacts on Jupiter's moons, probably Metis and Adrastea.

Tests of general relativity

[edit]On October 10, 2003, the mission's science team announced the results of tests of Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity, performed by using radio waves transmitted from the Cassini space probe.[71] The radio scientists measured a frequency shift in the radio waves to and from the spacecraft, as they passed close to the Sun. According to the general theory of relativity, a massive object like the Sun causes space-time to curve, causing a beam of radiowaves travelling out of its gravitational well to decrease in frequency and radiowaves travelling into the gravitational well to increase in frequency, referred to as gravitational redshift / blueshift.

Although some measurable deviations from the values calculated using the general theory of relativity are predicted by some unusual cosmological models, no such deviations were found by this experiment. Previous tests using radiowaves transmitted by the Viking and Voyager space probes were in agreement with the calculated values from general relativity to within an accuracy of one part in one thousand. The more refined measurements from the Cassini space probe experiment improved this accuracy to about one part in 51,000.[a] The data firmly support Einstein's general theory of relativity.[72]

New moons of Saturn

[edit]

In total, the Cassini mission discovered seven new moons orbiting Saturn.[73] Using images taken by Cassini, researchers discovered Methone, Pallene and Polydeuces in 2004,[74] although later analysis revealed that Voyager 2 had photographed Pallene in its 1981 flyby of the ringed planet.[75]

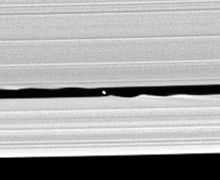

On May 1, 2005, a new moon was discovered by Cassini in the Keeler gap. It was given the designation S/2005 S 1 before being named Daphnis. A fifth new moon was discovered by Cassini on May 30, 2007, and was provisionally labeled S/2007 S 4. It is now known as Anthe. A press release on February 3, 2009, showed a sixth new moon found by Cassini. The moon is approximately 500 m (0.3 mi) in diameter within the G-ring of the ring system of Saturn, and is now named Aegaeon (formerly S/2008 S 1).[76] A press release on November 2, 2009, mentions the seventh new moon found by Cassini on July 26, 2009. It is presently labeled S/2009 S 1 and is approximately 300 m (980 ft) in diameter in the B-ring system.[77]

On April 14, 2014, NASA scientists reported the possible beginning of a new moon in Saturn's A Ring.[78]

Phoebe flyby

[edit]

On June 11, 2004, Cassini flew by the moon Phoebe. This was the first opportunity for close-up studies of this moon (Voyager 2 performed a distant flyby in 1981 but returned no detailed images). It also was Cassini's only possible flyby for Phoebe due to the mechanics of the available orbits around Saturn.[79]

The first close-up images were received on June 12, 2004, and mission scientists immediately realized that the surface of Phoebe looks different from asteroids visited by spacecraft. Parts of the heavily cratered surface look very bright in those pictures, and it is currently believed that a large amount of water ice exists under its immediate surface.

Saturn rotation

[edit]In an announcement on June 28, 2004, Cassini program scientists described the measurement of the rotational period of Saturn.[80] Because there are no fixed features on the surface that can be used to obtain this period, the repetition of radio emissions was used. This new data agreed with the latest values measured from Earth, and constituted a puzzle to the scientists. It turns out that the radio rotational period had changed since it was first measured in 1980 by Voyager 1, and it was now 6 minutes longer. This, however, does not indicate a change in the overall spin of the planet. It is thought to be due to variations in the upper atmosphere and ionosphere at the latitudes which are magnetically connected to the radio source region.[81]

In 2019 NASA announced Saturn's rotational period as 10 hours, 33 minutes, 38 seconds, calculated using Saturnian ring seismology. Vibrations from Saturn's interior cause oscillations in its gravitational field. This energy is absorbed by ring particles in specific locations, where it accumulates until it is released in a wave.[82] Scientists used data from more than 20 of these waves to construct a family of models of Saturn's interior, providing basis for calculating its rotational period.[83]

Orbiting Saturn

[edit]

On July 1, 2004, the spacecraft flew through the gap between the F and G rings and achieved orbit, after a seven-year voyage.[84] It was the first spacecraft to orbit Saturn.

The Saturn Orbital Insertion (SOI) maneuver performed by Cassini was complex, requiring the craft to orient its High-Gain Antenna away from Earth and along its flight path, to shield its instruments from particles in Saturn's rings. Once the craft crossed the ring plane, it had to rotate again to point its engine along its flight path, and then the engine fired to decelerate the craft by 622 m/s to allow Saturn to capture it.[85] Cassini was captured by Saturn's gravity at around 8:54 pm Pacific Daylight Time on June 30, 2004. During the maneuver Cassini passed within 20,000 km (12,000 mi) of Saturn's cloud tops.

When Cassini was in Saturnian orbit, departure from the Saturn system was evaluated in 2008 during end of mission planning.[86][clarification needed]

Titan flybys

[edit]

Cassini had its first flyby of Saturn's largest moon, Titan, on July 2, 2004, a day after orbit insertion, when it approached to within 339,000 km (211,000 mi) of Titan. Images taken through special filters (able to see through the moon's global haze) showed south polar clouds thought to be composed of methane and surface features with widely differing brightness. On October 27, 2004, the spacecraft executed the first of the 45 planned close flybys of Titan when it passed a mere 1,200 km (750 mi) above the moon. Almost four gigabits of data were collected and transmitted to Earth, including the first radar images of the moon's haze-enshrouded surface. It revealed the surface of Titan (at least the area covered by radar) to be relatively level, with topography reaching no more than about 50 m (160 ft) in altitude. The flyby provided a remarkable increase in imaging resolution over previous coverage. Images with up to 100 times better resolution were taken and are typical of resolutions planned for subsequent Titan flybys. Cassini collected pictures of Titan and the lakes of methane were similar to the lakes of water on Earth.

Huygens lands on Titan

[edit]| External image | |

|---|---|

ESA/NASA/JPL/University of Arizona (ESA hosting) |

Cassini released the Huygens probe on December 25, 2004, by means of a spring and spiral rails intended to rotate the probe for greater stability. It entered the atmosphere of Titan on January 14, 2005, and after a two-and-a-half-hour descent landed on solid ground.[6] Although Cassini successfully relayed 350 of the pictures that it received from Huygens of its descent and landing site, a malfunction in one of the communications channels resulted in the loss of a further 350 pictures. [87]

Enceladus flybys

[edit]

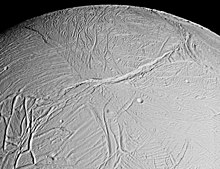

During the first two close flybys of the moon Enceladus in 2005, Cassini discovered a deflection in the local magnetic field that is characteristic for the existence of a thin but significant atmosphere. Other measurements obtained at that time point to ionized water vapor as its main constituent. Cassini also observed water ice geysers erupting from the south pole of Enceladus, which gives more credibility to the idea that Enceladus is supplying the particles of Saturn's E ring. Mission scientists began to suspect that there may be pockets of liquid water near the surface of the moon that fuel the eruptions.[88]

On March 12, 2008, Cassini made a close fly-by of Enceladus, passing within 50 km of the moon's surface.[89] The spacecraft passed through the plumes extending from its southern geysers, detecting water, carbon dioxide and various hydrocarbons with its mass spectrometer, while also mapping surface features that are at much higher temperature than their surroundings with the infrared spectrometer.[90] Cassini was unable to collect data with its cosmic dust analyzer due to an unknown software malfunction.

On November 21, 2009, Cassini made its eighth flyby of Enceladus,[91] this time with a different geometry, approaching within 1,600 km (990 mi) of the surface. The Composite Infrared Spectrograph (CIRS) instrument produced a map of thermal emissions from the Baghdad Sulcus 'tiger stripe'. The data returned helped create a detailed and high resolution mosaic image of the southern part of the moon's Saturn-facing hemisphere.

On April 3, 2014, nearly ten years after Cassini entered Saturn's orbit, NASA reported evidence of a large salty internal ocean of liquid water in Enceladus. The presence of an internal salty ocean in contact with the moon's rocky core, places Enceladus "among the most likely places in the Solar System to host alien microbial life".[92][93][94] On June 30, 2014, NASA celebrated ten years of Cassini exploring Saturn and its moons, highlighting the discovery of water activity on Enceladus among other findings.[95]

In September 2015, NASA announced that gravitational and imaging data from Cassini were used to analyze the librations of Enceladus' orbit and determined that the moon's surface is not rigidly joined to its core, concluding that the underground ocean must therefore be global in extent.[96]

On October 28, 2015, Cassini performed a close flyby of Enceladus, coming within 49 km (30 mi) of the surface, and passing through the icy plume above the south pole.[97]

On December 14, 2023, astronomers reported the first time discovery, in the plumes of Enceladus, of hydrogen cyanide, a possible chemical essential for life as we know it, as well as other organic molecules, some of which are yet to be better identified and understood. According to the researchers, "these [newly discovered] compounds could potentially support extant microbial communities or drive complex organic synthesis leading to the origin of life".[98][99]

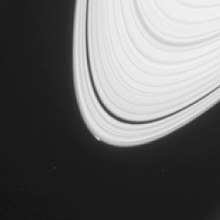

Radio occultations of Saturn's rings

[edit]In May 2005, Cassini began a series of radio occultation experiments, to measure the size-distribution of particles in Saturn's rings, and measure the atmosphere of Saturn itself. For over four months, the craft completed orbits designed for this purpose. During these experiments, it flew behind the ring plane of Saturn, as seen from Earth, and transmitted radio waves through the particles. The radio signals received on Earth were analyzed, for frequency, phase, and power shift of the signal to determine the structure of the rings.

Spokes in rings verified

[edit]На снимках, сделанных 5 сентября 2005 года, Кассини обнаружил спицы в кольцах Сатурна. [100] Ранее его видел только визуальный наблюдатель Стивен Джеймс О'Мира в 1977 году, а затем подтвердили космические зонды "Вояджер" в начале 1980-х годов. [101] [102]

Озера Титана

[ редактировать ]

Радиолокационные изображения, полученные 21 июля 2006 года, показывают озера жидких углеводородов (таких как метан и этан ) в северных широтах Титана. Это первое открытие существующих ныне озер где-либо за пределами Земли. Размеры озер варьируются от одного до ста километров в поперечнике. [88]

13 марта 2007 года Лаборатория реактивного движения объявила, что обнаружила убедительные доказательства существования морей метана и этана в северном полушарии Титана. По крайней мере одно из них больше, чем любое из Великих озер в Северной Америке. [103]

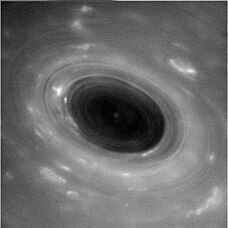

Сатурн ураган

[ редактировать ]В ноябре 2006 года учёные обнаружили на южном полюсе Сатурна бурю с отчетливой стенкой глаза . Это характерно для урагана на Земле и никогда раньше не наблюдалось на других планетах. В отличие от земного урагана, шторм кажется неподвижным на полюсе. Шторм имеет ширину 8000 км (5000 миль) и высоту 70 км (43 мили), скорость ветра составляет 560 км/ч (350 миль в час). [104]

Облет Япета

[ редактировать ]

10 сентября 2007 года «Кассини» завершил облёт странной двухцветной луны, имеющей форму грецкого ореха, Япета . Изображения были сделаны на высоте 1600 км (1000 миль) над поверхностью. Когда он отправлял изображения обратно на Землю, в него попал космический луч , который вынудил его временно перейти в безопасный режим . Все данные облета были восстановлены. [105]

Продление миссии

[ редактировать ]15 апреля 2008 года «Кассини» получил финансирование на 27-месячную расширенную миссию. Он состоял из еще 60 витков Сатурна , еще 21 близкого пролета Титана, семи - Энцелада, шести - Мимаса, восьми - Тефии и по одному целевому пролету - Дионы , Реи и Елены . [106] Расширенная миссия началась 1 июля 2008 года и была переименована в миссию Кассини по равноденствию , поскольку миссия совпала с равноденствием Сатурна . [107]

Второе продление миссии

[ редактировать ]В НАСА было подано предложение о втором продлении миссии (сентябрь 2010 г. - май 2017 г.), предварительно названном расширенной-расширенной миссией или XXM. [108] Эта программа (60 миллионов долларов в год) была одобрена в феврале 2010 года и переименована в « Миссию солнцестояния Кассини» . [109] Он включал в себя еще 155 облетов вокруг Сатурна Кассини , 54 дополнительных облета Титана и еще 11 облетов Энцелада.

Великий шторм 2010 года и его последствия

[ редактировать ]

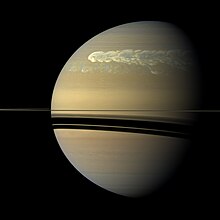

25 октября 2012 года «Кассини» стал свидетелем последствий мощной бури Большого Белого Пятна , которая повторяется на Сатурне примерно каждые 30 лет. [110] Данные составного инфракрасного спектрометра (CIRS) указали на мощный разряд во время шторма, который вызвал скачок температуры в стратосфере Сатурна на 83 К (83 °C; 149 °F) выше нормы. огромное увеличение содержания этиленового Одновременно с этим исследователи НАСА в Исследовательском центре Годдарда в Гринбелте, штат Мэриленд, обнаружили газа. Этилен — бесцветный газ, который крайне редко встречается на Сатурне и производится как естественным путем, так и из искусственных источников на Земле. Шторм, вызвавший этот разряд, впервые наблюдался космическим кораблем 5 декабря 2010 года в северном полушарии Сатурна. Шторм является первым в своем роде, наблюдаемым с космического корабля на орбите вокруг Сатурна, а также первым, наблюдаемым в тепловом инфракрасном диапазоне волн, что позволяет ученым наблюдать за температурой атмосферы Сатурна и отслеживать явления, невидимые невооруженным глазом. . Всплеск этиленового газа, образовавшегося в результате шторма, достиг уровня, который в 100 раз превышал тот, который считался возможным для Сатурна. Ученые также определили, что увиденный шторм был самым большим и горячим стратосферным вихрем, когда-либо обнаруженным в Солнечной системе, первоначально он был больше, чем у Юпитера. Большое Красное Пятно .

Венера проходит

[ редактировать ]21 декабря 2012 года Кассини наблюдал прохождение Венеры через Солнце. Прибор VIMS анализировал солнечный свет, проходящий через атмосферу Венеры. VIMS ранее наблюдал транзит экзопланеты HD 189733 b . [111]

День, когда Земля улыбнулась

[ редактировать ]

19 июля 2013 года зонд был направлен в сторону Земли, чтобы сделать изображение Земли и Луны как часть многокадрового портрета всей системы Сатурна при естественном освещении. Событие было уникальным, поскольку впервые НАСА проинформировало общественность о том, что фотография делается с большого расстояния заранее. [112] [113] Команда фотографов заявила, что хочет, чтобы люди улыбались и махали в небо, а Кассини ученый Кэролин Порко описала этот момент как шанс «отпраздновать жизнь на Бледно-голубой точке ». [114]

Рея пролетает

[ редактировать ]10 февраля 2015 года космический корабль Кассини приблизился к Рее , приблизившись на расстояние 47 000 км (29 000 миль). [115] Космический корабль наблюдал за Луной с помощью своих камер, создав цветные изображения Реи с самым высоким разрешением. [116]

Пролет Гипериона

[ редактировать ]«Кассини» Последний облет спутника Сатурна Гипериона совершил 31 мая 2015 года на расстоянии около 34 000 км (21 000 миль). [117]

Пролет Дионы

[ редактировать ]Кассини совершил свой последний облет спутника Сатурна Дионы 17 августа 2015 года на расстоянии около 475 км (295 миль). Предыдущий облет состоялся 16 июня. [118]

Шестиугольник меняет цвет

[ редактировать ]В период с 2012 по 2016 год устойчивый шестиугольный рисунок облаков на северном полюсе Сатурна изменился с преимущественно синего цвета на более золотистый. [119] Одна из теорий заключается в сезонных изменениях: длительное воздействие солнечного света может создавать дымку, когда полюс поворачивается к Солнцу. [119] Ранее отмечалось, что в период с 2004 по 2008 год на Сатурне в целом было меньше синего цвета. [120]

- 2012 и 2016 годы: изменение цвета шестиугольника.

- 2013 и 2017 годы: изменение цвета шестиугольника

Гранд-финал и разрушение

[ редактировать ]

- Кассини

- Сатурн

включал Конец Кассини серию близких проходов Сатурна, сближение внутри колец , а затем вход в атмосферу Сатурна 15 сентября 2017 года для уничтожения космического корабля. [6] [12] [86] Этот метод был выбран для обеспечения защиты и предотвращения биологического загрязнения любого из спутников Сатурна, которые, как считалось, потенциально пригодны для жизни . [121]

В 2008 году был оценен ряд вариантов достижения этой цели, каждый из которых имел различные финансовые, научные и технические проблемы. Кратковременное воздействие на Сатурн для завершения миссии было оценено как «отличное» по причинам: «Вариант D-образного кольца удовлетворяет недостигнутым целям AO; [ необходимо определение ] дешево и легко достижимо», а столкновение с ледяной луной было оценено как «хорошо» за то, что оно «дешево и достижимо в любом месте и в любое время». [86]

В 2013–2014 годах были проблемы с получением НАСА финансирования правительства США для Гранд-финала. Две фазы Гранд-финала в конечном итоге стали эквивалентом двух отдельных «Дискавери» миссий класса , поскольку Гранд-финал полностью отличался от основной Кассини регулярной миссии . Правительство США в конце 2014 года одобрило Гранд-финал стоимостью 200 миллионов долларов. Это было намного дешевле, чем строительство двух новых зондов в отдельных «Дискавери» . миссиях класса [122]

29 ноября 2016 года космический корабль совершил облет Титана, который доставил его к вратам орбит F-кольца: это было начало фазы Гранд Финала, кульминацией которой стало столкновение с планетой. [123] [124] Последний пролет Титана 22 апреля 2017 года снова изменил орбиту, чтобы пролететь через разрыв между Сатурном и его внутренним кольцом несколькими днями позже, 26 апреля. Кассини пролетел примерно на 3100 км (1900 миль) над облачным слоем Сатурна и на высоте 320 км (200 миль). ) от видимого края внутреннего кольца; он успешно сделал снимки атмосферы Сатурна и на следующий день начал возвращать данные. [125] После еще 22 витков через разрыв миссия завершилась погружением в атмосферу Сатурна 15 сентября; Сигнал был потерян в 11:55:46 UTC 15 сентября 2017 года, всего на 30 секунд позже, чем прогнозировалось. Предполагается, что космический корабль сгорел примерно через 45 секунд после последней передачи.

В сентябре 2018 года НАСА выиграло премию «Эмми» за выдающуюся оригинальную интерактивную программу за презентацию грандиозного финала миссии «Кассини» на Сатурне . [126]

В декабре 2018 года Netflix транслировал «Миссию НАСА Кассини» в сериале « 7 дней вне», документируя последние дни работы над миссией Кассини перед тем, как космический корабль врезался в Сатурн, чтобы завершить свой грандиозный финал.

В январе 2019 года : Кассини было опубликовано новое исследование с использованием данных, собранных во время фазы Гранд-финала

- Последние близкие проходы мимо колец и планеты позволили ученым измерить продолжительность дня на Сатурне: 10 часов, 33 минуты и 38 секунд.

- Кольца Сатурна относительно новые, им от 10 до 100 миллионов лет. [16]

Миссии

[ редактировать ]Эксплуатация космического корабля была организована в виде серии миссий. [17] Каждый из них структурирован в соответствии с определенным объемом финансирования, целями и т. д. [17] По меньшей мере 260 ученых из 17 стран работали над миссией Кассини-Гюйгенс ; кроме того, над проектированием, изготовлением и запуском миссии работали тысячи людей. [128]

- Prime Mission, июль 2004 г. - июнь 2008 г. [129] [130]

- Миссия Кассини Равноденствие представляла собой двухлетнее продление миссии, которое длилось с июля 2008 года по сентябрь 2010 года. [17]

- Миссия «Кассини Солнцестояние» работала с октября 2010 года по апрель 2017 года. [17] [131] (Также известная как миссия XXM.) [120]

- Гранд-финал (космический корабль направлен к Сатурну), апрель 2017 г. - 15 сентября 2017 г. [131]

- Сатурн Кассини , 2016 г.

- Кассини-Гюйгенс в цифрах

(сентябрь 2017 г.)

Глоссарий

[ редактировать ]- AACS: Подсистема управления ориентацией и артикуляцией

- ACS: Подсистема контроля ориентации

- AFC: Бортовой компьютер AACS

- ARWM: шарнирно-сочлененный механизм реактивного колеса

- ASI: Agenzia Spaziale Italiana, итальянское космическое агентство.

- BIU: Блок интерфейса шины

- БОЛ: Начало жизни

- CAM: Совещание командования по утверждению

- CDS: Подсистема управления и данных — компьютер Кассини, который управляет инструментами и собирает данные с них.

- ЦИКЛОПС: Центральная операционная лаборатория Cassini Imaging. Архивировано 1 мая 2008 г., в Wayback Machine.

- CIMS: Кассини Система управления информацией

- CIRS: композитный инфракрасный спектрометр

- DCSS: Подсистема управления спуском

- DSCC: Центр дальней космической связи

- DSN: Сеть дальнего космоса (большие антенны вокруг Земли)

- DTSTART: Старт с мертвым временем

- ELS: Электронный спектрометр (часть прибора CAPS)

- МНВ: Конец миссии

- ERT: время приема с Земли, UTC события.

- ЕКА: Европейское космическое агентство

- ESOC: Европейский центр космических операций

- FSW: летное программное обеспечение

- HGA: Антенна с высоким коэффициентом усиления

- HMCS: «Гюйгенс» Система мониторинга и управления

- HPOC: «Гюйгенс» Центр управления зондом

- IBS: ионно-лучевой спектрометр (часть прибора CAPS)

- IEB: расширенные блоки прибора (последовательности команд прибора)

- IMS: ионный масс-спектрометр (часть прибора CAPS)

- ITL: Комплексная испытательная лаборатория - симулятор космического корабля.

- IVP: Распространитель инерционных векторов

- LGA: Антенна с низким коэффициентом усиления

- NAC: узкоугольная камера

- НАСА: Национальное управление по аэронавтике и исследованию космического пространства, космическое агентство США.

- OTM: маневр балансировки орбиты

- PDRS: Подсистема ретрансляции данных зонда

- PHSS: Подсистема жгута проводов зонда

- POSW: встроенное программное обеспечение зонда

- ППС: Силовая и пиротехническая подсистема

- PRA: Антенна реле зонда

- PSA: Авионика поддержки зондов

- PSIV: предварительная интеграция и проверка последовательностей

- PSE: оборудование для поддержки зондов

- RCS: Система управления реакцией

- RFS: Радиочастотная подсистема

- RPX: пересечение плоскости кольца

- RWA: Реактивное колесо в сборе

- SCET: Время события космического корабля

- SCR: запросы на изменение последовательности

- SKR: Километровое излучение Сатурна

- SOI: Выход на орбиту Сатурна (1 июля 2004 г.)

- СОП: План научных операций

- SSPS: полупроводниковый выключатель питания

- ССР: твердотельный рекордер

- SSUP: Процесс обновления научных данных и последовательностей

- TLA: Тепловые жалюзи в сборе

- USO: Ультрастабильный генератор

- ВРХУ: Блоки переменного радиоизотопного нагревателя

- WAC: широкоугольная камера

- XXM: Расширенная-расширенная миссия

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Европланета , сеть передачи данных

- Галилей , орбитальный аппарат Юпитера и входной зонд (1989–2003 гг.)

- В кольцах Сатурна

- Список миссий на внешние планеты

- Десятилетний обзор планетарной науки

- Хронология Кассини -Гюйгенса

Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ На данный момент это лучшее измерение постньютоновского параметра γ ; результат γ = 1 + (2,1 ± 2,3) × 10 −5 согласуется с предсказанием стандартной общей теории относительности, γ = 1

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ «Гюйгенс» . sci.esa.int . ЕКА . 1 сентября 2019 года . Проверено 30 июля 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и «Кассини – Гюйгенс: краткие факты» . science.nasa.gov . НАСА . Проверено 1 июля 2014 г.

- ^ Гюнтер Д. Кребс. «Кассини/Гюйгенс» . Космическая страница Гюнтера . Проверено 15 июня 2016 г.

- ^ Тодд Дж. Барбер (23 августа 2010 г.). «Кассини инсайдера: мощность, двигательная установка и Эндрю Гинг» . science.nasa.gov . НАСА . Проверено 20 августа 2011 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б округ Колумбия Браун; Л. Кантильо; П. Дычес (15 сентября 2017 г.). «Космический корабль НАСА Кассини завершает историческое исследование Сатурна» . jpl.nasa.gov . НАСА / Лаборатория реактивного движения . Проверено 16 сентября 2017 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Кеннет Чанг (14 сентября 2017 г.). «Кассини исчезает на Сатурне, его миссия празднуется и оплакивается» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Проверено 15 сентября 2017 г.

- ^ Пресс-конференция Кассини после окончания миссии на YouTube

- ^ Б. Каземинежад; Д. Х. Аткинсон; JP Lebreton (май 2011 г.). «Новый полюс Титана: последствия для траектории входа и спуска Гюйгенса, а также координат приземления» . Достижения в космических исследованиях . 47 (9): 1622–1632. Бибкод : 2011AdSpR..47.1622K . дои : 10.1016/j.asr.2011.01.019 . Проверено 4 января 2018 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Программа «Внешние планеты и океанические миры»» . science.nasa.gov . НАСА . Проверено 12 июля 2017 г.

- ^ Джонатан Корум (18 декабря 2015 г.). «Картирование спутников Сатурна» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Проверено 19 декабря 2015 г.

- ^ П. Дычес; округ Колумбия Браун; Л. Кантильо (29 августа 2017 г.). «Погружение Сатурна приближается к космическому кораблю Кассини» . science.nasa.gov . НАСА . Проверено 30 августа 2017 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Деннис Овербай (8 сентября 2017 г.). «Кассини летит навстречу огненной смерти на Сатурне» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Проверено 10 сентября 2017 г.

- ^ Дэйв Мошер (6 апреля 2017 г.). «НАСА этим летом уничтожит зонд Сатурн стоимостью 3,26 миллиарда долларов, чтобы защитить инопланетный водный мир» . Бизнес-инсайдер . Проверено 2 мая 2017 г.

- ^ Кеннет Чанг (3 мая 2017 г.). «Звуки космоса, когда аппарат НАСА Кассини ныряет к Сатурну» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Проверено 4 мая 2017 г.

- ^ «Первое погружение Кассини между Сатурном и его кольцами» . jpl.nasa.gov . НАСА / Лаборатория реактивного движения . 27 апреля 2017 года . Проверено 28 июля 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д «Кассини-Гюйгенс — наука НАСА» . science.nasa.gov . НАСА . Проверено 25 января 2019 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и «Миссия Кассини Равноденствие» . sci.esa.int . ЕКА . 18 октября 2011 года . Проверено 15 апреля 2017 г.

- ^ «Отделение зонда Гюйгенс и фаза выбега» . sci.esa.int . ЕКА . 1 сентября 2019 года . Проверено 22 августа 2022 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Пол Ринкон (14 сентября 2017 г.). « "Наши Сатурновые годы" — эпическое путешествие Кассини-Гюйгенса к планете, окруженной кольцами, рассказанное людьми, которые сделали это событие возможным» . Новости Би-би-си . Проверено 15 сентября 2017 г.

- ^ «Кассини-Гюйгенс» . АСИ . Декабрь 2008. Архивировано из оригинала 21 сентября 2017 года . Проверено 16 апреля 2017 г.

- ^ Э. А. Миллер; Г. Кляйн; Д. В. Юргенс; К. Мехаффи; Дж. М. Осеас; и др. (7 октября 1996 г.). «Спектрометр визуального и инфракрасного картирования для Кассини» (PDF) . В Линде Хорн (ред.). Кассини/Гюйгенс: Миссия к системам Сатурна . Том. 2803. стр. 206–220. Бибкод : 1996SPIE.2803..206M . дои : 10.1117/12.253421 . S2CID 34965357 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 9 августа 2017 года . Проверено 14 августа 2017 г.

- ^ Ф.М. Рейнингер; М. Дами; Р. Паолинетти; и др. (июнь 1994 г.). «Видимый инфракрасный картографический спектрометр - видимый канал (ВИМС-В)». В Д. Л. Кроуфорде; Э. Р. Крейн (ред.). Приборы в астрономии VIII . Том. 2198. стр. 239–250. Бибкод : 1994SPIE.2198..239R . дои : 10.1117/12.176753 . S2CID 128716661 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б округ Колумбия Браун; К. Мартинес (15 апреля 2008 г.). «НАСА продлевает грандиозное путешествие Кассини по Сатурну» . jpl.nasa.gov . НАСА / Лаборатория реактивного движения . Проверено 14 августа 2017 г.

- ^ «Маринер Марк II (Кассини)» . Планетарное общество . Архивировано из оригинала 24 октября 2020 года . Проверено 14 апреля 2021 г.

- ^ «Кассини-Гюйгенс: цели миссии» . sci.esa.int . ЕКА . 27 марта 2012 г.

- ^ «Кассини-Гюйгенс: Краткое описание миссии» . sci.esa.int . ЕКА . Проверено 3 февраля 2017 г.

- ^ «Кассини: Часто задаваемые вопросы» . science.nasa.gov . НАСА . Проверено 24 января 2014 г.

- ^ Дэйв Мошер (15 апреля 2008 г.). «НАСА продлевает миссию зонда Кассини на Сатурне» . Space.com . Проверено 1 сентября 2010 г.

- ^ Клара Московиц (4 февраля 2010 г.). «Зонд Кассини-Сатурн продлил срок службы на 7 лет» . Space.com . Проверено 20 августа 2011 г.

- ^ Салли К. Райд (август 1987 г.). Лидерство и будущее Америки в космосе (Отчет). НАСА . п. 27. НАСА-ТМ-89638.

- ^ Хлыст; Д. Готье; Т. Оуэн (13–17 апреля 2004 г.). Генезис Кассини-Гюйгенса . Титан – от открытия до встречи: Международная конференция по случаю 375-го й день рождения Христиана Гюйгенса. ESTEC, Нордвейк, Нидерланды. п. 218. Стартовый код : 2004ESASP1278..211I .

- ^ Ройс Ренсбергер (28 ноября 1988 г.). «Европейцы поддерживают совместную космическую миссию» . Вашингтон Пост . Проверено 15 сентября 2017 г.

- ^ Дэн Морган (18 октября 1989 г.). «Большое увеличение утверждено на жилье и ветеринарную помощь» . Вашингтон Пост . Проверено 15 сентября 2017 г.

- ^ Уильям Дж. Броуд (8 сентября 1997 г.). «Использование плутониевого топлива в миссии «Сатурн» вызывает предупреждение об опасности» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Проверено 1 сентября 2010 г.

- ^ «Десятки арестованных в знак протеста против космической миссии на плутониевом топливе» . CNN . 4 октября 1997 года . Проверено 1 сентября 2010 г.

- ^ Кристофер Бойд (5 октября 1997 г.). «27 арестованных в ходе протеста Кассини» . Орландо Сентинел . Архивировано из оригинала 17 февраля 2015 года . Проверено 1 сентября 2010 г.

- ^ «Космический корабль «Кассини» близок к старту, но критики возражают против риска . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 12 октября 1997 года . Проверено 1 сентября 2010 г.

- ^ Дэниел Сорид (18 августа 1999 г.). «Активисты стоят на своем, даже когда Кассини благополучно уплывает» . Space.com . Проверено 1 сентября 2010 г.

- ^ «Космический корабль Кассини» . www.esa.int . ЕКА . Проверено 5 апреля 2018 г.

- ^ «Космический корабль Кассини и зонд Гюйгенс» . НАСА / Лаборатория реактивного движения . Май 1999 г. JPL 400-777 . Проверено 5 апреля 2018 г.

- ^ А. Кустенис; Ф. В. Тейлор (2008). Титан: исследование земного мира . Серия по физике атмосферы, океана и планет. Том. 4 (2-е изд.). Всемирная научная. п. 75. ИСБН 978-981-270-501-3 .

- ^ Тодд Дж. Барбер (9 июля 2018 г.). Окончательная летная характеристика двигательной установки Кассини . 54 й Совместная конференция AIAA/SAE/ASEE по двигательной установке. дои : 10.2514/6.2018-4546 . Проверено 1 июля 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Ж. Грандидье; Дж. Б. Гилберт; Г. А. Карр (2017). Подсистема питания Кассини (PDF) . Ядерные и новые технологии для космоса (NETS), 2017. Орландо, Флорида, США: НАСА / Лаборатория реактивного движения .

- ^ Мэри Бет Мюрилл (21 августа 1997 г.). «Сигнатуры с космического корабля Земли на Сатурн» . science.nasa.gov . НАСА . Проверено 10 октября 2017 г.

- ^ «616 400 подписей» . science.nasa.gov . НАСА . 17 декабря 2004 года . Проверено 10 октября 2017 г.

- ^ Деннис Овербай (6 августа 2014 г.). «Погоня за штормом на Сатурне» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Проверено 7 августа 2014 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м н «Орбитальный аппарат Кассини — наука НАСА» . science.nasa.gov . НАСА . Проверено 30 июля 2024 г.

- ^ «Добро пожаловать на домашнюю страницу SwRI Cassini/CAPS» . caps.space.swri.edu . СвРИ . Архивировано из оригинала 8 октября 2018 года . Проверено 20 августа 2011 г.

- ^ «Значимые события Кассини: 14.03.2012 – 20.03.2012» . science.nasa.gov . НАСА . Проверено 13 декабря 2018 г.

- ^ Н. Альтобелли; Ф. Постберг; К. Фиге; М. Триелофф; Х. Кимура; и др. (2016). «Поток и состав межзвездной пыли на Сатурне по данным анализатора космической пыли Кассини». Наука . 352 (6283): 312–318. Бибкод : 2016Sci...352..312A . дои : 10.1126/science.aac6397 . ПМИД 27081064 . S2CID 24111692 .

- ^ Дж. Х. Уэйт; С. Льюис; В. Т. Каспржак; В.Г. Аничич; Блок БП; и др. (2004). «Исследование ионного и нейтрального масс-спектрометра Кассини (INMS)» (PDF) . Обзоры космической науки . 114 (1–4): 113–231. Бибкод : 2004ССРв..114..113Вт . дои : 10.1007/s11214-004-1408-2 . hdl : 2027.42/43764 . S2CID 120116482 .

- ^ «Добро пожаловать на домашнюю страницу SwRI Cassini/INMS» . inms.space.swri.edu . СвРИ . Архивировано из оригинала 18 августа 2011 года . Проверено 20 августа 2011 г.

- ^ СС Порко; РА Запад; С. Сквайрс; А. МакИвен; П. Томас; и др. (2004). «Наука о визуализации Кассини: характеристики прибора и ожидаемые научные исследования на Сатурне». Обзоры космической науки . 115 (1–4): 363–497. Бибкод : 2004ССРв..115..363П . дои : 10.1007/s11214-004-1456-7 . S2CID 122119953 .

- ^ М. К. Догерти; С. Келлок; диджей Саутвуд; А. Балог; Э. Дж. Смит; и др. (2004). «Исследование магнитного поля Кассини» (PDF) . Обзоры космической науки . 114 (1–4): 331–383. Бибкод : 2004ССРв..114..331Д . CiteSeerX 10.1.1.454.6826 . дои : 10.1007/s11214-004-1432-2 . S2CID 3035894 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 10 августа 2017 года . Проверено 1 ноября 2017 г.

- ^ «Кассини/МИМИ: ИНКА» . sd-www.jhuapl.edu . Университет Джона Хопкинса / APL . Проверено 20 августа 2011 г.

- ^ С.М. Кримигис; Д. Г. Митчелл; округ Колумбия Гамильтон; С. Ливи; Дж. Дандурас; и др. (2004). «Прибор для получения изображений магнитосферы (MIMI) в миссии Кассини к Сатурну/Титану». Обзоры космической науки . 114 (1–4): 233–329. Бибкод : 2004ССРв..114..233К . дои : 10.1007/s11214-004-1410-8 . S2CID 108288660 .

- ^ Л.В. Эспозито; К. А. Барт; Дж. Э. Колвелл; генеральный менеджер Лоуренс; МЫ МакКлинток; и др. «Исследование спектрографа ультрафиолетового изображения Кассини». Обзоры космической науки . 115 (1–4): 299–361. дои : 10.1007/s11214-004-1455-8 .

- ^ Дж. Э. Колвелл; Л.В. Эспозито; Р.Г. Джероусек; М. Сремчевич; Д. Петтис; ET Брэдли (2010). «Наблюдение звездного затмения колец Сатурна с помощью Cassini UVIS» . Астрономический журнал . 140 (6): 1569–1578. Бибкод : 2010AJ....140.1569C . дои : 10.1088/0004-6256/140/6/1569 .

- ^ Си Джей Хансен; Л. Эспозито; АИФ Стюарт; Дж. Колвелл; А. Хендрикс; и др. (2006). «Шлейф водяного пара Энцелада». Наука . 311 (5766): 1422–1425. Бибкод : 2006Sci...311.1422H . дои : 10.1126/science.1121254 . JSTOR 3845771 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и «Почему миссия Кассини не может использовать солнечные батареи» (PDF) . saturn.jpl.nasa.gov . НАСА / Лаборатория реактивного движения . 6 декабря 1996 г. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 26 февраля 2015 г. . Проверено 21 марта 2014 г.

- ^ Г.Л. Беннетт; Джей Джей Ломбардо; Р. Дж. Хемлер; Г. Сильверман; К.В. Уитмор; и др. (26–29 июня 2006 г.). Смелая миссия: универсальный радиоизотопный термоэлектрический генератор с источником тепла (PDF) . 4 й Международная конференция и выставка по технологиям преобразования энергии (IECEC). Сан-Диего, Калифорния, США. п. 4. АИАА 2006-4096 . Проверено 30 августа 2022 г.

- ^ Мельцер 2015 , с. 70.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Окончательное заявление Кассини о воздействии на окружающую среду» . science.nasa.gov . НАСА . Проверено 19 января 2012 г.

- ^ Виктория П. Фриденсен (1999). «Глава 3» . Пространство протеста: исследование выбора технологий, восприятия риска и освоения космоса (магистерская диссертация). hdl : 10919/36022 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 6 марта 2002 г. Проверено 28 февраля 2011 г.

- ^ Мичио Каку (5 октября 1997 г.). «Научная критика рисков аварии космической миссии Кассини» . Компания Animated Software . Архивировано из оригинала 9 июля 2021 года . Проверено 15 января 2021 г.

- ^ Эдвин П. Кан (ноябрь 1994 г.). Процесс и методология разработки словаря телеметрии Cassini G&C . 3 р-д Международный симпозиум по операциям космических миссий и наземным системам данных. Гринбелт . Проверено 10 мая 2013 г.

- ^ С. Лингард; П. Норрис (июнь 2005 г.). «Как приземлиться на Титан» . Ингения Онлайн . Архивировано из оригинала 21 июля 2011 года . Проверено 26 июля 2024 г.

- ^ Джеймс Оберг (17 января 2005 г.). «Как Гюйгенс избежал катастрофы» . Космический обзор . Проверено 18 января 2005 г.

- ^ «Доступны новые изображения астероида Кассини» . Solarsystem.nasa.gov (пресс-релиз). НАСА . 11 февраля 2000 года . Проверено 15 октября 2010 г.

- ^ Си Джей Хансен; С. Дж. Болтон; Д.Л. Мэтсон; Эл Джей Спилкер; Дж. П. Лебретон (2004). «Облет Юпитера Кассини – Гюйгенс». Икар . 172 (1): 1–8. Бибкод : 2004Icar..172....1H . дои : 10.1016/j.icarus.2004.06.018 .

- ^ Б. Бертотти; Л. Иесс; П. Тортора (2003). «Испытание общей теории относительности с использованием радиосвязи с космическим кораблем Кассини». Природа . 425 (6956): 374–376. Бибкод : 2003Natur.425..374B . дои : 10.1038/nature01997 . ПМИД 14508481 . S2CID 4337125 .

- ^ Изабель Дюме (24 сентября 2003 г.). «Общая теория относительности прошла тест Кассини» . Мир физики . Проверено 28 июля 2024 г.

- ^ Мельцер 2015 , стр. 346–351.

- ^ «Новейшим спутникам Сатурна даны имена» . Новости Би-би-си . 28 февраля 2005 года . Проверено 1 сентября 2016 г.

- ^ Дж. Н. Спитале; Р.А. Джейкобсон; СС Порко; В.М. Оуэн-младший (2006). «Орбиты малых спутников Сатурна получены на основе совмещенных исторических Кассини наблюдений и изображений » . Астрономический журнал . 132 (2): 692–710. Бибкод : 2006AJ....132..692S . дои : 10.1086/505206 .

- ^ «Сюрприз! У Сатурна в кольце спрятан маленький спутник» . Новости Эн-Би-Си . 3 марта 2009 года . Проверено 29 августа 2015 г.

- ^ СС Свинья; DWE Green (2 ноября 2009 г.). «Циркуляр МАС № 9091» . ЦИКЛОП: Кассини . ISSN 0081-0304 . Проверено 20 августа 2011 г.

- ^ Дж. Платт; округ Колумбия Браун (14 апреля 2014 г.). «Снимки НАСА Кассини могут показать рождение спутника Сатурна» . jpl.nasa.gov . НАСА / Лаборатория реактивного движения . Проверено 14 апреля 2014 г.

- ^ СС Порко; Э. Бейкер; Дж. Барбара; К. Берле; А. Браич; и др. (2005). «Cassini Imaging Science: первые результаты по Фебе и Япету» (PDF) . Наука . 307 (5713): 1237–1242. Бибкод : 2005Sci...307.1237P . дои : 10.1126/science.1107981 . ПМИД 15731440 . S2CID 20749556 .

- ^ К. Мартинес; Дж. Галлуццо (27 июня 2004 г.). «Ученые считают, что период вращения Сатурна — загадка» . Solarsystem.nasa.gov . НАСА . Проверено 20 августа 2011 г.

- ^ Нахид Чоудхури (2022). «Вызванные погодой полярные сияния Сатурна модулируют колебания магнитного поля и радиоизлучения» . Письма о геофизических исследованиях . 49 (е2021GL096492). Бибкод : 2022GeoRL..4996492C . дои : 10.1029/2021GL096492 .

- ^ Дж. Маккартни; Дж. А. Вендель (18 января 2019 г.). «Ученые наконец узнали, сколько времени на Сатурне» . jpl.nasa.gov . НАСА / Лаборатория реактивного движения . Проверено 22 июня 2020 г.

- ^ С. Манькович; М. С. Марли; Джей Джей Фортни; Н. Мовшовиц (2018). «Сейсмология кольца Кассини как исследование внутренней части Сатурна I: жесткое вращение» . Астрофизический журнал . 871 (1): 1. arXiv : 1805.10286 . Бибкод : 2019ApJ...871....1M . дои : 10.3847/1538-4357/aaf798 . S2CID 67840660 .

- ^ СС Порко; Б. Ауличино (2007). «Кассини: первая тысяча дней». Американский учёный . Том. 95, нет. 4. С. 334–341. дои : 10.1511/2007.66.334 . ISSN 0003-0996 . JSTOR 27858995 .

- ^ Дэйв Дуди (8–15 марта 2003 г.). Кассини-Гюйгенс: Полеты с тяжелыми приборами приближаются к Сатурну и Титану . Материалы аэрокосмической конференции IEEE 2003 г. (кат. № 03TH8652). Том. 8. Монтана, США: НАСА . стр. 3637–3646. дои : 10.1109/AERO.2003.1235547 . Проверено 20 августа 2011 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Линда Спилкер (1 апреля 2008 г.). «Расширенные миссии Кассини» (PDF) . НАСА / Лаборатория реактивного движения . Проверено 20 августа 2011 г.

- ^ Чарльз К. Чой (14 января 2005 г.). «Зонд «Гюйгенс» предоставил первые изображения поверхности Титана» . Space.com . Проверено 9 января 2015 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б округ Колумбия Браун; Дж. Р. Кук (5 июля 2011 г.). «Космический корабль Кассини зафиксировал изображения и звуки большого шторма на Сатурне» . Solarsystem.nasa.gov . НАСА . Проверено 20 августа 2011 г.

- ^ К. Мартинес; округ Колумбия Браун (10 марта 2008 г.). «Космический корабль Кассини нырнет в водный шлейф спутника Сатурна» . science.nasa.gov . НАСА . Проверено 9 ноября 2020 г.

- ^ К. Мартинес; округ Колумбия Браун (25 марта 2008 г.). «Кассини пробует органический материал на гейзерной луне Сатурна» . Solarsystem.nasa.gov . НАСА . Проверено 20 июля 2021 г.

- ^ «Кассини отправляет обратно изображения Энцелада в преддверии зимы» . Физика.орг . 23 ноября 2009 года . Проверено 13 декабря 2018 г.

- ^ Джонатан Амос (3 апреля 2014 г.). «Спутник Сатурна, Энцелад, скрывает «великое озеро» воды» . Новости Би-би-си . Проверено 7 апреля 2014 г.

- ^ Л. Иесс; диджей Стивенсон; М. Паризи; Д. Хемингуэй; Р.А. Джейкобсон; и др. (4 апреля 2014 г.). «Гравитационное поле и внутренняя структура Энцелада» (PDF) . Наука . 344 (6179): 78–80. Бибкод : 2014Sci...344...78I . дои : 10.1126/science.1250551 . ПМИД 24700854 . S2CID 28990283 .

- ^ Ян Сэмпл (3 апреля 2014 г.). «Океан, обнаруженный на Энцеладе, может быть лучшим местом для поиска инопланетной жизни » Хранитель . Проверено 4 апреля 2014 г.

- ^ П. Дычес; В. Клавин (25 июня 2014 г.). «Кассини» отмечает 10-летие исследования Сатурна . jpl.nasa.gov . НАСА / Лаборатория реактивного движения . Проверено 26 июня 2014 г.

- ^ П. Дычес; округ Колумбия Браун; Л. Кантильо (15 сентября 2015 г.). «Кассини обнаружил глобальный океан на спутнике Сатурна Энцеладе» . jpl.nasa.gov . НАСА / Лаборатория реактивного движения . Проверено 16 сентября 2015 г.

- ^ П. Дычес; округ Колумбия Браун; Л. Кантильо (28 октября 2015 г.). «Завершено самое глубокое в истории погружение через шлейф Энцелада» . Solarsystem.nasa.gov . НАСА . Проверено 29 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Кеннет Чанг (14 декабря 2023 г.). «Ядовитый газ намекает на возможность существования жизни на океанском спутнике Сатурна» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 14 декабря 2023 года . Проверено 15 декабря 2023 г.

- ^ Дж. С. Питер; Т. А. Нордхайм; КП Хэнд (14 декабря 2023 г.). «Обнаружение HCN и разнообразной окислительно-восстановительной химии в шлейфе Энцелада» . Природная астрономия . 8 (2): 164–173. arXiv : 2301.05259 . дои : 10.1038/s41550-023-02160-0 . S2CID 255825649 . Архивировано из оригинала 15 декабря 2023 года . Проверено 16 декабря 2023 г.