Позднее плейстоценовое вымирание

Эта статья имеет несколько вопросов. Пожалуйста, помогите улучшить его или обсудить эти вопросы на странице разговоров . ( Узнайте, как и когда удалить эти сообщения )

|

в Поздний плейстоцен начале голоцена увидел исчезновение большинства мировой мегафауны (обычно определяемой как виды животных, имеющие массы тела более 44 килограммов (97 фунтов)),), [ 1 ] что привело к краху в плотности и разнообразии фауны по всему миру. [ 2 ] Вымирание во время позднего плейстоцена отличаются от предыдущих вымираний из -за его крайнего смещения по отношению к крупным животным (при этом мелких животных в основном не затронуты) и широко распространенное отсутствие экологической преемственности , чтобы заменить эти вымершие виды мегафауна, [ 3 ] и сдвиг режима ранее установленных отношений фауны и мест обитания, как следствие. Сроки и серьезность вымираний варьировались в зависимости от региона и, как считается, были обусловлены различными комбинациями человеческих и климатических факторов. [ 3 ] Считается, что влияние человека на популяции мегафауны было обусловлено охотой («Overkill»), [ 4 ] [ 5 ] а также, возможно, изменение окружающей среды. [ 6 ] Относительная важность климатических факторов человека и климатических факторов в исчезновении стала предметом длительных противоречий. [ 3 ]

Основные вымирания произошли в Австралии-новой Гвинее ( Сахул ), начиная примерно 50 000 лет назад и в Америке около 13 000 лет назад, совпадая со ранними миграциями человека в эти регионы. [ 7 ] Вымирание в северной Евразии было ошеломлено в течение десятков тысяч лет в период с 50 000 до 10 000 лет назад, [ 2 ] В то время как вымирание в Америке было практически одновременно, что больше всего 3000 лет не более 3000 лет. [ 4 ] [ 8 ] В целом, в конце плейстоцена около 65% всех видов мегафауна по всему миру вымерли, вымерли, [ 9 ] Выращиваясь до 72% в Северной Америке, на 83% в Южной Америке и 88% в Австралии, [ 10 ] Всем более 1000 килограммов (2200 фунтов) вымерли в Австралии и Америке, [ 11 ] и около 80% во всем мире. [ 12 ] Африка, Южная Азия и Юго -Восточная Азия испытали более умеренные вымирания, чем другие регионы. [ 10 ]

Вымирание биогеографической сферой

[ редактировать ]Краткое содержание

[ редактировать ]| Биогеографическая сфера | Гиганты (более 1000 кг) |

Очень большой (400–1000 кг) |

Большой (150–400 кг) |

Умеренно большой (50–150 кг) |

Середина (10–50 кг) |

Общий | Регионы включены | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Начинать | Потеря | % | Начинать | Потеря | % | Начинать | Потеря | % | Начинать | Потеря | % | Начинать | Потеря | % | Начинать | Потеря | % | ||

| Афротропный | 6 | −1 | 16.6% | 4 | −1 | 25% | 25 | −3 | 12% | 32 | 0 | 0% | 69 | −2 | 2.9% | 136 | -7 | 5.1% | Транс-Сахара Африка и Аравия |

| Индомалайя | 5 | −2 | 40% | 6 | −1 | 16.7% | 10 | −1 | 10% | 20 | −3 | 15% | 56 | −1 | 1.8% | 97 | -8 | 8.2% | Индийский субконтинент , Юго -Восточная Азия и Южный Китай |

| Палеарктический | 8 | −8 | 100% | 10 | −5 | 50% | 14 | −5 | 35.7% | 23 | −3 | 15% | 41 | −1 | 2.4% | 96 | -22 | 22.9% | Евразия и Северная Африка |

| Недалеко | 5 | −5 | 100% | 10 | −8 | 80% | 26 | −22 | 84.6% | 20 | −13 | 65% | 25 | −9 | 36% | 86 | -57 | 66% | Северная Америка |

| Неотропный | 9 | −9 | 100% | 12 | −12 | 100% | 17 | −14 | 82% | 20 | −11 | 55% | 35 | −5 | 14.3% | 93 | -51 | 54% | Южная Америка , Центральная Америка , Южная Флорида и Карибский бассейн |

| Австралий | 4 | −4 | 100% | 5 | −5 | 100% | 6 | −6 | 100% | 16 | −13 | 81.2% | 25 | −10 | 40% | 56 | -38 | 67% | Австралия , Новая Гвинея , Новая Зеландия и соседние острова. |

| Глобальный | 33 | −26 | 78.8% | 46 | −31 | 67.4% | 86 | −47 | 54.7% | 113 | −41 | 36.3% | 215 | −23 | 10.1% | 493 | -168 | 34% | |

Введение

[ редактировать ]

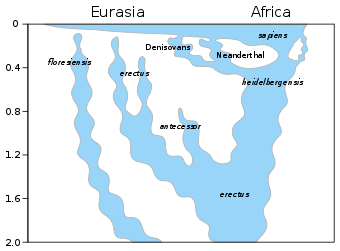

Поздний плейстоцен увидел вымирание многих млекопитающих, весом более 40 килограммов (88 фунтов), в том числе около 80% млекопитающих более 1 тонны. Доля вымирания мегафауны постепенно больше, чем дальше, чем на расстоянии миграции человека от Африки, причем самые высокие показатели вымирания в Австралии, а также в Северной и Южной Америке. [ 12 ]

Повышенная степень вымирания отражает схему миграции современных людей: чем дальше от Африки, в последнее время люди населяли область, тем меньше времени в этих условиях (включая ее мегафауна) приходилось привыкнуть к людям (и наоборот).

Есть две основные гипотезы, чтобы объяснить это исчезновение:

- Изменение климата , связанное с продвижением и отступлением основных ледяных шапок или ледяных щитов, что приводит к снижению благоприятной среды обитания.

- Охота на человека, вызывающая истощение популяций Мегафауны, обычно известного как «излишний». [ 14 ]

Существуют некоторые несоответствия между текущими доступными данными и доисторической гипотезой излишки. Например, существуют неоднозначности во время сроков австралийского вымирания мегафауны. [ 14 ] Доказательства, подтверждающие доисторическую гипотезу излишков, включают в себя устойчивость Мегафауны на некоторых островах на протяжении тысячелетий после исчезновения их континентальных кузенов. Например, наземные ленивцы выжили на долгое как вымерли островах земные после того , лени Антильских время Тысячи лет после того, как они исчезли с континентальных берегов северной части Тихого океана. [ 15 ] Позднее исчезновение этих островов коррелирует с более поздней колонизацией этих островов людьми.

Первоначальные дебаты о том, были ли время прибытия человека или изменение климата, представляли собой основную причину вымираний мегафауна, были основаны на палеонтологических данных в сочетании с методами геологических знакомств. Недавно генетический анализ выживших популяций мегафауны предоставил новые доказательства, что привело к выводу: «Неспособность климата предсказать наблюдаемое снижение населения мегафауны, особенно в течение последних 75 000 лет, подразумевает, что воздействие на человека стало основным фактором динамики мегафауны динамики. примерно в эту дату. " [ 16 ]

Недавние исследования показывают, что каждый вид по -разному реагировал на изменения окружающей среды, и ни один фактор сам по себе объясняет большое разнообразие вымираний. Причины могут включать взаимодействие изменения климата , конкуренцию между видами , нестабильной динамикой популяции и хищничеством человека. [ 17 ]

Африка

[ редактировать ]Хотя Африка была одним из наименее пострадавших регионов, регион все еще испытывал вымирание, особенно в течение позднего плейстоцен-голоценового перехода. Эти вымирания, вероятно, были преимущественно климатически обусловлены изменениями в местах обитания на пастбищах. [ 18 ]

- Копыт

- Ровные носки копыли

- Суида (свинья)

- Metridiochoerus (Ssp.)

- Kolpochoerus (ssp.)

- Bovidae (бычьи, антилопа)

- Гигантский Буффало ( Syncus old )

- Мегалотрагу

- Rusingoryx

- Южный Спрингбок ( Antidorcas Australis )

- Springbok ( Antidorcas Bondi )

- Дамаленкус Гипсодон

- Дамалкус Ниро

- Атлантическая Газель ( Газелла Атлантика )

- Газелла Тингитана

- Каприна

- Макания ?

- Cervidae (олень)

- Megaceroides Algericus (Северная Африка)

- Суида (свинья)

- Странные носки копыли

- Rhinoceros (Rhinocerotidae).

- Узкотух носорог ( Стефанорхинус Хемитух , Северная Африка)

- Ceratotherium mauritanicum

- Wild Equus spp.

- Кабаллиновые лошади

- Лошадь Алджикус (Северная Африка)

- Семейный осли ( задницы)

- Мелькианская лошадь (Северная Африка)

- Зебры

- Гигантская зебра ( Equus capensis )

- Сахаран зебра ( Equus ) [ 19 ]

- Кабаллиновые лошади

- Rhinoceros (Rhinocerotidae).

- Ровные носки копыли

- Пробный

- Elephantidae (слоны)

- Palaeoloxodon iolensis ? (Другие авторы предполагают, что этот таксон вымер в конце среднего плейстоцена)

- Elephantidae (слоны)

- Роденция

- Paraethomys filfilae ?

Южная Азия и Юго -Восточная Азия

[ редактировать ]

Время вымирания на индийском субконтиненте неясно из -за отсутствия надежных датирования. [ 20 ] Подобные проблемы были зарегистрированы для китайских сайтов, хотя нет никаких доказательств того, что ни один из мегафаунских таксонов выжил в голоцен в этом регионе. [ 21 ] Вымирание в Юго -Восточной Азии и Южно -Китай, как было предложено, является результатом перехода окружающей среды с открытой к закрытой лесной среде обитания. [ 22 ]

- Копыт

- Ровные носки копыли

- Несколько Bovidae Spp.

- Босс Palaesondaicus (предок Banteng )

- Cebu Tamaraw ( Bubalus cebuensis )

- Гровеси Бубалус [ 23 ]

- Короткий рогный буйвол ( Bubalus mephistopheles )

- Bubalus palaeokerabau

- Hippopotamidae

- Гексапротодон (индийский субконтинент и Юго -Восточная Азия) [ 24 ]

- Несколько Bovidae Spp.

- Странные носки копыли

- Equus spp.

- Equus namadicus (индийский субконтинент)

- Yunnan Horse ( Equus yunanensis )

- Гигантский тапир ( Тапирус Август, Юго -Восточная Азия и Южный Китай)

- TAPRUS SINENSIS

- Equus spp.

- Ровные носки копыли

- Фолидота

- Гигантский азиатский панголин ( Manis Palaeojavanica )

- Хищник

- Каноформа

- Артоид

- Медведь

- Ailuropoda baconi (предок гигантской панде )

- Медведь

- Артоид

- Каноформа

- Афротерия

- Афроинсектифилия

- Orycteropodidae/tubulidentata

- Aardvark ( Orycteropus afer ; Исправлен в Южной Азии около 13 000 г. до н.э.) [ 25 ] [ 26 ]

- Orycteropodidae/tubulidentata

- Paenungulata

- Ттитерия

- Водородые

- Stegodontidae

- Стегодон Spp . (Включая Стегодон Флоренсис на Флоресе, Стегодон Ориенталис в Восточной и Юго -Восточной Азии и Стегодон С.П. на индийском субконтиненте)

- Elephantidae

- Palaeoloxodon spp.

- Palaeoloxodon Namadicus (индийский субконтинент, возможно, также Юго -Восточная Азия)

- Palaeoloxodon spp.

- Stegodontidae

- Водородые

- Ттитерия

- Афроинсектифилия

- Птицы

- Японская безлетная утка ( Shiriyanetta Hasegawai ) [ 27 ]

- Leptoptilos robustus

- Рептилии

- Крокодилия

- Testudines (черепахи и черепахи)

- Приматы

- Несколько симианских (Simiiformes) Spp.

- Понго ( орангутанцы )

- Pongo weidenreichi (Южный Китай)

- Различные Homo spp. (архаичные люди)

- Homo erectus soloensis (java)

- Homo floresiensis (Flores)

- Homo luzonensis (Лусон, Филиппины)

- Денисованы ( Homo sp.)

- Понго ( орангутанцы )

- Несколько симианских (Simiiformes) Spp.

Европа, Северная и Восточная Азия

[ редактировать ]

Палеарктическое царство охватывает весь европейский континент и простирается в Северную Азию через Кавказ и Центральную Азию в северную Китай , Сибири и Берингюю . Вымирание было более серьезным в северной Евразии, чем в Африке или Южной и Юго -Восточной Азии. Эти вымирания были ошеломлены в течение десятков тысяч лет, охватывающих примерно за 50 000 лет до настоящего (BP) до 10 000 лет BP, с умеренными адаптированными видами, такими как прямой слон и узко-носовой носорог, как правило, выливают ранее, чем адаптированный холод Виды, такие как шерстяные мамонт и шерстяные носороги . Изменение климата считалось вероятным основным фактором в вымирании, возможно, в сочетании с охотой на человека. [ 2 ]

- Копыт

- Ровные копытные млекопитающие

- Различные Bovidae Spp.

- Степи бизона ( Bison Priscus )

- Baikal Yak ( Boss Baikalensis ) [ 28 ]

- Европейский водный буйвол ( Bubalus murrensis )

- Европейский тар ( Hemitragus cedrensis ) [ 29 ] [ 30 ]

- Гигантский Muskox ( тюрьмы ) [ 31 ]

- Северная Сайга Антилопа ( Saiga Borealis ) [ 32 ]

- Антилопа с извергнутой рогом ( Spirocerus kiakhtensis ) [ 33 ] [ 34 ]

- Антилопа с козью ( Parabubalis capricornis ) [ 33 ] [ 34 ]

- Bubalus Wansijocki (вымерший Буффало, уроженец Северного Китая)

- Различные оленя (Cervidae) Spp.

- Гигантский олень /ирландский лось ( мегалоцерос Giganteus )

- Критский олень ( Candiacervus spp.)

- Haploidoceros Mediterraneus [ 35 ] [ 36 ]

- Sinomegaceros spp. (в том числе Sinomegaceros Yabei в Японии, Sinomegaceros Ordosianus и, возможно, Sinomegaceros Pachyosteus в Китае). [ 37 ]

- Карликовый олени Рюку ( Cervus astylodon )

- Все местные бегемоты Spp. [ 38 ]

- Amphibius Gippopotamus (Европейский диапазон, все еще существующий в Африке)

- Мальтийский карликовый бегемопот ( бегемота -мелитенсис )

- Кипр Дварф Бегемопотамус ( минор бегемота )

- Сицилийский бегемой карликовый

- Camelus Knoblochi [ 39 ] и другие Camelus spp.

- Различные Bovidae Spp.

- Нечетные копытные млекопитающие

- Различный Equus spp. например

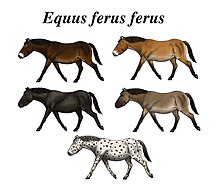

- Различные подвиды дикой лошади (например, коня в. Французский , [ 40 ] [ 41 ] Equus C. Латипсы [ 34 ] [ 40 ] [ 42 ] C. Ураленсис [ 40 ] )

- Equus dalianensis (виды диких лошадей, известные из северного Китая)

- Европейская дикая задница ( Equus hydruntinus ) (выжила в Refugia в Анатолии до позднего голоцена)

- Equus ovodovi (выжил в Refugia в Северном Китае до позднего голоцена)

- Все местные носороги (Rhinocerotidae) Spp.

- Elasmotherium

- Шерстяные носороги ( античность Coelodonta )

- STEPHANORHINUS SPP.

- Rhinoceros Merck ( Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis )

- Узкотух носорог ( Стефанорхин Гемиотоух )

- Различный Equus spp. например

- Ровные копытные млекопитающие

- Хищник

- Каноформа

- Canidae

- Собака

- Волки

- Пещера волка ( Canis Lupus spelaeus )

- Удачный волк ( страх эоноциона ) [ 43 ]

- Джоли

- Европейский Dhole ( Cuon Alpinus europaeus )

- Сардинский DHOLE ( Cynotherium Sardous )

- Волки

- Собака

- Артоид

- Различные Ursus spp.

- Степи -буровый медведь ( урсус " тюрьмы ") [ 44 ]

- Gamssulzen Cave Bear ( медведь введен ) [ 45 ]

- Плейстоцен маленький пещерный медведь ( ursus rossicus )

- Пещерный медведь ( Ursus spelaeus )

- Гигантский белый медведь ( Ursus maritimus tyrant )

- Синяк

- Mustelidae

- Несколько выдр (Lutrinae) Spp.

- Прочная плейстоценовая европейская выдла ( Cyrnoonyx )

- Алгаролутра

- Сардинская гигантская выдра ( мегаленгидрис Barbaricina )

- Сардинскую карликовую выдру ( сардолутра )

- Критская выдца ( Lutrogale Crite )

- Несколько выдр (Lutrinae) Spp.

- Mustelidae

- Различные Ursus spp.

- Canidae

- Фелифемия

- Различные Felidae (Cats) Spp.

- Homotherium latidens (иногда называемый кошками с насадкой)

- Пещера Линкс ( Lynx Lynx Spelaeus ) [ 46 ]

- Essoire Lynx ( Lynx issiodorensis )

- Panthera spp.

- Пещера льва ( Panthera spelaea )

- Европейский леопард ледникового периода ( Panthera Pardus Spelaea )

- Hyeenidae (Hyenas)

- Пещера гиена ( Crocuta Crocuta Spelaea и Crocuta Crocuta в последний раз )

- "Hyaena" Приска

- Различные Felidae (Cats) Spp.

- Каноформа

- Все местные слоны (Elephantidae) Spp.

- Мамонт

- Шерстяной мамонт ( Mammuthus primigenius )

- Карликовый сардинский мамонт ( Маммут -Ламарморай )

- Прямого слона ( Antiquus Palaeoloxodon ) (Европа) (Европа) (Европа)

- Палеолоксадон Науманни (Япония, возможно, также Корея и северный Китай)

- Palaeoloxodon huaihoensis (Китай)

- Карликовый слон

- PalaeOloxodon Creutzburgi (Крит)

- Кипра Дварф Слон ( Palaeoloxodon Cypriotes )

- Palaeoloxodon mnaidriensis (Сицилия)

- Мамонт

- Грызуны

- Allocricetus stusae

- Cricetus Major (альтернативно Cricetus cricetus major )

- Dicrostonyx Gulielmi (предок арктического лемминга )

- Гигантский евразийский дикобраз ( Hystrix Refossa )

- Уголп Сп. (Мальтийский и сицилийский гигант Giachuse) [ 47 ]

- Marmota paleocaucasica

- Microtus grafi

- Mimomys spp.

- М. Пиренакус

- М. Чандоленсис

- Pliomys lenki

- Spermophilus citelloides

- Spermophilus severskensis

- Спермофил больше

- Trogonther Cuvieri (большой бобр)

- Лагоморфа

- Кролик Танайт (альтернативно нервную тана )

- Pika ( Ochotona ) spp. e.g.

- Гигантская пика ( Achotona Whartoni )

- Tonomochota spp.

- T. Khasanensis

- T. sikhotana

- Т. майор

- Птицы

- Азиатский страус ( страус )

- Якутиан Гусь ( рассматривает Djuktiensis )

- Различные европейские кран spp. (Род Grus )

- ГРУС ПРИМЕНТИЯ

- ГРУС МЕЛИТЕНСИС

- Критская сова ( Афин Крит )

- Приматы

- Гомо

- Денисованы ( Homo sp.)

- Неандертальцы ( Homo ( Sapiens ) Неандерталенсис ; выжил до 40 000 лет назад на полуостровах иберийском полуострове)

- Гомо

- Рептилии

- Solitudo Sicula ; Выжил на Сицилии примерно до 12 500 лет назад.

- White Siculimelitensis ; от Мальты .

Северная Америка

[ редактировать ]Вымирание в Северной Америке было сконцентрировано в конце позднего плейстоцена, около 13 800–11 400 лет до настоящего времени, которые совпадали с началом более молодого периода охлаждения в дьясах , а также возникновения культуры охотника-собирателя . Относительная важность человеческих и климатических факторов в североамериканских вымираниях была предметом значительных споров. Вымирание составило около 35 родов. [ 4 ] Радиоуглеродистый рекорд для Северной Америки к югу от региона Аляски-Юкон был описан как «неадекватный» для создания надежной хронологии. [ 48 ]

Североамериканские вымирание (отмечены как травоядные ( H ) или плотоядные ( C )) включены:

- Копыт

- Ровные копытные млекопитающие

- Различные Bovidae Spp.

- Большинство форм плейстоценового бизона (только бизон в Северной Америке и Bison Bonasus в Евразии, выжил)

- Древний бизон ( антиккус бизон ) ( h )

- Длиннохоронные/гигантские бизоны ( бизоны латифронс ) ( h )

- Степи бизона ( Bison Priscus ) ( H )

- Bison occidentalis ( h )

- Несколько членов Caprinae ( Muskox выжил)

- Гигантский Muskox ( тюрьмы ) ( H )

- Кустарник ( Euceratherimium collinum ) ( h )

- Harlan's Muskox ( Bootherium Bombifrons ) ( H )

- Волс ( Soergelia Mayfieldi ) ( ) ( H H) (H )

- Горный козел Харрингтона ( Oreamnos Harringtoni ; меньшее и более южное распределение, чем ее выживший родственник ) ( H )

- Саи Антилопа ( Saiga Tatatarica ; Extirpatted) ( H )

- Большинство форм плейстоценового бизона (только бизон в Северной Америке и Bison Bonasus в Евразии, выжил)

- Олень

- Стаг-Моуз ( Серванги Скотти ) ( H )

- Американские горные оленя ( Odocoileus Lucasi ) ( H )

- Torontoceros hypnogeos ( h )

- Различные роды Antilocapridae ( пронхорны выжили)

- Capromeryx ( h )

- Стокосеросы ( H )

- Tetrameryx ( H )

- Тихоокеанский пронгорн ( Antilocapra pacifica ) ( H )

- Несколько Peccary (Tayassuidae) Spp.

- Пеккари с плоским головом ( Platygonus ) ( h )

- Длинно-носовой пекари ( mylohyus ) ( h )

- Вороночный пекари ( DiCotyles Tajacu ; Extirpated, полузареколонизированный диапазон) ( H ) ( Muknalia Minimus -младший синоним)

- Различные члены Camelidae

- Западный верблюд ( Camelops Hesternus ) ( H )

- Упорные ламмы ( Hemiauchenia ssp.) ( H )

- Стаут ногеной лама ( Palaeolama Ssp.) ( H )

- Различные Bovidae Spp.

- Нечетные копытные млекопитающие

- Все местные формы Equidae

- Кабаллинские истинные лошади ( Equus Cf. Ferus ) из позднего плейстоцена Северной Америки исторически были назначены многим различным видам, включая Equus Fraternus , Equus Scotti и Equus Lambei , но таксономия этих лошадей неясно, и многие из этих видов могут Будьте синонимом друг друга, возможно, представляя только один вид. [ 49 ] [ 50 ] [ 51 ]

- Упорные ноги ( Haringtonhippus Francisci / Equus Francisci ; ( H )

- Тапиру ( тапирус ; три вида)

- Калифорнийский тапир ( Tapirus californicus ) ( h )

- Тапир Мерриама ( Тапирус Мерриариами ) ( ч )

- Тем не менее, тапир ( тапирус neodo ) ( h )

- Все местные формы Equidae

- † Порядок notoungulata

- Миксотоксадон [ 52 ] [ 53 ] ( H )

- Ровные копытные млекопитающие

- Хищник

- Фелифемия

- Несколько Felidae Spp.

- Saberlooths ( † Machairodontinae )

- Smilodon Fatal (Sabretooth Cat) ( c )

- Domotherium serum scimitar-toothed cat ( c )

- Американский гепарда ( miracinonyx trumani ; не настоящий гепарда)

- Cougar ( Puma Concolor ; Megafaunal Ecomorph Extirpated из Северной Америки, южноамериканская популяция рефонизировала прежний диапазон) ( C )

- Jaguarundi ( herpailurus yagouarundi ; экстрапельно, полузареколонизированный диапазон) ( c )

- Марго ( Лептардс ; экстрализовано) ( с )

- Ocelot ( Leopardus pardalis ; extirpated, range незначительно реколонизирован) ( c )

- Ягуары

- Плейстоцен Североамериканский Ягуар ( Пантера Онка Августа ; Ассортимент полуэколонизирована другими подвидом) ( C )

- Северная Америка Ягуар

- Panthera Balamoides (сомнительная, предполагается, что является младшим синонимом короткого лица Bear Arctotherium )

- Львы

- Американский лев ( Panthera Atrox ) ( C )

- Пещер -львы ( Panthera Spelaea ; присутствует только на Аляске и Юконе) ( C )

- Saberlooths ( † Machairodontinae )

- Несколько Felidae Spp.

- Каноформа

- Canidae

- Удачный волк ( Aenocyon Dread ) ( c )

- Плейстоценовый койот ( canis ) ( c )

- Мегафаунал волк , например

- Беринговый Волк ( Canis Lupus Ssp.) ( C )

- Dhole ( cuon alpinus ; extirpated) ( c )

- Протоцион Троглодиты [ 54 ] ( C )

- Артоид

- Синяк

- Mephitidae

- Скунк с коротким лицом ( брахипротома obtusata ) [ 55 ] ( C )

- Mustelidae

- Степи POLECAT ( Mustela Eversmanii ; Исправлен) [ 56 ] ( C )

- Mephitidae

- Различный медведь (Ursidae) Spp.

- Arctodus we ( c )

- Флорида Spectacled Bear ( Tremarctos floridanus ) ( c )

- Южноамериканский медведь с коротким лицом ( Arctotherium winingi ) [ 57 ] [ 54 ] ( C )

- Гигантский белый медведь ( Ursus maritimus tyrant ; возможные жители) ( c )

- Синяк

- Canidae

- Фелифемия

- Афротерия

- Paenungulata

- Ттитерия

- Все местные SPP. Progoscidea

- Мастододоны

- Американский мастодон ( Mammut Americanum ) ( H )

- Pacific Mastodon ( Mammut Peace ) ( h ) (Validcure)

- Gomphotheriidae spp.

- Cuvieronius [ 58 ] ( H )

- Мамонт ( Маммута ) Spp.

- Колумбийский мамонт ( Mammouthus columbus ) ( H )

- Пигмейный мамонт ( мамутх ) ( h )

- Шерстяной мамонт ( Mammuthus primigenius ) ( h )

- Мастододоны

- Сирения

- Dugongidae

- Морская корова Стеллера ( гидродамалис -гигас ; изгнан из Северной Америки, выжила в Берингии до 18 -го века) ( h )

- Dugongidae

- Все местные SPP. Progoscidea

- Ттитерия

- Paenungulata

- Euarchontoglires

- Летучие мыши

- Вампирская летучая мышь ( Desmodus stocki ) ( c )

- Нетронутая усатая летучая мышь ( Pteronotus ( Phyllodia ) Pristinus ) ( c )

- Грызуны

- Гигантский бобр ( кастороиды ) Spp.

- Castoroides Ohioensis ( H )

- Castoroides Leiseyorum ( H )

- Дикобраз Кляйна ( Эретизон Кляни ) [ 59 ] ( H )

- Гигантские островные оленьи мыши ( Peromyscus nesodytes ) ( C )

- Neochhoerus spp. НАПРИМЕР

- Капибара Пинкни ( Neochoerus pinckneyi ) ( H )

- Neochoerus aesop ( h )

- Neotoma findleyi

- Neotoma pygmaea

- Synaptomys Australis

- Все гигантские хутам (heptaxodontidae) spp.

- Гигантская гигантская мута ( Амблирхиза Инундуда ; может расти так же большим, как американский черный медведь ) ( h )

- Гигантская гигантская хюция ( elasmodontomys diagonally ) ( h )

- Мыши с витой зубью ( кемизия ) ( H )

- Ключевая мышь Осборна ( Clidomys Osborn's ) ( H )

- Xaymaca fulvopulvis ( h )

- Гигантский бобр ( кастороиды ) Spp.

- Лагоморфы

- Ацтлан Кролик ( Aztlanolagus sp.) ( H )

- Гигантская Пика ( Ошотона Уортони ) ( ч )

- Летучие мыши

- Eulipotyphla

- Xenarthra

- Пилоз

- Гигантский муравьер ( Myrmecophaga tridactyla ; extirpated, частично реколонизирован) [ 60 ] [ 61 ] ( C )

- Все оставшиеся грунтовые ленивцы Spp.

- Eremotherium ( Megatheriid Giant Ground Lloth) ( H )

- Nothrotheriops ( nothrotheriid mange lloth) ( h )

- Megalonychid Ground Lloth Spp.

- MyLodontid Marly Lloth Spp.

- Paramylodon ( h )

- Cingulata

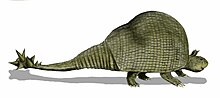

- Все члены Glyptodontinae

- Глиптотерай [ 66 ] ( H )

- Красивый Армадильо ( Dasypus bellus ) [ 67 ] ( H )

- Pachyarmatherium

- All Pampatheriidae spp.

- Холмесина ( ч )

- Pamphatherium ( h )

- Все члены Glyptodontinae

- Пилоз

- Птицы

- Водяная птица

- Утки

- Бермудская безлетная утка ( Anas Pachyscelus ) ( H )

- Калифорнийская нелетающая морская утка ( Чендитс Лави ) ( с )

- Мексиканская жесткая утка ( Оксира Запатима ) [ 57 ] ( H )

- Neochen Barbadiana ( H )

- Утки

- Турция ( Мелеагрис ) Spp.

- Калифорнийская индейка ( Meleagris Californica ) ( H )

- Мелеагрис [ 57 ] ( H )

- Различные Gruiformes spp.

- Все пещерные железные дороги ( Nesotrochis ) Spp. например

- Антильский пещерный рельс ( Nesotrochis debooyi ) ( c )

- Barbados Rail ( undere_s ) ( c )

- Кубинский безлеточный кран ( антигоновый кубинс ) ( h )

- В Brea Crane ( Page Grus ) ( H )

- Все пещерные железные дороги ( Nesotrochis ) Spp. например

- Различные фламинго (Phoenicopteridae) spp.

- Минут фламинго ( феникоптерс минута ) [ 68 ] ( C )

- Флаламинго Коупа ( Phoenicopterus copei ) [ 69 ] ( C )

- Dow's Puffin ( Fratercula Dowi ) ( C )

- Плейстоцен Мексиканский дайвер Spp.

- Стои

- La Brea/Asphalt stork (Ciconia maltha)[57] (C)

- Wetmore's stork (Mycteria wetmorei)[57] (C)

- Pleistocene Mexican cormorants spp. (genus Phalacrocorax)[57]

- Phalacrocorax goletensis (C)

- Phalacrocorax chapalensis (C)

- All remaining teratorn (Teratornithidae) spp.

- Several New World vultures (Cathartidae) spp.

- Pleistocene black vulture (Coragyps occidentalis ssp.) (C)

- Megafaunal Californian condor (Gymnogyps amplus) (C)

- Clark's condor (Breagyps clarki) (C)

- Cuban condor (Gymnogyps varonai) (C)

- Several Accipitridae spp.

- American neophrone vulture (Neophrontops americanus)[57][70] (C)

- Woodward's eagle (Amplibuteo woodwardi) (C)

- Cuban great hawk (Buteogallus borrasi) (C)

- Daggett's eagle (Buteogallus daggetti) (C)

- Fragile eagle (Buteogallus fragilis) (C)

- Cuban giant hawk (Gigantohierax suarezi)[71][72] (C)

- Errant eagle (Neogyps errans) (C)

- Grinnell's crested eagle (Spizaetus grinnelli)[57] (C)

- Willett's hawk-eagle (Spizaetus willetti)[57] (C)

- Caribbean titan hawk (Titanohierax) (C)

- Several owl (Strigiformes) spp.

- Brea miniature owl (Asphaltoglaux) (C)

- Kurochkin's pygmy owl (Glaucidium kurochkini) (C)

- Brea owl (Oraristix brea) (C)

- Cuban giant owl (Ornimegalonyx) (C)

- Bermuda flicker (Colaptes oceanicus) (C)

- Several caracara (Caracarinae) spp.

- Bahaman terrestrial caracara (Caracara sp.) (C)

- Puerto Rican terrestrial caracara (Caracara sp.) (C)

- Jamaican caracara (Carcara tellustris) (C)

- Cuban caracara (Milvago sp.) (C)

- Hispaniolan caracara (Milvago sp.) (C)

- Psittacopasserae

- Psittaciformes

- Mexican thick-billed parrot (Rhynchopsitta phillipsi)[57] (H)

- Psittaciformes

- Водяная птица

- Several giant tortoise spp.

- Hesperotestudo (H)

- Gopherus spp.

- Chelonoidis spp.

The survivors are in some ways as significant as the losses: bison (H), grey wolf (C), lynx (C), grizzly bear (C), American black bear (C), deer (e.g. caribou, moose, wapiti (elk), Odocoileus spp.) (H), pronghorn (H), white-lipped peccary (H), muskox (H), bighorn sheep (H), and mountain goat (H); the list of survivors also include species which were extirpated during the Quaternary extinction event, but recolonised at least part of their ranges during the mid-Holocene from South American relict populations, such as the cougar (C), jaguar (C), giant anteater (C), collared peccary (H), ocelot (C) and jaguarundi (C). All save the pronghorns and giant anteaters were descended from Asian ancestors that had evolved with human predators.[73] Pronghorns are the second-fastest land mammal (after the cheetah), which may have helped them elude hunters. More difficult to explain in the context of overkill is the survival of bison, since these animals first appeared in North America less than 240,000 years ago and so were geographically removed from human predators for a sizeable period of time.[74][75][76] Because ancient bison evolved into living bison,[77][78] there was no continent-wide extinction of bison at the end of the Pleistocene (although the genus was regionally extirpated in many areas). The survival of bison into the Holocene and recent times is therefore inconsistent with the overkill scenario. [citation needed]By the end of the Pleistocene, when humans first entered North America, these large animals had been geographically separated from intensive human hunting for more than 200,000 years. Given this enormous span of geologic time, bison would almost certainly have been very nearly as naive as native North American large mammals.[citation needed]

The culture that has been connected with the wave of extinctions in North America is the paleo-American culture associated with the Clovis people (q.v.), who were thought to use spear throwers to kill large animals. The chief criticism of the "prehistoric overkill hypothesis" has been that the human population at the time was too small and/or not sufficiently widespread geographically to have been capable of such ecologically significant impacts. This criticism does not mean that climate change scenarios explaining the extinction are automatically to be preferred by default, however, any more than weaknesses in climate change arguments can be taken as supporting overkill. Some form of a combination of both factors could be plausible, and overkill would be a lot easier to achieve large-scale extinction with an already stressed population due to climate change.

South America

[edit]

South America suffered among the worst losses of the continents, with around 83% of its megafauna going extinct.[10] These extinctions postdate the arrival of modern humans in South America around 15,000 years ago. Both human and climatic factors have been attributed as factors in the extinctions by various authors.[79] Although some megafauna has been historically suggested to have survived into the early Holocene based on radiocarbon dates this may be the result of dating errors due to contamination.[80] The extinctions are coincident with the end of the Antarctic Cold Reversal (a cooling period earlier and less severe than the Northern Hemisphere Younger Dryas) and the emergence of Fishtail projectile points, which became widespread across South America. Fishtail projectile points are thought to have been used in big game hunting, though direct evidence of exploitation of extinct megafauna by humans is rare,[79] though megafauna exploitation has been documented at a number of sites.[80][81] Fishtail points rapidly disappeared after the extinction of the megafauna, and were replaced by other styles more suited to hunting smaller prey.[79] Some authors have proposed the "Broken Zig-Zag" model, where human hunting and climate change causing a reduction in open habitats preferred by megafauna were synergistic factors in megafauna extinction in South America.[82]

- Ungulates

- Even-Toed Hoofed Mammals

- Several Cervidae (deer) spp.

- Morenelaphus

- Antifer

- Agalmaceros blicki[83][84] (potentially synonym of modern white-tailed deer)

- Odocoileus salinae[85][86]

- Various Camelidae spp.

- Eulamaops

- Stilt legged llama Hemiauchenia

- Stout legged llama Palaeolama

- Several Cervidae (deer) spp.

- Odd-Toed Hoofed Mammals

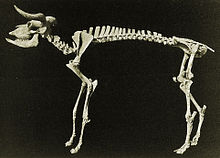

- All remaining Meridiungulata genera

- Order Litopterna

- Order Notoungulata

- Toxodontidae

- Piauhytherium (Some authors regard this taxon as synonym of Trigodonops)

- Mixotoxodon

- Toxodon

- Trigodonops

- Toxodontidae

- Even-Toed Hoofed Mammals

- Carnivora

- Feliformia

- Several Felidae spp.

- Saber-toothed cat (Smilodon) spp.[93]

- Smilodon fatalis (northwestern South America)

- Smilodon populator (eastern and southern South America)

- Patagonian jaguar (Panthera onca mesembrina) (some authors have suggested that these remains actually belong to the American lion instead[94])

- Saber-toothed cat (Smilodon) spp.[93]

- Several Felidae spp.

- Caniformia

- Canidae

- Dire wolf (Aenocyon dirus)

- Nehring's wolf (Canis nehringi)

- Protocyon spp.[95]

- Pleistocene bush dog (Speothos pacivorus)

- Arctoidea

- South American short-faced bear (Arctotherium spp.)

- Canidae

- Feliformia

- Rodents

- Bats

- Giant vampire bat (Desmodus draculae)

- All remaining Gomphotheridae spp.

- Xenarthrans

- All remaining ground sloth genera

- Megatheriidae spp.

- Nothrotheriidae spp.

- Megalonychidae spp.

- Mylodontidae spp. (including Scelidotheriinae)

- All remaining Glyptodontinae spp.

- Several Dasypodidae spp.

- Beautiful armadillo (Dasypus bellus)

- Eutatus

- Pachyarmatherium

- Propaopus[38][86]

- All Pampatheriidae spp.

- Holmesina (et 'Chlamytherium occidentale')[104][105]

- Pampatherium[106]

- Tonnicinctus[106]

- All remaining ground sloth genera

- Birds

- Various Caracarinae spp.

- Venezuelan caracara (Caracara major)[107]

- Seymour's caracara (Caracara seymouri)[108]

- Peruvian caracara (Milvago brodkorbi)[109]

- Various Cathartidae spp.

- Pampagyps imperator

- Geronogyps reliquus

- Wingegyps cartellei

- Pleistovultur nevesi

- Various Tadorninae spp.

- Psilopterus (small terror bird remains dated to the Late Pleistocene,[110][111] but these are disputed)[112]

- Various Caracarinae spp.

- Reptiles

- Crocs & Gators

- Testudines

- Chelonoidis lutzae (Argentina)

- Peltocephalus maturin[113]

Sahul (Australia-New Guinea) and the Pacific

[edit]

A scarcity of reliably dated megafaunal bone deposits has made it difficult to construct timelines for megafaunal extinctions in certain areas, leading to a divide among researches about when and how megafaunal species went extinct.[114][115]

There are at least three hypotheses regarding the extinction of the Australian megafauna:

- that they went extinct with the arrival of the Aboriginal Australians on the continent,

- that they went extinct due to natural climate change.

This theory is based on evidence of megafauna surviving until 40,000 years ago, a full 30,000 years after homo sapiens first landed in Australia, and thus that the two groups coexisted for a long time. Evidence of these animals existing at that time come from fossil records and ocean sediment. To begin with, sediment core drilled in the Indian Ocean off the SW coast of Australia indicate the existence of a fungus called Sporormiella, which survived off the dung of plant-eating mammals. The abundance of these spores in the sediment prior to 45,000 years ago indicates that many large mammals existed in the southwest Australian landscape until that point. The sediment data also indicates that the megafauna population collapsed within a few thousand years, around the 45,000 years ago, suggesting a rapid extinction event.[116] In addition, fossils found at South Walker Creek, which is the youngest megafauna site in northern Australia, indicate that at least 16 species of megafauna survived there until 40,000 years ago. Furthermore, there is no firm evidence of homo sapiens living at South Walker Creek 40,000 years ago, therefore no human cause can be attributed to the extinction of these megafauna. However, there is evidence of major environmental deterioration of South Water Creek 40,000 years ago, which may have caused the extinct event. These changes include increased fire, reduction in grasslands, and the loss of fresh water.[117] The same environmental deterioration is seen across Australia at the time, further strengthening the climate change argument. Australia's climate at the time could best be described as an overall drying of the landscape due to lower precipitation, resulting in less fresh water availability and more drought conditions. Overall, this led to changes in vegetation, increased fires, overall reduction in grasslands, and a greater competition for already scarce fresh water.[118] These environmental changes proved to be too much for the Australian megafauna to cope with, causing the extinction of 90% of megafauna species.

- The third hypothesis shared by some scientists is that human impacts and natural climate changes led to the extinction of Australian megafauna. About 75% of Australia is semi-arid or arid, so it makes sense that megafauna species used the same fresh water resources as humans. This competition could have led to more hunting of megafauna.[119] Furthermore, Homo sapiens used fire agriculture[clarification needed] to burn impassable[clarification needed] land. This further diminished the already disappearing grassland which contained plants that were a key dietary component of herbivorous megafauna. While there is no scientific consensus on this, it is plausible that homo sapiens and natural climate change had a combined impact. Overall, there is a great deal of evidence for humans being the culprit, but by ruling out climate change completely as a cause of the Australian megafauna extinction we are not getting the whole picture. The climate change in Australia 45,000 years ago destabilized the ecosystem, making it particularly vulnerable to hunting and fire agriculture by humans; this is probably what led to the extinction of the Australian megafauna.

Several studies provide evidence that climate change caused megafaunal extinction during the Pleistocene in Australia. One group of researchers analyzed fossilized teeth found at Cuddie Springs in southeastern Australia. By analyzing oxygen isotopes, they measured aridity, and by analyzing carbon isotopes and dental microwear texture analysis, they assessed megafaunal diets and vegetation. During the middle Pleistocene, southeastern Australia was dominated by browsers, including fauna that consumed C4 plants. By the late Pleistocene, the C4 plant dietary component had decreased considerably. This shift may have been caused by increasingly arid conditions, which may have caused dietary restrictions. Other isotopic analyses of eggshells and wombat teeth also point to a decline of C4 vegetation after 45 Ka. This decline in C4 vegetation is coincident with increasing aridity. Increasingly arid conditions in southeastern Australia during the late Pleistocene may have stressed megafauna, and contributed to their decline.[120]

In Sahul (a former continent composed of Australia and New Guinea), the sudden and extensive spate of extinctions occurred earlier than in the rest of the world.[121][122][123][124] Most evidence points to a 20,000 year period after human arrival circa 63,000 BCE,[125] but scientific argument continues as to the exact date range.[126] In the rest of the Pacific (other Australasian islands such as New Caledonia, and Oceania) although in some respects far later, endemic fauna also usually perished quickly upon the arrival of humans in the late Pleistocene and early Holocene.

- Marsupials

- Various members of Diprotodontidae

- Diprotodon (largest known marsupial)

- Hulitherium tomasetti

- Maokopia ronaldi

- Zygomaturus

- Palorchestes ("marsupial tapir")

- Various members of Vombatidae

- Lasiorhinus angustidens (giant wombat)

- Phascolonus (giant wombat)

- Ramasayia magna (giant wombat)

- Vombatus hacketti (Hackett's wombat)

- Warendja wakefieldi (dwarf wombat)

- Sedophascolomys (giant wombat)

- Phascolarctos stirtoni (giant koala)

- Marsupial lion (Thylacoleo carnifex)

- Borungaboodie (giant potoroo)

- Various members of Macropodidae (kangaroos, wallabies, etc.)

- Procoptodon (short-faced kangaroos) e.g.

- Sthenurus (giant kangaroo)

- Simosthenurus (giant kangaroo)

- Various Macropus (giant kangaroo) spp. e.g.

- Protemnodon spp. (giant wallaby)

- Troposodon (wallaby)[121][122][127][128][129][130]

- Bohra (giant tree kangaroo)

- Propleopus oscillans (omnivorous, giant musky rat-kangaroo)

- Nombe

- Congruus

- Various forms of Sarcophilus (Tasmanian devil)

- Sarcophilus laniarius (25% larger than modern species, unclear if it is actually a distinct species from living Tasmanian devil[131])

- Sarcophilus moornaensis

- Various members of Diprotodontidae

- Monotremes: egg-laying mammals.

- Echidna

- Murrayglossus hacketti (giant echidna)

- Megalibgwilia ramsayi

- Echidna

- Birds

- Pygmy Cassowary (Casuarius lydekkeri)

- Genyornis (a two-meter-tall (6.6 ft) dromornithid

- Giant malleefowl (Progura gallinacea)

- Cryptogyps lacertosus

- Dynatoaetus gaffae

- Several Phoenicopteridae spp.

- Xenorhynchopsis spp. (Australian flamingo)[132]

- Xenorhynchopsis minor

- Xenorhynchopsis tibialis

- Reptiles

- Crocs & Gators

Quinkana was one of the last surviving land crocodiles - Ikanogavialis (the last fully marine crocodilian)

- Paludirex (Australian freshwater mekosuchine crocodiian)

- Quinkana (Australian terrestrial mekosuchine crocodilian, apex predator)

- Volia (a two-to-three meter long mekosuchine crocodylian, apex predator of Pleistocene Fiji)

- Mekosuchus

- Mekosuchus inexpectatus (New Caledonian land crocodile)

- Mekosuchus kalpokasi (Vanuatu land crocodile)

- Varanus sp. (Pleistocene and Holocene New Caledonia)

- Megalania (Varanus pricus) (a giant predatory monitor lizard comparable or larger than the Komodo dragon)

- Snakes

- Several spp. of Meiolaniidae (giant armoured turtles)

- Crocs & Gators

Causes

[edit]History of research

[edit]During the 19th century, a number of scientists remarked on the topic of megafaunal extinction:[133][134]

It is impossible to reflect without the deepest astonishment, on the changed state of [South America]. Formerly it must have swarmed with great monsters, like the southern parts of Africa, but now we find only the tapir, guanaco, armadillo, capybara; mere pigmies compared to antecedents races... Since their loss, no very great physical changes can have taken place in the nature of the Country. What then has exterminated so many living creatures?

— Charles Darwin, The Voyage of the Beagle (1834)

It is clear, therefore, that we are now in an altogether exceptional period of the earth's history. We live in a zoologically impoverished world, from which all the hugest, and fiercest, and strangest forms have recently disappeared; and it is, no doubt, a much better world for us now they have gone. Yet it is surely a marvellous fact, and one that has hardly been sufficiently dwelt upon, this sudden dying out of so many large mammalia, not in one place only but over half the land surface of the globe. We cannot but believe that there must have been some physical cause for this great change; and it must have been a cause capable of acting almost simultaneously over large portions of the earth's surface, and one which, as far as the Tertiary period at least is concerned, was of an exceptional character.

— Alfred Russel Wallace, The geographical distribution of animals; with a study of the relations of living and extinct faunas as elucidating the past changes of the Earth's surface (1876)

Discussion of the topic became more widespread during the 20th century, particularly following the proposal of the "overkill hypothesis" by Paul Schultz Martin during the 1960s. By the end of the 20th century, two "camps" of researchers had emerged on the topic, one supporting climate change, the other supporting human hunting as the primary cause of the extinctions.[134]

Hunting

[edit]The hunting hypothesis suggests that humans hunted megaherbivores to extinction, which in turn caused the extinction of carnivores and scavengers which had preyed upon those animals.[135][136][137] This hypothesis holds Pleistocene humans responsible for the megafaunal extinction. One variant, known as blitzkrieg, portrays this process as relatively quick. Some of the direct evidence for this includes: fossils of some megafauna found in conjunction with human remains, embedded arrows and tool cut marks found in megafaunal bones, and European cave paintings that depict such hunting. Biogeographical evidence is also suggestive: the areas of the world where humans evolved currently have more of their Pleistocene megafaunal diversity (the elephants and rhinos of Asia and Africa) compared to other areas such as Australia, the Americas, Madagascar and New Zealand without the earliest humans. The overkill hypothesis, a variant of the hunting hypothesis, was proposed in 1966 by Paul S. Martin,[138] Professor of Geosciences Emeritus at the Desert Laboratory of the University of Arizona.[139]

Circumstantially, the close correlation in time between the appearance of humans in an area and extinction there provides weight for this scenario.[140][9][3] Radiocarbon dating has supported the plausibility of this correlation being reflective of causation.[141] The megafaunal extinctions covered a vast period of time and highly variable climatic situations. The earliest extinctions in Australia were complete approximately 50,000 BP, well before the Last Glacial Maximum and before rises in temperature. The most recent extinction in New Zealand was complete no earlier than 500 BP and during a period of cooling. In between these extremes megafaunal extinctions have occurred progressively in such places as North America, South America and Madagascar with no climatic commonality. The only common factor that can be ascertained is the arrival of humans.[142][143] This phenomenon appears even within regions. The mammal extinction wave in Australia about 50,000 years ago coincides not with known climatic changes, but with the arrival of humans. In addition, large mammal species like the giant kangaroo Protemnodon appear to have succumbed sooner on the Australian mainland than on Tasmania, which was colonised by humans a few thousand years later.[144][145] A study published in 2015 supported the hypothesis further by running several thousand scenarios that correlated the time windows in which each species is known to have become extinct with the arrival of humans on different continents or islands. This was compared against climate reconstructions for the last 90,000 years. The researchers found correlations of human spread and species extinction indicating that the human impact was the main cause of the extinction, while climate change exacerbated the frequency of extinctions. The study, however, found an apparently low extinction rate in the fossil record of mainland Asia.[146][147] A 2020 study published in Science Advances found that human population size and/or specific human activities, not climate change, caused rapidly rising global mammal extinction rates during the past 126,000 years. Around 96% of all mammalian extinctions over this time period are attributable to human impacts. According to Tobias Andermann, lead author of the study, "these extinctions did not happen continuously and at constant pace. Instead, bursts of extinctions are detected across different continents at times when humans first reached them. More recently, the magnitude of human driven extinctions has picked up the pace again, this time on a global scale."[148][149] On a related note, the population declines of still extant megafauna during the Pleistocene have also been shown to correlate with human expansion rather than climate change.[16]

The extinction's extreme bias towards larger animals further supports a relationship with human activity rather than climate change.[150] There is evidence that the average size of mammalian fauna declined over the course of the Quaternary,[151] a phenomenon that was likely linked to disproportionate hunting of large animals by humans.[5]

Extinction through human hunting has been supported by archaeological finds of mammoths with projectile points embedded in their skeletons, by observations of modern naive animals allowing hunters to approach easily[152][153][154] and by computer models by Mosimann and Martin,[155] and Whittington and Dyke,[156] and most recently by Alroy.[157]

Major objections have been raised regarding the hunting hypothesis. Notable among them is the sparsity of evidence of human hunting of megafauna.[158][159][160] There is no archeological evidence that in North America megafauna other than mammoths, mastodons, gomphotheres and bison were hunted, despite the fact that, for example, camels and horses are very frequently reported in fossil history.[161] Overkill proponents, however, say this is due to the fast extinction process in North America and the low probability of animals with signs of butchery to be preserved.[162] The majority of North American taxa have too sparse a fossil record to accurately assess the frequency of human hunting of them.[10] A study by Surovell and Grund concluded "archaeological sites dating to the time of the coexistence of humans and extinct fauna are rare. Those that preserve bone are considerably more rare, and of those, only a very few show unambiguous evidence of human hunting of any type of prey whatsoever."[163] Eugene S. Hunn points out that the birthrate in hunter-gatherer societies is generally too low, that too much effort is involved in the bringing down of a large animal by a hunting party, and that in order for hunter-gatherers to have brought about the extinction of megafauna simply by hunting them to death, an extraordinary amount of meat would have had to have been wasted.[164]

Second-order predation

[edit]

The Second-Order Predation Hypothesis says that as humans entered the New World they continued their policy of killing predators, which had been successful in the Old World but because they were more efficient and because the fauna, both herbivores and carnivores, were more naive, they killed off enough carnivores to upset the ecological balance of the continent, causing overpopulation, environmental exhaustion, and environmental collapse. The hypothesis accounts for changes in animal, plant, and human populations.

The scenario is as follows:

- After the arrival of H. sapiens in the New World, existing predators must share the prey populations with this new predator. Because of this competition, populations of original, or first-order, predators cannot find enough food; they are in direct competition with humans.

- Second-order predation begins as humans begin to kill predators.

- Prey populations are no longer well controlled by predation. Killing of nonhuman predators by H. sapiens reduces their numbers to a point where these predators no longer regulate the size of the prey populations.

- Lack of regulation by first-order predators triggers boom-and-bust cycles in prey populations. Prey populations expand and consequently overgraze and over-browse the land. Soon the environment is no longer able to support them. As a result, many herbivores starve. Species that rely on the slowest recruiting food become extinct, followed by species that cannot extract the maximum benefit from every bit of their food.

- Boom-bust cycles in herbivore populations change the nature of the vegetative environment, with consequent climatic impacts on relative humidity and continentality. Through overgrazing and overbrowsing, mixed parkland becomes grassland, and climatic continentality increases.

The second-order predation hypothesis has been supported by a computer model, the Pleistocene extinction model (PEM), which, using the same assumptions and values for all variables (herbivore population, herbivore recruitment rates, food needed per human, herbivore hunting rates, etc.) other than those for hunting of predators. It compares the overkill hypothesis (predator hunting = 0) with second-order predation (predator hunting varied between 0.01 and 0.05 for different runs). The findings are that second-order predation is more consistent with extinction than is overkill[165][166] (results graph at left). The Pleistocene extinction model is the only test of multiple hypotheses and is the only model to specifically test combination hypotheses by artificially introducing sufficient climate change to cause extinction. When overkill and climate change are combined they balance each other out. Climate change reduces the number of plants, overkill removes animals, therefore fewer plants are eaten. Second-order predation combined with climate change exacerbates the effect of climate change.[167] (results graph at right). The second-order predation hypothesis is further supported by the observation above that there was a massive increase in bison populations.[168]

However, this hypothesis has been criticised on the grounds that the multispecies model produces a mass extinction through indirect competition between herbivore species: small species with high reproductive rates subsidize predation on large species with low reproductive rates.[157] All prey species are lumped in the Pleistocene extinction model. Also, the control of population sizes by predators is not fully supported by observations of modern ecosystems.[169] The hypothesis further assumes decreases in vegetation due to climate change, but deglaciation doubled the habitable area of North America. Any vegetational changes that did occur failed to cause almost any extinctions of small vertebrates, and they are more narrowly distributed on average, which detractors cite as evidence against the hypothesis.

Competition for water

[edit]In southeastern Australia, the scarcity of water during the interval in which humans arrived in Australia suggests that human competition with megafauna for precious water sources may have played a role in the extinction of the latter.[119]

Landscape alteration

[edit]One consequence of the colonisation by humans of lands previously uninhabited by them may have been the introduction of new fire regimes because of extensive fire use by humans.[7] There is evidence that anthropogenic fire use had major impacts on the local environments in both Australia[6] and North America.[170]

Climate change

[edit]At the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, when scientists first realized that there had been glacial and interglacial ages, and that they were somehow associated with the prevalence or disappearance of certain animals, they surmised that the termination of the Pleistocene ice age might be an explanation for the extinctions.

The most obvious change associated with the termination of an ice age is the increase in temperature. Between 15,000 BP and 10,000 BP, a 6 °C increase in global mean annual temperatures occurred. This was generally thought to be the cause of the extinctions. According to this hypothesis, a temperature increase sufficient to melt the Wisconsin ice sheet could have placed enough thermal stress on cold-adapted mammals to cause them to die. Their heavy fur, which helps conserve body heat in the glacial cold, might have prevented the dumping of excess heat, causing the mammals to die of heat exhaustion. Large mammals, with their reduced surface area-to-volume ratio, would have fared worse than small mammals. A study covering the past 56,000 years indicates that rapid warming events with temperature changes of up to 16 °C (29 °F) had an important impact on the extinction of megafauna. Ancient DNA and radiocarbon data indicates that local genetic populations were replaced by others within the same species or by others within the same genus. Survival of populations was dependent on the existence of refugia and long distance dispersals, which may have been disrupted by human hunters.[171]

Other scientists have proposed that increasingly extreme weather—hotter summers and colder winters—referred to as "continentality", or related changes in rainfall caused the extinctions. It has been shown that vegetation changed from mixed woodland-parkland to separate prairie and woodland.[172][173][174] This may have affected the kinds of food available. Shorter growing seasons may have caused the extinction of large herbivores and the dwarfing of many others. In this case, as observed, bison and other large ruminants would have fared better than horses, elephants and other monogastrics, because ruminants are able to extract more nutrition from limited quantities of high-fiber food and better able to deal with anti-herbivory toxins.[175][176][177] So, in general, when vegetation becomes more specialized, herbivores with less diet flexibility may be less able to find the mix of vegetation they need to sustain life and reproduce, within a given area. Increased continentality resulted in reduced and less predictable rainfall limiting the availability of plants necessary for energy and nutrition.[178][179][180] It has been suggested that this change in rainfall restricted the amount of time favorable for reproduction.[181][182] This could disproportionately harm large animals, since they have longer, more inflexible mating periods, and so may have produced young at unfavorable seasons (i.e., when sufficient food, water, or shelter was unavailable because of shifts in the growing season). In contrast, small mammals, with their shorter life cycles, shorter reproductive cycles, and shorter gestation periods, could have adjusted to the increased unpredictability of the climate, both as individuals and as species which allowed them to synchronize their reproductive efforts with conditions favorable for offspring survival. If so, smaller mammals would have lost fewer offspring and would have been better able to repeat the reproductive effort when circumstances once more favored offspring survival.[183] A study looking at the environmental conditions across Europe, Siberia and the Americas from 25,000 to 10,000 YBP found that prolonged warming events leading to deglaciation and maximum rainfall occurred just prior to the transformation of the rangelands that supported megaherbivores into widespread wetlands that supported herbivore-resistant plants. The study proposes that moisture-driven environmental change led to the megafaunal extinctions and that Africa's trans-equatorial position allowed rangeland to continue to exist between the deserts and the central forests, therefore fewer megafauna species became extinct there.[171]

Evidence in Southeast Asia, in contrast to Europe, Australia, and the Americas, suggests that climate change and an increasing sea level were significant factors in the extinction of several herbivorous species. Alterations in vegetation growth and new access routes for early humans and mammals to previously isolated, localized ecosystems were detrimental to select groups of fauna.[184]

Some evidence from Europe also suggests climatic changes were responsible for extinctions there, as the individuals extinctions tended to occur during times of environmental change and did not correlate particularly well with human migrations.[2]

In Australia, some studies have suggested that extinctions of megafauna began before the peopling of the continent, favouring climate change as the driver.[185]

In Beringia, megafauna may have gone extinct because of particularly intense paludification and because the land connection between Eurasia and North America flooded before the Cordilleran Ice Sheet retreated far enough to reopen the corridor between Beringia and the remainder of North America.[186] Woolly mammoths became extirpated from Beringia because of climatic factors, although human activity also played a synergistic role in their decline.[187] In North America, a Radiocarbon-dated Event-Count (REC) modelling study found that megafaunal declines in North America correlated with climatic changes instead of human population expansion.[188]

In the North American Great Lakes region, the population declines of mastodons and mammoths have been found to correlate with climatic fluctuations during the Younger Dryas rather than human activity.[189]

In the Argentine Pampas, the flooding of vast swathes of the once much larger Pampas grasslands may have played a role in the extinctions of its megafaunal assemblages.[8]

Critics object that since there were multiple glacial advances and withdrawals in the evolutionary history of many of the megafauna, it is rather implausible that only after the last glacial maximum would there be such extinctions. Proponents of climate change as the extinction event's cause like David J. Meltzer suggest that the last deglaciation may have been markedly different from previous ones.[190] Also, one study suggests that the Pleistocene megafaunal composition may have differed markedly from that of earlier interglacials, making the Pleistocene populations particularly vulnerable to changes in their environment.[191]

Studies propose that the annual mean temperature of the current interglacial that we have seen for the last 10,000 years is no higher than that of previous interglacials, yet most of the same large mammals survived similar temperature increases.[192][193][194] In addition, numerous species such as mammoths on Wrangel Island and St. Paul Island survived in human-free refugia despite changes in climate.[195] This would not be expected if climate change were responsible (unless their maritime climates offered some protection against climate change not afforded to coastal populations on the mainland). Under normal ecological assumptions island populations should be more vulnerable to extinction due to climate change because of small populations and an inability to migrate to more favorable climes.[citation needed]

Critics have also identified a number of problems with the continentality hypotheses. Megaherbivores have prospered at other times of continental climate. For example, megaherbivores thrived in Pleistocene Siberia, which had and has a more continental climate than Pleistocene or modern (post-Pleistocene, interglacial) North America.[196][197][198] The animals that became extinct actually should have prospered during the shift from mixed woodland-parkland to prairie, because their primary food source, grass, was increasing rather than decreasing.[199][198][200] Although the vegetation did become more spatially specialized, the amount of prairie and grass available increased, which would have been good for horses and for mammoths, and yet they became extinct. This criticism ignores the increased abundance and broad geographic extent of Pleistocene bison at the end of the Pleistocene, which would have increased competition for these resources in a manner not seen in any earlier interglacials.[191] Although horses became extinct in the New World, they were successfully reintroduced by the Spanish in the 16th century—into a modern post-Pleistocene, interglacial climate. Today there are feral horses still living in those same environments. They find a sufficient mix of food to avoid toxins, they extract enough nutrition from forage to reproduce effectively and the timing of their gestation is not an issue. Of course, this criticism ignores the obvious fact that present-day horses are not competing for resources with ground sloths, mammoths, mastodons, camels, llamas, and bison. Similarly, mammoths survived the Pleistocene Holocene transition on isolated, uninhabited islands in the Mediterranean Sea until 4,000 to 7,000 years ago,[201] as well as on Wrangel Island in the Siberian Arctic.[202] Additionally, large mammals should have been able to migrate, permanently or seasonally, if they found the temperature too extreme, the breeding season too short, or the rainfall too sparse or unpredictable.[203] Seasons vary geographically. By migrating away from the equator, herbivores could have found areas with growing seasons more favorable for finding food and breeding successfully. Modern-day African elephants migrate during periods of drought to places where there is apt to be water.[204] Large animals also store more fat in their bodies than do medium-sized animals and this should have allowed them to compensate for extreme seasonal fluctuations in food availability.[205]

Some evidence weighs against climate change as a valid hypothesis as applied to Australia. It has been shown that the prevailing climate at the time of extinction (40,000–50,000 BP) was similar to that of today, and that the extinct animals were strongly adapted to an arid climate. The evidence indicates that all of the extinctions took place in the same short time period, which was the time when humans entered the landscape. The main mechanism for extinction was probably fire (started by humans) in a then much less fire-adapted landscape. Isotopic evidence shows sudden changes in the diet of surviving species, which could correspond to the stress they experienced before extinction.[206][207][208]

Some evidence obtained from analysis of the tusks of mastodons from the American Great Lakes region appears inconsistent with the climate change hypothesis. Over a span of several thousand years prior to their extinction in the area, the mastodons show a trend of declining age at maturation. This is the opposite of what one would expect if they were experiencing stresses from deteriorating environmental conditions, but is consistent with a reduction in intraspecific competition that would result from a population being reduced by human hunting.[209]

It may be observed that neither the overkill nor the climate change hypotheses can fully explain events: browsers, mixed feeders and non-ruminant grazer species suffered most, while relatively more ruminant grazers survived.[210] However, a broader variation of the overkill hypothesis may predict this, because changes in vegetation wrought by either Second Order Predation (see below)[167][211] or anthropogenic fire preferentially selects against browse species.[citation needed]

Disease

[edit]The hyperdisease hypothesis, as advanced by Ross D. E. MacFee and Preston A. Marx, attributes the extinction of large mammals during the late Pleistocene to indirect effects of the newly arrived aboriginal humans.[212][213][214] In more recent times, disease has driven many vulnerable species to extinction; the introduction of avian malaria and avipoxvirus, for example, has greatly decreased the populations of the endemic birds of Hawaii, with some going extinct.[215] The hyperdisease hypothesis proposes that humans or animals traveling with them (e.g., chickens or domestic dogs) introduced one or more highly virulent diseases into vulnerable populations of native mammals, eventually causing extinctions. The extinction was biased toward larger-sized species because smaller species have greater resilience because of their life history traits (e.g., shorter gestation time, greater population sizes, etc.). Humans are thought to be the cause because other earlier immigrations of mammals into North America from Eurasia did not cause extinctions.[212] A similar suggestion is that pathogens were transmitted by the expanding humans via the domesticated dogs they brought with them.[216] A related theory proposes that a highly contagious prion disease similar to chronic wasting disease or scrapie that was capable of infecting a large number of species was the culprit. Animals weakened by this "superprion" would also have easily become reservoirs of viral and bacterial diseases as they succumbed to neurological degeneration from the prion, causing a cascade of different diseases to spread among various mammal species. This theory could potentially explain the prevalence of heterozygosity at codon 129 of the prion protein gene in humans, which has been speculated to be the result of natural selection against homozygous genotypes that were more susceptible to prion disease and thus potentially a tell-tale of a major prion pandemic that affected humans of or younger than reproductive age far in the past and disproportionately killed before they could reproduce those with homozygous genotypes at codon 129.[217]

If a disease was indeed responsible for the end-Pleistocene extinctions, then there are several criteria it must satisfy (see Table 7.3 in MacPhee & Marx 1997). First, the pathogen must have a stable carrier state in a reservoir species. That is, it must be able to sustain itself in the environment when there are no susceptible hosts available to infect. Second, the pathogen must have a high infection rate, such that it is able to infect virtually all individuals of all ages and sexes encountered. Third, it must be extremely lethal, with a mortality rate of c. 50–75%. Finally, it must have the ability to infect multiple host species without posing a serious threat to humans. Humans may be infected, but the disease must not be highly lethal or able to cause an epidemic.[citation needed]

As with other hypotheses, a number of counterarguments to the hyperdisease hypothesis have been put forth. Generally speaking, disease has to be very virulent to kill off all the individuals in a genus or species. Even such a virulent disease as West Nile fever is unlikely to have caused extinction.[218] The disease would need to be implausibly selective while being simultaneously implausibly broad. Such a disease needs to be capable of killing off wolves such as Canis dirus or goats such as Oreamnos harringtoni while leaving other very similar species (Canis lupus and Oreamnos americanus, respectively) unaffected. It would need to be capable of killing off flightless birds while leaving closely related flighted species unaffected. Yet while remaining sufficiently selective to afflict only individual species within genera it must be capable of fatally infecting across such clades as birds, marsupials, placentals, testudines, and crocodilians. No disease with such a broad scope of fatal infectivity is known, much less one that remains simultaneously incapable of infecting numerous closely related species within those disparate clades. On the other hand, this objection does not account for the possibility of a variety of different diseases being introduced around the same era.[citation needed] Numerous species including wolves, mammoths, camelids, and horses had emigrated continually between Asia and North America over the past 100,000 years. For the disease hypothesis to be applicable there it would require that the population remain immunologically naive despite this constant transmission of genetic and pathogenic material.[citation needed] The dog-specific hypothesis in particular cannot account for several major extinction events, notably the Americas (for reasons already covered) and Australia. Dogs did not arrive in Australia until approximately 35,000 years after the first humans arrived there, and approximately 30,000 years after the Australian megafaunal extinction was complete.[citation needed]

Extraterrestrial impact

[edit]An extraterrestrial impact, which has occasionally been proposed as a cause of the Younger Dryas,[219] has been suggested by some authors as a potential cause of the extinction of North America's megafauna due to the temporal proximity between a proposed date for such an impact and the following megafaunal extinctions.[220][4] However, the Younger Dryas impact hypothesis lacks widespread support among scholars due to various inconsistencies in the hypothesis,[221][222] and has been comprehensively refuted.[223]

Geomagnetic field weakening

[edit]Around 41,500 years ago, the Earth's magnetic field weakened in an event known as the Laschamp event. This weakening may have caused increased flux of UV-B radiation and has been suggested by a few authors as a cause of megafaunal extinctions in the Late Quaternary.[224] The full effects of such events on the biosphere are poorly understood, however these explanations have been criticized as they do not account for the population bottlenecks seen in many megafaunal species and nor is there evidence for extreme radio-isotopic changes during the event. Considering these factors, causation is unlikely.[225][226]

Effects

[edit]The extinction of the megafauna has been argued by some authors to be disappearance of the mammoth steppe rather than the other way around. Alaska now has low nutrient soil unable to support bison, mammoths, and horses. R. Dale Guthrie has claimed this as a cause of the extinction of the megafauna there; however, he may be interpreting it backwards. The loss of large herbivores to break up the permafrost allows the cold soils that are unable to support large herbivores today. Today, in the arctic, where trucks have broken the permafrost grasses and diverse flora and fauna can be supported.[227][228] In addition, Chapin (Chapin 1980) showed that simply adding fertilizer to the soil in Alaska could make grasses grow again like they did in the era of the mammoth steppe. Possibly, the extinction of the megafauna and the corresponding loss of dung is what led to low nutrient levels in modern-day soil and therefore is why the landscape can no longer support megafauna.

However, more recent authors have viewed it as more likely that the collapse of the mammoth steppe was driven by climatic warming, which in turn impacted the megafauna, rather than the other way around.[229]

Megafauna play a significant role in the lateral transport of mineral nutrients in an ecosystem, tending to translocate them from areas of high to those of lower abundance. They do so by their movement between the time they consume the nutrient and the time they release it through elimination (or, to a much lesser extent, through decomposition after death).[230] In South America's Amazon Basin, it is estimated that such lateral diffusion was reduced over 98% following the megafaunal extinctions that occurred roughly 12,500 years ago.[231][232] Given that phosphorus availability is thought to limit productivity in much of the region, the decrease in its transport from the western part of the basin and from floodplains (both of which derive their supply from the uplift of the Andes) to other areas is thought to have significantly impacted the region's ecology, and the effects may not yet have reached their limits.[232] The extinction of the mammoths allowed grasslands they had maintained through grazing habits to become birch forests.[233] The new forest and the resulting forest fires may have induced climate change.[233] Such disappearances might be the result of the proliferation of modern humans.[234][235]

Large populations of megaherbivores have the potential to contribute greatly to the atmospheric concentration of methane, which is an important greenhouse gas. Modern ruminant herbivores produce methane as a byproduct of foregut fermentation in digestion, and release it through belching or flatulence. Today, around 20% of annual methane emissions come from livestock methane release. In the Mesozoic, it has been estimated that sauropods could have emitted 520 million tons of methane to the atmosphere annually,[236] contributing to the warmer climate of the time (up to 10 °C warmer than at present).[236][237] This large emission follows from the enormous estimated biomass of sauropods, and because methane production of individual herbivores is believed to be almost proportional to their mass.[236]

Recent studies have indicated that the extinction of megafaunal herbivores may have caused a reduction in atmospheric methane. One study examined the methane emissions from the bison that occupied the Great Plains of North America before contact with European settlers. The study estimated that the removal of the bison caused a decrease of as much as 2.2 million tons per year.[238] Another study examined the change in the methane concentration in the atmosphere at the end of the Pleistocene epoch after the extinction of megafauna in the Americas. After early humans migrated to the Americas about 13,000 BP, their hunting and other associated ecological impacts led to the extinction of many megafaunal species there. Calculations suggest that this extinction decreased methane production by about 9.6 million tons per year. This suggests that the absence of megafaunal methane emissions may have contributed to the abrupt climatic cooling at the onset of the Younger Dryas. The decrease in atmospheric methane that occurred at that time, as recorded in ice cores, was 2–4 times more rapid than any other decrease in the last half million years, suggesting that an unusual mechanism was at work.[239]

The extermination of megafauna left many niches vacant, which has been cited as an explanation for the vulnerability and fragility of many ecosystems to destruction in the later Holocene extinction. The comparative lack of megafauna in modern ecosystems has reduced high-order interactions among surviving species, reducing ecological complexity.[240] This depauperate, post-megafaunal ecological state has been associated with diminished ecological resilience to stressors.[241] Many extant species of plants have adaptations that were advantageous in the presence of megafauna but are now useless in their absence.[242] The demise of megafaunal ecosystem engineers in the Arctic that maintained open grassland environments has been highly detrimental to shorebirds of the genus Numenius.[243]

Relationship to later extinctions