КТ

| КТ | |

|---|---|

Современный компьютерный томограф (2021 г.), КТ с подсчетом фотонов (Siemens NAEOTOM Alpha) | |

| Другие имена | X-ray computed tomography (X-ray CT), computerized axial tomography scan (CAT scan),[1] компьютерная томография, компьютерная томография |

| ICD-10-PCS | B?2 |

| ICD-9-CM | 88.38 |

| MeSH | D014057 |

| OPS-301 code | 3–20...3–26 |

| MedlinePlus | 003330 |

Компьютерная томография ( КТ ; ранее называвшаяся компьютерной аксиальной томографией или компьютерной томографией ) — это метод медицинской визуализации , используемый для получения детальных внутренних изображений тела. [2] Персонал, выполняющий компьютерную томографию, называется рентгенологами или радиологическими технологами. [3] [4]

В компьютерных томографах используется вращающаяся рентгеновская трубка и ряд детекторов, помещенных в гентри, рентгеновских лучей для измерения ослабления различными тканями внутри тела. Множественные рентгеновские измерения, сделанные под разными углами, затем обрабатываются на компьютере с использованием алгоритмов томографической реконструкции для создания томографических изображений (поперечных сечений) (виртуальных «срезов») тела. КТ можно использовать у пациентов с металлическими имплантатами или кардиостимуляторами, которым магнитно-резонансная томография (МРТ) противопоказана .

Since its development in the 1970s, CT scanning has proven to be a versatile imaging technique. While CT is most prominently used in medical diagnosis, it can also be used to form images of non-living objects. The 1979 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded jointly to South African-American physicist Allan MacLeod Cormack and British electrical engineer Godfrey Hounsfield "for the development of computer-assisted tomography".[5][6]

Types

[edit]On the basis of image acquisition and procedures, various type of scanners are available in the market.

Sequential CT

[edit]Sequential CT, also known as step-and-shoot CT, is a type of scanning method in which the CT table moves stepwise. The table increments to a particular location and then stops which is followed by the X-ray tube rotation and acquisition of a slice. The table then increments again, and another slice is taken. The table movement stops while taking slices. This results in an increased time of scanning.[7]

Spiral CT

[edit]

Spinning tube, commonly called spiral CT, or helical CT, is an imaging technique in which an entire X-ray tube is spun around the central axis of the area being scanned. These are the dominant type of scanners on the market because they have been manufactured longer and offer a lower cost of production and purchase. The main limitation of this type of CT is the bulk and inertia of the equipment (X-ray tube assembly and detector array on the opposite side of the circle) which limits the speed at which the equipment can spin. Some designs use two X-ray sources and detector arrays offset by an angle, as a technique to improve temporal resolution.[8][9]

Electron beam tomography

[edit]Electron beam tomography (EBT) is a specific form of CT in which a large enough X-ray tube is constructed so that only the path of the electrons, travelling between the cathode and anode of the X-ray tube, are spun using deflection coils.[10] This type had a major advantage since sweep speeds can be much faster, allowing for less blurry imaging of moving structures, such as the heart and arteries.[11] Fewer scanners of this design have been produced when compared with spinning tube types, mainly due to the higher cost associated with building a much larger X-ray tube and detector array and limited anatomical coverage.[12]

Dual Energy CT

[edit]Dual Energy CT, also known as Spectral CT, is an advancement of Computed Tomography in which two energies are used to create two sets of data.[13] A Dual Energy CT may employ Dual source, Single source with dual detector layer, Single source with energy switching methods to get two different sets of data.[14]

- Dual source CT is an advanced scanner with a two X-ray tube detector system, unlike conventional single tube systems.[15][16] These two detector systems are mounted on a single gantry at 90° in the same plane.[17] Dual Source CT scanners allow fast scanning with higher temporal resolution by acquiring a full CT slice in only half a rotation. Fast imaging reduces motion blurring at high heart rates and potentially allowing for shorter breath-hold time. This is particularly useful for ill patients having difficulty holding their breath or unable to take heart-rate lowering medication.[17][18]

- Single Source with Energy switching is another mode of Dual energy CT in which a single tube is operated at two different energies by switching the energies frequently.[19][20]

CT perfusion imaging

[edit]

CT perfusion imaging is a specific form of CT to assess flow through blood vessels whilst injecting a contrast agent.[21] Blood flow, blood transit time, and organ blood volume, can all be calculated with reasonable sensitivity and specificity.[21] This type of CT may be used on the heart, although sensitivity and specificity for detecting abnormalities are still lower than for other forms of CT.[22] This may also be used on the brain, where CT perfusion imaging can often detect poor brain perfusion well before it is detected using a conventional spiral CT scan.[21][23] This is better for stroke diagnosis than other CT types.[23]

PET CT

[edit]

Positron emission tomography–computed tomography is a hybrid CT modality which combines, in a single gantry, a positron emission tomography (PET) scanner and an X-ray computed tomography (CT) scanner, to acquire sequential images from both devices in the same session, which are combined into a single superposed (co-registered) image. Thus, functional imaging obtained by PET, which depicts the spatial distribution of metabolic or biochemical activity in the body can be more precisely aligned or correlated with anatomic imaging obtained by CT scanning.[24]

PET-CT gives both anatomical and functional details of an organ under examination and is helpful in detecting different type of cancers.[25][26]

Medical use

[edit]Since its introduction in the 1970s,[27] CT has become an important tool in medical imaging to supplement conventional X-ray imaging and medical ultrasonography. It has more recently been used for preventive medicine or screening for disease, for example, CT colonography for people with a high risk of colon cancer, or full-motion heart scans for people with a high risk of heart disease. Several institutions offer full-body scans for the general population although this practice goes against the advice and official position of many professional organizations in the field primarily due to the radiation dose applied.[28]

The use of CT scans has increased dramatically over the last two decades in many countries.[29] An estimated 72 million scans were performed in the United States in 2007 and more than 80 million in 2015.[30][31]

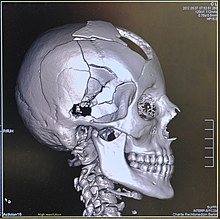

Head

[edit]

CT scanning of the head is typically used to detect infarction (stroke), tumors, calcifications, haemorrhage, and bone trauma.[32] Of the above, hypodense (dark) structures can indicate edema and infarction, hyperdense (bright) structures indicate calcifications and haemorrhage and bone trauma can be seen as disjunction in bone windows. Tumors can be detected by the swelling and anatomical distortion they cause, or by surrounding edema. CT scanning of the head is also used in CT-guided stereotactic surgery and radiosurgery for treatment of intracranial tumors, arteriovenous malformations, and other surgically treatable conditions using a device known as the N-localizer.[33][34][35][36][37][38]

Neck

[edit]Contrast CT is generally the initial study of choice for neck masses in adults.[39] CT of the thyroid plays an important role in the evaluation of thyroid cancer.[40] CT scan often incidentally finds thyroid abnormalities, and so is often the preferred investigation modality for thyroid abnormalities.[40]

Lungs

[edit]A CT scan can be used for detecting both acute and chronic changes in the lung parenchyma, the tissue of the lungs.[41] It is particularly relevant here because normal two-dimensional X-rays do not show such defects. A variety of techniques are used, depending on the suspected abnormality. For evaluation of chronic interstitial processes such as emphysema, and fibrosis,[42] thin sections with high spatial frequency reconstructions are used; often scans are performed both on inspiration and expiration. This special technique is called high resolution CT that produces a sampling of the lung, and not continuous images.[43]

Bronchial wall thickening can be seen on lung CTs and generally (but not always) implies inflammation of the bronchi.[44]

An incidentally found nodule in the absence of symptoms (sometimes referred to as an incidentaloma) may raise concerns that it might represent a tumor, either benign or malignant.[45] Perhaps persuaded by fear, patients and doctors sometimes agree to an intensive schedule of CT scans, sometimes up to every three months and beyond the recommended guidelines, in an attempt to do surveillance on the nodules.[46] However, established guidelines advise that patients without a prior history of cancer and whose solid nodules have not grown over a two-year period are unlikely to have any malignant cancer.[46] For this reason, and because no research provides supporting evidence that intensive surveillance gives better outcomes, and because of risks associated with having CT scans, patients should not receive CT screening in excess of those recommended by established guidelines.[46]

Angiography

[edit]

Computed tomography angiography (CTA) is a type of contrast CT to visualize the arteries and veins throughout the body.[47] This ranges from arteries serving the brain to those bringing blood to the lungs, kidneys, arms and legs. An example of this type of exam is CT pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) used to diagnose pulmonary embolism (PE). It employs computed tomography and an iodine-based contrast agent to obtain an image of the pulmonary arteries.[48][49][50]

Cardiac

[edit]A CT scan of the heart is performed to gain knowledge about cardiac or coronary anatomy.[51] Traditionally, cardiac CT scans are used to detect, diagnose, or follow up coronary artery disease.[52] More recently CT has played a key role in the fast-evolving field of transcatheter structural heart interventions, more specifically in the transcatheter repair and replacement of heart valves.[53][54][55]

The main forms of cardiac CT scanning are:

- Coronary CT angiography (CCTA): the use of CT to assess the coronary arteries of the heart. The subject receives an intravenous injection of radiocontrast, and then the heart is scanned using a high-speed CT scanner, allowing radiologists to assess the extent of occlusion in the coronary arteries, usually to diagnose coronary artery disease.[56][57]

- Coronary CT calcium scan: also used for the assessment of severity of coronary artery disease. Specifically, it looks for calcium deposits in the coronary arteries that can narrow arteries and increase the risk of a heart attack.[58] A typical coronary CT calcium scan is done without the use of radiocontrast, but it can possibly be done from contrast-enhanced images as well.[59]

To better visualize the anatomy, post-processing of the images is common.[52] Most common are multiplanar reconstructions (MPR) and volume rendering. For more complex anatomies and procedures, such as heart valve interventions, a true 3D reconstruction or a 3D print is created based on these CT images to gain a deeper understanding.[60][61][62][63]

Abdomen and pelvis

[edit]

CT is an accurate technique for diagnosis of abdominal diseases like Crohn's disease,[64] GIT bleeding, and diagnosis and staging of cancer, as well as follow-up after cancer treatment to assess response.[65] It is commonly used to investigate acute abdominal pain.[66]

Non-enhanced computed tomography is today the gold standard for diagnosing urinary stones.[67] The size, volume and density of stones can be estimated to help clinicians guide further treatment; size is especially important in predicting spontaneous passage of a stone.[68]

Axial skeleton and extremities

[edit]For the axial skeleton and extremities, CT is often used to image complex fractures, especially ones around joints, because of its ability to reconstruct the area of interest in multiple planes. Fractures, ligamentous injuries, and dislocations can easily be recognized with a 0.2 mm resolution.[69][70] With modern dual-energy CT scanners, new areas of use have been established, such as aiding in the diagnosis of gout.[71]

Biomechanical use

[edit]CT is used in biomechanics to quickly reveal the geometry, anatomy, density and elastic moduli of biological tissues.[72][73]

Other uses

[edit]Industrial use

[edit]Industrial CT scanning (industrial computed tomography) is a process which uses X-ray equipment to produce 3D representations of components both externally and internally. Industrial CT scanning has been used in many areas of industry for internal inspection of components. Some of the key uses for CT scanning have been flaw detection, failure analysis, metrology, assembly analysis, image-based finite element methods[74] and reverse engineering applications. CT scanning is also employed in the imaging and conservation of museum artifacts.[75]

Aviation security

[edit]CT scanning has also found an application in transport security (predominantly airport security) where it is currently used in a materials analysis context for explosives detection CTX (explosive-detection device)[76][77][78][79] and is also under consideration for automated baggage/parcel security scanning using computer vision based object recognition algorithms that target the detection of specific threat items based on 3D appearance (e.g. guns, knives, liquid containers).[80][81][82] Its usage in airport security pioneered at Shannon Airport in March 2022 has ended the ban on liquids over 100 ml there, a move that Heathrow Airport plans for a full roll-out on 1 December 2022 and the TSA spent $781.2 million on an order for over 1,000 scanners, ready to go live in the summer.

Geological use

[edit]X-ray CT is used in geological studies to quickly reveal materials inside a drill core.[83] Dense minerals such as pyrite and barite appear brighter and less dense components such as clay appear dull in CT images.[84]

Cultural heritage use

[edit]X-ray CT and micro-CT can also be used for the conservation and preservation of objects of cultural heritage. For many fragile objects, direct research and observation can be damaging and can degrade the object over time. Using CT scans, conservators and researchers are able to determine the material composition of the objects they are exploring, such as the position of ink along the layers of a scroll, without any additional harm. These scans have been optimal for research focused on the workings of the Antikythera mechanism or the text hidden inside the charred outer layers of the En-Gedi Scroll. However, they are not optimal for every object subject to these kinds of research questions, as there are certain artifacts like the Herculaneum papyri in which the material composition has very little variation along the inside of the object. After scanning these objects, computational methods can be employed to examine the insides of these objects, as was the case with the virtual unwrapping of the En-Gedi scroll and the Herculaneum papyri.[85] Micro-CT has also proved useful for analyzing more recent artifacts such as still-sealed historic correspondence that employed the technique of letterlocking (complex folding and cuts) that provided a "tamper-evident locking mechanism".[86][87] Further examples of use cases in archaeology is imaging the contents of sarcophagi or ceramics.[88]

Recently, CWI in Amsterdam has collaborated with Rijksmuseum to investigate art object inside details in the framework called IntACT.[89]

Micro organism research

[edit]Varied types of fungus can degrade wood to different degrees, one Belgium research group has been used X-ray CT 3 dimension with sub-micron resolution unveiled fungi can penetrate micropores of 0.6 μm[90] under certain conditions.

Timber sawmill

[edit]Sawmills use industrial CT scanners to detect round defects, for instance knots, to improve total value of timber productions. Most sawmills are planning to incorporate this robust detection tool to improve productivity in the long run, however initial investment cost is high.

Interpretation of results

[edit]Presentation

[edit]

− Average intensity projection

− Maximum intensity projection

− Thin slice (median plane)

− Volume rendering by high and low threshold for radiodensity

The result of a CT scan is a volume of voxels, which may be presented to a human observer by various methods, which broadly fit into the following categories:

- Slices (of varying thickness). Thin slice is generally regarded as planes representing a thickness of less than 3 mm.[91][92] Thick slice is generally regarded as planes representing a thickness between 3 mm and 5 mm.[92][93]

- Projection, including maximum intensity projection[94] and average intensity projection

- Volume rendering (VR)[94]

Technically, all volume renderings become projections when viewed on a 2-dimensional display, making the distinction between projections and volume renderings a bit vague. The epitomes of volume rendering models feature a mix of for example coloring and shading in order to create realistic and observable representations.[95][96]

Two-dimensional CT images are conventionally rendered so that the view is as though looking up at it from the patient's feet.[97] Hence, the left side of the image is to the patient's right and vice versa, while anterior in the image also is the patient's anterior and vice versa. This left-right interchange corresponds to the view that physicians generally have in reality when positioned in front of patients.[98]

Grayscale

[edit]Pixels in an image obtained by CT scanning are displayed in terms of relative radiodensity. The pixel itself is displayed according to the mean attenuation of the tissue(s) that it corresponds to on a scale from +3,071 (most attenuating) to −1,024 (least attenuating) on the Hounsfield scale. A pixel is a two dimensional unit based on the matrix size and the field of view. When the CT slice thickness is also factored in, the unit is known as a voxel, which is a three-dimensional unit.[99] Water has an attenuation of 0 Hounsfield units (HU), while air is −1,000 HU, cancellous bone is typically +400 HU, and cranial bone can reach 2,000 HU.[100] The attenuation of metallic implants depends on the atomic number of the element used: Titanium usually has an amount of +1000 HU, iron steel can completely block the X-ray and is, therefore, responsible for well-known line-artifacts in computed tomograms. Artifacts are caused by abrupt transitions between low- and high-density materials, which results in data values that exceed the dynamic range of the processing electronics.[101]

Windowing

[edit]CT data sets have a very high dynamic range which must be reduced for display or printing. This is typically done via a process of "windowing", which maps a range (the "window") of pixel values to a grayscale ramp. For example, CT images of the brain are commonly viewed with a window extending from 0 HU to 80 HU. Pixel values of 0 and lower, are displayed as black; values of 80 and higher are displayed as white; values within the window are displayed as a gray intensity proportional to position within the window.[102] The window used for display must be matched to the X-ray density of the object of interest, in order to optimize the visible detail.[103] Window width and window level parameters are used to control the windowing of a scan.[104]

Multiplanar reconstruction and projections

[edit]

Multiplanar reconstruction (MPR) is the process of converting data from one anatomical plane (usually transverse) to other planes. It can be used for thin slices as well as projections. Multiplanar reconstruction is possible as present CT scanners provide almost isotropic resolution.[105]

MPR is used almost in every scan. The spine is frequently examined with it.[106] An image of the spine in axial plane can only show one vertebral bone at a time and cannot show its relation with other vertebral bones. By reformatting the data in other planes, visualization of the relative position can be achieved in sagittal and coronal plane.[107]

New software allows the reconstruction of data in non-orthogonal (oblique) planes, which help in the visualization of organs which are not in orthogonal planes.[108][109] It is better suited for visualization of the anatomical structure of the bronchi as they do not lie orthogonal to the direction of the scan.[110]

Curved-plane reconstruction (or curved planar reformation = CPR) is performed mainly for the evaluation of vessels. This type of reconstruction helps to straighten the bends in a vessel, thereby helping to visualize a whole vessel in a single image or in multiple images. After a vessel has been "straightened", measurements such as cross-sectional area and length can be made. This is helpful in preoperative assessment of a surgical procedure.[111]

For 2D projections used in radiation therapy for quality assurance and planning of external beam radiotherapy, including digitally reconstructed radiographs, see Beam's eye view.

| Type of projection | Schematic illustration | Examples (10 mm slabs) | Description | Uses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average intensity projection (AIP) |  | The average attenuation of each voxel is displayed. The image will get smoother as slice thickness increases. It will look more and more similar to conventional projectional radiography as slice thickness increases. | Useful for identifying the internal structures of a solid organ or the walls of hollow structures, such as intestines. | |

| Maximum intensity projection (MIP) |  | The voxel with the highest attenuation is displayed. Therefore, high-attenuating structures such as blood vessels filled with contrast media are enhanced. | Useful for angiographic studies and identification of pulmonary nodules. | |

| Minimum intensity projection (MinIP) |  | The voxel with the lowest attenuation is displayed. Therefore, low-attenuating structures such as air spaces are enhanced. | Useful for assessing the lung parenchyma. |

Volume rendering

[edit]

A threshold value of radiodensity is set by the operator (e.g., a level that corresponds to bone). With the help of edge detection image processing algorithms a 3D model can be constructed from the initial data and displayed on screen. Various thresholds can be used to get multiple models, each anatomical component such as muscle, bone and cartilage can be differentiated on the basis of different colours given to them. However, this mode of operation cannot show interior structures.[113]

Surface rendering is limited technique as it displays only the surfaces that meet a particular threshold density, and which are towards the viewer. However, In volume rendering, transparency, colours and shading are used which makes it easy to present a volume in a single image. For example, Pelvic bones could be displayed as semi-transparent, so that, even viewing at an oblique angle one part of the image does not hide another.[114]

Image quality

[edit]Dose versus image quality

[edit]An important issue within radiology today is how to reduce the radiation dose during CT examinations without compromising the image quality. In general, higher radiation doses result in higher-resolution images,[115] while lower doses lead to increased image noise and unsharp images. However, increased dosage raises the adverse side effects, including the risk of radiation-induced cancer – a four-phase abdominal CT gives the same radiation dose as 300 chest X-rays.[116] Several methods that can reduce the exposure to ionizing radiation during a CT scan exist.[117]

- New software technology can significantly reduce the required radiation dose. New iterative tomographic reconstruction algorithms (e.g., iterative Sparse Asymptotic Minimum Variance) could offer super-resolution without requiring higher radiation dose.[118]

- Individualize the examination and adjust the radiation dose to the body type and body organ examined. Different body types and organs require different amounts of radiation.[119]

- Higher resolution is not always suitable, such as detection of small pulmonary masses.[120]

Artifacts

[edit]Although images produced by CT are generally faithful representations of the scanned volume, the technique is susceptible to a number of artifacts, such as the following:[121][122]Chapters 3 and 5

- Streak artifact

- Streaks are often seen around materials that block most X-rays, such as metal or bone. Numerous factors contribute to these streaks: under sampling, photon starvation, motion, beam hardening, and Compton scatter. This type of artifact commonly occurs in the posterior fossa of the brain, or if there are metal implants. The streaks can be reduced using newer reconstruction techniques.[123] Approaches such as metal artifact reduction (MAR) can also reduce this artifact.[124][125] MAR techniques include spectral imaging, where CT images are taken with photons of different energy levels, and then synthesized into monochromatic images with special software such as GSI (Gemstone Spectral Imaging).[126]

- Partial volume effect

- This appears as "blurring" of edges. It is due to the scanner being unable to differentiate between a small amount of high-density material (e.g., bone) and a larger amount of lower density (e.g., cartilage).[127] The reconstruction assumes that the X-ray attenuation within each voxel is homogeneous; this may not be the case at sharp edges. This is most commonly seen in the z-direction (craniocaudal direction), due to the conventional use of highly anisotropic voxels, which have a much lower out-of-plane resolution, than in-plane resolution. This can be partially overcome by scanning using thinner slices, or an isotropic acquisition on a modern scanner.[128]

- Ring artifact

- Probably the most common mechanical artifact, the image of one or many "rings" appears within an image. They are usually caused by the variations in the response from individual elements in a two dimensional X-ray detector due to defect or miscalibration.[129] Ring artifacts can largely be reduced by intensity normalization, also referred to as flat field correction.[130] Remaining rings can be suppressed by a transformation to polar space, where they become linear stripes.[129] A comparative evaluation of ring artefact reduction on X-ray tomography images showed that the method of Sijbers and Postnov can effectively suppress ring artefacts.[131]

- Noise

- This appears as grain on the image and is caused by a low signal to noise ratio. This occurs more commonly when a thin slice thickness is used. It can also occur when the power supplied to the X-ray tube is insufficient to penetrate the anatomy.[132]

- Windmill

- Streaking appearances can occur when the detectors intersect the reconstruction plane. This can be reduced with filters or a reduction in pitch.[133][134]

- Beam hardening

- This can give a "cupped appearance" when grayscale is visualized as height. It occurs because conventional sources, like X-ray tubes emit a polychromatic spectrum. Photons of higher photon energy levels are typically attenuated less. Because of this, the mean energy of the spectrum increases when passing the object, often described as getting "harder". This leads to an effect increasingly underestimating material thickness, if not corrected. Many algorithms exist to correct for this artifact. They can be divided into mono- and multi-material methods.[123][135][136]

Advantages

[edit]CT scanning has several advantages over traditional two-dimensional medical radiography. First, CT eliminates the superimposition of images of structures outside the area of interest.[137] Second, CT scans have greater image resolution, enabling examination of finer details. CT can distinguish between tissues that differ in radiographic density by 1% or less.[138] Third, CT scanning enables multiplanar reformatted imaging: scan data can be visualized in the transverse (or axial), coronal, or sagittal plane, depending on the diagnostic task.[139]

The improved resolution of CT has permitted the development of new investigations. For example, CT angiography avoids the invasive insertion of a catheter. CT scanning can perform a virtual colonoscopy with greater accuracy and less discomfort for the patient than a traditional colonoscopy.[140][141] Virtual colonography is far more accurate than a barium enema for detection of tumors and uses a lower radiation dose.[142]

CT is a moderate-to-high radiation diagnostic technique. The radiation dose for a particular examination depends on multiple factors: volume scanned, patient build, number and type of scan protocol, and desired resolution and image quality.[143] Two helical CT scanning parameters, tube current and pitch, can be adjusted easily and have a profound effect on radiation. CT scanning is more accurate than two-dimensional radiographs in evaluating anterior interbody fusion, although they may still over-read the extent of fusion.[144]

Adverse effects

[edit]Cancer

[edit]The radiation used in CT scans can damage body cells, including DNA molecules, which can lead to radiation-induced cancer.[145] The radiation doses received from CT scans is variable. Compared to the lowest dose X-ray techniques, CT scans can have 100 to 1,000 times higher dose than conventional X-rays.[146] However, a lumbar spine X-ray has a similar dose as a head CT.[147] Articles in the media often exaggerate the relative dose of CT by comparing the lowest-dose X-ray techniques (chest X-ray) with the highest-dose CT techniques. In general, a routine abdominal CT has a radiation dose similar to three years of average background radiation.[148]

Large scale population-based studies have consistently demonstrated that low dose radiation from CT scans has impacts on cancer incidence in a variety of cancers.[149][150][151][152] For example, in a large population-based cohort it was found that up to 4% of brain cancers were caused by CT scan radiation.[153] Some experts project that in the future, between three and five percent of all cancers would result from medical imaging.[146] An Australian study of 10.9 million people reported that the increased incidence of cancer after CT scan exposure in this cohort was mostly due to irradiation. In this group, one in every 1,800 CT scans was followed by an excess cancer. If the lifetime risk of developing cancer is 40% then the absolute risk rises to 40.05% after a CT. The risks of CT scan radiation are especially important in patients undergoing recurrent CT scans within a short time span of one to five years.[154][155][156]

Some experts note that CT scans are known to be "overused," and "there is distressingly little evidence of better health outcomes associated with the current high rate of scans."[146] On the other hand, a recent paper analyzing the data of patients who received high cumulative doses showed a high degree of appropriate use.[157] This creates an important issue of cancer risk to these patients. Moreover, a highly significant finding that was previously unreported is that some patients received >100 mSv dose from CT scans in a single day,[155] which counteracts existing criticisms some investigators may have on the effects of protracted versus acute exposure.

There are contrarian views and the debate is ongoing. Some studies have shown that publications indicating an increased risk of cancer from typical doses of body CT scans are plagued with serious methodological limitations and several highly improbable results,[158] concluding that no evidence indicates such low doses cause any long-term harm.[159][160][161]One study estimated that as many as 0.4% of cancers in the United States resulted from CT scans, and that this may have increased to as much as 1.5 to 2% based on the rate of CT use in 2007.[145] Others dispute this estimate,[162] as there is no consensus that the low levels of radiation used in CT scans cause damage. Lower radiation doses are used in many cases, such as in the investigation of renal colic.[163]

A person's age plays a significant role in the subsequent risk of cancer.[164] Estimated lifetime cancer mortality risks from an abdominal CT of a one-year-old is 0.1%, or 1:1000 scans.[164] The risk for someone who is 40 years old is half that of someone who is 20 years old with substantially less risk in the elderly.[164] The International Commission on Radiological Protection estimates that the risk to a fetus being exposed to 10 mGy (a unit of radiation exposure) increases the rate of cancer before 20 years of age from 0.03% to 0.04% (for reference a CT pulmonary angiogram exposes a fetus to 4 mGy).[165] A 2012 review did not find an association between medical radiation and cancer risk in children noting however the existence of limitations in the evidences over which the review is based.[166] CT scans can be performed with different settings for lower exposure in children with most manufacturers of CT scans as of 2007 having this function built in.[167] Furthermore, certain conditions can require children to be exposed to multiple CT scans.[145]

Current recommendations are to inform patients of the risks of CT scanning.[168] However, employees of imaging centers tend not to communicate such risks unless patients ask.[169]

Contrast reactions

[edit]In the United States half of CT scans are contrast CTs using intravenously injected radiocontrast agents.[170] The most common reactions from these agents are mild, including nausea, vomiting, and an itching rash. Severe life-threatening reactions may rarely occur.[171] Overall reactions occur in 1 to 3% with nonionic contrast and 4 to 12% of people with ionic contrast.[172] Skin rashes may appear within a week to 3% of people.[171]

The old radiocontrast agents caused anaphylaxis in 1% of cases while the newer, low-osmolar agents cause reactions in 0.01–0.04% of cases.[171][173] Death occurs in about 2 to 30 people per 1,000,000 administrations, with newer agents being safer.[172][174]There is a higher risk of mortality in those who are female, elderly or in poor health, usually secondary to either anaphylaxis or acute kidney injury.[170]

The contrast agent may induce contrast-induced nephropathy.[175] This occurs in 2 to 7% of people who receive these agents, with greater risk in those who have preexisting kidney failure,[175] preexisting diabetes, or reduced intravascular volume. People with mild kidney impairment are usually advised to ensure full hydration for several hours before and after the injection. For moderate kidney failure, the use of iodinated contrast should be avoided; this may mean using an alternative technique instead of CT. Those with severe kidney failure requiring dialysis require less strict precautions, as their kidneys have so little function remaining that any further damage would not be noticeable and the dialysis will remove the contrast agent; it is normally recommended, however, to arrange dialysis as soon as possible following contrast administration to minimize any adverse effects of the contrast.

In addition to the use of intravenous contrast, orally administered contrast agents are frequently used when examining the abdomen.[176] These are frequently the same as the intravenous contrast agents, merely diluted to approximately 10% of the concentration. However, oral alternatives to iodinated contrast exist, such as very dilute (0.5–1% w/v) barium sulfate suspensions. Dilute barium sulfate has the advantage that it does not cause allergic-type reactions or kidney failure, but cannot be used in patients with suspected bowel perforation or suspected bowel injury, as leakage of barium sulfate from damaged bowel can cause fatal peritonitis.[177]

Side effects from contrast agents, administered intravenously in some CT scans, might impair kidney performance in patients with kidney disease, although this risk is now believed to be lower than previously thought.[178][175]

Scan dose

[edit]| Examination | Typical effective dose (mSv) to the whole body | Typical absorbed dose (mGy) to the organ in question |

|---|---|---|

| Annual background radiation | 2.4[179] | 2.4[179] |

| Chest X-ray | 0.02[180] | 0.01–0.15[181] |

| Head CT | 1–2[164] | 56[182] |

| Screening mammography | 0.4[165] | 3[145][181] |

| Abdominal CT | 8[180] | 14[182] |

| Chest CT | 5–7[164] | 13[182] |

| CT colonography | 6–11[164] | |

| Chest, abdomen and pelvis CT | 9.9[182] | 12[182] |

| Cardiac CT angiogram | 9–12[164] | 40–100[181] |

| Barium enema | 15[145] | 15[181] |

| Neonatal abdominal CT | 20[145] | 20[181] |

The table reports average radiation exposures; however, there can be a wide variation in radiation doses between similar scan types, where the highest dose could be as much as 22 times higher than the lowest dose.[164] A typical plain film X-ray involves radiation dose of 0.01 to 0.15 mGy, while a typical CT can involve 10–20 mGy for specific organs, and can go up to 80 mGy for certain specialized CT scans.[181]

For purposes of comparison, the world average dose rate from naturally occurring sources of background radiation is 2.4 mSv per year, equal for practical purposes in this application to 2.4 mGy per year.[179] While there is some variation, most people (99%) received less than 7 mSv per year as background radiation.[183] Medical imaging as of 2007 accounted for half of the radiation exposure of those in the United States with CT scans making up two thirds of this amount.[164] In the United Kingdom it accounts for 15% of radiation exposure.[165] The average radiation dose from medical sources is ≈0.6 mSv per person globally as of 2007.[164] Those in the nuclear industry in the United States are limited to doses of 50 mSv a year and 100 mSv every 5 years.[164]

Lead is the main material used by radiography personnel for shielding against scattered X-rays.

Radiation dose units

[edit]The radiation dose reported in the gray or mGy unit is proportional to the amount of energy that the irradiated body part is expected to absorb, and the physical effect (such as DNA double strand breaks) on the cells' chemical bonds by X-ray radiation is proportional to that energy.[184]

The sievert unit is used in the report of the effective dose. The sievert unit, in the context of CT scans, does not correspond to the actual radiation dose that the scanned body part absorbs but to another radiation dose of another scenario, the whole body absorbing the other radiation dose and the other radiation dose being of a magnitude, estimated to have the same probability to induce cancer as the CT scan.[185] Thus, as is shown in the table above, the actual radiation that is absorbed by a scanned body part is often much larger than the effective dose suggests. A specific measure, termed the computed tomography dose index (CTDI), is commonly used as an estimate of the radiation absorbed dose for tissue within the scan region, and is automatically computed by medical CT scanners.[186]

The equivalent dose is the effective dose of a case, in which the whole body would actually absorb the same radiation dose, and the sievert unit is used in its report. In the case of non-uniform radiation, or radiation given to only part of the body, which is common for CT examinations, using the local equivalent dose alone would overstate the biological risks to the entire organism.[187][188][189]

Effects of radiation

[edit]Most adverse health effects of radiation exposure may be grouped in two general categories:

- deterministic effects (harmful tissue reactions) due in large part to the killing/malfunction of cells following high doses;[190]

- stochastic effects, i.e., cancer and heritable effects involving either cancer development in exposed individuals owing to mutation of somatic cells or heritable disease in their offspring owing to mutation of reproductive (germ) cells.[191]

The added lifetime risk of developing cancer by a single abdominal CT of 8 mSv is estimated to be 0.05%, or 1 one in 2,000.[192]

Because of increased susceptibility of fetuses to radiation exposure, the radiation dosage of a CT scan is an important consideration in the choice of medical imaging in pregnancy.[193][194]

Excess doses

[edit]In October, 2009, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) initiated an investigation of brain perfusion CT (PCT) scans, based on radiation burns caused by incorrect settings at one particular facility for this particular type of CT scan. Over 200 patients were exposed to radiation at approximately eight times the expected dose for an 18-month period; over 40% of them lost patches of hair. This event prompted a call for increased CT quality assurance programs. It was noted that "while unnecessary radiation exposure should be avoided, a medically needed CT scan obtained with appropriate acquisition parameter has benefits that outweigh the radiation risks."[164][195] Similar problems have been reported at other centers.[164] These incidents are believed to be due to human error.[164]

Procedure

[edit]CT scan procedure varies according to the type of the study and the organ being imaged. The patient is made to lie on the CT table and the centering of the table is done according to the body part. The IV line is established in case of contrast-enhanced CT. After selecting proper[clarification needed] and rate of contrast from the pressure injector, the scout is taken to localize and plan the scan. Once the plan is selected, the contrast is given. The raw data is processed according to the study and proper windowing is done to make scans easy to diagnose.[196]

Preparation

[edit]Patient preparation may vary according to the type of scan. The general patient preparation includes.[196]

- Signing the informed consent.

- Removal of metallic objects and jewelry from the region of interest.

- Changing to the hospital gown according to hospital protocol.

- Checking of kidney function, especially creatinine and urea levels (in case of CECT).[197]

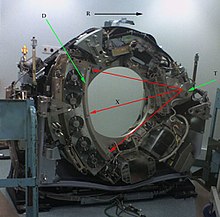

Mechanism

[edit]

T: X-ray tube

D: X-ray detectors

X: X-ray beam

R: Gantry rotation

Computed tomography operates by using an X-ray generator that rotates around the object; X-ray detectors are positioned on the opposite side of the circle from the X-ray source.[199] As the X-rays pass through the patient, they are attenuated differently by various tissues according to the tissue density.[200] A visual representation of the raw data obtained is called a sinogram, yet it is not sufficient for interpretation.[201] Once the scan data has been acquired, the data must be processed using a form of tomographic reconstruction, which produces a series of cross-sectional images.[202] These cross-sectional images are made up of small units of pixels or voxels.[203]

Pixels in an image obtained by CT scanning are displayed in terms of relative radiodensity. The pixel itself is displayed according to the mean attenuation of the tissue(s) that it corresponds to on a scale from +3,071 (most attenuating) to −1,024 (least attenuating) on the Hounsfield scale. A pixel is a two dimensional unit based on the matrix size and the field of view. When the CT slice thickness is also factored in, the unit is known as a voxel, which is a three-dimensional unit.[203]

Water has an attenuation of 0 Hounsfield units (HU), while air is −1,000 HU, cancellous bone is typically +400 HU, and cranial bone can reach 2,000 HU or more (os temporale) and can cause artifacts. The attenuation of metallic implants depends on the atomic number of the element used: Titanium usually has an amount of +1000 HU, iron steel can completely extinguish the X-ray and is, therefore, responsible for well-known line-artifacts in computed tomograms. Artifacts are caused by abrupt transitions between low- and high-density materials, which results in data values that exceed the dynamic range of the processing electronics. Two-dimensional CT images are conventionally rendered so that the view is as though looking up at it from the patient's feet.[97] Hence, the left side of the image is to the patient's right and vice versa, while anterior in the image also is the patient's anterior and vice versa. This left-right interchange corresponds to the view that physicians generally have in reality when positioned in front of patients.

Initially, the images generated in CT scans were in the transverse (axial) anatomical plane, perpendicular to the long axis of the body. Modern scanners allow the scan data to be reformatted as images in other planes. Digital geometry processing can generate a three-dimensional image of an object inside the body from a series of two-dimensional radiographic images taken by rotation around a fixed axis.[121] These cross-sectional images are widely used for medical diagnosis and therapy.[204]

Contrast

[edit]Contrast media used for X-ray CT, as well as for plain film X-ray, are called radiocontrasts. Radiocontrasts for CT are, in general, iodine-based.[205] This is useful to highlight structures such as blood vessels that otherwise would be difficult to delineate from their surroundings. Using contrast material can also help to obtain functional information about tissues. Often, images are taken both with and without radiocontrast.[206]

History

[edit]The history of X-ray computed tomography goes back to at least 1917 with the mathematical theory of the Radon transform.[207][208] In October 1963, William H. Oldendorf received a U.S. patent for a "radiant energy apparatus for investigating selected areas of interior objects obscured by dense material".[209] The first commercially viable CT scanner was invented by Godfrey Hounsfield in 1972.[210]

It is often claimed that revenues from the sales of The Beatles' records in the 1960s helped fund the development of the first CT scanner at EMI. The first production X-ray CT machines were in fact called EMI scanners.[211]

Etymology

[edit]The word tomography is derived from the Greek tome 'slice' and graphein 'to write'.[212] Computed tomography was originally known as the "EMI scan" as it was developed in the early 1970s at a research branch of EMI, a company best known today for its music and recording business.[213] It was later known as computed axial tomography (CAT or CT scan) and body section röntgenography.[214]

The term CAT scan is no longer in technical use because current CT scans enable for multiplanar reconstructions. This makes CT scan the most appropriate term, which is used by radiologists in common vernacular as well as in textbooks and scientific papers.[215][216][217]

In Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), computed axial tomography was used from 1977 to 1979, but the current indexing explicitly includes X-ray in the title.[218]

The term sinogram was introduced by Paul Edholm and Bertil Jacobson in 1975.[219]

Society and culture

[edit]Campaigns

[edit]In response to increased concern by the public and the ongoing progress of best practices, the Alliance for Radiation Safety in Pediatric Imaging was formed within the Society for Pediatric Radiology. In concert with the American Society of Radiologic Technologists, the American College of Radiology and the American Association of Physicists in Medicine, the Society for Pediatric Radiology developed and launched the Image Gently Campaign which is designed to maintain high-quality imaging studies while using the lowest doses and best radiation safety practices available on pediatric patients.[220] This initiative has been endorsed and applied by a growing list of various professional medical organizations around the world and has received support and assistance from companies that manufacture equipment used in Radiology.

Following upon the success of the Image Gently campaign, the American College of Radiology, the Radiological Society of North America, the American Association of Physicists in Medicine and the American Society of Radiologic Technologists have launched a similar campaign to address this issue in the adult population called Image Wisely.[221]

The World Health Organization and International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) of the United Nations have also been working in this area and have ongoing projects designed to broaden best practices and lower patient radiation dose.[222][223]

Prevalence

[edit]| Country | Value |

|---|---|

| 111.49 | |

| 64.35 | |

| 43.68 | |

| 42.64 | |

| 39.72 | |

| 39.28 | |

| 39.13 | |

| 38.18 | |

| 35.13 | |

| 34.71 | |

| 34.22 | |

| 28.64 | |

| 24.51 | |

| 24.27 | |

| 23.33 | |

| 19.14 | |

| 18.59 | |

| 18.22 | |

| 17.36 | |

| 17.28 | |

| 16.88 | |

| 16.77 | |

| 16.69 | |

| 15.76 | |

| 15.28 | |

| 15.00 | |

| 14.77 | |

| 13.48 | |

| 13.00 | |

| 9.53 | |

| 9.19 | |

| 5.83 | |

| 1.24 |

Use of CT has increased dramatically over the last two decades.[29] An estimated 72 million scans were performed in the United States in 2007,[30] accounting for close to half of the total per-capita dose rate from radiologic and nuclear medicine procedures.[225] Of the CT scans, six to eleven percent are done in children,[165] an increase of seven to eightfold from 1980.[164] Similar increases have been seen in Europe and Asia.[164] In Calgary, Canada, 12.1% of people who present to the emergency with an urgent complaint received a CT scan, most commonly either of the head or of the abdomen. The percentage who received CT, however, varied markedly by the emergency physician who saw them from 1.8% to 25%.[226] In the emergency department in the United States, CT or MRI imaging is done in 15% of people who present with injuries as of 2007 (up from 6% in 1998).[227]

Увеличение использования компьютерной томографии было наибольшим в двух областях: скрининг взрослых (скрининговая КТ легких у курильщиков, виртуальная колоноскопия, КТ-скрининг сердца и КТ всего тела у бессимптомных пациентов) и КТ-визуализация детей. Сокращение времени сканирования примерно до 1 секунды, устраняющее строгую необходимость оставаться неподвижным или находиться в седативном состоянии, является одной из основных причин значительного увеличения педиатрической популяции (особенно для диагностики аппендицита ). [145] По состоянию на 2007 год в США часть компьютерной томографии выполняется без необходимости. [167] По некоторым оценкам, это число составляет 30%. [165] Для этого есть ряд причин, в том числе: юридические проблемы, финансовые стимулы и желание общественности. [167] Например, некоторые здоровые люди охотно платят за компьютерную томографию всего тела в качестве скрининга . В этом случае совсем не очевидно, что выгоды перевешивают риски и затраты. Принятие решения о том, лечить ли инциденталомы и каким образом , является сложным, радиационное воздействие немаловажно, а деньги на сканирование включают в себя альтернативные издержки . [167]

Производители

[ редактировать ]Основными производителями устройств и оборудования для компьютерной томографии являются: [228]

GE Healthcare

GE Healthcare  Сименс Здоровье

Сименс Здоровье  Canon Medical Systems Corporation (ранее Toshiba Medical Systems)

Canon Medical Systems Corporation (ранее Toshiba Medical Systems)  Koninklijke Philips N.V.

Koninklijke Philips N.V.  Fujifilm Healthcare (ранее Hitachi Medical Systems)

Fujifilm Healthcare (ранее Hitachi Medical Systems)  Нойсофт Медицинские Системы

Нойсофт Медицинские Системы  Юнайтед Имиджинг

Юнайтед Имиджинг

Исследовать

[ редактировать ]Компьютерная томография с подсчетом фотонов — это метод компьютерной томографии, который в настоящее время находится в стадии разработки. [ на момент? ] В типичных компьютерных томографах используются детекторы, интегрирующие энергию; Фотоны измеряются как напряжение на конденсаторе, пропорциональное обнаруженному рентгеновскому излучению. Однако этот метод чувствителен к шуму и другим факторам, которые могут повлиять на линейность зависимости напряжения от интенсивности рентгеновского излучения. [229] Детекторы счета фотонов (PCD) по-прежнему подвержены влиянию шума, но он не меняет измеренное количество фотонов. PCD имеют несколько потенциальных преимуществ, включая улучшение отношения сигнала (и контрастности) к шуму, снижение доз, улучшение пространственного разрешения и за счет использования нескольких энергий различение нескольких контрастных агентов. [230] [231] PCD только недавно стали возможными в компьютерных томографах благодаря усовершенствованиям в технологиях детекторов, которые могут справиться с объемом и скоростью необходимых данных. По состоянию на февраль 2016 года КТ для подсчета фотонов используется на трех объектах. [232] Некоторые ранние исследования показали, что потенциал снижения дозы КТ с подсчетом фотонов для визуализации молочной железы является очень многообещающим. [233] Ввиду недавних данных о высоких кумулятивных дозах, получаемых пациентами при повторных компьютерных томографиях, возникла необходимость в разработке технологий и методов сканирования, которые снижают дозы ионизирующего излучения, получаемые пациентами, до уровней субмиллизивертов ( субмЗв в литературе) во время компьютерной томографии. процесс, цель, которая затянулась. [234] [155] [156] [157]

См. также

[ редактировать ]Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ «КТ – Клиника Мэйо» . mayoclinic.org. Архивировано из оригинала 15 октября 2016 года . Проверено 20 октября 2016 г.

- ^ Гермена С., Янг М. (2022 г.), «Процедуры получения изображений компьютерной томографии» , StatPearls , Остров сокровищ, Флорида: StatPearls Publishing, PMID 34662062 , получено 24 ноября 2023 г.

- ^ «Страница пациента» . ARRT – Американский регистр радиологических технологов . Архивировано из оригинала 9 ноября 2014 года.

- ^ «Информация об индивидуальной государственной лицензии» . Американское общество радиологических технологов. Архивировано из оригинала 18 июля 2013 года . Проверено 19 июля 2013 г.

- ^ «Нобелевская премия по физиологии и медицине 1979 года» . NobelPrize.org . Проверено 10 августа 2019 г.

- ^ «Нобелевская премия по физиологии и медицине 1979 года» . NobelPrize.org . Проверено 28 октября 2023 г.

- ^ Терьер Ф, Гроссхольц М, Беккер КД (06 декабря 2012 г.). Спиральная КТ брюшной полости . Springer Science & Business Media. п. 4. ISBN 978-3-642-56976-0 .

- ^ Фишман ЭК, Джеффри РБ (1995). Спиральная КТ: принципы, методы и клиническое применение . Рэйвен Пресс. ISBN 978-0-7817-0218-8 .

- ^ Се Дж (2003). Компьютерная томография: принципы, конструкция, артефакты и последние достижения . СПАЙ Пресс. п. 265. ИСБН 978-0-8194-4425-7 .

- ^ Стреруп Дж. (02.01.2020). Компьютерная томография сердечно-сосудистой системы . Издательство Оксфордского университета. ISBN 978-0-19-880927-2 .

- ^ Талисетти А., Джелнин В., Руис С., Джон Э., Бенедетти Э., Теста Г., Холтерман А.С., Холтерман М.Дж. (декабрь 2004 г.). «Электронно-лучевая компьютерная томография — ценный и безопасный инструмент визуализации для педиатрических хирургических пациентов». Журнал детской хирургии . 39 (12): 1859–1862. дои : 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.08.024 . ISSN 1531-5037 . ПМИД 15616951 .

- ^ Рецкий М. (31 июля 2008 г.). «Электронно-лучевая компьютерная томография: проблемы и возможности» . Процессия по физике . 1 (1): 149–154. Бибкод : 2008PhPro...1..149R . дои : 10.1016/j.phpro.2008.07.090 .

- ^ Джонсон Т., Финк С., Шенберг С.О., Райзер М.Ф. (18 января 2011 г.). Двухэнергетическая КТ в клинической практике . Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-642-01740-7 .

- ^ Джонсон Т., Финк С., Шёнберг С.О., Райзер М.Ф. (18 января 2011 г.). Двухэнергетическая КТ в клинической практике . Springer Science & Business Media. п. 8. ISBN 978-3-642-01740-7 .

- ^ Карраскоса П.М., Кюри Р.К., Гарсиа М.Ю., Лейпциг Х.А. (03.10.2015). Двухэнергетическая КТ в сердечно-сосудистой визуализации . Спрингер. ISBN 978-3-319-21227-2 .

- ^ Шмидт Б., Флор Т. (01.11.2020). «Принципы и применение КТ с двумя источниками» . Физика Медика . 125 лет рентгена. 79 : 36–46. дои : 10.1016/j.ejmp.2020.10.014 . ISSN 1120-1797 . ПМИД 33115699 . S2CID 226056088 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Зейденстикер PR, Хофманн Л.К. (24 мая 2008 г.). КТ с двумя источниками . Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-540-77602-4 .

- ^ Шмидт Б., Флор Т. (01.11.2020). «Принципы и применение КТ с двумя источниками» . Physica Medica: Европейский журнал медицинской физики . 79 : 36–46. дои : 10.1016/j.ejmp.2020.10.014 . ISSN 1120-1797 . ПМИД 33115699 . S2CID 226056088 .

- ^ Махмуд У, Хорват Н., Хорват Й.В., Райан Д., Гао Й., Каролло Г., ДеОкампо Р., До РК, Кац С., Герст С., Шмидтлейн Ч.Р., Дауэр Л., Эрди Й., Маннелли Л. (май 2018 г.). «Двуэнергетическая КТ с быстрым переключением кВп: ценность реконструированных двухэнергетических КТ-изображений и оценка дозы на орган при многофазных КТ печени» . Европейский журнал радиологии . 102 : 102–108. дои : 10.1016/j.ejrad.2018.02.022 . ISSN 0720-048X . ПМЦ 5918634 . ПМИД 29685522 .

- ^ Джонсон Т.Р. (ноябрь 2012 г.). «Двуэнергетический трансформатор тока: общие принципы» . Американский журнал рентгенологии . 199 (5_добавление): S3 – S8. дои : 10.2214/AJR.12.9116 . ISSN 0361-803X . ПМИД 23097165 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Виттсак Х.Дж., Вольшлегер А., Ритцль Э., Кляйзер Р., Конен М., Зейтц Р., Мёддер Ю (01.01.2008). «КТ-перфузионная визуализация человеческого мозга: расширенный анализ деконволюции с использованием циркулянтного разложения по сингулярным значениям». Компьютеризированная медицинская визуализация и графика . 32 (1): 67–77. doi : 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2007.09.004 . ISSN 0895-6111 . ПМИД 18029143 .

- ^ Уильямс М., Ньюби Д. (1 августа 2016 г.). «КТ-визуализация перфузии миокарда: современное состояние и направления на будущее». Клиническая радиология . 71 (8): 739–749. дои : 10.1016/j.crad.2016.03.006 . ISSN 0009-9260 . ПМИД 27091433 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Донахью Дж., Винтермарк М. (01 февраля 2015 г.). «Перфузионная КТ и визуализация острого инсульта: основы, применение и обзор литературы». Журнал нейрорадиологии . 42 (1): 21–29. дои : 10.1016/j.neurad.2014.11.003 . ISSN 0150-9861 . ПМИД 25636991 .

- ^ Блоджетт Т.М., Мельцер CC, Таунсенд Д.В. (февраль 2007 г.). «ПЭТ/КТ: форма и функции» . Радиология . 242 (2): 360–385. дои : 10.1148/radiol.2422051113 . ISSN 0033-8419 . ПМИД 17255408 .

- ^ Черник И, Дизендорф Э, Баумерт Б.Г., Райнер Б., Бургер С., Дэвис Дж., Лютольф У.М., Штайнерт Х.К., Фон Шультесс Г.К. (ноябрь 2003 г.). «Планирование лучевого лечения с использованием интегрированной позитронно-эмиссионной и компьютерной томографии (ПЭТ/КТ): технико-экономическое обоснование» . Международный журнал радиационной онкологии, биологии, физики . 57 (3): 853–863. дои : 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00346-8 . ISSN 0360-3016 . ПМИД 14529793 .

- ^ Уль-Хассан Ф., Кук Дж.Дж. (август 2012 г.). «ПЭТ/КТ в онкологии» . Клиническая медицина . 12 (4): 368–372. doi : 10.7861/clinmedicine.12-4-368 . ISSN 1470-2118 . ПМЦ 4952129 . ПМИД 22930885 .

- ^ Карри Т.С., Дауди Дж.Э., Марри Р.К. (1990). Физика диагностической радиологии Кристенсена . Липпинкотт Уильямс и Уилкинс. п. 289. ИСБН 978-0-8121-1310-5 .

- ^ «КТ-скрининг» (PDF) . hps.org . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 13 октября 2016 года . Проверено 1 мая 2018 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Смит-Биндман Р., Липсон Дж., Маркус Р., Ким К.П., Махеш М., Гулд Р., Беррингтон де Гонсалес А., Мильоретти Д.Л. (декабрь 2009 г.). «Доза радиации, связанная с обычными компьютерными томографическими исследованиями, и связанный с ней риск развития рака на протяжении всей жизни» . Архив внутренней медицины . 169 (22): 2078–2086. doi : 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.427 . ПМЦ 4635397 . ПМИД 20008690 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Беррингтон де Гонсалес А., Махеш М., Ким К.П., Бхаргаван М., Льюис Р., Меттлер Ф., Лэнд С. (декабрь 2009 г.). «Прогнозируемый риск рака по данным компьютерной томографии, выполненной в США в 2007 году» . Арх. Стажер. Мед . 169 (22): 2071–7. doi : 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.440 . ПМК 6276814 . ПМИД 20008689 .

- ^ «Опасности компьютерной томографии и рентгеновских лучей – отчеты потребителей» . Проверено 16 мая 2018 г.

- ^ Американская академия хирургов-ортопедов, Американский колледж врачей скорой помощи, UMBC (20 марта 2017 г.). Транспорт для интенсивной терапии . Джонс и Бартлетт Обучение. п. 389. ИСБН 978-1-284-04099-9 .

- ^ Галлоуэй Р. младший (2015). «Введение и исторические перспективы хирургии под визуальным контролем». В Голби А.Дж. (ред.). Нейрохирургия под визуальным контролем . Амстердам: Эльзевир. стр. 3–4. ISBN 978-0-12-800870-6 .

- ^ Це В., Калани М., Адлер-младший (2015). «Методы стереотаксической локализации». В Чин Л.С., Регина В.Ф. (ред.). Принципы и практика стереотаксической радиохирургии . Нью-Йорк: Спрингер. п. 28. ISBN 978-0-387-71070-9 .

- ^ Салех Х., Кассас Б. (2015). «Разработка стереотаксических рамок для краниального лечения» . Бенедикт С.Х., Шлезингер DJ, Гетч С.Дж., Кавана Б.Д. (ред.). Стереотаксическая радиохирургия и стереотаксическая лучевая терапия тела . Бока-Ратон: CRC Press. стр. 156–159. ISBN 978-1-4398-4198-3 .

- ^ Хан Ф.Р., Хендерсон Дж.М. (2013). «Хирургические методы глубокой стимуляции мозга». В Лозано А.М., Халлет М. (ред.). Стимуляция мозга . Справочник по клинической неврологии. Том. 116. Амстердам: Эльзевир. стр. 28–30. дои : 10.1016/B978-0-444-53497-2.00003-6 . ISBN 978-0-444-53497-2 . ПМИД 24112882 .

- ^ Арль Дж (2009). «Развитие классики: аппарат Тодда-Уэллса, стереотаксические рамки BRW и CRW». В Лозано А.М., Гильденберг П.Л., Таскер Р.Р. (ред.). Учебник стереотаксической и функциональной нейрохирургии . Берлин: Springer-Verlag. стр. 456–461. ISBN 978-3-540-69959-0 .

- ^ Браун Р.А., Нельсон Дж.А. (июнь 2012 г.). «Изобретение N-локализатора для стереотаксической нейрохирургии и его использование в стереотаксической системе Брауна-Робертса-Уэллса». Нейрохирургия . 70 (2 дополнительных оперативника): 173–176. дои : 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318246a4f7 . ПМИД 22186842 . S2CID 36350612 .

- ^ Дэниел Дж. Дешлер, Джозеф Зенга. «Оценка массы шеи у взрослых» . До настоящего времени . Последнее обновление этой темы: 4 декабря 2017 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Бин Саидан М., Альджохани И.М., Хушаим А.О., Бухари С.К., Эльнаас С.Т. (2016). «Компьютерная томография щитовидной железы: графический обзор различных патологий» . Взгляды на визуализацию . 7 (4): 601–617. дои : 10.1007/s13244-016-0506-5 . ISSN 1869-4101 . ПМЦ 4956631 . ПМИД 27271508 .

- ^ Компьютерная томография легких . Шпрингер Берлин Гейдельберг. 2007. стр. 40, 47. ISBN. 978-3-642-39518-5 .

- ^ КТ легких высокого разрешения . Липпинкотт Уильямс и Уилкинс. 2009. стр. 81, 568. ISBN. 978-0-7817-6909-9 .

- ^ Мартинес-Хименес С., Росадо-де-Кристенсон М.Л., Картер Б.В. (22 июля 2017 г.). Специализированная визуализация: электронная книга HRCT легких . Elsevier Науки о здоровье. ISBN 978-0-323-52495-7 .

- ^ Юранга Вираккоди. «Утолщение бронхиальной стенки» . Радиопедия . Архивировано из оригинала 06 января 2018 г. Проверено 05 января 2018 г.

- ^ Винер Р.С., Гулд М.К., Волошин С., Шварц Л.М., Кларк Дж.А. (2012). « Что вы имеете в виду под пятном?»: Качественный анализ реакций пациентов на дискуссии с врачами по поводу легочных узелков» . Грудь . 143 (3): 672–677. дои : 10.1378/сундук.12-1095 . ПМК 3590883 . ПМИД 22814873 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Американский колледж торакальных врачей , Американское торакальное общество (сентябрь 2013 г.), «Пять вопросов, которые должны задать врачи и пациенты» , «Выбирая мудро» , Американский колледж торакальных врачей и Американское торакальное общество, заархивировано из оригинала 3 ноября 2013 г. , получено 6 января 2013 г. , который цитирует

- МакМахон Х., Остин Дж.Х., Гамсу Дж., Херольд СиДжей, Джетт Дж.Р., Найдич Д.П., Патц Э.Ф., Свенсен С.Дж. (2005). «Руководство по лечению небольших легочных узлов, обнаруженных при компьютерной томографии: заявление Общества Флейшнера1». Радиология . 237 (2): 395–400. дои : 10.1148/radiol.2372041887 . ПМИД 16244247 . S2CID 14498160 .

- Гулд М.К., Флетчер Дж., Яннеттони М.Д., Линч В.Р., Мидтун Д.Э., Найдич Д.П., Ост Д.Э. (2007). «Обследование пациентов с легочными узлами: когда возникает рак легких?» *. Грудь . 132 (3_добавление): 108S–130S. дои : 10.1378/сундук.07-1353 . ПМИД 17873164 . S2CID 16449420 .

- Смит-Биндман Р., Липсон Дж., Маркус Р., Ким К.П., Махеш М., Гулд Р., Беррингтон де Гонсалес А., Мильоретти Д.Л. (2009). «Доза радиации, связанная с обычными компьютерными томографическими исследованиями, и связанный с ней риск развития рака в течение всей жизни» . Архив внутренней медицины . 169 (22): 2078–2086. doi : 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.427 . ПМЦ 4635397 . ПМИД 20008690 .

- Винер Р.С., Гулд М.К., Волошин С., Шварц Л.М., Кларк Дж.А. (2012). « Что вы имеете в виду под пятном?»: Качественный анализ реакций пациентов на дискуссии с врачами по поводу легочных узелков» . Грудь . 143 (3): 672–677. дои : 10.1378/сундук.12-1095 . ПМК 3590883 . ПМИД 22814873 .

- ^ Макдермотт М., Джейкобс Т., Моргенштерн Л. (01.01.2017), Вейдикс Э.Ф., Крамер А.Х. (ред.), «Глава 10 – Неотложная помощь при остром ишемическом инсульте», Справочник по клинической неврологии , Неврология интенсивной терапии, часть I, 140 , Elsevier: 153–176, doi : 10.1016/b978-0-444-63600-3.00010-6 , PMID 28187798

- ^ «Компьютерная томографическая ангиография (КТА)» . www.hopkinsmedicine.org . 19 ноября 2019 года . Проверено 21 марта 2021 г.

- ^ Земан Р.К., Сильверман П.М., Вьеко П.Т., Костелло П. (1 ноября 1995 г.). «КТ-ангиография» . Американский журнал рентгенологии . 165 (5): 1079–1088. дои : 10.2214/ajr.165.5.7572481 . ISSN 0361-803X . ПМИД 7572481 .

- ^ Рамальо Дж., Кастильо М. (31 марта 2014 г.). Сосудистая визуализация центральной нервной системы: физические принципы, клиническое применение и новые методы . Джон Уайли и сыновья. п. 69. ИСБН 978-1-118-18875-0 .

- ^ «КТ сердца – НХЛБИ, НИЗ» . www.nhlbi.nih.gov . Архивировано из оригинала 1 декабря 2017 г. Проверено 22 ноября 2017 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Вихманн Дж.Л. «КТ сердца | Справочная статья по радиологии | Radiopaedia.org» . Radiopaedia.org . Архивировано из оригинала 1 декабря 2017 г. Проверено 22 ноября 2017 г.

- ^ Марван М., Ахенбах С. (февраль 2016 г.). «Роль КТ сердца перед транскатетерной имплантацией аортального клапана (TAVI)». Текущие кардиологические отчеты . 18 (2): 21. дои : 10.1007/s11886-015-0696-3 . ISSN 1534-3170 . ПМИД 26820560 . S2CID 41535442 .

- ^ Мосс А.Дж., Двек М.Р., Драйсбах Дж.Г., Уильямс М.К., Мак С.М., Картлидж Т., Никол ЭД, Морган-Хьюз Г.Дж. (01.11.2016). «Дополнительная роль КТ сердца в оценке дисфункции замещения аортального клапана» . Открытое сердце . 3 (2): e000494. doi : 10.1136/openhrt-2016-000494 . ISSN 2053-3624 . ПМК 5093391 . ПМИД 27843568 .

- ^ Терио-Лозье П., Спазиано М., Вакерисо Б., Бютье Дж., Мартуччи Дж., Пьяцца Н. (сентябрь 2015 г.). «Компьютерная томография структурных заболеваний сердца и вмешательств» . Обзор интервенционной кардиологии . 10 (3): 149–154. дои : 10.15420/ICR.2015.10.03.149 . ISSN 1756-1477 . ПМЦ 5808729 . ПМИД 29588693 .

- ^ Пассариелло Р. (30 марта 2006 г.). Многодетекторная КТ-ангиография . Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-540-26984-7 .

- ^ Радиологическое общество Северной Америки, Американский колледж радиологии. «Коронарная компьютерная томографическая ангиография (ККТА)» . www.radiologyinfo.org . Проверено 19 марта 2021 г.

- ^ «Сканирование сердца (сканирование коронарного кальция)» . Клиника Майо. Архивировано из оригинала 5 сентября 2015 года . Проверено 9 августа 2015 г.

- ^ ван дер Бейл Н., Джоемай Р.М., Гелейнс Дж., Бакс Дж.Дж., Шуйф Дж.Д., де Роос А., Крофт Л.Дж. (2010). «Оценка уровня кальция в коронарной артерии Агатстона с использованием КТ-коронарографии с контрастированием». Американский журнал рентгенологии . 195 (6): 1299–1305. дои : 10.2214/AJR.09.3734 . ISSN 0361-803X . ПМИД 21098187 .

- ^ Вукичевич М., Мосадык Б., Мин Дж.К., Литтл Ш.Х. (февраль 2017 г.). «Сердечная 3D-печать и ее будущие направления» . JACC: Сердечно-сосудистая визуализация . 10 (2): 171–184. дои : 10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.12.001 . ISSN 1876-7591 . ПМЦ 5664227 . ПМИД 28183437 .

- ^ Ван Д.Д., Энг М., Гринбаум А., Майерс Э., Форбс М., Пантелик М., Сонг Т., Нельсон С., Дивайн Дж., Тейлор А., Вайман Дж., Герреро М., Ледерман Р.Дж., Паоне Дж., О'Нил В. (2016). «Инновационное лечение митрального клапана с помощью 3D-визуализации в клинике Генри Форда» . JACC: Сердечно-сосудистая визуализация . 9 (11): 1349–1352. дои : 10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.01.017 . ПМК 5106323 . ПМИД 27209112 . Архивировано из оригинала 1 декабря 2017 г. Проверено 22 ноября 2017 г.

- ^ Ван Д.Д., Энг М., Гринбаум А., Майерс Э., Форбс М., Пантелик М., Сонг Т., Нельсон С., Дивайн Дж. (ноябрь 2016 г.). «Прогнозирование обструкции LVOT после TMVR» . JACC: Сердечно-сосудистая визуализация . 9 (11): 1349–1352. дои : 10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.01.017 . ISSN 1876-7591 . ПМК 5106323 . ПМИД 27209112 .

- ^ Джейкобс С., Грюнерт Р., Мор Ф.В., Фальк В. (февраль 2008 г.). «3D-изображение сердечных структур с использованием 3D-моделей сердца для планирования кардиохирургии: предварительное исследование» . Интерактивная сердечно-сосудистая и торакальная хирургия . 7 (1): 6–9. дои : 10.1510/icvts.2007.156588 . ISSN 1569-9285 . ПМИД 17925319 .

- ^ Фурукава А, Саотоме Т, Ямасаки М, Маэда К, Нитта Н, Такахаши М, Цудзикава Т, Фудзияма Ю, Мурата К, Сакамото Т (01 мая 2004 г.). «Поперечное изображение при болезни Крона» . Радиографика . 24 (3): 689–702. дои : 10.1148/rg.243035120 . ISSN 0271-5333 . ПМИД 15143222 .

- ^ КТ острого отдела живота . Шпрингер Берлин Гейдельберг. 2011. с. 37. ИСБН 978-3-540-89232-8 .

- ^ Джей П. Хайкен, Дуглас С. Кац (2014). «Неотложная радиология брюшной полости и таза: визуализация нетравматического и травматического острого отдела живота» . В Й. Ходлере, Р.А. Кубик-Хухе, Г.К. фон Шультессе, Гл. Л. Золликофер (ред.). Заболевания органов брюшной полости и таза . Спрингер Милан. п. 3. ISBN 978-88-470-5659-6 .

- ^ Сколарикос А., Неисиус А., Петрик А., Сомани Б., Томас К., Гамбаро Г. (март 2022 г.). Рекомендации ЕАУ по мочекаменной болезни . Амстердам: Европейская ассоциация урологов . ISBN 978-94-92671-16-5 .

- ^ Миллер О.Ф., Кейн CJ (сентябрь 1999 г.). «Время прохождения камня при наблюдаемых камнях мочеточника: руководство по обучению пациентов». Журнал урологии . 162 (3 Часть 1): 688–691. дои : 10.1097/00005392-199909010-00014 . ПМИД 10458343 .

- ^ «Перелом лодыжки» . orthinfo.aaos.org . Американская ассоциация хирургов-ортопедов. Архивировано из оригинала 30 мая 2010 года . Проверено 30 мая 2010 г.

- ^ Баквалтер, Кеннет А. и др. (11 сентября 2000 г.). «Визуализация скелетно-мышечной системы с помощью многосрезовой КТ». Американский журнал рентгенологии . 176 (4): 979–986. дои : 10.2214/ajr.176.4.1760979 . ПМИД 11264094 .

- ^ Рамон А., Бом-Сигранд А., Поттечер П., Ришетт П., Майльферт Дж.Ф., Девильерс Х., Орнетти П. (01.03.2018). «Роль двухэнергетической КТ в диагностике и наблюдении за подагрой: систематический анализ литературы». Клиническая ревматология . 37 (3): 587–595. дои : 10.1007/s10067-017-3976-z . ISSN 0770-3198 . ПМИД 29350330 . S2CID 3686099 .

- ^ Кивени Т.М. (март 2010 г.). «Биомеханическая компьютерная томография - неинвазивный анализ прочности костей с использованием изображений клинической компьютерной томографии». Анналы Нью-Йоркской академии наук . 1192 (1): 57–65. Бибкод : 2010NYASA1192...57K . дои : 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05348.x . ISSN 1749-6632 . ПМИД 20392218 . S2CID 24132358 .

- ^ Барбер А., Тоцци Г., Пани М. (07.03.2019). Биомеханика на основе компьютерной томографии . Фронтирс Медиа С.А. п. 20. ISBN 978-2-88945-780-9 .

- ^ Эванс Л.М., Маргеттс Л., Казаленьо В., Левер Л.М., Бушелл Дж., Лоу Т., Уоллворк А., Янг П., Линдеманн А. (28 мая 2015 г.). «Нестационарный термический конечно-элементный анализ моноблока CFC–Cu ИТЭР с использованием данных рентгеновской томографии» . Термоядерная инженерия и дизайн . 100 : 100–111. Бибкод : 2015FusED.100..100E . дои : 10.1016/j.fusengdes.2015.04.048 . hdl : 10871/17772 . Архивировано из оригинала 16 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Пейн, Эмма Мари (2012). «Методы визуализации в консервации» (PDF) . Журнал консервации и музейных исследований . 10 (2): 17–29. дои : 10.5334/jcms.1021201 .

- ^ П. Бабахейдарян, Д. Кастанон (2018). «Совместная реконструкция и классификация материалов в спектральной КТ». Гринберг Дж.А., Гем М.Е., Нейфельд М.А., Ашок А. (ред.). Обнаружение аномалий и визуализация с помощью рентгеновских лучей (ADIX) III . п. 12. дои : 10.1117/12.2309663 . ISBN 978-1-5106-1775-9 . S2CID 65469251 .

- ^ П. Джин, Э. Ханеда, К. Д. Зауэр, К. А. Бауман (июнь 2012 г.). «Алгоритм трехмерной многосрезовой спиральной компьютерной томографии на основе модели для приложений транспортной безопасности» (PDF) . Вторая международная конференция по формированию изображений в рентгеновской компьютерной томографии . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 11 апреля 2015 г. Проверено 5 апреля 2015 г.

- ^ П. Джин, Э. Ханеда, К. А. Бауман (ноябрь 2012 г.). «Неявные априорные модели Гиббса для томографической реконструкции» (PDF) . Сигналы, системы и компьютеры (ASILOMAR), Протокол сорок шестой конференции Asilomar 2012 г., посвященной . IEEE. стр. 613–636. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 11 апреля 2015 г. Проверено 5 апреля 2015 г.

- ^ С. Дж. Киснер, П. Джин, К. А. Бауман, К. Д. Зауэр, В. Гармс, Т. Гейбл, С. О, М. Мерцбахер, С. Скаттер (октябрь 2013 г.). «Инновационное взвешивание данных для итеративной реконструкции в спиральном компьютерном сканере багажа» (PDF) . Технологии безопасности (ICCST), 2013 г. 47-я Международная Карнаханская конференция по . IEEE. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 10 апреля 2015 г. Проверено 5 апреля 2015 г.

- ^ Мегерби, Н., Флиттон, Г.Т., Брекон, Т.П. (сентябрь 2010 г.). «Подход на основе классификатора для обнаружения потенциальных угроз при досмотре багажа на основе компьютерной томографии» (PDF) . Учеб. Международная конференция по обработке изображений . IEEE. стр. 1833–1836. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.188.5206 . дои : 10.1109/ICIP.2010.5653676 . ISBN 978-1-4244-7992-4 . S2CID 3679917 . Проверено 5 ноября 2013 г. [ постоянная мертвая ссылка ]

- ^ Мегерби Н., Хан Дж., Флиттон Г.Т., Брекон Т.П. (сентябрь 2012 г.). «Сравнение подходов к классификации для обнаружения угроз при досмотре багажа на основе компьютерной томографии» (PDF) . Учеб. Международная конференция по обработке изображений . IEEE. стр. 3109–3112. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.391.2695 . дои : 10.1109/ICIP.2012.6467558 . ISBN 978-1-4673-2533-2 . S2CID 6924816 . Проверено 5 ноября 2013 г. [ постоянная мертвая ссылка ]

- ^ Флиттон, Г.Т., Брекон, Т.П., Мегерби, Н. (сентябрь 2013 г.). «Сравнение трехмерных дескрипторов точек интереса с применением к обнаружению объектов багажа в аэропорту на сложных компьютерных изображениях» (PDF) . Распознавание образов . 46 (9): 2420–2436. Бибкод : 2013PatRe..46.2420F . дои : 10.1016/j.patcog.2013.02.008 . hdl : 1826/15213 . S2CID 3687379 . Проверено 5 ноября 2013 г. [ постоянная мертвая ссылка ]

- ^ «Лаборатория | О Чикю | Глубоководное научное буровое судно ЧИКЮ» . www.jamstec.go.jp . Проверено 24 октября 2019 г.

- ^ Тонай С., Кубо Ю., Цанг М.Ю., Боуден С., Иде К., Хиросе Т., Камия Н., Ямамото Ю., Ян К., Ямада Ю., Мороно Ю. (2019). «Новый метод контроля качества геологических кернов с помощью рентгеновской компьютерной томографии: применение в экспедиции IODP 370» . Границы в науках о Земле . 7 . дои : 10.3389/feart.2019.00117 . hdl : 2164/12811 . ISSN 2296-6463 . S2CID 171394807 .

- ^ Силз В.Б., Паркер К.С., Сигал М., Тов Е., Шор П., Порат Ю. (2016). «От порчи к открытию через виртуальное разворачивание: Чтение свитка из Эн-Геди» . Достижения науки . 2 (9): e1601247. Бибкод : 2016SciA....2E1247S . дои : 10.1126/sciadv.1601247 . ISSN 2375-2548 . ПМК 5031465 . ПМИД 27679821 .

- ^ Кастелланос С (2 марта 2021 г.). «Письмо, запечатанное на протяжении веков, было прочитано, даже не открывая его» . Уолл Стрит Джорнал . Проверено 2 марта 2021 г.

- ^ Дамброджио Дж., Гассаи А., Стараза Смит Д., Джексон Х., Демейн М.Л. (2 марта 2021 г.). «Открытие истории посредством автоматического виртуального развертывания запечатанных документов, полученных с помощью рентгеновской микротомографии» . Природные коммуникации . 12 (1): 1184. Бибкод : 2021NatCo..12.1184D . дои : 10.1038/s41467-021-21326-w . ПМЦ 7925573 . ПМИД 33654094 .

- ^ Расширенные методы документации при изучении коринфской чернофигурной росписи ваз на YouTube, демонстрирующие компьютерную томографию и выкатывание арибалла № G26, археологическая коллекция, Университет Граца . Видео было визуализировано с использованием GigaMesh Software Framework , см. дои:10.11588/heidok.00025189 . Карл С., Байер П., Мара Х. , Мартон А. (2019), «Передовые методы документирования при изучении коринфской чернофигурной вазовой живописи» (PDF) , Материалы 23-й Международной конференции по культурному наследию и новым технологиям (CHNT23) , Вена, Австрия, ISBN 978-3-200-06576-5 , получено 9 января 2020 г.

- ^ «КТ ДЛЯ АРТ» . НИКАС . Проверено 4 июля 2023 г.

- ^ Бульке Й.В., Бун М., Акер Й.В., Хооребеке Л.В. (октябрь 2009 г.). «Трёхмерная рентгеновская визуализация и анализ грибов на древесине и в ней» . Микроскопия и микроанализ . 15 (5): 395–402. Бибкод : 2009MiMic..15..395V . дои : 10.1017/S1431927609990419 . hdl : 1854/LU-675607 . ISSN 1435-8115 . ПМИД 19709462 . S2CID 15637414 .

- ^ Голдман Л.В. (2008). «Принципы КТ: многосрезовая КТ» . Журнал технологий ядерной медицины . 36 (2): 57–68. дои : 10.2967/jnmt.107.044826 . ISSN 0091-4916 . ПМИД 18483143 .