Соломонские острова

Соломонские острова Соломон Элан ( Пейн ) | |

|---|---|

| Девиз: «Ведение - это служить» | |

| Гимн: « Боже, спасти наши Соломонские острова » [ 1 ] Duration: 1 minute and 4 seconds. | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Honiara 9°25′55″S 159°57′20″E / 9.43194°S 159.95556°E |

| Official languages | |

| Ethnic groups (2016) |

|

| Religion (2016)[2] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Solomon Islander Solomonese |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Charles III |

| David Tiva Kapu | |

| Jeremiah Manele | |

| Legislature | National Parliament |

| Independence | |

• from the United Kingdom | 7 July 1978 |

| Area | |

• Total | 28,896[3] km2 (11,157 sq mi) (139th) |

• Water (%) | 3.2% |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | 734,887 (167th) |

• 2019 census | 721,956 |

• Density | 24.2/km2 (62.7/sq mi) (200th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2013) | medium inequality |

| HDI (2022) | medium (156th) |

| Currency | Solomon Islands dollar (SBD) |

| Time zone | UTC+11 (Solomon Islands Time) |

• Summer (DST) | UTCdoes not have (Solomon Islands does not have an associated daylight saving time) |

| Drives on | left |

| Calling code | +677 |

| ISO 3166 code | SB |

| Internet TLD | .sb |

Соломонские острова , [ 7 ] также известен просто как Соломонс , [ 8 ] является страной, состоящей из шести крупных островов и более 900 небольших островов в Меланезии , часть Океании , к северо -востоку от Австралии. Он прямо примыкает к Папуа -Новой Гвинеи на западе, Австралии на юго -запад, Новой Каледонии и Вануату на юго -востоке, Фиджи , Уоллис и Футуне и Тувалу на востоке, а также Науру и федеративные штаты Микронезия на севере. Он имеет общую площадь 28 896 квадратных километров (11 157 кв. МИ), [ 9 ] и население 734 887, согласно официальным оценкам за середину 2023 года. [ 10 ] Его столица и крупнейший город, Хониара , расположен на крупнейшем острове, Гуадалканал . Страна получает свое название из более широкой области архипелага Соломонских островов , который представляет собой коллекцию меланезийских островов, в которую также включают автономный регион Бугенвилля (в настоящее время часть Папуа -Новой Гвинеи ), но исключает острова Санта -Круз .

The islands have been settled since at least some time between 30,000 and 28,800 BC, with later waves of migrants, notably the Lapita people, mixing and producing the modern indigenous Solomon Islanders population. In 1568, the Spanish navigator Álvaro de Mendaña was the first European to visit them.[11] Though not named by Mendaña, it is believed that the islands were called "the Solomons" by those who later received word of his voyage and mapped his discovery.[12] Mendaña returned decades later, in 1595, and another Spanish expedition, led by Portuguese navigator Pedro Fernandes de Queirós, visited the Solomons in 1606.

In June 1893, Captain Herbert Gibson of HMS Curacoa declared the southern Solomon Islands a British protectorate.[13][14] During World War II, the Solomon Islands campaign (1942–1945) saw fierce fighting between the United States, British Imperial forces, and the Empire of Japan, including the Battle of Guadalcanal.

The official name of the then-British administration was changed from the "British Solomon Islands Protectorate" to "The Solomon Islands" in 1975, and self-government was achieved the following year. Independence was obtained, and the name changed to just "Solomon Islands" (without the definite article), in 1978. At independence, Solomon Islands became a constitutional monarchy. The King of Solomon Islands is Charles III, who is represented in the country by a governor-general appointed on the advice of the prime minister.

Name

[edit]In 1568, the Spanish navigator Álvaro de Mendaña was the first European to visit the Solomon Islands archipelago but did not name the archipelago at that time, only certain individual islands. Though not named by Mendaña, the islands were subsequently referred to as Islas Salomón (Solomon Islands) by others following reports of his voyage optimistically conflated with stories of the wealthy biblical King Solomon, believing them to be the Bible-mentioned city of Ophir.[11][15][16] During most of the colonial period, the territory's official name was the "British Solomon Islands Protectorate" until independence in 1978, when it was changed to "Solomon Islands" as defined in the Constitution of Solomon Islands and as a Commonwealth realm under this name.[17][18]

The definite article, "the", has not been part of the country's official name since independence but remains for all references to the area pre-independence and is sometimes used, both within and outside the country. Colloquially, the islands are referred to simply as "the Solomons".[8]

History

[edit]Prehistory

[edit]

The Solomons were first settled by people coming from the Bismarck Islands and New Guinea during the Pleistocene era c. 30,000–28,000 BC, based on archaeological evidence found at Kilu Cave on Buka Island in the Autonomous Region of Bougainville, Papua New Guinea.[19][20] At this point sea levels were lower and Buka and Bougainville were physically joined to the southern Solomons in one landmass ("Greater Bougainville"), though it is unclear precisely how far south these early settlers spread as no other archaeological sites from this period have been found.[19] As sea levels rose as the Ice Age ended c. 4000–3500 BC, the Greater Bougainville landmass split into the numerous islands that exist today.[19][21] Evidence of later human settlements dating to c. 4500–2500 BC have been found at Poha Cave and Vatuluma Posovi Cave on Guadalcanal.[19] The ethnic identity of these early peoples is unclear, though it is thought that the speakers of the Central Solomon languages (a self-contained language family unrelated to other languages spoken in the Solomons) likely represent the descendants of these earlier settlers.

From c. 1200–800 BC Austronesian Lapita people began arriving from the Bismarcks with their characteristic ceramics.[19][22] Evidence for their presence has been found across the Solomon archipelago, as well at the Santa Cruz Islands in the south-east, with different islands being settled at different times.[19] Linguistic and genetic evidence suggests that the Lapita people "leap-frogged" the already inhabited main Solomon Islands and settled first on the Santa Cruz group, with later back-migrations bringing their culture to the main group.[23][24] These peoples mixed with the native Solomon Islanders and over time their languages became dominant, with most of the 60–70 languages spoken there belonging to the Oceanic branch of the Austronesian language family.[25] Then, as now, communities tended to exist in small villages practising subsistence agriculture, though extensive inter-island trade networks existed.[19] Numerous ancient burial sites and other evidence of permanent settlements have been found from the period AD 1000–1500 throughout the islands, one of the most prominent examples being the Roviana cultural complex centred on the islands off the southern coast of New Georgia, where a large number of megalithic shrines and other structures were constructed in the 13th century.[26] The people of Solomon Islands were notorious for headhunting and cannibalism before the arrival of the Europeans.[27][28]

Arrival of Europeans (1568–1886)

[edit]

The first European to visit the islands was the Spanish navigator Álvaro de Mendaña de Neira, sailing from Peru in 1568.[29] Landing on Santa Isabel on 7 February, Mendaña explored several of the other islands including Makira, Guadalcanal and Malaita.[29][30][31] Relations with the native Solomon Islanders were initially cordial, although they often soured as time went by.[29] As a result, Mendaña returned to Peru in August 1568.[29] He returned to the Solomons with a larger crew on a second voyage in 1595, aiming to colonise the islands.[29] They landed on Nendö in the Santa Cruz Islands and established a small settlement at Gracioso Bay.[29] However, the settlement failed due to poor relations with the native peoples and epidemics of disease amongst the Spanish which caused numerous deaths, with Mendaña himself dying in October.[29][31] The new commander Pedro Fernandes de Queirós thus decided to abandon the settlement and they sailed north to the Spanish territory of the Philippines.[29] Queirós later returned to the area in 1606, where he sighted Tikopia and Taumako, though this voyage was primarily to Vanuatu in the search of Terra Australis.[31][32]

Save for Abel Tasman's sighting of the remote Ontong Java Atoll in 1648, no European sailed to the Solomons again until 1767, when the British explorer Philip Carteret sailed by the Santa Cruz Islands, Malaita and, continuing further north, Bougainville and the Bismarck Islands.[21][31] French explorers also reached the Solomons, with Louis Antoine de Bougainville naming Choiseul in 1768 and Jean-François de Surville exploring the islands in 1769.[21] In 1788 John Shortland, captaining a supply ship for Britain's new Australian colony at Botany Bay, sighted the Treasury and Shortland Islands.[21][31] That same year the French explorer Jean-François de La Pérouse was wrecked on Vanikoro; a rescue expedition led by Bruni d'Entrecasteaux sailed to Vanikoro but found no trace of La Pérouse.[21][33][34] The fate of La Pérouse was not confirmed until 1826, when the English merchant Peter Dillon visited Tikopia and discovered items belonging to La Pérouse in the possession of the local people, confirmed by the subsequent voyage of Jules Dumont d'Urville in 1828.[31][35]

Some of the earliest regular foreign visitors to the islands were whaling vessels from Britain, the United States and Australia.[31][36] They came for food, wood and water from late in the 18th century, establishing a trading relationship with the Solomon Islanders and later taking aboard islanders to serve as crewmen on their ships.[37] Relations between the islanders and visiting seamen were not always good and sometimes there was bloodshed.[31][38] A knock-on effect of the greater European contact was the spread of diseases to which local peoples had no immunity, as well as a shift in the balance of power between coastal groups, who had access to European weapons and technology, and inland groups who did not.[31] In the second half of the 1800s more traders arrived seeking turtleshells, sea cucumbers, copra and sandalwood, occasionally establishing semi-permanent trading stations.[31] However, initial attempts at more long-term settlement, such as Benjamin Boyd's colony on Guadalcanal in 1851, were unsuccessful.[31][39]

Beginning in the 1840s, and accelerating in the 1860s, islanders began to be recruited (or often kidnapped) as labourers for the colonies in Australia, Fiji and Samoa in a process known as "blackbirding".[31][40] Conditions for workers were often poor and exploitative, and local islanders often violently attacked any Europeans who appeared on their island.[31] The blackbird trade was chronicled by prominent Western writers, such as Joe Melvin and Jack London.[41][42] Christian missionaries also began visiting the Solomons from the 1840s, beginning with an attempt by French Catholics under Jean-Baptiste Epalle to establish a mission on Santa Isabel, which was abandoned after Epalle was killed by islanders in 1845.[21][40] Anglican missionaries began arriving from the 1850s, followed by other denominations, over time gaining a large number of converts.[43]

Colonial period (1886–1978)

[edit]Establishment of colonial rule

[edit]In 1884, Germany annexed northeast New Guinea and the Bismarck Archipelago and, in 1886, extended its rule over the North Solomon Islands, covering Bougainville, Buka, Choiseul, Santa Isabel, the Shortlands and Ontong Java atoll.[44] In 1886 Germany and Britain confirmed this arrangement, with the British gaining a "sphere of influence" over the southern Solomons.[45] Germany paid little attention to the islands, with German authorities based in New Guinea not even visiting the area until 1888.[45] The German presence, along with pressure from the missionaries to rein in the excesses of the coercive labour recruitment practices, known as blackbirding, prompted the British to declare a protectorate over the southern Solomons in March 1893, initially encompassing New Georgia, Malaita, Guadalcanal, Makira, Mono Island and the central Nggela Islands.[13][46]

In April 1896, colonial official Charles Morris Woodford was appointed as the British Acting Deputy Commissioner, and he was confirmed in his position in the following year. The Colonial Office appointed Woodford as the Resident Commissioner in the Solomon Islands on 17 February 1897. He was directed to control the coercive labour recruitment practices, known as blackbirding, operating in the Solomon Island waters and to stop the illegal trade in firearms.[13][46] Woodford set up an administrative headquarters on the small island of Tulagi, and in 1898 and 1899 the Rennell and Bellona Islands, Sikaiana, the Santa Cruz Islands and outlying islands such as Anuta, Fataka, Temotu and Tikopia were added to the protectorate.[46][47] In 1900, under the terms of the Tripartite Convention of 1899, Germany ceded the Northern Solomon to Britain, minus Buka and Bougainville, the latter becoming part of German New Guinea despite geographically belonging to the Solomons archipelago.[40]

Woodford's underfunded administration struggled to maintain law and order on the remote colony.[13] From the late 1890s until the early 1900s, there were numerous instances of European merchants and colonists being killed by islanders; the British response was to deploy Royal Navy warships to launch punitive expeditions against the villages which were responsible for the murders.[13] Arthur Mahaffy was appointed at the Deputy Commissioner in January 1898.[48][47] He was based in Gizo, his duties included suppressing headhunting in New Georgia and neighbouring islands.[47]

The British colonial government attempted to encourage the establishment of plantations by colonists; however, by 1902, there were only about 80 European colonists residing on the islands.[49] Attempts at economic development met with mixed results, though Levers Pacific Plantations Ltd., a subsidiary of Lever Brothers, managed to establish a profitable copra plantation industry which employed many islanders.[49] Small scale mining and logging industries were also developed.[50][51] However, the colony remained something of a backwater, with education, medical and other social services being under the administration of the missionaries.[40] Violence also continued, most notably with the murder of colonial administrator William R. Bell by Basiana of the Kwaio people on Malaita in 1927, as Bell attempted to enforce an unpopular head tax. Several Kwaio were killed in a retaliatory raid, and Basiana and his accomplices executed.[52]

World War II

[edit]From 1942 until the end of 1943, the Solomon Islands were the scene of several major land, sea, and air battles between the Allies and the Japanese Empire's armed forces.[53] Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, war was declared between Japan and the Allied Powers, and the Japanese, seeking to protect their southern flank, invaded South-East Asia and New Guinea. In May 1942 the Japanese launched Operation Mo, occupying Tulagi and most of the western Solomon Islands, including Guadalcanal where they began work on an airstrip.[54] The British administration had already relocated to Auki, Malaita and most of the European population had been evacuated to Australia.[54] The Allies counter-invaded Guadalcanal in August 1942, followed by the New Georgia campaign in 1943, both of which were turning points in the Pacific War, stopping and then countering the Japanese advance.[53] The conflict resulted in hundreds of thousands of Allied, Japanese and civilian deaths, as well an immense destruction across the islands. The Solomon Islands Campaign cost the Allies approximately 7,100 men, 29 ships, and 615 aircraft. The Japanese lost 31,000 men, 38 ships, and 683 aircraft. [53]

Coastwatchers from the Solomon Islands played a major role in providing intelligence and rescuing other Allied servicemen.[54] U.S. Admiral William Halsey, the commander of Allied forces during the Battle for Guadalcanal, recognised the coastwatchers' contributions by stating "The coastwatchers saved Guadalcanal and Guadalcanal saved the South Pacific."[55] In addition around 3,200 men served in the Solomon Islands Labour Corps and some 6,000 enlisted in the British Solomon Islands Protectorate Defence Force, with their exposure to the Americans leading to several social and political transformations.[56] For example, the Americans had extensively developed Honiara, with the capital shifting there from Tulagi in 1952, and the Pijin language was heavily influenced by the communication between Americans and the Islands inhabitants.[57]

-

The aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6) under aerial attack during the Battle of the Eastern Solomons

-

US Marines rest during the 1942 Guadalcanal Campaign.

-

American forces landing at Rendova Island.

-

The Cactus Air Force at Henderson Field, Guadalcanal in October 1942.

-

The coastwatcher Jacob C. Vouza on Guadalcanal.

-

Members of the British Solomon Islands Protectorate Defence Force in 1943.

Post-war period and the lead-up to independence

[edit]In 1943–44 the Malaita-based chief Aliki Nono'ohimae had founded the Maasina Rule movement (aka the Native Council Movement, literally "Brotherhood Rule"), and was later joined by another chief, Hoasihau.[58] Their aims were to improve the economic well-being of native Solomon Islanders, gain greater autonomy and to act as a liaison between Islanders and the colonial administration.[40][59] The movement was especially popular with ex-Labour Corp members and after the war its numbers swelled, with the movement spreading to other islands.[59] Alarmed at the growth of the movement, the British launched "Operation De-Louse" in 1947–8 and arrested most of the Maasina leaders.[59][58] Malaitans then organised a campaign of civil disobedience, prompting mass arrests.[58] In 1950 a new Resident Commissioner, Henry Gregory-Smith, arrived and released the leaders of the movement, though the disobedience campaign continued.[58] In 1952 new High Commissioner (later Governor) Robert Stanley met with leaders of the movement and agreed to the creation of an island council.[58][60] In late 1952 Stanley formally moved the capital of the territory to Honiara.[61] In the early 1950s the possibility of transferring sovereignty of the islands to Australia was discussed by the British and Australian governments; however, the Australians were reluctant to accept the financial burden of administering the territory and the idea was shelved.[62][63]

With decolonisation sweeping the colonial world, and Britain no longer willing (or able) to bear the financial burdens of the Empire, the colonial authorities sought to prepare the Solomons for self-governance. Appointed Executive and Legislative Councils were established in 1960, with a degree of elected Solomon Islander representation introduced in 1964 and then extended in 1967.[40][64][65] A new constitution was drawn up in 1970 which merged the two Councils into one Governing Council, though the British Governor still retained extensive powers.[40][66] Discontent with this prompted the creation of a new constitution in 1974 which reduced much of the Governor's remaining powers and created the post of Chief Minister, first held by Solomon Mamaloni.[40][67] Full self-government for the territory was achieved in 1976, a year after the independence of neighbouring Papua New Guinea from Australia.[40] Meanwhile, discontent grew in the Western islands, with many fearing marginalisation in future a Honiara- or Malaita-dominated state, prompting the formation of the Western Breakaway Movement.[67] A conference held in London in 1977 agreed that the Solomons would gain full independence the following year.[67] Under the terms of the Solomon Islands Act 1978 the country was annexed to Her Majesty's dominions and granted independence on 7 July 1978. The first prime minister was Sir Peter Kenilorea of the Solomon Islands United Party (SIUP), with Elizabeth II becoming Queen of Solomon Islands, represented locally by a Governor General.

-

Postage stamp with portrait of Queen Elizabeth II, 1968

-

The Solomon Islands Independence Ceremony on 7 July 1978

-

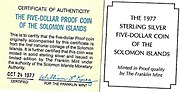

The Five Dollar Proof Coin

-

The Five Dollar Proof Coin of the Solomon Islands 24 October 1977

Independence era (1978–present)

[edit]Early post-independence years

[edit]Peter Kenilorea went on to win the 1980 Solomon Islands general election, serving as PM until 1981, when he was replaced by Solomon Mamaloni of the People's Alliance Party (PAP) after a no confidence vote.[68] Mamaloni created the Central Bank and national airline, and pushed for greater autonomy for individual islands of the country.[69] Kenilorea returned to power after winning the 1984 election, though his second term lasted only two years before he was replaced by Ezekiel Alebua following allegations of misuse of French aid money.[70][71] In 1986 the Solomons helped found the Melanesian Spearhead Group, aimed at fostering cooperation and trade in the region.[72] After winning the 1989 election Mamaloni and the PAP returned to power, with Mamaloni dominating Solomon Islands politics from the early to mid 1990s (save for the one year Premiership of Francis Billy Hilly). Mamaloni made efforts to make the Solomons a republic; however, these were unsuccessful.[69] He also had to deal with the effects of the conflict in neighbouring Bougainville which broke out in 1988, causing many refugees to flee to the Solomons.[73] Tensions arose with Papua New Guinea as PNG forces frequently entered Solomons territory in the pursuit of rebels.[73] The situation calmed down and relations improved following the end of the conflict in 1998. Meanwhile, the country's financial situation continued to deteriorate, with much of the budget coming from the logging industry, often conducted at an unsustainable rate, not helped by Mamaloni's creation of a 'discretionary fund' for use by politicians, which fostered fraud and corruption.[69] Discontent with his rule led to a split in the PAP, and Mamaloni lost the 1993 election to Billy Hilly, though Hilly was later sacked by the Governor-General after a number of defections caused him to lose his majority, allowing Mamaloni to return to power in 1994, where he remained until 1997.[69] Excessive logging, government corruption and unsustainable levels of public spending continued to grow, and public discontent caused Mamaloni to lose the 1997 election.[69][74] The new prime minister, Bartholomew Ulufa'alu of the Solomon Islands Liberal Party, attempted to enact economic reforms; however, his premiership soon became engulfed in a serious ethnic conflict known as "The Tensions".[75]

Ethnic violence (1998–2003)

[edit]| Solomon Islands conflict | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Isatabu Freedom Movement | Malaita Eagle Force | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Harold Keke | Jimmy Lusibaea | ||||||

Commonly referred to as the tensions or the ethnic tension, the initial civil unrest was mainly characterised by fighting between the Isatabu Freedom Movement (IFM, also known as the Guadalcanal Revolutionary Army and the Isatabu Freedom Fighters) and the Malaita Eagle Force (as well as the Marau Eagle Force).[76] For many years people from the island of Malaita had been migrating to Honiara and Guadalcanal, attracted primarily by the greater economic opportunities available there.[77] The large influx caused tensions with native Guadalcanal islanders (known as Guales), and in late 1998 the IFM was formed and began a campaign of intimidation and violence towards Malaitan settlers.[76][74] Thousands of Malaitans subsequently fled back to Malaita or to Honiara, and in mid-1999 the Malaita Eagle Force (MEF) was established to protect Malaitans on Guadalcanal.[74][76] In late 1999, after several failed attempts at brokering a peace deal, Prime Minister Bartholomew Ulufa'alu declared a four-month state of emergency, and also requested assistance from Australia and New Zealand, but his appeal was rejected.[76][74] Meanwhile, law and order on Guadalcanal collapsed, with an ethnically divided police unable to assert authority and many of their weapons depots being raided by the militias; by this point the MEF controlled Honiara with the IFM controlling the rest of Guadalacanal.[77][74]

In April 2003, seven Christian brothers – Brother Robin Lindsay and his companions – were killed on the Weather Coast of Guadalcanal by the rebel leader Harold Keke. Six had gone in search of their Brother Nathaniel, who it turns out had already been tortured and killed. During the tensions Nathaniel had befriended the militant group but Harold Keke accused him of being a government spy and he was beaten to death while singing hymns.[78] They are commemorated by the church on 24 April.

On 5 June 2000 Ulufa'alu was kidnapped by the MEF who felt that, although he was a Malaitan, he was not doing enough to protect their interests.[74] Ulufa'alu subsequently resigned in exchange for his release.[76] Manasseh Sogavare, who had earlier been Finance Minister in Ulufa'alu's government but had subsequently joined the opposition, was elected as prime minister by 23–21 over the Rev. Leslie Boseto. However, Sogavare's election was immediately shrouded in controversy because six MPs (thought to be supporters of Boseto) were unable to attend parliament for the crucial vote.[79] On 15 October 2000 the Townsville Peace Agreement was signed by the MEF, elements of the IFM, and the Solomon Islands Government.[80][76] This was closely followed by the Marau Peace agreement in February 2001, signed by the Marau Eagle Force, the IFM, the Guadalcanal Provincial Government, and the Solomon Islands Government.[76] However, a key Guale militant leader, Harold Keke, refused to sign the agreement, causing a split with the Guale groups.[77] Subsequently, Guale signatories to the agreement led by Andrew Te'e joined with the Malaitan-dominated police to form the 'Joint Operations Force'.[77] During the next two years the conflict moved to the remote Weathercoast region of southern Guadalcanal as the Joint Operations unsuccessfully attempted to capture Keke and his group.[76]

By early 2001 the economy had collapsed and the government was bankrupt.[74] New elections in December 2001 brought Allan Kemakeza into the Prime Minister's chair, with the support of his People's Alliance Party and the Association of Independent Members. Law and order deteriorated as the nature of the conflict shifted: there was continuing violence on the Weathercoast, whilst militants in Honiara increasingly turned their attention to crime, extortion and banditry.[77] The Department of Finance would often be surrounded by armed men when funding was due to arrive. In December 2002, Finance Minister Laurie Chan resigned after being forced at gunpoint to sign a cheque made out to some of the militants.[citation needed] Conflict also broke out in Western Province between locals and Malaitan settlers.[citation needed] Renegade members of the Bougainville Revolutionary Army (BRA) were invited in as a protection force but ended up causing as much trouble as they prevented.[77] The prevailing atmosphere of lawlessness, widespread extortion, and ineffective police prompted a formal request by the Solomon Islands Government for outside help; the request was unanimously supported in Parliament.[77]

In July 2003, Australian and Pacific Islands police and troops arrived in Solomon Islands under the auspices of the Australian-led Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI).[76] A sizeable international security contingent of 2,200 police and troops, led by Australia and New Zealand, and with representatives from about 15 other Pacific nations, began arriving the next month under Operation Helpem Fren.[77] The situation improved dramatically, with violence ending and Harold Keke surrendering to the force.[81] Some 200 people had been killed in the conflict.[77] Since this time some commentators have considered the country a failed state, with the nation having failed to build an inclusive national identity capable of overriding local island and ethnic loyalties.[74][82] However, other academics argue that, rather than being a 'failed state', it is an unformed state: a state that never consolidated even after decades of independence.[83] Furthermore, some scholars, such Kabutaulaka (2001) and Dinnen (2002) argue that the 'ethnic conflict' label is an oversimplification.[84]

Post-conflict era

[edit]Kemakeza remained in office until April 2006, when he lost the 2006 Solomon Islands general election and Snyder Rini became PM. However, allegations that Rini had used bribes from Chinese businessmen to buy the votes of members of Parliament led to mass rioting in the capital Honiara, concentrated on the city's Chinatown area. A deep underlying resentment against the minority Chinese business community led to much of Chinatown in the city being destroyed.[85] Tensions were also increased by the belief that large sums of money were being exported to China. China sent chartered aircraft to evacuate hundreds of Chinese who fled to avoid the riots.[citation needed] Evacuation of Australian and British citizens was on a much smaller scale.[citation needed] Additional Australian, New Zealand and Fijian police and troops were dispatched to try to quell the unrest. Rini eventually resigned before facing a motion of no-confidence in Parliament, and Parliament elected Manasseh Sogavare as prime minister.[86][87]

Sogavare struggled to assert his authority and was also hostile to the Australian presence in the country; after one failed attempt, he was removed in a no confidence vote in 2007 and replaced by Derek Sikua of the Solomon Islands Liberal Party.[88] In 2008 a Truth and Reconciliation Commission was established to examine and help heal the wounds of the 'tension' years.[89][90] Sikua lost the 2010 Solomon Islands general election to Danny Philip, though after a vote of no confidence in him following allegations of corruption, Philip was ousted and replaced by Gordon Darcy Lilo.[91][92] Sogavare returned to power after the 2014 election, and oversaw the withdrawal of RAMSI forces from the country in 2017.[77] Sogavare was ousted in a no confidence vote in 2017, which saw Rick Houenipwela come to power; however, Sogavare returned to the prime ministership after winning the 2019 election, sparking rioting in Honiara.[93][94] In 2019 Sogavare announced that the Solomons would be switching recognition from Taiwan to China.[95][96]

On 25 November 2019, Solomon Islands launched a national ocean policy to achieve the sustainable development and use of the ocean for the benefit of the people of the island nation.

In November 2021, there was mass rioting and unrest.[97] The Solomon Islands Government requested assistance from Australia under the 2017 Bilateral Security Treaty and Australia provided a deployment of Australian Federal Police and Defence Forces.[98]

In March 2022, Solomon Islands signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) on policing cooperation with China and was also reported to be in the process of concluding a security agreement with China. The agreement with China could allow an ongoing Chinese military and naval presence in the Solomons. A spokesperson for Australia's Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade said that, while "Pacific Island nations have the right to make sovereign decisions", Australia "would be concerned by any actions that destabilise the security of our region".[99][100] There are similar concerns in New Zealand and the United States.[101] China donated a shipment of replica firearms to the Solomon Islands police for training.[102] Solomon Islands and China signed a security co-operation agreement in April to promote social stability and long-term peace and security in Solomon Islands.[103] The BBC reported that, according to a leaked draft of the agreement verified by the Australian government, Beijing could deploy forces to Solomon Islands "to assist in maintaining social order". Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare said the pact would not "undermine peace and harmony" in the region and was aimed at protecting the Solomon's internal security situation. China confirmed that the social-order clause had been maintained in the final agreement.[104]

In February 2023, further protests broke out after the Premier of Malaita Province Daniel Suidani was removed from office after a vote of no confidence from the provincial legislature.[105][106] In May 2024, Jeremiah Manele was elected as Solomon Islands new prime minister to succeed Manasseh Sogavare.[107]

Politics

[edit]

Solomon Islands is a constitutional monarchy and has a parliamentary system of government. As King of Solomon Islands, Charles III is head of state; he is represented by the Governor-General who is chosen by the Parliament for a five-year term. There is a unicameral parliament of 50 members, elected for four-year terms. However, Parliament may be dissolved by majority vote of its members before the completion of its term.

Parliamentary representation is based on single-member constituencies. Suffrage is universal for citizens over age 21.[108] The head of government is the prime minister, who is elected by Parliament and chooses the cabinet. Each ministry is headed by a cabinet member, who is assisted by a permanent secretary, a career public servant who directs the staff of the ministry.

Solomon Islands governments are characterised by weak political parties (see List of political parties in Solomon Islands) and highly unstable parliamentary coalitions. They are subject to frequent votes of no confidence, leading to frequent changes in government leadership and cabinet appointments.

Land ownership is reserved for Solomon Islanders. The law provides that resident expatriates, such as the Chinese and Kiribati, may obtain citizenship through naturalisation. Land generally is still held on a family or village basis and may be handed down from mother or father according to local custom. The islanders are reluctant to provide land for nontraditional economic undertakings, and this has resulted in continual disputes over land ownership.

No military forces are maintained by Solomon Islands(Since 1978) although a police force of nearly 500 includes a border protection unit. The police also are responsible for fire service, disaster relief, and maritime surveillance. The police force is headed by a commissioner, appointed by the governor-general and responsible to the prime minister. On 27 December 2006, the Solomon Islands government took steps to prevent the country's Australian police chief from returning to the Pacific nation. On 12 January 2007, Australia replaced its top diplomat expelled from Solomon Islands for political interference in a conciliatory move aimed at easing a four-month dispute between the two countries.

On 13 December 2007, Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare was toppled by a vote of no confidence in Parliament,[109] following the defection of five ministers to the opposition. It was the first time a prime minister had lost office in this way in Solomon Islands. On 20 December, the parliament elected the opposition's candidate (and former Minister for Education) Derek Sikua as prime minister, in a vote of 32 to 15.[110][111]

In April 2019, Manasseh Sogavare was elected as prime minister for fourth time, causing protests and demonstrations against the decision.[112]

Judiciary

[edit]The Governor-General appoints the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court on the advice of the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition. The Governor-General appoints the other justices with the advice of a judicial commission. The current Chief Justice is Sir Albert Palmer.

Since March 2014 Justice Edwin Goldsbrough has served as the President of the Court of Appeal for Solomon Islands. Justice Goldsbrough has previously served a five-year term as a Judge of the High Court of Solomon Islands (2006–2011). Justice Edwin Goldsbrough then served as the Chief Justice of the Turks and Caicos Islands.[113]

Foreign relations

[edit]

Solomon Islands is a member of the United Nations, Interpol, Commonwealth of Nations, Pacific Islands Forum, Pacific Community, International Monetary Fund, and the African, Caribbean, and Pacific (ACP) countries (Lomé Convention).

Until September 2019, it was one of the few countries to recognise the Republic of China (Taiwan) and maintain formal diplomatic relations with it. The relationship was terminated in September 2019 by Solomon Islands, which switched recognition to the People's Republic of China (PRC).[114] Relations with Papua New Guinea, which had become strained because of an influx of refugees from the Bougainville rebellion and attacks on the northern islands of Solomon Islands by elements pursuing Bougainvillean rebels, have been repaired. A 1998 peace accord on Bougainville removed the armed threat, and the two nations regularised border operations in a 2004 agreement.[115] Since 2022, ties with China have been rapidly increasing, with Solomon Islands signing a security pact that allows the country to call for Chinese security forces to quell unrest.[116][117]

In March 2017, at the 34th regular session of the UN Human Rights Council, Vanuatu made a joint statement on behalf of Solomon Islands and some other Pacific nations raising human rights violations in the Western New Guinea, which claimed by International Parliamentarians for West Papua (IPWP) that West Papua has been occupied by Indonesia since 1963,[118] and requested that the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights produce a report.[119][120] Indonesia rejected Vanuatu's allegations, replying that Vanuatu does not represent the people of Papua and it should "stop fantasizing" that it does.[121][120] More than 100,000 Papuans have died during a 50-year Papua conflict.[122] In September 2017, at the 72nd Session of the UN General Assembly, the Prime Ministers of Solomon Islands, Tuvalu and Vanuatu once again raised human rights abuses in Indonesian-occupied West Papua.[123]

Military

[edit]Although the locally recruited British Solomon Islands Protectorate Defence Force was part of Allied Forces taking part in fighting in the Solomons during the Second World War, the country has not had any regular military forces since independence. The various paramilitary elements of the Royal Solomon Islands Police Force (RSIPF) were disbanded and disarmed in 2003 following the intervention of the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI). RAMSI had a small military detachment headed by an Australian commander with responsibilities for assisting the police element of RAMSI in internal and external security. The RSIPF still operates two Pacific class patrol boats (RSIPV Auki and RSIPV Lata), which constitute the de facto navy of Solomon Islands.

In the long term, it is anticipated that the RSIPF will resume the defence role of the country. The police force is headed by a commissioner, appointed by the Governor-General and responsible to the Minister of Police, National Security & Correctional Services.

The police budget of Solomon Islands has been strained due to a four-year civil war. Following Cyclone Zoe's strike on the islands of Tikopia and Anuta in December 2002, Australia had to provide the Solomon Islands government with SI$200,000 (A$50,000) for fuel and supplies for the patrol boat Lata to sail with relief supplies. (Part of the work of RAMSI includes assisting the Solomon Islands government to stabilise its budget.)

Administrative divisions

[edit]For local government, the country is divided into ten administrative areas, of which nine are provinces administered by elected provincial assemblies and the tenth is the capital Honiara, administered by the Honiara Town Council.

| # | Province | Capital | Premier | Area (km2) |

Population census 1999 |

Population census 2009 |

Population census 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tulagi | Stanely Manetiva | 615 | 21,577 | 26,051 | 30,318 | |

| 2 | Taro Island | Harrison Benjamin | 3,837 | 20,008 | 26,372 | 30,775 | |

| 3 | Honiara | Francis Belande Sade | 5,336 | 60,275 | 107,090 | 154,022 | |

| 4 | Buala | Lesley Kikolo | 4,136 | 20,421 | 26,158 | 31,420 | |

| 5 | Kirakira | Julian Maka'a | 3,188 | 31,006 | 40,419 | 51,587 | |

| 6 | Auki | Martin Fini | 4,225 | 122,620 | 157,405 | 172,740 | |

| 7 | Tigoa | Japhet Tuhanuku | 671 | 2,377 | 3,041 | 4,100 | |

| 8 | Lata | Clay Forau | 895 | 18,912 | 21,362 | 25,701 | |

| 9 | Gizo | David Gina | 5,475 | 62,739 | 76,649 | 94,106 | |

| – | Honiara | Eddie Siapu (Mayor) | 22 | 49,107 | 73,910 | 129,569 | |

| Solomon Islands | Honiara | – | 30,407 | 409,042 | 558,457 | 720,956 |

- ^ excluding the Capital Territory of Honiara

Islands by province

[edit]Human rights

[edit]There are human rights concerns and issues in regards to education, water/water security, sanitation, gender equality, and domestic violence aswell as other.

Homosexuality is illegal in Solomon Islands.[124]

Geography

[edit]

Solomon Islands is an island nation that lies east of Papua New Guinea and consists of six major islands and over 900 smaller islands. The major part of the nation of Solomon Islands covers many of the mountainous volcanic islands of the Solomon Islands archipelago, which includes Choiseul, the Shortland Islands, the New Georgia Islands, Santa Isabel, the Russell Islands, the Florida Islands, Tulagi, Malaita, Maramasike, Ulawa, Owaraha (Santa Ana), Makira (San Cristobal), and the main island of Guadalcanal. Solomon Islands also includes smaller, isolated low atolls and volcanic islands such as Sikaiana, Rennell Island, Bellona Island, the Santa Cruz Islands and tiny outliers such as Tikopia, Anuta, and Fatutaka. Although Bougainville is the largest island in the Solomon Islands archipelago it is politically an autonomous region of Papua New Guinea and does not form part of the nation of Solomon Islands.

The country's islands lie between latitudes 5° and 13°S, and longitudes 155° and 169°E. The distance between the westernmost and easternmost islands is about 1,500 kilometres (930 mi). The Santa Cruz Islands (of which Tikopia is part) are situated north of Vanuatu and are especially isolated at more than 200 kilometres (120 mi) from the other islands.

Climate

[edit]The islands' ocean-equatorial climate is extremely humid throughout the year, with a mean temperature of 26.5 °C (79.7 °F) and few extremes of temperature or weather. June through August is the cooler period. Though seasons are not pronounced, the northwesterly winds of November through April bring more frequent rainfall and occasional squalls or cyclones. The annual rainfall is about 3,050 millimetres (120 in). According to the WorldRiskReport 2021, the island state ranks second among the countries with the highest disaster risk worldwide.[125]

In 2023 the governments of Solomon Islands and other island states at risk from climate change (Fiji, Niue, Tuvalu, Tonga and Vanuatu) launched the "Port Vila Call for a Just Transition to a Fossil Fuel Free Pacific", calling for the phaseout of fossil fuels and the 'rapid and just transition' to renewable energy and strengthening environmental law including introducing the crime of ecocide.[126][127][128]

| Climate data for Honiara (Köppen Af) |

|---|

Ecology

[edit]

The Solomon Islands archipelago is part of two distinct terrestrial ecoregions. Most of the islands are part of the Solomon Islands rain forests ecoregion, which also includes the islands of Bougainville and Buka; these forests have come under pressure from forestry activities. The Santa Cruz Islands are part of the Vanuatu rain forests ecoregion, together with the neighbouring archipelago of Vanuatu.[130] The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 7.19/10, ranking it 48th globally out of 172 countries.[131] Soil quality ranges from extremely rich volcanic (there are volcanoes with varying degrees of activity on some of the larger islands) to relatively infertile limestone. More than 230 varieties of orchids and other tropical flowers brighten the landscape. Mammals are scarce on the islands, with the only terrestrial mammals being bats and small rodents. Birds and reptiles, however, are abundant.[citation needed]

The islands contain several active and dormant volcanoes. The Tinakula and Kavachi volcanoes are the most active.

On the southern side of Vangunu Island, the forests around the tiny community of Zaira are unique, providing habitat for at least three vulnerable species of animals. The 200 human inhabitants of the area have been trying to get the forests declared a protected area, so that logging and mining cannot disturb and pollute the pristine forests and coastline.[132]

The baseline survey of marine biodiversity in the Solomon Islands that was carried out in 2004,[133] found 474 species of corals in the Solomons as well as nine species which could be new to science. This is the second highest diversity of corals in the World, second only to the Raja Ampat Islands in eastern Indonesia.[134]

Water and sanitation

[edit]Scarcity of fresh water sources and lack of sanitation has been a constant challenge facing Solomon Islands. Reducing the number of those living without access to fresh water and sanitation by half was one of the 2015 Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) implemented by the United Nations through Goal 7, to ensure environmental sustainability.[135] Though the islands generally have access to fresh water sources, it is typically only available in the state's capital of Honiara,[135] and it is not guaranteed all year long. According to a UNICEF report, the capital's poorest communities do not have access to adequate places to relieve their waste, and an estimated 70% Solomon Island schools have no access to safe and clean water for drinking, washing and relieving of waste.[135] Lack of safe drinking water in school-age children results in high risks of contracting fatal diseases such as cholera and typhoid.[136] The number of Solomon Islanders living with piped drinking water has been decreasing since 2011, while those living with non-piped water increased between 2000 and 2010. Nevertheless, one improvement is that those living with non-piped water has been decreasing consistently since 2011.[137]

In addition, the Solomon Islands Second Rural Development Program, enacted in 2014 and active until 2020, has been working to deliver competent infrastructure and other vital services to rural areas and villages of Solomon Islands,[138] which suffer the most from lack of safe drinking water and proper sanitation. Through improved infrastructure, services and resources, the program has also encouraged farmers and other agricultural sectors, through community-driven efforts, to connect them to the market, thus promoting economic growth.[136] Rural villages such as Bolava, found in the Western Province of Solomon Islands, have benefited greatly from the program, with the implementation of water tanks and rain catchment and water storage systems.[136] Not only has the improved infrastructure increased the quality of life in Solomon Islands, the services are also operated and developed by the community, thus creating a sense of communal pride and achievement among those previously living in hazardous conditions. The program is funded by various international development actors such as the World Bank, European Union, International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), and the Australian and Solomon Islands governments.[136]

Earthquakes

[edit]On 2 April 2007 at 07:39:56 local time (UTC+11) an earthquake with magnitude 8.1 on the Mw scale occurred at hypocentre S8.453 E156.957, 349 kilometres (217 mi) northwest of the island's capital, Honiara and south-east of the capital of Western Province, Gizo, at a depth of 10 km (6.2 miles).[139] More than 44 aftershocks with magnitude 5.0 or greater occurred up until 22:00:00 UTC, Wednesday, 4 April 2007. A tsunami followed killing at least 52 people, destroying more than 900 homes and leaving thousands of people homeless.[140] Land upthrust extended the shoreline of one island, Ranongga, by up to 70 metres (230 ft) exposing many once pristine coral reefs.[141]

On 6 February 2013, an earthquake with magnitude of 8.0 occurred at epicentre S10.80 E165.11 in the Santa Cruz Islands followed by a tsunami up to 1.5 metres. At least nine people were killed and many houses demolished. The main quake was preceded by a sequence of earthquakes with a magnitude of up to 6.0.[citation needed]

Economy

[edit]

Solomon Islands' per-capita GDP of $600 ranks it as a least developed country, and more than 75% of its labour force is engaged in subsistence agriculture and fishing. Most manufactured goods and petroleum products must be imported. Only 3.9% of the area of the islands are used for agriculture, and 78.1% are covered by forests making the Solomon Islands the 103rd ranked country covered by forests worldwide.[142][clarification needed]

The Solomon Islands Government was insolvent by 2002. Since the RAMSI intervention in 2003, the government has recast its budget. It has consolidated and renegotiated its domestic debt and with Australian backing, is now seeking to renegotiate its foreign obligations. Principal aid donors are Australia, New Zealand, the European Union, Japan, and Taiwan.

Currency

[edit]The Solomon Islands dollar (ISO 4217 code: SBD) was introduced in 1977, replacing the Australian dollar at par. Its symbol is "SI$", but the "SI" prefix may be omitted if there is no confusion with other currencies also using the dollar sign "$". It is subdivided into 100 cents. Local shell money is still important for traditional and ceremonial purposes in certain provinces and, in some remote parts of the country, for trade. Shell money was a widely used traditional currency in the Pacific Islands; in Solomon Islands, it is mostly manufactured in Malaita and Guadalcanal but can be bought elsewhere, such as the Honiara Central Market.[143] The barter system often replaces money of any kind in remote areas.

Exports

[edit]Until 1998, when world prices for tropical timber fell steeply, timber was Solomon Islands' main export product, and, in recent years, Solomon Islands forests were dangerously overexploited. In the wake of the ethnic violence in June 2000, exports of palm oil and gold ceased while exports of timber fell.

Recently,[when?] Solomon Islands courts have re-approved the export of live dolphins for profit, most recently to Dubai, United Arab Emirates. This practice was originally stopped by the government in 2004 after international uproar over a shipment of 28 live dolphins to Mexico. The move resulted in criticism from both Australia and New Zealand as well as several conservation organisations. As of 2019, rough wood still makes up two-thirds of export[citation needed].

Agriculture

[edit]In 2017 317,682 tons of coconuts were harvested making the country the 18th ranked producer of coconuts worldwide, and 24% of the exports corresponded to copra.[144] Cocoa beans are mainly grown on the islands Guadalcanal, Makira and Malaita. In 2017 4,940 tons of cocoa beans were harvested making the Solomon Islands the 27th ranked producer of cocoa worldwide.[145] Growth of production and export of copra and cacao, however, is hampered by old age of most coconut and cacao trees. In 2017 285,721 tons of palm oil were produced, making Solomon Islands the 24th ranked producer of palm oil worldwide.[146]

Other important cash crops and exports include copra, cacao and palm oil.

For the local market but not for export many families grow taro (2017: 45,901 tons),[147] rice (2017: 2,789 tons),[148] yams (2017: 44,940 tons)[149] and bananas (2017: 313 tons).[150] Tobacco (2017: 118 tons)[151] and spices (2017: 217 tons).[152]

The agriculture on the Solomon Islands is hampered by a very severe lack of agricultural machines.

Mining

[edit]In 1998 gold mining began at Gold Ridge on Guadalcanal. Minerals exploration in other areas continued. The islands are rich in undeveloped mineral resources such as lead, zinc, nickel, and gold. Negotiations are underway that may lead to the eventual reopening of the Gold Ridge mine which was closed after the riots in 2006.

Rennell Island bauxite mine operated from 2011 to 2021 on Rennell Island, leaving behind serious ecological damage after multiple spills.[153][154]

Fisheries

[edit]Solomon Islands' fisheries also offer prospects for export and domestic economic expansion. A Japanese joint venture, Solomon Taiyo Ltd., which operated the only fish cannery in the country, closed in mid-2000 as a result of the ethnic disturbances. Though the plant has reopened under local management, the export of tuna has not resumed.

Tourism

[edit]Tourism, particularly diving, could become an important service industry for Solomon Islands. Tourism growth, however, is hampered by lack of infrastructure and transportation limitations. In 2017, Solomon Islands was visited by 26,000 tourists making the country one of the least frequently-visited countries of the world.[155] The Solomon Island government hoped to increase the number of tourists up to 30,000 by the end of 2019 and up to 60,000 tourists per year by the end of 2025.[156] In 2019 the Solomon Islands were visited by 28,900 tourists and in 2020 by 4,400.[157]

Energy

[edit]Команда разработчиков возобновляемых источников энергии, работающих в Южной части Тихоокеанской комиссии по прикладной геологической комиссии (SOPAC) и финансируемых Партнерством возобновляемых источников энергии и энергоэффективности (REEEP), разработала схему, которая позволяет местным сообществам получить доступ к возобновляемой энергии, такой как солнечная энергия, вода и Ветряная мощность, без необходимости собрать значительные суммы денег. В соответствии с этой схемой, островитян, которые не могут платить за солнечные фонари в наличных деньгах, могут заплатить вместо этого в натуральной форме. [ 158 ]

Инфраструктура

[ редактировать ]Полевою соединения

[ редактировать ]Solomon Airlines соединяет международный аэропорт Хониары с Нади на Фиджи , Порт -Вила в Вануату и Брисбен в Австралии, а также с более чем 20 внутренними аэропортами в каждой провинции страны. Для продвижения туризма Solomon Airlines представила еженедельное прямое полетное соединение между Брисбеном и Мундой в 2019 году. [ 159 ] Virgin Australia соединяет Хониару с Брисбеном два раза в неделю. Большинство внутренних аэропортов доступны только для небольших самолетов, так как у них есть короткие травянистые взлетно -посадочные полосы.

Дороги

[ редактировать ]Дорожной системы на Соломоновых островах недостаточна, и железных дорог нет. Самые важные дороги соединяют Хониару с Ламби (58 км; 36 миль) в западной части Гуадалканала и с Аолой (75 км; 47 миль) в восточной части. [ 160 ] Есть несколько автобусов, и они не распространяются в соответствии с фиксированным графиком. В Хониаре нет автобусной терминала. Самая важная автобусная остановка находится перед центральным рынком.

Паромы

[ редактировать ]Большинство островов можно добраться от паром из Хониары. Существует ежедневная связь от Хониары с Ауки через Тулаги высокоскоростным катамараном.

Демография

[ редактировать ]| Население [ 161 ] [ 162 ] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Год | Миллион | ||

| 1950 | 0.09 | ||

| 2000 | 0.4 | ||

| 2021 | 0.7 | ||

Общая численность населения при переписи в ноябре 2019 года составила 721 455. По состоянию на 2021 год [update]В Соломоновых островах было 707 851 человек. [ 161 ] [ 162 ]

Этнические группы

[ редактировать ]

Большинство островитян Соломона являются этнически меланезийскими (95,3%). Полинезийские (3,1%) и микронезийские (1,2%) являются двумя другими значимыми группами. [ 163 ] Есть несколько тысяч европейцев и аналогичное количество этнических китайцев . [ 85 ]

Языки

[ редактировать ]В то время как английский является официальным языком, только 1–2% населения способны свободно общаться на английском языке. Тем не менее, английский креольский, Соломонс Пиджин , является фактическим лингва франка страны, на которой говорят большинство населения, наряду с местными языками коренных народов. Пиджин тесно связан с Током Писином, на котором говорится в Папуа -Новой Гвинее.

Количество местных языков, перечисленных для Соломоновых островов, составляет 74, из которых 70 являются живыми языками, а 4 вымерли, согласно этнологу, языкам мира . [ 164 ] Западные океанические языки (преимущественно юго -восточной соломонической группы ) говорят на центральных островах. Полинезийские языки говорят на Реннелле и Беллоне на юге, Тикопии , Ануте и Фатутаке на Дальний Восток, Сикааяна на северо -востоке и Луаниуа на севере ( атолл Ontong Java , также известный как лорд Хоу Атолл ). Иммигрантское население из Кирибати ( I-Кирибати ) говорит Гилбертезе .

Большинство языков коренных народов являются австронезийскими языками . Центральные соломонские языки, такие как Bilua , Lavukaleve , Savosavo и Touo, составляют независимую семью в папуавообразовательных языках . [ 165 ]

Религия

[ редактировать ]

Религия Соломоновых островов составляет 92% христианин. Основными христианскими конфессиями являются: Англиканская 35%, католическая 19%, Евангельская церковь Южного моря 17%, Объединенная церковь 11%и адвентисты седьмого дня 10%. Другими христианскими конфессиями являются свидетели Иеговы , новая апостольская церковь (80 церквей) и Церковь Иисуса Христа Святых последних дней .

Еще 5% придерживаются убеждений аборигенов. Оставшиеся 3% придерживаются ислама или веры Бахажи . Согласно самым последним сообщениям, ислам на Соломоновых островах состоит из примерно 350 мусульман, [ 166 ] в том числе члены исламской общины Ахмадийя . [ 167 ]

Здоровье

[ редактировать ]См. Здоровье на Соломоновых островах

Образование

[ редактировать ]

Образование на Соломоновых островах не является обязательным, и только 60 процентов детей школьного возраста имеют доступ к начальному образованию. [ 168 ] [ 169 ] В разных местах есть детские сады, в том числе столица, но они не бесплатны.

С 1990 по 1994 год зачисление валовой начальной школы выросло с 84,5 процента до 96,6 процента. [ 168 ] Уровень посещаемости начальной школы был недоступен для Соломоновых островов с 2001 года. [ 168 ] Хотя показатели зачисления указывают на уровень приверженности образованию, они не всегда отражают участие детей в школе. [ 168 ] Департамент образования и усилий по развитию человеческих ресурсов и планы по расширению учебных заведений и увеличении зачисления. Тем не менее, этим действиям было затруднено отсутствие государственного финансирования, ошибочные программы обучения учителей, плохая координация программ и неспособность правительства платить учителям. [ 168 ] Процент бюджета правительства, выделенный на образование, составил 9,7 процента в 1998 году, по сравнению с 13,2 процента в 1990 году. [ 168 ] Мужское образование, как правило, выше, чем женское образование. [ 169 ] Университет южной части Тихого океана , в котором есть кампусы в 12 странах острова Тихоокеанского океана, имеет кампус в Гуадалканале . [ 170 ] Уровень грамотности взрослого населения составил 84,1%в 2015 году (мужчины 88,9%, женщины 79,23%). [ 171 ]

Инициатива по измерению прав человека (HRMI) [ 172 ] обнаруживает, что Соломоновые острова выполняют только 70,1% от того, что он должен выполнять для права на образование на основе уровня дохода в стране. [ 173 ] HRMI разрушает право на образование, рассматривая права как на начальное образование, так и на среднее образование. Принимая во внимание уровень дохода Соломонских островов, нация достигает 94,9% от того, что должно быть возможно в зависимости от его ресурсов (доход) для начального образования, но только 45,4% для среднего образования. [ 173 ]

Культура

[ редактировать ]

Культура Соломоновых островов отражает степень дифференциации и разнообразия среди групп, живущих в архипелаге Соломонских островов , который находится в меланезии в Тихом океане , а народы отличаются островками, языком, топографией и географией. Культурная территория включает в себя национальный штат Соломоновые острова и остров Бугенвиль , который является частью Папуа -Новой Гвинеи . [ 174 ] Соломоновые острова включают в себя некоторые культурные полинезийские общества, которые лежат за пределами основного региона полинезийского влияния, известного как Полинезийский треугольник . есть семь полинезийских выбросов На Соломоновых островах : Анута , Беллона , Онтонг Ява , Реннелл , Сикааяна , Тикопия и Ваеакау-Таумако . Соломоновые острова Искусство и ремесла покрывают широкий спектр тканых предметов, резных артефактов дерева, камня и раковины в стилях, специфичных для разных провинций:

-

Прачечная корзина

-

Резной рыбы

-

Bukhaware подносы

-

Резное блюдо, инкрустированное матери,

-

Резные длинные лодки

-

Гнус отвратительные головы

-

Салатная чаша и подача ложки и вилки

-

Деревянные религиозные объекты перед церковью всех святых, Хониара

Malaitan Shell-Money, изготовленный в лагуне Langa Langa , является традиционной валютой, используемой в Малаите и по всему Соломоновым островам. Деньги состоит из небольших полированных дисков с оболочкой, которые пробурены и размещены на струнах. [ 175 ] В Solomons Tectus Niloticus собирается, что традиционно превращалось в такие предметы, как жемчужные пуговицы и украшения. [ 176 ] [ 177 ]

Гендерное неравенство и домашнее насилие

[ редактировать ]Соломоновые острова имеют один из самых высоких показателей семейного и сексуального насилия (FSV) в мире, причем 64% женщин в возрасте от 15 до 49 лет сообщили о физическом и/или сексуальном насилии со стороны партнера. [ 178 ] Согласно отчету Всемирной организации здравоохранения (ВОЗ), опубликованным в 2011 году, «причины гендерного насилия (ГБВ) многочисленны, но в первую очередь это связано с гендерным неравенством и его проявлениями». [ 179 ] В отчете говорится:

- «На Соломоновых островах GBV в значительной степени нормализован: 73% мужчин и 73% женщин считают, что насилие в отношении женщин оправдано, особенно для неверности и« непослушания », как когда женщины не выполняют гендерные роли, которые общество налагает . ' Например, женщины, которые полагали, что они могут иногда отказаться от секса, в четыре раза чаще испытали GBV от интимного партнера, которые мужчины назвали приемлемость насилия и гендерного неравенства в качестве двух основных причин GBV, и почти все они сообщили о том, что они поражают своих партнеров как женщин как партнеров как «Форма дисциплины», предполагая, что женщины могут улучшить ситуацию с помощью «обучения], чтобы подчиняться им . »

Другим проявлением и водителем гендерного неравенства на Соломоновых островах является традиционная практика цены на невесту . Хотя конкретные обычаи варьируются между сообществами, заплатить цену невесты считается аналогичной названием недвижимости, предоставляя мужчин владение женщинами. Гендерные нормы мужественности, как правило, поощряют мужчин «контролировать» своих жен, часто благодаря насилию, в то время как женщины чувствовали, что цены на невесту помешают им покинуть мужчин. Другой отчет, опубликованный ВОЗ в 2013 году, нарисовал такой же мрачную картину. [ 180 ]

В 2014 году Соломоновые острова официально запустили Закон о защите семьи 2014 года, который был нацелен на борьбу с насилием в семье в стране. [ 181 ] Хотя в системе здравоохранения разрабатываются многочисленные вмешательства, а также в системе уголовного правосудия, эти вмешательства все еще находятся в зачаточном состоянии и в значительной степени связаны с западными протоколами. Следовательно, чтобы эти модели были эффективными, необходимо время и приверженность для изменения культурного восприятия домашнего насилия на Соломоновых островах. [ 178 ]

Литература

[ редактировать ]Авторы с Соломоновых островов включают в себя романистов Джон Саунана и Рексфорд Ороталоа и поэт Джулли Макини.

СМИ

[ редактировать ]Газеты

[ редактировать ]Есть одна ежедневная газета, Solomon Star , один ежедневный веб -сайт онлайн -новостей, Solomon Times Online (www.solomontimes.com), две еженедельные документы, Solomons Voice и Solomon Times и две ежемесячные документы, Agrikalsa Nius и гражданская пресса .

Радио

[ редактировать ]Радио является наиболее влиятельным типом СМИ на Соломоновых островах из -за языковых различий, неграмотности, [ 182 ] и сложность получения телевизионных сигналов в некоторых частях страны. Королевская корпорация Solomon Islands (SIBC) управляет службами общественного радио, включая национальные станции Radio Happy Isles 1037 на Dial and Wantok FM 96.3, и радиостанции Radio Happy Lagoon и, ранее, Radio Temotu. Есть две коммерческие FM -станции, Z FM в 99,5 в Хониаре, но дебиторская задолженность в течение подавляющего большинства островов из Хониары и, Paoa FM в 97,7 в Хониаре (также транслируя 107,5 в Ауки) и одна радиостанция FM Community,, также радиостанция сообщества,, также Gold Ridge FM на 88,7.

Телевидение

[ редактировать ]Никакая телевизионная служба не покрывает все Соломоновые острова, но некоторое освещение доступно в шести основных центрах в четырех из девяти провинций. Спутниковые телеканалы могут быть получены. В Honiara есть бесплатный HD Digital TV, аналоговое телевидение и онлайн-сервис под названием Telekom Television Limited, управляемый Telekom Co. Solomon Мировые новости . Жители также могут подписаться на Satsol, цифровой сервис платного телевидения, переводимых спутникового телевидения.

Музыка

[ редактировать ]

Традиционная меланезийская музыка на Соломоновых островах включает в себя как групповой, так и сольный вокал, SLIT-Drum и Panpipe ансамблы . Бамбуковая музыка получила последователи в 1920 -х годах. В 1950 -х годах Эдвин Нанау Ситори написал песню « Walkabout Long Chinatown », которую правительство назвало неофициальной « национальной песней » на Соломоновых островах. [ 183 ] Современная популярная музыка Solomon Islander включает в себя различные виды рок и регги, а также островную музыку . [ Проверьте цитату синтаксис ]]

Спорт

[ редактировать ]Союз регби : Национальная команда Союза по регби Соломон -островов с 1969 года играет в международных участках. Он принимал участие в квалификационном турнире Океании для чемпионатов мира по регби 2003 и 2007 годов, но не имел права ни в одном случае.

Футбол Ассоциации : Национальная футбольная команда Соломонских островов оказалась среди самых успешных в Океании и является частью Конфедерации OFC в ФИФА. В настоящее время они занимают 141 -е место из 210 команд в мировом рейтинге FIFA. Команда стала первой командой, которая победила Новую Зеландию в квалификации на место в плей-офф против Австралии для квалификации на чемпионате мира 2006 года . Они были побеждены 7–0 в Австралии и 2–1 дома.

Фусал : тесно связан с футболом ассоциации. 14 июня 2008 года Национальная команда по футзалам Соломонских островов , Курукуру, выиграла чемпионат по футзалу Океании на Фиджи, чтобы квалифицировать их для чемпионата мира по футзалу 2008 года , который проходил в Бразилии с 30 сентября по 19 октября 2008 года. Соломонские острова - это Фузальные защитники чемпионов в регионе Океании. В 2008 и 2009 годах Курукуру выиграл чемпионат Фусала Океании на Фиджи. В 2009 году они победили принимающую страну Фиджи 8–0, чтобы претендовать на название. В настоящее время Курукуру держит мировой рекорд за самый быстрый ворот, забитый в официальном матче по футзалу. Он был установлен капитаном Курукуру Эллиотом Рагомо, который забил против Новой Каледонии через три секунды в игре в июле 2009 года. [ 184 ] Они также, однако, имеют менее завидную запись о худшем поражении в истории чемпионата мира по футзалу , [ нужно разъяснения ] Когда в 2008 году они были избиты Россией с двумя голами до тридцати одного. [ 185 ]

Пляжный футбол : Национальная футбольная команда Solomon Islands , Bylikiki Boys, статистически является самой успешной командой в Океании. Они выиграли все три региональных чемпионата на сегодняшний день, тем самым каждый раз, квалифицируясь каждый раз на чемпионате мира по футболу FIFA Beach . Bylikiki Boys занимают четырнадцатые в мире по состоянию на 2010 год [update], выше, чем любая другая команда из Океании. [ 186 ]

Соломоновые острова организовали Тихоокеанские игры 2023 года . [ 187 ]

Смотрите также

[ редактировать ]Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ «Национальный парламент Соломонских островов Daily Hansard: первая встреча - восьмая сессия во вторник 9 мая 2006 года» (PDF) . www.parliament.gov.sb . 2006. с. 12. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 30 октября 2012 года . Получено 3 января 2019 года .

- ^ «Религии на Соломоновых островах | Pew-Grf» . Архивировано с оригинала 23 января 2014 года.

- ^ «Соломоновые острова: география» . ЦРУ Факт. Архивировано из оригинала 22 октября 2021 года . Получено 25 июля 2023 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый «База данных мировой экономической перспективы (Соломоновые острова)» . Всемирные экономические перспективы, апрель 2024 года . Международный валютный фонд . Апрель 2024 года. Архивировано с оригинала 26 апреля 2024 года . Получено 26 апреля 2024 года .

- ^ «Коэффициент индекса Джини» . ЦРУ мира по фактам. Архивировано из оригинала 17 июля 2021 года . Получено 16 июля 2021 года .

- ^ «Отчет о развитии человека 2023-24» (PDF) . Программа развития Организации Объединенных Наций . Программа развития Организации Объединенных Наций. 13 марта 2024 года. С. 274–277. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 1 мая 2024 года . Получено 3 мая 2024 года .

- ^ «Соломоновые острова, кантри,» . Архивировано из оригинала 22 декабря 2022 года . Получено 22 декабря 2022 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Джон Прадос, Острова Судьба , Даттон Калибр, 2012, P, 20 и Passim

- ^ «Соломоновые острова: география» . ЦРУ Факт. Архивировано из оригинала 22 октября 2021 года . Получено 25 июля 2023 года .

- ^ Соломонские острова Национальное статистическое управление - оценка по состоянию на 1 июля 2023 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный 1542 ? Библиотека Принстонского университета. Архивировано из апреля оригинальности Получено 8 февраля

- ^ «Альваро де Мендан ~ де Нейра и Педро Фернандес де Кейрос» . Library.princeton.edu . Архивировано из оригинала 9 августа 2022 года . Получено 9 августа 2022 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и Лоуренс, Дэвид Рассел (октябрь 2014 г.). «Глава 6 Британские Соломонские острова Протекторат: колониализм без капитала» (PDF) . Натуралист и его «прекрасные острова»: Чарльз Моррис Вудфорд в западной части Тихого океана . Anu Press. ISBN 9781925022032 Полем Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 25 сентября 2022 года . Получено 30 марта 2019 года .

- ^ Содружество и колониальное право Кеннета Робертса-Врэя , Лондон, Стивенс, 1966. С. 897

- ^ «Лорд Горонви-Робертс, выступая в Палате лордов, HL Deb 27 апреля 1978 года. Vol 390 CC2003-19» . Парламентские дебаты (Хансард) . 27 апреля 1978 года. Архивировано из оригинала 16 июня 2018 года . Получено 19 ноября 2014 года .

- ^ Hogbin, H. In, Эксперименты по цивилизации: влияние европейской культуры на местное сообщество Соломоновых островов , Нью -Йорк: Schocken Books, 1970

- ^ «Международная энциклопедия сравнительного права: рассрочка 37» под редакцией К. Цвейгерта, S-65

- ^ Британские Соломонские острова протекторат (название территории) Орден 1975

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин Уолтер, Ричард; Шеппард, Питер (февраль 2009 г.). «Обзор археологии острова Соломон» . Исследовательские ворота . Получено 31 августа 2020 года .

- ^ Шеппард, Питер Дж . 800

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон "Исследование" . Соломоновая энциклопедия. Архивировано с оригинала 27 октября 2020 года . Получено 1 сентября 2020 года .

- ^ Кирх, Патрик Винтон (2002). На дороге ветра: археологическая история Тихоокеанских островов . Беркли, Калифорния: издательство Калифорнийского университета. ISBN 0-520-23461-8

- ^ Уолтер, Ричард; Шеппард, Питер (2001). «Пересмотренная модель истории культуры Соломонских островов». Журнал полевой археологии : 27–295. Citeseerx 10.1.1.580.3329 .

- ^ «Древние Соломонские острова мтДНК: оценка поселения голоцена и влияние европейского контакта» (PDF) . Геномик . Журнал археологической науки. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 2 февраля 2021 года . Получено 1 сентября 2020 года .

- ^ Ples Blong Iumi: Соломонские острова за последние четыре тысячи лет , Хью Ларейси (ред.), Университет южной части Тихого океана, 1989, ISBN 982-02-0027-X

- ^ Питер Дж. Шепард; Ричард Уолтер; Такуя Нагаока. «Археология охоты на головы в лагуне Ровиана, Новая Грузия» . Журнал Полинезийского общества. Архивировано из оригинала 21 апреля 2012 года . Получено 1 сентября 2020 года .

- ^ « От примитива до постколониального при меланезии и антропологии ». Брюс М. Кнауфт (1999). Университет Мичиганской прессы . п. 103. ISBN 0-472-06687-0

- ^ «Король каннибальных островов» . Время . 11 мая 1942 года. Архивировано из оригинала 12 января 2008 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час 1542 ? Библиотека Принстонского университета. Архивировано из апреля оригинальности Получено 8 февраля

- ^ Шарп, Эндрю Открытие Тихоокеанских островов Кларендон Пресс, Оксфорд, 1960, с.45.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час я Дж k л м Лоуренс, Дэвид Рассел (2014). «3. Коммерция, торговля и труд». Натуралист и его «красивые острова»: Чарльз Моррис Вудфорд в западной части Тихого океана . Ану Пресс. С. 35–62. ISBN 9781925022032 Полем JSTOR J.CTT13WVG4.8 .

- ^ Келли, Селус, Оф -австриец Святого Духа. Журнал Fray Martin de Muniilla Ofm и других документов, связанных с путешествием Педро Фернандеса из Квира, чтобы быть на юге (1605–1606) и Францисканского миссионерского плана (1617–1627) Кембридж, П.

- ^ «Судьба Ла Перуза» . Откройте для себя коллекции . Государственная библиотека штата Новый Южный Уэльс. Архивировано из оригинала 17 мая 2013 года . Получено 7 февраля 2013 года .

- ^ Дуйкер, Эдвард (сентябрь 2002 г.). «В поисках лапериза» . NLA News Том XII номер 12 . Национальная библиотека Австралии. Архивировано из оригинала 19 мая 2007 года . Получено 1 сентября 2020 года .

- ^ «После поиска Vanikoro-In The Lapérouse Expedition (музей Лаперуза)» . Альби, Франция : Лапир-Франс. Архивировано из оригинала 5 октября 2011 года . Получено 24 июля 2010 года .

- ^ Роберт Лэнгдон (ред.), Куда пошли: указатель для тихоокеанских портов и островов, посещаемых американскими киториями (и некоторыми другими кораблями) в 19 -м веке (1984), Канберре, Бюро рукописи Тихого океана, стр. 229–232 ISBN 0-86784-471-X .

- ^ Джудит А. Беннетт, богатство Соломонов: история тихоокеанского архипелага, 1800–1978 , (1987), Гонолулу, Университет Гавайской прессы, стр.24–31 и Приложение 3. ISBN 0-8248-1078-3

- ^ Беннетт, 27–30; Марк Ховард, «Три капитана Сиднейского китогона 1830 -х годов», Великий круг , 40 (2) декабря 2018 года, 83–84.

- ^ Уолш, GP (1966). «Бойд, Бенджамин (1801–1851)» . Австралийский словарь биографии . Канберра: Национальный центр биографии, Австралийский национальный университет . С. 140–142. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7 Полем ISSN 1833-7538 . OCLC 70677943 . Получено 7 апреля 2019 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час я «Проблема на Соломоновых островах» (PDF) . ООН Департамент политических дел. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 22 октября 2020 года . Получено 3 сентября 2020 года .

- ^ Коррис, Питер. «Джозеф Далгарно Мелвин (1852–1909)». Мелвин, Джозеф Далгарно (1852–1909) . Австралийский национальный университет. Архивировано с оригинала 9 января 2015 года . Получено 11 января 2018 года .

- ^ Лондон, Джек (1911). Круиз Снарка . Компания Macmillan . Получено 16 января 2008 года .

- ^ «Религия» . Соломоновая энциклопедия. Архивировано с оригинала 27 октября 2020 года . Получено 1 сентября 2020 года .

- ^ «Немецкая Новая Гвинея» . Соломоновая энциклопедия. Архивировано с оригинала 27 октября 2020 года . Получено 2 сентября 2020 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Сак, Питер (2005). «Немецкое колониальное правление в северных соломонах». В Ригане, Энтони; Гриффин, Хельга-Мария (ред.). Бугенвилль перед конфликтом . Незнакомец журналистика. С. 77–107. ISBN 9781921934230 Полем JSTOR J.CTT1BGZBGG.14 . Архивировано из оригинала 16 апреля 2021 года . Получено 3 сентября 2020 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в «Британские Соломонские острова Протекторат, Прокламация» . Соломоновая энциклопедия. Архивировано из оригинала 19 октября 2021 года . Получено 2 сентября 2020 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Лоуренс, Дэвид Рассел (октябрь 2014 г.). «Глава 7 Расширение протектората 1898–1900» (PDF) . Натуралист и его «прекрасные острова»: Чарльз Моррис Вудфорд в западной части Тихого океана . Ану Пресс. С. 198–206. ISBN 9781925022032 Полем Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 27 октября 2020 года . Получено 3 сентября 2020 года .

- ^ «Махаффи, Артур (1869 - 1919)» . Соломоновые острова Историческая энциклопедия 1893-1978. 2003. Архивировано из оригинала 25 июня 2021 года . Получено 24 марта 2024 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Лоуренс, Дэвид Рассел (октябрь 2014 г.). «Глава 9 Экономика плантации» (PDF) . Натуралист и его «прекрасные острова»: Чарльз Моррис Вудфорд в западной части Тихого океана . Anu Press. С. 245–249. ISBN 9781925022032 Полем Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 30 марта 2019 года . Получено 3 сентября 2020 года .

- ^ «Лесное хозяйство» . Соломоновая энциклопедия. Архивировано с оригинала 27 октября 2020 года . Получено 2 сентября 2020 года .