Queen Victoria

| Victoria | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Alexander Bassano, 1882 | |

| Queen of the United Kingdom | |

| Reign | 20 June 1837 – 22 January 1901 |

| Coronation | 28 June 1838 |

| Predecessor | William IV |

| Successor | Edward VII |

| Empress of India | |

| Reign | 1 May 1876 – 22 January 1901 |

| Imperial Durbar | 1 January 1877 |

| Predecessor | Position established |

| Successor | Edward VII |

| Born | Princess Alexandrina Victoria of Kent 24 May 1819 Kensington Palace, London, England |

| Died | 22 January 1901 (aged 81) Osborne House, Isle of Wight, England |

| Burial | 4 February 1901 Royal Mausoleum, Frogmore, Windsor |

| Spouse | |

| Issue |

|

| House | Hanover |

| Father | Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn |

| Mother | Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld |

| Religion | Protestant[a] |

| Signature |  |

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days—which was longer than those of any of her predecessors—constituted the Victorian era. It was a period of industrial, political, scientific, and military change within the United Kingdom, and was marked by a great expansion of the British Empire. In 1876, the British Parliament voted to grant her the additional title of Empress of India.

Victoria was the daughter of Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn (the fourth son of King George III), and Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld. After the deaths of her father and grandfather in 1820, she was raised under close supervision by her mother and her comptroller, John Conroy. She inherited the throne aged 18 after her father's three elder brothers died without surviving legitimate issue. Victoria, a constitutional monarch, attempted privately to influence government policy and ministerial appointments; publicly, she became a national icon who was identified with strict standards of personal morality.

Victoria married her first cousin, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, in 1840. Their nine children married into royal and noble families across the continent, earning Victoria the sobriquet "grandmother of Europe". After Albert's death in 1861, Victoria plunged into deep mourning and avoided public appearances. As a result of her seclusion, British republicanism temporarily gained strength, but in the latter half of her reign, her popularity recovered. Her Golden and Diamond jubilees were times of public celebration. Victoria died at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight, at the age of 81. The last British monarch of the House of Hanover, she was succeeded by her son Edward VII of the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha.

Early life

Birth and ancestry

Victoria's father was Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn, the fourth son of King George III and Queen Charlotte. Until 1817, King George's only legitimate grandchild was Edward's niece Princess Charlotte of Wales, the daughter of George, Prince Regent (who would become George IV). Princess Charlotte's death in 1817 precipitated a succession crisis that brought pressure on Prince Edward and his unmarried brothers to marry and have children. In 1818, the Duke of Kent married Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, a widowed German princess with two children—Carl (1804–1856) and Feodora (1807–1872)—by her first marriage to Emich Carl, 2nd Prince of Leiningen. Her brother Leopold was Princess Charlotte's widower and later the first king of Belgium. The Duke and Duchess of Kent's only child, Victoria was born at 4:15 a.m. on Monday 24 May 1819 at Kensington Palace in London.[1]

Victoria was christened privately by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Charles Manners-Sutton, on 24 June 1819 in the Cupola Room at Kensington Palace.[b] She was baptised Alexandrina after one of her godparents, Tsar Alexander I of Russia, and Victoria, after her mother. Additional names proposed by her parents—Georgina (or Georgiana), Charlotte, and Augusta—were dropped on the instructions of the Prince Regent.[2]

At birth, Victoria was fifth in the line of succession after the four eldest sons of George III: George, Prince Regent (later George IV); Frederick, Duke of York; William, Duke of Clarence (later William IV); and Victoria's father, Edward, Duke of Kent.[3] Prince George had no surviving children, and Prince Frederick had no children; further, both were estranged from their wives, who were both past child-bearing age, so the two eldest brothers were unlikely to have any further legitimate children. William married in 1818, in a joint ceremony with his brother Edward, but both of William's legitimate daughters died as infants. The first of these was Princess Charlotte, who was born and died on 27 March 1819, two months before Victoria was born. Victoria's father died in January 1820, when Victoria was less than a year old. A week later her grandfather died and was succeeded by his eldest son as George IV. Victoria was then third in line to the throne after Frederick and William. She was fourth in line while William's second daughter, Princess Elizabeth, lived, from 10 December 1820 to 4 March 1821.[4]

Heir presumptive

Prince Frederick died in 1827, followed by George IV in 1830; their next surviving brother succeeded to the throne as William IV, and Victoria became heir presumptive. The Regency Act 1830 made special provision for Victoria's mother to act as regent in case William died while Victoria was still a minor.[5] King William distrusted the Duchess's capacity to be regent, and in 1836 he declared in her presence that he wanted to live until Victoria's 18th birthday, so that a regency could be avoided.[6]

Victoria later described her childhood as "rather melancholy".[7] Her mother was extremely protective, and Victoria was raised largely isolated from other children under the so-called "Kensington System", an elaborate set of rules and protocols devised by the Duchess and her ambitious and domineering comptroller, Sir John Conroy, who was rumoured to be the Duchess's lover.[8] The system prevented the princess from meeting people whom her mother and Conroy deemed undesirable (including most of her father's family), and was designed to render her weak and dependent upon them.[9] The Duchess avoided the court because she was scandalised by the presence of King William's illegitimate children.[10] Victoria shared a bedroom with her mother every night, studied with private tutors to a regular timetable, and spent her play-hours with her dolls and her King Charles Spaniel, Dash.[11] Her lessons included French, German, Italian, and Latin,[12] but she spoke only English at home.[13]

In 1830, the Duchess and Conroy took Victoria across the centre of England to visit the Malvern Hills, stopping at towns and great country houses along the way.[14] Similar journeys to other parts of England and Wales were taken in 1832, 1833, 1834 and 1835. To the King's annoyance, Victoria was enthusiastically welcomed in each of the stops.[15] William compared the journeys to royal progresses and was concerned that they portrayed Victoria as his rival rather than his heir presumptive.[16] Victoria disliked the trips; the constant round of public appearances made her tired and ill, and there was little time for her to rest.[17] She objected on the grounds of the King's disapproval, but her mother dismissed his complaints as motivated by jealousy and forced Victoria to continue the tours.[18] At Ramsgate in October 1835, Victoria contracted a severe fever, which Conroy initially dismissed as a childish pretence.[19] While Victoria was ill, Conroy and the Duchess unsuccessfully badgered her to make Conroy her private secretary.[20] As a teenager, Victoria resisted persistent attempts by her mother and Conroy to appoint him to her staff.[21] Once queen, she banned him from her presence, but he remained in her mother's household.[22]

By 1836, Victoria's maternal uncle Leopold, who had been King of the Belgians since 1831, hoped to marry her to Prince Albert,[23] the son of his brother Ernest I, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. Leopold arranged for Victoria's mother to invite her Coburg relatives to visit her in May 1836, with the purpose of introducing Victoria to Albert.[24] William IV, however, disapproved of any match with the Coburgs, and instead favoured the suit of Prince Alexander of the Netherlands, second son of the Prince of Orange.[25] Victoria was aware of the various matrimonial plans and critically appraised a parade of eligible princes.[26] According to her diary, she enjoyed Albert's company from the beginning. After the visit she wrote, "[Albert] is extremely handsome; his hair is about the same colour as mine; his eyes are large and blue, and he has a beautiful nose and a very sweet mouth with fine teeth; but the charm of his countenance is his expression, which is most delightful."[27] Alexander, on the other hand, she described as "very plain".[28]

Victoria wrote to King Leopold, whom she considered her "best and kindest adviser",[29] to thank him "for the prospect of great happiness you have contributed to give me, in the person of dear Albert ... He possesses every quality that could be desired to render me perfectly happy. He is so sensible, so kind, and so good, and so amiable too. He has besides the most pleasing and delightful exterior and appearance you can possibly see."[30] However at 17, Victoria, though interested in Albert, was not yet ready to marry. The parties did not undertake a formal engagement, but assumed that the match would take place in due time.[31]

Accession and early reign

Victoria turned 18 on 24 May 1837, and a regency was avoided. Less than a month later, on 20 June 1837, William IV died at the age of 71, and Victoria became Queen of the United Kingdom.[c] In her diary she wrote, "I was awoke at 6 o'clock by Mamma, who told me the Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Conyngham were here and wished to see me. I got out of bed and went into my sitting-room (only in my dressing gown) and alone, and saw them. Lord Conyngham then acquainted me that my poor Uncle, the King, was no more, and had expired at 12 minutes past 2 this morning, and consequently that I am Queen."[32] Official documents prepared on the first day of her reign described her as Alexandrina Victoria, but the first name was withdrawn at her own wish and not used again.[33]

Since 1714, Britain had shared a monarch with Hanover in Germany, but under Salic law, women were excluded from the Hanoverian succession. While Victoria inherited the British throne, her father's unpopular younger brother, Ernest Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, became King of Hanover. He was Victoria's heir presumptive until she had a child.[34]

At the time of Victoria's accession, the government was led by the Whig prime minister Lord Melbourne. He at once became a powerful influence on the politically inexperienced monarch, who relied on him for advice.[35] Charles Greville supposed that the widowed and childless Melbourne was "passionately fond of her as he might be of his daughter if he had one", and Victoria probably saw him as a father figure.[36] Her coronation took place on 28 June 1838 at Westminster Abbey. Over 400,000 visitors came to London for the celebrations.[37] She became the first sovereign to take up residence at Buckingham Palace[38] and inherited the revenues of the duchies of Lancaster and Cornwall as well as being granted a civil list allowance of £385,000 per year. Financially prudent, she paid off her father's debts.[39]

At the start of her reign Victoria was popular,[40] but her reputation suffered in an 1839 court intrigue when one of her mother's ladies-in-waiting, Lady Flora Hastings, developed an abdominal growth that was widely rumoured to be an out-of-wedlock pregnancy by Sir John Conroy.[41] Victoria believed the rumours.[42] She hated Conroy, and despised "that odious Lady Flora",[43] because she had conspired with Conroy and the Duchess in the Kensington System.[44] At first, Lady Flora refused to submit to an intimate medical examination, until in mid-February she eventually acquiesced, and was found to be a virgin.[45] Conroy, the Hastings family, and the opposition Tories organised a press campaign implicating the Queen in the spreading of false rumours about Lady Flora.[46] When Lady Flora died in July, the post-mortem revealed a large tumour on her liver that had distended her abdomen.[47] At public appearances, Victoria was hissed and jeered as "Mrs. Melbourne".[48]

In 1839, Melbourne resigned after Radicals and Tories (both of whom Victoria detested) voted against a bill to suspend the constitution of Jamaica. The bill removed political power from plantation owners who were resisting measures associated with the abolition of slavery.[49] The Queen commissioned a Tory, Robert Peel, to form a new ministry. At the time, it was customary for the prime minister to appoint members of the Royal Household, who were usually his political allies and their spouses. Many of the Queen's ladies of the bedchamber were wives of Whigs, and Peel expected to replace them with wives of Tories. In what became known as the "bedchamber crisis", Victoria, advised by Melbourne, objected to their removal. Peel refused to govern under the restrictions imposed by the Queen, and consequently resigned his commission, allowing Melbourne to return to office.[50]

Marriage and public life

Though Victoria was now queen, as an unmarried young woman she was required by social convention to live with her mother, despite their differences over the Kensington System and her mother's continued reliance on Conroy.[51] The Duchess was consigned to a remote apartment in Buckingham Palace, and Victoria often refused to see her.[52] When Victoria complained to Melbourne that her mother's proximity promised "torment for many years", Melbourne sympathised but said it could be avoided by marriage, which Victoria called a "schocking [sic] alternative".[53] Victoria showed interest in Albert's education for the future role he would have to play as her husband, but she resisted attempts to rush her into wedlock.[54]

Victoria continued to praise Albert following his second visit in October 1839. They felt mutual affection and the Queen proposed to him on 15 October 1839, just five days after he had arrived at Windsor.[55] They were married on 10 February 1840, in the Chapel Royal of St James's Palace, London. Victoria was love-struck. She spent the evening after their wedding lying down with a headache, but wrote ecstatically in her diary:

I NEVER, NEVER spent such an evening!!! MY DEAREST DEAREST DEAR Albert ... his excessive love & affection gave me feelings of heavenly love & happiness I never could have hoped to have felt before! He clasped me in his arms, & we kissed each other again & again! His beauty, his sweetness & gentleness—really how can I ever be thankful enough to have such a Husband! ... to be called by names of tenderness, I have never yet heard used to me before—was bliss beyond belief! Oh! This was the happiest day of my life![56]

Albert became an important political adviser as well as the Queen's companion, replacing Melbourne as the dominant influential figure in the first half of her life.[57] Victoria's mother was evicted from the palace, to Ingestre House in Belgrave Square. After the death of Victoria's aunt Princess Augusta in 1840, the Duchess was given both Clarence House and Frogmore House.[58] Through Albert's mediation, relations between mother and daughter slowly improved.[59]

During Victoria's first pregnancy in 1840, in the first few months of the marriage, 18-year-old Edward Oxford attempted to assassinate her while she was riding in a carriage with Prince Albert on her way to visit her mother. Oxford fired twice, but either both bullets missed or, as he later claimed, the guns had no shot.[60] He was tried for high treason, found not guilty by reason of insanity, committed to an insane asylum indefinitely, and later sent to live in Australia.[61] In the immediate aftermath of the attack, Victoria's popularity soared, mitigating residual discontent over the Hastings affair and the bedchamber crisis.[62] Her daughter, also named Victoria, was born on 21 November 1840. The Queen hated being pregnant,[63] viewed breast-feeding with disgust,[64] and thought newborn babies were ugly.[65] Nevertheless, over the following seventeen years, she and Albert had a further eight children: Albert Edward, Alice, Alfred, Helena, Louise, Arthur, Leopold and Beatrice.[66]

The household was largely run by Victoria's childhood governess, Baroness Louise Lehzen from Hanover. Lehzen had been a formative influence on Victoria[67] and had supported her against the Kensington System.[68] Albert, however, thought that Lehzen was incompetent and that her mismanagement threatened his daughter Victoria's health. After a furious row between Victoria and Albert over the issue, Lehzen was pensioned off in 1842, and Victoria's close relationship with her ended.[69]

On 29 May 1842, Victoria was riding in a carriage along The Mall, London, when John Francis aimed a pistol at her, but the gun did not fire. The assailant escaped; the following day, Victoria drove the same route, though faster and with a greater escort, in a deliberate attempt to bait Francis into taking a second aim and catch him in the act. As expected, Francis shot at her, but he was seized by plainclothes policemen, and convicted of high treason. On 3 July, two days after Francis's death sentence was commuted to transportation for life, John William Bean also tried to fire a pistol at the Queen, but it was loaded only with paper and tobacco and had too little charge.[70] Edward Oxford felt that the attempts were encouraged by his acquittal in 1840.[71] Bean was sentenced to 18 months in jail.[71] In a similar attack in 1849, unemployed Irishman William Hamilton fired a powder-filled pistol at Victoria's carriage as it passed along Constitution Hill, London.[72] In 1850, the Queen did sustain injury when she was assaulted by a possibly insane ex-army officer, Robert Pate. As Victoria was riding in a carriage, Pate struck her with his cane, crushing her bonnet and bruising her forehead. Both Hamilton and Pate were sentenced to seven years' transportation.[73]

Melbourne's support in the House of Commons weakened through the early years of Victoria's reign, and in the 1841 general election the Whigs were defeated. Peel became prime minister, and the ladies of the bedchamber most associated with the Whigs were replaced.[74]

In 1845, Ireland was hit by a potato blight.[76] In the next four years, over a million Irish people died and another million emigrated in what became known as the Great Famine.[77] In Ireland, Victoria was labelled "The Famine Queen".[78][79] In January 1847 she personally donated £2,000 (equivalent to between £230,000 and £8.5 million in 2022)[80] to the British Relief Association, more than any other individual famine relief donor,[81] and supported the Maynooth Grant to a Roman Catholic seminary in Ireland, despite Protestant opposition.[82] The story that she donated only £5 in aid to the Irish, and on the same day gave the same amount to Battersea Dogs Home, was a myth generated towards the end of the 19th century.[83]

By 1846, Peel's ministry faced a crisis involving the repeal of the Corn Laws. Many Tories—by then known also as Conservatives—were opposed to the repeal, but Peel, some Tories (the free-trade oriented liberal conservative "Peelites"), most Whigs and Victoria supported it. Peel resigned in 1846, after the repeal narrowly passed, and was replaced by Lord John Russell.[84]

| Victoria's British prime ministers | |

| Year | Prime Minister (party) |

|---|---|

| 1835 | Viscount Melbourne (Whig) |

| 1841 | Sir Robert Peel (Conservative) |

| 1846 | Lord John Russell (Whig) |

| 1852 (February) | Earl of Derby (Conservative) |

| 1852 (December) | Earl of Aberdeen (Peelite) |

| 1855 | Viscount Palmerston (Liberal) |

| 1858 | Earl of Derby (Conservative) |

| 1859 | Viscount Palmerston (Liberal) |

| 1865 | Earl Russell, Lord John Russell (Liberal) |

| 1866 | Earl of Derby (Conservative) |

| 1868 (February) | Benjamin Disraeli (Conservative) |

| 1868 (December) | William Gladstone (Liberal) |

| 1874 | Benjamin Disraeli, Lord Beaconsfield (Conservative) |

| 1880 | William Gladstone (Liberal) |

| 1885 | Marquess of Salisbury (Conservative) |

| 1886 (February) | William Gladstone (Liberal) |

| 1886 (July) | Marquess of Salisbury (Conservative) |

| 1892 | William Gladstone (Liberal) |

| 1894 | Earl of Rosebery (Liberal) |

| 1895 | Marquess of Salisbury (Conservative) |

| See List of prime ministers of Queen Victoria for details of her British and overseas premiers | |

Internationally, Victoria took a keen interest in the improvement of relations between France and Britain.[85] She made and hosted several visits between the British royal family and the House of Orleans, who were related by marriage through the Coburgs. In 1843 and 1845, she and Albert stayed with King Louis Philippe I at Château d'Eu in Normandy; she was the first British or English monarch to visit a French monarch since the meeting of Henry VIII of England and Francis I of France on the Field of the Cloth of Gold in 1520.[86] When Louis Philippe made a reciprocal trip in 1844, he became the first French king to visit a British sovereign.[87] Louis Philippe was deposed in the revolutions of 1848, and fled to exile in England.[88] At the height of a revolutionary scare in the United Kingdom in April 1848, Victoria and her family left London for the greater safety of Osborne House,[89] a private estate on the Isle of Wight that they had purchased in 1845 and redeveloped.[90] Demonstrations by Chartists and Irish nationalists failed to attract widespread support, and the scare died down without any major disturbances.[91] Victoria's first visit to Ireland in 1849 was a public relations success, but it had no lasting impact or effect on the growth of Irish nationalism.[92]

Russell's ministry, though Whig, was not favoured by the Queen.[93] She found particularly offensive the Foreign Secretary, Lord Palmerston, who often acted without consulting the Cabinet, the Prime Minister, or the Queen.[94] Victoria complained to Russell that Palmerston sent official dispatches to foreign leaders without her knowledge, but Palmerston was retained in office and continued to act on his own initiative, despite her repeated remonstrances. It was only in 1851 that Palmerston was removed after he announced the British government's approval of President Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte's coup in France without consulting the Prime Minister.[95] The following year, President Bonaparte was declared Emperor Napoleon III, by which time Russell's administration had been replaced by a short-lived minority government led by Lord Derby.[96]

In 1853, Victoria gave birth to her eighth child, Leopold, with the aid of the new anaesthetic, chloroform. She was so impressed by the relief it gave from the pain of childbirth that she used it again in 1857 at the birth of her ninth and final child, Beatrice, despite opposition from members of the clergy, who considered it against biblical teaching, and members of the medical profession, who thought it dangerous.[97] Victoria may have had postnatal depression after many of her pregnancies.[66] Letters from Albert to Victoria intermittently complain of her loss of self-control. For example, about a month after Leopold's birth Albert complained in a letter to Victoria about her "continuance of hysterics" over a "miserable trifle".[98]

In early 1855, the government of Lord Aberdeen, who had replaced Derby, fell amidst recriminations over the poor management of British troops in the Crimean War. Victoria approached both Derby and Russell to form a ministry, but neither had sufficient support, and Victoria was forced to appoint Palmerston as prime minister.[99]

Napoleon III, Britain's closest ally as a result of the Crimean War,[66] visited London in April 1855, and from 17 to 28 August the same year Victoria and Albert returned the visit.[100] Napoleon III met the couple at Boulogne and accompanied them to Paris.[101] They visited the Exposition Universelle (a successor to Albert's 1851 brainchild the Great Exhibition) and Napoleon I's tomb at Les Invalides (to which his remains had only been returned in 1840), and were guests of honour at a 1,200-guest ball at the Palace of Versailles.[102] This marked the first time that a reigning British monarch had been to Paris in over 400 years.[103]

On 14 January 1858, an Italian refugee from Britain called Felice Orsini attempted to assassinate Napoleon III with a bomb made in England.[104] The ensuing diplomatic crisis destabilised the government, and Palmerston resigned. Derby was reinstated as prime minister.[105] Victoria and Albert attended the opening of a new basin at the French military port of Cherbourg on 5 August 1858, in an attempt by Napoleon III to reassure Britain that his military preparations were directed elsewhere. On her return Victoria wrote to Derby reprimanding him for the poor state of the Royal Navy in comparison to the French Navy.[106] Derby's ministry did not last long, and in June 1859 Victoria recalled Palmerston to office.[107]

Eleven days after Orsini's assassination attempt in France, Victoria's eldest daughter married Prince Frederick William of Prussia in London. They had been betrothed since September 1855, when Princess Victoria was 14 years old; the marriage was delayed by the Queen and her husband Albert until the bride was 17.[108] The Queen and Albert hoped that their daughter and son-in-law would be a liberalising influence in the enlarging Prussian state.[109] The Queen felt "sick at heart" to see her daughter leave England for Germany; "It really makes me shudder", she wrote to Princess Victoria in one of her frequent letters, "when I look round to all your sweet, happy, unconscious sisters, and think I must give them up too – one by one."[110] Almost exactly a year later, the Princess gave birth to the Queen's first grandchild, Wilhelm, who would become the last German emperor.[66]

Widowhood and isolation

In March 1861, Victoria's mother died, with Victoria at her side. Through reading her mother's papers, Victoria discovered that her mother had loved her deeply;[111] she was heart-broken, and blamed Conroy and Lehzen for "wickedly" estranging her from her mother.[112] To relieve his wife during her intense and deep grief,[113] Albert took on most of her duties, despite being ill himself with chronic stomach trouble.[114] In August, Victoria and Albert visited their son, Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, who was attending army manoeuvres near Dublin, and spent a few days holidaying in Killarney. In November, Albert was made aware of gossip that his son had slept with an actress in Ireland.[115] Appalled, he travelled to Cambridge, where his son was studying, to confront him.[116]

By the beginning of December, Albert was very unwell.[117] He was diagnosed with typhoid fever by William Jenner, and died on 14 December 1861. Victoria was devastated.[118] She blamed her husband's death on worry over the Prince of Wales's philandering. He had been "killed by that dreadful business", she said.[119] She entered a state of mourning and wore black for the remainder of her life. She avoided public appearances and rarely set foot in London in the following years.[120] Her seclusion earned her the nickname "widow of Windsor".[121] Her weight increased through comfort eating, which reinforced her aversion to public appearances.[122]

Victoria's self-imposed isolation from the public diminished the popularity of the monarchy, and encouraged the growth of the republican movement.[123] She did undertake her official government duties, yet chose to remain secluded in her royal residences—Windsor Castle, Osborne House, and the private estate in Scotland that she and Albert had acquired in 1847, Balmoral Castle. In March 1864, a protester stuck a notice on the railings of Buckingham Palace that announced "these commanding premises to be let or sold in consequence of the late occupant's declining business".[124] Her uncle Leopold wrote to her advising her to appear in public. She agreed to visit the gardens of the Royal Horticultural Society at Kensington and take a drive through London in an open carriage.[125]

Through the 1860s, Victoria relied increasingly on a manservant from Scotland, John Brown.[126] Rumours of a romantic connection and even a secret marriage appeared in print, and some referred to the Queen as "Mrs. Brown".[127] The story of their relationship was the subject of the 1997 movie Mrs. Brown. A painting by Sir Edwin Henry Landseer depicting the Queen with Brown was exhibited at the Royal Academy, and Victoria published a book, Leaves from the Journal of Our Life in the Highlands, which featured Brown prominently and in which the Queen praised him highly.[128]

Palmerston died in 1865, and after a brief ministry led by Russell, Derby returned to power. In 1866, Victoria attended the State Opening of Parliament for the first time since Albert's death.[129] The following year she supported the passing of the Reform Act 1867 which doubled the electorate by extending the franchise to many urban working men,[130] though she was not in favour of votes for women.[131] Derby resigned in 1868, to be replaced by Benjamin Disraeli, who charmed Victoria. "Everyone likes flattery," he said, "and when you come to royalty you should lay it on with a trowel."[132] With the phrase "we authors, Ma'am", he complimented her.[133] Disraeli's ministry only lasted a matter of months, and at the end of the year his Liberal rival, William Ewart Gladstone, was appointed prime minister. Victoria found Gladstone's demeanour far less appealing; he spoke to her, she is thought to have complained, as though she were "a public meeting rather than a woman".[134]

In 1870 republican sentiment in Britain, fed by the Queen's seclusion, was boosted after the establishment of the Third French Republic.[135] A republican rally in Trafalgar Square demanded Victoria's removal, and Radical MPs spoke against her.[136] In August and September 1871, she was seriously ill with an abscess in her arm, which Joseph Lister successfully lanced and treated with his new antiseptic carbolic acid spray.[137] In late November 1871, at the height of the republican movement, the Prince of Wales contracted typhoid fever, the disease that was believed to have killed his father, and Victoria was fearful her son would die.[138] As the tenth anniversary of her husband's death approached, her son's condition grew no better, and Victoria's distress continued.[139] To general rejoicing, he recovered.[140] Mother and son attended a public parade through London and a grand service of thanksgiving in St Paul's Cathedral on 27 February 1872, and republican feeling subsided.[141]

On the last day of February 1872, two days after the thanksgiving service, 17-year-old Arthur O'Connor, a great-nephew of Irish MP Feargus O'Connor, waved an unloaded pistol at Victoria's open carriage just after she had arrived at Buckingham Palace. Brown, who was attending the Queen, grabbed him and O'Connor was later sentenced to 12 months' imprisonment,[142] and a birching.[143] As a result of the incident, Victoria's popularity recovered further.[144]

Empress of India

After the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the British East India Company, which had ruled much of India, was dissolved, and Britain's possessions and protectorates on the Indian subcontinent were formally incorporated into the British Empire. The Queen had a relatively balanced view of the conflict, and condemned atrocities on both sides.[145] She wrote of "her feelings of horror and regret at the result of this bloody civil war",[146] and insisted, urged on by Albert, that an official proclamation announcing the transfer of power from the company to the state "should breathe feelings of generosity, benevolence and religious toleration".[147] At her behest, a reference threatening the "undermining of native religions and customs" was replaced by a passage guaranteeing religious freedom.[147]

In the 1874 general election, Disraeli was returned to power. He passed the Public Worship Regulation Act 1874, which removed Catholic rituals from the Anglican liturgy and which Victoria strongly supported.[149] She preferred short, simple services, and personally considered herself more aligned with the presbyterian Church of Scotland than the episcopal Church of England.[150] Disraeli also pushed the Royal Titles Act 1876 through Parliament, so that Victoria took the title "Empress of India" from 1 May 1876.[151] The new title was proclaimed at the Delhi Durbar of 1 January 1877.[152]

On 14 December 1878, the anniversary of Albert's death, Victoria's second daughter Alice, who had married Louis of Hesse, died of diphtheria in Darmstadt. Victoria noted the coincidence of the dates as "almost incredible and most mysterious".[153] In May 1879, she became a great-grandmother (on the birth of Princess Feodora of Saxe-Meiningen) and passed her "poor old 60th birthday". She felt "aged" by "the loss of my beloved child".[154]

Between April 1877 and February 1878, she threatened five times to abdicate while pressuring Disraeli to act against Russia during the Russo-Turkish War, but her threats had no impact on the events or their conclusion with the Congress of Berlin.[155] Disraeli's expansionist foreign policy, which Victoria endorsed, led to conflicts such as the Anglo-Zulu War and the Second Anglo-Afghan War. "If we are to maintain our position as a first-rate Power", she wrote, "we must ... be Prepared for attacks and wars, somewhere or other, CONTINUALLY."[156] Victoria saw the expansion of the British Empire as civilising and benign, protecting native peoples from more aggressive powers or cruel rulers: "It is not in our custom to annexe countries", she said, "unless we are obliged & forced to do so."[157] To Victoria's dismay, Disraeli lost the 1880 general election, and Gladstone returned as prime minister.[158] When Disraeli died the following year, she was blinded by "fast falling tears",[159] and erected a memorial tablet "placed by his grateful Sovereign and Friend, Victoria R.I."[160]

On 2 March 1882, Roderick Maclean, a disgruntled poet apparently offended by Victoria's refusal to accept one of his poems,[161] shot at the Queen as her carriage left Windsor railway station. Gordon Chesney Wilson and another schoolboy from Eton College struck him with their umbrellas, until he was hustled away by a policeman.[162] Victoria was outraged when he was found not guilty by reason of insanity,[163] but was so pleased by the many expressions of loyalty after the attack that she said it was "worth being shot at—to see how much one is loved".[164]

On 17 March 1883, Victoria fell down some stairs at Windsor, which left her lame until July; she never fully recovered and was plagued with rheumatism thereafter.[165] John Brown died 10 days after her accident, and to the consternation of her private secretary, Sir Henry Ponsonby, Victoria began work on a eulogistic biography of Brown.[166] Ponsonby and Randall Davidson, Dean of Windsor, who had both seen early drafts, advised Victoria against publication, on the grounds that it would stoke the rumours of a love affair.[167] The manuscript was destroyed.[168] In early 1884, Victoria did publish More Leaves from a Journal of a Life in the Highlands, a sequel to her earlier book, which she dedicated to her "devoted personal attendant and faithful friend John Brown".[169] On the day after the first anniversary of Brown's death, Victoria was informed by telegram that her youngest son, Leopold, had died in Cannes. He was "the dearest of my dear sons", she lamented.[170] The following month, Victoria's youngest child, Beatrice, met and fell in love with Prince Henry of Battenberg at the wedding of Victoria's granddaughter Princess Victoria of Hesse and by Rhine to Henry's brother Prince Louis of Battenberg. Beatrice and Henry planned to marry, but Victoria opposed the match at first, wishing to keep Beatrice at home to act as her companion. After a year, she was won around to the marriage by their promise to remain living with and attending her.[171]

Victoria was pleased when Gladstone resigned in 1885 after his budget was defeated.[172] She thought his government was "the worst I have ever had", and blamed him for the death of General Gordon during the Siege of Khartoum.[173] Gladstone was replaced by Lord Salisbury. Salisbury's government only lasted a few months, however, and Victoria was forced to recall Gladstone, whom she referred to as a "half crazy & really in many ways ridiculous old man".[174] Gladstone attempted to pass a bill granting Ireland home rule, but to Victoria's glee it was defeated.[175] In the ensuing election, Gladstone's party lost to Salisbury's and the government switched hands again.[176]

Golden and Diamond Jubilees

In 1887, the British Empire celebrated Victoria's Golden Jubilee. She marked the fiftieth anniversary of her accession on 20 June with a banquet to which 50 kings and princes were invited. The following day, she participated in a procession and attended a thanksgiving service in Westminster Abbey.[177] By this time, Victoria was once again extremely popular.[178] Two days later on 23 June,[179] she engaged two Indian Muslims as waiters, one of whom was Abdul Karim. He was soon promoted to "Munshi": teaching her Urdu and acting as a clerk.[180][181][182] Her family and retainers were appalled, and accused Abdul Karim of spying for the Muslim Patriotic League, and biasing the Queen against the Hindus.[183] Equerry Frederick Ponsonby (the son of Sir Henry) discovered that the Munshi had lied about his parentage, and reported to Lord Elgin, Viceroy of India, "the Munshi occupies very much the same position as John Brown used to do."[184] Victoria dismissed their complaints as racial prejudice.[185] Abdul Karim remained in her service until he returned to India with a pension, on her death.[186]

Victoria's eldest daughter became empress consort of Germany in 1888, but she was widowed a little over three months later, and Victoria's eldest grandchild became German Emperor as Wilhelm II. Victoria and Albert's hopes of a liberal Germany would go unfulfilled, as Wilhelm was a firm believer in autocracy. Victoria thought he had "little heart or Zartgefühl [tact] – and ... his conscience & intelligence have been completely wharped [sic]".[187]

Gladstone returned to power after the 1892 general election; he was 82 years old. Victoria objected when Gladstone proposed appointing the Radical MP Henry Labouchère to the Cabinet, so Gladstone agreed not to appoint him.[188] In 1894, Gladstone retired and, without consulting the outgoing prime minister, Victoria appointed Lord Rosebery as prime minister.[189] His government was weak, and the following year Lord Salisbury replaced him. Salisbury remained prime minister for the remainder of Victoria's reign.[190]

On 23 September 1896, Victoria surpassed her grandfather George III as the longest-reigning monarch in British history. The Queen requested that any special celebrations be delayed until 1897, to coincide with her Diamond Jubilee,[191] which was made a festival of the British Empire at the suggestion of the Colonial Secretary, Joseph Chamberlain.[192] The prime ministers of all the self-governing Dominions were invited to London for the festivities.[193] One reason for including the prime ministers of the Dominions and excluding foreign heads of state was to avoid having to invite Victoria's grandson Wilhelm II, who, it was feared, might cause trouble at the event.[194]

The Queen's Diamond Jubilee procession on 22 June 1897 followed a route six miles long through London and included troops from all over the empire. The procession paused for an open-air service of thanksgiving held outside St Paul's Cathedral, throughout which Victoria sat in her open carriage, to avoid her having to climb the steps to enter the building. The celebration was marked by vast crowds of spectators and great outpourings of affection for the 78-year-old Queen.[195]

Declining health and death

Victoria regularly holidayed in mainland Europe. In 1889, during a stay in Biarritz, she became the first reigning monarch from Britain to visit Spain by briefly crossing the border.[196] By April 1900, the Boer War was so unpopular in mainland Europe that her annual trip to France seemed inadvisable. Instead, the Queen went to Ireland for the first time since 1861, in part to acknowledge the contribution of Irish regiments to the South African war.[197]

In July 1900, Victoria's second son, Alfred ("Affie"), died. "Oh, God! My poor darling Affie gone too", she wrote in her journal. "It is a horrible year, nothing but sadness & horrors of one kind & another."[198]

Following a custom she maintained throughout her widowhood, Victoria spent the Christmas of 1900 at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight. Rheumatism in her legs had rendered her disabled, and her eyesight was clouded by cataracts.[199] Through early January, she felt "weak and unwell",[200] and by mid-January she was "drowsy [...] dazed, [and] confused".[201] Her favourite pet Pomeranian, Turi, was laid on her bed as a last request.[202] She died aged 81 on 22 January 1901, at half past six in the evening, in the presence of her eldest son, Albert Edward, and grandson Wilhelm II. Albert Edward immediately succeeded as Edward VII.[203]

В 1897 году Виктория написала инструкцию о своих похоронах , которые должны были быть военными, как и подобает солдатской дочери и главе армии. [66] and white instead of black.[204] On 25 January, Edward VII and Wilhelm II, together with Prince Arthur, helped lift her body into the coffin.[205] She was dressed in a white dress and her wedding veil.[206] По ее просьбе ее врач и костюмеры положили в гроб вместе с ней множество сувениров в память о ее большой семье, друзьях и слугах. Один из халатов Альберта был положен рядом с ней вместе с гипсовой повязкой его руки, а прядь волос Джона Брауна вместе с его фотографией была помещена в ее левую руку, скрыта от взглядов семьи тщательно расположен букет цветов. [ 66 ] [ 207 ] Среди украшений, помещенных на Викторию, было обручальное кольцо матери Брауна, которое Браун подарил Виктории в 1883 году. [ 66 ] Ее похороны состоялись в субботу, 2 февраля, в часовне Святого Георгия в Виндзорском замке , и после двух дней лежания она была похоронена рядом с принцем Альбертом в Королевском мавзолее Фрогмор в Большом Виндзорском парке . [ 208 ]

С правлением в 63 года, семь месяцев и два дня Виктория была самым долгоправящим британским монархом и самой долгоправящей королевой в мировой истории, пока ее праправнучка Елизавета II не превзошла ее 9 сентября 2015 года. [ 209 ] Она была последним монархом Британии из Ганноверского дома ; ее сын Эдуард VII принадлежал к дому ее мужа Саксен-Кобург-Гота . [ 210 ]

Наследие

Репутация

По словам одного из ее биографов, Джайлса Сент-Обина, во взрослой жизни Виктория писала в среднем 2500 слов в день. [ 214 ] С июля 1832 года и до самой смерти она вела подробный дневник , который в итоге составил 122 тома. [ 215 ] После смерти Виктории ее литературным душеприказчиком была назначена ее младшая дочь, принцесса Беатрис. Беатрис расшифровала и отредактировала дневники, рассказывающие о вступлении Виктории на престол, и при этом сожгла оригиналы. [ 216 ] Несмотря на это разрушение, большая часть дневников все еще существует. Помимо отредактированной копии Беатрис, лорд Эшер расшифровал тома с 1832 по 1861 год, прежде чем Беатрис уничтожила их. [ 217 ] Часть обширной переписки Виктории была опубликована в томах под редакцией А.С. Бенсона , Гектора Болито , Джорджа Эрла Бакла , лорда Эшера, Роджера Фулфорда и Ричарда Хафа , среди других. [ 218 ]

В более поздние годы Виктория была полной, неряшливой и ростом около пяти футов (1,5 метра), но создавала величественный имидж. [ 219 ] Она была непопулярна в первые годы своего вдовства, но пользовалась большой любовью в 1880-х и 1890-х годах, когда она олицетворяла империю как доброжелательная матриархальная фигура. [ 220 ] Только после публикации ее дневника и писем степень ее политического влияния стала известна широкой общественности. [ 66 ] [ 221 ] Биографии Виктории, написанные до того, как стала доступна большая часть первичного материала, такие как Стрейчи » Литтона «Королева Виктория 1921 года, теперь считаются устаревшими. [ 222 ] Биографии, написанные Элизабет Лонгфорд и Сесилом Вудэм-Смитом в 1964 и 1972 годах соответственно, до сих пор вызывают широкое восхищение. [ 223 ] Они и другие приходят к выводу, что Виктория как человек была эмоциональной, упрямой, честной и откровенной. [ 224 ]

Во время правления Виктории продолжалось постепенное установление современной конституционной монархии в Великобритании. Реформы системы голосования увеличили власть Палаты общин за счет Палаты лордов и монарха. [ 225 ] В 1867 году Уолтер Бэджхот писал, что монарх сохранил только «право на то, чтобы с ним советовались, право поощрять и право предупреждать». [ 226 ] Поскольку монархия Виктории стала скорее символической, чем политической, она уделяла большое внимание морали и семейным ценностям, в отличие от сексуальных, финансовых и личных скандалов, которые были связаны с предыдущими членами Ганноверской палаты и дискредитировали монархию. Концепция «семейной монархии», которую мог идентифицировать растущий средний класс, укрепилась. [ 227 ]

Потомки и гемофилия

Связи Виктории с королевскими семьями Европы принесли ей прозвище «бабушка Европы». [ 228 ] Из внуков Виктории и Альберта до совершеннолетия дожили 34 человека. [ 66 ]

Младший сын Виктории, Леопольд, заболел гемофилией B, связанной со свертываемостью крови , и по крайней мере две из ее пяти дочерей, Алиса и Беатрис, были носителями этого заболевания. Среди королевских больных гемофилией Виктории были ее правнуки, Алексей Николаевич, царевич России ; Альфонсо, принц Астурийский ; и Инфанте Гонсало из Испании . [ 229 ] Наличие заболевания у потомков Виктории, но не у ее предков, привело к современным предположениям, что ее настоящий отец был не герцогом Кентским , а больным гемофилией. [ 230 ] Документальных свидетельств того, что мать Виктории была больна гемофилией, не существует, а поскольку болезнью всегда страдали мужчины-носители, даже если бы такой мужчина существовал, он был бы серьезно болен. [ 231 ] Более вероятно, что мутация возникла спонтанно, поскольку отцу Виктории на момент зачатия было более 50 лет, а гемофилия чаще возникает у детей отцов старшего возраста. [ 232 ] Спонтанные мутации составляют около трети случаев. [ 233 ]

Титулы, стили, почести и оружие

Названия и стили

королевы В конце ее правления полный стиль был таким: «Ее Величество Виктория, милостью Божией, королева Соединенного Королевства Великобритании и Ирландии , Защитница веры , Императрица Индии». [ 234 ]

Почести

Британские награды

- Орден королевской семьи Георга IV , 1826 г. [ 235 ]

- Основатель Креста Виктории, 5 февраля 1856 г. [ 236 ]

- Основатель и суверен Ордена Звезды Индии , 25 июня 1861 г. [ 237 ]

- Основатель и суверен Королевского ордена Виктории и Альберта , 10 февраля 1862 г. [ 238 ]

- Основатель и суверен Ордена Короны Индии , 1 января 1878 г. [ 239 ]

- Основатель и суверен Ордена Индийской Империи , 1 января 1878 г. [ 240 ]

- Основатель и суверен Королевского Красного Креста , 27 апреля 1883 г. [ 241 ]

- Основатель и государь Ордена « За выдающиеся заслуги» , 6 ноября 1886 г. [ 242 ]

- Медаль Альберта Королевского общества искусств , 1887 г. [ 243 ]

- Основатель и суверен Королевского Викторианского ордена , 23 апреля 1896 г. [ 244 ]

Иностранные награды

- Испания :

- Дама ордена королевы Марии Луизы , 21 декабря 1833 г. [ 245 ]

- Большой крест ордена Карла III [ 246 ]

- Португалия :

- Дама ордена королевы Святой Изабеллы , 23 февраля 1836 г. [ 247 ]

- Большой крест ордена Непорочного зачатия Вила-Висоза [ 246 ]

- Россия : Большой крест Святой Екатерины , 26 июня 1837 г. [ 248 ]

- Франция : Большой крест Почетного легиона , 5 сентября 1843 г. [ 249 ]

- Мексика / Мексиканская империя :

- Большой крест Национального ордена Гваделупской , 1854 г. [ 250 ]

- Большой крест Императорского ордена Сан-Карлоса , 1866 г. [ 251 ]

- Пруссия : Дама ордена Луизы 1-й дивизии, 11 июня 1857 г. [ 252 ]

- Бразилия : Большой крест ордена Педро I , 3 декабря 1872 г. [ 253 ]

- Персия : [ 254 ]

- Орден Солнца 1-й степени в бриллиантах, 20 июня 1873 г.

- Орден Августовского портрета, 20 июня 1873 г.

- Делать :

- Большой крест Белого слона , 1880 г. [ 255 ]

- Дама ордена Королевского Дома Чакри , 1887 г. [ 256 ]

- Гавайи : Большой крест ордена Камехамеха I с воротником, июль 1881 г. [ 257 ]

- Сербия : [ 258 ] [ 259 ]

- Большой крест Таковского креста , 1882 г.

- Большой крест Белого орла , 1883 г.

- Большой крест Святого Саввы , 1897 г.

- Гессен и Рейн : Дама Золотого Льва , 25 апреля 1885 г. [ 260 ]

- Болгария : Орден Болгарского Красного Креста , август 1887 г. [ 261 ]

- Эфиопия : Большой крест Печати Соломона , 22 июня 1897 г. - подарок к бриллиантовому юбилею. [ 262 ]

- Черногория : Большой крест ордена князя Данило I , 1897 г. [ 263 ]

- Саксен-Кобург и Гота : Серебряная свадебная медаль герцога Альфреда и герцогини Марии, 23 января 1899 г. [ 264 ]

Оружие

Будучи Суверенной, Виктория использовала королевский герб Соединенного Королевства . Поскольку она не могла унаследовать трон Ганновера, на ее руках не было ганноверских символов, которые использовались ее непосредственными предшественниками. Ее руки несли все ее преемники на престоле. [ 265 ]

Семья

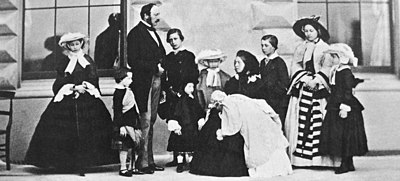

Слева направо: принц Альфред и принц Уэльский ; королева и принц Альберт ; Принцессы Алиса , Елена и Виктория

Проблема

| Имя | Рождение | Смерть | Супруга и дети [ 234 ] [ 266 ] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Виктория, Принцесса Роял |

1840 21 ноября |

1901 5 августа |

Замужем в 1858 году за Фридрихом , впоследствии императором Германии и королем Пруссии (1831–1888); 4 сына (включая Вильгельма II, немецкого императора ), 4 дочери (включая греческую королеву Софию ) |

| Эдвард VII | 1841 9 ноября |

1910 6 мая |

Женился в 1863 г. на принцессе Датской Александре (1844–1925); 3 сына (включая короля Соединенного Королевства Георга V ), 3 дочери (включая королеву Норвегии Мод ) |

| Принцесса Алиса | 1843 25 апреля |

1878 14 декабря |

Замужем в 1862 г. за Людовиком IV, великим герцогом Гессенским и Рейнским (1837–1892); 2 сына, 5 дочерей (в том числе российская императрица Александра Федоровна ) |

| Альфред, герцог Саксен-Кобургский и Гота |

1844 6 августа |

1900 31 июля |

Женился в 1874 г. на великой княгине Российской Марии Александровне (1853–1920); 2 сына (1 мертворожденный ), 4 дочери (включая королеву Румынии Марию ) |

| Принцесса Елена | 1846 25 мая |

1923 9 июня |

Замужем в 1866 г. за принцем Кристианом Шлезвиг-Гольштейнским (1831–1917); 4 сына (1 мертворожденный ), 2 дочери |

| Принцесса Луиза | 1848 18 марта |

1939 3 декабря |

Замужем в 1871 году за Джоном Кэмпбеллом , маркизом Лорном, впоследствии девятым герцогом Аргайл (1845–1914); нет проблем |

| Принц Артур, герцог Коннахт и Страттерн |

1850 1 мая |

1942 16 января |

Женился в 1879 г. на принцессе Луизе Маргарите Прусской (1860–1917); 1 сын, 2 дочери (включая кронпринцессу Швеции Маргарет ) |

| принц Леопольд, герцог Олбани |

1853 7 апреля |

1884 28 марта |

Женился в 1882 г. на принцессе Елене Вальдекской и Пирмонтской (1861–1922); 1 сын, 1 дочь |

| Принцесса Беатрис | 1857 14 апреля |

1944 26 октября |

Замужем в 1885 г. за принцем Генрихом Баттенбергским (1858–1896); 3 сына, 1 дочь ( королева Испании Виктория Евгения ) |

Родословная

| Предки королевы Виктории [ 265 ] |

|---|

Генеалогическое древо

- Красные границы обозначают британских монархов.

- Жирными границами обозначены дети британских монархов.

| Семья королевы Виктории, охватывающая период правления ее деда Георга III до ее внука Георга V. |

|---|

Примечания

- ↑ Будучи монархом, Виктория была Верховным губернатором англиканской церкви . Она также была связана с Шотландской церковью .

- ^ царь Ее крестными родителями были российский Александр I (представленный ее дядей Фредериком, герцогом Йоркским ), ее дядя Джордж, принц-регент , ее тетя королева Шарлотта Вюртембергская (представленная тетей Виктории принцессой Августой ) и бабушка Виктории по материнской линии , вдовствующая герцогиня Саксен-Кобург-Заальфельд (представлен тетей Виктории принцессой Марией, герцогиней Глостерской и Эдинбург ).

- ↑ В соответствии со статьей 2 Закона о регентстве 1830 года прокламация Совета по присоединению объявила Викторию преемницей короля, «сохраняя права любого потомства Его покойного Величества короля Вильгельма Четвертого, которое может быть рождено от супруги его покойного величества». «№ 19509» , «Лондонская газета» , 20 июня 1837 г., стр. 1581 г.

Ссылки

Цитаты

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 3–12; Стрейчи, стр. 1–17; Вудхэм-Смит, стр. 15–29.

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 12–13; Лонгфорд, с. 23; Вудхэм-Смит, стр. 34–35.

- ^ Лонгфорд, с. 24

- ^ Уорсли, с. 41.

- ^ Хибберт, с. 31; Сент-Обин, с. 26; Вудэм-Смит, с. 81

- ^ Хибберт, с. 46; Лонгфорд, с. 54; Сент-Обин, с. 50; Уоллер, с. 344; Вудэм-Смит, с. 126

- ^ Хибберт, с. 19; Маршалл, с. 25

- ^ Хибберт, с. 27; Лонгфорд, стр. 35–38, 118–119; Сент-Обин, стр. 21–22; Вудхэм-Смит, стр. 70–72. По мнению этих биографов, слухи были ложными.

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 27–28; Уоллер, стр. 341–342; Вудхэм-Смит, стр. 63–65.

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 32–33; Лонгфорд, стр. 38–39, 55; Маршалл, с. 19

- ^ Уоллер, стр. 338–341; Вудхэм-Смит, стр. 68–69, 91.

- ^ Хибберт, с. 18; Лонгфорд, с. 31; Вудхэм-Смит, стр. 74–75.

- ^ Лонгфорд, с. 31; Вудэм-Смит, с. 75

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 34–35.

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 35–39; Вудхэм-Смит, стр. 88–89, 102.

- ^ Хибберт, с. 36; Вудхэм-Смит, стр. 89–90.

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 35–40; Вудхэм-Смит, стр. 92, 102.

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 38–39; Лонгфорд, с. 47; Вудхэм-Смит, стр. 101–102.

- ^ Хибберт, с. 42; Вудэм-Смит, с. 105

- ^ Хибберт, с. 42; Лонгфорд, стр. 47–48; Маршалл, с. 21

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 42, 50; Вудэм-Смит, с. 135

- ^ Маршалл, с. 46; Сент-Обин, с. 67; Уоллер, с. 353

- ^ Лонгфорд, стр. 29, 51; Уоллер, с. 363; Вайнтрауб, стр. 43–49.

- ^ Лонгфорд, с. 51; Вайнтрауб, стр. 43–49.

- ^ Лонгфорд, стр. 51–52; Сент-Обин, с. 43; Вайнтрауб, стр. 43–49; Вудэм-Смит, с. 117

- ^ Вайнтрауб, стр. 43–49.

- ^ Виктория, цитируется в Marshall, p. 27 и Вайнтрауб, с. 49

- ^ Виктория, цитируется в Хибберте, стр. 99; Сент-Обин, с. 43; Вайнтрауб, с. 49 и Вудэм-Смит, с. 119

- ^ Журнал Виктории , октябрь 1835 г., цитируется в Сент-Обине, стр. 36 и Вудэм-Смит, с. 104

- ^ Хибберт, с. 102; Маршалл, с. 60; Уоллер, с. 363; Вайнтрауб, с. 51; Вудэм-Смит, с. 122

- ^ Уоллер, стр. 363–364; Вайнтрауб, стр. 53, 58, 64 и 65.

- ^ Сент-Обин, стр. 55–57; Вудэм-Смит, с. 138

- ^ Вудхэм-Смит, с. 140

- ^ Паккард, стр. 14–15.

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 66–69; Сент-Обин, с. 76; Вудхэм-Смит, стр. 143–147.

- ^ Гревилл, цитируется в Хибберте, стр. 67; Лонгфорд, с. 70 и Вудхэм-Смит, стр. 143–144.

- ^ Коронация королевы Виктории 1838 г. , Британская монархия, заархивировано из оригинала 3 февраля 2016 г. , получено 28 января 2016 г.

- ^ Сент-Обин, с. 69; Уоллер, с. 353

- ^ Хибберт, с. 58; Лонгфорд, стр. 73–74; Вудэм-Смит, с. 152

- ^ Маршалл, с. 42; Сент-Обин, стр. 63, 96.

- ^ Маршалл, с. 47; Уоллер, с. 356; Вудхэм-Смит, стр. 164–166.

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 77–78; Лонгфорд, с. 97; Сент-Обин, с. 97; Уоллер, с. 357; Вудэм-Смит, с. 164

- ^ Журнал Виктории, 25 апреля 1838 г., цитируется в Woodham-Smith, p. 162

- ^ Сент-Обин, с. 96; Вудхэм-Смит, стр. 162, 165.

- ^ Хибберт, с. 79; Лонгфорд, с. 98; Сент-Обин, с. 99; Вудэм-Смит, с. 167

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 80–81; Лонгфорд, стр. 102–103; Сент-Обин, стр. 101–102.

- ^ Лонгфорд, с. 122; Маршалл, с. 57; Сент-Обин, с. 104; Вудэм-Смит, с. 180

- ^ Хибберт, с. 83; Лонгфорд, стр. 120–121; Маршалл, с. 57; Сент-Обин, с. 105; Уоллер, с. 358

- ^ Сент-Обин, с. 107; Вудэм-Смит, с. 169

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 94–96; Маршалл, стр. 53–57; Сент-Обин, стр. 109–112; Уоллер, стр. 359–361; Вудхэм-Смит, стр. 170–174.

- ^ Лонгфорд, с. 84; Маршалл, с. 52

- ^ Лонгфорд, с. 72; Уоллер, с. 353

- ^ Вудхэм-Смит, с. 175

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 103–104; Маршалл, стр. 60–66; Вайнтрауб, с. 62

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 107–110; Сент-Обин, стр. 129–132; Вайнтрауб, стр. 77–81; Вудхэм-Смит, стр. 182–184, 187.

- ^ Хибберт, с. 123; Лонгфорд, с. 143; Вудэм-Смит, с. 205

- ^ Сент-Обин, с. 151

- ^ Хибберт, с. 265, Вудэм-Смит, с. 256

- ^ Маршалл, с. 152; Сент-Обин, стр. 174–175; Вудэм-Смит, с. 412

- ^ Чарльз, с. 23

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 421–422; Сент-Обин, стр. 160–161.

- ^ Вудхэм-Смит, с. 213

- ^ Хибберт, с. 130; Лонгфорд, с. 154; Маршалл, с. 122; Сент-Обин, с. 159; Вудэм-Смит, с. 220

- ^ Хибберт, с. 149; Сент-Обин, с. 169

- ^ Хибберт, с. 149; Лонгфорд, с. 154; Маршалл, с. 123; Уоллер, с. 377

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж Мэтью, ХГЧ ; Рейнольдс, К.Д. (октябрь 2009 г.) [2004], «Виктория (1819–1901)», Оксфордский национальный биографический словарь (онлайн-изд.), Oxford University Press, doi : 10.1093/ref:odnb/36652 (подписка или публичная библиотека Великобритании) членство обязательно.)

- ^ Вудхэм-Смит, с. 100

- ^ Лонгфорд, с. 56; Сент-Обин, с. 29

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 150–156; Маршалл, с. 87; Сент-Обин, стр. 171–173; Вудхэм-Смит, стр. 230–232.

- ^ Чарльз, с. 51; Хибберт, стр. 422–423; Сент-Обин, стр. 162–163.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хибберт, с. 423; Сент-Обин, с. 163

- ^ Лонгфорд, с. 192

- ^ Сент-Обин, с. 164

- ^ Маршалл, стр. 95–101; Сент-Обин, стр. 153–155; Вудхэм-Смит, стр. 221–222.

- ^ Королева Виктория и королевская принцесса , Королевская коллекция, заархивировано из оригинала 17 января 2016 года , получено 29 марта 2013 года.

- ^ Вудхэм-Смит, с. 281

- ^ Лонгфорд, с. 359

- ↑ Название статьи Мод Гонн 1900 года о визите королевы Виктории в Ирландию.

- ^ Харрисон, Шейн (15 апреля 2003 г.), «Ссора с королевой голода в ирландском порту» , BBC News , заархивировано из оригинала 19 сентября 2019 г. , получено 29 марта 2013 г.

- ^ Офицер Лоуренс Х.; Уильямсон, Сэмюэл Х. (2024), Пять способов расчета относительной стоимости суммы в британских фунтах с 1270 года по настоящее время , MeasuringWorth , получено 8 июня 2024 г.

- ^ Кинели, Кристина, Частные ответы на голод , Университетский колледж Корка, заархивировано из оригинала 6 апреля 2013 г. , получено 29 марта 2013 г.

- ^ Лонгфорд, с. 181

- ^ Кенни, Мэри (2009), Корона и Трилистник: любовь и ненависть между Ирландией и британской монархией , Дублин: Новый остров, ISBN 978-1-905494-98-9

- ^ Сент-Обин, с. 215

- ^ Сент-Обин, с. 238

- ^ Лонгфорд, стр. 175, 187; Сент-Обин, стр. 238, 241; Вудхэм-Смит, стр. 242, 250.

- ^ Вудхэм-Смит, с. 248

- ^ Хибберт, с. 198; Лонгфорд, с. 194; Сент-Обин, с. 243; Вудхэм-Смит, стр. 282–284.

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 201–202; Маршалл, с. 139; Сент-Обин, стр. 222–223; Вудхэм-Смит, стр. 287–290.

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 161–164; Маршалл, с. 129; Сент-Обин, стр. 186–190; Вудхэм-Смит, стр. 274–276.

- ^ Лонгфорд, стр. 196–197; Сент-Обин, с. 223; Вудхэм-Смит, стр. 287–290.

- ^ Лонгфорд, с. 191; Вудэм-Смит, с. 297

- ^ Сент-Обин, с. 216

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 196–198; Сент-Обин, с. 244; Вудхэм-Смит, стр. 298–307.

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 204–209; Маршалл, стр. 108–109; Сент-Обин, стр. 244–254; Вудхэм-Смит, стр. 298–307.

- ^ Сент-Обин, стр. 255, 298.

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 216–217; Сент-Обин, стр. 257–258.

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 217–220; Вудхэм-Смит, стр. 328–331.

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 227–228; Лонгфорд, стр. 245–246; Сент-Обин, с. 297; Вудхэм-Смит, стр. 354–355.

- ^ Вудхэм-Смит, стр. 357–360.

- ^ Королева Виктория, «Суббота, 18 августа 1855 года» , Журналы королевы Виктории , том. 40, с. 93, заархивировано из оригинала 25 ноября 2021 г. , получено 2 июня 2012 г. - через Королевские архивы.

- ^ Визит королевы Виктории в 1855 году , Версальский замок, заархивировано из оригинала 11 января 2013 года , получено 29 марта 2013 года.

- ^ «Королева Виктория в Париже» , Royal Collection Trust , заархивировано из оригинала 29 августа 2022 года , получено 29 августа 2022 года.

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 241–242; Лонгфорд, стр. 280–281; Сент-Обин, с. 304; Вудэм-Смит, с. 391

- ^ Хибберт, с. 242; Лонгфорд, с. 281; Маршалл, с. 117

- ^ Наполеон III принимает королеву Викторию в Шербуре, 5 августа 1858 года , Королевские музеи Гринвича, заархивировано из оригинала 3 апреля 2012 года , получено 29 марта 2013 года.

- ^ Хибберт, с. 255; Маршалл, с. 117

- ^ Лонгфорд, стр. 259–260; Вайнтрауб, стр. 326 и далее.

- ^ Лонгфорд, с. 263; Вайнтрауб, стр. 326, 330.

- ^ Хибберт, с. 244

- ^ Хибберт, с. 267; Лонгфорд, стр. 118, 290; Сент-Обин, с. 319; Вудэм-Смит, с. 412

- ^ Хибберт, с. 267; Маршалл, с. 152; Вудэм-Смит, с. 412

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 265–267; Сент-Обин, с. 318; Вудхэм-Смит, стр. 412–413.

- ^ Уоллер, с. 393; Вайнтрауб, с. 401

- ^ Хибберт, с. 274; Лонгфорд, с. 293; Сент-Обин, с. 324; Вудэм-Смит, с. 417

- ^ Лонгфорд, с. 293; Маршалл, с. 153; Стрейчи, с. 214

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 276–279; Сент-Обин, с. 325; Вудхэм-Смит, стр. 422–423.

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 280–292; Маршалл, с. 154

- ^ Хибберт, с. 299; Сент-Обин, с. 346

- ^ Сент-Обин, с. 343

- ^ например, Стрейчи, с. 306

- ^ Ридли, Джейн (27 мая 2017 г.), «Королева Виктория, отягощенная горем и ужинами из шести блюд» , The Spectator , заархивировано из оригинала 28 августа 2018 г. , получено 28 августа 2018 г.

- ^ Маршалл, стр. 170–172; Сент-Обин, с. 385

- ^ Хибберт, с. 310; Лонгфорд, с. 321; Сент-Обин, стр. 343–344; Уоллер, с. 404

- ^ Хибберт, с. 310; Лонгфорд, с. 322

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 323–324; Маршалл, стр. 168–169; Сент-Обин, стр. 356–362.

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 321–322; Лонгфорд, стр. 327–328; Маршалл, с. 170

- ^ Хибберт, с. 329; Сент-Обин, стр. 361–362.

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 311–312; Лонгфорд, с. 347; Сент-Обин, с. 369

- ^ Сент-Обин, стр. 374–375.

- ^ Маршалл, с. 199; Стрейчи, с. 299

- ^ Хибберт, с. 318; Лонгфорд, с. 401; Сент-Обин, с. 427; Стрейчи, с. 254

- ^ Бакл, Джордж Эрл ; Монипенни, В. Ф. (1910–1920) Жизнь Бенджамина Дизраэли, графа Биконсфилда , том. 5, с. 49, цитируется по Стрейчи, с. 243

- ^ Хибберт, с. 320; Стрейчи, стр. 246–247.

- ^ Лонгфорд, с. 381; Сент-Обин, стр. 385–386; Стрейчи, с. 248

- ^ Сент-Обин, стр. 385–386; Стрейчи, стр. 248–250.

- ^ Лонгфорд, с. 385

- ^ Хибберт, с. 343

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 343–344; Лонгфорд, с. 389; Маршалл, с. 173

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 344–345.

- ^ Хибберт, с. 345; Лонгфорд, стр. 390–391; Маршалл, с. 176; Сент-Обин, с. 388

- ^ Чарльз, с. 103; Хибберт, стр. 426–427; Сент-Обин, стр. 388–389.

- ^ Слушания Олд-Бейли онлайн , Суд над Артуром О'Коннором . (t18720408-352, 8 апреля 1872 г.).

- ^ Хибберт, с. 427; Маршалл, с. 176; Сент-Обин, с. 389

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 249–250; Вудхэм-Смит, стр. 384–385.

- ^ Вудхэм-Смит, с. 386

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хибберт, с. 251; Вудэм-Смит, с. 386

- ^ Сент-Обин, с. 335

- ^ Хибберт, с. 361; Лонгфорд, с. 402; Маршалл, стр. 180–184; Уоллер, с. 423

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 295–296; Уоллер, с. 423

- ^ Хибберт, с. 361; Лонгфорд, стр. 405–406; Маршалл, с. 184; Сент-Обин, с. 434; Уоллер, с. 426

- ^ Уоллер, с. 427

- ^ Дневник и письма Виктории, цитируемые в Лонгфорде, стр. 425

- ^ Виктория, цитируется в Лонгфорде, стр. 426

- ^ Лонгфорд, стр. 412–413.

- ^ Лонгфорд, с. 426

- ^ Лонгфорд, с. 411

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 367–368; Лонгфорд, с. 429; Маршалл, с. 186; Сент-Обин, стр. 442–444; Уоллер, стр. 428–429.

- ↑ Письмо Виктории Монтегю Корри, 1-му барону Роутону , цитируется в Хибберте, стр. 369

- ^ Лонгфорд, с. 437

- ^ Хибберт, с. 420; Сент-Обин, с. 422

- ^ Хибберт, с. 420; Сент-Обин, с. 421

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 420–421; Сент-Обин, с. 422; Стрейчи, с. 278

- ^ Хибберт, с. 427; Лонгфорд, с. 446; Сент-Обин, с. 421

- ^ Лонгфорд, стр. 451–452.

- ^ Лонгфорд, с. 454; Сент-Обин, с. 425; Хибберт, с. 443

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 443–444; Сент-Обин, стр. 425–426.

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 443–444; Лонгфорд, с. 455

- ^ Хибберт, с. 444; Сент-Обин, с. 424; Уоллер, с. 413

- ^ Лонгфорд, с. 461

- ^ Лонгфорд, стр. 477–478.

- ^ Хибберт, с. 373; Сент-Обин, с. 458

- ^ Уоллер, с. 433; см. также Хибберт, стр. 370–371 и Маршалл, стр. 191–193.

- ^ Хибберт, с. 373; Лонгфорд, с. 484

- ^ Хибберт, с. 374; Лонгфорд, с. 491; Маршалл, с. 196; Сент-Обин, стр. 460–461.

- ^ Сент-Обин, стр. 460–461.

- ^ Королева Виктория , королевский двор, заархивировано из оригинала 13 марта 2021 года , получено 29 марта 2013 года.

- ^ Маршалл, стр. 210–211; Сент-Обин, стр. 491–493.

- ^ Лонгфорд, с. 502

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 447–448; Лонгфорд, с. 508; Сент-Обин, с. 502; Уоллер, с. 441

- ^ «Выставлена рабочая тетрадь королевы Виктории на урду» , BBC News , 15 сентября 2017 г., заархивировано из оригинала 1 декабря 2017 г. , получено 23 ноября 2017 г.

- ^ Хант, Кристин (20 сентября 2017 г.), «Виктория и Абдул: Дружба, которая скандализировала Англию» , Смитсоновский институт , заархивировано из оригинала 1 декабря 2017 г. , получено 23 ноября 2017 г.

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 448–449.

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 449–451.

- ^ Хибберт, с. 447; Лонгфорд, с. 539; Сент-Обин, с. 503; Уоллер, с. 442

- ^ Хибберт, с. 454

- ^ Хибберт, с. 382

- ^ Хибберт, с. 375; Лонгфорд, с. 519

- ^ Хибберт, с. 376; Лонгфорд, с. 530; Сент-Обин, с. 515

- ^ Хибберт, с. 377

- ^ Хибберт, с. 456

- ^ Лонгфорд, с. 546; Сент-Обин, стр. 545–546.

- ^ Маршалл, стр. 206–207, 211; Сент-Обин, стр. 546–548.

- ^ Макмиллан, Маргарет (2013), Война, положившая конец миру , Random House , стр. 29, ISBN 978-0-8129-9470-4

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 457–458; Маршалл, стр. 206–207, 211; Сент-Обин, стр. 546–548.

- ^ Хибберт, с. 436; Сент-Обин, с. 508

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 437–438; Лонгфорд, стр. 554–555; Сент-Обин, с. 555

- ^ Лонгфорд, с. 558

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 464–466, 488–489; Стрейчи, с. 308; Уоллер, с. 442

- ↑ Журнал Виктории, 1 января 1901 г., цитируется по Хибберту, стр. 492; Лонгфорд, с. 559 и Сент-Обин, с. 592

- ^ Ее личный врач сэр Джеймс Рид, 1-й баронет , цитируется по Хибберту, стр. 492

- ^ Раппапорт, Хелен (2003), «Животные», Королева Виктория: биографический спутник , Abc-Clio, стр. 34–39, ISBN 978-1-85109-355-7

- ^ Лонгфорд, стр. 561–562; Сент-Обин, с. 598

- ^ Хибберт, с. 497; Лонгфорд, с. 563

- ^ Сент-Обин, с. 598

- ^ Лонгфорд, с. 563

- ^ Хибберт, с. 498

- ^ Лонгфорд, с. 565; Сент-Обин, с. 600

- ^ Гандер, Кашмира (26 августа 2015 г.), «Королева Елизавета II станет самым долгоправящим монархом Великобритании, превзойдя королеву Викторию» , The Daily Telegraph , Лондон, заархивировано из оригинала 19 сентября 2015 г. , получено 9 сентября 2015 г.

- ^ Вейр, Элисон (1996). Королевские семьи Великобритании: Полная генеалогия (пересмотренная редакция). Лондон: Рэндом Хаус. п. 317. ИСБН 978-0-7126-7448-5 .

- ^ Фулфорд, Роджер (1967) «Виктория», Энциклопедия Collier's , США: Crowell, Collier and Macmillan Inc., vol. 23, с. 127

- ^ Эшли, Майк (1998) Британские монархи , Лондон: Робинсон, ISBN 1-84119-096-9 , с. 690

- ^ Пример из письма, написанного фрейлиной Мари Малле, урожденной Адин, цитируется в Hibbert, p. 471

- ^ Хибберт, с. хв; Сент-Обин, с. 340

- ^ Сент-Обин, с. 30; Вудэм-Смит, с. 87

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 503–504; Сент-Обин, с. 30; Вудхэм-Смит, стр. 88, 436–437.

- ^ Хибберт, с. 503

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 503–504; Сент-Обин, с. 624

- ^ Хибберт, стр. 61–62; Лонгфорд, стр. 89, 253; Сент-Обин, стр. 48, 63–64.

- ^ Маршалл, с. 210; Уоллер, стр. 419, 434–435, 443.

- ^ Уоллер, с. 439

- ^ Сент-Обин, с. 624

- ^ Хибберт, с. 504; Сент-Обин, с. 623

- ^ например, Хибберт, с. 352; Стрейчи, с. 304; Вудэм-Смит, с. 431

- ^ Уоллер, с. 429

- ^ Бэджхот, Уолтер (1867), Английская конституция , Лондон: Чепмен и Холл, стр. 103

- ^ Сент-Обин, стр. 602–603; Стрейчи, стр. 303–304; Уоллер, стр. 366, 372, 434.

- ^ Эриксон, Кэролли (1997) Ее маленькое величество: Жизнь королевы Виктории , Нью-Йорк: Саймон и Шустер, ISBN 0-7432-3657-2

- ^ Рогаев Евгений Иванович; Григоренко Анастасия П.; Фасхутдинова, Гульназ; Киттлер, Эллен Л.В.; Моляка, Юрий К. (2009), «Анализ генотипа определяет причину «королевской болезни» », Science , 326 (5954): 817, Бибкод : 2009Sci...326..817R , doi : 10.1126/science.1180660 , ISSN 0036-8075 , ПМИД 19815722 , С2КИД 206522975

- ^ Поттс и Поттс, стр. 55–65, цитируется в Хибберте, стр. 217; Паккард, стр. 42–43.

- ↑ Джонс, Стив (1996) В крови , BBC документальный фильм

- ^ МакКьюсик, Виктор А. (1965), «Королевская гемофилия», Scientific American , 213 (2): 91, Бибкод : 1965SciAm.213b..88M , doi : 10.1038/scientificamerican0865-88 , PMID 14319025 ; Джонс, Стив (1993), Язык генов , Лондон: HarperCollins , стр. 69, ISBN 0-00-255020-2 ; Джонс, Стив (1993), В крови: Бог, гены и судьба , Лондон: HarperCollins, стр. 270, ISBN 0-00-255511-5 ; Раштон, Алан Р. (2008), Королевские болезни: наследственные болезни в королевских домах Европы , Виктория, Британская Колумбия : Траффорд, стр. 31–32, ISBN 978-1-4251-6810-0

- ^ Гемофилия B , Национальный фонд гемофилии, 5 марта 2014 г., заархивировано из оригинала 24 марта 2015 г. , получено 29 марта 2015 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Альманах Уитакера (1900), факсимильное переиздание, 1998, Лондон: Канцелярский офис, ISBN 0-11-702247-0 , с. 86

- ^ Риск, Джеймс; Паунолл, Генри; Стэнли, Дэвид; Тамплин, Джон; Мартин, Стэнли (2001), Royal Service , том. 2, Лингфилд: Издательство Третьего тысячелетия/Викторианское издательство, стр. 16–19.

- ^ «№ 21846» , The London Gazette , 5 февраля 1856 г., стр. 410–411.

- ^ «№ 22523» , «Лондонская газета» , 25 июня 1861 г., стр. 2621

- ^ Уитакер, Джозеф (1894), Альманах на год Господа нашего... , Дж. Уитакер, стр. 112, заархивировано из оригинала 22 марта 2023 года , получено 15 декабря 2019 года.

- ^ «№ 24539» , «Лондонская газета» , 4 января 1878 г., стр. 113

- ^ Шоу, Уильям Артур (1906), «Введение» , «Рыцари Англии» , том. 1, Лондон: Шерратт и Хьюз, с. xxxi

- ^ « Королевский Красный Крест. Архивировано 28 ноября 2019 года в Wayback Machine ». КАРАНК – Корпус медсестер Королевской армии королевы Александры . Проверено 28 ноября 2019 г.

- ^ «№ 25641» , The London Gazette , 9 ноября 1886 г., стр. 5385–5386.

- ^ Медаль Альберта , Королевское общество искусств , Лондон, Великобритания, заархивировано из оригинала 8 июня 2011 г. , получено 12 декабря 2019 г.

- ^ «№ 26733» , «Лондонская газета» , 24 апреля 1896 г., стр. 2455

- ^ «Королевский орден благородных дам королевы Марии Луизы» , Ручной календарь и путеводитель для посторонних в Мадриде (на испанском языке), Мадрид: Imprenta Real, стр. 91, 1834 г., заархивировано из оригинала 28 марта 2021 г. , получено 21 ноября 2019 г. - через Hathitrust.org.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кимизука, Я хочу (2004), Голубая лента Ее Величества: Орден Подвязки и британская дипломатия [ Ее Величество Голубая лента королевы: Орден Подвязки и британская дипломатия ] (на японском языке), Токио: NTT Publishing, стр. 303, ISBN 978-4-7571-4073-8 , заархивировано из оригинала 22 марта 2023 года , получено 13 сентября 2020 года.

- ^ Браганса, Хосе Висенте де (2014), «Agraciamentos Portugals Aos Príncipes da Casa Saxe-Coburgo-Gota» [португальские почести, присужденные принцам дома Саксен-Кобург и Гота], Pro Phalaris (на португальском языке), vol. 9–10, с. 6, заархивировано из оригинала 25 ноября 2021 г. , получено 28 ноября 2019 г.

- ^ Ордена Св. Екатерины [Кавалеры ордена Святой Екатерины], Список кавалерам россійских императорских и царских орденов [ Список кавалеров Российского Императорского и Царского орденов ] (на русском языке), Санкт-Петербург: Типография II отделения Канцелярии Его Императорского Величества, 1850, с. 15, заархивировано из оригинала 22 марта 2023 г. , получено 20 октября 2019 г.

- ^ Ваттель, Мишель; Ваттель, Беатрис (2009), Большой крест Почетного легиона с 1805 года по наши дни. Французские и иностранные владельцы (на французском языке), Париж: Архивы и культура, стр. 21, 460, 564, ISBN 978-2-35077-135-9

- ^ «Раздел IV: Ордена Империи» , Императорский альманах за 1866 год (на испанском языке), Мехико: Imp. Дж. М. Лара, 1866, с. 244 , заархивировано из оригинала 22 марта 2023 года , получено 13 сентября 2020 года.

- ^ Ольвера Айес, Дэвид А. (2020), «Императорский орден Сан-Карлоса», Cuadernos del Cronista Editores, Мексика

- ^ Королева Виктория, «Четверг, 11 июня 1857 года» , Журналы королевы Виктории , том. 43, с. 171, заархивировано из оригинала 25 ноября 2021 г. , получено 2 июня 2012 г. - через Королевские архивы.

- ^ Королева Виктория, «Вторник, 3 декабря 1872 года» , Журналы королевы Виктории , том. 61, с. 333, заархивировано из оригинала 25 ноября 2021 г. , получено 2 июня 2012 г. - через Королевские архивы.

- ^ Насер ад-Дин Шах Каджар (1874 г.), «Глава IV: Англия» , Дневник Его Величества Персидского шаха во время его путешествия по Европе в 1873 году нашей эры: дословный перевод , перевод Редхауса, Джеймса Уильяма , Лондон: Джон Мюррей, п. 149

- ^ «Судебный циркуляр», Court and Social, The Times , вып. 29924, Лондон, 3 июля 1880 г., полковник G, с. 11

- ^ Известие о получении королевской грамоты Послание короля европейской страны, который рад получить письмо от Его Величества Короля. (PDF) , Королевский правительственный вестник Таиланда (на тайском языке), 5 мая 1887 г., заархивировано из оригинала (PDF) 21 октября 2020 г. , получено 8 мая 2019 г.

- ^ Калакауа своей сестре, 24 июля 1881 г., цитируется у Грира, Ричарда А. (редактор, 1967) « Королевский турист - письма Калакауа домой из Токио в Лондон. Архивировано 19 октября 2019 г. в Wayback Machine », Hawaiian Journal of History , vol. . 5, с. 100

- ^ Акович, Драгомир (2012), Слава и честь: Почести среди сербов, Сербы среди почестей (на сербском языке), Белград: Službeni Glasnik, стр. 364

- ^ «Две королевские семьи – исторические связи» , Королевская семья Сербии , 13 марта 2016 г., заархивировано из оригинала 6 декабря 2019 г. , получено 6 декабря 2019 г.

- ^ «Орден Золотого Льва» , Список Ордена Великого герцога Гессенского (на немецком языке), Дармштадт: Staatsverlag, 1885, стр. 35 , заархивировано из оригинала 6 сентября 2021 г. , получено 6 сентября 2021 г. — через Hathitrust.org.

- ^ «Почетный знак Красного Креста» , болгарские королевские награды , заархивировано из оригинала 15 декабря 2019 г. , получено 15 декабря 2019 г.

- ^ «Императорские ордена и награды Эфиопии» , Королевский совет Эфиопии , заархивировано из оригинала 26 декабря 2012 г. , получено 21 ноября 2019 г.

- ^ "Орден Государя Князя Данилы I" . orderofdanilo.org . Архивировано 9 октября 2010 года в Wayback Machine.

- ^ «Серебряная свадебная медаль герцога Альфреда Саксен-Кобургского и великой герцогини Марии» , Королевская коллекция , заархивировано из оригинала 12 декабря 2019 года , получено 12 декабря 2019 года.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Лоуда, Иржи ; Маклаган, Майкл (1999), Линии преемственности: геральдика королевских семей Европы , Лондон: Литтл, Браун, стр. 32, 34, ISBN 978-1-85605-469-0

- ^ Альманах Уитакера (1993), Краткое издание, Лондон: Дж. Уитакер и сыновья, ISBN 0-85021-232-4 , стр. 134–136

Библиография

- Чарльз, Барри (2012), Убей королеву! Восемь покушений на королеву Викторию , Страуд: Amberley Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4456-0457-2

- Хибберт, Кристофер (2000), Королева Виктория: Личная история , Лондон: HarperCollins, ISBN 0-00-638843-4

- Лонгфорд, Элизабет (1964), Виктория Р.И. , Лондон: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, ISBN 0-297-17001-5

- Маршалл, Дороти (1972), Жизнь и времена королевы Виктории (переиздание 1992 года), Лондон: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, ISBN 0-297-83166-6

- Паккард, Джерролд М. (1998), Дочери Виктории , Нью-Йорк: St. Martin's Press, ISBN 0-312-24496-7

- Поттс, DM ; Поттс, WTW (1995), Ген королевы Виктории: гемофилия и королевская семья , Страуд: Алан Саттон, ISBN 0-7509-1199-9

- Сент-Обин, Джайлз (1991), Королева Виктория: Портрет , Лондон: Синклер-Стивенсон, ISBN 1-85619-086-2

- Стрейчи, Литтон (1921), королева Виктория , Лондон: Чатто и Виндус

- Уоллер, Морин (2006), Суверенные дамы: Шесть правящих королев Англии , Лондон: Джон Мюррей , ISBN 0-7195-6628-2

- Вайнтрауб, Стэнли (1997), Альберт: Некоронованный король , Лондон: Джон Мюррей , ISBN 0-7195-5756-9

- Вудхэм-Смит, Сесил (1972), Королева Виктория: Ее жизнь и времена 1819–1861 , Лондон: Хэмиш Гамильтон, ISBN 0-241-02200-2

- Уорсли, Люси (2018), королева Виктория - дочь, жена, мать, вдова , Лондон: Hodder & Stoughton Ltd, ISBN 978-1-4736-5138-8

Первоисточники

- Бенсон, AC ; Эшер, виконт , ред. (1907), Письма королевы Виктории: Подборка переписки Ее Величества между 1837 и 1861 годами , Лондон: Джон Мюррей

- Болито, Гектор , изд. (1938), Письма королевы Виктории из архивов Дома Бранденбург-Пруссия , Лондон: Торнтон Баттерворт

- Бакл, Джордж Эрл , изд. (1926), Письма королевы Виктории, 2-я серия 1862–1885 , Лондон: Джон Мюррей

- Бакл, Джордж Эрл, изд. (1930), Письма королевы Виктории, 3-я серия 1886–1901 , Лондон: Джон Мюррей

- Коннелл, Брайан (1962), Регина против Пальмерстона: переписка между королевой Викторией и ее министром иностранных дел и премьер-министром, 1837–1865 , Лондон: братья Эванс