Мохаммад Реза Пехлеви

В этой статье есть несколько проблем. Пожалуйста, помогите улучшить его или обсудите эти проблемы на странице обсуждения . ( Узнайте, как и когда удалять эти шаблонные сообщения )

|

| Мохаммад Реза Пехлеви Мохаммадреза Пехлеви | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Король королей Свет арийцев | |||||

Официальный портрет, 1973 год. | |||||

| Шах Ирана | |||||

| Царствование | 16 сентября 1941 г. - 11 февраля 1979 г. | ||||

| Коронация | 26 октября 1967 г. | ||||

| Предшественник | Реза Шах | ||||

| Преемник | Монархия отменена Рухолла Хомейни (как верховный лидер ) | ||||

| Рожденный | 26 октября 1919 г. Тегеран , величественное государство Иран | ||||

| Умер | 27 июля 1980 г. ( 60 лет Каир , Египет | ||||

| Супруг | |||||

| Проблема | |||||

| |||||

| Альма-матер | |||||

| Дом | Пехлеви | ||||

| Отец | Реза Шах | ||||

| Мать | Тадж ол-Молук | ||||

| Религия | Двенадцать шиитов | ||||

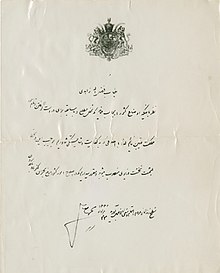

| Подпись |  Персидская подпись  Латинская подпись | ||||

| Военная служба | |||||

| Филиал/служба | Имперская иранская армия | ||||

| Лет службы | 1936–1979 | ||||

| Классифицировать | Маршалл Маршал Императорского флота Ирана Маршал Имперских ВВС Ирана | ||||

| Команды | Инспекционный отдел армии | ||||

Мохаммед Реза Пехлеви [ а ] (26 октября 1919 г. - 27 июля 1980 г.), которого в западном мире обычно называют Мохаммад Реза Шах , [ б ] или просто Шах был последним монархом Ирана . Он начал править Имперским государством Иран после того, как сменил своего отца Реза-шаха в 1941 году, и оставался у власти до тех пор, пока не был свергнут иранской революцией 1979 года , которая отменила монархию страны и основала Исламскую Республику Иран . В 1967 году он принял титул Шаханшах ( букв. « Царь королей » ). [ 1 ] и держал несколько других, в том числе Арьямер ( букв. « Свет арийцев » ) и Бозорг Артештаран ( букв. « Командующий Великой армией » ).

Он был вторым и последним правящим монархом династии Пехлеви, правившим Ираном . Его мечта о том, что он называл « Великой цивилизацией » ( تمدن بزرگ ) в Иране, привела к его лидерству в быстрой промышленной и военной модернизации, а также экономических и социальных реформах. [ 2 ] [ 3 ]

Во время Второй мировой войны англо -советское вторжение в Иран вынудило отречься от престола отца Пехлеви, Реза-шаха, которого он сменил. Во время правления Пехлеви принадлежавшая Великобритании нефтяная промышленность была национализирована премьер-министром Мохаммадом Мосаддыком заручился поддержкой национального парламента Ирана , который в этом . Однако Мосаддык был свергнут в результате иранского государственного переворота 1953 года , который был осуществлен иранскими военными под эгидой Великобритании и США. Впоследствии иранское правительство централизовало власть под руководством Пехлеви и вернуло иностранные нефтяные компании в промышленность страны посредством Соглашения о консорциуме 1954 года . [ 4 ]

В 1963 году Мохаммад Реза представил Белую революцию — серию экономических, социальных и политических реформ, направленных на превращение Ирана в мировую державу и модернизацию нации путём национализации ключевых отраслей промышленности и перераспределения земли . Режим также реализовал иранскую националистическую политику, сделав Кира Великого , Цилиндр Кира и Могилу Кира Великого популярными символами Ирана . Шах инициировал крупные инвестиции в инфраструктуру, субсидии и земельные гранты для крестьянского населения, распределение прибыли для промышленных рабочих, строительство ядерных объектов, национализацию природных ресурсов Ирана и программы повышения грамотности, которые считались одними из самых эффективных в мире. Шах также ввел тарифы экономической политики и льготные кредиты для иранских предприятий, которые стремились создать независимую экономику страны. Производство автомобилей, бытовой техники и других товаров в Иране существенно возросло, что привело к созданию нового класса промышленников, изолированного от угроз иностранной конкуренции. К 1970-м годам Шах считался выдающимся государственным деятелем и использовал свою растущую власть, чтобы преодолеть Договор купли-продажи 1973 года . Кульминацией этих реформ стали десятилетия устойчивого экономического роста, который сделал Иран одной из самых быстрорастущих экономик как среди развитых, так и среди развивающихся стран . За время его 37-летнего правления Иран потратил миллиарды долларов на промышленность, образование, здравоохранение и военные расходы и добился темпов экономического роста, превосходящих США, Великобританию и Францию. Ирана Аналогичным образом, национальный доход вырос в 423 раза, и в стране наблюдался беспрецедентный рост дохода на душу населения (который достиг самого высокого уровня за всю историю Ирана) и высокий уровень урбанизации . К 1977 году внимание Мохаммеда Резы к расходам на оборону, которые он рассматривал как средство прекращения интервенции иностранных держав в страну, достигло кульминации в том, что иранская армия стала пятой по силе вооруженной силой в мире. [ 5 ]

По мере роста политических волнений по всему Ирану в конце 1970-х гг. [ 6 ] Положение Мохаммада Резы в стране стало несостоятельным из-за резни на площади Джале , в ходе которой иранские военные убили и ранили десятки протестующих в Тегеране . [ 7 ] и поджог Cinema Rex в Абадане , ответственность за который ошибочно возложили на иранское разведывательное агентство САВАК . 1979 года На конференции в Гваделупе западные союзники Мохаммеда Резы заявили, что не существует реального способа спасти иранскую монархию от свержения. В конце концов шах покинул Иран в изгнании 17 января 1979 года. [ 8 ] Хотя он и говорил некоторым западным современникам, что предпочел бы покинуть страну, чем стрелять в свой народ, [ 9 ] оценки общего числа смертей во время Исламской революции колеблются от 540 до 2000 (данные независимых исследований) до 60 000 (данные исламского правительства ). [ 10 ] После формальной отмены иранской монархии мусульманский священнослужитель Рухолла Хомейни взял на себя руководство страной в качестве Верховного лидера Ирана . Мохаммад Реза умер в изгнании в Египте предоставил ему политическое убежище , где президент Египта Анвар Садат . После его смерти его сын Реза Пехлеви объявил себя новым шахом Ирана в изгнании.

Ранняя жизнь, семья и образование

[ редактировать ]

Мохаммад Реза родился в Тегеране , в Великом Государстве Иран , в семье Реза-хана (позже Реза-шаха Пехлеви, первого шаха династии Пехлеви ) и его второй жены Тадж ол-Молук . Он был старшим сыном своего отца и третьим из его одиннадцати. дети. Его отец был из Мазендарани. выходцем [ 11 ] [ 12 ] [ 13 ] родился в Алаште уезда Савадкух Мазандаран провинции . Он был бригадным генералом Персидской казачьей бригады , зачисленным в 7-й Савадкухский полк, участвовавший в англо-персидской войне в 1856 году. [ 14 ] Мать Мохаммеда Резы была мусульманской иммигранткой из Грузии (тогда входившей в состав Российской империи ), [ 15 ] чья семья эмигрировала в материковый Иран после того, как Иран был вынужден уступить все свои территории на Кавказе после русско-персидских войн несколькими десятилетиями ранее. [ 16 ] Она была азербайджанского происхождения, родилась в Баку , Российская империя (ныне Азербайджан ).

Мохаммад Реза родился со своей сестрой-близнецом Ашрафом . Однако он, Ашраф, его братья и сестры Шамс и Али Реза , а также его старшая сводная сестра Фатиме не принадлежали к королевской семье по рождению, поскольку их отец стал шахом только в 1925 году. Тем не менее, Реза Хан всегда был убежден, что его внезапная причуда удача началась в 1919 году с рождением у него сына, которого прозвали хошгадам («птица доброго предзнаменования»). [ 17 ] Как и у большинства иранцев того времени, у Реза-хана не было фамилии. После персидского государственного переворота 1921 года, в результате которого был свергнут Ахмад Шах Каджар , Реза Хану сообщили, что ему понадобится фамилия для своего дома. Это побудило его принять закон, предписывающий всем иранцам взять фамилию; он выбрал себе фамилию Пехлеви, которая является названием среднеперсидского языка , происходящего от древнеперсидского . [ 18 ] На коронации своего отца 24 апреля 1926 года Мохаммед Реза был провозглашен наследным принцем . [ 18 ] [ 19 ]

Семья

[ редактировать ]Мохаммад Реза описал своего отца в своей книге « Миссия для моей страны » как «одного из самых устрашающих людей», которых он когда-либо знал, изобразив Реза Хана как властного человека с жестоким характером. [ 20 ] Крепкий, свирепый и очень амбициозный солдат, ставший первым персом, который командовал элитной казачьей бригадой, обученной русскими, Реза Хан любил бить подчинённых в пах, которые не подчинялись его приказам. выросший под его тенью, Мохаммад Реза был глубоко напуганным и неуверенным в себе мальчиком По словам ирано-американского историка Аббаса Милани, . [ 21 ]

Реза Хан считал, что если отцы проявляют любовь к своим сыновьям, это приводит к гомосексуализму в дальнейшей жизни, поэтому, чтобы гарантировать, что его любимый сын был гетеросексуальным, он отказывал ему в любви и привязанности, когда он был молод, хотя позже он стал более нежным по отношению к наследному принцу, когда он был подростком. [ 22 ] Реза Хан всегда обращался к своему сыну как шома («сэр») и отказывался использовать более неформальное обращение («вы»), а сын, в свою очередь, обращался к нему с той же формальностью. [ 23 ] Польский журналист Рышард Капусцинский заметил в своей книге «Шах шахов» , что, глядя на старые фотографии Реза-хана и его сына, он был поражен тем, насколько самоуверенным и уверенным выглядел Реза-хан в своей военной форме, в то время как Мохаммед Реза выглядел нервным и нервным в своей форме. униформе, стоящей рядом с отцом. [ 24 ]

В 1930-х годах Реза Хан был откровенным поклонником Адольфа Гитлера , не столько из-за расизма и антисемитизма Гитлера, сколько потому, что он, как и Реза Хан, поднялся из ничем не примечательного происхождения и стал заметным лидером 20-го века . [ 25 ] Реза Хан часто внушил своему сыну свою веру в то, что историю творят такие великие люди, как он сам, и что настоящий лидер — это автократ . [ 25 ] Реза Хан был крупным мускулистым мужчиной ростом более 6 футов 4 дюймов (1,93 м), из-за чего его сын сравнил его с горой. Всю свою жизнь Мохаммад Реза был одержим ростом и ростом, носил туфли-лифты, чтобы казаться выше, чем был на самом деле, часто хвастался, что самая высокая гора Ирана — гора Дамавенд выше, чем любая вершина в Европе или Японии, и заявлял, что он всегда был больше всего привлекают высоких женщин. [ 26 ] Будучи шахом, Мохаммад Реза постоянно унижал своего отца в частной жизни, называя его бандитским казаком, который ничего не добился на посту шаха. Фактически, он почти вычеркнул своего отца из истории во время своего правления, до такой степени, что намекнул, что Дом Пехлеви начал свое правление в 1941 году, а не в 1925 году. [ 27 ]

Мать Мохаммада Резы, Тадж ол-Молук, была напористой женщиной и к тому же очень суеверной. Она верила, что сны — это послания из другого мира, приносила в жертву ягнят, чтобы принести удачу и отпугнуть злых духов, и одевала своих детей защитными амулетами, чтобы отразить силу сглаза . [ 28 ] Тадж ол-Молук был главной эмоциональной поддержкой ее сына, и она воспитала в нем веру в то, что судьба выбрала его для великих дел, что прорицатели, с которыми она консультировалась, интерпретировали ее сны как доказательство. [ 29 ] Мохаммад Реза вырос в окружении женщин, поскольку основное влияние на него оказали его мать, старшая сестра Шамс и сестра-близнец Ашраф, что привело американского психоаналитика и политического экономиста Марвина Зониса к выводу, что это было «со стороны женщин и, очевидно, со стороны женщин». одних только женщин», что будущий шах «получил всю психологическую поддержку, которую он мог получить в детстве». [ 30 ] Традиционно дети мужского пола считались предпочтительнее девочек, и в детстве Мохаммеда Резу часто баловали мать и сестры. [ 30 ] Мохаммад Реза был очень близок со своей сестрой-близняшкой Ашраф, которая прокомментировала: «Именно это близнецовое родство и эти отношения с моим братом питали и поддерживали меня на протяжении всего моего детства… Неважно, как я буду поддерживать эту связь в последующие годы… иногда даже в отчаянии - чтобы найти собственную личность и цель, я оставался неразрывно связанным со своим братом... всегда центром моего существования был и остается Мохаммад Реза». [ 31 ]

Став наследным принцем, Мохаммад Реза был забран у своей матери и сестер, чтобы дать ему «мужественное образование» офицерам, выбранным его отцом, который также приказал, чтобы все, включая его мать, братьев и сестер, обращались к наследному принцу как «мужественное образование». Ваше Высочество». [ 23 ] По словам Зониса, результатом его противоречивого воспитания любящей, хотя и собственнической и суеверной матерью и властным отцом-солдатом стало то, что Мохаммед Реза стал «молодым человеком с низкой самооценкой, который маскировал свою неуверенность в себе, свою нерешительность». , его пассивность, его зависимость и его застенчивость с мужской бравадой, импульсивностью и высокомерием». Это сделало его человеком явных противоречий, утверждает Зонис, поскольку наследный принц был «одновременно нежным и жестоким, замкнутым и активным, зависимым и напористым, слабым и могущественным». [ 32 ]

Образование

[ редактировать ]

К тому времени, когда Мохаммеду Резе исполнилось 11 лет, его отец прислушался к рекомендации Абдолхоссейна Теймурташа , министра суда, и отправил сына в Institut Le Rosey , швейцарскую школу-интернат, для дальнейшего обучения. Мохаммад Реза уехал из Ирана в Швейцарию 7 сентября 1931 года. [ 33 ] В свой первый день в качестве студента в Ле-Рози наследный принц вызвал недовольство группы своих сокурсников, потребовав, чтобы они все стояли по стойке смирно, когда он проходил мимо, как все делали в Иране. В ответ один из американских студентов избил его, и он быстро научился смиряться с тем, что люди в Швейцарии не будут уважать его так, как он привык дома. [ 34 ] Будучи студентом, Мохаммад Реза играл в соревновательный футбол , но школьные записи показывают, что его главной проблемой как игрока была его «робость», поскольку наследный принц боялся рисковать. [ 35 ] Он получил образование на французском языке в Ле-Рози, и время, проведенное там, оставило у Мохаммада Резы всю пожизненную любовь ко всему французскому. [ 36 ] В статьях, которые он написал на французском языке для студенческой газеты в 1935 и 1936 годах, Мохаммед Реза хвалил Ле Рози за расширение его кругозора и знакомство с европейской цивилизацией . [ 35 ]

Мохаммад Реза был первым иранским принцем в очереди на престол, которого отправили за границу для получения иностранного образования, и оставался там в течение следующих четырех лет, прежде чем вернуться, чтобы получить аттестат средней школы в Иране в 1936 году. Вернувшись в страну, Корона Принц был зарегистрирован в местной военной академии в Тегеране , где он оставался зачисленным до 1938 года, получив звание младшего лейтенанта. После окончания учебы Мохаммед Реза был быстро повышен до звания капитана, и это звание он сохранял, пока не стал шахом. Во время учебы в колледже молодой принц был назначен инспектором армии и три года путешествовал по стране, осматривая как гражданские, так и военные объекты. [ 19 ] [ 37 ]

Мохаммад Реза свободно говорил на английском, французском и немецком языках, помимо своего родного персидского языка . [ 38 ]

Во время пребывания в Швейцарии Мохаммед Реза подружился со своим учителем Эрнестом Перроном , который познакомил его с французской поэзией , и под его влиянием Шатобриан и Рабле стали его «любимыми французскими авторами». [ 39 ] Наследному принцу настолько понравился Перрон, что, вернувшись в Иран в 1936 году, он привез Перрона с собой, поселив своего лучшего друга в Мраморном дворце . [ 40 ] Перрон жил в Иране до своей смерти в 1961 году и, будучи лучшим другом Мохаммеда Резы, обладал значительной закулисной властью. [ 41 ] После иранской исламской революции в 1979 году новый режим опубликовал бестселлер « Эрнест Перрон, муж шаха Ирана» Мохаммеда Пуркяна, в котором утверждалось о гомосексуальных отношениях между шахом и Перроном. Даже сегодня это остается официальной интерпретацией их отношений со стороны Исламской Республики Иран . [ 42 ] Марвин Зонис охарактеризовал книгу как длинную и лишенную доказательств гомосексуальных отношений между ними, отметив, что все придворные шаха отвергли утверждение о том, что Перрон был любовником шаха. Он утверждал, что волевой Реза Хан, который был очень гомофобным , не позволил бы Перрону переехать в Мраморный дворец в 1936 году, если бы он считал, что Перрон был любовником его сына. [ 43 ]

Прийти к власти

[ редактировать ]Первый брак

[ редактировать ]

Одной из главных инициатив иранской и турецкой внешней политики был Саадабадский пакт 1937 года — альянс, объединивший Турцию , Иран, Ирак и Афганистан с целью создания мусульманского блока, который, как надеялись, будет сдерживать любых агрессоров. . Президент Турции Мустафа Кемаль Ататюрк во время визита последнего предположил своему другу Реза Хану, что брак между иранским и египетским дворами будет выгоден для двух стран и их династий, поскольку это может привести к присоединению Египта к Саадабадскому пакту. [ 44 ] Дилаварская принцесса Египта Фавзия (5 ноября 1921 — 2 июля 2013) была дочерью короля Египта Фуада I и Назли Сабри и сестрой короля Египта Фарука I. По предложению Ататюрка Мохаммад Реза и египетская принцесса Фавзия поженились 15 марта 1939 года во дворце Абдин в Каире . [ 44 ] Реза Шах в церемонии не участвовал. [ 44 ] Во время своего визита в Египет Мохаммед Реза был очень впечатлен величием египетского двора, когда он посетил различные дворцы, построенные Исмаилом-пашой , также известным как «Исмаил Великолепный», знаменитым хедивом Египта, который тратил большие деньги, и решили, что Ирану нужны столь же грандиозные дворцы, соответствующие им. [ 45 ]

В браке Мохаммеда Резы и Фавзии родился ребенок, принцесса Шахназ Пехлеви (родилась 27 октября 1940 года). Их брак не был счастливым, поскольку наследный принц открыто изменял, и его часто видели разъезжающим по Тегерану на одной из своих дорогих машин с одной из своих подруг. [ 46 ] Кроме того, властная и собственническая мать Мохаммада Резы считала свою невестку соперницей в любви сына и стала унижать принцессу Фавзию, муж которой встал на сторону своей матери. [ 46 ] Тихая, застенчивая женщина, Фавзия описала свой брак как несчастный, чувствуя себя очень нежеланной и нелюбимой семьей Пехлеви и жаждущей вернуться в Египет. [ 46 ] В своей книге «Миссия для моей страны » 1961 года Мохаммад Реза написал, что «единственным счастливым светлым моментом» за весь его брак с Фаузией было рождение дочери. [ 47 ]

Англо-советское вторжение и свержение его отца Реза Шаха

[ редактировать ]

Между тем, в разгар Второй мировой войны в 1941 году нацистская Германия начала операцию «Барбаросса» и вторглась в Советский Союз , нарушив пакт Молотова-Риббентропа . Это оказало серьезное влияние на Иран, который заявил о нейтралитете в конфликте. [ 48 ] Летом 1941 года советские и британские дипломаты передали многочисленные сообщения, в которых предупреждали, что они рассматривают присутствие немцев, управляющих иранскими государственными железными дорогами, как угрозу, подразумевающую войну, если немцы не будут уволены. [ 49 ] Великобритания хотела поставлять оружие в Советский Союз по иранским железным дорогам, а заявления немецких менеджеров иранских железных дорог о том, что они не будут сотрудничать, заставили как Советы, так и британцев настаивать на том, чтобы немцы, нанятые Реза-ханом, были немедленно уволены. [ 49 ] Будучи ближайшим советником своего отца, наследный принц Мохаммад Реза не счел нужным поднимать вопрос о возможном англо-советском вторжении в Иран, беспечно заверив отца, что ничего не произойдет. [ 49 ] Американский историк иранского происхождения Аббас Милани писал об отношениях между Реза-ханом и наследным принцем в то время, отмечая: «Будучи теперь постоянным спутником его отца, эти двое мужчин советовались практически по каждому решению». [ 50 ]

Позже в том же году британские и советские войска оккупировали Иран в результате военного вторжения , вынудив Реза-шаха отречься от престола. [ 51 ] 25 августа 1941 года британские и австралийские военно-морские силы атаковали Персидский залив , в то время как Советский Союз проводил наземное вторжение с севера. На второй день вторжения, когда советские ВВС бомбили Тегеран, Мохаммад Реза был шокирован, увидев, что иранская армия просто развалилась, а тысячи напуганных офицеров и солдат по всему Тегерану сняли форму, чтобы дезертировать и бежать. несмотря на то, что еще не видел боя. [ 52 ] Отражая панику, группа высокопоставленных иранских генералов позвонила наследному принцу, чтобы получить его благословение на проведение встречи, чтобы обсудить, как лучше всего сдаться. [ 50 ] Когда Реза-хан узнал о встрече, он пришел в ярость и напал на одного из своих генералов, Ахмада Нахджавана , ударив его хлыстом, сорвав с него медали и чуть ли не лично казнив его, прежде чем его сын убедил его обратиться в общий суд. - вместо этого попал в военную службу. [ 50 ] Крах иранской армии, над созданием которой его отец так усердно трудился, унизил его сына, который поклялся, что никогда больше не увидит такого поражения Ирана, предвещая последующую одержимость будущего шаха военными расходами. [ 52 ]

Восхождение на престол

[ редактировать ]

16 сентября 1941 года премьер-министр Мохаммад Али Форуги и министр иностранных дел Али Сохейли присутствовали на специальной сессии парламента, на которой объявили об отставке Реза-шаха и о том, что его должен заменить Мохаммад Реза. На следующий день, в 16:30 , Мохаммад Реза принес присягу и был тепло принят парламентариями. На обратном пути во дворец улицы были заполнены людьми, ликующе приветствовавшими нового шаха, казалось, с большим энтузиазмом, чем хотелось бы союзникам. [ 53 ] Британцы хотели бы вернуть Каджара на трон, но главным претендентом Каджара на трон был принц Хамид Мирза , офицер Королевского флота , который не говорил по-персидски, поэтому британцы были вынуждены признать Мохаммада Резу шахом. . [ 54 ] Главным советским интересом в 1941 году было обеспечение политической стабильности для обеспечения поставок союзников, что означало принятие восхождения на престол Мохаммеда Резы. После его престолонаследия Иран стал основным каналом британской, а затем и американской помощи СССР во время войны. Этот массивный маршрут снабжения стал известен как Персидский коридор . [ 55 ]

Большая заслуга в организации плавного перехода власти от короля к наследному принцу принадлежит усилиям Мохаммеда Али Форуги. [ 56 ] Страдая от стенокардии , хрупкий Форуги был вызван во дворец и назначен премьер-министром, когда Реза-шах опасался конца династии Пехлеви после того, как союзники вторглись в Иран в 1941 году. [ 57 ] Когда Реза Шах обратился к нему за помощью, чтобы гарантировать, что союзники не положат конец династии Пехлеви, Форуги отложил в сторону свои неблагоприятные личные чувства из-за того, что с 1935 года он был отстранен от политической деятельности. Наследный принц с изумлением признался британскому министру, что Форуги «едва ли ожидал, что любой сын Реза-шаха будет цивилизованным человеком», [ 57 ] но Форуги успешно сорвал планы союзников провести более радикальные изменения в политической инфраструктуре Ирана. [ 58 ]

Всеобщая амнистия была объявлена через два дня после восшествия на престол Мохаммеда Резы 19 сентября 1941 года. Все политические деятели, потерпевшие опалу во время правления его отца, были реабилитированы, а политика принудительного раскрытия информации, начатая его отцом в 1935 году, была отменена. Несмотря на просвещенные решения молодого короля, британский министр в Тегеране сообщил в Лондон, что «молодой шах получил довольно спонтанный прием во время своего первого публичного опыта, возможно, скорее [из-за] облегчения в связи с исчезновением его отца, чем из-за общественной привязанности к нему». ". В первые дни своего пребывания на посту шаха Мохаммаду Резе не хватало уверенности в себе, и большую часть времени он проводил с Перроном, сочиняя стихи на французском языке. [ 59 ]

В 1942 году Мохаммад Реза встретил Венделла Уилки , кандидата от республиканской партии на пост президента США на выборах 1940 года , который сейчас находился в кругосветном турне с целью продвижения своей политики «одного мира». Уилки впервые взял шаха в полет. [ 60 ] Премьер-министр Ахмад Кавам посоветовал шаху не летать с Уилки, заявив, что он никогда не встречал человека с более серьезной проблемой метеоризма, но шах рискнул. [ 60 ] Мохаммед Реза сказал Уилки, что во время полета он «хотел не спать бесконечно». [ 60 ] Наслаждаясь полетом, Мохаммад Реза нанял американского пилота Дика Коллбарна, чтобы тот научил его летать. По прибытии в Мраморный дворец Колбарн отметил, что «у шаха должно быть двадцать пять автомобилей, построенных по индивидуальному заказу... «Бьюики» , «Кадиллаки» , шесть «Роллс-Ройсов» , « Мерседес ». [ 60 ] Во время Тегеранской конференции с союзными войсками в 1943 году шах был унижен, когда встретил Иосифа Сталина , который посетил его в Мраморном дворце и не позволил присутствовать телохранителям шаха, охранявшим их только Красная Армия . [ 61 ]

Мнение о правлении его отца

[ редактировать ]Несмотря на публичное восхищение, которое он выражал в последующие годы, Мохаммед Реза испытывал серьезные опасения не только по поводу грубых и грубых политических средств, принятых его отцом, но и по поводу его бесхитростного подхода к государственным делам. Молодой шах обладал гораздо более утонченным темпераментом, и среди сомнительных событий, которые «преследовали его, когда он был королем», были политический позор, нанесенный его отцом Теймурташу , увольнение Форуги в середине 1930-х годов и Али Акбар Давар. Самоубийство в 1937 году. [ 62 ] Еще более важным решением, бросившим длинную тень, было катастрофическое и одностороннее соглашение, которое его отец заключил с Англо-Персидской нефтяной компанией (APOC) в 1933 году, которое поставило под угрозу способность страны получать более выгодные доходы от нефти, добываемой из страна.

Отношения с сосланным отцом

[ редактировать ]Мохаммад Реза выразил беспокойство за своего отца в изгнании, который ранее жаловался британскому губернатору Маврикия , что жизнь на острове является одновременно климатической и социальной тюрьмой. Внимательно следя за своей жизнью в изгнании, Мохаммад Реза при любой возможности возражал против обращения своего отца с британцами. Они отправляли друг другу письма, хотя доставка часто задерживалась, и Мохаммад Реза поручил своему другу Эрнесту Перрону лично доставить записанное на пленку послание любви и уважения к отцу, привезя с собой запись своего голоса: [ 63 ]

Мой дорогой сын, с тех пор, как я подал в отставку в твою пользу и покинул свою страну, моим единственным удовольствием было видеть твое искреннее служение своей стране. Я всегда знал, что ваша молодость и ваша любовь к стране — это огромные резервуары силы, которые вы сможете использовать, чтобы стойко противостоять трудностям, с которыми вы сталкиваетесь, и что, несмотря на все проблемы, вы выйдете из этого испытания с честью. Не проходит и минуты, чтобы я не думал о вас, и все же единственное, что делает меня счастливым и удовлетворенным, — это мысль о том, что вы проводите свое время на службе Ирану. Вы должны всегда быть в курсе того, что происходит в стране. Вы не должны поддаваться корыстным и ложным советам. Вы должны оставаться твердыми и постоянными. Вы никогда не должны бояться событий, которые происходят на вашем пути. Теперь, когда вы взяли на свои плечи это тяжелое бремя в такие мрачные дни, вы должны знать, что ценой, которую придется заплатить за малейшую ошибку с вашей стороны, могут стать наши двадцать лет службы и имя нашей семьи. Вы никогда не должны поддаваться тревоге или отчаянию; скорее, вы должны сохранять спокойствие и настолько прочно укорениться на своем месте, чтобы никакая сила не могла надеяться поколебать постоянство вашей воли. [ 64 ]

Начало холодной войны

[ редактировать ]

В 1945–46 годах главным вопросом иранской политики было спонсируемое Советским Союзом сепаратистское правительство в иранском Азербайджане и Курдистане , что сильно встревожило шаха. Он неоднократно конфликтовал со своим премьер-министром Ахмадом Кавамом , которого считал слишком просоветским. [ 65 ] В то же время растущая популярность коммунистической партии Туде обеспокоила Мохаммеда Резу, который чувствовал, что существует серьезная вероятность того, что они возглавят переворот. [ 66 ] В июне 1946 года Мохаммад Реза почувствовал облегчение, когда Красная Армия вышла из Ирана. [ 67 ] В письме лидеру азербайджанских коммунистов Джафару Пишевари Сталин написал, что ему пришлось уйти из Ирана, иначе американцы не уйдут из Китая , и он хотел помочь китайским коммунистам в их гражданской войне против Гоминьдана. . [ 68 ] Однако режим Пишевари оставался у власти в Тебризе (Азербайджан), и Мохаммад Реза стремился подорвать попытки Кавама заключить соглашение с Пишевари, чтобы избавиться от обоих. [ 69 ] 11 декабря 1946 года иранская армия , возглавляемая лично шахом, вошла в иранский Азербайджан, и режим Пишевари рухнул без особого сопротивления, при этом большая часть боевых действий происходила между простыми людьми, которые нападали на функционеров Пишевари, которые жестоко обращались с ними. [ 69 ] В своих заявлениях тогда и позже Мохаммад Реза объяснял свой легкий успех в Азербайджане своей «мистической силой». [ 70 ] Зная о склонности Кавама к коррупции, шах использовал эту проблему как повод для его увольнения. [ 71 ] К этому времени жена шаха Фавзия вернулась в Египет, и, несмотря на попытки короля Фарука убедить ее вернуться в Иран, она отказалась ехать, что привело к тому, что Мохаммед Реза развелся с ней 17 ноября 1948 года. [ 72 ]

К тому времени Мохаммад Реза, будучи квалифицированным пилотом, был очарован полетами и техническими деталями самолетов, и любое оскорбление в его адрес всегда было попыткой «подрезать [ему] крылья». Мохаммад Реза направил на Имперские ВВС Ирана больше денег , чем на любой другой вид вооруженных сил, и его любимой формой была форма маршала Имперских ВВС Ирана. [ 73 ] Марвин Зонис писал, что одержимость Мохаммада Резы полетами отражала комплекс Икара , также известный как «вознесение», форму нарциссизма, основанную на «жажде нежеланного внимания и восхищения» и «желании преодолеть гравитацию, стоять прямо, расти». высокий... прыгать или качаться в воздухе, карабкаться, подниматься, летать». [ 74 ]

Мохаммад Реза часто говорил о женщинах как о сексуальных объектах , которые существовали только для того, чтобы доставлять ему удовольствие, и во время интервью 1973 года с итальянской журналисткой Орианой Фаллачи она яростно возражала против его отношения к женщинам. [ 75 ] Будучи постоянным посетителем ночных клубов Италии, Франции и Великобритании, Мохаммад Реза был связан романтическими отношениями с несколькими актрисами, включая Джин Тирни , Ивонн Де Карло и Сильвану Мангано . [ 76 ]

На молодого шаха было совершено как минимум два безуспешных покушения. 4 февраля 1949 года он присутствовал на ежегодной церемонии, посвященной основанию Тегеранского университета . [ 77 ] На церемонии боевик Фахр-Арай произвел в него пять выстрелов с расстояния около трех метров. Лишь один из выстрелов попал в короля, задев его щеку. Нападавший был мгновенно застрелен находившимися рядом офицерами. После расследования Фахр-Арай был объявлен членом коммунистической партии Туде . [ 78 ] что впоследствии было запрещено. [ 79 ] Однако есть свидетельства того, что потенциальный убийца был не членом Туде, а религиозным фундаменталистом, членом Фадаиян-и Ислам . [ 76 ] [ 80 ] Тем не менее Туде подвергались обвинениям и преследованиям. [ 81 ]

Второй женой шаха была Сорайя Исфандиари-Бахтиари , наполовину немка, наполовину иранка и единственная дочь Халила Исфандиари-Бахтиари , посла Ирана в Западной Германии, и его жены Евы Карл. Ее представил шаху Форух Зафар Бахтиари, близкий родственник Сорайи, через фотографию, сделанную Гударзом Бахтиари в Лондоне по просьбе Форуха Зафара. Они поженились 12 февраля 1951 года. [ 44 ] согласно официальному объявлению, когда Сорайе было 18 лет. Однако ходили слухи, что на самом деле ей было 16, а шаху — 32. [ 82 ] В детстве ее наставляла и воспитывала фрау Мантель, и поэтому она не имела должных знаний об Иране, как она сама признавалась в своих личных мемуарах, заявляя: «Я была дурой - я почти ничего не знала о географии, легендах и легендах. моей страны, ничего из ее истории, ничего из мусульманской религии». [ 65 ]

Национализация нефти и иранский государственный переворот 1953 года.

[ редактировать ]

К началу 1950-х годов политический кризис, назревавший в Иране, привлек внимание британских и американских политических лидеров. После выборов в законодательные органы Ирана в 1950 году был избран премьер-министром в 1951 году . Мохаммад Мосаддык Он был приверженцем национализации иранской нефтяной промышленности, контролируемой Англо-Иранской нефтяной компанией (AIOC) (ранее Англо-Персидская нефтяная компания или APOC). [ 83 ] Под руководством Мосаддыка и его националистического движения иранский парламент единогласно проголосовал за национализацию нефтяной промышленности, тем самым закрыв чрезвычайно прибыльную АМОК, которая была опорой британской экономики и обеспечивала ей политическое влияние в регионе. [ 84 ]

В начале конфронтации американские политические симпатии к Ирану исходили от администрации Трумэна . [ 85 ] В частности, Мосаддыка воодушевили советы и рекомендации, которые он получил от американского посла в Тегеране Генри Ф. Грейди . Однако в конечном итоге американские политики потеряли терпение, и к тому времени, когда к власти пришла республиканская администрация президента Дуайта Д. Эйзенхауэра , опасения, что коммунисты готовы свергнуть правительство, стали всепоглощающей проблемой. Позднее эти опасения были отвергнуты как «параноидальные» в ретроспективных комментариях правительственных чиновников США по поводу переворота. Незадолго до президентских выборов 1952 года в США британское правительство пригласило офицера Центрального разведывательного управления (ЦРУ) Кермита Рузвельта-младшего в Лондон, чтобы предложить сотрудничество в разработке секретного плана по отстранению Мосаддыка от должности. [ 86 ] Это будет первая из трех операций по «смене режима» под руководством директора ЦРУ Аллена Даллеса (две другие - это успешный государственный переворот в Гватемале, спровоцированный ЦРУ в 1954 году , и неудавшееся в заливе Свиней вторжение на Кубу ).

Под руководством Рузвельта американское ЦРУ и британская секретная разведывательная служба (СИС) финансировали и возглавили тайную операцию по свержению Мосаддыка с помощью нелояльных правительству вооруженных сил. Так называемая операция «Аякс» . [ 87 ] Заговор зависел от подписанного Мохаммадом Резой приказа об увольнении Мосаддыка с поста премьер-министра и замене его генералом Фазлоллой Захеди - выбор, согласованный британцами и американцами. [ 88 ] [ 89 ] [ 90 ]

Перед попыткой государственного переворота американское посольство в Тегеране сообщило, что народная поддержка Мосаддыка остается сильной. прямого контроля над армией Премьер-министр потребовал от Меджлиса . Учитывая ситуацию, наряду с сильной личной поддержкой -консерватора премьер-министра Уинстона Черчилля и министра иностранных дел Энтони Идена в отношении тайных действий, американское правительство дало добро комитету, на котором присутствовал госсекретарь Джон Фостер Даллес , директор Центрального разведывательного управления США. Аллен Даллес , Кермит Рузвельт-младший, Хендерсон, [ ВОЗ? ] и министр обороны Чарльз Эрвин Уилсон . Кермит Рузвельт-младший вернулся в Иран 13 июля 1953 года, а затем снова 1 августа 1953 года на свою первую встречу с королем. В полночь его забрала машина и отвезла во дворец. Он лег на сиденье и накрылся одеялом, пока охранники махали водителю рукой через ворота. Шах сел в машину, и Рузвельт объяснил задачу. ЦРУ подкупило его 1 миллионом долларов в иранской валюте, которую Рузвельт хранил в большом сейфе — громоздком тайнике, учитывая тогдашний обменный курс 1000 риалов за 15 долларов США . [ 91 ]

Тем временем коммунисты устроили массовые демонстрации, чтобы перехватить инициативы Мосаддыка, а Соединенные Штаты активно строили заговор против него. 16 августа 1953 года правое крыло армии атаковало. Вооружившись приказом шаха, оно назначило генерала Фазлоллу Захеди премьер-министром. Коалиция мафии и отставных офицеров, близкая к дворцу, осуществила этот государственный переворот. Они потерпели полную неудачу, и шах бежал из страны в Багдад , а затем в Рим . «Эттелаат» , крупнейшая ежедневная газета страны, и ее прошахский издатель Аббас Масуди раскритиковали его, назвав поражение «унизительным». [ 92 ]

Во время пребывания шаха в Риме британский дипломат сообщил, что монарх проводил большую часть своего времени в ночных клубах с королевой Сорайей или своей последней любовницей, написав: «Он ненавидит принимать решения, и на него нельзя рассчитывать, что он будет придерживаться их, когда они приняты. нет морального мужества и легко поддается страху». [ 93 ] Чтобы заставить его поддержать переворот, его сестра-близнец принцесса Ашраф , которая была намного жестче его и несколько раз публично ставила под сомнение его мужественность, посетила его 29 июля 1953 года, чтобы отругать его, заставив подписать указ об увольнении Мосаддыка. [ 94 ]

За несколько дней до второй попытки государственного переворота коммунисты выступили против Мосаддыка. Оппозиция против него чрезвычайно возросла. Они бродили по Тегерану, поднимая красные флаги и снося статуи Реза Шаха. Это было отвергнуто консервативными священнослужителями, такими как Кашани , и Национального фронта, лидерами такими как Хоссейн Макки , которые встали на сторону короля. 18 августа 1953 года Мосаддык защитил правительство от нового нападения. Партизаны Туде были избиты и рассеяны. [ 95 ] У партии Туде не было другого выбора, кроме как признать поражение.

Тем временем, согласно заговору ЦРУ, Захеди обратился к военным, заявил, что является законным премьер-министром, и обвинил Мосаддыка в организации государственного переворота путем игнорирования указа шаха. Сын Захеди Ардешир выступал в качестве связующего звена между ЦРУ и его отцом. 19 августа 1953 года прошахские партизаны, подкупленные 100 000 долларов из фондов ЦРУ, наконец появились и прошли маршем из южного Тегерана в центр города, где к ним присоединились и другие. Банды с дубинками, ножами и камнями контролировали улицы, переворачивая грузовики Туде. и избиение антишахских активистов. Когда Рузвельт поздравлял Захеди в подвале своего укрытия, ворвалась толпа нового премьер-министра и понесла его на своих плечах наверх. В тот вечер Хендерсон предложил Ардаширу не причинять вреда Мосаддыку. Рузвельт передал Захеди 900 000 долларов США, оставшиеся от средств операции «Аякс». [ 96 ]

После недолгого изгнания в Италию шах вернулся в Иран, на этот раз благодаря успешной второй попытке государственного переворота. Свергнутый Мосаддык был арестован и предан суду, при этом король вмешался и смягчил его приговор до трех лет. [ 97 ] за которым последует жизнь во внутренней ссылке. Захеди был назначен преемником Мосаддыка. [ 98 ] Хотя Мохаммад Реза вернулся к власти, он так и не распространил элитный статус суда на технократов и интеллектуалов, вышедших из иранских и западных университетов. Действительно, его система раздражала новые классы, поскольку им было запрещено участвовать в реальной власти. [ 99 ]

Самоутверждение: от номинального монарха к эффективному авторитарному режиму

[ редактировать ]

После государственного переворота 1953 года Мохаммад Реза широко рассматривался как номинальный монарх, а премьер-министр генерал Фазлолла Захеди считал себя и считался другими «сильным человеком» Ирана. [ 100 ] Мохаммад Реза боялся, что история повторится, помня, как его отец был генералом, который захватил власть в результате государственного переворота в 1921 году и свергнул последнего Каджара-шаха в 1925 году, и его главной заботой в 1953–1955 годах была нейтрализация Захеди. [ 101 ] Американские и британские дипломаты в своих докладах в Вашингтон и Лондон в 1950-х годах открыто пренебрегали лидерскими способностями Мохаммада Резы, называя шаха безвольным и трусливым человеком, неспособным принять решение. [ 101 ] Презрение, с которым иранская элита относилась к шаху, привело к периоду в середине 1950-х годов, когда элита проявляла враждебные тенденции, враждуя между собой теперь, когда Мосаддык был свергнут, что в конечном итоге позволило Мохаммаду Резе сразиться с различными фракциями в элите. заявить о себе как о лидере нации. [ 101 ]

Сам факт того, что Мохаммеда Реза считали трусом и несущественным, оказался преимуществом, поскольку шах оказался ловким политиком, натравливая фракции в элите и американцев против британцев с целью стать автократом на практике, как ну и в теории. [ 101 ] Сторонники запрещенного Национального фронта подвергались преследованиям, но в своем первом важном решении на посту лидера Мохаммед Реза вмешался и обеспечил, чтобы большинство членов Национального фронта, привлеченных к суду, таких как сам Мосаддык, не были казнены, как многие ожидали. [ 102 ] Многие в иранской элите были откровенно разочарованы тем, что Мохаммад Реза не провел ожидаемую кровавую чистку и не повесил Мосаддыка и его последователей, как они того хотели и ожидали. [ 102 ] В 1954 году, когда двенадцать университетских профессоров выступили с публичным заявлением с критикой переворота 1953 года, все они были уволены со своих должностей, но в первом из своих многочисленных актов «великодушия» по отношению к Национальному фронту Мохаммад Реза вмешался и восстановил их в должности. [ 103 ] Мохаммад Реза очень старался привлечь на свою сторону сторонников Национального фронта, переняв некоторые из их риторики и решая их проблемы, например, заявляя в нескольких выступлениях о своей обеспокоенности экономическими условиями третьего мира и бедностью, которые преобладали в Иране, - вопрос, который раньше его мало интересовало. [ 104 ]

Мохаммад Реза был полон решимости скопировать Мосаддыка, который завоевал популярность, обещая широкие социально-экономические реформы, и хотел создать массовую базу власти, поскольку он не хотел зависеть от традиционных элит, которые хотели его только как легитимизирующего номинального руководителя. [ 102 ] В 1955 году Мохаммад Реза уволил генерала Захеди с поста премьер-министра и назначил его заклятого врага, технократа Хоссейна Ала , которого он, в свою очередь, уволил в 1957 году. премьер-министром [ 105 ] Начиная с 1955 года Мохаммад Реза начал потихоньку культивировать левых интеллектуалов, многие из которых поддерживали Национальный фронт, а некоторые были связаны с запрещенной партией Туде, прося у них совета о том, как лучше всего реформировать Иран. [ 106 ] Именно в этот период Мохаммад Реза начал воспринимать образ «прогрессивного» шаха, реформатора, который модернизирует Иран, который в своих речах нападал на «реакционную» и «феодальную» социальную систему, которая тормозила прогресс, приводила к созданию земли. реформировать и дать женщинам равные права. [ 106 ]

Будучи преисполнен решимости править и править, именно в середине 1950-х годов Мохаммед Реза начал продвигать государственный культ вокруг Кира Великого, которого изображали как великого шаха, реформировавшего страну и построившего империю, явно параллельную ему самому. [ 106 ] Наряду с этим изменением имиджа Мохаммад Реза начал говорить о своем желании «спасти» Иран, долге, который, как он утверждал, был дан ему Богом, и пообещал, что под его руководством Иран достигнет западного уровня жизни в ближайшем будущем. . [ 107 ] В этот период Мохаммад Реза искал поддержки улемов и возобновил традиционную политику преследования тех иранцев, которые принадлежали к вере бахаи , позволив снести главный храм бахаи в Тегеране в 1955 году и приняв закон, запрещающий бахаи посещать собираясь в группы. [ 107 ] Британский дипломат сообщил в 1954 году, что Реза-хан «должно быть, переворачивался в гробу в Рей . Видеть, как высокомерие и наглость мулл снова свирепствуют в священном городе! Как старый тиран, должно быть, презирает слабость своего сына, который позволил этим буйным священникам вернуть себе столь большую часть своего реакционного влияния!» [ 107 ] К этому времени брак шаха находился под напряжением, поскольку королева Сорая жаловалась на власть лучшего друга Мохаммада Резы Эрнеста Перрона, которого она называла «шетуном » и «хромающим дьяволом». [ 108 ] Перрон был человеком, которого сильно возмущало его влияние на Мохаммада Резу, и враги часто описывали его как «дьявольского» и «таинственного» персонажа, чье положение было личным секретарем, но который был одним из ближайших советников шаха, имевшим далеко идущие больше власти, чем предполагала его должность. [ 109 ]

В исследовании 1957 года, составленном Госдепартаментом США , Мохаммеда Резу хвалили за его «растущую зрелость» и за отсутствие необходимости «обращаться за советом на каждом шагу», как было сделано в предыдущем исследовании 1951 года. [ 110 ] 27 февраля 1958 года был сорван военный переворот с целью свержения шаха под руководством генерала Валиоллы Гарани, что привело к серьезному кризису в ирано-американских отношениях, когда появились доказательства того, что соратники Гарани встречались с американскими дипломатами в Афинах, что шах использовал для потребовать, чтобы впредь никакие американские официальные лица не могли встречаться с его противниками. [ 111 ] Еще одной проблемой в ирано-американских отношениях были подозрения Мохаммеда Резы в том, что Соединенные Штаты недостаточно заинтересованы в защите Ирана, отметив, что американцы отказались присоединиться к Багдадскому пакту , а военные исследования показали, что Иран может продержаться лишь несколько дней в Иране. события советского вторжения. [ 112 ]

В январе 1959 года шах начал переговоры о пакте о ненападении с Советским Союзом, к которому, как он утверждал, его привело отсутствие американской поддержки. [ 113 ] Получив письмо с умеренными угрозами от президента Эйзенхауэра, предостерегающего его от подписания договора, Мохаммад Реза решил не подписывать, что привело к крупной советской пропаганде, призывающей к его свержению. [ 114 ] Советский лидер Никита Хрущев приказал убить Мохаммада Резу. [ 115 ] Признак власти Мохаммада Резы появился в 1959 году, когда британская компания выиграла контракт с иранским правительством, который был внезапно расторгнут и вместо этого передан Siemens. [ 116 ] Расследование, проведенное британским посольством, вскоре выявило причину: Мохаммед Реза хотел переспать с женой торгового агента «Сименс» в Иране, а агент «Сименс» согласился позволить своей жене переспать с шахом в обмен на возврат контракта, который он только что проиграл. [ 116 ] 24 июля 1959 года Мохаммад Реза де-факто признал Израиль, разрешив открыть в Тегеране израильское торговое представительство, которое функционировало как фактическое посольство, - шаг, который оскорбил многих в исламском мире. [ 117 ] Когда Эйзенхауэр посетил Иран 14 декабря 1959 года, Мохаммад Реза сказал ему, что Иран столкнулся с двумя основными внешними угрозами: Советским Союзом на севере и новым просоветским революционным правительством в Ираке на западе. Это побудило его попросить значительно увеличить американскую военную помощь, заявив, что его страна находится на переднем крае холодной войны и нуждается в как можно большей военной мощи. [ 117 ]

Брак шаха и Сорайи распался в 1958 году, когда стало очевидно, что даже с помощью врачей она не может иметь детей. Позже Сорая рассказала The New York Times , что у шаха не было другого выбора, кроме как развестись с ней, и что он тяжело переживал это решение. [ 118 ] Однако сообщается, что даже после свадьбы шах по-прежнему очень любил Сорайю, и сообщается, что они встречались несколько раз после развода и что после развода она прожила комфортную жизнь как богатая женщина, хотя и была никогда не женился повторно; [ 119 ] ему выплачивают ежемесячную зарплату в размере около 7000 долларов из Ирана. [ 120 ] После ее смерти в 2001 году в возрасте 69 лет в Париже на аукционе было выставлено на аукцион имущество стоимостью три миллиона долларов, кольцо с бриллиантом весом 22,37 карата и автомобиль Rolls-Royce 1958 года выпуска. [ 121 ]

Впоследствии Пехлеви заявил о своей заинтересованности в женитьбе на принцессе Марии Габриэлле Савойской , дочери свергнутого итальянского короля Умберто II . Сообщается, что Папа Иоанн XXIII наложил вето на это предложение. В редакционной статье о слухах, окружающих брак «мусульманского государя и католической принцессы», ватиканская газета L'Osservatore Romano назвала этот брак «серьезной опасностью». [ 122 ] особенно учитывая, что согласно Кодексу канонического права 1917 года католик, вступивший в брак с разведенным человеком, автоматически и мог быть формально отлучен от церкви .

На президентских выборах в США 1960 года шах отдал предпочтение кандидату от республиканской партии, действующему вице-президенту Ричарду Никсону , с которым он впервые встретился в 1953 году и который ему весьма понравился, и, согласно дневнику его лучшего друга Асадоллы Алама , Мохаммад Реза внес деньги в Предвыборная кампания Никсона 1960 года. [ 123 ] Отношения с победителем выборов 1960 года демократом Джоном Кеннеди не были дружескими. [ 123 ] Пытаясь наладить отношения после поражения Никсона, Мохаммад Реза отправил генерала Теймура Бахтияра из САВАК на встречу с Кеннеди в Вашингтон 1 марта 1961 года. [ 124 ] От Кермита Рузвельта Мохаммад Реза узнал, что Бахтияр во время своей поездки в Вашингтон просил американцев поддержать планируемый им переворот, что значительно усилило опасения шаха по поводу Кеннеди. [ 124 ] 2 мая 1961 года в Иране началась забастовка учителей, в которой приняли участие 50 000 человек, которая, по мнению Мохаммеда Резы, была делом рук ЦРУ. [ 125 ] Мохаммеду Резе пришлось уволить своего премьер-министра Джафара Шарифа-Эмами и уступить учителям, узнав, что армия, вероятно, не будет стрелять по демонстрантам. [ 126 ] В 1961 году Бахтияр был уволен с поста руководителя САВАК и выслан из Ирана в 1962 году после столкновения между демонстрирующими студентами университета и армией 21 января 1962 года, в результате которого погибли трое человек. [ 127 ] В апреле 1962 года, когда Мохаммад Реза посетил Вашингтон, он был встречен демонстрациями иранских студентов американских университетов, которые, по его мнению, были организованы генеральным прокурором США Робертом Кеннеди , братом президента и ведущим антипехлеви-голосом в администрации Кеннеди. . [ 128 ] После этого Мохаммад Реза посетил Лондон. В знак изменившейся динамики в англо-иранских отношениях шах обиделся, когда ему сообщили, что он может присоединиться к королеве Елизавете II на ужине в Букингемском дворце , который был дан в чью-то честь, и настаивал на том, что он успешно поужинает с королевой. только тогда, когда дается в его собственную честь. [ 128 ]

Mohammad Reza's first major clash with Ayatollah Khomeini occurred in 1962, when the Shah changed the local laws to allow Iranian Jews, Christians, Zoroastrians, and Baha'i to take the oath of office for municipal councils using their holy books instead of the Koran.[129] Khomeini wrote to the Shah to say this was unacceptable and that only the Koran could be used to swear in members of the municipal councils regardless of what their religion was, writing that he heard "Islam is not indicated as a precondition for standing for office and women are being granted the right to vote...Please order all laws inimical to the sacred and official faith of the country to be eliminated from government policies."[129] The Shah wrote back, addressing Khomeini as Hojat-al Islam rather than as Ayatollah, declining his request.[129] Feeling pressure from demonstrations organised by the clergy, the Shah withdrew the offending law, but it was reinstated with the White Revolution of 1963.[130]

Middle years

[edit]The White Revolution

[edit]

Conflict with Islamists

[edit]In 1963, Mohammad Reza launched the White Revolution, a series of far-reaching reforms, which caused much opposition from the religious scholars. They were enraged that the referendum approving of the White Revolution in 1963 allowed women to vote, with the Ayatollah Khomeini saying in his sermons that the fate of Iran should never be allowed to be decided by women.[131] In 1963 and 1964, nationwide demonstrations against Mohammad Reza's rule took place all over Iran, with the centre of the unrest being the holy city of Qom.[132] Students studying to be imams at Qom were most active in the protests, and Ayatollah Khomeini emerged as one of the leaders, giving sermons calling for the Shah's overthrow.[132] At least 200 people were killed, with the police throwing some students to their deaths from high buildings, and Khomeini was exiled to Iraq in August 1964.[133]

The second attempt on the Shah's life occurred on 10 April 1965.[134] A soldier shot his way through the Marble Palace. The assassin was killed before he reached the royal quarters, but two civilian guards died protecting the Shah.[135]

Conflict with communists

[edit]According to Vladimir Kuzichkin, a former KGB officer who defected to MI-6, the Soviet Union also targeted the Shah. The Soviets tried to use a TV remote control to detonate a bomb-laden Volkswagen Beetle; the TV remote failed to function.[136] A high-ranking Romanian defector, Ion Mihai Pacepa, also supported this claim, asserting that he had been the target of various assassination attempts by Soviet agents for many years.[137]

Pahlavi's court

[edit]

Mohammad Reza's third and final wife was Farah Diba (born 14 October 1938), the only child of Sohrab Diba, a captain in the Imperial Iranian Army (son of an Iranian ambassador to the Romanov Court in St. Petersburg, Russia), and his wife, the former Farideh Ghotbi. They were married in 1959, and Queen Farah was crowned Shahbanu, or Empress, a title created especially for her in 1967. Previous royal consorts had been known as "Malakeh" (Arabic: Malika), or Queen. The couple remained together for 21 years, until the Shah's death. They had four children together:

- Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi (born 31 October 1960), heir to the now defunct Iranian throne. Reza Pahlavi is the founder and leader of National Council of Iran, a government in exile of Iran;

- Princess Farahnaz Pahlavi (born 12 March 1963);

- Prince Ali Reza Pahlavi (28 April 1966 – 4 January 2011);

- Princess Leila Pahlavi (27 March 1970 – 10 June 2001).

One of Mohammad Reza's favourite activities was watching films and his favourites were light French comedies and Hollywood action films, much to the disappointment of Farah who tried hard to interest him in more serious films.[138] Mohammad Reza was frequently unfaithful towards Farah, and his right-hand man Asadollah Alam regularly imported tall European women for "outings" with the Shah, though Alam's diary also mentions that if women from the "blue-eyed world" were not available, he would bring the Shah "local product".[139] Mohammad Reza had an insatiable appetite for sex, and Alam's diary has the Shah constantly telling him he needed to have sex several times a day, every day, or otherwise he would fall into depression.[139] When Farah found out about his affairs in 1973, Alam blamed the prime minister Amir Abbas Hoveyda while the Shah thought it was the KGB. Milani noted that neither admitted it was the Shah's "crass infidelities" that caused this issue.[139] Milani further wrote that "Alam, in his most destructive moments of sycophancy, reassured the Shah—or his "master" as he calls him—that the country was prosperous and no one begrudged the King a bit of fun". He also had a passion for automobiles and aeroplanes, and by the middle 1970s, the Shah had amassed one of the world's largest collection of luxury cars and planes.[140] His visits to the West were invariably the occasions for major protests by the Confederation of Iranian Students, an umbrella group of far-left Iranian university students studying abroad, and Mohammad Reza had one of the world's largest security details as he lived in constant fear of assassination.[127]

Milani described Mohammad Reza's court as open and tolerant, noting that his and Farah's two favourite interior designers, Keyvan Khosrovani and Bijan Saffari, were openly gay, and were not penalised for their sexual orientation with Khosrovani often giving advice to the Shah about how to dress.[141] Milani noted the close connection between architecture and power in Iran as architecture is the "poetry of power" in Iran.[141] In this sense, the Niavaran Palace, with its mixture of modernist style, heavily influenced by current French styles and traditional Persian style, reflected Mohammad Reza's personality.[142] Mohammad Reza was a Francophile whose court had a decidedly French ambiance to it.[143]

Mohammad Reza commissioned a documentary from the French filmmaker Albert Lamorisse meant to glorify Iran under his rule. But he was annoyed that the film focused only on Iran's past, writing to Lamorisse there were no modern buildings in his film, which he charged made Iran look "backward".[138] Mohammad Reza's office was functional whose ceilings and walls were decorated with Qajar art.[144] Farah began collecting modern art and by the early 1970s owned works by Picasso, Gauguin, Chagall, and Braque, which added to the modernist feel of the Niavaran Palace.[143]

Imperial coronation

[edit]On 26 October 1967, twenty-six years into his reign as Shah ("King"), he took the ancient title Shāhanshāh ("Emperor" or "King of Kings") in a lavish coronation ceremony held in Tehran. He said that he chose to wait until this moment to assume the title because in his own opinion he "did not deserve it" up until then; he is also recorded as saying that there was "no honour in being Emperor of a poor country" (which he viewed Iran as being until that time).[145]

2,500-year celebration of the Persian Empire

[edit]

As part of his efforts to modernise Iran and give the Iranian people a non-Islamic identity, Mohammad Reza quite consciously started to celebrate Iranian history before the Arab conquest with a special focus on the Achaemenid period.[146] In October 1971, he marked the anniversary of 2,500 years of continuous Persian monarchy since the founding of the Achaemenid Empire by Cyrus the Great. Concurrent with this celebration, Mohammad Reza changed the benchmark of the Iranian calendar from the Hijrah to the beginning of the First Persian Empire, measured from Cyrus the Great's coronation.[147]

At the celebration at Persepolis in 1971, the Shah had an elaborate fireworks show intended to send a dual message; that Iran was still faithful to its ancient traditions and that Iran had transcended its past to become a modern nation, that Iran was not "stuck in the past", but as a nation that embraced modernity had chosen to be faithful to its past.[148] The message was further reinforced the next day when the "Parade of Persian History" was performed at Persepolis when 6,000 soldiers dressed in the uniforms of every dynasty from the Achaemenids to the Pahlavis marched past Mohammad Reza in a grand parade that many contemporaries remarked "surpassed in sheer spectacle the most florid celluloid imaginations of Hollywood epics".[148] To complete the message, Mohammad Reza finished off the celebrations by opening a brand new museum in Tehran, the Shahyad Aryamehr, that was housed in a very modernistic building and attended another parade in the newly opened Aryamehr Stadium, intended to give a message of "compressed time" between antiquity and modernity.[148] A brochure put up by the Celebration Committee explicitly stated the message: "Only when change is extremely rapid, and the past ten years have proved to be so, does the past attain new and unsuspected values worth cultivating", going on to say the celebrations were held because "Iran has begun to feel confident of its modernization".[148] Milani noted it was a sign of the liberalization of the middle years of Mohammad Reza's reign that Hussein Amanat, the architect who designed the Shahyad was a young Baha'i from a middle-class family who did not belong to the "thousand families" that traditionally dominated Iran, writing that only in this moment in Iranian history such a thing was possible.[149]

Role at OPEC

[edit]1973 Arab–Israeli War

[edit]Prior to the 1973 oil embargo Iran spearheaded OPEC's aim for higher oil prices. When raising oil prices Iran would point out the rising inflation as a means to justify the price increases.[150] In the aftermath of the Yom Kippur War, Arab states employed an oil embargo in 1973 against Western nations. Although the Shah declared neutrality, he sought to exploit the lack of crude oil supply to Iran's benefit. The Shah held a meeting of Persian Gulf oil producers declaring they should double the price of oil for the second time in a year. The price hike resulted in an “oil shock” that crippled Western economies while Iran saw a rapid growth of oil revenues. Iranian oil incomes doubled to $4.6 billion in 1973–1974 and spiked to $17.8 billion in the following year. As a result, the Shah had established himself as the dominant figure of OPEC, having control over oil prices and production. Iran experienced an economic growth rate of 33% in 1973 and 40% the next year, and GNP expanded 50% in the next year.[151]

The Shah directed the growth in oil revenues back into the domestic economy. Elementary school education was made free and mandatory, major investments were made in the military, and in 1974, 16 billion dollars were spent on building new schools and hospitals. The Shah's oil coup signaled that the United States had lost the ability to influence Iranian foreign and economic policy.[151] Under the Shah, Iran dominated OPEC and middle eastern oil exports.[152]

Nationalist Iran

[edit]By the 19th century, the Persian word Vatan began to refer to a national homeland by many intellectuals in Iran. The education system was largely controlled by Shiite clergy who utilized a Maktab system in which open political discussion of modernization was prevented. However, a number of scholarly intellectuals including Mirzā FathʿAli Ākhundzādeh, Mirzā Āqā Khān Kermāni and Mirzā Malkam Khān began to criticize Islam's role in public life while promoting a secular identity for Iran. Over time studies of Iran's glorious history and present reality of a declined Qajar period led many to question what led to Iran's decline.[153] Ultimately Iranian history was categorized into two periods pre-Islamic and Islamic. Iran's pre-Islamic period was seen as prosperous while the Arab invasions were seen as, ‘a political catastrophe that pummelled the superior Iranian civilization under its hoof.’[154] Therefore, as a result of the growing number of Iranian intellectuals in the 1800s, the Ancient Persian Empire symbolized modernity and originality, while the Islamic period brought by Arab invasions brought Iran to a period of backwardness.[153]

Ultimately these revelations in Iran would lead to the rise of Aryan nationalism in Iran and the perception of an 'intellectual awakening', as described by Homa Katouzian. In Europe, many concepts of Aryan Nationalism were directed at the anti-Jewish sentiment. In contrast, Iran's Aryan nationalism was deeply rooted in Persian history and became synonymous with an anti-Arab sentiment instead. Furthermore, the Achaemenid and Sasanian periods were perceived as the real Persia, a Persia which commanded the respect of the world and was void of foreign culture before the Arab invasions.[153]

Thus, under the Pahlavi state, these ideas of Aryan and pre-Islamic Iranian nationalism continued with the rise of Reza Shah. Under the last Shah, the tomb of Cyrus the Great was established as a significant site for all Iranians. The Mission for My Country, written by the Shah, described Cyrus as ‘one of the most dynamic men in history’ and that ‘wherever Cyrus conquered, he would pardon the very people who had fought him, treat them well, and keep them in their former posts ... While Iran at the time knew nothing of democratic political institutions, Cyrus nevertheless demonstrated some of the qualities which provide the strength of the great modern democracies’. The Cyrus Cylinder also became an important cultural symbol and Pahlavi successfully popularized the decree as an ancient declaration of human rights.[153] The Shah employed titles like Āryāmehr and Shāhanshāh in order to emphasize Iranian supremacy and the kings of Iran.[155]

The Shah continued on with his father's ideas of Iranian nationalism concluding Arabs as the utmost other. Nationalist narratives which were widely accepted by a majority of Iranians portraying Arabs as hostile to Pahlavi's revival of ‘modern’ and ‘authentic’ Iran.[156]

Economic growth

[edit]

In the 1970s, Iran had an economic growth rate equal to that of South Korea, Turkey and Taiwan, and Western journalists all regularly predicted that Iran would become a First World nation within the next generation.[157] Significantly, a "reverse brain drain" had begun with Iranians who had been educated in the West returning home to take up positions in government and business.[158] The firm of Iran National ran by the Khayami brothers had become by 1978 the largest automobile manufacturer in the Middle East producing 136,000 cars every year while employing 12,000 people in Mashhad.[158] Mohammad Reza had strong étatist tendencies and was deeply involved in the economy, with his economic policies bearing a strong resemblance to the same étatist policies being pursued simultaneously by General Park Chung-hee in South Korea. Mohammad Reza considered himself to be a socialist, saying he was "more socialist and revolutionary than anyone".[158] Reflecting his self-proclaimed socialist tendencies, although unions were illegal, the Shah brought in labour laws that were "surprisingly fair to workers".[159] Iran in the 1960s and 70s was a tolerant place for the Jewish minority with one Iranian Jew, David Menasheri, remembering that Mohammad Reza's reign was the "golden age" for Iranian Jews when they were equals, and when the Iranian Jewish community was one of the wealthiest Jewish communities in the world. The Baha'i minority also did well after the bout of persecution in the mid-1950s ended with several Baha'i families rising to prominence in the world of Iranian business.[160]

Under his reign, Iran experienced over a decade of double-digit GDP growth coupled with major investments in military and infrastructure.[161]

The Shah's first economic plan was geared towards large infrastructure projects and improving the agricultural sector which led to the development of many major dams particularly in Karaj, Safīdrūd, and Dez. The next economic plan was directed and characterized by an expansion in the credit and monetary policy of a nation which resulted in a rapid expansion of Iran's private sector, particularly construction. From the period 1955–1959, real gross fixed capital formation in the private sector saw an average annual increase of 39.3%.[162] The private sector credit rose by 46 percent in 1957, 61 percent in 1958, and 32 percent in 1959 (Central Bank of Iran, Annual Report, 1960 and 1961). By 1963, the Shah had begun a redistribution of land offering compensation to landlords valued on previous tax assessments, and the land obtained by the government was then sold on favorable terms to Iranian peasants.[163] The Shah also initiated the nationalization of forests and pastures, female suffrage, profit-sharing for industrial workers, privatization of state industries, and formation of literacy corps. These developments marked a turning point in Iranian history as the nation prepared to embark on a rapid and aggressive industrialization process.[162]

1963–1978 represented the longest period of sustained growth in per capita real income the Iranian economy ever experienced. During the 1963–77 period gross Domestic Product (GDP) grew by an average annual rate of 10.5% with an annual population growth rate of around 2.7% placing Iran as one of the fasted growing economies in the world. Iran's GDP per capita was $170 in 1963 and rose to $2,060 by 1977. The growth was not just a result of increased oil revenues. In fact, the non-oil GDPs grew by an average annual rate of 11.5 percent, which was higher than the average annual rate of growth experienced in oil revenues. By the fifth economic planning, oil GDP rose to 15.3% strongly outpacing growth rates in oil revenue which only saw .5% growth. From 1963 to 1977 the industrial and the service sectors experienced annual growth rates of 15.0 and 14.3 percent, respectively. The manufacturing of cars, television sets, refrigerators, and other household goods increased substantially in Iran. For instance, over the small period of 1969 to 1977, the number of private cars produced in Iran increased steadily from 29,000 to 132,000 and the number of television sets produced rose from 73,000 in 1969 to 352,000 in 1975.[162]

The growth of industrial sectors in Iran led to substantial urbanization of the country. The extent of urbanization rose from 31 percent in 1956 to 49 percent in 1978. By the mid-1970s Iran's national debt was paid off, turning the nation from a debtor to a creditor nation. The balances on the nation's account for the 1959–78 period actually resulted in a surplus of funds of approximately $15.17 billion. The Shah's fifth five-year economic plan sought to achieve a reduction in foreign imports through the use of higher tariffs on consumer goods, preferential bank loans to the industrialists, maintenance of an overvalued rial, and food subsidies in urban areas. These developments led to the development of a new large industrialist class in Iran and the nation's industrial structure was extremely insulated from threats of foreign competition.[162]

In 1976, Iran saw its largest-ever GDP uptick, thanks in large part to the Shah's economic policies. According to the World Bank, when valued in 2010 dollars, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi improved the country's per-capita GDP to $10,261, the highest at any point in Iran's history.[164]

According to economist Fereydoun Khavand, “During these 15 years, the average annual growth rate of the country fluctuated above 10%. The total volume of Iran's economy increased nearly fivefold during this period. In contrast, during the past 40 years, Iran's average annual economic growth rate has been only about two percent. Considering the growth rate of Iran's population in the post-revolution period, the average per capita growth rate of Iran in the last 40 years is estimated between zero percent and half a percent. Among the main factors hindering the growth rate in Iran are a lack of a favorable business environment, severe investment weakness, very low levels of productivity, and constant tension in the country's regional and global relations.”[165]

Many European, American, and Japanese investment firms sought business ventures and to open up headquarters in Iran. According to one American investment banker:

"They are now dependent on Western technology, but what happens when they produce and export steel and copper, when they reduce their agricultural problems? They'll eat everybody else in the Middle East alive.”[166]

Relationship with the Western world

[edit]By the 1960s and 1970s, Iranian oil revenues experienced rapid growth. By the mid-1960s Iran saw "weakened U.S. influence in Iranian politics" and a strengthening in the power of the Iranian state. According to Homa Katouzian, the perception that the US was the instructor of the Shah's regime due to their support for the 1953 coup contradicted the reality that "its real influence" in domestic Iranian politics and policy "declined considerably".[167] In 1973 the Shah initiated an oil price hike with his control of OPEC further demonstrating the US no longer had influence over Iranian foreign and economic policies.[151] In response to American media outlets critical of him, the Shah claimed that Iran's oil price hikes did little to contribute to the rising inflation in the United States. Pahlavi also implied criticism of the US for not taking the lead on anti-communist efforts.[168]

In 1974 during the oil crisis, the Shah began an atomic nuclear energy policy prompting US Trade Administrator William E. Simon to denounce the Shah as a "nut." In response, US President Nixon publicly apologized to the Shah and through a letter in order to disassociate the president and the United States from the statement. Simon's statement illustrated the growing American tensions with Iran over the Shah's raising of oil prices. Nixon's apology covered up the reality that the Shah's ambitions to become the leader in the Persian Gulf Area and the Indian Ocean basin was placing a serious strain on his relationship with the United States, particularly as India had tested its first atomic bomb in May 1974.[169]

Many critics labeled the Shah as a Western and American "puppet", an accusation that has been disproven as unfounded by contemporary scholars due to the Shah's strong regional and nationalist ambitions which often led Tehran to disputes with its Western allies.[170] In particular, the Carter administration which took control of the White House in 1977 saw the Shah as a troublesome ally and sought change in Iran's political system.[171]

By the 1970s, the Shah had become a strongman. His power had dramatically increased both in Iran and internationally, and on the tenth anniversary of the White Revolution, he challenged The Consortium Agreement of 1954 and terminated the agreement after negotiations with the oil consortium resulting in the establishment of 1973 Sale and Purchase Agreement.[172][173]

Khomeini accused the Shah of false rumors and employed Soviet methods of deception. The accusations were amplified by international media outlets which widely propagated the information and protests were widely shown on Iranian televisions.[174]

Many Iranian students studied across Western Europe and the United States where ideas of liberalism, democracy, and counterculture flourished. Among left-leaning Westerners, the Shah's reign was seen as equivalent to that of right-wing hate figures. Western anti-Shah fervor broadcast by European and American media outlets was ultimately adopted by Iranian students and intellectuals studying the West who accused the shah of Westoxification when it was the students themselves who were adopting Western liberalism they experienced during their studies. These Western ideas of liberalism resulted in utopian visions for revolution and social change. In turn, the Shah criticized Western democracies and equated them to chaos. Furthermore, the Shah chastised Americans and Europeans as being "lazy," and "lacking discipline," and criticized their student radicalism as being caused by Western decline. President Nixon expressed his concern to the Shah that Iranian students in the United States would similarly become radicalized, asking the Shah:[175]

“Are your students infected?” and “Can you do anything?”

Foreign relations and policies

[edit]France

[edit]

In 1961, the Francophile Mohammad Reza visited Paris to meet his favourite leader, General Charles de Gaulle of France.[176] Mohammad Reza saw height as the measure of a man and a woman (the Shah had a marked preference for tall women) and the 6 feet 5 inches (1.96 m) de Gaulle was his most admired leader. Mohammad Reza loved to be compared to his "ego ideal" of General de Gaulle, and his courtiers constantly flattered him by calling him Iran's de Gaulle.[176] During the French trip, Queen Farah, who shared her husband's love of French culture and language, befriended the culture minister André Malraux, who arranged for the exchange of cultural artifacts between French and Iranian museums and art galleries, a policy that remained a key component of Iran's cultural diplomacy until 1979.[177] Many of the legitimising devices of the regime such as the constant use of referendums were modelled after de Gaulle's regime.[177] Intense Francophiles, Mohammad Reza and Farah preferred to speak French rather than Persian to their children.[178] Mohammad Reza built the Niavaran Palace which took up 840 square metres (9,000 sq ft) and whose style was a blend of Persian and French architecture.[179]

United States

[edit]The Shah's diplomatic foundation was the United States' guarantee that it would protect his regime, enabling him to stand up to larger enemies. While the arrangement did not preclude other partnerships and treaties, it helped to provide a somewhat stable environment in which Mohammad Reza could implement his reforms. Another factor guiding Mohammad Reza in his foreign policy was his wish for financial stability, which required strong diplomatic ties. A third factor was his wish to present Iran as a prosperous and powerful nation; this fuelled his domestic policy of Westernisation and reform. A final component was his promise that communism could be halted at Iran's border if his monarchy was preserved. By 1977, the country's treasury, the Shah's autocracy, and his strategic alliances seemed to form a protective layer around Iran.[180]