Лошадь

| Лошадь | |

|---|---|

| |

Одомашненное

| |

| Научная классификация | |

| Домен: | Эукариота |

| Королевство: | Животное |

| Филум: | Chordata |

| Сорт: | Млекопитающие |

| Заказ: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Equidae |

| Genus: | Equus |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | E. f. caballus

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Equus ferus caballus | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

at least 48 published | |

Лошадь лошадь ( дикая лошадь ) [ 2 ] [ 3 ] это одомашненное , односпальное млекопитающее . Они принадлежат к таксономическому семейному Equidae и являются одним из двух существующих подвидов Equus Ferus . За последние 45 до 55 миллионов лет лошадь развивалась из небольшого мультипадающего существа, близкого к Эохиппусу , в крупное, однодержанное животное сегодня. Люди начали одомашнивать лошадей около 4000 г. до н.э. , и их одомашнивание , как полагают, было широко распространено на 3000 г. до н.э. Лошади в подвиде Кабаллус одомашнены, хотя некоторые одомашненные популяции живут в дикой природе как диких лошадей . Эти дикие популяции не являются настоящими дикими лошадьми , которые являются лошадьми, которые никогда не были одомашнены и исторически связаны с категорией видов Мегафауны. Существует обширный специализированный словарный запас, используемый для описания концепций, связанных с лошадью, охватывающий все, от анатомии до этапов жизни, размера, цветов , маркировки , пород , локомоции и поведения.

Horses are adapted to run, allowing them to quickly escape predators, and possess a good sense of balance and a strong fight-or-flight response. Related to this need to flee from predators in the wild is an unusual trait: horses are able to sleep both standing up and lying down, with younger horses tending to sleep significantly more than adults.[4] У лошадей, называемых кобылами , носят молодых в течение приблизительно 11 месяцев, а молодая лошадь, называемая жеребенком , могут стоять и бежать вскоре после рождения. Большинство одомашненных лошадей начинают тренироваться под седлом или в жгуте в возрасте от двух до четырех лет. Они достигают полного развития взрослых к пяти лет и имеют среднюю продолжительность жизни от 25 до 30 лет.

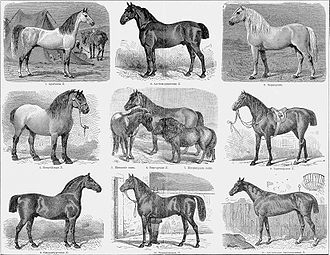

Horse breeds are loosely divided into three categories based on general temperament: spirited "hot bloods" with speed and endurance; "cold bloods", such as draft horses and some ponies, suitable for slow, heavy work; and "warmbloods", developed from crosses between hot bloods and cold bloods, often focusing on creating breeds for specific riding purposes, particularly in Europe. There are more than 300 breeds of horse in the world today, developed for many different uses.

Horses and humans interact in a wide variety of sport competitions and non-competitive recreational pursuits as well as in working activities such as police work, agriculture, entertainment, and therapy. Horses were historically used in warfare, from which a wide variety of riding and driving techniques developed, using many different styles of equipment and methods of control. Many products are derived from horses, including meat, milk, hide, hair, bone, and pharmaceuticals extracted from the urine of pregnant mares. Humans provide domesticated horses with food, water, and shelter, as well as attention from specialists such as veterinarians and farriers.

Biology

Lifespan and life stages

Depending on breed, management and environment, the modern domestic horse has a life expectancy of 25 to 30 years.[7] Uncommonly, a few animals live into their 40s and, occasionally, beyond.[8] The oldest verifiable record was "Old Billy", a 19th-century horse that lived to the age of 62.[7] In modern times, Sugar Puff, who had been listed in Guinness World Records as the world's oldest living pony, died in 2007 at age 56.[9]

Regardless of a horse or pony's actual birth date, for most competition purposes a year is added to its age each January 1 of each year in the Northern Hemisphere[7][10] and each August 1 in the Southern Hemisphere.[11] The exception is in endurance riding, where the minimum age to compete is based on the animal's actual calendar age.[12]

The following terminology is used to describe horses of various ages:

- Foal

- A horse of either sex less than one year old. A nursing foal is sometimes called a suckling, and a foal that has been weaned is called a weanling.[13] Most domesticated foals are weaned at five to seven months of age, although foals can be weaned at four months with no adverse physical effects.[14]

- Yearling

- A horse of either sex that is between one and two years old.[15]

- Colt

- A male horse under the age of four.[16] A common terminology error is to call any young horse a "colt", when the term actually only refers to young male horses.[17]

- Filly

- A female horse under the age of four.[13]

- Mare

- A female horse four years old and older.[18]

- Stallion

- A non-castrated male horse four years old and older.[19] The term "horse" is sometimes used colloquially to refer specifically to a stallion.[20]

- Gelding

- A castrated male horse of any age.[13]

In horse racing, these definitions may differ: For example, in the British Isles, Thoroughbred horse racing defines colts and fillies as less than five years old.[21] However, Australian Thoroughbred racing defines colts and fillies as less than four years old.[22]

Size and measurement

The height of horses is measured at the highest point of the withers, where the neck meets the back.[23] This point is used because it is a stable point of the anatomy, unlike the head or neck, which move up and down in relation to the body of the horse.

In English-speaking countries, the height of horses is often stated in units of hands and inches: one hand is equal to 4 inches (101.6 mm). The height is expressed as the number of full hands, followed by a point, then the number of additional inches, and ending with the abbreviation "h" or "hh" (for "hands high"). Thus, a horse described as "15.2 h" is 15 hands plus 2 inches, for a total of 62 inches (157.5 cm) in height.[24]

The size of horses varies by breed, but also is influenced by nutrition. Light-riding horses usually range in height from 14 to 16 hands (56 to 64 inches, 142 to 163 cm) and can weigh from 380 to 550 kilograms (840 to 1,210 lb).[25] Larger-riding horses usually start at about 15.2 hands (62 inches, 157 cm) and often are as tall as 17 hands (68 inches, 173 cm), weighing from 500 to 600 kilograms (1,100 to 1,320 lb).[26] Heavy or draft horses are usually at least 16 hands (64 inches, 163 cm) high and can be as tall as 18 hands (72 inches, 183 cm) high. They can weigh from about 700 to 1,000 kilograms (1,540 to 2,200 lb).[27]

The largest horse in recorded history was probably a Shire horse named Mammoth, who was born in 1848. He stood 21.2 1⁄4 hands (86.25 inches, 219 cm) high and his peak weight was estimated at 1,524 kilograms (3,360 lb).[28] The record holder for the smallest horse ever is Thumbelina, a fully mature miniature horse affected by dwarfism. She was 43 centimetres; 4.1 hands (17 in) tall and weighed 26 kg (57 lb).[29][30]

Ponies

Ponies are taxonomically the same animals as horses. The distinction between a horse and pony is commonly drawn on the basis of height, especially for competition purposes. However, height alone is not dispositive; the difference between horses and ponies may also include aspects of phenotype, including conformation and temperament.

The traditional standard for height of a horse or a pony at maturity is 14.2 hands (58 inches, 147 cm). An animal 14.2 hands (58 inches, 147 cm) or over is usually considered to be a horse and one less than 14.2 hands (58 inches, 147 cm) a pony,[31]: 12 but there are many exceptions to the traditional standard. In Australia, ponies are considered to be those under 14 hands (56 inches, 142 cm).[32] For competition in the Western division of the United States Equestrian Federation, the cutoff is 14.1 hands (57 inches, 145 cm).[33] The International Federation for Equestrian Sports, the world governing body for horse sport, uses metric measurements and defines a pony as being any horse measuring less than 148 centimetres (58.27 in) at the withers without shoes, which is just over 14.2 hands (58 inches, 147 cm), and 149 centimetres (58.66 in; 14.2+1⁄2 hands), with shoes.[34]

Height is not the sole criterion for distinguishing horses from ponies. Breed registries for horses that typically produce individuals both under and over 14.2 hands (58 inches, 147 cm) consider all animals of that breed to be horses regardless of their height.[35] Conversely, some pony breeds may have features in common with horses, and individual animals may occasionally mature at over 14.2 hands (58 inches, 147 cm), but are still considered to be ponies.[36]

Ponies often exhibit thicker manes, tails, and overall coat. They also have proportionally shorter legs, wider barrels, heavier bone, shorter and thicker necks, and short heads with broad foreheads. They may have calmer temperaments than horses and also a high level of intelligence that may or may not be used to cooperate with human handlers.[31]: 11–12 [failed verification] Small size, by itself, is not an exclusive determinant. For example, the Shetland pony which averages 10 hands (40 inches, 102 cm), is considered a pony.[31]: 12 Conversely, breeds such as the Falabella and other miniature horses, which can be no taller than 76 centimetres; 7.2 hands (30 in), are classified by their registries as very small horses, not ponies.[37]

Genetics

Horses have 64 chromosomes.[38] The horse genome was sequenced in 2007. It contains 2.7 billion DNA base pairs,[39] which is larger than the dog genome, but smaller than the human genome or the bovine genome.[40] The map is available to researchers.[41]

Colors and markings

Horses exhibit a diverse array of coat colors and distinctive markings, described by a specialized vocabulary. Often, a horse is classified first by its coat color, before breed or sex.[42] Horses of the same color may be distinguished from one another by white markings,[43] which, along with various spotting patterns, are inherited separately from coat color.[44]

Many genes that create horse coat colors and patterns have been identified. Current genetic tests can identify at least 13 different alleles influencing coat color,[45] and research continues to discover new genes linked to specific traits. The basic coat colors of chestnut and black are determined by the gene controlled by the Melanocortin 1 receptor,[46] also known as the "extension gene" or "red factor".[45] Its recessive form is "red" (chestnut) and its dominant form is black.[47] Additional genes control suppression of black color to point coloration that results in a bay, spotting patterns such as pinto or leopard, dilution genes such as palomino or dun, as well as greying, and all the other factors that create the many possible coat colors found in horses.[45]

Horses that have a white coat color are often mislabeled; a horse that looks "white" is usually a middle-aged or older gray. Grays are born a darker shade, get lighter as they age, but usually keep black skin underneath their white hair coat (with the exception of pink skin under white markings). The only horses properly called white are born with a predominantly white hair coat and pink skin, a fairly rare occurrence.[47] Different and unrelated genetic factors can produce white coat colors in horses, including several different alleles of dominant white and the sabino-1 gene.[48] However, there are no "albino" horses, defined as having both pink skin and red eyes.[49]

Reproduction and development

Gestation lasts approximately 340 days, with an average range 320–370 days,[50][51] and usually results in one foal; twins are rare.[52] Horses are a precocial species, and foals are capable of standing and running within a short time following birth.[53] Foals are usually born in the spring. The estrous cycle of a mare occurs roughly every 19–22 days and occurs from early spring into autumn. Most mares enter an anestrus period during the winter and thus do not cycle in this period.[54] Foals are generally weaned from their mothers between four and six months of age.[55]

Horses, particularly colts, are sometimes physically capable of reproduction at about 18 months, but domesticated horses are rarely allowed to breed before the age of three, especially females.[31]: 129 Horses four years old are considered mature, although the skeleton normally continues to develop until the age of six; maturation also depends on the horse's size, breed, sex, and quality of care. Larger horses have larger bones; therefore, not only do the bones take longer to form bone tissue, but the epiphyseal plates are larger and take longer to convert from cartilage to bone. These plates convert after the other parts of the bones, and are crucial to development.[56]

Depending on maturity, breed, and work expected, horses are usually put under saddle and trained to be ridden between the ages of two and four.[57] Although Thoroughbred race horses are put on the track as young as the age of two in some countries,[58] horses specifically bred for sports such as dressage are generally not put under saddle until they are three or four years old, because their bones and muscles are not solidly developed.[59] For endurance riding competition, horses are not deemed mature enough to compete until they are a full 60 calendar months (five years) old.[12]

Anatomy

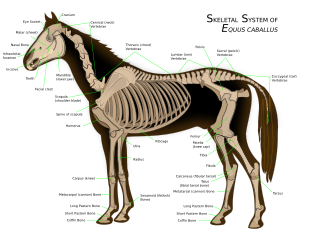

Skeletal system

The horse skeleton averages 205 bones.[60] A significant difference between the horse skeleton and that of a human is the lack of a collarbone—the horse's forelimbs are attached to the spinal column by a powerful set of muscles, tendons, and ligaments that attach the shoulder blade to the torso. The horse's four legs and hooves are also unique structures. Their leg bones are proportioned differently from those of a human. For example, the body part that is called a horse's "knee" is actually made up of the carpal bones that correspond to the human wrist. Similarly, the hock contains bones equivalent to those in the human ankle and heel. The lower leg bones of a horse correspond to the bones of the human hand or foot, and the fetlock (incorrectly called the "ankle") is actually the proximal sesamoid bones between the cannon bones (a single equivalent to the human metacarpal or metatarsal bones) and the proximal phalanges, located where one finds the "knuckles" of a human. A horse also has no muscles in its legs below the knees and hocks, only skin, hair, bone, tendons, ligaments, cartilage, and the assorted specialized tissues that make up the hoof.[61]

Hooves

The critical importance of the feet and legs is summed up by the traditional adage, "no foot, no horse".[62] The horse hoof begins with the distal phalanges, the equivalent of the human fingertip or tip of the toe, surrounded by cartilage and other specialized, blood-rich soft tissues such as the laminae. The exterior hoof wall and horn of the sole is made of keratin, the same material as a human fingernail.[63] The result is that a horse, weighing on average 500 kilograms (1,100 lb),[64] travels on the same bones as would a human on tiptoe.[65] For the protection of the hoof under certain conditions, some horses have horseshoes placed on their feet by a professional farrier. The hoof continually grows, and in most domesticated horses needs to be trimmed (and horseshoes reset, if used) every five to eight weeks,[66] though the hooves of horses in the wild wear down and regrow at a rate suitable for their terrain.

Teeth

Horses are adapted to grazing. In an adult horse, there are 12 incisors at the front of the mouth, adapted to biting off the grass or other vegetation. There are 24 teeth adapted for chewing, the premolars and molars, at the back of the mouth. Stallions and geldings have four additional teeth just behind the incisors, a type of canine teeth called "tushes". Some horses, both male and female, will also develop one to four very small vestigial teeth in front of the molars, known as "wolf" teeth, which are generally removed because they can interfere with the bit. There is an empty interdental space between the incisors and the molars where the bit rests directly on the gums, or "bars" of the horse's mouth when the horse is bridled.[67]

An estimate of a horse's age can be made from looking at its teeth. The teeth continue to erupt throughout life and are worn down by grazing. Therefore, the incisors show changes as the horse ages; they develop a distinct wear pattern, changes in tooth shape, and changes in the angle at which the chewing surfaces meet. This allows a very rough estimate of a horse's age, although diet and veterinary care can also affect the rate of tooth wear.[7]

Digestion

Horses are herbivores with a digestive system adapted to a forage diet of grasses and other plant material, consumed steadily throughout the day. Therefore, compared to humans, they have a relatively small stomach but very long intestines to facilitate a steady flow of nutrients. A 450-kilogram (990 lb) horse will eat 7 to 11 kilograms (15 to 24 lb) of food per day and, under normal use, drink 38 to 45 litres (8.4 to 9.9 imp gal; 10 to 12 US gal) of water. Horses are not ruminants, having only one stomach, like humans. But unlike humans, they can digest cellulose, a major component of grass, through the process of hindgut fermentation. Cellulose fermentation by symbiotic bacteria and other microbes occurs in the cecum and the large intestine. Horses cannot vomit, so digestion problems can quickly cause colic, a leading cause of death.[68] Although horses do not have a gallbladder, they tolerate high amounts of fat in their diet.[69][70]

Senses

The horses' senses are based on their status as prey animals, where they must be aware of their surroundings at all times.[71] They are lateral-eyed, meaning that their eyes are positioned on the sides of their heads.[72] This means that horses have a range of vision of more than 350°, with approximately 65° of this being binocular vision and the remaining 285° monocular vision.[73] Horses have excellent day and night vision, but they have two-color, or dichromatic vision; their color vision is somewhat like red-green color blindness in humans, where certain colors, especially red and related colors, appear as a shade of green.[74]

Their sense of smell, while much better than that of humans, is not quite as good as that of a dog. It is believed to play a key role in the social interactions of horses as well as detecting other key scents in the environment. Horses have two olfactory centers. The first system is in the nostrils and nasal cavity, which analyze a wide range of odors. The second, located under the nasal cavity, are the vomeronasal organs, also called Jacobson's organs. These have a separate nerve pathway to the brain and appear to primarily analyze pheromones.[75]

A horse's hearing is good,[71] and the pinna of each ear can rotate up to 180°, giving the potential for 360° hearing without having to move the head.[76] Noise affects the behavior of horses and certain kinds of noise may contribute to stress—a 2013 study in the UK indicated that stabled horses were calmest in a quiet setting, or if listening to country or classical music, but displayed signs of nervousness when listening to jazz or rock music. This study also recommended keeping music under a volume of 21 decibels.[77] An Australian study found that stabled racehorses listening to talk radio had a higher rate of gastric ulcers than horses listening to music, and racehorses stabled where a radio was played had a higher overall rate of ulceration than horses stabled where there was no radio playing.[78]

Horses have a great sense of balance, due partly to their ability to feel their footing and partly to highly developed proprioception—the unconscious sense of where the body and limbs are at all times.[79] A horse's sense of touch is well-developed. The most sensitive areas are around the eyes, ears, and nose.[80] Horses are able to sense contact as subtle as an insect landing anywhere on the body.[81]

Horses have an advanced sense of taste, which allows them to sort through fodder and choose what they would most like to eat,[82] and their prehensile lips can easily sort even small grains. Horses generally will not eat poisonous plants, however, there are exceptions; horses will occasionally eat toxic amounts of poisonous plants even when there is adequate healthy food.[83]

Movement

-

Walk 5–8 km/h (3.1–5.0 mph)

-

Trot 8–13 km/h (5.0–8.1 mph)

-

Pace 8–13 km/h (5.0–8.1 mph)

-

Canter 16–27 km/h (9.9–16.8 mph)

-

Gallop 40–48 km/h (25–30 mph), record: 70.76 km/h (43.97 mph)

All horses move naturally with four basic gaits:[84]

- the four-beat walk, which averages 6.4 kilometres per hour (4.0 mph);

- the two-beat trot or jog at 13 to 19 kilometres per hour (8.1 to 11.8 mph) (faster for harness racing horses);

- the canter or lope, a three-beat gait that is 19 to 24 kilometres per hour (12 to 15 mph);

- the gallop, which averages 40 to 48 kilometres per hour (25 to 30 mph),[85] but the world record for a horse galloping over a short, sprint distance is 70.76 kilometres per hour (43.97 mph).[86]

Besides these basic gaits, some horses perform a two-beat pace, instead of the trot.[87] There also are several four-beat 'ambling' gaits that are approximately the speed of a trot or pace, though smoother to ride. These include the lateral rack, running walk, and tölt as well as the diagonal fox trot.[88] Ambling gaits are often genetic in some breeds, known collectively as gaited horses.[89] These horses replace the trot with one of the ambling gaits.[90]

Behavior

Horses are prey animals with a strong fight-or-flight response. Their first reaction to a threat is to startle and usually flee, although they will stand their ground and defend themselves when flight is impossible or if their young are threatened.[91] They also tend to be curious; when startled, they will often hesitate an instant to ascertain the cause of their fright, and may not always flee from something that they perceive as non-threatening. Most light horse riding breeds were developed for speed, agility, alertness and endurance; natural qualities that extend from their wild ancestors. However, through selective breeding, some breeds of horses are quite docile, particularly certain draft horses.[92]

Horses are herd animals, with a clear hierarchy of rank, led by a dominant individual, usually a mare. They are also social creatures that are able to form companionship attachments to their own species and to other animals, including humans. They communicate in various ways, including vocalizations such as nickering or whinnying, mutual grooming, and body language. Many horses will become difficult to manage if they are isolated, but with training, horses can learn to accept a human as a companion, and thus be comfortable away from other horses.[93] However, when confined with insufficient companionship, exercise, or stimulation, individuals may develop stable vices, an assortment of bad habits, mostly stereotypies of psychological origin, that include wood chewing, wall kicking, "weaving" (rocking back and forth), and other problems.[94]

Intelligence and learning

Studies have indicated that horses perform a number of cognitive tasks on a daily basis, meeting mental challenges that include food procurement and identification of individuals within a social system. They also have good spatial discrimination abilities.[95] They are naturally curious and apt to investigate things they have not seen before.[96] Studies have assessed equine intelligence in areas such as problem solving, speed of learning, and memory. Horses excel at simple learning, but also are able to use more advanced cognitive abilities that involve categorization and concept learning. They can learn using habituation, desensitization, classical conditioning, and operant conditioning, and positive and negative reinforcement.[95] One study has indicated that horses can differentiate between "more or less" if the quantity involved is less than four.[97]

Domesticated horses may face greater mental challenges than wild horses, because they live in artificial environments that prevent instinctive behavior whilst also learning tasks that are not natural.[95] Horses are animals of habit that respond well to regimentation, and respond best when the same routines and techniques are used consistently. One trainer believes that "intelligent" horses are reflections of intelligent trainers who effectively use response conditioning techniques and positive reinforcement to train in the style that best fits with an individual animal's natural inclinations.[98]

Temperament

Horses are mammals. As such, they are warm-blooded, or endothermic creatures, as opposed to cold-blooded, or poikilothermic animals. However, these words have developed a separate meaning in the context of equine terminology, used to describe temperament, not body temperature. For example, the "hot-bloods", such as many race horses, exhibit more sensitivity and energy,[99] while the "cold-bloods", such as most draft breeds, are quieter and calmer.[100] Sometimes "hot-bloods" are classified as "light horses" or "riding horses",[101] with the "cold-bloods" classified as "draft horses" or "work horses".[102]

"Hot blooded" breeds include "oriental horses" such as the Akhal-Teke, Arabian horse, Barb, and now-extinct Turkoman horse, as well as the Thoroughbred, a breed developed in England from the older oriental breeds.[99] Hot bloods tend to be spirited, bold, and learn quickly. They are bred for agility and speed.[103] They tend to be physically refined—thin-skinned, slim, and long-legged.[104] The original oriental breeds were brought to Europe from the Middle East and North Africa when European breeders wished to infuse these traits into racing and light cavalry horses.[105][106]

Muscular, heavy draft horses are known as "cold bloods." They are bred not only for strength, but also to have the calm, patient temperament needed to pull a plow or a heavy carriage full of people.[100] They are sometimes nicknamed "gentle giants".[107] Well-known draft breeds include the Belgian and the Clydesdale.[107] Some, like the Percheron, are lighter and livelier, developed to pull carriages or to plow large fields in drier climates.[108] Others, such as the Shire, are slower and more powerful, bred to plow fields with heavy, clay-based soils.[109] The cold-blooded group also includes some pony breeds.[110]

"Warmblood" breeds, such as the Trakehner or Hanoverian, developed when European carriage and war horses were crossed with Arabians or Thoroughbreds, producing a riding horse with more refinement than a draft horse, but greater size and milder temperament than a lighter breed.[111] Certain pony breeds with warmblood characteristics have been developed for smaller riders.[112] Warmbloods are considered a "light horse" or "riding horse".[101]

Today, the term "Warmblood" refers to a specific subset of sport horse breeds that are used for competition in dressage and show jumping.[113] Strictly speaking, the term "warm blood" refers to any cross between cold-blooded and hot-blooded breeds.[114] Examples include breeds such as the Irish Draught or the Cleveland Bay. The term was once used to refer to breeds of light riding horse other than Thoroughbreds or Arabians, such as the Morgan horse.[103]

Sleep patterns

Horses are able to sleep both standing up and lying down. In an adaptation from life in the wild, horses are able to enter light sleep by using a "stay apparatus" in their legs, allowing them to doze without collapsing.[115] Horses sleep better when in groups because some animals will sleep while others stand guard to watch for predators. A horse kept alone will not sleep well because its instincts are to keep a constant eye out for danger.[116]

Unlike humans, horses do not sleep in a solid, unbroken period of time, but take many short periods of rest. Horses spend four to fifteen hours a day in standing rest, and from a few minutes to several hours lying down. Total sleep time in a 24-hour period may range from several minutes to a couple of hours,[116] mostly in short intervals of about 15 minutes each.[117] The average sleep time of a domestic horse is said to be 2.9 hours per day.[118]

Horses must lie down to reach REM sleep. They only have to lie down for an hour or two every few days to meet their minimum REM sleep requirements.[116] However, if a horse is never allowed to lie down, after several days it will become sleep-deprived, and in rare cases may suddenly collapse because it slips, involuntarily, into REM sleep while still standing.[119] This condition differs from narcolepsy, although horses may also suffer from that disorder.[120]

Taxonomy and evolution

The horse adapted to survive in areas of wide-open terrain with sparse vegetation, surviving in an ecosystem where other large grazing animals, especially ruminants, could not.[121] Horses and other equids are odd-toed ungulates of the order Perissodactyla, a group of mammals dominant during the Tertiary period. In the past, this order contained 14 families, but only three—Equidae (the horse and related species), Tapiridae (the tapir), and Rhinocerotidae (the rhinoceroses)—have survived to the present day.[122]

The earliest known member of the family Equidae was the Hyracotherium, which lived between 45 and 55 million years ago, during the Eocene period. It had 4 toes on each front foot, and 3 toes on each back foot.[123] The extra toe on the front feet soon disappeared with the Mesohippus, which lived 32 to 37 million years ago.[124] Over time, the extra side toes shrank in size until they vanished. All that remains of them in modern horses is a set of small vestigial bones on the leg below the knee,[125] known informally as splint bones.[126] Their legs also lengthened as their toes disappeared until they were a hooved animal capable of running at great speed.[125] By about 5 million years ago, the modern Equus had evolved.[127] Equid teeth also evolved from browsing on soft, tropical plants to adapt to browsing of drier plant material, then to grazing of tougher plains grasses. Thus proto-horses changed from leaf-eating forest-dwellers to grass-eating inhabitants of semi-arid regions worldwide, including the steppes of Eurasia and the Great Plains of North America.

By about 15,000 years ago, Equus ferus was a widespread holarctic species. Horse bones from this time period, the late Pleistocene, are found in Europe, Eurasia, Beringia, and North America.[128] Yet between 10,000 and 7,600 years ago, the horse became extinct in North America.[129][130][131] The reasons for this extinction are not fully known, but one theory notes that extinction in North America paralleled human arrival.[132] Another theory points to climate change, noting that approximately 12,500 years ago, the grasses characteristic of a steppe ecosystem gave way to shrub tundra, which was covered with unpalatable plants.[133]

Wild species surviving into modern times

A truly wild horse is a species or subspecies with no ancestors that were ever successfully domesticated. Therefore, most "wild" horses today are actually feral horses, animals that escaped or were turned loose from domestic herds and the descendants of those animals.[134] Only two wild subspecies, the tarpan and the Przewalski's horse, survived into recorded history and only the latter survives today.

The Przewalski's horse (Equus ferus przewalskii), named after the Russian explorer Nikolai Przhevalsky, is a rare Asian animal. It is also known as the Mongolian wild horse; Mongolian people know it as the taki, and the Kyrgyz people call it a kirtag. The subspecies was presumed extinct in the wild between 1969 and 1992, while a small breeding population survived in zoos around the world. In 1992, it was reestablished in the wild by the conservation efforts of numerous zoos.[135] Today, a small wild breeding population exists in Mongolia.[136][137] There are additional animals still maintained at zoos throughout the world.

Their status as a truly wild horse was called into question when domestic horses of the 5,000-year-old Botai culture of Central Asia were found more closely related to Przewalski's horses than to E. f. caballus. The study raised the possibility that modern Przewalski's horses could be the feral descendants of the domestic Botai horses. However, it remains possible that both the Botai horses and the modern Przewalski's horses descend separately from the same ancient wild Przewalski's horse population.[138][139][140]

The tarpan or European wild horse (Equus ferus ferus) was found in Europe and much of Asia. It survived into the historical era, but became extinct in 1909, when the last captive died in a Russian zoo.[141] Thus, the genetic line was lost. Attempts have been made to recreate the tarpan,[141][142][143] which resulted in horses with outward physical similarities, but nonetheless descended from domesticated ancestors and not true wild horses.

Periodically, populations of horses in isolated areas are speculated to be relict populations of wild horses, but generally have been proven to be feral or domestic. For example, the Riwoche horse of Tibet was proposed as such,[137] but testing did not reveal genetic differences from domesticated horses.[144] Similarly, the Sorraia of Portugal was proposed as a direct descendant of the Tarpan on the basis of shared characteristics,[145][146] but genetic studies have shown that the Sorraia is more closely related to other horse breeds, and that the outward similarity is an unreliable measure of relatedness.[145][147]

Other modern equids

Besides the horse, there are six other species of genus Equus in the Equidae family. These are the ass or donkey, Equus asinus; the mountain zebra, Equus zebra; plains zebra, Equus quagga; Grévy's zebra, Equus grevyi; the kiang, Equus kiang; and the onager, Equus hemionus.[148]

Horses can crossbreed with other members of their genus. The most common hybrid is the mule, a cross between a "jack" (male donkey) and a mare. A related hybrid, a hinny, is a cross between a stallion and a "jenny" (female donkey).[149] Other hybrids include the zorse, a cross between a zebra and a horse.[150] With rare exceptions, most hybrids are sterile and cannot reproduce.[151]

Domestication and history

Domestication of the horse most likely took place in central Asia prior to 3500 BCE. Two major sources of information are used to determine where and when the horse was first domesticated and how the domesticated horse spread around the world. The first source is based on palaeological and archaeological discoveries; the second source is a comparison of DNA obtained from modern horses to that from bones and teeth of ancient horse remains.

The horse was domesticated by the Indo-Europeans in Eurasia.[152][153][154] The earliest archaeological evidence for the domestication of the horse comes from sites in Ukraine and Kazakhstan, dating to approximately 4000–3500 BCE.[155][156][157] By 3000 BCE, the horse was completely domesticated and by 2000 BCE there was a sharp increase in the number of horse bones found in human settlements in northwestern Europe, indicating the spread of domesticated horses throughout the continent.[158] The most recent, but most irrefutable evidence of domestication comes from sites where horse remains were interred with chariots in graves of the Indo-European Sintashta and Petrovka cultures c. 2100 BCE.[159]

A 2021 genetic study suggested that most modern domestic horses descend from the lower Volga-Don region. Ancient horse genomes indicate that these populations influenced almost all local populations as they expanded rapidly throughout Eurasia, beginning about 4,200 years ago. It also shows that certain adaptations were strongly selected due to riding, and that equestrian material culture, including Sintashta spoke-wheeled chariots spread with the horse itself.[160][161]

Domestication is also studied by using the genetic material of present-day horses and comparing it with the genetic material present in the bones and teeth of horse remains found in archaeological and palaeological excavations. The variation in the genetic material shows that very few wild stallions contributed to the domestic horse,[162][163] while many mares were part of early domesticated herds.[147][164][165] This is reflected in the difference in genetic variation between the DNA that is passed on along the paternal, or sire line (Y-chromosome) versus that passed on along the maternal, or dam line (mitochondrial DNA). There are very low levels of Y-chromosome variability,[162][163] but a great deal of genetic variation in mitochondrial DNA.[147][164][165] There is also regional variation in mitochondrial DNA due to the inclusion of wild mares in domestic herds.[147][164][165][166] Another characteristic of domestication is an increase in coat color variation.[167] In horses, this increased dramatically between 5000 and 3000 BCE.[168]

Before the availability of DNA techniques to resolve the questions related to the domestication of the horse, various hypotheses were proposed. One classification was based on body types and conformation, suggesting the presence of four basic prototypes that had adapted to their environment prior to domestication.[110] Another hypothesis held that the four prototypes originated from a single wild species and that all different body types were entirely a result of selective breeding after domestication.[169] However, the lack of a detectable substructure in the horse has resulted in a rejection of both hypotheses.

Feral populations

Feral horses are born and live in the wild, but are descended from domesticated animals.[134] Many populations of feral horses exist throughout the world.[170][171] Studies of feral herds have provided useful insights into the behavior of prehistoric horses,[172] as well as greater understanding of the instincts and behaviors that drive horses that live in domesticated conditions.[173]

There are also semi-feral horses in many parts of the world, such as Dartmoor and the New Forest in the UK, where the animals are all privately owned but live for significant amounts of time in "wild" conditions on undeveloped, often public, lands. Owners of such animals often pay a fee for grazing rights.[174][175]

Breeds

The concept of purebred bloodstock and a controlled, written breed registry has come to be particularly significant and important in modern times. Sometimes purebred horses are incorrectly or inaccurately called "thoroughbreds". Thoroughbred is a specific breed of horse, while a "purebred" is a horse (or any other animal) with a defined pedigree recognized by a breed registry.[176] Horse breeds are groups of horses with distinctive characteristics that are transmitted consistently to their offspring, such as conformation, color, performance ability, or disposition. These inherited traits result from a combination of natural crosses and artificial selection methods. Horses have been selectively bred since their domestication. An early example of people who practiced selective horse breeding were the Bedouin, who had a reputation for careful practices, keeping extensive pedigrees of their Arabian horses and placing great value upon pure bloodlines.[177] These pedigrees were originally transmitted via an oral tradition.[178] In the 14th century, Carthusian monks of southern Spain kept meticulous pedigrees of bloodstock lineages still found today in the Andalusian horse.[179]

Breeds developed due to a need for "form to function", the necessity to develop certain characteristics in order to perform a particular type of work.[180] Thus, a powerful but refined breed such as the Andalusian developed as riding horses with an aptitude for dressage.[180] Heavy draft horses were developed out of a need to perform demanding farm work and pull heavy wagons.[181] Other horse breeds had been developed specifically for light agricultural work, carriage and road work, various sport disciplines, or simply as pets.[182] Some breeds developed through centuries of crossing other breeds, while others descended from a single foundation sire, or other limited or restricted foundation bloodstock. One of the earliest formal registries was General Stud Book for Thoroughbreds, which began in 1791 and traced back to the foundation bloodstock for the breed.[183] There are more than 300 horse breeds in the world today.[184]

Interaction with humans

Worldwide, horses play a role within human cultures and have done so for millennia. Horses are used for leisure activities, sports, and working purposes. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that in 2008, there were almost 59,000,000 horses in the world, with around 33,500,000 in the Americas, 13,800,000 in Asia and 6,300,000 in Europe and smaller portions in Africa and Oceania. There are estimated to be 9,500,000 horses in the United States alone.[185] The American Horse Council estimates that horse-related activities have a direct impact on the economy of the United States of over $39 billion, and when indirect spending is considered, the impact is over $102 billion.[186] In a 2004 "poll" conducted by Animal Planet, more than 50,000 viewers from 73 countries voted for the horse as the world's 4th favorite animal.[187]

Communication between human and horse is paramount in any equestrian activity;[188] to aid this process horses are usually ridden with a saddle on their backs to assist the rider with balance and positioning, and a bridle or related headgear to assist the rider in maintaining control.[189] Sometimes horses are ridden without a saddle,[190] and occasionally, horses are trained to perform without a bridle or other headgear.[191] Many horses are also driven, which requires a harness, bridle, and some type of vehicle.[192]

Sport

Historically, equestrians honed their skills through games and races. Equestrian sports provided entertainment for crowds and honed the excellent horsemanship that was needed in battle. Many sports, such as dressage, eventing, and show jumping, have origins in military training, which were focused on control and balance of both horse and rider. Other sports, such as rodeo, developed from practical skills such as those needed on working ranches and stations. Sport hunting from horseback evolved from earlier practical hunting techniques.[188] Horse racing of all types evolved from impromptu competitions between riders or drivers. All forms of competition, requiring demanding and specialized skills from both horse and rider, resulted in the systematic development of specialized breeds and equipment for each sport. The popularity of equestrian sports through the centuries has resulted in the preservation of skills that would otherwise have disappeared after horses stopped being used in combat.[188]

Horses are trained to be ridden or driven in a variety of sporting competitions. Examples include show jumping, dressage, three-day eventing, competitive driving, endurance riding, gymkhana, rodeos, and fox hunting.[193] Horse shows, which have their origins in medieval European fairs, are held around the world. They host a huge range of classes, covering all of the mounted and harness disciplines, as well as "In-hand" classes where the horses are led, rather than ridden, to be evaluated on their conformation. The method of judging varies with the discipline, but winning usually depends on style and ability of both horse and rider.[194] Sports such as polo do not judge the horse itself, but rather use the horse as a partner for human competitors as a necessary part of the game. Although the horse requires specialized training to participate, the details of its performance are not judged, only the result of the rider's actions—be it getting a ball through a goal or some other task.[195] Examples of these sports of partnership between human and horse include jousting, in which the main goal is for one rider to unseat the other,[196] and buzkashi, a team game played throughout Central Asia, the aim being to capture a goat carcass while on horseback.[195]

Скачки - это конная спорт и крупная международная индустрия, наблюдаемая почти во всех странах мира. Есть три типа: «плоские» гонки; крутой , т.е. мчатся по прыжкам; и гоночные гонки , где лошади ходят или темп, притягивая водителя в маленькую легкую тележку, известную как угрюмого . [ 197 ] Основная часть экономического значения скачек заключается в азартных играх , связанных с ним. [ 198 ]

Работа

Есть определенные рабочие места, которые лошади делают очень хорошо, и никакая технология еще не разработала, чтобы полностью заменить их. Например, конные полицейские лошади по -прежнему эффективны для определенных типов патрульных обязанностей и контроля толпы. [ 199 ] крупного рогатого скота Ранчо по -прежнему требуют, чтобы гонщики вернулись на лошадях, чтобы собрать скот, которые разбросаны по отдаленной, бурной местности. [ 200 ] Поисковые и спасательные организации в некоторых странах зависят от конных команд, чтобы найти людей, особенно туристов и детей, а также оказывать помощь в оказании помощи стихийным бедствиям. [ 201 ] Лошади также могут использоваться в районах, где необходимо избежать нарушения транспортных средств для деликатной почвы, таких как природные запасы. Они также могут быть единственной формой транспорта, разрешенной в районах дикой природы . Лошади тише, чем моторизованные транспортные средства. Сотрудники правоохранительных органов , такие как Park Rangers или Game Wardens, могут использовать лошадей для патрулей, а лошади или мулы также могут использоваться для очистки троп или других работ в районах грубой местности, где транспортные средства менее эффективны. [ 202 ]

Хотя оборудование заменило лошадей во многих частях мира, около 100 миллионов лошадей, ослов и мулов все еще используются для сельского хозяйства и транспортировки в менее развитых районах. Это число включает в себя около 27 миллионов рабочих животных только в Африке. [ 203 ] Некоторые практики управления земельными ресурсами, такие как культивирование и ведение журнала, могут эффективно выполняться с лошадьми. В сельском хозяйстве используется меньше ископаемого топлива, и увеличение сохранения окружающей среды со временем происходит с использованием черновых животных , таких как лошадей. [ 204 ] [ 205 ] Рубляция с лошадьми может привести к уменьшению повреждения структуры почвы и меньшему повреждению деревьев из -за более селективной лесозаготовки. [ 206 ]

Война

Лошади использовались в войне для большинства зарегистрированной истории. Первое археологическое свидетельство лошадей, используемых в войне, от 4000 до 3000 г. до н.э. [ 207 ] и использование лошадей в войне было широко распространено к концу бронзового века . [ 208 ] [ 209 ] Хотя механизация в значительной степени заменила лошадь как оружие войны, лошади все еще видны сегодня при ограниченном военном использовании, в основном для церемониальных целей или для разведывательных и транспортных мероприятий в районах грубой местности, где моторизованные транспортные средства неэффективны. Лошади использовались в 21 -м веке ополченцами Джанджавида в войне в Дарфуре . [ 210 ]

Развлечения и культура

Современные лошади часто используются, чтобы воссоздать многие из их исторических целей работы. У лошадей используются подлинное оборудование, которое является подлинным или тщательно воссозданной репликой, в различных исторических реконструкциях живых действий конкретных периодов истории, особенно воссозданий известных сражений. [ 211 ] Лошади также используются для сохранения культурных традиций и для церемониальных целей. Такие страны, как Соединенное Королевство, по-прежнему используют конные вагоны для передачи королевской семьи и других вип-персон на определенные культурно значимые события. [ 212 ] Публичные выставки являются еще одним примером, таким как Budweiser Clydesdales , которые можно увидеть в парадах и других общественных условиях, команда черновых лошадей , которые тянут пивной универсал, похожий на то, что использовалось до изобретения современного моторизованного грузовика. [ 213 ]

Лошади часто используются на телевидении, фильмах и литературе. Иногда они представлены в качестве основного героя в фильмах о конкретных животных, но также используются в качестве визуальных элементов, которые обеспечивают точность исторических историй. [ 214 ] Как живые лошади, так и знаковые изображения лошадей используются в рекламе для продвижения различных продуктов. [ 215 ] Лошадь часто появляется в слоях оружия в геральдике , в различных позах и оборудовании. [ 216 ] Мифологии . многих культур, в том числе греко-римский , индуистский , исламский и германский , включают ссылки как на нормальных лошадей, так и с крыльями или дополнительными конечностями, и множество мифов также призывают лошадь нарисовать колесницы луны и солнца [ 217 ] Лошадь также появляется в 12-летнем цикле животных на китайском зодиаке, связанном с китайским календарем . [ 218 ]

логотипов Pinto , Ford Ford Ford для Mustang служат многих современных включая , автомобильных Bronco названий Лошади вдохновением , и Haflining , Pegaso , Porsche , Rolls , Ferrari , Carlsson , Kamaz , Licorne La Puch - Steyr - Corre Royce Camargue [ 219 ] [ 220 ] [ 221 ] Indian TVS Motor Company также использует лошадь на своих мотоциклах и скутерах.

Терапевтическое использование

Люди всех возрастов с физическими и умственными нарушениями получают полезные результаты от связи с лошадьми. Терапевтическая езда используется для умственного и физического стимуляции инвалидов и помогает им улучшить свою жизнь за счет улучшения баланса и координации, повышения уверенности в себе и большего чувства свободы и независимости. [ 222 ] Преимущества конной деятельности для людей с ограниченными возможностями также были признаны с добавлением конных событий на Паралимпийские игры и признание пара-экранистов Международной федерацией для конных видов спорта (FEI). [ 223 ] Гиппотерапия и терапевтическая верховая езда - это названия для различных стратегий лечения физической, профессиональной и речевой терапии, которые используют движение лошадей. В гиппотерапии терапевт использует движение лошади для улучшения когнитивной, координации, баланса и тонких моторных навыков своего пациента, тогда как терапевтическая верховая езда использует определенные навыки верховой езды. [ 224 ]

Лошади также дают психологические преимущества людям, независимо от того, на самом деле они ездят или нет. лошадей» или «Фацилитированная на «Терапия с помощью лошади Основные изменения жизни. [ 225 ] Существуют также экспериментальные программы, использующие лошадей в условиях тюрьмы . Воздействие на лошадей, по -видимому, улучшает поведение заключенных и помогает уменьшить рецидивизм , когда они уходят. [ 226 ]

Продукция

Лошади - это сырье для многих продуктов, изготовленных людьми на протяжении всей истории, в том числе побочных продуктов от убийства лошадей, а также материалов, собранных у живых лошадей.

Продукты, собранные у живых лошадей, включают кобылу молоко, используемые людьми с большими стадами лошадей, такими как монголы , которые позволяют ему бродить, чтобы производить кумис . [ 227 ] Кровь лошадей когда -то использовалась в качестве пищи монголами и другими кочевыми племенами, которые нашли это удобным источником питания во время путешествия. Пить кровь своих лошадей позволило монголам ездить в течение длительных периодов времени, не останавливаясь, чтобы поесть. [ 227 ] Препарат Прамарин представляет собой смесь эстрогенов извлеченных из мочи беременных кобыл ( в E , до гнарскую ) , и ранее был широко используемым лекарственным средством для заместительной гормональной терапии . [ 228 ] Хвостовые волосы лошадей могут быть использованы для изготовления бантов для струнных инструментов, таких как скрипка , альт , виолончель и двойной бас . [ 229 ]

Конное мясо использовалось в качестве пищи для людей и плотоядных животных на протяжении веков. Приблизительно 5 миллионов лошадей каждый год убивают мясо во всем мире. [ 230 ] Его едят во многих частях света, хотя потребление табу в некоторых культурах, [ 231 ] и предмет политических споров в других. [ 232 ] Кожа лошади -сиде использовалась для ботинок, перчаток, курток , [ 233 ] бейсбол , [ 234 ] и бейсбольные перчатки. Комы лошадей также могут быть использованы для производства клея животных . [ 235 ] Кости лошадей можно использовать для изготовления орудий. [ 236 ] В частности, в итальянской кухне кошачья голень заострена в зонд, называемыйвинто , который используется для проверки готовности ветчины (свиньи), когда она лечит. [ 237 ] В Азии саба представляет собой сосуд -консер -домик, используемый при производстве Кумиса . [ 238 ]

Уход

Лошади пасутся для хорошего качества животными, а их основным источником питательных веществ является корм от сена или пастбища . [ 239 ] Они могут потреблять примерно от 2% до 2,5% от веса тела в сухой подаче каждый день. Следовательно, 450-килограмм (990 фунтов) взрослая лошадь может съесть до 11 килограммов (24 фунта) пищи. [ 240 ] Иногда концентрированный корм, такой как зерно , питается в дополнение к пастбищам или сенам, особенно когда животное очень активное. [ 241 ] Когда зерно кормятся, диетологи лошадей рекомендуют, чтобы 50% или более диеты животного по весу все еще были кормом. [ 242 ]

Лошади требуются обильный запас чистой воды, минимум от 38 до 45 литров (от 10 до 12 американских гал) в день. [ 243 ] Хотя лошади адаптированы к жизни на улице, они требуют укрытия от ветра и осадков , которые могут варьироваться от простого сарай или укрытия до тщательно продуманной конюшни . [ 244 ]

Лошади нуждаются в обычной за копытом уходе от кузнеца , а также прививками для защиты от различных заболеваний, а также зубные обследования от ветеринара или специализированного стоматолога лошадей. [ 245 ] Если в сарае держатся лошадей, они требуют регулярных ежедневных упражнений для их физического здоровья и психического благополучия. [ 246 ] При выводе на улице они требуют, чтобы хорошо, крепкие, крепкие заборы , которые были бы безопасно сдерживаться. [ 247 ] Регулярное уход также полезно, чтобы помочь лошади сохранить хорошее здоровье шерсть и лежащую в основе кожи. [ 248 ]

Изменение климата

По состоянию на 2019 год в мире насчитывается около 17 миллионов лошадей. Здоровая температура тела для взрослых лошадей находится в диапазоне от 37,5 до 38,5 ° C (99,5 и 101,3 ° F), что они могут поддерживать, в то время как температура окружающей среды составляет от 5 до 25 ° C (41 и 77 ° F). Тем не менее, напряженные физические упражнения повышают температуру тела ядра на 1 ° C (1,8 ° F)/минуту, так как 80% энергии, используемой мышцами лошадей, выделяется в качестве тепла. Наряду с бычьями и приматами , лошади являются единственной группой животных, которая использует потоотделение в качестве основного метода терморегуляции: на самом деле это может составлять до 70% их потери тепла, а лошади потеют в три раза больше, чем люди, проходя сравнительно напряженные физическая активность. В отличие от людей, этот пот создается не эккринными железами , а апокринными железами . [ 250 ] В горячих условиях лошади в течение трех часов упражнения по умеренному интервалу могут потерять от 30 до 35 л воды и 100 г натрия, 198 г холорида и 45 г калия. [ 250 ] В другом отличие от людей их пот гипертонический и содержит белок, называемый латерин , [ 251 ] что позволяет ему легче распространяться по всему телу и пенить , а не капать. Эти адаптации частично предназначены для компенсации их нижнего соотношения поверхности к массе, что затрудняет пассивно излучать тепло. Тем не менее, длительное воздействие очень горячих и/или влажных состояний приведет к таким последствиям, как ангидроз , тепловой удар или повреждение головного мозга, потенциально кульминационные в смерти, если они не рассматриваются с такими мерами, как применение холодной воды. Кроме того, около 10% инцидентов, связанных с переносом лошадей, были связаны с тепловым стрессом. Эти проблемы, как ожидается, ухудшится в будущем. [ 249 ]

Африканская лошадь (AHS) - это вирусное заболевание со смертностью, близкой к 90% у лошадей, и 50% в мулах . Midge, Culicoides Imicola , является основным вектором AHS, и его распространение, как ожидается, выиграет от изменения климата. [ 252 ] Распространение вируса Хендры от ее хозяев летающих лис на лошадей также может увеличиться, так как будущее потепление расширит географический диапазон хозяев. Было подсчитано, что в рамках сценариев «умеренного» и высокого климата RCP4,5 изменения и RCP8,5 число угрожаемых лошадей увеличится на 110 000 и 165 000, соответственно, или на 175 и 260%. [ 253 ]Смотрите также

- Глоссарий конных терминов

- Списки тем, связанных с лошадьми

- Список исторических лошадей

- Дюльменер

- Лошадь в скандинавской мифологии

- Французская лошадь

- Солатре лошадь

- Лошадь реформа

Ссылки

- ^ Линнеус, Чарльз (1758). Система природы по трем королевствам природы, в соответствии с классами, порядками, родами, видами, с характерами, различиями, синонимичными местами . Тол. 1 (10 -е изд.). Холмия (Лоуренс Сальвии). п. 73. Архивировано из оригинала 2018-10-12 . Получено 2008-09-08 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Grubb, P. (2005). «Порядок Perissodactyla» . В Уилсоне, де ; Ридер, DM (ред.). Виды млекопитающих мира: таксономическая и географическая ссылка (3 -е изд.). Johns Hopkins University Press. С. 630–631. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0 Полем OCLC 62265494 .

- ^ Международная комиссия по зоологической номенклатуре (2003). «Использование 17 конкретных названий, основанных на диких видах, которые предварительно датируются или современны с именами, основанными на домашних животных (Lepidoptera, Osteichthyes, Mammalia): консервативное. Мнение 2027 (случай 3010)» . Бык Zool. Номенсл . 60 (1): 81–84. Архивировано из оригинала на 2007-08-21.

- ^ "Знаете ли вы, как спят лошади?" Полем Архивировано с оригинала 22 января 2018 года . Получено 12 сентября 2018 года .

- ^ Гуди, Джон (2000). Анатомия лошадей (2 -е изд.). Ja Allen. ISBN 0-85131-769-3 .

- ^ Паворд, Тони; Pavord, Marcy (2007). Полное ветеринарное руководство для лошадей . Дэвид и Чарльз. ISBN 978-0-7153-1883-6 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Вход , с. 46–50

- ^ Райт Б. (29 марта 1999 г.). «Возраст лошади» . Министерство сельского хозяйства, продовольственных и сельских дел . Правительство Онтарио. Архивировано из оригинала 20 января 2010 года . Получено 2009-10-21 .

- ^ Райдер, Эрин. «Самый старый живой пони в мире умирает в 56» . Лошадь . Архивировано из оригинала 2014-01-24 . Получено 2007-05-31 .

- ^ Британское лошадиное общество (1966). Руководство по верховой езде Британского конного общества и Пони Клуб (6 -е издание, переиздано 1970 года изд.). Кенилворт, Великобритания: Британское лошадиное общество. п. 255 ISBN 0-9548863-1-3 .

- ^ «Правила австралийской книги по факультету» (PDF) . Австралийский жокей -клуб. 2007. с. 7. Архивировано из оригинала 2013-04-24 . Получено 2008-07-09 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Требования к возрасту лошадей для аттракционов AERC» . Американская конференция по верховой езде. Архивировано из оригинала 2011-08-11 . Получено 2011-07-25 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Пение , с

- ^ Гиффин , с. 431

- ^ Сенмингер , с

- ^ Сенмингер , с

- ^ Беккер, Марти; Павия, Одри; Спадафори, Джина; Беккер, Тереза (2007). лошади спят, стоя? Почему HCI. п. 23 ISBN 978-0-7573-0608-2 .

- ^ Сенмингер , с

- ^ Сенмингер , с

- ^ Сенмингер , с

- ^ «Глоссарий сроков скачек» . Equibase.com . Equibase Company, LLC. Архивировано с оригинала на 2008-05-12 . Получено 2008-04-03 .

- ^ «Правила австралийской книги по факультету» . Австралийский Jockey Club Ltd и Victoria Racing Club Ltd. Июль 2008 г. с. 9. Архивировано из оригинала 2013-04-24 . Получено 2010-02-05 .

- ^ Уитакер , с. 77

- ^ Сенмингер , с

- ^ Bongianni , записи 1, 68, 69

- ^ Bongianni , записи 12, 30, 31, 32, 75

- ^ Bongianni , записи 86, 96, 97

- ^ Уитакер , с. 60

- ^ Дуглас, Джефф (2007-03-19). «Самая маленькая лошадь в мире имеет высокий заказ» . The Washington Post . Ассошиэйтед Пресс . Архивировано из оригинала 2017-03-15 . Получено 2017-03-14 .

- ^ «Познакомьтесь с самой маленькой лошадью в мире, которая короче, чем борзая» . Guinness World Records . 2019-09-05. Архивировано из оригинала 2021-08-04 . Получено 2021-07-06 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Ensminger, M. Eugene (1991). Лошади и подтяжка (пересмотренный изд.). Бостон, Массачусетс: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0395544130 Полем OCLC 21561287 . OL 1877441M .

- ^ Хоулетт, Лорна; Филипп Мэтьюз (1979). Пони в Австралии . Milson's Point, NSW: Philip Mathews Publishers. п. 14. ISBN 0-908001-13-4 .

- ^ «2012 г. Книга правил США в Соединенных Штатах» . Конная федерация Соединенных Штатов. п. Правило WS 101. Архивировано из оригинала 2012-04-15.

- ^ «Приложение XVII: выдержки из правил для пони -гонщиков и детей, 9 -е издание» (PDF) . Fédération Equestre Internationale. 2009. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 2012-09-11 . Получено 2010-03-07 .

- ^ Например, The Missouri Fox Totter или арабская лошадь . См. McBane , с. 192, 218

- ^ Например, валлийский пони . См. McBane , с. 52–63

- ^ McBane , p. 200

- ^ «Числа хромосом у разных видов» . Vivo.colostate.edu. 1998-01-30. Архивировано из оригинала 2013-05-11 . Получено 2013-04-17 .

- ^ «Геном секвенирования лошади расширяет понимание лошадей, заболеваний человека» . Колледж ветеринарной медицины Корнелльского университета. 2012-08-21. Архивировано из оригинала 2017-10-10 . Получено 2013-04-01 .

- ^ Уэйд, С. М; Джулотто, E; Sigurdsson, S; Золи, м; Gnerre, S; Imsland, F; Lear, T. L; Адельсон Д. Л; Бейли, E; Беллоне Р.Р; Блокировщик, h; Distl, o; Эдгар Р. С; Гарбер, м; Leeb, t; Mauceli, E; Macleod, J. N; Пенедо, MC T; Рейсон, Дж. М; Шарп, Т; Фогель, J; Андерссон, L; Анцзак, Д. Ф; Biagi, T; Биннс, М. М; Чоудхари, Б. П; Coleman, S. J; Della Valle, G; Fryc, s; И др. (2009-11-05). «Секстичный геном домашней лошади» . Наука . 326 (5954): 865–867. Bibcode : 2009Sci ... 326..865W . Doi : 10.1126/science.1178158 . ISSN 0036-8075 . PMC 3785132 . PMID 19892987 . Архивировано из оригинала 2018-11-18 . Получено 2013-04-01 .

- ^ "Ensembl Genome Browser 71: Equus caballus - описание" . Uswest.ensembl.org. Архивировано из оригинала 2017-10-10 . Получено 2013-04-17 .

- ^ Vogel, Colin BVM (1995). Полное руководство по уходу за лошадьми . Нью -Йорк: Dorling Kindersley Publishing, Inc. с. 14 ISBN 0-7894-0170-3 Полем OCLC 32168476 .

- ^ Миллс, Брюс; Барбара Карн (1988). Основное руководство по уходу за лошадьми и управлением . Нью -Йорк: Книжный дом Хауэлла. С. 72–73. ISBN 0-87605-871-3 Полем OCLC 17507227 .

- ^ Corum, Stephanie J. (1 мая 2003 г.). «Лошадь другого цвета» . Лошадь . Архивировано с оригинала 2015-09-18 . Получено 2010-02-11 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в "Цветовые тесты коня" . Ветеринарная генетическая лаборатория . Калифорнийский университет. Архивировано из оригинала 2008-02-19 . Получено 2008-05-01 .

- ^ Marklund, L.; М. Йоханссон Моллер; К. Сандберг; Л. Андерссон (1996). «Миссенс-мутация в гене для меланоцит-стимулирующего гормонального рецептора (MC1R) связана с цветом каштального пальто у лошадей». Геном млекопитающих . 7 (12): 895–899. doi : 10.1007/s003359900264 . PMID 8995760 . S2CID 29095360 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Введение в генетику цвета пальто» . Ветеринарная генетическая лаборатория . Калифорнийский университет. Архивировано из оригинала 2017-10-10 . Получено 2008-05-01 .

- ^ HAASE B; Brooks SA; Schlumbaum a; и др. (2007). «Аллельная гетерогенность в локусе для лошадей в доминантных белых (w) лошадях» . PLOS Genetics . 3 (11): E195. doi : 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030195 . PMC 2065884 . PMID 17997609 .

- ^ Мау, C.; Poncet, PA; Бухер, Б.; Stranzinger, G.; Ридер С. (2004). «Генетическое картирование доминирующего белого (W), гомозиготное смертельное состояние в лошади ( Equus caballus )». Журнал разведения животных и генетики . 121 (6): 374–383. doi : 10.1111/j.1439-0388.2004.00481.x .

- ^ Сенмингер , с

- ^ "Как долго беременна лошадь?" Полем Разговоры о газоне . Получено 2023-03-25 .

- ^ Джонсон, Том. «Редкие жеребята -близнецы, родившиеся в ветеринарной больнице: вступления в близнецы. Вопрос номер один на десять тысяч» . Служба связи, Университет штата Оклахома . Государственный университет штата Оклахома. Архивировано из оригинала 2012-10-12 . Получено 2008-09-23 .

- ^ Миллер, Роберт М.; Рик Лэмб (2005). Революция в верховой езде и что это значит для человечества . Guilford, CT: Lyons Press. С. 102–103. ISBN 1-59228-387-х Полем OCLC 57005594 .

- ^ Сенмингер , с

- ^ Клайн, Кевин Х. (2010-10-07). «Уменьшение напряжения от груди у жеребят» . Расширение Университета штата Монтана. Архивировано из оригинала 2012-03-22 . Получено 2012-04-03 .

- ^ McIlwraith, CW "Ортопедическое заболевание развития: проблемы конечностей у молодых лошадей" . Ортопедический исследовательский центр . Университет штата Колорадо. Архивировано из оригинала 2013-01-14 . Получено 2008-04-20 .

- ^ Томас, Хизер Смит (2003). Руководство Storey по тренировочным лошадям: наземная работа, вождение, езда . Северный Адамс, Массачусетс: Storey Publishing. п. 163 . ISBN 1-58017-467-1 .

- ^ «2-летние гонки (США и Канада)» . Онлайн -книга фактов . Жокейный клуб. Архивировано из оригинала 2013-02-16 . Получено 2008-04-28 .

- ^ Брайант, Дженнифер Олсон; Джордж Уильямс (2006). Руководство USDF по выездке . Storey Publishing. С. 271–272. ISBN 978-1-58017-529-6 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 2023-03-20 . Получено 2020-09-28 .

- ^ Эванс, Дж. (1990). Лошадь (второе изд.). Нью -Йорк: Фримен. п. 90 ISBN 0-7167-1811-1 Полем OCLC 20132967 .

- ^ Ensmings , с. 21–25

- ^ Сенмингер , с

- ^ Гиффин , с. 304

- ^ Гиффин , с. 457

- ^ Фусс, Тереза А. «Да, голени соединены с костью голеностопного сустава» . Питомца . Университет Иллинойса. Архивировано из оригинала 9 сентября 2006 года . Получено 2008-04-05 .

- ^ Гиффин , с. 310–312

- ^ Крелинг, Кай (2005). "Зубы лошади" . Зубы лошадей и их проблемы: профилактика, признание и лечение . Гилфорд, CT: Globe Pequot. С. 12–13. ISBN 1-59228-696-8 Полем OCLC 59163221 . [ Постоянная мертвая ссылка ]

- ^ Гиффин , с. 175

- ^ Валентин, Бет А.; Ван Саун, Роберт Дж.; Томпсон, Кент Н.; Хинц, Гарольд Ф. (2001). «Роль диетического углевода и жира у лошадей с миопатией для хранения полисахаридов лошадей» . Журнал Американской ветеринарной медицинской ассоциации . 219 (11): 1537–1544. doi : 10.2460/javma.2001.219.1537 . PMID 11759989 .

- ^ Эллис, Гарольд (2010). «Желтый мочевой пузырь и желчные воздуховоды» . Хирургия (Оксфорд) . 28 (5): 218–221. doi : 10.1016/j.mpsur.2010.02.007 . Архивировано из оригинала 2021-05-12 . Получено 2021-05-11 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Вход , стр. 309–310

- ^ «Опубликовано положение глаз и изучение гибкости животных» . Лошадь . 7 марта 2010 г. Архивировано с оригинала 2015-07-23 . Получено 2010-03-11 . Пресс-релиз, ссылаясь на февраль 2010 года, журнал анатомии, доктор Натан Джеффри, соавтор Университета Ливерпуля.

- ^ Sellnow, Les (2004). Счастливые тропы: ваш полный путеводитель по веселой и безопасной езде по тропам . Eclipse Press. п. 46 ISBN 1-58150-114-5 Полем OCLC 56493380 .

- ^ Макдоннелл, Сью (1 июня 2007 г.). «В живом цвете» . Лошадь . Архивировано из оригинала 2007-09-27 . Получено 2007-07-27 .

- ^ Бриггс, Карен (2013-12-11). «Суммановое обоняние» . Лошадь. Архивировано с оригинала 2018-02-01 . Получено 2013-12-15 .

- ^ Майерс, Джейн (2005). Собственная лошадь: полное руководство по безопасности лошадей . Коллингвуд, Великобритания: CSIRO Publishing. п. 7. ISBN 0-643-09245-5 Полем OCLC 65466652 . Архивировано из оригинала 2023-03-20 . Получено 2020-09-28 .

- ^ Лесте-Лассерр, Криста (18 января 2013 г.). «Влияние музыкального жанра на поведение лошадей оценивается» . Лошадь . Публикации кровавой лошади. Архивировано с оригинала 10 октября 2017 года . Получено 23 января 2013 года .

- ^ Исследовательский персонал Кентукки (15 февраля 2010 г.). «Радио, вызывающие язвы желудка» . Лошадиные . Кентукки исследования лошадей. Архивировано с оригинала 10 октября 2017 года . Получено 23 января 2013 года .

- ^ Томас, Хизер Смит. "Истинный смысл лошади" . Чистокровные времена . Компания чистокровных времен. Архивировано из оригинала 2012-11-02 . Получено 2008-07-08 .

- ^ Cirelli, Al Jr.; Бренда Облако. «Руководство по обращению и катания на лошадях, часть 1: чувства лошадей» (PDF) . Совместное расширение . Университет Невады. п. 4. Архивированный (PDF) из оригинала 2015-09-08 . Получено 2008-07-09 .

- ^ Хайрстон, Рэйчел; Мадлен Ларсен (2004). Основы лошади . Нью -Йорк: Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. с. 77 ISBN 0-8069-8817-7 Полем OCLC 53186526 .

- ^ Миллер , с. 28

- ^ Густавсон, Кэрри. «Лошади -пастбище не место для ядовитых растений» . Колонна домашних животных 24 июля 2000 г. Университет Иллинойса. Архивировано из оригинала 9 августа 2007 года . Получено 2008-07-09 .

- ^ Харрис , с. 32

- ^ Харрис , с. 47–49

- ^ «Самая быстрая скорость для скаковой лошади» . Guinness World Records . 14 мая 2008 года. Архивировано из оригинала 28 августа 2017 года . Получено 8 января 2013 года .

- ^ Харрис , с. 50

- ^ Либерман, Бобби (2007). «Легкие походки лошадей». Equus (359): 47–51.

- ^ Equus персонал (2007). «Породит эту походку». Equus (359): 52–54.

- ^ Харрис , с. 50–55

- ^ «Лошади борьба против инстинкта полета» . расширение. 2009-09-24. Архивировано из оригинала 2013-05-15 . Получено 2013-04-17 .

- ^ McBane, Susan (1992). Естественный подход к управлению лошадьми . Лондон: Метуэн. С. 226–228. ISBN 0-413-62370-x Полем OCLC 26359746 .

- ^ Ensmings , с. 305–309

- ^ Принц, Элеонора Ф.; Гайделл М. Коллиер (1974). Основное всадка: английский и западный . Нью -Йорк: Doubleday. С. 214–223 . ISBN 0-385-06587-6 Полем OCLC 873660 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Кларксон, Нил (2007-04-16). «Понимание конного интеллекта» . Horsetalk 2007 . Хрохотал. Архивировано из оригинала 2013-01-24 . Получено 2008-09-16 .

- ^ Дорранс, Билл (1999). Истинное верховой езды через чувство . Гилфорд, CT: Lion Press. п. 1. ISBN 1-58574-321-6 .

- ^ Лесте-Лассерр, Криста. «Лошади демонстрируют способность учитывать в новом исследовании» . Лошадь . Архивировано с оригинала 2016-01-01 . Получено 2009-12-06 .

- ^ Coarse, Джим (2008-06-17). «То, что Большой Браун не мог сказать вам, и мистер Эд сохранили себя (часть 1)» . Кровавая лошадь . Архивировано из оригинала 2012-05-21 . Получено 2008-09-16 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Белкнап , с. 255

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Белкнап , с. 112

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Вход , с. 71–73

- ^ Сенмингер , с

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Цена , с. 18

- ^ Difilippis, Chris (2006). Книга по уходу за лошадью . Avon, MA: Adams Media. п. 4. ISBN 978-1-59337-530-0 Полем OCLC 223814651 .

- ^ Уитакер , с. 43

- ^ Whitaker , pp. 194–197

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Цена , с. 15

- ^ Bongianni , запись 87

- ^ Ensmings , с. 124–125

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Беннетт, Деб (1998). Завоеватели: корни всаждения нового мира (первое изд.). Solvang, CA: Amigo Publications, Inc. p. 7. ISBN 0-9658533-0-6 Полем OCLC 39709067 .

- ^ Эдвардс , с. 122–123

- ^ Примерами являются австралийский пони и Коннемара , см. Эдвардс , с. 178–179, 208–209

- ^ Цена, Стивен Д.; Ширс, Джесси (2007). Словарь всадника из прессы Лиона (пересмотренный изд.). Guilford, CT: Lyons Press. п. 231. ISBN 978-1-59921-036-0 .

- ^ Белкнап , с. 523

- ^ Паско, Элейн. «Как лошади спят» . Equisearch.com . Архивировано из оригинала 2007-09-27 . Получено 2007-03-23 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Паско, Элейн (2002-03-12). «Как спят лошади, стр. 2 - силовая дремота» . Equisearch.com . Архивировано из оригинала 2007-09-27 . Получено 2007-03-23 .

- ^ Пение , с.

- ^ Голландия, Дженнифер С. (июль 2011 г.). "40 подмигиваний?". National Geographic . 220 (1).

- ^ Equus Magazine сотрудники. «Видео по расстройству сна» . Equisearch.com . Архивировано из оригинала на 2007-05-10 . Получено 2007-03-23 .

- ^ Смит, BP (1996). Внутренняя медицина крупного животного (второе изд.). Сент -Луис, Миссури: Мосби. С. 1086–1087. ISBN 0-8151-7724-0 Полем OCLC 33439780 .

- ^ Будианский, Стивен (1997). Природа лошадей . Нью -Йорк: Свободная пресса. п. 31 ISBN 0-684-82768-9 Полем OCLC 35723713 .

- ^ Майерс, Фил. «Порядок Perissodactyla» . Интернет -разнообразие животных . Мичиганский университет. Архивировано из оригинала 2013-01-22 . Получено 2008-07-09 .

- ^ "Hyracotherium" . Ископаемые лошади в киберпространстве . Флоридский музей естественной истории . Архивировано из оригинала 2013-01-31 . Получено 2008-07-09 .

- ^ «Месохипп» . Ископаемые лошади в киберпространстве . Флоридский музей естественной истории. Архивировано из оригинала 2013-01-22 . Получено 2008-07-09 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Эволюция лошадей» . Лошадь . Американский музей естественной истории. Архивировано из оригинала 2013-01-28 . Получено 2008-07-09 .

- ^ Миллер , с. 20

- ^ "Equus" . Ископаемые лошади в киберпространстве . Флоридский музей естественной истории. Архивировано из оригинала 2013-01-22 . Получено 2008-07-09 .

- ^ Weinstock, J.; и др. (2005). «Эволюция, систематика и филогеография плейстоценовых лошадей в новом мире: молекулярная перспектива» . PLOS Биология . 3 (8): E241. doi : 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030241 . PMC 1159165 . PMID 15974804 .

- ^ Вила, С.; и др. (2001). «Широко распространенное происхождение домашних лошадей» (PDF) . Наука . 291 (5503): 474–477. Bibcode : 2001sci ... 291..474V . doi : 10.1126/science.291.5503.474 . PMID 11161199 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 2012-10-13 . Получено 2009-03-17 .

- ^ Луис, Кристина; и др. (2006). «Иберийское происхождение пород лошадей Нового Света» . Кватернарные науки обзоры . 97 (2): 107–113. doi : 10.1093/jhered/esj020 . PMID 16489143 .

- ^ Хейл, Джеймс; и др. (2009). «Древняя ДНК раскрывает позднее выживание мамонта и лошади во внутренней Аляске» . ПНА . 106 (52): 22352–22357. Bibcode : 2009pnas..10622352H . doi : 10.1073/pnas.0912510106 . PMC 2795395 . PMID 20018740 .

- ^ Buck, Caitlin E.; Бард, Эдуард (2007). «Календарная хронология для плейстоценового мамонта и вымирания лошадей в Северной Америке на основе байесовской калибровки радиоуглерода» . Кватернарные науки обзоры . 26 (17–18): 2031–2035. Bibcode : 2007qsrv ... 26.2031b . doi : 10.1016/j.quascirev.2007.06.013 . Архивировано с оригинала 2018-11-06 . Получено 2017-09-06 .

- ^ Lequire, Elise (2004-01-04). «Нет травы, нет лошади» . Лошадь. Архивировано из оригинала 2013-01-09 . Получено 2009-06-08 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Олсен, Сандра Л. (1996). «Охотники на лошадях ледникового периода» . Лошади во времени (первое изд.). Boulder, CO: Roberts Rinehart Publishers. п. 46 ISBN 1-57098-060-8 Полем OCLC 36179575 .

- ^ «Необычайное возвращение от грани исчезновения для последней дикой лошади в мире» . ZSL Press Leleases . Зоологическое общество Лондона. 2005-12-19. Архивировано с оригинала 2013-05-16 . Получено 2012-06-06 .

- ^ "Дом" . Основа для сохранения и защиты лошади PRZEWALSKI. Архивировано из оригинала 2017-10-10 . Получено 2008-04-03 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Донер , с. 298–299

- ^ Пенниси, Элизабет (22 февраля 2018 г.). «Древняя ДНК уносит семейное древо лошади» . Sciencemag.org . Архивировано из оригинала 21 сентября 2022 года . Получено 30 июня 2022 года .

- ^ Орландо, Людович; Outram, Alan K.; Librado, Pablo; Уиллерслев, Эске; Зайберт, Виктор; Мерц, Ильжа; Мерц, Виктор; Уолнер, Барбара; Людвиг, Арне (6 апреля 2018 г.). «Древние геномы возвращаются к происхождению домашних лошадей и празвальски» . Наука . 360 (6384): 111–114. Bibcode : 2018sci ... 360..111G . doi : 10.1126/science.aao3297 . HDL : 10871/31710 . ISSN 0036-8075 . PMID 29472442 .

- ^ «Древняя ДНК исключает лучшую ставку археологов для одомашнивания лошадей» . Arstechnica . 25 февраля 2018 года. Архивировано с оригинала 25 июня 2020 года . Получено 24 июня 2020 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Донер , с. 300

- ^ "Тарпан" . Породы скота . Государственный университет штата Оклахома. Архивировано из оригинала на 2009-01-16 . Получено 2009-01-13 .

- ^ «Пони из прошлого?: Пара Орегона оживляет доисторические лошадей Тарпана» . Ежедневный курьер . 21 июня 2002 года. Архивировано с оригинала 2021-04-17 . Получено 2009-10-21 .

- ^ Peissel, Michel (2002). Тибет: Секретный континент . Макмиллан. п. 36. ISBN 0-312-30953-8 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 2023-03-20 . Получено 2020-09-28 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Royo, LJ; Отчет, я.; Beja-Pereira, A.; Молина, А.; Фернандес, я.; Джордана, Дж.; Gomems, E.; Gutierrez, JP; Goycheche, F. (2005). «Происхождение иберийской жизни ДНК » Дом наследственности 96 (6): 663–669. doi : /si1 10.1093 16251517PMID

- ^ Эдвардс , с. 104–105

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Лира, Хайме; и др. (2010). «Древняя ДНК раскрывает следы иберийских неолитических и бронзовых линий у современных иберийских лошадей» (PDF) . Молекулярная экология . 19 (1): 64–78. Bibcode : 2010molec..19 ... 64L . doi : 10.1111/j.1365-294x.2009.04430.x . PMID 19943892 . S2CID 1376591 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 2017-08-10 . Получено 2018-04-20 .

- ^ Паллас (1775). "Equus Hemionus" . Виды млекопитающих Уилсона и Ридера в мире . Университет Бакнелла . Архивировано с оригинала 26 сентября 2013 года . Получено 1 сентября 2010 года .

- ^ «Информация о муле» . BMS -сайт . Британское общество мулов. Архивировано из оригинала 2017-10-10 . Получено 2008-07-10 .

- ^ «Гибрид Zebra - милый сюрприз» . BBC News . 26 июня 2001 года. Архивировано с оригинала 2017-06-14 . Получено 2010-02-06 .

- ^ «Удовлетворяющее рождение: случай жеребенка мула» . Npr.org . Национальное общественное радио. Архивировано из оригинала 2008-12-06 . Получено 2008-08-16 .