Nicolas Bourbaki

| Association des collaborateurs de Nicolas Bourbaki | |

Bourbaki congress at Dieulefit in 1938. From left, Simone Weil,[a] Charles Pisot, André Weil, Jean Dieudonné (sitting), Claude Chabauty, Charles Ehresmann, and Jean Delsarte.[2] | |

| Named after | Charles-Denis Bourbaki |

|---|---|

| Formation | 10 December 1934 (first unofficial meeting) 10–17 July 1935 (first official, founding conference) |

| Founders | |

| Founded at | Latin Quarter, Paris, France (first unofficial meeting) Besse-en-Chandesse, France (first official, founding conference) |

| Type | Voluntary association |

| Purpose | Publication of textbooks in pure mathematics |

| Headquarters | École Normale Supérieure, Paris |

Membership | Confidential |

Official language | French |

| Website | www |

Formerly called | Committee for the Treatise on Analysis |

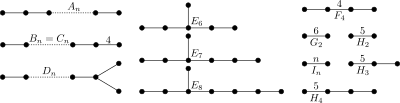

Nicolas Bourbaki (French: [nikɔla buʁbaki]) is the collective pseudonym of a group of mathematicians, predominantly French alumni of the École normale supérieure (ENS). Founded in 1934–1935, the Bourbaki group originally intended to prepare a new textbook in analysis. Over time the project became much more ambitious, growing into a large series of textbooks published under the Bourbaki name, meant to treat modern pure mathematics. The series is known collectively as the Éléments de mathématique (Elements of Mathematics), the group's central work. Topics treated in the series include set theory, abstract algebra, topology, analysis, Lie groups and Lie algebras.

Bourbaki was founded in response to the effects of the First World War which caused the death of a generation of French mathematicians; as a result, young university instructors were forced to use dated texts. While teaching at the University of Strasbourg, Henri Cartan complained to his colleague André Weil of the inadequacy of available course material, which prompted Weil to propose a meeting with others in Paris to collectively write a modern analysis textbook. The group's core founders were Cartan, Claude Chevalley, Jean Delsarte, Jean Dieudonné and Weil; others participated briefly during the group's early years, and membership has changed gradually over time. Although former members openly discuss their past involvement with the group, Bourbaki has a custom of keeping its current membership secret.

The group's name derives from the 19th century French general Charles-Denis Bourbaki, who had a career of successful military campaigns before suffering a dramatic loss in the Franco-Prussian War.[3] The name was therefore familiar to early 20th-century French students. Weil remembered an ENS student prank in which an upperclassman posed as a professor and presented a "theorem of Bourbaki"; the name was later adopted.

The Bourbaki group holds regular private conferences for the purpose of drafting and expanding the Éléments. Topics are assigned to subcommittees, drafts are debated, and unanimous agreement is required before a text is deemed fit for publication. Although slow and labor-intensive, the process results in a work which meets the group's standards for rigour and generality. The group is also associated with the Séminaire Bourbaki, a regular series of lectures presented by members and non-members of the group, also published and disseminated as written documents. Bourbaki maintains an office at the ENS.[4]

Nicolas Bourbaki was influential in 20th-century mathematics, particularly during the middle of the century when volumes of the Éléments appeared frequently. The group is noted among mathematicians for its rigorous presentation and for introducing the notion of a mathematical structure, an idea related to the broader, interdisciplinary concept of structuralism.[5][6][7] Bourbaki's work informed the New Math, a trend in elementary math education during the 1960s. Although the group remains active, its influence is considered to have declined due to infrequent publication of new volumes of the Éléments. However, since 2012 the group has published four new (or significantly revised) volumes, the most recent in 2023 (treating spectral theory). Moreover, at least three further volumes are under preparation.

Background

[edit]

Charles-Denis Sauter Bourbaki was a successful general during the era of Napoleon III, serving in the Crimean War and other conflicts. During the Franco-Prussian war however, Charles-Denis Bourbaki suffered a major defeat in which the Armée de l'Est, under his command, retreated across the Swiss border and was disarmed. The general unsuccessfully attempted suicide. The dramatic story of his defeat was known in the French popular consciousness following his death.[8][9]

In the early 20th century, the First World War affected Europeans of all professions and social classes, including mathematicians and male students who fought and died in the front. For example, the French mathematician Gaston Julia, a pioneer in the study of fractals, lost his nose during the war and wore a leather strap over the affected part of his face for the rest of his life. The deaths of ENS students resulted in a lost generation in the French mathematical community;[10] the estimated proportion of ENS mathematics students (and French students generally) who died in the war ranges from one-quarter to one-half, depending on the intervals of time (c. 1900–1918, especially 1910–1916) and populations considered.[11][12] Furthermore, Bourbaki founder André Weil remarked in his memoir Apprenticeship of a Mathematician that France and Germany took different approaches with their intelligentsia during the war: while Germany protected its young students and scientists, France instead committed them to the front, owing to the French culture of egalitarianism.[12]

A succeeding generation of mathematics students attended the ENS during the 1920s, including Weil and others, the future founders of Bourbaki. During his time as a student, Weil recalled a prank in which an upperclassman, Raoul Husson, posed as a professor and gave a math lecture, ending with a prompt: "Theorem of Bourbaki: you are to prove the following...". Weil was also aware of a similar stunt around 1910[3] in which a student claimed to be from the fictional, impoverished nation of "Poldevia" and solicited the public for donations.[13][14] Weil had strong interests in languages and Indian culture, having learned Sanskrit and read the Bhagavad Gita.[15][16] After graduating from the ENS and obtaining his doctorate, Weil took a teaching stint at the Aligarh Muslim University in India. While there, Weil met the mathematician Damodar Kosambi, who was engaged in a power struggle with one of his colleagues. Weil suggested that Kosambi write an article with material attributed to one "Bourbaki", in order to show off his knowledge to the colleague.[17] Kosambi took the suggestion, attributing the material discussed in the article to "the little-known Russian mathematician D. Bourbaki, who was poisoned during the Revolution." It was the first article in the mathematical literature with material attributed to the eponymous "Bourbaki".[18][19][20] Weil's stay in India was short-lived; he attempted to revamp the mathematics department at Aligarh, without success.[21] The university administration planned to fire Weil and promote his colleague Vijayaraghavan to the vacated position. However, Weil and Vijayaraghavan respected one another. Rather than play any role in the drama, Vijayaraghavan instead resigned, later informing Weil of the plan.[22] Weil returned to Europe to seek another teaching position. He ended up at the University of Strasbourg, joining his friend and colleague Henri Cartan.[23]

The Bourbaki collective

[edit]

Founding

[edit]During their time together at Strasbourg, Weil and Cartan regularly complained to each other regarding the inadequacy of available course material for calculus instruction. In his memoir Apprenticeship, Weil described his solution in the following terms: "One winter day toward the end of 1934, I came upon a great idea that would put an end to these ceaseless interrogations by my comrade. 'We are five or six friends', I told him some time later, 'who are in charge of the same mathematics curriculum at various universities. Let us all come together and regulate these matters once and for all, and after this, I shall be delivered of these questions.' I was unaware of the fact that Bourbaki was born at that instant."[23] Cartan confirmed the account.[24]

The first, unofficial meeting of the Bourbaki collective took place at noon on Monday, 10 December 1934, at the Café Grill-Room A. Capoulade, Paris, in the Latin Quarter.[25][26][27][28][b] Six mathematicians were present: Henri Cartan, Claude Chevalley, Jean Delsarte, Jean Dieudonné, René de Possel, and André Weil. Most of the group were based outside Paris and were in town to attend the Julia Seminar, a conference prepared with the help of Gaston Julia at which several future Bourbaki members and associates presented.[30][31][c] The group resolved to collectively write a treatise on analysis, for the purpose of standardizing calculus instruction in French universities. The project was especially meant to supersede the text of Édouard Goursat, which the group found to be badly outdated, and to improve its treatment of Stokes' Theorem.[27][35][36][37] The founders were also motivated by a desire to incorporate ideas from the Göttingen school, particularly from exponents Hilbert, Noether and B.L. van der Waerden. Further, in the aftermath of World War I, there was a certain nationalist impulse to save French mathematics from decline, especially in competition with Germany. As Dieudonné stated in an interview, "Without meaning to boast, I can say that it was Bourbaki that saved French mathematics from extinction."[38]

Jean Delsarte was particularly favorable to the collective aspect of the proposed project, observing that such a working style could insulate the group's work against potential later individual claims of copyright.[35][39][d] As various topics were discussed, Delsarte also suggested that the work begin in the most abstract, axiomatic terms possible, treating all of mathematics prerequisite to analysis from scratch.[41][42] The group agreed to the idea, and this foundational area of the proposed work was referred to as the "Abstract Packet" (Paquet Abstrait).[43][44][45] Working titles were adopted: the group styled itself as the Committee for the Treatise on Analysis, and their proposed work was called the Treatise on Analysis (Traité d'analyse).[46][47] In all, the collective held ten preliminary biweekly meetings at A. Capoulade before its first official, founding conference in July 1935.[47][48] During this early period, Paul Dubreil, Jean Leray and Szolem Mandelbrojt joined and participated. Dubreil and Leray left the meetings before the following summer, and were respectively replaced by new participants Jean Coulomb and Charles Ehresmann.[46][49]

The group's official founding conference was held in Besse-en-Chandesse, from 10 to 17 July 1935.[50][51] At the time of the official founding, the membership consisted of the six attendees at the first lunch of 10 December 1934, together with Coulomb, Ehresmann and Mandelbrojt. On 16 July, the members took a walk to alleviate the boredom of unproductive proceedings. During the malaise, some decided to skinny-dip in the nearby Lac Pavin, repeatedly yelling "Bourbaki!"[52] At the close of the first official conference, the group renamed itself "Bourbaki", in reference to the general and prank as recalled by Weil and others.[45][e] During 1935, the group also resolved to establish the mathematical personhood of their collective pseudonym by getting an article published under its name.[50][54] A first name had to be decided; a full name was required for publication of any article. To this end, René de Possel's wife Eveline "baptized" the pseudonym with the first name of Nicolas, becoming Bourbaki's "godmother".[50][55][56][57] This allowed for the publication of a second article with material attributed to Bourbaki, this time under "his" own name.[58] Henri Cartan's father Élie Cartan, also a mathematician and supportive of the group, presented the article to the publishers, who accepted it.[54]

At the time of Bourbaki's founding, René de Possel and his wife Eveline were in the process of divorcing. Eveline remarried to André Weil in 1937, and de Possel left the Bourbaki collective some time later. This sequence of events has caused speculation that de Possel left the group because of the remarriage,[59] however this suggestion has also been criticized as possibly historically inaccurate, since de Possel is supposed to have remained active in Bourbaki for years after André's marriage to Eveline.[60]

World War II

[edit]Bourbaki's work slowed significantly during the Second World War, though the group survived and later flourished. Some members of Bourbaki were Jewish and therefore forced to flee from certain parts of Europe at certain times. Weil, who was Jewish, spent the summer of 1939 in Finland with his wife Eveline, as guests of Lars Ahlfors. Due to their travel near the border, the couple were suspected as Soviet spies by Finnish authorities near the onset of the Winter War, and André was later arrested.[61] According to an anecdote, Weil was to have been executed but for the passing mention of his case to Rolf Nevanlinna, who asked that Weil's sentence be commuted.[62] However, the accuracy of this detail is dubious.[63] Weil reached the United States in 1941, later taking another teaching stint in São Paulo from 1945 to 1947 before settling at the University of Chicago from 1947 to 1958 and finally the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, where he spent the remainder of his career. Although Weil remained in touch with the Bourbaki collective and visited Europe and the group periodically following the war, his level of involvement with Bourbaki never returned to that at the time of founding.

Second-generation Bourbaki member Laurent Schwartz was also Jewish and found pickup work as a math teacher in rural Vichy France. Moving from village to village, Schwartz planned his movements in order to evade capture by the Nazis.[64] On one occasion Schwartz found himself trapped overnight in a certain village, as his expected transportation home was unavailable. There were two inns in town: a comfortable, well-appointed one, and a very poor one with no heating and bad beds. Schwartz's instinct told him to stay at the poor inn; overnight, the Nazis raided the good inn, leaving the poor inn unchecked.[65]

Meanwhile, Jean Delsarte, a Catholic, was mobilized in 1939 as the captain of an audio reconnaissance battery. He was forced to lead the unit's retreat from the northeastern part of France toward the south. While passing near the Swiss border, Delsarte overheard a soldier say "We are the army of Bourbaki";[66][67] the 19th-century general's retreat was known to the French. Delsarte had coincidentally led a retreat similar to that of the collective's namesake.

Postwar until the present

[edit]Following the war, Bourbaki had solidified the plan of its work and settled into a productive routine. Bourbaki regularly published volumes of the Éléments during the 1950s and 1960s, and enjoyed its greatest influence during this period.[68][69] Over time the founding members gradually left the group, slowly being replaced with younger newcomers including Jean-Pierre Serre and Alexander Grothendieck. Serre, Grothendieck and Laurent Schwartz were awarded the Fields Medal during the postwar period, in 1954, 1966 and 1950 respectively. Later members Alain Connes and Jean-Christophe Yoccoz also received the Fields Medal, in 1982 and 1994 respectively.[70]

The later practice of accepting scientific awards contrasted with some of the founders' views.[71] During the 1930s, Weil and Delsarte petitioned against a French national scientific "medal system" proposed by the Nobel physics laureate Jean Perrin. Weil and Delsarte felt that the institution of such a system would increase unconstructive pettiness and jealousy in the scientific community.[72] Despite this, the Bourbaki group had previously successfully petitioned Perrin for a government grant to support its normal operations.[73] Like the founders, Grothendieck was also averse to awards, albeit for pacifist reasons. Although Grothendieck was awarded the Fields Medal in 1966, he declined to attend the ceremony in Moscow, in protest of the Soviet government.[74] In 1988, Grothendieck rejected the Crafoord Prize outright, citing no personal need to accept prize money, lack of recent relevant output, and general distrust of the scientific community.[75]

Born to Jewish anarchist parentage, Grothendieck survived the Holocaust and advanced rapidly in the French mathematical community, despite poor education during the war.[76] Grothendieck's teachers included Bourbaki's founders, and so he joined the group. During Grothendieck's membership, Bourbaki reached an impasse concerning its foundational approach. Grothendieck advocated for a reformulation of the group's work using category theory as its theoretical basis, as opposed to set theory. The proposal was ultimately rejected[77][78][79] in part because the group had already committed itself to a rigid track of sequential presentation, with multiple already-published volumes. Following this, Grothendieck left Bourbaki "in anger".[37][64][80] Biographers of the collective have described Bourbaki's unwillingness to start over in terms of category theory as a missed opportunity.[64][81][82] However, Bourbaki has in 2023 announced that a book on category theory is currently under preparation (see below the last paragraph of this section).

During the founding period, the group chose the Parisian publisher Hermann to issue installments of the Éléments. Hermann was led by Enrique Freymann, a friend of the founders willing to publish the group's project, despite financial risk. During the 1970s, Bourbaki entered a protracted legal battle with Hermann over matters of copyright and royalty payment. Although the Bourbaki group won the suit and retained collective copyright of the Éléments, the dispute slowed the group's productivity.[83][84] Former member Pierre Cartier described the lawsuit as a pyrrhic victory, saying: "As usual in legal battles, both parties lost and the lawyer got rich."[64] Later editions of the Éléments were published by Masson, and modern editions are published by Springer.[85] From the 1980s through the 2000s, Bourbaki published very infrequently, with the result that in 1998 Le Monde pronounced the collective "dead".[86]

However, in 2012 Bourbaki resumed the publication of the Éléments with a revised chapter 8 of algebra, the first 4 chapters of a new book on algebraic topology, and two volumes on spectral theory (the first of which is an expanded and revised version of the edition of 1967 while the latter consist of three new chapters). Moreover, the text of the two latest volumes announces that books on category theory and modular forms are currently under preparation (in addition to the latter part of the book on algebraic topology).[87][88]

Working method

[edit]

Bourbaki holds periodic conferences for the purpose of expanding the Éléments; these conferences are the central activity of the group's working life. Subcommittees are assigned to write drafts on specific material, and the drafts are later presented, vigorously debated, and re-drafted at the conferences. Unanimous agreement is required before any material is deemed acceptable for publication.[90][91][92] A given piece of material may require six or more drafts over a period of several years, and some drafts are never developed into completed work.[91][93] Bourbaki's writing process has therefore been described as "Sisyphean".[92] Although the method is slow, it yields a final product which satisfies the group's standards for mathematical rigour, one of Bourbaki's main priorities in the treatise. Bourbaki's emphasis on rigour was a reaction to the style of Henri Poincaré, who stressed the importance of free-flowing mathematical intuition at the cost of thorough presentation.[f] During the project's early years, Dieudonné served as the group's scribe, authoring several final drafts which were ultimately published. For this purpose, Dieudonné adopted an impersonal writing style which was not his own, but which was used to craft material acceptable to the entire group.[94][95] Dieudonné reserved his personal style for his own work; like all members of Bourbaki, Dieudonné also published material under his own name,[96] including the nine-volume Éléments d'analyse, a work explicitly focused on analysis and of a piece with Bourbaki's initial intentions.

Most of the final drafts of Bourbaki's Éléments carefully avoided using illustrations, favoring a formal presentation based only in text and formulas. An exception to this was the treatment of Lie groups and Lie algebras (especially in chapters 4–6), which did make use of diagrams and illustrations. The inclusion of illustration in this part of the work was due to Armand Borel. Borel was minority-Swiss in a majority-French collective, and self-deprecated as "the Swiss peasant", explaining that visual learning was important to the Swiss national character.[64][97] When asked about the dearth of illustration in the work, former member Pierre Cartier replied:

The Bourbaki were Puritans, and Puritans are strongly opposed to pictorial representations of truths of their faith. The number of Protestants and Jews in the Bourbaki group was overwhelming. And you know that the French Protestants especially are very close to Jews in spirit.

— Pierre Cartier[64]

The conferences have historically been held at quiet rural areas.[98] These locations contrast with the lively, sometimes heated debates which have occurred. Laurent Schwartz reported an episode in which Weil slapped Cartan on the head with a draft. The hotel's proprietor saw the incident and assumed that the group would split up, but according to Schwartz, "peace was restored within ten minutes."[99] The historical, confrontational style of debate within Bourbaki has been partly attributed to Weil, who believed that new ideas have a better chance of being born in confrontation than in an orderly discussion.[91][99] Schwartz related another illustrative incident: Dieudonné was adamant that topological vector spaces must appear in the work before integration, and whenever anyone suggested that the order be reversed, he would loudly threaten his resignation. This became an in-joke among the group; Roger Godement's wife Sonia attended a conference, aware of the idea, and asked for proof. As Sonia arrived at a meeting, a member suggested that integration must appear before topological vector spaces, which triggered Dieudonné's usual reaction.[99]

Despite the historical culture of heated argument, Bourbaki thrived during the middle of the twentieth century. Bourbaki's ability to sustain such a collective, critical approach has been described as "something unusual",[100] surprising even its own members. In founder Henri Cartan's words, "That a final product can be obtained at all is a kind of miracle that none of us can explain."[101][102] It has been suggested that the group survived because its members believed strongly in the importance of their collective project, despite personal differences.[91][103] When the group overcame difficulties or developed an idea that they liked, they would sometimes say l'esprit a soufflé ("the spirit breathes").[91][104] Historian Liliane Beaulieu noted that the "spirit"—which might be an avatar, the group mentality in action, or Bourbaki "himself"—was part of an internal culture and mythology which the group used to form its identity and perform work.[105]

Humor

[edit]Humor has been an important aspect of the group's culture, beginning with Weil's memories of the student pranks involving "Bourbaki" and "Poldevia". For example, in 1939 the group released a wedding announcement for the marriage of "Betti Bourbaki" (daughter of Nicolas) to one "H. Pétard" (H. "Firecrackers" or "Hector Pétard"), a "lion hunter".[106] Hector Pétard was itself a pseudonym, but not one originally coined by the Bourbaki members. The Pétard moniker was originated by Ralph P. Boas, Frank Smithies and other Princeton mathematicians who were aware of the Bourbaki project; inspired by them, the Princeton mathematicians published an article on the "mathematics of lion hunting". After meeting Boas and Smithies, Weil composed the wedding announcement, which contained several mathematical puns.[107] Bourbaki's internal newsletter La Tribu has sometimes been issued with humorous subtitles to describe a given conference, such as "The Extraordinary Congress of Old Fogies" (where anyone older than 30 was considered a fogy) or "The Congress of the Motorization of the Trotting Ass" (an expression used to describe the routine unfolding of a mathematical proof, or process).[108][109]

During the 1940s–1950s,[110][111] the American Mathematical Society received applications for individual membership from Bourbaki. They were rebuffed by J.R. Kline who understood the entity to be a collective, inviting them to re-apply for institutional membership. In response, Bourbaki floated a rumor that Ralph Boas was not a real person, but a collective pseudonym of the editors of Mathematical Reviews with which Boas had been affiliated. The reason for targeting Boas was because he had known the group in its earlier days when they were less strict with secrecy, and he'd described them as a collective in an article for the Encyclopædia Britannica.[112] In November 1968, a mock obituary of Nicolas Bourbaki was released during one of the seminars.[113][114]

The group developed some variants of the word "Bourbaki" for internal use. The noun "Bourbaki" might refer to the group proper or to an individual member, e.g. "André Weil was a Bourbaki." "Bourbakist" is sometimes used to refer to members[37] but also denotes associates, supporters, and enthusiasts.[115][116] To "bourbakize" meant to take a poor existing text and to improve it through an editing process.[93]

Bourbaki's culture of humor has been described as an important factor in the group's social cohesion and capacity to survive, smoothing over tensions of heated debate.[117] As of 2024, a Twitter account registered to "Betty_Bourbaki" provides regular updates on the group's activity.[118]

Works

[edit]Bourbaki's work includes a series of textbooks, a series of printed lecture notes, journal articles, and an internal newsletter. The textbook series Éléments de mathématique (Elements of mathematics) is the group's central work. The Séminaire Bourbaki is a lecture series held regularly under the group's auspices, and the talks given are also published as lecture notes. Journal articles have been published with authorship attributed to Bourbaki, and the group publishes an internal newsletter La Tribu (The Tribe) which is distributed to current and former members.[119][120]

Éléments de mathématique

[edit]Like those before him, Bourbaki insisted on setting mathematics in a “formalized language” with crystal-clear deductions based on strict formal rules. When Bertrand Russell and Alfred North Whitehead applied this approach at the turn of the twentieth century, they famously filled over 700 pages with formal symbols before establishing the proposition usually abbreviated as 1+1=2. Bourbaki's formalism would dwarf even this, requiring some 4.5 trillion symbols just to define the number 1.[121]

Michael Barany[122]

The content of the Éléments is divided into books—major topics of discussion, volumes—individual, physical books, and chapters, together with certain summaries of results, historical notes, and other details. The volumes of the Éléments have had a complex publication history. Material has been revised for new editions, published chronologically out of order of its intended logical sequence, grouped together and partitioned differently in later volumes, and translated into English. For example, the second book on Algebra was originally released in eight French volumes: the first in 1942 being chapter 1 alone, and the last in 1980 being chapter 10 alone. This presentation was later condensed into five volumes with chapters 1–3 in the first volume, chapters 4–7 in the second, and chapters 8–10 each remaining the third through fifth volumes of that portion of the work.[119] The English edition of Bourbaki's Algebra consists of translations of the three volumes consisting of chapters 1–3, 4–7 and 8, with chapters 9 and 10 unavailable in English as of 2024.

When Bourbaki's founders began working on the Éléments, they originally conceived of it as a "treatise on analysis", the proposed work having a working title of the same name (Traité d'analyse). The opening part was to comprehensively deal with the foundations of mathematics prior to analysis, and was referred to as the "Abstract Packet". Over time, the members developed this proposed "opening section" of the work to the point that it would instead run for several volumes and comprise a major part of the work, covering set theory, abstract algebra, and topology. Once the project's scope expanded far beyond its original purpose, the working title Traité d'analyse was dropped in favor of Éléments de mathématique.[45] The unusual, singular "Mathematic" was meant to connote Bourbaki's belief in the unity of mathematics.[123][124][125] The first six books of the Éléments, representing the first half of the work, are numbered sequentially and ordered logically, with a given statement being established only on the basis of earlier results.[126] This first half of the work bore the subtitle Les structures fondamentales de l’analyse (Fundamental Structures of Analysis),[119][127][128] covering established mathematics (algebra, analysis) in the group's style. The second half of the work consists of unnumbered books treating modern areas of research (Lie groups, commutative algebra), each presupposing the first half as a shared foundation but without dependence on each other. This second half of the work, consisting of newer research topics, does not have a corresponding subtitle.

The volumes of the Éléments published by Hermann were indexed by chronology of publication and referred to as fascicules: installments in a large work. Some volumes did not consist of the normal definitions, proofs, and exercises in a math textbook, but contained only summaries of results for a given topic, stated without proof. These volumes were referred to as Fascicules de résultats, with the result that fascicule may refer to a volume of Hermann's edition, or to one of the "summary" sections of the work (e.g. Fascicules de résultats is translated as "Summary of Results" rather than "Installment of Results", referring to the content rather than a specific volume).[g] The first volume of Bourbaki's Éléments to be published was the Summary of Results in the Theory of Sets, in 1939.[64][119][131] Similarly one of the work's later books, Differential and Analytic Manifolds, consisted only of two volumes of summaries of results, with no chapters of content having been published.

Later installments of the Éléments appeared infrequently during the 1980s and 1990s. A volume of Commutative Algebra (chapters 8–9) was published in 1983, and no other volumes were issued until the appearance of the same book's tenth chapter in 1998. During the 2010s, Bourbaki increased its productivity. A re-written and expanded version of the eighth chapter of Algebra appeared in 2012, the first four chapters of a new book treating Algebraic Topology was published in 2016, and the first two chapters of a revised and expanded edition of Spectral Theory was issued in 2019 while the remaining three (completely new) chapters appeared in 2023.

| Year | Book | References |

|---|---|---|

| 1954 | Theory of Sets | [132] |

| 1942 | Algebra | [133][134][135] |

| 1940 | General Topology | |

| 1949 | Functions of a Real Variable | |

| 1953 | Topological Vector Spaces | |

| 1952 | Integration | [136][137] |

| 1960 | Lie Groups and Lie Algebras | |

| 1961 | Commutative Algebra | [138] |

| 1967 | Spectral Theory | |

| 1967 | Differential and Analytic Manifolds | |

| 2016 | Algebraic Topology | [139] |

| 1960 | Elements of the History of Mathematics |

Séminaire Bourbaki

[edit]The Séminaire Bourbaki has been held regularly since 1948, and lectures are presented by non-members and members of the collective. As of 2024 the Séminaire Bourbaki has run to over a thousand recorded lectures in its written incarnation, denoted chronologically by simple numbers.[140] At the time of a June 1999 lecture given by Jean-Pierre Serre on the topic of Lie groups, the total lectures given in the series numbered 864, corresponding to roughly 10,000 pages of printed material.[141]

Articles

[edit]

Several journal articles have appeared in the mathematical literature with material or authorship attributed to Bourbaki; unlike the Éléments, they were typically written by individual members[119] and not crafted through the usual process of group consensus. Despite this, Jean Dieudonné's essay "The Architecture of Mathematics" has become known as Bourbaki's manifesto.[142][143] Dieudonné addressed the issue of overspecialization in mathematics, to which he opposed the inherent unity of mathematic (as opposed to mathematics) and proposed mathematical structures as useful tools which can be applied to several subjects, showing their common features.[144] To illustrate the idea, Dieudonné described three different systems in arithmetic and geometry and showed that all could be described as examples of a group, a specific kind of (algebraic) structure.[145] Dieudonné described the axiomatic method as "the 'Taylor system' for mathematics" in the sense that it could be used to solve problems efficiently.[146][i] Such a procedure would entail identifying relevant structures and applying established knowledge about the given structure to the specific problem at hand.[146]

- Kosambi, D.D. (1931). "On a Generalization of the Second Theorem of Bourbaki". Bulletin of the Academy of Sciences of the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh, Allahabad, India. 1: 145–47. ISBN 978-81-322-3674-0. Reprinted in Ramaswamy, Ramakrishna, ed. (2016). D.D. Kosambi: Selected Works in Mathematics and Statistics. Springer. pp. 55–57. doi:10.1007/978-81-322-3676-4_6. Kosambi attributed material in the article to "D. Bourbaki", the first mention of the eponymous Bourbaki in the literature.

- Bourbaki, Nicolas (1935). "Sur un théorème de Carathéodory et la mesure dans les espaces topologiques". Comptes rendus de l'Académie des Sciences. 201: 1309–11. Presumptive author: André Weil.

- —— (1938). "Sur les espaces de Banach". Comptes rendus de l'Académie des Sciences. 206: 1701–04. Presumptive author: Jean Dieudonné.

- ——; Dieudonné, Jean (1939). "Note de tératopologie II". Revue scientifique (Or, "Revue rose"): 180–81. Presumptive author: Jean Dieudonné. Second in a series of three articles.

- —— (1941). "Espaces minimaux et espaces complètement séparés". Comptes rendus de l'Académie des Sciences. 212: 215–18. Presumptive author: Jean Dieudonné or André Weil.

- —— (1948). "L'architecture des mathématiques". In Le Lionnais, François (ed.). Les grands courants de la pensée mathématique. Actes Sud. pp. 35–47. Presumptive author: Jean Dieudonné.

- —— (1949). "Foundations of Mathematics for the Working Mathematician". Journal of Symbolic Logic. 14 (1): 1–8. doi:10.2307/2268971. JSTOR 2268971. S2CID 26516355. Presumptive author: André Weil.

- —— (1949). "Sur le théorème de Zorn". Archiv der Mathematik. 2 (6): 433–37. doi:10.1007/BF02036949. S2CID 117826806. Presumptive author: Henri Cartan or Jean Dieudonné.

- —— (1950). "The Architecture of Mathematics". American Mathematical Monthly. 57 (4): 221–32. doi:10.1080/00029890.1950.11999523. JSTOR 2305937. Presumptive author: Jean Dieudonné. Authorized translation of the book chapter L'architecture des mathématiques, appearing in English as a journal article.

- —— (1950). "Sur certains espaces vectoriels topologiques". Annales de l'Institut Fourier. 2: 5–16. doi:10.5802/aif.16. Presumptive authors: Jean Dieudonné and Laurent Schwartz.

La Tribu

[edit]La Tribu is Bourbaki's internal newsletter, distributed to current and former members. The newsletter usually documents recent conferences and activity in a humorous, informal way, sometimes including poetry.[147] Member Pierre Samuel wrote the newsletter's narrative sections for several years.[148] Early editions of La Tribu and related documents have been made publicly available by Bourbaki.[33]

Historian Liliane Beaulieu examined La Tribu and Bourbaki's other writings, describing the group's humor and private language as an "art of memory" which is specific to the group and its chosen methods of operation.[149] Because of the group's secrecy and informal organization, individual memories are sometimes recorded in a fragmentary way, and may not have significance to other members.[150] On the other hand, the predominantly French, ENS background of the members, together with stories of the group's early period and successes, create a shared culture and mythology which is drawn upon for group identity. La Tribu usually lists the members present at a conference, together with any visitors, family members or other friends in attendance. Humorous descriptions of location or local "props" (cars, bicycles, binoculars, etc.) can also serve as mnemonic devices.[108]

Membership

[edit]As of 2000, Bourbaki has had "about forty" members.[151] Historically the group has numbered about ten[152] to twelve[64] members at any given point, although it was briefly (and officially) limited to nine members at the time of founding.[47] Bourbaki's membership has been described in terms of generations:

Bourbaki was always a very small group of mathematicians, typically numbering about twelve people. Its first generation was that of the founding fathers, those who created the group in 1934: Weil, Cartan, Chevalley, Delsarte, de Possel, and Dieudonné. Others joined the group, and others left its ranks, so that some years later there were about twelve members, and that number remained roughly constant. Laurent Schwartz was the only mathematician to join Bourbaki during the war, so his is considered an intermediate generation. After the war, a number of members joined: Jean-Pierre Serre, Pierre Samuel, Jean-Louis Koszul, Jacques Dixmier, Roger Godement, and Sammy Eilenberg. These people constituted the second generation of Bourbaki. In the 1950s, the third generation of mathematicians joined Bourbaki. These people included Alexandre Grothendieck, François Bruhat, Serge Lang, the American mathematician John Tate, Pierre Cartier, and the Swiss mathematician Armand Borel.[64][153]

After the first three generations there were roughly twenty later members, not including current participants. Bourbaki has a custom of keeping its current membership secret, a practice meant to ensure that its output is presented as a collective, unified effort under the Bourbaki pseudonym, not attributable to any one author (e.g. for purposes of copyright or royalty payment). This secrecy is also intended to deter unwanted attention which could disrupt normal operations. However, former members freely discuss Bourbaki's internal practices upon departure.[64][154]

Prospective members are invited to conferences and styled as guinea pigs, a process meant to vet the newcomer's mathematical ability.[64][155] In the event of agreement between the group and the prospect, the prospect eventually becomes a full member.[j] The group is supposed to have an age limit: active members are expected to retire at (or about) 50 years of age.[64][92] At a 1956 conference, Cartan read a letter from Weil which proposed a "gradual disappearance" of the founding members, forcing younger members to assume full responsibility for Bourbaki's operations.[37][160] This rule is supposed to have resulted in a complete change of personnel by 1958.[55] However, historian Liliane Beaulieu has been critical of the claim. She reported never having found written affirmation of the rule,[161] and has indicated that there have been exceptions.[162] The age limit is thought to express the founders' intent that the project should continue indefinitely, operated by people at their best mathematical ability—in the mathematical community, there is a widespread belief that mathematicians produce their best work while young.[160][163] Among full members there is no official hierarchy; all operate as equals, having the ability to interrupt conference proceedings at any point, or to challenge any material presented. However, André Weil has been described as "first among equals" during the founding period, and was given some deference.[164] On the other hand, the group has also poked fun at the idea that older members should be afforded greater respect.[165]

Bourbaki conferences have also been attended by members' family, friends, visiting mathematicians, and other non-members of the group.[k] Bourbaki is not known ever to have had any female members.[92][152]

| Generation | Name | Born | ENS[l] | Joined[m][n] | Left | Died | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First[o] | Core members | Henri Cartan | 1904 | 1923 | 1934 | c. 1956–58 | 2008 |

| Claude Chevalley | 1909 | 1926 | 1934 | c. 1956–58 | 1984 | ||

| Jean Delsarte | 1903 | 1922 | 1934 | c. 1956–58 | 1968 | ||

| Jean Dieudonné | 1906 | 1924 | 1934 | c. 1956–58 | 1992 | ||

| André Weil | 1906 | 1922 | 1934 | c. 1956–58 | 1998 | ||

| Minor members | Jean Coulomb | 1904 | 1923 | 1935 | 1937 | 1999 | |

| Paul Dubreil | 1904 | 1923 | 1935 | 1935 | 1994 | ||

| Charles Ehresmann | 1905 | 1924 | 1935 | 1950 | 1979 | ||

| Jean Leray | 1906 | 1926 | 1935 | 1935 | 1998 | ||

| Szolem Mandelbrojt | 1899 | — | 1935 | — | 1983 | ||

| René de Possel | 1905 | 1923 | 1934 | — | 1974 | ||

| Second[p] | Jacques Dixmier | 1924 | 1942 | — | — | — | |

| Samuel Eilenberg | 1913 | — | c. 1951 | 1966 | 1998 | ||

| Roger Godement | 1921 | 1940 | — | — | 2016 | ||

| Jean-Louis Koszul | 1921 | 1940 | — | — | 2018 | ||

| Pierre Samuel | 1921 | 1940 | 1947 | 1971 | 2009 | ||

| Laurent Schwartz | 1916 | 1934 | — | — | 2002 | ||

| Jean-Pierre Serre | 1926 | 1945 | — | — | — | ||

| Третий | Armand Borel | 1923 | — | c. 1953 | 1973 | 2003 | |

| François Bruhat | 1929 | 1948 | — | — | 2007 | ||

| Pierre Cartier | 1932 | 1950 | 1955 | 1983 | — | ||

| Alexander Grothendieck | 1928 | 1945 | 1955 | 1960 | 2014 | ||

| Серж Ланг | 1927 | — | — | — | 2005 | ||

| Джон Тейт | 1925 | — | — | — | 2019 | ||

| Более поздние участники [д] [р] | Хайман Басс | 1932 | — | — | — | — | |

| Арно Бовиль | 1947 | 1966 | — | 1997 | — | ||

| Жерар Бен Арус | 1957 | 1977 | — | — | — | ||

| Дэниел Беннекин | 1952 | 1972 | — | — | — | ||

| Клод Шаботи | 1910 | 1929 | — | — | 1990 | ||

| Ален Конн | 1947 | 1966 | — | — | — | ||

| Мишель Демазюр | 1937 | 1955 | — | в. 1985 год | — | ||

| Адриан Дуади | 1935 | 1954 | — | — | 2006 | ||

| Патрик Жерар [ фр ] | 1961 | 1981 | — | — | — | ||

| Гай Хенниарт | 1953 | 1973 | — | — | — | ||

| Люк Иллюзия | 1940 | 1959 | — | — | — | ||

| Пьер Джадж | 1959 | 1977 | — | — | — | ||

| Жиль Лебо | 1954 | 1974 | — | — | — | ||

| Андре Мартино | 1930 | 1949 | — | — | 1972 | ||

| Оливье Матье | 1960 | 1980 | 1989 | в. 2010 год | — | ||

| Луи Буте де Монвель | 1941 | 1960 | 1971 | 1991 | 2014 | ||

| Джозеф Остерле | 1954 | 1973 | — | — | — | ||

| Шарль Писо | 1909 | 1929 | — | — | 1984 | ||

| Мишель Рейно | 1938 | 1958 | — | — | 2018 | ||

| Марк Россо | 1962 | 1982 | — | — | — | ||

| Жорж Скандалис | 1955 | 1975 | — | — | — | ||

| Бернар Тейсье | 1945 | — | — | — | — | ||

| Жан-Луи Вердье | 1937 | 1955 | — | — | 1989 | ||

| Жан-Кристоф Йоккоз | 1957 | 1975 | в. 1995 год | в. 1995 год | 2016 | ||

Влияние и критика

[ редактировать ]Бурбаки оказал влияние на математику 20-го века и оказал некоторое междисциплинарное влияние на гуманитарные науки и искусство, хотя степень последнего влияния является предметом споров. Группу хвалили и критиковали за метод презентации, стиль работы и выбор математических тем.

Влияние

[ редактировать ]Бурбаки ввел несколько математических обозначений, которые до сих пор используются. Вейль взял букву Ø норвежского алфавита и использовал ее для обозначения пустого множества . . [175] Впервые это обозначение появилось в «Сводке результатов по теории множеств» . [176] и продолжает использоваться. Слова инъективный , сюръективный и биективный были введены для обозначения функций , которые удовлетворяют определенным свойствам. [177] [178] Бурбаки использовал простой язык для обозначения некоторых геометрических объектов, называя их паве ( брусчаткой ) и булями ( шарами ) в отличие от « параллелотопов » или « гиперсфероидов ». [179] Точно так же в своей трактовке топологических векторных пространств Бурбаки определил бочку как множество, которое является выпуклым , сбалансированным , поглощающим и замкнутым . [180] Группа гордилась этим определением, полагая, что форма винной бочки символизирует свойства математического объекта. [181] [182] Бурбаки также использовал символ « опасного изгиба » ☡ на полях текста, чтобы указать на особенно трудный фрагмент материала. Наибольшее влияние Бурбаки пользовался в 1950-е и 1960-е годы, когда отрывки из «Элементов» часто публиковались .

Бурбаки оказал междисциплинарное влияние на другие области, включая антропологию и психологию . Это влияние было в контексте структурализма , школы мысли в гуманитарных науках , которая подчеркивает отношения между объектами над самими объектами, преследуемой в различных областях другими французскими интеллектуалами. В 1943 году Андре Вейль встретился с антропологом Клодом Леви-Стросом в Нью-Йорке, где они некоторое время сотрудничали. По просьбе Леви-Стросса Вейль написал краткое приложение, описывающее правила брака для четырех классов людей в аборигенов Австралии обществе , используя математическую модель, основанную на теории групп . [5] [183] Результат был опубликован в качестве приложения к книге Леви-Стросса « Элементарные структуры родства » , работе, исследующей семейные структуры и табу на инцест в человеческих культурах. [184] В 1952 году Жан Дьедонне и Жан Пиаже приняли участие в междисциплинарной конференции по математическим и ментальным структурам. Дьедонне описал математические «материнские структуры» в терминах проекта Бурбаки: композиция, соседство и порядок. [185] Затем Пиаже выступил с докладом о психических процессах детей и считал, что только что описанные им психологические понятия очень похожи на математические понятия, только что описанные Дьедонне. [186] [187] По словам Пиаже, они были «впечатлены друг другом». [188] Психоаналитику Жаку Лакану понравился стиль совместной работы Бурбаки, и он предложил аналогичную коллективную группу в психологии, но эта идея не была реализована. [189]

Бурбаки также цитировали философы -постструктуралисты . В своей совместной работе «Анти-Эдип» Жиль Делёз и Феликс Гваттари представили критику капитализма . Авторы привели использование Бурбаки аксиоматического метода (с целью установления истины) как явный контрпример процессам управления , которые вместо этого стремятся к экономической эффективности . Авторы сказали об аксиоматике Бурбаки, что «они не образуют систему Тейлора», перевернув фразу, использованную Дьедонне в «Архитектуре математики». [146] [190] В «Состоянии постмодерна » Жан-Франсуа Лиотар раскритиковал «легитимацию знания», процесс, посредством которого утверждения принимаются как действительные. В качестве примера Лиотар привел Бурбаки как группу, производящую знания в рамках заданной системы правил. [191] [192] Лиотар противопоставлял иерархическую, «структуралистскую» математику Бурбаки теории катастроф Рене Тома и фракталам Бенуа Мандельброта . [с] выражая предпочтение последней «постмодернистской науке», которая проблематизировала математику с помощью «фрактов, катастроф и прагматических парадоксов». [191] [192]

Хотя биограф Амир Аксель подчеркивал влияние Бурбаки на другие дисциплины в середине 20-го века, Морис Машаал смягчал утверждения о влиянии Бурбаки следующими словами:

Хотя структуры Бурбаки часто упоминались на конференциях и публикациях по общественным наукам того времени, похоже, что они не сыграли реальной роли в развитии этих дисциплин. Дэвид Обен, историк науки, анализировавший роль Бурбаки в структуралистском движении во Франции, считает, что роль Бурбаки заключалась в «культурном связующем звене». [194] По словам Обена, хотя у Бурбаки не было никакой миссии за пределами математики, группа представляла собой своего рода связующее звено между различными культурными движениями того времени. Бурбаки дал простое и относительно точное определение понятий и структур, которое, по мнению философов и социологов, имело фундаментальное значение в их дисциплинах и служило связующим звеном между различными областями знаний. Несмотря на поверхностный характер этих связей, различные школы структуралистского мышления, в том числе и Бурбаки, смогли поддержать друг друга. Поэтому не случайно в конце 1960-х годов эти школы пережили одновременный упадок.

Критике подверглось и влияние «структурализма» на саму математику. Историк математики Лео Корри утверждал, что использование Бурбаки математических структур не имело значения в « Элементах» , поскольку оно было установлено в «Теории множеств» и впоследствии нечасто цитировалось. [199] [200] [201] [202] Корри описал «структурный» взгляд на математику, продвигаемый Бурбаки, как «образ знания» — концепцию научной дисциплины — в отличие от элемента «корпуса знаний» дисциплины, который относится к фактическим научным результатам в сама дисциплина. [200]

Бурбаки также имел некоторое влияние в искусстве. Литературный коллектив Oulipo был основан 24 ноября 1960 года при обстоятельствах, аналогичных основаниям Бурбаки: участники первоначально встретились в ресторане. Хотя некоторые члены Улипо были математиками, целью группы было создание экспериментальной литературы , играя с языком. Улипо часто использовал математически обоснованные методы письма с ограничениями , такие как метод S + 7 . Член Улипо Раймон Кено присутствовал на конференции Бурбаки в 1962 году. [187] [203]

В 2016 году анонимная группа экономистов совместно написала заметку, в которой обвиняла авторов и редактора в академических нарушениях статьи, опубликованной в American Economic Review . [204] [205] Заметка была опубликована под именем Николя Беарбаки в честь Николя Бурбаки. [206]

В 2018 году американский музыкальный дуэт One Pilots выпустил концептуальный альбом Trench Twenty . Концептуальной основой альбома стал мифический город «Дема», которым управляют девять «епископов»; одного из епископов звали «Нико», сокращенно от Николя Бурбаки. Другого епископа звали Андре, что может относиться к Андре Вейлю. После выпуска альбома в Интернете резко возросло количество поисковых запросов по запросу «Николя Бурбаки». [37] [v]

Хвалить

[ редактировать ]Некоторые математики высоко оценили работу Бурбаки. В рецензии на книгу Эмиль Артин описал Éléments в общих и позитивных терминах:

Наше время является свидетелем создания монументального труда: изложения всей современной математики. Более того, это изложение сделано таким образом, чтобы стала ясно видна общая связь между различными разделами математики, чтобы структура, поддерживающая всю структуру, не устаревала за очень короткое время и могла легко поглощать новые знания. идеи.

— Эмиль Артин [133]

Среди томов «Элементов » работа Бурбаки по группам Ли и алгебрам Ли была отмечена как «превосходная». [195] став стандартным справочником по этой теме. В частности, бывший участник Арман Борель охарактеризовал том с главами 4–6 как «одну из самых успешных книг Бурбаки». [208] Успех этой части работы объясняется тем, что книги были написаны, когда ведущими экспертами по этой теме были члены Бурбаки. [64] [209]

Жан-Пьер Бургиньон выразил признательность Семинару Бурбаки, заявив, что он изучил на его лекциях большой объем материала и регулярно ссылался на его печатные конспекты лекций. [210] Он также похвалил « Элементы» за «несколько превосходных и очень умных доказательств». [211]

Критика

[ редактировать ]Бурбаки также подвергался критике со стороны нескольких математиков, в том числе его бывших членов, по разным причинам. Критика включала выбор представления одних тем в рамках Éléments за счет других, [В] неприязнь к методу изложения определенных тем, неприязнь к стилю работы группы и воспринимаемый элитарный менталитет вокруг проекта Бурбаки и его книг, особенно в самые продуктивные годы коллектива в 1950-х и 1960-х годах.

Обсуждения Бурбаки « Элементов» привели к включению некоторых тем, а другие не рассматривались. Когда в интервью 1997 года его спросили о темах, не включенных в Éléments , бывший участник Пьер Картье ответил:

По сути, нет никакого анализа, выходящего за рамки основ: ничего об уравнениях в частных производных , ничего о вероятности . Там также нет ничего о комбинаторике , ничего об алгебраической топологии , [х] ничего о конкретной геометрии . А Бурбаки никогда серьезно не задумывался о логике . Сам Дьедонне резко выступал против логики. все, что связано с математической физикой . В тексте Бурбаки полностью отсутствует

— Пьер Картье [64]

Хотя Бурбаки решил рассматривать математику с ее основ, окончательное решение группы в терминах теории множеств сопровождалось несколькими проблемами. Члены Бурбаки были математиками, а не логиками , и поэтому коллектив имел ограниченный интерес к математической логике . [93] Как говорили сами бурбаки о книге по теории множеств, она была написана «с болью и без удовольствия, но нам пришлось это сделать». [214] Дьедонне лично заметил в другом месте, что девяносто пять процентов математиков «наплевать» на математическую логику. [215] В ответ логик Адриан Матиас резко раскритиковал основополагающую концепцию Бурбаки, отметив, что она не принимает во внимание результаты Гёделя . [216] [217]

Бурбаки также повлиял на «Новую математику», провалившуюся [218] реформа западного математического образования на начальном и среднем уровнях, в которой упор делался на абстракцию, а не на конкретные примеры. В середине 20-го века реформа базового математического образования была стимулирована осознанной необходимостью создать математически грамотную рабочую силу для современной экономики, а также для конкуренции с Советским Союзом . Во Франции это привело к созданию Комиссии Лихнеровича 1967 года, которую возглавил Андре Лихнерович и в которую входили некоторые (действующие и бывшие) члены Бурбаки. Хотя члены Бурбаки ранее (и индивидуально) реформировали преподавание математики на университетском уровне, они имели менее непосредственное участие во внедрении Новой математики на уровнях начальной и средней школы. Новые реформы математики привели к созданию учебного материала, который был непонятен как ученикам, так и учителям и не отвечал познавательным потребностям младших школьников. Попытка реформы подверглась резкой критике со стороны Дьедонне, а также со стороны краткого участника Бурбаки Жана Лере. [219] Помимо французских математиков, французские реформы также встретили резкую критику со стороны математика советского происхождения Владимира Арнольда , который утверждал, что в его время, когда он был студентом и учителем в Москве, преподавание математики было прочно основано на анализе и геометрии и переплеталось с задачи классической механики; следовательно, французские реформы не могут быть законной попыткой подражать советскому научному образованию. В 1997 году, выступая на конференции по преподаванию математики в Париже, он прокомментировал Бурбаки, заявив: «Настоящие математики не объединяются в банды, но слабым нужны банды, чтобы выжить». и предположил, что объединение Бурбаки из-за «суперабстрактности» было похоже на объединение групп математиков XIX века, объединенных антисемитизмом. [220]

Позже Дьедонне сожалел, что успех Бурбаки способствовал снобизму в отношении чистой математики во Франции в ущерб прикладной математике . В интервью он сказал: «Можно сказать, что в течение сорока лет после Пуанкаре во Франции не было серьезной прикладной математики. Был даже снобизм по отношению к чистой математике. Когда замечали талантливого студента, ему говорили: «Вы должен заниматься чистой математикой». С другой стороны, можно было бы посоветовать посредственному студенту заниматься прикладной математикой, думая: «Это все, на что он способен! ... На самом деле все наоборот. Вы не сможете хорошо работать в прикладной математике, пока не сможете хорошо работать в чистой математике». [221] Клод Шевалле подтвердил наличие элитарной культуры внутри Бурбаки, охарактеризовав ее как «абсолютную уверенность в нашем превосходстве над другими математиками». [93] Александр Гротендик также подтвердил элитарный менталитет Бурбаки. [79] Некоторые математики, особенно геометры и прикладные математики, сочли влияние Бурбаки удушающим. [222] Решение Бенуа Мандельброта эмигрировать в Соединенные Штаты в 1958 году было частично мотивировано желанием избежать влияния Бурбаки во Франции. [223]

Несколько связанных критических замечаний в адрес Éléments касались его целевой аудитории и цели его представления. Тома « Элементов» начинаются с примечания к читателю, в котором говорится, что серия «сначала изучает математику и дает полные доказательства» и что «выбранный нами метод изложения является аксиоматическим и абстрактным и обычно исходит из общих к особенностям». [224] Несмотря на вступительный язык, предполагаемой аудиторией Бурбаки являются не абсолютные новички в математике, а скорее студенты, аспиранты и профессора, знакомые с математическими концепциями. [225] Клод Шевалле сказал, что Éléments «бесполезны для новичка». [226] а Пьер Картье пояснил: «Недоразумение заключалось в том, что это должно быть учебником для всех. Это было большой катастрофой». [64]

Работа разделена на две половины. В то время как первая половина — «Основные структуры анализа» — посвящена устоявшимся предметам, вторая половина посвящена современным областям исследований, таким как коммутативная алгебра и спектральная теория. Этот раскол в работе связан с историческим изменением цели трактата. Содержание Éléments состоит из теорем, доказательств, упражнений и соответствующих комментариев — обычного материала в учебниках по математике. Несмотря на эту презентацию, первая половина была написана не как оригинальное исследование , а скорее как реорганизованное изложение устоявшихся знаний. В этом смысле первая половина «Элементов» была больше похожа на энциклопедию , чем на серию учебников. Как заметил Картье: «Недоразумение заключалось в том, что многие люди считали, что ее следует преподавать так, как написано в книгах. Первые книги Бурбаки можно воспринимать как энциклопедию математики... Если рассматривать ее как учебник, это катастрофа». [64]

Строгое и упорядоченное изложение материала в первой половине «Элементов» должно было стать основой для любых дальнейших дополнений. Однако развитие современных математических исследований оказалось трудно адаптировать к организационной схеме Бурбаки. Эту трудность объясняют изменчивым и динамичным характером текущих исследований, которые, будучи новыми, не урегулированы и не полностью поняты. [195] [227] Стиль Бурбаки был описан как особая научная парадигма , которая была заменена в результате смены парадигмы . Например, Ян Стюарт процитировал Воана Джонса новую работу по теории узлов как пример топологии, которая была создана без зависимости от системы Бурбаки. [228] Влияние Бурбаки со временем снизилось; [228] этот спад частично объясняется отсутствием в трактате некоторых современных тем, таких как теория категорий. [81] [82]

Хотя многочисленные критические замечания указывали на недостатки проекта коллектива, одна из них также указала на его силу: Бурбаки стал «жертвой собственного успеха». [195] в том смысле, что он выполнил то, что намеревался сделать, достигнув своей первоначальной цели — представить подробный трактат по современной математике. [229] [230] [231] Эти факторы побудили биографа Мориса Машаля завершить свое рассмотрение Бурбаки следующими словами:

Такое предприятие заслуживает восхищения своим размахом, энтузиазмом и самоотверженностью, своим сильным коллективным характером. Несмотря на некоторые ошибки, Бурбаки все-таки добавил немного «чести человеческого духа». В эпоху, когда спорт и деньги являются такими великими идолами цивилизации, это немалое достоинство.

— Морис Машал [232]

См. также

[ редактировать ]Другие коллективные математические псевдонимы

Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ Симона Вейль не была участницей группы; она была философом, а не математиком. Однако она посетила несколько ранних конференций, чтобы поддержать своего брата Андре, а также изучить математику. [1]

- ↑ Ресторан, которого больше нет, находился на бульваре Сен-Мишель, 63. [29]

- ↑ Семинар Джулии проводился каждый второй понедельник во второй половине дня. [32] Ранние обеденные встречи Бурбаки в 1934–1935 годах обычно проводились в одни и те же понедельники, непосредственно перед семинаром. [30] [33] [34]

- ↑ Положительное мнение Дельсарта о коллективном проекте не было зафиксировано в протоколе первого собрания. Предполагается, что он выразил это мнение в другом месте, а Картан и Вейль в конечном итоге приписали это мнение ему. Однако это мнение тесно связано с сформировавшимся со временем стилем работы Бурбаки. [40]

- ↑ Математик Стерлинг К. Бербериан предположил другое возможное происхождение имени Бурбаки: Октава Мирбо 1900 года роман «Дневник горничной» , в котором описан еж по имени Бурбаки, который жадно ест. Однако Машааль отверг эту связь как маловероятную, поскольку основатели никогда не ссылались на роман, а только на генерала и анекдот о Хассоне. [53]

- ^ «Бурбаки пришел к соглашению с Пуанкаре только после долгой борьбы. Когда я присоединился к группе в пятидесятые годы, ценить Пуанкаре было вообще не модно. Он был старомодным». —Пьер Картье [64]

- ↑ Историк математики Лео Корри также заметил, что фраза «Сводка результатов» вводит в заблуждение по определенной причине: вместо этого она относится к содержанию « Элементов» , а не к истории публикации его томов. [129] [130]

- ^ Годы относятся к дате публикации первого тома каждой книги, который также содержит первую соответствующую главу. Есть два исключения: первая опубликованная часть «Теории множеств» представляла собой сводку результатов в 1939 году, а ее первая полноценная глава появилась только в 1954 году. Для дифференциальных и аналитических многообразий только двухтомное резюме результатов было опубликовано в 1967 и 1971 годы, без появления соответствующих глав.

- ↑ Дьедонне сразу же квалифицировал это сравнение как «очень плохую аналогию», продолжая: «математик не работает ни как машина, ни как рабочий на движущейся ленте; мы не можем переоценить фундаментальную роль, которую сыграл в его исследовании особая интуиция, которая не является популярной чувственной интуицией, а скорее своего рода прямым предсказанием... нормального поведения... математических существ». [146]

- ^ Примеры подопытных кроликов, которые посещали конференции, не обязательно присоединяясь, включают одну «Мирлес», которая присутствовала на официальной учредительной конференции в Бесс-ан-Шандессе, Марселя Берже , Жана Жиро , Бернара Мальгранжа и Рене Тома . [156] [157] [158] В список также включены другие морские свинки и посетители. [159]

- ↑ В 1948 году некто Николаидис Бурбаки, дипломат и родственник одноименного французского генерала, разыскал группу, чтобы понять, почему была взята фамилия. Дипломат и математический коллектив встречались в дружеских отношениях, а Николаидис был гостем на некоторых конференциях группы. [166] [167]

- ^ Даты относятся к поступлению в университет , а не к выпуску.

- ^ Секретность и неформальность Бурбаки затруднили установление дат вступления и ухода членов. Для бывших членов с неопределенными датами было высказано предположение, что периоды расцвета участников ( около 25–50 лет ) являются наилучшей доступной оценкой. [160]

- ↑ Некоторые участники посещали конференции в качестве подопытных кроликов в течение нескольких лет, прежде чем стали полноправными членами. Арманд Борель начал посещать конференции Бурбаки ок. 1949 г., став полноправным членом c. 1953 г. и уезжает в 1973 г. [172] Пьер Картье впервые посетил конференцию Бурбаки в качестве подопытного кролика в 1951 году, стал полноправным членом в 1955 году и покинул ее в 1983 году. [64] [173] Если источники делают различие, дата полного членства указывается или приближается.

- ↑ В состав поколения основателей коллектива входила основная группа из пяти человек. [124] который руководил ее деятельностью и устанавливал ее нормы, оставаясь активным в течение нескольких лет. Еще шесть второстепенных членов участвовали на краткосрочной основе в первые дни его существования, от нескольких месяцев до нескольких лет.

- ↑ Аксель описал Шварца как члена представителей разных поколений, единственного, кто присоединился во время Второй мировой войны. Однако Шварц не участвовал в создании группы.

- ^ Большинство других участников родились после трех вышеупомянутых поколений и поэтому были активны в группе позже. Однако двое родились современниками поколения основателей: Шарль Писо в 1909 году и Клод Шаботи в 1910 году.

- ↑ Картье и Аксель также описали четвертое поколение членов Бурбаки (в отличие от более поздних членов в целом), бывших учеников Гротендика, которые присоединились к нему в 1960-х годах. [64] [80] Это может относиться к тем из докторантов Гротендика, которые позже стали членами Бурбаки, таким как Мишель Демазюр и Жан-Луи Вердье . [174]

- ↑ Мандельброт был племянником основателя Бурбаки Солема Мандельбройта. [115] [193] Как и один из первых соратников Бурбаки Гастон Джулия, Мандельброт также работал над фракталами.

- ↑ Морис Машаал и Амир Аксель написали отдельные биографии Бурбаки, обе опубликованы в 2006 году. В обзоре обеих книг Майкл Атья написал, что «основные исторические факты хорошо известны и изложены в обеих рецензируемых книгах». Однако Атья назвал книгу Машааля лучшей из двух и раскритиковал книгу Акселя, написав: «Я не был убежден ни в полной надежности ее источников (Акцеля), ни в ее философских авторитетах». Атья также написал, что сотрудничество между Вейлем и Леви-Стросом было «слегка слабой связью», которую Аксель использовал, чтобы сделать «грандиозные» заявления о масштабах междисциплинарного влияния Бурбаки. [195]

- ↑ В письме в журнал Mathematical Intelligencer в 2011 году математик Жан-Мишель Кантор [де] резко критиковал представление о том, что математические структуры Бурбаки имеют какое-либо отношение к структурализму гуманитарных наук, отвергая связи, установленные Акселем в 2006 году. [196] Кантор заметил, что две версии структурализма развивались независимо друг от друга и что концепция структуры Леви-Стросса произошла от кружка пражского лингвистического , а не от Бурбаки. С другой стороны, Аксель уже признал лингвистические истоки структурализма гуманитарных наук. [197] В 1997 году Дэвид Обен упреждающе смягчил обе крайности, отметив, что две школы мысли имели разное происхождение, но также имели определенные взаимодействия и «общие черты». Обен также процитировал Леви-Стросса, чтобы показать, что последний пришел к определенным выводам в антропологии независимо от математической помощи Вейля, хотя помощь Вейля обеспечила подтверждение выводов Леви-Стросса. [198] Это подорвало аргумент Акселя о том, что математика и Бурбаки сыграли важную роль в развитии структурализма в гуманитарных науках, хотя Обен также подчеркивал, что между двумя школами было определенное сотрудничество.

- ^ Точно так же Бурбаки создал прозвища для своих членов. Жана Дельсарта называли «епископом», что могло быть отсылкой к его католицизму. [207]

- ^ Этот конкретный момент сам по себе подвергся критике. Было замечено, что несправедливо критиковать работу по определенной теме за то, что она не затрагивает другие темы. [212] [213]

- ^ С тех пор Бурбаки опубликовал книгу по алгебраической топологии.

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Аксель , стр. 123–25.

- ^ Машааль , с. 31.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Вейль, Андре (1992). Ученичество математика . Биркхойзер Верлаг. стр. 93–122 . ISBN 978-3764326500 .

- ^ Болье 1999 , с. 221.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Аксель , стр. 129–48.

- ^ Обен , с. 314.

- ^ Машааль , стр. 70–85.

- ^ Аксель , стр. 61–63.

- ^ Машааль , стр. 22–25.

- ^ Борель , с. 373.

- ^ Аксель , с. 82.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Машааль , стр. 44–45.

- ^ Аксель , стр. 63–65.

- ^ Машааль , с. 23.

- ^ Аксель , стр. 25–26.

- ^ Машааль , стр. 35–37.

- ^ Болье 1999 , с. 239.

- ^ Аксель , с. 65.

- ^ Косамби, Дамодар Дхармананда (2016). «Об одном обобщении второй теоремы Бурбаки». Д.Д. Косамби . стр. 55–57. дои : 10.1007/978-81-322-3676-4_6 . ISBN 978-81-322-3674-0 .

- ^ Машааль , с. 26.

- ^ Машааль , с. 35.

- ^ Аксель , стр. 32–34.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Аксель , с. 81.

- ^ Машааль , с. 4.

- ^ Аксель , стр. 82–83.

- ^ Болье 1993 , с. 28.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Машааль , с. 6.

- ^ О'Коннор, Джон Дж.; Робертсон, Эдмунд Ф. (декабрь 2005 г.). «Бурбаки: предвоенные годы» . Мактутор .

- ^ Болье 1993 , с. 29.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Болье 1993 , с. 32.

- ^ Машааль , стр. 6–7, 102–03.

- ^ Машааль , с. 103.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Архив Ассоциации коллаборационистов Николя Бурбаки» .

- ^ «Календарь на 1935 год (Франция)» . Время и дата .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Аксель , с. 84.

- ^ Болье 1999 , с. 233.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Мишон, Жерар П. «Многоликий Николя Бурбаки» . Нумерикана .

- ^ Машааль , стр. 38–45.

- ^ Машааль , стр. 7, 14.

- ^ Болье 1993 , стр. 28–29.

- ^ Аксель , стр. 85–86.

- ^ Обен , с. 303.

- ^ Аксель , с. 86.

- ^ Болье 1993 , с. 30.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Машааль , с. 11.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Аксель , с. 87.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Машааль , с. 8.

- ^ Болье 1993 , с. 33.

- ^ Машааль , стр. 8–9.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Аксель , с. 90.

- ^ Машааль , с. 10.

- ^ Машааль , с. 22.

- ^ Машааль , стр. 25–26.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Машааль , стр. 27–29.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Мейнард, Роберт (21 октября 2001 г.). «Движение Бурбаки» (PDF) . academie-stanislas.org .

- ^ Машааль , с. 27.

- ^ Макклири, Джон (10 декабря 2004 г.). «Бурбаки и алгебраическая топология» (PDF) . math.vassar.edu . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 30 октября 2006 г.

- ^ Бурбаки, Николя (18 ноября 1935 г.). «Об одной теореме Каратеодори и измерении в топологических пространствах» . Известия Академии наук . 201 : 1309–11.

- ^ Машааль , с. 17.

- ^ «Ухабистая дорога к Первому съезду Бурбаки» . Neverendingbooks.org . 22 октября 2009 г.

- ^ «Рольф Неванлинна» . icmihistory.unito.it .

- ^ Аксель , стр. 17–36.

- ^ Осмо Пеконен : Дело Вейля в Хельсинки в 1939 году , Gazette des mathematiciens 52 (апрель 1992 г.), стр. 13–20. С послесловием Андре Вейля.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м н тот п д р с Сенешаль , стр. 22–28.

- ^ Аксель , с. 40.

- ^ Аксель , с. 98.

- ^ Машааль , стр. 20–24.

- ^ Аксель , с. 117.

- ^ Болье 1999 , с. 237.

- ^ Машааль , с. 19.

- ^ Гуедж , с. 19.

- ^ Машааль , с. 49.

- ^ Машааль , стр. 14–16.

- ^ «Сэр Майкл Атья вспоминает победу Филдса» . Международный конгресс математиков . 3 августа 2018 г. Архивировано из оригинала 22 сентября 2019 г. . Проверено 15 февраля 2020 г. .

- ^ Гротендик, Александр. «Письмо о премии Крафорда, английский перевод» (PDF) . Архивировано из оригинала 6 января 2006 года . Проверено 17 июня 2005 г.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: исходный статус URL неизвестен ( ссылка ) - ^ Аксель , стр. 9–10.

- ^ Обен , с. 328.

- ^ Болье 1999 , стр. 236–37.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Корри 2009 , стр. 38–51.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Аксель , с. 119.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Аксель , с. 205.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Машааль , стр. 81–84.

- ^ Аксель , стр. 205–206.

- ^ Машааль , стр. 7, 51–54.

- ^ Серия «Элементы математики» в Springer

- ^ Машааль , с. 146.

- ^ Бурбаки, Николя (2019). Спектральные теории: главы 1 и 2 — Второе издание, переработанное и дополненное . Элементы математики. Спрингер. п. II.299. ISBN 978-3030140632 .

- ^ Бурбаки, Николя (2023b). Спектральные теории: главы с 3 по 5 . Элементы математики. Спрингер. п. В.416. ISBN 978-3031195044 .

- ^ Бурбаки, Николя (2002). Группы Ли и алгебры Ли, главы 4–6 . Спрингер. стр. 205–206. ISBN 978-3540691716 .

- ^ Аксель , с. 92.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Борель , с. 375.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Гедж , с. 18.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Гедж , с. 20.

- ^ Аксель , с. 116.

- ^ Борель , с. 376.

- ^ Машааль , с. 69.

- ^ Аксель , стр. 111–12.

- ^ Болье 1999 , стр. 225–26.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Машааль , стр. 112–13.

- ^ Кауфман, Луи Х. (2005). Предисловие. BIOS: исследование творения . Сабелли, Гектор. Серия «Узлы и все такое». Том. 35. Сингапур: World Scientific . п. 423. ИСБН 978-9812561039 .

- ^ Корри, Лео (1997). «Истоки вечной истины в современной математике: от Гильберта до Бурбаки и далее» . Наука в контексте . 10 (2): 279. doi : 10.1017/S0269889700002659 . S2CID 54803469 .

- ^ Корри 2004 , с. 309.

- ^ Аксель , с. 115.

- ^ Машааль , с. 112.

- ^ Болье 1999 , с. 245.

- ^ Болье 1999 , стр. 239–40.

- ^ Машааль , стр. 30, 113–14.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Болье 1999 , с. 226.

- ^ Машааль , стр. 110–11.

- ^ Болье 1999 , с. 241.

- ^ Машааль , стр. 33–34.

- ^ Аксель , стр. 121–23.

- ^ Болье 1999 , стр. 241–42.

- ^ «По Гроту. IV.22» . Neverendingbooks.org . 1 октября 2016 года . Проверено 24 октября 2018 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Болье 1993 , с. 31.

- ^ Болье 1999 , с. 227.

- ^ Машааль , с. 115.

- ^ Бетти_Бурбаки. «Официальный Twitter-аккаунт Ассоциации коллаборационистов Н. Бурбаки» . Твиттер .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж «Элементы математики» . Архив Бурбаки .

- ^ Машааль , стр. 108–09.

- ^ Матиас, ARD (2002). «Срок продолжительностью 4 523 659 424 929» . Синтезируйте . 133 (1/2): 75–86. дои : 10.1023/А:1020827725055 . ISSN 0039-7857 . JSTOR 20117295 . Проверено 5 января 2024 г.

АБСТРАКТНЫЙ. Бурбаки предполагают, что их определение числа 1 насчитывает несколько десятков тысяч символов. Мы показываем, что это существенно заниженная оценка, поскольку истинное количество символов равно количеству символов в заголовке, не считая 1 179 618 517 981 связей между символами, которые необходимы для устранения неоднозначности всего выражения.

- ^ Барани, Майкл (24 марта 2021 г.). «Математические шутники за спиной Николя Бурбаки» . JSTOR Daily . Проверено 5 января 2024 г.

- ^ Аксель , стр. 99–100.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Борель , с. 374.

- ^ Машааль , с. 55.

- ^ Теория множеств , стр. v-vi.

- ^ Машааль , с. 83.

- ^ Азимов, Исаак (20 марта 1991 г.). предисловие. История математики . Бойер , Карл Б .; Мерцбах, Ута К. (второе изд.). Уайли. п. 629. ИСБН 9780471543978 .

- ^ Корри 1992 , с. 326.

- ^ Корри 2004 , с. 320.

- ^ Машааль , с. 52.

- ^ Багемил, Фредерик (1958). «Обзор: Теория ансамблей (Глава III)» (PDF) . Бюллетень Американского математического общества . 64 (6): 390–91. дои : 10.1090/s0002-9904-1958-10248-7 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Артин, Эмиль (1953). «Обзор: Элементы математики Н. Бурбаки, Книга II, Алгебра . Главы I – VII» (PDF) . Бюллетень Американского математического общества . 59 (5): 474–79. дои : 10.1090/s0002-9904-1953-09725-7 .

- ^ Розенберг, Алекс (1960). «Рецензия: Элементы математики Н. Бурбаки. Книга II, Алгебра. Глава VIII, Модули и полупростые кольца » (PDF) . Бюллетень Американского математического общества . 66 (1): 16–19. дои : 10.1090/S0002-9904-1960-10371-0 .

- ^ Каплански, Ирвинг (1960). «Обзор: Полуторалинейные формы и квадратичные формы Н. Бурбаки, Элементы математики I, Книга II» (PDF) . Бюллетень Американского математического общества . 66 (4): 266–67. дои : 10.1090/s0002-9904-1960-10461-2 .

- ^ Халмош, Пол (1953). «Обзор: Интеграция (главы I – IV) Н. Бурбаки» (PDF) . Бюллетень Американского математического общества . 59 (3): 249–55. дои : 10.1090/S0002-9904-1953-09698-7 .

- ^ Манро, Мэн (1958). «Обзор: Интеграция (Глава V) Н. Бурбаки» (PDF) . Бюллетень Американского математического общества . 64 (3): 105–06. дои : 10.1090/s0002-9904-1958-10176-7 .

- ^ Нагата, Масаеши (1985). « Элементы математики. Коммутативная алгебра» , Н. Бурбаки, главы 8 и 9» (PDF) . Бюллетень Американского математического общества . Новая серия. 12 (1): 175–77. дои : 10.1090/s0273-0979-1985-15338-8 .

- ^ Бурбаки, Николя (2016). Алгебраическая топология, главы с 1 по 4 . Спрингер. дои : 10.1007/978-3-662-49361-8 . ISBN 978-3-662-49360-1 . Проверено 8 февраля 2016 г.

- ^ «Редакторы семинарии» . Ассоциация сотрудников Николя Бурбаки.

- ^ Машааль , стр. 98–99.

- ^ Обен , стр. 305–08.

- ^ Корри 1997 , стр. 272–73.

- ^ Корри 2004 , стр. 303–05.

- ^ Бурбаки 1950 , стр. 224–26.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Бурбаки 1950 , с. 227.

- ^ Машааль , стр. 108–11.

- ^ Болье 1999 , с. 234.

- ^ Болье 1999 , с. 224.

- ^ Болье 1999 , стр. 231–32.

- ^ Машааль , с. 18.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Болье 1999 , с. 220.

- ^ Аксель , стр. 108–09.

- ^ Машааль , с. 14.

- ^ Машааль , с. 16.

- ^ Обен , с. 330.

- ^ Болье 1999 , с. 242.

- ^ Машааль , стр. 9, 109, 130.

- ^ «Члены, присутствующие на собраниях» . Архив Бурбаки .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Машааль , стр. 18–19.

- ^ Обен , с. 298.

- ^ Болье 1999 , с. 248.

- ^ Обен , с. 304.

- ^ Машааль , с. 12.

- ^ Машааль , стр. 111–12.

- ^ Болье 1999 , с. 236.

- ^ Машааль , стр. 29, 33.

- ^ Кремер 2006 , стр. 149–150.

- ^ Корри 2009 , стр. 581–584.