Венгерское дворянство

| История Венгрии |

|---|

|

|

|

с В Венгерском королевстве существовал дворянский класс людей, большинство из которых владели земельной собственностью 11 века до середины 20 века . Первоначально дворянами считались самые разные люди, но с конца XII века благородными считались только высокопоставленные королевские чиновники. Большинство аристократов заявляли о своем происхождении от вождей периода, предшествовавшего созданию королевства около 1000 года; другие произошли от западноевропейских рыцарей, поселившихся в Венгрии. низшего ранга Воины замка также владели земельной собственностью и служили в королевской армии. С 1170-х годов большинство привилегированных мирян называли себя королевскими слугами, чтобы подчеркнуть свою прямую связь с монархами. Золотая булла 1222 года установила их свободы, особенно освобождение от налогов и ограничение военных повинностей. С 1220-х годов королевские слуги были связаны с дворянством, а высшие чиновники были известны как бароны королевства. только те, кто владел аллодами – землями, свободными от обязательств, но другие привилегированные группы землевладельцев, известные как Истинными дворянами считались условные дворяне тоже существовали.

In the 1280s, Simon of Kéza was the first to claim that noblemen held authority in the kingdom. The counties developed into institutions of noble autonomy, and the nobles' delegates attended the Diets (parliaments). The wealthiest barons built stone castles allowing them to control vast territories, but royal authority was restored in the early 14th century. In 1351, King Louis I introduced an entail system and enacted the principle of "one and the selfsame liberty" of all noblemen, but legal distinctions between true noblemen and conditional nobles prevailed. The most powerful nobles employed lesser noblemen as their familiares (retainers) but this private link did not sever the familiaris' direct subjection to the monarch. According to customary law, only males inherited noble estates, but under the Hungarian royal prerogative of prefection the kings could promote "a daughter to a son", allowing her to inherit her father's lands. Noblewomen who had married a commoner could also claim their inheritance – the daughters' quarter (that is one-quarter of their father's possessions) – in land.

Although the Tripartitum – a frequently cited compilation of customary law published in 1514 – reinforced the idea that all noblemen were equal, the monarchs granted hereditary titles to powerful aristocrats, and the poorest nobles lost their tax exemption from the mid-16th century. In the early modern period, because of the expansion of the Ottoman Empire, Hungary was divided into three parts: Royal Hungary, Transylvania and Ottoman Hungary. The princes of Transylvania supported the noblemen's fight against the Habsburg dynasty in Royal Hungary, but prevented the Transylvanian noblemen from challenging their own authority. Ennoblement of whole groups of people was not unusual in the 17th century. Examples include the 10,000 hajdú who received nobility as a group in 1605. After the Diet was divided into two chambers in Royal Hungary in 1608, noblemen with a hereditary title had a seat in the upper house, other nobles sent delegates to the lower house.

After the Ottomans' defeat in the Great Turkish War in the late 17th century, Transylvania and Ottoman Hungary were integrated into the Habsburg monarchy. The Habsburgs confirmed the nobles' privileges several times, but their attempts to strengthen royal authority regularly brought them into conflicts with the nobility, who represented nearly five percent of the population. Reformist noblemen demanded the abolition of noble privileges from the 1790s, but their program was enacted only during the Hungarian Revolution of 1848. Most noblemen lost their estates after the emancipation of their serfs, but the aristocrats preserved their distinguished social status. State administration employed thousands of impoverished noblemen in Austria-Hungary. Prominent (mainly Jewish) bankers and industrialists were awarded with nobility, but their social status remained inferior to traditional aristocrats. Noble titles were abolished only in 1947, months after Hungary was proclaimed a republic.

Origins

[edit]

The Magyars (or Hungarians) lived in the Pontic steppes when they first appear in written sources from the mid-9th century.[1] Muslim merchants described them as wealthy nomadic warriors, but they also noticed the Magyars had extensive arable lands.[2][3] The Magyars crossed the Carpathian Mountains after the Pechenegs invaded their lands in 894 or 895.[4] They settled in the lowlands along the Middle Danube, annihilated Moravia and defeated the Bavarians in the 900s.[5][6] According to some scholarly theories, at least three Hungarian noble clans[note 1] were descended from Moravian aristocrats who survived the Magyar conquest.[8] Historians who are convinced that the Vlachs (or Romanians) were already present in the Carpathian Basin in the late 9th century propose that the Vlach knezes (or chieftains) also endured.[9][10] Neither of these hypotheses are universally accepted.[11][12]

Around 950, the Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (r. 913–959) wrote that the Hungarians were organized into "tribes", and each had its own "prince".[13][14] The tribal leaders most probably bore the title úr (now "lord"), as it is suggested by Hungarian terms deriving from this word, such as ország (now "realm") and uralkodni ("to rule").[15] The Emperor noted the Magyars spoke both Hungarian and "the tongue of the Chazars"[16] (a powerful steppe people), showing that at least their leaders were bilingual.[17]

The Magyars lived a nomadic or semi-nomadic life but archaeological research shows that most settlements consisted of small pit-houses and log cabins in the 10th century. Tents in use are only mentioned in 12th-century literary sources.[18] No archeological finds evidence fortresses in the Carpathian Basin in the 10th century, but fortresses were also rare in Western Europe during the same period.[19][20] A larger log cabin – measuring five by five metres (16 ft × 16 ft) – which was built on a foundation of stones in Borsod was tentatively identified as the local leader's household.[19]

More than a 1,000 graves yielding sabres, arrow-heads and bones of horses show that mounted warriors formed a significant group in the 10th century.[21] The highest-ranking Hungarians were buried either in large cemeteries (where hundreds of their men were buried without weapons around their leader's burial place), or in small cemeteries with 25–30 graves.[22] The wealthy warriors' burial sites yielded richly decorated horse harness, and sabretaches ornamented with precious metal plaques.[23] Rich women's graves contained their braid ornaments and rings made of silver or gold and decorated with precious stones.[23] The most widespread decorative motifs which can be regarded as tribal totems – the griffin, wolf and hind – were rarely applied in Hungarian heraldry in the following centuries.[24] Defeats during the Hungarian invasions of Europe and clashes with the paramount rulers from the Árpád dynasty had decimated the leading families by the end of the 10th century.[25] The Gesta Hungarorum, a chronicle written around 1200, claimed that dozens of noble kindred flourishing in the late 12th century[note 2] had been descended from tribal leaders, but most modern scholars do not regard this list as a reliable source.[27][26]

Middle Ages

[edit]Development

[edit]Stephen I (r. 997–1038), who was crowned the first king of Hungary in 1000 or 1001, defeated the last resisting tribal chieftains.[28][29] Earthen forts were built throughout the kingdom and most of them developed into centers of royal administration.[30] About 30 administrative units, known as counties, were established before 1040; more than 40 new counties were organized during the next centuries.[31][32][33] Each county was headed by a royal official, the ispán.[34] The royal court provided further career opportunities.[35] As the historian Martyn Rady noted, the "royal household was the greatest provider of largesse in the kingdom" where the royal family owned more than two thirds of all lands.[36] The palatine – the head of the royal household – was the highest-ranking royal official.[37]

The kings from the Árpád dynasty appointed their officials from among the members of about 110 aristocratic clans.[37][38] These aristocrats were descended either from native (that is, Magyar, Kabar, Pecheneg or Slavic) chiefs, or from foreign knights who had migrated to the country in the 11th and 12th centuries.[39][40] The foreign knights had been trained in the Western European art of war, which contributed to the development of heavy cavalry in Hungary.[41][42] Their descendants were labelled as newcomers for centuries,[43] but intermarriage between natives and newcomers was not rare, which enabled their integration in two or three generations.[44] The monarchs pursued an expansionist policy from the late 11th century.[45] Ladislaus I (r. 1077–1095) seized Slavonia – the plains between the river Drava and the Dinaric Alps – in the 1090s.[46][47] His successor, Coloman (r. 1095–1116), was crowned king of Croatia in 1102.[48] Both realms retained their own customs, and Hungarians rarely received land grants in Croatia.[48] According to customary law, Croatians could not be obliged to cross the river Drava to fight in the royal army at their own expense.[49]

The earliest royal decrees authorized landowners to dispose freely of their private estates, but customary law prescribed that inherited lands could only be transferred with the consent of the owner's kinsmen who could potentially inherit them.[50][51] From the early 12th century, only family lands traceable back to a grant made by Stephen I could be inherited by the deceased owner's distant relatives; other estates escheated to the Crown if their owner did not have offspring or brothers.[51][52] Aristocratic families held their inherited domains in common for generations before the 13th century.[41] Thereafter the division of inherited property became the standard practice.[41] Even families descended from wealthy clans could become impoverished through the regular divisions of their estates.[53]

Medieval documents mention the basic unit of estate organization as praedium or allodium.[54][55] A praedium was a piece of land (either a whole village or part of it) with well-marked borders.[54][55] Archaeologist Mária Wolf identifies the small motte forts, built on artificial mounds and protected by a ditch and a palisade that appeared in the 12th century, as the centers of private estates.[56] Most wealthy landowners' domains consisted of scattered praedia, in several villages.[57] Due to the scarcity of documentary evidence, the size of the private estates cannot be determined.[58] The descendants of Otto Győr, the ispán of Somogy County remained wealthy landowners even after he donated 360 households to the newly established Zselicszentjakab Abbey in 1061.[59] The establishment of monasteries by wealthy individuals was common.[41] Such proprietary monasteries served as burial places for their founders and the founders' descendants, who were regarded as the co-owners, or from the 13th century, co-patrons, of the monastery.[41] Serfs cultivated part of the praedium, but other plots were hired out in return for in-kind taxes.[55]

The term "noble" was rarely used and poorly defined before the 13th century: it could refer to a courtier, a landowner with judicial powers, or even to a common warrior.[38] The existence of a diverse group of warriors, who were subjected to the monarch, royal officials or prelates is well documented.[60] The castle warriors, who were exempt from taxation, held hereditary landed property around the royal castles.[61][62] Lightly armored horsemen, known as lövők (or archers), and armed castle folk, mentioned as őrök (or guards), defended the borderlands.[63]

Golden Bulls

[edit]

Official documents from the end of the 12th century only mentioned court dignitaries and ispáns as noblemen.[38] This group had adopted most elements of chivalric culture.[64][65] They regularly named their children after Paris of Troy, Hector, Tristan, Lancelot and other heroes of Western European chivalric romances.[64] The first tournaments were held around the same time.[66]

The regular alienation of royal estates is well-documented from the 1170s.[67] The monarchs granted immunities, exempting the grantee's estates from the jurisdiction of the ispáns, or even renouncing royal revenues that had been collected there.[67] Béla III (r. 1172–1196) was the first Hungarian monarch to give away a whole county to a nobleman: he granted Modrus in Croatia to Bartholomew of Krk in 1193, stipulating that the grantee was to equip warriors for the royal army.[68] Béla's son, Andrew II (r. 1205–1235), decided to "alter the conditions" of his realm and "distribute castles, counties, lands and other revenues" to his officials, as he narrated in a document in 1217.[69] Instead of granting the estates in fief, with an obligation to render future services, he gave them as allods, in reward for the grantee's previous acts.[70] The great officers who were the principal beneficiaries of his grants were mentioned as barons of the realm from the late 1210s.[71][72]

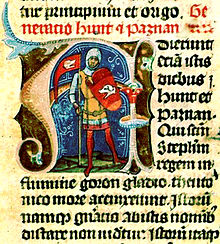

Donations of such a large scale accelerated the development of a wealthy group of landowners, most descending from a high-ranking kindred.[71][72] Some wealthy landowners[note 3] could afford to build stone castles.[73] Closely related aristocrats were distinguished from other lineages through a reference to their (actual or presumed) common ancestor with the words de genere ("from the kindred").[74] Families descending from the same kindred adopted similar insignia.[note 4][75] The author of the Gesta Hungarorum fabricated genealogies for them and emphasized that they could never be excluded from "the honor of the realm",[76] that is from state administration.[53]

The new owners of the transferred royal estates wanted to subjugate the freemen, castle warriors and other privileged groups of people living in or around their domains.[77] The threatened groups wanted to achieve confirmation of their status as royal servants, emphasizing that they were only to serve the king.[78][79] Béla III issued the first extant royal charter about the grant of this rank to a castle warrior.[80] Andrew II's Golden Bull of 1222 enacted royal servants' privileges.[81] They were exempt from taxation; they were to fight in the royal army without proper compensation only if enemy forces invaded the kingdom; only the monarch or the palatine could judge their cases.[82][83][84] According to the Golden Bull, only royal servants who died without a son could freely will their estates, but even in this case, their daughters were entitled to the daughters' quarter.[82][85] The final article of the Golden Bull authorized the bishops, barons and other nobles to resist the monarch if he ignored its provisions.[86] Most provisions of the Golden Bull were first confirmed in 1231.[87]

The clear definition of the royal servants' liberties distinguished them from all other privileged groups, whose military obligations remained theoretically unlimited.[81] From the 1220s, the royal servants were regularly called noblemen and started to develop their own corporate institutions at the county level.[88] In 1232, the royal servants of Zala County asked Andrew II to authorize them "to judge and do justice", stating that the county had slipped into anarchy.[89] The king granted their request and Bartholomew, Bishop of Veszprém, sued one Ban Oguz for properties before their community.[89]

The first Mongol invasion of Hungary in 1241 proved the importance of well-fortified locations and heavily armored cavalry.[90][91] In the following decades, Béla IV of Hungary (r. 1235–1270) gave away large parcels of the royal demesne, expecting that the new owners would build stone castles there.[92][93] Béla's burdensome castle-building program was unpopular, but achieved his aim: almost 70 castles were built or reconstructed during his reign.[94] More than half of the new or reconstructed castles were in noblemen's domains.[95] Most new castles were erected on rocky peaks, mainly along the western and northern borderlands.[96] The spread of stone castles profoundly changed the structure of landholding, because castles could not be maintained without proper income.[97] Lands and villages were legally attached to each castle, and castles were thereafter always transferred and inherited along with these "appurtenances".[98]

The royal servants were legally identified as nobles in 1267.[99] That year "the nobles of all Hungary, called royal servants" persuaded Béla IV and his son, Stephen V (r. 1270–1272), to hold an assembly and confirm their collective privileges.[99] Other groups of land-holding warriors could also be called nobles, but they were always distinguished from the true noblemen.[100][101] They held their estates conditionally, as they were required to provide well-defined services to another lord, hence their groups are now collectively known as conditional nobles.[102] The noble Vlach knezes who had landed property in the Banate of Severin were obliged to fight in the army of the ban (or royal governor).[103] Most warriors known as the "noble sons of servants" were descended from freemen or liberated serfs who received estates from Béla IV in Upper Hungary on the condition that they were to equip jointly a fixed number of knights.[100][104] The nobles of the Church formed the armed retinue of the wealthiest prelates.[101][105] The nobles of Turopolje in Slavonia were required to provide food and fodder to high-ranking royal officials.[106] Two privileged groups, the Székelys and Saxons firmly protected their communal liberties, which prevented their leaders from exercising noble privileges in the Székely and Saxon territories in Transylvania.[107] Székelys and Saxons could only enjoy the liberties of noblemen if they held estates outside the lands of the two privileged communities.[107]

Most noble families failed to adopt a strategy to avoid the division of their inherited estates into dwarf-holdings through generations.[108] Daughters could only demand the cash equivalent of the quarter of their father's estates,[109] but younger sons rarely remained unmarried.[108] Impoverished noblemen had little chance to receive land grants from the kings, because they were unable to participate in the monarchs' military campaigns,[110] but commoners who bravely fought in the royal army were regularly ennobled.[111]

Self-government and oligarchs

[edit]

The historian Erik Fügedi noted that "castle bred castle" in the second half of the 13th century: if a landowner erected a fortress, his neighbors would also build one to defend their own estates.[112] Between 1271 and 1320, noblemen or prelates built at least 155 new fortresses. In comparison, only about a dozen castles were erected on the royal demesne.[113] Most castles consisted of a tower, surrounded by a fortified courtyard, but the tower could also be built into the walls.[114] Noblemen who could not erect fortresses were occasionally forced to abandon their inherited estates or seek the protection of more powerful lords, even through renouncing their liberties.[note 5][116]

The lords of the castles had to hire a professional staff for the defence of the castle and the management of its appurtenances.[117] They primarily employed nobles who held nearby estates, which gave rise to the development of a new institution, known as familiaritas.[118][119] A familiaris was a nobleman who entered into the service of a wealthier landowner in exchange for a fixed salary or a portion of revenue, or rarely for the ownership or usufruct (right to enjoyment) of a piece of land.[119] Unlike a conditional noble, a familiaris remained de jure an independent landholder, only subject to the monarch.[115][120]

From the 1270s, the monarchs' coronation oath included a promise to respect the noblemen's liberties.[121] The counties gradually transformed into an institution of the noblemen's local autonomy.[122] Noblemen regularly discussed local matters at the counties' general assemblies.[123][124] The sedria (the counties' law courts) became important elements in the administration of justice.[89] They were headed by the ispáns or their deputies, but they consisted of four (in Slavonia and Transylvania, two) elected local noblemen, known as judges of the nobles.[89][99]

Hungary fell into a state of anarchy because of the minority of Ladislaus IV (r. 1272–1290) in the early 1270s. To restore public order, the prelates convoked the barons and the delegates of the noblemen and the nomadic Cumans who had settled in Hungary to a general assembly near Pest in 1277. This first Diet (or parliament) declared the fifteen-year-old monarch to be of age in an attempt to put en end to the anarchy.[125] In the early 1280s, Simon of Kéza associated the Hungarian nation with the nobility in his Deeds of the Hungarians, emphasizing that the community of noblemen held real authority.[121][126]

The barons took advantage of the weakening of royal authority and seized large, contiguous territories.[127] The monarchs could not appoint and dismiss their officials at will anymore.[127] The most powerful barons – known as oligarchs in modern historiography – appropriated royal prerogatives, combining private lordship with their administrative powers.[128] When Andrew III (r. 1290–1301), the last male member of the Árpád dynasty, died in 1301, about a dozen lords[note 6] held sway over most parts of the kingdom.[130]

Age of the Angevins

[edit]

Ladislaus IV's great-nephew, Charles I (r. 1301–1342), who was a scion of the Capetian House of Anjou, restored royal power in the 1310s and 1320s.[131] He seized the oligarchs' castles mainly by force, which again secured the preponderance of the royal demesne.[132] He refuted the Golden Bull in 1318 and claimed that noblemen had to fight in his army at their own expense.[133] He ignored customary law and regularly "promoted a daughter to a son", granting her the right to inherit her father's estates.[134][135][136] The King reorganized the royal household, appointing pages and knights to form his permanent retinue.[137] He established the Order of Saint George, which was the first chivalric order in Europe.[132][66] Charles I was the first Hungarian monarch to grant coats of arms (or rather crests) to his subjects.[138] He based royal administration on honors (or office fiefs), distributing most counties and royal castles among his highest-ranking officials.[131][132][139] These "baronies", as the historian Matteo Villani (d. 1363) recorded it in about 1350, were "neither hereditary nor lifelong", but Charles rarely dismissed his most trusted barons.[140][141] Each baron was required to hold his own banderium (or armed retinue), distinguished by his own banner.[142]

In 1351, Charles's son and successor, Louis I (r. 1342–1382) confirmed all provisions of the Golden Bull, save the one that authorized childless noblemen to freely will their estates.[143][144] Instead, he introduced an entail system, prescribing that childless noblemen's landed property "should descend to their brothers, cousins and kinsmen".[145] This new concept of aviticitas also protected the Crown's interests: only kin within the third degree could inherit a nobleman's property and noblemen who had only more distant relatives could not dispose of their property without the king's consent.[146] Louis I emphasized all noblemen enjoyed "one and the selfsame liberty" in his realms[143] and secured all privileges that nobles owned in Hungary proper to their Slavonian and Transylvanian peers.[147] He rewarded dozens of Vlach knezes with true nobility for military merits.[148] The vast majority of the Upper Hungarian "noble sons of servants" achieved the status of true noblemen without a formal royal act, because the memory of their conditional landholding fell into oblivion.[149] Most of them preferred Slavic names even in the 14th century, showing that they spoke the local Slavic vernacular.[150] Other groups of conditional nobles remained distinguished from true noblemen.[151] They developed their own institutions of self-government, known as seats or districts.[152] Louis decreed that only Catholic noblemen and knezes could hold landed property in the district of Karánsebes (now Caransebeș in Romania) in 1366, but Eastern Orthodox landowners were not forced to convert to Catholicism in other territories of the kingdom.[153] Even the Catholic bishop of Várad (now Oradea in Romania) authorized his Vlach voivodes (leaders) to employ Orthodox priests.[154] The king granted the Transylvanian district of Fogaras (around present-day Făgăraș in Romania) to Vladislav I of Wallachia (r. 1364–1377) in fief in 1366.[155] In his new duchy, Vladislav donated estates to Wallachian boyars; their legal status was similar to the position of the knezes in other regions of Hungary.[156]

Royal charters customarily identified noblemen and landowners from the second half of the 14th century.[157] A man who lived in his own house on his own estates was described as living "in the way of nobles", in contrast with those who did not own landed property and lived "in the way of peasants".[147] A verdict of 1346 declared that a noble woman who was given in marriage to a commoner should receive her inheritance "in the form of an estate in order to preserve the nobility of the descendants born of the ignoble marriage".[158] According to the local customs of certain counties, her husband was also regarded as a nobleman – a noble by his wife.[159]

The peasants' legal position had been standardized in almost the entire kingdom by the 1350s.[144][160] The free peasant tenants were to pay seigneurial taxes, but were rarely obliged to provide labour service.[144] In 1351, the king ordered that the ninth – a tax payable to the landowners – was to be collected from all tenants, thus preventing landowners from offering lower taxes to persuade tenants to move from other lords' lands to their estates.[145] In 1328, all landowners were authorized to administer justice on their estates "in all cases except cases of theft, robbery, assault or arson" which remained under the jurisdiction of the sedria.[161] The kings started to grant noblemen the right to execute or mutilate criminals who were captured in their estates.[162] The most influential noblemen's estates were also exempted of the jurisdiction of the counties' law courts.[163]

Emerging estates

[edit]

Royal power quickly declined after Louis I died in 1382.[164] His son-in-law, Sigismund of Luxembourg (r. 1387–1437), entered into a formal league with the aristocrats who had elected him king in early 1387.[165] Initially, when his position was weak, he gave away more than half of the 150 royal castles to his supporters, although this abated when he strengthened his authority in the early 15th century.[166] His favorites were foreigners,[note 7] but old Hungarian families[note 8] also took advantage of his magnanimity.[169] The wealthiest noblemen, known as magnates, built comfortable castles in the countryside which became important centers of social life.[170] These fortified manor houses always contained a hall for representative purposes and a private chapel.[171] Sigismund regularly invited the magnates to the royal council, even if they did not hold higher offices.[172] He founded a new chivalric order, the Order of the Dragon, in 1408 to reward his most loyal supporters.[173]

The expansion of the Ottoman Empire reached the southern frontiers in the 1390s.[174] A large anti-Ottoman crusade ended with a catastrophic defeat near Nicopolis in 1396.[175] Next year, Sigismund held a Diet in Temesvár (now Timișoara in Romania) to strengthen the defence system.[175][176] He confirmed the Golden Bull, but without the two provisions that limited the noblemen's military obligations and established their right to resist the monarchs.[175] The Diet obliged all landowners to equip one archer for every 20 peasant plots on their domains to serve in the royal army.[177][178] Sigismund granted large estates in Hungary to neighboring Orthodox rulers[note 9] to secure their alliance.[180] They established Basilite monasteries on their estates.[181]

Sigismund's son-in-law, Albert of Habsburg (r. 1438–1439), was elected king in early 1438, but only after he promised always to make important decisions with the consent of the royal council.[182][183] After he died in 1439, a civil war broke out between the partisans of his son, Ladislaus the Posthumous (r. 1440–1457), and the supporters of the child king's rival, Vladislaus III of Poland (r. 1440–1444).[184] Ladislaus the Posthumous was crowned without election with the Holy Crown of Hungary, but the Diet proclaimed the coronation invalid, stating that "the crowning of kings is always dependent on the will of the kingdom's inhabitants, in whose consent both the effectiveness and the force of the crown reside".[185] Vladislaus died fighting the Ottomans during the Crusade of Varna in 1444 and the Diet elected seven captains in chief to administer the kingdom. The talented military commander, John Hunyadi (d. 1456), was elected the sole regent in 1446.[186]

The Diet developed from a consultative body into an important institution of law making in the 1440s.[186] The magnates were always invited to attend it in person.[185] Lesser noblemen were also entitled to attend the Diet, but in most cases they were represented by delegates, who were almost always the magnates' familiares.[187]

Birth of titled nobility and the Tripartitum

[edit]

Hunyadi was the first noble to receive a hereditary title from a Hungarian king, when Ladislaus the Posthumous granted him the Saxon district of Bistritz (now Bistrița in Romania) with the title perpetual count in 1453.[188][189] Hunyadi's son, Matthias Corvinus (r. 1458–1490), who was elected king in 1458, rewarded further noblemen with the same title.[190] Fügedi states that 16 December 1487 was the "birthday of the estate of magnates in Hungary",[191] because an armistice signed on this day listed 23 Hungarian "natural barons", contrasting them with the high officers of state, who were mentioned as "barons of office".[172][191] Corvinus' successor, Vladislaus II (r. 1490–1516), and Vladislaus' son, Louis II (r. 1516–1526), formally began to reward important persons of their government with the hereditary title of baron.[192]

Differences in the nobles' wealth increased in the second half of the 15th century.[193] About 30 families owned more than a quarter of the territory of the kingdom when Corvinus died in 1490.[193] A further tenth of all lands in the kingdom was in the possession of about 55 wealthy noble families.[193] Other nobles held almost one third of the lands, but this group included 12–13,000 peasant-nobles who owned a single plot (or a part of it) and had no tenants. The Diets regularly compelled the peasant-nobles to pay tax on their plots.[194] Average magnates held about 50 villages, but the regular division of inherited landed property could lead to the impoverishment of aristocratic families.[note 10][196] Strategies applied to avoid this – family planning and celibacy – led to the extinction of most aristocratic families after a few generations.[note 11][195]

The Diet ordered the compilation of customary law in 1498.[197] The jurist István Werbőczy (d. 1541) completed the task, presenting a law-book at the Diet in 1514.[197][198] His Tripartitum – The Customary Law of the Renowned Kingdom of Hungary in Three Parts – was never enacted, but it was consulted at the law courts for centuries.[199][200] It summarized the noblemen's fundamental privileges in four points:[201] noblemen were only subject to the monarch's authority and could only be arrested in a due legal process; furthermore, they were exempt from all taxes and were entitled to resist the king if he attempted to interfere with their privileges.[202] Werbőczy also implied that Hungary was actually a republic of nobles headed by a monarch, stating that all noblemen "are members of the Holy Crown"[203] of Hungary.[201] Quite anachronistically, he emphasized the idea of all noblemen's legal equality, but he had to admit that the high officers of the realm, whom he mentioned as "true barons", were legally distinguished from other nobles.[204] He also mentioned the existence of a distinct group, who were barons "in name only", but without specifying their peculiar status.[143]

The Tripartitum regarded the kindred as the basic unit of nobility.[205] A noble father exercised almost autocratic authority over his sons, because he could imprison them or offer them as a hostage for himself. His authority ended only if he divided his estates with his sons, but the division could rarely be enforced.[206] The "betrayal of fraternal blood" (that is, a kinsman's "deceitful, sly, and fraudulent ... disinheritance")[207] was a serious crime, which was punished by loss of honor and the confiscation of all property.[208] Although the Tripartitum did not explicitly mention it, a nobleman's wife was also subject to his authority. She received her dower from her husband at the consummation of their marriage.[209] If her husband died, she inherited his best coach-horses and clothes.[210]

Demand for foodstuffs grew rapidly in Western Europe in the 1490s.[211] The landowners wanted to take advantage of the growing prices.[212] They demanded labour service from their peasant tenants and started to collect the seigneurial taxes in kind.[213] The Diets passed decrees that restricted the peasants' right to free movement and increased their burdens.[211] The peasants' grievances unexpectedly culminated in a rebellion in May 1514.[211][214] The rebels captured manor houses and murdered dozens of noblemen, especially on the Great Hungarian Plain.[215] The voivode of Transylvania, John Zápolya, annihilated their main army at Temesvár on 15 July. György Dózsa and other leaders of the peasant war were tortured and executed, but most rebels received a pardon.[216] The Diet punished the peasantry as a group, condemning them to perpetual servitude and depriving them of the right of free movement.[216][217] The Diet also enacted the serfs' obligation to provide one day's labour service for their lords each week.[217]

Early modern and modern times

[edit]Tripartite Hungary

[edit]The Ottomans annihilated the royal army at the Battle of Mohács.[218] Louis II died fleeing from the battlefield and two claimants, John Zápolya (r. 1526–1540) and Ferdinand of Habsburg (r. 1526–1564), were elected kings.[219] Ferdinand tried to reunite Hungary after Zápolya died in 1540, but the Ottoman Sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent (r. 1520–1566), intervened and captured Buda in 1541.[220] The sultan allowed Zápolya's widow, Isabella Jagiellon (d. 1559), to rule the lands east of the river Tisza on behalf of her infant son, John Sigismund (r. 1540–1571), in return for a yearly tribute.[221] His decision divided Hungary into three parts: the Ottomans occupied the central territories; John Sigismund's eastern Hungarian Kingdom developed into the autonomous Principality of Transylvania; and the Habsburg monarchs preserved the northern and western territories (or Royal Hungary).[222]

Most noblemen fled from the central regions to the unoccupied territories.[223] Peasants who lived along the borders paid taxes both to the Ottomans and their former lords.[224] Commoners were regularly recruited to serve in the royal army or in the magnates' retinues to replace the noblemen who had perished during fights.[225] The irregular hajdú foot-soldiers – mainly runaway serfs and dispossessed noblemen – became important elements of the defence forces.[225][226] Stephen Bocskai, Prince of Transylvania (r. 1605–1606), settled 10,000 hajdús in seven villages and exempted them from taxation in 1605, which was the "largest collective ennoblement" in the history of Hungary.[227][228]

In addition to the Székely and Saxon leaders, the noblemen formed one of the three nations (or Estates of the realm) in Transylvania, but they could rarely challenge the princes' authority.[229] In Royal Hungary, the magnates successfully protected the noble privileges, because their vast domains were almost completely exempt from royal officials' authority.[230] Their manors were fortified in the "Hungarian manner" (with walls made of earth and timber) in the 1540s.[231] Noblemen in Royal Hungary could also count on the support of the Transylvanian princes against the Habsburg monarchs.[230] Intermarriages among Austrian, Czech and Hungarian aristocrats[note 12] gave rise to the development of a "supranational aristocracy" in the Habsburg monarchy.[233] Foreign aristocrats regularly received Hungarian citizenship, and Hungarian noblemen were often naturalized in the Habsburgs' other realms.[note 13][235] The Habsburg kings rewarded the most powerful magnates with hereditary titles such as baron from the 1530s.[192]

The aristocrats supported the spread of the Reformation.[236] Most noblemen adhered to Lutheranism in the western regions of Royal Hungary, but Calvinism was the dominant religion in Transylvania and other regions.[237] John Sigismund promoted Unitarian views,[238] but most Unitarian noblemen perished in battles in the early 1600s.[239] The Habsburgs remained staunch supporters of the Catholic Counter-Reformation and the most prominent aristocratic families[note 14] converted to Catholicism in Royal Hungary in the 1630s.[240][241] The Calvinist princes of Transylvania supported their co-religionists.[240] Gabriel Bethlen granted nobility to all Calvinist pastors.[242]

The kings and the Transylvanian princes regularly ennobled commoners, but often without granting landed property to them.[243] Jurisprudence maintained that only those who owned land cultivated by serfs could be regarded as fully fledged noblemen.[244] Armalists – noblemen who held a charter of ennoblement, but not a single plot of land – and peasant-nobles continued to pay taxes, for which they were collectively known as taxed nobility.[244] Nobility could be purchased from the kings who were often in need of funds. Landowners also benefitted from the ennoblement of their serfs, because they could demand a fee for their consent.[245]

The Diet was officially divided into two chambers in Royal Hungary in 1608.[246][247] All adult male members of the titled noble families had a seat in the Upper House.[247] The lesser noblemen elected two or three delegates at the general assemblies of the counties to represent them in the Lower House. The Croatian and Slavonian magnates also had seats at the Upper House, and the sabor (or Diet) of Croatia and Slavonia sent delegates to the Lower House.[246]

Liberation and war of independence

[edit]

Forces from the Holy Roman Empire and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth inflicted a crushing defeat on the Ottomans at Vienna in 1683.[248] The Ottomans were expelled from Buda in 1686. Michael I Apafi, the prince of Transylvania (r. 1661–1690), acknowledged the suzerainty of Emperor Leopold I, who was also king of Hungary (r. 1657–1705), in 1687.[249] Grateful for the liberation of Buda, the Diet abolished the noblemen's right to resist the monarch for the defense of their liberties.[250] In 1688, the Diet authorized the aristocrats to establish a special trust, known as fideicommissum, with royal consent to prevent the distribution of their landed wealth among their descendants. In accordance with the traditional concept of aviticitas, inherited estates could not be subject to the trust. Estates in fideicommissum were always held by one person, but he was responsible for the proper boarding of his relatives.[251]

The liberation of central Hungary continued, and the Ottomans were forced to acknowledge the loss of the territory in 1699.[250] Leopold set up a special committee to distribute the lands in the reconquered territories.[252] The descendants of the noblemen who had held estates there before the Ottoman conquest were required to provide documentary evidence to substantiate their claims to the ancestral lands.[252] Even if they could present documents, they were to pay a fee – a tenth of the value of the claimed property – as compensation for the costs of the liberation war.[252][253] Few noblemen could meet the criteria and more than half of the recovered lands were distributed among foreigners.[254] They were naturalized, but most of them never visited Hungary.[255]

The Habsburg administration doubled the amount of the taxes to be collected in Hungary and demanded almost one third of the taxes (1.25 million florins) from the clergy and the nobility. The palatine, Prince Paul Esterházy (d. 1713), convinced the monarch to reduce the noblemen's tax burden to 0.25 million florins, but the difference was to be paid by the peasantry.[256] Leopold did not trust the Hungarians, because a group of magnates had conspired against him in the 1670s.[250] Mercenaries replaced the Hungarian garrisons, and they frequently plundered the countryside.[250][256] The monarch also supported Cardinal Leopold Karl von Kollonitsch's attempts to restrict the Protestants' rights. Tens of thousands of Catholic Germans and Orthodox Serbs were settled in the reconquered territories.[253]

The outbreak of the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1715) provided an opportunity for the discontented Hungarians to rise against Leopold. They regarded one of the wealthiest aristocrats, Prince Francis II Rákóczi (d. 1735), as their leader.[256] Rákóczi's War of Independence lasted from 1703 to 1711.[250] Although the rebels were forced to yield, the Treaty of Szatmár granted a general amnesty for them and the new Habsburg monarch, Charles III (r. 1711–1740), promised to respect the privileges of the Estates of the realm.[257]

Cooperation and absolutism

[edit]

Charles III again confirmed the privileges of the Estates of the "Kingdom of Hungary, and the Parts, Kingdoms and Provinces thereto annexed" in 1723 in return for the enactment of the Pragmatic Sanction which established his daughters' right to succeed him.[258][259] Montesquieu, who visited Hungary in 1728, regarded the relationship between the king and the Diet as a good example of the separation of powers.[260] The magnates almost monopolized the highest offices, but both the Hungarian Court Chancellery – the supreme body of royal administration – and the Lieutenancy Council – the most important administrative office – also employed lesser noblemen.[261] In practice, Protestants were excluded from public offices after a royal decree, the Carolina Resolutio, obliged all candidates to take an oath on the Virgin Mary.[262]

The Peace of Szatmár and the Pragmatic Sanction maintained that the Hungarian nation consisted of the privileged groups, independent of their ethnicity,[263] but the first debates along ethnic lines occurred in the early 18th century.[264] The jurist Mihály Bencsik claimed that the burghers of Trencsén (now Trenčín in Slovakia) should not send delegates to the Diet because their ancestors had been forced to yield to the conquering Magyars in the 890s.[265] A priest, Ján B. Magin, wrote a response, arguing that ethnic Slovaks and Hungarians enjoyed the same rights.[266] In Transylvania, a bishop of the Romanian Greek Catholic Church, Baron Inocențiu Micu-Klein (d. 1768), tried to speak "on behalf of the whole Romanian nation in Transylvania" at the Diet in 1737 but he could not finish the speech because other delegates stated that he could refer only to the Romanians or to the Romanian people for the Romanian Nation did not exist. Five years later, he unsuccessfully demanded the recognition of the Romanians as the fourth Nation on ethnic grounds.[267]

Maria Theresa (r. 1740–1780) succeeded Charles III in 1740, which gave rise to the War of the Austrian Succession.[268] The noble delegates offered their "lives and blood" for their new "king" and the declaration of the general levy of the nobility was crucial at the beginning of the war.[258] Grateful for their support, Maria Theresa strengthened the links between the Hungarian nobility and the monarch.[269][270] She established the Theresian Academy and the Royal Hungarian Bodyguard for young Hungarian noblemen.[271] Both institutions enabled the spread of the ideas of the Age of Enlightenment.[note 15][272][273] Freemasonry became popular, especially among the magnates, but masonic lodges were also open to untitled noblemen and professionals.[273]

Культурные различия между магнатами и мелкими дворянами росли. Магнаты переняли образ жизни имперской аристократии, перемещаясь между своими летними дворцами в Вене и недавно построенными великолепными резиденциями в Венгрии. [ 274 ] Князь Миклош Эстерхази (ум. 1790) нанял знаменитого композитора Йозефа Гайдна . Граф Янош Фекете (ум. 1803), ярый защитник дворянских привилегий, засыпал французского философа Вольтера письмами и дилетантскими стихами. [ 275 ] Граф Миклош Палфи (ум. 1773) предложил обложить дворян налогом для финансирования постоянной армии. [ 276 ] Большинство дворян не желали отказываться от своих привилегий. [ 277 ] Мелкие дворяне также настаивали на своем традиционном образе жизни и жили в простых домах, построенных из дерева или утрамбованной глины. [ 278 ]

Мария Терезия не проводила сеймов после 1764 года. [ 276 ] Отношения помещиков и их крепостных она урегулировала царским указом 1767 года. [ 279 ] Ее сын и преемник Иосиф II ( годы правления 1780–1790 ), которого высмеивали как «короля в шляпе», так и не был коронован, потому что хотел избежать коронационной присяги. [ 280 ] Он провел реформы, которые явно противоречили местным обычаям. [ 281 ] Он заменил графства округами и назначил королевских чиновников для управления ими. Он также отменил крепостное право, обеспечив всем крестьянам право на свободное передвижение после восстания румынских крепостных в Трансильвании . [ 282 ] Он приказал провести первую перепись населения в Венгрии в 1784 году. [ 283 ] По его данным, дворянство составляло около 4,5% мужского населения в землях Венгерской короны (из них 155 519 дворян в собственно Венгрии и 42 098 дворян в Трансильвании, Хорватии и Славонии). [ 284 ] [ 285 ] Доля дворян была значительно выше (шесть–шестнадцать процентов) в северо-восточных и восточных графствах и меньше (три процента) в Хорватии и Славонии. [ 284 ] Бедные дворяне, которых высмеивали как «дворян семи сливовых деревьев» или «дворян, носящих сандалии», составляли почти 90 процентов дворянства. [ 286 ] Предыдущие исследования дворянства показывают, что более половины дворянских родов получили свой сан после 1550 года. [ 245 ]

Национальное пробуждение

[ редактировать ]

Немногочисленные дворяне-реформаторы с энтузиазмом встретили известие о Французской революции . Йожеф Хайноци (ум. 1795) перевел Декларацию прав человека и гражданина на латынь , а Янош Лачковиц (ум. 1795) опубликовал ее венгерский перевод. [ 287 ] Чтобы успокоить венгерскую знать, Иосиф II на смертном одре в 1790 году отменил почти все свои реформы. [ 288 ] Его преемник, Леопольд II ( годы правления 1790–1792 ), созвал Сейм и подтвердил свободы сословий королевства, подчеркнув, что Венгрия является «свободным и независимым» королевством, управляемым своими собственными законами. [ 282 ] [ 289 ] Новости о якобинском терроре во Франции укрепили королевскую власть. [ 290 ] Хайночи и другие радикальные (или «якобинские») дворяне, обсуждавшие возможность отмены всех привилегий в тайных обществах, были схвачены и казнены или заключены в тюрьму в 1795 году. [ 291 ] Сеймы проголосовали за налоги и рекрутов, которых преемник Леопольда, Франциск ( годы правления 1792–1835 ), требовал между 1792 и 1811 годами. [ 292 ]

Последний общий сбор дворянства был объявлен в 1809 году, но Наполеон легко разгромил дворянские войска под Дьёром . [ 292 ] Расцвет сельского хозяйства побудил землевладельцев занимать деньги и покупать новые поместья или основывать мельницы во время войны, но большинство из них обанкротились после восстановления мира в 1814 году. [ 293 ] Концепция aviticitas не позволяла кредиторам получить свои деньги, а должникам - продать свое имущество. [ 294 ] Радикальная знать сыграла решающую роль в реформаторском движении начала XIX века. [ 295 ] Гергели Бержевичи (ум. 1822) уже около 1800 года объяснял отсталость местной экономики крестьянским крепостным правом. [ 296 ] Ференц Казинци (ум. 1831) и Янош Бацаньи (ум. 1845) инициировали языковую реформу , опасаясь исчезновения венгерского языка. [ 295 ] Поэт Шандор Петефи (ум. 1849), простой человек, высмеивал консервативных дворян в своем стихотворении «Венгерский дворянин» , противопоставляя их устаревшую гордость и праздный образ жизни. [ 297 ]

С 1820-х годов в политической жизни доминировало новое поколение дворян-реформаторов. [ 298 ] Граф Иштван Сечени (ум. 1860) требовал отмены отработочной повинности и повинной системы крепостных, заявляя, что «мы, зажиточные землевладельцы, являемся главным препятствием на пути прогресса и большего развития нашего отечества». [ 299 ] Он основал клубы в Прессбурге и Пеште и пропагандировал скачки, поскольку хотел поощрять регулярные встречи магнатов, мелких дворян и бюргеров. [ 300 ] Друг Сечени, барон Миклош Весселеньи (ум. 1850), требовал создания конституционной монархии и защиты гражданских прав . [ 301 ] Меньший дворянин Лайош Кошут (ум. 1894) стал лидером самых радикальных политиков 1840-х годов. [ 300 ] Он заявил, что сеймы и графства являются институтами привилегированных групп и что только более широкое общественное движение может обеспечить развитие Венгрии. [ 302 ]

С конца эпохи Просвещения национальность все больше и больше ассоциировалась с разговорным языком. Предсказания -романтика немецкого философа Иоганна Готфрида Гердера (ум. 1803) о неизбежной ассимиляции малых народов в большую языковую группу разожгли пламя языкового национализма. [ 303 ] Хотя этнические венгры составляли лишь около 38 процентов населения, [ 304 ] Официальное использование венгерского языка распространилось с конца 18 века. [ 305 ] Кошут заявил, что все, кто хочет пользоваться свободами нации, должны изучать венгерский язык. [ 306 ] Напротив, словак Людовит Штур (ум. 1856) заявил, что венгерская нация состоит из многих национальностей, и их лояльность можно укрепить за счет официального использования их языков. [ 307 ] Граф Янко Драшкович (ум. 1856) рекомендовал хорватскому заменить латынь в качестве официального языка в Хорватии и Славонии. [ 308 ]

Революция и неоабсолютизм

[ редактировать ]

Новости о революциях 1848 года достигли Пешта 15 марта 1848 года. [ 309 ] Молодые интеллектуалы провозгласили радикальную программу, известную как « Двенадцать пунктов» , требующую равных гражданских прав для всех граждан. [ 310 ] Граф Лайош Баттьяни (ум. 1849) был назначен первым премьер-министром Венгрии. [ 311 ] Сейм быстро принял большинство Двенадцати пунктов, и Фердинанд V ( годы правления 1835–1848 ) санкционировал их в апреле. [ 309 ]

Апрельские законы отменили освобождение дворян от налогов и авитиситас . [ 312 ] магнатов но 31 фидеикомисса осталась нетронутой. [ 313 ] Хотя крестьяне-арендаторы получили право собственности на свои участки, помещикам была обещана компенсация. [ 312 ] [ 314 ] Взрослые мужчины, владевшие более 0,032 км 2 (7,9 акров) пахотных земель или городских поместий стоимостью не менее 300 флоринов – около четверти взрослого мужского населения – было предоставлено право голоса на парламентских выборах. [ 312 ] Было подтверждено исключительное право дворян на выборах в графствах, в противном случае этнические меньшинства могли бы легко доминировать в общих собраниях во многих графствах. [ 312 ] Дворяне составили около четверти членов нового парламента, собравшегося после всеобщих выборов 5 июля. [ 315 ]

Словацкие делегаты потребовали автономии для всех этнических меньшинств на своей ассамблее в мае. [ 316 ] [ 317 ] Аналогичные требования были приняты на встрече румынских делегатов. [ 318 ] [ 319 ] Советники Фердинанда V убедили запретителя (или губернатора) Хорватии барона Йосипа Елачича (ум. 1859) вторгнуться в Венгрию в сентябре. [ 320 ] [ 321 ] Разразилась новая война за независимость, и 14 апреля 1849 года венгерский парламент сверг династию Габсбургов. [ 322 ] Николай I из России ( годы правления 1825–1855 ) вмешался на стороне легитимистов, и российские войска одолели венгерскую армию, вынудив ее сдаться 13 августа. [ 322 ] [ 323 ]

Венгрия, Хорватия (и Славония) и Трансильвания были включены как отдельные королевства в состав Австрийской империи . [ 324 ] Советники молодого императора Франца Иосифа ( годы правления 1848–1916 ) заявили, что Венгрия потеряла свои исторические права, а консервативные венгерские аристократы [ примечание 16 ] не смог убедить его восстановить старую конституцию. [ 325 ] Дворяне, сохранившие верность Габсбургам, назначались на высокие должности. [ примечание 17 ] но большинство новых чиновников были выходцами из других провинций империи. [ 326 ] [ 327 ] Подавляющее большинство дворян избрало путь пассивного сопротивления: они не занимали должностей в государственном управлении и молчаливо препятствовали выполнению императорских указов. [ 328 ] [ 329 ] Безымянный дворянин из округа Зала Ференц Деак (ум. 1876) стал их лидером примерно в 1854 году. [ 325 ] [ 329 ] Они пытались сохранить атмосферу превосходства, но их подавляющее большинство в последующие десятилетия ассимилировалось с местным крестьянством или мелкой буржуазией. [ 330 ] В отличие от них магнаты, сохранившие за собой около четверти всех земель, могли легко привлечь средства развивающегося банковского сектора для модернизации своих поместий. [ 330 ]

Австро-Венгрия

[ редактировать ]Деак и его последователи знали, что великие державы не поддерживают распад Австрийской империи. [ 331 ] Поражение Австрии в австро-прусской войне 1866 года ускорило сближение короля и партии Деака , что привело к австро-венгерскому компромиссу 1867 года . [ 332 ] Собственно Венгрия и Трансильвания были объединены. [ 333 ] и автономия Венгрии была восстановлена в рамках Двойной монархии Австро-Венгрии . [ 334 ] В следующем году Хорватско-Венгерское поселение компетенцию восстановило союз собственно Венгрии и Хорватии, но закрепило за хорватским сабором во внутренних делах, образовании и правосудии. [ 335 ]

Компромисс укрепил позиции традиционной политической элиты. [ 336 ] Только около шести процентов населения могло голосовать на всеобщих выборах. [ 336 ] С 1867 по 1918 год более половины премьер-министров и одна треть министров были назначены из числа магнатов. [ 337 ] Помещики составляли большинство членов парламента. [ 336 ] Половина мест в муниципальных собраниях сохранилась за крупнейшими налогоплательщиками. [ 338 ] Дворяне также доминировали в государственном управлении, поскольку десятки тысяч обедневших дворян устроились на работу в министерства или на государственные железные дороги и почтовые отделения. [ 339 ] [ 340 ] Они были ярыми сторонниками мадьяризации , отрицая использование языков меньшинств. [ 341 ] Аристократка-эмигрантка баронесса Эмма Орчи (ум. 1947) писала свои романы на английском языке в Соединенном Королевстве. Она покинула Венгрию вместе со своими родителями, когда рабочие фермы, опасаясь потерять работу, подожгли поместье Орчи в Абадсалоке в 1868 году. Ее первый роман с участием Алого Пимпернеля – «первого персонажа, которого можно было назвать супергероем » ( Стэн Ли ) – был опубликован в 1905 году. [ 342 ]

Только дворянин, владевший поместьем площадью не менее 1,15 км. 2 (280 акров) считались зажиточными, но количество поместий такого размера быстро уменьшалось. [ примечание 18 ] [ 340 ] Магнаты воспользовались банкротствами мелких дворян и в тот же период купили новые поместья. [ 343 ] Были созданы новые фидеикомиссы , которые позволяли магнатам сохранять наследство от своих земельных богатств. [ 343 ] Аристократы регулярно назначались в советы директоров банков и компаний. [ примечание 19 ] [ 344 ]

Евреи были движущей силой развития финансового и промышленного секторов. [ 345 ] В 1910 году еврейским бизнесменам принадлежало более половины компаний и более четырех пятых банков. [ 345 ] Они также купили земельную собственность и приобрели почти пятую часть имений площадью 1,15–5,75 км . 2 (280–1420 акров) к 1913 году. [ 345 ] Наиболее выдающиеся еврейские мещане были награждены дворянством. [ примечание 20 ] а в 1918 году насчитывалось 26 аристократических семей и 320 дворянских семей еврейского происхождения. [ 347 ] Многие из них обратились в христианство , но другие дворяне не считали их себе равными. [ 297 ]

Революции и контрреволюция

[ редактировать ]Первая мировая война привела к распаду Австро-Венгрии в 1918 году. [ 348 ] Астровая революция - движение леволиберальной Партии независимости , Социал-демократической партии и Радикальной гражданской партии - убедила Карла IV ( годы правления 1916–1918 ) назначить радикального графа Михая Кароли (ум. 1955), премьер-министром 31 октября. [ 349 ] [ 350 ] После роспуска нижней палаты Венгрия была провозглашена республикой . 16 ноября [ 351 ] Венгерский национальный совет принял земельную реформу, устанавливающую максимальный размер поместий в 1,15 квадратных километров (280 акров) и предписывающую распределять любые излишки среди местного крестьянства. [ 352 ] Каройи, чьи унаследованные владения были заложены банкам, был первым, кто осуществил реформу. [ 352 ]

Союзные державы разрешили Румынии оккупировать новые территории и приказали отвести Королевскую венгерскую армию почти до реки Тиса 26 февраля 1919 года. [ 353 ] [ 354 ] Каройи подал в отставку, и Венгерской коммунистической партии лидер Бела Кун (ум. 1938) объявил о создании Венгерской Советской Республики . 21 марта [ 355 ] Все поместья площадью более 0,43 км 2 (110 акров), а все частные компании, в которых работало более 20 человек, были национализированы . [ 356 ] Большевики не смогли остановить румынское вторжение , и 1 августа их лидеры бежали из Венгрии. [ 357 ] После недолгого временного правительства промышленник Иштван Фридрих (ум. 1951) 6 августа сформировал коалиционное правительство при поддержке союзных держав. [ 358 ] Программа национализации большевиков была отменена. [ 358 ] Венгерская социал-демократическая партия бойкотировала всеобщие выборы в начале 1920 года . [ 358 ] Новый однопалатный сейм Венгрии восстановил венгерскую монархию , но без восстановления Габсбургов. [ 358 ] Вместо этого 1 марта 1920 года регентом был избран дворянин-кальвинист Миклош Хорти (ум. 1957). [ 359 ] [ 360 ] Венгрия была вынуждена признать потерю более двух третей своей территории и более 60 процентов своего населения (включая одну треть этнических венгров) по Трианонскому договору от 4 июня. [ 358 ]

Хорти так и не был коронован королем и поэтому не мог даровать дворянство, но он учредил новый орден за заслуги — Орден за храбрость . [ 361 ] Его члены получили наследственный титул витез («храбрый»). [ 361 ] Им также были предоставлены земельные участки, что возобновило «средневековую связь между землевладением и служением короне» ( Брайан Картледж ). [ 361 ] Два трансильванских аристократа, графы Пал Телеки (ум. 1941) и Иштван Бетлен (ум. 1946), были самыми влиятельными политиками в межвоенный период . [ 362 ] События 1918–1919 годов убедили их в том, что только «консервативная демократия», в которой доминирует землевладельческое дворянство, может обеспечить стабильность. [ 363 ] Большинство министров и большинство членов парламента были дворянами. [ 364 ] Была проведена консервативная аграрная реформа, ограничившая 8,5% всех пахотных земель, но почти треть земель осталась во владении около 400 магнатских семей. [ 365 ] Двухпалатный парламент был восстановлен в 1926 году, в верхней палате которого доминировали аристократы, прелаты и высокопоставленные чиновники. [ 366 ] [ 367 ]

Антисемитизм был ведущей идеологией в 1920-х и 1930-х годах. [ 368 ] Закон numerus clausus ограничивал прием еврейских студентов в университеты. [ 369 ] [ 370 ] Граф Фидель Палфи (ум. 1946) был одной из ведущих фигур национал-социалистических движений, но большинство аристократов презирали радикализм «старшин и экономок». [ 371 ] Венгрия участвовала во вторжении стран Оси в Югославию в апреле 1941 года и присоединилась к войне против Советского Союза после бомбардировки Кассы в конце июня. [ 372 ] Опасаясь выхода Венгрии из войны, нацистская Германия оккупировала страну в ходе операции «Маргарете» 19 марта 1944 года. [ 373 ] Сотни тысяч евреев и десятки тысяч цыган были переведены в нацистские концентрационные лагеря при содействии местных властей. [ 374 ] [ 375 ] Богатейшие бизнес-магнаты еврейского происхождения были вынуждены отказаться от своих компаний и банков, чтобы спасти свою жизнь и жизнь своих родственников. [ примечание 21 ] [ 374 ]

Падение венгерского дворянства

[ редактировать ]

Советская Красная Армия достигла границ Венгрии и к 6 декабря 1944 года овладела Великой Венгерской равниной. [ 376 ] Делегаты из городов и деревень региона учредили Временное национальное собрание в Дебрецене , которое 22 декабря избрало новое правительство. [ 376 ] [ 377 ] Три выдающихся антинацистских аристократа [ примечание 22 ] имел место в собрании. [ 378 ] Временное национальное правительство вскоре пообещало земельную реформу, а также отмену всех «антидемократических» законов. [ 379 ] Последние немецкие войска Вермахта покинули Венгрию 4 апреля 1945 года. [ 380 ]

Имре Надь (ум. 1958), коммунистический министр сельского хозяйства, объявил земельную реформу 17 марта 1945 года. [ 381 ] Все домены длиной более 5,75 км. 2 (1420 акров) были конфискованы, а владельцы более мелких поместий могли сохранить за собой максимум 0,58–1,73 км . 2 (140–430 соток) земли. [ 381 ] [ 382 ] Земельная реформа, как отмечал Картледж, уничтожила дворянство и устранила «элементы феодализма, которые сохранялись в Венгрии дольше, чем где-либо еще в Европе». [ 381 ] Аналогичные земельные реформы были проведены в Румынии и Чехословакии . [ 383 ] В обеих странах этнические венгерские аристократы были приговорены к смертной казни или тюремному заключению как предполагаемые военные преступники. [ примечание 23 ] [ 383 ] Венгерские аристократы [ примечание 24 ] могли сохранить свои поместья только в Бургенланде (в Австрии) после 1945 года. [ 384 ]

Советские военные власти контролировали всеобщие выборы и формирование коалиционного правительства в конце 1945 года. [ 385 ] Новый парламент провозгласил Вторую Венгерскую республику 1 февраля 1946 года. [ 386 ] Опрос общественного мнения показал, что более 75 процентов мужчин и 66 процентов женщин были против использования дворянских титулов в 1946 году. [ 387 ] Парламент принял акт, отменявший все дворянские звания и родственные им стили , а также запрещавший их использование. [ 388 ] Новый закон вступил в силу 14 февраля 1947 года. [ 389 ]

Неофициальное дворянство

[ редактировать ]

Коммунисты взяли под полный контроль правительство в период с 1947 по 1949 год, а Венгрия была провозглашена « народной республикой ». 20 августа 1949 года [ 390 ] Аристократы были объявлены «классовыми врагами», и большинство из них были интернированы в «социальные лагеря» – фактически, принудительные трудовые лагеря – для работы на полях Великой Венгерской равнины. [ 391 ] Массовые внутренние депортации произошли в 1950 и 1951 годах. Почти все аристократы были интернированы из Будапешта в малонаселенные деревни на востоке Венгрии, в основном в районе Хортобадь, в течение двух месяцев, в мае – июле 1951 года. Цифры итогового отчета показывают, что 9 герцогов, 163 графа. За этот период из столицы были депортированы 121 барон и 8 дворян-рыцарей – всего 301 аристократ – и их семьи. Депортированным было запрещено покидать пределы закрепленного за ними села, и они находились под постоянным наблюдением полиции. Их лишили имущества, имущества и гражданских прав – им запретили участвовать в выборах. Большинство из них могли работать физическим трудом в сельском хозяйстве в совхозах на ограниченной основе, но их лишения были постоянными. [ 392 ]

Некоторые левые аристократы пытались сотрудничать с новым режимом, но коммунистические лидеры им не доверяли. [ примечание 25 ] [ 393 ] В результате хрущевской оттепели интернированным было разрешено покинуть трудовые лагеря, но прежние дома им не были возвращены. [ 394 ] Хотя коммунистические историки сделали все возможное, чтобы доказать выдающуюся роль аристократов во время неудавшейся антикоммунистической венгерской революции 1956 года , лишь немногие аристократы приняли активное участие. [ примечание 26 ] [ 396 ] Многие аристократы покинули страну после подавления восстания 1956 года. [ 397 ] В 1960-е и 1970-е годы люди аристократического происхождения в основном работали в качестве рабочих. [ 391 ] а их детям требовалось специальное разрешение на обучение в университетах до 1962 года. [ 398 ] [ 399 ] Хотя официальная дискриминация была отменена, бывшие аристократы редко назначались на более высокие должности. [ примечание 27 ] [ 400 ] Петер Эстерхази (ум. 2016 г.) стал знаменитым писателем в последние десятилетия коммунистического режима. [ 401 ]

Коммунистическая однопартийная система рухнула в конце 1980-х годов, и в 1989 году Венгрия была провозглашена республикой. [ 402 ] Первый премьер-министр демократической эпохи Йожеф Анталл (ум. 1993) предлагал должности в государственном управлении аристократам, вернувшимся в Венгрию, но аристократия не вернула себе прежнее положение. [ 399 ] Реституция бывшей собственности была важным политическим вопросом в большинстве новых демократий в начале 1990-х годов. В Венгрии реституция в натуральной форме была исключена, поскольку многие объекты ранее конфискованной собственности уже были приватизированы в последние годы коммунистического режима. Вместо этого первоначальным владельцам и их потомкам была предоставлена денежная компенсация, но ее сумма была ограничена примерно 70 000 долларов США. Напротив, реституция в натуральной форме была предпочтительным методом реституции в Чехословакии, и первоначальные владельцы также могли требовать реституции в натуральной форме в Румынии и Польше. [ 403 ] Венгерские аристократы вернули себе часть своей прежней собственности в Румынии, и по крайней мере одна венгерская дворянская семья также конфисковала собственность в Чехии, Польше и Словакии в ходе процесса реституции. [ примечание 28 ] [ 404 ]

Венгерский закон, запрещающий использование дворянских званий и стилей, не был отменен, и Конституционный суд Венгрии заявил в 2009 и 2010 годах, что этот запрет полностью соответствует пересмотренной Конституции Венгрии 1949 года . В декабре 2010 года два члена правой группы «Йоббик» представили проект отмены запрета, но через две недели отозвали его. [ 405 ] По инициативе бывшего аристократа Яноша Ньяри в 1994 году в Будапеште был создан частный клуб «Ассоциация венгерских дворянских семей» для людей благородного происхождения. В 2007 году ассоциация стала членом Европейской комиссии дворянства . [ 406 ]

См. также

[ редактировать ]Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ↑ Историк Ян Лукачка относит кланы Хонт-Пазмани , Мишкольц и Богат-Радваны к благородным родственникам моравского происхождения. [ 7 ]

- ^ Среди них кланы Бар-Калан , Чак , Кан , Лад и Семере считали себя потомками одного из семи легендарных лидеров мадьяр-завоевателей. [ 26 ]

- ^ Андроник Аба построил каменный замок в Фюзере , а каменный замок в Кабольде (ныне Коберсдорф в Австрии) был построен Поузой Сзаком. [ 73 ]

- ^ Например, семьи из рода Аба имели на гербе орла, а чаки приняли льва. [ 43 ]

- ↑ Согласно земельному реестру XV века, многие церковные дворяне в епископстве Веспрем происходили от настоящих дворян, искавших защиты епископов. [ 115 ]

- ^ Самый могущественный олигарх Мэтью Чак доминировал более чем в дюжине графств на северо-западе Венгрии; Ладислав Кан был фактическим правителем Трансливании; а Павел Шубич правил Хорватией и Далмацией. [ 129 ]

- ^ Штирийский Герман Целье (ум. 1435) стал крупнейшим землевладельцем Славонии; поляк Стибор из Стиборича (ум. 1414) владел девятью замками и 140 деревнями на северо-востоке Венгрии; и Фридрих Гогенцоллерн (ум. 1440) был назначен управлять графствами. [ 167 ]

- ^ Розгони среди были местных Семьи Батори, Переньи и бенефициаров грантов Сигизмунда. [ 168 ]

- ^ Мирча I Валахский ( годы правления 1386–1418 ) был награжден Фогарасом; Стефан Лазаревич , деспот Сербии ( годы правления 1389–1427 ), получил более десятка замков. [ 179 ]

- ↑ Например, Стивен Банфи из Лошонца (ум. 1459) владел 68 деревнями в 1459 году, но те же деревни были разделены между его 14 потомками в 1526 году. [ 195 ]

- ↑ Из 36 богатейших семей конца 1430-х годов до 1490 года дожили 27 семей, а до 1570 года — только восемь семей. [ 195 ]

- ^ Браки детей и внуков Магдолны Секели (ум. 1556) от трех ее мужей установили тесные родственные связи между венграми Сехи и Турзо , хорватско-венгерским Зринским , чехом Коловратом , Лобковичем , Пернштейном и Рожмберком , а также Австрийские или немецкие семьи Арко, Зальм и Унгнад. [ 232 ]

- ^ Тирольский граф Пирчо фон Арко (женившийся на венгерке Маргит Сечи) был натурализован в Венгрии в 1559 году; венгерский барон Симон Форгач (женившийся на австрийке Урсуле Пемффлингер) получил гражданство Нижней Австрии в 1568 году и Моравии в 1581 году. [ 234 ]

- ↑ Семьи Баттяни Иллешази , . , Надасди и Турзо были первыми, обратившимися в католицизм [ 240 ]

- ↑ Бывший королевский телохранитель Дьёрдь Бессеней (ум. 1811) написал брошюры о важности образования и развития венгерского языка в 1770-х годах. [ 272 ]

- ^ Графы Эмиль Дессевфи (ум. 1866), Антал Сецен (ум. 1896) и Дьёрдь Аппони (ум. 1899) были ведущими консервативными аристократами. [ 325 ]

- ↑ Граф Ференц Зичи (ум. 1900) имел место в Императорском совете, граф Ференц Надасди был назначен имперским министром юстиции. [ 325 ]

- ^ Количество поместий площадью 1,15–5,75 км . 2 (280–1420 акров) уменьшились с 20 000 до 10 000 с 1867 по 1900 год. [ 340 ]

- ^ В 1905 году в советах директоров входили 88 графов и 66 баронов. [ 344 ]

- ^ Хенрик Левай (ум. 1901), основавший первую венгерскую страховую компанию, был удостоен дворянства в 1868 году и получил титул барона в 1897 году; Жигмонд Корнфельд (ум. 1909), который был «венгерским финансовым и промышленным гигантом того времени», был назначен бароном. [ 346 ]

- ↑ Хорины, Вайсы и Корнфельды предоставили немецким властям аренду своей собственности сроком на двадцать пять лет в обмен на бесплатный пропуск в Португалию. [ 374 ]

- ^ Графы Дьюла Дессевфи (ум. 2000), Михай Каройи и Геза Телеки (ум. 1983). [ 378 ]

- ↑ Барон Жигмонд Кемени был заключен в тюрьму за инициирование казни 191 еврея в Румынии, хотя на самом деле он приносил им еду. [ 383 ]

- ^ Семьи Баттяни, Баттяни-Страттман, Эрдёди, Эстерхази и Зичи. [ 384 ]

- ↑ Известная как «Красная герцогиня», Маргит Одескальки (ум. 1982) закончила школу Венгерской коммунистической партии, но ее отозвали из посольства Венгрии в Вашингтоне. (ум. 1957), родившийся в семье Паллавичини , Антал Палинкас был приговорен к смертной казни по сфабрикованным обвинениям и казнен, хотя служил высокопоставленным офицером в коммунистической армии. [ 393 ]

- ^ Кароли Хуэн-Хедервари (ум. 1960) инициировал реорганизацию Католической народной партии ; Максимилиан Кенигсегг-Роттенфельс (ум. 1997) был избран своими коллегами членом совета рабочих ремонтной мастерской. В Румынии по меньшей мере пять бывших аристократов были приговорены к тюремному заключению за «заговор против государства» в связи с демонстрациями, организованными с целью выразить сочувствие венгерской революции. [ 395 ]

- ↑ Дирижер Миклош Лукач (ум. 1980) был назначен директором Венгерского государственного оперного театра , а Янош Меран стал главой промышленного кооператива в Корёсладани . [ 400 ]

- ^ Примеры включают Фаркаша Банфи, который вернул себе бывший замок Банфи в Фугаде ( Чьюгузель , Румыния), и Тибора Калноки, который захватил замки своих предков в Миклошваре и Сепсикёрёспатак ( Миклошоара и Валя Кришулуй , Румыния). Калноки также вернули себе ранее конфискованную собственность в Чехии, Польше и Словакии. [ 404 ]

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Беренд, Урбанчик и Вишевский 2013 , стр. 71–73.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , стр. 8, 17.

- ^ Зимони 2016 , стр. 160, 306–308, 359.

- ^ Беренд, Урбанчик и Вишевский 2013 , стр. 76–77.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , стр. 12–13.

- ^ Беренд, Урбанчик и Вишевский 2013 , стр. 76–78.

- ^ Лукачка 2011 , стр. 33–36.

- ^ Лукачка 2011 , стр. 31, 33–36.

- ^ Джорджеску 1991 , стр. 40.

- ^ Поп 2013 , с. 40.

- ^ Вольф 2003 , с. 329.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , стр. 117–118.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , стр. 8, 20.

- ^ Беренд, Урбанчик и Вишевский 2013 , стр. 105.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , с. 20.

- ^ Константин Багрянородный: Об управлении Империей (гл. 39), с. 175

- ^ Назад, 1993 г. , стр. 273.

- ^ Вольф 2003 , стр. 326–327.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Вольф 2003 , с. 327.

- ^ Беренд, Урбанчик и Вишевский 2013 , стр. 107.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , с. 16.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , с. 17.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Ревес 2003 , с. 341.

- ^ Rady 2000 , p. 12.

- ^ Rady 2000 , pp. 12–13.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Энгель 2001 , с. 85.

- ^ Rady 2000 , pp. 12–13, 185 (notes 7–8).

- ^ Картледж 2011 , с. 11.

- ^ Беренд, Урбанчик и Вишевский 2013 , стр. 148–150.

- ^ Вольф 2003 , с. 330.

- ^ Беренд, Урбанчик и Вишевский 2013 , стр. 149, 207–208.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , с. 73.

- ^ Rady 2000 , pp. 18–19.

- ^ Беренд, Урбанчик и Вишевский 2013 , стр. 149, 210.

- ^ Беренд, Урбанчик и Вишевский 2013 , стр. 193.

- ^ Rady 2000 , pp. 16–17.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Энгель 2001 , с. 40.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Rady 2000 , p. 28.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , стр. 85–86.

- ^ Rady 2000 , pp. 28–29.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Rady 2000 , p. 29.

- ^ Fügedi & Bak 2012 , с. 324.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Энгель 2001 , с. 86.

- ^ Fügedi & Bak 2012 , с. 326.

- ^ Короткий 2006 , с. 267.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , с. 33.

- ^ Магаш 2007 , стр. 48.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Короткое 2006 , с. 266.

- ^ Магаш 2007 , стр. 51.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , стр. 76–77.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Беренд, Урбанчик и Вишевский 2013 , стр. 298.

- ^ Rady 2000 , pp. 25–26.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Энгель 2001 , с. 87.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Энгель 2001 , с. 80.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Беренд, Урбанчик и Вишевский 2013 , стр. 299.

- ^ Вольф 2003 , с. 331.

- ^ Беренд, Урбанчик и Вишевский 2013 , стр. 297.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , с. 81.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , стр. 81, 87.

- ^ Беренд, Урбанчик и Вишевский 2013 , стр. 201.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , стр. 71–72.

- ^ Короткий 2006 , с. 401.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , стр. 73–74.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Rady 2000 , pp. 128–129.

- ^ Fügedi & Bak 2012 , с. 328.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Rady 2000 , p. 129.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Rady 2000 , p. 31.

- ^ Беренд, Урбанчик и Вишевский 2013 , стр. 286.

- ^ Картледж 2011 , с. 20.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , с. 93.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Энгель 2001 , с. 92.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Беренд, Урбанчик и Вишевский, 2013 , стр. 426–427.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Фугеди 1986а , с. 48.

- ^ Rady 2000 , p. 23.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , стр. 86–87.

- ^ Аноним, Нотариус короля Белы: Деяния венгров (гл. 6), с. 19.

- ^ Rady 2000 , p. 35.

- ^ Rady 2000 , p. 36.

- ^ Беренд, Урбанчик и Вишевский 2013 , стр. 426.

- ^ Фугеди 1998 , с. 35.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Энгель 2001 , с. 94.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Картледж 2011 , с. 21.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , с. 95.

- ^ Rady 2000 , pp. 40, 103.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , с. 177.

- ^ Беренд, Урбанчик и Вишевский 2013 , стр. 429.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , с. 96.

- ^ Беренд, Урбанчик и Вишевский 2013 , стр. 431.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Rady 2000 , p. 41.

- ^ Котлер 1999 , с. 78–80.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , стр. 103–105.

- ^ Беренд, Урбанчик и Вишевский 2013 , стр. 430.

- ^ Фугеди 1986a , с. 51.

- ^ Фугеди 1986a , стр. 52, 56.

- ^ Фугеди 1986a , с. 56.

- ^ Фугеди 1986a , с. 60.

- ^ Фугеди 1986a , стр. 65, 73–74.

- ^ Фугеди 1986a , с. 74.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Энгель 2001 , с. 120.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Rady 2000 , p. 86.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Энгель 2001 , с. 84.

- ^ Rady 2000 , p. 79.

- ^ Rady 2000 , p. 91.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , стр. 104–105.

- ^ Rady 2000 , p. 83.

- ^ Rady 2000 , p. 81.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Маккай 1994 , стр. 208–209.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Rady 2000 , p. 46.

- ^ Фугеди 1998 , с. 28.

- ^ Rady 2000 , p. 48.

- ^ Фугеди 1998 , стр. 41–42.

- ^ Фугеди 1986a , стр. 72–73.

- ^ Фугеди 1986a , стр. 54, 82.

- ^ Фугеди 1986a , с. 87.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Rady 2000 , p. 112.

- ^ Rady 2000 , pp. 112–113, 200.

- ^ Фугеди 1986a , стр. 77–78.

- ^ Фугеди 1986a , с. 78.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Rady 2000 , p. 110.

- ^ Контлер 1999 , с. 76.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Беренд, Урбанчик и Вишевский 2013 , стр. 432.

- ^ Беренд, Урбанчик и Вишевский 2013 , стр. 431–432.

- ^ Rady 2000 , p. 42.

- ^ Беренд, Урбанчик и Вишевский 2013 , стр. 273.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , с. 108.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , с. 122.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Энгель 2001 , с. 124.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , с. 125.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , с. 126.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , стр. 126–127.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Картледж 2011 , с. 34.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Графтер 1999 , с. 89.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , стр. 141–142.

- ^ Фугеди 1998 , с. 52.

- ^ Rady 2000 , p. 108.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , стр. 178–179.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , с. 146.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , с. 147.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , с. 151.

- ^ Rady 2000 , p. 137.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , стр. 151–153, 342.

- ^ Rady 2000 , pp. 146-147.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Фугеди 1998 , с. 34.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Графтер 1999 , с. 97.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Картледж 2011 , с. 40.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , с. 178.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Энгель 2001 , с. 175.

- ^ Поп 2013 , стр. 198–212.

- ^ Rady 2000 , p. 89.

- ^ Лукачка 2011 , стр. 37.

- ^ Rady 2000 , pp. 84, 89, 93.

- ^ Rady 2000 , pp. 89, 93.

- ^ Поп 2013 , стр. 470–471, 475.

- ^ Поп 2013 , стр. 256–257.

- ^ Энгель 2001 , с. 165.