Augmented reality

Augmented reality (AR) is an interactive experience that combines the real world and computer-generated 3D content. The content can span multiple sensory modalities, including visual, auditory, haptic, somatosensory and olfactory.[1] AR can be defined as a system that incorporates three basic features: a combination of real and virtual worlds, real-time interaction, and accurate 3D registration of virtual and real objects.[2] The overlaid sensory information can be constructive (i.e. additive to the natural environment), or destructive (i.e. masking of the natural environment).[3] As such, it is one of the key technologies in the reality-virtuality continuum.[4]

This experience is seamlessly interwoven with the physical world such that it is perceived as an immersive aspect of the real environment.[3] In this way, augmented reality alters one's ongoing perception of a real-world environment, whereas virtual reality completely replaces the user's real-world environment with a simulated one.[5][6]

Augmented reality is largely synonymous with mixed reality. There is also overlap in terminology with extended reality and computer-mediated reality.

The primary value of augmented reality is the manner in which components of the digital world blend into a person's perception of the real world, not as a simple display of data, but through the integration of immersive sensations, which are perceived as natural parts of an environment. The earliest functional AR systems that provided immersive mixed reality experiences for users were invented in the early 1990s, starting with the Virtual Fixtures system developed at the U.S. Air Force's Armstrong Laboratory in 1992.[3][7][8] Commercial augmented reality experiences were first introduced in entertainment and gaming businesses.[9] Subsequently, augmented reality applications have spanned commercial industries such as education, communications, medicine, and entertainment. In education, content may be accessed by scanning or viewing an image with a mobile device or by using markerless AR techniques.[10][11][12]

Augmented reality can be used to enhance natural environments or situations and offers perceptually enriched experiences. With the help of advanced AR technologies (e.g. adding computer vision, incorporating AR cameras into smartphone applications, and object recognition) the information about the surrounding real world of the user becomes interactive and digitally manipulated.[13] Information about the environment and its objects is overlaid on the real world. This information can be virtual. Augmented Reality is any experience which is artificial and which adds to the already existing reality.[14][15][16][17][18] or real, e.g. seeing other real sensed or measured information such as electromagnetic radio waves overlaid in exact alignment with where they actually are in space.[19][20][21] Augmented reality also has a lot of potential in the gathering and sharing of tacit knowledge. Augmentation techniques are typically performed in real-time and in semantic contexts with environmental elements. Immersive perceptual information is sometimes combined with supplemental information like scores over a live video feed of a sporting event. This combines the benefits of both augmented reality technology and heads up display technology (HUD).

Comparison with virtual reality[edit]

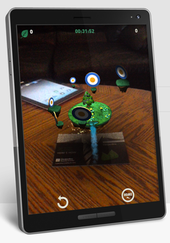

In virtual reality (VR), the users' perception is completely computer-generated, whereas with augmented reality (AR), it is partially generated and partially from the real world.[22][23] For example, in architecture, VR can be used to create a walk-through simulation of the inside of a new building; and AR can be used to show a building's structures and systems super-imposed on a real-life view. Another example is through the use of utility applications. Some AR applications, such as Augment, enable users to apply digital objects into real environments, allowing businesses to use augmented reality devices as a way to preview their products in the real world.[24] Similarly, it can also be used to demo what products may look like in an environment for customers, as demonstrated by companies such as Mountain Equipment Co-op or Lowe's who use augmented reality to allow customers to preview what their products might look like at home through the use of 3D models.[25]

Augmented reality (AR) differs from virtual reality (VR) in the sense that in AR part of the surrounding environment is 'real' and AR is just adding layers of virtual objects to the real environment. On the other hand, in VR the surrounding environment is completely virtual and computer generated. A demonstration of how AR layers objects onto the real world can be seen with augmented reality games. WallaMe is an augmented reality game application that allows users to hide messages in real environments, utilizing geolocation technology in order to enable users to hide messages wherever they may wish in the world.[26] Such applications have many uses in the world, including in activism and artistic expression.[27]

History[edit]

- 1901: L. Frank Baum, an author, first mentions the idea of an electronic display/spectacles that overlays data onto real life (in this case 'people'). It is named a 'character marker'.[28]

- 1957–62: Morton Heilig, a cinematographer, creates and patents a simulator called Sensorama with visuals, sound, vibration, and smell.

- 1968: Ivan Sutherland creates the first head-mounted display that has graphics rendered by a computer.[29]

- 1975: Myron Krueger creates Videoplace to allow users to interact with virtual objects.

- 1980: The research by Gavan Lintern of the University of Illinois is the first published work to show the value of a heads up display for teaching real-world flight skills.[30]

- 1980: Steve Mann creates the first wearable computer, a computer vision system with text and graphical overlays on a photographically mediated scene.[31]

- 1986: Within IBM, Ron Feigenblatt describes the most widely experienced form of AR today (viz. "magic window," e.g. smartphone-based Pokémon Go), use of a small, "smart" flat panel display positioned and oriented by hand.[32][33]

- 1987: Douglas George and Robert Morris create a working prototype of an astronomical telescope-based "heads-up display" system (a precursor concept to augmented reality) which superimposed in the telescope eyepiece, over the actual sky images, multi-intensity star, and celestial body images, and other relevant information.[34]

- 1990: The term augmented reality is attributed to Thomas P. Caudell, a former Boeing researcher.[35]

- 1992: Louis Rosenberg developed one of the first functioning AR systems, called Virtual Fixtures, at the United States Air Force Research Laboratory—Armstrong, that demonstrated benefit to human perception.[36]

- 1992: Steven Feiner, Blair MacIntyre and Doree Seligmann present an early paper on an AR system prototype, KARMA, at the Graphics Interface conference.

- 1993: The CMOS active-pixel sensor, a type of metal–oxide–semiconductor (MOS) image sensor, was developed at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.[37] CMOS sensors are later widely used for optical tracking in AR technology.[38]

- 1993: Mike Abernathy, et al., report the first use of augmented reality in identifying space debris using Rockwell WorldView by overlaying satellite geographic trajectories on live telescope video.[39]

- 1993: A widely cited version of the paper above is published in Communications of the ACM – Special issue on computer augmented environments, edited by Pierre Wellner, Wendy Mackay, and Rich Gold.[40]

- 1993: Loral WDL, with sponsorship from STRICOM, performed the first demonstration combining live AR-equipped vehicles and manned simulators. Unpublished paper, J. Barrilleaux, "Experiences and Observations in Applying Augmented Reality to Live Training", 1999.[41]

- 1994: Julie Martin creates first 'Augmented Reality Theater production', Dancing in Cyberspace, funded by the Australia Council for the Arts, features dancers and acrobats manipulating body–sized virtual object in real time, projected into the same physical space and performance plane. The acrobats appeared immersed within the virtual object and environments. The installation used Silicon Graphics computers and Polhemus sensing system.

- 1996: General Electric develops system for projecting information from 3D CAD models onto real-world instances of those models.[42]

- 1998: Spatial augmented reality introduced at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill by Ramesh Raskar, Welch, Henry Fuchs.[43]

- 1999: Frank Delgado, Mike Abernathy et al. report successful flight test of LandForm software video map overlay from a helicopter at Army Yuma Proving Ground overlaying video with runways, taxiways, roads and road names.[44][45]

- 1999: The US Naval Research Laboratory engages on a decade-long research program called the Battlefield Augmented Reality System (BARS) to prototype some of the early wearable systems for dismounted soldier operating in urban environment for situation awareness and training.[46]

- 1999: NASA X-38 flown using LandForm software video map overlays at Dryden Flight Research Center.[47]

- 2000: Rockwell International Science Center demonstrates tetherless wearable augmented reality systems receiving analog video and 3-D audio over radio-frequency wireless channels. The systems incorporate outdoor navigation capabilities, with digital horizon silhouettes from a terrain database overlain in real time on the live outdoor scene, allowing visualization of terrain made invisible by clouds and fog.[48][49]

- 2004: An outdoor helmet-mounted AR system was demonstrated by Trimble Navigation and the Human Interface Technology Laboratory (HIT lab).[50]

- 2006: Outland Research develops AR media player that overlays virtual content onto a users view of the real world synchronously with playing music, thereby providing an immersive AR entertainment experience.[51][52]

- 2008: Wikitude AR Travel Guide launches on 20 Oct 2008 with the G1 Android phone.[53]

- 2009: ARToolkit was ported to Adobe Flash (FLARToolkit) by Saqoosha, bringing augmented reality to the web browser.[54]

- 2012: Launch of Lyteshot, an interactive AR gaming platform that utilizes smart glasses for game data

- 2015: Microsoft announced the HoloLens augmented reality headset, which uses various sensors and a processing unit to display virtual imagery over the real world.[55]

- 2016: Niantic released Pokémon Go for iOS and Android in July 2016. The game quickly became one of the most popular smartphone applications and in turn spikes the popularity of augmented reality games.[56]

- 2018: Magic Leap launched the Magic Leap One augmented reality headset.[57] Leap Motion announced the Project North Star augmented reality headset, and later released it under an open source license.[58][59][60][61]

- 2019: Microsoft announced HoloLens 2 with significant improvements in terms of field of view and ergonomics.[62]

- 2022: Magic Leap launched the Magic Leap 2 headset.[63]

Hardware[edit]

Augmented reality requires hardware components including a processor, display, sensors, and input devices. Modern mobile computing devices like smartphones and tablet computers contain these elements, which often include a camera and microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) sensors such as an accelerometer, GPS, and solid state compass, making them suitable AR platforms.[64][65]

Displays[edit]

Various technologies can be used to display augmented reality, including optical projection systems, monitors, and handheld devices. Two of the display technologies used in augmented reality are diffractive waveguides and reflective waveguides.

A head-mounted display (HMD) is a display device worn on the forehead, such as a harness or helmet-mounted. HMDs place images of both the physical world and virtual objects over the user's field of view. Modern HMDs often employ sensors for six degrees of freedom monitoring that allow the system to align virtual information to the physical world and adjust accordingly with the user's head movements.[66][67][68] HMDs can provide VR users with mobile and collaborative experiences.[69] Specific providers, such as uSens and Gestigon, include gesture controls for full virtual immersion.[70][71]

Vuzix is a company that has produced a number of head-worn optical see through displays marketed for augmented reality.[72][73][74]

Eyeglasses[edit]

AR displays can be rendered on devices resembling eyeglasses. Versions include eyewear that employs cameras to intercept the real world view and re-display its augmented view through the eyepieces[75] and devices in which the AR imagery is projected through or reflected off the surfaces of the eyewear lens pieces.[76][77][78]

The EyeTap (also known as Generation-2 Glass[79]) captures rays of light that would otherwise pass through the center of the lens of the wearer's eye, and substitutes synthetic computer-controlled light for each ray of real light. The Generation-4 Glass[79] (Laser EyeTap) is similar to the VRD (i.e. it uses a computer-controlled laser light source) except that it also has infinite depth of focus and causes the eye itself to, in effect, function as both a camera and a display by way of exact alignment with the eye and resynthesis (in laser light) of rays of light entering the eye.[80]

HUD[edit]

A head-up display (HUD) is a transparent display that presents data without requiring users to look away from their usual viewpoints. A precursor technology to augmented reality, heads-up displays were first developed for pilots in the 1950s, projecting simple flight data into their line of sight, thereby enabling them to keep their "heads up" and not look down at the instruments. Near-eye augmented reality devices can be used as portable head-up displays as they can show data, information, and images while the user views the real world. Many definitions of augmented reality only define it as overlaying the information.[81][82] This is basically what a head-up display does; however, practically speaking, augmented reality is expected to include registration and tracking between the superimposed perceptions, sensations, information, data, and images and some portion of the real world.[83]

Contact lenses[edit]

Contact lenses that display AR imaging are in development. These bionic contact lenses might contain the elements for display embedded into the lens including integrated circuitry, LEDs and an antenna for wireless communication. The first contact lens display was patented in 1999 by Steve Mann and was intended to work in combination with AR spectacles, but the project was abandoned,[84][85] then 11 years later in 2010–2011.[86][87][88][89] Another version of contact lenses, in development for the U.S. military, is designed to function with AR spectacles, allowing soldiers to focus on close-to-the-eye AR images on the spectacles and distant real world objects at the same time.[90][91]

At CES 2013, a company called Innovega also unveiled similar contact lenses that required being combined with AR glasses to work.[92]

Many scientists have been working on contact lenses capable of different technological feats. A patent filed by Samsung describes an AR contact lens, that, when finished, will include a built-in camera on the lens itself.[93] The design is intended to control its interface by blinking an eye. It is also intended to be linked with the user's smartphone to review footage, and control it separately. When successful, the lens would feature a camera, or sensor inside of it. It is said that it could be anything from a light sensor, to a temperature sensor.

The first publicly unveiled working prototype of an AR contact lens not requiring the use of glasses in conjunction was developed by Mojo Vision and announced and shown off at CES 2020.[94][95][96]

Virtual retinal display[edit]

A virtual retinal display (VRD) is a personal display device under development at the University of Washington's Human Interface Technology Laboratory under Dr. Thomas A. Furness III.[97] With this technology, a display is scanned directly onto the retina of a viewer's eye. This results in bright images with high resolution and high contrast. The viewer sees what appears to be a conventional display floating in space.[98]

Several of tests were done to analyze the safety of the VRD.[97] In one test, patients with partial loss of vision—having either macular degeneration (a disease that degenerates the retina) or keratoconus—were selected to view images using the technology. In the macular degeneration group, five out of eight subjects preferred the VRD images to the cathode-ray tube (CRT) or paper images and thought they were better and brighter and were able to see equal or better resolution levels. The Keratoconus patients could all resolve smaller lines in several line tests using the VRD as opposed to their own correction. They also found the VRD images to be easier to view and sharper. As a result of these several tests, virtual retinal display is considered safe technology.

Virtual retinal display creates images that can be seen in ambient daylight and ambient room light. The VRD is considered a preferred candidate to use in a surgical display due to its combination of high resolution and high contrast and brightness. Additional tests show high potential for VRD to be used as a display technology for patients that have low vision.

Handheld[edit]

A Handheld display employs a small display that fits in a user's hand. All handheld AR solutions to date opt for video see-through. Initially handheld AR employed fiducial markers,[99] and later GPS units and MEMS sensors such as digital compasses and six degrees of freedom accelerometer–gyroscope. Today simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM) markerless trackers such as PTAM (parallel tracking and mapping) are starting to come into use. Handheld display AR promises to be the first commercial success for AR technologies. The two main advantages of handheld AR are the portable nature of handheld devices and the ubiquitous nature of camera phones. The disadvantages are the physical constraints of the user having to hold the handheld device out in front of them at all times, as well as the distorting effect of classically wide-angled mobile phone cameras when compared to the real world as viewed through the eye.[100]

Projection mapping[edit]

Projection mapping augments real-world objects and scenes without the use of special displays such as monitors, head-mounted displays or hand-held devices. Projection mapping makes use of digital projectors to display graphical information onto physical objects. The key difference in projection mapping is that the display is separated from the users of the system. Since the displays are not associated with each user, projection mapping scales naturally up to groups of users, allowing for collocated collaboration between users.

Examples include shader lamps, mobile projectors, virtual tables, and smart projectors. Shader lamps mimic and augment reality by projecting imagery onto neutral objects. This provides the opportunity to enhance the object's appearance with materials of a simple unit—a projector, camera, and sensor.

Other applications include table and wall projections. Virtual showcases, which employ beam splitter mirrors together with multiple graphics displays, provide an interactive means of simultaneously engaging with the virtual and the real.

A projection mapping system can display on any number of surfaces in an indoor setting at once. Projection mapping supports both a graphical visualization and passive haptic sensation for the end users. Users are able to touch physical objects in a process that provides passive haptic sensation.[18][43][101][102]

Tracking[edit]

Modern mobile augmented-reality systems use one or more of the following motion tracking technologies: digital cameras and/or other optical sensors, accelerometers, GPS, gyroscopes, solid state compasses, radio-frequency identification (RFID). These technologies offer varying levels of accuracy and precision. These technologies are implemented in the ARKit API by Apple and ARCore API by Google to allow tracking for their respective mobile device platforms.

Input devices[edit]

Techniques include speech recognition systems that translate a user's spoken words into computer instructions, and gesture recognition systems that interpret a user's body movements by visual detection or from sensors embedded in a peripheral device such as a wand, stylus, pointer, glove or other body wear.[103][104][105][106] Products which are trying to serve as a controller of AR headsets include Wave by Seebright Inc. and Nimble by Intugine Technologies.

Computer[edit]

Computers are responsible for graphics in augmented reality. For camera-based 3D tracking methods, a computer analyzes the sensed visual and other data to synthesize and position virtual objects. With the improvement of technology and computers, augmented reality is going to lead to a drastic change on ones perspective of the real world.[107]

Computers are improving at a very fast rate, leading to new ways to improve other technology. Computers are the core of augmented reality.[108] The computer receives data from the sensors which determine the relative position of an objects' surface. This translates to an input to the computer which then outputs to the users by adding something that would otherwise not be there. The computer comprises memory and a processor.[109] The computer takes the scanned environment then generates images or a video and puts it on the receiver for the observer to see. The fixed marks on an object's surface are stored in the memory of a computer. The computer also withdraws from its memory to present images realistically to the onlooker.

Projector[edit]

Projectors can also be used to display AR contents. The projector can throw a virtual object on a projection screen and the viewer can interact with this virtual object. Projection surfaces can be many objects such as walls or glass panes.[110]

Networking[edit]

Mobile augmented reality applications are gaining popularity because of the wide adoption of mobile and especially wearable devices. However, they often rely on computationally intensive computer vision algorithms with extreme latency requirements. To compensate for the lack of computing power, offloading data processing to a distant machine is often desired. Computation offloading introduces new constraints in applications, especially in terms of latency and bandwidth. Although there are a plethora of real-time multimedia transport protocols, there is a need for support from network infrastructure as well.[111]

Software and algorithms[edit]

A key measure of AR systems is how realistically they integrate virtual imagery with the real world. The software must derive real world coordinates, independent of camera, and camera images. That process is called image registration, and uses different methods of computer vision, mostly related to video tracking.[112][113] Many computer vision methods of augmented reality are inherited from visual odometry.

Usually those methods consist of two parts. The first stage is to detect interest points, fiducial markers or optical flow in the camera images. This step can use feature detection methods like corner detection, blob detection, edge detection or thresholding, and other image processing methods.[114][115] The second stage restores a real world coordinate system from the data obtained in the first stage. Some methods assume objects with known geometry (or fiducial markers) are present in the scene. In some of those cases the scene 3D structure should be calculated beforehand. If part of the scene is unknown simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM) can map relative positions. If no information about scene geometry is available, structure from motion methods like bundle adjustment are used. Mathematical methods used in the second stage include: projective (epipolar) geometry, geometric algebra, rotation representation with exponential map, kalman and particle filters, nonlinear optimization, robust statistics.[citation needed]

In augmented reality, the distinction is made between two distinct modes of tracking, known as marker and markerless. Markers are visual cues which trigger the display of the virtual information.[116] A piece of paper with some distinct geometries can be used. The camera recognizes the geometries by identifying specific points in the drawing. Markerless tracking, also called instant tracking, does not use markers. Instead, the user positions the object in the camera view preferably in a horizontal plane. It uses sensors in mobile devices to accurately detect the real-world environment, such as the locations of walls and points of intersection.[117]

Augmented Reality Markup Language (ARML) is a data standard developed within the Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC),[118] which consists of Extensible Markup Language (XML) grammar to describe the location and appearance of virtual objects in the scene, as well as ECMAScript bindings to allow dynamic access to properties of virtual objects.

To enable rapid development of augmented reality applications, software development applications have emerged, including Lens Studio from Snapchat and Spark AR from Facebook. Augmented reality Software Development Kits (SDKs) have been launched by Apple and Google.[119][120]

Development[edit]

AR systems rely heavily on the immersion of the user. The following lists some considerations for designing augmented reality applications:

Environmental/context design[edit]

Context Design focuses on the end-user's physical surrounding, spatial space, and accessibility that may play a role when using the AR system. Designers should be aware of the possible physical scenarios the end-user may be in such as:

- Public, in which the users use their whole body to interact with the software

- Personal, in which the user uses a smartphone in a public space

- Intimate, in which the user is sitting with a desktop and is not really moving

- Private, in which the user has on a wearable.[121]

By evaluating each physical scenario, potential safety hazards can be avoided and changes can be made to greater improve the end-user's immersion. UX designers will have to define user journeys for the relevant physical scenarios and define how the interface reacts to each.

Another aspect of context design involves the design of the system's functionality and its ability to accommodate user preferences.[122][123] While accessibility tools are common in basic application design, some consideration should be made when designing time-limited prompts (to prevent unintentional operations), audio cues and overall engagement time. It is important to note that in some situations, the application's functionality may hinder the user's ability. For example, applications that is used for driving should reduce the amount of user interaction and use audio cues instead.

Interaction design[edit]

Interaction design in augmented reality technology centers on the user's engagement with the end product to improve the overall user experience and enjoyment. The purpose of interaction design is to avoid alienating or confusing the user by organizing the information presented. Since user interaction relies on the user's input, designers must make system controls easier to understand and accessible. A common technique to improve usability for augmented reality applications is by discovering the frequently accessed areas in the device's touch display and design the application to match those areas of control.[124] It is also important to structure the user journey maps and the flow of information presented which reduce the system's overall cognitive load and greatly improves the learning curve of the application.[125]

In interaction design, it is important for developers to utilize augmented reality technology that complement the system's function or purpose.[126] For instance, the utilization of exciting AR filters and the design of the unique sharing platform in Snapchat enables users to augment their in-app social interactions. In other applications that require users to understand the focus and intent, designers can employ a reticle or raycast from the device.[122]

Visual design[edit]

To improve the graphic interface elements and user interaction, developers may use visual cues to inform the user what elements of UI are designed to interact with and how to interact with them. Visual cue design can make interactions seem more natural.[121]

In some augmented reality applications that use a 2D device as an interactive surface, the 2D control environment does not translate well in 3D space, which can make users hesitant to explore their surroundings. To solve this issue, designers should apply visual cues to assist and encourage users to explore their surroundings.

It is important to note the two main objects in AR when developing VR applications: 3D volumetric objects that are manipulated and realistically interact with light and shadow; and animated media imagery such as images and videos which are mostly traditional 2D media rendered in a new context for augmented reality.[121] When virtual objects are projected onto a real environment, it is challenging for augmented reality application designers to ensure a perfectly seamless integration relative to the real-world environment, especially with 2D objects. As such, designers can add weight to objects, use depths maps, and choose different material properties that highlight the object's presence in the real world. Another visual design that can be applied is using different lighting techniques or casting shadows to improve overall depth judgment. For instance, a common lighting technique is simply placing a light source overhead at the 12 o’clock position, to create shadows on virtual objects.[121]

Uses[edit]

Augmented reality has been explored for many uses, including gaming, medicine, and entertainment. It has also been explored for education and business.[127] Example application areas described below include archaeology, architecture, commerce and education. Some of the earliest cited examples include augmented reality used to support surgery by providing virtual overlays to guide medical practitioners, to AR content for astronomy and welding.[8][128]

Archaeology[edit]

AR has been used to aid archaeological research. By augmenting archaeological features onto the modern landscape, AR allows archaeologists to formulate possible site configurations from extant structures.[129] Computer generated models of ruins, buildings, landscapes or even ancient people have been recycled into early archaeological AR applications.[130][131][132] For example, implementing a system like VITA (Visual Interaction Tool for Archaeology) will allow users to imagine and investigate instant excavation results without leaving their home. Each user can collaborate by mutually "navigating, searching, and viewing data". Hrvoje Benko, a researcher in the computer science department at Columbia University, points out that these particular systems and others like them can provide "3D panoramic images and 3D models of the site itself at different excavation stages" all the while organizing much of the data in a collaborative way that is easy to use. Collaborative AR systems supply multimodal interactions that combine the real world with virtual images of both environments.[133]

Architecture[edit]

AR can aid in visualizing building projects. Computer-generated images of a structure can be superimposed onto a real-life local view of a property before the physical building is constructed there; this was demonstrated publicly by Trimble Navigation in 2004. AR can also be employed within an architect's workspace, rendering animated 3D visualizations of their 2D drawings. Architecture sight-seeing can be enhanced with AR applications, allowing users viewing a building's exterior to virtually see through its walls, viewing its interior objects and layout.[134][135][50]

With continual improvements to GPS accuracy, businesses are able to use augmented reality to visualize georeferenced models of construction sites, underground structures, cables and pipes using mobile devices.[136] Augmented reality is applied to present new projects, to solve on-site construction challenges, and to enhance promotional materials.[137] Examples include the Daqri Smart Helmet, an Android-powered hard hat used to create augmented reality for the industrial worker, including visual instructions, real-time alerts, and 3D mapping.

Following the Christchurch earthquake, the University of Canterbury released CityViewAR,[138] which enabled city planners and engineers to visualize buildings that had been destroyed.[139] This not only provided planners with tools to reference the previous cityscape, but it also served as a reminder of the magnitude of the resulting devastation, as entire buildings had been demolished.

Education and Training[edit]

In educational settings, AR has been used to complement a standard curriculum. Text, graphics, video, and audio may be superimposed into a student's real-time environment. Textbooks, flashcards and other educational reading material may contain embedded "markers" or triggers that, when scanned by an AR device, produced supplementary information to the student rendered in a multimedia format.[140][141][142] The 2015 Virtual, Augmented and Mixed Reality: 7th International Conference mentioned Google Glass as an example of augmented reality that can replace the physical classroom.[143] First, AR technologies help learners engage in authentic exploration in the real world, and virtual objects such as texts, videos, and pictures are supplementary elements for learners to conduct investigations of the real-world surroundings.[144]

As AR evolves, students can participate interactively and interact with knowledge more authentically. Instead of remaining passive recipients, students can become active learners, able to interact with their learning environment. Computer-generated simulations of historical events allow students to explore and learning details of each significant area of the event site.[145]

In higher education, Construct3D, a Studierstube system, allows students to learn mechanical engineering concepts, math or geometry.[146] Chemistry AR apps allow students to visualize and interact with the spatial structure of a molecule using a marker object held in the hand.[147] Others have used HP Reveal, a free app, to create AR notecards for studying organic chemistry mechanisms or to create virtual demonstrations of how to use laboratory instrumentation.[148] Anatomy students can visualize different systems of the human body in three dimensions.[149] Using AR as a tool to learn anatomical structures has been shown to increase the learner knowledge and provide intrinsic benefits, such as increased engagement and learner immersion.[150][151]

AR has been used to develop different safety training application for several types of disasters such as, earthquakes and building fire.[152][153] Further, several AR solutions have been proposed and tested to navigate building evacuees towards safe places in both large scale and small scale disasters.[154][155] Further, AR applications can have several overlapping with many other digital technologies, such as BIM, internet of things and artificial intelligence, to generate smarter safety training and navigation solutions.[156]

Industrial manufacturing[edit]

AR is used to substitute paper manuals with digital instructions which are overlaid on the manufacturing operator's field of view, reducing mental effort required to operate.[157] AR makes machine maintenance efficient because it gives operators direct access to a machine's maintenance history.[158] Virtual manuals help manufacturers adapt to rapidly-changing product designs, as digital instructions are more easily edited and distributed compared to physical manuals.[157]

Digital instructions increase operator safety by removing the need for operators to look at a screen or manual away from the working area, which can be hazardous. Instead, the instructions are overlaid on the working area.[159][160] The use of AR can increase operators' feeling of safety when working near high-load industrial machinery by giving operators additional information on a machine's status and safety functions, as well as hazardous areas of the workspace.[159][161]

Commerce[edit]

AR is used to integrate print and video marketing. Printed marketing material can be designed with certain "trigger" images that, when scanned by an AR-enabled device using image recognition, activate a video version of the promotional material. A major difference between augmented reality and straightforward image recognition is that one can overlay multiple media at the same time in the view screen, such as social media share buttons, the in-page video even audio and 3D objects. Traditional print-only publications are using augmented reality to connect different types of media.[162][163][164][165][166]

AR can enhance product previews such as allowing a customer to view what's inside a product's packaging without opening it.[167] AR can also be used as an aid in selecting products from a catalog or through a kiosk. Scanned images of products can activate views of additional content such as customization options and additional images of the product in its use.[168]

By 2010, virtual dressing rooms had been developed for e-commerce.[169]

In 2012, a mint used AR techniques to market a commemorative coin for Aruba. The coin itself was used as an AR trigger, and when held in front of an AR-enabled device it revealed additional objects and layers of information that were not visible without the device.[170][171]

In 2018, Apple announced Universal Scene Description (USDZ) AR file support for iPhones and iPads with iOS 12. Apple has created an AR QuickLook Gallery that allows masses to experience augmented reality on their own Apple device.[172]

In 2018, Shopify, the Canadian e-commerce company, announced AR Quick Look integration. Their merchants will be able to upload 3D models of their products and their users will be able to tap on the models inside the Safari browser on their iOS devices to view them in their real-world environments.[173]

In 2018, Twinkl released a free AR classroom application. Pupils can see how York looked over 1,900 years ago.[174] Twinkl launched the first ever multi-player AR game, Little Red[175] and has over 100 free AR educational models.[176]

Augmented reality is becoming more frequently used for online advertising. Retailers offer the ability to upload a picture on their website and "try on" various clothes which are overlaid on the picture. Even further, companies such as Bodymetrics install dressing booths in department stores that offer full-body scanning. These booths render a 3-D model of the user, allowing the consumers to view different outfits on themselves without the need of physically changing clothes.[177] For example, JC Penney and Bloomingdale's use "virtual dressing rooms" that allow customers to see themselves in clothes without trying them on.[178] Another store that uses AR to market clothing to its customers is Neiman Marcus.[179] Neiman Marcus offers consumers the ability to see their outfits in a 360-degree view with their "memory mirror".[179] Makeup stores like L'Oreal, Sephora, Charlotte Tilbury, and Rimmel also have apps that utilize AR.[180] These apps allow consumers to see how the makeup will look on them.[180] According to Greg Jones, director of AR and VR at Google, augmented reality is going to "reconnect physical and digital retail".[180]

AR technology is also used by furniture retailers such as IKEA, Houzz, and Wayfair.[180][178] These retailers offer apps that allow consumers to view their products in their home prior to purchasing anything.[180] [181]In 2017, Ikea announced the Ikea Place app. It contains a catalogue of over 2,000 products—nearly the company's full collection of sofas, armchairs, coffee tables, and storage units which one can place anywhere in a room with their phone.[182] The app made it possible to have 3D and true-to-scale models of furniture in the customer's living space. IKEA realized that their customers are not shopping in stores as often or making direct purchases anymore.[183][184] Shopify's acquisition of Primer, an AR app aims to push small and medium-sized sellers towards interactive AR shopping with easy to use AR integration and user experience for both merchants and consumers.[185] AR helps the retail industry reduce operating costs. Merchants upload product information to the AR system, and consumers can use mobile terminals to search and generate 3D maps.[186]

Literature[edit]

The first description of AR as it is known today was in Virtual Light, the 1994 novel by William Gibson. In 2011, AR was blended with poetry by ni ka from Sekai Camera in Tokyo, Japan. The prose of these AR poems come from Paul Celan, Die Niemandsrose, expressing the aftermath of the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami.[187]

Visual art[edit]

AR applied in the visual arts allows objects or places to trigger artistic multidimensional experiences and interpretations of reality.

The Australian new media artist Jeffrey Shaw pioneered Augmented Reality in three artworks: Viewpoint in 1975, Virtual Sculptures in 1987 and The Golden Calf in 1993.[189][190] He continues to explore new permutations of AR in numerous recent works.

Augmented reality can aid in the progression of visual art in museums by allowing museum visitors to view artwork in galleries in a multidimensional way through their phone screens.[191] The Museum of Modern Art in New York has created an exhibit in their art museum showcasing AR features that viewers can see using an app on their smartphone.[192] The museum has developed their personal app, called MoMAR Gallery, that museum guests can download and use in the augmented reality specialized gallery in order to view the museum's paintings in a different way.[193] This allows individuals to see hidden aspects and information about the paintings, and to be able to have an interactive technological experience with artwork as well.

AR technology was used in Nancy Baker Cahill's "Margin of Error" and "Revolutions,"[194] the two public art pieces she created for the 2019 Desert X exhibition.[195]

AR technology aided the development of eye tracking technology to translate a disabled person's eye movements into drawings on a screen.[196]

A Danish artist, Olafur Eliasson, has placed objects like burning suns, extraterrestrial rocks, and rare animals, into the user's environment.[197] Martin & Muñoz started using Augmented Reality (AR) technology in 2020 to create and place virtual works, based on their snow globes, in their exhibitions and in user's environments. Their first AR work was presented at the Cervantes Institute in New York in early 2022.[198]

Fitness[edit]

AR hardware and software for use in fitness includes smart glasses made for biking and running, with performance analytics and map navigation projected onto the user's field of vision,[199] and boxing, martial arts, and tennis, where users remain aware of their physical environment for safety.[200] Fitness-related games and software include Pokémon Go and Jurassic World Alive.[201]

Human–computer interaction[edit]

Human–computer interaction (HCI) is an interdisciplinary area of computing that deals with design and implementation of systems that interact with people. Researchers in HCI come from a number of disciplines, including computer science, engineering, design, human factor, and social science, with a shared goal to solve problems in the design and the use of technology so that it can be used more easily, effectively, efficiently, safely, and with satisfaction.[202]

According to a 2017 Time article, in about 15 to 20 years it is predicted that augmented reality and virtual reality are going to become the primary use for computer interactions.[203]

Remote collaboration[edit]

Primary school children learn easily from interactive experiences. As an example, astronomical constellations and the movements of objects in the solar system were oriented in 3D and overlaid in the direction the device was held, and expanded with supplemental video information. Paper-based science book illustrations could seem to come alive as video without requiring the child to navigate to web-based materials.

In 2013, a project was launched on Kickstarter to teach about electronics with an educational toy that allowed children to scan their circuit with an iPad and see the electric current flowing around.[204] While some educational apps were available for AR by 2016, it was not broadly used. Apps that leverage augmented reality to aid learning included SkyView for studying astronomy,[205] AR Circuits for building simple electric circuits,[206] and SketchAr for drawing.[207]

AR would also be a way for parents and teachers to achieve their goals for modern education, which might include providing more individualized and flexible learning, making closer connections between what is taught at school and the real world, and helping students to become more engaged in their own learning.

Emergency management/search and rescue[edit]

Augmented reality systems are used in public safety situations, from super storms to suspects at large.

As early as 2009, two articles from Emergency Management discussed AR technology for emergency management. The first was "Augmented Reality—Emerging Technology for Emergency Management", by Gerald Baron.[208] According to Adam Crow,: "Technologies like augmented reality (ex: Google Glass) and the growing expectation of the public will continue to force professional emergency managers to radically shift when, where, and how technology is deployed before, during, and after disasters."[209]

Another early example was a search aircraft looking for a lost hiker in rugged mountain terrain. Augmented reality systems provided aerial camera operators with a geographic awareness of forest road names and locations blended with the camera video. The camera operator was better able to search for the hiker knowing the geographic context of the camera image. Once located, the operator could more efficiently direct rescuers to the hiker's location because the geographic position and reference landmarks were clearly labeled.[210]

Social interaction[edit]

AR can be used to facilitate social interaction. An augmented reality social network framework called Talk2Me enables people to disseminate information and view others' advertised information in an augmented reality way. The timely and dynamic information sharing and viewing functionalities of Talk2Me help initiate conversations and make friends for users with people in physical proximity.[211] However, use of an AR headset can inhibit the quality of an interaction between two people if one isn't wearing one if the headset becomes a distraction.[212]

Augmented reality also gives users the ability to practice different forms of social interactions with other people in a safe, risk-free environment. Hannes Kauffman, Associate Professor for virtual reality at TU Vienna, says: "In collaborative augmented reality multiple users may access a shared space populated by virtual objects, while remaining grounded in the real world. This technique is particularly powerful for educational purposes when users are collocated and can use natural means of communication (speech, gestures, etc.), but can also be mixed successfully with immersive VR or remote collaboration."[This quote needs a citation] Hannes cites education as a potential use of this technology.

Video games[edit]

The gaming industry embraced AR technology. A number of games were developed for prepared indoor environments, such as AR air hockey, Titans of Space, collaborative combat against virtual enemies, and AR-enhanced pool table games.[213][214][215]

In 2010, Ogmento became the first AR gaming startup to receive VC Funding. The company went on to produce early location-based AR games for titles like Paranormal Activity: Sanctuary, NBA: King of the Court, and Halo: King of the Hill. The companies computer vision technology was eventually repackaged and sold to Apple, became a major contribution to ARKit.[216]

Augmented reality allows video game players to experience digital game play in a real-world environment. Niantic released the augmented reality mobile game Pokémon Go.[217] Disney has partnered with Lenovo to create the augmented reality game Star Wars: Jedi Challenges that works with a Lenovo Mirage AR headset, a tracking sensor and a Lightsaber controller, scheduled to launch in December 2017.[218]

Industrial design[edit]

AR allows industrial designers to experience a product's design and operation before completion. Volkswagen has used AR for comparing calculated and actual crash test imagery.[219] AR has been used to visualize and modify car body structure and engine layout. It has also been used to compare digital mock-ups with physical mock-ups to find discrepancies between them.[220][221]

Healthcare planning, practice and education[edit]

One of the first applications of augmented reality was in healthcare, particularly to support the planning, practice, and training of surgical procedures. As far back as 1992, enhancing human performance during surgery was a formally stated objective when building the first augmented reality systems at U.S. Air Force laboratories.[3] Since 2005, a device called a near-infrared vein finder that films subcutaneous veins, processes and projects the image of the veins onto the skin has been used to locate veins.[222][223] AR provides surgeons with patient monitoring data in the style of a fighter pilot's heads-up display, and allows patient imaging records, including functional videos, to be accessed and overlaid. Examples include a virtual X-ray view based on prior tomography or on real-time images from ultrasound and confocal microscopy probes,[224] visualizing the position of a tumor in the video of an endoscope,[225] or radiation exposure risks from X-ray imaging devices.[226][227] AR can enhance viewing a fetus inside a mother's womb.[228] Siemens, Karl Storz and IRCAD have developed a system for laparoscopic liver surgery that uses AR to view sub-surface tumors and vessels.[229]AR has been used for cockroach phobia treatment[230] and to reduce the fear of spiders.[231] Patients wearing augmented reality glasses can be reminded to take medications.[232] Augmented reality can be very helpful in the medical field.[233] It could be used to provide crucial information to a doctor or surgeon without having them take their eyes off the patient. On 30 April 2015 Microsoft announced the Microsoft HoloLens, their first attempt at augmented reality. The HoloLens has advanced through the years and is capable of projecting holograms for near infrared fluorescence based image guided surgery.[234] As augmented reality advances, it finds increasing applications in healthcare. Augmented reality and similar computer based-utilities are being used to train medical professionals.[235][236] In healthcare, AR can be used to provide guidance during diagnostic and therapeutic interventions e.g. during surgery. Magee et al.,[237] for instance, describe the use of augmented reality for medical training in simulating ultrasound-guided needle placement. A very recent study by Akçayır, Akçayır, Pektaş, and Ocak (2016) revealed that AR technology both improves university students' laboratory skills and helps them to build positive attitudes relating to physics laboratory work.[238] Recently, augmented reality began seeing adoption in neurosurgery, a field that requires heavy amounts of imaging before procedures.[239]

Spatial immersion and interaction[edit]

Augmented reality applications, running on handheld devices utilized as virtual reality headsets, can also digitize human presence in space and provide a computer generated model of them, in a virtual space where they can interact and perform various actions. Such capabilities are demonstrated by Project Anywhere, developed by a postgraduate student at ETH Zurich, which was dubbed as an "out-of-body experience".[240][241][242]

Flight training[edit]

Building on decades of perceptual-motor research in experimental psychology, researchers at the Aviation Research Laboratory of the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign used augmented reality in the form of a flight path in the sky to teach flight students how to land an airplane using a flight simulator. An adaptive augmented schedule in which students were shown the augmentation only when they departed from the flight path proved to be a more effective training intervention than a constant schedule.[30][243] Flight students taught to land in the simulator with the adaptive augmentation learned to land a light aircraft more quickly than students with the same amount of landing training in the simulator but with constant augmentation or without any augmentation.[30]

Military[edit]

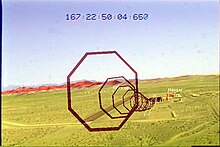

An interesting early application of AR occurred when Rockwell International created video map overlays of satellite and orbital debris tracks to aid in space observations at Air Force Maui Optical System. In their 1993 paper "Debris Correlation Using the Rockwell WorldView System" the authors describe the use of map overlays applied to video from space surveillance telescopes. The map overlays indicated the trajectories of various objects in geographic coordinates. This allowed telescope operators to identify satellites, and also to identify and catalog potentially dangerous space debris.[39]

Starting in 2003 the US Army integrated the SmartCam3D augmented reality system into the Shadow Unmanned Aerial System to aid sensor operators using telescopic cameras to locate people or points of interest. The system combined fixed geographic information including street names, points of interest, airports, and railroads with live video from the camera system. The system offered a "picture in picture" mode that allows it to show a synthetic view of the area surrounding the camera's field of view. This helps solve a problem in which the field of view is so narrow that it excludes important context, as if "looking through a soda straw". The system displays real-time friend/foe/neutral location markers blended with live video, providing the operator with improved situational awareness.

Researchers at USAF Research Lab (Calhoun, Draper et al.) found an approximately two-fold increase in the speed at which UAV sensor operators found points of interest using this technology.[244] This ability to maintain geographic awareness quantitatively enhances mission efficiency. The system is in use on the US Army RQ-7 Shadow and the MQ-1C Gray Eagle Unmanned Aerial Systems.

In combat, AR can serve as a networked communication system that renders useful battlefield data onto a soldier's goggles in real time. From the soldier's viewpoint, people and various objects can be marked with special indicators to warn of potential dangers. Virtual maps and 360° view camera imaging can also be rendered to aid a soldier's navigation and battlefield perspective, and this can be transmitted to military leaders at a remote command center.[245] The combination of 360° view cameras visualization and AR can be used on board combat vehicles and tanks as circular review system.

AR can be an effective tool for virtually mapping out the 3D topologies of munition storages in the terrain, with the choice of the munitions combination in stacks and distances between them with a visualization of risk areas.[246][unreliable source?] The scope of AR applications also includes visualization of data from embedded munitions monitoring sensors.[246]

[edit]

The NASA X-38 was flown using a hybrid synthetic vision system that overlaid map data on video to provide enhanced navigation for the spacecraft during flight tests from 1998 to 2002. It used the LandForm software which was useful for times of limited visibility, including an instance when the video camera window frosted over leaving astronauts to rely on the map overlays.[44] The LandForm software was also test flown at the Army Yuma Proving Ground in 1999. In the photo at right one can see the map markers indicating runways, air traffic control tower, taxiways, and hangars overlaid on the video.[45]

AR can augment the effectiveness of navigation devices. Information can be displayed on an automobile's windshield indicating destination directions and meter, weather, terrain, road conditions and traffic information as well as alerts to potential hazards in their path.[247][248][249] Since 2012, a Swiss-based company WayRay has been developing holographic AR navigation systems that use holographic optical elements for projecting all route-related information including directions, important notifications, and points of interest right into the drivers' line of sight and far ahead of the vehicle.[250][251] Aboard maritime vessels, AR can allow bridge watch-standers to continuously monitor important information such as a ship's heading and speed while moving throughout the bridge or performing other tasks.[252]

Workplace[edit]

Augmented reality may have a positive impact on work collaboration as people may be inclined to interact more actively with their learning environment. It may also encourage tacit knowledge renewal which makes firms more competitive. AR was used to facilitate collaboration among distributed team members via conferences with local and virtual participants. AR tasks included brainstorming and discussion meetings utilizing common visualization via touch screen tables, interactive digital whiteboards, shared design spaces and distributed control rooms.[253][254][255]

In industrial environments, augmented reality is proving to have a substantial impact with more and more use cases emerging across all aspect of the product lifecycle, starting from product design and new product introduction (NPI) to manufacturing to service and maintenance, to material handling and distribution. For example, labels were displayed on parts of a system to clarify operating instructions for a mechanic performing maintenance on a system.[256][257] Assembly lines benefited from the usage of AR. In addition to Boeing, BMW and Volkswagen were known for incorporating this technology into assembly lines for monitoring process improvements.[258][259][260] Big machines are difficult to maintain because of their multiple layers or structures. AR permits people to look through the machine as if with an x-ray, pointing them to the problem right away.[261]

As AR technology has evolved and second and third generation AR devices come to market, the impact of AR in enterprise continues to flourish. In the Harvard Business Review, Magid Abraham and Marco Annunziata discuss how AR devices are now being used to "boost workers' productivity on an array of tasks the first time they're used, even without prior training".[262] They contend that "these technologies increase productivity by making workers more skilled and efficient, and thus have the potential to yield both more economic growth and better jobs".[262]

Broadcast and live events[edit]

Weather visualizations were the first application of augmented reality in television. It has now become common in weather casting to display full motion video of images captured in real-time from multiple cameras and other imaging devices. Coupled with 3D graphics symbols and mapped to a common virtual geospatial model, these animated visualizations constitute the first true application of AR to TV.

AR has become common in sports telecasting. Sports and entertainment venues are provided with see-through and overlay augmentation through tracked camera feeds for enhanced viewing by the audience. Examples include the yellow "first down" line seen in television broadcasts of American football games showing the line the offensive team must cross to receive a first down. AR is also used in association with football and other sporting events to show commercial advertisements overlaid onto the view of the playing area. Sections of rugby fields and cricket pitches also display sponsored images. Swimming telecasts often add a line across the lanes to indicate the position of the current record holder as a race proceeds to allow viewers to compare the current race to the best performance. Other examples include hockey puck tracking and annotations of racing car performance[263] and snooker ball trajectories.[112][264]

AR has been used to enhance concert and theater performances. For example, artists allow listeners to augment their listening experience by adding their performance to that of other bands/groups of users.[265][266][267]

Tourism and sightseeing[edit]

Travelers may use AR to access real-time informational displays regarding a location, its features, and comments or content provided by previous visitors. Advanced AR applications include simulations of historical events, places, and objects rendered into the landscape.[268][269][270]

AR applications linked to geographic locations present location information by audio, announcing features of interest at a particular site as they become visible to the user.[271][272][273]

Translation[edit]

AR systems such as Word Lens can interpret the foreign text on signs and menus and, in a user's augmented view, re-display the text in the user's language. Spoken words of a foreign language can be translated and displayed in a user's view as printed subtitles.[274][275][276]

Music[edit]

It has been suggested that augmented reality may be used in new methods of music production, mixing, control and visualization.[277][278][279][280]

In a proof-of-concept project Ian Sterling, an interaction design student at California College of the Arts, and software engineer Swaroop Pal demonstrated a HoloLens app whose primary purpose is to provide a 3D spatial UI for cross-platform devices—the Android Music Player app and Arduino-controlled Fan and Light—and also allow interaction using gaze and gesture control.[281][282][283][284]

Research by members of the CRIStAL at the University of Lille makes use of augmented reality to enrich musical performance. The ControllAR project allows musicians to augment their MIDI control surfaces with the remixed graphical user interfaces of music software.[285] The Rouages project proposes to augment digital musical instruments to reveal their mechanisms to the audience and thus improve the perceived liveness.[286] Reflets is a novel augmented reality display dedicated to musical performances where the audience acts as a 3D display by revealing virtual content on stage, which can also be used for 3D musical interaction and collaboration.[287]

Snapchat[edit]

Snapchat users have access to augmented reality in the app through use of camera filters. In September 2017, Snapchat updated its app to include a camera filter that allowed users to render an animated, cartoon version of themselves called "Bitmoji". These animated avatars would be projected in the real world through the camera, and can be photographed or video recorded.[288] In the same month, Snapchat also announced a new feature called "Sky Filters" that will be available on its app. This new feature makes use of augmented reality to alter the look of a picture taken of the sky, much like how users can apply the app's filters to other pictures. Users can choose from sky filters such as starry night, stormy clouds, beautiful sunsets, and rainbow.[289]

Concerns[edit]

Reality modifications[edit]

In a paper titled "Death by Pokémon GO", researchers at Purdue University's Krannert School of Management claim the game caused "a disproportionate increase in vehicular crashes and associated vehicular damage, personal injuries, and fatalities in the vicinity of locations, called PokéStops, where users can play the game while driving."[290] Using data from one municipality, the paper extrapolates what that might mean nationwide and concluded "the increase in crashes attributable to the introduction of Pokémon GO is 145,632 with an associated increase in the number of injuries of 29,370 and an associated increase in the number of fatalities of 256 over the period of 6 July 2016, through 30 November 2016." The authors extrapolated the cost of those crashes and fatalities at between $2bn and $7.3 billion for the same period. Furthermore, more than one in three surveyed advanced Internet users would like to edit out disturbing elements around them, such as garbage or graffiti.[291] They would like to even modify their surroundings by erasing street signs, billboard ads, and uninteresting shopping windows. So it seems that AR is as much a threat to companies as it is an opportunity. Although, this could be a nightmare to numerous brands that do not manage to capture consumer imaginations it also creates the risk that the wearers of augmented reality glasses may become unaware of surrounding dangers. Consumers want to use augmented reality glasses to change their surroundings into something that reflects their own personal opinions. Around two in five want to change the way their surroundings look and even how people appear to them. [citation needed]

Next, to the possible privacy issues that are described below, overload and over-reliance issues are the biggest danger of AR. For the development of new AR-related products, this implies that the user-interface should follow certain guidelines as not to overload the user with information while also preventing the user from over-relying on the AR system such that important cues from the environment are missed.[18] This is called the virtually-augmented key.[18] Once the key is ignored, people might not desire the real world anymore.

Privacy concerns[edit]

The concept of modern augmented reality depends on the ability of the device to record and analyze the environment in real time. Because of this, there are potential legal concerns over privacy. While the First Amendment to the United States Constitution allows for such recording in the name of public interest, the constant recording of an AR device makes it difficult to do so without also recording outside of the public domain. Legal complications would be found in areas where a right to a certain amount of privacy is expected or where copyrighted media are displayed.

In terms of individual privacy, there exists the ease of access to information that one should not readily possess about a given person. This is accomplished through facial recognition technology. Assuming that AR automatically passes information about persons that the user sees, there could be anything seen from social media, criminal record, and marital status.[292]

The Code of Ethics on Human Augmentation, which was originally introduced by Steve Mann in 2004 and further refined with Ray Kurzweil and Marvin Minsky in 2013, was ultimately ratified at the virtual reality Toronto conference on 25 June 2017.[293][294][295][296]

Property law[edit]

The interaction of location-bound augmented reality with property law is largely undefined.[297][298] Several models have been analysed for how this interaction may be resolved in a common law context: an extension of real property rights to also cover augmentations on or near the property with a strong notion of trespassing, forbidding augmentations unless allowed by the owner; an 'open range' system, where augmentations are allowed unless forbidden by the owner; and a 'freedom to roam' system, where real property owners have no control over non-disruptive augmentations.[299]

One issue experienced during the Pokémon Go craze was the game's players disturbing owners of private property while visiting nearby location-bound augmentations, which may have been on the properties or the properties may have been en route. The terms of service of Pokémon Go explicitly disclaim responsibility for players' actions, which may limit (but may not totally extinguish) the liability of its producer, Niantic, in the event of a player trespassing while playing the game: by Niantic's argument, the player is the one committing the trespass, while Niantic has merely engaged in permissible free speech. A theory advanced in lawsuits brought against Niantic is that their placement of game elements in places that will lead to trespass or an exceptionally large flux of visitors can constitute nuisance, despite each individual trespass or visit only being tenuously caused by Niantic.[300][301][302]

Another claim raised against Niantic is that the placement of profitable game elements on land without permission of the land's owners is unjust enrichment.[303] More hypothetically, a property may be augmented with advertising or disagreeable content against its owner's wishes.[304] Under American law, these situations are unlikely to be seen as a violation of real property rights by courts without an expansion of those rights to include augmented reality (similarly to how English common law came to recognise air rights).[303]

An article in the Michigan Telecommunications and Technology Law Review argues that there are three bases for this extension, starting with various understanding of property. The personality theory of property, outlined by Margaret Radin, is claimed to support extending property rights due to the intimate connection between personhood and ownership of property; however, her viewpoint is not universally shared by legal theorists.[305] Under the utilitarian theory of property, the benefits from avoiding the harms to real property owners caused by augmentations and the tragedy of the commons, and the reduction in transaction costs by making discovery of ownership easy, were assessed as justifying recognising real property rights as covering location-bound augmentations, though there does remain the possibility of a tragedy of the anticommons from having to negotiate with property owners slowing innovation.[306] Finally, following the 'property as the law of things' identification as supported by Thomas Merrill and Henry E Smith, location-based augmentation is naturally identified as a 'thing', and, while the non-rivalrous and ephemeral nature of digital objects presents difficulties to the excludeability prong of the definition, the article argues that this is not insurmountable.[307]

Some attempts at legislative regulation have been made in the United States. Milwaukee County, Wisconsin attempted to regulate augmented reality games played in its parks, requiring prior issuance of a permit,[308] but this was criticised on free speech grounds by a federal judge;[309] and Illinois considered mandating a notice and take down procedure for location-bound augmentations.[310]

An article for the Iowa Law Review observed that dealing with many local permitting processes would be arduous for a large-scale service,[311] and, while the proposed Illinois mechanism could be made workable,[312] it was reactive and required property owners to potentially continually deal with new augmented reality services; instead, a national-level geofencing registry, analogous to a do-not-call list, was proposed as the most desirable form of regulation to efficiently balance the interests of both providers of augmented reality services and real property owners.[313] An article in the Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment and Technology Law, however, analyses a monolithic do-not-locate registry as an insufficiently flexible tool, either permitting unwanted augmentations or foreclosing useful applications of augmented reality.[314] Instead, it argues that an 'open range' model, where augmentations are permitted by default but property owners may restrict them on a case-by-case basis (and with noncompliance treated as a form of trespass), will produce the socially-best outcome.[315]

Notable researchers[edit]

- Ivan Sutherland invented the first VR head-mounted display at Harvard University.

- Steve Mann formulated an earlier concept of mediated reality in the 1970s and 1980s, using cameras, processors, and display systems to modify visual reality to help people see better (dynamic range management), building computerized welding helmets, as well as "augmediated reality" vision systems for use in everyday life. He is also an adviser to Meta.[316]

- Ronald Azuma is a scientist and author of works on AR.

- Dieter Schmalstieg and Daniel Wagner developed a marker tracking systems for mobile phones and PDAs in 2009.[317]

- Jeri Ellsworth headed a research effort for Valve on augmented reality (AR), later taking that research to her own start-up CastAR. The company, founded in 2013, eventually shuttered. Later, she created another start-up based on the same technology called Tilt Five; another AR start-up formed by her with the purpose of creating a device for digital board games.[318]

In media[edit]

The futuristic short film Sight[319] features contact lens-like augmented reality devices.[320][321]

See also[edit]

- ARTag – Fiduciary marker

- Browser extension, also known as Augmented browsing – Program that extends the functionality of a web browser

- Augmented reality-based testing – type of testing

- Augmented web – Web technology

- Automotive head-up display – Advanced driver assistance system

- Bionic contact lens – Proposed device to display information

- Computer-mediated reality – Ability to manipulate one's perception of reality through the use of a computer

- Cyborg – Being with both organic and biomechatronic body parts

- Head-mounted display – Type of display device

- Holography – Recording to reproduce a three-dimensional light field

- List of augmented reality software

- Location-based service – General class of computer program-level services that use location data to control features

- Смешанная реальность – объединение реального и виртуального миров для создания новой среды.

- Оптический головной дисплей – Тип носимого устройства

- Имитированная реальность - концепция ложной версии реальности.

- Smartglasses – очки для портативного компьютера.

- Виртуальная реальность – опыт, смоделированный на компьютере

- Визуально-гаптическая смешанная реальность

- Носимый компьютер - небольшое вычислительное устройство, носимое на теле.

Ссылки [ править ]

- ^ Чипрессо, Пьетро; Джильоли, Ирен Алиса Чикки; Рая, из; Рива, Джузеппе (7 декабря 2011 г.). «Прошлое, настоящее и будущее исследований виртуальной и дополненной реальности: сетевой и кластерный анализ литературы» . Границы в психологии . 9 : 2086. doi : 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02086 . ПМК 6232426 . ПМИД 30459681 .

- ^ У, Синь-Кай; Ли, Сильвия Вен-Ю; Чанг, Синь-И; Лян, Джых-Чонг (март 2013 г.). «Современное состояние, возможности и проблемы дополненной реальности в образовании...». Компьютеры и образование . 62 : 41–49. дои : 10.1016/j.compedu.2012.10.024 . S2CID 15218665 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д Розенберг, Луи Б. (1992). «Использование виртуальных приспособлений в качестве наложений на восприятие для повышения производительности оператора в удаленных средах» . Архивировано из оригинала 10 июля 2019 года.

- ^ Милгрэм, Пол; Такемура, Харуо; Уцуми, Акира; Кишино, Фумио (21 декабря 1995 г.). «Дополненная реальность: класс отображений континуума реальности-виртуальности» . Телеманипуляторы и технологии телеприсутствия . 2351 . ШПАЙ: 282–292. Бибкод : 1995SPIE.2351..282M . дои : 10.1117/12.197321 .

- ^ налог, «Определение виртуальной реальности: аспекты, определяющие телеприсутствие» . Архивировано из оригинала 17 июля 2022 года . Проверено 27 ноября 2018 г. , факультет коммуникаций Стэнфордского университета. 15 октября 1993 г.

- ^ Знакомство с виртуальными средами. Архивировано 21 апреля 2016 года в Национальном центре суперкомпьютерных приложений Wayback Machine , Университет Иллинойса.

- ^ Розенберг, Л.Б. (1993). «Виртуальные приспособления: инструменты восприятия для манипуляций с телероботами». Материалы ежегодного международного симпозиума IEEE по виртуальной реальности . стр. 76–82. дои : 10.1109/VRAIS.1993.380795 . ISBN 0-7803-1363-1 . S2CID 9856738 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Дупчик, Кевин (6 сентября 2016 г.). «Я видел будущее через гололинзы Microsoft» . Популярная механика .

- ^ Арай, Кохей, изд. (2022), «Дополненная реальность: размышления за тридцать лет» , Материалы конференции Future Technologies Conference (FTC) 2021, Том 1 , Конспекты лекций по сетям и системам, том. 358, Чам: Springer International Publishing, стр. 1–11, номер номера : 10.1007/978-3-030-89906-6_1 , ISBN. 978-3-030-89905-9 , S2CID 239881216

- ^ Моро, Кристиан; Бирт, Джеймс; Стромберга, Зейн; Фелпс, Шарлотта; Кларк, Джастин; Глазиу, Пол; Скотт, Анна Мэй (2021). «Усовершенствования виртуальной и дополненной реальности для выполнения тестов студентов-медиков и естественных наук по физиологии и анатомии: систематический обзор и метаанализ» . Образование в области анатомических наук . 14 (3): 368–376. дои : 10.1002/ase.2049 . ISSN 1935-9772 . ПМИД 33378557 . S2CID 229929326 .

- ^ «Как преобразовать ваш класс с помощью дополненной реальности — EdSurge News» . 2 ноября 2015 г.

- ^ Краббен, Ян ван дер (16 октября 2018 г.). «Почему нам нужно больше технологий в историческом образовании» . древний.eu . Архивировано из оригинала 23 октября 2018 года . Проверено 23 октября 2018 г.

- ^ Дарган, Шавета; Бансал, Шалли; Миттал, Аджай; Кумар, Кришан (2023). «Дополненная реальность: комплексный обзор» . Архив вычислительных методов в технике . 30 (2): 1057–1080. дои : 10.1007/s11831-022-09831-7 . Проверено 27 февраля 2024 г.

- ^ Хегде, Навин (19 марта 2023 г.). «Что такое дополненная реальность» . Кодегрес . Проверено 19 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Чен, Брайан (25 августа 2009 г.). «Если вы не видите данные, вы не видите» . Проводной . Проверено 18 июня 2019 г.

- ^ Максвелл, Керри. «Дополненная реальность» . macmillandictionary.com . Проверено 18 июня 2019 г.

- ^ «Дополненная реальность (AR)» . дополненная реальность.com . Архивировано из оригинала 5 апреля 2012 года . Проверено 18 июня 2019 г.